«Vape» redirects here. For the Argentine reconnaissance vehicle, see VAPE.

A first-generation e-cigarette that resembles a tobacco cigarette, with a battery portion that can be disconnected and recharged using the USB power charger

Various types of e-cigarettes, including a disposable e-cigarette, a rechargeable e-cigarette, a medium-size tank device, large-size tank devices, an e-cigar, and an e-pipe

An electronic cigarette[note 1][1] is an electronic device that simulates tobacco smoking. It consists of an atomizer, a power source such as a battery, and a container such as a cartridge or tank. Instead of smoke, the user inhales vapor.[2] As such, using an e-cigarette is often called «vaping«.[3] The atomizer is a heating element that vaporizes a liquid solution called e-liquid,[4] which quickly cools into an aerosol of tiny droplets, vapor and air.[5] E-cigarettes are activated by taking a puff or pressing a button.[3][6] Some look like traditional cigarettes,[3][7] and most kinds are reusable.[8] The vapor mainly comprises propylene glycol and/or glycerin, usually with nicotine and flavoring. Its exact composition varies, and depends on several things including user behavior.[note 2]

Vaping is likely less harmful than smoking, but still harmful.[9][10][11] E-cigarette vapor contains fewer toxins than cigarette smoke. It contains traces of harmful substances not found in cigarette smoke.[11]

Nicotine is highly addictive.[12][13][14] Users become physically and psychologically dependent.[15] Scientists do not know whether e-cigarettes are harmful to humans long-term[16][17] because it is hard to separate the effects of vaping from the effects of smoking when so many people both vape and smoke.[18][19] E-cigarettes have not been used widely enough or for long enough to be sure.[20][21][22]

For people trying to quit smoking, e-cigarette use alongside prescribed nicotine replacement therapy leads to a higher quit rate.[23][24] For people trying to quit smoking without medical help, e-cigarettes have not been found to raise quit rates.[25][26]

Construction

Exploded view of an e-cigarette with transparent clearomizer and changeable dual-coil head. This model allows for a wide range of settings.

An electronic cigarette consists of an atomizer, a power source such as a battery, and a container for e-liquid such as a cartridge or tank.

E-cigarettes have evolved over time, and the different designs are classified in generations. First-generation e-cigarettes tend to look like traditional cigarettes and are called «cigalikes».[27][28] Second-generation devices are larger and look less like traditional cigarettes.[29] Third-generation devices include mechanical mods and variable voltage devices.[27] The fourth-generation includes sub-ohm tanks (meaning they have electrical resistance of less than 1 ohm) and temperature control.[30] There are also pod mod devices that use protonated nicotine, rather than free-base nicotine found in earlier generations,[31] providing higher nicotine yields.[32][33]

E-liquid

The mixture used in vapor products such as e-cigarettes is called e-liquid.[34] E-liquid formulations vary widely.[28][35] A typical e-liquid is composed of propylene glycol and glycerin (95%) and a combination of flavorings, nicotine, and other additives (5%).[36][37] The flavorings may be natural, artificial,[35] or organic.[38] Over 80 harmful chemicals such as formaldehyde and metallic nanoparticles have been found in e-liquids at trace quantities.[39] There are many e-liquid manufacturers,[40] and more than 15,000 flavors.[41]

Most countries regulate what e-liquids can contain. In the US, there are Food and Drug Administration (FDA) compulsory manufacturing standards[42] and American E-liquid Manufacturing Standards Association (AEMSA) recommended manufacturing standards.[43] European Union standards are published in the EU Tobacco Products Directive.[44]

Use

Popularity

Estimated trends in the global number of vapers

Since entering the market around 2003, e-cigarette use has risen rapidly.[45][46][47] In 2011 there were about 7 million adult e-cigarette users globally, increasing to 68 million in 2020 compared with 1.1 billion cigarette smokers.[48] There was a further rise to 82 million e-cigarette users in 2021.[49] This increase has been attributed to targeted marketing, lower cost compared to conventional cigarettes, and the better safety profile of e-cigarettes compared to tobacco.[50] E-cigarette use is highest in China, the US, and Europe, with China having the most users.[6][51]

Motivation

There are varied reasons for e-cigarette use.[6] Most users are trying to quit smoking,[53] but a large proportion of use is recreational or as an attempt to get around smoke-free laws.[6][7][54][53] Many people vape because they believe vaping is safer than smoking.[55][56][57] The wide choice of flavors and lower price compared to cigarettes are also important factors.[58]

Other motivations include reduced odor and fewer stains.[59] E-cigarettes also appeal to technophiles who enjoy customizing their devices.[59]

Gateway theory

The gateway hypothesis is the idea that using less harmful drugs can lead to more harmful ones.[60] Evidence shows that many users who begin by vaping will go onto also smoke traditional cigarettes.[61][62][63][61][64] People with mental illnesses, who as a group are more susceptible to nicotine addiction, are at particularly high risk of dual use.[65][66]

However, an association between vaping and subsequent smoking does not necessarily imply a causal gateway effect.[67] Instead, people may have underlying characteristics that predispose them to both activities.[68][69] There is a genetic association between smoking, vaping, gambling, promiscuity and other risk-taking behaviors.[70] Young people with poor executive functioning use e-cigarettes, cigarettes, and alcohol at higher rates than their peers.[71] E-cigarette users are also more likely to take both marijuana and unprescribed Adderall or Ritalin.[72] Longitudinal studies of e-cigarettes and smoking have been criticized for failing to adequately control for these and other confounding factors.[73][74][75]

Smoking rates have continually declined as e-cigarettes have grown in popularity, especially among young people, suggesting that there is little evidence for a gateway effect at the population level.[68][69] This observation has been criticized, however, for ignoring the effect of anti-smoking interventions.[76]

Young adult and teen use

Worldwide, increasing numbers of young people are vaping.[77][78] With access to e-cigarettes, young people’s tobacco use has dropped by about 75%.[79][80][81][82]

Most young e-cigarette users have never smoked,[83] but there is a substantial minority who both vape and smoke.[84] Young people who would not smoke are vaping.[85][54] Young people who smoke tobacco or marijuana, or who drink alcohol, are much more likely to vape.[86][87] Among young people who have tried vaping, most used a flavored product the first time.[86][88]

Vaping correlates with smoking among young people, even in those who would otherwise be unlikely to smoke.[89] Experimenting with vaping encourages young people to continue smoking.[90] A 2015 study found minors had little resistance to buying e-cigarettes online.[91] Teenagers may not admit to using e-cigarettes, but use, for instance, a hookah pen.[92] As a result, self-reporting may be lower in surveys.[92]

More recent studies show a trend of an increasing percentage of youths who use e-cigarettes. In 2018, 20% of high school students were using e-cigarettes. In 2020 however, this number increased to 50% of high school students reported to have used e-cigarettes.[93] Similarly in Canada there has been trend showing 29% of youths reporting to have used e-cigarettes in 2017, increasing to 37% in 2018.[94]

Health effects

The health risks of e-cigarettes are not known for certain, but the risk of serious adverse events is thought to be low,[95][96] and e-cigarettes are likely safer than combusted tobacco products.[note 3][90][98] According to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, «Laboratory tests of e-cigarette ingredients, in vitro toxicological tests, and short-term human studies suggest that e-cigarettes are likely to be far less harmful than combustible tobacco cigarettes.»[11] When provided alongside professional help and nicotine replacement therapy , e-cigarettes can help people quit smoking.[99]

Some of the most common but less serious adverse effects include abdominal pain, headache, blurry vision,[100][101] throat and mouth irritation, vomiting, nausea, and coughing.[84] Nicotine is addictive and harmful to fetuses, children, and young people.[102] In 2019 and 2020, an outbreak of severe vaping lung illness in the US was strongly linked to vitamin E acetate by the CDC. While it is still widely debated which particular component of vape liquid is the cause of illness, vitamin E acetate, specifically, has been identified as a potential culprit in vape-related illnesses.[103] There was likely more than one cause of the outbreak.[104][105] E-cigarettes produce similar levels of particulates to tobacco cigarettes.[106] There is «only limited evidence showing adverse respiratory and cardiovascular effects in humans», with the authors of a 2020 review calling for more long-term studies on the subject.[106] E-cigarettes increase the risk of asthma by 40% and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by 50% compared to not using nicotine at all.[107]

