This article is about the FC Barcelona–Real Madrid CF rivalry. For other uses, see El Clásico (disambiguation).

Team kits – Real Madrid in white, Barcelona in blue and garnet |

|

| Location | Spain |

|---|---|

| Teams | Barcelona Real Madrid |

| First meeting | FC Barcelona 3–1 Madrid FC 1902 Copa de la Coronación (13 May 1902) |

| Latest meeting | Real Madrid 3–1 Barcelona La Liga (16 October 2022) |

| Next meeting | Barcelona v Real Madrid La Liga (19 March 2023) |

| Stadiums | Camp Nou (Barcelona) Santiago Bernabéu (Real Madrid) |

| Statistics | |

| Meetings total | Competitive matches: 250 Exhibition matches: 34 Total matches: 284 |

| Most wins | Competitive matches: Real Madrid (101) Exhibition matches: Barcelona (20) Total matches: Barcelona (117) |

| Most player appearances | Lionel Messi Sergio Ramos (45 each) |

| Top scorer | Lionel Messi (26)[note 1] |

| Largest victory | Real Madrid 11–1 Barcelona Copa del Rey (19 June 1943) |

El Clásico or el clásico[1] (Spanish pronunciation: [el ˈklasiko]; Catalan: El Clàssic,[2] pronounced [əl ˈklasik]; «The Classic») is the name given to any football match between rival clubs FC Barcelona and Real Madrid. Originally referring to competitions held in the Spanish championship, the term now includes every match between the clubs, such as those in the UEFA Champions League and Copa del Rey. It is considered one of the biggest club football games in the world, and is among the most viewed annual sporting events.[3][4][5] A fixture known for its intensity, it has featured memorable goal celebrations from both teams, often involving mocking the opposition.[6][7]

The rivalry comes about as Madrid and Barcelona are the two largest cities in Spain, and they are sometimes identified with opposing political positions, with Real Madrid viewed as representing Spanish nationalism and Barcelona viewed as representing Catalan nationalism.[8][9] The rivalry is regarded as one of the biggest in world sport.[10][11][12] The two clubs are among the richest and most successful football clubs in the world; in 2014 Forbes ranked Barcelona and Real Madrid the world’s two most valuable sports teams.[4] Both clubs have a global fanbase; they are the world’s two most followed sports teams on social media.[13][14]

Real Madrid leads in head-to-head results in competitive matches with 101 wins to Barcelona’s 97 with 52 draws; Barcelona leads in exhibition matches with 20 victories to Madrid’s 4 with 10 draws and in total matches with 117 wins to Madrid’s 105 with 62 draws as of the match played on 16 October 2022. Along with Athletic Bilbao, they are the only clubs in La Liga to have never been relegated.

Rivalry

History

Santiago Bernabéu. The home fans are displaying the white of Real Madrid before El Clásico. Spanish flags are also a common sight at Real Madrid games.

Camp Nou. The home fans of FC Barcelona are creating a mosaic of the Catalan flag before El Clasico. The top right corner of the club’s crest also features a Catalan flag.

The conflict between Real Madrid and Barcelona has long surpassed the sporting dimension,[15][16] so much that elections to the clubs’ presidencies have been strongly politicized.[17] Phil Ball, the author of Morbo: The Story of Spanish Football, says about the match; «they hate each other with an intensity that can truly shock the outsider».[18]

As early as the 1930s, Barcelona «had developed a reputation as a symbol of Catalan identity, opposed to the centralising tendencies of Madrid».[19][20] In 1936, when Francisco Franco started the coup d’état against the democratic Second Spanish Republic, the president of Barcelona, Josep Sunyol, member of the Republican Left of Catalonia and Deputy to The Cortes, was arrested and executed without trial by Franco’s troops[17] (Sunyol was exercising his political activities, visiting Republican troops north of Madrid).[19] During the dictatorships of Miguel Primo de Rivera and especially Francisco Franco, all regional languages and identities in Spain were frowned upon and restrained. As such, most citizens of Barcelona were in strong opposition to the fascist-like regime. In this period, Barcelona gained their motto Més que un club (English: More than a club) because of its alleged connection to Catalan nationalist as well as to progressive beliefs.[21]

There’s an ongoing controversy as to what extent Franco’s rule (1939–75) influenced the activities and on-pitch results of both Barcelona and Real Madrid. Most historians agree that Franco did not have a preferred football team, but his Spanish nationalist beliefs led him to associate himself with the establishment teams, such as Atlético Aviación and Madrid FC (that recovered its royal name after the fall of the Republic). On the other hand, he also wanted the renamed CF Barcelona succeed as «Spanish team» rather than a Catalan one.[22][23] During the early years of Franco’s rule, Real Madrid weren’t particularly successful, winning two Copa del Generalísimo titles and a Copa Eva Duarte; Barcelona claimed three league titles, one Copa del Generalísimo and one Copa Eva Duarte. During that period, Atlético Aviación were believed to be the preferred team over Real Madrid. The most contested stories of the period include Real Madrid’s 11–1 home win against Barcelona in the Copa del Generalísimo, where the Catalan team alleged intimidation, and the controversial transfer of Alfredo Di Stéfano to Real Madrid despite his agreement with Barcelona. The latter transfer was part of Real Madrid chairman Santiago Bernabéu’s «revolution» that ushered in the era of unprecedented dominance. Bernabéu, himself a veteran of the Civil War who fought for Franco’s forces, saw Real Madrid on top not only of Spanish but also European football, helping create the European Cup, the first true competition for Europe’s best club sides. His vision was fulfilled when Real Madrid not only started winning consecutive league titles but also swept the first five editions of the European Cup in the 1950s.[24] These events had a profound impact on Spanish football and influenced Franco’s attitude. According to historians, during this time he realized the importance of Real Madrid for his regime’s international image, and the club became his preferred team until his death. Fernando Maria Castiella, who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs under Franco from 1957 until 1969, noted that «[Real Madrid] is the best embassy we have ever had.» Franco died in 1975, and the Spanish transition to democracy soon followed. Under his rule, Real Madrid had won 14 league titles, 6 Copa del Generalísimo titles, 1 Copa Eva Duarte, 6 European Cups, 2 Latin Cups and 1 Intercontinental Cup. In the same period, Barcelona had won 8 league titles, 9 Copa del Generalísimo titles, 3 Copa Eva Duarte titles, 3 Inter-Cities Fairs Cups and 2 Latin Cups.[22][23]

The image for both clubs was further affected by the creation of ultras groups, some of which became hooligans. In 1980, Ultras Sur was founded as a far-right-leaning Real Madrid ultras group, followed in 1981 by the foundation of the initially left-leaning and later on far-right, Barcelona ultras group Boixos Nois. Both groups became known for their violent acts,[17][25][26] and one of the most conflictive factions of Barcelona supporters, the Casuals, became a full-fledged criminal organisation.[27]

For many people, Barcelona is still considered as «the rebellious club», or the alternative pole to «Real Madrid’s conservatism».[28][29] According to polls released by CIS (Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas), Real Madrid is the favorite team of most of the Spanish residents, while Barcelona stands in the second position. In Catalonia, forces of all the political spectrum are overwhelmingly in favour of Barcelona. Nevertheless, the support of the blaugrana club goes far beyond from that region, earning its best results among young people, sustainers of a federal structure of Spain and citizens with left-wing ideology, in contrast with Real Madrid fans which politically tend to adopt right-wing views.[30][31]

1943 Copa del Generalísimo semi-finals

On 13 June 1943, Real Madrid beat Barcelona 11–1 at the Chamartín in the second leg of the Copa del Generalísimo semi-finals (the Copa del Presidente de la República[32] having been renamed in honour of General Franco).[33] The first leg, played at the Les Corts in Catalonia, had ended with Barcelona winning 3–0. Madrid complained about all the three goals that referee Fombona Fernández had allowed for Barcelona,[34] with the home supporters also whistling Madrid throughout, whom they accused of employing roughhouse tactics, and Fombona for allowing them to. Barça’s Josep Escolà was stretchered off in the first half with José María Querejeta’s stud marks in his stomach. A campaign began in Madrid. The newspaper Ya reported the whistling as a «clear intention to attack the representatives of Spain.»[35] Barcelona player Josep Valle recalled: «The press officer at the DND and ABC newspaper wrote all sorts of scurrilous lies, really terrible things, winding up the Madrid fans like never before». Former Real Madrid goalkeeper Eduardo Teus, who admitted that Madrid had «above all played hard», wrote in a newspaper: «the ground itself made Madrid concede two of the three goals, goals that were totally unfair».[36]

Barcelona fans were banned from traveling to Madrid. Real Madrid released a statement after the match which former club president Ramón Mendoza explained, «The message got through that those fans who wanted to could go to El Club bar on Calle de la Victoria where Madrid’s social center was. There, they were given a whistle. Others had whistles handed to them with their tickets.» The day of the second leg, the Barcelona team were insulted and stones were thrown at their bus as soon as they left their hotel. Barcelona’s striker Mariano Gonzalvo said of the incident, «Five minutes before the game had started, our penalty area was already full of coins.» Barcelona goalkeeper Lluis Miró rarely approached his line—when he did, he was armed with stones. As Francisco Calvet told the story, «They were shouting: Reds! Separatists!… a bottle just missed Sospedra that would have killed him if it had hit him. It was all set up.»[37]

