§ 17. Названия исторических эпох, событий, съездов, геологических периодов

1. В названиях исторических эпох и событий первое слово (и все имена собственные) пишется с прописной буквы; родовые наименования (эпоха, век и т. п.) пишутся со строчной буквы: Древний Китай, Древняя Греция, Древний Рим (‘государство’; но: древний Рим — ‘город’), Римская империя, Киевская Русь; Крестовые походы, эпоха Возрождения, Высокое Возрождение, Ренессанс, Реформация, эпоха Просвещения, Смутное время, Петровская эпоха (но: допетровская эпоха, послепетровская эпоха); Куликовская битва, Бородинский бой; Семилетняя война, Великая Отечественная война (традиционное написание), Война за независимость (в Северной Америке); Июльская монархия, Вторая империя, Пятая республика; Парижская коммуна, Версальский мир, Декабрьское вооружённое восстание 1905 года (но: декабрьское восстание 1825 года).

2. В официальных названиях конгрессов, съездов, конференций первое слово (обычно это слова Первый, Второй и т. д.; Всероссийский, Всесоюзный, Всемирный, Международный и т. п.) и все имена собственные пишутся с прописной буквы: Всероссийский съезд учителей, Первый всесоюзный съезд писателей, Всемирный конгресс сторонников мира, Международный астрономический съезд, Женевская конференция, Базельский конгресс I Интернационала.

После порядкового числительного, обозначенного цифрой, сохраняется написание первого слова с прописной буквы: 5-й Международный конгресс преподавателей, XX Международный Каннский кинофестиваль.

3. Названия исторических эпох, периодов и событий, не являющиеся именами собственными, а также названия геологических периодов пишутся со строчной буквы: античный мир, средневековье, феодализм, русско-турецкие войны, наполеоновские войны; гражданская война (но: Гражданская война в России и США); мезозойская эра, меловой период, эпоха палеолита, каменный век, ледниковый период.

На нашем сайте в электронном виде представлен справочник по орфографии русского языка. Справочником можно пользоваться онлайн, а можно бесплатно скачать на свой компьютер.

Надеемся, онлайн-справочник поможет вам изучить правописание и синтаксис русского языка!

РОССИЙСКАЯ АКАДЕМИЯ НАУК

Отделение историко-филологических наук Институт русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова

ПРАВИЛА РУССКОЙ ОРФОГРАФИИ И ПУНКТУАЦИИ

ПОЛНЫЙ АКАДЕМИЧЕСКИЙ СПРАВОЧНИК

Авторы:

Н. С. Валгина, Н. А. Еськова, О. Е. Иванова, С. М. Кузьмина, В. В. Лопатин, Л. К. Чельцова

Ответственный редактор В. В. Лопатин

Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации. Полный академический справочник / Под ред. В.В. Лопатина. — М: АСТ, 2009. — 432 с.

ISBN 978-5-462-00930-3

Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации. Полный академический справочник / Под ред. В.В. Лопатина. — М: Эксмо, 2009. — 480 с.

ISBN 978-5-699-18553-5

Справочник представляет собой новую редакцию действующих «Правил русской орфографии и пунктуации», ориентирован на полноту правил, современность языкового материала, учитывает существующую практику письма.

Полный академический справочник предназначен для самого широкого круга читателей.

Предлагаемый справочник подготовлен Институтом русского языка им. В. В. Виноградова РАН и Орфографической комиссией при Отделении историко-филологических наук Российской академии наук. Он является результатом многолетней работы Орфографической комиссии, в состав которой входят лингвисты, преподаватели вузов, методисты, учителя средней школы.

В работе комиссии, многократно обсуждавшей и одобрившей текст справочника, приняли участие: канд. филол. наук Б. 3. Бук-чина, канд. филол. наук, профессор Н. С. Валгина, учитель русского языка и литературы С. В. Волков, доктор филол. наук, профессор В. П. Григорьев, доктор пед. наук, профессор А. Д. Дейкина, канд. филол. наук, доцент Е. В. Джанджакова, канд. филол. наук Н. А. Еськова, академик РАН А. А. Зализняк, канд. филол. наук О. Е. Иванова, канд. филол. наук О. Е. Кармакова, доктор филол. наук, профессор Л. Л. Касаткин, академик РАО В. Г. Костомаров, академик МАНПО и РАЕН О. А. Крылова, доктор филол. наук, профессор Л. П. Крысин, доктор филол. наук С. М. Кузьмина, доктор филол. наук, профессор О. В. Кукушкина, доктор филол. наук, профессор В. В. Лопатин (председатель комиссии), учитель русского языка и литературы В. В. Луховицкий, зав. лабораторией русского языка и литературы Московского института повышения квалификации работников образования Н. А. Нефедова, канд. филол. наук И. К. Сазонова, доктор филол. наук А. В. Суперанская, канд. филол. наук Л. К. Чельцова, доктор филол. наук, профессор А. Д. Шмелев, доктор филол. наук, профессор М. В. Шульга. Активное участие в обсуждении и редактировании текста правил принимали недавно ушедшие из жизни члены комиссии: доктора филол. наук, профессора В. Ф. Иванова, Б. С. Шварцкопф, Е. Н. Ширяев, кандидат филол. наук Н. В. Соловьев.

Основной задачей этой работы была подготовка полного и отвечающего современному состоянию русского языка текста правил русского правописания. Действующие до сих пор «Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации», официально утвержденные в 1956 г., были первым общеобязательным сводом правил, ликвидировавшим разнобой в правописании. Со времени их выхода прошло ровно полвека, на их основе были созданы многочисленные пособия и методические разработки. Естественно, что за это время в формулировках «Правил» обнаружился ряд существенных пропусков и неточностей.

Неполнота «Правил» 1956 г. в большой степени объясняется изменениями, произошедшими в самом языке: появилось много новых слов и типов слов, написание которых «Правилами» не регламентировано. Например, в современном языке активизировались единицы, стоящие на грани между словом и частью слова; среди них появились такие, как мини, макси, видео, аудио, медиа, ретро и др. В «Правилах» 1956 г. нельзя найти ответ на вопрос, писать ли такие единицы слитно со следующей частью слова или через дефис. Устарели многие рекомендации по употреблению прописных букв. Нуждаются в уточнениях и дополнениях правила пунктуации, отражающие стилистическое многообразие и динамичность современной речи, особенно в массовой печати.

Таким образом, подготовленный текст правил русского правописания не только отражает нормы, зафиксированные в «Правилах» 1956 г., но и во многих случаях дополняет и уточняет их с учетом современной практики письма.

Регламентируя правописание, данный справочник, естественно, не может охватить и исчерпать все конкретные сложные случаи написания слов. В этих случаях необходимо обращаться к орфографическим словарям. Наиболее полным нормативным словарем является в настоящее время академический «Русский орфографический словарь» (изд. 2-е, М., 2005), содержащий 180 тысяч слов.

Данный справочник по русскому правописанию предназначается для преподавателей русского языка, редакционно-издательских работников, всех пишущих по-русски.

Для облегчения пользования справочником текст правил дополняется указателями слов и предметным указателем.

Составители приносят благодарность всем научным и образовательным учреждениям, принявшим участие в обсуждении концепции и текста правил русского правописания, составивших этот справочник.

