гепатит с

-

1

Гепатит

— hepatitis;

Большой русско-латинский словарь Поляшева > Гепатит

-

2

hepatitis

,tidis f

гепатит-воспалительное заболевание печени

Латинский для медиков > hepatitis

См. также в других словарях:

-

Гепатит — Микрофотография клеток печени, поражённой ал … Википедия

-

Гепатит B — МКБ 10 B16.16., B18.018.0 B … Википедия

-

Гепатит А — МКБ 10 BB 15 15. 15. МКБ 9 070.1 070.1 070.1 DiseasesDB … Википедия

-

Гепатит E — МКБ 10 B … Википедия

-

Гепатит — острое или хроническое воспаление печени. Существует несколько форм гепатита, различаемых в зависимости от вызвавшей их причины. Острые токсические гепатиты, вызываемые лекарственными продуктами, грибными ядами бледной поганки, сморчков… … Справочник по болезням

-

ГЕПАТИТ — ГЕПАТИТ, воспаление печени, может быть одним из проявлений инфекционного заболевания. Ранние признаки включают летаргию, тошноту, лихорадку, желтуху, мышечные и суставные боли. В настоящее время выявлено пять различных вирусов гепатита: А, В, С,… … Научно-технический энциклопедический словарь

-

ГЕПАТИТ — (греч., от hepar печень, и lithos камень). 1) печеночный камень, часто встречающийся в сланце; у древних считался драгоценным камнем. 2) воспаление печени. Словарь иностранных слов, вошедших в состав русского языка. Чудинов А.Н., 1910. ГЕПАТИТ… … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

-

Гепатит C — МКБ 10 B … Википедия

-

Гепатит D — МКБ 10 B17.017.0, B18.018.0 МКБ 9 … Википедия

-

ГЕПАТИТ — (от греческого hepar, родительный падеж hepatos печень), группа воспалительных заболеваний печени инфекционной (например, гепатит вирусный) или неинфекционной (например, при отравлениях) природы у человека и животных. Нарушения функции печени при … Современная энциклопедия

-

ГЕПАТИТ — (от греч. hepar род. п. hepatos печень), группа воспалительных заболеваний печени инфекционной (напр., гепатит вирусный) или неинфекционной (напр., при отравлениях) природы у человека и животных. Нарушения функции печени при остром гепатите часто … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

Синонимы слова «ГЕПАТИТ»:

БОЛЕЗНЬ, ГЕПАТОЛИТ

Смотреть что такое ГЕПАТИТ в других словарях:

ГЕПАТИТ

коричневая разновидность барита, пропитанная битуминозными веществами. Встречается в Конгсберге (в Норвегии) и провинции Скон в Швеции.

ГЕПАТИТ

(от греч. hepar, родительный падеж hepatos — печень) общее название воспалительных заболеваний печени, возникающих от различных причин и имеющих… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

ГЕПАТИТ, -а, м. Воспалительное заболевание печени. Инфекционный(вирусный) г. II прил. гепатитный, -ая, -ое.

ГЕПАТИТ

гепатит м. Болезнь, характеризующаяся воспалением печени и обычно сопровождающаяся желтизной кожного покрова, белков глаз и т.п.

ГЕПАТИТ

гепатит

сущ., кол-во синонимов: 2

• болезнь (995)

• гепатолит (2)

Словарь синонимов ASIS.В.Н. Тришин.2013.

.

Синонимы:

болезнь, гепатолит

ГЕПАТИТ

Гепатит — коричневая разновидность барита, пропитанная битуминозными веществами. Встречается в Конгсберге (в Норвегии) и провинции Скон в Швеции.

ГЕПАТИТ

гепатит (hepatitis; гепат- + -ит) — воспаление печени. гепатит агрессивный (h. aggressiva) — см. Гепатит активный. гепатит активный (h. activ… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

(hepatitis; Гепат- + -ит)воспаление печени.

Гепати́т агресси́вный (h. aggressiva) — см. Гепатит активный.

Гепати́т акти́вный (h. activa; син.: Г. агр… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

ГЕПАТИТострое или хроническое воспаление печени. Существует несколько форм гепатита, дифференцируемых в зависимости от вызвавшей их причины. Гепатит могут вызвать некоторые лекарственные вещества, например транквилизаторы (успокаивающие средства) или антибиотики в случае их длительного применения. Токсические гепатиты, обусловленные воздействием на печеночную ткань определенных химических соединений, таких, как четыреххлористый углерод, некоторые сульфаниламиды или алкоголь, возникают в первую очередь у людей с предшествовавшими нарушениями функций печени. Иногда гепатиты связаны с инфекционными или системными заболеваниями. Они наблюдаются при инфекционном мононуклеозе, сифилисе, туберкулезе, как осложнение при амебной дизентерии, при некоторых болезнях соединительной ткани, например системной красной волчанке.Чаще всего встречаются вирусные гепатиты, и их выделяют в отдельную группу. Они вызываются разными вирусами, причем заражение каждым вирусом имеет свои отличительные особенности. Гепатит A, ранее известный как инфекционный гепатит, или болезнь Боткина, возникает при заражении алиментарным (через рот) путем: вирус гепатита A попадает в организм с частицами фекалий в пище или воде, в экзотических случаях — с сырыми моллюсками. Гепатит B, или сывороточный гепатит, вызывается вирусом гепатита B при попадании его непосредственно в кровоток, например при переливаниях инфицированной крови, использовании загрязненных игл для внутривенных инъекций или общих игл для татуировки, при порезах (например, у хирургов и медицинских работников) или даже в результате половых контактов, если один из партнеров инфицирован. Сходным путем передается и вирус гепатита C, обозначавшегося ранее как гепатит «ни A, ни B». К тому же семейству вирусов, что и вирус гепатита C, относится и недавно описанный вирус гепатита G. Гепатит E встречается в основном в развивающихся странах и передается, как и гепатит А, фекально-оральным способом. Шестой вирус — «дельта-агент», или вирус гепатита D, — сопутствующая гепатиту B инфекция; этот вирус размножается только в присутствии вируса гепатита B (самостоятельно размножаться в клетке он не может из-за дефектности своего генома) и тоже передается с кровью. Заражение им значительно усугубляет тяжесть течения гепатита B: возможно развитие т.н. «фульминантного» (молниеносного) гепатита, часто со смертельным исходом.Диагноз. Заболевания, вызываемые разными вирусами гепатита, имеют много общих признаков, связанных с нарушением функции печеночных клеток. К клиническим симптомам гепатита относятся болезненность в правом подреберье, увеличение размеров печени (край печени выступает из-под реберной дуги, закруглен и мягок) и желтуха (пожелтение кожи и склер). Исследования крови выявляют нарушения функции печени и помогают определить вирус, хотя иногда тип гепатита можно приближенно установить по данным анамнеза. Так, если больной приехал из Западной Африки или другого региона, где распространен гепатит А, то у него вероятнее всего именно этот тип вирусного гепатита; если гепатит связан с предшествующим переливанием крови и у больного в течение нескольких недель или месяцев отмечается желтуха, то наиболее вероятные возбудители — вирусы гепатита B, C или G. Неожиданная активация патологического процесса и резкое ухудшение состояния больного могут свидетельствовать о дополнительной инфекции вирусом гепатита D. В последние годы отмечено повышение заболеваемости гепатитами A и B среди гомосексуалов-мужчин и гепатитами B и C среди наркоманов, использующих внутривенное введение наркотиков.Течение болезни. Инкубационный период при гепатите A продолжается 2-6 недель. При гепатитах, связанных с переливанием крови (B, C и G), инкубационный период более продолжителен и длится от 6 недель до 6 месяцев, в среднем ок. 2-3 месяцев.При гепатите B лихорадка и желтуха развиваются довольно быстро; при гепатите A начало болезни протекает в стертой форме. Наблюдаются тошнота и рвота, плохой аппетит, иногда жидкий стул. Больные жалуются на болезненность в правой верхней части живота.Острый период при вирусных гепатитах обычно продолжается несколько недель, иногда до 2 месяцев и даже дольше. Полное выздоровление занимает 4-6 месяцев.В некоторых случаях люди, перенесшие вирусный гепатит (особенно гепатит B), становятся вирусоносителями. У них отсутствуют клинические проявления болезни, однако вирус сохраняется в организме и может инфицировать других людей. При гепатитах B и C иногда развиваются хронические формы гепатита с менее отчетливой симптоматикой, без выраженных проявлений болезни в течение многих месяцев и даже лет. У больных хроническим гепатитом возможно развитие цирроза печени, и у части из них в конечном итоге возникает рак печени.Лечение. Не существует специфического лечения гепатитов. Обычно рекомендуются покой и высококалорийная диета, богатая белками, углеводами и витаминами. Больным в течение 6-12 месяцев необходимо воздерживаться от потребления алкоголя, который ухудшает состояние печени.После выздоровления в организме синтезируются антитела против вируса, вызвавшего заболевание. Однако они защищают только от повторного заражения вирусом того же типа. В очагах инфекции для профилактики вирусных гепатитов, особенно гепатита A, используют донорский иммуноглобулин. Для активной иммунизации в группах риска заражения гепатитом B применяют вакцины. См. также ВИРУСЫ; ЖЕЛТУХА…. смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

