This article is about the Greek mythological monster. For other uses, see Gorgon (disambiguation).

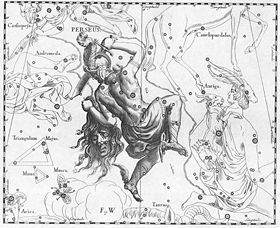

A Gorgon (/ˈɡɔːrɡən/; plural: Gorgons, Ancient Greek: Γοργών/Γοργώ Gorgṓn/Gorgṓ) is a creature in Greek mythology. Gorgons occur in the earliest examples of Greek literature. While descriptions of Gorgons vary, the term most commonly refers to three sisters who are described as having hair made of living, venomous snakes and horrifying visages that turned those who beheld them to stone. Traditionally, two of the Gorgons, Stheno and Euryale, were immortal, but their sister Medusa was not[1] and was slain by the demigod and hero Perseus.

Etymology[edit]

The name derives from the Ancient Greek word gorgós (γοργός), which means ‘grim or dreadful’, and appears to come from the same root as the Sanskrit word garjana (गर्जन), which means a guttural sound, similar to the growling of a beast,[2] thus possibly originating as an onomatopoeia.

Depictions[edit]

Gorgons were a popular image in Greek mythology, appearing in the earliest of written records of Ancient Greek religious beliefs such as those of Homer, which may date to as early as 1194–1184 BC. Because of their legendary and powerful gaze that could turn one to stone, images of the Gorgons were put upon objects and buildings for protection. An image of a Gorgon holds the primary location at the pediment of the temple at Corfu, which is the oldest stone pediment in Greece, and is dated to c. 600 BC.

A marble statue 1.35 m (53 inches) high of a Gorgon, dating from the 6th century BC, was found almost intact in 1993, in an ancient public building in Parikia, Paros capital, Greece (Archaeological Museum of Paros no. 1285, see pictures below). It is thought originally to have belonged to a temple.

The concept of the Gorgon is at least as old in classical Greek mythology as Perseus and Zeus. Gorgoneia (figures depicting a Gorgon head; see below) first appear in Greek art at the turn of the 8th century BC. One of the earliest representations is on an electrum stater discovered during excavations at Parium. Other early eighth-century examples were found at Tiryns. Going even further back into history, there is a similar image from the palace of Knossos, datable to the 15th century BC. Marija Gimbutas even argues that «the Gorgon extends back to at least 6000 BC, as a ceramic mask from the Sesklo culture …». She also identifies the prototype of the Gorgoneion in Neolithic art motifs, especially in anthropomorphic vases and terracotta masks inlaid with gold.

Pausanias (5.10.4, 8.47.5, many other places), a geographer of the 2nd century AD, supplies details of where and how Gorgons were represented in Ancient Greek art and architecture.

The large Gorgon eyes, as well as Athena’s «flashing» eyes, are symbols termed «the divine eyes» by Gimbutas (who did not originate the perception); they appear also in Athena’s sacred bird, the little owl. They may be represented by spirals, wheels, concentric circles, swastikas, firewheels, and other images. The awkward stance of the gorgon, with arms and legs at angles is closely associated with these symbols as well.

Some Gorgons are shown with broad, round heads, serpentine locks of hair, large staring eyes, wide mouths, tongues lolling, the tusks of swine, large projecting teeth, flared nostrils, and sometimes short, coarse beards. (In some cruder representations, stylized hair or blood flowing under the severed head of the Gorgon suggests a beard or wings.[3])

Some reptilian attributes such as a belt made of snakes and snakes emanating from the head or entwined in the hair, as in the temple of Artemis in Corfu, are symbols likely derived from the guardians closely associated with early Greek religious concepts at the centers such as Delphi where the dragon Delphyne lived and the priestess Pythia delivered oracles. The skin of the dragon was said to be made of impenetrable scales.

-

-

Gorgon of Paros, marble statue at the Archaeological Museum of Paros, 6th century BC, Cyclades, Greece

-

Gorgon of Paros, marble statue at the Archaeological Museum of Paros, 6th century BC, Cyclades, Greece

-

Disk-fibula with a gorgoneion, bronze with repoussé decoration, second half of the 6th century BC (Louvre)

-

Winged goddess with a Gorgon’s head, orientalizing plate, c.600 BC, from Kameiros, Rhodes

Origins[edit]

A number of early classics scholars interpreted the myth of the Medusa as a quasi-historical, or «sublimated», memory of an actual invasion.[4][a]

The legend of Perseus beheading Medusa means, specifically, that «the Hellenes overran the goddess’s chief shrines» and «stripped her priestesses of their Gorgon masks», the latter being apotropaic faces worn to frighten away the profane.

That is to say, there occurred in the early thirteenth century B.C. an actual historic rupture, a sort of sociological trauma, which has been registered in this myth, much as what Freud terms the latent content of a neurosis is registered in the manifest content of a dream: Registered yet hidden, registered in the unconscious yet unknown or misconstrued by the conscious mind.

— J. Campbell (1968)[6][b]

While seeking origins others have suggested examination of some similarities to the Babylonian creature, Humbaba, in the Gilgamesh epic.[7]

Classical tradition[edit]

Transitions in religious traditions over such long periods of time may make some strange turns. Gorgons are often depicted as having wings, brazen claws, the tusks of boars, and scaly skin. The oldest oracles were said to be protected by serpents and a Gorgon image was often associated with those temples. Lionesses or sphinxes are frequently associated with the Gorgon as well. The powerful image of the Gorgon was adopted for the classical images and myths of Athena and Zeus, perhaps being worn in continuation of a more ancient religious imagery. In late myths, the Gorgons were said to be the daughters of two sea deities: Keto, the sea monster, and Phorcys, her brother-husband.

Homer, the author of the oldest known work of European literature, speaks only of one Gorgon, whose head is represented in the Iliad as fixed in the centre of the aegis of Athena:

About her shoulders she flung the tasselled aegis, fraught with terror … and therein is the head of the dread monster, the Gorgon, dread and awful …

Its earthly counterpart is a device on the shield of Agamemnon:

… and therein was set as a crown the Gorgon, grim of aspect, glaring terribly, and about her were Terror and Rout.

In the Odyssey, the Gorgon is a monster of the underworld into which the earliest Greek deities were cast:

… and pale fear seized me, lest august Persephone might send forth upon me from out of the house of Hades the head of the Gorgon, that awful monster…

Around 700 BC, Hesiod imagines the Gorgons as sea daemons and increases the number of them to three – Stheno (the mighty), Euryale (the far-springer, or of the wide sea), and Medusa (the queen), and makes them the daughters of the sea deities Keto and Phorcys. Their home is on the farthest side of the western ocean; according to later authorities, in Libya. Ancient Libya is identified as a possible source of the deity, Neith, who also was a creation deity in Ancient Egypt and, when the Greeks occupied Egypt, they said that Neith was called Athene in Greece.

Of the three Gorgons in classical Greek mythology, only Medusa is mortal.

The Attic tradition, reproduced in Euripides (Ion), regarded the Gorgon as a monster, produced by Gaia to aid her children, the Titans, against the new Olympian deities. Classical interpretations suggest that Gorgon was slain by Athena, who wore her skin thereafter.

The Bibliotheca provides a good summary of the Gorgon myth. Much later stories claim that each of three Gorgon sisters, Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa, had snakes for hair, and that they had the power to turn anyone who looked at them to stone. According to Ovid, a Roman poet writing in 8 AD, whose most famous work was heavily involved in the depiction of Greek myths, Medusa alone had serpents in her hair, and he explained that this was due to Athena (Roman Minerva) cursing her. Medusa had copulated with Poseidon (Roman Neptune) in a temple of Athena after he was aroused by the golden color of Medusa’s hair. Athena therefore changed the enticing golden locks into serpents.

Virgil mentions that the Gorgons lived in the entrance of the Underworld. Diodorus and Palaephatus mention that the Gorgons lived in the Gorgades, islands in the Aethiopian Sea. The main island was called Cerna. Henry T. Riley suggests these islands may correspond to Cape Verde.

According to Pseudo-Hyginus the «Gorgo Aix» (Γοργώ Aιξ), daughter of Helios, was killed by Zeus during the Titanomachy. From her skin, a goat-like hide rimmed with serpents, he made his famous aegis, and placed her fearsome visage upon it. This he gave to Athena. Then Aix became the goat Capra (Greek: Aix), on the left shoulder of the constellation Auriga. A primeval Gorgon was sometimes said to be the father of Medusa and her sister Gorgons by the sea Goddess Ceto. This figure may have been the same as Gorgo Aix as the primal Gorgon was of an indeterminable gender.