Авторы

Ав. — Л.Авилова

Айт. — Ч. Айтматов

Акун. — Б. Акунин

Ам. — Н. Амосов

А. Меж. — А. Межиров

Ард. — В. Ардаматский

Ас. — Н. Асеев

Аст. — В. Астафьев

А. Т. — А. Н. Толстой

Ахм. — А. Ахматова

Ахмад. — Б. Ахмадулина

- Цвет. — А. И. Цветаева

Багр. — Э. Багрицкий

Бар. — Е. А. Баратынский

Бек. — М. Бекетова

Бел. — В. Белов

Белин. — В. Г. Белинский

Бергг. — О. Берггольц

Бит. — А. Битов

Бл. — А. А. Блок

Бонд. — Ю. Бондарев

Б. П. — Б. Полевой

Б. Паст. — Б. Пастернак

Булг. — М. А. Булгаков

Бун. — И.А.Бунин

- Бык. — В. Быков

Возн. — А. Вознесенский

Вороб. — К. Воробьев

Г. — Н. В. Гоголь

газ. — газета

Гарш. — В. М. Гаршин

Гейч. — С. Гейченко

Гил. — В. А. Гиляровский

Гонч. — И. А. Гончаров

Гр. — А. С. Грибоедов

Гран. — Д. Гранин

Грин — А. Грин

Дост. — Ф. М. Достоевский

Друн. — Ю. Друнина

Евт. — Е. Евтушенко

Е. П. — Е. Попов

Ес. — С. Есенин

журн. — журнал

Забол. — Н. Заболоцкий

Зал. — С. Залыгин

Зерн. — Р. Зернова

Зл. — С. Злобин

Инб. — В. Инбер

Ис — М. Исаковский

Кав. — В. Каверин

Каз. — Э. Казакевич

Кат. — В. Катаев

Кис. — Е. Киселева

Кор. — В. Г. Короленко

Крут. — С. Крутилин

Крыл. — И. А. Крылов

Купр. — А. И. Куприн

Л. — М. Ю. Лермонтов

Леон. — Л. Леонов

Лип. — В. Липатов

Лис. — К. Лисовский

Лих. — Д. С. Лихачев

Л. Кр. — Л. Крутикова

Л. Т. — Л. Н. Толстой

М. — В. Маяковский

Майк. — А. Майков

Мак. — В. Маканин

М. Г. — М. Горький

Мих. — С. Михалков

Наб. — В. В. Набоков

Нагиб. — Ю. Нагибин

Некр. — H.A. Некрасов

Н.Ил. — Н. Ильина

Н. Матв. — Н. Матвеева

Нов.-Пр. — А. Новиков-Прибой

Н. Остр. — H.A. Островский

Ок. — Б. Окуджава

Орл. — В. Орлов

П. — A.C. Пушкин

Пан. — В. Панова

Панф. — Ф. Панферов

Пауст. — К. Г. Паустовский

Пелев. — В. Пелевин

Пис. — А. Писемский

Плат. — А. П. Платонов

П. Нил. — П. Нилин

посл. — пословица

Пришв. — М. М. Пришвин

Расп. — В. Распутин

Рожд. — Р. Рождественский

Рыб. — А. Рыбаков

Сим. — К. Симонов

Сн. — И. Снегова

Сол. — В. Солоухин

Солж. — А. Солженицын

Ст. — К. Станюкович

Степ. — Т. Степанова

Сух. — В. Сухомлинский

Т. — И.С.Тургенев

Тв. — А. Твардовский

Тендр. — В. Тендряков

Ток. — В. Токарева

Триф. — Ю. Трифонов

Т. Толст. — Т. Толстая

Тын. — Ю. Н. Тынянов

Тютч. — Ф. И. Тютчев

Улиц. — Л. Улицкая

Уст. — Т. Устинова

Фад. — А. Фадеев

Фед. — К. Федин

Фурм. — Д. Фурманов

Цвет. — М. И. Цветаева

Ч.- А. П. Чехов

Чак. — А. Чаковский

Чив. — В. Чивилихин

Чуд. — М. Чудакова

Шол. — М. Шолохов

Шукш. — В. Шукшин

Щерб. — Г. Щербакова

Эр. — И.Эренбург

Ответ:

Правильное написание слова — палеолит

Ударение и произношение — палеол`ит

Значение слова -ранний период каменного века (примерно до 10 тысячелетия до н. э.)

Пример:

Эпоха палеолита.

Выберите, на какой слог падает ударение в слове — КРОВОТОЧИТЬ?

или

Слово состоит из букв:

П,

А,

Л,

Е,

О,

Л,

И,

Т,

Похожие слова:

палеолитический

Рифма к слову палеолит

митрополит, болит, ипполит, позволит, веселит, медлит, велит, бурлит, разлит, скалит, мыслит, квит, представит, приводит, губит, грабит, обидит, доводит, проводит, ездит, объявит, производит, разбит, загалдит, приготовит, сидит, правит, орбит, съездит, оставит, кредит, ставит, исправит, доставит, победит, убедит, предоставит, руководит, бит, видит, благословит, убит, заставит, бисквит, любит, гвоздит, увидит, отбит, ловит, уввдит, поставит, воодушевит, составит, поправит, избавит, задавит, готовит, побит, подбит, полюбит, управит

Толкование слова. Правильное произношение слова. Значение слова.

Hunting a glyptodon. Painting by Heinrich Harder c. 1920. Glyptodons were hunted to extinction within two millennia after humans’ arrival in South America.

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός palaios, «old» and λίθος lithos, «stone»), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehistoric technology.[1] It extends from the earliest known use of stone tools by hominins, c. 3.3 million years ago, to the end of the Pleistocene, c. 11,650 cal BP.[2]

The Paleolithic Age in Europe preceded the Mesolithic Age, although the date of the transition varies geographically by several thousand years. During the Paleolithic Age, hominins grouped together in small societies such as bands and subsisted by gathering plants, fishing, and hunting or scavenging wild animals.[3] The Paleolithic Age is characterized by the use of knapped stone tools, although at the time humans also used wood and bone tools. Other organic commodities were adapted for use as tools, including leather and vegetable fibers; however, due to rapid decomposition, these have not survived to any great degree.

About 50,000 years ago, a marked increase in the diversity of artifacts occurred. In Africa, bone artifacts and the first art appear in the archaeological record. The first evidence of human fishing is also noted, from artifacts in places such as Blombos cave in South Africa. Archaeologists classify artifacts of the last 50,000 years into many different categories, such as projectile points, engraving tools, Sharp knife blades, and drilling and piercing tools.

Humankind gradually evolved from early members of the genus Homo—such as Homo habilis, who used simple stone tools—into anatomically modern humans as well as behaviourally modern humans by the Upper Paleolithic.[4] During the end of the Paleolithic Age, specifically the Middle or Upper Paleolithic Age, humans began to produce the earliest works of art and to engage in religious or spiritual behavior such as burial and ritual.[5][page needed][6][need quotation to verify] Conditions during the Paleolithic Age went through a set of glacial and interglacial periods in which the climate periodically fluctuated between warm and cool temperatures. Archaeological and genetic data suggest that the source populations of Paleolithic humans survived in sparsely-wooded areas and dispersed through areas of high primary productivity while avoiding dense forest-cover.[7]

By c. 50,000 – c. 40,000 BP, the first humans set foot in Australia. By c. 45,000 BP, humans lived at 61°N latitude in Europe.[8] By c. 30,000 BP, Japan was reached, and by c. 27,000 BP humans were present in Siberia, above the Arctic Circle.[8] By the end of the Upper Paleolithic Age humans had crossed Beringia and expanded throughout the Americas.[9][10]

Etymology[edit]

The term «Palaeolithic» was coined by archaeologist John Lubbock in 1865.[11] It derives from Greek: παλαιός, palaios, «old»; and λίθος, lithos, «stone», meaning «old age of the stone» or «Old Stone Age».

Paleogeography and climate[edit]

Temperature rise marking the end of the Paleolithic, as derived from ice core data.

The Paleolithic coincides almost exactly with the Pleistocene epoch of geologic time, which lasted from 2.6 million years ago to about 12,000 years ago.[12] This epoch experienced important geographic and climatic changes that affected human societies.

During the preceding Pliocene, continents had continued to drift from possibly as far as 250 km (160 mi) from their present locations to positions only 70 km (43 mi) from their current location. South America became linked to North America through the Isthmus of Panama, bringing a nearly complete end to South America’s distinctive marsupial fauna. The formation of the isthmus had major consequences on global temperatures, because warm equatorial ocean currents were cut off, and the cold Arctic and Antarctic waters lowered temperatures in the now-isolated Atlantic Ocean.

Most of Central America formed during the Pliocene to connect the continents of North and South America, allowing fauna from these continents to leave their native habitats and colonize new areas.[13] Africa’s collision with Asia created the Mediterranean, cutting off the remnants of the Tethys Ocean. During the Pleistocene, the modern continents were essentially at their present positions; the tectonic plates on which they sit have probably moved at most 100 km (62 mi) from each other since the beginning of the period.[14]

Climates during the Pliocene became cooler and drier, and seasonal, similar to modern climates. Ice sheets grew on Antarctica. The formation of an Arctic ice cap around 3 million years ago is signaled by an abrupt shift in oxygen isotope ratios and ice-rafted cobbles in the North Atlantic and North Pacific Ocean beds.[15] Mid-latitude glaciation probably began before the end of the epoch. The global cooling that occurred during the Pliocene may have spurred on the disappearance of forests and the spread of grasslands and savannas.[13]

The Pleistocene climate was characterized by repeated glacial cycles during which continental glaciers pushed to the 40th parallel in some places. Four major glacial events have been identified, as well as many minor intervening events. A major event is a general glacial excursion, termed a «glacial». Glacials are separated by «interglacials». During a glacial, the glacier experiences minor advances and retreats. The minor excursion is a «stadial»; times between stadials are «interstadials». Each glacial advance tied up huge volumes of water in continental ice sheets 1,500–3,000 m (4,900–9,800 ft) deep, resulting in temporary sea level drops of 100 m (330 ft) or more over the entire surface of the Earth. During interglacial times, such as at present, drowned coastlines were common, mitigated by isostatic or other emergent motion of some regions.

The effects of glaciation were global. Antarctica was ice-bound throughout the Pleistocene and the preceding Pliocene. The Andes were covered in the south by the Patagonian ice cap. There were glaciers in New Zealand and Tasmania. The now decaying glaciers of Mount Kenya, Mount Kilimanjaro, and the Ruwenzori Range in east and central Africa were larger. Glaciers existed in the mountains of Ethiopia and to the west in the Atlas mountains. In the northern hemisphere, many glaciers fused into one. The Cordilleran Ice Sheet covered the North American northwest; the Laurentide covered the east. The Fenno-Scandian ice sheet covered northern Europe, including Great Britain; the Alpine ice sheet covered the Alps. Scattered domes stretched across Siberia and the Arctic shelf. The northern seas were frozen. During the late Upper Paleolithic (Latest Pleistocene) c. 18,000 BP, the Beringia land bridge between Asia and North America was blocked by ice,[14] which may have prevented early Paleo-Indians such as the Clovis culture from directly crossing Beringia to reach the Americas.

