История персонажа

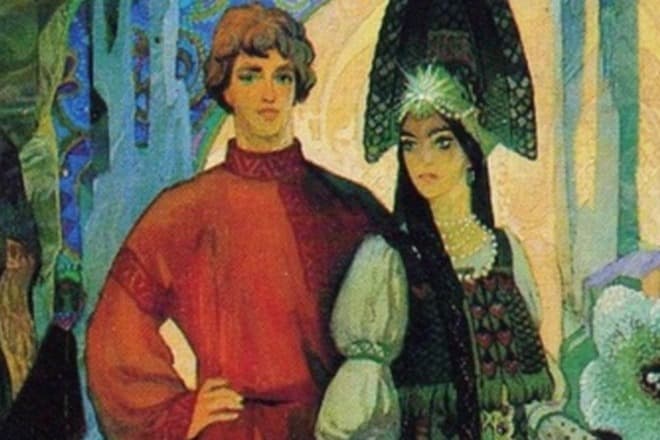

Сказы Павла Бажова таят в себе национальный колорит, описания простых русских людей и сочетают действительность с фантастическим началом. В сочинении «Каменный цветок» главным героем стал мастер-ремесленник по имени Данила. О приключениях мужчины автор и ведет речь в произведении.

История создания персонажа

У персонажа Данилы-мастера существовал прототип. Им оказался Данила Зверев, виртуозно работавший с камнем. Конечно, мужчина не работал с малахитом, считающимся самоцветом, да и Хозяйка Медной горы не сводила с ним знакомства. Но этот человек познакомил писателя с таинственным миром натуральных камней.

Описывая героя-ремесленника, Бажов сочетает в его образе сразу несколько характеристик. Мастером считается человек, обладающий большим багажом знаний и умений. Работавшие на уральских заводах специалисты переняли мастерство у зарубежных коллег.

Будучи тружениками, они вызывали глубокое уважение. Без перерыва работавший Данила демонстрировал качество, типичное для работников этой области. Перфекционист, он старался создать запоминающееся творение. Связь с язычеством на Руси – еще один нюанс, на который обращает внимание автор сказки. Чтобы узнать великую тайну, Данила отправляется к мифической Хозяйке Медной горы, а не к божественному провидению.

Книга сочинений Павла Бажова объединяет истории простых работяг Урала, учившихся чувствовать «душу» камня и очищать ее от оков грубого материала, создавая уникальные вещи. Автор упоминает о тяжести такого труда, о том, как нелегко проходит жизнь простых железодобытчиков и тех, кто ваяет из бездушного камня неповторимые произведения искусства.

Любопытно, что наравне с вымышленными персонажами и героями, чьи образы сочинены по подобию знакомых писателю мастеров, в сюжете присутствуют и личности, чьи имена были известны читателям. Отдельная роль отведена Иванко Крылатко, под именем которого описан Иван Вушуев, знаменитый камнерез.

Образ в сказках

Сказка «Каменный цветок», изданная в 1938 году, создавалась с оглядкой на уральский фольклор. Сказы местных жителей дополнили сочинения Бажова традиционным колоритом. Наряду с фантастическими деталями автор делает акцент и на драматической подоплеке сюжета. Мечта и реальность, искусство и быт сталкиваются в произведении.

Биография главного героя описана подробно и становится основой сюжетной линии. Данилу с детства звали «недокормышем». Худенький мальчик отличался от сверстников мечтательностью и задумчивостью. Он был наблюдателен. Взрослые, поняв, что тяжелая работа ему не по плечу, отправили Данилушку смотреть за коровами. Это задание оказалось сложным, потому что мальчик часто засматривался на окружающие его предметы, увлекался насекомыми, растениями и всем, что попадалось на глаза.

Привычка приглядываться к деталям оказалась полезной, когда Данилу отдали на обучение к мастеру Прокопьичу. Подросток обладал удивительным чувством прекрасного, пригодившимся в профессии. Он знал, как лучше работать с камнем и видел недостатки изделия и преимущества материала. Когда Данила вырос, его вкус, стиль работы и талант стали притчей во языцех. Терпение и отдача, с которыми ваял мастер, очень ценились окружающими и стали причиной появления его незаурядных изделий.

Несмотря на похвалы, Данила стремился к большему. Он мечтал показать людям истинную мощь камня. Юноша вспомнил сказки, которые слышал от ведуньи. Они гласили о каменном цветке, раскрывающем суть прекрасного и приносящем несчастье. Чтобы раздобыть невиданное чудо, Данила отправился на поклон к Хозяйке Медной горы. Он пошла навстречу мастеру и предъявила чудесный цветок. Сознание Данилы затуманилось, он потерял голову. Мастер бросил невесту Катю и сгинул без вести. Ходили слухи, что он пошел в услужение к Хозяйке Медной горы.

Последующая жизнь Данилы описана автором в произведениях «Горный мастер» и «Хрупкая веточка». Эти сказки были изданы в сборнике под названием «Малахитовая шкатулка». Главной задачей Бажова стала идея показать муки поисков истины и гармонии в творческом деле, жажду постижения прекрасного.

Интересные факты

- Экранизация сказки впервые состоялась в 1946 году. Снять фильм решил режиссер Александр Птушко. Фильм стал симбиозом сказок о каменном цветке и о горном мастере. Владимир Дружников выступил в картине в образе Данилы-мастера. Автором сценария выступил сам Бажов. В 1947 году проект был отмечен призом на Каннском кинофестивале и получил Сталинскую премию.

- В 1977 году Олег Николаевский создал мультфильм по мотивам сказки Бажова. Кукольная телепостановка включала и работу актеров.

- В 1978 году Инесса Ковалевская сняла мультфильм по произведению «Горный мастер». Рисованная сказка транслируется на телевидении и сегодня.

|

Данила-мастер

|

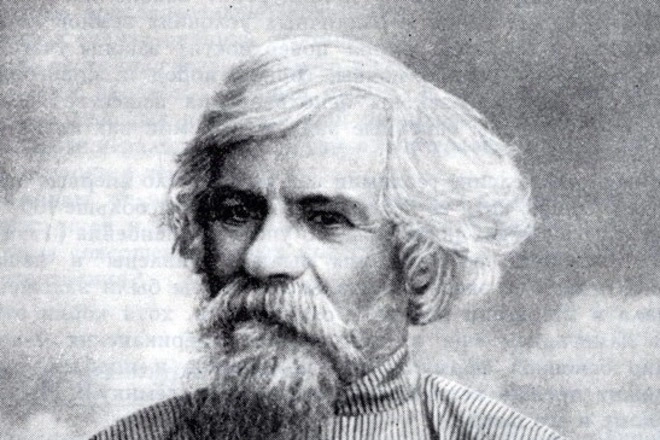

Павел Петрович Бажов – писатель, который, несомненно, прославил Урал на всю Россию. С тех пор, как был опубликован сборник его сказов «Малахитовая шкатулка», сменилось не одно поколение, и ассоциативный ряд «Урал – малахит – Хозяйка Медной горы» уже успел засесть у жителей постсоветского пространства где-то в генетической памяти. Думаю, ни для кого не секрет, что свои сказы Бажов не придумывал с нуля, а лишь литературно адаптировал слышанные им в детстве и юности местные былички и предания. Героев своих произведений он тоже предпочитал, что называется, «писать с натуры».

Действительно, практически каждый персонаж «Малахитовой шкатулки» имеет свой реальный исторический прототип. Не стал исключением и, пожалуй, один из наиболее известных бажовских героев – Данила-мастер. Да-да, тот самый, который, осиротев, учился камнерезному делу у старого Прокопьича, долго корпел над чашей из малахита, а потом, в некотором смысле, заложил душу Хозяйке Медной горы, чтобы хотя бы одним глазком взглянуть на каменный цветок – «философский камень» уральских камнерезов. Если кто-то позабыл, его приключения описаны в сказах «Каменный цветок», «Горный мастер» и «Хрупкая веточка». А на создание образа самого знаменитого мастера-камнереза Бажова вдохновила биография известного уральского горщика Данилы Зверева.

«.вот так-то и дошло дело до Данилки Недокормыша. Сиротка круглый был этот парнишечко. Годов, поди, тогда двенадцати, а то и боле. На ногах высоконький, а худой-расхудой, в чём душа держится. Ну, а с лица чистенький. Волосёнки кудрявеньки, глазёнки голубеньки».

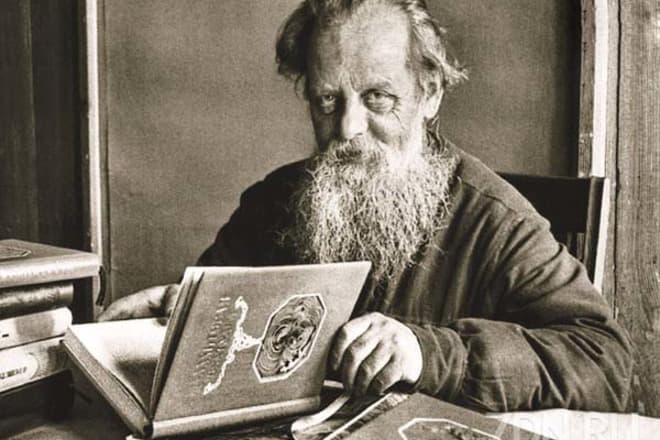

Данила Кондратьевич Зверев родился в 1858 году в деревне Колташи, расположенной практически в самом центре знаменитой самоцветной полосы Урала, протянувшейся к западу от города Реж. Зверев и вправду рано осиротел, потеряв родителей, а его воспитанием занимались дед с бабкой, старшие братья и сёстры. С самого детства он был слаб здоровьем, часто болел, рос худеньким и маленьким. За это соседи и сверстники прозвали его Данилой Лёгоньким.

На заводскую работу либо в гору все ж таки не отдали – шибко жидко место, на неделю не хватит. Поставил его приказчик в подпаски. И тут Данилко не вовсе гож пришелся. Парнишечко ровно старательный, а всё у него оплошка выходит. Всё будто думает о чём-то. Уставится глазами на травинку, а коровы-то – вон где!».

