Считаем по-китайски

Несмотря на то, что китайская система чисел логична и последовательна, в ней есть некоторые особенности, с первого взгляда сложные для непосвящённого. Однако стоит лишь познакомиться с ними поближе — и всё становится на свои места. Уделив пару минут времени на изучение данного аспекта языка, вы в дальнейшем сможете писать, читать и считать самые сложные китайские числа.

Считаем от одного до ста

Единичные цифры просты, их список приведен ниже.

| Цифра | Китайский | Пиньинь |

| 0 | 零,〇 | líng |

| 1 | 一 | yī |

| 2 | 二 | èr |

| 3 | 三 | sān |

| 4 | 四 | sì |

| 5 | 五 | wǔ |

| 6 | 六 | liù |

| 7 | 七 | qī |

| 8 | 八 | bā |

| 9 | 九 | jiǔ |

| 10 | 十 | shí |

Числа от 11 до 19

Одиннадцать, двенадцать и другие числа до девятнадцати формируются вполне логично: иероглиф 十 shí, десять ставится перед единичной цифрой от одного 一 yī до девяти 九 jiǔ. Так одиннадцать — это 十一 shíyī, двенадцать 十二 shí’èr, тринадцать 十三 shísān и так далее, до девятнадцати 十九 shíjiǔ.

Примеры:

- 十一 shí yī 11

- 十二 shí èr 12

- 十三 shí sān 13

- 十四 shí sì 14

- 十五 shí wǔ 15

- 十六 shí liù 16

- 十七 shí qī 17

- 十八 shí bā 18

- 十九 shí jiǔ 19

Десятки

Если счёт пошёл на десятки, то уже перед иероглифом «десять» 十 shí ставится соответствующая количеству десятков цифра: двадцать — это 二十 èrshí, тридцать 三十 sānshí и так далее. После десятков ставятся единицы: двадцать три 二十三 èrshí sān, тридцать четыре 三十四 sānshí sì, девяносто девять 九十九 jiǔshí jiǔ. Всё логично и последовательно.

Только не забудьте, что число одиннадцать (и другие, см. примеры выше) — это не 一十一 yī shí yī, а просто 十一 shí yī. Иероглиф 一 yī в десятках используется только при написании более крупных чисел, например, 111, 1111 и т. д.

Примеры:

- 二十 èr shí 20

- 三十 sān shí 30

- 四十 sì shí 40

- 五十 wǔ shí 50

- 二十三 èr shí sān 23

- 三十九 sān shí jiǔ 39

- 四十四 sì shí sì 44

- 九十七 jiǔ shí qī 97

- 八十二 bā shí èr 82

- 七十三 qī shí sān 73

- 十一 shí yī 11

И, наконец, сто обозначается иероглифами 一百 yībǎi — одна сотня. Теперь вы знаете, как считать от одного до ста по-китайски.

После ста

От сотни до тысячи

Система с сотнями аналогична таковой с десятками. Для краткости: двести пятьдесят — это 二百五 èrbǎi wǔ. Однако если требуется поставить после числа счётное слово, то придется употребить в полном виде: 两百五十 (liǎng bǎi wǔshí — перед счётным словом с сотнями и более вместо 二 используется 两).

Примеры:

- 一百一十一 yī bǎi yī shí yī 111

- 一百一 yī bǎi yī 110

- 二百一十 èr bǎi yī shí 210

- 两百一十个人 liǎng bǎi yī shí gèrén 210 человек

- 三百五十 sān bǎi wǔ shí 350

- 九百九十 jiǔ bǎi jiǔ shí 990

- 八百七 bā bǎi qī 870

- 五百五 wǔ bǎi wǔ 550

- 四百六 sì bǎi liù 460

- 六百八十 liù bǎi bā shí 680

Число 101

Если посередине числа находится ноль, он обозначается иероглифом 零 или 〇 (líng — «ноль»). В конце нули не пишутся.

Примеры:

- 一百零一 yī bǎi líng yī 101

- 三百零五 sān bǎi líng wǔ 305

- 九百零九 jiǔ bǎi líng jiǔ 909

- 两百零六 liǎng bǎi líng liù 206

- 四百 sìbǎi 400

После тысячи

千 qiān с китайского — «тысяча». Правила аналогичны сотням, только вне зависимости от количества нулей посередине явно обозначается лишь один.

Примеры:

- 一千零一 yīqiān líng yī 1001

- 一千零一十 yīqiān líng yīshí 1010

- 一千零一十一 yīqiān líng yīshíyī 1011

- 一千零一十九 yīqiān líng yīshíjiǔ 1019

- 一千零二十 yīqiān líng èrshí 1020

- 一千一百 yīqiān yībǎi 1100

- 一千一百零一 yīqiān yībǎi líng yī 1101

- 一千一百一十 yīqiān yībǎi yīshí 1110

- 九千九百九十九 jiǔqiān jiǔbǎi jiǔshí jiǔ 9999

Больше примеров

| Цифра | Китайский | Пиньинь | Русский |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 一 | yī | один |

| 10 | 十 | shí | десять |

| 13 | 十三 | shísān | тринадцать |

| 20 | 二十 | èrshí | двадцать |

| 21 | 二十一 | èrshí yī | двадцать один |

| 99 | 九十九 | jiǔshí jiǔ | девяносто девять |

| 100 | 一百 | yībǎi | сто |

| 101 | 一百零一 | yībǎi líng yī | сто один |

| 110 | 一百一十 | yībǎi yīshí | сто десять |

| 119 | 一百一十九 | yībǎi yīshí jiǔ | сто девятнадцать |

Уникальные числа

В китайском языке есть две цифры, которых нет ни в русском, ни в английском (точнее, есть уникальные слова, обозначающие числа, которые в других языках являются комбинациями цифр).

- 万 wàn — 10 000, десять тысяч;

- 亿 yì — 100 000 000, сто миллионов.

万 wàn используется очень часто и является камнем преткновения для большинства изучающих китайский язык. В русском и других языках числа обычно разбиваются на разряды по три цифры с конца. Из-за наличия 万 в китайском лучше разбивать числа на группы по 4 цифры с конца, например:

- 一万二千 yī wàn èr qiān 1 2000 (вместо 12 000)

- 一万两千个人 yī wàn liǎng qiān gè rén 1 2000 человек

Разбейте число 12000 на разряды по 3 цифры — 12 000, и станет очевидно, что это двенадцать тысяч. Пойдя китайским путем, разбейте его на группы по 4, и получится 1 2000 一万二千 (yī wàn èr qiān, один вань и две тысячи) — всё просто и логично.

Еще примеры:

| Разряд по 3 | Русский | Разряд по 4 | Китайский | Пиньинь |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 000 | десять тысяч | 1 0000 | 一万 | yī wàn |

| 13 200 | тринадцать тысяч двести | 1 3200 | 一万三千二百 | yī wàn sānqiān èr bǎi |

| 56 700 | пятьдесят тысяч семьсот | 5 6700 | 五万六千七百 | wǔ wàn liùqiān qībǎi |

Считаем до 100 (一百)

11 (10 + 1) = 十一

15 (10 + 5) = 十五

20 (2 * 10) = 二十

23 (20 + 3) = 二十三

Считаем до 1000 (一千)

200 – (2 * 100) = 二百

876 – (8 * 100 + 70 + 6) = 八百七十六

Считаем до 10 000 (十千)

2000 – (2 * 1000) = 二千

7865 – (7 * 1000 + 800 + 60 + 5) = 七千八百六十五

Считаем до 100 000 (十万)

20 000 – (2 * 10 000) = 二万

86 532 – (8 * 10 000 + 6000 + 500 + 30 + 2) = 八万六千五百三十二

Считаем до 1 000 000 (百万)

500 000 – (50 * 10 000) = 五十万

734 876 – (73 * 10 000 + 4 * 1000 + 800 + 70 + 6) = 七十三万四千八百七十六

Считаем до 10 000 000 (一千万)

5 000 000 – (500 * 10 000) = 五百万

7 854 329 – (785 * 10 000 + 4 * 1000 + 300 + 20 + 9) = 七百八十五万四千三百二十九

Считаем до 100 000 000 (一亿)

25 000 000 – (2500 * 10 000) = 二千五百万

65 341 891 – (6534 * 10 000 + 1000 + 800 + 90 + 1) = 六千五百三十四万一千八百九十一

Считаем до 10 000 000 000 (十亿)

456 000 000 – (4 * 100 000 000 + 5600 * 10 000) = 四亿五千六百万

789 214 765 – (7 * 100 000 000 + 8921 * 10 000 + 4000 + 700 + 60 + 5) = 七亿八千九百二十一万四千七百六十五

Структура чисел в китайском языке

| 亿 | 千万 | 百万 | 十万 | 万 | 千 | 百 | 十 | 一 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yì | qiān wàn | bǎi wàn | shí wàn | wàn | qiān | bǎi | shí | yī |

| Сотни миллионов | Десятки миллионов | Миллионы | Сотни тысяч | Десятки тысяч | Тысячи | Сотни | Десятки | Единицы |

Большие числа

Как говорилось выше, в китайском языке числа делятся на разряды несколько иным образом, чем в русском. Мы привыкли разбивать большие числа на группы по количеству тысяч, китайцы же — по количеству десятков тысяч 万 wàn. Большинству изучающих китайский сложно понять эту структуру, но есть способы упростить её понимание и запомнить, как формируются даже очень большие цифры.

Десять тысяч 万 wàn

Число «десять тысяч» выражается одним иероглифом 万 wàn. К примеру, 11 000 на китайском не будет записано как 十一千 (shíyī qiān, одиннадцать тысяч), правильный вариант: 一万一千 (yī wàn yīqiān, один вань и одна тысяча). Самый простой способ запомнить это: отсчитывать четыре знака от конца числа и ставить запятую — тогда станет видно, где вань, а где тысячи.

Сто миллионов 亿 yì

После 99 999 999 следует другая уникальная китайская цифра 亿 yì, используемая для обозначения одной сотни миллионов. Число 1 101 110 000 будет записано как 十一亿零一百十一万 shíyī yì líng yībǎi shíyī wàn. Опять же, запомнить это проще, если разбить на 4 разряда.

Как запомнить

Ещё один способ запомнить, как пишутся большие китайские числа — это выучить некоторые из них. Один миллион, к примеру, 一百万 yībǎi wàn. Затем 一千万 (yīqiān wàn, десять миллионов). Этот путь проще потому, что вам не придется снова и снова считать множество нулей.

Стоит выучить наизусть:

- 一百万 (часто используется) yībǎi wàn миллион

- 十三亿 (население Китая) shísān yì 1,3 миллиарда человек

Примеры:

Вот еще некоторые примеры больших чисел на китайском:

- 52 152 = 五万二千一百五十二 wǔ wàn èrqiān yībǎi wǔ shí èr

- 27 214 896 = 二千七百二十一万四千八百九十六 èr qiān qībǎi èrshíyī wàn sìqiān bābǎi jiǔ shí liù

- 414 294 182 = 四亿一千四百二十九万四千一百八十二 sì yì yīqiān sìbǎi èrshíjiǔ wàn sìqiān yībǎi bāshí’èr

Дроби, проценты и отрицательные числа

Для обозначения процентов китайцы используют слово 百分之 bǎi fēn zhī, ставя его перед числом, например: 百分之五十六 (bǎi fēn zhī wǔshí liù, 56%).

Запятую в дробях выражают иероглифом 点 diǎn и после нее называют числа по порядку со всеми нулями, например: 123,00456 一百二十三点零零四五六 yībǎi èrshí sān diǎn líng líng sì wǔ liù.