According to Mark Lynas (through collected data), the Pleistocene’s overall climate could be characterized as a continuous El Niño with trade winds in the south Pacific weakening or heading east, warm air rising near Peru, warm water spreading from the west Pacific and the Indian Ocean to the east Pacific, and other El Niño markers.[16]

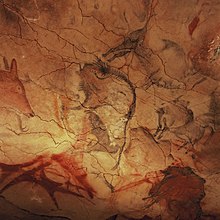

The Paleolithic is often held to finish at the end of the ice age (the end of the Pleistocene epoch), and Earth’s climate became warmer. This may have caused or contributed to the extinction of the Pleistocene megafauna, although it is also possible that the late Pleistocene extinctions were (at least in part) caused by other factors such as disease and overhunting by humans.[17][18] New research suggests that the extinction of the woolly mammoth may have been caused by the combined effect of climatic change and human hunting.[18] Scientists suggest that climate change during the end of the Pleistocene caused the mammoths’ habitat to shrink in size, resulting in a drop in population. The small populations were then hunted out by Paleolithic humans.[18] The global warming that occurred during the end of the Pleistocene and the beginning of the Holocene may have made it easier for humans to reach mammoth habitats that were previously frozen and inaccessible.[18] Small populations of woolly mammoths survived on isolated Arctic islands, Saint Paul Island and Wrangel Island, until c. 3700 BP and c. 1700 BP respectively. The Wrangel Island population became extinct around the same time the island was settled by prehistoric humans.[19] There is no evidence of prehistoric human presence on Saint Paul island (though early human settlements dating as far back as 6500 BP were found on the nearby Aleutian Islands).[20]

| Age (before) |

America | Atlantic Europe | Maghreb | Mediterranean Europe | Central Europe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10,000 years | Flandrian interglacial | Flandriense | Mellahiense | Versiliense | Flandrian interglacial |

| 80,000 years | Wisconsin | Devensiense | Regresión | Regresión | Wisconsin Stage |

| 140,000 years | Sangamoniense | Ipswichiense | Ouljiense | Tirreniense II y III | Eemian Stage |

| 200,000 years | Illinois | Wolstoniense | Regresión | Regresión | Wolstonian Stage |

| 450,000 years | Yarmouthiense | Hoxniense | Anfatiense | Tirreniense I | Hoxnian Stage |

| 580,000 years | Kansas | Angliense | Regresión | Regresión | Kansan Stage |

| 750,000 years | Aftoniense | Cromeriense | Maarifiense | Siciliense | Cromerian Complex |

| 1,100,000 years | Nebraska | Beestoniense | Regresión | Regresión | Beestonian stage |

| 1,400,000 years | interglacial | Ludhamiense | Messaudiense | Calabriense | Donau-Günz |

Paleolithic people[edit]

An artist’s rendering of a temporary wood house, based on evidence found at Terra Amata (in Nice, France) and dated to the Lower Paleolithic (c. 400,000 BP)[22]

Nearly all of our knowledge of Paleolithic people and way of life comes from archaeology and ethnographic comparisons to modern hunter-gatherer cultures such as the !Kung San who live similarly to their Paleolithic predecessors.[23] The economy of a typical Paleolithic society was a hunter-gatherer economy.[24] Humans hunted wild animals for meat and gathered food, firewood, and materials for their tools, clothes, or shelters.[24]

Population density was very low, around only 0.4 inhabitants per square kilometre (1/sq mi).[3] This was most likely due to low body fat, infanticide, high levels of physical activity among women,[25] late weaning of infants, and a nomadic lifestyle.[3] Like contemporary hunter-gatherers, Paleolithic humans enjoyed an abundance of leisure time unparalleled in both Neolithic farming societies and modern industrial societies.[24][26] At the end of the Paleolithic, specifically the Middle or Upper Paleolithic, people began to produce works of art such as cave paintings, rock art and jewellery and began to engage in religious behavior such as burials and rituals.[27]

Homo erectus[edit]

At the beginning of the Paleolithic, hominins were found primarily in eastern Africa, east of the Great Rift Valley. Most known hominin fossils dating earlier than one million years before present are found in this area, particularly in Kenya, Tanzania, and Ethiopia.

By c. 2,000,000 – c. 1,500,000 BP, groups of hominins began leaving Africa and settling southern Europe and Asia. Southern Caucasus was occupied by c. 1,700,000 BP, and northern China was reached by c. 1,660,000 BP. By the end of the Lower Paleolithic, members of the hominin family were living in what is now China, western Indonesia, and, in Europe, around the Mediterranean and as far north as England, France, southern Germany, and Bulgaria. Their further northward expansion may have been limited by the lack of control of fire: studies of cave settlements in Europe indicate no regular use of fire prior to c. 400,000 – c. 300,000 BP.[28]

East Asian fossils from this period are typically placed in the genus Homo erectus. Very little fossil evidence is available at known Lower Paleolithic sites in Europe, but it is believed that hominins who inhabited these sites were likewise Homo erectus. There is no evidence of hominins in America, Australia, or almost anywhere in Oceania during this time period.

Fates of these early colonists, and their relationships to modern humans, are still subject to debate. According to current archaeological and genetic models, there were at least two notable expansion events subsequent to peopling of Eurasia c. 2,000,000 – c. 1,500,000 BP. Around 500,000 BP a group of early humans, frequently called Homo heidelbergensis, came to Europe from Africa and eventually evolved into Homo neanderthalensis (Neanderthals). In the Middle Paleolithic, Neanderthals were present in the region now occupied by Poland.

Both Homo erectus and Homo neanderthalensis became extinct by the end of the Paleolithic. Descended from Homo sapiens, the anatomically modern Homo sapiens sapiens emerged in eastern Africa c. 200,000 BP, left Africa around 50,000 BP, and expanded throughout the planet. Multiple hominid groups coexisted for some time in certain locations. Homo neanderthalensis were still found in parts of Eurasia c. 30,000 BP years, and engaged in an unknown degree of interbreeding with Homo sapiens sapiens. DNA studies also suggest an unknown degree of interbreeding between Homo sapiens sapiens and Homo sapiens denisova.[29]

Hominin fossils not belonging either to Homo neanderthalensis or to Homo sapiens species, found in the Altai Mountains and Indonesia, were radiocarbon dated to c. 30,000 – c. 40,000 BP and c. 17,000 BP respectively.

For the duration of the Paleolithic, human populations remained low, especially outside the equatorial region. The entire population of Europe between 16,000 and 11,000 BP likely averaged some 30,000 individuals, and between 40,000 and 16,000 BP, it was even lower at 4,000–6,000 individuals.[30] However, remains of thousands of butchered animals and tools made by Palaeolithic humans were found in Lapa do Picareiro (pt), a cave in Portugal, dating back between 41,000 and 38,000 years ago.[31]

Technology and crafts[edit]

Some researchers have noted that science, limited in that age to some early ideas about astronomy (or cosmology), had limited impact on Paleolithic technology. Making fire was part of the knowledge system, and it was possible without an understanding of chemical processes, These types of practical skills are sometimes called crafts. Religion, superstitution or appeals to the supernatural may have played a part in the cultural explanations of phenomena like combustion.[32]

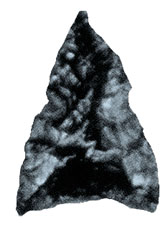

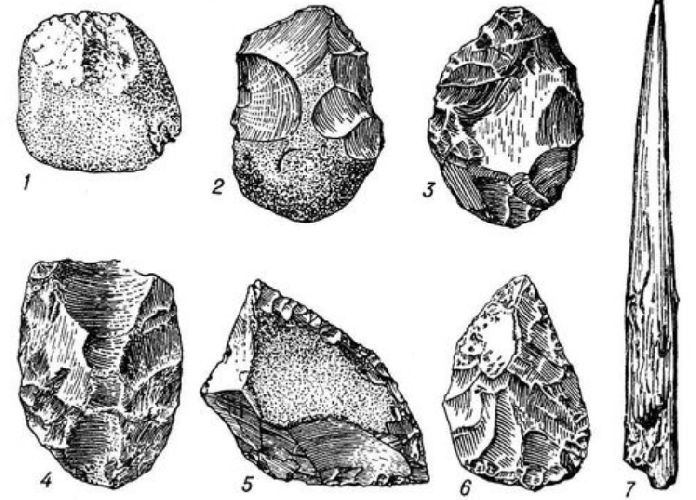

Tools[edit]

Paleolithic humans made tools of stone, bone (primarily deer), and wood.[24] The early paleolithic hominins, Australopithecus, were the first users of stone tools. Excavations in Gona, Ethiopia have produced thousands of artifacts, and through radioisotopic dating and magnetostratigraphy, the sites can be firmly dated to 2.6 million years ago. Evidence shows these early hominins intentionally selected raw stone with good flaking qualities and chose appropriate sized stones for their needs to produce sharp-edged tools for cutting.[33]

The earliest Paleolithic stone tool industry, the Oldowan, began around 2.6 million years ago.[34] It produced tools such as choppers, burins, and stitching awls. It was completely replaced around 250,000 years ago by the more complex Acheulean industry, which was first conceived by Homo ergaster around 1.8–1.65 million years ago.[35] The Acheulean implements completely vanish from the archaeological record around 100,000 years ago and were replaced by more complex Middle Paleolithic tool kits such as the Mousterian and the Aterian industries.[36]

Lower Paleolithic humans used a variety of stone tools, including hand axes and choppers. Although they appear to have used hand axes often, there is disagreement about their use. Interpretations range from cutting and chopping tools, to digging implements, to flaking cores, to the use in traps, and as a purely ritual significance, perhaps in courting behavior. William H. Calvin has suggested that some hand axes could have served as «killer Frisbees» meant to be thrown at a herd of animals at a waterhole so as to stun one of them. There are no indications of hafting, and some artifacts are far too large for that. Thus, a thrown hand axe would not usually have penetrated deeply enough to cause very serious injuries. Nevertheless, it could have been an effective weapon for defense against predators. Choppers and scrapers were likely used for skinning and butchering scavenged animals and sharp-ended sticks were often obtained for digging up edible roots. Presumably, early humans used wooden spears as early as 5 million years ago to hunt small animals, much as their relatives, chimpanzees, have been observed to do in Senegal, Africa.[37] Lower Paleolithic humans constructed shelters, such as the possible wood hut at Terra Amata.

