Мао Цзэдун (26 декабря 1893 г.— 9 сентября 1976 г.)

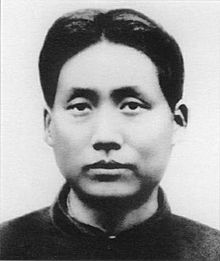

Мао родился в крестьянской семье в деревне Шаошань уезда Сянтань провинции Хунань. Отец его был, по крестьянским меркам, зажиточным кулаком, Мао с ним не ладил и при первой возможности свалил из родного дома. Сам Мао рассказывает о своих родственниках: «…У меня было три брата, двое из них убиты гоминьдановцами. Моя жена тоже стала жертвой гоминьдана. Младшую сестру убил гоминьдан. У меня был племянник, его тоже убил гоминьдан».

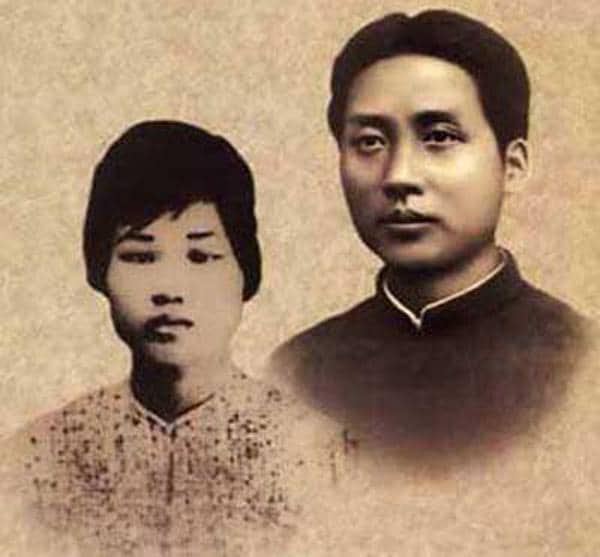

Мао был женат четыре раза (первый брак, в ранней юности, был навязан родителями, поэтому его обычно не считают). Вторая жена – Ян Кайхуэй (Yang Kaihui) была убита гоминьдановцами в 1930 г. Третья – Хэ Цзычжэнь (He Zizhen); брак распался после её отъезда на лечение в Советский Союз. Четвёртая – Цзян Цин (Jiang Qing) – была арестована после смерти Мао и умерла (или покончила с собой) в тюрьме в 1991 г. Чтобы избежать путаницы приводим другие имена, которые она носила: Ли Цзинь («Стоптанный Башмачок»), Ли Юньхэ («Небесная Журавушка»), Лань Пин (蓝苹, «Голубое Яблочко»); Цзян Цин означает «Лазурная Речка».

С Ян Кайхуэй у Мао было два сына. Старший, Мао Аньин (Mao Anying), родился в 1922 г., был воином-интернационалистом и погиб при американской бомбёжке в 1950 г. в Корее. Младший, Мао Аньцин (Mao Anqing), после казни матери в 1930 г. остался в «буржуазной» семье её родственников, и, согласно хунвэйбинским источникам, подвергался столь дурному обращению, что повредился умом.

Как правильно пишется имя Мао Цзэдуна?

Мао Цзэдун. Заметьте, что «Мао» — это фамилия, а «Цзэдун» — имя. Все остальные варианты написания – с сочетанием «Дз» или буквой «е» вместо «э», а тем более в три слова — неправильны; дефис в имени нежелателен. «Цзе» и «цзэ» — это разные слоги. «Цзедун» — так называется уезд в г. Цзеян, и вовсе не в честь Мао Цзэдуна; это означает «Восточный Цзе[ян]».

Написание «Мао Цзэдун» соответствует правилам, основанным на созданной в ⅩⅨ веке транскрипционной системе отца Палладия (Кафарова), священника Русской православной миссии в Пекине. Транскрипция Палладия официально признана китайскими лингвистами; она обязательно употребляется в китайско-русских словарях, в том числе и издаваемых в Китае. Для некоторых широко известных названий и имён в русском языке сохранилось устоявшееся ранее неправильное написание: Пекин, Чан Кайши.

В пиньине (официальной латинской транскрипции китайского языка) «Мао Цзэдун» соответствует «Mao Zedong». Во многих англоязычных источниках встречается транскрипция Уэйда-Джайлса, согласно которой пишется «Mao Tse-tung».

Ссылки

- Публикации на Маоизм.Ру

- В Маоистской библиотеке

|

Mao Zedong |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 毛泽东 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

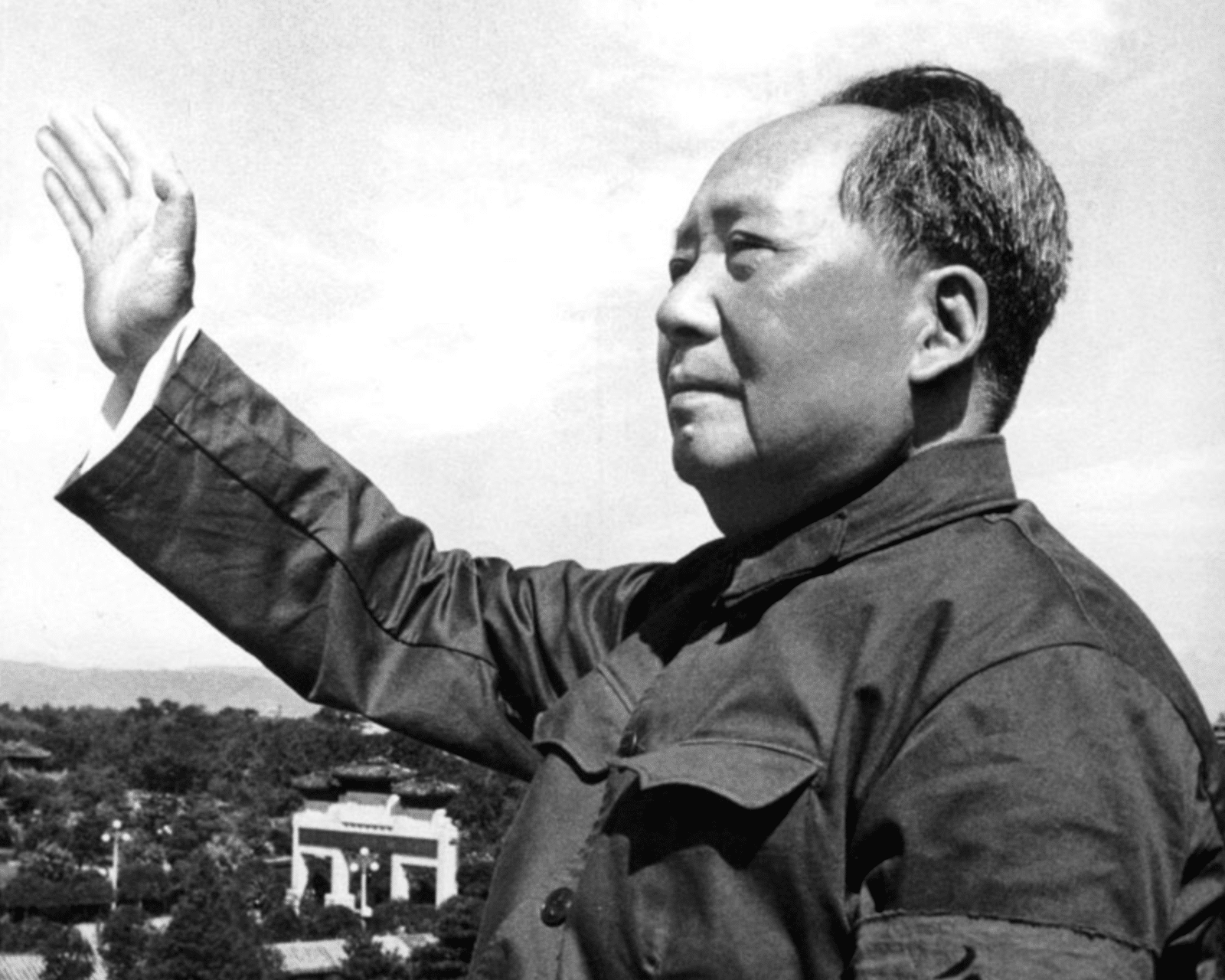

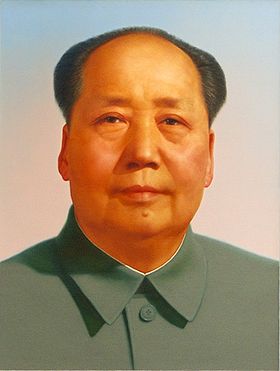

Mao in 1959 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Communist Party of China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 20 March 1943 – 9 September 1976 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Liu Shaoqi Lin Biao Zhou Enlai Hua Guofeng |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Zhang Wentian (as General Secretary) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Hua Guofeng | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1st Chairman of the People’s Republic of China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 27 September 1954 – 27 April 1959 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | Zhou Enlai | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Zhu De | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Liu Shaoqi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Central Military Commission | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 8 September 1954 – 9 September 1976 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Zhu De Lin Biao Ye Jianying |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Hua Guofeng | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Central People’s Government | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 October 1949 – 27 September 1954 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | Zhou Enlai | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 26 December 1893 Shaoshan, Hunan, Qing Dynasty |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 9 September 1976 (aged 82) Beijing, People’s Republic of China |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Chairman Mao Memorial Hall | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Communist Party of China (1921–1976) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other political affiliations |

Kuomintang (1925–1926) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouses |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 10, including: Mao Anying Mao Anqing Mao Anlong Yang Yuehua Li Min Li Na |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Hunan First Normal University | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 毛泽东 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 毛澤東 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Courtesy name | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 润之 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 潤之 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Central institution membership

Other offices held

Paramount Leader of

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mao Zedong[a] (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which he led as the chairman of the Chinese Communist Party from the establishment of the PRC in 1949 until his death in 1976. Ideologically a Marxist–Leninist, his theories, military strategies, and political policies are collectively known as Maoism.

Mao was the son of a prosperous peasant in Shaoshan, Hunan. He supported Chinese nationalism and had an anti-imperialist outlook early in his life, and was particularly influenced by the events of the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 and May Fourth Movement of 1919. He later adopted Marxism–Leninism while working at Peking University as a librarian and became a founding member of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), leading the Autumn Harvest Uprising in 1927. During the Chinese Civil War between the Kuomintang (KMT) and the CCP, Mao helped to found the Chinese Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army, led the Jiangxi Soviet’s radical land reform policies, and ultimately became head of the CCP during the Long March. Although the CCP temporarily allied with the KMT under the Second United Front during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), China’s civil war resumed after Japan’s surrender, and Mao’s forces defeated the Nationalist government, which withdrew to Taiwan in 1949.