Pregnancy

The British Royal College of Midwives states: «While vaping devices such as electronic cigarettes (e-cigs) do contain some toxins, they are at far lower levels than found in tobacco smoke. If a pregnant woman who has been smoking chooses to use an e-cig and it helps her to quit smoking and stay smokefree, she should be supported to do so.» Based on the available evidence on e-cigarette safety, there was also «no reason to believe that use of an e-cig has any adverse effect on breastfeeding.» The statement went on to say, «vaping should continue, if it is helpful to quitting smoking and staying smokefree». The UK National Health Service says: «If using an e-cigarette helps you to stop smoking, it is much safer for you and your baby than continuing to smoke.» Many women who vape continue to do so during pregnancy because of the perceived safety of e-cigarettes compared to tobacco.[108]

United States

In one of the few studies identified, a 2015 survey of 316 pregnant women in a Maryland clinic found that the majority had heard of e-cigarettes, 13% had used them, and 0.6% were current daily users.[86] These findings are of concern because the dose of nicotine delivered by e-cigarettes can be as high or higher than that delivered by traditional cigarettes.[86]

Data from two states in the Pregnancy Risk Assessment System (PRAMS) show that in 2015—roughly the mid-point of the study period—10.8% of the sample used e-cigarettes in the three months prior to the pregnancy while 7.0%, 5.8%, and 1.4% used these products at the time of the pregnancy, in the first trimester, and at birth respectively.[109] According to National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from 2014 to 2017, 38.9% of pregnant smokers used e-cigarettes compared to only 13.5% of non-pregnant, reproductive age women smokers.[110] A health economic study found that passing an e-cigarette minimum legal sale age law in the United States increased teenage prenatal smoking by 0.6 percentage points and had no effect on birth outcomes.[111] Nevertheless, additional research needs to be done on the health effects of electronic cigarette use during pregnancy.[112][113]

According to the CDC, E-cigarettes are not safe during pregnancy. «Although the aerosol of e-cigarettes generally has fewer harmful substances than cigarette smoke, e-cigarettes and other products containing nicotine are not safe to use during pregnancy. Nicotine is a health danger for pregnant women and developing babies and can damage a developing baby’s brain and lungs. Also, some of the flavorings used in e-cigarettes may be harmful to a developing baby.»[114]

Harm reduction

Harm reduction refers to any reduction in harm from a prior level.[116] Harm minimization strives to reduce harms to the lowest achievable level.[116] When a person does not want to quit nicotine, harm minimization means striving to eliminate tobacco exposure by replacing it with vaping.[116] E-cigarettes can reduce smokers’ exposure to carcinogens and other toxic chemicals found in tobacco.[4]

Tobacco harm reduction has been a controversial area of tobacco control.[117] Health advocates have been slow to support a harm reduction method out of concern that tobacco companies cannot be trusted to sell products that will lower the risks associated with tobacco use.[117] A large number of smokers want to reduce harm from smoking by using e-cigarettes.[118] The argument for harm reduction does not take into account the adverse effects of nicotine.[47] There cannot be a defensible reason for harm reduction in children who are vaping with a base of nicotine.[119] Quitting smoking is the most effective strategy to tobacco harm reduction.[120]

Tobacco smoke contains 100 known carcinogens and 900 potentially cancer-causing chemicals, but e-cigarette vapor contains less of the potential carcinogens than found in tobacco smoke.[121] A study in 2015 using a third-generation device found levels of formaldehyde were greater than with cigarette smoke when adjusted to a maximum power setting.[122] E-cigarettes cannot be considered safe because there is no safe level for carcinogens.[117] Due to their similarity to traditional cigarettes, e-cigarettes could play a valuable role in tobacco harm reduction.[123] However, the public health community remains divided concerning the appropriateness of endorsing a device whose safety and efficacy for smoking cessation remain unclear.[123] Overall, the available evidence supports the cautionary implementation of harm reduction interventions aimed at promoting e-cigarettes as attractive and competitive alternatives to cigarette smoking, while taking measures to protect vulnerable groups and individuals.[123]

The core concern is that smokers who could have quit entirely will develop an alternative nicotine addiction.[117] Dual use may be an increased risk to a smoker who continues to use even a minimal amount of traditional cigarettes, rather than quitting.[84] Because of the convenience of e-cigarettes, it may further increase the risk of addiction.[124] The promotion of vaping as a harm reduction aid is premature,[125] while a 2011 review found they appear to have the potential to lower tobacco-related death and disease.[117] Evidence to substantiate the potential of vaping to lower tobacco-related death and disease is unknown.[126] The health benefits of reducing cigarette use while vaping is unclear.[127] E-cigarettes could have an influential role in tobacco harm reduction.[123] The authors warned against the potential harm of excessive regulation and advised health professionals to consider advising smokers who are reluctant to quit by other methods to switch to e-cigarettes as a safer alternative to smoking.[128] A 2014 review recommended that regulations for e-cigarettes could be similar to those for dietary supplements or cosmetic products to not limit their potential for harm reduction.[129] A 2012 review found e-cigarettes could considerably reduce traditional cigarettes use and they likely could be used as a lower risk replacement for traditional cigarettes, but there is not enough data on their safety and efficacy to draw definite conclusions.[130] There is no research available on vaping for reducing harm in high-risk groups such as people with mental disorders.[131]

A 2014 PHE report concluded that hazards associated with products currently on the market are probably low, and apparently much lower than smoking.[118] However, harms could be reduced further through reasonable product standards.[118] The British Medical Association encourages health professionals to recommend conventional nicotine replacement therapies, but for patients unwilling to use or continue using such methods, health professionals may present e-cigarettes as a lower-risk option than tobacco smoking.[132] The American Association of Public Health Physicians (AAPHP) suggests those who are unwilling to quit tobacco smoking or unable to quit with medical advice and pharmaceutical methods should consider other nicotine-containing products such as e-cigarettes and smokeless tobacco for long-term use instead of smoking.[133] A 2014 WHO report concluded that some smokers will switch completely to e-cigarettes from traditional tobacco but a «sizeable» number will use both.[62] This report found that such «dual-use» of e-cigarettes and tobacco «will have much smaller beneficial effects on overall survival compared with quitting smoking completely.»[62]

Smoking cessation

The use of e-cigarettes for quitting smoking is controversial.[134] Limited evidence suggests that e-cigarettes probably do help people to stop smoking when used in clinical settings.[24] However, according to a review article by Hussein Traboulsi et al. in May 2020, a study by Dr Peter Hajek also resulted in more smokers becoming dual users than succeeded in complete abstinence; «Nonetheless, the continued use of and dependence on nicotine and the creation of dual users were issues in this trial…Additionally, while 18% of the e-cigarette users achieved complete abstinence, 25% (110/438) became dual users of e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes.»[135] Data regarding their use includes at least 26 randomized controlled trials[24] and a number of user surveys, case reports, and cohort studies.[136] At least once recent review (2019) found that vaping did not seem to greatly increase the odds of quitting smoking.[137] As a result of the data being confronted with methodological and study design limitations, no firm conclusions can be drawn in respect to their efficacy and safety.[138] A 2016 review found that the combined abstinence rate among smokers using e-cigarettes in prospective studies was 29.1%.[134] The same review noted that few clinical trials and prospective studies had yet been conducted on their effectiveness, and only one randomized clinical trial had included a group using other quit smoking methods.[134] No long-term trials have been conducted for their use as a smoking cessation aid.[139] It is still not evident as to whether vaping can adequately assist with quitting smoking at the population level.[140] A 2015 PHE report recommends for smokers who cannot or do not want to quit to use e-cigarettes as one of the main steps to lower smoking-related disease,[141] while a 2015 US PSTF statement found there is not enough evidence to recommend e-cigarettes for quitting smoking in adults, pregnant women, and adolescents.[53] In 2021 the US PSTF concluded the evidence is still insufficient to recommend e-cigarettes for quitting smoking, finding that the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined.[142] As of January 2018, systematic reviews collectively agreed that there is insufficient evidence to unequivocally determine whether vaping helped people abstain from smoking.[143] A 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 studies found that on the whole as consumer products e-cigarettes do not increase quitting smoking.[25] A 2021 review came to the same conclusion.[26]

A recent 2022 study showed that E-cigarettes could actually lead people to smoke tobacco. Because the nicotine in e-cigarettes is addicting, it can cause new smokers to try tobacco and can cause current smokers to revert to using cigarettes[94]

