Logo used since 2014 |

|

|

Screenshot Screenshot of Netflix’s English website in 2019 |

|

| Type of business | Public |

|---|---|

|

Type of site |

OTT streaming platform |

| Available in |

List

|

| Traded as |

|

| Founded | August 29, 1997; 25 years ago[3] in Scotts Valley, California, U.S. |

| Headquarters | Los Gatos, California, U.S. |

| Area served | Worldwide (excluding Mainland China, North Korea, Russia and Syria)[4][5] |

| Founder(s) |

|

| Key people |

|

| Industry | Technology & Entertainment industry, mass media |

| Products |

|

| Services |

|

| Revenue | |

| Operating income | |

| Net income | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

| Employees | 12,135 (2021) |

| Divisions |

|

| Subsidiaries |

|

| URL | www.netflix.com |

| Registration | Required |

| Users | |

| [11][12] |

Netflix, Inc. is an American subscription video on-demand over-the-top streaming service and production company based in Los Gatos, California. Founded in 1997 by Reed Hastings and Marc Randolph in Scotts Valley, California, it offers a film and television series library through distribution deals as well as its own productions, known as Netflix Originals.

As of September 2022, Netflix had 222 million subscribers worldwide, including 73.3 million in the United States and Canada; 73.0 million in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, 39.6 million in Latin America and 34.8 million in the Asia-Pacific region.[12] It is available worldwide aside from Mainland China, Syria, North Korea, and Russia. Netflix has played a prominent role in independent film distribution, and it is a member of the Motion Picture Association.

Netflix can be accessed via web browsers or via application software installed on smart TVs, set-top boxes connected to televisions, tablet computers, smartphones, digital media players, Blu-ray players, video game consoles and virtual reality headsets on the list of Netflix-compatible devices.[13][14][15][16] It is available in 4K resolution.[17] In the United States, the company provided Digital Video Disc (DVD)[18] and Blu-ray rentals delivered individually via the United States Postal Service from regional warehouses.[19]

Netflix initially both sold and rented DVDs by mail, but the sales were eliminated within a year to focus on the DVD rental business.[20][21] In 2007, Netflix introduced streaming media and video on demand. The company expanded to Canada in 2010, followed by Latin America and the Caribbean. Netflix entered the film and television production industry in 2013, debuting its first series House of Cards. In January 2016, it expanded to an additional 130 countries and then operated in 190 countries.

The company is ranked 115th on the Fortune 500[22] and 219th on the Forbes Global 2000.[23] It is the second largest entertainment/media company by market capitalization as of February 2022.[24] In 2021, Netflix was ranked as the eighth-most trusted brand globally by Morning Consult.[25] During the 2010s, Netflix was the top-performing stock in the S&P 500 stock market index, with a total return of 3,693%.[26][27]

Netflix is headquartered in Los Gatos, California, in Santa Clara County,[28][29] with the two CEOs, Hastings and Ted Sarandos, split between Los Gatos and Los Angeles, respectively.[30][31][32] It also operates international offices in Asia, Europe and Latin America including in Canada, France, Brazil, the Netherlands, India, Italy, Japan, Poland, South Korea and the United Kingdom. The company has production hubs in Los Angeles,[33] Albuquerque,[34] London,[35] Madrid, Vancouver and Toronto.[36] Compared to other distributors, Netflix pays more for TV shows up front, but keeps more «upside» (i.e. future revenue opportunities from possible syndication, merchandising, etc.) on big hits.[37][38]

History[edit]

First logo, used from 1997 to 2000

Second logo, used from 2000 to 2001

Third logo, used from 2001 to 2014

Fourth and current logo, used since 2014

Launch as a mail-based rental business (1997–2006)[edit]

Marc Randolph, co-founder of Netflix and the first CEO of the company

Reed Hastings, co-founder and the current chairman and CEO

Netflix was founded by Marc Randolph and Reed Hastings on August 29, 1997 in Scotts Valley, California. Hastings, a computer scientist and mathematician, was a co-founder of Pure Atria, which was acquired by Rational Software Corporation that year for $750 million, then the biggest acquisition in Silicon Valley history.[39] Randolph had worked as a marketing director for Pure Atria after Pure Atria acquired a company where Randolph worked. He was previously a co-founder of MicroWarehouse, a computer mail-order company as well as vice president of marketing for Borland International.[40][41] Hastings and Randolph came up with the idea for Netflix while carpooling between their homes in Santa Cruz, California and Pure Atria’s headquarters in Sunnyvale.[21] Patty McCord, later head of human resources at Netflix, was also in the carpool group.[42] Randolph admired Amazon.com and wanted to find a large category of portable items to sell over the Internet using a similar model. Hastings and Randolph considered and rejected selling and renting VHS tapes as too expensive to stock and too delicate to ship.[40] When they heard about DVDs, first introduced in the United States in early 1997, they tested the concept of selling or renting DVDs by mail by mailing a compact disc to Hastings’s house in Santa Cruz.[40] When the disc arrived intact, they decided to enter the $16 billion home-video sales and rental industry.[40][21] Hastings is often quoted saying that he decided to start Netflix after being fined $40 at a Blockbuster store for being late to return a copy of Apollo 13, a claim since repudiated by Randolph.[21] Hastings invested $2.5 million into Netflix from the sale of Pure Atria.[43][21] Netflix launched as the first DVD rental and sales website with 30 employees and 925 titles available—nearly all DVDs published.[21][44][45] Randolph and Hastings met with Jeff Bezos, where Amazon offered to acquire Netflix for between $14 and $16 million. Fearing competition from Amazon, Randolph at first thought the offer was fair but Hastings, who owned 70% of the company, turned it down on the plane ride home.[46][47]

Initially, Netflix offered a per-rental model for each DVD but introduced a monthly subscription concept in September 1999.[48] The per-rental model was dropped by early 2000, allowing the company to focus on the business model of flat-fee unlimited rentals without due dates, late fees, shipping and handling fees, or per-title rental fees.[49] In September 2000, during the dot-com bubble, while Netflix was suffering losses, Hastings and Randolph offered to sell the company to Blockbuster LLC for $50 million. John Antioco, CEO of Blockbuster, thought the offer was a joke and declined, saying «The dot-com hysteria is completely overblown.»[50][51] While Netflix experienced fast growth in early 2001, the continued effects of the dot-com bubble collapse and the September 11 attacks caused the company to hold off plans for its initial public offering (IPO) and to lay off one-third of its 120 employees.[52]

Opened Netflix rental envelope containing a DVD copy of Coach Carter (2005)

DVD players were a popular gift for holiday sales in late 2001, and demand for DVD subscription services were «growing like crazy», according to chief talent officer Patty McCord.[53] The company went public on May 29, 2002, selling 5.5 million shares of common stock at US$15.00 per share.[54] In 2003, Netflix was issued a patent by the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office to cover its subscription rental service and several extensions.[55] Netflix posted its first profit in 2003, earning $6.5 million on revenues of $272 million; by 2004, profit had increased to $49 million on over $500 million in revenues.[56] In 2005, 35,000 different films were available, and Netflix shipped 1 million DVDs out every day.[57]

In 2004, Blockbuster introduced a DVD rental service, which not only allowed users to check out titles through online sites but allowed for them to return them at brick-and-mortar stores.[58] By 2006, Blockbuster’s service reached two million users, and while trailing Netflix’s subscriber count, was drawing business away from Netflix. Netflix lowered fees in 2007.[56] While it was an urban legend that Netflix ultimately «killed» Blockbuster in the DVD rental market, Blockbuster’s debt load and internal disagreements hurt the company.[58]

On April 4, 2006, Netflix filed a patent infringement lawsuit in which it demanded a jury trial in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, alleging that Blockbuster LLC’s online DVD rental subscription program violated two patents held by Netflix. The first cause of action alleged Blockbuster’s infringement of copying the «dynamic queue» of DVDs available for each customer, Netflix’s method of using the ranked preferences in the queue to send DVDs to subscribers, and Netflix’s method permitting the queue to be updated and reordered.[59] The second cause of action alleged infringement of the subscription rental service as well as Netflix’s methods of communication and delivery.[60] The companies settled their dispute on June 25, 2007; terms were not disclosed.[61][62][63][64]

On October 1, 2006, Netflix announced the Netflix Prize, $1,000,000 to the first developer of a video-recommendation algorithm that could beat its existing algorithm Cinematch, at predicting customer ratings by more than 10%. On September 21, 2009, it awarded the $1,000,000 prize to team «BellKor’s Pragmatic Chaos.»[65] Cinematch, launched in 2000, is a recommendation system that recommended movies to its users, many of which they might not ever had heard of before.[66][67]

