Not to be confused with Maradona.

|

Madonna |

|

|---|---|

Madonna performing on her Rebel Heart Tour in 2015 |

|

| Born |

Madonna Louise Ciccone August 16, 1958 (age 64) Bay City, Michigan, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1979–present |

| Organizations |

|

| Works |

|

| Spouses |

Sean Penn (m. 1985; div. 1989) Guy Ritchie (m. 2000; div. 2008) |

| Partner | Carlos Leon (1995–1997) |

| Children | 6 |

| Relatives | Christopher Ciccone (brother) |

| Awards |

|

| Musical career | |

| Origin | New York City, U.S. |

| Genres |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Labels |

|

| Formerly of |

|

| Website | madonna.com |

| Signature | |

|

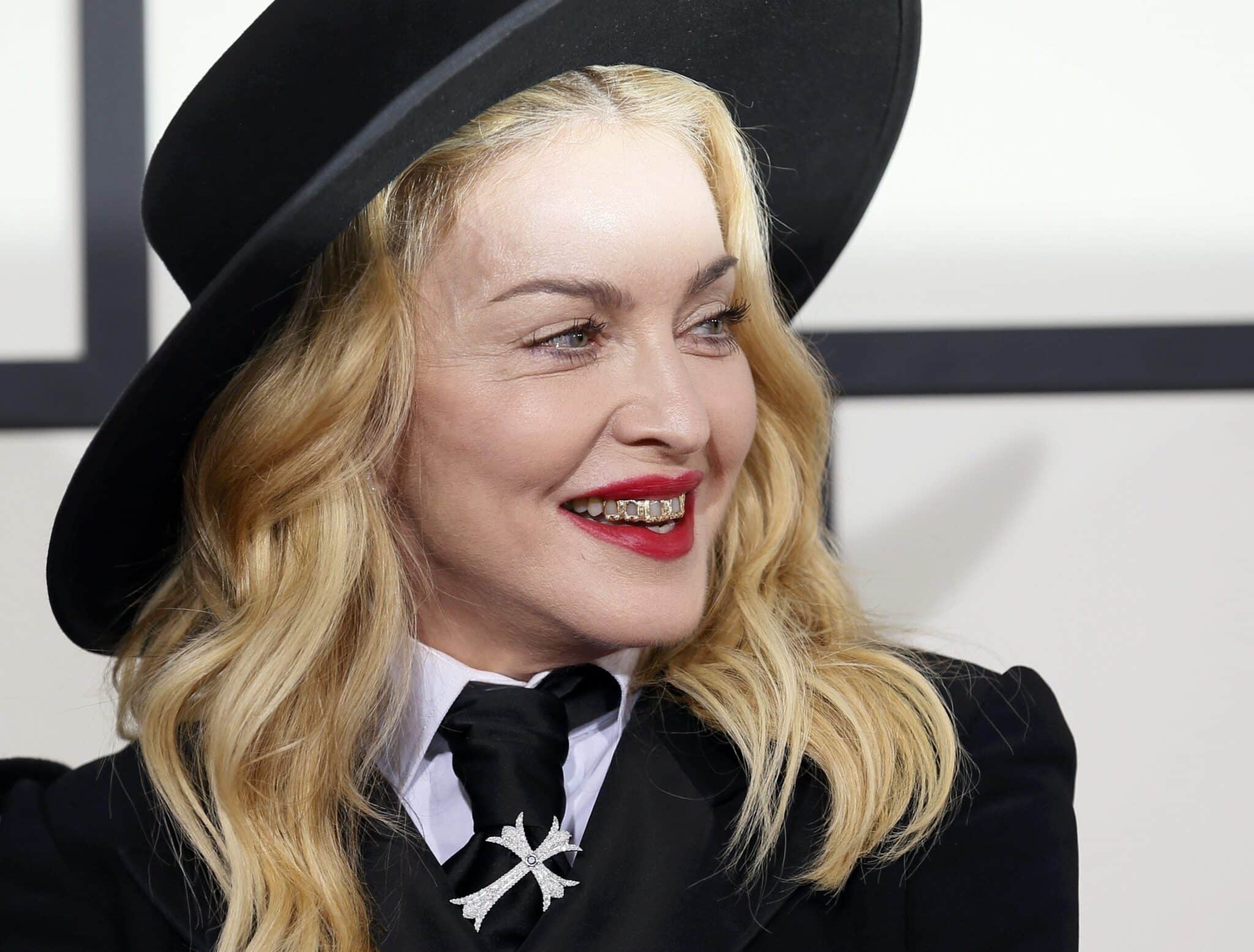

Madonna Louise Ciccone[a] (; Italian: [tʃikˈkoːne]; born August 16, 1958) is an American singer-songwriter and actress. Dubbed the «Queen of Pop», Madonna has been noted for her continual reinvention and versatility in music production, songwriting, and visual presentation. She has pushed the boundaries of artistic expression in mainstream music, while continuing to maintain control over every aspect of her career.[2] Her works, which incorporate social, political, sexual, and religious themes, have generated both controversy and critical acclaim. A prominent cultural figure crossing both the 20th and 21st centuries, Madonna remains one of the most «well-documented figures of the modern age»,[3] with a broad amount of scholarly reviews and literature works on her, as well as an academic mini subdiscipline devoted to her named Madonna studies.

At 20 years old, Madonna moved to New York City in 1978 to pursue a career in modern dance. After performing as a drummer, guitarist, and vocalist in the rock bands Breakfast Club and Emmy, she rose to solo stardom with her debut studio album, Madonna (1983). She followed it with a series of successful albums, including all-time bestsellers Like a Virgin (1984), True Blue (1986) and The Immaculate Collection (1990) as well as universally acclaimed Grammy Award winning albums Ray of Light (1998) and Confessions on a Dance Floor (2005). Madonna has amassed many chart-topping singles throughout her career, including «Like a Virgin», «La Isla Bonita», «Like a Prayer», «Vogue», «Take a Bow», «Frozen», «Music», «Hung Up», and «4 Minutes».

Madonna’s popularity was enhanced by roles in films such as Desperately Seeking Susan (1985), Dick Tracy (1990), A League of Their Own (1992), and Evita (1996). While Evita won her a Golden Globe Award for Best Actress, many of her other films were not as well received. As a businesswoman, Madonna founded the company Maverick in 1992. It included Maverick Records, one of the most successful artist-run labels in history. Her other ventures include fashion brands, written works, health clubs, and filmmaking. She contributes to various charities, having founded the Ray of Light Foundation in 1998 and Raising Malawi in 2006.

With sales of over 300 million records worldwide, Madonna is the best-selling female recording artist of all time. She is the most successful solo artist in the history of the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 chart and has achieved the most number-one singles by a woman in Australia, Canada, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Madonna has been awarded with seven Grammy Awards, two Golden Globe Awards, five Billboard Music Awards, and twenty MTV Video Music Awards. With a revenue of over U.S. $1.5 billion from her concert tickets, she remains the highest-grossing female touring artist worldwide. Forbes has named Madonna the annual top-earning female musician a record 11 times across four decades (1980s–2010s). She was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2008, her first year of eligibility. Madonna was ranked as the greatest woman in music by VH1, and as the greatest music video artist ever by MTV and Billboard. Rolling Stone also listed her among its greatest artists and greatest songwriters of all time.

Life and career

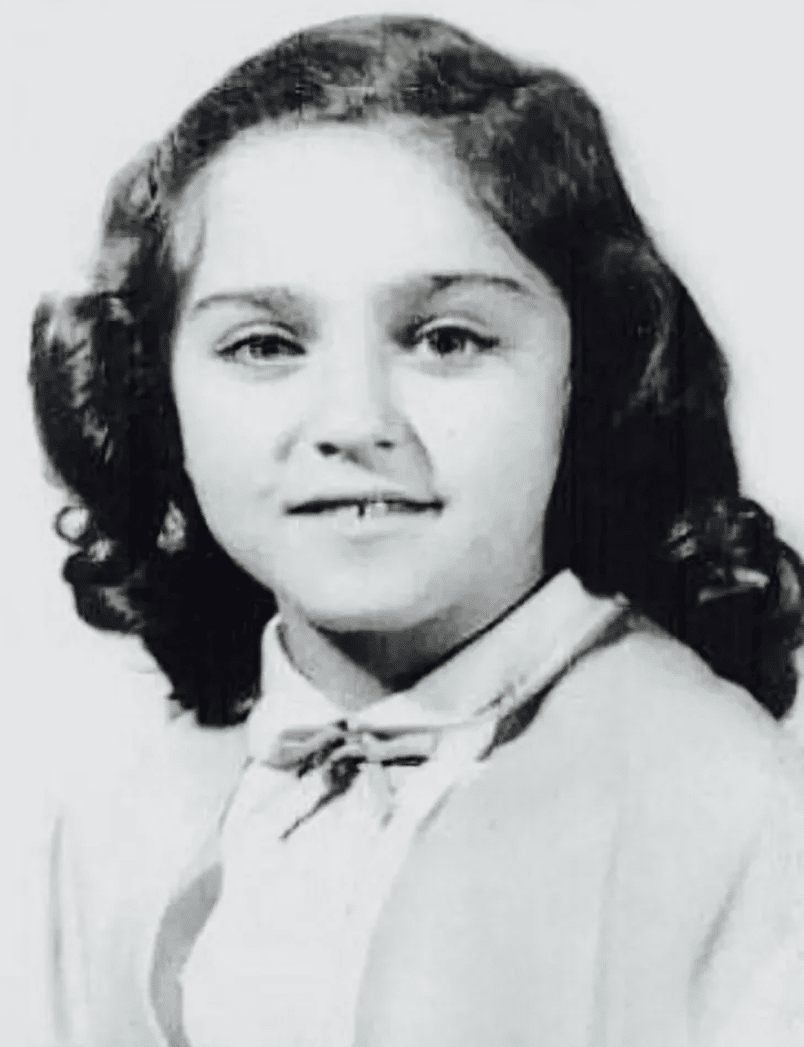

1958–1978: Early life

Madonna Louise Ciccone[4] was born on August 16, 1958, in Bay City, Michigan, to Catholic parents Madonna Louise née Fortin (1933-1963) and Silvio Anthony «Tony» Ciccone (born 1931).[5][6] Her father’s parents were Italian emigrants from Pacentro while her mother was of French-Canadian descent.[7] Tony Ciccone worked as an engineer designer for Chrysler and General Motors. Since Madonna had the same name as her mother, family members called her «Little Nonnie».[8] Her mother died of breast cancer on December 1, 1963. She later adopted Veronica as a confirmation name when getting confirmed in the Catholic Church in 1966.[9] Madonna was raised in the Detroit suburbs of Pontiac and Avon Township (now Rochester Hills), alongside her two older brothers, Anthony and Martin, and three younger siblings, Paula, Christopher, and Melanie.[10] In 1966, Tony married the family’s housekeeper Joan Gustafson. They had two children, Jennifer and Mario.[10] Madonna resented her father for getting remarried and began rebeling against him, which strained their relationship for many years afterward.[5]

Madonna attended St. Frederick’s and St. Andrew’s Catholic Elementary Schools, and West Middle School. She was known for her high grade point average and achieved notoriety for her unconventional behavior. Madonna would perform cartwheels and handstands in the hallways between classes, dangle by her knees from the monkey bars during recess, and pull up her skirt during class—all so that the boys could see her underwear.[11] She later admitted to seeing herself in her youth as a «lonely girl who was searching for something. I wasn’t rebellious in a certain way. I cared about being good at something. I didn’t shave my underarms and I didn’t wear make-up like normal girls do. But I studied and I got good grades… I wanted to be somebody.»[5]

Madonna’s father put her in classical piano lessons, but she later convinced him to allow her to take ballet lessons.[12] Christopher Flynn, her ballet teacher, persuaded her to pursue a career in dance.[13] Madonna later attended Rochester Adams High School and became a straight-A student as well as a member of its cheerleading squad.[14][15] After graduating, she received a dance scholarship to the University of Michigan and studied over the summer at the American Dance Festival in Durham, North Carolina.[16][17]

