For other historical states known as Rusʹ, see Rus.

Coordinates: 50°27′N 30°31′E / 50.450°N 30.517°E

|

Kievan Rusʹ Роусь (Old East Slavic) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 882–1240 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Rurikid princely emblems depicted on coins: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

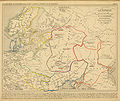

A map of Kievan Rusʹ after the death of Yaroslav I in 1054 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Kiev (882–1240) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Rusʹ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Grand Prince of Kiev | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 882–912 (first) |

Oleg the Seer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1236–1240 (last) |

Michael of Chernigov | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Veche, Prince Council | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Established |

882 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Conquest of Khazar Khaganate |

965–969 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

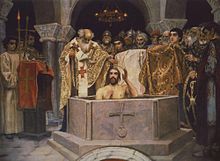

• Baptism of Rusʹ |

c. 988 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Russkaya Pravda |

early 11th century | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Mongol invasion of Rusʹ |

1240 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1000[1] | 1,330,000 km2 (510,000 sq mi) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1000[1] |

5.4 million | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Grivna | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kievan Rusʹ,[2] also known as Kyivan Rusʹ[3][4][5] (Old East Slavic: Роусь, romanized: Rusĭ, or роусьскаѧ землѧ, romanized: rusĭskaę zemlę, lit. ‘Rusʹ land’; Old Norse: Garðaríki),[6][7] was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.[8][9] Encompassing a variety of polities and peoples, including East Slavic, Norse,[10][11] and Finnic, it was ruled by the Rurik dynasty, founded by the Varangian prince Rurik.[9] The modern nations of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine all claim Kievan Rusʹ as their cultural ancestor,[12] with Belarus and Russia deriving their names from it. At its greatest extent in the mid-11th century, Kievan Rusʹ stretched from the White Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south and from the headwaters of the Vistula in the west to the Taman Peninsula in the east,[13][14] uniting the East Slavic tribes.[8]

According to the Primary Chronicle, the first ruler to start uniting East Slavic lands into what would become Kievan Rusʹ was Prince Oleg (879–912). He extended his control from Novgorod south along the Dnieper river valley to protect trade from Khazar incursions from the east,[8] and took control of the city of Kiev. Sviatoslav I (943–972) achieved the first major territorial expansion of the state, fighting a war of conquest against the Khazars. Vladimir the Great (980–1015) introduced Christianity with his own baptism and, by decree, extended it to all inhabitants of Kiev and beyond. Kievan Rusʹ reached its greatest extent under Yaroslav the Wise (1019–1054); his sons assembled and issued its first written legal code, the Russkaya Pravda, shortly after his death.[15]

The state began to decline in the late 11th century, gradually disintegrating into various rival regional powers throughout the 12th century.[16] It was further weakened by external factors, such as the decline of the Byzantine Empire, its major economic partner, and the accompanying diminution of trade routes through its territory.[17] It finally fell to the Mongol invasion in the mid-13th century, though the Rurik dynasty would continue to rule until the death of Feodor I of Russia in 1598.[18]

Name

During its existence, Kievan Rusʹ was known as the «land of the Rus» (Old East Slavic: ро́усьскаѧ землѧ, from the ethnonym Ро́усь; Greek: Ῥῶς; Arabic: الروس ar-Rūs), in Greek as Ῥωσία, in Old French as Russie, Rossie, in Latin as Rusia or Russia (with local German spelling variants Ruscia and Ruzzia), and from the 12th century also as Ruthenia or Rutenia.[19][20] Various etymologies have been proposed, including Ruotsi, the Finnish designation for Sweden or Ros, a tribe from the middle Dnieper valley region.[21]

According to the prevalent theory, the name Rusʹ, like the Proto-Finnic name for Sweden (*rootsi), is derived from an Old Norse term for ‘men who row’ (rods-) because rowing was the main method of navigating the rivers of Eastern Europe, and could be linked to the Swedish coastal area of Roslagen (Rus-law) or Roden, as it was known in earlier times.[22][23] The name Rusʹ would then have the same origin as the Finnish and Estonian names for Sweden: Ruotsi and Rootsi.[23][24]

The term Kievan Rusʹ[25][26] (Russian: Ки́евская Русь, romanized: Kiyevskaya Rus) was coined in the 19th century in Russian historiography to refer to the period when the centre was in Kiev.[27] In the 19th century it also appeared in Ukrainian: Ки́ївська Русь, romanized: Kyivska Rus.[28] In English, the term was introduced in the early 20th century, when it was found in the 1913 English translation of Vasily Klyuchevsky’s A History of Russia,[29] to distinguish the early polity from successor states, which were also named Rusʹ. The variant Kyivan Rusʹ appeared in English-language scholarship by the 1950s.[30] Later, the Russian term was rendered into Belarusian: Кіеўская Русь, romanized: Kiyewskaya Rus’ or Kijeŭskaja Ruś and Rusyn: Київска Русь, romanized: Kyïvska Rus′.

The historically accurate but rare spelling Kyevan Rusʹ, based on Old East Slavic Kyjevŭ (Kыѥвъ) ‘Kyiv’, is also occasionally seen.[31][32][33]

History

Origin

Prior to the emergence of Kievan Rusʹ in the 9th century, most of the area north of the Black Sea, which roughly overlaps with modern-day Ukraine and Belarus, was primarily populated by eastern Slavic tribes.[34] In the northern region around Novgorod were the Ilmen Slavs[35] and neighboring Krivichi, who occupied territories surrounding the headwaters of the West Dvina, Dnieper and Volga rivers. To their north, in the Ladoga and Karelia regions, were the Finnic Chud tribe. In the south, in the area around Kiev, were the Poliane, a group of Slavicized tribes with Iranian origins,[36] the Drevliane to the west of the Dnieper, and the Severiane to the east. To their north and east were the Vyatichi, and to their south was forested land settled by Slav farmers, giving way to steppelands populated by nomadic herdsmen.

An approximate ethno-linguistic map of Kievan Rusʹ in the 9th century: Five Volga Finnic groups of the Merya, Mari, Muromians, Meshchera and Mordvins are shown as surrounded by the Slavs to the west; the three Finnic groups of the Veps, Ests and Chuds, and Indo-European Balts to the northwest; the Permians to the northeast the (Turkic) Bulghars and Khazars to the southeast and south.

There was once controversy over whether the Rusʹ were Varangians or Slavs, however, more recently scholarly attention has focused more on debating how quickly an ancestrally Norse people assimilated into Slavic culture.[37] This uncertainty is due largely to a paucity of contemporary sources. Attempts to address this question instead rely on archaeological evidence, the accounts of foreign observers, and legends and literature from centuries later.[38] To some extent the controversy is related to the foundation myths of modern states in the region.[39] This often unfruitful debate over origins has periodically devolved into competing nationalist narratives of dubious scholarly value being promoted directly by various government bodies, in a number of states. This was seen in the Stalinist period, when Soviet historiography sought to distance the Rusʹ from any connection to Germanic tribes, in an effort to dispel Nazi propaganda claiming the Russian state owed its existence and origins to the supposedly racially superior Norse tribes.[40] More recently, in the context of resurgent nationalism in post-Soviet states, Anglophone scholarship has analyzed renewed efforts to use this debate to create ethno-nationalist foundation stories, with governments sometimes directly involved in the project.[41] Conferences and publications questioning the Norse origins of the Rusʹ have been supported directly by state policy in some cases, and the resultant foundation myths have been included in some school textbooks in Russia.[42]

While Varangians were Norse traders and Vikings,[43][44][45] some Russian and Ukrainian nationalist historians argue that the Rusʹ were themselves Slavs (see Anti-Normanism).[46][47][48] Normanist theories focus on the earliest written source for the East Slavs, the Primary Chronicle,[49] which was produced in the 12th century.[50] Nationalist accounts on the other hand have suggested that the Rusʹ were present before the arrival of the Varangians,[51] noting that only a handful of Scandinavian words can be found in Russian and that Scandinavian names in the early chronicles were soon replaced by Slavic names.[52]

Nevertheless, the close connection between the Rusʹ and the Norse is confirmed both by extensive Scandinavian settlement in Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine and by Slavic influences in the Swedish language.[53][54] Though the debate over the origin of the Rusʹ remains politically charged, there is broad agreement that if the proto-Rusʹ were indeed originally Norse, they were quickly nativized, adopting Slavic languages and other cultural practices. This position, roughly representing a scholarly consensus (at least outside of nationalist historiography), was summarized by the historian, F. Donald Logan, «in 839, the Rus were Swedes; in 1043 the Rus were Slavs».[55] Recent scholarship has attempted to move past the narrow and politicized debate on origins, to focus on how and why assimilation took place so quickly. Some modern DNA testing also points to Viking origins, not only of some of the early Rusʹ princely family and/or their retinues, but also links to possible brethren from neighboring countries like Sviatopolk I of Kiev.

