| Peter I | ||

|---|---|---|

Portrait by Jean-Marc Nattier, after 1717 |

||

| Tsar / Emperor of Russia[note 1] | ||

| Reign | 7 May 1682 – 8 February 1725 | |

| Coronation | 25 June 1682 | |

| Predecessor | Feodor III | |

| Successor | Catherine I | |

| Co-monarch | Ivan V (1682–1696) | |

| Regent | Sophia Alekseyevna (1682–1689) | |

| Born | 9 June 1672 Moscow, Tsardom of Russia |

|

| Died | 8 February 1725 (aged 52) Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

|

| Burial |

Peter and Paul Cathedral |

|

| Consort |

Eudoxia Lopukhina (m. 1689; div. 1698) Martha Skavronskaya (m. 1707) |

|

| Issue among others |

|

|

|

||

| House | Romanov | |

| Father | Alexis of Russia | |

| Mother | Natalya Naryshkina | |

| Religion | Russian Orthodoxy | |

| Signature |

Peter I (9 June [O.S. 30 May] 1672 – 8 February [O.S. 28 January] 1725),[note 2] most commonly known as Peter the Great,[pron 1] was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from 7 May [O.S. 27 April] 1682 to 1721 and subsequently the Russian Empire until his death in 1725, jointly ruling with his elder half-brother, Ivan V until 1696. He is primarily credited with the modernisation of the country, transforming it into a European power.

Through a number of successful wars, he captured ports at Azov and the Baltic Sea, laying the groundwork for the Imperial Russian Navy, ending uncontested Swedish supremacy in the Baltic and beginning the Tsardom’s expansion into a much larger empire that became a major European power. He led a cultural revolution that replaced some of the traditionalist and medieval social and political systems with ones that were modern, scientific, Westernised and based on the Enlightenment.[1] Peter’s reforms had a lasting impact on Russia, and many institutions of the Russian government trace their origins to his reign. He adopted the title of Emperor in place of the old title of Tsar in 1721, and founded and developed the city of Saint Petersburg, which remained the capital of Russia until 1918.

The first Russian university—Saint Petersburg State University—was founded a year before his death, in 1724. The second one, Moscow State University, was founded 30 years after his death, during the reign of his daughter Elizabeth.

Title

The imperial title of Peter the Great was the following:[2]

By the grace of God, the most excellent and great sovereign emperor Pyotr Alekseevich the ruler of all the Russias: of Moscow, of Kiev, of Vladimir, of Novgorod, Tsar of Kazan, Tsar of Astrakhan and Tsar of Siberia, sovereign of Pskov, great prince of Smolensk, of Tver, of Yugorsk, of Perm, of Vyatka, of Bulgaria and others, sovereign and great prince of the Novgorod Lower lands, of Chernigov, of Ryazan, of Rostov, of Yaroslavl, of Belozersk, of Udora, of Kondia and the sovereign of all the northern lands, and the sovereign of the Iverian lands, of the Kartlian and Georgian Kings, of the Kabardin lands, of the Circassian and Mountain princes and many other states and lands western and eastern here and there and the successor and sovereign and ruler.

Early life

Peter was named after the apostle, and described as a newborn as «with good health, his mother’s black, vaguely Tatar eyes, and a tuft of auburn hair».[3] He was educated from an early age by several tutors commissioned by his father, Tsar Alexis of Russia, most notably Nikita Zotov, Patrick Gordon, and Paul Menesius. On 29 January 1676, Alexis died, leaving the sovereignty to Peter’s elder half-brother, the weak and sickly Feodor III of Russia.[4] Throughout this period, the government was largely run by Artamon Matveev, an enlightened friend of Alexis, the political head of the Naryshkin family and one of Peter’s greatest childhood benefactors.

This position changed when Feodor died in 1682. As Feodor did not leave any children, a dispute arose between the Miloslavsky family (Maria Miloslavskaya was the first wife of Alexis I) and Naryshkin family (Natalya Naryshkina was his second) over who should inherit the throne. Peter’s other half-brother, Ivan V of Russia, was next in line, but was chronically ill and of infirm mind. Consequently, the Boyar Duma (a council of Russian nobles) chose the 10-year-old Peter to become Tsar, with his mother as regent.

Peter the Great as a child

This arrangement was brought before the people of Moscow, as ancient tradition demanded, and was ratified. Sophia, one of Alexis’ daughters from his first marriage, led a rebellion of the Streltsy (Russia’s elite military corps) in April–May 1682. In the subsequent conflict, some of Peter’s relatives and friends were murdered, including Matveev, and Peter witnessed some of these acts of political violence.[5]

The Streltsy made it possible for Sophia, the Miloslavskys (the clan of Ivan) and their allies to insist that Peter and Ivan be proclaimed joint Tsars, with Ivan being acclaimed as the senior. Sophia then acted as regent during the minority of the sovereigns and exercised all power. For seven years, she ruled as an autocrat. A large hole was cut in the back of the dual-seated throne used by Ivan and Peter. Sophia would sit behind the throne and listen as Peter conversed with nobles, while feeding him information and giving him responses to questions and problems. This throne can be seen in the Kremlin Armoury in Moscow.

Peter was not particularly concerned that others ruled in his name. He engaged in such pastimes as shipbuilding and sailing, as well as mock battles with his toy army. Peter’s mother sought to force him to adopt a more conventional approach and arranged his marriage to Eudoxia Lopukhina in 1689.[6] The marriage was a failure, and ten years later Peter forced his wife to become a nun and thus freed himself from the union.

By the summer of 1689, Peter, then age 17, planned to take power from his half-sister Sophia, whose position had been weakened by two unsuccessful Crimean campaigns against the Crimean Khanate in an attempt to stop devastating Crimean Tatar raids into Russia’s southern lands. When she learned of his designs, Sophia conspired with some leaders of the Streltsy, who continually aroused disorder and dissent. Peter, warned by others from the Streltsy, escaped in the middle of the night to the impenetrable monastery of Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra; there he slowly gathered adherents who perceived he would win the power struggle. Sophia was eventually overthrown, with Peter I and Ivan V continuing to act as co-tsars. Peter forced Sophia to enter a convent, where she gave up her name and her position as a member of the royal family.[7]

The Tsardom of Russia, c. 1700

Still, Peter could not acquire actual control over Russian affairs. Power was instead exercised by his mother, Natalya Naryshkina. It was only when Natalya died in 1694 that Peter, then aged 22, became an independent sovereign.[8] Formally, Ivan V was a co-ruler with Peter, though being ineffective. Peter became the sole ruler when Ivan died in 1696 without male offspring, two years later.

Peter grew to be extremely tall as an adult, especially for the time period, reportedly standing 6 ft 8 in (2.03 m).[8] Peter, however, lacked the overall proportional heft and bulk generally found in a man that size. Both his hands and feet were small,[9][citation needed] and his shoulders were narrow for his height; likewise, his head was small for his tall body. Added to this were Peter’s noticeable facial tics, and he may have suffered from petit mal seizures, a form of epilepsy.[10]

During his youth, Peter befriended Patrick Gordon, Franz Lefort and several other foreigners in Russian service and was a frequent guest in Moscow’s German Quarter, where he met his Dutch mistress Anna Mons.

Reign

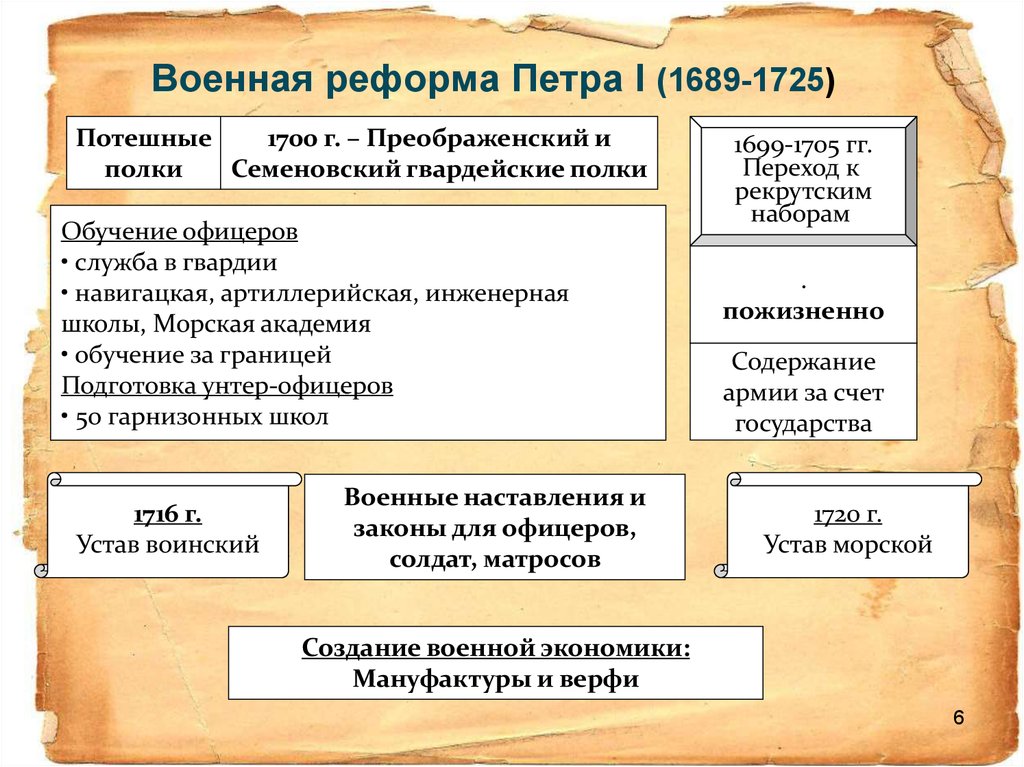

Peter implemented sweeping reforms aimed at modernizing Russia.[11] Heavily influenced by his advisors from Western Europe, Peter reorganized the Russian army along modern lines and dreamed of making Russia a maritime power. He faced much opposition to these policies at home but brutally suppressed rebellions against his authority, including by the Streltsy, Bashkirs, Astrakhan, and the greatest civil uprising of his reign, the Bulavin Rebellion.

