Всего найдено: 11

Две точки на конце предложения не ставятся, а если после сокращения идет текст в скобках? Например: Стоимость аренды — 10000 р./мес. (плюс вода и электричество по счетчикам)

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В этом случае ставится точка после закрывающей скобки.

Скажите, пожалуйста, правильно ли в тексте употребляется слово «заём». Или надо все-таки «займ»? Микрозаём – это: от 30 тыс. руб. до 3 млн. руб. на срок от 3 мес. до 3 лет; погашение ежемесячными равными срочными уплатами (аннуитетными платежами) по ставке 10% годовых (по отдельным программам – 7%); отсутствие «комиссий» и «скрытых платежей»; предоставление льготного периода (только уплата процентов) на срок до 3 месяцев; возможность полного или частичного досрочного погашения задолженности уже после 3‑х месяцев со дня предоставления займа без дополнительных расходов заёмщика. Микрозаёмы в размере до 500 тыс. руб. включительно могут предоставляться без залога, под поручительства юридических или физических лиц. В Фонде действуют специальные программы предоставления микрозаёмов: для крестьянских (фермерских) хозяйств; для начинающих предпринимателей – победителей областного и муниципальных конкурсов на предоставление субсидий на начало собственного дела; «Тендерный заём» – для субъектов малого и среднего предпринимательства, участвующих в конкурсных процедурах по закупке товаров, работ и услуг для государственных и муниципальных нужд; совмещение микрозаёмов и лизинговых схем финансирования (по отдельным соглашениям с лизинговыми компаниями).

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В именительном падеже ед. числа правильно только заём, все остальные падежные формы образуются от основы займ-: займа, займу и т. д.; во множественном числе: займы, займов, займам и т. д. Поэтому правильно: микрозаём, но микрозаймы.

Подскажите, пожалуйста, нужна ли запятая перед «по результатам мониторинга»: Sед – стоимость единицы рабочего времени, руб./мес., устанавливается как среднее арифметическое значение величин заработной платы(,) по результатам мониторинга рынка компаний, функционирующих на рынке работ и услуг по организации и проведению конкурентных процедур по г. Москве в 2013 году (по официальным данным трех организаций).

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Запятая перед по результатам не требуется.

Следует отметить, что в целом фраза воспринимается крайне тяжело.

Как правильно сократить выражение «полтора года»: это 1,5 года или 1,6 года?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Полтора года — это 1,5 года или 1 г. 6 мес.

Здравствуйте! Хотя «Спрашивайте — не отвечаем»:), но очень надеюсь-таки получить ответ на многоочередной вопрос.

Нужно ли ставить точку после сокращений в мед. справочниках : «Препарат принимают… каждые 2 нед … в течение 1мес «?

И где найти это правило?

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

После сокращений нед. и мес. (неделя и месяц) точка ставится. Эти сокращения можно найти в орфографических словарях и в словарях сокращений. Они подчиняются стандартным правилам графического сокращения слов.

Надо ли ставить точку в сокращении мес(.)?

Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Да, точка после сокращения мес. ставится.

Как написать в объявлении о работе сокращение «тыс/мес» или «тыс./мес.» Строгая ли это норма?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Грамматически верно с точками.

Вероятно, такой вопрос уже задавался, но что-то я не могу найти…

Как правильно писать сокращенные наименования отрезков времени (секунды, часа, суток, недели, месяца) — с точкой или без? По-моему, правильно «с» (или «сек.»), «ч.», «сут.», «нед.», «мес.«.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно: _с., сек., ч., сут., нед., мес._ (с точками).

Добраый день!

Подскажите, пожалуйста,в каких случаях в русском языке употребляется сокращение от слова «месяц» — мес без точки. Может быть по системе СИ, как секунда (с)?

С уважением и надеждой на ответ

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корректные варианты: _мес._ (с точкой) и _м-ц_ (без точки).

Какие знаки препинания нужны в следующих случаях:

1). Калорийность (?) 88,5 ккал.

2). Срок годности (?) 18 мес.

3). Масса нетто (?) 75 г.

Каким правилом в данных случаях нужно руководствоваться?

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Тире ставится, если один из главных членов предложения выражен формой именительного падежа существительного, а другой — числительным либо оборотом с числительным: _Калорийность — 88,5 ккал. Срок годности — 18 мес. Масса нетто — 75 г._

Добрый вечер!

Как правильно сокращать слова: месяц, неделя, тысяча, минуиа?

Ставятся ли при сокращении точки?

Заранее благодарю, Лариса.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: _мес._ (с точкой) и _м-ц_ (без точек); _нед._ (с точкой); _тыс._ (с точкой) и _т._ (с точкой); _мин._ (с точкой) и _м._ (с точкой).

Как сокращённо обозначаются названия месяцев года и дней недели на русском и английском языках.

В вебе нередко появляются задачи когда необходимо работать с названиями дней недели и месяцами года. Это небольшая памятка с принятыми сокращениями для названий месяцев года и дней недели.

Сокращенные до 3 букв названия месяцев

Сокращения названия месяцев принято делать до 3-х символов.

| Месяц | Русский | Английский |

|---|---|---|

| Январь | Янв | Jan |

| Февраль | Фев | Feb |

| Март | Мар | Mar |

| Апрель | Апр | Apr |

| Май | Май | May |

| Июнь | Июн | Jun |

| Июль | Июл | Jul |

| Август | Авг | Aug |

| Сентябрь | Сен | Sep |

| Октябрь | Окт | Oct |

| Ноябрь | Ноя | Nov |

| Декабрь | Дек | Dec |

Массивы из названий месяцев года

const monthsRus = ['Январь', 'Февраль', 'Март', 'Апрель', 'Май', 'Июнь', 'Июль', 'Август', 'Сентябрь', 'Октябрь', 'Ноябрь', 'Декабрь'];

const monthsRu = ['Янв', 'Фев', 'Мар', 'Апр', 'Май', 'Июн', 'Июл', 'Авг', 'Сен', 'Окт', 'Ноя', 'Дек'];

const monthsEng = ['January', 'February', 'March', 'April', 'May', 'June', 'July', 'August', 'September', 'October', 'November', 'December'];

const monthsEn = ['Jan', 'Feb', 'Mar', 'Apr', 'May', 'Jun', 'Jul', 'Aug', 'Sep', 'Oct', 'Nov', 'Dec'];Сокращения названий дней недели

Названия дней недели имеют сокращения до 2-х и 3-х символов.

В календарях принято сокращать названия дней недели до 2-х букв, а в строках до 3-х.

| День недели | 2 буквы | 3 буквы | Английский | 2 буквы | 3 буквы |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Понедельник | Пн | Пнд | Monday | Mo | Mon |

| Вторник | Вт | Втр | Tuesday | Tu | Tue |

| Среда | Ср | Сре | Wednesday | We | Wed |

| Четверг | Чт | Чтв | Thursday | Th | Thu |

| Пятница | Пт | Птн | Friday | Fr | Fri |

| Суббота | Сб | Суб | Saturday | Sa | Sat |

| Воскресенье | Вс | Вск | Sunday | Su | Sun |

Массивы названий дней недели

Так как основным языком для веба является английский язык, массивы названий дней недели начинаются с воскресенья (на английский манер). Если английский вариант не нужен, просто переставьте воскресение на последнее место.

const dayRu = ['Вс', 'Пн', 'Вт', 'Ср', 'Чт', 'Пт', 'Сб'];

const dayRus = ['Вск', 'Пнд', 'Втр', 'Сре', 'Чтв', 'Птн', 'Суб'];

const dayRussian = ['Воскресенье', 'Понедельник', 'Вторник', 'Среда', 'Четверг', 'Пятница', 'Суббота'];

const dayEn = ['Su', 'Mo', 'Tu', 'We', 'Th', 'Fr', 'Sa'];

const dayEng = ['Sun', 'Mon', 'Tue', 'Wed', 'Thu', 'Fri', 'Sat'];

const dayEnglish = ['Sunday', 'Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday', 'Saturday'];

This article is about menstruation in humans. For menstruation in other mammals, see Menstruation (mammal).

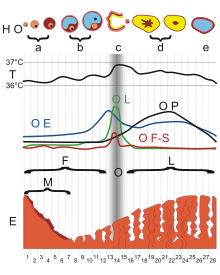

Diagram illustrating how the uterus lining builds up and breaks down during the menstrual cycle

Menstruation (also known as a period, among other colloquial terms) is the regular discharge of blood and mucosal tissue from the inner lining of the uterus through the vagina. The menstrual cycle is characterized by the rise and fall of hormones. Menstruation is triggered by falling progesterone levels and is a sign that pregnancy has not occurred.

