|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chromium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | silvery metallic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Cr) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chromium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 24 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

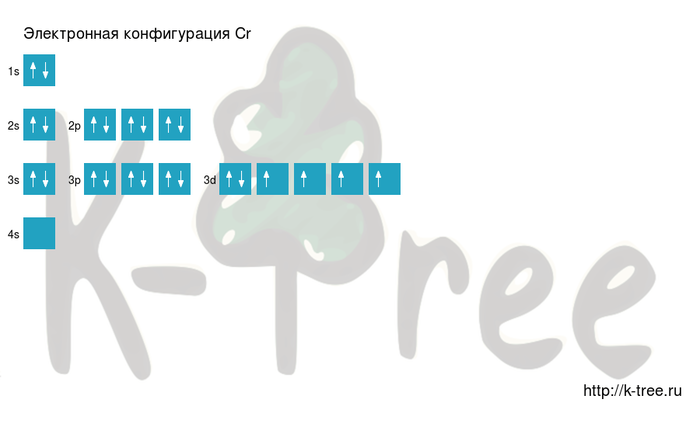

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d5 4s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 13, 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 2180 K (1907 °C, 3465 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 2944 K (2671 °C, 4840 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 7.15 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 6.3 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 21.0 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 347 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 23.35 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −4, −2, −1, 0, +1, +2, +3, +4, +5, +6 (depending on the oxidation state, an acidic, basic, or amphoteric oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.66 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 128 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 139±5 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of chromium |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | body-centered cubic (bcc)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 5940 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 4.9 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 93.9 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 125 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | antiferromagnetic (rather: SDW)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | +280.0×10−6 cm3/mol (273 K)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 279 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 115 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 160 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.21 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 8.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 1060 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 687–6500 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-47-3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery and first isolation | Louis Nicolas Vauquelin (1794, 1797) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of chromium

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Chromium is a chemical element with the symbol Cr and atomic number 24. It is the first element in group 6. It is a steely-grey, lustrous, hard, and brittle transition metal.[4]

Chromium metal is valued for its high corrosion resistance and hardness. A major development in steel production was the discovery that steel could be made highly resistant to corrosion and discoloration by adding metallic chromium to form stainless steel. Stainless steel and chrome plating (electroplating with chromium) together comprise 85% of the commercial use. Chromium is also greatly valued as a metal that is able to be highly polished while resisting tarnishing. Polished chromium reflects almost 70% of the visible spectrum, and almost 90% of infrared light.[5] The name of the element is derived from the Greek word χρῶμα, chrōma, meaning color,[6] because many chromium compounds are intensely colored.

Industrial production of chromium proceeds from chromite ore (mostly FeCr2O4) to produce ferrochromium, an iron-chromium alloy, by means of aluminothermic or silicothermic reactions. Ferrochromium is then used to produce alloys such as stainless steel. Pure chromium metal is produced by a different process: roasting and leaching of chromite to separate it from iron, followed by reduction with carbon and then aluminium.

In the United States, trivalent chromium (Cr(III)) ion is considered an essential nutrient in humans for insulin, sugar, and lipid metabolism.[7] However, in 2014, the European Food Safety Authority, acting for the European Union, concluded that there was insufficient evidence for chromium to be recognized as essential.[8]

While chromium metal and Cr(III) ions are considered non-toxic, hexavalent chromium, Cr(VI), is toxic and carcinogenic. According to the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), chromium trioxide that is used in industrial electroplating processes is a «substance of very high concern» (SVHC).[9]

Abandoned chromium production sites often require environmental cleanup.[10]

Physical properties[edit]

Atomic[edit]

Chromium is the fourth transition metal found on the periodic table, and has an electron configuration of [Ar] 3d5 4s1. It is also the first element in the periodic table whose ground-state electron configuration violates the Aufbau principle. This occurs again later in the periodic table with other elements and their electron configurations, such as copper, niobium, and molybdenum.[11] This occurs because electrons in the same orbital repel each other due to their like charges. In the previous elements, the energetic cost of promoting an electron to the next higher energy level is too great to compensate for that released by lessening inter-electronic repulsion. However, in the 3d transition metals, the energy gap between the 3d and the next-higher 4s subshell is very small, and because the 3d subshell is more compact than the 4s subshell, inter-electron repulsion is smaller between 4s electrons than between 3d electrons. This lowers the energetic cost of promotion and increases the energy released by it, so that the promotion becomes energetically feasible and one or even two electrons are always promoted to the 4s subshell. (Similar promotions happen for every transition metal atom but one, palladium.)[12]

Chromium is the first element in the 3d series where the 3d electrons start to sink into the nucleus; they thus contribute less to metallic bonding, and hence the melting and boiling points and the enthalpy of atomisation of chromium are lower than those of the preceding element vanadium. Chromium(VI) is a strong oxidising agent in contrast to the molybdenum(VI) and tungsten(VI) oxides.[13]

Bulk[edit]

Sample of pure chromium metal

Chromium is extremely hard, and is the third hardest element behind carbon (diamond) and boron. Its Mohs hardness is 8.5, which means that it can scratch samples of quartz and topaz, but can be scratched by corundum. Chromium is highly resistant to tarnishing, which makes it useful as a metal that preserves its outermost layer from corroding, unlike other metals such as copper, magnesium, and aluminium.

Chromium has a melting point of 1907 °C (3465 °F), which is relatively low compared to the majority of transition metals. However, it still has the second highest melting point out of all the Period 4 elements, being topped by vanadium by 3 °C (5 °F) at 1910 °C (3470 °F). The boiling point of 2671 °C (4840 °F), however, is comparatively lower, having the fourth lowest boiling point out of the Period 4 transition metals alone behind copper, manganese and zinc.[note 1] The electrical resistivity of chromium at 20 °C is 125 nanoohm-meters.

Chromium has a high specular reflection in comparison to other transition metals. In infrared, at 425 μm, chromium has a maximum reflectance of about 72%, reducing to a minimum of 62% at 750 μm before rising again to 90% at 4000 μm.[5] When chromium is used in stainless steel alloys and polished, the specular reflection decreases with the inclusion of additional metals, yet is still high in comparison with other alloys. Between 40% and 60% of the visible spectrum is reflected from polished stainless steel.[5] The explanation on why chromium displays such a high turnout of reflected photon waves in general, especially the 90% in infrared, can be attributed to chromium’s magnetic properties.[14] Chromium has unique magnetic properties — chromium is the only elemental solid that shows antiferromagnetic ordering at room temperature and below. Above 38 °C, its magnetic ordering becomes paramagnetic.[2] The antiferromagnetic properties, which cause the chromium atoms to temporarily ionize and bond with themselves, are present because the body-centric cubic’s magnetic properties are disproportionate to the lattice periodicity. This is due to the magnetic moments at the cube’s corners and the unequal, but antiparallel, cube centers.[14] From here, the frequency-dependent relative permittivity of chromium, deriving from Maxwell’s equations and chromium’s antiferromagnetism, leaves chromium with a high infrared and visible light reflectance.[15]

Passivation[edit]

Chromium metal left standing in air is passivated — it forms a thin, protective, surface layer of oxide. This layer has a spinel structure a few atomic layers thick; it is very dense and inhibits the diffusion of oxygen into the underlying metal. In contrast, iron forms a more porous oxide through which oxygen can migrate, causing continued rusting.[16] Passivation can be enhanced by short contact with oxidizing acids like nitric acid. Passivated chromium is stable against acids. Passivation can be removed with a strong reducing agent that destroys the protective oxide layer on the metal. Chromium metal treated in this way readily dissolves in weak acids.[17]

Chromium, unlike iron and nickel, does not suffer from hydrogen embrittlement. However, it does suffer from nitrogen embrittlement, reacting with nitrogen from air and forming brittle nitrides at the high temperatures necessary to work the metal parts.[18]

Isotopes[edit]

Naturally occurring chromium is composed of four stable isotopes; 50Cr, 52Cr, 53Cr and 54Cr, with 52Cr being the most abundant (83.789% natural abundance). 50Cr is observationally stable, as it is theoretically capable of decaying to 50Ti via double electron capture with a half-life of no less than 1.3×1018 years. Twenty-five radioisotopes have been characterized, ranging from 42Cr to 70Cr; the most stable radioisotope is 51Cr with a half-life of 27.7 days. All of the remaining radioactive isotopes have half-lives that are less than 24 hours and the majority less than 1 minute. Chromium also has two metastable nuclear isomers.[19]

