This article is about the German eszett. For the Greek letter that looks similar, see Beta. For the Chinese radical, see 阝. For the Malayalam script, see ഭ.

Not to be confused with the Latin letter B.

| ẞ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ẞ ß | ||||

|

||||

| Usage | ||||

| Writing system | Latin script | |||

| Type | Alphabetic | |||

| Language of origin | Early New High German | |||

| Phonetic usage | [s] | |||

| Unicode codepoint | U+1E9E, U+00DF |

|||

| History | ||||

| Development |

|

|||

| Time period | ~1300s to present | |||

| Descendants | None | |||

| Sisters | None | |||

| Transliteration equivalents | ss, sz | |||

| Other | ||||

| Other letters commonly used with | ss, sz | |||

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

In German orthography, the letter ß, called Eszett (IPA: [ɛsˈtsɛt] ess-TSET) and scharfes S (IPA: [ˌʃaʁfəs ˈʔɛs], «sharp S»), represents the /s/ phoneme in Standard German when following long vowels and diphthongs.

The letter-name Eszett combines the names of the letters of ⟨s⟩ (Es) and ⟨z⟩ (Zett) in German. The character’s Unicode names in English are sharp s[1] and eszett.[1] The Eszett letter is used only in German, and can be typographically replaced with the double-s digraph ⟨ss⟩, if the ß-character is unavailable. In the 20th century, the ß-character was replaced with ss in the spelling of Swiss Standard German (Switzerland and Liechtenstein), while remaining Standard German spelling in other varieties of German language.[2]

The letter originates as the ⟨sz⟩ digraph as used in late medieval and early modern German orthography, represented as a ligature of ⟨ſ⟩ (long s) and ⟨ʒ⟩ (tailed z) in blackletter typefaces, yielding ⟨ſʒ⟩.[a] This developed from an earlier usage of ⟨z⟩ in Old and Middle High German to represent a separate sibilant sound from ⟨s⟩; when the difference between the two sounds was lost in the 13th century, the two symbols came to be combined as ⟨sz⟩ in some situations.

Traditionally, ⟨ß⟩ did not have a capital form, although some type designers introduced de facto capitalized variants.

In 2017, the Council for German Orthography officially adopted a capital, ⟨ẞ⟩, into German orthography, ending a long orthographic debate.[3]

⟨ß⟩ was encoded by ECMA-94 (1985) at position 223 (hexadecimal DF), inherited by Latin-1 and Unicode (U+00DF ß LATIN SMALL LETTER SHARP S).[4]

The HTML entity ß was introduced with HTML 2.0 (1995). The capital (U+1E9E ẞ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER SHARP S) was encoded by ISO 10646 in 2008.

Usage[edit]

Current usage[edit]

In standard German, three letters or combinations of letters commonly represent [s] (the voiceless alveolar fricative) depending on its position in a word: ⟨s⟩, ⟨ss⟩, and ⟨ß⟩. According to current German orthography, ⟨ß⟩ represents the sound [s]:

- when it is written after a diphthong or long vowel and is not followed by another consonant in the word stem: Straße, Maß, groß, heißen [Exceptions: aus and words with final devoicing (e.g., Haus)];[5] and

- when a word stem ending with ⟨ß⟩ takes an inflectional ending beginning with a consonant: heißt, größte.[6]

In verbs with roots where the vowel changes length, this means that some forms may be written with ⟨ß⟩, others with ⟨ss⟩: wissen, er weiß, er wusste.[5]

The use of ⟨ß⟩ distinguishes minimal pairs such as reißen (IPA: [ˈʁaɪsn̩], to rip) and reisen (IPA: [ˈʁaɪzn̩], to travel) on the one hand ([s] vs. [z]), and Buße (IPA: [ˈbuːsə], penance) and Busse (IPA: [ˈbʊsə], buses) on the other (long vowel before ⟨ß⟩, short vowel before ⟨ss⟩).[7]: 123

Some proper names may use ⟨ß⟩ after a short vowel, following the old orthography; this is also true of some words derived from proper names (e.g., Litfaßsäule; advertising column, named after Ernst Litfaß).[8]: 180

In pre-1996 orthography[edit]

Replacement street sign in Aachen, adapted to the 1996 spelling reform (old: Kongreßstraße, new: Kongressstraße)

According to the orthography in use in German prior to the German orthography reform of 1996, ⟨ß⟩ was written to represent [s]:

- word internally following a long vowel or diphthong: Straße, reißen; and

- at the end of a syllable or before a consonant, so long as [s] is the end of the word stem: muß, faßt, wäßrig.[8]: 176

In the old orthography, word stems spelled ⟨ss⟩ internally could thus be written ⟨ß⟩ in certain instances, without this reflecting a change in vowel length: küßt (from küssen), faßt (from fassen), verläßlich and Verlaß (from verlassen), kraß (comparative: krasser).[7]: 121–23 [9] In rare occasions, the difference between ⟨ß⟩ and ⟨ss⟩ could help differentiate words: Paßende (expiration of a pass) and passende (appropriate).[8]: 178

Substitution and all caps[edit]

Capitalization as SZ on a Bundeswehr crate (ABSCHUSZGERAET for Abschußgerät ‘launcher’)

If no ⟨ß⟩ is available, ⟨ss⟩ or ⟨sz⟩ is used instead (⟨sz⟩ especially in Hungarian-influenced eastern Austria). Until 2017, there was no official capital form of ⟨ß⟩; a capital form was nevertheless frequently used in advertising and government bureaucratic documents.[10]: 211 In June of that year, the Council for German Orthography officially adopted a rule that ⟨ẞ⟩ would be an option for capitalizing ⟨ß⟩ besides the previous capitalization as ⟨SS⟩ (i.e., variants STRASSE and STRAẞE would be accepted as equally valid).[11]

[12] Prior to this time, it was recommended to render ⟨ß⟩ as ⟨SS⟩ in allcaps except when there was ambiguity, in which case it should be rendered as ⟨SZ⟩. The common example for such a case was IN MASZEN (in Maßen «in moderate amounts») vs. IN MASSEN (in Massen «in massive amounts»), where the difference between the spelling in ⟨ß⟩ vs. ⟨ss⟩ could actually reverse the conveyed meaning.[citation needed]

Switzerland and Liechtenstein[edit]

In Swiss Standard German, ⟨ss⟩ usually replaces every ⟨ß⟩.[13][14] This is officially sanctioned by the reformed German orthography rules, which state in §25 E2: «In der Schweiz kann man immer „ss“ schreiben» («In Switzerland, one may always write ‘ss'»). Liechtenstein follows the same practice. There are very few instances where the difference between spelling ⟨ß⟩ and ⟨ss⟩ affects the meaning of a word, and these can usually be told apart by context.[10]: 230 [15]

Other uses[edit]

Use of ß (blackletter ‘ſz’) in Sorbian: wyßokoſcʒ́i («highest», now spelled wysokosći). Text of Luke 2:14, in a church in Oßling.

Occasionally, ⟨ß⟩ has been used in unusual ways:

- As a surrogate for Greek lowercase ⟨β⟩ (beta), which looks fairly similar. This was used in older operating systems, the character encoding of which (notably Latin-1 and Windows-1252) did not support easy use of Greek letters. Additionally, the original IBM DOS code page, CP437 (aka OEM-US) conflates the two characters, with a glyph that minimizes their differences placed between the Greek letters ⟨α⟩ (alpha) and ⟨γ⟩ (gamma) but named «Sharp s Small».[16]

- In Prussian Lithuanian, as in the first book published in Lithuanian, Martynas Mažvydas’ Simple Words of Catechism,[17] as well as in Sorbian (see example on the left).

- For sadhe in Akkadian glosses, in place of the standard ⟨ṣ⟩, when that character is unavailable due to limitations of HTML.[18]

- The letter appeared in the alphabet made by Jan Kochanowski for Polish language, that was used from 16th until 18th century. It represented the voiceless postalveolar fricative ([ʃ]) sound.[19][20] It was for example used in Jakub Wujek Bible.[21]

History[edit]

Origin and development[edit]

As a result of the High German consonant shift, Old High German developed a sound generally spelled ⟨zz⟩ or ⟨z⟩ that was probably pronounced [s] and was contrasted with a sound, probably pronounced [s̠] (voiceless alveolar retracted sibilant) or [z̠] (voiced alveolar retracted sibilant), depending on the place in the word, and spelled ⟨s⟩.[22] Given that ⟨z⟩ could also represent the affricate [ts], some attempts were made to differentiate the sounds by spelling [s] as ⟨zss⟩ or ⟨zs⟩: wazssar (German: Wasser), fuozssi (German: Füße), heizsit (German: heißt).[23] In Middle High German, ⟨zz⟩ simplified to ⟨z⟩ at the end of a word or after a long vowel, but was retained word internally after a short vowel: wazzer (German: Wasser) vs. lâzen (German: lassen) and fuoz (German: Fuß).[24]

Use of the late medieval ligature ⟨ſz⟩ in Ulrich Füetrer’s Buch der Abenteuer: «uſz» (modern German aus).

In the thirteenth century, the phonetic difference between ⟨z⟩ and ⟨s⟩ was lost at the beginning and end of words in all dialects except for Gottscheerish.[22] Word-internally, Old and Middle High German ⟨s⟩ came to be pronounced [z] (the voiced alveolar sibilant), while Old and Middle High German ⟨z⟩ continued to be pronounced [s]. This produces the contrast between modern standard German reisen and reißen. The former is pronounced IPA: [ˈʁaɪzn̩] and comes from Middle High German: reisen, while the latter is pronounced IPA: [ˈʁaɪsn̩] and comes from Middle High German: reizen.[25]

In the late medieval and early modern periods, [s] was frequently spelled ⟨sz⟩ or ⟨ss⟩. The earliest appearance of ligature resembling the modern ⟨ß⟩ is in a fragment of a manuscript of the poem Wolfdietrich from around 1300.[10]: 214 [25] In the Gothic book hands and bastarda scripts of the late medieval period, ⟨sz⟩ is written with long s and the Blackletter «tailed z», as ⟨ſʒ⟩. A recognizable ligature representing the ⟨sz⟩ digraph develops in handwriting in the early 14th century.[26]: 67–76

An early modern printed rhyme by Hans Sachs showing several instances of ß as a clear ligature of ⟨ſz⟩: «groß», «stoß», «Laß», «baß» (= modern «besser»), and «Faß».

