In computer science a for-loop or for loop is a control flow statement for specifying iteration. Specifically, a for loop functions by running a section of code repeatedly until a certain condition has been satisfied.

For-loops have two parts: a header and a body. The header defines the iteration and the body is the code that is executed once per iteration. The header often declares an explicit loop counter or loop variable. This allows the body to know which iteration is being executed. For-loops are typically used when the number of iterations is known before entering the loop. For-loops can be thought of as shorthands for while-loops which increment and test a loop variable.

Various keywords are used to indicate the usage of a for loop: descendants of ALGOL use «for», while descendants of Fortran use «do». There are other possibilities, for example COBOL which uses «PERFORM VARYING».

The name for-loop comes from the word for. For is used as the keyword in many programming languages to introduce a for-loop. The term in English dates to ALGOL 58 and was popularized in ALGOL 60. It is the direct translation of the earlier German für and was used in Superplan (1949–1951) by Heinz Rutishauser. Rutishauser was involved in defining ALGOL 58 and ALGOL 60.[citation needed] The loop body is executed «for» the given values of the loop variable. This is more explicit in ALGOL versions of the for statement where a list of possible values and increments can be specified.

In Fortran and PL/I, the keyword DO is used for the same thing and it is called a do-loop; this is different from a do-while loop.

FOR[edit]

For loop illustration, from i=0 to i=2, resulting in data1=200

A for-loop statement is available in most imperative programming languages. Even ignoring minor differences in syntax there are many differences in how these statements work and the level of expressiveness they support. Generally, for-loops fall into one of the following categories:

Traditional for-loops[edit]

The for-loop of languages like ALGOL, Simula, BASIC, Pascal, Modula, Oberon, Ada, Matlab, Ocaml, F#, and so on, requires a control variable with start- and end-values, which looks something like this:

for i = first to last do statement (* or just *) for i = first..last do statement

Depending on the language, an explicit assignment sign may be used in place of the equal sign (and some languages require the word int even in the numerical case). An optional step-value (an increment or decrement ≠ 1) may also be included, although the exact syntaxes used for this differs a bit more between the languages. Some languages require a separate declaration of the control variable, some do not.

Another form was popularized by the C programming language. It requires 3 parts: the initialization (loop variant), the condition, and the advancement to the next iteration. All these three parts are optional.[1] This type of «semicolon loops» came from B programming language and it was originally invented by Stephen Johnson.[2]

In the initialization part, any variables needed are declared (and usually assigned values). If multiple variables are declared, they should all be of the same type. The condition part checks a certain condition and exits the loop if false, even if the loop is never executed. If the condition is true, then the lines of code inside the loop are executed. The advancement to the next iteration part is performed exactly once every time the loop ends. The loop is then repeated if the condition evaluates to true.

Here is an example of the C-style traditional for-loop in Java.

// Prints the numbers from 0 to 99 (and not 100), each followed by a space. for (int i=0; i<100; i++) { System.out.print(i); System.out.print(' '); } System.out.println();

These loops are also sometimes called numeric for-loops when contrasted with foreach loops (see below).

Iterator-based for-loops[edit]

This type of for-loop is a generalisation of the numeric range type of for-loop, as it allows for the enumeration of sets of items other than number sequences. It is usually characterized by the use of an implicit or explicit iterator, in which the loop variable takes on each of the values in a sequence or other data collection. A representative example in Python is:

for item in some_iterable_object: do_something() do_something_else()

Where some_iterable_object is either a data collection that supports implicit iteration (like a list of employee’s names), or may in fact be an iterator itself. Some languages have this in addition to another for-loop syntax; notably, PHP has this type of loop under the name for each, as well as a three-expression for-loop (see below) under the name for.

Vectorised for-loops[edit]

Some languages offer a for-loop that acts as if processing all iterations in parallel, such as the for all keyword in FORTRAN 95 which has the interpretation that all right-hand-side expressions are evaluated before any assignments are made, as distinct from the explicit iteration form. For example, in the for statement in the following pseudocode fragment, when calculating the new value for A(i), except for the first (with i = 2) the reference to A(i - 1) will obtain the new value that had been placed there in the previous step. In the for all version, however, each calculation refers only to the original, unaltered A.

for i := 2 : N - 1 do A(i) := [A(i - 1) + A(i) + A(i + 1)] / 3; next i; for all i := 2 : N - 1 do A(i) := [A(i - 1) + A(i) + A(i + 1)] / 3;

The difference may be significant.

Some languages (such as FORTRAN 95, PL/I) also offer array assignment statements, that enable many for-loops to be omitted. Thus pseudocode such as A := 0; would set all elements of array A to zero, no matter its size or dimensionality. The example loop could be rendered as

A(2 : N - 1) := [A(1 : N - 2) + A(2 : N - 1) + A(3 : N)] / 3;

But whether that would be rendered in the style of the for-loop or the for all-loop or something else may not be clearly described in the compiler manual.

Compound for-loops[edit]

Introduced with ALGOL 68 and followed by PL/I, this allows the iteration of a loop to be compounded with a test, as in

for i := 1 : N while A(i) > 0 do etc.

That is, a value is assigned to the loop variable i and only if the while expression is true will the loop body be executed. If the result were false the for-loop’s execution stops short. Granted that the loop variable’s value is defined after the termination of the loop, then the above statement will find the first non-positive element in array A (and if no such, its value will be N + 1), or, with suitable variations, the first non-blank character in a string, and so on.

Loop counters[edit]

In computer programming, a loop counter is a control variable that controls the iterations of a loop (a computer programming language construct). It is so named because most uses of this construct result in the variable taking on a range of integer values in some orderly sequences (example., starting at 0 and end at 10 in increments of 1)

Loop counters change with each iteration of a loop, providing a unique value for each individual iteration. The loop counter is used to decide when the loop should terminate and for the program flow to continue to the next instruction after the loop.

A common identifier naming convention is for the loop counter to use the variable names i, j, and k (and so on if needed), where i would be the most outer loop, j the next inner loop, etc. The reverse order is also used by some programmers. This style is generally agreed to have originated from the early programming of Fortran[citation needed], where these variable names beginning with these letters were implicitly declared as having an integer type, and so were obvious choices for loop counters that were only temporarily required. The practice dates back further to mathematical notation where indices for sums and multiplications are often i, j, etc. A variant convention is the use of reduplicated letters for the index, ii, jj, and kk, as this allows easier searching and search-replacing than using a single letter.[3]

Example[edit]

An example of C code involving nested for loops, where the loop counter variables are i and j:

for (i = 0; i < 100; i++) { for (j = i; j < 10; j++) { some_function(i, j); } }

For loops in C can also be used to print the reverse of a word. As:

for (i = 0; i < 6; i++) { scanf("%c", &a[i]); } for (i = 4; i >= 0; i--) { printf("%c", a[i]); }

Here, if the input is apple, the output will be elppa.

Additional semantics and constructs[edit]

Use as infinite loops[edit]

This C-style for-loop is commonly the source of an infinite loop since the fundamental steps of iteration are completely in the control of the programmer. In fact, when infinite loops are intended, this type of for-loop can be used (with empty expressions), such as:

This style is used instead of infinite while (1) loops to avoid a type conversion warning in some C/C++ compilers.[4] Some programmers prefer the more succinct for (;;) form over the semantically equivalent but more verbose while (true) form.

Early exit and continuation[edit]

Some languages may also provide other supporting statements, which when present can alter how the for-loop iteration proceeds.

Common among these are the break and continue statements found in C and its derivatives.

The break statement causes the inner-most loop to be terminated immediately when executed.

The continue statement will move at once to the next iteration without further progress through the loop body for the current iteration.

A for statement also terminates when a break, goto, or return statement within the statement body is executed. [Wells]

Other languages may have similar statements or otherwise provide means to alter the for-loop progress; for example in FORTRAN 95:

DO I = 1, N statements !Executed for all values of "I", up to a disaster if any. IF (no good) CYCLE !Skip this value of "I", continue with the next. statements !Executed only where goodness prevails. IF (disaster) EXIT !Abandon the loop. statements !While good and, no disaster. END DO !Should align with the "DO".

Some languages offer further facilities such as naming the various loop statements so that with multiple nested loops there is no doubt as to which loop is involved. Fortran 95, for example:

X1:DO I = 1,N statements X2:DO J = 1,M statements IF (trouble) CYCLE X1 statements END DO X2 statements END DO X1

Thus, when «trouble» is detected in the inner loop, the CYCLE X1 (not X2) means that the skip will be to the next iteration for I, not J. The compiler will also be checking that each END DO has the appropriate label for its position: this is not just a documentation aid. The programmer must still code the problem correctly, but some possible blunders will be blocked.

Loop variable scope and semantics[edit]

Different languages specify different rules for what value the loop variable will hold on termination of its loop, and indeed some hold that it «becomes undefined». This permits a compiler to generate code that leaves any value in the loop variable, or perhaps even leaves it unchanged because the loop value was held in a register and never stored to memory. Actual behaviour may even vary according to the compiler’s optimization settings, as with the Honywell Fortran66 compiler.

In some languages (not C or C++) the loop variable is immutable within the scope of the loop body, with any attempt to modify its value being regarded as a semantic error. Such modifications are sometimes a consequence of a programmer error, which can be very difficult to identify once made. However, only overt changes are likely to be detected by the compiler. Situations where the address of the loop variable is passed as an argument to a subroutine make it very difficult to check, because the routine’s behavior is in general unknowable to the compiler. Some examples in the style of Fortran:

DO I = 1, N I = 7 !Overt adjustment of the loop variable. Compiler complaint likely. Z = ADJUST(I) !Function "ADJUST" might alter "I", to uncertain effect. normal statements !Memory might fade that "I" is the loop variable. PRINT (A(I), B(I), I = 1, N, 2) !Implicit for-loop to print odd elements of arrays A and B, reusing "I"... PRINT I !What value will be presented? END DO !How many times will the loop be executed?

