In computer programming, an assignment statement sets and/or re-sets the value stored in the storage location(s) denoted by a variable name; in other words, it copies a value into the variable. In most imperative programming languages, the assignment statement (or expression) is a fundamental construct.

Today, the most commonly used notation for this operation is x = expr (originally Superplan 1949–51, popularized by Fortran 1957 and C). The second most commonly used notation is[1] x := expr (originally ALGOL 1958, popularised by Pascal).[2] Many other notations are also in use. In some languages, the symbol used is regarded as an operator (meaning that the assignment statement as a whole returns a value). Other languages define assignment as a statement (meaning that it cannot be used in an expression).

Assignments typically allow a variable to hold different values at different times during its life-span and scope. However, some languages (primarily strictly functional languages) do not allow that kind of «destructive» reassignment, as it might imply changes of non-local state. The purpose is to enforce referential transparency, i.e. functions that do not depend on the state of some variable(s), but produce the same results for a given set of parametric inputs at any point in time. Modern programs in other languages also often use similar strategies, although less strict, and only in certain parts, in order to reduce complexity, normally in conjunction with complementing methodologies such as data structuring, structured programming and object orientation.

Semantics[edit]

An assignment operation is a process in imperative programming in which different values are associated with a particular variable name as time passes.[1] The program, in such model, operates by changing its state using successive assignment statements.[2][3] Primitives of imperative programming languages rely on assignment to do iteration.[4] At the lowest level, assignment is implemented using machine operations such as MOVE or STORE.[2][4]

Variables are containers for values. It is possible to put a value into a variable and later replace it with a new one. An assignment operation modifies the current state of the executing program.[3] Consequently, assignment is dependent on the concept of variables. In an assignment:

- The

expressionis evaluated in the current state of the program. - The

variableis assigned the computed value, replacing the prior value of that variable.

Example: Assuming that a is a numeric variable, the assignment a := 2*a means that the content of the variable a is doubled after the execution of the statement.

An example segment of C code:

int x = 10; float y; x = 23; y = 32.4f;

In this sample, the variable x is first declared as an int, and is then assigned the value of 10. Notice that the declaration and assignment occur in the same statement. In the second line, y is declared without an assignment. In the third line, x is reassigned the value of 23. Finally, y is assigned the value of 32.4.

For an assignment operation, it is necessary that the value of the expression is well-defined (it is a valid rvalue) and that the variable represents a modifiable entity (it is a valid modifiable (non-const) lvalue). In some languages, typically dynamic ones, it is not necessary to declare a variable prior to assigning it a value. In such languages, a variable is automatically declared the first time it is assigned to, with the scope it is declared in varying by language.

Single assignment[edit]

Any assignment that changes an existing value (e.g. x := x + 1) is disallowed in purely functional languages.[4] In functional programming, assignment is discouraged in favor of single assignment, also called initialization. Single assignment is an example of name binding and differs from assignment as described in this article in that it can only be done once, usually when the variable is created; no subsequent reassignment is allowed.

An evaluation of expression does not have a side effect if it does not change an observable state of the machine,[5] and produces same values for same input.[4] Imperative assignment can introduce side effects while destroying and making the old value unavailable while substituting it with a new one,[6] and is referred to as destructive assignment for that reason in LISP and functional programming, similar to destructive updating.

Single assignment is the only form of assignment available in purely functional languages, such as Haskell, which do not have variables in the sense of imperative programming languages[4] but rather named constant values possibly of compound nature with their elements progressively defined on-demand. Purely functional languages can provide an opportunity for computation to be performed in parallel, avoiding the von Neumann bottleneck of sequential one step at a time execution, since values are independent of each other.[7]

Impure functional languages provide both single assignment as well as true assignment (though true assignment is typically used with less frequency than in imperative programming languages). For example, in Scheme, both single assignment (with let) and true assignment (with set!) can be used on all variables, and specialized primitives are provided for destructive update inside lists, vectors, strings, etc. In OCaml, only single assignment is allowed for variables, via the let name = value syntax; however destructive update can be used on elements of arrays and strings with separate <- operator, as well as on fields of records and objects that have been explicitly declared mutable (meaning capable of being changed after their initial declaration) by the programmer.

Functional programming languages that use single assignment include Clojure (for data structures, not vars), Erlang (it accepts multiple assignment if the values are equal, in contrast to Haskell), F#, Haskell, JavaScript (for constants), Lava, OCaml, Oz (for dataflow variables, not cells), Racket (for some data structures like lists, not symbols), SASL, Scala (for vals), SISAL, Standard ML. Non-backtracking Prolog code can be considered explicit single-assignment, explicit in a sense that its (named) variables can be in explicitly unassigned state, or be set exactly once. In Haskell, by contrast, there can be no unassigned variables, and every variable can be thought of as being implicitly set, when it is created, to its value (or rather to a computational object that will produce its value on demand).

Value of an assignment[edit]

In some programming languages, an assignment statement returns a value, while in others it does not.

In most expression-oriented programming languages (for example, C), the assignment statement returns the assigned value, allowing such idioms as x = y = a, in which the assignment statement y = a returns the value of a, which is then assigned to x. In a statement such as while ((ch = getchar()) != EOF) {…}, the return value of a function is used to control a loop while assigning that same value to a variable.

In other programming languages, Scheme for example, the return value of an assignment is undefined and such idioms are invalid.

In Haskell,[8] there is no variable assignment; but operations similar to assignment (like assigning to a field of an array or a field of a mutable data structure) usually evaluate to the unit type, which is represented as (). This type has only one possible value, therefore containing no information. It is typically the type of an expression that is evaluated purely for its side effects.

Variant forms of assignment[edit]

Certain use patterns are very common, and thus often have special syntax to support them. These are primarily syntactic sugar to reduce redundancy in the source code, but also assists readers of the code in understanding the programmer’s intent, and provides the compiler with a clue to possible optimization.

Augmented assignment[edit]

The case where the assigned value depends on a previous one is so common that many imperative languages, most notably C and the majority of its descendants, provide special operators called augmented assignment, like *=, so a = 2*a can instead be written as a *= 2.[3] Beyond syntactic sugar, this assists the task of the compiler by making clear that in-place modification of the variable a is possible.

Chained assignment[edit]

A statement like w = x = y = z is called a chained assignment in which the value of z is assigned to multiple variables w, x, and y. Chained assignments are often used to initialize multiple variables, as in

a = b = c = d = f = 0

Not all programming languages support chained assignment. Chained assignments are equivalent to a sequence of assignments, but the evaluation strategy differs between languages. For simple chained assignments, like initializing multiple variables, the evaluation strategy does not matter, but if the targets (l-values) in the assignment are connected in some way, the evaluation strategy affects the result.

In some programming languages (C for example), chained assignments are supported because assignments are expressions, and have values. In this case chain assignment can be implemented by having a right-associative assignment, and assignments happen right-to-left. For example, i = arr[i] = f() is equivalent to arr[i] = f(); i = arr[i]. In C++ they are also available for values of class types by declaring the appropriate return type for the assignment operator.