В своих родных Колташах Данила пас коров, но, по его собственным воспоминаниям, отличался мечтательностью и задумчивостью. Последствия данная черта характера имела для мальчика самые что ни на есть плачевные – за недосмотр за стадом он не раз бывал жестоко порот. Дом, где Зверев провёл первую половину жизни, до наших дней не сохранился. Зато неподалёку от Колташей на берегу реки Реж имеется скала со смешным названием Ёжик. Говорят, в тени этого камня любил сидеть маленький Данила.

«Был в ту пору мастер Прокопьич. По камнерезному делу первый. Лучше его никто не мог. В пожилых годах был. Вот барин и велел приказчику поставить к этому Прокопьичу парнишек на выучку.

— Пущай-де переймут всё до тонкости.

Только Прокопьич – то ли ему жаль было расставаться со своим мастерством, то ли ещё что – учил шибко худо. Всё у него с рывка да с тычка.».

Прокопьич тоже существовал в действительности. Его полное имя – Самойла Прокопьевич Южаков. Он жил в деревне Южаково, что в паре десятков километров к северу от Колташей. Именно Южаков стал наставником Данилы Зверева. Правда, уже здесь начинаются значительные расхождения исторических фактов с сюжетом бажовского сказа. Дело в том, что реальный Прокопьич был не камнерезом, а горщиком – так называли людей, которые искали и исследовали новые месторождения. По сути горщики были предшественниками современных геологов, хотя, в духе того времени, зачастую им приходилось выполнять гораздо более широкий круг «обязанностей».

Так что с малых лет Данила Зверев начал постигать мастерство горщика, а не камнереза. Кстати, есть версия, что он решил податься в горщики, чтобы «откосить» от армии. Якобы, его дед в молодости попал в солдаты, а домой вернулся уже глубоким стариком. Он внушил Даниле, что солдатская служба – тяжкое наказание, которого лучше бы по возможности избежать. В то время горщиков в солдаты не забирали: специалисты в горном деле приносили казне хороший доход.

— Погоди ты маленько! Вот только камень подходящий подберу.

И повадился он на медный рудник – на Гумешки-то. Когда в шахту спустится, по забоям обойдет, когда наверху камни перебирает.

«А что, – думает, – если сходить на Змеиную?».

Змеиную горку Данилушко хорошо знал. Тут же она была, недалеко от Гумешек. Теперь её нет, давно всю срыли, а раньше камень поверху брали. Вот на другой день и пошел туда Данилушко. Горка хоть небольшая, а крутенькая. С одной стороны и вовсе как срезано. Все пласты видно, лучше некуда.».

В отличие от многих других горщиков, полагавшихся на приметы и интуицию, Зверев больше доверял собственным знаниям, опыту и трудолюбию. Как только сходил снег, он уходил из деревни, целыми днями бродил по лесам, по берегам рек, в заповедных местах – искал редкие камни. Разведочные шурфы он не копал, вместо этого предпочитая осматривать промоины на склонах оврагов, корни вывороченных ветром деревьев или просто перебирать отвалы, оставшиеся после добычи золота. Нередко поиски оканчивались успехом. Каждый раз, находя драгоценные камни, Зверев примечал, какие признаки указывают на их наличие.

Большинству старателей было свойственно сразу спускать всё, что они находили. Но Зверев был не таким. Свои находки он не разбазаривал, а до поры до времени сохранял, чтобы при случае продать повыгоднее. Но богатства знаменитый мастер не нажил – деньги его не интересовали. Горщика увлекал сам поиск, очаровывала красота уральского камня – но не прельщала материальная сторона вопроса. Зверев охотно помогал односельчанам, делился с нуждающимися. Часто вспоминают такой случай: однажды, продав крупную партию камней в Екатеринбурге, Зверев вернулся в родную деревню с двумя возами пряников, которые раздал соседям.

«Данилушко поднял голову, а напротив, у другой-то стены, сидит Медной горы Хозяйка. По красоте-то да по платью малахитову Данилушко сразу её признал. Сидит – молчит, глядит на то место, где Хозяйка, и будто ничего не видит. Она тоже молчит, вроде как призадумалась. Потом и спрашивает:

— Ну, что Данило-мастер, не вышла твоя дурман-чаша?

— Не вышла, – отвечает.

— А ты не вешай голову-то! Другое попытай. Камень тебе будет, по твоим мыслям».

Стоит ли говорить, что Хозяйку Медной горы Данила Зверев так и не встретил. Хотя бы потому, что на той самой Медной горе в окрестностях современного Полевского ни разу не бывал. Вместо Хозяйки он повстречал академика Александра Евгеньевича Ферсмана, который приехал в Колташи для изучения режевских месторождений. Эта встреча для Зверева стала почти такой же судьбоносной, как и для Данилы-мастера.

В Париже вот-вот должна была состояться Х Всемирная художественно-промышленная выставка. Специально для неё в России решили изготовить карту Франции методом флорентийской мозаики. Подбор камней для этой работы Ферсман порекомендовал поручить именно Даниле Звереву. Горщик из Колташей охотно откликнулся на приглашение, приехал в Екатеринбург, где поселился в доме сына своего бывшего наставника Самойлы Прокопьевича Южакова и принял самое деятельное участие в создании уникального экспоната. На выставке карта имела большой успех и получила высшую награду. В Россию мозаика в итоге так и не вернулась: от имени императора Николая II её подарили президенту Французской Республики Эмилю Лубе. Ныне она хранится в музее Второй империи в городе Компьень. А для Музея истории камнерезного и ювелирного искусства в Екатеринбурге впоследствии была изготовлена её точная копия.

Уезжать из большого города Зверев уже не захотел. В Екатеринбурге ему было суждено провести всю оставшуюся жизнь. Кстати, на Урале до сих пор бытует легенда, будто горщик, покидая Колташи, спрятал в окрестностях деревни клад, состоящий из самых ценных камней, найденных им в молодости. За последние сто лет самоцветы искали многие, но в поисках пока что никто не преуспел.

Начало XX века ознаменовалось активной разведкой новых месторождений, в том числе и на Урале. В этих реалиях горщики были как никогда востребованы, так что Данила Кондратьевич не сидел сложа руки – и, прямо скажем, не бедствовал. На его положении не сильно сказались и революционные события 1917 года – ведь опытные специалисты нужны были молодой советской власти ничуть не меньше, чем поверженному царизму. Так, после революции Зверев подрабатывал оценщиком драгоценных камней. По заказам горных предприятий и банков он оценивал драгоценности, конфискованные у покинувших Советскую Россию в годы Гражданской войны эмигрантов. Именно он поспособствовал передаче множества настоящих сокровищ в собственность государства – впоследствии многие камни и самоцветы, прошедшие через его руки, были переданы в музеи.

«Вот и стали Данило с Катей в своей избушке жить. Хорошо, сказывают, жили, согласно. По работе-то Данилу все горным мастером звали. Против него никто не мог сделать. И достаток у них появился. Ребятишек многонько народилось. Восемь, слышь-ко, человек, и все парнишечки. Мать-то не раз ревливала: хоть бы одна девчонка на поглядку. А отец, знай, похохатывает:

— Такое, видно, наше с тобой положенье!».

Семья у Данилы Кондратьевича и вправду была большая. Он был дважды женат, от двух браков у него было девять детей. Жили дружно в большом двухэтажном доме. Весь первый этаж занимала мастерская, в которой горщик передавал сыновьям своё мастерство. Те в итоге оказались талантливыми последователями отца. Так, Григорий и Алексей Зверевы впоследствии занимались подбором камней для звёзд на башнях Московского Кремля и принимали участие в создании самой дорогой в мире карты – карты индустриализации Советского Союза. Кстати, по сохранившимся данным, сам Данила Зверев в 1925 году консультировал специалистов, подбиравших камень для мавзолея Ленина. Такая вот история.

«Так с той поры Данилушку и найти не могли. Кто говорил, что он ума лишился, в лесу загинул, а кто опять сказывал – Хозяйка взяла его в горные мастера.».

В 1935 году престарелый Зверев тяжело заболел. Предположительно, у него случился инсульт, потому что у горщика повредились речь и сознание, а вся левая половина тела оказалась парализована. Прикованный к постели, Данила Кондратьевич прожил ещё три года и умер 8 декабря 1938 года в возрасте восьмидесяти лет.

В заключение следует добавить, что при жизни Данила Кондратьевич был хорошо знаком с Павлом Петровичем Бажовым. Немудрено, что автор уральских сказов положил многие факты из биографии знаменитого горщика в основу своих произведений. Помимо уже упомянутой в начале статьи «трилогии» о Даниле-мастере, жизненный путь Зверева в художественной форме выведен в сказе «Далевое глядельце» – там он выступил в роли Трофима по прозвищу Тяжёлая Котомка. Так что, как говорится, сказка ложь, да в ней намёк.

| «The Stone Flower» | ||

|---|---|---|

| by Pavel Bazhov | ||

| Original title | Каменный цветок | |

| Translator | Alan Moray Williams (first), Eve Manning, et al. | |

| Country | Soviet Union | |

| Language | Russian | |

| Series | The Malachite Casket collection (list of stories) | |

| Genre(s) | skaz | |

| Published in | Literaturnaya Gazeta | |

| Publication type | Periodical | |

| Publisher | The Union of Soviet Writers | |

| Media type | Print (newspaper, hardback and paperback) | |

| Publication date | 10 May 1938 | |

| Chronology | ||

|

«The Stone Flower» (Russian: Каменный цветок, tr. Kamennyj tsvetok, IPA: [ˈkamʲənʲɪj tsvʲɪˈtok]), also known as «The Flower of Stone«, is a folk tale (also known as skaz) of the Ural region of Russia collected and reworked by Pavel Bazhov, and published in Literaturnaya Gazeta on 10 May 1938 and in Uralsky Sovremennik. It was later released as a part of the story collection The Malachite Box. «The Stone Flower» is considered to be one of the best stories in the collection.[1] The story was translated from Russian into English by Alan Moray Williams in 1944, and several times after that.

