|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mercury | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

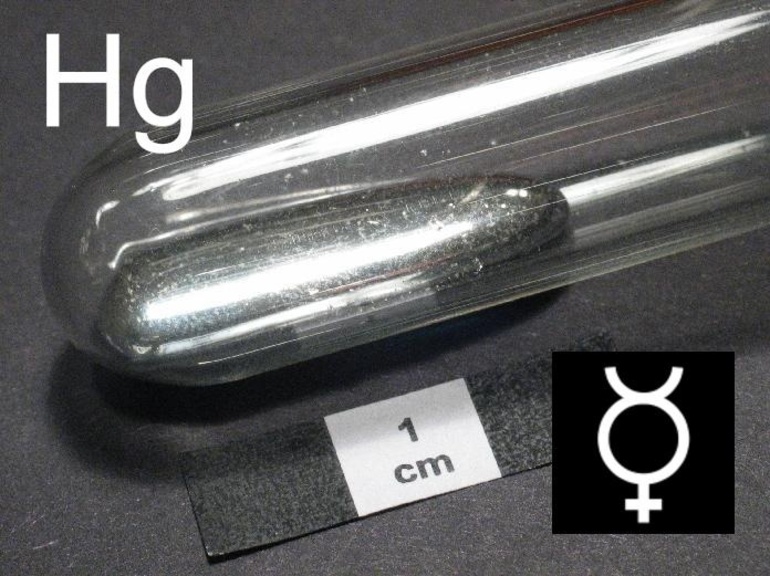

| Appearance | shiny, silvery liquid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Hg) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mercury in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 80 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Xe] 4f14 5d10 6s2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 18, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | liquid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 234.3210 K (−38.8290 °C, −37.8922 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 629.88 K (356.73 °C, 674.11 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 13.534 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Triple point | 234.3156 K, 1.65×10−7 kPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 1750 K, 172.00 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 2.29 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 59.11 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 27.983 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

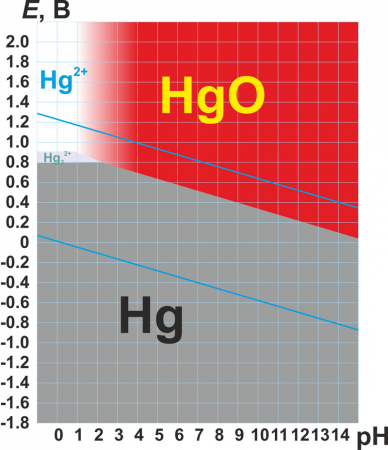

| Oxidation states | −2 , +1, +2 (a mildly basic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.00 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 151 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 132±5 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 155 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of mercury |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | rhombohedral

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound | liquid: 1451.4 m/s (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 60.4 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 8.30 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 961 nΩ⋅m (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | −33.44×10−6 cm3/mol (293 K)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7439-97-6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Ancient Egyptians (before 1500 BCE) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Symbol | «Hg»: from its Latin name hydrargyrum, itself from Greek hydrárgyros, ‘water-silver’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Main isotopes of mercury

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Mercury is a chemical element with the symbol Hg and atomic number 80. It is also known as quicksilver and was formerly named hydrargyrum ( hy-DRAR-jər-əm) from the Greek words hydor (water) and argyros (silver).[4] A heavy, silvery d-block element, mercury is the only metallic element that is known to be liquid at standard temperature and pressure; the only other element that is liquid under these conditions is the halogen bromine, though metals such as caesium, gallium, and rubidium melt just above room temperature.

Mercury occurs in deposits throughout the world mostly as cinnabar (mercuric sulfide). The red pigment vermilion is obtained by grinding natural cinnabar or synthetic mercuric sulfide.

Mercury is used in thermometers, barometers, manometers, sphygmomanometers, float valves, mercury switches, mercury relays, fluorescent lamps and other devices, though concerns about the element’s toxicity have led to mercury thermometers and sphygmomanometers being largely phased out in clinical environments in favor of alternatives such as alcohol- or galinstan-filled glass thermometers and thermistor- or infrared-based electronic instruments. Likewise, mechanical pressure gauges and electronic strain gauge sensors have replaced mercury sphygmomanometers.

Mercury remains in use in scientific research applications and in amalgam for dental restoration in some locales. It is also used in fluorescent lighting. Electricity passed through mercury vapor in a fluorescent lamp produces short-wave ultraviolet light, which then causes the phosphor in the tube to fluoresce, making visible light.

Mercury poisoning can result from exposure to water-soluble forms of mercury (such as mercuric chloride or methylmercury), by inhalation of mercury vapor, or by ingesting any form of mercury.

Properties

Physical properties

Mercury is a heavy, silvery-white metal that is liquid at room temperature. Compared to other metals, it is a poor conductor of heat, but a fair conductor of electricity.[6]

It has a freezing point of −38.83 °C and a boiling point of 356.73 °C,[7][8][9] both the lowest of any stable metal, although preliminary experiments on copernicium and flerovium have indicated that they have even lower boiling points.[10] This effect is due to lanthanide contraction and relativistic contraction reducing the radius of the outermost electrons, and thus weakening the metallic bonding in mercury.[8] Upon freezing, the volume of mercury decreases by 3.59% and its density changes from 13.69 g/cm3 when liquid to 14.184 g/cm3 when solid. The coefficient of volume expansion is 181.59 × 10−6 at 0 °C, 181.71 × 10−6 at 20 °C and 182.50 × 10−6 at 100 °C (per °C). Solid mercury is malleable and ductile and can be cut with a knife.[11]

Table of thermal and physical properties of liquid mercury:[12][13]

| Temperature (°C) | Density (kg/m^3) | Specific heat (kJ/kg K) | Kinematic viscosity (m^2/s) | Conductivity (W/m K) | Thermal diffusivity (m^2/s) | Prandtl Number | Bulk modulus (K^-1) |

| 0 | 13628.22 | 0.1403 | 1.24E-07 | 8.2 | 4.30E-06 | 0.0288 | 0.000181 |

| 20 | 13579.04 | 0.1394 | 1.14E-07 | 8.69 | 4.61E-06 | 0.0249 | 0.000181 |

| 50 | 13505.84 | 0.1386 | 1.04E-07 | 9.4 | 5.02E-06 | 0.0207 | 0.000181 |

| 100 | 13384.58 | 0.1373 | 9.28E-08 | 10.51 | 5.72E-06 | 0.0162 | 0.000181 |

| 150 | 13264.28 | 0.1365 | 8.53E-08 | 11.49 | 6.35E-06 | 0.0134 | 0.000181 |

| 200 | 13144.94 | 0.157 | 8.02E-08 | 12.34 | 6.91E-06 | 0.0116 | 0.000181 |

| 250 | 13025.6 | 0.1357 | 7.65E-08 | 13.07 | 7.41E-06 | 0.0103 | 0.000183 |

| 315.5 | 12847 | 0.134 | 6.73E-08 | 14.02 | 8.15E-06 | 0.0083 | 0.000186 |

Chemical properties

Mercury does not react with most acids, such as dilute sulfuric acid, although oxidizing acids such as concentrated sulfuric acid and nitric acid or aqua regia dissolve it to give sulfate, nitrate, and chloride. Like silver, mercury reacts with atmospheric hydrogen sulfide. Mercury reacts with solid sulfur flakes, which are used in mercury spill kits to absorb mercury (spill kits also use activated carbon and powdered zinc).[14]

Amalgams

Mercury-discharge spectral calibration lamp

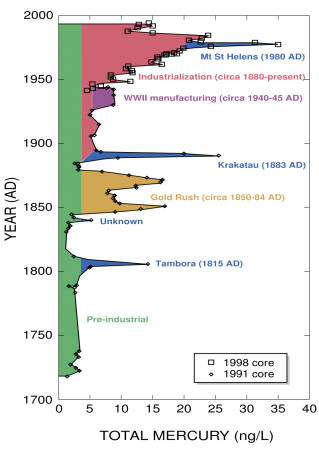

Mercury dissolves many metals such as gold and silver to form amalgams. Iron is an exception, and iron flasks have traditionally been used to trade mercury. Several other first row transition metals with the exception of manganese, copper and zinc are also resistant in forming amalgams. Other elements that do not readily form amalgams with mercury include platinum.[15][16] Sodium amalgam is a common reducing agent in organic synthesis, and is also used in high-pressure sodium lamps.