Гепатит — острое или хроническое воспаление печени. Существует несколько форм гепатита, различаемых в зависимости от вызвавшей их причины. Острые токси… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

ГЕПАТИТ(греч., от hepar — печень, и lithos — камень). 1) печеночный камень, часто встречающийся в сланце; у древних считался драгоценным камнем. 2) вос… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

(hepatitis) воспаление печени, вызванное наличием вирусов, токсических веществ или нарушением иммунитета в организме человека. Инфекционный гепатит (infectious hepatitis) вызывается вирусами, четыре основных типа которых считаются причиной развития у человека соответственно гепатита А, гепатита В, гепатита С и гепатита D; наличие в организме этих вирусов может быть установлено с помощью соответствующего анализа крови. К другим вирусам, которые могут привести к развитию гепатита, относится вирус ЭпстайнаБарра. См. также Entamoeba. Заражение гепатитом A (hepatitis A) (или эпидемическим гепатитом (epidemic hepatitis)) происходит через зараженную больным человеком или вирусоносителем пищу или воду, особенно в местах с плохими санитарными условиями. После инкубационного периода, длящегося 15-40 дней, у человека повышается температура и развивается слабость. Примерно через неделю кожа начинает желтеть (см. Желтуха); такая се окраска может сохраняться в течение трех недель. Больной остается заразным на протяжении всего этого времени. Серьезные осложнения этого заболевания встречаются редко; после перенесения его у человека вырабатывается стойкий иммунитет. Инъекции гамма-глобулина являются лишь временной мерой защиты от этой болезни, поэтому более предпочтительной для защиты от этого заболевания оказывается активная иммунизация населения. Заражение гепатитом В (hepatitis В) (ранее он назывался сывороточным гепатитом (serum hepatitis)) происходит через инфицированную кровь и продукты крови, иглы для инъекций или иглы для нанесения татуировок, во время переливания крови или при половом контакте: это очень распространенное среди наркоманов заболевание. Симптомы болезни развиваются внезапно после инкубационного периода, составляющего от 1 до б месяцев; к ним относятся: головная боль, повышение температуры, озноб, общая слабость и желтуха. Большинство больных постепенно выздоравливают, однако смертность от этого заболевания составляет 5-20%. Наличие отдельного вируса, вызывающего у человека гепатит С (hepatitis С), было выявлено лишь недавно; заражение им происходит аналогично гепатиту В. Гепатит D (hepatitis D) развивается у человека только одновременно с гепатитом В или после него. Хронический гепатит (chronic hepatitis) может длиться месяцы и годы, в конце концов приводя к циррозу печени (см. также Гепатома). Причиной его может являться постоянное присутствие в организме вируса гепатита (обычно гепатита В или С), избавиться от которого можно с помощью интерферона, или наличие аутоиммунной болезни, которая успешно лечится кортикостероидами или иммуносупрессорной терапией…. смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

гепатит (Hepatitis; от греч. hēpar род. п. hēpatos печень), воспаление соединительнотканной стромы печени, сопровождающееся дистрофическими, некроб… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

м. hepatitis вирусный острый паренхиматозный гепатит — acute yellow atrophy of liver, acute parenchymatous hepatitis передаваемый через инфицированную воду гепатит — waterborne type of hepatitis<p>— агрессивный гепатит — активный хронический гепатит — активный гепатит — аллергический гепатит — амёбный гепатит — аскаридозный гепатит — безжелтушный гепатит — бруцеллёзный гепатит — вирусный гепатит — вирусный безжелтушный гепатит — вирусный желтушный гепатит — вирусный затяжной гепатит — вирусный малый гепатит — вирусный персистирующий гепатит — вирусный плазмоцитоклеточный гепатит — вирусный рецидивирующий гепатит — вирусный гепатит типа А — вирусный гепатит типа В — вирусный гепатит типа C — вирусный гепатит типа D — волчаночный гепатит — врождённый гепатит — галотановый гепатит — гелиотропный гепатит — герпетический гепатит — гигантоклеточный гепатит — гнойный гепатит — гуммозный гепатит — диффузный гепатит — диффузный мезенхимальный гепатит — вирусный гепатит затяжного типа — инокуляционный гепатит — интерлобулярный гепатит — интерстициальный гепатит — инфекционный гепатит — латентный гепатит — лекарственный гепатит — лучевой гепатит — люпоидный гепатит — люэтический гепатит — лямблиозный гепатит — малярийный гепатит — междольковый гепатит — мезенхимальный гепатит — метаболический гепатит — молниеносный гепатит — мононуклеозный гепатит — некротический гепатит — острый гепатит — очаговый гепатит — парентеральный гепатит — паренхиматозный гепатит — персистирующий гепатит — гепатит плода — подострый гепатит — посттрансфузионный гепатит — продуктивный гепатит — протозойный гепатит — реактивный гепатит — ревматический гепатит — свинцовый гепатит — септический гепатит — серозный гепатит — сифилитический гепатит — скарлатинозный гепатит — скоротечный гепатит — скрытый гепатит — сывороточный гепатит — токсико-аллергический гепатит — токсико-химический гепатит — токсический гепатит — трофопатический гепатит — туберкулёзный гепатит — фетальный гепатит — фульминантный гепатит — холангиогенный гепатит — холангиолитический гепатит — холестатический гепатит — хронический гепатит — шприцевой гепатит — экспериментальный гепатит — энзоотический гепатит — эпидемический гепатит — эпителиальный гепатит</p><div class=»fb-quote»></div>… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

ГЕПАТИТ, воспаление печени, может быть одним из проявлений инфекционного заболевания. Ранние признаки включают летаргию, тошноту, лихорадку, желтуху, м… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

m

Hepatitis f, Leberentzündung f

токсический профессиональный гепатит — arbeitsbedingte toxische Hepatitis f

гепатит Аагрессивный гепатитактивный гепатитбезжелтушный гепатитгепатит Ввирусный гепатитволчаночный гепатитврождённый гигантоклеточный гепатитгерпетический гепатитжелтушный гепатитинтерлобулярный гепатитинтерстициальный гепатитинфекционный гепатитлекарственный гепатитлюпоидный гепатитмезенхимальный гепатитметаболический гепатитмолниеносный гепатитмононуклеозный гепатитнеспецифический гепатитни В гепатит ни Аоблитерирующий сегментарный гепатиточаговый гепатитпаренхиматозный гепатитперсистирующий гепатитпосттрансфузионный гепатитпродуктивный гепатитпротозойный гепатитреактивный гепатитрецидивирующий гепатитсептический гепатитсерозный гепатитсывороточный гепатиттоксико-аллергический гепатиттоксический гепатиттрансфузионный гепатиттрофопатический гепатитфетальный гепатитфульминантный гепатитхолангиогенный гепатит… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

ГЕПАТИ́Т, у, ч., вет., мед.Загальна назва запальних захворювань печінки.Через погані побутові умови діти наражаються на інфекційний гепатит та інші сер… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

– общее название острых и хронических диффузных воспалительных заболеваний печени различной этиологии.

Гепатит может быть первичным, и в этом случае он является самостоятельным заболеванием, или вторичным, тогда он представляет собой проявление другой болезни. Развитие первичного гепатита связано с воздействием гепатотропных факторов – вирусов, алкоголя (алкогольный гепатит), лекарственных средств (медикаментозный гепатит) или химических веществ (токсический гепатит). Гепатит бывает врожденным заболеванием (фетальный, или врожденный, гепатит); его причинами являются вирусная инфекция, несовместимость крови матери и плода и др. Вторичный гепатит возникает на фоне инфекций, интоксикаций, при заболеваниях желудочно-кишечного тракта, диффузных болезнях соединительной ткани как одно из их проявлений…. смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

1) Орфографическая запись слова: гепатит2) Ударение в слове: гепат`ит3) Деление слова на слоги (перенос слова): гепатит4) Фонетическая транскрипция сло… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

ЖОВТЯНИ́ЦЯ (захворювання печінки), ЖОВТУ́ХА розм., ГЕПАТИ́Т книжн. Йому (Суворову) вдруге зробили операцію, після якої він захворів на жовтяницю (С. До… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

-у, ч. Загальна назва запальних захворювань печінки. •• Вірусний гепатит — інфекційне захворювання, збудником якого є вірус, що фільтрується. Променев… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

ГЕПАТИТ а, м. hépatite <гр. hepar печень. мед. Воспаление печени. Крысин 1998. — Лекс. СИС 1954: гепати/т.

