|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickel | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | lustrous, metallic, and silver with a gold tinge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Ni) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickel in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 28 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d8 4s2 or [Ar] 3d9 4s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 16, 2 or 2, 8, 17, 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1728 K (1455 °C, 2651 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 3003 K (2730 °C, 4946 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 8.908 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 7.81 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 17.48 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 379 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 26.07 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −2, −1, 0, +1,[2] +2, +3, +4[3] (a mildly basic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.91 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 124 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 124±4 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 163 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of nickel |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic (fcc)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 4900 m/s (at r.t.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 13.4 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 90.9 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 69.3 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | ferromagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 200 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 76 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 180 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 4.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 638 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 667–1600 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-02-0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery and first isolation | Axel Fredrik Cronstedt (1751) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of nickel

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow to react with air under standard conditions because a passivation layer of nickel oxide forms on the surface that prevents further corrosion. Even so, pure native nickel is found in Earth’s crust only in tiny amounts, usually in ultramafic rocks,[4][5] and in the interiors of larger nickel–iron meteorites that were not exposed to oxygen when outside Earth’s atmosphere.

Meteoric nickel is found in combination with iron, a reflection of the origin of those elements as major end products of supernova nucleosynthesis. An iron–nickel mixture is thought to compose Earth’s outer and inner cores.[6]

Use of nickel (as natural meteoric nickel–iron alloy) has been traced as far back as 3500 BCE. Nickel was first isolated and classified as an element in 1751 by Axel Fredrik Cronstedt, who initially mistook the ore for a copper mineral, in the cobalt mines of Los, Hälsingland, Sweden. The element’s name comes from a mischievous sprite of German miner mythology, Nickel (similar to Old Nick), who personified the fact that copper-nickel ores resisted refinement into copper. An economically important source of nickel is the iron ore limonite, which is often 1–2% nickel. Other important nickel ore minerals include pentlandite and a mix of Ni-rich natural silicates known as garnierite. Major production sites include the Sudbury region, Canada (which is thought to be of meteoric origin), New Caledonia in the Pacific, and Norilsk, Russia.

Nickel is one of four elements (the others are iron, cobalt, and gadolinium)[7] that are ferromagnetic at about room temperature. Alnico permanent magnets based partly on nickel are of intermediate strength between iron-based permanent magnets and rare-earth magnets. The metal is used chiefly in alloys and corrosion-resistant plating. About 68% of world production is used in stainless steel. A further 10% is used for nickel-based and copper-based alloys, 9% for plating, 7% for alloy steels, 3% in foundries, and 4% in other applications such as in rechargeable batteries,[8] including those in electric vehicles (EVs).[9] Nickel is widely used in coins, though nickel-plated objects sometimes provoke nickel allergy. As a compound, nickel has a number of niche chemical manufacturing uses, such as a catalyst for hydrogenation, cathodes for rechargeable batteries, pigments and metal surface treatments.[10] Nickel is an essential nutrient for some microorganisms and plants that have enzymes with nickel as an active site.[11]

Properties

Atomic and physical properties

Nickel is a silvery-white metal with a slight golden tinge that takes a high polish. It is one of only four elements that are ferromagnetic at or near room temperature; the others are iron, cobalt and gadolinium. Its Curie temperature is 355 °C (671 °F), meaning that bulk nickel is non-magnetic above this temperature.[13][7] The unit cell of nickel is a face-centered cube with the lattice parameter of 0.352 nm, giving an atomic radius of 0.124 nm. This crystal structure is stable to pressures of at least 70 GPa. Nickel is hard, malleable and ductile, and has a relatively high electrical and thermal conductivity for transition metals.[14] The high compressive strength of 34 GPa, predicted for ideal crystals, is never obtained in the real bulk material due to formation and movement of dislocations. However, it has been reached in Ni nanoparticles.[15]

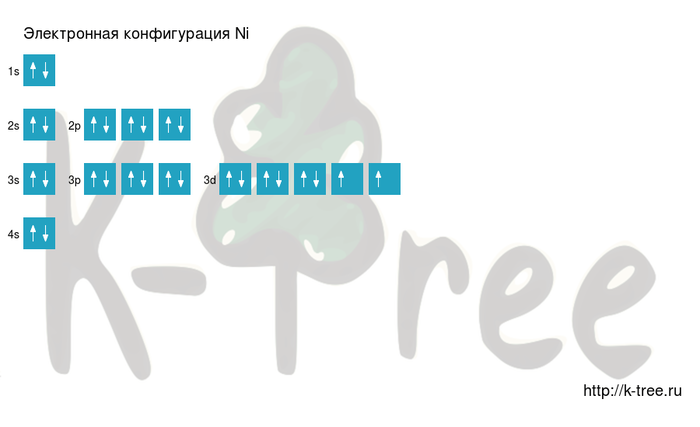

Electron configuration dispute

Nickel has two atomic electron configurations, [Ar] 3d8 4s2 and [Ar] 3d9 4s1, which are very close in energy; [Ar] denotes the complete argon core structure. There is some disagreement on which configuration has the lower energy.[16] Chemistry textbooks quote nickel’s electron configuration as [Ar] 4s2 3d8,[17] also written [Ar] 3d8 4s2.[18] This configuration agrees with the Madelung energy ordering rule, which predicts that 4s is filled before 3d. It is supported by the experimental fact that the lowest energy state of the nickel atom is a 3d8 4s2 energy level, specifically the 3d8(3F) 4s2 3F, J = 4 level.[19]

However, each of these two configurations splits into several energy levels due to fine structure,[19] and the two sets of energy levels overlap. The average energy of states with [Ar] 3d9 4s1 is actually lower than the average energy of states with [Ar] 3d8 4s2. Therefore, the research literature on atomic calculations quotes the ground state configuration as [Ar] 3d9 4s1.[16]

Isotopes

The isotopes of nickel range in atomic weight from 48 u (48

Ni) to 78 u (78

Ni).[20]

Natural nickel is composed of five stable isotopes, 58

Ni, 60

Ni, 61

Ni, 62

Ni and 64

Ni, of which 58

Ni is the most abundant (68.077% natural abundance).[20]

Nickel-62 has the highest binding energy per nucleon of any nuclide: 8.7946 MeV/nucleon.[21][22] Its binding energy is greater than both 56

Fe and 58

Fe, more abundant nuclides often incorrectly cited as having the highest binding energy.[23] Though this would seem to predict nickel as the most abundant heavy element in the universe, the high rate of photodisintegration of nickel in stellar interiors causes iron to be by far the most abundant.[23]

Nickel-60 is the daughter product of the extinct radionuclide 60

Fe (half-life 2.6 million years). Due to the long half-life of 60

Fe, its persistence in materials in the Solar System may generate observable variations in the isotopic composition of 60

Ni. Therefore, the abundance of 60

Ni in extraterrestrial material may give insight into the origin of the Solar System and its early history.[24]

At least 26 nickel radioisotopes have been characterized; the most stable are 59

Ni with half-life 76,000 years, 63

Ni (100 years), and 56

Ni (6 days). All other radioisotopes have half-lives less than 60 hours and most these have half-lives less than 30 seconds. This element also has one meta state.[20]

Radioactive nickel-56 is produced by the silicon burning process and later set free in large amounts in type Ia supernovae. The shape of the light curve of these supernovae at intermediate to late-times corresponds to the decay via electron capture of 56

Ni to cobalt-56 and ultimately to iron-56.[25] Nickel-59 is a long-lived cosmogenic radionuclide; half-life 76,000 years. 59

Ni has found many applications in isotope geology. 59

Ni has been used to date the terrestrial age of meteorites and to determine abundances of extraterrestrial dust in ice and sediment. The half-life of nickel-78 was recently measured at 110 milliseconds, and is believed an important isotope in supernova nucleosynthesis of elements heavier than iron.[26] 48Ni, discovered in 1999, is the most proton-rich heavy element isotope known. With 28 protons and 20 neutrons, 48Ni is «doubly magic», as is 78Ni with 28 protons and 50 neutrons. Both are therefore unusually stable for nuclei with so large a proton–neutron imbalance.[20][27]