Mercury readily combines with aluminium to form a mercury-aluminium amalgam when the two pure metals come into contact. Since the amalgam destroys the aluminium oxide layer which protects metallic aluminium from oxidizing in-depth (as in iron rusting), even small amounts of mercury can seriously corrode aluminium. For this reason, mercury is not allowed aboard an aircraft under most circumstances because of the risk of it forming an amalgam with exposed aluminium parts in the aircraft.[17]

Mercury embrittlement is the most common type of liquid metal embrittlement.

Isotopes

There are seven stable isotopes of mercury, with 202

Hg being the most abundant (29.86%). The longest-lived radioisotopes are 194

Hg with a half-life of 444 years, and 203

Hg with a half-life of 46.612 days. Most of the remaining radioisotopes have half-lives that are less than a day. 199

Hg and 201

Hg are the most often studied NMR-active nuclei, having spins of 1⁄2 and 3⁄2 respectively.[6] For the synthesis of precious metals two stable mercury isotopes are of potential interest — the trace isotope 196

Hg and the more abundant 198

Hg. Both are «one neutron removed» from 197

Hg, a radioisotope which decays to 197

Au, the only known stable isotope of gold. However, the rarity of 196

Hg and the high energy requirements of nuclear reactions «knocking out» a neutron from 198

Hg (either via photodisintegration or via a (n,2n) reaction involving fast neutrons), have thus far ruled out practical application of this «real philosopher’s stone».

Etymology

The symbol for the planet Mercury (☿) has been used since ancient times to represent the element

«Hg» is the modern chemical symbol for mercury. It is an abbreviation of hydrargyrum, a romanized form of the ancient Greek name for mercury, ὑδράργυρος (hydrargyros). Hydrargyros is a Greek compound word meaning «water-silver», from ὑδρ— (hydr-), the root of ὕδωρ (hydor) «water», and ἄργυρος (argyros) «silver». Like the English name quicksilver («living-silver»), this name was due to mercury’s liquid and shiny properties.

The modern English name «mercury» comes from the planet Mercury. In medieval alchemy, the seven known metals—quicksilver, gold, silver, copper, iron, lead, and tin—were associated with the seven planets. Quicksilver was associated with the fastest planet, which had been named after the Roman god Mercury, who was associated with speed and mobility. The astrological symbol for the planet became one of the alchemical symbols for the metal, and «Mercury» became an alternative name for the metal. Mercury is the only metal for which the alchemical planetary name survives, as it was decided it was preferable to «quicksilver» as a chemical name.[18][19]

History

Mercury was found in Egyptian tombs that date from 1500 BC.[20]

In China and Tibet, mercury use was thought to prolong life, heal fractures, and maintain generally good health, although it is now known that exposure to mercury vapor leads to serious adverse health effects.[21] The first emperor of a unified China, Qín Shǐ Huáng Dì—allegedly buried in a tomb that contained rivers of flowing mercury on a model of the land he ruled, representative of the rivers of China—was reportedly killed by drinking a mercury and powdered jade mixture formulated by Qin alchemists intended as an elixir of immortality.[22][23] Khumarawayh ibn Ahmad ibn Tulun, the second Tulunid ruler of Egypt (r. 884–896), known for his extravagance and profligacy, reportedly built a basin filled with mercury, on which he would lie on top of air-filled cushions and be rocked to sleep.[24]

In November 2014 «large quantities» of mercury were discovered in a chamber 60 feet below the 1800-year-old pyramid known as the «Temple of the Feathered Serpent,» «the third largest pyramid of Teotihuacan,» Mexico along with «jade statues, jaguar remains, a box filled with carved shells and rubber balls».[25]

Aristotle recounts that Daedalus made a wooden statue of Venus move by pouring quicksilver in its interior.[26] In Greek mythology Daedalus gave the appearance of voice in his statues using quicksilver. The ancient Greeks used cinnabar (mercury sulfide) in ointments; the ancient Egyptians and the Romans used it in cosmetics. In Lamanai, once a major city of the Maya civilization, a pool of mercury was found under a marker in a Mesoamerican ballcourt.[27][28] By 500 BC mercury was used to make amalgams (Medieval Latin amalgama, «alloy of mercury») with other metals.[29]

Alchemists thought of mercury as the First Matter from which all metals were formed. They believed that different metals could be produced by varying the quality and quantity of sulfur contained within the mercury. The purest of these was gold, and mercury was called for in attempts at the transmutation of base (or impure) metals into gold, which was the goal of many alchemists.[18]

The mines in Almadén (Spain), Monte Amiata (Italy), and Idrija (now Slovenia) dominated mercury production from the opening of the mine in Almadén 2500 years ago, until new deposits were found at the end of the 19th century.[30]

Occurrence

Mercury is an extremely rare element in Earth’s crust, having an average crustal abundance by mass of only 0.08 parts per million (ppm).[31] Because it does not blend geochemically with those elements that constitute the majority of the crustal mass, mercury ores can be extraordinarily concentrated considering the element’s abundance in ordinary rock. The richest mercury ores contain up to 2.5% mercury by mass, and even the leanest concentrated deposits are at least 0.1% mercury (12,000 times average crustal abundance). It is found either as a native metal (rare) or in cinnabar, metacinnabar, sphalerite, corderoite, livingstonite and other minerals, with cinnabar (HgS) being the most common ore.[32][33] Mercury ores often occur in hot springs or other volcanic regions.[34]

Beginning in 1558, with the invention of the patio process to extract silver from ore using mercury, mercury became an essential resource in the economy of Spain and its American colonies. Mercury was used to extract silver from the lucrative mines in New Spain and Peru. Initially, the Spanish Crown’s mines in Almadén in Southern Spain supplied all the mercury for the colonies.[35] Mercury deposits were discovered in the New World, and more than 100,000 tons of mercury were mined from the region of Huancavelica, Peru, over the course of three centuries following the discovery of deposits there in 1563. The patio process and later pan amalgamation process continued to create great demand for mercury to treat silver ores until the late 19th century.[36]

Former mines in Italy, the United States and Mexico, which once produced a large proportion of the world supply, have now been completely mined out or, in the case of Slovenia (Idrija) and Spain (Almadén), shut down due to the fall of the price of mercury. Nevada’s McDermitt Mine, the last mercury mine in the United States, closed in 1992. The price of mercury has been highly volatile over the years and in 2006 was $650 per 76-pound (34.46 kg) flask.[37]

Mercury is extracted by heating cinnabar in a current of air and condensing the vapor. The equation for this extraction is

- HgS + O2 → Hg + SO2

In 2005, China was the top producer of mercury with almost two-thirds global share followed by Kyrgyzstan.[38]: 47 Several other countries are believed to have unrecorded production of mercury from copper electrowinning processes and by recovery from effluents.

Because of the high toxicity of mercury, both the mining of cinnabar and refining for mercury are hazardous and historic causes of mercury poisoning.[39] In China, prison labor was used by a private mining company as recently as the 1950s to develop new cinnabar mines. Thousands of prisoners were used by the Luo Xi mining company to establish new tunnels.[40] Worker health in functioning mines is at high risk.

A newspaper claimed that an unidentified European Union directive calling for energy-efficient lightbulbs to be made mandatory by 2012 encouraged China to re-open cinnabar mines to obtain the mercury required for CFL bulb manufacture. Environmental dangers have been a concern, particularly in the southern cities of Foshan and Guangzhou, and in Guizhou province in the southwest.[40]

Abandoned mercury mine processing sites often contain very hazardous waste piles of roasted cinnabar calcines. Water run-off from such sites is a recognized source of ecological damage. Former mercury mines may be suited for constructive re-use. For example, in 1976 Santa Clara County, California purchased the historic Almaden Quicksilver Mine and created a county park on the site, after conducting extensive safety and environmental analysis of the property.[41]

Chemistry

All known mercury compounds exhibit one of two positive oxidation states: I and II. Experiments have failed to unequivocally demonstrate any higher oxidation states: both the claimed 1976 electrosynthesis of an unstable Hg(III) species and 2007 cryogenic isolation of HgF4 have disputed interpretations and remain difficult (if not impossible) to reproduce.[42]

Compounds of mercury(I)

Unlike its lighter neighbors, cadmium and zinc, mercury usually forms simple stable compounds with metal-metal bonds. Most mercury(I) compounds are diamagnetic and feature the dimeric cation, Hg2+

2. Stable derivatives include the chloride and nitrate. Treatment of Hg(I) compounds complexation with strong ligands such as sulfide, cyanide, etc. induces disproportionation to Hg2+

and elemental mercury.[43] Mercury(I) chloride, a colorless solid also known as calomel, is really the compound with the formula Hg2Cl2, with the connectivity Cl-Hg-Hg-Cl. It is a standard in electrochemistry. It reacts with chlorine to give mercuric chloride, which resists further oxidation. Mercury(I) hydride, a colorless gas, has the formula HgH, containing no Hg-Hg bond.

