концлагерь

- концлагерь

-

концлагерь

концентрационный лагерь

Словарь сокращений и аббревиатур.

.

2015.

Синонимы:

Смотреть что такое «концлагерь» в других словарях:

-

концлагерь — концлагерь … Орфографический словарь-справочник

-

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ — КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ, концлагеря, муж. (неол. офиц.). Концентрационный лагерь, место, где содержатся военнопленные, заложники, а также социально опасные лица. Заключить в концлагерь. (Образовано из слова лагерь и сокращения слова концентрационный.)… … Толковый словарь Ушакова

-

концлагерь — лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти Словарь русских синонимов. концлагерь сущ., кол во синонимов: 3 • лагерь (34) • … Словарь синонимов

-

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ — «Дружба». Жарг. шк. Шутл. ирон. Школа. (Запись 2004 г.). Концлагерь «Улыбка». Жарг. студ. Шутл. ирон. Студенческое общежитие с очень строгим комендантом. ВМН 2003, 69 … Большой словарь русских поговорок

-

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ — КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ, я, мн. я, ей, муж. Сокращение: концентрационный лагерь. | прил. концлагерный, ая, ое. Толковый словарь Ожегова. С.И. Ожегов, Н.Ю. Шведова. 1949 1992 … Толковый словарь Ожегова

-

Концлагерь — концентрационный лагерь. В период II мировой войны концлагеря создавались фашистской Германией для изоляции противников нацистского режима… Источник: СПРАВОЧНИК О МЕСТАХ ХРАНЕНИЯ ДОКУМЕНТОВ О НЕМЕЦКО ФАШИСТСКИХ ЛАГЕРЯХ, ГЕТТО, ДРУГИХ МЕСТАХ… … Официальная терминология

-

концлагерь — концлагерь, мн. концлагеря, род. концлагерей и концлагери, концлагерей … Словарь трудностей произношения и ударения в современном русском языке

-

Концлагерь — Концентрационный лагерь (концлагерь) термин, обозначающий специально оборудованный центр массового силового заключения и содержания следующих категорий граждан различных стран: военнопленных различных войн и конфликтов; политических заключенных… … Википедия

-

Концлагерь Омарска — был концентрационным лагерем под управлением боснийских сербов в небольшом городе Омарска около Приедора на севере Боснии и Герцеговины. Был основан во время Приедорской бойни для хорватов, как для женщин, так и для мужчин.[1][2] Использовался с… … Википедия

-

Концлагерь терпимости — Эпизод «Южного парка» Концлагерь терпимости The Death Camp of Tolerance … Википедия

Толковый словарь русского языка. Поиск по слову, типу, синониму, антониму и описанию. Словарь ударений.

Найдено определений: 18

концлагерь

ТОЛКОВЫЙ СЛОВАРЬ

м.

Содержащий в огромных количествах и в невероятно тяжёлых условиях заключённых, подлежащих физическому уничтожению; концентрационный лагерь (о лагерях для военнопленных, политических противников и инакомыслящих — в фашистской Германии, в оккупированных ею странах во время Второй мировой войны, а также в странах с тоталитарным режимом в годы репрессий).

ТОЛКОВЫЙ СЛОВАРЬ УШАКОВА

КОНЦЛА́ГЕРЬ, концлагеря, муж. (неол. офиц.). Концентрационный лагерь, место, где содержатся военнопленные, заложники, а также социально опасные лица. Заключить в концлагерь. (Образовано из слова лагерь и сокращения слова концентрационный.)

ТОЛКОВЫЙ СЛОВАРЬ ОЖЕГОВА

КОНЦЛА́ГЕРЬ, -я, мн. -я, -ей, муж. Сокращение: концентрационный лагерь.

| прил. концлагерный, -ая, -ое.

ЭНЦИКЛОПЕДИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

КОНЦЛА́ГЕРЬ -я; -лагеря́; м. Концентрационный лагерь.

АКАДЕМИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

-я, мн. -лагеря́, м.

Концентрационный лагерь.

ПОГОВОРКИ

Концлагерь «Дружба». Жарг. шк. Шутл.-ирон. Школа. (Запись 2004 г.).

Концлагерь «Улыбка». Жарг. студ. Шутл.-ирон. Студенческое общежитие с очень строгим комендантом. ВМН 2003, 69.

СЛИТНО. РАЗДЕЛЬНО. ЧЕРЕЗ ДЕФИС

концла/герь, -я, мн. концлагеря/, -е/й

ОРФОГРАФИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

концла́герь, -я, мн. ч. -я́, -е́й

СЛОВАРЬ УДАРЕНИЙ

ко́нцла́герь, -я; мн. -лагеря́, -е́й

ТРУДНОСТИ ПРОИЗНОШЕНИЯ И УДАРЕНИЯ

концла́герь, мн. концлагеря́, род. концлагере́й и концла́гери, концла́герей.

ФОРМЫ СЛОВ

концла́герь, концлагеря́, концла́геря, концлагере́й, концла́герю, концлагеря́м, концла́герем, концлагеря́ми, концла́гере, концлагеря́х

СИНОНИМЫ

сущ., кол-во синонимов: 3

лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти

МОРФЕМНО-ОРФОГРАФИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

ГРАММАТИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

СКАНВОРДЫ

— «Зона смерти» в фашистской Германии.

— Что организовали фашисты около польского города Освенцим?

— Фабрика смерти.

ПОЛЕЗНЫЕ СЕРВИСЫ

концлагерь «дружба»

ПОГОВОРКИ

Жарг. шк. Шутл.-ирон. Школа. (Запись 2004 г.).

ПОЛЕЗНЫЕ СЕРВИСЫ

концлагерь «улыбка»

ПОГОВОРКИ

Жарг. студ. Шутл.-ирон. Студенческое общежитие с очень строгим комендантом. ВМН 2003, 69.

ПОЛЕЗНЫЕ СЕРВИСЫ

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

«…Концлагерь — концентрационный лагерь. В период II мировой войны концлагеря создавались фашистской Германией для изоляции противников нацистского режима…»

Источник:

«СПРАВОЧНИК О МЕСТАХ ХРАНЕНИЯ ДОКУМЕНТОВ О НЕМЕЦКО-ФАШИСТСКИХ ЛАГЕРЯХ, ГЕТТО, ДРУГИХ МЕСТАХ ПРИНУДИТЕЛЬНОГО СОДЕРЖАНИЯ И НАСИЛЬСТВЕННОМ ВЫВОЗЕ ГРАЖДАН НА РАБОТЫ В ГЕРМАНИЮ И ДРУГИЕ СТРАНЫ ЕВРОПЫ В ПЕРИОД ВЕЛИКОЙ ОТЕЧЕСТВЕННОЙ ВОЙНЫ 1941 — 1945 ГГ.»

Синонимы:

лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти

КОНЬЯК ВЫДЕРЖАННЫЙ →← КОНЦЕССИЯ ТЕНЕВАЯ

Синонимы слова «КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ»:

ЛАГЕРЬ, ЛАГЕРЬ СМЕРТИ, ФАБРИКА СМЕРТИ

Смотреть что такое КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ в других словарях:

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ, -я, мн. -я, -ей, м. Сокращение: концентрационный лагерь. IIприл. концлагерный, -ая, -ое.

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

концлагерь м. (концентрационный лагерь)concentration camp

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

концлагерь

лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти

Словарь русских синонимов.

концлагерь

сущ., кол-во синонимов: 3

• лагерь (34)

• лагерь смерти (2)

• фабрика смерти (2)

Словарь синонимов ASIS.В.Н. Тришин.2013.

.

Синонимы:

лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти… смотреть

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

Нарко Нарк Налог Нал Накр Накол Нагорье Нагоец Нагло Наглец Нагель Лье Лоренц Лор Лонг Лок Лог Лерка Лера Леон Ленька Лень Ленца Ленка Лена Лен Лекарь Лек Легонька Легко Лганье Ларь Ларец Ларек Ларго Лань Ланец Лакец Лак Лагерь Лаг Крон Кроль Креол Крень Крен Кранц Кранец Кран Корье Корь Корн Корец Корень Корел Коран Кораль Кора Конь Концлагерь Конец Кон Колье Колер Кола Кол Коан Кнр Кнель Клон Клер Клен Кларен Клан Керн Кеньга Кенарь Кенар Кен Кельн Келарь Кегль Кеа Карнеол Карло Карл Карен Карел Каре Карго Каон Канцлер Канцер Кан Калонг Кале Кал Кагор Каг Ерь Ера Енол Ель Елка Елань Егорка Егор Гренок Грена Грелка Грек Грац Грань Гран Горн Горлан Горка Горк Горец Горенка Горелка Горе Горал Гор Гонка Гонец Гон Голье Голь Голец Голень Гол Гко Герц Геркон Герань Геракл Гера Генка Ген Гель Гарь Гарнец Нацело Ганец Гало Галеон Нгал Гален Гак Гаер Нега Негр Нель Арон Арно Арк Арен Арек Арго Нерол Нло Ногаец Ангел Алкен Ален Акр Акно Агро Агор Агнец Норка Нора Ангелок Ноль Нок Англо Анголец Нога Анк Анкер Аон Аргон Нерка Нер… смотреть