Минус в отрицательных числах обозначают иероглифом 负 fù, например: -150 负一百五 fù yībǎi wǔ.

Гигантские числа

Здесь, просто для справки, мы приведем список китайских чисел по возрастанию вместе с количеством нулей после знака. А всех, кому хочется что-нибудь посчитать по-китайски приглашаем опробовать наш онлайн-конвертер чисел в иероглифы.

| Число | Пиньинь | Нули |

| 十 | shí | 1 |

| 百 | bǎi | 2 |

| 千 | qiān | 3 |

| 万 | wàn | 4 |

| 亿 | yì | 8 |

| 兆 | zhào | 12 |

| 京 | jīng | 16 |

| 垓 | gāi | 20 |

| 秭 | zǐ | 24 |

| 穰 | ráng | 28 |

| 沟 | gōu | 32 |

| 涧 | jiàn | 36 |

| 正 | zhèng | 40 |

| 载 | zài | 44 |

| 极恒河沙 | jí héng hé shā | 48 |

| 阿僧只 | ā sēng zhǐ | 52 |

| 那由他 | nà yóu tā | 56 |

| 不可思议 | bùkě sīyì | 60 |

| 无量 | wúliàng | 64 |

| 大数 | dà shù | 68 |

Китайские числительные – обозначение и произношение

Как и любая часть речи китайского языка, числительные требуют досконального изучения и практики. Если ехать в эту страну, в любом случае пригодиться составление чисел, ведь придется обращаться в магазины, кассы.

Содержание

- 1 Как выглядят цифры в Китае

- 2 Китайские цифры иероглифами

- 3 Счет по-китайски от 1 до 10 с обозначением и произношением

- 4 Цифры по-китайском от 11 до 100

- 4.1 Как написать десятки

- 5 Счетные слова: что это и для чего используются

- 6 Любимые и нелюбимые цифры китайцев

Как выглядят цифры в Китае

Логика и последовательность в написании китайских цифр-иероглифов есть и очень важно её запомнить. Обратить внимание, что некоторые чиста могут произносится практически одинаково.

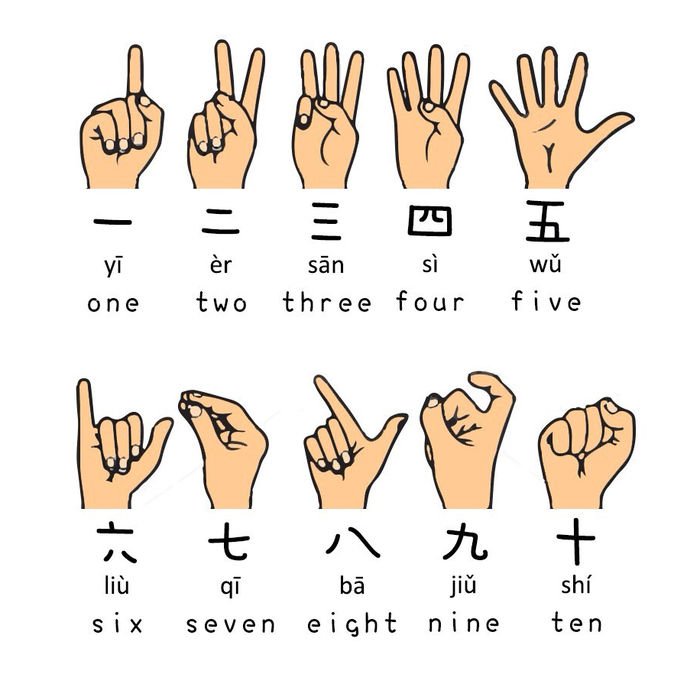

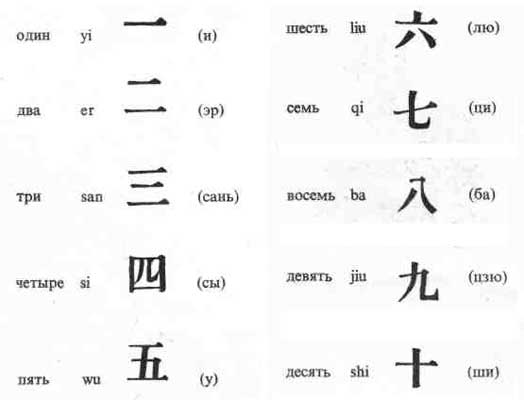

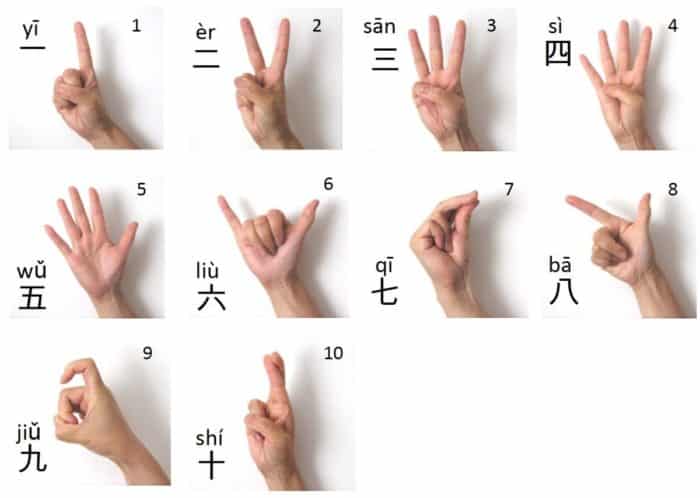

Чтобы знать китайские цифры от 1 до 10, нужно только запомнить написание иероглифов и их произношение. Пишутся они не сложно, особенно первые три цифры, которые изображаются в виде обычных горизонтальных линий. Немного сложнее будет запомнить, начиная с 4. Начиная с 11, нужно запоминать логические правила составления для каждого десятка.

Китайские цифры иероглифами

Как и буквы, в китайской письменности цифры обозначаются иероглифами. Для жителей европейских и американских стран это непривычная система символов. Кроме того, что нужно запомнить, как они правильно пишутся и выговариваются, учесть, что в китайском языке они не поддаются склонению по падежам, числам, родам.

Нужно запомнить и то, что в Китае есть два вида числительных. Обычный вид (форма) применяется в повседневном быту китайцев. Формальная запись применяется в официальных учреждениях: например, в магазинах (чеки). Цифры в формальной записи – это более усложненный вариант символов.

Китайские цифры от 1 до 10 выучить не сложно, главное запомнить само написание иероглифа и как он правильно произносится:

零 – 0 – líng

一 – 1 – yī – самый постой символ в китайском языке в виде обычной горизонтальной линии. Такими же простыми в написании являются 2 и 3.

二 – 2 – èr

三 – 3 – sān

四 – 4 – sì

五 – 5 – wǔ – ассоциируется с 5 элементами философии Китая.

六 – 6 – liù

七 – 7 – qī

八 – 8 – bā

九 – 9 – jiǔ

十 – 10 – shí

Цифры по-китайском от 11 до 100

Образование цифр до 99 имеет свои особенности. Запомнить правила не сложно.

Цифры от 11 до 19 формировать следующим образом: символ 十(10) ставят перед цифрой, которая обозначает единицы, т.е. если хотим сказать по-китайски 12, получится десять два.

Примеры формирования:

- 11 – 十一[shí yī]

- 12 – 十二 [shí èr]

- 13 – 十三 [shí sān]

- 14 – 十四 [shí sì]

- 15 – 十五 [shí wǔ]

- 16 – 十六 [shí liù]

- 17 – 十七 [shí qī]

- 18 – 十八 [shí bā]

- 19 – 十九 [shí jiǔ]

Как написать десятки

Для этого ставится китайский иероглиф, обозначающий «десять», а перед ним еще один иероглиф, который обозначает количество десятков. После знака «10» ставится единица.

Пример формирования:

20 – 二十 [èr shí, 2 + 10]

30 – 三十 [sān shí, 3 + 10]

70 – 七十 [qī shí, 7 + 10]

44 – 四十四 [sì shí sì, 4+10+4]

73 – 七十三 [qī shí sān, 7 + 10 + 3]

39 – 三十九 [sān shí jiǔ, 3 + 10 +9]

Если нужно сказать «100», то ставится иероглиф 一百 (yībǎi), что в переводе обозначает «первая сотня».

Счетные слова: что это и для чего используются

Для жителей России, которые изучают китайский, понятие «счетные слова» может показаться необычным. Но если обратить внимание, то они есть и в русском языке и часто стоят между самим числом и предметом, который исчисляет. Это могут быть слова «листы» – 3 листа бумаги, «пара» – 2 пары сапог, «штуки».

В китайском языке счетных слов намного больше – отдельное слово для каждой группы существительных. При одновременном использовании числа и счетного слова, словосочетания формируются по такой условной формуле: цифра + счетное слово + существительное.

На то, какое счетное слово выбрать, может повлиять признаки нескольких предметов – их размер, форма, состояние.

Если к существительному не подходит ни одно счетное слово (иероглиф), то можно использовать универсальные счетные слова, которые могут указывать на обобщенность слова или его нейтральность.

Те, кто только начал изучать китайский, должны запомнить, что счетное число ставится в обязательном порядке, если есть число и существительное возле него. Если иероглифы, к примеру, переводятся, как «два друга», то со счетным словом дословно перевод будет следующим «два штуки друга».

Любимые и нелюбимые цифры китайцев

Сегодня китайцы, как и сотни лет назад, продолжают чтить традиции. Если в планах есть посетить страну, то прежде, чем завести разговор с китайцем, в котором будут упомянуты цифры, лучше позаботиться об их правильном произношении и значении.

Какие цифры китайцы любят:

- Единицей обозначают первенство, лидерство в делах.

- Если перевести дословно произношение на русский, то оно будет обозначать «без проблем, гладко». Её ассоциируют с везением и удачей, благоприятными событиями. Особенно приносит удачу тем, кто занимается бизнесом или только начал его развивать. В самые большие государственные или личные праздники принято желать «двойную 6».

- В китайцев ассоциируется с богатством. Иногда дарят что-то или приносят именно в таком количестве, чтобы пожелать таким образом человеку больших денег и удачи. Приверженцы буддизма считают восьмерку чем-то сокровенным. Не зря ведь даже в 2008 году Олимпийские игры начались 8.08 в 8 вечера.

- Обозначает «длинный, долговременный». Чаще всего употребляется с понятием «вечная любовь», «гармония». Еще при императорах на его одежде рисовали 9 драконов, у каждого из них было по 9 детей (согласно древним мифам).

Положительно относятся они и к 10. Современное изображение и то, что было раньше, немного отличаются. Сегодня этот иероглиф ассоциируется с целостностью, завершенностью каких-то дел.

Цифры, которые китайцы обходят стороной:

- В прямом смысле слова китайцы боятся этой цифры. Для них она сравнима со смертью и способна навести ужас на местных жителей. Они стараются иметь минимальное количество «4» в своей жизни и не выбирают с ней номера квартир, телефонов. Если даже в кафе заказать столик на 4, то от официанта скорее можно услышать, что заказ на 3+1 человек, но цифра 4 не произносится. Но есть люди, которые не придерживаются этих суеверий – им намного проще морально. К тому же, имеют возможность приобрести вещи, связанные с цифрой «4» с огромной скидкой.

- Ассоциируется со скандалами и невезеньем. Хотя есть и неоднозначность этих данных – по китайским верованиям мир поделен на две части – Инь и Янь.

Изучать китайские цифры – не самое простое задание, но в этих знаниях есть последовательность и логика. Если её понять, то никакие сложности не будут страшны.

Ни у кого не возникнет сомнений в сложности китайского языка. Для его изучения лучше запастись терпением и приготовиться потратить кучу времени. Ведь китайские символы и цифры совершенно непохожи на те, что мы привыкли использовать каждый день.