Синонимы:

болезнь, гепатолит

ГЕПАТИТ

корень — ГЕПАТ; суффикс — ИТ; нулевое окончание;Основа слова: ГЕПАТИТВычисленный способ образования слова: Суффиксальный∩ — ГЕПАТ; ∧ — ИТ; ⏰Слово Гепат… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

ГЕПАТИТ (от греческого hepar, родительный падеж hepatos — печень), группа воспалительных заболеваний печени инфекционной (например, гепатит вирусный) или неинфекционной (например, при отравлениях) природы у человека и животных. Нарушения функции печени при остром гепатите часто сопровождаются желтухой. Хронический гепатит может привести к развитию цирроза печени. <br>… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

(от греч. печень), группа воспалит. заболеваний печени инф. (напр., гепатит вирусный) или неинф. (напр., при отравлениях) природы у человека и животных… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

(от греческого hepar, родительный падеж hepatos — печень), группа воспалительных заболеваний печени инфекционной (например, гепатит вирусный) или неинфекционной (например, при отравлениях) природы у человека и животных. Нарушения функции печени при остром гепатите часто сопровождаются желтухой. Хронический гепатит может привести к развитию цирроза печени…. смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

ГЕПАТИТ (от греч . hepar, род. п. hepatos — печень), группа воспалительных заболеваний печени инфекционной (напр., гепатит вирусный) или неинфекционной (напр., при отравлениях) природы у человека и животных. Нарушения функции печени при остром гепатите часто сопровождаются желтухой. Хронический гепатит может привести к развитию цирроза печени.<br><br><br>… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

ГЕПАТИТ (от греч. hepar — род. п. hepatos — печень), группа воспалительных заболеваний печени инфекционной (напр., гепатит вирусный) или неинфекционной (напр., при отравлениях) природы у человека и животных. Нарушения функции печени при остром гепатите часто сопровождаются желтухой. Хронический гепатит может привести к развитию цирроза печени.<br>… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

— м-л, разнов. барита, содер. битумы. Геологический словарь: в 2-х томах. — М.: Недра.Под редакцией К. Н. Паффенгольца и др..1978.Синонимы:

болезнь… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

— (от греч. hepar — род. п. hepatos — печень), группа воспалительныхзаболеваний печени инфекционной (напр., гепатит вирусный) илинеинфекционной (напр., при отравлениях) природы у человека и животных.Нарушения функции печени при остром гепатите часто сопровождаютсяжелтухой. Хронический гепатит может привести к развитию цирроза печени…. смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

-а, м.

Общее название воспалительных заболеваний печени, обычно сопровождаемых желтизной кожи, белков глаз и т. д.[От греч. ‛η̃πας, ‛η̃πατος — печень]… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

гепати́т,

гепати́ты,

гепати́та,

гепати́тов,

гепати́ту,

гепати́там,

гепати́т,

гепати́ты,

гепати́том,

гепати́тами,

гепати́те,

гепати́тах

(Источник: «Полная акцентуированная парадигма по А. А. Зализняку»)

.

Синонимы:

болезнь, гепатолит… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

-у, ч. Загальна назва запальних захворювань печінки.Вірусний гепатит — інфекційне захворювання, збудником якого є вірус, що фільтрується.Променевий геп… смотреть

ГЕПАТИТ

м мед

hepatite fСинонимы:

болезнь, гепатолит

ГЕПАТИТ

Ударение в слове: гепат`итУдарение падает на букву: иБезударные гласные в слове: гепат`ит

ГЕПАТИТ

сущ. муж. родамед.гепатит -у

ГЕПАТИТ

гепати’т, гепати’ты, гепати’та, гепати’тов, гепати’ту, гепати’там, гепати’т, гепати’ты, гепати’том, гепати’тами, гепати’те, гепати’тах

ГЕПАТИТ

гепати́тСинонимы:

болезнь, гепатолит

ГЕПАТИТ

м.

epatite f

инфекционный / вирусный гепатит — epatite virale

Итальяно-русский словарь.2003.

Синонимы:

болезнь, гепатолит

ГЕПАТИТ

гепат’ит, -аСинонимы:

болезнь, гепатолит

ГЕПАТИТ

гепатит, гепат′ит, -а, м. Воспалительное заболевание печени. Инфекционный (вирусный) г.прил. ~ный, -ая, -ое.

ГЕПАТИТ

ГЕПАТИТ, -а, м. Воспалительное заболевание печени. Инфекционный (вирусный) гепатит || прилагательное гепатитный, -ая, -ое.

ГЕПАТИТ

(2 м)Синонимы:

болезнь, гепатолит

ГЕПАТИТ

hepatitСинонимы:

болезнь, гепатолит

ГЕПАТИТ

דלקת הכבדСинонимы:

болезнь, гепатолит

ГЕПАТИТ

hepatiteСинонимы:

болезнь, гепатолит

ГЕПАТИТ

肝炎〔阳〕肝炎. Синонимы:

болезнь, гепатолит

ГЕПАТИТ

Начальная форма — Гепатит, винительный падеж, единственное число, мужской род, неодушевленное

ГЕПАТИТ

(бауырға салқын тию ауруы).; гепатит гнойный іріңді гепатит;- гепатит токсический улы гепатит

ГЕПАТИТ

гепати́т

[від грец. ήπαρ (ήπατος) – печінка]

запальне захворювання печінки.

ГЕПАТИТ

Тепа Ипат Гит Гетит Гет Гепатит Гап Тета Тип Агит Тит Пат Петит Пие Тег

ГЕПАТИТ

гепатит [ гр. мраг (hepaloe) печень] — воспаление печени.

ГЕПАТИТ

гепатит; ч.

(гр., печінка)

запальне захворювання печінки.

ГЕПАТИТ

(hepatitis; гепат- + -ит) воспаление печени.

ГЕПАТИТ

гепатит

қубод, зотулкабид, гепатит

ГЕПАТИТ

гепати́т

іменник чоловічого роду

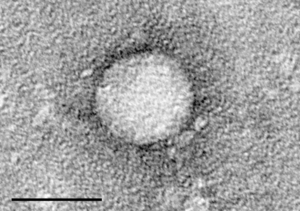

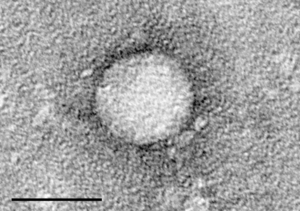

| Hepatitis C | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Electron micrograph of hepatitis C virus from cell culture (scale = 50 nanometers) | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology, Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Typically none[1] |

| Complications | Liver failure, liver cancer, esophageal and gastric varices[2] |

| Duration | Long term (80%)[1] |

| Causes | Hepatitis C virus usually spread by blood-to-blood contact[1][3] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood testing for antibodies or viral RNA[1] |

| Prevention | Sterile needles, testing donated blood[4] |

| Treatment | Medications, liver transplant[5] |

| Medication | Antivirals (sofosbuvir, simeprevir, others)[1][4] |

| Frequency | 58 million (2019)[6] |

| Deaths | 290,000 (2019)[6] |

Hepatitis C is an infectious disease caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) that primarily affects the liver;[2] it is a type of viral hepatitis.[7] During the initial infection people often have mild or no symptoms.[1] Occasionally a fever, dark urine, abdominal pain, and yellow tinged skin occurs.[1] The virus persists in the liver in about 75% to 85% of those initially infected.[1] Early on, chronic infection typically has no symptoms.[1] Over many years however, it often leads to liver disease and occasionally cirrhosis.[1] In some cases, those with cirrhosis will develop serious complications such as liver failure, liver cancer, or dilated blood vessels in the esophagus and stomach.[2]

HCV is spread primarily by blood-to-blood contact associated with injection drug use, poorly sterilized medical equipment, needlestick injuries in healthcare, and transfusions.[1][3] Using blood screening, the risk from a transfusion is less than one per two million.[1] It may also be spread from an infected mother to her baby during birth.[1] It is not spread by superficial contact.[4] It is one of five known hepatitis viruses: A, B, C, D, and E.[8]

Diagnosis is by blood testing to look for either antibodies to the virus or viral RNA.[1] In the United States, screening for HCV infection is recommended in all adults age 18 to 79 years old.[9]

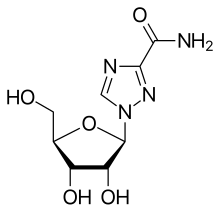

There is no vaccine against hepatitis C.[1][10] Prevention includes harm reduction efforts among people who inject drugs, testing donated blood, and treatment of people with chronic infection.[4][11] Chronic infection can be cured more than 95% of the time with antiviral medications such as sofosbuvir or simeprevir.[6][1][4] Peginterferon and ribavirin were earlier generation treatments that had a cure rate of less than 50% and greater side effects.[4][12] Getting access to the newer treatments, however, can be expensive.[4] Those who develop cirrhosis or liver cancer may require a liver transplant.[5] Hepatitis C is the leading reason for liver transplantation, though the virus usually recurs after transplantation.[5]

An estimated 58 million people worldwide were infected with hepatitis C in 2019. Approximately 290,000 deaths from the virus, mainly from liver cancer and cirrhosis attributed to hepatitis C, also occurred in 2019.[13] The existence of hepatitis C – originally identifiable only as a type of non-A non-B hepatitis – was suggested in the 1970s and proven in 1989.[14] Hepatitis C infects only humans and chimpanzees.[15]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Acute infection[edit]

Acute symptoms develop in some 20–30% of those infected.[1] When this occurs, it is generally 4–12 weeks following infection (but it may take from 2 weeks to 6 months for acute symptoms to appear).[1][4]

Symptoms are generally mild and vague, and may include fatigue, nausea and vomiting, fever, muscle or joint pains, abdominal pain, decreased appetite and weight loss, jaundice (occurs in ~25% of those infected), dark urine, and clay-coloured stools.[1][16][17] Acute liver failure due to acute hepatitis C is exceedingly rare.[18] Symptoms and laboratory findings suggestive of liver disease should prompt further tests and can thus help establish a diagnosis of hepatitis C infection early on.[17]