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

1) Орфографическая запись слова: концлагерь2) Ударение в слове: концл`агерь3) Деление слова на слоги (перенос слова): концлагерь4) Фонетическая транскр… смотреть

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

концла/герь, -я, мн. концлагеря/, -е/й

Синонимы:

лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

корень — КОНЦ; корень — ЛАГЕРЬ; нулевое окончание;Основа слова: КОНЦЛАГЕРЬВычисленный способ образования слова: Бессуфиксальный или другой∩ — КОНЦ; ∩ -… смотреть

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

Концлагерь «Дружба». Жарг. шк. Шутл.-ирон. Школа. (Запись 2004 г.).Концлагерь «Улыбка». Жарг. студ. Шутл.-ирон. Студенческое общежитие с очень строгим … смотреть

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

концла́герь,

концлагеря́,

концла́геря,

концлагере́й,

концла́герю,

концлагеря́м,

концла́герь,

концлагеря́,

концла́герем,

концлагеря́ми,

концла́гере,

концлагеря́х

(Источник: «Полная акцентуированная парадигма по А. А. Зализняку»)

.

Синонимы:

лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти… смотреть

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

ко́нцла́герь, -я; мн. -лагеря́, -е́йСинонимы:

лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

(2 м); мн. концлагеря/, Р. концлагере/йСинонимы:

лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

скр от концентрационный лагерьcampo de concentraçãoСинонимы:

лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ концлагеря, м. (нов. офиц.). концентрационный лагерь, место, где содержатся военнопленные, заложники, а также социально опасные лица. Заключить в концлагерь. (Образовано из слова лагерь и сокращения слова концентрационный.)<br><br><br>… смотреть

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

м.(концентрационный лагерь) camp m de concentrationСинонимы:

лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

м. (мн. концлагеря)(концентрационный лагерь) campo de concentración

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

-я, мн. -лагеря́, м.

Концентрационный лагерь.Синонимы:

лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

концлагерьמַחֲנֵה רִיכּוּז ז’ [ר’ מַחֲנוֹת-]Синонимы:

лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

Ударение в слове: концл`агерьУдарение падает на букву: аБезударные гласные в слове: концл`агерь

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

Rzeczownik концлагерь m obóz koncentracyjny

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

концл’агерь, -я, мн. ч. -‘я, -‘ейСинонимы:

лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

м. (концентрационный лагерь) camp m de concentration

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

концла’герь, концлагеря’, концла’геря, концлагере’й, концла’герю, концлагеря’м, концла’герь, концлагеря’, концла’герем, концлагеря’ми, концла’гере, концлагеря’х… смотреть

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

м.

(концентрационный лагерь) campo di concentramento / sterminio, lager нем.

Итальяно-русский словарь.2003.

Синонимы:

лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти… смотреть

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

мtoplama kampıСинонимы:

лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

концлагерьСинонимы:

лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

концлагерь, концл′агерь, -я, мн. ч. -я, -ей, м. Сокращение: концентрационный лагерь.прил. концлагерный, -ая, -ое.

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

〈复〉 -я〔阳〕集中营. Синонимы:

лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ, -я, мн. -я, -ей, м. Сокращение: концентрационный лагерь. || прилагательное концлагерный, -ая, -ое.

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

Начальная форма — Концлагерь, винительный падеж, единственное число, мужской род, неодушевленное

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

м.

(концентрационный лагерь) см. концентрационный (концентрационный лагерь).

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

концлагерь м (концентрационный лагерь) το στρατόπεδο συγκέντρωσης

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

концлагерь лагерь, лагерь смерти, фабрика смерти

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

М (концентрационный лагерь) konslager, həbs düşərgəsi.

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ

концлагерь концл`агерь, -я, мн. -`я, -`ей

КОНЦЛАГЕРЬ «УЛЫБКА»

Жарг. студ. Шутл.-ирон. Студенческое общежитие с очень строгим комендантом. ВМН 2003, 69.

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps[a] on its own territory and in parts of German-occupied Europe.

The first camps were established in March 1933 immediately after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany. Following the 1934 purge of the SA, the concentration camps were run exclusively by the SS via the Concentration Camps Inspectorate and later the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office. Initially, most prisoners were members of the Communist Party of Germany, but as time went on different groups were arrested, including «habitual criminals», «asocials», and Jews. After the beginning of World War II, people from German-occupied Europe were imprisoned in the concentration camps. Following Allied military victories, the camps were gradually liberated in 1944 and 1945, although hundreds of thousands of prisoners died in the death marches.

More than 1,000 concentration camps (including subcamps) were established during the history of Nazi Germany and around 1.65 million people were registered prisoners in the camps at one point. Around a million died during their imprisonment. Many of the former camps have been turned into museums commemorating the victims of the Nazi regime, while the camp system has become a symbol of violence and terror.

Background

Concentration camps are conventionally held to have been invented by the British during the Second Boer War, but historian Dan Stone argues that there were precedents in other countries and that camps were «the logical extension of phenomena that had long characterized colonial rule».[3] Although the word «concentration camp» has acquired the connotation of murder because of the Nazi concentration camps, the British camps in South Africa did not involve systematic murder. The German Empire also established concentration camps during the Herero and Namaqua genocide (1904–1907); the death rate of these camps was 45 percent, twice that of the British camps.[4]

During the First World War, eight to nine million prisoners of war were held in prisoner-of-war camps, some of them at locations which were later the sites of Nazi camps, such as Theresienstadt and Mauthausen. Many prisoners held by Germany died as a result of intentional withholding of food and dangerous working conditions in violation of the 1907 Hague Convention.[5] In countries such as France, Belgium, Italy, Austria-Hungary, and Germany, civilians deemed to be of «enemy origin» were denaturalized. Hundreds of thousands were interned and subject to forced labor in harsh conditions.[6] During the Armenian genocide perpetrated by the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Armenians were held in camps during their deportation into the Syrian Desert.[7] In postwar Germany, «unwanted foreigners»—primarily Eastern European Jews—were warehoused at Cottbus-Sielow and Stargard.[8]

History

Early camps (1933–1934)

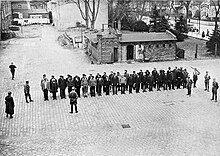

Prisoners guarded by SA men line up in the yard of Oranienburg, 6 April 1933

On 30 January 1933, Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany after striking a backroom deal with the previous chancellor, Franz von Papen.[9] The Nazis had no plan for concentration camps prior to their seizure of power.[10] The concentration camp system arose in the following months due to the desire to suppress tens of thousands of Nazi opponents in Germany. The Reichstag fire in February 1933 was the pretext for mass arrests. The Reichstag Fire Decree eliminated the right to personal freedom enshrined in the Weimar Constitution and provided a legal basis for detention without trial.[9][11] The first camp was Nohra, established on 3 March 1933 in a school.[12]

The number of prisoners in 1933–1934 is difficult to determine; historian Jane Caplan estimated it at 50,000, with arrests perhaps exceeding 100,000.[12] Eighty percent of prisoners were members of the Communist Party of Germany and ten percent members of the Social Democratic Party of Germany.[13] Many prisoners were released in late 1933, and after a Christmas amnesty, there were only a few dozen camps left.[14] About 70 camps were established in 1933, in any convenient structure that could hold prisoners, including vacant factories, prisons, country estates, schools, workhouses, and castles.[12][11] There was no national system;[14] camps were operated by local police, SS, and SA, state interior ministries, or a combination of the above.[12][11] The early camps in 1933–1934 were heterogenous and fundamentally differed from the post-1935 camps in organization, conditions, and the groups imprisoned.[15]

Institutionalization (1934–1937)

On 26 June 1933, Himmler appointed Theodor Eicke the second commandant of Dachau, which became the model followed by other camps. Eicke drafted the Disciplinary and Penal Code, a manual which specified draconian punishments for disobedient prisoners.[16] He also created a system of prisoner functionaries, which later developed into the camp elders, block elders, and kapo of later camps.[17] In May 1934, Lichtenburg was taken over by the SS from the Prussian bureaucracy, marking the beginning of a transition set in motion by Heinrich Himmler, then chief of the Gestapo (secret police).[18] Following the purge of the SA on 30 June 1934, in which Eicke took a leading role, the remaining SA-run camps were taken over by the SS.[13][19] In December 1934, Eicke was appointed the first inspector of the Concentration Camps Inspectorate (IKL); only camps managed by the IKL were designated «concentration camps».[13]