Peter implemented social modernization in an absolute manner by introducing French and western dress to his court and requiring courtiers, state officials, and the military to shave their beards and adopt modern clothing styles.[12] One means of achieving this end was the introduction of taxes for long beards and robes in September 1698.[13]

In his process to westernize Russia, he wanted members of his family to marry other European royalty. In the past, his ancestors had been snubbed at the idea, but now, it was proving fruitful. He negotiated with Frederick William, Duke of Courland to marry his niece, Anna Ivanovna. He used the wedding in order to launch his new capital, St Petersburg, where he had already ordered building projects of westernized palaces and buildings. Peter hired Italian and German architects to design it.[14]

As part of his reforms, Peter started an industrialization effort that was slow but eventually successful. Russian manufacturing and main exports were based on the mining and lumber industries. For example, by the end of the century Russia came to export more iron than any other country in the world.[15]

To improve his nation’s position on the seas, Peter sought more maritime outlets. His only outlet at the time was the White Sea at Arkhangelsk. The Baltic Sea was at the time controlled by Sweden in the north, while the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea were controlled by the Ottoman Empire and Safavid Empire respectively in the south.

Peter attempted to acquire control of the Black Sea, which would require expelling the Tatars from the surrounding areas. As part of an agreement with Poland that ceded Kiev to Russia, Peter was forced to wage war against the Crimean Khan and against the Khan’s overlord, the Ottoman Sultan. Peter’s primary objective became the capture of the Ottoman fortress of Azov, near the Don River. In the summer of 1695 Peter organized the Azov campaigns to take the fortress, but his attempts ended in failure.

Peter returned to Moscow in November 1695 and began building a large navy. He launched about thirty ships against the Ottomans in 1696, capturing Azov in July of that year. On 12 September 1698, Peter officially founded the first Russian Navy base, Taganrog on the Sea of Azov.

Grand Embassy

Portrait of Peter I by Godfrey Kneller, 1698. This portrait was Peter’s gift to the King of England.

Peter knew that Russia could not face the Ottoman Empire alone. In 1697, he traveled «incognito» to Western Europe on an 18-month journey with a large Russian delegation–the so-called «Grand Embassy». He used a fake name, allowing him to escape social and diplomatic events, but since he was far taller than most others, he did not fool anyone of importance. One goal was to seek the aid of European monarchs, but Peter’s hopes were dashed. France was a traditional ally of the Ottoman Sultan, and Austria was eager to maintain peace in the east while conducting its own wars in the west. Peter, furthermore, had chosen an inopportune moment: the Europeans at the time were more concerned about the War of Spanish Succession over who would succeed the childless King Charles II of Spain than about fighting the Ottoman Sultan.[6]

The «Grand Embassy» continued nevertheless. While visiting the Netherlands, Peter learned much about life in Western Europe. He studied shipbuilding [16] in Zaandam (the house he lived in is now a museum, the Czar Peter House) and Amsterdam, where he visited, among others, the upper-class De Wilde family. Jacob de Wilde, a collector-general with the Admiralty of Amsterdam, had a well-known collection of art and coins, and De Wilde’s daughter Maria de Wilde made an engraving of the meeting between Peter and her father, providing visual evidence of «the beginning of the West European classical tradition in Russia».[17] According to Roger Tavernier, Peter the Great later acquired De Wilde’s collection.[18]

Thanks to the mediation of Nicolaes Witsen, mayor of Amsterdam and an expert on Russia, the Tsar was given the opportunity to gain practical experience in the largest shipyard in the world, belonging to the Dutch East India Company, for a period of four months. The Tsar helped with the construction of an East Indiaman ship specially laid down for him: Peter and Paul. During his stay the Tsar engaged many skilled workers such as builders of locks, fortresses, shipwrights, and seamen—including Cornelis Cruys, a vice-admiral who became, under Franz Lefort, the Tsar’s advisor in maritime affairs. Peter later put his knowledge of shipbuilding to use in helping build Russia’s navy.[19] Peter paid a visit to surgeon Frederik Ruysch, who taught him how to draw teeth and catch butterflies, and to Ludolf Bakhuysen, a painter of seascapes. Jan van der Heyden, the inventor of the fire hose, received Peter, who was keen to learn and pass on his knowledge to his countrymen. On 16 January 1698 Peter organized a farewell party and invited Johan Huydecoper van Maarsseveen, who had to sit between Lefort and the Tsar and drink.[20]

The frigate Pieter and Paul on the IJ while Peter stands on the small ship on the right

In England, Peter met with King William III, visited Greenwich and Oxford, posed for Sir Godfrey Kneller, and saw a Royal Navy Fleet Review at Deptford. He studied the English techniques of city-building he would later use to great effect at Saint Petersburg.[21]

The Embassy next went to Leipzig, Dresden, Prague and Vienna. Peter spoke with Augustus II the Strong and Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor.[21]

Peter’s visit was cut short in 1698, when he was forced to rush home by a rebellion of the Streltsy. The rebellion was easily crushed before Peter returned home from England; of the Tsar’s troops, only one was killed. Peter nevertheless acted ruthlessly towards the mutineers. Over one thousand two hundred of the rebels were tortured and executed, and Peter ordered that their bodies be publicly exhibited as a warning to future conspirators.[22] The Streltsy were disbanded, some of the rebels were deported to Siberia, and the individual they sought to put on the Throne —

Peter’s half-sister Sophia — was forced to become a nun.

In 1698, Peter sent a delegation to Malta, under boyar Boris Sheremetev, to observe the training and abilities of the Knights of Malta and their fleet. Sheremetev investigated the possibility of future joint ventures with the Knights, including action against the Turks and the possibility of a future Russian naval base.[23]

Peter’s visits to the West impressed upon him the notion that European customs were in several respects superior to Russian traditions. He commanded all of his courtiers and officials to wear European clothing and cut off their long beards, causing his Boyars, who were very fond of their beards, great upset.[24] Boyars who sought to retain their beards were required to pay an annual beard tax of one hundred rubles. Peter also sought to end arranged marriages, which were the norm among the Russian nobility, because he thought such a practice was barbaric and led to domestic violence, since the partners usually resented each other.[25]

In 1699, Peter changed the date of the celebration of the new year from 1 September to 1 January. Traditionally, the years were reckoned from the purported creation of the World, but after Peter’s reforms, they were to be counted from the birth of Christ. Thus, in the year 7207 of the old Russian calendar, Peter proclaimed that the Julian Calendar was in effect and the year was 1700.[26]

Great Northern War

Peter made a temporary peace with the Ottoman Empire that allowed him to keep the captured fort of Azov, and turned his attention to Russian maritime supremacy. He sought to acquire control of the Baltic Sea, which had been taken by the Swedish Empire a half-century earlier. Peter declared war on Sweden, which was at the time led by the young King Charles XII. Sweden was also opposed by Denmark–Norway, Saxony, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

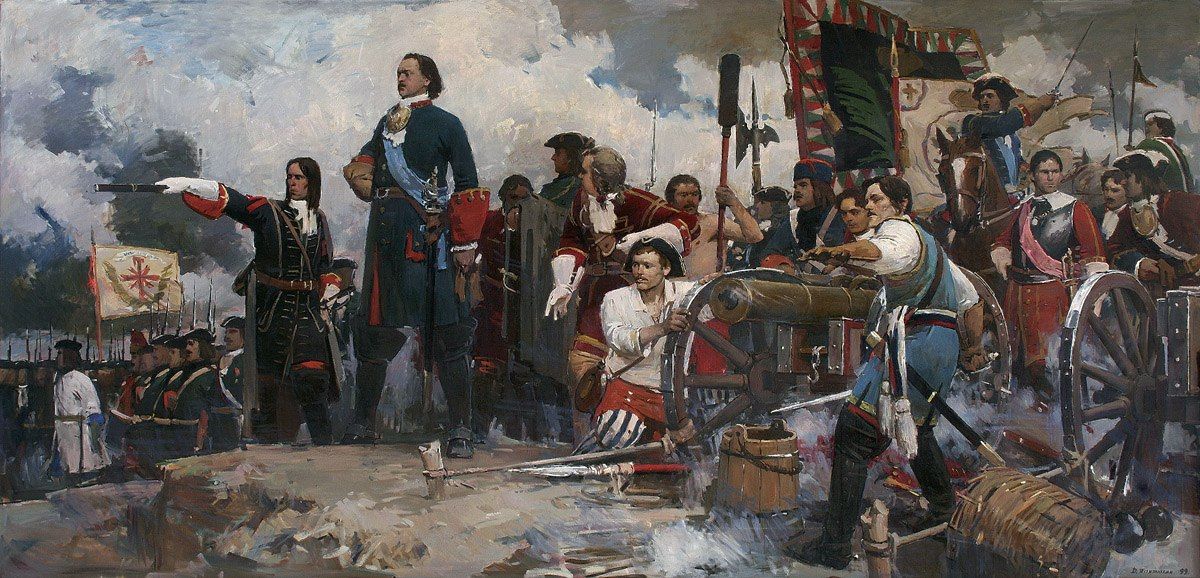

Peter I of Russia pacifies his marauding troops after retaking Narva in 1704, by Nikolay Sauerweid, 1859

Russia was ill-prepared to fight the Swedes, and their first attempt at seizing the Baltic coast ended in disaster at the Battle of Narva in 1700. In the conflict, the forces of Charles XII, rather than employ a slow methodical siege, attacked immediately using a blinding snowstorm to their advantage. After the battle, Charles XII decided to concentrate his forces against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, which gave Peter time to reorganize the Russian army.