By the late 1400s, the choice of spelling between ⟨sz⟩ and ⟨ss⟩ was usually based on the sound’s position in the word rather than etymology: ⟨sz⟩ (⟨ſz⟩) tended to be used in word final position: uſz (Middle High German: ûz, German: aus), -nüſz (Middle High German: -nüss(e), German: -nis); ⟨ss⟩ (⟨ſſ⟩) tended to be used when the sound occurred between vowels: groſſes (Middle High German: grôzes, German: großes).[27]: 171 While Martin Luther’s early 16th-century printings also contain spellings such as heyße (German: heiße), early modern printers mostly changed these to ⟨ſſ⟩: heiſſe. Around the same time, printers began to systematically distinguish between das (the, that [pronoun]) and daß (that [conjunction]).[27]: 215

In modern German, the Old and Middle High German ⟨z⟩ is now represented by either ⟨ss⟩, ⟨ß⟩, or, if there are no related forms in which [s] occurs intervocalically, with ⟨s⟩: messen (Middle High German: mezzen), Straße (Middle High German: strâze), and was (Middle High German: waz).[24]

Standardization of use[edit]

The pre-1996 German use of ⟨ß⟩ was codified by the eighteenth-century grammarians Johann Christoph Gottsched (1748) and Johann Christoph Adelung (1793) and made official for all German-speaking countries by the German Orthographic Conference of 1901. In this orthography, the use of ⟨ß⟩ was modeled after the use of long and «round»-s in Fraktur. ⟨ß⟩ appeared both word internally after long vowels and also in those positions where Fraktur required the second s to be a «round» or «final» s, namely the ends of syllables or the ends of words.[10]: 217–18 In his Deutsches Wörterbuch (1854) Jacob Grimm called for ⟨ß⟩ or ⟨sz⟩ to be written for all instances of Middle and Old High German etymological ⟨z⟩ (e.g., eß instead of es from Middle High German: ez); however, his etymological proposal could not overcome established usage.[27]: 269

In Austria-Hungary prior to the German Orthographic Conference of 1902, an alternative rule formulated by Johann Christian August Heyse in 1829 had been officially taught in the schools since 1879, although this spelling was not widely used. Heyse’s rule matches current usage after the German orthography reform of 1996 in that ⟨ß⟩ was only used after long vowels.[10]: 219

Use in Roman type[edit]

The ſs ligature used for Latin in 16th-century printing (utiliſsimæ)

Essen with ſs-ligature reads Eßen (Latin Blaeu atlas, text printed in Antiqua, 1650s)

Although there are early examples in Roman type (called Antiqua in a German context) of a ⟨ſs⟩-ligature that looks like the letter ⟨ß⟩, it was not commonly used for ⟨sz⟩.[28][29] These forms generally fell out of use in the eighteenth century and were used in Italic text only;[26]: 73 German works printed in Roman type in the late 18th and early 19th centuries such as Johann Gottlieb Fichte’s Wissenschaftslehre did not provide any equivalent to the ⟨ß⟩. Jacob Grimm began using ⟨ß⟩ in his Deutsche Grammatik (1819), however it varied with ⟨ſſ⟩ word internally.[26]: 74 Grimm eventually rejected the use of the character; in their Deutsches Wörterbuch (1838), the Brothers Grimm favored writing it as ⟨sz⟩.[29]: 2 The First Orthographic Conference in Berlin (1876) recommended that ß be represented as ⟨ſs⟩ — however, both suggestions were ultimately rejected.[27]: 269 [10]: 222 In 1879, a proposal for various letter forms was published in the Journal für Buchdruckerkunst. A committee of the Typographic Society of Leipzig chose the «Sulzbacher form». In 1903 it was proclaimed as the new standard for the Eszett in Roman type.[29]: 3–5

Until the abolition of Fraktur in 1941, it was nevertheless common for family names to be written with ⟨ß⟩ in Fraktur and ⟨ss⟩ in Roman type. The formal abolition resulted in inconsistencies in how names such as Heuss/Heuß are written in modern German.[8]: 176

Abolition and attempted abolitions[edit]

The Swiss and Liechtensteiners ceased to use ⟨ß⟩ in the twentieth century. This has been explained variously by the early adoption of Roman type in Switzerland, the use of typewriters in Switzerland that did not include ⟨ß⟩ in favor of French and Italian characters, and peculiarities of Swiss German that cause words spelled with ⟨ß⟩ or ⟨ss⟩ to be pronounced with gemination.[10]: 221–22 The Education Council of Zurich had decided to stop teaching the letter in 1935, whereas the Neue Zürcher Zeitung continued to write ⟨ß⟩ until 1971.[30] Swiss newspapers continued to print in Fraktur until the end of the 1940s, and the abandonment of ß by most newspapers corresponded to them switching to Roman typesetting.[31]

When the Nazi German government abolished the use of blackletter typesetting in 1941, it was originally planned to also abolish the use of ⟨ß⟩. However, Hitler intervened to retain ⟨ß⟩, while deciding against the creation of a capital form.[32] In 1954, a group of reformers in West Germany similarly proposed, among other changes to German spelling, the abolition of ⟨ß⟩; their proposals were publicly opposed by German-language writers Thomas Mann, Hermann Hesse, and Friedrich Dürrenmatt and were never implemented.[33] Although the German Orthography Reform of 1996 reduced the use of ⟨ß⟩ in standard German, Adrienne Walder writes that an abolition outside of Switzerland appears unlikely.[10]: 235

Development of a capital form[edit]

Uppercase ß on a book cover from 1957

Because ⟨ß⟩ had been treated as a ligature, rather than as a full letter of the German alphabet, it had no capital form in early modern typesetting. There were, however, proposals to introduce capital forms of ⟨ß⟩ for use in allcaps writing (where ⟨ß⟩ would otherwise usually be represented as either ⟨SS⟩ or ⟨SZ⟩). A capital was first seriously proposed in 1879, but did not enter official or widespread use.[34] Historical typefaces offering a capitalized eszett mostly date to the time between 1905 and 1930. The first known typefaces to include capital eszett were produced by the Schelter & Giesecke foundry in Leipzig, in 1905/06. Schelter & Giesecke at the time widely advocated the use of this type, but its use nevertheless remained very limited.

The preface to the 1925 edition of the Duden dictionary expressed the desirability of a separate glyph for capital ⟨ß⟩:

Die Verwendung zweier Buchstaben für einen Laut ist nur ein Notbehelf, der aufhören muss, sobald ein geeigneter Druckbuchstabe für das große ß geschaffen ist.[35]

The use of two letters for a single phoneme is makeshift, to be abandoned as soon as a suitable type for the capital ß has been developed.

The Duden was edited separately in East and West Germany during the 1950s to 1980s. The East German Duden of 1957 (15th ed.) introduced a capital ⟨ß⟩, in its typesetting without revising the rule for capitalization. The 16th edition of 1969 still announced that an uppercase ⟨ß⟩ was in development and would be introduced in the future. The 1984 edition again removed this announcement and simply stated that there is no capital version of ⟨ß⟩.[36]

In the 2000s, there were renewed efforts on the part of certain typographers to introduce a capital, ⟨ẞ⟩. A proposal to include a corresponding character in the Unicode set submitted in 2004[37] was rejected.[38][39] A second proposal submitted in 2007 was successful, and the character was included in Unicode version 5.1.0 in April 2008 (U+1E9E ẞ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER SHARP S).[40] The international standard associated with Unicode (UCS), ISO/IEC 10646, was updated to reflect the addition on 24 June 2008. The capital was finally adopted as an option in standard German orthography in 2017.[12]

Representation[edit]

Graphical variants[edit]

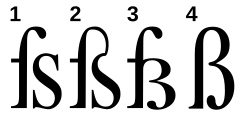

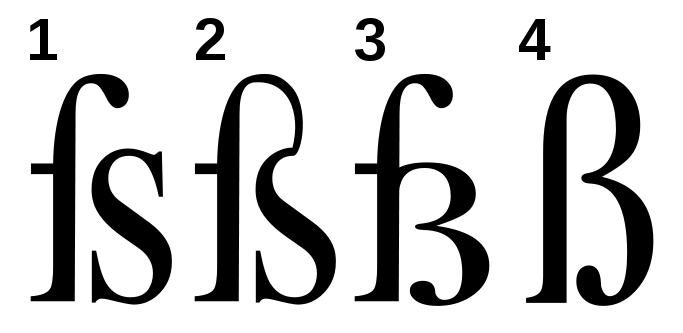

The recommendation of the Sulzbacher form (1903) was not followed universally in 20th-century printing.

There were four distinct variants of ⟨ß⟩ in use in Antiqua fonts:

Four forms of Antiqua Eszett: 1. ſs, 2. ſs ligature, 3. ſʒ ligature, 4. Sulzbacher form

- ⟨ſs⟩ without ligature, but as a single type, with reduced spacing between the two letters;

- the ligature of ⟨ſ⟩ and ⟨s⟩ inherited from the 16th-century Antiqua typefaces;

- a ligature of ⟨ſ⟩ and ⟨ʒ⟩, adapting the blackletter ligature to Antiqua; and

- the Sulzbacher form.

The first variant (no ligature) has become practically obsolete. Most modern typefaces follow either 2 or 4, with 3 retained in occasional usage, notably in street signs in Bonn and Berlin. The design of modern ⟨ß⟩ tends to follow either the Sulzbacher form, in which ⟨ʒ⟩ (tailed z) is clearly visible, or else be made up of a clear ligature of ⟨ſ⟩ and ⟨s⟩.[29]: 2

Three contemporary handwritten forms of ‘ß’ demonstrated in the word aß, «(I/he/she/it) ate»

Use of typographic variants in street signs:

-

Two distinct blackletter typefaces in Mainz. The red sign spells Straße with ſs; the blue sign uses the standard blackletter ſʒ ligature.