Following the acute phase, the infection may resolve spontaneously in 10–50% of affected people; this occurs more frequently in young people, and females.[16]

Chronic infection[edit]

About 80% of those exposed to the virus develop a chronic infection.[19] This is defined as the presence of detectable viral replication for at least six months. Most experience minimal or no symptoms during the initial few decades of the infection.[20] Chronic hepatitis C can be associated with fatigue[21] and mild cognitive problems.[22] Chronic infection after several years may cause cirrhosis or liver cancer.[5] The liver enzymes measured from blood samples are normal in 7–53%.[23] (Elevated levels indicate liver cells are being damaged by the virus or other disease). Late relapses after apparent cure have been reported, but these can be difficult to distinguish from reinfection.[23]

Fatty changes to the liver occur in about half of those infected and are usually present before cirrhosis develops.[24][25] Usually (80% of the time) this change affects less than a third of the liver.[24] Worldwide hepatitis C is the cause of 27% of cirrhosis cases and 25% of hepatocellular carcinoma.[26] About 10–30% of those infected develop cirrhosis over 30 years.[5][17] Cirrhosis is more common in those also infected with hepatitis B, schistosoma, or HIV, in alcoholics and in those of male sex.[17] In those with hepatitis C, excess alcohol increases the risk of developing cirrhosis 5-fold.[27] Those who develop cirrhosis have a 20-fold greater risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. This transformation occurs at a rate of 1–3% per year.[5][17] Being infected with hepatitis B in addition to hepatitis C increases this risk further.[28]

Liver cirrhosis may lead to portal hypertension, ascites (accumulation of fluid in the abdomen), easy bruising or bleeding, varices (enlarged veins, especially in the stomach and esophagus), jaundice, and a syndrome of cognitive impairment known as hepatic encephalopathy.[29] Ascites occurs at some stage in more than half of those who have a chronic infection.[30]

[edit]

The most common problem due to hepatitis C but not involving the liver is mixed cryoglobulinemia (usually the type II form) – an inflammation of small and medium-sized blood vessels.[31][32] Hepatitis C is also associated with autoimmune disorders such as Sjögren’s syndrome, lichen planus, a low platelet count, porphyria cutanea tarda, necrolytic acral erythema, insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus, diabetic nephropathy, autoimmune thyroiditis, and B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders.[34] 20–30% of people infected have rheumatoid factor – a type of antibody.[35] Possible associations include Hyde’s prurigo nodularis[36] and membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis.[21] Cardiomyopathy with associated abnormal heart rhythms has also been reported.[37] A variety of central nervous system disorders has been reported.[38] Chronic infection seems to be associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer.[10][39] People may experience other issues in the mouth such as dryness, salivary duct stones, and crusted lesions around the mouth.[40][41][42]

Occult infection[edit]

Persons who have been infected with hepatitis C may appear to clear the virus but remain infected.[43] The virus is not detectable with conventional testing but can be found with ultra-sensitive tests.[44] The original method of detection was by demonstrating the viral genome within liver biopsies, but newer methods include an antibody test for the virus’ core protein and the detection of the viral genome after first concentrating the viral particles by ultracentrifugation.[45] A form of infection with persistently moderately elevated serum liver enzymes but without antibodies to hepatitis C has also been reported.[46] This form is known as cryptogenic occult infection.

Several clinical pictures have been associated with this type of infection.[47] It may be found in people with anti-hepatitis-C antibodies but with normal serum levels of liver enzymes; in antibody-negative people with ongoing elevated liver enzymes of unknown cause; in healthy populations without evidence of liver disease; and in groups at risk for HCV infection including those on hemodialysis or family members of people with occult HCV. The clinical relevance of this form of infection is under investigation.[48] The consequences of occult infection appear to be less severe than with chronic infection but can vary from minimal to hepatocellular carcinoma.[45]

The rate of occult infection in those apparently cured is controversial but appears to be low.[23] 40% of those with hepatitis but with both negative hepatitis C serology and the absence of detectable viral genome in the serum have hepatitis C virus in the liver on biopsy.[49] How commonly this occurs in children is unknown.[50]

Virology[edit]

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a small, enveloped, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus.[5] It is a member of the genus Hepacivirus in the family Flaviviridae.[21] There are seven major genotypes of HCV, which are known as genotypes one to seven.[51] The genotypes are divided into several subtypes with the number of subtypes depending on the genotype. In the United States, about 70% of cases are caused by genotype 1, 20% by genotype 2 and about 1% by each of the other genotypes.[17] Genotype 1 is also the most common in South America and Europe.[5]

The half life of the virus particles in the serum is around 3 hours and may be as short as 45 minutes.[52][53] In an infected person, about 1012 virus particles are produced each day.[52] In addition to replicating in the liver the virus can multiply in lymphocytes.[54]

Transmission[edit]

Hepatitis C infection in the United States by source

Percutaneous contact with contaminated blood is responsible for most infections; however, the method of transmission is strongly dependent on both geographic region and economic status.[55] Indeed, the primary route of transmission in the developed world is injection drug use, while in the developing world the main methods are blood transfusions and unsafe medical procedures.[3] The cause of transmission remains unknown in 20% of cases;[56] however, many of these are believed to be accounted for by injection drug use.[16]

Drug use[edit]

Injection drug use (IDU) is a major risk factor for hepatitis C in many parts of the world.[57] Of 77 countries reviewed, 25 (including the United States) were found to have a prevalence of hepatitis C of between 60% and 80% among people who use injection drugs.[19][57] Twelve countries had rates greater than 80%.[19] It is believed that ten million intravenous drug users are infected with hepatitis C; China (1.6 million), the United States (1.5 million), and Russia (1.3 million) have the highest absolute totals.[19] Occurrence of hepatitis C among prison inmates in the United States is 10 to 20 times that of the occurrence observed in the general population; this has been attributed to high-risk behavior in prisons such as IDU and tattooing with non-sterile equipment.[58][59] Shared intranasal drug use may also be a risk factor.[60]

Healthcare exposure[edit]

Blood transfusion, transfusion of blood products, or organ transplants without HCV screening carry significant risks of infection.[17] The United States instituted universal screening in 1992,[61] and Canada instituted universal screening in 1990.[62] This decreased the risk from one in 200 units[61] to between one in 10,000 to one in 10,000,000 per unit of blood.[16][56] This low risk remains as there is a period of about 11–70 days between the potential blood donor’s acquiring hepatitis C and the blood’s testing positive depending on the method.[56] Some countries do not screen for hepatitis C due to the cost.[26]

Those who have experienced a needle stick injury from someone who was HCV positive have about a 1.8% chance of subsequently contracting the disease themselves.[17] The risk is greater if the needle in question is hollow and the puncture wound is deep.[26] There is a risk from mucosal exposures to blood, but this risk is low, and there is no risk if blood exposure occurs on intact skin.[26]

Hospital equipment has also been documented as a method of transmission of hepatitis C, including reuse of needles and syringes; multiple-use medication vials; infusion bags; and improperly sterilized surgical equipment, among others.[26] Limitations in the implementation and enforcement of stringent standard precautions in public and private medical and dental facilities are known to have been the primary cause of the spread of HCV in Egypt, the country that had the highest rate of infection in the world in 2012, and currently has one of the lowest in the world in 2021.[63][64]

For more, see HONOReform (Hepatitis Outbreaks National Organization for Reform).

Sexual intercourse[edit]

Sexual transmission of hepatitis C is uncommon.[12] Studies examining the risk of HCV transmission between heterosexual partners, when one is infected and the other is not, have found very low risks.[12] Sexual practices that involve higher levels of trauma to the anogenital mucosa, such as anal penetrative sex, or that occur when there is a concurrent sexually transmitted infection, including HIV or genital ulceration, present greater risks.[12][65] The United States Department of Veterans Affairs recommends condom use to prevent hepatitis C transmission in those with multiple partners, but not those in relationships that involve only a single partner.[66]

Body modification[edit]

Tattooing is associated with two to threefold increased risk of hepatitis C.[67] This could be due to either improperly sterilized equipment or contamination of the dyes being used.[67] Tattoos or piercings performed either before the mid-1980s, «underground», or nonprofessionally are of particular concern, since sterile techniques in such settings may be lacking. The risk also appears to be greater for larger tattoos.[67] It is estimated that nearly half of prison inmates share unsterilized tattooing equipment.[67] It is rare for tattoos in a licensed facility to be directly associated with HCV infection.[68]

Shared personal items[edit]

Personal-care items such as razors, toothbrushes, and manicuring or pedicuring equipment can be contaminated with blood. Sharing such items can potentially lead to exposure to HCV.[69][70] Appropriate caution should be taken regarding any medical condition that results in bleeding, such as cuts and sores.[70] HCV is not spread through casual contact, such as hugging, kissing, or sharing eating or cooking utensils,[70] nor is it transmitted through food or water.[71]

Mother-to-child transmission[edit]

Mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis C occurs in fewer than 10% of pregnancies.[72] There are no measures that alter this risk.[72] It is not clear when transmission occurs during pregnancy, but it may occur both during gestation and at delivery.[56] A long labor is associated with a greater risk of transmission.[26] There is no evidence that breastfeeding spreads HCV; however, to be cautious, an infected mother is advised to avoid breastfeeding if her nipples are cracked and bleeding,[73] or if her viral loads are high.[56]

