Добрый вам день, дорогой друг!

По поводу пата у начинающих шахматистов нередко возникают вопросы. Что означает пат? Это проигрыш или ничья? Надо ли стремиться к пату? И так далее. В этой статье вы узнаете, что такое пат в шахматах и получите ответы на все вопросы.

Вначале небольшое отступление. Если вы хотите научиться играть в шахматы с нуля, то получите от нас вот этот бесплатный материал и научитесь играть в шахматы уже через 48 минут:

СКАЧАТЬ БЕСПЛАТНО

- Что такое пат?

- Что означает пат в партии?

- Типичные позиции

- «Вынужденный» пат

- Прием «Бешеная ладья»

- Этюдные паты

- Как залезть в пат?

Что такое пат?

Определение: пат – это позиция на доске, в которой игрок, за которым право хода, — не может сделать ход, не нарушая шахматных правил.

Проще говоря, ему «некуда ходить».

При этом, что важно, — король не атакован, то есть не находится под шахом.

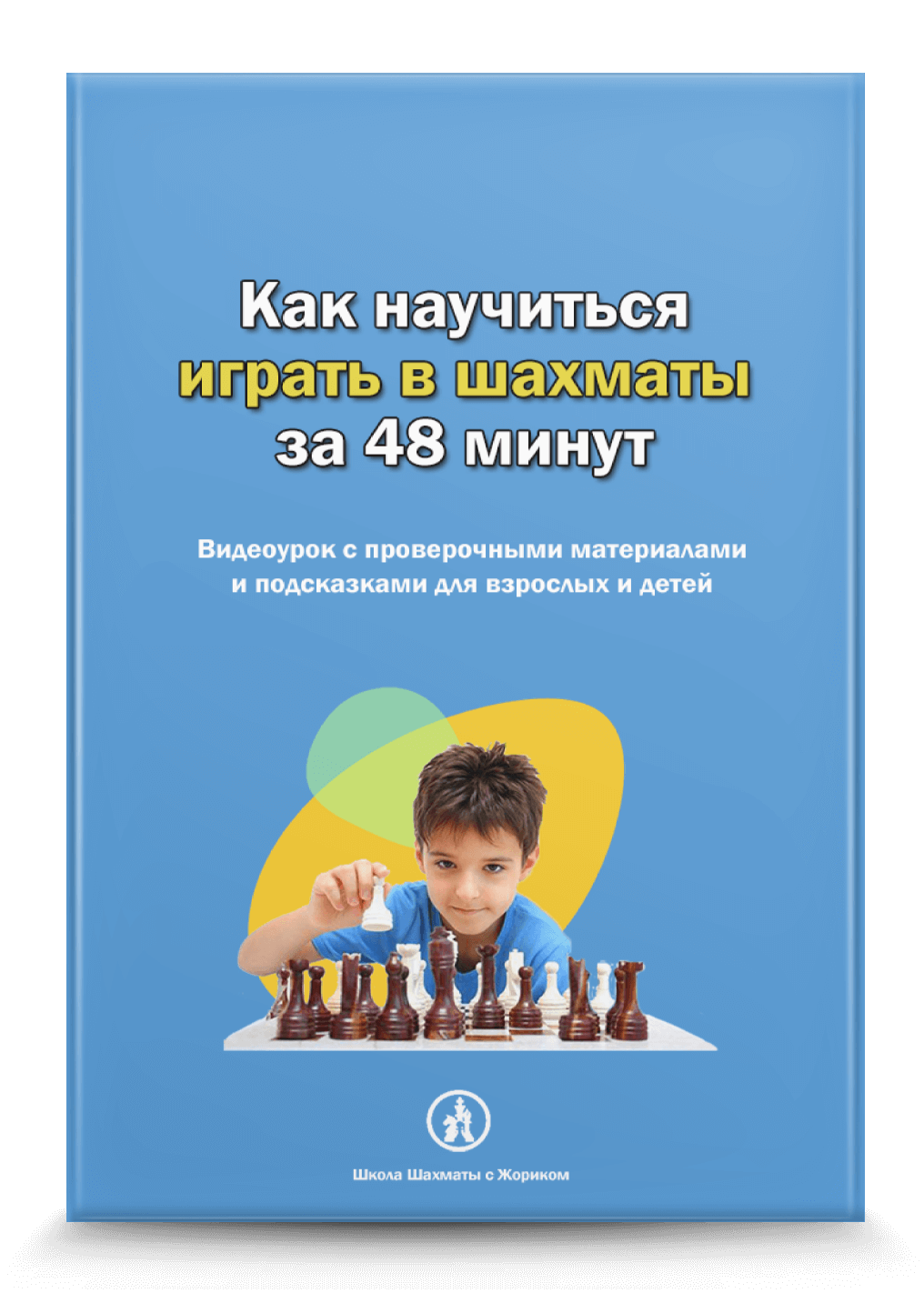

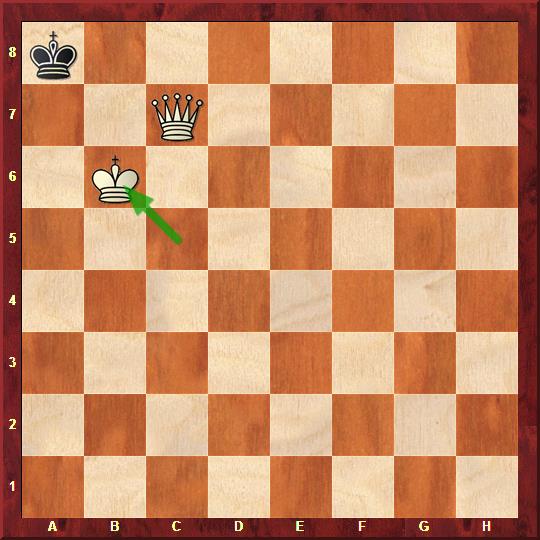

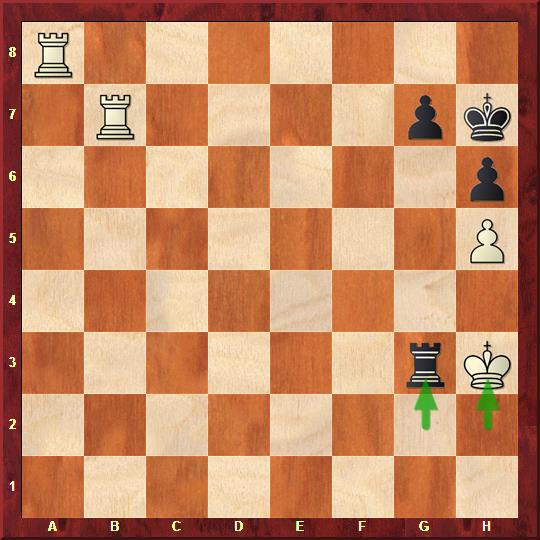

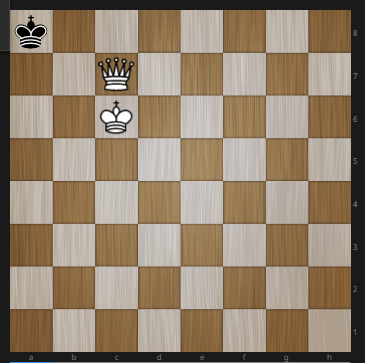

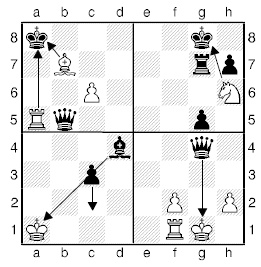

Пример:

Все поля, куда может сходить черный король, — бьются белыми фигурами. А по правилам, король не может находиться под боем. Пешки черных также не могут двигаться. При этом король черных не атакован. На доске пат.

Что означает пат в партии?

Патовая позиция на доске означает, что партия закончилась вничью. Обычно в такой ситуации споров у игроков не возникает.

Однако бывают и всплески эмоций. Особенность пата в том, что одна из сторон на момент пата обычно имеет большой перевес и уже предвкушает победу. Пат для такого игрока является неожиданностью, что иногда приводит к эмоциональным реакциям.

Рекомендую относиться к этому с пониманием. В самых «тяжелых» случаях, – пригласите судью, он зафиксирует ничью.

Типичные позиции

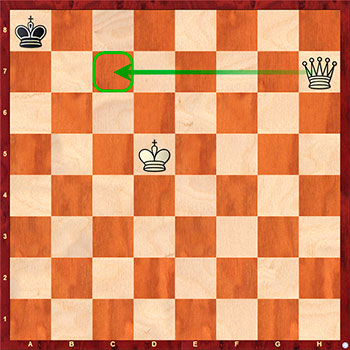

Самый типичный случай – пат по невнимательности. Например:

Белые дали шах ферзем на с7, черный король ушел в угол.

Белые сыграли Крс5-в6 ??, потирая руки и намереваясь следующим ходом поставить мат ферзем. Однако… у черного короля нет ходов! Что это означает, вы уже знаете. Как не прискорбно для белых, — на доске ничья.

«Вынужденный» пат

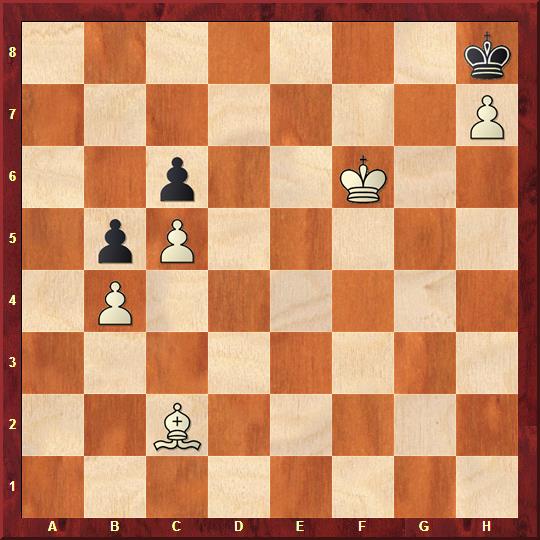

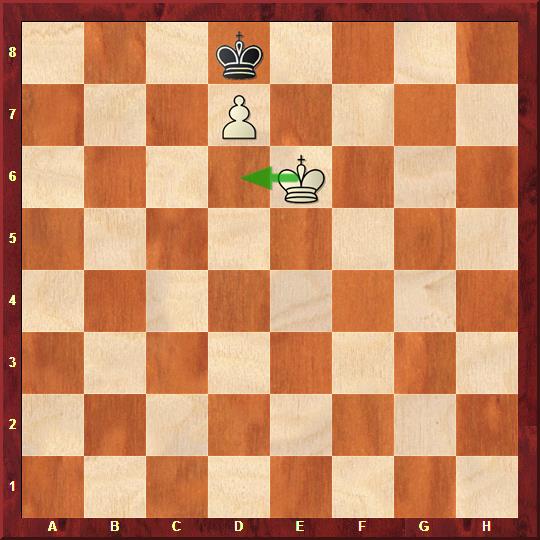

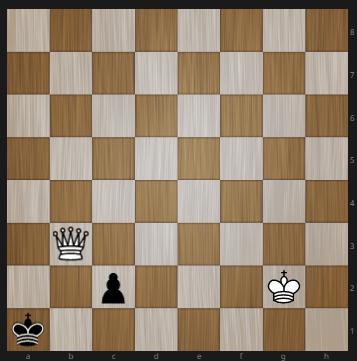

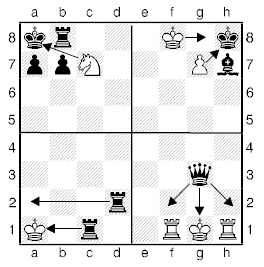

Очень частое окончание – король и пешка против короля. Финальная позиция:

У белых выбор невелик – отойти, теряя пешку, или сыграть Крe6-d6 с патом.

