| Indian Ocean | |

|---|---|

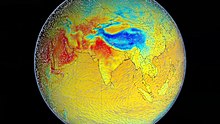

Extent of the Indian Ocean according to International Hydrographic Organization |

|

| Location | South and Southeast Asia, Western Asia, Northeast, East and Southern Africa and Australia |

| Coordinates | 20°S 80°E / 20°S 80°ECoordinates: 20°S 80°E / 20°S 80°E |

| Type | Ocean |

| Max. length | 9,600 km (6,000 mi) (Antarctica to Bay of Bengal)[1] |

| Max. width | 7,600 km (4,700 mi) (Africa to Australia)[1] |

| Surface area | 70,560,000 km2 (27,240,000 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 3,741 m (12,274 ft) |

| Max. depth | 7,258 m (23,812 ft) (Java Trench) |

| Shore length1 | 66,526 km (41,337 mi)[2] |

| Settlements | List |

| References | [3] |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. |

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world’s five oceanic divisions, covering 70,560,000 km2 (27,240,000 sq mi) or ~19.8% of the water on Earth’s surface.[4] It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by the Southern Ocean or Antarctica, depending on the definition in use.[5] Along its core, the Indian Ocean has some large marginal or regional seas such as the Arabian Sea, Laccadive Sea, Bay of Bengal, and Andaman Sea.

Etymology[edit]

A 1747 map of Africa with the Indian Ocean referred to as the Eastern Ocean

A 1658 naval map by Janssonius depicting the Indian Ocean, India and Arabia.

The Indian Ocean has been known by its present name since at least 1515 when the Latin form Oceanus Orientalis Indicus («Indian Eastern Ocean») is attested, named after India, which projects into it. It was earlier known as the Eastern Ocean, a term that was still in use during the mid-18th century (see map), as opposed to the Western Ocean (Atlantic) before the Pacific was surmised.[6]

Conversely, Chinese explorers in the Indian Ocean during the 15th century called it the Western Oceans.[7]

In Ancient Greek geography, the Indian Ocean region known to the Greeks was called the Erythraean Sea.[8]

Geography[edit]

The ocean-floor of the Indian Ocean is divided by spreading ridges and crisscrossed by aseismic structures

A composite satellite image centred on the Indian Ocean

Extent and data[edit]

The Indian Ocean, according to the CIA The World Factbook[9] (blue area), and as defined by the IHO (black outline — excluding marginal waterbodies).

The borders of the Indian Ocean, as delineated by the International Hydrographic Organization in 1953 included the Southern Ocean but not the marginal seas along the northern rim, but in 2000 the IHO delimited the Southern Ocean separately, which removed waters south of 60°S from the Indian Ocean but included the northern marginal seas.[10][11] Meridionally, the Indian Ocean is delimited from the Atlantic Ocean by the 20° east meridian, running south from Cape Agulhas, and from the Pacific Ocean by the meridian of 146°49’E, running south from the southernmost point of Tasmania. The northernmost extent of the Indian Ocean (including marginal seas) is approximately 30° north in the Persian Gulf.[11]

The Indian Ocean covers 70,560,000 km2 (27,240,000 sq mi), including the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf but excluding the Southern Ocean, or 19.5% of the world’s oceans; its volume is 264,000,000 km3 (63,000,000 cu mi) or 19.8% of the world’s oceans’ volume; it has an average depth of 3,741 m (12,274 ft) and a maximum depth of 7,906 m (25,938 ft).[4]

All of the Indian Ocean is in the Eastern Hemisphere and the centre of the Eastern Hemisphere, the 90th meridian east, passes through the Ninety East Ridge.

Coasts and shelves[edit]

In contrast to the Atlantic and Pacific, the Indian Ocean is enclosed by major landmasses and an archipelago on three sides and does not stretch from pole to pole, and can be likened to an embayed ocean. It is centered on the Indian Peninsula. Although this subcontinent has played a significant role in its history, the Indian Ocean has foremostly been a cosmopolitan stage, interlinking diverse regions by innovations, trade, and religion since early in human history.[12]

The active margins of the Indian Ocean have an average depth (land to shelf break[13]) of 19 ± 0.61 km (11.81 ± 0.38 mi) with a maximum depth of 175 km (109 mi). The passive margins have an average depth of 47.6 ± 0.8 km (29.58 ± 0.50 mi).[14]

The average width of the slopes of the continental shelves are 50.4–52.4 km (31.3–32.6 mi) for active and passive margins respectively, with a maximum depth of 205.3–255.2 km (127.6–158.6 mi).[15]

In correspondence of the Shelf break, also known as Hinge zone, the Bouguer gravity ranges from 0 to 30 mGals that is unusual for a continental region of around 16 km thick sediments. It has been hypothesized that the «Hinge zone may represent the relict of continental and proto-oceanic crustal boundary formed during the rifting of India from Antarctica.»[16]

Australia, Indonesia, and India are the three countries with the longest shorelines and exclusive economic zones. The continental shelf makes up 15% of the Indian Ocean.

More than two billion people live in countries bordering the Indian Ocean, compared to 1.7 billion for the Atlantic and 2.7 billion for the Pacific (some countries border more than one ocean).[2]

Rivers[edit]

The Indian Ocean drainage basin covers 21,100,000 km2 (8,100,000 sq mi), virtually identical to that of the Pacific Ocean and half that of the Atlantic basin, or 30% of its ocean surface (compared to 15% for the Pacific). The Indian Ocean drainage basin is divided into roughly 800 individual basins, half that of the Pacific, of which 50% are located in Asia, 30% in Africa, and 20% in Australasia. The rivers of the Indian Ocean are shorter on average (740 km (460 mi)) than those of the other major oceans. The largest rivers are (order 5) the Zambezi, Ganges-Brahmaputra, Indus, Jubba, and Murray rivers and (order 4) the Shatt al-Arab, Wadi Ad Dawasir (a dried-out river system on the Arabian Peninsula) and Limpopo rivers.[17]

After the breakup of East Gondwana and the formation of the Himalayas, the Ganges-Brahmaputra rivers flow into the world’s largest delta known as the Bengal delta or Sunderbans.[16]

Marginal seas[edit]

Marginal seas, gulfs, bays and straits of the Indian Ocean include:[11]

Along the east coast of Africa, the Mozambique Channel separates Madagascar from mainland Africa, while the Sea of Zanj is located north of Madagascar.

On the northern coast of the Arabian Sea, Gulf of Aden is connected to the Red Sea by the strait of Bab-el-Mandeb. In the Gulf of Aden, the Gulf of Tadjoura is located in Djibouti and the Guardafui Channel separates Socotra island from the Horn of Africa. The northern end of the Red Sea terminates in the Gulf of Aqaba and Gulf of Suez. The Indian Ocean is artificially connected to the Mediterranean Sea without ship lock through the Suez Canal, which is accessible via the Red Sea.

The Arabian Sea is connected to the Persian Gulf by the Gulf of Oman and the Strait of Hormuz. In the Persian Gulf, the Gulf of Bahrain separates Qatar from the Arabic Peninsula.

Along the west coast of India, the Gulf of Kutch and Gulf of Khambat are located in Gujarat in the northern end while the Laccadive Sea separates the Maldives from the southern tip of India.

The Bay of Bengal is off the east coast of India. The Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait separates Sri Lanka from India, while the Adam’s Bridge separates the two. The Andaman Sea is located between the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Islands.

In Indonesia, the so-called Indonesian Seaway is composed of the Malacca, Sunda and Torres Straits.

The Gulf of Carpentaria of located on the Australian north coast while the Great Australian Bight constitutes a large part of its southern coast.[18][19][20]

- Arabian Sea — 3.862 million km2

- Bay of Bengal — 2.172 million km2

- Andaman Sea — 797,700 km2

- Laccadive Sea — 786,000 km2

- Mozambique Channel — 700,000 km2

- Timor Sea — 610,000 km2

- Red Sea — 438,000 km2

- Gulf of Aden — 410,000 km2

- Persian Gulf — 251,000 km2

- Flores Sea — 240,000 km2

- Molucca Sea — 200,000 km2

- Oman Sea — 181,000 km2

- Great Australian Bight — 45,926 km2

- Gulf of Aqaba — 239 km2

- Gulf of Khambhat

- Gulf of Kutch

- Gulf of Suez

Climate[edit]

During summer, warm continental masses draw moist air from the Indian Ocean hence producing heavy rainfall. The process is reversed during winter, resulting in dry conditions.

Several features make the Indian Ocean unique. It constitutes the core of the large-scale Tropical Warm Pool which, when interacting with the atmosphere, affects the climate both regionally and globally. Asia blocks heat export and prevents the ventilation of the Indian Ocean thermocline. That continent also drives the Indian Ocean monsoon, the strongest on Earth, which causes large-scale seasonal variations in ocean currents, including the reversal of the Somali Current and Indian Monsoon Current. Because of the Indian Ocean Walker circulation there are no continuous equatorial easterlies. Upwelling occurs near the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula in the Northern Hemisphere and north of the trade winds in the Southern Hemisphere. The Indonesian Throughflow is a unique Equatorial connection to the Pacific.[21]

The climate north of the equator is affected by a monsoon climate. Strong north-east winds blow from October until April; from May until October south and west winds prevail. In the Arabian Sea, the violent Monsoon brings rain to the Indian subcontinent. In the southern hemisphere, the winds are generally milder, but summer storms near Mauritius can be severe. When the monsoon winds change, cyclones sometimes strike the shores of the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal.[22]

Some 80% of the total annual rainfall in India occurs during summer and the region is so dependent on this rainfall that many civilisations perished when the Monsoon failed in the past. The huge variability in the Indian Summer Monsoon has also occurred pre-historically, with a strong, wet phase 33,500–32,500 BP; a weak, dry phase 26,000–23,500 BC; and a very weak phase 17,000–15,000 BP,

corresponding to a series of dramatic global events: Bølling-Allerød, Heinrich, and Younger Dryas.[23]

Air pollution in South Asia spread over the Bay of Bengal and beyond.