Fire use[edit]

Fire was used by the Lower Paleolithic hominins Homo erectus and Homo ergaster as early as 300,000 to 1.5 million years ago and possibly even earlier by the early Lower Paleolithic (Oldowan) hominin Homo habilis or by robust Australopithecines such as Paranthropus.[3] However, the use of fire only became common in the societies of the following Middle Stone Age and Middle Paleolithic.[2] Use of fire reduced mortality rates and provided protection against predators.[38] Early hominins may have begun to cook their food as early as the Lower Paleolithic (c. 1.9 million years ago) or at the latest in the early Middle Paleolithic (c. 250,000 years ago).[39] Some scientists have hypothesized that hominins began cooking food to defrost frozen meat, which would help ensure their survival in cold regions.[39]

Archaeologists cite morphological shifts in cranial anatomy as evidence for emergence of cooking and food processing technologies. These morphological changes include decreases in molar and jaw size, thinner tooth enamel, and decrease in gut volume [40]

During much of the Pleistocene epoch, our ancestors relied on simple food processing techniques such as roasting[41]

The Upper Palaeolithic saw the emergence of boiling, an advance in food processing technology which rendered plant foods more digestible, decreased their toxicity, and maximised their nutritional value [42] Thermally altered rock (heated stones) are easily identifiable in the archaeological record. Stone-boiling and pit-baking were common techniques which involved heating large pebbles then transferring the hot stones into a perishable container to heat the water [43] This technology is typified in the Middle Palaeolithic example of the Abri Pataud hearths [44]

Raft[edit]

The Lower Paleolithic Homo erectus possibly invented rafts (c. 840,000 – c. 800,000 BP) to travel over large bodies of water, which may have allowed a group of Homo erectus to reach the island of Flores and evolve into the small hominin Homo floresiensis. However, this hypothesis is disputed within the anthropological community.[45][46] The possible use of rafts during the Lower Paleolithic may indicate that Lower Paleolithic hominins such as Homo erectus were more advanced than previously believed, and may have even spoken an early form of modern language.[45] Supplementary evidence from Neanderthal and modern human sites located around the Mediterranean Sea, such as Coa de sa Multa (c. 300,000 BP), has also indicated that both Middle and Upper Paleolithic humans used rafts to travel over large bodies of water (i.e. the Mediterranean Sea) for the purpose of colonizing other bodies of land.[45][47]

Advanced tools[edit]

By around 200,000 BP, Middle Paleolithic stone tool manufacturing spawned a tool making technique known as the prepared-core technique, that was more elaborate than previous Acheulean techniques.[4] This technique increased efficiency by allowing the creation of more controlled and consistent flakes.[4] It allowed Middle Paleolithic humans to create stone tipped spears, which were the earliest composite tools, by hafting sharp, pointy stone flakes onto wooden shafts. In addition to improving tool making methods, the Middle Paleolithic also saw an improvement of the tools themselves that allowed access to a wider variety and amount of food sources. For example, microliths or small stone tools or points were invented around 70,000–65,000 BP and were essential to the invention of bows and spear throwers in the following Upper Paleolithic.[38]

Harpoons were invented and used for the first time during the late Middle Paleolithic (c. 90,000 BP); the invention of these devices brought fish into the human diets, which provided a hedge against starvation and a more abundant food supply.[47][48] Thanks to their technology and their advanced social structures, Paleolithic groups such as the Neanderthals—who had a Middle Paleolithic level of technology—appear to have hunted large game just as well as Upper Paleolithic modern humans.[49] and the Neanderthals in particular may have likewise hunted with projectile weapons.[50] Nonetheless, Neanderthal use of projectile weapons in hunting occurred very rarely (or perhaps never) and the Neanderthals hunted large game animals mostly by ambushing them and attacking them with mêlée weapons such as thrusting spears rather than attacking them from a distance with projectile weapons.[27][51]

Other inventions[edit]

During the Upper Paleolithic, further inventions were made, such as the net (c. 22,000 or c. 29,000 BP)[38] bolas,[52] the spear thrower (c. 30,000 BP), the bow and arrow (c. 25,000 or c. 30,000 BP)[3] and the oldest example of ceramic art, the Venus of Dolní Věstonice (c. 29,000 – c. 25,000 BP).[3] Kilu Cave at Buku island, Solomon Islands, demonstrates navigation of some 60 km of open ocean at 30,000 BCcal.[53]

Early dogs were domesticated sometime between 30,000 and 14,000 BP, presumably to aid in hunting.[54] However, the earliest instances of successful domestication of dogs may be much more ancient than this. Evidence from canine DNA collected by Robert K. Wayne suggests that dogs may have been first domesticated in the late Middle Paleolithic around 100,000 BP or perhaps even earlier.[55]

Archaeological evidence from the Dordogne region of France demonstrates that members of the European early Upper Paleolithic culture known as the Aurignacian used calendars (c. 30,000 BP). This was a lunar calendar that was used to document the phases of the moon. Genuine solar calendars did not appear until the Neolithic.[56] Upper Paleolithic cultures were probably able to time the migration of game animals such as wild horses and deer.[57] This ability allowed humans to become efficient hunters and to exploit a wide variety of game animals.[57] Recent research indicates that the Neanderthals timed their hunts and the migrations of game animals long before the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic.[49]

[edit]

Humans may have taken part in long-distance trade between bands for rare commodities and raw materials (such as stone needed for making tools) as early as 120,000 years ago in Middle Paleolithic.

The social organization of the earliest Paleolithic (Lower Paleolithic) societies remains largely unknown to scientists, though Lower Paleolithic hominins such as Homo habilis and Homo erectus are likely to have had more complex social structures than chimpanzee societies.[58] Late Oldowan/Early Acheulean humans such as Homo ergaster/Homo erectus may have been the first people to invent central campsites or home bases and incorporate them into their foraging and hunting strategies like contemporary hunter-gatherers, possibly as early as 1.7 million years ago;[4] however, the earliest solid evidence for the existence of home bases or central campsites (hearths and shelters) among humans only dates back to 500,000 years ago.[4]

Similarly, scientists disagree whether Lower Paleolithic humans were largely monogamous or polygynous.[58] In particular, the Provisional model suggests that bipedalism arose in pre-Paleolithic australopithecine societies as an adaptation to monogamous lifestyles; however, other researchers note that sexual dimorphism is more pronounced in Lower Paleolithic humans such as Homo erectus than in modern humans, who are less polygynous than other primates, which suggests that Lower Paleolithic humans had a largely polygynous lifestyle, because species that have the most pronounced sexual dimorphism tend more likely to be polygynous.[59]

Human societies from the Paleolithic to the early Neolithic farming tribes lived without states and organized governments. For most of the Lower Paleolithic, human societies were possibly more hierarchical than their Middle and Upper Paleolithic descendants, and probably were not grouped into bands,[60] though during the end of the Lower Paleolithic, the latest populations of the hominin Homo erectus may have begun living in small-scale (possibly egalitarian) bands similar to both Middle and Upper Paleolithic societies and modern hunter-gatherers.[60]

Middle Paleolithic societies, unlike Lower Paleolithic and early Neolithic ones, consisted of bands that ranged from 20–30 or 25–100 members and were usually nomadic.[3][60] These bands were formed by several families. Bands sometimes joined together into larger «macrobands» for activities such as acquiring mates and celebrations or where resources were abundant.[3] By the end of the Paleolithic era (c. 10,000 BP), people began to settle down into permanent locations, and began to rely on agriculture for sustenance in many locations. Much evidence exists that humans took part in long-distance trade between bands for rare commodities (such as ochre, which was often used for religious purposes such as ritual[61][56]) and raw materials, as early as 120,000 years ago in Middle Paleolithic.[27] Inter-band trade may have appeared during the Middle Paleolithic because trade between bands would have helped ensure their survival by allowing them to exchange resources and commodities such as raw materials during times of relative scarcity (i.e. famine, drought).[27] Like in modern hunter-gatherer societies, individuals in Paleolithic societies may have been subordinate to the band as a whole.[23][24] Both Neanderthals and modern humans took care of the elderly members of their societies during the Middle and Upper Paleolithic.[27]

Some sources claim that most Middle and Upper Paleolithic societies were possibly fundamentally egalitarian[3][24][47][62] and may have rarely or never engaged in organized violence between groups (i.e. war).[47][63][64][65]

