|

Volgograd Волгоград |

|

|---|---|

|

City[1] |

|

|

Top-down, left-to-right: The Motherland Calls on Mamayev Kurgan, the railway station, Eternal flame, The Metrotram, Gerhardt’s Mill, Central embankment |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Anthem: none[3] | |

|

Location of Volgograd |

|

|

Volgograd Location of Volgograd Volgograd Volgograd (European Russia) Volgograd Volgograd (Europe) |

|

| Coordinates: 48°42′31″N 44°30′53″E / 48.70861°N 44.51472°ECoordinates: 48°42′31″N 44°30′53″E / 48.70861°N 44.51472°E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Volgograd Oblast[2] |

| Founded | 1589[4] |

| City status since | 1780[1] |

| Government | |

| • Body | City Duma[5] |

| • Head[5] | Alexander Chunakov[citation needed] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 859.35 km2 (331.80 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 80 m (260 ft) |

| Population

(2010 Census)[6] |

|

| • Total | 1,021,215 |

| • Estimate

(2018)[7] |

1,013,533 (−0.8%) |

| • Rank | 12th in 2010 |

| • Density | 1,200/km2 (3,100/sq mi) |

|

Administrative status |

|

| • Subordinated to | city of oblast significance of Volgograd[2] |

| • Capital of | Volgograd Oblast[2], city of oblast significance of Volgograd[2] |

|

Municipal status |

|

| • Urban okrug | Volgograd Urban Okrug[8] |

| • Capital of | Volgograd Urban Okrug[8] |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK |

| Postal code(s)[10] |

400000–400002, 400005–400012, 400015–400017, 400019–400023, 400026, 400029, 400031–400034, 400036, 400038–400040, 400042, 400046, 400048–400055, 400057–400059, 400062–400067, 400069, 400071–400076, 400078–400082, 400084, 400086–400089, 400093, 400094, 400096–400098, 400105, 400107, 400108, 400110–400112, 400117, 400119–400125, 400127, 400131, 400136–400138, 400700, 400880, 400890, 400899, 400921–400942, 400960–400965, 400967, 400970–400979, 400990–400993 |

| Dialing code(s) | +7 8442 |

| OKTMO ID | 18701000001 |

| City Day | Second Sunday of September[1] |

| Website | www.volgadmin.ru |

Volgograd (Russian: Волгогра́д, IPA: [vəɫɡɐˈɡrat] (listen)), formerly Tsaritsyn (Цари́цын, Tsarítsyn; [tsɐˈrʲitsɨn]) (1589–1925), and Stalingrad (Сталингра́д, Stalingrád; [stəlʲɪnˈɡrat] (

listen)) (1925–1961), is the largest city and the administrative centre of Volgograd Oblast, Russia. The city lies on the western bank of the Volga, covering an area of 859.4 square kilometres (331.8 square miles), with a population of slightly over 1 million residents.[11] Volgograd is the sixteenth-largest city by population size in Russia,[12] the second-largest city of the Southern Federal District, and the fourth-largest city on the Volga.

The city was founded as the fortress of Tsaritsyn in 1589. By the nineteenth century, Tsaritsyn had become an important river-port and commercial centre, leading to its population to grow rapidly. In November 1917, at the start of the Russian Civil War, Tsaritsyn came under Bolshevik control. It fell briefly to the White Army in mid-1919 but returned to Bolshevik control in January 1920. In 1925, the city was renamed Stalingrad in honor of Joseph Stalin, who then ruled the country. During World War II, Axis forces attacked the city, leading to the Battle of Stalingrad, one of, if not the largest and bloodiest battles in the history of warfare, from which it received the title of Hero City. In 1961, Nikita Khrushchev’s administration renamed the city to Volgograd as part of de-Stalinization. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the city became the administrative centre of Volgograd Oblast.

Volgograd today is the site of The Motherland Calls, an 85-meter high statue dedicated to the heroes of the Battle of Stalingrad, which is the tallest statue in Europe, as well as the tallest statue of a woman in the world. The city has many tourist attractions, such as museums, sandy beaches, and a self-propelled floating church. Volgograd was one of the host cities of the 2018 FIFA World Cup.[13]

Etymology[edit]

Tsaritsyn has been linked to Turkic Sāriğšin or *Sāriğsın meaning «Yellow tomb» or Sāriğšın «City of the Yellow (Golden) Throne».[14]

History[edit]

Tsaritsyn[edit]

Although the city may have originated in 1555, documented evidence of Tsaritsyn at the confluence of the Tsaritsa [ru] and Volga rivers dates from 1589.[4] Grigori Zasekin established the fortress Sary Su («yellow water» in the local Tatar language), or Sary Sin («yellow river»), as part of the defenses of the unstable southern border of the Tsardom of Russia. The structure stood slightly above the mouth of the Tsaritsa River on the right bank. It soon became the nucleus of a trading settlement.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the garrison consisted of 350 to 400 people. In 1607 the fortress garrison rebelled for six months against the troops of Tsar Vasili Shuisky. In the following year saw the construction of the first stone church in the city, dedicated to St. John the Baptist.

In 1670 troops of Stepan Razin captured the fortress; they left after a month. In 1708 the insurgent Cossack Kondraty Bulavin (died July 1708) held the fortress. In 1717 in the Kuban pogrom [ru], raiders from the Kuban under the command of the Crimean Tatar Bakhti Gerai [ru] blockaded the town and enslaved thousands in the area. In August 1774 Cossack leader Yemelyan Pugachev unsuccessfully attempted to storm the city.

In 1691 Moscow established a customs-post at Tsaritsyn.[15] In 1708 Tsaritsyn was assigned to the Kazan Governorate; in 1719[citation needed] to the Astrakhan Governorate. According to the census in 1720, the city had a population of 408 people. In 1773 the settlement was designated as a provincial and district town. From 1779 it belonged to the Saratov Viceroyalty. In 1780 the city came under the newly established Saratov Governorate.

In the nineteenth century, Tsaritsyn became an important river-port and commercial center. As a result, it also became a hub for migrant workers; in 1895 alone, over 50,000 peasant migrants came to Tsaritsyn in search of work.[16] The population expanded rapidly, increasing from fewer than 3,000 people in 1807 to about 84,000 in 1900. By 1914, the population had again jumped and was estimated at 130,000.[17] Sources show 893 Jews registered as living there in 1897, with the number exceeding 2,000 by the middle of the 1920s.[18] At the turn of the nineteenth century, Tsaritsyn was essentially a frontier town; almost all of the structures were wooden, with neither paved roads nor electricity.[17] The first railway reached the town in 1862. The first theatre opened in 1872, the first cinema in 1907. In 1913 Tsaritsyn got its first tram-line, and the city’s first electric lights were installed in the city center.

Between 1903 and 1907, the area was one of the least healthy in Europe, with a mortality rate of 33.6 for every 1000 persons. Untreated sewage spilled into the river, causing several cholera epidemics between 1907 and 1910.[17] Although the region had an active Sanitary Executive Commission that sent out instructions on the best ways to prevent outbreaks and dispatched a delegate from the Anti-Plague Commission to Tsaritsyn in 1907, local municipal officials did not put any precautions into place, citing economic considerations. The city’s drinking water came directly from the river, the intake pipe dangerously close to both the port and the sewage drain. There were neither funds nor political will to close the port (the main hub of economic activity) or move the intake pipes. As a result, in the three years spanning 1908 to 1910, Tsaritsyn lost 1,045 people to cholera. With a population of only 102,452 at the time, that amounts to a staggering 1.01% loss of the population.[16]

Between 1908 and 1911, Tsaritsyn was home to Sergei Trufanov, also known as the ‘mad monk’ Iliodor. He spent most of his time causing infighting and power struggles within the Russian Orthodox Church, fomenting anti-semitic zeal and violence in local populations, attacking the press, denouncing local municipal officials and causing unrest wherever he went. The most permanent mark he left on the city was the Holy Spirit Monastery (Russian: Свято-Духовский монастырь), built in 1909, parts of which still stand today.[17]

In light of the explosive population growth, the lack of political action on sanitation and housing, the multiple epidemics and the presence of volatile personalities, it is no surprise that the lower Volga region was a hotbed of revolutionary activity and civil unrest. The inability of the Tsarist government to provide basic protections from cholera on the one hand and subjecting the populace to strict but ineffective health measures on the other, caused multiple riots in 1829, in the 1890’s and throughout the first decade of the 1900s, setting the stage for multiple Russian revolutions and adding fuel to the political fire.[16] During the Russian Civil War of 1917–1923, Tsaritsyn came under Soviet control from November 1917. In 1918 White Movement troops under Pyotr Krasnov, the Ataman of the Don Cossack Host, besieged Tsaritsyn. The Reds repulsed three assaults by the Whites. However, in June 1919 the White Armed Forces of South Russia, under the command of General Denikin, captured Tsaritsyn, and held it until January 1920. The fighting from July 1918 to January 1920 became known as the Battle for Tsaritsyn.

