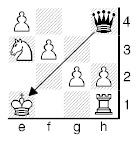

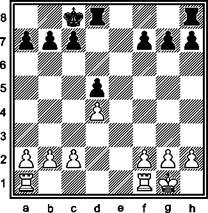

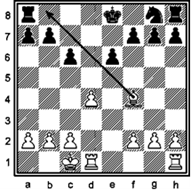

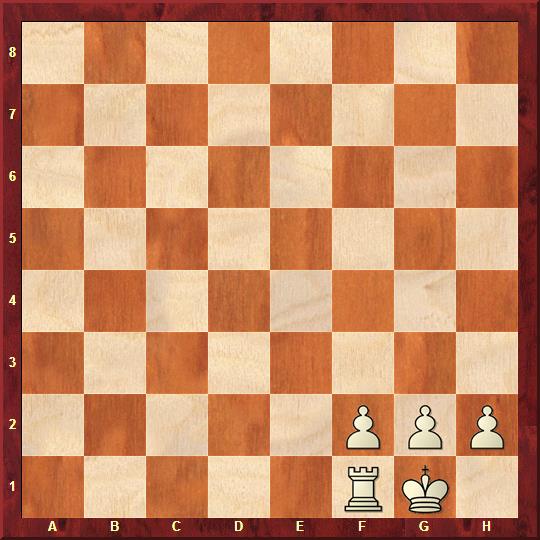

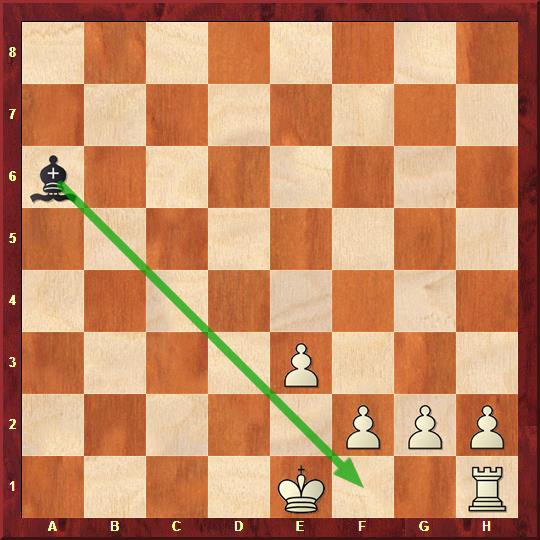

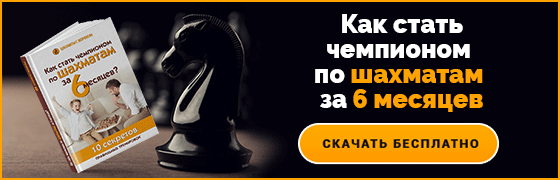

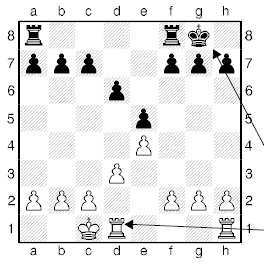

Initial positions of kings and rooks. Kings may castle to the indicated squares. |

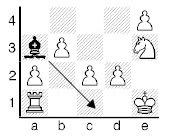

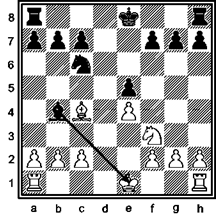

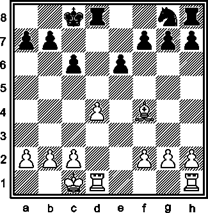

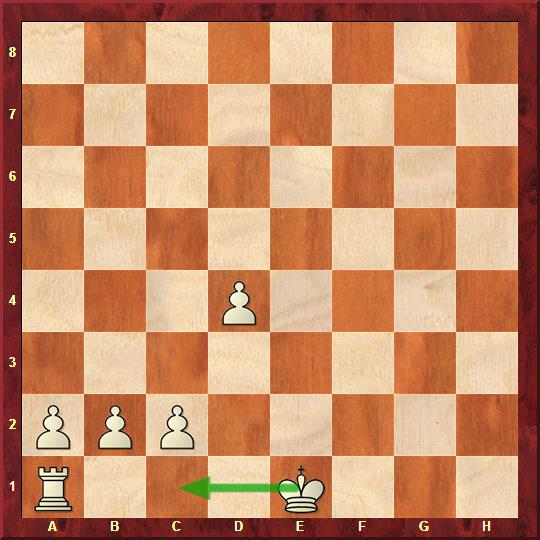

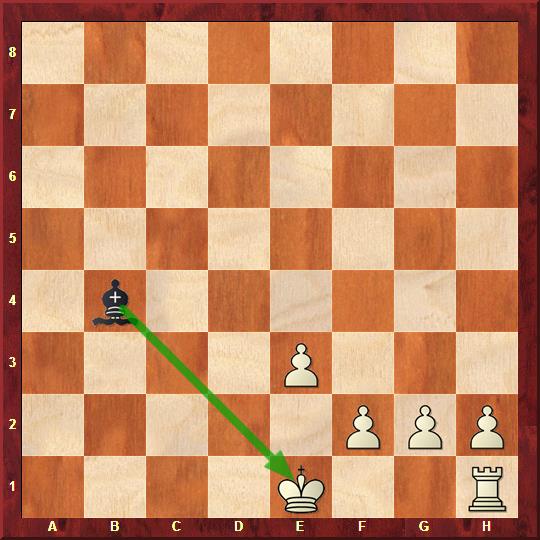

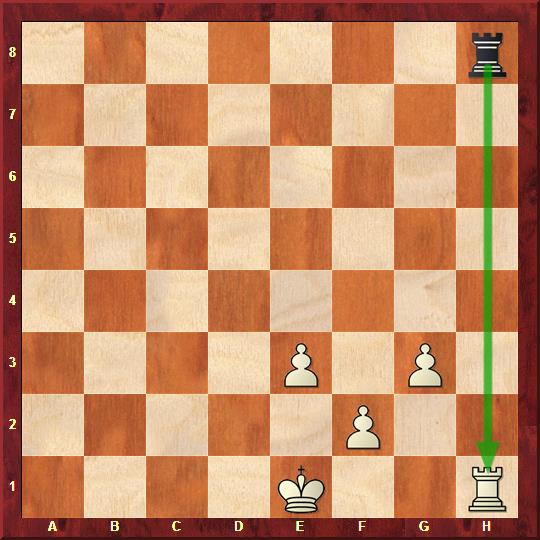

White has castled kingside; Black has castled queenside. |

Castling is a move in chess. It consists of moving one’s king two squares toward a rook on the same rank and then moving the rook to the square that the king passed over.[2] Castling is permitted only if neither the king nor the rook has previously moved; the squares between the king and the rook are vacant; and the king does not leave, cross over, or end up on a square attacked by an opposing piece. Castling is the only move in chess in which two pieces are moved at once.[3]

Castling with the king’s rook is called castling kingside, and castling with the queen’s rook is called castling queenside. In both algebraic and descriptive notation, castling kingside is written as 0-0 and castling queenside as 0-0-0.

Castling originates from the king’s leap, a two-square king move added to European chess between the 14th and 15th centuries, and took on its present form in the 17th century; however, local variations in castling rules were common, persisting in Italy until the late 19th century. Castling does not exist in Asian games of the chess family, such as shogi, xiangqi, and janggi, but it commonly appears in variants of Western chess.

Rules[edit]

Description[edit]

During castling, the king is shifted two squares toward a rook of the same color on the same rank, and the rook is transferred to the square crossed by the king. There are two forms of castling:[4]

- Castling kingside (also called short castling) consists of moving the king to g1 and the rook to f1 for White, or moving the king to g8 and the rook to f8 for Black.

- Castling queenside (also called long castling) consists of moving the king to c1 and the rook to d1 for White, or moving the king to c8 and the rook to d8 for Black.

Requirements[edit]

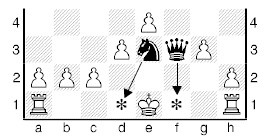

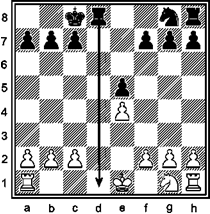

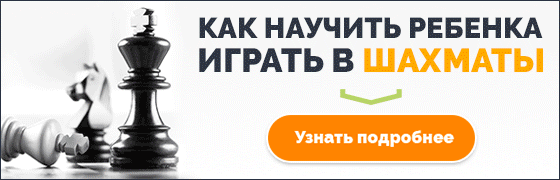

White cannot castle queenside because the knight is in the way. White can castle kingside. |

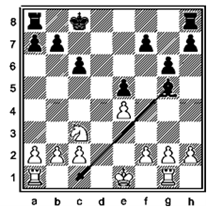

Black cannot castle on either side because he is in check by the white queen. |

White cannot castle queenside because Black’s queen controls c1. White can castle kingside even though the h1-rook is under attack. |

Black cannot castle kingside, as the white queen attacks f8. Black can castle queenside despite the white queen’s attack on b8. |

Castling is permitted provided all of the following conditions are met:[5]

- Neither the king nor the rook has previously moved.

- There are no pieces between the king and the rook.

- The king is not currently in check.

- The king does not pass through or finish on a square that is attacked by an enemy piece.

Conditions 3 and 4 can be summarized by the mnemonic: A player may not castle out of, through, or into check.

Castling rules often cause confusion, even occasionally among high-level players.[6] To clarify:

- The rook can be under attack.

- The rook can pass through an attacked square. (White can castle queenside even if Black is attacking b1; Black can castle queenside even if White is attacking b8.)

- The king can have been in check earlier in the game.

