Десятичные дроби – для чайников

Действия с десятичными дробями – деление умножение, сложение, вычитание, сравнение. Разбор примеров.

Все это здесь.

Между прочим, большинство ошибок на экзаменах происходят как раз из-за незнания простейших действий вроде этих.

Так что читай эту статью и отрабатывай скиллы.

Десятичные дроби – коротко о главном

1. Определение

Десятичной дробью называется обыкновенная дробь, знаменателем которой является ( 10) в какой-либо степени.

2. Конечная и бесконечная десятичная дробь

Десятичная дробь может быть:

- конечной, если она содержит конечное число цифр после запятой (( displaystyle frac{8}{10}, frac{13}{100},frac{49}{1000}));

- бесконечной, в том числе периодичной, если конечное число цифр определить не определено (( 0,05882352941…));

- периодической, если её последовательность цифр после запятой, начиная с некоторого места, представляет собой периодически повторяющуюся группу цифр (( displaystyle frac{1}{7}=0,underbrace{142857}_{{период}}underbrace{142857}_{период}142…=0,left( 142857 right)))

3. Свойства десятичных дробей

- Десятичная дробь не меняется, если справа добавить нули ( displaystyle frac{3}{100}=0,03=0,030=0,030000)и т.д.;

- Десятичная дробь не меняется, если удалить нули, расположенные в конце десятичной дроби: ( 0,014330000=0,01433);

- Десятичная дробь возрастает в ( 10), ( 100), ( 1000) и т.д. раз, если перенести десятичную точку на одну, две, три и т.д. позиций вправо: ( 0,0125cdot 100=1,25) (перенесли запятую на ( 2) знака вправо – умножили на ( 100) и дробь возросла в ( 100) раз);

- Десятичная дробь уменьшается в ( 10), ( 100), ( 1000) и т.д. раз, если перенести десятичную точку на одну, две, три и т.д. позиций влево: ( 124,56:100=1,2456) (перенесли запятую на ( 2) знака влево – разделили на ( 100) и дробь уменьшилась в ( 100) раз).

4. Сложение десятичных дробей

Сложение происходит, как и сложение натуральных чисел в столбик, при этом запятая в ответе ставиться четко на том же месте, как и в складываемых числах.

5. Вычитание десятичных дробей

Так же, как и при сложении, при вычитании десятичные дроби записываются «столбиком»:

6. Умножение десятичных дробей

Десятичные дроби также записываются в столбик и умножаются как обыкновенные числа. При умножении нам неважно, стоят ли запятые под запятыми и так далее.

Однако, удобно, когда числа выровнены по правому краю – умножение происходит более упорядочено.

7. Деление десятичных дробей

Деление десятичной дроби на натуральное число

- Делим десятичную дробь на натуральное число по правилам деления в столбик, не обращая внимания на запятую в делимом (то число, которое мы делим на какое-либо другое число)

- Ставим в частном запятую, когда заканчивается деление целой части делимого.

Деление десятичных дробей друг на друга

- Считаем количество знаков справа от запятой в десятичной дроби.

- Умножаем и делимое, и делитель на 10, 100 или 1000 и т.д., в зависимости от того, сколько мы насчитали знаков в первом пункте. Умножать необходимо, чтобы превратить десятичную дробь в целое число.

Десятичные дроби – подробнее

Конечно, ты знаешь, что такое обыкновенная дробь. Например, ( displaystyle frac{1}{3}, frac{1}{4},frac{5}{112}).

Наравне с приведенными выше дробями существуют дроби ( displaystyle frac{8}{10}, frac{13}{100},frac{49}{1000}) и т.д.

Такие дроби можно записать намного удобнее и более кратко, то есть:

( displaystyle frac{8}{10}=0,8)

( displaystyle frac{13}{100}=0,13)

( displaystyle frac{49}{1000}=0,049)

Данного вида дроби называются десятичными. Иными словами:

Десятичной дробью называется обыкновенная дробь, знаменателем которой является ( 10) в какой-либо степени (первый пример – ( 10) в первой степени, второй – ( 10) во второй степени и т.д.).

Ты наверняка знаешь, что каждая цифра после запятой имеет свое название. На всякий случай напомню тебе про них, чтобы в дальнейшем мы говорили на одном языке:

Это огромное число читается по следующему алгоритму:

- Сначала читается число, стоящее до запятой и добавляется слово «целых»: ««( 46) целых»;

- Затем читается как обыкновенное число слева после запятой и добавляется слово, обозначающее название самой последней цифры. В нашем случае – «одна тысяча двести тридцать четыре десятитысячные».

А теперь прочитаем все вместе – «( 46) целых одна тысяча двести тридцать четыре десятитысячные». Разобрался? Переходим к визуализации полученных знаний!

Итак, небольшая тренировка на понимание, что такое эта десятичная дробь! Нарисуй квадрат ( 10) на ( 10) и закрась какую-нибудь его часть равную:

- ( 0,05;)

- ( 0,4;)

- ( 0,27;)

- ( 0,245)

Справился? Проверяем, что у тебя получилось.

Во-первых, квадрат ( 10) на ( 10) состоит из ( 100) клеточек. Соответственно, ( 0.05) – ( 5) клеточек из ( 100); ( 0,4) – ( 40) клеточек из ( 100) и так далее.

Наверняка, наибольшее затруднение составило последнее число – ( -0,245). На картинке это необходимо отразить как 24,5 клетки.

В общем, смотри:

С понятиями разобрались, теперь научимся переводить из десятичной дроби в обыкновенную и обратно.

Перевод из десятичной дроби в обыкновенную и обратно

Попробуй перевести:

- ( 0,136)

- ( 0,2436)

- ( 0,0456)

- ( 0,21)

Сравним ответы:

- ( displaystyle 0,136=frac{136}{1000})

- ( displaystyle 0,2436=frac{2436}{10000})

- ( displaystyle 0,0456=frac{456}{10000})

- ( displaystyle 0,21=frac{21}{100})

Уверена, что ты с легкостью справился! А как насчет обратного перевода? Из обыкновенных в десятичные?

Попробуй свои силы на вот этих дробях:

- ( displaystyle frac{2}{10})

- ( displaystyle frac{3}{100})

- ( displaystyle frac{4}{1000})

- ( displaystyle frac{4562}{100})

А вот и ответы:

- ( displaystyle frac{2}{10}=0,2)

- ( displaystyle frac{3}{100}=0,03)

- ( displaystyle frac{4}{1000}=0,004)

- ( displaystyle frac{4562}{100}=45frac{62}{100}=45,62)

Если ты со всем справился, можешь пропускать следующий абзац, а если где-то допустил ошибку, внимательно прочти о том, как легко и 100% правильно переводить дроби из обыкновенных в десятичные.

- Смотрим на дробь и определяем, есть ли у нее целая часть? Если есть, выделяем целую часть, записываем ее, и ставим запятую.

- После запятой должно быть столько знаков, сколько нулей стоит в знаменателе. Например, дробь ( displaystyle frac{4}{1000}) – ( 3) нуля в знаменателе, соответственно, мы как бы мысленно выделяем ( 3) ячейки.

- Затем записываем числитель – ( 4), но выравниваем его по правому краю, а в пустые ячейки вставляем нули.

Разобрался? Посмотри еще раз эту маленькую «инструкцию»:

Я думаю, ты во всем-всем разобрался! Потренируемся? Попробуй поработать еще с вот этими дробями:

- ( displaystyle frac{26}{10})

- ( displaystyle frac{43}{100})

- ( displaystyle frac{99}{1000})

- ( displaystyle frac{3562}{100})

А теперь ответы:

- ( displaystyle frac{26}{10}=2,6)

- ( displaystyle frac{43}{100}=0,43)

- ( displaystyle frac{99}{1000}=0,099)

- ( displaystyle frac{3562}{100}=35,62)

Виды десятичных дробей

Десятичная дробь может быть:

- конечной, если она содержит конечное число цифр после запятой (( displaystyle frac{8}{10}, frac{13}{100},frac{49}{1000}));

- бесконечной, в том числе периодичной, если конечное число цифр определить не определено (( 0,05882352941…));

- периодической, если её последовательность цифр после запятой, начиная с некоторого места, представляет собой периодически повторяющуюся группу цифр (( displaystyle frac{1}{7}=0,underbrace{142857}_{{период}}underbrace{142857}_{период}142…=0,left( 142857 right))).

Поговорим сначала о конечных дробях.

Конечная десятичная дробь

Само собой понятно, что дроби ( displaystyle frac{8}{10}, frac{13}{100},frac{49}{1000}) являются конечными, ведь знаменатель дроби уже представлен как единица с последующими нулями, и поэтому мы сразу можем сказать, что данную обыкновенную дробь можно перевести в конечную десятичную. А что ты скажешь насчет этой дроби: ( displaystyle frac{1}{4})? Ее знаменатель далеко не единица с последующими нулями, но ты четко знаешь, что у нее есть десятичный «аналог»:

( displaystyle frac{1}{4}=frac{1cdot 25}{4cdot 25}=frac{25}{100}=0,25)

То есть, чтобы определить, можно ли перевести дробь в десятичную, необходимо умножить числитель и знаменатель на одно и то же число, такое, чтобы знаменатель стал равен ( 10), ( 100), ( 1000) и так далее.