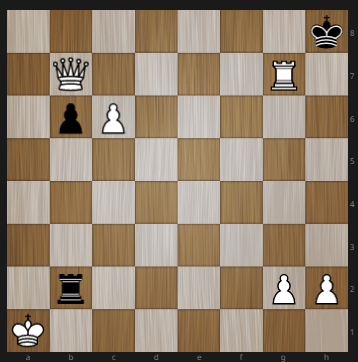

Прием «Бешеная ладья»

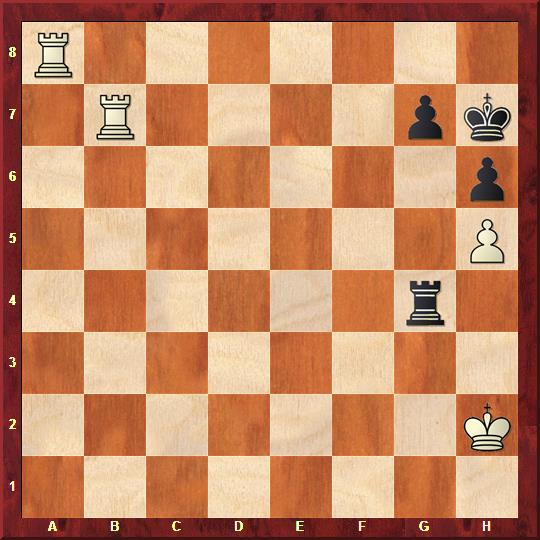

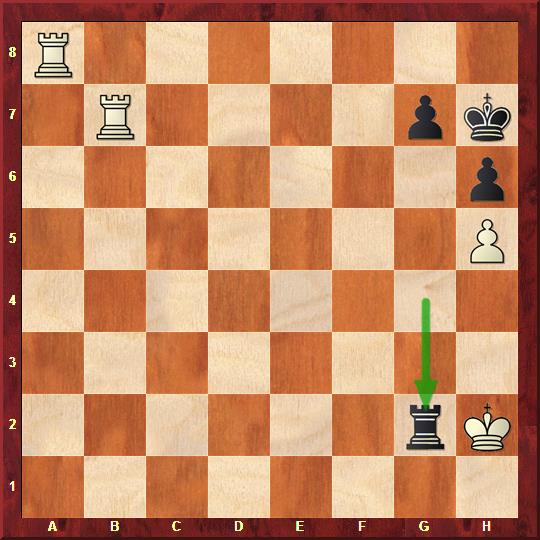

Что означает столь угрожающая характеристика, проще показать на примере:

У белых на целую ладью больше. Ход черных. Что делать? Дать шах на h4 и выиграть пешку h5? Это не спасет партию. С лишней ладьей белые легко выиграют.

К счастью, ситуация такова, что у черных кроме ладьи, — нечем ходить.

Включаем логику и…. Правильно! Ладью следует пожертвовать!

1… Лg4-g2+!!

Теперь если 2.Крh2:g2 – на доске пат.

А что делать? Если 2.Крh2-h1, то 2…Лg2-g1+!. Или 2.Крh2-h3 Лg2-g3+!

И ладью бить нельзя, — пат, и вырваться к центру доски белый король не может. Ничья.

Прием «бешеная ладья» является типичным, хотя и встречается не так часто на практике.

Однако его нужно знать и помнить. Дабы не допустить превращение ладьи в «бешеную», имея перевес или воспользоваться этой возможностью в худшей позиции, как черные в нашем примере.

Этюдные паты

Изредка в шахматах встречаются паты, к которым можно прийти этюдным путем. Этюды- отдельная тема и мы их будем обсуждать в других статьях. Решение этюдов весьма полезно, в том числе для детей.

Кстати, пример с бешенной ладьей также несет в себе комбинационные этюдные мотивы.

Как залезть в пат?

Специально играть на пат в худшей позиции я бы не советовал. Возможность пата возникает в шахматах не так часто. По моему опыту, может получиться так: вы намеренно ухудшаете свою позицию в надежде на пат, но добиться пата не получается. Так бывает чаще всего.

Просто рекомендую изучить типичные патовые позиции и приемы (например та же «бешеная ладья»). С опытом вы научитесь загодя замечать, когда патовые возможности можно использовать.

Благодарю за интерес к статье.

Если вы нашли ее полезной, сделайте следующее:

- Поделитесь с друзьями, нажав на кнопки социальных сетей.

- Напишите комментарий (внизу страницы)

- Подпишитесь на обновления блога (форма под кнопками соцсетей) и получайте статьи к себе на почту.

Удачного вам дня!

Example of stalemate

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Black to move is stalemated. Black is not currently in check and has no legal move since every square to which the king might move is under attack by White.[1]

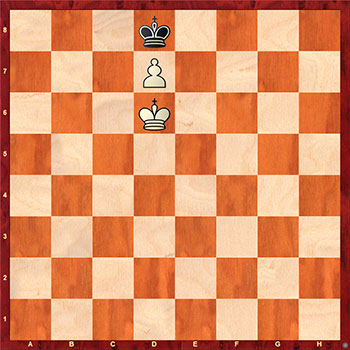

Stalemate is a situation in the game of chess where the player whose turn it is to move is not in check and has no legal move. Stalemate results in a draw. During the endgame, stalemate is a resource that can enable the player with the inferior position to draw the game rather than lose.[2] In more complex positions, stalemate is much rarer, usually taking the form of a swindle that succeeds only if the superior side is inattentive.[citation needed] Stalemate is also a common theme in endgame studies and other chess problems.

The outcome of a stalemate was standardized as a draw in the 19th century. Before this standardization, its treatment varied widely, including being deemed a win for the stalemating player, a half-win for that player, or a loss for that player; not being permitted; and resulting in the stalemated player missing a turn. Stalemate rules vary in other games of the chess family.

Etymology and usage[edit]

The first recorded use of stalemate is from 1765. It is a compounding of Middle English stale and mate (meaning checkmate). Stale is probably derived from Anglo-French estale meaning «standstill», a cognate of «stand» and «stall», both ultimately derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *sta-. The first recorded use in a figurative sense is in 1885.[3][4]

Stalemate has become a widely used metaphor for other situations where there is a conflict or contest between two parties, such as war or political negotiations, and neither side is able to achieve victory, resulting in what is also called an impasse, a deadlock, or a Mexican standoff. Chess writers note that this usage is a misnomer because, unlike in chess, the situation is often a temporary one that is ultimately resolved, even if it seems currently intractable.[5][6][7][8][9][10]

The term «stalemate» is sometimes used incorrectly as a generic term for a draw in chess. While draws are common, they are rarely the direct result of stalemate.[11]

Examples[edit]

With Black to move, Black is stalemated in diagrams 1 to 4. Stalemate is an important factor in the endgame – the endgame setup in diagram 1, for example, quite frequently is relevant in play (see King and pawn versus king endgame). The position in diagram 1 occurred in an 1898 game between Amos Burn and Harry Pillsbury[12] and also in a 1925 game between Savielly Tartakower and Richard Réti.[13] The same position, except shifted to the e-file, occurred in a 2009 game between Gata Kamsky and Vladimir Kramnik.[14]

The position in diagram 3 is an example of a pawn drawing against a queen. Stalemates of this sort can often save a player from losing an apparently hopeless position (see Queen versus pawn endgame).

Examples from games[edit]

Anand versus Kramnik[edit]

Anand vs. Kramnik, 2007

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Before 65…Kxf5, stalemate

In this position from the game Viswanathan Anand–Vladimir Kramnik from the 2007 World Chess Championship,[15] Black played 65…Kxf5, stalemating White.[16] (Any other move by Black loses.)

Korchnoi versus Karpov[edit]

Korchnoi vs. Karpov, 1978

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Position after 124.Bc3–g7

An intentional stalemate occurred on the 124th move of the fifth game of the 1978 World Championship match between Viktor Korchnoi and Anatoly Karpov.[17] The game had been a theoretical draw for many moves.[18][19] White’s bishop is useless; it cannot defend the queening square at a8 nor attack the black pawn on the light a4-square. If the white king heads towards the black pawn, the black king can move towards a8 and set up a fortress.

The players were not on speaking terms, however, so neither would offer a draw by agreement. On his 124th move, White played 124.Bg7, delivering stalemate. Korchnoi said that it gave him pleasure to stalemate Karpov and that it was slightly humiliating.[20] Until 2021, this was the longest game played in a World Chess Championship final match, as well as the only World Championship game to end in stalemate before 2007.[21]

Bernstein versus Smyslov[edit]

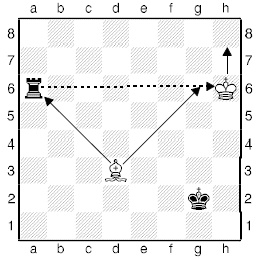

Black to move … |

… fell into a stalemate trap. |

Sometimes, a surprise stalemate saves a game. In the game between Ossip Bernstein–Vasily Smyslov[22] (see first diagram), Black can win by sacrificing the f-pawn and using the king to support the b-pawn. However, Smyslov thought it was good to advance the b-pawn because he could win the white rook with a skewer if it captured the pawn. Play went:

- 1… b2?? 2. Rxb2!

Now 2…Rh2+ 3.Kf3! Rxb2 is stalemate (see analysis diagram). Smyslov played 2…Kg4, and the game was drawn after 3.Kf1 (see Rook and pawn versus rook endgame).[23]

Matulović versus Minev[edit]

White to move |

Stalemate if White had played 4.Rxa6 |

Whereas the possibility of stalemate arose in the Bernstein–Smyslov game because of a blunder, it can also arise without one, as in the game Milan Matulović–Nikolay Minev (see first diagram). Play continued:

- 1. Rc6 Kg5 2. Kh3 Kh5 3. f4

The only meaningful attempt to make progress. Now all moves by Black (like 3…Ra3+?) lose, with one exception.

- 3… Rxa6!

Now 4.Rxa6 would be stalemate. White played 4.Rc5+ instead, and the game was drawn several moves later.[24]

Williams versus Harrwitz[edit]

Position after 72.Ka1 |

Position after 84.Rb3! If Black takes the rook either way, the result is stalemate. |

In the game Elijah Williams–Daniel Harrwitz[25] (see first diagram), Black was up a knight and a pawn in an endgame. This would normally be a decisive material advantage, but Black could find no way to make progress because of various stalemate resources available to White. The game continued:

- 72… Ra8 73. Rc1

Avoiding the threatened 73…Nc2+.

- 73… Ke3 74. Rc4 Ra4 75. Rc1 Kd2 76. Rc4 Kd3

76…Nc2+ 77.Rxc2+! Kxc2 is stalemate.

- 77. Rc3+! Kd4

77…Kxc3 is stalemate.

