Как правильно пишется словосочетание «финансовая грамотность»

- Как правильно пишется слово «финансовый»

- Как правильно пишется слово «грамотность»

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: марсельеза — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к слову «финансовый»

Ассоциации к слову «грамотность»

Синонимы к словосочетанию «финансовая грамотность»

Предложения со словосочетанием «финансовая грамотность»

- Рисунок 5. Зависимость уровня финансовой грамотности от возраста населения.

- Выход данной книги является событием как для российского научного мира, так и для практики применения блокчейна, не говоря уже о решении актуальнейшей задачи повышения финансовой грамотности населения.

- Одним из самых масштабных исследований финансовой грамотности населения в последние годы, стало глобальное исследование рейтингового агентстваStandard&Poor’s проведённого в 2014 году.

- (все предложения)

Значение словосочетания «финансовая грамотность»

-

Финансовая грамотность — совокупность знаний о финансовых рынках, особенностях их функционирования и регулирования, профессиональных участниках и предлагаемых ими финансовых инструментах, продуктах и услугах, умение их использовать с полным осознанием последствий своих действий и готовностью принять на себя ответственность за принимаемые решения. (Википедия)

Все значения словосочетания ФИНАНСОВАЯ ГРАМОТНОСТЬ

Афоризмы русских писателей со словом «грамотность»

- Я — за изучение именно литературной техники, то есть грамотности, то есть умения затрачивать наименьшее количество слов для достижения наибольшего количества эффекта, наибольшей простоты, пластичности и картинности изображаемых словами вещей, лиц, пейзажей, событий — вообще явлений социального бытия.

- (все афоризмы русских писателей)

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Financial literacy is the possession of the set of skills and knowledge that allows an individual to make informed and effective decisions with all of their financial resources. Raising interest in personal finance is now a focus of state-run programs in countries including Australia, Canada, Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom.[1][2] Understanding basic financial concepts allows people to know how to navigate in the financial system. People with appropriate financial literacy training make better financial decisions and manage money better than those without such training.[3]

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) started an inter-governmental project in 2003 with the objective of providing ways to improve financial education and literacy standards through the development of common financial literacy principles. In March 2008, the OECD launched the International Gateway for Financial Education, which aims to serve as a clearinghouse for financial education programs, information and research worldwide.[4] In the UK, the alternative term «financial capability» is used by the state and its agencies: the Financial Services Authority (FSA) in the UK started a national strategy on financial capability in 2003. The US government established its Financial Literacy and Education Commission in 2003.[5]

Definitions of financial literacy[edit]

There is a diversity of definitions used by NGOs, think tanks, and advocacy groups but in its broadest sense financial literacy is an awareness or understanding of money.[6] Some of the definitions below are closely aligned with “skills and knowledge”, whereas others take broader views:

- The Government Accountability Office definition (2010) is “the ability to make informed judgments and to take effective actions regarding the current and future use and management of money. It includes the ability to understand financial choices, plan for the future, spend wisely, and manage the challenges associated with life events such as a job loss, saving for retirement, or paying for a child’s education”.[7]

- The Financial Literacy and Education Commission (2020) includes a notion of personal capability in its definition as “the skills, knowledge and tools that equip people to make individual financial decisions and actions to attain their goals; this may also be known as financial capability, especially when paired with access to financial products and services.”.[8]

- The National Financial Educators Council adds a psychological component defining financial literacy as “possessing the skills and knowledge on financial matters to confidently take effective action that best fulfills an individual’s personal, family and global community goals.”[6]

- The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2018 published a definition in two parts. The first part refers to kinds of thinking and behaviour, while the second part refers to the purposes for developing the particular literacy. “Financial literacy is the knowledge and understanding of financial concepts and risks, and the skills, motivation and confidence to apply such knowledge and understanding in order to make effective decisions across a range of financial contexts, to improve the financial well-being of individuals and society, and to enable participation in economic life”.[9]

International findings[edit]

An international OECD study was published in late 2005 analysing financial literacy surveys in OECD countries. A selection of findings[10] included:

- In Australia, 67 percent of respondents indicated that they understood the concept of compound interest, yet when they were asked to solve a problem using the concept only 28 percent had a good level of understanding.

- A British survey found that consumers do not actively seek out financial information. The information they do receive is acquired by chance, for example, by picking up a pamphlet at a bank or having a chance talk with a bank employee.

- A Canadian survey found that respondents considered choosing the right investments to be more stressful than going to the dentist.

- A survey of Korean high-school students showed that they had failing scores—that is, they answered fewer than 60 percent of the questions correctly—on tests designed to measure their ability to choose and manage a credit card, their knowledge about saving and investing for retirement, and their awareness of risk and the importance of insuring against it.

- A survey in the US found that four out of ten American workers are not saving for retirement.

«Yet it is encouraging that the few financial education programmes which have been evaluated have been found to be reasonably effective. Research in the US shows that workers increase their participation in 401(k) plans (a type of retirement plan, with special tax advantages, which allows employees to save and invest for their own retirement) when employers offer financial education programmes, whether in the form of brochures or seminars.»[10][11]

However, academic analyses of financial education have found no evidence of measurable success at improving participants’ financial well-being.[12][13]

According to 2014 Asian Development Bank survey, more Mongolians have expanded their financial options, and for instance now compare the interest rates of loans and savings services through the successful launch of the TV drama with focus on the fiscal literacy of poor and non-poor vulnerable households.[14] Given that 80% of Mongolians cited TV as their main source of information, TV serial dramas were identified as the most effective vehicle for messages on financial literacy.[14]

Asia–Pacific, Middle East, and Africa[edit]

A survey of women consumers across Asia Pacific Middle East Africa (APMEA) comprises basic money management, financial planning and investment. The top ten of APMEA Women MasterCard’s Financial Literacy Index are Thailand 73.9, New Zealand 71.3, Australia 70.2, Vietnam 70.1, Singapore 69.4, Taiwan 68.7, Philippines 68.2, Hong Kong 68.0, Indonesia 66.5 and Malaysia 66.0.[15]

Australia[edit]

The Australian Government established a National Consumer and Financial Literacy Taskforce in 2004, which recommended the establishment of the Financial Literacy Foundation in 2005. In 2008, the functions of the Foundation were transferred to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC). The Australian Government also runs a range of programs (such as Money Management) to improve the financial literacy of its Indigenous population, particularly those living in remote communities.

In 2011 ASIC released a National Financial Literacy Strategy—informed by an earlier ASIC research report ‘Financial Literacy and Behavioural Change’—to enhance the financial wellbeing of all Australians by improving financial literacy levels. The strategy has four pillars:[16]

- Education

- Trusted and independent information, tools and support

- Additional solutions to drive improved financial wellbeing and behavioural change

- Partnerships with the sectors involved with financial literacy, measuring its impact and promoting best practice

ASIC’s MoneySmart website was one of the key initiatives in the government’s strategy. It replaced the FIDO and Understanding Money websites.

ASIC also has a MoneySmart Teaching website[17] for teachers and educators. It provides professional learning and other resources to help educators integrate consumer and financial literacy into teaching and learning programs.

The Know Risk Network of web and phone apps, newsletters, videos and website[18] was developed by insurance membership body ANZIIF to educate consumers on insurance and risk management.

India[edit]

National Centre for Financial Education (NCFE), a non-profit company, was created under section 8 of companies act 2013, to promote financial literacy in India.[19] It is promoted by four major financial regulators Reserve Bank of India, SEBI, IRDA and PFRDA.[20]

NCFE conducted a benchmark survey of financial literacy in 2015 to find the level of financial awareness in India.[21] It organises various programs to improve the financial literacy including collaborating with schools and developing new curriculum to include financial management concepts.[22] It also conducts a yearly financial literacy test.[19] The list of topics covered by NCFE in its awareness programs includes investments, types of bank accounts, services offered by banks, Aadhaar card, demat account, pan cards, power of compounding, digital payments, protection against financial frauds etc.[22]

Saudi Arabia[edit]

A nationwide survey was conducted by SEDCO Holding in Saudi Arabia in 2012 to understand the level of financial literacy in the youth.[23] The survey involved a thousand young Saudi nationals, and the results showed that only 11 percent kept track of their spending, although 75 percent thought they understood the basics of money management. An in-depth analysis of SEDCO’s survey revealed that 45 percent of youngsters did not save any money at all, while only 20 percent saved 10 percent of their monthly income. In terms of spending habits, the study indicated that items such as mobile phones and travel accounted for nearly 80 percent of purchases. Regarding financing their lifestyle, 46 percent of youth relied on their parents to fund big ticket items. 90 percent of the respondents stated that they were interested in increasing their financial knowledge.