-

1636 View of Tsaritsyn

-

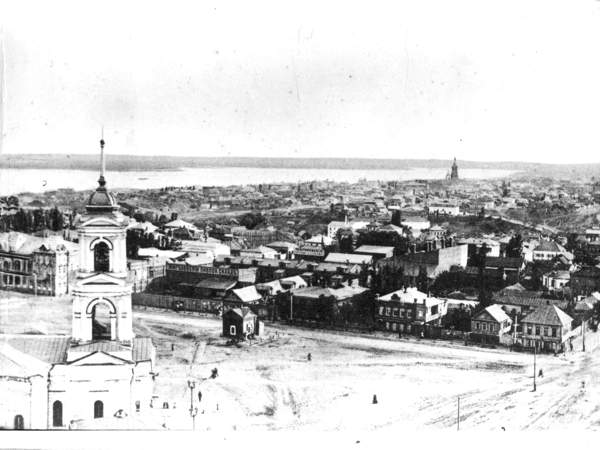

Pre-revolutionary Tsaritsyn

-

1914 City tram on Gogolya St.

Stalingrad[edit]

On April 10, 1925, the city was renamed Stalingrad, in honor of Joseph Stalin, General Secretary of the Communist Party.[19][20] This was officially to recognize the city and Stalin’s role in its defense against the Whites between 1918 and 1920.[21]

Once the Soviets established control, ethnic and religious minorities were targeted. The only Jewish school in the area was closed down in 1926.[18] In 1928, a campaign was launched by the Regional Executive Council to close down the synagogue in Stalingrad. Due to local pushback, they were not successful until 1929, when the council convened a Special Commission. The Commission convinced local municipal powers that the building was in need of major repairs, was unsafe and much too small for the over 800 worshippers who regularly showed up for high holidays.[18]

In 1931, the German settlement-colony Old Sarepta (founded in 1765) became a district of Stalingrad. Renamed Krasnoarmeysky Rayon (or «Red Army District»), it was the largest area of the city. The first higher education institute was opened in 1930. A year later, the Stalingrad Industrial Pedagogical Institute, now Volgograd State Pedagogical University, was opened. Under Stalin, the city became a center of heavy industry and transshipment by rail and river.

Battle of Stalingrad[edit]

Street in Stalingrad, 1942

Factory after bombing, 1943

During World War II, German and Axis forces attacked the city, and in 1942 it was the site of one of the pivotal battles of the war. The Battle of Stalingrad was the deadliest single battle in the history of warfare (casualties estimates vary between 1,250,000[22] and 1,798,619[23]).

The battle began on August 23, 1942, and on the same day, the city suffered heavy aerial bombardment that reduced most of it to rubble. Martial law had already been declared in the city on July 14. By September, the fighting reached the city center. The fighting was of unprecedented intensity; the city’s central railway station changed hands thirteen times, and the Mamayev Kurgan (one of the highest points of the city) was captured and recaptured eight times.

By early November, the German forces controlled 90 percent of the city and had cornered the Soviets in two narrow pockets, but they were unable to eliminate the last pockets of Soviet resistance before Soviet forces launched a huge counterattack on November 19. This resulted in the Soviet encirclement of the German Sixth Army and other Axis units. On January 31, 1943 the Sixth Army’s commander, Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus, surrendered, and by February 2, with the elimination of straggling German troops, the Battle of Stalingrad was over.

The bombing campaign and five months of fighting that followed utterly destroyed 99% of the city.[24]

In 1945 the Soviet Union awarded Stalingrad the title Hero City for its resistance. Great Britain’s King George VI awarded the citizens of Stalingrad the jeweled «Sword of Stalingrad» in recognition of their bravery.

A number of cities around the world (especially those that had suffered similar wartime devastation) established sister, friendship, and twinning links (see list below) in the spirit of solidarity or reconciliation. One of the first «sister city» projects was that established during World War II between Stalingrad and Coventry in the United Kingdom; both had suffered extensive devastation from aerial bombardment. In March 2022 this twinning link was paused because of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[25]

Volgograd[edit]

Building of the Oblast Duma

On 10 November 1961, Nikita Khrushchev’s administration changed the name of the city to Volgograd («Volga City») as part of his programme of de-Stalinization following Stalin’s death. This action was and remains somewhat controversial, because Stalingrad has such importance as a symbol of resistance during World War II.

During Konstantin Chernenko’s brief rule in 1984, proposals were floated to revive the city’s Stalinist name for that reason. There was a strong degree of local support for a reversion, but the Russian government did not accept such proposals.[citation needed]

On May 21, 2007, Roman Grebennikov of Communist Party was elected as mayor with 32.47% of the vote, a plurality. Grebennikov became Russia’s youngest mayor of a federal subject administrative center at the time.

In 2010, Russian monarchists and leaders of the Orthodox organizations demanded that the city should take back its original name of Tsaritsyn, but the authorities rejected their proposal.

On January 30, 2013, the Volgograd City Council passed a measure to use the title «Hero City Stalingrad» in city statements on nine specific dates annually.[26][27][28] On the following dates, the title «Hero City Stalingrad» can officially be used in celebrations:

- February 2 (end of the Battle of Stalingrad),

- February 23 (Defender of the Fatherland Day),

- May 9 (Victory Day),

- June 22 (start of Operation Barbarossa),

- August 23 (start of the Battle of Stalingrad),

- September 2 (Victory over Japan Day),

- November 19 (start of Operation Uranus),

- December 9 (Day of the Fatherland’s Heroes)[26]

In addition, 50,000 people signed a petition to Vladimir Putin, asking that the city’s name be permanently changed to Stalingrad.[27] President Putin has replied that such a move should be preceded by a local referendum and that the Russian authorities will look into how to bring about such a referendum.[29]

Politics[edit]

In 2011, the City Duma canceled direct election of the mayor and confirmed the position of City Manager. This was short-lived, as in March 2012, Volgograd residents voted for relevant amendments to the city charter to reinstate the direct mayoral elections.[30]

Administrative and municipal status[edit]

View of Voroshilovsky City District of Volgograd

Volgograd is the administrative center of Volgograd Oblast.[31] Within the framework of administrative divisions, it is incorporated as the city of oblast significance of Volgograd—an administrative unit with the status equal to that of the districts.[2] As a municipal division, the city of oblast significance of Volgograd is incorporated as Volgograd Urban Okrug.[8]

Economy[edit]

Although the city was on an important trade route for moving timber, grain, cotton, cast iron, fish, salt and linseed oil, the economic reach of the Volga was relatively small. When the first rail lines were linked up to Moscow in 1871, this isolated area was suddenly and efficiently connected to the rest of the empire. Thanks to that connection, the province became a major producer, processor and exporter of grain, supplying most of Russia. By the 1890s, the economy of Volgograd (then Tsaritsyn), relied mainly on the trade of grain, naphtha, fish and salt.[16] Modern Volgograd remains an important industrial city. Industries include shipbuilding, oil refining, steel and aluminum production, manufacture of heavy machinery and vehicles at the Volgograd Tractor Plant and Titan-Barrikady plant, and chemical production. The large Volgograd Hydroelectric Plant is a short distance to the north of Volgograd.

Transportation[edit]

Volgograd is a major railway junction served by the Privolzhskaya Railway. Rail links from the Volgograd railway station include Moscow; Saratov; Astrakhan; the Donbas region of Ukraine; the Caucasus and Siberia. It stands at the east end of the Volga–Don Canal, opened in 1952 to link the two great rivers of Southern Russia. European route E40, the longest European route connecting Calais in France with Ridder in Kazakhstan, passes through Volgograd. The M6 highway between Moscow and the Caspian Sea also passes through the city. The Volgograd Bridge, under construction since 1995, was inaugurated in October 2009.[32] The city river terminal is the center for local passenger shipping along the Volga River.

The Volgograd International Airport provides air links to major Russian cities as well as Antalya, Yerevan and Aktau.

Volgograd’s public transport system includes a light rail service known as the Volgograd Metrotram. Local public transport is provided by buses, trolleybuses and trams.

The Volga River still is a very important communication channel.