-

An Amazon with her shield bearing the Gorgon head image. Tondo of an Attic red-figure kylix, 510–500 BC

-

Athena wears the ancient form of the Gorgon head on her aegis, as the huge serpent who guards the golden fleece regurgitates Jason; cup by Douris, Classical Greece, early fifth century BC (Vatican Museum)

Perseus and Medusa[edit]

Further information: Medusa

In late myths, Medusa was the only one of the three Gorgons who was not immortal.[8] King Polydectes sent Perseus to kill Medusa in hopes of getting him out of the way, while he pursued Perseus’s mother, Danae. Some of these myths relate that Perseus was armed with a scythe from Hermes and a mirror (or a shield) from Athena.[9] Perseus could safely cut off Medusa’s head without turning to stone by looking only at her reflection in the shield. From the blood that spurted from her neck and falling into the sea, sprang Pegasus[10] and Chrysaor, her sons by Poseidon. Other sources say that each drop of blood became a snake.[11] Perseus is said by some to have given the head, which retained the power of turning into stone all who looked upon it, to Athena. She then placed it on the mirrored shield called Aegis[12] and she gave it to Zeus. Another source says that Perseus buried the head in the marketplace of Argos.[13]

According to other accounts, either he or Athena used the head to turn Atlas into stone,[14] transforming him into the Atlas Mountains that held up both heaven and earth. He also used the Gorgon against Cetus (when saving Andromeda) and a competing suitor, Phineas, Andromeda’s cousin. Ultimately, he used her against King Polydectes. When Perseus returned to the court of the king, Polydectes asked if he had the head of Medusa. Perseus replied «here it is» and held it aloft, turning the whole court to stone.[15]

Protective and healing powers[edit]

Archaic (Etruscan) fanged goggle-eyed Gorgon flanked by standing winged lionesses or sphinxes on a hydria from Vulci, 540–530 BC

In Ancient Greece a Gorgoneion (a stone head, engraving, or drawing of a Gorgon face, often with snakes protruding wildly and the tongue sticking out between her fangs) frequently was used as an apotropaic symbol and placed on doors, walls, floors, coins, shields, breastplates, and tombstones in the hopes of warding off evil. In this regard Gorgoneia are similar to the sometimes grotesque faces on Chinese soldiers’ shields, also used generally as an amulet, a protection against the evil eye. Likewise, in Hindu mythology, Kali is often shown with a protruding tongue and snakes around her head.

The Ancient Silver Gorgon Coin is a hemidrachm that was struck in the Greek city of Parium in the 5th century B.C. Parium was a major coastal cite in the Mysia region on the Hellespont, the peninsula now known as the Dardanelles in western Turkey. The city was close to the Greek region of Lydia, which produced the first coins in about 650 B.C. The Gorgon coin from Parium was issued only a few generations later, making it one of the world’s earliest coins. Ancient Greek coins usually feature images of specific Gods or symbols that represented the issuing city or state, and it is likely that the Parium had a connection to the legends of the Gorgons. The ancient Greeks believed that the Gorgons lived in the west, near the setting sun, and since Parium was near the western limits if the known Greek world, it was an appropriate place for the Gorgon Coin to be issued. [16]

In some Greek myths, blood taken from the right side of a Gorgon could bring the dead back to life, yet blood taken from the left side was an instantly fatal poison.[17] Athena gave a vial of the healing blood to Asclepius, which ultimately brought about his demise.

Heracles is said to have obtained a lock of Medusa’s hair (which possessed the same powers as the head) from Athena and to have given it to Sterope,[18] the daughter of Cepheus, as a protection for the town of Tegea against attack. According to the later idea of Medusa as a beautiful maiden, whose hair had been changed into snakes by Athena, the head was represented in works of art with a wonderfully handsome face, wrapped in the calm repose of death.

Cultural depictions of Gorgons[edit]

Gorgons, especially Medusa, have become a common image and symbol in Western culture since their origins in Greek mythology, appearing in art, literature, and elsewhere throughout history. In A Tale of Two Cities, for example, Charles Dickens compares the exploitative French aristocracy to «the Gorgon» — He devotes an entire chapter to this extended metaphor.

One of the more recent and famous uses of Gorgons comes from the book series Percy Jackson and the Olympians, in which we see Medusa in the first book. Her sisters, Stheno and Euryale, are seen later in the series.

Another modern depiction of Gorgons is seen in the movie Clash of the Titans, a movie loosely based on the tale of Perseus.

Genealogy[edit]

| Gaia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pontus | Thalassa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nereus | Thaumas | Phorcys | Ceto | Eurybia | The Telchines | Halia | Aphrodite[c] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Echidna | The Gorgons | The Graeae | Ladon | The Hesperides | Thoosa[d] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stheno | Deino | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Euryale | Enyo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Medusa[e] | Pemphredo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes[edit]

- ^ A large part of Greek myth is politico-religious history. Bellerophon masters winged Pegasus and kills the Chimaera. Perseus, in a variant of the same legend, flies through the air and beheads Pegasus’s mother, the Gorgon Medusa; much as Marduk, a Babylonian hero, kills the she-monster Tiamat, Goddess of the Seal. Perseus’s name should properly be spelled Perseus, ‘the destroyer’; and he was not, as Professor Kerenyi has suggested, an archetypal Death-figure but, probably, represented the patriarchal Hellenes who invaded Greece and Asia Minor early in the second millennium BC, and challenged the power of the Triple-goddess. Pegasus had been sacred to her because the horse with its moon-shaped hooves figured in the rain-making ceremonies and the installment of sacred kings; his wings were symbolical of a celestial nature, rather than speed. Jane Harrison has pointed out[4] that Medusa was once the goddess herself, hiding behind a prophylactic Gorgon mask: A hideous face intended to warn the profane against trespassing on her Mysteries. Perseus beheads Medusa: that is, the Hellenes overran the goddess’s chief shrines, stripped her priestesses of their Gorgon masks, and took possession of the sacred horses – an early representation of the goddess with a Gorgon’s head and a mare’s body has been found in Boeotia. Bellerophon, Perseus’s double, kills the Lycian Chimaera, that is: The Hellenes annulled the ancient Medusan calendar, and replaced it with another.

— R. Graves (1955)[5] - ^ We have already spoken of Medusa and of the powers of her blood to render both life and death. We may now think of the legend of her slayer, Perseus, by whom her head was removed and presented to Athene. Professor Hainmond assigns the historical King Perseus of Mycenae to a date c. 1290 B.C., as the founder of a dynasty; and Robert Graves – whose two volumes on The Greek Myths are particularly noteworthy for their suggestive historical applications – proposes that the legend of Perseus beheading Medusa means, specifically, that «the Hellenes overran the goddess’s chief shrines» and «stripped her priestesses of their Gorgon masks», the latter being apotropaic faces worn to frighten away the profane. That is to say, there occurred in the early thirteenth century B.C. an actual historic rupture, a sort of sociological trauma, which has been registered in this myth, much as what Freud terms the latent content of a neurosis is registered in the manifest content of a dream: Registered yet hidden, registered in the unconscious yet unknown or misconstrued by the conscious mind. And in every such screening myth – in every such mythology (that of the Bible being, as we have just seen, another of the kind) – there enters in an essential duplicity, the consequences of which cannot be disregarded or suppressed.

— J. Campbell (1968)[6] - ^ There are two major conflicting stories for Aphrodite’s origins: Hesiod[19] claims that she was «born» from the foam of the sea after Cronus castrated Uranus, thus making her Uranus’ daughter; but Homer[20]: Book V has Aphrodite as daughter of Zeus and Dione. According to Plato,[21] the two were entirely separate entities: Aphrodite Ourania and Aphrodite Pandemos.

- ^ Homer names Thoosa as a daughter of Phorcys, without specifying her mother.[22]: 1.70–73

- ^ Most sources describe Medusa as the daughter of Phorcys and Ceto, though the author Hyginus (Fabulae Preface) makes Medusa the daughter of Gorgon and Ceto.

References[edit]

- ^ Hes. Th. 270 1

- ^ Feldman, Thalia (1965). «Gorgo and the origins of fear». Arion. 4 (3): 484–94. JSTOR 20162978.