In 1978, Madonna dropped out of college and relocated to New York City.[18] She said of her move to New York, «It was the first time I’d ever taken a plane, the first time I’d ever gotten a taxi cab. I came here with $35 in my pocket. It was the bravest thing I’d ever done.»[19] Madonna soon found an apartment in the Alphabet City neighborhood of the East Village[20] and had little money while working at Dunkin’ Donuts and with modern dance troupes, taking classes at the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and eventually performing with Pearl Lang Dance Theater.[21][17][22] She also studied dance under the tutelage of Martha Graham, the noted American dancer and choreographer.[23] Madonna started to work as a backup dancer for other established artists. One night, while returning from a rehearsal, a pair of men held her at knifepoint and forced her to perform fellatio. She later found the incident to be «a taste of my weakness, it showed me that I still could not save myself in spite of all the strong-girl show. I could never forget it.»[24]

1979–1983: Career beginnings, rock bands, and Madonna

In 1979, Madonna became romantically involved with musician Dan Gilroy.[25] Shortly after meeting him, she successfully auditioned to perform in Paris with French disco artist Patrick Hernandez as his backup singer and dancer.[21] During her three months with Hernandez’s troupe, she also traveled to Tunisia before returning to New York in August 1979.[25][26] Madonna moved into an abandoned synagog where Gilroy lived and rehearsed in Corona, Queens.[21][11] Together they formed her first band, the Breakfast Club, for which Madonna sang and played drums and guitar.[27] While with the band, Madonna briefly worked as a coat-check girl at the Russian Tea Room, and she made her acting debut in the low-budget indie film A Certain Sacrifice, which was not released until 1985.[28][29] In 1980, Madonna left the Breakfast Club with drummer Stephen Bray, who was her boyfriend in Michigan, and they formed the band Emmy and the Emmys.[30] They rekindled their romance and moved into the Music Building in Manhattan.[21] The two began writing songs together and they recorded a four-song demo tape in November 1980, but soon after, Madonna decided to promote herself as a solo artist.[31][21]

In March 1981, Camille Barbone, who ran Gotham Records in the Music Building, signed Madonna to a contract with Gotham and worked as her manager until February 1982.[32][33][34] Madonna frequented nightclubs to get disc jockeys to play her demo.[35] DJ Mark Kamins at Danceteria took an interest in her music and they began dating.[36] Kamins arranged a meeting with Madonna and Seymour Stein, the president of Sire Records, a subsidiary of Warner Bros. Records.[35] Madonna signed a deal for a total of three singles, with an option for an album.[37]

Kamins produced her debut single, «Everybody», which was released in October 1982.[35] In December 1982, Madonna performed the song live for the first time at Danceteria.[38][39] She made her first television appearance performing «Everybody» on Dancin’ On Air in January 1983.[40] In February 1983, she promoted the single with nightclub performances in the United Kingdom.[41] Her second single, «Burning Up», was released in March 1983. Both singles reached number three on Billboard magazine’s Hot Dance Club Songs chart.[42] During this period, Madonna was in a relationship with artist Jean-Michel Basquiat and living at his loft in SoHo.[43][44] Basquiat introduced her to art curator Diego Cortez, who had managed some punk bands and co-founded the Mudd Club.[45] Madonna invited Cortez to be her manager, but he declined.[45]

Following the success of the singles, Warner hired Reggie Lucas to produce her self-titled debut album, Madonna.[46] However, Madonna was dissatisfied with the completed tracks and disagreed with Lucas’ production techniques, so she decided to seek additional help.[47] She asked John «Jellybean» Benitez, the resident DJ at Fun House, to help finish the album’s production and a romance ensued.[48] Benitez remixed most of the tracks and produced «Holiday», which was her first international top-ten song. The album was released in July 1983, and peaked at number eight on the Billboard 200. It yielded two top-ten singles on the Billboard Hot 100, «Borderline» and «Lucky Star».[49] In the fall of 1983, Madonna’s new manager, Feddy DeMann, secured a meeting for her with film producer Jon Peters, who asked her to play the part of a club singer in the romantic drama Vision Quest.[50]

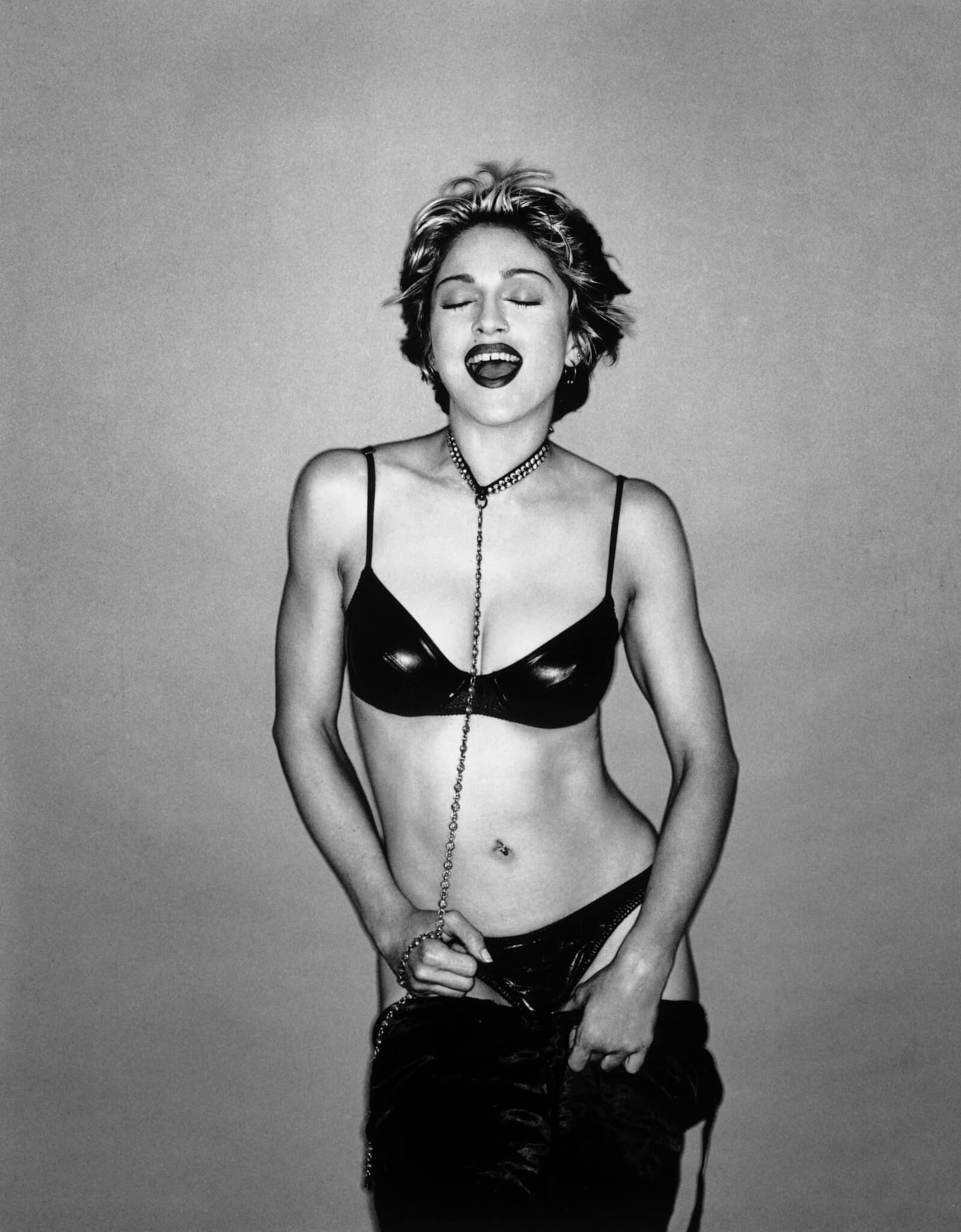

1984–1987: Like a Virgin, first marriage, True Blue, and Who’s That Girl

In January 1984, Madonna gained more exposure by performing on American Bandstand and Top of the Pops.[51][52] Her image, performances, and music videos influenced young girls and women.[53] Madonna’s style became one of the female fashion trends of the 1980s.[54] Created by stylist and jewelry designer Maripol, the look consisted of lace tops, skirts over capri pants, fishnet stockings, jewelry bearing the crucifix, bracelets, and bleached hair.[55][56][57] Madonna’s popularity continued to rise globally with the release of her second studio album, Like a Virgin, in November 1984. It became her first number-one album in Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain, the UK, and the US.[58][59] Like a Virgin became the first album by a female to sell over five million copies in the U.S.[60] It was later certified diamond in by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), and has sold over 21 million copies worldwide.[61]

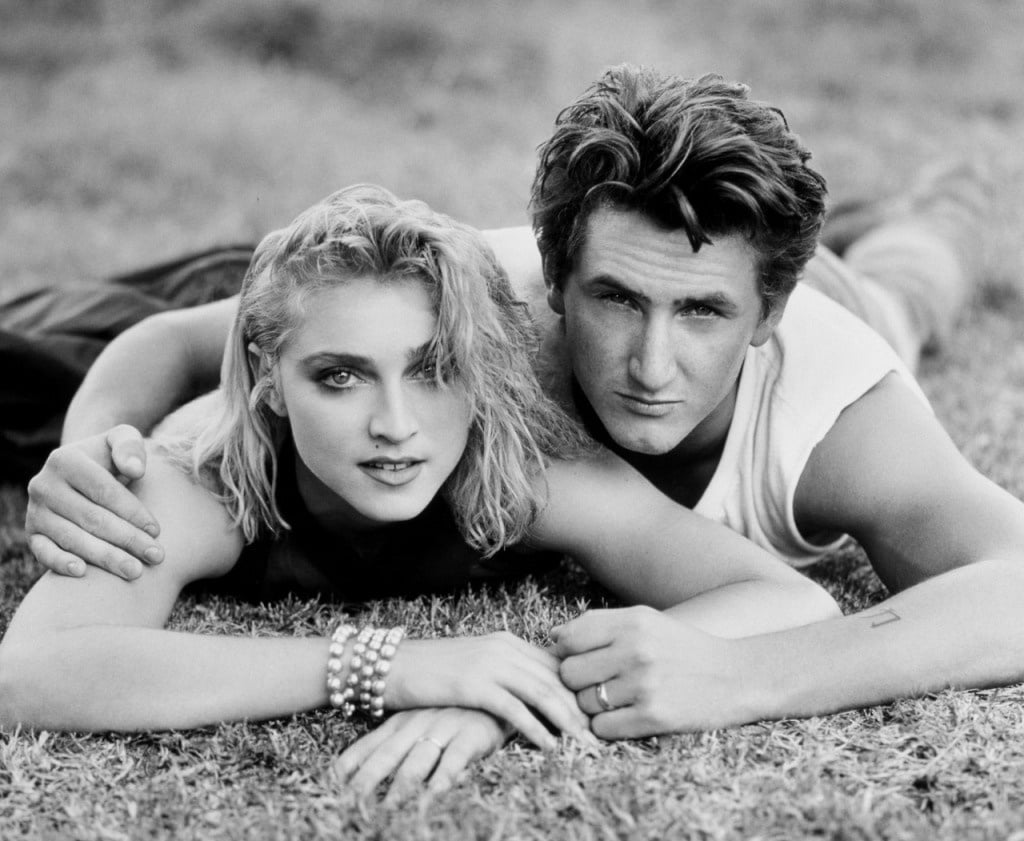

Madonna performing at the Live Aid charity concert on July 1985

The album’s title track served as its first single, and topped the Hot 100 chart for six consecutive weeks.[62] It attracted the attention of conservative organizations who complained that the song and its accompanying video promoted premarital sex and undermined family values,[63] and moralists sought to have the song and video banned.[64] Madonna received huge media coverage for her performance of «Like a Virgin» at the first 1984 MTV Video Music Awards. Wearing a wedding dress and white gloves, Madonna appeared on stage atop a giant wedding cake and then rolled around suggestively on the floor. MTV retrospectively considered it one of the «most iconic» pop performances of all time.[65] The second single, «Material Girl», reached number two on the Hot 100.[49] While filming the single’s music video, Madonna started dating actor Sean Penn. They married on her birthday in 1985.[66]

Madonna entered mainstream films in February 1985, beginning with her cameo in Vision Quest. The soundtrack contained two new singles, her U.S. number-one single, «Crazy for You», and another track «Gambler».[49] She also played the title role in the 1985 comedy Desperately Seeking Susan, a film which introduced the song «Into the Groove», her first number-one single in the UK.[67] Her popularity caused the film to be perceived as a Madonna vehicle, despite how she was not billed as a lead actress.[68] The New York Times film critic Vincent Canby named it one of the ten best films of 1985.[69]