-

-

-

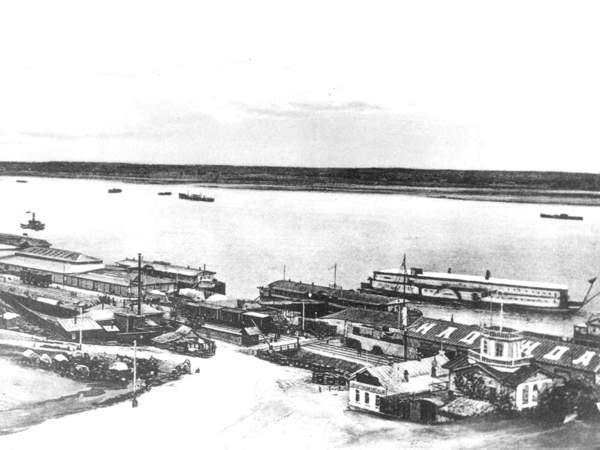

Riverboat Station

Population[edit]

|

|

Ethnic composition[edit]

At the time of the official 2010 Census, the ethnic makeup of the city’s population whose ethnicity was known (999,785) was:[36]

| Ethnicity | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Russians | 922,321 | 92.3% |

| Armenians | 15,200 | 1.5% |

| Ukrainians | 12,216 | 1.2% |

| Tatars | 9,760 | 1.0% |

| Azerbaijanis | 6,679 | 0.7% |

| Kazakhs | 3,831 | 0.4% |

| Belarusians | 2,639 | 0.3% |

| Koreans | 2,389 | 0.2% |

| Others | 24,750 | 2.5% |

Culture[edit]

Mamayev Kurgan Memorial Complex[edit]

A memorial complex commemorating the battle of Stalingrad, dominated by an immense allegorical sculpture The Motherland Calls, was erected on the Mamayev Kurgan (Russian: Мамаев Курган), the hill that saw some of the most intense fighting during the battle. This complex includes the Hall of Military Glory, a circular building housing an eternal flame and bearing plaques with the names of the fallen heroes of the Battle of Stalingrad. This memorial features an hourly changing of the guard that draws many tourists during the warmer months. Across from this Hall, there is a statue called Mother’s Sorrow, which depicts a grieving woman holding a fallen soldier in her arms. During the summer months, this statue is surrounded by a small water feature, called the Lake of Tears. Further down the hill of this complex, there is a Plaza of Heroes (also known as Heroes’ Square), featuring multiple allegorical sculptures of heroic deeds. This plaza is sometimes referred to by the title of the most famous of these sculptures, called «Having withstood, we conquered death».

Panorama Museum[edit]

Panorama Museum of the Battle of Stalingrad, including Gerhardt’s Mill

The Panorama Museum of the Battle of Stalingrad is a large cultural complex that sits on the shore of the Volga river. It is located on the site of the «Penza Defense Junction», a group of buildings along Penzenskaya Street (now Sovetskaya Street), which was defended by the 13th Guards Rifle Division. The complex includes Gerhardt’s Mill, which is preserved in its bombed out state. The museum on the complex grounds houses the largest painting in Russia, a panoramic painting of the battlefield as seen from Mamayev Kurgan, where «The Motherland Calls» statue now stands. This museum also features Soviet military equipment from the 1940s, numerous exhibits of weapons (including a rifle of the famous sniper Vasily Zaytsev), uniforms, personal belongings of generals and soldiers involved in the battle and detailed maps and timelines of the battle.

Planetarium[edit]

The Volgograd Planetarium was a gift from East Germany in honor of what would have been Stalin’s 70th birthday.[37] Neoclassical in style, the building facade is designed like a Roman temple, with six Tuscan columns topped by capitals decorated with stars. Designed by Vera Ignatyevna Mukhina, the dome is crowned by a female personification of Peace, holding an astrolabe with a dove. Opened in 1954, it was only the second purpose-built planetarium in the Soviet Union. The entryway interior features a mural of Stalin in the white uniform of a naval admiral, surrounded by lilies and doves, more symbols of peace. On either side of the mural, are busts of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, a Soviet rocket scientist, and Yuri Gagarin, a Soviet pilot and cosmonaut and the first human to venture into outer space. On the second floor, there are large stained glass windows, featuring images related to Soviet space exploration. The planetarium was outfitted with a Zeiss projector, the first produced by the Carl Zeiss Company in their Jena plant after the end of World War 2.[38] The projector supplied was the UPP-23/1s model, which was produced between 1954 and 1964; it is still operational and in regular use at the Volgograd Planetarium. The projector was supplemented by a digital system in 2019; the Fulldome Pro model LDX12. Zeiss also provided the 365mm refractor telescope for the observatory, which is still in operation today.[39] The planetarium hosts scientific and educational lectures, provides Fulldome shows, has scheduled tours, features daytime and nighttime observations and runs an astronomy club for children.[40]

Other[edit]

Across the street from the Panorama Museum, stands Pavlov’s House, another surviving monument to the Battle of Stalingrad. Several monuments and memorials can be found nearby, including a statue of Lenin, a statue in honor of children who survived war and another to the Pavlov’s House defenders.

The Musical Instrument Museum is a branch of the Volgograd regional Museum of local lore.

Religion[edit]

As a port city along an important and busy trading route, Volgograd has always been a diverse place. An 1897 survey reveals 893 Jews (512 men and 381 women), 1,729 Muslims (938 men and 791 women), and 193 Catholics (116 men and 77 women).[41]

Holy Spirit Monastery[edit]

Holy Spirit Monastery, before 1923

Land for the Holy Spirit Monastery was originally allocated in 1904, but construction did not begin until 1909 and was not complete until 1911. Sergei Trufanov, also known as the ‘mad monk’ of Tsaritsyn, was the driving force behind fundraising and getting the project off the ground.[17] The original complex had a church that could accommodate 6,000 people, the monastery itself could house 500 and an auditorium that held 1,000. There was a school, space for workshops, a printing office and an almshouse. The land the monastery stood on also hosted multiple gardens, a fountain and several inner yards.[42]

In 1912, the monastery was divided to a male and female section, housing both monks and nuns. In 1914, the school on the grounds of the Holy Spirit Monastery became part of the city school system and in 1915, housed 53 girls whose fathers were on the front lines. During the Russian Civil War, an infirmary was set up and the complex was alternately used by both the Bolsheviks and the Whites. In 1923, once the area was under firm Bolshevik control, the monastery was closed. During the following decades, the complex was used as an orphanage, a library, a cinema and a student hostel. Eventually, many of the buildings fell into disuse and became dilapidated. At the onset of World War 2, the complex was given to the military and many of the original buildings were demolished.[43]

After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, the Volgograd diocese was established and the military began the process of transferring what was left of the Holy Spirit Monastery back to the church. A theological school was established in 1992 and restoration of the site continues today.[44]

Alexander Nevsky Cathedral[edit]

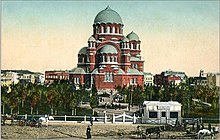

Original Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Tsaritsyn, before 1932

Construction of the cathedral began on April 22, 1901, with the laying of the foundation stone by Bishop Hermogenes. The domes were installed in 1915 and consecration took place on May 19, 1918. Almost as soon as it was built, the cathedral fell out of use. The Soviet powers closed it down officially in 1929, with the crosses and bells removed and the liturgical objects confiscated. The cathedral was then used as a motor depot and eventually demolished in 1932. In 2001, the long project of rebuilding the cathedral was begun. The first foundation stone was laid in 2016 and the finished replica was finally consecrated in 2021 by Patriarch Kirill.[45]

The new church stands in central Volgograd, bounded by Communist Street (Russian: Коммунистическая Улица) and Mir Street (Russian: Улица Мира) on the north and south and Volodarsk Street (Russian: Улица Володарского) and Gogol Street (Russian: Улица Гоголя) on the west and east, respectively. This area is also a park, called Alexander’s Garden (Russian: Александровский Сад). The cathedral stands across the street from a World War 2 monument, and a statue of and chapel for, the eponymous Alexander Nevsky.

Floating Churches[edit]

Original St.Nicholas floating church, consecrated in 1910

Volgograd hosts one of the few self-propelled floating churches in the world: the chapel boat of Saint Vladimir of Volgograd. Spearheaded by Vladimir Koretsky and assisted by a Dutch Orthodox priest who was part of the organization Aid to the Church in Need (ACN), the Saint Vladimir was consecrated in October 2004 on the shore of the Volga. Originally a decommissioned landing craft found in a shipyard outside St. Petersburg, it took two years to convert it into a floating church. The boat chapel sports three shining domes and was decorated with icons and religious motifs by a local Volgograd artist. On its maiden voyage, the Saint Vladimir reached Astrakhan in the south and Saratov in the north; traveling an 800 kilometer (~500 mile) span of the Volga River.[46]

In addition to this self propelled church, Vladimir Koretsky first built two other floating churches in Volgograd, both of which must be towed by another craft. The Saint Innocent was originally a repair vessel and was located in a shipyard in Volgograd. Despite it being in poor condition, the boat had good sized cabins and a kitchen unit; the hull was restored, the largest cabins were merged and a single shining dome was added. Icons and sacred relics were donated by parishes from all over the country and the floating church was consecrated on 22 May 1998. During its first year in operation, it visited 28 villages, where 446 people were baptised and 1,500 received communion. The Saint Innocent was mobile for four months of the year, operating mostly on the Don River, and spent the rest of the time moored in Pyatimorsk, providing a semi permanent church for that rural locality.[46]

Due to the success of the Saint Innocent, the ACN launched the creation of a second floating church, this time built atop an old barge. Christened the Saint Nicholas, in honor of the original floating church built in 1910, it was moored at a yacht club in Volgograd for several years, serving as a place of worship for passing ships crews. It was later towed to Oktyabrsky, a remote southern village of the Volgograd Oblast, to serve as a semi-permanent church.[46]