In Python, assignment statements are not expressions and thus do not have a value. Instead, chained assignments are a series of statements with multiple targets for a single expression. The assignments are executed left-to-right so that i = arr[i] = f() evaluates the expression f(), then assigns the result to the leftmost target, i, and then assigns the same result to the next target, arr[i], using the new value of i.[9] This is essentially equivalent to tmp = f(); i = tmp; arr[i] = tmp though no actual variable is produced for the temporary value.

Parallel assignment[edit]

Some programming languages, such as APL, Common Lisp,[10] Go,[11] JavaScript (since 1.7), PHP, Maple, Lua, occam 2,[12] Perl,[13] Python,[14] REBOL, Ruby,[15] and PowerShell allow several variables to be assigned in parallel, with syntax like:

a, b := 0, 1

which simultaneously assigns 0 to a and 1 to b. This is most often known as parallel assignment; it was introduced in CPL in 1963, under the name simultaneous assignment,[16] and is sometimes called multiple assignment, though this is confusing when used with «single assignment», as these are not opposites. If the right-hand side of the assignment is a single variable (e.g. an array or structure), the feature is called unpacking[17] or destructuring assignment:[18]

var list := {0, 1}

a, b := list

The list will be unpacked so that 0 is assigned to a and 1 to b. Furthermore,

a, b := b, a

swaps the values of a and b. In languages without parallel assignment, this would have to be written to use a temporary variable

var t := a a := b b := t

since a := b; b := a leaves both a and b with the original value of b.

Some languages, such as Go and Python, combine parallel assignment, tuples, and automatic tuple unpacking to allow multiple return values from a single function, as in this Python example,

def f(): return 1, 2 a, b = f()

while other languages, such as C# and Rust, shown here, require explicit tuple construction and deconstruction with parentheses:

// Valid C# or Rust syntax (a, b) = (b, a);

// C# tuple return (string, int) f() => ("foo", 1); var (a, b) = f();

// Rust tuple return let f = || ("foo", 1); let (a, b) = f();

This provides an alternative to the use of output parameters for returning multiple values from a function. This dates to CLU (1974), and CLU helped popularize parallel assignment generally.

C# additionally allows generalized deconstruction assignment with implementation defined by the expression on the right-hand side, as the compiler searches for an appropriate instance or extension Deconstruct method on the expression, which must have output parameters for the variables being assigned to.[19] For example, one such method that would give the class it appears in the same behavior as the return value of f() above would be

void Deconstruct(out string a, out int b) { a = "foo"; b = 1; }

In C and C++, the comma operator is similar to parallel assignment in allowing multiple assignments to occur within a single statement, writing a = 1, b = 2 instead of a, b = 1, 2.

This is primarily used in for loops, and is replaced by parallel assignment in other languages such as Go.[20]

However, the above C++ code does not ensure perfect simultaneity, since the right side of the following code a = b, b = a+1 is evaluated after the left side. In languages such as Python, a, b = b, a+1 will assign the two variables concurrently, using the initial value of a to compute the new b.

Assignment versus equality[edit]

The use of the equals sign = as an assignment operator has been frequently criticized, due to the conflict with equals as comparison for equality. This results both in confusion by novices in writing code, and confusion even by experienced programmers in reading code. The use of equals for assignment dates back to Heinz Rutishauser’s language Superplan, designed from 1949 to 1951, and was particularly popularized by Fortran:

A notorious example for a bad idea was the choice of the equal sign to denote assignment. It goes back to Fortran in 1957[a] and has blindly been copied by armies of language designers. Why is it a bad idea? Because it overthrows a century old tradition to let “=” denote a comparison for equality, a predicate which is either true or false. But Fortran made it to mean assignment, the enforcing of equality. In this case, the operands are on unequal footing: The left operand (a variable) is to be made equal to the right operand (an expression). x = y does not mean the same thing as y = x.[21]

— Niklaus Wirth, Good Ideas, Through the Looking Glass

Beginning programmers sometimes confuse assignment with the relational operator for equality, as «=» means equality in mathematics, and is used for assignment in many languages. But assignment alters the value of a variable, while equality testing tests whether two expressions have the same value.

In some languages, such as BASIC, a single equals sign ("=") is used for both the assignment operator and the equality relational operator, with context determining which is meant. Other languages use different symbols for the two operators. For example:

- In ALGOL and Pascal, the assignment operator is a colon and an equals sign (

":=") while the equality operator is a single equals ("="). - In C, the assignment operator is a single equals sign (

"=") while the equality operator is a pair of equals signs ("=="). - In R, the assignment operator is basically

<-, as inx <- value, but a single equals sign can be used in certain contexts.

The similarity in the two symbols can lead to errors if the programmer forgets which form («=«, «==«, «:=«) is appropriate, or mistypes «=» when «==» was intended. This is a common programming problem with languages such as C (including one famous attempt to backdoor the Linux kernel),[22] where the assignment operator also returns the value assigned (in the same way that a function returns a value), and can be validly nested inside expressions. If the intention was to compare two values in an if statement, for instance, an assignment is quite likely to return a value interpretable as Boolean true, in which case the then clause will be executed, leading the program to behave unexpectedly. Some language processors (such as gcc) can detect such situations, and warn the programmer of the potential error.

Notation[edit]

The two most common representations for the copying assignment are equals sign (=) and colon-equals (:=). Both forms may semantically denote either an assignment statement or an assignment operator (which also has a value), depending on language and/or usage.

-

variable = expressionFortran, PL/I, C (and descendants such as C++, Java, etc.), Bourne shell, Python, Go (assignment to pre-declared variables), R, PowerShell, Nim, etc. variable := expressionALGOL (and derivatives), Simula, CPL, BCPL, Pascal[23] (and descendants such as Modula), Mary, PL/M, Ada, Smalltalk, Eiffel,[24][25] Oberon, Dylan,[26] Seed7, Python (an assignment expression),[27] Go (shorthand for declaring and defining a variable),[28] Io, AMPL, ML (assigning to a reference value),[29] AutoHotkey etc.

Other possibilities include a left arrow or a keyword, though there are other, rarer, variants:

-

variable << expressionMagik variable <- expressionF#, OCaml, R, S variable <<- expressionR assign("variable", expression)R variable ← expressionAPL,[30] Smalltalk, BASIC Programming variable =: expressionJ LET variable = expressionBASIC let variable := expressionXQuery set variable to expressionAppleScript set variable = expressionC shell Set-Variable variable (expression)PowerShell variable : expressionMacsyma, Maxima, K variable: expressionRebol var variable expressionmIRC scripting language reference-variable :- reference-expressionSimula

Mathematical pseudo code assignments are generally depicted with a left-arrow.

Some platforms put the expression on the left and the variable on the right:

Some expression-oriented languages, such as Lisp[31][32] and Tcl, uniformly use prefix (or postfix) syntax for all statements, including assignment.

See also[edit]

- Assignment operator in C++

- Operator (programming)

- Name binding

- Unification (computing)

- Immutable object

- Const-correctness

Notes[edit]

- ^ Use of

=predates Fortran, though it was popularized by Fortran.