Beginning in April 1985, Madonna embarked on her first concert tour in North America, the Virgin Tour, with the Beastie Boys as her opening act. The tour saw the peak of Madonna wannabe phenomenon, with many female attendees dressing like her.[70] At that time, she released two more hits, «Angel» and «Dress You Up», making all four singles from the album peak inside the top five on the Hot 100 chart.[71] In July, Penthouse and Playboy magazines published a number of nude photos of Madonna, taken when she moonlighted as an art model in 1978.[72] She had posed for the photographs because she needed money at the time, and was paid as little as $25 a session.[73] The publication of the photos caused a media uproar, but Madonna remained «unapologetic and defiant».[74] The photographs were ultimately sold for up to $100,000.[73] She referred to these events at the 1985 outdoor Live Aid charity concert, saying that she would not take her jacket off because «[the media] might hold it against me ten years from now.»[74][75]

In June 1986, Madonna released her third studio album, True Blue, which was inspired by and dedicated to her husband Penn.[76] Rolling Stone was impressed with the effort, writing that the album «sound[s] as if it comes from the heart».[77] Five singles were released—»Live to Tell», «Papa Don’t Preach», «True Blue», «Open Your Heart», and «La Isla Bonita»—all of which reached number one in the U.S. or the UK.[49][78] The album topped the charts in 28 countries worldwide, an unprecedented achievement at the time, and remains Madonna’s bestselling studio album, with sales of 25 million copies.[79][80] True Blue was featured in the 1992 edition of Guinness World Records as the bestselling album by a woman of all time.[81]

Madonna starred in the critically panned film Shanghai Surprise in 1986, for which she received her first Golden Raspberry Award for Worst Actress.[82] She made her theatrical debut in a production of David Rabe’s Goose and Tom-Tom; the film and play both co-starred Penn.[83] The next year, Madonna was featured in the film Who’s That Girl. She contributed four songs to its soundtrack, including the title track and «Causing a Commotion».[84] Madonna embarked on the Who’s That Girl World Tour in June 1987, which continued until September.[85][86] It broke several attendance records, including over 130,000 people in a show near Paris, which was then a record for the highest-attended female concert of all time.[87] Later that year, she released a remix album of past hits, You Can Dance, which reached number 14 on the Billboard 200.[58][88] After a tumultuous two years’ marriage, Madonna filed for divorce from Penn on December 4, 1987, but withdrew the petition a few weeks later.[89][90]

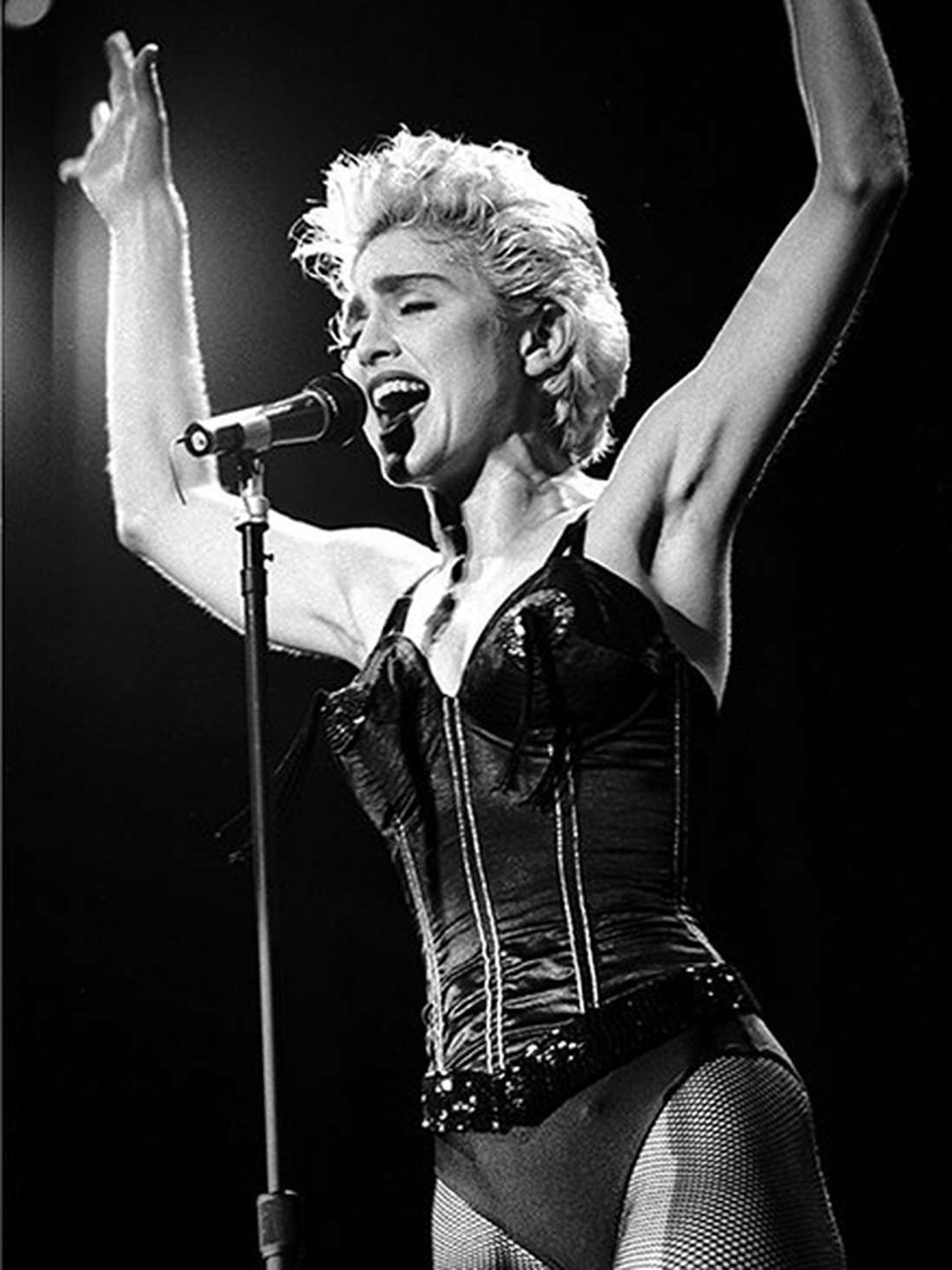

1988–1991: Like a Prayer, Dick Tracy, and Truth or Dare

Madonna performing during one of the dates of 1990’s Blond Ambition World Tour, which was named one of the greatest concert tours of the past 50 years by Rolling Stone magazine[91]

She made her Broadway debut in the production of Speed-the-Plow at the Royale Theatre from May to August 1988.[92][93] According to the Associated Press, Madonna filed an assault report against Penn after an alleged incident at their Malibu home during the New Year’s weekend.[94][95] Madonna filed for divorce on January 5, 1989, and the following week she reportedly asked that no criminal charges be pressed.[96][94]

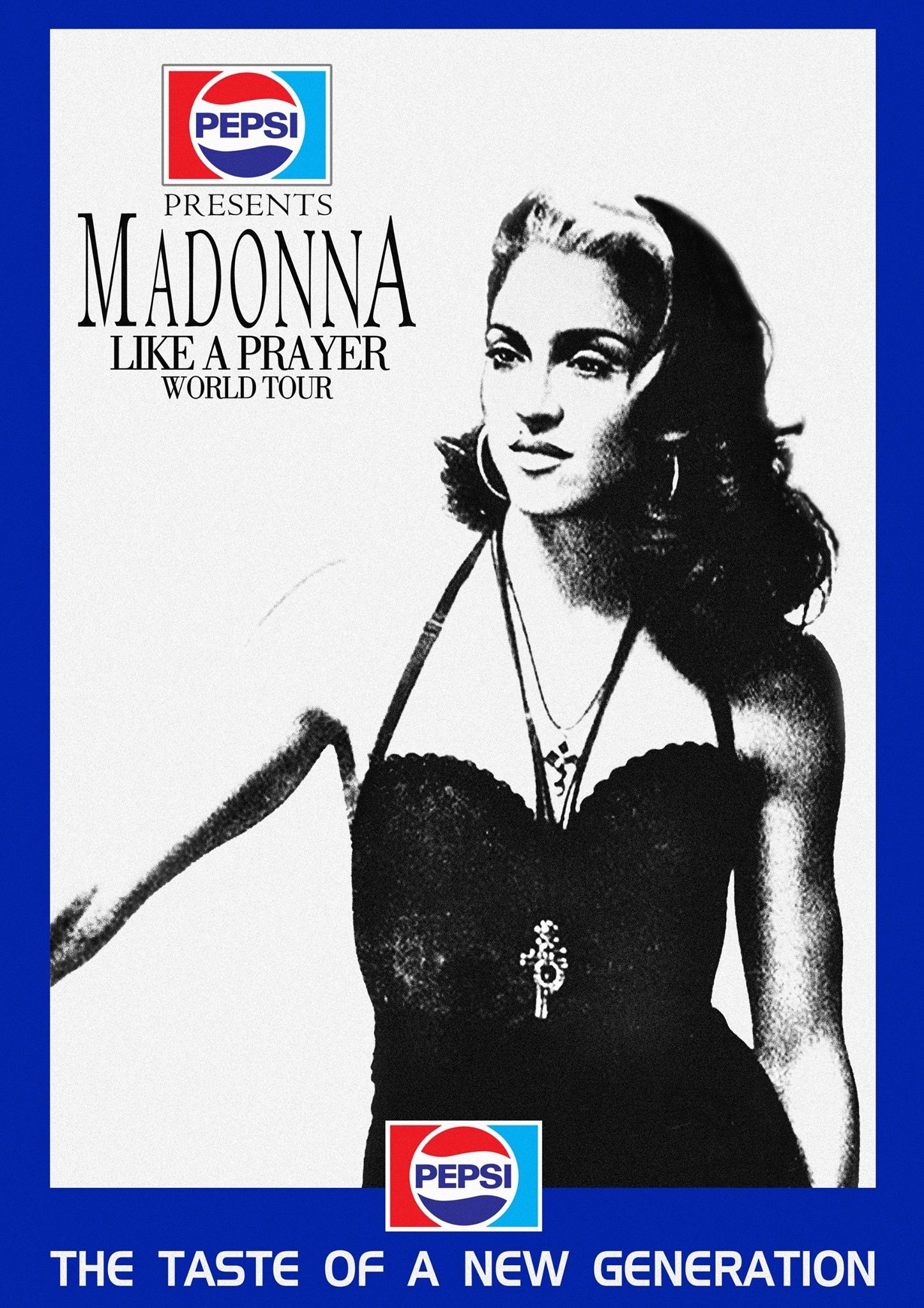

In January 1989, Madonna signed an endorsement deal with soft-drink manufacturer Pepsi.[97] In one Pepsi commercial, she debuted «Like a Prayer», the lead single and title track from her fourth studio album. The music video featured Catholic symbols such as stigmata and cross burning, and a dream of making love to a saint, leading the Vatican to condemn the video. Religious groups sought to ban the commercial and boycott Pepsi products. Pepsi revoked the commercial and canceled her sponsorship contract.[98][99] «Like a Prayer» topped the charts in many countries, becoming her seventh number-one on the Hot 100.[84][49]

Madonna co-wrote and co-produced the album Like a Prayer with Patrick Leonard, Stephen Bray, and Prince.[100] Music critic J. D. Considine from Rolling Stone praised it «as close to art as pop music gets … proof not only that Madonna should be taken seriously as an artist but that hers is one of the most compelling voices of the Eighties.»[101] Like a Prayer peaked at number one on the Billboard 200 and sold 15 million copies worldwide.[58][102] Other successful singles from the album were «Express Yourself» and «Cherish», which both peaked at number two in the US, as well as the UK top-five «Dear Jessie» and the U.S. top-ten «Keep It Together».[84][49] By the end of the 1980s, Madonna was named as the «Artist of the Decade» by MTV, Billboard and Musician magazine.[103][104][105]