-

Sulzbacher form in the German Einbahnstraße («one-way street») sign

Capital ß in a web application

The inclusion of a capital ⟨ẞ⟩ in ISO 10646 in 2008 revived the century-old debate among font designers as to how such a character should be represented. The main difference in the shapes of ⟨ẞ⟩ in contemporary fonts is the depiction with a diagonal straight line vs. a curved line in its upper right part, reminiscent of the ligature of tailed z or of round s, respectively. The code chart published by the Unicode Consortium favours the former possibility,[41] which has been adopted by Unicode capable fonts including Arial, Calibri, Cambria, Courier New, Dejavu Serif, Liberation Sans, Liberation Mono, Linux Libertine and Times New Roman; the second possibility is more rare, adopted by Dejavu Sans. Some fonts adopt a third possibility in representing ⟨ẞ⟩ following the Sulzbacher form of ⟨ß⟩, reminiscent of the Greek ⟨β⟩ (beta); such a shape has been adopted by FreeSans and FreeSerif, Liberation Serif and Verdana.[42]

Keyboards and encoding[edit]

In Germany and Austria, a ‘ß’ key is present on computer and typewriter keyboards, normally to the right-hand end on the number row.

The German typewriter keyboard layout was defined in DIN 2112, first issued in 1928.[43]

In other countries, the letter is not marked on the keyboard, but a combination of other keys can produce it. Often, the letter is input using a modifier and the ‘s’ key. The details of the keyboard layout depend on the input language and operating system: on some keyboards with US-International (or local ‘extended’) setting, the symbol is created using AltGrs (or CtrlAlts) in Microsoft Windows, Linux and ChromeOS; in MacOS, one uses ⌥ Options on the US, US-Extended, and UK keyboards. In Windows, one can use Alt+0223. On Linux Composess works, and ComposeSS for uppercase.

Some modern virtual keyboards show ß when the user presses and holds the ‘s’ key.

The HTML entity for ⟨ß⟩ is ß. Its code point in the ISO 8859 character encoding versions 1, 2, 3, 4, 9, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16 and identically in Unicode is 223, or DF in hexadecimal. In TeX and LaTeX, ss produces ß. A German language support package for LaTeX exists in which ß is produced by "s (similar to umlauts, which are produced by "a, "o, and "u with this package).[44]

In modern browsers, «ß» will be converted to «SS» when the element containing it is set to uppercase using text-transform: uppercase in Cascading Style Sheets. The JavaScript in Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox will convert «ß» to «SS» when converted to uppercase (e.g., "ß".toUpperCase()).[citation needed]

| Preview | ẞ | ß | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | LATIN CAPITAL LETTER SHARP S | LATIN SMALL LETTER SHARP S | ||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 7838 | U+1E9E | 223 | U+00DF |

| UTF-8 | 225 186 158 | E1 BA 9E | 195 159 | C3 9F |

| Numeric character reference | ẞ | ẞ | ß | ß |

| Named character reference | ß | |||

| ISO 8859[b] and Windows-125x[c] | 223 | DF | ||

| Mac OS script encodings[d] | 167 | A7 | ||

| DOS code page 437,[69] 850[70] | 225 | E1 | ||

| EUC-KR[71] / UHC[72] | 169 172 | A9 AC | ||

| GB 18030[73] | 129 53 254 50 | 81 35 FE 32 | 129 48 137 56 | 81 30 89 38 |

| EBCDIC 037,[74] 500,[75] 1026[76] | 89 | 59 | ||

| ISO/IEC 6937 | 251 | FB | ||

| Shift JIS-2004[77] | 133 116 | 85 74 | ||

| EUC-JIS-2004[78] | 169 213 | A9 D5 | ||

| KPS 9566-2003[79] | 174 223 | AE DF | ||

| LaTeX[80] | [e] | ss |

See also[edit]

- long s

- β – Second letter of the Greek alphabet

- 阝 – Element used in Chinese Kangxi writing

- Sz – Digraph of the Latin script

Notes[edit]

- ^ The IPA symbol ezh (ʒ) is the most similar to the Blackletter z (

) and is used in this article for convenience despite its technical inaccuracy.

- ^ Parts

1,[45]

2,[46]

3,[47]

4,[48]

9,[49]

10,[50]

13,[51]

14,[52]

15[53] and

16.[54] - ^ Code pages

1250,[55]

1252,[56]

1254,[57]

1257[58] and

1258.[59] - ^ Mac OS

Roman,[60]

Icelandic,[61]

Croatian,[62]

Central European,[63]

Celtic,[64]

Gaelic,[65]

Romanian,[66]

Greek[67] and

Turkish.[68] - ^ The

SSmacro exists as the uppercase counterpart ofss, but displays as a doubled capital S.[80]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Unicode Consortium (2018), «C1 Controls and Latin-1 Supplement, Range 0080–00FF» (PDF), The Unicode Standard, Version 11.0, retrieved 2018-08-09.

- ^ Leitfaden zur deutschen Rechtschreibung («Guide to German Orthography») Archived 2012-07-08 at the Wayback Machine, 3rd edition (2007) (in German) from the Swiss Federal Chancellery, retrieved 22-Apr-2012

- ^ Ha, Thu-Huong. «Germany has ended a century-long debate over a missing letter in its alphabet». Retrieved 9 August 2017.

According to the council’s 2017 spelling manual: When writing the uppercase [of ß], write SS. It’s also possible to use the uppercase ẞ. Example: Straße — STRASSE — STRAẞE.

- ^ C1 Controls and Latin-1 Supplement glossed ‘uppercase is «SS» or 1E9E ẞ; typographically the glyph for this character can be based on a ligature of 017F ſ, with either 0073 s or with an old-style glyph for 007A z (the latter similar in appearance to 0292 ʒ). Both forms exist interchangeably today.’

- ^ a b «Deutsche Rechschreibung: 2.3 Besonderheiten bei [s] § 25». Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ Duden: Die Grammatik (9 ed.). 2016. p. 84.

- ^ a b Augst, Gerhard; Stock, Eberhard (1997). «Laut-Buchstaben-Zuordnung». In Augst, Gerhard; et al. (eds.). Zur Neuregelung der deutschen Rechtschreibung: Begründung und Kritik. Max Niemeyer. ISBN 3-484-31179-7.

- ^ a b c d Poschenrieder, Thorwald (1997). «S-Schreibung — Überlieferung oder Reform?». In Eroms, Hans-Werner; Munske, Horst Haider (eds.). Die Rechtschreibreform: Pro und Kontra. Erich Schmidt. ISBN 3-50303786-1.

- ^ Munske, Horst Haider (2005). Lob der Rechtschreibung: Warum wir schreiben, wie wir schreiben. C. H. Beck. p. 66. ISBN 3-406-52861-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Walder, Adrienne (2020). «Das versale Eszett: Ein neuer Buchstabe im deutschen Alphabet». Zeitschrift für Germanitische Linguistik. 48 (2): 211–237. doi:10.1515/zgl-2020-2001. S2CID 225226660.

- ^ 3. Bericht des Rats für deutsche Rechtschreibung 2011–2016 (2016), p. 7.

- ^ a b «Deutsche Rechtschreibung Regeln und Wörterverzeichnis: Aktualisierte Fassung des amtlichen Regelwerks entsprechend den Empfehlungen des Rats für deutsche Rechtschreibung 2016» (PDF). §25, E3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-07-06. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

E3: Bei Schreibung mit Großbuchstaben schreibt man SS. Daneben ist auch die Verwendung des Großbuchstabens ẞ möglich. Beispiel: Straße – STRASSE – STRAẞE. [When writing in all caps, one writes SS. It is also permitted to write ẞ. Example: Straße – STRASSE – STRAẞE.]

- ^ Peter Gallmann. [de] «Warum die Schweizer weiterhin kein Eszett schreiben.» in Die Neuregelung der deutschen Rechtschreibung. Begründung und Kritik. Gerhard Augst, et al., eds. Niemayer: 1997. (Archived.)

- ^ «Rechtscreibung: Leitfaden zur deutschen Rechtschreibung.» Schweizerische Bundeskanzlei, in Absprache mit der Präsidentin der Staatsschreiberkonferenz. 2017. pp. 19, 21–22.

- ^ «Rechtscreibung: Leitfaden zur deutschen Rechtschreibung.» Schweizerische Bundeskanzlei, in Absprache mit der Präsidentin der Staatsschreiberkonferenz. 2017. pp. 21–22.

- ^ «Code Page (CPGID): 00437». IBM software FTP server. IBM. 1984. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ Zinkevičius, Zigmas (1996). The History of the Lithuanian Language. Vilnius: Science and Encyclopedia Publishers. p. 230-236. ISBN 9785420013632.

- ^ Black, J.A.; Cunningham, G.; Fluckiger-Hawker, E.; Robson, E.; Zólyomi, G. (1998–2021). «ETCSL display conventions». The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Oxford University. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ «Skąd się wzięły znaki diakrytyczne?». 2plus3d.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2021-04-21. Retrieved 2021-08-29.

- ^ «Bon ton Ę-Ą. Aby pismo było polskie». idb.neon24.pl (in Polish).

- ^ «Tłumaczenia ksiąg biblijnych na język polski». bibliepolskie.pl (in Polish).

- ^ a b Salmons, Joseph (2018). A History of German: What the past reveals about today’s language (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-19-872302-8.

- ^ Braune, Wilhelm (2004). Althochdeutsche Grammatik I. Max Niemeyer. p. 152. ISBN 3-484-10861-4.

- ^ a b Paul, Hermann (1998). Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik (24 ed.). Max Niemeyer. p. 163. ISBN 3-484-10233-0.

- ^ a b Penzl, Herbert (1968). «Die mittelhochdeutschen Sibilanten und ihre Weiterentwicklung». Word. 24 (1–3): 344, 348. doi:10.1080/00437956.1968.11435536.

- ^ a b c Brekle, Herbert E. (2001). «Zur handschriftlichen und typographischen Geschichte der Buchstabenligatur ß aus gotisch-deutschen und humanistisch-italienischen Kontexten». Gutenberg-Jahrbuch. Mainz. 76. ISSN 0072-9094.