Real Madrid went 2–0 up within half an hour. The third goal brought with it a sending off for Barcelona’s Benito García after he made what Calvet claimed was a «completely normal tackle». Madrid’s José Llopis Corona recalled, «At which point, they got a bit demoralized,» while Ángel Mur countered, «at which point, we thought: ‘go on then, score as many as you want’.» Madrid scored in minutes 31′, 33′, 35′, 39′, 43′ and 44′, as well as two goals ruled out for offside, made it 8–0. Juan Samaranch wrote: «In that atmosphere and with a referee who wanted to avoid any complications, it was humanly impossible to play… If the azulgranas had played badly, really badly, the scoreboard would still not have reached that astronomical figure. The point is that they did not play at all.»[38] Both clubs were fined 2,500 pesetas by the Royal Spanish Football Federation and, although Barcelona appealed, it made no difference. Piñeyro resigned in protest, complaining of «a campaign that the press has run against Barcelona for a week and which culminated in the shameful day at Chamartín».[39][40]

The match report in the newspaper La Prensa described Barcelona’s only goal as a «reminder that there was a team there who knew how to play football and that if they did not do so that afternoon, it was not exactly their fault».[41] Another newspaper called the scoreline «as absurd as it was abnormal».[34] According to football writer Sid Lowe, «There have been relatively few mentions of the game [since] and it is not a result that has been particularly celebrated in Madrid. Indeed, the 11–1 occupies a far more prominent place in Barcelona’s history. This was the game that first formed the identification of Madrid as the team of the dictatorship and Barcelona as its victims.»[34] Fernando Argila, Barcelona’s reserve goalkeeper from the game, said, «There was no rivalry. Not, at least, until that game.»[42]

Di Stéfano transfer

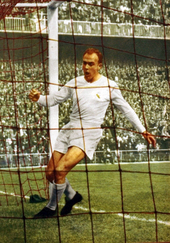

Alfredo Di Stéfano’s controversial 1953 transfer to Real Madrid instead of Barcelona intensified the rivalry.

The rivalry was intensified during the 1950s when the clubs disputed the signing of Alfredo Di Stéfano. Di Stéfano had impressed both Barcelona and Real Madrid while playing for Los Millionarios in Bogotá, Colombia, during a players’ strike in his native Argentina. Soon after Millonarios’ return to Colombia, Barcelona directors visited Buenos Aires and agreed with River Plate, the last FIFA-affiliated team to have held Di Stéfano’s rights, for his transfer in 1954 for the equivalent of 150 million Italian lira ($200,000 according to other sources[specify]). This started a battle between the two Spanish rivals for his rights.[43] FIFA appointed Armando Muñoz Calero, former president of the Spanish Football Federation as mediator. Calero decided to let Di Stéfano play the 1953–54 and 1955–56 seasons in Madrid, and the 1954–55 and 1956–57 seasons in Barcelona.[44][45] The agreement was approved by the Football Association and their respective clubs. Although the Catalans agreed, the decision created various discontent among the Blaugrana members and the president was forced to resign in September 1953. Barcelona sold Madrid their half-share, and Di Stéfano moved to Los Blancos, signing a four-year contract. Real paid 5.5 million Spanish pesetas for the transfer, plus a 1.3 million bonus for the purchase,[failed verification] an annual fee to be paid to the Millonarios, and a 16,000 salary for Di Stéfano with a bonus double that of his teammates, for a total of 40% of the annual revenue of the Madrid club.[45]

Di Stéfano became integral in the subsequent success achieved by Real Madrid, scoring twice in his first game against Barcelona. With him, Madrid won the first five editions of the European Cup.[46] The 1960s saw the rivalry reach the European stage when Real Madrid and Barcelona met twice in the European Cup, with Madrid triumphing en route to their fifth consecutive title in 1959–60 and Barcelona prevailing en route to losing the final in 1960–61.

Luís Figo transfer

Luís Figo’s transfer from Barcelona to Real Madrid in 2000 resulted in a hate campaign by some of his former club’s fans.

In 2000, Real Madrid’s then-presidential candidate, Florentino Pérez, offered Barcelona’s vice-captain Luís Figo $2.4 million to sign an agreement binding him to Madrid if he won the elections. If the player broke the deal, he would have to pay Pérez $30 million in compensation. When his agent confirmed the deal, Figo denied everything, insisting, «I’ll stay at Barcelona whether Pérez wins or loses.» He accused the presidential candidate of «lying» and «fantasizing». He told Barcelona teammates Luis Enrique and Pep Guardiola he was not leaving and they conveyed the message to the Barcelona squad.[47]

On 9 July, Sport ran an interview in which he said, «I want to send a message of calm to Barcelona’s fans, for whom I always have and always will feel great affection. I want to assure them that Luís Figo will, with absolute certainty, be at the Camp Nou on the 24th to start the new season… I’ve not signed a pre-contract with a presidential candidate at Real Madrid. No. I’m not so mad as to do a thing like that.»[47]

The only way Barcelona could prevent Figo’s transfer to Real Madrid was to pay the penalty clause, $30 million. That would have effectively meant paying the fifth highest transfer fee in history to sign their own player. Barcelona’s new president, Joan Gaspart, called the media and told them, «Today, Figo gave me the impression that he wanted to do two things: get richer and stay at Barça.» Only one of them happened. The following day, 24 July, Figo was presented in Madrid and handed his new shirt by Alfredo Di Stéfano. His buyout clause was set at $180 million. Gaspart later admitted, «Figo’s move destroyed us.»[48]

On his return to Barcelona in a Real Madrid shirt, banners with «Judas», «Scum» and «Mercenary» were hung around the stadium. Thousands of fake 10,000 peseta notes had been printed and emblazoned with his image, were among the missiles of oranges, bottles, cigarette lighters, even a couple of mobile phones were thrown at him.[49] In his third season with Real Madrid, the 2002 Clásico at Camp Nou produced one of the defining images of the rivalry. Figo was mercilessly taunted throughout; missiles of coins, a knife, a whisky bottle, were raining down from the stands, mostly from areas populated by the Boixos Nois where he had been taking a corner. Among the debris was a pig’s head.[50][51]

Recent issues

In 2005, Ronaldinho became the second Barcelona player, after Diego Maradona in 1983, to receive a standing ovation from Real Madrid fans at the Santiago Bernabéu.

During the last three decades, the rivalry has been augmented by the modern Spanish tradition of the pasillo, where one team is given the guard of honor by the other team, once the former clinches the La Liga trophy before El Clásico takes place. This has happened in three occasions. First, during El Clásico that took place on 30 April 1988, where Real Madrid won the championship on the previous round. Then, three years later, when Barcelona won the championship two rounds before El Clásico on 8 June 1991.[52] The last pasillo, and most recent, took place on 7 May 2008, and this time Real Madrid had won the championship.[53] In May 2018, Real Madrid refused to perform pasillo to Barcelona even though the latter had already wrapped up the championship a round prior to their meeting.[54] Real Madrid’s coach at the time, Zinedine Zidane, reasoned that Barcelona also refused to perform it five months earlier, on 23 December 2017, when Real Madrid were the FIFA Club World Cup champions.[55]

The two teams met again in the UEFA Champions League semi-finals in 2002, with Real winning 2–0 in Barcelona and drawing 1–1 in Madrid, resulting in a 3–1 aggregate win for Los Blancos. The tie was dubbed by Spanish media as the «Match of the Century».[56]

While El Clásico is regarded as one of the fiercest rivalries in world football, there have been rare moments when fans have shown praise for a player on the opposing team. In 1980, Laurie Cunningham was the first Real Madrid player to receive applause from Barcelona fans at Camp Nou; after excelling during the match, and with Madrid winning 2–0, Cunningham left the field to a standing ovation from the locals.[57][58] On 26 June 1983, during the second leg of the Copa de la Liga final at the Santiago Bernabéu in Madrid, having dribbled past the Real Madrid goalkeeper, Barcelona star Diego Maradona ran towards an empty goal before stopping just as the Madrid defender Juan José came sliding in an attempt to block the shot and crashed into the post, before Maradona slotted the ball into the net.[57] The manner of Maradona’s goal led to many Madrid fans inside the stadium start applauding.[57][59] In November 2005, Ronaldinho became the second Barcelona player to receive a standing ovation from Madrid fans at the Santiago Bernabéu.[57] After dribbling through the Madrid defence twice to score two goals in a 3–0 win, Madrid fans paid homage to his performance with applause.[60][61] On 21 November 2015, Andrés Iniesta became the third Barcelona player to receive applause from Real Madrid fans while he was substituted during a 4–0 away win, with Iniesta scoring Barça’s third. He was already a popular figure throughout Spain for scoring the nation’s World Cup winning goal in 2010.[62]

A 2007 survey by the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas showed that 32% of the Spanish population supported Real Madrid, while 25% supported Barcelona. In third place came Valencia, with 5%.[63] According to an Ikerfel poll in 2011, Barcelona is the most popular team in Spain with 44% of preferences, while Real Madrid is second with 37%. Atlético Madrid, Valencia and Athletic Bilbao complete the top five.[64]

The rivalry intensified in 2011, when Barcelona and Real Madrid were scheduled to meet each other four times in 18 days, including the Copa Del Rey final and UEFA Champions League semi-finals. Several accusations of unsportsmanlike behaviour from both teams and a war of words erupted throughout the fixtures which included four red cards. Spain national team coach Vicente del Bosque stated that he was «concerned» that due to the rising hatred between the two clubs, that this could cause friction in the Spain team.[65]