Tournament rules[edit]

Under the rules used by FIDE and enforced in most tournaments, castling is considered a king move, so the king must be touched first; if the rook is touched first, a rook move must be made instead. As usual, the player may choose another legal destination square for the king until releasing it. When the two-square king move is completed, however, the player is committed to castling if it is legal, and the rook must be moved accordingly. The entire move must be completed with one hand. A player who illegally attempts to castle must return the king and the rook to their original places and then make a legal king move if possible (which may include castling on the other side). If there is no legal king move, the touch-move rule does not apply to the rook.[7]

Under US Chess Federation rules, a player who intends to castle and touches the rook first would suffer no penalty and would be permitted to castle, provided castling is legal in the position. These tournament rules are not commonly enforced in informal play or commonly known by casual players.[8][9]

Castling rights[edit]

An unmoved king has castling rights with an unmoved rook of the same color on the same rank. In the context of threefold and fivefold repetition, two positions with different castling rights are considered to be different positions.

Example[edit]

Karpov vs. Miles, 1986

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

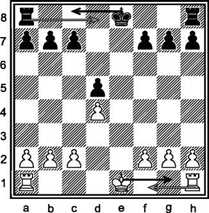

Position after 22.Nb5

In a 1986 game between Anatoly Karpov and Tony Miles,[10] play continued from the diagrammed position as follows:

- 22… Ra4 23. Nc3 Ra8 24. Nb5 Ra4 25. Nc3 Ra8 26. Nb5

With his 26th move, Karpov attempted to claim a draw by threefold repetition, thinking that the positions after his 22nd, 24th, and 26th moves were the same. However, it was pointed out to him that the position after his 22nd move had different castling rights than the positions after his 24th and 26th moves, rendering his claim illegal. As a result, Karpov was penalized three minutes on his clock. The game ended in a draw.

Notation[edit]

Both algebraic notation and descriptive notation indicate kingside castling as 0-0 and queenside castling as 0-0-0 (with the digit zero). Portable Game Notation and some publications instead use O-O for kingside castling and O-O-O for queenside castling (with the letter O). ICCF numeric notation indicates castling based on the starting and ending squares of the king; thus, castling kingside is written as 5171 for White and 5878 for Black, and castling queenside is written as 5131 for White and 5838 for Black.

History[edit]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Castling under medieval rules. Symbol color corresponds to king color. Circles represent English, Spanish, French, and Lombardy movement; crosses represent Lombardy movement only.

Castling has its roots in the king’s leap. There were two forms of the leap: the king would move once like a knight, or the king would move two squares on its first move. The knight move might be used early in the game to get the king to safety or later in the game to escape a threat. This second form was played in Europe as early as the 13th century. In North Africa, the king was transferred to a safe square by a two-move procedure: the king moved to the player’s second rank, and the rook and king moved to each other’s original squares.[11]

Various forms of castling were developed due to the spread of rule sets during the 15th and 16th centuries which increased the power of the queen and bishop, allowing these pieces to attack from a distance and from both sides of the board, thus increasing the importance of king safety.[12]

The rule of castling has varied by location and time. In medieval England, Spain, and France, the white king was allowed to jump to c1, c2, d3, e3, f3, or g1[13] if no capture was made and the king was not in check and did not move over check; the black king might move analogously. In Lombardy, the white king might also jump to a2, b1, or h1, with corresponding squares applying to the black king. Later, in Germany and Italy, the rule was changed such that the king move was accompanied by a pawn move.

In the Göttingen manuscript (c. 1500) and a game published by Luis Ramírez de Lucena in 1498, castling consisted of moving the rook and then moving the king on separate moves.

The current version of castling was established in France in 1620 and in England in 1640.[14]

In Rome, from the early 17th century until the late 19th century, the rook might be placed on any square up to and including the king’s square, and the king might be moved to any square on the other side of the rook. This was called free castling.

In the 1811 edition of his chess treatise, Johann Allgaier introduced the 0-0 notation. He differentiated between 0-0r (right) and 0-0l (left). The 0-0-0 notation for queenside castling was introduced in 1837 by Aaron Alexandre.[15] The practice was adopted in the first edition (1843) of the influential Handbuch des Schachspiels and soon became standard. In English descriptive notation, the word «Castles» was originally spelled out, adding «K’s R» or «Q’s R» if disambiguation was necessary; eventually, the 0-0 and 0-0-0 notation was borrowed from the algebraic system.

Strategic and tactical concepts[edit]

Strategy[edit]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Position after 10.0-0-0: Opposite castling in the Yugoslav Attack

Castling is generally an important goal in the opening: it moves the king to safety away from the center of the board, and it moves the rook to a more active position in the center of the board.

The choice regarding to which side one castles often hinges on an assessment of the trade-off between king safety and activity of the rook. Kingside castling is generally slightly safer because the king ends up closer to the edge of the board and can usually defend all of the pawns on the castled side. In queenside castling, the king is placed closer to the center and does not defend the pawn on the a-file; for these reasons, the king is often subsequently moved to the b-file. In addition, queenside castling is initially obstructed by more pieces than kingside castling is; therefore, it takes longer to set up than kingside castling. On the other hand, queenside castling places the rook more efficiently on the central d-file, where it is often immediately active; meanwhile, with kingside castling, a tempo may be required to move the rook to a more effective square.

One may forgo castling for various reasons. In positions where one’s opponent cannot organize an attack on one’s centralized king, castling may be unnecessary or even detrimental. In addition, a rook can be more active near the edges of the board than in the center in certain situations, such as if it is able to fight for control of an open or semi-open file.

Kingside castling occurs more frequently than queenside castling. It is common for both players to castle kingside, somewhat uncommon for one player to castle kingside and the other queenside, and rare for both players to castle queenside. If one player castles kingside and the other queenside, it is called opposite (or opposite-side) castling. Castling on opposite sides usually results in a fierce fight, as each player’s pawns are free to advance to attack the opposing king’s castled position without exposing the player’s own castled king. Opposite castling is a common feature of many openings, such as the Yugoslav Attack.

Tactics involving castling[edit]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

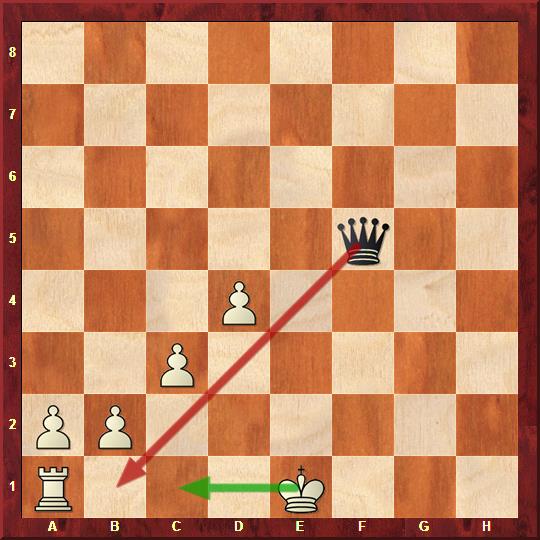

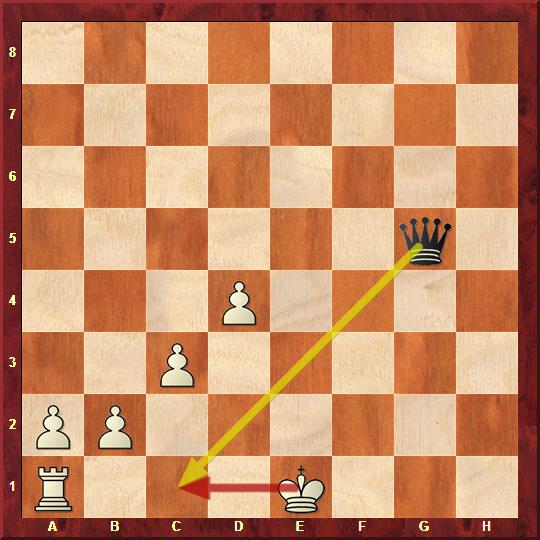

Black to play

Tactical patterns involving castling are rare. One pattern involves castling queenside to deliver a double attack: the king attacks a rook (on b2 for White or b7 for Black), while the rook attacks a second opposing piece (usually the king). In the example on the right, from the game Mattison–Millers, Königsberg 1926, Black played 13…Rxb2?? and resigned after 14.0-0-0+, which wins the rook.[16]

Chess historian Edward Winter has proposed the name «Thornton castling trap» for this pattern, in reference to the earliest known example, Thornton–Boultbee, published in the Brooklyn Chess Chronicle in 1884. Other chess writers such as Gary Lane have since adopted this term.[17]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

White to play

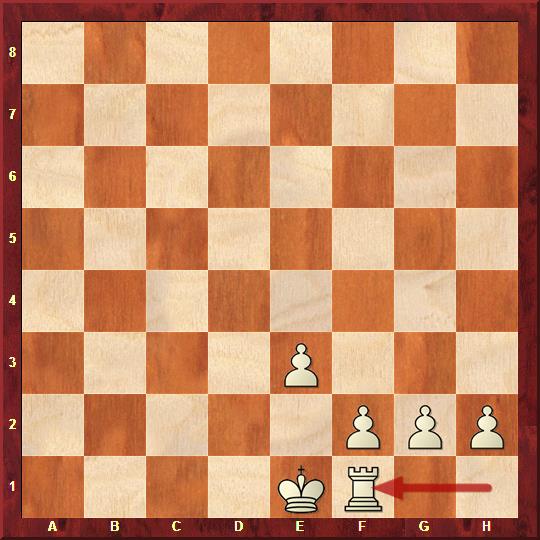

Another example of tactical castling is illustrated in the diagrammed position from the correspondence game Gurvich–Pampin, 1976. After 1.Qxd8+ Kxd8 2.0-0-0+ Ke7 3.Nxb5, White wins a rook by castling with check and simultaneously unpinning the knight.[18]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Black to play

