| Density | |

|---|---|

A test tube holding four non-miscible colored liquids with different densities |

|

|

Common symbols |

ρ, D |

| SI unit | kg/m3 |

| Extensive? | No |

| Intensive? | Yes |

| Conserved? | No |

|

Derivations from |

|

| Dimension |  |

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the substance’s mass per unit of volume. The symbol most often used for density is ρ (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter D can also be used. Mathematically, density is defined as mass divided by volume:[1]

where ρ is the density, m is the mass, and V is the volume. In some cases (for instance, in the United States oil and gas industry), density is loosely defined as its weight per unit volume,[2] although this is scientifically inaccurate – this quantity is more specifically called specific weight.

For a pure substance the density has the same numerical value as its mass concentration.

Different materials usually have different densities, and density may be relevant to buoyancy, purity and packaging. Osmium and iridium are the densest known elements at standard conditions for temperature and pressure.

To simplify comparisons of density across different systems of units, it is sometimes replaced by the dimensionless quantity «relative density» or «specific gravity», i.e. the ratio of the density of the material to that of a standard material, usually water. Thus a relative density less than one relative to water means that the substance floats in water.

The density of a material varies with temperature and pressure. This variation is typically small for solids and liquids but much greater for gases. Increasing the pressure on an object decreases the volume of the object and thus increases its density. Increasing the temperature of a substance (with a few exceptions) decreases its density by increasing its volume. In most materials, heating the bottom of a fluid results in convection of the heat from the bottom to the top, due to the decrease in the density of the heated fluid, which causes it to rise relative to denser unheated material.

The reciprocal of the density of a substance is occasionally called its specific volume, a term sometimes used in thermodynamics. Density is an intensive property in that increasing the amount of a substance does not increase its density; rather it increases its mass.

Other conceptually comparable quantities or ratios include specific density, relative density (specific gravity), and specific weight.

History

In a well-known but probably apocryphal tale, Archimedes was given the task of determining whether King Hiero’s goldsmith was embezzling gold during the manufacture of a golden wreath dedicated to the gods and replacing it with another, cheaper alloy.[3] Archimedes knew that the irregularly shaped wreath could be crushed into a cube whose volume could be calculated easily and compared with the mass; but the king did not approve of this. Baffled, Archimedes is said to have taken an immersion bath and observed from the rise of the water upon entering that he could calculate the volume of the gold wreath through the displacement of the water. Upon this discovery, he leapt from his bath and ran naked through the streets shouting, «Eureka! Eureka!» (Εύρηκα! Greek «I have found it»). As a result, the term «eureka» entered common parlance and is used today to indicate a moment of enlightenment.

The story first appeared in written form in Vitruvius’ books of architecture, two centuries after it supposedly took place.[4] Some scholars have doubted the accuracy of this tale, saying among other things that the method would have required precise measurements that would have been difficult to make at the time.[5][6]

Measurement of density

A number of techniques as well as standards exist for the measurement of density of materials. Such techniques include the use of a hydrometer (a buoyancy method for liquids), Hydrostatic balance (a buoyancy method for liquids and solids), immersed body method (a buoyancy method for liquids), pycnometer (liquids and solids), air comparison pycnometer (solids), oscillating densitometer (liquids), as well as pour and tap (solids).[7] However, each individual method or technique measures different types of density (e.g. bulk density, skeletal density, etc.), and therefore it is necessary to have an understanding of the type of density being measured as well as the type of material in question.

Unit

From the equation for density (ρ = m/V), mass density has any unit that is mass divided by volume. As there are many units of mass and volume covering many different magnitudes there are a large number of units for mass density in use. The SI unit of kilogram per cubic metre (kg/m3) and the cgs unit of gram per cubic centimetre (g/cm3) are probably the most commonly used units for density. One g/cm3 is equal to 1000 kg/m3. One cubic centimetre (abbreviation cc) is equal to one millilitre. In industry, other larger or smaller units of mass and or volume are often more practical and US customary units may be used. See below for a list of some of the most common units of density.

Homogeneous materials

The density at all points of a homogeneous object equals its total mass divided by its total volume. The mass is normally measured with a scale or balance; the volume may be measured directly (from the geometry of the object) or by the displacement of a fluid. To determine the density of a liquid or a gas, a hydrometer, a dasymeter or a Coriolis flow meter may be used, respectively. Similarly, hydrostatic weighing uses the displacement of water due to a submerged object to determine the density of the object.

Heterogeneous materials

If the body is not homogeneous, then its density varies between different regions of the object. In that case the density around any given location is determined by calculating the density of a small volume around that location. In the limit of an infinitesimal volume the density of an inhomogeneous object at a point becomes:

Non-compact materials

In practice, bulk materials such as sugar, sand, or snow contain voids. Many materials exist in nature as flakes, pellets, or granules.

Voids are regions which contain something other than the considered material. Commonly the void is air, but it could also be vacuum, liquid, solid, or a different gas or gaseous mixture.

The bulk volume of a material—inclusive of the void fraction—is often obtained by a simple measurement (e.g. with a calibrated measuring cup) or geometrically from known dimensions.

Mass divided by bulk volume determines bulk density. This is not the same thing as volumetric mass density.

To determine volumetric mass density, one must first discount the volume of the void fraction. Sometimes this can be determined by geometrical reasoning. For the close-packing of equal spheres the non-void fraction can be at most about 74%. It can also be determined empirically. Some bulk materials, however, such as sand, have a variable void fraction which depends on how the material is agitated or poured. It might be loose or compact, with more or less air space depending on handling.

In practice, the void fraction is not necessarily air, or even gaseous. In the case of sand, it could be water, which can be advantageous for measurement as the void fraction for sand saturated in water—once any air bubbles are thoroughly driven out—is potentially more consistent than dry sand measured with an air void.

In the case of non-compact materials, one must also take care in determining the mass of the material sample. If the material is under pressure (commonly ambient air pressure at the earth’s surface) the determination of mass from a measured sample weight might need to account for buoyancy effects due to the density of the void constituent, depending on how the measurement was conducted. In the case of dry sand, sand is so much denser than air that the buoyancy effect is commonly neglected (less than one part in one thousand).

Mass change upon displacing one void material with another while maintaining constant volume can be used to estimate the void fraction, if the difference in density of the two voids materials is reliably known.

Changes of density

In general, density can be changed by changing either the pressure or the temperature. Increasing the pressure always increases the density of a material. Increasing the temperature generally decreases the density, but there are notable exceptions to this generalization. For example, the density of water increases between its melting point at 0 °C and 4 °C; similar behavior is observed in silicon at low temperatures.

The effect of pressure and temperature on the densities of liquids and solids is small. The compressibility for a typical liquid or solid is 10−6 bar−1 (1 bar = 0.1 MPa) and a typical thermal expansivity is 10−5 K−1. This roughly translates into needing around ten thousand times atmospheric pressure to reduce the volume of a substance by one percent. (Although the pressures needed may be around a thousand times smaller for sandy soil and some clays.) A one percent expansion of volume typically requires a temperature increase on the order of thousands of degrees Celsius.

In contrast, the density of gases is strongly affected by pressure. The density of an ideal gas is

where M is the molar mass, P is the pressure, R is the universal gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature. This means that the density of an ideal gas can be doubled by doubling the pressure, or by halving the absolute temperature.

In the case of volumic thermal expansion at constant pressure and small intervals of temperature the temperature dependence of density is

where

Density of solutions

The density of a solution is the sum of mass (massic) concentrations of the components of that solution.

Mass (massic) concentration of each given component ρi in a solution sums to density of the solution,

Expressed as a function of the densities of pure components of the mixture and their volume participation, it allows the determination of excess molar volumes:

provided that there is no interaction between the components.

Knowing the relation between excess volumes and activity coefficients of the components, one can determine the activity coefficients:

Densities

Various materials

- Selected chemical elements are listed here. For the densities of all chemical elements, see List of chemical elements

| Material | ρ (kg/m3)[note 1] | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen | 0.0898 | |

| Helium | 0.179 | |

| Aerographite | 0.2 | [note 2][8][9] |

| Metallic microlattice | 0.9 | [note 2] |

| Aerogel | 1.0 | [note 2] |

| Air | 1.2 | At sea level |

| Tungsten hexafluoride | 12.4 | One of the heaviest known gases at standard conditions |