- 78. Rc1 Ra3 79. Rd1+ Kc5

79…Rd3 80.Rxd3+! leaves Black with either insufficient material to win after 80…Nxd3 81.Kxa2 or a standard fortress in a corner draw after 80…Kxd3.

- 80. Rc1+ Kb5 81. Rc7 Nd5 82. Rc2 Nc3?? 83. Rb2+ Kc4 84. Rb3! (second diagram)

Now the players agreed to a draw, since 84…Kxb3 or 84…Rxb3 is stalemate, as is 84…Ra8 85.Rxc3+! Kxc3.

Black could still have won the game until his critical mistake on move 82. Instead of 82…Nc3, 82…Nb4 wins; for example, after 83.Rc8 Re3 84.Rb8+ Kc5 85.Rc8+ Kd5 86.Rd8+ Kc6 87.Ra8 Re1+ 88.Kb2 Kc5 89.Kc3 a1=Q+, Black wins.[citation needed]

Carlsen versus Van Wely[edit]

Carlsen vs. Van Wely, 2007

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

White to make his 109th move

This 2007 game, Magnus Carlsen–Loek van Wely, ended in stalemate.[26] White used the second-rank defense in a rook and bishop versus rook endgame for 46 moves. The fifty-move rule was about to come into effect, under which White could claim a draw. The game ended:

- 109. Rd2+ Bxd2 ½–½

White was stalemated.[27]

More complex examples[edit]

Although stalemate usually occurs in the endgame, it can also occur with more pieces on the board. Outside of relatively simple endgame positions, such as those above, stalemate occurs rarely, usually when the side with the superior position has overlooked the possibility of stalemate.[28] This is typically realized by the inferior side’s sacrifice of one or more pieces in order to force stalemate. A piece that is offered as a sacrifice to bring about stalemate is sometimes called a desperado.

Evans versus Reshevsky[edit]

Position before White’s 47th move |

Position after 50.Rxg7+!, the eternal rook |

One of the best-known examples of the desperado is the game Larry Evans–Samuel Reshevsky[29] that was dubbed «The Swindle of the Century».[30] Evans sacrificed his queen on move 49 and offered his rook on move 50. White’s rook has been called the eternal rook. Capturing it results in stalemate, but otherwise it stays on the seventh rank and checks Black’s king ad infinitum (i.e. perpetual check). The game would inevitably end in a draw by agreement, by threefold repetition, or by an eventual claim under the fifty-move rule.[31]

- 47. h4! Re2+ 48. Kh1 Qxg3??

After 48…Qg6! 49.Rf8 Qe6! 50.Rh8+ Kg6, Black remains a piece ahead after 51.Qxe6 Nxe6, or forces mate after 51.gxf4 Re1+ and 52…Qa2+.[32]

- 49. Qg8+! Kxg8 50. Rxg7+!

Gelfand versus Kramnik[edit]

Position after 67.Re7 |

Possible stalemate |

The position at right occurred in Boris Gelfand–Vladimir Kramnik, 1994 FIDE Candidates match, game 6, in Sanghi Nagar, India.[33] Kramnik, down two pawns and on the defensive, would be very happy with a draw. Gelfand has just played 67. Re4–e7? (see first diagram), a strong-looking move that threatens 68.Qxf6, winning a third pawn, or 68.Rc7, further constricting Black. Black responded 67… Qc1! If White takes Black’s undefended rook with 68.Qxd8, Black’s desperado queen forces the draw with 68…Qh1+ 69.Kg3 Qh2+!, compelling 70.Kxh2 stalemate (second diagram). If White avoids the stalemate with 68.Rxg7+ Kxg7 69.Qxd8, Black draws by perpetual check with 69…Qh1+ 70.Kg3 Qg1+ 71.Kf4 Qc1+! 72.Ke4 Qc6+! 73.Kd3!? (73.d5 Qc4+; 73.Qd5 Qc2+) Qxf3+! 74.Kd2 Qg2+! 75.Kc3 Qc6+ 76.Kb4 Qb5+ 77.Ka3 Qd3+. Gelfand played 68. d5 instead but still only drew.

Troitsky versus Vogt[edit]

White, on move, sets a trap with 1.Rd1! |

Position after 3…Qxd1, stalemate |

In Troitsky–Vogt[clarification needed : full name], 1896, the famous endgame study composer Alexey Troitsky pulled off an elegant swindle in actual play. After Troitsky’s 1. Rd1!, Black fell into the trap with the seemingly crushing 1… Bh3?, threatening 2…Qg2#. The game concluded 2. Rxd8+ Kxd8 3. Qd1+! Qxd1 stalemate. White’s bishop, knight, and f-pawn are all pinned and unable to move.[34]

In studies[edit]

White to play and draw |

Incredibly, the possibility of stalemate allows White, three pieces down, to draw. |

Stalemate is a frequent theme in endgame studies[35] and other chess compositions. An example is the «White to Play and Draw» study at right, composed by the American master Frederick Rhine[36] and published in 2006.[37] White saves a draw with 1. Ne5+! Black wins after 1.Nb4+? Kb5! or 1.Qe8+? Bxe8 2.Ne5+ Kb5! 3.Rxb2+ Nb3. 1… Bxe5 After 1…Kb5? 2.Rxb2+ Nb3 3.Rxc4! Qxe3 (best; 3…Qb8+ 4.Kd7 Qxh8 5.Rxb3+ forces checkmate) 4.Rxb3+! Qxb3 5.Qh1! Bf5+ 6.Kd8!, White is winning. 2. Qe8+! 2.Qxe5? Qb7+ 3.Kd8 Qd7#. 2… Bxe8 3. Rh6+ Bd6 3…Kb5 4.Rxb6+ Kxb6 5.Nxc4+ also leads to a drawn endgame. Not 5.Rxb2+? Bxb2 6.Nc4+ Kb5 7.Nxb2 Bh5! trapping White’s knight. 4. Rxd6+! Kxd6 5. Nxc4+! Nxc4 6. Rxb6+ Nxb6+ Moving the king is actually a better try, but the resulting endgame of two knights and a bishop against a rook is a well-established theoretical draw.[38][39][40][41] 7. Kd8! (rightmost diagram) Black is three pieces ahead, but if White is allowed to take the bishop, the two knights are insufficient to force checkmate. The only way to save the bishop is to move it, resulting in stalemate. A similar idea occasionally enables the inferior side to save a draw in the ending of bishop, knight, and king versus lone king.

White to play and draw |

Final position |

At right is a composition by A. J. Roycroft which was published in the British Chess Magazine in 1957. White draws with 1. c7! after which there are two main lines:

- 1… f5 2. c8=Q (if 2.c8=R? then 2…Bc3 3.Rxc3 Qg7#) 2… Bc3 3. Qxf5+ draws by stalemate.

- 1… g5 (1…Ka1 2.c8=R transposes) 2. c8=R!! (2.c8=Q? Ka1 3.Qc2 [or 3.Qc1+] b1=Q+ wins) 2… Ka1 (2…Ng6 3.Rc1+ forces Black to capture, stalemating White) 3. Rc2!! (not 3.Rc1+?? b1=Q+! 4.Rxb1+ Bxb1#; now White threatens 4.Rxb2 and 5.Rxa2+, forcing stalemate or perpetual check) 3… Bc4 (trying to get in a check; 3…b1=Q, 3…b1=B, and 3…Bb1 are all stalemate; 3…Ng6 4.Rc1+!) 4. Rc1+ Ka2 5. Ra1+ Kb3 6. Ra3+ Kc2 7. Rc3+ Kd2 8. Rc2+ (rightmost diagram). As in Evans–Reshevsky, Black cannot escape the «eternal rook».[42]

In problems[edit]

Sam Loyd

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Shortest stalemate

Sam Loyd

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Stalemate with all pieces on board

Some chess problems require «White to move and stalemate Black in n moves» (rather than the more common «White to move and checkmate Black in n moves»). Problemists have also tried to construct the shortest possible game ending in stalemate. Sam Loyd devised one just ten moves long: 1.e3 a5 2.Qh5 Ra6 3.Qxa5 h5 4.Qxc7 Rah6 5.h4 f6 6.Qxd7+ Kf7 7.Qxb7 Qd3 8.Qxb8 Qh7 9.Qxc8 Kg6 10.Qe6 (diagram at left). A similar stalemate is reached after: 1.d4 c5 2.dxc5 f6 3.Qxd7+ Kf7 4.Qxd8 Bf5 5.Qxb8 h5 6.Qxa8 Rh6 7.Qxb7 a6 8.Qxa6 Bh7 9.h4 Kg6 10.Qe6 (Frederick Rhine).

Loyd also demonstrated that stalemate can occur with all the pieces on the board: 1.d4 d6 2.Qd2 e5 3.a4 e4 4.Qf4 f5 5.h3 Be7 6.Qh2 Be6 7.Ra3 c5 8.Rg3 Qa5+ 9.Nd2 Bh4 10.f3 Bb3 11.d5 e3 12.c4 f4 (diagram at right). Games such as this are occasionally played in tournaments as a pre-arranged draw.[43]

Double stalemate[edit]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Double stalemate position

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Another double stalemate

There are chess compositions featuring double stalemate. At left and at right are double stalemate positions, in which neither side has a legal move. Double stalemate is theoretically possible in a practical game, though is not known to ever have happened.[citation needed] Consider the following position:

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Potential gamelike position

The game draws after a waiting move like 1.Rg2 (1…b2+ 2.Rxb2; 1…c2 2.Rg4!). However, White has 1.Rb2?, an interesting blunder: if Black errs by 1…cxb2+? then White draws by 2.Kb1, creating a double stalemate position. Black could win by 1…c2! putting White in zugzwang.[citation needed]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Fastest known double stalemate: after 18…dxe3

The fastest known game ending in a double stalemate position was discovered by Enzo Minerva and published in the Italian newspaper l’Unità on 14 August 2007: 1.c4 d5 2.Qb3 Bh3 3.gxh3 f5 4.Qxb7 Kf7 5.Qxa7 Kg6 6.f3 c5 7.Qxe7 Rxa2 8.Kf2 Rxb2 9.Qxg7+ Kh5 10.Qxg8 Rxb1 11.Rxb1 Kh4 12.Qxh8 h5 13.Qh6 Bxh6 14.Rxb8 Be3+ 15.dxe3 Qxb8 16.Kg2 Qf4 17.exf4 d4 18.Be3 dxe3.[44]

History of the stalemate rule[edit]

The stalemate rule has had a convoluted history.[45] Although stalemate is universally recognized as a draw today, that has not been the case for much of the game’s history. In the forerunners to modern chess, such as chaturanga, delivering stalemate resulted in a loss.[46] However, this was changed in shatranj, where stalemating was a win. This practice persisted in chess as played in early 15th-century Spain.[47] However, Lucena (c. 1497) treated stalemate as an inferior form of victory;[48] it won only half the stake in games played for money, and this continued to be the case in Spain as late as 1600.[49] From about 1600 to 1800, the rule in England was that stalemate was a loss for the player administering it, a rule that the eminent chess historian H. J. R. Murray believes may have been adopted from Russian chess.[50] That rule disappeared in England before 1820, being replaced by the French and Italian rule that a stalemate was a drawn game.[51]

Throughout history, a stalemate has at various times been:

- A win for the stalemating player in 10th century Arabia[52] and parts of medieval Europe.[53][54]

- A half-win for the stalemating player. In a game played for stakes, they would win half the stake (18th century Spain).[55]