One trial studied the medical effects that dual smoking had on a person’s sleep. This trial was done to simulate a tobacco smoker using e-cigarettes to quit or reduce smoking. The results of this study showed that subjects who used e-cigarettes as well as ignitable tobacco had moderate to severe effects on their sleep. Patients reported irritability and trouble sleeping and restless sleep. The results indicated a positive correlation between increased dual smoking and sleeping troubles.[144]

A small number of studies have looked at whether using e-cigarettes reduces the number of cigarettes smokers consume.[145] E-cigarette use may decrease the number of cigarettes smoked,[146] but smoking just one to four cigarettes daily greatly increases the risk of cardiovascular disease compared to not smoking.[84] The extent to which decreasing cigarette smoking with vaping leads to quitting is unknown.[147]

It is unclear whether e-cigarettes are only helpful for particular types of smokers.[148] Vaping with nicotine may reduce tobacco use among daily smokers.[149] Whether vaping is effective for quitting smoking may depend on whether it was used as part of an effort to quit.[145]

Comparing e-cigarettes to nicotine replacement therapy, a 2022 Cochrane review found «high-certainty evidence» that e-cigarettes with nicotine are more effective than nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) for quitting smoking (9 to 14 might successfully stop, compared to 6 of 100).[23] However, some studies have people who vaped were not more likely to give up smoking than people who did not vape.[150] and previous reviews have found that e-cigarettes were not been proven to be more effective than smoking cessation medicine[151][152] and regulated US FDA medicine.[153][154] A randomized trial stated 29% of e-cigarette users were still vaping at 6 months, while only 8% of patch users still wore patches at 6 months,[152] suggesting that some people are switching to cigarettes rather than fully quitting all tobacco use.[155] The potential adverse effects such as normalizing smoking have not been adequately studied.[156] While some surveys reported improved quitting smoking, particularly with intensive e-cigarette users, several studies showed a decline in quitting smoking in dual users of cigarettes and e-cigarettes.[3] Compared to many alternative quitting smoking medicines in early development in clinical trials including e-cigarettes, cytisine may be the most encouraging in efficacy and safety with an inexpensive price.[157] Other kinds of nicotine replacement products are usually covered by health systems, but because e-cigarettes are not medically licensed they are not covered.[155]

One of the challenges in studying e-cigarettes is that there are hundreds of brands and models of e-cigarettes sold that vary in the design and operation of the devices and composition of the liquid, and the technology continues to change.[99] E-cigarettes have not been subjected to the same type of efficacy testing as nicotine replacement products.[158] There are also social concerns — use of e-cigarettes may normalize tobacco use and prolong cigarette use for people who could have quit instead, or it could put extra pressure on smokers to stop cigarette smoking because e-cigarettes are a more socially acceptable alternative.[123] The evidence indicates smokers are more frequently able to completely quit smoking using tank devices compared to cigalikes, which may be due to their more efficient nicotine delivery.[159] There is low quality evidence that vaping assists smokers to quit smoking in the long-term compared with nicotine-free vaping.[159] Nicotine-containing e-cigarettes were associated with greater effectiveness for quitting smoking than e-cigarettes without nicotine.[160] A 2013 study in smokers who were not trying to quit, found that vaping, with or without nicotine decreased the number of cigarettes consumed.[161] E-cigarettes without nicotine may reduce tobacco cravings because of the smoking-related physical stimuli.[117] A 2015 meta-analysis on clinical trials found that e-cigarettes containing nicotine are more effective than nicotine-free ones for quitting smoking.[160] They compared their finding that nicotine-containing e-cigarettes helped 20% of people quit with the results from other studies that found nicotine replacement products helps 10% of people quit.[160] A 2016 review found low quality evidence of a trend towards benefit of e-cigarettes with nicotine for smoking cessation.[138] In terms of whether flavored e-cigarettes assisted quitting smoking, the evidence is inconclusive.[88] Tentative evidence indicates that health warnings on vaping products may influence users to give up vaping.[162]

As of 2020, the efficacy and safety of vaping for quitting smoking during pregnancy was unknown.[163] No research is available to provide details on the efficacy of vaping for quitting smoking during pregnancy.[126] There is robust evidence that vaping is not effective for quitting smoking among adolescents.[89] In view of the shortage of evidence, vaping is not recommend for cancer patients, although for all patients vaping is likely less dangerous than smoking cigarettes.[164] The effectiveness of vaping for quitting smoking among vulnerable groups is uncertain.[165]

Safety

As of 2015, research had not yet provided a consensus on the risks of e-cigarette use.[154][53][153] There is little data about their safety, and a considerable variety of liquids are used as carriers,[166] and thus are present in the aerosol delivered to the user.[84] Reviews of the safety of e-cigarettes have reached quite different conclusions.[167] A 2014 WHO report cautioned about potential risks of using e-cigarettes.[168] Regulated US FDA products such as nicotine inhalers may be safer than e-cigarettes,[125] but e-cigarettes are generally seen as safer than combusted tobacco products[90][98] such as cigarettes and cigars.[90] The risk of early death is anticipated to be similar to that of smokeless tobacco.[169] Since vapor does not contain tobacco and does not involve combustion, users may avoid several harmful constituents usually found in tobacco smoke,[170] such as ash, tar, and carbon monoxide.[171] However, e-cigarette use with or without nicotine cannot be considered risk-free[172] because the long-term effects of e-cigarette use are unknown.[159][169][96]

The cytotoxicity of e-liquids varies,[174] and contamination with various chemicals have been detected in the liquid.[35] Metal parts of e-cigarettes in contact with the e-liquid can contaminate it with metal particles.[170] Many chemicals including carbonyl compounds such as formaldehyde can inadvertently be produced when the nichrome wire (heating element) that touches the e-liquid is heated and chemically reacted with the liquid.[175] Normal usage of e-cigarettes,[122] and reduced voltage (3.0 V[2]) devices generate very low levels of formaldehyde.[175] The later-generation and «tank-style» e-cigarettes with a higher voltage (5.0 V[174]) may generate equal or higher levels of formaldehyde compared to smoking.[3] A 2015 report by Public Health England found that high levels of formaldehyde only occurred in overheated «dry-puffing».[176] Users detect the «dry puff» (also known as a «dry hit»[177]) and avoid it, and they concluded that «There is no indication that EC users are exposed to dangerous levels of aldehydes.»[176] However, e-cigarette users may «learn» to overcome the unpleasant taste due to elevated aldehyde formation, when the nicotine craving is high enough.[178] Another common chemical found in e-cigarettes is ketene. When it enters the lungs after inhaled, this chemical causes damage to the cellular structure of lung tissue causing the cells to not function at maximum capacity and not absorb gasses as readily. This can cause shortness of breath which can lead to other health conditions such as tachycardia and respiratory failure. E-cigarette users who use devices that contain nicotine are exposed to its potentially harmful effects.[93] Nicotine is associated with cardiovascular disease, possible birth defects, and poisoning.[158] In vitro studies of nicotine have associated it with cancer, but carcinogenicity has not been demonstrated in vivo.[158] There is inadequate research to show that nicotine is associated with cancer in humans.[179] The risk is probably low from the inhalation of propylene glycol and glycerin.[128] No information is available on the long-term effects of the inhalation of flavors.[35]

In October 2021, researchers at Johns Hopkins University reported over 2,000 unknown chemicals in the vape clouds that they tested from Vuse, Juul, Blu and Mi-Salt vape devices.[180]

In 2019–2020, there was an outbreak of vaping-related lung illness in the US and Canada, primarily related to vaping THC with vitamin E acetate.[181][182]