Such a double attack can also be made by castling kingside, though this is much rarer. In this position from the blindfold game Karjakin–Carlsen, 2007, the move 19…0-0 indirectly threatens both to deliver back-rank mate and to win the h7-rook. Black will thus win the g5-knight next move; 20.Rh6 Bxg5 21.Rxg6+ Kh7 22.Rxg5 would not work, as it would be met by 22…Rf1#.[19]

Examples[edit]

- Viktor Korchnoi, in his 1974 Candidates final match with Anatoly Karpov, asked the arbiter if castling was legal when the castling rook was under attack.[20] The arbiter answered in the affirmative, Korchnoi executed the move, and Karpov resigned shortly after.[21]

- Castling occurred three times in the game Wolfgang Heidenfeld–Nick Kerins, Dublin 1973. The third instance of castling, the second one by White, was illegal, as the white king had already moved. The game is as follows:[22]

- 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Be3 Nf6 4.e5 Nfd7 5.f4 c5 6.c3 Nc6 7.Nf3 Qb6 8.Qd2 c4 9.Be2 Na5 10.0-0 f5 11.Ng5 Be7 12.g4 Bxg5 13.fxg5 Nf8 14.gxf5 exf5 15.Bf3 Be6 16.Qg2 0-0-0 17.Na3 Ng6 18.Qd2 f4 19.Bf2 Bh3 20.Rfb1 Bf5 21.Nc2 h6 22.gxh6 Rxh6 23.Nb4 Qe6 24.Qe2 Ne7 25.b3 Qg6+ 26.Kf1 Bxb1 27.bxc4 dxc4 28.Qb2 Bd3+ 29.Ke1 Be4 30.Qe2 Bxf3 31.Qxf3 Rxh2 32.d5 Qf5 33.0-0-0 Rh3 34.Qe2 Rxc3+ 35.Kb2 Rh3 36.d6 Nec6 37.Nxc6 Nxc6 38.e6 Qe5+ 39.Qxe5 Nxe5 40.d7+ Nxd7 0–1

Averbakh vs. Purdy[edit]

Averbakh vs. Purdy, 1960

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Black to move castled queenside, with the rook going over the attacked b8-square.

In the game Yuri Averbakh–Cecil Purdy (1960),[23] when Purdy castled queenside, Averbakh queried the move, pointing out that the rook had passed over an attacked square. Purdy indicated e8 and c8 and said, «The king», in an attempt to explain that this was forbidden only for the king. Averbakh replied, «Only the king? Not the rook?». Averbakh’s colleague Vladimir Bagirov then explained the castling rules to him in Russian, and the game continued.[24][25][26]

Edward Lasker vs. Thomas[edit]

Ed. Lasker vs. Thomas, 1912

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Position after 17…Kg1

In the game Edward Lasker–Sir George Thomas (London 1912),[27] White could have checkmated with 18.0-0-0#, but he instead played 18.Kd2#.[28] (See Edward Lasker’s notable games.)

Prins vs. Day[edit]

Prins vs. Day, 1968

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

White to play

The diagram shows the final position of the game Lodewijk Prins–Lawrence Day (1968), where White resigned.[29] Had the game continued, Black could have checkmated by castling:

- 29. Kf6 Qf5+ 30. Kg7 Qg6+ 31. Kh8 0-0-0#

(See Lawrence Day’s notable chess games.)

Feuer vs. O’Kelly[edit]

Feuer vs. O’Kelly, 1934

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Feuer–O’Kelly, 1934 Belgian championship. The game ended 10….Rxb2 11.dxe5 dxe5?? 12.Qxd8+ Kxd8 13.0-0-0+ and O’Kelly resigned since the rook is lost.

In the 1934 Belgian Championship,[30] Otto Feuer caught Albéric O’Kelly in the Thornton castling trap. In the position in the diagram, the game continued 10…Rxb2 11.dxe5 dxe5?? 12.Qxd8+ Kxd8 13.0-0-0+, and O’Kelly resigned. Feuer’s last move simultaneously gave check and attacked the rook on b2.

Fischer vs. Najdorf[edit]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

White to play

The diagram illustrates the consequences of losing castling rights. Fischer, with the white pieces, played 16.Ng7+ Ke7 17.Nf5+ Ke8.[31] Although all the pieces were now on the same squares, the two positions were not considered identical, as Black, having moved his king, no longer had the right to castle. White now had time to build pressure on the black king without worrying that the king could escape by castling.

Artificial castling[edit]

Artificial castling, also known as castling by hand,[32] is a maneuver whereby a player achieves a castled position without the use of castling.[33]

Example[edit]

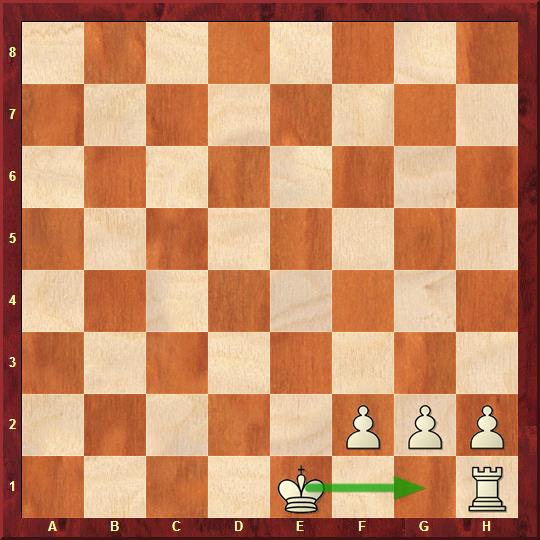

White to play |

Position after 4.Kg1 |

In the first diagram:

- 1. Nxe5 Bxf2+?!

Black sees that if he plays 1…Nxe5, White responds with 2.d4, winning back the minor piece with a fork and taking control of the center. Instead of allowing this, Black hopes to cause trouble for White by returning the piece while depriving White of the right to castle. However, White can easily castle artificially. For example:

- 2. Kxf2 Nxe5 3. Rf1

White begins castling artificially.

- 3… Ne7 4. Kg1 (second diagram)

White has achieved a normal castled position via several moves. With the bishop pair and a central pawn majority, White has a slight advantage.

Castling in chess variants[edit]

Variants of Western chess often include castling in their rule sets, sometimes in a modified form.

In variants played on a standard 8×8 board, castling is often the same as in standard chess. This includes variants which replace the king with a different royal piece, as is the case with the knight in Knightmate. Some variants, however, have different rules; for example, in Chess960, the king may move more or fewer than two squares (including none) while castling, depending on the starting position.

Castling can also be adapted to variants with different board sizes and shapes. Some such variants, like Capablanca chess (10×8) or chess on a really big board (16×16), preserve the castling movement of the rooks, meaning it is the king that moves a different distance along the board. Conversely, other games, like Dragonfly (7×7), specify that the king still castles two squares in each direction, and the rook is the piece that moves differently. In a few variants, most notably Wildebeest chess (11×10), the player may choose to move the king any distance and move the rook accordingly.

Castling sometimes features in chess variants not played on a square grid, such as masonic chess, triangular chess, Shafran’s and Brusky’s hexagonal chess, and millennium 3D chess. In 5D Chess with Multiverse Time Travel, castling is possible within the spatial dimensions but not across time or between timelines.

Some chess variants do not feature castling, such as losing chess, where the king is not royal, and Grand Chess, where the rooks have significantly more opening mobility.

In a handicap game with rook odds, the player giving odds may castle with the absent rook, moving only the king.[34][35]

Chess without castling[edit]

Writing in 2019, former world chess champion Vladimir Kramnik proposed a variant of chess where players would not have the ability to castle. This variant would reduce king safety, theoretically leading to more dynamic games, as it would be considerably harder to force a draw and the pieces would be forced to engage in a mêlée.[36] In 2021, former world champion Viswanathan Anand defeated Kramnik in a no-castling exhibition match under classical time controls 2.5-1.5.[37]

Castling in chess problems[edit]

Castling features in some chess problems. The earliest known study containing castling was published in 1843 by Julius Mendheim.[38] Castling is common in retrograde analysis problems. By chess problem convention, if a player’s king and rook are on their original squares, the player is assumed to have castling rights unless it can be proven otherwise. In some retrograde analysis problems, one of the players (usually White) may castle or capture en passant in order to prove that the opponent has previously moved their king or rook and therefore cannot castle.

Armand Lapierre

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

White to play and mate in two

The diagram to the right shows a mate in two. 1.Rad1? 0-0 does not work. The key is 1.0-0-0!, demonstrating that the white king had not moved yet and that the rook on d4 must therefore be a promoted piece, which proves that either the black king or black rook has moved to let it off the back rank, invalidating Black’s right to castle; after any move by Black, 2.Rd8# is mate.[39]

Siegfried Hornecker

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Helpmate in three with Koko fairy condition[40] (each piece must end up adjacent to another piece when moving)[41]

Some joke chess problems involve castling with a promoted rook of the opponent’s color. In orthodox chess, this would be illegal since the rook would be giving check to the king, but if there are fairy conditions in play that prevent check under some circumstances, such castling would have been legal under the 1993 FIDE Laws, which did not specify that the rook and king had to be of the same color.[citation needed]

The diagrammed problem involves castling with an opposing rook. The solution (Black’s move being given first per helpmate convention) is:

- 1. Bg7 h8=R 2. Bf6 Kg6 3. 0-0 Kh7#

The allowance of castling with a «phantom rook» in handicap games has also been used in joke problems.[citation needed] Many other joke variations on castling are possible.