| Liquid hydrogen | 70 | At approx. −255 °C |

| Styrofoam | 75 | Approx.[10] |

| Cork | 240 | Approx.[10] |

| Pine | 373 | [11] |

| Lithium | 535 | Least dense metal |

| Wood | 700 | Seasoned, typical[12][13] |

| Oak | 710 | [11] |

| Potassium | 860 | [14] |

| Ice | 916.7 | At temperature < 0 °C |

| Cooking oil | 910–930 | |

| Sodium | 970 | |

| Water (fresh) | 1,000 | At 4 °C, the temperature of its maximum density |

| Water (salt) | 1,030 | 3% |

| Liquid oxygen | 1,141 | At approx. −219 °C |

| Nylon | 1,150 | |

| Plastics | 1,175 | Approx.; for polypropylene and PETE/PVC |

| Glycerol | 1,261 | [15] |

| Tetrachloroethene | 1,622 | |

| Sand | 1,600 | Between 1,600 and 2000 [16] |

| Magnesium | 1,740 | |

| Beryllium | 1,850 | |

| Silicon | 2,330 | |

| Concrete | 2,400 | [17][18] |

| Glass | 2,500 | [19] |

| Quartzite | 2,600 | [16] |

| Granite | 2,700 | [16] |

| Gneiss | 2,700 | [16] |

| Aluminium | 2,700 | |

| Limestone | 2,750 | Compact[16] |

| Basalt | 3,000 | [16] |

| Diiodomethane | 3,325 | Liquid at room temperature |

| Diamond | 3,500 | |

| Titanium | 4,540 | |

| Selenium | 4,800 | |

| Vanadium | 6,100 | |

| Antimony | 6,690 | |

| Zinc | 7,000 | |

| Chromium | 7,200 | |

| Tin | 7,310 | |

| Manganese | 7,325 | Approx. |

| Iron | 7,870 | |

| Mild Steel | 7,850 | |

| Niobium | 8,570 | |

| Brass | 8,600 | [18] |

| Cadmium | 8,650 | |

| Cobalt | 8,900 | |

| Nickel | 8,900 | |

| Copper | 8,940 | |

| Bismuth | 9,750 | |

| Molybdenum | 10,220 | |

| Silver | 10,500 | |

| Lead | 11,340 | |

| Thorium | 11,700 | |

| Rhodium | 12,410 | |

| Mercury | 13,546 | |

| Tantalum | 16,600 | |

| Uranium | 18,800 | |

| Tungsten | 19,300 | |

| Gold | 19,320 | |

| Plutonium | 19,840 | |

| Rhenium | 21,020 | |

| Platinum | 21,450 | |

| Iridium | 22,420 | |

| Osmium | 22,570 | Densest element |

Notes:

|

Others

| Entity | ρ (kg/m3) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Interstellar medium | 1×10−19 | Assuming 90% H, 10% He; variable T |

| The Earth | 5,515 | Mean density.[20] |

| Earth’s inner core | 13,000 | Approx., as listed in Earth.[21] |

| The core of the Sun | 33,000–160,000 | Approx.[22] |

| White dwarf star | 2.1×109 | Approx.[23] |

| Atomic nuclei | 2.3×1017 | Does not depend strongly on size of nucleus[24] |

| Neutron star | 1×1018 |

Water

| Temp. (°C)[note 1] | Density (kg/m3) |

|---|---|

| −30 | 983.854 |

| −20 | 993.547 |

| −10 | 998.117 |

| 0 | 999.8395 |

| 4 | 999.9720 |

| 10 | 999.7026 |

| 15 | 999.1026 |

| 20 | 998.2071 |

| 22 | 997.7735 |

| 25 | 997.0479 |

| 30 | 995.6502 |

| 40 | 992.2 |

| 60 | 983.2 |

| 80 | 971.8 |

| 100 | 958.4 |

Notes:

|

Air

Air density vs. temperature

| T (°C) | ρ (kg/m3) |

|---|---|

| −25 | 1.423 |

| −20 | 1.395 |

| −15 | 1.368 |

| −10 | 1.342 |

| −5 | 1.316 |

| 0 | 1.293 |

| 5 | 1.269 |

| 10 | 1.247 |

| 15 | 1.225 |

| 20 | 1.204 |

| 25 | 1.184 |

| 30 | 1.164 |

| 35 | 1.146 |

Molar volumes of liquid and solid phase of elements

Molar volumes of liquid and solid phase of elements

Common units

The SI unit for density is:

- kilogram per cubic metre (kg/m3)

The litre and tonne are not part of the SI, but are acceptable for use with it, leading to the following units:

- kilogram per litre (kg/L)

- gram per millilitre (g/mL)

- tonne per cubic metre (t/m3)

Densities using the following metric units all have exactly the same numerical value, one thousandth of the value in (kg/m3). Liquid water has a density of about 1 kg/dm3, making any of these SI units numerically convenient to use as most solids and liquids have densities between 0.1 and 20 kg/dm3.

- kilogram per cubic decimetre (kg/dm3)

- gram per cubic centimetre (g/cm3)

- 1 g/cm3 = 1000 kg/m3

- megagram (metric ton) per cubic metre (Mg/m3)

In US customary units density can be stated in:

- Avoirdupois ounce per cubic inch (1 g/cm3 ≈ 0.578036672 oz/cu in)

- Avoirdupois ounce per fluid ounce (1 g/cm3 ≈ 1.04317556 oz/US fl oz = 1.04317556 lb/US fl pint)

- Avoirdupois pound per cubic inch (1 g/cm3 ≈ 0.036127292 lb/cu in)

- pound per cubic foot (1 g/cm3 ≈ 62.427961 lb/cu ft)

- pound per cubic yard (1 g/cm3 ≈ 1685.5549 lb/cu yd)

- pound per US liquid gallon (1 g/cm3 ≈ 8.34540445 lb/US gal)

- pound per US bushel (1 g/cm3 ≈ 77.6888513 lb/bu)

- slug per cubic foot

Imperial units differing from the above (as the Imperial gallon and bushel differ from the US units) in practice are rarely used, though found in older documents. The Imperial gallon was based on the concept that an Imperial fluid ounce of water would have a mass of one Avoirdupois ounce, and indeed 1 g/cm3 ≈ 1.00224129 ounces per Imperial fluid ounce = 10.0224129 pounds per Imperial gallon. The density of precious metals could conceivably be based on Troy ounces and pounds, a possible cause of confusion.

Knowing the volume of the unit cell of a crystalline material and its formula weight (in daltons), the density can be calculated. One dalton per cubic ångström is equal to a density of 1.660 539 066 60 g/cm3.

See also

- Densities of the elements (data page)

- List of elements by density

- Air density

- Area density

- Bulk density

- Buoyancy

- Charge density

- Density prediction by the Girolami method

- Dord

- Energy density

- Lighter than air

- Linear density

- Number density

- Orthobaric density

- Paper density

- Specific weight

- Spice (oceanography)

- Standard temperature and pressure

References

- ^ The National Aeronautic and Atmospheric Administration’s Glenn Research Center. «Gas Density Glenn research Center». grc.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ^ «Density definition in Oil Gas Glossary». Oilgasglossary.com. Archived from the original on August 5, 2010. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ^ Archimedes, A Gold Thief and Buoyancy Archived August 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine – by Larry «Harris» Taylor, Ph.D.

- ^ Vitruvius on Architecture, Book IX, paragraphs 9–12, translated into English and in the original Latin.

- ^ «EXHIBIT: The First Eureka Moment». Science. 305 (5688): 1219e. 2004. doi:10.1126/science.305.5688.1219e.

- ^ «Fact or Fiction?: Archimedes Coined the Term «Eureka!» in the Bath». Scientific American. December 2006.

- ^ «Test No. 109: Density of Liquids and Solids». OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 1. October 2, 2012. doi:10.1787/9789264123298-en. ISBN 9789264123298. ISSN 2074-5753.

- ^ New carbon nanotube struructure aerographite is lightest material champ Archived October 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Phys.org (July 13, 2012). Retrieved on July 14, 2012.

- ^ Aerographit: Leichtestes Material der Welt entwickelt – SPIEGEL ONLINE Archived October 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Spiegel.de (July 11, 2012). Retrieved on July 14, 2012.

- ^ a b «Re: which is more bouyant [sic] styrofoam or cork». Madsci.org. Archived from the original on February 14, 2011. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ^ a b Serway, Raymond; Jewett, John (2005), Principles of Physics: A Calculus-Based Text, Cengage Learning, p. 467, ISBN 0-534-49143-X, archived from the original on May 17, 2016

- ^ «Wood Densities». www.engineeringtoolbox.com. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ «Density of Wood». www.simetric.co.uk. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ Bolz, Ray E.; Tuve, George L., eds. (1970). «§1.3 Solids—Metals: Table 1-59 Metals and Alloys—Miscellaneous Properties». CRC Handbook of tables for Applied Engineering Science (2nd ed.). CRC Press. p. 117. ISBN 9781315214092.

- ^ glycerol composition at Archived February 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Physics.nist.gov. Retrieved on July 14, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Sharma, P.V. (1997), Environmental and Engineering Geophysics, Cambridge University Press, p. 17, doi:10.1017/CBO9781139171168, ISBN 9781139171168

- ^ «Density of Concrete — The Physics Factbook». hypertextbook.com.

- ^ a b Young, Hugh D.; Freedman, Roger A. (2012). University Physics with Modern Physics. Addison-Wesley. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-321-69686-1.

- ^ «Density of Glass — The Physics Factbook». hypertextbook.com.

- ^ Density of the Earth, wolframalpha.com, archived from the original on October 17, 2013

- ^ Density of Earth’s core, wolframalpha.com, archived from the original on October 17, 2013

- ^ Density of the Sun’s core, wolframalpha.com, archived from the original on October 17, 2013

- ^ Johnson, Jennifer. «Extreme Stars: White Dwarfs & Neutron Stars]» (PDF). lecture notes, Astronomy 162. Ohio State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 25, 2007.

- ^ «Nuclear Size and Density». HyperPhysics. Georgia State University. Archived from the original on July 6, 2009.

External links

- «Density» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). 1911.

- «Density» . The New Student’s Reference Work . 1914.

- Video: Density Experiment with Oil and Alcohol

- Video: Density Experiment with Whiskey and Water

- Glass Density Calculation – Calculation of the density of glass at room temperature and of glass melts at 1000 – 1400°C

- List of Elements of the Periodic Table – Sorted by Density

- Calculation of saturated liquid densities for some components

- Field density test

- Water – Density and specific weight

- Temperature dependence of the density of water – Conversions of density units

- A delicious density experiment

- Water density calculator Archived July 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Water density for a given salinity and temperature.