Some Upper Paleolithic societies in resource-rich environments (such as societies in Sungir, in what is now Russia) may have had more complex and hierarchical organization (such as tribes with a pronounced hierarchy and a somewhat formal division of labor) and may have engaged in endemic warfare.[47][66] Some argue that there was no formal leadership during the Middle and Upper Paleolithic. Like contemporary egalitarian hunter-gatherers such as the Mbuti pygmies, societies may have made decisions by communal consensus decision making rather than by appointing permanent rulers such as chiefs and monarchs.[6] Nor was there a formal division of labor during the Paleolithic. Each member of the group was skilled at all tasks essential to survival, regardless of individual abilities. Theories to explain the apparent egalitarianism have arisen, notably the Marxist concept of primitive communism.[67][68] Christopher Boehm (1999) has hypothesized that egalitarianism may have evolved in Paleolithic societies because of a need to distribute resources such as food and meat equally to avoid famine and ensure a stable food supply.[69] Raymond C. Kelly speculates that the relative peacefulness of Middle and Upper Paleolithic societies resulted from a low population density, cooperative relationships between groups such as reciprocal exchange of commodities and collaboration on hunting expeditions, and because the invention of projectile weapons such as throwing spears provided less incentive for war, because they increased the damage done to the attacker and decreased the relative amount of territory attackers could gain.[65] However, other sources claim that most Paleolithic groups may have been larger, more complex, sedentary and warlike than most contemporary hunter-gatherer societies, due to occupying more resource-abundant areas than most modern hunter-gatherers who have been pushed into more marginal habitats by agricultural societies.[70]

Anthropologists have typically assumed that in Paleolithic societies, women were responsible for gathering wild plants and firewood, and men were responsible for hunting and scavenging dead animals.[3][47] However, analogies to existent hunter-gatherer societies such as the Hadza people and the Aboriginal Australians suggest that the sexual division of labor in the Paleolithic was relatively flexible. Men may have participated in gathering plants, firewood and insects, and women may have procured small game animals for consumption and assisted men in driving herds of large game animals (such as woolly mammoths and deer) off cliffs.[47][64] Additionally, recent research by anthropologist and archaeologist Steven Kuhn from the University of Arizona is argued to support that this division of labor did not exist prior to the Upper Paleolithic and was invented relatively recently in human pre-history.[71][72] Sexual division of labor may have been developed to allow humans to acquire food and other resources more efficiently.[72] Possibly there was approximate parity between men and women during the Middle and Upper Paleolithic, and that period may have been the most gender-equal time in human history.[63][73][74] Archaeological evidence from art and funerary rituals indicates that a number of individual women enjoyed seemingly high status in their communities, and it is likely that both sexes participated in decision making.[74] The earliest known Paleolithic shaman (c. 30,000 BP) was female.[75] Jared Diamond suggests that the status of women declined with the adoption of agriculture because women in farming societies typically have more pregnancies and are expected to do more demanding work than women in hunter-gatherer societies.[76] Like most modern hunter-gatherer societies, Paleolithic and Mesolithic groups probably followed a largely ambilineal approach. At the same time, depending on the society, the residence could be virilocal, uxorilocal, and sometimes the spouses could live with neither the husband’s relatives nor the wife’s relatives at all. Taken together, most likely, the lifestyle of hunter-gatherers can be characterized as multilocal.[38]

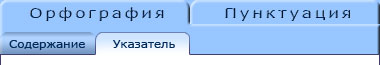

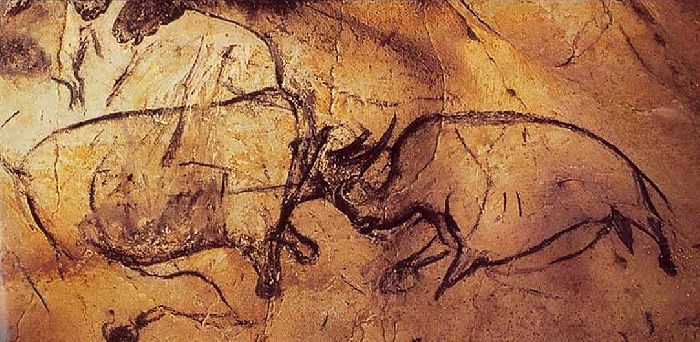

Sculpture and painting[edit]

Early examples of artistic expression, such as the Venus of Tan-Tan and the patterns found on elephant bones from Bilzingsleben in Thuringia, may have been produced by Acheulean tool users such as Homo erectus prior to the start of the Middle Paleolithic period. However, the earliest undisputed evidence of art during the Paleolithic comes from Middle Paleolithic/Middle Stone Age sites such as Blombos Cave–South Africa–in the form of bracelets,[77] beads,[78] rock art,[61] and ochre used as body paint and perhaps in ritual.[47][61] Undisputed evidence of art only becomes common in the Upper Paleolithic.[79]

Lower Paleolithic Acheulean tool users, according to Robert G. Bednarik, began to engage in symbolic behavior such as art around 850,000 BP. They decorated themselves with beads and collected exotic stones for aesthetic, rather than utilitarian qualities.[80] According to him, traces of the pigment ochre from late Lower Paleolithic Acheulean archaeological sites suggests that Acheulean societies, like later Upper Paleolithic societies, collected and used ochre to create rock art.[80] Nevertheless, it is also possible that the ochre traces found at Lower Paleolithic sites is naturally occurring.[81]

Upper Paleolithic humans produced works of art such as cave paintings, Venus figurines, animal carvings, and rock paintings.[82] Upper Paleolithic art can be divided into two broad categories: figurative art such as cave paintings that clearly depicts animals (or more rarely humans); and nonfigurative, which consists of shapes and symbols.[82] Cave paintings have been interpreted in a number of ways by modern archaeologists. The earliest explanation, by the prehistorian Abbe Breuil, interpreted the paintings as a form of magic designed to ensure a successful hunt.[83] However, this hypothesis fails to explain the existence of animals such as saber-toothed cats and lions, which were not hunted for food, and the existence of half-human, half-animal beings in cave paintings. The anthropologist David Lewis-Williams has suggested that Paleolithic cave paintings were indications of shamanistic practices, because the paintings of half-human, half-animal figures and the remoteness of the caves are reminiscent of modern hunter-gatherer shamanistic practices.[83] Symbol-like images are more common in Paleolithic cave paintings than are depictions of animals or humans, and unique symbolic patterns might have been trademarks that represent different Upper Paleolithic ethnic groups.[82] Venus figurines have evoked similar controversy. Archaeologists and anthropologists have described the figurines as representations of goddesses, pornographic imagery, apotropaic amulets used for sympathetic magic, and even as self-portraits of women themselves.[47][84]

R. Dale Guthrie[85] has studied not only the most artistic and publicized paintings, but also a variety of lower-quality art and figurines, and he identifies a wide range of skill and ages among the artists. He also points out that the main themes in the paintings and other artifacts (powerful beasts, risky hunting scenes and the over-sexual representation of women) are to be expected in the fantasies of adolescent males during the Upper Paleolithic.

The «Venus» figurines have been theorized, not universally, as representing a mother goddess; the abundance of such female imagery has inspired the theory that religion and society in Paleolithic (and later Neolithic) cultures were primarily interested in, and may have been directed by, women. Adherents of the theory include archaeologist Marija Gimbutas and feminist scholar Merlin Stone, the author of the 1976 book When God Was a Woman.[86][87] Other explanations for the purpose of the figurines have been proposed, such as Catherine McCoid and LeRoy McDermott’s hypothesis that they were self-portraits of woman artists[84] and R.Dale Gutrie’s hypothesis that served as «stone age pornography».

Music[edit]

The origins of music during the Paleolithic are unknown. The earliest forms of music probably did not use musical instruments other than the human voice or natural objects such as rocks. This early music would not have left an archaeological footprint. Music may have developed from rhythmic sounds produced by daily chores, for example, cracking open nuts with stones. Maintaining a rhythm while working may have helped people to become more efficient at daily activities.[88] An alternative theory originally proposed by Charles Darwin explains that music may have begun as a hominin mating strategy. Bird and other animal species produce music such as calls to attract mates.[89] This hypothesis is generally less accepted than the previous hypothesis, but nonetheless provides a possible alternative.

Upper Paleolithic (and possibly Middle Paleolithic)[90] humans used flute-like bone pipes as musical instruments,[47][91] and music may have played a large role in the religious lives of Upper Paleolithic hunter-gatherers. As with modern hunter-gatherer societies, music may have been used in ritual or to help induce trances. In particular, it appears that animal skin drums may have been used in religious events by Upper Paleolithic shamans, as shown by the remains of drum-like instruments from some Upper Paleolithic graves of shamans and the ethnographic record of contemporary hunter-gatherer shamanic and ritual practices.[75][82]

Religion and beliefs[edit]

Picture of a half-human, half-animal being in a Paleolithic cave painting in Dordogne. France. Some archaeologists believe that cave paintings of half-human, half-animal beings may be evidence for early shamanic practices during the Paleolithic.