Vertical castling[edit]

C. Staugaard

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

White to play and mate in two

Vertical castling, also known as «Pam–Krabbé castling» or «Staugaard castling», is an illegal move that consists of castling with an unmoved promoted rook on the e-file. For example, White might move the king from e1 to e3 and the rook from e8 to e2. Vertical castling has been used in a few novelty chess problems.[42][43]

In 1907, C. Staugaard composed a twomover where White promotes a pawn to a rook and then castles vertically with the newly promoted rook (with the king ending up on e3 and the rook ending up on e2), since the rook has not moved. It is unclear whether the rules at the time specified that the rook should be on the same rank as the king, which would have made this «vertical castling» illegal.

Tim Krabbé’s 1985 book Chess Curiosities includes a problem featuring vertical castling, along with an incorrect claim that the problem’s 1973 publication prompted FIDE to amend the castling laws in 1974 to add the requirement that the king and rook be on the same rank. In reality, the original FIDE Laws from 1930 explicitly stated that castling must be done with a king and a rook on the same rank (traverse in French).[44]

Nomenclature[edit]

In most European languages, the term for castling is derived from the Persian rukh (e.g. rochieren, rochada, enroque), while queenside and kingside castling are referred to using the adjectives meaning «long» and «short» (or «big» and «small»), respectively.

References[edit]

- ^ a b «FIDE Laws of Chess taking effect from 1 January 2018». FIDE. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ Article 3.8.2 in FIDE Laws of Chess[1]

- ^ Pandolfini, Bruce (1992), Pandolfini’s Chess Complete: The Most Comprehensive Guide to the Game, from History to Strategy, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 9780671701864, retrieved 13 January 2014

- ^ (Hooper & Whyld 1992)

- ^ Article 3.8.2 in FIDE Laws of Chess[1]

- ^ Korn, Walter (October 1961). «The Rules of Castling» (PDF). Chess Review. Vol. 29. p. 298. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-09-18. Retrieved 2022-03-03.

on castling, considerable confusion often reigns among beginners

- ^ (Just & Burg 2003:13–14, 17–18, 23)

- ^ (Just & Burg 2003:13–14, 17–18, 23)

- ^ William Hartston notes in Teach Yourself Chess that «most chess players refrain from demonstrations of ambidexterity.»

- ^ «Karpov vs. Miles, 1986». Chessgames.com. Retrieved 2022-03-25.

- ^ (Davidson 1981:48)

- ^ (Davidson 1981:16)

- ^ c1, c2, c3, d3, e3, f3, g1, g2, or g3 according to H. J. R. Murray

- ^ (Sunnucks 1970:66)

- ^ Stefan Bücker: «Was bedeutet 0-0?» (What does 0-0 mean?), in: Kaissiber, No. 18, 2002, pp.70–71

- ^ https://www.chessgames.com/perl/chessgame?gid=1621031 Mattison-Millers 1926 at chessgames.com

- ^ Edward Winter, C.N. 5916 — ‘Thornton castling trap’ (C.N. 4078), 27 December 2008

- ^ George Huczek (2017). A to Z Chess Tactics. Batsford. pp. 001–349. ISBN 978-1-8499-4446-5.

- ^ Tim Krabbé, Open chess diary, item 391

- ^ «Korchnoi vs. Karpov, Moscow 1974». Chessgames.com.

- ^ Larry Evans (16 July 1995). «Castling Confuses Even Grandmasters». Sun Sentinel.

- ^ «Chess Records». Tim Krabbé. (click on: «Greatest number of castlings»)

- ^ «Averbakh vs. Purdy, Adelaide 1960». Chessgames.com.

- ^ Cecil Purdy, Doesn’t Know the Moves!, Chess World, October 1960, p, 198, reproduced by Edward Winter, Chess Notes 9622

- ^ (Evans 1970:38–39)

- ^ (Lombardy & Daniels 1975:188)

- ^ «Ed. Lasker vs. Thomas, London 1912». Chessgames.com.

- ^ Edward Lasker, Chess for Fun and Chess for Blood, Dover Publications, 1962, p. 120.

- ^ «Prins vs. Day, Lugano 1968». Chessgames.com.

- ^ «Feuer vs. O’Kelly, Liege 1934». Chessgames.com.

- ^ «Fischer vs. Najdorf, Varna, 1962». Chessgames.com.

- ^ Aramil, William (2008-10-07). The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Chess Openings: Discover the First-Move Strategies of Champions. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-4406-5185-4.

- ^ Bronznik, Valeri (2014-02-18). Techniques of Positional Play: 45 Practical Methods to Gain the Upper Hand in Chess. New In Chess. ISBN 978-90-5691-473-8.

- ^ Walker, George (1841). «The Chess Player». p. 74.

- ^

Abrahams, Gerald (1948), Chess, Teach Yourself Books, English Universities Press, p. 59 - ^ Kramnik (VladimirKramnik), Vladimir. «Kramnik And AlphaZero: How To Rethink Chess». Chess.com. Retrieved 2020-02-05.

- ^ «No-Castling Chess: Anand holds Kramnik, wins Sparkassen Trophy». The Times of India. 18 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ Hornecker, Siegfried. «Study of the Month — A short history of endgame study castling I». ChessBase. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ «Yet another chess problem database». Yet another chess problem database. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Hornecker, Siegfried (9 October 2011). «P1204776». Die Schwalbe (in German). Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ «Chess Problem Fairy Definitions». StrateGems — US Chess Problem Magazine. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ «Staugaard castling at Die Schwalbe».

- ^ «Pam-Krabbé castling at yacpdb».

- ^ Règle du Jeu d’Échecs de la F. I. D. E. (édition officielle 1930), (in French), FIDE, 1930 (via wikisource)

Bibliography

- Davidson, Henry (1981) [1949], A Short History of Chess, McKay, ISBN 978-0-679-14550-9

- Evans, Larry (1970), Chess Catechism, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 0-671-20491-2

- Hooper, David; Whyld, Kenneth (1992), «castling», The Oxford Companion to Chess (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280049-3

- Just, Tim; Burg, Daniel B. (2003), U.S. Chess Federation’s Official Rules of Chess (5th ed.), McKay, ISBN 0-8129-3559-4

- Lombardy, William; Daniels, David (1975), Chess Panorama, Chilton, ISBN 0-8019-6078-9

- Murray, H. J. R. (2012) [1913], A History of Chess, Skyhorse, ISBN 978-1-62087-062-4

- Schiller, Eric (2003), Official Rules of Chess (2nd ed.), Cardoza Publishing, ISBN 978-1-58042-092-1

- Sunnucks, Anne (1970), «castling», The Encyclopaedia of Chess, St. Martins Press, ISBN 978-0-7091-4697-1

- «Castling in Chess» by Edward Winter

External links[edit]

- «Mate by Castling» Game Collection at Chessgames.com

Initial positions of kings and rooks. Kings may castle to the indicated squares. |

White has castled kingside; Black has castled queenside. |

Castling is a move in chess. It consists of moving one’s king two squares toward a rook on the same rank and then moving the rook to the square that the king passed over.[2] Castling is permitted only if neither the king nor the rook has previously moved; the squares between the king and the rook are vacant; and the king does not leave, cross over, or end up on a square attacked by an opposing piece. Castling is the only move in chess in which two pieces are moved at once.[3]

Castling with the king’s rook is called castling kingside, and castling with the queen’s rook is called castling queenside. In both algebraic and descriptive notation, castling kingside is written as 0-0 and castling queenside as 0-0-0.

Castling originates from the king’s leap, a two-square king move added to European chess between the 14th and 15th centuries, and took on its present form in the 17th century; however, local variations in castling rules were common, persisting in Italy until the late 19th century. Castling does not exist in Asian games of the chess family, such as shogi, xiangqi, and janggi, but it commonly appears in variants of Western chess.

Rules[edit]

Description[edit]

During castling, the king is shifted two squares toward a rook of the same color on the same rank, and the rook is transferred to the square crossed by the king. There are two forms of castling:[4]

- Castling kingside (also called short castling) consists of moving the king to g1 and the rook to f1 for White, or moving the king to g8 and the rook to f8 for Black.

- Castling queenside (also called long castling) consists of moving the king to c1 and the rook to d1 for White, or moving the king to c8 and the rook to d8 for Black.

Requirements[edit]

White cannot castle queenside because the knight is in the way. White can castle kingside. |

Black cannot castle on either side because he is in check by the white queen. |

White cannot castle queenside because Black’s queen controls c1. White can castle kingside even though the h1-rook is under attack. |

Black cannot castle kingside, as the white queen attacks f8. Black can castle queenside despite the white queen’s attack on b8. |

Castling is permitted provided all of the following conditions are met:[5]

- Neither the king nor the rook has previously moved.

- There are no pieces between the king and the rook.

- The king is not currently in check.

- The king does not pass through or finish on a square that is attacked by an enemy piece.

Conditions 3 and 4 can be summarized by the mnemonic: A player may not castle out of, through, or into check.

Castling rules often cause confusion, even occasionally among high-level players.[6] To clarify:

- The rook can be under attack.

- The rook can pass through an attacked square. (White can castle queenside even if Black is attacking b1; Black can castle queenside even if White is attacking b8.)

- The king can have been in check earlier in the game.

Tournament rules[edit]

Under the rules used by FIDE and enforced in most tournaments, castling is considered a king move, so the king must be touched first; if the rook is touched first, a rook move must be made instead. As usual, the player may choose another legal destination square for the king until releasing it. When the two-square king move is completed, however, the player is committed to castling if it is legal, and the rook must be moved accordingly. The entire move must be completed with one hand. A player who illegally attempts to castle must return the king and the rook to their original places and then make a legal king move if possible (which may include castling on the other side). If there is no legal king move, the touch-move rule does not apply to the rook.[7]

Under US Chess Federation rules, a player who intends to castle and touches the rook first would suffer no penalty and would be permitted to castle, provided castling is legal in the position. These tournament rules are not commonly enforced in informal play or commonly known by casual players.[8][9]

Castling rights[edit]

An unmoved king has castling rights with an unmoved rook of the same color on the same rank. In the context of threefold and fivefold repetition, two positions with different castling rights are considered to be different positions.