Indicative of its tendency to bond to itself, mercury forms mercury polycations, which consist of linear chains of mercury centers, capped with a positive charge. One example is Hg2+

3(AsF−

6)

2.[44]

Compounds of mercury(II)

Mercury(II) is the most common oxidation state and is the main one in nature as well. All four mercuric halides are known. They form tetrahedral complexes with other ligands but the halides adopt linear coordination geometry, somewhat like Ag+ does. Best known is mercury(II) chloride, an easily sublimating white solid. HgCl2 forms coordination complexes that are typically tetrahedral, e.g. HgCl2−

4.

Mercury(II) oxide, the main oxide of mercury, arises when the metal is exposed to air for long periods at elevated temperatures. It reverts to the elements upon heating near 400 °C, as was demonstrated by Joseph Priestley in an early synthesis of pure oxygen.[14] Hydroxides of mercury are poorly characterized, as they are for its neighbors gold and silver.

Being a soft metal, mercury forms very stable derivatives with the heavier chalcogens. Preeminent is mercury(II) sulfide, HgS, which occurs in nature as the ore cinnabar and is the brilliant pigment vermillion. Like ZnS, HgS crystallizes in two forms, the reddish cubic form and the black zinc blende form.[6] The latter sometimes occurs naturally as metacinnabar.[33] Mercury(II) selenide (HgSe) and mercury(II) telluride (HgTe) are also known, these as well as various derivatives, e.g. mercury cadmium telluride and mercury zinc telluride being semiconductors useful as infrared detector materials.[45]

Mercury(II) salts form a variety of complex derivatives with ammonia. These include Millon’s base (Hg2N+), the one-dimensional polymer (salts of HgNH+

2)

n), and «fusible white precipitate» or [Hg(NH3)2]Cl2. Known as Nessler’s reagent, potassium tetraiodomercurate(II) (HgI2−

4) is still occasionally used to test for ammonia owing to its tendency to form the deeply colored iodide salt of Millon’s base.

Mercury fulminate is a detonator widely used in explosives.[6]

Organomercury compounds

Organic mercury compounds are historically important but are of little industrial value in the western world. Mercury(II) salts are a rare example of simple metal complexes that react directly with aromatic rings. Organomercury compounds are always divalent and usually two-coordinate and linear geometry. Unlike organocadmium and organozinc compounds, organomercury compounds do not react with water. They usually have the formula HgR2, which are often volatile, or HgRX, which are often solids, where R is aryl or alkyl and X is usually halide or acetate. Methylmercury, a generic term for compounds with the formula CH3HgX, is a dangerous family of compounds that are often found in polluted water.[46] They arise by a process known as biomethylation.

Applications

Mercury is used primarily for the manufacture of industrial chemicals or for electrical and electronic applications. It is used in some liquid-in-glass thermometers, especially those used to measure high temperatures. A still increasing amount is used as gaseous mercury in fluorescent lamps, while most of the other applications are slowly being phased out due to health and safety regulations. In some applications, mercury is replaced with less toxic but considerably more expensive Galinstan alloy.[47]

Medicine

Mercury and its compounds have been used in medicine, although they are much less common today than they once were, now that the toxic effects of mercury and its compounds are more widely understood. An example of the early therapeutic application of mercury of was published in 1787 by James Lind.[48]

The first edition of the Merck’s Manual (1899) featured many mercuric compounds[49] such as:

- Mercauro

- Mercuro-iodo-hemol.

- Mercury-ammonium chloride

- Mercury Benzoate

- Mercuric

- Mercury Bichloride (Corrosive Mercuric Chloride, U.S.P.)

- Mercury Chloride

- Mild Mercury Cyanide

- Mercury Succinimide

- Mercury Iodide

- Red Mercury Biniodide

- Mercury Iodide

- Yellow Mercury Proto-iodide

- Black (Hahnemann), Soluble Mercury Oxide

- Red Mercury Oxide

- Yellow Mercury Oxide

- Mercury Salicylate

- Mercury Succinimide

- Mercury Imido-succinate

- Mercury Sulphate

- Basic Mercury Subsulphate; Turpeth Mineral

- Mercury Tannate

- Mercury-Ammonium Chloride

Mercury is an ingredient in dental amalgams. Thiomersal (called Thimerosal in the United States) is an organic compound used as a preservative in vaccines, though this use is in decline.[50] Thiomersal is metabolized to ethyl mercury. Although it was widely speculated that this mercury-based preservative could cause or trigger autism in children, scientific studies showed no evidence supporting any such link.[51] Nevertheless, thiomersal has been removed from, or reduced to trace amounts in all U.S. vaccines recommended for children 6 years of age and under, with the exception of inactivated influenza vaccine.[52]

Another mercury compound, merbromin (Mercurochrome), is a topical antiseptic used for minor cuts and scrapes that is still in use in some countries.

Mercury in the form of one of its common ores, cinnabar, is used in various traditional medicines, especially in traditional Chinese medicine. Review of its safety has found that cinnabar can lead to significant mercury intoxication when heated, consumed in overdose, or taken long term, and can have adverse effects at therapeutic doses, though effects from therapeutic doses are typically reversible. Although this form of mercury appears to be less toxic than other forms, its use in traditional Chinese medicine has not yet been justified, as the therapeutic basis for the use of cinnabar is not clear.[53]

Today, the use of mercury in medicine has greatly declined in all respects, especially in developed countries. Thermometers and sphygmomanometers containing mercury were invented in the early 18th and late 19th centuries, respectively. In the early 21st century, their use is declining and has been banned in some countries, states and medical institutions. In 2002, the U.S. Senate passed legislation to phase out the sale of non-prescription mercury thermometers. In 2003, Washington and Maine became the first states to ban mercury blood pressure devices.[54] Mercury compounds are found in some over-the-counter drugs, including topical antiseptics, stimulant laxatives, diaper-rash ointment, eye drops, and nasal sprays. The FDA has «inadequate data to establish general recognition of the safety and effectiveness» of the mercury ingredients in these products.[55] Mercury is still used in some diuretics although substitutes now exist for most therapeutic uses.

Production of chlorine and caustic soda

Chlorine is produced from sodium chloride (common salt, NaCl) using electrolysis to separate the metallic sodium from the chlorine gas. Usually the salt is dissolved in water to produce a brine. By-products of any such chloralkali process are hydrogen (H2) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH), which is commonly called caustic soda or lye. By far the largest use of mercury[56][57] in the late 20th century was in the mercury cell process (also called the Castner-Kellner process) where metallic sodium is formed as an amalgam at a cathode made from mercury; this sodium is then reacted with water to produce sodium hydroxide.[58] Many of the industrial mercury releases of the 20th century came from this process, although modern plants claimed to be safe in this regard.[57] After about 1985, all new chloralkali production facilities that were built in the United States used membrane cell or diaphragm cell technologies to produce chlorine.

Laboratory uses

Some medical thermometers, especially those for high temperatures, are filled with mercury; they are gradually disappearing. In the United States, non-prescription sale of mercury fever thermometers has been banned since 2003.[59]

Some transit telescopes use a basin of mercury to form a flat and absolutely horizontal mirror, useful in determining an absolute vertical or perpendicular reference. Concave horizontal parabolic mirrors may be formed by rotating liquid mercury on a disk, the parabolic form of the liquid thus formed reflecting and focusing incident light. Such liquid-mirror telescopes are cheaper than conventional large mirror telescopes by up to a factor of 100, but the mirror cannot be tilted and always points straight up.[60][61][62]

Liquid mercury is a part of popular secondary reference electrode (called the calomel electrode) in electrochemistry as an alternative to the standard hydrogen electrode. The calomel electrode is used to work out the electrode potential of half cells.[63] Last, but not least, the triple point of mercury, −38.8344 °C, is a fixed point used as a temperature standard for the International Temperature Scale (ITS-90).[6]

In polarography both the dropping mercury electrode[64] and the hanging mercury drop electrode[65] use elemental mercury. This use allows a new uncontaminated electrode to be available for each measurement or each new experiment.