Pavel Bazhov indicated that all his stories can be divided into two groups based on tone: «child-toned» (e.g. «Silver Hoof») with simple plots, children as the main characters, and a happy ending,[2] and «adult-toned». He called «The Stone Flower» the «adult-toned» story.[3]

The tale is told from the point of view of the imaginary Grandpa Slyshko (Russian: Дед Слышко, tr. Ded Slyshko; lit. «Old Man Listenhere»).[4]

Publication[edit]

The Moscow critic Viktor Pertsov read the manuscript of «The Stone Flower» in the spring of 1938, when he traveled across the Urals with his literary lectures. He was very impressed by it and published the shortened story in Literaturnaya Gazeta on 10 May 1938.[5] His complimenting review The fairy tales of the Old Urals (Russian: Сказки старого Урала, tr. Skazki starogo Urala) which accompanied the publication.[6]

After the appearance in Literaturnaya Gazeta, the story was published in first volume of the Uralsky Sovremennik in 1938.[7][8] It was later released as a part of Malachite Box collection on 28 January 1939.[9]

In 1944 the story was translated from Russian into English by Alan Moray Williams and published by Hutchinson as a part of the collection The Malachite Casket: Tales from the Urals.[10] The title was translated as «The Stone Flower».[11] In the 1950s translation of The Malachite Casket was made by Eve Manning[12][13] The story was published as «The Flower of Stone».[14]

The story was published in the collection Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov, published by Penguin Books in 2012. The title was translated by Anna Gunin as «The Stone Flower».[15]

Plot summary[edit]

The main character of the story, Danilo, is a weakling and a scatterbrain, and people from the village find him strange. He is sent to study under the stone-craftsman Prokopich. One day he is given an order to make a fine-molded cup, which he creates after a thornapple. It turns out smooth and neat, but not beautiful enough for Danilo’s liking. He is dissatisfied with the result. He says that even the simplest flower «brings joy to your heart», but his stone cup will bring joy to no one. Danilo feels as if he just spoils the stone. An old man tells him the legend that a most beautiful Stone Flower grows in the domain of the Mistress of the Copper Mountain, and those who see it start to understand the beauty of stone, but «life loses all its sweetness» for them. They become the Mistress’s mountain craftsmen forever. Danilo’s fiancée Katyenka asks him to forget it, but Danilo longs to see the Flower. He goes to the copper mine and finds the Mistress of the Copper Mountain. He begs her to show him the Flower. The Mistress reminds him of his fiancée and warns Danilo that he would never want to go back to his people, but he insists. She then shows him the Malachite Flower. Danilo goes back to the village, destroys his stone cup and then disappears. «Some said he’d taken leave of his senses and died somewhere in the woods, but others said the Mistress had taken him to her mountain workshop forever».[16]

Sources[edit]

The main character of the story, Danilo the Craftsman, was based on the real miner Danila Zverev (Russian: Данила Кондратьевич Зверев, tr. Danila Kondratyevich Zverev; 1858–1938).[17] Bazhov met him at the lapidary studio in Sverdlovsk. Zverev was born, grew up and spent most of his life in Koltashi village, Rezhevsky District.[18] Before the October Revolution Zverev moved to Yekaterinburg, where he took up gemstone assessment. Bazhov later created another skaz about his life, «Dalevoe glyadeltse». Danila Zverev and Danilo the Craftsman share many common traits, e.g. both lost their parents early, both tended cattle and were punished for their dreaminess, both suffered from poor health since childhood. Danila Zverev was so short and thin that the villagers gave him the nickname «Lyogonkiy» (Russian: Лёгонький, lit. ‘»Lightweight»‘). Danilo from the story had another nickname «Nedokormysh» (Russian: Недокормыш, lit. ‘»Underfed» or «Famished»‘). Danila Zverev’s teacher Samoil Prokofyich Yuzhakov (Russian: Самоил Прокофьич Южаков) became the source of inpisration for Danilo the Craftsman’s old teacher Prokopich.[17]

Themes[edit]

During Soviet times, every edition of The Malachite Box was usually prefaced by an essay by a famous writer or scholar, commenting on the creativity of the Ural miners, cruel landlords, social oppression and the «great workers unbroken by the centuries of slavery».[19] The later scholars focused more on the relationship of the characters with nature, the Mountain and the mysterious in general.[20] Maya Nikulina comments that Danilo is the creator who is absolutely free from all ideological, social and political contexts. His talent comes from the connection with the secret force, which controls all his movements. Moreover, the local landlord, while he exists, is unimportant for Danilo’s story. Danilo’s issues with his employer are purely aesthetic, i.e., a custom-made vase was ordered, but Danilo, as an artist, only desires to understand the beauty of stone, and this desire takes him away from life.[21]

The Stone Flower is the embodiment of the absolute magic power of stone and the absolute beauty, which is beyond mortals’ reach.[22]

Many noted that the Mistress’ world represents the realm of the dead,[23][24] which is emphasized not only by its location underneath the human world but also mostly by its mirror-like, uncanny, imitation or negation of the living world.[23] Everything looks strange there, even the trees are cold and smooth like stone. The Mistress herself does not eat or drink, she does not leave any traces, her clothing is made of stone and so on. The Mountain connects her to the world of the living, and Danilo metaphorically died for the world, when we went to her.[24] Mesmerized by the Flower, Danilo feels at his own wedding as if he were at a funeral. A contact with the Mistress is a symbolic manifestation of death. Marina Balina noted that as one of the «mountain spirits», she does not hesitate to kill those who did not pass her tests, but even those who had been rewarded by her do not live happily ever after, as shown with Stepan in «The Mistress of the Copper Mountain».[23] The Mistress was also interpreted as the manifestation of female sexuality. «The Mistress exudes sexual attraction and appears as its powerful source».[25] Mark Lipovetsky commented that Mistress embodies the struggle and unity between Eros and Thanatos. The Flower is made of cold stone for that very reason: it points at death along with sexuality.[26] All sexual references in Pavel Bazhov’s stories are very subtle, owing to Soviet puritanism.[27]

Danilo is a classical Bazhov binary character. On the one hand, he is a truth seeker and a talented craftsman, on the other hand, he is an outsider, who violates social norms, destroys the lives of the loved ones and his own.[28] The author of The Fairy Tale Encyclopedia suggests that the Mistress represents the conflict between human kind and nature. She compares the character with Mephistopheles, because a human needs to wager his soul with the Mistress in order to get the ultimate knowledge. Danilo wagers his soul for exceptional craftsmanship skills.[29] However, the Mistress does not force anyone to abandon their moral values, and therefore «is not painted in dark colours».[30] Lyudmila Skorino believed that she represented the nature of the Urals, which inspires a creative person with its beauty.[31]

Denis Zherdev commented that the Mistress’s female domain is the world of chaos, destruction and spontaneous uncontrolled acts of creation (human craftsmen are needed for the controlled creation). Although the characters are so familiar with the female world that the appearance of the Mistress is regarded as almost natural and even expected, the female domain collides with the ordered factory world, and brings in randomness, variability, unpredictability and capriciousness. Direct contact with the female power is a violation of the world order and therefore brings destruction or chaos.[32]

One of the themes is how to become a true artist and the subsequent self-fulfillment. The Soviet critics’ point of view was that the drama of Danilo came from the fact that he was a serf, and therefore did not receive the necessary training to complete the task. However, modern critics disagree and state that the plot of the artist’s dissatisfaction is very popular in literature. Just like in the Russian poem The Sylph, written by Vladimir Odoyevsky, Bazhov raises the issue that the artist can reach his ideal only when he comes in with the otherworldly.[33]

Sequels[edit]

«The Master Craftsman»[edit]

«The Master Craftsman» redirects here. For a member of a guild, see Master craftsman.

«The Master Craftsman» (Russian: Горный мастер, tr. Gornyj master) was serialized in Na Smenu! from 14 to 26 January 1939, in Oktyabr (issues 5–6), and in Rabotnitsa magazine (issues 18–19).[34][35] In 1944 the story was translated from Russian into English by Alan Moray Williams and published by Hutchinson as a part of the collection The Malachite Casket: Tales from the Urals. The title was translated as «The Master Craftsman».[36] In the 1950s translation of The Malachite Casket, made by Eve Manning, the story was published as «The Mountain Craftsman«.[37] The story was published in the collection Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov, published by Penguin Books in 2012. The title was translated by Anna Gunin as «The Mountain Master«.[38]

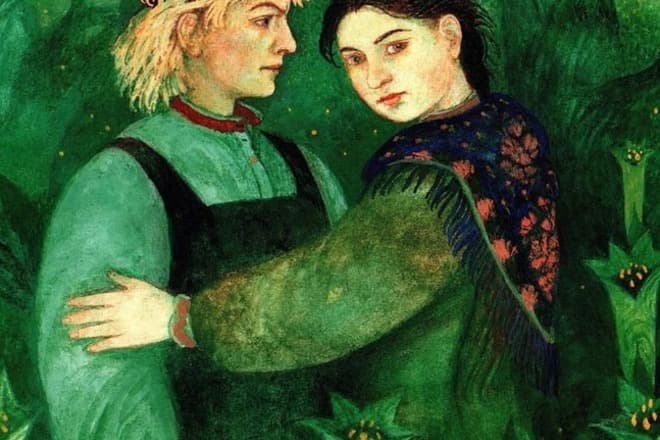

The story begins after the disappearance of Danilo. For several years Danilo’s betrothed Katyenka (Katya) waits for him and stays unmarried despite the fact that everyone laughs at her. She is the only person who believes that Danilo will return. She is quickly nicknamed «Dead Man’s Bride». When both of her parents die, she moves away from her family and goes to Danilo’s house and takes care of his old teacher Prokopich, although she knows that living with a man can ruin her reputation. Prokopich welcomes her happily. He earns some money by gem-cutting, Katya runs the house, cooks, and does the gardening. When Prokopich gets too old to work, Katya realizes that she cannot possibly support herself by needlework alone. She asks him to teach her some stone craft. Prokopich laughs at first, because he does not believe gem-cutting is a suitable job for a woman, but soon relents. He teaches her how to work with malachite. After he dies, Katya decides to live in the house alone. Her strange behaviour, her refusal to marry someone and lead a normal life cause people at the village to think that she is insane or even a witch, but Katya firmly believes that Danilo will «learn all he wants to know, there in the mountain, and then he’ll come».[39] She wants to try making medallions and selling them. There are no gemstones left, so she goes to the forest, finds an exceptional piece of gemstone and starts working. After the medallions are finished, she goes to the town to the merchant who used to buy Prokopich’s work. He reluctantly buys them all, because her work is very beautiful. Katya feels as if this was a token from Danilo. She runs back to the forest and starts calling for him. The Mistress of the Copper Mountain appears. Katya bravely demands that she gives Danilo back. The Mistress takes her to Danilo and says: «Well, Danilo the Master Craftsman, now you must choose. If you go with her you forget all that is mine, if you remain here, then you must forget her and all living people».[40] Danilo chooses Katya, saying that he thinks about her every moment. The Mistress is pleased with Katya’s bravery and rewards her by letting Danilo remember everything that he had learned in the Mountain. She then warns Danilo to never tell anyone about his life there. The couple thanks the Mistress and goes back to the village. When asked about his disappearance, Danilo claims that he simply left to Kolyvan to train under another craftsman. He marries Katya. His works is extraordinary, and everyone starts calling him «the mountain craftsman».