A fixture known for its intensity and indiscipline, it has also featured memorable goal celebrations from both teams, often involving mocking the opposition.[6] In October 1999, Real Madrid forward Raúl silenced 100,000 Barcelona fans at the Camp Nou when he scored before he celebrated by putting a finger to his lips as if telling the crowd to be quiet.[6][66] In 2009 Barcelona captain Carles Puyol kissed his Catalan armband in front of Madrid fans at the Bernabéu.[6] Cristiano Ronaldo twice gestured to the hostile crowd to «calm down» after scoring against Barcelona at the Camp Nou in 2012 and 2016.[6] In April 2017, Messi celebrated his 93rd-minute winner for Barcelona against Real Madrid at the Bernabéu by taking off his Barcelona shirt and holding it up to incensed Real Madrid fans – with his name and number facing them.[6] Later that year, in August, Ronaldo was subbed on in the first leg of the Supercopa de España, proceeded to score in the 80th minute and took his shirt off before holding it up to Barça’s fans with his name and number facing them.[67]

The passion of the rivalry has extended to women’s football, although Real Madrid Femenino was only formed officially in 2020 whereas FC Barcelona Femení is 30 years older and had been one of the country’s leading clubs for much of that time. The second leg of the UEFA Women’s Champions League quarter-finals between the clubs at Camp Nou on 30 March 2022 was attended by 91,553 spectators; at the time, this was the largest known attendance for a women’s football match since the 1971 Mexico–Denmark game (110,000).[68][69][70][71] Reigning continental champions Barça won 5–2 on the day and 8–3 on aggregate.[71] The attendance was later surpassed in the semi-finals match between Barcelona and VfL Wolfsburg.[68]

Player rivalries

László Kubala and Alfredo Di Stéfano

Until the early 1950s, Real Madrid was not a regular title contender in Spain, having won only two Primera División titles between 1929 and 1953.[72] However, things changed for Real after the arrival of Alfredo Di Stéfano in 1953, Paco Gento in the same year, Raymond Kopa in 1956, and Ferenc Puskás in 1958. Real Madrid’s strength increased in this period until the team dominated Spain and Europe, while Barcelona relied on its Hungarian star László Kubala and Luis Suárez, who joined in 1955 in addition to the Hungarian players Sándor Kocsis and Zoltán Czibor and the Brazilian Evaristo. With the arrival of Kubala and Di Stéfano, Barcelona and Real Madrid became among the most important European clubs in those years, and the players represented the turning point in the history of their teams.[73][74][75]

With Kubala and Di Stéfano, a rivalry was born, but it would still take a long time to become what it is today.[76] This period was characterized by the abundance of matches in different tournaments, as they faced each other in all the tournaments available at the time, especially at the European level, where they met twice in two consecutive seasons. In their period, El Clásico was played 26 times: Real won 13 matches, Barcelona 10 matches, and 3 ended in a draw. Di Stéfano scored 14 and Kubala scored 4 goals in those matches.

Cristiano Ronaldo and Lionel Messi

The rivalry between Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo between 2009 and 2018 has been the most competitive in El Clásico history, with both players being their clubs’ all-time top scorers. In their period, many records were broken for both clubs; the two players alternated as top scorers in La Liga and the Champions League during most seasons while they were with Real Madrid and Barcelona.[77] During this period, Ronaldo won the European Golden Shoe three times, while Messi won it five times. In addition, they won the Ballon d’Or four times each.[78]

During the nine years they played together in Spain, the two players scored a total of 922 goals, including 38 goals in El Clásico matches, 20 scored by Messi and 18 by Ronaldo. As of 2022, Ronaldo is the all-time top scorer in the UEFA Champions League, followed by Messi in the second place.[79] In addition, Messi is the all-time top scorer of La Liga, and Ronaldo is ranked second. Both players contributed to their club’s record for the most points in La Liga history, with 100 points in the 2011–12 and 2012–13 seasons, respectively.

The Messi–Ronaldo rivalry was characterized by a lot of goals scored by both players, in addition to many domestic and European titles that they were a major reason for achieving them. In their period, they contributed to the dominance of their clubs in Europe, as they won six Champions League titles in eight seasons, including five consecutive seasons between 2014 and 2018.[80] In El Clásico matches, Messi has scored 26 goals in his career which is a record. Ronaldo has scored 18, which is the joint second most in the fixture’s history alongside Di Stéfano. Ronaldo, on the other hand, has a slight advantage in terms of minutes per goal ratio, scoring a goal for every 141 minutes played in El Clásico matches. Only slightly behind is Messi, scoring a goal every 151.54 minutes.[81]

In their period, the rivalry between Real Madrid and Barcelona has been encapsulated by the rivalry between Ronaldo and Messi.[82] Following the star signings of Neymar and Luis Suárez by Barcelona, and Gareth Bale and Karim Benzema by Real, the rivalry was expanded to a battle of the clubs’ attacking trios, nicknamed «BBC» (Bale, Benzema, Cristiano) and «MSN» (Messi, Suárez, Neymar).[83] Ronaldo left Real for Juventus in 2018, and in the week prior to the first meeting of the teams in the 2018–19 La Liga, Messi sustained an arm injury ruling him out of the match. It would be the first time since 2007 that the Clásico had featured neither player, with some in the media describing it as the ‘end of an era’.[84][85] Barcelona won the match 5–1.[86]

Statistics

Matches summary

- As of 16 October 2022

| Matches | Wins | Draws | Goals | Home wins | Home draws | Away wins | Other venue wins | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMA | BAR | RMA | BAR | RMA | BAR | RMA | BAR | RMA | BAR | RMA | BAR | |||

| La Liga | 185 | 77 | 73 | 35 | 298 | 296 | 55 | 50 | 15 | 20 | 22 | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| Copa de la Coronación[a] | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Copa del Rey | 35 | 12 | 15 | 8 | 65 | 67 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5[b] | 4 | 3 |

| Copa de la Liga | 6 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Supercopa de España | 15 | 9 | 4 | 2 | 33 | 20 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| UEFA Champions League | 8 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 13 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| All competitions | 250 | 101 | 97 | 52 | 418 | 409 | 67 | 63 | 25 | 27 | 29 | 30 | 5 | 4 |

| Exhibition games | 34 | 4 | 20 | 10 | 43 | 84 | 2 | 11 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 3 |

| All matches | 284 | 105 | 117 | 62 | 461 | 493 | 69 | 74 | 29 | 33 | 29 | 36 | 7 | 7 |

- ^ Although not recognized by the current Royal Spanish Football Federation as an official match, it is still considered a competitive match between Barcelona and Real Madrid by statistics sources[87] and the media.[88]

- ^ Not including the 1968 Copa del Generalísimo Final, which was held at Santiago Bernabéu and won by Barcelona, as it was technically a neutral venue.

Head-to-head ranking in La Liga (1929–2022)

- Total: Real Madrid with 47 higher finishes, Barcelona with 44 higher finishes (as of the end of the 2021–22 season).

- The biggest difference in positions for Real Madrid from Barcelona is 10 places in the 1941–42 season; the biggest difference in positions for Barcelona from Real Madrid is 10 places in the 1947–48 season.

Hat-tricks

As of 20 March 2022, 21 different players have scored a hat-trick in official El Clásico matches. 14 of the 25 hat-tricks came from Real Madrid players.

| No. | Player | For | Score | Date | Competition | Stadium |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Real Madrid | 4–1 (H) | 2 April 1916 | 1916 Copa del Rey | Campo de O’Donnell (Atlético Madrid) | |

| 2 | Real Madrid | 6–6 (N) | 13 April 1916 | 1916 Copa del Rey | Campo de O’Donnell (Atlético Madrid) | |

| 3 | Barcelona | 6–6 (N) | 13 April 1916 | 1916 Copa del Rey | Campo de O’Donnell (Atlético Madrid) | |

| 4 | Real Madrid | 6–6 (N) | 13 April 1916 | 1916 Copa del Rey | Campo de O’Donnell (Atlético Madrid) | |

| 5 | Barcelona | 1–5 (A) | 18 April 1926 | 1926 Copa del Rey | Estadio Chamartín | |

| 6 | Real Madrid | 5–1 (H) | 30 March 1930 | 1929–30 La Liga | Estadio Chamartín | |

| 7 | Real Madrid | 8–2 (H) | 3 February 1935 | 1934–35 La Liga | Estadio Chamartín | |

| 8 | Real Madrid | 8–2 (H) | 3 February 1935 | 1934–35 La Liga | Estadio Chamartín | |

| 9 | Barcelona | 5–0 (H) | 21 April 1935 | 1934–35 La Liga | Camp de Les Corts | |

| 10 | Real Madrid | 11–1 (H) | 13 June 1943 | 1943 Copa del Generalísimo | Estadio Chamartín | |

| 11 | Real Madrid | 11–1 (H) | 13 June 1943 | 1943 Copa del Generalísimo | Estadio Chamartín | |

| 12 | Real Madrid | 6–1 (H) | 18 September 1949 | 1949–50 La Liga | Estadio Chamartín | |

| 13 | Real Madrid | 4–1 (H) | 14 January 1951 | 1950–51 La Liga | Estadio Chamartín | |

| 14 | Barcelona | 4–2 (H) | 2 March 1952 | 1951–52 La Liga | Camp de Les Corts | |

| 15 | Barcelona | 6–1 (H) | 19 May 1957 | 1957 Copa del Generalísimo | Camp de Les Corts | |

| 16 | Barcelona | 4–0 (H) | 26 October 1958 | 1958–59 La Liga | Camp Nou | |

| 17 | Real Madrid | 1–5 (A) | 27 January 1963 | 1962–63 La Liga | Camp Nou | |

| 18 | Real Madrid | 4–0 (H) | 30 March 1964 | 1963–64 La Liga | Santiago Bernabéu Stadium | |

| 19 | Real Madrid | 4–1 (H) | 8 November 1964 | 1964–65 La Liga | Santiago Bernabéu Stadium | |

| 20 | Barcelona | 3–2 (H) | 31 January 1987 | 1986–87 La Liga | Camp Nou | |

| 21 | Barcelona | 5–0 (H) | 8 January 1994 | 1993–94 La Liga | Camp Nou | |

| 22 | Real Madrid | 5–0 (H) | 7 January 1995 | 1994–95 La Liga | Santiago Bernabéu Stadium | |

| 23 | Barcelona | 3–3 (H) | 10 March 2007 | 2006–07 La Liga | Camp Nou | |

| 24 | Barcelona | 3–4 (A) | 23 March 2014 | 2013–14 La Liga | Santiago Bernabéu Stadium | |

| 25 | Barcelona | 5–1 (H) | 28 October 2018 | 2018–19 La Liga | Camp Nou |

Notes

- 4 = 4 goals scored; (H) = Home, (A) = Away, (N) = Neutral location; home team score listed first.