- A win for the stalemated player in 9th century India,[56] 17th century Russia,[57] on the Central Plain of Europe in the 17th century,[58] and 17th–18th century England.[59][60] This rule continued to be published in Hoyle’s Games Improved as late as 1866.[61][62]

- Illegal. If White made a move that would stalemate Black, he had to retract it and make a different move (Eastern Asia until the early 20th century). Murray likewise wrote that in Hindustani chess and Parsi chess, two of the three principal forms of chess played in India as of 1913,[63] a player was not allowed to play a move that would stalemate the opponent.[64] The same was true of Burmese chess, another chess variant, at the time of writing.[65] Stalemate was not permitted in most of the Eastern Asiatic forms of the game (specifically in Burma, India, Japan, and Siam) until early in the 20th century.[66]

- The forfeiture of the stalemated player’s turn to move (medieval France),[67][68] although other medieval French sources treat stalemate as a draw.[69]

- A draw. This was the rule in 13th-century Italy[70] and also stated in the German Cracow Poem (1422), that noted, however, that some players treated stalemate as equivalent to checkmate.[71] This rule was ultimately adopted throughout Europe, but not in England until the 19th century, after being introduced there by Jacob Sarratt.[72][73][74]

Proposed rule change[edit]

Periodically, writers have argued that stalemate should again be made a win for the side causing the stalemate. Grandmaster Larry Kaufman writes, «In my view, calling stalemate a draw is totally illogical, since it represents the ultimate zugzwang, where any move would get your king taken».[75] The British master T. H. Tylor argued in a 1940 article in the British Chess Magazine that the present rule, treating stalemate as a draw, «is without historical foundation and irrational, and primarily responsible for a vast percentage of draws, and hence should be abolished».[76] Years later, Fred Reinfeld wrote, «When Tylor wrote his attack on the stalemate rule, he released about his unhappy head a swarm of peevish maledictions that are still buzzing.»[77] Larry Evans calls the proposal to make stalemate a win for the stalemating player a «crude proposal that … would radically alter centuries of tradition and make chess boring».[78] This rule change would cause a greater emphasis on material; an extra pawn would be a greater advantage than it is today.

Rules in other chess variants[edit]

Not all variants of chess consider the stalemate to be a draw. Many regional variants, as well some variants of Western chess, have adopted their own rules on how to treat the stalemated player. In chaturanga, which is widely considered to be the common ancestor of all variants of chess, a stalemate was a win for the stalemated player.[79][80] Around the 7th century, this game was adopted in the Middle East as shatranj with very similar rules to its predecessor; however, the stalemate rule was changed to its exact opposite: i.e. it was a win for the player delivering the stalemate.[81] This game was in turn introduced to the western world, where it would eventually evolve to modern-day (Western) chess, although the stalemate rule for Western chess was not standardised as a draw until the 19th century (see history of the rule).

Modern Asian variants[edit]

Chaturanga also evolved into several other games in various regions of Asia, all of which have varying rules on stalemating:

- In makruk (Thai chess), a stalemate results in a draw, like in Western chess.[82]

- In shogi (Japanese chess) and the majority of its variants, a stalemate is a win for the player delivering the stalemate.[83] This is because historically, the objective of shogi was to capture the opponent’s king rather than to checkmate it; thus, a stalemate was no different from a checkmate, as both outcomes would typically result in the king’s capture in the next move. The official rules of shogi (but not most of its variants) have since altered the objective of the game to checkmate, however stalemate is still considered a form of checkmate and thus a win for the stalemating player. However, in shogi (and in any variant of the game that features drops), stalemates are extremely rare due to the fact that no piece ever goes entirely out of play.

- Xiangqi (Chinese chess) and janggi (Korean chess), despite being very similar to each other in terms of both the board and the pieces, have adopted different rules for what happens in the case of a stalemate. In xiangqi, like in shogi, it results in an immediate loss for the stalemated player, and there is no explicit distinction between it and checkmate.[84] Janggi, on the other hand, allows the stalemated player to pass their turn; i.e., the player may (and in fact must) leave the general (analogous to the chess king) in position and make no move when stalemated.[85]

- In sittuyin (Myanma/Burmese chess), stalemates are avoided altogether, as delivering them is illegal. Players are not allowed to leave the opponent with no legal moves without putting the king into check.[86]

Western chess variants[edit]

The majority of variants of Western chess do not specify any alterations to the rule of stalemate. There are some variants, however, where the rule is specified to differ from that of standard chess:

- In losing chess, the stalemate rule varies depending on the version being played.[87] According to the «international» rules, a stalemate is simply a win for the stalemated player. The Free Internet Chess Server, however, grants a win to the player with fewer pieces remaining on the board (regardless of who delivered the stalemate); if both players have the same number of pieces it is a draw.[88] There is also a «joint» FICS/international rule, according to which a stalemate is only a win if both sources agree that it is a win (i.e. it counts as a win for the stalemated player if that player also happens to have fewer pieces remaining); in all other cases it is a draw.

- In Gliński’s hexagonal chess, stalemate is neither a draw nor a full win. Instead, in tournament games, the player who delivers the stalemate earns 3⁄4 point, while the stalemated player receives 1⁄4 point.[89] It is unknown whether a stalemate should be considered a draw or a win in a friendly game.

See also[edit]

- Checkmate

- Desperado

- Draw (chess)

- Glossary of chess

- Rules of chess

- Swindle (chess)

Notes[edit]

- ^ Polgar & Truong 2005:33

- ^ Hooper & Whyld 1992:387

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «stalemate |». www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ «Definition of STALEMATE». www.merriam-webster.com. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ Golombek 1977:304

- ^ Soltis 1978:54

- ^ Golombek wrote, «The word ‘stalemate’ has been taken into the English language to mean (wrongly) a temporary state of impasse.» Soltis wrote:

There is a world of difference between no choice … and a poor choice. Editorial writers often talk about a political stalemate when the analogy they probably have in mind is a political «zugzwang». In stalemate a player has no legal moves, period. In zugzwang he has nothing pleasant to do.

- ^ Hoffman, Gil (2013-07-02). «Left blames PM for stalemate on peace talks». The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- ^

Purnick, Joyce (1988-01-06). «Threat by Wagner to Resign Solved Schools Stalemate». The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-07-05. - ^

Gordon, Meghan (2008-05-21). «Huey P. Long widening stalemate appears resolved». Retrieved 2013-07-05. - ^ British Chess Magazine, September 1911, p. 342, Stalemate

- ^ Burn vs. Pillsbury, 1898

- ^ Tartakower vs. Réti 1925

- ^ Kamsky vs. Kramnik

- ^ «Anand vs. Kramnik, Mexico City 2007». Chessgames.com.

- ^ Benko 2008:49

- ^ Karpov vs. Korchnoi

- ^ Károlyi & Aplin 2007:170

- ^ Griffiths 1992:43–46

- ^ Kasparov 2006:120

- ^ Fox & James 1993:236

- ^ «Bernstein vs. Smyslov, Groningen 1946». Chessgames.com.

- ^ Minev 2004:21

- ^ Minev 2004:22

- ^ «Williams vs. Harrwitz, London 1846». Chessgames.com.

- ^ «Carlsen vs. Van Wely, Wijk aan Zee 2007». Chessgames.com.

- ^ Nunn 2009:200

- ^ Pachman 1973:17

- ^ «Evans vs. Reshevsky, New York 1963/64». Chessgames.com.

- ^ Larry Evans, Chess Catechism, Simon and Schuster, 1970, p. 66. SBN 671-21531-0. It appears that Evans himself was the first to refer to the game as the «Swindle of the Century» in print, in his annotations in American Chess Quarterly magazine, of which he was the Editor-in-Chief. American Chess Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Winter, 1964), p. 171. Hans Kmoch referred to the conclusion of the game as «A Hilarious Finish». Hans Kmoch, «United States Championship», Chess Review, March 1964, pp. 76–79, at p. 79. Also available on DVD (p. 89 of «Chess Review 1964» PDF file).

- ^ Averbakh 1996:80–81

- ^ Hans Kmoch, «United States Championship», Chess Review, March 1964, pp. 76–79, at p. 79. Also available on DVD (p. 89 of «Chess Review 1964» PDF file).

- ^ «Gelfand vs. Kramnik, Sanghi Nagar 1994». Chessgames.com.

- ^ O’Keefe, Jack (August–September 1973). «Stalemate!». Michigan Chess. pp. 4–6. Archived from the original on 2012-05-02. Retrieved 2016-11-22 – via Michigan Chess Association Webzine July 1999.

- ^ Hooper & Whyld 1992:388

- ^ United States Chess Federation rating card for Frederick S. Rhine

- ^ Benko 2006:49

- ^ Fine & Benko 2003:524

- ^ Müller & Lamprecht 2001:403

- ^ Staunton 1847:439

- ^ This can be confirmed, as to this position, by the Shredder Six-Piece Database.

- ^ Roycroft 1972:294

- ^ Hohmeister vs. Frank 1993

- ^ The previous record (37 ply, i.e. 18.5 moves) was held by the German composer Eduard Schildberg, and was published in the Deutsches Wochenschach in 1915.

Antonio Garofalo (2007). «Best Problems» (PDF). pp. 23 (numbered «95» at bottom of page). Retrieved 2008-09-01. - ^ Murray 1913:61

- ^ Murray 1913:229, 267

- ^ Murray 1913:781

- ^ Murray 1913:461

- ^ Murray 1913:833

- ^ Murray 1913:60–61, 466

- ^ Murray 1913:391

- ^ Davidson 1981:65

- ^ Murray 1913:463–64, 781

- ^ McCrary 2004:26

- ^ Davidson 1981:65

- ^ Murray 1913:56–57, 60–61

- ^ Davidson 1981:65

- ^ Murray 1913:388–89

- ^ Murray 1913:60–61, 466

- ^ Saul’s Famous game of Chesse-play (London 1614) explained the reason for this rule as follows: «He that hath put his adversary’s King into a stale, loseth the game, because he hath disturbed the course of the game, which can only end with the grand Check-mate.» Murray, p. 466 & n. 32. McCrary, p. 26. Murray derides the rule as «illogical», Murray, p. 61, and Saul’s explanation as «puerile», id., p. 466.

- ^ Sunnucks 1970:438

- ^ Murray wrote in 1913, «The rule still appeared in editions after 1857, and I have met with players who argued that the rule was so.» Murray, p. 391 n. 47.