Nickel-63 is a contaminant found in the support structure of nuclear reactors. It is produced through neutron capture by nickel-62. Small amounts have also been found near nuclear weapon test sites in the South Pacific.[28]

Occurrence

Widmanstätten pattern showing the two forms of nickel-iron, kamacite and taenite, in an octahedrite meteorite

On Earth, nickel occurs most often in combination with sulfur and iron in pentlandite, with sulfur in millerite, with arsenic in the mineral nickeline, and with arsenic and sulfur in nickel galena.[29] Nickel is commonly found in iron meteorites as the alloys kamacite and taenite. Nickel in meteorites was first detected in 1799 by Joseph-Louis Proust, a French chemist who then worked in Spain. Proust analyzed samples of the meteorite from Campo del Cielo (Argentina), which had been obtained in 1783 by Miguel Rubín de Celis, discovering the presence in them of nickel (about 10%) along with iron.[30]

The bulk of nickel is mined from two types of ore deposits. The first is laterite, where the principal ore mineral mixtures are nickeliferous limonite, (Fe,Ni)O(OH), and garnierite (a mixture of various hydrous nickel and nickel-rich silicates). The second is magmatic sulfide deposits, where the principal ore mineral is pentlandite: (Ni,Fe)9S8.[31]

Indonesia and Australia have the biggest estimated reserves, at 43.6% of world total.[32]

Identified land-based resources throughout the world averaging 1% nickel or greater comprise at least 130 million tons of nickel (about the double of known reserves). About 60% is in laterites and 40% in sulfide deposits.[33]

On geophysical evidence, most of the nickel on Earth is believed to be in Earth’s outer and inner cores. Kamacite and taenite are naturally occurring alloys of iron and nickel. For kamacite, the alloy is usually in the proportion of 90:10 to 95:5, though impurities (such as cobalt or carbon) may be present. Taenite is 20% to 65% nickel. Kamacite and taenite are also found in nickel iron meteorites.[34]

Compounds

The most common oxidation state of nickel is +2, but compounds of Ni0, Ni+, and Ni3+ are well known, and the exotic oxidation states Ni2− and Ni− have been produced and studied.[35]

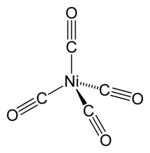

Nickel(0)

Nickel tetracarbonyl (Ni(CO)4), discovered by Ludwig Mond,[36] is a volatile, highly toxic liquid at room temperature. On heating, the complex decomposes back to nickel and carbon monoxide:

- Ni(CO)4 ⇌ Ni + 4 CO

This behavior is exploited in the Mond process for purifying nickel, as described above. The related nickel(0) complex bis(cyclooctadiene)nickel(0) is a useful catalyst in organonickel chemistry because the cyclooctadiene (or cod) ligands are easily displaced.

Nickel(I)

Structure of

[Ni2(CN)6]4− ion[37]

Nickel(I) complexes are uncommon, but one example is the tetrahedral complex NiBr(PPh3)3. Many nickel(I) complexes have Ni–Ni bonding, such as the dark red diamagnetic K4[Ni2(CN)6] prepared by reduction of K2[Ni2(CN)6] with sodium amalgam. This compound is oxidized in water, liberating H2.[37]

It is thought that the nickel(I) oxidation state is important to nickel-containing enzymes, such as [NiFe]-hydrogenase, which catalyzes the reversible reduction of protons to H2.[38]

Nickel(II)

Color of various Ni(II) complexes in aqueous solution. From left to right,

[Ni(NH3)6]2+,

[Ni(NH2CH2CH2NH2)]2+,

[NiCl4]2−,

[Ni(H2O)6]2+

Nickel(II) forms compounds with all common anions, including sulfide, sulfate, carbonate, hydroxide, carboxylates, and halides. Nickel(II) sulfate is produced in large amounts by dissolving nickel metal or oxides in sulfuric acid, forming both a hexa- and heptahydrate[39] useful for electroplating nickel. Common salts of nickel, such as chloride, nitrate, and sulfate, dissolve in water to give green solutions of the metal aquo complex [Ni(H2O)6]2+.[40]

The four halides form nickel compounds, which are solids with molecules with octahedral Ni centres. Nickel(II) chloride is most common, and its behavior is illustrative of the other halides. Nickel(II) chloride is made by dissolving nickel or its oxide in hydrochloric acid. It is usually found as the green hexahydrate, whose formula is usually written NiCl2·6H2O. When dissolved in water, this salt forms the metal aquo complex [Ni(H2O)6]2+. Dehydration of NiCl2·6H2O gives yellow anhydrous NiCl2.[41]

Some tetracoordinate nickel(II) complexes, e.g. bis(triphenylphosphine)nickel chloride, exist both in tetrahedral and square planar geometries. The tetrahedral complexes are paramagnetic; the square planar complexes are diamagnetic. In having properties of magnetic equilibrium and formation of octahedral complexes, they contrast with the divalent complexes of the heavier group 10 metals, palladium(II) and platinum(II), which form only square-planar geometry.[35]

Nickelocene is known; it has an electron count of 20, making it relatively unstable.[citation needed][42]

Nickel(III) and (IV)

Many Ni(III) compounds are known. The first such compounds are [Ni(PR3)2X2], where X = Cl, Br, I and R = ethyl, propyl, butyl.[43] Further, Ni(III) forms simple salts with fluoride[44] or oxide ions. Ni(III) can be stabilized by σ-donor ligands such as thiols and organophosphines.[37]

Ni(III) occurs in nickel oxide hydroxide, which is used as the cathode in many rechargeable batteries, including nickel-cadmium, nickel-iron, nickel hydrogen, and nickel-metal hydride, and used by certain manufacturers in Li-ion batteries.[45]

Ni(IV) occurs in the mixed oxide BaNiO3. Ni(IV) remains a rare oxidation state and very few compounds are known.[46][47][48][49]

History

Because nickel ores are easily mistaken for ores of silver and copper, understanding of this metal and its use, is relatively recent. But unintentional use of nickel is ancient, and can be traced back as far as 3500 BCE. Bronzes from what is now Syria have been found to contain as much as 2% nickel.[50] Some ancient Chinese manuscripts suggest that «white copper» (cupronickel, known as baitong) was used there in 1700-1400 BCE. This Paktong white copper was exported to Britain as early as the 17th century, but the nickel content of this alloy was not discovered until 1822.[51] Coins of nickel-copper alloy were minted by Bactrian kings Agathocles, Euthydemus II, and Pantaleon in the 2nd century BCE, possibly out of the Chinese cupronickel.[52]

In medieval Germany, a metallic yellow mineral was found in the Erzgebirge (Ore Mountains) that resembled copper ore. But when miners were unable to get any copper from it, they blamed a mischievous sprite of German mythology, Nickel (similar to Old Nick), for besetting the copper. They called this ore Kupfernickel from German Kupfer ‘copper’.[53][54][55][56] This ore is now known as the mineral nickeline (formerly niccolite[57]), a nickel arsenide. In 1751, Baron Axel Fredrik Cronstedt tried to extract copper from kupfernickel at a cobalt mine in the village of Los, Sweden, and instead produced a white metal that he named nickel after the spirit that had given its name to the mineral.[58] In modern German, Kupfernickel or Kupfer-Nickel designates the alloy cupronickel.[14]

