Sake can be served in a wide variety of cups. Pictured is a sakazuki (a flat, saucer-like cup), an ochoko (a small, cylindrical cup), and a masu (a wooden, box-like cup) |

|

| Type | Alcoholic beverage |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Japan |

| Alcohol by volume | 15–22% |

| Ingredients | Rice, water, Aspergillus oryzae (kōji-kin)[a], yeast |

Sake bottle, Japan, c. 1740

Sake, also spelled saké (sake (酒, Sake) SAH-kee, SAK-ay;[3][4] also referred to as Japanese rice wine),[5] is an alcoholic beverage of Japanese origin made by fermenting rice that has been polished to remove the bran. Despite the name Japanese rice wine, sake, and indeed any East Asian rice wine (such as huangjiu and cheongju), is produced by a brewing process more akin to that of beer, where starch is converted into sugars which ferment into alcohol, whereas in wine, alcohol is produced by fermenting sugar that is naturally present in fruit, typically grapes.

The brewing process for sake differs from the process for beer, where the conversion from starch to sugar and then from sugar to alcohol occurs in two distinct steps. Like other rice wines, when sake is brewed, these conversions occur simultaneously. The alcohol content differs between sake, wine, and beer; while most beer contains 3–9% ABV, wine generally contains 9–16% ABV,[6] and undiluted sake contains 18–20% ABV (although this is often lowered to about 15% by diluting with water before bottling).

In Japanese, the character sake (kanji: 酒, Japanese pronunciation: [sake]) can refer to any alcoholic drink, while the beverage called sake in English is usually termed nihonshu (日本酒; meaning ‘Japanese alcoholic drink’). Under Japanese liquor laws, sake is labeled with the word seishu (清酒; ‘refined alcohol’), a synonym not commonly used in conversation.

In Japan, where it is the national beverage, sake is often served with special ceremony, where it is gently warmed in a small earthenware or porcelain bottle and sipped from a small porcelain cup called a sakazuki. As with wine, the recommended serving temperature of sake varies greatly by type.

Sake now enjoys an international reputation. Of the more than 800 junmai ginjō-shu evaluated by Robert Parker’s team, 78 received a score of 90 or more (eRobertParker,2016).[7]

History[edit]

Until the Kamakura period[edit]

The origin of sake is unclear; however, the method of fermenting rice into alcohol spread to Japan from China around 500BCE.[8] The earliest reference to the use of alcohol in Japan is recorded in the Book of Wei in the Records of the Three Kingdoms. This 3rd-century Chinese text speaks of Japanese drinking and dancing.[9]

Alcoholic beverages (酒, sake) are mentioned several times in the Kojiki, Japan’s first written history, which was compiled in 712. Bamforth (2005) places the probable origin of true sake (which is made from rice, water, and kōji mold (麹, Aspergillus oryzae)) in the Nara period (710–794).[10] The fermented food fungi traditionally used for making alcoholic beverages in China and Korea for a long time were fungi belonging to Rhizopus and Mucor, whereas in Japan, except in the early days, the fermented food fungus used for sake brewing was Aspergillus oryzae.[11][12][1] Some scholars believe the Japanese domesticated the mutated, detoxified Aspergillus flavus to give rise to Aspergillus oryzae.[12][13][14]

In the Heian period (794–1185), sake was used for religious ceremonies, court festivals, and drinking games.[10] Sake production was a government monopoly for a long time, but in the 10th century, temples and shrines began to brew sake, and they became the main centers of production for the next 500 years.

Muromachi period[edit]

Before the 1440s in the Muromachi period (1333-1573), the Buddhist temple Shōryaku-ji invented various innovative methods for making sake. Because these production methods are the origin of the basic production methods for sake brewing today, Shoryakuji is often said to be the birthplace of seishu (清酒). Until then, most sake had been nigorizake with a different process from today’s, but after that, clear seishu was established. The main production methods established by Shōryaku-ji are the use of all polished rice (morohaku zukuri, 諸白造り), three-stage fermentation (sandan zikomi, 三段仕込み), brewing of starter mash using acidic water produced by lactic acid fermentation (bodaimoto zukuri, 菩提酛づくり), and pasteurization (hiire, 火入れ). This method of producing starter mash is called bodaimoto, which is the origin of kimoto. These innovations made it possible to produce sake with more stable quality than before, even in temperate regions. These things are described in Goshu no nikki (ja:御酒之日記), the oldest known technical book on sake brewing written in 1355 or 1489, and Tamonin nikki (ja:多門院日記), a diary written between 1478 and 1618 by monks of Kōfuku-ji Temple in the Muromachi period.[15][16][17]

A huge tub (ja:桶) with a capacity of 10 koku (1,800 liters) was invented at the end of the Muromachi period, making it possible to mass-produce sake more efficiently than before. Until then, sake had been made in jars with a capacity of 1, 2, or 3 koku at the most, and some sake brewers used to make sake by arranging 100 jars.[18][19]

In the 16th century, the technique of distillation was introduced into the Kyushu district from Ryukyu.[9] The brewing of shōchū, called «Imo–sake» started and was sold at the central market in Kyoto.

Edo period[edit]

By the Genroku era (1688–1704) of the Edo period (1603–1867), a brewing method called hashira jōchū (柱焼酎) was developed in which a small amount of distilled alcohol (shōchū) was added to the mash to make it more aromatic and lighter in taste, while at the same preventing deterioration in quality. This originates from the distilled alcohol addition used in modern sake brewing.[20]

The Nada-Gogō area in Hyōgo Prefecture, the largest producer of modern sake, was formed during this period. When the population of Edo, modern-day Tokyo, began to grow rapidly in the early 1600s, brewers who made sake in inland areas such as Fushimi, Itami, and Ikeda moved to the Nada-Gogō area on the coast, where the weather and water quality were perfect for brewing sake and convenient for shipping it to Edo. In the Genroku era, when the culture of the chōnin class, the common people, prospered, the consumption of sake increased rapidly, and large quantities of taruzake (樽酒) were shipped to Edo. 80% of the sake drunk in Edo during this period was from Nada-Gogō. Many of today’s major sake producers, including Hakutsuru (ja:白鶴), Ōzeki (ja:大関), Niihonsakari (ja:日本盛), Kikumasamune (ja:菊正宗), Kenbishi (ja:剣菱) and Sawanotsuru, are breweries in Nada-Gogō.[21]

During this period, frequent natural disasters and bad weather caused rice shortages, and the Tokugawa shogunate issued sake brewing restrictions 61 times.[22] In the early Edo period, there was a sake brewing technique called shiki jōzō (四季醸造) that was optimized for each season. In 1667, the technique of kanzukuri (寒造り) for making sake in winter was improved, and in 1673, when the Tokugawa shogunate banned brewing other than kanzukuri because of a shortage of rice, the technique of sake brewing in the four seasons ceased, and it became common to make sake only in winter until industrial technology began to develop in the 20th century.[23] During this period, aged for three, five, or nine years, koshu (古酒) was a luxury, but its deliciousness was known to the common people.[22]

In the 18th century, Engelbert Kaempfer[24] and Isaac Titsingh[25] published accounts identifying sake as a popular alcoholic beverage in Japan, but Titsingh was the first to try to explain and describe the process of sake brewing. The work of both writers was widely disseminated throughout Europe at the beginning of the 19th century.[26]

From the Meiji era to the early Shōwa era[edit]

Starting around the beginning of the Meiji era (1868-1912), the technique for making sake began to develop rapidly. Breeding was actively carried out in various parts of Japan to produce sake rice optimized for sake brewing. Ise Nishiki developed in 1860, Omachi (ja:雄町) developed in 1866 and Shinriki developed in 1877 are the earliest representative varieties. In 1923, Yamada Nishiki, later called the «king of sake rice,» was produced.[23] Among more than 123 varieties of sake rice as of 2019, Yamada Nishiki ranks first in production and Omachi fourth.[27] The government opened the sake-brewing research institute in 1904, and in 1907 the first government-run sake-tasting competition was held. In 1904, the National Brewing Laboratory developed yamahai, a new method of making starter mash, and in 1910, a further improvement, sokujō, was developed.[23] Yeast strains specifically selected for their brewing properties were isolated, and enamel-coated steel tanks arrived. The government started hailing the use of enamel tanks as easy to clean, lasting forever, and devoid of bacterial problems. (The government considered wooden tubs (ja:桶) to be unhygienic because of the potential bacteria living in the wood.) Although these things are true, the government also wanted more tax money from breweries, as using wooden tubs means a significant amount of sake is lost to evaporation (approximately 3%), which could have otherwise been taxed. This was the temporary end of the wooden-tubs age of sake, and the use of wooden tubs in brewing was temporarily eliminated.[28]

In Japan, sake has long been taxed by the national government. In 1878, the liquor tax accounted for 12.3% of the national tax revenue, excluding local taxes, and in 1888 it was 26.4%, and in 1899 it was 38.8%, finally surpassing the land tax of 35.6%.[22] In 1899, the government banned home brewing in anticipation of financial pressure from the First Sino-Japanese War and in preparation for the Russo-Japanese War. Since home-brewed sake is tax-free, the logic was that by banning the home-brewing of sake, sales would increase, and more tax revenue would be collected. This was the end of home-brewed sake.[29] The Meiji government adopted a system in which taxes were collected when sake was finished, instead of levying taxes on the amount and price of sake at the time of sale to ensure more revenue from liquor taxes. The liquor tax for the sake produced in a given year had to be paid to the government during that fiscal year, so the breweries tried to make money by selling the sake as soon as possible. This destroyed the market for aged koshu, which had been popular until then, and it was only in 1955 that sake breweries began to make koshu again.[22]