All of these floating churches were inspired by the original; a retrofitted tug-passenger steamer, which ran between Kazan and Astrakhan, named the Saint Nicholas. Commissioned in 1858, it was first christened the Kriushi, then the Pirate, until it was purchased by the Astrakhan diocese in 1910 and converted into a church. It served for 8 years, traveling up and down the Volga River, sometimes clocking 4,000 miles a year. Much like every other church in Russia, it was decommissioned in 1918 by the Soviets. It made such an impact on the local population however, that almost 80 years later, it was the inspiration for a new «flotilla of God».[46]

Volgograd Synagogue[edit]

First Volgograd Synagogue

Also known as Beit David Synagogue, it was named after David Kolotilin, a Jewish leader during the Soviet period. Although some sources claim that this was the first synagogue to serve the Jews of Volgograd, was constructed in 1888, and its original purpose was exclusively that of a synagogue, there is little evidence to support this. What little documentation exists suggests that it was indeed built at the turn of the century, but its original purpose is unknown.[33] In fact, a 1903 tourist guide to Tsaritsyn, warns that almost all of the buildings in the town are wooden and makes no mention of this structure, so an 1888 construction date is highly unlikely.[17] It is a two-story, rectangular building, made of brick and richly decorated. The architectural style is typical of residential buildings constructed in Tsaritsyn after the turn of the century.[47] The original building barely survived the Battle of Stalingrad; it was in ruins as late as 1997, with broken windows and gaping holes made by Nazi bombs. Some sources suggest that the building was reconstructed, but not restored, by 1999.[33] Emissaries of the Chabad-Lubavitch organization launched a campaign to return the building to the Jewish community and were finally successful in 2003. With the help of multiple fundraising campaigns and generous donors, including Edward Shifrin and Alex Schneider, the synagogue was restored. An annex was constructed in 2005 to mimic the original style and the building was rededicated in 2007.[48] The prayer hall can be found on the first floor, with communal offices on the second.[33] Located at 2 Balachninskaya Street in the center of Volgograd. In addition to regular religious services, it also hosts a soup kitchen, a Jewish day school and an overnight children’s camp. As of 2022, the community is led by Rabbi Zalman Yoffe.[49]

Education[edit]

Higher education facilities include:

- Volgograd State University

- Volgograd State Technical University (former Volgograd Polytechnical University)[50]

- Volgograd State Agriculture University

- Volgograd State Medical University[51]

- Volgograd State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering

- Volgograd Academy of Industry

- Volgograd Academy of Business Administration[52]

- Volgograd State Pedagogical University

Sports[edit]

| Club | Sport | Founded | Current League | League Tier |

Stadium |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rotor Volgograd | Football | 1929 | Russian Professional Football League | 1st | Volgograd Arena |

| Olimpia Volgograd | Football | 1989 | Volgograd Oblast Football Championship | 5th | Olimpia Stadium |

| Kaustik Volgograd | Handball | 1929 | Handball Super League | 1st | Dynamo Sports Complex |

| Dynamo Volgograd | Handball | 1929 | Women’s Handball Super League | 1st | Dynamo Sports Complex |

| Krasny Oktyabr Volgograd | Basketball | 2012 | VTB United League | 2nd | Trade Unions Sports Palace |

| Spartak Volgograd | Water Polo | 1994 | Russian Water Polo Championship | 1st | CVVS |

Volgograd was a host city to four matches of the FIFA World Cup in 2018. A new modern stadium, Volgograd Arena, was built for this occasion on the bank of the Volga River to serve as the venue. The stadium has a seating capacity for 45,000 people, including a press box, a VIP box and seats for people with limited mobility.[citation needed]

Notable people[edit]

- Nikolay Davydenko, tennis player

- Sasha Filippov, spy

- Oleg Grebnev, handball player

- Yekaterina Grigoryeva, sprinter

- Larisa Ilchenko, long-distance swimmer

- Yelena Isinbayeva, pole vaulter

- Lev Ivanov, association football manager

- Yuriy Kalitvintsev, association football manager

- Elem Klimov, film director

- Egor Koulechov professional basketball player

- Alexey Kravtsov, jurist

- Vladimir Kryuchkov, statesman

- Tatyana Lebedeva, jumper

- Maxim Marinin, figure skater

- Maksim Opalev, sprint canoeist

- Aleksandra Pakhmutova, composer

- Denis Pankratov, Olympic swimmer

- Evgeni Plushenko, Olympic figure skater

- Yevgeny Sadovyi, Olympic swimmer

- Natalia Shipilova, handball player

- Yelena Slesarenko, high jumper

- Leonid Slutsky, football coach

- Yuliya Sotnikova, 400m athlete

- Yulia MacLean Townsend, classical opera singer

- Igor Vasilev, handball player

- Oleg Veretennikov, association football player

- Natalia Vikhlyantseva, tennis player

- Vasily Zaytsev, Soviet sniper and a Hero of the Soviet Union

International relations[edit]

|

|

This article needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (April 2022) |

Volgograd is/was twinned with:[53]

Coventry, United Kingdom (1944-2022[54])

Ostrava, Czech Republic (1949–2022[55])

Kemi, Finland (1953)

Liège, Belgium (1959-2022[56])

Dijon, France (1959)

Turin, Italy (1961, renewed 2011,[57][58] renewed 2020[59])

Port Said, Egypt (1962)

Chennai, India (1967)

Hiroshima, Japan (1972)

Cologne, Germany (1988)

Chemnitz, Germany (1988)

Cleveland, Ohio United States (1990)

Jilin City, China (1994)

Kruševac, Serbia (1999)

Ruse, Bulgaria (2001)

Płońsk, Poland (2008-2022[60])

İzmir, Turkey (2011)

Chengdu, China (2011)

Olevano Romano, Italy (2014)

Ortona, Italy (2014)

Yerevan, Armenia (2015)

- Several communities in France and Italy have streets or avenues named after Stalingrad, hence Place de Stalingrad in Paris and the eponymous Paris Métro station of Stalingrad.

Climate[edit]

Volgograd has a cold semi arid climate (Köppen: BSk) with hot summers and cold winters. Precipitation is low and spread more or less evenly throughout the year.[61]

| Climate data for Volgograd (1991–2020, extremes 1938–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.3 (54.1) |

15.8 (60.4) |

20.5 (68.9) |

29.2 (84.6) |

37.2 (99.0) |

39.4 (102.9) |

41.8 (107.2) |

42.6 (108.7) |

37.8 (100.0) |

31.0 (87.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

12.3 (54.1) |

42.6 (108.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −3.4 (25.9) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

4.6 (40.3) |

15.5 (59.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

27.9 (82.2) |

30.5 (86.9) |

29.6 (85.3) |

22.2 (72.0) |

13.4 (56.1) |

4.0 (39.2) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

13.6 (56.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −6.3 (20.7) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

0.2 (32.4) |

9.5 (49.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.6 (70.9) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.0 (73.4) |

16.0 (60.8) |

8.5 (47.3) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

8.6 (47.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −9.0 (15.8) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

4.2 (39.6) |

10.5 (50.9) |

15.4 (59.7) |

17.8 (64.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

10.5 (50.9) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −33.0 (−27.4) |

−32.5 (−26.5) |

−25.8 (−14.4) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

2.0 (35.6) |

7.4 (45.3) |

4.5 (40.1) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

−25.8 (−14.4) |

−27.8 (−18.0) |

−33.0 (−27.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 20 (0.8) |

14 (0.6) |

19 (0.7) |

13 (0.5) |

28 (1.1) |

20 (0.8) |

16 (0.6) |

11 (0.4) |

19 (0.7) |

22 (0.9) |

15 (0.6) |

20 (0.8) |

217 (8.5) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 11 (4.3) |

18 (7.1) |

10 (3.9) |

1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.4) |

6 (2.4) |

18 (7.1) |

| Average rainy days | 9 | 7 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 123 |

| Average snowy days | 20 | 18 | 11 | 2 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 1 | 9 | 18 | 79 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 88 | 86 | 81 | 64 | 57 | 56 | 53 | 51 | 61 | 73 | 86 | 89 | 70 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 66.1 | 96.9 | 138.4 | 204.2 | 290.8 | 308.4 | 329.3 | 300.2 | 228.9 | 155.8 | 63.6 | 42.5 | 2,225.1 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net[62] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weatherbase (sun only)[63] |

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c Charter of Volgograd, Preamble

- ^ a b c d e Law #139-OD

- ^ Official website of Volgograd. Конкурс на создание гимна Волгограда будет проведен повторно (in Russian)

- ^ a b Энциклопедия Города России. Moscow: Большая Российская Энциклопедия. 2003. pp. 81–83. ISBN 5-7107-7399-9.