Originally, the only source for nickel was the rare Kupfernickel. Beginning in 1824, nickel was obtained as a byproduct of cobalt blue production. The first large-scale smelting of nickel began in Norway in 1848 from nickel-rich pyrrhotite. The introduction of nickel in steel production in 1889 increased the demand for nickel; the nickel deposits of New Caledonia, discovered in 1865, provided most of the world’s supply between 1875 and 1915. The discovery of the large deposits in the Sudbury Basin, Canada in 1883, in Norilsk-Talnakh, Russia in 1920, and in the Merensky Reef, South Africa in 1924, made large-scale nickel production possible.[51]

Coinage

Aside from the aforementioned Bactrian coins, nickel was not a component of coins until the mid-19th century.[citation needed]

Canada

99.9% nickel five-cent coins were struck in Canada (the world’s largest nickel producer at the time) during non-war years from 1922 to 1981; the metal content made these coins magnetic.[59] During the war years 1942–45, most or all nickel was removed from Canadian and US coins to save it for making armor.[54][60] Canada used 99.9% nickel from 1968 in its higher-value coins until 2000.[citation needed]

Switzerland

Coins of nearly pure nickel were first used in 1881 in Switzerland.[61]

United Kingdom

Birmingham forged nickel coins in c. 1833 for trading in Malaysia.[62]

United States

In the United States, the term «nickel» or «nick» originally applied to the copper-nickel Flying Eagle cent, which replaced copper with 12% nickel 1857–58, then the Indian Head cent of the same alloy from 1859 to 1864. Still later, in 1865, the term designated the three-cent nickel, with nickel increased to 25%. In 1866, the five-cent shield nickel (25% nickel, 75% copper) appropriated the designation, which has been used ever since for the subsequent 5-cent pieces. This alloy proportion is not ferromagnetic.

The US nickel coin contains 0.04 ounces (1.1 g) of nickel, which at the April 2007 price was worth 6.5 cents, along with 3.75 grams of copper worth about 3 cents, with a total metal value of more than 9 cents. Since the face value of a nickel is 5 cents, this made it an attractive target for melting by people wanting to sell the metals at a profit. The United States Mint, anticipating this practice, implemented new interim rules on December 14, 2006, subject to public comment for 30 days, which criminalized the melting and export of cents and nickels.[63] Violators can be punished with a fine of up to $10,000 and/or a maximum of five years in prison.[64] As of September 19, 2013, the melt value of a US nickel (copper and nickel included) is $0.045 (90% of the face value).[65]

Current use

In the 21st century, the high price of nickel has led to some replacement of the metal in coins around the world. Coins still made with nickel alloys include one- and two-euro coins, 5¢, 10¢, 25¢, 50¢, and $1 U.S. coins,[66] and 20p, 50p, £1, and £2 UK coins. From 2012 on the nickel-alloy used for 5p and 10p UK coins was replaced with nickel-plated steel. This ignited a public controversy regarding the problems of people with nickel allergy.[61]

World production

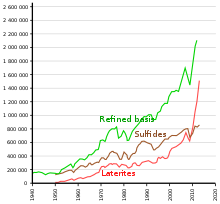

Time trend of nickel production[67]

Nickel ores grade evolution in some leading nickel producing countries or regions.

An estimated 2.7 million tonnes (t) of nickel per year are mined worldwide; Indonesia (1,000,000 t), the Philippines (370,000 t), Russia (250,000 t), New Caledonia (France) (190,000 t), Australia (160,000 t) and Canada (130,000 t) are the largest producers as of 2021.[68] The largest nickel deposits in non-Russian Europe are in Finland and Greece. Identified land-based sources averaging at least 1% nickel contain at least 130 million tonnes of nickel. About 60% is in laterites and 40% is in sulfide deposits. Also, extensive nickel sources are found in the depths of the Pacific Ocean, especially in an area called the Clarion Clipperton Zone in the form of polymetallic nodules peppering the seafloor at 3.5–6 km below sea level.[69][70] These nodules are composed of numerous rare-earth metals and are estimated to be 1.7% nickel.[71] With advances in science and engineering, regulation is currently being set in place by the International Seabed Authority to ensure that these nodules are collected in an environmentally conscientious manner while adhering to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.[72]

The one place in the United States where nickel has been profitably mined is Riddle, Oregon, with several square miles of nickel-bearing garnierite surface deposits. The mine closed in 1987.[73][74] The Eagle mine project is a new nickel mine in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Construction was completed in 2013, and operations began in the third quarter of 2014.[75] In the first full year of operation, the Eagle Mine produced 18,000 t.[75]

Production

Evolution of the annual nickel extraction, according to ores.

Nickel is obtained through extractive metallurgy: it is extracted from ore by conventional roasting and reduction processes that yield metal of greater than 75% purity. In many stainless steel applications, 75% pure nickel can be used without further purification, depending on impurities.[39]

Traditionally, most sulfide ores are processed using pyrometallurgical techniques to produce a matte for further refining. Recent advances in hydrometallurgical techniques result in significantly purer metallic nickel product. Most sulfide deposits have traditionally been processed by concentration through a froth flotation process followed by pyrometallurgical extraction. In hydrometallurgical processes, nickel sulfide ores are concentrated with flotation (differential flotation if Ni/Fe ratio is too low) and then smelted. The nickel matte is further processed with the Sherritt-Gordon process. First, copper is removed by adding hydrogen sulfide, leaving a concentrate of cobalt and nickel. Then, solvent extraction is used to separate the cobalt and nickel, with the final nickel content greater than 99%.[citation needed]

Electrorefining

A second common refining process is leaching the metal matte into a nickel salt solution, followed by electrowinning the nickel from solution by plating it onto a cathode as electrolytic nickel.[76]

Mond process

The purest metal is obtained from nickel oxide by the Mond process, which gives a purity of over 99.99%.[77] The process was patented by Ludwig Mond and has been in industrial use since before the beginning of the 20th century. In this process, nickel is reacted with carbon monoxide in the presence of a sulfur catalyst at around 40–80 °C to form nickel carbonyl. In a similar reaction with iron, iron pentacarbonyl can form, though this reaction is slow. If necessary, the nickel may be separated by distillation. Dicobalt octacarbonyl is also formed in nickel distillation as a by-product, but it decomposes to tetracobalt dodecacarbonyl at the reaction temperature to give a non-volatile solid.[78]

Nickel is obtained from nickel carbonyl by one of two processes. It may be passed through a large chamber at high temperatures in which tens of thousands of nickel spheres (pellets) are constantly stirred. The carbonyl decomposes and deposits pure nickel onto the spheres. In the alternate process, nickel carbonyl is decomposed in a smaller chamber at 230 °C to create a fine nickel powder. The byproduct carbon monoxide is recirculated and reused. The highly pure nickel product is known as «carbonyl nickel».[79]

Market value

The market price of nickel surged throughout 2006 and the early months of 2007; as of April 5, 2007, the metal was trading at US$52,300/tonne or $1.47/oz.[80] The price later fell dramatically; as of September 2017, the metal was trading at $11,000/tonne, or $0.31/oz.[81] During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, worries about sanctions on Russian nickel exports triggered a short squeeze, causing the price of nickel to quadruple in just two days, reaching US$100,000 per tonne.[82][83] The London Metal Exchange cancelled contracts worth $3.9 billion and suspended nickel trading for over a week.[84] Analyst Andy Home argued that such price shocks are exacerbated by the purity requirements imposed by metal markets: only Grade I (99.8% pure) metal can be used as a commodity on the exchanges, but most of the world’s supply is either in ferro-nickel alloys or lower-grade purities.[85]

Applications

Nickel foam (top) and its internal structure (bottom)

Global use of nickel is currently 68% in stainless steel, 10% in nonferrous alloys, 9% electroplating, 7% alloy steel, 3% foundries, and 4% other (including batteries).[8]

Nickel is used in many recognizable industrial and consumer products, including stainless steel, alnico magnets, coinage, rechargeable batteries (e.g. nickel-iron), electric guitar strings, microphone capsules, plating on plumbing fixtures,[86] and special alloys such as permalloy, elinvar, and invar. It is used for plating and as a green tint in glass. Nickel is preeminently an alloy metal, and its chief use is in nickel steels and nickel cast irons, in which it typically increases the tensile strength, toughness, and elastic limit. It is widely used in many other alloys, including nickel brasses and bronzes and alloys with copper, chromium, aluminium, lead, cobalt, silver, and gold (Inconel, Incoloy, Monel, Nimonic).[76]

A «horseshoe magnet» made of alnico nickel alloy.