Усвоил? Постарайся представить в виде конечной десятичной дроби следующие обыкновенные дроби:

- ( displaystyle frac{1}{5})

- ( displaystyle frac{1}{8})

- ( displaystyle frac{3}{5})

- ( displaystyle frac{1}{16})

Сравним наши ответы:

- ( displaystyle frac{1cdot 2}{5cdot 2}=frac{2}{10}=0,2)

- ( displaystyle frac{125}{1000}=0,125)

- ( displaystyle frac{3}{5}=frac{6}{10}=0,6)

- ( displaystyle frac{1}{16}=frac{625}{10000}=0,0625)

Справился? Молодец. Выходим на новый уровень и переходим к бесконечным десятичным дробям.

Бесконечная десятичная дробь

Итак, бери калькулятор и дели ( 1) на ( 17). Поделил? Ты получил ( 0,05882352941) и дальше окошко калькулятора не показывает… Это тоже является десятичной дробью, только данная десятичная дробь является бесконечной. Ты сейчас скажешь, а как же наше определение?

Десятичной дробью называется обыкновенная дробь, знаменателем которой является ( 10) в какой-либо степени (первый пример – ( 10) в первой степени, второй – ( 10) во второй степени и т.д.).

Все очень просто и никаких противоречий с определением нет. В данном случае нам необходимо привести наш знаменатель к ( {{10}^{n}}), с учетом, что ( n) это какое-либо бесконечное число, которое мы не можем «обозреть» взглядом», или иными словами – ( nto +infty )

Таким образом:

Бесконечной десятичной дробью называется обыкновенная дробь, в записи которой после запятой содержится бесконечное количество цифр.

Как правило, в задачах, где встречаются бесконечные десятичные дроби, просят указать ответ либо с округлением (например, до десятых, или до сотых), либо записать в виде обыкновенной дроби, то есть как ( displaystyle frac{1}{17}).

Подумай, какой самый популярный пример можно привести на тему «бесконечная десятичная дробь»? Правильно! Число ( pi ) является бесконечной десятичной дробью. Во всем мире люди договорились, что для решения математических задач принято, что ( pi =3,14), но это далеко не так. Число ( pi ) не имеет определенного завершения. Оно настолько бесконечно, что ежегодно в мире проводятся соревнования по запоминанию числа ( pi ). Мировой рекорд по запоминанию знаков числа ( pi ) после запятой принадлежит китайцу Лю Чао, который в 2006 году в течение 24 часов и 4 минут воспроизвёл 67 890 знаков после запятой без ошибки! Все 67 890 знаков после запятой мы приводить не будем, а приведем несколько сокращенную запись:

( pi =3,1415926535text{ }8979323846text{ }2643383279text{ }5028841971)

Думаю, этого хватит, чтобы оценить «масштабы» данного числа.

Наравне с бесконечными десятичными дробями существуют периодические десятичные дроби. Они так же не имеют конца, но последующие числа в них повторяются, например, попробуй перевести в десятичную дробь ( displaystyle frac{1}{3}). Что у тебя получилось?

( displaystyle frac{1}{3}=0,333333333….)

Чтобы не повторять число ( 3) много много раз, решили говорить «ноль целых и три в периоде», так как тройка будет повторяться после запятой бесконечное число раз. Из этого умозаключения следует определение:

Дробь называется периодической, если её последовательность цифр после запятой, начиная с некоторого места, представляет собой периодически повторяющуюся группу цифр.

Чтобы кратко записать такую дробь, период (повторяющиеся цифры после запятой) пишут в скобках:

( displaystyle frac{1}{3}=0,underbrace{3}_{период}33333333….=0,left( 3 right))

( displaystyle frac{1}{7}=0,underbrace{142857}_{{период}}underbrace{142857}_{период}142…=0,left( 142857 right))

Важно, что период не может начинаться слева от запятой:

( displaystyle frac{100}{7}=underbrace{14,2857}_{не период}1428571428571…=14,left( 285714 right)).

Свойства десятичных дробей

Существует четыре свойства десятичных дробей. Они очень простые, и ты 100% знаешь о всех них, но давай их перечислим и вспомним:

1. Десятичная дробь не меняется, если справа добавить нули

( displaystyle frac{3}{100}=0,03=0,030=0,030000)и т.д.

2. Десятичная дробь не меняется, если удалить нули, расположенные в конце десятичной дроби:

( 0,014330000=0,01433)

ВНИМАНИЕ!!! Нельзя удалять нули, расположенные не в конце десятичной дроби!!!!

( 0,014330000ne 0,1433)

3. Десятичная дробь возрастает в ( 10), ( 100), ( 1000) и т.д. раз, если перенести десятичную точку на одну, две, три и т.д. позиций вправо:

( 0,0125cdot 100=1,25) (перенесли запятую на ( 2) знака вправо – умножили на ( 100) и дробь возросла в ( 100) раз)

4. Десятичная дробь уменьшается в ( 10), ( 100), ( 1000) и т.д. раз, если перенести десятичную точку на одну, две, три и т.д. позиций влево:

( 124,56:100=1,2456) (перенесли запятую на ( 2) знака влево – разделили на ( 100) и дробь уменьшилась в ( 100) раз)

Последние два свойства позволяют быстро умножать и делить десятичные дроби на ( 10), ( 100), ( 1000) и т.д. о чем подробнее мы поговорим чуть ниже.

Действия с десятичными дробями

Десятичные дроби – это обычные числа. Мы можем складывать их, вычитать из одной другую, умножать и делить.

Очень важно уметь правильно производить с ними математические действия, так как зачастую именно от арифметических ошибок зависит твоя оценка на экзамене.

Несомненно, ты знаешь, как все это делать, но на всякий случай, дам тебе краткую инструкцию к применению.

Как складывать десятичные дроби

При сложении десятичные дроби записываются «столбиком», так чтобы одноимённые разряды находились друг под другом без смещения. Соответственно, запятые стоят четко друг под другом.

Разберемся на примере:

Сложение происходит, как и сложение натуральных чисел в столбик, при этом запятая в ответе ставится четко на том же месте, как и в складываемых числах.

Если исходные числа имеют разное количество знаков после запятой, то к дроби с меньшим количеством десятичных знаков нужно приписать необходимое число нулей, чтобы уравнять в дробях количество знаков после запятой.

Если при сложении в сумме мы получаем больше ( 10), то одна единица прибавляется к сумме при сложении цифр следующего разряда.

Решим наш пример, учтя все правила:

Разобрался? Посчитай в столбик самостоятельно:

- ( 0,0125+0,141)

- ( 2,4225+0,34)

- ( 122,4355+1,34)

- ( 2,435+12,3)

Сравним ответы:

- ( 0,0125+0,141=0,1535)

- ( 2,4225+0,34=2,7625)

- ( 122,4355+1,34=123,7755)

- ( 2,435+12,3=14,735)

Как вычитать десятичные дроби

Так же, как и при сложении, при вычитании десятичные дроби записываются «столбиком», так чтобы одноимённые разряды находились друг под другом без смещения.

Соответственно, запятые стоят четко друг под другом.

Вычитание происходит, как и вычитание натуральных чисел в столбик, при этом запятая в ответе ставиться четко на том же месте, как и в числах, с которыми мы работаем.

Если исходные числа имеют разное количество знаков после запятой, то к дроби с меньшим количеством десятичных знаков нужно приписать необходимое число нулей, чтобы уравнять в дробях количество знаков после запятой.

Если при вычитании получается, что мы из меньшего числа вычитаем большее, то мы как бы занимаем десяток у более высокого разряда (при вычитании сотых частей, берем десяток у десятых, при вычитании десятых – у единиц и так далее), не забывая уменьшить вычитаемое число у заимствованного разряда.

Посмотрим подробно на примере:

Думаю, с рисунком тебе стало все понятно. Попробуй посчитать в столбик следующие выражения:

- ( 0,0125-0,141)

- ( 2,4225-0,34)

- ( 122,4355-1,34)

- ( 12,435-12,3)

Сравним полученные ответы:

- ( 0,0125-0,141=-0,1285)

- ( 2,4225-0,34=2,0825)

- ( 122,4355-1,34=121,0955)

- ( 12,435-12,3=0,135)

Как умножать десятичные дроби

Десятичные дроби также записываются в столбик и умножаются как обыкновенные числа. При умножении нам неважно, стоят ли запятые под запятыми и так далее.

Однако, удобно, когда числа выровнены по правому краю – умножение происходит более упорядочено.

Мы начинаем запись числа, получающего при перемножении, под тем разрядом второго числа, на который умножаем. Далее мы суммируем полученные числа и только затем ставим запятую.

Чтобы определить, между какими числами должна стоять запятая, мы должны посмотреть, сколько чисел стоит после знака запятой у первого множителя, сколько у второго, сложить их и отсчитать справа данное количество чисел.

Непонятно? Смотри:

Как ты видишь, при перемножении мы будем складывать столько слагаемых, сколько разрядов содержится во втором множителе, поэтому удобней записывать числа так, чтобы первый множитель был по количеству чисел больше, чем второй.

Таким способом мы значительно снизим вероятность ошибок.

Не веришь? Смотри:

Если при умножении мы получаем число, которое больше ( 9), например ( 12), то единицу мы прибавляем к значению, полученному при умножении последующих чисел следующего десятка.

Соответственно, если получаем, например, ( 24), то прибавляем ( 2).