In early 1934, the number of prisoners was still falling and it was uncertain if the system would continue to exist. By mid-1935, there were only five camps, holding 4,000 prisoners, and 13 employees at the central IKL office. At the same time, 100,000 people were imprisoned in German jails, a quarter of those for political offenses.[20] Believing Nazi Germany to be imperiled by internal enemies, Himmler called for a war against the «organized elements of sub-humanity», including communists, socialists, Jews, Freemasons, and criminals. Himmler won Hitler’s backing and was appointed Chief of German Police on 17 June 1936.[21] Of the six SS camps operational as of mid-1936, only two (Dachau and Lichtenburg) still existed by 1938. In the place of the camps that closed down, Eicke opened new camps at Sachsenhausen (September 1936) and Buchenwald (July 1937). Unlike earlier camps, the newly opened camps were purpose-built, isolated from the population and the rule of law, enabling the SS to exert absolute power.[22] Prisoners, who previously wore civilian clothes, were forced to wear uniforms with Nazi concentration camp badges. The number of prisoners began to rise again, from 4,761 on 1 November 1936 to 7,750 by the end of 1937.[23]

Rapid expansion (1937–1939)

Forced labor at Sachsenhausen brickworks

By the end of June 1938, the prisoner population had expanded threefold in the previous six months, to 24,000 prisoners. The increase was fueled by arrests of those considered habitual criminals or asocials.[23] According to SS chief Heinrich Himmler, the «criminal» prisoners at concentration camps needed to be isolated from society because they had committed offenses of a sexual or violent nature. In fact, most of the criminal prisoners were working-class men who had resorted to petty theft to support their families.[24] Nazi raids of perceived asocials, including the arrest of 10,000 people in June 1938,[25] targeted homeless people and the mentally ill, as well as the unemployed.[26] Although the Nazis had previously targeted social outsiders, the influx of new prisoners meant that political prisoners became a minority.[25]

To house the new prisoners, three new camps were established: Flossenbürg (May 1938) near the Czechoslovak border, Mauthausen (August 1938) in territory annexed from Austria, and Ravensbrück (May 1939) the first purpose-built camp for female prisoners.[23] The mass arrests were partly motivated by economic factors. Recovery from the Great Depression lowered the unemployment rate, so «work-shy» elements would be arrested to keep others working harder. At the same time, Himmler was also focusing on exploiting prisoners’ labor within the camp system. Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, had grand plans for creating monumental Nazi architecture. The SS company German Earth and Stone Works (DEST) was set up with funds from Speer’s agency for exploiting prisoner labour to extract building materials. Flossenbürg and Mauthausen had been built adjacent to quarries, and DEST also set up brickworks at Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen.[27][28]

Political prisoners were also arrested in larger numbers, including Jehovah’s Witnesses and German émigrés who returned home. Czech and Austrian anti-Nazis were arrested after the annexation of their countries in 1938 and 1939.[29] Jews were also increasingly targeted, with 2,000 Viennese Jews arrested after the Nazi annexation. After the Kristallnacht pogrom in November 1938, 26,000 Jewish men were deported to concentration camps following mass arrests, overwhelming the capacity of the system. These prisoners were subject to unprecedented abuse leading to hundreds of deaths—more people died at Dachau in the four months after Kristallnacht than in the previous five years. Most of the Jewish prisoners were soon released, often after promising to emigrate.[29][30]

World War II

At the end of August 1939, prisoners of Flossenbürg, Sachsenhausen, and other concentration camps were murdered as part of false flag attacks staged by Germany to justify the invasion of Poland.[31] During the war, the camps became increasingly brutal and lethal due to the plans of the Nazi leadership: most victims died in the second half of the war.[32] Five new camps were opened between the start of the war and the end of 1941: Neuengamme (early 1940), outside of Hamburg; Auschwitz (June 1940), which initially operated as a concentration camp for Polish resistance activists; Gross-Rosen (May 1941) in Silesia; and Natzweiler (May 1941) in territory annexed from France.[33][34] The first satellite camps were also established, administratively subordinated to one of the main camps.[33] The number of prisoners tripled from 21,000 in August 1939 to around 70,000 to 80,000 in early 1942.[34] This expansion was driven by the demand for forced labor and later the invasion of the Soviet Union; new camps were sent up near quarries (Natzweiler and Gross-Rosen) or brickworks (Neuengamme).[33][35]

Concentration camp prisoners at a Messerschmitt AG aircraft factory, probably 1943

In April 1941, the high command of the SS ordered the murder of ill and exhausted prisoners who could no longer work (especially those deemed racially inferior). Victims were selected by camp personnel or traveling doctors, and were removed from the camps to be murdered in euthanasia centers. By April 1942, when the operation finished, at least 6,000 and as many as 20,000 people had been killed[36][37]—the first act of systematic killing in the camp system.[38] Beginning in August 1941, selected Soviet prisoners of war were killed within the concentration camps, usually within a few days of their arrival. By mid-1942, when the operation finished, at least 34,000 Soviet prisoners had been murdered. At Auschwitz, the SS used Zyklon B to kill Soviet prisoners in improvised gas chambers.[39][36]

In 1942, the emphasis of the camps shifted to the war effort; by 1943, two-thirds of prisoners were employed by war industries.[40] The death rate skyrocketed with an estimated half of the 180,000 prisoners admitted between July and November 1942 dying by the end of that interval. Orders to reduce deaths in order to spare inmate productivity had little effect in practice.[41][42] During the second half of the war, Auschwitz swelled in size—fueled by the deportation of hundreds of thousands of Jews—and became the center of the camp system. It was the deadliest concentration camp and Jews sent there faced a virtual death sentence even if they were not immediately killed, as most were. In August 1943, 74,000 of the 224,000 registered prisoners in all SS concentration camps were in Auschwitz.[43] In 1943 and early 1944, additional concentration camps—Riga in Latvia, Kovno in Lithuania, Vaivara in Estonia, and Kraków-Plaszów in Poland—were converted from ghettos or labor camps; these camps were populated almost entirely by Jewish prisoners.[44][45] Along with the new main camps, many satellite camps were set up to more effectively leverage prisoner labor for the war effort.[46]

Organization

Fence at Flossenbürg. Expensive security measures distinguished the concentration camps from other Nazi detention facilities.[47]

Beginning in the mid-1930s, the camps were organized according to the following structure: commandant/adjutant, political department, protective custody camp, administration [de], camp doctor, and guard command.[48] In November 1940, the IKL came under the control of the SS Main Command Office and the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) took on the responsibility of detaining and releasing concentration camp prisoners.[49] In 1942, the IKL was subordinated to the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office (SS-WVHA) to improve the camps’ integration into the war economy.[50] Despite changes in the structure, the IKL remained directly responsible to Himmler.[49]

The camps under the IKL were guarded by members of the SS-Totenkopfverbande («deaths’ head»). The guards were housed in barracks adjacent to the camp and their duties were to guard the perimeter of the camp as well as work details. They were officially forbidden from entering the camps, although this rule was not followed.[51] Towards the end of the 1930s, the SS-Totenkopfverbande expanded its operations and set up military units, which followed the Einsatzgruppen death squads and massacred Polish Jews as well as Soviet prisoners of war.[52] Older general SS personnel, and those wounded or disabled, replaced those assigned to combat duties.[53] As the war progressed, a more diverse group was recruited to guard the expanding camp system, including female guards (who were not part of the SS). During the second half of the war, army and air force personnel were recruited, making up as many as 52 percent of guards by January 1945. The manpower shortage was reduced by relying on guard dogs and delegating some duties to prisoners.[54] Corruption was widespread.[55]

Most of the camp SS leadership was middle-class and came from the war youth generation [de], who were hard-hit by the economic crisis and feared decline in status. Most had joined the Nazi movement by September 1931 and were offered full-time employment in 1933.[56] SS leaders typically lived with their wives and children near the camps where they worked, often engaging prisoners for domestic labor.[57] Perpetration by this leadership was based on their tight social bonds, a perceived common sense that the aims of the system were good, as well as the opportunity for material gain.[58]

Prisoners

New prisoners who survived a weeklong trip in open boxcars awaiting disinfection at Mauthausen

Prisoners lined up for roll call at Sachsenhausen, 1941

Before World War II, most prisoners in the concentration camps were Germans.[49] After the expansion of Nazi Germany, people from countries occupied by the Wehrmacht were targeted and detained in concentration camps.[59][49] In Western Europe, arrests focused on resistance fighters and saboteurs, but in Eastern Europe arrests included mass roundups aimed at the implementation of Nazi population policy and the forced recruitment of workers. This led to a predominance of Eastern Europeans, especially Poles, who made up the majority of the population of some camps. By the end of the war, only 5 to 10 percent of the camp population was «Reich Germans» from Germany or Austria.[49] In late 1941, many Soviet prisoners of war were transferred to special annexes of the concentration camps. Intended as a labor reserve, they were deliberately subject to mass starvation.[36]