The first period, a point in time known as menarche, usually begins between the ages of 12 and 15.[1] Menstruation starting as young as 8 years would still be considered normal.[2] The average age of the first period is generally later in the developing world, and earlier in the developed world.[3] The typical length of time between the first day of one period and the first day of the next is 21 to 45 days in young women. In adults, the range is between 21 and 31 days with the average being 28 days.[2][3] Bleeding usually lasts around 2 to 7 days. Periods stop during pregnancy and typically do not resume during the initial months of breastfeeding.[2] Menstruation stops occurring after menopause, which usually occurs between 45 and 55 years of age.[4]

Up to 80% of women do not experience problems sufficient to disrupt daily functioning either during menstruation or in the days leading up to menstruation. Symptoms in advance of menstruation that do interfere with normal life are called premenstrual syndrome (PMS). Some 20 to 30% of women experience PMS, with 3 to 8% experiencing severe symptoms.[5] These include acne, tender breasts, bloating, feeling tired, irritability, and mood changes.[6] Other symptoms some women experience include painful periods and heavy bleeding during menstruation and abnormal bleeding at any time during the menstrual cycle.[2] A lack of periods, known as amenorrhea, is when periods do not occur by age 15 or have not re-occurred in 90 days.[2]

Characteristics

Length and duration

The first menstrual period occurs after the onset of pubertal growth, and is called menarche. The average age of menarche is 12 to 15 years.[1][7] However, it may occur as early as eight.[2] The average age of the first period is generally later in the developing world, and earlier in the developed world.[3][8] The average age of menarche has changed little in the United States since the 1950s.[3]

Menstruation is the most visible phase of the menstrual cycle and its beginning is used as the marker between cycles. The first day of menstrual bleeding is the date used for the last menstrual period (LMP). The typical length of time between the first day of one period and the first day of the next is 21 to 45 days in young women, and 21 to 31 days in adults.[2][3] The average length is 28 days; one study estimated it at 29.3 days.[9] The variability of menstrual cycle lengths is highest for women under 25 years of age and is lowest, that is, most regular, for ages 25 to 39 years.[10] The variability increases slightly for women aged 40 to 44 years.[10]

Perimenopause is when a woman’s fertility declines, and menstruation occurs less regularly in the years leading up to the final menstrual period, when a woman stops menstruating completely and is no longer fertile. The medical definition of menopause is one year without a period and typically occurs between 45 and 55 years in Western countries.[4][11]: 381 Menopause before age 45 is considered premature in industrialized countries.[12] Like the age of menarche, the age of menopause is largely a result of cultural and biological factors.[dubious – discuss][failed verification] Illnesses, certain surgeries, or medical treatments may cause menopause to occur earlier than it might have otherwise.[13]

Bleeding

The average volume of menstrual fluid during a monthly menstrual period is 35 millilitres (2.4 US tbsp) with 10–80 millilitres (0.68–5.41 US tbsp) considered typical. Menstrual fluid is the correct name for the flow, although many people prefer to refer to it as menstrual blood. Menstrual fluid is reddish-brown, a slightly darker color than venous blood.[11]: 381

About half of menstrual fluid is blood. This blood contains sodium, calcium, phosphate, iron, and chloride, the extent of which depends on the woman. As well as blood, the fluid consists of cervical mucus, vaginal secretions, and endometrial tissue. Vaginal fluids in menses mainly contribute water, common electrolytes, organ moieties, and at least 14 proteins, including glycoproteins.[14]

Many women and girls notice blood clots during menstruation. These appear as clumps of blood that may look like tissue. If there was a miscarriage or a stillbirth, examination under a microscope can confirm if it was endometrial tissue or pregnancy tissue (products of conception) that was shed.[15] Sometimes menstrual clots or shed endometrial tissue is incorrectly thought to indicate an early-term miscarriage of an embryo. An enzyme called plasmin – contained in the endometrium – tends to inhibit the blood from clotting.[medical citation needed]

The amount of iron lost in menstrual fluid is relatively small for most women.[better source needed][16] In one study, premenopausal women who exhibited symptoms of iron deficiency were given endoscopies. 86% of them actually had gastrointestinal disease and were at risk of being misdiagnosed simply because they were menstruating.[non-primary source needed][17] Heavy menstrual bleeding, occurring monthly, can result in anemia.[18]

Hormonal changes

The menstrual cycle is a series of natural changes in hormone production and the structures of the uterus and ovaries of the female reproductive system that make pregnancy possible. The ovarian cycle controls the production and release of eggs and the cyclic release of estrogen and progesterone. The uterine cycle governs the preparation and maintenance of the lining of the uterus (womb) to receive an embryo. These cycles are concurrent and coordinated, normally last between 21 and 35 days, with a median length of 28 days, and continue for about 30–45 years.

Naturally occurring hormones drive the cycles; the cyclical rise and fall of the follicle stimulating hormone prompts the production and growth of oocytes (immature egg cells). The hormone estrogen stimulates the uterus lining (endometrium) to thicken to accommodate an embryo should fertilization occur. The blood supply of the thickened lining provides nutrients to a successfully implanted embryo. If implantation does not occur, the lining breaks down and blood is released. Triggered by falling progesterone levels, menstruation (a «period», in common parlance) is the cyclical shedding of the lining, and is a sign that pregnancy has not occurred.

Side effects

Menstrual health overview

Although a normal and natural process,[19] some women experience premenstrual syndrome with symptoms that may include acne, tender breasts, and tiredness.[20] More severe symptoms that affect daily living are classed as premenstrual dysphoric disorder and are experienced by 3 to 8% of women.[21][22][20][23] Dysmenorrhea (menstrual cramps or period pain) is felt as painful cramps in the abdomen that can spread to the back and upper thighs during the first few days of menstruation.[24][25][26] Debilitating period pain is not normal and can be a sign of something severe such as endometriosis.[27] These issues can significantly affect a woman’s health and quality of life and timely interventions can improve the lives of these women.[28]

There are common culturally communicated misbeliefs that the menstrual cycle affects women’s moods, causes depression or irritability, or that menstruation is a painful, shameful or unclean experience. Often a woman’s normal mood variation is falsely attributed to the menstrual cycle. Much of the research is weak, but there appears to be a very small increase in mood fluctuations during the luteal and menstrual phases, and a corresponding decrease during the rest of the cycle.[29] Changing levels of estrogen and progesterone across the menstrual cycle exert systemic effects on aspects of physiology including the brain, metabolism, and musculoskeletal system. The result can be subtle physiological and observable changes to women’s athletic performance including strength, aerobic, and anaerobic performance.[30]

Moods and premenstrual syndrome (PMS)

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) refers to emotional and physical symptoms that regularly occur in the one to two weeks before the start of each menstrual period.[31][32] Symptoms resolve around the time menstrual bleeding begins.[33] Different women experience different symptoms.[31] Premenstrual syndrome is commonly noted by at least one physical, emotional, or behavioral symptom, that resolves with menses.[34] The range of symptoms is wide, and most commonly are breast tenderness, bloating, headache, mood swings, depression, anxiety, anger, and irritability. They must interfere with daily living, during two menstrual cycles of prospective recording.[34] These symptoms are nonspecific and may be seen in women without PMS. Often PMS-related symptoms are present for about six days.[35] An individual’s pattern of symptoms may change over time.[35] Symptoms do not occur during pregnancy or following menopause.[33]

Diagnosis requires a consistent pattern of emotional and physical symptoms occurring after ovulation and before menstruation to a degree that interferes with normal life.[32] Emotional symptoms must not be present during the initial part of the menstrual cycle.[32] A daily list of symptoms over a few months may help in diagnosis.[35] Other disorders that cause similar symptoms need to be excluded before a diagnosis is made.[35]

The cause of PMS is unknown, but the underlying mechanism is believed to involve changes in hormone levels.[33] Reducing salt, alcohol, caffeine, and stress along with increasing exercise is typically all that is recommended in those with mild symptoms.[33] Calcium and vitamin D supplementation may be useful in some.[35] Anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen or naproxen may help with physical symptoms.[33] In those with more significant symptoms birth control pills or the diuretic spironolactone may be useful.[33][35]

Over 90% of women report having some premenstrual symptoms, such as bloating, headaches, and moodiness.[31] Premenstrual symptoms generally do not cause substantial disruption, and qualify as PMS in approximately 20 to 30% of pre-menopausal women.[35] Antidepressants of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors class may be used to treat the emotional symptoms of PMS.[31]

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a more severe form of PMS that has greater psychological symptoms.[35][33] PMDD affects less than 5% of women of child-bearing age.[31]