Легко ли изучать?

Основная сложность в китайском языке – иероглифы. Древний алфавит Китая, изобретенный за 1500 тыс. лет до нашей эры, в настоящее время является уникальной и единственной в мире системой, где используются не буквы, а рисунки. Их настолько много, что запомнить все невозможно. Количество иероглифов достигает нескольких тысяч, именно поэтому его изучение – процесс долгий и кропотливый.

Китайская система, в отличие от своих собратьев, изобретенных в стародавние времена во многих древних цивилизациях, приспособилась к мировым изменениям, однако для самих китайцев является подходящим и традиционным способом письма и счета.

Для других людей сложны для восприятия не только слова, заключающиеся в таких рисунках, но и цифры на китайском языке. Ведь держать в голове столько изображений, обозначающих определенное количество, достаточно трудно.

Ну а самым простым аспектом, с которого начинают изучать этот язык, считаются простые цифры.

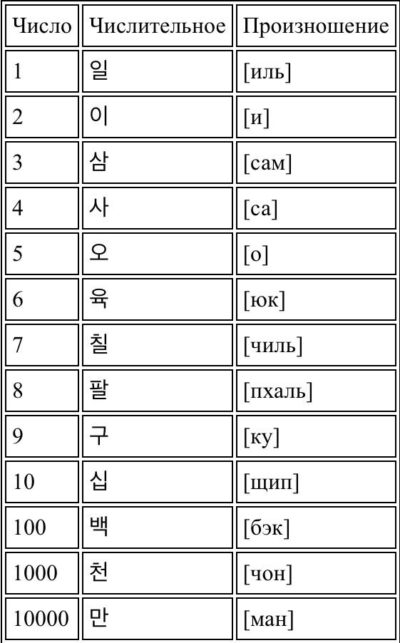

Учим счет от 1 до 10 с произношением

Но важны не только китайские иероглифы, но и их произношение. Счет от одного до десяти с русской транскрипцией:

- 1 (一) – Ии. Произносится с долгим звуком «и»;

- 2 (二) – Ар. Понизьте интонацию, произнося звук «р»;

- 3 (三) – Сан. Голос не изменяется;

- 4 (四) – Су. Интонация понижается;

- 5 (五) – Вуу. Вначале понизьте, а потом повысьте голос;

- 6 (六) – Лии-йу. Понижение голоса. При произношении звук «й» плавно переходит в «у», поэтому почти не слышится;

- 7 (七) – Чии. Голос не изменяется;

- 8 (八) – Баа. Интонация также не меняется.

- 9 (九) – Джии-йуу. Долгий звук «и», аналогично числу 6, переходит в длинное «у». Голос понижается в начале и после повышается;

- 10 (十) – Шур. Произносится с постепенным повышением голоса.

Немного об интонации. Повышение голоса означает изменение высоты, произношение похоже на то, будто вы задаете какой-то вопрос. Понижение – как будто вы говорите при вздохе.

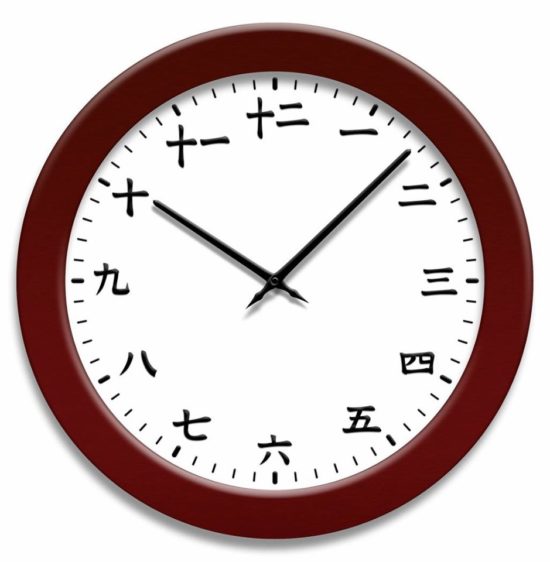

Цифры – довольно распространенные символы в любом языке. Они используются, когда мы хотим узнать сколько времени или цену на товар, при оплате в транспорте. Поэтому изучить их нужно как можно скорее.

Цифры от 11 и выше

Числа на китайском группируются в определенные разряды. Эта система логична и имеет определенную последовательность. Но не обошлось без своеобразных особенностей, которые сначала кажутся трудными для понимания.

В счете от 11 до 19 пишется иероглиф 10 (Шур), к которому прибавляются цифры от 1 до 9. Так, число 15 будет звучать как Шур Вуу (十一).

Практически по такой же логике складываются десятки. К числу 10 в этом случае прибавляется цифра, обозначающая количество десятков, в качестве приставки:

- 20 (二十) будет читаться как Аршур;

- 30 (三十) – Саншур;

- 40 (四十) – Сушур и так далее.

Числа от 100 и дальше строятся аналогично, в сопоставлении простых цифр. Здесь важно запомнить, как на китайском произносится 100 (一百) – «и бай».

Сложность в том, что к каждому числительному закреплен свой иероглиф. Поэтому запомнить такой поток рисунков могут только самые терпеливые и горящие настоящим желанием выучить китайский язык.

Как выглядят цифры в Китае

Свою особенность имеет цифра 2. Выступая в роли числительного, то есть, когда нам нужно что-то посчитать, она произносится ни «ар», а «лян», а выглядеть соответствующий иероглиф будет так: 两. Однако во множественных числах двойка сохраняет свою основную внешность. Поэтому фраза «22 книги» будет иметь перевод «二十二本书». Если же она повторяется несколько раз, то вначале пишется «лян», а последующие будут читаться как «ар».

В номерах телефонов цифра 2 будет обычной, а вот произношение единицы меняется. Вместо «Ии» диктуют «Яо» — yāo. Например, номер 16389294872 будет выглядеть как 幺六三八九二九四八七二.

Многие числа на китайском языке имеют одинаковое созвучие со словами. Этот факт не остался в стороне, а носители очень часто к этому прибегают. Так они могут рассказать о своей любви с помощью цифр 520 -我爱你.

Любимые и нелюбимые цифры китайцев

Китай – страна, где помнят и чтут традиции. Поэтому для того, чтобы разобраться в произношении некоторых чисел, нужно знать, что они значат для этого народа.

Свою любовь китайцы проявляют к:

- 1. Чаще всего она используется, чтобы обозначить лидерство или первостепенность – «первый в соревнованиях», «первый в университете», «первый прочитал эту книгу».

- 6. Русский перевод китайского иероглифа — «гладко, без проблем» — 溜 (顺溜 (shùnliu). Она ассоциируется с благоприятностью и везением и поэтому так полюбилась в Китае.

- 8. Похоже по звучанию со словом «богатство» -发. Китайцы любят пожелать больших денег, поэтому число считается удачным. Также восьмерка встречается в мифологии и у буддистов является чем-то сакральным.

- 9. Как «долгий» (久) звучит иероглиф девятки, что ассоциируется с вечной любовью.

Цифры, к которым относятся с опасением:

- Китайцы страдают от, так называемой, тетрофобии. Число 4 созвучно слову «смерть», что доводит жителей страны до дрожи. Избегают всего, что связано с четверкой: номеров телефонов, квартир, домов и даже этажей. Хотя в этом есть свои плюсы для тех, кто не подвержен суевериям: все такие предметы можно приобрести с огромной скидкой.

- Число 2 имеет неоднозначное положение в обществе китайцев. Его относят к несчастливым, так как оно связано со ссорами. Но одновременно по верованию жителей весь мир разделен на две части: черную и белую, более известные как Инь и Ян. Поэтому наряду с конфликтностью китайская двойка – символ брака и любви.

Заключение

Несмотря на всю сложность китайский язык достаточно логичен и последователен, а для терпеливого ученика это будет увлекательное погружение в мир китайской культуры. Изучение иероглифов откроет для Вас еще одну сторону – искусство каллиграфии, которое местные жители называют «музыкой для глаз».

Chinese numerals are words and characters used to denote numbers in Chinese.

Today, speakers of Chinese use three written numeral systems: the system of Arabic numerals used worldwide, and two indigenous systems. The more familiar indigenous system is based on Chinese characters that correspond to numerals in the spoken language. These may be shared with other languages of the Chinese cultural sphere such as Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese. Most people and institutions in China primarily use the Arabic or mixed Arabic-Chinese systems for convenience, with traditional Chinese numerals used in finance, mainly for writing amounts on cheques, banknotes, some ceremonial occasions, some boxes, and on commercials.[citation needed]

The other indigenous system consists of the Suzhou numerals, or huama, a positional system, the only surviving form of the rod numerals. These were once used by Chinese mathematicians, and later by merchants in Chinese markets, such as those in Hong Kong until the 1990s, but were gradually supplanted by Arabic numerals.

Characters used to represent numbers[edit]

Chinese and Arabic numerals may coexist, as on this kilometer marker: 1,620 km (1,010 mi) on Hwy G209 (G二〇九)

The Chinese character numeral system consists of the Chinese characters used by the Chinese written language to write spoken numerals. Similar to spelling-out numbers in English (e.g., «one thousand nine hundred forty-five»), it is not an independent system per se. Since it reflects spoken language, it does not use the positional system as in Arabic numerals, in the same way that spelling out numbers in English does not.

Standard numbers[edit]

There are characters representing the numbers zero through nine, and other characters representing larger numbers such as tens, hundreds, thousands, ten thousands and hundred millions. There are two sets of characters for Chinese numerals: one for everyday writing, known as xiǎoxiě (traditional Chinese: 小寫; simplified Chinese: 小写; lit. ‘small writing’), and one for use in commercial, accounting or financial contexts, known as dàxiě (traditional Chinese: 大寫; simplified Chinese: 大写; lit. ‘big writing’). The latter arose because the characters used for writing numerals are geometrically simple, so simply using those numerals cannot prevent forgeries in the same way spelling numbers out in English would.[1] A forger could easily change the everyday characters 三十 (30) to 五千 (5000) just by adding a few strokes. That would not be possible when writing using the financial characters 參拾 (30) and 伍仟 (5000). They are also referred to as «banker’s numerals», «anti-fraud numerals», or «banker’s anti-fraud numerals». For the same reason, rod numerals were never used in commercial records.