While the Poles fought the Swedes, Peter founded the city of Saint Petersburg in 1703, in Ingermanland (a province of the Swedish Empire that he had captured). It was named after his patron saint Saint Peter. He forbade the building of stone edifices outside Saint Petersburg, which he intended to become Russia’s capital, so that all stonemasons could participate in the construction of the new city. Peter moved the capital to St. Petersburg in 1703. While the city was being built he lived in a three-room log cabin with Catherine, where she did the cooking and caring for the children, and he tended a garden as though they were an ordinary couple.[citation needed] Between 1713 and 1728, and from 1732 to 1918, Saint Petersburg was the capital of imperial Russia.

Following several defeats, Polish King Augustus II the Strong abdicated in 1706. Swedish king Charles XII turned his attention to Russia, invading it in 1708. After crossing into Russia, Charles defeated Peter at Golovchin in July. In the Battle of Lesnaya, Charles suffered his first loss after Peter crushed a group of Swedish reinforcements marching from Riga. Deprived of this aid, Charles was forced to abandon his proposed march on Moscow.[27]

Charles XII refused to retreat to Poland or back to Sweden and instead invaded Ukraine. Peter withdrew his army southward, employing scorched earth, destroying along the way anything that could assist the Swedes. Deprived of local supplies, the Swedish army was forced to halt its advance in the winter of 1708–1709. In the summer of 1709, they resumed their efforts to capture Russian-ruled Ukraine, culminating in the Battle of Poltava on 27 June. The battle was a decisive defeat for the Swedish forces, ending Charles’ campaign in Ukraine and forcing him south to seek refuge in the Ottoman Empire. Russia had defeated what was considered to be one of the world’s best militaries, and the victory overturned the view that Russia was militarily incompetent. In Poland, Augustus II was restored as King.

Peter, overestimating the support he would receive from his Balkan allies, attacked the Ottoman Empire, initiating the Russo-Turkish War of 1710.[28] Peter’s campaign in the Ottoman Empire was disastrous, and in the ensuing Treaty of the Pruth, Peter was forced to return the Black Sea ports he had seized in 1697.[28] In return, the Sultan expelled Charles XII.

The Ottomans called him Mad Peter (Turkish: deli Petro), for his willingness to sacrifice large numbers of his troops in wartime.[29]

Normally, the Boyar Duma would have exercised power during his absence. Peter, however, mistrusted the boyars; he instead abolished the Duma and created a Senate of ten members. The Senate was founded as the highest state institution to supervise all judicial, financial and administrative affairs. Originally established only for the time of the monarch’s absence, the Senate became a permanent body after his return. A special high official, the Ober-Procurator, served as the link between the ruler and the senate and acted, in Peter own words, as «the sovereign’s eye». Without his signature no Senate decision could go into effect; the Senate became one of the most important institutions of Imperial Russia.[30]

Peter’s northern armies took the Swedish province of Livonia (the northern half of modern Latvia, and the southern half of modern Estonia), driving the Swedes into Finland. In 1714 the Russian fleet won the Battle of Gangut. Most of Finland was occupied by the Russians.

In 1716 and 1717, the Tsar revisited the Netherlands and went to see Herman Boerhaave. He continued his travel to the Austrian Netherlands and France, where he obtained many books and proposed a marriage between his daughter and King Louis XV. Peter obtained the assistance of the Electorate of Hanover and the Kingdom of Prussia.

The Tsar’s navy was powerful enough that the Russians could penetrate Sweden. Still, Charles XII refused to yield, and not until his death in battle in 1718 did peace become feasible. After the battle near Åland, Sweden made peace with all powers but Russia by 1720. In 1721, the Treaty of Nystad ended the Great Northern War. Russia acquired Ingria, Estonia, Livonia, and a substantial portion of Karelia. In turn, Russia paid two million Riksdaler and surrendered most of Finland. The Tsar retained some Finnish lands close to Saint Petersburg, which he had made his capital in 1712.[31]

Later years

Diamond order of Peter the Great

Peter’s last years were marked by further reform in Russia. On 22 October 1721, soon after peace was made with Sweden, he was officially proclaimed Emperor of All Russia. Some proposed that he take the title Emperor of the East, but he refused. Gavrila Golovkin, the State Chancellor, was the first to add «the Great, Father of His Country, Emperor of All the Russias» to Peter’s traditional title Tsar following a speech by the archbishop of Pskov in 1721. Peter’s imperial title was recognized by Augustus II of Poland, Frederick William I of Prussia, and Frederick I of Sweden, but not by the other European monarchs. In the minds of many, the word emperor connoted superiority or pre-eminence over kings. Several rulers feared that Peter would claim authority over them, just as the Holy Roman Emperor had claimed suzerainty over all Christian nations.

In 1717, Alexander Bekovich-Cherkassky led the first Russian military expedition into Central Asia against the Khanate of Khiva. The expedition ended in complete disaster when the entire expeditionary force was slaughtered.

In 1718, Peter investigated why the formerly Swedish province of Livonia was so orderly. He discovered that the Swedes spent as much administering Livonia (300 times smaller than his empire) as he spent on the entire Russian bureaucracy. He was forced to dismantle the province’s government.[32]

Peter I by I.Nikitin (1720s, Russian museum)

After 1718, Peter established colleges in place of the old central agencies of government, including foreign affairs, war, navy, expense, income, justice, and inspection. Later others were added. Each college consisted of a president, a vice-president, a number of councilors and assessors, and a procurator. Some foreigners were included in various colleges but not as president. Peter believed he did not have enough loyal and talented persons to put in full charge of the various departments. Peter preferred to rely on groups of individuals who would keep check on one another.[33] Decisions depended on the majority vote.

In 1722, Peter created a new order of precedence known as the Table of Ranks. Formerly, precedence had been determined by birth. To deprive the Boyars of their high positions, Peter directed that precedence should be determined by merit and service to the Emperor. The Table of Ranks continued to remain in effect until the Russian monarchy was overthrown in 1917.

Peter decided that all of the children of the nobility should have some early education, especially in the areas of sciences. Therefore, on 28 February 1714, he issued a decree calling for compulsory education, which dictated that all Russian 10- to 15-year-old children of the nobility, government clerks, and lesser-ranked officials must learn basic mathematics and geometry, and should be tested on the subjects at the end of their studies.[34]

The once powerful Persian Safavid Empire to the south was in deep decline. Taking advantage of the profitable situation, Peter launched the Russo-Persian War of 1722–1723, otherwise known as «The Persian Expedition of Peter the Great», which drastically increased Russian influence for the first time in the Caucasus and Caspian Sea region, and prevented the Ottoman Empire from making territorial gains in the region. After considerable success and the capture of many provinces and cities in the Caucasus and northern mainland Persia, the Safavids were forced to hand over territory to Russia, comprising Derbent, Shirvan, Gilan, Mazandaran, Baku, and Astrabad. However, within twelve years all the territories would be ceded back to Persia, now led by the charismatic military genius Nader Shah, as part of the Treaties of Resht and Ganja respectively, and the Russo-Persian alliance against the Ottoman Empire, which was the common enemy of both.[35]

Peter introduced new taxes to fund improvements in Saint Petersburg. He abolished the land tax and household tax and replaced them with a poll tax. The taxes on land and on households were payable only by individuals who owned property or maintained families; the new head taxes, however, were payable by serfs and paupers. In 1725 the construction of Peterhof, a palace near Saint Petersburg, was completed. Peterhof (Dutch for «Peter’s Court») was a grand residence, becoming known as the «Russian Versailles».