The Indian Ocean is the warmest ocean in the world.[24] Long-term ocean temperature records show a rapid, continuous warming in the Indian Ocean, at about 1.2 °C (34.2 °F) (compared to 0.7 °C (33.3 °F) for the warm pool region) during 1901–2012.[25] Research indicates that human induced greenhouse warming, and changes in the frequency and magnitude of El Niño (or the Indian Ocean Dipole), events are a trigger to this strong warming in the Indian Ocean.[25]

South of the Equator (20–5°S), the Indian Ocean is gaining heat from June to October, during the austral winter, while it is losing heat from November to March, during the austral summer.[26]

In 1999, the Indian Ocean Experiment showed that fossil fuel and biomass burning in South and Southeast Asia caused air pollution (also known as the Asian brown cloud) that reach as far as the Intertropical Convergence Zone at 60°S. This pollution has implications on both a local and global scale.[27]

Oceanography[edit]

Forty percent of the sediment of the Indian Ocean is found in the Indus and Ganges fans. The oceanic basins adjacent to the continental slopes mostly contain terrigenous sediments. The ocean south of the polar front (roughly 50° south latitude) is high in biologic productivity and dominated by non-stratified sediment composed mostly of siliceous oozes. Near the three major mid-ocean ridges the ocean floor is relatively young and therefore bare of sediment, except for the Southwest Indian Ridge due to its ultra-slow spreading rate.[28]

The ocean’s currents are mainly controlled by the monsoon. Two large gyres, one in the northern hemisphere flowing clockwise and one south of the equator moving anticlockwise (including the Agulhas Current and Agulhas Return Current), constitute the dominant flow pattern. During the winter monsoon (November–February), however, circulation is reversed north of 30°S and winds are weakened during winter and the transitional periods between the monsoons.[29]

The Indian Ocean contains the largest submarine fans of the world, the Bengal Fan and Indus Fan, and the largest areas of slope terraces and rift valleys.

[30]

The inflow of deep water into the Indian Ocean is 11 Sv, most of which comes from the Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW). The CDW enters the Indian Ocean through the Crozet and Madagascar basins and crosses the Southwest Indian Ridge at 30°S. In the Mascarene Basin the CDW becomes a deep western boundary current before it is met by a re-circulated branch of itself, the North Indian Deep Water. This mixed water partly flows north into the Somali Basin whilst most of it flows clockwise in the Mascarene Basin where an oscillating flow is produced by Rossby waves.[31]

Water circulation in the Indian Ocean is dominated by the Subtropical Anticyclonic Gyre, the eastern extension of which is blocked by the Southeast Indian Ridge and the 90°E Ridge. Madagascar and the Southwest Indian Ridge separate three cells south of Madagascar and off South Africa. North Atlantic Deep Water reaches into the Indian Ocean south of Africa at a depth of 2,000–3,000 m (6,600–9,800 ft) and flows north along the eastern continental slope of Africa. Deeper than NADW, Antarctic Bottom Water flows from Enderby Basin to Agulhas Basin across deep channels (<4,000 m (13,000 ft)) in the Southwest Indian Ridge, from where it continues into the Mozambique Channel and Prince Edward Fracture Zone.[32]

North of 20° south latitude the minimum surface temperature is 22 °C (72 °F), exceeding 28 °C (82 °F) to the east. Southward of 40° south latitude, temperatures drop quickly.[22]

The Bay of Bengal contributes more than half (2,950 km3 or 710 cu mi) of the runoff water to the Indian Ocean. Mainly in summer, this runoff flows into the Arabian Sea but also south across the Equator where it mixes with fresher seawater from the Indonesian Throughflow. This mixed freshwater joins the South Equatorial Current in the southern tropical Indian Ocean.[33]

Sea surface salinity is highest (more than 36 PSU) in the Arabian Sea because evaporation exceeds precipitation there. In the Southeast Arabian Sea salinity drops to less than 34 PSU. It is the lowest (c. 33 PSU) in the Bay of Bengal because of river runoff and precipitation. The Indonesian Throughflow and precipitation results in lower salinity (34 PSU) along the Sumatran west coast. Monsoonal variation results in eastward transportation of saltier water from the Arabian Sea to the Bay of Bengal from June to September and in westerly transport by the East India Coastal Current to the Arabian Sea from January to April.[34] It is found that Arabian Sea warming is in response to the reduction in lower monsoon circulation in recent decades.[35]

An Indian Ocean garbage patch was discovered in 2010 covering at least 5 million square kilometres (1.9 million square miles). Riding the southern Indian Ocean Gyre, this vortex of plastic garbage constantly circulates the ocean from Australia to Africa, down the Mozambique Channel, and back to Australia in a period of six years, except for debris that gets indefinitely stuck in the centre of the gyre.[36]

The garbage patch in the Indian Ocean will, according to a 2012 study, decrease in size after several decades to vanish completely over centuries. Over several millennia, however, the global system of garbage patches will accumulate in the North Pacific.[37]

There are two amphidromes of opposite rotation in the Indian Ocean, probably caused by Rossby wave propagation.[38]

Icebergs drift as far north as 55° south latitude, similar to the Pacific but less than in the Atlantic where icebergs reach up to 45°S. The volume of iceberg loss in the Indian Ocean between 2004 and 2012 was 24 Gt.[39]

Since the 1960s, anthropogenic warming of the global ocean combined with contributions of freshwater from retreating land ice causes a global rise in sea level. Sea level also increases in the Indian Ocean, except in the south tropical Indian Ocean where it decreases, a pattern most likely caused by rising levels of greenhouse gases.[40]

Marine life[edit]

A dolphin off Western Australia and a swarm of surgeonfish near Maldives Islands represents the well-known, exotic fauna of the warmer parts of the Indian Ocean. King Penguins on a beach in the Crozet Archipelago near Antarctica attract fewer tourists.

Among the tropical oceans, the western Indian Ocean hosts one of the largest concentrations of phytoplankton blooms in summer, due to the strong monsoon winds. The monsoonal wind forcing leads to a strong coastal and open ocean upwelling, which introduces nutrients into the upper zones where sufficient light is available for photosynthesis and phytoplankton production. These phytoplankton blooms support the marine ecosystem, as the base of the marine food web, and eventually the larger fish species. The Indian Ocean accounts for the second-largest share of the most economically valuable tuna catch.[41] Its fish are of great and growing importance to the bordering countries for domestic consumption and export. Fishing fleets from Russia, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan also exploit the Indian Ocean, mainly for shrimp and tuna.[3]

Research indicates that increasing ocean temperatures are taking a toll on the marine ecosystem. A study on the phytoplankton changes in the Indian Ocean indicates a decline of up to 20% in the marine plankton in the Indian Ocean, during the past six decades. The tuna catch rates have also declined 50–90% during the past half-century, mostly due to increased industrial fisheries, with the ocean warming adding further stress to the fish species.[42]

Endangered and vulnerable marine mammals and turtles:[43]

| Name | Distribution | Trend |

|---|---|---|

| Endangered | ||

| Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea) |

Southwest Australia | Decreasing |

| Blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) |

Global | Increasing |

| Sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis) |

Global | Increasing |

| Irrawaddy dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris) |

Southeast Asia | Decreasing |

| Indian Ocean humpback dolphin (Sousa plumbea) |

Western Indian Ocean | Decreasing |

| Green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) |

Global | Decreasing |

| Vulnerable | ||

| Dugong (Dugong dugon) |

Equatorial Indian Ocean and Pacific | Decreasing |

| Sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) |

Global | Unknown |

| Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) |

Global | Increasing |

| Australian snubfin dolphin (Orcaella heinsohni) |

Northern Australia, New Guinea | Decreasing |

| Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) |

Southeast Asia | Decreasing |

| Indo-Pacific finless porpoise (Neophocaena phocaenoides) |

Northern Indian Ocean, Southeast Asia | Decreasing |

| Australian humpback dolphin (Sousa sahulensis) |

Northern Australia, New Guinea | Decreasing |

| Leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) |

Global | Decreasing |

| Olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) |

Global | Decreasing |

| Loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) |

Global | Decreasing |

80% of the Indian Ocean is open ocean and includes nine large marine ecosystems: the Agulhas Current, Somali Coastal Current, Red Sea, Arabian Sea, Bay of Bengal, Gulf of Thailand, West Central Australian Shelf, Northwest Australian Shelf, and Southwest Australian Shelf. Coral reefs cover c. 200,000 km2 (77,000 sq mi). The coasts of the Indian Ocean includes beaches and intertidal zones covering 3,000 km2 (1,200 sq mi) and 246 larger estuaries. Upwelling areas are small but important. The hypersaline salterns in India covers between 5,000–10,000 km2 (1,900–3,900 sq mi) and species adapted for this environment, such as Artemia salina and Dunaliella salina, are important to bird life.[44]

Left: Mangroves (here in East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia) are the only tropical to subtropical forests adapted for a coastal environment. From their origin on the coasts of the Indo-Malaysian region, they have reached a global distribution.

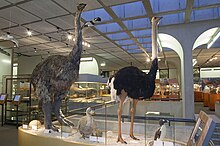

Right: The coelacanth (here a model from Oxford), thought extinct for million years, was rediscovered in the 20th century. The Indian Ocean species is blue whereas the Indonesian species is brown.