Through its division Red Envelope Entertainment, Netflix licensed and distributed independent films such as Born into Brothels and Sherrybaby. In late 2006, Red Envelope Entertainment also expanded into producing original content with filmmakers such as John Waters.[68] Netflix closed Red Envelope Entertainment in 2008.[69][70]

Transition to streaming services (2007–2012)[edit]

In January 2007, the company launched a streaming media service, introducing video on demand via the Internet. However, at that time it only had 1,000 films available for streaming, compared to 70,000 available on DVD.[71] The company had for some time considered offering movies online, but it was only in the mid-2000s that data speeds and bandwidth costs had improved sufficiently to allow customers to download movies from the net. The original idea was a «Netflix box» that could download movies overnight, and be ready to watch the next day. By 2005, Netflix had acquired movie rights and designed the box and service. But after witnessing how popular streaming services such as YouTube were despite the lack of high-definition content, the concept of using a hardware device was scrapped and replaced with a streaming concept.[72]

In February 2007, Netflix delivered its billionth DVD, a copy of Babel to a customer in Texas.[73][74] In April 2007, Netflix recruited Anthony Wood, one of the early DVR business pioneers, to build a «Netflix Player» that would allow streaming content to be played directly on a television set rather than a PC or laptop.[75] While the player was initially developed at Netflix, Reed Hastings eventually shut down the project to help encourage other hardware manufacturers to include built-in Netflix support.[76][77]

In January 2008, all rental-disc subscribers became entitled to unlimited streaming at no additional cost. This change came in a response to the introduction of Hulu and to Apple’s new video-rental services.[78][79][page needed] In August 2008, the Netflix database was corrupted and the company was not able to ship DVDs to customers for 3 days, leading the company to move all its data to the Amazon Web Services cloud.[80] In November 2008, Netflix began offering subscribers rentals on Blu-ray and discontinued its sale of used DVDs.[81] In 2009, Netflix streams overtook DVD shipments.[82]

On January 6, 2010, Netflix agreed with Warner Bros. to delay new release rentals 28 days prior to retail, in an attempt to help studios sell physical copies, and similar deals involving Universal Pictures and 20th Century Fox were reached on April 9.[83][84][85] In July 2010, Netflix signed a deal to stream movies of Relativity Media.[86] In August 2010, Netflix reached a five-year deal worth nearly $1 billion to stream films from Paramount, Lionsgate and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. The deal increased Netflix’s annual spending fees, adding roughly $200 million per year. It spent $117 million in the first six months of 2010 on streaming, up from $31 million in 2009.[87] On September 22, 2010, the company first began offering streaming service to the international market, in Canada.[88][89] In November 2010, Netflix began offering a standalone streaming service separate from DVD rentals.[90]

In 2010, Netflix acquired the rights to Breaking Bad, produced by Sony Pictures Television, after the show’s third season, at a point where original broadcaster AMC had expressed the possibility of cancelling the show. Sony pushed Netflix to release Breaking Bad in time for the fourth season, which as a result, greatly expanded the show’s audience on AMC due to new viewers binging on the Netflix past episodes, and doubling the viewership by the time of the fifth season. Breaking Bad is considered the first such show to have this «Netflix effect.»[91]

In January 2011, Netflix introduced a Netflix button for certain remote controls, allowing users to instantly access Netflix on compatible devices.[92] In May 2011, Netflix’s streaming business became the largest source of Internet streaming traffic in North America, accounting for 30% of traffic during peak hours.[93][94][95][96] On July 12, 2011, Netflix announced that it would separate its existing subscription plans into two separate plans: one covering the streaming and the other DVD rental services.[97][98] The cost for streaming would be $7.99 per month, while DVD rental would start at the same price.[99] In September 2011, Netflix announced a content deal with DreamWorks Animation.[100] In September 2011, Netflix expanded to 43 countries in Latin America.[101][102][103] On September 18, 2011, Netflix announced its intentions to rebrand and restructure its DVD home media rental service as an independent subsidiary called Qwikster, separating DVD rental and streaming services.[104][105][106][107][108] On October 10, 2011, Netflix announced that it would retain its DVD service under the name Netflix and that its streaming and DVD-rental plans would remain branded together.[109][110]

On January 4, 2012, Netflix started its expansion to Europe, launching in the United Kingdom and Ireland.[111] In February 2012, Netflix signed a licensing deal with The Weinstein Company.[112][113] In March 2012, Netflix acquired the domain name DVD.com.[114] By 2016, Netflix rebranded its DVD-by-mail service under the name DVD.com, A Netflix Company.[115][116] In April 2012, Netflix filed with the Federal Election Commission (FEC) to form a political action committee (PAC) called FLIXPAC.[117] Netflix spokesperson Joris Evers tweeted that the intent was to «engage on issues like net neutrality, bandwidth caps, UBB and VPPA».[118][119] In June 2012, Netflix signed a deal with Open Road Films.[120][121]

On August 23, 2012, Netflix and The Weinstein Company signed a multi-year output deal for RADiUS-TWC films.[122][123] In September 2012, Epix signed a five-year streaming deal with Netflix. For the initial two years of this agreement, first-run and back-catalog content from Epix was exclusive to Netflix. Epix films came to Netflix 90 days after premiering on Epix.[124] These included films from Paramount, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and Lionsgate.[125][126]

On October 18, 2012, Netflix launched in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden.[127][128] On December 4, 2012, Netflix and Disney announced an exclusive multi-year agreement for first-run United States subscription television rights to Walt Disney Studios’ animated and live-action films, with classics such as Dumbo, Alice in Wonderland and Pocahontas available immediately and others available on Netflix beginning in 2016.[129] Direct-to-video releases were made available in 2013.[130][131] The agreement with Disney ended in 2019 due to the launch of Disney+. Netflix retained the rights to continue streaming the Marvel series that were produced for the service until March 1, 2022, following Disney’s reacquisition of the rights to those series.[132]

On January 14, 2013, Netflix signed an agreement with Time Warner’s Turner Broadcasting System and Warner Bros. Television to distribute Cartoon Network, Warner Bros. Animation, and Adult Swim content, as well as TNT’s Dallas, beginning in March 2013. The rights to these programs were given to Netflix shortly after deals with Viacom to stream Nickelodeon and Nick Jr. programs expired.[133]

Development of original programming (2013–2017)[edit]

In 2013, the company decided to slow launches in Europe to control subscription costs.[134]

In February 2013, Netflix announced it would be hosting its own awards ceremony, The Flixies.[135]

On March 13, 2013, Netflix added a Facebook sharing feature, letting United States subscribers access «Watched by your friends» and «Friends’ Favorites» by agreeing.[136] This was not legal until the Video Privacy Protection Act was modified in early 2013.[137]

In February 2013, DreamWorks Animation and Netflix co-produced Turbo Fast, based on the movie Turbo, which premiered in July.[138][139] Netflix has since become a major distributor of animated family and kid shows.

In July 2013, Orange Is the New Black debuted on Netflix,[140] which became Netflix’s most-watched original series.[141][142]

On August 1, 2013, Netflix reintroduced the «Profiles» feature that permits accounts to accommodate up to five user profiles.[143][144][145][146]

In September 2013, Netflix launched in the Netherlands and was then available in 40 countries.[147][148]

In November 2013, Netflix and Marvel Television announced a five-season deal to produce live-action Marvel superhero-focused series: Daredevil, Jessica Jones, Iron Fist and Luke Cage. The deal involves the release of four 13-episode seasons that culminate in a mini-series called The Defenders. Daredevil and Jessica Jones premiered in 2015.[149][150][151] The Luke Cage series premiered on September 30, 2016, followed by Iron Fist on March 17, 2017, and The Defenders on August 18, 2017.[152][153] The series, however, were removed from Netflix on March 1, 2022, following Disney’s announcement to reacquire the series’ rights after Netflix’s deal expired.