Illness and death

In the winter of 1723, Peter, whose overall health was never robust, began having problems with his urinary tract and bladder. In the summer of 1724, a team of doctors performed surgery releasing upwards of four pounds of blocked urine. Peter remained bedridden until late autumn. In the first week of October, restless and certain he was cured, Peter began a lengthy inspection tour of various projects. According to legend, in November, at Lakhta along the Finnish Gulf to inspect some ironworks, Peter saw a group of soldiers drowning near shore and, wading out into near-waist deep water, came to their rescue.[36]

This icy water rescue is said to have exacerbated Peter’s bladder problems and caused his death. The story, however, has been viewed with skepticism by some historians, pointing out that the German chronicler Jacob von Staehlin is the only source for the story, and it seems unlikely that no one else would have documented such an act of heroism. This, plus the interval of time between these actions and Peter’s death seems to preclude any direct link.[citation needed]

In early January 1725, Peter was struck once again with uremia. Legend has it that before lapsing into unconsciousness Peter asked for a paper and pen and scrawled an unfinished note that read: «Leave all to …» and then, exhausted by the effort, asked for his daughter Anna to be summoned.[note 3]

Peter died between four and five in the morning 8 February 1725. An autopsy revealed his bladder to be infected with gangrene.[10] He was fifty-two years, seven months old when he died, having reigned forty-two years. He is interred in Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Religion

Peter founded The All-Joking, All-Drunken Synod of Fools and Jesters,[37] an organization that mocked the Orthodox and Catholic Church when he was eighteen. In January 1695, Peter refused to partake in a traditional Russian Orthodox ceremony of the Epiphany Ceremony, and would often schedule events for The All-Joking, All-Drunken Synod of Fools and Jesters to directly conflict with the Church.[38]

Peter was brought up in the Russian Orthodox faith, but he had low regard for the Church hierarchy, which he kept under tight governmental control. The traditional leader of the Church was the Patriarch of Moscow. In 1700, when the office fell vacant, Peter refused to name a replacement, allowing the Patriarch’s Coadjutor (or deputy) to discharge the duties of the office. Peter could not tolerate the patriarch exercising power superior to the Tsar, as indeed had happened in the case of Philaret (1619–1633) and Nikon (1652–66). The Church reform of Peter the Great therefore abolished the Patriarchate, replacing it with a Holy Synod that was under the control of a Procurator, and the Tsar appointed all bishops.[citation needed]

In 1721, Peter followed the advice of Theophan Prokopovich in designing the Holy Synod as a council of ten clergymen. For leadership in the church, Peter turned increasingly to Ukrainians, who were more open to reform, but were not well loved by the Russian clergy. Peter implemented a law that stipulated that no Russian man could join a monastery before the age of fifty. He felt that too many able Russian men were being wasted on clerical work when they could be joining his new and improved army.[39][40]

A clerical career was not a route chosen by upper-class society. Most parish priests were sons of priests and were very poorly educated and paid. The monks in the monasteries had a slightly higher status; they were not allowed to marry. Politically, the church was impotent.[41]

Marriages and family

Peter the Great had two wives, with whom he had fourteen children, three of whom survived to adulthood. Peter’s mother selected his first wife, Eudoxia Lopukhina, with the advice of other nobles in 1689.[42] This was consistent with previous Romanov tradition by choosing a daughter of a minor noble. This was done to prevent fighting between the stronger noble houses and to bring fresh blood into the family.[43] He also had a mistress from Holland, Anna Mons.[42]

Upon his return from his European tour in 1698, Peter sought to end his unhappy marriage. He divorced the Tsaritsa and forced her to join a convent.[42] The Tsaritsa had borne Peter three children, although only one, Alexei Petrovich, Tsarevich of Russia, had survived past his childhood.

He took Marta Helena Skowrońska, a Polish-Lithuanian peasant, as a mistress some time between 1702 and 1704.[44] Marta converted to the Russian Orthodox Church and took the name Catherine.[45] Though no record exists, Catherine and Peter are described as having married secretly between 23 Oct and 1 December 1707 in St. Petersburg.[46] Peter valued Catherine and married her again (this time officially) at Saint Isaac’s Cathedral in Saint Petersburg on 19 February 1712.

His eldest child and heir, Alexei, was suspected of being involved in a plot to overthrow the Emperor. Alexei was tried and confessed under torture during questioning conducted by a secular court. He was convicted and sentenced to be executed. The sentence could be carried out only with Peter’s signed authorization, and Alexei died in prison, as Peter hesitated before making the decision. Alexei’s death most likely resulted from injuries suffered during his torture.[47] Alexei’s mother Eudoxia had also been punished; she was dragged from her home, tried on false charges of adultery, publicly flogged, and finally confined in monasteries while forbidden to be talked to.

In 1724, Peter had his second wife, Catherine, crowned as Empress, although he remained Russia’s actual ruler. All of Peter’s male children had died.

Issue

By his two wives, he had fourteen children. These included three sons named Pavel and three sons named Peter, all of whom died in infancy. Only three of his children survived to adulthood: Alexei, Anna Petrovna, and Elizabeth. He had only two grandchildren: Peter II and Peter III.[citation needed]

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| By Eudoxia Lopukhina | |||

| Alexei Petrovich, Tsarevich of Russia | 18 February 1690[48] | 26 June 1718,[48] age 28 | Married 1711, Charlotte Christine of Brunswick-Lüneburg; had issue |

| Alexander Petrovich | 13 October 1691 | 14 May 1692, age 7 months | |

| Pavel Petrovich | 1693 | 1693 | |

| By Catherine I | |||

| Peter Petrovich | 1704[48] | in infancy[48] | Born and died before the official marriage of his parents |

| Paul Petrovich | 1705[48] | in infancy[48] | Born and died before the official marriage of his parents |

| Catherine Petrovna | Dec 1706[48] | Jun 1708,[48] age 18 months | Born and died before the official marriage of her parents |

| Anna Petrovna | 27 January 1708 | 15 May 1728, age 20 | Married 1725, Karl Friedrich, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp; had issue |

| Yelisaveta Petrovna, later Empress Elizabeth |

29 December 1709 | 5 January 1762, age 52 | Reputedly married 1742, Alexei Grigorievich, Count Razumovsky; no issue |

| Maria Petrovna | 20 March 1713 | 27 May 1715, age 2 | |

| Margarita Petrovna | 19 September 1714 | 7 June 1715, age 9 months | |

| Peter Petrovich | 15 November 1715 | 19 April 1719, age 3 | |

| Pavel Petrovich | 13 January 1717 | 14 January 1717, age 1 day | |

| Natalia Petrovna | 31 August 1718 | 15 March 1725, age 6 | |

| Peter Petrovich | 7 October 1723 | 7 October 1723, born and died same day |

Mistresses and illegitimate children

- Princess Maria Cantemir of Moldavia (1700 – 1754), daughter of Dimitrie Cantemir[49]

- Unnamed son (1722 – 1723) – who died prematurely.[50] According to other sources, the baby was stilborn.[51]

- Lady Mary Hamilton, Catherina I’s lady in waiting of Scottish descent.[52][53]

- miscarriage (1715)[54]

- Unnamed child (1717 – 1718)[55]

- Unnamed child

Legacy

Monument to Peter the Great in St. Petersburg

Peter’s legacy has always been a major concern of Russian intellectuals. Riasanovsky points to a «paradoxical dichotomy» in the black and white images such as God/Antichrist, educator/ignoramus, architect of Russia’s greatness/destroyer of national culture, father of his country/scourge of the common man. Voltaire’s 1759 biography gave 18th-century Russians a man of the Enlightenment, while Alexander Pushkin’s «The Bronze Horseman» poem of 1833 gave a powerful romantic image of a creator-god.[56][57][58] Slavophiles in mid-19th century deplored Peter’s westernization of Russia. Western writers and political analysts recounted «The Testimony» or secret will of Peter the Great. It supposedly revealed his grand evil plot for Russia to control the world via conquest of Constantinople, Afghanistan and India. It was a forgery made in Paris at Napoleon’s command when he started his invasion of Russia in 1812. Nevertheless, it is still quoted in foreign policy circles.[59] The Communists executed the last Romanovs, and their historians such as Mikhail Pokrovsky presented strongly negative views of the entire dynasty. Stalin however admired how Peter strengthened the state, and wartime, diplomacy, industry, higher education, and government administration. Stalin wrote in 1928, «when Peter the Great, who had to deal with more developed countries in the West, feverishly built works in factories for supplying the army and strengthening the country’s defenses, this was an original attempt to leap out of the framework of backwardness.»[60] As a result, Soviet historiography emphasizes both the positive achievement and the negative factor of oppressing the common people.[61]

After the fall of Communism in 1991, scholars and the general public in Russia and the West gave fresh attention to Peter and his role in Russian history. His reign is now seen as the decisive formative event in the Russian imperial past. Many new ideas have merged, such as whether he strengthened the autocratic state or whether the tsarist regime was not statist enough given its small bureaucracy.[62] Modernization models have become contested ground.[63] Historian Ia. Vodarsky said in 1993 that Peter, «did not lead the country on the path of accelerated economic, political and social development, did not force it to ‘achieve a leap’ through several stages…. On the contrary, these actions to the greatest degree put a brake on Russia’s progress and created conditions for holding it back for one and a half centuries!» [64] The autocratic powers that Stalin admired appeared as a liability to Evgeny Anisimov, who complained that Peter was, «the creator of the administrative command system and the true ancestor of Stalin.»[65]

According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, «He did not completely bridge the gulf between Russia and the Western countries, but he achieved considerable progress in development of the national economy and trade, education, science and culture, and foreign policy. Russia became a great power, without whose concurrence no important European problem could thenceforth be settled. His internal reforms achieved progress to an extent that no earlier innovator could have envisaged.»[66]

While the cultural turn in historiography has downplayed diplomatic, economic and constitutional issues, new cultural roles have been found for Peter, for example in architecture and dress. James Cracraft argues:

- The Petrine revolution in Russia—subsuming in this phrase the many military, naval, governmental, educational, architectural, linguistic, and other internal reforms enacted by Peter’s regime to promote Russia’s rise as a major European power—was essentially a cultural revolution, one that profoundly impacted both the basic constitution of the Russian Empire and, perforce, its subsequent development.[67]

Popular culture

Peter has been featured in many histories, novels, plays, films, monuments and paintings.[68][69] They include the poems The Bronze Horseman, Poltava and the unfinished novel The Moor of Peter the Great, all by Alexander Pushkin. The former dealt with The Bronze Horseman, an equestrian statue raised in Peter’s honour. Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy wrote a biographical historical novel about him, named Pëtr I, in the 1930s.