On 1 October 1949, Mao proclaimed the foundation of the PRC, a Marxist–Leninist single-party state controlled by the CCP. In the following years he solidified his control through the Chinese Land Reform against landlords, the Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries, the «Three-anti and Five-anti Campaigns», and through a psychological victory in the Korean War, which altogether resulted in the deaths of several million Chinese. From 1953 to 1958, Mao played an important role in enforcing planned economy in China, constructing the first Constitution of the PRC, launching the industrialisation program, and initiating military projects such as the «Two Bombs, One Satellite» project and Project 523. His foreign policies during this time were dominated by the Sino-Soviet split which drove a wedge between China and the Soviet Union. In 1955, Mao launched the Sufan movement, and in 1957 he launched the Anti-Rightist Campaign, in which at least 550,000 people, mostly intellectuals and dissidents, were persecuted.[2] In 1958, he launched the Great Leap Forward that aimed to rapidly transform China’s economy from agrarian to industrial, which led to the deadliest famine in history and the deaths of 15–55 million people between 1958 and 1962. In 1963, Mao launched the Socialist Education Movement, and in 1966 he initiated the Cultural Revolution, a program to remove «counter-revolutionary» elements in Chinese society which lasted 10 years and was marked by violent class struggle, widespread destruction of cultural artifacts, and an unprecedented elevation of Mao’s cult of personality. Tens of millions of people were persecuted during the Revolution, while the estimated number of deaths ranges from hundreds of thousands to millions. After years of ill health, Mao suffered a series of heart attacks in 1976 and died at the age of 82. During Mao’s era, China’s population grew from around 550 million to over 900 million while the government did not strictly enforce its family planning policy.

A controversial figure within and outside China, Mao is still regarded as one of the most influential figures of the twentieth century. Beyond politics, Mao is also known as a theorist, military strategist, and poet. During the Mao era, China was heavily involved with other southeast Asian communist conflicts such as the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Cambodian Civil War, which brought the Khmer Rouge to power. The government during Mao’s rule was responsible for vast numbers of deaths with estimates ranging from 40 to 80 million victims through starvation, persecution, prison labour, and mass executions.[3][4][5][6] Mao has been praised for transforming China from a semi-colony to a leading world power, with greatly advanced literacy, women’s rights, basic healthcare, primary education and life expectancy.[7][8][9][10]

English romanisation of name

During Mao’s lifetime, the English-language media universally rendered his name as Mao Tse-tung, using the Wade-Giles system of transliteration for Standard Chinese though with the circumflex accent in the syllable Tsê dropped. Due to its recognizability, the spelling was used widely, even by the Foreign Ministry of the PRC after Hanyu Pinyin became the PRC’s official romanisation system for Mandarin Chinese in 1958; the well-known booklet of Mao’s political statements, The Little Red Book, was officially entitled Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung in English translations. While the pinyin-derived spelling Mao Zedong is increasingly common, the Wade-Giles-derived spelling Mao Tse-tung continues to be used in modern publications to some extent.[11]

Early life

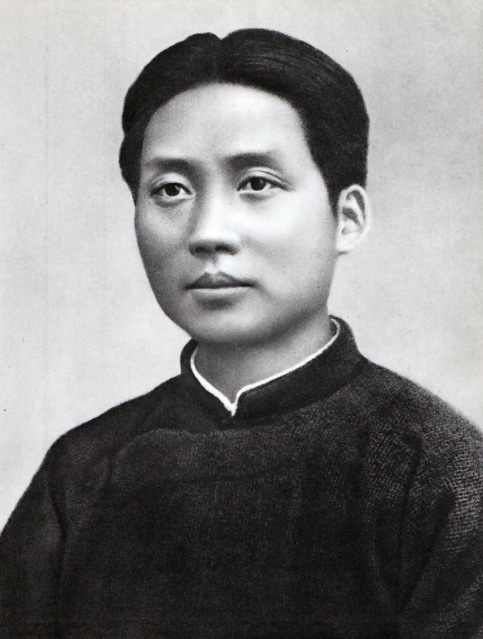

Youth and the Xinhai Revolution: 1893–1911

Mao Zedong was born on 26 December 1893, in Shaoshan village, Hunan.[12] His father, Mao Yichang, was a formerly impoverished peasant who had become one of the wealthiest farmers in Shaoshan. Growing up in rural Hunan, Mao described his father as a stern disciplinarian, who would beat him and his three siblings, the boys Zemin and Zetan, as well as an adopted girl, Zejian.[13] Mao’s mother, Wen Qimei, was a devout Buddhist who tried to temper her husband’s strict attitude.[14] Mao too became a Buddhist, but abandoned this faith in his mid-teenage years.[14] At age 8, Mao was sent to Shaoshan Primary School. Learning the value systems of Confucianism, he later admitted that he did not enjoy the classical Chinese texts preaching Confucian morals, instead favouring classic novels like Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margin.[15] At age 13, Mao finished primary education, and his father united him in an arranged marriage to the 17-year-old Luo Yixiu, thereby uniting their land-owning families. Mao refused to recognise her as his wife, becoming a fierce critic of arranged marriage and temporarily moving away. Luo was locally disgraced and died in 1910, at only 21 years old.[16]

While working on his father’s farm, Mao read voraciously[17] and developed a «political consciousness» from Zheng Guanying’s booklet which lamented the deterioration of Chinese power and argued for the adoption of representative democracy.[18] Interested in history, Mao was inspired by the military prowess and nationalistic fervour of George Washington and Napoleon Bonaparte.[19] His political views were shaped by Gelaohui-led protests which erupted following a famine in Changsha, the capital of Hunan; Mao supported the protesters’ demands, but the armed forces suppressed the dissenters and executed their leaders.[20] The famine spread to Shaoshan, where starving peasants seized his father’s grain. He disapproved of their actions as morally wrong, but claimed sympathy for their situation.[21] At age 16, Mao moved to a higher primary school in nearby Dongshan,[22] where he was bullied for his peasant background.[23]

In 1911, Mao began middle school in Changsha.[24] Revolutionary sentiment was strong in the city, where there was widespread animosity towards Emperor Puyi’s absolute monarchy and many were advocating republicanism. The republicans’ figurehead was Sun Yat-sen, an American-educated Christian who led the Tongmenghui society.[25] In Changsha, Mao was influenced by Sun’s newspaper, The People’s Independence (Minli bao),[26] and called for Sun to become president in a school essay.[27] As a symbol of rebellion against the Manchu monarch, Mao and a friend cut off their queue pigtails, a sign of subservience to the emperor.[28]

Inspired by Sun’s republicanism, the army rose up across southern China, sparking the Xinhai Revolution. Changsha’s governor fled, leaving the city in republican control.[29] Supporting the revolution, Mao joined the rebel army as a private soldier, but was not involved in fighting. The northern provinces remained loyal to the emperor, and hoping to avoid a civil war, Sun—proclaimed «provisional president» by his supporters—compromised with the monarchist general Yuan Shikai. The monarchy was abolished, creating the Republic of China, but the monarchist Yuan became president. The revolution over, Mao resigned from the army in 1912, after six months as a soldier.[30] Around this time, Mao discovered socialism from a newspaper article; proceeding to read pamphlets by Jiang Kanghu, the student founder of the Chinese Socialist Party, Mao remained interested yet unconvinced by the idea.[31]

Fourth Normal School of Changsha: 1912–1919

Over the next few years, Mao Zedong enrolled and dropped out of a police academy, a soap-production school, a law school, an economics school, and the government-run Changsha Middle School.[32] Studying independently, he spent much time in Changsha’s library, reading core works of classical liberalism such as Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations and Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws, as well as the works of western scientists and philosophers such as Darwin, Mill, Rousseau, and Spencer.[33] Viewing himself as an intellectual, years later he admitted that at this time he thought himself better than working people.[34] He was inspired by Friedrich Paulsen, a neo-Kantian philosopher and educator whose emphasis on the achievement of a carefully defined goal as the highest value led Mao to believe that strong individuals were not bound by moral codes but should strive for a great goal.[35] His father saw no use in his son’s intellectual pursuits, cut off his allowance and forced him to move into a hostel for the destitute.[36]

Mao desired to become a teacher and enrolled at the Fourth Normal School of Changsha, which soon merged with the First Normal School of Hunan, widely seen as the best in Hunan.[37] Befriending Mao, professor Yang Changji urged him to read a radical newspaper, New Youth (Xin qingnian), the creation of his friend Chen Duxiu, a dean at Peking University. Although he was a supporter of Chinese nationalism, Chen argued that China must look to the west to cleanse itself of superstition and autocracy.[38]

In his first school year, Mao befriended an older student, Xiao Zisheng; together they went on a walking tour of Hunan, begging and writing literary couplets to obtain food.[39]

A popular student, in 1915 Mao was elected secretary of the Students Society. He organised the Association for Student Self-Government and led protests against school rules.[40] Mao published his first article in New Youth in April 1917, instructing readers to increase their physical strength to serve the revolution.[41] He joined the Society for the Study of Wang Fuzhi (Chuan-shan Hsüeh-she), a revolutionary group founded by Changsha literati who wished to emulate the philosopher Wang Fuzhi.[42] In spring 1917, he was elected to command the students’ volunteer army, set up to defend the school from marauding soldiers.[43] Increasingly interested in the techniques of war, he took a keen interest in World War I, and also began to develop a sense of solidarity with workers.[44] Mao undertook feats of physical endurance with Xiao Zisheng and Cai Hesen, and with other young revolutionaries they formed the Renovation of the People Study Society in April 1918 to debate Chen Duxiu’s ideas. Desiring personal and societal transformation, the Society gained 70–80 members, many of whom would later join the Communist Party.[45] Mao graduated in June 1919, ranked third in the year.[46]

Early revolutionary activity

Beijing, anarchism, and Marxism: 1917–1919

Mao moved to Beijing, where his mentor Yang Changji had taken a job at Peking University.[47] Yang thought Mao exceptionally «intelligent and handsome»,[48] securing him a job as assistant to the university librarian Li Dazhao, who would become an early Chinese Communist.[49] Li authored a series of New Youth articles on the October Revolution in Russia, during which the Communist Bolshevik Party under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin had seized power. Lenin was an advocate of the socio-political theory of Marxism, first developed by the German sociologists Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, and Li’s articles added Marxism to the doctrines in Chinese revolutionary movement.[50]

Becoming «more and more radical», Mao was initially influenced by Peter Kropotkin’s anarchism, which was the most prominent radical doctrine of the day. Chinese anarchists, such as Cai Yuanpei, Chancellor of Peking University, called for complete social revolution in social relations, family structure, and women’s equality, rather than the simple change in the form of government called for by earlier revolutionaries. He joined Li’s Study Group and «developed rapidly toward Marxism» during the winter of 1919.[51] Paid a low wage, Mao lived in a cramped room with seven other Hunanese students, but believed that Beijing’s beauty offered «vivid and living compensation».[52] A number of his friends took advantage of the anarchist-organised Mouvement Travail-Études to study in France, but Mao declined, perhaps because of an inability to learn languages.[53]