Diagnosis[edit]

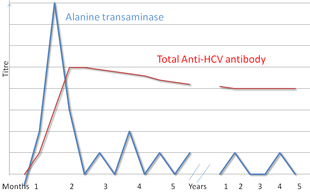

Serologic profile of Hepatitis C infection

There are a number of diagnostic tests for hepatitis C, including HCV antibody enzyme immunoassay (ELISA), recombinant immunoblot assay, and quantitative HCV RNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR).[17] HCV RNA can be detected by PCR typically one to two weeks after infection, while antibodies can take substantially longer to form and thus be detected.[29]

Diagnosing patients is generally a challenge as patients with acute illness generally present with mild, non-specific flu-like symptoms,[74] while the transition from acute to chronic is sub-clinical.[75] Chronic hepatitis C is defined as infection with the hepatitis C virus persisting for more than six months based on the presence of its RNA.[20] Chronic infections are typically asymptomatic during the first few decades,[20] and thus are most commonly discovered following the investigation of elevated liver enzyme levels or during a routine screening of high-risk individuals. Testing is not able to distinguish between acute and chronic infections.[26] Diagnosis in infants is difficult as maternal antibodies may persist for up to 18 months.[50]

Serology[edit]

Hepatitis C testing typically begins with blood testing to detect the presence of antibodies to the HCV, using an enzyme immunoassay.[17] If this test is positive, a confirmatory test is then performed to verify the immunoassay and to determine the viral load.[17] A recombinant immunoblot assay is used to verify the immunoassay and the viral load is determined by an HCV RNA polymerase chain reaction.[17] If there is no RNA and the immunoblot is positive, it means that the person tested had a previous infection but cleared it either with treatment or spontaneously; if the immunoblot is negative, it means that the immunoassay was wrong.[17] It takes about 6–8 weeks following infection before the immunoassay will test positive.[21] A number of tests are available as point-of-care testing (POCT), which can provide results within 30 minutes.[76]

Liver enzymes are variable during the initial part of the infection[20] and on average begin to rise at seven weeks after infection.[21] The elevation of liver enzymes does not closely follow disease severity.[21]

Biopsy[edit]

Liver biopsies are used to determine the degree of liver damage present; however, there are risks from the procedure.[5] The typical changes seen are lymphocytes within the parenchyma, lymphoid follicles in portal triad, and changes to the bile ducts.[5] There are a number of blood tests available that try to determine the degree of hepatic fibrosis and alleviate the need for biopsy.[5]

Screening[edit]

It is believed that only 5–50% of those infected in the United States and Canada are aware of their status.[67] Routine screening for those between the ages of 18 and 79 was recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force in 2020.[9] Previously, testing was recommended for those at high risk, including injection drug users, those who have received blood transfusions before 1992,[60] those who have been incarcerated, those on long-term hemodialysis,[60] and those with tattoos.[67] Screening is also recommended for those with elevated liver enzymes, as this is frequently the only sign of chronic hepatitis.[77] As of 2012, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends a single screening test for those born between 1945 and 1965.[78][79][80][81] In Canada, a one-time screening is recommended for those born between 1945 and 1975.[82]

Prevention[edit]

As of 2016, no approved vaccine protects against contracting hepatitis C.[83] A combination of harm reduction strategies, such as the provision of new needles and syringes and treatment of substance use, decreases the risk of hepatitis C in people using injection drugs by about 75%.[84] The screening of blood donors is important at a national level, as is adhering to universal precautions within healthcare facilities.[21] In countries where there is an insufficient supply of sterile syringes, medications should be given orally rather than via injection (when possible).[26] Recent research also suggests that treating people with active infection, thereby reducing the potential for transmission, may be an effective preventive measure.[11]

Treatment[edit]

Those with chronic hepatitis C are advised to avoid alcohol and medications that are toxic to the liver.[17] They should also be vaccinated against hepatitis A and hepatitis B due to the increased risk if also infected.[17] Use of acetaminophen is generally considered safe at reduced doses.[12] Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are not recommended in those with advanced liver disease due to an increased risk of bleeding.[12] Ultrasound surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma is recommended in those with accompanying cirrhosis.[17] Coffee consumption has been associated with[vague] a slower rate of liver scarring in those infected with HCV.[12]

Medications[edit]

Approximately 90% of chronic cases clear with treatment.[4] Treatment with antiviral medication is recommended for all people with proven chronic hepatitis C who are not at high risk of death from other causes.[85] People with the highest complication risk, which is based on the degree of liver scarring, should be treated first.[85] The initial recommended treatment depends on the type of hepatitis C virus, if the person has received previous hepatitis C treatment, and whether the person has cirrhosis.[86] Direct-acting antivirals are the preferred treatment and have been validated by testing for virus particles in patients’ blood.[87]

No prior treatment[edit]

- HCV genotype 1a (no cirrhosis): 8 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir or ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (the latter for people who do not have HIV/AIDS, are not African-American, and have less than 6 million HCV viral copies per milliliter of blood) or 12 weeks of elbasvir/grazoprevir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, or sofosbuvir/velpatasvir.[88] Sofosbuvir with either daclatasvir or simeprevir may also be used.[86]

- HCV genotype 1a (with compensated cirrhosis): 12 weeks of elbasvir/grazoprevir, glecaprevir/pibrentasvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, or sofosbuvir/velpatasvir. An alternative treatment regimen of elbasvir/grazoprevir with weight-based ribavirin for 16 weeks can be used if the HCV is found to have antiviral resistance mutations against NS5A protease inhibitors.[89]

- HCV genotype 1b (no cirrhosis): 8 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir or ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (with the aforementioned limitations for the latter as above) or 12 weeks of elbasvir/grazoprevir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, or sofosbuvir/velpatasvir. Alternative regimens include 12 weeks of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir with dasabuvir or 12 weeks of sofosbuvir with either daclatasvir or simeprevir.[90]

- HCV genotype 1b (with compensated cirrhosis): 12 weeks of elbasvir/grazoprevir, glecaprevir/pibrentasvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, or sofosbuvir/velpatasvir. A 12-week course of paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir with dasabuvir may also be used.[91]

- HCV genotype 2 (no cirrhosis): 8 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir or 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir. Alternatively, 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/daclatasvir can be used.[92]

- HCV genotype 2 (with compensated cirrhosis): 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir or glecaprevir/pibrentasvir. An alternative regimen of sofosbuvir/daclatasvir can be used for 16–24 weeks.[93]

- HCV genotype 3 (no cirrhosis): 8 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir or 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir or sofosbuvir and daclatasvir.[94]

- HCV genotype 3 (with compensated cirrhosis): 12 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir, sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, or if certain antiviral mutations are present, 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir (when certain antiviral mutations are present), or 24 weeks of sofosbuvir and daclatasvir.[95]

- HCV genotype 4 (no cirrhosis): 8 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir or 12 weeks of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, elbasvir/grazoprevir, or ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. A 12-week regimen of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir is also acceptable in combination with weight-based ribavirin.[96]

- HCV genotype 4 (with compensated cirrhosis): A 12-week regimen of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, glecaprevir/pibrentasavir, elbasvir/grazoprevir, or ledipasvir/sofosbuvir is recommended. A 12-week course of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir with weight-based ribavirin is an acceptable alternative.[97]

- HCV genotype 5 or 6 (with or without compensated cirrhosis): If no cirrhosis is present, then 8 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir is recommended. If cirrhosis is present, then a 12-week course of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir, sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, or ledipasvir/sofosbuvir is warranted.[98]

More than 90% of people with chronic infection can be cured when treated with medications.[99] However, accessing these treatments can be expensive.[4] The combination of sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, and voxilaprevir may be used in those who have previously been treated with sofosbuvir or other drugs that inhibit NS5A and were not cured.[100]

Prior to 2011, treatments consisted of a combination of pegylated interferon alpha and ribavirin for a period of 24 or 48 weeks, depending on HCV genotype.[17] This treatment produces cure rates of between 70 and 80% for genotype 2 and 3, respectively, and 45 to 70% for genotypes 1 and 4.[101] Adverse effects with these treatments were common, with 50 to 60% of those being treated experiencing flu-like symptoms and nearly a third experiencing depression or other emotional issues.[17] Treatment during the first six months of infection (the acute stage) is more effective than when hepatitis C has entered the chronic stage.[29] In those with chronic hepatitis B, treatment for hepatitis C results in reactivation of hepatitis B about 25% of the time.[102]

Surgery[edit]

Cirrhosis due to hepatitis C is a common reason for liver transplantation,[29] though the virus usually (80–90% of cases) recurs afterwards.[5][103] Infection of the graft leads to 10–30% of people developing cirrhosis within five years.[104] Treatment with pegylated interferon and ribavirin post-transplant decreases the risk of recurrence to 70%.[105] A 2013 review found no clear evidence as to whether antiviral medication is useful if the graft became reinfected.[106]

Alternative medicine[edit]