- ^ Murray 1913:78

- ^ Murray 1913:82, 84

- ^ Murray 1913:113

- ^ Davidson 1981:65

- ^ Murray 1913:464–66

- ^ Davidson 1981:64–65

- ^ Murray 1913:464–66

- ^ Murray 1913:461–62

- ^ Murray 1913:463–64

- ^ Murray 1913:391

- ^ Davidson 1981:64–66

- ^ Sunnucks 1970:438

- ^ Kaufman 2009

- ^ Reinfeld 1959:242–44

- ^ Reinfeld 1959:242

- ^ Evans 2007:234

- ^ Murray 1913:229, 267

- ^ Chaturangs – Game rules

- ^ Shatranj

- ^ Makruk: Thai chess

- ^ Rules – Japanese Game Shogi

- ^ BrainKing – Game rules (Chinese Chess)

- ^ Janggi – Korean Chess

- ^ How to Play Sittuyin – Burmese Chess – Myanmar Chess

- ^ Alexander 1973:107

- ^ Losing Chess

- ^ Gliński’s Hexagonal Chess

References[edit]

- Alexander, C.H.O’D. (1973), A Book of Chess, New York: Harper & Row, ISBN 978-0-0601-0048-3

- Averbakh, Yuri (1996-08-01), Chess Middlegames: Essential Knowledge, Cadogan Chess, ISBN 978-1-8574-4125-3

- Benko, Pal (May 2006), «Benko’s Bafflers», Chess Life (May): 49

- Benko, Pal (January 2008), «The 2007 World Championship», Chess Life (January): 48–49

- Davidson, Henry A. (1949), A Short History of Chess, Greenberg, ISBN 978-0-307-82829-3, LCCN 68-22441, retrieved 2016-11-22

- Evans, Larry (1970-08-20), Chess Catechism, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-0-6712-0491-4

- Evans, Larry (2009-11-06), This Crazy World of Chess, Cardoza Publishing, ISBN 978-1580422185

- Fine, Reuben; Benko, Pal (2003) [1941], Basic Chess Endings, David McKay, ISBN 0-8129-3493-8

- Fox, Mike; James, Richard (1993), The Even More Complete Chess Addict (2 ed.), London: Faber & Faber, ISBN 978-0-5711-7040-1

- Golombek, Harry (1977), Golombek’s Encyclopedia of Chess, Crown Publishers, ISBN 0-517-53146-1

- Griffiths, Peter (1992), Exploring the Endgame, American Chess Promotions, ISBN 0-939298-83-X

- Hooper, David; Whyld, Kenneth (1992), «stalemate», The Oxford Companion to Chess (2 ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280049-3

- Károlyi, Tibor; Aplin, Nick (2007), Endgame Virtuoso Anatoly Karpov, New In Chess, ISBN 978-90-5691-202-4

- Kaufman, Larry (2009), «Middlegame Zugzwang and a Previously Unknown Bobby Fischer Game», Chess Life (September): 35

- McCrary, John (2004), «The Evolution of Special Draw Rules», Chess Life (November): 26–27

- Minev, Nikolay (2004), A Practical Guide to Rook Endgames, Russell Enterprises, ISBN 1-888690-22-4

- Müller, Karsten; Lamprecht, Frank (2001), Fundamental Chess Endings, Gambit Publications, ISBN 1-901983-53-6

- Murray, H. J. R. (1913), A History of Chess, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-827403-3

- Nunn, John (2009), Understanding Chess Endgames, Gambit Publications, ISBN 978-1-906454-11-1

- Pachman, Ludek (1973), Attack and Defense in Modern Chess Tactics, David McKay

- Polgar, Susan; Truong, Paul (2005), A World Champion’s Guide to Chess, Random House, ISBN 978-0-8129-3653-7

- Reinfeld, Fred, ed. (1959) [First published in 1951 by David McKay], The Treasury of Chess Lore, New York: Dover, ISBN 978-0-4862-0458-1, OL 16542177M

- Roycroft, A.J. (1972), Test Tube Chess, Stackpole Books, ISBN 0-8117-1734-8

- Soltis, Andy (1978), Chess to Enjoy, Stein and Day, ISBN 978-0-8128-2331-8

- Staunton, Howard (1847), The Chess-Player’s Handbook, London: Henry G. Bohn, ISBN 978-1-3434-0465-6, retrieved 2016-11-22

- Sunnucks, Anne (1976) [First published 1970-04-29], The Encyclopaedia of Chess (2 ed.), London: Robert Hale Ltd, ISBN 978-0-7091-4697-1

External links[edit]

Look up stalemate in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Edward Winter, Stalemate

- «Chess: Stalemate by Self-Blockade» by Edward Winter

- Edward Winter, 5929. Stalemate

- «Stalemate!» Game Collection at chessgames.com

- Spassky vs. Keres, 1961, ended in stalemate

- A Defensive Brilliancy

- Example of «stalemate» in politics

Example of stalemate

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Black to move is stalemated. Black is not currently in check and has no legal move since every square to which the king might move is under attack by White.[1]

Stalemate is a situation in the game of chess where the player whose turn it is to move is not in check and has no legal move. Stalemate results in a draw. During the endgame, stalemate is a resource that can enable the player with the inferior position to draw the game rather than lose.[2] In more complex positions, stalemate is much rarer, usually taking the form of a swindle that succeeds only if the superior side is inattentive.[citation needed] Stalemate is also a common theme in endgame studies and other chess problems.

The outcome of a stalemate was standardized as a draw in the 19th century. Before this standardization, its treatment varied widely, including being deemed a win for the stalemating player, a half-win for that player, or a loss for that player; not being permitted; and resulting in the stalemated player missing a turn. Stalemate rules vary in other games of the chess family.

Etymology and usage[edit]

The first recorded use of stalemate is from 1765. It is a compounding of Middle English stale and mate (meaning checkmate). Stale is probably derived from Anglo-French estale meaning «standstill», a cognate of «stand» and «stall», both ultimately derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *sta-. The first recorded use in a figurative sense is in 1885.[3][4]

Stalemate has become a widely used metaphor for other situations where there is a conflict or contest between two parties, such as war or political negotiations, and neither side is able to achieve victory, resulting in what is also called an impasse, a deadlock, or a Mexican standoff. Chess writers note that this usage is a misnomer because, unlike in chess, the situation is often a temporary one that is ultimately resolved, even if it seems currently intractable.[5][6][7][8][9][10]

The term «stalemate» is sometimes used incorrectly as a generic term for a draw in chess. While draws are common, they are rarely the direct result of stalemate.[11]

Examples[edit]

With Black to move, Black is stalemated in diagrams 1 to 4. Stalemate is an important factor in the endgame – the endgame setup in diagram 1, for example, quite frequently is relevant in play (see King and pawn versus king endgame). The position in diagram 1 occurred in an 1898 game between Amos Burn and Harry Pillsbury[12] and also in a 1925 game between Savielly Tartakower and Richard Réti.[13] The same position, except shifted to the e-file, occurred in a 2009 game between Gata Kamsky and Vladimir Kramnik.[14]

The position in diagram 3 is an example of a pawn drawing against a queen. Stalemates of this sort can often save a player from losing an apparently hopeless position (see Queen versus pawn endgame).

Examples from games[edit]

Anand versus Kramnik[edit]

Anand vs. Kramnik, 2007

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Before 65…Kxf5, stalemate

In this position from the game Viswanathan Anand–Vladimir Kramnik from the 2007 World Chess Championship,[15] Black played 65…Kxf5, stalemating White.[16] (Any other move by Black loses.)

Korchnoi versus Karpov[edit]

Korchnoi vs. Karpov, 1978

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Position after 124.Bc3–g7

An intentional stalemate occurred on the 124th move of the fifth game of the 1978 World Championship match between Viktor Korchnoi and Anatoly Karpov.[17] The game had been a theoretical draw for many moves.[18][19] White’s bishop is useless; it cannot defend the queening square at a8 nor attack the black pawn on the light a4-square. If the white king heads towards the black pawn, the black king can move towards a8 and set up a fortress.

The players were not on speaking terms, however, so neither would offer a draw by agreement. On his 124th move, White played 124.Bg7, delivering stalemate. Korchnoi said that it gave him pleasure to stalemate Karpov and that it was slightly humiliating.[20] Until 2021, this was the longest game played in a World Chess Championship final match, as well as the only World Championship game to end in stalemate before 2007.[21]

Bernstein versus Smyslov[edit]

Black to move … |

… fell into a stalemate trap. |

Sometimes, a surprise stalemate saves a game. In the game between Ossip Bernstein–Vasily Smyslov[22] (see first diagram), Black can win by sacrificing the f-pawn and using the king to support the b-pawn. However, Smyslov thought it was good to advance the b-pawn because he could win the white rook with a skewer if it captured the pawn. Play went:

- 1… b2?? 2. Rxb2!

Now 2…Rh2+ 3.Kf3! Rxb2 is stalemate (see analysis diagram). Smyslov played 2…Kg4, and the game was drawn after 3.Kf1 (see Rook and pawn versus rook endgame).[23]

Matulović versus Minev[edit]

White to move |

Stalemate if White had played 4.Rxa6 |

Whereas the possibility of stalemate arose in the Bernstein–Smyslov game because of a blunder, it can also arise without one, as in the game Milan Matulović–Nikolay Minev (see first diagram). Play continued:

- 1. Rc6 Kg5 2. Kh3 Kh5 3. f4

The only meaningful attempt to make progress. Now all moves by Black (like 3…Ra3+?) lose, with one exception.

- 3… Rxa6!

Now 4.Rxa6 would be stalemate. White played 4.Rc5+ instead, and the game was drawn several moves later.[24]

Williams versus Harrwitz[edit]

Position after 72.Ka1 |

Position after 84.Rb3! If Black takes the rook either way, the result is stalemate. |

In the game Elijah Williams–Daniel Harrwitz[25] (see first diagram), Black was up a knight and a pawn in an endgame. This would normally be a decisive material advantage, but Black could find no way to make progress because of various stalemate resources available to White. The game continued:

- 72… Ra8 73. Rc1

Avoiding the threatened 73…Nc2+.

- 73… Ke3 74. Rc4 Ra4 75. Rc1 Kd2 76. Rc4 Kd3

76…Nc2+ 77.Rxc2+! Kxc2 is stalemate.

- 77. Rc3+! Kd4

77…Kxc3 is stalemate.

- 78. Rc1 Ra3 79. Rd1+ Kc5

79…Rd3 80.Rxd3+! leaves Black with either insufficient material to win after 80…Nxd3 81.Kxa2 or a standard fortress in a corner draw after 80…Kxd3.

- 80. Rc1+ Kb5 81. Rc7 Nd5 82. Rc2 Nc3?? 83. Rb2+ Kc4 84. Rb3! (second diagram)

Now the players agreed to a draw, since 84…Kxb3 or 84…Rxb3 is stalemate, as is 84…Ra8 85.Rxc3+! Kxc3.

Black could still have won the game until his critical mistake on move 82. Instead of 82…Nc3, 82…Nb4 wins; for example, after 83.Rc8 Re3 84.Rb8+ Kc5 85.Rc8+ Kd5 86.Rd8+ Kc6 87.Ra8 Re1+ 88.Kb2 Kc5 89.Kc3 a1=Q+, Black wins.[citation needed]

Carlsen versus Van Wely[edit]

Carlsen vs. Van Wely, 2007

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

White to make his 109th move

This 2007 game, Magnus Carlsen–Loek van Wely, ended in stalemate.[26] White used the second-rank defense in a rook and bishop versus rook endgame for 46 moves. The fifty-move rule was about to come into effect, under which White could claim a draw. The game ended:

- 109. Rd2+ Bxd2 ½–½

White was stalemated.[27]

More complex examples[edit]

Although stalemate usually occurs in the endgame, it can also occur with more pieces on the board. Outside of relatively simple endgame positions, such as those above, stalemate occurs rarely, usually when the side with the superior position has overlooked the possibility of stalemate.[28] This is typically realized by the inferior side’s sacrifice of one or more pieces in order to force stalemate. A piece that is offered as a sacrifice to bring about stalemate is sometimes called a desperado.