- The 1922 German silent film Peter the Great directed by Dimitri Buchowetzki and starring Emil Jannings as Peter

- The 1937–1938 Soviet Union (Russia) film Peter the First

- The 1976 film Skaz pro to, kak tsar Pyotr arapa zhenil (How Tsar Peter the Great Married Off His Moor), starring Aleksey Petrenko as Peter, and Vladimir Vysotsky as Abram Petrovich Gannibal, shows Peter’s attempt to build the Baltic Fleet.

- The 2007 film The Sovereign’s Servant depicts the unsavoury brutal side of Peter during the campaign.

- Peter was played by Jan Niklas and Maximilian Schell in the 1986 NBC miniseries Peter the Great.

- A character based on Peter plays a major role in The Age of Unreason, a series of four alternate history novels written by American science fiction and fantasy author Gregory Keyes.

- Peter is one of many supporting characters in Neal Stephenson’s Baroque Cycle – mainly featuring in the third novel, The System of the World.

- Peter was portrayed on BBC Radio 4 by Isaac Rouse as a boy, Will Howard as a young adult and Elliot Cowan as an adult in the radio plays Peter the Great: The Gamblers[70] and Peter the Great: The Queen of Spades,[71] written by Mike Walker and which were the last two plays in the first series of Tsar. The plays were broadcast on 25 September and 2 October 2016.

- A verse in the Engineers’ Drinking Song references Peter the Great:

There was a man named Peter the Great who was a Russian Tzar;

When remodeling his the castle put the throne behind the bar;

He lined the walls with vodka, rum, and 40 kinds of beers;

And advanced the Russian culture by 120 years!

- Peter was played by Jason Isaacs in the 2020 ‘antihistory’ Hulu series The Great. [72]

- Peter is featured as the leader of the Russian civilization in the computer game Sid Meier’s Civilization VI.[73]

See also

- Government reform of Peter the Great

- History of the administrative division of Russia

- Russian battlecruiser Pyotr Velikiy, a Russian Navy battle cruiser named after Peter the Great

- History of Russia (1721–96)

- Rulers of Russia family tree

- Peter the Great Statue

- Military history of the Russian Empire § Peter the Great, on the modernization of the Russian military under Peter the Great

- List of people known as «the Great»

Notes

- ^ Russian: Пётр Вели́кий, tr. Pyotr Velíkiy, IPA: [ˈpʲɵtr vʲɪˈlʲikʲɪj]) or Pyotr Alekséyevich (Russian: Пётр Алексе́евич, IPA: [ˈpʲɵtr ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪtɕ]

- ^ Office renamed from «Tsar» to «Emperor» on 2 November 1721.

- ^ Dates indicated by the letters «O.S.» are in the Julian calendar with the start of year adjusted to 1 January. All other dates in this article are in Gregorian calendar (see Adoption of the Gregorian calendar#Adoption in Eastern Europe).

- ^ The ‘Leave all …» story first appears in H-F de Bassewitz Russkii arkhiv 3 (1865). Russian historian E.V. Anisimov contends that Bassewitz’s aim was to convince readers that Anna, not Empress Catherine, was Peter’s intended heir.

References

- ^ Cracraft 2003.

- ^ Лакиер А. Б. §66. Надписи вокруг печати. Соответствие их с государевым титулом. // Русская геральдика. – СПб., 1855.

- ^ Robert K. Massie, Peter the Great: His Life and World (1980), p. 22.

- ^ Massie, 25–26.

- ^ Riasanovsky 2000, p. 214.

- ^ a b Riasanovsky 2000, p. 218.

- ^ Massie, (1980) pp 96–106.

- ^ a b Riasanovsky 2000, p. 216.

- ^ Merriman, John (15 September 2008). «Peter the Great and the Territorial Expansion of Russia». Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ^ a b Hughes 2007, pp. 179–82.

- ^ Evgenii V. Anisimov, The Reforms of Peter the Great: Progress Through Violence in Russia (Routledge, 2015)

- ^ Riasanovsky 2000, p. 221.

- ^ Abbott, Peter (1902). Peter the Great. Project Gutenberg online edition.

- ^ Montefiore p. 187.

- ^ Roberts, J. M.; Westad, Odd Arne (2014). The Penguin history of the world (Sixth revised ed.). London. ISBN 978-1-84614-443-1. OCLC 862761245.

- ^ Peter the Great: Part 1 of 3 (The Carpenter Czar) Archived 28 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Radio Netherlands Archives. 8 June 1996. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ Wes 1992, p. 14.

- ^ Tavernier 2006, p. 349.

- ^ Massie 1980, pp. 183–188.

- ^ Petros Mirilas, et al. «The monarch and the master: Peter the Great and Frederik Ruysch.» Archives of Surgery 141.6 (2006): 602-606.

- ^ a b Massie 1980, p. 191.

- ^ Riasanovsky 2000, p. 220.

- ^ «Russian Grand Priory – Timeline». 2004. Archived from the original on 8 February 2008. Retrieved 9 February 2008.

- ^ O.L. D’Or. «Russia as an Empire». The Moscow News weekly. pp. Russian. Archived from the original (PHP) on 3 June 2006. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- ^ Dmytryshyn 1974, p. 21.

- ^ Oudard 1929, p. 197.

- ^ Massie 1980, p. 453.

- ^ a b Riasanovsky 2000, p. 224.

- ^ Rory, Finnin (2022). Blood of Others: Stalin’s Crimean Atrocity and the Poetics of Solidarity. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4875-3700-5. OCLC 1314897094.

- ^ Palmer & Colton 1992, pp. 242–43.

- ^ Cracraft 2003, p. 37.

- ^ Pipes 1974, p. 281.

- ^ Palmer & Colton 1992, p. 245.

- ^ Dmytryshyn 1974, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Lee 2013, p. 31.

- ^ Bain 1905.

- ^ Massie, Robert K. (October 1981). Peter the Great: His Life and World. New York City: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-29806-3.

- ^ Bushkovitch, Paul A. (January 1990). «The Epiphany Ceremony of the Russian Court in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries». Russian Review. Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Editors and Board of Trustees of the Russian Review. 49 (1): 1–17. doi:10.2307/130080. JSTOR 130080.

- ^ Dmytryshyn 1974, p. 18.

- ^ James Cracraft, The church reform of Peter the Great (1971).

- ^ Lindsey Hughes, Russia in the Age of Peter the Great (1998) pp. 332–56.

- ^ a b c Hughes 2004, p. 134.

- ^ Hughes 2004, p. 133.

- ^ Hughes 2004, p. 131,134.

- ^ Hughes 2004, p. 131.

- ^ Hughes 2004, p. 136.

- ^ Massie 1980, pp. 76, 377, 707.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hughes 2004, p. 135.

- ^ Peter the Great: A Life From Beginning to. Hourly History. 2018. ISBN 978-1-7239-6063-5.

- ^ Douglas Liversidge (1968). Peter the Great, the Reformer-tsar. F. Watts. ISBN 978-0-85166-295-4.

- ^ Petre P. Panaitescu, Dimitrie Cantemir. Viața și opera, col. Biblioteca Istorică, vol. III, Ed. Academiei RPR, București, 1958, p. 141.

- ^ Peter the Great: A Life From Beginning to. Hourly History. 2018. ISBN 1-7239-6063-2

- ^ Lady Mary insisted that her child (born 1717) was fathered bt her lover.

- ^ Peter the Great: A Life From Beginning to. Archived 26 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine Hourly History. 2018. ISBN 1-7239-6063-2.

- ^ Peter the Great: A Life From Beginning to. Archived 26 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine Hourly History. 2018. ISBN 1-7239-6063-2.

- ^ Nicholas Riasanovsky, The Image of Peter the Great in Russian History and Thought (1985) pp. 57, 84, 279, 283.

- ^ A. Lenton, «Voltaire and Peter the Great» History Today (1968) 18#10 online Archived 13 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kathleen Scollins, «Cursing at the Whirlwind: The Old Testament Landscape of The Bronze Horseman.» Pushkin Review 16.1 (2014): 205-231 online Archived 26 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Albert Resis, «Russophobia and the ‘Testament’ of Peter the Great, 1812-1980 Slavic Review 44#4 (1985), pp. 681-693 online[dead link]

- ^ Lindsey Hughes, Russia in the Age of Peter the Great (1998) p 464.

- ^ Riasanovsky, p. 305.

- ^ Zitser, 2005.

- ^ Waugh, 2001

- ^ Hughes, p. 464

- ^ Hughes, p. 465.

- ^ «Peter I». Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ James Cracraft, «The Russian Empire as Cultural Construct,» Journal of the Historical Society (2010) 10#2 pp. 167–188, quoting p 170.

- ^ Nicholas V. Riasanovsky, The Image of Peter the Great in Russian History and Thought (1985).

- ^ Lindsey Hughes, «‘What manner of man did we lose?’: Death-bed images of Peter the Great.» Russian History 35.1-2 (2008): 45-61.

- ^ BBC Radio 4 – Drama, Tsar, Peter the Great: The Gamblers Archived 25 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine. BBC. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ BBC Radio 4 – Drama, Tsar, Peter the Great: Queen of Spades Archived 29 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine. BBC. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ «The Great (2020)». IMDB. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ Civilization 6 Leader and Civilization Breakdown — Montezuma to Shaka Archived 18 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine. GameRant. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

Sources

- Anisimov, Evgenii V. (2015) The Reforms of Peter the Great: Progress Through Violence in Russia (Routledge)

- Bain, R. Nisbet (1905). Peter the Great and his pupils. Cambridge UP. Archived from the original on 26 May 2007.