Cramps

In most women, various physical changes are brought about by fluctuations in hormone levels during the menstrual cycle. This includes muscle contractions of the uterus (menstrual cramping) that can precede or accompany menstruation. Many women experience painful cramps, also known as dysmenorrhea, during menstruation.[36] Among adult women, that pain is severe enough to affect daily activity in only 2%–28%.[36] Severe symptoms that disrupt daily activities and functioning may be diagnosed as premenstrual dysphoric disorder.[37] These symptoms can be severe enough to affect a person’s performance at work, school, and in everyday activities in a small percentage of women.[5]

When severe pelvic pain and bleeding suddenly occur or worsen during a cycle, this could be due to ectopic pregnancy and spontaneous abortion. This is checked by using a pregnancy test, ideally as soon as unusual pain begins, because ectopic pregnancies can be life‑threatening.[38]

The most common treatment for menstrual cramps are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs can be used to reduce moderate to severe pain, and all appear similar.[39] About 1 in 5 women do not respond to NSAIDs and require alternative therapy, such as simple analgesics or heat pads.[40] Other medications for pain management include aspirin or paracetamol and combined oral contraceptives. Although combined oral contraceptives may be used, there is insufficient evidence for the efficacy of intrauterine progestogens.[39]

One review found tentative evidence that acupuncture may be useful, at least in the short term.[41] Another review found insufficient evidence to determine an effect.[42]

Interactions with other conditions

Known interactions between the menstrual cycle and certain health conditions include:

- Some women with neurological conditions experience increased activity of their conditions at about the same time during each menstrual cycle. For example, drops in estrogen levels may trigger migraines,[medical citation needed] [43] especially when the woman who has migraines is also taking the birth control pill.

- Many women with epilepsy have more seizures in a pattern linked to the menstrual cycle; this is called «catamenial epilepsy».[44] Different patterns seem to exist (such as seizures coinciding with the time of menstruation, or coinciding with the time of ovulation), and the frequency with which they occur has not been firmly established.

- Research indicates that women have a significantly higher likelihood of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in the pre-ovulatory stage, than post-ovulatory stage.[45]

Sexual activity

Sexual feelings and behaviors change during the menstrual cycle. Before and during ovulation, high levels of estrogen and androgens result in women having a relatively increased interest in sexual activity, and relatively lower interest directly prior to and during menstruation.[46] Unlike other mammals, women may show interest in sexual activity across all days of the menstrual cycle, regardless of fertility.[47]

There is no reliable scientific evidence that would advise against sexual intercourse during menstruation based on medical grounds.[medical citation needed]

Fertility aspects

Peak fertility (the time with the highest likelihood of pregnancy resulting from sexual intercourse) occurs during just a few days of the cycle: usually two days before and two days after the ovulation date.[48] This corresponds to the second and the beginning of the third week in a 28-day cycle. This fertile window varies from woman to woman, just as the ovulation date often varies from cycle to cycle for the same woman.[49] A variety of methods have been developed to help individual women estimate the relatively fertile and the relatively infertile days in the cycle; these systems are called fertility awareness.[medical citation needed]

Menstrual disorders

Infrequent or irregular ovulation is called oligoovulation.[50] The absence of ovulation is called anovulation. Normal menstrual flow can occur without ovulation preceding it: an anovulatory cycle. In some cycles, follicular development may start but not be completed; nevertheless, estrogens will be formed and stimulate the uterine lining. Anovulatory flow resulting from a very thick endometrium caused by prolonged, continued high estrogen levels is called estrogen breakthrough bleeding. Anovulatory bleeding triggered by a sudden drop in estrogen levels is called withdrawal bleeding.[51] Anovulatory cycles commonly occur before menopause (perimenopause) and in women with polycystic ovary syndrome.[52]

Very little flow (less than 10 ml) is called hypomenorrhea. Regular cycles with intervals of 21 days or fewer are polymenorrhea; frequent but irregular menstruation is known as metrorrhagia. Sudden heavy flows or amounts greater than 80 ml are termed menorrhagia.[53] Heavy menstruation that occurs frequently and irregularly is menometrorrhagia. The term for cycles with intervals exceeding 35 days is oligomenorrhea.[54] Amenorrhea refers to more than three[53] to six[54] months without menses (while not being pregnant) during a woman’s reproductive years. The term for painful periods is dysmenorrhea.

There is a wide spectrum of differences in how women experience menstruation. There are several ways that someone’s menstrual cycle can differ from the norm:

| Term | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Oligomenorrhea | Infrequent periods |

| Hypomenorrhea | Short or light periods |

| Polymenorrhea | Frequent periods (more frequently than every 21 days) |

| Hypermenorrhea | Heavy or long periods (soaking a sanitary napkin or tampon every hour, menstruating longer than 7 days) |

| Dysmenorrhea | Painful periods |

| Intermenstrual bleeding | Breakthrough bleeding (also called spotting) |

| Amenorrhea | Absent periods |

Extreme psychological stress can also result in periods stopping.[55] More severe symptoms of anxiety or depression may be signs of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) with is a depressive disorder.[56]

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is a hormonally caused bleeding abnormality. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding typically occurs in premenopausal women who do not ovulate normally (i.e. are anovulatory). All these bleeding abnormalities need medical attention; they may indicate hormone imbalances, uterine fibroids, or other problems. As pregnant women may bleed, a pregnancy test forms part of the evaluation of abnormal bleeding.[medical citation needed]

Women who had undergone female genital mutilation (particularly type III- infibulation) a practice common in parts of Africa, may experience menstrual problems, such as slow and painful menstruation, that is caused by the near-complete sealing off of the vagina.[57]

Dysmenorrhea

Dysmenorrhea, also known as period pain, painful periods or menstrual cramps, is pain during menstruation.[58][59][60] Its usual onset occurs around the time that menstruation begins.[61] Symptoms typically last less than three days.[61] The pain is usually in the pelvis or lower abdomen.[61] Other symptoms may include back pain, diarrhea or nausea.[61]

Dysmenorrhea can occur without an underlying problem.[62][63] Underlying issues that can cause dysmenorrhea include uterine fibroids, adenomyosis, and most commonly, endometriosis.[62] It is more common among those with heavy periods, irregular periods, those whose periods started before twelve years of age and those who have a low body weight.[61] A pelvic exam and ultrasound in individuals who are sexually active may be useful for diagnosis.[61] Conditions that should be ruled out include ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, interstitial cystitis and chronic pelvic pain.[61]

Dysmenorrhea occurs less often in those who exercise regularly and those who have children early in life.[61] Treatment may include the use of a heating pad.[62] Medications that may help include NSAIDs such as ibuprofen, hormonal birth control and the IUD with progestogen.[61][62] Taking vitamin B1 or magnesium may help.[60] Evidence for yoga, acupuncture and massage is insufficient.[61] Surgery may be useful if certain underlying problems are present.[60]

Estimates of the percentage of female adolescents, and women of reproductive age affected are between 50% and 90%.[58][63] It is the most common menstrual disorder.[60] Typically, it starts within a year of the first menstrual period.[61] When there is no underlying cause, often the pain improves with age or following having a child.[60]

Menstrual hygiene management

The elements of a tampon with applicator. Left: the bigger tube («penetrator»). Center: cotton tampon with attached string. Right: the narrower tube.

Menstrual products (also called «feminine hygiene» products) are made to absorb or catch menstrual blood. A number of different products are available – some are disposable, some are reusable. Where women can afford it, items used to absorb or catch menses are usually commercially manufactured products. Menstruating women manage menstruation primarily by wearing menstrual products such as tampons, napkins or menstrual cups to catch the menstrual blood.

The main disposable products (commercially manufactured) include:

- Sanitary napkins (also called sanitary towels or pads) – Rectangular pieces of material worn attached to the underwear to absorb menstrual flow, often with an adhesive backing to hold the pad in place. Disposable pads may contain wood pulp or gel products, usually with a plastic lining and bleached.

- Tampons – Disposable cylinders of treated rayon/cotton blends or all-cotton fleece, usually bleached, that are inserted into the vagina to absorb menstrual flow.

The main reusable products include:

- Menstrual cups – A firm, flexible bell-shaped device worn inside the vagina to collect menstrual flow.

- Reusable cloth pads – Pads that are made of cotton (often organic), terrycloth, or flannel, and may be handsewn (from material or reused old clothes and towels) or storebought.

- Padded panties or period-proof underwear – Reusable cloth (usually cotton) underwear with extra absorbent layers sewn in to absorb flow.

