Гуманитарная помощь — вид безвозмездной помощи (содействия); средства для жизни, бесплатно распространяемые среди населения районов, охваченных гуманитарной катастрофой или стоящих на её грани. Для условий вооруженного конфликта Международный суд ООН определил допустимую гуманитарную помощь как «предоставление продовольствия, одежды, лекарств и другой гуманитарной помощи, но это не включает предоставления оружия, систем вооружения, боеприпасов или другого оборудования, автотранспортных средств и материалов, которые могут быть использованы для причинения серьёзных телесных повреждений или явиться причиной смерти».

Все значения словосочетания «гуманитарная помощь»

-

Тот, кто имеет много, делится, голодающий получает гуманитарную помощь.

-

Когда привозят гуманитарную помощь, мы дружно становимся в очередь, чтоб дети наши не погибли с голоду.

-

Иногда им даже слали гуманитарную помощь, с неба, и они ещё больше убеждались, что нужно продолжать говорить в рацию из кокоса.

- (все предложения)

- продовольственная помощь

- оказание помощи

- фонд помощи

- оказывать помощь

- экономическая помощь

- (ещё синонимы…)

- помощь

- (ещё ассоциации…)

- гуманитарные науки

- бакалавр гуманитарных наук

- раздавать гуманитарную помощь

- (полная таблица сочетаемости…)

- скорая помощь

- помощь человека

- оказание помощи

- понадобилась помощь

- оказать помощь

- (полная таблица сочетаемости…)

- Разбор по составу слова «гуманитарный»

- Разбор по составу слова «помощь»

- Как правильно пишется слово «гуманитарный»

- Как правильно пишется слово «помощь»

Морфемный разбор слова:

Однокоренные слова к слову:

гуманитарная помощь

1 гуманитарная помощь

2 гуманитарная помощь

At first money transfers from private persons to private persons were not called “humanitarian aid”, but in August a new instruction was issued.

3 гуманитарная помощь

Тематики

4 гуманитарная помощь

5 гуманитарная помощь

6 гуманитарная помощь

7 гуманитарная помощь

8 гуманитарная помощь

9 гуманитарная помощь

См. также в других словарях:

Гуманитарная помощь — мероприятия, осуществляемые в целях облегчения тягот мирного населения в условиях войн, конфликтов и различных бедствий путем обеспечения населения жизненно необходимыми предметами потребления, которые проводят как в рамках операции по… … Словарь черезвычайных ситуаций

ГУМАНИТАРНАЯ ПОМОЩЬ — безвозмездная материальная помощь, оказываемая из гуманитарных соображений, исходя из чувства сострадания, заботы о ближних. Райзберг Б.А., Лозовский Л.Ш., Стародубцева Е.Б.. Современный экономический словарь. 2 е изд., испр. М.: ИНФРА М. 479 с … Экономический словарь

ГУМАНИТАРНАЯ ПОМОЩЬ — безвозмездная материальная помощь, оказываемая из гуманитарных соображений, исходя из чувства сострадания, заботы о ближних. Мероприятия, осуществляемые для облегчения страданий людей, особенно в обстоятельствах, когда ответственные органы власти … Юридическая энциклопедия

ГУМАНИТАРНАЯ ПОМОЩЬ — по законодательству РФ безвозмездно передаваемые юридическим и физическим лицам продовольствие, товары первой необходимости, иные предметы, направляемые из зарубежных стран в Россию для улучшения условий жизни и быта малообеспеченных групп… … Юридический словарь

гуманитарная помощь — — [http://www.iks media.ru/glossary/index.html?glossid=2400324] Тематики электросвязь, основные понятия EN humanitarian assistance … Справочник технического переводчика

Гуманитарная помощь — Берлинцы наблюдают за посадкой «изюмного бомбардировщика» в аэропорту Темпельхоф. 1948 г. Гуманитарная помощь вид безвозмездной помощи (содействия); средства для … Википедия

Гуманитарная помощь — всего лишь не военная помощь (смысл, несколько отличающийся от ассоциирующего понятия гуманитарные дисциплины ), то есть в западной терминологии помощь может быть либо военной (военное вмешательство), либо гуманитарной (другое вмешательство?) … Теоретические аспекты и основы экологической проблемы: толкователь слов и идеоматических выражений

ГУМАНИТАРНАЯ ПОМОЩЬ — безвозмездная материальная помощь, оказываемая из гуманитарных соображений, исходя та чувства сострадания, заботы о ближних … Энциклопедический словарь экономики и права

гуманитарная помощь — безвозмездная материальная помощь, оказываемая из гуманитарных соображений, исходя из чувства сострадания, заботы о ближних … Словарь экономических терминов

Гуманитарная помощь — Жарг. шк. Шутл. Подсказка. (Запись 2003 г.) … Большой словарь русских поговорок

гуманитарная помощь — по законодательству РФ безвозмездно передаваемые юридическим и физическим лицам продовольствие, товары первой необходимости, иные предметы, направляемые из зарубежных стран в Россию для улучшения условий жизни и быта малообеспеченных групп… … Большой юридический словарь

Источник

Гуманитарная помощь: особенности оказания и роль нашей страны

Для гуманитарной помощи характерна безотлагательность ее оказания, и этим она отличается от иностранной помощи. Претендовать на ее получение могут все пострадавшие от стихийных бедствий или военных действий. Обычно она организуется под предводительством ООН.

История гуманитарной помощи

Первыми, кто начал работать в этом направлении, были религиозные миссионеры европейского и североамериканского происхождения, которые вели свою деятельность на территории малоразвитых государств.

В первой половине 20 века добровольная гуманитарная помощь оказывалась пострадавшим от геноцида армянам. А в 20-х годах – жертвам голодомора на территории Поволжья.

Практика оказания гуманитарной помощи стала быстро расти после завершения Второй мировой. Такая деятельность велась как светскими, так и религиозными учреждениями. Особенно активно нарастали потоки жизненно важных грузов за последние 15 лет.

Цели гумпомощи

Гуманитарная помощь преследует следующие цели:

При оказании гуманитарной помощи стараются следовать следующим принципам: беспристрастности, гуманности и соблюдении нейтралитета.

Основными направлениями такой созидательной деятельности в критических ситуациях являются следующие:

Участие ООН

В составе Организации Объединенных наций есть специальное Управление, координирующее подобные действия. В 2008 году был принят единый день гуманитарной помощи.

Наиболее значительный вклад вносит Всемирная продовольственная программа при ООН, которая специализируется на предоставлении продуктов питания нуждающимся. Под ее предводительством такая помощь, в одном только 2006 году, была оказана 87,8 миллионам нуждающихся, включая 56 млн детей из 78 стран.

Также при ООН создан фонд для оказания детской помощи. Организация рекомендует направлять усилия на помощь детям тех стран, где происходят вооруженные конфликты, а также правительствам этих стран.

Оказание помощи беженцам

Такая практика возникла во времена Второй мировой войны для оказания помощи пострадавшим европейцам. Вопросы оказания такой помощи решаются при ООН. Значительные усилия были направлены на решение проблем беженцев из Палестины, потерявших свои дома и оставшихся без средств к существованию.

Современные тенденции

В последнее время наблюдается возрастание и объединение усилий со стороны международного сообщества в целях более масштабного осуществления гуманитарной деятельности, которая постепенно приобретает глобальные масштабы. Инициаторами таких миссий в последние годы являются как отдельные государства, так и международные организации.

Растет международное сотрудничество и кооперация различных стран в целях более слаженного и адекватного реагирования в случае масштабных происшествий и катастроф. Участвуют в этом, в частности, международные и межправительственные организации. Происходит интеграция их ресурсов и возможностей.

Отмечено усиление гуманитарной активности со стороны ООН и прочих международных организаций. Россия также стала принимать более активное участие в этом процессе. Курирует эту деятельность в нашей стране МЧС России. Помощь была оказана большому количеству стран, расположенных на разных континентах. Нашими спасателями были спасены тысячи людей. В места ЧП были доставлены необходимые грузы, медикаменты, продовольствие на общую сумму, исчисляемую миллиардами рублей. Таким образом, гуманитарная помощь России другим странам тоже заметно выросла. Все это способствует улучшению имиджа нашей страны на мировой арене.

Россия отправила гуманитарную помощь не только в страны дальнего зарубежья. В последние годы, в связи с обострением ситуации на востоке Украины, в нашей стране регулярно формируются конвои из грузовиков с продовольственными грузами, которые доставляются в Ростовскую область, а оттуда направляются по трассам регионального значения в город Луганск. Первые караваны грузовиков шли практически под прицелом украинских силовиков, а затем ситуация стала менее рискованной. Таким образом оказывается гуманитарная помощь Донбассу.

Источник

Значение слова «гуманитарный»

1. Относящийся к общественным наукам, изучающим человека и его культуру. Гуманитарное образование.