When World War II brought rice shortages, the sake-brewing industry was hampered as the government discouraged the use of rice for brewing. As early as the late 17th century, it had been discovered that small amounts of distilled alcohol could be added to sake before pressing to extract aromas and flavors from the rice solids. During the war, large amounts of distilled alcohol and glucose were added to small quantities of rice mash, increasing the yield by as much as four times. A few breweries were producing «sake» that contained no rice. The quality of sake during this time varied considerably. Incidentally, as of 2022, so much distilled alcohol is not allowed to be added, and under the provisions of the Liquor Tax Act, 50% of the weight of rice is the upper limit for the most inexpensive sake classified as futsū-shu.[30]

Since the mid-Showa era[edit]

Postwar, breweries slowly recovered, and the quality of sake gradually increased. The term ginzō (吟造), which means carefully brewed sake, first appeared at the end of the Edo period, and the term ginjō (吟醸), which has the same meaning, first appeared in 1894. However, ginjō-shu (吟醸酒), which is popular in the world today, was created by the development of various sake production techniques from the 1930s to around 1975. From 1930 to 1931, a new type of rice milling machine was invented, which made it possible to make rice with a polishing ratio of about 50%, removing the miscellaneous taste derived from the surface part of the rice grain to make sake with a more aromatic and refreshing taste than before. In 1936, Yamada Nishiki, the most suitable sake rice for brewing ginjō-shu, became the recommended variety of Hyogo Prefecture. Around 1953, the «Kyokai yeast No. 9» (kyokai kyu-gō kōbo, 協会9号酵母) was invented, which produced fruit-like aromas like apples and bananas but also excelled in fermentation. From around 1965, more and more manufacturers began to work on the research and development of ginjō-shu, and by about 1968, the Kyokai yeast No. 9 began to be used throughout Japan. In the 1970s, temperature control technology in the mash production process improved dramatically. And by slowly fermenting rice at low temperatures using high-milled rice and a newly developed yeast, ginjō-shu with a fruity flavor was created. At that time, ginjō-shu was a special sake exhibited at competitive exhibitions and was not on the market. From around 1975, ginjō-shu began to be marketed and was widely distributed in the 1980s, and in 1990, with the definition of what can be labeled as ginjō-shu, more and more brewers began to sell ginjō-shu. The growing popularity of ginjō-shu has prompted research into yeast, and many yeasts with various aromas optimized for ginjō-shu have been developed.[31][32]

In 1973, the National Tax Agency’s brewing research institute developed kijōshu (貴醸酒).[33]

New players on the scene—beer, wine, and spirits—became popular in Japan, and in the 1960s, beer consumption surpassed sake for the first time. Sake consumption continued to decrease while the quality of sake steadily improved. While the rest of the world may be drinking more sake and the quality of sake has been increasing, sake production in Japan has been declining since the mid-1970s.[34] The number of sake breweries is also declining. While there were 3,229 breweries nationwide in fiscal 1975, the number had fallen to 1,845 in 2007.[35] In recent years, exports have rapidly increased due to the growing popularity of sake worldwide. Sake exports in 2021 were six times larger than those in 2009.[36] As of 2021, the value of Japan’s liquor exports was about 114.7 billion yen, with Japanese whiskey first at 46.1 billion yen and sake second at 40.2 billion yen.[37] Today, sake has become a world beverage with a few breweries in China, Southeast Asia, South America, North America, and Australia.[38]

More breweries are also turning to older methods of production. For example, since the 21st century, the use of wooden tubs has increased again due to the development of sanitary techniques. The use of wooden tubs for fermentation has the advantage of allowing various microorganisms living in the wood to affect sake, allowing more complex fermentation and producing sake with different characteristics. It is also known that the antioxidants contained in wood have a positive effect on sake.[39][40]

Oldest sake brewery[edit]

The oldest sake brewing company still in operation, as confirmed by historical documents, is the Sudo Honke in Kasama, Ibaraki, founded in 1141 during the Heian Period (794–1185).[41] Sudō Honke was also the first sake brewery to sell both namazake and hiyaoroshi. Hiyaoroshi refers to sake that is finished in winter, pasteurized once in early spring, stored and aged for a little while during the summer, and shipped in the fall without being pasteurized a second time.[42]

In terms of excavated archaeological evidence, the oldest known sake brewery is from the 15th century near an area that was owned by Tenryū-ji, in Ukyō-ku, Kyoto. Unrefined sake was squeezed out at the brewery, and there are about 180 holes (60 cm wide, 20 cm deep) for holding storage jars. A hollow (1.8 meter wide, 1 meter deep) for a pot to collect drops of pressed sake and 14th-century Bizen ware jars were also found. It is estimated to be utilized until the Onin War (1467–1477). Sake was brewed at Tenryū-ji during the Muromachi Period (1336–1573).[43]

Production[edit]

Sake brewery, Takayama, with a sugitama (杉玉) globe of cedar leaves indicating sake.

Rice[edit]

The rice used for brewing sake is called sakamai 酒米 (さかまい) (‘sake rice’), or officially shuzō kōtekimai 酒造好適米 (しゅぞうこうてきまい) (‘sake-brewing suitable rice’).[44] There are at least 123 types of sake rice in Japan.[27] Among these, Yamada Nishiki, Gohyakumangoku (ja:五百万石), Miyama Nishiki (ja:美山錦) and Omachi (ja:雄町) rice are popular.[27] The grain is larger, stronger (if a grain is small or weak, it will break in the process of polishing), and contains less protein and lipid than ordinary table rice. Because of the cost, ordinary table rice, which is cheaper than sake rice, is sometimes used for sake brewing, but because sake rice has been improved and optimized for sake brewing, few people eat it.[45][46]

Premium sake is mostly made from sake rice. However, non-premium sake is mostly made from table rice. According to the Japan Sake and Shochu Makers Association, premium sake makes up 25% of total sake production, and non-premium sake (futsushu) makes up 75% of sake production. In 2008, a total of 180,000 tons of polished rice were used in sake brewing, of which sake rice accounted for 44,000 tons (24%), and table rice accounted for 136,000 tons (76%).[47]

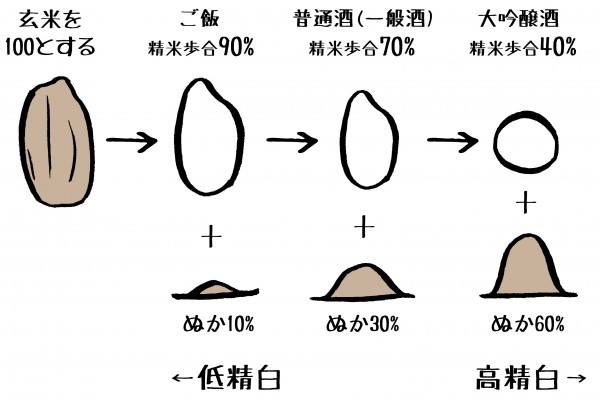

Sake rice is usually polished to a much higher degree than ordinary table rice. The reason for polishing is a result of the composition and structure of the rice grain itself. The core of the rice grain is rich in starch, while the outer layers of the grain contain higher concentrations of fats, vitamins, and proteins. Since a higher concentration of fat and protein in the sake would lead to off-flavors and contribute rough elements to the sake, the outer layers of the sake rice grain is milled away in a polishing process, leaving only the starchy part of the grain (some sake brewers remove over 60% of the rice grain in the polishing process). That desirable pocket of starch in the center of the grain is called the shinpaku (心白, しんぱく). It usually takes two to three days to polish rice down to less than half its original size. The rice powder by-product of polishing is often used for making rice crackers, Japanese sweets (i.e. Dango), and other food stuffs.[45][46]

If the sake is made with rice with a higher percentage of its husk and the outer portion of the core milled off, then more rice will be required to make that particular sake, which will take longer to produce. Thus, sake made with rice that has been highly milled is usually more expensive than sake that has been made with less-polished rice. This does not always mean that sake made with highly-milled rice is of better quality than sake made with rice milled less. Sake made with highly-milled rice has a strong aroma and a light taste without miscellaneous taste. It maximizes the fruity flavor of ginjō. On the other hand, sake made with less milled rice but with attention to various factors tends to have a rich sweetness and flavor derived from rice.[45][46]

Rice polishing ratio, called Seimai-buai 精米歩合 (せいまいぶあい) (see Glossary of sake terms) measures the degree of rice polishing. For example, a rice polishing ratio of 70% means that 70% of the original rice grain remains and 30% has been polished away.[48]

Water[edit]

Water is involved in almost every major sake brewing process, from washing the rice to diluting the final product before bottling. The mineral content of the water can be important in the final product. Iron will bond with an amino acid produced by the kōji to produce off flavors and a yellowish color. Manganese, when exposed to ultraviolet light, will also contribute to discoloration. Conversely, potassium, magnesium, and phosphoric acid serve as nutrients for yeast during fermentation and are considered desirable.[49] The yeast will use those nutrients to work faster and multiply resulting in more sugar being converted into alcohol. While soft water will typically yield sweeter sake, hard water with a higher nutrient content is known for producing drier-style sake.