References[edit]

- ^ a b «2cs24 Declarative». www.csc.liv.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 24 April 2006. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ a b c «Imperative Programming». uah.edu. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ a b c Ruediger-Marcus Flaig (2008). Bioinformatics programming in Python: a practical course for beginners. Wiley-VCH. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-3-527-32094-3. Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Crossing borders: Explore functional programming with Haskell Archived November 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, by Bruce Tate

- ^ Mitchell, John C. (2003). Concepts in programming languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-521-78098-8. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ «Imperative Programming Languages (IPL)» (PDF). gwu.edu. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ John C. Mitchell (2003). Concepts in programming languages. Cambridge University Press. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-0-521-78098-8. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ Hudak, Paul (2000). The Haskell School of Expression: Learning Functional Programming Through Multimedia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64408-9.

- ^ «7. Simple statements — Python 3.6.5 documentation». docs.python.org. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ «CLHS: Macro SETF, PSETF». Common Lisp Hyperspec. LispWorks. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ The Go Programming Language Specification: Assignments

- ^ INMOS Limited, ed. (1988). Occam 2 Reference Manual. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-629312-3.

- ^ Wall, Larry; Christiansen, Tom; Schwartz, Randal C. (1996). Perl Programming Language (2 ed.). Cambridge: O´Reilly. ISBN 1-56592-149-6.

- ^ Lutz, Mark (2001). Python Programming Language (2 ed.). Sebastopol: O´Reilly. ISBN 0-596-00085-5.

- ^ Thomas, David; Hunt, Andrew (2001). Programming Ruby: The Pragmatic Programmer’s Guide. Upper Saddle River: Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-201-71089-7.

- ^ D.W. Barron et al., «The main features of CPL», Computer Journal 6:2:140 (1963). full text (subscription)

- ^ «PEP 3132 — Extended Iterable Unpacking». legacy.python.org. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ «Destructuring assignment». MDN Web Docs. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ «Deconstructing tuples and other types». Microsoft Docs. Microsoft. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ Effective Go: for,

«Finally, Go has no comma operator and ++ and — are statements not expressions. Thus if you want to run multiple variables in a for you should use parallel assignment (although that precludes ++ and —).» - ^ Niklaus Wirth. «Good Ideas, Through the Looking Glass». CiteSeerX 10.1.1.88.8309.

- ^ Corbet (6 November 2003). «An attempt to backdoor the kernel».

- ^ Moore, Lawrie (1980). Foundations of Programming with Pascal. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-470-26939-1.

- ^ Meyer, Bertrand (1992). Eiffel the Language. Hemel Hempstead: Prentice Hall International(UK). ISBN 0-13-247925-7.

- ^ Wiener, Richard (1996). An Object-Oriented Introduction to Computer Science Using Eiffel. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-183872-5.

- ^ Feinberg, Neal; Keene, Sonya E.; Mathews, Robert O.; Withington, P. Tucker (1997). Dylan Programming. Massachusetts: Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-201-47976-1.

- ^ «PEP 572 – Assignment Expressions». python.org. 28 February 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ «The Go Programming Language Specification — The Go Programming Language». golang.org. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ Ullman, Jeffrey D. (1998). Elements of ML Programming: ML97 Edition. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-790387-1.

- ^ Iverson, Kenneth E. (1962). A Programming Language. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-43014-5. Archived from the original on 2009-06-04. Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- ^ Graham, Paul (1996). ANSI Common Lisp. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-370875-6.

- ^ Steele, Guy L. (1990). Common Lisp: The Language. Lexington: Digital Press. ISBN 1-55558-041-6.

- ^ Dybvig, R. Kent (1996). The Scheme Programming Language: ANSI Scheme. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-454646-6.

- ^ Smith, Jerry D. (1988). Introduction to Scheme. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-496712-7.

- ^ Abelson, Harold; Sussman, Gerald Jay; Sussman, Julie (1996). Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs. New Jersey: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-000484-6.

In computer programming, an assignment statement sets and/or re-sets the value stored in the storage location(s) denoted by a variable name; in other words, it copies a value into the variable. In most imperative programming languages, the assignment statement (or expression) is a fundamental construct.

Today, the most commonly used notation for this operation is x = expr (originally Superplan 1949–51, popularized by Fortran 1957 and C). The second most commonly used notation is[1] x := expr (originally ALGOL 1958, popularised by Pascal).[2] Many other notations are also in use. In some languages, the symbol used is regarded as an operator (meaning that the assignment statement as a whole returns a value). Other languages define assignment as a statement (meaning that it cannot be used in an expression).

Assignments typically allow a variable to hold different values at different times during its life-span and scope. However, some languages (primarily strictly functional languages) do not allow that kind of «destructive» reassignment, as it might imply changes of non-local state. The purpose is to enforce referential transparency, i.e. functions that do not depend on the state of some variable(s), but produce the same results for a given set of parametric inputs at any point in time. Modern programs in other languages also often use similar strategies, although less strict, and only in certain parts, in order to reduce complexity, normally in conjunction with complementing methodologies such as data structuring, structured programming and object orientation.

Semantics[edit]

An assignment operation is a process in imperative programming in which different values are associated with a particular variable name as time passes.[1] The program, in such model, operates by changing its state using successive assignment statements.[2][3] Primitives of imperative programming languages rely on assignment to do iteration.[4] At the lowest level, assignment is implemented using machine operations such as MOVE or STORE.[2][4]

Variables are containers for values. It is possible to put a value into a variable and later replace it with a new one. An assignment operation modifies the current state of the executing program.[3] Consequently, assignment is dependent on the concept of variables. In an assignment:

- The

expressionis evaluated in the current state of the program. - The

variableis assigned the computed value, replacing the prior value of that variable.

Example: Assuming that a is a numeric variable, the assignment a := 2*a means that the content of the variable a is doubled after the execution of the statement.

An example segment of C code:

int x = 10; float y; x = 23; y = 32.4f;

In this sample, the variable x is first declared as an int, and is then assigned the value of 10. Notice that the declaration and assignment occur in the same statement. In the second line, y is declared without an assignment. In the third line, x is reassigned the value of 23. Finally, y is assigned the value of 32.4.

For an assignment operation, it is necessary that the value of the expression is well-defined (it is a valid rvalue) and that the variable represents a modifiable entity (it is a valid modifiable (non-const) lvalue). In some languages, typically dynamic ones, it is not necessary to declare a variable prior to assigning it a value. In such languages, a variable is automatically declared the first time it is assigned to, with the scope it is declared in varying by language.

Single assignment[edit]

Any assignment that changes an existing value (e.g. x := x + 1) is disallowed in purely functional languages.[4] In functional programming, assignment is discouraged in favor of single assignment, also called initialization. Single assignment is an example of name binding and differs from assignment as described in this article in that it can only be done once, usually when the variable is created; no subsequent reassignment is allowed.

An evaluation of expression does not have a side effect if it does not change an observable state of the machine,[5] and produces same values for same input.[4] Imperative assignment can introduce side effects while destroying and making the old value unavailable while substituting it with a new one,[6] and is referred to as destructive assignment for that reason in LISP and functional programming, similar to destructive updating.