Example[edit]

Karpov vs. Miles, 1986

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Position after 22.Nb5

In a 1986 game between Anatoly Karpov and Tony Miles,[10] play continued from the diagrammed position as follows:

- 22… Ra4 23. Nc3 Ra8 24. Nb5 Ra4 25. Nc3 Ra8 26. Nb5

With his 26th move, Karpov attempted to claim a draw by threefold repetition, thinking that the positions after his 22nd, 24th, and 26th moves were the same. However, it was pointed out to him that the position after his 22nd move had different castling rights than the positions after his 24th and 26th moves, rendering his claim illegal. As a result, Karpov was penalized three minutes on his clock. The game ended in a draw.

Notation[edit]

Both algebraic notation and descriptive notation indicate kingside castling as 0-0 and queenside castling as 0-0-0 (with the digit zero). Portable Game Notation and some publications instead use O-O for kingside castling and O-O-O for queenside castling (with the letter O). ICCF numeric notation indicates castling based on the starting and ending squares of the king; thus, castling kingside is written as 5171 for White and 5878 for Black, and castling queenside is written as 5131 for White and 5838 for Black.

History[edit]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Castling under medieval rules. Symbol color corresponds to king color. Circles represent English, Spanish, French, and Lombardy movement; crosses represent Lombardy movement only.

Castling has its roots in the king’s leap. There were two forms of the leap: the king would move once like a knight, or the king would move two squares on its first move. The knight move might be used early in the game to get the king to safety or later in the game to escape a threat. This second form was played in Europe as early as the 13th century. In North Africa, the king was transferred to a safe square by a two-move procedure: the king moved to the player’s second rank, and the rook and king moved to each other’s original squares.[11]

Various forms of castling were developed due to the spread of rule sets during the 15th and 16th centuries which increased the power of the queen and bishop, allowing these pieces to attack from a distance and from both sides of the board, thus increasing the importance of king safety.[12]

The rule of castling has varied by location and time. In medieval England, Spain, and France, the white king was allowed to jump to c1, c2, d3, e3, f3, or g1[13] if no capture was made and the king was not in check and did not move over check; the black king might move analogously. In Lombardy, the white king might also jump to a2, b1, or h1, with corresponding squares applying to the black king. Later, in Germany and Italy, the rule was changed such that the king move was accompanied by a pawn move.

In the Göttingen manuscript (c. 1500) and a game published by Luis Ramírez de Lucena in 1498, castling consisted of moving the rook and then moving the king on separate moves.

The current version of castling was established in France in 1620 and in England in 1640.[14]

In Rome, from the early 17th century until the late 19th century, the rook might be placed on any square up to and including the king’s square, and the king might be moved to any square on the other side of the rook. This was called free castling.

In the 1811 edition of his chess treatise, Johann Allgaier introduced the 0-0 notation. He differentiated between 0-0r (right) and 0-0l (left). The 0-0-0 notation for queenside castling was introduced in 1837 by Aaron Alexandre.[15] The practice was adopted in the first edition (1843) of the influential Handbuch des Schachspiels and soon became standard. In English descriptive notation, the word «Castles» was originally spelled out, adding «K’s R» or «Q’s R» if disambiguation was necessary; eventually, the 0-0 and 0-0-0 notation was borrowed from the algebraic system.

Strategic and tactical concepts[edit]

Strategy[edit]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Position after 10.0-0-0: Opposite castling in the Yugoslav Attack

Castling is generally an important goal in the opening: it moves the king to safety away from the center of the board, and it moves the rook to a more active position in the center of the board.

The choice regarding to which side one castles often hinges on an assessment of the trade-off between king safety and activity of the rook. Kingside castling is generally slightly safer because the king ends up closer to the edge of the board and can usually defend all of the pawns on the castled side. In queenside castling, the king is placed closer to the center and does not defend the pawn on the a-file; for these reasons, the king is often subsequently moved to the b-file. In addition, queenside castling is initially obstructed by more pieces than kingside castling is; therefore, it takes longer to set up than kingside castling. On the other hand, queenside castling places the rook more efficiently on the central d-file, where it is often immediately active; meanwhile, with kingside castling, a tempo may be required to move the rook to a more effective square.

One may forgo castling for various reasons. In positions where one’s opponent cannot organize an attack on one’s centralized king, castling may be unnecessary or even detrimental. In addition, a rook can be more active near the edges of the board than in the center in certain situations, such as if it is able to fight for control of an open or semi-open file.

Kingside castling occurs more frequently than queenside castling. It is common for both players to castle kingside, somewhat uncommon for one player to castle kingside and the other queenside, and rare for both players to castle queenside. If one player castles kingside and the other queenside, it is called opposite (or opposite-side) castling. Castling on opposite sides usually results in a fierce fight, as each player’s pawns are free to advance to attack the opposing king’s castled position without exposing the player’s own castled king. Opposite castling is a common feature of many openings, such as the Yugoslav Attack.

Tactics involving castling[edit]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Black to play

Tactical patterns involving castling are rare. One pattern involves castling queenside to deliver a double attack: the king attacks a rook (on b2 for White or b7 for Black), while the rook attacks a second opposing piece (usually the king). In the example on the right, from the game Mattison–Millers, Königsberg 1926, Black played 13…Rxb2?? and resigned after 14.0-0-0+, which wins the rook.[16]

Chess historian Edward Winter has proposed the name «Thornton castling trap» for this pattern, in reference to the earliest known example, Thornton–Boultbee, published in the Brooklyn Chess Chronicle in 1884. Other chess writers such as Gary Lane have since adopted this term.[17]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

White to play

Another example of tactical castling is illustrated in the diagrammed position from the correspondence game Gurvich–Pampin, 1976. After 1.Qxd8+ Kxd8 2.0-0-0+ Ke7 3.Nxb5, White wins a rook by castling with check and simultaneously unpinning the knight.[18]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Black to play

Such a double attack can also be made by castling kingside, though this is much rarer. In this position from the blindfold game Karjakin–Carlsen, 2007, the move 19…0-0 indirectly threatens both to deliver back-rank mate and to win the h7-rook. Black will thus win the g5-knight next move; 20.Rh6 Bxg5 21.Rxg6+ Kh7 22.Rxg5 would not work, as it would be met by 22…Rf1#.[19]

Examples[edit]

- Viktor Korchnoi, in his 1974 Candidates final match with Anatoly Karpov, asked the arbiter if castling was legal when the castling rook was under attack.[20] The arbiter answered in the affirmative, Korchnoi executed the move, and Karpov resigned shortly after.[21]

- Castling occurred three times in the game Wolfgang Heidenfeld–Nick Kerins, Dublin 1973. The third instance of castling, the second one by White, was illegal, as the white king had already moved. The game is as follows:[22]

- 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Be3 Nf6 4.e5 Nfd7 5.f4 c5 6.c3 Nc6 7.Nf3 Qb6 8.Qd2 c4 9.Be2 Na5 10.0-0 f5 11.Ng5 Be7 12.g4 Bxg5 13.fxg5 Nf8 14.gxf5 exf5 15.Bf3 Be6 16.Qg2 0-0-0 17.Na3 Ng6 18.Qd2 f4 19.Bf2 Bh3 20.Rfb1 Bf5 21.Nc2 h6 22.gxh6 Rxh6 23.Nb4 Qe6 24.Qe2 Ne7 25.b3 Qg6+ 26.Kf1 Bxb1 27.bxc4 dxc4 28.Qb2 Bd3+ 29.Ke1 Be4 30.Qe2 Bxf3 31.Qxf3 Rxh2 32.d5 Qf5 33.0-0-0 Rh3 34.Qe2 Rxc3+ 35.Kb2 Rh3 36.d6 Nec6 37.Nxc6 Nxc6 38.e6 Qe5+ 39.Qxe5 Nxe5 40.d7+ Nxd7 0–1

Averbakh vs. Purdy[edit]

Averbakh vs. Purdy, 1960

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Black to move castled queenside, with the rook going over the attacked b8-square.

In the game Yuri Averbakh–Cecil Purdy (1960),[23] when Purdy castled queenside, Averbakh queried the move, pointing out that the rook had passed over an attacked square. Purdy indicated e8 and c8 and said, «The king», in an attempt to explain that this was forbidden only for the king. Averbakh replied, «Only the king? Not the rook?». Averbakh’s colleague Vladimir Bagirov then explained the castling rules to him in Russian, and the game continued.[24][25][26]

Edward Lasker vs. Thomas[edit]

Ed. Lasker vs. Thomas, 1912

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Position after 17…Kg1

In the game Edward Lasker–Sir George Thomas (London 1912),[27] White could have checkmated with 18.0-0-0#, but he instead played 18.Kd2#.[28] (See Edward Lasker’s notable games.)

Prins vs. Day[edit]

Prins vs. Day, 1968

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

White to play

The diagram shows the final position of the game Lodewijk Prins–Lawrence Day (1968), where White resigned.[29] Had the game continued, Black could have checkmated by castling:

- 29. Kf6 Qf5+ 30. Kg7 Qg6+ 31. Kh8 0-0-0#

(See Lawrence Day’s notable chess games.)

Feuer vs. O’Kelly[edit]

Feuer vs. O’Kelly, 1934

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Feuer–O’Kelly, 1934 Belgian championship. The game ended 10….Rxb2 11.dxe5 dxe5?? 12.Qxd8+ Kxd8 13.0-0-0+ and O’Kelly resigned since the rook is lost.