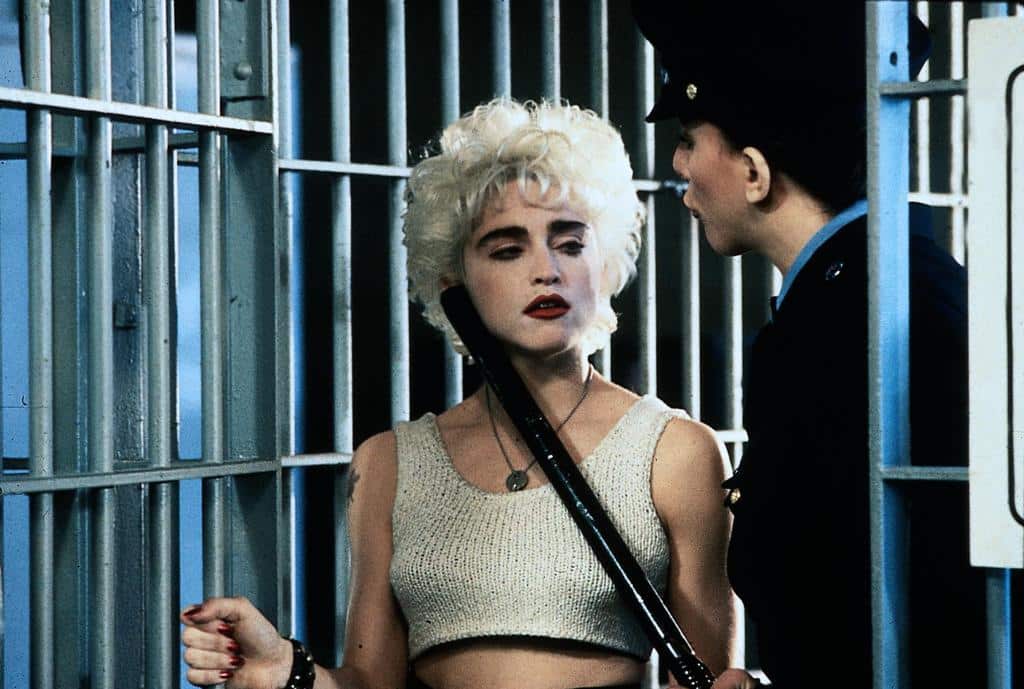

Madonna starred as Breathless Mahoney in the film Dick Tracy (1990), with Warren Beatty playing the title role.[106] The film went to number one on the U.S. box office for two weeks and Madonna received a Saturn Award nomination for Best Actress.[107] To accompany the film, she released the soundtrack album, I’m Breathless, which included songs inspired by the film’s 1930s setting. It also featured the U.S. number-one song «Vogue» and «Sooner or Later».[108][109] While shooting the film, Madonna began a relationship with Beatty, which dissolved shortly after the premiere.[110][111]

In April 1990, Madonna began her Blond Ambition World Tour, which ended in August.[112] Rolling Stone called it an «elaborately choreographed, sexually provocative extravaganza» and proclaimed it «the best tour of 1990».[113] The tour generated strong negative reaction from religious groups for her performance of «Like a Virgin», during which two male dancers caressed her body before she simulated masturbation.[85] In response, Madonna said, «The tour in no way hurts anybody’s sentiments. It’s for open minds and gets them to see sexuality in a different way. Their own and others».[114] The live recording of the tour won Madonna her first Grammy Award, in the category of Best Long Form Music Video.[115]

The Immaculate Collection, Madonna’s first greatest-hits compilation album, was released in November 1990. It included two new songs, «Justify My Love» and «Rescue Me».[116] The album was certified diamond by RIAA and sold over 30 million copies worldwide, becoming the best-selling compilation album by a solo artist in history.[117][118] «Justify My Love» reached number one in the U.S. becoming her ninth number-one on the Hot 100.[49] Her then-boyfriend model Tony Ward co-starred in the music video, which featured scenes of sadomasochism, bondage, same-sex kissing, and brief nudity.[119][120] The video was deemed too sexually explicit for MTV and was banned from the network.[121] Her first documentary film, Truth or Dare (known as In Bed with Madonna outside North America), was released in May 1991.[122] Chronicling her Blond Ambition World Tour, it became the highest-grossing documentary of all time (surpassed eleven years later by Michael Moore’s Bowling for Columbine).[123]

1992–1997: Maverick, Erotica, Sex, Bedtime Stories, Evita, and motherhood

Madonna during one of the concerts of 1993’s the Girlie Show, which was launched to promote her fifth studio album Erotica. For the album, she incorporated a dominatrix alter-ego named Mistress Dita, based on actress Dita Parlo.[124]

In 1992, Madonna starred in A League of Their Own as Mae Mordabito, a baseball player on an all-women’s team. It reached number one on the box-office and became the tenth-highest-grossing film of the year in the U.S.[125] She recorded the film’s theme song, «This Used to Be My Playground», which became her tenth number-one on the Billboard Hot 100, the most by any female artist at the time.[49] In April, Madonna founded her own entertainment company, Maverick, consisting of a record company (Maverick Records), a film production company (Maverick Films), and associated music publishing, television broadcasting, book publishing and merchandising divisions.[126] The deal was a joint venture with Time Warner and paid Madonna an advance of $60 million. It gave her 20% royalties from the music proceedings, the highest rate in the industry at the time, equaled only by Michael Jackson’s royalty rate established a year earlier with Sony.[126] Her company later went on to become one of the most successful artist-run labels in history, producing multi-platinum artists such as Alanis Morissette and Michelle Branch.[127][128] Later that year, Madonna co-sponsored the first museum retrospective for her former boyfriend Jean-Michel Basquiat at the Whitney Museum of American Art.[129][130]

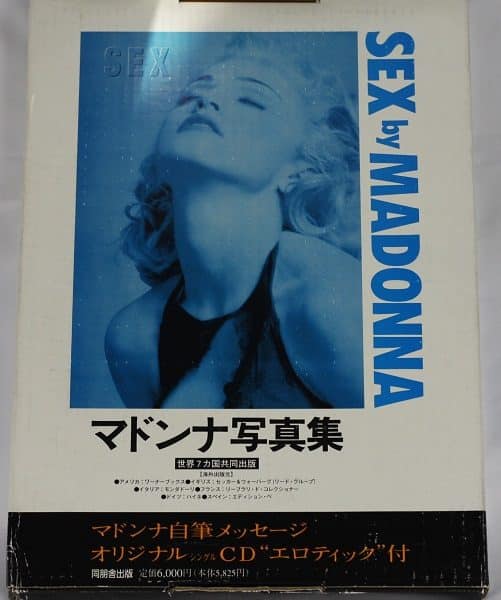

In October 1992, Madonna simultaneously released her fifth studio album, Erotica, and her coffee table book, Sex.[131] Consisting of sexually provocative and explicit images, photographed by Steven Meisel, the book received strong negative reaction from the media and the general public, but sold 1.5 million copies at $50 each in a matter of days.[132][133] The widespread backlash overshadowed Erotica, which ended up as her lowest selling album at the time.[133] Despite positive reviews, it became her first studio album since her debut album not to score any chart-topper in the U.S. The album entered the Billboard 200 at number two and yielded the Hot 100 top-ten hits «Erotica» and «Deeper and Deeper».[58][49] Madonna continued her provocative imagery in the 1993 erotic thriller, Body of Evidence, a film which contained scenes of sadomasochism and bondage. It was poorly received by critics.[134][135] She also starred in the film Dangerous Game, which was released straight to video in North America. The New York Times described the film as «angry and painful, and the pain feels real.»[136]

In September 1993, Madonna embarked on the Girlie Show, in which she dressed as a whip-cracking dominatrix surrounded by topless dancers. In Puerto Rico she rubbed the island’s flag between her legs on stage, resulting in outrage among the audience.[85] In March 1994, she appeared as a guest on the Late Show with David Letterman, using profanity that required censorship on television, and handing Letterman a pair of her panties and asking him to smell it.[137] The releases of her sexually explicit book, album and film, and the aggressive appearance on Letterman all made critics question Madonna as a sexual renegade. Critics and fans reacted negatively, who commented that «she had gone too far» and that her career was over.[138] Around this time, Madonna briefly dated basketball player Dennis Rodman and rapper Tupac Shakur.[139][140][141]

Biographer J. Randy Taraborrelli described her ballad «I’ll Remember» (1994) as an attempt to tone down her provocative image. The song was recorded for Alek Keshishian’s 1994 film With Honors.[142] She made a subdued appearance with Letterman at an awards show and appeared on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno after realizing that she needed to change her musical direction in order to sustain her popularity.[143] With her sixth studio album, Bedtime Stories (1994), Madonna employed a softer image to try to improve the public perception.[143] The album debuted at number three on the Billboard 200 and generated two U.S. top-five hits, «Secret» and «Take a Bow», the latter topping the Hot 100 for seven weeks, the longest period of any Madonna single.[144] Something to Remember, a collection of ballads, was released in November 1995. The album featured three new songs: «You’ll See», «One More Chance», and a cover of Marvin Gaye’s «I Want You».[49][145] An enthusiastic collector of modern art, Madonna sponsored the first major retrospective of Tina Modotti’s work at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1995.[146] The following year, she sponsored an exhibition of Basquiat’s paintings at the Serpentine Gallery in London.[147] The following year, she sponsored artist Cindy Sherman’s retrospective at the MoMA in New York.[148]

This is the role I was born to play. I put everything of me into this because it was much more than a role in a movie. It was exhilarating and intimidating at the same time. And I am prouder of Evita than anything else I have done.

—Madonna talking about her role in Evita[149]

In February 1996, Madonna began filming the musical Evita in Argentina.[150] For a long time, Madonna had desired to play Argentine political leader Eva Perón and wrote to director Alan Parker to explain why she would be perfect for the part. After securing the title role, she received vocal coaching and learned about the history of Argentina and Perón. During filming Madonna became ill several times, after finding out that she was pregnant, and from the intense emotional effort required with the scenes.[151] Upon Evita‘s release in December 1996, Madonna’s performance received praise from film critics.[152][153][154] Zach Conner of Time magazine remarked, «It’s a relief to say that Evita is pretty damn fine, well cast and handsomely visualized. Madonna once again confounds our expectations.»[155] For the role, she won the Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in Motion Picture Musical or Comedy.[156]

The Evita soundtrack, containing songs mostly performed by Madonna, was released as a double album.[157] It included «You Must Love Me» and «Don’t Cry for Me Argentina»; the latter reached number one in countries across Europe.[158] Madonna was presented with the Artist Achievement Award by Tony Bennett at the 1996 Billboard Music Awards.[159] On October 14, 1996, she gave birth to Lourdes «Lola» Maria Ciccone Leon, her daughter with fitness trainer Carlos Leon.[160][161] Biographer Mary Cross writes that although Madonna often worried that her pregnancy would harm Evita, she reached some important personal goals: «Now 38 years old, Madonna had at last triumphed on screen and achieved her dream of having a child, both in the same year. She had reached another turning point in her career, reinventing herself and her image with the public.»[162] Her relationship with Carlos Leon ended in May 1997 and she declared that they were «better off as best friends».[163][164]

1998–2002: Ray of Light, Music, second marriage, and touring comeback

Madonna playing guitar during 2001’s Drowned World Tour, the most lucrative concert tour of the year by a solo artist

After Lourdes’s birth, Madonna became involved in Eastern mysticism and Kabbalah, introduced to her by actress Sandra Bernhard.[165] Her seventh studio album, Ray of Light, (1998) reflected this change in her perception and image.[166][167] She collaborated with electronica producer William Orbit and wanted to create a sound that could blend dance music with pop and British rock.[168] American music critic Ann Powers explained that what Madonna searched for with Orbit «was a kind of a lushness that she wanted for this record. Techno and rave were happening in the 90s and had a lot of different forms. There was very experimental, more hard stuff like Aphex Twin. There was party stuff like Fatboy Slim. That’s not what Madonna wanted for this. She wanted something more like a singer-songwriter, really. And William Orbit provided her with that.»[168]

The album garnered critical acclaim, with Slant Magazine calling it «one of the great pop masterpieces of the ’90s»[169] Ray of Light was honored with four Grammy Awards—including Best Pop Album and Best Dance Recording—and was nominated for both Album of the Year and Record of the Year.[170] Rolling Stone listed it among «The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time».[171] Commercially, the album peaked at number-one in numerous countries and sold more than 16 million copies worldwide.[172] The album’s lead single, «Frozen», became Madonna’s first single to debut at number one in the UK, while in the U.S. it became her sixth number-two single, setting another record for Madonna as the artist with the most number-two hits.[49][173] The second single, «Ray of Light», debuted at number five on the Billboard Hot 100.[174] The 1998 edition of Guinness Book of World Records documented that «no female artist has sold more records than Madonna around the world».[175]