Проиллюстрируем данное правило:

Разобрался? Дорешай данный пример самостоятельно.

Сколько у тебя получилось? У меня ( 10,33911).

А теперь пора приступить к некоторым очень важным моментам, которые помогут сохранить время на экзамене.

Как делить десятичные дроби

Теперь ты знаешь о десятичных дробях почти все. Осталось только разобраться с тем, как их делить друг на друга.

Если ты отлично это представляешь, смело пропускай данный подраздел. Если нет – смотри инструкцию к применению.

Итак. Мы рассмотрим два вида деления:

- деление десятичной дроби на натуральное число;

- деление десятичной дроби на десятичную дробь.

Начнем с деления десятичной дроби на натуральное число.

Чтобы делить десятичную дробь на натуральное число, необходимо пользоваться следующими правилами:

- Делим десятичную дробь на натуральное число по правилам деления в столбик, не обращая внимания на запятую в делимом (то число, которое мы делим на какое-либо другое число)

- Ставим в частном запятую, когда заканчивается деление целой части делимого.

Важно!!!

Если целая часть делимого меньше делителя, то в частном ставим ( 0) целых. Логично, правда?

Рассмотрим на конкретном примере:

Усвоил? Раздели столбиком следующие числа:

- ( 135,2:5)

- ( 16,4:2)

- ( 158,14:4)

- ( 2,456:2)

- ( 0,626:2)

Сравним наши ответы:

- ( 135,2:5=27,04)

- ( 16,4:2=8,2)

- ( 158,14:4=39,535)

- ( 2,456:2=1,228)

- ( 0,626:2=0,313)

Вспомни теперь свойства десятичных дробей, описанные ранее: если нам необходимо разделить дробь на ( 10), ( 100), ( 1000) и так далее, нет необходимости делать это в столбик – мы можем просто перенести запятую на столько цифр влево, сколько нулей у нас в делителе.

Например: ( 135,2:10=13,52).

А теперь попробуй самостоятельно:

- ( 135,2:100)

- ( 16,4:10)

- ( 158,14:1000)

- ( 2,456:10)

Перенес? Смотри, что у меня получилось:

- ( 135,2:100=1,352)

- ( 16,4:10=1,64)

- ( 158,14:1000=0,15814)

- ( 2,456:10=0,2456)

Молодец! Переходим к делению десятичных дробей друг на друга.

Деление десятичных дробей друг на друга

Итак, для того чтобы это делать существует три правила:

- Считаем количество знаков справа от запятой в десятичной дроби.

- Умножаем и делимое, и делитель на ( 10), ( 100) или ( 1000) и т.д., в зависимости от того, сколько мы насчитали знаков в первом пункте. Умножать необходимо, чтобы превратить десятичную дробь в целое число.

- Делим числа как натуральные.

ВАЖНО!!! При умножении мы смотрим, в каком из чисел, участвующих в делении, присутствует наибольшее количество знаков после запятой? Ориентируясь именно на это число мы умножаем на ( 10), ( 100), ( 1000) и так далее.

Рассмотрим на примере ( 16,4:0,02)

В каком числе у нас стоит наибольшее количество знаков после запятой? Правильно, во втором, то есть в делителе: после нуля стоит два знака. Что из этого следует? Что мы умножаем и делимое и делитель на ( 100)!

Что дальше? Мы получаем следующий пример: ( 1640:2) Посчитай, сколько это будет самостоятельно. У меня получилось ( 820).

Рассмотрим примерчик посложнее: ( 5,31:0,3)

Самое большое количество знаков после запятой содержится в первом числе – их два, соответственно, умножаем оба числа, участвующего в делении на ( 100). Получаем: ( 531:30).

А теперь делим в столбик:

Ты видишь, что нацело разделить не получилось, мы «снесли» еще один ноль, и только тогда пришли к ответу, поэтому сразу после окончания деления нашего делимого, мы ставим запятую.

Теперь ты полностью готов совершать любые действия с десятичными дробями. Молодец! Рассмотрим только, как их сравнивать, хотя я думаю, ты уже и сам с этим справишься!

Как сравнивать десятичные дроби

Мы можем сравнивать десятичные дроби двумя способами.

Способ первый – поразрядно.

Допустим, нам необходимо сравнить ( 5,365 V 5,36)

1. Смотрим, одинаковое ли количество знаков после запятой стоит у каждой дроби? Нет? Значит дописываем справа необходимое количество нулей (ты же помнишь, что от дописывания нулей дробь неизменна, правда?)

Что у нас получилось? Верно: ( 5,365 V 5,360)

2. Начинаем сравнивать слева направо: целую часть с целой, десятые части с десятыми и так далее. Когда одна из частей дроби оказывается больше аналогичной части другой, эта дробь и больше.

Перейдем к нашему примеру: целые части у нас одинаковы – их значение ( 5). Десятые тоже – ( 3). Сотые – ( 6), а вот тысячные у первой дроби ( 5), а у второй ( 0). Что больше: ( 5) или ( 0)? Верно, ( 5), соответственно:

( 5,365 > 5,360)

Способ второй – с помощью умножения.

Внимательно смотрим на дроби. На сколько нам нужно умножить два числа, чтобы сравнивать целые числа? Смотрим на ту дробь, у которой знаков после запятой больше, то есть на первую. У нее после запятой ( 3) знака, соответственно, чтобы сделать из нее целое число, необходимо умножить на ( 1000) Умножаем обе дроби на это значение:

( 5,365cdot 1000 V 5,36cdot 1000)

( 5365 V 5360)

Эти числа ты сравнишь без проблем:

( 5365 > 5360)

Заметь, результат получился одинаковый. Теперь попробуй сравнить дроби самостоятельно любым наиболее удобным для тебя способом:

- ( 21,34 V 20,34)

- ( 0,34 V 0,341)

- ( 120,15 V 1210,16)

- ( 10,565 V 10,465)

Справился? Смотри что вышло:

- ( 21,34 > 20,34)

- ( 0,34 < 0,341)

- ( 120,15 < 1210,16)

- ( 10,565 > 10,465)

Вот теперь ты усвоил дроби полностью!

Самые бюджетные курсы по подготовке к ЕГЭ на 90+

Алексей Шевчук – ведущий курсов

- тысячи учеников, поступивших в лучшие ВУЗы страны

- автор понятного всем учебника по математике ЮКлэва (с сотнями благодарных отзывов);

- закончил МФТИ, преподавал на малом физтехе;

- репетиторский стаж – 19 лет (c 2003 года);

- в 2021 году сдал ЕГЭ (математика 100 баллов, физика 100 баллов, информатика 98 баллов – как обычно дурацкая ошибка:);

- отзыв на Профи.ру: “Рейтинг: 4,87 из 5. Очень хвалят. Такую отметку получают опытные специалисты с лучшими отзывами”.

В данной публикации мы рассмотрим, что из себя представляет десятичная дробь, как она пишется и читается, какой обыкновенной дроби соответствует и в чем заключается ее основное свойство. К теоретическому материалу прилагаются примеры для лучшего понимания.

- Определение десятичной дроби

- Запись десятичной дроби

-

Чтение десятичной дроби

- Основное свойство десятичной дроби

Определение десятичной дроби

Десятичная дробь – это особый вид записи обыкновенной дроби, знаменатель которой равен 10, 100, 1000, 10000 и т.д.

Такие дроби вместо привычного варианта написания ( с числителем, знаменателем и черточкой-разделителем), принято записывать так: 0,3 ; 2,6 ; 5,62 ; 7,238 и т.д.

Десятичные дроби бывают двух типов:

- конечные – после запятой конечное количество цифр;

- бесконечные – после запятой количество цифр бесконечно. Чаще всего такие дроби округляются до 1-3 цифр после запятой.

Запись десятичной дроби

Десятичная дробь состоит из целой и дробной частей, между которыми находится десятичный разделитель – в виде запятой или точки.

Соответствие десятичной дроби обыкновенной:

- Целая часть (слева от запятой) аналогична той, что и при записи смешанных дробей (неправильную следует, также, переводить в смешанную). Если дробь правильная (числитель меньше знаменателя), то целая часть равна 0.

- Дробная часть (справа от запятой) содержит те же цифры, что и числитель дробной части, если бы мы представили дробь в виде обыкновенной.

- Количество цифр после запятой ограничено тем, на какое число делится числитель в обыкновенной дроби (количество цифр равно количеству нулей после единицы):

- 1 цифра – на 10;

- 2 цифры – на 100;

- 3 цифры – на 1000

- 4 цифры – на 10000;

- и т.д.

Примеры:

0,3 =

3/10

, т.к. после запятой одна цифра.

2,6 = 2

6/10

=

26/10

, т.к. после запятой одна цифра.

5,62 = 5

62/100

=

562/100

, т.к. после запятой две цифры.

7,238 = 7

238/1000

=

7238/1000

, т.к. после запятой три цифры.

Примечание: Если в десятичной дроби сразу после запятой идут нули и затем только цифры, то в виде обыкновенной дроби это выглядит так: числитель – только цифры без нулей, знаменатель – единица и количество нулей, соответствующее количеству цифр после запятой.

Например:

Чтение десятичной дроби

Читается десятичная дробь следующим образом: сначала произносится целая часть с добавление слова “целых”, затем дробная – с указанием разряда, который зависит от количества цифр после запятой:

- 1 цифра – “десятых”;

- 2 цифры – “сотых”;

- 3 цифры – “тысячных”;

- 4 цифры – “десятитысячных”;

- и т.д.