Most Jews who were persecuted and killed during the Holocaust were never prisoners in concentration camps.[49] Significant numbers of Jews were imprisoned beginning in November 1938 because of Kristallnacht, after which they were always overrepresented as prisoners.[60] During the height of the Holocaust from 1941 to 1943, the Jewish population of the concentration camps was low.[30] Extermination camps for the mass murder of Jews—Kulmhof, Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka—were set up outside the concentration camp system.[61][62] The existing IKL camps Auschwitz and Majdanek gained additional function as extermination camps.[43][63] After mid-1943, some forced-labor camps for Jews and some Nazi ghettos were converted into concentration camps.[30] Other Jews entered the concentration camp system after being deported to Auschwitz.[64] Despite many deaths, as many as 200,000 Jews survived the war inside the camp system.[30]

Conditions

Conditions worsened after the outbreak of war due to reduction in food, worsening housing, and increase in work. Deaths from disease and malnutrition increased, outpacing other causes of death. However, the food provided was usually sufficient to sustain life.[49] Life in the camps has often been depicted as a Darwinian struggle for survival, although some mutual aid existed. Individual efforts to survive, sometimes at others’ expense, could hamper the aggregate survival rate.[65]

The influx of non-German prisoners from 1939 changed the previous hierarchy based on triangle to one based on nationality.[49] Jews, Slavic prisoners, and Spanish Republicans were targeted for especially harsh treatment which led to a high mortality rate during the first half of the war. In contrast, Reich Germans enjoyed favorable treatment compared to other nationalities.[49]

A minority of prisoners obtained substantially better treatment than the rest because they were prisoner functionaries (mostly Germans) or skilled laborers.[42] Prisoner functionaries served at the whim of the SS and could be dismissed for insufficient strictness. As a result, sociologist Wolfgang Sofsky emphasizes that «They took over the role of the SS in order to prevent SS encroachment» and other prisoners remembered them for their brutality.[66]

Forced labor

Mauthausen prisoners forced to work at the Wiener Graben quarry, 1942

Hard labor was a fundamental component of the concentration camp system and an aspect in the daily life of prisoners.[67] However, the forced labor deployment was largely determined by external political and economic factors that drove demand for labor.[68] During the first years of the camps, unemployment was high and prisoners were forced to perform economically valueless but strenuous tasks, such as farming on moorland (such as at Esterwegen).[35] Other prisoners had to work on constructing and expanding the camps.[69] In the years before World War II, quarrying and bricklaying for the SS company DEST played a central role in prisoner labor. Despite prisoners’ increasing economic importance, conditions declined; prisoners were seen as expendable so each influx of prisoners was followed by increasing death rate.[70][71]

Private sector cooperation remained marginal to the overall concentration camp system for the first half of the war.[36][72] After the failure to take Moscow in late 1941, the demand for armaments increased. The WVHA sought out partnerships with private industry and Speer’s Armaments Ministry.[73] In September 1942, Himmler and Speer agreed to use prisoners in armaments production and to repair damage from Allied bombing. Local authorities and private companies could hire prisoners at a fixed daily cost. This decision paved the way for the establishment of many subcamps located near workplaces.[73][74] More workers were obtained through transfers from prisons and forced labor programs, causing the prisoner population to double twice by mid-1944.[73] Subcamps where prisoners did construction work had significantly higher death rates than those that worked in munitions manufacture.[75] By the end of the war, main camps were functioning more and more as transfer stations from which prisoners were redirected to subcamps.[45]

At their peak in 1945, concentration camp prisoners made up 3 percent of workers in Germany.[76] Historian Marc Buggeln estimates that no more than 1 percent of the labor for Germany’s arms production came from concentration camp prisoners.[76]

Public perception

Arrests of Germans in 1933 were often accompanied by public humiliation or beatings. If released, prisoners might return home with visible marks of abuse or psychological breakdown. Using a «dual strategy of publicity and secrecy», the regime directed terror both at the direct victim as well as the entire society in order to eliminate its opponents and deter resistance.[77] Beginning in March 1933, detailed reports on camp conditions were published in the press.[78] Nazi propaganda demonized the prisoners as race traitors, sexual degenerates, and criminals and presented the camps as sites of re-education.[79][78] After 1933, reports in the press were scarce but larger numbers of people were arrested and people who interacted with the camps, such as those who registered deaths, could make conclusions about the camp conditions and discuss with acquaintances.[80]

The visibility of the camps heightened during the war due to increasing prisoner numbers, the establishment of many subcamps in proximity to German civilians, and the use of labor deployments outside the camps.[81] These subcamps, often established in town centers in such locations as schools, restaurants, barracks, factory buildings, or military camps, were joint ventures between industry and the SS. An increasing number of German civilians interacted with the camps: entrepreneurs and landowners provided land or services, doctors decided which prisoners were healthy enough to continue working, foremen oversaw labor deployments, and administrators helped with logistics.[82] SS construction brigades were in demand by municipalities to clear bomb debris and rebuild.[83][84] For the prisoners, chances of survival rarely improved despite the contact with the outside world, although those few Germans who tried to help did not encounter punishment.[85] Germans were often shocked to see the reality of the concentration camps up close, but reluctant to aid the prisoners because of fear that they would be imprisoned as well.[86] Others found the poor state of the prisoners to confirm Nazi propaganda about them.[87]

Historian Robert Gellately argues that «the Germans generally turned out to be proud and pleased that Hitler and his henchmen were putting away certain kinds of people who did not fit in, or who were regarded as ‘outsiders’, ‘asocials’, ‘useless eaters’, or ‘criminals‘«.[88] According to historian Karola Fings, fear of arrest did not undermine public support for the camps because Germans saw the prisoners rather than the guards as criminals.[89] She writes that demand for SS construction brigades «points to general acceptance of the concentration camps».[83]

Statistics

Number of prisoners in the system

Timeline of the establishment of camps (black for main camps, orange for early camps and subcamps)

There were 27 main camps and, according to historian Nikolaus Wachsmann’s estimate, more than 1,100 satellite camps.[90] This is a cumulative figure that counts all the subcamps that existed at one point; historian Karin Orth estimates the number of subcamps to have been 186 at the end of 1943, 341 or more in June 1944, and at least 662 in January 1945.[91]

The camps were concentrated in prewar Germany and to a lesser extent territory annexed to Germany. No camps were built on the territory of Germany’s allies that enjoyed even nominal independence.[92] Each camp housed either men, women, or a mixed population. Women’s camps were mostly for armaments production and located primarily in northern Germany, Thuringia, or the Sudetenland, while men’s camps had a wider geographical distribution. Sex segregation decreased over the course of the war and mixed camps predominated outside of Germany’s prewar borders.[93]

Around 1.65 million people were registered prisoners in the camps, of whom, according to Wagner, nearly a million died during their imprisonment.[63] Historian Adam Tooze counts the number of survivors at no more than 475,000, calculating that at least 1.1 million of the registered prisoners must have died. According to his estimate, at least 800,000 of the murdered prisoners were not Jewish.[94] In addition to the registered prisoners who died, a million Jews were gassed upon arriving in Auschwitz; including these victims, the total death toll is estimated at 1.8 to more than two million.[95][96] Most of the fatalities occurred during the second half of World War II, including at least a third of the 700,000 prisoners who were registered as of January 1945.[95]

Death marches and liberation

Major evacuations of the camps occurred in mid-1944 from the Baltics and eastern Poland, January 1945 from western Poland and Silesia, and in March 1945 from concentration camps in Germany.[97] Both Jewish and non-Jewish prisoners died in large numbers as a consequence of these death marches.[98]

Many prisoners died after liberation due to their poor physical condition.[99]

The camps as seen by Western Allied liberators in 1945 upon their liberation have played a prominent part in perceptions of the camp system as a whole.[100]

Legacy

Since their liberation, the Nazi concentration camp system has come to symbolize violence and terror in the modern world.[101][102]

After the war, most Germans rejected the crimes associated with the concentration camps, while denying any knowledge or responsibility.[103] Under the West German policy of Wiedergutmachung (lit. ‘making good again’), some survivors of concentration camps received compensation for their imprisonment. A few perpetrators were put on trial after the war.[104]

Accounts of the concentration camps—both condemnatory and sympathetic—were publicized outside of Germany before World War II.[105] Many survivors testified about their experiences or wrote memoirs after the war. Some of these accounts have become internationally famous, such as Primo Levi’s 1947 book, If This is a Man.[106] The concentration camps have been the subject of historical writings since Eugen Kogon’s 1946 study, Der SS-Staat [de] («The SS State»).[107][108] Substantial research did not begin until the 1980s. Scholarship has focused on the fate of groups of prisoners, the organization of the camp system, and aspects such as forced labor.[106] As late as the 1990s, German local and economic history omitted mention of the camps or presented them as exclusively the responsibility of the SS.[109] Two scholarly encyclopedias of the concentration camps have been published: Der Ort des Terrors and Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos.[110] According to Caplan and Wachsmann, «more books have been published on the Nazi camps than any other site of detention and terror in history».[111]

Stone argues that the Nazi concentration camp system inspired similar atrocities by other regimes, including the Argentine military junta during the Dirty War, the Pinochet regime in Chile, and Pitești Prison in the Romanian People’s Republic.[112]

Sources

Notes

- ^ German: Konzentrationslager, KL (officially) or KZ (more commonly).[1] The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as concentration camps operated by Germany’s allies.[2]

Citations

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 635, note 9.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 50.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 11.