- ^ a b Charter of Volgograd, Article 22

- ^ Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1 [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- ^ «26. Численность постоянного населения Российской Федерации по муниципальным образованиям на 1 января 2018 года». Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ a b c Law #1031-OD

- ^ «Об исчислении времени». Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). June 3, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ^ Почта России. Информационно-вычислительный центр ОАСУ РПО. (Russian Post). Поиск объектов почтовой связи (Postal Objects Search) (in Russian)

- ^ «RUSSIA: Južnyj Federal’nyj Okrug: Southern Federal District». City Population.de. August 4, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ «Оценка численности постоянного населения по субъектам Российской Федерации». Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ «World Cup 2018 stadiums: Complete guide to all 12 venues in 11 Russian cities — CBSSports.com», June 27, 2018 «The industrial city of Volgograd … plays host to the following group stage games: Tunisia vs. England on June 18, Nigeria vs. Iceland on June 22, Saudi Arabia vs. Egypt on June 25 and Japan vs. Poland on June 28.»

- ^ Benjamin Golden, Peter (1980). Khazar Studies: an Historical-Philological Inquiry into the Origins of the Khazars. Akadémiai Kiadó — Budapest. p. 238.

- ^ «Volgograd: History and Myth — GeoHistory». October 10, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Henze, Charlotte E. (2015). Disease, Health Care and Government in Late Imperial Russia; Life and Death on the Volga, 1823-1914. Routledge. ISBN 9781138967779.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dixon, Simon (2010). «The ‘Mad Monk’ Iliodor in Tsaritsyn». The Slavonic and East European Review. 88 (1/2): 377–415. JSTOR 20780425. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c Krapivensky, Solomon Eliazarovich (1993). «The Jewish community of Tsaritsyn (Volgograd) at the turn of the nineteenth century». Proceedings of the World Congress of Jewish Studies; Division B, the History of the Jewish People. 3: 31–35. JSTOR 23536822. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ Lutz-Auras, Ludmilla (2012). «Auf Stalin, Sieg Und Vaterland!»: Politisierung Der Kollektiven Erinnerung an Den Zweiten Weltkrieg in Russland (in German). Springer-Verlag. p. 189. ISBN 978-3658008215.

- ^ Mccauley, Martin (2013). Stalin and Stalinism (3 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1317863687.

10 April 1925: Tsaritsyn is renamed Stalingrad.

- ^ Brewer’s Dictionary of 20th Century Phrase and Fable

- ^ Grant, R. G. (2005). Battle: A Visual Journey Through 5,000 Years of Combat. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 0-7566-1360-4.

- ^ Wagner, Margaret; et al. (2007). The Library of Congress World War II Companion. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-5219-5.

- ^ Craig, William (1973). Enemy at the Gates: The Battle for Stalingrad. Reader’s Digest Press. p. 385. ISBN 0141390174.

- ^ «Council sends letter to Russian twin».

- ^ a b Decision #72/2149

- ^ a b «Russia revives Stalingrad city name». The Daily Telegraph. January 31, 2013. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- ^ «Stalingrad name to be revived for anniversaries». BBC News Online. February 1, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- ^ «Putin says Russian city Volgograd can become Stalingrad again». TASS.

- ^ «Волгоград сдался выборам». www.gazeta.ru. 2012.

- ^ Europa Publications (February 26, 2004). «Southern Federal Okrug». The Territories of the Russian Federation 2004. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 174. ISBN 9781857432480. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

The Oblast’s administrative center is at Volgograd.

- ^ Иванов открыл в Волгограде самый большой мост в Европе (in Russian). Vesti. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Levin, Vladimir; Berezin, Anna (2021). Cohen-Mushlin, Aliza; Oleshkevich, Ekaterina (eds.). «Jewish Material Culture along the Volga Preliminary Expedition Report» (PDF). Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ Seltzer, Leon E. (1952). The Columbia Lippincott gazetteer of the world. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 1818.

- ^ a b c d e f «Volgograd Population». worldpopulationreview.com. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ «Национальный состав городских округов и муниципальных районов» (PDF). Итоги Всероссийской переписи населения 2010 года по Волгоградской области. Территориальный орган Федеральной службы государственной статистики по Волгоградской области. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 4, 2017. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- ^ «About Planetarium/Story». VolgogradPlanetarium.ru. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ Firebrace, William (2017). Star Theatre: The Story of the Planetarium. United Kingdom: Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781780238883.

- ^ «Volgograd Planetarium». World Planetarium Database. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ «Services». VolgogradPlanetarium.ru. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ «Tsaritsyn Synagogue». Tsaritsyn Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ «Construction of the Monastery». www.sdmon.ru (Holy Spirit Monastery). Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ «Monastery Transformations». www.sdmon.ru (Holy Spirit Monastery). Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ «Monastery Restoration». www.sdmon.ru (Holy Spirit Monastery). Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ «Patriarch Kirill Consecrates Restored St. Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Volgograd». www.pravmir.com. September 20, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Barba Lata, Iulian V.; Minca, Claudio (2018). «The floating churches of Volgograd: river topologies and warped spatialities of faith». Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 43 (1): 122–136. doi:10.1111/tran.12208.

- ^ Serebryanaya, V; Kolyshev, Yu (2020). «Regional tradition in the architectural culture of Nizhneye Povolzhye (by the example of the Volgograd region)». IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 962 (3): 032043. Bibcode:2020MS&E..962c2043S. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/962/3/032043. S2CID 229477037. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ «Dedication of New Synagogue in «Stalin’s City»«. www.chabad.org. November 30, 2007. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ «Jewish Community of Volgograd». www.chabad.org. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ «Volgograd State Technical University – Main page». Vstu.ru. August 21, 2011. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ^ Россия. «Volgograd State Medical University (VolSMU)». Volgmed.ru. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ^ «Волгоградская Академия Государственной Службы — Новости». June 27, 2007. Archived from the original on June 27, 2007. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- ^ «Города-побратимы». volgadmin.ru (in Russian). Volgograd. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ Murray, Jessica (March 23, 2022). «Coventry no longer twinned with Volgograd in protest over Ukraine war». The Guardian. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ «OSTRAVA WILL TERMINATE THE PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENTS WITH DONETSK AND VOLGOGRAD». www.ostrava.cz. March 23, 2022.

- ^ Bechet, Marc. «Liège suspends its twinning with Volgograd». www.dhnet.be (DH Les Sports+) (in French). Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ «International Relations; Agreement with Volgograd». Citta’ di Torino (City of Turin). Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ «Twin Cities of Volgograd». Official Website of Volgograd. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ «International Relations; Volgograd Russian Federation — Agreement (2020)». Citta’ di Torino (City of Turin). Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ «Płońsk suspends cooperation with the Russian Volgograd». March 1, 2022. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ «Volgograd, Russia Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)». Weatherbase. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- ^ «Pogoda.ru.net» (in Russian). Retrieved November 8, 2021.

- ^ «Weatherbase: Historical Weather for Volgograd, Russia». Weatherbase. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

Sources[edit]

- Волгоградский городской Совет народных депутатов. Постановление №20/362 от 29 июня 2005 г. «Устав города-героя Волгограда», в ред. Решения №32/1000 от 15 июля 2015 г. «О внесении изменений и дополнений в Устав города-героя Волгограда». Вступил в силу 10 марта 2006 г. (за исключением отдельных положений). Опубликован: «Волгоградская газета», №7, 9 марта 2006 г. (Volgograd City Council of People’s Deputies. Resolution #20/362 of June 29, 2005 Charter of the Hero City of Volgograd, as amended by the Decision #32/1000 of July 15, 2015 On Amending and Supplementing the Charter of the Hero City of Volgograd. Effective as of March 10, 2006 (with the exception of certain clauses).).

- Волгоградская областная Дума. Закон №139-ОД от 7 октября 1997 г. «Об административно-территориальном устройстве Волгоградской области», в ред. Закона №107-ОД от 10 июля 2015 г. «О внесении изменений в отдельные законодательные акты Волгоградской области в связи с приведением их в соответствие с Уставом Волгоградской области». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: «Волгоградская правда», №207, 1 ноября 1997 г. (Volgograd Oblast Duma. Law #139-OD of October 7, 1997 On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Volgograd Oblast, as amended by the Law #107-OD of July 10, 2015 On Amending Various Legislative Acts of Volgograd Oblast to Ensure Compliance with the Charter of Volgograd Oblast. Effective as of the day of the official publication.).

- Волгоградская областная Дума. Закон №1031-ОД от 21 марта 2005 г. «О наделении города-героя Волгограда статусом городского округа и установлении его границ», в ред. Закона №2013-ОД от 22 марта 2010 г «О внесении изменений в Закон Волгоградской области от 21 марта 2005 г. №1031-ОД «О наделении города-героя Волгограда статусом городского округа и установлении его границ»». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования (22 марта 2005 г.). Опубликован: «Волгоградская правда», №49, 22 марта 2005 г. (Volgograd Oblast Duma. Law #1031-OD of March 21, 2005 On Granting Urban Okrug Status to the Hero City of Volgograd and on Establishing Its Borders, as amended by the Law #2013-OD of March 22, 2010 On Amending the Law of Volgograd Oblast #1031-OD of March 21, 2005 «On Granting Urban Okrug Status to the Hero City of Volgograd and on Establishing Its Borders». Effective as of the day of the official publication (March 22, 2005).).