A common approach is to calculate the iteration count at the start of a loop (with careful attention to overflow as in for i := 0 : 65535 do ... ; in sixteen-bit integer arithmetic) and with each iteration decrement this count while also adjusting the value of I: double counting results. However, adjustments to the value of I within the loop will not change the number of iterations executed.

Still another possibility is that the code generated may employ an auxiliary variable as the loop variable, possibly held in a machine register, whose value may or may not be copied to I on each iteration. Again, modifications of I would not affect the control of the loop, but now a disjunction is possible: within the loop, references to the value of I might be to the (possibly altered) current value of I or to the auxiliary variable (held safe from improper modification) and confusing results are guaranteed. For instance, within the loop a reference to element I of an array would likely employ the auxiliary variable (especially if it were held in a machine register), but if I is a parameter to some routine (for instance, a print-statement to reveal its value), it would likely be a reference to the proper variable I instead. It is best to avoid such possibilities.

Adjustment of bounds[edit]

Just as the index variable might be modified within a for-loop, so also may its bounds and direction. But to uncertain effect. A compiler may prevent such attempts, they may have no effect, or they might even work properly — though many would declare that to do so would be wrong. Consider a statement such as

for i := first : last : step do A(i) := A(i) / A(last);

If the approach to compiling such a loop was to be the evaluation of first, last and step and the calculation of an iteration count via something like (last - first)/step once only at the start, then if those items were simple variables and their values were somehow adjusted during the iterations, this would have no effect on the iteration count even if the element selected for division by A(last) changed.

List of value ranges[edit]

PL/I and Algol 68, allows loops in which the loop variable is iterated over a list of ranges of values instead of a single range. The following PL/I example will execute the loop with six values of i: 1, 7, 12, 13, 14, 15:

do i = 1, 7, 12 to 15; /*statements*/ end;

Equivalence with while-loops[edit]

A for-loop is generally equivalent to a while-loop:

factorial := 1

for counter from 2 to 5

factorial := factorial * counter

counter := counter - 1

print counter + "! equals " + factorial

is equivalent to:

factorial := 1

counter := 1

while counter < 5

counter := counter + 1

factorial := factorial * counter

print counter + "! equals " + factorial

as demonstrated by the output of the variables.

Timeline of the for-loop syntax in various programming languages[edit]

Given an action that must be repeated, for instance, five times, different languages’ for-loops will be written differently. The syntax for a three-expression for-loop is nearly identical in all languages that have it, after accounting for different styles of block termination and so on.

1957: FORTRAN[edit]

Fortran’s equivalent of the for loop is the DO loop,

using the keyword do instead of for,

The syntax of Fortran’s DO loop is:

DO label counter = first, last, step statements label statement

The following two examples behave equivalently to the three argument for-loop in other languages,

initializing the counter variable to 1, incrementing by 1 each iteration of the loop and stopping at five (inclusive).

DO 9, COUNTER = 1, 5, 1 WRITE (6,8) COUNTER 8 FORMAT( I2 ) 9 CONTINUE

In Fortran 77 (or later), this may also be written as:

do counter = 1, 5 write(*, '(i2)') counter end do

The step part may be omitted if the step is one. Example:

* DO loop example. PROGRAM MAIN SUM SQ = 0 DO 199 I = 1, 9999999 IF (SUM SQ.GT.1000) GO TO 200 199 SUM SQ = SUM SQ + I**2 200 PRINT 206, SUMSQ 206 FORMAT( I2 ) END

Spaces are irrelevant in fixed-form Fortran statements, thus SUM SQ is the same as SUMSQ. In the modern free-form Fortran style, blanks are significant.

In Fortran 90, the GO TO may be avoided by using an EXIT statement.

* DO loop example. program main implicit none integer :: sumsq integer :: i sumsq = 0 do i = 1, 9999999 if (sumsq > 1000.0) exit sumsq = sumsq + i**2 end do print *, sumsq end program

1958: ALGOL[edit]

ALGOL 58 introduced the for statement, using the form as Superplan:

FOR Identifier = Base (Difference) Limit

For example to print 0 to 10 incremented by 1:

FOR x = 0 (1) 10 BEGIN PRINT (FL) = x END

1960: COBOL[edit]

COBOL was formalized in late 1959 and has had many elaborations. It uses the PERFORM verb which has many options. Originally all loops had to be out-of-line with the iterated code occupying a separate paragraph. Ignoring the need for declaring and initialising variables, the COBOL equivalent of a for-loop would be.

PERFORM SQ-ROUTINE VARYING I FROM 1 BY 1 UNTIL I > 1000 SQ-ROUTINE ADD I**2 TO SUM-SQ.

In the 1980s the addition of in-line loops and «structured» statements such as END-PERFORM resulted in a for-loop with a more familiar structure.

PERFORM VARYING I FROM 1 BY 1 UNTIL I > 1000 ADD I**2 TO SUM-SQ. END-PERFORM

If the PERFORM verb has the optional clause TEST AFTER, the resulting loop is slightly different: the loop body is executed at least once, before any test.

1964: BASIC[edit]

Loops in BASIC are sometimes called for-next loops.

10 REM THIS FOR LOOP PRINTS ODD NUMBERS FROM 1 TO 15 20 FOR I = 1 TO 15 STEP 2 30 PRINT I 40 NEXT I

Notice that the end-loop marker specifies the name of the index variable, which must correspond to the name of the index variable in the start of the for-loop. Some languages (PL/I, FORTRAN 95 and later) allow a statement label on the start of a for-loop that can be matched by the compiler against the same text on the corresponding end-loop statement. Fortran also allows the EXIT and CYCLE statements to name this text; in a nest of loops this makes clear which loop is intended. However, in these languages the labels must be unique, so successive loops involving the same index variable cannot use the same text nor can a label be the same as the name of a variable, such as the index variable for the loop.

1964: PL/I[edit]

do counter = 1 to 5 by 1; /* "by 1" is the default if not specified */ /*statements*/; end;

The LEAVE statement may be used to exit the loop. Loops can be labeled, and leave may leave a specific labeled loop in a group of nested loops. Some PL/I dialects include the ITERATE statement to terminate the current loop iteration and begin the next.

1968: Algol 68[edit]

ALGOL 68 has what was considered the universal loop, the full syntax is:

FOR i FROM 1 BY 2 TO 3 WHILE i≠4 DO ~ OD

Further, the single iteration range could be replaced by a list of such ranges. There are several unusual aspects of the construct

- only the

do ~ odportion was compulsory, in which case the loop will iterate indefinitely. - thus the clause

to 100 do ~ od, will iterate exactly 100 times. - the

whilesyntactic element allowed a programmer to break from aforloop early, as in:

INT sum sq := 0;

FOR i

WHILE

print(("So far:", i, new line)); # Interposed for tracing purposes. #

sum sq ≠ 70↑2 # This is the test for the WHILE #

DO

sum sq +:= i↑2

OD

Subsequent extensions to the standard Algol68 allowed the to syntactic element to be replaced with upto and downto to achieve a small optimization. The same compilers also incorporated:

until- for late loop termination.

foreach- for working on arrays in parallel.

1970: Pascal[edit]

for Counter := 1 to 5 do (*statement*);

Decrementing (counting backwards) is using downto keyword instead of to, as in:

for Counter := 5 downto 1 do (*statement*);

The numeric-range for-loop varies somewhat more.

1972: C/C++[edit]

for (initialization; condition; increment/decrement) statement

The statement is often a block statement; an example of this would be:

//Using for-loops to add numbers 1 - 5 int sum = 0; for (int i = 0; i < 5; ++i) { sum += i; }

The ISO/IEC 9899:1999 publication (commonly known as C99) also allows initial declarations in for loops. All the three sections in the for loop are optional, with an empty condition equivalent to true.

1972: Smalltalk[edit]

1 to: 5 do: [ :counter | "statements" ]

Contrary to other languages, in Smalltalk a for-loop is not a language construct but defined in the class Number as a method with two parameters, the end value and a closure, using self as start value.

1980: Ada[edit]

for Counter in 1 .. 5 loop -- statements end loop;

The exit statement may be used to exit the loop. Loops can be labeled, and exit may leave a specifically labeled loop in a group of nested loops:

Counting: for Counter in 1 .. 5 loop Triangle: for Secondary_Index in 2 .. Counter loop -- statements exit Counting; -- statements end loop Triangle; end loop Counting;

1980: Maple[edit]

Maple has two forms of for-loop, one for iterating of a range of values, and the other for iterating over the contents of a container. The value range form is as follows:

for i from f by b to t while w do

# loop body

od;

All parts except do and od are optional. The for i part, if present, must come first. The remaining parts (from f, by b, to t, while w) can appear in any order.

Iterating over a container is done using this form of loop:

for e in c while w do

# loop body

od;

The in c clause specifies the container, which may be a list, set, sum, product, unevaluated function, array, or an object implementing an iterator.

A for-loop may be terminated by od, end, or end do.