According to James B. Harrod humankind first developed religious and spiritual beliefs during the Middle Paleolithic or Upper Paleolithic.[92] Controversial scholars of prehistoric religion and anthropology, James Harrod and Vincent W. Fallio, have recently proposed that religion and spirituality (and art) may have first arisen in Pre-Paleolithic chimpanzees[93] or Early Lower Paleolithic (Oldowan) societies.[94][95] According to Fallio, the common ancestor of chimpanzees and humans experienced altered states of consciousness and partook in ritual, and ritual was used in their societies to strengthen social bonding and group cohesion.[94]

Middle Paleolithic humans’ use of burials at sites such as Krapina, Croatia (c. 130,000 BP) and Qafzeh, Israel (c. 100,000 BP) have led some anthropologists and archaeologists, such as Philip Lieberman, to believe that Middle Paleolithic humans may have possessed a belief in an afterlife and a «concern for the dead that transcends daily life».[5] Cut marks on Neanderthal bones from various sites, such as Combe-Grenal and Abri Moula in France, suggest that the Neanderthals—like some contemporary human cultures—may have practiced ritual defleshing for (presumably) religious reasons. According to recent archaeological findings from Homo heidelbergensis sites in Atapuerca, humans may have begun burying their dead much earlier, during the late Lower Paleolithic; but this theory is widely questioned in the scientific community.

Likewise, some scientists have proposed that Middle Paleolithic societies such as Neanderthal societies may also have practiced the earliest form of totemism or animal worship, in addition to their (presumably religious) burial of the dead. In particular, Emil Bächler suggested (based on archaeological evidence from Middle Paleolithic caves) that a bear cult was widespread among Middle Paleolithic Neanderthals.[96] A claim that evidence was found for Middle Paleolithic animal worship c. 70,000 BCE originates from the Tsodilo Hills in the African Kalahari desert has been denied by the original investigators of the site.[97] Animal cults in the Upper Paleolithic, such as the bear cult, may have had their origins in these hypothetical Middle Paleolithic animal cults.[98] Animal worship during the Upper Paleolithic was intertwined with hunting rites.[98] For instance, archaeological evidence from art and bear remains reveals that the bear cult apparently involved a type of sacrificial bear ceremonialism, in which a bear was shot with arrows, finished off by a shot or thrust in the lungs, and ritually worshipped near a clay bear statue covered by a bear fur with the skull and the body of the bear buried separately.[98] Barbara Ehrenreich controversially theorizes that the sacrificial hunting rites of the Upper Paleolithic (and by extension Paleolithic cooperative big-game hunting) gave rise to war or warlike raiding during the following Epipaleolithic and Mesolithic or late Upper Paleolithic.[64]

The existence of anthropomorphic images and half-human, half-animal images in the Upper Paleolithic may further indicate that Upper Paleolithic humans were the first people to believe in a pantheon of gods or supernatural beings,[99] though such images may instead indicate shamanistic practices similar to those of contemporary tribal societies.[83] The earliest known undisputed burial of a shaman (and by extension the earliest undisputed evidence of shamans and shamanic practices) dates back to the early Upper Paleolithic era (c. 30,000 BP) in what is now the Czech Republic.[75] However, during the early Upper Paleolithic it was probably more common for all members of the band to participate equally and fully in religious ceremonies, in contrast to the religious traditions of later periods when religious authorities and part-time ritual specialists such as shamans, priests and medicine men were relatively common and integral to religious life.[24]

Religion was possibly apotropaic; specifically, it may have involved sympathetic magic.[47] The Venus figurines, which are abundant in the Upper Paleolithic archaeological record, provide an example of possible Paleolithic sympathetic magic, as they may have been used for ensuring success in hunting and to bring about fertility of the land and women.[3] The Upper Paleolithic Venus figurines have sometimes been explained as depictions of an earth goddess similar to Gaia, or as representations of a goddess who is the ruler or mother of the animals.[98][100] James Harrod has described them as representative of female (and male) shamanistic spiritual transformation processes.[101]

Diet and nutrition[edit]

People may have first fermented grapes in animal skin pouches to create wine during the Paleolithic age.[102]

Paleolithic hunting and gathering people ate varying proportions of vegetables (including tubers and roots), fruit, seeds (including nuts and wild grass seeds) and insects, meat, fish, and shellfish.[103][104] However, there is little direct evidence of the relative proportions of plant and animal foods.[105] Although the term «paleolithic diet», without references to a specific timeframe or locale, is sometimes used with an implication that most humans shared a certain diet during the entire era, that is not entirely accurate. The Paleolithic was an extended period of time, during which multiple technological advances were made, many of which had impact on human dietary structure. For example, humans probably did not possess the control of fire until the Middle Paleolithic,[106] or tools necessary to engage in extensive fishing.[citation needed] On the other hand, both these technologies are generally agreed to have been widely available to humans by the end of the Paleolithic (consequently, allowing humans in some regions of the planet to rely heavily on fishing and hunting). In addition, the Paleolithic involved a substantial geographical expansion of human populations. During the Lower Paleolithic, ancestors of modern humans are thought to have been constrained to Africa east of the Great Rift Valley. During the Middle and Upper Paleolithic, humans greatly expanded their area of settlement, reaching ecosystems as diverse as New Guinea and Alaska, and adapting their diets to whatever local resources were available.

Another view is that until the Upper Paleolithic, humans were frugivores (fruit eaters) who supplemented their meals with carrion, eggs, and small prey such as baby birds and mussels, and only on rare occasions managed to kill and consume big game such as antelopes.[107] This view is supported by studies of higher apes, particularly chimpanzees. Chimpanzees are the closest to humans genetically, sharing more than 96% of their DNA code with humans, and their digestive tract is functionally very similar to that of humans.[108] Chimpanzees are primarily frugivores, but they could and would consume and digest animal flesh, given the opportunity. In general, their actual diet in the wild is about 95% plant-based, with the remaining 5% filled with insects, eggs, and baby animals.[109][110] In some ecosystems, however, chimpanzees are predatory, forming parties to hunt monkeys.[111] Some comparative studies of human and higher primate digestive tracts do suggest that humans have evolved to obtain greater amounts of calories from sources such as animal foods, allowing them to shrink the size of the gastrointestinal tract relative to body mass and to increase the brain mass instead.[112][113]

Anthropologists have diverse opinions about the proportions of plant and animal foods consumed. Just as with still existing hunters and gatherers, there were many varied «diets» in different groups, and also varying through this vast amount of time. Some paleolithic hunter-gatherers consumed a significant amount of meat and possibly obtained most of their food from hunting,[114] while others were believed to have a primarily plant-based diet.[71] Most, if not all, are believed to have been opportunistic omnivores.[115] One hypothesis is that carbohydrate tubers (plant underground storage organs) may have been eaten in high amounts by pre-agricultural humans.[116][117][118][119] It is thought that the Paleolithic diet included as much as 1.65–1.9 kg (3.6–4.2 lb) per day of fruit and vegetables.[120] The relative proportions of plant and animal foods in the diets of Paleolithic people often varied between regions, with more meat being necessary in colder regions (which were not populated by anatomically modern humans until c. 30,000 – c. 50,000 BP).[121] It is generally agreed that many modern hunting and fishing tools, such as fish hooks, nets, bows, and poisons, were not introduced until the Upper Paleolithic and possibly even Neolithic.[38] The only hunting tools widely available to humans during any significant part of the Paleolithic were hand-held spears and harpoons. There is evidence of Paleolithic people killing and eating seals and elands as far as c. 100,000 BP. On the other hand, buffalo bones found in African caves from the same period are typically of very young or very old individuals, and there is no evidence that pigs, elephants, or rhinos were hunted by humans at the time.[122]

Paleolithic peoples suffered less famine and malnutrition than the Neolithic farming tribes that followed them.[23][123] This was partly because Paleolithic hunter-gatherers accessed a wider variety of natural foods, which allowed them a more nutritious diet and a decreased risk of famine.[23][25][76] Many of the famines experienced by Neolithic (and some modern) farmers were caused or amplified by their dependence on a small number of crops.[23][25][76] It is thought that wild foods can have a significantly different nutritional profile than cultivated foods.[124] The greater amount of meat obtained by hunting big game animals in Paleolithic diets than Neolithic diets may have also allowed Paleolithic hunter-gatherers to enjoy a more nutritious diet than Neolithic agriculturalists.[123] It has been argued that the shift from hunting and gathering to agriculture resulted in an increasing focus on a limited variety of foods, with meat likely taking a back seat to plants.[125] It is also unlikely that Paleolithic hunter-gatherers were affected by modern diseases of affluence such as type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and cerebrovascular disease, because they ate mostly lean meats and plants and frequently engaged in intense physical activity,[126][127] and because the average lifespan was shorter than the age of common onset of these conditions.[128][129]

Large-seeded legumes were part of the human diet long before the Neolithic Revolution, as evident from archaeobotanical finds from the Mousterian layers of Kebara Cave, in Israel.[130] There is evidence suggesting that Paleolithic societies were gathering wild cereals for food use at least as early as 30,000 years ago.[131] However, seeds—such as grains and beans—were rarely eaten and never in large quantities on a daily basis.[132] Recent archaeological evidence also indicates that winemaking may have originated in the Paleolithic, when early humans drank the juice of naturally fermented wild grapes from animal-skin pouches.[102] Paleolithic humans consumed animal organ meats, including the livers, kidneys, and brains. Upper Paleolithic cultures appear to have had significant knowledge about plants and herbs and may have sometimes practiced rudimentary forms of horticulture.[133] In particular, bananas and tubers may have been cultivated as early as 25,000 BP in southeast Asia.[70] In the Paleolithic Levant, 23,000 years ago, cereals cultivation of emmer, barley, and oats has been observed near the Sea of Galilee.[134][135]

Late Upper Paleolithic societies also appear to have occasionally practiced pastoralism and animal husbandry, presumably for dietary reasons. For instance, some European late Upper Paleolithic cultures domesticated and raised reindeer, presumably for their meat or milk, as early as 14,000 BP.[54] Humans also probably consumed hallucinogenic plants during the Paleolithic.[3] The Aboriginal Australians have been consuming a variety of native animal and plant foods, called bushfood, for an estimated 60,000 years, since the Middle Paleolithic.