- Волгоградская городская Дума. Решение №72/2149 от 30 января 2013 г. «Об использовании наименования «город-герой Сталинград»», в ред. Решения №9/200 от 23 декабря 2013 г. «О внесении изменений в пункт 1 Порядка использования наименования «город-герой Сталинград», определённого Решением Волгоградской городской Думы от 30.01.2013 №72/2149 «Об использовании наименования «город-герой Сталинград»». Вступил в силу со дня принятия. Опубликован: «Городские вести. Царицын – Сталинград – Волгоград», #10, 2 февраля 2013 г. (Volgograd City Duma. Decision #72/2149 of January 30, 2013 On Using the Name of the «Hero City Stalingrad», as amended by the Decision #9/200 of December 23, 2013 On Amending Item 1 of the Procedures for Usage of the Name «Hero City Stalingrad», Adopted by the January 30, 2013 Decision #72/2149 of Volgograd City Duma «On Using the Name of the «Hero City Stalingrad». Effective as of the day of adoption.).

Bibliography[edit]

External links[edit]

|

Volgograd Волгоград |

|

|---|---|

|

City[1] |

|

|

Top-down, left-to-right: The Motherland Calls on Mamayev Kurgan, the railway station, Eternal flame, The Metrotram, Gerhardt’s Mill, Central embankment |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Anthem: none[3] | |

|

Location of Volgograd |

|

|

Volgograd Location of Volgograd Volgograd Volgograd (European Russia) Volgograd Volgograd (Europe) |

|

| Coordinates: 48°42′31″N 44°30′53″E / 48.70861°N 44.51472°ECoordinates: 48°42′31″N 44°30′53″E / 48.70861°N 44.51472°E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Volgograd Oblast[2] |

| Founded | 1589[4] |

| City status since | 1780[1] |

| Government | |

| • Body | City Duma[5] |

| • Head[5] | Alexander Chunakov[citation needed] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 859.35 km2 (331.80 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 80 m (260 ft) |

| Population

(2010 Census)[6] |

|

| • Total | 1,021,215 |

| • Estimate

(2018)[7] |

1,013,533 (−0.8%) |

| • Rank | 12th in 2010 |

| • Density | 1,200/km2 (3,100/sq mi) |

|

Administrative status |

|

| • Subordinated to | city of oblast significance of Volgograd[2] |

| • Capital of | Volgograd Oblast[2], city of oblast significance of Volgograd[2] |

|

Municipal status |

|

| • Urban okrug | Volgograd Urban Okrug[8] |

| • Capital of | Volgograd Urban Okrug[8] |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK |

| Postal code(s)[10] |

400000–400002, 400005–400012, 400015–400017, 400019–400023, 400026, 400029, 400031–400034, 400036, 400038–400040, 400042, 400046, 400048–400055, 400057–400059, 400062–400067, 400069, 400071–400076, 400078–400082, 400084, 400086–400089, 400093, 400094, 400096–400098, 400105, 400107, 400108, 400110–400112, 400117, 400119–400125, 400127, 400131, 400136–400138, 400700, 400880, 400890, 400899, 400921–400942, 400960–400965, 400967, 400970–400979, 400990–400993 |

| Dialing code(s) | +7 8442 |

| OKTMO ID | 18701000001 |

| City Day | Second Sunday of September[1] |

| Website | www.volgadmin.ru |

Volgograd (Russian: Волгогра́д, IPA: [vəɫɡɐˈɡrat] (listen)), formerly Tsaritsyn (Цари́цын, Tsarítsyn; [tsɐˈrʲitsɨn]) (1589–1925), and Stalingrad (Сталингра́д, Stalingrád; [stəlʲɪnˈɡrat] (

listen)) (1925–1961), is the largest city and the administrative centre of Volgograd Oblast, Russia. The city lies on the western bank of the Volga, covering an area of 859.4 square kilometres (331.8 square miles), with a population of slightly over 1 million residents.[11] Volgograd is the sixteenth-largest city by population size in Russia,[12] the second-largest city of the Southern Federal District, and the fourth-largest city on the Volga.

The city was founded as the fortress of Tsaritsyn in 1589. By the nineteenth century, Tsaritsyn had become an important river-port and commercial centre, leading to its population to grow rapidly. In November 1917, at the start of the Russian Civil War, Tsaritsyn came under Bolshevik control. It fell briefly to the White Army in mid-1919 but returned to Bolshevik control in January 1920. In 1925, the city was renamed Stalingrad in honor of Joseph Stalin, who then ruled the country. During World War II, Axis forces attacked the city, leading to the Battle of Stalingrad, one of, if not the largest and bloodiest battles in the history of warfare, from which it received the title of Hero City. In 1961, Nikita Khrushchev’s administration renamed the city to Volgograd as part of de-Stalinization. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the city became the administrative centre of Volgograd Oblast.

Volgograd today is the site of The Motherland Calls, an 85-meter high statue dedicated to the heroes of the Battle of Stalingrad, which is the tallest statue in Europe, as well as the tallest statue of a woman in the world. The city has many tourist attractions, such as museums, sandy beaches, and a self-propelled floating church. Volgograd was one of the host cities of the 2018 FIFA World Cup.[13]

Etymology[edit]

Tsaritsyn has been linked to Turkic Sāriğšin or *Sāriğsın meaning «Yellow tomb» or Sāriğšın «City of the Yellow (Golden) Throne».[14]

History[edit]

Tsaritsyn[edit]

Although the city may have originated in 1555, documented evidence of Tsaritsyn at the confluence of the Tsaritsa [ru] and Volga rivers dates from 1589.[4] Grigori Zasekin established the fortress Sary Su («yellow water» in the local Tatar language), or Sary Sin («yellow river»), as part of the defenses of the unstable southern border of the Tsardom of Russia. The structure stood slightly above the mouth of the Tsaritsa River on the right bank. It soon became the nucleus of a trading settlement.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the garrison consisted of 350 to 400 people. In 1607 the fortress garrison rebelled for six months against the troops of Tsar Vasili Shuisky. In the following year saw the construction of the first stone church in the city, dedicated to St. John the Baptist.

In 1670 troops of Stepan Razin captured the fortress; they left after a month. In 1708 the insurgent Cossack Kondraty Bulavin (died July 1708) held the fortress. In 1717 in the Kuban pogrom [ru], raiders from the Kuban under the command of the Crimean Tatar Bakhti Gerai [ru] blockaded the town and enslaved thousands in the area. In August 1774 Cossack leader Yemelyan Pugachev unsuccessfully attempted to storm the city.

In 1691 Moscow established a customs-post at Tsaritsyn.[15] In 1708 Tsaritsyn was assigned to the Kazan Governorate; in 1719[citation needed] to the Astrakhan Governorate. According to the census in 1720, the city had a population of 408 people. In 1773 the settlement was designated as a provincial and district town. From 1779 it belonged to the Saratov Viceroyalty. In 1780 the city came under the newly established Saratov Governorate.

In the nineteenth century, Tsaritsyn became an important river-port and commercial center. As a result, it also became a hub for migrant workers; in 1895 alone, over 50,000 peasant migrants came to Tsaritsyn in search of work.[16] The population expanded rapidly, increasing from fewer than 3,000 people in 1807 to about 84,000 in 1900. By 1914, the population had again jumped and was estimated at 130,000.[17] Sources show 893 Jews registered as living there in 1897, with the number exceeding 2,000 by the middle of the 1920s.[18] At the turn of the nineteenth century, Tsaritsyn was essentially a frontier town; almost all of the structures were wooden, with neither paved roads nor electricity.[17] The first railway reached the town in 1862. The first theatre opened in 1872, the first cinema in 1907. In 1913 Tsaritsyn got its first tram-line, and the city’s first electric lights were installed in the city center.