- ^ gorgo-harpers 3

- ^ a b Harrison, Jane Ellen (5 June 1991) [1908]. Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 187–188. ISBN 978-0691015149.

- ^ Graves, Robert (1955). The Greek Myths. Penguin Books. pp. 17, 244. ISBN 978-0241952740.

- ^ a b Campbell, Joseph (1968). Occidental Mythology. The Masks of God. Vol. 3. Penguin Books. pp. 152–153. ISBN 978-0140194418.

- ^ Hopkins, Clark (1934). Assyrian Elements in the Perseus-Gorgon Story. American Journal of Archaeology. Vol. 38. Archaeological Institute of America. pp. 341–358. doi:10.2307/498901. JSTOR 498901. S2CID 191408685.

- ^ Hes. Th. 270 1

- ^ perseus-bio-1

- ^ Apollod. 2.3 4

- ^ Medusa 1

- ^ *gorgw/

- ^ Paus. 2.21 5

- ^ Luc. 9.619 1

- ^ Strab. 10.5 10

- ^ Steven Bonacorsi, President of the International standard for Lean Six Sigma (ISLSS) and Owner of the NGC Gorgon Coin Certified by NGC https://www.ngccoin.com/certlookup/5873659-131/NGCAncients/, and Purchased by PCS https://www.pcscoins.com/home

- ^ Eur. Ion 998

- ^ Apollod. 2.7 15

- ^ Hesiod. Theogony.

- ^ Homer. Iliad.

- ^ Plato. Symposium. 180e.

- ^ Homer. Odyssey.

Sources[edit]

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Gorgon, Gorgons». Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 257.

- Additional material has been added from the 1824 Lemprière’s Classical Dictionary.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gorgons.

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

This article is about the Greek mythological monster. For other uses, see Gorgon (disambiguation).

A Gorgon (/ˈɡɔːrɡən/; plural: Gorgons, Ancient Greek: Γοργών/Γοργώ Gorgṓn/Gorgṓ) is a creature in Greek mythology. Gorgons occur in the earliest examples of Greek literature. While descriptions of Gorgons vary, the term most commonly refers to three sisters who are described as having hair made of living, venomous snakes and horrifying visages that turned those who beheld them to stone. Traditionally, two of the Gorgons, Stheno and Euryale, were immortal, but their sister Medusa was not[1] and was slain by the demigod and hero Perseus.

Etymology[edit]

The name derives from the Ancient Greek word gorgós (γοργός), which means ‘grim or dreadful’, and appears to come from the same root as the Sanskrit word garjana (गर्जन), which means a guttural sound, similar to the growling of a beast,[2] thus possibly originating as an onomatopoeia.

Depictions[edit]

Gorgons were a popular image in Greek mythology, appearing in the earliest of written records of Ancient Greek religious beliefs such as those of Homer, which may date to as early as 1194–1184 BC. Because of their legendary and powerful gaze that could turn one to stone, images of the Gorgons were put upon objects and buildings for protection. An image of a Gorgon holds the primary location at the pediment of the temple at Corfu, which is the oldest stone pediment in Greece, and is dated to c. 600 BC.

A marble statue 1.35 m (53 inches) high of a Gorgon, dating from the 6th century BC, was found almost intact in 1993, in an ancient public building in Parikia, Paros capital, Greece (Archaeological Museum of Paros no. 1285, see pictures below). It is thought originally to have belonged to a temple.

The concept of the Gorgon is at least as old in classical Greek mythology as Perseus and Zeus. Gorgoneia (figures depicting a Gorgon head; see below) first appear in Greek art at the turn of the 8th century BC. One of the earliest representations is on an electrum stater discovered during excavations at Parium. Other early eighth-century examples were found at Tiryns. Going even further back into history, there is a similar image from the palace of Knossos, datable to the 15th century BC. Marija Gimbutas even argues that «the Gorgon extends back to at least 6000 BC, as a ceramic mask from the Sesklo culture …». She also identifies the prototype of the Gorgoneion in Neolithic art motifs, especially in anthropomorphic vases and terracotta masks inlaid with gold.

Pausanias (5.10.4, 8.47.5, many other places), a geographer of the 2nd century AD, supplies details of where and how Gorgons were represented in Ancient Greek art and architecture.

The large Gorgon eyes, as well as Athena’s «flashing» eyes, are symbols termed «the divine eyes» by Gimbutas (who did not originate the perception); they appear also in Athena’s sacred bird, the little owl. They may be represented by spirals, wheels, concentric circles, swastikas, firewheels, and other images. The awkward stance of the gorgon, with arms and legs at angles is closely associated with these symbols as well.

Some Gorgons are shown with broad, round heads, serpentine locks of hair, large staring eyes, wide mouths, tongues lolling, the tusks of swine, large projecting teeth, flared nostrils, and sometimes short, coarse beards. (In some cruder representations, stylized hair or blood flowing under the severed head of the Gorgon suggests a beard or wings.[3])

Some reptilian attributes such as a belt made of snakes and snakes emanating from the head or entwined in the hair, as in the temple of Artemis in Corfu, are symbols likely derived from the guardians closely associated with early Greek religious concepts at the centers such as Delphi where the dragon Delphyne lived and the priestess Pythia delivered oracles. The skin of the dragon was said to be made of impenetrable scales.

-

-

Gorgon of Paros, marble statue at the Archaeological Museum of Paros, 6th century BC, Cyclades, Greece

-

Gorgon of Paros, marble statue at the Archaeological Museum of Paros, 6th century BC, Cyclades, Greece

-

Disk-fibula with a gorgoneion, bronze with repoussé decoration, second half of the 6th century BC (Louvre)

-

Winged goddess with a Gorgon’s head, orientalizing plate, c.600 BC, from Kameiros, Rhodes

Origins[edit]

A number of early classics scholars interpreted the myth of the Medusa as a quasi-historical, or «sublimated», memory of an actual invasion.[4][a]

The legend of Perseus beheading Medusa means, specifically, that «the Hellenes overran the goddess’s chief shrines» and «stripped her priestesses of their Gorgon masks», the latter being apotropaic faces worn to frighten away the profane.

That is to say, there occurred in the early thirteenth century B.C. an actual historic rupture, a sort of sociological trauma, which has been registered in this myth, much as what Freud terms the latent content of a neurosis is registered in the manifest content of a dream: Registered yet hidden, registered in the unconscious yet unknown or misconstrued by the conscious mind.

— J. Campbell (1968)[6][b]

While seeking origins others have suggested examination of some similarities to the Babylonian creature, Humbaba, in the Gilgamesh epic.[7]

Classical tradition[edit]

Transitions in religious traditions over such long periods of time may make some strange turns. Gorgons are often depicted as having wings, brazen claws, the tusks of boars, and scaly skin. The oldest oracles were said to be protected by serpents and a Gorgon image was often associated with those temples. Lionesses or sphinxes are frequently associated with the Gorgon as well. The powerful image of the Gorgon was adopted for the classical images and myths of Athena and Zeus, perhaps being worn in continuation of a more ancient religious imagery. In late myths, the Gorgons were said to be the daughters of two sea deities: Keto, the sea monster, and Phorcys, her brother-husband.

Homer, the author of the oldest known work of European literature, speaks only of one Gorgon, whose head is represented in the Iliad as fixed in the centre of the aegis of Athena:

About her shoulders she flung the tasselled aegis, fraught with terror … and therein is the head of the dread monster, the Gorgon, dread and awful …

Its earthly counterpart is a device on the shield of Agamemnon:

… and therein was set as a crown the Gorgon, grim of aspect, glaring terribly, and about her were Terror and Rout.

In the Odyssey, the Gorgon is a monster of the underworld into which the earliest Greek deities were cast:

… and pale fear seized me, lest august Persephone might send forth upon me from out of the house of Hades the head of the Gorgon, that awful monster…

Around 700 BC, Hesiod imagines the Gorgons as sea daemons and increases the number of them to three – Stheno (the mighty), Euryale (the far-springer, or of the wide sea), and Medusa (the queen), and makes them the daughters of the sea deities Keto and Phorcys. Their home is on the farthest side of the western ocean; according to later authorities, in Libya. Ancient Libya is identified as a possible source of the deity, Neith, who also was a creation deity in Ancient Egypt and, when the Greeks occupied Egypt, they said that Neith was called Athene in Greece.

Of the three Gorgons in classical Greek mythology, only Medusa is mortal.