Because nickel is resistant to corrosion, it was occasionally used as a substitute for decorative silver. Nickel was also occasionally used in some countries after 1859 as a cheap coinage metal (see above), but in the later years of the 20th century, it was replaced by cheaper stainless steel (i.e., iron) alloys, except in the United States and Canada.[citation needed]

Nickel is an excellent alloying agent for certain precious metals and is used in the fire assay as a collector of platinum group elements (PGE). As such, nickel can fully collect all six PGEs from ores, and can partially collect gold. High-throughput nickel mines may also do PGE recovery (mainly platinum and palladium); examples are Norilsk, Russia and the Sudbury Basin, Canada.[87]

Nickel foam or nickel mesh is used in gas diffusion electrodes for alkaline fuel cells.[88][89]

Nickel and its alloys are often used as catalysts for hydrogenation reactions. Raney nickel, a finely divided nickel-aluminium alloy, is one common form, though related catalysts are also used, including Raney-type catalysts.[citation needed]

Nickel is naturally magnetostrictive: in the presence of a magnetic field, the material undergoes a small change in length.[90][91] The magnetostriction of nickel is on the order of 50 ppm and is negative, indicating that it contracts.[92]

Nickel is used as a binder in the cemented tungsten carbide or hardmetal industry and used in proportions of 6% to 12% by weight. Nickel makes the tungsten carbide magnetic and adds corrosion-resistance to the cemented parts, though the hardness is less than those with cobalt binder.[93]

63

Ni, with half-life 100.1 years, is useful in krytron devices as a beta particle (high-speed electron) emitter to make ionization by the keep-alive electrode more reliable.[94] It is being investigated as a power source for betavoltaic batteries.[95][96]

Around 27% of all nickel production is used for engineering, 10% for building and construction, 14% for tubular products, 20% for metal goods, 14% for transport, 11% for electronic goods, and 5% for other uses.[8]

Raney nickel is widely used for hydrogenation of unsaturated oils to make margarine, and substandard margarine and leftover oil may contain nickel as a contaminant. Forte et al. found that type 2 diabetic patients have 0.89 ng/mL of Ni in the blood relative to 0.77 ng/mL in control subjects.[97]

Biological role

It was not recognized until the 1970s, but nickel is known to play an important role in the biology of some plants, bacteria, archaea, and fungi.[98][99][100] Nickel enzymes such as urease are considered virulence factors in some organisms.[101][102] Urease catalyzes hydrolysis of urea to form ammonia and carbamate.[99][98] NiFe hydrogenases can catalyze oxidation of H2 to form protons and electrons; and also the reverse reaction, the reduction of protons to form hydrogen gas.[99][98] A nickel-tetrapyrrole coenzyme, cofactor F430, is present in methyl coenzyme M reductase, which can catalyze the formation of methane, or the reverse reaction, in methanogenic archaea (in +1 oxidation state).[103] One of the carbon monoxide dehydrogenase enzymes consists of an Fe-Ni-S cluster.[104] Other nickel-bearing enzymes include a rare bacterial class of superoxide dismutase[105] and glyoxalase I enzymes in bacteria and several eukaryotic trypanosomal parasites[106] (in other organisms, including yeast and mammals, this enzyme contains divalent Zn2+).[107][108][109][110][111]

Dietary nickel may affect human health through infections by nickel-dependent bacteria, but nickel may also be an essential nutrient for bacteria living in the large intestine, in effect functioning as a prebiotic.[112] The US Institute of Medicine has not confirmed that nickel is an essential nutrient for humans, so neither a Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) nor an Adequate Intake have been established. The tolerable upper intake level of dietary nickel is 1 mg/day as soluble nickel salts. Estimated dietary intake is 70 to 100 µg/day; less than 10% is absorbed. What is absorbed is excreted in urine.[113] Relatively large amounts of nickel – comparable to the estimated average ingestion above – leach into food cooked in stainless steel. For example, the amount of nickel leached after 10 cooking cycles into one serving of tomato sauce averages 88 µg.[114][115]

Nickel released from Siberian Traps volcanic eruptions is suspected of helping the growth of Methanosarcina, a genus of euryarchaeote archaea that produced methane in the Permian–Triassic extinction event, the biggest known mass extinction.[116]

Toxicity

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling: | |

|

Pictograms |

|

|

Signal word |

Danger |

|

Hazard statements |

H317, H351, H372, H412 |

|

Precautionary statements |

P201, P202, P260, P264, P270, P272, P273, P280, P302+P352, P308+P313, P333+P313, P363, P405, P501[117] |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

2 0 0 |

The major source of nickel exposure is oral consumption, as nickel is essential to plants.[118] Typical background concentrations of nickel do not exceed 20 ng/m3 in air, 100 mg/kg in soil, 10 mg/kg in vegetation, 10 μg/L in freshwater and 1 μg/L in seawater.[119] Environmental concentrations may be increased by human pollution. For example, nickel-plated faucets may contaminate water and soil; mining and smelting may dump nickel into wastewater; nickel–steel alloy cookware and nickel-pigmented dishes may release nickel into food. Air may be polluted by nickel ore refining and fossil fuel combustion. Humans may absorb nickel directly from tobacco smoke and skin contact with jewelry, shampoos, detergents, and coins. A less common form of chronic exposure is through hemodialysis as traces of nickel ions may be absorbed into the plasma from the chelating action of albumin.[citation needed]

The average daily exposure is not a threat to human health. Most nickel absorbed by humans is removed by the kidneys and passed out of the body through urine or is eliminated through the gastrointestinal tract without being absorbed. Nickel is not a cumulative poison, but larger doses or chronic inhalation exposure may be toxic, even carcinogenic, and constitute an occupational hazard.[120]

Nickel compounds are classified as human carcinogens[121][122][123][124] based on increased respiratory cancer risks observed in epidemiological studies of sulfidic ore refinery workers.[125] This is supported by the positive results of the NTP bioassays with Ni sub-sulfide and Ni oxide in rats and mice.[126][127] The human and animal data consistently indicate a lack of carcinogenicity via the oral route of exposure and limit the carcinogenicity of nickel compounds to respiratory tumours after inhalation.[128][129] Nickel metal is classified as a suspect carcinogen;[121][122][123] there is consistency between the absence of increased respiratory cancer risks in workers predominantly exposed to metallic nickel[125] and the lack of respiratory tumours in a rat lifetime inhalation carcinogenicity study with nickel metal powder.[130] In the rodent inhalation studies with various nickel compounds and nickel metal, increased lung inflammations with and without bronchial lymph node hyperplasia or fibrosis were observed.[124][126][130][131] In rat studies, oral ingestion of water-soluble nickel salts can trigger perinatal mortality in pregnant animals.[132] Whether these effects are relevant to humans is unclear as epidemiological studies of highly exposed female workers have not shown adverse developmental toxicity effects.[133]

People can be exposed to nickel in the workplace by inhalation, ingestion, and contact with skin or eye. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set the legal limit (permissible exposure limit) for the workplace at 1 mg/m3 per 8-hour workday, excluding nickel carbonyl. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) sets the recommended exposure limit (REL) at 0.015 mg/m3 per 8-hour workday. At 10 mg/m3, nickel is immediately dangerous to life and health.[134] Nickel carbonyl [Ni(CO)4] is an extremely toxic gas. The toxicity of metal carbonyls is a function of both the toxicity of the metal and the off-gassing of carbon monoxide from the carbonyl functional groups; nickel carbonyl is also explosive in air.[135][136]