In February 2014, Netflix discovered that Comcast Cable was slowing its traffic down and agreed to pay Comcast to directly connect to the Comcast network.[154][155][156]

On March 7, 2014, new Star Wars content was released on Netflix’s streaming service: the sixth season of the television series Star Wars: The Clone Wars, as well as all five prior and the feature film.[157]

In April 2014, Netflix signed Arrested Development creator Mitchell Hurwitz and his production firm The Hurwitz Company to a multi-year deal to create original projects for the service.[158]

In May 2014, Netflix acquired streaming rights to films produced by Sony Pictures Animation.[159]

In June 2014, Netflix unveiled a global rebranding: a new logo, which uses a modern typeface with the drop shadowing removed, and a new website UI.[160]

In September 2014, Netflix became available in Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, and Switzerland.[161]

On September 10, 2014, Netflix participated in Internet Slowdown Day by deliberately slowing down its speed in protest of net neutrality laws.[162]

In October 2014, Netflix announced a four-film deal with Adam Sandler and his Happy Madison Productions.[163]

In April 2015, following the launch of Daredevil, Netflix director of content operations Tracy Wright announced that Netflix had added support for audio description (a narration track with aural descriptions of key visual elements for the blind or visually impaired), and had begun to work with its partners to add descriptions to its other original series over time.[164][165] The following year, as part of a settlement with the American Council of the Blind, Netflix agreed to provide descriptions for its original series within 30 days of their premiere, and add screen reader support and the ability to browse content by availability of descriptions.[166]

In March 2015, Netflix expanded to Australia and New Zealand.[167][168] In September 2015, Netflix launched in Japan, its first country in Asia.[169][170][171] In October 2015, Netflix launched in Italy, Portugal, and Spain.[172]

In January 2016, at the 2016 Consumer Electronics Show, Netflix announced a major international expansion of its service into 130 additional countries. It then had become available worldwide except China, Syria, North Korea, Kosovo and Crimea.[173]

In May 2016, Netflix created a tool called Fast.com to determine the speed of an Internet connection.[174] It received praise for being «simple» and «easy to use», and does not include online advertising, unlike competitors.[175][176][177]

On November 30, 2016, Netflix launched an offline playback feature, allowing users of the Netflix mobile apps on Android or iOS to cache content on their devices in standard or high quality for viewing offline, without an Internet connection.[178][179][180][181]

In 2016, Netflix released an estimated 126 original series or films, more than any other network or cable channel.[37]

In 2016, Netflix announced plans to expand its in-house production division and produced TV series including The Ranch and Chelsea.[182]

In February 2017, Netflix signed a music publishing deal with BMG Rights Management, whereby BMG will oversee rights outside of the United States for music associated with Netflix original content. Netflix continues to handle these tasks in-house in the United States.[183]

On April 25, 2017, Netflix signed a licensing deal with IQiyi, a Chinese video streaming platform owned by Baidu, to allow selected Netflix original content to be distributed in China on the platform.[184][185]

On August 7, 2017, in the first acquisition of an entire company, Netflix acquired Millarworld, the creator-owned publishing company of comic book writer Mark Millar.[6]

On August 14, 2017, Netflix announced that it had entered into an exclusive development deal with Shonda Rhimes and her production company Shondaland.[186]

In September 2017, Netflix announced it would offer its low-broadband mobile technology to airlines to provide better in-flight Wi-Fi so that passengers can watch movies on Netflix while on planes.[187]

In September 2017, Minister of Heritage Mélanie Joly announced that Netflix had agreed to make a CA$500 million (US$400 million) investment over the next five years in producing content in Canada. The company denied that the deal was intended to result in a tax break.[188][189] Netflix realized this goal by December 2018.[190]

In October 2017, Netflix iterated a goal of having half of its library consist of original content by 2019, announcing a plan to invest $8 billion on original content in 2018. There will be a particular focus on films and anime through this investment, with a plan to produce 80 original films and 30 anime series.[191]

In October 2017, Netflix introduced the «Skip Intro» feature which allows customers to skip the intros to shows on its platform. They do so through a variety of techniques including manual reviewing, audio tagging, and machine learning.[192][193]

In November 2017, Netflix signed an exclusive multi-year deal with Orange Is the New Black creator Jenji Kohan.[194]

In November 2017, Netflix withdrew from co-hosting the 75th Golden Globe Awards with The Weinstein Company due to the Harvey Weinstein sexual abuse cases.[195]

Expansion into international productions (2017–2020)[edit]

In November 2017, Netflix announced that it would be making its first original Colombian series, to be executive produced by Ciro Guerra.[196] In December 2017, Netflix signed Stranger Things director-producer Shawn Levy and his production company 21 Laps Entertainment to what sources say is a four-year deal.[197] In 2017, Netflix invested in distributing exclusive stand-up comedy specials from Dave Chappelle, Louis C.K., Chris Rock, Jim Gaffigan, Bill Burr and Jerry Seinfeld.[198]

In February 2018, Netflix acquired the rights to The Cloverfield Paradox from Paramount Pictures for $50 million and launched on its service on February 4, 2018, shortly after airing its first trailer during Super Bowl LII. Analysts believed that Netflix’s purchase of the film helped to make the film instantly profitable for Paramount compared to a more traditional theatrical release, while Netflix benefited from the surprise reveal.[199][200] Other films acquired by Netflix include international distribution for Paramount’s Annihilation[200] and Universal’s News of the World and worldwide distribution of Universal’s Extinction,[201] Warner Bros.’ Mowgli: Legend of the Jungle,[202] Paramount’s The Lovebirds[203] and 20th Century Studios’ The Woman in the Window.[204] In March, the service ordered Formula 1: Drive to Survive, a racing docuseries following teams in the Formula One world championship.[205]

In March 2018, Sky UK announced an agreement with Netflix to integrate Netflix’s subscription VOD offering into its pay-TV service. Customers with its high-end Sky Q set-top box and service will be able to see Netflix titles alongside their regular Sky channels.[206] In October 2022, Netflix revealed that its annual revenue from the UK subscribers in 2021 was £1.4bn.[207]

In April 2018, Netflix pulled out of the Cannes Film Festival, in response to new rules requiring competition films to have been released in French theaters. The Cannes premiere of Okja in 2017 was controversial, and led to discussions over the appropriateness of films with simultaneous digital releases being screened at an event showcasing theatrical film; audience members also booed the Netflix production logo at the screening. Netflix’s attempts to negotiate to allow a limited release in France were curtailed by organizers, as well as French cultural exception law—where theatrically screened films are legally forbidden from being made available via video-on-demand services until at least 36 months after their release.[208][209][210] Besides traditional Hollywood markets as well as from partners like the BBC, Sarandos said the company also looking to expand investments in non-traditional foreign markets due to the growth of viewers outside of North America. At the time, this included programs such as Dark from Germany, Ingobernable from Mexico and 3% from Brazil.[211][212][213]

On May 22, 2018, former president Barack Obama and his wife Michelle Obama signed a deal to produce docu-series, documentaries and features for Netflix under the Obamas’ newly formed production company, Higher Ground Productions.[214][215]

In June 2018, Netflix announced a partnership with Telltale Games to port its adventure games to the service in a streaming video format, allowing simple controls through a television remote.[216][217] The first game, Minecraft: Story Mode, was released in November 2018.[218] In July 2018, Netflix earned the most Emmy nominations of any network for the first time with 112 nods. On August 27, 2018, the company signed a five-year exclusive overall deal with international best–selling author Harlan Coben.[219] On the same day, the company inked an overall deal with Gravity Falls creator Alex Hirsch.[220] In October 2018, Netflix paid under $30 million to acquire Albuquerque Studios (ABQ Studios), a $91 million film and TV production facility with eight sound stages in Albuquerque, New Mexico, for its first U.S. production hub, pledging to spend over $1 billion over the next decade to create one of the largest film studios in North America.[221][222] In November 2018, Paramount Pictures signed a multi-picture film deal with Netflix, making Paramount the first major film studio to sign a deal with Netflix.[223] A sequel to AwesomenessTV’s To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before was released on Netflix under the title To All the Boys: P.S. I Still Love You as part of the agreement.[224] In December 2018, the company announced a partnership with ESPN Films on a television documentary chronicling Michael Jordan and the 1997–98 Chicago Bulls season titled The Last Dance. It was released internationally on Netflix and became available for streaming in the United States three months after a broadcast airing on ESPN.[225][226]

In January 2019, Sex Education made its debut as a Netflix original series with much critical acclaim.[227] On January 22, 2019, Netflix sought and was approved for membership into the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), as the first streaming service to become a member of the association.[228] In February 2019, The Haunting creator Mike Flanagan joined frequent collaborator Trevor Macy as a partner in Intrepid Pictures and the duo signed an exclusive overall deal with Netflix to produce television content.[229] On May 9, 2019, Netflix contracted with Dark Horse Entertainment to make television series and films based on comics from Dark Horse Comics.[230] In July 2019, Netflix announced that it would be opening a hub at Shepperton Studios as part of a deal with Pinewood Group.[231] In early August 2019, Netflix negotiated an exclusive multi-year film and television deal with Game of Thrones creators and showrunners David Benioff and D.B. Weiss.[232][233][234][235][236] The first Netflix production created by Benioff and Weiss was planned as an adaptation of Liu Cixin’s science fiction novel The Three-Body Problem, part of the Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy.[237] On September 30, 2019, in addition to renewing Stranger Things for a fourth season, Netflix announced signing the series’ creators The Duffer Brothers to a nine-figure deal for additional films and televisions shows over multiple years.[238]