1982: Maxima CAS[edit]

In Maxima CAS one can use also non integer values :

for x:0.5 step 0.1 thru 0.9 do

/* "Do something with x" */

1982: PostScript[edit]

The for-loop, written as [initial] [increment] [limit] { ... } for initialises an internal variable, executes the body as long as the internal variable is not more than limit (or not less, if increment is negative) and, at the end of each iteration, increments the internal variable. Before each iteration, the value of the internal variable is pushed onto the stack.[5]

There is also a simple repeat-loop.

The repeat-loop, written as X { ... } repeat, repeats the body exactly X times.[6]

1983: Ada 83 and above[edit]

procedure Main is Sum_Sq : Integer := 0; begin for I in 1 .. 9999999 loop if Sum_Sq <= 1000 then Sum_Sq := Sum_Sq + I**2 end if; end loop; end;

1984: MATLAB[edit]

for n = 1:5 -- statements end

After the loop, n would be 5 in this example.

As i is used for the Imaginary unit, its use as a loop variable is discouraged.

1987: Perl[edit]

for ($counter = 1; $counter <= 5; $counter++) { # implicitly or predefined variable # statements; } for (my $counter = 1; $counter <= 5; $counter++) { # variable private to the loop # statements; } for (1..5) { # variable implicitly called $_; 1..5 creates a list of these 5 elements # statements; } statement for 1..5; # almost same (only 1 statement) with natural language order for my $counter (1..5) { # variable private to the loop # statements; }

(Note that «there’s more than one way to do it» is a Perl programming motto.)

1988: Mathematica[edit]

The construct corresponding to most other languages’ for-loop is called Do in Mathematica

Mathematica also has a For construct that mimics the for-loop of C-like languages

For[x= 0 , x <= 1, x += 0.1, f[x] ]

1989: Bash[edit]

# first form for i in 1 2 3 4 5 do # must have at least one command in loop echo $i # just print value of i done

# second form for (( i = 1; i <= 5; i++ )) do # must have at least one command in loop echo $i # just print value of i done

Note that an empty loop (i.e., one with no commands between do and done) is a syntax error. If the above loops contained only comments, execution would result in the message «syntax error near unexpected token ‘done'».

1990: Haskell[edit]

The built-in imperative forM_ maps a monadic expression into a list, as

forM_ [1..5] $ indx -> do statements

or get each iteration result as a list in

statements_result_list <- forM [1..5] $ indx -> do statements

But, if you want to save the space of the [1..5] list,

a more authentic monadic forLoop_ construction can be defined as

import Control.Monad as M forLoopM_ :: Monad m => a -> (a -> Bool) -> (a -> a) -> (a -> m ()) -> m () forLoopM_ indx prop incr f = do f indx M.when (prop next) $ forLoopM_ next prop incr f where next = incr indx

and used as:

forLoopM_ (0::Int) (< len) (+1) $ indx -> do -- whatever with the index

1991: Oberon-2, Oberon-07, or Component Pascal[edit]

FOR Counter := 1 TO 5 DO (* statement sequence *) END

Note that in the original Oberon language the for-loop was omitted in favor of the more general Oberon loop construct. The for-loop was reintroduced in Oberon-2.

1991: Python[edit]

Python does not contain the classical for loop, rather a foreach loop is used to iterate over the output of the built-in range() function which returns an iterable sequence of integers.

for i in range(1, 6): # gives i values from 1 to 5 inclusive (but not 6) # statements print(i) # if we want 6 we must do the following for i in range(1, 6 + 1): # gives i values from 1 to 6 # statements print(i)

Using range(6) would run the loop from 0 to 5.

1993: AppleScript[edit]

repeat with i from 1 to 5 -- statements log i end repeat

You can also iterate through a list of items, similar to what you can do with arrays in other languages:

set x to {1, "waffles", "bacon", 5.1, false} repeat with i in x log i end repeat

You may also use exit repeat to exit a loop at any time. Unlike other languages, AppleScript does not currently have any command to continue to the next iteration of a loop.

1993: Crystal[edit]

for i = start, stop, interval do -- statements end

So, this code

for i = 1, 5, 2 do print(i) end

will print:

For-loops can also loop through a table using

to iterate numerically through arrays and

to iterate randomly through dictionaries.

Generic for-loop making use of closures:

for name, phone, address in contacts() do -- contacts() must be an iterator function end

1995: CFML[edit]

Script syntax[edit]

Simple index loop:

for (i = 1; i <= 5; i++) { // statements }

Using an array:

for (i in [1,2,3,4,5]) { // statements }

Using a list of string values:

loop index="i" list="1;2,3;4,5" delimiters=",;" { // statements }

The above list example is only available in the dialect of CFML used by Lucee and Railo.

Tag syntax[edit]

Simple index loop:

<cfloop index="i" from="1" to="5"> <!--- statements ---> </cfloop>

Using an array:

<cfloop index="i" array="#[1,2,3,4,5]#"> <!--- statements ---> </cfloop>

Using a «list» of string values:

<cfloop index="i" list="1;2,3;4,5" delimiters=",;"> <!--- statements ---> </cfloop>

1995: Java[edit]

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) { //perform functions within the loop; //can use the statement 'break;' to exit early; //can use the statement 'continue;' to skip the current iteration }

For the extended for-loop, see Foreach loop § Java.

1995: JavaScript[edit]

JavaScript supports C-style «three-expression» loops. The break and continue statements are supported inside loops.

for (var i = 0; i < 5; i++) { // ... }

Alternatively, it is possible to iterate over all keys of an array.

for (var key in array) { // also works for assoc. arrays // use array[key] ... }

1995: PHP[edit]

This prints out a triangle of *

for ($i = 0; $i <= 5; $i++) { for ($j = 0; $j <= $i; $j++) { echo "*"; } echo "<br />n"; }

1995: Ruby[edit]

for counter in 1..5 # statements end 5.times do |counter| # counter iterates from 0 to 4 # statements end 1.upto(5) do |counter| # statements end

Ruby has several possible syntaxes, including the above samples.

1996: OCaml[edit]

See expression syntax.[7]

(* for_statement := "for" ident '=' expr ( "to" ∣ "downto" ) expr "do" expr "done" *) for i = 1 to 5 do (* statements *) done ;; for j = 5 downto 0 do (* statements *) done ;;

1998: ActionScript 3[edit]

for (var counter:uint = 1; counter <= 5; counter++){ //statement; }

2008: Small Basic[edit]

For i = 1 To 10 ' Statements EndFor

2008: Nim[edit]

Nim has a foreach-type loop and various operations for creating iterators.[8]

for i in 5 .. 10: # statements

2009: Go[edit]

for i := 0; i <= 10; i++ { // statements }

2010: Rust[edit]

for i in 0..10 { // statements }

2012: Julia[edit]

for j = 1:10 # statements end

See also[edit]

- Do while loop

- Foreach

- While loop

References[edit]

- ^ «For loops in C++».

- ^ Ken Thompson. «VCF East 2019 — Brian Kernighan interviews Ken Thompson». Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

I saw Johnson’s semicolon version of the for loop and I put that in [B], I stole it.

- ^ http://www.knosof.co.uk/vulnerabilities/loopcntrl.pdf Analysis of loop control variables in C

- ^ «Compiler Warning (level 4) C4127». Microsoft. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ^ PostScript Language Reference. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. p. 596. ISBN 0-201-37922-8.

- ^ «PostScript Tutorial — Loops».

- ^ «OCaml expression syntax». Archived from the original on 2013-04-12. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- ^ https://nim-lang.org/docs/system.html#…i%2CT%2CT «.. iterator»

In computer science a for-loop or for loop is a control flow statement for specifying iteration. Specifically, a for loop functions by running a section of code repeatedly until a certain condition has been satisfied.

For-loops have two parts: a header and a body. The header defines the iteration and the body is the code that is executed once per iteration. The header often declares an explicit loop counter or loop variable. This allows the body to know which iteration is being executed. For-loops are typically used when the number of iterations is known before entering the loop. For-loops can be thought of as shorthands for while-loops which increment and test a loop variable.

Various keywords are used to indicate the usage of a for loop: descendants of ALGOL use «for», while descendants of Fortran use «do». There are other possibilities, for example COBOL which uses «PERFORM VARYING».

The name for-loop comes from the word for. For is used as the keyword in many programming languages to introduce a for-loop. The term in English dates to ALGOL 58 and was popularized in ALGOL 60. It is the direct translation of the earlier German für and was used in Superplan (1949–1951) by Heinz Rutishauser. Rutishauser was involved in defining ALGOL 58 and ALGOL 60.[citation needed] The loop body is executed «for» the given values of the loop variable. This is more explicit in ALGOL versions of the for statement where a list of possible values and increments can be specified.

In Fortran and PL/I, the keyword DO is used for the same thing and it is called a do-loop; this is different from a do-while loop.

FOR[edit]

For loop illustration, from i=0 to i=2, resulting in data1=200

A for-loop statement is available in most imperative programming languages. Even ignoring minor differences in syntax there are many differences in how these statements work and the level of expressiveness they support. Generally, for-loops fall into one of the following categories:

Traditional for-loops[edit]

The for-loop of languages like ALGOL, Simula, BASIC, Pascal, Modula, Oberon, Ada, Matlab, Ocaml, F#, and so on, requires a control variable with start- and end-values, which looks something like this:

for i = first to last do statement (* or just *) for i = first..last do statement

Depending on the language, an explicit assignment sign may be used in place of the equal sign (and some languages require the word int even in the numerical case). An optional step-value (an increment or decrement ≠ 1) may also be included, although the exact syntaxes used for this differs a bit more between the languages. Some languages require a separate declaration of the control variable, some do not.