Singapore[edit]

In Singapore, the National Institute of Education Singapore established the inaugural Financial Literacy Hub for Teachers[24] in 2007 to empower school teachers to infuse financial literacy into core curriculum subjects to embed pedagogically sound activities to engage students in learning. Such day-today relevant and authentic illustrations enhance the experiential learning to build financial capability in youth. Integral to evidence-based practices in schools, research on financial literacy is spearheaded by the Hub, which has published numerous impact studies on the effectiveness of financial literacy programs and on the perceptions and attitudes of teachers and students.

The Singapore government through the Monetary Authority of Singapore funded the setting up of the Institute for Financial Literacy[25] in July 2012. The institute is managed jointly by MoneySENSE[26] (a national financial education programme) and the Singapore Polytechnic.[27] This Institute aims to build core financial capabilities across a broad spectrum of the Singapore population by providing free and unbiased financial education programmes to working adults and their families. From July 2012 to May 2017, the Institute reached out to more than 110,000 people in Singapore via workshops and talks.

Europe[edit]

France[edit]

In 2016, France introduced a national economic, budgetary and financial education (EDUFI) strategy based on OECD principles.[28] The government designated the Banque de France as the national operator in charge of implementing the policy.[29]

This government-led strategy aims to promote financial literacy in French society. Measures include financial education and budget planning courses for young people. Entrepreneurs and financially vulnerable individuals also receive support to develop skills in this area.[29]

The Banque de France conducts periodic surveys on the level of understanding, attitudes and behaviour of the French population regarding budgetary and financial matters. It also carries out awareness-raising measures on topics such as overindebtedness, bank inclusion schemes, means of payment, bank accounts, credit, savings and insurance.

The Cité de l’Économie opened to the public in June 2019. This institution is the first French museum dedicated entirely to fostering economic literacy in an instructive and entertaining way. It is funded by the Banque de France in cooperation with several partners, including the Ministry for Education, the Institut pour l’Éducation Financière du Public (IEFP – Institute for Public Financial Education) and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.[30]

Belgium[edit]

The FSMA is tasked with contributing to better financial literacy of savers and investors that will enable individual savers, insured persons, shareholders and investors in Belgium to be in a better position in their relationships with their financial institutions. As a result, they will be less likely to purchase products that are not suited to their profile.[31]

Switzerland[edit]

A study measured financial literacy among 1500 households in German-speaking Switzerland.[32] Testing the three concepts compound interest, inflation, and risk diversification, results show that the level of financial literacy in Switzerland is high compared to results for other European countries or the US population. Results of the study further show that higher financial literacy is correlated with financial market participation and mortgage borrowing. A related study among 15-year-old students in the Canton of Fribourg shows substantial differences in the level of financial literacy between French- and German speaking students.[33]

The Swiss National Bank aims at improving financial literacy through its initiative iconomix that targets upper secondary school students.[34]

The new public school curriculum will cover financial literacy in public schools.

United Kingdom[edit]

The UK has a dedicated body to promote financial capability – the Money Advice Service.

The Financial Services Act 2010 included a provision for the FSA to establish the Consumer Financial Education Body, known as CFEB. From April 26, 2010, CFEB continued the work of the FSA’s Financial Capability Division independently of the FSA, and on April 4, 2011, was rebranded as the Money Advice Service.

The strategy previously involved the FSA spending about £10 million a year[35] across a seven-point plan. The priority areas were:

- New parents

- Schools (a programme being delivered by pfeg)

- Young adults

- Workplace

- Consumer communications

- Online tools

- Money advice

A baseline survey[35] conducted 5,300 interviews across the UK in 2005. The report identified four themes:

- Many people are failing to plan ahead

- Many people are taking on financial risks without realising it

- Problems of debt are severe for a small proportion of the population, and many more people may be affected in an economic downturn

- The under-40s are, on average, less financially capable than their elders

«In short, unless steps are taken to improve levels of financial capability, we are storing up trouble for the future.»[35]

There are also numerous charities in the United Kingdom working to improve financial literacy such as MyBnk, Citizens Advice Bureau and the Personal Finance Education Group.

Financial literacy within the UK’s armed forces is provided through the MoneyForce program, run by the Royal British Legion in association with the Ministry of Defence and the Money Advice Service.[36]

Americas[edit]

Canada[edit]

In 2006, Canadian securities regulators commissioned two national investor surveys[37][38] to gauge people’s knowledge and experience with investments and fraud. The results from both studies demonstrated there is a need better to educate and inform investors about capital markets and investment fraud. Education in this area is particularly important as investors take on more risk and responsibility of managing their retirement savings, and a large baby boomer population enters the retirement years across North America.

In 2005, the British Columbia Securities Commission (BCSC) funded the Eron Mortgage Study.[39] It was the first systematic study of a single investment fraud, focusing on more than 2,200 Eron Mortgage investors. Among other things, the report identified that investors approaching retirement without adequate resources and affluent middle-aged men were vulnerable to investment fraud. The report suggests investor education will become even more important as the baby boomer generation enters retirement.

In Canada, Financial Literacy Month takes place during the month of November to encourage Canadians to take control of their financial well-being and invest into their financial futures by learning about topics of personal finance. Canada has also established a government entity to «promotes financial education and raises consumers’ awareness of their rights and responsibilities».[40] The agency also «ensures federally regulated financial entities comply with consumer protection measures.[40]

United States[edit]

In the US, a national nonprofit organization, the Jump$tart Coalition for Personal Financial Literacy, is a collection of corporate, academic, non-profit and government organizations that work for financial education since 1995.

The United States Department of the Treasury established its Office of Financial Education in 2002; and the US Congress established the Financial Literacy and Education Commission under the Financial Literacy and Education Improvement Act in 2003. The Commission published its National Strategy on Financial Literacy[1] in 2006.[41]

While many organizations have supported the financial literacy movement, they may differ on their definitions of financial literacy. In a report by the President’s Advisory Council on Financial Literacy, the authors called for a consistent definition of financial literacy by which financial literacy education programs can be judged. They defined financial literacy as «the ability to use knowledge and skills to manage financial resources effectively for a lifetime of financial well-being.»[42]

The Council for Economic Education (CEE) conducted a 2009 Survey of the States and found that 44 states currently have K-12 personal finance education or guidelines in place.[43] However, «only 17 states require high school students to take a course in personal finance.»[44]

The Center For Financial Literacy at Champlain College conducts a biannual survey of statewide high school financial literacy requirements across the nation. The 2017 survey found that Utah had the highest state requirement in the nation, while in Alaska, Delaware, Washington, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Rhode Island and South Dakota, students are entirely dependent on the initiative of their local school board.[45]

In July 2010, the United States Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act), which created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). The CFPB has been tasked, among other mandates, with promoting financial education through its Consumer Engagement & Education group.[46]

Brazil[edit]

Between 2018 and 2019, surveys were performed for a myriad of players in the Brazilian financial market. Among them, B3 (stock exchange), ANBIMA, CVM e Ilumeo Institute.[47] Following these surveys, Brazil defined action plans, the National Strategy about Financial Education (ENEF).[48]

Academic research[edit]

Accounting literacy[edit]

The 1999 Blue Ribbon Committee on Improving the Effectiveness of Corporate Audit Committees recommended that publicly traded companies have at least three members with «a certain basic ‘financial literacy’. Such ‘literacy’ signifies the ability to read and understand fundamental financial statements, including a company’s balance sheet, income statement and cash flow statement.»[49]

Academic researchers have explored the relationship between financial literacy and accounting literacy. In this context Roman L. Weil defines financial literacy as «the ability to understand the important accounting judgments management makes, why management makes them, and how management can use those judgments to manipulate financial statements».[50]

Critical financial literacy[edit]

Some financial literacy researchers have raised questions about the political character of financial literacy education, arguing that it justifies the shifting of greater financial risk (e.g. tuition fees, pensions, health care costs, etc.) to individuals from corporations and governments. Many of these researchers argue for a financial literacy education that is more critically oriented and broader in focus: an education that helps individuals better understand systemic injustice and social exclusion, rather than one which understands financial failure as an individual problem and the character of financial risk as apolitical. Many of these researchers work within social justice, critical pedagogy, feminist and critical race theory paradigms.[51][52][53][54][55][56]

See also[edit]

- Financial deepening

- Financial ethics

- Financial inclusion

- Financial literacy curriculum

- Financial Literacy Month

- Financial regulation

- Financial social work

- Information literacies

References[edit]

- ^ a b Financial Literacy and Education Commission (23 June 2006). «Taking Ownership of the Future: The National Strategy for Financial Literacy» (PDF). mymoney.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ «Financial Literacy Education in Ontario Schools». edu.gov.on.ca. Ontario Ministry of Education. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ Lusardi, A; Mitchell, O (2011). «Financial Literacy Around the World: An Overview». Journal of Pension Economics and Finance. 10 (4): 497–508. doi:10.3386/w17107. PMC 5445931. PMID 28553190.

