Дон Кихот

- Дон Кихот

-

Д’он Ких’от, -а (лит. персонаж) и донких’от, -а (благородный наивный мечтатель)

Русский орфографический словарь. / Российская академия наук. Ин-т рус. яз. им. В. В. Виноградова. — М.: «Азбуковник».

.

1999.

Смотреть что такое «Дон Кихот» в других словарях:

-

Дон-Кихот — и Санчо Панса Иллюстрация Гюстава Доре к роману «Дон Кихот» Дон Кихот (исп. Don Quijote, Don Quixote орфография времён Сервантеса) центральный образ романа «Хитроумный идальго Дон Кихот Ламанчский» (El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quijote de la… … Википедия

-

Дон-Кихот — центральный образ романа «Хитроумный гидальго Дон Кихот Ламанчский» (Hingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de la Mancha) испанского писателя Мигеля де Сервантеса Сааведры (1547 1616). Этот роман, впоследствии переведенный на все европейские языки,… … Литературная энциклопедия

-

дон кихот — ДОН КИХОТ, ДОНКИШОТ а, м. don Quichotte <исп. Don Quijote. Бесплодный мечтатель, наивный идеалист, фантазер (по имени героя романа Сервантеса). Сл. 18. В книжных лавках продаются анекдоты древних пошехонцев, или руские докишоты: книга новая в… … Исторический словарь галлицизмов русского языка

-

Дон Кихот — (Оренбург,Россия) Категория отеля: 2 звездочный отель Адрес: Улица Волгоградская 3, Оренбург … Каталог отелей

-

Дон Кихот — Главный герой романа «Дон Кихот» (полное авторское название романа «Славный рыцарь Дон Кихот Ламанчский», 1615) испанского писателя Мигеля Сервантеса де Сааведра (1547 1616). Первый русский перевод романа вышел (1769) под названием «Неслыханный… … Словарь крылатых слов и выражений

-

Дон Кихот — (Don Quijote), герой романа М. Сервантеса «Хитроумный идальго Дон Кихот Ламанчский» (1605). Имя Дон Кихота стало нарицательным для обозначения человека, чьё благородство, великодушие и готовность на рыцарские подвиги вступают в трагическое… … Энциклопедический словарь

-

Дон Кихот — (Yërzovka,Россия) Категория отеля: Адрес: Ерзовка, 670км, Yërzovka, Россия … Каталог отелей

-

Дон Кихот — Дон Кихот. Иллюстрация К. Алонсо. Буэнос Айрес. 1958. ДОН КИХОТ, герой романа М. Сервантеса; один из вечных образов, ставший символом человека, чье благородство, великодушие и готовность на рыцарские подвиги вступают в трагическое противоречие с… … Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

-

ДОН-КИХОТ — Имя героя романа испанского писателя Сервантеса, сделавшееся нарицательным для обозначения людей идеалистов, не понимающих практической жизни и, вследствие того, попадающих и глупые и смешные положения. Словарь иностранных слов, вошедших в состав … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

-

ДОН КИХОТ — (Don Quijote) герой романа М. Сервантеса Хитроумный идальго Дон Кихот Ламанчский (1605). Имя Дон Кихота стало нарицательным для обозначения человека, чье благородство, великодушие и готовность на рыцарские подвиги вступают в трагическое… … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

дон кихот — [< соб. исп. – герой романа Сервантеса “Дон Кихот Ламанчский” (начало 17 в.)] – бескорыстный, но смешной мечтатель, создавший себе фантастический, нежизненный идеал и растрачивающий свои силы в борьбе с воображаемыми препятствиями. Большой… … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

Смотреть что такое ДОН КИХОТ в других словарях:

ДОН КИХОТ

(Don Quijote) герой романа М. Сервантеса «Хитроумный идальго Дон Кихот Ламанчский» (2 тт., 1605—1615). Странствуя по разорённой и угнетённой Исп… смотреть

ДОН КИХОТ

ДОН КИХОТ (Don Quijote), герой романа

М. Сервантеса «Хитроумный идальго Дон Кихот Ламанчский» (2 тт.,

1605-1615). Странствуя по разорённой и угнетённ… смотреть

ДОН КИХОТ

Дон Кихот

Главный герой романа «Дон Кихот» (полное авторское название романа «Славный рыцарь Дон-Кихот Ламанчский», 1615) испанского писателя Миге… смотреть

ДОН КИХОТ

ДОН КИХОТ, ДОНКИШОТ а, м. don Quichotte <исп. Don Quijote. Бесплодный мечтатель, наивный идеалист, фантазер (по имени героя романа Сервантеса). Сл…. смотреть

ДОН КИХОТ

1) Орфографическая запись слова: дон кихот2) Ударение в слове: Д`он Ких`от3) Деление слова на слоги (перенос слова): дон кихот4) Фонетическая транскрип… смотреть

ДОН КИХОТ

дон кихот

[< соб. исп. – герой романа Сервантеса “Дон Кихот Ламанчский” (начало 17 в.)] – бескорыстный, но смешной мечтатель, создавший себе фантастич… смотреть

ДОН КИХОТ

, герой романа М. Сервантеса; один из вечных образов, ставший символом человека, чье благородство, великодушие и готовность на рыцарские подвиги вступают в трагическое противоречие с действительностью. В более широком смысле имя Дон Кихота и понятие донкихотство используются как символ бесперспективности, «безумности» идеальных порывов, их несовместимости с торжествующей прозой жизни, заведомой неустранимости абсолютного разрыва между ними. В массовом сознании сохраняется интерпретация Дон Кихота как комического персонажа.

<p class=»tab»></p>… смотреть

ДОН КИХОТ

малая планета номер 3552, Амур. Среднее расстояние до Солнца 4,23 а. е. (632,9 млн км), эксцентриситет орбиты 0,713 (самый большой среди Амуров), наклон к плоскости эклиптики 30,8 градусов. Период обращения вокруг Солнца 8,70 земных лет. Имеет неправильную форму, максимальный поперечник 18,7 км, масса 6,50*10^15 кг. Была открыта Полем Уайлдом 26 мая 1983 и получила условное обозначение 1983 SA. Название было утверждено Международным Астрономическим Союзом в честь Дона Кихота.

Астрономический словарь.EdwART.2010…. смотреть

ДОН КИХОТ

ДОН КИХОТ (Don Quijote), герой романа М. Сервантеса «Хитроумный идальго Дон Кихот Ламанчский» (1605). Имя Дон Кихота стало нарицательным для обозначения человека, чье благородство, великодушие и готовность на рыцарские подвиги вступают в трагическое противоречие с действительностью.<br><br><br>… смотреть

ДОН КИХОТ

ДОН КИХОТ (Don Quijote) — герой романа М. Сервантеса «Хитроумный идальго Дон Кихот Ламанчский» (1605). Имя Дон Кихота стало нарицательным для обозначения человека, чье благородство, великодушие и готовность на рыцарские подвиги вступают в трагическое противоречие с действительностью.<br>… смотреть

ДОН КИХОТ

Ударение в слове: Д`он Ких`отУдарение падает на буквы: о,оБезударные гласные в слове: Д`он Ких`от

ДОН КИХОТ

Дон Кихот Д`он Ких`от, -а (лит. персонаж) и донких`от, -а (благородный наивный мечтатель)

ДОН КИХОТ

Начальная форма — Дон кихот, неизменяемое, женский род, одушевленное, фамилия

ДОН КИХОТ

м.

Don Chisciotte

Итальяно-русский словарь.2003.

ДОН КИХОТ (DON QUIJOTE)

ДОН КИХОТ (Don Quijote), герой романа М. Сервантеса «Хитроумный идальго Дон Кихот Ламанчский» (1605). Имя Дон Кихота стало нарицательным для обозначения человека, чье благородство, великодушие и готовность на рыцарские подвиги вступают в трагическое противоречие с действительностью…. смотреть

ДОН КИХОТ (DON QUIJOTE)

ДОН КИХОТ (Don Quijote) , герой романа М. Сервантеса «Хитроумный идальго Дон Кихот Ламанчский» (1605). Имя Дон Кихота стало нарицательным для обозначения человека, чье благородство, великодушие и готовность на рыцарские подвиги вступают в трагическое противоречие с действительностью…. смотреть

ДОН КИХОТ ЛАМАНЧСКИЙ

ДОН КИХОТ ЛАМАНЧСКИЙ (исп. Don Quijote de la Mancha < quijote — набедренник, часть рыцарских лат) — герой романа Мигеля де Сервантеса Сааведры «Хитроум… смотреть

А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

До́н Кихо́т, -а (лит. персонаж) и донкихо́т, -а (благородный наивный мечтатель)

Рядом по алфавиту:

До́н Кихо́т , -а (лит. персонаж) и донкихо́т, -а (благородный наивный мечтатель)

донжуани́зм , -а

донжуа́нский

донжуа́нство , -а

донжуа́нствовать , -твую, -твует

дони́занный , кр. ф. -ан, -ана

дониза́ть , -ижу́, -и́жет

до́низу , нареч. (све́рху до́низу; гора́ от верши́ны и до́низу заросла́ ежеви́кой)

дони́зывание , -я

дони́зывать(ся) , -аю, -ает(ся)

доникониа́нский , (ист.)