Between 1903 and 1907, the area was one of the least healthy in Europe, with a mortality rate of 33.6 for every 1000 persons. Untreated sewage spilled into the river, causing several cholera epidemics between 1907 and 1910.[17] Although the region had an active Sanitary Executive Commission that sent out instructions on the best ways to prevent outbreaks and dispatched a delegate from the Anti-Plague Commission to Tsaritsyn in 1907, local municipal officials did not put any precautions into place, citing economic considerations. The city’s drinking water came directly from the river, the intake pipe dangerously close to both the port and the sewage drain. There were neither funds nor political will to close the port (the main hub of economic activity) or move the intake pipes. As a result, in the three years spanning 1908 to 1910, Tsaritsyn lost 1,045 people to cholera. With a population of only 102,452 at the time, that amounts to a staggering 1.01% loss of the population.[16]

Between 1908 and 1911, Tsaritsyn was home to Sergei Trufanov, also known as the ‘mad monk’ Iliodor. He spent most of his time causing infighting and power struggles within the Russian Orthodox Church, fomenting anti-semitic zeal and violence in local populations, attacking the press, denouncing local municipal officials and causing unrest wherever he went. The most permanent mark he left on the city was the Holy Spirit Monastery (Russian: Свято-Духовский монастырь), built in 1909, parts of which still stand today.[17]

In light of the explosive population growth, the lack of political action on sanitation and housing, the multiple epidemics and the presence of volatile personalities, it is no surprise that the lower Volga region was a hotbed of revolutionary activity and civil unrest. The inability of the Tsarist government to provide basic protections from cholera on the one hand and subjecting the populace to strict but ineffective health measures on the other, caused multiple riots in 1829, in the 1890’s and throughout the first decade of the 1900s, setting the stage for multiple Russian revolutions and adding fuel to the political fire.[16] During the Russian Civil War of 1917–1923, Tsaritsyn came under Soviet control from November 1917. In 1918 White Movement troops under Pyotr Krasnov, the Ataman of the Don Cossack Host, besieged Tsaritsyn. The Reds repulsed three assaults by the Whites. However, in June 1919 the White Armed Forces of South Russia, under the command of General Denikin, captured Tsaritsyn, and held it until January 1920. The fighting from July 1918 to January 1920 became known as the Battle for Tsaritsyn.

-

1636 View of Tsaritsyn

-

Pre-revolutionary Tsaritsyn

-

1914 City tram on Gogolya St.

Stalingrad[edit]

On April 10, 1925, the city was renamed Stalingrad, in honor of Joseph Stalin, General Secretary of the Communist Party.[19][20] This was officially to recognize the city and Stalin’s role in its defense against the Whites between 1918 and 1920.[21]

Once the Soviets established control, ethnic and religious minorities were targeted. The only Jewish school in the area was closed down in 1926.[18] In 1928, a campaign was launched by the Regional Executive Council to close down the synagogue in Stalingrad. Due to local pushback, they were not successful until 1929, when the council convened a Special Commission. The Commission convinced local municipal powers that the building was in need of major repairs, was unsafe and much too small for the over 800 worshippers who regularly showed up for high holidays.[18]

In 1931, the German settlement-colony Old Sarepta (founded in 1765) became a district of Stalingrad. Renamed Krasnoarmeysky Rayon (or «Red Army District»), it was the largest area of the city. The first higher education institute was opened in 1930. A year later, the Stalingrad Industrial Pedagogical Institute, now Volgograd State Pedagogical University, was opened. Under Stalin, the city became a center of heavy industry and transshipment by rail and river.

Battle of Stalingrad[edit]

Street in Stalingrad, 1942

Factory after bombing, 1943

During World War II, German and Axis forces attacked the city, and in 1942 it was the site of one of the pivotal battles of the war. The Battle of Stalingrad was the deadliest single battle in the history of warfare (casualties estimates vary between 1,250,000[22] and 1,798,619[23]).

The battle began on August 23, 1942, and on the same day, the city suffered heavy aerial bombardment that reduced most of it to rubble. Martial law had already been declared in the city on July 14. By September, the fighting reached the city center. The fighting was of unprecedented intensity; the city’s central railway station changed hands thirteen times, and the Mamayev Kurgan (one of the highest points of the city) was captured and recaptured eight times.

By early November, the German forces controlled 90 percent of the city and had cornered the Soviets in two narrow pockets, but they were unable to eliminate the last pockets of Soviet resistance before Soviet forces launched a huge counterattack on November 19. This resulted in the Soviet encirclement of the German Sixth Army and other Axis units. On January 31, 1943 the Sixth Army’s commander, Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus, surrendered, and by February 2, with the elimination of straggling German troops, the Battle of Stalingrad was over.

The bombing campaign and five months of fighting that followed utterly destroyed 99% of the city.[24]

In 1945 the Soviet Union awarded Stalingrad the title Hero City for its resistance. Great Britain’s King George VI awarded the citizens of Stalingrad the jeweled «Sword of Stalingrad» in recognition of their bravery.

A number of cities around the world (especially those that had suffered similar wartime devastation) established sister, friendship, and twinning links (see list below) in the spirit of solidarity or reconciliation. One of the first «sister city» projects was that established during World War II between Stalingrad and Coventry in the United Kingdom; both had suffered extensive devastation from aerial bombardment. In March 2022 this twinning link was paused because of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[25]

Volgograd[edit]

Building of the Oblast Duma

On 10 November 1961, Nikita Khrushchev’s administration changed the name of the city to Volgograd («Volga City») as part of his programme of de-Stalinization following Stalin’s death. This action was and remains somewhat controversial, because Stalingrad has such importance as a symbol of resistance during World War II.

During Konstantin Chernenko’s brief rule in 1984, proposals were floated to revive the city’s Stalinist name for that reason. There was a strong degree of local support for a reversion, but the Russian government did not accept such proposals.[citation needed]

On May 21, 2007, Roman Grebennikov of Communist Party was elected as mayor with 32.47% of the vote, a plurality. Grebennikov became Russia’s youngest mayor of a federal subject administrative center at the time.

In 2010, Russian monarchists and leaders of the Orthodox organizations demanded that the city should take back its original name of Tsaritsyn, but the authorities rejected their proposal.

On January 30, 2013, the Volgograd City Council passed a measure to use the title «Hero City Stalingrad» in city statements on nine specific dates annually.[26][27][28] On the following dates, the title «Hero City Stalingrad» can officially be used in celebrations:

- February 2 (end of the Battle of Stalingrad),

- February 23 (Defender of the Fatherland Day),

- May 9 (Victory Day),

- June 22 (start of Operation Barbarossa),

- August 23 (start of the Battle of Stalingrad),

- September 2 (Victory over Japan Day),

- November 19 (start of Operation Uranus),

- December 9 (Day of the Fatherland’s Heroes)[26]

In addition, 50,000 people signed a petition to Vladimir Putin, asking that the city’s name be permanently changed to Stalingrad.[27] President Putin has replied that such a move should be preceded by a local referendum and that the Russian authorities will look into how to bring about such a referendum.[29]

Politics[edit]

In 2011, the City Duma canceled direct election of the mayor and confirmed the position of City Manager. This was short-lived, as in March 2012, Volgograd residents voted for relevant amendments to the city charter to reinstate the direct mayoral elections.[30]

Administrative and municipal status[edit]

View of Voroshilovsky City District of Volgograd

Volgograd is the administrative center of Volgograd Oblast.[31] Within the framework of administrative divisions, it is incorporated as the city of oblast significance of Volgograd—an administrative unit with the status equal to that of the districts.[2] As a municipal division, the city of oblast significance of Volgograd is incorporated as Volgograd Urban Okrug.[8]

Economy[edit]

Although the city was on an important trade route for moving timber, grain, cotton, cast iron, fish, salt and linseed oil, the economic reach of the Volga was relatively small. When the first rail lines were linked up to Moscow in 1871, this isolated area was suddenly and efficiently connected to the rest of the empire. Thanks to that connection, the province became a major producer, processor and exporter of grain, supplying most of Russia. By the 1890s, the economy of Volgograd (then Tsaritsyn), relied mainly on the trade of grain, naphtha, fish and salt.[16] Modern Volgograd remains an important industrial city. Industries include shipbuilding, oil refining, steel and aluminum production, manufacture of heavy machinery and vehicles at the Volgograd Tractor Plant and Titan-Barrikady plant, and chemical production. The large Volgograd Hydroelectric Plant is a short distance to the north of Volgograd.

Transportation[edit]

Volgograd is a major railway junction served by the Privolzhskaya Railway. Rail links from the Volgograd railway station include Moscow; Saratov; Astrakhan; the Donbas region of Ukraine; the Caucasus and Siberia. It stands at the east end of the Volga–Don Canal, opened in 1952 to link the two great rivers of Southern Russia. European route E40, the longest European route connecting Calais in France with Ridder in Kazakhstan, passes through Volgograd. The M6 highway between Moscow and the Caspian Sea also passes through the city. The Volgograd Bridge, under construction since 1995, was inaugurated in October 2009.[32] The city river terminal is the center for local passenger shipping along the Volga River.

The Volgograd International Airport provides air links to major Russian cities as well as Antalya, Yerevan and Aktau.

Volgograd’s public transport system includes a light rail service known as the Volgograd Metrotram. Local public transport is provided by buses, trolleybuses and trams.

The Volga River still is a very important communication channel.