T denotes Traditional Chinese characters, while S denotes Simplified Chinese characters.

| Financial | Normal | Value | Pīnyīn (Mandarin) |

Jyutping (Cantonese) |

Pe̍h-ōe-jī (Hokkien) |

Wugniu (Shanghainese) |

Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Character (T) | Character (S) | Character (T) | Character (S) | |||||

| 零 | 零 | 〇 | 0 | líng | ling4 | khòng/lêng | lin | Usually 零 is preferred, but in some areas, 〇 may be a more common informal way to represent zero. The original Chinese character is 空 or 〇, 零 is referred as remainder something less than 1 yet not nil [說文] referred. The traditional 零 is more often used in schools. In Unicode, 〇 is treated as a Chinese symbol or punctuation, rather than a Chinese ideograph. |

| 壹 | 一 | 1 | yī | jat1 | it/chi̍t | iq | Also 弌 (obsolete financial), can be easily manipulated into 弍 (two) or 弎 (three). | |

| 貳 | 贰 | 二 | 2 | èr | ji6 | jī/nn̄g | gni/er/lian | Also 弍 (obsolete financial), can be easily manipulated into 弌 (one) or 弎 (three). Also 兩 (T) or 两 (S), see Characters with regional usage section. |

| 參 | 参 | 三 | 3 | sān | saam1 | sam/saⁿ | sé | Also 弎 (obsolete financial), which can be easily manipulated into 弌 (one) or 弍 (two). |

| 肆 | 四 | 4 | sì | sei3 | sù/sì | sy | Also 䦉 (obsolete financial)[nb 1] | |

| 伍 | 五 | 5 | wǔ | ng5 | ngó͘/gō͘ | ng | ||

| 陸 | 陆 | 六 | 6 | liù | luk6 | lio̍k/la̍k | loq | |

| 柒 | 七 | 7 | qī | cat1 | chhit | chiq | ||

| 捌 | 八 | 8 | bā | baat3 | pat/peh | paq | ||

| 玖 | 九 | 9 | jiǔ | gau2 | kiú/káu | cieu | ||

| 拾 | 十 | 10 | shí | sap6 | si̍p/cha̍p | zeq | Although some people use 什 as financial[citation needed], it is not ideal because it can be easily manipulated into 伍 (five) or 仟 (thousand). | |

| 佰 | 百 | 100 | bǎi | baak3 | pek/pah | paq | ||

| 仟 | 千 | 1,000 | qiān | cin1 | chhian/chheng | chi | ||

| 萬 | 萬 | 万 | 104 | wàn | maan6 | bān | ve | Chinese numbers group by ten-thousands; see Reading and transcribing numbers below. |

| 億 | 億 | 亿 | 105/108 | yì | jik1 | ek | i | For variant meanings and words for higher values, see Large numbers below and ja:大字 (数字). |

Characters with regional usage[edit]

| Financial | Normal | Value | Pinyin (Mandarin) | Standard alternative | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 空 | 0 | kòng | 零 | Historically, the use of 空 for «zero» predates 零. This is now archaic in most varieties of Chinese, but it is still used in Southern Min. | |

| 洞 | 0 | dòng | 零 | Literally means «a hole» and is analogous to the shape of «0» and «〇», it is used to unambiguously pronounce «#0» in radio communication. [2][3] | |

| 幺 | 1 | yāo | 一 | Literally means «the smallest», it is used to unambiguously pronounce «#1» in radio communication. [2][3] This usage is not observed in Cantonese except for 十三幺 (a special winning hand) in Mahjong. | |

| 蜀 | 1 | shǔ | 一 | In most Min varieties, there are two words meaning «one». For example, in Hokkien, chi̍t is used before a classifier: «one person» is chi̍t ê lâng, not it ê lâng. In written Hokkien, 一 is often used for both chi̍t and it, but some authors differentiate, writing 蜀 for chi̍t and 一 for it. | |

| 兩(T) or 两(S) |

2 | liǎng | 二 | Used instead of 二 before a classifier. For example, «two people» is «两个人», not «二个人». However, in some lects, such as Shanghainese, 兩 is the generic term used for two in most contexts, such as «四十兩» and not «四十二». It appears where «a pair of» would in English, but 两 is always used in such cases. It is also used for numbers, with usage varying from dialect to dialect, even person to person. For example, «2222» can be read as «二千二百二十二», «兩千二百二十二» or even «兩千兩百二十二» in Mandarin. It is used to unambiguously pronounce «#2» in radio communication. [2][3] | |

| 倆(T) or 俩(S) |

2 | liǎ | 兩 | In regional dialects of Northeastern Mandarin, 倆 represents a «lazy» pronunciation of 兩 within the local dialect. It can be used as an alternative for 兩个 «two of» (e.g. 我们倆 Wǒmen liǎ, «the two of us», as opposed to 我们兩个 Wǒmen liǎng gè). A measure word (such as 个) never follows after 倆. | |

| 仨 | 3 | sā | 三 | In regional dialects of Northeastern Mandarin, 仨 represents a «lazy» pronunciation of three within the local dialect. It can be used as a general number to represent «three» (e.g.第仨号 dì sā hào, «number three»; 星期仨 xīngqīsā, «Wednesday»), or as an alternative for 三个 «three of» (e.g. 我们仨 Wǒmen sā, «the three of us», as opposed to 我们三个 Wǒmen sān gè). Regardless of usage, a measure word (such as 个) never follows after 仨. | |

| 拐 | 7 | guǎi | 七 | Literally means «a turn» or «a walking stick» and is analogous to the shape of «7» and «七», it is used to unambiguously pronounce «#7» in radio communication. [2][3] | |

| 勾 | 9 | gōu | 九 | Literally means «a hook» and is analogous to the shape of «9», it is used to unambiguously pronounce «#9» in radio communication. [2][3] | |

| 呀 | 10 | yà | 十 | In spoken Cantonese, 呀 (aa6) can be used in place of 十 when it is used in the middle of a number, preceded by a multiplier and followed by a ones digit, e.g. 六呀三, 63; it is not used by itself to mean 10. This usage is not observed in Mandarin. | |

| 念 | 廿 | 20 | niàn | 二十 | A contraction of 二十. The written form is still used to refer to dates, especially Chinese calendar dates. Spoken form is still used in various dialects of Chinese. See Reading and transcribing numbers section below. In spoken Cantonese, 廿 (jaa6) can be used in place of 二十 when followed by another digit such as in numbers 21-29 (e.g. 廿三, 23), a measure word (e.g. 廿個), a noun, or in a phrase like 廿幾 («twenty-something»); it is not used by itself to mean 20. 卄 is a rare variant. |

| 卅 | 30 | sà | 三十 | A contraction of 三十. The written form is still used to abbreviate date references in Chinese. For example, May 30 Movement (五卅運動). Spoken form is still used in various dialects of Chinese. In spoken Cantonese, 卅 (saa1) can be used in place of 三十 when followed by another digit such as in numbers 31–39, a measure word (e.g. 卅個), a noun, or in phrases like 卅幾 («thirty-something»); it is not used by itself to mean 30. When spoken 卅 is pronounced as 卅呀 (saa1 aa6). Thus 卅一 (31), is pronounced as saa1 aa6 jat1. |

|

| 卌 | 40 | xì | 四十 | A contraction of 四十. Found in historical writings written in Classical Chinese. Spoken form is still used in various dialects of Chinese, albeit very rare. See Reading and transcribing numbers section below. In spoken Cantonese 卌 (sei3) can be used in place of 四十 when followed by another digit such as in numbers 41–49, a measure word (e.g. 卌個), a noun, or in phrases like 卌幾 («forty-something»); it is not used by itself to mean 40. When spoken, 卌 is pronounced as 卌呀 (sei3 aa6). Thus 卌一 (41), is pronounced as sei3 aa6 jat1. |

|

| 皕 | 200 | bì | 二百 | Very rarely used; one example is in the name of a library in Huzhou, 皕宋樓 (Bìsòng Lóu). |

Large numbers[edit]

For numbers larger than 10,000, similarly to the long and short scales in the West, there have been four systems in ancient and modern usage. The original one, with unique names for all powers of ten up to the 14th, is ascribed to the Yellow Emperor in the 6th century book by Zhen Luan, Wujing suanshu (Arithmetic in Five Classics). In modern Chinese only the second system is used, in which the same ancient names are used, but each represents a number 10,000 (myriad, 萬 wàn) times the previous:

| Character (T) | 萬 | 億 | 兆 | 京 | 垓 | 秭 | 穰 | 溝 | 澗 | 正 | 載 | Factor of increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Character (S) | 万 | 亿 | 兆 | 京 | 垓 | 秭 | 穰 | 沟 | 涧 | 正 | 载 | |

| Pinyin | wàn | yì | zhào | jīng | gāi | zǐ | ráng | gōu | jiàn | zhèng | zǎi | |

| Jyutping | maan6 | jik1 | siu6 | ging1 | goi1 | zi2 | joeng4 | kau1 | gaan3 | zing3 | zoi2 | |

| Hokkien POJ | bān | ek | tiāu | keng | kai | chí | jiông | ko͘ | kàn | chèng | cháiⁿ | |

| Shanghainese | ve | i | zau | cín | ké | tsy | gnian | kéu | ké | tsen | tse | |

| Alternative | 經/经 | 𥝱 | 壤 | |||||||||

| Rank | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | =n |

| «short scale» (下數) |

104 | 105 | 106 | 107 | 108 | 109 | 1010 | 1011 | 1012 | 1013 | 1014 | =10n+3

Each numeral is 10 (十 shí) times the previous. |

| «myriad scale» (萬進, current usage) |

104 | 108 | 1012 | 1016 | 1020 | 1024 | 1028 | 1032 | 1036 | 1040 | 1044 | =104n

Each numeral is 10,000 (萬 (T) or 万 (S) wàn) times the previous. |

| «mid-scale» (中數) |

104 | 108 | 1016 | 1024 | 1032 | 1040 | 1048 | 1056 | 1064 | 1072 | 1080 | =108(n-1)

Starting with 亿, each numeral is 108 (萬乘以萬 (T) or 万乘以万 (S) wàn chéng yǐ wàn, 10000 times 10000) times the previous. |

| «long scale» (上數) |

104 | 108 | 1016 | 1032 | 1064 | 10128 | 10256 | 10512 | 101024 | 102048 | 104096 | =102n+1

Each numeral is the square of the previous. This is similar to the -yllion system. |

In practice, this situation does not lead to ambiguity, with the exception of 兆 (zhào), which means 1012 according to the system in common usage throughout the Chinese communities as well as in Japan and Korea, but has also been used for 106 in recent years (especially in mainland China for megabyte). To avoid problems arising from the ambiguity, the PRC government never uses this character in official documents, but uses 万亿 (wànyì) or 太 (tài, as the translation for tera) instead. Partly due to this, combinations of 万 and 亿 are often used instead of the larger units of the traditional system as well, for example 亿亿 (yìyì) instead of 京. The ROC government in Taiwan uses 兆 (zhào) to mean 1012 in official documents.

Large numbers from Buddhism[edit]

Numerals beyond 載 zǎi come from Buddhist texts in Sanskrit, but are mostly found in ancient texts. Some of the following words are still being used today, but may have transferred meanings.

| Character (T) | Character (S) | Pinyin | Jyutping | Hokkien POJ | Shanghainese | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 極 | 极 | jí | gik1 | ke̍k | jiq5 | 1048 | Literally means «Extreme». |

| 恆河沙 | 恒河沙 | héng hé shā | hang4 ho4 sa1 | hêng-hô-soa | ghen3-wu-so | 1052[citation needed] | Literally means «Sands of the Ganges»; a metaphor used in a number of Buddhist texts referring to the grains of sand in the Ganges River. |

| 阿僧祇 | ā sēng qí | aa1 zang1 kei4 | a-seng-kî | a1-sen-ji | 1056 | From Sanskrit Asaṃkhyeya असंख्येय, meaning «incalculable, innumerable, infinite». | |

| 那由他 | nà yóu tā | naa5 jau4 taa1 | ná-iû-thaⁿ | na1-yeu-tha | 1060 | From Sanskrit nayuta नियुत, meaning «myriad». | |

| 不可思議 | 不可思议 | bùkě sīyì | bat1 ho2 si1 ji3 | put-khó-su-gī | peq4-khu sy1-gni | 1064 | Literally translated as «unfathomable». This word is commonly used in Chinese as a chengyu, meaning «unimaginable», instead of its original meaning of the number 1064. |

| 無量大數 | 无量大数 | wú liàng dà shù | mou4 loeng6 daai6 sou3 | bû-liōng tāi-siàu | m3-lian du3-su | 1068 | «无量» literally translated as «without measure», and can mean 1068. This word is also commonly used in Chinese as a commendatory term, means «no upper limit». E.g.: 前途无量 lit. front journey no limit, which means «a great future». «大数» literally translated as «a large number; the great number», and can mean 1072. |

Small numbers[edit]

The following are characters used to denote small order of magnitude in Chinese historically. With the introduction of SI units, some of them have been incorporated as SI prefixes, while the rest have fallen into disuse.

| Character(s) (T) | Character(s) (S) | Pinyin | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 漠 | mò | 10−12 | (Ancient Chinese)

皮 corresponds to the SI prefix pico-. |

|

| 渺 | miǎo | 10−11 | (Ancient Chinese) | |

| 埃 | āi | 10−10 | (Ancient Chinese) | |

| 塵 | 尘 | chén | 10−9 | Literally, «Dust»

奈 (T) or 纳 (S) corresponds to the SI prefix nano-. |

| 沙 | shā | 10−8 | Literally, «Sand» | |

| 纖 | 纤 | xiān | 10−7 | Literally, «Fiber» |

| 微 | wēi | 10−6 | still in use, corresponds to the SI prefix micro-. | |

| 忽 | hū | 10−5 | (Ancient Chinese) | |

| 絲 | 丝 | sī | 10−4 | also 秒.