- ^ «International Gateway for Financial Education > Home». financial-education.org.

- ^ «Financial Literacy – The CQ Researcher Blog». cqresearcherblog.blogspot.com.

- ^ a b «Financial Literacy Definition, National Financial Educators Council».

- ^ «Factors Affecting the Financial Literacy of Individuals with Limited English Proficiency, Report to Congressional Committees, United States Government Accountability Office».

- ^ «US National Strategy for Financial Literacy 2020».

- ^ «PISA 2018 Financial Literacy Framework».

- ^ a b «Hecklinger, Richard E. Deputy Secretary-General of the OECD speaking January 9, 2006 at The Smith Institute, London». New Statesman. June 5, 2006. Archived from the original on July 20, 2006.

- ^ Clark, Robert (2014). «Can Simple Informational Nudges Increase Employee Participation in a 401 (k) Plan?». Southern Economic Journal. 80 (3): 677–701. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.681.2621. doi:10.4284/0038-4038-2012.199. S2CID 155064531 – via Business Source Complete.

- ^ «Shawn Cole & Gauri Kartini Shastry, If You Are So Smart, Why Aren’t You Rich? The Effects of Education, Financial Literacy and Cognitive Ability on Financial Market Participation (November 2008)» (PDF). afi.es.

- ^ Willis, Lauren E. (2008-02-28). «Evidence and Ideology in Assessing the Effectiveness of Financial Literacy Education». SSRN. SSRN 1098270.

- ^ a b Enkhbold, Enerelt (2016). TV drama promotes financial education in Mongolia. ADB Blog

- ^ «Indian women surpass Chinese in financial literacy». The Times of India. March 1, 2011. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012.

- ^ «About the National Financial Literacy Strategy». financialliteracy.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2011-03-14.

- ^ «Teaching: A comprehensive program to develop consumer and financial capability in young Australians». moneysmart.gov.au. 2018-10-30.

- ^ «Know Risk». anziif.com. ANZIIF.

- ^ a b «Financial Planning: Make financial literacy part of school studies». DNA India. 2019-01-07. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ «SEBI wants govt rethink on RBI representation on its board». Moneycontrol. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ «Agricultural reform: How to boost farmer income – Decoded here». The Financial Express. 2018-12-18. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ a b «Students to get lessons on PAN card, I-T returns & more | Indore News». The Times of India. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ Saudi Gazette (2012-09-06). «SEDCO launches Riyali financial literacy program». Saudi Gazette. Archived from the original on 2013-10-19. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ «Citi-NIE Financial Literacy Hub for Teachers». finlit.nie.edu.sg. Archived from the original on 2013-07-19.

- ^ «The MoneySENSE Singapore Polytechnic Institute For Financial Literacy». finlit.sg.

- ^ Reading Room. «MoneySENSE». moneysense.gov.sg.

- ^ «Home – Singapore Polytechnic». sp.edu.sg.

- ^ Finances.gouv.fr (2016-12-20). «Comité national de l’éducation financière : une stratégie nationale d’éducation financière pour tous les Français» (PDF).

- ^ a b «Economic and financial education». Banque de France. 2016-12-09. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ «Partenaires | Citéco». www.citeco.fr. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ About the FSMA, retrieved 17-8-16

- ^ «Financial Literacy and Retirement Planning in Switzerland» (PDF). gflec.org.

- ^ Brown, M.; Henchoz, C.; Spycher, T. (2018). «Culture and financial literacy: Evidence from a within-country language border». Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. 150: 62–85. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2018.03.011.

- ^ «Iconomix webpage», Swiss National Bank

- ^ a b c «Financial capability in the UK: Delivering Change», Financial Services Authority, 2006, p. 1 Archived 2017-01-20 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 1-84518-418-1

- ^ «MoneyForce». RBL. 12 March 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Canadian Securities Administrators and Innovative Research Group, Inc. (24 October 2006). «CSA Investor Index» (PDF). csa-acvm.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2007.

- ^ Canadian Securities Administrators and Innovative Research Group, Inc. (25 September 2007). «2007 CSA Investor Study: Understanding the Social Impact of Investment Fraud» (PDF). bcsc.bc.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-10-25.

- ^ Eron Mortgage Study, Neil Boyd, Professor and Associate Director, School of Criminology Simon Fraser University, March 31, 2005 [1]

- ^ a b «Financial Consumer Agency of Canada». canada.ca. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ «Financial Literacy and Education Commission | U.S. Department of the Treasury». home.treasury.gov. Retrieved 2020-11-18.

- ^ President’s Advisory Council on Financial Literacy (January 2009). «2008 Annual Report to the President» (PDF). ustreas.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 2, 2010.

- ^ «National Endowment for Financial Education». NEFE. Archived from the original on 2013-10-19. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ Folger, Jean (30 April 2013). «Teaching Financial Literacy to Teens». investopedia.com.

- ^ «Is Your State Making the Grade: 2017 National Report Card on State Efforts to Improve Financial Literacy in High Schools». Center For Financial Literacy. Champlain College. 12 December 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ «About us > Consumer Financial Protection Bureau». Consumerfinance.gov. 2013-08-13. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ «Os desafios da educação financeira no Brasil». Medium. 2020-02-04. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

- ^ «ENEF Brazil — National Strategy about Financial Education». ENEF. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

- ^ «Report and Recommendations of the Blue Ribbon Committee on Improving the Effectiveness of Corporate Audit Committees». The Business Lawyer. 54 (3): 1067–1095. 1999. Retrieved 2020-12-17.

- ^ Weil, Roman L. (May 2004). «Audit Committees Can’t Add». Harvard Business Review (Interview). Interviewed by Gardiner Morse. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Publishing. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ Arthur, Chris (2012). Arthur, Chris (ed.). Financial Literacy Education: Neoliberalism, the Consumer and the Citizen. Educational Futures: Rethinking Theory and Practice. Vol. 53. Rotterdam; Boston: Sense Publishers. doi:10.1007/978-94-6091-918-3. ISBN 9789460919183. OCLC 811002204.

- ^ Pinto, Laura Elizabeth; Coulson, Elizabeth (20 December 2011). «Social justice and the gender politics of financial literacy education». Journal of the Canadian Association for Curriculum Studies. 9 (2): 54–85. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ Lucey, Thomas A; Laney, James D. (2012). Reframing Financial Literacy: Exploring the Value of Social Currency. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing. ISBN 9781617357190. OCLC 766607825.

- ^ Williams, Toni (April 2007). «Empowerment of whom and for what? Financial literacy education and the new regulation of consumer financial services» (PDF). Law & Policy. 29 (2): 226–256. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9930.2007.00254.x. SSRN 972551.

- ^ Pinto, Laura Elizabeth (2013). «When politics trump evidence: financial literacy education narratives following the global financial crisis». Journal of Education Policy. 28 (1): 95–120. doi:10.1080/02680939.2012.690163. S2CID 153428102.

- ^ Hütten, Moritz; Maman, Daniel; Rosenhek, Zeev; Thiemann, Matthias (2018). «Critical financial literacy: an agenda». International Journal of Pluralism and Economics Education. 9 (3): 274–291. doi:10.1504/IJPEE.2018.093405.

Further reading[edit]

- Aprea, Carmela; Wuttke, Eveline; Breuer, Klaus; Koh, Noi Keng; Davies, Peter; Greimel-Fuhrmann, Bettina; Lopus, Jane S., eds. (2016). International Handbook of Financial Literacy. Singapore: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-0360-8. ISBN 9789811003585. OCLC 948244069.

- Arthur, Chris (2019). «Financial literacy and entrepreneurship education: an ethics for capital or the other?». In Saltman, Kenneth J.; Means, Alexander J. (eds.). The Wiley Handbook of Global Educational Reform. Wiley Handbooks in Education. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 435–465. doi:10.1002/9781119082316.ch21. ISBN 9781119083078. OCLC 1048657132.

- Birkenmaier, Julie; Sherraden, Margaret S.; Curley, Jami, eds. (2013). Financial Capability and Asset Development: Research, Education, Policy, And Practice. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199755950.001.0001. ISBN 9780199755950. OCLC 806221695.