- ^ Stone 2017, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Stone 2017, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 25.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 28.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 31.

- ^ a b White 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, p. 19.

- ^ a b c Buggeln 2015, p. 334.

- ^ a b c d White 2009, p. 5.

- ^ a b c White 2009, p. 8.

- ^ a b Wachsmann 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Orth 2009a, p. 183.

- ^ White 2009, p. 7.

- ^ White 2009, p. 10.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, p. 21.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, p. 22.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b c Wachsmann 2009, p. 23.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, pp. 295–296.

- ^ a b Wachsmann 2009, p. 24.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Orth 2009a, pp. 185–186.

- ^ a b Wachsmann 2009, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b c d Dean 2020, p. 265.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, pp. 342–343.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 402.

- ^ a b c Wachsmann 2009, p. 27.

- ^ a b Orth 2009a, p. 186.

- ^ a b Wagner 2009, p. 130.

- ^ a b c d Orth 2009a, p. 188.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, p. 28.

- ^ Orth 2009b, p. 52.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, p. 29.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, p. 30.

- ^ a b Orth 2009a, p. 190.

- ^ a b Wachsmann 2009, p. 31.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, p. 32.

- ^ a b Orth 2009a, p. 191.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, p. 34.

- ^ Dean 2020, p. 267.

- ^ Orth 2009b, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Orth 2009a, p. 187.

- ^ Orth 2009b, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Orth 2009b, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Orth 2009b, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Orth 2009b, p. 47.

- ^ Orth 2009b, p. 48.

- ^ Orth 2009b, p. 53.

- ^ Orth 2009b, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Orth 2009b, p. 51.

- ^ Orth 2009b, p. 54.

- ^ Stone 2017, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 44.

- ^ Sofsky 2013, p. 12.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b Wagner 2009, p. 127.

- ^ Dean 2020, p. 274.

- ^ Stone 2017, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Buggeln 2014, p. 160.

- ^ Fings 2008, p. 220.

- ^ Wagner 2009, p. 129.

- ^ Orth 2009a, p. 185.

- ^ Buggeln 2015, p. 339.

- ^ Wagner 2009, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Buggeln 2015, p. 342.

- ^ a b c Orth 2009a, p. 189.

- ^ Fings 2009, p. 116.

- ^ Orth 2009a, p. 192.

- ^ a b Buggeln 2015, p. 359.

- ^ Fings 2009, p. 110.

- ^ a b Fings 2009, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Stone 2017, pp. 36, 38.

- ^ Fings 2009, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Fings 2009, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Fings 2009, pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b Fings 2008, p. 217.

- ^ Knowles et al. 2014, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Fings 2009, pp. 117, 119.

- ^ Fings 2009, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Fings 2009, p. 119.

- ^ Gellately 2002, p. vii.

- ^ Fings 2009, p. 113.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 15.

- ^ Orth 2009a, p. 195, fn 49.

- ^ Knowles et al. 2014, pp. 28, 30.

- ^ Knowles et al. 2014, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Tooze 2006, p. 523.

- ^ a b Orth 2009a, p. 194.

- ^ Goeschel & Wachsmann 2010, p. 515.

- ^ Blatman 2010, p. 9.

- ^ Blatman 2010, p. 10.

- ^ Blatman 2010, p. 2.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 54.

- ^ Buggeln 2015, p. 333.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 39.

- ^ Fings 2009, p. 108.

- ^ Marcuse 2009, p. 204.

- ^ Stone 2017, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b Caplan & Wachsmann 2009, p. 5.

- ^ Blatman 2010, p. 17.

- ^ Caplan & Wachsmann 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Fings 2009, p. 114.

- ^ Caplan & Wachsmann 2009, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Caplan & Wachsmann 2009, p. 6.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 81.

Sources

- Blatman, Daniel (2010). The Death Marches: The Final Phase of Nazi Genocide. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05919-1.

- Buggeln, Marc (2014). Slave Labor in Nazi Concentration Camps. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-870797-4.

- Buggeln, Marc (2015). «Forced Labour in Nazi Concentration Camps». Global Convict Labour. Brill. pp. 333–360. ISBN 978-90-04-28501-9.

- Caplan, Jane; Wachsmann, Nikolaus (2009). «Introduction». Concentration Camps in Nazi Germany: The New Histories. Routledge. pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-1-135-26322-5.

- Dean, Martin C. (2020). «Survivors of the Holocaust within the Nazi Universe of Camps». A Companion to the Holocaust. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 263–277. ISBN 978-1-118-97049-2.

- Fings, Karola (2008) [2004]. «Slaves for the ‘Home Front’: War Society and Concentration Camps». German Wartime Society 1939-1945: Politicization, Disintegration, and the Struggle for Survival. Germany and the Second World War. Vol. IX/I. Clarendon Press. pp. 207–286. ISBN 978-0-19-160860-5.

- Fings, Karola (2009). «The public face of the camps». Concentration Camps in Nazi Germany: The New Histories. Routledge. pp. 108–126. ISBN 978-1-135-26322-5.

- Gellately, Robert (2002). Backing Hitler: Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-160452-2.

- Goeschel, Christian; Wachsmann, Nikolaus (2010). «Before Auschwitz: The Formation of the Nazi Concentration Camps, 1933-9». Journal of Contemporary History. 45 (3): 515–534. doi:10.1177/0022009410366554.

- Knowles, Anne Kelly; Jaskot, Paul B.; Blackshear, Benjamin Perry; De Groot, Michael; Yule, Alexander (2014). «Mapping the SS Concentration Camps». Geographies of the Holocaust. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-01211-1.

- Marcuse, Harold (2009). «The afterlife of the camps». Concentration Camps in Nazi Germany: The New Histories. Routledge. pp. 186–211. ISBN 978-1-135-26322-5.

- Orth, Karin (2009a). «The Genesis and Structure of the National Socialist Concentration Camps». Early Camps, Youth Camps, and Concentration Camps and Subcamps under the SS-Business Administration Main Office (WVHA). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 1. Indiana University Press. pp. 183–196. ISBN 978-0-253-35328-3.

- Orth, Karin (2009b). «The concentration camp personnel». Concentration Camps in Nazi Germany: The New Histories. Routledge. pp. 44–57. ISBN 978-1-135-26322-5.

- Sofsky, Wolfgang (2013) [1993]. The Order of Terror: The Concentration Camp. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2218-8.

- Stone, Dan (2017). Concentration Camps: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-103502-9.

- Tooze, Adam (2006). The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9566-4.

- Wachsmann, Nikolaus (2009). «The dynamics of destruction: The development of the concentration camps, 1933–1945». Concentration Camps in Nazi Germany: The New Histories. Routledge. pp. 17–43. ISBN 978-1-135-26322-5.

- Wachsmann, Nikolaus (2015). KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-11825-9.

- Wagner, Jens-Christian (2009). «Work and extermination in the concentration camps». Concentration Camps in Nazi Germany: The New Histories. Routledge. pp. 127–148. ISBN 978-1-135-26322-5.

- White, Joseph Robert (2009). «Introduction to the Early Camps». Early Camps, Youth Camps, and Concentration Camps and Subcamps under the SS-Business Administration Main Office (WVHA). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 1. Indiana University Press. pp. 3–16. ISBN 978-0-253-35328-3.

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps[a] on its own territory and in parts of German-occupied Europe.

The first camps were established in March 1933 immediately after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany. Following the 1934 purge of the SA, the concentration camps were run exclusively by the SS via the Concentration Camps Inspectorate and later the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office. Initially, most prisoners were members of the Communist Party of Germany, but as time went on different groups were arrested, including «habitual criminals», «asocials», and Jews. After the beginning of World War II, people from German-occupied Europe were imprisoned in the concentration camps. Following Allied military victories, the camps were gradually liberated in 1944 and 1945, although hundreds of thousands of prisoners died in the death marches.

More than 1,000 concentration camps (including subcamps) were established during the history of Nazi Germany and around 1.65 million people were registered prisoners in the camps at one point. Around a million died during their imprisonment. Many of the former camps have been turned into museums commemorating the victims of the Nazi regime, while the camp system has become a symbol of violence and terror.