2. Устар. То же, что гуманный. Простая, ясная, подлинно гуманитарная справедливость говорит нам, что продукт труда должен принадлежать тому, кто его сделал, а не тому, кто приказал сделать. М. Горький, О культурах. Литература наших дней — подлинно народное и нужное всему народу высокое гуманитарное искусство. А. Н. Толстой, О литературе и войне.

Источник (печатная версия): Словарь русского языка: В 4-х т. / РАН, Ин-т лингвистич. исследований; Под ред. А. П. Евгеньевой. — 4-е изд., стер. — М.: Рус. яз.; Полиграфресурсы, 1999; (электронная версия): Фундаментальная электронная библиотека

ГУМАНИТА’РНЫЙ, ая, ое [от латин. humanitas — высокая образованность, букв. человечество] (книжн.). Относящийся к циклу наук о человеке и культуре (в противоп. наукам о природе). Гуманитарное образование. Гуманитарные науки.

Источник: «Толковый словарь русского языка» под редакцией Д. Н. Ушакова (1935-1940); (электронная версия): Фундаментальная электронная библиотека

гуманита́рный

1. связанный с научными дисциплинами, изучающими человека, человеческое общество, культуру ◆ Гуманитарные дисциплины.

2. связанный с правами человека ◆ Гуманитарная катастрофа.

Источник

Оказание гуманитарной помощи

Одна из целей Организации Объединенных Наций, как указано в ее Уставе, заключается в «осуществлении международного сотрудничества в разрешении международных проблем экономического, социального, культурного и гуманитарного характера». ООН впервые приступила к выполнению этой задачи после Второй мировой войны на разоренном Европейском континенте, который она помогала отстроить заново.

В настоящее время международное сообщество полагается на Организацию Объединенных Наций в вопросах координации операций по оказанию чрезвычайной и долгосрочной помощи, включая продовольствие, жилье, медицинские принадлежности и материально-техническую поддержку.

УКГВ и система ООН

«Каждый день просыпаюсь в надежде помочь. Помочь нуждающимся». Психотерапефт лагеря для ВПЛ Атма, которая и сама является переселенцем с 2012 года, регулярно посещает семьи перемещенных лиц, чтобы поговорить об их проблемах и предложить поддержку детям, потерявшим родителей. УКГВ

Управление по координации гуманитарных вопросов (УКГВ), являющееся частью Секретариата Организации Объединенных Наций, несет ответственность за объединение гуманитарных организаций в целях обеспечения согласованного реагирования на чрезвычайные ситуации. Эта задача решается посредством Межведомственного постоянного комитета, членами которого являются учреждения системы ООН, ответственные за оказание чрезвычайной помощи. Скоординированный общесистемный подход к оказанию гуманитарной помощи имеет важное значение для быстрого и эффективного содействия нуждающимся.

Мандат УКГВ сформулирован в резолюции 46/182 Генеральной Ассамблеи от декабря 1991 года, в которой говорится: «Руководящая роль Генерального секретаря имеет решающее значение и должна быть укреплена в целях обеспечения большей готовности к стихийным бедствиям и другим чрезвычайным ситуациям. Это должно быть достигнуто посредством скоординированной поддержки мер по предупреждению и обеспечению готовности и оптимального использования, в частности, межучрежденческого комитета, призывов к совместным действиям, центрального чрезвычайного оборотного фонда и реестра резервных потенциалов».

УКГВ и СЕРФ

2020 год был беспрецедентным с точки зрения испытаний, которым подверглись люди по всему миру. По линии СЕРФ в кратчайшие сроки была выделена рекордная сумма в 900 миллионов долларов США для оказания жизненно важной помощи в 52 странах. СЕРФ также предоставил 225 миллионов долларов США двадцати странам, которые не получали достаточного финансирования для борьбы с кризисом. Впервые в мире были выделены средства для борьбы с пандемией. Впервые за всю свою историю своей работы СЕРФ выделил средства неправительственным организациям, что помогло партнерским организациям, занимающимся предоставлением гуманитарной помощи, охватить наиболее нуждающиеся группы. СЕРФ

Центральный фонд реагирования на чрезвычайные ситуации (СЕРФ), управляемый УКГВ, является одним из самых быстрых и наиболее эффективных способов оказания поддержки оперативному гуманитарному реагированию на потребности людей, пострадавших в результате стихийных бедствий и вооруженных конфликтов. СЕРФ получает добровольные взносы круглогодично, чтобы обеспечить немедленное финансирование спасительных гуманитарных операций в любой точке мира.

Подразделения ООН, несущие главную ответственность за доставку гуманитарной помощи

Четыре подразделения ООН: ПРООН, УВКБ, ЮНИСЕФ и ВПП играют ведущую роль в деле оказания чрезвычайной помощи.

Всемирная организация здравоохранения (ВОЗ) осуществляет координацию международного реагирования на чрезвычайные ситуации в области здравоохранения.

Координация на национальном уровне

Программа развития Организации Объединенных Наций (ПРООН) отвечает за оперативную деятельность в целях смягчения последствий стихийных бедствий и готовности к ним. При возникновении чрезвычайных ситуаций координаторы-резиденты ПРООН призваны координировать усилия по оказанию помощи на национальном уровне.

ПРООН: Oбзор за 2020 год

Помощь беженцам

Управление Верховного комиссара ООН по делам беженцев ООН (УВКБ ООН) возникло после Второй мировой войны для оказания помощи перемещенным в ходе этого конфликта европейцам. Управление проводит и координирует международные действия по защите беженцев и решению проблем беженцев во всем мире.

Генеральная Ассамблея учредила Ближневосточное агентство Организации Объединенных Наций для помощи палестинским беженцам и организации работ (БАПОР) для оказания экстренной помощи 750000 палестинских беженцев, которые потеряли свои дома и средства к существованию в результате арабо-израильского конфликта 1948 года. Сегодня около 5 миллионов палестинских беженцев имеют право на услуги БАПОР.

19 сентября 2016 года Генеральная Ассамблея ООН провела заседание высокого уровня, посвященное масштабным перемещениям беженцев и мигрантов, с целью объединения усилий стран на основе более гуманного и скоординированного подхода.

УВКБ ООН: Что тебе нужно, чтобы согреться. Нил Гейман.

Помощь детям

С момента своего основания Детский фонд ООН (ЮНИСЕФ) стремится охватить своей деятельностью максимальное число детей путем принятия наиболее эффективных и недорогостоящих решений для противодействия самым серьезным угрозам для их выживания. ЮНИСЕФ также настоятельно рекомендует правительствам и воюющим сторонам повышать эффективность своих действий по защите детей.

Основные обязательства в отношении детей в ходе гуманитарных акций лежат в основе нормативных документов и гуманитарной деятельности ЮНИСЕФ. Именно этими обязательствами руководствуется ЮНИСЕФ в своей деятельности по защите прав детей в условиях гуманитарных кризисов. Основные обязательства обеспечивают соблюдение принципов равенства, транспарентности, ответственного и ориентированного на конечный результат подхода, что позволяет последовательно и своевременно осуществлять гуманитарную деятельность на коллективной основе.

ЮНИСЕФ: Призыв к действию, Генриетта Х. Форе

Искоренение голода

The Всемирная продовольственная программа ООН (ВПП) обеспечивает оказание помощи миллионам людей, которые становятся жертвами стихийных бедствий, конфликтов и чрезвычайных ситуаций. Она отвечает за мобилизацию продовольствия и средств для его транспортировки в рамках всех крупномасштабных операций помощи беженцам, координируемых УВКБ.

Продовольственная и сельскохозяйственная организация Объединенных Наций (ФАО) часто помогает фермерам после наводнений, вспышек эпидемий скота и аналогичных чрезвычайных ситуаций.

Глобальная система информации и раннего оповещения ФАО в области продовольствия и сельского хозяйства непрерывно отслеживает перспективы производства зерновых культур и ситуацию с продовольственной безопасностью на глобальном, региональном, национальном и субнациональном уровнях и предупреждает о возникновении продовольственных проблем и чрезвычайных ситуаций.

ФАО: Глобальный отчет о продовольственных кризисах 2020 года, Доминик Бюржон.

Здравоохранение

В рамках системы Организации Объединенных Наций Отдел чрезвычайной и гуманитарной помощи Всемирной организации здравоохранения (ВОЗ) осуществляет координацию международного реагирования на чрезвычайные ситуации в области здравоохранения. ВОЗ несет ответственность за обеспечение ведущей роли при решении проблем глобального здравоохранения, формирования повестки дня в области медицинских исследований, установления норм и стандартов, разработки научно обоснованных директив, обеспечения технической поддержки странам, а также мониторинга и оценки тенденций в области здравоохранения.