Evans versus Reshevsky[edit]

Position before White’s 47th move |

Position after 50.Rxg7+!, the eternal rook |

One of the best-known examples of the desperado is the game Larry Evans–Samuel Reshevsky[29] that was dubbed «The Swindle of the Century».[30] Evans sacrificed his queen on move 49 and offered his rook on move 50. White’s rook has been called the eternal rook. Capturing it results in stalemate, but otherwise it stays on the seventh rank and checks Black’s king ad infinitum (i.e. perpetual check). The game would inevitably end in a draw by agreement, by threefold repetition, or by an eventual claim under the fifty-move rule.[31]

- 47. h4! Re2+ 48. Kh1 Qxg3??

After 48…Qg6! 49.Rf8 Qe6! 50.Rh8+ Kg6, Black remains a piece ahead after 51.Qxe6 Nxe6, or forces mate after 51.gxf4 Re1+ and 52…Qa2+.[32]

- 49. Qg8+! Kxg8 50. Rxg7+!

Gelfand versus Kramnik[edit]

Position after 67.Re7 |

Possible stalemate |

The position at right occurred in Boris Gelfand–Vladimir Kramnik, 1994 FIDE Candidates match, game 6, in Sanghi Nagar, India.[33] Kramnik, down two pawns and on the defensive, would be very happy with a draw. Gelfand has just played 67. Re4–e7? (see first diagram), a strong-looking move that threatens 68.Qxf6, winning a third pawn, or 68.Rc7, further constricting Black. Black responded 67… Qc1! If White takes Black’s undefended rook with 68.Qxd8, Black’s desperado queen forces the draw with 68…Qh1+ 69.Kg3 Qh2+!, compelling 70.Kxh2 stalemate (second diagram). If White avoids the stalemate with 68.Rxg7+ Kxg7 69.Qxd8, Black draws by perpetual check with 69…Qh1+ 70.Kg3 Qg1+ 71.Kf4 Qc1+! 72.Ke4 Qc6+! 73.Kd3!? (73.d5 Qc4+; 73.Qd5 Qc2+) Qxf3+! 74.Kd2 Qg2+! 75.Kc3 Qc6+ 76.Kb4 Qb5+ 77.Ka3 Qd3+. Gelfand played 68. d5 instead but still only drew.

Troitsky versus Vogt[edit]

White, on move, sets a trap with 1.Rd1! |

Position after 3…Qxd1, stalemate |

In Troitsky–Vogt[clarification needed : full name], 1896, the famous endgame study composer Alexey Troitsky pulled off an elegant swindle in actual play. After Troitsky’s 1. Rd1!, Black fell into the trap with the seemingly crushing 1… Bh3?, threatening 2…Qg2#. The game concluded 2. Rxd8+ Kxd8 3. Qd1+! Qxd1 stalemate. White’s bishop, knight, and f-pawn are all pinned and unable to move.[34]

In studies[edit]

White to play and draw |

Incredibly, the possibility of stalemate allows White, three pieces down, to draw. |

Stalemate is a frequent theme in endgame studies[35] and other chess compositions. An example is the «White to Play and Draw» study at right, composed by the American master Frederick Rhine[36] and published in 2006.[37] White saves a draw with 1. Ne5+! Black wins after 1.Nb4+? Kb5! or 1.Qe8+? Bxe8 2.Ne5+ Kb5! 3.Rxb2+ Nb3. 1… Bxe5 After 1…Kb5? 2.Rxb2+ Nb3 3.Rxc4! Qxe3 (best; 3…Qb8+ 4.Kd7 Qxh8 5.Rxb3+ forces checkmate) 4.Rxb3+! Qxb3 5.Qh1! Bf5+ 6.Kd8!, White is winning. 2. Qe8+! 2.Qxe5? Qb7+ 3.Kd8 Qd7#. 2… Bxe8 3. Rh6+ Bd6 3…Kb5 4.Rxb6+ Kxb6 5.Nxc4+ also leads to a drawn endgame. Not 5.Rxb2+? Bxb2 6.Nc4+ Kb5 7.Nxb2 Bh5! trapping White’s knight. 4. Rxd6+! Kxd6 5. Nxc4+! Nxc4 6. Rxb6+ Nxb6+ Moving the king is actually a better try, but the resulting endgame of two knights and a bishop against a rook is a well-established theoretical draw.[38][39][40][41] 7. Kd8! (rightmost diagram) Black is three pieces ahead, but if White is allowed to take the bishop, the two knights are insufficient to force checkmate. The only way to save the bishop is to move it, resulting in stalemate. A similar idea occasionally enables the inferior side to save a draw in the ending of bishop, knight, and king versus lone king.

White to play and draw |

Final position |

At right is a composition by A. J. Roycroft which was published in the British Chess Magazine in 1957. White draws with 1. c7! after which there are two main lines:

- 1… f5 2. c8=Q (if 2.c8=R? then 2…Bc3 3.Rxc3 Qg7#) 2… Bc3 3. Qxf5+ draws by stalemate.

- 1… g5 (1…Ka1 2.c8=R transposes) 2. c8=R!! (2.c8=Q? Ka1 3.Qc2 [or 3.Qc1+] b1=Q+ wins) 2… Ka1 (2…Ng6 3.Rc1+ forces Black to capture, stalemating White) 3. Rc2!! (not 3.Rc1+?? b1=Q+! 4.Rxb1+ Bxb1#; now White threatens 4.Rxb2 and 5.Rxa2+, forcing stalemate or perpetual check) 3… Bc4 (trying to get in a check; 3…b1=Q, 3…b1=B, and 3…Bb1 are all stalemate; 3…Ng6 4.Rc1+!) 4. Rc1+ Ka2 5. Ra1+ Kb3 6. Ra3+ Kc2 7. Rc3+ Kd2 8. Rc2+ (rightmost diagram). As in Evans–Reshevsky, Black cannot escape the «eternal rook».[42]

In problems[edit]

Sam Loyd

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Shortest stalemate

Sam Loyd

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Stalemate with all pieces on board

Some chess problems require «White to move and stalemate Black in n moves» (rather than the more common «White to move and checkmate Black in n moves»). Problemists have also tried to construct the shortest possible game ending in stalemate. Sam Loyd devised one just ten moves long: 1.e3 a5 2.Qh5 Ra6 3.Qxa5 h5 4.Qxc7 Rah6 5.h4 f6 6.Qxd7+ Kf7 7.Qxb7 Qd3 8.Qxb8 Qh7 9.Qxc8 Kg6 10.Qe6 (diagram at left). A similar stalemate is reached after: 1.d4 c5 2.dxc5 f6 3.Qxd7+ Kf7 4.Qxd8 Bf5 5.Qxb8 h5 6.Qxa8 Rh6 7.Qxb7 a6 8.Qxa6 Bh7 9.h4 Kg6 10.Qe6 (Frederick Rhine).

Loyd also demonstrated that stalemate can occur with all the pieces on the board: 1.d4 d6 2.Qd2 e5 3.a4 e4 4.Qf4 f5 5.h3 Be7 6.Qh2 Be6 7.Ra3 c5 8.Rg3 Qa5+ 9.Nd2 Bh4 10.f3 Bb3 11.d5 e3 12.c4 f4 (diagram at right). Games such as this are occasionally played in tournaments as a pre-arranged draw.[43]

Double stalemate[edit]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Double stalemate position

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Another double stalemate

There are chess compositions featuring double stalemate. At left and at right are double stalemate positions, in which neither side has a legal move. Double stalemate is theoretically possible in a practical game, though is not known to ever have happened.[citation needed] Consider the following position:

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Potential gamelike position

The game draws after a waiting move like 1.Rg2 (1…b2+ 2.Rxb2; 1…c2 2.Rg4!). However, White has 1.Rb2?, an interesting blunder: if Black errs by 1…cxb2+? then White draws by 2.Kb1, creating a double stalemate position. Black could win by 1…c2! putting White in zugzwang.[citation needed]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Fastest known double stalemate: after 18…dxe3

The fastest known game ending in a double stalemate position was discovered by Enzo Minerva and published in the Italian newspaper l’Unità on 14 August 2007: 1.c4 d5 2.Qb3 Bh3 3.gxh3 f5 4.Qxb7 Kf7 5.Qxa7 Kg6 6.f3 c5 7.Qxe7 Rxa2 8.Kf2 Rxb2 9.Qxg7+ Kh5 10.Qxg8 Rxb1 11.Rxb1 Kh4 12.Qxh8 h5 13.Qh6 Bxh6 14.Rxb8 Be3+ 15.dxe3 Qxb8 16.Kg2 Qf4 17.exf4 d4 18.Be3 dxe3.[44]

History of the stalemate rule[edit]

The stalemate rule has had a convoluted history.[45] Although stalemate is universally recognized as a draw today, that has not been the case for much of the game’s history. In the forerunners to modern chess, such as chaturanga, delivering stalemate resulted in a loss.[46] However, this was changed in shatranj, where stalemating was a win. This practice persisted in chess as played in early 15th-century Spain.[47] However, Lucena (c. 1497) treated stalemate as an inferior form of victory;[48] it won only half the stake in games played for money, and this continued to be the case in Spain as late as 1600.[49] From about 1600 to 1800, the rule in England was that stalemate was a loss for the player administering it, a rule that the eminent chess historian H. J. R. Murray believes may have been adopted from Russian chess.[50] That rule disappeared in England before 1820, being replaced by the French and Italian rule that a stalemate was a drawn game.[51]

Throughout history, a stalemate has at various times been:

- A win for the stalemating player in 10th century Arabia[52] and parts of medieval Europe.[53][54]

- A half-win for the stalemating player. In a game played for stakes, they would win half the stake (18th century Spain).[55]

- A win for the stalemated player in 9th century India,[56] 17th century Russia,[57] on the Central Plain of Europe in the 17th century,[58] and 17th–18th century England.[59][60] This rule continued to be published in Hoyle’s Games Improved as late as 1866.[61][62]

- Illegal. If White made a move that would stalemate Black, he had to retract it and make a different move (Eastern Asia until the early 20th century). Murray likewise wrote that in Hindustani chess and Parsi chess, two of the three principal forms of chess played in India as of 1913,[63] a player was not allowed to play a move that would stalemate the opponent.[64] The same was true of Burmese chess, another chess variant, at the time of writing.[65] Stalemate was not permitted in most of the Eastern Asiatic forms of the game (specifically in Burma, India, Japan, and Siam) until early in the 20th century.[66]

- The forfeiture of the stalemated player’s turn to move (medieval France),[67][68] although other medieval French sources treat stalemate as a draw.[69]

- A draw. This was the rule in 13th-century Italy[70] and also stated in the German Cracow Poem (1422), that noted, however, that some players treated stalemate as equivalent to checkmate.[71] This rule was ultimately adopted throughout Europe, but not in England until the 19th century, after being introduced there by Jacob Sarratt.[72][73][74]

Proposed rule change[edit]

Periodically, writers have argued that stalemate should again be made a win for the side causing the stalemate. Grandmaster Larry Kaufman writes, «In my view, calling stalemate a draw is totally illogical, since it represents the ultimate zugzwang, where any move would get your king taken».[75] The British master T. H. Tylor argued in a 1940 article in the British Chess Magazine that the present rule, treating stalemate as a draw, «is without historical foundation and irrational, and primarily responsible for a vast percentage of draws, and hence should be abolished».[76] Years later, Fred Reinfeld wrote, «When Tylor wrote his attack on the stalemate rule, he released about his unhappy head a swarm of peevish maledictions that are still buzzing.»[77] Larry Evans calls the proposal to make stalemate a win for the stalemating player a «crude proposal that … would radically alter centuries of tradition and make chess boring».[78] This rule change would cause a greater emphasis on material; an extra pawn would be a greater advantage than it is today.