Background

Concentration camps are conventionally held to have been invented by the British during the Second Boer War, but historian Dan Stone argues that there were precedents in other countries and that camps were «the logical extension of phenomena that had long characterized colonial rule».[3] Although the word «concentration camp» has acquired the connotation of murder because of the Nazi concentration camps, the British camps in South Africa did not involve systematic murder. The German Empire also established concentration camps during the Herero and Namaqua genocide (1904–1907); the death rate of these camps was 45 percent, twice that of the British camps.[4]

During the First World War, eight to nine million prisoners of war were held in prisoner-of-war camps, some of them at locations which were later the sites of Nazi camps, such as Theresienstadt and Mauthausen. Many prisoners held by Germany died as a result of intentional withholding of food and dangerous working conditions in violation of the 1907 Hague Convention.[5] In countries such as France, Belgium, Italy, Austria-Hungary, and Germany, civilians deemed to be of «enemy origin» were denaturalized. Hundreds of thousands were interned and subject to forced labor in harsh conditions.[6] During the Armenian genocide perpetrated by the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman Armenians were held in camps during their deportation into the Syrian Desert.[7] In postwar Germany, «unwanted foreigners»—primarily Eastern European Jews—were warehoused at Cottbus-Sielow and Stargard.[8]

History

Early camps (1933–1934)

Prisoners guarded by SA men line up in the yard of Oranienburg, 6 April 1933

On 30 January 1933, Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany after striking a backroom deal with the previous chancellor, Franz von Papen.[9] The Nazis had no plan for concentration camps prior to their seizure of power.[10] The concentration camp system arose in the following months due to the desire to suppress tens of thousands of Nazi opponents in Germany. The Reichstag fire in February 1933 was the pretext for mass arrests. The Reichstag Fire Decree eliminated the right to personal freedom enshrined in the Weimar Constitution and provided a legal basis for detention without trial.[9][11] The first camp was Nohra, established on 3 March 1933 in a school.[12]

The number of prisoners in 1933–1934 is difficult to determine; historian Jane Caplan estimated it at 50,000, with arrests perhaps exceeding 100,000.[12] Eighty percent of prisoners were members of the Communist Party of Germany and ten percent members of the Social Democratic Party of Germany.[13] Many prisoners were released in late 1933, and after a Christmas amnesty, there were only a few dozen camps left.[14] About 70 camps were established in 1933, in any convenient structure that could hold prisoners, including vacant factories, prisons, country estates, schools, workhouses, and castles.[12][11] There was no national system;[14] camps were operated by local police, SS, and SA, state interior ministries, or a combination of the above.[12][11] The early camps in 1933–1934 were heterogenous and fundamentally differed from the post-1935 camps in organization, conditions, and the groups imprisoned.[15]

Institutionalization (1934–1937)

On 26 June 1933, Himmler appointed Theodor Eicke the second commandant of Dachau, which became the model followed by other camps. Eicke drafted the Disciplinary and Penal Code, a manual which specified draconian punishments for disobedient prisoners.[16] He also created a system of prisoner functionaries, which later developed into the camp elders, block elders, and kapo of later camps.[17] In May 1934, Lichtenburg was taken over by the SS from the Prussian bureaucracy, marking the beginning of a transition set in motion by Heinrich Himmler, then chief of the Gestapo (secret police).[18] Following the purge of the SA on 30 June 1934, in which Eicke took a leading role, the remaining SA-run camps were taken over by the SS.[13][19] In December 1934, Eicke was appointed the first inspector of the Concentration Camps Inspectorate (IKL); only camps managed by the IKL were designated «concentration camps».[13]

In early 1934, the number of prisoners was still falling and it was uncertain if the system would continue to exist. By mid-1935, there were only five camps, holding 4,000 prisoners, and 13 employees at the central IKL office. At the same time, 100,000 people were imprisoned in German jails, a quarter of those for political offenses.[20] Believing Nazi Germany to be imperiled by internal enemies, Himmler called for a war against the «organized elements of sub-humanity», including communists, socialists, Jews, Freemasons, and criminals. Himmler won Hitler’s backing and was appointed Chief of German Police on 17 June 1936.[21] Of the six SS camps operational as of mid-1936, only two (Dachau and Lichtenburg) still existed by 1938. In the place of the camps that closed down, Eicke opened new camps at Sachsenhausen (September 1936) and Buchenwald (July 1937). Unlike earlier camps, the newly opened camps were purpose-built, isolated from the population and the rule of law, enabling the SS to exert absolute power.[22] Prisoners, who previously wore civilian clothes, were forced to wear uniforms with Nazi concentration camp badges. The number of prisoners began to rise again, from 4,761 on 1 November 1936 to 7,750 by the end of 1937.[23]

Rapid expansion (1937–1939)

Forced labor at Sachsenhausen brickworks

By the end of June 1938, the prisoner population had expanded threefold in the previous six months, to 24,000 prisoners. The increase was fueled by arrests of those considered habitual criminals or asocials.[23] According to SS chief Heinrich Himmler, the «criminal» prisoners at concentration camps needed to be isolated from society because they had committed offenses of a sexual or violent nature. In fact, most of the criminal prisoners were working-class men who had resorted to petty theft to support their families.[24] Nazi raids of perceived asocials, including the arrest of 10,000 people in June 1938,[25] targeted homeless people and the mentally ill, as well as the unemployed.[26] Although the Nazis had previously targeted social outsiders, the influx of new prisoners meant that political prisoners became a minority.[25]

To house the new prisoners, three new camps were established: Flossenbürg (May 1938) near the Czechoslovak border, Mauthausen (August 1938) in territory annexed from Austria, and Ravensbrück (May 1939) the first purpose-built camp for female prisoners.[23] The mass arrests were partly motivated by economic factors. Recovery from the Great Depression lowered the unemployment rate, so «work-shy» elements would be arrested to keep others working harder. At the same time, Himmler was also focusing on exploiting prisoners’ labor within the camp system. Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, had grand plans for creating monumental Nazi architecture. The SS company German Earth and Stone Works (DEST) was set up with funds from Speer’s agency for exploiting prisoner labour to extract building materials. Flossenbürg and Mauthausen had been built adjacent to quarries, and DEST also set up brickworks at Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen.[27][28]

Political prisoners were also arrested in larger numbers, including Jehovah’s Witnesses and German émigrés who returned home. Czech and Austrian anti-Nazis were arrested after the annexation of their countries in 1938 and 1939.[29] Jews were also increasingly targeted, with 2,000 Viennese Jews arrested after the Nazi annexation. After the Kristallnacht pogrom in November 1938, 26,000 Jewish men were deported to concentration camps following mass arrests, overwhelming the capacity of the system. These prisoners were subject to unprecedented abuse leading to hundreds of deaths—more people died at Dachau in the four months after Kristallnacht than in the previous five years. Most of the Jewish prisoners were soon released, often after promising to emigrate.[29][30]

World War II

At the end of August 1939, prisoners of Flossenbürg, Sachsenhausen, and other concentration camps were murdered as part of false flag attacks staged by Germany to justify the invasion of Poland.[31] During the war, the camps became increasingly brutal and lethal due to the plans of the Nazi leadership: most victims died in the second half of the war.[32] Five new camps were opened between the start of the war and the end of 1941: Neuengamme (early 1940), outside of Hamburg; Auschwitz (June 1940), which initially operated as a concentration camp for Polish resistance activists; Gross-Rosen (May 1941) in Silesia; and Natzweiler (May 1941) in territory annexed from France.[33][34] The first satellite camps were also established, administratively subordinated to one of the main camps.[33] The number of prisoners tripled from 21,000 in August 1939 to around 70,000 to 80,000 in early 1942.[34] This expansion was driven by the demand for forced labor and later the invasion of the Soviet Union; new camps were sent up near quarries (Natzweiler and Gross-Rosen) or brickworks (Neuengamme).[33][35]

Concentration camp prisoners at a Messerschmitt AG aircraft factory, probably 1943

In April 1941, the high command of the SS ordered the murder of ill and exhausted prisoners who could no longer work (especially those deemed racially inferior). Victims were selected by camp personnel or traveling doctors, and were removed from the camps to be murdered in euthanasia centers. By April 1942, when the operation finished, at least 6,000 and as many as 20,000 people had been killed[36][37]—the first act of systematic killing in the camp system.[38] Beginning in August 1941, selected Soviet prisoners of war were killed within the concentration camps, usually within a few days of their arrival. By mid-1942, when the operation finished, at least 34,000 Soviet prisoners had been murdered. At Auschwitz, the SS used Zyklon B to kill Soviet prisoners in improvised gas chambers.[39][36]

In 1942, the emphasis of the camps shifted to the war effort; by 1943, two-thirds of prisoners were employed by war industries.[40] The death rate skyrocketed with an estimated half of the 180,000 prisoners admitted between July and November 1942 dying by the end of that interval. Orders to reduce deaths in order to spare inmate productivity had little effect in practice.[41][42] During the second half of the war, Auschwitz swelled in size—fueled by the deportation of hundreds of thousands of Jews—and became the center of the camp system. It was the deadliest concentration camp and Jews sent there faced a virtual death sentence even if they were not immediately killed, as most were. In August 1943, 74,000 of the 224,000 registered prisoners in all SS concentration camps were in Auschwitz.[43] In 1943 and early 1944, additional concentration camps—Riga in Latvia, Kovno in Lithuania, Vaivara in Estonia, and Kraków-Plaszów in Poland—were converted from ghettos or labor camps; these camps were populated almost entirely by Jewish prisoners.[44][45] Along with the new main camps, many satellite camps were set up to more effectively leverage prisoner labor for the war effort.[46]