Madonna founded Ray of Light Foundation which focused on women, education, global development and humanitarian.[176] She recorded the single «Beautiful Stranger» for the 1999 film Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me, which earned her a Grammy Award for Best Song Written for a Motion Picture, Television or Other Visual Media.[115] Madonna starred in the 2000 comedy-drama film The Next Best Thing, directed by John Schlesinger. The film opened at number two on the U.S. box office with $5.9 million grossed in its first week, but this quickly diminished.[177] She also contributed two songs to the film’s soundtrack—a cover of Don McLean’s 1971 song «American Pie» and an original song «Time Stood Still»—the former became her ninth UK number-one single.[178]

Madonna released her eighth studio album, Music, in September 2000. It featured elements from the electronica-inspired Ray of Light era, and like its predecessor, received acclaim from critics. Collaborating with French producer Mirwais Ahmadzaï, Madonna commented: «I love to work with the weirdos that no one knows about—the people who have raw talent and who are making music unlike anyone else out there. Music is the future of sound.»[179] Stephen Thomas Erlewine from AllMusic felt that «Music blows by in a kaleidoscopic rush of color, technique, style and substance. It has so many depth and layers that it’s easily as self-aware and earnest as Ray of Light.»[180] The album took the number-one position in more than 20 countries worldwide and sold four million copies in the first ten days.[170] In the U.S., Music debuted at the top, and became her first number-one album in eleven years since Like a Prayer.[181] It produced three singles: the Hot 100 number-one «Music», «Don’t Tell Me», and «What It Feels Like for a Girl».[49] The music video of «What It Feels Like for a Girl» depicted Madonna committing acts of crime and vandalism, and was banned by MTV and VH1.[182]

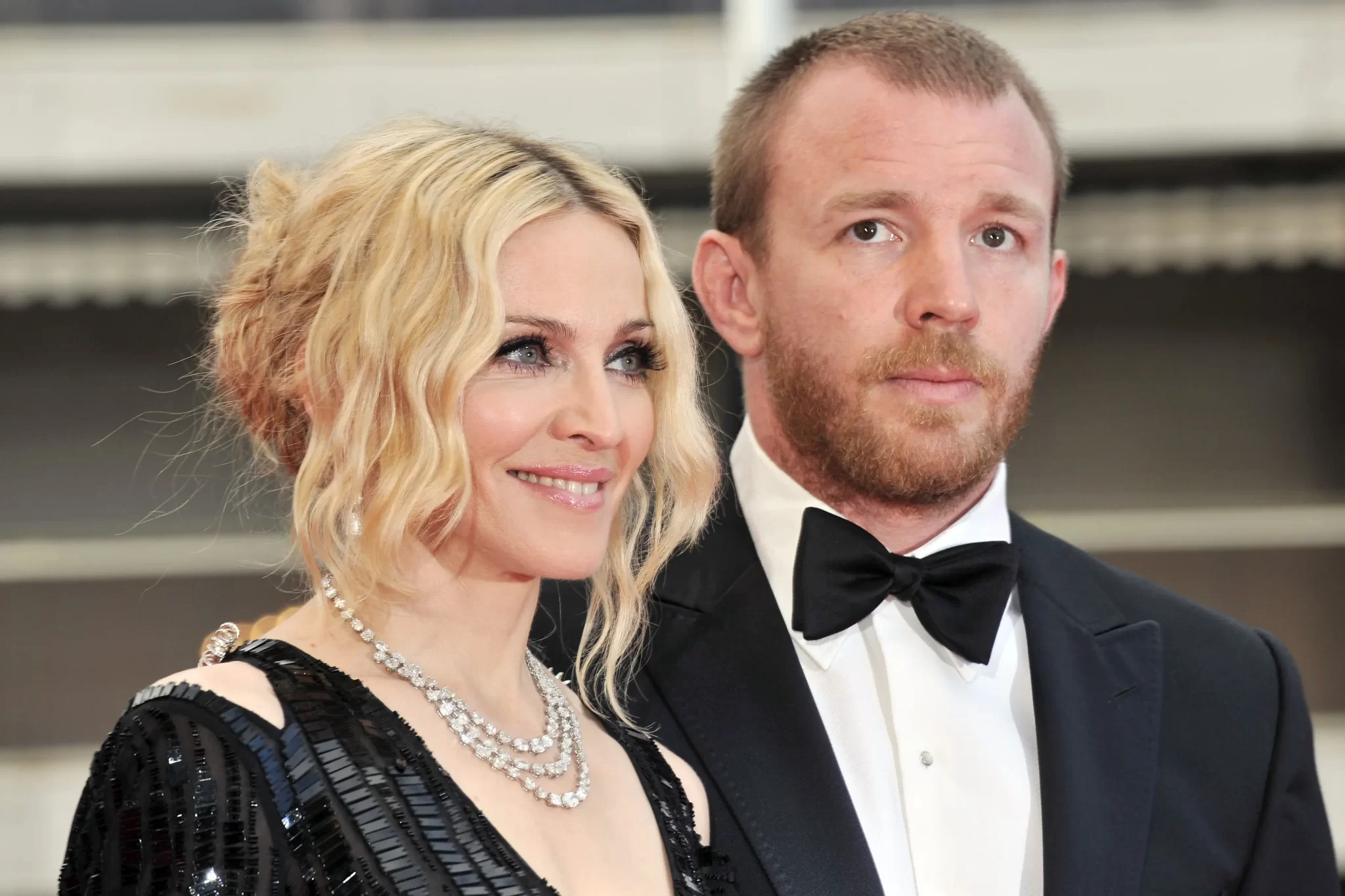

Madonna met director Guy Ritchie in the summer of 1998, and gave birth to their son Rocco John Ritchie in Los Angeles on August 11, 2000.[183] Rocco and Madonna suffered complications from the birth due to her experiencing placenta praevia.[184] He was christened at Dornoch Cathedral in Dornoch, Scotland, on December 21, 2000.[185] Madonna married Ritchie the following day at nearby Skibo Castle.[186][187] After an eight-year absence from touring, Madonna started her Drowned World Tour in June 2001.[85] The tour visited cities in the U.S. and Europe and was the highest-grossing concert tour of the year by a solo artist, earning $75 million from 47 sold-out shows.[188] She also released her second greatest-hits collection, GHV2, which compiled 15 singles during the second decade of her recording career. The album debuted at number seven on the Billboard 200 and sold seven million units worldwide.[189][190]

Madonna starred in the film Swept Away, directed by Ritchie. Released direct-to-video in the UK, the film was a commercial and critical failure.[191] In May 2002 she appeared in London in the West End play Up For Grabs at the Wyndhams Theatre (billed as ‘Madonna Ritchie’), to universally bad reviews and was described as «the evening’s biggest disappointment» by one.[192][193] That October, she released «Die Another Day», the title song of the James Bond film Die Another Day, in which she had a cameo role, described by Peter Bradshaw from The Guardian as «incredibly wooden».[194] The song reached number eight on the Billboard Hot 100 and was nominated for both a Golden Globe Award for Best Original Song and a Golden Raspberry Award for Worst Original Song.[49]

2003–2006: American Life and Confessions on a Dance Floor

Madonna again broke records in 2004, when her Re-Invention concert tour was named the year’s highest-grossing.

In 2003, Madonna collaborated with fashion photographer Steven Klein for an exhibition installation named X-STaTIC Pro=CeSS, which ran from March to May in New York’s Deitch Projects gallery and also traveled the world in an edited form.[195] The same year, Madonna released her ninth studio album, American Life, which was based on her observations of American society.[196] She explained that the record was «like a trip down memory lane, looking back at everything I’ve accomplished and all the things I once valued and all the things that were important to me.» Larry Flick from The Advocate felt that «American Life is an album that is among her most adventurous and lyrically intelligent» while condemning it as «a lazy, half-arsed effort to sound and take her seriously.»[197][198] The original music video of its title track caused controversy due to its violence and anti-war imagery, and was withdrawn after the 2003 invasion of Iraq started. Madonna voluntarily censored herself for the first time in her career due to the political climate of the country, saying that «there was a lynch mob mentality that was going on that wasn’t pretty and I have children to protect.»[199] The song stalled at number 37 on the Hot 100,[49] while the album became her lowest-selling album at that point with four million copies worldwide.[200]

Madonna gave another provocative performance later that year at the 2003 MTV Video Music Awards, when she kissed singers Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera while singing the track «Hollywood».[201][202] In October 2003, she provided guest vocals on Spears’ single «Me Against the Music».[203] It was followed with the release of Remixed & Revisited. The EP contained remixed versions of songs from American Life and included «Your Honesty», a previously unreleased track from the Bedtime Stories recording sessions.[204] Madonna also signed a contract with Callaway Arts & Entertainment to be the author of five children’s books. The first of these books, titled The English Roses, was published in September 2003. The story was about four English schoolgirls and their envy and jealousy of each other.[205] The book debuted at the top of The New York Times Best Seller list and became the fastest-selling children’s picture book of all time.[206] Madonna donated all of its proceeds to a children’s charity.[207]

The next year Madonna and Maverick sued Warner Music Group and its former parent company Time Warner, claiming that mismanagement of resources and poor bookkeeping had cost the company millions of dollars. In return, Warner filed a countersuit alleging that Maverick had lost tens of millions of dollars on its own.[127][208] The dispute was resolved when the Maverick shares, owned by Madonna and Ronnie Dashev, were purchased by Warner. Madonna and Dashev’s company became a wholly-owned subsidiary of Warner Music, but Madonna was still signed to Warner under a separate recording contract.[127]

In mid-2004, Madonna embarked on the Re-Invention World Tour in the U.S., Canada, and Europe. It became the highest-grossing tour of 2004, earning around $120 million and became the subject of her documentary I’m Going to Tell You a Secret.[209][210] In November 2004, she was inducted into the UK Music Hall of Fame as one of its five founding members, along with the Beatles, Elvis Presley, Bob Marley, and U2.[211] Rolling Stone ranked her at number 36 on its special issue of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time, featuring an article about her written by Britney Spears.[212] In January 2005, Madonna performed a cover version of the John Lennon song «Imagine» at Tsunami Aid.[213] She also performed at the Live 8 benefit concert in London in July 2005.[214]

When I wrote American Life, I was very agitated by what was going on in the world around me, […] I was angry. I had a lot to get off my chest. I made a lot of political statements. But now, I feel that I just want to have fun; I want to dance; I want to feel buoyant. And I want to give other people the same feeling. There’s a lot of madness in the world around us, and I want people to be happy.