- Bryant, John Hope (2013). «Economic growth and sustainability rooted in financial literacy». In Madhavan, Guruprasad; Oakley, Barbara; Green, David; Koon, David; Low, Penny (eds.). Practicing Sustainability. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 95–99. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-4349-0_19. ISBN 9781461443483. OCLC 793571943.

- Dworsky, Lawrence N. (2009). Understanding the Mathematics of Personal Finance: An Introduction to Financial Literacy. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9780470538395. ISBN 9780470497807. OCLC 318971496.

- Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (August 2009). «Community Investments, Volume 21, Issue 2: Financial Education». frbsf.org.

- Mitchell, Olivia S.; Lusardi, Annamaria, eds. (2011). Financial Literacy: Implications for Retirement Security and the Financial Marketplace. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199696819.001.0001. ISBN 9780199696819. OCLC 727704973.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2005). Improving Financial Literacy: Analysis of Issues and Policies. Paris: OECD. doi:10.1787/9789264012578-en. ISBN 9789264012561. OCLC 62777366.

- Willis, Lauren E. (2012). «Financial education: lessons not learned and lessons learned». In Bodie, Zvi; Siegel, Laurence B.; Stanton, Lisa (eds.). Life-Cycle Investing: Financial Education and Consumer Protection. Charlottesville, VA: Research Foundation of CFA Institute. pp. 125–138. ISBN 9781934667521.

- Willis, Lauren E. (Winter 2017). «Finance-informed citizens, citizen-informed finance: an essay occasioned by the International Handbook of Financial Literacy«. Journal of Social Science Education. 16 (4): 16–27. doi:10.4119/jsse-848.

- Xiao, Jing Jian, ed. (2016) [2008]. Handbook of Consumer Finance Research (2nd ed.). Cham: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28887-1. ISBN 9783319288857. OCLC 932096049.

External links[edit]

- Money Smart Financial Education Program from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, available at Wikimedia Commons

Financial literacy is the possession of the set of skills and knowledge that allows an individual to make informed and effective decisions with all of their financial resources. Raising interest in personal finance is now a focus of state-run programs in countries including Australia, Canada, Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom.[1][2] Understanding basic financial concepts allows people to know how to navigate in the financial system. People with appropriate financial literacy training make better financial decisions and manage money better than those without such training.[3]

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) started an inter-governmental project in 2003 with the objective of providing ways to improve financial education and literacy standards through the development of common financial literacy principles. In March 2008, the OECD launched the International Gateway for Financial Education, which aims to serve as a clearinghouse for financial education programs, information and research worldwide.[4] In the UK, the alternative term «financial capability» is used by the state and its agencies: the Financial Services Authority (FSA) in the UK started a national strategy on financial capability in 2003. The US government established its Financial Literacy and Education Commission in 2003.[5]

Definitions of financial literacy[edit]

There is a diversity of definitions used by NGOs, think tanks, and advocacy groups but in its broadest sense financial literacy is an awareness or understanding of money.[6] Some of the definitions below are closely aligned with “skills and knowledge”, whereas others take broader views:

- The Government Accountability Office definition (2010) is “the ability to make informed judgments and to take effective actions regarding the current and future use and management of money. It includes the ability to understand financial choices, plan for the future, spend wisely, and manage the challenges associated with life events such as a job loss, saving for retirement, or paying for a child’s education”.[7]

- The Financial Literacy and Education Commission (2020) includes a notion of personal capability in its definition as “the skills, knowledge and tools that equip people to make individual financial decisions and actions to attain their goals; this may also be known as financial capability, especially when paired with access to financial products and services.”.[8]

- The National Financial Educators Council adds a psychological component defining financial literacy as “possessing the skills and knowledge on financial matters to confidently take effective action that best fulfills an individual’s personal, family and global community goals.”[6]

- The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2018 published a definition in two parts. The first part refers to kinds of thinking and behaviour, while the second part refers to the purposes for developing the particular literacy. “Financial literacy is the knowledge and understanding of financial concepts and risks, and the skills, motivation and confidence to apply such knowledge and understanding in order to make effective decisions across a range of financial contexts, to improve the financial well-being of individuals and society, and to enable participation in economic life”.[9]

International findings[edit]

An international OECD study was published in late 2005 analysing financial literacy surveys in OECD countries. A selection of findings[10] included:

- In Australia, 67 percent of respondents indicated that they understood the concept of compound interest, yet when they were asked to solve a problem using the concept only 28 percent had a good level of understanding.

- A British survey found that consumers do not actively seek out financial information. The information they do receive is acquired by chance, for example, by picking up a pamphlet at a bank or having a chance talk with a bank employee.

- A Canadian survey found that respondents considered choosing the right investments to be more stressful than going to the dentist.

- A survey of Korean high-school students showed that they had failing scores—that is, they answered fewer than 60 percent of the questions correctly—on tests designed to measure their ability to choose and manage a credit card, their knowledge about saving and investing for retirement, and their awareness of risk and the importance of insuring against it.

- A survey in the US found that four out of ten American workers are not saving for retirement.

«Yet it is encouraging that the few financial education programmes which have been evaluated have been found to be reasonably effective. Research in the US shows that workers increase their participation in 401(k) plans (a type of retirement plan, with special tax advantages, which allows employees to save and invest for their own retirement) when employers offer financial education programmes, whether in the form of brochures or seminars.»[10][11]

However, academic analyses of financial education have found no evidence of measurable success at improving participants’ financial well-being.[12][13]

According to 2014 Asian Development Bank survey, more Mongolians have expanded their financial options, and for instance now compare the interest rates of loans and savings services through the successful launch of the TV drama with focus on the fiscal literacy of poor and non-poor vulnerable households.[14] Given that 80% of Mongolians cited TV as their main source of information, TV serial dramas were identified as the most effective vehicle for messages on financial literacy.[14]

Asia–Pacific, Middle East, and Africa[edit]

A survey of women consumers across Asia Pacific Middle East Africa (APMEA) comprises basic money management, financial planning and investment. The top ten of APMEA Women MasterCard’s Financial Literacy Index are Thailand 73.9, New Zealand 71.3, Australia 70.2, Vietnam 70.1, Singapore 69.4, Taiwan 68.7, Philippines 68.2, Hong Kong 68.0, Indonesia 66.5 and Malaysia 66.0.[15]

Australia[edit]

The Australian Government established a National Consumer and Financial Literacy Taskforce in 2004, which recommended the establishment of the Financial Literacy Foundation in 2005. In 2008, the functions of the Foundation were transferred to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC). The Australian Government also runs a range of programs (such as Money Management) to improve the financial literacy of its Indigenous population, particularly those living in remote communities.

In 2011 ASIC released a National Financial Literacy Strategy—informed by an earlier ASIC research report ‘Financial Literacy and Behavioural Change’—to enhance the financial wellbeing of all Australians by improving financial literacy levels. The strategy has four pillars:[16]

- Education

- Trusted and independent information, tools and support

- Additional solutions to drive improved financial wellbeing and behavioural change

- Partnerships with the sectors involved with financial literacy, measuring its impact and promoting best practice

ASIC’s MoneySmart website was one of the key initiatives in the government’s strategy. It replaced the FIDO and Understanding Money websites.

ASIC also has a MoneySmart Teaching website[17] for teachers and educators. It provides professional learning and other resources to help educators integrate consumer and financial literacy into teaching and learning programs.

The Know Risk Network of web and phone apps, newsletters, videos and website[18] was developed by insurance membership body ANZIIF to educate consumers on insurance and risk management.

India[edit]

National Centre for Financial Education (NCFE), a non-profit company, was created under section 8 of companies act 2013, to promote financial literacy in India.[19] It is promoted by four major financial regulators Reserve Bank of India, SEBI, IRDA and PFRDA.[20]

NCFE conducted a benchmark survey of financial literacy in 2015 to find the level of financial awareness in India.[21] It organises various programs to improve the financial literacy including collaborating with schools and developing new curriculum to include financial management concepts.[22] It also conducts a yearly financial literacy test.[19] The list of topics covered by NCFE in its awareness programs includes investments, types of bank accounts, services offered by banks, Aadhaar card, demat account, pan cards, power of compounding, digital payments, protection against financial frauds etc.[22]

Saudi Arabia[edit]

A nationwide survey was conducted by SEDCO Holding in Saudi Arabia in 2012 to understand the level of financial literacy in the youth.[23] The survey involved a thousand young Saudi nationals, and the results showed that only 11 percent kept track of their spending, although 75 percent thought they understood the basics of money management. An in-depth analysis of SEDCO’s survey revealed that 45 percent of youngsters did not save any money at all, while only 20 percent saved 10 percent of their monthly income. In terms of spending habits, the study indicated that items such as mobile phones and travel accounted for nearly 80 percent of purchases. Regarding financing their lifestyle, 46 percent of youth relied on their parents to fund big ticket items. 90 percent of the respondents stated that they were interested in increasing their financial knowledge.