Ahmad ibn Fadlan, an Arab traveler during the 10th century, provided one of the earliest written descriptions of the Rusʹ: «They are as tall as a date palm, blond and ruddy, so that they do not need to wear a tunic nor a cloak; rather the men among them wear garments that only cover half of his body and leaves one of his hands free.»[56] Liutprand of Cremona, who was twice an envoy to the Byzantine court (949 and 968), identifies the «Russi» with the Norse («the Russi, whom we call Norsemen by another name»)[57] but explains the name as a Greek term referring to their physical traits («A certain people made up of a part of the Norse, whom the Greeks call […] the Russi on account of their physical features, we designate as Norsemen because of the location of their origin.»).[58] Leo the Deacon, a 10th-century Byzantine historian and chronicler, refers to the Rusʹ as «Scythians» and notes that they tended to adopt Greek rituals and customs.[59] But ‘Scythians’ in Greek parlance is used predominantly as a generic term for nomads.

Invitation of the Varangians

According to the Primary Chronicle, the territories of the East Slavs in the 9th century were divided between the Varangians and the Khazars.[60] The Varangians are first mentioned imposing tribute from Slavic and Finnic tribes in 859.[61] In 862, the Finnic and Slavic tribes in the area of Novgorod rebelled against the Varangians, driving them «back beyond the sea and, refusing them further tribute, set out to govern themselves.» The tribes had no laws, however, and soon began to make war with one another, prompting them to invite the Varangians back to rule them and bring peace to the region:

They said to themselves, «Let us seek a prince who may rule over us, and judge us according to the Law.» They accordingly went overseas to the Varangian Rusʹ. … The Chuds, the Slavs, the Krivichs and the Ves then said to the Rusʹ, «Our land is great and rich, but there is no order in it. Come to rule and reign over us». They thus selected three brothers with their kinfolk, who took with them all the Rusʹ and migrated.[62]

The three brothers—Rurik, Sineus and Truvor—established themselves in Novgorod, Beloozero and Izborsk, respectively.[63] Two of the brothers died, and Rurik became the sole ruler of the territory and progenitor of the Rurik dynasty.[64] A short time later, two of Rurik’s men, Askold and Dir, asked him for permission to go to Tsargrad (Constantinople). On their way south, they discovered «a small city on a hill,» Kiev, captured it and the surrounding country from the Khazars, populated the region with more Varangians, and «established their dominion over the country of the Polyanians.»[65][66]

The Chronicle reports that Askold and Dir continued to Constantinople with a navy to attack the city in 863–66, catching the Byzantines by surprise and ravaging the surrounding area,[66] though other accounts date the attack in 860.[67] Patriarch Photius vividly describes the «universal» devastation of the suburbs and nearby islands,[68] and another account further details the destruction and slaughter of the invasion.[69] The Rusʹ turned back before attacking the city itself, due either to a storm dispersing their boats, the return of the Emperor, or in a later account, due to a miracle after a ceremonial appeal by the Patriarch and the Emperor to the Virgin.[70] The attack was the first encounter between the Rusʹ and Byzantines and led the Patriarch to send missionaries north to engage and attempt to convert the Rusʹ and the Slavs.[71][72]

Foundation of the Kievan state

East-Slavic tribes and peoples, 8th–9th centuries

Rurik led the Rusʹ until his death in about 879, bequeathing his kingdom to his kinsman, Prince Oleg, as regent for his young son, Igor.[66][73] In 880–82, Oleg led a military force south along the Dnieper river, capturing Smolensk and Lyubech before reaching Kiev, where he deposed and killed Askold and Dir, proclaimed himself prince, and declared Kiev the «mother of Rusʹ cities.»[note 1][75] Oleg set about consolidating his power over the surrounding region and the riverways north to Novgorod, imposing tribute on the East Slav tribes.[65][76]

In 883, he conquered the Drevlians, imposing a fur tribute on them. By 885 he had subjugated the Poliane, Severiane, Vyatichi, and Radimichs, forbidding them to pay further tribute to the Khazars. Oleg continued to develop and expand a network of Rusʹ forts in Slav lands, begun by Rurik in the north.[77]

The new Kievan state prospered due to its abundant supply of furs, beeswax, honey and slaves for export,[78] and because it controlled three main trade routes of Eastern Europe. In the north, Novgorod served as a commercial link between the Baltic Sea and the Volga trade route to the lands of the Volga Bulgars, the Khazars, and across the Caspian Sea as far as Baghdad, providing access to markets and products from Central Asia and the Middle East.[79][80] Trade from the Baltic also moved south on a network of rivers and short portages along the Dnieper known as the «route from the Varangians to the Greeks,» continuing to the Black Sea and on to Constantinople.[81]

Kiev was a central outpost along the Dnieper route and a hub with the east–west overland trade route between the Khazars and the Germanic lands of Central Europe.[81] and may have been a staging post for Radhanite Jewish traders between Western Europe, Itil and China.[82] These commercial connections enriched Rusʹ merchants and princes, funding military forces and the construction of churches, palaces, fortifications, and further towns.[80] Demand for luxury goods fostered production of expensive jewelry and religious wares, allowing their export, and an advanced credit and money-lending system may have also been in place.[78]

Early foreign relations

Volatile steppe politics

The rapid expansion of the Rusʹ to the south led to conflict and volatile relationships with the Khazars and other neighbors on the Pontic steppe.[83][84][85] The Khazars dominated trade from the Volga-Don steppes to the eastern Crimea and the northern Caucasus during the 8th century during an era historians call the ‘Pax Khazarica’,[86] trading and frequently allying with the Byzantine Empire against Persians and Arabs. In the late 8th century, the collapse of the Göktürk Khaganate led the Magyars and the Pechenegs, Ugrians and Turkic peoples from Central Asia, to migrate west into the steppe region,[87] leading to military conflict, disruption of trade, and instability within the Khazar Khaganate.[88] The Rusʹ and Slavs had earlier allied with the Khazars against Arab raids on the Caucasus, but they increasingly worked against them to secure control of the trade routes.[89]

The Byzantine Empire was able to take advantage of the turmoil to expand its political influence and commercial relationships, first with the Khazars and later with the Rusʹ and other steppe groups.[83] The Byzantines established the Theme of Cherson, formally known as Klimata, in the Crimea in the 830s to defend against raids by the Rusʹ and to protect vital grain shipments supplying Constantinople.[90] Cherson also served as a key diplomatic link with the Khazars and others on the steppe, and it became the centre of Black Sea commerce.[91] The Byzantines also helped the Khazars build a fortress at Sarkel on the Don river to protect their northwest frontier against incursions by the Turkic migrants and the Rusʹ, and to control caravan trade routes and the portage between the Don and Volga rivers.[92]

The expansion of the Rusʹ put further military and economic pressure on the Khazars, depriving them of territory, tributaries and trade.[93] In around 890, Oleg waged an indecisive war in the lands of the lower Dniester and Dnieper rivers with the Tivertsi and the Ulichs, who were likely acting as vassals of the Magyars, blocking Rusʹ access to the Black Sea.[94][95] In 894, the Magyars and Pechenegs were drawn into the wars between the Byzantines and the Bulgarian Empire. The Byzantines arranged for the Magyars to attack Bulgarian territory from the north, and Bulgaria in turn persuaded the Pechenegs to attack the Magyars from their rear.[96][97]

Boxed in, the Magyars were forced to migrate further west across the Carpathian Mountains into the Hungarian plain, depriving the Khazars of an important ally and a buffer from the Rusʹ.[96][97] The migration of the Magyars allowed Rusʹ access to the Black Sea,[98] and they soon launched excursions into Khazar territory along the sea coast, up the Don river, and into the lower Volga region. The Rusʹ were raiding and plundering into the Caspian Sea region from 864,[note 2] with the first large-scale expedition in 913, when they extensively raided Baku, Gilan, Mazandaran and penetrated into the Caucasus.[note 3][101][102]

As the 10th century progressed, the Khazars were no longer able to command tribute from the Volga Bulgars, and their relationship with the Byzantines deteriorated, as Byzantium increasingly allied with the Pechenegs against them.[103] The Pechenegs were thus secure to raid the lands of the Khazars from their base between the Volga and Don rivers, allowing them to expand to the west.[84] Rusʹ relations with the Pechenegs were complex, as the groups alternately formed alliances with and against one another. The Pechenegs were nomads roaming the steppe raising livestock which they traded with the Rusʹ for agricultural goods and other products.[104]

The lucrative Rusʹ trade with the Byzantine Empire had to pass through Pecheneg-controlled territory, so the need for generally peaceful relations was essential. Nevertheless, while the Primary Chronicle reports the Pechenegs entering Rusʹ territory in 915 and then making peace, they were waging war with one another again in 920.[105][106] Pechenegs are reported assisting the Rusʹ in later campaigns against the Byzantines, yet allied with the Byzantines against the Rusʹ at other times.[107]