- ^ a b c d Young, Christopher; Gloning, Thomas (2004). A History of the German Language Through Texts. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-86263-9.

- ^ Mosley, James (2008-01-31), «Esszet or ß», Typefoundry, retrieved 2019-05-05

- ^ a b c d Jamra, Mark (2006), «The Eszett», TypeCulture, retrieved 2019-05-05

- ^ Ammon, Ulrich (1995). Die deutsche Sprache in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz: das Problem der nationalen Varietäten. de Gruyter. p. 254. ISBN 9783110147537.

- ^ Gallmann, Paul (1997). «Warum die Schweizer weiterhin kein Eszett schreiben» (PDF). In Augst, Gerhard; Blüml, Karl; Nerius, Dieter; Sitta, Horst (eds.). Die Neuregelung der deutschenRechtschreibung. Begründung und Kritik. Max Niemeyer. pp. 135–140.

- ^ Schreiben des Reichsministers und Chefs der Reichskanzlei an den Reichsminister des Innern vom 20. Juli 1941. BA, Potsdam, R 1501, Nr. 27180. cited in: Der Schriftstreit von 1881 bis 1941 von Silvia Hartman, Peter Lang Verlag. ISBN 978-3-631-33050-0

- ^ Kranz, Florian (1998). Eine Schifffahrt mit drei f: Positives zur Rechtschreibreform. Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht. pp. 30–31. ISBN 3-525-34005-2.

- ^ Signa – Beiträge zur Signographie. Heft 9, 2006.

- ^ Vorbemerkungen, XII. In: Duden – Rechtschreibung. 9. Auflage, 1925

- ^ Der Große Duden. 25. Auflage, Leipzig 1984, S. 601, K 41.

- ^ Andreas Stötzner. «Proposal to encode Latin Capital Letter Double S (rejected)» (PDF). Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- ^ «Approved Minutes of the UTC 101 / L2 198 Joint Meeting, Cupertino, CA – November 15-18, 2004». Unicode Consortium. 2005-02-10. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

The UTC concurs with Stoetzner that Capital Double S is a typographical issue. Therefore the UTC believes it is inappropriate to encode it as a separate character.

- ^ «Archive of Notices of Non-Approval». Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

2004-Nov-18, rejected by the UTC as a typographical issue, inappropriate for encoding as a separate character. Rejected also on the grounds that it would cause casing implementation issues for legacy German data.

- ^ «DIN_29.1_SCHARF_S_1.3_E» (PDF). Retrieved 2014-01-30.

«Unicode chart» (PDF). Retrieved 2014-01-30. - ^ «Latin Extended Additional» (PDF).

- ^ «LATIN CAPITAL LETTER SHARP S (U+1E9E) Font Support». www.fileformat.info.

- ^ Vom Sekretariat zum Office Management: Geschichte — Gegenwart — Zukunft, Springer-Verlag (2013), p. 68.

- ^ «German». ShareLaTeX. 2016. Reference guide. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-07-27]. «ISO/IEC 8859-1:1998 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-07-27]. «ISO/IEC 8859-2:1999 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-07-27]. «ISO/IEC 8859-3:1999 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-07-27]. «ISO/IEC 8859-4:1998 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-07-27]. «ISO/IEC 8859-9:1999 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-10-11]. «ISO/IEC 8859-10:1998 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-07-27]. «ISO/IEC 8859-13:1998 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Kuhn, Markus; Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-07-27]. «ISO/IEC 8859-14:1999 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Kuhn, Markus; Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-07-27]. «ISO/IEC 8859-15:1999 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Kuhn, Markus (2015-12-02) [2001-07-26]. «ISO/IEC 8859-16:2001 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1998-04-15). «cp1250 to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1998-04-15). «cp1252 to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1998-04-15). «cp1254 to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1998-04-15). «cp1257 to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1998-04-15). «cp1258 to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-05) [1995-04-15]. «Map (external version) from Mac OS Roman character set to Unicode 2.1 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-05) [1995-04-15]. «Map (external version) from Mac OS Icelandic character set to Unicode 2.1 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-04) [1995-04-15]. «Map (external version) from Mac OS Croatian character set to Unicode 2.1 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-04) [1995-04-15]. «Map (external version) from Mac OS Central European character set to Unicode 2.1 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-01). «Map (external version) from Mac OS Celtic character set to Unicode 2.1 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-01). «Map (external version) from Mac OS Gaelic character set to Unicode 3.0 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-05) [1995-04-15]. «Map (external version) from Mac OS Romanian character set to Unicode 3.0 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-05) [1995-04-15]. «Map (external version) from Mac OS Greek character set to Unicode 2.1 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-05) [1995-04-15]. «Map (external version) from Mac OS Turkish character set to Unicode 2.1 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1996-04-24). «cp437_DOSLatinUS to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1996-04-24). «cp850_DOSLatin1 to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Unicode Consortium; IBM. «IBM-970». International Components for Unicode.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (2000). «cp949 to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Standardization Administration of China (SAC) (2005-11-18). GB 18030-2005: Information Technology—Chinese coded character set.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1996-04-24). «cp037_IBMUSCanada to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1996-04-24). «cp500_IBMInternational to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1996-04-24). «cp1026_IBMLatin5Turkish to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Project X0213 (2009-05-03). «Shift_JIS-2004 (JIS X 0213:2004 Appendix 1) vs Unicode mapping table».

- ^ Project X0213 (2009-05-03). «EUC-JIS-2004 (JIS X 0213:2004 Appendix 3) vs Unicode mapping table».

- ^ «KPS 9566-2003 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ a b Pakin, Scott (2020-06-25). «The Comprehensive LATEX Symbol List» (PDF).

This article is about the German eszett. For the Greek letter that looks similar, see Beta. For the Chinese radical, see 阝. For the Malayalam script, see ഭ.

Not to be confused with the Latin letter B.

| ẞ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ẞ ß | ||||

|

||||

| Usage | ||||

| Writing system | Latin script | |||

| Type | Alphabetic | |||

| Language of origin | Early New High German | |||

| Phonetic usage | [s] | |||

| Unicode codepoint | U+1E9E, U+00DF |

|||

| History | ||||

| Development |

|

|||

| Time period | ~1300s to present | |||

| Descendants | None | |||

| Sisters | None | |||

| Transliteration equivalents | ss, sz | |||

| Other | ||||

| Other letters commonly used with | ss, sz | |||

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

In German orthography, the letter ß, called Eszett (IPA: [ɛsˈtsɛt] ess-TSET) and scharfes S (IPA: [ˌʃaʁfəs ˈʔɛs], «sharp S»), represents the /s/ phoneme in Standard German when following long vowels and diphthongs.

The letter-name Eszett combines the names of the letters of ⟨s⟩ (Es) and ⟨z⟩ (Zett) in German. The character’s Unicode names in English are sharp s[1] and eszett.[1] The Eszett letter is used only in German, and can be typographically replaced with the double-s digraph ⟨ss⟩, if the ß-character is unavailable. In the 20th century, the ß-character was replaced with ss in the spelling of Swiss Standard German (Switzerland and Liechtenstein), while remaining Standard German spelling in other varieties of German language.[2]

The letter originates as the ⟨sz⟩ digraph as used in late medieval and early modern German orthography, represented as a ligature of ⟨ſ⟩ (long s) and ⟨ʒ⟩ (tailed z) in blackletter typefaces, yielding ⟨ſʒ⟩.[a] This developed from an earlier usage of ⟨z⟩ in Old and Middle High German to represent a separate sibilant sound from ⟨s⟩; when the difference between the two sounds was lost in the 13th century, the two symbols came to be combined as ⟨sz⟩ in some situations.

Traditionally, ⟨ß⟩ did not have a capital form, although some type designers introduced de facto capitalized variants.

In 2017, the Council for German Orthography officially adopted a capital, ⟨ẞ⟩, into German orthography, ending a long orthographic debate.[3]

⟨ß⟩ was encoded by ECMA-94 (1985) at position 223 (hexadecimal DF), inherited by Latin-1 and Unicode (U+00DF ß LATIN SMALL LETTER SHARP S).[4]

The HTML entity ß was introduced with HTML 2.0 (1995). The capital (U+1E9E ẞ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER SHARP S) was encoded by ISO 10646 in 2008.

Usage[edit]

Current usage[edit]

In standard German, three letters or combinations of letters commonly represent [s] (the voiceless alveolar fricative) depending on its position in a word: ⟨s⟩, ⟨ss⟩, and ⟨ß⟩. According to current German orthography, ⟨ß⟩ represents the sound [s]:

- when it is written after a diphthong or long vowel and is not followed by another consonant in the word stem: Straße, Maß, groß, heißen [Exceptions: aus and words with final devoicing (e.g., Haus)];[5] and

- when a word stem ending with ⟨ß⟩ takes an inflectional ending beginning with a consonant: heißt, größte.[6]

In verbs with roots where the vowel changes length, this means that some forms may be written with ⟨ß⟩, others with ⟨ss⟩: wissen, er weiß, er wusste.[5]

The use of ⟨ß⟩ distinguishes minimal pairs such as reißen (IPA: [ˈʁaɪsn̩], to rip) and reisen (IPA: [ˈʁaɪzn̩], to travel) on the one hand ([s] vs. [z]), and Buße (IPA: [ˈbuːsə], penance) and Busse (IPA: [ˈbʊsə], buses) on the other (long vowel before ⟨ß⟩, short vowel before ⟨ss⟩).[7]: 123

Some proper names may use ⟨ß⟩ after a short vowel, following the old orthography; this is also true of some words derived from proper names (e.g., Litfaßsäule; advertising column, named after Ernst Litfaß).[8]: 180

In pre-1996 orthography[edit]

Replacement street sign in Aachen, adapted to the 1996 spelling reform (old: Kongreßstraße, new: Kongressstraße)

According to the orthography in use in German prior to the German orthography reform of 1996, ⟨ß⟩ was written to represent [s]:

- word internally following a long vowel or diphthong: Straße, reißen; and

- at the end of a syllable or before a consonant, so long as [s] is the end of the word stem: muß, faßt, wäßrig.[8]: 176