Singapore[edit]

In Singapore, the National Institute of Education Singapore established the inaugural Financial Literacy Hub for Teachers[24] in 2007 to empower school teachers to infuse financial literacy into core curriculum subjects to embed pedagogically sound activities to engage students in learning. Such day-today relevant and authentic illustrations enhance the experiential learning to build financial capability in youth. Integral to evidence-based practices in schools, research on financial literacy is spearheaded by the Hub, which has published numerous impact studies on the effectiveness of financial literacy programs and on the perceptions and attitudes of teachers and students.

The Singapore government through the Monetary Authority of Singapore funded the setting up of the Institute for Financial Literacy[25] in July 2012. The institute is managed jointly by MoneySENSE[26] (a national financial education programme) and the Singapore Polytechnic.[27] This Institute aims to build core financial capabilities across a broad spectrum of the Singapore population by providing free and unbiased financial education programmes to working adults and their families. From July 2012 to May 2017, the Institute reached out to more than 110,000 people in Singapore via workshops and talks.

Europe[edit]

France[edit]

In 2016, France introduced a national economic, budgetary and financial education (EDUFI) strategy based on OECD principles.[28] The government designated the Banque de France as the national operator in charge of implementing the policy.[29]

This government-led strategy aims to promote financial literacy in French society. Measures include financial education and budget planning courses for young people. Entrepreneurs and financially vulnerable individuals also receive support to develop skills in this area.[29]

The Banque de France conducts periodic surveys on the level of understanding, attitudes and behaviour of the French population regarding budgetary and financial matters. It also carries out awareness-raising measures on topics such as overindebtedness, bank inclusion schemes, means of payment, bank accounts, credit, savings and insurance.

The Cité de l’Économie opened to the public in June 2019. This institution is the first French museum dedicated entirely to fostering economic literacy in an instructive and entertaining way. It is funded by the Banque de France in cooperation with several partners, including the Ministry for Education, the Institut pour l’Éducation Financière du Public (IEFP – Institute for Public Financial Education) and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.[30]

Belgium[edit]

The FSMA is tasked with contributing to better financial literacy of savers and investors that will enable individual savers, insured persons, shareholders and investors in Belgium to be in a better position in their relationships with their financial institutions. As a result, they will be less likely to purchase products that are not suited to their profile.[31]

Switzerland[edit]

A study measured financial literacy among 1500 households in German-speaking Switzerland.[32] Testing the three concepts compound interest, inflation, and risk diversification, results show that the level of financial literacy in Switzerland is high compared to results for other European countries or the US population. Results of the study further show that higher financial literacy is correlated with financial market participation and mortgage borrowing. A related study among 15-year-old students in the Canton of Fribourg shows substantial differences in the level of financial literacy between French- and German speaking students.[33]

The Swiss National Bank aims at improving financial literacy through its initiative iconomix that targets upper secondary school students.[34]

The new public school curriculum will cover financial literacy in public schools.

United Kingdom[edit]

The UK has a dedicated body to promote financial capability – the Money Advice Service.

The Financial Services Act 2010 included a provision for the FSA to establish the Consumer Financial Education Body, known as CFEB. From April 26, 2010, CFEB continued the work of the FSA’s Financial Capability Division independently of the FSA, and on April 4, 2011, was rebranded as the Money Advice Service.

The strategy previously involved the FSA spending about £10 million a year[35] across a seven-point plan. The priority areas were:

- New parents

- Schools (a programme being delivered by pfeg)

- Young adults

- Workplace

- Consumer communications

- Online tools

- Money advice

A baseline survey[35] conducted 5,300 interviews across the UK in 2005. The report identified four themes:

- Many people are failing to plan ahead

- Many people are taking on financial risks without realising it

- Problems of debt are severe for a small proportion of the population, and many more people may be affected in an economic downturn

- The under-40s are, on average, less financially capable than their elders

«In short, unless steps are taken to improve levels of financial capability, we are storing up trouble for the future.»[35]

There are also numerous charities in the United Kingdom working to improve financial literacy such as MyBnk, Citizens Advice Bureau and the Personal Finance Education Group.

Financial literacy within the UK’s armed forces is provided through the MoneyForce program, run by the Royal British Legion in association with the Ministry of Defence and the Money Advice Service.[36]

Americas[edit]

Canada[edit]

In 2006, Canadian securities regulators commissioned two national investor surveys[37][38] to gauge people’s knowledge and experience with investments and fraud. The results from both studies demonstrated there is a need better to educate and inform investors about capital markets and investment fraud. Education in this area is particularly important as investors take on more risk and responsibility of managing their retirement savings, and a large baby boomer population enters the retirement years across North America.

In 2005, the British Columbia Securities Commission (BCSC) funded the Eron Mortgage Study.[39] It was the first systematic study of a single investment fraud, focusing on more than 2,200 Eron Mortgage investors. Among other things, the report identified that investors approaching retirement without adequate resources and affluent middle-aged men were vulnerable to investment fraud. The report suggests investor education will become even more important as the baby boomer generation enters retirement.

In Canada, Financial Literacy Month takes place during the month of November to encourage Canadians to take control of their financial well-being and invest into their financial futures by learning about topics of personal finance. Canada has also established a government entity to «promotes financial education and raises consumers’ awareness of their rights and responsibilities».[40] The agency also «ensures federally regulated financial entities comply with consumer protection measures.[40]

United States[edit]

In the US, a national nonprofit organization, the Jump$tart Coalition for Personal Financial Literacy, is a collection of corporate, academic, non-profit and government organizations that work for financial education since 1995.

The United States Department of the Treasury established its Office of Financial Education in 2002; and the US Congress established the Financial Literacy and Education Commission under the Financial Literacy and Education Improvement Act in 2003. The Commission published its National Strategy on Financial Literacy[1] in 2006.[41]

While many organizations have supported the financial literacy movement, they may differ on their definitions of financial literacy. In a report by the President’s Advisory Council on Financial Literacy, the authors called for a consistent definition of financial literacy by which financial literacy education programs can be judged. They defined financial literacy as «the ability to use knowledge and skills to manage financial resources effectively for a lifetime of financial well-being.»[42]

The Council for Economic Education (CEE) conducted a 2009 Survey of the States and found that 44 states currently have K-12 personal finance education or guidelines in place.[43] However, «only 17 states require high school students to take a course in personal finance.»[44]

The Center For Financial Literacy at Champlain College conducts a biannual survey of statewide high school financial literacy requirements across the nation. The 2017 survey found that Utah had the highest state requirement in the nation, while in Alaska, Delaware, Washington, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Rhode Island and South Dakota, students are entirely dependent on the initiative of their local school board.[45]

In July 2010, the United States Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act), which created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). The CFPB has been tasked, among other mandates, with promoting financial education through its Consumer Engagement & Education group.[46]

Brazil[edit]

Between 2018 and 2019, surveys were performed for a myriad of players in the Brazilian financial market. Among them, B3 (stock exchange), ANBIMA, CVM e Ilumeo Institute.[47] Following these surveys, Brazil defined action plans, the National Strategy about Financial Education (ENEF).[48]

Academic research[edit]

Accounting literacy[edit]

The 1999 Blue Ribbon Committee on Improving the Effectiveness of Corporate Audit Committees recommended that publicly traded companies have at least three members with «a certain basic ‘financial literacy’. Such ‘literacy’ signifies the ability to read and understand fundamental financial statements, including a company’s balance sheet, income statement and cash flow statement.»[49]

Academic researchers have explored the relationship between financial literacy and accounting literacy. In this context Roman L. Weil defines financial literacy as «the ability to understand the important accounting judgments management makes, why management makes them, and how management can use those judgments to manipulate financial statements».[50]

Critical financial literacy[edit]

Some financial literacy researchers have raised questions about the political character of financial literacy education, arguing that it justifies the shifting of greater financial risk (e.g. tuition fees, pensions, health care costs, etc.) to individuals from corporations and governments. Many of these researchers argue for a financial literacy education that is more critically oriented and broader in focus: an education that helps individuals better understand systemic injustice and social exclusion, rather than one which understands financial failure as an individual problem and the character of financial risk as apolitical. Many of these researchers work within social justice, critical pedagogy, feminist and critical race theory paradigms.[51][52][53][54][55][56]

See also[edit]

- Financial deepening

- Financial ethics

- Financial inclusion

- Financial literacy curriculum

- Financial Literacy Month

- Financial regulation

- Financial social work

- Information literacies

References[edit]

- ^ a b Financial Literacy and Education Commission (23 June 2006). «Taking Ownership of the Future: The National Strategy for Financial Literacy» (PDF). mymoney.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ «Financial Literacy Education in Ontario Schools». edu.gov.on.ca. Ontario Ministry of Education. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ Lusardi, A; Mitchell, O (2011). «Financial Literacy Around the World: An Overview». Journal of Pension Economics and Finance. 10 (4): 497–508. doi:10.3386/w17107. PMC 5445931. PMID 28553190.