Например:

- 0,2 – ноль целых, две десятых;

- 0,54 – ноль целых, пятьдесят четыре сотых;

- 7,8 – семь целых, восемь десятых;

- 12,64 – двенадцать целых шестьдесят четыре сотых;

- 10,056 – десять целых пятьдесят шесть тысячных.

Основное свойство десятичной дроби

Величина десятичной дроби не изменится, если справа к ней добавить любое количество нулей. Т.е. если такие нули встречаются, их можно просто отбросить (только те нули, которые расположены справа от цифр в дробной части).

Например:

- 0,3000 = 0,3;

- 0,25000 = 0,25;

- 2,0500000 = 2,05;

- 16,15400000 = 16,154.

The decimal numeral system (also called the base-ten positional numeral system and denary [1] or decanary) is the standard system for denoting integer and non-integer numbers. It is the extension to non-integer numbers of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system.[2] The way of denoting numbers in the decimal system is often referred to as decimal notation.[3]

A decimal numeral (also often just decimal or, less correctly, decimal number), refers generally to the notation of a number in the decimal numeral system. Decimals may sometimes be identified by a decimal separator (usually «.» or «,» as in 25.9703 or 3,1415).[4] Decimal may also refer specifically to the digits after the decimal separator, such as in «3.14 is the approximation of π to two decimals«. Zero-digits after a decimal separator serve the purpose of signifying the precision of a value.

The numbers that may be represented in the decimal system are the decimal fractions. That is, fractions of the form a/10n, where a is an integer, and n is a non-negative integer.

The decimal system has been extended to infinite decimals for representing any real number, by using an infinite sequence of digits after the decimal separator (see decimal representation). In this context, the decimal numerals with a finite number of non-zero digits after the decimal separator are sometimes called terminating decimals. A repeating decimal is an infinite decimal that, after some place, repeats indefinitely the same sequence of digits (e.g., 5.123144144144144… = 5.123144).[5] An infinite decimal represents a rational number, the quotient of two integers, if and only if it is a repeating decimal or has a finite number of non-zero digits.

Origin[edit]

Ten digits on two hands, the possible origin of decimal counting

Many numeral systems of ancient civilizations use ten and its powers for representing numbers, possibly because there are ten fingers on two hands and people started counting by using their fingers. Examples are firstly the Egyptian numerals, then the Brahmi numerals, Greek numerals, Hebrew numerals, Roman numerals, and Chinese numerals. Very large numbers were difficult to represent in these old numeral systems, and only the best mathematicians were able to multiply or divide large numbers. These difficulties were completely solved with the introduction of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system for representing integers. This system has been extended to represent some non-integer numbers, called decimal fractions or decimal numbers, for forming the decimal numeral system.

Decimal notation[edit]

For writing numbers, the decimal system uses ten decimal digits, a decimal mark, and, for negative numbers, a minus sign «−». The decimal digits are 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9;[6] the decimal separator is the dot «.» in many countries (mostly English-speaking),[7] and a comma «,» in other countries.[4]

For representing a non-negative number, a decimal numeral consists of

- either a (finite) sequence of digits (such as «2017»), where the entire sequence represents an integer,

- or a decimal mark separating two sequences of digits (such as «20.70828»)

-

.

If m > 0, that is, if the first sequence contains at least two digits, it is generally assumed that the first digit am is not zero. In some circumstances it may be useful to have one or more 0’s on the left; this does not change the value represented by the decimal: for example, 3.14 = 03.14 = 003.14. Similarly, if the final digit on the right of the decimal mark is zero—that is, if bn = 0—it may be removed; conversely, trailing zeros may be added after the decimal mark without changing the represented number; [note 1] for example, 15 = 15.0 = 15.00 and 5.2 = 5.20 = 5.200.

For representing a negative number, a minus sign is placed before am.

The numeral

.

The integer part or integral part of a decimal numeral is the integer written to the left of the decimal separator (see also truncation). For a non-negative decimal numeral, it is the largest integer that is not greater than the decimal. The part from the decimal separator to the right is the fractional part, which equals the difference between the numeral and its integer part.

When the integral part of a numeral is zero, it may occur, typically in computing, that the integer part is not written (for example, .1234, instead of 0.1234). In normal writing, this is generally avoided, because of the risk of confusion between the decimal mark and other punctuation.

In brief, the contribution of each digit to the value of a number depends on its position in the numeral. That is, the decimal system is a positional numeral system.

Decimal fractions[edit]

Decimal fractions (sometimes called decimal numbers, especially in contexts involving explicit fractions) are the rational numbers that may be expressed as a fraction whose denominator is a power of ten.[8] For example, the decimals

More generally, a decimal with n digits after the separator (a point or comma) represents the fraction with denominator 10n, whose numerator is the integer obtained by removing the separator.

It follows that a number is a decimal fraction if and only if it has a finite decimal representation.

Expressed as a fully reduced fraction, the decimal numbers are those whose denominator is a product of a power of 2 and a power of 5. Thus the smallest denominators of decimal numbers are

Real number approximation[edit]

Decimal numerals do not allow an exact representation for all real numbers, e.g. for the real number π. Nevertheless, they allow approximating every real number with any desired accuracy, e.g., the decimal 3.14159 approximates the real π, being less than 10−5 off; so decimals are widely used in science, engineering and everyday life.

More precisely, for every real number x and every positive integer n, there are two decimals L and u with at most n digits after the decimal mark such that L ≤ x ≤ u and (u − L) = 10−n.

Numbers are very often obtained as the result of measurement. As measurements are subject to measurement uncertainty with a known upper bound, the result of a measurement is well-represented by a decimal with n digits after the decimal mark, as soon as the absolute measurement error is bounded from above by 10−n. In practice, measurement results are often given with a certain number of digits after the decimal point, which indicate the error bounds. For example, although 0.080 and 0.08 denote the same number, the decimal numeral 0.080 suggests a measurement with an error less than 0.001, while the numeral 0.08 indicates an absolute error bounded by 0.01. In both cases, the true value of the measured quantity could be, for example, 0.0803 or 0.0796 (see also significant figures).

Infinite decimal expansion[edit]

For a real number x and an integer n ≥ 0, let [x]n denote the (finite) decimal expansion of the greatest number that is not greater than x that has exactly n digits after the decimal mark. Let di denote the last digit of [x]i. It is straightforward to see that [x]n may be obtained by appending dn to the right of [x]n−1. This way one has

- [x]n = [x]0.d1d2…dn−1dn,

and the difference of [x]n−1 and [x]n amounts to

,

which is either 0, if dn = 0, or gets arbitrarily small as n tends to infinity. According to the definition of a limit, x is the limit of [x]n when n tends to infinity. This is written as![{textstyle ;x=lim _{nrightarrow infty }[x]_{n};}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4726bcc43d70340455e0f0340fa72d52ee7e420d)

- x = [x]0.d1d2…dn…,

which is called an infinite decimal expansion of x.

Conversely, for any integer [x]0 and any sequence of digits

If all dn for n > N equal to 9 and [x]n = [x]0.d1d2…dn, the limit of the sequence![{textstyle ;([x]_{n})_{n=1}^{infty }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b1ebb69f79147f59b60a7fc1079add44c50c1331)

Any such decimal fraction, i.e.: dn = 0 for n > N, may be converted to its equivalent infinite decimal expansion by replacing dN by dN − 1 and replacing all subsequent 0s by 9s (see 0.999…).

In summary, every real number that is not a decimal fraction has a unique infinite decimal expansion. Each decimal fraction has exactly two infinite decimal expansions, one containing only 0s after some place, which is obtained by the above definition of [x]n, and the other containing only 9s after some place, which is obtained by defining [x]n as the greatest number that is less than x, having exactly n digits after the decimal mark.

Rational numbers[edit]

Long division allows computing the infinite decimal expansion of a rational number. If the rational number is a decimal fraction, the division stops eventually, producing a decimal numeral, which may be prolongated into an infinite expansion by adding infinitely many zeros. If the rational number is not a decimal fraction, the division may continue indefinitely. However, as all successive remainders are less than the divisor, there are only a finite number of possible remainders, and after some place, the same sequence of digits must be repeated indefinitely in the quotient. That is, one has a repeating decimal. For example,

- 1/81 = 0. 012345679 012… (with the group 012345679 indefinitely repeating).

The converse is also true: if, at some point in the decimal representation of a number, the same string of digits starts repeating indefinitely, the number is rational.

| For example, if x is | 0.4156156156… |

| then 10,000x is | 4156.156156156… |

| and 10x is | 4.156156156… |

| so 10,000x − 10x, i.e. 9,990x, is | 4152.000000000… |

| and x is | 4152/9990 |

or, dividing both numerator and denominator by 6, 692/1665.

Decimal computation[edit]

Most modern computer hardware and software systems commonly use a binary representation internally (although many early computers, such as the ENIAC or the IBM 650, used decimal representation internally).[9]

For external use by computer specialists, this binary representation is sometimes presented in the related octal or hexadecimal systems.

For most purposes, however, binary values are converted to or from the equivalent decimal values for presentation to or input from humans; computer programs express literals in decimal by default. (123.1, for example, is written as such in a computer program, even though many computer languages are unable to encode that number precisely.)