At the university, Mao was snubbed by other students due to his rural Hunanese accent and lowly position. He joined the university’s Philosophy and Journalism Societies and attended lectures and seminars by the likes of Chen Duxiu, Hu Shih, and Qian Xuantong.[54] Mao’s time in Beijing ended in the spring of 1919, when he travelled to Shanghai with friends who were preparing to leave for France.[55] He did not return to Shaoshan, where his mother was terminally ill. She died in October 1919 and her husband died in January 1920.[56]

New Culture and political protests: 1919–1920

On 4 May 1919, students in Beijing gathered at the Tiananmen to protest the Chinese government’s weak resistance to Japanese expansion in China. Patriots were outraged at the influence given to Japan in the Twenty-One Demands in 1915, the complicity of Duan Qirui’s Beiyang Government, and the betrayal of China in the Treaty of Versailles, wherein Japan was allowed to receive territories in Shandong which had been surrendered by Germany. These demonstrations ignited the nationwide May Fourth Movement and fuelled the New Culture Movement which blamed China’s diplomatic defeats on social and cultural backwardness.[57]

In Changsha, Mao had begun teaching history at the Xiuye Primary School[58] and organising protests against the pro-Duan Governor of Hunan Province, Zhang Jingyao, popularly known as «Zhang the Venomous» due to his corrupt and violent rule.[59] In late May, Mao co-founded the Hunanese Student Association with He Shuheng and Deng Zhongxia, organising a student strike for June and in July 1919 began production of a weekly radical magazine, Xiang River Review. Using vernacular language that would be understandable to the majority of China’s populace, he advocated the need for a «Great Union of the Popular Masses», strengthened trade unions able to wage non-violent revolution.[clarification needed] His ideas were not Marxist, but heavily influenced by Kropotkin’s concept of mutual aid.[60]

Students in Beijing rallying during the May Fourth Movement

Zhang banned the Student Association, but Mao continued publishing after assuming editorship of the liberal magazine New Hunan (Xin Hunan) and offered articles in popular local newspaper Ta Kung Pao. Several of these advocated feminist views, calling for the liberation of women in Chinese society; Mao was influenced by his forced arranged-marriage.[61] In December 1919, Mao helped organise a general strike in Hunan, securing some concessions, but Mao and other student leaders felt threatened by Zhang, and Mao returned to Beijing, visiting the terminally ill Yang Changji.[62] Mao found that his articles had achieved a level of fame among the revolutionary movement, and set about soliciting support in overthrowing Zhang.[63] Coming across newly translated Marxist literature by Thomas Kirkup, Karl Kautsky, and Marx and Engels—notably The Communist Manifesto—he came under their increasing influence, but was still eclectic in his views.[64]

Mao visited Tianjin, Jinan, and Qufu,[65] before moving to Shanghai, where he worked as a laundryman and met Chen Duxiu, noting that Chen’s adoption of Marxism «deeply impressed me at what was probably a critical period in my life». In Shanghai, Mao met an old teacher of his, Yi Peiji, a revolutionary and member of the Kuomintang (KMT), or Chinese Nationalist Party, which was gaining increasing support and influence. Yi introduced Mao to General Tan Yankai, a senior KMT member who held the loyalty of troops stationed along the Hunanese border with Guangdong. Tan was plotting to overthrow Zhang, and Mao aided him by organising the Changsha students. In June 1920, Tan led his troops into Changsha, and Zhang fled. In the subsequent reorganisation of the provincial administration, Mao was appointed headmaster of the junior section of the First Normal School. Now receiving a large income, he married Yang Kaihui, daughter of Yang Changji, in the winter of 1920.[66][67]

Founding the Chinese Communist Party: 1921–1922

The Chinese Communist Party was founded by Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao in the French concession of Shanghai in 1921 as a study society and informal network. Mao set up a Changsha branch, also establishing a branch of the Socialist Youth Corps and a Cultural Book Society which opened a bookstore to propagate revolutionary literature throughout Hunan.[68] He was involved in the movement for Hunan autonomy, in the hope that a Hunanese constitution would increase civil liberties and make his revolutionary activity easier. When the movement was successful in establishing provincial autonomy under a new warlord, Mao forgot his involvement.[69] By 1921, small Marxist groups existed in Shanghai, Beijing, Changsha, Wuhan, Guangzhou, and Jinan; it was decided to hold a central meeting, which began in Shanghai on 23 July 1921. The first session of the National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party was attended by 13 delegates, Mao included. After the authorities sent a police spy to the congress, the delegates moved to a boat on South Lake near Jiaxing, in Zhejiang, to escape detection. Although Soviet and Comintern delegates attended, the first congress ignored Lenin’s advice to accept a temporary alliance between the Communists and the «bourgeois democrats» who also advocated national revolution; instead they stuck to the orthodox Marxist belief that only the urban proletariat could lead a socialist revolution.[70]

Mao was now party secretary for Hunan stationed in Changsha, and to build the party there he followed a variety of tactics.[71] In August 1921, he founded the Self-Study University, through which readers could gain access to revolutionary literature, housed in the premises of the Society for the Study of Wang Fuzhi, a Qing dynasty Hunanese philosopher who had resisted the Manchus.[71] He joined the YMCA Mass Education Movement to fight illiteracy, though he edited the textbooks to include radical sentiments.[72] He continued organising workers to strike against the administration of Hunan Governor Zhao Hengti.[73] Yet labour issues remained central. The successful and famous Anyuan coal mines strikes [zh] (contrary to later Party historians) depended on both «proletarian» and «bourgeois» strategies. Liu Shaoqi and Li Lisan and Mao not only mobilised the miners, but formed schools and cooperatives and engaged local intellectuals, gentry, military officers, merchants, Red Gang dragon heads and even church clergy.[74] Mao’s labour organizing work in the Anyuan mines also involved his wife Yang Kaihui, who worked for women’s rights, including literacy and educational issues, in the nearby peasant communities.[75] Although Mao and Yang were not the originators of this political organizing method of combining labor organizing among male workers with a focus on women’s rights issues in their communities, they were among the most effective at using this method.[75] Mao’s political organizing success in the Anyuan mines resulted in Chen Duxiu inviting him to become a member of the Communist Party’s Central Committee.[76]

Mao claimed that he missed the July 1922 Second Congress of the Communist Party in Shanghai because he lost the address. Adopting Lenin’s advice, the delegates agreed to an alliance with the «bourgeois democrats» of the KMT for the good of the «national revolution». Communist Party members joined the KMT, hoping to push its politics leftward.[77]

Mao enthusiastically agreed with this decision, arguing for an alliance across China’s socio-economic classes, and eventually rose to become propaganda chief of the KMT.[67] Mao was a vocal anti-imperialist and in his writings he lambasted the governments of Japan, the UK and US, describing the latter as «the most murderous of hangmen».[78]

Collaboration with the Kuomintang: 1922–1927

Mao giving speeches to the masses (no audio)

At the Third Congress of the Communist Party in Shanghai in June 1923, the delegates reaffirmed their commitment to working with the KMT. Supporting this position, Mao was elected to the Party Committee, taking up residence in Shanghai.[79] At the First KMT Congress, held in Guangzhou in early 1924, Mao was elected an alternate member of the KMT Central Executive Committee, and put forward four resolutions to decentralise power to urban and rural bureaus. His enthusiastic support for the KMT earned him the suspicion of Li Li-san, his Hunan comrade.[80]

In late 1924, Mao returned to Shaoshan, perhaps to recuperate from an illness. He found that the peasantry were increasingly restless and some had seized land from wealthy landowners to found communes. This convinced him of the revolutionary potential of the peasantry, an idea advocated by the KMT leftists but not the Communists.[81] In the winter of 1925, Mao fled to Guangzhou after his revolutionary activities attracted the attention of Zhao’s regional authorities.[82] There, he ran the 6th term of the KMT’s Peasant Movement Training Institute from May to September 1926.[83][84] The Peasant Movement Training Institute under Mao trained cadre and prepared them for militant activity, taking them through military training exercises and getting them to study basic left-wing texts.[85]

Mao Zedong around the time of his work at Guangzhou’s PMTI in 1925

When party leader Sun Yat-sen died in May 1925, he was succeeded by Chiang Kai-shek, who moved to marginalise the left-KMT and the Communists.[86] Mao nevertheless supported Chiang’s National Revolutionary Army, who embarked on the Northern Expedition attack in 1926 on warlords.[87] In the wake of this expedition, peasants rose up, appropriating the land of the wealthy landowners, who were in many cases killed. Such uprisings angered senior KMT figures, who were themselves landowners, emphasising the growing class and ideological divide within the revolutionary movement.[88]

Third Plenum of the KMT Central Executive Committee in March 1927. Mao is third from the right in the second row.

In March 1927, Mao appeared at the Third Plenum of the KMT Central Executive Committee in Wuhan, which sought to strip General Chiang of his power by appointing Wang Jingwei leader. There, Mao played an active role in the discussions regarding the peasant issue, defending a set of «Regulations for the Repression of Local Bullies and Bad Gentry», which advocated the death penalty or life imprisonment for anyone found guilty of counter-revolutionary activity, arguing that in a revolutionary situation, «peaceful methods cannot suffice».[89][90] In April 1927, Mao was appointed to the KMT’s five-member Central Land Committee, urging peasants to refuse to pay rent. Mao led another group to put together a «Draft Resolution on the Land Question», which called for the confiscation of land belonging to «local bullies and bad gentry, corrupt officials, militarists and all counter-revolutionary elements in the villages». Proceeding to carry out a «Land Survey», he stated that anyone owning over 30 mou (four and a half acres), constituting 13% of the population, were uniformly counter-revolutionary. He accepted that there was great variation in revolutionary enthusiasm across the country, and that a flexible policy of land redistribution was necessary.[91] Presenting his conclusions at the Enlarged Land Committee meeting, many expressed reservations, some believing that it went too far, and others not far enough. Ultimately, his suggestions were only partially implemented.[92]

Civil War

Nanchang and Autumn Harvest Uprisings: 1927

Fresh from the success of the Northern Expedition against the warlords, Chiang turned on the Communists, who by now numbered in the tens of thousands across China. Chiang ignored the orders of the Wuhan-based left KMT government and marched on Shanghai, a city controlled by Communist militias. As the Communists awaited Chiang’s arrival, he loosed the White Terror, massacring 5000 with the aid of the Green Gang.[90][93] In Beijing, 19 leading Communists were killed by Zhang Zuolin.[94][95] That May, tens of thousands of Communists and those suspected of being communists were killed, and the CCP lost approximately 15,000 of its 25,000 members.[95]

The CCP continued supporting the Wuhan KMT government, a position Mao initially supported,[95] but by the time of the CCP’s Fifth Congress he had changed his mind, deciding to stake all hope on the peasant militia.[96] The question was rendered moot when the Wuhan government expelled all Communists from the KMT on 15 July.[96] The CCP founded the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army of China, better known as the «Red Army», to battle Chiang. A battalion led by General Zhu De was ordered to take the city of Nanchang on 1 August 1927, in what became known as the Nanchang Uprising. They were initially successful, but were forced into retreat after five days, marching south to Shantou, and from there they were driven into the wilderness of Fujian.[96] Mao was appointed commander-in-chief of the Red Army and led four regiments against Changsha in the Autumn Harvest Uprising, in the hope of sparking peasant uprisings across Hunan. On the eve of the attack, Mao composed a poem—the earliest of his to survive—titled «Changsha». His plan was to attack the KMT-held city from three directions on 9 September, but the Fourth Regiment deserted to the KMT cause, attacking the Third Regiment. Mao’s army made it to Changsha, but could not take it; by 15 September, he accepted defeat and with 1000 survivors marched east to the Jinggang Mountains of Jiangxi.[97][98]

Base in Jinggangshan: 1927–1928

革命不是請客吃飯,不是做文章,不是繪畫繡花,不能那樣雅緻,那樣從容不迫,文質彬彬,那樣溫良恭讓。革命是暴動,是一個階級推翻一個階級的暴烈的行動。

Revolution is not a dinner party, nor an essay, nor a painting, nor a piece of embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another.