Organization

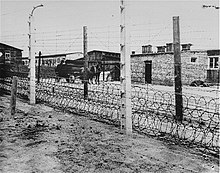

Fence at Flossenbürg. Expensive security measures distinguished the concentration camps from other Nazi detention facilities.[47]

Beginning in the mid-1930s, the camps were organized according to the following structure: commandant/adjutant, political department, protective custody camp, administration [de], camp doctor, and guard command.[48] In November 1940, the IKL came under the control of the SS Main Command Office and the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) took on the responsibility of detaining and releasing concentration camp prisoners.[49] In 1942, the IKL was subordinated to the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office (SS-WVHA) to improve the camps’ integration into the war economy.[50] Despite changes in the structure, the IKL remained directly responsible to Himmler.[49]

The camps under the IKL were guarded by members of the SS-Totenkopfverbande («deaths’ head»). The guards were housed in barracks adjacent to the camp and their duties were to guard the perimeter of the camp as well as work details. They were officially forbidden from entering the camps, although this rule was not followed.[51] Towards the end of the 1930s, the SS-Totenkopfverbande expanded its operations and set up military units, which followed the Einsatzgruppen death squads and massacred Polish Jews as well as Soviet prisoners of war.[52] Older general SS personnel, and those wounded or disabled, replaced those assigned to combat duties.[53] As the war progressed, a more diverse group was recruited to guard the expanding camp system, including female guards (who were not part of the SS). During the second half of the war, army and air force personnel were recruited, making up as many as 52 percent of guards by January 1945. The manpower shortage was reduced by relying on guard dogs and delegating some duties to prisoners.[54] Corruption was widespread.[55]

Most of the camp SS leadership was middle-class and came from the war youth generation [de], who were hard-hit by the economic crisis and feared decline in status. Most had joined the Nazi movement by September 1931 and were offered full-time employment in 1933.[56] SS leaders typically lived with their wives and children near the camps where they worked, often engaging prisoners for domestic labor.[57] Perpetration by this leadership was based on their tight social bonds, a perceived common sense that the aims of the system were good, as well as the opportunity for material gain.[58]

Prisoners

New prisoners who survived a weeklong trip in open boxcars awaiting disinfection at Mauthausen

Prisoners lined up for roll call at Sachsenhausen, 1941

Before World War II, most prisoners in the concentration camps were Germans.[49] After the expansion of Nazi Germany, people from countries occupied by the Wehrmacht were targeted and detained in concentration camps.[59][49] In Western Europe, arrests focused on resistance fighters and saboteurs, but in Eastern Europe arrests included mass roundups aimed at the implementation of Nazi population policy and the forced recruitment of workers. This led to a predominance of Eastern Europeans, especially Poles, who made up the majority of the population of some camps. By the end of the war, only 5 to 10 percent of the camp population was «Reich Germans» from Germany or Austria.[49] In late 1941, many Soviet prisoners of war were transferred to special annexes of the concentration camps. Intended as a labor reserve, they were deliberately subject to mass starvation.[36]

Most Jews who were persecuted and killed during the Holocaust were never prisoners in concentration camps.[49] Significant numbers of Jews were imprisoned beginning in November 1938 because of Kristallnacht, after which they were always overrepresented as prisoners.[60] During the height of the Holocaust from 1941 to 1943, the Jewish population of the concentration camps was low.[30] Extermination camps for the mass murder of Jews—Kulmhof, Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka—were set up outside the concentration camp system.[61][62] The existing IKL camps Auschwitz and Majdanek gained additional function as extermination camps.[43][63] After mid-1943, some forced-labor camps for Jews and some Nazi ghettos were converted into concentration camps.[30] Other Jews entered the concentration camp system after being deported to Auschwitz.[64] Despite many deaths, as many as 200,000 Jews survived the war inside the camp system.[30]

Conditions

Conditions worsened after the outbreak of war due to reduction in food, worsening housing, and increase in work. Deaths from disease and malnutrition increased, outpacing other causes of death. However, the food provided was usually sufficient to sustain life.[49] Life in the camps has often been depicted as a Darwinian struggle for survival, although some mutual aid existed. Individual efforts to survive, sometimes at others’ expense, could hamper the aggregate survival rate.[65]

The influx of non-German prisoners from 1939 changed the previous hierarchy based on triangle to one based on nationality.[49] Jews, Slavic prisoners, and Spanish Republicans were targeted for especially harsh treatment which led to a high mortality rate during the first half of the war. In contrast, Reich Germans enjoyed favorable treatment compared to other nationalities.[49]

A minority of prisoners obtained substantially better treatment than the rest because they were prisoner functionaries (mostly Germans) or skilled laborers.[42] Prisoner functionaries served at the whim of the SS and could be dismissed for insufficient strictness. As a result, sociologist Wolfgang Sofsky emphasizes that «They took over the role of the SS in order to prevent SS encroachment» and other prisoners remembered them for their brutality.[66]

Forced labor

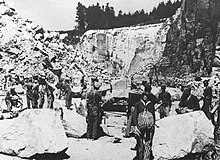

Mauthausen prisoners forced to work at the Wiener Graben quarry, 1942

Hard labor was a fundamental component of the concentration camp system and an aspect in the daily life of prisoners.[67] However, the forced labor deployment was largely determined by external political and economic factors that drove demand for labor.[68] During the first years of the camps, unemployment was high and prisoners were forced to perform economically valueless but strenuous tasks, such as farming on moorland (such as at Esterwegen).[35] Other prisoners had to work on constructing and expanding the camps.[69] In the years before World War II, quarrying and bricklaying for the SS company DEST played a central role in prisoner labor. Despite prisoners’ increasing economic importance, conditions declined; prisoners were seen as expendable so each influx of prisoners was followed by increasing death rate.[70][71]

Private sector cooperation remained marginal to the overall concentration camp system for the first half of the war.[36][72] After the failure to take Moscow in late 1941, the demand for armaments increased. The WVHA sought out partnerships with private industry and Speer’s Armaments Ministry.[73] In September 1942, Himmler and Speer agreed to use prisoners in armaments production and to repair damage from Allied bombing. Local authorities and private companies could hire prisoners at a fixed daily cost. This decision paved the way for the establishment of many subcamps located near workplaces.[73][74] More workers were obtained through transfers from prisons and forced labor programs, causing the prisoner population to double twice by mid-1944.[73] Subcamps where prisoners did construction work had significantly higher death rates than those that worked in munitions manufacture.[75] By the end of the war, main camps were functioning more and more as transfer stations from which prisoners were redirected to subcamps.[45]

At their peak in 1945, concentration camp prisoners made up 3 percent of workers in Germany.[76] Historian Marc Buggeln estimates that no more than 1 percent of the labor for Germany’s arms production came from concentration camp prisoners.[76]

Public perception

Arrests of Germans in 1933 were often accompanied by public humiliation or beatings. If released, prisoners might return home with visible marks of abuse or psychological breakdown. Using a «dual strategy of publicity and secrecy», the regime directed terror both at the direct victim as well as the entire society in order to eliminate its opponents and deter resistance.[77] Beginning in March 1933, detailed reports on camp conditions were published in the press.[78] Nazi propaganda demonized the prisoners as race traitors, sexual degenerates, and criminals and presented the camps as sites of re-education.[79][78] After 1933, reports in the press were scarce but larger numbers of people were arrested and people who interacted with the camps, such as those who registered deaths, could make conclusions about the camp conditions and discuss with acquaintances.[80]

The visibility of the camps heightened during the war due to increasing prisoner numbers, the establishment of many subcamps in proximity to German civilians, and the use of labor deployments outside the camps.[81] These subcamps, often established in town centers in such locations as schools, restaurants, barracks, factory buildings, or military camps, were joint ventures between industry and the SS. An increasing number of German civilians interacted with the camps: entrepreneurs and landowners provided land or services, doctors decided which prisoners were healthy enough to continue working, foremen oversaw labor deployments, and administrators helped with logistics.[82] SS construction brigades were in demand by municipalities to clear bomb debris and rebuild.[83][84] For the prisoners, chances of survival rarely improved despite the contact with the outside world, although those few Germans who tried to help did not encounter punishment.[85] Germans were often shocked to see the reality of the concentration camps up close, but reluctant to aid the prisoners because of fear that they would be imprisoned as well.[86] Others found the poor state of the prisoners to confirm Nazi propaganda about them.[87]