In February 2019, scientists reported evidence, based on isotope studies, that at least some Neanderthals may have eaten meat.[136][137][138] People during the Middle Paleolithic, such as the Neanderthals and Middle Paleolithic Homo sapiens in Africa, began to catch shellfish for food as revealed by shellfish cooking in Neanderthal sites in Italy about 110,000 years ago and in Middle Paleolithic Homo sapiens sites at Pinnacle Point, South Africa around 164,000 BP.[47][139] Although fishing only became common during the Upper Paleolithic,[47][140] fish have been part of human diets long before the dawn of the Upper Paleolithic and have certainly been consumed by humans since at least the Middle Paleolithic.[57] For example, the Middle Paleolithic Homo sapiens in the region now occupied by the Democratic Republic of the Congo hunted large 6 ft (1.8 m)-long catfish with specialized barbed fishing points as early as 90,000 years ago.[47][57] The invention of fishing allowed some Upper Paleolithic and later hunter-gatherer societies to become sedentary or semi-nomadic, which altered their social structures.[91] Example societies are the Lepenski Vir as well as some contemporary hunter-gatherers, such as the Tlingit. In some instances (at least the Tlingit), they developed social stratification, slavery, and complex social structures such as chiefdoms.[38]

Anthropologists such as Tim White suggest that cannibalism was common in human societies prior to the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic, based on the large amount of “butchered human» bones found in Neanderthal and other Lower/Middle Paleolithic sites.[141] Cannibalism in the Lower and Middle Paleolithic may have occurred because of food shortages.[142] However, it may have been for religious reasons, and would coincide with the development of religious practices thought to have occurred during the Upper Paleolithic.[98][143] Nonetheless, it remains possible that Paleolithic societies never practiced cannibalism, and that the damage to recovered human bones was either the result of excarnation or predation by carnivores such as saber-toothed cats, lions, and hyenas.[98]

A modern-day diet known as the Paleolithic diet exists, based on restricting consumption to the foods presumed to be available to anatomically modern humans prior to the advent of settled agriculture.[144]

See also[edit]

- Abbassia Pluvial

- Bontnewydd Palaeolithic site

- Caveman

- Japanese Paleolithic

- Lascaux

- Last Glacial Maximum

- List of Paleolithic archaeological sites by continent

- Luzia Woman

- Mousterian Pluvial

- Origins of society

- Palaeoarchaeology

- Settlement of the Americas

- Turkana Boy

References[edit]

- ^ Christian, David (2014). Big History: Between Nothing and Everything. New York: McGraw Hill Education. p. 93.

- ^ a b Toth, Nicholas; Schick, Kathy (2007). «Overview of Paleolithic Archaeology». In Henke, H. C. Winfried; Hardt, Thorolf; Tatersall, Ian (eds.). Handbook of Paleoanthropology. Vol. 3. Berlin; Heidelberg; New York: Springer. pp. 1943–1963. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-33761-4_64. ISBN 978-3-540-32474-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l McClellan (2006). Science and Technology in World History: An Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 6–12. ISBN 978-0-8018-8360-6.

- ^ a b c d e Contributed by Richard B. Potts, B.A., Ph.D. «Human Evolution». Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lieberman, Philip (1991). Uniquely Human. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-92183-2.

- ^ a b Kusimba, Sibel (2003). African Foragers: Environment, Technology, Interactions. Rowman Altamira. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-7591-0154-8.

- ^ Gavashelishvili, A.; Tarkhnishvili, D. (2016). «Biomes and human distribution during the last ice age». Global Ecology and Biogeography. 25 (5): 563–74. doi:10.1111/geb.12437.

- ^ a b Weinstock, John. «Sami Prehistory Revisited: transactions, admixture and assimilation in the phylogeographic picture of Scandinavia». University of Texas.

- ^

Goebel, Ted; Waters, Michael R.; O’Rourke, Dennis H. (14 March 2008). «The Late Pleistocene Dispersal of Modern Humans in the Americas» (PDF). Science. 319 (5869): 1497–502. Bibcode:2008Sci…319.1497G. doi:10.1126/science.1153569. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 18339930. S2CID 36149744. - ^ Bennett, Matthew R.; Bustos, David; Pigati, Jeffrey S.; Springer, Kathleen B.; Urban, Thomas M.; Holliday, Vance T.; Reynolds, Sally C.; Budka, Marcin; Honke, Jeffrey S.; Hudson, Adam M.; Fenerty, Brendan; Connelly, Clare; Martinez, Patrick J.; Santucci, Vincent L.; Odess, Daniel (23 September 2021). «Evidence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum». Science. 373 (6562): 1528–1531. Bibcode:2021Sci…373.1528B. doi:10.1126/science.abg7586. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 34554787. S2CID 237616125.

- ^ Lubbock, John (2005) [1872]. «4». Pre-Historic Times, as Illustrated by Ancient Remains, and the Manners and Customs of Modern Savages. Williams and Norgate. p. 75. ISBN 978-1421270395 – via Elibron Classics.

- ^ «The Pleistocene Epoch». University of California Museum of Paleontology. Archived from the original on 24 August 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ^ a b «University of California Museum of Paleontology website the Pliocene epoch». University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ a b Scotese, Christopher. «Paleomap project». The Earth has been in an Ice House Climate for the last 30 million years. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- ^ Van Andel, Tjeerd H. (1994). New Views on an Old Planet: A History of Global Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 454. ISBN 978-0-521-44243-5.

- ^ Six Degrees Could Change The World Mark Lynas interview. National Geographic Channel.

- ^ «University of California Museum of Paleontology website the Pleistocene epoch(accessed March 25)». University of California Museum of Paleontology. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, Kimberly. «Climate Change, Then Humans, Drove Mammoths Extinct from National Geographic». National Geographic news. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ^ Nowak, Ronald M. (1999). Walker’s Mammals of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- ^ «Phylogeographic Analysis of the mid-Holocene Mammoth from Qagnax Cave, St. Paul Island, Alaska» (PDF). Harvard University.

- ^ Gamble, Clive (1990). El poblamiento Paleolítico de Europa [The Paleolithic settlement of Europe] (in Spanish). Barcelona: Editorial Crítica. ISBN 84-7423-445-X.

- ^ Musée de Préhistoire Terra Amata. «Le site acheuléen de Terra Amata» [The Acheulean site of Terra Amata]. Musée de Préhistoire Terra Amata (in French). Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Stavrianos, Leften Stavros (1997). Lifelines from Our Past: A New World History. New Jersey: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-13-357005-2. pp. 9–13 p. 70

- ^ a b c d e f g Stavrianos, Leften Stavros (1991). A Global History from Prehistory to the Present. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. pp. 9–13. ISBN 978-0-13-357005-2.

- ^ a b c «The Consequences of Domestication and Sedentism by Emily Schultz, et al». Primitivism.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ Armesto, Felipe Fernandez (2003). Ideas that changed the world. New York: Dorling Kindersley limited. pp. 10, 400. ISBN 978-0-7566-3298-4.

- ^ a b c d e Hillary Mayell. «When Did «Modern» Behavior Emerge in Humans?». National Geographic News. Retrieved 5 February 2008.

- ^ Roebroeks, Wil; Villa, Paola (14 March 2011). «On the earliest evidence for habitual use of fire in Europe». PNAS. 108 (13): 5209–5214. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.5209R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1018116108. PMC 3069174. PMID 21402905.

- ^ Ewen, Callaway (22 September 2011). «First Aboriginal genome sequenced». Nature News. doi:10.1038/news.2011.551.

- ^ Bocquet-Appel, Jean-Pierre; et al. (2005). «Estimates of Upper Palaeolithic meta-population size in Europe from archaeological data» (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 32 (11): 1656–1668. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2005.05.006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ «More surprises about Palaeolithic humans». Cosmos Magazine. 29 September 2020.

- ^ McClellan, James E.; Dorn, Harold (2006). Science and Technology in World History. United States: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 13.

- ^ Semaw, Sileshi (2000). «The World’s Oldest Stone Artefacts from Gona, Ethiopia: Their Implications for Understanding Stone Technology and Patterns of Human Evolution Between 2.6–1.5 Million Years Ago». Journal of Archaeological Science. 27 (12): 1197–214. doi:10.1006/jasc.1999.0592. S2CID 1490212.

- ^ Klein, R. (1999). The Human Career. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226439631.