- Not including friendly matches.

Stadiums

- As of 16 October 2022

Since the first match in 1902, the official Clásico matches have been held at thirteen stadiums, twelve of those in Spain. The following table shows the details of the stadiums that hosted the Clásico.[91] The following table does not include other stadiums that hosted the friendly matches.

| El Clásico stadiums | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stadium | Owner | Results | Notes | Honours | ||

| RMA | Draws | BAR | ||||

| Hipódromo de la Castellana | Community of Madrid | 0 | 0 | 1 | The first match in El Clásico’s history was played on 13 May 1902 at the old horse racing track in Madrid. The occasion was the semi-final round of the Copa de la Coronación («Coronation Cup») in honor of Alfonso XIII, the first official tournament ever played in Spain. | Copa de la Coronación (1) |

| Total: 1 | ||||||

| Camp del carrer Muntaner | Espanyol | 0 | 0 | 1 | Although it was Espanyol’s stadium at the time, it hosted the first leg of the 1916 Copa del Rey semi-finals. | Copa del Rey (1) |

| Total: 1 | ||||||

| Campo de O’Donnell | Atlético Madrid | 2 | 1 | 0 | The official stadium of Atlético Madrid (1913–1923), where three matches were held to determine the qualification for the Copa del Rey final in 1916. It should not be confused with the Real Madrid stadium at that time of the same name. | Copa del Rey (3) |

| Total: 3 | ||||||

| Chamartín | Real Madrid | 12 | 1 | 4 | The official stadium of Real Madrid (1924–1946). | Copa del Rey/Copa del Generalísimo (2) La Liga (15) |

| Total: 17 | ||||||

| Camp de Les Corts | Barcelona | 7 | 5 | 18 | The official stadium of Barcelona (1922–1957), where the first El Clásico match in La Liga history was held. | Copa del Rey/Copa del Generalísimo (4) La Liga (26) |

| Total: 30 | ||||||

| Mestalla | Valencia | 3 | 0 | 1 | The official stadium of Valencia (1923–present), where Real Madrid and Barcelona faced each other in four Copa del Rey finals: 1936, 1990, 2011 and 2014. | Copa del Rey/Copa del Presidente de la República (4) |

| Total: 4 | ||||||

| Metropolitano de Madrid | Atlético Madrid | 1 | 1 | 0 | The official stadium of Atlético Madrid (1923–1936, 1943–1966), which hosted two league matches when Real Madrid temporarily used it as their home stadium in the 1946–47 season and the first half of the 1947–48 season, while the club was facilitating the construction of the Estadio Real Madrid Club de Fútbol (now Santiago Bernabeu) and the subsequent move there. | La Liga (2) |

| Total: 2 | ||||||

| Santiago Bernabéu | Real Madrid | 51 | 22 | 27 | The official stadium of Real Madrid (1947–present), it hosted more El Clásico matches than any other stadium so far. | La Liga (75) Copa del Rey/Copa del Generalísimo (11) Copa de la Liga (3) Supercopa de España (7) European Cup/Champions League (4) |

| Total: 100 | ||||||

| Camp Nou | Barcelona | 22 | 22 | 44 | The official stadium of Barcelona (1958–present). | La Liga (66) Copa del Rey/Copa del Generalísimo (8) Copa de la Liga (3) Supercopa de España (7) European Cup/Champions League (4) |

| Total: 88 | ||||||

| Vicente Calderón | Atlético Madrid | 1 | 0 | 0 | The official stadium of Atlético Madrid (1966–2017), where the 1974 Copa del Generalísimo Final was held. | Copa del Generalísimo (1) |

| Total: 1 | ||||||

| La Romareda | Real Zaragoza | 0 | 0 | 1 | The official stadium of Real Zaragoza (1957–present), where the 1983 Copa del Rey Final was held. | Copa del Rey (1) |

| Total: 1 | ||||||

| Alfredo Di Stéfano | Real Madrid | 1 | 0 | 0 | Real Madrid’s temporary stadium (2020–2021), which the club used due to the COVID-19 pandemic and to facilitate the ongoing renovations of the Santiago Bernabéu. | La Liga (1) |

| Total: 1 | ||||||

| King Fahd International Stadium | Government of Saudi Arabia | 1 | 0 | 0 | The first stadium outside of Spain to host an El Clásico match, as part of the 2021–22 Supercopa de España. | Supercopa de España (1) |

| Total: 1 |

Honours

The rivalry reflected in El Clásico matches comes about as Barcelona and Real Madrid are the most successful football clubs in Spain. As seen below, Real Madrid leads Barcelona 99 to 97 in terms of official overall trophies.[92] While the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup is recognised as the predecessor to the UEFA Cup, and the Latin Cup is recognised as one of the predecessors of the European Cup, both were not organised by UEFA. Consequently, UEFA does not consider clubs’ records in the Fairs Cup nor Latin Cup to be part of their European record.[93] However, FIFA does view the competitions as a major honour.[94][95] The one-off Ibero-American Cup was later recognised as an official tournament organised by CONMEBOL and the Royal Spanish Football Federation.[96]

| Barcelona | Competition | Real Madrid |

|---|---|---|

| Domestic | ||

| 26 | La Liga | 35 |

| 31 | Copa del Rey | 19 |

| 13 | Supercopa de España | 12 |

| 3 | Copa Eva Duarte (defunct) | 1 |

| 2 | Copa de la Liga (defunct) | 1 |

| 75 | Aggregate | 68 |

| European and Worldwide | ||

| 5 | UEFA Champions League | 14 |

| 4 | UEFA Cup Winners’ Cup (defunct) | — |

| — | UEFA Europa League | 2 |

| 5 | UEFA Super Cup | 5 |

| 3 | Inter-Cities Fairs Cup (defunct) | — |

| 2 | Latin Cup (defunct) | 2 |

| — | Ibero-American Cup (defunct) | 1 |

| — | Intercontinental Cup (defunct) | 3 |

| 3 | FIFA Club World Cup | 4 |

| 22 | Aggregate | 31 |

| 97 | Total aggregate | 99 |

Records

- Friendly matches are not included in the following records unless otherwise noted.

Results

Biggest wins (5+ goals)

| Winning margin | Result | Date | Competition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | Real Madrid 11–1 Barcelona | 19 June 1943 | Copa del Rey |

| 6 | Real Madrid 8–2 Barcelona | 3 February 1935 | La Liga |

| 5 | Barcelona 7–2 Real Madrid | 24 September 1950 | |

| Barcelona 6–1 Real Madrid | 19 May 1957 | Copa del Rey | |

| Real Madrid 6–1 Barcelona | 18 September 1949 | La Liga | |

| Barcelona 5–0 Real Madrid | 21 April 1935 | ||

| Barcelona 5–0 Real Madrid | 25 March 1945 | ||

| Real Madrid 5–0 Barcelona | 5 October 1953 | ||

| Real Madrid 0–5 Barcelona | 17 February 1974 | ||

| Barcelona 5–0 Real Madrid | 8 January 1994 | ||

| Real Madrid 5–0 Barcelona | 7 January 1995 | ||

| Barcelona 5–0 Real Madrid | 29 November 2010 |

Most goals in a match

| Goals | Result | Date | Competition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | Real Madrid 6–6 Barcelona | 13 April 1916 | Copa del Rey |

| Real Madrid 11–1 Barcelona | 13 June 1943 | ||

| 10 | Real Madrid 8–2 Barcelona | 3 February 1935 | La Liga |

| Barcelona 5–5 Real Madrid | 10 January 1943 | ||

| 9 | Barcelona 7–2 Real Madrid | 24 September 1950 | |

| 8 | Barcelona 3–5 Real Madrid | 4 December 1960 | |

| Real Madrid 2–6 Barcelona | 2 May 2009 |

Longest runs

Most consecutive wins

| Games | Club | Period |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | Real Madrid | 22 April 1962 – 28 February 1965 |

| 5 | Barcelona | 13 December 2008 – 29 November 2010 |

| 5 | Real Madrid | 1 March 2020 – 20 March 2022 |

Most consecutive draws

| Games | Period |

|---|---|

| 3 | 11 September 1991 – 7 March 1992 |

| 3 | 1 May 2002 – 20 April 2003 |

Most consecutive matches without a draw

| Games | Period |

|---|---|

| 16 | 25 January 1948 – 21 November 1954 |

| 15 | 23 November 1960 – 19 March 1967 |

| 12 | 4 December 1977 – 26 March 1983 |

| 11 | 19 May 1957 – 27 April 1960 |

| 9 | 5 March 1933 – 28 January 1940 |

Longest undefeated runs

| Games | Club | Period |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | Real Madrid | 3 March 2001 – 6 December 2003 |