Single assignment is the only form of assignment available in purely functional languages, such as Haskell, which do not have variables in the sense of imperative programming languages[4] but rather named constant values possibly of compound nature with their elements progressively defined on-demand. Purely functional languages can provide an opportunity for computation to be performed in parallel, avoiding the von Neumann bottleneck of sequential one step at a time execution, since values are independent of each other.[7]

Impure functional languages provide both single assignment as well as true assignment (though true assignment is typically used with less frequency than in imperative programming languages). For example, in Scheme, both single assignment (with let) and true assignment (with set!) can be used on all variables, and specialized primitives are provided for destructive update inside lists, vectors, strings, etc. In OCaml, only single assignment is allowed for variables, via the let name = value syntax; however destructive update can be used on elements of arrays and strings with separate <- operator, as well as on fields of records and objects that have been explicitly declared mutable (meaning capable of being changed after their initial declaration) by the programmer.

Functional programming languages that use single assignment include Clojure (for data structures, not vars), Erlang (it accepts multiple assignment if the values are equal, in contrast to Haskell), F#, Haskell, JavaScript (for constants), Lava, OCaml, Oz (for dataflow variables, not cells), Racket (for some data structures like lists, not symbols), SASL, Scala (for vals), SISAL, Standard ML. Non-backtracking Prolog code can be considered explicit single-assignment, explicit in a sense that its (named) variables can be in explicitly unassigned state, or be set exactly once. In Haskell, by contrast, there can be no unassigned variables, and every variable can be thought of as being implicitly set, when it is created, to its value (or rather to a computational object that will produce its value on demand).

Value of an assignment[edit]

In some programming languages, an assignment statement returns a value, while in others it does not.

In most expression-oriented programming languages (for example, C), the assignment statement returns the assigned value, allowing such idioms as x = y = a, in which the assignment statement y = a returns the value of a, which is then assigned to x. In a statement such as while ((ch = getchar()) != EOF) {…}, the return value of a function is used to control a loop while assigning that same value to a variable.

In other programming languages, Scheme for example, the return value of an assignment is undefined and such idioms are invalid.

In Haskell,[8] there is no variable assignment; but operations similar to assignment (like assigning to a field of an array or a field of a mutable data structure) usually evaluate to the unit type, which is represented as (). This type has only one possible value, therefore containing no information. It is typically the type of an expression that is evaluated purely for its side effects.

Variant forms of assignment[edit]

Certain use patterns are very common, and thus often have special syntax to support them. These are primarily syntactic sugar to reduce redundancy in the source code, but also assists readers of the code in understanding the programmer’s intent, and provides the compiler with a clue to possible optimization.

Augmented assignment[edit]

The case where the assigned value depends on a previous one is so common that many imperative languages, most notably C and the majority of its descendants, provide special operators called augmented assignment, like *=, so a = 2*a can instead be written as a *= 2.[3] Beyond syntactic sugar, this assists the task of the compiler by making clear that in-place modification of the variable a is possible.

Chained assignment[edit]

A statement like w = x = y = z is called a chained assignment in which the value of z is assigned to multiple variables w, x, and y. Chained assignments are often used to initialize multiple variables, as in

a = b = c = d = f = 0

Not all programming languages support chained assignment. Chained assignments are equivalent to a sequence of assignments, but the evaluation strategy differs between languages. For simple chained assignments, like initializing multiple variables, the evaluation strategy does not matter, but if the targets (l-values) in the assignment are connected in some way, the evaluation strategy affects the result.

In some programming languages (C for example), chained assignments are supported because assignments are expressions, and have values. In this case chain assignment can be implemented by having a right-associative assignment, and assignments happen right-to-left. For example, i = arr[i] = f() is equivalent to arr[i] = f(); i = arr[i]. In C++ they are also available for values of class types by declaring the appropriate return type for the assignment operator.

In Python, assignment statements are not expressions and thus do not have a value. Instead, chained assignments are a series of statements with multiple targets for a single expression. The assignments are executed left-to-right so that i = arr[i] = f() evaluates the expression f(), then assigns the result to the leftmost target, i, and then assigns the same result to the next target, arr[i], using the new value of i.[9] This is essentially equivalent to tmp = f(); i = tmp; arr[i] = tmp though no actual variable is produced for the temporary value.

Parallel assignment[edit]

Some programming languages, such as APL, Common Lisp,[10] Go,[11] JavaScript (since 1.7), PHP, Maple, Lua, occam 2,[12] Perl,[13] Python,[14] REBOL, Ruby,[15] and PowerShell allow several variables to be assigned in parallel, with syntax like:

a, b := 0, 1

which simultaneously assigns 0 to a and 1 to b. This is most often known as parallel assignment; it was introduced in CPL in 1963, under the name simultaneous assignment,[16] and is sometimes called multiple assignment, though this is confusing when used with «single assignment», as these are not opposites. If the right-hand side of the assignment is a single variable (e.g. an array or structure), the feature is called unpacking[17] or destructuring assignment:[18]

var list := {0, 1}

a, b := list

The list will be unpacked so that 0 is assigned to a and 1 to b. Furthermore,

a, b := b, a

swaps the values of a and b. In languages without parallel assignment, this would have to be written to use a temporary variable

var t := a a := b b := t

since a := b; b := a leaves both a and b with the original value of b.

Some languages, such as Go and Python, combine parallel assignment, tuples, and automatic tuple unpacking to allow multiple return values from a single function, as in this Python example,

def f(): return 1, 2 a, b = f()

while other languages, such as C# and Rust, shown here, require explicit tuple construction and deconstruction with parentheses:

// Valid C# or Rust syntax (a, b) = (b, a);

// C# tuple return (string, int) f() => ("foo", 1); var (a, b) = f();

// Rust tuple return let f = || ("foo", 1); let (a, b) = f();

This provides an alternative to the use of output parameters for returning multiple values from a function. This dates to CLU (1974), and CLU helped popularize parallel assignment generally.

C# additionally allows generalized deconstruction assignment with implementation defined by the expression on the right-hand side, as the compiler searches for an appropriate instance or extension Deconstruct method on the expression, which must have output parameters for the variables being assigned to.[19] For example, one such method that would give the class it appears in the same behavior as the return value of f() above would be

void Deconstruct(out string a, out int b) { a = "foo"; b = 1; }

In C and C++, the comma operator is similar to parallel assignment in allowing multiple assignments to occur within a single statement, writing a = 1, b = 2 instead of a, b = 1, 2.

This is primarily used in for loops, and is replaced by parallel assignment in other languages such as Go.[20]

However, the above C++ code does not ensure perfect simultaneity, since the right side of the following code a = b, b = a+1 is evaluated after the left side. In languages such as Python, a, b = b, a+1 will assign the two variables concurrently, using the initial value of a to compute the new b.

Assignment versus equality[edit]

The use of the equals sign = as an assignment operator has been frequently criticized, due to the conflict with equals as comparison for equality. This results both in confusion by novices in writing code, and confusion even by experienced programmers in reading code. The use of equals for assignment dates back to Heinz Rutishauser’s language Superplan, designed from 1949 to 1951, and was particularly popularized by Fortran:

A notorious example for a bad idea was the choice of the equal sign to denote assignment. It goes back to Fortran in 1957[a] and has blindly been copied by armies of language designers. Why is it a bad idea? Because it overthrows a century old tradition to let “=” denote a comparison for equality, a predicate which is either true or false. But Fortran made it to mean assignment, the enforcing of equality. In this case, the operands are on unequal footing: The left operand (a variable) is to be made equal to the right operand (an expression). x = y does not mean the same thing as y = x.[21]

— Niklaus Wirth, Good Ideas, Through the Looking Glass

Beginning programmers sometimes confuse assignment with the relational operator for equality, as «=» means equality in mathematics, and is used for assignment in many languages. But assignment alters the value of a variable, while equality testing tests whether two expressions have the same value.