E-cigarettes create vapor that consists of fine and ultrafine particles of particulate matter, with the majority of particles in the ultrafine range.[84] The vapor have been found to contain propylene glycol, glycerin, nicotine, flavors, small amounts of toxicants,[84] carcinogens,[128] and heavy metals, as well as metal nanoparticles, and other substances.[84] Many carcinogenic compounds have been detected in e-cigarettes, such as N-Nitrosonornicotine (NNN), N-Nitrosoanatabine (NAT), etc., all of which have been proven to be harmful to human health.[183] Exactly what the vapor consists of varies in composition and concentration across and within manufacturers, and depends on the contents of the liquid, the physical and electrical design of the device, and user behavior, among other factors.[2] E-cigarette vapor potentially contains harmful chemicals not found in tobacco smoke.[91] The majority of toxic chemicals found in cigarette smoke are absent in e-cigarette vapor.[184] E-cigarette vapor contains lower concentrations of potentially toxic chemicals than with cigarette smoke.[185] Those which are present, are mostly below 1% of the corresponding levels permissible by workplace safety standards.[98] But workplace safety standards do not recognize exposure to certain vulnerable groups such as people with medical ailments, children, and infants who may be exposed to second-hand vapor.[84] Concern exists that some of the mainstream vapor exhaled by e-cigarette users may be inhaled by bystanders, particularly indoors,[45] although e-cigarette pollutant levels are much lower than for cigarettes and likely to pose a much lower risk, if any, compared to cigarettes.[128] E-cigarette use by a parent might lead to inadvertent health risks to offspring.[36] A 2014 review recommended that e-cigarettes should be regulated for consumer safety.[129] There is limited information available on the environmental issues around production, use, and disposal of e-cigarettes that use cartridges.[186] E-cigarettes that are not reusable may contribute to the problem of electronic waste.[131]

Addiction

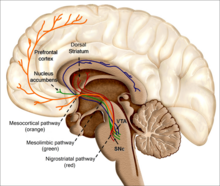

Nicotine, a key ingredient[187] in most e-liquids,[note 4][4] is well-recognized as one of the most addictive substances, as addictive as heroin and cocaine.[31] Addiction is believed to be a disorder of experience-dependent brain plasticity.[189] The reinforcing effects of nicotine play a significant role in the beginning and continuing use of the drug.[190] First-time nicotine users develop a dependence about 32% of the time.[191] Chronic nicotine use involves both psychological and physical dependence.[192] Nicotine-containing e-cigarette vapor induces addiction-related neurochemical, physiological and behavioral changes.[193] Nicotine affects neurological, neuromuscular, cardiovascular, respiratory, immunological and gastrointestinal systems.[194] Neuroplasticity within the brain’s reward system occurs as a result of long-term nicotine use, leading to nicotine dependence.[195] The neurophysiological activities that are the basis of nicotine dependence are intricate.[196] It includes genetic components, age, gender, and the environment.[196] Nicotine addiction is a disorder which alters different neural systems such as dopaminergic, glutamatergic, GABAergic, serotoninergic, that take part in reacting to nicotine.[197] Long-term nicotine use affects a broad range of genes associated with neurotransmission, signal transduction, and synaptic architecture.[198] The ability to quitting smoking is affected by genetic factors, including genetically based differences in the way nicotine is metabolized.[199]

The reinforcing effects of addictive drugs, such as nicotine, are associated with its ability to excite the mesolimbic and dopaminergic systems.[200]

How does the nicotine in e-cigarettes affect the brain?[201] Until about age 25, the brain is still growing.[201] Each time a new memory is created or a new skill is learned, stronger connections – or synapses – are built between brain cells.[201] Young people’s brains build synapses faster than adult brains.[201] Because addiction is a form of learning, adolescents can get addicted more easily than adults.[201] The nicotine in e-cigarettes and other tobacco products can also prime the adolescent brain for addiction to other drugs such as cocaine.[201]

Nicotine is a parasympathomimetic stimulant[202] that binds to and activates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain,[147] which subsequently causes the release of dopamine and other neurotransmitters, such as norepinephrine, acetylcholine, serotonin, gamma-aminobutyric acid, glutamate, endorphins,[203] and several neuropeptides, including proopiomelanocortin-derived α-MSH and adrenocorticotropic hormone.[204] Corticotropin-releasing factor, Neuropeptide Y, orexins, and norepinephrine are involved in nicotine addiction.[205] Continuous exposure to nicotine can cause an increase in the number of nicotinic receptors, which is believed to be a result of receptor desensitization and subsequent receptor upregulation.[203] Long-term exposure to nicotine can also result in downregulation of glutamate transporter 1.[206] Long-term nicotine exposure upregulates cortical nicotinic receptors, but it also lowers the activity of the nicotinic receptors in the cortical vasodilation region.[207] These effects are not easily understood.[207] With constant use of nicotine, tolerance occurs at least partially as a result of the development of new nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain.[203] After several months of nicotine abstinence, the number of receptors go back to normal.[147] The extent to which alterations in the brain caused by nicotine use are reversible is not fully understood.[198] Nicotine also stimulates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the adrenal medulla, resulting in increased levels of epinephrine and beta-endorphin.[203] Its physiological effects stem from the stimulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, which are located throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems.[208]

When nicotine intake stops, the upregulated nicotinic acetylcholine receptors induce withdrawal symptoms.[147] These symptoms can include cravings for nicotine, anger, irritability, anxiety, depression, impatience, trouble sleeping, restlessness, hunger, weight gain, and difficulty concentrating.[209] When trying to quit smoking with vaping a base containing nicotine, symptoms of withdrawal can include irritability, restlessness, poor concentration, anxiety, depression, and hunger.[138] The changes in the brain cause a nicotine user to feel abnormal when not using nicotine.[210] In order to feel normal, the user has to keep his or her body supplied with nicotine.[210] E-cigarettes may reduce cigarette craving and withdrawal symptoms.[211] It is not clear whether e-cigarette use will decrease or increase overall nicotine addiction,[212] but the nicotine content in e-cigarettes is adequate to sustain nicotine dependence.[213] Chronic nicotine use causes a broad range of neuroplastic adaptations, making quitting hard to accomplish.[196] A 2015 study found that users vaping non-nicotine e-liquid exhibited signs of dependence.[214] Experienced users tend to take longer puffs which may result in higher nicotine intake.[101] It is difficult to assess the impact of nicotine dependence from e-cigarette use because of the wide range of e-cigarette products.[213] The addiction potential of e-cigarettes may have risen because as they have progressed, they have delivered nicotine better.[215]

A 2015 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) policy statement stressed «the potential for these products to addict a new generation of youth to nicotine and reverse more than 50 years of public health gains in tobacco control.»[216] The World Health Organization (WHO) is concerned about starting nicotine use among non-smokers,[62] and the National Institute on Drug Abuse said e-cigarettes could maintain nicotine addiction in those who are attempting to quit.[217] The limited available data suggests that the likelihood of excessive use of e-cigarettes is smaller than traditional cigarettes.[218] No long-term studies have been done on the effectiveness of e-cigarettes in treating tobacco addiction,[125] but some evidence suggests that dual use of e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes may be associated with greater nicotine dependence.[3]

There is concern that children may progress from vaping to smoking.[62] Adolescents are likely to underestimate nicotine’s addictiveness.[219] Vulnerability to the brain-modifying effects of nicotine, along with youthful experimentation with e-cigarettes, could lead to a lifelong addiction.[92] A long-term nicotine addiction from using a vape may result in using other tobacco products.[220] The majority of addiction to nicotine starts during youth and young adulthood.[221] Adolescents are more likely to become nicotine dependent than adults.[89] The adolescent brain seems to be particularly sensitive to neuroplasticity as a result of nicotine.[198] Minimal exposure could be enough to produce neuroplastic alterations in the very sensitive adolescent brain.[198] A 2014 review found that in studies up to a third of youth who have not tried a traditional cigarette have used e-cigarettes.[84] The degree to which teens are using e-cigarettes in ways the manufacturers did not intend, such as increasing the nicotine delivery, is unknown,[222] as is the extent to which e-cigarette use may lead to addiction or substance dependence in youth.[222]

Positions

Because of overlap with tobacco laws and medical drug policies, e-cigarette legislation is being debated[when?] in many countries.[184] The revised EU Tobacco Products Directive came into effect in May 2016, providing stricter regulations for e-cigarettes.[223] In February 2010 the US District Court ruled against the FDA’s seizure of E-Cigarettes as a «drug-device» and in December 2010 the US Court of Appeals confirmed them to be tobacco products which were by then subject to regulation under the 2009 FSPTC Act.[224] In August 2016, the US FDA extended its regulatory power to include e-cigarettes, cigars, and «all other tobacco products».[225] Large tobacco companies have[when?] greatly increased their marketing efforts.[125]