Coral reefs, sea grass beds, and mangrove forests are the most productive ecosystems of the Indian Ocean — coastal areas produce 20 tones per square kilometre of fish. These areas, however, are also being urbanised with populations often exceeding several thousand people per square kilometre and fishing techniques become more effective and often destructive beyond sustainable levels while the increase in sea surface temperature spreads coral bleaching.[45]

Mangroves covers 80,984 km2 (31,268 sq mi) in the Indian Ocean region, or almost half of the world’s mangrove habitat, of which 42,500 km2 (16,400 sq mi) is located in Indonesia, or 50% of mangroves in the Indian Ocean. Mangroves originated in the Indian Ocean region and have adapted to a wide range of its habitats but it is also where it suffers its biggest loss of habitat.[46]

In 2016 six new animal species were identified at hydrothermal vents in the Southwest Indian Ridge: a «Hoff» crab, a «giant peltospirid» snail, a whelk-like snail, a limpet, a scaleworm and a polychaete worm.[47]

The West Indian Ocean coelacanth was discovered in the Indian Ocean off South Africa in the 1930s and in the late 1990s another species, the Indonesian coelacanth, was discovered off Sulawesi Island, Indonesia. Most extant coelacanths have been found in the Comoros. Although both species represent an order of lobe-finned fishes known from the Early Devonian (410 mya) and though extinct 66 mya, they are morphologically distinct from their Devonian ancestors. Over millions of years, coelacanths evolved to inhabit different environments — lungs adapted for shallow, brackish waters evolved into gills adapted for deep marine waters.[48]

Biodiversity[edit]

Of Earth’s 36 biodiversity hotspot nine (or 25%) are located on the margins of the Indian Ocean.

- Madagascar and the islands of the western Indian Ocean (Comoros, Réunion, Mauritius, Rodrigues, the Seychelles, and Socotra), includes 13,000 (11,600 endemic) species of plants; 313 (183) birds; reptiles 381 (367); 164 (97) freshwater fishes; 250 (249) amphibians; and 200 (192) mammals.[49]

The origin of this diversity is debated; the break-up of Gondwana can explain vicariance older than 100 mya, but the diversity on the younger, smaller islands must have required a Cenozoic dispersal from the rims of the Indian Ocean to the islands. A «reverse colonisation», from islands to continents, apparently occurred more recently; the chameleons, for example, first diversified on Madagascar and then colonised Africa. Several species on the islands of the Indian Ocean are textbook cases of evolutionary processes; the dung beetles, day geckos, and lemurs are all examples of adaptive radiation.[citation needed]

Many bones (250 bones per square metre) of recently extinct vertebrates have been found in the Mare aux Songes swamp in Mauritius, including bones of the Dodo bird (Raphus cucullatus) and Cylindraspis giant tortoise. An analysis of these remains suggests a process of aridification began in the southwest Indian Ocean began around 4,000 years ago.[50]

- Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany (MPA); 8,100 (1,900 endemic) species of plants; 541 (0) birds; 205 (36) reptiles; 73 (20) freshwater fishes; 73 (11) amphibians; and 197 (3) mammals.[49]

Mammalian megafauna once widespread in the MPA was driven to near extinction in the early 20th century. Some species have been successfully recovered since then — the population of white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum simum) increased from less than 20 individuals in 1895 to more than 17,000 as of 2013. Other species are still dependent of fenced areas and management programs, including black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis minor), African wild dog (Lycaon pictus), cheetah (Acynonix jubatus), elephant (Loxodonta africana), and lion (Panthera leo).[51]

- Coastal forests of eastern Africa; 4,000 (1,750 endemic) species of plants; 636 (12) birds; 250 (54) reptiles; 219 (32) freshwater fishes; 95 (10) amphibians; and 236 (7) mammals.[49]

This biodiversity hotspot (and namesake ecoregion and «Endemic Bird Area») is a patchwork of small forested areas, often with a unique assemblage of species within each, located within 200 km (120 mi) from the coast and covering a total area of c. 6,200 km2 (2,400 sq mi). It also encompasses coastal islands, including Zanzibar and Pemba, and Mafia.[52]

- Horn of Africa; 5,000 (2,750 endemic) species of plants; 704 (25) birds; 284 (93) reptiles; 100 (10) freshwater fishes; 30 (6) amphibians; and 189 (18) mammals.[49]

This area, one of the only two hotspots that are entirely arid, includes the Ethiopian Highlands, the East African Rift valley, the Socotra islands, as well as some small islands in the Red Sea and areas on the southern Arabic Peninsula. Endemic and threatened mammals include the dibatag (Ammodorcas clarkei) and Speke’s gazelle (Gazella spekei); the Somali wild ass (Equus africanus somaliensis) and hamadryas baboon (Papio hamadryas). It also contains many reptiles.[53]

In Somalia, the centre of the 1,500,000 km2 (580,000 sq mi) hotspot, the landscape is dominated by Acacia-Commiphora deciduous bushland, but also includes the Yeheb nut (Cordeauxia edulus) and species discovered more recently such as the Somali cyclamen (Cyclamen somalense), the only cyclamen outside the Mediterranean. Warsangli linnet (Carduelis johannis) is an endemic bird found only in northern Somalia. An unstable political situation and mismanagement has resulted in overgrazing which has produced one of the most degraded hotspots where only c. 5 % of the original habitat remains.[54]

- The Western Ghats–Sri Lanka; 5,916 (3,049 endemic) species of plants; 457 (35) birds; 265 (176) reptiles; 191 (139) freshwater fishes; 204 (156) amphibians; and 143 (27) mammals.[49]

Encompassing the west coast of India and Sri Lanka, until c. 10,000 years ago a landbridge connected Sri Lanka to the Indian Subcontinent, hence this region shares a common community of species.[55]

- Indo-Burma; 13.500 (7,000 endemic) species of plants; 1,277 (73) birds; 518 (204) reptiles; 1,262 (553) freshwater fishes; 328 (193) amphibians; and 401 (100) mammals.[49]

Indo-Burma encompasses a series of mountain ranges, five of Asia’s largest river systems, and a wide range of habitats. The region has a long and complex geological history, and long periods rising sea levels and glaciations have isolated ecosystems and thus promoted a high degree of endemism and speciation. The region includes two centres of endemism: the Annamite Mountains and the northern highlands on the China-Vietnam border.[56]

Several distinct floristic regions, the Indian, Malesian, Sino-Himalayan, and Indochinese regions, meet in a unique way in Indo-Burma and the hotspot contains an estimated 15,000–25,000 species of vascular plants, many of them endemic.[57]

- Sundaland; 25,000 (15,000 endemic) species of plants; 771 (146) birds; 449 (244) reptiles; 950 (350) freshwater fishes; 258 (210) amphibians; and 397 (219) mammals.[49]

Sundaland encompasses 17,000 islands of which Borneo and Sumatra are the largest. Endangered mammals include the Bornean and Sumatran orangutans, the proboscis monkey, and the Javan and Sumatran rhinoceroses.[58]

- Wallacea; 10,000 (1,500 endemic) species of plants; 650 (265) birds; 222 (99) reptiles; 250 (50) freshwater fishes; 49 (33) amphibians; and 244 (144) mammals.[49]

- Southwest Australia; 5,571 (2,948 endemic) species of plants; 285 (10) birds; 177 (27) reptiles; 20 (10) freshwater fishes; 32 (22) amphibians; and 55 (13) mammals.[49]

Stretching from Shark Bay to Israelite Bay and isolated by the arid Nullarbor Plain, the southwestern corner of Australia is a floristic region with a stable climate in which one of the world’s largest floral biodiversity and an 80% endemism has evolved. From June to September it is an explosion of colours and the Wildflower Festival in Perth in September attracts more than half a million visitors.[59]

Geology[edit]

Left: The oldest ocean floor of the Indian Ocean formed c. 150 Ma when the Indian Subcontinent and Madagascar broke-up from Africa. Right: The India–Asia collision c. 40 Ma completed the closure of the Tethys Ocean (grey areas north of India). Geologically, the Indian Ocean is the ocean floor that opened up south of India.

As the youngest of the major oceans,[60] the Indian Ocean has active spreading ridges that are part of the worldwide system of mid-ocean ridges. In the Indian Ocean these spreading ridges meet at the Rodrigues Triple Point with the Central Indian Ridge, including the Carlsberg Ridge, separating the African Plate from the Indian Plate; the Southwest Indian Ridge separating the African Plate from the Antarctic Plate; and the Southeast Indian Ridge separating the Australian Plate from the Antarctic Plate. The Central Indian Ridge is intercepted by the Owen Fracture Zone.[61]

Since the late 1990s, however, it has become clear that this traditional definition of the Indo-Australian Plate cannot be correct; it consists of three plates — the Indian Plate, the Capricorn Plate, and Australian Plate — separated by diffuse boundary zones.[62]

Since 20 Ma the African Plate is being divided by the East African Rift System into the Nubian and Somalia plates.[63]

There are only two trenches in the Indian Ocean: the 6,000 km (3,700 mi)-long Java Trench between Java and the Sunda Trench and the 900 km (560 mi)-long Makran Trench south of Iran and Pakistan.[61]

A series of ridges and seamount chains produced by hotspots pass over the Indian Ocean. The Réunion hotspot (active 70–40 million years ago) connects Réunion and the Mascarene Plateau to the Chagos-Laccadive Ridge and the Deccan Traps in north-western India; the Kerguelen hotspot (100–35 million years ago) connects the Kerguelen Islands and Kerguelen Plateau to the Ninety East Ridge and the Rajmahal Traps in north-eastern India; the Marion hotspot (100–70 million years ago) possibly connects Prince Edward Islands to the Eighty Five East Ridge.[64] These hotspot tracks have been broken by the still active spreading ridges mentioned above.[61]