- Liquid density calculator Select a liquid from the list and calculate density as a function of temperature.

- Gas density calculator Calculate density of a gas for as a function of temperature and pressure.

- Densities of various materials.

- Determination of Density of Solid, instructions for performing classroom experiment.

- Lam EJ, Alvarez MN, Galvez ME, Alvarez EB (2008). «A model for calculating the density of aqueous multicomponent electrolyte solutions». Journal of the Chilean Chemical Society. 53 (1): 1393–8. doi:10.4067/S0717-97072008000100015.

- Radović IR, Kijevčanin ML, Tasić AŽ, Djordjević BD, Šerbanović SP (2010). «Derived thermodynamic properties of alcohol+ cyclohexylamine mixtures». Journal of the Serbian Chemical Society. 75 (2): 283–293. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.424.3486. doi:10.2298/JSC1002283R.

| Density | |

|---|---|

A test tube holding four non-miscible colored liquids with different densities |

|

|

Common symbols |

ρ, D |

| SI unit | kg/m3 |

| Extensive? | No |

| Intensive? | Yes |

| Conserved? | No |

|

Derivations from |

|

| Dimension |  |

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the substance’s mass per unit of volume. The symbol most often used for density is ρ (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter D can also be used. Mathematically, density is defined as mass divided by volume:[1]

where ρ is the density, m is the mass, and V is the volume. In some cases (for instance, in the United States oil and gas industry), density is loosely defined as its weight per unit volume,[2] although this is scientifically inaccurate – this quantity is more specifically called specific weight.

For a pure substance the density has the same numerical value as its mass concentration.

Different materials usually have different densities, and density may be relevant to buoyancy, purity and packaging. Osmium and iridium are the densest known elements at standard conditions for temperature and pressure.

To simplify comparisons of density across different systems of units, it is sometimes replaced by the dimensionless quantity «relative density» or «specific gravity», i.e. the ratio of the density of the material to that of a standard material, usually water. Thus a relative density less than one relative to water means that the substance floats in water.

The density of a material varies with temperature and pressure. This variation is typically small for solids and liquids but much greater for gases. Increasing the pressure on an object decreases the volume of the object and thus increases its density. Increasing the temperature of a substance (with a few exceptions) decreases its density by increasing its volume. In most materials, heating the bottom of a fluid results in convection of the heat from the bottom to the top, due to the decrease in the density of the heated fluid, which causes it to rise relative to denser unheated material.

The reciprocal of the density of a substance is occasionally called its specific volume, a term sometimes used in thermodynamics. Density is an intensive property in that increasing the amount of a substance does not increase its density; rather it increases its mass.

Other conceptually comparable quantities or ratios include specific density, relative density (specific gravity), and specific weight.

History

In a well-known but probably apocryphal tale, Archimedes was given the task of determining whether King Hiero’s goldsmith was embezzling gold during the manufacture of a golden wreath dedicated to the gods and replacing it with another, cheaper alloy.[3] Archimedes knew that the irregularly shaped wreath could be crushed into a cube whose volume could be calculated easily and compared with the mass; but the king did not approve of this. Baffled, Archimedes is said to have taken an immersion bath and observed from the rise of the water upon entering that he could calculate the volume of the gold wreath through the displacement of the water. Upon this discovery, he leapt from his bath and ran naked through the streets shouting, «Eureka! Eureka!» (Εύρηκα! Greek «I have found it»). As a result, the term «eureka» entered common parlance and is used today to indicate a moment of enlightenment.

The story first appeared in written form in Vitruvius’ books of architecture, two centuries after it supposedly took place.[4] Some scholars have doubted the accuracy of this tale, saying among other things that the method would have required precise measurements that would have been difficult to make at the time.[5][6]

Measurement of density

A number of techniques as well as standards exist for the measurement of density of materials. Such techniques include the use of a hydrometer (a buoyancy method for liquids), Hydrostatic balance (a buoyancy method for liquids and solids), immersed body method (a buoyancy method for liquids), pycnometer (liquids and solids), air comparison pycnometer (solids), oscillating densitometer (liquids), as well as pour and tap (solids).[7] However, each individual method or technique measures different types of density (e.g. bulk density, skeletal density, etc.), and therefore it is necessary to have an understanding of the type of density being measured as well as the type of material in question.

Unit

From the equation for density (ρ = m/V), mass density has any unit that is mass divided by volume. As there are many units of mass and volume covering many different magnitudes there are a large number of units for mass density in use. The SI unit of kilogram per cubic metre (kg/m3) and the cgs unit of gram per cubic centimetre (g/cm3) are probably the most commonly used units for density. One g/cm3 is equal to 1000 kg/m3. One cubic centimetre (abbreviation cc) is equal to one millilitre. In industry, other larger or smaller units of mass and or volume are often more practical and US customary units may be used. See below for a list of some of the most common units of density.

Homogeneous materials

The density at all points of a homogeneous object equals its total mass divided by its total volume. The mass is normally measured with a scale or balance; the volume may be measured directly (from the geometry of the object) or by the displacement of a fluid. To determine the density of a liquid or a gas, a hydrometer, a dasymeter or a Coriolis flow meter may be used, respectively. Similarly, hydrostatic weighing uses the displacement of water due to a submerged object to determine the density of the object.

Heterogeneous materials

If the body is not homogeneous, then its density varies between different regions of the object. In that case the density around any given location is determined by calculating the density of a small volume around that location. In the limit of an infinitesimal volume the density of an inhomogeneous object at a point becomes:

Non-compact materials

In practice, bulk materials such as sugar, sand, or snow contain voids. Many materials exist in nature as flakes, pellets, or granules.

Voids are regions which contain something other than the considered material. Commonly the void is air, but it could also be vacuum, liquid, solid, or a different gas or gaseous mixture.

The bulk volume of a material—inclusive of the void fraction—is often obtained by a simple measurement (e.g. with a calibrated measuring cup) or geometrically from known dimensions.

Mass divided by bulk volume determines bulk density. This is not the same thing as volumetric mass density.

To determine volumetric mass density, one must first discount the volume of the void fraction. Sometimes this can be determined by geometrical reasoning. For the close-packing of equal spheres the non-void fraction can be at most about 74%. It can also be determined empirically. Some bulk materials, however, such as sand, have a variable void fraction which depends on how the material is agitated or poured. It might be loose or compact, with more or less air space depending on handling.

In practice, the void fraction is not necessarily air, or even gaseous. In the case of sand, it could be water, which can be advantageous for measurement as the void fraction for sand saturated in water—once any air bubbles are thoroughly driven out—is potentially more consistent than dry sand measured with an air void.

In the case of non-compact materials, one must also take care in determining the mass of the material sample. If the material is under pressure (commonly ambient air pressure at the earth’s surface) the determination of mass from a measured sample weight might need to account for buoyancy effects due to the density of the void constituent, depending on how the measurement was conducted. In the case of dry sand, sand is so much denser than air that the buoyancy effect is commonly neglected (less than one part in one thousand).

Mass change upon displacing one void material with another while maintaining constant volume can be used to estimate the void fraction, if the difference in density of the two voids materials is reliably known.

Changes of density

In general, density can be changed by changing either the pressure or the temperature. Increasing the pressure always increases the density of a material. Increasing the temperature generally decreases the density, but there are notable exceptions to this generalization. For example, the density of water increases between its melting point at 0 °C and 4 °C; similar behavior is observed in silicon at low temperatures.

The effect of pressure and temperature on the densities of liquids and solids is small. The compressibility for a typical liquid or solid is 10−6 bar−1 (1 bar = 0.1 MPa) and a typical thermal expansivity is 10−5 K−1. This roughly translates into needing around ten thousand times atmospheric pressure to reduce the volume of a substance by one percent. (Although the pressures needed may be around a thousand times smaller for sandy soil and some clays.) A one percent expansion of volume typically requires a temperature increase on the order of thousands of degrees Celsius.

In contrast, the density of gases is strongly affected by pressure. The density of an ideal gas is

where M is the molar mass, P is the pressure, R is the universal gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature. This means that the density of an ideal gas can be doubled by doubling the pressure, or by halving the absolute temperature.

In the case of volumic thermal expansion at constant pressure and small intervals of temperature the temperature dependence of density is

where

Density of solutions

The density of a solution is the sum of mass (massic) concentrations of the components of that solution.

Mass (massic) concentration of each given component ρi in a solution sums to density of the solution,

Expressed as a function of the densities of pure components of the mixture and their volume participation, it allows the determination of excess molar volumes:

provided that there is no interaction between the components.