Literally, «Thread» |

| 毫 | háo | 10−3 | also 毛.

still in use, corresponds to the SI prefix milli-. |

|

| 厘 | lí | 10−2 | also 釐.

still in use, corresponds to the SI prefix centi-. |

|

| 分 | fēn | 10−1 | still in use, corresponds to the SI prefix deci-. |

Small numbers from Buddhism[edit]

| Character(s) (T) | Character(s) (S) | Pinyin | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 涅槃寂靜 | 涅槃寂静 | niè pán jì jìng | 10−24 | Literally, «Nirvana’s Tranquility»

攸 (T) or 幺 (S) corresponds to the SI prefix yocto-. |

| 阿摩羅 | 阿摩罗 | ā mó luó | 10−23 | (Ancient Chinese, from Sanskrit अमल amala) |

| 阿頼耶 | 阿赖耶 | ā lài yē | 10−22 | (Ancient Chinese, from Sanskrit आलय ālaya) |

| 清靜 | 清净 | qīng jìng | 10−21 | Literally, «Quiet»

介 (T) or 仄 (S) corresponds to the SI prefix zepto-. |

| 虛空 | 虚空 | xū kōng | 10−20 | Literally, «Void» |

| 六德 | liù dé | 10−19 | (Ancient Chinese) | |

| 剎那 | 刹那 | chà nà | 10−18 | Literally, «Brevity», from Sanskrit क्षण ksaṇa

阿 corresponds to the SI prefix atto-. |

| 彈指 | 弹指 | tán zhǐ | 10−17 | Literally, «Flick of a finger». Still commonly used in the phrase «弹指一瞬间» (A very short time) |

| 瞬息 | shùn xī | 10−16 | Literally, «Moment of Breath». Still commonly used in Chengyu «瞬息万变» (Many things changed in a very short time) | |

| 須臾 | 须臾 | xū yú | 10−15 | (Ancient Chinese, rarely used in Modern Chinese as «a very short time»)

飛 (T) or 飞 (S) corresponds to the SI prefix femto-. |

| 逡巡 | qūn xún | 10−14 | (Ancient Chinese) | |

| 模糊 | mó hu | 10−13 | Literally, «Blurred» |

SI prefixes[edit]

In the People’s Republic of China, the early translation for the SI prefixes in 1981 was different from those used today. The larger (兆, 京, 垓, 秭, 穰) and smaller Chinese numerals (微, 纖, 沙, 塵, 渺) were defined as translation for the SI prefixes as mega, giga, tera, peta, exa, micro, nano, pico, femto, atto, resulting in the creation of yet more values for each numeral.[4]

The Republic of China (Taiwan) defined 百萬 as the translation for mega and 兆 as the translation for tera. This translation is widely used in official documents, academic communities, informational industries, etc. However, the civil broadcasting industries sometimes use 兆赫 to represent «megahertz».

Today, the governments of both China and Taiwan use phonetic transliterations for the SI prefixes. However, the governments have each chosen different Chinese characters for certain prefixes. The following table lists the two different standards together with the early translation.

| Value | Symbol | English | Early translation | PRC standard | ROC standard | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1024 | Y | yotta- | 尧 | yáo | 佑 | yòu | ||

| 1021 | Z | zetta- | 泽 | zé | 皆 | jiē | ||

| 1018 | E | exa- | 穰[4] | ráng | 艾 | ài | 艾 | ài |

| 1015 | P | peta- | 秭[4] | zǐ | 拍 | pāi | 拍 | pāi |

| 1012 | T | tera- | 垓[4] | gāi | 太 | tài | 兆 | zhào |

| 109 | G | giga- | 京[4] | jīng | 吉 | jí | 吉 | jí |

| 106 | M | mega- | 兆[4] | zhào | 兆 | zhào | 百萬 | bǎiwàn |

| 103 | k | kilo- | 千 | qiān | 千 | qiān | 千 | qiān |

| 102 | h | hecto- | 百 | bǎi | 百 | bǎi | 百 | bǎi |

| 101 | da | deca- | 十 | shí | 十 | shí | 十 | shí |

| 100 | (base) | one | 一 | yī | 一 | yī | ||

| 10−1 | d | deci- | 分 | fēn | 分 | fēn | 分 | fēn |

| 10−2 | c | centi- | 厘 | lí | 厘 | lí | 厘 | lí |

| 10−3 | m | milli- | 毫 | háo | 毫 | háo | 毫 | háo |

| 10−6 | µ | micro- | 微[4] | wēi | 微 | wēi | 微 | wēi |

| 10−9 | n | nano- | 纖[4] | xiān | 纳 | nà | 奈 | nài |

| 10−12 | p | pico- | 沙[4] | shā | 皮 | pí | 皮 | pí |

| 10−15 | f | femto- | 塵[4] | chén | 飞 | fēi | 飛 | fēi |

| 10−18 | a | atto- | 渺[4] | miǎo | 阿 | à | 阿 | à |

| 10−21 | z | zepto- | 仄 | zè | 介 | jiè | ||

| 10−24 | y | yocto- | 幺 | yāo | 攸 | yōu |

Reading and transcribing numbers[edit]

Whole numbers[edit]

Multiple-digit numbers are constructed using a multiplicative principle; first the digit itself (from 1 to 9), then the place (such as 10 or 100); then the next digit.

In Mandarin, the multiplier 兩 (liǎng) is often used rather than 二 (èr) for all numbers 200 and greater with the «2» numeral (although as noted earlier this varies from dialect to dialect and person to person). Use of both 兩 (liǎng) or 二 (èr) are acceptable for the number 200. When writing in the Cantonese dialect, 二 (yi6) is used to represent the «2» numeral for all numbers. In the southern Min dialect of Chaozhou (Teochew), 兩 (no6) is used to represent the «2» numeral in all numbers from 200 onwards. Thus:

| Number | Structure | Characters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandarin | Cantonese | Chaozhou | Shanghainese | ||

| 60 | [6] [10] | 六十 | 六十 | 六十 | 六十 |

| 20 | [2] [10] or [20] | 二十 | 二十 or 廿 | 二十 | 廿 |

| 200 | [2] (èr or liǎng) [100] | 二百 or 兩百 | 二百 or 兩百 | 兩百 | 兩百 |

| 2000 | [2] (èr or liǎng) [1000] | 二千 or 兩千 | 二千 or 兩千 | 兩千 | 兩千 |

| 45 | [4] [10] [5] | 四十五 | 四十五 or 卌五 | 四十五 | 四十五 |

| 2,362 | [2] [1000] [3] [100] [6] [10] [2] | 兩千三百六十二 | 二千三百六十二 | 兩千三百六十二 | 兩千三百六十二 |

For the numbers 11 through 19, the leading «one» (一; yī) is usually omitted. In some dialects, like Shanghainese, when there are only two significant digits in the number, the leading «one» and the trailing zeroes are omitted. Sometimes, the one before «ten» in the middle of a number, such as 213, is omitted. Thus:

| Number | Strict Putonghua | Colloquial or dialect usage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Characters | Structure | Characters | |

| 14 | [10] [4] | 十四 | ||

| 12000 | [1] [10000] [2] [1000] | 一萬兩千 | [1] [10000] [2] | 一萬二 or 萬二 |

| 114 | [1] [100] [1] [10] [4] | 一百一十四 | [1] [100] [10] [4] | 一百十四 |

| 1158 | [1] [1000] [1] [100] [5] [10] [8] | 一千一百五十八 | See note 1 below |

Notes:

- Nothing is ever omitted in large and more complicated numbers such as this.

In certain older texts like the Protestant Bible or in poetic usage, numbers such as 114 may be written as [100] [10] [4] (百十四).

Outside of Taiwan, digits are sometimes grouped by myriads instead of thousands. Hence it is more convenient to think of numbers here as in groups of four, thus 1,234,567,890 is regrouped here as 12,3456,7890. Larger than a myriad, each number is therefore four zeroes longer than the one before it, thus 10000 × wàn (萬) = yì (億). If one of the numbers is between 10 and 19, the leading «one» is omitted as per the above point. Hence (numbers in parentheses indicate that the number has been written as one number rather than expanded):

| Number | Structure | Taiwan | Mainland China |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12,345,678,902,345 (12,3456,7890,2345) |

(12) [1,0000,0000,0000] (3456) [1,0000,0000] (7890) [1,0000] (2345) | 十二兆三千四百五十六億七千八百九十萬兩千三百四十五 | 十二兆三千四百五十六亿七千八百九十万二千三百四十五 |

In Taiwan, pure Arabic numerals are officially always and only grouped by thousands.[5] Unofficially, they are often not grouped, particularly for numbers below 100,000. Mixed Arabic-Chinese numerals are often used in order to denote myriads. This is used both officially and unofficially, and come in a variety of styles:

| Number | Structure | Mixed numerals |

|---|---|---|

| 12,345,000 | (1234) [1,0000] (5) [1,000] | 1,234萬5千[6] |

| 123,450,000 | (1) [1,0000,0000] (2345) [1,0000] | 1億2345萬[7] |

| 12,345 | (1) [1,0000] (2345) | 1萬2345[8] |

Interior zeroes before the unit position (as in 1002) must be spelt explicitly. The reason for this is that trailing zeroes (as in 1200) are often omitted as shorthand, so ambiguity occurs. One zero is sufficient to resolve the ambiguity. Where the zero is before a digit other than the units digit, the explicit zero is not ambiguous and is therefore optional, but preferred. Thus:

| Number | Structure | Characters |

|---|---|---|

| 205 | [2] [100] [0] [5] | 二百零五 |

| 100,004 (10,0004) |

[10] [10,000] [0] [4] | 十萬零四 |

| 10,050,026 (1005,0026) |

(1005) [10,000] (026) or (1005) [10,000] (26) |

一千零五萬零二十六 or 一千零五萬二十六 |

Fractional values[edit]

To construct a fraction, the denominator is written first, followed by 分; fēn; ‘parts’, then the literary possessive particle 之; zhī; ‘of this’, and lastly the numerator. This is the opposite of how fractions are read in English, which is numerator first. Each half of the fraction is written the same as a whole number. For example, to express «two thirds», the structure «three parts of-this two» is used. Mixed numbers are written with the whole-number part first, followed by 又; yòu; ‘and’, then the fractional part.

| Fraction | Structure |

|---|---|

| 2⁄3 |

三 sān 3 分 fēn parts 之 zhī of this 二 èr 2 |

| 15⁄32 |

三 sān 3 十 shí 10 二 èr 2 分 fēn parts 之 zhī of this 十 shí 10 五 wǔ 5 |

| 1⁄3000 |

三 sān 3 千 qiān 1000 分 fēn parts 之 zhī of this 一 yī 1 |

| 3 5⁄6 |

三 sān 3 又 yòu and 六 liù 6 分 fēn parts 之 zhī of this 五 wǔ 5 |

Percentages are constructed similarly, using 百; bǎi; ‘100’ as the denominator. (The number 100 is typically expressed as 一百; yībǎi; ‘one hundred’, like the English «one hundred». However, for percentages, 百 is used on its own.)

| Percentage | Structure |

|---|---|

| 25% |

百 bǎi 100 分 fēn parts 之 zhī of this 二 èr 2 十 shí 10 五 wǔ 5 |

| 110% |

百 bǎi 100 分 fēn parts 之 zhī of this 一 yī 1 百 bǎi 100 一 yī 1 十 shí 10 |

Because percentages and other fractions are formulated the same, Chinese are more likely than not to express 10%, 20% etc. as «parts of 10» (or 1/10, 2/10, etc. i.e. 十分之一; shí fēnzhī yī, 十分之二; shí fēnzhī èr, etc.) rather than «parts of 100» (or 10/100, 20/100, etc. i.e. 百分之十; bǎi fēnzhī shí, 百分之二十; bǎi fēnzhī èrshí, etc.)