В 21-м веке здоровье является общей ответственностью, включая равный доступ к первичной помощи и коллективную защиту от транснациональных угроз.

ВОЗ: Глобальный ответ на глобальную пандемию

Где находятся организации ООН, занимающиеся оказанием гуманитарной помощи?

Управление по координации гуманитарных вопросов (УКГВ)

Расположенное в штаб-квартире ООН в Нью-Йорке Управление по координации гуманитарных вопросов (УКГВ, часть Секретариата ООН) имеет региональные и страновые отделения в Западной и Центральной Африке, на Ближнем Востоке и в Северной Африке, в Азии и Тихоокеанском регионе, Южной и Восточной Африке, Латинской Америке и Карибском бассейне, а также группы советников по гуманитарным вопросам во многих странах.

Источник

Оказание гуманитарной помощи

Одна из целей Организации Объединенных Наций, как указано в ее Уставе, заключается в «осуществлении международного сотрудничества в разрешении международных проблем экономического, социального, культурного и гуманитарного характера». ООН впервые приступила к выполнению этой задачи после Второй мировой войны на разоренном Европейском континенте, который она помогала отстроить заново.

В настоящее время международное сообщество полагается на Организацию Объединенных Наций в вопросах координации операций по оказанию чрезвычайной и долгосрочной помощи, включая продовольствие, жилье, медицинские принадлежности и материально-техническую поддержку.

УКГВ и система ООН

«Каждый день просыпаюсь в надежде помочь. Помочь нуждающимся». Психотерапефт лагеря для ВПЛ Атма, которая и сама является переселенцем с 2012 года, регулярно посещает семьи перемещенных лиц, чтобы поговорить об их проблемах и предложить поддержку детям, потерявшим родителей. УКГВ

Управление по координации гуманитарных вопросов (УКГВ), являющееся частью Секретариата Организации Объединенных Наций, несет ответственность за объединение гуманитарных организаций в целях обеспечения согласованного реагирования на чрезвычайные ситуации. Эта задача решается посредством Межведомственного постоянного комитета, членами которого являются учреждения системы ООН, ответственные за оказание чрезвычайной помощи. Скоординированный общесистемный подход к оказанию гуманитарной помощи имеет важное значение для быстрого и эффективного содействия нуждающимся.

Мандат УКГВ сформулирован в резолюции 46/182 Генеральной Ассамблеи от декабря 1991 года, в которой говорится: «Руководящая роль Генерального секретаря имеет решающее значение и должна быть укреплена в целях обеспечения большей готовности к стихийным бедствиям и другим чрезвычайным ситуациям. Это должно быть достигнуто посредством скоординированной поддержки мер по предупреждению и обеспечению готовности и оптимального использования, в частности, межучрежденческого комитета, призывов к совместным действиям, центрального чрезвычайного оборотного фонда и реестра резервных потенциалов».

УКГВ и СЕРФ

2020 год был беспрецедентным с точки зрения испытаний, которым подверглись люди по всему миру. По линии СЕРФ в кратчайшие сроки была выделена рекордная сумма в 900 миллионов долларов США для оказания жизненно важной помощи в 52 странах. СЕРФ также предоставил 225 миллионов долларов США двадцати странам, которые не получали достаточного финансирования для борьбы с кризисом. Впервые в мире были выделены средства для борьбы с пандемией. Впервые за всю свою историю своей работы СЕРФ выделил средства неправительственным организациям, что помогло партнерским организациям, занимающимся предоставлением гуманитарной помощи, охватить наиболее нуждающиеся группы. СЕРФ

Центральный фонд реагирования на чрезвычайные ситуации (СЕРФ), управляемый УКГВ, является одним из самых быстрых и наиболее эффективных способов оказания поддержки оперативному гуманитарному реагированию на потребности людей, пострадавших в результате стихийных бедствий и вооруженных конфликтов. СЕРФ получает добровольные взносы круглогодично, чтобы обеспечить немедленное финансирование спасительных гуманитарных операций в любой точке мира.

Подразделения ООН, несущие главную ответственность за доставку гуманитарной помощи

Четыре подразделения ООН: ПРООН, УВКБ, ЮНИСЕФ и ВПП играют ведущую роль в деле оказания чрезвычайной помощи.

Всемирная организация здравоохранения (ВОЗ) осуществляет координацию международного реагирования на чрезвычайные ситуации в области здравоохранения.

Координация на национальном уровне

Программа развития Организации Объединенных Наций (ПРООН) отвечает за оперативную деятельность в целях смягчения последствий стихийных бедствий и готовности к ним. При возникновении чрезвычайных ситуаций координаторы-резиденты ПРООН призваны координировать усилия по оказанию помощи на национальном уровне.

ПРООН: Oбзор за 2020 год

Помощь беженцам

Управление Верховного комиссара ООН по делам беженцев ООН (УВКБ ООН) возникло после Второй мировой войны для оказания помощи перемещенным в ходе этого конфликта европейцам. Управление проводит и координирует международные действия по защите беженцев и решению проблем беженцев во всем мире.

Генеральная Ассамблея учредила Ближневосточное агентство Организации Объединенных Наций для помощи палестинским беженцам и организации работ (БАПОР) для оказания экстренной помощи 750000 палестинских беженцев, которые потеряли свои дома и средства к существованию в результате арабо-израильского конфликта 1948 года. Сегодня около 5 миллионов палестинских беженцев имеют право на услуги БАПОР.

19 сентября 2016 года Генеральная Ассамблея ООН провела заседание высокого уровня, посвященное масштабным перемещениям беженцев и мигрантов, с целью объединения усилий стран на основе более гуманного и скоординированного подхода.

УВКБ ООН: Что тебе нужно, чтобы согреться. Нил Гейман.

Помощь детям

С момента своего основания Детский фонд ООН (ЮНИСЕФ) стремится охватить своей деятельностью максимальное число детей путем принятия наиболее эффективных и недорогостоящих решений для противодействия самым серьезным угрозам для их выживания. ЮНИСЕФ также настоятельно рекомендует правительствам и воюющим сторонам повышать эффективность своих действий по защите детей.

Основные обязательства в отношении детей в ходе гуманитарных акций лежат в основе нормативных документов и гуманитарной деятельности ЮНИСЕФ. Именно этими обязательствами руководствуется ЮНИСЕФ в своей деятельности по защите прав детей в условиях гуманитарных кризисов. Основные обязательства обеспечивают соблюдение принципов равенства, транспарентности, ответственного и ориентированного на конечный результат подхода, что позволяет последовательно и своевременно осуществлять гуманитарную деятельность на коллективной основе.

ЮНИСЕФ: Призыв к действию, Генриетта Х. Форе

Искоренение голода

The Всемирная продовольственная программа ООН (ВПП) обеспечивает оказание помощи миллионам людей, которые становятся жертвами стихийных бедствий, конфликтов и чрезвычайных ситуаций. Она отвечает за мобилизацию продовольствия и средств для его транспортировки в рамках всех крупномасштабных операций помощи беженцам, координируемых УВКБ.

Продовольственная и сельскохозяйственная организация Объединенных Наций (ФАО) часто помогает фермерам после наводнений, вспышек эпидемий скота и аналогичных чрезвычайных ситуаций.

Глобальная система информации и раннего оповещения ФАО в области продовольствия и сельского хозяйства непрерывно отслеживает перспективы производства зерновых культур и ситуацию с продовольственной безопасностью на глобальном, региональном, национальном и субнациональном уровнях и предупреждает о возникновении продовольственных проблем и чрезвычайных ситуаций.

ФАО: Глобальный отчет о продовольственных кризисах 2020 года, Доминик Бюржон.

Здравоохранение

В рамках системы Организации Объединенных Наций Отдел чрезвычайной и гуманитарной помощи Всемирной организации здравоохранения (ВОЗ) осуществляет координацию международного реагирования на чрезвычайные ситуации в области здравоохранения. ВОЗ несет ответственность за обеспечение ведущей роли при решении проблем глобального здравоохранения, формирования повестки дня в области медицинских исследований, установления норм и стандартов, разработки научно обоснованных директив, обеспечения технической поддержки странам, а также мониторинга и оценки тенденций в области здравоохранения.

В 21-м веке здоровье является общей ответственностью, включая равный доступ к первичной помощи и коллективную защиту от транснациональных угроз.

ВОЗ: Глобальный ответ на глобальную пандемию

Где находятся организации ООН, занимающиеся оказанием гуманитарной помощи?

Управление по координации гуманитарных вопросов (УКГВ)

Расположенное в штаб-квартире ООН в Нью-Йорке Управление по координации гуманитарных вопросов (УКГВ, часть Секретариата ООН) имеет региональные и страновые отделения в Западной и Центральной Африке, на Ближнем Востоке и в Северной Африке, в Азии и Тихоокеанском регионе, Южной и Восточной Африке, Латинской Америке и Карибском бассейне, а также группы советников по гуманитарным вопросам во многих странах.