On November 13, 2019, Netflix and Nickelodeon entered into a multi-year agreement to produce several original animated feature films and television series based on Nickelodeon’s library of characters. This agreement expanded on their existing relationship, in which new specials based on the past Nickelodeon series Invader Zim and Rocko’s Modern Life (Invader Zim: Enter the Florpus and Rocko’s Modern Life: Static Cling respectively) were released by Netflix. Other new projects planned under the team-up include a music project featuring Squidward Tentacles from the animated television series SpongeBob SquarePants, and films based on The Loud House and Rise of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.[239][240][241] In November 2019, Netflix announced it had signed a long-term lease to save the Paris Theatre, the last single-screen movie theater in Manhattan. The company oversaw several renovations at the theater, including new seats and a concession stand.[242][243][244]

Ted Sarandos, longtime CCO and named co-CEO in 2020

In January 2020, Netflix announced a new four-film deal with Adam Sandler worth up to $275 million.[245] On February 25, 2020, Netflix formed partnerships with six Japanese creators to produce an original Japanese anime project. This partnership includes manga creator group CLAMP, mangaka Shin Kibayashi, mangaka Yasuo Ohtagaki, novelist and film director Otsuichi, novelist Tow Ubutaka, and manga creator Mari Yamazaki.[246] On March 4, 2020, ViacomCBS announced that it will be producing two spin-off films based on SpongeBob SquarePants for Netflix.[247] On April 7, 2020, Peter Chernin’s Chernin Entertainment made a multi-year first-look deal with Netflix to make films.[248] On May 29, 2020, Netflix announced the acquisition of Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre from the American Cinematheque to use as a special events venue.[249][8][250] In July 2020, Netflix appointed Sarandos as co-CEO.[30][251] In July 2020, Netflix invested in Black Mirror creators Charlie Brooker and Annabel Jones’ new production outfit Broke And Bones.[9]

In September 2020, Netflix signed a multi-million dollar deal with the Duke and Duchess of Sussex. Harry and Meghan agreed to a multi-year deal promising to create TV shows, films, and children’s content as part of their commitment to stepping away from the duties of the royal family.[252][253] In September 2020, Hastings released a book about the Netflix culture titled No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention, which was co-authored by Erin Meyer.[254] In December 2020, Netflix signed a first-look deal with Millie Bobby Brown to develop and star in several projects including a potential action franchise.[255]

Expansion into gaming, Squid Game (2021–present)[edit]

In March 2021, Netflix earned the most Academy Award nominations of any studio, with 36. Netflix won seven Academy Awards, which was the most by any studio. Later that year, Netflix also won more Emmys than any other network or studio with 44 wins, tying the record for most Emmys won in a single year set by CBS in 1974. On April 8, 2021, Sony Pictures Entertainment announced an agreement for Netflix to hold the U.S. pay television window rights to its releases beginning in 2022, replacing Starz and expanding upon an existing agreement with Sony Pictures Animation. The agreement also includes a first-look deal for any future direct-to-streaming films being produced by Sony Pictures, with Netflix required to commit to a minimum number of them.[256][257][258] On April 27, 2021, Netflix announced that it was opening its first Canadian headquarters in Toronto.[259] The company also announced that it would open an office in Sweden as well as Rome and Istanbul to increase its original content in those regions.[260]

In early June, Netflix hosted a first-ever week-long virtual event called “Geeked Week,” where it shared exclusive news, new trailers, cast appearances and more about upcoming genre titles like The Witcher, The Cuphead Show!, and The Sandman.[261]

On June 7, 2021, Jennifer Lopez’s Nuyorican Productions signed a multi-year first-look deal with Netflix spanning feature films, TV series, and unscripted content, with an emphasis on projects that support diverse female actors, writers, and filmmakers.[262] On June 10, 2021, Netflix announced it was launching an online store for curated products tied to the Netflix brand and shows such as Stranger Things and The Witcher.[263][264] On June 21, 2021, Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Partners signed a deal with Netflix to release multiple new feature films for the streaming service.[265][266] On June 30, 2021, Powerhouse Animation Studios (the studio behind Netflix’s Castlevania) announced signing a first-look deal with the streamer to produce more animated series.[267]

In July 2021, Netflix hired Mike Verdu, a former executive from Electronic Arts and Facebook, as vice president of game development, along with plans to add video games by 2022.[268] Netflix announced plans to release mobile games which would be included in subscribers’ plans to the service.[269] Trial offerings were first launched for Netflix users in Poland in August 2021, offering premium mobile games based on Stranger Things including Stranger Things 3: The Game, for free to subscribers through the Netflix mobile app.[270]

On July 14, 2021, Netflix signed a first-look deal with Joey King, star of The Kissing Booth franchise, in which King will produce and develop films for Netflix via her All The King’s Horses production company.[271] On July 21, 2021, Zack Snyder, director of Netflix’s Army of the Dead, announced he had signed his production company The Stone Quarry to a first-look deal with; his upcoming projects include a sequel to Army of the Dead, the sci-fi adventure film Rebel Moon.[272][273][274][275] In 2019, he agreed to produce an anime-style web series inspired by Norse mythology.[276][277]

As of August 2021, Netflix Originals made up 40% of Netflix’s overall library in the United States.[278] The company announced that «TUDUM: A Netflix Global Fan Event», a three-hour virtual behind the scenes featuring first-look reveals for 100 of the streamer’s series, films and specials, would have its inaugural show in late September 2021.[279][280] According to Netflix, the show garnered 25.7 million views across Netflix’s 29 Netflix YouTube channels, Twitter, Twitch, Facebook, TikTok and Tudum.com.[281]

Also in September, the company announced The Queen’s Ball: A Bridgerton Experience, launching in 2022 in Los Angeles, Chicago, Montreal, and Washington, D.C..[282]

Squid Game, a South Korean survival drama created and produced by Hwang Dong-hyuk, had been acquired and produced by Netflix in 2019 as part of its expansion of foreign works and was released worldwide in multiple languages on September 17, 2021. The show rapidly became the service’s most-watched show within a week of its launch in many markets, including Korea, the U.S. and the United Kingdom.[213] Within its first 28 days on the service, Squid Game drew more than 111 million viewers, surpassing Bridgerton and becoming Netflix’s most-watched show.[283] On September 20, 2021, Netflix signed a long-term lease deal with Aviva Investors to operate and expand the Longcross Studios in Surrey, UK.[284] On September 21, 2021, Netflix announced that it would acquire the Roald Dahl Story Company, which manages the rights to Roald Dahl’s stories and characters, for an undisclosed price and would operate it as an independent company.[285][286][287][288]

The company acquired Night School Studio, an independent video game developer, in September 2021.[289] Netflix officially launched mobile games on November 2, 2021, for Android users around the world. Through the app, subscribers had free access to five games, including two previously made Stranger Things titles. Netflix stated that they intend to add more games to this service over time.[290] On November 9, the collection launched for iOS.[291] Some games in the collection require an active internet connection to play, while others will be available offline. Netflix Kids’ accounts will not have games available.[292]

On October 13, 2021, Netflix announced the launch of the Netflix Book Club, where readers will hear about new books, films, and series adaptations and have exclusive access to each book’s adaptation process. Netflix will partner with Starbucks to bring the book club to life via a social series called But Have You Read the Book?. Uzo Aduba will serve as the inaugural host of the series and announce monthly book selections set to be adapted by the streamer. Aduba will also speak with the cast, creators, and authors about the book adaptation process over a cup of coffee at Starbucks.[293][294] Through October 2021, Netflix commonly reported viewership for its programming based on the number of viewers or households that watched a show in a given period (such as the first 28 days from its premiere) for at least two minutes. On the announcement of its quarterly earnings in October 2021, the company stated that it would switch its viewership metrics to measuring the number of hours that a show was watched, including rewatches, which the company said was closer to the measurements used in linear broadcast television, and thus «our members and the industry can better measure success in the streaming world.»[295] On November 16, 2021, Netflix announced the launch of «Top10 on Netflix.com», a new website with weekly global and country lists of the most popular titles on their service based on their new viewership metrics.[296]

On November 22, 2021, Netflix announced that it would acquire Scanline VFX, the visual effects and animation company behind Cowboy Bebop and Stranger Things.[297] On the same day, Roberto Patino signed a deal with Netflix and established his own production banner, Analog Inc., in partnership with the company. Patino’s first project under the deal is a series adaptation of Image Comics’ Nocterra.[298] On December 6, 2021, Netflix and Stage 32 announced that they have teamed up the workshops at the Creating Content for the Global Marketplace program.[299] On December 7, 2021, Netflix partnered with IllumiNative, a woman-led non-profit organization, for the Indigenous Producers Training Program.[300][301]