донима́ние , -я

донима́ть(ся) , -а́ю, -а́ет(ся)

донице́ттиевский , (от Донице́тти)

до́нка , -и, р. мн. до́нок

донкерма́н , -а

донкихо́тишка , -и, р. мн. -шек, м.

донкихо́тский , и донкихо́товский

донкихо́тство , -а

донкихо́тствовать , -твую, -твует

до́нна , -ы (в Италии: госпожа)

до́нник , -а

до́нниковый

до́нный

до́но-во́лжский , (до́но-во́лжская культу́ра, археол.)

доновозаве́тный

до́нор , -а

до́нор-активи́ст , до́нора-активи́ста

до́норно-акце́пторный

до́норный

до́норский

- Словарь галлицизмов русского языка

ДОН КИХОТ, ДОНКИШОТ а, м. don Quichotte <�исп. Don Quijote. Бесплодный мечтатель, наивный идеалист, фантазер (по имени героя романа Сервантеса). Сл. 18. В книжных лавках продаются анекдоты древних пошехонцев, или руские докишоты: книга новая в своем роде и презабавная. Объявления 1798 г. // РС 1875 3 664. [Мелодор:] Мне право уже наскучило быть Дон-Кишотом, гоняться .. за пустою мечтою, и смешить холодных людей моими пламенными воздохами. Карамзин Соч. 1803 7 227. Верьте мне, что нынешний век наполнен множеством Дон-Кишотов всякаго рода. Письма масон. 96. Нынче век ни Дон-Кишота, ни Дон-Кихота. 1839. Данилов 2 36. В Гишпании, в родине славного Донкишота. 1815. Лицейский мудрец. // Грот Лицей 302. Генерал Пиллер-Пильхау длинный сухой мужчина, прежде писал он свою фамилию Пиллер-Пильшау. Кто-то спросил Остен-Сакена, когда сделал он эту перемену. С тех пор, отвечал он, что стали писать не дон-Кишот, а дон Кихот. 1854. Вяземский Ст. зап. кн. // ПСС 10 130. — Лекс. Энц. лекс. 1841; Дрн-Кихот и Дон Кишот; Толль 1864: Дон Кихот, донкихот; САН 1895: Дон-Кихот; Ож. 1949: донкихОт, Сл. 18: дон кишот 1773 ( -кихот 1720, Кихот 1821, -од 1770 также слитно и дефис).

Источник:

Исторический словарь галлицизмов русского языка. — М.: Словарное издательство ЭТС. Николай Иванович Епишкин, 2010.

на Gufo.me

Значения в других словарях

- Дон Кихот —

орф. Дон Кихот, -а (лит. персонаж) и донкихот, -а (благородный наивный мечтатель)

Орфографический словарь Лопатина - дон кихот —

Дон Кихот м. Литературный персонаж одноименного романа испанского писателя М. Сервантеса — благородный, великодушный и готовый на рыцарские подвиги человек.

Толковый словарь Ефремовой - Дон Кихот —

(Don Quijote) герой романа М. Сервантеса «Хитроумный идальго Дон Кихот Ламанчский» (2 тт., 1605—1615). Странствуя по разорённой и угнетённой Испании конца…

Большая советская энциклопедия - дон кихот —

[< соб. исп. – герой романа Сервантеса “Дон Кихот Ламанчский” (начало 17 в.)] – бескорыстный, но смешной мечтатель, создавший себе фантастический, нежизненный идеал и растрачивающий свои силы в борьбе с воображаемыми препятствиями.

Большой словарь иностранных слов - ДОН КИХОТ —

ДОН КИХОТ (Don Quijote) — герой романа М. Сервантеса «Хитроумный идальго Дон Кихот Ламанчский» (1605). Имя Дон Кихота стало нарицательным для обозначения человека, чье благородство, великодушие и готовность на рыцарские подвиги вступают в трагическое противоречие с действительностью.

Большой энциклопедический словарь

§ 123. Пишутся

раздельно:

Сочетания русского имени с отчеством и фамилией или только с

фамилией, напр.: Александр Сергеевич Пушкин, Лев Толстой.

Имена исторических и легендарных лиц, состоящие из имени и

прозвища, напр.: Владимир Красное Солнышко, Всеволод Большое

Гнездо, Ричард Львиное Сердце, Александр Невский, Илья Муромец, Василий

Блаженный, Пётр Великий, Плиний Старший, Мария Египетская; так же

пишутся подобные по структуре имена литературных персонажей, клички животных,

напр.: Федька Умойся Грязью, Белый Бим Чёрное Ухо.

Примечание. Составные имена (в том числе

исторических лиц, святых, фольклорных персонажей и др.), в которых вторая часть

является не прозвищем, а нарицательным именем в роли приложения, пишутся через

дефис, напр.: Рокфеллер-старший,

Дюма-сын; Илья-пророк, Николай-угодник (и Никола-угодник); Иван-царевич, Иванушка-дурачок.

3. Двойные, тройные и т. д. нерусские (европейские,

американские) составные имена, напр.: Гай Юлий Цезарь, Жан Жак

Руссо, Джордж Ноэл Гордон Байрон, Генри Уордсуорт Лонг- фелло, Чарлз Спенсер

Чаплин, Хосе Рауль Капабланка, Эрих Ма- рия Ремарк, Иоанн Павел II.

Примечание. По закрепившейся традиции

некоторые имена пишутся через дефис, напр.: Франц-Иосиф, Мария-Антуанетта.

4. Китайские, бирманские, вьетнамские, индонезийские, корейские,

японские личные имена, напр.: Лю Хуацин, Сунь Ятсен, Дэн Сяопин,

Ле Зуан, Ким Ир Сен, Фом Ван Донг, У Ганг Чжи, Акира Куросава, Сацуо Ямамото.

Примечание. Китайские личные имена, состоящие

из трех частей (типа Дэн Сяопин),

пишутся в два слова.

5. Западноевропейские и южноамериканские фамилии, включающие

в свой состав служебные элементы (артикли, предлоги, частицы) ван,

да, дас, де, делла, дель, дер, ды, дос, дю, ла, ле, фон и т. п., напр.: Ван Дейк, Ле Шапелье, Леонардо да Винчи, Леконт де Лиль, Роже Мартен

дю Тар, Пьеро делла Франческа, Вальтер фон дер Фогельвейде, Герберт фон Караян.

Примечание 1. Служебный элемент и в испанских фамилиях

выделяется двумя дефисами, напр.: Хосе

Ортега-и-Гассет, Риего-и-Нуньес.

Примечание 2. В русской передаче некоторых

иноязычных фамилий артикли традиционно пишутся слитно с последующей частью (вопреки

написанию в языке-источнике), напр.: Лафонтен, Лагарп, Делагарди.

Примечание 3. Об использовании апострофа в

иностранных фамилиях с начальными элементами Д’ и О’ (Д’Аламбер, О’Хара и т. п.) см. § 115.

6. Итальянские, испанские, португальские имена и фамилии с

предшествующими им словами дон, донья, донна, дона, напр.:

дон Фернандо, дон Педро, донья Клемента, донна Мария.

Примечание. Имена литературных героев Дон Жуан и Дон Кихот, употребленные

в нарицательном смысле, пишутся со строчной буквы и слитно: донжуан, донкихот.

§ 160. Служебные

слова (артикли, предлоги и др.) ван, да, дас, де, делла, дель,

дер, ди, дос, дю, ла, ле, фон и т. п., входящие в состав

западноевропейских и южноамериканских фамилий, пишутся со строчной буквы,

напр.: Людвиг ван Бетховен, Леонардо да Винчи, Оноре де Бальзак,

Лопе де Вега, Альфред де Мюссе, Хуана Инес де ла Крус, Лукка делла Роббиа,

Андреа дель Сарто, Роже Мартен дю Гар, Женни фон Вестфален, Макс фон дер Грюн,

Жанна д`Арк; Ортега-и-Гассет, Риего-и-Нуньес.

Примечание 1. В некоторых личных именах

служебные слова традиционно пишутся с прописной буквы (как правило, если

прописная пишется в языке-источнике), напр.: Ван Гог, Д`Аламбер, Шарль Де Костер, Эдуардо Де

Филиппо, Ди Витторио, Этьен Ла Боэси, Анри Луи Ле Шателье, Ле Корбюзье, Эль

Греко, Дос Пассос.

Примечание 2. Начальные части фамилий Мак-, О’, Сан-, Сен-, Сент- пишутся

с прописной буквы, напр.: Мак-Грегор,

О’Нил, Фрэнк О’Коннор, Хосе Сан-Мартин, Сен-Жюст, Сен-Санс, Сен-Симон,

Сент-Бее, Антуан де Сент-Экзюпери.

Примечание 3. Слова дон, донья, донна, дона, предшествующие

итальянским, испанским, португальским именам и фамилиям, пишутся со строчной

буквы, напр.: дон Базилио, дон

Сезар де Базан, донья Долорес; однако в именах литературных

героев Дон Кихот и Дон Жуан слово

дон пишется с

прописной (ср. донкихот, донжуан в

нарицательном смысле).

До́н Кихо́т

До́н Кихо́т, -а (лит. персонаж) и донкихо́т, -а (благородный наивный мечтатель)

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я обязательно научусь отличать широко распространённые слова от узкоспециальных.

Насколько понятно значение слова телеграфно (наречие):

Ассоциации к слову «дон»

Синонимы к слову «дон»

Предложения со словосочетанием «Дон Кихот»

- – Нигилист-одиночка, дон кихот современного розлива со своими тараканами в голове.