Knowing the relation between excess volumes and activity coefficients of the components, one can determine the activity coefficients:

Densities

Various materials

- Selected chemical elements are listed here. For the densities of all chemical elements, see List of chemical elements

| Material | ρ (kg/m3)[note 1] | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen | 0.0898 | |

| Helium | 0.179 | |

| Aerographite | 0.2 | [note 2][8][9] |

| Metallic microlattice | 0.9 | [note 2] |

| Aerogel | 1.0 | [note 2] |

| Air | 1.2 | At sea level |

| Tungsten hexafluoride | 12.4 | One of the heaviest known gases at standard conditions |

| Liquid hydrogen | 70 | At approx. −255 °C |

| Styrofoam | 75 | Approx.[10] |

| Cork | 240 | Approx.[10] |

| Pine | 373 | [11] |

| Lithium | 535 | Least dense metal |

| Wood | 700 | Seasoned, typical[12][13] |

| Oak | 710 | [11] |

| Potassium | 860 | [14] |

| Ice | 916.7 | At temperature < 0 °C |

| Cooking oil | 910–930 | |

| Sodium | 970 | |

| Water (fresh) | 1,000 | At 4 °C, the temperature of its maximum density |

| Water (salt) | 1,030 | 3% |

| Liquid oxygen | 1,141 | At approx. −219 °C |

| Nylon | 1,150 | |

| Plastics | 1,175 | Approx.; for polypropylene and PETE/PVC |

| Glycerol | 1,261 | [15] |

| Tetrachloroethene | 1,622 | |

| Sand | 1,600 | Between 1,600 and 2000 [16] |

| Magnesium | 1,740 | |

| Beryllium | 1,850 | |

| Silicon | 2,330 | |

| Concrete | 2,400 | [17][18] |

| Glass | 2,500 | [19] |

| Quartzite | 2,600 | [16] |

| Granite | 2,700 | [16] |

| Gneiss | 2,700 | [16] |

| Aluminium | 2,700 | |

| Limestone | 2,750 | Compact[16] |

| Basalt | 3,000 | [16] |

| Diiodomethane | 3,325 | Liquid at room temperature |

| Diamond | 3,500 | |

| Titanium | 4,540 | |

| Selenium | 4,800 | |

| Vanadium | 6,100 | |

| Antimony | 6,690 | |

| Zinc | 7,000 | |

| Chromium | 7,200 | |

| Tin | 7,310 | |

| Manganese | 7,325 | Approx. |

| Iron | 7,870 | |

| Mild Steel | 7,850 | |

| Niobium | 8,570 | |

| Brass | 8,600 | [18] |

| Cadmium | 8,650 | |

| Cobalt | 8,900 | |

| Nickel | 8,900 | |

| Copper | 8,940 | |

| Bismuth | 9,750 | |

| Molybdenum | 10,220 | |

| Silver | 10,500 | |

| Lead | 11,340 | |

| Thorium | 11,700 | |

| Rhodium | 12,410 | |

| Mercury | 13,546 | |

| Tantalum | 16,600 | |

| Uranium | 18,800 | |

| Tungsten | 19,300 | |

| Gold | 19,320 | |

| Plutonium | 19,840 | |

| Rhenium | 21,020 | |

| Platinum | 21,450 | |

| Iridium | 22,420 | |

| Osmium | 22,570 | Densest element |

Notes:

|

Others

| Entity | ρ (kg/m3) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Interstellar medium | 1×10−19 | Assuming 90% H, 10% He; variable T |

| The Earth | 5,515 | Mean density.[20] |

| Earth’s inner core | 13,000 | Approx., as listed in Earth.[21] |

| The core of the Sun | 33,000–160,000 | Approx.[22] |

| White dwarf star | 2.1×109 | Approx.[23] |

| Atomic nuclei | 2.3×1017 | Does not depend strongly on size of nucleus[24] |

| Neutron star | 1×1018 |

Water

| Temp. (°C)[note 1] | Density (kg/m3) |

|---|---|

| −30 | 983.854 |

| −20 | 993.547 |

| −10 | 998.117 |

| 0 | 999.8395 |

| 4 | 999.9720 |

| 10 | 999.7026 |

| 15 | 999.1026 |

| 20 | 998.2071 |

| 22 | 997.7735 |

| 25 | 997.0479 |

| 30 | 995.6502 |

| 40 | 992.2 |

| 60 | 983.2 |

| 80 | 971.8 |

| 100 | 958.4 |

Notes:

|

Air

Air density vs. temperature

| T (°C) | ρ (kg/m3) |

|---|---|

| −25 | 1.423 |

| −20 | 1.395 |

| −15 | 1.368 |

| −10 | 1.342 |

| −5 | 1.316 |

| 0 | 1.293 |

| 5 | 1.269 |

| 10 | 1.247 |

| 15 | 1.225 |

| 20 | 1.204 |

| 25 | 1.184 |

| 30 | 1.164 |

| 35 | 1.146 |

Molar volumes of liquid and solid phase of elements

Molar volumes of liquid and solid phase of elements

Common units

The SI unit for density is:

- kilogram per cubic metre (kg/m3)

The litre and tonne are not part of the SI, but are acceptable for use with it, leading to the following units:

- kilogram per litre (kg/L)

- gram per millilitre (g/mL)

- tonne per cubic metre (t/m3)

Densities using the following metric units all have exactly the same numerical value, one thousandth of the value in (kg/m3). Liquid water has a density of about 1 kg/dm3, making any of these SI units numerically convenient to use as most solids and liquids have densities between 0.1 and 20 kg/dm3.

- kilogram per cubic decimetre (kg/dm3)

- gram per cubic centimetre (g/cm3)

- 1 g/cm3 = 1000 kg/m3

- megagram (metric ton) per cubic metre (Mg/m3)

In US customary units density can be stated in:

- Avoirdupois ounce per cubic inch (1 g/cm3 ≈ 0.578036672 oz/cu in)

- Avoirdupois ounce per fluid ounce (1 g/cm3 ≈ 1.04317556 oz/US fl oz = 1.04317556 lb/US fl pint)

- Avoirdupois pound per cubic inch (1 g/cm3 ≈ 0.036127292 lb/cu in)

- pound per cubic foot (1 g/cm3 ≈ 62.427961 lb/cu ft)

- pound per cubic yard (1 g/cm3 ≈ 1685.5549 lb/cu yd)

- pound per US liquid gallon (1 g/cm3 ≈ 8.34540445 lb/US gal)

- pound per US bushel (1 g/cm3 ≈ 77.6888513 lb/bu)

- slug per cubic foot

Imperial units differing from the above (as the Imperial gallon and bushel differ from the US units) in practice are rarely used, though found in older documents. The Imperial gallon was based on the concept that an Imperial fluid ounce of water would have a mass of one Avoirdupois ounce, and indeed 1 g/cm3 ≈ 1.00224129 ounces per Imperial fluid ounce = 10.0224129 pounds per Imperial gallon. The density of precious metals could conceivably be based on Troy ounces and pounds, a possible cause of confusion.

Knowing the volume of the unit cell of a crystalline material and its formula weight (in daltons), the density can be calculated. One dalton per cubic ångström is equal to a density of 1.660 539 066 60 g/cm3.

See also

- Densities of the elements (data page)

- List of elements by density

- Air density

- Area density

- Bulk density

- Buoyancy

- Charge density

- Density prediction by the Girolami method

- Dord

- Energy density

- Lighter than air

- Linear density

- Number density

- Orthobaric density

- Paper density

- Specific weight

- Spice (oceanography)

- Standard temperature and pressure

References

- ^ The National Aeronautic and Atmospheric Administration’s Glenn Research Center. «Gas Density Glenn research Center». grc.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ^ «Density definition in Oil Gas Glossary». Oilgasglossary.com. Archived from the original on August 5, 2010. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ^ Archimedes, A Gold Thief and Buoyancy Archived August 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine – by Larry «Harris» Taylor, Ph.D.

- ^ Vitruvius on Architecture, Book IX, paragraphs 9–12, translated into English and in the original Latin.

- ^ «EXHIBIT: The First Eureka Moment». Science. 305 (5688): 1219e. 2004. doi:10.1126/science.305.5688.1219e.

- ^ «Fact or Fiction?: Archimedes Coined the Term «Eureka!» in the Bath». Scientific American. December 2006.

- ^ «Test No. 109: Density of Liquids and Solids». OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 1. October 2, 2012. doi:10.1787/9789264123298-en. ISBN 9789264123298. ISSN 2074-5753.

- ^ New carbon nanotube struructure aerographite is lightest material champ Archived October 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Phys.org (July 13, 2012). Retrieved on July 14, 2012.

- ^ Aerographit: Leichtestes Material der Welt entwickelt – SPIEGEL ONLINE Archived October 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Spiegel.de (July 11, 2012). Retrieved on July 14, 2012.

- ^ a b «Re: which is more bouyant [sic] styrofoam or cork». Madsci.org. Archived from the original on February 14, 2011. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ^ a b Serway, Raymond; Jewett, John (2005), Principles of Physics: A Calculus-Based Text, Cengage Learning, p. 467, ISBN 0-534-49143-X, archived from the original on May 17, 2016

- ^ «Wood Densities». www.engineeringtoolbox.com. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ «Density of Wood». www.simetric.co.uk. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ Bolz, Ray E.; Tuve, George L., eds. (1970). «§1.3 Solids—Metals: Table 1-59 Metals and Alloys—Miscellaneous Properties». CRC Handbook of tables for Applied Engineering Science (2nd ed.). CRC Press. p. 117. ISBN 9781315214092.

- ^ glycerol composition at Archived February 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Physics.nist.gov. Retrieved on July 14, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Sharma, P.V. (1997), Environmental and Engineering Geophysics, Cambridge University Press, p. 17, doi:10.1017/CBO9781139171168, ISBN 9781139171168

- ^ «Density of Concrete — The Physics Factbook». hypertextbook.com.

- ^ a b Young, Hugh D.; Freedman, Roger A. (2012). University Physics with Modern Physics. Addison-Wesley. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-321-69686-1.

- ^ «Density of Glass — The Physics Factbook». hypertextbook.com.