- Bushkovitch, Paul (2003). Peter the Great. Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-9639-0. online

- Cracraft, James (2003). The Revolution of Peter the Great. Harvard UP.

- Dmytryshyn, Basil (1974). Modernization of Russia Under Peter I and Catherine II. Wiley.

- Grey, Ian (1960). Peter the Great: Emperor of All Russia. Philadelphia, Lippincott.

- Hughes, John R. (2007). «The seizures of Peter Alexeevich». Epilepsy & Behavior. 10 (1): 179–82. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.11.005. PMID 17174607. S2CID 25504057.

- Hughes, Lindsey (1998). Russia in the Age of Peter the Great. Yale UP. ISBN 978-0-300-08266-1. online

- Hughes, Lindsey (2001). Peter the Great and the West: New Perspectives. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-92009-1.

- Hughes, Lindsey (2002). Peter the Great: A Biography. Yale UP. ISBN 978-0-300-10300-7.

- Lee, Stephen J. (2013). Peter the Great. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-45325-0.

- Massie, Robert K. (1980). Peter the Great: His Life and World. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-29145-5., a popular biography; online

- Hughes, Lindsey (2004). «Catherine I of Russia, Consort to Peter the Great». In Campbell Orr, Clarissa (ed.). Queenship in Europe 1660–1815: The Role of the Consort. Cambridge UP. pp. 131–54. ISBN 978-0-521-81422-5.

- Montefiore, Simon Sebag (2016). The Romanovs: 1613–1918. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

- Oudard, Georges (1929). Peter the Great. Translated by Atkinson, Frederick. New York, NY: Payson and Clarke. LCCN 29-027809. OL 7431283W.

- Pipes, Richard (1974). Russia under the old regime.

- Raeff, Mafrc, ed. (1963). Peter the Great, Reformer or Revolutionary?.

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas (2000). A History of Russia (6th ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford UP. online

- Tavernier, Roger (2006). Russia and the Low Countries: An International Bibliography, 1500–2000. Barkhuis. p. 349. ISBN 978-90-77089-04-0.

- Wes, Martinus A. (1992). Classics in Russia, 1700–1855: Between Two Bronze Horsemen. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09664-6.

- Palmer, R.R.; Colton, Joel (1992). A History of the Modern World.

- Historiography and memory

- Brown, Peter B. «Towards a Psychohistory of Peter the Great: Trauma, Modeling, and Coping in Peter’s Personality.» Russian History 35#1-2 (2008): 19–44.

- Brown, Peter B. «Gazing Anew at Poltava: Perspectives from the Military Revolution Controversy, Comparative History, and Decision-Making Doctrines.» Harvard Ukrainian Studies 31.1/4 (2009): 107–133. online Archived 15 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Cracraft, James. «Kliuchevskii on Peter the Great.» Canadian-American Slavic Studies 20.4 (1986): 367–381.

- Daqiu, Zhu. «Cultural Memory and the Image of Peter the Great in Russian Literature.» Russian Literature & Arts 2 (2014): 19+.

- Gasiorowska, Xenia. The image of Peter the Great in Russian fiction (1979) online

- Platt, Kevin M. F. Terror and Greatness: Ivan and Peter as Russian Myths (2011)

- Raef, Mark, ed. Peter the Great, Reformer or Revolutionary? (1963) excerpts from scholars and primary sources online Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Resis, Albert. «Russophobia and the» Testament» of Peter the Great, 1812–1980.» Slavic Review 44.4 (1985): 681-693 online[dead link].

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas V. The Image of Peter the Great in Russian History and Thought (1985).

- Waugh, Daniel Clarke. «We have never been modern: Approaches to the study of Russia in the age of Peter the Great.» Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas H. 3 (2001): 321-345 online in English Archived 19 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- Zitser, Ernest A. (Spring 2005). «Post-Soviet Peter: New Histories of the Late Muscovite and Early Imperial Russian Court». Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. 6 (2): 375–92. doi:10.1353/kri.2005.0032. S2CID 161390436.

- Zitser, Ernest A. «The Difference that Peter I Made.» in The Oxford Handbook of Modern Russian History. ed. by Simon Dixon (2013) online[dead link]

Further reading

- Anderson, M.S. «Russia under Peter the Great and the changed relations of East and West.» in J.S. Bromley, ed., The New Cambridge Modern History: VI: 1688-1715 (1970) pp. 716–40.

- Anisimov, Evgenii V. The Reforms of Peter the Great: Progress through Coercion in Russia (1993) online

- Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). «Peter I.» . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 288–91.

- Bushkovitch, Paul. Peter the Great: The Struggle for Power, 1671–1725 (2001) online

- Cracraft, James. The Revolution of Peter the Great (2003) online

- Duffy, Christopher. Russia’s Military Way to the West: Origins and Nature of Russian Military Power 1700-1800 (Routledge, 2015) pp 9–41

- Graham, Stephen. Peter The Great (1929) online

- Kamenskii, Aleksandr. The Russian Empire in the Eighteenth Century: Searching for a Place in the World(1997) pp 39–164.

- Kluchevsky, V.O. A history of Russia vol 4 (1926) online pp 1–230.

- Cracraft, James. «Kliuchevskii on Peter the Great.» Canadian-American Slavic Studies 20.4 (1986): 367–381.

- Oliva, Lawrence Jay. ed. Russia in the era of Peter the Great (1969), excerpts from primary and secondary sources two week borrowing

- Pares, Bernard. A History Of Russia (1947) pp 193–225. online

- Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, David, and Bruce W. Menning, eds. Reforming the Tsar’s Army – Military Innovation in Imperial Russia from Peter the Great to the Revolution (Cambridge UP, 2004) 361 pp. scholarly essays

- Sumner, B. H. Peter the Great and the emergence of Russia (1950), brief history by scholar online

External links

- Romanovs. The third film. Peter I, Catherine I on YouTube – Historical reconstruction The Romanovs. StarMedia. Babich-Design (Russia, 2013)

- Peter the Great, a Tsar who Loved Science by Philippe Testard-Vaillant

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by

Feodor III |

Tsar of Russia 1682–1721 with Ivan V |

Russian Empire |

| New title | Emperor of Russia 1721–1725 |

Succeeded by

Catherine I |

| Preceded by

Frederick |

Duke of Estonia and Livonia 1721–1725 |

| Peter I | ||

|---|---|---|

Portrait by Jean-Marc Nattier, after 1717 |

||

| Tsar / Emperor of Russia[note 1] | ||

| Reign | 7 May 1682 – 8 February 1725 | |

| Coronation | 25 June 1682 | |

| Predecessor | Feodor III | |

| Successor | Catherine I | |

| Co-monarch | Ivan V (1682–1696) | |

| Regent | Sophia Alekseyevna (1682–1689) | |

| Born | 9 June 1672 Moscow, Tsardom of Russia |

|

| Died | 8 February 1725 (aged 52) Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

|

| Burial |

Peter and Paul Cathedral |

|

| Consort |

Eudoxia Lopukhina (m. 1689; div. 1698) Martha Skavronskaya (m. 1707) |

|

| Issue among others |

|

|

|

||

| House | Romanov | |

| Father | Alexis of Russia | |

| Mother | Natalya Naryshkina | |

| Religion | Russian Orthodoxy | |

| Signature |

Peter I (9 June [O.S. 30 May] 1672 – 8 February [O.S. 28 January] 1725),[note 2] most commonly known as Peter the Great,[pron 1] was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from 7 May [O.S. 27 April] 1682 to 1721 and subsequently the Russian Empire until his death in 1725, jointly ruling with his elder half-brother, Ivan V until 1696. He is primarily credited with the modernisation of the country, transforming it into a European power.

Through a number of successful wars, he captured ports at Azov and the Baltic Sea, laying the groundwork for the Imperial Russian Navy, ending uncontested Swedish supremacy in the Baltic and beginning the Tsardom’s expansion into a much larger empire that became a major European power. He led a cultural revolution that replaced some of the traditionalist and medieval social and political systems with ones that were modern, scientific, Westernised and based on the Enlightenment.[1] Peter’s reforms had a lasting impact on Russia, and many institutions of the Russian government trace their origins to his reign. He adopted the title of Emperor in place of the old title of Tsar in 1721, and founded and developed the city of Saint Petersburg, which remained the capital of Russia until 1918.

The first Russian university—Saint Petersburg State University—was founded a year before his death, in 1724. The second one, Moscow State University, was founded 30 years after his death, during the reign of his daughter Elizabeth.

Title

The imperial title of Peter the Great was the following:[2]

By the grace of God, the most excellent and great sovereign emperor Pyotr Alekseevich the ruler of all the Russias: of Moscow, of Kiev, of Vladimir, of Novgorod, Tsar of Kazan, Tsar of Astrakhan and Tsar of Siberia, sovereign of Pskov, great prince of Smolensk, of Tver, of Yugorsk, of Perm, of Vyatka, of Bulgaria and others, sovereign and great prince of the Novgorod Lower lands, of Chernigov, of Ryazan, of Rostov, of Yaroslavl, of Belozersk, of Udora, of Kondia and the sovereign of all the northern lands, and the sovereign of the Iverian lands, of the Kartlian and Georgian Kings, of the Kabardin lands, of the Circassian and Mountain princes and many other states and lands western and eastern here and there and the successor and sovereign and ruler.