Источник

Теперь вы знаете какие однокоренные слова подходят к слову Как пишется гуманитарная помощь, а так же какой у него корень, приставка, суффикс и окончание. Вы можете дополнить список однокоренных слов к слову «Как пишется гуманитарная помощь», предложив свой вариант в комментариях ниже, а также выразить свое несогласие проведенным с морфемным разбором.

Как написать слово «гуманитарный» правильно? Где поставить ударение, сколько в слове ударных и безударных гласных и согласных букв? Как проверить слово «гуманитарный»?

гуманита́рный

Правильное написание — гуманитарный, ударение падает на букву: а, безударными гласными являются: у, а, и, ы.

Выделим согласные буквы — гуманитарный, к согласным относятся: г, м, н, т, р, й, звонкие согласные: г, м, н, р, й, глухие согласные: т.

Количество букв и слогов:

- букв — 12,

- слогов — 5,

- гласных — 5,

- согласных — 7.

Формы слова: гуманита́рный.

толковый словарь

прил.

1. Связанный с научными дисциплинами, изучающими человеческое общество, человека и его культуру.

2. Связанный с правами и интересами человека, обращенный к человеческой личности.

3. Осуществляемый из гуманных соображений; бескорыстный.

ГУМАНИТА́РНЫЙ — прил., употр. сравн. часто

1. Гуманитарными называют такие науки, специальности, образование и т. п., которые связаны с изучением культурного наследия человеческого общества, например истории, философии, литературы.

Он поступил в гуманитарный вуз. | Помимо технических, в этом университете преподают и гуманитарные дисциплины.

2. Гуманитарная помощь — это продукты, одежда и медикаменты, которые посылают людям, оказавшимся в трудном положении в какой-либо части земли.

Различные страны через отделения Красного Креста предоставляют беженцам гуманитарную помощь.

3. Гуманитарная катастрофа — это ситуация, при которой большое количество людей оказывается в бедственном положении.

Серьёзные последствия наводнения в этом регионе обозреватели называют гуманитарной катастрофой.

толковый словарь ушакова

ГУМАНИТА́РНЫЙ, гуманитарная, гуманитарное (от лат. humanitas — высокая образованность, букв. человечество) (книжн.). Относящийся к циклу наук о человеке и культуре (в противоп. наукам о природе). Гуманитарное образование. Гуманитарные науки.

толковый словарь ожегова

ГУМАНИТА́РНЫЙ, -ая, -ое; -рен, -рна.

1. Обращённый к человеческой личности, к правам и интересам человека. Гуманитарные проблемы. Гуманитарная помощь (бескорыстная помощь нуждающимся).

2. полн. О науках: относящийся к изучению общества, культуры и истории народа в отличие от естественных и технических наук. Гуманитарное образование (основанное на изучении таких наук).

| сущ. гуманитарность, -и, жен. (к 1 знач.).

популярный словарь

Гуманитарный

-ая, -ое

1) О науках: относящийся к изучению человеческого общества, его истории и культуры.

Гуманитарное образование.

2) Обращенный к человеку, к его правам и интересам, человеколюбивый.

Гуманитарный груз.

Гуманитарная помощь.

Синонимы:

благотвори́тельный

Родственные слова:

гуманита́рность

Этимология:

От французского humanitaire ‘гуманитарный’, ‘человеколюбивый’, ‘гуманный’ (← лат. humanitas ‘человеческая природа’, ‘человеческое достоинство’, ‘человеколюбие’, ‘образованность’, ‘духовная культура’). В русском языке — с середины XIX в., первоначально применительно к общественным наукам.

Гуманита́рное пра́во — нормы международного права, направленные на защиту прав и свобод человека.

энциклопедический словарь

ГУМАНИТА́РНЫЙ -ая, -ое. [франц. humanitaire, от лат. humanitas — человеческая природа, образованность]

1. Относящийся к наукам, изучающим историю и культуру человеческого общества. Г-ые науки (общественные науки: философия, история, литературоведение, языкознание и т.п. в отличие от естественных и технических). Г-ое образование (основанное на таких науках). Г. институт (дающий такое образование).

2. Основанный на любви к человеку и заботе о нём. Г-ая помощь.

* * *

гуманита́рный (франц. humanitaire, от лат. humanitas — человеческая природа, образованность), обращённый к человеческой личности, к правам и интересам человека, например гуманитарные проблемы, гуманитарная помощь, гуманитарные науки (филология, искусствознание, история и т. п.).

* * *

ГУМАНИТАРНЫЙ — ГУМАНИТА́РНЫЙ (франц. humanitaire, от лат. humanitas — человеческая природа, образованность), обращенный к человеческой личности, к правам и интересам человека, напр. гуманитарные проблемы, гуманитарная помощь, гуманитарные науки (филология, искусство, история и т. п.).

большой энциклопедический словарь

ГУМАНИТАРНЫЙ (франц. humanitaire — от лат. humanitas — человеческая природа, образованность), обращенный к человеческой личности, к правам и интересам человека, напр. гуманитарные проблемы, гуманитарная помощь, гуманитарные науки (филология, искусство, история и т. п.).

академический словарь

-ая, -ое.

1. Относящийся к общественным наукам, изучающим человека и его культуру.

Гуманитарное образование.

2. устар.

То же, что гуманный.

Простая, ясная, подлинно гуманитарная справедливость говорит нам, что продукт труда должен принадлежать тому, кто его сделал, а не тому, кто приказал сделать. М. Горький, О культурах.

Литература наших дней — подлинно народное и нужное всему народу высокое гуманитарное искусство. А. Н. Толстой, О литературе и войне.

иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

ГУМАНИТАРНЫЙ (французское humanitaire, от латинского humanitas — человеческая природа, образованность), обращенный к человеческой личности, к правам и интересам человека, например гуманитарные проблемы, гуманитарная помощь, гуманитарные науки (филология, искусствознание, история и т.п.). Сравни также Гуманный.

орфографический словарь

словарь ударений

формы слов

гуманита́рный, гуманита́рная, гуманита́рное, гуманита́рные, гуманита́рного, гуманита́рной, гуманита́рных, гуманита́рному, гуманита́рным, гуманита́рную, гуманита́рною, гуманита́рными, гуманита́рном, гуманита́рен, гуманита́рна, гуманита́рно, гуманита́рны, гуманита́рнее, погуманита́рнее, гуманита́рней, погуманита́рней

синонимы

прил., кол-во синонимов: 2

морфемно-орфографический словарь

грамматический словарь

словарь галлицизмов русского языка

ГУМАНИТАРНЫЙ ая, ое. humanitaire adj.

. Связанный с науками, изучающими человеческое общество, человека и его культуру. Гуманитарное образование. БАС-2. В idées sociales, humanitaires Вяземский видит раскрашенных курв, бродящих по-миру. 1843. А.Тургенев — П. Вяземскому. // ОАВ 4 244. Так, литература эта, преследуя незыблемые духовные интересы, делалась, однакож, попеременно романтическою, легитимическою, гуманитарною, следуя шаг за шагом за господствующим направлением. 1846. Анненков Париж. письма 152. || Связанный с правами и интересами человека обращенный к человеческой личности. Гуманитарная помощь. Сотрудничество в гуманитарной сфере. БАС-2. Бетховен смотрел на симфонии гораздо серьезнее, чем его предшественники, сфера поэзии его была несравненно шире, глубже, всемирнее, как говорят иначе, «гуманитарнее» (тогда как у Гайдна, отчасти и у Моцарта, сфера поэзии иногда чисто немецкая). 1852. А. Серов Ст. о муз. 1 235. Встретил я однажды одного знакомого первоклассника в новых джинсах и спросил, откуда у него такая обнова. Не мама ли с папой купили. — Нет, — ответил мальчик, штаны гуманитарные. Из гуманитарной, стало быть, помощи. Я не поленился узнать, что же это слово. по его мнению обозначает. Ответ поступил незамедли гуманитарный — значит бесплатный. Нева 1997 5 178.

словарь иностранных слов

ГУМАНИТАРНЫЙ [< лат. humanitas — человеческая природа] — 1) относящийся к общественным наукам, изучающим человека и его культуру; 2) гуманный, человеколюбивый, благотворительный.

полезные сервисы

«Succour» redirects here. For the album, see Succour (album).