- ^ Density of the Earth, wolframalpha.com, archived from the original on October 17, 2013

- ^ Density of Earth’s core, wolframalpha.com, archived from the original on October 17, 2013

- ^ Density of the Sun’s core, wolframalpha.com, archived from the original on October 17, 2013

- ^ Johnson, Jennifer. «Extreme Stars: White Dwarfs & Neutron Stars]» (PDF). lecture notes, Astronomy 162. Ohio State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 25, 2007.

- ^ «Nuclear Size and Density». HyperPhysics. Georgia State University. Archived from the original on July 6, 2009.

External links

- «Density» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). 1911.

- «Density» . The New Student’s Reference Work . 1914.

- Video: Density Experiment with Oil and Alcohol

- Video: Density Experiment with Whiskey and Water

- Glass Density Calculation – Calculation of the density of glass at room temperature and of glass melts at 1000 – 1400°C

- List of Elements of the Periodic Table – Sorted by Density

- Calculation of saturated liquid densities for some components

- Field density test

- Water – Density and specific weight

- Temperature dependence of the density of water – Conversions of density units

- A delicious density experiment

- Water density calculator Archived July 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Water density for a given salinity and temperature.

- Liquid density calculator Select a liquid from the list and calculate density as a function of temperature.

- Gas density calculator Calculate density of a gas for as a function of temperature and pressure.

- Densities of various materials.

- Determination of Density of Solid, instructions for performing classroom experiment.

- Lam EJ, Alvarez MN, Galvez ME, Alvarez EB (2008). «A model for calculating the density of aqueous multicomponent electrolyte solutions». Journal of the Chilean Chemical Society. 53 (1): 1393–8. doi:10.4067/S0717-97072008000100015.

- Radović IR, Kijevčanin ML, Tasić AŽ, Djordjević BD, Šerbanović SP (2010). «Derived thermodynamic properties of alcohol+ cyclohexylamine mixtures». Journal of the Serbian Chemical Society. 75 (2): 283–293. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.424.3486. doi:10.2298/JSC1002283R.

В этой статье мы коснемся нескольких краеугольных понятий в химии, без которых совершенно невозможно

решение задач. Старайтесь понять смысл физических величин, чтобы усвоить эту тему.

Я постараюсь приводить как можно больше примеров по ходу этой статьи, в ходе изучения вы увидите множество примеров

по данной теме.

Относительная атомная масса — Ar

Представляет собой массу атома, выраженную в атомных единицах массы. Относительные атомные массы указаны в периодической

таблице Д.И. Менделеева. Так, один атом водорода имеет атомную массу = 1, кислород = 16, кальций = 40.

Относительная молекулярная масса — Mr

Относительная молекулярная масса складывается из суммы относительных атомных масс всех атомов, входящих в состав вещества.

В качестве примера найдем относительные молекулярные массы кислорода, воды, перманганата калия и медного купороса:

Mr (O2) = (2 × Ar(O)) = 2 × 16 = 32

Mr (H2O) = (2 × Ar(H)) + Ar(O) = (2 × 1) + 16 = 18

Mr (KMnO4) = Ar(K) + Ar(Mn) + (4 × Ar(O)) = 39 + 55 + (4 * 16) = 158

Mr (CuSO4*5H2O) = Ar(Cu) + Ar(S) + (4 × Ar(O)) + (5 × ((Ar(H) × 2) +

Ar(O))) = 64 + 32 + (4 × 16) + (5 × ((1 × 2) + 16)) = 160 + 5 * 18 = 250

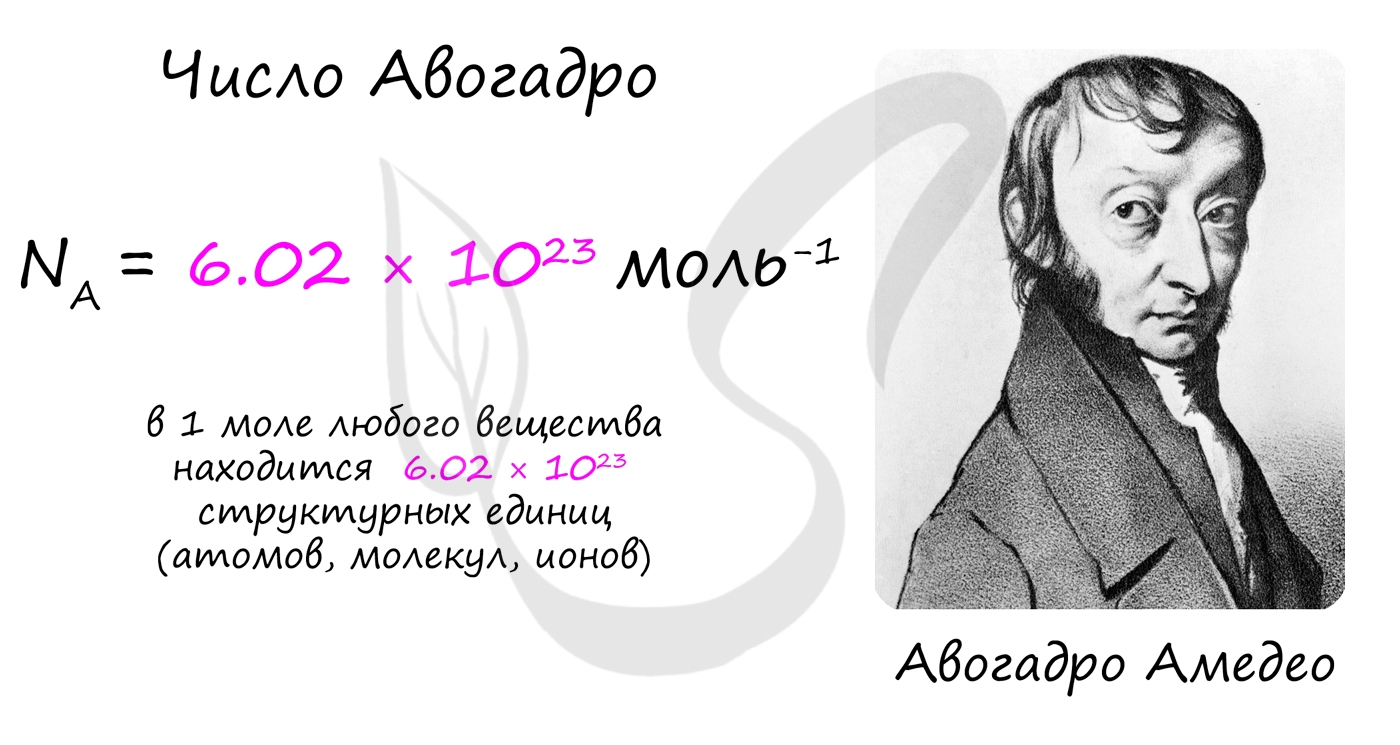

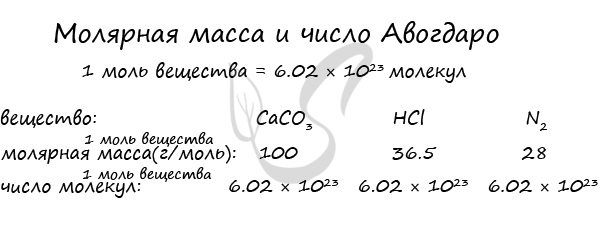

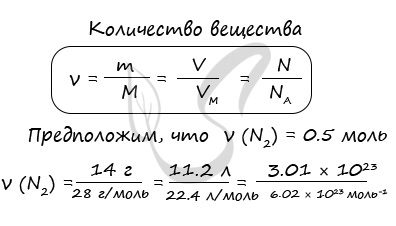

Моль и число Авогадро

Моль — единица количества вещества (в системе единиц СИ), определяемая как количество вещества, содержащее столько же структурных единиц

этого вещества (молекул, атомов, ионов) сколько содержится в 12 г изотопа 12C, т.е. 6 × 1023.

Число Авогадро (постоянная Авогадро, NA) — число частиц (молекул, атомов, ионов) содержащихся в одном моле любого вещества.

Больше всего мне хотелось бы, чтобы вы поняли физический смысл изученных понятий. Моль — международная единица количества вещества, которая

показывает, сколько атомов, молекул или ионов содержится в определенной массе или конкретном объеме вещества. Один моль любого вещества

содержит 6.02 × 1023 атомов/молекул/ионов — вот самое важное, что сейчас нужно понять.

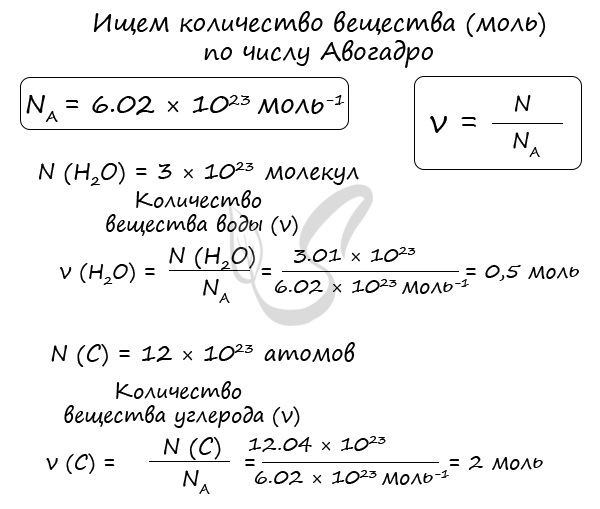

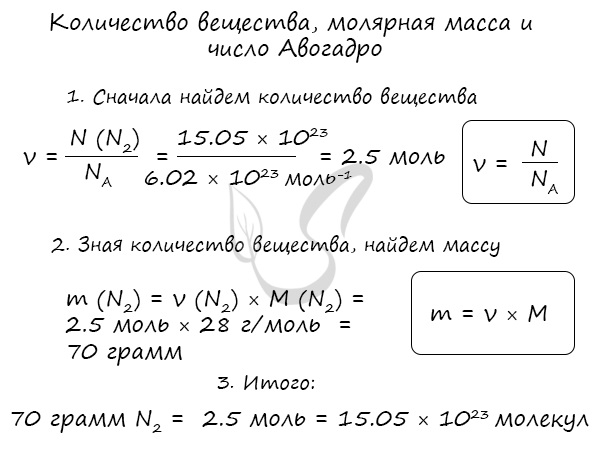

Иногда в задачах бывает дано число Авогадро, и от вас требуется найти, какое вам дали количество вещества (моль). Количество вещества в химии

обозначается N, ν (по греч. читается «ню»).