Mercury-containing compounds are also of use in the field of structural biology. Mercuric compounds such as mercury(II) chloride or potassium tetraiodomercurate(II) can be added to protein crystals in an effort to create heavy atom derivatives that can be used to solve the phase problem in X-ray crystallography via isomorphous replacement or anomalous scattering methods.

Niche uses

Gaseous mercury is used in mercury-vapor lamps and some «neon sign» type advertising signs and fluorescent lamps. Those low-pressure lamps emit very spectrally narrow lines, which are traditionally used in optical spectroscopy for calibration of spectral position. Commercial calibration lamps are sold for this purpose; reflecting a fluorescent ceiling light into a spectrometer is a common calibration practice.[66] Gaseous mercury is also found in some electron tubes, including ignitrons, thyratrons, and mercury arc rectifiers.[67] It is also used in specialist medical care lamps for skin tanning and disinfection.[68] Gaseous mercury is added to cold cathode argon-filled lamps to increase the ionization and electrical conductivity. An argon-filled lamp without mercury will have dull spots and will fail to light correctly. Lighting containing mercury can be bombarded/oven pumped only once. When added to neon filled tubes the light produced will be inconsistent red/blue spots until the initial burning-in process is completed; eventually it will light a consistent dull off-blue color.[69]

-

The deep violet glow of a mercury vapor discharge in a germicidal lamp, whose spectrum is rich in invisible ultraviolet radiation.

-

Skin tanner containing a low-pressure mercury vapor lamp and two infrared lamps, which act both as light source and electrical ballast

-

Assorted types of fluorescent lamps.

-

The miniaturized Deep Space Atomic Clock is a linear ion-trap-based mercury ion clock, designed for precise and real-time radio navigation in deep space.

The Deep Space Atomic Clock (DSAC) under development by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory utilises mercury in a linear ion-trap-based clock. The novel use of mercury allows very compact atomic clocks, with low energy requirements, and is therefore ideal for space probes and Mars missions.[70]

Cosmetics

Mercury, as thiomersal, is widely used in the manufacture of mascara. In 2008, Minnesota became the first state in the United States to ban intentionally added mercury in cosmetics, giving it a tougher standard than the federal government.[71]

A study in geometric mean urine mercury concentration identified a previously unrecognized source of exposure (skin care products) to inorganic mercury among New York City residents. Population-based biomonitoring also showed that mercury concentration levels are higher in consumers of seafood and fish meals.[72]

Skin whitening

Mercury is effective as an active ingredient in skin whitening compounds used to depigment skin.[73] The Minamata Convention on Mercury limits the concentration of mercury in such whiteners to 1 part per million. However, as of 2022, many commercially sold whitener products continue to exceed that limit, and are considered toxic.[74]

Firearms

Mercury(II) fulminate is a primary explosive which is mainly used as a primer of a cartridge in firearms.

Historic uses

A single-pole, single-throw (SPST) mercury switch

Many historic applications made use of the peculiar physical properties of mercury, especially as a dense liquid and a liquid metal:

- Quantities of liquid mercury ranging from 90 to 600 grams (3.2 to 21.2 oz) have been recovered from elite Maya tombs (100–700 AD)[25] or ritual caches at six sites. This mercury may have been used in bowls as mirrors for divinatory purposes. Five of these date to the Classic Period of Maya civilization (c. 250–900) but one example predated this.[75]

- In Islamic Spain, it was used for filling decorative pools. Later, the American artist Alexander Calder built a mercury fountain for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 World Exhibition in Paris. The fountain is now on display at the Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona.[76]

- Mercury was used inside wobbler lures. Its heavy, liquid form made it useful since the lures made an attractive irregular movement when the mercury moved inside the plug. Such use was stopped due to environmental concerns, but illegal preparation of modern fishing plugs has occurred.

- The Fresnel lenses of old lighthouses used to float and rotate in a bath of mercury which acted like a bearing.[77]

- Mercury sphygmomanometers (blood pressure meter), barometers, diffusion pumps, coulometers, and many other laboratory instruments took advantage of mercury’s properties as a very dense, opaque liquid with a nearly linear thermal expansion.[78]

- As an electrically conductive liquid, it was used in mercury switches (including home mercury light switches installed prior to 1970), tilt switches used in old fire detectors, and tilt switches in some home thermostats.[79]

- Owing to its acoustic properties, mercury was used as the propagation medium in delay-line memory devices used in early digital computers of the mid-20th century.

- Experimental mercury vapor turbines were installed to increase the efficiency of fossil-fuel electrical power plants.[80] The South Meadow power plant in Hartford, CT employed mercury as its working fluid, in a binary configuration with a secondary water circuit, for a number of years starting in the late 1920s in a drive to improve plant efficiency. Several other plants were built, including the Schiller Station in Portsmouth, NH, which went online in 1950. The idea did not catch on industry-wide due to the weight and toxicity of mercury, as well as the advent of supercritical steam plants in later years.[81][82]

- Similarly, liquid mercury was used as a coolant for some nuclear reactors; however, sodium is proposed for reactors cooled with liquid metal, because the high density of mercury requires much more energy to circulate as coolant.[83]

- Mercury was a propellant for early ion engines in electric space propulsion systems. Advantages were mercury’s high molecular weight, low ionization energy, low dual-ionization energy, high liquid density and liquid storability at room temperature. Disadvantages were concerns regarding environmental impact associated with ground testing and concerns about eventual cooling and condensation of some of the propellant on the spacecraft in long-duration operations. The first spaceflight to use electric propulsion was a mercury-fueled ion thruster developed at NASA Glenn Research Center and flown on the Space Electric Rocket Test «SERT-1» spacecraft launched by NASA at its Wallops Flight Facility in 1964. The SERT-1 flight was followed up by the SERT-2 flight in 1970. Mercury and caesium were preferred propellants for ion engines until Hughes Research Laboratory performed studies finding xenon gas to be a suitable replacement. Xenon is now the preferred propellant for ion engines as it has a high molecular weight, little or no reactivity due to its noble gas nature, and has a high liquid density under mild cryogenic storage.[84][85]

Other applications made use of the chemical properties of mercury:

- The mercury battery is a non-rechargeable electrochemical battery, a primary cell, that was common in the middle of the 20th century. It was used in a wide variety of applications and was available in various sizes, particularly button sizes. Its constant voltage output and long shelf life gave it a niche use for camera light meters and hearing aids. The mercury cell was effectively banned in most countries in the 1990s due to concerns about the mercury contaminating landfills.[86]

- Mercury was used for preserving wood, developing daguerreotypes, silvering mirrors, anti-fouling paints (discontinued in 1990), herbicides (discontinued in 1995), interior latex paint, handheld maze games, cleaning, and road leveling devices in cars. Mercury compounds have been used in antiseptics, laxatives, antidepressants, and in antisyphilitics.

- It was allegedly used by allied spies to sabotage Luftwaffe planes: a mercury paste was applied to bare aluminium, causing the metal to rapidly corrode; this would cause structural failures.[87]

- Chloralkali process: The largest industrial use of mercury during the 20th century was in electrolysis for separating chlorine and sodium from brine; mercury being the anode of the Castner-Kellner process. The chlorine was used for bleaching paper (hence the location of many of these plants near paper mills) while the sodium was used to make sodium hydroxide for soaps and other cleaning products. This usage has largely been discontinued, replaced with other technologies that utilize membrane cells.[88]

- As electrodes in some types of electrolysis, batteries (mercury cells), sodium hydroxide and chlorine production, handheld games, catalysts, insecticides.