There are fewer seamounts in the Indian Ocean than in the Atlantic and Pacific. These are typically deeper than 3,000 m (9,800 ft) and located north of 55°S and west of 80°E. Most originated at spreading ridges but some are now located in basins far away from these ridges. The ridges of the Indian Ocean form ranges of seamounts, sometimes very long, including the Carlsberg Ridge, Madagascar Ridge, Central Indian Ridge, Southwest Indian Ridge, Chagos-Laccadive Ridge, 85°E Ridge, 90°E Ridge, Southeast Indian Ridge, Broken Ridge, and East Indiaman Ridge. The Agulhas Plateau and Mascarene Plateau are the two major shallow areas.[32]

The opening of the Indian Ocean began c. 156 Ma when Africa separated from East Gondwana. The Indian Subcontinent began to separate from Australia-Antarctica 135–125 Ma and as the Tethys Ocean north of India began to close 118–84 Ma the Indian Ocean opened behind it.[61]

History[edit]

The Indian Ocean, together with the Mediterranean, has connected people since ancient times, whereas the Atlantic and Pacific have had the roles of barriers or mare incognitum. The written history of the Indian Ocean, however, has been Eurocentric and largely dependent on the availability of written sources from the colonial era. This history is often divided into an ancient period followed by an Islamic period; the subsequent periods are often subdivided into Portuguese, Dutch, and British periods.[65]

A concept of an «Indian Ocean World» (IOW), similar to that of the «Atlantic World», exists but emerged much more recently and is not well established. The IOW is, nevertheless, sometimes referred to as the «first global economy» and was based on the monsoon which linked Asia, China, India, and Mesopotamia. It developed independently from the European global trade in the Mediterranean and Atlantic and remained largely independent from them until European 19th-century colonial dominance.[66]

The diverse history of the Indian Ocean is a unique mix of cultures, ethnic groups, natural resources, and shipping routes. It grew in importance beginning in the 1960s and 1970s and, after the Cold War, it has undergone periods of political instability, most recently with the emergence of India and China as regional powers.[67]

First settlements[edit]

According to the Coastal hypothesis, modern humans spread from Africa along the northern rim of the Indian Ocean.

Pleistocene fossils of Homo erectus and other pre–H. sapiens hominid fossils, similar to H. heidelbergensis in Europe, have been found in India. According to the Toba catastrophe theory, a supereruption c. 74,000 years ago at Lake Toba, Sumatra, covered India with volcanic ashes and wiped out one or more lineages of such archaic humans in India and Southeast Asia.[68]

The Out of Africa theory states that Homo sapiens spread from Africa into mainland Eurasia. The more recent Southern Dispersal or Coastal hypothesis instead advocates that modern humans spread along the coasts of the Arabic Peninsula and southern Asia. This hypothesis is supported by mtDNA research which reveals a rapid dispersal event during the Late Pleistocene (11,000 years ago). This coastal dispersal, however, began in East Africa 75,000 years ago and occurred intermittently from estuary to estuary along the northern perimeter of the Indian Ocean at a rate of 0.7–4.0 km (0.43–2.49 mi) per year. It eventually resulted in modern humans migrating from Sunda over Wallacea to Sahul (Southeast Asia to Australia).[69]

Since then, waves of migration have resettled people and, clearly, the Indian Ocean littoral had been inhabited long before the first civilisations emerged. 5000–6000 years ago six distinct cultural centres had evolved around the Indian Ocean: East Africa, the Middle East, the Indian Subcontinent, South East Asia, the Malay World, and Australia; each interlinked to its neighbours.[70]

Food globalisation began on the Indian Ocean littoral c. 4.000 years ago. Five African crops — sorghum, pearl millet, finger millet, cowpea, and hyacinth bean — somehow found their way to Gujarat in India during the Late Harappan (2000–1700 BCE). Gujarati merchants evolved into the first explorers of the Indian Ocean as they traded African goods such as ivory, tortoise shells, and slaves. Broomcorn millet found its way from Central Asia to Africa, together with chicken and zebu cattle, although the exact timing is disputed. Around 2000 BCE black pepper and sesame, both native to Asia, appear in Egypt, albeit in small quantities. Around the same time the black rat and the house mouse emigrate from Asia to Egypt. Banana reached Africa around 3000 years ago.[71]

At least eleven prehistoric tsunamis have struck the Indian Ocean coast of Indonesia between 7400 and 2900 years ago. Analysing sand beds in caves in the Aceh region, scientists concluded that the intervals between these tsunamis have varied from series of minor tsunamis over a century to dormant periods of more than 2000 years preceding megathrusts in the Sunda Trench. Although the risk for future tsunamis is high, a major megathrust such as the one in 2004 is likely to be followed by a long dormant period.[72]

A group of scientists have argued that two large-scale impact events have occurred in the Indian Ocean: the Burckle Crater in the southern Indian Ocean in 2800 BCE and the Kanmare and Tabban craters in the Gulf of Carpentaria in northern Australia in 536 CE. Evidences for these impacts, the team argue, are micro-ejecta and Chevron dunes in southern Madagascar and in the Australian gulf. Geological evidences suggest the tsunamis caused by these impacts reached 205 m (673 ft) above sea level and 45 km (28 mi) inland. The impact events must have disrupted human settlements and perhaps even contributed to major climate changes.[73]

Antiquity[edit]

The history of the Indian Ocean is marked by maritime trade; cultural and commercial exchange probably date back at least seven thousand years.[74] Human culture spread early on the shores of the Indian Ocean and was always linked to the cultures of the Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf. Before c. 2000 BCE, however, cultures on its shores were only loosely tied to each other; bronze, for example, was developed in Mesopotamia c. 3000 BCE but remained uncommon in Egypt before 1800 BCE.[75]

During this period, independent, short-distance oversea communications along its littoral margins evolved into an all-embracing network. The début of this network was not the achievement of a centralised or advanced civilisation but of local and regional exchange in the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and the Arabian Sea. Sherds of Ubaid (2500–500 BCE) pottery have been found in the western Gulf at Dilmun, present-day Bahrain; traces of exchange between this trading centre and Mesopotamia. The Sumerians traded grain, pottery, and bitumen (used for reed boats) for copper, stone, timber, tin, dates, onions, and pearls.[76]

Coast-bound vessels transported goods between the Indus Valley civilisation (2600–1900 BCE) in the Indian subcontinent (modern-day Pakistan and Northwest India) and the Persian Gulf and Egypt.[74]

The Red Sea, one of the main trade routes in Antiquity, was explored by Egyptians and Phoenicians during the last two millennia BCE. In the 6th century, BCE Greek explorer Scylax of Caryanda made a journey to India, working for the Persian king Darius, and his now-lost account put the Indian Ocean on the maps of Greek geographers. The Greeks began to explore the Indian Ocean following the conquests of Alexander the Great, who ordered a circumnavigation of the Arabian Peninsula in 323 BCE. During the two centuries that followed the reports of the explorers of Ptolemaic Egypt resulted in the best maps of the region until the Portuguese era many centuries later. The main interest in the region for the Ptolemies was not commercial but military; they explored Africa to hunt for war elephants.[77]

The Rub’ al Khali desert isolates the southern parts of the Arabic Peninsula and the Indian Ocean from the Arabic world. This encouraged the development of maritime trade in the region linking the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf to East Africa and India. The monsoon (from mawsim, the Arabic word for season), however, was used by sailors long before being «discovered» by Hippalus in the 1st century. Indian wood have been found in Sumerian cities, there is evidence of Akkad coastal trade in the region, and contacts between India and the Red Sea dates back to 2300 B.C. The archipelagoes of the central Indian Ocean, the Laccadive and Maldive islands, were probably populated during the 2nd century B.C. from the Indian mainland. They appear in written history in the account of merchant Sulaiman al-Tajir in the 9th century but the treacherous reefs of the islands were most likely cursed by the sailors of Aden long before the islands were even settled.[78]

Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, an Alexandrian guide to the world beyond the Red Sea — including Africa and India — from the first century CE, not only gives insights into trade in the region but also shows that Roman and Greek sailors had already gained knowledge about the monsoon winds.[74] The contemporaneous settlement of Madagascar by Austronesian sailors shows that the littoral margins of the Indian Ocean were being both well-populated and regularly traversed at least by this time. Albeit the monsoon must have been common knowledge in the Indian Ocean for centuries.[74]

The Indian Ocean’s relatively calmer waters opened the areas bordering it to trade earlier than the Atlantic or Pacific oceans. The powerful monsoons also meant ships could easily sail west early in the season, then wait a few months and return eastwards. This allowed ancient Indonesian peoples to cross the Indian Ocean to settle in Madagascar around 1 CE.[79]

In the 2nd or 1st century BCE, Eudoxus of Cyzicus was the first Greek to cross the Indian Ocean. The probably fictitious sailor Hippalus is said to have learnt the direct route from Arabia to India around this time.[80] During the 1st and 2nd centuries AD intensive trade relations developed between Roman Egypt and the Tamil kingdoms of the Cheras, Cholas and Pandyas in Southern India. Like the Indonesian people above, the western sailors used the monsoon to cross the ocean. The unknown author of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea describes this route, as well as the commodities that were traded along various commercial ports on the coasts of the Horn of Africa and India circa 1 CE. Among these trading settlements were Mosylon and Opone on the Red Sea littoral.[8]

Age of Discovery[edit]