Other books[edit]

This family’s story continues in «A Fragile Twig», published in 1940.[41] «A Fragile Twig» focuses on Katyenka and Danilo’s son Mitya. This is the last tale about Danilo’s family. Bazhov had plans for the fourth story about Danilo’s family, but it was never written. In the interview to a Soviet newspaper Vechernyaya Moskva the writer said: «I am going to finish «The Stone Flower» story. I would like to write about the heirs of the protagonist, Danilo, [I would like] to write about their remarkable skills and aspirations for the future. I’m thinking about leading the story to the present day».[42] This plan was later abandoned.

Reception and legacy[edit]

The Stone Flower in the early design of Polevskoy’s coat of arms (1981).[43]

The current flag of Polevskoy features the Mistress of the Copper Mountain (depicted as a lizard) inside the symbolic representation of the Stone Flower.

Danilo the Craftsman became one of the best known characters of Bazhov’s tales.[21] The fairy tale inspired numerous adaptations, including films and stage adaptations. It is included in the school reading curriculum.[44] «The Stone Flower» is typically adapted with «The Master Craftsman».

- The Stone Flower Fountain at the VDNKh Center, Moscow (1953).

- The Stone Flower Fountain in Yekaterinburg (1960).[45] Project by Pyotr Demintsev.[46]

It generated a Russian catchphrase «How did that Stone Flower come out?» (Russian: «Не выходит у тебя Каменный цветок?», tr. Ne vykhodit u tebja Kamennyj tsvetok?, lit. «Naught came of your Stone Flower?»),[47] derived from these dialogue:

«Well, Danilo the Craftsman, so naught came of your thornapple?»

«No, naught came of it,» he said.[48]

The style of the story was praised.[49]

Films[edit]

- The Stone Flower, a 1946 Soviet film;[50] incorporates plot elements from the stories «The Mistress of the Copper Mountain» and «The Master Craftsman».

- The Stone Flower, a 1977 animated film;[51] based on «The Stone Flower» and «The Master Craftsman»

- The Master Craftsman, a 1978 animated film made by Soyuzmultfilm studio,[52] based on «The Stone Flower» and «The Master Craftsman».

- The Book of Masters, a 2009 Russian language fantasy film, is loosely based on Bazhov’s tales, including «The Stone Flower».[53][54]

- The Stone Flower (another title: Skazy), a television film of two-episodes that premiered on 1 January 1988. This film is a photoplay (a theatrical play that has been filmed for showing as a film) based on the 1987 play of the Maly Theatre. It was directed by Vitaly Ivanov, with the music composed by Nikolai Karetnikov, and released by Studio Ekran. It starred Yevgeny Samoylov, Tatyana Lebedeva, Tatyana Pankova, Oleg Kutsenko.[55]

Theatre[edit]

- The Stone Flower, the 1944 ballet composed by Alexander Fridlender.[8]

- Klavdiya Filippova combined «The Stone Flower» with «The Master Craftsman» to create the children’s play The Stone Flower.[56] It was published in Sverdlovsk as a part of the 1949 collection Plays for Children’s Theatre Based on Bazhov’s Stories.[56]

- The Stone Flower, an opera in four acts by Kirill Molchanov. Sergey Severtsev wrote the Russian language libretto. It was the first opera of Molchanov.[57] It premiered on 10 December 1950 in Moscow at the Stanislavski and Nemirovich-Danchenko Music Theatre.[58] The role of Danila (tenor) was sung by Mechislav Shchavinsky, Larisa Adveyeva sung the Mistress of the Copper Mountain (mezzo-soprano), Dina Potapovskaya sung Katya (coloratura soprano).[59][60]

- The Tale of the Stone Flower, the 1954 ballet composed by Sergei Prokofiev.[61]

- Skazy, also called The Stone Flower, the 1987 play of the Maly Theatre.[55]

Notes[edit]

- ^ «Bazhov Pavel Petrovitch». The Russian Academy of Sciences Electronic Library IRLI (in Russian). The Russian Literature Institute of the Pushkin House, RAS. pp. 151–152. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Litovskaya 2014, p. 247.

- ^ «Bazhov P. P. The Malachite Box» (in Russian). Bibliogid. 13 May 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Balina, Marina; Goscilo, Helena; Lipovetsky, Mark (25 October 2005). Politicizing Magic: An Anthology of Russian and Soviet Fairy Tales. The Northwestern University Press. p. 115. ISBN 9780810120327.

- ^ Slobozhaninova, Lidiya (2004). «Malahitovaja shkatulka Bazhova vchera i segodnja» “Малахитовая шкатулка” Бажова вчера и сегодня [Bazhov’s Malachite Box yesterday and today]. Ural (in Russian). Yekaterinburg. 1.

- ^ Komlev, Andrey (2004). «Bazhov i Sverdlovskoe otdelenie Sojuza sovetskih pisatelej» Бажов и Свердловское отделение Союза советских писателей [Bazhov and the Sverdlovsk department of the Union of the Soviet writers]. Ural (in Russian). Yekaterinburg. 1.

- ^ Bazhov 1952, p. 243.

- ^ a b «Kamennyj tsvetok» (in Russian). FantLab. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ «The Malachite Box» (in Russian). The Live Book Museum. Yekaterinburg. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ The malachite casket; tales from the Urals, (Book, 1944). WorldCat. OCLC 1998181.

- ^ Bazhov 1944, p. 76.

- ^ «Malachite casket : tales from the Urals / P. Bazhov ; [translated from the Russian by Eve Manning ; illustrated by O. Korovin ; designed by A. Vlasova]». The National Library of Australia. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Malachite casket; tales from the Urals. (Book, 1950s). WorldCat. OCLC 10874080.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 9.

- ^ Russian magic tales from Pushkin to Platonov (Book, 2012). WorldCat.org. OCLC 802293730.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 67.

- ^ a b «Родина Данилы Зверева». А.В. Рычков, Д.В. Рычков «Лучшие путешествия по Среднему Уралу». (in Russian). geocaching.su. 28 July 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ Dobrovolsky, Evgeni (1981). Оптимальный вариант. Sovetskaya Rossiya. p. 5.

- ^ Nikulina 2003, p. 76.

- ^ Nikulina 2003, p. 77.

- ^ a b Nikulina 2003, p. 80.

- ^ Prikazchikova, E. (2003). «Каменная сила медных гор Урала» [The Stone Force of The Ural Copper Mountains] (PDF). Izvestiya of the Ural State University (in Russian). The Ural State University (28): 16.

- ^ a b c Balina 2013, p. 273.

- ^ a b Shvabauer, Nataliya (10 January 2009). «Типология фантастических персонажей в фольклоре горнорабочих Западной Европы и России» [The Typology of the Fantastic Characters in the Miners’ Folklore of Western Europe and Russia] (PDF). Dissertation (in Russian). The Ural State University. p. 147. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Balina 2013, p. 270.

- ^ Lipovetsky 2014, p. 220.

- ^ Lipovetsky 2014, p. 218.

- ^ Zherdev, Denis (2003). «Binarnost kak element pojetiki bazhovskikh skazov» Бинарность как элемент поэтики бажовских сказов [Binarity as the Poetic Element in Bazhov’s Skazy] (PDF). Izvestiya of the Ural State University (in Russian). The Ural State University (28): 46–57.

- ^ Budur 2005, p. 124.

- ^ Budur 2005, p. 285.

- ^ Bazhov 1952, p. 232.

- ^ Zherdev, Denis. «Poetika skazov Bazhova» Поэтика сказов Бажова [The poetics of Bazhov’s stories] (in Russian). Research Library Mif.Ru. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ Sozina, E. «O nekotorykh motivah russkoj klassicheskoj literatury v skazah P. P. Bazhova o masterah О некоторых мотивах русской классической литературы в сказах П. П. Бажова о «мастерах» [On some Russian classical literature motives in P. P. Bazhov’s «masters» stories.]» in: P. P. Bazhov i socialisticheskij realizm.

- ^ «Горный мастер» [The Master Craftsman] (in Russian). FantLab. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ Bazhov 1952 (1), p. 243.

- ^ Bazhov 1944, p. 95.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 68.

- ^ Russian magic tales from Pushkin to Platonov (Book, 2012). WorldCat.org. OCLC 802293730.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 70.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 80.

- ^ Izmaylova, A. B. «Сказ П.П. Бажова «Хрупкая веточка» в курсе «Русская народная педагогика»» [P. Bazhov’s skaz A Fragile Twig in the course The Russian Folk Pedagogics] (PDF) (in Russian). The Vladimir State University. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ «The interview with P. Bazhov». Vechernyaya Moskva (in Russian). Mossovet. 31 January 1948.: «Собираюсь закончить сказ о «Каменном цветке». Мне хочется показать в нем преемников его героя, Данилы, написать об их замечательном мастерстве, устремлении в будущее. Действие сказа думаю довести до наших дней».

- ^ «Городской округ г. Полевской, Свердловская область» [Polevskoy Town District, Sverdlovsk Oblast]. Coats of arms of Russia (in Russian). Heraldicum.ru. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ Korovina, V. «Программы общеобразовательных учреждений» [The educational institutions curriculum] (in Russian). Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ «Средний Урал отмечает 130-летие со дня рождения Павла Бажова» (in Russian). Yekaterinburg Online. 27 January 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ «Фонтан «Каменный цветок» на площади Труда в Екатеринбурге отремонтируют за месяц: Общество: Облгазета».