- Mercury was once used as a gun barrel bore cleaner.[89][90]

- From the mid-18th to the mid-19th centuries, a process called «carroting» was used in the making of felt hats. Animal skins were rinsed in an orange solution (the term «carroting» arose from this color) of the mercury compound mercuric nitrate, Hg(NO3)2·2H2O.[91] This process separated the fur from the pelt and matted it together. This solution and the vapors it produced were highly toxic. The United States Public Health Service banned the use of mercury in the felt industry in December 1941. The psychological symptoms associated with mercury poisoning inspired the phrase «mad as a hatter». Lewis Carroll’s «Mad Hatter» in his book Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was a play on words based on the older phrase, but the character himself does not exhibit symptoms of mercury poisoning.[92]

- Gold and silver mining. Historically, mercury was used extensively in hydraulic gold mining in order to help the gold to sink through the flowing water-gravel mixture. Thin gold particles may form mercury-gold amalgam and therefore increase the gold recovery rates.[6] Large-scale use of mercury stopped in the 1960s. However, mercury is still used in small scale, often clandestine, gold prospecting. It is estimated that 45,000 metric tons of mercury used in California for placer mining have not been recovered.[93] Mercury was also used in silver mining.[94]

Historic medicinal uses

Mercury(I) chloride (also known as calomel or mercurous chloride) has been used in traditional medicine as a diuretic, topical disinfectant, and laxative. Mercury(II) chloride (also known as mercuric chloride or corrosive sublimate) was once used to treat syphilis (along with other mercury compounds), although it is so toxic that sometimes the symptoms of its toxicity were confused with those of the syphilis it was believed to treat.[95] It is also used as a disinfectant. Blue mass, a pill or syrup in which mercury is the main ingredient, was prescribed throughout the 19th century for numerous conditions including constipation, depression, child-bearing and toothaches.[96] In the early 20th century, mercury was administered to children yearly as a laxative and dewormer, and it was used in teething powders for infants. The mercury-containing organohalide merbromin (sometimes sold as Mercurochrome) is still widely used but has been banned in some countries such as the U.S.[97]

Toxicity and safety

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling: | |

|

Pictograms |

|

|

Signal word |

Danger |

|

Hazard statements |

H330, H360D, H372, H410 |

|

Precautionary statements |

P201, P233, P260, P273, P280, P304, P308, P310, P313, P340, P391, P403[98] |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

2 0 0 |

Mercury and most of its compounds are extremely toxic and must be handled with care; in cases of spills involving mercury (such as from certain thermometers or fluorescent light bulbs), specific cleaning procedures are used to avoid exposure and contain the spill.[99] Protocols call for physically merging smaller droplets on hard surfaces, combining them into a single larger pool for easier removal with an eyedropper, or for gently pushing the spill into a disposable container. Vacuum cleaners and brooms cause greater dispersal of the mercury and should not be used. Afterwards, fine sulfur, zinc, or some other powder that readily forms an amalgam (alloy) with mercury at ordinary temperatures is sprinkled over the area before itself being collected and properly disposed of. Cleaning porous surfaces and clothing is not effective at removing all traces of mercury and it is therefore advised to discard these kinds of items should they be exposed to a mercury spill.

Mercury can be absorbed through the skin and mucous membranes and mercury vapors can be inhaled, so containers of mercury are securely sealed to avoid spills and evaporation. Heating of mercury, or of compounds of mercury that may decompose when heated, should be carried out with adequate ventilation in order to minimize exposure to mercury vapor. The most toxic forms of mercury are its organic compounds, such as dimethylmercury and methylmercury. Mercury can cause both chronic and acute poisoning.

Releases in the environment

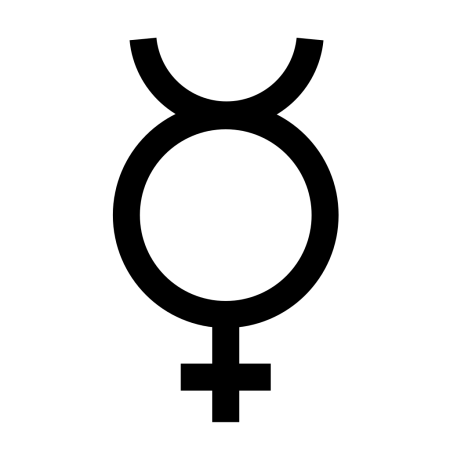

Amount of atmospheric mercury deposited at Wyoming’s Upper Fremont Glacier over the last 270 years

Preindustrial deposition rates of mercury from the atmosphere may be about 4 ng /(1 L of ice deposit). Although that can be considered a natural level of exposure, regional or global sources have significant effects. Volcanic eruptions can increase the atmospheric source by 4–6 times.[100]

Natural sources, such as volcanoes, are responsible for approximately half of atmospheric mercury emissions. The human-generated half can be divided into the following estimated percentages:[101][102][103]

- 65% from stationary combustion, of which coal-fired power plants are the largest aggregate source (40% of U.S. mercury emissions in 1999). This includes power plants fueled with gas where the mercury has not been removed. Emissions from coal combustion are between one and two orders of magnitude higher than emissions from oil combustion, depending on the country.[101]

- 11% from gold production. The three largest point sources for mercury emissions in the U.S. are the three largest gold mines. Hydrogeochemical release of mercury from gold-mine tailings has been accounted as a significant source of atmospheric mercury in eastern Canada.[104]

- 6.8% from non-ferrous metal production, typically smelters.

- 6.4% from cement production.

- 3.0% from waste disposal, including municipal and hazardous waste, crematoria, and sewage sludge incineration.

- 3.0% from caustic soda production.

- 1.4% from pig iron and steel production.

- 1.1% from mercury production, mainly for batteries.

- 2.0% from other sources.

The above percentages are estimates of the global human-caused mercury emissions in 2000, excluding biomass burning, an important source in some regions.[101]

Recent atmospheric mercury contamination in outdoor urban air was measured at 0.01–0.02 μg/m3. A 2001 study measured mercury levels in 12 indoor sites chosen to represent a cross-section of building types, locations and ages in the New York area. This study found mercury concentrations significantly elevated over outdoor concentrations, at a range of 0.0065 – 0.523 μg/m3. The average was 0.069 μg/m3.[105]

Artificial lakes, or reservoirs, may be contaminated with mercury due to the absorption by the water of mercury from submerged trees and soil.

For example, Williston Lake in northern British Columbia, created by the damming of the Peace River in 1968, is still sufficiently contaminated with mercury that it is inadvisable to consume fish from the lake.[106][107] Permafrost soils have accumulated mercury through atmospheric deposition,[108] and permafrost thaw in cryospheric regions is also a mechanism of mercury release into lakes, rivers, and wetlands.[109][110]

Mercury also enters into the environment through the improper disposal (e.g., land filling, incineration) of certain products. Products containing mercury include: auto parts, batteries, fluorescent bulbs, medical products, thermometers, and thermostats.[111] Due to health concerns (see below), toxics use reduction efforts are cutting back or eliminating mercury in such products. For example, the amount of mercury sold in thermostats in the United States decreased from 14.5 tons in 2004 to 3.9 tons in 2007.[112]

Most thermometers now use pigmented alcohol instead of mercury. Mercury thermometers are still occasionally used in the medical field because they are more accurate than alcohol thermometers, though both are commonly being replaced by electronic thermometers and less commonly by galinstan thermometers. Mercury thermometers are still widely used for certain scientific applications because of their greater accuracy and working range.

Historically, one of the largest releases was from the Colex plant, a lithium isotope separation plant at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The plant operated in the 1950s and 1960s. Records are incomplete and unclear, but government commissions have estimated that some two million pounds of mercury are unaccounted for.[113]

A serious industrial disaster was the dumping of waste mercury compounds into Minamata Bay, Japan, between 1932 and 1968. It is estimated that over 3,000 people suffered various deformities, severe mercury poisoning symptoms or death from what became known as Minamata disease.[114][115]

The tobacco plant readily absorbs and accumulates heavy metals such as mercury from the surrounding soil into its leaves. These are subsequently inhaled during tobacco smoking.[116] While mercury is a constituent of tobacco smoke,[117] studies have largely failed to discover a significant correlation between smoking and Hg uptake by humans compared to sources such as occupational exposure, fish consumption, and amalgam tooth fillings.[118]

Sediment contamination

Sediments within large urban-industrial estuaries act as an important sink for point source and diffuse mercury pollution within catchments.[119] A 2015 study of foreshore sediments from the Thames estuary measured total mercury at 0.01 to 12.07 mg/kg with mean of 2.10 mg/kg and median of 0.85 mg/kg (n=351).[119] The highest mercury concentrations were shown to occur in and around the city of London in association with fine grain muds and high total organic carbon content.[119] The strong affinity of mercury for carbon rich sediments has also been observed in salt marsh sediments of the River Mersey mean of 2 mg/kg up to 5 mg/kg.[120] These concentrations are far higher than those shown in salt marsh river creek sediments of New Jersey and mangroves of Southern China which exhibit low mercury concentrations of about 0.2 mg/kg.[121][122]