Preferred sailing routes across the Indian Ocean

Unlike the Pacific Ocean where the civilization of the Polynesians reached most of the far-flung islands and atolls and populated them, almost all the islands, archipelagos and atolls of the Indian Ocean were uninhabited until colonial times. Although there were numerous ancient civilizations in the coastal states of Asia and parts of Africa, the Maldives were the only island group in the Central Indian Ocean region where an ancient civilization flourished.[81] Maldivians, on their annual trade trip, took their oceangoing trade ships to Sri Lanka rather than mainland India, which is much closer, because their ships were dependent of the Indian Monsoon Current.[82]

Arabic missionaries and merchants began to spread Islam along the western shores of the Indian Ocean from the 8th century, if not earlier. A Swahili stone mosque dating to the 8th–15th centuries has been found in Shanga, Kenya. Trade across the Indian Ocean gradually introduced Arabic script and rice as a staple in Eastern Africa.[83]

Muslim merchants traded an estimated 1000 African slaves annually between 800 and 1700, a number that grew to c. 4000 during the 18th century, and 3700 during the period 1800–1870. Slave trade also occurred in the eastern Indian Ocean before the Dutch settled there around 1600 but the volume of this trade is unknown.[84]

From 1405 to 1433 admiral Zheng He said to have led large fleets of the Ming Dynasty on several treasure voyages through the Indian Ocean, ultimately reaching the coastal countries of East Africa.[85]

The Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope during his first voyage in 1497 and became the first European to sail to India. The Swahili people he encountered along the African east coast lived in a series of cities and had established trade routes to India and to China. Among them, the Portuguese kidnapped most of their pilots in coastal raids and onboard ships. A few of the pilots, however, were gifts by local Swahili rulers, including the sailor from Gujarat, a gift by a Malindi ruler in Kenya, who helped the Portuguese to reach India. In expeditions after 1500, the Portuguese attacked and colonised cities along the African coast.[86]

European slave trade in the Indian Ocean began when Portugal established Estado da Índia in the early 16th century. From then until the 1830s, c. 200 slaves were exported from Mozambique annually and similar figures has been estimated for slaves brought from Asia to the Philippines during the Iberian Union (1580–1640).[84]

The Ottoman Empire began its expansion into the Indian Ocean in 1517 with the conquest of Egypt under Sultan Selim I. Although the Ottomans shared the same religion as the trading communities in the Indian Ocean the region was unexplored by them. Maps that included the Indian Ocean had been produced by Muslim geographers centuries before the Ottoman conquests; Muslim scholars, such as Ibn Battuta in the 14th Century, had visited most parts of the known world; contemporarily with Vasco da Gama, Arab navigator Ahmad ibn Mājid had compiled a guide to navigation in the Indian Ocean; the Ottomans, nevertheless, began their own parallel era of discovery which rivalled the European expansion.[87]

The establishment of the Dutch East India Company in the early 17th century lead to a quick increase in the volume of the slave trade in the region; there were perhaps up to 500,000 slaves in various Dutch colonies during the 17th and 18th centuries in the Indian Ocean. For example, some 4000 African slaves were used to build the Colombo fortress in Dutch Ceylon. Bali and neighbouring islands supplied regional networks with c. 100,000–150,000 slaves 1620–1830. Indian and Chinese slave traders supplied Dutch Indonesia with perhaps 250,000 slaves during the 17th and 18th centuries.[84]

The East India Company (EIC) was established during the same period and in 1622 one of its ships carried slaves from the Coromandel Coast to Dutch East Indies. The EIC mostly traded in African slaves but also some Asian slaves purchased from Indian, Indonesian and Chinese slave traders. The French established colonies on the islands of Réunion and Mauritius in 1721; by 1735 some 7,200 slaves populated the Mascarene Islands, a number which had reached 133,000 in 1807. The British captured the islands in 1810, however, and because the British had prohibited the slave trade in 1807 a system of clandestine slave trade developed to bring slaves to French planters on the islands; in all 336,000–388,000 slaves were exported to the Mascarene Islands from 1670 until 1848.[84]

In all, European traders exported 567,900–733,200 slaves within the Indian Ocean between 1500 and 1850 and almost that same amount were exported from the Indian Ocean to the Americas during the same period. Slave trade in the Indian Ocean was, nevertheless, very limited compared to c. 12,000,000 slaves exported across the Atlantic.[84]

Modern era[edit]

Malé’s population has increased from 20,000 people in 1987 to more than 220,000 people in 2020.

Scientifically, the Indian Ocean remained poorly explored before the International Indian Ocean Expedition in the early 1960s. However, the Challenger expedition 1872–1876 only reported from south of the polar front. The Valdivia expedition 1898–1899 made deep samples in the Indian Ocean. In the 1930s, the John Murray Expedition mainly studied shallow-water habitats. The Swedish Deep Sea Expedition 1947–1948 also sampled the Indian Ocean on its global tour and the Danish Galathea sampled deep-water fauna from Sri Lanka to South Africa on its second expedition 1950–1952. The Soviet research vessel Vityaz also did research in the Indian Ocean.[1]

The Suez Canal opened in 1869 when the Industrial Revolution dramatically changed global shipping – the sailing ship declined in importance as did the importance of European trade in favour of trade in East Asia and Australia.[88]

The construction of the canal introduced many non-indigenous species into the Mediterranean. For example, the goldband goatfish (Upeneus moluccensis) has replaced the red mullet (Mullus barbatus); since the 1980s huge swarms of scyphozoan jellyfish (Rhopilema nomadica) have affected tourism and fisheries along the Levantian coast and clogged power and desalination plants. Plans announced in 2014 to build a new, much larger Suez Canal parallel to the 19th-century canal will most likely boost the economy in the region but also cause ecological damage in a much wider area.[89]

Throughout the colonial era, islands such as Mauritius were important shipping nodes for the Dutch, French, and British. Mauritius, an inhabited island, became populated by slaves from Africa and indenture labour from India. The end of World War II marked the end of the colonial era. The British left Mauritius in 1974 and with 70% of the population of Indian descent, Mauritius became a close ally of India. In the 1980s, during the Cold War, the South African regime acted to destabilise several island nations in the Indian Ocean, including the Seychelles, Comoros, and Madagascar. India intervened in Mauritius to prevent a coup d’état, backed up by the United States who feared the Soviet Union could gain access to Port Louis and threaten the U.S. base on Diego Garcia.[90]

Iranrud is an unrealised plan by Iran and the Soviet Union to build a canal between the Caspian Sea and the Persian Gulf.

Testimonies from the colonial era are stories of African slaves, Indian indentured labourers, and white settlers. But, while there was a clear racial line between free men and slaves in the Atlantic World, this delineation is less distinct in the Indian Ocean — there were Indian slaves and settlers as well as black indentured labourers. There were also a string of prison camps across the Indian Ocean, such as Cellular Jail in the Andamans, in which prisoners, exiles, POWs, forced labourers, merchants, and people of different faiths were forcefully united. On the islands of the Indian Ocean, therefore, a trend of creolisation emerged.[91]

On 26 December 2004 fourteen countries around the Indian Ocean were hit by a wave of tsunamis caused by the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake. The waves radiated across the ocean at speeds exceeding 500 km/h (310 mph), reached up to 20 m (66 ft) in height, and resulted in an estimated 236,000 deaths.[92]

In the late 2000s, the ocean evolved into a hub of pirate activity. By 2013, attacks off the Horn region’s coast had steadily declined due to active private security and international navy patrols, especially by the Indian Navy.[93]

Malaysian Airlines Flight 370, a Boeing 777 airliner with 239 persons on board, disappeared on 8 March 2014 and is alleged to have crashed into the southern Indian Ocean about 2,500 km (1,600 mi) from the coast of southwest Western Australia. Despite an extensive search, the whereabouts of the remains of the aircraft is unknown.[94]

The Sentinelese people of North Sentinel Island, which lies near South Andaman Island in the Bay of Bengal, have been called by experts the most isolated people in the world.[95]

The sovereignty of the Chagos Archipelago in the Indian Ocean is disputed between the United Kingdom and Mauritius.[96] In February 2019, the International Court of Justice in The Hague issued an advisory opinion stating that the UK must transfer the Chagos Archipelago to Mauritius.[97]

On 26 February 2022, an AB Aviation Flight 1103 Cessna 208 crashed into Indian Ocean, killing all 14 on board.[98]

Trade[edit]

The sea lanes in the Indian Ocean are considered among the most strategically important in the world with more than 80 percent of the world’s seaborne trade in oil transits through the Indian Ocean and its vital chokepoints, with 40 percent passing through the Strait of Hormuz, 35 percent through the Strait of Malacca and 8 percent through the Bab el-Mandab Strait.[99]

The Indian Ocean provides major sea routes connecting the Middle East, Africa, and East Asia with Europe and the Americas. It carries a particularly heavy traffic of petroleum and petroleum products from the oil fields of the Persian Gulf and Indonesia. Large reserves of hydrocarbons are being tapped in the offshore areas of Saudi Arabia, Iran, India, and Western Australia. An estimated 40% of the world’s offshore oil production comes from the Indian Ocean.[3] Beach sands rich in heavy minerals, and offshore placer deposits are actively exploited by bordering countries, particularly India, Pakistan, South Africa, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand.