Early life

Peter was named after the apostle, and described as a newborn as «with good health, his mother’s black, vaguely Tatar eyes, and a tuft of auburn hair».[3] He was educated from an early age by several tutors commissioned by his father, Tsar Alexis of Russia, most notably Nikita Zotov, Patrick Gordon, and Paul Menesius. On 29 January 1676, Alexis died, leaving the sovereignty to Peter’s elder half-brother, the weak and sickly Feodor III of Russia.[4] Throughout this period, the government was largely run by Artamon Matveev, an enlightened friend of Alexis, the political head of the Naryshkin family and one of Peter’s greatest childhood benefactors.

This position changed when Feodor died in 1682. As Feodor did not leave any children, a dispute arose between the Miloslavsky family (Maria Miloslavskaya was the first wife of Alexis I) and Naryshkin family (Natalya Naryshkina was his second) over who should inherit the throne. Peter’s other half-brother, Ivan V of Russia, was next in line, but was chronically ill and of infirm mind. Consequently, the Boyar Duma (a council of Russian nobles) chose the 10-year-old Peter to become Tsar, with his mother as regent.

Peter the Great as a child

This arrangement was brought before the people of Moscow, as ancient tradition demanded, and was ratified. Sophia, one of Alexis’ daughters from his first marriage, led a rebellion of the Streltsy (Russia’s elite military corps) in April–May 1682. In the subsequent conflict, some of Peter’s relatives and friends were murdered, including Matveev, and Peter witnessed some of these acts of political violence.[5]

The Streltsy made it possible for Sophia, the Miloslavskys (the clan of Ivan) and their allies to insist that Peter and Ivan be proclaimed joint Tsars, with Ivan being acclaimed as the senior. Sophia then acted as regent during the minority of the sovereigns and exercised all power. For seven years, she ruled as an autocrat. A large hole was cut in the back of the dual-seated throne used by Ivan and Peter. Sophia would sit behind the throne and listen as Peter conversed with nobles, while feeding him information and giving him responses to questions and problems. This throne can be seen in the Kremlin Armoury in Moscow.

Peter was not particularly concerned that others ruled in his name. He engaged in such pastimes as shipbuilding and sailing, as well as mock battles with his toy army. Peter’s mother sought to force him to adopt a more conventional approach and arranged his marriage to Eudoxia Lopukhina in 1689.[6] The marriage was a failure, and ten years later Peter forced his wife to become a nun and thus freed himself from the union.

By the summer of 1689, Peter, then age 17, planned to take power from his half-sister Sophia, whose position had been weakened by two unsuccessful Crimean campaigns against the Crimean Khanate in an attempt to stop devastating Crimean Tatar raids into Russia’s southern lands. When she learned of his designs, Sophia conspired with some leaders of the Streltsy, who continually aroused disorder and dissent. Peter, warned by others from the Streltsy, escaped in the middle of the night to the impenetrable monastery of Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra; there he slowly gathered adherents who perceived he would win the power struggle. Sophia was eventually overthrown, with Peter I and Ivan V continuing to act as co-tsars. Peter forced Sophia to enter a convent, where she gave up her name and her position as a member of the royal family.[7]

The Tsardom of Russia, c. 1700

Still, Peter could not acquire actual control over Russian affairs. Power was instead exercised by his mother, Natalya Naryshkina. It was only when Natalya died in 1694 that Peter, then aged 22, became an independent sovereign.[8] Formally, Ivan V was a co-ruler with Peter, though being ineffective. Peter became the sole ruler when Ivan died in 1696 without male offspring, two years later.

Peter grew to be extremely tall as an adult, especially for the time period, reportedly standing 6 ft 8 in (2.03 m).[8] Peter, however, lacked the overall proportional heft and bulk generally found in a man that size. Both his hands and feet were small,[9][citation needed] and his shoulders were narrow for his height; likewise, his head was small for his tall body. Added to this were Peter’s noticeable facial tics, and he may have suffered from petit mal seizures, a form of epilepsy.[10]

During his youth, Peter befriended Patrick Gordon, Franz Lefort and several other foreigners in Russian service and was a frequent guest in Moscow’s German Quarter, where he met his Dutch mistress Anna Mons.

Reign

Peter implemented sweeping reforms aimed at modernizing Russia.[11] Heavily influenced by his advisors from Western Europe, Peter reorganized the Russian army along modern lines and dreamed of making Russia a maritime power. He faced much opposition to these policies at home but brutally suppressed rebellions against his authority, including by the Streltsy, Bashkirs, Astrakhan, and the greatest civil uprising of his reign, the Bulavin Rebellion.

Peter implemented social modernization in an absolute manner by introducing French and western dress to his court and requiring courtiers, state officials, and the military to shave their beards and adopt modern clothing styles.[12] One means of achieving this end was the introduction of taxes for long beards and robes in September 1698.[13]

In his process to westernize Russia, he wanted members of his family to marry other European royalty. In the past, his ancestors had been snubbed at the idea, but now, it was proving fruitful. He negotiated with Frederick William, Duke of Courland to marry his niece, Anna Ivanovna. He used the wedding in order to launch his new capital, St Petersburg, where he had already ordered building projects of westernized palaces and buildings. Peter hired Italian and German architects to design it.[14]

As part of his reforms, Peter started an industrialization effort that was slow but eventually successful. Russian manufacturing and main exports were based on the mining and lumber industries. For example, by the end of the century Russia came to export more iron than any other country in the world.[15]

To improve his nation’s position on the seas, Peter sought more maritime outlets. His only outlet at the time was the White Sea at Arkhangelsk. The Baltic Sea was at the time controlled by Sweden in the north, while the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea were controlled by the Ottoman Empire and Safavid Empire respectively in the south.

Peter attempted to acquire control of the Black Sea, which would require expelling the Tatars from the surrounding areas. As part of an agreement with Poland that ceded Kiev to Russia, Peter was forced to wage war against the Crimean Khan and against the Khan’s overlord, the Ottoman Sultan. Peter’s primary objective became the capture of the Ottoman fortress of Azov, near the Don River. In the summer of 1695 Peter organized the Azov campaigns to take the fortress, but his attempts ended in failure.

Peter returned to Moscow in November 1695 and began building a large navy. He launched about thirty ships against the Ottomans in 1696, capturing Azov in July of that year. On 12 September 1698, Peter officially founded the first Russian Navy base, Taganrog on the Sea of Azov.

Grand Embassy

Portrait of Peter I by Godfrey Kneller, 1698. This portrait was Peter’s gift to the King of England.

Peter knew that Russia could not face the Ottoman Empire alone. In 1697, he traveled «incognito» to Western Europe on an 18-month journey with a large Russian delegation–the so-called «Grand Embassy». He used a fake name, allowing him to escape social and diplomatic events, but since he was far taller than most others, he did not fool anyone of importance. One goal was to seek the aid of European monarchs, but Peter’s hopes were dashed. France was a traditional ally of the Ottoman Sultan, and Austria was eager to maintain peace in the east while conducting its own wars in the west. Peter, furthermore, had chosen an inopportune moment: the Europeans at the time were more concerned about the War of Spanish Succession over who would succeed the childless King Charles II of Spain than about fighting the Ottoman Sultan.[6]

The «Grand Embassy» continued nevertheless. While visiting the Netherlands, Peter learned much about life in Western Europe. He studied shipbuilding [16] in Zaandam (the house he lived in is now a museum, the Czar Peter House) and Amsterdam, where he visited, among others, the upper-class De Wilde family. Jacob de Wilde, a collector-general with the Admiralty of Amsterdam, had a well-known collection of art and coins, and De Wilde’s daughter Maria de Wilde made an engraving of the meeting between Peter and her father, providing visual evidence of «the beginning of the West European classical tradition in Russia».[17] According to Roger Tavernier, Peter the Great later acquired De Wilde’s collection.[18]

Thanks to the mediation of Nicolaes Witsen, mayor of Amsterdam and an expert on Russia, the Tsar was given the opportunity to gain practical experience in the largest shipyard in the world, belonging to the Dutch East India Company, for a period of four months. The Tsar helped with the construction of an East Indiaman ship specially laid down for him: Peter and Paul. During his stay the Tsar engaged many skilled workers such as builders of locks, fortresses, shipwrights, and seamen—including Cornelis Cruys, a vice-admiral who became, under Franz Lefort, the Tsar’s advisor in maritime affairs. Peter later put his knowledge of shipbuilding to use in helping build Russia’s navy.[19] Peter paid a visit to surgeon Frederik Ruysch, who taught him how to draw teeth and catch butterflies, and to Ludolf Bakhuysen, a painter of seascapes. Jan van der Heyden, the inventor of the fire hose, received Peter, who was keen to learn and pass on his knowledge to his countrymen. On 16 January 1698 Peter organized a farewell party and invited Johan Huydecoper van Maarsseveen, who had to sit between Lefort and the Tsar and drink.[20]

The frigate Pieter and Paul on the IJ while Peter stands on the small ship on the right

In England, Peter met with King William III, visited Greenwich and Oxford, posed for Sir Godfrey Kneller, and saw a Royal Navy Fleet Review at Deptford. He studied the English techniques of city-building he would later use to great effect at Saint Petersburg.[21]

The Embassy next went to Leipzig, Dresden, Prague and Vienna. Peter spoke with Augustus II the Strong and Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor.[21]

Peter’s visit was cut short in 1698, when he was forced to rush home by a rebellion of the Streltsy. The rebellion was easily crushed before Peter returned home from England; of the Tsar’s troops, only one was killed. Peter nevertheless acted ruthlessly towards the mutineers. Over one thousand two hundred of the rebels were tortured and executed, and Peter ordered that their bodies be publicly exhibited as a warning to future conspirators.[22] The Streltsy were disbanded, some of the rebels were deported to Siberia, and the individual they sought to put on the Throne —

Peter’s half-sister Sophia — was forced to become a nun.