Occupational exposure

EPA workers clean up residential mercury spill in 2004

Due to the health effects of mercury exposure, industrial and commercial uses are regulated in many countries. The World Health Organization, OSHA, and NIOSH all treat mercury as an occupational hazard, and have established specific occupational exposure limits. Environmental releases and disposal of mercury are regulated in the U.S. primarily by the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

Fish

Fish and shellfish have a natural tendency to concentrate mercury in their bodies, often in the form of methylmercury, a highly toxic organic compound of mercury. Species of fish that are high on the food chain, such as shark, swordfish, king mackerel, bluefin tuna, albacore tuna, and tilefish contain higher concentrations of mercury than others. Because mercury and methylmercury are fat soluble, they primarily accumulate in the viscera, although they are also found throughout the muscle tissue.[123] Mercury presence in fish muscles can be studied using non-lethal muscle biopsies.[124] Mercury present in prey fish accumulates in the predator that consumes them. Since fish are less efficient at depurating than accumulating methylmercury, methylmercury concentrations in the fish tissue increase over time. Thus species that are high on the food chain amass body burdens of mercury that can be ten times higher than the species they consume. This process is called biomagnification. Mercury poisoning happened this way in Minamata, Japan, now called Minamata disease.

Cosmetics

Some facial creams contain dangerous levels of mercury. Most contain comparatively non-toxic inorganic mercury, but products containing highly toxic organic mercury have been encountered.[125][126]

Effects and symptoms of mercury poisoning

Toxic effects include damage to the brain, kidneys and lungs. Mercury poisoning can result in several diseases, including acrodynia (pink disease), Hunter-Russell syndrome, and Minamata disease.

Symptoms typically include sensory impairment (vision, hearing, speech), disturbed sensation and a lack of coordination. The type and degree of symptoms exhibited depend upon the individual toxin, the dose, and the method and duration of exposure. Case–control studies have shown effects such as tremors, impaired cognitive skills, and sleep disturbance in workers with chronic exposure to mercury vapor even at low concentrations in the range 0.7–42 μg/m3.[127][128] A study has shown that acute exposure (4–8 hours) to calculated elemental mercury levels of 1.1 to 44 mg/m3 resulted in chest pain, dyspnea, cough, hemoptysis, impairment of pulmonary function, and evidence of interstitial pneumonitis.[129] Acute exposure to mercury vapor has been shown to result in profound central nervous system effects, including psychotic reactions characterized by delirium, hallucinations, and suicidal tendency. Occupational exposure has resulted in broad-ranging functional disturbance, including erethism, irritability, excitability, excessive shyness, and insomnia. With continuing exposure, a fine tremor develops and may escalate to violent muscular spasms. Tremor initially involves the hands and later spreads to the eyelids, lips, and tongue. Long-term, low-level exposure has been associated with more subtle symptoms of erethism, including fatigue, irritability, loss of memory, vivid dreams and depression.[130][131]

Treatment

Research on the treatment of mercury poisoning is limited. Currently available drugs for acute mercurial poisoning include chelators N-acetyl-D, L-penicillamine (NAP), British Anti-Lewisite (BAL), 2,3-dimercapto-1-propanesulfonic acid (DMPS), and dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA). In one small study including 11 construction workers exposed to elemental mercury, patients were treated with DMSA and NAP.[132] Chelation therapy with both drugs resulted in the mobilization of a small fraction of the total estimated body mercury. DMSA was able to increase the excretion of mercury to a greater extent than NAP.[133]

Regulations

International

140 countries agreed in the Minamata Convention on Mercury by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) to prevent emissions.[134] The convention was signed on 10 October 2013.[135]

United States

In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency is charged with regulating and managing mercury contamination. Several laws give the EPA this authority, including the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, and the Safe Drinking Water Act. Additionally, the Mercury-Containing and Rechargeable Battery Management Act, passed in 1996, phases out the use of mercury in batteries, and provides for the efficient and cost-effective disposal of many types of used batteries.[136] North America contributed approximately 11% of the total global anthropogenic mercury emissions in 1995.[137]

The United States Clean Air Act, passed in 1990, put mercury on a list of toxic pollutants that need to be controlled to the greatest possible extent. Thus, industries that release high concentrations of mercury into the environment agreed to install maximum achievable control technologies (MACT). In March 2005, the EPA promulgated a regulation[138] that added power plants to the list of sources that should be controlled and instituted a national cap and trade system. States were given until November 2006 to impose stricter controls, but after a legal challenge from several states, the regulations were struck down by a federal appeals court on 8 February 2008. The rule was deemed not sufficient to protect the health of persons living near coal-fired power plants, given the negative effects documented in the EPA Study Report to Congress of 1998.[139] However newer data published in 2015 showed that after introduction of the stricter controls mercury declined sharply, indicating that the Clean Air Act had its intended impact.[140]

The EPA announced new rules for coal-fired power plants on 22 December 2011.[141] Cement kilns that burn hazardous waste are held to a looser standard than are standard hazardous waste incinerators in the United States, and as a result are a disproportionate source of mercury pollution.[142]

European Union

In the European Union, the directive on the Restriction of the Use of Certain Hazardous Substances in Electrical and Electronic Equipment (see RoHS) bans mercury from certain electrical and electronic products, and limits the amount of mercury in other products to less than 1000 ppm.[143] There are restrictions for mercury concentration in packaging (the limit is 100 ppm for sum of mercury, lead, hexavalent chromium and cadmium) and batteries (the limit is 5 ppm).[144] In July 2007, the European Union also banned mercury in non-electrical measuring devices, such as thermometers and barometers. The ban applies to new devices only, and contains exemptions for the health care sector and a two-year grace period for manufacturers of barometers.[145]

Norway

Norway enacted a total ban on the use of mercury in the manufacturing and import/export of mercury products, effective 1 January 2008.[146] In 2002, several lakes in Norway were found to have a poor state of mercury pollution, with an excess of 1 μg/g of mercury in their sediment.[147]

In 2008, Norway’s Minister of Environment Development Erik Solheim said: «Mercury is among the most dangerous environmental toxins. Satisfactory alternatives to Hg in products are

available, and it is therefore fitting to induce a ban.»[148]

Sweden

Products containing mercury were banned in Sweden in 2009.[149][150]

Denmark

In 2008, Denmark also banned dental mercury amalgam,[148] except for molar masticating surface fillings in permanent (adult) teeth.

See also

- Mercury pollution in the ocean

- Red mercury

- COLEX process (isotopic separation)

References

- ^ «Standard Atomic Weights: Mercury». CIAAW. 2011.

- ^ «Magnetic Susceptibility of the Elements And Inorganic Compounds» (PDF). www-d0.fnal.gov. Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory: DØ Experiment (lagacy document). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2004. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ «Definition of hydrargyrum | Dictionary.com». Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2022. Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ «New 12-sided pound coin to enter circulation in March». BBC News. 1 January 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Hammond, C. R. «The Elements» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2008. in Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ Senese, F. «Why is mercury a liquid at STP?». General Chemistry Online at Frostburg State University. Archived from the original on 4 April 2007. Retrieved 1 May 2007.

- ^ a b Norrby, L.J. (1991). «Why is mercury liquid? Or, why do relativistic effects not get into chemistry textbooks?». Journal of Chemical Education. 68 (2): 110. Bibcode:1991JChEd..68..110N. doi:10.1021/ed068p110. S2CID 96003717.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. pp. 4.125–4.126. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ «Dynamic Periodic Table». www.ptable.com. Archived from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Simons, E. N. (1968). Guide to Uncommon Metals. Frederick Muller. p. 111.

- ^ Holman, Jack P. (2002). Heat Transfer (9th ed.). New York, NY: cGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. pp. 600–606. ISBN 9780072406559.

- ^ Incropera 1 Dewitt 2 Bergman 3 Lavigne 4, Frank P. 1 David P. 2 Theodore L. 3 Adrienne S. 4 (2007). Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer (6th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. pp. 941–950. ISBN 9780471457282.