53Cr is the radiogenic decay product of 53Mn (half-life 3.74 million years).[20] Chromium isotopes are typically collocated (and compounded) with manganese isotopes. This circumstance is useful in isotope geology. Manganese-chromium isotope ratios reinforce the evidence from 26Al and 107Pd concerning the early history of the Solar System. Variations in 53Cr/52Cr and Mn/Cr ratios from several meteorites indicate an initial 53Mn/55Mn ratio that suggests Mn-Cr isotopic composition must result from in-situ decay of 53Mn in differentiated planetary bodies. Hence 53Cr provides additional evidence for nucleosynthetic processes immediately before coalescence of the Solar System.[21]

The isotopes of chromium range in atomic mass from 43 u (43Cr) to 67 u (67Cr). The primary decay mode before the most abundant stable isotope, 52Cr, is electron capture and the primary mode after is beta decay.[19] 53Cr has been posited as a proxy for atmospheric oxygen concentration.[22]

Chemistry and compounds[edit]

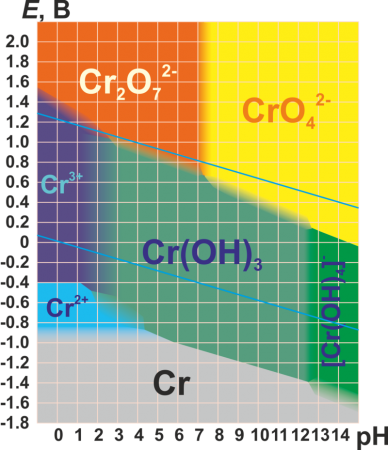

The Pourbaix diagram for chromium in pure water, perchloric acid, or sodium hydroxide[23][24]

Chromium is a member of group 6, of the transition metals. The +3 and +6 states occur most commonly within chromium compounds, followed by +2; charges of +1, +4 and +5 for chromium are rare, but do nevertheless occasionally exist.[25][26]

Common oxidation states[edit]

| Oxidation states[note 2][26] |

|

|---|---|

| −4 (d10) | Na4[Cr(CO)4][27] |

| −2 (d8) | Na 2[Cr(CO) 5] |

| −1 (d7) | Na 2[Cr 2(CO) 10] |

| 0 (d6) | Cr(C 6H 6) 2 |

| +1 (d5) | K 3[Cr(CN) 5NO] |

| +2 (d4) | CrCl 2 |

| +3 (d3) | CrCl 3 |

| +4 (d2) | K 2CrF 6 |

| +5 (d1) | K 3Cr(O 2) 4 |

| +6 (d0) | K 2CrO 4 |

Chromium(0)[edit]

Many Cr(0) complexes are known. Bis(benzene)chromium and chromium hexacarbonyl are highlights in organochromium chemistry.

Chromium(II)[edit]

Chromium(II) compounds are uncommon, in part because they readily oxidize to chromium(III) derivatives in air. Water-stable chromium(II) chloride CrCl

2 that can be made by reducing chromium(III) chloride with zinc. The resulting bright blue solution created from dissolving chromium(II) chloride is stable at neutral pH.[17] Some other notable chromium(II) compounds include chromium(II) oxide CrO, and chromium(II) sulfate CrSO

4. Many chromium(II) carboxylates are known. The red chromium(II) acetate (Cr2(O2CCH3)4) is somewhat famous. It features a Cr-Cr quadruple bond.[28]

Chromium(III)[edit]

Anhydrous chromium(III) chloride (CrCl3)

A large number of chromium(III) compounds are known, such as chromium(III) nitrate, chromium(III) acetate, and chromium(III) oxide.[29] Chromium(III) can be obtained by dissolving elemental chromium in acids like hydrochloric acid or sulfuric acid, but it can also be formed through the reduction of chromium(VI) by cytochrome c7.[30] The Cr3+

ion has a similar radius (63 pm) to Al3+

(radius 50 pm), and they can replace each other in some compounds, such as in chrome alum and alum.

Chromium(III) tends to form octahedral complexes. Commercially available chromium(III) chloride hydrate is the dark green complex [CrCl2(H2O)4]Cl. Closely related compounds are the pale green [CrCl(H2O)5]Cl2 and violet [Cr(H2O)6]Cl3. If anhydrous violet[31] chromium(III) chloride is dissolved in water, the violet solution turns green after some time as the chloride in the inner coordination sphere is replaced by water. This kind of reaction is also observed with solutions of chrome alum and other water-soluble chromium(III) salts. A tetrahedral coordination of chromium(III) has been reported for the Cr-centered Keggin anion [α-CrW12O40]5–.[32]

Chromium(III) hydroxide (Cr(OH)3) is amphoteric, dissolving in acidic solutions to form [Cr(H2O)6]3+, and in basic solutions to form [Cr(OH)

6]3−

. It is dehydrated by heating to form the green chromium(III) oxide (Cr2O3), a stable oxide with a crystal structure identical to that of corundum.[17]

Chromium(VI)[edit]

Chromium(VI) compounds are oxidants at low or neutral pH. Chromate anions (CrO2−

4) and dichromate (Cr2O72−) anions are the principal ions at this oxidation state. They exist at an equilibrium, determined by pH:

- 2 [CrO4]2− + 2 H+ ⇌ [Cr2O7]2− + H2O

Chromium(VI) oxyhalides are known also and include chromyl fluoride (CrO2F2) and chromyl chloride (CrO

2Cl

2).[17] However, despite several erroneous claims, chromium hexafluoride (as well as all higher hexahalides) remains unknown, as of 2020.[33]

Sodium chromate is produced industrially by the oxidative roasting of chromite ore with sodium carbonate. The change in equilibrium is visible by a change from yellow (chromate) to orange (dichromate), such as when an acid is added to a neutral solution of potassium chromate. At yet lower pH values, further condensation to more complex oxyanions of chromium is possible.

Both the chromate and dichromate anions are strong oxidizing reagents at low pH:[17]

- Cr

2O2−

7 + 14 H

3O+

+ 6 e− → 2 Cr3+

+ 21 H

2O (ε0 = 1.33 V)

They are, however, only moderately oxidizing at high pH:[17]

- CrO2−

4 + 4 H

2O + 3 e− → Cr(OH)

3 + 5 OH−

(ε0 = −0.13 V)

Chromium(VI) compounds in solution can be detected by adding an acidic hydrogen peroxide solution. The unstable dark blue chromium(VI) peroxide (CrO5) is formed, which can be stabilized as an ether adduct CrO

5·OR

2.[17]

Chromic acid has the hypothetical formula H

2CrO

4. It is a vaguely described chemical, despite many well-defined chromates and dichromates being known. The dark red chromium(VI) oxide CrO

3, the acid anhydride of chromic acid, is sold industrially as «chromic acid».[17] It can be produced by mixing sulfuric acid with dichromate and is a strong oxidizing agent.

Other oxidation states[edit]

Compounds of chromium(V) are rather rare; the oxidation state +5 is only realized in few compounds but are intermediates in many reactions involving oxidations by chromate. The only binary compound is the volatile chromium(V) fluoride (CrF5). This red solid has a melting point of 30 °C and a boiling point of 117 °C. It can be prepared by treating chromium metal with fluorine at 400 °C and 200 bar pressure. The peroxochromate(V) is another example of the +5 oxidation state. Potassium peroxochromate (K3[Cr(O2)4]) is made by reacting potassium chromate with hydrogen peroxide at low temperatures. This red brown compound is stable at room temperature but decomposes spontaneously at 150–170 °C.[34]

Compounds of chromium(IV) are slightly more common than those of chromium(V). The tetrahalides, CrF4, CrCl4, and CrBr4, can be produced by treating the trihalides (CrX

3) with the corresponding halogen at elevated temperatures. Such compounds are susceptible to disproportionation reactions and are not stable in water. Organic compounds containing Cr(IV) state such as chromium tetra t-butoxide are also known.[35]

Most chromium(I) compounds are obtained solely by oxidation of electron-rich, octahedral chromium(0) complexes. Other chromium(I) complexes contain cyclopentadienyl ligands. As verified by X-ray diffraction, a Cr-Cr quintuple bond (length 183.51(4) pm) has also been described.[36] Extremely bulky monodentate ligands stabilize this compound by shielding the quintuple bond from further reactions.