Several alternative therapies are claimed by their proponents to be helpful for hepatitis C, including milk thistle, ginseng, and colloidal silver.[107] However, no alternative therapy has been shown to improve outcomes for hepatitis C patients, and no evidence exists that alternative therapies have any effect on the virus.[107][108][109]

Prognosis[edit]

Disability-adjusted life year for hepatitis C in 2004 per 100,000 inhabitants

|

no data <10 10–15 15–20 20–25 25–30 30–35 |

35–40 40–45 45–50 50–75 75–100 >100 |

The responses to treatment is measured by sustained viral response (SVR), defined as the absence of detectable RNA of the hepatitis C virus in blood serum for at least 24 weeks after discontinuing treatment,[110] and rapid virological response (RVR), defined as undetectable levels achieved within four weeks of treatment. Successful treatment decreases the future risk of hepatocellular carcinoma by 75%.[111]

Prior to 2012, sustained response occurred in about 40–50% of those with HCV genotype 1 who received 48 weeks of treatment.[5] A sustained response was seen in 70–80% of people with HCV genotypes 2 and 3 following 24 weeks of treatment.[5] A sustained response occurs for about 65% of those with genotype 4 after 48 weeks of treatment. For those with HCV genotype 6, a 48-week treatment protocol of pegylated interferon and ribavirin results in a higher rate of sustained responses than for genotype 1 (86% vs. 52%). Further studies are needed to determine results for shorter 24-week treatments and for those given at lower dosages.[112]

Spontaneous resolution[edit]

Depending on a variety of patient factors, between 15 and 45% of those with acute HCV infections will spontaneously clear the virus within six months, before the infection is considered chronic.[4] Spontaneous resolution following acute infection appears more common in females and in patients who are younger, and may be influenced by certain genetic factors.[16] Chronic HCV infection may also resolve spontaneously months or years after the acute phase has passed, though this is unusual.[16]

Epidemiology[edit]

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (July 2020) |

Percentage of people infected with hepatitis C by country in 2019

The World Health Organization estimated in a 2021 report that 58 million people globally were living with chronic hepatitis C as of 2019.[13] About 1.5 million people are infected per year, and about 290,000 people die yearly from hepatitis C-related diseases, mainly from liver cancer and cirrhosis.[113]

Hepatitis C infection rates increased substantially in the 20th century due to a combination of intravenous drug abuse and the reuse of poorly sterilized medical equipment.[26] However, advancements in treatment have led to notable declines in chronic infections and deaths from the virus. As a result, the number of chronic patients receiving treatment worldwide has grown from about 950,000 in 2015 to 9.4 million in 2019. During the same period, hepatitis C deaths declined from about 400,000 to 290,000.[4][13]

Previously, a 2013 study found high infection rates (>3.5% population infected) in Central and East Asia, North Africa and the Middle East, intermediate infection rates (1.5–3.5%) in South and Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, Andean, Central and Southern Latin America, Caribbean, Oceania, Australasia and Central, Eastern and Western Europe; and low infection rates (<1.5%) in Asia-Pacific, Tropical Latin America and North America.[114]

Among those chronically infected, the risk of cirrhosis after 20 years varies between studies but has been estimated at ~10–15% for men and ~1–5% for women. The reason for this difference is not known. Once cirrhosis is established, the rate of developing hepatocellular carcinoma is ~1–4% per year.[115] Rates of new infections have decreased in the Western world since the 1990s due to improved screening of blood before transfusion.[29]

In Egypt, following Egypt’s 2030 Vision, the country managed to bring down the infection rates of Hepatitis C from 22% in 2011 to just 2% in 2021.[63] It was believed that the high prevalence in Egypt was linked to a discontinued mass-treatment campaign for schistosomiasis, using improperly sterilized glass syringes.[26]

In the United States, about 2% of people have chronic hepatitis C.[17] In 2014, an estimated 30,500 new acute hepatitis C cases occurred (0.7 per 100,000 population), an increase from 2010 to 2012.[116] The number of deaths from hepatitis C has increased to 15,800 in 2008[117] having overtaken HIV/AIDS as a cause of death in the US in 2007.[118] In 2014 it was the single greatest cause of infectious death in the United States.[119] This mortality rate is expected to increase, as those infected by transfusion before HCV testing become apparent.[120] In Europe the percentage of people with chronic infections has been estimated to be between 0.13 and 3.26%.[121]

In the United Kingdom about 118,000 people were chronically infected in 2019.[122] About half of people using a needle exchange in London in 2017/8 tested positive for hepatitis C of which half were unaware that they had it.[123] As part of a bid to eradicate hepatitis C by 2025 NHS England conducted a large procurement exercise in 2019. Merck Sharp & Dohme, Gilead Sciences, and Abbvie were awarded contracts, which, together, are worth up to £1 billion over five years.[124]

The total number of people with this infection is higher in some countries in Africa and Asia.[125] Countries with particularly high rates of infection include Pakistan (4.8%) and China (3.2%).[126]

Since 2014, extremely effective medication have been available to eradication the disease in 8–12 weeks in most people.[127] In 2015 about 950,000 people were treated while 1.7 million new infections occurred, meaning that overall the number of people with HCV increased.[127] These numbers differ by country and improved in 2016, with some countries achieving higher cure rates than new infection rates (mostly high income countries).[127] By 2018, twelve countries are on track to achieve HCV elimination.[127] While antiviral agents will curb new infections, it is less clear whether they impact overall deaths and morbidity.[127] Furthermore, for them to be effective, people need to be aware of their infection – it is estimated that worldwide only 20% of infected people are aware of their infection (in the US fewer than half were aware).[127]

History[edit]

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2020: Seminal experiments by HJ Alter, M Houghton and CM Rice leading to the discovery of HCV as the causative agent of non-A, non-B hepatitis.

In the mid-1970s, Harvey J. Alter, Chief of the Infectious Disease Section in the Department of Transfusion Medicine at the National Institutes of Health, and his research team demonstrated how most post-transfusion hepatitis cases were not due to hepatitis A or B viruses. Despite this discovery, international research efforts to identify the virus, initially called non-A, non-B hepatitis (NANBH), failed for the next decade. In 1987, Michael Houghton, Qui-Lim Choo, and George Kuo at Chiron Corporation, collaborating with Daniel W. Bradley at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, used a novel molecular cloning approach to identify the unknown organism and develop a diagnostic test.[128] In 1988, Alter confirmed the virus by verifying its presence in a panel of NANBH specimens, and Chiron announced its discovery at a Washington, DC Press conference in May, 1988.

At the time, Chiron was in talks with the Japanese health ministry to sell a biotech version of the Hepatitis B vaccine. Simultaneously, Emperor Hirohito had developed cancer and required numerous blood transfusions. The Japanese health ministry placed a screening order for Chiron’s experimental NANBH test. Chiron’s Japanese marketing subsidiary, Diagnostic Systems KK invented the term «Hepatitis C» in November, 1988 in Tokyo news reports publicizing the testing of the Emperor’s blood.[129] Chiron managed to sell a screening order to the Japanese health ministry in November 1988, earning the company $60 million a year. However, because Chiron had not published any of its research and did not make a culture model available to other researchers to verify Chiron’s discovery, Hepatitis C earned the nickname «The Emperor’s New Virus.»

In April 1989, the «discovery» of HCV was published in two articles in the journal Science.[130][131] Chiron filed for several patents on the virus and its diagnosis.[132] A competing patent application by the CDC was dropped in 1990 after Chiron paid $1.9 million to the CDC and $337,500 to Bradley. In 1994, Bradley sued Chiron, seeking to invalidate the patent, have himself included as a coinventor, and receive damages and royalty income. He dropped the suit in 1998 after losing before an appeals court.[133]

Because of the unique molecular «isolation» of the Hepatitis C virus, although Houghton and Kuo’s team at Chiron had discovered strong biochemical markers for the virus and the test proved effective at reducing cases of post-transfusion hepatitis, the existence of a Hepatitis C virus was essentially inferred.[134] In 1992, the San Francisco Chronicle reported the virus had never been observed under an electron microscope.[135] In 1997, the American FDA approved the first Hepatitis C drug on the basis of a Surrogate Marker called «Sustained Virological Response.» In response, the pharmaceutical industry established a nationwide network of «Astro-Turf» patient advocacy groups to raise awareness (and fear) of the disease.[136]

Hepatitis C was finally «discovered» in 2005 when a Japanese team was able to propagate a molecular clone in a cell culture called Huh7.[137] This discovery enabled proper characterization of the viral particle and rapid research into the development of protease inhibitors replacing early interferon treatments. The first of these, Sovaldi, was approved on December 6, 2013. These drugs are marketed as «cures;» however, because they were approved on the basis of surrogate markers and not clinical endpoints such as prolonging life or improving liver health, many experts question their value.[138][needs update][139]

After blood screening began, a notable Hepatitis C prevalence was discovered in Egypt, which claimed six million individuals were infected by unsterile needles in a late 1970’s mass chemotherapy campaign to eliminate snail fever.[140]

On October 5, 2020, Houghton and Alter, together with Charles M. Rice, were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work.[141][142]

Society and culture[edit]