- ^ «International Gateway for Financial Education > Home». financial-education.org.

- ^ «Financial Literacy – The CQ Researcher Blog». cqresearcherblog.blogspot.com.

- ^ a b «Financial Literacy Definition, National Financial Educators Council».

- ^ «Factors Affecting the Financial Literacy of Individuals with Limited English Proficiency, Report to Congressional Committees, United States Government Accountability Office».

- ^ «US National Strategy for Financial Literacy 2020».

- ^ «PISA 2018 Financial Literacy Framework».

- ^ a b «Hecklinger, Richard E. Deputy Secretary-General of the OECD speaking January 9, 2006 at The Smith Institute, London». New Statesman. June 5, 2006. Archived from the original on July 20, 2006.

- ^ Clark, Robert (2014). «Can Simple Informational Nudges Increase Employee Participation in a 401 (k) Plan?». Southern Economic Journal. 80 (3): 677–701. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.681.2621. doi:10.4284/0038-4038-2012.199. S2CID 155064531 – via Business Source Complete.

- ^ «Shawn Cole & Gauri Kartini Shastry, If You Are So Smart, Why Aren’t You Rich? The Effects of Education, Financial Literacy and Cognitive Ability on Financial Market Participation (November 2008)» (PDF). afi.es.

- ^ Willis, Lauren E. (2008-02-28). «Evidence and Ideology in Assessing the Effectiveness of Financial Literacy Education». SSRN. SSRN 1098270.

- ^ a b Enkhbold, Enerelt (2016). TV drama promotes financial education in Mongolia. ADB Blog

- ^ «Indian women surpass Chinese in financial literacy». The Times of India. March 1, 2011. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012.

- ^ «About the National Financial Literacy Strategy». financialliteracy.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2011-03-14.

- ^ «Teaching: A comprehensive program to develop consumer and financial capability in young Australians». moneysmart.gov.au. 2018-10-30.

- ^ «Know Risk». anziif.com. ANZIIF.

- ^ a b «Financial Planning: Make financial literacy part of school studies». DNA India. 2019-01-07. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ «SEBI wants govt rethink on RBI representation on its board». Moneycontrol. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ «Agricultural reform: How to boost farmer income – Decoded here». The Financial Express. 2018-12-18. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ a b «Students to get lessons on PAN card, I-T returns & more | Indore News». The Times of India. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ Saudi Gazette (2012-09-06). «SEDCO launches Riyali financial literacy program». Saudi Gazette. Archived from the original on 2013-10-19. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ «Citi-NIE Financial Literacy Hub for Teachers». finlit.nie.edu.sg. Archived from the original on 2013-07-19.

- ^ «The MoneySENSE Singapore Polytechnic Institute For Financial Literacy». finlit.sg.

- ^ Reading Room. «MoneySENSE». moneysense.gov.sg.

- ^ «Home – Singapore Polytechnic». sp.edu.sg.

- ^ Finances.gouv.fr (2016-12-20). «Comité national de l’éducation financière : une stratégie nationale d’éducation financière pour tous les Français» (PDF).

- ^ a b «Economic and financial education». Banque de France. 2016-12-09. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ «Partenaires | Citéco». www.citeco.fr. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ About the FSMA, retrieved 17-8-16

- ^ «Financial Literacy and Retirement Planning in Switzerland» (PDF). gflec.org.

- ^ Brown, M.; Henchoz, C.; Spycher, T. (2018). «Culture and financial literacy: Evidence from a within-country language border». Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. 150: 62–85. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2018.03.011.

- ^ «Iconomix webpage», Swiss National Bank

- ^ a b c «Financial capability in the UK: Delivering Change», Financial Services Authority, 2006, p. 1 Archived 2017-01-20 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 1-84518-418-1

- ^ «MoneyForce». RBL. 12 March 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Canadian Securities Administrators and Innovative Research Group, Inc. (24 October 2006). «CSA Investor Index» (PDF). csa-acvm.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2007.

- ^ Canadian Securities Administrators and Innovative Research Group, Inc. (25 September 2007). «2007 CSA Investor Study: Understanding the Social Impact of Investment Fraud» (PDF). bcsc.bc.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-10-25.

- ^ Eron Mortgage Study, Neil Boyd, Professor and Associate Director, School of Criminology Simon Fraser University, March 31, 2005 [1]

- ^ a b «Financial Consumer Agency of Canada». canada.ca. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ «Financial Literacy and Education Commission | U.S. Department of the Treasury». home.treasury.gov. Retrieved 2020-11-18.

- ^ President’s Advisory Council on Financial Literacy (January 2009). «2008 Annual Report to the President» (PDF). ustreas.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 2, 2010.

- ^ «National Endowment for Financial Education». NEFE. Archived from the original on 2013-10-19. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ Folger, Jean (30 April 2013). «Teaching Financial Literacy to Teens». investopedia.com.

- ^ «Is Your State Making the Grade: 2017 National Report Card on State Efforts to Improve Financial Literacy in High Schools». Center For Financial Literacy. Champlain College. 12 December 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ «About us > Consumer Financial Protection Bureau». Consumerfinance.gov. 2013-08-13. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ «Os desafios da educação financeira no Brasil». Medium. 2020-02-04. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

- ^ «ENEF Brazil — National Strategy about Financial Education». ENEF. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

- ^ «Report and Recommendations of the Blue Ribbon Committee on Improving the Effectiveness of Corporate Audit Committees». The Business Lawyer. 54 (3): 1067–1095. 1999. Retrieved 2020-12-17.

- ^ Weil, Roman L. (May 2004). «Audit Committees Can’t Add». Harvard Business Review (Interview). Interviewed by Gardiner Morse. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Publishing. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ Arthur, Chris (2012). Arthur, Chris (ed.). Financial Literacy Education: Neoliberalism, the Consumer and the Citizen. Educational Futures: Rethinking Theory and Practice. Vol. 53. Rotterdam; Boston: Sense Publishers. doi:10.1007/978-94-6091-918-3. ISBN 9789460919183. OCLC 811002204.

- ^ Pinto, Laura Elizabeth; Coulson, Elizabeth (20 December 2011). «Social justice and the gender politics of financial literacy education». Journal of the Canadian Association for Curriculum Studies. 9 (2): 54–85. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ Lucey, Thomas A; Laney, James D. (2012). Reframing Financial Literacy: Exploring the Value of Social Currency. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing. ISBN 9781617357190. OCLC 766607825.

- ^ Williams, Toni (April 2007). «Empowerment of whom and for what? Financial literacy education and the new regulation of consumer financial services» (PDF). Law & Policy. 29 (2): 226–256. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9930.2007.00254.x. SSRN 972551.

- ^ Pinto, Laura Elizabeth (2013). «When politics trump evidence: financial literacy education narratives following the global financial crisis». Journal of Education Policy. 28 (1): 95–120. doi:10.1080/02680939.2012.690163. S2CID 153428102.

- ^ Hütten, Moritz; Maman, Daniel; Rosenhek, Zeev; Thiemann, Matthias (2018). «Critical financial literacy: an agenda». International Journal of Pluralism and Economics Education. 9 (3): 274–291. doi:10.1504/IJPEE.2018.093405.

Further reading[edit]

- Aprea, Carmela; Wuttke, Eveline; Breuer, Klaus; Koh, Noi Keng; Davies, Peter; Greimel-Fuhrmann, Bettina; Lopus, Jane S., eds. (2016). International Handbook of Financial Literacy. Singapore: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-0360-8. ISBN 9789811003585. OCLC 948244069.

- Arthur, Chris (2019). «Financial literacy and entrepreneurship education: an ethics for capital or the other?». In Saltman, Kenneth J.; Means, Alexander J. (eds.). The Wiley Handbook of Global Educational Reform. Wiley Handbooks in Education. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 435–465. doi:10.1002/9781119082316.ch21. ISBN 9781119083078. OCLC 1048657132.