—Madonna talking about Confessions on a Dance Floor.[215]

Her tenth studio album, Confessions on a Dance Floor, was released in November 2005. Musically the album was structured like a club set composed by a DJ. It was acclaimed by critics, with Keith Caulfield from Billboard commenting that the album was a «welcome return to form for the Queen of Pop.»[216] The album won a Grammy Award for Best Electronic/Dance Album.[115] Confessions on a Dance Floor and its lead single, «Hung Up», went on to reach number one in 40 and 41 countries respectively, earning a place in Guinness World Records.[217] The song contained a sample of ABBA’s «Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight)», only the second time that ABBA has allowed their work to be used. ABBA songwriter Björn Ulvaeus remarked «It is a wonderful track—100 per cent solid pop music.»[218] «Sorry», the second single, became Madonna’s twelfth number-one single in the UK.[67]

Madonna embarked on the Confessions Tour in May 2006, which had a global audience of 1.2 million and grossed over $193.7 million, becoming the highest-grossing tour to that date for a female artist.[219] Madonna used religious symbols, such as the crucifix and Crown of Thorns, in the performance of «Live to Tell». It caused the Russian Orthodox Church and the Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia to urge all their members to boycott her concert.[220] At the same time, the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) announced officially that Madonna had sold over 200 million copies of her albums alone worldwide.[221]

While on tour Madonna founded charitable organization Raising Malawi and partially funded an orphanage in and traveling to that country.[222] While there, she decided to adopt a boy named David Banda in October 2006.[223] The adoption raised strong public reaction, because Malawian law requires would-be parents to reside in Malawi for one year before adopting, which Madonna did not do.[224] She addressed this on The Oprah Winfrey Show, saying that there were no written adoption laws in Malawi that regulated foreign adoption. Madonna described how Banda had been suffering from pneumonia after surviving malaria and tuberculosis when they first met.[225] Banda’s biological father, Yohane, commented, «These so-called human rights activists are harassing me every day, threatening me that I am not aware of what I am doing … They want me to support their court case, a thing I cannot do for I know what I agreed with Madonna and her husband.» The adoption was finalized in May 2008.[226][227]

2007–2011: Filmmaking, Hard Candy, and business ventures

Madonna released and performed the song «Hey You» at the London Live Earth concert in July 2007.[229] She announced her departure from Warner Bros. Records, and declared a new $120 million, ten-year 360 deal with Live Nation.[230] In 2008, Madonna produced and wrote I Am Because We Are, a documentary on the problems faced by Malawians; it was directed by Nathan Rissman, who worked as Madonna’s gardener.[231] She also directed her first film, Filth and Wisdom. The plot of the film revolved around three friends and their aspirations. The Times said she had «done herself proud» while The Daily Telegraph described the film as «not an entirely unpromising first effort [but] Madonna would do well to hang on to her day job.»[232][233] On March 10, 2008, Madonna was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in her first year of eligibility.[234] She did not sing at the ceremony but asked fellow Hall of Fame inductees and Michigan natives the Stooges to perform her songs «Burning Up» and «Ray of Light».[235]

Madonna released her eleventh studio album, Hard Candy, in April 2008. Containing R&B and urban pop influences, the songs on Hard Candy were autobiographical in nature and saw Madonna collaborating with Justin Timberlake, Timbaland, Pharrell Williams and Nate «Danja» Hills.[236] The album debuted at number one in 37 countries and on the Billboard 200.[237][238] Caryn Ganz from Rolling Stone complimented it as an «impressive taste of her upcoming tour»,[239] while BBC correspondent Mark Savage panned it as «an attempt to harness the urban market».[240]

«4 Minutes» was released as the album’s lead single and peaked at number three on the Billboard Hot 100. It was Madonna’s 37th top-ten hit on the chart and pushed her past Elvis Presley as the artist with the most top-ten hits.[241] In the UK she retained her record for the most number-one singles for a female artist; «4 Minutes» becoming her thirteenth.[242] At the 23rd Japan Gold Disc Awards, Madonna received her fifth Artist of the Year trophy from Recording Industry Association of Japan, the most for any artist.[243] To further promote the album, she embarked on the Sticky & Sweet Tour, her first major venture with Live Nation. With a total gross of $408 million, it ended up as the second highest-grossing tour of all time, behind the Rolling Stones’s A Bigger Bang Tour.[244] It remained the highest-grossing tour by a solo artist until Roger Waters’ the Wall Live surpassed it in 2013.[245]

In July 2008, Christopher Ciccone released a book titled Life with My Sister Madonna, which caused a rift between Madonna and him, because of unsolicited publication.[246] By fall, Madonna filed for divorce from Ritchie, citing irreconcilable differences.[247] In December 2008, Madonna’s spokesperson announced that Madonna had agreed to a divorce settlement with Ritchie, the terms of which granted him between £50–60 million ($68.49–82.19 million), a figure that included the couple’s London pub and residence and Wiltshire estate in England.[248] The marriage was dissolved by District Judge Reid by decree nisi at the clinical Principal Registry of the Family Division in High Holborn, London. They entered a compromise agreement for Rocco and David, then aged eight and three respectively, and divided the children’s time between Ritchie’s London home and Madonna’s in New York, where the two were joined by Lourdes.[249][250] Soon after, Madonna applied to adopt Chifundo «Mercy» James from Malawi in May 2009, but the country’s High Court rejected the application because Madonna was not a resident there.[251] She re-appealed, and on June 12, 2009, the Supreme Court of Malawi granted her the right to adopt Mercy.[252]

Madonna concluded her contract with Warner by releasing her third greatest-hits album, Celebration, in September 2009. It contained the new songs «Celebration» and «Revolver» along with 34 hits spanning her musical career with the label.[253] Celebration reached number one in several countries, including Canada, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom.[254] She appeared at the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards to speak in tribute to deceased pop singer Michael Jackson.[255] Madonna ended the 2000s as the bestselling single artist of the decade in the U.S. and the most-played artist of the decade in the UK.[256][257] Billboard also announced her as the third top-touring artist of the decade—behind only the Rolling Stones and U2—with a gross of over $801 million, 6.3 million attendance and 244 sell-outs of 248 shows.[258]

Madonna performed at the Hope for Haiti Now: A Global Benefit for Earthquake Relief concert in January 2010.[259] Her third live album, Sticky & Sweet Tour, was released in April, debuting at number ten on the Billboard 200.[58] It also became her 20th top-ten on the Oricon Albums Chart, breaking the Beatles’ record for the most top-ten album by an international act in Japan.[260] Madonna granted American television show, Glee, the rights to her entire catalog of music, and the producers created an episode featuring her songs exclusively.[261] She also collaborated with Lourdes and released the Material Girl clothing line, inspired by her punk-girl style when she rose to fame in the 1980s.[262] In October, she opened a series of fitness centers around the world named Hard Candy Fitness,[263] and three months later unveiled a second fashion brand called Truth or Dare which included footwear, perfumes, underclothing, and accessories.[264]

Madonna directed her second feature film, W.E., a biographical account about the affair between King Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson. Co-written with Alek Keshishian, the film was premiered at the 68th Venice International Film Festival in September 2011.[265] Critical and commercial response to the film was negative.[266][267] Madonna contributed the ballad «Masterpiece» for the film’s soundtrack, which won her a Golden Globe Award for Best Original Song.[268]

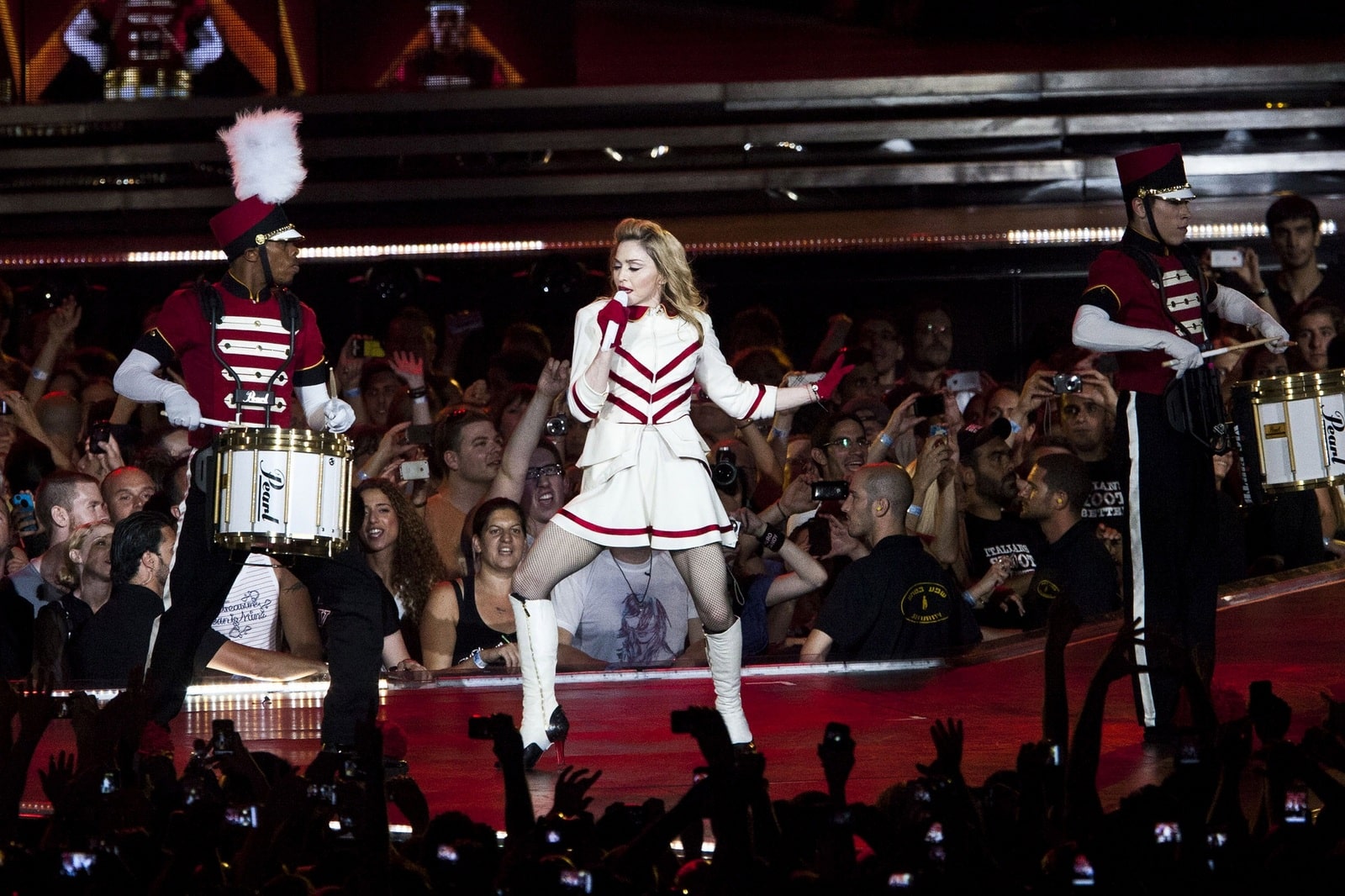

2012–2017: Super Bowl XLVI halftime show, MDNA, and Rebel Heart

In February 2012, Madonna headlined the Super Bowl XLVI halftime show at the Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis, Indiana.[269] Her performance was visualized by Cirque Du Soleil and Jamie King and featured special guests LMFAO, Nicki Minaj, M.I.A. and CeeLo Green. It became the then most-watched Super Bowl halftime show in history with 114 million viewers, higher than the game itself.[270] During the event, she performed «Give Me All Your Luvin'», the lead single from her twelfth studio album, MDNA. It became her record-extending 38th top-ten single on the Billboard Hot 100.[271]

MDNA was released in March 2012 and saw collaboration with various producers, including William Orbit and Martin Solveig.[272] It was her first release under her three-album deal with Interscope Records, which she signed as a part of her 360 deal with Live Nation.[273] She was signed to the record label since Live Nation was unable to distribute music recordings.[274] MDNA became Madonna’s fifth consecutive studio record to debut at the top of the Billboard 200.[275] The album was mostly promoted by the MDNA Tour, which lasted from May to December 2012.[276] The tour featured controversial subjects such as violence, firearms, human rights, nudity and politics. With a gross of $305.2 million from 88 sold-out shows, it became the highest-grossing tour of 2012 and then-tenth highest-grossing tour of all time.[277] Madonna was named the top-earning celebrity of the year by Forbes, earning an estimated $125 million.[278]

Madonna collaborated with Steven Klein and directed a 17-minute film, secretprojectrevolution, which was released on BitTorrent in September 2013.[279] With the film she launched the Art for Freedom initiative, which helped to promote «art and free speech as a means to address persecution and injustice across the globe». The website for the project included over 3,000 art related submissions since its inception, with Madonna regularly monitoring and enlisting other artists like David Blaine and Katy Perry as guest curators.[280]

By 2013, Madonna’s Raising Malawi had built ten schools to educate 4,000 children in Malawi at a value of $400,000.[281] When Madonna visited the schools in April 2013, President of Malawi Joyce Banda accused her of exaggerating the charity’s contribution.[282] Madonna was saddened by Banda’s statement, but clarified that she had «no intention of being distracted by these ridiculous allegations». It was later confirmed that Banda had not approved the statement released by her press team.[283] Madonna also visited her hometown Detroit during May 2014 and donated funds to help with the city’s bankruptcy.[284] The same year, her business ventures extended to skin care products with the launch of MDNA Skin in Tokyo, Japan.[285]

Madonna’s thirteenth studio album, Rebel Heart, was released in March 2015, three months after its thirteen demos leaked onto the Internet.[286] Unlike her previous efforts, which involved only a few people, Madonna worked with a large number of collaborators, including Avicii, Diplo and Kanye West.[287][288] Introspection was listed as one of the foundational themes prevalent on the record, along with «genuine statements of personal and careerist reflection».[289] Madonna explained to Jon Pareles of The New York Times that although she has never looked back at her past endeavors, reminiscing about it felt right for Rebel Heart.[290] Music critics responded positively towards the album, calling it her best effort in a decade.[291]

With 2015–2016’s Rebel Heart Tour, Madonna extended her record as the highest-grossing solo touring artist with total gross of $1.131 billion; a record that began with 1990’s Blond Ambition World Tour.