In some languages, such as BASIC, a single equals sign ("=") is used for both the assignment operator and the equality relational operator, with context determining which is meant. Other languages use different symbols for the two operators. For example:

- In ALGOL and Pascal, the assignment operator is a colon and an equals sign (

":=") while the equality operator is a single equals ("="). - In C, the assignment operator is a single equals sign (

"=") while the equality operator is a pair of equals signs ("=="). - In R, the assignment operator is basically

<-, as inx <- value, but a single equals sign can be used in certain contexts.

The similarity in the two symbols can lead to errors if the programmer forgets which form («=«, «==«, «:=«) is appropriate, or mistypes «=» when «==» was intended. This is a common programming problem with languages such as C (including one famous attempt to backdoor the Linux kernel),[22] where the assignment operator also returns the value assigned (in the same way that a function returns a value), and can be validly nested inside expressions. If the intention was to compare two values in an if statement, for instance, an assignment is quite likely to return a value interpretable as Boolean true, in which case the then clause will be executed, leading the program to behave unexpectedly. Some language processors (such as gcc) can detect such situations, and warn the programmer of the potential error.

Notation[edit]

The two most common representations for the copying assignment are equals sign (=) and colon-equals (:=). Both forms may semantically denote either an assignment statement or an assignment operator (which also has a value), depending on language and/or usage.

-

variable = expressionFortran, PL/I, C (and descendants such as C++, Java, etc.), Bourne shell, Python, Go (assignment to pre-declared variables), R, PowerShell, Nim, etc. variable := expressionALGOL (and derivatives), Simula, CPL, BCPL, Pascal[23] (and descendants such as Modula), Mary, PL/M, Ada, Smalltalk, Eiffel,[24][25] Oberon, Dylan,[26] Seed7, Python (an assignment expression),[27] Go (shorthand for declaring and defining a variable),[28] Io, AMPL, ML (assigning to a reference value),[29] AutoHotkey etc.

Other possibilities include a left arrow or a keyword, though there are other, rarer, variants:

-

variable << expressionMagik variable <- expressionF#, OCaml, R, S variable <<- expressionR assign("variable", expression)R variable ← expressionAPL,[30] Smalltalk, BASIC Programming variable =: expressionJ LET variable = expressionBASIC let variable := expressionXQuery set variable to expressionAppleScript set variable = expressionC shell Set-Variable variable (expression)PowerShell variable : expressionMacsyma, Maxima, K variable: expressionRebol var variable expressionmIRC scripting language reference-variable :- reference-expressionSimula

Mathematical pseudo code assignments are generally depicted with a left-arrow.

Some platforms put the expression on the left and the variable on the right:

Some expression-oriented languages, such as Lisp[31][32] and Tcl, uniformly use prefix (or postfix) syntax for all statements, including assignment.

See also[edit]

- Assignment operator in C++

- Operator (programming)

- Name binding

- Unification (computing)

- Immutable object

- Const-correctness

Notes[edit]

- ^ Use of

=predates Fortran, though it was popularized by Fortran.

References[edit]

- ^ a b «2cs24 Declarative». www.csc.liv.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 24 April 2006. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ a b c «Imperative Programming». uah.edu. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ a b c Ruediger-Marcus Flaig (2008). Bioinformatics programming in Python: a practical course for beginners. Wiley-VCH. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-3-527-32094-3. Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Crossing borders: Explore functional programming with Haskell Archived November 19, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, by Bruce Tate

- ^ Mitchell, John C. (2003). Concepts in programming languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-521-78098-8. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ «Imperative Programming Languages (IPL)» (PDF). gwu.edu. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ John C. Mitchell (2003). Concepts in programming languages. Cambridge University Press. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-0-521-78098-8. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ Hudak, Paul (2000). The Haskell School of Expression: Learning Functional Programming Through Multimedia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64408-9.

- ^ «7. Simple statements — Python 3.6.5 documentation». docs.python.org. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ «CLHS: Macro SETF, PSETF». Common Lisp Hyperspec. LispWorks. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ The Go Programming Language Specification: Assignments

- ^ INMOS Limited, ed. (1988). Occam 2 Reference Manual. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-629312-3.

- ^ Wall, Larry; Christiansen, Tom; Schwartz, Randal C. (1996). Perl Programming Language (2 ed.). Cambridge: O´Reilly. ISBN 1-56592-149-6.

- ^ Lutz, Mark (2001). Python Programming Language (2 ed.). Sebastopol: O´Reilly. ISBN 0-596-00085-5.

- ^ Thomas, David; Hunt, Andrew (2001). Programming Ruby: The Pragmatic Programmer’s Guide. Upper Saddle River: Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-201-71089-7.

- ^ D.W. Barron et al., «The main features of CPL», Computer Journal 6:2:140 (1963). full text (subscription)

- ^ «PEP 3132 — Extended Iterable Unpacking». legacy.python.org. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ «Destructuring assignment». MDN Web Docs. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ «Deconstructing tuples and other types». Microsoft Docs. Microsoft. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ Effective Go: for,

«Finally, Go has no comma operator and ++ and — are statements not expressions. Thus if you want to run multiple variables in a for you should use parallel assignment (although that precludes ++ and —).» - ^ Niklaus Wirth. «Good Ideas, Through the Looking Glass». CiteSeerX 10.1.1.88.8309.

- ^ Corbet (6 November 2003). «An attempt to backdoor the kernel».

- ^ Moore, Lawrie (1980). Foundations of Programming with Pascal. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-470-26939-1.

- ^ Meyer, Bertrand (1992). Eiffel the Language. Hemel Hempstead: Prentice Hall International(UK). ISBN 0-13-247925-7.

- ^ Wiener, Richard (1996). An Object-Oriented Introduction to Computer Science Using Eiffel. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-183872-5.

- ^ Feinberg, Neal; Keene, Sonya E.; Mathews, Robert O.; Withington, P. Tucker (1997). Dylan Programming. Massachusetts: Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-201-47976-1.

- ^ «PEP 572 – Assignment Expressions». python.org. 28 February 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ «The Go Programming Language Specification — The Go Programming Language». golang.org. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ Ullman, Jeffrey D. (1998). Elements of ML Programming: ML97 Edition. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-790387-1.

- ^ Iverson, Kenneth E. (1962). A Programming Language. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-43014-5. Archived from the original on 2009-06-04. Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- ^ Graham, Paul (1996). ANSI Common Lisp. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-370875-6.

- ^ Steele, Guy L. (1990). Common Lisp: The Language. Lexington: Digital Press. ISBN 1-55558-041-6.

- ^ Dybvig, R. Kent (1996). The Scheme Programming Language: ANSI Scheme. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-454646-6.

- ^ Smith, Jerry D. (1988). Introduction to Scheme. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-496712-7.

- ^ Abelson, Harold; Sussman, Gerald Jay; Sussman, Julie (1996). Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs. New Jersey: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-000484-6.