| 7 | Real Madrid | 31 January 1932 – 3 February 1935 |

| 7 | Real Madrid | 22 April 1962 – 18 February 1965 |

| 7 | Barcelona | 27 April 2011 – 25 January 2012 |

| 7 | Barcelona | 23 December 2017 – 18 December 2019 |

Longest undefeated runs in the league

| Games | Club | Period |

|---|---|---|

| 7 (5 wins) |

Real Madrid | 31 January 1932 – 3 February 1935 |

| 7 (5 wins) |

Barcelona | 13 December 2008 – 10 December 2011 |

| 7 (4 wins) |

Barcelona | 3 December 2016 – 18 December 2019 |

| 6 (6 wins) |

Real Madrid | 30 September 1962 – 28 February 1965 |

| 6 (4 wins) |

Barcelona | 11 May 1997 – 13 October 1999 |

| 6 (3 wins) |

Barcelona | 28 November 1971 – 17 February 1974 |

| 5 (4 wins) |

Barcelona | 30 March 1947 – 15 January 1949 |

| 5 (4 wins) |

Real Madrid | 18 December 2019 – 24 October 2021 |

| 5 (3 wins) |

Barcelona | 11 May 1975 – 30 January 1977 |

| 5 (3 wins) |

Real Madrid | 1 April 2006 – 7 May 2008 |

Most consecutive matches without conceding a goal

| Games | Club | Period |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | Barcelona | 3 April 1972 – 17 February 1974 |

| 3 | Real Madrid | 29 June 1974 – 11 May 1975 |

| 3 | Barcelona | 29 November 2009 – 29 November 2010 |

| 3 | Barcelona | 27 February 2019 – 18 December 2019 |

Most consecutive games scoring

| Games | Club | Period |

|---|---|---|

| 24 | Barcelona | 27 April 2011 – 13 August 2017 |

| 21 | Barcelona | 30 November 1980 – 31 January 1987 |

| 18 | Real Madrid | 3 May 2011 – 22 March 2015 |

| 13 | Real Madrid | 1 December 1946 – 23 November 1952 |

| 13 | Real Madrid | 15 February 1959 – 21 January 1962 |

| 13 | Real Madrid | 22 April 1962 – 9 April 1968 |

| 12 | Real Madrid | 5 December 1990 – 16 December 1993 |

| 10 | Barcelona | 11 September 1991 – 7 May 1994 |

| 10 | Barcelona | 30 January 1997 – 13 October 1999 |

Other records

- Most common result: 2–1 (45 times)

- Least common result: 11–1, 8–2, 7–2, 6–6, 6–2, 5–5 and 5–3 (once each)

- Most common draw result: 1–1 (25 times)

Players

- As of 16 October 2022

Goalscoring

Lionel Messi is the all-time top scorer in El Clásico history with 26 goals.

Top goalscorers

- Players in bold are still active for Real Madrid or Barcelona.

- Numbers in bold are the record for goals in the competition.

- Does not include friendly matches.

| Rank | Player | Club | La Liga | Copa | Supercopa | League Cup | Europe | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Barcelona | 18 | — | 6 | — | 2 | 26 | |

| 2 | Real Madrid | 14 | 2 | — | — | 2 | 18 | |

| Real Madrid | 9 | 5 | 4 | — | — | 18 | ||

| 4 | Real Madrid | 11 | — | 3 | — | 1 | 15 | |

| 5 | Barcelona | 12 | 2 | — | — | — | 14 | |

| Real Madrid | 10 | 2 | — | — | 2 | 14 | ||

| Real Madrid | 9 | 2 | — | — | 3 | 14 | ||

| 8 | Real Madrid | 9 | 2 | — | 1 | — | 12 | |

| Real Madrid | 8 | 1 | 3 | — | — | 12 | ||

| 10 | Barcelona | 9 | 2 | — | — | — | 11 | |

| 11 | Real Madrid | 8 | — | 2 | — | — | 10 | |

| Real Madrid | 8 | — | — | 2[note 2] | — | 10 | ||

| Both clubs | 4 | 6 | — | — | — | 10 | ||

| 14 | Barcelona | 8 | 1 | — | — | — | 9 | |

| 15 | Real Madrid | 8 | — | — | — | — | 8 | |

| Real Madrid | 8 | — | — | — | — | 8 | ||

| Real Madrid | 4 | 2 | 2 | — | — | 8 | ||

| Real Madrid | 4 | 4 | — | — | — | 8 | ||

| Barcelona | 2 | 5 | — | — | 1 | 8 | ||

| Barcelona | 2 | 4 | — | — | 2 | 8 | ||

| Real Madrid | — | 8 | — | — | — | 8 |

Consecutive goalscoring

| Player | Club | Consecutive matches | Total goals in the run | Start | End |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real Madrid | 6 | 7 | 2011–12 Copa del Rey (quarter-finals 1st leg) | 2012–13 La Liga (7th round) | |

| Real Madrid | 5 | 5 | 1992–93 La Liga (20th round) | 1993 Supercopa de España (2nd leg) | |

| Real Madrid | 4 | 8 | 1916 Copa del Rey (semi-finals 1st leg) | 1916 Copa del Rey (semi-finals 2nd replay) | |

| Real Madrid | 4 | 5 | 1935–36 La Liga (7th round) | 1939–40 La Liga (9th round) | |

| Barcelona | 4 | 5 | 2004–05 La Liga (12th round) | 2005–06 La Liga (31st round) | |

| Barcelona | 4 | 4 | 1997 Supercopa de España (1st leg) | 1997–98 La Liga (28th round) |

Most appearances

Sergio Ramos has made the most appearances for Real Madrid in El Clásico, with 45.

- Players in bold are still active for Real Madrid or Barcelona.[97]

| Apps | Player | Club |

|---|---|---|

| 45 | Sergio Ramos | Real Madrid |

| Lionel Messi | Barcelona | |

| 44 | Sergio Busquets | Barcelona |

| 42 | Francisco Gento | Real Madrid |

| Manuel Sanchís | Real Madrid | |

| Xavi | Barcelona | |

| 40 | Gerard Piqué[98] | Barcelona |

| 39 | Karim Benzema | Real Madrid |

| 38 | Andrés Iniesta | Barcelona |

| 37 | Fernando Hierro | Real Madrid |

| Raúl | Real Madrid | |

| Iker Casillas | Real Madrid | |

| 35 | Santillana | Real Madrid |

Goalkeeping

Most clean sheets

| Player | Club | Period | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | 2002–2014 | 7 | |

| Barcelona | 1986–1994 | 6 | |

| Real Madrid | 1986–1997 | 6 | |

| Real Madrid | 1999–2015 | 6 |

Consecutive clean sheets

| Player | Club | Consecutive clean sheets | Start | End |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | 3 | 1971–72 La Liga (28th round) | 1972–73 La Liga (22th round) | |

| Barcelona | 3 | 2009–10 La Liga (12th round) | 2010–11 La Liga (13th round) | |

| Barcelona | 3 | 2018–19 Copa del Rey (semi-finals 2nd leg) | 2019–20 La Liga (10th round) |

Other records

- Most assists: 14 –

Lionel Messi[99]

- Most assists in one match: 4 –

Xavi (2 May 2009, La Liga)[100]

- Most assists in one season: 5 –

Lionel Messi (2011–12)

- Most penalties scored: 6 –

Lionel Messi

- Most direct free kicks scored: 2

- Most matches won: 21 –

Francisco Gento[101]

- Most matches lost: 20 –

Sergio Ramos

- Most hat-tricks: 2

- Youngest scorer: 17 years, 356 days –

Alfonso Navarro, 1946–47 La Liga, 30 March 1947

- Oldest scorer: 37 years, 164 days –

Alfredo Di Stéfano, 1963–64 La Liga, 15 December 1963

- Fastest goal: 21 seconds –

Karim Benzema, 2011–12 La Liga, 10 December 2011[102][103]

- Fastest penalty scored: 2 minutes –

Pirri, 1976–77 La Liga, 30 January 1977

- Most different tournaments scored in: 4 –

Pedro (La Liga, UEFA Champions League, Copa del Rey and Supercopa de España)

- Most seasons scored in: 11 –

Francisco Gento: (1954–55, 1958–59, 1959–60, 1960–61, 1961–62, 1962–63, 1963–64, 1965–66, 1967–68, 1968–69 and 1969–70)

- Most goals in one season: 8 –

Santiago Bernabéu (1915–16)

- Most different stadiums scored in: 4

Managers

- As of 16 October 2022

Most appearances

| Rank | Coach | Nation | Team | Matches | Years | Competition(s) (matches) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Miguel Muñoz | Real Madrid | 36 | 1960–1974 | La Liga (27) Copa del Rey (5) European Cup (4) |

|

| 2 | Johan Cruyff | Barcelona | 25 | 1988–1996 | La Liga (16) Copa del Rey (3) Supercopa de España (6) |

|

| 3 | José Mourinho | Real Madrid | 17 | 2010–2013 | La Liga (6) Copa del Rey (5) Supercopa de España (4) UEFA Champions League (2) |

|

| 4 | Pep Guardiola | Barcelona | 15 | 2008–2012 | La Liga (8) Copa del Rey (3) Supercopa de España (2) UEFA Champions League (2) |

|

| 5 | Rinus Michels | Barcelona | 13 | 1971–1975 1976–1978 |

La Liga (12) Copa del Rey (1) |

|

| 6 | Terry Venables | Barcelona | 12 | 1984–1987 | La Liga (8) Copa de la Liga (4) |

|

| 7 | Leo Beenhakker | Real Madrid | 11 | 1986–1989 1992 |

La Liga (9) Supercopa de España (2) |

|

| Zinedine Zidane | Real Madrid | 2016–2018 2019–2021 |

La Liga (9) Supercopa de España (2) |

Most wins

| Rank | Coach | Club | Period | Wins |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Real Madrid | 1960–1974 | 16 | |

| 2 | Barcelona | 1988–1996 | 9 | |

| Barcelona | 2008–2012 | |||

| 4 | Barcelona | 1984–1987 | 6 | |

| Real Madrid | 2016–2018 2019–2021 |

Personnel at both clubs

Players

Javier Saviola was the most recent player to transfer directly between the two rivals, in 2007.[104]

After signing for Barcelona in 2022, Marcos Alonso became the most recent player to play for both clubs.