Rusʹ–Byzantine relations

After the Rusʹ attack on Constantinople in 860, the Byzantine Patriarch Photius sent missionaries north to convert the Rusʹ and the Slavs to Christianity. Prince Rastislav of Moravia had requested the Emperor to provide teachers to interpret the holy scriptures, so in 863 the brothers Cyril and Methodius were sent as missionaries, due to their knowledge of the Slavonic language.[72][108][109] The Slavs had no written language, so the brothers devised the Glagolitic alphabet, later replaced by Cyrillic (developed in the First Bulgarian Empire) and standardized the language of the Slavs, later known as Old Church Slavonic. They translated portions of the Bible and drafted the first Slavic civil code and other documents, and the language and texts spread throughout Slavic territories, including Kievan Rusʹ. The mission of Cyril and Methodius served both evangelical and diplomatic purposes, spreading Byzantine cultural influence in support of imperial foreign policy.[110] In 867 the Patriarch announced that the Rusʹ had accepted a bishop, and in 874 he speaks of an «Archbishop of the Rusʹ.»[71]

Relations between the Rusʹ and Byzantines became more complex after Oleg took control over Kiev, reflecting commercial, cultural, and military concerns.[111] The wealth and income of the Rusʹ depended heavily upon trade with Byzantium. Constantine Porphyrogenitus described the annual course of the princes of Kiev, collecting tribute from client tribes, assembling the product into a flotilla of hundreds of boats, conducting them down the Dnieper to the Black Sea, and sailing to the estuary of the Dniester, the Danube delta, and on to Constantinople.[104][112] On their return trip they would carry silk fabrics, spices, wine, and fruit.[71][113]

The importance of this trade relationship led to military action when disputes arose. The Primary Chronicle reports that the Rusʹ attacked Constantinople again in 907, probably to secure trade access. The Chronicle glorifies the military prowess and shrewdness of Oleg, an account imbued with legendary detail.[71][113] Byzantine sources do not mention the attack, but a pair of treaties in 907 and 911 set forth a trade agreement with the Rusʹ,[105][114] the terms suggesting pressure on the Byzantines, who granted the Rusʹ quarters and supplies for their merchants and tax-free trading privileges in Constantinople.[71][115]

The Chronicle provides a mythic tale of Oleg’s death. A sorcerer prophesies that the death of the Grand Prince would be associated with a certain horse. Oleg has the horse sequestered, and it later dies. Oleg goes to visit the horse and stands over the carcass, gloating that he had outlived the threat, when a snake strikes him from among the bones, and he soon becomes ill and dies.[116][117] The Chronicle reports that Prince Igor succeeded Oleg in 913, and after some brief conflicts with the Drevlians and the Pechenegs, a period of peace ensued for over twenty years.

In 941, Igor led another major Rusʹ attack on Constantinople, probably over trading rights again.[71][118] A navy of 10,000 vessels, including Pecheneg allies, landed on the Bithynian coast and devastated the Asiatic shore of the Bosphorus.[119] The attack was well timed, perhaps due to intelligence, as the Byzantine fleet was occupied with the Arabs in the Mediterranean, and the bulk of its army was stationed in the east. The Rusʹ burned towns, churches and monasteries, butchering the people and amassing booty. The emperor arranged for a small group of retired ships to be outfitted with Greek fire throwers and sent them out to meet the Rusʹ, luring them into surrounding the contingent before unleashing the Greek fire.[120]

Liutprand of Cremona wrote that «the Rusʹ, seeing the flames, jumped overboard, preferring water to fire. Some sank, weighed down by the weight of their breastplates and helmets; others caught fire.» Those captured were beheaded. The ploy dispelled the Rusʹ fleet, but their attacks continued into the hinterland as far as Nicomedia, with many atrocities reported as victims were crucified and set up for use as targets. At last a Byzantine army arrived from the Balkans to drive the Rusʹ back, and a naval contingent reportedly destroyed much of the Rusʹ fleet on its return voyage (possibly an exaggeration since the Rusʹ soon mounted another attack). The outcome indicates increased military might by Byzantium since 911, suggesting a shift in the balance of power.[119]

Igor returned to Kiev keen for revenge. He assembled a large force of warriors from among neighboring Slavs and Pecheneg allies, and sent for reinforcements of Varangians from «beyond the sea.»[120][121] In 944 the Rusʹ force advanced again on the Greeks, by land and sea, and a Byzantine force from Cherson responded. The Emperor sent gifts and offered tribute in lieu of war, and the Rusʹ accepted. Envoys were sent between the Rusʹ, the Byzantines, and the Bulgarians in 945, and a peace treaty was completed. The agreement again focused on trade, but this time with terms less favorable to the Rusʹ, including stringent regulations on the conduct of Rusʹ merchants in Cherson and Constantinople and specific punishments for violations of the law.[122] The Byzantines may have been motivated to enter the treaty out of concern of a prolonged alliance of the Rusʹ, Pechenegs, and Bulgarians against them,[123] though the more favorable terms further suggest a shift in power.[119]

Sviatoslav

Following the death of Grand Prince Igor in 945, his wife Olga ruled as regent in Kiev until their son Sviatoslav reached maturity (c. 963).[note 4] His decade-long reign over Rusʹ was marked by rapid expansion through the conquest of the Khazars of the Pontic steppe and the invasion of the Balkans. By the end of his short life, Sviatoslav carved out for himself the largest state in Europe, eventually moving his capital from Kiev to Pereyaslavets on the Danube in 969.

In contrast with his mother’s conversion to Christianity, Sviatoslav, like his druzhina, remained a staunch pagan. Due to his abrupt death in an ambush in 972, Sviatoslav’s conquests, for the most part, were not consolidated into a functioning empire, while his failure to establish a stable succession led to a fratricidal feud among his sons, which resulted in two of his three sons being killed.

Reign of Vladimir and Christianisation

It is not clearly documented when the title of the Grand Duke was first introduced, but the importance of the Kiev principality was recognized after the death of Sviatoslav I in 972 and the ensuing struggle between Vladimir the Great and Yaropolk I. The region of Kiev dominated the state of Kievan Rusʹ for the next two centuries. The grand prince or grand duke (Belarusian: вялікі князь, romanized: vyaliki knyaz’ or vialiki kniaź, Russian: великий князь, romanized: velikiy kniaz, Rusyn: великый князь, romanized: velykŷĭ kni͡az′, Ukrainian: великий князь, romanized: velykyi kniaz) of Kiev controlled the lands around the city, and his formally subordinate relatives ruled the other cities and paid him tribute. The zenith of the state’s power came during the reigns of Vladimir the Great (980–1015) and Prince Yaroslav I the Wise (1019–1054). Both rulers continued the steady expansion of Kievan Rusʹ that had begun under Oleg.

Vladimir had been prince of Novgorod when his father Sviatoslav I died in 972. He was forced to flee to Scandinavia in 976 after his half-brother Yaropolk had murdered his other brother Oleg and taken control of Rus. In Scandinavia, with the help of his relative Earl Håkon Sigurdsson, ruler of Norway, Vladimir assembled a Viking army and reconquered Novgorod and Kiev from Yaropolk.[124]

As Prince of Kiev, Vladimir’s most notable achievement was the Christianization of Kievan Rusʹ, a process that began in 988. The Primary Chronicle states that when Vladimir had decided to accept a new faith instead of the traditional idol-worship (paganism) of the Slavs, he sent out some of his most valued advisors and warriors as emissaries to different parts of Europe. They visited the Christians of the Latin Rite, the Jews, and the Muslims before finally arriving in Constantinople. They rejected Islam because, among other things, it prohibited the consumption of alcohol, and Judaism because the god of the Jews had permitted his chosen people to be deprived of their country.[125]

They found the ceremonies in the Roman church to be dull. But at Constantinople, they were so astounded by the beauty of the cathedral of Hagia Sophia and the liturgical service held there that they made up their minds there and then about the faith they would like to follow. Upon their arrival home, they convinced Vladimir that the faith of the Byzantine Rite was the best choice of all, upon which Vladimir made a journey to Constantinople and arranged to marry Princess Anna, the sister of Byzantine emperor Basil II.[125]

Ivan Eggink’s painting represents Vladimir listening to the Orthodox priests, while the papal envoy stands aside in discontent.

Vladimir’s choice of Eastern Christianity may also have reflected his close personal ties with Constantinople, which dominated the Black Sea and hence trade on Kiev’s most vital commercial route, the Dnieper River. Adherence to the Eastern Church had long-range political, cultural, and religious consequences. The church had a liturgy written in Cyrillic and a corpus of translations from Greek that had been produced for the Slavic peoples. This literature facilitated the conversion to Christianity of the Eastern Slavs and introduced them to rudimentary Greek philosophy, science, and historiography without the necessity of learning Greek (there were some merchants who did business with Greeks and likely had an understanding of contemporary business Greek).[126]

In contrast, educated people in medieval Western and Central Europe learned Latin. Enjoying independence from the Roman authority and free from tenets of Latin learning, the East Slavs developed their own literature and fine arts, quite distinct from those of other Eastern Orthodox countries.[citation needed] (See Old East Slavic language and Architecture of Kievan Rus for details). Following the Great Schism of 1054, the Rusʹ church maintained communion with both Rome and Constantinople for some time, but along with most of the Eastern churches it eventually split to follow the Eastern Orthodox. That being said, unlike other parts of the Greek world, Kievan Rusʹ did not have a strong hostility to the Western world.[127]

Golden age

Yaroslav, known as «the Wise», struggled for power with his brothers. A son of Vladimir the Great, he was prince of Novgorod at the time of his father’s death in 1015. Subsequently, his eldest surviving brother, Svyatopolk the Accursed, according to domestic but not foreign sources, killed three of his other brothers and seized power in Kiev. Yaroslav, with the active support of the Novgorodians and the help of Viking mercenaries, defeated Svyatopolk and became the grand prince of Kiev in 1019.[128]

Although he first established his rule over Kiev in 1019, he did not have uncontested rule of all of Kievan Rusʹ until 1036. Like Vladimir, Yaroslav was eager to improve relations with the rest of Europe, especially the Byzantine Empire. Yaroslav’s granddaughter, Eupraxia, the daughter of his son Vsevolod I, Prince of Kiev, was married to Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor. Yaroslav also arranged marriages for his sister and three daughters to the kings of Poland, France, Hungary and Norway.