Due to poverty, some women cannot afford commercial feminine hygiene products.[64][65] Instead, they use materials found in the environment or other improvised materials.[66][67] «Period poverty» is a global issue affecting women and girls who do not have access to safe, hygienic sanitary products.[68] In addition, solid waste disposal systems in developing countries are often lacking, which means women have no proper place to dispose used products, such as pads.[69] Inappropriate disposal of used materials also creates pressures on sanitation systems as menstrual hygiene products can create blockages of toilets, pipes and sewers.[64]

Menstrual suppression

Due to hormonal contraception

Half-used blister pack of a combined oral contraceptive. The white pills are placebos, mainly for the purpose of reminding the woman to continue taking the pills.

Menstruation can be delayed by the use of progesterone or progestins. For this purpose, oral administration of progesterone or progestin during cycle day 20 has been found to effectively delay menstruation for at least 20 days, with menstruation starting after 2–3 days have passed since discontinuing the regimen.[70]

Hormonal contraception affects the frequency, duration, severity, volume, and regularity of menstruation and menstrual symptoms. The most common form of hormonal contraception is the combined birth control pill, which contains both estrogen and progestogen. Although the primary function of the pill is to prevent pregnancy, it may be used to improve some menstrual symptoms and syndromes which affect menstruation, such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, adenomyosis, amenorrhea, menstrual cramps, menstrual migraines, menorrhagia (excessive menstrual bleeding), menstruation-related or fibroid-related anemia and dysmenorrhea (painful menstruation) by creating regularity in menstrual cycles and reducing overall menstrual flow.[71][72]

Using the combined birth control pill, it is also possible for a woman to delay or eliminate menstrual periods, a practice called menstrual suppression.[73] Some women do this simply for convenience in the short-term,[74] while others prefer to eliminate periods altogether when possible. This can be done either by skipping the placebo pills, or using an extended cycle combined oral contraceptive pill, which were first marketed in the U.S. in the early 2000s. This continuous administration of active pills without the placebo can lead to the achievement of amenorrhea in 80% of users within 1 year of use.[75]

Due to breastfeeding

Breastfeeding causes negative feedback to occur on pulse secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and luteinizing hormone (LH).[76] Depending on the strength of the negative feedback, breastfeeding women may experience complete suppression of follicular development, follicular development but no ovulation, or normal menstrual cycles may resume.[77] Suppression of ovulation is more likely when suckling occurs more frequently.[78] The production of prolactin in response to suckling is important to maintaining lactational amenorrhea.[79] On average, women who are fully breastfeeding whose infants suckle frequently experience a return of menstruation at fourteen and a half months postpartum. There is a wide range of response among individual breastfeeding women, however, with some experiencing return of menstruation at two months and others remaining amenorrheic for up to 42 months postpartum.[80]

Society and culture

Traditions, taboos and education

Many religions have menstruation-related traditions, for example: Islam prohibits sexual contact with women during menstruation in the 2nd chapter of the Quran.[81] Some scholars argue that menstruating women are in a state in which they are unable to maintain wudhu, and are therefore prohibited from touching the Arabic version of the Qur’an. Other biological and involuntary functions such as vomiting, bleeding, sexual intercourse, and going to the bathroom also invalidate one’s wudhu.[82] In Judaism, a woman during menstruation is called Niddah and may be banned from certain actions. For example, the Jewish Torah prohibits sexual intercourse with a menstruating woman.[83] In Hinduism, menstruating women are traditionally considered ritually impure and given rules to follow.[84][85]

Menstruation education is frequently taught in combination with sex education at school in Western countries, although girls may prefer their mothers to be the primary source of information about menstruation and puberty.[86] Information about menstruation is often shared among friends and peers, which may promote a more positive outlook on puberty.[87] The quality of menstrual education in a society determines the accuracy of people’s understanding of the process.[88] In many Western countries where menstruation is a taboo subject, girls tend to conceal the fact that they may be menstruating and struggle to ensure that they give no sign of menstruation.[88] Effective educational programs are essential to providing children and adolescents with clear and accurate information about menstruation. Schools can be an appropriate place for menstrual education to take place.[89] Programs led by peers or third-party agencies are another option.[89] Low-income girls are less likely to receive proper sex education on puberty, leading to a decreased understanding of why menstruation occurs and the associated physiological changes that take place. This has been shown to cause the development of a negative attitude towards menstruation.[90]

Seclusion during menstruation

Awareness raising through education is taking place among women and girls to modify or eliminate the practice of chhaupadi in Nepal.

In some cultures, women were isolated during menstruation due to menstrual taboos.[91] This is because they are seen as unclean, dangerous, or bringing bad luck to those who encounter them. These practices are common in parts of South Asia including India.[92] A 1983 report found women refraining from household chore during this period in India.[93] Chhaupadi is a social practice that occurs in the western part of Nepal for Hindu women, which prohibits a woman from participating in everyday activities during menstruation. Women are considered impure during this time and are kept out of the house and have to live in a shed. Although chhaupadi was outlawed by the Supreme Court of Nepal in 2005, the tradition is slow to change.[94][95] Women and girls in cultures which practice such seclusion are often confined to menstruation huts, which are places of isolation used by cultures with strong menstrual taboos. The practice has recently come under fire due to related fatalities. Nepal criminalized the practice in 2017 after deaths were reported after the elongated isolation periods, but «the practice of isolating menstruating women and girls continues.»[96]

Beliefs around synchrony

Effects of the moon

Even though the average length of the human menstrual cycle is similar to that of the lunar cycle, in modern humans there is no relation between the two.[97] The relationship is believed to be a coincidence.[98][99] Light exposure does not appear to affect the menstrual cycle in humans.[100] A meta-analysis of studies from 1996 showed no correlation between the human menstrual cycle and the lunar cycle,[101] nor did data analyzed by period-tracking app Clue, submitted by 1.5 million women, of 7.5 million menstrual cycles, however the lunar cycle and the average menstrual cycle were found to be basically equal in length.[102]

Cohabitation

Beginning in 1971, some research suggested that menstrual cycles of cohabiting women became synchronized (menstrual synchrony).[103] Subsequent research has called this hypothesis into question.[104] A 2013 review concluded that menstrual synchrony likely does not exist.[105]

Work

Some countries, mainly in Asia, have menstrual leave to provide women with either paid or unpaid leave of absence from their employment while they are menstruating.[106] Countries with policies include Japan, Taiwan, Indonesia, and South Korea.[107][108] The practice is controversial due to concerns that it bolsters the perception of women as weak, inefficient workers,[106] as well as concerns that it is unfair to men,[109][110] and that it furthers gender stereotypes and the medicalization of menstruation.[107]

Menstruation activism

Menstruation activism has become more prominent during third-wave feminism, with a range of arguments being made across global scholarship and cultures. Much of the menstruation activism in the West has centered on arguments against what many feminists believe to be the misuse of menstruation to ‘prove’ female biological inferiority.[111] While some feminists have argued that Western patriarchy has used the inability for women to control their menstruation as evidence of the female body suffering from limitations,[112] others have focused on historical works that deem menstrual blood ‘dirtier’ than other blood, because it results from the failed reproductive cycle.[111] Activists in literary fields and gender studies have noted a history of menstruation as being symbolic for evil or secrecy, and argue against the long standing stigmatization of menstruation in order to elevate masculinity.[112] Thus, menstrual activism has grown to include a variety of arguments, including, but not limited to: social, philosophical, political, and theoretical. All of these efforts make up the Menstrual Equity Movement, which seeks to correct menstruation as a driving force for social and political inequality.[113]

One focus of activism has been to challenge high taxes on menstrual products, otherwise known as period tax.[114] In recent years, activists around the world have turned their attention to lowering and/or abolishing the higher taxes placed on menstrual products, because some states and countries consider them «luxury items».[114] In the US, the tax on menstrual products can reach up to 10%, depending on state legislature.[115] In 2020, Hungary had one of the largest, taxing up to 27% on menstrual products.[115] Still, some activists have raised concerns that the focus on period tax is halting broader, more important activism, like challenging the social and medical stigma that surrounds menstruation.[116] Still, the movement to lower period tax has persisted, and has been deeply connected to another movement against period poverty.