- Barcelona to Real Madrid

- Real Madrid to Barcelona

| From Barcelona to Real Madrid | 17 |

| From Barcelona to another club before Real Madrid | 5 |

| Total | 22 |

| From Real Madrid to Barcelona | 5 |

| From Real Madrid to another club before Barcelona | 10 |

| Total | 15 |

| Total switches | 37 |

Managers

Only two coaches have been at the helm of both clubs:

Enrique Fernández

- Barcelona: 1947–1950

- Real Madrid: 1953–1954

Radomir Antić

- Real Madrid: 1991–1992

- Barcelona: 2003

See also

- El Clásico (basketball)

- Madrid Derby

- Derbi barceloní

- Major football rivalries

- National and regional identity in Spain

- Nationalism and sport

- Sports rivalry

Notes

- ^ Does not include a goal scored in the friendly 2017 International Champions Cup.

- ^ Sharing record with Diego Maradona, Jorge Valdano and Paco Clos.

- ^ Moved to Madrid for studying purposes and joined Real Madrid.[105]

- ^ Only played for Real Madrid between 1906–1908 on loan from Barcelona, as he went to live in Madrid for working purposes.[106]

- ^ Only played one game for Real Madrid in 1908 on loan from Barcelona, a common practice at the time when it was allowed to call up players from other teams. After that match, he continued to play for Barcelona.[107]

- ^ He moved again from Real Madrid to Barcelona in 1954 (via Lleida, Osasuna and España Industrial).[109]

- ^ Never played any official match for Barcelona or Real Madrid but signed with both teams.[110]

- ^ Never played an official match for Barcelona.[111]

- ^ Only played one match for Barcelona in the 1909 Copa del Rey on loan from Real Madrid, a common practice at the time when it was allowed to call up players from other teams. After that match, he continued to play for Real Madrid.[112]

References

- ^ «el clásico, en minúscula y sin comillas». fundeu.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ «El clàssic es jugarà dilluns». El Punt. 18 November 2010. Archived from the original on 31 December 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ Stevenson, Johanthan (12 December 2008). «Barca & Real renew El Clasico rivalry». BBC Sport. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ^ a b «Lionel Messi Reaches $50 Million-A-Year Deal With Barcelona». Forbes. Retrieved 1 October 2014

- ^ Benjamin Morris (26 March 2015). «Is Messi vs. Ronaldo Bigger Than The Super Bowl?». FiveThirtyEight.

- ^ a b c d e f «Real Madrid-Barcelona: Celebrations in enemy territory». Marca. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ El Clasico: Real Madrid Vs Barcelona • Fights, Fouls, Dives & Red Cards

- ^ «Castilian Oppression v Catalan Nationalism – «El Gran Classico»«. Footballblog.co.uk. 2 September 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ «Barcelona in the strange and symbolic eye of a storm over Catalonia». The Guardian. 2 October 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ «AFP: Barcelona vs Real Madrid rivalry comes to the fore». 14 April 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Rookwood, Dan (28 August 2002). «The bitterest rivalry in world football». The Guardian. London.

- ^ «El Clasico: When stars collide». FIFA.com. Retrieved 21 October 2014

- ^ «Barça, the most loved club in the world». Marca. Retrieved 8 May 2015

- ^ Ozanian, Mike. «Barcelona becomes first sports team to have 50 million Facebook fans». Forbes.com.

- ^ Palomares, Cristina The quest for survival after Franco: moderate Francoism and the slow journey, p.231

- ^ Cambio 16, 6–12, Enero 1975 p.18

- ^ a b c McNeill, Donald (1999) Urban change and the European left: tales from the new Barcelona p.61

- ^ Ball, Phil (21 April 2002). «Mucho morbo». The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ a b Burns, Jimmy, ‘Don Patricio O’Connell: An Irishman and the Politics of Spanish Football’ in «Irish Migration Studies in Latin America» 6:1 (March 2008), p. 44. Available online pg. 3,pg. 4. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ Ham, Anthony p. 221

- ^ Ball, Phil p. 88

- ^ a b Fitzgerald, Nick. «The story of Real Madrid and the Franco regime». thesefootballtimes.co. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ a b Kelly, Ryan. «General Franco, Real Madrid & the king: The history behind club’s link to Spain’s establishment». goal.com. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ «SANTIAGO BERNABÉU 1943–1978». realmadrid.com. Real Madrid C.F. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ «The Ultra Sur | El Centrocampista — Spanish Football and La Liga News in English». El Centrocampista. 27 October 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Dos Manzanas (14 June 2011). «Tres Boixos Nois detenidos por agredir a una mujer transexual en Barcelona». Dos manzanas. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ «La mafia de boixos nois se especializó en atracar a narcos — Sociedad — El Periódico». Elperiodico.com. 11 September 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ «Great similarities between Barcelona and Celtic». vavel.com. 21 April 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ «FourFourTwo’s 50 Biggest Derbies in the World, No.2: Barcelona vs Real Madrid». fourfourtwo.com. 29 April 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ «La izquierda es culé y la derecha, merengue, según el CIS». LaVanguardia.com (in Spanish). 20 July 2009. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ^ Rusiñol, Pere (23 February 2003). «¿Del Madrid o del Barça?». El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ «Copa del Presidente de la II República 1932 – 1936».

- ^ «Real Madrid v Barcelona: six of the best ‘El Clásicos’«. The Telegraph. London. 9 December 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ a b c «Sid Lowe: Fear and loathing in La Liga.. Barcelona vs Real Madrid» p. 67. Random House. 26 September 2013

- ^ Phil Ball (2001). Morbo: the story of Spanish football. Reading: WSC Books. p. 25.

- ^ «Sid Lowe: Fear and loathing in La Liga.. Barcelona vs Real Madrid» p. 68. Random House. 26 September 2013

- ^ «Sid Lowe: Fear and loathing in La Liga.. Barcelona vs Real Madrid» p. 70. Random House. 26 September 2013

- ^ Lowe, Sid. p. 74

- ^ Spaaij, Ramn (2006). Understanding football hooliganism: a comparison of six Western European football clubs. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-5629-445-8. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ Lowe, Sid. p. 73

- ^ Lowe, Sid. p. 72

- ^ «Sid Lowe: Fear and loathing in La Liga.. Barcelona vs Real Madrid» p. 77. Random House. 26 September 2013

- ^ «Barcelona did not renounce Di Stefano… they were robbed». Sport.es. 29 April 2016. Archived from the original on 7 August 2022.

- ^ «Di Stéfano y la decisión salomónica de la FIFA [Di Stéfano and the Solomonic decision of FIFA]». La Voz de Galicia. 31 May 2022. Archived from the original on 7 August 2022.

- ^ a b «BBC SPORT | Football | Alfredo Di Stefano: Did General Franco halt Barcelona transfer?». BBC News. 7 July 2014. Archived from the original on 8 February 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ «Alfredo di Stéfano was one of football’s greatest trailblazers». The Guardian. 7 July 2014. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ a b Lowe, Sid. p. 344

- ^ «Sid Lowe: Fear and loathing in La Liga.. Barcelona vs Real Madrid» p. 345, 346. Random House. 26 September 2013

- ^ Lowe, Sid. p. 339

- ^ Lowe, Sid. p. 338

- ^ Jefferies, Tony (27 November 2002). «Barcelona are braced for a stiff penalty». The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ Deportes. «(Spanish)». 20minutos.es. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ «Real Madrid v. Barcelona: A Glance Back at Past Pasillos | Futfanatico: Breaking Soccer News». Futfanatico. 5 December 2011. Archived from the original on 1 December 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ «The pasillo controversy: Real Madrid should respect Barcelona with guard of honour». Goal.com. 4 May 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ ««No le haremos pasillo al Barça porque ellos no nos lo hicieron»«. As.com (in Spanish). 5 May 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ «Real win Champions League showdown». BBC News. 11 December 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- ^ a b c d «Applauding the enemy», FIFA.com, 15 February 2014

- ^ «Real Madrid vs Barcelona: El-Clasico Preview», The Independent, 17 January 2012,

- ^ «30 years since Maradona stunned the Santiago Bernabéu». FC Barcelona. Retrieved 2 October 2014

- ^ «Rampant Ronaldinho receives standing ovation». BBC News. 11 December 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ «Real Madrid 0 Barcelona 3: Bernabeu forced to pay homage as Ronaldinho soars above the galacticos». The Independent. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ^ «Real Madrid Fans Applaud Barcelona’s Andres Iniesta In ‘El Clasico’«. NESN. 21 November 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ «CIS Mayo 2007» (PDF) (in Spanish). Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. May 2007. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ^ «España se pasa del Madrid al Barcelona». as.com (in Spanish). 10 October 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ^ Sapa-DPA (29 April 2011). «Del Bosque concerned over Real-Barca conflict — SuperSport — Football». SuperSport. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ «When Raul ended Madrid’s humiliation, silenced Nou Camp». Egypt Today. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ «Cristiano Ronaldo scores and is sent off in win over Barcelona». The Guardian.