In 1698, Peter sent a delegation to Malta, under boyar Boris Sheremetev, to observe the training and abilities of the Knights of Malta and their fleet. Sheremetev investigated the possibility of future joint ventures with the Knights, including action against the Turks and the possibility of a future Russian naval base.[23]

Peter’s visits to the West impressed upon him the notion that European customs were in several respects superior to Russian traditions. He commanded all of his courtiers and officials to wear European clothing and cut off their long beards, causing his Boyars, who were very fond of their beards, great upset.[24] Boyars who sought to retain their beards were required to pay an annual beard tax of one hundred rubles. Peter also sought to end arranged marriages, which were the norm among the Russian nobility, because he thought such a practice was barbaric and led to domestic violence, since the partners usually resented each other.[25]

In 1699, Peter changed the date of the celebration of the new year from 1 September to 1 January. Traditionally, the years were reckoned from the purported creation of the World, but after Peter’s reforms, they were to be counted from the birth of Christ. Thus, in the year 7207 of the old Russian calendar, Peter proclaimed that the Julian Calendar was in effect and the year was 1700.[26]

Great Northern War

Peter made a temporary peace with the Ottoman Empire that allowed him to keep the captured fort of Azov, and turned his attention to Russian maritime supremacy. He sought to acquire control of the Baltic Sea, which had been taken by the Swedish Empire a half-century earlier. Peter declared war on Sweden, which was at the time led by the young King Charles XII. Sweden was also opposed by Denmark–Norway, Saxony, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Peter I of Russia pacifies his marauding troops after retaking Narva in 1704, by Nikolay Sauerweid, 1859

Russia was ill-prepared to fight the Swedes, and their first attempt at seizing the Baltic coast ended in disaster at the Battle of Narva in 1700. In the conflict, the forces of Charles XII, rather than employ a slow methodical siege, attacked immediately using a blinding snowstorm to their advantage. After the battle, Charles XII decided to concentrate his forces against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, which gave Peter time to reorganize the Russian army.

While the Poles fought the Swedes, Peter founded the city of Saint Petersburg in 1703, in Ingermanland (a province of the Swedish Empire that he had captured). It was named after his patron saint Saint Peter. He forbade the building of stone edifices outside Saint Petersburg, which he intended to become Russia’s capital, so that all stonemasons could participate in the construction of the new city. Peter moved the capital to St. Petersburg in 1703. While the city was being built he lived in a three-room log cabin with Catherine, where she did the cooking and caring for the children, and he tended a garden as though they were an ordinary couple.[citation needed] Between 1713 and 1728, and from 1732 to 1918, Saint Petersburg was the capital of imperial Russia.

Following several defeats, Polish King Augustus II the Strong abdicated in 1706. Swedish king Charles XII turned his attention to Russia, invading it in 1708. After crossing into Russia, Charles defeated Peter at Golovchin in July. In the Battle of Lesnaya, Charles suffered his first loss after Peter crushed a group of Swedish reinforcements marching from Riga. Deprived of this aid, Charles was forced to abandon his proposed march on Moscow.[27]

Charles XII refused to retreat to Poland or back to Sweden and instead invaded Ukraine. Peter withdrew his army southward, employing scorched earth, destroying along the way anything that could assist the Swedes. Deprived of local supplies, the Swedish army was forced to halt its advance in the winter of 1708–1709. In the summer of 1709, they resumed their efforts to capture Russian-ruled Ukraine, culminating in the Battle of Poltava on 27 June. The battle was a decisive defeat for the Swedish forces, ending Charles’ campaign in Ukraine and forcing him south to seek refuge in the Ottoman Empire. Russia had defeated what was considered to be one of the world’s best militaries, and the victory overturned the view that Russia was militarily incompetent. In Poland, Augustus II was restored as King.

Peter, overestimating the support he would receive from his Balkan allies, attacked the Ottoman Empire, initiating the Russo-Turkish War of 1710.[28] Peter’s campaign in the Ottoman Empire was disastrous, and in the ensuing Treaty of the Pruth, Peter was forced to return the Black Sea ports he had seized in 1697.[28] In return, the Sultan expelled Charles XII.

The Ottomans called him Mad Peter (Turkish: deli Petro), for his willingness to sacrifice large numbers of his troops in wartime.[29]

Normally, the Boyar Duma would have exercised power during his absence. Peter, however, mistrusted the boyars; he instead abolished the Duma and created a Senate of ten members. The Senate was founded as the highest state institution to supervise all judicial, financial and administrative affairs. Originally established only for the time of the monarch’s absence, the Senate became a permanent body after his return. A special high official, the Ober-Procurator, served as the link between the ruler and the senate and acted, in Peter own words, as «the sovereign’s eye». Without his signature no Senate decision could go into effect; the Senate became one of the most important institutions of Imperial Russia.[30]

Peter’s northern armies took the Swedish province of Livonia (the northern half of modern Latvia, and the southern half of modern Estonia), driving the Swedes into Finland. In 1714 the Russian fleet won the Battle of Gangut. Most of Finland was occupied by the Russians.

In 1716 and 1717, the Tsar revisited the Netherlands and went to see Herman Boerhaave. He continued his travel to the Austrian Netherlands and France, where he obtained many books and proposed a marriage between his daughter and King Louis XV. Peter obtained the assistance of the Electorate of Hanover and the Kingdom of Prussia.

The Tsar’s navy was powerful enough that the Russians could penetrate Sweden. Still, Charles XII refused to yield, and not until his death in battle in 1718 did peace become feasible. After the battle near Åland, Sweden made peace with all powers but Russia by 1720. In 1721, the Treaty of Nystad ended the Great Northern War. Russia acquired Ingria, Estonia, Livonia, and a substantial portion of Karelia. In turn, Russia paid two million Riksdaler and surrendered most of Finland. The Tsar retained some Finnish lands close to Saint Petersburg, which he had made his capital in 1712.[31]

Later years

Diamond order of Peter the Great

Peter’s last years were marked by further reform in Russia. On 22 October 1721, soon after peace was made with Sweden, he was officially proclaimed Emperor of All Russia. Some proposed that he take the title Emperor of the East, but he refused. Gavrila Golovkin, the State Chancellor, was the first to add «the Great, Father of His Country, Emperor of All the Russias» to Peter’s traditional title Tsar following a speech by the archbishop of Pskov in 1721. Peter’s imperial title was recognized by Augustus II of Poland, Frederick William I of Prussia, and Frederick I of Sweden, but not by the other European monarchs. In the minds of many, the word emperor connoted superiority or pre-eminence over kings. Several rulers feared that Peter would claim authority over them, just as the Holy Roman Emperor had claimed suzerainty over all Christian nations.

In 1717, Alexander Bekovich-Cherkassky led the first Russian military expedition into Central Asia against the Khanate of Khiva. The expedition ended in complete disaster when the entire expeditionary force was slaughtered.

In 1718, Peter investigated why the formerly Swedish province of Livonia was so orderly. He discovered that the Swedes spent as much administering Livonia (300 times smaller than his empire) as he spent on the entire Russian bureaucracy. He was forced to dismantle the province’s government.[32]

Peter I by I.Nikitin (1720s, Russian museum)

After 1718, Peter established colleges in place of the old central agencies of government, including foreign affairs, war, navy, expense, income, justice, and inspection. Later others were added. Each college consisted of a president, a vice-president, a number of councilors and assessors, and a procurator. Some foreigners were included in various colleges but not as president. Peter believed he did not have enough loyal and talented persons to put in full charge of the various departments. Peter preferred to rely on groups of individuals who would keep check on one another.[33] Decisions depended on the majority vote.

In 1722, Peter created a new order of precedence known as the Table of Ranks. Formerly, precedence had been determined by birth. To deprive the Boyars of their high positions, Peter directed that precedence should be determined by merit and service to the Emperor. The Table of Ranks continued to remain in effect until the Russian monarchy was overthrown in 1917.

Peter decided that all of the children of the nobility should have some early education, especially in the areas of sciences. Therefore, on 28 February 1714, he issued a decree calling for compulsory education, which dictated that all Russian 10- to 15-year-old children of the nobility, government clerks, and lesser-ranked officials must learn basic mathematics and geometry, and should be tested on the subjects at the end of their studies.[34]

The once powerful Persian Safavid Empire to the south was in deep decline. Taking advantage of the profitable situation, Peter launched the Russo-Persian War of 1722–1723, otherwise known as «The Persian Expedition of Peter the Great», which drastically increased Russian influence for the first time in the Caucasus and Caspian Sea region, and prevented the Ottoman Empire from making territorial gains in the region. After considerable success and the capture of many provinces and cities in the Caucasus and northern mainland Persia, the Safavids were forced to hand over territory to Russia, comprising Derbent, Shirvan, Gilan, Mazandaran, Baku, and Astrabad. However, within twelve years all the territories would be ceded back to Persia, now led by the charismatic military genius Nader Shah, as part of the Treaties of Resht and Ganja respectively, and the Russo-Persian alliance against the Ottoman Empire, which was the common enemy of both.[35]