Rules in other chess variants[edit]

Not all variants of chess consider the stalemate to be a draw. Many regional variants, as well some variants of Western chess, have adopted their own rules on how to treat the stalemated player. In chaturanga, which is widely considered to be the common ancestor of all variants of chess, a stalemate was a win for the stalemated player.[79][80] Around the 7th century, this game was adopted in the Middle East as shatranj with very similar rules to its predecessor; however, the stalemate rule was changed to its exact opposite: i.e. it was a win for the player delivering the stalemate.[81] This game was in turn introduced to the western world, where it would eventually evolve to modern-day (Western) chess, although the stalemate rule for Western chess was not standardised as a draw until the 19th century (see history of the rule).

Modern Asian variants[edit]

Chaturanga also evolved into several other games in various regions of Asia, all of which have varying rules on stalemating:

- In makruk (Thai chess), a stalemate results in a draw, like in Western chess.[82]

- In shogi (Japanese chess) and the majority of its variants, a stalemate is a win for the player delivering the stalemate.[83] This is because historically, the objective of shogi was to capture the opponent’s king rather than to checkmate it; thus, a stalemate was no different from a checkmate, as both outcomes would typically result in the king’s capture in the next move. The official rules of shogi (but not most of its variants) have since altered the objective of the game to checkmate, however stalemate is still considered a form of checkmate and thus a win for the stalemating player. However, in shogi (and in any variant of the game that features drops), stalemates are extremely rare due to the fact that no piece ever goes entirely out of play.

- Xiangqi (Chinese chess) and janggi (Korean chess), despite being very similar to each other in terms of both the board and the pieces, have adopted different rules for what happens in the case of a stalemate. In xiangqi, like in shogi, it results in an immediate loss for the stalemated player, and there is no explicit distinction between it and checkmate.[84] Janggi, on the other hand, allows the stalemated player to pass their turn; i.e., the player may (and in fact must) leave the general (analogous to the chess king) in position and make no move when stalemated.[85]

- In sittuyin (Myanma/Burmese chess), stalemates are avoided altogether, as delivering them is illegal. Players are not allowed to leave the opponent with no legal moves without putting the king into check.[86]

Western chess variants[edit]

The majority of variants of Western chess do not specify any alterations to the rule of stalemate. There are some variants, however, where the rule is specified to differ from that of standard chess:

- In losing chess, the stalemate rule varies depending on the version being played.[87] According to the «international» rules, a stalemate is simply a win for the stalemated player. The Free Internet Chess Server, however, grants a win to the player with fewer pieces remaining on the board (regardless of who delivered the stalemate); if both players have the same number of pieces it is a draw.[88] There is also a «joint» FICS/international rule, according to which a stalemate is only a win if both sources agree that it is a win (i.e. it counts as a win for the stalemated player if that player also happens to have fewer pieces remaining); in all other cases it is a draw.

- In Gliński’s hexagonal chess, stalemate is neither a draw nor a full win. Instead, in tournament games, the player who delivers the stalemate earns 3⁄4 point, while the stalemated player receives 1⁄4 point.[89] It is unknown whether a stalemate should be considered a draw or a win in a friendly game.

See also[edit]

- Checkmate

- Desperado

- Draw (chess)

- Glossary of chess

- Rules of chess

- Swindle (chess)

Notes[edit]

- ^ Polgar & Truong 2005:33

- ^ Hooper & Whyld 1992:387

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «stalemate |». www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ «Definition of STALEMATE». www.merriam-webster.com. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ Golombek 1977:304

- ^ Soltis 1978:54

- ^ Golombek wrote, «The word ‘stalemate’ has been taken into the English language to mean (wrongly) a temporary state of impasse.» Soltis wrote:

There is a world of difference between no choice … and a poor choice. Editorial writers often talk about a political stalemate when the analogy they probably have in mind is a political «zugzwang». In stalemate a player has no legal moves, period. In zugzwang he has nothing pleasant to do.

- ^ Hoffman, Gil (2013-07-02). «Left blames PM for stalemate on peace talks». The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- ^

Purnick, Joyce (1988-01-06). «Threat by Wagner to Resign Solved Schools Stalemate». The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-07-05. - ^

Gordon, Meghan (2008-05-21). «Huey P. Long widening stalemate appears resolved». Retrieved 2013-07-05. - ^ British Chess Magazine, September 1911, p. 342, Stalemate

- ^ Burn vs. Pillsbury, 1898

- ^ Tartakower vs. Réti 1925

- ^ Kamsky vs. Kramnik

- ^ «Anand vs. Kramnik, Mexico City 2007». Chessgames.com.

- ^ Benko 2008:49

- ^ Karpov vs. Korchnoi

- ^ Károlyi & Aplin 2007:170

- ^ Griffiths 1992:43–46

- ^ Kasparov 2006:120

- ^ Fox & James 1993:236

- ^ «Bernstein vs. Smyslov, Groningen 1946». Chessgames.com.

- ^ Minev 2004:21

- ^ Minev 2004:22

- ^ «Williams vs. Harrwitz, London 1846». Chessgames.com.

- ^ «Carlsen vs. Van Wely, Wijk aan Zee 2007». Chessgames.com.

- ^ Nunn 2009:200

- ^ Pachman 1973:17

- ^ «Evans vs. Reshevsky, New York 1963/64». Chessgames.com.

- ^ Larry Evans, Chess Catechism, Simon and Schuster, 1970, p. 66. SBN 671-21531-0. It appears that Evans himself was the first to refer to the game as the «Swindle of the Century» in print, in his annotations in American Chess Quarterly magazine, of which he was the Editor-in-Chief. American Chess Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Winter, 1964), p. 171. Hans Kmoch referred to the conclusion of the game as «A Hilarious Finish». Hans Kmoch, «United States Championship», Chess Review, March 1964, pp. 76–79, at p. 79. Also available on DVD (p. 89 of «Chess Review 1964» PDF file).

- ^ Averbakh 1996:80–81

- ^ Hans Kmoch, «United States Championship», Chess Review, March 1964, pp. 76–79, at p. 79. Also available on DVD (p. 89 of «Chess Review 1964» PDF file).

- ^ «Gelfand vs. Kramnik, Sanghi Nagar 1994». Chessgames.com.

- ^ O’Keefe, Jack (August–September 1973). «Stalemate!». Michigan Chess. pp. 4–6. Archived from the original on 2012-05-02. Retrieved 2016-11-22 – via Michigan Chess Association Webzine July 1999.

- ^ Hooper & Whyld 1992:388

- ^ United States Chess Federation rating card for Frederick S. Rhine

- ^ Benko 2006:49

- ^ Fine & Benko 2003:524

- ^ Müller & Lamprecht 2001:403

- ^ Staunton 1847:439

- ^ This can be confirmed, as to this position, by the Shredder Six-Piece Database.

- ^ Roycroft 1972:294

- ^ Hohmeister vs. Frank 1993

- ^ The previous record (37 ply, i.e. 18.5 moves) was held by the German composer Eduard Schildberg, and was published in the Deutsches Wochenschach in 1915.

Antonio Garofalo (2007). «Best Problems» (PDF). pp. 23 (numbered «95» at bottom of page). Retrieved 2008-09-01. - ^ Murray 1913:61

- ^ Murray 1913:229, 267

- ^ Murray 1913:781

- ^ Murray 1913:461

- ^ Murray 1913:833

- ^ Murray 1913:60–61, 466

- ^ Murray 1913:391

- ^ Davidson 1981:65

- ^ Murray 1913:463–64, 781

- ^ McCrary 2004:26

- ^ Davidson 1981:65

- ^ Murray 1913:56–57, 60–61

- ^ Davidson 1981:65

- ^ Murray 1913:388–89

- ^ Murray 1913:60–61, 466

- ^ Saul’s Famous game of Chesse-play (London 1614) explained the reason for this rule as follows: «He that hath put his adversary’s King into a stale, loseth the game, because he hath disturbed the course of the game, which can only end with the grand Check-mate.» Murray, p. 466 & n. 32. McCrary, p. 26. Murray derides the rule as «illogical», Murray, p. 61, and Saul’s explanation as «puerile», id., p. 466.

- ^ Sunnucks 1970:438

- ^ Murray wrote in 1913, «The rule still appeared in editions after 1857, and I have met with players who argued that the rule was so.» Murray, p. 391 n. 47.

- ^ Murray 1913:78

- ^ Murray 1913:82, 84

- ^ Murray 1913:113

- ^ Davidson 1981:65

- ^ Murray 1913:464–66

- ^ Davidson 1981:64–65

- ^ Murray 1913:464–66

- ^ Murray 1913:461–62

- ^ Murray 1913:463–64

- ^ Murray 1913:391

- ^ Davidson 1981:64–66

- ^ Sunnucks 1970:438

- ^ Kaufman 2009

- ^ Reinfeld 1959:242–44

- ^ Reinfeld 1959:242

- ^ Evans 2007:234

- ^ Murray 1913:229, 267

- ^ Chaturangs – Game rules

- ^ Shatranj

- ^ Makruk: Thai chess

- ^ Rules – Japanese Game Shogi

- ^ BrainKing – Game rules (Chinese Chess)

- ^ Janggi – Korean Chess

- ^ How to Play Sittuyin – Burmese Chess – Myanmar Chess

- ^ Alexander 1973:107

- ^ Losing Chess

- ^ Gliński’s Hexagonal Chess

References[edit]

- Alexander, C.H.O’D. (1973), A Book of Chess, New York: Harper & Row, ISBN 978-0-0601-0048-3

- Averbakh, Yuri (1996-08-01), Chess Middlegames: Essential Knowledge, Cadogan Chess, ISBN 978-1-8574-4125-3

- Benko, Pal (May 2006), «Benko’s Bafflers», Chess Life (May): 49

- Benko, Pal (January 2008), «The 2007 World Championship», Chess Life (January): 48–49

- Davidson, Henry A. (1949), A Short History of Chess, Greenberg, ISBN 978-0-307-82829-3, LCCN 68-22441, retrieved 2016-11-22

- Evans, Larry (1970-08-20), Chess Catechism, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-0-6712-0491-4

- Evans, Larry (2009-11-06), This Crazy World of Chess, Cardoza Publishing, ISBN 978-1580422185

- Fine, Reuben; Benko, Pal (2003) [1941], Basic Chess Endings, David McKay, ISBN 0-8129-3493-8

- Fox, Mike; James, Richard (1993), The Even More Complete Chess Addict (2 ed.), London: Faber & Faber, ISBN 978-0-5711-7040-1

- Golombek, Harry (1977), Golombek’s Encyclopedia of Chess, Crown Publishers, ISBN 0-517-53146-1

- Griffiths, Peter (1992), Exploring the Endgame, American Chess Promotions, ISBN 0-939298-83-X

- Hooper, David; Whyld, Kenneth (1992), «stalemate», The Oxford Companion to Chess (2 ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280049-3

- Károlyi, Tibor; Aplin, Nick (2007), Endgame Virtuoso Anatoly Karpov, New In Chess, ISBN 978-90-5691-202-4