Another form was popularized by the C programming language. It requires 3 parts: the initialization (loop variant), the condition, and the advancement to the next iteration. All these three parts are optional.[1] This type of «semicolon loops» came from B programming language and it was originally invented by Stephen Johnson.[2]

In the initialization part, any variables needed are declared (and usually assigned values). If multiple variables are declared, they should all be of the same type. The condition part checks a certain condition and exits the loop if false, even if the loop is never executed. If the condition is true, then the lines of code inside the loop are executed. The advancement to the next iteration part is performed exactly once every time the loop ends. The loop is then repeated if the condition evaluates to true.

Here is an example of the C-style traditional for-loop in Java.

// Prints the numbers from 0 to 99 (and not 100), each followed by a space. for (int i=0; i<100; i++) { System.out.print(i); System.out.print(' '); } System.out.println();

These loops are also sometimes called numeric for-loops when contrasted with foreach loops (see below).

Iterator-based for-loops[edit]

This type of for-loop is a generalisation of the numeric range type of for-loop, as it allows for the enumeration of sets of items other than number sequences. It is usually characterized by the use of an implicit or explicit iterator, in which the loop variable takes on each of the values in a sequence or other data collection. A representative example in Python is:

for item in some_iterable_object: do_something() do_something_else()

Where some_iterable_object is either a data collection that supports implicit iteration (like a list of employee’s names), or may in fact be an iterator itself. Some languages have this in addition to another for-loop syntax; notably, PHP has this type of loop under the name for each, as well as a three-expression for-loop (see below) under the name for.

Vectorised for-loops[edit]

Some languages offer a for-loop that acts as if processing all iterations in parallel, such as the for all keyword in FORTRAN 95 which has the interpretation that all right-hand-side expressions are evaluated before any assignments are made, as distinct from the explicit iteration form. For example, in the for statement in the following pseudocode fragment, when calculating the new value for A(i), except for the first (with i = 2) the reference to A(i - 1) will obtain the new value that had been placed there in the previous step. In the for all version, however, each calculation refers only to the original, unaltered A.

for i := 2 : N - 1 do A(i) := [A(i - 1) + A(i) + A(i + 1)] / 3; next i; for all i := 2 : N - 1 do A(i) := [A(i - 1) + A(i) + A(i + 1)] / 3;

The difference may be significant.

Some languages (such as FORTRAN 95, PL/I) also offer array assignment statements, that enable many for-loops to be omitted. Thus pseudocode such as A := 0; would set all elements of array A to zero, no matter its size or dimensionality. The example loop could be rendered as

A(2 : N - 1) := [A(1 : N - 2) + A(2 : N - 1) + A(3 : N)] / 3;

But whether that would be rendered in the style of the for-loop or the for all-loop or something else may not be clearly described in the compiler manual.

Compound for-loops[edit]

Introduced with ALGOL 68 and followed by PL/I, this allows the iteration of a loop to be compounded with a test, as in

for i := 1 : N while A(i) > 0 do etc.

That is, a value is assigned to the loop variable i and only if the while expression is true will the loop body be executed. If the result were false the for-loop’s execution stops short. Granted that the loop variable’s value is defined after the termination of the loop, then the above statement will find the first non-positive element in array A (and if no such, its value will be N + 1), or, with suitable variations, the first non-blank character in a string, and so on.

Loop counters[edit]

In computer programming, a loop counter is a control variable that controls the iterations of a loop (a computer programming language construct). It is so named because most uses of this construct result in the variable taking on a range of integer values in some orderly sequences (example., starting at 0 and end at 10 in increments of 1)

Loop counters change with each iteration of a loop, providing a unique value for each individual iteration. The loop counter is used to decide when the loop should terminate and for the program flow to continue to the next instruction after the loop.

A common identifier naming convention is for the loop counter to use the variable names i, j, and k (and so on if needed), where i would be the most outer loop, j the next inner loop, etc. The reverse order is also used by some programmers. This style is generally agreed to have originated from the early programming of Fortran[citation needed], where these variable names beginning with these letters were implicitly declared as having an integer type, and so were obvious choices for loop counters that were only temporarily required. The practice dates back further to mathematical notation where indices for sums and multiplications are often i, j, etc. A variant convention is the use of reduplicated letters for the index, ii, jj, and kk, as this allows easier searching and search-replacing than using a single letter.[3]

Example[edit]

An example of C code involving nested for loops, where the loop counter variables are i and j:

for (i = 0; i < 100; i++) { for (j = i; j < 10; j++) { some_function(i, j); } }

For loops in C can also be used to print the reverse of a word. As:

for (i = 0; i < 6; i++) { scanf("%c", &a[i]); } for (i = 4; i >= 0; i--) { printf("%c", a[i]); }

Here, if the input is apple, the output will be elppa.

Additional semantics and constructs[edit]

Use as infinite loops[edit]

This C-style for-loop is commonly the source of an infinite loop since the fundamental steps of iteration are completely in the control of the programmer. In fact, when infinite loops are intended, this type of for-loop can be used (with empty expressions), such as:

This style is used instead of infinite while (1) loops to avoid a type conversion warning in some C/C++ compilers.[4] Some programmers prefer the more succinct for (;;) form over the semantically equivalent but more verbose while (true) form.

Early exit and continuation[edit]

Some languages may also provide other supporting statements, which when present can alter how the for-loop iteration proceeds.

Common among these are the break and continue statements found in C and its derivatives.

The break statement causes the inner-most loop to be terminated immediately when executed.

The continue statement will move at once to the next iteration without further progress through the loop body for the current iteration.

A for statement also terminates when a break, goto, or return statement within the statement body is executed. [Wells]

Other languages may have similar statements or otherwise provide means to alter the for-loop progress; for example in FORTRAN 95:

DO I = 1, N statements !Executed for all values of "I", up to a disaster if any. IF (no good) CYCLE !Skip this value of "I", continue with the next. statements !Executed only where goodness prevails. IF (disaster) EXIT !Abandon the loop. statements !While good and, no disaster. END DO !Should align with the "DO".

Some languages offer further facilities such as naming the various loop statements so that with multiple nested loops there is no doubt as to which loop is involved. Fortran 95, for example:

X1:DO I = 1,N statements X2:DO J = 1,M statements IF (trouble) CYCLE X1 statements END DO X2 statements END DO X1

Thus, when «trouble» is detected in the inner loop, the CYCLE X1 (not X2) means that the skip will be to the next iteration for I, not J. The compiler will also be checking that each END DO has the appropriate label for its position: this is not just a documentation aid. The programmer must still code the problem correctly, but some possible blunders will be blocked.

Loop variable scope and semantics[edit]

Different languages specify different rules for what value the loop variable will hold on termination of its loop, and indeed some hold that it «becomes undefined». This permits a compiler to generate code that leaves any value in the loop variable, or perhaps even leaves it unchanged because the loop value was held in a register and never stored to memory. Actual behaviour may even vary according to the compiler’s optimization settings, as with the Honywell Fortran66 compiler.

In some languages (not C or C++) the loop variable is immutable within the scope of the loop body, with any attempt to modify its value being regarded as a semantic error. Such modifications are sometimes a consequence of a programmer error, which can be very difficult to identify once made. However, only overt changes are likely to be detected by the compiler. Situations where the address of the loop variable is passed as an argument to a subroutine make it very difficult to check, because the routine’s behavior is in general unknowable to the compiler. Some examples in the style of Fortran:

DO I = 1, N I = 7 !Overt adjustment of the loop variable. Compiler complaint likely. Z = ADJUST(I) !Function "ADJUST" might alter "I", to uncertain effect. normal statements !Memory might fade that "I" is the loop variable. PRINT (A(I), B(I), I = 1, N, 2) !Implicit for-loop to print odd elements of arrays A and B, reusing "I"... PRINT I !What value will be presented? END DO !How many times will the loop be executed?

A common approach is to calculate the iteration count at the start of a loop (with careful attention to overflow as in for i := 0 : 65535 do ... ; in sixteen-bit integer arithmetic) and with each iteration decrement this count while also adjusting the value of I: double counting results. However, adjustments to the value of I within the loop will not change the number of iterations executed.

Still another possibility is that the code generated may employ an auxiliary variable as the loop variable, possibly held in a machine register, whose value may or may not be copied to I on each iteration. Again, modifications of I would not affect the control of the loop, but now a disjunction is possible: within the loop, references to the value of I might be to the (possibly altered) current value of I or to the auxiliary variable (held safe from improper modification) and confusing results are guaranteed. For instance, within the loop a reference to element I of an array would likely employ the auxiliary variable (especially if it were held in a machine register), but if I is a parameter to some routine (for instance, a print-statement to reveal its value), it would likely be a reference to the proper variable I instead. It is best to avoid such possibilities.

Adjustment of bounds[edit]

Just as the index variable might be modified within a for-loop, so also may its bounds and direction. But to uncertain effect. A compiler may prevent such attempts, they may have no effect, or they might even work properly — though many would declare that to do so would be wrong. Consider a statement such as

for i := first : last : step do A(i) := A(i) / A(last);

If the approach to compiling such a loop was to be the evaluation of first, last and step and the calculation of an iteration count via something like (last - first)/step once only at the start, then if those items were simple variables and their values were somehow adjusted during the iterations, this would have no effect on the iteration count even if the element selected for division by A(last) changed.