- Birkenmaier, Julie; Sherraden, Margaret S.; Curley, Jami, eds. (2013). Financial Capability and Asset Development: Research, Education, Policy, And Practice. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199755950.001.0001. ISBN 9780199755950. OCLC 806221695.

- Bryant, John Hope (2013). «Economic growth and sustainability rooted in financial literacy». In Madhavan, Guruprasad; Oakley, Barbara; Green, David; Koon, David; Low, Penny (eds.). Practicing Sustainability. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 95–99. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-4349-0_19. ISBN 9781461443483. OCLC 793571943.

- Dworsky, Lawrence N. (2009). Understanding the Mathematics of Personal Finance: An Introduction to Financial Literacy. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9780470538395. ISBN 9780470497807. OCLC 318971496.

- Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (August 2009). «Community Investments, Volume 21, Issue 2: Financial Education». frbsf.org.

- Mitchell, Olivia S.; Lusardi, Annamaria, eds. (2011). Financial Literacy: Implications for Retirement Security and the Financial Marketplace. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199696819.001.0001. ISBN 9780199696819. OCLC 727704973.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2005). Improving Financial Literacy: Analysis of Issues and Policies. Paris: OECD. doi:10.1787/9789264012578-en. ISBN 9789264012561. OCLC 62777366.

- Willis, Lauren E. (2012). «Financial education: lessons not learned and lessons learned». In Bodie, Zvi; Siegel, Laurence B.; Stanton, Lisa (eds.). Life-Cycle Investing: Financial Education and Consumer Protection. Charlottesville, VA: Research Foundation of CFA Institute. pp. 125–138. ISBN 9781934667521.

- Willis, Lauren E. (Winter 2017). «Finance-informed citizens, citizen-informed finance: an essay occasioned by the International Handbook of Financial Literacy«. Journal of Social Science Education. 16 (4): 16–27. doi:10.4119/jsse-848.

- Xiao, Jing Jian, ed. (2016) [2008]. Handbook of Consumer Finance Research (2nd ed.). Cham: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28887-1. ISBN 9783319288857. OCLC 932096049.

External links[edit]

- Money Smart Financial Education Program from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, available at Wikimedia Commons

На букву Ф Со слова «финансовая»

Фраза «финансовая грамотность»

Фраза состоит из двух слов и 21 букв без пробелов.

- Синонимы к фразе

- Написание фразы наоборот

- Написание фразы в транслите

- Написание фразы шрифтом Брайля

- Передача фразы на азбуке Морзе

- Произношение фразы на дактильной азбуке

- Остальные фразы со слова «финансовая»

- Остальные фразы из 2 слов

ФИНАНСОВАЯ ГРАМОТНОСТЬ за 6 минут | Контроль личных финансов

Азбука финансовой грамотности! Сборник №2 | Смешарики Пин-Код

ОСНОВЫ ФИНАНСОВОЙ ГРАМОТНОСТИ. С Чего Начать Осваивать Финансовую Грамотность / Павел Багрянцев

Мысли миллиардера: КАК ЖИТЬ без ДОЛГОВ? Деньги в КРЕДИТ ЗЛО? Работа и финансовая грамотность.

Смешарики 2D | Азбука финансовой грамотности — ВСЕ СЕРИИ! Сборник

Дискуссия — Смешарики Пинкод. Азбука финансовой грамотности | ПРЕМЬЕРА 2020!

Синонимы к фразе «финансовая грамотность»

Какие близкие по смыслу слова и фразы, а также похожие выражения существуют. Как можно написать по-другому или сказать другими словами.

Фразы

- + базовые знания −

- + биржевая торговля −

- + богатый папа −

- + вовлечённость персонала −

- + заниматься инвестированием −

- + зарабатывание денег −

- + инвестиционная стратегия −

- + ипотечное кредитование −

- + клиентская база −

- + ключевые компетенции −

- + коммерческое предприятие −

- + коммуникативные навыки −

- + личные финансы −

- + начинающие предприниматели −

- + пассивный доход −

- + персональный бренд −

- + применять на практике −

- + проектное финансирование −

- + процесс обучения −

- + развитие бизнеса −

- + сетевой маркетинг −

- + сложный процент −

- + студенческий кредит −

- + учебный материал −

Ваш синоним добавлен!

Написание фразы «финансовая грамотность» наоборот

Как эта фраза пишется в обратной последовательности.

ьтсонтомарг яавоснаниф 😀

Написание фразы «финансовая грамотность» в транслите

Как эта фраза пишется в транслитерации.

в латинской🇬🇧 finansovaya gramotnost

Как эта фраза пишется в пьюникоде — Punycode, ACE-последовательность IDN

xn--80aafwzbhxw2j xn--80af2aeebjngd4i

Как эта фраза пишется в английской Qwerty-раскладке клавиатуры.

abyfycjdfzuhfvjnyjcnm

Написание фразы «финансовая грамотность» шрифтом Брайля

Как эта фраза пишется рельефно-точечным тактильным шрифтом.

⠋⠊⠝⠁⠝⠎⠕⠺⠁⠫⠀⠛⠗⠁⠍⠕⠞⠝⠕⠎⠞⠾

Передача фразы «финансовая грамотность» на азбуке Морзе

Как эта фраза передаётся на морзянке.

⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ ⋅ – – ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ – – – ⋅ – – ⋅ – ⋅ – ⋅ – – – ⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ ⋅ – – – – – – – – ⋅ – – – ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ – – ⋅ ⋅ –

Произношение фразы «финансовая грамотность» на дактильной азбуке

Как эта фраза произносится на ручной азбуке глухонемых (но не на языке жестов).

Передача фразы «финансовая грамотность» семафорной азбукой

Как эта фраза передаётся флажковой сигнализацией.

Остальные фразы со слова «финансовая»

Какие ещё фразы начинаются с этого слова.

- финансовая академия

- финансовая аренда

- финансовая аристократия

- финансовая база

- финансовая безопасность

- финансовая власть

- финансовая война

- финансовая выгода

- финансовая газета

- финансовая глобализация

- финансовая группа

- финансовая деятельность

- финансовая деятельность государства

- финансовая дисциплина

- финансовая документация

- финансовая доступность

- финансовая зависимость

- финансовая защищённость

- финансовая империя

- финансовая инспекция

- финансовая информация

- финансовая инфраструктура

- финансовая инъекция

- финансовая катастрофа

Ваша фраза добавлена!

Остальные фразы из 2 слов

Какие ещё фразы состоят из такого же количества слов.

- а вдобавок

- а вдруг

- а ведь

- а вот

- а если

- а ещё

- а именно

- а капелла

- а каторга

- а ну-ка

- а приятно

- а также

- а там

- а то

- аа говорит

- аа отвечает

- аа рассказывает

- ааронов жезл

- аароново благословение

- аароново согласие

- аб ово

- абажур лампы

- абазинская аристократия

- абазинская литература

Комментарии

21:42

Что значит фраза «финансовая грамотность»? Как это понять?..

Ответить

12:04

×

Здравствуйте!

У вас есть вопрос или вам нужна помощь?

Спасибо, ваш вопрос принят.

Ответ на него появится на сайте в ближайшее время.

А Б В Г Д Е Ё Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Ъ Ы Ь Э Ю Я

Транслит Пьюникод Шрифт Брайля Азбука Морзе Дактильная азбука Семафорная азбука

Палиндромы Сантана

Народный словарь великого и могучего живого великорусского языка.

Онлайн-словарь слов и выражений русского языка. Ассоциации к словам, синонимы слов, сочетаемость фраз. Морфологический разбор: склонение существительных и прилагательных, а также спряжение глаголов. Морфемный разбор по составу словоформ.

По всем вопросам просьба обращаться в письмошную.

Финансовая грамотность – достаточный уровень знаний и навыков в области финансов, который позволяет правильно оценивать ситуацию на рынке и принимать разумные решения.