Historian Robert Gellately argues that «the Germans generally turned out to be proud and pleased that Hitler and his henchmen were putting away certain kinds of people who did not fit in, or who were regarded as ‘outsiders’, ‘asocials’, ‘useless eaters’, or ‘criminals‘«.[88] According to historian Karola Fings, fear of arrest did not undermine public support for the camps because Germans saw the prisoners rather than the guards as criminals.[89] She writes that demand for SS construction brigades «points to general acceptance of the concentration camps».[83]

Statistics

Number of prisoners in the system

Timeline of the establishment of camps (black for main camps, orange for early camps and subcamps)

There were 27 main camps and, according to historian Nikolaus Wachsmann’s estimate, more than 1,100 satellite camps.[90] This is a cumulative figure that counts all the subcamps that existed at one point; historian Karin Orth estimates the number of subcamps to have been 186 at the end of 1943, 341 or more in June 1944, and at least 662 in January 1945.[91]

The camps were concentrated in prewar Germany and to a lesser extent territory annexed to Germany. No camps were built on the territory of Germany’s allies that enjoyed even nominal independence.[92] Each camp housed either men, women, or a mixed population. Women’s camps were mostly for armaments production and located primarily in northern Germany, Thuringia, or the Sudetenland, while men’s camps had a wider geographical distribution. Sex segregation decreased over the course of the war and mixed camps predominated outside of Germany’s prewar borders.[93]

Around 1.65 million people were registered prisoners in the camps, of whom, according to Wagner, nearly a million died during their imprisonment.[63] Historian Adam Tooze counts the number of survivors at no more than 475,000, calculating that at least 1.1 million of the registered prisoners must have died. According to his estimate, at least 800,000 of the murdered prisoners were not Jewish.[94] In addition to the registered prisoners who died, a million Jews were gassed upon arriving in Auschwitz; including these victims, the total death toll is estimated at 1.8 to more than two million.[95][96] Most of the fatalities occurred during the second half of World War II, including at least a third of the 700,000 prisoners who were registered as of January 1945.[95]

Death marches and liberation

Major evacuations of the camps occurred in mid-1944 from the Baltics and eastern Poland, January 1945 from western Poland and Silesia, and in March 1945 from concentration camps in Germany.[97] Both Jewish and non-Jewish prisoners died in large numbers as a consequence of these death marches.[98]

Many prisoners died after liberation due to their poor physical condition.[99]

The camps as seen by Western Allied liberators in 1945 upon their liberation have played a prominent part in perceptions of the camp system as a whole.[100]

Legacy

Since their liberation, the Nazi concentration camp system has come to symbolize violence and terror in the modern world.[101][102]

After the war, most Germans rejected the crimes associated with the concentration camps, while denying any knowledge or responsibility.[103] Under the West German policy of Wiedergutmachung (lit. ‘making good again’), some survivors of concentration camps received compensation for their imprisonment. A few perpetrators were put on trial after the war.[104]

Accounts of the concentration camps—both condemnatory and sympathetic—were publicized outside of Germany before World War II.[105] Many survivors testified about their experiences or wrote memoirs after the war. Some of these accounts have become internationally famous, such as Primo Levi’s 1947 book, If This is a Man.[106] The concentration camps have been the subject of historical writings since Eugen Kogon’s 1946 study, Der SS-Staat [de] («The SS State»).[107][108] Substantial research did not begin until the 1980s. Scholarship has focused on the fate of groups of prisoners, the organization of the camp system, and aspects such as forced labor.[106] As late as the 1990s, German local and economic history omitted mention of the camps or presented them as exclusively the responsibility of the SS.[109] Two scholarly encyclopedias of the concentration camps have been published: Der Ort des Terrors and Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos.[110] According to Caplan and Wachsmann, «more books have been published on the Nazi camps than any other site of detention and terror in history».[111]

Stone argues that the Nazi concentration camp system inspired similar atrocities by other regimes, including the Argentine military junta during the Dirty War, the Pinochet regime in Chile, and Pitești Prison in the Romanian People’s Republic.[112]

Sources

Notes

- ^ German: Konzentrationslager, KL (officially) or KZ (more commonly).[1] The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as concentration camps operated by Germany’s allies.[2]

Citations

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 635, note 9.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 50.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 11.

- ^ Stone 2017, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Stone 2017, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 25.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 28.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 31.

- ^ a b White 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, p. 19.

- ^ a b c Buggeln 2015, p. 334.

- ^ a b c d White 2009, p. 5.

- ^ a b c White 2009, p. 8.

- ^ a b Wachsmann 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Orth 2009a, p. 183.

- ^ White 2009, p. 7.

- ^ White 2009, p. 10.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, p. 21.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, p. 22.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b c Wachsmann 2009, p. 23.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, pp. 295–296.

- ^ a b Wachsmann 2009, p. 24.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Orth 2009a, pp. 185–186.

- ^ a b Wachsmann 2009, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b c d Dean 2020, p. 265.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, pp. 342–343.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 402.

- ^ a b c Wachsmann 2009, p. 27.

- ^ a b Orth 2009a, p. 186.

- ^ a b Wagner 2009, p. 130.

- ^ a b c d Orth 2009a, p. 188.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, p. 28.

- ^ Orth 2009b, p. 52.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, p. 29.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, p. 30.

- ^ a b Orth 2009a, p. 190.

- ^ a b Wachsmann 2009, p. 31.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, p. 32.

- ^ a b Orth 2009a, p. 191.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, p. 34.

- ^ Dean 2020, p. 267.

- ^ Orth 2009b, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Orth 2009a, p. 187.

- ^ Orth 2009b, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Orth 2009b, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Orth 2009b, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Orth 2009b, p. 47.

- ^ Orth 2009b, p. 48.

- ^ Orth 2009b, p. 53.

- ^ Orth 2009b, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Orth 2009b, p. 51.

- ^ Orth 2009b, p. 54.

- ^ Stone 2017, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 44.

- ^ Sofsky 2013, p. 12.

- ^ Wachsmann 2009, pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b Wagner 2009, p. 127.

- ^ Dean 2020, p. 274.

- ^ Stone 2017, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Buggeln 2014, p. 160.

- ^ Fings 2008, p. 220.

- ^ Wagner 2009, p. 129.

- ^ Orth 2009a, p. 185.

- ^ Buggeln 2015, p. 339.

- ^ Wagner 2009, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Buggeln 2015, p. 342.

- ^ a b c Orth 2009a, p. 189.

- ^ Fings 2009, p. 116.

- ^ Orth 2009a, p. 192.

- ^ a b Buggeln 2015, p. 359.

- ^ Fings 2009, p. 110.

- ^ a b Fings 2009, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Stone 2017, pp. 36, 38.

- ^ Fings 2009, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Fings 2009, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Fings 2009, pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b Fings 2008, p. 217.

- ^ Knowles et al. 2014, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Fings 2009, pp. 117, 119.

- ^ Fings 2009, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Fings 2009, p. 119.

- ^ Gellately 2002, p. vii.

- ^ Fings 2009, p. 113.

- ^ Wachsmann 2015, p. 15.

- ^ Orth 2009a, p. 195, fn 49.

- ^ Knowles et al. 2014, pp. 28, 30.

- ^ Knowles et al. 2014, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Tooze 2006, p. 523.

- ^ a b Orth 2009a, p. 194.

- ^ Goeschel & Wachsmann 2010, p. 515.

- ^ Blatman 2010, p. 9.

- ^ Blatman 2010, p. 10.

- ^ Blatman 2010, p. 2.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 54.

- ^ Buggeln 2015, p. 333.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 39.

- ^ Fings 2009, p. 108.

- ^ Marcuse 2009, p. 204.

- ^ Stone 2017, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b Caplan & Wachsmann 2009, p. 5.

- ^ Blatman 2010, p. 17.

- ^ Caplan & Wachsmann 2009, p. 3.

- ^ Fings 2009, p. 114.

- ^ Caplan & Wachsmann 2009, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Caplan & Wachsmann 2009, p. 6.

- ^ Stone 2017, p. 81.

Sources

- Blatman, Daniel (2010). The Death Marches: The Final Phase of Nazi Genocide. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05919-1.

- Buggeln, Marc (2014). Slave Labor in Nazi Concentration Camps. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-870797-4.

- Buggeln, Marc (2015). «Forced Labour in Nazi Concentration Camps». Global Convict Labour. Brill. pp. 333–360. ISBN 978-90-04-28501-9.

- Caplan, Jane; Wachsmann, Nikolaus (2009). «Introduction». Concentration Camps in Nazi Germany: The New Histories. Routledge. pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-1-135-26322-5.

- Dean, Martin C. (2020). «Survivors of the Holocaust within the Nazi Universe of Camps». A Companion to the Holocaust. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 263–277. ISBN 978-1-118-97049-2.

- Fings, Karola (2008) [2004]. «Slaves for the ‘Home Front’: War Society and Concentration Camps». German Wartime Society 1939-1945: Politicization, Disintegration, and the Struggle for Survival. Germany and the Second World War. Vol. IX/I. Clarendon Press. pp. 207–286. ISBN 978-0-19-160860-5.