The Attic tradition, reproduced in Euripides (Ion), regarded the Gorgon as a monster, produced by Gaia to aid her children, the Titans, against the new Olympian deities. Classical interpretations suggest that Gorgon was slain by Athena, who wore her skin thereafter.

The Bibliotheca provides a good summary of the Gorgon myth. Much later stories claim that each of three Gorgon sisters, Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa, had snakes for hair, and that they had the power to turn anyone who looked at them to stone. According to Ovid, a Roman poet writing in 8 AD, whose most famous work was heavily involved in the depiction of Greek myths, Medusa alone had serpents in her hair, and he explained that this was due to Athena (Roman Minerva) cursing her. Medusa had copulated with Poseidon (Roman Neptune) in a temple of Athena after he was aroused by the golden color of Medusa’s hair. Athena therefore changed the enticing golden locks into serpents.

Virgil mentions that the Gorgons lived in the entrance of the Underworld. Diodorus and Palaephatus mention that the Gorgons lived in the Gorgades, islands in the Aethiopian Sea. The main island was called Cerna. Henry T. Riley suggests these islands may correspond to Cape Verde.

According to Pseudo-Hyginus the «Gorgo Aix» (Γοργώ Aιξ), daughter of Helios, was killed by Zeus during the Titanomachy. From her skin, a goat-like hide rimmed with serpents, he made his famous aegis, and placed her fearsome visage upon it. This he gave to Athena. Then Aix became the goat Capra (Greek: Aix), on the left shoulder of the constellation Auriga. A primeval Gorgon was sometimes said to be the father of Medusa and her sister Gorgons by the sea Goddess Ceto. This figure may have been the same as Gorgo Aix as the primal Gorgon was of an indeterminable gender.

-

An Amazon with her shield bearing the Gorgon head image. Tondo of an Attic red-figure kylix, 510–500 BC

-

Athena wears the ancient form of the Gorgon head on her aegis, as the huge serpent who guards the golden fleece regurgitates Jason; cup by Douris, Classical Greece, early fifth century BC (Vatican Museum)

Perseus and Medusa[edit]

Further information: Medusa

In late myths, Medusa was the only one of the three Gorgons who was not immortal.[8] King Polydectes sent Perseus to kill Medusa in hopes of getting him out of the way, while he pursued Perseus’s mother, Danae. Some of these myths relate that Perseus was armed with a scythe from Hermes and a mirror (or a shield) from Athena.[9] Perseus could safely cut off Medusa’s head without turning to stone by looking only at her reflection in the shield. From the blood that spurted from her neck and falling into the sea, sprang Pegasus[10] and Chrysaor, her sons by Poseidon. Other sources say that each drop of blood became a snake.[11] Perseus is said by some to have given the head, which retained the power of turning into stone all who looked upon it, to Athena. She then placed it on the mirrored shield called Aegis[12] and she gave it to Zeus. Another source says that Perseus buried the head in the marketplace of Argos.[13]

According to other accounts, either he or Athena used the head to turn Atlas into stone,[14] transforming him into the Atlas Mountains that held up both heaven and earth. He also used the Gorgon against Cetus (when saving Andromeda) and a competing suitor, Phineas, Andromeda’s cousin. Ultimately, he used her against King Polydectes. When Perseus returned to the court of the king, Polydectes asked if he had the head of Medusa. Perseus replied «here it is» and held it aloft, turning the whole court to stone.[15]

Protective and healing powers[edit]

Archaic (Etruscan) fanged goggle-eyed Gorgon flanked by standing winged lionesses or sphinxes on a hydria from Vulci, 540–530 BC

In Ancient Greece a Gorgoneion (a stone head, engraving, or drawing of a Gorgon face, often with snakes protruding wildly and the tongue sticking out between her fangs) frequently was used as an apotropaic symbol and placed on doors, walls, floors, coins, shields, breastplates, and tombstones in the hopes of warding off evil. In this regard Gorgoneia are similar to the sometimes grotesque faces on Chinese soldiers’ shields, also used generally as an amulet, a protection against the evil eye. Likewise, in Hindu mythology, Kali is often shown with a protruding tongue and snakes around her head.

The Ancient Silver Gorgon Coin is a hemidrachm that was struck in the Greek city of Parium in the 5th century B.C. Parium was a major coastal cite in the Mysia region on the Hellespont, the peninsula now known as the Dardanelles in western Turkey. The city was close to the Greek region of Lydia, which produced the first coins in about 650 B.C. The Gorgon coin from Parium was issued only a few generations later, making it one of the world’s earliest coins. Ancient Greek coins usually feature images of specific Gods or symbols that represented the issuing city or state, and it is likely that the Parium had a connection to the legends of the Gorgons. The ancient Greeks believed that the Gorgons lived in the west, near the setting sun, and since Parium was near the western limits if the known Greek world, it was an appropriate place for the Gorgon Coin to be issued. [16]

In some Greek myths, blood taken from the right side of a Gorgon could bring the dead back to life, yet blood taken from the left side was an instantly fatal poison.[17] Athena gave a vial of the healing blood to Asclepius, which ultimately brought about his demise.

Heracles is said to have obtained a lock of Medusa’s hair (which possessed the same powers as the head) from Athena and to have given it to Sterope,[18] the daughter of Cepheus, as a protection for the town of Tegea against attack. According to the later idea of Medusa as a beautiful maiden, whose hair had been changed into snakes by Athena, the head was represented in works of art with a wonderfully handsome face, wrapped in the calm repose of death.

Cultural depictions of Gorgons[edit]

Gorgons, especially Medusa, have become a common image and symbol in Western culture since their origins in Greek mythology, appearing in art, literature, and elsewhere throughout history. In A Tale of Two Cities, for example, Charles Dickens compares the exploitative French aristocracy to «the Gorgon» — He devotes an entire chapter to this extended metaphor.

One of the more recent and famous uses of Gorgons comes from the book series Percy Jackson and the Olympians, in which we see Medusa in the first book. Her sisters, Stheno and Euryale, are seen later in the series.

Another modern depiction of Gorgons is seen in the movie Clash of the Titans, a movie loosely based on the tale of Perseus.

Genealogy[edit]

| Gaia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pontus | Thalassa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nereus | Thaumas | Phorcys | Ceto | Eurybia | The Telchines | Halia | Aphrodite[c] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Echidna | The Gorgons | The Graeae | Ladon | The Hesperides | Thoosa[d] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stheno | Deino | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Euryale | Enyo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Medusa[e] | Pemphredo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes[edit]

- ^ A large part of Greek myth is politico-religious history. Bellerophon masters winged Pegasus and kills the Chimaera. Perseus, in a variant of the same legend, flies through the air and beheads Pegasus’s mother, the Gorgon Medusa; much as Marduk, a Babylonian hero, kills the she-monster Tiamat, Goddess of the Seal. Perseus’s name should properly be spelled Perseus, ‘the destroyer’; and he was not, as Professor Kerenyi has suggested, an archetypal Death-figure but, probably, represented the patriarchal Hellenes who invaded Greece and Asia Minor early in the second millennium BC, and challenged the power of the Triple-goddess. Pegasus had been sacred to her because the horse with its moon-shaped hooves figured in the rain-making ceremonies and the installment of sacred kings; his wings were symbolical of a celestial nature, rather than speed. Jane Harrison has pointed out[4] that Medusa was once the goddess herself, hiding behind a prophylactic Gorgon mask: A hideous face intended to warn the profane against trespassing on her Mysteries. Perseus beheads Medusa: that is, the Hellenes overran the goddess’s chief shrines, stripped her priestesses of their Gorgon masks, and took possession of the sacred horses – an early representation of the goddess with a Gorgon’s head and a mare’s body has been found in Boeotia. Bellerophon, Perseus’s double, kills the Lycian Chimaera, that is: The Hellenes annulled the ancient Medusan calendar, and replaced it with another.

— R. Graves (1955)[5] - ^ We have already spoken of Medusa and of the powers of her blood to render both life and death. We may now think of the legend of her slayer, Perseus, by whom her head was removed and presented to Athene. Professor Hainmond assigns the historical King Perseus of Mycenae to a date c. 1290 B.C., as the founder of a dynasty; and Robert Graves – whose two volumes on The Greek Myths are particularly noteworthy for their suggestive historical applications – proposes that the legend of Perseus beheading Medusa means, specifically, that «the Hellenes overran the goddess’s chief shrines» and «stripped her priestesses of their Gorgon masks», the latter being apotropaic faces worn to frighten away the profane. That is to say, there occurred in the early thirteenth century B.C. an actual historic rupture, a sort of sociological trauma, which has been registered in this myth, much as what Freud terms the latent content of a neurosis is registered in the manifest content of a dream: Registered yet hidden, registered in the unconscious yet unknown or misconstrued by the conscious mind. And in every such screening myth – in every such mythology (that of the Bible being, as we have just seen, another of the kind) – there enters in an essential duplicity, the consequences of which cannot be disregarded or suppressed.