The first region known for having great water was the Nada-Gogō in Hyōgo Prefecture. A particular water source called Miyamizu was found to produce high-quality sake and attracted many producers to the region. Today Hyōgo has the most sake brewers of any prefecture.[49]

Typically breweries obtain water from wells, though surface water can be used. Breweries may use tap water and filter and adjust components.[49]

Kōji-kin[edit]

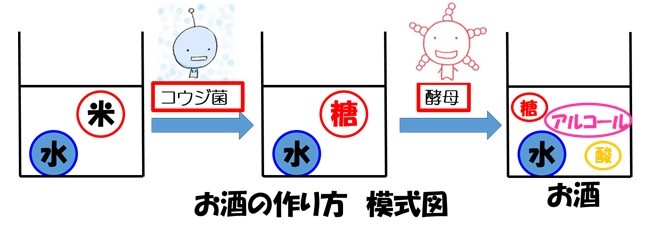

Kōji-kin (Aspergillus oryzae) spores are another important component of sake. Kōji-kin is an enzyme-secreting fungus.[50] In Japan, kōji-kin is used to make various fermented foods, including miso (a paste made from soybeans) and shoyu (soy sauce).[50] It is also used to make alcoholic beverages, notably sake.[50] During sake brewing, spores of kōji-kin are scattered over steamed rice to produce kōji (rice in which kōji-kin spores are cultivated).[51] Under warm and moist conditions, the kōji-kin spores germinate and release amylases (enzymes that convert the rice starches into maltose and glucose). This conversion of starch into simple sugars (e.g., glucose or maltose) is called saccharification. Yeast then ferment the glucose and other sugar into alcohol.[51] Saccharification also occurs in beer brewing, where mashing is used to convert starches from barley into maltose.[51] However, whereas fermentation occurs after saccharification in beer brewing, saccharification (via kōji-kin) and fermentation (via yeast) occur simultaneously in sake brewing (see «Fermentation» below).[51]

As kōji-kin is a microorganism used to manufacture food, its safety profile concerning humans and the environment in sake brewing and other food-making processes must be considered. Various health authorities, including Health Canada and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), consider kōji-kin (A. oryzae) generally safe for use in food fermentation, including sake brewing.[50] When assessing its safety, it is important to note that A. oryzae lacks the ability to produce toxins, unlike the closely related Aspergillus flavus.[50] To date, there have been several reported cases of animals (e.g. parrots, a horse) being infected with A. oryzae.[52] In these cases the animals infected with A. oryzae were already weakened due to predisposing conditions such as recent injury, illness or stress, hence were susceptible to infections in general.[52] Aside from these cases, there is no evidence to indicate A. oryzae is a harmful pathogen to either plants or animals in the scientific literature.[52] Therefore, Health Canada considers A. oryzae «unlikely to be a serious hazard to livestock or to other organisms,» including «healthy or debilitated humans.» [52] Given its safety record in the scientific literature and extensive history of safe use (spanning several hundred years) in the Japanese food industry, the FDA and World Health Organization (WHO) also support the safety of A. oryzae for use in the production of foods like sake.[50] In the US, the FDA classifies A.oryzae as a Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) organism.[50]

Fermentation[edit]

Moromi (the main fermenting mash) undergoing fermentation

Sake fermentation is a three-step process called sandan shikomi.[53] The first step, called hatsuzoe, involves steamed rice, water, and kōji-kin being added to the yeast starter called shubo: a mixture of steamed rice, water, kōji, and yeast.[53] This mixture becomes known as the moromi (the main mash during sake fermentation).[53] The high yeast content of the shubo promotes the fermentation of the moromi.[53]

On the second day, the mixture stands for a day to let the yeast multiply.[53]

The second step (the third day of the process), called nakazoe, involves the addition of a second batch of kōji, steamed rice, and water to the mixture.[53] On the fourth day of the fermentation, the third step of the process, called tomezoe, takes place.[53] Here, the third and final batch of kōji, steamed rice, and water is added to the mixture to complete the three-step process.[53]

The fermentation process of sake is a multiple parallel fermentation unique to sake.[53] Multiple parallel fermentation is the conversion of starch into glucose followed by immediate conversion into alcohol.[54] This process distinguishes sake from other liquors like beer because it occurs in a single vat, whereas with beer, for instance, starch-to-glucose conversion and glucose-to-alcohol conversion occur in separate vats.[54] The breakdown of starch into glucose is caused by the kōji-kin fungus, while the conversion of glucose into alcohol is caused by yeast.[54] Due to the yeast being available as soon as the glucose is produced, the conversion of glucose to alcohol is very efficient in sake brewing.[54] This results in sake having a generally higher alcohol content than other types of liquor.[54]

After the fermentation process is complete, the fermented moromi is pressed to remove the sake lees and then pasteurized and filtered for color.[53] The sake is then stored in bottles under cold conditions (see «Maturation» below).[53]

The process of making sake can range from 60–90 days (2–3 months), while the fermentation alone can take two weeks.[55] On the other hand, ginjō-shu takes about 30 days for fermentation alone.[31]

Maturation[edit]

Like other brewed beverages, sake tends to benefit from a period of storage. Nine to twelve months are required for the sake to mature. Maturation is caused by physical and chemical factors such as oxygen supply, the broad application of external heat, nitrogen oxides, aldehydes, and amino acids, among other unknown factors.[56]

Tōji[edit]

Tōji (杜氏) is the job title of the sake brewer, named after Du Kang. It is a highly respected job in the Japanese society, with tōji being regarded like musicians or painters. The title of tōji was historically passed from father to son. Today new tōji are either veteran brewery workers or are trained at universities. While modern breweries with cooling tanks operate year-round, most old-fashioned sake breweries are seasonal, operating only in the cool winter months. During the summer and fall, most tōji work elsewhere, commonly on farms, only periodically returning to the brewery to supervise storage conditions or bottling operations.[57]

Varieties[edit]

Special-designation sake[edit]

There are two basic types of sake: Futsū-shu (普通酒, ordinary sake) and Tokutei meishō-shu (特定名称酒, special-designation sake). Futsū-shu is the equivalent of table wine and accounts for 57% of sake production as of 2020.[58] Tokutei meishō-shu refers to premium sake distinguished by the degree to which the rice has been polished and the added percentage of brewer’s alcohol or the absence of such additives. There are eight varieties of special-designation sake.[59]

Ginjō (吟醸) is sake made using a special method called ginjō-zukuri (吟醸造り), in which rice is slowly fermented for about 30 days at a low temperature of 5 to 10 degrees Celsius (41 to 50 degrees Fahrenheit).[31] Sake made in ginjō-zukuri is characterized by fruity flavors like apples and bananas. In general, the flavor of sake tends to deteriorate when it is affected by ultraviolet rays or high temperatures, especially for sake made in ginjō-zukuri and unpasteurized namazake. Therefore, it is recommended that sake with the name ginjō be transported and stored in cold storage. It’s also recommended to drink chilled to maximize its fruity flavor.[60]

Junmai (純米) is a term used for the sake that is made of pure rice wine without any additional distilled alcohol.[61] Special-designation sake, which is not labeled Junmai, has an appropriate amount of distilled alcohol added. The maximum amount of distilled alcohol added to futsū-shu is 50% of the rice weight, mainly to increase the volume, while the maximum amount of distilled alcohol added to special-designation sake is 10% of the rice weight, to make the sake more aromatic and light in taste, and to prevent the growth of lactic acid bacteria, which deteriorate the flavor of the sake.[30][59] It is often misunderstood that the addition of distilled alcohol is of poor quality, but that is not the case with the addition of distilled alcohol to special-designation sake. Specifically, 78.3% of the sake entered in the Zenkoku shinshu kanpyōkai (全国新酒鑑評会, National New Sake Appraisal), the largest sake contest, had distilled alcohol added, and 91.1% of the winning sake had it added.[62] It should be noted, however, that the most important aspect of the contest is the brewing technique, not whether it tastes and flavor good or not.[63]

Sake made with highly-milled rice has a strong aroma and a light taste without miscellaneous taste. It maximizes the fruity flavor of ginjō. On the other hand, sake made with less milled rice but with attention to various factors tends to have a rich sweetness and flavor derived from rice.[45][46]

The certification requirements for special-designation sake must meet the conditions listed below, as well as the superior aroma and color specified by the National Tax Agency.[59]

The listing below often has the highest price at the top:

| Special Designation[59] | Ingredients[59] | Rice Polishing Ratio (percent rice remaining)[59] | Percentage of Kōji rice[59] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Junmai Daiginjō-shu (純米大吟醸酒, Pure rice, Great Choicest brew[31]) | Rice, Kōji rice | 50% or less, and produced by slowly fermenting rice at low temperatures of 5 to 10 degrees Celsius.[31] | At least 15% |

| Daiginjō-shu (大吟醸酒, Great Choicest brew) | Rice, Kōji rice, Distilled alcohol[note 1] | 50% or less, and produced by slowly fermenting rice at low temperatures of 5 to 10 degrees Celsius.[31] | At least 15% |

| Junmai Ginjō-shu (純米吟醸酒, Pure rice, Choicest brew) | Rice, Kōji rice | 60% or less, and produced by slowly fermenting rice at low temperatures of 5 to 10 degrees Celsius.[31] | At least 15% |

| Ginjō-shu (吟醸酒, Choicest brew) | Rice, Kōji rice, Distilled alcohol[note 1] | 60% or less, and produced by slowly fermenting rice at low temperatures of 5 to 10 degrees Celsius.[31] | At least 15% |

| Tokubetsu Junmai-shu (特別純米酒, Special pure rice) | Rice, Kōji rice | 60% or less, or produced by special brewing method[note 2] | At least 15% |

| Tokubetsu Honjōzō-shu (特別本醸造酒, Special Genuine brew) | Rice, Kōji rice, Distilled alcohol[note 1] | 60% or less, or produced by special brewing method[note 2] | At least 15% |

| Junmai-shu (純米酒, Pure rice) | Rice, Kōji rice | Regulations do not stipulate a rice polishing ratio[64] | At least 15% |

| Honjōzō-shu (本醸造酒, Genuine brew) | Rice, Kōji rice, Distilled alcohol[note 1] | 70% or less | At least 15% |

- ^ a b c d The weight of added alcohol must be below 10% of the weight of the rice (after polishing) used in the brewing process.