Mombasa Port on Kenya’s Indian Ocean coast

In particular, the maritime part of the Silk Road leads through the Indian Ocean on which a large part of the global container trade is carried out. The Silk Road runs with its connections from the Chinese coast and its large container ports to the south via Hanoi to Jakarta, Singapore and Kuala Lumpur through the Strait of Malacca via the Sri Lankan Colombo opposite the southern tip of India via Malé, the capital of the Maldives, to the East African Mombasa, from there to Djibouti, then through the Red Sea over the Suez Canal into the Mediterranean, there via Haifa, Istanbul and Athens to the Upper Adriatic to the northern Italian junction of Trieste with its international free port and its rail connections to Central and Eastern Europe.[100][101][102][103]

The Silk Road has become internationally important again on the one hand through European integration, the end of the Cold War and free world trade and on the other hand through Chinese initiatives. Chinese companies have made investments in several Indian Ocean ports, including Gwadar, Hambantota, Colombo and Sonadia. This has sparked a debate about the strategic implications of these investments.[104] There are also Chinese investments and related efforts to intensify trade in East Africa and in European ports such as Piraeus and Trieste.[105][106][107]

See also[edit]

- Antarctica

- Erythraean Sea

- Indo-Pacific

- Indian Ocean in World War II

- Indian Ocean literature

- Indian Ocean Naval Symposium

- Indian Ocean Research Group

- Indian Ocean slave trade

- List of islands in the Indian Ocean

- List of ports and harbours of the Indian Ocean

- List of sovereign states and dependent territories in the Indian Ocean

- Indian Ocean Rim Association

- Maritime Silk Road

- Southern Ocean

- Territorial claims in Antarctica

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c Demopoulos, Smith & Tyler 2003, Introduction, p. 219

- ^ a b Keesing & Irvine 2005, Introduction, p. 11–12; Table 1, p.12

- ^ a b c CIA World Fact Book 2018

- ^ a b Eakins & Sharman 2010

- ^ «‘Indian Ocean’ — Merriam-Webster Dictionary Online». Retrieved 7 July 2012.

ocean E of Africa, S of Asia, W of Australia, & N of Antarctica area ab 73,427,795 square kilometres (28,350,630 sq mi)

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «Indian Ocean». Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ Hui 2010, Abstract

- ^ a b Anonymous (1912). Periplus of the Erythraean Sea . Translated by Schoff, Wilfred Harvey.

- ^ «Indian Ocean». The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ IHO 1953

- ^ a b c IHO 2002

- ^ Prange 2008, Fluid Borders: Encompassing the Ocean, pp. 1382–1385

- ^ «Continental Shelf». National Geographic Society. 4 March 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ^ Harris et al. 2014, Table 2, p. 11

- ^ Harris et al. 2014, Table 3, p. 11

- ^ a b N. Damodara; V. Vijaya Rao; Kalachand Sain; A.S.S.S.R.S. Prasad; A.S.N. Murty (3 January 2017). Basement configuration of the West Bengal sedimentary basin, India as revealed by seismic refraction tomography: its tectonic implications. Geophysical Journal International. Vol. 208. Oxford University Press. pp. 1490–1507. doi:10.1093/gji/ggw461. ISSN 1365-246X. OCLC 6930280725.

- ^ Vörösmarty et al. 2000, Drainage basin area of each ocean, pp. 609–616; Table 5, p 614; Reconciling Continental and Oceanic Perspectives, pp. 616–617

- ^ «The World’s Biggest Oceans and Seas». Live Science. 4 June 2010.

- ^ «World Map / World Atlas / Atlas of the World Including Geography Facts and Flags — WorldAtlas.com».

- ^ «List of seas».

- ^ Schott, Xie & McCreary 2009, Introduction, pp. 1–2

- ^ a b «U.S. Navy Oceanographer». Archived from the original on 2 August 2001. Retrieved 4 August 2001.

- ^ Dutt et al. 2015, Abstract; Introduction, pp. 5526–5527

- ^ «Which Ocean is the Warmest?». Worldatlas. 17 September 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ a b Roxy et al. 2014, Abstract

- ^ Carton, Chepurin & Cao 2000, p. 321

- ^ Lelieveld et al. 2001, Abstract

- ^ Ewing et al. 1969, Abstract

- ^ Shankar, Vinayachandran & Unnikrishnan 2002, Introduction, pp. 64–66

- ^ Harris et al. 2014, Geomorphic characteristics of ocean regions, pp. 17–18

- ^ Wilson et al. 2012, Regional setting and hydrography, pp. 4–5; Fig. 1, p. 22

- ^ a b Rogers 2012, The Southern Indian Ocean and its Seamounts, pp. 5–6

- ^ Sengupta, Bharath Raj & Shenoi 2006, Abstract; p. 4

- ^ Felton 2014, Results, pp. 47–48; Average for Table 3.1, p. 55

- ^ Pratik, Kad; Parekh, Anant; Karmakar, Ananya; Chowdary, Jasti S.; Gnanaseelan, C. (1 April 2019). «Recent changes in the summer monsoon circulation and their impact on dynamics and thermodynamics of the Arabian Sea». Theoretical and Applied Climatology. 136 (1): 321–331. Bibcode:2019ThApC.136..321P. doi:10.1007/s00704-018-2493-6. ISSN 1434-4483. S2CID 126114281.

- ^ Parker, Laura (4 April 2014). «Plane Search Shows World’s Oceans Are Full of Trash». National Geographic News. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Van Sebille, England & Froyland 2012

- ^ Chen & Quartly 2005, pp. 5–6

- ^ Matsumoto et al. 2014, pp. 3454–3455

- ^ Han et al. 2010, Abstract

- ^ FAO 2016

- ^ Roxy 2016, Discussion, pp. 831–832

- ^ «IUCN Red List». IUCN. Retrieved 8 July 2019.. Search parametres: Mammalia/Testudines, EN/VU, Indian Ocean Antarctic/Eastern/Western

- ^ Wafar et al. 2011, Marine ecosystems of the IO

- ^ Lindén & Souter 2005, Foreword, pp. 5–6

- ^ Kathiresan & Rajendran 2005, Introduction; Mangrove habitat, pp. 104–105

- ^ «New marine life found in deep sea vents». BBC News. 15 December 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ Cupello et al. 2019, Introduction, p. 29

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mittermeier et al. 2011, Table 1.2, pp. 12–13

- ^ Rijsdijk et al. 2009, Abstract

- ^ Di Minin et al. 2013, «The Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany biodiversity hotspot is internationally recognized…»»

- ^ WWF-EARPO 2006, The unique coastal forests of eastern Africa, p. 3

- ^ «Horn of Africa». CEPF. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ Ullah & Gadain 2016, Importance of biodiversity, pp. 17–19; Biodiversity of Somalia, pp.25–26

- ^ Bossuyt et al. 2004

- ^ CEPF 2012: Indo-Burma, Geography, Climate, and History, p. 30

- ^ CEPF 2012: Indo-Burma, Species Diversity and Endemism, p. 36

- ^ «Sundaland: About this hotspot». CEPF. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ^ Ryan 2009

- ^ Stow 2006

- ^ a b c d Chatterjee, Goswami & Scotese 2013, Tectonic setting of the Indian Ocean, p. 246

- ^ Royer & Gordon 1997, Abstract

- ^ Bird 2003, Somalia Plate (SO), pp. 39–40

- ^ Müller, Royer & Lawver 1993, Fig. 1, p. 275

- ^ Parthasarathi & Riello 2014, Time and the Indian Ocean, pp. 2–3

- ^ Campbell 2017, The Concept of the Indian Ocean World (IOW), pp. 25–26

- ^ Bouchard & Crumplin 2010, Abstract

- ^ Patnaik & Chauhan 2009, Abstract

- ^ Bulbeck 2007, p. 315

- ^ McPherson 1984, History and Patterns, pp. 5–6

- ^ Boivin et al. 2014, The Earliest Evidence, pp. 4–7

- ^ Rubin et al. 2017, Abstract

- ^ Gusiakov et al. 2009, Abstract

- ^ a b c d Alpers 2013, Chapter 1. Imagining the Indian Ocean, pp. 1–2

- ^ Beaujard & Fee 2005, p. 417

- ^ Alpers 2013, Chapter 2. The Ancient Indian Ocean, pp. 19–22

- ^ Burstein 1996, pp. 799–801

- ^ Forbes 1981, Southern Arabia and the Central Indian Ocean: Pre- Islamic Contacts, pp. 62–66

- ^ Fitzpatrick & Callaghan 2009, The colonisation of Madagascar, pp. 47–48

- ^ El-Abbadi 2000

- ^ Cabrero 2004, p. 32

- ^ Romero-Frias 2016, Abstract; p. 3

- ^ LaViolette 2008, Conversion to Islam and Islamic Practice, pp. 39–40

- ^ a b c d e Allen 2017, Slave Trading in the Indian Ocean: An Overview, pp. 295–299

- ^ Dreyer 2007, p. 1

- ^ Felber Seligman 2006, The East African Coast, pp. 90–95

- ^ Casale 2003

- ^ Fletcher 1958, Abstract

- ^ Galil et al. 2015, pp. 973–974

- ^ Brewster 2014b, Excerpt

- ^ Hofmeyr 2012, Crosscutting Diasporas, pp. 587–588

- ^ Telford & Cosgrave 2007, Immediate effects of the disaster, pp. 33–35

- ^ Arnsdorf 2013

- ^ MacLeod, Winter & Gray 2014

- ^ Nuwer, Rachel (4 August 2014). «Anthropology: The sad truth about uncontacted tribes». BBC.

- ^ «Chagos Islands dispute: UK ‘threatened’ Mauritius». BBC News. 27 August 2018.

- ^ «Foreign Office quietly rejects International Court ruling to hand back Chagos Islands». inews.co.uk. 18 June 2020.

- ^ «Database: 2022». ASN. Aviation Safety Network. 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ DeSilva-Ranasinghe, Sergei (2 March 2011). «Why the Indian Ocean Matters». The Diplomat.

- ^ Bernhard Simon: Can The New Silk Road Compete With The Maritime Silk Road? in The Maritime Executive, 1 January 2020.