— J. Campbell (1968)[6] - ^ There are two major conflicting stories for Aphrodite’s origins: Hesiod[19] claims that she was «born» from the foam of the sea after Cronus castrated Uranus, thus making her Uranus’ daughter; but Homer[20]: Book V has Aphrodite as daughter of Zeus and Dione. According to Plato,[21] the two were entirely separate entities: Aphrodite Ourania and Aphrodite Pandemos.

- ^ Homer names Thoosa as a daughter of Phorcys, without specifying her mother.[22]: 1.70–73

- ^ Most sources describe Medusa as the daughter of Phorcys and Ceto, though the author Hyginus (Fabulae Preface) makes Medusa the daughter of Gorgon and Ceto.

References[edit]

- ^ Hes. Th. 270 1

- ^ Feldman, Thalia (1965). «Gorgo and the origins of fear». Arion. 4 (3): 484–94. JSTOR 20162978.

- ^ gorgo-harpers 3

- ^ a b Harrison, Jane Ellen (5 June 1991) [1908]. Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 187–188. ISBN 978-0691015149.

- ^ Graves, Robert (1955). The Greek Myths. Penguin Books. pp. 17, 244. ISBN 978-0241952740.

- ^ a b Campbell, Joseph (1968). Occidental Mythology. The Masks of God. Vol. 3. Penguin Books. pp. 152–153. ISBN 978-0140194418.

- ^ Hopkins, Clark (1934). Assyrian Elements in the Perseus-Gorgon Story. American Journal of Archaeology. Vol. 38. Archaeological Institute of America. pp. 341–358. doi:10.2307/498901. JSTOR 498901. S2CID 191408685.

- ^ Hes. Th. 270 1

- ^ perseus-bio-1

- ^ Apollod. 2.3 4

- ^ Medusa 1

- ^ *gorgw/

- ^ Paus. 2.21 5

- ^ Luc. 9.619 1

- ^ Strab. 10.5 10

- ^ Steven Bonacorsi, President of the International standard for Lean Six Sigma (ISLSS) and Owner of the NGC Gorgon Coin Certified by NGC https://www.ngccoin.com/certlookup/5873659-131/NGCAncients/, and Purchased by PCS https://www.pcscoins.com/home

- ^ Eur. Ion 998

- ^ Apollod. 2.7 15

- ^ Hesiod. Theogony.

- ^ Homer. Iliad.

- ^ Plato. Symposium. 180e.

- ^ Homer. Odyssey.

Sources[edit]

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Gorgon, Gorgons». Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 257.

- Additional material has been added from the 1824 Lemprière’s Classical Dictionary.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gorgons.

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Горгоны.

Горго́на Меду́за (точнее Медуса, др.-греч. Μέδουσα — «стражник, защитница, повелительница») — наиболее известная из сестёр горгон, чудовище с женским лицом и змеями вместо волос[1]. Её взгляд обращал человека в камень. Была убита Персеем. Упомянута в «Одиссее» (XI 634).

Написание: «горгона Медуза», где «горгона» — вид чудовища, а «Медуза» — имя собственное[2]. Своё имя морская медуза получила из-за сходства с шевелящимися волосами-змеями легендарной горгоны Медузы из греческой мифологии.

Содержание

- 1 Миф

- 1.1 Происхождение Медузы

- 1.2 Смерть Медузы

- 1.3 Голова Медузы

- 1.4 Интерпретации

- 2 Античные источники

- 3 В искусстве

- 3.1 Верования и амулеты

- 3.2 В русской средневековой культуре

- 3.3 Голова горгоны Медузы как эмблема

- 3.4 В западноевропейской живописи и скульптуре

- 3.5 В западноевропейской литературе

- 3.6 В современной культуре

- 4 Горгона в кино

- 4.1 Битва титанов

- 4.2 Перси Джексон и похититель молний

- 5 Примечания

- 6 Литература

- 7 См. также

- 8 Ссылки

Миф

Происхождение Медузы

Младшая дочь Форка и Кето (по версии, дочь Горгона[3]). Единственная смертная из горгон.

По версии, она была девушкой с красивыми волосами, и хотела состязаться с Афиной в красоте. Её изнасиловал Посейдон в храме Афины, и Афина превратила её волосы в гидр[4]. Посейдон соблазнил её, превратившись в птицу[5].

Смерть Медузы

Одним из заданий, данных Персею царем Полидектом было убийство горгоны Медузы. Справиться с чудовищем герою помогли боги — Афина и Гермес. По их совету перед тем, как отправиться в бой, он посетил вещих старух — сестёр грай, (которые были также сёстрами горгон), имевших на троих один глаз и один зуб. Хитростью Персей похитил у них зуб и глаз, а вернул лишь в обмен на крылатые сандалии, волшебный мешок и шапку-невидимку Аида. Грайи показали Персею путь к горгонам. Гермес подарил ему острый кривой нож. Вооружившись этим подарком, Персей прибыл к горгонам. Поднявшись в воздух на крылатых сандалиях, он смог отрубить голову смертной Медузе, одной из трёх сестёр горгон, смотря в отражение на полированном медном щите Афины — ведь взгляд Медузы обращал всё живое в камень. От сестёр Медузы Персей скрылся с помощью шапки-невидимки, спрятав трофей в заплечную сумку.

- (И повествует Персей, как) скалы,

- Скрытые, смело пройдя с их страшным лесом трескучим,

- К дому Горгон подступил; как видел везде на равнине

- И на дорогах — людей и животных подобья, тех самых,

- Что обратились в кремень, едва увидали Медузу;

- Как он, однако, в щите, что на левой руке, отраженным

- Медью впервые узрел ужасающий образ Медузы;

- Тяжким как пользуясь сном, и её и гадюк охватившим,

- Голову с шеи сорвал; и ещё — как Пегас быстрокрылый

- С братом его родились из пролитой матерью крови.

- (Овидий. «Метаморфозы», IV, 775—790)[6].

«Голова Медузы», Рубенс (1618)

Во время этого поединка Медуза была беременна от Посейдона. Из обезглавленного тела Медузы с потоком крови вышли её дети от Посейдона — великан Хрисаор (отец трехтелого Гериона) и крылатый конь Пегас. Из капель крови, упавшей в пески Ливии, появились ядовитые змеи и уничтожили в ней все живое (по Лукану, это были т. н. Ливийские змеи[7]: аспид, амфисбена, аммодит и василиск). Локальная легенда гласит, что из потока крови, пролившегося в океан, появились кораллы.

Афина дала Асклепию кровь, вытекшую из жил горгоны Медузы. Кровь, которая текла из левой части, несла смерть, а из правой — использовалась Асклепием для спасения людей.

По другой версии, Медуза рождена Геей и убита Афиной во время гигантомахии[8]. Согласно Евгемеру, её убила Афина[9]. В подражание жалам Горгоны Афина изобрела двойной авлос[10].

Считается, что мифы о горгоне Медузе имеют связь с культом скифской змееногой богини-прародительницы Табити, свидетельством существования которой являются упоминания в античных источниках и археологические находки изображений. В эллинизированной версии эта «горгона Медуза» от связи с Гераклом породила скифский народ.

Роспись амфоры мастера Андокида с изображением добычи Золотого руна Ясоном. Фрагмент с изображением Афины Паллады в эгиде, украшенной головой горгоны Медузы.

Голова Медузы

И в отрубленном состоянии взгляд головы горгоны сохранял способность превращать людей в камень. Персей воспользовался головой Медузы в бою с Кето (Китом) — драконоподобным морским чудовищем (и матерью горгон), которое было послано Посейдоном опустошать Эфиопию. Показав лик Медузы Кето, Персей превратил её в камень и спас Андромеду, царскую дочь, которую предназначили в жертву Кето. Перед этим он превратил в камень титана Атланта, поддерживающего небесный свод неподалеку от острова горгон, и тот превратился в гору Атлас в современном Марокко.