From September 2015 to March 2016, Madonna embarked on the Rebel Heart Tour to promote the album. The tour traveled throughout North America, Europe and Asia and was Madonna’s first visit to Australia in 23 years, where she also performed a one-off show for her fans.[292][293] Rebel Heart Tour grossed a total of $169.8 million from the 82 shows, with over 1.045 million ticket sales.[294] While on tour, Madonna became engaged in a legal battle with Ritchie, over the custody of their son Rocco. The dispute started when Rocco decided to continue living in England with Ritchie when the tour had visited there, while Madonna wanted him to travel with her. Court hearings took place in both New York and London. After multiple deliberations, Madonna withdrew her application for custody and decided to resolve the matter privately.[295]

In October 2016, Billboard named Madonna its Woman of the Year. Her «blunt and brutally honest» speech about ageism and sexism at the ceremony received widespread coverage in the media.[296][297] The next month Madonna, who actively supported Hillary Clinton during the 2016 U.S. presidential election, performed an impromptu acoustic concert at Washington Square Park in support of Clinton’s campaign.[298] Upset that Donald Trump won the election, Madonna spoke out against him at the Women’s March on Washington, a day after his inauguration.[299] She sparked controversy when she said that she «thought a lot about blowing up the White House».[300] The following day, Madonna asserted she was «not a violent person» and that her words had been «taken wildly out of context».[301]

In February 2017, Madonna adopted four-year-old twin sisters from Malawi named Estere and Stella,[302][303] and she moved to live in Lisbon, Portugal in summer 2017 with her adoptive children.[304] In July, she opened the Mercy James Institute for Pediatric Surgery and Intensive Care in Malawi, a children’s hospital built by her Raising Malawi charity.[305] The live album chronicling the Rebel Heart Tour was released in September 2017, and won Best Music Video for Western Artists at the 32nd Japan Gold Disc Award.[306][307] That month, Madonna launched MDNA Skin in select stores in the United States.[308] A few months earlier, the auction house Gotta Have Rock and Roll had put up Madonna’s personal items like love letters from Tupac Shakur, cassettes, underwear and a hairbrush for sale. Darlene Lutz, an art dealer who had initiated the auction, was sued by Madonna’s representatives to stop the proceedings. Madonna clarified that her celebrity status «does not obviate my right to maintain my privacy, including with regard to highly personal items». Madonna lost the case and the presiding judge ruled in favor of Lutz who was able to prove that in 2004 Madonna made a legal agreement with her for selling the items.[309]

2018–present: Madame X, catalog reissues, and autobiographical film

While living in Lisbon, Madonna met Dino D’Santiago, who introduced her to many local musicians playing fado, morna, and samba music. They regularly invited her to their «living room sessions», thus she was inspired to make her 14th studio album, Madame X.[310] Madonna produced the album with several musicians, primarily her longtime collaborator Mirwais and Mike Dean.[311] The album was critically well received, with NME deeming it «bold, bizarre, self-referential and unlike anything Madonna has ever done before.»[312] Released in June 2019, Madame X debuted atop the Billboard 200, becoming her ninth number-one album there.[313] All four of its singles—»Medellín», «Crave», «I Rise», and «I Don’t Search I Find»—topped the Billboard Dance Club Songs chart, extending her record for most number-one entries on the chart.[314]

The previous month, Madonna appeared as the interval act at the Eurovision Song Contest 2019 and performed «Like a Prayer», and then «Future» with rapper Quavo.[315] Her Madame X Tour, an all-theatre tour in select cities across North America and Europe, began on September 17, 2019. In addition to much smaller venues compared to her previous tours, she implemented a no-phone policy in order to maximize the intimacy of the concert.[316] According to Pollstar, the tour earned $51.4 million in ticket sales.[317] That December, Madonna started dating Ahlamalik Williams, a dancer who began accompanying her on the Rebel Heart Tour in 2015.[318][319] However, the Madame X Tour faced several cancellations due to her recurring knee injury, and eventually ended abruptly on March 8, 2020, three days before its planned final date, after the French government banned gatherings of more than 1,000 people due to COVID-19 pandemic.[320][321] She later admitted to testing positive for coronavirus antibodies,[322] and donated $1 million to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to help fund research creating a new vaccine.[323]

Madonna and Missy Elliott provided guest vocals on Dua Lipa’s single «Levitating», from Lipa’s 2020 remix album Club Future Nostalgia.[324] She also started work on a film biopic about her life, for which she enlisted screenwriter Erin Cressida Wilson to help with the script.[325][326][327] Madonna released Madame X, a documentary film chronicling the tour of the same name, on Paramount+ in October 2021.[328] On her 63rd birthday, she officially announced her return to Warner in a global partnership which grants the label her entire recorded music catalog, including the last three albums released under Interscope. Under the contract, Madonna launched a series of catalog reissues beginning in 2022, to commemorate the 40th anniversary of her recording career. A remix album titled Finally Enough Love: 50 Number Ones was released on August 19, with an 16-track abridged edition being available for streaming since June 24.[329] Consisting of her 50 number-one songs on Billboard‘s Dance Club Songs chart, the remix album highlighted «how meaningful dance music has always been» to Madonna’s career, and became her 23rd top-ten album on the Billboard 200.[330][331]

In September 2022, Madonna released «Hung Up on Tokischa», a remix of «Hung Up», featuring rapper Tokischa. The song utilizes dembow.[332][333] On December 29, 2022, Madonna released the demo version of «Back That Up to the Beat» to all digital outlets. The song was originally recorded in 2015 sessions, with an alternative version being released on the deluxe 2-CD version of her 2019 Madame X album.[334]

Artistry

Influences

Historians, musicians, and anthropologists trace her influences—from African American gospel music to Japanese fashion, Middle Eastern spirituality to feminist art history—and the ways she borrows, adapts, and interprets them

—National Geographic Society on Madonna’s influences.[335]

According to Taraborrelli, the death of her mother had the most influence in shaping Madonna into the woman she would become. He believed that the devastation and abandonment Madonna felt at the loss of her mother taught her «a valuable lesson, that she would have to remain strong for herself because, she feared weakness—particularly her own.»[5] Author Lucy O’Brien opines that the impact of the sexual assault Madonna suffered in her young adult years was the motivating factor behind everything she has done, more important than the death of her mother: «It’s not so much grief at her mother’s death that drives her, as the sense of abandonment that left her unprotected. She encountered her own worst possible scenario, becoming a victim of male violence, and thereafter turned that full-tilt into her work, reversing the equation at every opportunity.»[336]

Madonna was influenced by Debbie Harry (left) and Chrissie Hynde (right), whom she called «strong, independent women who wrote their own music and evolved on their own».[337]

Madonna has called Nancy Sinatra one of her idols. She said Sinatra’s «These Boots Are Made for Walkin'» made a major impression on her.[338] As a young woman, she attempted to broaden her taste in literature, art, and music, and during this time became interested in classical music. She noted that her favorite style was baroque, and loved Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Frédéric Chopin because she liked their «feminine quality».[339] Madonna’s major influences include Debbie Harry, Chrissie Hynde, Karen Carpenter, the Supremes and Led Zeppelin, as well as dancers Martha Graham and Rudolf Nureyev.[337][340] She also grew up listening to David Bowie, whose show was the first rock concert she ever attended.[341]

During her childhood, Madonna was inspired by actors, later saying, «I loved Carole Lombard and Judy Holliday and Marilyn Monroe. They were all incredibly funny … and I saw myself in them … my girlishness, my knowingness and my innocence.»[338] Her «Material Girl» music video recreated Monroe’s look in the song «Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend», from the film Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953). She studied the screwball comedies of the 1930s, particularly those of Lombard, in preparation for the film Who’s That Girl. The video for «Express Yourself» (1989) was inspired by Fritz Lang’s silent film Metropolis (1927). The video for «Vogue» recreated the style of Hollywood glamour photographs, in particular those by Horst P. Horst, and imitated the poses of Marlene Dietrich, Carole Lombard, and Rita Hayworth, while the lyrics referred to many of the stars who had inspired her, including Bette Davis, described by Madonna as an idol.[114][342]

Influences also came to her from the art world, such as through the works of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo.[343] The music video of the song «Bedtime Story» featured images inspired by the paintings of Kahlo and Remedios Varo.[344] Madonna is also a collector of Tamara de Lempicka’s Art Deco paintings and has included them in her music videos and tours.[345] Her video for «Hollywood» (2003) was an homage to the work of photographer Guy Bourdin; Bourdin’s son subsequently filed a lawsuit for unauthorized use of his father’s work.[346] Pop artist Andy Warhol’s use of sadomasochistic imagery in his underground films were reflected in the music videos for «Erotica» and «Deeper and Deeper».[347]

Madonna’s Catholic background has been reflected throughout her career, from her fashion use of rosary to her musical outputs, including on Like a Prayer (1989).[348][349] Her album MDNA (2012) has also drawn many influences from her Catholic upbringing, and since 2011 she has been attending meetings and services at an Opus Dei center, a Catholic institution that encourages spirituality through everyday life.[350] In a 2016 interview, she commented: «I always feel some kind of inexplicable connection with Catholicism. It kind of shows up in all of my work, as you may have noticed.»[351] Her study of the Kabbalah was also observed in Madonna’s music, especially albums like Ray of Light and Music.[352] Speaking of religion in a 2019 interview with Harry Smith of Today Madonna stated, «The God that I believe in, created the world […] He/Her/They [sic] isn’t a God to fear, it’s a God to give thanks to.» In an appearance on Andrew Denton’s Interview she added, «The idea that in any church you go, you see a man on a cross and everyone genuflects and prays to him […] in a way it’s paganism/idolatry because people are worshipping a thing.»[353][354]

Musical style and composition

[Madonna] is a brilliant pop melodist and lyricist. I was knocked out by the quality of the writing [during Ray of Light sessions]… I know she grew up on Joni Mitchell and Motown, and to my ears she embodies the best of both worlds. She is a wonderful confessional songwriter, as well as being a superb hit chorus pop writer.

—Rick Nowels, on co-writing with Madonna.[355]

Madonna’s music has been the subject of much analysis and scrutiny. Robert M. Grant, author of Contemporary Strategy Analysis (2005), commented that Madonna’s musical career has been a continuous experimentation with new musical ideas and new images and a constant quest for new heights of fame and acclaim.[356] Thomas Harrison in the book Pop Goes the Decade: The Eighties deemed Madonna «an artist who pushed the boundaries» of what a female singer could do, both visually and lyrically.[357] Professor Santiago Fouz-Hernández asserted, «While not gifted with an especially powerful or wide-ranging voice, Madonna has worked to expand her artistic palette to encompass diverse musical, textual and visual styles and various vocal guises, all with the intention of presenting herself as a mature musician.»[358]

Madonna has remained in charge in every aspect of her career, including as a writer and producer in most of her own music.[359][360] Her desire for control had already been seen during the making of her debut album, where she fought Reggie Lucas over his production output. However, it was not until her third album that Warner allowed Madonna to produce her own album.[361] Stan Hawkins, author of Settling the Pop Score explained, «it is as musician and producer that Madonna is one of the few female artists to have broken into the male domain of the recording studio. Undoubtedly, Madonna is fully aware that women have been excluded from the musical workplace on most levels, and has set out to change this.»[362] Producer Stuart Price stated: «You don’t produce Madonna, you collaborate with her… She has her vision and knows how to get it.»[363] Despite being labeled a «control freak», Madonna has said that she valued input from her collaborators.[364] She further explained:

I like to have control over most of the things in my career but I’m not a tyrant. I don’t have to have it on my album that it’s written, arranged, produced, directed, and stars Madonna. To me, to have total control means you can lose objectivity. What I like is to be surrounded by really, talented intelligent people that you can trust. And ask them for their advice and get their input.[365]

Madonna’s early songwriting skill was developed during her time with the Breakfast Club in 1979.[366] She subsequently became the sole writer of five songs on her debut album, including «Lucky Star» which she composed on synthesizer.[367] As a songwriter, Madonna has registered more than 300 tracks to ASCAP, including 18 songs written entirely by herself.[368] Rolling Stone has named her «an exemplary songwriter with a gift for hooks and indelible lyrics.»[369] Despite having worked with producers across many genres, the magazine noted that Madonna’s compositions have been «consistently stamped with her own sensibility and inflected with autobiographical detail.» Patrick Leonard, who co-wrote many of her hit songs, called Madonna «a helluva songwriter», explaining: «Her sensibility about melodic line—from the beginning of the verse to the end of the verse and how the verse and the chorus influence each other—is very deep. Many times she’s singing notes that no one would’ve thought of but her.»[371] Barry Walters from Spin credited her songwriting as the reason of her musical consistency.[372] Madonna has been nominated for being inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame three times.[373] In 2015, Rolling Stone ranked Madonna at number 56 on the «100 Greatest Songwriters of All Time» list.