In the old orthography, word stems spelled ⟨ss⟩ internally could thus be written ⟨ß⟩ in certain instances, without this reflecting a change in vowel length: küßt (from küssen), faßt (from fassen), verläßlich and Verlaß (from verlassen), kraß (comparative: krasser).[7]: 121–23 [9] In rare occasions, the difference between ⟨ß⟩ and ⟨ss⟩ could help differentiate words: Paßende (expiration of a pass) and passende (appropriate).[8]: 178

Substitution and all caps[edit]

Capitalization as SZ on a Bundeswehr crate (ABSCHUSZGERAET for Abschußgerät ‘launcher’)

If no ⟨ß⟩ is available, ⟨ss⟩ or ⟨sz⟩ is used instead (⟨sz⟩ especially in Hungarian-influenced eastern Austria). Until 2017, there was no official capital form of ⟨ß⟩; a capital form was nevertheless frequently used in advertising and government bureaucratic documents.[10]: 211 In June of that year, the Council for German Orthography officially adopted a rule that ⟨ẞ⟩ would be an option for capitalizing ⟨ß⟩ besides the previous capitalization as ⟨SS⟩ (i.e., variants STRASSE and STRAẞE would be accepted as equally valid).[11]

[12] Prior to this time, it was recommended to render ⟨ß⟩ as ⟨SS⟩ in allcaps except when there was ambiguity, in which case it should be rendered as ⟨SZ⟩. The common example for such a case was IN MASZEN (in Maßen «in moderate amounts») vs. IN MASSEN (in Massen «in massive amounts»), where the difference between the spelling in ⟨ß⟩ vs. ⟨ss⟩ could actually reverse the conveyed meaning.[citation needed]

Switzerland and Liechtenstein[edit]

In Swiss Standard German, ⟨ss⟩ usually replaces every ⟨ß⟩.[13][14] This is officially sanctioned by the reformed German orthography rules, which state in §25 E2: «In der Schweiz kann man immer „ss“ schreiben» («In Switzerland, one may always write ‘ss'»). Liechtenstein follows the same practice. There are very few instances where the difference between spelling ⟨ß⟩ and ⟨ss⟩ affects the meaning of a word, and these can usually be told apart by context.[10]: 230 [15]

Other uses[edit]

Use of ß (blackletter ‘ſz’) in Sorbian: wyßokoſcʒ́i («highest», now spelled wysokosći). Text of Luke 2:14, in a church in Oßling.

Occasionally, ⟨ß⟩ has been used in unusual ways:

- As a surrogate for Greek lowercase ⟨β⟩ (beta), which looks fairly similar. This was used in older operating systems, the character encoding of which (notably Latin-1 and Windows-1252) did not support easy use of Greek letters. Additionally, the original IBM DOS code page, CP437 (aka OEM-US) conflates the two characters, with a glyph that minimizes their differences placed between the Greek letters ⟨α⟩ (alpha) and ⟨γ⟩ (gamma) but named «Sharp s Small».[16]

- In Prussian Lithuanian, as in the first book published in Lithuanian, Martynas Mažvydas’ Simple Words of Catechism,[17] as well as in Sorbian (see example on the left).

- For sadhe in Akkadian glosses, in place of the standard ⟨ṣ⟩, when that character is unavailable due to limitations of HTML.[18]

- The letter appeared in the alphabet made by Jan Kochanowski for Polish language, that was used from 16th until 18th century. It represented the voiceless postalveolar fricative ([ʃ]) sound.[19][20] It was for example used in Jakub Wujek Bible.[21]

History[edit]

Origin and development[edit]

As a result of the High German consonant shift, Old High German developed a sound generally spelled ⟨zz⟩ or ⟨z⟩ that was probably pronounced [s] and was contrasted with a sound, probably pronounced [s̠] (voiceless alveolar retracted sibilant) or [z̠] (voiced alveolar retracted sibilant), depending on the place in the word, and spelled ⟨s⟩.[22] Given that ⟨z⟩ could also represent the affricate [ts], some attempts were made to differentiate the sounds by spelling [s] as ⟨zss⟩ or ⟨zs⟩: wazssar (German: Wasser), fuozssi (German: Füße), heizsit (German: heißt).[23] In Middle High German, ⟨zz⟩ simplified to ⟨z⟩ at the end of a word or after a long vowel, but was retained word internally after a short vowel: wazzer (German: Wasser) vs. lâzen (German: lassen) and fuoz (German: Fuß).[24]

Use of the late medieval ligature ⟨ſz⟩ in Ulrich Füetrer’s Buch der Abenteuer: «uſz» (modern German aus).

In the thirteenth century, the phonetic difference between ⟨z⟩ and ⟨s⟩ was lost at the beginning and end of words in all dialects except for Gottscheerish.[22] Word-internally, Old and Middle High German ⟨s⟩ came to be pronounced [z] (the voiced alveolar sibilant), while Old and Middle High German ⟨z⟩ continued to be pronounced [s]. This produces the contrast between modern standard German reisen and reißen. The former is pronounced IPA: [ˈʁaɪzn̩] and comes from Middle High German: reisen, while the latter is pronounced IPA: [ˈʁaɪsn̩] and comes from Middle High German: reizen.[25]

In the late medieval and early modern periods, [s] was frequently spelled ⟨sz⟩ or ⟨ss⟩. The earliest appearance of ligature resembling the modern ⟨ß⟩ is in a fragment of a manuscript of the poem Wolfdietrich from around 1300.[10]: 214 [25] In the Gothic book hands and bastarda scripts of the late medieval period, ⟨sz⟩ is written with long s and the Blackletter «tailed z», as ⟨ſʒ⟩. A recognizable ligature representing the ⟨sz⟩ digraph develops in handwriting in the early 14th century.[26]: 67–76

An early modern printed rhyme by Hans Sachs showing several instances of ß as a clear ligature of ⟨ſz⟩: «groß», «stoß», «Laß», «baß» (= modern «besser»), and «Faß».

By the late 1400s, the choice of spelling between ⟨sz⟩ and ⟨ss⟩ was usually based on the sound’s position in the word rather than etymology: ⟨sz⟩ (⟨ſz⟩) tended to be used in word final position: uſz (Middle High German: ûz, German: aus), -nüſz (Middle High German: -nüss(e), German: -nis); ⟨ss⟩ (⟨ſſ⟩) tended to be used when the sound occurred between vowels: groſſes (Middle High German: grôzes, German: großes).[27]: 171 While Martin Luther’s early 16th-century printings also contain spellings such as heyße (German: heiße), early modern printers mostly changed these to ⟨ſſ⟩: heiſſe. Around the same time, printers began to systematically distinguish between das (the, that [pronoun]) and daß (that [conjunction]).[27]: 215

In modern German, the Old and Middle High German ⟨z⟩ is now represented by either ⟨ss⟩, ⟨ß⟩, or, if there are no related forms in which [s] occurs intervocalically, with ⟨s⟩: messen (Middle High German: mezzen), Straße (Middle High German: strâze), and was (Middle High German: waz).[24]

Standardization of use[edit]

The pre-1996 German use of ⟨ß⟩ was codified by the eighteenth-century grammarians Johann Christoph Gottsched (1748) and Johann Christoph Adelung (1793) and made official for all German-speaking countries by the German Orthographic Conference of 1901. In this orthography, the use of ⟨ß⟩ was modeled after the use of long and «round»-s in Fraktur. ⟨ß⟩ appeared both word internally after long vowels and also in those positions where Fraktur required the second s to be a «round» or «final» s, namely the ends of syllables or the ends of words.[10]: 217–18 In his Deutsches Wörterbuch (1854) Jacob Grimm called for ⟨ß⟩ or ⟨sz⟩ to be written for all instances of Middle and Old High German etymological ⟨z⟩ (e.g., eß instead of es from Middle High German: ez); however, his etymological proposal could not overcome established usage.[27]: 269

In Austria-Hungary prior to the German Orthographic Conference of 1902, an alternative rule formulated by Johann Christian August Heyse in 1829 had been officially taught in the schools since 1879, although this spelling was not widely used. Heyse’s rule matches current usage after the German orthography reform of 1996 in that ⟨ß⟩ was only used after long vowels.[10]: 219

Use in Roman type[edit]

The ſs ligature used for Latin in 16th-century printing (utiliſsimæ)

Essen with ſs-ligature reads Eßen (Latin Blaeu atlas, text printed in Antiqua, 1650s)

Although there are early examples in Roman type (called Antiqua in a German context) of a ⟨ſs⟩-ligature that looks like the letter ⟨ß⟩, it was not commonly used for ⟨sz⟩.[28][29] These forms generally fell out of use in the eighteenth century and were used in Italic text only;[26]: 73 German works printed in Roman type in the late 18th and early 19th centuries such as Johann Gottlieb Fichte’s Wissenschaftslehre did not provide any equivalent to the ⟨ß⟩. Jacob Grimm began using ⟨ß⟩ in his Deutsche Grammatik (1819), however it varied with ⟨ſſ⟩ word internally.[26]: 74 Grimm eventually rejected the use of the character; in their Deutsches Wörterbuch (1838), the Brothers Grimm favored writing it as ⟨sz⟩.[29]: 2 The First Orthographic Conference in Berlin (1876) recommended that ß be represented as ⟨ſs⟩ — however, both suggestions were ultimately rejected.[27]: 269 [10]: 222 In 1879, a proposal for various letter forms was published in the Journal für Buchdruckerkunst. A committee of the Typographic Society of Leipzig chose the «Sulzbacher form». In 1903 it was proclaimed as the new standard for the Eszett in Roman type.[29]: 3–5

Until the abolition of Fraktur in 1941, it was nevertheless common for family names to be written with ⟨ß⟩ in Fraktur and ⟨ss⟩ in Roman type. The formal abolition resulted in inconsistencies in how names such as Heuss/Heuß are written in modern German.[8]: 176

Abolition and attempted abolitions[edit]