- ^ a b A special brewing method needs to be explained on the label.

Ways to make the starter mash[edit]

- Kimoto (生酛) is the traditional orthodox method for preparing the starter mash, which includes the laborious process of using poles to mix it into a paste, known as yama-oroshi. This method was the standard for 300 years, but it is rare today.

- Yamahai (山廃) is a simplified version of the kimoto method, introduced in the early 1900s. Yamahai skips the step of making a paste out of the starter mash. That step of the kimoto method is known as yama-oroshi, and the full name for yamahai is yama-oroshi haishi (山卸廃止), meaning ‘discontinuation of yama-oroshi. While the yamahai method was originally developed to speed production time compared to the kimoto method, it is slower than the modern method and is now used only in specialty brews for the earthy flavors it produces.

- Sokujō (速醸), ‘quick fermentation,’ is the modern method of preparing the starter mash. Lactic acid, produced naturally in the two slower traditional methods, is added to the starter to inhibit unwanted bacteria. Sokujō sake tends to have a lighter flavor than kimoto or yamahai.

Different handling after fermentation[edit]

The blue sake bottle displays «Yamada Nishiki» (山田錦) and «Junmai Daiginjo» (純米大吟醸) on the bottom label and «Bingakoi muroka nama genshu» (瓶囲無濾過生原酒) and «requiring refrigeration» (要冷蔵) on the top label. The label on the pink sake bottle indicates Usunigori muroka nama genshu.

The characteristics of sake listed below are generally described on the label attached to the sake bottle. For example, «Shiboritate muroka nama genshu» (しぼりたて無濾過生原酒) indicates that all the conditions of shiboritate, muroka, namazake and genshu below are satisfied.

- Namazake (生酒) is sake that has not been pasteurized. It requires refrigerated storage and has a shorter shelf-life than pasteurized sake. Since namazake is not pasteurized, it is generally characterized by a strong, fresh, sweet, and fruity flavor that is easy for beginners to enjoy. Also, because fermentation continues in the bottle, the change in flavor can be enjoyed over time, and some are effervescent due to the production of gases during fermentation.[65]

- Genshu (原酒) is undiluted sake. Most sake is diluted with water after brewing to lower the alcohol content from 18–20% down to 14–16%, but genshu is not.

- Muroka (無濾過) means unfiltered. It refers to sake that has not been carbon filtered but which has been pressed and separated from the lees and thus is clear, not cloudy. Carbon filtration can remove desirable flavors and odors as well as bad ones, thus muroka sake has stronger flavors than filtered varieties.

- Jikagumi (直汲み) is sake made by squeezing mash and putting the freshly made sake directly into a bottle without transferring it to a tank. It is generally effervescent and has a strong flavor because it is filled in the bottle with as little exposure to the air as possible to the freshest liquor that continues to ferment. It is a sake that maximizes the advantages of namazake or shinoritate.[66]

- Nigorizake (濁り酒) is cloudy sake. The sake is passed through a loose mesh to separate it from the mash. In the production process of nigorizake, rough cloth or colander is used to separate mash. It is not filtered after that, and there is much rice sediment in the bottle. It is generally characterized by its rich sweetness derived from rice. Nigorizake is sometimes unpasteurized namazake, which means that it is still fermenting and has a effervescent quality. Therefore, shaking the bottle or exposing it to high temperatures may cause the sake to spurt out of the bottle, so care should be taken when opening the bottle. When first opening the bottle, the cap should be slightly opened and then closed repeatedly to release the gas that has filled the bottle little by little.[67] To maximize the flavor of nigorizake, there are some tips on how to drink it. First drink only the clear supernatant, then close the cap and slowly turn the bottle upside down to mix the sediment with the clear sake to enjoy the change in flavor.[68]

- Origarami (おりがらみ) is a sake with less turbidity than nigorizake. Origarami is filtered differently from nigorizake and is filtered in the same way as ordinary sake. The reason mash lees are precipitated in the bottle is that the process of making ordinary sake, in which lees are precipitated and the supernatant is scooped up and bottled to complete the product, is omitted. Sake that is lightly cloudy like origarami is also called usunigori (薄濁り) or kasumizake (霞酒).[69]

- Seishu (清酒), ‘clear/clean sake,’ is the Japanese legal definition of sake and refers to sake in which the solids have been strained out, leaving clear liquid. Thus doburoku (see below) is not seishu and therefore are not actually sake under Japanese law. Although Nigorizake is cloudy, it is legally classified as seishu because it goes through the process of filtering through a mesh.[70]

- Koshu (古酒) is ‘aged sake’. Most sake does not age well, but this specially-made type can age for decades, turning yellow and acquiring a honeyed flavor.

- Taruzake (樽酒) is sake aged in wooden barrels or bottled in wooden casks. The wood used is Cryptomeria (杉, sugi), which is also known as Japanese cedar. Sake casks are often tapped ceremonially to open buildings, businesses, parties, etc. Because the wood imparts a strong flavor, premium sake is rarely used for this type.

- Shiboritate (搾立て), ‘freshly pressed,’ refers to sake that has been shipped without the traditional six-month aging/maturation period. The result is usually a more acidic, «greener» sake.

- Fukurozuri (袋吊り) is a method of separating sake from the lees without external pressure by hanging the mash in bags and allowing the liquid to drip out under its weight. Sake produced this way is sometimes called shizukuzake (雫酒), meaning ‘drip sake’.

- Tobingakoi (斗瓶囲い) is sake pressed into 18-liter (4.0 imp gal; 4.8 U.S. gal) bottles (tobin) with the brewer selecting the best sake of the batch for shipping.

Others[edit]

- Amazake (甘酒) is a traditional sweet, low-alcoholic Japanese drink made from fermented rice.

- Doburoku (濁酒) is the classic home-brew style of sake (although home brewing is illegal in Japan). It is created by simply adding kōji mold to steamed rice and water and letting the mixture ferment. It is sake made without separating mash. The resulting sake is somewhat like a chunkier version of nigorizake.

- Jizake (地酒) is locally brewed sake, the equivalent of microbrewing beer.

- Kijōshu (貴醸酒) is sake made using sake instead of water. A typical sake is made using 130 liters of water for every 100 kilograms of rice, while kijōshu is made using 70 liters of water and 60 liters of sake for every 100 kilograms of rice. Kijōshu is characterized by its unique rich sweetness, aroma and thickness, which can be best brought out when aged to an amber color. kijōshu is often more expensive than ordinary sake because it was developed in 1973 by the National Tax Agency’s brewing research institute for the purpose of making expensive sake that can be served at government banquets for state guests. The method of making sake using sake instead of water is similar to the sake brewing method called shiori described in the Engishiki compiled in 927. Because the term kijōshu is trademarked, sake makers not affiliated with the Kijōshu Association (貴醸酒協会) can not use the name. Therefore, when non-member sake manufacturers sell kijōshu, they use terms such as saijō jikomi (再醸仕込み) to describe the process.[33][71]

- Kuroshu (黒酒) is sake made from unpolished rice (i.e., brown rice), and is more like huangjiu.

- Teiseihaku-shu (低精白酒) is sake with a deliberately high rice-polishing ratio. It is generally held that the lower the rice polishing ratio (the percent weight after polishing), the better the potential of the sake. Circa 2005, teiseihaku-shu has been produced as a specialty sake made with high rice-polishing ratios, usually around 80%, to produce sake with the characteristic flavor of rice itself.

- Akaisake (赤い酒), literally ‘red sake,’ is produced by using red yeast rice kōji Monascus purpureus (紅麹, benikōji), giving the sake a pink-tinted appearance similar to rosé wine.[72]

Some other terms commonly used in connection with sake:

- Nihonshu-do (日本酒度), also called the Sake Meter Value or SMV

-

- Specific gravity is measured on a scale weighing the same volume of water at 4 °C (39 °F) and sake at 15 °C (59 °F). The sweeter the sake, the lower the number (or more negative); the drier the sake, the higher the number. When the SMV was first used, 0 was the point between sweet and dry sake. Now +3 is considered neutral.

- Seimai-buai (精米歩合) is the rice polishing ratio (or milling rate), the percentage of weight remaining after polishing. Generally, the lower the number, the higher the sake’s complexity. A lower percentage usually results in a fruitier and more complex sake, whereas a higher percentage will taste more like rice.