- ^ a b «Barcelona presume récord de asistencia femenil, aunque México tiene uno mayor [Barcelona claims female attendance record, although Mexico has a higher one]». ESPN. 22 April 2022. Archived from the original on 23 April 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ Kraft, Justin (22 April 2022). «Frauenfußball: «Weltrekord» des FC Barcelona im Camp Nou ist keiner [FC Barcelona’s «world record» at Camp Nou is not one]». SPOX. Goal. Archived from the original on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ «Redefining the Sport, Redefining the Culture». Fútbol with Grant Wahl. 20 April 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ a b Gulino, Joey (30 March 2022). «Record 91,553 fans watch Barcelona women oust Real Madrid from Champions League». Yahoo Sports. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ «Primera División – Champions». worldfootball.net. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ «Historias de la Liga: el año en que Kubala entrenó a Di Stéfano». martiperarnau.com (in Spanish).

- ^ «Kubala e Di Stefano: le nuove stelle del cinema spagnolo durante il franchismo». academia.edu (in Italian).

- ^ «Messi y Cristiano; Di Stéfano y Kubala: La lucha entre Barça y Madrid». lavanguardia.com (in Spanish).

- ^ «Real Madrid: Kubala’s last battle against Real Madrid». spainsnews.com.

- ^ «EXCLUSIVE: Cristiano Ronaldo’s former coach explains impact of Lionel Messi rivalrys». Daily Mirror. 21 March 2022.

- ^ «List of Men’s Ballon d’Or award winners». topendsports.com.

- ^ «Champions League all-time top scorers: Cristiano Ronaldo, Lionel Messi, Robert Lewandowski, Karim Benzema». UEFA. 28 June 2022.

- ^ «Champions League – Champions». worldfootball.net. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ «Messi & Ronaldo El Clásico Stats».

- ^ Bate, Adam (25 October 2013). «Fear and Loathing». Sky Sports. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ «El club de los 100: MSN 91-88 BBC». Marca. 24 October 2015.

- ^ «Barcelona vs Real Madrid: First Clasico without Lionel Messi or Cristiano Ronaldo since 2007 marks end of era». Evening Standard. 26 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ «No Messi or Ronaldo in El Clasico for first time since 2007». FourFourTwo. 20 October 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ «Barcelona 5–1 Real Madrid». BBC Sport. 28 October 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ «FC Barcelona vs Real Madrid CF since 1902». rsssf.com. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ «Real Madrid – Barcelona: Igualdad total en los 35 Clásicos en Copa» (in Spanish). Marca. 27 February 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ La Vanguardia (20 September 1949). «Match report – Real Madrid 6–1 Barcelona». p. 16. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ «Match report – Real Madrid 6–1 Barcelona (BDFutbol)». bdfutbol.com. Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2021.

- ^ «Eighteenth different Clásico venue». FC Barcelona. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ Copa Eva Duarte (defunct) is not listed as an official title by the UEFA, but it is considered as such by the RFEF, as it is the direct predecessor of the Supercopa de España

- ^ «UEFA Europa League: History: New format provides fresh impetus». UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ «Classic Football: Clubs: FC Barcelona». FIFA.com. Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ Rimet, Pierre (4 January 1951). Rodrigues Filho, Mário (ed.). «Cartas de Paris — Das pirâmides do Egito ao colosso do Maracanã, com o Sr. Jules Rimet» [Letters from Paris — From the pyramids of Egypt to the colossus of Maracanã, with Mr. Jules Rimet]. Jornal dos Sports (in Portuguese). No. 6554. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. p. 5. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

A Taça Latina é uma competição criada pela F. I. F. A. a pedido dos quatro países que a disputam atualmente. Mas o Regulamento é feito por uma Comissão composta por membros das Federações concorrentes e de fato a F. I. F. A. não participa ativamente na organização

- ^ Las competiciones oficiales de la CONMEBOL

- ^ «Barcelona – Real Madrid: Ansu Fati, Ramos set Clásico records». AS.com. 18 December 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ «Piqué, Clásico matches» (in Spanish). BDFutbol. 29 December 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ «Barcelona: Messi finishes 2017 ahead of Cristiano Ronaldo with 54 goals». marca.com. 23 December 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ «Barcelona are back! Xavi’s masterplan comes to life in Clasico crushing of Real Madrid». goal.com. 20 March 2022. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ Players with the most El Clasico wins MisterChip, 23 December 2017

- ^ Real Madrid’s Karim Benzema scores fastest-ever The fastest goal in El Clasico history https://www.sportsbignews.com/

- ^ «The record breakers of LaLiga Santander’s #ElClasico». La Liga. Madrid.

- ^ «5 Player Transfers Between Real Madrid and Barcelona». 90min.com. 14 July 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ^ Payarols, Lluís (27 February 2013). «El hijo de Isaac Albéniz, primer tránsfuga Barça-Madrid». Sport (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ «Saviola, el último tránsfuga». Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 28 December 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ Magallón, Fernando (14 July 2007). «Saviola es el 16º que deja el Barça por el Madrid». Diario AS (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ Navarro: Joaquín Navarro Perona, BDFutbol

- ^ Navarro: Alfonso Navarro Perona, BDFutbol

- ^ Jové, Oriol (5 August 2018). «El ‘Kubala’ de la UE Lleida». Diari Segre (in Spanish). Lleida. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ Closa, Toni; Pablo, Josep; Salas, José Alberto; Mas, Jordi (2015). Gran diccionari de jugadors del Barça (in Catalan). Barcelona: Base. ISBN 978-84-16166-62-6.

- ^ Salinas, David (2015). El rey de Copas. Cien años del Barcelona en la Copa de España (1909-2019) (in Spanish). Barcelona: Meteora. ISBN 9788492874125.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to El Clásico.

- Ball, Phill (2003). Morbo: The Story of Spanish Football. WSC Books Limited. ISBN 0-9540134-6-8.

- Farred, Grant (2008). Long distance love: a passion for football. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-59213-374-1.

- Lowe, Sid (2013). Fear and Loathing in La Liga: Barcelona vs Real Madrid. Random House. ISBN 9780224091800.

This article is about the FC Barcelona–Real Madrid CF rivalry. For other uses, see El Clásico (disambiguation).

Team kits – Real Madrid in white, Barcelona in blue and garnet |

|

| Location | Spain |

|---|---|

| Teams | Barcelona Real Madrid |

| First meeting | FC Barcelona 3–1 Madrid FC 1902 Copa de la Coronación (13 May 1902) |

| Latest meeting | Real Madrid 3–1 Barcelona La Liga (16 October 2022) |

| Next meeting | Barcelona v Real Madrid La Liga (19 March 2023) |

| Stadiums | Camp Nou (Barcelona) Santiago Bernabéu (Real Madrid) |

| Statistics | |

| Meetings total | Competitive matches: 250 Exhibition matches: 34 Total matches: 284 |

| Most wins | Competitive matches: Real Madrid (101) Exhibition matches: Barcelona (20) Total matches: Barcelona (117) |

| Most player appearances | Lionel Messi Sergio Ramos (45 each) |

| Top scorer | Lionel Messi (26)[note 1] |

| Largest victory | Real Madrid 11–1 Barcelona Copa del Rey (19 June 1943) |

El Clásico or el clásico[1] (Spanish pronunciation: [el ˈklasiko]; Catalan: El Clàssic,[2] pronounced [əl ˈklasik]; «The Classic») is the name given to any football match between rival clubs FC Barcelona and Real Madrid. Originally referring to competitions held in the Spanish championship, the term now includes every match between the clubs, such as those in the UEFA Champions League and Copa del Rey. It is considered one of the biggest club football games in the world, and is among the most viewed annual sporting events.[3][4][5] A fixture known for its intensity, it has featured memorable goal celebrations from both teams, often involving mocking the opposition.[6][7]

The rivalry comes about as Madrid and Barcelona are the two largest cities in Spain, and they are sometimes identified with opposing political positions, with Real Madrid viewed as representing Spanish nationalism and Barcelona viewed as representing Catalan nationalism.[8][9] The rivalry is regarded as one of the biggest in world sport.[10][11][12] The two clubs are among the richest and most successful football clubs in the world; in 2014 Forbes ranked Barcelona and Real Madrid the world’s two most valuable sports teams.[4] Both clubs have a global fanbase; they are the world’s two most followed sports teams on social media.[13][14]

Real Madrid leads in head-to-head results in competitive matches with 101 wins to Barcelona’s 97 with 52 draws; Barcelona leads in exhibition matches with 20 victories to Madrid’s 4 with 10 draws and in total matches with 117 wins to Madrid’s 105 with 62 draws as of the match played on 16 October 2022. Along with Athletic Bilbao, they are the only clubs in La Liga to have never been relegated.

Rivalry

History

Santiago Bernabéu. The home fans are displaying the white of Real Madrid before El Clásico. Spanish flags are also a common sight at Real Madrid games.

Camp Nou. The home fans of FC Barcelona are creating a mosaic of the Catalan flag before El Clasico. The top right corner of the club’s crest also features a Catalan flag.