The Swiss and Liechtensteiners ceased to use ⟨ß⟩ in the twentieth century. This has been explained variously by the early adoption of Roman type in Switzerland, the use of typewriters in Switzerland that did not include ⟨ß⟩ in favor of French and Italian characters, and peculiarities of Swiss German that cause words spelled with ⟨ß⟩ or ⟨ss⟩ to be pronounced with gemination.[10]: 221–22 The Education Council of Zurich had decided to stop teaching the letter in 1935, whereas the Neue Zürcher Zeitung continued to write ⟨ß⟩ until 1971.[30] Swiss newspapers continued to print in Fraktur until the end of the 1940s, and the abandonment of ß by most newspapers corresponded to them switching to Roman typesetting.[31]

When the Nazi German government abolished the use of blackletter typesetting in 1941, it was originally planned to also abolish the use of ⟨ß⟩. However, Hitler intervened to retain ⟨ß⟩, while deciding against the creation of a capital form.[32] In 1954, a group of reformers in West Germany similarly proposed, among other changes to German spelling, the abolition of ⟨ß⟩; their proposals were publicly opposed by German-language writers Thomas Mann, Hermann Hesse, and Friedrich Dürrenmatt and were never implemented.[33] Although the German Orthography Reform of 1996 reduced the use of ⟨ß⟩ in standard German, Adrienne Walder writes that an abolition outside of Switzerland appears unlikely.[10]: 235

Development of a capital form[edit]

Uppercase ß on a book cover from 1957

Because ⟨ß⟩ had been treated as a ligature, rather than as a full letter of the German alphabet, it had no capital form in early modern typesetting. There were, however, proposals to introduce capital forms of ⟨ß⟩ for use in allcaps writing (where ⟨ß⟩ would otherwise usually be represented as either ⟨SS⟩ or ⟨SZ⟩). A capital was first seriously proposed in 1879, but did not enter official or widespread use.[34] Historical typefaces offering a capitalized eszett mostly date to the time between 1905 and 1930. The first known typefaces to include capital eszett were produced by the Schelter & Giesecke foundry in Leipzig, in 1905/06. Schelter & Giesecke at the time widely advocated the use of this type, but its use nevertheless remained very limited.

The preface to the 1925 edition of the Duden dictionary expressed the desirability of a separate glyph for capital ⟨ß⟩:

Die Verwendung zweier Buchstaben für einen Laut ist nur ein Notbehelf, der aufhören muss, sobald ein geeigneter Druckbuchstabe für das große ß geschaffen ist.[35]

The use of two letters for a single phoneme is makeshift, to be abandoned as soon as a suitable type for the capital ß has been developed.

The Duden was edited separately in East and West Germany during the 1950s to 1980s. The East German Duden of 1957 (15th ed.) introduced a capital ⟨ß⟩, in its typesetting without revising the rule for capitalization. The 16th edition of 1969 still announced that an uppercase ⟨ß⟩ was in development and would be introduced in the future. The 1984 edition again removed this announcement and simply stated that there is no capital version of ⟨ß⟩.[36]

In the 2000s, there were renewed efforts on the part of certain typographers to introduce a capital, ⟨ẞ⟩. A proposal to include a corresponding character in the Unicode set submitted in 2004[37] was rejected.[38][39] A second proposal submitted in 2007 was successful, and the character was included in Unicode version 5.1.0 in April 2008 (U+1E9E ẞ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER SHARP S).[40] The international standard associated with Unicode (UCS), ISO/IEC 10646, was updated to reflect the addition on 24 June 2008. The capital was finally adopted as an option in standard German orthography in 2017.[12]

Representation[edit]

Graphical variants[edit]

The recommendation of the Sulzbacher form (1903) was not followed universally in 20th-century printing.

There were four distinct variants of ⟨ß⟩ in use in Antiqua fonts:

Four forms of Antiqua Eszett: 1. ſs, 2. ſs ligature, 3. ſʒ ligature, 4. Sulzbacher form

- ⟨ſs⟩ without ligature, but as a single type, with reduced spacing between the two letters;

- the ligature of ⟨ſ⟩ and ⟨s⟩ inherited from the 16th-century Antiqua typefaces;

- a ligature of ⟨ſ⟩ and ⟨ʒ⟩, adapting the blackletter ligature to Antiqua; and

- the Sulzbacher form.

The first variant (no ligature) has become practically obsolete. Most modern typefaces follow either 2 or 4, with 3 retained in occasional usage, notably in street signs in Bonn and Berlin. The design of modern ⟨ß⟩ tends to follow either the Sulzbacher form, in which ⟨ʒ⟩ (tailed z) is clearly visible, or else be made up of a clear ligature of ⟨ſ⟩ and ⟨s⟩.[29]: 2

Three contemporary handwritten forms of ‘ß’ demonstrated in the word aß, «(I/he/she/it) ate»

Use of typographic variants in street signs:

-

Two distinct blackletter typefaces in Mainz. The red sign spells Straße with ſs; the blue sign uses the standard blackletter ſʒ ligature.

-

Sulzbacher form in the German Einbahnstraße («one-way street») sign

Capital ß in a web application

The inclusion of a capital ⟨ẞ⟩ in ISO 10646 in 2008 revived the century-old debate among font designers as to how such a character should be represented. The main difference in the shapes of ⟨ẞ⟩ in contemporary fonts is the depiction with a diagonal straight line vs. a curved line in its upper right part, reminiscent of the ligature of tailed z or of round s, respectively. The code chart published by the Unicode Consortium favours the former possibility,[41] which has been adopted by Unicode capable fonts including Arial, Calibri, Cambria, Courier New, Dejavu Serif, Liberation Sans, Liberation Mono, Linux Libertine and Times New Roman; the second possibility is more rare, adopted by Dejavu Sans. Some fonts adopt a third possibility in representing ⟨ẞ⟩ following the Sulzbacher form of ⟨ß⟩, reminiscent of the Greek ⟨β⟩ (beta); such a shape has been adopted by FreeSans and FreeSerif, Liberation Serif and Verdana.[42]

Keyboards and encoding[edit]

In Germany and Austria, a ‘ß’ key is present on computer and typewriter keyboards, normally to the right-hand end on the number row.

The German typewriter keyboard layout was defined in DIN 2112, first issued in 1928.[43]

In other countries, the letter is not marked on the keyboard, but a combination of other keys can produce it. Often, the letter is input using a modifier and the ‘s’ key. The details of the keyboard layout depend on the input language and operating system: on some keyboards with US-International (or local ‘extended’) setting, the symbol is created using AltGrs (or CtrlAlts) in Microsoft Windows, Linux and ChromeOS; in MacOS, one uses ⌥ Options on the US, US-Extended, and UK keyboards. In Windows, one can use Alt+0223. On Linux Composess works, and ComposeSS for uppercase.

Some modern virtual keyboards show ß when the user presses and holds the ‘s’ key.

The HTML entity for ⟨ß⟩ is ß. Its code point in the ISO 8859 character encoding versions 1, 2, 3, 4, 9, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16 and identically in Unicode is 223, or DF in hexadecimal. In TeX and LaTeX, ss produces ß. A German language support package for LaTeX exists in which ß is produced by "s (similar to umlauts, which are produced by "a, "o, and "u with this package).[44]

In modern browsers, «ß» will be converted to «SS» when the element containing it is set to uppercase using text-transform: uppercase in Cascading Style Sheets. The JavaScript in Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox will convert «ß» to «SS» when converted to uppercase (e.g., "ß".toUpperCase()).[citation needed]

| Preview | ẞ | ß | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | LATIN CAPITAL LETTER SHARP S | LATIN SMALL LETTER SHARP S | ||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 7838 | U+1E9E | 223 | U+00DF |

| UTF-8 | 225 186 158 | E1 BA 9E | 195 159 | C3 9F |

| Numeric character reference | ẞ | ẞ | ß | ß |

| Named character reference | ß | |||

| ISO 8859[b] and Windows-125x[c] | 223 | DF | ||

| Mac OS script encodings[d] | 167 | A7 | ||

| DOS code page 437,[69] 850[70] | 225 | E1 | ||

| EUC-KR[71] / UHC[72] | 169 172 | A9 AC | ||

| GB 18030[73] | 129 53 254 50 | 81 35 FE 32 | 129 48 137 56 | 81 30 89 38 |

| EBCDIC 037,[74] 500,[75] 1026[76] | 89 | 59 | ||

| ISO/IEC 6937 | 251 | FB | ||

| Shift JIS-2004[77] | 133 116 | 85 74 | ||

| EUC-JIS-2004[78] | 169 213 | A9 D5 | ||

| KPS 9566-2003[79] | 174 223 | AE DF | ||

| LaTeX[80] | [e] | ss |

See also[edit]

- long s

- β – Second letter of the Greek alphabet

- 阝 – Element used in Chinese Kangxi writing

- Sz – Digraph of the Latin script

Notes[edit]

- ^ The IPA symbol ezh (ʒ) is the most similar to the Blackletter z (

) and is used in this article for convenience despite its technical inaccuracy.

- ^ Parts

1,[45]

2,[46]

3,[47]

4,[48]

9,[49]

10,[50]

13,[51]

14,[52]

15[53] and

16.[54] - ^ Code pages

1250,[55]

1252,[56]

1254,[57]

1257[58] and

1258.[59] - ^ Mac OS

Roman,[60]

Icelandic,[61]

Croatian,[62]

Central European,[63]

Celtic,[64]

Gaelic,[65]

Romanian,[66]

Greek[67] and

Turkish.[68] - ^ The

SSmacro exists as the uppercase counterpart ofss, but displays as a doubled capital S.[80]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Unicode Consortium (2018), «C1 Controls and Latin-1 Supplement, Range 0080–00FF» (PDF), The Unicode Standard, Version 11.0, retrieved 2018-08-09.

- ^ Leitfaden zur deutschen Rechtschreibung («Guide to German Orthography») Archived 2012-07-08 at the Wayback Machine, 3rd edition (2007) (in German) from the Swiss Federal Chancellery, retrieved 22-Apr-2012

- ^ Ha, Thu-Huong. «Germany has ended a century-long debate over a missing letter in its alphabet». Retrieved 9 August 2017.

According to the council’s 2017 spelling manual: When writing the uppercase [of ß], write SS. It’s also possible to use the uppercase ẞ. Example: Straße — STRASSE — STRAẞE.