On December 9, 2021, Netflix announced the launch of «Tudum,» an official companion website that offers news, exclusive interviews and behind-the-scenes videos for its original television shows and films.[302] On December 13, 2021, Netflix signed a multi-year overall deal with Kalinda Vazquez.[303] On December 16, 2021, Netflix signed a multi-year creative partnership with Spike Lee and his production company 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks to develop film and television projects.[304] In December 2021, former Netflix engineer Sung Mo Jun was sentenced to 2 years in prison for an insider trading scheme where he leaked subscriber numbers in advance of official releases.[305][306]

In compliance with the EU Audiovisual Media Services Directive and its implementation in France, Netflix reached commitments with French broadcasting authorities and film guilds, as required by law, to invest a specific amount of its annual revenue into original French films and series. These films must be theatrically released and would not be allowed to be carried on Netflix until 15 months after their release.[307][308]

In January 2022, Netflix ordered additional sports docuseries from Drive to Survive producers Box to Box Films, including a series that would follow PGA Tour golfers, and another that would follow professional tennis players on the ATP and WTA Tour circuits.[309][310]

The company announced plans to acquire Next Games in March 2022 for €65 million as part of Netflix’s expansions into gaming. Next Games had developed the mobile title Stranger Things: Puzzle Tales as well as two The Walking Dead mobile games.[311] Later in the month, Netflix also acquired the Texas-based mobile game developer, Boss Fight Entertainment, for an undisclosed sum.[312]

On March 15, 2022, Netflix announced a partnership with Dr. Seuss Enterprises to produce five new series and specials based on Seuss properties following the success of Green Eggs and Ham.[313][314] On March 29, 2022, Netflix announced that it would open an office in Poland to serve as a hub for its original productions across Central and Eastern Europe.[315] On March 30, 2022, Netflix extended its lease agreement with Martini Film Studios, just outside Vancouver, Canada, for another five years.[316] On March 31, 2022, Netflix ordered a docuseries that would follow teams in the 2022 Tour de France, which would also be co-produced by Box to Box Films.[317]

Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Netflix suspended its operations and future projects in Russia.[318][5] It also announced that it would not comply with a proposed directive by Roskomnadzor requiring all internet streaming services with more than 100,000 subscribers to integrate the major free-to-air channels (which are primarily state-owned).[319] A month later, ex-Russian subscribers filed a class action lawsuit against Netflix.[320][321]

At the end of Q1 2022, Netflix announced a decline in subscribers with almost 200,000 fewer viewers than at the end of the previous year.[322] Netflix stated that 100 million households globally were sharing passwords to their account with others, and that Canada and the United States accounted for 30 million of them. Following these announcements, Netflix’s stock price fell by 35 percent.[323][324][325][326] By June 2022, Netflix had laid off 450 full-time and contract employees as part of the company’s plan to trim costs amid lower than expected subscriber growth. The layoffs represented approximately 2 percent of the workforce and spread across the company globally.[327][328][329][330]

On April 13, 2022, Netflix released the series Our Great National Parks, which was hosted and narrated by former US President Barack Obama.[331] It also partnered with Group Effort Initiative, a company founded by Ryan Reynolds and Blake Lively, to provide opportunities behind the camera for those in underrepresented communities.[332] On the same day, Netflix partnered with Lebanon-based Arab Fund For Arts And Culture for supporting the Arab female filmmakers. It will provide a one-time grant of $250,000 to female producers and directors in the Arab world through the company’s Fund for Creative Equity.[333] Also on the same day, Netflix announced an Exploding Kittens mobile card game tied to a new animated TV series, which will launch in May.[334] Netflix announced that they have formed a creative partnership with J. Miles Dale.[335] The company also formed a partnership with Japan’s Studio Colorido, signing a multi-film deal to boost their anime content in Asia. The streaming giant is said to co-produce three feature films with the studio, the first of which will premiere in September 2022.[336]

On April 28, 2022, the company launched its inaugural Netflix Is a Joke comedy festival, featuring more than 250 shows over 12 nights at 30-plus locations across Los Angeles, including the first-ever stand-up show at Dodger Stadium.[337][338]

The first volume of Stranger Things 4 logged Netflix’s biggest premiere weekend ever for an original series with 286.79 million hours viewed.[339] This was preceded by a new Stranger Things interactive experience hosted in New York City that was developed by the show’s creators.[340] After the release of the second volume of Stranger Things 4 on July 1, 2022, it became Netflix’s second title to receive more than one billion hours viewed.[341]

On July 19, 2022, Netflix announced plans to acquire Australian animation studio Animal Logic.[342][343]

On July 22, 2022, it was reported that Netflix lost almost a million subscribers, which reduced its total subscribers down to 220.7 million.[344][345]

On September 5, 2022, it was reported that Netflix opened its office in Warsaw, Poland, responsible for the service’s operations in 28 markets in Central and Eastern Europe.[346]

On October 4, 2022, Netflix have signed a creative partnership with Andrea Berloff and John Gatins.[347]

On October 11, 2022, Netflix signed up to the Broadcasters’ Audience Research Board for external measurement of viewership in the UK.[348]

On October 12, 2022, Netflix signed to build a production complex at Fort Monmouth in Eatontown, New Jersey.[349]

At the end of Q3, it was reported that Netflix gained 2.41 million new subscribers, including a gain of 100,000 in North America, totaling 223.1 million subscribers worldwide. This exceeded Netflix’s prediction of a gain of 1 million subscribers for the quarter.[350]

On October 18, 2022, Netflix announced they are exploring a cloud gaming offering as well as opening a new gaming studio in Southern California.[351]

Availability and access[edit]

Global availability[edit]

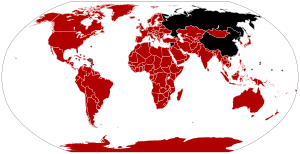

Availability of Netflix, as of March 2022:

Available

Netflix is available in every country and territory except for China, North Korea, Crimea, Syria and Russia.[354]

In January 2016, Netflix announced it would begin VPN blocking since they can be used to watch videos from a country where they are unavailable.[355] The result of the VPN block is that people can only watch videos available worldwide and other videos are hidden from search results.[356] Variety is present on Netflix. Hebrew and right-to-left interface orientation, which is a common localization strategy in many markets, are what define the Israeli user interface’s localization, and in some regions, Netflix offers a more affordable mobile-only subscription.[357]

Subscriptions[edit]

Globally, Netflix had 223.09 million paying subscribers at the end of Q3 2022.[358][359] Customers can subscribe to one of three plans; the difference in plans relate to video resolution, the number of simultaneous streams, and the number of devices to which content can be downloaded.[360]

At the end of Q1 2022, Netflix estimated that 100 million households globally were sharing passwords to their account with others.[325] In March 2022, Netflix began to charge a fee for additional users in Chile, Peru, and Costa Rica to attempt to control account sharing.[323][324][325] On July 18, 2022, Netflix announced that it would test the account sharing feature in more countries, including Argentina, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras.[361] On October 17, Netflix launched Profile Transfer to help end account sharing.[362]

In July 13, 2022, Netflix announced a partnership with Microsoft to launch an advertising-supported subscription plan.[363] On August 17, 2022, it was reported that Netflix’s planned advertising tier would not allow subscribers to download content like the existing ad-free platform.[364] On July 20, 2022, it was announced that the advertising-supported tier would be coming to Netflix in 2023 but it would not feature the full library of content.[365] Netflix US launched with 5.1% of the library unavailable including 60 Netflix Originals.[366] In September, Netflix announced that the launch would be moved up to November 1, 2022,[367][368] but in October, the launch date was changed to November 3, 2022. The ad-supported plan is called «Basic with Ads» and it costs $6.99 per month in the United States.[369] In Canada, the plan was launched two days later, on November 1.[370]

Device support[edit]

Netflix can be accessed via an internet browser on PCs, while Netflix apps are available on various platforms, including Blu-ray Disc players, tablet computers, mobile phones, smart TVs, digital media players, and video game consoles (including Xbox 360 and newer, and PlayStation 3 and newer).