Both computer hardware and software also use internal representations which are effectively decimal for storing decimal values and doing arithmetic. Often this arithmetic is done on data which are encoded using some variant of binary-coded decimal,[10][11] especially in database implementations, but there are other decimal representations in use (including decimal floating point such as in newer revisions of the IEEE 754 Standard for Floating-Point Arithmetic).[12]

Decimal arithmetic is used in computers so that decimal fractional results of adding (or subtracting) values with a fixed length of their fractional part always are computed to this same length of precision. This is especially important for financial calculations, e.g., requiring in their results integer multiples of the smallest currency unit for book keeping purposes. This is not possible in binary, because the negative powers of

History[edit]

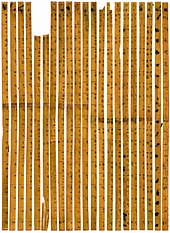

The world’s earliest decimal multiplication table was made from bamboo slips, dating from 305 BCE, during the Warring States period in China.

Many ancient cultures calculated with numerals based on ten, sometimes argued due to human hands typically having ten fingers/digits.[15] Standardized weights used in the Indus Valley civilization (c. 3300–1300 BCE) were based on the ratios: 1/20, 1/10, 1/5, 1/2, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500, while their standardized ruler – the Mohenjo-daro ruler – was divided into ten equal parts.[16][17][18] Egyptian hieroglyphs, in evidence since around 3000 BCE, used a purely decimal system,[19] as did the Cretan hieroglyphs (c. 1625−1500 BCE) of the Minoans whose numerals are closely based on the Egyptian model.[20][21] The decimal system was handed down to the consecutive Bronze Age cultures of Greece, including Linear A (c. 18th century BCE−1450 BCE) and Linear B (c. 1375−1200 BCE) – the number system of classical Greece also used powers of ten, including, Roman numerals, an intermediate base of 5.[22] Notably, the polymath Archimedes (c. 287–212 BCE) invented a decimal positional system in his Sand Reckoner which was based on 108[22] and later led the German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss to lament what heights science would have already reached in his days if Archimedes had fully realized the potential of his ingenious discovery.[23] Hittite hieroglyphs (since 15th century BCE) were also strictly decimal.[24]

Some non-mathematical ancient texts such as the Vedas, dating back to 1700–900 BCE make use of decimals and mathematical decimal fractions.[25]

The Egyptian hieratic numerals, the Greek alphabet numerals, the Hebrew alphabet numerals, the Roman numerals, the Chinese numerals and early Indian Brahmi numerals are all non-positional decimal systems, and required large numbers of symbols. For instance, Egyptian numerals used different symbols for 10, 20 to 90, 100, 200 to 900, 1000, 2000, 3000, 4000, to 10,000.[26]

The world’s earliest positional decimal system was the Chinese rod calculus.[27]

The world’s earliest positional decimal system

Upper row vertical form

Lower row horizontal form

History of decimal fractions[edit]

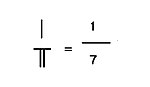

counting rod decimal fraction 1/7

Decimal fractions were first developed and used by the Chinese in the end of 4th century BCE,[28] and then spread to the Middle East and from there to Europe.[27][29] The written Chinese decimal fractions were non-positional.[29] However, counting rod fractions were positional.[27]

Qin Jiushao in his book Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections (1247[30]) denoted 0.96644 by

-

-

-

-

- 寸

, meaning

- 寸

- 096644

-

-

-

J. Lennart Berggren notes that positional decimal fractions appear for the first time in a book by the Arab mathematician Abu’l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi written in the 10th century.[31] The Jewish mathematician Immanuel Bonfils used decimal fractions around 1350, anticipating Simon Stevin, but did not develop any notation to represent them.[32] The Persian mathematician Jamshīd al-Kāshī claimed to have discovered decimal fractions himself in the 15th century.[31] Al Khwarizmi introduced fraction to Islamic countries in the early 9th century; a Chinese author has alleged that his fraction presentation was an exact copy of traditional Chinese mathematical fraction from Sunzi Suanjing.[27] This form of fraction with numerator on top and denominator at bottom without a horizontal bar was also used by al-Uqlidisi and by al-Kāshī in his work «Arithmetic Key».[27][33]

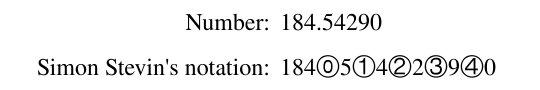

A forerunner of modern European decimal notation was introduced by Simon Stevin in the 16th century.[34]

John Napier introduced using the period (.) to separate the integer part of a decimal number from the fractional part in his book on constructing tables of logarithms, published posthumously in 1620.[35]: p. 8, archive p. 32)

Natural languages[edit]

A method of expressing every possible natural number using a set of ten symbols emerged in India. Several Indian languages show a straightforward decimal system. Many Indo-Aryan and Dravidian languages have numbers between 10 and 20 expressed in a regular pattern of addition to 10.[36]

The Hungarian language also uses a straightforward decimal system. All numbers between 10 and 20 are formed regularly (e.g. 11 is expressed as «tizenegy» literally «one on ten»), as with those between 20 and 100 (23 as «huszonhárom» = «three on twenty»).

A straightforward decimal rank system with a word for each order (10 十, 100 百, 1000 千, 10,000 万), and in which 11 is expressed as ten-one and 23 as two-ten-three, and 89,345 is expressed as 8 (ten thousands) 万 9 (thousand) 千 3 (hundred) 百 4 (tens) 十 5 is found in Chinese, and in Vietnamese with a few irregularities. Japanese, Korean, and Thai have imported the Chinese decimal system. Many other languages with a decimal system have special words for the numbers between 10 and 20, and decades. For example, in English 11 is «eleven» not «ten-one» or «one-teen».

Incan languages such as Quechua and Aymara have an almost straightforward decimal system, in which 11 is expressed as ten with one and 23 as two-ten with three.

Some psychologists suggest irregularities of the English names of numerals may hinder children’s counting ability.[37]

Other bases[edit]

Some cultures do, or did, use other bases of numbers.

- Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures such as the Maya used a base-20 system (perhaps based on using all twenty fingers and toes).

- The Yuki language in California and the Pamean languages[38] in Mexico have octal (base-8) systems because the speakers count using the spaces between their fingers rather than the fingers themselves.[39]

- The existence of a non-decimal base in the earliest traces of the Germanic languages is attested by the presence of words and glosses meaning that the count is in decimal (cognates to «ten-count» or «tenty-wise»); such would be expected if normal counting is not decimal, and unusual if it were.[40][41] Where this counting system is known, it is based on the «long hundred» = 120, and a «long thousand» of 1200. The descriptions like «long» only appear after the «small hundred» of 100 appeared with the Christians. Gordon’s Introduction to Old Norse Archived 2016-04-15 at the Wayback Machine p. 293, gives number names that belong to this system. An expression cognate to ‘one hundred and eighty’ translates to 200, and the cognate to ‘two hundred’ translates to 240. Goodare details the use of the long hundred in Scotland in the Middle Ages, giving examples such as calculations where the carry implies i C (i.e. one hundred) as 120, etc. That the general population were not alarmed to encounter such numbers suggests common enough use. It is also possible to avoid hundred-like numbers by using intermediate units, such as stones and pounds, rather than a long count of pounds. Goodare gives examples of numbers like vii score, where one avoids the hundred by using extended scores. There is also a paper by W.H. Stevenson, on ‘Long Hundred and its uses in England’.[42][43]

- Many or all of the Chumashan languages originally used a base-4 counting system, in which the names for numbers were structured according to multiples of 4 and 16.[44]

- Many languages[45] use quinary (base-5) number systems, including Gumatj, Nunggubuyu,[46] Kuurn Kopan Noot[47] and Saraveca. Of these, Gumatj is the only true 5–25 language known, in which 25 is the higher group of 5.

- Some Nigerians use duodecimal systems.[48] So did some small communities in India and Nepal, as indicated by their languages.[49]

- The Huli language of Papua New Guinea is reported to have base-15 numbers.[50] Ngui means 15, ngui ki means 15 × 2 = 30, and ngui ngui means 15 × 15 = 225.

- Umbu-Ungu, also known as Kakoli, is reported to have base-24 numbers.[51] Tokapu means 24, tokapu talu means 24 × 2 = 48, and tokapu tokapu means 24 × 24 = 576.

- Ngiti is reported to have a base-32 number system with base-4 cycles.[45]

- The Ndom language of Papua New Guinea is reported to have base-6 numerals.[52] Mer means 6, mer an thef means 6 × 2 = 12, nif means 36, and nif thef means 36×2 = 72.

See also[edit]

- Algorism

- Binary-coded decimal (BCD)

- Decimal classification

- Decimal computer

- Decimal time

- Decimal representation

- Decimal section numbering

- Decimal separator

- Decimalisation

- Densely packed decimal (DPD)

- Duodecimal

- Octal

- Scientific notation

- Serial decimal

- SI prefix

Notes[edit]

- ^ Sometimes, the extra zeros are used for indicating the accuracy of a measurement. For example, «15.00 m» may indicate that the measurement error is less than one centimetre (0.01 m), while «15 m» may mean that the length is roughly fifteen metres and that the error may exceed 10 centimetres.