Chromium compound determined experimentally to contain a Cr-Cr quintuple bond

Occurrence[edit]

Chromium is the 21st[37] most abundant element in Earth’s crust with an average concentration of 100 ppm. Chromium compounds are found in the environment from the erosion of chromium-containing rocks, and can be redistributed by volcanic eruptions. Typical background concentrations of chromium in environmental media are: atmosphere <10 ng/m3; soil <500 mg/kg; vegetation <0.5 mg/kg; freshwater <10 μg/L; seawater <1 μg/L; sediment <80 mg/kg.[38] Chromium is mined as chromite (FeCr2O4) ore.[39]

About two-fifths of the chromite ores and concentrates in the world are produced in South Africa, about a third in Kazakhstan,[40] while India, Russia, and Turkey are also substantial producers. Untapped chromite deposits are plentiful, but geographically concentrated in Kazakhstan and southern Africa.[41] Although rare, deposits of native chromium exist.[42][43] The Udachnaya Pipe in Russia produces samples of the native metal. This mine is a kimberlite pipe, rich in diamonds, and the reducing environment helped produce both elemental chromium and diamonds.[44]

The relation between Cr(III) and Cr(VI) strongly depends on pH and oxidative properties of the location. In most cases, Cr(III) is the dominating species,[23] but in some areas, the ground water can contain up to 39 µg/L of total chromium, of which 30 µg/L is Cr(VI).[45]

History[edit]

Early applications[edit]

Chromium minerals as pigments came to the attention of the west in the eighteenth century. On 26 July 1761, Johann Gottlob Lehmann found an orange-red mineral in the Beryozovskoye mines in the Ural Mountains which he named Siberian red lead.[46][47] Though misidentified as a lead compound with selenium and iron components, the mineral was in fact crocoite with a formula of PbCrO4.[48] In 1770, Peter Simon Pallas visited the same site as Lehmann and found a red lead mineral that was discovered to possess useful properties as a pigment in paints. After Pallas, the use of Siberian red lead as a paint pigment began to develop rapidly throughout the region.[49] Crocoite would be the principal source of chromium in pigments until the discovery of chromite many years later.[50]

The red color of rubies is due to trace amounts of chromium within the corundum.

In 1794, Louis Nicolas Vauquelin received samples of crocoite ore. He produced chromium trioxide (CrO3) by mixing crocoite with hydrochloric acid.[48] In 1797, Vauquelin discovered that he could isolate metallic chromium by heating the oxide in a charcoal oven, for which he is credited as the one who truly discovered the element.[51][52] Vauquelin was also able to detect traces of chromium in precious gemstones, such as ruby and emerald.[48][53]

During the nineteenth century, chromium was primarily used not only as a component of paints, but in tanning salts as well. For quite some time, the crocoite found in Russia was the main source for such tanning materials. In 1827, a larger chromite deposit was discovered near Baltimore, United States, which quickly met the demand for tanning salts much more adequately than the crocoite that had been used previously.[54] This made the United States the largest producer of chromium products until the year 1848, when larger deposits of chromite were uncovered near the city of Bursa, Turkey.[39] With the development of metallurgy and chemical industries in the Western world, the need for chromium increased.[55]

Chromium is also famous for its reflective, metallic luster when polished. It is used as a protective and decorative coating on car parts, plumbing fixtures, furniture parts and many other items, usually applied by electroplating. Chromium was used for electroplating as early as 1848, but this use only became widespread with the development of an improved process in 1924.[56]

Production[edit]

World production trend of chromium

Chromium, remelted in a horizontal arc zone-refiner, showing large visible crystal grains

Approximately 28.8 million metric tons (Mt) of marketable chromite ore was produced in 2013, and converted into 7.5 Mt of ferrochromium.[41] According to John F. Papp, writing for the USGS, «Ferrochromium is the leading end use of chromite ore, [and] stainless steel is the leading end use of ferrochromium.»[41]

The largest producers of chromium ore in 2013 have been South Africa (48%), Kazakhstan (13%), Turkey (11%), and India (10%), with several other countries producing the rest of about 18% of the world production.[41]

The two main products of chromium ore refining are ferrochromium and metallic chromium. For those products the ore smelter process differs considerably. For the production of ferrochromium, the chromite ore (FeCr2O4) is reduced in large scale in electric arc furnace or in smaller smelters with either aluminium or silicon in an aluminothermic reaction.[57]

Chromium ore output in 2002[58]

For the production of pure chromium, the iron must be separated from the chromium in a two step roasting and leaching process. The chromite ore is heated with a mixture of calcium carbonate and sodium carbonate in the presence of air. The chromium is oxidized to the hexavalent form, while the iron forms the stable Fe2O3. The subsequent leaching at higher elevated temperatures dissolves the chromates and leaves the insoluble iron oxide. The chromate is converted by sulfuric acid into the dichromate.[57]

- 4 FeCr2O4 + 8 Na2CO3 + 7 O2 → 8 Na2CrO4 + 2 Fe2O3 + 8 CO2

- 2 Na2CrO4 + H2SO4 → Na2Cr2O7 + Na2SO4 + H2O

The dichromate is converted to the chromium(III) oxide by reduction with carbon and then reduced in an aluminothermic reaction to chromium.[57]

- Na2Cr2O7 + 2 C → Cr2O3 + Na2CO3 + CO

- Cr2O3 + 2 Al → Al2O3 + 2 Cr

Applications[edit]

The creation of metal alloys account for 85% of the available chromium’s usage. The remainder of chromium is used in the chemical, refractory, and foundry industries.[59]

Metallurgy[edit]

Stainless steel cutlery made from Cromargan 18/10, containing 18% chromium

The strengthening effect of forming stable metal carbides at grain boundaries, and the strong increase in corrosion resistance made chromium an important alloying material for steel. High-speed tool steels contain between 3 and 5% chromium. Stainless steel, the primary corrosion-resistant metal alloy, is formed when chromium is introduced to iron in concentrations above 11%.[60] For stainless steel’s formation, ferrochromium is added to the molten iron. Also, nickel-based alloys have increased strength due to the formation of discrete, stable, metal, carbide particles at the grain boundaries. For example, Inconel 718 contains 18.6% chromium. Because of the excellent high-temperature properties of these nickel superalloys, they are used in jet engines and gas turbines in lieu of common structural materials.[61] ASTM B163 relies on Chromium for condenser and heat-exchanger tubes, while castings with high strength at elevated temperatures that contain Chromium are standardised with ASTM A567.[62] AISI type 332 is used where high temperature would normally cause carburization, oxidation or corrosion.[63] Incoloy 800 «is capable of remaining stable and maintaining its austenitic structure even after long time exposures to high temperatures».[64] Nichrome is used as resistance wire for heating elements in things like toasters and space heaters. These uses make chromium a strategic material. Consequently, during World War II, U.S. road engineers were instructed to avoid chromium in yellow road paint, as it «may become a critical material during the emergency.»[65] The United States likewise considered chromium «essential for the German war industry» and made intense diplomatic efforts to keep it out of the hands of Nazi Germany.[66]

Decorative chrome plating on a motorcycle

The high hardness and corrosion resistance of unalloyed chromium makes it a reliable metal for surface coating; it is still the most popular metal for sheet coating, with its above-average durability, compared to other coating metals.[67] A layer of chromium is deposited on pretreated metallic surfaces by electroplating techniques. There are two deposition methods: thin, and thick. Thin deposition involves a layer of chromium below 1 µm thickness deposited by chrome plating, and is used for decorative surfaces. Thicker chromium layers are deposited if wear-resistant surfaces are needed. Both methods use acidic chromate or dichromate solutions. To prevent the energy-consuming change in oxidation state, the use of chromium(III) sulfate is under development; for most applications of chromium, the previously established process is used.[56]

In the chromate conversion coating process, the strong oxidative properties of chromates are used to deposit a protective oxide layer on metals like aluminium, zinc, and cadmium. This passivation and the self-healing properties of the chromate stored in the chromate conversion coating, which is able to migrate to local defects, are the benefits of this coating method.[68] Because of environmental and health regulations on chromates, alternative coating methods are under development.[69]

Chromic acid anodizing (or Type I anodizing) of aluminium is another electrochemical process that does not lead to the deposition of chromium, but uses chromic acid as an electrolyte in the solution. During anodization, an oxide layer is formed on the aluminium. The use of chromic acid, instead of the normally used sulfuric acid, leads to a slight difference of these oxide layers.[70]