Humanitarian aid is material and logistic assistance to people who need help. It is usually short-term help until the long-term help by the government and other institutions replaces it. Among the people in need are the homeless, refugees, and victims of natural disasters, wars, and famines. Humanitarian relief efforts are provided for humanitarian purposes and include natural disasters and man-made disasters. The primary objective of humanitarian aid is to save lives, alleviate suffering, and maintain human dignity. It may, therefore, be distinguished from development aid, which seeks to address the underlying socioeconomic factors which may have led to a crisis or emergency. There is a debate on linking humanitarian aid and development efforts, which was reinforced by the World Humanitarian Summit in 2016. However, the conflation is viewed critically by practitioners.[1]

Humanitarian aid is seen as «a fundamental expression of the universal value of solidarity between people and a moral imperative».[2] Humanitarian aid can come from either local or international communities. In reaching out to international communities, the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)[3] of the United Nations (UN) is responsible for coordination responses to emergencies. It taps to the various members of Inter-Agency Standing Committee, whose members are responsible for providing emergency relief. The four UN entities that have primary roles in delivering humanitarian aid are United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Food Programme (WFP).[4]

Humanitarian Aid being distributed in Haiti

The International Committee of the Red Cross understands humanitarian relief as a norm in both international and non-international armed conflicts, and countries or war parties that prevent humanitarian relief are generally widely criticized.[5] According to The Overseas Development Institute, a London-based research establishment, whose findings were released in April 2009 in the paper «Providing aid in insecure environments: 2009 Update», the most lethal year for aid providers in the history of humanitarianism was 2008, in which 122 aid workers were murdered and 260 assaulted. The countries deemed least safe were Somalia and Afghanistan.[6] In 2014, Humanitarian Outcomes reported that the countries with the highest incidents were: Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Pakistan, Somalia, Yemen and Kenya.[7]

According to the Global Humanitarian Overview of OCHA, 274 million people need humanitarian assistance and protection in 2022, or 1 out of 29 people worldwide.[8]

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

The beginnings of organized international humanitarian aid can be traced to the late 19th century. Early campaigns include British aid to distressed populations on the continent and in Sweden during the Napoleonic Wars,[9][10] and the international relief campaigns during the Great Irish Famine in the 1840s.[11][12]

In 1854, when the Crimean War began[13] Florence Nightingale and her team of 38 nurses arrived to Barracks Hospital of Scutari where there were thousands of sick and wounded soldiers.[14] Nightingale and her team watched as the understaffed military hospitals struggled to maintain hygienic conditions and meet the needs of patients.[13] Ten times more soldiers were dying of disease than from battle wounds.[15] Typhus, typhoid, cholera and dysentery were common in the army hospitals.[15] Nightingale and her team established a kitchen, laundry and increased hygiene. More nurses arrived to aid in the efforts and the General Hospital at Scutari was able to care for 6,000 patients.[14]

Nightingale’s contributions still influence humanitarian aid efforts. This is especially true in regard to Nightingale’s use of statistics and measures of mortality and morbidity. Nightingale used principles of new science and statistics to measure progress and plan for her hospital.[15] She kept records of the number and cause of deaths in order to continuously improve the conditions in hospitals.[16] Her findings were that in every 1,000 soldiers, 600 were dying of communicable and infectious diseases.[17] She worked to improve hygiene, nutrition and clean water and decreased the mortality rate from 60% to 42% to 2.2%.[17] All of these improvements are pillars of modern humanitarian intervention. Once she returned to Great Britain she campaigned for the founding of the Royal Commission on the Health of the Army.[16] She advocated for the use of statistics and coxcombs to portray the needs of those in conflict settings.[16][18]

The most well-known origin story of formalized humanitarian aid is that of Henri Dunant, a Swiss businessman and social activist, who upon seeing the sheer destruction and inhumane abandonment of wounded soldiers from the Battle of Solferino in June 1859, canceled his plans and began a relief response.[19] Despite little to no experience as a medical physician, Dunant worked alongside local volunteers to assist the wounded soldiers from all warring parties, including Austrian, Italian and French casualties, in any way he could including the provision of food, water, and medical supplies. His graphic account of the immense suffering he witnessed, written in his book A Memory of Solferino, became a foundational text to modern humanitarianism.[20]

A Memory of Solferino changed the world in a way that no one, let alone Dunant, could have foreseen nor truly appreciated at the time. To start, Dunant was able to profoundly stir the emotions of his readers by bringing the battle and suffering into their homes, equipping them to understand the current barbaric state of war and treatment of soldiers after they were injured or killed; in of themselves these accounts altered the course of history.[21] Beyond this, in his two-week experience attending to the wounded soldiers of all nationalities, Dunant inadvertently established the vital conceptual pillars of what would later become the International Committee of the Red Cross and International Humanitarian Law: impartiality and neutrality.[22] Dunant took these ideas and came up with two more ingenious concepts that would profoundly alter the practice of war; first Dunant envisioned a creation of permanent volunteer relief societies, much like the ad hoc relief group he coordinated in Solferino, to assist wounded soldiers; next Dunant began an effort to call for the adoption of a treaty which would guarantee the protection of wounded soldiers and any who attempted to come to their aid.[23]

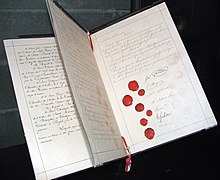

After publishing his foundational text in 1862, progress came quickly for Dunant and his efforts to create a permanent relief society and International Humanitarian Law. The embryonic formation of the International Committee of the Red Cross had begun to take shape in 1863 when the private Geneva Society of Public Welfare created a permanent sub-committee called «The International Committee for Aid to Wounded in Situations of War». Composed of five Geneva citizens, this committee endorsed Dunant’s vision to legally neutralize medical personnel responding to wounded soldiers.[24][25] The constitutive conference of this committee in October 1863 created the statutory foundation of the International Committee of the Red Cross in their resolutions regarding national societies, caring for the wounded, their symbol, and most importantly the indispensable neutrality of ambulances, hospitals, medical personnel and the wounded themselves.[26] Beyond this, in order to solidify humanitarian practice, the Geneva Society of Public Welfare hosted a convention between 8 and 22 August 1864 at the Geneva Town Hall with 16 diverse States present, including many governments of Europe, the Ottoman Empire, the United States of America (USA), Brazil and Mexico.[27] This diplomatic conference was exceptional, not due to the number or status of its attendees but rather because of its very raison d’être. Unlike many diplomatic conferences before it, this conference’s purpose was not to reach a settlement after a conflict nor to mediate between opposing interests; indeed this conference was to lay down rules for the future of conflict with aims to protect medical services and those wounded in battle.[28]

The first of the renowned Geneva Conventions was signed on 22 August 1864; never before in history has a treaty so greatly impacted how warring parties engage with one another.[29] The basic tenents of the convention outlined the neutrality of medical services, including hospitals, ambulances, and related personnel, the requirement to care for and protect the sick and wounded during the conflict and something of particular symbolic importance to the International Committee of the Red Cross: the Red Cross emblem.[30] For the first time in contemporary history, it was acknowledged by a representative selection of states that war had limits. The significance only grew with time in the revision and adaptation of the Geneva Convention in 1906, 1929 and 1949; additionally, supplementary treaties granted protection to hospital ships, prisoners of war and most importantly to civilians in wartime.[31]

The International Committee of the Red Cross exists to this day as the guardian of International Humanitarian Law and as one of the largest providers of humanitarian aid in the world.[32]

Another such examples occurred in response to the Northern Chinese Famine of 1876–1879, brought about by a drought that began in northern China in 1875 and led to crop failures in the following years. As many as 10 million people may have died in the famine.[33] British missionary Timothy Richard first called international attention to the famine in Shandong in the summer of 1876 and appealed to the foreign community in Shanghai for money to help the victims. The Shandong Famine Relief Committee was soon established with the participation of diplomats, businessmen, and Protestant and Roman Catholic missionaries.[34] To combat the famine, an international network was set up to solicit donations. These efforts brought in 204,000 silver taels, the equivalent of $7–10 million in 2012 silver prices.[35]

A simultaneous campaign was launched in response to the Great Famine of 1876–78 in India. Although the authorities have been criticized for their laissez-faire attitude during the famine, relief measures were introduced towards the end. A Famine Relief Fund was set up in the United Kingdom and had raised £426,000 within the first few months.

1980s[edit]

RAF C-130 airdropping food during 1985 famine

Early attempts were in private hands and were limited in their financial and organizational capabilities. It was only in the 1980s, that global news coverage and celebrity endorsement were mobilized to galvanize large-scale government-led famine (and other forms of) relief in response to disasters around the world. The 1983–85 famine in Ethiopia caused upwards of 1 million deaths and was documented by a BBC news crew, with Michael Buerk describing «a biblical famine in the 20th Century» and «the closest thing to hell on Earth».[36]

Live Aid, a 1985 fund-raising effort headed by Bob Geldof induced millions of people in the West to donate money and to urge their governments to participate in the relief effort in Ethiopia. Some of the proceeds also went to the famine hit areas of Eritrea.[37]

2000s[edit]

A 2004 reform initiative by Jan Egeland, resulted in the creation of the Humanitarian Cluster System, designed to improve coordination between humanitarian agencies working on the same issues.[38]

2010s[edit]

World Humanitarian Summit[edit]

The first global summit on humanitarian diplomacy was held in 2016 in Istanbul, Turkey.[39] An initiative of United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, the World Humanitarian Summit included participants from governments, civil society organizations, private organizations, and groups affected by humanitarian need. Issues that were discussed included: preventing and ending conflict, managing crises, and aid financing.