List of value ranges[edit]

PL/I and Algol 68, allows loops in which the loop variable is iterated over a list of ranges of values instead of a single range. The following PL/I example will execute the loop with six values of i: 1, 7, 12, 13, 14, 15:

do i = 1, 7, 12 to 15; /*statements*/ end;

Equivalence with while-loops[edit]

A for-loop is generally equivalent to a while-loop:

factorial := 1

for counter from 2 to 5

factorial := factorial * counter

counter := counter - 1

print counter + "! equals " + factorial

is equivalent to:

factorial := 1

counter := 1

while counter < 5

counter := counter + 1

factorial := factorial * counter

print counter + "! equals " + factorial

as demonstrated by the output of the variables.

Timeline of the for-loop syntax in various programming languages[edit]

Given an action that must be repeated, for instance, five times, different languages’ for-loops will be written differently. The syntax for a three-expression for-loop is nearly identical in all languages that have it, after accounting for different styles of block termination and so on.

1957: FORTRAN[edit]

Fortran’s equivalent of the for loop is the DO loop,

using the keyword do instead of for,

The syntax of Fortran’s DO loop is:

DO label counter = first, last, step statements label statement

The following two examples behave equivalently to the three argument for-loop in other languages,

initializing the counter variable to 1, incrementing by 1 each iteration of the loop and stopping at five (inclusive).

DO 9, COUNTER = 1, 5, 1 WRITE (6,8) COUNTER 8 FORMAT( I2 ) 9 CONTINUE

In Fortran 77 (or later), this may also be written as:

do counter = 1, 5 write(*, '(i2)') counter end do

The step part may be omitted if the step is one. Example:

* DO loop example. PROGRAM MAIN SUM SQ = 0 DO 199 I = 1, 9999999 IF (SUM SQ.GT.1000) GO TO 200 199 SUM SQ = SUM SQ + I**2 200 PRINT 206, SUMSQ 206 FORMAT( I2 ) END

Spaces are irrelevant in fixed-form Fortran statements, thus SUM SQ is the same as SUMSQ. In the modern free-form Fortran style, blanks are significant.

In Fortran 90, the GO TO may be avoided by using an EXIT statement.

* DO loop example. program main implicit none integer :: sumsq integer :: i sumsq = 0 do i = 1, 9999999 if (sumsq > 1000.0) exit sumsq = sumsq + i**2 end do print *, sumsq end program

1958: ALGOL[edit]

ALGOL 58 introduced the for statement, using the form as Superplan:

FOR Identifier = Base (Difference) Limit

For example to print 0 to 10 incremented by 1:

FOR x = 0 (1) 10 BEGIN PRINT (FL) = x END

1960: COBOL[edit]

COBOL was formalized in late 1959 and has had many elaborations. It uses the PERFORM verb which has many options. Originally all loops had to be out-of-line with the iterated code occupying a separate paragraph. Ignoring the need for declaring and initialising variables, the COBOL equivalent of a for-loop would be.

PERFORM SQ-ROUTINE VARYING I FROM 1 BY 1 UNTIL I > 1000 SQ-ROUTINE ADD I**2 TO SUM-SQ.

In the 1980s the addition of in-line loops and «structured» statements such as END-PERFORM resulted in a for-loop with a more familiar structure.

PERFORM VARYING I FROM 1 BY 1 UNTIL I > 1000 ADD I**2 TO SUM-SQ. END-PERFORM

If the PERFORM verb has the optional clause TEST AFTER, the resulting loop is slightly different: the loop body is executed at least once, before any test.

1964: BASIC[edit]

Loops in BASIC are sometimes called for-next loops.

10 REM THIS FOR LOOP PRINTS ODD NUMBERS FROM 1 TO 15 20 FOR I = 1 TO 15 STEP 2 30 PRINT I 40 NEXT I

Notice that the end-loop marker specifies the name of the index variable, which must correspond to the name of the index variable in the start of the for-loop. Some languages (PL/I, FORTRAN 95 and later) allow a statement label on the start of a for-loop that can be matched by the compiler against the same text on the corresponding end-loop statement. Fortran also allows the EXIT and CYCLE statements to name this text; in a nest of loops this makes clear which loop is intended. However, in these languages the labels must be unique, so successive loops involving the same index variable cannot use the same text nor can a label be the same as the name of a variable, such as the index variable for the loop.

1964: PL/I[edit]

do counter = 1 to 5 by 1; /* "by 1" is the default if not specified */ /*statements*/; end;

The LEAVE statement may be used to exit the loop. Loops can be labeled, and leave may leave a specific labeled loop in a group of nested loops. Some PL/I dialects include the ITERATE statement to terminate the current loop iteration and begin the next.

1968: Algol 68[edit]

ALGOL 68 has what was considered the universal loop, the full syntax is:

FOR i FROM 1 BY 2 TO 3 WHILE i≠4 DO ~ OD

Further, the single iteration range could be replaced by a list of such ranges. There are several unusual aspects of the construct

- only the

do ~ odportion was compulsory, in which case the loop will iterate indefinitely. - thus the clause

to 100 do ~ od, will iterate exactly 100 times. - the

whilesyntactic element allowed a programmer to break from aforloop early, as in:

INT sum sq := 0;

FOR i

WHILE

print(("So far:", i, new line)); # Interposed for tracing purposes. #

sum sq ≠ 70↑2 # This is the test for the WHILE #

DO

sum sq +:= i↑2

OD

Subsequent extensions to the standard Algol68 allowed the to syntactic element to be replaced with upto and downto to achieve a small optimization. The same compilers also incorporated:

until- for late loop termination.

foreach- for working on arrays in parallel.

1970: Pascal[edit]

for Counter := 1 to 5 do (*statement*);

Decrementing (counting backwards) is using downto keyword instead of to, as in:

for Counter := 5 downto 1 do (*statement*);

The numeric-range for-loop varies somewhat more.

1972: C/C++[edit]

for (initialization; condition; increment/decrement) statement

The statement is often a block statement; an example of this would be:

//Using for-loops to add numbers 1 - 5 int sum = 0; for (int i = 0; i < 5; ++i) { sum += i; }

The ISO/IEC 9899:1999 publication (commonly known as C99) also allows initial declarations in for loops. All the three sections in the for loop are optional, with an empty condition equivalent to true.

1972: Smalltalk[edit]

1 to: 5 do: [ :counter | "statements" ]

Contrary to other languages, in Smalltalk a for-loop is not a language construct but defined in the class Number as a method with two parameters, the end value and a closure, using self as start value.

1980: Ada[edit]

for Counter in 1 .. 5 loop -- statements end loop;

The exit statement may be used to exit the loop. Loops can be labeled, and exit may leave a specifically labeled loop in a group of nested loops:

Counting: for Counter in 1 .. 5 loop Triangle: for Secondary_Index in 2 .. Counter loop -- statements exit Counting; -- statements end loop Triangle; end loop Counting;

1980: Maple[edit]

Maple has two forms of for-loop, one for iterating of a range of values, and the other for iterating over the contents of a container. The value range form is as follows:

for i from f by b to t while w do

# loop body

od;

All parts except do and od are optional. The for i part, if present, must come first. The remaining parts (from f, by b, to t, while w) can appear in any order.

Iterating over a container is done using this form of loop:

for e in c while w do

# loop body

od;

The in c clause specifies the container, which may be a list, set, sum, product, unevaluated function, array, or an object implementing an iterator.

A for-loop may be terminated by od, end, or end do.

1982: Maxima CAS[edit]

In Maxima CAS one can use also non integer values :

for x:0.5 step 0.1 thru 0.9 do

/* "Do something with x" */

1982: PostScript[edit]

The for-loop, written as [initial] [increment] [limit] { ... } for initialises an internal variable, executes the body as long as the internal variable is not more than limit (or not less, if increment is negative) and, at the end of each iteration, increments the internal variable. Before each iteration, the value of the internal variable is pushed onto the stack.[5]

There is also a simple repeat-loop.

The repeat-loop, written as X { ... } repeat, repeats the body exactly X times.[6]

1983: Ada 83 and above[edit]

procedure Main is Sum_Sq : Integer := 0; begin for I in 1 .. 9999999 loop if Sum_Sq <= 1000 then Sum_Sq := Sum_Sq + I**2 end if; end loop; end;

1984: MATLAB[edit]

for n = 1:5 -- statements end

After the loop, n would be 5 in this example.

As i is used for the Imaginary unit, its use as a loop variable is discouraged.

1987: Perl[edit]

for ($counter = 1; $counter <= 5; $counter++) { # implicitly or predefined variable # statements; } for (my $counter = 1; $counter <= 5; $counter++) { # variable private to the loop # statements; } for (1..5) { # variable implicitly called $_; 1..5 creates a list of these 5 elements # statements; } statement for 1..5; # almost same (only 1 statement) with natural language order for my $counter (1..5) { # variable private to the loop # statements; }

(Note that «there’s more than one way to do it» is a Perl programming motto.)

1988: Mathematica[edit]

The construct corresponding to most other languages’ for-loop is called Do in Mathematica

Mathematica also has a For construct that mimics the for-loop of C-like languages

For[x= 0 , x <= 1, x += 0.1, f[x] ]

1989: Bash[edit]

# first form for i in 1 2 3 4 5 do # must have at least one command in loop echo $i # just print value of i done

# second form for (( i = 1; i <= 5; i++ )) do # must have at least one command in loop echo $i # just print value of i done

Note that an empty loop (i.e., one with no commands between do and done) is a syntax error. If the above loops contained only comments, execution would result in the message «syntax error near unexpected token ‘done'».