Sensitized persons may show a skin contact allergy to nickel known as a contact dermatitis. Highly sensitized persons may also react to foods with high nickel content.[137] Patients with pompholyx may also be sensitive to nickel. Nickel is the top confirmed contact allergen worldwide, partly due to its use in jewelry for pierced ears.[138] Nickel allergies affecting pierced ears are often marked by itchy, red skin. Many earrings are now made without nickel or with low-release nickel[139] to address this problem. The amount allowed in products that contact human skin is now regulated by the European Union. In 2002, researchers found that the nickel released by 1 and 2 euro coins, far exceeded those standards. This is believed to be due to a galvanic reaction.[140] Nickel was voted Allergen of the Year in 2008 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.[141] In August 2015, the American Academy of Dermatology adopted a position statement on the safety of nickel: «Estimates suggest that contact dermatitis, which includes nickel sensitization, accounts for approximately $1.918 billion and affects nearly 72.29 million people.»[137]

Reports show that both the nickel-induced activation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1) and the up-regulation of hypoxia-inducible genes are caused by depletion of intracellular ascorbate. The addition of ascorbate to the culture medium increased the intracellular ascorbate level and reversed both the metal-induced stabilization of HIF-1- and HIF-1α-dependent gene expression.[142][143]

References

- ^ «Standard Atomic Weights: Nickel». CIAAW. 2007.

- ^ Pfirrmann, Stefan; Limberg, Christian; Herwig, Christian; Stößer, Reinhard; Ziemer, Burkhard (2009). «A Dinuclear Nickel(I) Dinitrogen Complex and its Reduction in Single-Electron Steps». Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 48 (18): 3357–61. doi:10.1002/anie.200805862. PMID 19322853.

- ^ Carnes, Matthew; Buccella, Daniela; Chen, Judy Y.-C.; Ramirez, Arthur P.; Turro, Nicholas J.; Nuckolls, Colin; Steigerwald, Michael (2009). «A Stable Tetraalkyl Complex of Nickel(IV)». Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 48 (2): 290–4. doi:10.1002/anie.200804435. PMID 19021174.

- ^ Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C., eds. (1990). «Nickel» (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. Vol. I. Chantilly, VA, US: Mineralogical Society of America. ISBN 978-0962209703.

- ^ «Nickel: Nickel mineral information and data». Mindat.org. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 2, 2016.

- ^ Stixrude, Lars; Waserman, Evgeny; Cohen, Ronald (November 1997). «Composition and temperature of Earth’s inner core». Journal of Geophysical Research. 102 (B11): 24729–24740. Bibcode:1997JGR…10224729S. doi:10.1029/97JB02125.

- ^ a b Coey, J. M. D.; Skumryev, V.; Gallagher, K. (1999). «Rare-earth metals: Is gadolinium really ferromagnetic?». Nature. 401 (6748): 35–36. Bibcode:1999Natur.401…35C. doi:10.1038/43363. S2CID 4383791.

- ^ a b c «Nickel Use In Society». Nickel Institute. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017.

- ^ Treadgold, Tim. «Gold Is Hot But Nickel Is Hotter As Demand Grows For Batteries In Electric Vehicles». Forbes. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- ^ «Nickel Compounds – The Inside Story». Nickel Institute. Archived from the original on August 31, 2018.

- ^ Mulrooney, Scott B.; Hausinger, Robert P. (June 1, 2003). «Nickel uptake and utilization by microorganisms». FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 27 (2–3): 239–261. doi:10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00042-1. ISSN 0168-6445. PMID 12829270.

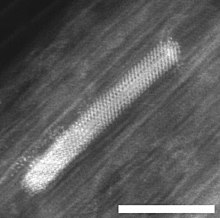

- ^ Shiozawa, Hidetsugu; Briones-Leon, Antonio; Domanov, Oleg; Zechner, Georg; et al. (2015). «Nickel clusters embedded in carbon nanotubes as high performance magnets». Scientific Reports. 5: 15033. Bibcode:2015NatSR…515033S. doi:10.1038/srep15033. PMC 4602218. PMID 26459370.

- ^ Kittel, Charles (1996). Introduction to Solid State Physics. Wiley. p. 449. ISBN 978-0-471-14286-7.

- ^ a b Hammond, C.R.; Lide, C. R. (2018). «The elements». In Rumble, John R. (ed.). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (99th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 4.22. ISBN 9781138561632.

- ^ Sharma, A.; Hickman, J.; Gazit, N.; Rabkin, E.; Mishin, Y. (2018). «Nickel nanoparticles set a new record of strength». Nature Communications. 9 (1): 4102. Bibcode:2018NatCo…9.4102S. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06575-6. PMC 6173750. PMID 30291239.

- ^ a b Scerri, Eric R. (2007). The periodic table: its story and its significance. Oxford University Press. pp. 239–240. ISBN 978-0-19-530573-9.

- ^ Miessler, G.L. and Tarr, D.A. (1999) Inorganic Chemistry 2nd ed., Prentice–Hall. p. 38. ISBN 0138418918.

- ^ Petrucci, R.H. et al. (2002) General Chemistry 8th ed., Prentice–Hall. p. 950. ISBN 0130143294.

- ^ a b NIST Atomic Spectrum Database Archived March 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine To read the nickel atom levels, type «Ni I» in the Spectrum box and click on Retrieve data.

- ^ a b c d Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). «The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties» (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- ^ Shurtleff, Richard; Derringh, Edward (1989). «The Most Tightly Bound Nuclei». American Journal of Physics. 57 (6): 552. Bibcode:1989AmJPh..57..552S. doi:10.1119/1.15970. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ^ «Nuclear synthesis». hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ a b Fewell, M. P. (1995). «The atomic nuclide with the highest mean binding energy». American Journal of Physics. 63 (7): 653. Bibcode:1995AmJPh..63..653F. doi:10.1119/1.17828.

- ^ Caldwell, Eric. «Resources on Isotopes». United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Pagel, Bernard Ephraim Julius (1997). «Further burning stages: evolution of massive stars». Nucleosynthesis and chemical evolution of galaxies. pp. 154–160. ISBN 978-0-521-55958-4.

- ^ Castelvecchi, Davide (April 22, 2005). «Atom Smashers Shed Light on Supernovae, Big Bang». Archived from the original on July 23, 2012. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ^ W, P. (October 23, 1999). «Twice-magic metal makes its debut – isotope of nickel». Science News. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- ^ Carboneau, M. L.; Adams, J. P. (1995). «Nickel-63». National Low-Level Waste Management Program Radionuclide Report Series. 10. doi:10.2172/31669.

- ^ National Pollutant Inventory – Nickel and compounds Fact Sheet Archived December 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Npi.gov.au. Retrieved on January 9, 2012.

- ^ Calvo, Miguel (2019). Construyendo la Tabla Periódica. Zaragoza, Spain: Prames. p. 118. ISBN 978-84-8321-908-9.

- ^ Mudd, Gavin M. (2010). «Global trends and environmental issues in nickel mining: Sulfides versus laterites». Ore Geology Reviews. Elsevier BV. 38 (1–2): 9–26. doi:10.1016/j.oregeorev.2010.05.003. ISSN 0169-1368.

- ^ «Nickel reserves worldwide by country 2020». Statista. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ Kuck, Peter H. «Mineral Commodity Summaries 2019: Nickel» (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 21, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ Rasmussen, K. L.; Malvin, D. J.; Wasson, J. T. (1988). «Trace element partitioning between taenite and kamacite – Relationship to the cooling rates of iron meteorites». Meteoritics. 23 (2): a107–112. Bibcode:1988Metic..23..107R. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.1988.tb00905.x.

- ^ a b Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ «The Extraction of Nickel from its Ores by the Mond Process». Nature. 59 (1516): 63–64. 1898. Bibcode:1898Natur..59…63.. doi:10.1038/059063a0.