- ^ Kozhevnikov, Alexey (2004). Крылатые фразы и афоризмы отечественного кино [Catchphrases and aphorisms from Russian cinema] (in Russian). OLMA Media Group. p. 214. ISBN 9785765425671.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 231. In Russian: «Ну что, Данило-мастер, не вышла твоя дурман-чаша?» — «Не вышла, — отвечает.»

- ^ Eydinova, Viola (2003). «O stile Bazhova» О стиле Бажова [About Bazhov’s style]. Izvestiya of the Ural State University (in Russian). The Ural State University. 28: 40–46.

- ^ «The Stone Flower (1946)» (in Russian). The Russian Cinema Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ «A Stone Flower». Animator.ru. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ «Mining Master». Animator.ru. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ Sakharnova, Kseniya (21 October 2009). ««Книга мастеров»: герои русских сказок в стране Disney» [The Book of Masters: the Russian fairy tale characters in Disneyland] (in Russian). Profcinema Co. Ltd. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ Zabaluyev, Yaroslav (27 October 2009). «Nor have we seen its like before…» (in Russian). Gazeta.ru. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ a b «Каменный цветок 1987» [The Stone Flower 1987] (in Russian). Kino-teatr.ru. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ a b Litovskaya 2014, p. 250.

- ^ Rollberg, Peter (7 November 2008). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. Scarecrow Press. p. 461. ISBN 9780810862685.

- ^ «Опера Молчанова «Каменный цветок»» [Molchanov’s opera The Stone Flower] (in Russian). Belcanto.ru. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ The Union of the Soviet Composers, ed. (1950). Советская музыка [Soviet Music] (in Russian). Vol. 1–6. Государственное Музыкальное издательство. p. 109.

- ^ Medvedev, A (February 1951). «Каменный цветок» [The Stone Flower]. Smena (in Russian). Smena Publishing House. 2 (570).

- ^ Balina 2013, p. 263.

References[edit]

- Bazhov, Pavel (1952). Valentina Bazhova; Alexey Surkov; Yevgeny Permyak (eds.). Sobranie sochinenij v trekh tomakh Собрание сочинений в трех томах [Works. In Three Volumes] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Moscow: Khudozhestvennaya Literatura.

- Bazhov, Pavel; translated by Alan Moray Williams (1944). The Malachite Casket: tales from the Urals. Library of selected Soviet literature. The University of California: Hutchinson & Co. ltd. ISBN 9787250005603.

- Bazhov, Pavel; translated by Eve Manning (1950s). Malachite Casket: Tales from the Urals. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

- Lipovetsky, Mark (2014). «The Uncanny in Bazhov’s Tales». Quaestio Rossica (in Russian). The University of Colorado Boulder. 2 (2): 212–230. doi:10.15826/qr.2014.2.051. ISSN 2311-911X.

- Litovskaya, Mariya (2014). «Vzroslyj detskij pisatel Pavel Bazhov: konflikt redaktur» Взрослый детский писатель Павел Бажов: конфликт редактур [The Adult-Children’s Writer Pavel Bazhov: The Conflict of Editing]. Detskiye Chteniya (in Russian). 6 (2): 243–254.

- Balina, Marina; Rudova, Larissa (1 February 2013). Russian Children’s Literature and Culture. Literary Criticism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135865566.

- Budur, Naralya (2005). «The Mistress of the Copper Mountain». Skazochnaja enciklopedija Сказочная энциклопедия [The Fairy Tale Encyclopedia] (in Russian). Olma Media Group. ISBN 9785224048182.

- Nikulina, Maya (2003). «Pro zemelnye dela i pro tajnuju silu. O dalnikh istokakh uralskoj mifologii P.P. Bazhova» Про земельные дела и про тайную силу. О дальних истоках уральской мифологии П.П. Бажова [Of land and the secret force. The distant sources of P.P. Bazhov’s Ural mythology]. Filologichesky Klass (in Russian). Cyberleninka.ru. 9.

- P. P. Bazhov i socialisticheskij realizm // Tvorchestvo P.P. Bazhova v menjajushhemsja mire П. П. Бажов и социалистический реализм // Творчество П. П. Бажова в меняющемся мире [Pavel Bazhov and socialist realism // The works of Pavel Bazhov in the changing world]. The materials of the inter-university research conference devoted to the 125th birthday (in Russian). Yekaterinburg: The Ural State University. 28–29 January 2004. pp. 18–26.

| «The Stone Flower» | ||

|---|---|---|

| by Pavel Bazhov | ||

| Original title | Каменный цветок | |

| Translator | Alan Moray Williams (first), Eve Manning, et al. | |

| Country | Soviet Union | |

| Language | Russian | |

| Series | The Malachite Casket collection (list of stories) | |

| Genre(s) | skaz | |

| Published in | Literaturnaya Gazeta | |

| Publication type | Periodical | |

| Publisher | The Union of Soviet Writers | |

| Media type | Print (newspaper, hardback and paperback) | |

| Publication date | 10 May 1938 | |

| Chronology | ||

|

«The Stone Flower» (Russian: Каменный цветок, tr. Kamennyj tsvetok, IPA: [ˈkamʲənʲɪj tsvʲɪˈtok]), also known as «The Flower of Stone«, is a folk tale (also known as skaz) of the Ural region of Russia collected and reworked by Pavel Bazhov, and published in Literaturnaya Gazeta on 10 May 1938 and in Uralsky Sovremennik. It was later released as a part of the story collection The Malachite Box. «The Stone Flower» is considered to be one of the best stories in the collection.[1] The story was translated from Russian into English by Alan Moray Williams in 1944, and several times after that.

Pavel Bazhov indicated that all his stories can be divided into two groups based on tone: «child-toned» (e.g. «Silver Hoof») with simple plots, children as the main characters, and a happy ending,[2] and «adult-toned». He called «The Stone Flower» the «adult-toned» story.[3]

The tale is told from the point of view of the imaginary Grandpa Slyshko (Russian: Дед Слышко, tr. Ded Slyshko; lit. «Old Man Listenhere»).[4]

Publication[edit]

The Moscow critic Viktor Pertsov read the manuscript of «The Stone Flower» in the spring of 1938, when he traveled across the Urals with his literary lectures. He was very impressed by it and published the shortened story in Literaturnaya Gazeta on 10 May 1938.[5] His complimenting review The fairy tales of the Old Urals (Russian: Сказки старого Урала, tr. Skazki starogo Urala) which accompanied the publication.[6]

After the appearance in Literaturnaya Gazeta, the story was published in first volume of the Uralsky Sovremennik in 1938.[7][8] It was later released as a part of Malachite Box collection on 28 January 1939.[9]

In 1944 the story was translated from Russian into English by Alan Moray Williams and published by Hutchinson as a part of the collection The Malachite Casket: Tales from the Urals.[10] The title was translated as «The Stone Flower».[11] In the 1950s translation of The Malachite Casket was made by Eve Manning[12][13] The story was published as «The Flower of Stone».[14]

The story was published in the collection Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov, published by Penguin Books in 2012. The title was translated by Anna Gunin as «The Stone Flower».[15]

Plot summary[edit]

The main character of the story, Danilo, is a weakling and a scatterbrain, and people from the village find him strange. He is sent to study under the stone-craftsman Prokopich. One day he is given an order to make a fine-molded cup, which he creates after a thornapple. It turns out smooth and neat, but not beautiful enough for Danilo’s liking. He is dissatisfied with the result. He says that even the simplest flower «brings joy to your heart», but his stone cup will bring joy to no one. Danilo feels as if he just spoils the stone. An old man tells him the legend that a most beautiful Stone Flower grows in the domain of the Mistress of the Copper Mountain, and those who see it start to understand the beauty of stone, but «life loses all its sweetness» for them. They become the Mistress’s mountain craftsmen forever. Danilo’s fiancée Katyenka asks him to forget it, but Danilo longs to see the Flower. He goes to the copper mine and finds the Mistress of the Copper Mountain. He begs her to show him the Flower. The Mistress reminds him of his fiancée and warns Danilo that he would never want to go back to his people, but he insists. She then shows him the Malachite Flower. Danilo goes back to the village, destroys his stone cup and then disappears. «Some said he’d taken leave of his senses and died somewhere in the woods, but others said the Mistress had taken him to her mountain workshop forever».[16]

Sources[edit]

The main character of the story, Danilo the Craftsman, was based on the real miner Danila Zverev (Russian: Данила Кондратьевич Зверев, tr. Danila Kondratyevich Zverev; 1858–1938).[17] Bazhov met him at the lapidary studio in Sverdlovsk. Zverev was born, grew up and spent most of his life in Koltashi village, Rezhevsky District.[18] Before the October Revolution Zverev moved to Yekaterinburg, where he took up gemstone assessment. Bazhov later created another skaz about his life, «Dalevoe glyadeltse». Danila Zverev and Danilo the Craftsman share many common traits, e.g. both lost their parents early, both tended cattle and were punished for their dreaminess, both suffered from poor health since childhood. Danila Zverev was so short and thin that the villagers gave him the nickname «Lyogonkiy» (Russian: Лёгонький, lit. ‘»Lightweight»‘). Danilo from the story had another nickname «Nedokormysh» (Russian: Недокормыш, lit. ‘»Underfed» or «Famished»‘). Danila Zverev’s teacher Samoil Prokofyich Yuzhakov (Russian: Самоил Прокофьич Южаков) became the source of inpisration for Danilo the Craftsman’s old teacher Prokopich.[17]

Themes[edit]

During Soviet times, every edition of The Malachite Box was usually prefaced by an essay by a famous writer or scholar, commenting on the creativity of the Ural miners, cruel landlords, social oppression and the «great workers unbroken by the centuries of slavery».[19] The later scholars focused more on the relationship of the characters with nature, the Mountain and the mysterious in general.[20] Maya Nikulina comments that Danilo is the creator who is absolutely free from all ideological, social and political contexts. His talent comes from the connection with the secret force, which controls all his movements. Moreover, the local landlord, while he exists, is unimportant for Danilo’s story. Danilo’s issues with his employer are purely aesthetic, i.e., a custom-made vase was ordered, but Danilo, as an artist, only desires to understand the beauty of stone, and this desire takes him away from life.[21]