In addition, a growing number of multichannel television providers, including cable television and IPTV services, have added Netflix apps accessible within their own set-top boxes, sometimes with the ability for its content (along with those of other online video services) to be presented within a unified search interface alongside linear television programming as an «all-in-one» solution.[371][372][373][374]

Content[edit]

Original programming[edit]

A «Netflix Original» is content that is produced, co-produced, or distributed by Netflix exclusively on their services. Netflix funds their original shows differently than other TV networks when they sign a project, providing the money upfront and immediately ordering two seasons of most series.[375]

Over the years, Netflix output ballooned to a level unmatched by any television network or streaming service. According to Variety Insight, Netflix produced a total of 240 new original shows and movies in 2018, then climbed to 371 in 2019, a figure «greater than the number of original series that the entire U.S. TV industry released in 2005.»[376] The Netflix budget allocated to production increased annually, reaching $13.6 billion in 2021 and projected to hit $18.9 billion by 2025, a figure that once again overshadowed any of its competitors.[377] As of August 2022, Netflix Originals made up 50% of Netflix’s overall library in the United States.[378]

Film and television deals[edit]

Netflix has exclusive pay TV deals with several studios. The deals give Netflix exclusive streaming rights while adhering to the structures of traditional pay TV terms.

Distributors that have licensed content to Netflix include Warner Bros., Universal Pictures, Sony Pictures Entertainment and previously The Walt Disney Studios (including 20th Century Fox). Netflix also holds current and back-catalog rights to television programs distributed by Walt Disney Television, DreamWorks Classics, Kino International, Warner Bros. Television and CBS Media Ventures, along with titles from other companies such as Allspark (formerly Hasbro Studios), Saban Brands, and Funimation. Formerly, the streaming service also held rights to select television programs distributed by NBCUniversal Television Distribution, Sony Pictures Television and 20th Century Fox Television.

Netflix negotiated to distribute animated films from Universal that HBO declined to acquire, such as The Lorax, ParaNorman, and Minions.[379]

Netflix holds exclusive streaming rights to the film library of Studio Ghibli (with the exception of Grave of the Fireflies) worldwide except in the U.S., Canada, China and Japan as part of an agreement signed with Ghibli’s international sales holder Wild Bunch in 2020.

Gaming[edit]

In July 2021, Netflix hired Mike Verdu, a former executive from Electronic Arts and Facebook, as vice president of game development, along with plans to add video games by 2022.[380] Netflix announced plans to release mobile games which would be included in subscribers’ plans to the service.[381] Trial offerings were first launched for Netflix users in Poland in August 2021, offering premium mobile games based on Stranger Things including Stranger Things 3: The Game, for free to subscribers through the Netflix mobile app.[382]

Netflix officially launched mobile games on November 2, 2021, for Android users around the world. Through the app, subscribers had free access to five games, including two previously made Stranger Things titles. Netflix stated that they intend to add more games to this service over time.[383] On November 9, the collection launched for iOS.[384] Verdu said in October 2022 that besides continuing to expand their portfolio of games, they were also interested in cloud gaming options.[385]

To support the games effort, Netflix began acquiring and forming a number of studios. The company acquired Night School Studio, an independent video game developer, in September 2021.[386] They announced plans to acquire Next Games in March 2022 for €65 million as part of Netflix’s expansions into gaming. Next Games had developed the mobile title Stranger Things: Puzzle Tales as well as two The Walking Dead mobile games.[387] Later in the month, Netflix also acquired the Texas-based mobile game developer, Boss Fight Entertainment, for an undisclosed sum.[312] Netflix opened a mobile game studio in Helsinki, Finland in September 2022,[388] and a new studio, their fifth total, in southern California in October 2022,[385] alongside the acquisition of Spry Fox in Seattle.[389]

As of October 2022, the service had 35 games available, and Netflix stated they had more than 55 games in development.[390] By August 2022, Netflix’s gaming platform was reported to have an average 1.7 million users a day, less than 1% of the streaming service’s subscribers at the time.[391]

Technology[edit]

Content delivery[edit]

Netflix settlement freely peers with Internet service providers (ISPs) directly and at common Internet exchange points. In June 2012, a custom content delivery network, Open Connect, was announced.[392] For larger ISPs with over 100,000 subscribers, Netflix offers free Netflix Open Connect server appliances that cache their content within the ISPs’ data centers or networks to further reduce Internet transit costs.[393][394] By August 2016, Netflix closed its last physical data center, but continued to develop its Open Connect technology.[395] A 2016 study at the University of London detected 233 individual Open Connect locations on over six continents, with the largest amount of traffic in the USA, followed by Mexico.[396][397]

As of July 2017, Netflix series and movies accounted for more than a third of all prime-time download Internet traffic in North America.[398]

API[edit]

On October 1, 2008, Netflix offered access to its service via a public application programming interface (API).[399] It allowed access to data for all Netflix titles, and allows users to manage their movie queues. The API was free and allowed commercial use.[400] In June 2012, Netflix began to restrict the availability of its public API.[401] They instead focused on a small number of known partners using private interfaces, since most traffic came from those private interfaces.[402] In June 2014, Netflix announced they would be retiring the public API; it became effective November 14, 2014.[403] They then partnered with the developers of eight services deemed the most valuable, including Instant Watcher, Fanhattan, Yidio and Nextguide.[404]

Corporate affairs[edit]

Historical financials and membership growth[edit]

Worldwide VOD subscribers of Netflix[405]

| Year | Revenue in millions of US$ |

Employees | Paid memberships in millions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 682 | 2.5 | |

| 2006 | 997 | 4.0 | |

| 2007 | 1,205 | 7.3 | |

| 2008 | 1,365 | 9.4 | |

| 2009 | 1,670 | 11.9 | |

| 2010 | 2,163 | 2,180 | 18.3 |

| 2011 | 3,205 | 2,348 | 21.6 |

| 2012 | 3,609 | 2,045 | 30.4 |

| 2013 | 4,375 | 2,022 | 41.4 |

| 2014 | 5,505 | 2,450 | 54.5 |

| 2015 | 6,780 | 3,700 | 70.8 |

| 2016 | 8,831 | 4,700 | 89.1 |

| 2017 | 11,693 | 5,500 | 117.5 |

| 2018 | 15,794 | 7,100 | 139.3 |

| 2019 | 20,156 | 8,600 | 167.1 |

| 2020 | 24,996 | 9,400 | 203.7 |

| 2021 | 29,697 | 11,300 | 221.8 |

| Summation | 142,723 | 61,345 | 1,210.6 |

| Approximate average | 8,395 | 5,112 | 71 |

Corporate culture[edit]

Netflix’s original Los Gatos headquarters (2006-2022)[406]

Netflix’s current Los Gatos headquarters (2022-present)[406]

Netflix grants all employees extremely broad discretion with respect to business decisions, expenses, and vacation—but in return expects consistently high performance, as enforced by what is known as the «keeper test.»[407][408] All supervisors are expected to constantly ask themselves if they would fight to keep an employee. If the answer is no, then it is time to let that employee go.[409] A slide from an internal presentation on Netflix’s corporate culture summed up the test as: «Adequate performance gets a generous severance package.»[408] Such packages reportedly range from four months’ salary in the United States to as much as six months in the Netherlands.[409]

The company offers unlimited vacation time for salaried workers and allows employees to take any amount of their paychecks in stock options.[410]

About the culture that results from applying such a demanding test, Hastings has said that «You gotta earn your job every year at Netflix,»[411] and, «There’s no question it’s a tough place…There’s no question it’s not for everyone.»[412] Hastings has drawn an analogy to athletics: professional athletes lack long-term job security because an injury could end their career in any particular game, but they learn to put aside their fear of that constant risk and focus on working with great colleagues in the current moment.[413]

Environmental impact[edit]

In March 2021, Netflix announced that it would work to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions by the end of 2022, while investing in programs to preserve or restore ecosystems. The company stated that it would cut emissions from its operations and electricity use by 45 percent by 2030. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and lack of content production, Netflix had a 14 percent drop in emissions in 2020.[414][415] In 2021, Netflix bought 1.5 million carbon credits from 17 projects around the world.[416]

Awards[edit]

On July 18, 2013, Netflix earned the first Primetime Emmy Award nominations for original streaming programs at the 65th Primetime Emmy Awards. Three of its series, Arrested Development, Hemlock Grove and House of Cards, earned a combined 14 nominations (nine for House of Cards, three for Arrested Development and two for Hemlock Grove).[417] The House of Cards episode «Chapter 1» received four nominations for both the 65th Primetime Emmy Awards and 65th Primetime Creative Arts Emmy Awards, becoming the first episode of a streaming television series to receive a major Primetime Emmy Award nomination. With its win for Outstanding Cinematography for a Single-Camera Series, «Chapter 1» became the first episode from a streaming service to be awarded an Emmy.[417][418][419] David Fincher’s win for Directing for a Drama Series for House of Cards made the episode the first from a streaming service to win a Primetime Emmy.[420]