- Kasu (粕) are pressed sake lees, the solids left after pressing and filtering. These are used for making pickles, livestock feed, and shōchū, and as an ingredient in dishes like kasu soup.

Taste and flavor[edit]

The label on a bottle of sake gives a rough indication of its taste. Terms found on the label may include nihonshu-do (日本酒度), san-do (酸度), and aminosan-do (アミノ酸度).[73][failed verification]

Nihonshu-do (日本酒度) or Sake Meter Value (SMV) is calculated from the specific gravity of the sake and indicates the sugar and alcohol content of the sake on an arbitrary scale. Typical values are between −3 (sweet) and +10 (dry), equivalent to specific gravities ranging between 1.007 and 0.998, though the maximum range of Nihonshu-do can go much beyond that. The Nihonshu-do must be considered together with San-do to determine the overall perception of dryness-sweetness, richness-lightness characteristics of a sake (for example, a higher level of acidity can make a sweet sake taste drier than it actually is).[74][75]

San-do (酸度) indicates the concentration of acid, which is determined by titration with sodium hydroxide solution. This number equals the milliliters of titrant required to neutralize the acid in 10 mL (0.35 imp fl oz; 0.34 US fl oz) of sake.

Aminosan-do (アミノ酸度) indicates a taste of umami or savoriness. As the proportion of amino acids rises, the sake tastes more savory. This number is determined by titration of the sake with a mixture of sodium hydroxide solution and formaldehyde and is equal to the milliliters of titrant required to neutralize the amino acids in 10 mL of sake.

Sake can have many flavor notes, such as fruits, flowers, herbs, and spices. Many types of sake have notes of apple from ethyl caproate and banana from isoamyl acetate, particularly ginjōshu (吟醸酒).[76]

Serving sake[edit]

A glass of sake served at a Japanese restaurant in Lyon, France.

Overflowing glass inside a masu

«Sake Ewer from a Portable Picnic Set,» Japan, c. 1830–1839.

In Japan, sake is served chilled (reishu (冷酒)), at room temperature (jōon (常温)), or heated (atsukan 熱燗), depending on the preference of the drinker, the characteristics of the sake, and the season. Typically, hot sake is a winter drink, and high-grade sake is not usually drunk hot because the flavors and aromas may be lost. Most lower-quality sake is served hot because that is the traditional way, and it often tastes better that way, not so that flaws are covered up. There are gradations of temperature both for chilling and heating, about every 5 °C (9.0 °F), with hot sake generally served around 50 °C (122 °F), and chilled sake around 10 °C (50 °F), like white wine. Hot sake that has cooled (kanzamashi 燗冷まし) may be reheated.

Sake is traditionally drunk from small cups called choko or o-choko (お猪口) and poured into the choko from ceramic flasks called tokkuri. This is very common for hot sake, where the flask is heated in hot water, and the small cups ensure that the sake does not get cold in the cup, but it may also be used for chilled sake. Traditionally one does not pour one’s own drink, which is known as tejaku (手酌), but instead members of a party pour for each other, which is known as shaku (酌). This has relaxed in recent years but is generally observed on more formal occasions, such as business meals, and is still often observed for the first drink.

Another traditional cup is the masu, a box usually made of hinoki or sugi, which was originally used for measuring rice. The masu holds exactly one gō, 180.4 mL (6.35 imp fl oz; 6.10 US fl oz), so the sake is served by filling the masu to the brim; this is done for chilled or room temperature sake. In some Japanese restaurants, as a show of generosity, the server may put a glass inside the masu or put the masu on a saucer and pour until sake overflows and fills both containers.

Sake is traditionally served in units of gō, and this is still common, but other sizes are sometimes also available.

Saucer-like cups called sakazuki are also used, most commonly at weddings and other ceremonial occasions, such as the start of the year or the beginning of a kaiseki meal. In cheap bars, sake is often served at room temperature in glass tumblers and called koppu-zake (コップ酒). In more modern restaurants, wine glasses are also used, and recently footed glasses made specifically for premium sake have also come into use.

Traditionally sake is heated immediately before serving, but today restaurants may buy sake in boxes that can be heated in a specialized hot sake dispenser, thus allowing hot sake to be served immediately. However, this is detrimental to the flavor. There are also a variety of devices for heating sake and keeping it warm beyond the traditional tokkuri.

Aside from being served straight, sake can be used as a mixer for cocktails, such as tamagozake, saketinis, or nogasake.[77] Outside of Japan, the sake bomb, the origins of which are unclear,[78] has become a popular drink in bars and Asia-themed karaoke clubs.

The Japanese Sake Association encourages people to drink chaser water for their health, and the water is called Yawaragi-mizu.[79]

Seasonality[edit]

Sugitama (杉玉), globes of cedar leaves, at a brewery

Because the cooler temperatures make it more difficult for bacteria to grow, sake brewing traditionally took place mainly in winter, and this was especially true from 1673 during the Edo period until the early 20th century during the Showa era.[23] While it can now be brewed year-round, seasonality is still associated with sake, particularly artisanal ones. The most visible symbol of this is the sugitama (杉玉), a globe of cedar leaves traditionally hung outside a brewery when the new sake is brewed. The leaves start green but turn brown over time, reflecting the maturation of the sake. These are now hung outside many restaurants serving sake. The new year’s sake is called shinshu 新酒 (‘new sake’), and when initially released in late winter or early spring, many brewers have a celebration known as kurabiraki 蔵開き (warehouse opening). Traditionally sake was best transported in the cool spring to avoid spoilage in the summer heat, with a secondary transport in autumn, once the weather had cooled, known as hiyaoroshi 冷卸し (‘cold wholesale distribution’)—this autumn sake has matured over the summer.

Storage[edit]

Sake is sold in volume units divisible by 180 mL (6.3 imp fl oz; 6.1 US fl oz) (one gō), the traditional Japanese unit for cup size.[80] Sake is traditionally sold by the gō-sized cup, or in a 1.8 L (63 imp fl oz; 61 US fl oz) (one shō or ten gō)-sized flask (called an isshōbin, or ‘one shō-measure bottle’). Today sake is also often sold in 720 mL (25 imp fl oz; 24 US fl oz) bottles, which are divisible into four gō. Note that this is almost the same as the 750 mL (26 imp fl oz; 25 US fl oz) standard for wine bottles, which is divisible into four quarter bottles (187ml). Particularly in convenience stores, sake (generally of cheap quality) may be sold in a small 360 mL (13 imp fl oz; 12 US fl oz) bottle or a single serving 180 mL (6.3 imp fl oz; 6.1 US fl oz) (one gō) glass with a pull-off top (カップ酒 kappu-zake).

Generally, it is best to keep sake refrigerated in a cool or dark room, as prolonged exposure to heat or direct light will lead to spoilage. Sake stored at a relatively high temperature can lead to the formation of diketopiperazine, a cyclo (Pro-Leu) that makes it bitter as it ages [81] Sake has high microbiological stability due to its high content of ethanol, but incidences[spelling?] of spoilage have occurred. One of the microorganisms implicated in this spoilage is lactic acid bacteria (LAB) that has grown tolerant to ethanol and is referred to as hiochi-bacteria.[82] Sake stored at room temperature is best consumed within a few months after purchase.[83]

Sake can be stored for a long time due to its high alcohol content and has no use-by dates written on the bottle or label. However, there is a best before date for good drinking, and it depends on the type of sake, with the typical twice-pasteurized sake having a relatively long best before date. According to major sake brewer Gekkeikan, the best before date when unopened and stored in a dark place at about 20 degrees Celsius (68 degrees Fahrenheit) is one year after production for futsū-shu and honjōzō-shu, 10 months for ginjō-shu, junmai-shu, and sake pasteurized only once, and up to eight months for special namazake that can be distributed at room temperature.[84] According to Sawanotsuru, once pasteurized sake and unpasteurized namazake have a best before date of nine months after production.[85] Some sources also state that the best before date for unpasteurized namazake is three to six months after production. Namazake generally requires refrigeration at all times.[86][87] However, there are exceptions to these storage conditions, in which case the conditions are stated on the label. For example, sake under the brand name Aramasa (新政) must be kept refrigerated at all times, even if it is junmai-shu, which has been pasteurized.[88]

Once the sake is opened, it should be kept refrigerated, as the flavor deteriorates more quickly than before opening. Best before date after opening the bottle varies depending on the source. According to sake media outlet Sake no shizuku, which interviewed several major sake production companies, the responses from all companies were nearly identical. According to the responses, junmai type sake without added distilled alcohol has a best before date of 10 days after opening, while other types of sake with added distilled alcohol has a best before date of one month after opening.[89] According to the international sommelier of sake certified by SSI International, ginjō type sake, which is fermented at low temperature for a long time, has little flavor degradation for two to three days after opening and has a best before date of one week after opening. Other special designation sake and futsū-shu have little flavor degradation for 10 to 14 days after opening the bottle and have a best before date of one month after opening. Unpasteurized namazake deteriorates the fastest and should be drunk as soon as possible.[90]

These best before dates are shortened when stored at high temperatures or in bright places, especially under sunlight or fluorescent lights that emit ultraviolet rays.[90] On the other hand, the optimal temperature to minimize flavor degradation is minus 5 degrees Celsius (23 degrees Fahrenheit). It is also recommended that sake bottles be stored vertically. This is because if the bottle is placed horizontally, the sake is exposed to more air inside the bottle, which speeds up oxidation and may change the flavor when it comes in contact with the cap.[91]

If these types of sake, which were clear or white at first, turn yellow or brown, it is a sign that the flavor has deteriorated. The exception is aged koshu, which is amber in color from the time of shipment because it has been aged for several years to optimize its flavor.[85]

Ceremonial use[edit]

Sake is often consumed as part of Shinto purification rituals. Sake served to gods as offerings before drinking are called o-miki (御神酒) or miki (神酒).