Рассчитаем по формуле: ν = N/NA количество вещества 3.01 × 1023 молекул воды и 12.04 × 1023 атомов углерода.

Мы нашли количества вещества (моль) воды и углерода. Сейчас это может показаться очень абстрактным, но, иногда не зная, как найти

количество вещества, используя число Авогадро, решение задачи по химии становится невозможным.

Молярная масса — M

Молярная масса — масса одного моля вещества, выражается в «г/моль» (грамм/моль). Численно совпадает с изученной нами ранее

относительной молекулярной массой.

Рассчитаем молярные массы CaCO3, HCl и N2

M (CaCO3) = Ar(Ca) + Ar(C) + (3 × Ar(O)) = 40 + 12 + (3 × 16) = 100 г/моль

M (HCl) = Ar(H) + Ar(Cl) = 1 + 35.5 = 36.5 г/моль

M (N2) = Ar(N) × 2 = 14 × 2 = 28 г/моль

Полученные знания не должны быть отрывочны, из них следует создать цельную систему. Обратите внимание: только что мы рассчитали

молярные массы — массы одного моля вещества. Вспомните про число Авогадро.

Получается, что, несмотря на одинаковое число молекул в 1 моле (1 моль любого вещества содержит 6.02 × 1023 молекул),

молекулярные массы отличаются. Так, 6.02 × 1023 молекул N2 весят 28 грамм, а такое же количество молекул

HCl — 36.5 грамм.

Это связано с тем, что, хоть количество молекул одинаково — 6.02 × 1023, в их состав входят разные атомы, поэтому и

массы получаются разные.

Часто в задачах бывает дана масса, а от вас требуется рассчитать количество вещества, чтобы перейти к другому веществу в реакции.

Сейчас мы определим количество вещества (моль) 70 грамм N2, 50 грамм CaCO3, 109.5 грамм HCl. Их молярные

массы были найдены нам уже чуть раньше, что ускорит ход решения.

ν (CaCO3) = m(CaCO3) : M(CaCO3) = 50 г. : 100 г/моль = 0.5 моль

ν (HCl) = m(HCl) : M(HCl) = 109.5 г. : 36.5 г/моль = 3 моль

Иногда в задачах может быть дано число молекул, а вам требуется рассчитать массу, которую они занимают. Здесь нужно использовать

количество вещества (моль) как посредника, который поможет решить поставленную задачу.

Предположим нам дали 15.05 × 1023 молекул азота, 3.01 × 1023 молекул CaCO3 и 18.06 × 1023 молекул

HCl. Требуется найти массу, которую составляет указанное число молекул. Мы несколько изменим известную формулу, которая поможет нам связать

моль и число Авогадро.

Теперь вы всесторонне посвящены в тему. Надеюсь, что вы поняли, как связаны молярная масса, число Авогадро и количество вещества.

Практика — лучший учитель. Найдите самостоятельно подобные значения для оставшихся CaCO3 и HCl.

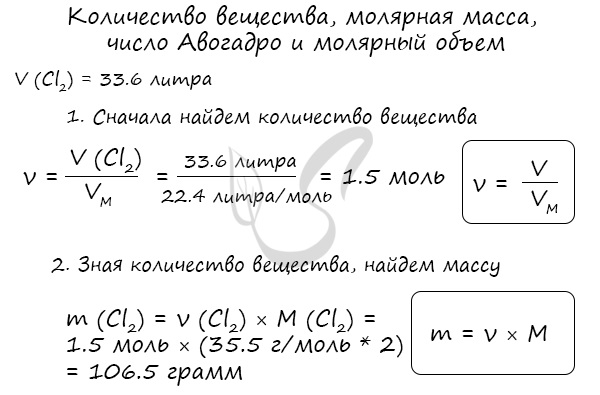

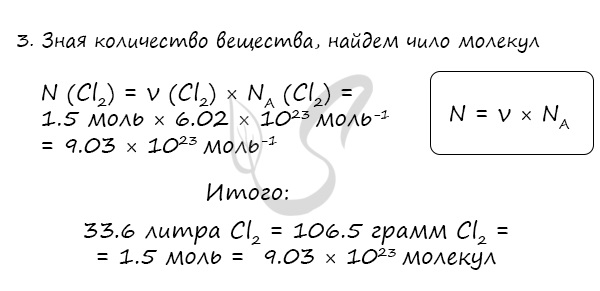

Молярный объем

Молярный объем — объем, занимаемый одним молем вещества. Примерно одинаков для всех газов при стандартной температуре

и давлении составляет 22.4 л/моль. Он обозначается как — VM.

Подключим к нашей системе еще одно понятие. Предлагаю найти количество вещества, количество молекул и массу газа объемом

33.6 литра. Поскольку показательно молярного объема при н.у. — константа (22.4 л/моль), то совершенно неважно, какой газ мы

возьмем: хлор, азот или сероводород.

Запомните, что 1 моль любого газа занимает объем 22.4 литра. Итак, приступим к решению задачи. Поскольку какой-то газ

все же надо выбрать, выберем хлор — Cl2.

Моль (количество вещества) — самое гибкое из всех понятий в химии. Количество вещества позволяет вам перейти и к

числу Авогадро, и к массе, и к объему. Если вы усвоили это, то главная задача данной статьи — выполнена

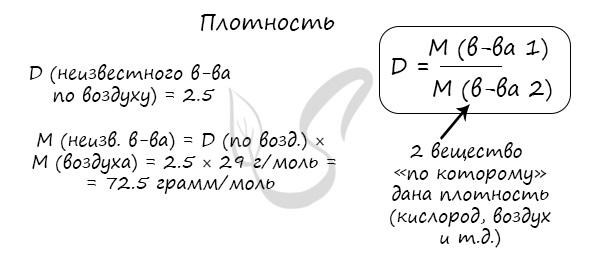

Относительная плотность и газы — D

Относительной плотностью газа называют отношение молярных масс (плотностей) двух газов. Она показывает, во сколько раз одно вещество

легче/тяжелее другого. D = M (1 вещества) / M (2 вещества).

В задачах бывает дано неизвестное вещество, однако известна его плотность по водороду, азоту, кислороду или

воздуху. Для того чтобы найти молярную массу вещества, следует умножить значение плотности на молярную массу

газа, по которому дана плотность.

Запомните, что молярная масса воздуха = 29 г/моль. Лучше объяснить, что такое плотность и с чем ее едят на примере.

Нам нужно найти молярную массу неизвестного вещества, плотность которого по воздуху 2.5

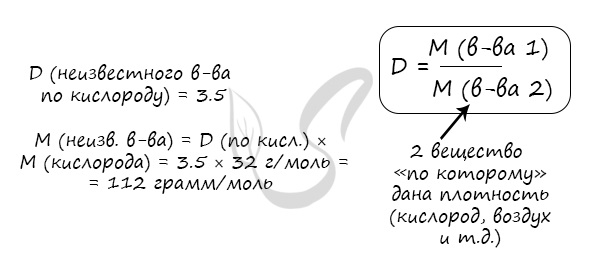

Предлагаю самостоятельно решить следующую задачку (ниже вы найдете решение): «Плотность неизвестного вещества по

кислороду 3.5, найдите молярную массу неизвестного вещества»

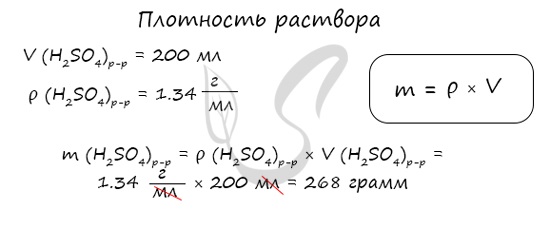

Относительная плотность и водный раствор — ρ

Пишу об этом из-за исключительной важности в решении

сложных задач, высокого уровня, где особенно часто упоминается плотность. Обозначается греческой буквой ρ.

Плотность является отражением зависимости массы от вещества, равна отношению массы вещества к единице его объема. Единицы

измерения плотности: г/мл, г/см3, кг/м3 и т.д.

Для примера решим задачку. Объем серной кислоты составляет 200 мл, плотность 1.34 г/мл. Найдите массу раствора. Чтобы не

запутаться в единицах измерения поступайте с ними как с самыми обычными числами: сокращайте при делении и умножении — так

вы точно не запутаетесь.

Иногда перед вами может стоять обратная задача, когда известна масса раствора, плотность и вы должны найти объем. Опять-таки,

если вы будете следовать моему правилу и относится к обозначенным условным единицам «как к числам», то не запутаетесь.