— Mao, February 1927[99]

The CCP Central Committee, hiding in Shanghai, expelled Mao from their ranks and from the Hunan Provincial Committee, as punishment for his «military opportunism», for his focus on rural activity, and for being too lenient with «bad gentry». The more orthodox Communists especially regarded the peasants as backward and ridiculed Mao’s idea of mobilizing them.[67] They nevertheless adopted three policies he had long championed: the immediate formation of Workers’ councils, the confiscation of all land without exemption, and the rejection of the KMT. Mao’s response was to ignore them.[100] He established a base in Jinggangshan City, an area of the Jinggang Mountains, where he united five villages as a self-governing state, and supported the confiscation of land from rich landlords, who were «re-educated» and sometimes executed. He ensured that no massacres took place in the region, and pursued a more lenient approach than that advocated by the Central Committee.[101] In addition to land redistribution, Mao promoted literacy and non-hierarchical organizational relationships in Jinggangshan, transforming the area’s social and economic life and attracted many local supporters.[102]

Mao proclaimed that «Even the lame, the deaf and the blind could all come in useful for the revolutionary struggle», he boosted the army’s numbers,[103] incorporating two groups of bandits into his army, building a force of around 1,800 troops.[104] He laid down rules for his soldiers: prompt obedience to orders, all confiscations were to be turned over to the government, and nothing was to be confiscated from poorer peasants. In doing so, he moulded his men into a disciplined, efficient fighting force.[103]

敵進我退,

敵駐我騷,

敵疲我打,

敵退我追。When the enemy advances, we retreat.

When the enemy rests, we harass him.

When the enemy avoids a battle, we attack.

When the enemy retreats, we advance.

— Mao’s advice in combating the Kuomintang, 1928[105][106]

Chinese Communist revolutionaries in the 1920s

In spring 1928, the Central Committee ordered Mao’s troops to southern Hunan, hoping to spark peasant uprisings. Mao was skeptical, but complied. They reached Hunan, where they were attacked by the KMT and fled after heavy losses. Meanwhile, KMT troops had invaded Jinggangshan, leaving them without a base.[107] Wandering the countryside, Mao’s forces came across a CCP regiment led by General Zhu De and Lin Biao; they united, and attempted to retake Jinggangshan. They were initially successful, but the KMT counter-attacked, and pushed the CCP back; over the next few weeks, they fought an entrenched guerrilla war in the mountains.[105][108] The Central Committee again ordered Mao to march to south Hunan, but he refused, and remained at his base. Contrastingly, Zhu complied, and led his armies away. Mao’s troops fended the KMT off for 25 days while he left the camp at night to find reinforcements. He reunited with the decimated Zhu’s army, and together they returned to Jinggangshan and retook the base. There they were joined by a defecting KMT regiment and Peng Dehuai’s Fifth Red Army. In the mountainous area they were unable to grow enough crops to feed everyone, leading to food shortages throughout the winter.[109][110]

In 1928, Mao met and married He Zizhen, an 18-year-old revolutionary who would bear him six children.[111][112]

Jiangxi Soviet Republic of China: 1929–1934

In January 1929, Mao and Zhu evacuated the base with 2,000 men and a further 800 provided by Peng, and took their armies south, to the area around Tonggu and Xinfeng in Jiangxi.[113] The evacuation led to a drop in morale, and many troops became disobedient and began thieving; this worried Li Lisan and the Central Committee, who saw Mao’s army as lumpenproletariat, that were unable to share in proletariat class consciousness.[114][115] In keeping with orthodox Marxist thought, Li believed that only the urban proletariat could lead a successful revolution, and saw little need for Mao’s peasant guerrillas; he ordered Mao to disband his army into units to be sent out to spread the revolutionary message. Mao replied that while he concurred with Li’s theoretical position, he would not disband his army nor abandon his base.[115][116] Both Li and Mao saw the Chinese revolution as the key to world revolution, believing that a CCP victory would spark the overthrow of global imperialism and capitalism. In this, they disagreed with the official line of the Soviet government and Comintern. Officials in Moscow desired greater control over the CCP and removed Li from power by calling him to Russia for an inquest into his errors.[117][118][119] They replaced him with Soviet-educated Chinese Communists, known as the «28 Bolsheviks», two of whom, Bo Gu and Zhang Wentian, took control of the Central Committee. Mao disagreed with the new leadership, believing they grasped little of the Chinese situation, and he soon emerged as their key rival.[118][120]

Military parade on the occasion of the founding of a Chinese Soviet Republic in 1931

In February 1930, Mao created the Southwest Jiangxi Provincial Soviet Government in the region under his control.[121] In November, he suffered emotional trauma after his second wife Yang Kaihui and sister were captured and beheaded by KMT general He Jian.[110][118][122] Facing internal problems, members of the Jiangxi Soviet accused him of being too moderate, and hence anti-revolutionary. In December, they tried to overthrow Mao, resulting in the Futian incident, during which Mao’s loyalists tortured many and executed between 2000 and 3000 dissenters.[123][124][125] The CCP Central Committee moved to Jiangxi which it saw as a secure area. In November, it proclaimed Jiangxi to be the Soviet Republic of China, an independent Communist-governed state. Although he was proclaimed Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars, Mao’s power was diminished, as his control of the Red Army was allocated to Zhou Enlai. Meanwhile, Mao recovered from tuberculosis.[126][127]

The KMT armies adopted a policy of encirclement and annihilation of the Red armies. Outnumbered, Mao responded with guerrilla tactics influenced by the works of ancient military strategists like Sun Tzu, but Zhou and the new leadership followed a policy of open confrontation and conventional warfare. In doing so, the Red Army successfully defeated the first and second encirclements.[128][129] Angered at his armies’ failure, Chiang Kai-shek personally arrived to lead the operation. He too faced setbacks and retreated to deal with the further Japanese incursions into China.[126][130] As a result of the KMT’s change of focus to the defence of China against Japanese expansionism, the Red Army was able to expand its area of control, eventually encompassing a population of 3 million.[129] Mao proceeded with his land reform program. In November 1931 he announced the start of a «land verification project» which was expanded in June 1933. He also orchestrated education programs and implemented measures to increase female political participation.[131] Chiang viewed the Communists as a greater threat than the Japanese and returned to Jiangxi, where he initiated the fifth encirclement campaign, which involved the construction of a concrete and barbed wire «wall of fire» around the state, which was accompanied by aerial bombardment, to which Zhou’s tactics proved ineffective. Trapped inside, morale among the Red Army dropped as food and medicine became scarce. The leadership decided to evacuate.[132]

Long March: 1934–1935

An overview map of the Long March

On 14 October 1934, the Red Army broke through the KMT line on the Jiangxi Soviet’s south-west corner at Xinfeng with 85,000 soldiers and 15,000 party cadres and embarked on the «Long March». In order to make the escape, many of the wounded and the ill, as well as women and children, were left behind, defended by a group of guerrilla fighters whom the KMT massacred.[133][134] The 100,000 who escaped headed to southern Hunan, first crossing the Xiang River after heavy fighting,[134][135] and then the Wu River, in Guizhou where they took Zunyi in January 1935. Temporarily resting in the city, they held a conference; here, Mao was elected to a position of leadership, becoming Chairman of the Politburo, and de facto leader of both Party and Red Army, in part because his candidacy was supported by Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin. Insisting that they operate as a guerrilla force, he laid out a destination: the Shenshi Soviet in Shaanxi, Northern China, from where the Communists could focus on fighting the Japanese. Mao believed that in focusing on the anti-imperialist struggle, the Communists would earn the trust of the Chinese people, who in turn would renounce the KMT.[136]

From Zunyi, Mao led his troops to Loushan Pass, where they faced armed opposition but successfully crossed the river. Chiang flew into the area to lead his armies against Mao, but the Communists outmanoeuvred him and crossed the Jinsha River.[137] Faced with the more difficult task of crossing the Tatu River, they managed it by fighting a battle over the Luding Bridge in May, taking Luding.[138] Marching through the mountain ranges around Ma’anshan,[139] in Moukung, Western Szechuan, they encountered the 50,000-strong CCP Fourth Front Army of Zhang Guotao, and together proceeded to Maoerhkai and then Gansu. Zhang and Mao disagreed over what to do; the latter wished to proceed to Shaanxi, while Zhang wanted to retreat east to Tibet or Sikkim, far from the KMT threat. It was agreed that they would go their separate ways, with Zhu De joining Zhang.[140] Mao’s forces proceeded north, through hundreds of kilometres of Grasslands, an area of quagmire where they were attacked by Manchu tribesman and where many soldiers succumbed to famine and disease.[141][142] Finally reaching Shaanxi, they fought off both the KMT and an Islamic cavalry militia before crossing the Min Mountains and Mount Liupan and reaching the Shenshi Soviet; only 7,000–8000 had survived.[142][143] The Long March cemented Mao’s status as the dominant figure in the party. In November 1935, he was named chairman of the Military Commission. From this point onward, Mao was the Communist Party’s undisputed leader, even though he would not become party chairman until 1943.[144]

Alliance with the Kuomintang: 1935–1940

Mao’s troops arrived at the Yan’an Soviet during October 1935 and settled in Pao An, until spring 1936. While there, they developed links with local communities, redistributed and farmed the land, offered medical treatment, and began literacy programs.[142][145][146] Mao now commanded 15,000 soldiers, boosted by the arrival of He Long’s men from Hunan and the armies of Zhu De and Zhang Guotao returned from Tibet.[145] In February 1936, they established the North West Anti-Japanese Red Army University in Yan’an, through which they trained increasing numbers of new recruits.[147] In January 1937, they began the «anti-Japanese expedition», that sent groups of guerrilla fighters into Japanese-controlled territory to undertake sporadic attacks.[148][149] In May 1937, a Communist Conference was held in Yan’an to discuss the situation.[150] Western reporters also arrived in the «Border Region» (as the Soviet had been renamed); most notable were Edgar Snow, who used his experiences as a basis for Red Star Over China, and Agnes Smedley, whose accounts brought international attention to Mao’s cause.[151]

In an effort to defeat the Japanese, Mao (left) agreed to collaborate with Chiang (right).