The scientific community in US and Europe are primarily concerned with their possible effect on public health.[226] There is concern among public health experts that e-cigarettes could renormalize smoking, weaken measures to control tobacco,[227] and serve as a gateway for smoking among youth.[228] The public health community is divided over whether to support e-cigarettes, because their safety and efficacy for quitting smoking is unclear.[123] Many in the public health community acknowledge the potential for their quitting smoking and decreasing harm benefits, but there remains a concern over their long-term safety and potential for a new era of users to get addicted to nicotine and then tobacco.[228] There is concern among tobacco control academics and advocates that prevalent universal vaping «will bring its own distinct but as yet unknown health risks in the same way tobacco smoking did, as a result of chronic exposure», among other things.[136]

Medical organizations differ in their views about the health implications of vaping.[229] There is general agreement that e-cigarettes expose users to fewer toxicants than tobacco cigarettes.[159] Some healthcare groups and policy makers have hesitated to recommend e-cigarettes for quitting smoking, because of limited evidence of effectiveness and safety.[159] Some have advocated bans on e-cigarette sales and others have suggested that e-cigarettes may be regulated as tobacco products but with less nicotine content or be regulated as a medicinal product.[99]

A 2019 World Health Organization (WHO) report found that the scientific evidence «does not support the tobacco industry’s claim that these products are less harmful relative to conventional tobacco products» and that there is insufficient evidence to support vaping as a smoking cessation tool.[230][231][232] Healthcare organizations in the UK (including the Royal College of Physicians and Public Health England) have encouraged smokers to switch to e-cigarettes or other nicotine replacements if they cannot quit, as this would potentially save millions of lives.[233][234] The American Cancer Society,[235] American Heart Association,[236] and the surgeon general of the United States have cautioned that accumulating evidence indicates e-cigarettes may have negative effects on the heart and lungs and should not be used to quit smoking without sufficient evidence that they are safe and effective.[237] In 2016, the US Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) stated that «Although ENDS [electronic nicotine delivery systems] may potentially provide cessation benefits to individual smokers, no ENDS have been approved as effective cessation aids.»[238] In 2019 the European Respiratory Society stated that «The long-term effects of ECIG use are unknown, and there is therefore no evidence that ECIGs are safer than tobacco in the long term»[96] and that «[t]he tobacco harm reduction strategy is based on well-meaning but incorrect or undocumented claims or assumptions.»[239][232] Following hundreds of possible cases of severe lung illness and five confirmed deaths associated with vaping in the US, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated on 6 September 2019 that people should consider not using vaping products while their investigation is ongoing.[240]

History

It is commonly stated that the modern e-cigarette was invented in 2003 by Chinese pharmacist Hon Lik, but tobacco companies had been developing nicotine aerosol generation devices since as early as 1963.[241]

Early prototypes & barriers to entry: 1920s – 90s

In 1927, Joseph Robinson applied for a patent for an electronic vaporizer to be used with medicinal compounds.[242] The patent was approved in 1930 but the device was never marketed.[243] In 1930, the United States Patent and Trademark Office reported a patent stating, «for holding medicinal compounds which are electrically or otherwise heated to produce vapors for inhalation.»[244] In 1934 and 1936, further similar patents were applied for.[244]

The earliest e-cigarette can be traced to American Herbert A. Gilbert,[245] who in 1963 applied for a patent for «a smokeless non-tobacco cigarette» that involved «replacing burning tobacco and paper with heated, moist, flavored air».[246][247] This device produced flavored steam without nicotine.[247] The patent was granted in 1965.[248] Gilbert’s invention was ahead of its time[249] and received little attention[250] and was never commercialized[247] because smoking was still fashionable at that time.[251] Gilbert said in 2013 that today’s electric cigarettes follow the basic design set forth in his original patent.[248]

The Favor cigarette, introduced in 1986 by public company Advanced Tobacco Products, was another early noncombustible product promoted as an alternative nicotine-containing tobacco product.[86] Favor was conceptualized by Phil Ray, one of the founders of Datapoint Corporation and inventors of the microprocessor. Development started in 1979 by Phil Ray and Norman Jacobson.[252] Favor was a «plastic, smoke-free product shaped and colored like a conventional cigarette that contained a filter paper soaked with liquid nicotine so users could draw a small dose by inhaling. There was no electricity, combustion, or smoke; it delivered only nicotine.»[253] Favor cigarettes were sold in California and several Southwestern states, marketed as «an alternative to smokers, and only to smokers, to use where smoking is unacceptable or prohibited.»[254] In 1987 the FDA exercised jurisdiction over products analogous to E-Cigarettes.[255] Advanced Tobacco Products never challenged the Warning Letter and ceased all distribution of Favor.[256] Rays’s wife Brenda Coffee coined the term vaping.[257] Philip Morris’ division NuMark, launched in 2013 the MarkTen e-cigarette that Philip Morris had been working on since 1990.[241]

Modern electronic cigarette: 2000s

Despite these earlier efforts, Hon Lik, a Chinese pharmacist and inventor, who worked as a research pharmacist for a company producing ginseng products,[258] is frequently credited with the invention of the modern e-cigarette.[241] Hon quit smoking after his father, also a heavy smoker, died of lung cancer.[258] In 2001, he thought of using a high frequency, piezoelectric ultrasound-emitting element to vaporize a pressurized jet of liquid containing nicotine.[259] This design creates a smoke-like vapor.[258] Hon said that using resistance heating obtained better results and the difficulty was to scale down the device to a small enough size.[259] Hon’s invention was intended to be an alternative to smoking.[259] Hon Lik sees the e-cigarette as comparable to the «digital camera taking over from the analogue camera.»[260] Ultimately, Hon Lik did not quit smoking. He is now a dual user, both smoking and vaping.[261]

The Ruyan e-cigar was first launched in China in 2004.[262]

Hon Lik registered a patent for the modern e-cigarette design in 2003.[259] Hon is credited with developing the first commercially successful electronic cigarette.[263] The e-cigarette was first introduced to the Chinese domestic market in 2004.[258] Many versions made their way to the US, sold mostly over the Internet by small marketing firms.[258] E-cigarettes entered the European market and the US market in 2006 and 2007.[193] The company that Hon worked for, Golden Dragon Holdings, registered an international patent in November 2007.[264] The company changed its name to Ruyan (如烟, literally «like smoke»[258]) later the same month,[265] and started exporting its products.[258] Many US and Chinese e-cigarette makers copied his designs illegally, so Hon has not received much financial reward for his invention (although some US manufacturers have compensated him through out-of-court settlements).[260] Ruyan later changed its company name to Dragonite International Limited.[265] As of 2014, most e-cigarettes used a battery-powered heating element rather than the earlier ultrasonic technology design.[28]

Initially, their performance did not meet the expectations of users.[266] The e-cigarette continued to evolve from the first-generation three-part device.[28] In 2007 British entrepreneurs Umer and Tariq Sheikh invented the cartomizer.[267] This is a mechanism that integrates the heating coil into the liquid chamber.[267] They launched this new device in the UK in 2008 under their Gamucci brand[268] and the design is now widely adopted by most «cigalike» brands.[28] Other users tinkered with various parts to produce more satisfactory homemade devices, and the hobby of «modding» was born.[269] The first mod to replace the e-cigarette’s case to accommodate a longer-lasting battery, dubbed the «screwdriver», was developed by Ted and Matt Rogers[269] in 2008.[266] Other enthusiasts built their own mods to improve functionality or aesthetics.[269] When pictures of mods appeared at online vaping forums many people wanted them, so some mod makers produced more for sale.[269]

In 2008, a consumer-created an e-cigarette called the screwdriver.[266] The device generated a lot of interest back then, as it let the user to vape for hours at one time.[269] The invention led to demand for customizable e-cigarettes, prompting manufacturers to produce devices with interchangeable components that could be selected by the user.[266] In 2009, Joyetech developed the eGo series[267] which offered the power of the screwdriver model and a user-activated switch to a wide market.[266] The clearomizer was invented in 2009.[267] Originating from the cartomizer design, it contained the wicking material, an e-liquid chamber, and an atomizer coil within a single clear component.[267] The clearomizer allows the user to monitor the liquid level in the device.[267] Soon after the clearomizer reached the market, replaceable atomizer coils and variable voltage batteries were introduced.[267] Clearomizers and eGo batteries became the best-selling customizable e-cigarette components in early 2012.[266]