In a ceremony called kagami biraki, wooden sake casks are opened with mallets during Shinto festivals, weddings, store openings, sports and election victories, and other celebrations. This sake, called iwai-zake (‘celebration sake’), is served freely to all to spread good fortune.

At the New Year, many Japanese people drink a special sake called toso. Toso is a sort of iwai-zake made by soaking tososan, a Chinese powdered medicine, overnight in sake. Even children sip a portion. In some regions, the first sips of toso are taken in order of age, from the youngest to the eldest.

-

A Shochikubai Komodaru (straw mat cask) of sake before the kagami biraki

Events[edit]

- October 1 is the official «Sake Day» (日本酒の日, Nihonshu no Hi) of Japan.[92] It is also called «World Sake Day». It was designated by the Japan Sake and Shochu Makers Association in 1978.

See also[edit]

- Amylolytic process

- Awamori, a distilled rice liquor produced in Okinawa

- The Birth of Saké

- Cheongju, a Korean equivalent

- Chuak, a Tripuri rice beer

- Glossary of sake terms

- Habushu, awamori liquor containing a snake

- Handia-an Indian equivalent.

- Kohama style, a method of sake brewing

- Mijiu, a Chinese equivalent

- Mirin, an essential condiment used in Japanese cuisine, which has been drunk as a sweet sake

- Toso, spiced medicinal sake

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Kenichiro Matsushima. 醤油づくりと麹菌の利用ー今までとこれからー (in Japanese). p. 643. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022.

- ^ 麹のこと Marukome co.,ltd.

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2011. p. 1546. ISBN 978-0-547-04101-8.

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Foreign Words and Phrases. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1997. p. 375. ISBN 0-19-860236-7.

- ^ «alcohol consumption». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- ^ Robinson, Jancis (2006). The Oxford Companion to Wine (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-19-860990-2.

- ^ Sato, Jun; Kohsaka, Ryo (June 2017). «Japanese s ake and evolution of technology: A comparative view with wine and its implications for regional branding and tourism». Journal of Ethnic Foods. 4 (2): 88–93. doi:10.1016/j.jef.2017.05.005.

- ^ «The History of Japanese Sake | JSS». Japan Sake and Shochu Makers Association | JSS (in Japanese). January 7, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ a b «sake | alcoholic beverage». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- ^ a b Morris, Ivan (1964). The World of the Shining Prince: Court Life in Ancient Japan. New York: Knopf.

- ^ Eiji Ichishima (March 20, 2015). 国際的に認知される日本の国菌 (in Japanese). Japan Society for Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Agrochemistry. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021.

- ^ a b Katsuhiko Kitamoto. 麹菌物語 (PDF) (in Japanese). The Society for Biotechnology, Japan. p. 424. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 31, 2022.

- ^ Katsuhiko Kitamoto. 家畜化された微生物、麹菌 その分子細胞生物学的解析から見えてきたこと (PDF) (in Japanese). The Society of Yeast Scientists. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 13, 2022.

- ^ Kiyoko Hayashi (July 19, 2021). 日本の発酵技術と歴史 (in Japanese). Discover Japan Inc. Archived from the original on November 10, 2022.

- ^ 清酒発祥の地 正暦寺 (in Japanese). Nara Prefecture. Archived from the original on October 11, 2021.

- ^ 正暦寺、清酒発祥の歴史 (in Japanese). Shōryaku-ji. Archived from the original on September 6, 2022.

- ^ Kazuha Seara (June 5, 2020). 原点回帰の「新」製法? — 菩提酛(ぼだいもと)、水酛(みずもと)を学ぶ (in Japanese). Sake street. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022.

- ^ 第七話 十石桶が出現 (in Japanese). Kikusui. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022.

- ^ 日本酒の「容器・流通イノベーション」の歴史と現在地 (in Japanese). Sake street. June 3, 2020. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022.

- ^ 九州人が日本酒復権に挑む、柱焼酎造りを復活 (in Japanese). Jyokai Times. July 13, 2005. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022.

- ^ «Exploring the Sake Breweries of Nada». Nippon.com. May 15, 2020. Archived from the original on November 9, 2022.

- ^ a b c d 政策によって姿を消した熟成古酒―明治時代における造石税と日本酒の関係 (in Japanese). Sake Times. January 13, 2017. Archived from the original on July 3, 2022.

- ^ a b c d 日本酒の歴史、起源から明治時代までの変遷を解説 (in Japanese). Nihonshu Lab. February 24, 2021. Archived from the original on December 11, 2022.

- ^ Kaempfer, Engelbert (1906). The History of Japan. Vol. I. p. 187.

- ^ Titsingh, Isaac. (1781). «Bereiding van de Sacki» («Production of Sake»), Verhandelingen van het Bataviaasch Genootschap (Transactions of the Batavian Academy). Vol. III. OCLC 9752305

- ^ Morewood, Samuel (1824). An Essay on the Inventions and Customs of Both Ancients and Moderns in the Use of Inebriating Liquors. Books on Demand. p. 136.

japan sacki.

- ^ a b c 資料2 酒造好適米の農産物検査結果(生産量)と令和元年産の生産量推計(銘柄別) (PDF) (in Japanese). Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (Japan). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 15, 2022.

- ^ 最後の大桶職人が抱く「木桶文化」存続の焦燥 (in Japanese). Toyo Keizai Online. July 27, 2017. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021.

- ^ 「ドブロク」から21世紀の新しい社会を展望する (in Japanese). Rural Culture Association Japan. December 2002. Archived from the original on January 19, 2020.

- ^ a b 「醸造アルコール」って何? なぜ使われているの (in Japanese). Tanoshii osake.com. February 7, 2022. Archived from the original on January 26, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h 「吟醸」のあゆみ 特別に吟味して醸造する酒として、長年かけ洗練 (in Japanese). Gekkeikan. Archived from the original on May 21, 2022.

- ^ 日本酒の歴史、昭和から戦後を経て現代までの変遷を解説 (in Japanese). Nihonshu Lab. March 2, 2021. Archived from the original on December 11, 2022.

- ^ a b Kojiro Takahashi. 月刊食品と容器 2014 Vol. 55. No. 7. 貴醸酒 (PDF) (in Japanese). 缶詰技術研究会. p. 408-411. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 1, 2020.

- ^ Gauntner, John (2002). The Sake Handbook. p. 78. ISBN 9780804834254.

- ^ Omura, Mika (November 6, 2009). «Weekend: Sake breweries go with the flow to survive». Retrieved December 29, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ コロナ禍でも海外ではプレミアムな日本酒が人気 2021 年度日本酒輸出実績 金額・数量ともに過去最高に 輸出額は遂に 401億円超え (in Japanese). Sake Brewery Press. February 7, 2022. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022.

- ^ 最近の日本産酒類の輸出動向について (PDF) (in Japanese). National Tax Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 1, 2022.

- ^ Hirano, Ko (May 4, 2019). «American-based breweries are creating their own brand of sake». The Japan Times Online. ISSN 0447-5763. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ なぜ今、【木桶】で酒を醸すのか。新政酒造が追い求める日本酒の本質 (in Japanese). Cuisine Kingdom. January 21, 2022. Archived from the original on December 12, 2022.

- ^ 唯一無二の味、「木桶」が醸す日本酒の秘密 (in Japanese). Forbes Japan. September 27, 2020. Archived from the original on December 15, 2022.

- ^ «日本最古の酒蔵ベスト5! ほか歴史の古い酒蔵は?». All About, Inc. June 13, 2010. Archived from the original on December 30, 2022. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ «歴史は850年超!日本最古の酒蔵、茨城・須藤本家に行ってきました». Sake Times. December 21, 2015. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ «Oldest sake brewery found at former temple site in Kyoto». The Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on January 19, 2020. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ «A handy guide to sake — Japan’s national drink». Japan Today. Retrieved November 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c d 酒米の王様「山田錦」 (in Japanese). Nippon.com. June 19, 2015. Archived from the original on June 25, 2017.

- ^ a b c d 日本酒の精米歩合について詳しく解説 精米歩合が高い=良いお米? (in Japanese). Nihonshu Lab. September 18, 2020. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022.

- ^ Page 15 and 37 https://www.nrib.go.jp/English/sake/pdf/guidesse01.pdf Archived November 11, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mathew, Sunalini (January 3, 2019). «Introducing sake». The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved November 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c Gauntner, John (September 30, 2014). «How Sake Is Made». Sake World. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Machida, Masayuki; Yamada, Osamu; Gomi, Katsuya (August 2008). «Genomics of Aspergillus oryzae: Learning from the History of Koji Mold and Exploration of Its Future». DNA Research. 15 (4): 173–183. doi:10.1093/dnares/dsn020. ISSN 1340-2838. PMC 2575883. PMID 18820080.