In Taiwan, the most common formation of percentages in the spoken language is the number per hundred followed by the word 趴; pā, a contraction of the Japanese パーセント; pāsento, itself taken from the English «percent». Thus 25% is 二十五趴; èrshíwǔ pā.[nb 2]

Decimal numbers are constructed by first writing the whole number part, then inserting a point (simplified Chinese: 点; traditional Chinese: 點; pinyin: diǎn), and finally the fractional part. The fractional part is expressed using only the numbers for 0 to 9, similarly to English.

| Decimal expression | Structure |

|---|---|

| 16.98 |

十 shí 10 六 liù 6 點 diǎn point 九 jiǔ 9 八 bā 8 |

| 12345.6789 |

一 yī 1 萬 wàn 10000 兩 liǎng 2 千 qiān 1000 三 sān 3 百 bǎi 100 四 sì 4 十 shí 10 五 wǔ 5 點 diǎn point 六 liù 6 七 qī 7 八 bā 8 九 jiǔ 9 |

| 75.4025 |

七 七 qī 7 十 十 shí 10 五 五 wǔ 5 點 點 diǎn point 四 四 sì 4 〇 零 líng 0 二 二 èr 2 五 五 wǔ 5 |

| 0.1 |

零 líng 0 點 diǎn point 一 yī 1 |

半; bàn; ‘half’ functions as a number and therefore requires a measure word. For example: 半杯水; bàn bēi shuǐ; ‘half a glass of water’.

Ordinal numbers[edit]

Ordinal numbers are formed by adding 第; dì («sequence») before the number.

| Ordinal | Structure |

|---|---|

| 1st |

第 dì sequence 一 yī 1 |

| 2nd |

第 dì sequence 二 èr 2 |

| 82nd |

第 dì sequence 八 bā 8 十 shí 10 二 èr 2 |

The Heavenly Stems are a traditional Chinese ordinal system.

Negative numbers[edit]

Negative numbers are formed by adding fù (负; 負) before the number.

| Number | Structure |

|---|---|

| −1158 |

負 fù negative 一 yī 1 千 qiān 1000 一 yī 1 百 bǎi 100 五 wǔ 5 十 shí 10 八 bā 8 |

| −3 5/6 |

負 fù negative 三 sān 3 又 yòu and 六 liù 6 分 fēn parts 之 zhī of this 五 wǔ 5 |

| −75.4025 |

負 fù negative 七 qī 7 十 shí 10 五 wǔ 5 點 diǎn point 四 sì 4 零 líng 0 二 èr 2 五 wǔ 5 |

Usage[edit]

Chinese grammar requires the use of classifiers (measure words) when a numeral is used together with a noun to express a quantity. For example, «three people» is expressed as 三个人; 三個人; sān ge rén , «three (ge particle) person», where 个/個 ge is a classifier. There exist many different classifiers, for use with different sets of nouns, although 个/個 is the most common, and may be used informally in place of other classifiers.

Chinese uses cardinal numbers in certain situations in which English would use ordinals. For example, 三楼/三樓; sān lóu (literally «three story/storey») means «third floor» («second floor» in British § Numbering). Likewise, 二十一世纪/二十一世紀; èrshí yī shìjì (literally «twenty-one century») is used for «21st century».[9]

Numbers of years are commonly spoken as a sequence of digits, as in 二零零一; èr líng líng yī («two zero zero one») for the year 2001.[10] Names of months and days (in the Western system) are also expressed using numbers: 一月; yīyuè («one month») for January, etc.; and 星期一; xīngqīyī («week one») for Monday, etc. There is only one exception: Sunday is 星期日; xīngqīrì, or informally 星期天; xīngqītiān, both literally «week day». When meaning «week», «星期» xīngqī and «禮拜; 礼拜» lǐbài are interchangeable. «禮拜天» lǐbàitiān or «禮拜日» lǐbàirì means «day of worship». Chinese Catholics call Sunday «主日» zhǔrì, «Lord’s day».[11]

Full dates are usually written in the format 2001年1月20日 for January 20, 2001 (using 年; nián «year», 月; yuè «month», and 日; rì «day») – all the numbers are read as cardinals, not ordinals, with no leading zeroes, and the year is read as a sequence of digits. For brevity the nián, yuè and rì may be dropped to give a date composed of just numbers. For example «6-4» in Chinese is «six-four», short for «month six, day four» i.e. June Fourth, a common Chinese shorthand for the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests (because of the violence that occurred on June 4). For another example 67, in Chinese is sixty seven, short for year nineteen sixty seven, a common Chinese shorthand for the Hong Kong 1967 leftist riots.

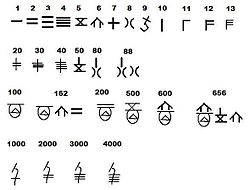

Counting rod and Suzhou numerals[edit]

In the same way that Roman numerals were standard in ancient and medieval Europe for mathematics and commerce, the Chinese formerly used the rod numerals, which is a positional system. The Suzhou numerals (simplified Chinese: 苏州花码; traditional Chinese: 蘇州花碼; pinyin: Sūzhōu huāmǎ) system is a variation of the Southern Song rod numerals. Nowadays, the huāmǎ system is only used for displaying prices in Chinese markets or on traditional handwritten invoices.

Hand gestures[edit]

Hand symbol for the number six

There is a common method of using of one hand to signify the numbers one to ten. While the five digits on one hand can easily express the numbers one to five, six to ten have special signs that can be used in commerce or day-to-day communication.

Historical use of numerals in China[edit]

Shang oracle bone numerals of 14th century B.C.[12]

West Zhou dynasty bronze script

Japanese counting board with grids

Most Chinese numerals of later periods were descendants of the Shang dynasty oracle numerals of the 14th century BC. The oracle bone script numerals were found on tortoise shell and animal bones. In early civilizations, the Shang were able to express any numbers, however large, with only nine symbols and a counting board though it was still not positional .[13]

Some of the bronze script numerals such as 1, 2, 3, 4, 10, 11, 12, and 13 became part of the system of rod numerals.

In this system, horizontal rod numbers are used for the tens, thousands, hundred thousands etc. It’s written in Sunzi Suanjing that «one is vertical, ten is horizontal».[14]

| 七 | 一 | 八 | 二 | 四 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 4 |

The counting rod numerals system has place value and decimal numerals for computation, and was used widely by Chinese merchants, mathematicians and astronomers from the Han dynasty to the 16th century.

In 690 AD, Empress Wǔ promulgated Zetian characters, one of which was «〇». The word is now used as a synonym for the number zero.[nb 3]

Alexander Wylie, Christian missionary to China, in 1853 already refuted the notion that «the Chinese numbers were written in words at length», and stated that in ancient China, calculation was carried out by means of counting rods, and «the written character is evidently a rude presentation of these». After being introduced to the rod numerals, he said «Having thus obtained a simple but effective system of figures, we find the Chinese in actual use of a method of notation depending on the theory of local value [i.e. place-value], several centuries before such theory was understood in Europe, and while yet the science of numbers had scarcely dawned among the Arabs.»[15]

During the Ming and Qing dynasties (after Arabic numerals were introduced into China), some Chinese mathematicians used Chinese numeral characters as positional system digits. After the Qing period, both the Chinese numeral characters and the Suzhou numerals were replaced by Arabic numerals in mathematical writings.

Cultural influences[edit]

Traditional Chinese numeric characters are also used in Japan and Korea and were used in Vietnam before the 20th century. In vertical text (that is, read top to bottom), using characters for numbers is the norm, while in horizontal text, Arabic numerals are most common. Chinese numeric characters are also used in much the same formal or decorative fashion that Roman numerals are in Western cultures. Chinese numerals may appear together with Arabic numbers on the same sign or document.

See also[edit]

- Chinese number gestures

- Numbers in Chinese culture

- Chinese units of measurement

- Chinese classifier

- Chinese grammar

- Japanese numerals

- Korean numerals

- Vietnamese numerals

- Celestial stem

- List of numbers in Sinitic languages

Notes[edit]

- ^ Variant Chinese character of 肆, with a 镸 radical next to a 四 character. Not all browsers may be able to display this character, which forms a part of the Unicode CJK Unified Ideographs Extension A group.

- ^ This usage can also be found in written sources, such as in the headline of this article (while the text uses «%») and throughout this article.

- ^ The code for the lowercase 〇 (IDEOGRAPHIC NUMBER ZERO) is U+3007, not to be confused with the O mark (CIRCLE).

References[edit]

- ^ 大寫數字『 Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e Li, Suming (18 March 2016). Qiao, Meng (ed.). ««军语»里的那些秘密 武警少将亲自为您揭开» [Secrets in the «Military Lingo», Reveled by PAP General]. People’s Armed Police. Retrieved 2021-06-18.

- ^ a b c d e 飛航管理程序 [Air Traffic Management Procedures] (14 ed.). 30 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k (in Chinese) 1981 Gazette of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China Archived 2012-01-11 at the Wayback Machine, No. 365 Archived 2014-11-04 at the Wayback Machine, page 575, Table 7: SI prefixes

- ^ 中華民國統計資訊網(專業人士). 中華民國統計資訊網 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ 中華民國統計資訊網(專業人士) (in Chinese). 中華民國統計資訊網. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ «石化氣爆 高市府代位求償訴訟中». 中央社即時新聞 CNA NEWS. 中央社即時新聞 CNA NEWS. Archived from the original on 1 August 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ «陳子豪雙響砲 兄弟連2天轟猿動紫趴». 中央社即時新聞 CNA NEWS. 中央社即時新聞 CNA NEWS. Archived from the original on 31 July 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ Yip, Po-Ching; Rimmington, Don, Chinese: A Comprehensive Grammar, Routledge, 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Yip, Po-Ching; Rimmington, Don, Chinese: A Comprehensive Grammar, Routledge, 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Days of the Week in Chinese: Three Different Words for ‘Week’ http://www.cjvlang.com/Dow/dowchin.html Archived 2016-03-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Shorter Science & Civilisation in China Vol 2, An abridgement by Colin Ronan of Joseph Needham’s original text, Table 20, p. 6, Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-23582-0

- ^ The Shorter Science & Civilisation in China Vol 2, An abridgement by Colin Ronan of Joseph Needham’s original text, p5, Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-23582-0

- ^ Chinese Wikisource Archived 2012-02-22 at the Wayback Machine 孫子算經: 先識其位,一從十橫,百立千僵,千十相望,萬百相當。

- ^ Alexander Wylie, Jottings on the Sciences of the Chinese, North Chinese Herald, 1853, Shanghai

Chinese numerals are words and characters used to denote numbers in Chinese.