- Kaufman, Larry (2009), «Middlegame Zugzwang and a Previously Unknown Bobby Fischer Game», Chess Life (September): 35

- McCrary, John (2004), «The Evolution of Special Draw Rules», Chess Life (November): 26–27

- Minev, Nikolay (2004), A Practical Guide to Rook Endgames, Russell Enterprises, ISBN 1-888690-22-4

- Müller, Karsten; Lamprecht, Frank (2001), Fundamental Chess Endings, Gambit Publications, ISBN 1-901983-53-6

- Murray, H. J. R. (1913), A History of Chess, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-827403-3

- Nunn, John (2009), Understanding Chess Endgames, Gambit Publications, ISBN 978-1-906454-11-1

- Pachman, Ludek (1973), Attack and Defense in Modern Chess Tactics, David McKay

- Polgar, Susan; Truong, Paul (2005), A World Champion’s Guide to Chess, Random House, ISBN 978-0-8129-3653-7

- Reinfeld, Fred, ed. (1959) [First published in 1951 by David McKay], The Treasury of Chess Lore, New York: Dover, ISBN 978-0-4862-0458-1, OL 16542177M

- Roycroft, A.J. (1972), Test Tube Chess, Stackpole Books, ISBN 0-8117-1734-8

- Soltis, Andy (1978), Chess to Enjoy, Stein and Day, ISBN 978-0-8128-2331-8

- Staunton, Howard (1847), The Chess-Player’s Handbook, London: Henry G. Bohn, ISBN 978-1-3434-0465-6, retrieved 2016-11-22

- Sunnucks, Anne (1976) [First published 1970-04-29], The Encyclopaedia of Chess (2 ed.), London: Robert Hale Ltd, ISBN 978-0-7091-4697-1

External links[edit]

Look up stalemate in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Edward Winter, Stalemate

- «Chess: Stalemate by Self-Blockade» by Edward Winter

- Edward Winter, 5929. Stalemate

- «Stalemate!» Game Collection at chessgames.com

- Spassky vs. Keres, 1961, ended in stalemate

- A Defensive Brilliancy

- Example of «stalemate» in politics

Слово «пат» — один из самых важных шахматных терминов. Это последняя надежда для игроков, которые защищают проигранную позицию. С помощью пата можно превратить проигрышную партию в ничью. Пат в шахматах может вызвать разочарование, счастье, волнение и эстетическое удовольствие.

Пат в шахматах: Определение

Определение пата в шахматах следующее: Пат – это особый тип ничьей. Он возникает в ситуации, когда у игрока, который должен сделать ход, нет разрешённого хода и его король не под шахом. Согласно шахматным правилам, если в игре возник пат, то это ничья.

Пат — это ресурс, который обычно возникает в эндшпиле. Игрок, защищающий худшую позицию, часто может путём добровольной отдачи материала создать патовую ситуацию в определённых позициях, чтобы не проиграть игру.

На первый взгляд правило может показаться нелогичным. Почему игра должна закончиться вничью, если ваш игрок лишил соперника любого допустимого хода? Разве это не должно закончиться сокрушительной победой более сильного? По этому вопросу уже было много споров. Однако действующие правила игры в шахматы определяют пат как ничью, и маловероятно, что это правило будет изменено в ближайшее время.

По этой причине мы не хотим добавлять ещё одно мнение по теме в этой статье. Вместо этого научим вас, как извлечь выгоду из пата в собственных шахматных партиях.

С одной стороны, мы хотим познакомить вас с патом как важным оборонительным ресурсом, когда вы защищаете безнадёжную позицию. С другой стороны, заострим ваше внимание на патовых идеях вашего оппонента, когда у вас явно лучшая позиция.

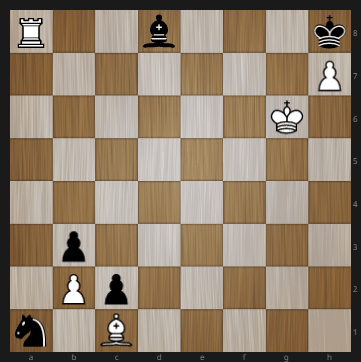

Чтобы понять ключевую идею пата в шахматах, давайте рассмотрим простой пример:

Пат — распространённый мотив пешечных окончаний. На приведённой выше диаграмме ходят чёрные, но у чёрного короля нет разрешённого поля для хода. Из-за того, что чёрный король не находится под шахом, на доске пат. Игра заканчивается вничью.

Теперь рассмотрим некоторые основные патовые шаблоны, с которыми должен быть знаком каждый шахматист.

Пат в шахматных партиях начинающих

Пат очень часто встречается в шахматах между новичками, особенно в детских шахматах. Игроки знают основные правила игры в шахматы, но имеют лишь смутное представление о том, как поставить мат сопернику в определённых ситуациях. Следующий пример — классический:

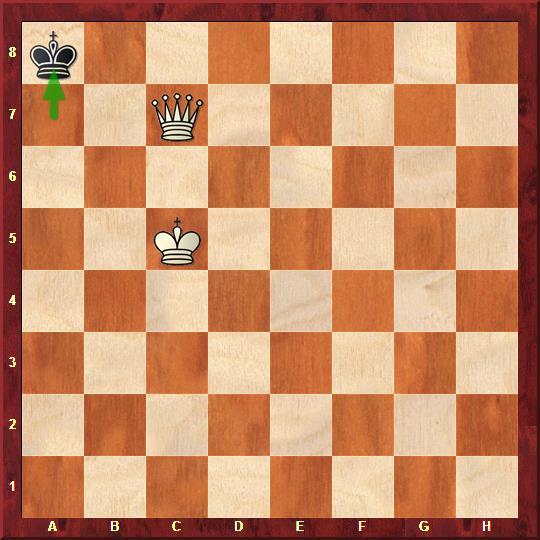

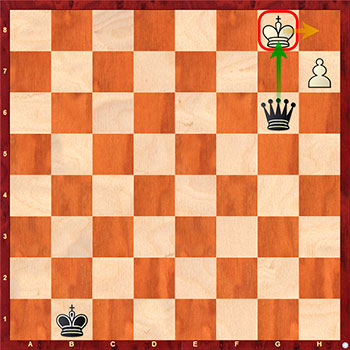

Объективно говоря, эта позиция полностью выигрышная для белых. У белых целый ферзь, а у чёрных только король. Тем не менее, многие начинающие игроки не знают как здесь поставить мат. Вместо того, чтобы приблизить своего короля к королю противника и помочь ферзю поставить мат, они отнимают у короля противника ещё больше полей.

На приведённой выше диаграмме 1.Qc7 на первый взгляд выглядит сильным ходом, загоняющим чёрного короля в угол. Однако проблема с этим ходом в том, что король не находится под шахом и не может делать никаких ходов. Поскольку у чёрных нет других фигур для хода на доске патовая позиция. Вместо этого белые могли просто заматовать чёрных в два хода, начав с 1.Kc6! Kb8 (Единственный допустимый ход чёрных) 2.Qb7#.

Пат в шахматном эндшпиле

Пат скорее всего, произойдёт в эндшпиле. С одной стороны, это может быть скрытый ресурс для проигрывающего игрока с целью спасти пол-очка. С другой стороны, патовые идеи имеют большое значение для многих теоретических окончаний:

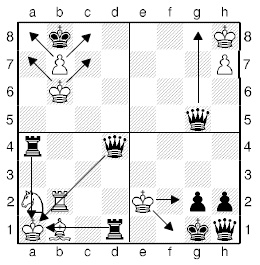

Пат в теоретических окончаниях

Эндшпиль король + слоновая пешка против ферзя который не поддерживается своим королём, является ничьей:

Важно отметить, что более слабая сторона может использовать тот же защитный ресурс для защиты в эндшпиле король и ладейная пешка против ферзя который не поддерживается своим королём:

Белый король находится под шахом. Однако белым не обязательно играть 1.Кf8?, отдавая пешку «h». Они могут сыграть 1.Kh8! Теперь у чёрных нет времени подвести своего короля ближе, так как после хода 1…Крc2 на доске будет пат.

Пат также является важным защитным ресурсом в более сложных теоретических окончаниях. Давайте посмотрим на эндшпиль ладья + слон против ладьи. Теоретически такое сочетание материалов — ничья. На практике, однако, даже сильные гроссмейстеры часто не в состоянии спасти партию. В этом эндшпиле есть две основные схемы защиты – позиция Кохрена и защита второй горизонтали. Знание последнего очень важно для турнирных игроков:

Эти примеры также преподают важный урок:

Нельзя недооценивать важность изучения теоретических окончаний. Если вы знакомы с наиболее важными теоретическими окончаниями и знаете, какие позиции являются ничейными или выигрышными, вы можете активно стремиться к ним в своих партиях – независимо от того, атакуете вы или обороняетесь. Если вы защищаете худшую позицию и знаете, что эндшпиль ладья + слон против ладьи — это ничья за счёт защиты второй горизонтали, вы можете попытаться активно стремиться к этой позиции.

Пат в практических окончаниях

Пат в шахматах — ценный инструмент, который может помочь спасти полностью проигранный или неполноценный эндшпиль.

В большинстве случаев патовые ситуации возникают из-за ошибки. Обычно такие ситуации возникают, когда игрок не замечает, что путём жертвы одной или нескольких фигур на доске возникнет пат.

Иногда в шахматах встречаются действительно удивительные способы ничьи через пат:

Пат в гроссмейстерских партиях

Даже шахматные гроссмейстеры иногда ошибаются и допускают пат. Давайте посмотрим какую-нибудь серьёзную игру, закончившуюся патом.

Bernstein – Smyslov (1946)

У бывшего чемпиона мира по шахматам Василия Смыслова (1957-1958) был выигрышный ладейный эндшпиль, но он упустил из виду патовый приём:

Патовая ситуация случалась даже в играх чемпионата мира по шахматам. Партия Ананд – Крамник, Мексика, 2007 г. – хорошая тому иллюстрация.

Пат в шахматных композициях

Пат — обычная тема в шахматных композициях. Следующая композиция была написана известным шахматным композитором Леонидом Куббелем.

Примечание: Если вы стремитесь к резкому увеличению шахматного уровня, то необходимо систематически работать над всеми элементами игры:

- Тактика

- Позиционная игра

- Атакующие навыки

- Техника эндшпиля

- Анализ классических игр

- Психологическая подготовка

- И еще многое другое

На первый взгляд кажется, что предстоит много работы. Но благодаря нашему учебному курсу Ваше обучение пройдёт легко, эффективно и с минимальными затратами времени. Присоединяйтесь к программе обучения «Шахматы. Перезагрузка за 21 День», прямо сейчас!

Пат в шахматах

- 03 Март 2018

-

24801

Бывает, что мат, как цель шахматной партии, определяют сравнением «взять в плен короля противника». Это не совсем правильно. Точнее будет «взять в плен короля противника и напасть на него своей фигурой». Для ситуации, когда король просто находится «в плену», но при этом ему никто не угрожает, т.е. не дает шах ни одна фигура противника, больше подходит определение — пат. Что же это — проигрыш или ничья? С помощью конкретных примеров и видео мы сейчас во всем разберемся.

Пат — это ситуация в шахматной партии, когда игрок не может сделать ход, не нарушая правил шахмат, но при этом его король не находится под атакой, ему не объявлен шах. Давайте сразу перейдем к примерам.