- ^ a b c Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. G. (2008). Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 729. ISBN 978-0-13-175553-6.

- ^ Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. G. (2012). Inorganic Chemistry (4th ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 764. ISBN 978-0273742753.

- ^ a b Lascelles, Keith; Morgan, Lindsay G.; Nicholls, David and Beyersmann, Detmar (2019) «Nickel Compounds» in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a17_235.pub3

- ^ «A Review on the Metal Complex of Nickel (Ii) Salicylhydroxamic Acid and its Aniline Adduct». www.heraldopenaccess.us. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ «metal — The Reaction Between Nickel and Hydrochloric Acid». Chemistry Stack Exchange. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ «course hero».

- ^ Jensen, K. A. (1936). «Zur Stereochemie des koordinativ vierwertigen Nickels». Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie. 229 (3): 265–281. doi:10.1002/zaac.19362290304.

- ^ Court, T. L.; Dove, M. F. A. (1973). «Fluorine compounds of nickel(III)». Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions (19): 1995. doi:10.1039/DT9730001995.

- ^ «Imara Corporation Launches; New Li-ion Battery Technology for High-Power Applications». Green Car Congress. December 18, 2008. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2009.

- ^ Spokoyny, Alexander M.; Li, Tina C.; Farha, Omar K.; Machan, Charles M.; She, Chunxing; Stern, Charlotte L.; Marks, Tobin J.; Hupp, Joseph T.; Mirkin, Chad A. (June 28, 2010). «Electronic Tuning of Nickel-Based Bis(dicarbollide) Redox Shuttles in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells». Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49 (31): 5339–5343. doi:10.1002/anie.201002181. PMID 20586090.

- ^ Hawthorne, M. Frederick (1967). «(3)-1,2-Dicarbollyl Complexes of Nickel(III) and Nickel(IV)». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 89 (2): 470–471. doi:10.1021/ja00978a065.

- ^ Camasso, N. M.; Sanford, M. S. (2015). «Design, synthesis, and carbon-heteroatom coupling reactions of organometallic nickel(IV) complexes». Science. 347 (6227): 1218–20. Bibcode:2015Sci…347.1218C. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.897.9273. doi:10.1126/science.aaa4526. PMID 25766226. S2CID 206634533.

- ^ Baucom, E. I.; Drago, R. S. (1971). «Nickel(II) and nickel(IV) complexes of 2,6-diacetylpyridine dioxime». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 93 (24): 6469–6475. doi:10.1021/ja00753a022.

- ^ Rosenberg, Samuel J. (1968). Nickel and Its Alloys. National Bureau of Standards. Archived from the original on May 23, 2012.

- ^ a b McNeil, Ian (1990). «The Emergence of Nickel». An Encyclopaedia of the History of Technology. Taylor & Francis. pp. 96–100. ISBN 978-0-415-01306-2.

- ^ Needham, Joseph; Wang, Ling; Lu, Gwei-Djen; Tsien, Tsuen-hsuin; Kuhn, Dieter and Golas, Peter J. (1974) Science and civilisation in China Archived May 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-08571-3, pp. 237–250.

- ^ Chambers Twentieth Century Dictionary, p888, W&R Chambers Ltd., 1977.

- ^ a b Baldwin, W. H. (1931). «The story of Nickel. I. How «Old Nick’s» gnomes were outwitted». Journal of Chemical Education. 8 (9): 1749. Bibcode:1931JChEd…8.1749B. doi:10.1021/ed008p1749.

- ^ Baldwin, W. H. (1931). «The story of Nickel. II. Nickel comes of age». Journal of Chemical Education. 8 (10): 1954. Bibcode:1931JChEd…8.1954B. doi:10.1021/ed008p1954.

- ^ Baldwin, W. H. (1931). «The story of Nickel. III. Ore, matte, and metal». Journal of Chemical Education. 8 (12): 2325. Bibcode:1931JChEd…8.2325B. doi:10.1021/ed008p2325.

- ^ Fleisher, Michael and Mandarino, Joel. Glossary of Mineral Species. Tucson, Arizona: Mineralogical Record, 7th ed. 1995.

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). «The discovery of the elements: III. Some eighteenth-century metals». Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (1): 22. Bibcode:1932JChEd…9…22W. doi:10.1021/ed009p22.

- ^ «Industrious, enduring–the 5-cent coin». Royal Canadian Mint. 2008. Archived from the original on January 26, 2009. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ Molloy, Bill (November 8, 2001). «Trends of Nickel in Coins – Past, Present and Future». The Nickel Institute. Archived from the original on September 29, 2006. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- ^ a b Lacey, Anna (June 22, 2013). «A bad penny? New coins and nickel allergy». BBC Health Check. Archived from the original on August 7, 2013. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- ^ «nikkelen dubbele wapenstuiver Utrecht». nederlandsemunten.nl. Archived from the original on January 7, 2015. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ^ United States Mint Moves to Limit Exportation & Melting of Coins Archived May 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The United States Mint, press release, December 14, 2006

- ^ «Prohibition on the Exportation, Melting, or Treatment of 5-Cent and One-Cent Coins». Federal Register. April 16, 2007. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ «United States Circulating Coinage Intrinsic Value Table». Coininflation.com. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ «Coin Specifications». usmint.gov. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ Kelly, T. D.; Matos, G. R. «Nickel Statistics» (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ «Mineral Commodity Summaries 2022 — Nickel» (PDF). US Geological Survey. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ «Nickel» (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries. January 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- ^ Gazley, Michael F.; Tay, Stephie; Aldrich, Sean. «Polymetallic Nodules». Research Gate. New Zealand Minerals Forum. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ Mero, J. L. (January 1, 1977). «Chapter 11 Economic Aspects of Nodule Mining». Marine Manganese Deposits. Elsevier Oceanography Series. Vol. 15. pp. 327–355. doi:10.1016/S0422-9894(08)71025-0. ISBN 9780444415240.

- ^ International Seabed Authority. «Strategic Plan 2019-2023» (PDF). isa.org. International Seabed Authority. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ «The Nickel Mountain Project» (PDF). Ore Bin. 15 (10): 59–66. 1953. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 12, 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ «Environment Writer: Nickel». National Safety Council. 2006. Archived from the original on August 28, 2006. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ a b «Operations & Development». Lundin Mining Corporation. Archived from the original on November 18, 2015. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ^ a b Davis, Joseph R. (2000). «Uses of Nickel». ASM Specialty Handbook: Nickel, Cobalt, and Their Alloys. ASM International. pp. 7–13. ISBN 978-0-87170-685-0.

- ^ Mond, L.; Langer, K.; Quincke, F. (1890). «Action of carbon monoxide on nickel». Journal of the Chemical Society. 57: 749–753. doi:10.1039/CT8905700749.

- ^ Kerfoot, Derek G. E. (2005). «Nickel». Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a17_157.

- ^ Neikov, Oleg D.; Naboychenko, Stanislav; Gopienko, Victor G & Frishberg, Irina V (January 15, 2009). Handbook of Non-Ferrous Metal Powders: Technologies and Applications. Elsevier. pp. 371–. ISBN 978-1-85617-422-0. Archived from the original on May 29, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- ^ «LME nickel price graphs». London Metal Exchange. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ^ «London Metal Exchange». LME.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2017.

- ^ Hume, Neil; Lockett, Hudson (March 8, 2022). «LME introduces emergency measures as nickel hits $100,000 a tonne». Financial Times. Archived from the original on December 10, 2022. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ Burton, Mark; Farchy, Jack; Cang, Alfred. «LME Halts Nickel Trading After Unprecedented 250% Spike». Bloomberg News. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ Farchy, Jack; Cang, Alfred; Burton, Mark (March 14, 2022). «The 18 Minutes of Trading Chaos That Broke the Nickel Market». Bloomberg News.