Mao in 1938, writing On Protracted War

On the Long March, Mao’s wife He Zizen had been injured by a shrapnel wound to the head. She travelled to Moscow for medical treatment; Mao proceeded to divorce her and marry an actress, Jiang Qing.[152][153] He Zizhen was reportedly «dispatched to a mental asylum in Moscow to make room» for Qing.[154] Mao moved into a cave-house and spent much of his time reading, tending his garden and theorising.[155] He came to believe that the Red Army alone was unable to defeat the Japanese, and that a Communist-led «government of national defence» should be formed with the KMT and other «bourgeois nationalist» elements to achieve this goal.[156] Although despising Chiang Kai-shek as a «traitor to the nation»,[157] on 5 May, he telegrammed the Military Council of the Nanking National Government proposing a military alliance, a course of action advocated by Stalin.[158] Although Chiang intended to ignore Mao’s message and continue the civil war, he was arrested by one of his own generals, Zhang Xueliang, in Xi’an, leading to the Xi’an Incident; Zhang forced Chiang to discuss the issue with the Communists, resulting in the formation of a United Front with concessions on both sides on 25 December 1937.[159]

The Japanese had taken both Shanghai and Nanking (Nanjing)—resulting in the Nanking Massacre, an atrocity Mao never spoke of all his life—and was pushing the Kuomintang government inland to Chungking.[160] The Japanese’s brutality led to increasing numbers of Chinese joining the fight, and the Red Army grew from 50,000 to 500,000.[161][162] In August 1938, the Red Army formed the New Fourth Army and the Eighth Route Army, which were nominally under the command of Chiang’s National Revolutionary Army.[163] In August 1940, the Red Army initiated the Hundred Regiments Campaign, in which 400,000 troops attacked the Japanese simultaneously in five provinces. It was a military success that resulted in the death of 20,000 Japanese, the disruption of railways and the loss of a coal mine.[162][164] From his base in Yan’an, Mao authored several texts for his troops, including Philosophy of Revolution, which offered an introduction to the Marxist theory of knowledge; Protracted Warfare, which dealt with guerrilla and mobile military tactics; and New Democracy, which laid forward ideas for China’s future.[165]

Resuming civil war: 1940–1949

In 1944, the U.S. sent a special diplomatic envoy, called the Dixie Mission, to the Chinese Communist Party. The American soldiers who were sent to the mission were favourably impressed. The party seemed less corrupt, more unified, and more vigorous in its resistance to Japan than the Kuomintang. The soldiers confirmed to their superiors that the party was both strong and popular over a broad area.[166] In the end of the mission, the contacts which the U.S. developed with the Chinese Communist Party led to very little.[166] After the end of World War II, the U.S. continued their diplomatic and military assistance to Chiang Kai-shek and his KMT government forces against the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) led by Mao Zedong during the civil war and abandoned the idea of a coalition government which would include the CCP.[167] Likewise, the Soviet Union gave support to Mao by occupying north-eastern China, and secretly giving it to the Chinese communists in March 1946.[168]

PLA troops, supported by captured M5 Stuart light tanks, attacking the Nationalist lines in 1948

In 1948, under direct orders from Mao, the People’s Liberation Army starved out the Kuomintang forces occupying the city of Changchun. At least 160,000 civilians are believed to have perished during the siege, which lasted from June until October. PLA lieutenant colonel Zhang Zhenglu, who documented the siege in his book White Snow, Red Blood, compared it to Hiroshima: «The casualties were about the same. Hiroshima took nine seconds; Changchun took five months.»[169] On 21 January 1949, Kuomintang forces suffered great losses in decisive battles against Mao’s forces.[170] In the early morning of 10 December 1949, PLA troops laid siege to Chongqing and Chengdu on mainland China, and Chiang Kai-shek fled from the mainland to Formosa (Taiwan).[170][171]

Leadership of China

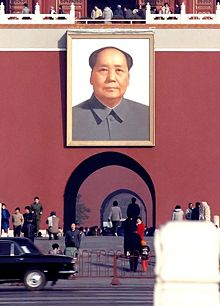

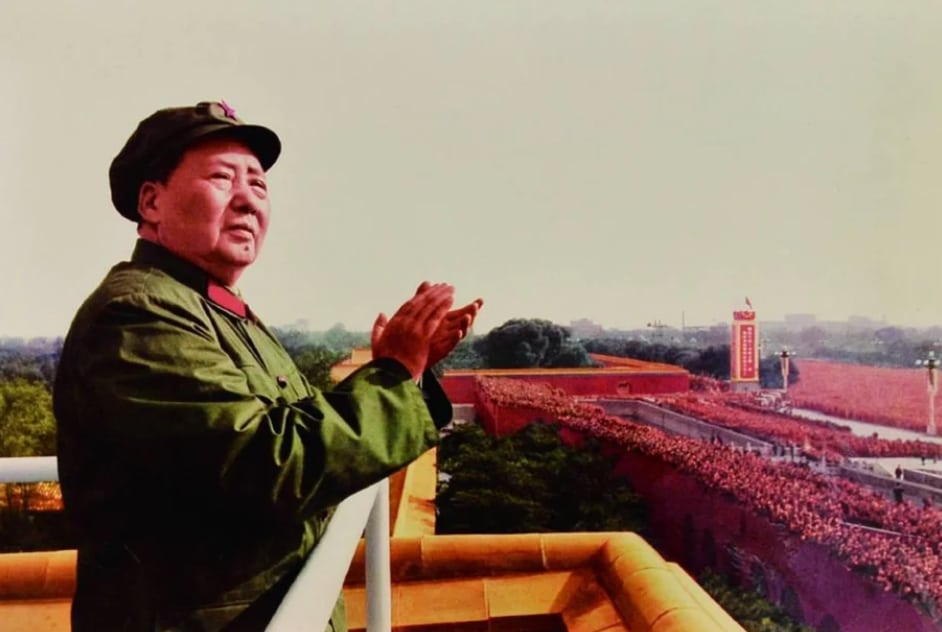

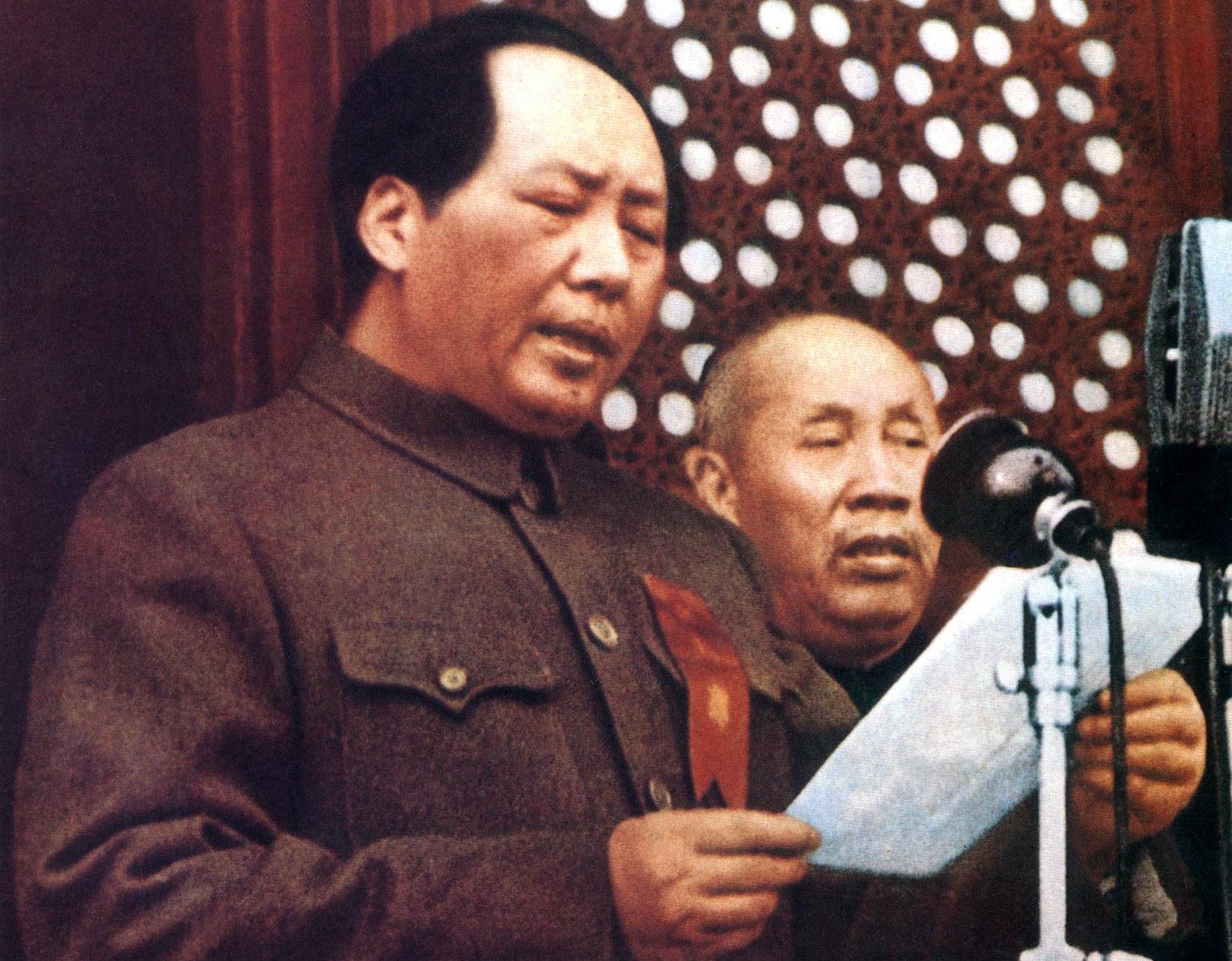

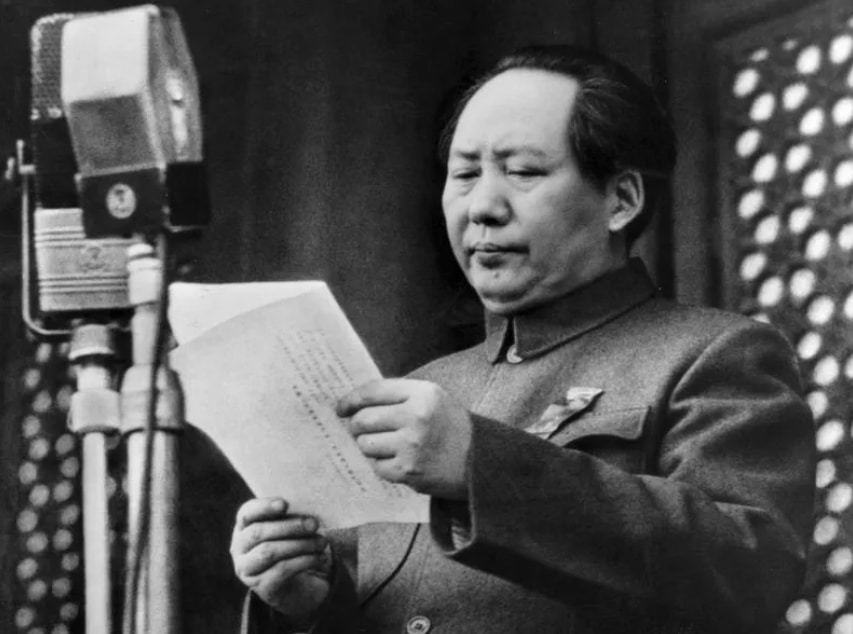

Mao Zedong declares the founding of the modern People’s Republic of China on 1 October 1949