On November 6, 2013, Netflix earned its first Grammy nomination when You’ve Got Time by Regina Spektor — the main title theme song for Orange Is the New Black — was nominated for Best Song Written for Visual Media.[421]

On December 12, 2013, the network earned six nominations for Golden Globe Awards, including four for House of Cards.[422] Among those nominations was Wright for Golden Globe Award for Best Actress – Television Series Drama for her portrayal of Claire Underwood, which she won. With the accolade, Wright became the first actress to win a Golden Globe for a streaming television series. It also marked Netflix’s first major acting award.[423][424][425] House of Cards and Orange is the New Black also won Peabody Awards in 2013.[426]

On Jan. 16, 2014, Netflix became the first streaming service to earn an Academy Award nomination when The Square was nominated for Best Documentary Feature.[427]

On July 10, 2014, Netflix received 31 Emmy nominations. Among other nominations, House of Cards received nominations for Outstanding Drama Series, Outstanding Directing in a Drama Series and Outstanding Writing in a Drama Series. Kevin Spacey and Robin Wright were nominated for Outstanding Lead Actor and Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series. Orange is the New Black was nominated in the comedy categories, earning nominations for Outstanding Comedy Series, Outstanding Writing for a Comedy Series and Outstanding Directing for a Comedy Series. Taylor Schilling, Kate Mulgrew, and Uzo Aduba were respectively nominated for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Comedy Series, Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Comedy Series and Outstanding Guest Actress in a Comedy Series (the latter was for Aduba’s recurring role in season one, as she was promoted to series regular for the show’s second season).[428]

Netflix got the largest share of 2016 Emmy award nominations, with 16 major nominations. However, streaming shows only got 24 nominations out of a total of 139, falling significantly behind cable. The 16 Netflix nominees were: House of Cards with Kevin Spacey, A Very Murray Christmas with Bill Murray, Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, Master of None, and Bloodline.[429]

Stranger Things received 19 nominations at the 2017 Primetime Emmy Awards, while The Crown received 13 nominations.[430]

In December 2017, Netflix was awarded PETA’s Company of the Year for promoting animal rights movies and documentaries like Forks Over Knives and What the Health.[431][432]

At the 90th Academy Awards, held on March 4, 2018, the film Icarus, distributed by Netflix, won its first Oscar for Best Documentary Feature. During his remarks backstage, director and writer Bryan Fogel remarked that Netflix had «single-handedly changed the documentary world.» Icarus had its premiere at the 2017 Sundance Film Festival and was bought by Netflix for $5 million, one of the biggest deals ever for a non-fiction film.[433] Netflix became the network whose programs received more nomination at the 2018 Primetime and Creative Arts Emmy Awards with 112 nominations, therefore breaking HBO’s 17-years record as a network whose programs received more nomination at the Emmys, which received 108 nominations.[434][435]

On January 22, 2019, films distributed by Netflix scored 15 nominations for the 91st Academy Awards, including Academy Award for Best Picture for Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma, which was nominated for 10 awards.[436] The 15 nominations equal the total nominations films distributed by Netflix had received in previous years.

In 2020, Netflix received 20 TV nominations and films distributed by Netflix also got 22 film nominations at the 78th Golden Globe Awards. It secured three out of the five nominations for best drama TV series for The Crown, Ozark and Ratched and four of the five nominations for best actress in a TV series: Olivia Colman, Emma Corrin, Laura Linney and Sarah Paulson.[437][438]

In 2020, Netflix earned 24 Academy Award nominations, marking the first time a streaming service led all studios.[439]

Films and programs distributed by Netflix received 30 nominations at the 2021 Screen Actors Guild Awards, more than any other distribution company, where their distributed films and programs won 7 awards including best motion picture for The Trial of the Chicago 7 and best TV drama for The Crown.[440][441] Netflix also received the most nominations of any studio at the 93rd Academy Awards — 35 total nominations with 7 award wins.[442][443]

In February 2022, The Power of the Dog gritty western distributed by Netflix and directed by Jane Campion, received 12 nominations, including Best Picture, for the 94th annual Academy Awards. Films distributed by the streamer received a total of 72 nominations.[444] Campion became the third female to receive the Best Director award, winning her second Oscar for The Power of the Dog.[445] At the 50th International Emmy Awards in November 2022, Netflix original Sex Education won Best Comedy Series.[446]

Criticism[edit]

Netflix has been subject to criticism from various groups and individuals as its popularity and market reach increased in the 2010s.

Customers have complained about price increases in Netflix offerings dating back to the company’s decision to separate its DVD rental and streaming services, which was quickly reversed. As Netflix increased its streaming output, it has faced calls to limit accessibility to graphic content and include viewer advisories for issues such as sensationalism and promotion of pseudoscience. Netflix’s content has also been criticized by disability rights advocates for lack of captioning quality.[447]

Some media organizations and competitors have criticized Netflix for selectively releasing ratings and viewer numbers of its original programming. The company has made claims boasting about viewership records without providing data to substantiate its successes or using problematic estimation methods.[448] In March 2020, some government agencies called for Netflix and other streamers to limit services due to increased broadband and energy consumption as use of the platform increased. In response, the company announced it would reduce bit rates across all streams in Europe, thus decreasing Netflix traffic on European networks by around 25 percent. These same steps were later taken in India.[citation needed]

In May 2022, Netflix’s shareholder Imperium Irrevocable Trust filed a lawsuit against the company for violating the U.S. securities laws.[449]

See also[edit]

- List of streaming media services

References[edit]

- ^ «Netflix is now available in Hindi». Netflix (Press release). August 9, 2020.

- ^ «APA KABAR INDONESIA? NETFLIX CAN NOW SPEAK BAHASA INDONESIA». Netflix (Press release). October 18, 2018.

- ^ «Business Search – Results». businesssearch.sos.ca.gov. Secretary of State of California. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017.

- ^ «Where is Netflix available?». Netflix. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Lang, Brent (March 6, 2022). «Netflix Suspends Service in Russia Amid Invasion of Ukraine». Variety. Penske Media Corporation. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ a b «Netflix buys Scots comic book firm Millarworld». BBC News. August 7, 2017. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017.

- ^ Hipes, Patrick (July 18, 2018). «Netflix Takes Top Awards Strategist Lisa Taback Off The Table». Deadline Hollywood.

- ^ a b McNary, Dave (May 29, 2020). «Netflix Closes Deal to Buy Hollywood’s Egyptian Theatre». Variety.

- ^ a b Kanter, Jake (July 30, 2020). «Netflix Quietly Strikes Landmark Investment Deal With ‘Black Mirror’ Creators Charlie Brooker & Annabel Jones». Deadline Hollywood.

- ^ «Netflix Second Quarter 2022 Earnings Interview» (Press release). July 19, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ «US SEC: 2021 Form 10-K Netflix, Inc». U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. January 27, 2022.

- ^ a b «Company Profile».

- ^ Johnson, Dave (June 3, 2019). «How to watch Netflix on your TV in 5 different ways». Business Insider.

- ^ Eddy, Max (September 2, 2021). «How to Unblock Netflix With a VPN». PC World.

- ^ Pendlebury, Ty (September 12, 2021). «What’s the best way to watch Netflix on my TV? How to get set up with streaming». CNET.

- ^ William, Ryan (February 24, 2021). «Netflix VR Guide: How to Watch Netflix in Virtual Reality». AR/VR Tips.

- ^ «How to watch Netflix in 4K Ultra HD». Netflix.

- ^ «DVD | Definition, Development, & Facts | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ «DVD Netflix: Rent Movies and TV Shows on DVD and Blu-ray». Netflix.

- ^ Pogue, David (January 25, 2007). «A Stream of Movies, Sort of Free». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Keating, Gina (October 11, 2012). Netflixed: The Epic Battle for America’s Eyeballs. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1-101-60143-3.

- ^ «Fortune 500: Netflix». Fortune.

- ^ «Forbes Global 2000: Netflix». Forbes.

- ^ Swartz, Jon (July 10, 2020). «Netflix shares close up 8% for yet another record high». MarketWatch.

- ^ Howard, Phoebe Wall (April 20, 2021). «Ford rated with Apple, Amazon, Pfizer in new consumer trust survey». Detroit Free Press.

- ^ Hough, Jack (December 18, 2019). «10 Stocks That Had Better Decades Than Amazon and Google». Barron’s.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Maggie (December 13, 2019). «Here are the best-performing stocks of the decade». CNBC.

- ^ Donato-Weinstein, Nathan (December 11, 2012). «Netflix officially signs on to new Los Gatos campus». American City Business Journals.