- ^ a b c d «How sake is made». Tengu Sake. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Government of Canada, Public Services and Procurement Canada. «Information archivée dans le Web» (PDF). publications.gc.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 27, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k «Brewing Process | How to | Japan Sake and Shochu Makers Association». www.japansake.or.jp. Archived from the original on July 30, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e «Multiple parallel fermentation: Japanese Sake». en-tradition.com. Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ Gauntner, John (September 29, 2014). «Sake brewing process». Sake World. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ National Research Institute of Brewing (March 2017). «Sake Brewing: The Integration of Science and Technology» (PDF). The Story of Sake.

- ^ «The People». eSake.

- ^ 付表2 特定名称の清酒のタイプ別製成数量の推移表 (PDF) (in Japanese). National Tax Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 31, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g 「清酒の製法品質表示基準」の概要 (in Japanese). National Tax Agency Japan. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022.

- ^ 日本酒の正しい保存方法は?保存時のポイントは紫外線と温度管理 (in Japanese). Sawanotsuru. December 3, 2018. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022.

- ^ Jennings, Holly (2012). Asian Cocktails: Creative Drinks Inspired by the East. ISBN 9781462905256.

- ^ 老舗酒蔵×日本酒ベンチャー×若手蒸留家が共同開発 楽しく、美味しく、学べる酒「すごい!!アル添」を2月12日販売開始 (in Japanese). PR Times. February 12, 2022. Archived from the original on April 28, 2022.

- ^ 金賞受賞酒が必ずしも「おいしい」とは限らない? ──「全国新酒鑑評会」の実態と意義 (in Japanese). Sake Times. May 17, 2017. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022.

- ^ WSET Level 3 Award in Sake Study Guide

- ^ 生酒は鮮度が命 おいしい飲み方や保存方法を覚えておこう (in Japanese). World Hi-Vision Channel, Inc. May 13, 2019. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022.

- ^ 直汲み、槽場汲みの日本酒. Kandaya

- ^ 【必見】にごり生酒を噴きこぼれないように開ける方法 (in Japanese). Sake Times. March 12, 2015. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022.

- ^ 実は1つで2度おいしい!日本酒にごり酒のおいしい飲み方はコレ! (in Japanese). Sakeno no Shizuku. November 3, 2020. Archived from the original on May 22, 2022.

- ^ 「おりがらみ」とはどんな日本酒? にごり酒とどう違う (in Japanese). Tanoshii osake.jp. October 27, 2022. Archived from the original on December 15, 2022.

- ^ にごり酒とは? 定義から種類、飲み方、おすすめ銘柄まで紹介 (in Japanese). Tanoshii osake.jp. December 23, 2022. Archived from the original on July 3, 2022.

- ^ Kazuha Sera (April 14, 2020). リッチな甘みのデザート酒 — 「貴醸酒」の製法と味わいの特徴を学ぶ (in Japanese). Sake street. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022.

- ^ «Hey, that’s a sake of a different color». November 25, 2001.

- ^ Gauntner, John (March 1, 2002). «The Nihonshu-do; Acidity in Sake». Sake World. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ^ «What’s Sake Meter Value (SMV)?». Ozeki Sake. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ «Sake Taste and Sake Scale». sakeexpert.com. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ «A Moment of Relaxation with the Aromas of Sake | GEKKEIKAN KYOTO SINCE 1637». www.gekkeikan.co.jp. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ Ume Cocktail Menu. Tucson, AZ: Ume Casino Del Sol, 2015. Print.[ISBN missing]

- ^ «An Ode to the Sake Bomb». Los Angeles Magazine. April 22, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- ^ «Yawaragi». japansake.or.jp.

- ^ «‘Letter Exchange between the ambassadors of Japan and the United States on Alcoholic Beverages (October 7, 2019)» (PDF).

- ^ (Lecture Note, October 2011).

- ^ (Suzuki et al., 2008).

- ^ «Sake Etiquette». www.esake.com. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- ^ 日本酒の賞味期間 吟醸酒は10カ月間 普通酒は1年間が目安 (in Japanese). Gekkeikan. Archived from the original on December 15, 2022.

- ^ a b 日本酒の賞味期限は?開栓前(未開封)/開栓(開封)後のおいしく飲める期間とは (in Japanese). Sawanotsuru. June 30, 2022. Archived from the original on July 3, 2022.

- ^ 美味しく飲むためのコツ!開封後の日本酒の保存方法と賞味期限とは? (in Japanese). World Hi-Vision Channel, Inc. September 12, 2019. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022.

- ^ 生酒の賞味期限は?冷蔵保存して半年以内に飲み切るのがベストなわけ (in Japanese). Sake no shizuku. April 24, 2020. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022.

- ^ (限定品) 新政(あらまさ) コスモス 2019 純米酒 一回火入れ 720ml 要冷蔵 (in Japanese). Rakuten. Archived from the original on December 30, 2022.

- ^ 酒造各社に聞いた日本酒の賞味期限は?未開封でも注意すべきポイント (in Japanese). Sake no shizuku. April 24, 2020. Archived from the original on May 22, 2022.

- ^ a b

日本酒に賞味期限はある?未開封時の賞味期限と開封後の保存方法 きき酒師が教える日本酒 (in Japanese). Oricon news. December 15, 2021. Archived from the original on December 23, 2022. - ^ 日本酒の正しい保存方法!期限から落とし穴まで総まとめ (in Japanese). Nihonshu Lab. September 7, 2022. Archived from the original on November 27, 2022.

- ^ «10月1日の「日本酒の日」には確かな根拠あり». Sake Service Institute. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

General sources[edit]

- Bamforth CW. (2005). «Sake.» Food, Fermentation and Micro-organisms. Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK: 143–153.

- Kobayashi T, Abe K, Asai K, Gomi K, Uvvadi PR, Kato M, Kitamoto K, Takeuchi M, Machida M. (2007). «Genomics of Aspergillus oryzae«. Biosci Biotechnol. Biochem. 71(3):646–670.

- Suzuki K, Asano S, Iijima K, Kitamoto K. (2008). «Sake and Beer Spoilage Lactic Acid Bacteria – A review.» The Inst of Brew & Distilling; 114(3):209–223.

- Uno T, Itoh A, Miyamoto T, Kubo M, Kanamaru K, Yamagata H, Yasufuku Y, Imaishi H. (2009). «Ferulic Acid Production in the Brewing of Rice Wine (Sake).» J Inst Brew. 115(2):116–121.

Further reading[edit]

- Aoki, Rocky, Nobu Mitsuhisa and Pierre A. Lehu (2003). Sake: Water from Heaven. New York: Universe Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7893-0847-4

- Bunting, Chris (2011). Drinking Japan. Singapore: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-4-8053-1054-0.

- Eckhardt, Fred (1993). Sake (U.S.A.): A Complete Guide to American Sake, Sake Breweries and Homebrewed Sake. Portland, Oregon: Fred Eckhardt Communications. ISBN 978-0-9606302-8-8.

- Gauntner, John (2002). The Sake Handbook. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-3425-4.

- Harper, Philip; Haruo Matsuzaki; Mizuho Kuwata; Chris Pearce (2006). The Book of Sake: A Connoisseurs Guide. Tokyo: Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-2998-0

- Kaempfer, Engelbert (1906). The History of Japan: Together with a Description of the Kingdom of Siam, 1690–92, Vol I. Vol II. Vol III. London: J. MacLehose and Sons. OCLC 5174460.

- Morewood, Samuel (1824). An Essay on the Inventions and Customs of Both Ancients and Moderns in the Use of Inebriating Liquors: Interspersed with Interesting Anecdotes, Illustrative of the Manners and Habits of the Principal Nations of the World, with an Historical View of the Extent and Practice of Distillation. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. OCLC 213677222.

- Titsingh, Issac (1781). «Bereiding van de Sacki» («Producing Sake»), Verhandelingen van het Bataviaasch Genootschap (Transactions of the Batavian Academy), Vol. III. OCLC 9752305.

Notes[edit]

- ^ In Japan, the term kōji may refer to all fungi used in fermented foods or to specific species of fungi, Aspergillus oryzae and Aspergillus sojae.[1][2]

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sake.

Look up sake in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Sake Service Institute

- Sake Education Council Archived September 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Sake Sommelier Association

- An Indispensable Guide to Sake and Japanese Culture

- What Does Sake Taste Like? Archived November 7, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

Sake can be served in a wide variety of cups. Pictured is a sakazuki (a flat, saucer-like cup), an ochoko (a small, cylindrical cup), and a masu (a wooden, box-like cup) |

|

| Type | Alcoholic beverage |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Japan |

| Alcohol by volume | 15–22% |

| Ingredients | Rice, water, Aspergillus oryzae (kōji-kin)[a], yeast |

Sake bottle, Japan, c. 1740

Sake, also spelled saké (sake (酒, Sake) SAH-kee, SAK-ay;[3][4] also referred to as Japanese rice wine),[5] is an alcoholic beverage of Japanese origin made by fermenting rice that has been polished to remove the bran. Despite the name Japanese rice wine, sake, and indeed any East Asian rice wine (such as huangjiu and cheongju), is produced by a brewing process more akin to that of beer, where starch is converted into sugars which ferment into alcohol, whereas in wine, alcohol is produced by fermenting sugar that is naturally present in fruit, typically grapes.