References[edit]

- ^ «denary». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Cajori, Florian (Feb 1926). «The History of Arithmetic. Louis Charles Karpinski». Isis. University of Chicago Press. 8 (1): 231–232. doi:10.1086/358384. ISSN 0021-1753.

- ^ Yong, Lam Lay; Se, Ang Tian (April 2004). Fleeting Footsteps. World Scientific. 268. doi:10.1142/5425. ISBN 978-981-238-696-0. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Weisstein, Eric W. (March 10, 2022). «Decimal Point». Wolfram MathWorld. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ The vinculum (overline) in 5.123144 indicates that the ‘144’ sequence repeats indefinitely, i.e. 5.123144144144144….

- ^ In some countries, such as Arab speaking ones, other glyphs are used for the digits

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Decimal». mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- ^ «Decimal Fraction». Encyclopedia of Mathematics. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ «Fingers or Fists? (The Choice of Decimal or Binary Representation)», Werner Buchholz, Communications of the ACM, Vol. 2 #12, pp. 3–11, ACM Press, December 1959.

- ^ Schmid, Hermann (1983) [1974]. Decimal Computation (1 (reprint) ed.). Malabar, Florida: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company. ISBN 0-89874-318-4.

- ^ Schmid, Hermann (1974). Decimal Computation (1st ed.). Binghamton, New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-76180-X.

- ^ Decimal Floating-Point: Algorism for Computers, Cowlishaw, Mike F., Proceedings 16th IEEE Symposium on Computer Arithmetic, ISBN 0-7695-1894-X, pp. 104–11, IEEE Comp. Soc., 2003

- ^ Decimal Arithmetic – FAQ

- ^ Decimal Floating-Point: Algorism for Computers, Cowlishaw, M. F., Proceedings 16th IEEE Symposium on Computer Arithmetic (ARITH 16), ISBN 0-7695-1894-X, pp. 104–11, IEEE Comp. Soc., June 2003

- ^ Dantzig, Tobias (1954), Number / The Language of Science (4th ed.), The Free Press (Macmillan Publishing Co.), p. 12, ISBN 0-02-906990-4

- ^ Sergent, Bernard (1997), Genèse de l’Inde (in French), Paris: Payot, p. 113, ISBN 2-228-89116-9

- ^ Coppa, A.; et al. (2006). «Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry: Flint tips were surprisingly effective for drilling tooth enamel in a prehistoric population». Nature. 440 (7085): 755–56. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..755C. doi:10.1038/440755a. PMID 16598247. S2CID 6787162.

- ^ Bisht, R. S. (1982), «Excavations at Banawali: 1974–77», in Possehl, Gregory L. (ed.), Harappan Civilisation: A Contemporary Perspective, New Delhi: Oxford and IBH Publishing Co., pp. 113–24

- ^ Georges Ifrah: From One to Zero. A Universal History of Numbers, Penguin Books, 1988, ISBN 0-14-009919-0, pp. 200–13 (Egyptian Numerals)

- ^ Graham Flegg: Numbers: their history and meaning, Courier Dover Publications, 2002, ISBN 978-0-486-42165-0, p. 50

- ^ Georges Ifrah: From One to Zero. A Universal History of Numbers, Penguin Books, 1988, ISBN 0-14-009919-0, pp. 213–18 (Cretan numerals)

- ^ a b «Greek numbers». Retrieved 2019-07-21.

- ^ Menninger, Karl: Zahlwort und Ziffer. Eine Kulturgeschichte der Zahl, Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 3rd. ed., 1979, ISBN 3-525-40725-4, pp. 150–53

- ^ Georges Ifrah: From One to Zero. A Universal History of Numbers, Penguin Books, 1988, ISBN 0-14-009919-0, pp. 218f. (The Hittite hieroglyphic system)

- ^ (Atharva Veda 5.15, 1–11)

- ^ Lam Lay Yong et al. The Fleeting Footsteps pp. 137–39

- ^ a b c d e Lam Lay Yong, «The Development of Hindu–Arabic and Traditional Chinese Arithmetic», Chinese Science, 1996 p. 38, Kurt Vogel notation

- ^ «Ancient bamboo slips for calculation enter world records book». The Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ^ a b Joseph Needham (1959). «Decimal System». Science and Civilisation in China, Volume III, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Jean-Claude Martzloff, A History of Chinese Mathematics, Springer 1997 ISBN 3-540-33782-2

- ^ a b Berggren, J. Lennart (2007). «Mathematics in Medieval Islam». In Katz, Victor J. (ed.). The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton University Press. p. 530. ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9.

- ^ Gandz, S.: The invention of the decimal fractions and the application of the exponential calculus by Immanuel Bonfils of Tarascon (c. 1350), Isis 25 (1936), 16–45.

- ^ Lay Yong, Lam. «A Chinese Genesis, Rewriting the history of our numeral system». Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 38: 101–08.

- ^ B. L. van der Waerden (1985). A History of Algebra. From Khwarizmi to Emmy Noether. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- ^ Napier, John (1889) [1620]. The Construction of the Wonderful Canon of Logarithms. Translated by Macdonald, William Rae. Edinburgh: Blackwood & Sons – via Internet Archive.

In numbers distinguished thus by a period in their midst, whatever is written after the period is a fraction, the denominator of which is unity with as many cyphers after it as there are figures after the period.

- ^ «Indian numerals». Ancient Indian mathematics. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2015-05-22.

- ^ Azar, Beth (1999). «English words may hinder math skills development». American Psychological Association Monitor. 30 (4). Archived from the original on 2007-10-21.

- ^ Avelino, Heriberto (2006). «The typology of Pame number systems and the limits of Mesoamerica as a linguistic area» (PDF). Linguistic Typology. 10 (1): 41–60. doi:10.1515/LINGTY.2006.002. S2CID 20412558. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2006-07-12.

- ^ Marcia Ascher. «Ethnomathematics: A Multicultural View of Mathematical Ideas». The College Mathematics Journal. JSTOR 2686959.

- ^ McClean, R. J. (July 1958), «Observations on the Germanic numerals», German Life and Letters, 11 (4): 293–99, doi:10.1111/j.1468-0483.1958.tb00018.x,

Some of the Germanic languages appear to show traces of an ancient blending of the decimal with the vigesimal system

. - ^ Voyles, Joseph (October 1987), «The cardinal numerals in pre-and proto-Germanic», The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 86 (4): 487–95, JSTOR 27709904.

- ^ Stevenson, W.H. (1890). «The Long Hundred and its uses in England». Archaeological Review. December 1889: 313–22.

- ^ Poole, Reginald Lane (2006). The Exchequer in the twelfth century : the Ford lectures delivered in the University of Oxford in Michaelmas term, 1911. Clark, NJ: Lawbook Exchange. ISBN 1-58477-658-7. OCLC 76960942.

- ^ There is a surviving list of Ventureño language number words up to 32 written down by a Spanish priest ca. 1819. «Chumashan Numerals» by Madison S. Beeler, in Native American Mathematics, edited by Michael P. Closs (1986), ISBN 0-292-75531-7.

- ^ a b Hammarström, Harald (17 May 2007). «Rarities in Numeral Systems». In Wohlgemuth, Jan; Cysouw, Michael (eds.). Rethinking Universals: How rarities affect linguistic theory (PDF). Empirical Approaches to Language Typology. Vol. 45. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter (published 2010). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2007.

- ^ Harris, John (1982). Hargrave, Susanne (ed.). «Facts and fallacies of aboriginal number systems» (PDF). Work Papers of SIL-AAB Series B. 8: 153–81. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-08-31.

- ^ Dawson, J. «Australian Aborigines: The Languages and Customs of Several Tribes of Aborigines in the Western District of Victoria (1881), p. xcviii.

- ^ Matsushita, Shuji (1998). Decimal vs. Duodecimal: An interaction between two systems of numeration. 2nd Meeting of the AFLANG, October 1998, Tokyo. Archived from the original on 2008-10-05. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- ^ Mazaudon, Martine (2002). «Les principes de construction du nombre dans les langues tibéto-birmanes». In François, Jacques (ed.). La Pluralité (PDF). Leuven: Peeters. pp. 91–119. ISBN 90-429-1295-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-28. Retrieved 2014-09-12.

- ^ Cheetham, Brian (1978). «Counting and Number in Huli». Papua New Guinea Journal of Education. 14: 16–35. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28.

- ^ Bowers, Nancy; Lepi, Pundia (1975). «Kaugel Valley systems of reckoning» (PDF). Journal of the Polynesian Society. 84 (3): 309–24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-04.

- ^ Owens, Kay (2001), «The Work of Glendon Lean on the Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania», Mathematics Education Research Journal, 13 (1): 47–71, Bibcode:2001MEdRJ..13…47O, doi:10.1007/BF03217098, S2CID 161535519, archived from the original on 2015-09-26

The decimal numeral system (also called the base-ten positional numeral system and denary [1] or decanary) is the standard system for denoting integer and non-integer numbers. It is the extension to non-integer numbers of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system.[2] The way of denoting numbers in the decimal system is often referred to as decimal notation.[3]

A decimal numeral (also often just decimal or, less correctly, decimal number), refers generally to the notation of a number in the decimal numeral system. Decimals may sometimes be identified by a decimal separator (usually «.» or «,» as in 25.9703 or 3,1415).[4] Decimal may also refer specifically to the digits after the decimal separator, such as in «3.14 is the approximation of π to two decimals«. Zero-digits after a decimal separator serve the purpose of signifying the precision of a value.