The Stone Flower is the embodiment of the absolute magic power of stone and the absolute beauty, which is beyond mortals’ reach.[22]

Many noted that the Mistress’ world represents the realm of the dead,[23][24] which is emphasized not only by its location underneath the human world but also mostly by its mirror-like, uncanny, imitation or negation of the living world.[23] Everything looks strange there, even the trees are cold and smooth like stone. The Mistress herself does not eat or drink, she does not leave any traces, her clothing is made of stone and so on. The Mountain connects her to the world of the living, and Danilo metaphorically died for the world, when we went to her.[24] Mesmerized by the Flower, Danilo feels at his own wedding as if he were at a funeral. A contact with the Mistress is a symbolic manifestation of death. Marina Balina noted that as one of the «mountain spirits», she does not hesitate to kill those who did not pass her tests, but even those who had been rewarded by her do not live happily ever after, as shown with Stepan in «The Mistress of the Copper Mountain».[23] The Mistress was also interpreted as the manifestation of female sexuality. «The Mistress exudes sexual attraction and appears as its powerful source».[25] Mark Lipovetsky commented that Mistress embodies the struggle and unity between Eros and Thanatos. The Flower is made of cold stone for that very reason: it points at death along with sexuality.[26] All sexual references in Pavel Bazhov’s stories are very subtle, owing to Soviet puritanism.[27]

Danilo is a classical Bazhov binary character. On the one hand, he is a truth seeker and a talented craftsman, on the other hand, he is an outsider, who violates social norms, destroys the lives of the loved ones and his own.[28] The author of The Fairy Tale Encyclopedia suggests that the Mistress represents the conflict between human kind and nature. She compares the character with Mephistopheles, because a human needs to wager his soul with the Mistress in order to get the ultimate knowledge. Danilo wagers his soul for exceptional craftsmanship skills.[29] However, the Mistress does not force anyone to abandon their moral values, and therefore «is not painted in dark colours».[30] Lyudmila Skorino believed that she represented the nature of the Urals, which inspires a creative person with its beauty.[31]

Denis Zherdev commented that the Mistress’s female domain is the world of chaos, destruction and spontaneous uncontrolled acts of creation (human craftsmen are needed for the controlled creation). Although the characters are so familiar with the female world that the appearance of the Mistress is regarded as almost natural and even expected, the female domain collides with the ordered factory world, and brings in randomness, variability, unpredictability and capriciousness. Direct contact with the female power is a violation of the world order and therefore brings destruction or chaos.[32]

One of the themes is how to become a true artist and the subsequent self-fulfillment. The Soviet critics’ point of view was that the drama of Danilo came from the fact that he was a serf, and therefore did not receive the necessary training to complete the task. However, modern critics disagree and state that the plot of the artist’s dissatisfaction is very popular in literature. Just like in the Russian poem The Sylph, written by Vladimir Odoyevsky, Bazhov raises the issue that the artist can reach his ideal only when he comes in with the otherworldly.[33]

Sequels[edit]

«The Master Craftsman»[edit]

«The Master Craftsman» redirects here. For a member of a guild, see Master craftsman.

«The Master Craftsman» (Russian: Горный мастер, tr. Gornyj master) was serialized in Na Smenu! from 14 to 26 January 1939, in Oktyabr (issues 5–6), and in Rabotnitsa magazine (issues 18–19).[34][35] In 1944 the story was translated from Russian into English by Alan Moray Williams and published by Hutchinson as a part of the collection The Malachite Casket: Tales from the Urals. The title was translated as «The Master Craftsman».[36] In the 1950s translation of The Malachite Casket, made by Eve Manning, the story was published as «The Mountain Craftsman«.[37] The story was published in the collection Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov, published by Penguin Books in 2012. The title was translated by Anna Gunin as «The Mountain Master«.[38]

The story begins after the disappearance of Danilo. For several years Danilo’s betrothed Katyenka (Katya) waits for him and stays unmarried despite the fact that everyone laughs at her. She is the only person who believes that Danilo will return. She is quickly nicknamed «Dead Man’s Bride». When both of her parents die, she moves away from her family and goes to Danilo’s house and takes care of his old teacher Prokopich, although she knows that living with a man can ruin her reputation. Prokopich welcomes her happily. He earns some money by gem-cutting, Katya runs the house, cooks, and does the gardening. When Prokopich gets too old to work, Katya realizes that she cannot possibly support herself by needlework alone. She asks him to teach her some stone craft. Prokopich laughs at first, because he does not believe gem-cutting is a suitable job for a woman, but soon relents. He teaches her how to work with malachite. After he dies, Katya decides to live in the house alone. Her strange behaviour, her refusal to marry someone and lead a normal life cause people at the village to think that she is insane or even a witch, but Katya firmly believes that Danilo will «learn all he wants to know, there in the mountain, and then he’ll come».[39] She wants to try making medallions and selling them. There are no gemstones left, so she goes to the forest, finds an exceptional piece of gemstone and starts working. After the medallions are finished, she goes to the town to the merchant who used to buy Prokopich’s work. He reluctantly buys them all, because her work is very beautiful. Katya feels as if this was a token from Danilo. She runs back to the forest and starts calling for him. The Mistress of the Copper Mountain appears. Katya bravely demands that she gives Danilo back. The Mistress takes her to Danilo and says: «Well, Danilo the Master Craftsman, now you must choose. If you go with her you forget all that is mine, if you remain here, then you must forget her and all living people».[40] Danilo chooses Katya, saying that he thinks about her every moment. The Mistress is pleased with Katya’s bravery and rewards her by letting Danilo remember everything that he had learned in the Mountain. She then warns Danilo to never tell anyone about his life there. The couple thanks the Mistress and goes back to the village. When asked about his disappearance, Danilo claims that he simply left to Kolyvan to train under another craftsman. He marries Katya. His works is extraordinary, and everyone starts calling him «the mountain craftsman».

Other books[edit]

This family’s story continues in «A Fragile Twig», published in 1940.[41] «A Fragile Twig» focuses on Katyenka and Danilo’s son Mitya. This is the last tale about Danilo’s family. Bazhov had plans for the fourth story about Danilo’s family, but it was never written. In the interview to a Soviet newspaper Vechernyaya Moskva the writer said: «I am going to finish «The Stone Flower» story. I would like to write about the heirs of the protagonist, Danilo, [I would like] to write about their remarkable skills and aspirations for the future. I’m thinking about leading the story to the present day».[42] This plan was later abandoned.

Reception and legacy[edit]

The Stone Flower in the early design of Polevskoy’s coat of arms (1981).[43]

The current flag of Polevskoy features the Mistress of the Copper Mountain (depicted as a lizard) inside the symbolic representation of the Stone Flower.

Danilo the Craftsman became one of the best known characters of Bazhov’s tales.[21] The fairy tale inspired numerous adaptations, including films and stage adaptations. It is included in the school reading curriculum.[44] «The Stone Flower» is typically adapted with «The Master Craftsman».

- The Stone Flower Fountain at the VDNKh Center, Moscow (1953).

- The Stone Flower Fountain in Yekaterinburg (1960).[45] Project by Pyotr Demintsev.[46]

It generated a Russian catchphrase «How did that Stone Flower come out?» (Russian: «Не выходит у тебя Каменный цветок?», tr. Ne vykhodit u tebja Kamennyj tsvetok?, lit. «Naught came of your Stone Flower?»),[47] derived from these dialogue:

«Well, Danilo the Craftsman, so naught came of your thornapple?»

«No, naught came of it,» he said.[48]

The style of the story was praised.[49]

Films[edit]

- The Stone Flower, a 1946 Soviet film;[50] incorporates plot elements from the stories «The Mistress of the Copper Mountain» and «The Master Craftsman».

- The Stone Flower, a 1977 animated film;[51] based on «The Stone Flower» and «The Master Craftsman»

- The Master Craftsman, a 1978 animated film made by Soyuzmultfilm studio,[52] based on «The Stone Flower» and «The Master Craftsman».

- The Book of Masters, a 2009 Russian language fantasy film, is loosely based on Bazhov’s tales, including «The Stone Flower».[53][54]

- The Stone Flower (another title: Skazy), a television film of two-episodes that premiered on 1 January 1988. This film is a photoplay (a theatrical play that has been filmed for showing as a film) based on the 1987 play of the Maly Theatre. It was directed by Vitaly Ivanov, with the music composed by Nikolai Karetnikov, and released by Studio Ekran. It starred Yevgeny Samoylov, Tatyana Lebedeva, Tatyana Pankova, Oleg Kutsenko.[55]

Theatre[edit]

- The Stone Flower, the 1944 ballet composed by Alexander Fridlender.[8]

- Klavdiya Filippova combined «The Stone Flower» with «The Master Craftsman» to create the children’s play The Stone Flower.[56] It was published in Sverdlovsk as a part of the 1949 collection Plays for Children’s Theatre Based on Bazhov’s Stories.[56]

- The Stone Flower, an opera in four acts by Kirill Molchanov. Sergey Severtsev wrote the Russian language libretto. It was the first opera of Molchanov.[57] It premiered on 10 December 1950 in Moscow at the Stanislavski and Nemirovich-Danchenko Music Theatre.[58] The role of Danila (tenor) was sung by Mechislav Shchavinsky, Larisa Adveyeva sung the Mistress of the Copper Mountain (mezzo-soprano), Dina Potapovskaya sung Katya (coloratura soprano).[59][60]

- The Tale of the Stone Flower, the 1954 ballet composed by Sergei Prokofiev.[61]

- Skazy, also called The Stone Flower, the 1987 play of the Maly Theatre.[55]

Notes[edit]

- ^ «Bazhov Pavel Petrovitch». The Russian Academy of Sciences Electronic Library IRLI (in Russian). The Russian Literature Institute of the Pushkin House, RAS. pp. 151–152. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Litovskaya 2014, p. 247.