The brewing process for sake differs from the process for beer, where the conversion from starch to sugar and then from sugar to alcohol occurs in two distinct steps. Like other rice wines, when sake is brewed, these conversions occur simultaneously. The alcohol content differs between sake, wine, and beer; while most beer contains 3–9% ABV, wine generally contains 9–16% ABV,[6] and undiluted sake contains 18–20% ABV (although this is often lowered to about 15% by diluting with water before bottling).

In Japanese, the character sake (kanji: 酒, Japanese pronunciation: [sake]) can refer to any alcoholic drink, while the beverage called sake in English is usually termed nihonshu (日本酒; meaning ‘Japanese alcoholic drink’). Under Japanese liquor laws, sake is labeled with the word seishu (清酒; ‘refined alcohol’), a synonym not commonly used in conversation.

In Japan, where it is the national beverage, sake is often served with special ceremony, where it is gently warmed in a small earthenware or porcelain bottle and sipped from a small porcelain cup called a sakazuki. As with wine, the recommended serving temperature of sake varies greatly by type.

Sake now enjoys an international reputation. Of the more than 800 junmai ginjō-shu evaluated by Robert Parker’s team, 78 received a score of 90 or more (eRobertParker,2016).[7]

History[edit]

Until the Kamakura period[edit]

The origin of sake is unclear; however, the method of fermenting rice into alcohol spread to Japan from China around 500BCE.[8] The earliest reference to the use of alcohol in Japan is recorded in the Book of Wei in the Records of the Three Kingdoms. This 3rd-century Chinese text speaks of Japanese drinking and dancing.[9]

Alcoholic beverages (酒, sake) are mentioned several times in the Kojiki, Japan’s first written history, which was compiled in 712. Bamforth (2005) places the probable origin of true sake (which is made from rice, water, and kōji mold (麹, Aspergillus oryzae)) in the Nara period (710–794).[10] The fermented food fungi traditionally used for making alcoholic beverages in China and Korea for a long time were fungi belonging to Rhizopus and Mucor, whereas in Japan, except in the early days, the fermented food fungus used for sake brewing was Aspergillus oryzae.[11][12][1] Some scholars believe the Japanese domesticated the mutated, detoxified Aspergillus flavus to give rise to Aspergillus oryzae.[12][13][14]

In the Heian period (794–1185), sake was used for religious ceremonies, court festivals, and drinking games.[10] Sake production was a government monopoly for a long time, but in the 10th century, temples and shrines began to brew sake, and they became the main centers of production for the next 500 years.

Muromachi period[edit]

Before the 1440s in the Muromachi period (1333-1573), the Buddhist temple Shōryaku-ji invented various innovative methods for making sake. Because these production methods are the origin of the basic production methods for sake brewing today, Shoryakuji is often said to be the birthplace of seishu (清酒). Until then, most sake had been nigorizake with a different process from today’s, but after that, clear seishu was established. The main production methods established by Shōryaku-ji are the use of all polished rice (morohaku zukuri, 諸白造り), three-stage fermentation (sandan zikomi, 三段仕込み), brewing of starter mash using acidic water produced by lactic acid fermentation (bodaimoto zukuri, 菩提酛づくり), and pasteurization (hiire, 火入れ). This method of producing starter mash is called bodaimoto, which is the origin of kimoto. These innovations made it possible to produce sake with more stable quality than before, even in temperate regions. These things are described in Goshu no nikki (ja:御酒之日記), the oldest known technical book on sake brewing written in 1355 or 1489, and Tamonin nikki (ja:多門院日記), a diary written between 1478 and 1618 by monks of Kōfuku-ji Temple in the Muromachi period.[15][16][17]

A huge tub (ja:桶) with a capacity of 10 koku (1,800 liters) was invented at the end of the Muromachi period, making it possible to mass-produce sake more efficiently than before. Until then, sake had been made in jars with a capacity of 1, 2, or 3 koku at the most, and some sake brewers used to make sake by arranging 100 jars.[18][19]

In the 16th century, the technique of distillation was introduced into the Kyushu district from Ryukyu.[9] The brewing of shōchū, called «Imo–sake» started and was sold at the central market in Kyoto.

Edo period[edit]

By the Genroku era (1688–1704) of the Edo period (1603–1867), a brewing method called hashira jōchū (柱焼酎) was developed in which a small amount of distilled alcohol (shōchū) was added to the mash to make it more aromatic and lighter in taste, while at the same preventing deterioration in quality. This originates from the distilled alcohol addition used in modern sake brewing.[20]

The Nada-Gogō area in Hyōgo Prefecture, the largest producer of modern sake, was formed during this period. When the population of Edo, modern-day Tokyo, began to grow rapidly in the early 1600s, brewers who made sake in inland areas such as Fushimi, Itami, and Ikeda moved to the Nada-Gogō area on the coast, where the weather and water quality were perfect for brewing sake and convenient for shipping it to Edo. In the Genroku era, when the culture of the chōnin class, the common people, prospered, the consumption of sake increased rapidly, and large quantities of taruzake (樽酒) were shipped to Edo. 80% of the sake drunk in Edo during this period was from Nada-Gogō. Many of today’s major sake producers, including Hakutsuru (ja:白鶴), Ōzeki (ja:大関), Niihonsakari (ja:日本盛), Kikumasamune (ja:菊正宗), Kenbishi (ja:剣菱) and Sawanotsuru, are breweries in Nada-Gogō.[21]

During this period, frequent natural disasters and bad weather caused rice shortages, and the Tokugawa shogunate issued sake brewing restrictions 61 times.[22] In the early Edo period, there was a sake brewing technique called shiki jōzō (四季醸造) that was optimized for each season. In 1667, the technique of kanzukuri (寒造り) for making sake in winter was improved, and in 1673, when the Tokugawa shogunate banned brewing other than kanzukuri because of a shortage of rice, the technique of sake brewing in the four seasons ceased, and it became common to make sake only in winter until industrial technology began to develop in the 20th century.[23] During this period, aged for three, five, or nine years, koshu (古酒) was a luxury, but its deliciousness was known to the common people.[22]

In the 18th century, Engelbert Kaempfer[24] and Isaac Titsingh[25] published accounts identifying sake as a popular alcoholic beverage in Japan, but Titsingh was the first to try to explain and describe the process of sake brewing. The work of both writers was widely disseminated throughout Europe at the beginning of the 19th century.[26]

From the Meiji era to the early Shōwa era[edit]

Starting around the beginning of the Meiji era (1868-1912), the technique for making sake began to develop rapidly. Breeding was actively carried out in various parts of Japan to produce sake rice optimized for sake brewing. Ise Nishiki developed in 1860, Omachi (ja:雄町) developed in 1866 and Shinriki developed in 1877 are the earliest representative varieties. In 1923, Yamada Nishiki, later called the «king of sake rice,» was produced.[23] Among more than 123 varieties of sake rice as of 2019, Yamada Nishiki ranks first in production and Omachi fourth.[27] The government opened the sake-brewing research institute in 1904, and in 1907 the first government-run sake-tasting competition was held. In 1904, the National Brewing Laboratory developed yamahai, a new method of making starter mash, and in 1910, a further improvement, sokujō, was developed.[23] Yeast strains specifically selected for their brewing properties were isolated, and enamel-coated steel tanks arrived. The government started hailing the use of enamel tanks as easy to clean, lasting forever, and devoid of bacterial problems. (The government considered wooden tubs (ja:桶) to be unhygienic because of the potential bacteria living in the wood.) Although these things are true, the government also wanted more tax money from breweries, as using wooden tubs means a significant amount of sake is lost to evaporation (approximately 3%), which could have otherwise been taxed. This was the temporary end of the wooden-tubs age of sake, and the use of wooden tubs in brewing was temporarily eliminated.[28]

In Japan, sake has long been taxed by the national government. In 1878, the liquor tax accounted for 12.3% of the national tax revenue, excluding local taxes, and in 1888 it was 26.4%, and in 1899 it was 38.8%, finally surpassing the land tax of 35.6%.[22] In 1899, the government banned home brewing in anticipation of financial pressure from the First Sino-Japanese War and in preparation for the Russo-Japanese War. Since home-brewed sake is tax-free, the logic was that by banning the home-brewing of sake, sales would increase, and more tax revenue would be collected. This was the end of home-brewed sake.[29] The Meiji government adopted a system in which taxes were collected when sake was finished, instead of levying taxes on the amount and price of sake at the time of sale to ensure more revenue from liquor taxes. The liquor tax for the sake produced in a given year had to be paid to the government during that fiscal year, so the breweries tried to make money by selling the sake as soon as possible. This destroyed the market for aged koshu, which had been popular until then, and it was only in 1955 that sake breweries began to make koshu again.[22]

When World War II brought rice shortages, the sake-brewing industry was hampered as the government discouraged the use of rice for brewing. As early as the late 17th century, it had been discovered that small amounts of distilled alcohol could be added to sake before pressing to extract aromas and flavors from the rice solids. During the war, large amounts of distilled alcohol and glucose were added to small quantities of rice mash, increasing the yield by as much as four times. A few breweries were producing «sake» that contained no rice. The quality of sake during this time varied considerably. Incidentally, as of 2022, so much distilled alcohol is not allowed to be added, and under the provisions of the Liquor Tax Act, 50% of the weight of rice is the upper limit for the most inexpensive sake classified as futsū-shu.[30]

Since the mid-Showa era[edit]