Позднее Персей таким же образом обратил в камень царя Полидекта и его прислужников, преследовавших Данаю, мать Персея. Затем голова Медузы была помещена на эгиду Афины («на грудь Афины»[11]) — в искусстве эту голову было принято изображать на доспехах на плече богини или под ключицами на её груди.

По Павсанию, её голова лежит в земляном холме около площади Аргоса[12]. Киклопы изготовили голову Медузы из мрамора и установили у храма Кефиса в Аргосе[13].

Интерпретации

Согласно рационалистическому истолкованию, она была дочерью царя Форка и царствовала над народом у озера Тритониды, водила ливийцев на войну, но ночью была изменнически убита. Карфагенский писатель Прокл называет её дикой женщиной из Ливийской пустыни[12]. По другому истолкованию, была гетерой, влюбилась в Персея и истратила свою молодость и состояние[14].

Животное горгона из Ливии описал Александр Миндский[15].

Античные источники

- упоминания у Гомера

- Гесиод: а поэмах «Теогония» и «Щит Геракла» упоминаются две из пяти сестер Медузы — Сфено и Евриала, а также описывается её смерть от руки Персея.

- Эсхил: в «Прикованном Прометее» он говорит о сестрах Медузы. В его трагедиях образ Медузы олицетворяет отвратительность зла и безжалостность человека.

- Пиндар: в «Двенадцатой пифийской оде» о происхождении флейты говорит, что инструмент был создан Афиной, впечатленной криками её сестер в день её смерти. Он описывает красоту и привлекательность Медузы, вдохновлявшую поэтов-романтиков на протяжении многих столетий. От него же исходят сведения о том, что жертвы горгоны окаменевают от её взгляда.

- Еврипид: в «Ионе» героиня Креуса описывает два небольших амулета, доставшихся ей от отца Эрихтония, который, в свою очередь, получил их от Афины. Каждый из амулетов содержит каплю крови Медузы. Одна из капель — благотворная, обладающая целительными свойствами, другая — яд из змеиного тела. Здесь, как и у Пиндара, Медуза — существо двойственное[16].

- Овидий: «Метаморфозы», 4-я и 5-я книги. Самое полное оформление легенды.

В искусстве

Изображалась в виде женщины со змеями вместо волос и кабаньими клыками вместо зубов. В эллинских изображениях иногда встречается прекрасная умирающая девушка-горгона.

Отдельная иконография — изображений отрубленной головы Медузы, либо в руках у Персея, на щите или эгиде Афины и Зевса. На прочих щитах превращалсь в декоративный мотив — горгонейон.

В скифском искусстве — заклинательная чаша-омфалос IV в. до н. э. из Куль-Обы (Керчь) с 24 головами.

Верования и амулеты

Древнеримская напольная мозаика с изображением горгонейона при входе в дом. Национальный археологический музей, Мадрид

Горгонейон — маска-талисман с изображением головы Медузы, которую изображали на одежде, предметах обихода, оружия, инструментах, украшениях, монетах и фасадах зданий. Традиция встречается и в Древней Руси.

В русской средневековой культуре

В славянских средневековых книжных легендах она превратилась в деву с волосами в виде змей — девицу Горгонию. Волхв, которому удаётся с помощью обмана обезглавить Горгонию и овладеть её головой, получает чудесное средство, дающее ему победу над любыми врагами. Также в славянских апокрифах — «зверь Горгоний», охраняющий рай от людей после грехопадения[17]. В романе «Александрия» головой овладевает Александр Македонский.

Голова горгоны Медузы как эмблема

- В средневековых книжных легендах владение головой горгоны приписывалось Александру Македонскому, чем объяснялись его победы над всеми народами[17]. В знаменитой помпейской мозаике доспех царя украшен на груди изображением головы горгоны.

- Остров Сицилия традиционно считается местом, где жили горгоны и была убита Медуза. Её изображение до сих пор украшает флаг этого региона[1].

- На старинных картах звёздного неба Персей традиционно изображается держащим в руке голову Медузы; её глаз — переменная звезда Алголь (бета Персея).

- Голова Медузы в период классицизма и ампира, воскресившего античные мотивы, в том числе и этот — горгонейон, стала традиционным декоративным элементом, сопутствующим военной арматуре в украшении зданий и оград. К примеру, она является очень часто встречающимся мотивом в чугунном и кованном декоре Санкт-Петербурга[18], красуясь, в частности, на ограде 1-го Инженерного моста и решетке Летнего сада.

- Медуза Ронданини стала эмблемой дома Версаче.

В западноевропейской живописи и скульптуре

Копией несохранившейся картины Леонардо да Винчи с изображением головы Медузы (описанной Вазари) принято считать работу Караваджо. На эту тему писали также Рубенс, Бёклин и другие.

В западноевропейской литературе

- В IX песне «Божественной комедии» перед Данте предстают три фурии; беснуясь и визжа, они призывают присутствующую там Медузу превратить его сердце в камень.

- В «Фаусте» Гёте горгона Медуза бродит по шабашу, приняв образ Гретхен (Маргариты), чем смущает доктора Фауста[19].

В современной культуре

- Das Medusenhaupt — работа Зигмунда Фрейда, анализ мифа с точки зрения психоанализа.

- Миф о Медузе был пересказан для детей К. И. Чуковским.

- Медуза Горгона является знаковым символом для современных феминисток. В частности, они возражают против использования образа невинно убиенной героической женщины в качестве логотипа модного дома Версаче.

- В фильме Альберто Де Мартино «Подвиги Геракла: Медуза Горгона» убийство чудовища приписано не Персею, а его более знаменитому единокровному брату.

- «Медуза-Горгона» — песня группы «Крематорий»

- Миф о Медузе упоминается в песне «Отражение» группы «Король и Шут»: «В сером мешке — тихие стоны, сердце моё как трофей Горгоны…»

- В серии книг Дмитрия Емца «Таня Гроттер» есть персонаж Медузия Горгонова

- Медуза Горгона является одним из героев в Dota

- Медуза Горгона — истинное имя слуги Райдер в аниме Fate/Stay Night .

- В честь Медузы Горгоны назван астероид 149 Медуза, открытый в 1875 году.

- Медуза Горгона встречается в фильме Перси Джексон и похититель молний, а также в фильме Битва Титанов и телевизионном фильме «Путешествие Единорога».

- В мультсериале MONSTER HIGH, один из главных персоонажей Дьюс Горгон, сын Медузы Горгоны

- В книге харьковских писателей Г. Л. Олди «Внук Персея: мой дедушка — истребитель» образ Медузы полностью переосмысливается. Имя жены Персея Андромеды и Медузы Горгоны содержит общий корень, из чего авторы дают понять читателю, что Медуза не была убита Персеем, она приняла сущность смертной и стала его женой.

- Медуза — одна из главных героинь аниме Soul Eater

Горгона в кино

Битва титанов

Злобное существо наполовину-человек- наполовину змея, у которой на голове вместо волос кишат змеи появляется в фильме Битва титанов (2010), роль играла топ-модель Наталья Водянова.

Перси Джексон и похититель молний

Также эта получеловек- полузмея на голове у которой вместо волос извивающиеся змеи встречается в фильме «Перси Джексон и похититель молний» (2010), роль исполнила актриса Ума Турман.

Примечания

- ↑ Псевдо-Аполлодор. Мифологическая библиотека II 3, 2; 4, 2-3; 5, 12; III 10, 3

- ↑ Согласно грамота.ру

- ↑ Гигин. Мифы 151

- ↑ Овидий. Метаморфозы IV 794—801

- ↑ Овидий. Метаморфозы VI 120

- ↑ Публий Овидий Назон. «Метаморфозы»

- ↑ Лукан. Фарсалия IX 700—733

- ↑ Еврипид. Ион 989—991

- ↑ Гигин. Астрономия II 12, 2

- ↑ Нонн. Деяния Диониса XXIV 36

- ↑ Павсаний. Описание Эллады I 24, 7

- ↑ 1 2 Павсаний. Описание Эллады II 21, 5

- ↑ Павсаний. Описание Эллады II 20, 6

- ↑ Гераклит-аллегорист. О невероятном 1

- ↑ Афиней. Пир мудрецов V 64, 221b-c

- ↑ «Экзотическая зоология»

- ↑ 1 2 Мифологический словарь. Русская мифология

- ↑ Военный декор петербургских мостов

- ↑ Гёте. «Фауст», сцена Вальпургиева ночь

Литература

- Паскаль Киньяр. Персей и Медуза // Киньяр П. Секс и страх: Эссе: Пер. с фр. — М.: Текст, 2000, с. 51-58.