The numbers that may be represented in the decimal system are the decimal fractions. That is, fractions of the form a/10n, where a is an integer, and n is a non-negative integer.

The decimal system has been extended to infinite decimals for representing any real number, by using an infinite sequence of digits after the decimal separator (see decimal representation). In this context, the decimal numerals with a finite number of non-zero digits after the decimal separator are sometimes called terminating decimals. A repeating decimal is an infinite decimal that, after some place, repeats indefinitely the same sequence of digits (e.g., 5.123144144144144… = 5.123144).[5] An infinite decimal represents a rational number, the quotient of two integers, if and only if it is a repeating decimal or has a finite number of non-zero digits.

Origin[edit]

Ten digits on two hands, the possible origin of decimal counting

Many numeral systems of ancient civilizations use ten and its powers for representing numbers, possibly because there are ten fingers on two hands and people started counting by using their fingers. Examples are firstly the Egyptian numerals, then the Brahmi numerals, Greek numerals, Hebrew numerals, Roman numerals, and Chinese numerals. Very large numbers were difficult to represent in these old numeral systems, and only the best mathematicians were able to multiply or divide large numbers. These difficulties were completely solved with the introduction of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system for representing integers. This system has been extended to represent some non-integer numbers, called decimal fractions or decimal numbers, for forming the decimal numeral system.

Decimal notation[edit]

For writing numbers, the decimal system uses ten decimal digits, a decimal mark, and, for negative numbers, a minus sign «−». The decimal digits are 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9;[6] the decimal separator is the dot «.» in many countries (mostly English-speaking),[7] and a comma «,» in other countries.[4]

For representing a non-negative number, a decimal numeral consists of

- either a (finite) sequence of digits (such as «2017»), where the entire sequence represents an integer,

- or a decimal mark separating two sequences of digits (such as «20.70828»)

-

.

If m > 0, that is, if the first sequence contains at least two digits, it is generally assumed that the first digit am is not zero. In some circumstances it may be useful to have one or more 0’s on the left; this does not change the value represented by the decimal: for example, 3.14 = 03.14 = 003.14. Similarly, if the final digit on the right of the decimal mark is zero—that is, if bn = 0—it may be removed; conversely, trailing zeros may be added after the decimal mark without changing the represented number; [note 1] for example, 15 = 15.0 = 15.00 and 5.2 = 5.20 = 5.200.

For representing a negative number, a minus sign is placed before am.

The numeral

.

The integer part or integral part of a decimal numeral is the integer written to the left of the decimal separator (see also truncation). For a non-negative decimal numeral, it is the largest integer that is not greater than the decimal. The part from the decimal separator to the right is the fractional part, which equals the difference between the numeral and its integer part.

When the integral part of a numeral is zero, it may occur, typically in computing, that the integer part is not written (for example, .1234, instead of 0.1234). In normal writing, this is generally avoided, because of the risk of confusion between the decimal mark and other punctuation.

In brief, the contribution of each digit to the value of a number depends on its position in the numeral. That is, the decimal system is a positional numeral system.

Decimal fractions[edit]

Decimal fractions (sometimes called decimal numbers, especially in contexts involving explicit fractions) are the rational numbers that may be expressed as a fraction whose denominator is a power of ten.[8] For example, the decimals

More generally, a decimal with n digits after the separator (a point or comma) represents the fraction with denominator 10n, whose numerator is the integer obtained by removing the separator.

It follows that a number is a decimal fraction if and only if it has a finite decimal representation.

Expressed as a fully reduced fraction, the decimal numbers are those whose denominator is a product of a power of 2 and a power of 5. Thus the smallest denominators of decimal numbers are

Real number approximation[edit]

Decimal numerals do not allow an exact representation for all real numbers, e.g. for the real number π. Nevertheless, they allow approximating every real number with any desired accuracy, e.g., the decimal 3.14159 approximates the real π, being less than 10−5 off; so decimals are widely used in science, engineering and everyday life.

More precisely, for every real number x and every positive integer n, there are two decimals L and u with at most n digits after the decimal mark such that L ≤ x ≤ u and (u − L) = 10−n.

Numbers are very often obtained as the result of measurement. As measurements are subject to measurement uncertainty with a known upper bound, the result of a measurement is well-represented by a decimal with n digits after the decimal mark, as soon as the absolute measurement error is bounded from above by 10−n. In practice, measurement results are often given with a certain number of digits after the decimal point, which indicate the error bounds. For example, although 0.080 and 0.08 denote the same number, the decimal numeral 0.080 suggests a measurement with an error less than 0.001, while the numeral 0.08 indicates an absolute error bounded by 0.01. In both cases, the true value of the measured quantity could be, for example, 0.0803 or 0.0796 (see also significant figures).

Infinite decimal expansion[edit]

For a real number x and an integer n ≥ 0, let [x]n denote the (finite) decimal expansion of the greatest number that is not greater than x that has exactly n digits after the decimal mark. Let di denote the last digit of [x]i. It is straightforward to see that [x]n may be obtained by appending dn to the right of [x]n−1. This way one has

- [x]n = [x]0.d1d2…dn−1dn,

and the difference of [x]n−1 and [x]n amounts to

,

which is either 0, if dn = 0, or gets arbitrarily small as n tends to infinity. According to the definition of a limit, x is the limit of [x]n when n tends to infinity. This is written as![{textstyle ;x=lim _{nrightarrow infty }[x]_{n};}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4726bcc43d70340455e0f0340fa72d52ee7e420d)

- x = [x]0.d1d2…dn…,

which is called an infinite decimal expansion of x.

Conversely, for any integer [x]0 and any sequence of digits

If all dn for n > N equal to 9 and [x]n = [x]0.d1d2…dn, the limit of the sequence![{textstyle ;([x]_{n})_{n=1}^{infty }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b1ebb69f79147f59b60a7fc1079add44c50c1331)

Any such decimal fraction, i.e.: dn = 0 for n > N, may be converted to its equivalent infinite decimal expansion by replacing dN by dN − 1 and replacing all subsequent 0s by 9s (see 0.999…).

In summary, every real number that is not a decimal fraction has a unique infinite decimal expansion. Each decimal fraction has exactly two infinite decimal expansions, one containing only 0s after some place, which is obtained by the above definition of [x]n, and the other containing only 9s after some place, which is obtained by defining [x]n as the greatest number that is less than x, having exactly n digits after the decimal mark.

Rational numbers[edit]

Long division allows computing the infinite decimal expansion of a rational number. If the rational number is a decimal fraction, the division stops eventually, producing a decimal numeral, which may be prolongated into an infinite expansion by adding infinitely many zeros. If the rational number is not a decimal fraction, the division may continue indefinitely. However, as all successive remainders are less than the divisor, there are only a finite number of possible remainders, and after some place, the same sequence of digits must be repeated indefinitely in the quotient. That is, one has a repeating decimal. For example,

- 1/81 = 0. 012345679 012… (with the group 012345679 indefinitely repeating).

The converse is also true: if, at some point in the decimal representation of a number, the same string of digits starts repeating indefinitely, the number is rational.

| For example, if x is | 0.4156156156… |

| then 10,000x is | 4156.156156156… |

| and 10x is | 4.156156156… |

| so 10,000x − 10x, i.e. 9,990x, is | 4152.000000000… |

| and x is | 4152/9990 |

or, dividing both numerator and denominator by 6, 692/1665.

Decimal computation[edit]

Most modern computer hardware and software systems commonly use a binary representation internally (although many early computers, such as the ENIAC or the IBM 650, used decimal representation internally).[9]

For external use by computer specialists, this binary representation is sometimes presented in the related octal or hexadecimal systems.

For most purposes, however, binary values are converted to or from the equivalent decimal values for presentation to or input from humans; computer programs express literals in decimal by default. (123.1, for example, is written as such in a computer program, even though many computer languages are unable to encode that number precisely.)

Both computer hardware and software also use internal representations which are effectively decimal for storing decimal values and doing arithmetic. Often this arithmetic is done on data which are encoded using some variant of binary-coded decimal,[10][11] especially in database implementations, but there are other decimal representations in use (including decimal floating point such as in newer revisions of the IEEE 754 Standard for Floating-Point Arithmetic).[12]

Decimal arithmetic is used in computers so that decimal fractional results of adding (or subtracting) values with a fixed length of their fractional part always are computed to this same length of precision. This is especially important for financial calculations, e.g., requiring in their results integer multiples of the smallest currency unit for book keeping purposes. This is not possible in binary, because the negative powers of

History[edit]

The world’s earliest decimal multiplication table was made from bamboo slips, dating from 305 BCE, during the Warring States period in China.