В ходе ваших действий «грамм» и «грамм» должны сократиться, а значит, в таком случае мы будем делить массу на плотность. В противном случае

вы бы получили граммы в квадрате

К примеру, даны масса раствора HCl — 150 грамм и плотность 1.76 г/мл. Нужно найти объем раствора.

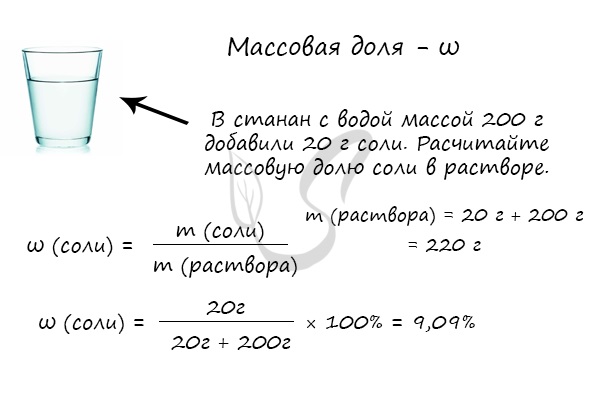

Массовая доля — ω

Массовой долей называют отношение массы растворенного вещества к массе раствора. Важно заметить, что в понятие раствора входит

как растворитель, так и само растворенное вещество.

Массовая доля вычисляется по формуле ω (вещества) = m (вещества) / m (раствора). Полученное число будет показывать массовую долю

в долях от единицы, если хотите получить в процентах — его нужно умножить на 100%. Продемонстрирую это на примере.

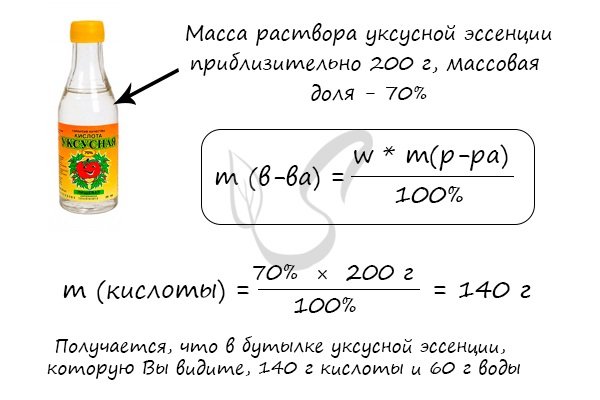

Решим несколько иную задачу и найдем массу чистой уксусной кислоты в широко известной уксусной эссенции.

© Беллевич Юрий Сергеевич 2018-2022

Данная статья написана Беллевичем Юрием Сергеевичем и является его интеллектуальной собственностью. Копирование, распространение

(в том числе путем копирования на другие сайты и ресурсы в Интернете) или любое иное использование информации и объектов

без предварительного согласия правообладателя преследуется по закону. Для получения материалов статьи и разрешения их использования,

обратитесь, пожалуйста, к Беллевичу Юрию.

Химические формулы

| № | Количественные характеристики вещества | Обозначение | Единицы измерения | Формула для расчета |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Плотность вещества | ρ | кг/м³ | ρ = m / V(Массу делим на объем вещества) |

| 2 | Относительная атомная масса элемента | Аr | — | Ar = ma / u см. в периодической система химических элементов |

| 3 | Атомная единица массы | u а.е.м. |

кг | u = 1/12 * ma (12C) const = 1.66*10-27 |

| 4 | Масса атома (абсолютная) | ma | кг | ma = Ar * u |

| 5 | Относительная молекулярная (формульная) масса вещества | Mr | — | Mr (AxBy)=m(AB) / u Mr(AxBy)=x*Ar(A) + y*Ar(B) |

| 6 | Масса молекулы (формульной единицы) | m M | кг | mM = Mr*u |

| 7 | Количество вещества | n | моль | n=m/M n=N/NA n=V/VM |

| 8 | Молярная масса (масса 1 моль вещества) | M | г/моль | M=m/n M=Mr M=Ar (для простых веществ) |

| 9 | Масса вещества | m | г (кг) | m=M*n m=ρ*V |

| 10 | Число структурных единиц | N | атомов, молекул, ионов, частиц, формульных единиц (Ф.Е.) | N=NA*n |

| 11 | Молярный объем — число 1 моль ГАЗООБРАЗНОГО вещества в нормальных условиях (н.у.) | VM | л/моль | const=22,4 |

| 12 | Объем газа при н.у. | V | л | V=VM*n V=m/ρ |

| 13 | Постоянная Авогадро | NA | частиц/моль | const=6,02*1023 |

| 14 | Массовая доля вещества (омега) | ωЭ/В | % | ωЭ/В = (Ar(э) * k) / Mr(В) |

Формулы и названия кислот. Формулы и названия кислотных остатков.

| Формула | Название кислоты | Формула кислотного остатка | Название кислотного остатка |

|---|---|---|---|

| HF | Фтороводород, плавиковая | F— | Фторид |

| HCl | Хлороводород, соляная | Cl— | Хлорид |

| HBr | Бромоводород | Br— | Бромид |

| HI | Йодоводород | I— | Йодид |

| H2S | Сероводород | S2- | Сульфид |

| HCN | Циановодородная | CN— | Цианид |

| HNO2 | Азотистая | NO2— | Нитрит |

| HNO3 | Азотная | NO3— | Нитрат |

| H3PO4 | Ортофосфорная | PO43- | Фосфат |

| H3AsO4 | Мышьяковая | AsO43- | Арсенат |

| H2SO3 | Сернистая | SO32- | Сульфит |

| H2SO4 | Серная | SO42- | Сульфат |

| H2CO3 | Угольная | CO32- | Карбонат |

| H2SiO3 | Кремниевая | SiO32- | Силикат |

| H2CrO4 | Хромовая | CrO42- | Хромат |

| H2Cr2O7 | Дихромовая | Cr2O72- | Дихромат |

| HMnO4 | Марганцовая | MnO4— | Перманганат |

| HClO | Хлорноватистая | ClO— | Гипохлорит |

| HClO2 | Хлористая | ClO2— | Хлорит |

| HClO3 | Хлорноватая | ClO3— | Хлорат |

| HClO4 | Хлорная | ClO4— | Перхлорат |

| HCOOH | Метановая, муравьиная | HCOO— | Формиат |

| CH3COOH | Этановая, уксусная | CH3COO— | Ацетат |

| H3C2O4 | Этандиовая, щавелевая | C2O42- | Оксалат |

Периодическая система Менделеева

Нажмите на картинку для увеличения

Из учебного курса химии и физики вспоминаются решения задач с использованием разных показателей.

Окружающие тела состоят из веществ, масса каждого зависит от размера, объема и других критериев.

Плотность вещества показывает численное выражение массы тела в определенном объеме.

Существуют разные виды скалярной физической величины.

Содержание

- Общая характеристика

- Основные понятия

- Влияние факторов

- Практическое применение

- Значение показателя

- Способы расчета и примеры

Общая характеристика

Каждый элемент занимает индивидуальную величину. Определение плотности может обозначаться греческой буквой ρ, D или d. Если объемы двух тел одинаковы, а массы различны, тогда плотности не идентичны.

Основные понятия

Определения и характеристики показателя известны с 7 класса школьной программы химии. Плотность представляет собой физическую величину о свойствах вещества. Это удельный вес любого элемента. Существует средняя и относительная плотность. Последняя классификация — это отношение плотности (П) вещества к П эталонного вещества. Часто за эталон принимают дистиллированную воду. Единица измерения П- кг/м3 в интернациональной системе.

Формула нахождения плотности:

P = m/V

Обозначения:

- m — масса.

- V — объем.

Кроме стандартной формулы плотности, применяемой для твердых состояний веществ, имеется формула для газообразных элементов в нормальных условиях.

ρ (газа) = M/Vm M

Расшифровка:

- М — молярная масса газа [г/моль].

- Vm — объем газа (в норме 22,4 л/моль).

Для сыпучих и пористых тел различают истинную плотность, вычисляемую без учета пустот, и удельную плотность, рассчитываемую как отношение массы вещества ко всему объему. Истинную П получают через коэффициент пористости — доли объема пустот в занимаемом объеме. Для сыпучих тел удельная П называется насыпной.

Низкие показатели П имеет среда между Галактиками (1033 кг/м3).

Способы измерения:

- Пикнометр. Измеряет истинную П.

- Ареометр, денсиметр, плотномер. Используется для жидкого состояния.

- Бурик. Измеряет П почвы.

Вещества состоят из молекулярных структур, масса тела формируется из скопления молекул. Аналогично вес пакета с карамелью складывается из масс всех конфет в мешке. Если все сладости одинаковые, то массу упаковки определяют умножением веса одной конфеты на количество штук.

Молекулярные частицы чистого вещества одинаковы, поэтому вес капли воды равен произведению массы 1 молекулы Н2О на число составляющих молекул в капле. Плотность вещества показывает, чему равна масса одного кубического метра.

Плотность воды — 1000 кг/м³, а масса 1 м³ Н2О равна 1000 килограмм. Это число можно вычислить, умножив массу 1 молекулы воды на количество молекулярных частиц, содержащихся в 1 м3 объема.

П льда составляет 900 кг/м³, это значит, что вес кубического метра льда равна 900 кг. Употребляют единицу измерения плотности г/см3.

При равнозначности физических масс двух тел их объемы различаются. Например, объём льда в девять раз больше объема бруска из металлического сплава. Масса тела распределяется неодинаково, устанавливает П в каждой точке тела.