См. также

- Горгоны — древнегреческие чудовища, сестры Медузы

- Медузы — обитатели моря получили свое название в честь горгоны с шевелящимися щупальцами.

- Горгонейон

- Голова Горгоны (значения)

- Василиск — другое чудовище с волшебным взглядом

Ссылки

| Горгона Медуза на Викискладе? |

- Горгоны на theoi.com

- Горгона Медуза в «Энциклопедии вымышленных существ». Галерея

- Миф об убийстве горгоны в изложении Куна

- Образ Медузы Горгоны в архаичном искусстве древней Греции

- Скифская змеиная (змееногая) богиня-прародительница

|

Негеральдические гербовые фигуры |

||

|---|---|---|

| Естественные | ангел • бук • бык • вепрь • волк • ворон • горностай • дельфин • жираф • змея • конь • крокодил • лев (леопард) • лилия • лисица • мартлет • медведь • муравей • овца • олень • орёл • петух • пёс • пчела • тигр |  |

| Фантастические | альфин • бабр • гарпия • грифон • двуглавый орёл • дракон • единорог • йейл • кентавр | |

| Искусственные | атом • лук • меч • подкова • солнце и луна • стрела • фасции |

| |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| География · Хронология · Флора · Фауна · Лошади · Катастеризм | |||||||||||||

| Первоначальные божества |

|

||||||||||||

| Титаны |

|

||||||||||||

| Олимпийские боги |

|

||||||||||||

| Посейдон · Амфитрита · Тритон · Океан · Тефида · Понт/Таласса · Нерей · Главк Морской · Протей · Форкий · Кето · Фетида | |||||||||||||

| Океаниды | Асия · Гесиона · Дорида · Евринома · Метида · Немесида · Стикс · Электра · Филира · Перса · Плейона · Климена · Каллироя | ||||||||||||

| Нереиды | Амфитрита · Фетида · Галатея · Немертея · Галена · Сао |

Хтонические

божества

Земля

Категории: Религия и мифология · Боги и богини · Герои и героини · Мифические народы · Мифические существа

Портал

Горго́на Меду́за (точнее Ме́дуса, др.-греч. Μέδουσα — «защитница, повелительница»[1]) — наиболее известная из трех сестёр горгон, чудовище с женским лицом и змеями вместо волос[2]. Её взгляд обращал человека в камень. Была убита Персеем. Упомянута в «Одиссее» (XI 634).

Своё имя морская медуза получила из-за сходства с шевелящимися волосами-змеями легендарной горгоны Медузы из греческой мифологии.

Содержание

- 1 Миф

- 1.1 Происхождение Медузы

- 1.2 Смерть Медузы

- 1.3 Голова Медузы

- 1.4 Интерпретации

- 2 Античные источники

- 3 В искусстве

- 3.1 Верования и амулеты

- 3.2 В русской средневековой культуре

- 3.3 Голова Медузы Горгоны как эмблема

- 3.4 В западноевропейской живописи и скульптуре

- 3.5 В западноевропейской литературе

- 3.6 В культуре

- 4 В кино и мультипликации

- 5 См. также

- 6 Примечания

- 7 Литература

- 8 Ссылки

Миф

Происхождение Медузы

Младшая дочь морского старца Форка и Кето (по другой версии, дочь Горгона[3]). Единственная смертная из горгон.

По поздней версии мифа, изложенной Овидием в «Метаморфозах», Медуза была девушкой с красивыми волосами. Бог Посейдон, превратившись в птицу[4], овладел Медузой в храме Афины, куда Медуза бросилась в поисках защиты от преследования Посейдона. Афина не только не помогла ей, но и превратила её волосы в гидр[5].

Смерть Медузы

Одним из заданий, данных Персею царём Полидектом, было убийство Горгоны Медузы. Справиться с чудовищем герою помогли боги — Афина и Гермес. По их совету перед тем, как отправиться в бой, он посетил вещих старух — сестёр грай, (которые были также Форкидами, сёстрами горгон), имевших на троих один глаз и один зуб. Хитростью Персей похитил у них зуб и глаз, а вернул лишь в обмен на крылатые сандалии, волшебный мешок и шапку-невидимку Аида. Грайи показали Персею путь к горгонам. Гермес подарил ему острый кривой нож. Вооружившись этим подарком, Персей прибыл к горгонам. Поднявшись в воздух на крылатых сандалиях, он смог отрубить голову смертной Медузе, одной из трёх сестёр горгон, смотря в отражение на полированном медном щите Афины — ведь взгляд Медузы обращал всё живое в камень. От сестёр Медузы Персей скрылся с помощью шапки-невидимки, спрятав трофей в заплечную сумку.

- (И повествует Персей, как) скалы,

- Скрытые, смело пройдя с их страшным лесом трескучим,

- К дому Горгон подступил; как видел везде на равнине

- И на дорогах — людей и животных подобья, тех самых,

- Что обратились в кремень, едва увидали Медузу;

- Как он, однако, в щите, что на левой руке, отраженным

- Медью впервые узрел ужасающий образ Медузы;

- Тяжким как пользуясь сном, и её и гадюк охватившим,

- Голову с шеи сорвал; и ещё — как Пегас быстрокрылый

- С братом его родились из пролитой матерью крови.

- (Овидий. «Метаморфозы», IV, 775—790)[6].

«Голова Медузы», Рубенс (1618)

Во время этого поединка Медуза была беременна от Посейдона. Из обезглавленного тела Медузы с потоком крови вышли её дети от Посейдона — великан Хрисаор (отец трёхтелого Гериона) и крылатый конь Пегас. Из капель крови, упавшей в пески Ливии, появились ядовитые змеи и уничтожили в ней всё живое (по Лукану, это были т. н. Ливийские змеи[7]: аспид, амфисбена, аммодит и василиск). Локальная легенда гласит, что из потока крови, пролившегося в океан, появились кораллы.

Афина дала Асклепию кровь, вытекшую из жил горгоны Медузы. Кровь, которая текла из левой части, несла смерть, а из правой — использовалась Асклепием для спасения людей.

По другой версии, Медуза рождена Геей и убита Афиной во время гигантомахии[8]. Согласно Евгемеру, её убила Афина[9]. В подражание жалам Горгоны Афина изобрела двойной авлос[10].

Роспись амфоры мастера Андокида с изображением добычи Золотого руна Ясоном. Фрагмент с изображением Афины Паллады в эгиде, украшенной головой горгоны Медузы

Голова Медузы

И в отрубленном состоянии взгляд головы горгоны сохранял способность превращать людей в камень. Персей воспользовался головой Медузы в бою с Кето (Китом) — драконоподобным морским чудовищем (и матерью горгон), которое было послано Посейдоном опустошать Эфиопию. Показав лик Медузы Кето, Персей превратил её в камень и спас Андромеду, царскую дочь, которую предназначили в жертву Кето. Перед этим он превратил в камень титана Атланта, поддерживающего небесный свод неподалеку от острова горгон, и тот превратился в гору Атлас в современном Марокко.

Позднее Персей таким же образом обратил в камень царя Полидекта и его прислужников, преследовавших Данаю, мать Персея. Затем голова Медузы была помещена на эгиду Афины («на грудь Афины»[11]) — в искусстве эту голову было принято изображать на доспехах на плече богини или под ключицами на её груди.

По Павсанию, её голова лежит в земляном холме около площади Аргоса[12]. Циклопы изготовили голову Медузы из мрамора и установили у храма Кефиса в Аргосе[13].

Интерпретации

Согласно рационалистическому истолкованию, она была дочерью царя Форка и царствовала над народом у озера Тритониды, водила ливийцев на войну, но ночью была изменнически убита. Карфагенский писатель Прокл называет её дикой женщиной из Ливийской пустыни[12]. По другому истолкованию, была гетерой, влюбилась в Персея и истратила свою молодость и состояние[14].

Животное горгона из Ливии описал Александр Миндский[15].

Античные источники

- упоминания у Гомера

- Гесиод: а поэмах «Теогония» и «Щит Геракла» упоминаются две из пяти сестер Медузы — Сфено и Эвриала, а также описывается её смерть от руки Персея.

- Эсхил: в «Прикованном Прометее» он говорит о сестрах Медузы. В его трагедиях образ Медузы олицетворяет отвратительность зла и безжалостность человека.