- ^ Marcus Hernig: Die Renaissance der Seidenstraße (2018), pp 112.

- ^ Wolf D. Hartmann, Wolfgang Maennig, Run Wang: Chinas neue Seidenstraße. (2017), pp 59.

- ^ Matteo Bressan: Opportunities and challenges for BRI in Europe in Global Time, 2 April 2019.

- ^ Brewster 2014a

- ^ Harry G. Broadman «Afrika´s Silk Road» (2007), pp 59.

- ^ Andreas Eckert: Mit Mao nach Daressalam, In: Die Zeit 28. March 2019, p 17.

- ^ Guido Santevecchi: Di Maio e la Via della Seta: «Faremo i conti nel 2020», siglato accordo su Trieste in Corriere della Sera, 5 November 2019.

Sources[edit]

- Allen, R. B. (2017). «Ending the history of silence: reconstructing European slave trading in the Indian Ocean» (PDF). Tempo. 23 (2): 294–313. doi:10.1590/tem-1980-542x2017v230206. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- Alpers, E.A. (2013). The Indian Ocean in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533787-7.

- Anirudh Deshpande (June 2015). «Review of Alpers, Edward A. The Indian Ocean in World History«. H-Net Reviews.

- Arnsdorf, Isaac (22 July 2013). «West Africa Pirates Seen Threatening Oil and Shipping». Bloomberg. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- Beaujard, P.; Fee, S. (2005). «The Indian Ocean in Eurasian and African world-systems before the sixteenth century». Journal of World History. 16 (4): 411–465. doi:10.1353/jwh.2006.0014. JSTOR 20079346. S2CID 145387071. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- Bird, P. (2003). «An updated digital model of plate boundaries». Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 4 (3): 1027. Bibcode:2003GGG…..4.1027B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.695.1640. doi:10.1029/2001GC000252. S2CID 9127133.

- Boivin, N.; Crowther, A.; Prendergast, M.; Fuller, D. Q. (2014). «Indian Ocean food globalisation and Africa» (PDF). African Archaeological Review. 31 (4): 547–581. doi:10.1007/s10437-014-9173-4. S2CID 59384628. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- Bossuyt, F.; Meegaskumbura, M.; Beenaerts, N.; Gower, D. J.; Pethiyagoda, R.; Roelants, K.; Mannaert, A.; Wilkinson, M.; Bahir, M. M.; Manamendra-Arachchi, K.; Ng; Schneider, C. J.; Oommen, O. V.; Milinkovitch, M. C. (2004). «Local endemism within the Western Ghats-Sri Lanka biodiversity hotspot» (PDF). Science. 306 (5695): 479–481. Bibcode:2004Sci…306..479B. doi:10.1126/science.1100167. PMID 15486298. S2CID 41762434. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- Bouchard, C.; Crumplin, W. (2010). «Neglected no longer: the Indian Ocean at the forefront of world geopolitics and global geostrategy». Journal of the Indian Ocean Region. 6 (1): 26–51. doi:10.1080/19480881.2010.489668. S2CID 154426445.

- Brewster, D. (2014a). «Beyond the String of Pearls: Is there really a Security Dilemma in the Indian Ocean?». Journal of the Indian Ocean Region. 10 (2): 133–149. doi:10.1080/19480881.2014.922350. hdl:1885/13060. S2CID 153404767.

- Brewster, D. (2014b). India’s Ocean: The story of India’s bid for regional leadership. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315815244. ISBN 978-1-315-81524-4.

- Bulbeck, D. (2007). «Where river meets sea: a parsimonious model for Homo sapiens colonization of the Indian Ocean rim and Sahul». Current Anthropology. 48 (2): 315–321. doi:10.1086/512988. S2CID 84420169.

- Burstein, S. M. (1996). «Ivory and Ptolemaic exploration of the Red Sea. The missing factor» (PDF). Topoi. 6 (2): 799–807. doi:10.3406/topoi.1996.1696. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- Cabrero, Ferran (2004). «Cultures del món: El desafiament de la diversitat» (PDF) (in Catalan). UNESCO. pp. 32–38 (Els maldivians: Mariners llegedaris). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- Campbell, G. (2017). «Africa, the Indian Ocean World, and the ‘Early Modern’: Historiographical Conventions and Problems». The Journal of Indian Ocean World Studies. 1 (1): 24–37. doi:10.26443/jiows.v1i1.25.

- Carton, J. A.; Chepurin, G.; Cao, X. (2000). «A simple ocean data assimilation analysis of the global upper ocean 1950–95. Part II: Results» (PDF). Journal of Physical Oceanography. 30 (2): 311–326. Bibcode:2000JPO….30..311C. doi:10.1175/1520-0485(2000)030<0311:ASODAA>2.0.CO;2.

- Casale, G. (2003). The Ottoman ‘Discovery’ of the Indian Ocean in the Sixteenth Century: The Age of Exploration from an Islamic Perspective. Seascape: Maritime Histories, Littoral Cultures, and Transoceanic Exchanges. Washington D.C.: Library of Congress. pp. 87–104. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- Ecosystem Profile: Indo-Burma Biodiversity Hotspot, 2011 Update (PDF) (Report). CEPF. 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Chatterjee, S.; Goswami, A.; Scotese, C. R. (2013). «The longest voyage: tectonic, magmatic, and paleoclimatic evolution of the Indian plate during its northward flight from Gondwana to Asia». Gondwana Research. 23 (1): 238–267. Bibcode:2013GondR..23..238C. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2012.07.001.

- Chen, G.; Quartly, G. D. (2005). «Annual amphidromes: a common feature in the ocean?» (PDF). IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters. 2 (4): 423–427. Bibcode:2005IGRSL…2..423C. doi:10.1109/LGRS.2005.854205. S2CID 34522950. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- «Oceans: Indian Ocean». CIA – The World Factbook. 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- Cupello, C.; Clément, G.; Meunier, F. J.; Herbin, M.; Yabumoto, Y.; Brito, P. M. (2019). «The long-time adaptation of coelacanths to moderate deep water: reviewing the evidences» (PDF). Bulletin of Kitakyushu Museum of Natural History and Human History Series A (Natural History). 17: 29–35. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- Demopoulos, A. W.; Smith, C. R.; Tyler, P. A. (2003). «The deep Indian Ocean floor». In Tyler, P. A. (ed.). Ecosystems of the world. Vol. 28. Ecosystems of the deep oceans. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. pp. 219–237. ISBN 978-0-444-82619-0. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- Di Minin, E.; Hunter, L. T. B.; Balme, G. A.; Smith, R. J.; Goodman, P. S.; Slotow, R (2013). «Creating Larger and Better Connected Protected Areas Enhances the Persistence of Big Game Species in the Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany Biodiversity Hotspot». PLOS ONE. 8 (8): e71788. Bibcode:2013PLoSO…871788D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0071788. PMC 3743761. PMID 23977144.

- Dreyer, E.L. (2007). Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433. New York: Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-0-321-08443-9. OCLC 64592164.

- Dutt, S.; Gupta, A. K.; Clemens, S. C.; Cheng, H.; Singh, R. K.; Kathayat, G.; Edwards, R. L. (2015). «Abrupt changes in Indian summer monsoon strength during 33,800 to 5500 years BP». Geophysical Research Letters. 42 (13): 5526–5532. Bibcode:2015GeoRL..42.5526D. doi:10.1002/2015GL064015.

- Eakins, B.W.; Sharman, G.F. (2010). «Volumes of the World’s Oceans from ETOPO1». Boulder, CO: NOAA National Geophysical Data Center. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- El-Abbadi, M. (2000). «The greatest emporium in the inhabited world». Coastal management sourcebooks 2. Paris: UNESCO. Archived from the original on 31 January 2012.

- Ewing, M.; Eittreim, S.; Truchan, M.; Ewing, J. I. (1969). «Sediment distribution in the Indian Ocean». Deep Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts. 16 (3): 231–248. Bibcode:1969DSRA…16..231E. doi:10.1016/0011-7471(69)90016-3.

- Felber Seligman, A. (2006). Ambassadors, Explorers and Allies: A Study of the African-European Relationships, 1400-1600 (PDF) (Thesis). University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- Felton, C. S. (2014). A study on atmospheric and oceanic processes in the north Indian Ocean (PDF) (Thesis). University of South Carolina. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- Fitzpatrick, S.; Callaghan, R. (2009). «Seafaring simulations and the origin of prehistoric settlers to Madagascar» (PDF). In Clark, G.R.; O’Connor, S.; Leach, B.F. (eds.). Islands of Inquiry: Colonisation, Seafaring and the Archaeology of Maritime Landscapes. ANU E Press. pp. 47–58. ISBN 978-1-921313-90-5. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- Fletcher, M. E. (1958). «The Suez Canal and world shipping, 1869–1914». The Journal of Economic History. 18 (4): 556–573. doi:10.1017/S0022050700107740. S2CID 153427820.

- «Tuna fisheries and utilization». Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- Forbes, A. (1981). «Southern Arabia and the Islamicisation of the Central Indian Ocean Archipelagoes» (PDF). Archipel. 21 (21): 55–92. doi:10.3406/arch.1981.1638. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Galil, B. S.; Boero, F.; Campbell, M. L.; Carlton, J. T.; Cook, E.; Fraschetti, S.; Gollasch, S.; Hewitt, C. L.; Jelmert, A.; Macpherson, E.; Marchini, A.; McKenzie, C.; Minchin, D.; Occhipinti-Ambrogi, A.; Ojaveer, H.; Olenin, S.; Piraino, S.; Ruiz, G. M. (2015). «‘Double trouble’: the expansion of the Suez Canal and marine bioinvasions in the Mediterranean Sea». Biological Invasions. 17 (4): 973–976. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.871.4133. doi:10.1007/s10530-014-0778-y. S2CID 10633560.