The conflict between Real Madrid and Barcelona has long surpassed the sporting dimension,[15][16] so much that elections to the clubs’ presidencies have been strongly politicized.[17] Phil Ball, the author of Morbo: The Story of Spanish Football, says about the match; «they hate each other with an intensity that can truly shock the outsider».[18]

As early as the 1930s, Barcelona «had developed a reputation as a symbol of Catalan identity, opposed to the centralising tendencies of Madrid».[19][20] In 1936, when Francisco Franco started the coup d’état against the democratic Second Spanish Republic, the president of Barcelona, Josep Sunyol, member of the Republican Left of Catalonia and Deputy to The Cortes, was arrested and executed without trial by Franco’s troops[17] (Sunyol was exercising his political activities, visiting Republican troops north of Madrid).[19] During the dictatorships of Miguel Primo de Rivera and especially Francisco Franco, all regional languages and identities in Spain were frowned upon and restrained. As such, most citizens of Barcelona were in strong opposition to the fascist-like regime. In this period, Barcelona gained their motto Més que un club (English: More than a club) because of its alleged connection to Catalan nationalist as well as to progressive beliefs.[21]

There’s an ongoing controversy as to what extent Franco’s rule (1939–75) influenced the activities and on-pitch results of both Barcelona and Real Madrid. Most historians agree that Franco did not have a preferred football team, but his Spanish nationalist beliefs led him to associate himself with the establishment teams, such as Atlético Aviación and Madrid FC (that recovered its royal name after the fall of the Republic). On the other hand, he also wanted the renamed CF Barcelona succeed as «Spanish team» rather than a Catalan one.[22][23] During the early years of Franco’s rule, Real Madrid weren’t particularly successful, winning two Copa del Generalísimo titles and a Copa Eva Duarte; Barcelona claimed three league titles, one Copa del Generalísimo and one Copa Eva Duarte. During that period, Atlético Aviación were believed to be the preferred team over Real Madrid. The most contested stories of the period include Real Madrid’s 11–1 home win against Barcelona in the Copa del Generalísimo, where the Catalan team alleged intimidation, and the controversial transfer of Alfredo Di Stéfano to Real Madrid despite his agreement with Barcelona. The latter transfer was part of Real Madrid chairman Santiago Bernabéu’s «revolution» that ushered in the era of unprecedented dominance. Bernabéu, himself a veteran of the Civil War who fought for Franco’s forces, saw Real Madrid on top not only of Spanish but also European football, helping create the European Cup, the first true competition for Europe’s best club sides. His vision was fulfilled when Real Madrid not only started winning consecutive league titles but also swept the first five editions of the European Cup in the 1950s.[24] These events had a profound impact on Spanish football and influenced Franco’s attitude. According to historians, during this time he realized the importance of Real Madrid for his regime’s international image, and the club became his preferred team until his death. Fernando Maria Castiella, who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs under Franco from 1957 until 1969, noted that «[Real Madrid] is the best embassy we have ever had.» Franco died in 1975, and the Spanish transition to democracy soon followed. Under his rule, Real Madrid had won 14 league titles, 6 Copa del Generalísimo titles, 1 Copa Eva Duarte, 6 European Cups, 2 Latin Cups and 1 Intercontinental Cup. In the same period, Barcelona had won 8 league titles, 9 Copa del Generalísimo titles, 3 Copa Eva Duarte titles, 3 Inter-Cities Fairs Cups and 2 Latin Cups.[22][23]

The image for both clubs was further affected by the creation of ultras groups, some of which became hooligans. In 1980, Ultras Sur was founded as a far-right-leaning Real Madrid ultras group, followed in 1981 by the foundation of the initially left-leaning and later on far-right, Barcelona ultras group Boixos Nois. Both groups became known for their violent acts,[17][25][26] and one of the most conflictive factions of Barcelona supporters, the Casuals, became a full-fledged criminal organisation.[27]

For many people, Barcelona is still considered as «the rebellious club», or the alternative pole to «Real Madrid’s conservatism».[28][29] According to polls released by CIS (Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas), Real Madrid is the favorite team of most of the Spanish residents, while Barcelona stands in the second position. In Catalonia, forces of all the political spectrum are overwhelmingly in favour of Barcelona. Nevertheless, the support of the blaugrana club goes far beyond from that region, earning its best results among young people, sustainers of a federal structure of Spain and citizens with left-wing ideology, in contrast with Real Madrid fans which politically tend to adopt right-wing views.[30][31]

1943 Copa del Generalísimo semi-finals

On 13 June 1943, Real Madrid beat Barcelona 11–1 at the Chamartín in the second leg of the Copa del Generalísimo semi-finals (the Copa del Presidente de la República[32] having been renamed in honour of General Franco).[33] The first leg, played at the Les Corts in Catalonia, had ended with Barcelona winning 3–0. Madrid complained about all the three goals that referee Fombona Fernández had allowed for Barcelona,[34] with the home supporters also whistling Madrid throughout, whom they accused of employing roughhouse tactics, and Fombona for allowing them to. Barça’s Josep Escolà was stretchered off in the first half with José María Querejeta’s stud marks in his stomach. A campaign began in Madrid. The newspaper Ya reported the whistling as a «clear intention to attack the representatives of Spain.»[35] Barcelona player Josep Valle recalled: «The press officer at the DND and ABC newspaper wrote all sorts of scurrilous lies, really terrible things, winding up the Madrid fans like never before». Former Real Madrid goalkeeper Eduardo Teus, who admitted that Madrid had «above all played hard», wrote in a newspaper: «the ground itself made Madrid concede two of the three goals, goals that were totally unfair».[36]

Barcelona fans were banned from traveling to Madrid. Real Madrid released a statement after the match which former club president Ramón Mendoza explained, «The message got through that those fans who wanted to could go to El Club bar on Calle de la Victoria where Madrid’s social center was. There, they were given a whistle. Others had whistles handed to them with their tickets.» The day of the second leg, the Barcelona team were insulted and stones were thrown at their bus as soon as they left their hotel. Barcelona’s striker Mariano Gonzalvo said of the incident, «Five minutes before the game had started, our penalty area was already full of coins.» Barcelona goalkeeper Lluis Miró rarely approached his line—when he did, he was armed with stones. As Francisco Calvet told the story, «They were shouting: Reds! Separatists!… a bottle just missed Sospedra that would have killed him if it had hit him. It was all set up.»[37]

Real Madrid went 2–0 up within half an hour. The third goal brought with it a sending off for Barcelona’s Benito García after he made what Calvet claimed was a «completely normal tackle». Madrid’s José Llopis Corona recalled, «At which point, they got a bit demoralized,» while Ángel Mur countered, «at which point, we thought: ‘go on then, score as many as you want’.» Madrid scored in minutes 31′, 33′, 35′, 39′, 43′ and 44′, as well as two goals ruled out for offside, made it 8–0. Juan Samaranch wrote: «In that atmosphere and with a referee who wanted to avoid any complications, it was humanly impossible to play… If the azulgranas had played badly, really badly, the scoreboard would still not have reached that astronomical figure. The point is that they did not play at all.»[38] Both clubs were fined 2,500 pesetas by the Royal Spanish Football Federation and, although Barcelona appealed, it made no difference. Piñeyro resigned in protest, complaining of «a campaign that the press has run against Barcelona for a week and which culminated in the shameful day at Chamartín».[39][40]

The match report in the newspaper La Prensa described Barcelona’s only goal as a «reminder that there was a team there who knew how to play football and that if they did not do so that afternoon, it was not exactly their fault».[41] Another newspaper called the scoreline «as absurd as it was abnormal».[34] According to football writer Sid Lowe, «There have been relatively few mentions of the game [since] and it is not a result that has been particularly celebrated in Madrid. Indeed, the 11–1 occupies a far more prominent place in Barcelona’s history. This was the game that first formed the identification of Madrid as the team of the dictatorship and Barcelona as its victims.»[34] Fernando Argila, Barcelona’s reserve goalkeeper from the game, said, «There was no rivalry. Not, at least, until that game.»[42]

Di Stéfano transfer

Alfredo Di Stéfano’s controversial 1953 transfer to Real Madrid instead of Barcelona intensified the rivalry.

The rivalry was intensified during the 1950s when the clubs disputed the signing of Alfredo Di Stéfano. Di Stéfano had impressed both Barcelona and Real Madrid while playing for Los Millionarios in Bogotá, Colombia, during a players’ strike in his native Argentina. Soon after Millonarios’ return to Colombia, Barcelona directors visited Buenos Aires and agreed with River Plate, the last FIFA-affiliated team to have held Di Stéfano’s rights, for his transfer in 1954 for the equivalent of 150 million Italian lira ($200,000 according to other sources[specify]). This started a battle between the two Spanish rivals for his rights.[43] FIFA appointed Armando Muñoz Calero, former president of the Spanish Football Federation as mediator. Calero decided to let Di Stéfano play the 1953–54 and 1955–56 seasons in Madrid, and the 1954–55 and 1956–57 seasons in Barcelona.[44][45] The agreement was approved by the Football Association and their respective clubs. Although the Catalans agreed, the decision created various discontent among the Blaugrana members and the president was forced to resign in September 1953. Barcelona sold Madrid their half-share, and Di Stéfano moved to Los Blancos, signing a four-year contract. Real paid 5.5 million Spanish pesetas for the transfer, plus a 1.3 million bonus for the purchase,[failed verification] an annual fee to be paid to the Millonarios, and a 16,000 salary for Di Stéfano with a bonus double that of his teammates, for a total of 40% of the annual revenue of the Madrid club.[45]

Di Stéfano became integral in the subsequent success achieved by Real Madrid, scoring twice in his first game against Barcelona. With him, Madrid won the first five editions of the European Cup.[46] The 1960s saw the rivalry reach the European stage when Real Madrid and Barcelona met twice in the European Cup, with Madrid triumphing en route to their fifth consecutive title in 1959–60 and Barcelona prevailing en route to losing the final in 1960–61.

Luís Figo transfer

Luís Figo’s transfer from Barcelona to Real Madrid in 2000 resulted in a hate campaign by some of his former club’s fans.