Yaroslav promulgated the first East Slavic law code, Russkaya Pravda; built Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kiev and Saint Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod; patronized local clergy and monasticism; and is said to have founded a school system. Yaroslav’s sons developed the great Kiev Pechersk Lavra (monastery), which functioned in Kievan Rusʹ as an ecclesiastical academy.

In the centuries that followed the state’s foundation, Rurik’s descendants shared power over Kievan Rusʹ. Princely succession moved from elder to younger brother and from uncle to nephew, as well as from father to son. Junior members of the dynasty usually began their official careers as rulers of a minor district, progressed to more lucrative principalities, and then competed for the coveted throne of Kiev.

Fragmentation and decline

The principalities of the later Kievan Rus (after the death of Yaroslav I in 1054)

The gradual disintegration of the Kievan Rusʹ began in the 11th century, after the death of Yaroslav the Wise. The position of the Grand Prince of Kiev was weakened by the growing influence of regional clans.

An unconventional power succession system was established (rota system) whereby power was transferred to the eldest member of the ruling dynasty rather than from father to son, i.e. in most cases to the eldest brother of the ruler, fomenting constant hatred and rivalry within the royal family.[citation needed] Familicide was frequently deployed to obtain power and can be traced particularly during the time of the Yaroslavichi (sons of Yaroslav), when the established system was skipped in the establishment of Vladimir II Monomakh as the Grand Prince of Kiev,[clarification needed] in turn creating major squabbles between Olegovichi from Chernigov, Monomakhs from Pereyaslav, Izyaslavichi from Turov/Volhynia, and Polotsk Princes.[citation needed]

The Nativity, a Kievan (possibly Galician) illumination from the Gertrude Psalter

The most prominent struggle for power was the conflict that erupted after the death of Yaroslav the Wise. The rival Principality of Polotsk was contesting the power of the Grand Prince by occupying Novgorod, while Rostislav Vladimirovich was fighting for the Black Sea port of Tmutarakan belonging to Chernigov.[citation needed] Three of Yaroslav’s sons that first allied together found themselves fighting each other especially after their defeat to the Cuman forces in 1068 at the Battle of the Alta River. At the same time, an uprising took place in Kiev, bringing to power Vseslav of Polotsk who supported the traditional Slavic paganism.[citation needed]

The ruling Grand Prince Iziaslav fled to Poland asking for support and in couple of years returned to establish the order.[citation needed] The affairs became even more complicated by the end of the 11th century driving the state into chaos and constant warfare. On the initiative of Vladimir II Monomakh in 1097 the first federal council of Kievan Rusʹ took place near Chernigov in the city of Liubech with the main intention to find an understanding among the fighting sides. However, even though that did not really stop the fighting, it certainly cooled things off.[citation needed]

By 1130, all descendants of Vseslav the Seer had been exiled to the Byzantine Empire by Mstislav the Great. The most fierce resistance to the Monomakhs was posed by the Olegovichi when the izgoi Vsevolod II managed to become the Grand Prince of Kiev. The Rostislavichi who had initially established in Halych lands by 1189 were defeated by the Monomakh-Piast descendant Roman the Great.[citation needed]

The decline of Constantinople—a main trading partner of Kievan Rusʹ—played a significant role in the decline of the Kievan Rusʹ. The trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks, along which the goods were moving from the Black Sea (mainly Byzantine) through eastern Europe to the Baltic, was a cornerstone of Kievan wealth and prosperity. These trading routes became less important as the Byzantine Empire declined in power and Western Europe created new trade routes to Asia and the Near East. As people relied less on passing through Kievan Rusʹ territories for trade, the Kievan Rusʹ economy suffered.[129]

The last ruler to maintain a united state was Mstislav the Great. After his death in 1132, the Kievan Rusʹ fell into recession and a rapid decline, and Mstislav’s successor Yaropolk II of Kiev, instead of focusing on the external threat of the Cumans, was embroiled in conflicts with the growing power of the Novgorod Republic. In March 1169, a coalition of native princes led by Andrei Bogolyubsky of Vladimir sacked Kiev.[130] This changed the perception of Kiev and was evidence of the fragmentation of the Kievan Rusʹ.[131] By the end of the 12th century, the Kievan state fragmented even further, into roughly twelve different principalities.[132]

The Crusades brought a shift in European trade routes that accelerated the decline of Kievan Rusʹ. In 1204, the forces of the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople, making the Dnieper trade route marginal.[17] At the same time, the Livonian Brothers of the Sword (of the Northern Crusades) were conquering the Baltic region and threatening the Lands of Novgorod. Concurrently with it, the Ruthenian Federation of Kievan Rusʹ started to disintegrate into smaller principalities as the Rurik dynasty grew. The local Orthodox Christianity of Kievan Rusʹ, while struggling to establish itself in the predominantly pagan state and losing its main base in Constantinople, was on the brink of extinction. Some of the main regional centres that developed later were Novgorod, Chernigov, Halych, Kiev, Ryazan, Vladimir-upon-Klyazma, Volodimer-Volyn and Polotsk.

Novgorod Republic

In the north, the Republic of Novgorod prospered because it controlled trade routes from the River Volga to the Baltic Sea. As Kievan Rusʹ declined, Novgorod became more independent. A local oligarchy ruled Novgorod; major government decisions were made by a town assembly, which also elected a prince as the city’s military leader. In 1136, Novgorod revolted against Kiev, and became independent.[133]

Now an independent city republic, and referred to as «Lord Novgorod the Great» it would spread its «mercantile interest» to the west and the north; to the Baltic Sea and the low-populated forest regions, respectively.[133] In 1169, Novgorod acquired its own archbishop, named Ilya, a sign of further increased importance and political independence. Novgorod enjoyed a wide degree of autonomy although being closely associated with the Kievan Rus.

Northeast

Map of the Grand Duchy of Kiev in 1139, where northeastern territories are identified as the trans-forest colonies (Zalesie) by Joachim Lelewel

In the northeast, Slavs from the Kievan region colonized the territory that later would become the Grand Duchy of Moscow by subjugating and merging with the Finnic tribes already occupying the area. The city of Rostov, the oldest centre of the northeast, was supplanted first by Suzdal and then by the city of Vladimir, which become the capital of Vladimir-Suzdal. The combined principality of Vladimir-Suzdal asserted itself as a major power in Kievan Rusʹ in the late 12th century.

In 1169, Prince Andrey Bogolyubskiy of Vladimir-Suzdal sacked the city of Kiev and took over the title of the grand prince to claim primacy in Rusʹ. Prince Andrey then installed his younger brother, who ruled briefly in Kiev while Andrey continued to rule his realm from Suzdal. In 1299, in the wake of the Mongol invasion, the metropolitan moved from Kiev to the city of Vladimir and Vladimir-Suzdal.

Southwest

To the southwest, the principality of Halych had developed trade relations with its Polish, Hungarian and Lithuanian neighbours and emerged as the local successor to Kievan Rusʹ. In 1199, Prince Roman Mstislavych united the two previously separate principalities of Halych and Volyn. In 1202 he conquered Kiev, and assumed the title of Knyaz of Kievan Rusʹ, which was held by the rulers of Vladimir-Suzdal since 1169.

His son, Prince Daniel (r. 1238–1264) looked for support from the West. He accepted a crown as a «Rex Rusiae» («King of Rus») from the Roman papacy, apparently doing so without breaking with Constantinople. In 1370, the patriarch of the Eastern Orthodox Church in Constantinople granted the King of Poland a metropolitan for his Ruthenian subjects.

Lithuanian rulers also requested and received a metropolitan for Novagrudok shortly afterwards. Cyprian, a candidate pushed by the Lithuanian rulers, became Metropolitan of Kiev in 1375 and metropolitan of Moscow in 1382; this way the church in the territory of former Kievan Rusʹ was reunited for some time. In 1439, Kiev became the seat of a separate «Metropolitan of Kiev, Halych and all Rusʹ» for all Greek Orthodox Christians under Polish-Lithuanian rule.