Mao proclaimed the establishment of The People’s Republic of China from the Gate of Heavenly Peace (Tian’anmen) on 1 October 1949, and later that week declared «The Chinese people have stood up» (中国人民从此站起来了).[172] Mao went to Moscow for long talks in the winter of 1949–50. Mao initiated the talks which focused on the political and economic revolution in China, foreign policy, railways, naval bases, and Soviet economic and technical aid. The resulting treaty reflected Stalin’s dominance and his willingness to help Mao.[173][174]

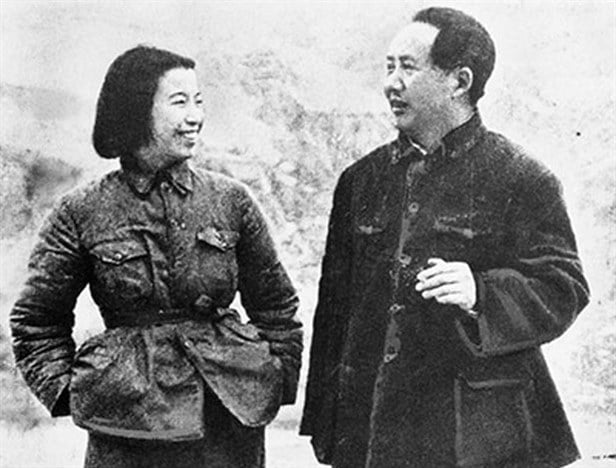

Mao with his fourth wife, Jiang Qing, called «Madame Mao», 1946

Mao pushed the Party to organise campaigns to reform society and extend control. These campaigns were given urgency in October 1950, when Mao made the decision to send the People’s Volunteer Army, a special unit of the People’s Liberation Army, into the Korean War and fight as well as to reinforce the armed forces of North Korea, the Korean People’s Army, which had been in full retreat. The United States placed a trade embargo on the People’s Republic as a result of its involvement in the Korean War, lasting until Richard Nixon’s improvements of relations. At least 180 thousand Chinese troops died during the war.[175]

Mao directed operations to the minutest detail. As the Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), he was also the Supreme Commander in Chief of the PLA and the People’s Republic and Chairman of the Party. Chinese troops in Korea were under the overall command of then newly installed Premier Zhou Enlai, with General Peng Dehuai as field commander and political commissar.[176]

During the land reform campaigns, large numbers of landlords and rich peasants were beaten to death at mass meetings organised by the Communist Party as land was taken from them and given to poorer peasants, which significantly reduced economic inequality.[177][178] The Campaign to Suppress Counter-revolutionaries[179] targeted bureaucratic burgeoisie, such as compradores, merchants and Kuomintang officials who were seen by the party as economic parasites or political enemies.[180] In 1976, the U.S. State department estimated as many as a million were killed in the land reform, and 800,000 killed in the counter-revolutionary campaign.[181]

Mao himself claimed that a total of 700,000 people were killed in attacks on «counter-revolutionaries» during the years 1950–1952.[182] Because there was a policy to select «at least one landlord, and usually several, in virtually every village for public execution»,[183] the number of deaths range between 2 million[183][184][179] and 5 million.[185][186] In addition, at least 1.5 million people,[187] perhaps as many as 4 to 6 million,[188] were sent to «reform through labour» camps where many perished.[188] Mao played a personal role in organising the mass repressions and established a system of execution quotas,[189] which were often exceeded.[179] He defended these killings as necessary for the securing of power.[190]

Mao at Joseph Stalin’s 70th birthday celebration in Moscow, December 1949

The Mao government is credited with eradicating both consumption and production of opium during the 1950s using unrestrained repression and social reform.[7][191] Ten million addicts were forced into compulsory treatment, dealers were executed, and opium-producing regions were planted with new crops. Remaining opium production shifted south of the Chinese border into the Golden Triangle region.[191]

Starting in 1951, Mao initiated two successive movements in an effort to rid urban areas of corruption by targeting wealthy capitalists and political opponents, known as the three-anti/five-anti campaigns. Whereas the three-anti campaign was a focused purge of government, industrial and party officials, the five-anti campaign set its sights slightly broader, targeting capitalist elements in general.[192] Workers denounced their bosses, spouses turned on their spouses, and children informed on their parents; the victims were often humiliated at struggle sessions, where a targeted person would be verbally and physically abused until they confessed to crimes. Mao insisted that minor offenders be criticised and reformed or sent to labour camps, «while the worst among them should be shot». These campaigns took several hundred thousand additional lives, the vast majority via suicide.[193]

In Shanghai, suicide by jumping from tall buildings became so commonplace that residents avoided walking on the pavement near skyscrapers for fear that suicides might land on them.[194] Some biographers have pointed out that driving those perceived as enemies to suicide was a common tactic during the Mao-era. In his biography of Mao, Philip Short notes that Mao gave explicit instructions in the Yan’an Rectification Movement that «no cadre is to be killed» but in practice allowed security chief Kang Sheng to drive opponents to suicide and that «this pattern was repeated throughout his leadership of the People’s Republic».[195]

Photo of Mao Zedong sitting, published in «Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung», ca. 1955

Following the consolidation of power, Mao launched the First Five-Year Plan (1953–1958), which emphasised rapid industrial development. Within industry, iron and steel, electric power, coal, heavy engineering, building materials, and basic chemicals were prioritised with the aim of constructing large and highly capital-intensive plants. Many of these plants were built with Soviet assistance and heavy industry grew rapidly.[196] Agriculture, industry and trade was organised on a collective basis (socialist cooperatives).[197] This period marked the beginning of China’s rapid industrialisation and it resulted in an enormous success.[198]

Programs pursued during this time include the Hundred Flowers Campaign, in which Mao indicated his supposed willingness to consider different opinions about how China should be governed. Given the freedom to express themselves, liberal and intellectual Chinese began opposing the Communist Party and questioning its leadership. This was initially tolerated and encouraged. After a few months, Mao’s government reversed its policy and persecuted those who had criticised the party, totalling perhaps 500,000,[199] as well as those who were merely alleged to have been critical, in what is called the Anti-Rightist Movement.

Li Zhisui, Mao’s physician, suggested that Mao had initially seen the policy as a way of weakening opposition to him within the party and that he was surprised by the extent of criticism and the fact that it came to be directed at his own leadership.[200]

Great Leap Forward

In January 1958, Mao launched the second Five-Year Plan, known as the Great Leap Forward, a plan intended to turn China from an agrarian nation to an industrialised one[201] and as an alternative model for economic growth to the Soviet model focusing on heavy industry that was advocated by others in the party. Under this economic program, the relatively small agricultural collectives that had been formed to date were rapidly merged into far larger people’s communes, and many of the peasants were ordered to work on massive infrastructure projects and on the production of iron and steel. Some private food production was banned, and livestock and farm implements were brought under collective ownership.[202][page needed]

Under the Great Leap Forward, Mao and other party leaders ordered the implementation of a variety of unproven and unscientific new agricultural techniques by the new communes. The combined effect of the diversion of labour to steel production and infrastructure projects, and cyclical natural disasters led to an approximately 15% drop in grain production in 1959 followed by a further 10% decline in 1960 and no recovery in 1961.[203]

In an effort to win favour with their superiors and avoid being purged, each layer in the party exaggerated the amount of grain produced under them. Based upon the falsely reported success, party cadres were ordered to requisition a disproportionately high amount of that fictitious harvest for state use, primarily for use in the cities and urban areas but also for export. The result, compounded in some areas by drought and in others by floods, was that farmers were left with little food for themselves and many millions starved to death in the Great Chinese Famine. The people of urban areas in China were given food stamps each month, but the people of rural areas were expected to grow their own crops and give some of the crops back to the government. The death count in rural parts of China surpassed the deaths in the urban centers. Additionally, the Chinese government continued to export food that could have been allocated to the country’s starving citizens.[204] The famine was a direct cause of the death of some 30 million Chinese peasants between 1959 and 1962.[205] Furthermore, many children who became malnourished during years of hardship died after the Great Leap Forward came to an end in 1962.[203]

In late autumn 1958, Mao condemned the practices that were being used during Great Leap Forward such as forcing peasants to do exhausting labour without enough food or rest which resulted in epidemics and starvation. He also acknowledged that anti-rightist campaigns were a major cause of «production at the expense of livelihood.» He refused to abandon the Great Leap Forward to solve these difficulties, but he did demand that they be confronted. After the July 1959 clash at Lushan Conference with Peng Dehuai, Mao launched a new anti-rightist campaign along with the radical policies that he previously abandoned. It wasn’t until the spring of 1960, that Mao would again express concern about abnormal deaths and other abuses, but he did not move to stop them. Bernstein concludes that the Chairman «wilfully ignored the lessons of the first radical phase for the sake of achieving extreme ideological and developmental goals».[206]

Jasper Becker notes that Mao was dismissive of reports he received of food shortages in the countryside and refused to change course, believing that peasants were lying and that rightists and kulaks were hoarding grain. He refused to open state granaries,[207] and instead launched a series of «anti-grain concealment» drives that resulted in numerous purges and suicides.[208] Other violent campaigns followed in which party leaders went from village to village in search of hidden food reserves, and not only grain, as Mao issued quotas for pigs, chickens, ducks and eggs. Many peasants accused of hiding food were tortured and beaten to death.[209]

The extent of Mao’s knowledge of the severity of the situation has been disputed. Mao’s personal physician, Li Zhisui, said that Mao may have been unaware of the extent of the famine, partly due to a reluctance of local officials to criticise his policies, and the willingness of his staff to exaggerate or outright fake reports.[210] Li writes that upon learning of the extent of the starvation, Mao vowed to stop eating meat, an action followed by his staff.[211]

Mao stepped down as President of China on 27 April 1959; however, he retained other top positions such as Chairman of the Communist Party and of the Central Military Commission.[212] The Presidency was transferred to Liu Shaoqi.[212] He was eventually forced to abandon the policy in 1962, and he lost political power to Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping.[213]