Содержание

- 1 Определение присваивания

- 1.1 Алгоритм работы оператора присваивания

- 1.2 Символ присваивания

- 1.3 Семантические особенности

- 1.3.1 Неоднозначность присваивания

- 1.3.2 Семантика ссылок

- 1.3.3 Подмена операции

- 2 Расширения конструкции присваивания

- 2.1 Множественные целевые объекты

- 2.2 Параллельное присваивание

- 2.3 Условные целевые объекты

- 2.4 Составные операторы присваивания

- 2.5 Унарные операторы присваивания

- 3 Реализация

- 4 Примечания

- 5 См. также

- 6 Литература

Присва́ивание (иногда присвое́ние) — механизм в программировании, позволяющий динамически изменять связи объектов данных (как правило, переменных) с их значениями. Строго говоря, изменение значений является побочным эффектом операции присвоения, и во многих современных языках программирования сама операция также возвращает некоторый результат (как правило, копию присвоенного значения). На физическом уровне результат операции присвоения состоит в проведении записи и перезаписи ячеек памяти или регистров процессора.

Присваивание является одной из центральных конструкций в императивных языках программирования, эффективно и просто реализуется на фон-неймановской архитектуре, которая является основой современных компьютеров.

В логическом программировании принят другой, алгебраический подход. Обычного («разрушающего») присвоения здесь нет. Существуют только неизвестные, которые ещё не вычислены, и соответствующие идентификаторы для обозначения этих неизвестных. Программа только определяет их значения, сами они постоянны. Конечно, в реализации программа производит запись в память, но языки программирования этого не отражают, давая программисту возможность работать с идентификаторами постоянных значений, а не с переменными.

В чистом функциональном программировании не используются переменные, и явный оператор присваивания не нужен.

Определение присваивания

Общий синтаксис простого присваивания выглядит следующим образом:

<выражение слева> <оператор присваивания > <выражение справа>

«Выражение слева» должно после вычисления привести к местоположению объекта данных, к целевой переменной, идентификатору ячейки памяти, в которую будет производиться запись. Такие ссылки называются «левосторонними значениями» (англ. lvalue). Типичные примеры левостороннего значения — имя переменной (x), путь к переменной в пространстве имён и библиотеках (Namespace.Library.Object.AnotherObject.Property), путь к массиву с выражением на месте индекса (this.a[i+j*k]), но ниже в данной статье приведены и более сложные варианты.

«Выражение справа» должно обозначать тем или иным способом ту величину, которая будет присвоена объекту данных. Таким образом, даже если справа стои́т имя той же переменной, что и слева, интерпретируется оно иначе — такие ссылки называются «правосторонними значениями» (англ. rvalue). Дальнейшие ограничения на выражение накладывает используемый язык: так, в статически типизированных языках оно должно иметь тот же тип, что и целевая переменная, либо тип, приводимый к нему; в некоторых языках (например, Си или a=b=c).

В роли оператора присваивания в языках программирования чаще всего выступают =, := или ←. Но специальный синтаксис может и не вводится — например, в

Данная запись эквивалентна вызову функции. Аналогично, в КОБОЛе старого стиля:

MULTIPLY 2 BY 2 GIVING FOUR.

Алгоритм работы оператора присваивания

- Вычислить левостороннее значение первого операнда. На этом этапе становится известным местонахождение целевого объекта, приёмника нового значения.

- Вычислить правостороннее значение второго операнда. Этот этап может быть сколь угодно большим и включать другие операторы (в том числе присвоения).

- Присвоить вычисленное правостороннее значение левостороннему значению. Во-первых, при конфликте типов должно быть осуществлено их приведение (либо выдано сообщение об ошибке ввиду его невозможности). Во-вторых, собственно присваивания значения в современных языках программирования может быть подменено и включать не только перенос значений ячеек памяти (например, в «свойства» объектов в C#, перегрузка операторов).

- Возвратить вычисленное правостороннее значение как результат выполнения операции. Требуется не во всех языках (например, не нужно в Паскале).

Символ присваивания

Выбор символа присваивания является поводом для споров разработчиков языков. Существует мнение, что использование символа = для присвоения запутывает программистов, а также ставит сложный для хорошего решения вопрос о выборе символа для оператора равенства.

Так, Никлаус Вирт утверждал[1]:

Эта плохая идея низвергает вековую традицию использования знака «=» для обозначения сравнения на равенство, предиката, принимающего значения «истина» или «ложь».

Выбор символа оператора равенства в языке при использовании = как присваивания решается:

- Введением нового символа языка для оператора проверки равенства.

Запись равенства в Си == является источником частых ошибок из-за возможности использования присваивания в управляющих конструкциях, но в других языках проблема решается введением дополнительных ограничений.

- Использованием этого же символа, значение определяется в зависимости от контекста.

Например, в выражении языка ПЛ/1:

А = В = С

переменной А присваивается булевское значение выражения отношения В = С. Такая запись приводит к снижению читабельности и редко используется.

Семантические особенности

Далеко не всегда «интуитивный» (для программистов императивных языков) способ интерпретации присваивания является единственно верным и возможным.

Бывает, по используемому синтаксису, в императивных языках невозможно понять как реализуется семантика присваивания, если это, явно, не определено в языке.

Например в Forth языке, используется присваивание значения, когда данные между операциями, проходят через стек данных, при этом сама операции не является указателем на связываемые данные, а только выполняет действия предписанные операции.

Следствием чего можно провести присваивание данных, сформированных(расположенных) далеко от операции присваивания.

Рассмотрим простой пример для вышесказанного:

Определение переменной AAA и следующей строкой присваивание ей значения 10 VARIABLE AAAA 10 AAA !

или так то же самое(семантически):

10 VARIABLE AAA AAA !

Неоднозначность присваивания

Рассмотрим пример:

X = 2 + 1

Это можно понять как «результат вычисления 2+1 (то есть 3) присваивается переменной X» или как «операция 2+1 присваивается переменной X». Если язык статически типизирован, то двусмысленности нет, она разрешается типом переменной X («целое число» или «операция»). В языке Пролог типизация динамическая, поэтому существуют две операции присвоения: is — присвоение эквивалентного значения и = — присвоение образца. В таком случае:

X is 2 + 1, X = 3 X = 2 + 1, X = 3

Первая последовательность будет признана верной, вторая — ложной.

Семантика ссылок

При работе с объектами больших размеров и сложной структуры многие языки используют так называемую «семантику ссылок». Это означает, что присвоения в классическом смысле не происходит, но считается, что значение целевой переменной располагается на том же месте, что и значение исходной. Например (

После этого b будет иметь значение [1, 1000, 3] — просто потому, что фактически его значение — это и есть значение a. Число ссылок на один и тот же объект данных называется его мощностью, а сам объект погибает (уничтожается или отдаётся сборщику мусора), когда его мощность достигает нуля. Языки программирования более низкого уровня (например, Си) позволяют программисту явно управлять тем, используется ли семантика указателей или семантика копирования.

Подмена операции

Многие языки предоставляют возможность подмены смысла присвоения: либо через механизм свойств, либо через перегрузку оператора присвоения. Подмена может понадобится для выполнения проверок на допустимость присваиваемого значения или любых других дополнительных операций. Перегрузка оператора присвоения часто используется для обеспечения «глубокого копирования», то есть копирования значений, а не ссылок, которые во многих языка копируются по умолчанию.