- ^ «Bazhov P. P. The Malachite Box» (in Russian). Bibliogid. 13 May 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Balina, Marina; Goscilo, Helena; Lipovetsky, Mark (25 October 2005). Politicizing Magic: An Anthology of Russian and Soviet Fairy Tales. The Northwestern University Press. p. 115. ISBN 9780810120327.

- ^ Slobozhaninova, Lidiya (2004). «Malahitovaja shkatulka Bazhova vchera i segodnja» “Малахитовая шкатулка” Бажова вчера и сегодня [Bazhov’s Malachite Box yesterday and today]. Ural (in Russian). Yekaterinburg. 1.

- ^ Komlev, Andrey (2004). «Bazhov i Sverdlovskoe otdelenie Sojuza sovetskih pisatelej» Бажов и Свердловское отделение Союза советских писателей [Bazhov and the Sverdlovsk department of the Union of the Soviet writers]. Ural (in Russian). Yekaterinburg. 1.

- ^ Bazhov 1952, p. 243.

- ^ a b «Kamennyj tsvetok» (in Russian). FantLab. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ «The Malachite Box» (in Russian). The Live Book Museum. Yekaterinburg. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ The malachite casket; tales from the Urals, (Book, 1944). WorldCat. OCLC 1998181.

- ^ Bazhov 1944, p. 76.

- ^ «Malachite casket : tales from the Urals / P. Bazhov ; [translated from the Russian by Eve Manning ; illustrated by O. Korovin ; designed by A. Vlasova]». The National Library of Australia. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Malachite casket; tales from the Urals. (Book, 1950s). WorldCat. OCLC 10874080.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 9.

- ^ Russian magic tales from Pushkin to Platonov (Book, 2012). WorldCat.org. OCLC 802293730.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 67.

- ^ a b «Родина Данилы Зверева». А.В. Рычков, Д.В. Рычков «Лучшие путешествия по Среднему Уралу». (in Russian). geocaching.su. 28 July 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ Dobrovolsky, Evgeni (1981). Оптимальный вариант. Sovetskaya Rossiya. p. 5.

- ^ Nikulina 2003, p. 76.

- ^ Nikulina 2003, p. 77.

- ^ a b Nikulina 2003, p. 80.

- ^ Prikazchikova, E. (2003). «Каменная сила медных гор Урала» [The Stone Force of The Ural Copper Mountains] (PDF). Izvestiya of the Ural State University (in Russian). The Ural State University (28): 16.

- ^ a b c Balina 2013, p. 273.

- ^ a b Shvabauer, Nataliya (10 January 2009). «Типология фантастических персонажей в фольклоре горнорабочих Западной Европы и России» [The Typology of the Fantastic Characters in the Miners’ Folklore of Western Europe and Russia] (PDF). Dissertation (in Russian). The Ural State University. p. 147. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Balina 2013, p. 270.

- ^ Lipovetsky 2014, p. 220.

- ^ Lipovetsky 2014, p. 218.

- ^ Zherdev, Denis (2003). «Binarnost kak element pojetiki bazhovskikh skazov» Бинарность как элемент поэтики бажовских сказов [Binarity as the Poetic Element in Bazhov’s Skazy] (PDF). Izvestiya of the Ural State University (in Russian). The Ural State University (28): 46–57.

- ^ Budur 2005, p. 124.

- ^ Budur 2005, p. 285.

- ^ Bazhov 1952, p. 232.

- ^ Zherdev, Denis. «Poetika skazov Bazhova» Поэтика сказов Бажова [The poetics of Bazhov’s stories] (in Russian). Research Library Mif.Ru. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ Sozina, E. «O nekotorykh motivah russkoj klassicheskoj literatury v skazah P. P. Bazhova o masterah О некоторых мотивах русской классической литературы в сказах П. П. Бажова о «мастерах» [On some Russian classical literature motives in P. P. Bazhov’s «masters» stories.]» in: P. P. Bazhov i socialisticheskij realizm.

- ^ «Горный мастер» [The Master Craftsman] (in Russian). FantLab. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ Bazhov 1952 (1), p. 243.

- ^ Bazhov 1944, p. 95.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 68.

- ^ Russian magic tales from Pushkin to Platonov (Book, 2012). WorldCat.org. OCLC 802293730.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 70.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 80.

- ^ Izmaylova, A. B. «Сказ П.П. Бажова «Хрупкая веточка» в курсе «Русская народная педагогика»» [P. Bazhov’s skaz A Fragile Twig in the course The Russian Folk Pedagogics] (PDF) (in Russian). The Vladimir State University. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ «The interview with P. Bazhov». Vechernyaya Moskva (in Russian). Mossovet. 31 January 1948.: «Собираюсь закончить сказ о «Каменном цветке». Мне хочется показать в нем преемников его героя, Данилы, написать об их замечательном мастерстве, устремлении в будущее. Действие сказа думаю довести до наших дней».

- ^ «Городской округ г. Полевской, Свердловская область» [Polevskoy Town District, Sverdlovsk Oblast]. Coats of arms of Russia (in Russian). Heraldicum.ru. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ Korovina, V. «Программы общеобразовательных учреждений» [The educational institutions curriculum] (in Russian). Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ «Средний Урал отмечает 130-летие со дня рождения Павла Бажова» (in Russian). Yekaterinburg Online. 27 January 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ «Фонтан «Каменный цветок» на площади Труда в Екатеринбурге отремонтируют за месяц: Общество: Облгазета».

- ^ Kozhevnikov, Alexey (2004). Крылатые фразы и афоризмы отечественного кино [Catchphrases and aphorisms from Russian cinema] (in Russian). OLMA Media Group. p. 214. ISBN 9785765425671.

- ^ Bazhov 1950s, p. 231. In Russian: «Ну что, Данило-мастер, не вышла твоя дурман-чаша?» — «Не вышла, — отвечает.»

- ^ Eydinova, Viola (2003). «O stile Bazhova» О стиле Бажова [About Bazhov’s style]. Izvestiya of the Ural State University (in Russian). The Ural State University. 28: 40–46.

- ^ «The Stone Flower (1946)» (in Russian). The Russian Cinema Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ «A Stone Flower». Animator.ru. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ «Mining Master». Animator.ru. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ Sakharnova, Kseniya (21 October 2009). ««Книга мастеров»: герои русских сказок в стране Disney» [The Book of Masters: the Russian fairy tale characters in Disneyland] (in Russian). Profcinema Co. Ltd. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ Zabaluyev, Yaroslav (27 October 2009). «Nor have we seen its like before…» (in Russian). Gazeta.ru. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ a b «Каменный цветок 1987» [The Stone Flower 1987] (in Russian). Kino-teatr.ru. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ a b Litovskaya 2014, p. 250.

- ^ Rollberg, Peter (7 November 2008). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. Scarecrow Press. p. 461. ISBN 9780810862685.

- ^ «Опера Молчанова «Каменный цветок»» [Molchanov’s opera The Stone Flower] (in Russian). Belcanto.ru. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ The Union of the Soviet Composers, ed. (1950). Советская музыка [Soviet Music] (in Russian). Vol. 1–6. Государственное Музыкальное издательство. p. 109.

- ^ Medvedev, A (February 1951). «Каменный цветок» [The Stone Flower]. Smena (in Russian). Smena Publishing House. 2 (570).

- ^ Balina 2013, p. 263.

References[edit]

- Bazhov, Pavel (1952). Valentina Bazhova; Alexey Surkov; Yevgeny Permyak (eds.). Sobranie sochinenij v trekh tomakh Собрание сочинений в трех томах [Works. In Three Volumes] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Moscow: Khudozhestvennaya Literatura.

- Bazhov, Pavel; translated by Alan Moray Williams (1944). The Malachite Casket: tales from the Urals. Library of selected Soviet literature. The University of California: Hutchinson & Co. ltd. ISBN 9787250005603.

- Bazhov, Pavel; translated by Eve Manning (1950s). Malachite Casket: Tales from the Urals. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

- Lipovetsky, Mark (2014). «The Uncanny in Bazhov’s Tales». Quaestio Rossica (in Russian). The University of Colorado Boulder. 2 (2): 212–230. doi:10.15826/qr.2014.2.051. ISSN 2311-911X.

- Litovskaya, Mariya (2014). «Vzroslyj detskij pisatel Pavel Bazhov: konflikt redaktur» Взрослый детский писатель Павел Бажов: конфликт редактур [The Adult-Children’s Writer Pavel Bazhov: The Conflict of Editing]. Detskiye Chteniya (in Russian). 6 (2): 243–254.

- Balina, Marina; Rudova, Larissa (1 February 2013). Russian Children’s Literature and Culture. Literary Criticism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135865566.

- Budur, Naralya (2005). «The Mistress of the Copper Mountain». Skazochnaja enciklopedija Сказочная энциклопедия [The Fairy Tale Encyclopedia] (in Russian). Olma Media Group. ISBN 9785224048182.

- Nikulina, Maya (2003). «Pro zemelnye dela i pro tajnuju silu. O dalnikh istokakh uralskoj mifologii P.P. Bazhova» Про земельные дела и про тайную силу. О дальних истоках уральской мифологии П.П. Бажова [Of land and the secret force. The distant sources of P.P. Bazhov’s Ural mythology]. Filologichesky Klass (in Russian). Cyberleninka.ru. 9.

- P. P. Bazhov i socialisticheskij realizm // Tvorchestvo P.P. Bazhova v menjajushhemsja mire П. П. Бажов и социалистический реализм // Творчество П. П. Бажова в меняющемся мире [Pavel Bazhov and socialist realism // The works of Pavel Bazhov in the changing world]. The materials of the inter-university research conference devoted to the 125th birthday (in Russian). Yekaterinburg: The Ural State University. 28–29 January 2004. pp. 18–26.

Начало

История начинается с рассказа о том, что после того, как пропал у девушки Кати ее жених Данила-мастер, совсем трудно стало ей жить. Ждет она своего суженого, думает, что вот-вот вернется, а от него ни весточки. Ее наперебой разные женихи сватают, а она только Данилу ждет.

Народ уже давно посчитал парня погибшим, оттого и прозвали Катю «мертвяковой невестой».