International growth: 2010s – present

| Tobacco company | Subsidiary company | Electronic cigarette |

|---|---|---|

| Imperial Tobacco | Fontem Ventures and Dragonite | Puritane[174] blu eCigs[270] |

| British American Tobacco | CN Creative and Nicoventures | Vype[174] |

| R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company | R. J. Reynolds Vapor Company | Vuse[174] |

| Altria ∗No longer sells e-cigarettes.[271] Altria acquired a 30% stake in Juul Labs.[272] |

Nu Mark, LLC[174] | MarkTen, Green Smoke[271] |

| Japan Tobacco International | Ploom | E-lites[174] LOGIC[273] |

International tobacco companies dismissed e-cigarettes as a fad at first.[274] However, recognizing the development of a potential new market sector that could render traditional tobacco products obsolete,[275] they began to produce and market their own brands of e-cigarettes and acquire existing e-cigarette companies.[276] They bought the largest e-cigarette companies.[123] blu eCigs, a prominent US e-cigarette manufacturer, was acquired by Lorillard Inc.[277] for $135 million in April 2012.[278] British American Tobacco was the first tobacco business to sell e-cigarettes in the UK.[279] They launched the e-cigarette Vype in July 2013,[279] while Imperial Tobacco’s Fontem Ventures acquired the intellectual property owned by Hon Lik through Dragonite International Limited for $US 75 million in 2013 and launched Puritane in partnership with Boots UK.[280] On 1 October 2013 Lorillard Inc. acquired another e-cigarette company, this time the UK based company SKYCIG.[281] SKY was rebranded as blu.[282] On 3 February 2014, Altria Group, Inc. acquired popular e-cigarette brand Green Smoke for $110 million.[283] The deal was finalized in April 2014 for $110 million with $20 million in incentive payments.[284] Altria also markets its own e-cigarette, the MarkTen, while Reynolds American has entered the sector with its Vuse product.[276] Philip Morris, the world’s largest tobacco company, purchased UK’s Nicocigs in June 2014.[285] On 30 April 2015, Japan Tobacco bought the US Logic e-cigarette brand.[273] Japan Tobacco also bought the UK E-Lites brand in June 2014.[273] On 15 July 2014, Lorillard sold blu to Imperial Tobacco as part of a deal for $7.1 billion.[270] As of 2018, 95% of e-cigarettes were made in China.[31]

In the UK, where most vaping uses refillable sets and e-liquid, there is now support from the National Health Service,[286] and other medical bodies now embrace the use of e-cigarettes as a viable way to quit smoking. This has contributed to record numbers of people vaping, with current vapers over 3.6 million as of June 2021.[287]

Society and culture

«Vaper» redirects here. Not to be confused with Vapor.

Consumers have shown passionate support for e-cigarettes that other nicotine replacement products did not receive.[118] They have a mass appeal that could challenge combustible tobacco’s market position.[118]

By 2013, a subculture had emerged calling itself «the vaping community».[288][289] Members often see e-cigarettes as a safer alternative to smoking,[128] and some view it as a hobby.[290] The online forum E-Cig-Reviews.com was one of the first major communities.[269] It and other online forums, such as UKVaper.org, were where the hobby of modding started.[269] There are also groups on Facebook and Reddit.[291] Online forums based around modding have grown in the vaping community.[292] Vapers embrace activities associated with e-cigarettes and sometimes evangelise for them.[293] E-cigarette companies have a substantial online presence, and there are many individual vapers who blog and tweet about e-cigarette related products.[294] A 2014 Postgraduate Medical Journal editorial said vapers «also engage in grossly offensive online attacks on anyone who has the temerity to suggest that ENDS are anything other than an innovation that can save thousands of lives with no risks».[294]

Contempt for Big Tobacco is part of vaping culture.[295][296] A 2014 review stated that tobacco and e-cigarette companies interact with consumers for their policy agenda.[84] The companies use websites, social media, and marketing to get consumers involved in opposing bills that include e-cigarettes in smoke-free laws.[84] This is similar to tobacco industry activity going back to the 1980s.[84] These approaches were used in Europe to minimize the EU Tobacco Products Directive in October 2013.[84] Grassroots lobbying also influenced the Tobacco Products Directive decision.[297] Tobacco companies have worked with organizations conceived to promote e-cigarette use, and these organizations have worked to hamper legislation intended at restricting e-cigarette use.[125]

A popular vaporizer used by American youth is Juul.[298] Close to 80% of respondents in a 2017 Truth Initiative study aged 15–24 reported using Juul also used the device in the last 30 days.[299] Teenagers use the verb «Juuling» to describe their use of Juul,[300] and Juuling is the subject of many memes on social media.[301] Students have commented on Twitter about using Juul in class.[302]

E-cigarette user blowing a cloud of aerosol (vapor). The activity is known as cloud-chasing.[303]

Large gatherings of vapers, called vape meets, take place around the US.[288] They focus on e-cigarette devices, accessories, and the lifestyle that accompanies them.[288] Vapefest, which started in 2010, is an annual show hosted by different cities.[291] People attending these meetings are usually enthusiasts that use specialized, community-made products not found in convenience stores or gas stations.[288] These products are mostly available online or in dedicated «vape» storefronts where mainstream e-cigarettes brands from the tobacco industry and larger e-cig manufacturers are not as popular.[304] Some vape shops have a vape bar where patrons can test out different e-liquids and socialize.[305] The Electronic Cigarette Convention in North America which started in 2013, is an annual show where companies and consumers meet up.[306]

A subclass of vapers configure their atomizers to produce large amounts of vapor by using low-resistance heating coils.[307] This practice is called «cloud-chasing».[308] By using a coil with very low resistance, the batteries are stressed to a potentially unsafe extent.[309] This could present a risk of dangerous battery failures.[309] As vaping comes under increased scrutiny, some members of the vaping community have voiced their concerns about cloud-chasing, stating the practice gives vapers a bad reputation when doing it in public.[310] The Oxford Dictionaries’ word of the year for 2014 was «vape».[311]

Regulation

Regulation of e-cigarettes varies across countries and states, ranging from no regulation to banning them entirely.[312] For instance, e-cigarettes containing nicotine are illegal in Japan, forcing the market to use heated tobacco products for cigarette alternatives.[313] Others have introduced strict restrictions and some have licensed devices as medicines such as in the UK.[157] However, as of February 2018, there is no e-cigarette device that has been given a medical license that is commercially sold or available by prescription in the UK.[314] As of 2015, around two thirds of major nations have regulated e-cigarettes in some way.[315] Because of the potential relationship with tobacco laws and medical drug policies, e-cigarette legislation is being debated in many countries.[184] The companies that make e-cigarettes have been pushing for laws that support their interests.[316] In 2016 the US Department of Transportation banned the use of e-cigarettes on commercial flights.[317] This regulation applies to all flights to and from the US.[317] In 2018, the Royal College of Physicians asked that a balance is found in regulations over e-cigarettes that ensure product safety while encouraging smokers to use them instead of tobacco, as well as keep an eye on any effects contrary to the control agencies for tobacco.[318]

The legal status of e-cigarettes is currently pending in many countries.[84] Many countries such as Brazil, Singapore, Uruguay,[157] and India have banned e-cigarettes.[319] Canada-wide in 2014, they were technically illegal to sell, as no nicotine-containing e-cigarettes are not regulated by Health Canada, but this is generally unenforced and they are commonly available for sale Canada-wide.[320] In 2016, Health Canada announced plans to regulate vaping products.[321] In the US and the UK, the use and sale to adults of e-cigarettes are legal.[322]: US [323]: UK The revised EU Tobacco Products Directive came into effect in May 2016, providing stricter regulations for e-cigarettes.[223] It limits e-cigarette advertising in print, on television and radio, along with reducing the level of nicotine in liquids and reducing the flavors used.[324] It does not ban vaping in public places.[325] It requires the purchaser for e-cigarettes to be at least 18 and does not permit buying them for anyone less than 18 years of age.[326] The updated Tobacco Products Directive has been disputed by tobacco lobbyists whose businesses could be impacted by these revisions.[327] As of 8 August 2016, the US FDA extended its regulatory power to include e-cigarettes, e-liquid and all related products.[225] Under this ruling the FDA will evaluate certain issues, including ingredients, product features and health risks, as well their appeal to minors and non-users.[328] The FDA rule also bans access to minors.[328] A photo ID is now required to buy e-cigarettes,[329] and their sale in all-ages vending machines is not permitted in the US.[328] As of August 2017, regulatory compliance deadlines relating to premarket review requirements for most e-cigarette and e-liquid products have been extended from November 2017 to 8 August 2022,[330][331] which attracted a lawsuit filed by the American Heart Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, and other plaintiffs.[332] In May 2016 the US FDA used its authority under the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act to deem e-cigarette devices and e-liquids to be tobacco products, which meant it intended to regulate the marketing, labelling, and manufacture of devices and liquids; vape shops that mix e-liquids or make or modify devices were considered manufacturing sites that needed to register with US FDA and comply with good manufacturing practice regulation.[238] E-cigarette and tobacco companies have recruited lobbyists in an effort to prevent the US FDA from evaluating e-cigarette products or banning existing products already on the market.[333]