Attendees at the summit agreed a series of reforms on aid spending called the Grand Bargain,[40] including a commitment to spend 25% of aid funds directly through local and national humanitarian aid organizations.[41]

Funding[edit]

Aid is funded by donations from individuals, corporations, governments and other organizations. The funding and delivery of humanitarian aid is increasingly international, making it much faster, more responsive, and more effective in coping to major emergencies affecting large numbers of people (e.g. see Central Emergency Response Fund). The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) coordinates the international humanitarian response to a crisis or emergency pursuant to Resolution 46/182 of the United Nations General Assembly. The need for aid is ever-increasing and has long outstripped the financial resources available.[42]

The Central Emergency Response Fund was created at the 2005 Central Emergency Response Fund at the United Nations General Assembly.[43]

Delivery of humanitarian aid[edit]

Truck for delivery of aid from Western to Eastern Europe

Methods of delivery[edit]

Humanitarian aid spans a wide range of activities, including providing food aid, shelter, education, healthcare or protection. The majority of aid is provided in the form of in-kind goods or assistance, with cash and vouchers constituting only 6% of total humanitarian spending.[44] However, evidence has shown how cash transfers can be better for recipients as it gives them choice and control, they can be more cost-efficient and better for local markets and economies.[44]

It is important to note that humanitarian aid is not only delivered through aid workers sent by bilateral, multilateral or intergovernmental organizations, such as the United Nations. Actors like the affected people themselves, civil society, local informal first-responders, civil society, the diaspora, businesses, local governments, military, local and international non-governmental organizations all play a crucial role in a timely delivery of humanitarian aid.[45]

How aid is delivered can affect the quality and quantity of aid. Often in disaster situations, international aid agencies work in hand with local agencies. There can be different arrangements on the role these agencies play, and such arrangement affects that quality of hard and soft aid delivered.[46]

Humanitarian access[edit]

Securing access to humanitarian aid in post-disasters, conflicts, and complex emergencies is a major concern for humanitarian actors. To win assent for interventions, aid agencies often espouse the principles of humanitarian impartiality and neutrality. However, gaining secure access often involves negotiation and the practice of humanitarian diplomacy.[47] In the arena of negotiations, humanitarian diplomacy is ostensibly used by humanitarian actors to try to persuade decision makers and leaders to act, at all times and in all circumstances, in the interest of vulnerable people and with full respect for fundamental humanitarian principles.[48] However, humanitarian diplomacy is also used by state actors as part of their foreign policy.[48]

United Nations’ response[edit]

The UN implements a multifaceted approach to assist migrants and refugees throughout their relocation process.[49] This includes the integration of their children into local education systems, maintenance of food security at the familial level, and provision of access to health services.[50] The approach also encompasses humanitarian transportation, the goal of which is to ensure migrants and refugees retain access to basic goods and services and the labor market.[49] Basic needs, including access to shelter, clean water, and child protection, are supplemented by the UN’s efforts to facilitate social integration and legal regularization for displaced individuals.[50]

Technology and humanitarian aid[edit]

Traditionally, humanitarian organizations have concentrated their efforts in the delivery of human, medical, food, shelter and water sanitation and hygiene resources during humanitarian emergencies.

Nevertheless, since the 2010 Haiti Earthquake, the institutional and operational focus of humanitarian aid has been on leveraging technology to enhance humanitarian action, ensuring that more formal relationships are established, and improving the interaction between formal humanitarian organizations such as the United Nations (UN) Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and informal volunteer and technological communities known as digital humanitarians.[51]

The recent rise in Big Data, high-resolution satellite imagery and new platforms powered by advanced computing have already prompted the development of crisis mapping to help humanitarian organizations make sense of the vast volume and velocity of information generated during disasters. For example, crowdsourcing maps (such as Open Street Maps) and social media messages in Twitter were used during the 2010 Haiti Earthquake and Hurricane Sandy to trace leads of missing people, infrastructure damages and rise new alerts for emergencies.[52]

Satellite imagery is now used to predict how many people will be displaced from their homes and where they will likely move. Such insights helps emergency personnel to identify how much aid in terms of water, food and medical care will be needed and where to send it before they conduct a Rapid Needs Assessment on the field, and at the same time it helps prevent putting the humanitarian organization personnel at risk. Artificial intelligence algorithms may instantaneously assess flooding, building and road damage based on satellite images and weather forecasts, allowing rescuers to distribute emergency aid more effectively and identify those still in danger and isolated from escape routes.[53]

Another example that illustrates technology used for humanitarian purposes is the Artificial Intelligence for Digital Response platform which is a free and open source software that automatically collects and classifies tweets that are posted during emergencies, humanitarian crises and disasters. AIDR uses human and machine intelligence to automatically tag up to thousands of messages per minute so humanitarian organizations are able to make faster decisions depending on the trends from the data collected during a specific kind of emergency.[54]

Big data for humanitarian operations provides a unique opportunity to access instantaneously contextual information about pending and ongoing humanitarian crises. The development of rigorous information management systems may lead to feasible mechanisms for forecasting and preventing crises. Nevertheless, there are important issues to be discussed concerning the veracity and validity of data. Data that are collected or generated through digital or mobile mechanisms will often pose additional challenges, especially regarding the verification when the information comes from social media. Though a significant amount of work is under way to develop software and algorithms for verifying crowdsourced or anonymously provided data, such tools are not yet operational or widely available. Also, multiple data transactions and increased complexity in data structures raise the potential for error in humanitarian data entry and interpretation, and this raises concerns about the accuracy and representativeness of data that is used for policy decisions in highly pressurized situations that demand quick decision-making.[51]

Gender and humanitarian aid[edit]

Even prior to a humanitarian crisis, gender differences exist. Women have limited access to paid work, are at risk of child marriage, and are more exposed to Gender based violence, such as rape and domestic abuse.[55] Conflict and natural disasters exacerbate women’s vulnerabilities.[56] When delivering humanitarian aid, it is thus important for humanitarian actors, such as the United Nations, to include challenges specific to women in their humanitarian response. The Inter-Agency Standing Committee provides guidelines for humanitarian actors on how be inclusive of gender when delivering humanitarian aid. It recommends agencies to collect data disaggregated by sex and age to better understand which group of the population is in need of what type of aid.[57] In recent years, the United Nations have been using sex and age disaggregated data more and more, consulting with gender specialists. In the assessment phase, several UN agencies meet to compile data and work on a humanitarian response plan.[58] Throughout the plans. women specific challenges are listed and sex and age disaggregated data are used so when they deliver aid to a country facing a humanitarian crisis, girls and women can have access to the aid they need.

Humanitarian aid and conflict[edit]

In addition to post-conflict settings, a large portion of aid is often directed at countries currently undergoing conflicts.[59] However, the effectiveness of humanitarian aid, particularly food aid, in conflict-prone regions has been criticized in recent years. There have been accounts of humanitarian aid being not only inefficacious, but actually fuelling conflicts in the recipient countries.[60] Aid stealing is one of the prime ways in which conflict is promoted by humanitarian aid. Aid can be seized by armed groups, and even if it does reach the intended recipients, «it is difficult to exclude local members of local militia group from being direct recipients if they are also malnourished and qualify to receive aid.»[60] Furthermore, analyzing the relationship between conflict and food aid, a recent research shows that the United States’ food aid promoted civil conflict in recipient countries on average. An increase in United States’ wheat aid increased the duration of armed civil conflicts in recipient countries, and ethnic polarization heightened this effect.[60] However, since academic research on aid and conflict focuses on the role of aid in post-conflict settings, the aforementioned finding is difficult to contextualize. Nevertheless, research on Iraq shows that «small-scale [projects], local aid spending … reduces conflict by creating incentives for average citizens to support the government in subtle ways.»[59] Similarly, another study also shows that aid flows can «reduce conflict because increasing aid revenues can relax government budget constraints, which can [in return] increase military spending and deter opposing groups from engaging in conflict.»[61] Thus, the impact of humanitarian aid on conflict may vary depending upon the type and mode in which aid is received, and, inter alia, the local socio-economic, cultural, historical, geographical and political conditions in the recipient countries.