Влияние факторов

П зависит от давления и температуры. При высоком давлении молекулы плотно прилегают друг к другу, поэтому вещество обладает значительной плотностью.

Зависимость показателей учитывается при расчете П. При повышении температуры П снижается из-за термического расширения, при котором объем вырастает, а масса остается прежней. Если температура снижается, П увеличивается, хотя имеются вещества, П которых при некоторых условиях температурного режима ведет себя иначе. Это вода, бронза, чугун. При фазовом переходе, модифицировании агрегатного состояния П меняется скачками. Условия вычисления зависят от свойств веществ, молекулярных элементов. Для разных природных объектов П изменяется в широком диапазоне.

П воды ниже П льда из-за молекулярной структуры твердой формы жидкости. Вещество, переходя из жидкой в твердую форму, изменяет молекулярную структуру, расстояние между составными частицами сужается и плотность увеличивается. Зимой, если забыть слить воду из труб, их разрывает на части после замерзания. На П Н2О влияют примеси. У морской воды знак П выше, чем у пресной. При соединении в одном стакане двух типов жидкости пресная останется на поверхности. Чем выше концентрация соли, тем больше П воды.

Когда плотность вещества больше П воды, оно полностью погрузится в воду. Предметы, сделанные из материала по низкой П, будут плавать на поверхности воды. На практике эти свойства используются человеком. Сооружая суда, инженеры-проектировщики применяют материалы с высокой П. Корабли, теплоходы, яхты смогут затонуть во время плавания, в корпусах суден создают специальные полости, наполненные воздухом, ведь его П ниже плотности воды.

Чтобы наживка для рыбалки погрузилась в воду, ее обременяют тяжелым по плотности материалом, например, грузиком из металла (чаще свинца). Плотность сплава выше, чем у Н2О.

Жирные пятна масла, нефти, бензина остаются на поверхности воды из-за низкой П маслянистых веществ.

Практическое применение

Из учебников химии и физики вычисляют уровень плотности по формуле. Но также это можно сделать, используя онлайн-систему.

Значение показателя

Окружающий мир состоит из разных веществ.

Скамейка в парке или баня за городом сооружены из древесины, подошва утюга, сковорода выполнены из металла, покрышка колеса, велосипеда — из резины. Каждый предмет имеет свой вес.

Черные дыры Вселенной составляют наибольшую плотность 1014 кг/м3. Самый низкий показатель имеет область между Галактиками (2•10−31—5•10−31 кг/м³).

Таблица плотности веществ

| Вещество | Плотность (кг/м3) |

| Сухой воздух | 1,293 |

| Металлы | |

| Осмий | 22,61 |

| Родий | 12,41 |

| Иридий | 22,56 |

| Плутоний | 19,84 |

| Палладий | 12,02 |

| Свинец | 11,35 |

| Платина | 19,59 |

| Золото | 19,30 |

| Сталь | 7,8 |

| Алюминий | 2,7 |

| Медь | 8,94 |

| Газы | |

| Азот | 1,25 |

| Аммиак | 0,771 |

| Аргон | 1,784 |

| Жидкий водород | 70 |

| Гелий в жидком состоянии | 130 |

| Водород | 0,09 |

| Водяной пар | 0,598 |

| Воздух | 1,293 |

| Хлор | 3,214 |

| О2 | 1,429 |

| Углекислый газ | 1,977 |

| Остальные вещества | |

| Тело человека | На вдохе 940-990, при выдохе — 1010-1070 |

| Пресная вода | 1000 |

| Солнце | 1410 |

| Гранит | 2600 |

| Земля | 5520 |

| Железо | 7874 |

| Бензин | 710 |

| Керосин | 820 |

| Молоко | 1040 |

| Этанол | 789 |

| Ацетон | 792 |

| Морская вода | 1030 |

| Древесина | |

| Пихта | 0,39 |

| Ива | 0,46 |

| Ель | 0,45 |

| Сосна | 0,52 |

| Дуб | 0,69 |

П металлов изменяется от минимального значения у лития, который легче Н2О, до максимального значения у осмия, который тяжелее драгоценных металлов.

Способы расчета и примеры

В сети Интернет существует множество приложений для онлайн-расчета плотности веществ или материалов. В стандартные поля калькулятора вводится основная информация: масса, объем, единицы измерения. Плотность вычисляется автоматически по заданным параметрам и выводится на экран интерфейса. Можно перевести информативные данные в нужную единицу измерения.

Без использования учебной информации показатель П можно определить через физические опыты. Для лабораторных изучений нужны весы, сантиметр, если исследуемое тело находится в твердом состоянии. Для жидкости необходима колба.

Сначала измеряют объем тела, записывая результат по цифровой шкале (в сантиметрах или миллилитрах).

Вычисляя объем деревянного бруска квадратной формы, параметр стороны возводится в третью степень. Измеряя объемные характеристики, тело ставят на весы и записывают значение массы. Рассчитывая жидкое состояние, учитывают массу сосуда, куда помещено исследуемое. В формулу подставляют данные и рассчитывают показатель.

Поскольку П измеряется в кг/л или в г/см³, то иногда приходится пересчитывать одни величины в другие.

В одном грамме содержится 0,001 кг, а один кубический сантиметр (см³) — это 0,000001 м³. В 1 г/(см)3 содержится 1000кг/м3.

Пример 1:

Необходимо найти плотность молока, если 350 г занимают 100 см3. Для решения используют формулу, где масса делится на объем.

Решение: P=m/V = 350/100= 3,5 г/см3.

Пример 2:

Необходимо определить П мела, если масса большого куска объемом 20 см3 составляет 48 грамм. П выразить в кг/м3 и вг/см3.

Решение:

Нужно перевести см3 в кубические метры, а граммы — в килограммы.

V = 20см3= 0,00002 м3.

M= 48 г = 0,048 кг.

Плотность мела составляет 0,048 кг/0,00002 м3 = 2400 кг/м3.

Выражаем в г/см3: 2400 кг/м3 = 2400*1000/1000000 см3 = 2,4 г/см3.

Один килограмм равен 1000 грамм, один кубический метр (1м3) содержит 1000000 см 3. Плотность получится 2,4 г/см3или 2400 кг/м3.

Показатель имеет большое значение в разных сферах жизни и деятельности. Он определяется по таблице или высчитывается расчетным путем.

Предыдущая

ФизикаПотенциал электрического поля — формулы определения, характеристика и единицы измерения

Следующая

ФизикаУравнение Бернулли — вывод формулы, физический смысл, примеры использования

Относительная плотность по… задачи

24-Фев-2013 | комментариев 26 | Лолита Окольнова

В ЕГЭ иногда встречаются задачи (часть С последнее задание), где в условии дана относительная плотность вещества по… водороду, кислороду, воздуху, азоту и т.д.

Например:

Относительная плотность вещества – отношение плотности вещества Б к плотности вещества А

Относительная плотность — величина безразмерная

Формула достаточно простая, и из нее вытекает другая формула —

Формула молярной массы вещества

Mr1 = D•Mr2

- Если дана относительная плотность паров по водороду, то Mr (вещества)=Mr(H2)•D=2 гмоль • D;

- если дана относительная плотность по воздуху, то Mr (вещества)=Mr(воздуха)•D=29 гмоль • D (обратите внимание, Mr(воздуха) принята равной 29 гмоль);

и т.д.

В условии задачи может быть полная формулировка — «относительная плотность (паров)…», а может быть просто «плотность вещества по…»

Давайте решим нашу задачу:

Дана плотность паров вещества по воздуху, значит, нам подходит формула молярной массы вещества —

Mr (вещества)=Mr(воздуха)•D=29 гмоль • D

Mr(вещества)=29 гмоль • 1.448 = 42 гмоль

Нам дан углеводород — СхHy, значит, мы можем найти Mr(Cx и Mr(Hy). Обратите внимание, именно молярные массы, т.к.у нас несколько атомов углерода и водорода.

Для этого надо молярную массу вещества умножить на процентное содержание элемента:

Mr(Cx)=Mr(вещества)•ω

Mr(Cx)= 42 гмоль · 0.8571=36 гмоль

x=Mr(Cx)Ar(C)=36 гмоль ÷ 12 гмоль =3.

Точно так же находим все данные для водорода:

Mr(Hy)=Mr(вещества)•ω

Mr(Hy)= 42 гмоль · 0.1429=6 гмоль

x=Mr(Hy)Ar(H)=6 гмоль ÷ 1 гмоль =6.

Искомое вещество — C3H6 — пропен.

Еще раз повторим определение —

Относительная плотность газа – это сравнение молярной или относительной молекулярной массы одного газа с аналогичным показателем другого газа.

Дана относительная плотность по аргону.

Mr (вещества)=Ar(Ar)•D

Mr (CxHy)=40 гмоль ·1.05=42 гмоль

Запишем уравнение горения:

СхHy + O2 = xCO2 + y2H2O

Найдем количество углекислого газа и воды:

n(CO2)=V22,4 лмоль = 33.622.4=1.5

n(H2O)=mMr=2718=1.5

Соотношение х : y2 как 1.5 : 1.5, т.е. y=2x, что соответствует общей формуле алкенов: CnH2n

Выражаем в общем виде молярную массу: Mr=Mr(C) + Mr(H)

12n +2n=42

n=3

Наше вещество — C3H6 — пропен

- pадание ЕГЭ по этой теме — задачи С5

Обсуждение: «Относительная плотность по… задачи»

(Правила комментирования)