-

-

-

Riverboat Station

Population[edit]

|

|

Ethnic composition[edit]

At the time of the official 2010 Census, the ethnic makeup of the city’s population whose ethnicity was known (999,785) was:[36]

| Ethnicity | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Russians | 922,321 | 92.3% |

| Armenians | 15,200 | 1.5% |

| Ukrainians | 12,216 | 1.2% |

| Tatars | 9,760 | 1.0% |

| Azerbaijanis | 6,679 | 0.7% |

| Kazakhs | 3,831 | 0.4% |

| Belarusians | 2,639 | 0.3% |

| Koreans | 2,389 | 0.2% |

| Others | 24,750 | 2.5% |

Culture[edit]

Mamayev Kurgan Memorial Complex[edit]

A memorial complex commemorating the battle of Stalingrad, dominated by an immense allegorical sculpture The Motherland Calls, was erected on the Mamayev Kurgan (Russian: Мамаев Курган), the hill that saw some of the most intense fighting during the battle. This complex includes the Hall of Military Glory, a circular building housing an eternal flame and bearing plaques with the names of the fallen heroes of the Battle of Stalingrad. This memorial features an hourly changing of the guard that draws many tourists during the warmer months. Across from this Hall, there is a statue called Mother’s Sorrow, which depicts a grieving woman holding a fallen soldier in her arms. During the summer months, this statue is surrounded by a small water feature, called the Lake of Tears. Further down the hill of this complex, there is a Plaza of Heroes (also known as Heroes’ Square), featuring multiple allegorical sculptures of heroic deeds. This plaza is sometimes referred to by the title of the most famous of these sculptures, called «Having withstood, we conquered death».

Panorama Museum[edit]

Panorama Museum of the Battle of Stalingrad, including Gerhardt’s Mill

The Panorama Museum of the Battle of Stalingrad is a large cultural complex that sits on the shore of the Volga river. It is located on the site of the «Penza Defense Junction», a group of buildings along Penzenskaya Street (now Sovetskaya Street), which was defended by the 13th Guards Rifle Division. The complex includes Gerhardt’s Mill, which is preserved in its bombed out state. The museum on the complex grounds houses the largest painting in Russia, a panoramic painting of the battlefield as seen from Mamayev Kurgan, where «The Motherland Calls» statue now stands. This museum also features Soviet military equipment from the 1940s, numerous exhibits of weapons (including a rifle of the famous sniper Vasily Zaytsev), uniforms, personal belongings of generals and soldiers involved in the battle and detailed maps and timelines of the battle.

Planetarium[edit]

The Volgograd Planetarium was a gift from East Germany in honor of what would have been Stalin’s 70th birthday.[37] Neoclassical in style, the building facade is designed like a Roman temple, with six Tuscan columns topped by capitals decorated with stars. Designed by Vera Ignatyevna Mukhina, the dome is crowned by a female personification of Peace, holding an astrolabe with a dove. Opened in 1954, it was only the second purpose-built planetarium in the Soviet Union. The entryway interior features a mural of Stalin in the white uniform of a naval admiral, surrounded by lilies and doves, more symbols of peace. On either side of the mural, are busts of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, a Soviet rocket scientist, and Yuri Gagarin, a Soviet pilot and cosmonaut and the first human to venture into outer space. On the second floor, there are large stained glass windows, featuring images related to Soviet space exploration. The planetarium was outfitted with a Zeiss projector, the first produced by the Carl Zeiss Company in their Jena plant after the end of World War 2.[38] The projector supplied was the UPP-23/1s model, which was produced between 1954 and 1964; it is still operational and in regular use at the Volgograd Planetarium. The projector was supplemented by a digital system in 2019; the Fulldome Pro model LDX12. Zeiss also provided the 365mm refractor telescope for the observatory, which is still in operation today.[39] The planetarium hosts scientific and educational lectures, provides Fulldome shows, has scheduled tours, features daytime and nighttime observations and runs an astronomy club for children.[40]

Other[edit]

Across the street from the Panorama Museum, stands Pavlov’s House, another surviving monument to the Battle of Stalingrad. Several monuments and memorials can be found nearby, including a statue of Lenin, a statue in honor of children who survived war and another to the Pavlov’s House defenders.

The Musical Instrument Museum is a branch of the Volgograd regional Museum of local lore.

Religion[edit]

As a port city along an important and busy trading route, Volgograd has always been a diverse place. An 1897 survey reveals 893 Jews (512 men and 381 women), 1,729 Muslims (938 men and 791 women), and 193 Catholics (116 men and 77 women).[41]

Holy Spirit Monastery[edit]

Holy Spirit Monastery, before 1923

Land for the Holy Spirit Monastery was originally allocated in 1904, but construction did not begin until 1909 and was not complete until 1911. Sergei Trufanov, also known as the ‘mad monk’ of Tsaritsyn, was the driving force behind fundraising and getting the project off the ground.[17] The original complex had a church that could accommodate 6,000 people, the monastery itself could house 500 and an auditorium that held 1,000. There was a school, space for workshops, a printing office and an almshouse. The land the monastery stood on also hosted multiple gardens, a fountain and several inner yards.[42]

In 1912, the monastery was divided to a male and female section, housing both monks and nuns. In 1914, the school on the grounds of the Holy Spirit Monastery became part of the city school system and in 1915, housed 53 girls whose fathers were on the front lines. During the Russian Civil War, an infirmary was set up and the complex was alternately used by both the Bolsheviks and the Whites. In 1923, once the area was under firm Bolshevik control, the monastery was closed. During the following decades, the complex was used as an orphanage, a library, a cinema and a student hostel. Eventually, many of the buildings fell into disuse and became dilapidated. At the onset of World War 2, the complex was given to the military and many of the original buildings were demolished.[43]

After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, the Volgograd diocese was established and the military began the process of transferring what was left of the Holy Spirit Monastery back to the church. A theological school was established in 1992 and restoration of the site continues today.[44]

Alexander Nevsky Cathedral[edit]

Original Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Tsaritsyn, before 1932

Construction of the cathedral began on April 22, 1901, with the laying of the foundation stone by Bishop Hermogenes. The domes were installed in 1915 and consecration took place on May 19, 1918. Almost as soon as it was built, the cathedral fell out of use. The Soviet powers closed it down officially in 1929, with the crosses and bells removed and the liturgical objects confiscated. The cathedral was then used as a motor depot and eventually demolished in 1932. In 2001, the long project of rebuilding the cathedral was begun. The first foundation stone was laid in 2016 and the finished replica was finally consecrated in 2021 by Patriarch Kirill.[45]

The new church stands in central Volgograd, bounded by Communist Street (Russian: Коммунистическая Улица) and Mir Street (Russian: Улица Мира) on the north and south and Volodarsk Street (Russian: Улица Володарского) and Gogol Street (Russian: Улица Гоголя) on the west and east, respectively. This area is also a park, called Alexander’s Garden (Russian: Александровский Сад). The cathedral stands across the street from a World War 2 monument, and a statue of and chapel for, the eponymous Alexander Nevsky.

Floating Churches[edit]

Original St.Nicholas floating church, consecrated in 1910

Volgograd hosts one of the few self-propelled floating churches in the world: the chapel boat of Saint Vladimir of Volgograd. Spearheaded by Vladimir Koretsky and assisted by a Dutch Orthodox priest who was part of the organization Aid to the Church in Need (ACN), the Saint Vladimir was consecrated in October 2004 on the shore of the Volga. Originally a decommissioned landing craft found in a shipyard outside St. Petersburg, it took two years to convert it into a floating church. The boat chapel sports three shining domes and was decorated with icons and religious motifs by a local Volgograd artist. On its maiden voyage, the Saint Vladimir reached Astrakhan in the south and Saratov in the north; traveling an 800 kilometer (~500 mile) span of the Volga River.[46]

In addition to this self propelled church, Vladimir Koretsky first built two other floating churches in Volgograd, both of which must be towed by another craft. The Saint Innocent was originally a repair vessel and was located in a shipyard in Volgograd. Despite it being in poor condition, the boat had good sized cabins and a kitchen unit; the hull was restored, the largest cabins were merged and a single shining dome was added. Icons and sacred relics were donated by parishes from all over the country and the floating church was consecrated on 22 May 1998. During its first year in operation, it visited 28 villages, where 446 people were baptised and 1,500 received communion. The Saint Innocent was mobile for four months of the year, operating mostly on the Don River, and spent the rest of the time moored in Pyatimorsk, providing a semi permanent church for that rural locality.[46]

Due to the success of the Saint Innocent, the ACN launched the creation of a second floating church, this time built atop an old barge. Christened the Saint Nicholas, in honor of the original floating church built in 1910, it was moored at a yacht club in Volgograd for several years, serving as a place of worship for passing ships crews. It was later towed to Oktyabrsky, a remote southern village of the Volgograd Oblast, to serve as a semi-permanent church.[46]

All of these floating churches were inspired by the original; a retrofitted tug-passenger steamer, which ran between Kazan and Astrakhan, named the Saint Nicholas. Commissioned in 1858, it was first christened the Kriushi, then the Pirate, until it was purchased by the Astrakhan diocese in 1910 and converted into a church. It served for 8 years, traveling up and down the Volga River, sometimes clocking 4,000 miles a year. Much like every other church in Russia, it was decommissioned in 1918 by the Soviets. It made such an impact on the local population however, that almost 80 years later, it was the inspiration for a new «flotilla of God».[46]

Volgograd Synagogue[edit]

First Volgograd Synagogue