- ^ a b Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Gmelin, Leopold (1852). Hand book of chemistry. Cavendish Society. pp. 103 (Na), 110 (W), 122 (Zn), 128 (Fe), 247 (Au), 338 (Pt). Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ^ Soratur (2002). Essentials of Dental Materials. Jaypee Brothers Publishers. p. 14. ISBN 978-81-7179-989-3. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016.

- ^ Vargel, C.; Jacques, M.; Schmidt, M. P. (2004). Corrosion of Aluminium. Elsevier. p. 158. ISBN 9780080444956.

- ^ a b Stillman, J. M. (2003). Story of Alchemy and Early Chemistry. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 7–9. ISBN 978-0-7661-3230-6.

- ^ Maurice Crosland (2004) Historical Studies in the Language of Chemistry

- ^ «Mercury and the environment — Basic facts». Environment Canada, Federal Government of Canada. 2004. Archived from the original on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2008.

- ^ «Mercury — Element of the ancients». Center for Environmental Health Sciences, Dartmouth College. Archived from the original on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ «Qin Shihuang». Ministry of Culture, People’s Republic of China. 2003. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 27 March 2008.

- ^ Wright, David Curtis (2001). The History of China. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 49. ISBN 9780313309403.

- ^ Sobernheim, Moritz (1987). «Khumārawaih». In Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor (ed.). E.J. Brill’s first encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936, Volume IV: ‘Itk–Kwaṭṭa. Leiden: BRILL. p. 973. ISBN 978-90-04-08265-6. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016.

- ^ a b Yuhas, Alan (24 April 2015). «Liquid mercury found under Mexican pyramid could lead to king’s tomb». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ De Anima. Chapter 3. 1907. CS1 maint: location (link)

- ^ Pendergast, David M. (6 August 1982). «Ancient maya mercury». Science. 217 (4559): 533–535. Bibcode:1982Sci…217..533P. doi:10.1126/science.217.4559.533. PMID 17820542. S2CID 39473822.

- ^ «Lamanai». Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ^ Hesse R W (2007). Jewelrymaking through history. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-313-33507-5.

- ^ Eisler, R. (2006). Mercury hazards to living organisms. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-9212-2.

- ^ Ehrlich, H. L.; Newman D. K. (2008). Geomicrobiology. CRC Press. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-8493-7906-2.

- ^ Rytuba, James J (2003). «Mercury from mineral deposits and potential environmental impact». Environmental Geology. 43 (3): 326–338. doi:10.1007/s00254-002-0629-5. S2CID 127179672.

- ^ a b «Metacinnabar: Mineral information, data and localities».

- ^ «Mercury Recycling in the United States in 2000» (PDF). USGS. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ Burkholder, M. & Johnson, L. (2008). Colonial Latin America. Oxford University Press. pp. 157–159. ISBN 978-0-19-504542-0.

- ^ Jamieson, R W (2000). Domestic Architecture and Power. Springer. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-306-46176-7.

- ^ Brooks, W. E. (2007). «Mercury» (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- ^

Hetherington, L. E.; Brown, T. J.; Benham, A. J.; Lusty, P. A. J.; Idoine, N. E. (2007). World mineral production: 2001–05 (PDF). Keyworth, Nottingham, UK: British Geological Survey (BGS), Natural Environment Research Council (NERC). ISBN 978-0-85272-592-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019. - ^ About the Mercury Rule Archived 1 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Act.credoaction.com (21 December 2011). Retrieved on 30 December 2012.

- ^ a b Sheridan, M. (3 May 2009). «‘Green’ Lightbulbs Poison Workers: hundreds of factory staff are being made ill by mercury used in bulbs destined for the West». The Sunday Times (of London, UK). Archived from the original on 17 May 2009.

- ^ Boulland M (2006). New Almaden. Arcadia Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-7385-3131-1.

- ^ For a general overview, see Riedel, S.; Kaupp, M. (2009). «The Highest Oxidation States of the Transition Metal Elements». Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 253 (5–6): 606–624. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2008.07.014.

The claimed 1976 synthesis is Deming, Richard L.; Allred, A. L.; Dahl, Alan R.; Herlinger, Albert W.; Kestner, Mark O. (July 1976). «Tripositive mercury. Low temperature electrochemical oxidation of 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecanemercury(II) tetrafluoroborate». Journal of the American Chemical Society. 98 (14): 4132–4137. doi:10.1021/ja00430a020; but note that Reidel & Kaupp cite more recent work arguing that the cyclam ligand is instead oxidized.

The claimed 2007 isolation is Xuefang Wang; Andrews, Lester; Riedel, Sebastian; Kaupp, Martin (2007). «Mercury Is a Transition Metal: The First Experimental Evidence for HgF4«. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46 (44): 8371–8375. doi:10.1002/anie.200703710. PMID 17899620, but the spectral identifications are disputed in Rooms, J. F.; Wilson, A. V.; Harvey, I.; Bridgeman, A. J.; Young, N. A. (2008). «Mercury-fluorine interactions: a matrix isolation investigation of Hg⋯F2, HgF2 and HgF4 in argon matrices». Phys Chem Chem Phys. 10 (31): 4594–605. Bibcode:2008PCCP…10.4594R. doi:10.1039/b805608k. PMID 18665309.

- ^ Henderson, W. (2000). Main group chemistry. Great Britain: Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-85404-617-1. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016.

- ^ Brown, I. D.; Gillespie, R. J.; Morgan, K. R.; Tun, Z.; Ummat, P. K. (1984). «Preparation and crystal structure of mercury hexafluoroniobate (Hg

3NbF

6) and mercury hexafluorotantalate (Hg

3TaF

6): mercury layer compounds». Inorganic Chemistry. 23 (26): 4506–4508. doi:10.1021/ic00194a020. - ^ Rogalski, A (2000). Infrared detectors. CRC Press. p. 507. ISBN 978-90-5699-203-3.

- ^ National Research Council (U.S.) – Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology (2000). Toxicological effects of methylmercury. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-07140-6.

- ^ Surmann, P; Zeyat, H (November 2005). «Voltammetric analysis using a self-renewable non-mercury electrode». Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 383 (6): 1009–13. doi:10.1007/s00216-005-0069-7. PMID 16228199. S2CID 22732411.

- ^ Lind, J (1787). «An Account of the Efficacy of Mercury in the Cure of Inflammatory Diseases, and the Dysentery». The London Medical Journal. 8 (Pt 1): 43–56. ISSN 0952-4177. PMC 5545546. PMID 29139904.

- ^ Merck’s Manual 1899 (First ed.). Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ FDA. «Thimerosal in Vaccines». Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 26 October 2006. Retrieved 25 October 2006.

- ^ Parker SK; Schwartz B; Todd J; Pickering LK (2004). «Thimerosal-containing vaccines and autistic spectrum disorder: a critical review of published original data». Pediatrics. 114 (3): 793–804. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.327.363. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-0434. PMID 15342856. S2CID 1752023. Erratum: Parker S, Todd J, Schwartz B, Pickering L (January 2005). «Thimerosal-containing vaccines and autistic spectrum disorder: a critical review of published original data». Pediatrics. 115 (1): 200. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-2402. PMID 15630018. S2CID 26700143.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - ^ «Thimerosal in vaccines». Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 6 September 2007. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- ^ Liu J; Shi JZ; Yu LM; Goyer RA; Waalkes MP (2008). «Mercury in traditional medicines: is cinnabar toxicologically similar to common mercurials?». Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood). 233 (7): 810–7. doi:10.3181/0712-MR-336. PMC 2755212. PMID 18445765.

- ^ «Two States Pass First-time Bans on Mercury Blood Pressure Devices». Health Care Without Harm. 2 June 2003. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2007.

- ^ «Title 21—Food and Drugs Chapter I—Food and Drug Administration Department of Health and Human Services Subchapter D—Drugs for Human Use Code of federal regulations». United States Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 1 May 2007.

- ^ «The CRB Commodity Yearbook (annual)». The CRB Commodity Yearbook: 173. 2000. ISSN 1076-2906.

- ^ a b Leopold, B. R. (2002). «Chapter 3: Manufacturing Processes Involving Mercury. Use and Release of Mercury in the United States» (PDF). National Risk Management Research Laboratory, Office of Research and Development, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Cincinnati, Ohio. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2007. Retrieved 1 May 2007.

- ^ «Chlorine Online Diagram of mercury cell process». Euro Chlor. Archived from the original on 2 September 2006. Retrieved 15 September 2006.