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (July 2020) |

World Hepatitis Day, held on July 28, is coordinated by the World Hepatitis Alliance.[143] The economic costs of hepatitis C are significant both to the individual and to society. In the United States the average lifetime cost of the disease was estimated at US$33,407 in 2003[144] with the cost of a liver transplant as of 2011 costing approximately US$200,000.[145] In Canada the cost of a course of antiviral treatment is as high as 30,000 CAD in 2003,[146] while the United States costs are between 9,200 and 17,600 in 1998 USD.[144] In many areas of the world, people are unable to afford treatment with antivirals as they either lack insurance coverage or the insurance they have will not pay for antivirals.[147] In the English National Health Service treatment rates for hepatitis C are higher among wealthier groups per 2010–2012 data.[148] Spanish anaesthetist Juan Maeso infected 275 patients between 1988 and 1997 as he used the same needles to give both himself and the patients opioids.[149] For this he was jailed.[150]

Special populations[edit]

Children and pregnancy[edit]

Compared with adults, infection in children is much less understood. Worldwide the prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in pregnant women and children has been estimated to 1–8% and 0.05–5% respectively.[151] The vertical transmission rate has been estimated to be 3–5% and there is a high rate of spontaneous clearance (25–50%) in the children. Higher rates have been reported for both vertical transmission (18%, 6–36% and 41%)[152][153] and prevalence in children (15%).[154]

In developed countries transmission around the time of birth is now the leading cause of HCV infection. In the absence of virus in the mother’s blood transmission seems to be rare.[153] Factors associated with an increased rate of infection include membrane rupture of longer than 6 hours before delivery and procedures exposing the infant to maternal blood.[155] Cesarean sections are not recommended. Breastfeeding is considered safe if the nipples are not damaged. Infection around the time of birth in one child does not increase the risk in a subsequent pregnancy. All genotypes appear to have the same risk of transmission.

HCV infection is frequently found in children who have previously been presumed to have non-A, non-B hepatitis and cryptogenic liver disease.[156] The presentation in childhood may be asymptomatic or with elevated liver function tests.[157] While infection is commonly asymptomatic both cirrhosis with liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma may occur in childhood.

Immunosuppressed[edit]

The rate of hepatitis C in immunosuppressed people is higher. This is particularly true in those with human immunodeficiency virus infection, recipients of organ transplants, and those with hypogammaglobulinemia.[158] Infection in these people is associated with an unusually rapid progression to cirrhosis. People with stable HIV who never received medication for HCV, may be treated with a combination of peginterferon plus ribavirin with caution to the possible side effects.[159]

Research[edit]

As of 2011, there are about one hundred medications in development for hepatitis C.[145] These include vaccines to treat hepatitis, immunomodulators, and cyclophilin inhibitors, among others.[160] These potential new treatments have come about due to a better understanding of the hepatitis C virus.[161] There are a number of vaccines under development and some have shown encouraging results.[83]

The combination of sofosbuvir and velpatasvir in one trial (reported in 2015) resulted in cure rates of 99%.[162] More studies are needed to investigate the role of the preventive antiviral medication against HCV recurrence after transplantation.[163]

Animal models[edit]

One barrier to finding treatments for hepatitis C is the lack of a suitable animal model. Despite moderate success, research highlights the need for pre-clinical testing in mammalian systems such as mouse, particularly for the development of vaccines in poorer communities. Chimpanzees remain the only available living system to study, yet their use has ethical concerns and regulatory restrictions. While scientists have made use of human cell culture systems such as hepatocytes, questions have been raised about their accuracy in reflecting the body’s response to infection.[164]

One aspect of hepatitis research is to reproduce infections in mammalian models. A strategy is to introduce liver tissues from humans into mice, a technique known as xenotransplantation. This is done by generating chimeric mice, and exposing the mice HCV infection. This engineering process is known to create humanized mice, and provide opportunities to study hepatitis C within the 3D architectural design of the liver and evaluating antiviral compounds.[164] Alternatively, generating inbred mice with susceptibility to HCV would simplify the process of studying mouse models.

See also[edit]

- PSI-6130, an experimental drug treatment

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s «Q&A for Health Professionals». Viral Hepatitis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ a b c Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 551–52. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- ^ a b c Maheshwari A, Thuluvath PJ (February 2010). «Management of acute hepatitis C». Clinics in Liver Disease. 14 (1): 169–76, x. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2009.11.007. PMID 20123448.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l «Hepatitis C Fact sheet N°164». WHO. July 2015. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Rosen HR (June 2011). «Clinical practice. Chronic hepatitis C infection». The New England Journal of Medicine. 364 (25): 2429–38. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1006613. PMID 21696309. S2CID 19755395.

- ^ a b c «Hepatitis C». World Health Organization. 9 July 2019. Archived from the original on 2020-05-26. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- ^ «Hepatitis MedlinePlus». U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

- ^ «Viral Hepatitis: A through E and Beyond». National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. April 2012. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ a b Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, Barry MJ, Cabana M, Caughey AB, et al. (March 2020). «Screening for Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Adolescents and Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement». JAMA. 323 (10): 970–975. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1123. PMID 32119076.

- ^ a b Webster DP, Klenerman P, Dusheiko GM (March 2015). «Hepatitis C». Lancet. 385 (9973): 1124–35. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62401-6. PMC 4878852. PMID 25687730.

- ^ a b Zelenev A, Li J, Mazhnaya A, Basu S, Altice FL (February 2018). «Hepatitis C virus treatment as prevention in an extended network of people who inject drugs in the USA: a modelling study». The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 18 (2): 215–224. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30676-X. PMC 5860640. PMID 29153265.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kim A (September 2016). «Hepatitis C Virus». Annals of Internal Medicine (Review). 165 (5): ITC33–ITC48. doi:10.7326/AITC201609060. PMID 27595226. S2CID 95756.

- ^ a b c «Global progress report on HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections, 2021». www.who.int. Retrieved 2022-01-19.

- ^ Houghton M (November 2009). «The long and winding road leading to the identification of the hepatitis C virus». Journal of Hepatology. 51 (5): 939–48. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2009.08.004. PMID 19781804.

- ^ Shors T (2011). Understanding viruses (2nd ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 535. ISBN 978-0-7637-8553-6. Archived from the original on 2016-05-15.

- ^ a b c d e f Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Advances in Treatment, Promise for the Future. Springer Verlag. 2011. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-4614-1191-8. Archived from the original on 2016-06-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Wilkins T, Malcolm JK, Raina D, Schade RR (June 2010). «Hepatitis C: diagnosis and treatment» (PDF). American Family Physician. 81 (11): 1351–7. PMID 20521755. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-05-21.

- ^ Rao, A; Rule, JA; Cerro-Chiang, G; Stravitz, RT; McGuire, BM; Lee, G; Fontana, RJ; Lee, WM (11 May 2022). «Role of Hepatitis C Infection in Acute Liver Injury/Acute Liver Failure in North America». Digestive Diseases and Sciences: 1–8. doi:10.1007/s10620-022-07524-6. PMC 9094131. PMID 35546205.

- ^ a b c d Nelson PK, Mathers BM, Cowie B, Hagan H, Des Jarlais D, Horyniak D, Degenhardt L (August 2011). «Global epidemiology of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: results of systematic reviews». Lancet. 378 (9791): 571–83. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61097-0. PMC 3285467. PMID 21802134.

- ^ a b c d Kanwal F, Bacon BR (2011). «Does Treatment Alter the Natural History of Chronic HCV?». In Schiffman ML (ed.). Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Advances in Treatment, Promise for the Future. Springer Verlag. pp. 103–04. ISBN 978-1-4614-1191-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ray SC, Thomas DL (2009). «Chapter 154: Hepatitis C». In Mandell GL, Bennett, Dolin R (eds.). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases (7th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-443-06839-3.

- ^ Forton DM, Allsop JM, Cox IJ, Hamilton G, Wesnes K, Thomas HC, Taylor-Robinson SD (October 2005). «A review of cognitive impairment and cerebral metabolite abnormalities in patients with hepatitis C infection». AIDS. 19 Suppl 3 (Suppl 3): S53-63. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000192071.72948.77. PMID 16251829.

- ^ a b c Nicot F (2004). «Chapter 19. Liver biopsy in modern medicine.». Occult hepatitis C virus infection: Where are we now?. ISBN 978-953-307-883-0.

- ^ a b El-Zayadi AR (July 2008). «Hepatic steatosis: a benign disease or a silent killer». World Journal of Gastroenterology. 14 (26): 4120–6. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.4120. PMC 2725370. PMID 18636654.

- ^ Paradis V, Bedossa P (December 2008). «Definition and natural history of metabolic steatosis: histology and cellular aspects». Diabetes & Metabolism. 34 (6 Pt 2): 638–42. doi:10.1016/S1262-3636(08)74598-1. PMID 19195624.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Alter MJ (May 2007). «Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection». World Journal of Gastroenterology. 13 (17): 2436–41. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i17.2436. PMC 4146761. PMID 17552026.

- ^ Mueller S, Millonig G, Seitz HK (July 2009). «Alcoholic liver disease and hepatitis C: a frequently underestimated combination». World Journal of Gastroenterology. 15 (28): 3462–71. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.3462. PMC 2715970. PMID 19630099. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ Fattovich G, Stroffolini T, Zagni I, Donato F (November 2004). «Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors». Gastroenterology. 127 (5 Suppl 1): S35-50. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.014. PMID 15508101.