The Great Leap Forward was a tragedy for the vast majority of the Chinese. Although the steel quotas were officially reached, almost all of the supposed steel made in the countryside was iron, as it had been made from assorted scrap metal in home-made furnaces with no reliable source of fuel such as coal. This meant that proper smelting conditions could not be achieved. According to Zhang Rongmei, a geometry teacher in rural Shanghai during the Great Leap Forward: «We took all the furniture, pots, and pans we had in our house, and all our neighbours did likewise. We put everything in a big fire and melted down all the metal».[citation needed] The worst of the famine was steered towards enemies of the state.[214] Jasper Becker explains: «The most vulnerable section of China’s population, around five percent, were those whom Mao called ‘enemies of the people’. Anyone who had in previous campaigns of repression been labeled a ‘black element’ was given the lowest priority in the allocation of food. Landlords, rich peasants, former members of the nationalist regime, religious leaders, rightists, counter-revolutionaries and the families of such individuals died in the greatest numbers.»[215]

According to official Chinese statistics for Second Five-Year Plan (1958–1962):»industrial output value value had doubled; the gross value of agricultural products increased by 35 percent; steel production in 1962 was between 10.6 million tons or 12 million tons; investment in capital construction rose to 40 percent from 35 percent in the First Five-Year Plan period; the investment in capital construction was doubled; and the average income of workers and farmers increased by up to 30 percent.»[216]

At a large Communist Party conference in Beijing in January 1962, dubbed the «Seven Thousand Cadres Conference», State Chairman Liu Shaoqi denounced the Great Leap Forward, attributing the project to widespread famine in China.[217] The overwhelming majority of delegates expressed agreement, but Defense Minister Lin Biao staunchly defended Mao.[217] A brief period of liberalisation followed while Mao and Lin plotted a comeback.[217] Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping rescued the economy by disbanding the people’s communes, introducing elements of private control of peasant smallholdings and importing grain from Canada and Australia to mitigate the worst effects of famine.[218]

Consequences

At the Lushan Conference in July/August 1959, several ministers expressed concern that the Great Leap Forward had not proved as successful as planned. The most direct of these was Minister of Defence and Korean War veteran General Peng Dehuai. Following Peng’s criticism of the Great Leap Forward, Mao orchestrated a purge of Peng and his supporters, stifling criticism of the Great Leap policies. Senior officials who reported the truth of the famine to Mao were branded as «right opportunists.»[219] A campaign against right-wing opportunism was launched and resulted in party members and ordinary peasants being sent to prison labour camps where many would subsequently die in the famine. Years later the CCP would conclude that as many as six million people were wrongly punished in the campaign.[220]

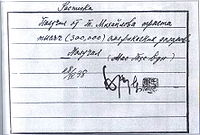

The number of deaths by starvation during the Great Leap Forward is deeply controversial. Until the mid-1980s, when official census figures were finally published by the Chinese Government, little was known about the scale of the disaster in the Chinese countryside, as the handful of Western observers allowed access during this time had been restricted to model villages where they were deceived into believing that the Great Leap Forward had been a great success. There was also an assumption that the flow of individual reports of starvation that had been reaching the West, primarily through Hong Kong and Taiwan, must have been localised or exaggerated as China was continuing to claim record harvests and was a net exporter of grain through the period. Because Mao wanted to pay back early to the Soviets debts totalling 1.973 billion yuan from 1960 to 1962,[221] exports increased by 50%, and fellow Communist regimes in North Korea, North Vietnam and Albania were provided grain free of charge.[207]

Censuses were carried out in China in 1953, 1964 and 1982. The first attempt to analyse this data to estimate the number of famine deaths was carried out by American demographer Dr. Judith Banister and published in 1984. Given the lengthy gaps between the censuses and doubts over the reliability of the data, an accurate figure is difficult to ascertain. Nevertheless, Banister concluded that the official data implied that around 15 million excess deaths incurred in China during 1958–61, and that based on her modelling of Chinese demographics during the period and taking account of assumed under-reporting during the famine years, the figure was around 30 million. Hu Yaobang, a high-ranking official of the CCP, states that 20 million people died according to official government statistics.[222] Yang Jisheng, a former Xinhua News Agency reporter who had privileged access and connections available to no other scholars, estimates a death toll of 36 million.[221] Frank Dikötter estimates that there were at least 45 million premature deaths attributable to the Great Leap Forward from 1958 to 1962.[223] Various other sources have put the figure at between 20 and 46 million.[224][225][226]

Split from Soviet Union

On the international front, the period was dominated by the further isolation of China. The Sino-Soviet split resulted in Nikita Khrushchev’s withdrawal of all Soviet technical experts and aid from the country. The split concerned the leadership of world communism. The USSR had a network of Communist parties it supported; China now created its own rival network to battle it out for local control of the left in numerous countries.[227] Lorenz M. Lüthi writes: «The Sino-Soviet split was one of the key events of the Cold War, equal in importance to the construction of the Berlin Wall, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Second Vietnam War, and Sino-American rapprochement. The split helped to determine the framework of the Second Cold War in general, and influenced the course of the Second Vietnam War in particular.»[228]

The split resulted from Nikita Khrushchev’s more moderate Soviet leadership after the death of Stalin in March 1953. Only Albania openly sided with China, thereby forming an alliance between the two countries which would last until after Mao’s death in 1976. Warned that the Soviets had nuclear weapons, Mao minimised the threat. Becker says that «Mao believed that the bomb was a ‘paper tiger’, declaring to Khrushchev that it would not matter if China lost 300 million people in a nuclear war: the other half of the population would survive to ensure victory».[229] Struggle against Soviet revisionism and U.S. imperialism was an important aspect of Mao’s attempt to direct the revolution in the right direction.[230]

Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution

During the early 1960s, Mao became concerned with the nature of post-1959 China. He saw that the revolution and Great Leap Forward had replaced the old ruling elite with a new one. He was concerned that those in power were becoming estranged from the people they were to serve. Mao believed that a revolution of culture would unseat and unsettle the «ruling class» and keep China in a state of «continuous revolution» that, theoretically, would serve the interests of the majority, rather than a tiny and privileged elite.[231] State Chairman Liu Shaoqi and General Secretary Deng Xiaoping favoured the idea that Mao be removed from actual power as China’s head of state and government but maintain his ceremonial and symbolic role as Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, with the party upholding all of his positive contributions to the revolution. They attempted to marginalise Mao by taking control of economic policy and asserting themselves politically as well. Many claim that Mao responded to Liu and Deng’s movements by launching the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in 1966. Some scholars, such as Mobo Gao, claim the case for this is overstated.[232] Others, such as Frank Dikötter, hold that Mao launched the Cultural Revolution to wreak revenge on those who had dared to challenge him over the Great Leap Forward.[233]

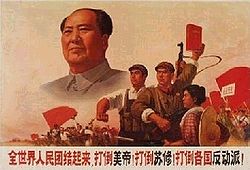

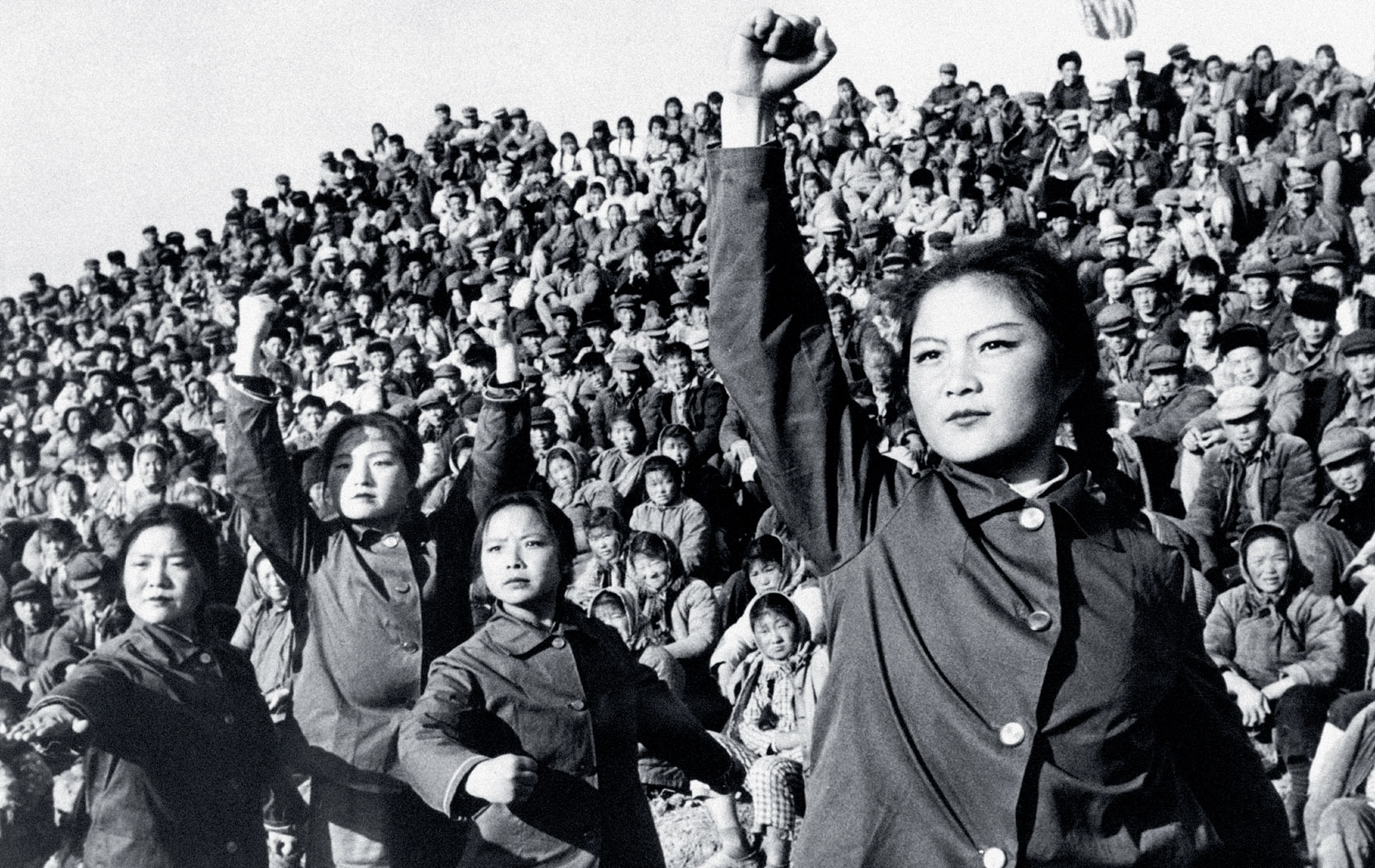

The Cultural Revolution led to the destruction of much of China’s traditional cultural heritage and the imprisonment of a huge number of Chinese citizens, as well as the creation of general economic and social chaos in the country. Millions of lives were ruined during this period, as the Cultural Revolution pierced into every part of Chinese life, depicted by such Chinese films as To Live, The Blue Kite and Farewell My Concubine. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of people, perhaps millions, perished in the violence of the Cultural Revolution.[226] This included prominent figures such as Liu Shaoqi.[234][235][236]