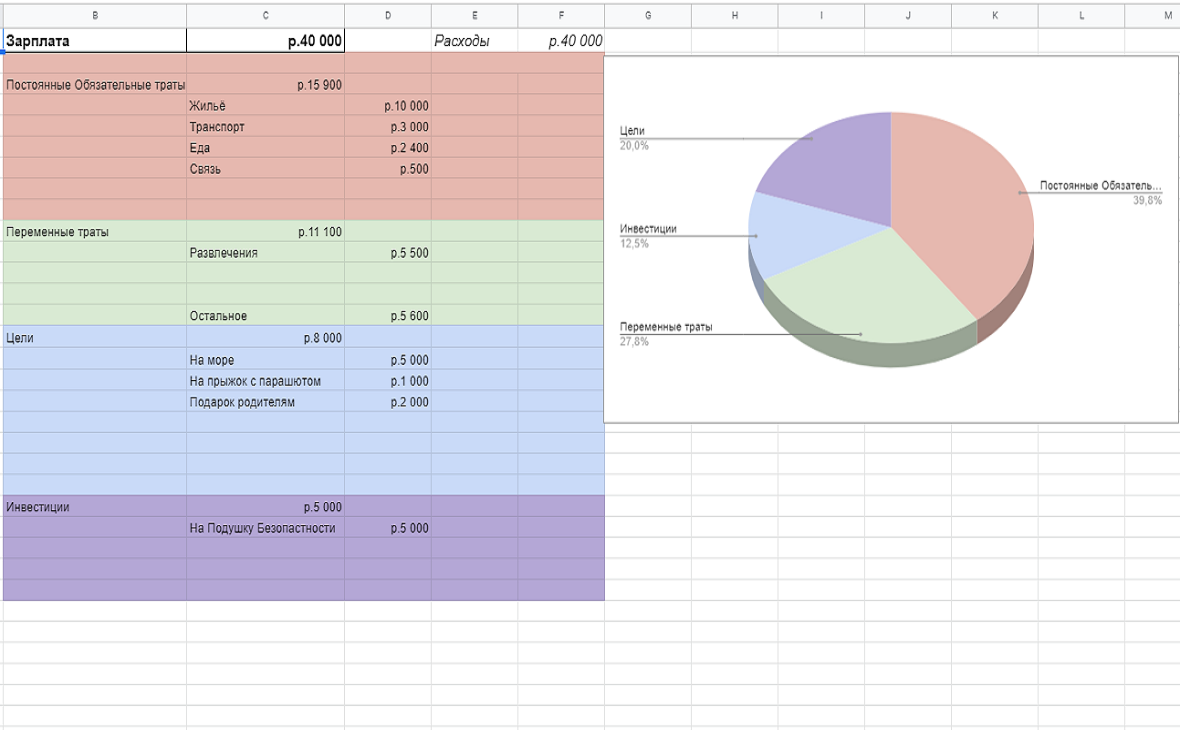

Знание ключевых финансовых понятий и умение их использовать на практике дает возможность человеку грамотно управлять своими денежными средствами. То есть вести учет доходов и расходов, избегать излишней задолженности, планировать личный бюджет, создавать сбережения. А также ориентироваться в сложных продуктах, предлагаемых финансовыми институтами, и приобретать их на основе осознанного выбора. Наконец, использовать накопительные и страховые инструменты.

Стоит отметить, что от общего уровня финансовой грамотности населения страны во многом зависит ее экономическое развитие. Низкий уровень таких знаний приводит к отрицательным последствиям не только для потребителей финансовых услуг, но и для государства, частного сектора и общества в целом. Поэтому разработка и внедрение программ по повышению финансовой грамотности населения – важное направление государственной политики во многих развитых странах, например в США, Великобритании и Австралии. Высокий уровень осведомленности жителей в области финансов способствует социальной и экономической стабильности в стране. Рост финансовой грамотности приводит к снижению рисков излишней личной задолженности граждан по потребительским кредитам, сокращению рисков мошенничества со стороны недобросовестных участников рынка и т. д.

В России финансовая грамотность находится на низком уровне. Лишь небольшая часть граждан ориентируется в услугах и продуктах, предлагаемых финансовыми институтами.

По данным Всемирного банка за 2008 год и последующего мониторинга Национального агентства финансовых исследований, 49% россиян хранят сбережения дома, а 62% предпочитают не использовать какие-либо финансовые услуги, считая их сложными и непонятными. О системе страхования вкладов осведомлено 45% взрослого населения России, причем половина из этого количества только слышали данное название, но не могут объяснить его. Лишь 25% россиян пользуются банковскими картами. При этом у держателей кредитных карт наблюдается низкий уровень знаний о рисках, связанных с этим продуктом. Только 11% россиян имеют стратегию накоплений на период пенсионного возраста (для сравнения: 63% – в Великобритании). Большинство наших сограждан принимают решения об управлении своими финансами не на основе анализа полученной информации, а по рекомендациям знакомых или заинтересованных сотрудников финансовых учреждений. Также следует отметить, что в России низкая информированность населения о том, какие права имеет потребитель финансовых услуг и как их защищать в случае нарушений. К примеру, свыше 60% семей не знают об обязанности банков раскрывать информацию об эффективной процентной ставке по кредиту, лишь 11% осведомлены об отсутствии государственной защиты в случае потери личных средств в инвестиционных фондах. Порядка 28% населения не признает личной ответственности за свои финансовые решения, считая, что государство все должно возмещать.

Такая статистика показывает, что заниматься повышением финансовой грамотности населения необходимо на государственном уровне.

Впервые эту проблему в России стали обсуждать в 2006 году на встрече в Санкт-Петербурге министров финансов G8, после чего меры по формированию финансовой грамотности в стране нашли отражение в целом ряде документов президента и правительства РФ.

Например, в Концепции долгосрочного социально-экономического развития РФ на период до 2020 года повышение финансовой грамотности обозначено в качестве одного из основных направлений формирования инвестиционного ресурса. В Стратегии развития финансового рынка РФ на период до 2020 года оно рассматривается в качестве важного фактора развития финансового рынка в России.

Министерство финансов РФ совместно с рядом федеральных органов исполнительной власти и при участии Всемирного банка ведет разработку программы повышения финансовой грамотности населения. Программа рассчитана на пять лет и на первом этапе будет реализовываться в нескольких российских регионах. Она будет включать в себя подготовку конкретных учебных программ и продуктов, совершенствование законодательства в сфере финансовых услуг и прав потребителей. Также данный проект должен по возможности объединить, обеспечить координацию уже реализуемых и готовящихся к запуску на разных уровнях программ и инициатив в сфере финансовой грамотности. Общий объем затрат составляет 110 млн долларов. Основная часть (80%) будет финансироваться из федерального бюджета, оставшаяся – за счет средств Всемирного банка.

На сегодняшний день по-прежнему большинство россиян получают теоретические знания в области финансов самостоятельно, посредством специализированных интернет-сайтов, телепередач, литературы, новостей, посещая курсы и тренинги, а опыт приобретают на собственных ошибках.

Наиболее известные интернет-ресурсы в области финансовой грамотности.

1. Информационный портал Банки.ру — крупнейший банковский сайт России. Повышению финансовой грамотности населения полностью посвящен раздел «Банковский словарь», в котором разъясняются финансовые и экономические понятия и термины, даются практические рекомендации потребителям финансовых услуг.

2. «Город финансов» – портал, созданный в рамках общефедеральной программы «Финансовая культура и безопасность граждан России».

3. «ФинграмТВ» — проект Ассоциации российских банков. Интернет-телеканал, ориентированный на повышение финансовой грамотности. На сайте можно посмотреть телевизионные лекции и получить консультации онлайн.

4. «Экспертная группа по финансовому просвещению при Федеральной службе по финансовым рынкам России».

5. «Финграмота.com» – официальный сайт Союза заемщиков и вкладчиков России.

6. «Азбука финансов» – проект по повышению финансовой грамотности, разработанный платежной системой Visa International при поддержке Министерства финансов РФ.

7. «Финансовая грамота» — совместный проект по повышению финансовой грамотности Российской экономической школы (РЭШ) и Фонда Citi.

По данным ВЦИОМ, каждому третьему россиянину иногда не хватает денег до зарплаты, а для каждого десятого это постоянная проблема. Часто вопрос не в низком достатке, а в неправильном управлении средствами

Что такое финансовая грамотность

Это набор навыков и знаний, которые помогают не тратить лишнего и приумножать накопления. К ним относятся планирование бюджета, знание кредитных и страховых продуктов, умение распоряжаться деньгами, правильно оплачивать счета, инвестировать и откладывать.

Среди стран G20 население России не добирает до средних показателей по уровню финансовой грамотности. Но чтобы повысить ее, достаточно освоить теоретические азы и прикладные приемы. Это позволит не переживать по поводу долгов и непредвиденных ситуаций, быть спокойным за свое долгосрочное будущее и достойно жить в настоящем.

Финансовая грамотность похожа на школьный предмет. Вы начинаете с базовых принципов и со временем осваиваете все больше полезных инструментов.

Фирма по финансовому консультированию Ramsey Solutions вывела три основных подхода, которыми пользуются люди, умеющие обращаться с деньгами.