Today, speakers of Chinese use three written numeral systems: the system of Arabic numerals used worldwide, and two indigenous systems. The more familiar indigenous system is based on Chinese characters that correspond to numerals in the spoken language. These may be shared with other languages of the Chinese cultural sphere such as Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese. Most people and institutions in China primarily use the Arabic or mixed Arabic-Chinese systems for convenience, with traditional Chinese numerals used in finance, mainly for writing amounts on cheques, banknotes, some ceremonial occasions, some boxes, and on commercials.[citation needed]

The other indigenous system consists of the Suzhou numerals, or huama, a positional system, the only surviving form of the rod numerals. These were once used by Chinese mathematicians, and later by merchants in Chinese markets, such as those in Hong Kong until the 1990s, but were gradually supplanted by Arabic numerals.

Characters used to represent numbers[edit]

Chinese and Arabic numerals may coexist, as on this kilometer marker: 1,620 km (1,010 mi) on Hwy G209 (G二〇九)

The Chinese character numeral system consists of the Chinese characters used by the Chinese written language to write spoken numerals. Similar to spelling-out numbers in English (e.g., «one thousand nine hundred forty-five»), it is not an independent system per se. Since it reflects spoken language, it does not use the positional system as in Arabic numerals, in the same way that spelling out numbers in English does not.

Standard numbers[edit]

There are characters representing the numbers zero through nine, and other characters representing larger numbers such as tens, hundreds, thousands, ten thousands and hundred millions. There are two sets of characters for Chinese numerals: one for everyday writing, known as xiǎoxiě (traditional Chinese: 小寫; simplified Chinese: 小写; lit. ‘small writing’), and one for use in commercial, accounting or financial contexts, known as dàxiě (traditional Chinese: 大寫; simplified Chinese: 大写; lit. ‘big writing’). The latter arose because the characters used for writing numerals are geometrically simple, so simply using those numerals cannot prevent forgeries in the same way spelling numbers out in English would.[1] A forger could easily change the everyday characters 三十 (30) to 五千 (5000) just by adding a few strokes. That would not be possible when writing using the financial characters 參拾 (30) and 伍仟 (5000). They are also referred to as «banker’s numerals», «anti-fraud numerals», or «banker’s anti-fraud numerals». For the same reason, rod numerals were never used in commercial records.

T denotes Traditional Chinese characters, while S denotes Simplified Chinese characters.

| Financial | Normal | Value | Pīnyīn (Mandarin) |

Jyutping (Cantonese) |

Pe̍h-ōe-jī (Hokkien) |

Wugniu (Shanghainese) |

Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Character (T) | Character (S) | Character (T) | Character (S) | |||||

| 零 | 零 | 〇 | 0 | líng | ling4 | khòng/lêng | lin | Usually 零 is preferred, but in some areas, 〇 may be a more common informal way to represent zero. The original Chinese character is 空 or 〇, 零 is referred as remainder something less than 1 yet not nil [說文] referred. The traditional 零 is more often used in schools. In Unicode, 〇 is treated as a Chinese symbol or punctuation, rather than a Chinese ideograph. |

| 壹 | 一 | 1 | yī | jat1 | it/chi̍t | iq | Also 弌 (obsolete financial), can be easily manipulated into 弍 (two) or 弎 (three). | |

| 貳 | 贰 | 二 | 2 | èr | ji6 | jī/nn̄g | gni/er/lian | Also 弍 (obsolete financial), can be easily manipulated into 弌 (one) or 弎 (three). Also 兩 (T) or 两 (S), see Characters with regional usage section. |

| 參 | 参 | 三 | 3 | sān | saam1 | sam/saⁿ | sé | Also 弎 (obsolete financial), which can be easily manipulated into 弌 (one) or 弍 (two). |

| 肆 | 四 | 4 | sì | sei3 | sù/sì | sy | Also 䦉 (obsolete financial)[nb 1] | |

| 伍 | 五 | 5 | wǔ | ng5 | ngó͘/gō͘ | ng | ||

| 陸 | 陆 | 六 | 6 | liù | luk6 | lio̍k/la̍k | loq | |

| 柒 | 七 | 7 | qī | cat1 | chhit | chiq | ||

| 捌 | 八 | 8 | bā | baat3 | pat/peh | paq | ||

| 玖 | 九 | 9 | jiǔ | gau2 | kiú/káu | cieu | ||

| 拾 | 十 | 10 | shí | sap6 | si̍p/cha̍p | zeq | Although some people use 什 as financial[citation needed], it is not ideal because it can be easily manipulated into 伍 (five) or 仟 (thousand). | |

| 佰 | 百 | 100 | bǎi | baak3 | pek/pah | paq | ||

| 仟 | 千 | 1,000 | qiān | cin1 | chhian/chheng | chi | ||

| 萬 | 萬 | 万 | 104 | wàn | maan6 | bān | ve | Chinese numbers group by ten-thousands; see Reading and transcribing numbers below. |

| 億 | 億 | 亿 | 105/108 | yì | jik1 | ek | i | For variant meanings and words for higher values, see Large numbers below and ja:大字 (数字). |

Characters with regional usage[edit]

| Financial | Normal | Value | Pinyin (Mandarin) | Standard alternative | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 空 | 0 | kòng | 零 | Historically, the use of 空 for «zero» predates 零. This is now archaic in most varieties of Chinese, but it is still used in Southern Min. | |

| 洞 | 0 | dòng | 零 | Literally means «a hole» and is analogous to the shape of «0» and «〇», it is used to unambiguously pronounce «#0» in radio communication. [2][3] | |

| 幺 | 1 | yāo | 一 | Literally means «the smallest», it is used to unambiguously pronounce «#1» in radio communication. [2][3] This usage is not observed in Cantonese except for 十三幺 (a special winning hand) in Mahjong. | |

| 蜀 | 1 | shǔ | 一 | In most Min varieties, there are two words meaning «one». For example, in Hokkien, chi̍t is used before a classifier: «one person» is chi̍t ê lâng, not it ê lâng. In written Hokkien, 一 is often used for both chi̍t and it, but some authors differentiate, writing 蜀 for chi̍t and 一 for it. | |

| 兩(T) or 两(S) |

2 | liǎng | 二 | Used instead of 二 before a classifier. For example, «two people» is «两个人», not «二个人». However, in some lects, such as Shanghainese, 兩 is the generic term used for two in most contexts, such as «四十兩» and not «四十二». It appears where «a pair of» would in English, but 两 is always used in such cases. It is also used for numbers, with usage varying from dialect to dialect, even person to person. For example, «2222» can be read as «二千二百二十二», «兩千二百二十二» or even «兩千兩百二十二» in Mandarin. It is used to unambiguously pronounce «#2» in radio communication. [2][3] | |

| 倆(T) or 俩(S) |

2 | liǎ | 兩 | In regional dialects of Northeastern Mandarin, 倆 represents a «lazy» pronunciation of 兩 within the local dialect. It can be used as an alternative for 兩个 «two of» (e.g. 我们倆 Wǒmen liǎ, «the two of us», as opposed to 我们兩个 Wǒmen liǎng gè). A measure word (such as 个) never follows after 倆. | |

| 仨 | 3 | sā | 三 | In regional dialects of Northeastern Mandarin, 仨 represents a «lazy» pronunciation of three within the local dialect. It can be used as a general number to represent «three» (e.g.第仨号 dì sā hào, «number three»; 星期仨 xīngqīsā, «Wednesday»), or as an alternative for 三个 «three of» (e.g. 我们仨 Wǒmen sā, «the three of us», as opposed to 我们三个 Wǒmen sān gè). Regardless of usage, a measure word (such as 个) never follows after 仨. | |

| 拐 | 7 | guǎi | 七 | Literally means «a turn» or «a walking stick» and is analogous to the shape of «7» and «七», it is used to unambiguously pronounce «#7» in radio communication. [2][3] | |

| 勾 | 9 | gōu | 九 | Literally means «a hook» and is analogous to the shape of «9», it is used to unambiguously pronounce «#9» in radio communication. [2][3] | |

| 呀 | 10 | yà | 十 | In spoken Cantonese, 呀 (aa6) can be used in place of 十 when it is used in the middle of a number, preceded by a multiplier and followed by a ones digit, e.g. 六呀三, 63; it is not used by itself to mean 10. This usage is not observed in Mandarin. | |

| 念 | 廿 | 20 | niàn | 二十 | A contraction of 二十. The written form is still used to refer to dates, especially Chinese calendar dates. Spoken form is still used in various dialects of Chinese. See Reading and transcribing numbers section below. In spoken Cantonese, 廿 (jaa6) can be used in place of 二十 when followed by another digit such as in numbers 21-29 (e.g. 廿三, 23), a measure word (e.g. 廿個), a noun, or in a phrase like 廿幾 («twenty-something»); it is not used by itself to mean 20. 卄 is a rare variant. |

| 卅 | 30 | sà | 三十 | A contraction of 三十. The written form is still used to abbreviate date references in Chinese. For example, May 30 Movement (五卅運動). Spoken form is still used in various dialects of Chinese. In spoken Cantonese, 卅 (saa1) can be used in place of 三十 when followed by another digit such as in numbers 31–39, a measure word (e.g. 卅個), a noun, or in phrases like 卅幾 («thirty-something»); it is not used by itself to mean 30. When spoken 卅 is pronounced as 卅呀 (saa1 aa6). Thus 卅一 (31), is pronounced as saa1 aa6 jat1. |

|

| 卌 | 40 | xì | 四十 | A contraction of 四十. Found in historical writings written in Classical Chinese. Spoken form is still used in various dialects of Chinese, albeit very rare. See Reading and transcribing numbers section below. In spoken Cantonese 卌 (sei3) can be used in place of 四十 when followed by another digit such as in numbers 41–49, a measure word (e.g. 卌個), a noun, or in phrases like 卌幾 («forty-something»); it is not used by itself to mean 40. When spoken, 卌 is pronounced as 卌呀 (sei3 aa6). Thus 卌一 (41), is pronounced as sei3 aa6 jat1. |

|

| 皕 | 200 | bì | 二百 | Very rarely used; one example is in the name of a library in Huzhou, 皕宋樓 (Bìsòng Lóu). |

Large numbers[edit]

For numbers larger than 10,000, similarly to the long and short scales in the West, there have been four systems in ancient and modern usage. The original one, with unique names for all powers of ten up to the 14th, is ascribed to the Yellow Emperor in the 6th century book by Zhen Luan, Wujing suanshu (Arithmetic in Five Classics). In modern Chinese only the second system is used, in which the same ancient names are used, but each represents a number 10,000 (myriad, 萬 wàn) times the previous:

| Character (T) | 萬 | 億 | 兆 | 京 | 垓 | 秭 | 穰 | 溝 | 澗 | 正 | 載 | Factor of increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Character (S) | 万 | 亿 | 兆 | 京 | 垓 | 秭 | 穰 | 沟 | 涧 | 正 | 载 | |

| Pinyin | wàn | yì | zhào | jīng | gāi | zǐ | ráng | gōu | jiàn | zhèng | zǎi | |

| Jyutping | maan6 | jik1 | siu6 | ging1 | goi1 | zi2 | joeng4 | kau1 | gaan3 | zing3 | zoi2 | |

| Hokkien POJ | bān | ek | tiāu | keng | kai | chí | jiông | ko͘ | kàn | chèng | cháiⁿ | |

| Shanghainese | ve | i | zau | cín | ké | tsy | gnian | kéu | ké | tsen | tse | |

| Alternative | 經/经 | 𥝱 | 壤 | |||||||||

| Rank | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | =n |

| «short scale» (下數) |

104 | 105 | 106 | 107 | 108 | 109 | 1010 | 1011 | 1012 | 1013 | 1014 | =10n+3

Each numeral is 10 (十 shí) times the previous. |

| «myriad scale» (萬進, current usage) |

104 | 108 | 1012 | 1016 | 1020 | 1024 | 1028 | 1032 | 1036 | 1040 | 1044 | =104n

Each numeral is 10,000 (萬 (T) or 万 (S) wàn) times the previous. |

| «mid-scale» (中數) |

104 | 108 | 1016 | 1024 | 1032 | 1040 | 1048 | 1056 | 1064 | 1072 | 1080 | =108(n-1)

Starting with 亿, each numeral is 108 (萬乘以萬 (T) or 万乘以万 (S) wàn chéng yǐ wàn, 10000 times 10000) times the previous. |

| «long scale» (上數) |

104 | 108 | 1016 | 1032 | 1064 | 10128 | 10256 | 10512 | 101024 | 102048 | 104096 | =102n+1

Each numeral is the square of the previous. This is similar to the -yllion system. |

In practice, this situation does not lead to ambiguity, with the exception of 兆 (zhào), which means 1012 according to the system in common usage throughout the Chinese communities as well as in Japan and Korea, but has also been used for 106 in recent years (especially in mainland China for megabyte). To avoid problems arising from the ambiguity, the PRC government never uses this character in official documents, but uses 万亿 (wànyì) or 太 (tài, as the translation for tera) instead. Partly due to this, combinations of 万 and 亿 are often used instead of the larger units of the traditional system as well, for example 亿亿 (yìyì) instead of 京. The ROC government in Taiwan uses 兆 (zhào) to mean 1012 in official documents.