1990: Haskell[edit]

The built-in imperative forM_ maps a monadic expression into a list, as

forM_ [1..5] $ indx -> do statements

or get each iteration result as a list in

statements_result_list <- forM [1..5] $ indx -> do statements

But, if you want to save the space of the [1..5] list,

a more authentic monadic forLoop_ construction can be defined as

import Control.Monad as M forLoopM_ :: Monad m => a -> (a -> Bool) -> (a -> a) -> (a -> m ()) -> m () forLoopM_ indx prop incr f = do f indx M.when (prop next) $ forLoopM_ next prop incr f where next = incr indx

and used as:

forLoopM_ (0::Int) (< len) (+1) $ indx -> do -- whatever with the index

1991: Oberon-2, Oberon-07, or Component Pascal[edit]

FOR Counter := 1 TO 5 DO (* statement sequence *) END

Note that in the original Oberon language the for-loop was omitted in favor of the more general Oberon loop construct. The for-loop was reintroduced in Oberon-2.

1991: Python[edit]

Python does not contain the classical for loop, rather a foreach loop is used to iterate over the output of the built-in range() function which returns an iterable sequence of integers.

for i in range(1, 6): # gives i values from 1 to 5 inclusive (but not 6) # statements print(i) # if we want 6 we must do the following for i in range(1, 6 + 1): # gives i values from 1 to 6 # statements print(i)

Using range(6) would run the loop from 0 to 5.

1993: AppleScript[edit]

repeat with i from 1 to 5 -- statements log i end repeat

You can also iterate through a list of items, similar to what you can do with arrays in other languages:

set x to {1, "waffles", "bacon", 5.1, false} repeat with i in x log i end repeat

You may also use exit repeat to exit a loop at any time. Unlike other languages, AppleScript does not currently have any command to continue to the next iteration of a loop.

1993: Crystal[edit]

for i = start, stop, interval do -- statements end

So, this code

for i = 1, 5, 2 do print(i) end

will print:

For-loops can also loop through a table using

to iterate numerically through arrays and

to iterate randomly through dictionaries.

Generic for-loop making use of closures:

for name, phone, address in contacts() do -- contacts() must be an iterator function end

1995: CFML[edit]

Script syntax[edit]

Simple index loop:

for (i = 1; i <= 5; i++) { // statements }

Using an array:

for (i in [1,2,3,4,5]) { // statements }

Using a list of string values:

loop index="i" list="1;2,3;4,5" delimiters=",;" { // statements }

The above list example is only available in the dialect of CFML used by Lucee and Railo.

Tag syntax[edit]

Simple index loop:

<cfloop index="i" from="1" to="5"> <!--- statements ---> </cfloop>

Using an array:

<cfloop index="i" array="#[1,2,3,4,5]#"> <!--- statements ---> </cfloop>

Using a «list» of string values:

<cfloop index="i" list="1;2,3;4,5" delimiters=",;"> <!--- statements ---> </cfloop>

1995: Java[edit]

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) { //perform functions within the loop; //can use the statement 'break;' to exit early; //can use the statement 'continue;' to skip the current iteration }

For the extended for-loop, see Foreach loop § Java.

1995: JavaScript[edit]

JavaScript supports C-style «three-expression» loops. The break and continue statements are supported inside loops.

for (var i = 0; i < 5; i++) { // ... }

Alternatively, it is possible to iterate over all keys of an array.

for (var key in array) { // also works for assoc. arrays // use array[key] ... }

1995: PHP[edit]

This prints out a triangle of *

for ($i = 0; $i <= 5; $i++) { for ($j = 0; $j <= $i; $j++) { echo "*"; } echo "<br />n"; }

1995: Ruby[edit]

for counter in 1..5 # statements end 5.times do |counter| # counter iterates from 0 to 4 # statements end 1.upto(5) do |counter| # statements end

Ruby has several possible syntaxes, including the above samples.

1996: OCaml[edit]

See expression syntax.[7]

(* for_statement := "for" ident '=' expr ( "to" ∣ "downto" ) expr "do" expr "done" *) for i = 1 to 5 do (* statements *) done ;; for j = 5 downto 0 do (* statements *) done ;;

1998: ActionScript 3[edit]

for (var counter:uint = 1; counter <= 5; counter++){ //statement; }

2008: Small Basic[edit]

For i = 1 To 10 ' Statements EndFor

2008: Nim[edit]

Nim has a foreach-type loop and various operations for creating iterators.[8]

for i in 5 .. 10: # statements

2009: Go[edit]

for i := 0; i <= 10; i++ { // statements }

2010: Rust[edit]

for i in 0..10 { // statements }

2012: Julia[edit]

for j = 1:10 # statements end

See also[edit]

- Do while loop

- Foreach

- While loop

References[edit]

- ^ «For loops in C++».

- ^ Ken Thompson. «VCF East 2019 — Brian Kernighan interviews Ken Thompson». Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

I saw Johnson’s semicolon version of the for loop and I put that in [B], I stole it.

- ^ http://www.knosof.co.uk/vulnerabilities/loopcntrl.pdf Analysis of loop control variables in C

- ^ «Compiler Warning (level 4) C4127». Microsoft. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ^ PostScript Language Reference. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. p. 596. ISBN 0-201-37922-8.

- ^ «PostScript Tutorial — Loops».

- ^ «OCaml expression syntax». Archived from the original on 2013-04-12. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- ^ https://nim-lang.org/docs/system.html#…i%2CT%2CT «.. iterator»

Программирование требует от пользователя наличия определенного багажа знаний и навыков. Без понимания некоторых базовых принципов создание качественного программного обеспечения невозможно.

Огромную роль при написании софта играют циклы. В данной статье речь зайдет о такой блок-схеме как For. Будут рассмотрены примеры, написанные на языках СИ-семейства. Все это пригодится новичкам, которые только познакомились с разработкой.

Термины – базовые понятия

Циклы, включая блок For – это не так трудно, как кажется на первых порах. Такая схема есть почти во всех языках программирования. Только перед его более детальном рассмотрением рекомендуется запомнить несколько базовых определений. Соответствующие термины помогут не запутаться новичкам, а также освежат знания опытных разработчиков.

Запомнить стоит такие понятия:

- Алгоритм – принципы, а также правила, помогающие решать конкретные задачи.

- Переменные – единицы хранения информации. Именованные ячейки.

- Константы – значения, которые не будут корректироваться по ходу реализации программного кода.

- Оператор – то, что умеет манипулировать через операнды.

- Операнд – объект, которым можно управлять через операторы.

- Итерация – один проход через набор операций в пределах исполняемого кода.

- Ключевое слово – специальное слово, зарезервированное языком программирования. Помогает описывать команды и операции, выполнять различные действия. Ключевое слово не может выступать именем переменной.

- Петля – инструкции, которые повторяют один и тот же процесс. Происходит это до тех пор, пока не будет выдана команда на остановку или пока не выполнено заданное условие.

Последний термин можно также описать словом «цикл». Программирование предусматривает огромное множество подобных «компонентов». Самый распространенный – это схема For.

Но сначала стоит запомнить, что есть еще и бесконечный цикл. Он представлен непрерывным повторением фрагмента приложения. Не прекращается самостоятельно. Чтобы затормозить соответствующий процесс, программисту предстоит использовать принудительную остановку.

Описание цикла

Оператор цикла For – это оператор управляющего характера в языке Си. Он позволяет реализовывать выполнения петли непосредственно в алгоритме. Пользуется спросом как у новичков, так и у опытных разработчиков.

Имеет такой синтаксис:

For (счетчик; условие; итератор)

{

// тело цикла

}

Именно такую схему необходимо использовать в будущем контенте. Но ее необходимо грамотно применять. А еще – понять принцип работы соответствующего блока.

Как функционирует

For – это цикл, который распространен в языках программирования. Встречается не только в СИ-семейству. Позволяет выполнять разнообразные команды по принципу петли. Работает по следующему алгоритму:

- Предусматривает три переменные в своем цикле. А именно – итератор, условие и счетчик.

- Объявляется при помощи ключевого слова «For».

- Счет объявляется всего один раз. Делается это в самом начале блока. Инициализация обычно происходит непосредственно после объявления.

- Происходит проверка заданного условия. Соответствующее «требование» — это булево выражение. Оно будет возвращать значение True/False.

- Если условие – это «Истина», то выполняются инструкции, прописанные внутри заданного цикла. Далее – инициализируется итератор. Обычно процесс предусматривает корректировку значения переменной. Происходит повторная проверка условия. Операция повторяется до тех пор, пока заданный «критерий» не определится системой как «Ложный».

- Когда условие, прописанное в теле For, изначально имеет «статус» False, происходит завершение «петли».

Соответствующий алгоритм помогает при различных задачах в разработке программного обеспечения. Пример – сортировка данных в пределах заданного массива.

Схематичное представление

Ниже представлена схема цикла For:

Эта визуальная форма представления «петли» поможет лучше понять, как функционирует заданная схема.

Итерации

А вот наглядный пример кода, который способствует более быстрому пониманию и усвоению итераций внутри For:

Здесь:

- счетчик – это int i = 1;

- условие – переменная < = 5;

- итератор – i++.

После того, как приложение окажется запущенным, произойдет следующее:

- Объявляется и проходит инициализацию переменная с именем i. Она получает значение 1.

- Проверяется условие, в котором i меньше или равно 5.

- Если утверждение верно, обрабатывается тело цикла. В представленной схеме происходит увеличение значения переменной на +1.

- Осуществляется замена i с последующей проверкой условия.

- Когда переменная в For будет равна 6, приложение завершит цикл.

А вот еще один пример. Он поможет вычислить сумму первых n натуральных чисел в заданной последовательности:

Результатом окажется надпись «Сумма первых 5 натуральных чисел = 15». В предложенном фрагменте объявлены сразу две переменные – n и sum.