Далее в кратком содержании по сказу Бажова «Горный мастер» упомянем о том, что вскоре умирают родители Кати. И вышла среди братьев и сестер Катерины ссора из-за того, кому в избе жить. Катя взяла и перешла в Данилы домик. Там еще жил приемный отец Данилы — Прокопьич. Стала Катя ему по хозяйству помогать. А потом заболел и старик Прокопьич.

Интересные факты

- Экранизация сказки впервые состоялась в 1946 году. Снять фильм решил режиссер Александр Птушко. Фильм стал симбиозом сказок о каменном цветке и о горном мастере. Владимир Дружников выступил в картине в образе Данилы-мастера. Автором сценария выступил сам Бажов. В 1947 году проект был отмечен призом на Каннском кинофестивале и получил Сталинскую премию.

- В 1977 году Олег Николаевский создал мультфильм по мотивам сказки Бажова. Кукольная телепостановка включала и работу актеров.

- В 1978 году Инесса Ковалевская сняла мультфильм по произведению «Горный мастер». Рисованная сказка транслируется на телевидении и сегодня.

Первый визит к Змеиной горке

Задумалась Катя, как они жить будут. И пока жив был еще дед, попросила дать уроки, как с камнем работать. А когда умер Прокопьич, пришлось ей одной выживать. Решила она как-то безделушку каменную смастерить, хватилась, а подходящих камешков-то и нет. Пришлось ей идти к Змеиной горке — там, у старого рудника, еще попадалось, она слышала, то, что нужно.

Отыскала подходящий малахит в лесу на самом верху горы, принесла домой и сразу села распиливать. Наделала бляшек и отнесла в городскую лавку, куда Данила и Прокопьич свои поделки сдавали. Получилась у нее работа хорошая, выдали Кате приличный заработок. Пришла она довольная домой и думает: отчего мне такой замечательный камешек попался, не Данила ли мне так весточку послал?

Горный мастер

Сказы Бажова — пожалуй, одна из самых ярких, образных представителей русской культуры, особенно уральской ее части. Очень уж они мне милы — и сюжетом, и языком, и образами — всем хороши! Язык, конечно, весьма и весьма архаичен, но даже при этом я купила бы эту книгу ребенку (своему ли, чужому ли — неважно). А это ведь неплохой показатель «хорошести» книги.

Сразу после возвращения в родной город из многолетней командировки, начал работу по изучению и написанию книг по истории и фольклора Урала. Так появились сказы.

( Личное отношение есть, а спойлеров нет)

Медной горы хозяйка

— тревожный сказ. Как-то неспокойно делается после его прочтения. Степан — простой человек, но при этом не лишенный житейской народной мудрости, интуиции, которая позволяет ему совершать верный выбор. Но Медной Горы Хозяйка не такая дама, чтоб так уж легко было от нее отступить. Уйти-то можно было, а думы остались. Что и привело к тому что привело. Жалко только Настасью, которая приобрела и потеряла одновременно, даже и не узнав об этом.

Приказчиковы

подошвы

— вечная история о том, как наказан злой власть имущий человек. Если можно, конечно, людьми назвать злодеев, глумящихся над рабочими крепостными.

Сочневы камешки

— эх, Ваня, Ваня, Ванечка… Как говорится, если гнилой ты человечишка, то подлостью разве в люди выбьешься? Начальство обмануть, подольститься — дело нехитрое, но Медной Горы Хозяйку не проведешь. Если уж Степан в свое время пострадал через нее, хотя она зла не желала ему, а так, околдовать слегка, зачаровать, то что уж говорить про Ваню. Ну туда ему и дорога. Заслужил.

Малахитовая шкатулка

— Татьянка, дочь Степана и Настасьи… А дочь ли она Насте-то? Вроде как да, родила ж она ее, не в поле нашла, а все такое чувство будто не без Хозяйки обошлось. И внешне, и силой характера — всем девка в нее! Замечательная история!

Каменный цветок

— вот и еще один парнишка околдован-очарован. Говоря современным языком, одолел его перфекционизм. Но ведь разве возможно остаться в своем уме, когда тебя сама Хозяйка чарует. Игра ей или по делу ли, а заполучила первого мастера, что на Урале был. Наверное..

Горный мастер

— русской девушке ничего не страшно: раз уж полюбит, не отступится. Все Катя смогла сделать, и сообразить как Данилу вызволить, из собственных дум его выманить да в деревню вернуть, как Хозяйку обойти, не испугалась ведь, а? Молодец девка, такая коня на скаку просто влегкую. Таких и любит Хозяйка, их и награждает.

Две ящерки

— помогает все же Хозяйка мастерам, которых приказчики лютуют, но только тем, кто и впрямь в работе себя покажет. А красивая-то какая! Сколько не читаю сказы, все никак от нее мужчины глаз отвести не могут. Каменная, а глаза горят.

Хрупкая веточка

— еще один русский мастер отличился искусной работой. Да и как ему не отличиться, когда он Данилы-мастера сынок? Сумел таки удивить народ да остаться в сердцах. Славный мальчик Митенька. А барину поделом!

Травяная западенка

— эта история мне меньше других приглянулась, не объяснить.. Хотя и жизненная, и справедливая.

Таюткино зеркальце

— каждому по заслугам от Хозяйки Медной Горы. И барин с барыней, и надзиратель — каждый получил свою долю, а наградила ребенка безвинного. Да только правильно пишет сказ — счастья особого не принесло, но жизнь прожила не хуже других. От беды в шахте уберегла, игрушку подарила на память, а уж чтоб всю дальнейшую жизнь.. Это сначала надо посмотреть какой вырастет Таютка-то.

Разные сказы, а объединяет их одно: любовь к трудовому народу, к людям, к талантливым мастерам и старательным работникам. Отличный сборник.

Видение

В следующем эпизоде краткого содержания «Горного мастера» расскажем о том, что Катерина снова пошла на ту горку. А за ней следом мужичок пошел, он тоже был камнерезом и решил посмотреть, где эта девка такой хороший материал взяла. Но Катя зашла в такую густую чащу, что он ее из виду потерял.

А она пришла на то место, где была, и видит — из той ямки другой камешек торчит. Вытащила она его и вдруг вспомнила Данилу, жениха своего, расплакалась. А потом, когда голову подняла, увидела, будто идет кто-то к ней и руки протягивает навстречу. Катя подумала, это Данила, и хотела было навстречу кинуться, да оступилась и упала, а потом уж в себя пришла, испугалась да домой вернулась.

Павел Бажов «Горный мастер»

Вообще то произведение вполне себе феминистическое, так как помимо любовной линии это ещё и история о женщине, которая живя в глубоко патриархальном обществе выбрала себе занятие, которое было зарезервировано исключительно за мужчинами и тем самым бросила вызов окружающей ей среде. Сцена, когда пьяные мужики ломились в дом Катерины и проявленная героиней решительность являются ключевой для произведения. В дальнейшем история Катерины могла сложиться абсолютно по-разному (например она могла не выручить Данилу и остаться в девках или найти себе нового жениха), в глазах родных и соседей она обрела право на самостоятельность.

Довод «в глубинке и таких слов не знали, а если знали, – то применяли их явно не в том контексте, в котором написан этот сказ» неудачен. Год написания сказа – 1939-й. К этому моменту уже свыше двадцати лет советская власть упорно, последовательно и очень активно проводила политику равноправия полов (то есть именно что феминизма). Женщины получили избирательные права. Государство гарантировало равную оплату труда. Были разрешены разводы (в том числе по инициативе женщин и с выплатой алиментов для детей). Женщинам стало доступно высшее образование (а ведь образование – главный социальный лифт в обществе). И, конечно, государственная пропаганда вовсю продвигала мысль о том, что женщина является хозяйкой собственной судьбы. Фильмы и книги того времени твердили, что для решительной и целеустремлённой женщины в советском государстве нет преград. Захочет – сама выберет себе профессию, а потом утрёт нос всем мужчинам, которые насмехались над ней (государственная награда за ударный труд прилагается). Захочет – выйдет за муж по любви, а не как ей укажут родственники. Киноленты тех лет вроде «Кубанских казаков» или «Свинарки и пастуха» как раз об этом.

«Горный мастер» прекрасно ложится в ряд подобных произведений. Однако для Бажова тема равенства полов не является главной в творчестве, поэтому феминистический мотив хотя и нашёл своё выражение в повести, однако не довлеет над всем произведением. В результате получилась вневременная, лишённая конкретной идеологической нагрузки история о сильной героине и максимально достоверно прописанными реалиями быта горнозаводских уральских посёлков. Ну и, конечно, Хозяйка Медной горы, которая хотя почти и не появляется на страницах сказа, но всё же является полноценной героиней этой истории.

Встреча с Хозяйкой

А по поселку слухи поползли, что «мертвякова невеста» по ночам к Змеиной горке ходит, «покойника ждет». И решила Катина родня следить за ней, чтобы беды не вышло.

Села дома Катя за работу, распилила камень, смотрит — а на нем узор, как будто две птицы навстречу друг другу летят. Поняла девушка, что это знак ей любимый дает, и снова побежала к горке. А братья-сестры увидели, что она из дому, и за ней.

Прибегает Катя к горе и неведомо как попадает в чудесный лес — травы там из камня, каменные деревья стоят, каменные птицы на них сидят. Такой непонятно где расположенный лес, что потеряли ее идущие за ней люди. И вот оно, ключевое событие сказа, так же как и краткого содержания «Горного мастера», появилась прямо перед Катей Каменной горы Хозяйка. Спрашивает она ее: «Чего тебе надо? Камешек, что ли, какой? Так бери да уходи поскорей».

А Катя отвечает ей храбро: «Верни мне жениха моего!» «А вот спросим у самого Данилы, — отвечает ей Хозяйка, — что он выберет: мастерство свое или любовь к тебе и жизнь среди людей». И говорит вышедшему из лесу Даниле, что тот забудет все свое умение, если вернется к Кате и людям. Но ответил Данила, что ни одной минуты не мог забыть он о невесте своей, все время ее вспоминал. Поэтому, дескать, никак не может остаться и возвращается домой.

И Хозяйка горы сделала прощальный подарок Даниле — оставила ему его талант и ремесло резать камень. Только приказала поляну эту волшебную с каменным лесом забыть покрепче.

Образ в сказках