- Пиндар: в «Двенадцатой пифийской оде» о происхождении флейты говорит, что инструмент был создан Афиной, впечатлённой криками сестер Медузы в день её смерти. Он описывает красоту и привлекательность Медузы, вдохновлявшую поэтов-романтиков на протяжении многих столетий. От него же исходят сведения о том, что жертвы горгоны окаменевают от её взгляда.

- Еврипид: в «Ионе» героиня Креуса описывает два небольших амулета, доставшихся ей от отца Эрихтония, который, в свою очередь, получил их от Афины. Каждый из амулетов содержит каплю крови Медузы. Одна из капель — благотворная, обладающая целительными свойствами, другая — яд из змеиного тела. Здесь, как и у Пиндара, Медуза — существо двойственное[16].

- Овидий: «Метаморфозы», 4-я и 5-я книги. Самое полное оформление легенды.

В искусстве

Изображалась в виде женщины со змеями вместо волос и кабаньими клыками вместо зубов. В эллинских изображениях иногда встречается прекрасная умирающая девушка-горгона.

Отдельная иконография — изображений отрубленной головы Медузы, либо в руках у Персея, на щите или эгиде Афины и Зевса. На прочих щитах превращалась в декоративный мотив — горгонейон.

В скифском искусстве — заклинательная чаша-омфалос IV в. до н. э. из Куль-Обы (Керчь) с 24 головами.

Верования и амулеты

Древнеримская напольная мозаика с изображением горгонейона при входе в дом. Национальный археологический музей, Мадрид

Горгонейон — маска-талисман с изображением головы Медузы, которую изображали на одежде, предметах обихода, оружия, инструментах, украшениях, монетах и фасадах зданий. Традиция встречается и в Древней Руси.

В русской средневековой культуре

В славянских средневековых книжных легендах она превратилась в деву с волосами в виде змей — девицу Горгонию. Волхв, которому удаётся с помощью обмана обезглавить Горгонию и овладеть её головой, получает чудесное средство, дающее ему победу над любыми врагами. Также в славянских апокрифах — «зверь Горгоний», охраняющий рай от людей после грехопадения[17]. В романе «Александрия» головой овладевает Александр Македонский.

Голова Медузы Горгоны как эмблема

- В средневековых книжных легендах владение головой горгоны приписывалось Александру Македонскому, чем объяснялись его победы над всеми народами[17]. В знаменитой помпейской мозаике доспех царя украшен на груди изображением головы горгоны.

- Остров Сицилия традиционно считается местом, где жили горгоны и была убита Медуза. Её изображение до сих пор украшает флаг этого региона [1].

- На старинных картах звёздного неба Персей традиционно изображается держащим в руке голову Медузы; её глаз — переменная звезда Алголь (бета Персея).

- Голова Медузы в период классицизма и ампира, воскресившего античные мотивы, в том числе и этот — горгонейон, стала традиционным декоративным элементом, сопутствующим военной арматуре в украшении зданий и оград. К примеру, она является очень часто встречающимся мотивом в чугунном и кованном декоре Санкт-Петербурга[18], красуясь, в частности, на ограде 1-го Инженерного моста и решетке Летнего сада.

- Медуза Ронданини стала эмблемой дома Версаче.

В западноевропейской живописи и скульптуре

Копией несохранившейся картины Леонардо да Винчи с изображением головы Медузы (описанной Вазари) принято считать работу Караваджо. На эту тему писали также Рубенс, Бёклин и другие.

В западноевропейской литературе

- В IX песне «Божественной комедии» перед Данте предстают три фурии; беснуясь и визжа, они призывают присутствующую там Медузу превратить его сердце в камень.

- В «Фаусте» Гёте горгона Медуза бродит по шабашу, приняв образ Гретхен (Маргариты), чем смущает доктора Фауста[19].

В культуре

- Das Medusenhaupt — работа Зигмунда Фрейда, анализ мифа с точки зрения психоанализа.

- Медуза Горгона является знаковым символом для современных феминисток. В частности, они возражают против использования образа невинно убиенной героической женщины в качестве логотипа модного дома Версаче[20][21].

- В честь Медузы Горгоны назван астероид 149 Медуза, открытый в 1875 году.

- В репертуаре группы Княzz есть песня с одноимённым названием.

- Истории Медузы посвящена песня Stare из одноимённого альбома группы Gorky Park

- В современной литературе Медуза Горгона представлена в книжной серии «Таня Гроттер» в роли Медузии Горгоновой — доцента, заместителя главы Тибидохса, преподавателя нежитеведения.

- В визуальном романе Fate/stay night Медуза участвует как Слуга класса Райдер (всадник). Её образ немного отличается от оригинального тем, что у неё нет волос-змей, но её способность обращать все живое в камень своим взглядом оказывается реальной. В битвах, она сражается верхом на белом пегасе по имени Беллерофонт.

В кино и мультипликации

- Перси Джексон и похититель молний

Также эта получеловек-полузмея, на голове у которой вместо волос извивающиеся змеи, встречается в фильме «Перси Джексон и похититель молний» (2010), роль исполнила актриса Ума Турман.

- Битва титанов;

Злобное существо, наполовину человек — наполовину змея, у которой на голове вместо волос кишат змеи, появляется в фильме «Битва титанов» (2010), роль играла топ-модель Наталья Водянова.

- Персей

В советском мультфильме 1973 года Горгона предстаёт обольстительной крылатой нимфой с огромными сверкающими и непрерывно меняющимися глазами, коллекционирующей у себя на острове каменные памятники своих жертв.

- Доктор Кто

В британском научно-фантастическом сериале Медуза Горгона появилась как вымышленное создание, ожившее в Земле Фантастики. Её появление произошло во 2 серии 6 сезона «Вор разума» (1969), где её сыграла Сью Палфорд.

- Путешествие «Единорога»

В этом американском фэнтези Медуза Горгона является одним из главных героев. Представлена в виде красивой девушки со змеями в виде волос и способностью превращать врагов в камень. Изначально являлась антагонистом, но позже переходит на положительную сторону. Роль исполнила Кира Клавелл.

См. также

- Горгоны

- Медузы

- Медуза

- Горгонейон

- Голова Горгоны

- Василиск

- Остров Горгона

Примечания

- ↑ Древнегреческое слово μέδουσα является действительным причастием настоящего времени в единственном числе женского рода от глагола μέδω — «защищать, покровительствовать, властвовать».

- ↑ Псевдо-Аполлодор. Мифологическая библиотека II 3, 2; 4, 2—3; 5, 12; III 10, 3.

- ↑ Гигин. Мифы 151.

- ↑ Овидий. Метаморфозы VI 120.

- ↑ Овидий. Метаморфозы IV 794—801.

- ↑ Публий Овидий Назон. «Метаморфозы».

- ↑ Лукан. Фарсалия IX 700—733.

- ↑ Еврипид. Ион 989—991.

- ↑ Гигин. Астрономия II 12, 2.

- ↑ Нонн. Деяния Диониса XXIV 36.

- ↑ Павсаний. Описание Эллады I 24, 7.

- ↑ 1 2 Павсаний. Описание Эллады II 21, 5.

- ↑ Павсаний. Описание Эллады II 20, 6.

- ↑ Гераклит-аллегорист. О невероятном 1.

- ↑ Афиней. Пир мудрецов V 64, 221b-c.

- ↑ «Экзотическая зоология»

- ↑ 1 2 Мифологический словарь. Русская мифология

- ↑ Военный декор петербургских мостов Архивная копия от 7 марта 2008 на Wayback Machine

- ↑ Гёте. «Фауст», сцена Вальпургиева ночь.

- ↑ Garber, Marjorie, Vickers, Nancy. The Medusa Reader. — Routledge, 2003. — ISBN 9780415900997.

- ↑ Stephenson, A. G. (1997). «Endless the Medusa: a feminist reading of Medusan imagery and the myth of the hero in Eudora Welty’s novels.»

Литература

- Паскаль Киньяр. Персей и Медуза // Киньяр П. Секс и страх: Эссе: Пер. с фр. — М.: Текст, 2000, с. 51—58.

- Штолль Генрих. «Мифы классической древности». Том 1. — «Aegitas», 2014. — 408 с.

Ссылки

| Горгона Медуза на Викискладе |

- Горгоны на theoi.com

- Горгона Медуза на сайте «Энциклопедия вымышленных существ». Галерея

- Миф об убийстве горгоны в изложении Куна

- Образ Медузы Горгоны в архаичном искусстве древней Греции

- Скифская змеиная (змееногая) богиня-прародительница