- ^ «Mercury Reduction Act of 2003». United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Environment and Public Works. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- ^ «Liquid-mirror telescope set to give stargazing a new spin». Govert Schilling. 14 March 2003. Archived from the original on 18 August 2003. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- ^ Gibson, B. K. (1991). «Liquid Mirror Telescopes: History». Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 85: 158. Bibcode:1991JRASC..85..158G.

- ^ «Laval University Liquid mirrors and adaptive optics group». Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ^ Brans, Y W; Hay W W (1995). Physiological monitoring and instrument diagnosis in perinatal and neonatal medicine. CUP Archive. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-521-41951-2.

- ^ Zoski, Cynthia G. (7 February 2007). Handbook of Electrochemistry. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-444-51958-0.

- ^ Kissinger, Peter; Heineman, William R. (23 January 1996). Laboratory Techniques in Electroanalytical Chemistry, Second Edition, Revised and Expanded (2nd ed.). CRC. ISBN 978-0-8247-9445-3.

- ^ Hopkinson, G. R.; Goodman, T. M.; Prince, S. R. (2004). A guide to the use and calibration of detector array equipment. SPIE Press. p. 125. Bibcode:2004gucd.book…..H. ISBN 978-0-8194-5532-1.

- ^ Howatson A H (1965). «Chapter 8». An Introduction to Gas Discharges. Oxford: Pergamon Press. ISBN 978-0-08-020575-5.

- ^ Milo G E; Casto B C (1990). Transformation of human diploid fibroblasts. CRC Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-8493-4956-0.

- ^ Shionoya, S. (1999). Phosphor handbook. CRC Press. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-8493-7560-6.

- ^ Robert L. Tjoelker; et al. (2016). «Mercury Ion Clock for a NASA Technology Demonstration Mission». IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control. 63 (7): 1034–1043. Bibcode:2016ITUFF..63.1034T. doi:10.1109/TUFFC.2016.2543738. PMID 27019481. S2CID 3245467.

- ^ «Mercury in your eye?». CIDPUSA. 16 February 2008. Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- ^ McKelvey W; Jeffery N; Clark N; Kass D; Parsons PJ. 2010 (2011). «Population-Based Inorganic Mercury Biomonitoring and the Identification of Skin Care Products as a Source of Exposure in New York City». Environ Health Perspect. 119 (2): 203–9. doi:10.1289/ehp.1002396. PMC 3040607. PMID 20923743.

- ^ Mohammed, Terry; Mohammed, Elisabeth; Bascombe, Shermel (9 October 2017). «The evaluation of total mercury and arsenic in skin bleaching creams commonly used in Trinidad and Tobago and their potential risk to the people of the Caribbean». Journal of Public Health Research. 6 (3): 1097. doi:10.4081/jphr.2017.1097. PMC 5736993. PMID 29291194.

- ^ Meera Senthilingam, «Skin whitening creams containing high levels of mercury continue to be sold on the world’s biggest e-commerce sites, new report finds», 9 March 2022, CNN https://www.cnn.com/2022/03/09/world/zmwg-skin-whitening-creams-mercury-ecommerce-sites-intl-cmd/index.html

- ^ Healy, Paul F.; Blainey, Marc G. (2011). «Ancient Maya Mosaic Mirrors: Function, Symbolism, And Meaning». Ancient Mesoamerica. 22 (2): 229–244 (241). doi:10.1017/S0956536111000241. S2CID 162282151.

- ^ Lew K. (2008). Mercury. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4042-1780-5.

- ^ Pearson L. F. (2003). Lighthouses. Osprey Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-7478-0556-4.

- ^ Ramanathan E. AIEEE Chemistry. Sura Books. p. 251. ISBN 978-81-7254-293-1.

- ^ Shelton, C. (2004). Electrical Installations. Nelson Thornes. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-7487-7979-6.

- ^ «Popular Science». The Popular Science Monthly. Bonnier Corporation. 118 (3): 40. 1931. ISSN 0161-7370.

- ^ Mueller, Grover C. (September 1929). Cheaper Power from Quicksilver. Popular Science.

- ^ Mercury as a Working Fluid. Museum of Retro Technology. 13 November 2008. Archived from the original on 21 February 2011.

- ^ Collier (1987). Introduction to Nuclear Power. Taylor & Francis. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-56032-682-3.

- ^ «Glenn Contributions to Deep Space 1». NASA. Archived from the original on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ «Electric space propulsion». Archived from the original on 30 May 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ «IMERC Fact Sheet: Mercury Use in Batteries». Northeast Waste Management Officials’ Association. January 2010. Archived from the original on 29 November 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ Gray, T. (22 September 2004). «The Amazing Rusting Aluminum». Popular Science. Archived from the original on 20 July 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ Dufault, Renee; Leblanc, Blaise; Schnoll, Roseanne; Cornett, Charles; Schweitzer, Laura; Wallinga, David; Hightower, Jane; Patrick, Lyn; Lukiw, Walter J. (2009). «Mercury from Chlor-alkali plants». Environmental Health. 8: 2. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-8-2. PMC 2637263. PMID 19171026. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012.

- ^ Francis, G. W. (1849). Chemical Experiments. D. Francis. p. 62.

- ^ Castles, W. T.; Kimball, V. F. (2005). Firearms and Their Use. Kessinger Publishing. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-4179-8957-7.

- ^ Lee, J. D. (1999). Concise Inorganic Chemistry. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-632-05293-6.

- ^ Waldron, H. A. (1983). «Did the Mad Hatter have mercury poisoning?». Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.). 287 (6409): 1961. doi:10.1136/bmj.287.6409.1961. PMC 1550196. PMID 6418283.

- ^ Alpers, C. N.; Hunerlach, M. P.; May, J. Y.; Hothem, R. L. «Mercury Contamination from Historical Gold Mining in California». U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 22 February 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ «Mercury amalgamation». Corrosion Doctors. Archived from the original on 19 May 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ Pimple, K. D.; Pedroni, J. A.; Berdon, V. (9 July 2002). «Syphilis in history». Poynter Center for the Study of Ethics and American Institutions at Indiana University-Bloomington. Archived from the original on 16 February 2005. Retrieved 17 April 2005.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Mayell, H. (17 July 2007). «Did Mercury in «Little Blue Pills» Make Abraham Lincoln Erratic?». National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 22 May 2008. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ^ «What happened to Mercurochrome?». 23 July 2004. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ «Mercury 294594». Sigma-Aldrich.

- ^ «Mercury: Spills, Disposal and Site Cleanup». Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- ^ «Glacial Ice Cores Reveal A Record of Natural and Anthropogenic Atmospheric Mercury Deposition for the Last 270 Years». United States Geological Survey (USGS). Archived from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 1 May 2007.

- ^ a b c Pacyna E G; Pacyna J M; Steenhuisen F; Wilson S (2006). «Global anthropogenic mercury emission inventory for 2000». Atmos Environ. 40 (22): 4048. Bibcode:2006AtmEn..40.4048P. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2006.03.041.

- ^ «What is EPA doing about mercury air emissions?». United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Archived from the original on 8 February 2007. Retrieved 1 May 2007.

- ^ Solnit, R. (September–October 2006). «Winged Mercury and the Golden Calf». Orion Magazine. Archived from the original on 5 October 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- ^ Maprani, Antu C.; Al, Tom A.; MacQuarrie, Kerry T.; Dalziel, John A.; Shaw, Sean A.; Yeats, Phillip A. (2005). «Determination of Mercury Evasion in a Contaminated Headwater Stream». Environmental Science & Technology. 39 (6): 1679–87. Bibcode:2005EnST…39.1679M. doi:10.1021/es048962j. PMID 15819225.

- ^ «Indoor Air Mercury» (PDF). newmoa.org. May 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ Meissner, Dirk (12 May 2015). «West Moberly First Nations concerned about mercury contamination in fish». CBC News. The Canadian Press. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Williston-Dinosaur Watershed Fish Mercury Investigation: 2017 Report» (PDF). Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program, Peace Region. June 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Schuster, Paul; Schaefer, Kevin; Aiken, George; Antweiler, Ronald; Dewild, John; et al. (2018). «Permafrost Stores a Globally Significant Amount of Mercury». Geophysical Research Letters. 45 (3): 1463–1471. Bibcode:2018GeoRL..45.1463S. doi:10.1002/2017GL075571.