However, a long and unsuccessful struggle against the Mongols combined with internal opposition to the prince and foreign intervention weakened Galicia-Volhynia. With the end of the Mstislavich branch of the Rurikids in the mid-14th century, Galicia-Volhynia ceased to exist; Poland conquered Halych; Lithuania took Volhynia, including Kiev, conquered by Gediminas in 1321 ending the rule of Rurikids in the city. Lithuanian rulers then assumed the title over Ruthenia.

Final disintegration

Following the Mongol invasion of Cumania (or the Kipchaks), in which case many Cuman rulers fled to Rusʹ, such as Köten, the state finally disintegrated under the pressure of the Mongol invasion of Rusʹ, fragmenting it into successor principalities who paid tribute to the Golden Horde (the so-called Tatar Yoke). In the late 15th century, the Muscovite Grand Dukes began taking over former Kievan territories and proclaimed themselves the sole legal successors of the Kievan principality according to the protocols of the medieval theory of translatio imperii.

On the western periphery, Kievan Rusʹ was succeeded by the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia. Later, as these territories, now part of modern central Ukraine and Belarus, fell to the Gediminids, the powerful, largely Ruthenized Grand Duchy of Lithuania drew heavily on Rusʹ cultural and legal traditions. From 1398 until the Union of Lublin in 1569 its full name was the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Ruthenia and Samogitia.[134] Due to the fact of the economic and cultural core of Rusʹ being located on the territory of modern Ukraine, Ukrainian historians and scholars consider Kievan Rusʹ to be a founding Ukrainian state.[12] After the Union of Lublin, the southern parts of the Grand Duchy were joined to the remnants of Galicia-Volhynia, forming a split of Ruthenia in the Lesser Poland Province, Crown of the Kingdom of Poland. This would almost be the modern borders between northern and southern Ruthenia, or modern Ukraine and Belarus, which have historically been influenced by Poland and Lithuania respectively.

On the north-eastern periphery of Kievan Rusʹ, traditions were adapted in the Vladimir-Suzdal Principality that gradually gravitated towards Moscow. To the very north, the Novgorod and Pskov Feudal Republics were less autocratic than Vladimir-Suzdal-Moscow until they were absorbed by the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Russian historians consider Kievan Rusʹ the first period of Russian history.

Economy

During the Kievan era, trade and transport depended largely on networks of rivers and portages.[135] By this period, trade networks had expanded to cater to more than just local demand. This is evidenced by a survey of glassware found in over 30 sites ranging from Suzdal, Drutsk and Belozeroo, which found that a substantial majority was manufactured in Kiev. Kiev was the main depot and transit point for trade between itself, Byzantium and the Black Sea region. Even though this trade network had already been existent, the volume of which had expanded rapidly in the 11th century. Kiev was also dominant in internal trade between the Rus towns; it held a monopoly on glassware products (glass vessels, glazed pottery and window glass) up until the early- to mid-12th century until which it lost its monopoly to the other Rus towns. Inlaid enamel production techniques was borrowed from Byzantine. Byzantine amphorae, wine and olive oil have been found along the middle Dnieper, suggesting trade between Kiev, along trade towns to Byzantium.[136]

The peoples of Rusʹ experienced a period of great economic expansion, opening trade routes with the Vikings to the north and west and with the Byzantine Greeks to the south and west; traders also began to travel south and east, eventually making contact with Persia and the peoples of Central Asia.

In winter, the ruler of Kiev went out on rounds, visiting Dregovichs, Krivichs, Drevlians, Severians, and other subordinated tribes. Some paid tribute in money, some in furs or other commodities, and some in slaves. This system was called poliudie.[137][138]

Society

Due to the expansion of trade and its geographical proximity, Kiev became the most important trade centre and chief among the communes; therefore the leader of Kiev gained political «control» over the surrounding areas. This princedom emerged from a coalition of traditional patriarchic family communes banded together in an effort to increase the applicable workforce and expand the productivity of the land. This union developed the first major cities in the Rusʹ and was the first notable form of self-government. As these communes became larger, the emphasis was taken off the family holdings and placed on the territory that surrounded. This shift in ideology became known as the vervʹ.

In the 11th and the 12th centuries, the princes and their retinues, which were a mixture of Slavic and Scandinavian elites, dominated the society of Kievan Rusʹ.[citation needed] Leading soldiers and officials received income and land from the princes in return for their political and military services. Kievan society lacked the class institutions and autonomous towns that were typical of Western European feudalism. Nevertheless, urban merchants, artisans and labourers sometimes exercised political influence through a city assembly, the veche (council), which included all the adult males in the population.

In some cases, the veche either made agreements with their rulers or expelled them and invited others to take their place. At the bottom of society was a stratum of slaves. More important was a class of tribute-paying peasants, who owed labour duty to the princes. The widespread personal serfdom characteristic of Western Europe did not exist in Kievan Rusʹ.

The change in political structure led to the inevitable development of the peasant class or smerds. The smerdy were free un-landed people that found work by labouring for wages on the manors that began to develop around 1031 as the vervʹ began to dominate socio-political structure. The smerdy were initially given equality in the Kievian law code; they were theoretically equal to the prince; so they enjoyed as much freedom as can be expected of manual labourers. However, in the 13th century, they slowly began to lose their rights and became less equal in the eyes of the law.

Historical assessment

Kievan Rusʹ, although sparsely populated compared to Western Europe,[139] was not only the largest contemporary European state in terms of area but also culturally advanced.[140] Literacy in Kiev, Novgorod and other large cities was high;[141][142] as birch bark documents attest, inhabitants exchanged love letters and prepared cheat sheets for schools. Novgorod had a sewage system and wood pavement not often found in other cities at the time.[143] The Russkaya Pravda confined punishments to fines and generally did not use capital punishment.[144] Certain rights were accorded to women, such as property and inheritance rights.[145][146][147]

The economic development of Kievan Rus may be reflected in its demographics. Around 1200, Kiev had a population of 50,000, followed by Novgorod and Chernigov, which each had around 30,000;[148] Constantinople, then one of the largest cities in the world, had a population of about 400,000 around 1180.[149] Soviet scholar Mikhail Tikhomirov calculated that Kievan Rusʹ had around 300 urban centres on the eve of the Mongol invasion.[150]

Kievan Rusʹ also played an important genealogical role in European politics. Yaroslav the Wise, whose stepmother belonged to the Macedonian dynasty that ruled the Byzantine Empire from 867 to 1056, married the only legitimate daughter of the king who Christianized Sweden. His daughters became queens of Hungary, France and Norway; his sons married the daughters of a Polish king and Byzantine emperor, and a niece of the Pope; and his granddaughters were a German empress and (according to one theory) the queen of Scotland. A grandson married the only daughter of the last Anglo-Saxon king of England. Thus the Rurikids were a well-connected royal family of the time.[151][152]

Foreign relations

Turkic peoples

From the 9th century, the Pecheneg nomads began an uneasy relationship with Kievan Rusʹ. For over two centuries they launched sporadic raids into the lands of Rusʹ, which sometimes escalated into full-scale wars (such as the 920 war on the Pechenegs by Igor of Kiev reported in the Primary Chronicle), but there were also temporary military alliances (e.g., the 943 Byzantine campaign by Igor).[note 5] In 968, the Pechenegs attacked and besieged the city of Kiev.[153] Some speculation exists that the Pechenegs drove off the Tivertsi and the Ulichs to the regions of the upper Dniester river in Bukovina. The Byzantine Empire was known to support the Pechenegs in their military campaigns against the Eastern Slavic states.[citation needed]

Boniak was a Cuman khan who led a series of invasions on Kievan Rusʹ. In 1096, Boniak attacked Kiev, plundered the Kiev Monastery of the Caves, and burned down the prince’s palace in Berestovo. He was defeated in 1107 by Vladimir Monomakh, Oleg, Sviatopolk and other Rusʹ princes.[154]

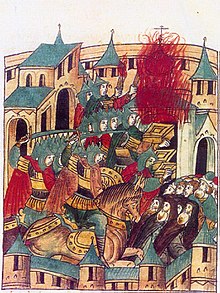

Mongols

The Mongol Empire invaded Kievan Rusʹ in the 13th century, destroying numerous cities, including Ryazan, Kolomna, Moscow, Vladimir and Kiev. Giovanni de Plano Carpini, the Pope’s envoy to the Mongol Great Khan, traveled through Kiev in February 1246 and wrote:[155]

When this was done, they [the Mongols, «Tartari«)] marched against Rusʹ, and made great havoc in it, destroyed cities and forts, and killed people. They besieged Kyiv, the metropolis of Rusʹ, for a long time, and finally took it and killed its citizens. From there, while passing through that land, we found innumerable skulls and bones of dead men, lying on the ground. For the city had been very large and populous, but now it seems reduced to nothing: for hardly more than two hundred houses remain, whose inhabitants are also held in absolute servitude.

Byzantine Empire

Byzantium quickly became the main trading and cultural partner for Kiev, but relations were not always friendly. The most serious conflict between the two powers was the war of 968–971 in Bulgaria, but several Rusʹ raiding expeditions against the Byzantine cities of the Black Sea coast and Constantinople itself are also recorded. Although most were repulsed, they were concluded by trade treaties that were generally favourable to the Rusʹ.