In the 1934 Belgian Championship,[30] Otto Feuer caught Albéric O’Kelly in the Thornton castling trap. In the position in the diagram, the game continued 10…Rxb2 11.dxe5 dxe5?? 12.Qxd8+ Kxd8 13.0-0-0+, and O’Kelly resigned. Feuer’s last move simultaneously gave check and attacked the rook on b2.

Fischer vs. Najdorf[edit]

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

White to play

The diagram illustrates the consequences of losing castling rights. Fischer, with the white pieces, played 16.Ng7+ Ke7 17.Nf5+ Ke8.[31] Although all the pieces were now on the same squares, the two positions were not considered identical, as Black, having moved his king, no longer had the right to castle. White now had time to build pressure on the black king without worrying that the king could escape by castling.

Artificial castling[edit]

Artificial castling, also known as castling by hand,[32] is a maneuver whereby a player achieves a castled position without the use of castling.[33]

Example[edit]

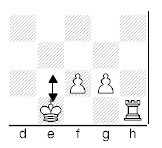

White to play |

Position after 4.Kg1 |

In the first diagram:

- 1. Nxe5 Bxf2+?!

Black sees that if he plays 1…Nxe5, White responds with 2.d4, winning back the minor piece with a fork and taking control of the center. Instead of allowing this, Black hopes to cause trouble for White by returning the piece while depriving White of the right to castle. However, White can easily castle artificially. For example:

- 2. Kxf2 Nxe5 3. Rf1

White begins castling artificially.

- 3… Ne7 4. Kg1 (second diagram)

White has achieved a normal castled position via several moves. With the bishop pair and a central pawn majority, White has a slight advantage.

Castling in chess variants[edit]

Variants of Western chess often include castling in their rule sets, sometimes in a modified form.

In variants played on a standard 8×8 board, castling is often the same as in standard chess. This includes variants which replace the king with a different royal piece, as is the case with the knight in Knightmate. Some variants, however, have different rules; for example, in Chess960, the king may move more or fewer than two squares (including none) while castling, depending on the starting position.

Castling can also be adapted to variants with different board sizes and shapes. Some such variants, like Capablanca chess (10×8) or chess on a really big board (16×16), preserve the castling movement of the rooks, meaning it is the king that moves a different distance along the board. Conversely, other games, like Dragonfly (7×7), specify that the king still castles two squares in each direction, and the rook is the piece that moves differently. In a few variants, most notably Wildebeest chess (11×10), the player may choose to move the king any distance and move the rook accordingly.

Castling sometimes features in chess variants not played on a square grid, such as masonic chess, triangular chess, Shafran’s and Brusky’s hexagonal chess, and millennium 3D chess. In 5D Chess with Multiverse Time Travel, castling is possible within the spatial dimensions but not across time or between timelines.

Some chess variants do not feature castling, such as losing chess, where the king is not royal, and Grand Chess, where the rooks have significantly more opening mobility.

In a handicap game with rook odds, the player giving odds may castle with the absent rook, moving only the king.[34][35]

Chess without castling[edit]

Writing in 2019, former world chess champion Vladimir Kramnik proposed a variant of chess where players would not have the ability to castle. This variant would reduce king safety, theoretically leading to more dynamic games, as it would be considerably harder to force a draw and the pieces would be forced to engage in a mêlée.[36] In 2021, former world champion Viswanathan Anand defeated Kramnik in a no-castling exhibition match under classical time controls 2.5-1.5.[37]

Castling in chess problems[edit]

Castling features in some chess problems. The earliest known study containing castling was published in 1843 by Julius Mendheim.[38] Castling is common in retrograde analysis problems. By chess problem convention, if a player’s king and rook are on their original squares, the player is assumed to have castling rights unless it can be proven otherwise. In some retrograde analysis problems, one of the players (usually White) may castle or capture en passant in order to prove that the opponent has previously moved their king or rook and therefore cannot castle.

Armand Lapierre

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

White to play and mate in two

The diagram to the right shows a mate in two. 1.Rad1? 0-0 does not work. The key is 1.0-0-0!, demonstrating that the white king had not moved yet and that the rook on d4 must therefore be a promoted piece, which proves that either the black king or black rook has moved to let it off the back rank, invalidating Black’s right to castle; after any move by Black, 2.Rd8# is mate.[39]

Siegfried Hornecker

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

Helpmate in three with Koko fairy condition[40] (each piece must end up adjacent to another piece when moving)[41]

Some joke chess problems involve castling with a promoted rook of the opponent’s color. In orthodox chess, this would be illegal since the rook would be giving check to the king, but if there are fairy conditions in play that prevent check under some circumstances, such castling would have been legal under the 1993 FIDE Laws, which did not specify that the rook and king had to be of the same color.[citation needed]

The diagrammed problem involves castling with an opposing rook. The solution (Black’s move being given first per helpmate convention) is:

- 1. Bg7 h8=R 2. Bf6 Kg6 3. 0-0 Kh7#

The allowance of castling with a «phantom rook» in handicap games has also been used in joke problems.[citation needed] Many other joke variations on castling are possible.

Vertical castling[edit]

C. Staugaard

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |

|

8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h |

White to play and mate in two

Vertical castling, also known as «Pam–Krabbé castling» or «Staugaard castling», is an illegal move that consists of castling with an unmoved promoted rook on the e-file. For example, White might move the king from e1 to e3 and the rook from e8 to e2. Vertical castling has been used in a few novelty chess problems.[42][43]

In 1907, C. Staugaard composed a twomover where White promotes a pawn to a rook and then castles vertically with the newly promoted rook (with the king ending up on e3 and the rook ending up on e2), since the rook has not moved. It is unclear whether the rules at the time specified that the rook should be on the same rank as the king, which would have made this «vertical castling» illegal.

Tim Krabbé’s 1985 book Chess Curiosities includes a problem featuring vertical castling, along with an incorrect claim that the problem’s 1973 publication prompted FIDE to amend the castling laws in 1974 to add the requirement that the king and rook be on the same rank. In reality, the original FIDE Laws from 1930 explicitly stated that castling must be done with a king and a rook on the same rank (traverse in French).[44]

Nomenclature[edit]

In most European languages, the term for castling is derived from the Persian rukh (e.g. rochieren, rochada, enroque), while queenside and kingside castling are referred to using the adjectives meaning «long» and «short» (or «big» and «small»), respectively.

References[edit]

- ^ a b «FIDE Laws of Chess taking effect from 1 January 2018». FIDE. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ Article 3.8.2 in FIDE Laws of Chess[1]

- ^ Pandolfini, Bruce (1992), Pandolfini’s Chess Complete: The Most Comprehensive Guide to the Game, from History to Strategy, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 9780671701864, retrieved 13 January 2014

- ^ (Hooper & Whyld 1992)

- ^ Article 3.8.2 in FIDE Laws of Chess[1]

- ^ Korn, Walter (October 1961). «The Rules of Castling» (PDF). Chess Review. Vol. 29. p. 298. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-09-18. Retrieved 2022-03-03.

on castling, considerable confusion often reigns among beginners

- ^ (Just & Burg 2003:13–14, 17–18, 23)

- ^ (Just & Burg 2003:13–14, 17–18, 23)

- ^ William Hartston notes in Teach Yourself Chess that «most chess players refrain from demonstrations of ambidexterity.»

- ^ «Karpov vs. Miles, 1986». Chessgames.com. Retrieved 2022-03-25.

- ^ (Davidson 1981:48)

- ^ (Davidson 1981:16)

- ^ c1, c2, c3, d3, e3, f3, g1, g2, or g3 according to H. J. R. Murray

- ^ (Sunnucks 1970:66)

- ^ Stefan Bücker: «Was bedeutet 0-0?» (What does 0-0 mean?), in: Kaissiber, No. 18, 2002, pp.70–71

- ^ https://www.chessgames.com/perl/chessgame?gid=1621031 Mattison-Millers 1926 at chessgames.com

- ^ Edward Winter, C.N. 5916 — ‘Thornton castling trap’ (C.N. 4078), 27 December 2008

- ^ George Huczek (2017). A to Z Chess Tactics. Batsford. pp. 001–349. ISBN 978-1-8499-4446-5.

- ^ Tim Krabbé, Open chess diary, item 391

- ^ «Korchnoi vs. Karpov, Moscow 1974». Chessgames.com.

- ^ Larry Evans (16 July 1995). «Castling Confuses Even Grandmasters». Sun Sentinel.

- ^ «Chess Records». Tim Krabbé. (click on: «Greatest number of castlings»)

- ^ «Averbakh vs. Purdy, Adelaide 1960». Chessgames.com.

- ^ Cecil Purdy, Doesn’t Know the Moves!, Chess World, October 1960, p, 198, reproduced by Edward Winter, Chess Notes 9622

- ^ (Evans 1970:38–39)

- ^ (Lombardy & Daniels 1975:188)

- ^ «Ed. Lasker vs. Thomas, London 1912». Chessgames.com.

- ^ Edward Lasker, Chess for Fun and Chess for Blood, Dover Publications, 1962, p. 120.

- ^ «Prins vs. Day, Lugano 1968». Chessgames.com.

- ^ «Feuer vs. O’Kelly, Liege 1934». Chessgames.com.

- ^ «Fischer vs. Najdorf, Varna, 1962». Chessgames.com.

- ^ Aramil, William (2008-10-07). The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Chess Openings: Discover the First-Move Strategies of Champions. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-4406-5185-4.

- ^ Bronznik, Valeri (2014-02-18). Techniques of Positional Play: 45 Practical Methods to Gain the Upper Hand in Chess. New In Chess. ISBN 978-90-5691-473-8.

- ^ Walker, George (1841). «The Chess Player». p. 74.

- ^

Abrahams, Gerald (1948), Chess, Teach Yourself Books, English Universities Press, p. 59 - ^ Kramnik (VladimirKramnik), Vladimir. «Kramnik And AlphaZero: How To Rethink Chess». Chess.com. Retrieved 2020-02-05.