Несколько выражений

Внутри For можно использовать сразу несколько выражений. Это значит, что схема предусматривает инициализацию пары-тройки счетчиков, а также итераторов. Лучше всего рассматривать данный процесс на наглядном примере:

Здесь произошла инициализация переменных, которые выступают в виде счетчиков – i и j. У итератора тоже присутствуют два выражения. На каждой итерации цикла j и i происходит увеличение на единицу.

Без объявления

Еще одна ситуация, предусматриваемая в программировании – это использование изучаемого цикла без предварительного объявления счетчиков и итераторов. В For соответствующие операции не являются обязательными. Запуск «петли» возможен без них. В этом случае принцип работы цикла подобен while:

Здесь:

- Счетчик и итератор не были объявлены программистом.

- Переменная i объявлена до заданного цикла. Ее значение будет увеличиваться внутри тела For.

- Представленный пример аналогичен первому представленному ранее образцу.

Условие цикла – это еще один необязательный компонент. Если оно отсутствует, имеет смысл говорить о бесконечной «петле».

Бесконечность

Бесконечный «повторяющийся блок кода» выполняется тогда, когда прописанное условие всегда выступает в качестве «истины». Наглядно ситуация выглядит так:

Здесь:

- Переменная i получила значение, равное 1.

- Условие, которое проверяется на истинность – i больше 0.

- Во время каждой совершаемой итерации значение i будет увеличиваться на единицу.

- Из вышесказанного следует, что на выходе приложение начнет ссылаться на то, что прописанное условие – истина. Значение False никогда не встретится.

Описанная ситуация приведет к бесконечному исполнению кода. Инициализировать цикл удается при помощи замены условия пробелом. Вот примеры:

Break и Continue

Работая с For, нужно обратить внимание на операторы break и continue. Первая «команда» помогает незамедлительно выйти из цикла. Исполнение утилиты продолжается со следующего идущего оператора.

Continue – это оператор, который вызывает пропуск оставшейся части тела. Далее – переводит программу к последующей итерации. В For и While continue помогает оценивать условие продолжения.

Пример с факториалом

Рассмотренный цикл – это то, что позволяет быстро производить весьма сложные вычисления. Вот – наглядный пример подсчета факториала:

Хотите освоить современную IT-специальность? Огромный выбор курсов по востребованным IT-направлениям есть в Otus!

Рассмотрим третью алгоритмическую структуру — цикл.

Циклом называется блок кода, который для решения задачи требуется повторить несколько раз.

Каждый цикл состоит из

- блока проверки условия повторения цикла

- тела цикла

Цикл выполняется до тех пор, пока блок проверки условия возвращает истинное значение.

Тело цикла содержит последовательность операций, которая выполняется в случае истинного условия повторения цикла. После выполнения последней операции тела цикла снова выполняется операция проверки условия повторения цикла. Если это условие не выполняется, то будет выполнена операция, стоящая непосредственно после цикла в коде программы.

В языке Си следующие виды циклов:

- while — цикл с предусловием;

- do…while — цикл с постусловием;

- for — параметрический цикл (цикл с заданным числом повторений).

Общая форма записи

while (Условие)

{

БлокОпераций;

}

Если Условие выполняется (выражение, проверяющее Условие, не равно нулю), то выполняется БлокОпераций, заключенный в фигурные скобки, затем Условие проверяется снова.

Последовательность действий, состоящая из проверки Условия и выполнения БлокаОпераций, повторяется до тех пор, пока выражение, проверяющее Условие, не станет ложным (равным нулю). При этом происходит выход из цикла, и производится выполнение операции, стоящей после оператора цикла.

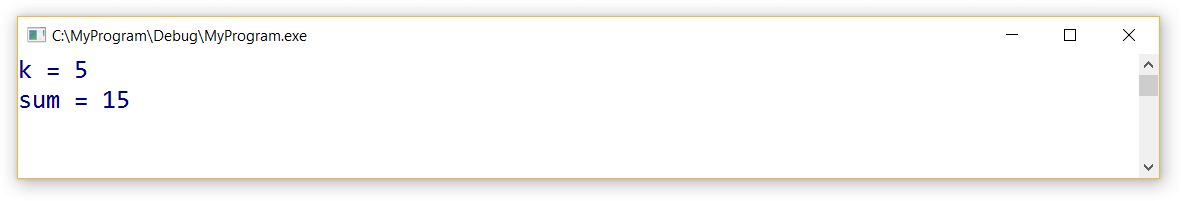

Пример на Си: Посчитать сумму чисел от 1 до введенного k

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

#define _CRT_SECURE_NO_WARNINGS // для возможности использования scanf

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int k; // объявляем целую переменную key

int i = 1;

int sum = 0; // начальное значение суммы равно 0

printf(«k = «);

scanf(«%d», &k); // вводим значение переменной k

while (i <= k) // пока i меньше или равно k

{

sum = sum + i; // добавляем значение i к сумме

i++; // увеличиваем i на 1

}

printf(«sum = %dn», sum); // вывод значения суммы

getchar(); getchar();

return 0;

}

Результат выполнения

При построении цикла while, в него необходимо включить конструкции, изменяющие величину проверяемого выражения так, чтобы в конце концов оно стало ложным (равным нулю). Иначе выполнение цикла будет осуществляться бесконечно (бесконечный цикл).

Пример бесконечного цикла

1

2

3

4

while (1)

{

БлокОпераций;

}

while — цикл с предусловием, поэтому вполне возможно, что тело цикла не будет выполнено ни разу если в момент первой проверки проверяемое условие окажется ложным.

Например, если в приведенном выше коде программы ввести k=-1, то получим результат

Цикл с постусловием do…while

Общая форма записи

do {

БлокОпераций;

} while (Условие);

Цикл do…while — это цикл с постусловием, где истинность выражения, проверяющего Условие проверяется после выполнения Блока Операций, заключенного в фигурные скобки. Тело цикла выполняется до тех пор, пока выражение, проверяющее Условие, не станет ложным, то есть тело цикла с постусловием выполнится хотя бы один раз.

Использовать цикл do…while лучше в тех случаях, когда должна быть выполнена хотя бы одна итерация, либо когда инициализация объектов, участвующих в проверке условия, происходит внутри тела цикла.

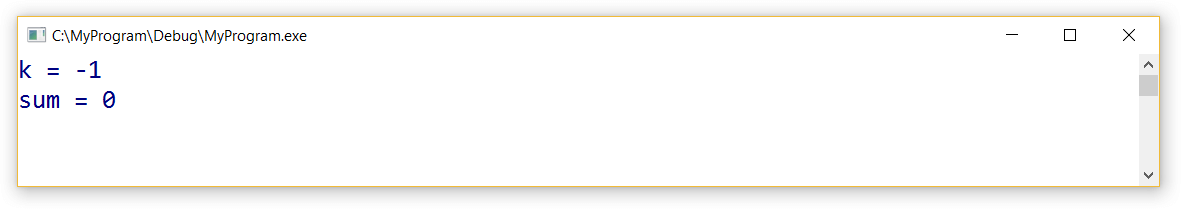

Пример на Си. Проверка, что пользователь ввел число от 0 до 10

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

#define _CRT_SECURE_NO_WARNINGS // для возможности использования scanf

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h> // для использования функции system()

int main() {

int num; // объявляем целую переменную для числа

system(«chcp 1251»); // переходим на русский язык в консоли

system(«cls»); // очищаем экран

do {

printf(«Введите число от 0 до 10: «); // приглашение пользователю

scanf(«%d», &num); // ввод числа

} while ((num < 0) || (num > 10)); // повторяем цикл пока num<0 или num>10

printf(«Вы ввели число %d», num); // выводим введенное значение num — от 0 до 10

getchar(); getchar();

return 0;

}

Результат выполнения:

Параметрический цикл for

Общая форма записи

for (Инициализация; Условие; Модификация)

{

БлокОпераций;

}

for — параметрический цикл (цикл с фиксированным числом повторений). Для организации такого цикла необходимо осуществить три операции:

- Инициализация — присваивание параметру цикла начального значения;

- Условие — проверка условия повторения цикла, чаще всего — сравнение величины параметра с некоторым граничным значением;

- Модификация — изменение значения параметра для следующего прохождения тела цикла.

Эти три операции записываются в скобках и разделяются точкой с запятой ;;. Как правило, параметром цикла является целочисленная переменная.

Инициализация параметра осуществляется только один раз — когда цикл for начинает выполняться.

Проверка Условия повторения цикла осуществляется перед каждым возможным выполнением тела цикла. Когда выражение, проверяющее Условие становится ложным (равным нулю), цикл завершается. Модификация параметра осуществляется в конце каждого выполнения тела цикла. Параметр может как увеличиваться, так и уменьшаться.