Period poverty is defined as a lack of access to anything dealing with menstruation, including hygienic products or facilities, education, and waste management.[115] A global study conducted in 2021 showed that roughly 500 million women and girls experience period poverty.[114] The effects of period poverty can range from physically not being able to attend school and/or work while menstruating, as well as negatively impact mental health.[114] A US study conducted in 2021 showed that roughly 68% of women who reported experiencing period poverty monthly, also expressed having feelings of moderate to severe depression.[114] This same study also revealed differences across racial lines in the US, as Latinx women reported the highest rates of period poverty, followed by Black women, and then white women, particularly from low-income communities.[114] Although research into period poverty has focused primarily on cisgender women in low/middle income communities and countries,[113] other scholars have begun examining how period poverty affects non-binary and transgender individuals as well.[113]

Menstrual pain and the LGBT community

Recent scholarship has argued that menstruation, although a strictly biological function, has been imbued with gender/sex identity.[117] Thus, as advocacy for, and awareness of transgender and non-binary individuals increases across the globe, menstrual activism is evolving as well. Effects of the gendered perceptions of menstruation on the LGBTQIA+ community differ, but current debates about the issue focus primarily on two key topics, transfeminine and transmasculine menstrual pain.[117]

Transmasculine menstrual pain, like transfeminine, includes both physical and mental components. As trans men and non-binary individuals may still menstruate, they often experience the same negative side-effects of menstruation, like cramping.[113] Similarly some argue that the negative effects it may have on mental health have been underexplored.[117] As menstruating conflicts with conventional ideas about masculinity,[111] activists are concerned about the dysphoric gender identity that can arise from menstruating, after someone has chosen to transition or adopt a gender identity not linked to their sex at birth.[117] Some AFAB individuals (assigned female at birth) and non-binary individuals have expressed concern about the tension between menstruating and affirming their chosen gender identity.[113] Scholars have begun arguing for a non-gendered conception of menstruation in both social and medical settings, in an attempt to alleviate the discomfort AFAB and non-binary individuals feel during menstruation.[113] Examples of this can include but are not limited to: using clinical, non-gendered language to describe menstruation, saying ‘cycle’ rather than ‘period’, or ‘menstrual products’ rather than ‘feminine hygiene products’.[113] Finally, researchers have also noted that many AFAB and non-binary individuals who menstruate encounter barriers in public restrooms, as men’s restrooms do not have sanitary disposal bins in the stalls, and there are often few cubicles in comparison to urinals. This results in AFAB and non-binary individuals having to wait for access to stalls, and dispose of their menstrual products in the public waste bin.[113] Thus, advocacy for gender-neutral bathrooms has become a more recent part of Menstruation Activism.[117][113]

Terminology

The word «menstruation» is etymologically related to «moon». The terms «menstruation» and «menses» are derived from the Latin mensis (month), which in turn relates to the Greek mene (moon) and to the roots of the English words month and moon.[118]

Some organizations have begun to use the term «menstruator» instead of «menstruating women», a term that has been in use since at least 2010.[119] The term menstruator is used by some activists and scholars in order to «express solidarity with women who do not menstruate, transgender men who do, and intersexual and genderqueer individuals».[119]: 950 However, use of the term «menstruators» has also been criticized by some feminists who consider sex differences important and the term woman to be necessary to resist patriarchy.[119]: 950 The term «people who menstruate» is also used.[120]

Other mammals

Most female mammals have an estrous cycle, but not all have a menstrual cycle that results in menstruation. Menstruation in mammals occurs in some close evolutionary relatives such as chimpanzees.[121]

See also

- Niddah (Jewish laws of menstruation)

References

- ^ a b Women’s Gynecologic Health. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. 2011. p. 94. ISBN 9780763756376. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g «Menstruation and the menstrual cycle fact sheet». Office of Women’s Health. 23 December 2014. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Diaz A, Laufer MR, Breech LL (November 2006). «Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign». Pediatrics. 118 (5): 2245–2250. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2481. PMID 17079600.

- ^ a b «Menopause: Overview». National Institutes of Health. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ a b Biggs WS, Demuth RH (October 2011). «Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder». American Family Physician. 84 (8): 918–924. PMID 22010771.

- ^ «Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) fact sheet». Office on Women’s Health. 23 December 2014. Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ^ Karapanou O, Papadimitriou A (September 2010). «Determinants of menarche». Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 8: 115. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-8-115. PMC 2958977. PMID 20920296.

- ^ Alvergne A, Högqvist Tabor V (June 2018). «Is Female Health Cyclical? Evolutionary Perspectives on Menstruation». Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 33 (6): 399–414. arXiv:1704.08590. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2018.03.006. PMID 29778270. S2CID 4581833.

- ^ Bull JR, Rowland SP, Scherwitzl EB, Scherwitzl R, Danielsson KG, Harper J (27 August 2019). «Real-world menstrual cycle characteristics of more than 600,000 menstrual cycles». NPJ Digital Medicine. 2 (1): 83. doi:10.1038/s41746-019-0152-7. PMC 6710244. PMID 31482137.

- ^ a b Chiazze L, Brayer FT, Macisco JJ, Parker MP, Duffy BJ (February 1968). «The length and variability of the human menstrual cycle». JAMA. 203 (6): 377–380. doi:10.1001/jama.1968.03140060001001. PMID 5694118.

- ^ a b Carlson KJ, Eisenstat SA, Ziporyn TD (2004). The new Harvard guide to women’s health. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01343-3.

- ^ «Clinical topic — Menopause». NHS. Archived from the original on 7 July 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

- ^ Mishra GD, Chung HF, Cano A, Chedraui P, Goulis DG, Lopes P, et al. (May 2019). «EMAS position statement: Predictors of premature and early natural menopause». Maturitas. 123: 82–88. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.03.008. hdl:10138/318039. PMID 31027683. S2CID 87361924.

- ^ Farage M (22 March 2013). The Vulva: Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology. CRC Press. pp. 155–158.

- ^ «Menstrual blood problems: Clots, color and thickness». WebMD. Archived from the original on 23 September 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ Clancy K (27 July 2011). «Iron-deficiency is not something you get just for being a lady». SciAm. Archived from the original on 17 March 2012.

- ^ Kepczyk T, Cremins JE, Long BD, Bachinski MB, Smith LR, McNally PR (January 1999). «A prospective, multidisciplinary evaluation of premenopausal women with iron-deficiency anemia». The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 94 (1): 109–115. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00780.x. PMID 9934740. S2CID 25975251.

- ^ Mansour D, Hofmann A, Gemzell-Danielsson K (January 2021). «A Review of Clinical Guidelines on the Management of Iron Deficiency and Iron-Deficiency Anemia in Women with Heavy Menstrual Bleeding». Advances in Therapy. 38 (1): 201–225. doi:10.1007/s12325-020-01564-y. PMC 7695235. PMID 33247314.

- ^ Prior 2020, p. 50.

- ^ a b Gudipally, Pratyusha R.; Sharma, Gyanendra K. (2022). «Premenstrual Syndrome». StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32809533. NBK560698.

- ^ Reed BF, Carr BR, Feingold KR, et al. (2018). «The Normal Menstrual Cycle and the Control of Ovulation». Endotext (Review). PMID 25905282. Archived from the original on 28 May 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ Appleton SM (March 2018). «Premenstrual syndrome: evidence-based evaluation and treatment». Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology (Review). 61 (1): 52–61. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000339. PMID 29298169. S2CID 28184066.

- ^ Ferries-Rowe E, Corey E, Archer JS (November 2020). «Primary Dysmenorrhea: Diagnosis and Therapy». Obstetrics and Gynecology. 136 (5): 1047–1058. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004096. PMID 33030880.

- ^ «Period pain». nhs.uk. 19 October 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Nagy, Hassan; Khan, Moien AB (2022). «Dysmenorrhea». StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32809669. NBK560834.

- ^ Baker FC, Lee KA (September 2018). «Menstrual cycle effects on sleep». Sleep Medicine Clinics (Review). 13 (3): 283–294. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2018.04.002. PMID 30098748. S2CID 51968811.

- ^ Maddern J, Grundy L, Castro J, Brierley SM (2020). «Pain in endometriosis». Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 14: 590823. doi:10.3389/fncel.2020.590823. PMC 7573391. PMID 33132854.

- ^ Matteson KA, Zaluski KM (September 2019). «Menstrual health as a part of preventive health care». Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America (Review). 46 (3): 441–453. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2019.04.004. PMID 31378287. S2CID 199437314.

- ^ Else-Quest & Hyde 2021, pp. 258–261.

- ^ Carmichael MA, Thomson RL, Moran LJ, Wycherley TP (February 2021). «The impact of menstrual cycle phase on athletes’ performance: a narrative review». Int J Environ Res Public Health (Review). 18 (4): 1667. doi:10.3390/ijerph18041667. PMC 7916245. PMID 33572406.

- ^ a b c d e «Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) | Office on Women’s Health». www.womenshealth.gov. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Dickerson, Lori M.; Mazyck, Pamela J.; Hunter, Melissa H. (2003). «Premenstrual Syndrome». American Family Physician. 67 (8): 1743–52. PMID 12725453. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g >«Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) fact sheet». Office on Women’s Health. 23 December 2014. Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ^ a b Tiranini L, Nappi RE (2022). «Recent advances in understanding/management of premenstrual dysphoric disorder/premenstrual syndrome». Fac Rev. 11: 11. doi:10.12703/r/11-11. PMC 9066446. PMID 35574174.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Biggs, WS; Demuth, RH (15 October 2011). «Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder». American Family Physician. 84 (8): 918–24. PMID 22010771.