- ^ «No-Castling Chess: Anand holds Kramnik, wins Sparkassen Trophy». The Times of India. 18 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ Hornecker, Siegfried. «Study of the Month — A short history of endgame study castling I». ChessBase. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ «Yet another chess problem database». Yet another chess problem database. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Hornecker, Siegfried (9 October 2011). «P1204776». Die Schwalbe (in German). Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ «Chess Problem Fairy Definitions». StrateGems — US Chess Problem Magazine. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ «Staugaard castling at Die Schwalbe».

- ^ «Pam-Krabbé castling at yacpdb».

- ^ Règle du Jeu d’Échecs de la F. I. D. E. (édition officielle 1930), (in French), FIDE, 1930 (via wikisource)

Bibliography

- Davidson, Henry (1981) [1949], A Short History of Chess, McKay, ISBN 978-0-679-14550-9

- Evans, Larry (1970), Chess Catechism, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 0-671-20491-2

- Hooper, David; Whyld, Kenneth (1992), «castling», The Oxford Companion to Chess (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280049-3

- Just, Tim; Burg, Daniel B. (2003), U.S. Chess Federation’s Official Rules of Chess (5th ed.), McKay, ISBN 0-8129-3559-4

- Lombardy, William; Daniels, David (1975), Chess Panorama, Chilton, ISBN 0-8019-6078-9

- Murray, H. J. R. (2012) [1913], A History of Chess, Skyhorse, ISBN 978-1-62087-062-4

- Schiller, Eric (2003), Official Rules of Chess (2nd ed.), Cardoza Publishing, ISBN 978-1-58042-092-1

- Sunnucks, Anne (1970), «castling», The Encyclopaedia of Chess, St. Martins Press, ISBN 978-0-7091-4697-1

- «Castling in Chess» by Edward Winter

External links[edit]

- «Mate by Castling» Game Collection at Chessgames.com

Рад приветствовать вас, дорогой друг!

Не так давно, краем уха услышал спор о том, что такое правильная рокировка. Один из спорщиков, к моему удивлению с пеной у рта доказывал на полном серьезе, что рокировка заключается в перемещении короля и ферзя. Неплохо, да? Как правильно делается рокировка в шахматах, — в сегодняшней статье.

Но вначале небольшое отступление. Раз уж вы попали на эту страницу, значит вы новичок, поэтому предлагаем вашему вниманию классный обучающий видеокурс «Как научить ребенка играть в шахматы». Благодаря ему вы и сами все правила изучите и усвоите, еще и ребенка от 4-х лет научите играть. Не пожалеете…

Если вы не любите читать, то смотрите видео:

Смотреть полный плейлист всех правил шахмат от А до Я на Ютуб (подписывайтесь на обновления).

- Что такое рокировка?

- Как делать рокировку?

- Зачем делать рокировку?

- Когда рокировку делать не следует

- Частая ошибка новичков

- Рокировка в шахматах Фишера

Что такое рокировка?

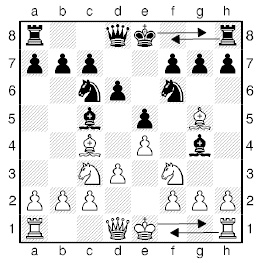

Рокировка – это ход с участием сразу двух фигур. А именно, короля и ладьи. При рокировке король перемещается изначальной позиции через поле (вправо, или влево). а ладья перескакивает через короля, становясь на соседнее поле.

Кстати, в некоторых статьях и руководствах автор этих строк встречал ошибку: пишут, что ладья становится на место короля. Это неправильно. Ладья встает рядом с королем.

Как делать рокировку?

Начинать рокировку следует с короля. Передвигаем короля на две клетки, затем берем ладью и переставляем через короля на соседнее с королем поле.

Это важный момент. Часто начинающие игроки забывают или просто не знают как делается рокировка, что может не много не мало напрочь испортить позицию и повлиять на результат партии. Подробнее об этой типичной ошибке – чуть ниже.

Зачем делать рокировку?

Мы с вами знаем, что короля важно оберегать. Рокировка – весьма удобный способ обезопасить своего монарха. То есть увести из центра доски, где обычно начинается борьба в дебюте.

На краю доски король под защитой пешек будет чувствовать себя безопаснее. Кроме того, ладья, участвующая в рокировке, — подтягивается к центру доски и открытым линиям.

Виды рокировки

Видов всего два: короткая и длинная.

Короткую рокировку мы уже видели, она делается с участием ладей h1 (белые) и h8 (черные).

Длинная рокировка:

Обратите внимание: король при длинной рокировке ходит через одно поле, не в коем случае не через два!

Правила рокировки

Рокировку делать разрешается, если:

1.Фигуры ,участвующие в рокировке, то есть король и ладья не сделали в этой партии ходов. Ни одного.

2.Между королем и ладьей отсутствуют другие фигуры. (в том числе чужие. То есть нельзя одновременно сделать рокировку и побить фигуру противника)

3.Король не находится под шахом. Иными словами, при шахе королю, — рокировать нельзя.

Если же под боем ладья – рокироваться можно.

4. Поле (клетка), через которое проскакивает король, не атаковано фигурами противника. Иными словами, рокироваться через «битое поле» короля не разрешается.

Подчеркиваю: «битое поле» относится к королю. Если пробивается поле (клетка), через которое проскакивает ладья при рокировке – рокировка разрешается. Пример:

5.Король после рокировки не попадает под удар (шах)

Рокировка – это один ход, а не два. Рокировку, как вы уже понимаете, может в партии сделать каждый из партнеров только один раз. В шахматной записи рокировка обозначается нулями: 0-0 -два нуля, –коротая, 0-0-0 — три нуля, — длинная

Когда рокировку делать не следует

Основная идея рокировки –безопасность короля. Если эта задача не выполняется, рокировка теряет смысл. Например:

После рокировки король не защищен своими пешками и фигурами. Он может стать легким объектом для атаки черных фигур. Например, после 1. 0-0 Фе7-h4

Гораздо разумнее пока воздержаться от немедленной рокировки или подготовить длинную рокировку ходом 1. Фd1-d2.

Частая ошибка новичков

Важно! Начинать рокировку следует с перемещения короля. Нельзя начинать рокировку с ладьи.

Помните фильм «Джентльмены удачи» и шахматные баталии на раздевание с участием Хмыря, Косого и «товарища» в исполнении Анатолия Папанова?

Так вот, герой Папанова делал рокировку неправильно. То есть, — вначале перемещал ладью, и только потом короля. Не мудрено, что столь «подкованный» шахматист остался в одних трусах.

Если вы начинаете рокировку с движения ладьи, внимательный соперник может потребовать сделать ход ладьей. В соответствии с правилом «взялся –ходи». Что получится – смотрите сами:

Ход абсолютно бессмысленный. Лучше бы его вообще не делать.

Когда вы играете в сети или с компьютером и начинаете рокировку с движения ладьи – программа разрешит вам сделать только ход ладьей. Короля переставить через ладью не удастся. Получиться то же что на предыдущей диаграмме. Впрочем, можете попробовать сами.

Также не рекомендую за доской делать рокировку двумя руками.

Рокировка в шахматах Фишера

Мы не будем подробно разбирать эту разновидность шахмат. Скажу только об особенностях рокировки. Правила такие:

- Где бы н находились король и ладья в начальной расстановке шахмат Фишера (она случайна) сделав рокировку, король и ладья становятся на поля, которые приняты в правилах рокировки в классических шахматах. То есть король на вертикали g (при короткой) или с (при длинной). Соответственно ладья на f или d.

- В шахматах Фишера рокировку разрешено делать, начиная с любой фигуры или передвигая их одновременно. При этом игрок должен перед ходом объявить: “Делаю рокировку”. Ход считается сделанным, когда переключены часы.

В заключение:

Когда наши президент и премьер поменялись должностями, в народе, да и в прессе, этот политический ход окрестили рокировкой. Как видите, емкие шахматные термины охотно используют не только шахматисты за доской.

Потом произошла обратная рокировка. А вот в шахматах обратная рокировка невозможна. Шахматы – мудрая игра. Разве не так? )

Благодарю за интерес к статье.

Если вы нашли ее полезной, сделайте следующее:

- Поделитесь с друзьями, нажав на кнопки социальных сетей.

- Напишите комментарий (внизу страницы)

- Подпишитесь на обновления блога (форма под кнопками соцсетей) и получайте статьи к себе на почту.

Удачного вам дня и хорошего настроения!

Урок одиннадцатый. Шахматная рокировка и все о ней.

Создано 18.06.2012 19:40

Автор: Костров В. и Давлетов Д.

Урок одиннадцатый. Шахматная рокировка и все о ней.

С чего мы начнём сегодняшний урок? Ты должен захватить центр, вывести своих двух коней и двух слонов на боевые позиции.

Фигуры вышли, и настал черёд королей. Неуютно они себя чувствуют в центре – над ними нависли грозные слоны, грозят прискакать кони. Поэтому Его Величество надо беречь от неприятностей. Для этого придумали специальную королевскую защиту – Шахматную Рокировку!

Для короля выстраивается уютный шахматный домик, из которого он спокойно может наблюдать за ходом сражения.

Вы знаете, что за один ход перемещается только одна шахматная фигура. Но один раз в партии делается исключение, когда могут передвинуться сразу две фигуры: ладья и король.

Как делают рокировку?

Король движется по направлению к ладье через одно поле (на поле того же цвета), а ладья перепрыгивает через короля и становится рядом.

Для чего делается рокировка?

Рокировка делается для защиты своего короля (для его безопасности). Посмотрите на позицию короля после рокировки. Ладья надежно защищает своего короля по 1-й линии, а пешки не дают вражеским фигурам даже приблизиться.

Какие бывают рокировки?