- ^ Home, Andy (March 10, 2022). «Column: Nickel, the devil’s metal with a history of bad behaviour». Reuters. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ American Plumbing Practice: From the Engineering Record (Prior to 1887 the Sanitary Engineer.) A Selected Reprint of Articles Describing Notable Plumbing Installations in the United States, and Questions and Answers on Problems Arising in Plumbing and House Draining. With Five Hundred and Thirty-six Illustrations. Engineering record. 1896. p. 119. Retrieved May 28, 2016.

- ^ «Platinum-Group Element — an overview | ScienceDirect Topics». www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved October 18, 2022.

- ^ Kharton, Vladislav V. (2011). Solid State Electrochemistry II: Electrodes, Interfaces and Ceramic Membranes. Wiley-VCH. pp. 166–. ISBN 978-3-527-32638-9. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ Bidault, F.; Brett, D. J. L.; Middleton, P. H.; Brandon, N. P. «A New Cathode Design for Alkaline Fuel Cells (AFCs)» (PDF). Imperial College London. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2011.

- ^ Magnetostrictive Materials Overview. University of California, Los Angeles.

- ^ Angara, Raghavendra (2009). High Frequency High Amplitude Magnetic Field Driving System for Magnetostrictive Actuators. Umi Dissertation Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 9781109187533.

- ^ Sofronie, Mihaela; Tolea, Mugurel; Popescu, Bogdan; Enculescu, Monica; Tolea, Felicia (September 7, 2021). «Magnetic and Magnetostrictive Properties of Ni50Mn20Ga27Cu3 Rapidly Quenched Ribbons». Materials. 14 (18): 5126. Bibcode:2021Mate…14.5126S. doi:10.3390/ma14185126. ISSN 1996-1944. PMC 8471753. PMID 34576350.

- ^ Cheburaeva, R. F.; Chaporova, I. N.; Krasina, T. I. (1992). «Structure and properties of tungsten carbide hard alloys with an alloyed nickel binder». Soviet Powder Metallurgy and Metal Ceramics. 31 (5): 423–425. doi:10.1007/BF00796252. S2CID 135714029.

- ^ «Krytron Pulse Power Switching Tubes». Silicon Investigations. 2011. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011.

- ^ Uhm, Y. R.; et al. (June 2016). «Study of a Betavoltaic Battery Using Electroplated Nickel-63 on Nickel Foil as a Power Source». Nuclear Engineering and Technology. 48 (3): 773–777. doi:10.1016/j.net.2016.01.010.

- ^ Bormashov, V. S.; et al. (April 2018). «High power density nuclear battery prototype based on diamond Schottky diodes». Diamond and Related Materials. 84: 41–47. Bibcode:2018DRM….84…41B. doi:10.1016/j.diamond.2018.03.006.

- ^ Khan, Abdul Rehman; Awan, Fazli Rabbi (January 8, 2014). «Metals in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes». Journal of Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders. 13 (1): 16. doi:10.1186/2251-6581-13-16. PMC 3916582. PMID 24401367.

- ^ a b c Astrid Sigel; Helmut Sigel; Roland K. O. Sigel, eds. (2008). Nickel and Its Surprising Impact in Nature. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 2. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-01671-8.

- ^ a b c Sydor, Andrew; Zamble, Deborah (2013). Banci, Lucia (ed.). Nickel Metallomics: General Themes Guiding Nickel Homeostasis. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 12. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 375–416. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-1_11. ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1. PMID 23595678.

- ^ Zamble, Deborah; Rowińska-Żyrek, Magdalena; Kozlowski, Henryk (2017). The Biological Chemistry of Nickel. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-1-78262-498-1.

- ^ Covacci, Antonello; Telford, John L.; Giudice, Giuseppe Del; Parsonnet, Julie; Rappuoli, Rino (May 21, 1999). «Helicobacter pylori Virulence and Genetic Geography». Science. 284 (5418): 1328–1333. Bibcode:1999Sci…284.1328C. doi:10.1126/science.284.5418.1328. PMID 10334982. S2CID 10376008.

- ^ Cox, Gary M.; Mukherjee, Jean; Cole, Garry T.; Casadevall, Arturo; Perfect, John R. (February 1, 2000). «Urease as a Virulence Factor in Experimental Cryptococcosis». Infection and Immunity. 68 (2): 443–448. doi:10.1128/IAI.68.2.443-448.2000. PMC 97161. PMID 10639402.

- ^

Stephen W., Ragdale (2014). «Chapter 6. Biochemistry of Methyl-Coenzyme M Reductase: The Nickel Metalloenzyme that Catalyzes the Final Step in Synthesis and the First Step in Anaerobic Oxidation of the Greenhouse Gas Methane«. In Peter M.H. Kroneck; Martha E. Sosa Torres (eds.). The Metal-Driven Biogeochemistry of Gaseous Compounds in the Environment. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 14. Springer. pp. 125–145. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9269-1_6. ISBN 978-94-017-9268-4. PMID 25416393. - ^

Wang, Vincent C.-C.; Ragsdale, Stephen W.; Armstrong, Fraser A. (2014). «Chapter 4. Investigations of the Efficient Electrocatalytic Interconversions of Carbon Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide by Nickel-Containing Carbon Monoxide Dehydrogenases». In Peter M.H. Kroneck; Martha E. Sosa Torres (eds.). The Metal-Driven Biogeochemistry of Gaseous Compounds in the Environment. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 14. Springer. pp. 71–97. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9269-1_4. ISBN 978-94-017-9268-4. PMC 4261625. PMID 25416391. - ^ Szilagyi, R. K.; Bryngelson, P. A.; Maroney, M. J.; Hedman, B.; et al. (2004). «S K-Edge X-ray Absorption Spectroscopic Investigation of the Ni-Containing Superoxide Dismutase Active Site: New Structural Insight into the Mechanism». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 126 (10): 3018–3019. doi:10.1021/ja039106v. PMID 15012109.

- ^ Greig N; Wyllie S; Vickers TJ; Fairlamb AH (2006). «Trypanothione-dependent glyoxalase I in Trypanosoma cruzi». Biochemical Journal. 400 (2): 217–23. doi:10.1042/BJ20060882. PMC 1652828. PMID 16958620.

- ^ Aronsson A-C; Marmstål E; Mannervik B (1978). «Glyoxalase I, a zinc metalloenzyme of mammals and yeast». Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 81 (4): 1235–1240. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(78)91268-8. PMID 352355.

- ^ Ridderström M; Mannervik B (1996). «Optimized heterologous expression of the human zinc enzyme glyoxalase I». Biochemical Journal. 314 (Pt 2): 463–467. doi:10.1042/bj3140463. PMC 1217073. PMID 8670058.

- ^ Saint-Jean AP; Phillips KR; Creighton DJ; Stone MJ (1998). «Active monomeric and dimeric forms of Pseudomonas putida glyoxalase I: evidence for 3D domain swapping». Biochemistry. 37 (29): 10345–10353. doi:10.1021/bi980868q. PMID 9671502.

- ^ Thornalley, P. J. (2003). «Glyoxalase I—structure, function and a critical role in the enzymatic defence against glycation». Biochemical Society Transactions. 31 (Pt 6): 1343–1348. doi:10.1042/BST0311343. PMID 14641060.

- ^ Vander Jagt DL (1989). «Unknown chapter title». In D Dolphin; R Poulson; O Avramovic (eds.). Coenzymes and Cofactors VIII: Glutathione Part A. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- ^ Zambelli, Barbara; Ciurli, Stefano (2013). «Chapter 10. Nickel: and Human Health». In Astrid Sigel; Helmut Sigel; Roland K. O. Sigel (eds.). Interrelations between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 13. Springer. pp. 321–357. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_10. ISBN 978-94-007-7499-5. PMID 24470096.

- ^ Nickel. IN: Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Copper Archived September 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. National Academy Press. 2001, PP. 521–529.