- ^ Roche, Hélène; Brugal, Jean-Philip; Delagnes, Anne; Feibel, Craig; Harmand, Sonia; Kibunjia, Mzalendo; Prat, Sandrine; Texier, Pierre-Jean (2003). «Les sites archéologiques plio-pléistocènes de la formation de Nachukui, Ouest-Turkana, Kenya: bilan synthétique 1997-2001» [The Plio-Pleistocene archaeological sites of the Nachukui formation, West-Turkana, Kenya: summary report 1997-2001]. Palevol Reports (in French). 2 (8): 663–673. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2003.06.001.

- ^ Clark, JD, Variability in primary and secondary technologies of the Later Acheulian in Africa in Milliken, S and Cook, J (eds), 2001

- ^ Weiss, Rick (22 February 2007). «Chimps Observed Making Their Own Weapons». The Washington Post.

- ^ a b c d e f Marlowe, F.W. (2005). «Hunter-gatherers and human evolution» (PDF). Evolutionary Anthropology. 14 (2): 15294. doi:10.1002/evan.20046. S2CID 53489209. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2008.

- ^ a b Wrangham R, Conklin-Brittain N (September 2003). «Cooking as a biological trait» (PDF). Comp Biochem Physiol A. 136 (1): 35–46. doi:10.1016/S1095-6433(03)00020-5. PMID 14527628. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2005.

- ^ Wrangham, R.W. 2009. Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human. Basic Books, New York.

- ^ Johns, T.A., Kubo, I. 1988. A survey of traditional methods employed for the detoxification of plant foods. Journal of Ethnobiology 8, 81–129.

- ^ Speth, J.D., 2015. When did humans learn to boil. PaleoAnthropology, 2015, pp.54-67.

- ^ Mousterian Brace 1997: 545

- ^ Movius Jr, H.L., 1966. The hearths of the Upper Perigordian and Aurignacian horizons at the Abri Pataud, Les Eyzies (Dordogne), and their possible significance. American Anthropologist, pp.296-325.

- ^ a b c «First Mariners Project Photo Gallery 1». Mc2.vicnet.net.au. Archived from the original on 25 October 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ «First Mariners – National Geographic project 2004». Mc2.vicnet.net.au. 2 October 2004. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Miller, Barbra; Wood, Bernard; Balansky, Andrew; Mercader, Julio; Panger, Melissa (2006). Anthropology. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. p. 768. ISBN 978-0-205-32024-0.

- ^ «Human Evolution,» Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007 Archived 2008-04-08 at the Wayback Machine Contributed by Richard B. Potts, B.A., Ph.D.

- ^ a b Ann Parson. «Neanderthals Hunted as Well as Humans, Study Says». National Geographic News. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ Boëda, E.; Geneste, J.M.; Griggo, C.; Mercier, N.; Muhesen, S.; Reyss, J.L.; Taha, A.; Valladas, H. (1999). «A Levallois point embedded in the vertebra of a wild ass (Equus africanus): Hafting, projectiles and Mousterian hunting». Antiquity. 73 (280): 394–402. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00088335. S2CID 163560577.

- ^ Balbirnie, Cameron (10 May 2005). «The icy truth behind Neanderthals». BBC News. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- ^ J. Chavaillon, D. Lavallée, « Bola », in Dictionnaire de la Préhistoire, PUF, 1988.

- ^ Wickler, Stephen. «Prehistoric Melanesian Exchange and Interaction: Recent Evidence from the Northern Solomon Islands» (PDF). Asian Perspectives. 29 (2): 135–154.

- ^ a b Lloyd, J & Mitchinson, J: «The Book of General Ignorance». Faber & Faber, 2006.

- ^ Mellot, Christine. «Stalking the ancient dog» (PDF). Science news. Retrieved 3 January 2008.

- ^ a b Armesto, Felipe Fernandez (2003). Ideas that changed the world. New York: Dorling Kindersley limited. p. 400. ISBN 978-0-7566-3298-4.; [1]

- ^ a b c d «Stone Age,» Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007 Archived 2009-11-01 at the Wayback Machine Contributed by Kathy Schick, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. and Nicholas Toth, B.A., M.A., Ph.D.

- ^ a b Nancy White. «Intro to archeology The First People and Culture». Introduction to archeology. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ^ Urquhart, James (8 August 2007). «Finds test human origins theory». BBC News. Retrieved 20 March 2008.

- ^ a b c Christopher Boehm (1999) «Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior» pp. 198–208 Harvard University Press

- ^ a b c Henahan, Sean. «Blombos Cave art». Science News. Retrieved 12 March 2008.

- ^ Christopher Boehm (1999) «Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior» p. 198 Harvard University Press

- ^ a b Gutrie, R. Dale (2005). The Nature of Paleolithic art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31126-5. pp. 420-22

- ^ a b c Ehrenreich, Barbara (1997). Blood Rites: Origins and History of the Passions of War. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-5787-4. p. 123

- ^ a b Kelly, Raymond (October 2005). «The evolution of lethal intergroup violence». PNAS. 102 (43): 15294–98. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10215294K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505955102. PMC 1266108. PMID 16129826.

- ^ Kelly, Raymond C. Warless societies and the origin of war. Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 2000.

- ^ Marx, Karl; Engels, Friedrich (1848). The Communist Manifesto. London. pp. 71, 87. ISBN 978-1-59986-995-7.

- ^ Rigby, Stephen Henry (1999). Marxism and History: A Critical Introduction. Manchester University Press. pp. 111, 314. ISBN 0-7190-5612-8.

- ^ Christopher Boehm (1999) «Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior» p. 192 Harvard university press

- ^ a b Kiefer, Thomas M. (Spring 2002). «Anthropology E-20». Lecture 8 Subsistence, Ecology and Food production. Harvard University. Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2008.

- ^ a b Dahlberg, Frances (1975). Woman the Gatherer. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02989-5.

- ^ a b Stefan Lovgren. «Sex-Based Roles Gave Modern Humans an Edge, Study Says». National Geographic News. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- ^ Stavrianos, Leften Stavros (1991). A Global History from Prehistory to the Present. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-357005-2.

the sexes were more equal during Paleolithic millennia than at any time since.

p. 9 - ^ a b Museum of Antiquites web site Archived 2007-11-21 at the Wayback Machine . Retrieved February 13, 2008.

- ^ a b c Tedlock, Barbara. 2005. The Woman in the Shaman’s Body: Reclaiming the Feminine in Religion and Medicine. New York: Bantam.

- ^ a b c Jared Diamond. «The Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race». Discover. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ Jonathan Amos (2004-04-15). «Cave yields ‘earliest jewellery’«. BBC News. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ Hillary Mayell. «Oldest Jewelry? «Beads» Discovered in African Cave». National Geographic News. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ^ «Human Evolution,» Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007 Archived 2009-10-31 at the Wayback Machine Contributed by Richard B. Potts, B.A., Ph.D.

- ^ a b Robert G. Bednarik. «Beads and the origins of symbolism». Archived from the original on 2018-10-26. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- ^ Klein, Richard G. (22 March 2002). The Dawn of Human Culture. ISBN 0-471-25252-2.

- ^ a b c d

«Paleolithic Art». Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia. 2007. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 20 March 2008. - ^ a b c Clottes, Jean. «Shamanism in Prehistory». Bradshaw foundation. Archived from the original on 30 April 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2008.

- ^ a b McDermott, LeRoy (1996). «Self-Representation in Upper Paleolithic Female Figurines». Current Anthropology. 37 (2): 227–275. doi:10.1086/204491. JSTOR 2744349. S2CID 144914396.

- ^ R. Dale Guthrie, The Nature of Paleolithic Art. University of Chicago Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-226-31126-5. Preface.

- ^ Stone, Merlin (1978). When God Was a Woman. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-15-696158-5.

- ^ Gimbutas, Marija (1991). The Civilization of the Goddess. ISBN 978-0062508041.

- ^ Bücher, Karl. Trabajo y ritmo [Work and rhythm] (in Spanish). Madrid: Biblioteca Científico-Filosófica.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (May 1998). The origin of man. Edimat books, S.A. ISBN 84-8403-034-2.

- ^ Nelson, D.E., Radiocarbon dating of bone and charcoal from Divje babe I cave, cited by Morley, p. 47

- ^ a b Bahn, Paul (1996) «The atlas of world archeology» Copyright 2000 The Brown Reference Group PLC

- ^ «About OriginsNet by James Harrod». Originsnet.org. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ «Appendices for chimpanzee spirituality by James Harrod» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ a b Fallio, Vincent W. (2006). New Developments in Consciousness Research. New York: Nova Publishers. pp. M1 98–109. ISBN 978-1-60021-247-5.

- ^ «Oldowan Art, Religion, Symbols, Mind by James Harrod». Originsnet.org. Archived from the original on 10 March 2010. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ Wunn, Ina (2000). «Beginning of Religion». Numen. 47 (4): 434–435. doi:10.1163/156852700511612.

- ^ Robbins, Lawrence H.; Campbell, Alec C.; Brook, George A.; Murphy, Michael L. (June 2007). «World’s Oldest Ritual Site? The «Python Cave» at Tsodilo Hills World Heritage Site, Botswana» (PDF). NYAME AKUMA, the Bulletin of the Society of Africanist Archaeologists (67). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Narr, Karl J. «Prehistoric religion». Britannica online encyclopedia 2008. Archived from the original on 9 April 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2008.

- ^ Steven Mithen (1996). The Prehistory of the Mind: The Cognitive Origins of Art, Religion and Science. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05081-1.