Waste and corruption in humanitarian aid[edit]

Waste and corruption are hard to quantify, in part because they are often a taboo subject, but they appear to be significant in humanitarian aid. For example, it has been estimated that over $8.75 billion was lost to waste, fraud, abuse and mismanagement in the Hurricane Katrina relief effort.[62] Non-governmental organizations have in recent years made great efforts to increase participation, accountability and transparency in dealing with aid, yet humanitarian assistance remains a poorly understood process to those meant to be receiving it—much greater investment needs to be made into researching and investing in relevant and effective accountability systems.[62]

However, there is little clear consensus on the trade-offs between speed and control, especially in emergency situations when the humanitarian imperative of saving lives and alleviating suffering may conflict with the time and resources required to minimise corruption risks.[62] Researchers at the Overseas Development Institute have highlighted the need to tackle corruption with, but not limited to, the following methods:[62]

- Resist the pressure to spend aid rapidly.

- Continue to invest in audit capacity, beyond simple paper trails;

- Establish and verify the effectiveness of complaints mechanisms, paying close attention to local power structures, security and cultural factors hindering complaints;

- Clearly explain the processes during the targeting and registration stages, highlighting points such as the fact that people should not make payments to be included, photocopy and read aloud any lists prepared by leaders or committees.

Contrary practice[edit]

Countries or war parties that prevent humanitarian relief are generally under unanimous criticism.[5] Such was the case for the Derg regime, preventing relief to the population of Tigray in the 1980s,[63] and the prevention of relief aid in the Tigray War of 2020–2021 by the Abiy Ahmed Ali regime of Ethiopia was again widely condemned.[64][65]

Aid workers[edit]

Aid workers are the people distributed internationally to do humanitarian aid work.

Composition[edit]

The total number of humanitarian aid workers around the world has been calculated by ALNAP, a network of agencies working in the Humanitarian System, as 210,800 in 2008. This is made up of roughly 50% from NGOs, 25% from the Red Cross/Red Crescent Movement and 25% from the UN system.[66] In 2010, it was reported that the humanitarian fieldworker population increased by approximately 6% per year over the previous 10 years.[67]

Psychological Issues[edit]

Aid workers are exposed to tough conditions and have to be flexible, resilient, and responsible in an environment that humans are not psychologically supposed to deal with, in such severe conditions that trauma is common. In recent years, a number of concerns have been raised about the mental health of aid workers.[68][69]

The most prevalent issue faced by humanitarian aid workers is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Adjustment to normal life again can be a problem, with feelings such as guilt being caused by the simple knowledge that international aid workers can leave a crisis zone, whilst nationals cannot.

A 2015 survey conducted by The Guardian, with aid workers of the Global Development Professionals Network, revealed that 79 percent experienced mental health issues.[70]

Abuse of power by aid workers[edit]

Reports of sexual exploitation in sexual exploitation and abuse in humanitarian response have been reported following humanitarian interventions in Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone in 2002,[71] in Central African Republic[72] and in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[73]

2021 reporting on a Racial Equity Index report indicated that just under two-thirds of aid workers have experienced racism and 98% of survey respondents witnessed racism.[74]

Standards[edit]

The humanitarian community has initiated a number of interagency initiatives to improve accountability, quality and performance in humanitarian action. Four of the most widely known initiatives are, ALNAP, the CHS Alliance, the Sphere Project and the Core Humanitarian Standard on Quality and Accountability (CHS). Representatives of these initiatives began meeting together on a regular basis in 2003 in order to share common issues and harmonise activities where possible.[75]

Sphere Project[edit]

The Sphere Project handbook, Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Disaster Response, which was produced by a coalition of leading non-governmental humanitarian agencies, lists the following principles of humanitarian action:

- The right to life with dignity

- The distinction between combatant and non-combatants

- The principle of non-refoulement

Core Humanitarian Standard on Quality and Accountability[edit]

Logo of the Core Humanitarian Standard

Another humanitarian standard used is the Core Humanitarian Standard on Quality and Accountability (CHS). It was approved by the CHS Technical Advisory Group in 2014, and has since been endorsed by many humanitarian actors such as «the Boards of the Humanitarian Accountability Partnership (HAP), People in Aid and the Sphere Project».[76] It comprises nine core standards, which are complemented by detailed guidance notes and indicators.

While some critics were questioning whether the sector will truly benefit from the implementation of yet another humanitarian standard, others have praised it for its simplicity.[77] Most notably, it has replaced the core standards of the Sphere Handbook[78] and it is regularly referred to and supported by officials from the United Nations, the EU, various NGOs and institutes.[79]

See also[edit]

- Attacks on humanitarian workers

- Hard Choices: Moral Dilemmas in Humanitarian Intervention

- Effective altruism

- Church asylum

- Humanitarian access

- Humanitarian corridor

- Humanitarian principles

- Humanitarian Response Index

- International humanitarian law

- Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action

- World Humanitarian Day

References[edit]

- ^ Sid Johann Peruvemba, Malteser International (31 May 2018). «Why the nexus is dangerous». D+C Development and Cooperation. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ «The State of Art of Humanitarian Action, (PDF). EUHAP» (PDF). euhap.eu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ «OCHA». unocha.org. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ «Deliver Humanitarian Aid». un.org. 7 December 2014. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ a b ICRC IHL dababase: Rule 55. Access for Humanitarian Relief to Civilians in Need Archived 15 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Archived copy» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 September 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ «Highest incident contexts (2012–2018)». Aid Worker Security Database. Humanitarian Outcomes. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ «Global Humanitarian Overview 2022». Global Humanitarian Overview. 5 November 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Götz, Norbert (2014). «Rationales of Humanitarianism: The Case of British Relief to Germany, 1805–1815». Journal of Modern European History. 12 (2): 186–199. doi:10.17104/1611-8944_2014_2_186. S2CID 143227029.

- ^ Götz, Norbert (2014). «The Good Plumpuddings’ Belief: British Voluntary Aid to Sweden During the Napoleonic Wars». International History Review. 37 (3): 519–539. doi:10.1080/07075332.2014.918559.

- ^ Kinealy, Christine (2013). Charity and the Great Hunger in Ireland: The Kindness of Strangers. London: Bloomsbury.

- ^ Götz, Norbert; Brewis, Georgina; Werther, Steffen (2020). Humanitarianism in the Modern World: The Moral Economy of Famine Relief. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108655903. ISBN 978-1-108-65590-3.

- ^ a b Hosein Karimi, Negin Masoudi Alavi. Florence Nightingale: The Mother of Nursing. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2015 Jun;4(2)

- ^ a b Joseph H. Choate. What Florence Nightingale Did for Mankind. Am J Nurs. 1911 Feb;11(5):346–57.

- ^ a b c Elizabeth Fee, Mary E. Garofalo. Florence Nightingale and the Crimean War.

- ^ a b c Understanding Uncertainty. Florence Nightingale and the Crimean War.

- ^ a b Hosein Karimi, Negin Masoudi Alavi. Florence Nightingale: The Mother of Nursing. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2015 Jun;4(2).

- ^ Forsythe, David. The Humanitarians: The International Committee of the Red Cross. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 15.

- ^ Haug, Hans. «The Fundamental Principles of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement» (PDF). Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ^ Barnett, Michael, and Weiss, Thomas. Humanitarianism in Question: Politics, Power, Ethics. (New York: Cornell University Press, 2008), 101.

- ^ Bugnion, Francois. «Birth of an Idea: The Founding of the International Committee of the Red Cross and of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement: From Solferino to the Original Geneva Convention (1859–1864).» International Review of the Red Cross 94 (2013): 1306.

- ^ Bugnion, Francois. «Birth of an Idea: The Founding of the International Committee of the Red Cross and of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement: From Solferino to the Original Geneva Convention (1859–1864).» International Review of the Red Cross 94 (2013): 1303

- ^ ugnion, Francois. «Birth of an Idea: The Founding of the International Committee of the Red Cross and of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement: From Solferino to the Original Geneva Convention (1859–1864).» International Review of the Red Cross 94 (2013): 1300

- ^ Forsythe, David. The Humanitarians: The International Committee of the Red Cross. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 17.

- ^ Bugnion, Francois. «Birth of an Idea: The Founding of the International Committee of the Red Cross and of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement: From Solferino to the Original Geneva Convention (1859–1864).» International Review of the Red Cross 94 (2013): 1311

- ^ Bugnion, Francois. «Birth of an Idea: The Founding of the International Committee of the Red Cross and of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement: From Solferino to the Original Geneva Convention (1859–1864).» International Review of the Red Cross 94 (2013): 1320.

- ^ Bugnion, Francois. «Birth of an Idea: The Founding of the International Committee of the Red Cross and of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement: From Solferino to the Original Geneva Convention (1859–1864).» International Review of the Red Cross 94 (2013): 1323.