- ^ a b Ju H, Jones M, Mishra G (1 January 2014). «The prevalence and risk factors of dysmenorrhea». Epidemiologic Reviews. 36 (1): 104–113. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxt009. PMID 24284871.

- ^ «Premenstrual syndrome (PMS)». womenshealth.gov. 12 July 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ «Ectopic Pregnancy Clinical Presentation: History, Physical Examination». emedicine.medscape.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2013.

- ^ a b Latthe PM, Champaneria R (October 2014). «Dysmenorrhoea». BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2014: 390–400. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.08.108. PMC 4205951. PMID 25338194.

- ^ Oladosu FA, Tu FF, Hellman KM (April 2018). «Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug resistance in dysmenorrhea: epidemiology, causes, and treatment». American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 218 (4): 390–400. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.08.108. PMC 5839921. PMID 28888592.

- ^ Woo HL, Ji HR, Pak YK, Lee H, Heo SJ, Lee JM, Park KS (June 2018). «The efficacy and safety of acupuncture in women with primary dysmenorrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis». Medicine. 97 (23): e11007. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000011007. PMC 5999465. PMID 29879061.

- ^ Smith CA, Armour M, Zhu X, Li X, Lu ZY, Song J (April 2016). «Acupuncture for dysmenorrhoea». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (4): CD007854. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007854.pub3. PMC 8406933. PMID 27087494.

- ^ Reddy N, Desai MN, Schoenbrunner A, Schneeberger S, Janis JE (March 2021). «The complex relationship between estrogen and migraines: a scoping review». Systematic Reviews. 10 (1): 72. doi:10.1186/s13643-021-01618-4. PMC 7948327. PMID 33691790.

- ^ Herzog AG (March 2008). «Catamenial epilepsy: definition, prevalence pathophysiology and treatment». Seizure. 17 (2): 151–159. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2007.11.014. PMID 18164632. S2CID 6903651.

- ^ Renstrom P, Ljungqvist A, Arendt E, Beynnon B, Fukubayashi T, Garrett W, et al. (June 2008). «Non-contact ACL injuries in female athletes: an International Olympic Committee current concepts statement». British Journal of Sports Medicine. 42 (6): 394–412. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.048934. PMC 3920910. PMID 18539658.

- ^ Levay S, Baldwin J, Baldwin J (2015). «Women’s Bodies». Discovering Human Sexuality. Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates, Inc. p. 44. ISBN 9781605352756.

- ^ Thornhill R, Gangestad SW (2008). «Background and Overview of the Book». The Evolutionary Biology of Human Female Sexuality. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780195340990.

- ^ «My Fertile Period». DuoFertility. Cambridge Temperature Concepts Limited. Archived from the original on 21 December 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- ^ Creinin MD, Keverline S, Meyn LA (October 2004). «How regular is regular? An analysis of menstrual cycle regularity». Contraception. 70 (4): 289–292. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2004.04.012. PMID 15451332.

- ^ Galan N (16 April 2008). «Oligoovulation». about.com. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ Weschler T (2002). Taking Charge of Your Fertility (Revised ed.). New York: HarperCollins. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-06-093764-5. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011.

- ^ Anovulation at eMedicine

- ^ a b Menstruation Disorders at eMedicine

- ^ a b Oriel KA, Schrager S (October 1999). «Abnormal uterine bleeding». American Family Physician. 60 (5): 1371–80, discussion 1381–2. PMID 10524483.

- ^ Meczekalski B, Katulski K, Czyzyk A, Podfigurna-Stopa A, Maciejewska-Jeske M (November 2014). «Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea and its influence on women’s health». Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 37 (11): 1049–1056. doi:10.1007/s40618-014-0169-3. PMC 4207953. PMID 25201001.

- ^ Mishra S, Elliott H, Marwaha R (2022). «Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder». StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30335340. NBK532307.

- ^ «Health risks of female genital mutilation (FGM)». World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014.

- ^ a b McKenna KA, Fogleman CD (August 2021). «Dysmenorrhea». Am Fam Physician. 104 (2): 164–170. PMID 34383437.

- ^ «Period Pain». MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine. 1 March 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (January 2015). «FAQ046 Dynsmenorrhea: Painful Periods» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Osayande AS, Mehulic S (March 2014). «Diagnosis and initial management of dysmenorrhea». American Family Physician. 89 (5): 341–346. PMID 24695505.

- ^ a b c d «Menstruation and the menstrual cycle fact sheet». Office of Women’s Health. 23 December 2014. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ a b «Dysmenorrhea and Endometriosis in the Adolescent». ACOG. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 20 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ a b Kaur R, Kaur K, Kaur R (2018). «Menstrual Hygiene, Management, and Waste Disposal: Practices and Challenges Faced by Girls/Women of Developing Countries». Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2018: 1730964. doi:10.1155/2018/1730964. PMC 5838436. PMID 29675047.

- ^ «Girls ‘too poor’ to buy sanitary protection missing school». BBC News. 14 March 2017.

- ^ Chin L (2014). Period of shame — The effects of menstrual hygiene management on rural women and girls’ quality of life in Savannakhet, Laos (Thesis).

- ^ House S, Mahon T, Cavill S (2013). «Menstrual Hygiene Matters: a resource for improving menstrual hygiene around the world». Reproductive Health Matters. 21 (41): 257–259. JSTOR 43288983.

- ^ «Period poverty». ActionAid UK.

- ^ Kjellén M, Pensulo C, Nordqvist P, Fogde M. Global Review of Sanitation System Trends and Interactions with Menstrual Management Practices: Report for the Menstrual Management and Sanitation Systems Project (Report). Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI).

- ^ Goldstuck N (1 December 2011). «Progestin potency – Assessment and relevance to choice of oral contraceptives». Middle East Fertility Society Journal. 16 (4): 248–253. doi:10.1016/j.mefs.2011.08.006.

- ^ CYWH Staff (18 October 2011). «Medical Uses of the Birth Control Pill». Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, Berry-Bibee E, Horton LG, Zapata LB, et al. (July 2016). «U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016». MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 65 (3): 1–103. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6503a1. PMID 27467196.

- ^ «Delaying your period with birth control pills». Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ «How can I delay my period while on holiday?». National Health Service, United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ^ Strandjord SE, Rome ES (September 2015). «Monthly Periods—Are They Necessary?». Pediatric Annals. 44 (9): e231–e236. doi:10.3928/00904481-20150910-11. PMID 26431242.

- ^ Infant and Young Child Feeding. World Health Organization. 2009.

- ^ McNeilly AS (2001). «Lactational control of reproduction». Reproduction, Fertility, and Development. 13 (7–8): 583–590. doi:10.1071/RD01056. PMID 11999309.

- ^ Kippley J, Kippley S (1996). The Art of Natural Family Planning (4th ed.). Cincinnati, OH: The Couple to Couple League. p. 347. ISBN 0-926412-13-2.

- ^ Stallings JF, Worthman CM, Panter-Brick C, Coates RJ (February 1996). «Prolactin response to suckling and maintenance of postpartum amenorrhea among intensively breastfeeding Nepali women». Endocrine Research. 22 (1): 1–28. doi:10.3109/07435809609030495. PMID 8690004.

- ^ «Breastfeeding: Does It Really Space Babies?». The Couple to Couple League International. Internet Archive. 17 January 2008. Archived from the original on 17 January 2008. Retrieved 21 September 2008., which cites:

- Kippley SK, Kippley JF (November–December 1972). «The relation between breastfeeding and amenorrhea: report of a survey». JOGN Nursing; Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 1 (4): 15–21. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.1972.tb00558.x. PMID 4485271.

- Kippley SK (November–December 1986). «Breastfeeding survey results similar to 1971 study». The CCL News. 13 (3): 10.

- Kippley SK (January–February 1987). «Breastfeeding survey results similar to 1971 study». The CCL News. 13 (4): 5.

- ^ «Surah Al-Baqarah — 222». Quran.com.

- ^ Bukhari S. «Chapter: 6, Menstrual Periods». ahadith.co.uk.

- ^ Leviticus 15:19-30, 18:19, 20:18

- ^ Dunnavant NC, Roberts TA (January 2013). «Restriction and renewal, pollution and power, constraint and community: The paradoxes of religious women’s experiences of menstruation». Sex Roles. 68 (1): 12–31. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0132-8. S2CID 144688091.

- ^ Garg S, Anand T (2015). «Menstruation related myths in India: strategies for combating it». Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 4 (2): 184–186. doi:10.4103/2249-4863.154627. PMC 4408698. PMID 25949964.