- ^ Kamerud KL; Hobbie KA; Anderson KA (August 28, 2013). «Stainless Steel Leaches Nickel and Chromium into Foods During Cooking». Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 61 (39): 9495–501. doi:10.1021/jf402400v. PMC 4284091. PMID 23984718.

- ^ Flint GN; Packirisamy S (1997). «Purity of food cooked in stainless steel utensils». Food Additives & Contaminants. 14 (2): 115–26. doi:10.1080/02652039709374506. PMID 9102344.

- ^

Schirber, Michael (July 27, 2014). «Microbe’s Innovation May Have Started Largest Extinction Event on Earth». Space.com. Astrobiology Magazine. Archived from the original on July 29, 2014. Retrieved July 29, 2014.…. That spike in nickel allowed methanogens to take off.

- ^ «Nickel 203904». Sigma Aldrich. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ^ Haber, Lynne T; Bates, Hudson K; Allen, Bruce C; Vincent, Melissa J; Oller, Adriana R (2017). «Derivation of an oral toxicity reference value for nickel». Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 87: S1–S18. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2017.03.011. PMID 28300623.

- ^ Rieuwerts, John (2015). The Elements of Environmental Pollution. London and New York: Earthscan Routledge. p. 255. ISBN 978-0-415-85919-6. OCLC 886492996.

- ^ Butticè, Claudio (2015). «Nickel Compounds». In Colditz, Graham A. (ed.). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Cancer and Society (Second ed.). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. pp. 828–831. ISBN 9781483345734.

- ^ a b IARC (2012). «Nickel and nickel compounds» Archived September 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine in IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. Volume 100C. pp. 169–218..

- ^ a b Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on Classification, Labelling and Packaging of Substances and Mixtures, Amending and Repealing Directives 67/548/EEC and 1999/45/EC and amending Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 [OJ L 353, 31.12.2008, p. 1]. Annex VI Archived March 14, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed July 13, 2017.

- ^ a b Globally Harmonised System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS) Archived August 29, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, 5th ed., United Nations, New York and Geneva, 2013..

- ^ a b National Toxicology Program. (2016). «Report on Carcinogens» Archived September 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, 14th ed. Research Triangle Park, NC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service..

- ^ a b «Report of the International Committee on Nickel Carcinogenesis in Man». Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 16 (1 Spec No): 1–82. 1990. doi:10.5271/sjweh.1813. JSTOR 40965957. PMID 2185539.

- ^ a b National Toxicology Program (1996). «NTP Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Nickel Subsulfide (CAS No. 12035-72-2) in F344 Rats and B6C3F1 Mice (Inhalation Studies)». National Toxicology Program Technical Report Series. 453: 1–365. PMID 12594522.

- ^ National Toxicology Program (1996). «NTP Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Nickel Oxide (CAS No. 1313-99-1) in F344 Rats and B6C3F1 Mice (Inhalation Studies)». National Toxicology Program Technical Report Series. 451: 1–381. PMID 12594524.

- ^ Cogliano, V. J; Baan, R; Straif, K; Grosse, Y; Lauby-Secretan, B; El Ghissassi, F; Bouvard, V; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L; Guha, N; Freeman, C; Galichet, L; Wild, C. P (2011). «Preventable exposures associated with human cancers». JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 103 (24): 1827–39. doi:10.1093/jnci/djr483. PMC 3243677. PMID 22158127.

- ^ Heim, K. E; Bates, H. K; Rush, R. E; Oller, A. R (2007). «Oral carcinogenicity study with nickel sulfate hexahydrate in Fischer 344 rats». Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 224 (2): 126–37. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2007.06.024. PMID 17692353.

- ^ a b Oller, A. R; Kirkpatrick, D. T; Radovsky, A; Bates, H. K (2008). «Inhalation carcinogenicity study with nickel metal powder in Wistar rats». Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 233 (2): 262–75. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2008.08.017. PMID 18822311.

- ^ National Toxicology Program (1996). «NTP Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Nickel Sulfate Hexahydrate (CAS No. 10101-97-0) in F344 Rats and B6C3F1 Mice (Inhalation Studies)». National Toxicology Program Technical Report Series. 454: 1–380. PMID 12587012.

- ^ Springborn Laboratories Inc. (2000). «An Oral (Gavage) Two-generation Reproduction Toxicity Study in Sprague-Dawley Rats with Nickel Sulfate Hexahydrate.» Final Report. Springborn Laboratories Inc., Spencerville. SLI Study No. 3472.4.

- ^ Vaktskjold, A; Talykova, L. V; Chashchin, V. P; Odland, J. O; Nieboer, E (2008). «Maternal nickel exposure and congenital musculoskeletal defects». American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 51 (11): 825–33. doi:10.1002/ajim.20609. PMID 18655106.

- ^ «CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards – Nickel metal and other compounds (as Ni)». www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on July 18, 2017. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- ^ Stellman, Jeanne Mager (1998). Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety: Chemical, industries and occupations. International Labour Organization. pp. 133–. ISBN 978-92-2-109816-4. Archived from the original on May 29, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- ^ Barceloux, Donald G.; Barceloux, Donald (1999). «Nickel». Clinical Toxicology. 37 (2): 239–258. doi:10.1081/CLT-100102423. PMID 10382559.

- ^ a b Position Statement on Nickel Sensitivity Archived September 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. American Academy of Dermatology(August 22, 2015)

- ^ Thyssen J. P.; Linneberg A.; Menné T.; Johansen J. D. (2007). «The epidemiology of contact allergy in the general population—prevalence and main findings». Contact Dermatitis. 57 (5): 287–99. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01220.x. PMID 17937743. S2CID 44890665.

- ^ Dermal Exposure: Nickel Alloys Archived February 22, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Nickel Producers Environmental Research Association (NiPERA), accessed 2016 Feb.11

- ^ Nestle, O.; Speidel, H.; Speidel, M. O. (2002). «High nickel release from 1- and 2-euro coins». Nature. 419 (6903): 132. Bibcode:2002Natur.419..132N. doi:10.1038/419132a. PMID 12226655. S2CID 52866209.

- ^ Dow, Lea (June 3, 2008). «Nickel Named 2008 Contact Allergen of the Year». Nickel Allergy Information. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009.

- ^ Salnikow, k.; Donald, S. P.; Bruick, R. K.; Zhitkovich, A.; et al. (September 2004). «Depletion of intracellular ascorbate by the carcinogenic metal nickel and cobalt results in the induction of hypoxic stress». Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (39): 40337–44. doi:10.1074/jbc.M403057200. PMID 15271983.

- ^ Das, K. K.; Das, S. N.; Dhundasi, S. A. (2008). «Nickel, its adverse health effects and oxidative stress» (PDF). Indian Journal of Medical Research. 128 (4): 117–131. PMID 19106437. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 10, 2009. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nickel.

Look up nickel in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Nickel at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- CDC – Nickel – NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic

- An occupational hygiene assessment of dermal nickel exposures in primary production industries by GW Hughson. Institute of Occupational Medicine Research Report TM/04/05

- An occupational hygiene assessment of dermal nickel exposures in primary production and primary user industries. Phase 2 Report by GW Hughson. Institute of Occupational Medicine Research Report TM/05/06

- «The metal that brought you cheap flights», BBC News

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickel | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | lustrous, metallic, and silver with a gold tinge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Ni) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickel in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 28 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d8 4s2 or [Ar] 3d9 4s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 16, 2 or 2, 8, 17, 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1728 K (1455 °C, 2651 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 3003 K (2730 °C, 4946 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 8.908 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 7.81 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 17.48 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 379 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 26.07 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −2, −1, 0, +1,[2] +2, +3, +4[3] (a mildly basic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.91 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 124 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 124±4 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 163 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of nickel |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic (fcc)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 4900 m/s (at r.t.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 13.4 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 90.9 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 69.3 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | ferromagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young’s modulus | 200 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||