In February 2014 the European Parliament passed regulations requiring standardization and quality control for liquids and vaporizers, disclosure of ingredients in liquids, and child-proofing and tamper-proofing for liquid packaging.[334] In April 2014 the US FDA published proposed regulations for e-cigarettes.[335][336] In the US some states tax e-cigarettes as tobacco products, and some state and regional governments have broadened their indoor smoking bans to include e-cigarettes.[337] As of April 2017, 12 US states and 615 localities had prohibited the use of e-cigarettes in venues in which traditional cigarette smoking was prohibited.[54] In 2015, at least 48 states and 2 territories had banned e-cigarette sales to minors.[338]

In November 2020, the New Zealand government passed a vaping regulation that requires vape stores to register as specialist vape retailers before they can sell e-cigarettes, the wider range of flavoured e-liquids, and other related vaping products. Vaping products are required to be notified by the government before they can be sold to ensure that the products are following safety requirements and ingredients in liquids do not contain prohibited substances.[339]

E-cigarettes containing nicotine have been listed as drug delivery devices in a number of countries, and the marketing of such products has been restricted or put on hold until safety and efficacy clinical trials are conclusive.[340] Since they do not contain tobacco, television advertising in the US is not restricted.[341] Some countries have regulated e-cigarettes as a medical product even though they have not approved them as a smoking cessation aid.[175] A 2014 review stated the emerging phenomenon of e-cigarettes has raised concerns in the health community, governments, and the general public and recommended that e-cigarettes should be regulated to protect consumers.[129] It added, «heavy regulation by restricting access to e-cigarettes would just encourage continuing use of much unhealthier tobacco smoking.»[129] A 2014 review said regulation of the e-cigarette should be considered on the basis of reported adverse health effects.[175]

Criticism of vaping bans

Critics of vaping bans state that vaping is a much safer alternative to smoking tobacco products and that vaping bans incentivize people to return to smoking cigarettes.[342] For example, critics cite the British Journal of Family Medicine in August 2015 which stated, «E-cigarettes are 95% safer than traditional smoking.»[343] Additionally, San Francisco’s chief economist, Ted Egan, when discussing the San Francisco vaping ban stated the city’s ban on e-cigarette sales will increase smoking as vapers switch to combustible cigarettes.[344] Critics of smoking bans stress the absurdity of criminalizing the sale of a safer alternative to tobacco while tobacco continues to be legal. Prominent proponents of smoking bans are not in favor of criminalizing tobacco either, but rather allowing consumers to have the choice to choose whatever products they desire.[342]

In 2022, after two years of review, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) denied Juul’s application to keep its tobacco and menthol flavored vaping products on the market.[345] Critics of this denial note that research published in Nicotine and Tobacco Research found that smokers who transitioned to Juuls in North America were significantly more likely to switch to vaping than those in the United Kingdom who only had access to lower-strength nicotine products.[346] This happens as the Biden Administration seeks to mandate low-nicotine cigarettes which, critics note, is not what makes cigarettes dangerous.[347] They also note that vaping does not contain many of the components that make smoking dangerous such as the combustion process and certain chemicals that are present in cigarettes that are not present in vape products.

Product liability

Multiple reports from the U.S. Fire Administration conclude that electronic cigarettes have been combusting and injuring people and surrounding areas.[348][349] The composition of a cigarette is the cause of this, as the cartridges that are meant to contain the liquid mixture are in such close proximity to the battery.[350] A research report by the U.S. Fire Administration supports this, stating that, «Unlike mobile phones, some e-cigarette lithium-ion batteries within e-cigarettes offer no protection to stop the coil overheating» .[349] In 2015 the U.S. Fire Administration noted in their report that electronic cigarettes are not created by Big Tobacco or other tobacco companies, but by independent factories that have little quality control.[349] Because of this low quality control when made, electronic cigarettes have led to incidents in which people are hurt, or in which the surrounding area is damaged.[349][348]

Marketing

They are marketed to men, women, and children as being safer than traditional cigarettes.[351] They are also marketed to non-smokers.[51] E-cigarette marketing is common.[227] There are growing concerns that e-cigarette advertising campaigns unjustifiably focus on young adults, adolescents, and women.[171] Large tobacco companies have greatly increased their marketing efforts.[125] This marketing trend may expand the use of e-cigarettes and contribute to re-glamorizing smoking.[352] Some companies may use e-cigarette advertising to advocate smoking, deliberately, or inadvertently, is an area of concern.[150] A 2014 review said, «the e-cigarette companies have been rapidly expanding using aggressive marketing messages similar to those used to promote cigarettes in the 1950s and 1960s.»[84] E-cigarette companies are using methods that were once used by the tobacco industry to persuade young people to start using cigarettes.[353] E-cigarettes are promoted to a certain extent to forge a vaping culture that entices non-smokers.[353] Themes in e-cigarette marketing, including sexual content and customer satisfaction, are parallel to themes and techniques that are appealing to youth and young adults in traditional cigarette advertising and promotion.[86] A 2017 review found «The tobacco industry sees a future where ENDS accompany and perpetuate, rather than supplant, tobacco use, especially targeting the youth.»[150] E-cigarettes and nicotine are regularly promoted as safe and even healthy in the media and on brand websites, which is an area of concern.[36]

While advertising of tobacco products is banned in most countries, television and radio e-cigarette advertising in several countries may be indirectly encouraging traditional cigarette use.[84] E-cigarette advertisements are also in magazines, newspapers, online, and in retail stores.[354] Between 2010 and 2014, e-cigarettes were second only to cigarettes as the top advertised product in magazines.[355] As cigarette companies have acquired the largest e-cigarette brands, they currently benefit from a dual market of smokers and e-cigarette users while simultaneously presenting themselves as agents of harm reduction.[123] This raises concerns about the appropriateness of endorsing a product that directly profits the tobacco industry.[123] There is no evidence that the cigarette brands are selling e-cigarettes as part of a plan to phase out traditional cigarettes, despite some stating to want to cooperate in «harm reduction».[84] E-cigarette advertising for using e-cigarettes as a quitting tool have been seen in the US, UK, and China, which have not been supported by regulatory bodies.[356] In the US, six large e-cigarette businesses spent $59.3 million on promoting e-cigarettes in 2013.[357] In the US and Canada, over $2 million is spent yearly on promoting e-cigarettes online.[353] E-cigarette websites often made unscientific health statements in 2012.[358] The ease to get past the age verification system at e-cigarette company websites allows underage individuals to access and be exposed to marketing.[358] Around half of e-cigarette company websites have a minimum age notice that prohibited underage individuals from entering.[51]

Celebrity endorsements are used to encourage e-cigarette use.[359] A 2012 national US television advertising campaign for e-cigarettes starred Stephen Dorff exhaling a «thick flume» of what the advertisement describes as «vapor, not tobacco smoke», exhorting smokers with the message «We are all adults here, it’s time to take our freedom back.»[278] Opponents of the tobacco industry state that the Blu advertisement, in a context of longstanding prohibition of tobacco advertising on television, seems to have resorted to advertising tactics that got former generations of people in the US addicted to traditional cigarettes.[278] Cynthia Hallett of Americans for Non-Smokers’ Rights described the US advertising campaign as attempting to «re-establish a norm that smoking is okay, that smoking is glamorous and acceptable».[278] University of Pennsylvania communications professor Joseph Cappella stated that the setting of the advertisement near an ocean was meant to suggest an association of clean air with the nicotine product.[278] In 2012 and 2013, e-cigarette companies advertised to a large television audience in the US which included 24 million youth.[360] The channels to which e-cigarette advertising reached the largest numbers of youth (ages 12–17) were AMC, Country Music Television, Comedy Central, WGN America, TV Land, and VH1.[360]