Madonna wrote all the lyrics and partial melodies of «Live to Tell», an adult contemporary ballad, which was noted as her first musical reinvention.[374]

Madonna’s discography is generally categorized as pop, electronica, and dance.[376][377] Nevertheless, Madonna’s first foray into the music industry was dabbling in rock music with Breakfast Club and Emmy.[378] As the frontwoman of Emmy, Madonna recorded about 12–14 songs that resemble the punk rock of that period.[366] Madonna soon abandoned playing rock songs by the time she signed to Gotham Records, which eventually dropped her since they were unhappy with her new funk direction.[379] According to Erlewine, Madonna began her career as a disco diva, in an era that did not have any such divas to speak of. In the beginning of the 1980s, disco was an anathema to the mainstream pop, and Madonna had a huge role in popularizing dance music as mainstream music.[380] Arie Kaplan in the book American Pop: Hit Makers, Superstars, and Dance Revolutionaries referred to Madonna as «a pioneer» of dance-pop.[381] According to Fouz-Hernández, «Madonna’s frequent use of dance idioms and subsequent association with gay or sexually liberated audiences, is seen as somehow inferior to ‘real’ rock and roll. But Madonna’s music refuses to be defined by narrow boundaries of gender, sexuality or anything else.»[358]

The «cold and emotional» ballad «Live to Tell», as well as its parent album True Blue (1986), is noted as Madonna’s first musical reinvention.[374] PopMatters writer Peter Piatkowski described it as a «very deliberate effort to present Madonna as a mature and serious artist.»[382] She continued producing ballads in between her upbeat material, although albums such as Madonna (1983) and Confessions on a Dance Floor (2005) consist of entirely dance tracks.[383][384] With Ray of Light (1998), critics acknowledged Madonna for bringing electronica from its underground status into massive popularity in mainstream music scene.[385] Her other sonically drastic ventures include the 1930s big-band jazz on I’m Breathless (1990);[386] lush R&B on Bedtime Stories (1994);[387] operatic show tunes on Evita (1996);[388] guitar-driven folk music on American Life (2003);[389] as well as multilingual world music on Madame X (2019).[390]

Voice and instruments

Possessing a mezzo-soprano vocal range,[392][393] Madonna has always been self-conscious about her voice.[394] Mark Bego, author of Madonna: Blonde Ambition, called her «the perfect vocalist for lighter-than-air songs», despite not being a «heavyweight talent».[395] According to Tony Sclafani from MSNBC, «Madonna’s vocals are the key to her rock roots. Pop vocalists usually sing songs ‘straight’, but Madonna employs subtext, irony, aggression and all sorts of vocal idiosyncrasies in the ways John Lennon and Bob Dylan did.»[378] Madonna used a bright, girlish vocal timbre in her early albums which became passé in her later works. The change was deliberate since she was constantly reminded of how the critics had once labeled her as «Minnie Mouse on helium».[394] During the filming of Evita (1996), Madonna had to take vocal lessons, which increased her range further. Of this experience she commented, «I studied with a vocal coach for Evita and I realized there was a whole piece of my voice I wasn’t using. Before, I just believed I had a really limited range and was going to make the most of it.»[375]

Besides singing, Madonna has the ability to play several musical instruments. Piano was the first instrument taught to her as a child.[27] In the late 1970s, she learned to play drum and guitar from her then-boyfriend Dan Gilroy, before joining the Breakfast Club lineup as the drummer.[396] She later played guitar with the band Emmy as well as on her own demo recordings.[397] After her career breakthrough, Madonna was absent performing with guitar for years, but she is credited for playing cowbell on Madonna (1983) and synthesizer on Like a Prayer (1989).[360] In 1999, Madonna had studied for three months to play the violin for the role as a violin teacher in the film Music of the Heart, but she eventually left the project before filming began.[398] Madonna decided to perform with guitar again during the promotion of Music (2000) and recruited guitarist Monte Pittman to help improve her skill.[399] Since then, Madonna has played guitar on every tour, as well as her studio albums.[360] She received a nomination for Les Paul Horizon Award at the 2002 Orville H. Gibson Guitar Awards.[400]

Music videos and performances

In The Madonna Companion, biographers Allen Metz and Carol Benson noted that Madonna had used MTV and music videos to establish her popularity and enhance her recorded work more than any other recent pop artist.[401] According to them, many of her songs have the imagery of the music video in strong context, while referring to the music. Cultural critic Mark C. Taylor in his book Nots (1993) felt that the postmodern art form par excellence is the video and the reigning «queen of video» is Madonna. He further asserted that «the most remarkable creation of MTV is Madonna. The responses to Madonna’s excessively provocative videos have been predictably contradictory.»[402] The media and public reaction towards her most-discussed songs such as «Papa Don’t Preach», «Like a Prayer», or «Justify My Love» had to do with the music videos created to promote the songs and their impact, rather than the songs themselves.[401] Morton felt that «artistically, Madonna’s songwriting is often overshadowed by her striking pop videos.»[403] In 2003, MTV named her «The Greatest Music Video Star Ever» and said that «Madonna’s innovation, creativity, and contribution to the music video art form is what won her the award.»[404][405] In 2020, Billboard ranked her atop the 100 Greatest Music Video Artists of All Time.[406]

Madonna’s live performances vary from choreographed routines such as voguing (above) to stripped-down ones with only a ukulele (below).

Madonna’s initial music videos reflected her American and Hispanic mixed street style combined with a flamboyant glamor.[401] She was able to transmit her avant-garde Downtown Manhattan fashion sense to the American audience.[407] The imagery and incorporation of Hispanic culture and Catholic symbolism continued with the music videos from the True Blue era.[408] Author Douglas Kellner noted, «such ‘multiculturalism’ and her culturally transgressive moves turned out to be highly successful moves that endeared her to large and varied youth audiences.»[409] Madonna’s Spanish look in the videos became the fashion trend of that time, in the form of boleros and layered skirts, accessorizing with rosary beads and a crucifix as in the video of «La Isla Bonita».[410][411] Academics noted that with her videos, Madonna was subtly reversing the usual role of male as the dominant sex.[412] This symbolism and imagery was probably the most prevalent in the music video for «Like a Prayer». The video included scenes of an African-American church choir, Madonna being attracted to a black saint statue, and singing in front of burning crosses.[413]

Madonna’s acting performances in films have frequently received poor reviews from film critics. Stephanie Zacharek stated in Time that, «[Madonna] seems wooden and unnatural as an actress, and it’s tough to watch because she’s clearly trying her damnedest.» According to biographer Andrew Morton, «Madonna puts a brave face on the criticism, but privately she is deeply hurt.»[414] After the critically panned box-office bomb Swept Away (2002), Madonna vowed never to act again in a film.[415][416] While reviewing her career retrospective titled Body of Work (2016) at New York’s Metrograph hall, The Guardian‘s Nigel M. Smith wrote that Madonna’s film career suffered mostly due to lack of proper material supplied to her, and she otherwise «could steal a scene for all the right reasons».[417]

Metz noted that Madonna represents a paradox as she is often perceived as living her whole life as a performance. While her big-screen performances are panned, her live performances are critical successes.[418] Madonna was the first artist to have her concert tours as reenactments of her music videos. Author Elin Diamond explained that reciprocally, the fact that images from Madonna’s videos can be recreated in a live setting enhances the original videos’ realism. She believed that «her live performances have become the means by which mediatized representations are naturalized».[419] Taraborrelli said that encompassing multimedia, latest technology and sound systems, Madonna’s concerts and live performances are «extravagant show piece[s], [and] walking art show[s].»[420]

Chris Nelson from The New York Times commented that «artists like Madonna and Janet Jackson set new standards for showmanship, with concerts that included not only elaborate costumes and precision-timed pyrotechnics but also highly athletic dancing. These effects came at the expense of live singing.»[421] Thor Christensen of The Dallas Morning News commented that while Madonna earned a reputation for lip-syncing during her 1990 Blond Ambition World Tour, she has subsequently reorganized her performances by «stay[ing] mostly still during her toughest singing parts and [leaves] the dance routines to her backup troupe … [r]ather than try to croon and dance up a storm at the same time.»[422] To allow for greater movement while dancing and singing, Madonna was one of the earliest adopters of hands-free radio-frequency headset microphones, with the headset fastened over the ears or the top of the head, and the microphone capsule on a boom arm that extended to the mouth. Because of her prominent usage, the microphone design came to be known as the «Madonna mic».[423][424]

Legacy

Madonna has built a legacy that transcends music and has been studied by sociologists, historians, and other scholars, contributing to the rise of Madonna studies, a subfield of American cultural studies.[426][427][428] According to Rodrigo Fresán, «saying that Madonna is just a pop star is as inappropriate as saying that Coca-Cola is just a soda. Madonna is one of the classic symbols of Made in USA.»[429] Rolling Stone Spain wrote, «She became the first master of viral pop in history, years before the internet was massively used. Madonna was everywhere; in the almighty music television channels, ‘radio formulas’, magazine covers and even in bookstores. A pop dialectic, never seen since the Beatles’s reign, which allowed her to keep on the edge of trend and commerciality.»[430] William Langley from The Daily Telegraph felt that «Madonna has changed the world’s social history, has done more things as more different people than anyone else is ever likely to.»[431] Professor Diane Pecknold noted that «nearly any poll of the biggest, greatest, or best in popular culture includes [Madonna’s] name».[428] In 2012, VH1 ranked Madonna as the greatest woman in music.[432] According to Acclaimed Music, which statistically aggregates hundreds of critics’ lists, Madonna is the most acclaimed female musician of all time.[433]

Spin writer Bianca Gracie stated that «the ‘Queen of Pop’ isn’t enough to describe Madonna—she is Pop. [She] formulated the blueprint of what a pop star should be.»[434] According to Sclafani, «It’s worth noting that before Madonna, most music mega-stars were guy rockers; after her, almost all would be female singers … When the Beatles hit America, they changed the paradigm of performer from solo act to band. Madonna changed it back—with an emphasis on the female.»[435] Howard Kramer, curatorial director of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, asserted that «Madonna and the career she carved out for herself made possible virtually every other female pop singer to follow … She certainly raised the standards of all of them … She redefined what the parameters were for female performers.»[436] Andy Bennett and Steve Waksman, authors of The SAGE Handbook of Popular Music (2014), noted that «almost all female pop stars of recent years—Britney Spears, Beyoncé, Rihanna, Katy Perry, Lady Gaga, and others—acknowledge the important influence of Madonna on their own careers.»[376] Madonna has also influenced male artists, inspiring rock frontmen Liam Gallagher of Oasis and Chester Bennington of Linkin Park to become musicians.[437][438]

Madonna’s use of sexual imagery has benefited her career and catalyzed public discourse on sexuality and feminism.[439] The Times wrote that she had «started a revolution amongst women in music … Her attitudes and opinions on sex, nudity, style, and sexuality forced the public to sit up and take notice.»[440] Professor John Fiske noted that the sense of empowerment that Madonna offers is inextricably connected with the pleasure of exerting some control over the meanings of self, of sexuality, and of one’s social relations.[441] In Doing Gender in Media, Art and Culture (2009), the authors noted that Madonna, as a female celebrity, performer, and pop icon, can unsettle standing feminist reflections and debates.[442] According to lesbian feminist Sheila Jeffreys, Madonna represents woman’s occupancy of what Monique Wittig calls the category of sex, as powerful, and appears to gleefully embrace the performance of the sexual corvée allotted to women.[443] Professor Sut Jhally has referred to her as «an almost sacred feminist icon».[444]