Такие механизмы позволяют обеспечить удобство при работе, так для программиста нет различия между использованием встроенного оператора и перегруженного. По этой же причине возможны проблемы, так как действия перегруженного оператора могут быть абсолютно отличны от действий оператора по умолчанию, а вызов функции не очевиден и легко может быть принят за встроенную операцию.

Расширения конструкции присваивания

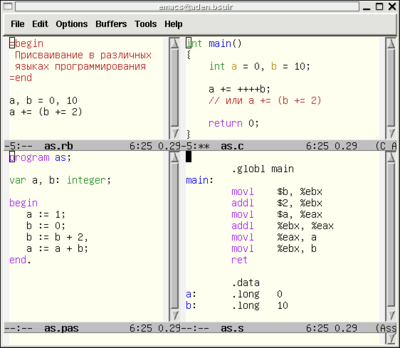

Конструкции присвоения в различных языках программирования

Поскольку операция присвоения является широко используемой, разработчики языков программирования пытаются разработать новые конструкции для упрощённой записи типичных операций (добавить в язык так называемый «синтаксический сахар»). Кроме этого в низкоуровневых языках программирования часто критерием включения операции является возможность компиляции в эффективный исполняемый код.[2] Особенно известен данным свойством язык Си.

Множественные целевые объекты

Одной из альтернатив простого оператора является возможность присвоения значения выражения нескольким объектам. Например, в языке ПЛ/1 оператор

SUM, TOTAL = 0

одновременно присваивает нулевое значение переменным SUM и TOTAL. В языке Ада присвоение также является оператором, а не выражением, поэтому запись множественного присвоения имеет вид:

SUM, TOTAL: Integer := 0;

Аналогичное присвоение в языке

sum = total = 0

В отличие от ПЛ/1, Ады и Питона, где множественное присвоение считается только сокращённой формой записи, в языках Си, Лисп и других данный синтаксис имеет строгую основу: просто оператор присвоения возвращает присвоенное им значение (см. выше). Таким образом, последний пример — это на самом деле:

sum = (total = 0)

Строчка такого вида сработает в Си (если добавить точку с запятой в конце), но вызовет ошибку в Питоне.

Параллельное присваивание

Некоторые языки, например Руби и

a, b = 1, 11

Считается, что такое присвоение выполняется одновременно и параллельно, что позволяет коротко реализовать с помощью такой конструкции операцию обмена значений двух переменных.

| запись с использованием параллельного присваивания | «традиционное» присвоение: требует дополнительной переменной и трёх операций |

|---|---|

a, b = b, a |

t = a a = b b = t |

Некоторые языки (например,

list($a, $b) = array($b, $a);

Условные целевые объекты

Некоторые языки программирования, например, C++ и

flag ? countl : count2 = О

присвоит 0 переменной count1 если flag истинно и count2, если flag ложно.

Другой вариант условного присваивания (Руби):

a ||= 10

Данная конструкция присваивает переменной a значение только в том случае, если значение ещё не присвоено или равно false.

Составные операторы присваивания

Составной оператор присваивания позволяет сокращённо задавать часто используемую форму присвоения. С помощью этого способа можно сократить запись присвоения, при котором целевая переменная используется в качестве первого операнда в правой части выражения, например:

а = а + b

Синтаксис составного оператора присваивания языка Си представляет собой объединение нужного бинарного оператора и оператора =. Например, следующие записи эквивалентны

sum += value; |

sum = sum + value; |

В языках программирования, поддерживающих составные операторы (C++, C#, Java и др.), обычно существуют версии для большинства бинарных операторов этих языков (+=, -=, &= и т. п.).

Унарные операторы присваивания

В языке программирования Си и большинстве производных от него есть два специальных унарных (то есть имеющих один аргумент) арифметических оператора, представляющих собой в действительности сокращённые присваивания . Эти операторы сочетают операции увеличения и уменьшения на единицу с присваиванием. Операторы ++ для увеличения и -- для уменьшения могут использоваться как префиксные операторы (то есть перед операндами) или как постфиксные (то есть после операндов), означая различный порядок вычислений. Оператор префиксной инкрементации возвращает уже увеличенное значение операнда, а постфиксной — исходное.

Ниже приведён пример использования оператора инкрементации для формирования завершённого оператора присвоения

| увеличение значения переменной на единицу | эквивалентная расширенная запись |

|---|---|

count ++; |

count = count + 1; |

Хоть это и не выглядит присваивания, но таковым является. Результат выполнения приведённого выше оператора равнозначен результату выполнения присваивания .

Операторы инкрементации и декрементации в языке Си часто являются сокращённой записью для формирования выражений, содержащих индексы массивов.

Реализация

Работа современных компьютеров состоит из считываний данных из памяти или устройства в регистры, выполнения операций над этими данными и записи в память или устройство. Основной операцией здесь является пересылка данных (из регистров в память, из памяти в регистр, из регистра в регистр). Соответственно, она выражается напрямую командами современных процессоров. Так для архитектуры mov и её разновидности для пересылки данных различных размеров. Операция присваивания (пересылка данных из одной ячейки памяти в другую) практически непосредственно реализуется данной командой. Вообще говоря, для выполнения пересылки данных в памяти требуется две инструкций: перемещение из памяти в регистр и из регистра в память, но при использовании оптимизации в большинстве случаев количество команд можно сократить.

Примечания

- ↑ Никлаус Вирт. Хорошие идеи: взгляд из Зазеркалья. Пер. Сергей Кузнецов (2006). Проверено 23 апреля 2006.

- ↑ В целях оптимизации многие операции совмещаются в присваиванием. Для сокращённых записей присвоения зачастую есть эквивалент в машинных инструкциях. Так, увеличение на единицу реализуется машинной инструкцией

inc, уменьшение на единицу —dec, сложение с присвоением —add, вычитание с присвоением —sub, команды условной пересылки —cmova,cmovnoи т. д.

См. также

- Подстановка

Литература

- Роберт В. Себеста. Основные концепции языков программирования = Concepts of Programming Languages. — 5-е изд. — М.: «Вильямс», 2001. — 672 с. — ISBN 0-201-75295-6

- М. Бен-Ари. Языки программирования. Практический сравнительный анализ. — М.: Мир, 2000. — 366 с. С. 71—74.

- В. Э. Вольфенгаген. Конструкции языков программирования. Приёмы описания. — М.: АО «Центр ЮрИнфоР», 2001. — 276 с. ISBN 5-89158-079-9. С. 128—131.

- Э. А. Опалева, В. П. Самойленко. Языки программирования и методы трансляции. — СПб.: БХВ-Петербург, 2005. — 480 с. ISBN 5-94157-327-8. С. 74—75.

- Т. Пратт, М. Зелковиц. Языки программирования: разработка и реализация. — 4-е изд. — СПб: Питер, 2002. — 688 с. ISBN 5-318-00189-0, ISBN 0-13-027678-2. С. 201—204.

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.

Оператор присваивания

Оператор присваивания — самый простой и наиболее распространённый оператор.