- Первое – мне могут позвонить, хотя сегодня это уже маловероятно, второе – а как же твой дон кихот, вы же тут вроде проездом?

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словосочетанием «Дон Кихот»

- Они были более честны, чем политически опытны, и забывали, что один Дон Кихот может убить целую идею рыцарства.

- Экипажем управлял Дон Кихот, погоняя четверку богато убранных золотой, спадающей до земли сеткой лошадей огромным копьем.

- Патрикей не стал далее дослушивать, а обернул свою скрипку и смычок куском старой кисеи и с той поры их уже не разворачивал; время, которое он прежде употреблял на игру на скрипке, теперь он простаивал у того же окна, но только лишь смотрел на небо и старался вообразить себе ту гармонию, на которую намекнул ему рыжий дворянин Дон-Кихот Рогожин.

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Значение слова «дон»

-

ДОН1, -а, м. и ДОН-… Частица, присоединяемая к мужским именам представителей знати в Испании. Дон Карлос. Дон-Кихот.

ДОН2 и ДОН-ДОН-ДОН, междом. Употребляется звукоподражательно для обозначения звона колокола или звука, издаваемого металлическими предметами при ударах по ним. (Малый академический словарь, МАС)

Все значения слова ДОН

Афоризмы русских писателей со словом «дон»

- На душе — лимонный свет заката,

И все то же слышно сквозь туман, —

За свободу в чувствах есть расплата,

Принимай же вызов, Дон-Жуан! - Когда переведутся Дон-Кихоты, пускай закроется книга Истории. В ней нечего будет читать.

- (все афоризмы русских писателей)

На нашем сайте в электронном виде представлен справочник по орфографии русского языка. Справочником можно пользоваться онлайн, а можно бесплатно скачать на свой компьютер.

Надеемся, онлайн-справочник поможет вам изучить правописание и синтаксис русского языка!

РОССИЙСКАЯ АКАДЕМИЯ НАУК

Отделение историко-филологических наук Институт русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова

ПРАВИЛА РУССКОЙ ОРФОГРАФИИ И ПУНКТУАЦИИ

ПОЛНЫЙ АКАДЕМИЧЕСКИЙ СПРАВОЧНИК

Авторы:

Н. С. Валгина, Н. А. Еськова, О. Е. Иванова, С. М. Кузьмина, В. В. Лопатин, Л. К. Чельцова

Ответственный редактор В. В. Лопатин

Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации. Полный академический справочник / Под ред. В.В. Лопатина. — М: АСТ, 2009. — 432 с.

ISBN 978-5-462-00930-3

Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации. Полный академический справочник / Под ред. В.В. Лопатина. — М: Эксмо, 2009. — 480 с.

ISBN 978-5-699-18553-5

Справочник представляет собой новую редакцию действующих «Правил русской орфографии и пунктуации», ориентирован на полноту правил, современность языкового материала, учитывает существующую практику письма.

Полный академический справочник предназначен для самого широкого круга читателей.

Предлагаемый справочник подготовлен Институтом русского языка им. В. В. Виноградова РАН и Орфографической комиссией при Отделении историко-филологических наук Российской академии наук. Он является результатом многолетней работы Орфографической комиссии, в состав которой входят лингвисты, преподаватели вузов, методисты, учителя средней школы.

В работе комиссии, многократно обсуждавшей и одобрившей текст справочника, приняли участие: канд. филол. наук Б. 3. Бук-чина, канд. филол. наук, профессор Н. С. Валгина, учитель русского языка и литературы С. В. Волков, доктор филол. наук, профессор В. П. Григорьев, доктор пед. наук, профессор А. Д. Дейкина, канд. филол. наук, доцент Е. В. Джанджакова, канд. филол. наук Н. А. Еськова, академик РАН А. А. Зализняк, канд. филол. наук О. Е. Иванова, канд. филол. наук О. Е. Кармакова, доктор филол. наук, профессор Л. Л. Касаткин, академик РАО В. Г. Костомаров, академик МАНПО и РАЕН О. А. Крылова, доктор филол. наук, профессор Л. П. Крысин, доктор филол. наук С. М. Кузьмина, доктор филол. наук, профессор О. В. Кукушкина, доктор филол. наук, профессор В. В. Лопатин (председатель комиссии), учитель русского языка и литературы В. В. Луховицкий, зав. лабораторией русского языка и литературы Московского института повышения квалификации работников образования Н. А. Нефедова, канд. филол. наук И. К. Сазонова, доктор филол. наук А. В. Суперанская, канд. филол. наук Л. К. Чельцова, доктор филол. наук, профессор А. Д. Шмелев, доктор филол. наук, профессор М. В. Шульга. Активное участие в обсуждении и редактировании текста правил принимали недавно ушедшие из жизни члены комиссии: доктора филол. наук, профессора В. Ф. Иванова, Б. С. Шварцкопф, Е. Н. Ширяев, кандидат филол. наук Н. В. Соловьев.

Основной задачей этой работы была подготовка полного и отвечающего современному состоянию русского языка текста правил русского правописания. Действующие до сих пор «Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации», официально утвержденные в 1956 г., были первым общеобязательным сводом правил, ликвидировавшим разнобой в правописании. Со времени их выхода прошло ровно полвека, на их основе были созданы многочисленные пособия и методические разработки. Естественно, что за это время в формулировках «Правил» обнаружился ряд существенных пропусков и неточностей.

Неполнота «Правил» 1956 г. в большой степени объясняется изменениями, произошедшими в самом языке: появилось много новых слов и типов слов, написание которых «Правилами» не регламентировано. Например, в современном языке активизировались единицы, стоящие на грани между словом и частью слова; среди них появились такие, как мини, макси, видео, аудио, медиа, ретро и др. В «Правилах» 1956 г. нельзя найти ответ на вопрос, писать ли такие единицы слитно со следующей частью слова или через дефис. Устарели многие рекомендации по употреблению прописных букв. Нуждаются в уточнениях и дополнениях правила пунктуации, отражающие стилистическое многообразие и динамичность современной речи, особенно в массовой печати.

Таким образом, подготовленный текст правил русского правописания не только отражает нормы, зафиксированные в «Правилах» 1956 г., но и во многих случаях дополняет и уточняет их с учетом современной практики письма.

Регламентируя правописание, данный справочник, естественно, не может охватить и исчерпать все конкретные сложные случаи написания слов. В этих случаях необходимо обращаться к орфографическим словарям. Наиболее полным нормативным словарем является в настоящее время академический «Русский орфографический словарь» (изд. 2-е, М., 2005), содержащий 180 тысяч слов.

Данный справочник по русскому правописанию предназначается для преподавателей русского языка, редакционно-издательских работников, всех пишущих по-русски.

Для облегчения пользования справочником текст правил дополняется указателями слов и предметным указателем.

Составители приносят благодарность всем научным и образовательным учреждениям, принявшим участие в обсуждении концепции и текста правил русского правописания, составивших этот справочник.

Авторы

Ав. — Л.Авилова

Айт. — Ч. Айтматов

Акун. — Б. Акунин

Ам. — Н. Амосов

А. Меж. — А. Межиров

Ард. — В. Ардаматский

Ас. — Н. Асеев

Аст. — В. Астафьев

А. Т. — А. Н. Толстой

Ахм. — А. Ахматова

Ахмад. — Б. Ахмадулина

- Цвет. — А. И. Цветаева

Багр. — Э. Багрицкий

Бар. — Е. А. Баратынский

Бек. — М. Бекетова

Бел. — В. Белов

Белин. — В. Г. Белинский

Бергг. — О. Берггольц

Бит. — А. Битов

Бл. — А. А. Блок

Бонд. — Ю. Бондарев

Б. П. — Б. Полевой

Б. Паст. — Б. Пастернак

Булг. — М. А. Булгаков

Бун. — И.А.Бунин

- Бык. — В. Быков

Возн. — А. Вознесенский

Вороб. — К. Воробьев

Г. — Н. В. Гоголь

газ. — газета

Гарш. — В. М. Гаршин

Гейч. — С. Гейченко

Гил. — В. А. Гиляровский

Гонч. — И. А. Гончаров

Гр. — А. С. Грибоедов

Гран. — Д. Гранин

Грин — А. Грин

Дост. — Ф. М. Достоевский

Друн. — Ю. Друнина

Евт. — Е. Евтушенко

Е. П. — Е. Попов

Ес. — С. Есенин

журн. — журнал

Забол. — Н. Заболоцкий

Зал. — С. Залыгин

Зерн. — Р. Зернова

Зл. — С. Злобин

Инб. — В. Инбер

Ис — М. Исаковский

Кав. — В. Каверин

Каз. — Э. Казакевич

Кат. — В. Катаев

Кис. — Е. Киселева

Кор. — В. Г. Короленко

Крут. — С. Крутилин

Крыл. — И. А. Крылов

Купр. — А. И. Куприн

Л. — М. Ю. Лермонтов

Леон. — Л. Леонов

Лип. — В. Липатов

Лис. — К. Лисовский

Лих. — Д. С. Лихачев

Л. Кр. — Л. Крутикова

Л. Т. — Л. Н. Толстой

М. — В. Маяковский

Майк. — А. Майков

Мак. — В. Маканин

М. Г. — М. Горький

Мих. — С. Михалков

Наб. — В. В. Набоков

Нагиб. — Ю. Нагибин

Некр. — H.A. Некрасов

Н.Ил. — Н. Ильина

Н. Матв. — Н. Матвеева

Нов.-Пр. — А. Новиков-Прибой

Н. Остр. — H.A. Островский

Ок. — Б. Окуджава

Орл. — В. Орлов

П. — A.C. Пушкин

Пан. — В. Панова

Панф. — Ф. Панферов

Пауст. — К. Г. Паустовский

Пелев. — В. Пелевин

Пис. — А. Писемский

Плат. — А. П. Платонов

П. Нил. — П. Нилин

посл. — пословица

Пришв. — М. М. Пришвин

Расп. — В. Распутин

Рожд. — Р. Рождественский

Рыб. — А. Рыбаков

Сим. — К. Симонов

Сн. — И. Снегова

Сол. — В. Солоухин

Солж. — А. Солженицын

Ст. — К. Станюкович

Степ. — Т. Степанова

Сух. — В. Сухомлинский

Т. — И.С.Тургенев

Тв. — А. Твардовский

Тендр. — В. Тендряков

Ток. — В. Токарева

Триф. — Ю. Трифонов

Т. Толст. — Т. Толстая

Тын. — Ю. Н. Тынянов

Тютч. — Ф. И. Тютчев

Улиц. — Л. Улицкая

Уст. — Т. Устинова

Фад. — А. Фадеев

Фед. — К. Федин

Фурм. — Д. Фурманов

Цвет. — М. И. Цветаева

Ч.- А. П. Чехов

Чак. — А. Чаковский

Чив. — В. Чивилихин

Чуд. — М. Чудакова

Шол. — М. Шолохов

Шукш. — В. Шукшин

Щерб. — Г. Щербакова

Эр. — И.Эренбург

Всего найдено: 11

Доброе утро! С праздниками! Прошу уточнить ответ на вопрос 308008 Есть множество источников, в т. ч. и советского времени, в которых Аль Капоне пишется раздельно, а имя Аль (уменьшительное от Альфонсо) склоняется (как склоняется Эд, Эл, Юз, Чак, Грег и т. п.). И хотелось бы развёрнутого обоснования, почему не склоняется первая часть псевдонима Аль Бано. Тот факт, что Аль Бано — псевдоним, не имеет значения, Максим Горький тоже псевдоним, но в нём прекрасно склоняются обе части. Аль можно трактовать как уменьшительное от Альбано точно так же, как от Альфредо (Аль Пачино). Кстати, в упомянутом вами Словаре имён собственных написание имени Аля Пачино приведено такое, что сразу нескольким людям плохо стало.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

А. А. Зализняк в примечании об именах собственных в «Грамматическом словаре русского языка» писал, что некоторые составные имена вошли в русский культурный фонд как целостные единицы, например: Тарас Бульба, Санчо Панса, Ходжа Насреддин, Леонардо да Винчи, Жюль Верн, Ян Гус. Среди них есть такие сочетания, в которых первый компонент в реальном грамотном узусе не склоняется (читать Жюль Верна, Марк Твена), склонение имен в подобных сочетаниях — пуристическая норма, соблюдаемая в изданиях. А. А. Зализняк к таким склоняемым формам дает помету офиц. В некоторых именных сочетаниях первый компонент никогда не склоняется, к ним относятся, например, имена персонажей Дон Кихот, Дон Карлос. Цельность, нечленимость этих сочетаний проявляется и в орфографии. Ср. написание и форму имени, относящегося к реальному историческому лицу и персонажу драмы Шиллера: За XIX век реликвия сменила нескольких хозяев и в 1895 году попала в руки дона Карлоса, графа Мадридского и легитимного претендента на французский трон и Роль Дон Карлоса создана, так сказать, по форме его таланта.

Псевдоним Аль Бано, к сожалению пока не зафиксированный в лингвистических словарях, можно отнести к категории целостных языковых единиц. Мы наблюдали за его употреблением в разных источниках: первый компонент устойчиво не склоняется. Способствует этому его краткость, совпадение по форме с арабским артиклем.

http://gramota.ru/slovari/dic/?word=росинант&all=x Правильно: Дон Кихота.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Спасибо! Поправили.

Здравствуйте! Как посоветуете писать «рыцарь печального образа»? Дело в том, что у вас на сайте в Русском орфографическом словаре под ред. В. В. Лопатина предлагается — Рыцарь печального образа. Из Розенталя другая выдержка: «Раздел 3. Употребление прописных букв §11. Собственные имена лиц и клички животных. 1. Имена, отчества, фамилии, прозвища, псевдонимы пишутся с прописной буквы: <…> Рыцарь Печального Образа (о Дон-Кихоте) и т. д.». Во Фразеологическом словаре русского литературного языка приводится цитата из Белинского. Отрывки из письма брату Константину, 15 окт. 1832: «Что же касается до тебя самого, то я сомневаюсь, что тебе очень бы хотелось исполнить своё намерение; ты не последний рыцарь печального образа и любишь донкихотствовать». Наконец, Русский язык. 40 самых необходимых правил орфографии и пунктуации — М. М. Баранова (книга доступна на проекте: гугл бук) — ссылаясь на Розенталя «Прописная или строчная» — М., 2003 и Лопатина «Как правильно? С большой или с маленькой?» — М., 2002, приводит пример: рыцарь Печального Образа. Так как же быть?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Это выражение по-разному фиксировалось в словарях и справочниках. Сейчас корректным является написание, соответствующее рекомендациям новейшего академического орфографического словаря – «Русского орфографического словаря» под ред. В. В. Лопатина и О. Е. Ивановой (4-е изд. М., 2012).

Добрый день! Повторю свой вопрос: «слёзы Дон Жуана» или слёзы «Дона Жуана», и что в данном случае Дон — титул? Следует ли из этого то же самое в отношении Дон (а) Кихота?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Дон в Испании и испаноязычных странах – форма почтительного упоминания или обращения к мужчине (употребляется перед именами собственными мужчин – представителей знати), т. е. это нарицательное существительное, и если мы возьмем какого-нибудь абстрактного дона Педро, в родительном падеже верно: слезы дона Педро. Однако в именах литературных героев Дон Кихот и Дон Жуан слово дон традиционно пишется с большой буквы и не склоняется (воспринимается как часть имени собственного). Правильно: слезы Дон Жуана, слезы Дон Кихота.

Найдите пожалуйста ошибки в следующих предложениях и приведите исправленный вариант.

К осени аппетитные плоды появляются и на садовых деревьях: яблоня, вишня, груша, слива.

Моя подруга любит чистоту, красивую посуду и читать.

Закончив объяснение, учительница предлагает классу решить несколько примеров.

Дон Кихот был высок и худой.

Каждая девушка ждет Его – своего Единственного, своего принца, обязательно придущего к ней однажды.

Глядя на тебя, мурашки бегут!

спасибо заранее))

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Поразмыслите самостоятельно над Вашим домашним заданием.

В именах собственных Дон-Жуан и Дон-Кихот нужен ли дефис? Спасибо

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно:

Дон Жуан, -а (лит. персонаж) и донжуан, -а (искатель любовных приключений)

Дон Кихот, -а (лит. персонаж) и донкихот, -а (благородный наивный мечтатель)

Не бойтесь быть «донкихотами». Нужны ли кавычки в слове «донкихотами». Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Кавычки не нужны.

Скажите, есть ли ошибки в этом предложение: Кто Вы, – Дон Кихот Ламанчский?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Надо оставить один знак: либо запятую, либо тире, в зависимости от смысла. Если это обращение к Дон Кихоту, правильно: Кто Вы, Дон Кихот Ламанчский? Если смысл ‘вы кто – Дон Кихот Ламанчский, что ли?’, правильно с тире.

Шляпа Дон Кихота или Дона Кихота?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно: _Дон Кихота_.

Добрый день!!!

Читаю «Дон Кихот» Мигеля де Сервантеса в переводе Н.Любимова (Издательство ЭКСМО, 2005 г.) и столкнулся со следующим затруднением в тексте:

«- Ну пусть это будет шутка, коли мы не имеем возможности отомстить взаправду, хотя я-то отлично знаю, было это взаправду или в шутку, и еще я знаю, что все это навеки запечатлелось в моей памяти, равно как и в моих костях».

Вопрос: правильно ли написание местоимения «я» с частицей «то» через дефис?Заранее признаетелен.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: частица _то_ с предшествующим словом пишется через дефис.

Балет «Дон Кихот» или «Дон-Кихот«?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: _балет «Дон Кихот»_.

«Quijote» redirects here. For the genus of gastropod, see Quijote (gastropod).

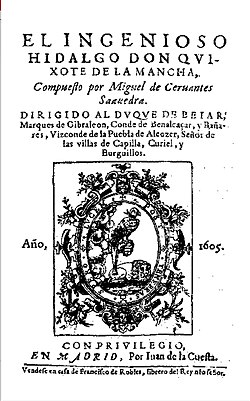

Don Quixote de la Mancha (1605, first edition) |

|

| Author | Miguel de Cervantes |

|---|---|

| Original title | El ingenioso hidalgo don Quixote de la Mancha |

| Country | Habsburg Spain |

| Language | Early Modern Spanish |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | Francisco de Robles |

|

Publication date |

1605 (Part One) 1615 (Part Two) |

|

Published in English |

1612 (Part One) 1620 (Part Two) |

| Media type | |

|

Dewey Decimal |

863 |

| LC Class | PQ6323 |

|

Original text |

El ingenioso hidalgo don Quixote de la Mancha at Spanish Wikisource |

| Translation | Don Quixote at Wikisource |

Don Quixote[a][b] is a Spanish epic novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts, in 1605 and 1615, its full title is The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha or, in Spanish, El ingenioso hidalgo don Quixote[b] de la Mancha (changing in Part 2 to El ingenioso caballero don Quixote[b] de la Mancha).[c] A founding work of Western literature, it is often labelled as the first modern novel[2][3] and one of the greatest works ever written.[4][5] Don Quixote is also one of the most-translated books in the world.[6]

The plot revolves around the adventures of a member of the lowest nobility, an hidalgo from La Mancha named Alonso Quijano, who reads so many chivalric romances that he either loses or pretends to have lost his mind in order to become a knight-errant (caballero andante) to revive chivalry and serve his nation, under the name Don Quixote de la Mancha.[b] He recruits a simple farmer, Sancho Panza, as his squire, who often employs a unique, earthy wit in dealing with Don Quixote’s rhetorical monologues on knighthood, already considered old-fashioned at the time, and representing the most droll realism in contrast to his master’s idealism. In the first part of the book, Don Quixote does not see the world for what it is and prefers to imagine that he is living out a knightly story that’s meant for the annals of all time.

The book had a major influence on the literary community, as evidenced by direct references in Alexandre Dumas’ The Three Musketeers (1844), Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), and Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac (1897),[citation needed] as well as the word quixotic.

When first published, Don Quixote was usually interpreted as a comic novel. After the successful French Revolution, it was better known for its presumed central ethic that in some ways individuals can be intelligent while their society is quite fanciful and was seen as a fascinating, enchanting or disenchanting book in this dynamic (and for among books). In the 19th century, it was seen as social commentary, but no one could easily tell «whose side Cervantes was on». Many critics came to view the work as a tragedy in which Don Quixote’s idealism and nobility are viewed by the post-chivalric world as not enough and are defeated and rendered useless by a common reality devoid of his «true» romantic inclinations; by the 20th century, the novel had come to occupy a canonical space as one of the foundations of letters in literature.

Summary[edit]

Illustration by Gustave Doré depicting the famous windmill scene

Cervantes wrote that the first chapters were taken from «the archives of La Mancha», and the rest were translated from an Arabic text by the Moorish historian Cide Hamete Benengeli. This metafictional trick appears to give a greater credibility to the text, implying that Don Quixote is a real character and that this has been researched from the logs of the events that truly occurred several decades prior to the recording of this account and the work of magical sage historians that are known to be involved here (this getting some explaining). However, it was also common practice in that era for fictional works to make some creative pretense for seeming factual to the readers, such as the common opening line of fairy tales «Once upon a time in a land far away…».

In the course of their travels, the protagonists meet innkeepers, prostitutes, goat-herders, soldiers, priests, escaped convicts and scorned lovers. The aforementioned characters sometimes tell tales that incorporate events from the real world. Their encounters are magnified by Don Quixote’s imagination into chivalrous quests. Don Quixote’s tendency to intervene violently in matters irrelevant to himself, and his habit of not paying debts, result in privations, injuries, and humiliations (with Sancho often the victim). Finally, Don Quixote is persuaded to return to his home village. The narrator hints that there was a third quest, saying that records of it have been lost, «…at any rate derived from authentic documents; tradition has merely preserved in the memory of La Mancha…» this third sally. A leaden box in possession of an old physician that was discovered at an old hermitage being rebuilt is related, containing «certain parchment manuscripts in Gothic character, but in Castilian verse» that seems to know the story even of Don Quixote’s burial and having «sundry epitaphs and eulogies». The narrator requesting not much for the «vast toil which it has cost him in examining and searching the Manchegan archives» volunteers to present what can be made out of them with the good nature of «…and will be encouraged to seek out and produce other histories…». A group of Academicians from a village of La Mancha are set forth. The most worm-eaten were given to an Academician «to make out their meaning conjecturally.» He’s been informed he means to publish these in hopes of a third sally.

Part 1 (1605)[edit]

For Cervantes and the readers of his day, Don Quixote was a one-volume book published in 1605, divided internally into four parts, not the first part of a two-part set. The mention in the 1605 book of further adventures yet to be told was totally conventional, does not indicate any authorial plans for a continuation, and was not taken seriously by the book’s first readers.[7]

The First Sally (Chapters 1–5)[edit]

Alonso Quixano, the protagonist of the novel (though he is not given this name until much later in the book), is a hidalgo (member of the lesser Spanish nobility), nearing 50 years of age, living in an unnamed section of La Mancha with his niece and housekeeper, as well as a stable boy who is never heard of again after the first chapter. Although Quixano is usually a rational man, in keeping with the humoral physiology theory of the time, not sleeping adequately—because he was reading—has caused his brain to dry. Quixano’s temperament is thus choleric, the hot and dry humor. As a result, he is easily given to anger[8] and believes every word of some of these fictional books of chivalry to be true such were the «complicated conceits»; «what Aristotle himself could not have made out or extracted had he come to life again for that special purpose».

«He commended, however, the author’s way of ending his book with the promise of that interminable adventure, and many a time was he tempted to take up his pen and finish it properly as is there proposed, which no doubt he would have done…». Having «greater and more absorbing thoughts», he reaches imitating the protagonists of these books, and he decides to become a knight errant in search of adventure. To these ends, he dons an old suit of armor, renames himself «Don Quixote», names his exhausted horse «Rocinante», and designates Aldonza Lorenzo, intelligence able to be gathered of her perhaps relating that of being a slaughterhouse worker with a famed hand for salting pigs, as his lady love, renaming her Dulcinea del Toboso, while she knows nothing of this. Expecting to become famous quickly, he arrives at an inn, which he believes to be a castle, calls the prostitutes he meets «ladies» (doncellas), and demands that the innkeeper, whom he takes to be the lord of the castle, dub him a knight. He goes along with it (in the meantime convincing Don Quixote to take to heart his need to have money and a squire and some magical cure for injuries) and having morning planned for it. Don Quixote starts the night holding vigil over his armor and shortly becomes involved in a fight with muleteers who try to remove his armor from the horse trough so that they can water their mules. In a pretended ceremony, the innkeeper dubs him a knight to be rid of him and sends him on his way right then.

Don Quixote next «helps» a servant named Andres who is tied to a tree and beaten by his master over disputed wages, and makes his master swear to treat him fairly, but in an example of transference his beating is continued (and in fact redoubled) as soon as Quixote leaves (later explained to Quixote by Andres). Don Quixote then encounters traders from Toledo, who «insult» the imaginary Dulcinea. He attacks them, only to be severely beaten and left on the side of the road, and is returned to his home by a neighboring peasant.

Destruction of Don Quixote’s library (Chapters 6–7)[edit]

While Don Quixote is unconscious in his bed, his niece, the housekeeper, the parish curate, and the local barber burn most of his chivalric and other books. A large part of this section consists of the priest deciding which books deserve to be burned and which to be saved. It is a scene of high comedy: If the books are so bad for morality, how does the priest know them well enough to describe every naughty scene? Even so, this gives an occasion for many comments on books Cervantes himself liked and disliked. For example, Cervantes’ own pastoral novel La Galatea is saved, while the rather unbelievable romance Felixmarte de Hyrcania is burned. After the books are dealt with, they seal up the room which contained the library, later telling Don Quixote that it was the action of a wizard (encantador).

The Second Sally (Chapters 8–10)[edit]

After a short period of feigning health, Don Quixote requests his neighbour, Sancho Panza, to be his squire, promising him a petty governorship (ínsula). Sancho is a poor and simple farmer but more practical than the head-in-the-clouds Don Quixote and agrees to the offer, sneaking away with Don Quixote in the early dawn. It is here that their famous adventures begin, starting with Don Quixote’s attack on windmills that he believes to be ferocious giants.

The two next encounter two Benedictine friars travelling on the road ahead of a lady in a carriage. The friars are not traveling with the lady, but happen to be travelling on the same road. Don Quixote takes the friars to be enchanters who hold the lady captive, knocks a friar from his horse, and is challenged by an armed Basque traveling with the company. As he has no shield, the Basque uses a pillow from the carriage to protect himself, which saves him when Don Quixote strikes him. Cervantes chooses this point, in the middle of the battle, to say that his source ends here. Soon, however, he resumes Don Quixote’s adventures after a story about finding Arabic notebooks containing the rest of the story by Cid Hamet Ben Engeli. The combat ends with the lady leaving her carriage and commanding those traveling with her to «surrender» to Don Quixote.

First editions of the first and second parts

The Pastoral Peregrinations (Chapters 11–15)[edit]

Sancho and Don Quixote fall in with a group of goat herders. Don Quixote tells Sancho and the goat herders about the «Golden Age» of man, in which property does not exist and men live in peace. The goatherders invite the Knight and Sancho to the funeral of Grisóstomo, a former student who left his studies to become a shepherd after reading pastoral novels (paralleling Don Quixote’s decision to become a knight), seeking the shepherdess Marcela. At the funeral Marcela appears — vindicating herself as the victim of a bad one-sided affair and from the bitter verses written about her by Grisóstomo claiming she’s just satisfied by her communing with nature now and is assuming her own autonomy and freedom from expectations put on. She disappears into the woods, and Don Quixote and Sancho follow. Ultimately giving up, the two dismount by a stream to rest. «A drove of Galician ponies belonging to certain Yanguesan carriers» are planned to feed there, and Rocinante (Don Quixote’s horse) attempts to mate with the ponies. The carriers hit Rocinante with clubs to dissuade him, whereupon Don Quixote tries to defend Rocinante. The carriers beat Don Quixote and Sancho, leaving them in great pain.

The Inn (Chapters 16–17)[edit]

After escaping the Yanguesan carriers, Don Quixote and Sancho ride to a nearby inn. Once again, Don Quixote imagines the inn is a castle, although Sancho is not quite convinced. Don Quixote is given a bed in a former hayloft, and Sancho sleeps on the rug next to the bed; they share the loft with a carrier. When night comes «… he began to feel uneasy and to consider the perilous risk which his virtue was about to encounter…». Don Quixote imagines the servant girl at the inn, Maritornes, to be this imagined beautiful princess now fallen in love with him «… and had promised to come to his bed for a while that night…», and makes her sit on his bed with him by holding her «… besides, to this impossibility another yet greater is to be added…». Having been waiting for Maritornes and seeing her held while trying to get free the carrier attacks Don Quixote «…and jealous that the Asturian should have broken her word with him for another…», breaking the fragile bed and leading to a large and chaotic fight in which Don Quixote and Sancho are once again badly hurt. Don Quixote’s explanation for everything is that they fought with an enchanted Moor. He also believes that he can cure their wounds with a mixture he calls «the balm of Fierabras», which only makes Sancho so sick that he should be at death’s door. Don Quixote’s not quite through with it yet, however, as his take on things can be different. Don Quixote and Sancho decide to leave the inn, but Quixote, following the example of the fictional knights, leaves without paying. Sancho, however, remains and ends up wrapped in a blanket and tossed up in the air (blanketed) by several mischievous guests at the inn, something that is often mentioned over the rest of the novel. After his release, he and Don Quixote continue their travels.

The galley slaves and Cardenio (Chapters 19–24)[edit]

Don Quixote de la Mancha and Sancho Panza, 1863, by Gustave Doré

After Don Quixote has adventures involving a dead body, a helmet (to Don Quixote), and freeing a group of galley slaves, he and Sancho wander into the Sierra Morena and there encounter the dejected and mostly mad Cardenio. Cardenio relates the first part of his story, in which he falls mutually in love with his childhood friend Lucinda, and is hired as the companion to the Duke’s son, leading to his friendship with the Duke’s younger son, Don Fernando. Cardenio confides in Don Fernando his love for Lucinda and the delays in their engagement, caused by Cardenio’s desire to keep with tradition. After reading Cardenio’s poems praising Lucinda, Don Fernando falls in love with her. Don Quixote interrupts when Cardenio’s transference of his misreading suggests his madness, over that his beloved may have become unfaithful, stems from Queen Madasima and Master Elisabad relationship in a chivalric novel (Lucinda and Don Fernando not at all the case, also). They get into a physical fight, ending with Cardenio beating all of them and walking away to the mountains.

The priest, the barber, and Dorotea (Chapters 25–31)[edit]

Quixote pines over Dulcinea’s lack of affection ability, imitating the penance of Beltenebros. Quixote sends Sancho to deliver a letter to Dulcinea, but instead Sancho finds the barber and priest from his village and brings them to Quixote. The priest and barber make plans with Sancho to trick Don Quixote to come home. They get the help of the hapless Dorotea, an amazingly beautiful woman whom they discover in the forest that has been deceived with Don Fernando by acts of love and marriage, as things just keep going very wrong for her after he had made it to her bedchamber one night «…by no fault of hers, has furnished matters…» She pretends that she is the Princess Micomicona and coming from Guinea desperate to get Quixote’s help with her fantastical story, «Which of the bystanders could have helped laughing to see the madness of the master and the simplicity of the servant?» Quixote runs into Andrés «…the next moment ran to Don Quixote and clasping him round the legs…» in need of further assistance who tells Don Quixote something about having «…meddled in other people’s affairs…».

Return to the inn (Chapters 32–42)[edit]

Convinced that he is on a quest to first return princess Micomicona to the throne of her kingdom before needing to go see Dulcinea at her request (a Sancho deception related to the letter Sancho says he’s delivered and has been questioned about), Quixote and the group return to the previous inn where the priest reads aloud the manuscript of the story of Anselmo (The Impertinently Curious Man) while Quixote, sleepwalking, battles with wine skins that he takes to be the giant who stole the princess Micomicona’s kingdom to victory, «there you see my master has already salted the giant.» A stranger arrives at the inn accompanying a young woman. The stranger is revealed to be Don Fernando, and the young woman Lucinda. Dorotea is reunited with Don Fernando and Cardenio with Lucinda. «…it may be by my death he will be convinced that I kept my faith to him to the last moment of life.» «…and, moreover, that true nobility consists in virtue, and if thou art wanting in that, refusing what in justice thou owest me, then even I have higher claims to nobility than thine.» A Christian captive from Moorish lands in company of an Arabic speaking lady (Zoraida) arrive and the captive is asked to tell the story of his life; «If your worships will give me your attention you will hear a true story which, perhaps, fictitious one constructed with ingenious and studied art can not come up to.» «…at any rate, she seemed to me the most beautiful object I had ever seen; and when, besides, I thought of all I owed to her I felt as though I had before me some heavenly being come to earth to bring me relief and happiness.» A judge arrives travelling with his beautiful and curiously smitten daughter, and it is found that the captive is his long-lost brother, and the two are reunited as Dona Clara’s (his daughter’s name) interest arrives with/at singing her songs from outside that night. Don Quixote’s explanation for everything now at this inn being «chimeras of knight-errantry». A prolonged attempt at reaching agreement on what are the new barber’s basin and some gear is an example of Quixote being «reasoned» with. «…behold with your own eyes how the discord of Agramante’s camp has come hither, and been transferred into the midst of us.» He goes on some here to explain what he is referring to with a reason for peace among them presented and what’s to be done. This works to create peacefulness for them but the officers, present now for a while, have one for him that he can not get out of though he goes through his usual reactions.

The ending (Chapters 45–52)[edit]

An officer of the Santa Hermandad has a warrant for Quixote’s arrest for freeing the galley slaves «…as Sancho had, with very good reason, apprehended.» The priest begs for the officer to have mercy on account of Quixote’s insanity. The officer agrees, and Quixote is locked in a cage and made to think that it is an enchantment and that there is a prophecy of him returned home afterwards that’s meaning pleases him. He has a learned conversation with a Toledo canon (church official) he encounters by chance on the road, in which the canon expresses his scorn for untruthful chivalric books, but Don Quixote defends them. The group stops to eat and lets Don Quixote out of the cage; he gets into a fight with a goatherd (Leandra transferred to a goat) and with a group of pilgrims (tries to liberate their image of Mary), who beat him into submission, and he is finally brought home. The narrator ends the story by saying that he has found manuscripts of Quixote’s further adventures.

Part 2[edit]

Illustration to The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha. Volume II.

Although the two parts are now published as a single work, Don Quixote, Part Two was a sequel published ten years after the original novel. While Part One was mostly farcical, the second half is more serious and philosophical about the theme of deception and «sophistry». Opening just prior to the third Sally, the first chapters of Part Two show Don Quixote found to be still some sort of a modern day «highly» literate know-it-all, knight errant that can recover quickly from injury — Sancho his squire, however.

|

|

This article is missing information about section. Please expand the article to include this information. Further details may exist on the talk page. (September 2022) |

Part Two of Don Quixote explores the concept of a character understanding that he is written about, an idea much explored in the 20th century. As Part Two begins, it is assumed that the literate classes of Spain have all read the first part of the story. Cervantes’ meta-fictional device was to make even the characters in the story familiar with the publication of Part One, as well as with an actually published, fraudulent Part Two.

The Third Sally[edit]

The narrator relates how Hamet Benengeli begins the eighth chapter with thanksgivings to Allah at having Don Quixote and Sancho «fairly afield» now (and going to El Toboso). Traveling all night, some religiosity and other matters are expressed between Don Quixote and Sancho with Sancho getting at that he thinks they should be better off by being «canonized and beatified.» They reach the city at daybreak and it’s decided to enter at nightfall, with Sancho aware that his Dulcinea story to Don Quixote was a complete fabrication (and again with good reason sensing a major problem); «Are we going, do you fancy, to the house of our wenches, like gallants who come and knock and go in at any hour, however late it may be?» The place is asleep and dark with the sounds of an intruder from animals heard and the matter absurd but a bad omen spooks Quixote into retreat and they leave before daybreak.

(Soon and yet to come, when a Duke and Duchess encounter the duo they already know their famous history and they themselves «very fond» of books of chivalry plan to «fall in with his humor and agree to everything he said» in accepting his advancements and then their terrible dismount setting forth a string of imagined adventures resulting in a series of practical jokes. Some of them put Don Quixote’s sense of chivalry and his devotion to Dulcinea through many tests.)

Now pressed into finding Dulcinea, Sancho is sent out alone again as a go-between with Dulcinea and decides they are both mad here but as for Don Quixote, «with a madness that mostly takes one thing for another» and plans to persuade him into seeing Dulcinea as a «sublimated presence» of a sorts. Sancho’s luck brings three focusing peasant girls along the road he was sitting not far from where he set out from and he quickly tells Don Quixote that they are Dulcinea and her ladies-in-waiting and as beautiful as ever, as they get unwittingly involved with the duo. As Don Quixote always only sees the peasant girls «…but open your eyes, and come and pay your respects to the lady of your thoughts…» carrying on for their part, «Hey-day! My grandfather!», Sancho always pretends (reversing some incidents of Part One and keeping to his plan) that their appearance is as Sancho is perceiving it as he explains its magnificent qualities (and must be an enchantment of some sort at work here). Don Quixote’s usual (and predictable) kind of belief in this matter results in «Sancho, the rogue» having «nicely befooled» him into thinking he’d met Dulcinea controlled by enchantment, but delivered by Sancho. Don Quixote then has the opportunity to purport that «for from a child I was fond of the play, and in my youth a keen lover of the actor’s art» while with players of a company and for him thus far an unusually high regard for poetry when with Don Diego de Miranda, «She is the product of an Alchemy of such virtue that he who is able to practice it, will turn her into pure gold of inestimable worth» «sublime conceptions». Don Quixote makes to the other world and somehow meets his fictional characters, at return reversing the timestamp of the usual event and with a possible apocryphal example. As one of his deeds, Don Quixote joins into a puppet troop, «Melisendra was Melisendra, Don Gaiferos Don Gaiferos, Marsilio Marsilio, and Charlemagne Charlemagne.»

Having created a lasting false premise for them, Sancho later gets his comeuppance for this when, as part of one of the Duke and Duchess’s pranks, the two are led to believe that the only method to release Dulcinea from this spell (if among possibilities under consideration, she has been changed rather than Don Quixote’s perception has been enchanted — which at one point he explains is not possible however) is for Sancho to give himself three thousand three hundred lashes. Sancho naturally resists this course of action, leading to friction with his master. Under the Duke’s patronage, Sancho eventually gets a governorship, though it is false, and he proves to be a wise and practical ruler although this ends in humiliation as well. Near the end, Don Quixote reluctantly sways towards sanity.

The lengthy untold «history» of Don Quixote’s adventures in knight-errantry comes to a close after his battle with the Knight of the White Moon (a young man from Don Quixote’s hometown who had previously posed as the Knight of Mirrors) on the beach in Barcelona, in which the reader finds him conquered. Bound by the rules of chivalry, Don Quixote submits to prearranged terms that the vanquished is to obey the will of the conqueror: here, it is that Don Quixote is to lay down his arms and cease his acts of chivalry for the period of one year (in which he may be cured of his madness). He and Sancho undergo one more prank that night by the Duke and Duchess before setting off. A play-like event, though perceived as mostly real life by Sancho and Don Quixote, over Altisidora’s required remedy from death (over her love for Don Quixote). «Print on Sancho’s face four-and-twenty smacks, and give him twelve pinches and six pin-thrusts in the back and arms.» Altisidora is first to visit in the morning taking away Don Quixote’s usual way for a moment or two, being back from the dead, but her story of the experience quickly snaps him back into his usual mode. Some others come around and it is decided to part that day.

«The duped Don Quixote did not miss a single stroke of the count…»; «…beyond measure joyful.» A once nearly deadly confrontation for them, on the way back home (along with some other situations maybe of note) Don Quixote and Sancho «resolve» the disenchantment of Dulcinea (being fresh from his success with Altisidora). Upon returning to his village, Don Quixote announces his plan to retire to the countryside as a shepherd (considered an erudite bunch for the most part), but his housekeeper urges him to stay at home. Soon after, he retires to his bed with a deathly illness, and later awakes from a dream, having fully become good. Sancho’s character tries to restore his faith and/or his interest of a disenchanted Dulcinea, but the Quexana character («…will have it his surname…» «…for here there is some difference of opinion among the authors who write on the subject…» «…it seems plain that he was called Quexana.») only renounces his previous ambition and apologizes for the harm he has caused. He dictates his will, which includes a provision that his niece will be disinherited if she marries a man who reads books of chivalry. After the Quexana character dies, the author emphasizes that there are no more adventures to relate and that any further books about Don Quixote would be spurious.

Don Quixote on a 1 Peseta banknote from 1951

Meaning[edit]

Harold Bloom says Don Quixote is the first modern novel, and that the protagonist is at war with Freud’s reality principle, which accepts the necessity of dying. Bloom says that the novel has an endless range of meanings, but that a recurring theme is the human need to withstand suffering.[9]

Edith Grossman, who wrote and published a highly acclaimed[10] English translation of the novel in 2003, says that the book is mostly meant to move people into emotion using a systematic change of course, on the verge of both tragedy and comedy at the same time. Grossman has stated:

The question is that Quixote has multiple interpretations […] and how do I deal with that in my translation. I’m going to answer your question by avoiding it […] so when I first started reading the Quixote I thought it was the most tragic book in the world, and I would read it and weep […] As I grew older […] my skin grew thicker […] and so when I was working on the translation I was actually sitting at my computer and laughing out loud. This is done […] as Cervantes did it […] by never letting the reader rest. You are never certain that you truly got it. Because as soon as you think you understand something, Cervantes introduces something that contradicts your premise.[11]

Themes[edit]

The novel’s structure is episodic in form. The full title is indicative of the tale’s object, as ingenioso (Spanish) means «quick with inventiveness»,[12] marking the transition of modern literature from dramatic to thematic unity. The novel takes place over a long period of time, including many adventures united by common themes of the nature of reality, reading, and dialogue in general.

Although burlesque on the surface, the novel, especially in its second half, has served as an important thematic source not only in literature but also in much of art and music, inspiring works by Pablo Picasso and Richard Strauss. The contrasts between the tall, thin, fancy-struck and idealistic Quixote and the fat, squat, world-weary Panza is a motif echoed ever since the book’s publication, and Don Quixote’s imaginings are the butt of outrageous and cruel practical jokes in the novel.

Even faithful and simple Sancho is forced to deceive him at certain points. The novel is considered a satire of orthodoxy, veracity and even nationalism. In exploring the individualism of his characters, Cervantes helped lead literary practice beyond the narrow convention of the chivalric romance. He spoofs the chivalric romance through a straightforward retelling of a series of acts that redound to the knightly virtues of the hero. The character of Don Quixote became so well known in its time that the word quixotic was quickly adopted by many languages. Characters such as Sancho Panza and Don Quixote’s steed, Rocinante, are emblems of Western literary culture. The phrase «tilting at windmills» to describe an act of attacking imaginary enemies (or an act of extreme idealism), derives from an iconic scene in the book.

It stands in a unique position between medieval romance and the modern novel. The former consist of disconnected stories featuring the same characters and settings with little exploration of the inner life of even the main character. The latter are usually focused on the psychological evolution of their characters. In Part I, Quixote imposes himself on his environment. By Part II, people know about him through «having read his adventures», and so, he needs to do less to maintain his image. By his deathbed, he has regained his sanity, and is once more «Alonso Quixano the Good».

Background[edit]

Sources[edit]

Sources for Don Quixote include the Castilian novel Amadis de Gaula, which had enjoyed great popularity throughout the 16th century. Another prominent source, which Cervantes evidently admires more, is Tirant lo Blanch, which the priest describes in Chapter VI of Quixote as «the best book in the world.» (However, the sense in which it was «best» is much debated among scholars. Since the 19th century, the passage has been called «the most difficult passage of Don Quixote«.)

The scene of the book burning gives an excellent list of Cervantes’ likes and dislikes about literature.

Cervantes makes a number of references to the Italian poem Orlando furioso. In chapter 10 of the first part of the novel, Don Quixote says he must take the magical helmet of Mambrino, an episode from Canto I of Orlando, and itself a reference to Matteo Maria Boiardo’s Orlando innamorato.[13] The interpolated story in chapter 33 of Part four of the First Part is a retelling of a tale from Canto 43 of Orlando, regarding a man who tests the fidelity of his wife.[14]

Another important source appears to have been Apuleius’s The Golden Ass, one of the earliest known novels, a picaresque from late classical antiquity. The wineskins episode near the end of the interpolated tale «The Curious Impertinent» in chapter 35 of the first part of Don Quixote is a clear reference to Apuleius, and recent scholarship suggests that the moral philosophy and the basic trajectory of Apuleius’s novel are fundamental to Cervantes’ program.[15] Similarly, many of both Sancho’s adventures in Part II and proverbs throughout are taken from popular Spanish and Italian folklore.

Cervantes’ experiences as a galley slave in Algiers also influenced Quixote.

Medical theories may have also influenced Cervantes’ literary process. Cervantes had familial ties to the distinguished medical community. His father, Rodrigo de Cervantes, and his great-grandfather, Juan Díaz de Torreblanca, were surgeons. Additionally, his sister, Andrea de Cervantes, was a nurse.[16] He also befriended many individuals involved in the medical field, in that he knew medical author Francisco Díaz, an expert in urology, and royal doctor Antonio Ponce de Santa Cruz who served as a personal doctor to both Philip III and Philip IV of Spain.[17]

Apart from the personal relations Cervantes maintained within the medical field, Cervantes’ personal life was defined by an interest in medicine. He frequently visited patients from the Hospital de Inocentes in Sevilla.[16] Furthermore, Cervantes explored medicine in his personal library. His library contained more than 200 volumes and included books like Examen de Ingenios by Juan Huarte and Practica y teórica de cirugía by Dionisio Daza Chacón that defined medical literature and medical theories of his time.[17]

Spurious Second Part by Avellaneda[edit]

It is not certain when Cervantes began writing Part Two of Don Quixote, but he had probably not proceeded much further than Chapter LIX by late July 1614. About September, however, a spurious Part Two, entitled Second Volume of the Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha: by the Licenciado (doctorate) Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda, of Tordesillas, was published in Tarragona by an unidentified Aragonese who was an admirer of Lope de Vega, rival of Cervantes.[18] It was translated into English by William Augustus Yardley, Esquire in two volumes in 1784.

Some modern scholars suggest that Don Quixote’s fictional encounter with Avellaneda in Chapter 59 of Part II should not be taken as the date that Cervantes encountered it, which may have been much earlier.

Avellaneda’s identity has been the subject of many theories, but there is no consensus as to who he was. In its prologue, the author gratuitously insulted Cervantes, who not surprisingly took offense and responded; the last half of Chapter LIX and most of the following chapters of Cervantes’ Segunda Parte lend some insight into the effects upon him; Cervantes manages to work in some subtle digs at Avellaneda’s own work, and in his preface to Part II, comes very near to criticizing Avellaneda directly.

In his introduction to The Portable Cervantes, Samuel Putnam, a noted translator of Cervantes’ novel, calls Avellaneda’s version «one of the most disgraceful performances in history».[19]

The second part of Cervantes’ Don Quixote, finished as a direct result of the Avellaneda book, has come to be regarded by some literary critics[20] as superior to the first part, because of its greater depth of characterization, its discussions, mostly between Quixote and Sancho, on diverse subjects, and its philosophical insights. In Cervantes’ Segunda Parte, Don Quixote visits a printing-house in Barcelona and finds Avellaneda’s Second Part being printed there, in an early example of metafiction.[21]

Other stories[edit]

Don Quixote, his horse Rocinante and his squire Sancho Panza after an unsuccessful attack on a windmill. By Gustave Doré.

Don Quixote, Part One contains a number of stories which do not directly involve the two main characters, but which are narrated by some of the picaresque figures encountered by the Don and Sancho during their travels. The longest and best known of these is «El Curioso Impertinente» (The Ill-Advised Curiosity), found in Part One, Book Four. This story, read to a group of travelers at an inn, tells of a Florentine nobleman, Anselmo, who becomes obsessed with testing his wife’s fidelity, and talks his close friend Lothario into attempting to seduce her, with disastrous results for all.

In Part Two, the author acknowledges the criticism of his digressions in Part One and promises to concentrate the narrative on the central characters (although at one point he laments that his narrative muse has been constrained in this manner). Nevertheless, «Part Two» contains several back narratives related by peripheral characters.

Several abridged editions have been published which delete some or all of the extra tales in order to concentrate on the central narrative.[22]

The Ill-Advised Curiosity summary[edit]

The story within a story relates that, for no particular reason, Anselmo decides to test the fidelity of his wife, Camilla, and asks his friend, Lothario, to seduce her. Thinking that to be madness, Lothario reluctantly agrees, and soon reports to Anselmo that Camilla is a faithful wife. Anselmo learns that Lothario has lied and attempted no seduction. He makes Lothario promise to try in earnest and leaves town to make this easier. Lothario tries and Camilla writes letters to her husband telling him of the attempts by Lothario and asking him to return. Anselmo makes no reply and does not return. Lothario then falls in love with Camilla, who eventually reciprocates, an affair between them ensues, but is not disclosed to Anselmo, and their affair continues after Anselmo returns.

One day, Lothario sees a man leaving Camilla’s house and jealously presumes she has taken another lover. He tells Anselmo that, at last, he has been successful and arranges a time and place for Anselmo to see the seduction. Before this rendezvous, however, Lothario learns that the man was the lover of Camilla’s maid. He and Camilla then contrive to deceive Anselmo further: When Anselmo watches them, she refuses Lothario, protests her love for her husband, and stabs herself lightly in the breast. Anselmo is reassured of her fidelity. The affair restarts with Anselmo none the wiser.

Later, the maid’s lover is discovered by Anselmo. Fearing that Anselmo will kill her, the maid says she will tell Anselmo a secret the next day. Anselmo tells Camilla that this is to happen, and Camilla expects that her affair is to be revealed. Lothario and Camilla flee that night. The maid flees the next day. Anselmo searches for them in vain before learning from a stranger of his wife’s affair. He starts to write the story, but dies of grief before he can finish.

Style[edit]

Spelling and pronunciation[edit]

Cervantes wrote his work in Early Modern Spanish, heavily borrowing from Old Spanish, the medieval form of the language. The language of Don Quixote, although still containing archaisms, is far more understandable to modern Spanish readers than is, for instance, the completely medieval Spanish of the Poema de mio Cid, a kind of Spanish that is as different from Cervantes’ language as Middle English is from Modern English. The Old Castilian language was also used to show the higher class that came with being a knight errant.

In Don Quixote, there are basically two different types of Castilian: Old Castilian is spoken only by Don Quixote, while the rest of the roles speak a contemporary (late 16th century) version of Spanish. The Old Castilian of Don Quixote is a humoristic resource—he copies the language spoken in the chivalric books that made him mad; and many times, when he talks nobody is able to understand him because his language is too old. This humorous effect is more difficult to see nowadays because the reader must be able to distinguish the two old versions of the language, but when the book was published it was much celebrated. (English translations can get some sense of the effect by having Don Quixote use King James Bible or Shakespearean English, or even Middle English.)

In Old Castilian, the letter x represented the sound written sh in modern English, so the name was originally pronounced [kiˈʃote]. However, as Old Castilian evolved towards modern Spanish, a sound change caused it to be pronounced with a voiceless velar fricative [x] sound (like the Scots or German ch), and today the Spanish pronunciation of «Quixote» is [kiˈxote]. The original pronunciation is reflected in languages such as Asturian, Leonese, Galician, Catalan, Italian, Portuguese, Turkish and French, where it is pronounced with a «sh» or «ch» sound; the French opera Don Quichotte is one of the best-known modern examples of this pronunciation.

Today, English speakers generally attempt something close to the modern Spanish pronunciation of Quixote (Quijote), as ,[1] although the traditional English spelling-based pronunciation with the value of the letter x in modern English is still sometimes used, resulting in or . In Australian English, the preferred pronunciation amongst members of the educated classes was until well into the 1970s, as part of a tendency for the upper class to «anglicise its borrowing ruthlessly».[23] The traditional English rendering is preserved in the pronunciation of the adjectival form quixotic, i.e., ,[24][25] defined by Merriam-Webster as the foolishly impractical pursuit of ideals, typically marked by rash and lofty romanticism.[26]

Setting[edit]

I suspect that in Don Quixote, it does not rain a single time. The landscapes described by Cervantes have nothing in common with

the landscapes of Castile: they are conventional landscapes, full of meadows, streams, and copses that belong in an Italian novel.

Cervantes’ story takes place on the plains of La Mancha, specifically the comarca of Campo de Montiel.

En un lugar de La Mancha, de cuyo nombre no quiero acordarme, no ha mucho tiempo que vivía un hidalgo de los de lanza en astillero, adarga antigua, rocín flaco y galgo corredor.

(Somewhere in La Mancha, in a place whose name I do not care to remember, a gentleman lived not long ago, one of those who has a lance and ancient shield on a shelf and keeps a skinny nag and a greyhound for racing.)— Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote, Volume I, Chapter I (translated by Edith Grossman)

The story also takes place in El Toboso where Don Quixote goes to seek Dulcinea’s blessings.

The location of the village to which Cervantes alludes in the opening sentence of Don Quixote has been the subject of debate since its publication over four centuries ago. Indeed, Cervantes deliberately omits the name of the village, giving an explanation in the final chapter:

Such was the end of the Ingenious Gentleman of La Mancha, whose village Cide Hamete would not indicate precisely, in order to leave all the towns and villages of La Mancha to contend among themselves for the right to adopt him and claim him as a son, as the seven cities of Greece contended for Homer.

— Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote, Volume II, Chapter 74

Theories[edit]

In 2004, a multidisciplinary team of academics from Complutense University, led by Francisco Parra Luna, Manuel Fernández Nieto, and Santiago Petschen Verdaguer, deduced that the village was that of Villanueva de los Infantes.[28] Their findings were published in a paper titled «‘El Quijote’ como un sistema de distancias/tiempos: hacia la localización del lugar de la Mancha«, which was later published as a book: El enigma resuelto del Quijote. The result was replicated in two subsequent investigations: «La determinación del lugar de la Mancha como problema estadístico» and «The Kinematics of the Quixote and the Identity of the ‘Place in La Mancha'».[29][30]

Researchers Isabel Sanchez Duque and Francisco Javier Escudero have found relevant information regarding the possible sources of inspiration of Cervantes for writing Don Quixote. Cervantes was friend of the family Villaseñor, which was involved in a combat with Francisco de Acuña. Both sides combated disguised as medieval knights in the road from El Toboso to Miguel Esteban in 1581. They also found a person called Rodrigo Quijada, who bought the title of nobility of «hidalgo», and created diverse conflicts with the help of a squire.[31][32]

Language[edit]