- ^ C1 Controls and Latin-1 Supplement glossed ‘uppercase is «SS» or 1E9E ẞ; typographically the glyph for this character can be based on a ligature of 017F ſ, with either 0073 s or with an old-style glyph for 007A z (the latter similar in appearance to 0292 ʒ). Both forms exist interchangeably today.’

- ^ a b «Deutsche Rechschreibung: 2.3 Besonderheiten bei [s] § 25». Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ^ Duden: Die Grammatik (9 ed.). 2016. p. 84.

- ^ a b Augst, Gerhard; Stock, Eberhard (1997). «Laut-Buchstaben-Zuordnung». In Augst, Gerhard; et al. (eds.). Zur Neuregelung der deutschen Rechtschreibung: Begründung und Kritik. Max Niemeyer. ISBN 3-484-31179-7.

- ^ a b c d Poschenrieder, Thorwald (1997). «S-Schreibung — Überlieferung oder Reform?». In Eroms, Hans-Werner; Munske, Horst Haider (eds.). Die Rechtschreibreform: Pro und Kontra. Erich Schmidt. ISBN 3-50303786-1.

- ^ Munske, Horst Haider (2005). Lob der Rechtschreibung: Warum wir schreiben, wie wir schreiben. C. H. Beck. p. 66. ISBN 3-406-52861-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Walder, Adrienne (2020). «Das versale Eszett: Ein neuer Buchstabe im deutschen Alphabet». Zeitschrift für Germanitische Linguistik. 48 (2): 211–237. doi:10.1515/zgl-2020-2001. S2CID 225226660.

- ^ 3. Bericht des Rats für deutsche Rechtschreibung 2011–2016 (2016), p. 7.

- ^ a b «Deutsche Rechtschreibung Regeln und Wörterverzeichnis: Aktualisierte Fassung des amtlichen Regelwerks entsprechend den Empfehlungen des Rats für deutsche Rechtschreibung 2016» (PDF). §25, E3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-07-06. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

E3: Bei Schreibung mit Großbuchstaben schreibt man SS. Daneben ist auch die Verwendung des Großbuchstabens ẞ möglich. Beispiel: Straße – STRASSE – STRAẞE. [When writing in all caps, one writes SS. It is also permitted to write ẞ. Example: Straße – STRASSE – STRAẞE.]

- ^ Peter Gallmann. [de] «Warum die Schweizer weiterhin kein Eszett schreiben.» in Die Neuregelung der deutschen Rechtschreibung. Begründung und Kritik. Gerhard Augst, et al., eds. Niemayer: 1997. (Archived.)

- ^ «Rechtscreibung: Leitfaden zur deutschen Rechtschreibung.» Schweizerische Bundeskanzlei, in Absprache mit der Präsidentin der Staatsschreiberkonferenz. 2017. pp. 19, 21–22.

- ^ «Rechtscreibung: Leitfaden zur deutschen Rechtschreibung.» Schweizerische Bundeskanzlei, in Absprache mit der Präsidentin der Staatsschreiberkonferenz. 2017. pp. 21–22.

- ^ «Code Page (CPGID): 00437». IBM software FTP server. IBM. 1984. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ Zinkevičius, Zigmas (1996). The History of the Lithuanian Language. Vilnius: Science and Encyclopedia Publishers. p. 230-236. ISBN 9785420013632.

- ^ Black, J.A.; Cunningham, G.; Fluckiger-Hawker, E.; Robson, E.; Zólyomi, G. (1998–2021). «ETCSL display conventions». The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Oxford University. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ «Skąd się wzięły znaki diakrytyczne?». 2plus3d.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2021-04-21. Retrieved 2021-08-29.

- ^ «Bon ton Ę-Ą. Aby pismo było polskie». idb.neon24.pl (in Polish).

- ^ «Tłumaczenia ksiąg biblijnych na język polski». bibliepolskie.pl (in Polish).

- ^ a b Salmons, Joseph (2018). A History of German: What the past reveals about today’s language (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-19-872302-8.

- ^ Braune, Wilhelm (2004). Althochdeutsche Grammatik I. Max Niemeyer. p. 152. ISBN 3-484-10861-4.

- ^ a b Paul, Hermann (1998). Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik (24 ed.). Max Niemeyer. p. 163. ISBN 3-484-10233-0.

- ^ a b Penzl, Herbert (1968). «Die mittelhochdeutschen Sibilanten und ihre Weiterentwicklung». Word. 24 (1–3): 344, 348. doi:10.1080/00437956.1968.11435536.

- ^ a b c Brekle, Herbert E. (2001). «Zur handschriftlichen und typographischen Geschichte der Buchstabenligatur ß aus gotisch-deutschen und humanistisch-italienischen Kontexten». Gutenberg-Jahrbuch. Mainz. 76. ISSN 0072-9094.

- ^ a b c d Young, Christopher; Gloning, Thomas (2004). A History of the German Language Through Texts. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-86263-9.

- ^ Mosley, James (2008-01-31), «Esszet or ß», Typefoundry, retrieved 2019-05-05

- ^ a b c d Jamra, Mark (2006), «The Eszett», TypeCulture, retrieved 2019-05-05

- ^ Ammon, Ulrich (1995). Die deutsche Sprache in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz: das Problem der nationalen Varietäten. de Gruyter. p. 254. ISBN 9783110147537.

- ^ Gallmann, Paul (1997). «Warum die Schweizer weiterhin kein Eszett schreiben» (PDF). In Augst, Gerhard; Blüml, Karl; Nerius, Dieter; Sitta, Horst (eds.). Die Neuregelung der deutschenRechtschreibung. Begründung und Kritik. Max Niemeyer. pp. 135–140.

- ^ Schreiben des Reichsministers und Chefs der Reichskanzlei an den Reichsminister des Innern vom 20. Juli 1941. BA, Potsdam, R 1501, Nr. 27180. cited in: Der Schriftstreit von 1881 bis 1941 von Silvia Hartman, Peter Lang Verlag. ISBN 978-3-631-33050-0

- ^ Kranz, Florian (1998). Eine Schifffahrt mit drei f: Positives zur Rechtschreibreform. Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht. pp. 30–31. ISBN 3-525-34005-2.

- ^ Signa – Beiträge zur Signographie. Heft 9, 2006.

- ^ Vorbemerkungen, XII. In: Duden – Rechtschreibung. 9. Auflage, 1925

- ^ Der Große Duden. 25. Auflage, Leipzig 1984, S. 601, K 41.

- ^ Andreas Stötzner. «Proposal to encode Latin Capital Letter Double S (rejected)» (PDF). Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- ^ «Approved Minutes of the UTC 101 / L2 198 Joint Meeting, Cupertino, CA – November 15-18, 2004». Unicode Consortium. 2005-02-10. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

The UTC concurs with Stoetzner that Capital Double S is a typographical issue. Therefore the UTC believes it is inappropriate to encode it as a separate character.

- ^ «Archive of Notices of Non-Approval». Unicode Consortium. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

2004-Nov-18, rejected by the UTC as a typographical issue, inappropriate for encoding as a separate character. Rejected also on the grounds that it would cause casing implementation issues for legacy German data.

- ^ «DIN_29.1_SCHARF_S_1.3_E» (PDF). Retrieved 2014-01-30.

«Unicode chart» (PDF). Retrieved 2014-01-30. - ^ «Latin Extended Additional» (PDF).

- ^ «LATIN CAPITAL LETTER SHARP S (U+1E9E) Font Support». www.fileformat.info.

- ^ Vom Sekretariat zum Office Management: Geschichte — Gegenwart — Zukunft, Springer-Verlag (2013), p. 68.

- ^ «German». ShareLaTeX. 2016. Reference guide. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-07-27]. «ISO/IEC 8859-1:1998 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-07-27]. «ISO/IEC 8859-2:1999 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-07-27]. «ISO/IEC 8859-3:1999 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-07-27]. «ISO/IEC 8859-4:1998 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-07-27]. «ISO/IEC 8859-9:1999 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-10-11]. «ISO/IEC 8859-10:1998 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-07-27]. «ISO/IEC 8859-13:1998 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Kuhn, Markus; Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-07-27]. «ISO/IEC 8859-14:1999 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Kuhn, Markus; Whistler, Ken (2015-12-02) [1999-07-27]. «ISO/IEC 8859-15:1999 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Kuhn, Markus (2015-12-02) [2001-07-26]. «ISO/IEC 8859-16:2001 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1998-04-15). «cp1250 to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1998-04-15). «cp1252 to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1998-04-15). «cp1254 to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1998-04-15). «cp1257 to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1998-04-15). «cp1258 to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-05) [1995-04-15]. «Map (external version) from Mac OS Roman character set to Unicode 2.1 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-05) [1995-04-15]. «Map (external version) from Mac OS Icelandic character set to Unicode 2.1 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-04) [1995-04-15]. «Map (external version) from Mac OS Croatian character set to Unicode 2.1 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-04) [1995-04-15]. «Map (external version) from Mac OS Central European character set to Unicode 2.1 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-01). «Map (external version) from Mac OS Celtic character set to Unicode 2.1 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-01). «Map (external version) from Mac OS Gaelic character set to Unicode 3.0 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-05) [1995-04-15]. «Map (external version) from Mac OS Romanian character set to Unicode 3.0 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-05) [1995-04-15]. «Map (external version) from Mac OS Greek character set to Unicode 2.1 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Apple Computer, Inc. (2005-04-05) [1995-04-15]. «Map (external version) from Mac OS Turkish character set to Unicode 2.1 and later». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1996-04-24). «cp437_DOSLatinUS to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1996-04-24). «cp850_DOSLatin1 to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Unicode Consortium; IBM. «IBM-970». International Components for Unicode.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (2000). «cp949 to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Standardization Administration of China (SAC) (2005-11-18). GB 18030-2005: Information Technology—Chinese coded character set.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1996-04-24). «cp037_IBMUSCanada to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1996-04-24). «cp500_IBMInternational to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Steele, Shawn (1996-04-24). «cp1026_IBMLatin5Turkish to Unicode table». Microsoft / Unicode Consortium.