Посмотрите: до ладьи «h» путь короля короче – две клетки, до ладьи «а» расстояние длиннее – целых три. Поэтому рокировки так и называют: длинная рокировка и короткая рокировка.

Как записывать рокировку?

Нужно сосчитать пустые клетки между ладьёй и королём, определить какая рокировка – короткая или длинная.

Вот эти клетки шахматисты договорились записывать НОЛИКАМИ:

- верхняя стрелка: 2 клетки – 2 нолика – короткая рокировка: 0 – 0

- нижняя стрелка: 3 клетки – 3 нолика – длинная рокировка: 0 – 0 – 0.

Когда нельзя делать рокировку?

А теперь самое грустное. Оказывается, существует много случаев, когда нельзя делать рокировку – целых шесть!!! Познакомимся со всеми.

НЕЛЬЗЯ делать рокировку, если:

- король уже ходил (на диаграмме король белых побывал на е2 и вернулся обратно);

- ладья уже ходила (делала ход на h3). Рокировку с ладьёй а1 делать можно, если, конечно, и она ещё не ходила;

- между королём и ладьёй находится какая-либо фигура (слон с1 не даёт возможности сделать рокировку). После отхода слона препятствие исчезает и рокировка становится возможной;

3а) нельзя одновременно побить фигуру противника и заодно сделать рокировку (0 : 0 или 0 : 0 : 0);

- королю шах (ферзь h4 атакует короля).

Белые могут сначала закрыться от шаха, например пешкой g2–g3, а затем сделать рокировку; - белый король после рокировки окажется под ударом фигуры противника – под шахом.

Слон не даёт возможность рокировать белым. Рокировку можно будет сделать, если прогнать или уничтожить слона. В этом может помочь конь е3:

1. Кe3 – c4 ! Чёрному слону приходится уйти; - король при рокировке должен перейти поле, которое атакует фигура противника (чёрный ферзь f3 и конь e3 контролируют (бьют) поля d1 и f1, поэтому рокировка ни в короткую, ни в длинную сторону невозможна).

Нельзя делать рокировку через «битое поле».

Чемпион мира Эммануил Ласкер предлагал такую формулировку правил 4, 5, 6:

Нельзя рокировать, если король или ладья попадают после рокировки под удар.

Интересное решение чемпиона мира.

Использование данного материала в интернете без указания ссылки на автора, сайт и книгу запрещено. Правами на издание книги и данного материала владеют авторы шахматного учебника «Шахматы для детей, родителей и учителей» Костров Всеволод и Давлетов Джалиль.

Как научиться играть в шахматы? Список всех шахматных уроков онлайн.

С вопросами обращайтесь по адресу: Этот адрес электронной почты защищен от спам-ботов. У вас должен быть включен JavaScript для просмотра.. Давайте уважать труд авторов, администраторов сайта и Детско-юношеской комиссии Санкт-Петербургской Шахматной Федерации.

Добавить комментарий

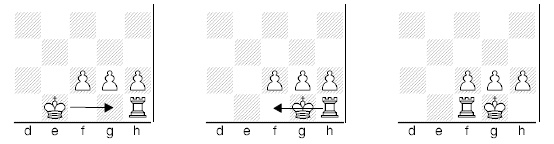

Поскольку король является самой важной фигурой, то разумно разместить его в безопасном месте. С этой целью делается рокировка.

Рокировка — ход короля, в котором одновременно передвигаются две фигуры: король и ладья. Первым переставляется король по направлению к ладье через одно поле, а ладья переставляется через короля в другую сторону и ставится рядом.

Следует обратить внимание, что именно ходом короля начинается рокировка. Если же начать рокировку с передвижения ладьи, то тогда король через ладью не переставляется.

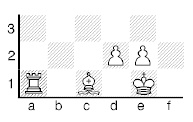

Рокировка бывает двух видов: короткая и длинная. Короткая рокировка делается на королевском фланге, а длинная — на ферзевом.

Предположим, в положении на диаграмме белые решили сделать короткую рокировку, а чёрные — длинную: 1. 0-0 1… 0-0-0 (запись короткой и длинной рокировки).

Позиция примет следующий вид. Короли теперь находятся под прикрытием пешек, а ладьи могут выходить в игру. Однако рокировку можно делать далеко не всегда.

Случаи, при которых рокировка не делается:

1. Если между королём и ладьёй стоит своя или вражеская фигура.

2. Король ранее делал ход.

3. Если ладья, с которой король намерен сделать рокировку, ранее делала ход.

4. Король находится под нападением неприятельской фигуры.

5. Если при выполнении рокировки, король встаёт на поле под нападением.

6. Если при выполнении рокировки, король передвигается через поле, находящееся под нападением (т. е. через «битое поле»).

Рассмотрим примеры:

В этом положении, рокировка белого короля временно невозможна из-за нападения на него слона b4. В связи с этим нужно сперва устранить нападение:

1. с3!

(перекрывая диагональ слону) и далее можно делать рокировку:

2. 0-0 или 2. 0-0-0.

Король белых не имеет права сделать рокировку, короткую из-за коня g1, а длинную из-за атаки чёрной ладьёй d8 поля d1 (т.е. поле d1 является «битым»).

Необходимо сначала вывести в игру коня g1, с последующей короткой рокировкой: 1. Kf3 2. -0-0

Несложно заметить, что чёрный король и белая ладья g1 уже делали ходы, следовательно, рокировка чёрного короля и короткая рокировка белого — невозможна. Если же белый король попробует сделать длинную рокировку, то на поле с1 его будет атаковать слон g5, значит и длинная рокировка белого короля тоже пока невозможна. Следует обратить особое внимание на следующую ситуацию:

Если через атакованное вражеской фигурой поле передвигается ладья (не король), то такую рокировку делать разрешено.

Эта ситуация часто ставит в тупик даже тех игроков, у кого есть разряд.

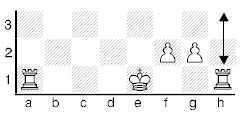

Короткая рокировка

Длинная рокировка

Рокиро́вка — особый ход в шахматах, заключающийся в горизонтальном перемещении короля в сторону ладьи своего цвета на 2 клетки и затем ладьи на соседнюю с королём клетку по другую сторону от короля. Каждая из сторон может сделать одну рокировку в течение партии.

Смысл рокировки в том, что она позволяет одним ходом значительно изменить позицию короля (переместив его в менее опасное место), одновременно выводя на центральные вертикали сильную фигуру — ладью.

Содержание

- 1 Описание хода

- 2 Условия рокировки

- 3 Этикет

- 4 Нотация

- 5 История

- 6 Варианты

- 7 Рокировка в шахматных программах

- 8 Интересные факты

- 9 См. также

- 10 Примечания

Описание хода

Рокировка — двойной ход, который выполняют король и ладья, ни разу не ходившие.

- Сначала король делает ход на две клетки в сторону ладьи.

- Затем ладья переносится через короля и ставится на следующее за ним поле.

Рокировка считается одним ходом, несмотря на то, что передвигаются две фигуры. Некоторые книги для начинающих[1] описывают рокировку как «ладья пододвигается вплотную к королю, а король перепрыгивает через неё» — так действительно проще понять двойной ход, но правило «тронул — ходи» требует начинать рокировку именно с короля.

Рокировка возможна в двух направлениях — в сторону королевского фланга (в короткую сторону) и в сторону ферзевого фланга (в длинную сторону). При короткой рокировке король оказывается на начальной позиции коня, ладья — на позиции королевского слона. При длинной — король на позиции ферзевого слона, ладья на начальной позиции ферзя (см. диаграмму).

Условия рокировки

- Рокировка невозможна:

- если король по ходу партии уже делал ходы (включая ход-рокировку)

- с той ладьёй, которая уже ходила

- «вертикальная рокировка» с ладьёй, превращённой из пешки.

- Рокировка временно невозможна:

- если поле, на котором находится король (король находится под шахом), или поле, которое он должен пересечь или занять, атаковано одной или несколькими фигурами противника;

- если между королем и ладьей, предназначенными для рокировки, находится какая-либо фигура[2].

В задачах и этюдах рокировка по умолчанию считается возможной, только если нельзя совершенно точно доказать с помощью ретроанализа, что король или ладья уже ходили.

Этикет

Правила шахмат требуют выполнять ходы только одной рукой[3]. Рокировка — это ход короля, поэтому игрок, выполняя её, должен сначала передвинуть короля, затем — ладью. В случае, когда игрок касается одновременно короля и ладьи, он обязан сделать рокировку в сторону этой ладьи, если такой ход возможен (если невозможен, игрок обязан сделать любой другой ход королём, включая рокировку в другую сторону)[4]. Если игрок ошибочно взялся сначала за ладью, он должен сделать ход ладьёй.

Если один из игроков сделал рокировку с нарушением правил, то он обязан поставить короля и ладью на их первоначальные места и сделать какой-нибудь ход королём, если такой ход возможен.

В шахматах Фишера в результате рокировки король и ладья встают на те же поля, что и в обычных шахматах. При этом, в зависимости от начальной расстановки фигур, двигаться могут и обе фигуры, и только король, и только ладья. Поэтому в них вышеописанное правило не действует и игрок вправе перемещать рокируемые фигуры в любом порядке; рокировка считается сделанной, когда переключены часы. Если игра идёт без контроля времени, то, во избежание дезориентации партнёра, рокирующийся игрок должен перед тем, как передвинуть фигуры, сказать «рокируюсь» или «делаю рокировку».

Нотация

В алгебраической нотации (как советской, так и зарубежной) рокировка в короткую сторону записывается как «0—0», в длинную как «0—0—0».

История

Рокировка — относительно недавнее европейское нововведение в шахматы, которое датируется XIV—XV вв. Поэтому более ранние азиатские версии шахмат не имеют такого хода.