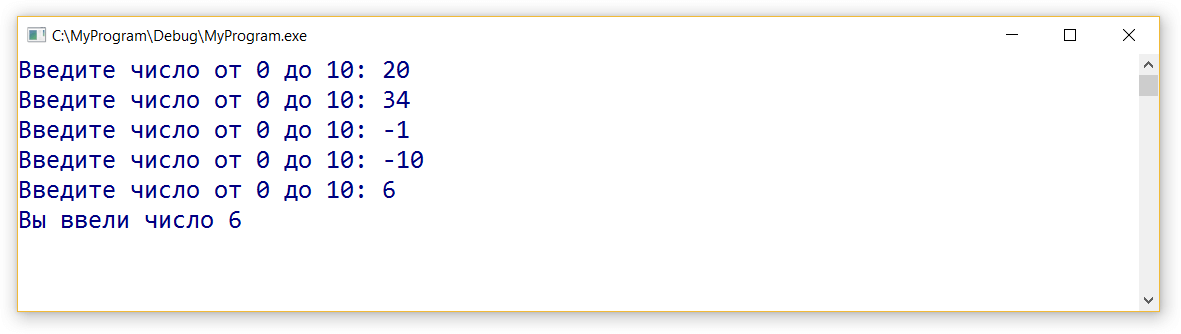

Пример на Си: Посчитать сумму чисел от 1 до введенного k

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

#define _CRT_SECURE_NO_WARNINGS // для возможности использования scanf

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int k; // объявляем целую переменную key

int sum = 0; // начальное значение суммы равно 0

printf(«k = «);

scanf(«%d», &k); // вводим значение переменной k

for(int i=1; i<=k; i++) // цикл для переменной i от 1 до k с шагом 1

{

sum = sum + i; // добавляем значение i к сумме

}

printf(«sum = %dn», sum); // вывод значения суммы

getchar(); getchar();

return 0;

}

Результат выполнения

В записи цикла for можно опустить одно или несколько выражений, но нельзя опускать точку с запятой, разделяющие три составляющие цикла.

Код предыдущего примера можно представить в виде

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

#define _CRT_SECURE_NO_WARNINGS // для возможности использования scanf

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int k; // объявляем целую переменную key

int sum = 0; // начальное значение суммы равно 0

printf(«k = «);

scanf(«%d», &k); // вводим значение переменной k

int i=1;

for(; i<=k; i++) // цикл для переменной i от 1 до k с шагом 1

{

sum = sum + i; // добавляем значение i к сумме

}

printf(«sum = %dn», sum); // вывод значения суммы

getchar(); getchar();

return 0;

}

Параметры, находящиеся в выражениях в заголовке цикла можно изменить при выполнении операции в теле цикла, например

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

#define _CRT_SECURE_NO_WARNINGS // для возможности использования scanf

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int k; // объявляем целую переменную key

int sum = 0; // начальное значение суммы равно 0

printf(«k = «);

scanf(«%d», &k); // вводим значение переменной k

for(int i=1; i<=k; ) // цикл для переменной i от 1 до k с шагом 1

{

sum = sum + i; // добавляем значение i к сумме

i++; // добавляем 1 к значению i

}

printf(«sum = %dn», sum); // вывод значения суммы

getchar(); getchar();

return 0;

}

В цикле for может использоваться операция запятая — , — для разделения нескольких выражений. Это позволяет включить в спецификацию цикла несколько инициализирующих или корректирующих выражений. Выражения, к которым применяется операция запятая, будут вычисляться слева направо.

Пример на Си:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

#define _CRT_SECURE_NO_WARNINGS // для возможности использования scanf

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int k; // объявляем целую переменную key

printf(«k = «);

scanf(«%d», &k); // вводим значение переменной k

for(int i=1, j=2; i<=k; i++, j+=2) // цикл для переменных

{ // (i от 1 до k с шагом 1) и (j от 2 с шагом 2)

printf(«i = %d j = %dn», i, j); // выводим значения i и j

}

getchar(); getchar();

return 0;

}

Результат выполнения

Вложенные циклы

В Си допускаются вложенные циклы, то есть когда один цикл находится внутри другого:

for (i = 0; i<n; i++) // внешний цикл — Цикл1

{

for (j = 0; j<n; j++) // вложенный цикл — Цикл2

{

; // блок операций Цикла2

}

// блок операций Цикла1;

}

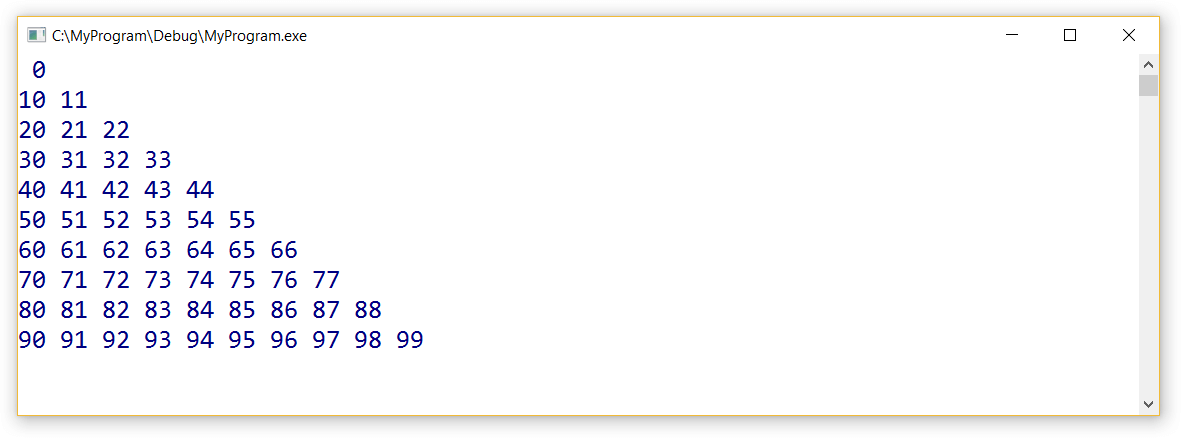

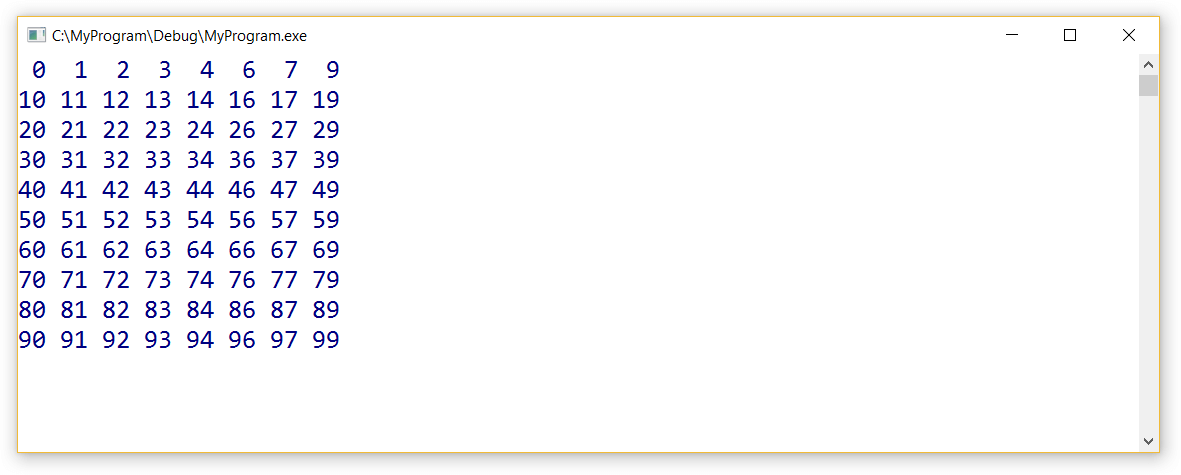

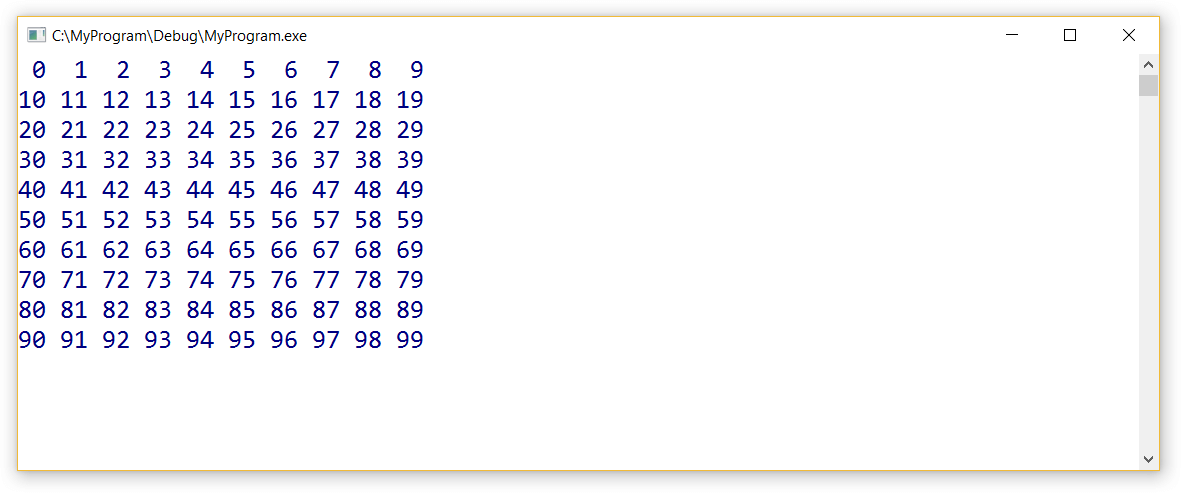

Пример: Вывести числа от 0 до 99, по 10 в каждой строке

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

#define _CRT_SECURE_NO_WARNINGS // для возможности использования scanf

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

for(int i=0; i<10; i++) // цикл для десятков

{

for (int j = 0; j < 10; j++) // цикл для единиц

{

printf(«%2d «, i * 10 + j); // выводим вычисленное число (2 знакоместа) и пробел

}

printf(«n»); // во внешнем цикле переводим строку

}

getchar(); // scanf() не использовался,

return 0; // поэтому консоль можно удержать одним вызовом getchar()

}

Результат выполнения

Рекомендации по выбору цикла