Rusʹ-Byzantine relations became closer following the marriage of the porphyrogenita Anna to Vladimir the Great, and the subsequent Christianization of the Rusʹ: Byzantine priests, architects and artists were invited to work on numerous cathedrals and churches around Rusʹ, expanding Byzantine cultural influence even further. Numerous Rusʹ served in the Byzantine army as mercenaries, most notably as the famous Varangian Guard.

Military campaigns

- Caspian expeditions of the Rusʹ (864–1041)

- Rusʹ–Byzantine Wars (830–1043)

- 1018 Polish intervention

Administrative divisions

- 11th century

- Novgorod Land 862–1478 the allied territory of Kievan Rusʹ; from 1136 the Novgorod Republic

- Principality of Rostov-Suzdal Rostov Principality until 1125; became Vladimir-Suzdal Principality in 1155

- Principality of Polotsk 9th century – 14th century (separatist territory, partial suzerainty under Kievan Rusʹ)

- Principality of Minsk

- Principality of Smolensk from 1054

- Principality of Pereyaslavl

- Principality of Volhynia

- Principality of Kiev from 1132 to 1399

- Principality of Galicia

- Principality of Turov and Pinsk

- Principality of Chernigov

- Murom-Ryazan Principality until 1078

- Principality of Novgorod-Seversk

- City of Tmutarakan from 988 until some time in the 12th century

- Belaya Vezha from 965 until some time in the 12th century

- Southern dependencies Oleshky, New Galich, Peresechen’

- Drevlian territories annexed to Rusʹ by Oleg ?–884; 912–946 (vassal of Rusʹ from 914, Drevlians Uprising in 945)

Principal cities

- Belgorod Kievsky, capital of Rusʹ under Rurik Rostislavich

- Chernigov, capital along with Kiev from 1024 to 1036 (joint rule between Yaroslav and Mstislav)

- Halych

- Kiev

- Minsk, centre of Principality of Minsk

- Murom

- Pereyaslavets, capital of Rusʹ from 969 to 971 (in present-day Romania)

- Polotsk

- Rostov Veliky

- Ryazan

- Smolensk

- Staraya Ladoga

- Suzdal

- Tmutarakan

- Novgorod

- Vladimir

- Vyshgorod, princes’ residence and royal library (at Mezhyhirya)

Religion

In 988, the Christian Church in Rusʹ territorially fell under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople after it was officially adopted as the state religion. According to several chronicles after that date the predominant cult of Slavic paganism was persecuted.

The exact date of creation of the Kiev Metropolis is uncertain, as well as its first church leader. It is generally considered that the first head was Michael I of Kiev; however, some sources claim it to be Leontiy, who is often placed after Michael or Anastas Chersonesos, who became the first bishop of the Church of the Tithes. The first metropolitan to be confirmed by historical sources is Theopemp, who was appointed by Patriarch Alexius of Constantinople in 1038. Before 1015 there were five dioceses: Kiev, Chernihiv, Bilhorod, Volodymyr, Novgorod, and soon thereafter Yuriy-upon-Ros. The Kiev Metropolitan sent his own delegation to the Council of Bari in 1098.

After the sacking of Kiev in 1169, part of the Kiev metropolis started to move[citation needed] to Vladimir-upon-Klyazma, concluding the move sometime after 1240 when Kiev was taken by Batu Khan. Metropolitan Maxim was the first metropolitan who chose Vladimir-upon-Klyazma as his official residence in 1299. As a result, in 1303, Lev I of Galicia petitioned Patriarch Athanasius I of Constantinople for the creation of a new Halych metropolis; however, it only existed until 1347.[citation needed]

The Church of the Tithes was chosen as the first Cathedral Temple. In 1037, the cathedral was transferred to the newly built Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kiev. Upon the transferring of the metropolitan seat in 1299, the Dormition Cathedral, Vladimir was chosen as the new cathedral.

By the mid-13th century, the dioceses of Kiev Metropolis (988) were as follows: Kiev (988), Pereyaslav, Chernihiv (991), Volodymyr-Volynsky (992), Turov (1005), Polotsk (1104), Novgorod (~990s), Smolensk (1137), Murom (1198), Peremyshl (1120), Halych (1134), Vladimir-upon-Klyazma (1215), Rostov (991), Bilhorod, Yuriy (1032), Chełm (1235) and Tver (1271). There also were dioceses in Zakarpattia and Tmutarakan. In 1261 the Sarai-Batu diocese was established.[citation needed]

Collection of maps

-

Map of 8th- to 9th-century Rusʹ by Leonard Chodzko (1861)

-

Map of 9th-century Rusʹ by Antoine Philippe Houze (1844)

-

Map of 9th-century Rusʹ by F. S. Weller (1893)

-

Map of Rusʹ in Europe in 1000 (1911)

-

Map of Rusʹ in 1097 (1911)

-

See also

- History of Belarus

- History of Russia

- History of Ukraine

- De Administrando Imperio

- Kyivan Rus’ Park

- Old Russian Chronicles

- Slavic studies

- Symbols of the Rurikids

- European Russia

Explanatory notes

- ^ Normanist scholars accept this moment as the foundation of the Kievan Rusʹ state, while anti-Normanists point to other Chronicle entries to argue that the East Slav Polianes were already in the process of forming a state independently.[74]

- ^ Abaskun, first recorded by Ptolemy as Socanaa, was documented in Arab sources as «the most famous port of the Khazarian Sea». It was situated within three days’ journey from Gorgan. The southern part of the Caspian Sea was known as the «Sea of Abaskun».[99]

- ^ The Khazar khagan initially granted the Rusʹ safe passage in exchange for a share of the booty but attacked them on their return voyage, killing most of the raiders and seizing their haul.[100]

- ^ If Olga was indeed born in 879, as the Primary Chronicle seems to imply, she would have been about 65 at the time of Sviatoslav’s birth. There are clearly some problems with chronology.

- ^ Ibn Haukal describes the Pechenegs as the long-standing allies of the Rusʹ people, whom they invariably accompanied during the 10th-century Caspian expeditions.

References

Citations

- ^ Б.Ц.Урланис. Рост населения в Европе (PDF) (in Russian). p. 89.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 55: «The Rise of Kievan Rus’»

- ^ Plokhy, Serhii (2006). The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 10.

The history of Kyivan (Kievan) Rus′, the medieval East Slavic state …

- ^ Rubin, Barnett R.; Snyder, Jack L. (1998). Post-Soviet Political Order: Conflict and State Building. London: Routledge. p. 93.

As the capital of Kyivan Rus …

- ^ «The Golden Age of Kyivan Rus´». gis.huri.harvard.edu. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ «Ukraine – History, section «Kyivan (Kievan) Rus»«. Encyclopedia Britannica. 5 March 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Zhdan, Mykhailo (1988). «Kyivan Rusʹ». Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ a b c John Channon & Robert Hudson, Penguin Historical Atlas of Russia (Penguin, 1995), p.14–16.

- ^ a b Kievan Rus, Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ «Rus | people | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ Little, Becky. «When Viking Kings and Queens Ruled Medieval Russia». HISTORY. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- ^ a b Plokhy, Serhii (2006). The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus (PDF). New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 10–15. ISBN 978-0-521-86403-9. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

For all the salient differences between these three post-Soviet nations, they have much in common when it comes to their culture and history, which goes back to Kievan Rusʹ, the medieval East Slavic state based in the capital of present-day Ukraine,

- ^ Kyivan Rusʹ, Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 2 (1988), Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies.

- ^ See Historical map of Kievan Rusʹ from 980 to 1054.

- ^ Bushkovitch, Paul. A Concise History of Russia. Cambridge University Press. 2011.

- ^ Paul Robert Magocsi, Historical Atlas of East Central Europe (1993), p.15.

- ^ a b «Civilization in Eastern Europe Byzantium and Orthodox Europe». occawlonline.pearsoned.com. 2000. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010.

- ^ Picková, Dana, O počátcích státu Rusů, in: Historický obzor 18, 2007, č.11/12, s. 253–261

- ^ (in Russian) Назаренко А. В. Глава I Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine // Древняя Русь на международных путях: Междисциплинарные очерки культурных, торговых, политических связей IX—XII вв. Archived 31 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine — М.: Языки русской культуры, 2001. — c. 40, 42—45, 49—50. — ISBN 5-7859-0085-8.

- ^ Magocsi (2010), p. 73.

- ^ Paul R. Magocsi, A History of Ukraine (2010), pp.56–57.

- ^ Blöndal, Sigfús (1978). The Varangians of Byzantium. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-03552-1. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ a b Stefan Brink, ‘Who were the Vikings?’, in The Viking World, ed. by Stefan Brink and Neil Price (Abingdon: Routledge, 2008), pp. 4–10 (pp. 6–7).

- ^ «Russ, adj. and n.» OED Online, Oxford University Press, June 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/169069. Accessed 12 January 2021.

- ^ «Kievan Rus | Britannica entry». Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ «Western civilization». Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ Tolochko, A. P. (1999). «Khimera «Kievskoy Rusi»«. Rodina (in Russian) (8): 29–33.