- ^ Bugnion, Francois. «Birth of an Idea: The Founding of the International Committee of the Red Cross and of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement: From Solferino to the Original Geneva Convention (1859–1864).» International Review of the Red Cross 94 (2013): 1324

- ^ Bugnion, Francois. «Birth of an Idea: The Founding of the International Committee of the Red Cross and of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement: From Solferino to the Original Geneva Convention (1859–1864).» International Review of the Red Cross 94 (2013): 1325

- ^ Bugnion, Francois. «Birth of an Idea: The Founding of the International Committee of the Red Cross and of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement: From Solferino to the Original Geneva Convention (1859–1864).» International Review of the Red Cross 94 (2013):1325

- ^ Bugnion, Francois. «Birth of an Idea: The Founding of the International Committee of the Red Cross and of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement: From Solferino to the Original Geneva Convention (1859–1864).» International Review of the Red Cross 94 (2013):1326

- ^ «Who we are». International Committee of the Red Cross. 28 July 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ Edgerton-Tarpley, Kathryn, «Pictures to Draw Tears from Iron» «Archived copy» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), accessed 25 December 2013 - ^ Janku, Andrea (2001) «The North-China Famine of 1876–1879: Performance and Impact of a Non-Event.» In: Measuring Historical Heat: Event, Performance, and Impact in China and the West. Symposium in Honour of Rudolf G. Wagner on His 60th Birthday. Heidelberg, 3–4 November, pp. 127–134

- ^ China Famine Relief Fund. Shanghai Committee (1879). The great famine : [Report of the Committee of the China Famine Relief Fund]. Cornell University Library. Shanghai : American Presbyterian Mission Press.

- ^ «How a Report on Ethiopia’s ‘Biblical Famine’ Changed the World». NBC News. 23 October 2014.

- ^ «In 1984 Eritrea was part of Ethiopia, where some of the song’s proceeds were spent». Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- ^ Stoddard, Abby; Harmer, Adele; Haver, Katherine; Salomons, Dirk; Wheeler, Victoria (November 2007). «Cluster Approach Evaluation» (PDF). ALNAP.

- ^ Rousseau, Elise; Sommo Pende, Achille (2020). Humanitarian diplomacy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ Parker, Ben (24 May 2016). «Is the Grand Bargain a Big Deal?». The New Humanitarian. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Goodwin, Ellen; Ager, Alastair (2021). «Localisation in the Context of UK Government Engagement With the Humanitarian Reform Agenda». Frontiers in Political Science. 3: 114. doi:10.3389/fpos.2021.687063. ISSN 2673-3145.

- ^ Hendrik Slusarenka (20 May 2018). «Aid in itself is not enough». D+C, development and cooperation. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ «United Nations Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF)». Devex.

- ^ a b [High Level Panel on Humanitarian Cash Transfers «Doing cash differently: How cash transfers can transform humanitarian aid». Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015. Doing cash differently: how cash transfers can transform humanitarian aid]

- ^ Leaving no one behind : humanitarian effectiveness in the age of the sustainable development goals. Easton, Matthew,, United Nations. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs,, Collaborative for Development Action., CDA Collaborative Learning Projects. [New York?]. 2016. ISBN 9789211320442. OCLC 946161611.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Henderson, J. Vernon; Lee, Yong Suk (2015). «Organization of Disaster Aid Delivery». Economic Development and Cultural Change. 63 (4): 617–664. doi:10.1086/681277. S2CID 14147459.

- ^ «Humanitarianism: An Overview».

- ^ a b Lauri, Antonio De (2018). «Humanitarian Diplomacy: A New Research Agenda». CMI Brief. 2018:4.

- ^ a b Stein, Eduardo; UNHCR; Refugees, IOM Joint Special Representative for; Venezuela, Migrants from; RMRP 2022, “Foreword” to the. «RMRP 2022 – FOR REFUGEES AND MIGRANTS FROM VENEZUELA». RMRP 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ a b «UNHCR Global Report 2020» (PDF). UNHCR. 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ a b Sandvik, Kristin (December 2014). «Humanitarian Technology: A Critical Research Agenda». International Review of the Red Cross. 96 (893): 219–242. doi:10.1017/S1816383114000344. S2CID 55335271. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Meier, Patrick (2015). Digital Humanitarians: How Big Data is Changing the Face of Humanitarian Response. E-Book: CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-1-4987-2652-8.

- ^ Van Heteren, Ashley (14 January 2020). «Natural disasters are increasing in frequency and ferocity. Here’s how AI can come to the rescue». World Economic Forum. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ «AIDR: Artificial Intelligence for Disaster Response». aidr.qcri.org. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Aolain, Ni; D, Fionnuala (19 May 2010). «Women, Vulnerability and Humanitarian Emergencies». SSRN 1611818.

- ^ Mazurana, Dyan; Benelli, Prisca; Walker, Peter (2013). «How sex- and age-disaggregated data and gender and generational analyses can improve humanitarian response». Disasters. 37 (s1): S68–S82. doi:10.1111/disa.12013. ISSN 1467-7717. PMID 23905768.

- ^ «The Gender Handbook for Humanitarian Action» (PDF). IASC. 2018.

- ^ «Humanitarian Response Plan | HumanitarianResponse». www.humanitarianresponse.info. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ a b Berman, Eli; Felter, Joe; Shapiro, Jacob; Troland, Erin (26 May 2013). «Effective aid in conflict zones». VoxEU.org. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017.

- ^ a b c Nunn, Nathan; Qian, Nancy (2014). «US Food Aid and Civil Conflict» (PDF). American Economic Review. 104 (6): 1630–1666. doi:10.1257/aer.104.6.1630. S2CID 12935268.

- ^ Qian, Nancy (18 August 2014). «Making Progress on Foreign Aid». Annual Review of Economics. 3.

- ^ a b c d Sarah Bailey (2008) Need and greed: corruption risks, perceptions and prevention in humanitarian assistance Archived 26 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine Overseas Development Institute

- ^ «Ethiopia : a country study | WorldCat.org». www.worldcat.org.

- ^ Psaledakis, Daphne (30 July 2021). «U.S. aid chief to travel to Ethiopia in diplomatic push on Tigray». Reuters – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ «Ethiopia’s Tigray crisis: Why it’s hard getting aid into the region». BBC News. 23 July 2021.

- ^ «State of the Humanitarian System report» (PDF). ALNAP. 2010. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2010.

- ^ «The State of the Humanitarian System» (PDF). ALNAP. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ «Health – The university course giving aid to aid workers». BBC News. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ «Health – Aid workers lack psychological support». BBC News. Archived from the original on 26 December 2002. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ «Guardian research suggests mental health crisis among aid workers». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ https://www.parliament.uk/globalassets/documents/commons-committees/international-development/2002-Report-of-sexual-exploitation-and-abuse-Save-the-Children.pdf Archived 8 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine[bare URL PDF]

- ^ Mwanyika, Elijah Mwasi (25 February 2021). «Sexual Exploitation and Abuse by Intervention Forces in Central African Republic». African Journal of Empirical Research. 2 (1): 63–78. doi:10.51867/ajer.v2i1.14. ISSN 2709-2607. S2CID 233976377.

- ^ Farge, Emma; Holland, Hereward (29 September 2021). «WHO employees took part in Congo sex abuse during Ebola crisis, report says». Reuters. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Delahunty, Stephen. «Almost two-thirds of aid workers have experienced racism, research indicates». www.thirdsector.co.uk. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ «HAP and People In Aid merge to become CHS Alliance». Elrha. 15 June 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ «Frequently Asked Questions – CHS». corehumanitarianstandard.org. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ Purvis, Katherine (11 June 2015). «Core Humanitarian Standard: do NGOs need another set of standards?». the Guardian. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ «The Sphere Project | New online course on the Core Humanitarian Standard | News». sphereproject.org. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ «Statements of support – CHS». corehumanitarianstandard.org. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

Further reading[edit]

- Götz, Norbert; Brewis, Georgina; Werther, Steffen (2020). Humanitarianism in the Modern World: The Moral Economy of Famine Relief. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108655903. ISBN 978-1-108-65590-3.

- James, Eric (2008). Managing Humanitarian Relief: An Operational Guide for NGOs. Rugby: Practical Action.

- Minear, Larry (2002). The Humanitarian Enterprise: Dilemmas and Discoveries. West Hartford, CT: Kumarian Press. ISBN 1-56549-149-1.

- Waters, Tony (2001). Bureaucratizing the Good Samaritan: The Limitations of Humanitarian Relief Operations. Boulder: Westview Press.

External links[edit]

- The Humanitarian Organisations Dataset (HOD): 2,505 organizations active in the humanitarian sector

- «Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance». alnap.org.

- «APCN (Africa Partner Country Network)». apan.org.

- «CE-DAT: The Complex Emergency Database». cedat.org.

- «Centre for Safety and Development». centreforsafety.org.

- «The Code of Conduct: humanitarian principles in practice». International Committee of the Red Cross. 20 September 2004.