Формат оператора присваивания

Оператор присваивания представляет собой запись, содержащую символ = (знак равенства),

слева от которого указано имя переменной, а справа — выражение. Оператор присваивания

заканчивается знаком ; (точка с запятой).

Переменная = Выражение; // Оператор присваивания

Оператор присваивания можно отличить в тексте программы по наличию знака равенства.

В качестве выражения может быть указана константа, переменная, вызов функции или

собственно выражение.

Правило исполнения оператора присваивания

| Вычислить значение выражения справа от знака равенства и полученное значение присвоить переменной, указанной слева от знака равенства. |

Оператор присваивания, как и любой другой оператор, является исполняемым. Это значит,

что запись, составляющая оператор присваивания, исполняется в соответствии с правилом.

При исполнении оператора присваивания вычисляется значение в правой части, а затем

это значение присваивается переменной слева от знака равенства. В результате исполнения

оператора присваивания переменная в левой части всегда получает новое значение;

это значение может отличаться или совпадать с предыдущим значением этой переменной.

Вычисление выражения в правой части оператора присваивания осуществляется в соответствии

с порядком вычисления выражений (см. Операции и выражения).

Примеры операторов присваивания

В операторе присваивания допускается объявление типа переменной слева от знака равенства:

int In = 3;

double Do = 2.0;

bool Bo = true;

color Co = 0x008000;

string St = "sss";

datetime Da= D'01.01.2004';

Ранее объявленные переменные используются в операторе присваивания без указания

типа.

In = 7;

Do = 23.5;

Bo = 0;

В операторе присваивания не допускается объявление типа переменной в правой части от знака равенства:

In = int In_2; // Объявление типа переменных в правой части запрещено

Do = double Do_2; // Объявление типа переменных в правой части запрещено

В операторе присваивания не допускается повторное объявление типа переменных.

int In; // Объявление типа переменной In

int In = In_2; // Не допускается повторное объявление переменной (In)

Примеры использования в правой части пользовательских и стандартных функций:

In = My_Function();

Do = Gipo(Do1,Do1);

Bo = IsConnected();

St = ObjectName(0);

Da = TimeCurrent();

Примеры использования в правой части выражений:

In = (My_Function()+In2)/2;

Do = MathAbs(Do1+Gipo(Do2,5)+2.5);

При вычислениях в операторе присваивания применяются правила приведения типов данных

(см. Приведение типов).

Примеры операторов присваивания краткой формы

В MQL4 используется также краткая форма записи операторов присваивания. Это — форма

операторов присваивания, в которой используются операции присвоения, отличные от

операции присвоения = (знак равенства) (см.

Операции и выражения). На операторы краткой формы распространяются те же правила и ограничения. Краткая

форма операторов присваивания используется в коде для наглядности. Программист

по своему усмотрению может использовать ту или иную форму оператора присваивания.

Любой оператор присваивания краткой формы может быть легко переписан в полноформатный,

при этом результат исполнения оператора не изменится.

In /= 33;

In = In/33;St += "_exp7";

St = St + "_exp7";

Присваивание

— это занесение значения в память. В

общем виде оператор присваивания

записывается так:

переменная

:=

выражение

Синтаксическая

диаграмма:

Здесь символами

:= обозначена операция присваивания.

Внутри знака операции пробелы не

допускаются.

Механизм выполнения

оператора присваивания такой: вычисляется

выражение и его результат заносится в

память по адресу, который определяется

именем переменной, находящейся слева

от знака операции. Схематично это полезно

представить себе так:

переменная

выражение.

Константа

и переменная являются частными случаями

выражения. Примеры операторов присваивания:

а

:= b

+ с / 2;

b

:= a:

а

:= b:

х := 1:

х := х + 0.5;

Обратите

внимание: b

:=а иа :=b

— это совершенно разные действия!

Примечание.

Чтобы не

перепутать, что чему присваивается,

запомните мнемоническое правило:

присваивание — это передача данных

«налево».

Начинающие

программисты часто делают ошибку,

воспринимая присваивание как аналог

равенства в математике. Чтобы избежать

этой ошибки, надо понимать механизм

работы оператора присваивания. Рассмотрим

для этого последний пример (х : = х + 0.5).

Сначала из ячейки памяти, в которой

хранится значение переменной х, выбирается

это значение. Затем к нему прибавляется

0,5, после чего

получившийся результат записывается

в ту же самую ячейку. При этом то, что

хранилось там ранее, теряется безвозвратно.

Операторы такого вида применяются в

программировании очень широко.

Правая

и левая части оператора присваивания

должны быть,

как правило, одного типа. Говоря более

точно, они должны быть совместимы по

присваиванию. Например, выражение

целого типа можно присвоить вещественной

переменной, потому что целые числа

являются подмножеством вещественных,

и информация при таком присваивании не

теряется:

вещественная

переменная := целое выражение;

11. Простейший ввод-вывод на Паскале

11.1. Стандартные файлы Input и Output

к

ввод исходных

данных ( из Input )

лавиатура

Программа

э

ЭХО

вывод результатов

(в Output)

консоль (оператора)

Все

программы должны обмениваться с внешней

средой информацией, т. е. принимать из

нее исходные данные и передавать в нее

полученные результаты. Устройство,

через которое происходит такой обмен,

называется консолью (console).

Консоль

— это комбинированное устройство, в

котором для ввода данных используется

клавиатура, а для вывода — экран монитора.

Поток

символов, вводимый с клавиатуры и поток

символов, выводимый на экран, принято

называть файлом

(файл

— именованная область данных, размещенная

на внешних носителях).

В

Паскале за двумя этими потоками символов

закреплены имена: Input

(ввод с клавиатуры) и Output

(вывод на экран). Это стандартные файлы,

которые открываются и закрываются

автоматически, хотя явно в операторах

ввода-вывода они могут не указываться.

Особенностью

файлов Input

и Output

является то, что ввод происходит в режиме

эхо-отображения

вводимых данных. Т.е. на экране происходит

отображение того, что вводят с клавиатуры.

Эхо-отображение заключается в том, что

информация в файле Output

изменяется не только при выводе в него,

но и при вводе информации из файла Input.

Это хорошо тем, что мы видим на экране

то, что вводится с клавиатуры, т.е. ввод

идет не вслепую.

Файлы

Input

и output

являются текстовыми

файлами,

т.е. они состоят из символьных строк

переменной

длины. Каждая

такая строка – это последовательность

символов, в конце которой стоит

с

признакEOLN

или <Ввод> или <Enter>

или или два кода #13+#10, где

-

#13

— символ «Возврата

каретки»»

(ВК или CR). На экране курсор устанавливается

в начало текущей строки; -

#10

– символ «Перевода

строки». На

экране курсор устанавливается на

следующей строке в текущей позиции.

В конце текстового

файла размещается символ конца файла

EOF с кодом #26.

С

каждым файлом связан указатель

на текущую позицию файла,

начиная с которой будет производиться

текущая операция ввода-вывода. При

запуске программы для каждого стандартного

файла эти указатели устанавливаются

на самое начало,

а в процессе работы с файлом после каждой

очередной операции ввода-вывода указатель

перемещается так, чтобы указывать на

фрагмент файла, с которого начнется

следующая операция.

Соседние файлы в папке WORD

- #

15.04.2015439.06 Кб286.docx

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #