Coordinates: 38°53′26″N 77°0′32″W / 38.89056°N 77.00889°W

|

United States Senate |

|

|---|---|

| 118th United States Congress | |

Seal of the U.S. Senate |

|

Flag of the U.S. Senate |

|

| Type | |

| Type |

Upper house of the United States Congress |

|

Term limits |

None |

| History | |

|

New session started |

January 3, 2023 |

| Leadership | |

|

President of the Senate |

Kamala Harris (D) |

|

President pro tempore |

Patty Murray (D) |

|

Majority Leader |

Chuck Schumer (D) |

|

Minority Leader |

Mitch McConnell (R) |

|

Majority Whip |

Dick Durbin (D) |

|

Minority Whip |

John Thune (R) |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 100 |

|

|

|

Political groups |

Majority (51)

Minority (48)

Vacant (1)

|

|

Length of term |

6 years |

| Elections | |

|

Voting system |

Plurality voting in 46 states[b]

Varies in 4 states

|

|

Last election |

November 8, 2022 (36 seats) |

|

Next election |

November 5, 2024 (34 seats) |

| Meeting place | |

|

|

| Senate Chamber United States Capitol Washington, D.C. United States |

|

| Website | |

| senate.gov | |

| Constitution | |

| United States Constitution | |

| Rules | |

| Standing Rules of the United States Senate |

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powers of the Senate are established by Article One of the United States Constitution.[3] The Senate is composed of senators, each of whom represents a single state in its entirety. Each of the 50 states is equally represented by two senators who serve staggered terms of six years, for a total of 100 senators. The vice president of the United States serves as presiding officer and president of the Senate by virtue of that office, despite not being a senator, and has a vote only if the Senate is equally divided. In the vice president’s absence, the president pro tempore, who is traditionally the senior member of the party holding a majority of seats, presides over the Senate.

As the upper chamber of Congress, the Senate has several powers of advice and consent which are unique to it. These include the approval of treaties, and the confirmation of Cabinet secretaries, federal judges (including Federal Supreme Court justices), flag officers, regulatory officials, ambassadors, other federal executive officials and federal uniformed officers. If no candidate receives a majority of electors for vice president, the duty falls to the Senate to elect one of the top two recipients of electors for that office. The Senate conducts trials of those impeached by the House.

The Senate has typically been considered both a more deliberative,[4] prestigious,[5][6][7] and controversial[8] body than the House of Representatives due to its longer terms, smaller size, and statewide constituencies, which historically led to a more collegial and less partisan atmosphere.[9]

From 1789 to 1913, senators were appointed by legislatures of the states they represented. They are now elected by popular vote following the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913. In the early 1920s, the practice of majority and minority parties electing their floor leaders began. The Senate’s legislative and executive business is managed and scheduled by the Senate majority leader.

The Senate chamber is located in the north wing of the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C.

History

The drafters of the Constitution struggled and debated more in the creation of the Senate than in any other part of the Constitution.[10] In the end, a bicameral Congress emerged primarily as a compromise between some smaller states who threatened to walk away if they lost any more power and larger ones.[11] The resulting congress with one chamber representing people equally, while the other maintains the equal power of smaller states from the existing arrangement (the Articles of Confederation), was known as the Connecticut Compromise. There was also a desire to have two Houses that could act as an internal check on each other. One was a «People’s House» directly elected by the people, and with short terms obliging the representatives to remain close to their constituents. The other represented the states to such extent as they retained some sovereignty except for the powers expressly delegated to the national government. The Constitution provides that the approval of both chambers is necessary for the passage of legislation.[12]

First convened in 1789, the Senate of the United States was formed on the example of the ancient Roman Senate. The name is derived from the senatus, Latin for council of elders (from senex meaning old man in Latin).[13]

James Madison made the only argument for minority [ie landholder] rights at the convention:[10]

In England, at this day, if elections were open to all classes of people, the property of landed proprietors would be insecure. An agrarian law would soon take place. If these observations remain just, our government ought to secure the permanent interests of the country against innovation. Landholders ought to have a share in the government, to support these invaluable interests, and to balance and check the other. They ought to be so constituted as to protect the minority of the opulent against the majority. The Senate, therefore, ought to be this body; and to answer these purposes, they ought to have permanency and stability.[14]

— Notes of the Secret Debates of the Federal Convention of 1787

Article Five of the Constitution stipulates that no constitutional amendment may be created to deprive a state of its equal suffrage in the Senate without that state’s consent. The District of Columbia and the territories are not entitled to representation or allowed to vote in either house of Congress. They have official non-voting delegates in the House of Representatives, but none in the Senate. The District of Columbia and Puerto Rico each additionally elect two «shadow senators», but they are officials of their respective local governments and not members of the U.S. Senate.[15] The United States has had 50 states since 1959,[16] thus the Senate has had 100 senators since 1959.[12]

Graph showing historical party control of the U.S. Senate, House and Presidency since 1855[17]

The disparity between the most and least populous states has grown since the Connecticut Compromise, which granted each state two members of the Senate and at least one member of the House of Representatives, for a total minimum of three presidential electors, regardless of population. In 1787, Virginia had roughly ten times the population of Rhode Island, whereas today California has roughly 70 times the population of Wyoming, based on the 1790 and 2020 censuses. Before the adoption of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913, senators were elected by the individual state legislatures.[18] Problems with repeated vacant seats due to the inability of a legislature to elect senators, intrastate political struggles, bribery and intimidation gradually led to a growing movement to amend the Constitution to allow for the direct election of senators.[19]

Current composition and election results

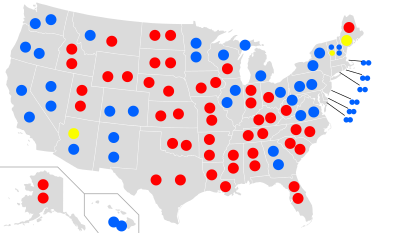

Members of the United States Senate for the 118th Congress

Current party standings

The party composition of the Senate during the 118th Congress:

| Affiliation | Members | |

|---|---|---|

| Republican | 48 | |

| Democratic | 48 | |

| Independents | 3[a] | |

| Vacant | 1 | |

| Total | 100 |

Membership

Qualifications

Article I, Section 3, of the Constitution, sets three qualifications for senators: (1) they must be at least 30 years old; (2) they must have been citizens of the United States for at least nine years; and (3) they must be inhabitants of the states they seek to represent at the time of their election. The age and citizenship qualifications for senators are more stringent than those for representatives. In Federalist No. 62, James Madison justified this arrangement by arguing that the «senatorial trust» called for a «greater extent of information and stability of character»:

A senator must be thirty years of age at least; as a representative must be twenty-five. And the former must have been a citizen nine years; as seven years are required for the latter. The propriety of these distinctions is explained by the nature of the senatorial trust, which, requiring greater extent of information and stability of character, requires at the same time that the senator should have reached a period of life most likely to supply these advantages; and which, participating immediately in transactions with foreign nations, ought to be exercised by none who are not thoroughly weaned from the prepossessions and habits incident to foreign birth and education. The term of nine years appears to be a prudent mediocrity between a total exclusion of adopted citizens, whose merits and talents may claim a share in the public confidence, and an indiscriminate and hasty admission of them, which might create a channel for foreign influence on the national councils.[20]

The Senate (not the judiciary) is the sole judge of a senator’s qualifications. During its early years, however, the Senate did not closely scrutinize the qualifications of its members. As a result, four senators who failed to meet the age requirement were nevertheless admitted to the Senate: Henry Clay (aged 29 in 1806), John Jordan Crittenden (aged 29 in 1817), Armistead Thomson Mason (aged 28 in 1816), and John Eaton (aged 28 in 1818). Such an occurrence, however, has not been repeated since.[21] In 1934, Rush D. Holt Sr. was elected to the Senate at the age of 29; he waited until he turned 30 (on the next June 19) to take the oath of office. In November 1972, Joe Biden was elected to the Senate at the age of 29, but he reached his 30th birthday before the swearing-in ceremony for incoming senators in January 1973.

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution disqualifies as senators any federal or state officers who had taken the requisite oath to support the Constitution but who later engaged in rebellion or aided the enemies of the United States. This provision, which came into force soon after the end of the Civil War, was intended to prevent those who had sided with the Confederacy from serving. That Amendment, however, also provides a method to remove that disqualification: a two-thirds vote of both chambers of Congress.

Elections and term

Originally, senators were selected by the state legislatures, not by popular elections. By the early years of the 20th century, the legislatures of as many as 29 states had provided for popular election of senators by referendums.[19] Popular election to the Senate was standardized nationally in 1913 by the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment.

Term

Senators serve terms of six years each; the terms are staggered so that approximately one-third of the seats are up for election every two years. This was achieved by dividing the senators of the 1st Congress into thirds (called classes), where the terms of one-third expired after two years, the terms of another third expired after four, and the terms of the last third expired after six years. This arrangement was also followed after the admission of new states into the union. The staggering of terms has been arranged such that both seats from a given state are not contested in the same general election, except when a vacancy is being filled. Current senators whose six-year terms are set to expire on January 3, 2025, belong to Class I. There is no constitutional limit to the number of terms a senator may serve.

The Constitution set the date for Congress to convene — Article 1, Section 4, Clause 2, originally set that date for the third day of December. The Twentieth Amendment, however, changed the opening date for sessions to noon on the third day of January, unless they shall by law appoint a different day. The Twentieth Amendment also states that the Congress shall assemble at least once every year, and allows the Congress to determine its convening and adjournment dates and other dates and schedules as it desires. Article 1, Section 3, provides that the president has the power to convene Congress on extraordinary occasions at his discretion.[22]

A member who has been elected, but not yet seated, is called a senator-elect; a member who has been appointed to a seat, but not yet seated, is called a senator-designate.

Elections

Elections to the Senate are held on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November in even-numbered years, Election Day, and coincide with elections for the House of Representatives.[23] Senators are elected by their state as a whole. The Elections Clause of the United States Constitution grants each state (and Congress, if it so desires to implement a uniform law) the power to legislate a method by which senators are elected. Ballot access rules for independent and minor party candidates also vary from state to state.

In 45 states, a primary election is held first for the Republican and Democratic parties (and a select few third parties, depending on the state) with the general election following a few months later. In most of these states, the nominee may receive only a plurality, while in some states, a runoff is required if no majority was achieved. In the general election, the winner is the candidate who receives a plurality of the popular vote.

However, in five states, different methods are used. In Georgia, a runoff between the top two candidates occurs if the plurality winner in the general election does not also win a majority. In California, Washington, and Louisiana, a nonpartisan blanket primary (also known as a «jungle primary» or «top-two primary») is held in which all candidates participate in a single primary regardless of party affiliation and the top two candidates in terms of votes received at the primary election advance to the general election, where the winner is the candidate with the greater number of votes. In Louisiana, the blanket primary is considered the general election and candidates receiving a majority of the votes is declared the winner, skipping a run-off. In Maine and Alaska, ranked-choice voting is used to nominate and elect candidates for federal offices, including the Senate.[24]

Vacancies

The Seventeenth Amendment requires that vacancies in the Senate be filled by special election. Whenever a senator must be appointed or elected, the secretary of the Senate mails one of three forms to the state’s governor to inform them of the proper wording to certify the appointment of a new senator.[25] If a special election for one seat happens to coincide with a general election for the state’s other seat, each seat is contested separately. A senator elected in a special election takes office as soon as possible after the election and serves until the original six-year term expires (i.e. not for a full-term).

The Seventeenth Amendment permits state legislatures to empower their governors to make temporary appointments until the required special election takes place.

The manner by which the Seventeenth Amendment is enacted varies among the states. A 2018 report breaks this down into the following three broad categories (specific procedures vary among the states):[26]

- Four states – North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin – do not empower their governors to make temporary appointments, relying exclusively on the required special election provision in the Seventeenth Amendment.[26]: 7–8

- Eight states – Alaska, Connecticut, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Texas, Vermont, and Washington – provide for gubernatorial appointments, but also require a special election on an accelerated schedule.[26]: 10–11

- The remaining thirty-eight states provide for gubernatorial appointments, «with the appointed senator serving the balance of the term or until the next statewide general election».[26]: 8–9

In ten states within the final category above – Arizona, Hawaii, Kentucky, Maryland, Montana, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Utah, West Virginia, and Wyoming – the governor must appoint someone of the same political party as the previous incumbent.[26]: 9 [27]

In September 2009, Massachusetts changed its law to enable the governor to appoint a temporary replacement for the late senator Edward Kennedy until the special election in January 2010.[28][29]

In 2004, Alaska enacted legislation and a separate ballot referendum that took effect on the same day, but that conflicted with each other. The effect of the ballot-approved law is to withhold from the governor authority to appoint a senator.[30] Because the 17th Amendment vests the power to grant that authority to the legislature – not the people or the state generally – it is unclear whether the ballot measure supplants the legislature’s statute granting that authority.[30] As a result, it is uncertain whether an Alaska governor may appoint an interim senator to serve until a special election is held to fill the vacancy.

In May 2021, Oklahoma permitted its governor again to appoint a successor who is of the same party as the previous senator for at least the preceding five years when the vacancy arises in an even-numbered year, only after the appointee has taken an oath not to run in either a regular or special Senate election.[27]

Oath

The Constitution requires that senators take an oath or affirmation to support the Constitution.[31] Congress has prescribed the following oath for all federal officials (except the President), including senators:

I, ___ ___, do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter. So help me God.[32]

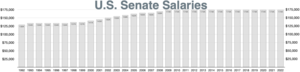

Salary and benefits

The annual salary of each senator, since 2009, is $174,000;[33] the president pro tempore and party leaders receive $193,400.[33][34] As of June 2003, at least 40 senators were millionaires;[35] in 2018, over 50 senators were millionaires.[36]

Along with earning salaries, senators receive retirement and health benefits that are identical to other federal employees, and are fully vested after five years of service.[34] Senators are covered by the Federal Employees Retirement System (FERS) or Civil Service Retirement System (CSRS). FERS has been the Senate’s retirement system since January 1, 1987, while CSRS applies only for those senators who were in the Senate from December 31, 1986, and prior. As it is for federal employees, congressional retirement is funded through taxes and the participants’ contributions. Under FERS, senators contribute 1.3% of their salary into the FERS retirement plan and pay 6.2% of their salary in Social Security taxes. The amount of a senator’s pension depends on the years of service and the average of the highest three years of their salary. The starting amount of a senator’s retirement annuity may not exceed 80% of their final salary. In 2006, the average annual pension for retired senators and representatives under CSRS was $60,972, while those who retired under FERS, or in combination with CSRS, was $35,952.[34]

Seniority

By tradition, seniority is a factor in the selection of physical offices and in party caucuses’ assignment of committees. When senators have been in office for the same length of time, a number of tiebreakers are used, including comparing their former government service and then their respective state population.[37]

The senator in each state with the longer time in office is known as the senior senator, while the other is the junior senator. For example, majority leader Chuck Schumer is the senior senator from New York, having served in the senate since 1999, while Kirsten Gillibrand is New York’s junior senator, having served since 2009.

Titles

Like members of the House of Representatives, Senators use the prefix «The Honorable» before their names.[38][39] Senators are usually identified in the media and other sources by party and state; for example, Democratic majority leader Chuck Schumer, who represents New York, may be identified as «D–New York». And sometimes they are identified as to whether they are the junior or senior senator in their state (see above). Unless in the context of elections, they are rarely identified by which one of the three classes of senators they are in.

Expulsion and other disciplinary actions

The Senate may expel a senator by a two-thirds vote. Fifteen senators have been expelled in the Senate’s history: William Blount, for treason, in 1797, and fourteen in 1861 and 1862 for supporting the Confederate secession. Although no senator has been expelled since 1862, many senators have chosen to resign when faced with expulsion proceedings – for example, Bob Packwood in 1995. The Senate has also censured and condemned senators; censure requires only a simple majority and does not remove a senator from office. Some senators have opted to withdraw from their re-election races rather than face certain censure or expulsion, such as Robert Torricelli in 2002.

Majority and minority parties

The «majority party» is the political party that either has a majority of seats or can form a coalition or caucus with a majority of seats; if two or more parties are tied, the vice president’s affiliation determines which party is the majority party. The next-largest party is known as the minority party. The president pro tempore, committee chairs, and some other officials are generally from the majority party; they have counterparts (for instance, the «ranking members» of committees) in the minority party. Independents and members of third parties (so long as they do not caucus support either of the larger parties) are not considered in determining which is the majority party.

Seating

At one end of the chamber of the Senate is a dais from which the presiding officer presides. The lower tier of the dais is used by clerks and other officials. One hundred desks are arranged in the chamber in a semicircular pattern and are divided by a wide central aisle. The Democratic Party traditionally sits to the presiding officer’s right, and the Republican Party traditionally sits to the presiding officer’s left, regardless of which party has a majority of seats.[40]

Each senator chooses a desk based on seniority within the party. By custom, the leader of each party sits in the front row along the center aisle. Forty-eight of the desks date back to 1819, when the Senate chamber was reconstructed after the original contents were destroyed in the 1812 Burning of Washington. Further desks of similar design were added as new states entered the Union.[41] It is a tradition that each senator who uses a desk inscribes their name on the inside of the desk’s drawer.[42]

Officers

Except for the president of the Senate (who is the vice president), the Senate elects its own officers,[3] who maintain order and decorum, manage and schedule the legislative and executive business of the Senate, and interpret the Senate’s rules, practices and precedents. Many non-member officers are also hired to run various day-to-day functions of the Senate.

Presiding officer

Under the Constitution, the vice president serves as president of the Senate. They may vote in the Senate (ex officio, for they are not an elected member of the Senate) in the case of a tie, but are not required to.[43] For much of the nation’s history the task of presiding over Senate sessions was one of the vice president’s principal duties (the other being to receive from the states the tally of electoral ballots cast for president and vice president and to open the certificates «in the Presence of the Senate and House of Representatives», so that the total votes could be counted). Since the 1950s, vice presidents have presided over few Senate debates. Instead, they have usually presided only on ceremonial occasions, such as swearing in new senators, joint sessions, or at times to announce the result of significant legislation or nomination, or when a tie vote on an important issue is anticipated.

The Constitution authorizes the Senate to elect a president pro tempore (Latin for «president for a time»), who presides over the chamber in the vice president’s absence and is, by custom, the senator of the majority party with the longest record of continuous service.[44] Like the vice president, the president pro tempore does not normally preside over the Senate, but typically delegates the responsibility of presiding to a majority-party senator who presides over the Senate, usually in blocks of one hour on a rotating basis. Frequently, freshmen senators (newly elected members) are asked to preside so that they may become accustomed to the rules and procedures of the body. It is said that, «in practice they are usually mere mouthpieces for the Senate’s parliamentarian, who whispers what they should do».[45]

The presiding officer sits in a chair in the front of the Senate chamber. The powers of the presiding officer of the Senate are far less extensive than those of the speaker of the House. The presiding officer calls on senators to speak (by the rules of the Senate, the first senator who rises is recognized); ruling on points of order (objections by senators that a rule has been breached, subject to appeal to the whole chamber); and announcing the results of votes.

Party leaders

Each party elects Senate party leaders. Floor leaders act as the party chief spokesmen. The Senate majority leader is responsible for controlling the agenda of the chamber by scheduling debates and votes. Each party elects an assistant leader (whip), who works to ensure that his party’s senators vote as the party leadership desires.

Non-member officers

In addition to the vice president, the Senate has several officers who are not members. The Senate’s chief administrative officer is the secretary of the Senate, who maintains public records, disburses salaries, monitors the acquisition of stationery and supplies, and oversees clerks. The assistant secretary of the Senate aids the secretary’s work. Another official is the sergeant at arms who, as the Senate’s chief law enforcement officer, maintains order and security on the Senate premises. The Capitol Police handle routine police work, with the sergeant at arms primarily responsible for general oversight. Other employees include the chaplain, who is elected by the Senate, and pages, who are appointed.

Procedure

Daily sessions

The Senate uses Standing Rules for operation. Like the House of Representatives, the Senate meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. At one end of the chamber of the Senate is a dais from which the presiding officer presides. The lower tier of the dais is used by clerks and other officials. Sessions of the Senate are opened with a special prayer or invocation and typically convene on weekdays. Sessions of the Senate are generally open to the public and are broadcast live on television, usually by C-SPAN 2.

Senate procedure depends not only on the rules, but also on a variety of customs and traditions. The Senate commonly waives some of its stricter rules by unanimous consent. Unanimous consent agreements are typically negotiated beforehand by party leaders. A senator may block such an agreement, but in practice, objections are rare. The presiding officer enforces the rules of the Senate, and may warn members who deviate from them. The presiding officer sometimes uses the gavel of the Senate to maintain order.

A «hold» is placed when the leader’s office is notified that a senator intends to object to a request for unanimous consent from the Senate to consider or pass a measure. A hold may be placed for any reason and can be lifted by a senator at any time. A senator may place a hold simply to review a bill, to negotiate changes to the bill, or to kill the bill. A bill can be held for as long as the senator who objects to the bill wishes to block its consideration.

Holds can be overcome, but require time-consuming procedures such as filing cloture. Holds are considered private communications between a senator and the leader, and are sometimes referred to as «secret holds». A senator may disclose the placement of a hold.

The Constitution provides that a majority of the Senate constitutes a quorum to do business. Under the rules and customs of the Senate, a quorum is always assumed present unless a quorum call explicitly demonstrates otherwise. A senator may request a quorum call by «suggesting the absence of a quorum»; a clerk then calls the roll of the Senate and notes which members are present. In practice, senators rarely request quorum calls to establish the presence of a quorum. Instead, quorum calls are generally used to temporarily delay proceedings; usually, such delays are used while waiting for a senator to reach the floor to speak or to give leaders time to negotiate. Once the need for a delay has ended, a senator may request unanimous consent to rescind the quorum call.

Debate

Debate, like most other matters governing the internal functioning of the Senate, is governed by internal rules adopted by the Senate. During a debate, senators may only speak if called upon by the presiding officer, but the presiding officer is required to recognize the first senator who rises to speak. Thus, the presiding officer has little control over the course of the debate. Customarily, the majority leader and minority leader are accorded priority during debates even if another senator rises first. All speeches must be addressed to the presiding officer, who is addressed as «Mr. President» or «Madam President», and not to another member; other Members must be referred to in the third person. In most cases, senators do not refer to each other by name, but by state or position, using forms such as «the senior senator from Virginia», «the gentleman from California», or «my distinguished friend the chairman of the Judiciary Committee». Senators address the Senate standing next to their desks.[46]

Apart from rules governing civility, there are few restrictions on the content of speeches; there is no requirement that speeches pertain to the matter before the Senate.

The rules of the Senate provide that no senator may make more than two speeches on a motion or bill on the same legislative day. A legislative day begins when the Senate convenes and ends with adjournment; hence, it does not necessarily coincide with the calendar day. The length of these speeches is not limited by the rules; thus, in most cases, senators may speak for as long as they please. Often, the Senate adopts unanimous consent agreements imposing time limits. In other cases (for example, for the budget process), limits are imposed by statute. However, the right to unlimited debate is generally preserved.

Within the United States, the Senate is sometimes referred to as «world’s greatest deliberative body».[47][48][49]

Filibuster and cloture

The filibuster is a tactic used to defeat bills and motions by prolonging debate indefinitely. A filibuster may entail long speeches, dilatory motions, and an extensive series of proposed amendments. The Senate may end a filibuster by invoking cloture. In most cases, cloture requires the support of three-fifths of the Senate; however, if the matter before the Senate involves changing the rules of the body – this includes amending provisions regarding the filibuster – a two-thirds majority is required. In current practice, the threat of filibuster is more important than its use; almost any motion that does not have the support of three-fifths of the Senate effectively fails. This means that 41 senators can make a filibuster happen. Historically, cloture has rarely been invoked because bipartisan support is usually necessary to obtain the required supermajority, so a bill that already has bipartisan support is rarely subject to threats of filibuster. However, motions for cloture have increased significantly in recent years.

If the Senate invokes cloture, the debate does not necessarily end immediately; instead, it is limited to up to 30 additional hours unless increased by another three-fifths vote. The longest filibuster speech in the Senate’s history was delivered by Strom Thurmond (D-SC), who spoke for over 24 hours in an unsuccessful attempt to block the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957.[50]

Under certain circumstances, the Congressional Budget Act of 1974 provides for a process called «reconciliation» by which Congress can pass bills related to the budget without those bills being subject to a filibuster. This is accomplished by limiting all Senate floor debate to 20 hours.[51]

Voting

When the debate concludes, the motion in question is put to a vote. The Senate often votes by voice vote. The presiding officer puts the question, and members respond either «Yea/Aye» (in favor of the motion) or «Nay» (against the motion). The presiding officer then announces the result of the voice vote. A senator, however, may challenge the presiding officer’s assessment and request a recorded vote. The request may be granted only if it is seconded by one-fifth of the senators present. In practice, however, senators second requests for recorded votes as a matter of courtesy. When a recorded vote is held, the clerk calls the roll of the Senate in alphabetical order; senators respond when their name is called. Senators who were not in the chamber when their name was called may still cast a vote so long as the voting remains open. The vote is closed at the discretion of the presiding officer, but must remain open for a minimum of 15 minutes. A majority of those voting determines whether the motion carries.[52] If the vote is tied, the vice president, if present, is entitled to cast a tie-breaking vote. If the vice president is not present, the motion fails.[53]

Filibustered bills require a three-fifths majority to overcome the cloture vote (which usually means 60 votes) and get to the normal vote where a simple majority (usually 51 votes) approves the bill. This has caused some news media to confuse the 60 votes needed to overcome a filibuster with the 51 votes needed to approve a bill, with for example USA Today erroneously stating «The vote was 58–39 in favor of the provision establishing concealed carry permit reciprocity in the 48 states that have concealed weapons laws. That fell two votes short of the 60 needed to approve the measure«.[52]

Closed session

On occasion, the Senate may go into what is called a secret or closed session. During a closed session, the chamber doors are closed, cameras are turned off, and the galleries are completely cleared of anyone not sworn to secrecy, not instructed in the rules of the closed session, or not essential to the session. Closed sessions are rare and usually held only when the Senate is discussing sensitive subject matter such as information critical to national security, private communications from the president, or deliberations during impeachment trials. A senator may call for and force a closed session if the motion is seconded by at least one other member, but an agreement usually occurs beforehand.[54] If the Senate does not approve the release of a secret transcript, the transcript is stored in the Office of Senate Security and ultimately sent to the national archives. The proceedings remain sealed indefinitely until the Senate votes to remove the injunction of secrecy.[55] In 1973, the House adopted a rule that all committee sessions should be open unless a majority on the committee voted for a closed session.

Calendars

The Senate maintains a Senate Calendar and an Executive Calendar.[56] The former identifies bills and resolutions awaiting Senate floor actions. The latter identifies executive resolutions, treaties, and nominations reported out by Senate committee(s) and awaiting Senate floor action. Both are updated each day the Senate is in session.

Committees

The Senate uses committees (and their subcommittees) for a variety of purposes, including the review of bills and the oversight of the executive branch. Formally, the whole Senate appoints committee members. In practice, however, the choice of members is made by the political parties. Generally, each party honors the preferences of individual senators, giving priority based on seniority. Each party is allocated seats on committees in proportion to its overall strength.

Most committee work is performed by 16 standing committees, each of which has jurisdiction over a field such as finance or foreign relations. Each standing committee may consider, amend, and report bills that fall under its jurisdiction. Furthermore, each standing committee considers presidential nominations to offices related to its jurisdiction. (For instance, the Judiciary Committee considers nominees for judgeships, and the Foreign Relations Committee considers nominees for positions in the Department of State.) Committees may block nominees and impede bills from reaching the floor of the Senate. Standing committees also oversee the departments and agencies of the executive branch. In discharging their duties, standing committees have the power to hold hearings and to subpoena witnesses and evidence.

The Senate also has several committees that are not considered standing committees. Such bodies are generally known as select or special committees; examples include the Select Committee on Ethics and the Special Committee on Aging. Legislation is referred to some of these committees, although the bulk of legislative work is performed by the standing committees. Committees may be established on an ad hoc basis for specific purposes; for instance, the Senate Watergate Committee was a special committee created to investigate the Watergate scandal. Such temporary committees cease to exist after fulfilling their tasks.

The Congress includes joint committees, which include members from both the Senate and the House of Representatives. Some joint committees oversee independent government bodies; for instance, the Joint Committee on the Library oversees the Library of Congress. Other joint committees serve to make advisory reports; for example, there exists a Joint Committee on Taxation. Bills and nominees are not referred to joint committees. Hence, the power of joint committees is considerably lower than those of standing committees.

Each Senate committee and subcommittee is led by a chair (usually a member of the majority party). Formerly, committee chairs were determined purely by seniority; as a result, several elderly senators continued to serve as chair despite severe physical infirmity or even senility.[57] Committee chairs are elected, but, in practice, seniority is rarely bypassed. The chairs hold extensive powers: they control the committee’s agenda, and so decide how much, if any, time to devote to the consideration of a bill; they act with the power of the committee in disapproving or delaying a bill or a nomination by the president; they manage on the floor of the full Senate the consideration of those bills the committee reports. This last role was particularly important in mid-century, when floor amendments were thought not to be collegial. They also have considerable influence: senators who cooperate with their committee chairs are likely to accomplish more good for their states than those who do not. The Senate rules and customs were reformed in the twentieth century, largely in the 1970s. Committee chairmen have less power and are generally more moderate and collegial in exercising it, than they were before reform.[58] The second-highest member, the spokesperson on the committee for the minority party, is known in most cases as the ranking member.[59] In the Select Committee on Intelligence and the Select Committee on Ethics, however, the senior minority member is known as the vice-chair.

Criticism

Critiques on policy gridlock and the Senate’s general usefulness as an institution, stem from a couple central points of criticism: the fact that power is still delegated to states instead of citizens, and specific Senate rules, such as the filibuster.[10]

Malapportioned

Malapportionment, where small state voters get significantly more voice than large state voters, violates the one person, one vote ideal.[60] New York Times opinion columnist David Leonhardt provides the example of how small states are so disproportionately non-Hispanic European American, that African Americans have only 75% of their proportionate voting power in the Senate, whereas Hispanic Americans have just 55%.[61] This results in smaller, whiter states (and thus their citizens) taking funding away from those with less representation.[62]

Rules

Critics argue the Senate’s obsolescence stems not just from partisan paralysis but also a preponderance of arcane rules.[63][64] The Senate filibuster, for example, is frequently debated as the Constitution specifies a simple majority threshold to pass legislation, and some critics feel the de facto three-fifths threshold for general legislation prevents beneficial laws from passing. Detractors also note that the filibuster, elevated in importance in 1917, was a tool most prominently and persistently wielded in defense of white supremacy.[10] The nuclear option was exercised by both parties in the 2010s to eliminate the filibuster for confirmations. Supporters generally consider the filibuster to be an important protection for the minority views and a check against the unfettered single-party rule when the same party holds the Presidency and a majority in both the House and Senate.

Senate office buildings

| External video |

|---|

There are presently three Senate office buildings located along Constitution Avenue, north of the Capitol. They are the Russell Senate Office Building, the Dirksen Senate Office Building, and the Hart Senate Office Building.

Functions

Legislation

Bills may be introduced in either chamber of Congress. However, the Constitution’s Origination Clause provides that «All bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives».[65] As a result, the Senate does not have the power to initiate bills imposing taxes. Furthermore, the House of Representatives holds that the Senate does not have the power to originate appropriation bills, or bills authorizing the expenditure of federal funds.[66][11][67][68] Historically, the Senate has disputed the interpretation advocated by the House. However, when the Senate originates an appropriations bill, the House simply refuses to consider it, thereby settling the dispute in practice. The constitutional provision barring the Senate from introducing revenue bills is based on the practice of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, in which money bills approved by Parliament have originated in the House of Commons per constitutional convention.[69]

Although the Constitution gave the House the power to initiate revenue bills, in practice the Senate is equal to the House in the respect of spending. As Woodrow Wilson wrote:

The Senate’s right to amend general appropriation bills has been allowed the widest possible scope. The upper house may add to them what it pleases; may go altogether outside of their original provisions and tack to them entirely new features of legislation, altering not only the amounts but even the objects of expenditure, and making out of the materials sent them by the popular chamber measures of an almost totally new character.[70]

The approval of both houses is required for any bill, including a revenue bill, to become law. Both Houses must pass the same version of the bill; if there are differences, they may be resolved by sending amendments back and forth or by a conference committee, which includes members of both bodies.

Checks and balances

The Constitution provides several unique functions for the Senate that form its ability to «check and balance» the powers of other elements of the federal government. These include the requirement that the Senate may advise and must consent to some of the president’s government appointments; also the Senate must consent to all treaties with foreign governments; it tries all impeachments, and it elects the vice president in the event no person gets a majority of the electoral votes.

The president can make certain appointments only with the advice and consent of the Senate. Officials whose appointments require the Senate’s approval include members of the Cabinet, heads of most federal executive agencies, ambassadors, justices of the Supreme Court, and other federal judges. Under Article II, Section 2, of the Constitution, a large number of government appointments are subject to potential confirmation; however, Congress has passed legislation to authorize the appointment of many officials without the Senate’s consent (usually, confirmation requirements are reserved for those officials with the most significant final decision-making authority). Typically, a nominee is the first subject to a hearing before a Senate committee. Thereafter, the nomination is considered by the full Senate. The majority of nominees are confirmed, but in a small number of cases each year, Senate committees purposely fail to act on a nomination to block it. In addition, the president sometimes withdraws nominations when they appear unlikely to be confirmed. Because of this, outright rejections of nominees on the Senate floor are infrequent (there have been only nine Cabinet nominees rejected outright in United States history).[71]

The powers of the Senate concerning nominations are, however, subject to some constraints. For instance, the Constitution provides that the president may make an appointment during a congressional recess without the Senate’s advice and consent. The recess appointment remains valid only temporarily; the office becomes vacant again at the end of the next congressional session. Nevertheless, presidents have frequently used recess appointments to circumvent the possibility that the Senate may reject the nominee. Furthermore, as the Supreme Court held in Myers v. United States, although the Senate’s advice and consent are required for the appointment of certain executive branch officials, it is not necessary for their removal.[72][73] Recess appointments have faced a significant amount of resistance and in 1960, the U.S. Senate passed a legally non-binding resolution against recess appointments.[citation needed]

The Senate also has a role in ratifying treaties. The Constitution provides that the president may only «make Treaties, provided two-thirds of the senators present concur» in order to benefit from the Senate’s advice and consent and give each state an equal vote in the process. However, not all international agreements are considered treaties under U.S. domestic law, even if they are considered treaties under international law. Congress has passed laws authorizing the president to conclude executive agreements without action by the Senate. Similarly, the president may make congressional-executive agreements with the approval of a simple majority in each House of Congress, rather than a two-thirds majority in the Senate. Neither executive agreements nor congressional-executive agreements are mentioned in the Constitution, leading some scholars such as Laurence Tribe and John Yoo[74] to suggest that they unconstitutionally circumvent the treaty-ratification process. However, courts have upheld the validity of such agreements.[75]

The Constitution empowers the House of Representatives to impeach federal officials for «Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors» and empowers the Senate to try such impeachments. If the sitting president of the United States is being tried, the chief justice of the United States presides over the trial. During an impeachment trial, senators are constitutionally required to sit on oath or affirmation. Conviction requires a two-thirds majority of the senators present. A convicted official is automatically removed from office; in addition, the Senate may stipulate that the defendant be banned from holding office. No further punishment is permitted during the impeachment proceedings; however, the party may face criminal penalties in a normal court of law.

The House of Representatives has impeached sixteen officials, of whom seven were convicted (one resigned before the Senate could complete the trial).[76] Only three presidents have been impeached: Andrew Johnson in 1868, Bill Clinton in 1998, and Donald Trump in 2019 and 2021. The trials of Johnson, Clinton and both Trump trials ended in acquittal; in Johnson’s case, the Senate fell one vote short of the two-thirds majority required for conviction.

Under the Twelfth Amendment, the Senate has the power to elect the vice president if no vice-presidential candidate receives a majority of votes in the Electoral College. The Twelfth Amendment requires the Senate to choose from the two candidates with the highest numbers of electoral votes. Electoral College deadlocks are rare. The Senate has only broken a deadlock once; in 1837, it elected Richard Mentor Johnson. The House elects the president if the Electoral College deadlocks on that choice.

See also

- Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate

- Elections in the United States

- List of African-American United States senators

- List of current United States senators

- United States presidents and control of Congress

- Women in the United States Senate

Notes

- ^ a b The independent senators, Angus King of Maine, Bernie Sanders of Vermont, and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, caucus with the Democrats.[1][2]

- ^ Alaska (for its primary elections only), California, and Washington additionally utilize a nonpartisan blanket primary, and Mississippi uses the two-round system, for their respective primary elections.

- ^ Louisiana uses a Louisiana primary.

References

- ^ «Maine Independent Angus King To Caucus With Senate Democrats». Politico. November 14, 2012. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2020.

Angus King of Maine, who cruised to victory last week running as an independent, said Wednesday that he will caucus with Senate Democrats. […] The Senate’s other independent, Bernie Sanders of Vermont, also caucuses with the Democrats.

- ^ Sinema, Kyrsten. «Sen. Kyrsten Sinema: Why I’m registering as an independent». The Arizona Republic. Retrieved December 9, 2022.

- ^ a b «Constitution of the United States». Senate.gov. Archived from the original on November 27, 2022. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ Amar, Vik D. (January 1, 1988). «The Senate and the Constitution». The Yale Law Journal. 97 (6): 1111–1130. doi:10.2307/796343. JSTOR 796343. S2CID 53702587. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ Stewart, Charles; Reynolds, Mark (January 1, 1990). «Television Markets and U.S. Senate Elections». Legislative Studies Quarterly. 15 (4): 495–523. doi:10.2307/439894. JSTOR 439894.

- ^ Richard L. Berke (September 12, 1999). «In Fight for Control of Congress, Tough Skirmishes Within Parties». The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ Joseph S. Friedman, undergraduate student (March 30, 2009). «The Rapid Sequence of Events Forcing the Senate’s Hand: A Reappraisal of the Seventeenth Amendment, 1890–1913». Curej – College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal.

- ^ Wirls, Daniel (2021). The Senate : from white supremacy to governmental gridlock. Charlottesville. pp. 2, 40, 44. ISBN 978-0-8139-4691-7. OCLC 1248598962.

- ^ Lee, Frances E. (June 16, 2006). «Agreeing to Disagree: Agenda Content and Senate Partisanship, 198». Legislative Studies Quarterly. 33 (2): 199–222. doi:10.3162/036298008784311000.

- ^ a b c d Wirls, Daniel (2021). The Senate : from white supremacy to governmental gridlock. Charlottesville. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-8139-4691-7. OCLC 1248598962.

- ^ a b Wirls, Daniel and Wirls, Stephen. The Invention of the United States Senate Archived February 12, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, p. 188 (Taylor & Francis 2004).

- ^ a b «U.S. Constitution: Article 1, Section 1«. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ «Merriam-Webster’s Online Dictionary: senate«. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ Robert Yates. Notes of the Secret Debates of the Federal Convention of 1787. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ^ «Non-voting members of Congress». Archived from the original on November 23, 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ «Hawaii becomes 50th state». History.com. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ «Party In Power – Congress and Presidency – A Visual Guide To The Balance of Power In Congress, 1945–2008». uspolitics.about.com. Archived from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- ^ Article I, Section 3: «The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two senators from each state, chosen by the legislature thereof, for six years; each Senator shall have one vote.»

- ^ a b «Direct Election of Senators». U.S. Senate official website. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ^ Federalist Papers, No. 62 Archived November 23, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Library of Congress.

- ^ «1801–1850, November 16, 1818: Youngest Senator». United States Senate. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- ^ «Dates of Sessions of the Congress». United States Senate. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- ^ 2 U.S.C. § 1

- ^ Brooks, James (December 14, 2020). «Election audit confirms win for Ballot Measure 2 and Alaska’s new ranked-choice voting system». Anchorage Daily News. Archived from the original on February 19, 2021. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ «The Term of A Senator – When Does It Begin and End? – Senate 98-29» (PDF). United States Senate. United States Printing Office. pp. 14–15. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 22, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Neale, Thomas H. (April 12, 2018). «U.S. Senate Vacancies: Contemporary Developments and Perspectives» (PDF). fas.org. Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 5, 2018. Retrieved October 13, 2018. NOTE: wherever present, references to page numbers in superscripts refer to the electronic (.pdf) pagination, not as found printed on the bottom margin of displayed pages.

- ^ a b «House approves appointment process for U.S. Senate vacancies». OCPA. Oklahoma Council of Public Affairs. May 27, 2021.

- ^ DeLeo, Robert A. (September 17, 2009). «Temporary Appointment of US Senator». Massachusetts Great and General Court. Archived from the original on August 29, 2019. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

- ^ DeLeo, Robert A. (September 17, 2009). «Temporary Appointment of US Senator Shall not be a candidate in special election». Massachusetts General Court. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ a b «Stevens could keep seat in Senate». Anchorage Daily News. October 28, 2009. Archived from the original on May 28, 2009.

- ^ United States Constitution, Article VI

- ^ See: 5 U.S.C. § 3331; see also: «U.S. Senate Oath of Office». Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ a b «Salaries». United States Senate. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ a b c «US Congress Salaries and Benefits». Usgovinfo.about.com. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- ^ Sean Loughlin and Robert Yoon (June 13, 2003). «Millionaires populate U.S. Senate». CNN. Archived from the original on December 23, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2006.

- ^ «Wealth of Congress». Roll Call. Archived from the original on November 12, 2019. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- ^ Baker, Richard A. «Traditions of the United States Senate» (PDF). United States Senate. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 11, 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- ^ Hickey, Robert. «Use of the Honorable for U.S. Elected Officials». formsofaddress.info. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

- ^ Mewborn, Mary K. «Too Many Honorables?». Washington Life. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016.

- ^ «Seating Arrangement». Senate Chamber Desks. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^ «Senate Chamber Desks – Overview». United States Senate. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ «Senate Chamber Desks – Desk Occupants». United States Senate. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved January 21, 2022.

- ^ «Glossary Term: vice president». senate.gov. United States Senate. Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ^ «Glossary Term: president pro tempore». senate.gov. United States Senate. Archived from the original on December 5, 2016. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ^ Mershon, Erin (August 2011). «Presiding Loses Its Prestige in Senate». Roll Call. rollcall.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ Martin B. Gold, Senate Procedure and Practice, p.39 Archived 2019-03-23 at the Wayback Machine: Every member, when he speaks, shall address the chair, standing in his place, and when he has finished, shall sit down.

- ^ «The World’s Greatest Deliberative Body». Time. July 5, 1993. Archived from the original on August 11, 2009.

- ^ «World’s greatest deliberative body watch». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2010.

- ^ «Senate reform: Lazing on a Senate afternoon». The Economist. Archived from the original on October 14, 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- ^ Quinton, Jeff (July 27, 2003). «Thurmond’s Filibuster». Backcountry Conservative. Archived from the original on June 14, 2006. Retrieved June 19, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Reconciliation, 2 U.S.C. § 641(e) (Procedure in the Senate).

- ^ a b «How majority rule works in the U.S. Senate». Nieman Watchdog. July 31, 2009. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ «Yea or Nay? Voting in the Senate». Senate.gov. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ Amer, Mildred (March 27, 2008). «Secret Sessions of Congress: A Brief Historical Overview» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 6, 2009.

- ^ Amer, Mildred (March 27, 2008). «Secret Sessions of the House and Senate» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 6, 2009.

- ^ «Calendars & Schedules». United States Senate. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021.

- ^ See, for examples, American Dictionary of National Biography on John Sherman and Carter Glass; in general, Ritchie, Congress, p. 209

- ^ Ritchie, Congress, p. 44. Zelizer, On Capitol Hill describes this process; one of the reforms is that seniority within the majority party can now be bypassed, so that chairs do run the risk of being deposed by their colleagues. See in particular p. 17, for the unreformed Congress, and pp.188–9, for the Stevenson reforms of 1977.

- ^ Ritchie, Congress, pp .44, 175, 209

- ^ Lazare, Daniel (December 2, 2014). «Abolish the Senate». jacobin.com. Retrieved December 24, 2022.

- ^ Leonhardt, David (October 14, 2018). «The Senate: Affirmative Action for White People». The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ Rusch, Elizabeth (2020). You call this democracy? : how to fix our government and deliver power to the people. Boston. ISBN 978-0-358-17692-3. OCLC 1124772479.

- ^ Mark Murray (August 2, 2010). «The inefficient Senate». Firstread.msnbc.msn.com. Archived from the original on August 10, 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- ^ Packer, George (January 7, 2009). «Filibusters and arcane obstructions in the Senate». The New Yorker. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- ^ «Constitution of the United States». Senate.gov. Archived from the original on February 10, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^

This article incorporates public domain material from James V. Saturno. The Origination Clause of the U.S. Constitution: Interpretation and Enforcement (PDF). Congressional Research Service.

- ^ Woodrow Wilson wrote that the Senate has extremely broad amendment authority with regard to appropriations bills, as distinguished from bills that levy taxes. See Wilson, Woodrow. Congressional Government: A Study in American Politics Archived February 12, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, pp. 155–156 (Transaction Publishers 2002).

- ^ According to the Library of Congress, the Constitution provides the origination requirement for revenue bills, whereas tradition provides the origination requirement for appropriation bills. See Sullivan, John. «How Our Laws Are Made Archived October 16, 2015, at the Wayback Machine», Library of Congress (accessed August 26, 2013).

- ^ Sargent, Noel. «Bills for Raising Revenue Under the Federal and State Constitutions Archived January 7, 2021, at the Wayback Machine», Minnesota Law Review, Vol. 4, p. 330 (1919).

- ^ Wilson Congressional Government, Chapter III: «Revenue and Supply». Text common to all printings or «editions»; in Papers of Woodrow Wilson it is Vol.4 (1968), p.91; for unchanged text, see p. 13, ibid.

- ^ King, Elizabeth. «This Is What Happened Last Time a Cabinet Nomination Was Rejected». time.com. Time USA, LLC. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- ^ «Recess Appointments FAQ» (PDF). US Senate, Congressional Research Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 29, 2017. Retrieved November 20, 2007.

- ^ Ritchie, Congress p. 178.

- ^ Bolton, John R. (January 5, 2009). «Restore the Senate’s Treaty Power». The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ For an example, and a discussion of the literature, see Laurence Tribe, «Taking Text and Structure Seriously: Reflections on Free-Form Method in Constitutional Interpretation Archived January 8, 2021, at the Wayback Machine», Harvard Law Review, Vol. 108, No. 6. (April 1995), pp. 1221–1303.

- ^ «Complete list of impeachment trials». United States Senate. Archived from the original on December 2, 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2007.

Bibliography

- Baker, Richard A. The Senate of the United States: A Bicentennial History Krieger, 1988.

- Baker, Richard A., ed., First Among Equals: Outstanding Senate Leaders of the Twentieth Century Congressional Quarterly, 1991.

- Barone, Michael, and Grant Ujifusa, The Almanac of American Politics 1976: The Senators, the Representatives and the Governors: Their Records and Election Results, Their States and Districts (1975); new edition every 2 years

- David W. Brady and Mathew D. McCubbins. Party, Process, and Political Change in Congress: New Perspectives on the History of Congress (2002)

- Caro, Robert A. The Years of Lyndon Johnson. Vol. 3: Master of the Senate. Knopf, 2002.

- Comiskey, Michael. Seeking Justices: The Judging of Supreme Court Nominees U. Press of Kansas, 2004.

- Congressional Quarterly Congress and the Nation XII: 2005–2008: Politics and Policy in the 109th and 110th Congresses (2010); massive, highly detailed summary of Congressional activity, as well as major executive and judicial decisions; based on Congressional Quarterly Weekly Report and the annual CQ almanac. The Congress and the Nation 2009–2012 vol XIII has been announced for September 2014 publication.

- Congressional Quarterly Congress and the Nation: 2001–2004 (2005);

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1997–2001 (2002)

- Congressional Quarterly. Congress and the Nation: 1993–1996 (1998)

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1989–1992 (1993)

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1985–1988 (1989)

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1981–1984 (1985)

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1977–1980 (1981)

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1973–1976 (1977)

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1969–1972 (1973)

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1965–1968 (1969)

- Congressional Quarterly, Congress and the Nation: 1945–1964 (1965), the first of the series

- Cooper, John Milton, Jr. Breaking the Heart of the World: Woodrow Wilson and the Fight for the League of Nations. Cambridge U. Press, 2001.

- Davidson, Roger H., and Walter J. Oleszek, eds. (1998). Congress and Its Members, 6th ed. Washington DC: Congressional Quarterly. (Legislative procedure, informal practices, and member information)

- Gould, Lewis L. The Most Exclusive Club: A History Of The Modern United States Senate (2005)

- Hernon, Joseph Martin. Profiles in Character: Hubris and Heroism in the U.S. Senate, 1789–1990 Sharpe, 1997.

- Hoebeke, C. H. The Road to Mass Democracy: Original Intent and the Seventeenth Amendment. Transaction Books, 1995. (Popular elections of senators)

- Lee, Frances E. and Oppenheimer, Bruce I. Sizing Up the Senate: The Unequal Consequences of Equal Representation. U. of Chicago Press 1999. 304 pp.

- MacNeil, Neil and Richard A. Baker. The American Senate: An Insider’s History. Oxford University Press, 2013. 455 pp.

- McFarland, Ernest W. The Ernest W. McFarland Papers: The United States Senate Years, 1940–1952. Prescott, Ariz.: Sharlot Hall Museum, 1995 (Democratic majority leader 1950–52)

- Malsberger, John W. From Obstruction to Moderation: The Transformation of Senate Conservatism, 1938–1952. Susquehanna U. Press 2000

- Mann, Robert. The Walls of Jericho: Lyndon Johnson, Hubert Humphrey, Richard Russell and the Struggle for Civil Rights. Harcourt Brace, 1996

- Ritchie, Donald A. (1991). Press Gallery: Congress and the Washington Correspondents. Harvard University Press.

- Ritchie, Donald A. (2001). The Congress of the United States: A Student Companion (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Ritchie, Donald A. (2010). The U.S. Congress: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Rothman, David. Politics and Power the United States Senate 1869–1901 (1966)

- Swift, Elaine K. The Making of an American Senate: Reconstitutive Change in Congress, 1787–1841. U. of Michigan Press, 1996

- Valeo, Frank. Mike Mansfield, Majority Leader: A Different Kind of Senate, 1961–1976 Sharpe, 1999 (Senate Democratic leader)

- VanBeek, Stephen D. Post-Passage Politics: Bicameral Resolution in Congress. U. of Pittsburgh Press 1995

- Weller, Cecil Edward, Jr. Joe T. Robinson: Always a Loyal Democrat. U. of Arkansas Press, 1998. (Arkansas Democrat who was Majority leader in 1930s)

- Wilson, Woodrow. Congressional Government. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1885; also 15th ed. 1900, repr. by photoreprint, Transaction books, 2002.

- Wirls, Daniel and Wirls, Stephen. The Invention of the United States Senate Johns Hopkins U. Press, 2004. (Early history)

- Zelizer, Julian E. On Capitol Hill : The Struggle to Reform Congress and its Consequences, 1948–2000 (2006)

- Zelizer, Julian E., ed. The American Congress: The Building of Democracy (2004) (overview)

Official Senate histories

- Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774–1989

The following are published by the Senate Historical Office.

- Robert Byrd. The Senate, 1789–1989. Four volumes.

- Vol. I, a chronological series of addresses on the history of the Senate

- Vol. II, a topical series of addresses on various aspects of the Senate’s operation and powers

- Vol. III, Classic Speeches, 1830–1993

- Vol. IV, Historical Statistics, 1789–1992

- Dole, Bob. Historical Almanac of the United States Senate

- Hatfield, Mark O., with the Senate Historical Office. Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789–1993 (essays reprinted online)

- Frumin, Alan S. Riddick’s Senate Procedure. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1992.

External links

This audio file was created from a revision of this article dated 4 August 2006, and does not reflect subsequent edits.

- The United States Senate Official Website

- Sortable contact data

- Senate Chamber Map

- Standing Rules of the Senate

- Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774 to Present

- List of Senators who died in office, via PoliticalGraveyard.com

- Chart of all U.S. Senate seat-holders, by state, 1978–present, via Texas Tech University

- A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787–1825 Archived July 25, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, via Tufts University

- Bill Hammons’ American Politics Guide – Members of Congress by Committee and State with Partisan Voting Index Archived December 30, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Works by or about United States Senate at Internet Archive

- First U.S. Senate session aired by C-SPAN via C-SPAN

- Senate Manual via govinfo.gov (U.S. Government Publishing Office)

- United States Senate Calendars and Schedules

- Information about U.S. Bills and Resolutions Archived January 2, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- Works by United States Senate at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Coordinates: 38°53′26″N 77°0′32″W / 38.89056°N 77.00889°W

|

United States Senate |

|

|---|---|

| 118th United States Congress | |

Seal of the U.S. Senate |

|

Flag of the U.S. Senate |

|

| Type | |

| Type |

Upper house of the United States Congress |

|

Term limits |

None |

| History | |

|

New session started |

January 3, 2023 |

| Leadership | |

|

President of the Senate |

Kamala Harris (D) |

|

President pro tempore |

Patty Murray (D) |

|

Majority Leader |

Chuck Schumer (D) |

|

Minority Leader |

Mitch McConnell (R) |

|

Majority Whip |

Dick Durbin (D) |

|

Minority Whip |

John Thune (R) |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 100 |

|

|

|

Political groups |

Majority (51)

Minority (48)

Vacant (1)

|

|

Length of term |

6 years |

| Elections | |

|

Voting system |

Plurality voting in 46 states[b]

Varies in 4 states

|

|

Last election |

November 8, 2022 (36 seats) |

|

Next election |

November 5, 2024 (34 seats) |

| Meeting place | |

|

|

| Senate Chamber United States Capitol Washington, D.C. United States |

|

| Website | |

| senate.gov | |

| Constitution | |

| United States Constitution | |

| Rules | |

| Standing Rules of the United States Senate |

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powers of the Senate are established by Article One of the United States Constitution.[3] The Senate is composed of senators, each of whom represents a single state in its entirety. Each of the 50 states is equally represented by two senators who serve staggered terms of six years, for a total of 100 senators. The vice president of the United States serves as presiding officer and president of the Senate by virtue of that office, despite not being a senator, and has a vote only if the Senate is equally divided. In the vice president’s absence, the president pro tempore, who is traditionally the senior member of the party holding a majority of seats, presides over the Senate.

As the upper chamber of Congress, the Senate has several powers of advice and consent which are unique to it. These include the approval of treaties, and the confirmation of Cabinet secretaries, federal judges (including Federal Supreme Court justices), flag officers, regulatory officials, ambassadors, other federal executive officials and federal uniformed officers. If no candidate receives a majority of electors for vice president, the duty falls to the Senate to elect one of the top two recipients of electors for that office. The Senate conducts trials of those impeached by the House.

The Senate has typically been considered both a more deliberative,[4] prestigious,[5][6][7] and controversial[8] body than the House of Representatives due to its longer terms, smaller size, and statewide constituencies, which historically led to a more collegial and less partisan atmosphere.[9]

From 1789 to 1913, senators were appointed by legislatures of the states they represented. They are now elected by popular vote following the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913. In the early 1920s, the practice of majority and minority parties electing their floor leaders began. The Senate’s legislative and executive business is managed and scheduled by the Senate majority leader.

The Senate chamber is located in the north wing of the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C.

History

The drafters of the Constitution struggled and debated more in the creation of the Senate than in any other part of the Constitution.[10] In the end, a bicameral Congress emerged primarily as a compromise between some smaller states who threatened to walk away if they lost any more power and larger ones.[11] The resulting congress with one chamber representing people equally, while the other maintains the equal power of smaller states from the existing arrangement (the Articles of Confederation), was known as the Connecticut Compromise. There was also a desire to have two Houses that could act as an internal check on each other. One was a «People’s House» directly elected by the people, and with short terms obliging the representatives to remain close to their constituents. The other represented the states to such extent as they retained some sovereignty except for the powers expressly delegated to the national government. The Constitution provides that the approval of both chambers is necessary for the passage of legislation.[12]

First convened in 1789, the Senate of the United States was formed on the example of the ancient Roman Senate. The name is derived from the senatus, Latin for council of elders (from senex meaning old man in Latin).[13]

James Madison made the only argument for minority [ie landholder] rights at the convention:[10]

In England, at this day, if elections were open to all classes of people, the property of landed proprietors would be insecure. An agrarian law would soon take place. If these observations remain just, our government ought to secure the permanent interests of the country against innovation. Landholders ought to have a share in the government, to support these invaluable interests, and to balance and check the other. They ought to be so constituted as to protect the minority of the opulent against the majority. The Senate, therefore, ought to be this body; and to answer these purposes, they ought to have permanency and stability.[14]

— Notes of the Secret Debates of the Federal Convention of 1787

Article Five of the Constitution stipulates that no constitutional amendment may be created to deprive a state of its equal suffrage in the Senate without that state’s consent. The District of Columbia and the territories are not entitled to representation or allowed to vote in either house of Congress. They have official non-voting delegates in the House of Representatives, but none in the Senate. The District of Columbia and Puerto Rico each additionally elect two «shadow senators», but they are officials of their respective local governments and not members of the U.S. Senate.[15] The United States has had 50 states since 1959,[16] thus the Senate has had 100 senators since 1959.[12]

Graph showing historical party control of the U.S. Senate, House and Presidency since 1855[17]

The disparity between the most and least populous states has grown since the Connecticut Compromise, which granted each state two members of the Senate and at least one member of the House of Representatives, for a total minimum of three presidential electors, regardless of population. In 1787, Virginia had roughly ten times the population of Rhode Island, whereas today California has roughly 70 times the population of Wyoming, based on the 1790 and 2020 censuses. Before the adoption of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913, senators were elected by the individual state legislatures.[18] Problems with repeated vacant seats due to the inability of a legislature to elect senators, intrastate political struggles, bribery and intimidation gradually led to a growing movement to amend the Constitution to allow for the direct election of senators.[19]

Current composition and election results

Members of the United States Senate for the 118th Congress

Current party standings

The party composition of the Senate during the 118th Congress:

| Affiliation | Members | |

|---|---|---|

| Republican | 48 | |

| Democratic | 48 | |

| Independents | 3[a] | |

| Vacant | 1 | |

| Total | 100 |

Membership

Qualifications