- ^ Колесса, Олександер Михайлович (1898). Столїтє обновленої українсько-руської лїтератури: (1798–1898). Львів: З друкарні Наукового Товариства імені Шевченка під зарядом К. Беднарського. p. 26.

В XII та XIII в., в часі, коли південна, Київська Русь породила такі перли літературні … (In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, at a time when southern, Kyivan Rusʹ gave birth to such literary pearls …)

- ^ Vasily Klyuchevsky, A History of Russia, vol. 3, pp. 98, 104

- ^ Oreletsky, Vasyl (1957). «The Leading Feature of Ukrainian Law» (PDF). The Ukrainian Review. 4 (3): 49. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Sempruch, Justyna; Willems, Katharina; Shook, Laura (2006). Multiple Marginalities: An Intercultural Dialogue on Gender in Education Across Europe and Africa. Königstein: Helmer.

the territory of Kyevan Rus

- ^ Wolynetz, Lubow K. (2005). The Tree of Life, The Sun, The Goddess: Symbolic Motifs in Ukrainian Folk Art. New York: Ukrainian Museum. p. 22.

early Kyevan Rusʹ princes

- ^ Crawford, Ross (30 July 2021). «Joy as Coventry’s Ukrainian Community Marks the Founding of the Church of St Volodymyr». Coventry Observer. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

the Christianisation of ‘Kyevan Rusʹ

- ^ Janet Martin, Medieval Russia, 980–1584 (Cambridge, 2003), pp.2–4.

- ^ Carl Waldman & Catherine Mason, Encyclopedia of European Peoples (2006), p.415.

- ^ Martin (2003), p.4.

- ^ Logan 2005, p. 184 «The controversies over the nature of the Rus and the origins of the Russian state have bedevilled Viking studies, and indeed Russian history, for well over a century. It is historically certain that the Rus were Swedes. The evidence is incontrovertible, and that a debate still lingers at some levels of historical writing is clear evidence of the holding power of received notions. The debate over this issue – futile, embittered, tendentious, doctrinaire – served to obscure the most serious and genuine historical problem which remains: the assimilation of these Viking Rus into the Slavic people among whom they lived. The principal historical question is not whether the Rus were Scandinavians or Slavs, but, rather, how quickly these Scandinavian Rus became absorbed into Slavic life and culture.»

- ^ Janet Martin, From Kiev to Muscovy: The Beginnings to 1450, in Russia: A History (Oxford Press, 1997, edited by Gregory Freeze), p. 2.

- ^ Magocsi (2010), p. 55.

- ^ Elena Melnikova, ‘The «Varangian Problem»: Science in the Grip of Ideology and Politics’, in Russia’s Identity in International Relations: Images, Perceptions, Misperceptions, ed. by Ray Taras (Abingdon: Routledge, 2013), pp. 42–52.

- ^ Jonathan Shepherd, «Review Article: Back in Old Rus and the USSR: Archaeology, History and Politics», English Historical Review, vol. 131 (no. 549) (2016), 384–405 doi:10.1093/ehr/cew104 (p. 387), citing Leo S. Klejn, Soviet Archaeology: Trends, Schools, and History, trans. by Rosh Ireland and Kevin Windle (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), p. 119.

- ^ Artem Istranin and Alexander Drono, «Competing historical Narratives in Russian Textbooks», in Mutual Images: Textbook Representations of Historical Neighbours in the East of Europe, ed. by János M. Bak and Robert Maier, Eckert. Dossiers, 10 ([Braunschweig]: Georg Eckert Institute for International Textbook Research, 2017), 31–43 (pp. 35–36).

- ^ «Kievan Rus». World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ Nikolay Karamzin (1818). History of the Russian State. Stuttgart: Steiner.

- ^ Sergey Solovyov (1851). History of Russia from the Earliest Times. Stuttgart: Steiner.

- ^ Magocsi (2010), p. 56.

- ^ Nicholas V. Riasanovsky, A History of Russia, pp. 23–28 (Oxford Press, 1984).

- ^ Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine Normanist theory

- ^ The Russian Primary Chronicle, Encyclopædia Britannica Online; Russian Primary Chronicle Archived 30 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Selected Text, University of Toronto (retrieved 4 June 2013).

- ^ Riasanovsky, p. 25.

- ^ Riasanovsky, pp. 25–27.

- ^ David R. Stone, A Military History of Russia: From Ivan the Terrible to the war in Chechnya (2006), pp. 2–3.

- ^ Williams, Tom (28 February 2014). «Vikings in Russia». blog.britishmuseum.org. The British Museum. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

Objects now on loan to the British Museum for the BP exhibition Vikings: life and legend indicate the extent of Scandinavian settlement from the Baltic to the Black Sea . . .

- ^ Franklin, Simon; Shepherd, Jonathan (1996). The Emergence of Rus: 750–1200. Longman History of Russia. Essex: Harlow. ISBN 0-582-49090-1.

- ^ Logan, F. Donald (2005). The Vikings in History. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-32756-3. p. 184

- ^ Fadlan, Ibn (2005). (Richard Frey) Ibn Fadlan’s Journey to Russia. Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers.

- ^ Rusios, quos alio nos nomine Nordmannos apellamus. (in Polish) Henryk Paszkiewicz (2000). Wzrost potęgi Moskwy, s.13, Kraków. ISBN 83-86956-93-3

- ^ Gens quaedam est sub aquilonis parte constituta, quam a qualitate corporis Graeci vocant […] Rusios, nos vero a positione loci nominamus Nordmannos. James Lea Cate. Medieval and Historiographical Essays in Honor of James Westfall Thompson. p.482. The University of Chicago Press, 1938

- ^ Leo the Deacon, The History of Leo the Deacon: Byzantine Military Expansion in the Tenth Century (Alice-Mary Talbot & Denis Sullivan, eds., 2005), pp. 193–94.

- ^ Magocsi (2010), p. 59.

- ^ Primary Chronicle Archived 30 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, p.6.

- ^ Primary Chronicle Archived 2014-05-30 at the Wayback Machine, pp.6–7.

- ^ Magocsi (2010), pp. 55, 59–60

- ^ Thomas McCray, Russia and the Former Soviet Republics (2006), p. 26

- ^ a b Janet Martin, «The First East Slavic State», A Companion to Russian History (Abbott Gleason, ed., 2009), p. 37

- ^ a b c Primary Chronicle Archived 30 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, p.8.

- ^ Georgije Ostrogorski, History of the Byzantine State (2002), p.228; George Majeska, «Rusʹ and the Byzantine Empire», A Companion to Russian History (Abbott Gleason, ed., 2009), p.51.

- ^ F. Donald Logan, The Vikings in History (2005), pp.172–73.

- ^ The Life of St. George of Amastris describes the Rusʹ as a barbaric people «who are brutal and crude and bear no remnant of love for humankind.» David Jenkins, The Life of St. George of Amastris Archived 5 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine (University of Notre Dame Press, 2001), p.18.

- ^ Primary Chronicle Archived 30 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, p.8; Ostrogorski (2002), p.228; Majeska (2009), p.51.

- ^ a b c d e f Majeska (2009), p.52.

- ^ a b Dimitri Obolensky, Byzantium and the Slavs (1994), p.245.

- ^ Martin (1997), p. 3.

- ^ Martin (2009), pp. 37–40.

- ^ Primary Chronicle Archived 30 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, pp.8–9.

- ^ Primary Chronicle Archived 30 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, p. 9.

- ^ George Vernadsky, Kievan Russia (1976), p. 23.

- ^ a b Walter Moss, A History of Russia: To 1917 (2005), p. 37.

- ^ Magocsi (2010), p. 96

- ^ a b Martin (2009), p. 47.

- ^ a b Martin (2009), pp. 40, 47.

- ^ Perrie, Maureen; Lieven, D. C. B.; Suny, Ronald Grigor (2006). The Cambridge History of Russia: Volume 1, From Early Rusʹ to 1689. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81227-6.

- ^ a b Magocsi (2010), p. 62.

- ^ a b Magocsi (2010), p.66.

- ^ Martin (2003), pp. 16–19.

- ^ Victor Spinei, The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth Century (2009), pp. 47–49.

- ^ Peter B. Golden, Central Asia in World History (2011), p. 63.

- ^ Magocsi (2010), pp.62–63.

- ^ Vernadsky (1976), p. 20.

- ^ Majeska (2009), p. 51.

- ^ Angeliki Papageorgiou, «Theme of Cherson (Klimata)», Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World (Foundation of the Hellenic World, 2008).

- ^ Kevin Alan Brook, The Jews of Khazaria (2006), pp. 31–32.

- ^ Martin (2003), pp. 15–16.

- ^ Vernadsky (1976), pp.24–25.

- ^ Spanei (2009), p.62.

- ^ a b John V. A. Fine, The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century (1991), pp. 138–139.

- ^ a b Spanei (2009), pp. 66, 70.

- ^ Vernadsky (1976), p. 28.