- ^ a b c d e Ozaras R, Tahan V (April 2009). «Acute hepatitis C: prevention and treatment». Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 7 (3): 351–61. doi:10.1586/eri.09.8. PMID 19344247. S2CID 25574917.

- ^ Zaltron S, Spinetti A, Biasi L, Baiguera C, Castelli F (2012). «Chronic HCV infection: epidemiological and clinical relevance». BMC Infectious Diseases. 12 Suppl 2 (Suppl 2): S2. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-12-S2-S2. PMC 3495628. PMID 23173556.

- ^ Dammacco F, Sansonno D (September 2013). «Therapy for hepatitis C virus-related cryoglobulinemic vasculitis». The New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (11): 1035–45. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1208642. PMID 24024840. S2CID 205116488.

- ^ Iannuzzella F, Vaglio A, Garini G (May 2010). «Management of hepatitis C virus-related mixed cryoglobulinemia». The American Journal of Medicine. 123 (5): 400–8. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.09.038. PMID 20399313.

- ^ Ko HM, Hernandez-Prera JC, Zhu H, Dikman SH, Sidhu HK, Ward SC, Thung SN (2012). «Morphologic features of extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C virus infection». Clinical & Developmental Immunology. 2012: 740138. doi:10.1155/2012/740138. PMC 3420144. PMID 22919404.

- ^ Dammacco F, Sansonno D, Piccoli C, Racanelli V, D’Amore FP, Lauletta G (2000). «The lymphoid system in hepatitis C virus infection: autoimmunity, mixed cryoglobulinemia, and Overt B-cell malignancy». Seminars in Liver Disease. 20 (2): 143–57. doi:10.1055/s-2000-9613. PMID 10946420.

- ^ Lee MR, Shumack S (November 2005). «Prurigo nodularis: a review». The Australasian Journal of Dermatology. 46 (4): 211–18, quiz 219–20. doi:10.1111/j.1440-0960.2005.00187.x. PMID 16197418. S2CID 30087432.

- ^ Matsumori A (2006). Role of hepatitis C virus in cardiomyopathies. Ernst Schering Research Foundation Workshop. Vol. 55. pp. 99–120. doi:10.1007/3-540-30822-9_7. ISBN 978-3-540-23971-0. PMID 16329660.

- ^ Monaco S, Ferrari S, Gajofatto A, Zanusso G, Mariotto S (2012). «HCV-related nervous system disorders». Clinical & Developmental Immunology. 2012: 236148. doi:10.1155/2012/236148. PMC 3414089. PMID 22899946.

- ^ Xu JH, Fu JJ, Wang XL, Zhu JY, Ye XH, Chen SD (July 2013). «Hepatitis B or C viral infection and risk of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies». World Journal of Gastroenterology. 19 (26): 4234–41. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i26.4234. PMC 3710428. PMID 23864789.

- ^ Lodi G, Porter SR, Scully C (July 1998). «Hepatitis C virus infection: Review and implications for the dentist». Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontics. 86 (1): 8–22. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.852.7880. doi:10.1016/S1079-2104(98)90143-3. PMID 9690239.

- ^ Carrozzo M, Gandolfo S (2003-03-01). «Oral diseases possibly associated with hepatitis C virus». Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine. 14 (2): 115–27. doi:10.1177/154411130301400205. PMID 12764074.

- ^ Little JW, Falace DA, Miller C, Rhodus NL (2013). Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patient. p. 151. ISBN 978-0323080286.

- ^ Sugden PB, Cameron B, Bull R, White PA, Lloyd AR (September 2012). «Occult infection with hepatitis C virus: friend or foe?». Immunology and Cell Biology. 90 (8): 763–73. doi:10.1038/icb.2012.20. PMID 22546735. S2CID 23845868.

- ^ Carreño V (November 2006). «Occult hepatitis C virus infection: a new form of hepatitis C». World Journal of Gastroenterology. 12 (43): 6922–5. doi:10.3748/wjg.12.6922. PMC 4087333. PMID 17109511.

- ^ a b Carreño García V, Nebreda JB, Aguilar IC, Quiroga Estévez JA (March 2011). «[Occult hepatitis C virus infection]». Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiologia Clinica. 29 Suppl 3: 14–9. doi:10.1016/S0213-005X(11)70022-2. PMID 21458706.

- ^ Pham TN, Coffin CS, Michalak TI (April 2010). «Occult hepatitis C virus infection: what does it mean?». Liver International. 30 (4): 502–11. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02193.x. PMID 20070513. S2CID 205651069.

- ^ Carreño V, Bartolomé J, Castillo I, Quiroga JA (June 2012). «New perspectives in occult hepatitis C virus infection». World Journal of Gastroenterology. 18 (23): 2887–94. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i23.2887. PMC 3380315. PMID 22736911.

- ^ Carreño V, Bartolomé J, Castillo I, Quiroga JA (May–June 2008). «Occult hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections». Reviews in Medical Virology. 18 (3): 139–57. doi:10.1002/rmv.569. PMID 18265423. S2CID 12331754.

- ^ Scott JD, Gretch DR (February 2007). «Molecular diagnostics of hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review». JAMA. 297 (7): 724–32. doi:10.1001/jama.297.7.724. PMID 17312292.

- ^ a b Robinson, JL (July 2008). «Vertical transmission of the hepatitis C virus: Current knowledge and issues». Paediatrics & Child Health. 13 (6): 529–41. doi:10.1093/pch/13.6.529. PMC 2532905. PMID 19436425.

- ^ Nakano T, Lau GM, Lau GM, Sugiyama M, Mizokami M (February 2012). «An updated analysis of hepatitis C virus genotypes and subtypes based on the complete coding region». Liver International. 32 (2): 339–45. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02684.x. PMID 22142261. S2CID 23271017.

- ^ a b Lerat H, Hollinger FB (January 2004). «Hepatitis C virus (HCV) occult infection or occult HCV RNA detection?». The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 189 (1): 3–6. doi:10.1086/380203. PMID 14702146.

- ^ Pockros P (2011). Novel and Combination Therapies for Hepatitis C Virus, An Issue of Clinics in Liver Disease. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-4557-7198-1. Archived from the original on 2016-05-21.

- ^ Zignego AL, Giannini C, Gragnani L, Piluso A, Fognani E (August 2012). «Hepatitis C virus infection in the immunocompromised host: a complex scenario with variable clinical impact». Journal of Translational Medicine. 10 (1): 158. doi:10.1186/1479-5876-10-158. PMC 3441205. PMID 22863056.

- ^ Hagan LM, Schinazi RF (February 2013). «Best strategies for global HCV eradication». Liver International. 33 Suppl 1 (s1): 68–79. doi:10.1111/liv.12063. PMC 4110680. PMID 23286849.

- ^ a b c d e Pondé RA (February 2011). «Hidden hazards of HCV transmission». Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 200 (1): 7–11. doi:10.1007/s00430-010-0159-9. PMID 20461405. S2CID 664199.

- ^ a b Xia X, Luo J, Bai J, Yu R (October 2008). «Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection among injection drug users in China: systematic review and meta-analysis». Public Health. 122 (10): 990–1003. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2008.01.014. PMID 18486955.

- ^ Imperial JC (June 2010). «Chronic hepatitis C in the state prison system: insights into the problems and possible solutions». Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 4 (3): 355–64. doi:10.1586/egh.10.26. PMID 20528122. S2CID 7931472.

- ^ Vescio MF, Longo B, Babudieri S, Starnini G, Carbonara S, Rezza G, Monarca R (April 2008). «Correlates of hepatitis C virus seropositivity in prison inmates: a meta-analysis». Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 62 (4): 305–13. doi:10.1136/jech.2006.051599. PMID 18339822. S2CID 206989111.

- ^ a b c Moyer VA (September 2013). «Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement». Annals of Internal Medicine. 159 (5): 349–57. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-5-201309030-00672. PMID 23798026. S2CID 8563203.

- ^ a b Marx J (2010). Rosen’s emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice (7th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier. p. 1154. ISBN 978-0-323-05472-0.

- ^ Day RA, Paul P, Williams B (2009). Brunner & Suddarth’s textbook of Canadian medical-surgical nursing (Canadian 2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1237. ISBN 978-0-7817-9989-8. Archived from the original on 2016-04-25.

- ^ a b «Hepatitis C prevalence in Egypt drops from 7% to 2% thanks to Sisi’s initiative». EgyptToday. 2021-02-06. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ «Highest Rates of Hepatitis C Virus Transmission Found in Egypt». Al Bawaaba. 2010-08-09. Archived from the original on 2012-05-15. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ^ Tohme RA, Holmberg SD (October 2010). «Is sexual contact a major mode of hepatitis C virus transmission?». Hepatology. 52 (4): 1497–505. doi:10.1002/hep.23808. PMID 20635398. S2CID 5592006.

- ^ «Hepatitis C Group Education Class». United States Department of Veteran Affairs. Archived from the original on 2011-11-09. Retrieved 2011-11-20.

- ^ a b c d e f Jafari S, Copes R, Baharlou S, Etminan M, Buxton J (November 2010). «Tattooing and the risk of transmission of hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta-analysis». International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 14 (11): e928-40. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2010.03.019. PMID 20678951.

- ^ «Hepatitis C» (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.