- ^ Sooki Z, Shariati M, Chaman R, Khosravi A, Effatpanah M, Keramat A (March 2016). «The Role of Mother in Informing Girls About Puberty: A Meta-Analysis Study». Nursing and Midwifery Studies. 5 (1): e30360. doi:10.17795/nmsjournal30360. PMC 4915208. PMID 27331056.

- ^ Hatami M, Kazemi A, Mehrabi T (30 December 2015). «Effect of peer education in school on sexual health knowledge and attitude in girl adolescents». Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 4: 78. doi:10.4103/2277-9531.171791 (inactive 31 December 2022). PMC 4944604. PMID 27462620.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2022 (link) - ^ a b Allen KR, Kaestle CE, Goldberg AE (February 2011). «More than just a punctuation mark: How boys and young men learn about menstruation». Journal of Family Issues. 32 (2): 129–56. doi:10.1177/0192513×10371609. S2CID 145531604.

- ^ a b Kirby D (February 2002). «The impact of schools and school programs upon adolescent sexual behavior». Journal of Sex Research. 39 (1): 27–33. doi:10.1080/00224490209552116. PMID 12476253. S2CID 45063072.

- ^ Herbert AC, Ramirez AM, Lee G, North SJ, Askari MS, West RL, Sommer M (April 2017). «Puberty Experiences of Low-Income Girls in the United States: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Literature From 2000 to 2014». The Journal of Adolescent Health. 60 (4): 363–379. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.10.008. PMID 28041680.

- ^ Gottlieb A (2020). «Chapter 14: Menstrual Taboos: Moving Beyond the Curse». In Bobel C, Winkler IG, Fahs B, Hasson KA, Kissling EA, Roberts T (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7_14. ISBN 978-981-15-0614-7. PMID 33347165. S2CID 226694557.

- ^ Kleinman A, Good BJ (1985). Culture and Depression: Studies in the Anthropology and Cross-Cultural Psychiatry of Affect and Disorder. University of California Press. pp. 203–204. ISBN 978-0-520-05883-5.

- ^ Delaney J, Lupton MJ, Toth E (1988). The Curse: A Cultural History of Menstruation. University of Illinois Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-252-01452-9.

- ^ «Nepal: Emerging from menstrual quarantine». United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). August 2011.

- ^ Sharma S (15 September 2005). «Women hail menstruation ruling». BBC News.

- ^ Canning M (September 2019). «Menstrual Health and the Problem with Menstrual Stigma». The Federation of American Women’s Clubs Overseas, Inc. (FAWCO).

- ^ Vertebrate Endocrinology (5 ed.). Academic Press. 2013. p. 361. ISBN 9780123964656.

- ^ Gutsch WA (1997). 1001 things everyone should know about the universe (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday. p. 57. ISBN 9780385482233.

- ^ Barash DP (2009). «Synchrony and Its Discontents». How women got their curves and other just-so stories evolutionary enigmas ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231518390.

- ^ Lopez KH (2013). Human Reproductive Biology. Academic Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780123821850. Archived from the original on 21 June 2015.

- ^ Adams C (24 September 1999). «What’s the link between the moon and menstruation?». The Straight Dope. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 6 June 2006.: Abell GO, Singer B (1983). Science and the Paranormal: Probing the Existence of the Supernatural. Scribner Book Company. ISBN 978-0-684-17820-2.

- ^ «The myth of moon phases and menstruation». Clue. 3 December 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ Stern K, McClintock MK (March 1998). «Regulation of ovulation by human pheromones». Nature. 392 (6672): 177–179. Bibcode:1998Natur.392..177S. doi:10.1038/32408. PMID 9515961. S2CID 4426700.

- ^ Adams C (20 December 2002). «Does menstrual synchrony really exist?». The Straight Dope. The Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- ^ Harris AL, Vitzthum VJ (2013). «Darwin’s legacy: an evolutionary view of women’s reproductive and sexual functioning». Journal of Sex Research. 50 (3–4): 207–246. doi:10.1080/00224499.2012.763085. PMID 23480070. S2CID 30229421.

- ^ a b Matchar E (16 May 2014). «Should Paid ‘Menstrual Leave’ Be a Thing?». The Atlantic. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ a b Levitt RA, Barnack-Tavlaris JL (2020). «Chapter 43: Addressing Menstruation in the Workplace: The Menstrual Leave Debate». In Bobel C, Winkler IG, Fahs B, Hasson KA, Kissling EA, Roberts T (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7_43. ISBN 978-981-15-0614-7. PMID 33347190. S2CID 226619907.

- ^ King S. (2021) Menstrual Leave: Good Intention, Poor Solution. In: Hassard J., Torres L.D. (eds) Aligning Perspectives in Gender Mainstreaming. Aligning Perspectives on Health, Safety and Well-Being. Springer, Cham. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-53269-7_9

- ^ Price C (11 October 2006). «Should women get paid menstruation leave?». Salon. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ «Menstrual Leave: Delightful or Discriminatory?». Lip Magazine. 4 August 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Przybylo E, Fahs B (2018). «Feels and Flows: On the Realness of Menstrual Pain and Cripping Menstrual Chronicity». Feminist Formations. 30 (1): 206–229. doi:10.1353/ff.2018.0010. S2CID 149707475. Project MUSE 692051 ProQuest 2156106534.

- ^ a b Frank SE (2020). «Queering Menstruation: Trans and Non‐Binary Identity and Body Politics». Sociological Inquiry. 90 (2): 371–404. doi:10.1111/soin.12355. S2CID 214355105.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lane B, Perez-Brumer A, Parker R, Sprong A, Sommer M (October 2022). «Improving menstrual equity in the USA: perspectives from trans and non-binary people assigned female at birth and health care providers». Culture, Health & Sexuality. 24 (10): 1408–1422. doi:10.1080/13691058.2021.1957151. PMID 34365908. S2CID 236959499.

- ^ a b c d e f Cardoso LF, Scolese AM, Hamidaddin A, Gupta J (January 2021). «Period poverty and mental health implications among college-aged women in the United States». BMC Women’s Health. 21 (1): 14. doi:10.1186/s12905-020-01149-5. PMC 7788986. PMID 33407330.

- ^ a b c Saygin D, Tabib T, Bittar HE, Valenzi E, Sembrat J, Chan SY, et al. (22 February 2022). «Transcriptional profiling of lung cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension». Pulmonary Circulation. 10 (1): e2022009. doi:10.29392/001c.32436. PMC 7052475. PMID 32166015.

- ^ Bobel C, Fahs B (2020). «From Bloodless Respectability to Radical Menstrual Embodiment: Shifting Menstrual Politics from Private to Public». Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 45 (4): 955–983. doi:10.1086/707802. S2CID 225085369.

- ^ a b c d e Frank SE (2020). «Queering Menstruation: Trans and Non‐Binary Identity and Body Politics». Sociological Inquiry. 90 (2): 371–404. doi:10.1111/soin.12355. S2CID 214355105.

- ^ Allen K (2007). The Reluctant Hypothesis: A History of Discourse Surrounding the Lunar Phase Method of Regulating Conception. Lacuna Press. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-9510974-2-7.

- ^ a b c Rydström K (2020). «Chapter 68: Degendering Menstruation: Making Trans Menstruators Matter». In Bobel C, Winkler IT, Fahs B, Hasson KA (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies. Singapore: Springer Singapore. pp. 945–959. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7_68. ISBN 978-981-15-0613-0. PMID 33347169.

- ^ Madani D (7 June 2020). «J.K. Rowling accused of transphobia after mocking ‘people who menstruate’ headline». NBC News. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ Strassmann BI (June 1996). «The evolution of endometrial cycles and menstruation». The Quarterly Review of Biology. 71 (2): 181–220. doi:10.1086/419369. PMID 8693059. S2CID 6207295.

Book sources

- Else-Quest N, Hyde JS (2021). «Psychology, gender, and health: psychological aspects of the menstrual cycle». The Psychology of Women and Gender: Half the Human Experience + (10th ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE Publishing. ISBN 978-1-544-39360-5.

- Prior JC (2020). «The menstrual cycle: its biology in the context of silent ovulatory disturbances». In Ussher JM, Chrisler JC, Perz J (eds.). Routledge International Handbook of Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health (1st ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-49026-0. OCLC 1121130010.

External links

This article is about menstruation in humans. For menstruation in other mammals, see Menstruation (mammal).

Diagram illustrating how the uterus lining builds up and breaks down during the menstrual cycle

Menstruation (also known as a period, among other colloquial terms) is the regular discharge of blood and mucosal tissue from the inner lining of the uterus through the vagina. The menstrual cycle is characterized by the rise and fall of hormones. Menstruation is triggered by falling progesterone levels and is a sign that pregnancy has not occurred.