- ^ Donato-Weinstein, Nathan (September 4, 2015). «Netflix seals big Los Gatos expansion». American City Business Journals.

- ^ a b Lee, Edmund (July 16, 2020). «Netflix Appoints Ted Sarandos as Co-Chief Executive». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020.

- ^ Shaw, Lucas (March 21, 2019). «Netflix’s Power Base Shifts Closer to Hollywood». Bloomberg News.

- ^ Owens, Jeremy C. (June 4, 2013). «Los Gatos approves controversial Netflix expansion». SiliconValley.com. San Jose Mercury News.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (January 5, 2021). «Los Angeles Production Grinds To A Halt Amid Covid-19 Surge; Netflix Is Latest Major Studio To Pause Filming». Deadline.

- ^ Bishop, Bryan (October 8, 2018). «Amazon prime buys up New Mexico studio facility for massive new production hub». The Verge.

- ^ Clarke, Stewart (July 3, 2019). «Netflix Creates U.K. Film and TV Production Hub at Shepperton Studios». Variety.

- ^ Green, Jennifer (April 4, 2019). «Netflix Unveils New Projects, Plans for Growth in Spain at Production Hub Inauguration». Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ a b Masters, Kim (September 14, 2016). «The Netflix Backlash: Why Hollywood Fears a Content Monopoly». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016.

- ^ Castillo, Michelle (August 15, 2018). «Netflix pays more for TV shows up front, but keeps more upside on big hits, insiders say». CNBC.

- ^ Hastings, Reed (December 1, 2005). «How I Did It: Reed Hastings, Netflix». Inc.

- ^ a b c d Xavier, Jon (January 9, 2014). «Netflix’s first CEO on Reed Hastings and how the company really got started Executive of the Year 2013». American City Business Journals.

- ^ Sperling, Nicole (September 15, 2019). «Long Before ‘Netflix and Chill,’ He Was the Netflix C.E.O.». The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 15, 2019.

- ^ Castillo, Michelle (May 23, 2017). «Reed Hastings’ story about the founding of Netflix has changed several times». Archived from the original on November 2, 2017.

- ^ Cohen, Alan (December 1, 2002). «The Great Race No startup has cashed in on the DVD’s rapid growth more than Netflix. Now Blockbuster and Wal-Mart want in. Can it outrun its big rivals?». CNN.

- ^ Rodriguez, Ashley (April 14, 2018). «Early images of Netflix.com show how far the service has come in its 20 years». Quartz.

- ^ Barrett, Brian; Parham, Jason; Raftery, Brian; Rubin, Peter; Watercutter, Angela (August 29, 2017). «Netflix Is Turning 20—But Its Birthday Doesn’t Matter». Wired.

- ^ Cuccinello, Hayley C. (September 17, 2019). «Netflix Cofounder Marc Randolph On Why He Left, Becoming A Mentor And His Love Of Chaos». Forbes.

- ^ Scipioni, Jade (September 21, 2019). «Why Netflix co-founders turned down Jeff Bezos’ offer to buy the company». CNBC.

- ^ O’Brien, Jeffrey M. (December 1, 2002). «The Netflix Effect». Wired. Archived from the original on September 5, 2013.

- ^ Huddleston Jr., Tom (September 22, 2020). «Netflix didn’t kill Blockbuster — how Netflix almost lost the movie rental wars». CNBC.

- ^ Chong, Celena (July 17, 2015). «Blockbuster’s CEO once passed up a chance to buy Netflix for only $50 million». Business Insider.

- ^ ZETLIN, MINDA (September 20, 2019). «Blockbuster Could Have Bought Netflix for $50 Million, but the CEO Thought It Was a Joke». Inc.

- ^ Giang, Vivian (February 17, 2016). «She Created Netflix’s Culture And It Ultimately Got Her Fired». Fast Company.

- ^ McCord, Patty (September 2014). «How Netflix Reinvented HR». Harvard Business Review.

- ^ «Netflix Announces Initial Public Offering» (Press release). May 22, 2002.

- ^ Hu, Jim. «Netflix sews up rental patent». CNET.

- ^ a b «Netflix lowers its online DVD rental fees». Associated Press. July 22, 2007 – via NBC News.

- ^ «Movies to go». The Economist. July 7, 2005. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008.

- ^ a b Huddleston Jr., Tom (September 22, 2020). «Netflix didn’t kill Blockbuster — how Netflix almost lost the movie rental wars». CNBC.

- ^ US patent 7024381, Hastings; W. Reed (Santa Cruz, CA), Randolph; Marc B. (Santa Cruz, CA), Hunt; Neil Duncan, «Approach for renting items to customers», issued 2006-04-04

- ^ US patent 6584450, Hastings; W. Reed (Santa Cruz, CA), Randolph; Marc B. (Santa Cruz, CA), Hunt; Neil Duncan (Mountain View, CA), «Method and apparatus for renting items», issued 2003-06-24

- ^ Bond, Paul (June 29, 2007). «Blockbuster to shutter 282 stores this year». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 21, 2010.

- ^ «Blockbuster Settles Fight With Netflix». The New York Times. Reuters. June 28, 2007. Archived from the original on July 1, 2007.

- ^ Patel, Nilay (June 27, 2007). «Netflix, Blockbuster settle patent dispute». Engadget.

- ^ CHENG, JACQUI (June 27, 2007). «Blockbuster and Netflix settle patent battle». Ars Technica.

- ^ «Netflix Prize Website». Archived from the original on December 10, 2006.

- ^ Jackson, Dan (July 7, 2017). «The Netflix Prize: How a $1 Million Contest Changed Binge-Watching Forever». Thrillist.

- ^ Van Buskirk, Elliott (September 22, 2009). «How the Netflix Prize Was Won». Wired.

- ^ Dornhelm, Rachel (December 8, 2006). «Netflix expands indie film biz». Marketplace. American Public Media. Archived from the original on December 10, 2006.

- ^ Jesdanun, Anick (July 23, 2008). «Netflix shuts movie financing arm to focus on core». The Sydney Morning Herald. Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 26, 2008.

- ^ Goldstein, Gregg (July 22, 2008). «Netflix closing Red Envelope». The Hollywood Reporter. Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 26, 2014.

- ^ «Netflix offers streaming movies to subscribers». January 16, 2007. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017.

- ^ Kyncl, Robert (September 13, 2017). «The inside story of how Netflix transitioned to digital video after seeing the power of YouTube». Vox Media. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017.

- ^ «Netflix delivers 1 billionth DVD». NBC News. Associated Press. February 25, 2007.

- ^ «Texas woman takes one-billionth Netflix delivery». Reuters. February 26, 2007.

- ^ Ogg, Erica (April 16, 2007). «Netflix appoints VP of Internet TV». CNET.

- ^ MANGALINDAN, JP (November 1, 2012). «Roku’s Anthony Wood looks beyond the box». Fortune.

- ^ Au-Yeung, Angel (December 31, 2019). «How Billionaire Anthony Wood Quit His Netflix Job, Founded Roku—And Then Quadrupled His Fortune In The Past Year». Forbes.

- ^ «Netflix Expands Internet Viewing Option». San Francisco Chronicle. Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 15, 2008.

- ^ «Netflix to lift limits on streaming movies». Los Angeles Daily News. Associated Press. January 14, 2008.

- ^ «Completing the Netflix Cloud Migration». Netflix. February 11, 2016.

- ^ Paul, Ian (November 5, 2008). «Netflix Stops Selling DVDs». The Washington Post.

- ^ Siegler, MG (February 24, 2009). «Netflix streams already rushing past DVDs in 2009?». VentureBeat.

- ^ «Warner Bros. Home Entertainment and Netflix Announce New Agreements Covering Availability of DVDs, Blu-ray and Streaming Content» (Press release). Warner Bros. January 6, 2010. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016.

- ^ «Universal Studios Home Entertainment and Netflix Announce New Distribution Deals for DVDs, Blu-ray, Disney and Streaming Content» (Press release). PR Newswire. April 9, 2010. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011.

- ^ «Twentieth Century Fox and Netflix Announce Comprehensive Strategic Agreement That Includes Physical and Digital Distribution» (Press release). PR Newswire. April 9, 2010. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016.

- ^ Zeidler, Sue (July 6, 2010). «Netflix signs movie deal with Relativity Media». Reuters. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015.

- ^ Stelter, Brian (August 10, 2010). «Netflix to Stream Films From Paramount, Lions Gate, MGM». The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 11, 2010.

- ^ «Netflix stumbles as it launches in Canada». Toronto Star. September 10, 2010. Archived from the original on December 9, 2014.