When Mao was informed of such losses, particularly that people had been driven to suicide, he is alleged to have commented: «People who try to commit suicide—don’t attempt to save them! … China is such a populous nation, it is not as if we cannot do without a few people.»[237] The authorities allowed the Red Guards to abuse and kill opponents of the regime. Said Xie Fuzhi, national police chief: «Don’t say it is wrong of them to beat up bad persons: if in anger they beat someone to death, then so be it.»[238] In August and September 1966, there were a reported 1,772 people murdered by the Red Guards in Beijing alone.[239]

It was during this period that Mao chose Lin Biao, who seemed to echo all of Mao’s ideas, to become his successor. Lin was later officially named as Mao’s successor. By 1971, a divide between the two men had become apparent. Official history in China states that Lin was planning a military coup or an assassination attempt on Mao. Lin Biao died on 13 September 1971, in a plane crash over the air space of Mongolia, presumably as he fled China, probably anticipating his arrest. The CCP declared that Lin was planning to depose Mao and posthumously expelled Lin from the party. At this time, Mao lost trust in many of the top CCP figures. The highest-ranking Soviet Bloc intelligence defector, Lt. Gen. Ion Mihai Pacepa claimed he had a conversation with Nicolae Ceaușescu, who told him about a plot to kill Mao Zedong with the help of Lin Biao organised by the KGB.[240]

Despite being considered a feminist figure by some and a supporter of women’s rights, documents released by the US Department of State in 2008 show that Mao declared women to be a «nonsense» in 1973, in conversation with Henry Kissinger, joking that «China is a very poor country. We don’t have much. What we have in excess is women. … Let them go to your place. They will create disasters. That way you can lessen our burdens.»[241] When Mao offered 10 million women, Kissinger replied by saying that Mao was «improving his offer».[242] Mao and Kissinger then agreed that their comments on women be removed from public records, prompted by a Chinese official who feared that Mao’s comments might incur public anger if released.[243]

In 1969, Mao declared the Cultural Revolution to be over, although various historians in and outside of China mark the end of the Cultural Revolution—as a whole or in part—in 1976, following Mao’s death and the arrest of the Gang of Four.[244] The Central Committee in 1981 officially declared the Cultural Revolution a «severe setback» for the PRC.[245] It is often looked at in all scholarly circles as a greatly disruptive period for China.[246] Despite the pro-poor rhetoric of Mao’s regime, his economic policies led to substantial poverty.[247] Some scholars, such as Lee Feigon and Mobo Gao, claim there were many great advances, and in some sectors the Chinese economy continued to outperform the West.[248]

Estimates of the death toll during the Cultural Revolution, including civilians and Red Guards, vary greatly. An estimate of around 400,000 deaths is a widely accepted minimum figure, according to Maurice Meisner.[249] MacFarquhar and Schoenhals assert that in rural China alone some 36 million people were persecuted, of whom between 750,000 and 1.5 million were killed, with roughly the same number permanently injured.[250]

Historian Daniel Leese writes that in the 1950s Mao’s personality was hardening: «The impression of Mao’s personality that emerges from the literature is disturbing. It reveals a certain temporal development from a down-to-earth leader, who was amicable when uncontested and occasionally reflected on the limits of his power, to an increasingly ruthless and self-indulgent dictator. Mao’s preparedness to accept criticism decreased continuously.»[251]

State visits

| Country | Date | Host |

|---|---|---|

| 16 December 1949 | Joseph Stalin | |

| 2–19 November 1957 | Nikita Khrushchev |

During his leadership, Mao travelled outside China on only two occasions, both state visits to the Soviet Union. His first visit abroad was to celebrate the 70th birthday of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, which was also attended by East German Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers Walter Ulbricht and Mongolian communist General Secretary Yumjaagiin Tsedenbal.[252] The second visit to Moscow was a two-week state visit of which the highlights included Mao’s attendance at the 40th anniversary (Ruby Jubilee) celebrations of the October Revolution (he attended the annual military parade of the Moscow Garrison on Red Square as well as a banquet in the Moscow Kremlin) and the International Meeting of Communist and Workers Parties, where he met with other communist leaders such as North Korea’s Kim Il-Sung[253] and Albania’s Enver Hoxha. When Mao stepped down as head of state on 27 April 1959, further diplomatic state visits and travels abroad were undertaken by President Liu Shaoqi, Premier Zhou Enlai and Deputy Premier Deng Xiaoping rather than Mao personally.[citation needed]

Death and aftermath

Mao’s health declined in his last years, probably aggravated by his chain-smoking.[254] It became a state secret that he suffered from multiple lung and heart ailments during his later years.[255] There are unconfirmed reports that he possibly had Parkinson’s disease[256] in addition to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease.[257]

His final public appearance—and the last known photograph of him alive—had been on 27 May 1976, when he met the visiting Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.[258] He suffered two major heart attacks, one in March and another in July, then a third on 5 September, rendering him an invalid. He died nearly four days later, at 00:10 on 9 September 1976, at the age of 82. The Communist Party delayed the announcement of his death until 16:00, when a national radio broadcast announced the news and appealed for party unity.[259]

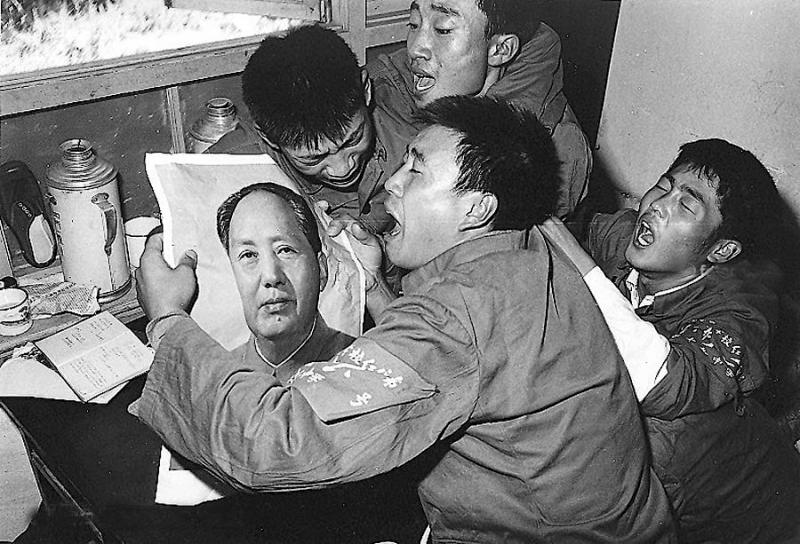

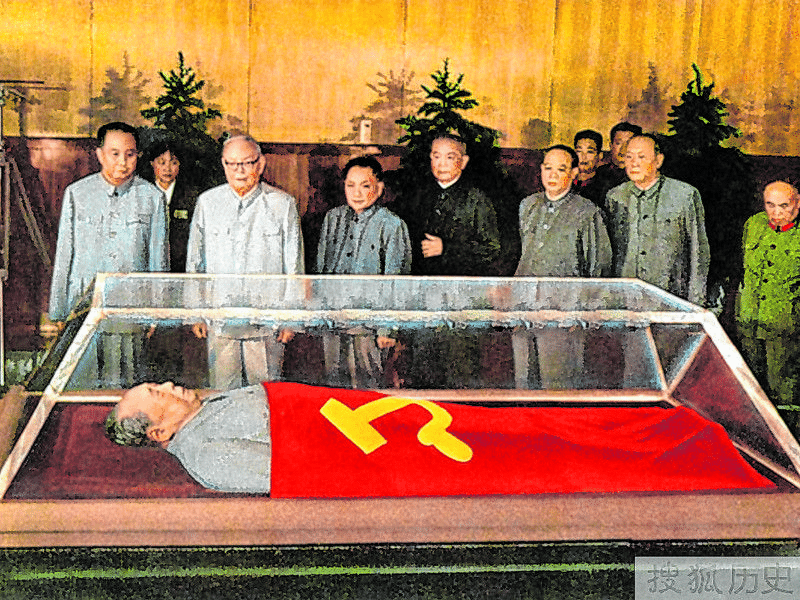

Mao’s embalmed body, draped in the CCP flag, lay in state at the Great Hall of the People for one week.[260] One million Chinese filed past to pay their final respects, many crying openly or displaying sadness, while foreigners watched on television.[261][262] Mao’s official portrait hung on the wall with a banner reading: «Carry on the cause left by Chairman Mao and carry on the cause of proletarian revolution to the end».[260] On 17 September the body was taken in a minibus to the 305 Hospital, where his internal organs were preserved in formaldehyde.[260]

On 18 September, guns, sirens, whistles and horns across China were simultaneously blown and a mandatory three-minute silence was observed.[263] Tiananmen Square was packed with millions of people and a military band played «The Internationale». Hua Guofeng concluded the service with a 20-minute-long eulogy atop Tiananmen Gate.[264] Despite Mao’s request to be cremated, his body was later permanently put on display in the Mausoleum of Mao Zedong, in order for the Chinese nation to pay its respects.[265]

Legacy

The simple facts of Mao’s career seem incredible: in a vast land of 400 million people, at age 28, with a dozen others, to found a party and in the next fifty years to win power, organize, and remold the people and reshape the land—history records no greater achievement. Alexander, Caesar, Charlemagne, all the kings of Europe, Napoleon, Bismarck, Lenin—no predecessor can equal Mao Tse-tung’s scope of accomplishment, for no other country was ever so ancient and so big as China.

— John King Fairbank, American historian[266]

Eternal rebel, refusing to be bound by the laws of God or man, nature or Marxism, he led his people for three decades in pursuit of a vision initially noble, which turned increasingly into a mirage, and then into a nightmare. Was he a Faust or Prometheus, attempting the impossible for the sake of humanity, or a despot of unbridled ambition, drunk with his own power and his own cleverness?

— Stuart R. Schram, The Thought of Mao Tse-Tung (1989)[267]

Mao remains a controversial figure and there is little agreement over his legacy both in China and abroad. He is regarded as one of the most important and influential individuals in the twentieth century.[268][269] He is also known as a political intellect, theorist, military strategist, poet, and visionary.[270] He was credited and praised for driving imperialism out of China,[271] having unified China and for ending the previous decades of civil war. He is also credited with having improved the status of women in China and for improving literacy and education. In December 2013, a poll from the state-run Global Times indicated that roughly 85% of the 1,045 respondents surveyed felt that Mao’s achievements outweighed his mistakes.[272]

His policies resulted in the deaths of tens of millions of people in China during his 27-year reign, more than any other 20th-century leader; estimates of the number of people who died under his regime range from 40 million to as many as 80 million,[273][274] done through starvation, persecution, prison labour in laogai, and mass executions.[195][273] Mao rarely gave direct instruction for peoples’ physical elimination.[b][195] According to biographer Philip Short, the overwhelming majority of those killed by Mao’s policies were unintended casualties of famine, while the other three or four million, in Mao’s view, were the necessary victim’s in the struggle to transform China.[275] Many sources describe Mao’s China as an autocratic and totalitarian regime responsible for mass repression, as well as the destruction of religious and cultural artifacts and sites (particularly during the Cultural Revolution).[276]