The first period, a point in time known as menarche, usually begins between the ages of 12 and 15.[1] Menstruation starting as young as 8 years would still be considered normal.[2] The average age of the first period is generally later in the developing world, and earlier in the developed world.[3] The typical length of time between the first day of one period and the first day of the next is 21 to 45 days in young women. In adults, the range is between 21 and 31 days with the average being 28 days.[2][3] Bleeding usually lasts around 2 to 7 days. Periods stop during pregnancy and typically do not resume during the initial months of breastfeeding.[2] Menstruation stops occurring after menopause, which usually occurs between 45 and 55 years of age.[4]

Up to 80% of women do not experience problems sufficient to disrupt daily functioning either during menstruation or in the days leading up to menstruation. Symptoms in advance of menstruation that do interfere with normal life are called premenstrual syndrome (PMS). Some 20 to 30% of women experience PMS, with 3 to 8% experiencing severe symptoms.[5] These include acne, tender breasts, bloating, feeling tired, irritability, and mood changes.[6] Other symptoms some women experience include painful periods and heavy bleeding during menstruation and abnormal bleeding at any time during the menstrual cycle.[2] A lack of periods, known as amenorrhea, is when periods do not occur by age 15 or have not re-occurred in 90 days.[2]

Characteristics

Length and duration

The first menstrual period occurs after the onset of pubertal growth, and is called menarche. The average age of menarche is 12 to 15 years.[1][7] However, it may occur as early as eight.[2] The average age of the first period is generally later in the developing world, and earlier in the developed world.[3][8] The average age of menarche has changed little in the United States since the 1950s.[3]

Menstruation is the most visible phase of the menstrual cycle and its beginning is used as the marker between cycles. The first day of menstrual bleeding is the date used for the last menstrual period (LMP). The typical length of time between the first day of one period and the first day of the next is 21 to 45 days in young women, and 21 to 31 days in adults.[2][3] The average length is 28 days; one study estimated it at 29.3 days.[9] The variability of menstrual cycle lengths is highest for women under 25 years of age and is lowest, that is, most regular, for ages 25 to 39 years.[10] The variability increases slightly for women aged 40 to 44 years.[10]

Perimenopause is when a woman’s fertility declines, and menstruation occurs less regularly in the years leading up to the final menstrual period, when a woman stops menstruating completely and is no longer fertile. The medical definition of menopause is one year without a period and typically occurs between 45 and 55 years in Western countries.[4][11]: 381 Menopause before age 45 is considered premature in industrialized countries.[12] Like the age of menarche, the age of menopause is largely a result of cultural and biological factors.[dubious – discuss][failed verification] Illnesses, certain surgeries, or medical treatments may cause menopause to occur earlier than it might have otherwise.[13]

Bleeding

The average volume of menstrual fluid during a monthly menstrual period is 35 millilitres (2.4 US tbsp) with 10–80 millilitres (0.68–5.41 US tbsp) considered typical. Menstrual fluid is the correct name for the flow, although many people prefer to refer to it as menstrual blood. Menstrual fluid is reddish-brown, a slightly darker color than venous blood.[11]: 381

About half of menstrual fluid is blood. This blood contains sodium, calcium, phosphate, iron, and chloride, the extent of which depends on the woman. As well as blood, the fluid consists of cervical mucus, vaginal secretions, and endometrial tissue. Vaginal fluids in menses mainly contribute water, common electrolytes, organ moieties, and at least 14 proteins, including glycoproteins.[14]

Many women and girls notice blood clots during menstruation. These appear as clumps of blood that may look like tissue. If there was a miscarriage or a stillbirth, examination under a microscope can confirm if it was endometrial tissue or pregnancy tissue (products of conception) that was shed.[15] Sometimes menstrual clots or shed endometrial tissue is incorrectly thought to indicate an early-term miscarriage of an embryo. An enzyme called plasmin – contained in the endometrium – tends to inhibit the blood from clotting.[medical citation needed]

The amount of iron lost in menstrual fluid is relatively small for most women.[better source needed][16] In one study, premenopausal women who exhibited symptoms of iron deficiency were given endoscopies. 86% of them actually had gastrointestinal disease and were at risk of being misdiagnosed simply because they were menstruating.[non-primary source needed][17] Heavy menstrual bleeding, occurring monthly, can result in anemia.[18]

Hormonal changes

The menstrual cycle is a series of natural changes in hormone production and the structures of the uterus and ovaries of the female reproductive system that make pregnancy possible. The ovarian cycle controls the production and release of eggs and the cyclic release of estrogen and progesterone. The uterine cycle governs the preparation and maintenance of the lining of the uterus (womb) to receive an embryo. These cycles are concurrent and coordinated, normally last between 21 and 35 days, with a median length of 28 days, and continue for about 30–45 years.

Naturally occurring hormones drive the cycles; the cyclical rise and fall of the follicle stimulating hormone prompts the production and growth of oocytes (immature egg cells). The hormone estrogen stimulates the uterus lining (endometrium) to thicken to accommodate an embryo should fertilization occur. The blood supply of the thickened lining provides nutrients to a successfully implanted embryo. If implantation does not occur, the lining breaks down and blood is released. Triggered by falling progesterone levels, menstruation (a «period», in common parlance) is the cyclical shedding of the lining, and is a sign that pregnancy has not occurred.

Side effects

Menstrual health overview

Although a normal and natural process,[19] some women experience premenstrual syndrome with symptoms that may include acne, tender breasts, and tiredness.[20] More severe symptoms that affect daily living are classed as premenstrual dysphoric disorder and are experienced by 3 to 8% of women.[21][22][20][23] Dysmenorrhea (menstrual cramps or period pain) is felt as painful cramps in the abdomen that can spread to the back and upper thighs during the first few days of menstruation.[24][25][26] Debilitating period pain is not normal and can be a sign of something severe such as endometriosis.[27] These issues can significantly affect a woman’s health and quality of life and timely interventions can improve the lives of these women.[28]

There are common culturally communicated misbeliefs that the menstrual cycle affects women’s moods, causes depression or irritability, or that menstruation is a painful, shameful or unclean experience. Often a woman’s normal mood variation is falsely attributed to the menstrual cycle. Much of the research is weak, but there appears to be a very small increase in mood fluctuations during the luteal and menstrual phases, and a corresponding decrease during the rest of the cycle.[29] Changing levels of estrogen and progesterone across the menstrual cycle exert systemic effects on aspects of physiology including the brain, metabolism, and musculoskeletal system. The result can be subtle physiological and observable changes to women’s athletic performance including strength, aerobic, and anaerobic performance.[30]

Moods and premenstrual syndrome (PMS)

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) refers to emotional and physical symptoms that regularly occur in the one to two weeks before the start of each menstrual period.[31][32] Symptoms resolve around the time menstrual bleeding begins.[33] Different women experience different symptoms.[31] Premenstrual syndrome is commonly noted by at least one physical, emotional, or behavioral symptom, that resolves with menses.[34] The range of symptoms is wide, and most commonly are breast tenderness, bloating, headache, mood swings, depression, anxiety, anger, and irritability. They must interfere with daily living, during two menstrual cycles of prospective recording.[34] These symptoms are nonspecific and may be seen in women without PMS. Often PMS-related symptoms are present for about six days.[35] An individual’s pattern of symptoms may change over time.[35] Symptoms do not occur during pregnancy or following menopause.[33]

Diagnosis requires a consistent pattern of emotional and physical symptoms occurring after ovulation and before menstruation to a degree that interferes with normal life.[32] Emotional symptoms must not be present during the initial part of the menstrual cycle.[32] A daily list of symptoms over a few months may help in diagnosis.[35] Other disorders that cause similar symptoms need to be excluded before a diagnosis is made.[35]

The cause of PMS is unknown, but the underlying mechanism is believed to involve changes in hormone levels.[33] Reducing salt, alcohol, caffeine, and stress along with increasing exercise is typically all that is recommended in those with mild symptoms.[33] Calcium and vitamin D supplementation may be useful in some.[35] Anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen or naproxen may help with physical symptoms.[33] In those with more significant symptoms birth control pills or the diuretic spironolactone may be useful.[33][35]

Over 90% of women report having some premenstrual symptoms, such as bloating, headaches, and moodiness.[31] Premenstrual symptoms generally do not cause substantial disruption, and qualify as PMS in approximately 20 to 30% of pre-menopausal women.[35] Antidepressants of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors class may be used to treat the emotional symptoms of PMS.[31]

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a more severe form of PMS that has greater psychological symptoms.[35][33] PMDD affects less than 5% of women of child-bearing age.[31]

Cramps