Many ancient cultures calculated with numerals based on ten, sometimes argued due to human hands typically having ten fingers/digits.[15] Standardized weights used in the Indus Valley civilization (c. 3300–1300 BCE) were based on the ratios: 1/20, 1/10, 1/5, 1/2, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, and 500, while their standardized ruler – the Mohenjo-daro ruler – was divided into ten equal parts.[16][17][18] Egyptian hieroglyphs, in evidence since around 3000 BCE, used a purely decimal system,[19] as did the Cretan hieroglyphs (c. 1625−1500 BCE) of the Minoans whose numerals are closely based on the Egyptian model.[20][21] The decimal system was handed down to the consecutive Bronze Age cultures of Greece, including Linear A (c. 18th century BCE−1450 BCE) and Linear B (c. 1375−1200 BCE) – the number system of classical Greece also used powers of ten, including, Roman numerals, an intermediate base of 5.[22] Notably, the polymath Archimedes (c. 287–212 BCE) invented a decimal positional system in his Sand Reckoner which was based on 108[22] and later led the German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss to lament what heights science would have already reached in his days if Archimedes had fully realized the potential of his ingenious discovery.[23] Hittite hieroglyphs (since 15th century BCE) were also strictly decimal.[24]

Some non-mathematical ancient texts such as the Vedas, dating back to 1700–900 BCE make use of decimals and mathematical decimal fractions.[25]

The Egyptian hieratic numerals, the Greek alphabet numerals, the Hebrew alphabet numerals, the Roman numerals, the Chinese numerals and early Indian Brahmi numerals are all non-positional decimal systems, and required large numbers of symbols. For instance, Egyptian numerals used different symbols for 10, 20 to 90, 100, 200 to 900, 1000, 2000, 3000, 4000, to 10,000.[26]

The world’s earliest positional decimal system was the Chinese rod calculus.[27]

The world’s earliest positional decimal system

Upper row vertical form

Lower row horizontal form

History of decimal fractions[edit]

counting rod decimal fraction 1/7

Decimal fractions were first developed and used by the Chinese in the end of 4th century BCE,[28] and then spread to the Middle East and from there to Europe.[27][29] The written Chinese decimal fractions were non-positional.[29] However, counting rod fractions were positional.[27]

Qin Jiushao in his book Mathematical Treatise in Nine Sections (1247[30]) denoted 0.96644 by

-

-

-

-

- 寸

, meaning

- 寸

- 096644

-

-

-

J. Lennart Berggren notes that positional decimal fractions appear for the first time in a book by the Arab mathematician Abu’l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi written in the 10th century.[31] The Jewish mathematician Immanuel Bonfils used decimal fractions around 1350, anticipating Simon Stevin, but did not develop any notation to represent them.[32] The Persian mathematician Jamshīd al-Kāshī claimed to have discovered decimal fractions himself in the 15th century.[31] Al Khwarizmi introduced fraction to Islamic countries in the early 9th century; a Chinese author has alleged that his fraction presentation was an exact copy of traditional Chinese mathematical fraction from Sunzi Suanjing.[27] This form of fraction with numerator on top and denominator at bottom without a horizontal bar was also used by al-Uqlidisi and by al-Kāshī in his work «Arithmetic Key».[27][33]

A forerunner of modern European decimal notation was introduced by Simon Stevin in the 16th century.[34]

John Napier introduced using the period (.) to separate the integer part of a decimal number from the fractional part in his book on constructing tables of logarithms, published posthumously in 1620.[35]: p. 8, archive p. 32)

Natural languages[edit]

A method of expressing every possible natural number using a set of ten symbols emerged in India. Several Indian languages show a straightforward decimal system. Many Indo-Aryan and Dravidian languages have numbers between 10 and 20 expressed in a regular pattern of addition to 10.[36]

The Hungarian language also uses a straightforward decimal system. All numbers between 10 and 20 are formed regularly (e.g. 11 is expressed as «tizenegy» literally «one on ten»), as with those between 20 and 100 (23 as «huszonhárom» = «three on twenty»).

A straightforward decimal rank system with a word for each order (10 十, 100 百, 1000 千, 10,000 万), and in which 11 is expressed as ten-one and 23 as two-ten-three, and 89,345 is expressed as 8 (ten thousands) 万 9 (thousand) 千 3 (hundred) 百 4 (tens) 十 5 is found in Chinese, and in Vietnamese with a few irregularities. Japanese, Korean, and Thai have imported the Chinese decimal system. Many other languages with a decimal system have special words for the numbers between 10 and 20, and decades. For example, in English 11 is «eleven» not «ten-one» or «one-teen».

Incan languages such as Quechua and Aymara have an almost straightforward decimal system, in which 11 is expressed as ten with one and 23 as two-ten with three.

Some psychologists suggest irregularities of the English names of numerals may hinder children’s counting ability.[37]

Other bases[edit]

Some cultures do, or did, use other bases of numbers.

- Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures such as the Maya used a base-20 system (perhaps based on using all twenty fingers and toes).

- The Yuki language in California and the Pamean languages[38] in Mexico have octal (base-8) systems because the speakers count using the spaces between their fingers rather than the fingers themselves.[39]

- The existence of a non-decimal base in the earliest traces of the Germanic languages is attested by the presence of words and glosses meaning that the count is in decimal (cognates to «ten-count» or «tenty-wise»); such would be expected if normal counting is not decimal, and unusual if it were.[40][41] Where this counting system is known, it is based on the «long hundred» = 120, and a «long thousand» of 1200. The descriptions like «long» only appear after the «small hundred» of 100 appeared with the Christians. Gordon’s Introduction to Old Norse Archived 2016-04-15 at the Wayback Machine p. 293, gives number names that belong to this system. An expression cognate to ‘one hundred and eighty’ translates to 200, and the cognate to ‘two hundred’ translates to 240. Goodare details the use of the long hundred in Scotland in the Middle Ages, giving examples such as calculations where the carry implies i C (i.e. one hundred) as 120, etc. That the general population were not alarmed to encounter such numbers suggests common enough use. It is also possible to avoid hundred-like numbers by using intermediate units, such as stones and pounds, rather than a long count of pounds. Goodare gives examples of numbers like vii score, where one avoids the hundred by using extended scores. There is also a paper by W.H. Stevenson, on ‘Long Hundred and its uses in England’.[42][43]

- Many or all of the Chumashan languages originally used a base-4 counting system, in which the names for numbers were structured according to multiples of 4 and 16.[44]

- Many languages[45] use quinary (base-5) number systems, including Gumatj, Nunggubuyu,[46] Kuurn Kopan Noot[47] and Saraveca. Of these, Gumatj is the only true 5–25 language known, in which 25 is the higher group of 5.

- Some Nigerians use duodecimal systems.[48] So did some small communities in India and Nepal, as indicated by their languages.[49]

- The Huli language of Papua New Guinea is reported to have base-15 numbers.[50] Ngui means 15, ngui ki means 15 × 2 = 30, and ngui ngui means 15 × 15 = 225.

- Umbu-Ungu, also known as Kakoli, is reported to have base-24 numbers.[51] Tokapu means 24, tokapu talu means 24 × 2 = 48, and tokapu tokapu means 24 × 24 = 576.

- Ngiti is reported to have a base-32 number system with base-4 cycles.[45]

- The Ndom language of Papua New Guinea is reported to have base-6 numerals.[52] Mer means 6, mer an thef means 6 × 2 = 12, nif means 36, and nif thef means 36×2 = 72.

See also[edit]

- Algorism

- Binary-coded decimal (BCD)

- Decimal classification

- Decimal computer

- Decimal time

- Decimal representation

- Decimal section numbering

- Decimal separator

- Decimalisation

- Densely packed decimal (DPD)

- Duodecimal

- Octal

- Scientific notation

- Serial decimal

- SI prefix

Notes[edit]

- ^ Sometimes, the extra zeros are used for indicating the accuracy of a measurement. For example, «15.00 m» may indicate that the measurement error is less than one centimetre (0.01 m), while «15 m» may mean that the length is roughly fifteen metres and that the error may exceed 10 centimetres.

References[edit]

- ^ «denary». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Cajori, Florian (Feb 1926). «The History of Arithmetic. Louis Charles Karpinski». Isis. University of Chicago Press. 8 (1): 231–232. doi:10.1086/358384. ISSN 0021-1753.

- ^ Yong, Lam Lay; Se, Ang Tian (April 2004). Fleeting Footsteps. World Scientific. 268. doi:10.1142/5425. ISBN 978-981-238-696-0. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Weisstein, Eric W. (March 10, 2022). «Decimal Point». Wolfram MathWorld. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ The vinculum (overline) in 5.123144 indicates that the ‘144’ sequence repeats indefinitely, i.e. 5.123144144144144….

- ^ In some countries, such as Arab speaking ones, other glyphs are used for the digits

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Decimal». mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- ^ «Decimal Fraction». Encyclopedia of Mathematics. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ «Fingers or Fists? (The Choice of Decimal or Binary Representation)», Werner Buchholz, Communications of the ACM, Vol. 2 #12, pp. 3–11, ACM Press, December 1959.

- ^ Schmid, Hermann (1983) [1974]. Decimal Computation (1 (reprint) ed.). Malabar, Florida: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company. ISBN 0-89874-318-4.

- ^ Schmid, Hermann (1974). Decimal Computation (1st ed.). Binghamton, New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-76180-X.

- ^ Decimal Floating-Point: Algorism for Computers, Cowlishaw, Mike F., Proceedings 16th IEEE Symposium on Computer Arithmetic, ISBN 0-7695-1894-X, pp. 104–11, IEEE Comp. Soc., 2003

- ^ Decimal Arithmetic – FAQ

- ^ Decimal Floating-Point: Algorism for Computers, Cowlishaw, M. F., Proceedings 16th IEEE Symposium on Computer Arithmetic (ARITH 16), ISBN 0-7695-1894-X, pp. 104–11, IEEE Comp. Soc., June 2003