The high toxicity of Cr(VI) compounds, used in the established chromium electroplating process, and the strengthening of safety and environmental regulations demand a search for substitutes for chromium, or at least a change to less toxic chromium(III) compounds.[56]

Pigment[edit]

The mineral crocoite (which is also lead chromate PbCrO4) was used as a yellow pigment shortly after its discovery. After a synthesis method became available starting from the more abundant chromite, chrome yellow was, together with cadmium yellow, one of the most used yellow pigments. The pigment does not photodegrade, but it tends to darken due to the formation of chromium(III) oxide. It has a strong color, and was used for school buses in the United States and for the postal services (for example, the Deutsche Post) in Europe. The use of chrome yellow has since declined due to environmental and safety concerns and was replaced by organic pigments or other alternatives that are free from lead and chromium. Other pigments that are based around chromium are, for example, the deep shade of red pigment chrome red, which is simply lead chromate with lead(II) hydroxide (PbCrO4·Pb(OH)2). A very important chromate pigment, which was used widely in metal primer formulations, was zinc chromate, now replaced by zinc phosphate. A wash primer was formulated to replace the dangerous practice of pre-treating aluminium aircraft bodies with a phosphoric acid solution. This used zinc tetroxychromate dispersed in a solution of polyvinyl butyral. An 8% solution of phosphoric acid in solvent was added just before application. It was found that an easily oxidized alcohol was an essential ingredient. A thin layer of about 10–15 µm was applied, which turned from yellow to dark green when it was cured. There is still a question as to the correct mechanism. Chrome green is a mixture of Prussian blue and chrome yellow, while the chrome oxide green is chromium(III) oxide.[71]

Chromium oxides are also used as a green pigment in the field of glassmaking and also as a glaze for ceramics.[72] Green chromium oxide is extremely lightfast and as such is used in cladding coatings. It is also the main ingredient in infrared reflecting paints, used by the armed forces to paint vehicles and to give them the same infrared reflectance as green leaves.[73]

Other uses[edit]

Red crystal of a ruby laser

Chromium(III) ions present in corundum crystals (aluminium oxide) cause them to be colored red; when corundum appears as such, it is known as a ruby. If the corundum is lacking in chromium(III) ions, it is known as a sapphire.[note 3] A red-colored artificial ruby may also be achieved by doping chromium(III) into artificial corundum crystals, thus making chromium a requirement for making synthetic rubies.[note 4][74] Such a synthetic ruby crystal was the basis for the first laser, produced in 1960, which relied on stimulated emission of light from the chromium atoms in such a crystal. Ruby has a laser transition at 694.3 nanometers, in a deep red color.[75]

Because of their toxicity, chromium(VI) salts are used for the preservation of wood. For example, chromated copper arsenate (CCA) is used in timber treatment to protect wood from decay fungi, wood-attacking insects, including termites, and marine borers.[76] The formulations contain chromium based on the oxide CrO3 between 35.3% and 65.5%. In the United States, 65,300 metric tons of CCA solution were used in 1996.[76]

Chromium(III) salts, especially chrome alum and chromium(III) sulfate, are used in the tanning of leather. The chromium(III) stabilizes the leather by cross linking the collagen fibers.[77] Chromium tanned leather can contain between 4 and 5% of chromium, which is tightly bound to the proteins.[39] Although the form of chromium used for tanning is not the toxic hexavalent variety, there remains interest in management of chromium in the tanning industry. Recovery and reuse, direct/indirect recycling,[78] and «chrome-less» or «chrome-free» tanning are practiced to better manage chromium usage.[79]

The high heat resistivity and high melting point makes chromite and chromium(III) oxide a material for high temperature refractory applications, like blast furnaces, cement kilns, molds for the firing of bricks and as foundry sands for the casting of metals. In these applications, the refractory materials are made from mixtures of chromite and magnesite. The use is declining because of the environmental regulations due to the possibility of the formation of chromium(VI).[57] [80]

Several chromium compounds are used as catalysts for processing hydrocarbons. For example, the Phillips catalyst, prepared from chromium oxides, is used for the production of about half the world’s polyethylene.[81] Fe-Cr mixed oxides are employed as high-temperature catalysts for the water gas shift reaction.[82][83] Copper chromite is a useful hydrogenation catalyst.[84]

Chromates of metals are used in humistor.[85]

Uses of compounds[edit]

- Chromium(IV) oxide (CrO2) is a magnetic compound. Its ideal shape anisotropy, which imparts high coercivity and remnant magnetization, made it a compound superior to γ-Fe2O3. Chromium(IV) oxide is used to manufacture magnetic tape used in high-performance audio tape and standard audio cassettes.[86]

- Chromium(III) oxide (Cr2O3) is a metal polish known as green rouge.[87][88]

- Chromic acid is a powerful oxidizing agent and is a useful compound for cleaning laboratory glassware of any trace of organic compounds.[89] It is prepared by dissolving potassium dichromate in concentrated sulfuric acid, which is then used to wash the apparatus. Sodium dichromate is sometimes used because of its higher solubility (50 g/L versus 200 g/L respectively). The use of dichromate cleaning solutions is now phased out due to the high toxicity and environmental concerns. Modern cleaning solutions are highly effective and chromium free.[90]

- Potassium dichromate is a chemical reagent, used as a titrating agent.[91]

- Chromates are added to drilling muds to prevent corrosion of steel under wet conditions.[92]

- Chrome alum is Chromium(III) potassium sulfate and is used as a mordant (i.e., a fixing agent) for dyes in fabric and in tanning.[93]

Biological role[edit]

The biologically beneficial effects of chromium(III) are debated.[94][95] Chromium is accepted by the U.S. National Institutes of Health as a trace element for its roles in the action of insulin, a hormone that mediates the metabolism and storage of carbohydrate, fat, and protein.[7] The mechanism of its actions in the body, however, have not been defined, leaving in question the essentiality of chromium.[96][97]

In contrast, hexavalent chromium (Cr(VI) or Cr6+) is highly toxic and mutagenic.[98] Ingestion of chromium(VI) in water has been linked to stomach tumors, and it may also cause allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).[99]

«Chromium deficiency», involving a lack of Cr(III) in the body, or perhaps some complex of it, such as glucose tolerance factor, is controversial.[7] Some studies suggest that the biologically active form of chromium (III) is transported in the body via an oligopeptide called low-molecular-weight chromium-binding substance (LMWCr), which might play a role in the insulin signaling pathway.[100]

The chromium content of common foods is generally low (1-13 micrograms per serving).[7][101] The chromium content of food varies widely, due to differences in soil mineral content, growing season, plant cultivar, and contamination during processing.[101] Chromium (and nickel) leach into food cooked in stainless steel, with the effect being largest when the cookware is new. Acidic foods that are cooked for many hours also exacerbate this effect.[102][103]

Dietary recommendations[edit]

There is disagreement on chromium’s status as an essential nutrient. Governmental departments from Australia, New Zealand, India, Japan, and the United States consider chromium essential[104][105][106][107] while the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) of the European Union does not.[108]

The U.S. National Academy of Medicine (NAM) updated the Estimated Average Requirements (EARs) and the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for chromium in 2001. For chromium, there was insufficient information to set EARs and RDAs, so its needs are described as estimates for Adequate Intakes (AIs). The current AIs of chromium for women ages 14 through 50 is 25 μg/day, and the AIs for women ages 50 and above is 20 μg/day. The AIs for women who are pregnant are 30 μg/day, and for women who are lactating, the set AIs are 45 μg/day. The AIs for men ages 14 through 50 are 35 μg/day, and the AIs for men ages 50 and above are 30 μg/day. For children ages 1 through 13, the AIs increase with age from 0.2 μg/day up to 25 μg/day. As for safety, the NAM sets Tolerable Upper Intake Levels (ULs) for vitamins and minerals when the evidence is sufficient. In the case of chromium, there is not yet enough information, hence no UL has been established. Collectively, the EARs, RDAs, AIs, and ULs are the parameters for the nutrition recommendation system known as Dietary Reference Intake (DRI).[107] Australia and New Zealand consider chromium to be an essential nutrient, with an AI of 35 μg/day for men, 25 μg/day for women, 30 μg/day for women who are pregnant, and 45 μg/day for women who are lactating. A UL has not been set due to the lack of sufficient data.[104] India considers chromium to be an essential nutrient, with an adult recommended intake of 33 μg/day.[105] Japan also considers chromium to be an essential nutrient, with an AI of 10 μg/day for adults, including women who are pregnant or lactating. A UL has not been set.[106] The EFSA of the European Union however, does not consider chromium to be an essential nutrient; chromium is the only mineral for which the United States and the European Union disagree.[108][109]

Labeling[edit]

For U.S. food and dietary supplement labeling purposes, the amount of the substance in a serving is expressed as a percent of the Daily Value (%DV). For chromium labeling purposes, 100% of the Daily Value was 120 μg. As of May 27, 2016, the percentage of daily value was revised to 35 μg to bring the chromium intake into a consensus with the official Recommended Dietary Allowance.[110][111] A table of the old and new adult daily values is provided at Reference Daily Intake.

Food sources[edit]

Food composition databases such as those maintained by the U.S. Department of Agriculture do not contain information on the chromium content of foods.[112] A wide variety of animal and vegetable foods contain chromium.[107] Content per serving is influenced by the chromium content of the soil in which the plants are grown, by foodstuffs fed to animals, and by processing methods, as chromium is leached into foods if processed or cooked in stainless steel equipment.[113] One diet analysis study conducted in Mexico reported an average daily chromium intake of 30 micrograms.[114] An estimated 31% of adults in the United States consume multi-vitamin/mineral dietary supplements,[115] which often contain 25 to 60 micrograms of chromium.

Supplementation[edit]

Chromium is an ingredient in total parenteral nutrition (TPN), because deficiency can occur after months of intravenous feeding with chromium-free TPN.[116] It is also added to nutritional products for preterm infants.[117] Although the mechanism of action in biological roles for chromium is unclear, in the United States chromium-containing products are sold as non-prescription dietary supplements in amounts ranging from 50 to 1,000 μg. Lower amounts of chromium are also often incorporated into multi-vitamin/mineral supplements consumed by an estimated 31% of adults in the United States.[115] Chemical compounds used in dietary supplements include chromium chloride, chromium citrate, chromium(III) picolinate, chromium(III) polynicotinate, and other chemical compositions.[7] The benefit of supplements has not been proven.[7][118]

Approved and disapproved health claims[edit]

In 2005, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration had approved a qualified health claim for chromium picolinate with a requirement for very specific label wording: «One small study suggests that chromium picolinate may reduce the risk of insulin resistance, and therefore possibly may reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes. FDA concludes, however, that the existence of such a relationship between chromium picolinate and either insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes is highly uncertain.» At the same time, in answer to other parts of the petition, the FDA rejected claims for chromium picolinate and cardiovascular disease, retinopathy or kidney disease caused by abnormally high blood sugar levels.[119] In 2010, chromium(III) picolinate was approved by Health Canada to be used in dietary supplements. Approved labeling statements include: a factor in the maintenance of good health, provides support for healthy glucose metabolism, helps the body to metabolize carbohydrates and helps the body to metabolize fats.[120] The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) approved claims in 2010 that chromium contributed to normal macronutrient metabolism and maintenance of normal blood glucose concentration, but rejected claims for maintenance or achievement of a normal body weight, or reduction of tiredness or fatigue.[121]

Given the evidence for chromium deficiency causing problems with glucose management in the context of intravenous nutrition products formulated without chromium,[116] research interest turned to whether chromium supplementation would benefit people who have type 2 diabetes but are not chromium deficient. Looking at the results from four meta-analyses, one reported a statistically significant decrease in fasting plasma glucose levels (FPG) and a non-significant trend in lower hemoglobin A1C.[122] A second reported the same,[123] a third reported significant decreases for both measures,[124] while a fourth reported no benefit for either.[125] A review published in 2016 listed 53 randomized clinical trials that were included in one or more of six meta-analyses. It concluded that whereas there may be modest decreases in FPG and/or HbA1C that achieve statistical significance in some of these meta-analyses, few of the trials achieved decreases large enough to be expected to be relevant to clinical outcome.[126]

Two systematic reviews looked at chromium supplements as a mean of managing body weight in overweight and obese people. One, limited to chromium picolinate, a popular supplement ingredient, reported a statistically significant −1.1 kg (2.4 lb) weight loss in trials longer than 12 weeks.[127] The other included all chromium compounds and reported a statistically significant −0.50 kg (1.1 lb) weight change.[128] Change in percent body fat did not reach statistical significance. Authors of both reviews considered the clinical relevance of this modest weight loss as uncertain/unreliable.[127][128] The European Food Safety Authority reviewed the literature and concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support a claim.[121]

Chromium is promoted as a sports performance dietary supplement, based on the theory that it potentiates insulin activity, with anticipated results of increased muscle mass, and faster recovery of glycogen storage during post-exercise recovery.[118][129][130] A review of clinical trials reported that chromium supplementation did not improve exercise performance or increase muscle strength.[131] The International Olympic Committee reviewed dietary supplements for high-performance athletes in 2018 and concluded there was no need to increase chromium intake for athletes, nor support for claims of losing body fat.[132]

Fresh-water fish[edit]

Chromium is naturally present in the environment in trace amounts, but industrial use in rubber and stainless steel manufacturing, chrome plating, dyes for textiles, tanneries and other uses contaminates aquatic systems. In Bangladesh, rivers in or downstream from industrialized areas exhibit heavy metal contamination. Irrigation water standards for chromium are 0.1 mg/L, but some rivers are more than five times that amount. The standard for fish for human consumption is less than 1 mg/kg, but many tested samples were more than five times that amount.[133] Chromium, especially hexavalent chromium, is highly toxic to fish because it is easily absorbed across the gills, readily enters blood circulation, crosses cell membranes and bioconcentrates up the food chain. In contrast, the toxicity of trivalent chromium is very low, attributed to poor membrane permeability and little biomagnification.[134]

Acute and chronic exposure to chromium(VI) affects fish behavior, physiology, reproduction and survival. Hyperactivity and erratic swimming have been reported in contaminated environments. Egg hatching and fingerling survival are affected. In adult fish there are reports of histopathological damage to liver, kidney, muscle, intestines, and gills. Mechanisms include mutagenic gene damage and disruptions of enzyme functions.[134]

There is evidence that fish may not require chromium, but benefit from a measured amount in diet. In one study, juvenile fish gained weight on a zero chromium diet, but the addition of 500 μg of chromium in the form of chromium chloride or other supplement types, per kilogram of food (dry weight), increased weight gain. At 2,000 μg/kg the weight gain was no better than with the zero chromium diet, and there were increased DNA strand breaks.[135]

Precautions[edit]

Water-insoluble chromium(III) compounds and chromium metal are not considered a health hazard, while the toxicity and carcinogenic properties of chromium(VI) have been known for a long time.[136] Because of the specific transport mechanisms, only limited amounts of chromium(III) enter the cells. Acute oral toxicity ranges between 50 and 150 mg/kg.[137] A 2008 review suggested that moderate uptake of chromium(III) through dietary supplements poses no genetic-toxic risk.[138] In the US, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has designated an air permissible exposure limit (PEL) in the workplace as a time-weighted average (TWA) of 1 mg/m3. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set a recommended exposure limit (REL) of 0.5 mg/m3, time-weighted average. The IDLH (immediately dangerous to life and health) value is 250 mg/m3.[139]

Chromium(VI) toxicity[edit]

The acute oral toxicity for chromium(VI) ranges between 1.5 and 3.3 mg/kg.[137] In the body, chromium(VI) is reduced by several mechanisms to chromium(III) already in the blood before it enters the cells. The chromium(III) is excreted from the body, whereas the chromate ion is transferred into the cell by a transport mechanism, by which also sulfate and phosphate ions enter the cell. The acute toxicity of chromium(VI) is due to its strong oxidant properties. After it reaches the blood stream, it damages the kidneys, the liver and blood cells through oxidation reactions. Hemolysis, renal, and liver failure result. Aggressive dialysis can be therapeutic.[140]

The carcinogenity of chromate dust has been known for a long time, and in 1890 the first publication described the elevated cancer risk of workers in a chromate dye company.[141][142] Three mechanisms have been proposed to describe the genotoxicity of chromium(VI). The first mechanism includes highly reactive hydroxyl radicals and other reactive radicals which are by products of the reduction of chromium(VI) to chromium(III). The second process includes the direct binding of chromium(V), produced by reduction in the cell, and chromium(IV) compounds to the DNA. The last mechanism attributed the genotoxicity to the binding to the DNA of the end product of the chromium(III) reduction.[143][144]

Chromium salts (chromates) are also the cause of allergic reactions in some people. Chromates are often used to manufacture, amongst other things, leather products, paints, cement, mortar and anti-corrosives. Contact with products containing chromates can lead to allergic contact dermatitis and irritant dermatitis, resulting in ulceration of the skin, sometimes referred to as «chrome ulcers». This condition is often found in workers that have been exposed to strong chromate solutions in electroplating, tanning and chrome-producing manufacturers.[145][146]

Environmental issues[edit]

Because chromium compounds were used in dyes, paints, and leather tanning compounds, these compounds are often found in soil and groundwater at active and abandoned industrial sites, needing environmental cleanup and remediation. Primer paint containing hexavalent chromium is still widely used for aerospace and automobile refinishing applications.[147]

In 2010, the Environmental Working Group studied the drinking water in 35 American cities in the first nationwide study. The study found measurable hexavalent chromium in the tap water of 31 of the cities sampled, with Norman, Oklahoma, at the top of list; 25 cities had levels that exceeded California’s proposed limit.[148]

The more toxic hexavalent chromium form can be reduced to the less soluble trivalent oxidation state in soils by organic matter, ferrous iron, sulfides, and other reducing agents, with the rates of such reduction being faster under more acidic conditions than under more alkaline ones. In contrast, trivalent chromium can be oxidized to hexavalent chromium in soils by manganese oxides, such as Mn(III) and Mn(IV) compounds. Since the solubility and toxicity of chromium (VI) are greater that those of chromium (III), the oxidation-reduction conversions between the two oxidation states have implications for movement and bioavailability of chromium in soils, groundwater, and plants.[149]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The melting/boiling point of transition metals are usually higher compared to the alkali metals, alkaline earth metals, and nonmetals, which is why the range of elements compared to chromium differed between comparisons

- ^ Most common oxidation states of chromium are in bold. The right column lists a representative compound for each oxidation state.

- ^ Any color of corundum (disregarding red) is known as a sapphire. If the corundum is red, then it is a ruby. Sapphires are not required to be blue corundum crystals, as sapphires can be other colors such as yellow and purple

- ^ When Cr3+

replaces Al3+

in corundum (aluminium oxide, Al2O3), pink sapphire or ruby is formed, depending on the amount of chromium.

References[edit]

- ^ «Standard Atomic Weights: Chromium». CIAAW. 1983.

- ^ a b Fawcett, Eric (1988). «Spin-density-wave antiferromagnetism in chromium». Reviews of Modern Physics. 60: 209. Bibcode:1988RvMP…60..209F. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.60.209.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ Brandes, EA; Greenaway, HT; Stone, HEN (1956). «Ductility in Chromium». Nature. 178 (4533): 587. Bibcode:1956Natur.178..587B. doi:10.1038/178587a0. S2CID 4221048.

- ^ a b c Coblentz, WW; Stair, R. «Reflecting power of beryllium, chromium, and several other metals» (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology. NIST Publications. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ χρῶμα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ a b c d e f «Chromium». Office of Dietary Supplements, US National Institutes of Health. 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ «Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for chromium». European Food Safety Authority. 18 September 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ «Substance Information — ECHA». echa.europa.eu. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ EPA (August 2000). «Abandoned Mine Site Characterization and Cleanup Handbook» (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ «The Nature of X-Ray Photoelectron Spectra». CasaXPS. Casa Software Ltd. 2005. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ Schwarz, W. H. Eugen (April 2010). «The Full Story of the Electron Configurations of the Transition Elements» (PDF). Journal of Chemical Education. 87 (4): 444–8. Bibcode:2010JChEd..87..444S. doi:10.1021/ed8001286. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 1004–5

- ^ a b Lind, Michael Acton (1972). «The infrared reflectivity of chromium and chromium-aluminium alloys». Iowa State University Digital Repository. Iowa State University. Bibcode:1972PhDT……..54L. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ Bos, Laurence William (1969). «Optical properties of chromium-manganese alloys». Iowa State University Digital Repository. Iowa State University. Bibcode:1969PhDT…….118B. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ Wallwork, GR (1976). «The oxidation of alloys». Reports on Progress in Physics. 39 (5): 401–485. Bibcode:1976RPPh…39..401W. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/39/5/001. S2CID 250853920.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Holleman, Arnold F; Wiber, Egon; Wiberg, Nils (1985). «Chromium». Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (in German) (91–100 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1081–1095. ISBN 978-3-11-007511-3.

- ^ National Research Council (U.S.). Committee on Coatings (1970). High-temperature oxidation-resistant coatings: coatings for protection from oxidation of superalloys, refractory metals, and graphite. National Academy of Sciences. ISBN 978-0-309-01769-5.

- ^ a b Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). «The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties» (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- ^ «Live Chart of Nuclides». International Atomic Energy Agency — Nuclear Data Section. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ Birck, JL; Rotaru, M; Allegre, C (1999). «53Mn-53Cr evolution of the early solar system». Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 63 (23–24): 4111–4117. Bibcode:1999GeCoA..63.4111B. doi:10.1016/S0016-7037(99)00312-9.

- ^ Frei, Robert; Gaucher, Claudio; Poulton, Simon W; Canfield, Don E (2009). «Fluctuations in Precambrian atmospheric oxygenation recorded by chromium isotopes». Nature. 461 (7261): 250–253. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..250F. doi:10.1038/nature08266. PMID 19741707. S2CID 4373201.

- ^ a b Kotaś, J.; Stasicka, Z. (2000). «Chromium occurrence in the environment and methods of its speciation». Environmental Pollution. 107 (3): 263–283. doi:10.1016/S0269-7491(99)00168-2. PMID 15092973.

- ^ Puigdomenech, Ignasi Hydra/Medusa Chemical Equilibrium Database and Plotting Software Archived 5 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine (2004) KTH Royal Institute of Technology

- ^ Clark, Jim. «Oxidation states (oxidation numbers)». Chemguide. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ a b Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Theopold, Klaus H.; Kucharczyk, Robin R. (15 December 2011), «Chromium: Organometallic Chemistry», in Scott, Robert A. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Inorganic and Bioinorganic Chemistry, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. eibc0042, doi:10.1002/9781119951438.eibc0042, ISBN 978-1-119-95143-8.

- ^ Cotton, FA; Walton, RA (1993). Multiple Bonds Between Metal Atoms. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-855649-7.

- ^ «Chromium(III) compounds». National Pollutant Inventory. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ Assfalg, M; Banci, L; Bertini, I; Bruschi, M; Michel, C; Giudici-Orticoni, M; Turano, P (31 July 2002). «NMR structural characterization of the reduction of chromium(VI) to chromium(III) by cytochrome c7». Protein Data Bank (1LM2). doi:10.2210/pdb1LM2/pdb. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ Luther, George W. (2016). «Introduction to Transition Metals». Inorganic Chemistry for Geochemistry & Environmental Sciences: Fundamentals & Applications. Hydrate (Solvate) Isomers. John Wiley & Sons. p. 244. ISBN 978-1118851371. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ Gumerova, Nadiia I.; Roller, Alexander; Giester, Gerald; Krzystek, J.; Cano, Joan; Rompel, Annette (19 February 2020). «Incorporation of CrIII into a Keggin Polyoxometalate as a Chemical Strategy to Stabilize a Labile {CrIIIO4} Tetrahedral Conformation and Promote Unattended Single-Ion Magnet Properties». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 142 (7): 3336–3339. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b12797. ISSN 0002-7863. PMC 7052816. PMID 31967803.

- ^ Seppelt, Konrad (28 January 2015). «Molecular Hexafluorides». Chemical Reviews. 115 (2): 1296–1306. doi:10.1021/cr5001783. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 25418862.

- ^ Haxhillazi, Gentiana (2003). Preparation, Structure and Vibrational Spectroscopy of Tetraperoxo Complexes of CrV+, VV+, NbV+ and TaV+ (PhD thesis). University of Siegen.

- ^ Thaler, Eric G.; Rypdal, Kristin; Haaland, Arne; Caulton, Kenneth G. (1 June 1989). «Structure and reactivity of chromium(4+) tert-butoxide». Inorganic Chemistry. 28 (12): 2431–2434. doi:10.1021/ic00311a035. ISSN 0020-1669.

- ^ Nguyen, T; Sutton, AD; Brynda, M; Fettinger, JC; Long, GJ; Power, PP (2005). «Synthesis of a stable compound with fivefold bonding between two chromium(I) centers». Science. 310 (5749): 844–847. Bibcode:2005Sci…310..844N. doi:10.1126/science.1116789. PMID 16179432. S2CID 42853922.

- ^ Emsley, John (2001). «Chromium». Nature’s Building Blocks: An A–Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford, England, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 495–498. ISBN 978-0-19-850340-8.

- ^ John Rieuwerts (14 July 2017). The Elements of Environmental Pollution. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-12679-7.

- ^ a b c National Research Council (U.S.). Committee on Biologic Effects of Atmospheric Pollutants (1974). Chromium. National Academy of Sciences. ISBN 978-0-309-02217-0.

- ^ Champion, Marc (11 January 2018). «How a Trump SoHo Partner Ended Up With Toxic Mining Riches From Kazakhstan». Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d Papp, John F. «Mineral Yearbook 2015: Chromium» (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ Fleischer, Michael (1982). «New Mineral Names» (PDF). American Mineralogist. 67: 854–860.

- ^ Chromium (with location data), Mindat.

- ^ Chromium from Udachnaya-Vostochnaya pipe, Daldyn, Daldyn-Alakit kimberlite field, Saha Republic (Sakha Republic; Yakutia), Eastern-Siberian Region, Russia, Mindat.

- ^ Gonzalez, A. R.; Ndung’u, K.; Flegal, A. R. (2005). «Natural Occurrence of Hexavalent Chromium in the Aromas Red Sands Aquifer, California». Environmental Science and Technology. 39 (15): 5505–5511. Bibcode:2005EnST…39.5505G. doi:10.1021/es048835n. PMID 16124280.

- ^ Meyer, RJ (1962). Chrom : Teil A — Lieferung 1. Geschichtliches · Vorkommen · Technologie · Element bis Physikalische Eigenschaften (in German). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg Imprint Springer. ISBN 978-3-662-11865-8. OCLC 913810356.

- ^ Lehmanni, Iohannis Gottlob (1766). De Nova Minerae Plumbi Specie Crystallina Rubra, Epistola.

- ^ a b c Guertin, Jacques; Jacobs, James Alan & Avakian, Cynthia P. (2005). Chromium (VI) Handbook. CRC Press. pp. 7–11. ISBN 978-1-56670-608-7.

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). «The discovery of the elements. V. Chromium, molybdenum, tungsten and uranium». Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (3): 459–73. Bibcode:1932JChEd…9..459W. doi:10.1021/ed009p459. ISSN 0021-9584.

- ^ Casteran, Rene. «Chromite mining». Oregon Encyclopedia. Portland State University and the Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ Vauquelin, Louis Nicolas (1798). «Memoir on a New Metallic Acid which exists in the Red Lead of Siberia». Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry, and the Arts. 3: 145–146.

- ^ Glenn, William (1895). «Chrome in the Southern Appalachian Region». Transactions of the American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical and Petroleum Engineers. 25: 482.

- ^ van der Krogt, Peter. «Chromium». Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- ^ Ortt, Richard A Jr. «Soldier’s Delight, Baltimore Country». Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Maryland Geological Survey. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ Bilgin, Arif; Çağlar, Burhan (eds.). Klasikten Moderne Osmanlı Ekonomisi. Turkey: Kronik Kitap. p. 240.

- ^ a b c Dennis, JK; Such, TE (1993). «History of Chromium Plating». Nickel and Chromium Plating. Woodhead Publishing. pp. 9–12. ISBN 978-1-85573-081-6.

- ^ a b c d Papp, John F. & Lipin, Bruce R. (2006). «Chromite». Industrial Minerals & Rocks: Commodities, Markets, and Uses (7th ed.). SME. ISBN 978-0-87335-233-8.

- ^ Papp, John F. «Mineral Yearbook 2002: Chromium» (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ Morrison, RD; Murphy, BL (4 August 2010). Environmental Forensics: Contaminant Specific Guide. Academic Press. ISBN 9780080494784.

- ^ Davis, JR (2000). Alloy digest sourcebook : stainless steels (in Afrikaans). Materials Park, OH: ASM International. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-0-87170-649-2. OCLC 43083287.

- ^ Bhadeshia, HK. «Nickel-Based Superalloys». University of Cambridge. Archived from the original on 25 August 2006. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ «Chromium, Nickel and Welding». IARC Monographs. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 49: 49–50. 1990.

- ^ «Stainless Steel Grade 332 (UNS S33200)». AZoNetwork. 5 March 2013.

- ^ «Super Alloy INCOLOY Alloy 800 (UNS N08800)». AZoNetwork. 3 July 2013.

- ^ «Manual On Uniform Traffic Control Devices (War Emergency Edition)» (PDF). Washington, DC: American Associan of State Highway Officials. November 1942. p. 52. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ State Department, United States. «Allied Relations and Negotiations with Turkey» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 November 2020.

- ^ Breitsameter, M (15 August 2002). «Thermal Spraying versus Hard Chrome Plating». Azo Materials. AZoNetwork. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ Edwards, J (1997). Coating and Surface Treatment Systems for Metals. Finishing Publications Ltd. and ASMy International. pp. 66–71. ISBN 978-0-904477-16-0.

- ^ Zhao J, Xia L, Sehgal A, Lu D, McCreery RL, Frankel GS (2001). «Effects of chromate and chromate conversion coatings on corrosion of aluminum alloy 2024-T3». Surface and Coatings Technology. 140 (1): 51–57. doi:10.1016/S0257-8972(01)01003-9. hdl:1811/36519.

- ^ Cotell, CM; Sprague, JA; Smidt, FA (1994). ASM Handbook: Surface Engineering. ASM International. ISBN 978-0-87170-384-2. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ Gettens, Rutherford John (1966). «Chrome yellow». Painting Materials: A Short Encyclopaedia. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 105–106. ISBN 978-0-486-21597-6.

- ^ Gerd Anger et al. «Chromium Compounds» Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2005, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a07_067

- ^ Marrion, Alastair (2004). The chemistry and physics of coatings. Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 287–. ISBN 978-0-85404-604-1.

- ^ Moss, SC; Newnham, RE (1964). «The chromium position in ruby» (PDF). Zeitschrift für Kristallographie. 120 (4–5): 359–363. Bibcode:1964ZK….120..359M. doi:10.1524/zkri.1964.120.4-5.359.

- ^ Webb, Colin E; Jones, Julian DC (2004). Handbook of Laser Technology and Applications: Laser design and laser systems. CRC Press. pp. 323–. ISBN 978-0-7503-0963-9.

- ^ a b Hingston, J; Collins, CD; Murphy, RJ; Lester, JN (2001). «Leaching of chromated copper arsenate wood preservatives: a review». Environmental Pollution. 111 (1): 53–66. doi:10.1016/S0269-7491(00)00030-0. PMID 11202715.

- ^ Brown, EM (1997). «A Conformational Study of Collagen as Affected by Tanning Procedures». Journal of the American Leather Chemists Association. 92: 225–233.

- ^ Sreeram, K.; Ramasami, T. (2003). «Sustaining tanning process through conservation, recovery and better utilization of chromium». Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 38 (3): 185–212. doi:10.1016/S0921-3449(02)00151-9.

- ^ Qiang, Taotao; Gao, Xin; Ren, Jing; Chen, Xiaoke; Wang, Xuechuan (9 December 2015). «A Chrome-Free and Chrome-Less Tanning System Based on the Hyperbranched Polymer». ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. 4 (3): 701–707. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b00917.

- ^ Barnhart, Joel (1997). «Occurrences, Uses, and Properties of Chromium». Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 26 (1): S3–S7. doi:10.1006/rtph.1997.1132. ISSN 0273-2300. PMID 9380835.

- ^ Weckhuysen, Bert M; Schoonheydt, Robert A (1999). «Olefin polymerization over supported chromium oxide catalysts» (PDF). Catalysis Today. 51 (2): 215–221. doi:10.1016/S0920-5861(99)00046-2. hdl:1874/21357. S2CID 98324455.

- ^ Twigg, MVE (1989). «The Water-Gas Shift Reaction». Catalyst Handbook. ISBN 978-0-7234-0857-4.

- ^ Rhodes, C; Hutchings, GJ; Ward, AM (1995). «Water-gas shift reaction: Finding the mechanistic boundary». Catalysis Today. 23: 43–58. doi:10.1016/0920-5861(94)00135-O.

- ^ Lazier, WA & Arnold, HR (1939). «Copper Chromite Catalyst». Organic Syntheses. 19: 31.; Collective Volume, vol. 2, p. 142

- ^ Kitagawa, Hiraku (April 1989). «LiTe and CaTe thin-film junctions as humidity sensors». Sensors and Actuators. 16 (4): 369–378. doi:10.1016/0250-6874(89)85007-3.

- ^ Mallinson, John C. (1993). «Chromium Dioxide». The foundations of magnetic recording. Academic Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-12-466626-9.

- ^ Toshiro Doi; Ioan D. Marinescu; Syuhei Kurokawa (30 November 2011). Advances in CMP Polishing Technologies. William Andrew. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-1-4377-7860-1.

- ^ Baral, Anil; Engelken, Robert D. (2002). «Chromium-based regulations and greening in metal finishing industries in the USA». Environmental Science & Policy. 5 (2): 121–133. doi:10.1016/S1462-9011(02)00028-X.

- ^ Soderberg, Tim (3 June 2019). «Oxidizing Agents». LibreTexts. MindTouch. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Roth, Alexander (1994). Vacuum Sealing Techniques. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 118–. ISBN 978-1-56396-259-2.

- ^ Lancashire, Robert J (27 October 2008). «Determination of iron using potassium dichromate: Redox indicators». The Department of Chemistry UWI, Jamaica. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Garverick, Linda (1994). Corrosion in the Petrochemical Industry. ASM International. ISBN 978-0-87170-505-1.

- ^ Shahid Ul-Islam (18 July 2017). Plant-Based Natural Products: Derivatives and Applications. Wiley. pp. 74–. ISBN 978-1-119-42388-1.

- ^ Vincent, JB (2013). «Chapter 6. Chromium: Is It Essential, Pharmacologically Relevant, or Toxic?». In Astrid Sigel; Helmut Sigel; Roland KO Sigel (eds.). Interrelations between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 13. Springer. pp. 171–198. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_6. ISBN 978-94-007-7499-5. PMID 24470092.

- ^ Maret, Wolfgang (2019). «Chapter 9. Chromium Supplementation in Human Health, Metabolic Syndrome, and Diabetes». In Sigel, Astrid; Freisinger, Eva; Sigel, Roland K. O.; Carver, Peggy L. (eds.). Essential Metals in Medicine:Therapeutic Use and Toxicity of Metal Ions in the Clinic. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 19. Berlin: de Gruyter GmbH. pp. 231–251. doi:10.1515/9783110527872-015. ISBN 978-3-11-052691-2. PMID 30855110.

- ^ European Food Safety Authority (2014). «Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for chromium». EFSA Journal. 12 (10): 3845. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2014.3845.

- ^ Di Bona KR, Love S, Rhodes NR, McAdory D, Sinha SH, Kern N, Kent J, Strickland J, Wilson A, Beaird J, Ramage J, Rasco JF, Vincent JB (2011). «Chromium is not an essential trace element for mammals: effects of a «low-chromium» diet». J Biol Inorg Chem. 16 (3): 381–390. doi:10.1007/s00775-010-0734-y. PMID 21086001. S2CID 22376660.

- ^ Wise, SS; Wise, JP, Sr (2012). «Chromium and genomic stability». Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 733 (1–2): 78–82. doi:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.12.002. PMC 4138963. PMID 22192535.

- ^ «ToxFAQs: Chromium». Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. February 2001. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- ^ Vincent, JB (2015). «Is the Pharmacological Mode of Action of Chromium(III) as a Second Messenger?». Biological Trace Element Research. 166 (1): 7–12. doi:10.1007/s12011-015-0231-9. PMID 25595680. S2CID 16895342.

- ^ a b Thor, MY; Harnack, L; King, D; Jasthi, B; Pettit, J (2011). «Evaluation of the comprehensiveness and reliability of the chromium composition of foods in the literature». Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 24 (8): 1147–1152. doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2011.04.006. PMC 3467697. PMID 23066174.

- ^ Kamerud KL; Hobbie KA; Anderson KA (2013). «Stainless steel leaches nickel and chromium into foods during cooking». Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 61 (39): 9495–9501. doi:10.1021/jf402400v. PMC 4284091. PMID 23984718.

- ^ Flint GN; Packirisamy S (1997). «Purity of food cooked in stainless steel utensils». Food Additives and Contaminants. 14 (2): 115–126. doi:10.1080/02652039709374506. PMID 9102344.

- ^ a b «Chromium». Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand. 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ a b «Nutrient Requirements and Recommended Dietary Allowances for Indians: A Report of the Expert Group of the Indian Council of Medical Research. pp.283-295 (2009)» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ a b «DRIs for Chromium (μg/day)» (PDF). Overview of Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese. 2015. p. 41. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ a b c «Chromium. IN: Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Chromium, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Chromium». Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Panel on Micronutrients, National Academy Press. 2001. pp. 197–223. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ a b «Overview on Dietary Reference Values for the EU population as derived by the EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies» (PDF). 2017.

- ^ Tolerable Upper Intake Levels For Vitamins And Minerals (PDF), European Food Safety Authority, 2006

- ^ «Federal Register May 27, 2016 Food Labeling: Revision of the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels. FR page 33982» (PDF).

- ^ «Daily Value Reference of the Dietary Supplement Label Database (DSLD)». Dietary Supplement Label Database (DSLD). Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ «USDA Food Composition Databases». United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service. April 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^

Kumpulainen, JT (1992). «Chromium content of foods and diets». Biological Trace Element Research. 32 (1–3): 9–18. doi:10.1007/BF02784582. PMID 1375091. S2CID 10189109. - ^ Grijalva Haro, MI; Ballesteros Vázquez, MN; Cabrera Pacheco, RM (2001). «Chromium content in foods and dietary intake estimation in the Northwest of Mexico». Arch Latinoam Nutr (in Spanish). 51 (1): 105–110. PMID 11515227.

- ^ a b Kantor, Elizabeth D; Rehm, Colin D; Du, Mengmeng; White, Emily; Giovannucci, Edward L (11 October 2017). «Trends in Dietary Supplement Use Among US Adults From 1999-2012». JAMA. 316 (14): 1464–1474. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.14403. PMC 5540241. PMID 27727382.

- ^ a b Stehle, P; Stoffel-Wagner, B; Kuh, KS (6 April 2014). «Parenteral trace element provision: recent clinical research and practical conclusions». European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 70 (8): 886–893. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2016.53. PMC 5399133. PMID 27049031.

- ^ Finch, Carolyn Weiglein (February 2015). «Review of trace mineral requirements for preterm infants: What are the current recommendations for clinical practice?». Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 30 (1): 44–58. doi:10.1177/0884533614563353. PMID 25527182.

- ^ a b Vincent, John B (2010). «Chromium: Celebrating 50 years as an essential element?». Dalton Transactions. 39 (16): 3787–3794. doi:10.1039/B920480F. PMID 20372701.

- ^ FDA Qualified Health Claims: Letters of Enforcement Discretion, Letters of Denial U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Docket #2004Q-0144 (August 2005).

- ^ «Monograph: Chromium (from Chromium picolinate)». Health Canada. 9 December 2009. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ a b Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to chromium and contribution to normal macronutrient metabolism (ID 260, 401, 4665, 4666, 4667), maintenance of normal blood glucose concentrations (ID 262, 4667), contribution to the maintenance or achievement of a normal body weight (ID 339, 4665, 4666), and reduction of tiredness and fatigue (ID 261) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 Archived 21 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine European Food Safety Authority EFSA J 2010;8(10)1732.

- ^ San Mauro-Martin I, Ruiz-León AM, Camina-Martín MA, Garicano-Vilar E, Collado-Yurrita L, Mateo-Silleras B, Redondo P (2016). «[Chromium supplementation in patients with type 2 diabetes and high risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials]». Nutr Hosp (in Spanish). 33 (1): 27. doi:10.20960/nh.27. PMID 27019254.