- ^ Project X0213 (2009-05-03). «Shift_JIS-2004 (JIS X 0213:2004 Appendix 1) vs Unicode mapping table».

- ^ Project X0213 (2009-05-03). «EUC-JIS-2004 (JIS X 0213:2004 Appendix 3) vs Unicode mapping table».

- ^ «KPS 9566-2003 to Unicode». Unicode Consortium.

- ^ a b Pakin, Scott (2020-06-25). «The Comprehensive LATEX Symbol List» (PDF).

Фото: Auf Deutsch

Как известно, в немецком языке есть 4 особых символа: три умлаута и странная буква, похожая на латинскую бета. В этой статье речь пойдёт как раз о ней. Встречайте: ß, эсцет, «scharfes S»!

ẞ в немецком: как называется?

У немецкой ẞ масса названий. Самое известное и популярное — эсцет (Eszett). Среди обозначений также можно встретить:

- Scharfes S («острая S»)

- Doppel-S («двойная S»)

- Buckel-S («горбатая S»)

- Rucksack-S («S с рюкзаком»)

- Фигурная S

ẞ в немецком алфавите: буква или нет?

Если посмотреть на этот вопрос под прямым углом, то с чего бы нам не включать эсцет в немецкий алфавит? Ну буква же! У лингвистов, правда, другое мнение. Дискуссии о том, стоит ли учитывать ẞ, ведутся аж с конца 19 века.

Эсцет в немецком – буква с историей. В общем и целом – это всего лишь лигатура, объединение двух символов – ſ (долгого S) и Z. Уже просматриваются очертания ẞ, да? Кстати, так как оба «родителя» согласные, эсцет тоже является согласной буквой.

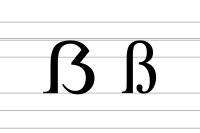

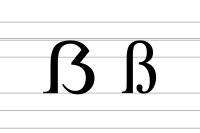

Фото: wikipedia.org

Различные варианты написания эсцет: 1 — Объединение долгой S и S (не лигатура); 2 — Эсцет-лигатура из долгой S и S; 3 — Эсцет-лигатура из долгой S и Z; 4 — Современная лигатура, похожая на латинскую бета

К тому же, несмотря на то, что ẞ используется только в немецком языке, некоторые немецкоязычные страны всё же решились отказаться от неё. Среди них Швейцария и Лихтенштейн: здесь эсцет просто заменили на «ss».

Как читается ẞ (эсцет) в немецком?

В немецком алфавите ß так и читается:

| Буква | Немецкая транскрипция | Русская транскрипция |

| ẞ, ß | [ɛs’t͡sɛt] | [эсцет] |

В словах эсцет читается как обычная S – [с]:

| Слово | Немецкая транскрипция | Русская транскрипция |

| Fuß

(стопа) |

[fu:s] | [фу:с] |

| beißen

(кусать) |

[ˈbaɪ̯sn̩] | [ˈбайсн] |

| mäßig

(умеренный) |

[ˈmɛːsɪç] | [ˈмэːсихь] |

Можно ли не использовать эсцет?

Зависит от того, с какой немецкоязычной страной вы взаимодействуете или собираетесь это делать. Так жителям Швейцарии и Лихтенштейна использование ẞ может показаться устаревшим, тогда как отказ от использования ẞ в Германии охарактеризует вас как носителя швейцарской версии языка. Общаясь с немцами онлайн и не имея под рукой немецкой раскладки эсцет можно спокойно заменять на «ss». В официальных документах и письмах лучше придерживаться правил страны обращения.

Буква, которая есть только в немецком языке

Отличительной особенностью немецкого языка является буква, или вернее знак — ß (эсцет или s острое). В настоящее время она используется только в немецком языке. В чем ее уникальность? Чем ß эсцет отличается от ss: произношением или употреблением на письме?

Для начала давайте разберемся, что такое ß (эсцет). В общем и целом – это всего лишь лигатура, которая представляет собой объединение двух символов – ſ (долгого S) и Z. Если внимательно присмотреться, то можно увидеть это объединение в очертании ß. Так как оба прародителя эсцета — согласные, то его тоже относят к согласным. Данная буква не входит в алфавит немецкого языка, но все равно имеет место быть в нем и употребляться на письме.

Как пишется эсцет: 1 — объединение долгой S и S (не лигатура); 2 — эсцет-лигатура из долгой S и S; 3 — эсцет-лигатура из долгой S и Z; 4 — современная лигатура, похожая на латинскую бета.

эсцета

Специфика использования эсцета в немецкоязычных странах

эсцета

Эсцет используется не во всех немецкоязычных странах. В Швейцарии s острое во всех случаях заменяют сочетанием ss. От редкой буквы швейцарцы стали избавляться в начале ХХ века. Одна из причин — распространение печатных машинок. В Швейцарии, где помимо немецкого языка государственными были еще французский с итальянским, на печатных машинках требовалось освободить место для знаков «ç», «à», «é» и «è». Последней от эсцет отказалась влиятельная швейцарская газета «Neue Zuercher Zeitung». В издании этот знак использовали вплоть до 1974 года. Но “смерть” знака ß все-таки наступила в Швейцарии и произошло это по естественным причинам.

На современном этапе ß (эсцет) довольно часто встречается в написании многих немецких слов: без нее не получится написать groß — большой или heißen — называться.

эсцет

Как правильно использовать эсцет на письме?

эсцет

Не только люди, которые изучают немецкий язык, но и коренные немцы, путаются при выборе ss и ß на письме. Происходит это по нескольким причинам. Одна из них — реформа правописания, результатом которой стало ограниченное использование буквы ß.

Также важно помнить, что буква ß в немецком соответствует двойной букве ss, однако правила немецкой орфографии различают употребление ß и ss на письме.

Правила правильного написание буквы ß и ss:

1. После кратких гласных a, u, e, а также в конце слова пишется ss:

der Pass — паспорт;

der Stress — стресс;

Russland — Россия;

russisch — русский;

das Wasser — вода;

essen — есть, принимать пищу;

das Schloss — замок;

dass — что, чтобы (союз);

verbessern — улучшать;

2. После долгих гласных зачастую пишется ß (эсцет):

grüßen (произношение) — приветствовать;

groß — большой;

die Straße — улица;

süß — сладкий;

der Fußball — футбол;

der Fuß — нога;

der Fußgänger — пешеход;

aß — ел, принимал пищу;

der Spaß — удовольствие;

die Maß — размер, мера;

die Maßnahme — мероприятие, действие;

abstoßend — отвратительный;

der Stoß — толчок.

3. После двойных гласных (дифтонгов ie, ei, eu, äu, au) пишется стоит ß, так как эти дифтонги имеют природу долгих гласных:

heißen (произношение) — называться;

draußen — снаружи;

der Blumenstrauß — букет;

schließlich — наконец, в конце концов;

schließen — закрывать;

außerdem — кроме того;

die Äußerung — признание, замечание;

Blumen gießen — поливать цветы;

das Äußere — внешность;

Исключение: das Eis — мороженое, das Eisen — железо, weise — мудрый, die Wiese — луг, der Beweis — доказательство и др.

4. В написание слов ЗАГЛАВНЫМИ БУКВАМИ ß почти всегда заменяется на SS.

Примеры:

SCHLIESSEN SIE DIE TÜR, BITTE! — Закрывайте дверь, пожалуйста!

ACHTUNG! FUSSGÄNGER, ÜBERQUEREN SIE HIER DIE STRASSE NICHT. — Внимание! Пешеходы, не переходите здесь дорогу!

эсцет

эсцет

эсцет

эсцет

- Предлоги места в немецком языке

- Определить род существительного в немецком легко: секреты использования der, die, das

- Немецкие существительные пишутся только с большой буквы: разбираемся почему?

- Немецкий алфавит с транскрипцией

- Склонение местоимений в немецком

Есть в немецком одна необычная буква, под названием “эсцет”. Выглядит она подстать своему названию: ẞß. Помимо своего основного названия у эсцета также есть и региональные произвища:

- scharfes S – острая S;

- Doppel-S – двойная S;

- Buckel-S – горбатая S;

- Rucksack-S – рюкзачная S;

- Dreierles-S – тройная S;

- Ringel-S – завитая S.

Несмотря на свой необычный вид, на деле эсцет не такой уж и страшный, поскольку он используется для обозначения обычного звука [s]. На немецкой клавиатуре эсцет находится в верхнем ряду, справа от цифры 0. Пусть эта информация поможет вам не запутаться в случае, если у вас стандартная английско-русская клавиатура, но при этом вы хотите пользоваться немецкой расскладкой.

Как в немецком появился эсцет?

У эсцета довольно запутанная история возникновения в немецком языке. Началось все еще около тысячи лет назад. В этот период немцы совершенно не могли определиться, что им делать с буквами S и Z. Их и их сочетания пихали практически куда угодно для обозначения абсолютно разных звуков. В итоге это привело к тому, что в средненемецком периоде простой звук [s] немцы стали записывать, с помощью сочетания S + Z. Отсюда впоследствии и произойдет название “эсцет” (нем. eszett).

В средненемецком периоде появляются первые задокументированные примеры написания эсцета при помощи лигатуры ß. Это, по сути, все те же буквы S + Z, просто S в данном случае очень вытянутая, а Z пишется небольшим крючком внизу. Со временем из-за того, что люди стремились писать все быстрее оба этих элемента стянулись и стали одним символом.

Пробный урок немецкого

Хотите учить немецкий, но не знаете с чего начать? Запишитесь на бесплатный пробный урок в нашем центре прямо сейчас! Откройте для себя увлекательный мир немецкого с Deutschklasse.

Эсцет в немецких словарях

В немецких словарях для упорядочивания слов эсцет обычно приравнивается к двойной S, но это не означает, что между ними можно поставить знак равно. Потому что эсцет используется либо после длинных гласных, либо после дифтонгов (сочетания гласных тиипа eu, au, ei и т.д.) В то время, как двойная SS значает, что стоящая перед ней гласная должна произноситься коротко. Давайте рассмотрим несколько примеров:

| Сочетание S+S | ß |

|---|---|

| essen | beißen |

| das Fass | der Fuß |

| nass | fleißig |

Эсцет в других языках