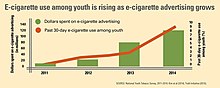

From 2011 to 2014, e-cigarette use among youth was rising as e-cigarette advertising increased.[361]

Since at least 2007, e-cigarettes have been heavily promoted across media outlets globally.[89] They are vigorously advertised, mostly through the Internet, as a safe substitute to traditional cigarettes, among other things.[45] E-cigarette companies promote their e-cigarette products on Facebook, Instagram,[354] YouTube, and Twitter.[362] They are promoted on YouTube by movies with sexual material and music icons, who encourage minors to «take their freedom back.»[150] They have partnered with a number of sports and music icons to promote their products.[363] Tobacco companies intensely market e-cigarettes to youth,[364] with industry strategies including cartoon characters and candy flavors.[365] Fruit flavored e-liquid is the most commonly marketed e-liquid flavor on social media.[366] E-cigarette companies commonly promote that their products contain only water, nicotine, glycerin, propylene glycol, and flavoring but this assertion is misleading as researchers have found differing amounts of heavy metals in the vapor, including chromium, nickel, tin, silver, cadmium, mercury, and aluminum.[91] The widespread assertion that e-cigarettes emit «only water vapor» is not true because the evidence demonstrates e-cigarette vapor contains possibly harmful chemicals such as nicotine, carbonyls, metals, and volatile organic compounds, in addition to particulate matter.[185] Massive advertising included the assertion that they would present little risk to non-users.[367] However, «disadvantages and side effects have been reported in many articles, and the unfavorable effects of its secondhand vapor have been demonstrated in many studies»,[367] and evidence indicates that use of e-cigarettes degrades indoor air quality.[106] Many e-cigarette companies market their products as a smoking cessation aid without evidence of effectiveness.[368] E-cigarette marketing has been found to make unsubstantiated health statements (e.g., that they help one quit smoking) including statements about improving psychiatric symptoms, which may be particularly appealing to smokers with mental illness.[58] E-cigarette marketing advocate weight control and emphasize use of nicotine with many flavors.[369] These marketing angles could particularly entice overweight people, youth, and vulnerable groups.[369] Some e-cigarette companies state that their products are green without supporting evidence which may be purely to increase their sales.[184]

Economics

The number of e-cigarettes sold increased every year from 2003 to 2014.[28] In 2015 a slowdown in the growth in usage occurred in the US.[370] As of January 2018, the growth in usage in the UK has slowed down since 2013.[371] As of 2014 there were at least 466 e-cigarette brands.[372] Worldwide e-cigarette sales in 2014 were around US$7 billion.[373] Worldwide e-cigarette sales in 2019 were about $19.3 billion.[374] E-cigarette sales could exceed traditional cigarette sales by 2023.[375] Approximately 30–50% of total e-cigarettes sales are handled on the internet.[45] Established tobacco companies have a significant share of the e-cigarette market.[92][376]

As of 2018, 95% of e-cigarette devices were made in China,[31] mainly in Shenzhen.[377][378] Chinese companies’ market share of e-liquid is low.[379] In 2014, online and offline sales starting increases.[380] Since combustible cigarettes are relatively inexpensive in China a lower price may not be large factor in marketing vaping products over there.[380]

In 2015, 80% of all e-cigarette sales in convenience stores in the US were products made by tobacco companies.[381] According to Nielsen Holdings, convenience store e-cigarette sales in the US went down for the first time during the four-week period ending on 10 May 2014.[382] Wells Fargo analyst Bonnie Herzog attributes this decline to a shift in consumers’ behavior, buying more specialized devices or what she calls «vapors-tanks-mods (VTMs)» that are not tracked by Nielsen.[382] Wells Fargo estimated that VTMs accounted for 57% of the 3.5 billion dollar market in the US for vapor products in 2015.[383] In 2014, dollar sales of customizable e-cigarettes and e-liquid surpassed sales of cigalikes in the US, even though, overall, customizables are a less expensive vaping option.[384] In 2014, the Smoke-Free Alternatives Trade Association estimated that there were 35,000 vape shops in the US, more than triple the number a year earlier.[385] However the 2015 slowdown in market growth affected VTMs as well.[370] Large tobacco retailers are leading the cigalike market.[386] «We saw the market’s sudden recognition that the cigarette industry seems to be in serious trouble, disrupted by the rise of vaping,» Mad Money’s Jim Cramer stated April 2018.[387] «Over the course of three short days, the tobacco stocks were bent, they were spindled and they were mutilated by the realization that electronic cigarettes have become a serious threat to the old-school cigarette makers,» he added.[387] In 2019, a vaping industry organization released a report stating that a possible US ban on e-cigarettes flavors can potentially effect greater than 150,000 jobs around the US.[388]

The leading seller in the e-cigarette market in the US is the Juul e-cigarette,[389] which was introduced in June 2015.[390] As of August 2018, Juul accounts for over 72% of the US e-cigarette market monitored by Nielsen, and its closest competitor—RJ Reynolds’ Vuse—makes up less than 10% of the market.[391] Juul rose to popularity quickly, growing by 700% in 2016 alone.[300] On 17 July 2018 Reynolds announced it will debut in August 2018 a pod mod type device similar Juul.[391] The popularity of the Juul pod system has led to a flood of other pod devices hitting the market.[392]

In Canada, e-cigarettes had an estimated value of 140 million CAD in 2015.[393] There are numerous e-cigarette retail shops in Canada.[394] A 2014 audit of retailers in four Canadian cities found that 94% of grocery stores, convenience stores, and tobacconist shops which sold e-cigarettes sold nicotine-free varieties only, while all vape shops stocked at least one nicotine-containing product.[395]

By 2015 the e-cigarette market had only reached a twentieth of the size of the tobacco market in the UK.[396] In the UK in 2015 the «most prominent brands of cigalikes» were owned by tobacco companies, however, with the exception of one model, all the tank types came from «non-tobacco industry companies».[397] Yet some tobacco industry products, while using prefilled cartridges, resemble tank models.[397]

France’s e-cigarette market was estimated by Groupe Xerfi to be €130 million in 2015.[398] Additionally, France’s e-liquid market was estimated at €265 million.[398] In December 2015, there were 2,400 vape shops in France, 400 fewer than in March of the same year.[398] Industry organization Fivape said the reduction was due to consolidation, not to reduced demand.[398]

Environmental impact

Compared to traditional cigarettes, reusable e-cigarettes do not create waste and potential litter from every use in the form of discarded cigarette butts.[399] Traditional cigarettes tend to end up in the ocean where they cause pollution,[399]

though once discarded they undergo biodegradation and photodegradation. Although some brands have begun recycling services for their e-cigarette cartridges and batteries, the prevalence of recycling is unknown.[186]

E-cigarettes that are not reusable contribute to the problem of electronic waste, which can create a hazard for people and other organisms.[131] If improperly disposed of, they can release heavy metals, nicotine, and other chemicals from batteries and unused e-liquid.[184][171]

A July 2018–April 2019 garbology study found e-cigarette products composed 19% of the waste from all traditional and electronic tobacco and cannabis products collected at 12 public high schools in Northern California.[400]

Philip Morris International’s IQOS device with charger and tobacco stick.

Other devices to deliver inhaled nicotine have been developed.[401] They aim to mimic the ritual and behavioral aspects of traditional cigarettes.[401]

British American Tobacco, through their subsidiary Nicoventures, licensed a nicotine delivery system based on existing asthma inhaler technology from UK-based healthcare company Kind Consumer.[402] In September 2014 a product based on this named Voke obtained approval from the United Kingdom’s Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency.[403]

In 2011 Philip Morris International bought the rights to a nicotine pyruvate technology developed by Jed Rose at Duke University.[404] The technology is based on the chemical reaction between pyruvic acid and nicotine, which produces an inhalable nicotine pyruvate vapor.[405] Philip Morris Products S.A. created a different kind e-cigarette named P3L.[406] The device is supplied with a cartridge that contains nicotine and lactic acid in different cavities.[406] When turned on and heated, the nicotine salt called nicotine lactate forms an aerosol.[406]