Large numbers from Buddhism[edit]

Numerals beyond 載 zǎi come from Buddhist texts in Sanskrit, but are mostly found in ancient texts. Some of the following words are still being used today, but may have transferred meanings.

| Character (T) | Character (S) | Pinyin | Jyutping | Hokkien POJ | Shanghainese | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 極 | 极 | jí | gik1 | ke̍k | jiq5 | 1048 | Literally means «Extreme». |

| 恆河沙 | 恒河沙 | héng hé shā | hang4 ho4 sa1 | hêng-hô-soa | ghen3-wu-so | 1052[citation needed] | Literally means «Sands of the Ganges»; a metaphor used in a number of Buddhist texts referring to the grains of sand in the Ganges River. |

| 阿僧祇 | ā sēng qí | aa1 zang1 kei4 | a-seng-kî | a1-sen-ji | 1056 | From Sanskrit Asaṃkhyeya असंख्येय, meaning «incalculable, innumerable, infinite». | |

| 那由他 | nà yóu tā | naa5 jau4 taa1 | ná-iû-thaⁿ | na1-yeu-tha | 1060 | From Sanskrit nayuta नियुत, meaning «myriad». | |

| 不可思議 | 不可思议 | bùkě sīyì | bat1 ho2 si1 ji3 | put-khó-su-gī | peq4-khu sy1-gni | 1064 | Literally translated as «unfathomable». This word is commonly used in Chinese as a chengyu, meaning «unimaginable», instead of its original meaning of the number 1064. |

| 無量大數 | 无量大数 | wú liàng dà shù | mou4 loeng6 daai6 sou3 | bû-liōng tāi-siàu | m3-lian du3-su | 1068 | «无量» literally translated as «without measure», and can mean 1068. This word is also commonly used in Chinese as a commendatory term, means «no upper limit». E.g.: 前途无量 lit. front journey no limit, which means «a great future». «大数» literally translated as «a large number; the great number», and can mean 1072. |

Small numbers[edit]

The following are characters used to denote small order of magnitude in Chinese historically. With the introduction of SI units, some of them have been incorporated as SI prefixes, while the rest have fallen into disuse.

| Character(s) (T) | Character(s) (S) | Pinyin | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 漠 | mò | 10−12 | (Ancient Chinese)

皮 corresponds to the SI prefix pico-. |

|

| 渺 | miǎo | 10−11 | (Ancient Chinese) | |

| 埃 | āi | 10−10 | (Ancient Chinese) | |

| 塵 | 尘 | chén | 10−9 | Literally, «Dust»

奈 (T) or 纳 (S) corresponds to the SI prefix nano-. |

| 沙 | shā | 10−8 | Literally, «Sand» | |

| 纖 | 纤 | xiān | 10−7 | Literally, «Fiber» |

| 微 | wēi | 10−6 | still in use, corresponds to the SI prefix micro-. | |

| 忽 | hū | 10−5 | (Ancient Chinese) | |

| 絲 | 丝 | sī | 10−4 | also 秒.

Literally, «Thread» |

| 毫 | háo | 10−3 | also 毛.

still in use, corresponds to the SI prefix milli-. |

|

| 厘 | lí | 10−2 | also 釐.

still in use, corresponds to the SI prefix centi-. |

|

| 分 | fēn | 10−1 | still in use, corresponds to the SI prefix deci-. |

Small numbers from Buddhism[edit]

| Character(s) (T) | Character(s) (S) | Pinyin | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 涅槃寂靜 | 涅槃寂静 | niè pán jì jìng | 10−24 | Literally, «Nirvana’s Tranquility»

攸 (T) or 幺 (S) corresponds to the SI prefix yocto-. |

| 阿摩羅 | 阿摩罗 | ā mó luó | 10−23 | (Ancient Chinese, from Sanskrit अमल amala) |

| 阿頼耶 | 阿赖耶 | ā lài yē | 10−22 | (Ancient Chinese, from Sanskrit आलय ālaya) |

| 清靜 | 清净 | qīng jìng | 10−21 | Literally, «Quiet»

介 (T) or 仄 (S) corresponds to the SI prefix zepto-. |

| 虛空 | 虚空 | xū kōng | 10−20 | Literally, «Void» |

| 六德 | liù dé | 10−19 | (Ancient Chinese) | |

| 剎那 | 刹那 | chà nà | 10−18 | Literally, «Brevity», from Sanskrit क्षण ksaṇa

阿 corresponds to the SI prefix atto-. |

| 彈指 | 弹指 | tán zhǐ | 10−17 | Literally, «Flick of a finger». Still commonly used in the phrase «弹指一瞬间» (A very short time) |

| 瞬息 | shùn xī | 10−16 | Literally, «Moment of Breath». Still commonly used in Chengyu «瞬息万变» (Many things changed in a very short time) | |

| 須臾 | 须臾 | xū yú | 10−15 | (Ancient Chinese, rarely used in Modern Chinese as «a very short time»)

飛 (T) or 飞 (S) corresponds to the SI prefix femto-. |

| 逡巡 | qūn xún | 10−14 | (Ancient Chinese) | |

| 模糊 | mó hu | 10−13 | Literally, «Blurred» |

SI prefixes[edit]

In the People’s Republic of China, the early translation for the SI prefixes in 1981 was different from those used today. The larger (兆, 京, 垓, 秭, 穰) and smaller Chinese numerals (微, 纖, 沙, 塵, 渺) were defined as translation for the SI prefixes as mega, giga, tera, peta, exa, micro, nano, pico, femto, atto, resulting in the creation of yet more values for each numeral.[4]

The Republic of China (Taiwan) defined 百萬 as the translation for mega and 兆 as the translation for tera. This translation is widely used in official documents, academic communities, informational industries, etc. However, the civil broadcasting industries sometimes use 兆赫 to represent «megahertz».

Today, the governments of both China and Taiwan use phonetic transliterations for the SI prefixes. However, the governments have each chosen different Chinese characters for certain prefixes. The following table lists the two different standards together with the early translation.

| Value | Symbol | English | Early translation | PRC standard | ROC standard | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1024 | Y | yotta- | 尧 | yáo | 佑 | yòu | ||

| 1021 | Z | zetta- | 泽 | zé | 皆 | jiē | ||

| 1018 | E | exa- | 穰[4] | ráng | 艾 | ài | 艾 | ài |

| 1015 | P | peta- | 秭[4] | zǐ | 拍 | pāi | 拍 | pāi |

| 1012 | T | tera- | 垓[4] | gāi | 太 | tài | 兆 | zhào |

| 109 | G | giga- | 京[4] | jīng | 吉 | jí | 吉 | jí |

| 106 | M | mega- | 兆[4] | zhào | 兆 | zhào | 百萬 | bǎiwàn |

| 103 | k | kilo- | 千 | qiān | 千 | qiān | 千 | qiān |

| 102 | h | hecto- | 百 | bǎi | 百 | bǎi | 百 | bǎi |

| 101 | da | deca- | 十 | shí | 十 | shí | 十 | shí |

| 100 | (base) | one | 一 | yī | 一 | yī | ||

| 10−1 | d | deci- | 分 | fēn | 分 | fēn | 分 | fēn |

| 10−2 | c | centi- | 厘 | lí | 厘 | lí | 厘 | lí |

| 10−3 | m | milli- | 毫 | háo | 毫 | háo | 毫 | háo |

| 10−6 | µ | micro- | 微[4] | wēi | 微 | wēi | 微 | wēi |

| 10−9 | n | nano- | 纖[4] | xiān | 纳 | nà | 奈 | nài |

| 10−12 | p | pico- | 沙[4] | shā | 皮 | pí | 皮 | pí |

| 10−15 | f | femto- | 塵[4] | chén | 飞 | fēi | 飛 | fēi |

| 10−18 | a | atto- | 渺[4] | miǎo | 阿 | à | 阿 | à |

| 10−21 | z | zepto- | 仄 | zè | 介 | jiè | ||

| 10−24 | y | yocto- | 幺 | yāo | 攸 | yōu |

Reading and transcribing numbers[edit]

Whole numbers[edit]

Multiple-digit numbers are constructed using a multiplicative principle; first the digit itself (from 1 to 9), then the place (such as 10 or 100); then the next digit.

In Mandarin, the multiplier 兩 (liǎng) is often used rather than 二 (èr) for all numbers 200 and greater with the «2» numeral (although as noted earlier this varies from dialect to dialect and person to person). Use of both 兩 (liǎng) or 二 (èr) are acceptable for the number 200. When writing in the Cantonese dialect, 二 (yi6) is used to represent the «2» numeral for all numbers. In the southern Min dialect of Chaozhou (Teochew), 兩 (no6) is used to represent the «2» numeral in all numbers from 200 onwards. Thus:

| Number | Structure | Characters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandarin | Cantonese | Chaozhou | Shanghainese | ||

| 60 | [6] [10] | 六十 | 六十 | 六十 | 六十 |

| 20 | [2] [10] or [20] | 二十 | 二十 or 廿 | 二十 | 廿 |

| 200 | [2] (èr or liǎng) [100] | 二百 or 兩百 | 二百 or 兩百 | 兩百 | 兩百 |

| 2000 | [2] (èr or liǎng) [1000] | 二千 or 兩千 | 二千 or 兩千 | 兩千 | 兩千 |

| 45 | [4] [10] [5] | 四十五 | 四十五 or 卌五 | 四十五 | 四十五 |

| 2,362 | [2] [1000] [3] [100] [6] [10] [2] | 兩千三百六十二 | 二千三百六十二 | 兩千三百六十二 | 兩千三百六十二 |

For the numbers 11 through 19, the leading «one» (一; yī) is usually omitted. In some dialects, like Shanghainese, when there are only two significant digits in the number, the leading «one» and the trailing zeroes are omitted. Sometimes, the one before «ten» in the middle of a number, such as 213, is omitted. Thus:

| Number | Strict Putonghua | Colloquial or dialect usage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Characters | Structure | Characters | |

| 14 | [10] [4] | 十四 | ||