- Gusiakov, V.; Abbott, D. H.; Bryant, E. A.; Masse, W. B.; Breger, D. (2009). «Mega tsunami of the world oceans: chevron dune formation, micro-ejecta, and rapid climate change as the evidence of recent oceanic bolide impacts». Geophysical Hazards. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 197–227. doi:10.7916/D84J0DWD.

- Han, W.; Meehl, G. A.; Rajagopalan, B.; Fasullo, J. T.; Hu, A.; Lin, J.; Large, W. G.; Wang, J.-W.; Quan, X.-W.; Trenary, L. L.; Wallcraft, A.; Shinoda, T.; Yeager, S. (2010). «Patterns of Indian Ocean sea-level change in a warming climate» (PDF). Nature Geoscience. 3 (8): 546–550. Bibcode:2010NatGe…3..546H. doi:10.1038/NGEO901. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- Harris, P. T.; Macmillan-Lawler, M.; Rupp, J.; Baker, E. K. (2014). «Geomorphology of the oceans». Marine Geology. 352: 4–24. Bibcode:2014MGeol.352….4H. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2014.01.011. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- Hofmeyr, I. (2012). «The complicating sea: the Indian Ocean as method» (PDF). Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East. 32 (3): 584–590. doi:10.1215/1089201X-1891579. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- Hui, C. H. (2010). «Huangming zuxun and Zheng He’s Voyages to the Western Oceans». Journal of Chinese Studies. 51: 67–85. hdl:10722/138150.

- «Limits of Oceans and Seas» (PDF). Nature. International Hydrographic Organization. 172 (4376): 484. 1953. Bibcode:1953Natur.172R.484.. doi:10.1038/172484b0. S2CID 36029611. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- «The Indian Ocean and its sub-divisions». International Hydrographic Organization, Special Publication N°23. 2002. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- Kathiresan, K.; Rajendran, N. (2005). «Mangrove ecosystems of the Indian Ocean region» (PDF). Indian Journal of Marine Sciences. 34 (1): 104–113. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- Keesing, J.; Irvine, T. (2005). «Coastal biodiversity in the Indian Ocean: The known, the unknown» (PDF). Indian Journal of Marine Sciences. 34 (1): 11–26. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- LaViolette, A. (2008). «Swahili cosmopolitanism in Africa and the Indian Ocean world, AD 600–1500». Archaeologies. 4 (1): 24–49. doi:10.1007/s11759-008-9064-x. S2CID 128591857. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- MacLeod, Calum; Winter, Michael; Gray, Allison (8 March 2014). «Beijing-bound flight from Malaysia missing». USA Today. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Lelieveld, J. O.; Crutzen, P. J.; Ramanathan, V.; Andreae, M. O.; Brenninkmeijer, C. A. M.; Campos, T.; Cass, G. R.; Dickerson, R. R.; Fischer, H.; de Gouw, J. A.; Hansel, A.; Jefferson, A.; Kley, D.; de Laat, A. T. J.; Lal, S.; Lawrence, M. G.; Lobert, J. M.; Mayol-Bracero, O.; Mitra, A. P.; Novakov, T.; Oltmans, S. J.; Prather, K. A.; Reiner, T.; Rodhe, H.; Scheeren, H. A.; Sikka, D.; Williams, J. (2001). «The Indian Ocean experiment: widespread air pollution from South and Southeast Asia» (PDF). Science. 291 (5506): 1031–1036. Bibcode:2001Sci…291.1031L. doi:10.1126/science.1057103. PMID 11161214. S2CID 2141541. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- Matsumoto, H.; Bohnenstiehl, D. R.; Tournadre, J.; Dziak, R. P.; Haxel, J. H.; Lau, T. K.; Fowler, M.; Salo, S. A. (2014). «Antarctic icebergs: A significant natural ocean sound source in the Southern Hemisphere» (PDF). Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 15 (8): 3448–3458. Bibcode:2014GGG….15.3448M. doi:10.1002/2014GC005454.

- McPherson, K. (1984). «Cultural Exchange in the Indian Ocean Region» (PDF). Westerly. 29 (4): 5–16. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- Mittermeier, R. A.; Turner, W. R.; Larsen, F. W.; Brooks, T. M.; Gascon, C. (2011). «Global biodiversity conservation: the critical role of hotspots». Biodiversity hotspots. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 3–22. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-20992-5_1. ISBN 978-3-642-20991-8. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- Müller, R. D.; Royer, J. Y.; Lawver, L. A. (1993). «Revised plate motions relative to the hotspots from combined Atlantic and Indian Ocean hotspot tracks» (PDF). Geology. 21 (3): 275–278. Bibcode:1993Geo….21..275D. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1993)021<0275:rpmrtt>2.3.co;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- Parthasarathi, P.; Riello, G. (2014). «The Indian Ocean in the long eighteenth century» (PDF). Eighteenth-Century Studies. 48 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1353/ecs.2014.0038. S2CID 19098934. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Patnaik, R.; Chauhan, P. (2009). «India at the cross-roads of human evolution» (PDF). Journal of Biosciences. 34 (5): 729. doi:10.1007/s12038-009-0056-9. PMID 20009268. S2CID 27338615. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- Prange, S. R. (2008). «Scholars and the sea: a historiography of the Indian Ocean». History Compass. 6 (5): 1382–1393. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2008.00538.x. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- Rijsdijk, K. F.; Hume, J. P.; Bunnik, F.; Florens, F. V.; Baider, C.; Shapiro, B.; van der Plicht, J.; Janoo, A.; Griffiths, O.; van den Hoek Ostende, L. W.; Cremer, H.; Vernimmen, T.; De Louw, P. G. B.; Bholah, A.; Saumtally, S.; Porch, N.; Haile, J.; Buckley, M.; Collins, M.; Gittenberger, E. (2009). «Mid-Holocene vertebrate bone Concentration-Lagerstätte on oceanic island Mauritius provides a window into the ecosystem of the dodo (Raphus cucullatus)» (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. 28 (1–2): 14–24. Bibcode:2009QSRv…28…14R. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2008.09.018. hdl:11370/bf8f6218-1f85-4100-8a90-02e5e70a89b6. S2CID 17113275.

- Rogers, A. (2012). Volume 1: Overview of seamount ecosystems and biodiversity (PDF). An ecosystem approach to management of seamounts in the Southern Indian Ocean. IUCN. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- Romero-Frias, Xavier (2016). «Rules for Maldivian Trading Ships Travelling Abroad (1925) and a Sojourn in Southern Ceylon». Politeja. 40: 69–84. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- Roxy, M.K. (2016). «A reduction in marine primary productivity driven by rapid warming over the tropical Indian Ocean» (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 43 (2): 826–833. Bibcode:2016GeoRL..43..826R. doi:10.1002/2015GL066979.

- Roxy, Mathew Koll; Ritika, Kapoor; Terray, Pascal; Masson, Sébastien (2014). «The Curious Case of Indian Ocean Warming» (PDF). Journal of Climate. 27 (22): 8501–8509. Bibcode:2014JCli…27.8501R. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00471.1. ISSN 0894-8755. S2CID 42480067. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Royer, J. Y.; Gordon, R. G. (1997). «The motion and boundary between the Capricorn and Australian plates». Science. 277 (5330): 1268–1274. doi:10.1126/science.277.5330.1268.

- Rubin, C. M.; Horton, B. P.; Sieh, K.; Pilarczyk, J. E.; Daly, P.; Ismail, N.; Parnell, A. C. (2017). «Highly variable recurrence of tsunamis in the 7,400 years before the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami». Nature Communications. 8: 160190. Bibcode:2017NatCo…816019R. doi:10.1038/ncomms16019. PMC 5524937. PMID 28722009.

- Ryan, J. (2009). «Plants that perform for you? From floral aesthetics to floraesthesis in the Southwest of Western Australia». Australian Humanities Review. 47: 117–140. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Schott, F. A.; Xie, S. P.; McCreary, J. P. (2009). «Indian Ocean circulation and climate variability» (PDF). Reviews of Geophysics. 47 (1): RG1002. Bibcode:2009RvGeo..47.1002S. doi:10.1029/2007RG000245. S2CID 15022438. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- Sengupta, D.; Bharath Raj, G. N.; Shenoi, S. S. C. (2006). «Surface freshwater from Bay of Bengal runoff and Indonesian throughflow in the tropical Indian Ocean». Geophysical Research Letters. 33 (22): L22609. Bibcode:2006GeoRL..3322609S. doi:10.1029/2006GL027573. S2CID 55182412.

- Shankar, D.; Vinayachandran, P. N.; Unnikrishnan, A. S. (2002). «The monsoon currents in the north Indian Ocean» (PDF). Progress in Oceanography. 52 (1): 63–120. Bibcode:2002PrOce..52…63S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.389.4733. doi:10.1016/S0079-6611(02)00024-1. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- Souter, D.; Lindén, O., eds. (2005). Coral reef degradation in the Indian Ocean: status report 2005 (PDF) (Report). Coastal Oceans Research and Development – Indian Ocean. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- Stow, D. A. V. (2006). Oceans: an illustrated reference. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 127 (Map of Indian Ocean). ISBN 978-0-226-77664-4.

- Telford, J.; Cosgrave, J. (2006). Joint evaluation of the international response to the Indian Ocean tsunami: Synthesis report (PDF) (Report). Tsunami Evaluation Coalition (TEC). Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- Ullah, S.; Gadain, H. (2016). National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) of Somalia (PDF) (Report). FAO-Somalia. Retrieved 18 August 2019.