- ^ B. N. Zakhoder (1898–1960). The Caspian Compilation of Records about Eastern Europe (online version).

- ^ Vernadsky (1976), pp. 32–33.

- ^ Gunilla Larsson. Ship and society: maritime ideology in Late Iron Age Sweden Uppsala Universitet, Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, 2007. ISBN 91-506-1915-2. p. 208.

- ^ Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique, Volume 35, Number 4. Mouton, 1994. (originally from the University of California, digitalised on 9 March 2010)

- ^ Moss (2005), p. 29.

- ^ a b Martin (2003), p. 17.

- ^ a b Magocsi (2010), p. 67.

- ^ The Russian Primary Chronicle, Laurentian Text (Samuel Hazzard Cross, trans., 1930), p. 71.

- ^ Moss (2005), pp.29–30.

- ^ Saints Cyril and Methodius, [1] Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Primary Chronicle, pp.62–63

- ^ Obolensky (1994), pp..244–246.

- ^ Magocsi (2010), pp.66–67

- ^ Vernadsky (1976), pp.28–31.

- ^ a b Vernadsky (1976), p.22.

- ^ John Lind, Varangians in Europe’s Eastern and Northern Periphery, Ennen & nyt (2004:4).

- ^ Logan (2005), p.192.

- ^ Vernadsky, pp.22–23

- ^ Chronicle, p.69

- ^ Chronicle, pp.71–72

- ^ a b c Ostrogorski, p.277

- ^ a b Logan, p.193.

- ^ Chronicle, p.72.

- ^ Chronicle, pp.73–78

- ^ Spinei, p.93.

- ^ «Vladimir I (grand prince of Kiev) – Encyclopædia Britannica». Britannica.com. 28 March 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ a b Janet Martin, Medieval Russia, 980–1584, (Cambridge, 1995), p. 6-7

- ^ Franklin, Simon (1992). «Greek in Kievan Rusʹ». Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 46: 69–81. doi:10.2307/1291640. JSTOR 1291640.

- ^ Colucci, Michele (1989). «The Image of Western Christianity in the Culture of Kievan Rusʹ». Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 12/13: 576–586.

- ^ «Yaroslav I (prince of Kiev) – Encyclopædia Britannica». Britannica.com. 22 May 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Thompson, John M. (John Means) (25 July 2017). Russia : a historical introduction from Kievan Rusʹ to the present. Ward, Christopher J., 1972– (Eighth ed.). New York, NY. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8133-4985-5. OCLC 987591571.

- ^ Franklin, Simon; Shepard, Jonathan (1996), The Emergence of Russia 750–1200, Routledge, pp. 323–4, ISBN 978-1-317-87224-5

- ^ Pelenski, Jaroslaw (1987). «The Sack of Kiev of 1169: Its Significance for the Succession to Kievan Rusʹ». Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 11: 303–316.

- ^ Kollmann, Nancy (1990). «Collateral Succession in Kievan Rus». Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 14: 377–387.

- ^ a b Magocsi 2010, p. 85.

- ^ Русина О.В. ВЕЛИКЕ КНЯЗІВСТВО ЛИТОВСЬКЕ // Енциклопедія історії України: Т. 1: А-В / Редкол.: В. А. Смолій (голова) та ін. НАН України. Інститут історії України. – К.: В-во «Наукова думка», 2003. – 688 с.: іл.

- ^ William H. McNeill (1 January 1979). Jean Cuisenier (ed.). Europe as a Cultural Area. World Anthropology. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-3-11-080070-8. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

For a while, it looked as if the Scandinavian thrust toward monarchy and centralization might succeed in building two impressive and imperial structures: a Danish empire of the northern seas, and a Varangian empire of the Russian rivers, headquartered at Kiev…. In the east, new hordes of steppe nomads, fresh from central Asia, intruded upon the river-based empire of the Varangians by taking over its southern portion.

- ^ Simon, Frank (1996). The Emergence of Rus, 750–1200. Longman. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-582-49091-8.

- ^ Martin, Janet (1995). Medieval Russia, 980–1584. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36832-4

- ^ История Европы с древнейших времен до наших дней. Т. 2. М.: Наука, 1988. ISBN 978-5-02-009036-1. С. 201.

- ^ «Medieval Sourcebook: Tables on Population in Medieval Europe». Fordham University. Archived from the original on 10 January 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^

Sherman, Charles Phineas (1917). «Russia». Roman Law in the Modern World. Boston: The Boston Book Company. p. 191.The adoption of Christianity by Vladimir… was followed by commerce with the Byzantine Empire. In its wake came Byzantine art and culture. And in the course of the next century, what is now Southeastern Russia became more advanced in civilization than any western European State of the period, for Russia came in for a share of Byzantine culture, then vastly superior to the rudeness of Western nations.

- ^ Tikhomirov, Mikhail Nikolaevich (1956). «Literacy among the citi dwellers». Drevnerusskie goroda (Cities of Ancient Rus) (in Russian). Moscow. p. 261. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2006.

- ^ Vernadsky, George (1973). «Russian Civilization in the Kievan Period: Education». Kievan Russia. Yale University Press. p. 426. ISBN 0-300-01647-6.

It is to the credit of Vladimir and his advisors they built not only churches but schools as well. This compulsory baptism was followed by compulsory education… Schools were thus founded not only in Kiev but also in provincial cities. From the «Life of St. Feodosi» we know that a school existed in Kursk around the year of 1023. By the time of Yaroslav’s reign (1019–54), education had struck roots and its benefits were apparent. Around 1030, Iaroslav founded a divinity school in Novgorod for 300 children of both laymen and clergy to be instructed in «book-learning». As a general measure, he made the parish priests «teach the people».

- ^ Miklashevsky, N.; et al. (2000). «Istoriya vodoprovoda v Rossii». ИСТОРИЯ ВОДОПРОВОДА В РОССИИ [History of water-supply in Russia] (in Russian). Saint Petersburg, Russia: ?. p. 240. ISBN 978-5-8206-0114-9.

- ^ «The most notable aspect of the criminal provisions was that punishments took the form of seizure of property, banishment, or, more often, payment of a fine. Even murder and other severe crimes (arson, organised horse thieving, and robbery) were settled by monetary fines. Although the death penalty had been introduced by Vladimir the Great, it too was soon replaced by fines.» Magocsi, Paul Robert (1996). A History of Ukraine, p. 90, Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-0830-5.

- ^ Tikhomirov, Mikhail Nikolaevich (1953). Пособие для изучения Русской Правды (in Russian) (2nd ed.). Moscow: Издание Московского университета. p. 190.

- ^ Janet Martin, Medieval Russia, 980–1584, (Cambridge, 1995), p. 72

- ^ Vernadsky, George (1973). «Social organization: Woman». Kievan Russia. Yale University Press. p. 426. ISBN 0-300-01647-6.

- ^ Janet Martin, Medieval Russia, 980–1584, (Cambridge, 1995), p. 61

- ^ J. Phillips, The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople page 144

- ^ Tikhomirov, Mikhail Nikolaevich (1956). «The origin of Russian cities». Drevnerusskie goroda (Cities of Ancient Rus) (in Russian). Moscow. pp. 36, 39, 43. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2006.

- ^ «In medieval Europe, a mark of a dynasty’s prestige and power was the willingness with which other leading dynasties entered into matrimonial relations with it. Measured by this standard, Yaroslav’s prestige must have been great indeed… . Little wonder that Iaroslav is often dubbed by historians as ‘the father-in-law of Europe.'» -(Subtelny, Orest (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-8020-5808-6.)

- ^ «By means of these marital ties, Kievan Rusʹ became well known throughout Europe.» —Magocsi, Paul Robert (1996). A History of Ukraine, p. 76, Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-0830-5.

- ^ Lowe, Steven; Ryaboy, Dmitriy V. The Pechenegs, History and Warfare.

- ^ Боняк [Boniak]. Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian). 1969–1978. Archived from the original on 6 July 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ Giovanni., Pian del Carpine (1903). Beazley, C. Raymond (ed.). The texts and versions of John De Plano Carpini and William De Rubruquis. London: Hakluyt Society. pp. 87–88. OCLC 733080786.

Quo facto, contra Russia perrexerunt, & mag nam stragem in ea fecerunt, ciuitates & castra destruxerunt, & homines occiderunt. Kiouiam, Russiæ metropolin, diu obsederunt, & tandem ceperunt, ac ciues interfecerunt. Vnde quando per illam terram ibamus, innumerabilia capita & ossa hominum mortuorum, iacentia super compum, inueniebamus. Fuerat enim vrbs valdè magna & populosa, nunc quasi ad nihilum est redacta : vix enim domus ibi remanserunt ducente, quarum etiam habitatores tenantur in maxima seruitute.

General sources

- Magocsi, Paul R. (2010). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-1021-7.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies. – Russia

Further reading

- Christian, David. A History of Russia, Mongolia and Central Asia. Blackwell, 1999.

- Franklin, Simon and Shepard, Jonathon, The Emergence of Rus, 750–1200. (Longman History of Russia, general editor Harold Shukman.) Longman, London, 1996. ISBN 0-582-49091-X