| Севастополь в Википедии | |

| Севастополь в Викицитатнике | |

| Севастополь в Викитеке | |

| Севастополь в Викиновостях | |

| Севастополь в Викигиде |

Русский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | Севасто́поль | Севасто́поли |

| Р. | Севасто́поля | Севасто́полей |

| Д. | Севасто́полю | Севасто́полям |

| В. | Севасто́поль | Севасто́поли |

| Тв. | Севасто́полем | Севасто́полями |

| Пр. | Севасто́поле | Севасто́полях |

Се—вас—то́—поль

Существительное, неодушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 2a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Имя собственное, топоним.

Корень: —.

Произношение

- МФА: ед. ч. [sʲɪvɐˈstopəlʲ], мн. ч. [sʲɪvɐˈstopəlʲɪ]

Семантические свойства

Значение

- геогр. портовый город на юго-западе Крымского полуострова, спорный между Россией и Украиной; согласно административно-территориальному делению России (которая фактически контролирует город с 2014 года) является городом федерального значения, согласно административно-территориальному делению Украины — городом с особым статусом ◆ Утренняя заря только что начинает окрашивать небосклон над Сапун-горою; темно-синяя поверхность моря уже сбросила с себя сумрак ночи и ждет первого луча, чтобы заиграть веселым блеском; с бухты несет холодом и туманом; снега нет ― все черно, но утренний резкий мороз хватает за лицо и трещит под ногами, и далекий неумолкаемый гул моря, изредка прерываемый раскатистыми выстрелами в Севастополе, один нарушает тишину утра. Л. Н. Толстой, «Севастопольские рассказы», Севастополь в декабре месяце, 1855 г. [НКРЯ] ◆ Все умы были прикованы к Севастополю… он боролся одиннадцать месяцев и пал, победоносный в своем падении. А. В. Амфитеатров, «Княжна», 1889–1895 гг. [НКРЯ] ◆ К середине апреля почти весь Крым был очищен. Остатки немецких войск отошли к Севастополю. Гитлер прислал пополнения. И. И. Минц, «Великая Отечественная война Советского Союза», 1947 г. [НКРЯ] ◆ Двенадцатый час вечера. В одиннадцать радио: Севастополь взят. Дорого, верно, достался! И. А. Бунин, «Дневники», 1940–1953 гг. [НКРЯ] ◆ Недалеко от Севастополя лежат живописные развалины древнего города. Б. Г. Петерс, «В поисках затонувшего судна», 1962 г. // «Спортсмен-подводник» [НКРЯ]

- геогр. село в Костанайской области в Казахстане ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы

- истор. Ахтиар (1783–1784, 1797–1826); разг. Севас

- —

Антонимы

- —

- —

Гиперонимы

- город федерального значения, город-герой, город, населённый пункт

- село

Гипонимы

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

|

Этимология

Происходит от Шаблон:этимология:Севастополь

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Перевод

| город-порт | |

|

| село в Казахстане | |

|

Библиография

Башкирский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

Севастополь

Существительное.

Имя собственное, топоним.

Корень: —.

Произношение

Семантические свойства

Значение

- Севастополь (аналогично русскому слову) ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы

Антонимы

- —

Гиперонимы

- ҡала

Гипонимы

- —

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от Шаблон:этимология:Севастополь

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Библиография

Лезгинский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

Севастополь

Существительное.

Имя собственное, топоним.

Корень: —.

Произношение

Семантические свойства

Значение

- Севастополь (аналогично русскому слову) ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы

Антонимы

- —

Гиперонимы

- шегьер

Гипонимы

- —

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от Шаблон:этимология:Севастополь

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Библиография

Монгольский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

Севастополь

Существительное.

Имя собственное, топоним.

Корень: —.

Произношение

Семантические свойства

Значение

- Севастополь (аналогично русскому слову) ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы

Антонимы

- —

Гиперонимы

- баатар-хот, хот

Гипонимы

- —

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от Шаблон:этимология:Севастополь

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Библиография

Осетинский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

Севастополь

Существительное.

Имя собственное, топоним.

Корень: —.

Произношение

Семантические свойства

Значение

- Севастополь (аналогично русскому слову) ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы

Антонимы

- —

Гиперонимы

- сахар (горӕт)

Гипонимы

- —

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от Шаблон:этимология:Севастополь

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Библиография

Русинский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

Севастополь

Существительное.

Имя собственное, топоним.

Корень: —.

Произношение

Семантические свойства

Значение

- Севастополь (аналогично русскому слову) ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы

Антонимы

- —

Гиперонимы

- місто

Гипонимы

- —

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от Шаблон:этимология:Севастополь

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Библиография

Татарский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

Севастополь

Существительное.

Имя собственное, топоним.

Корень: —.

Произношение

Семантические свойства

Значение

- Севастополь (аналогично русскому слову) ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы

- Акъяр

Антонимы

- —

Гиперонимы

- шәһәр (кала), торак пункт

Гипонимы

- —

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от Шаблон:этимология:Севастополь

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Библиография

Удмуртский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

Севастополь

Существительное.

Имя собственное, топоним.

Корень: —.

Произношение

Семантические свойства

Значение

- Севастополь (аналогично русскому слову) ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы

Антонимы

- —

Гиперонимы

- кар

Гипонимы

- —

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от Шаблон:этимология:Севастополь

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Библиография

Украинский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

Севастополь

Существительное, неодушевлённое.

Имя собственное, топоним.

Корень: —.

Произношение

Семантические свойства

Значение

- Севастополь (аналогично русскому слову) ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы

Антонимы

- —

Гиперонимы

- місто-герой, місто, населений пункт

Гипонимы

- —

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от Шаблон:этимология:Севастополь

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Библиография

Чеченский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

Севастополь

Существительное.

Имя собственное, топоним.

Корень: —.

Произношение

Семантические свойства

Значение

- Севастополь (аналогично русскому слову) ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы

Антонимы

- —

Гиперонимы

- гӀала

Гипонимы

- —

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от Шаблон:этимология:Севастополь

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Библиография

Чувашский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

Севастополь

Существительное.

Имя собственное, топоним.

Корень: —.

Произношение

Семантические свойства

Значение

- Севастополь (аналогично русскому слову) ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы

Антонимы

- —

Гиперонимы

- хула

Гипонимы

- —

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от Шаблон:этимология:Севастополь

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Библиография

Якутский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

Севастополь

Существительное.

Имя собственное, топоним.

Корень: —.

Произношение

Семантические свойства

Значение

- Севастополь (аналогично русскому слову) ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы

Антонимы

- —

Гиперонимы

- куорат

Гипонимы

- —

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от Шаблон:этимология:Севастополь

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Библиография

Значение слова «Севастополь»

Севасто́поль (укр. Севастополь, с 1783 по 1784 и с 1797 по 1826 годы — Ахтиар) — город на юго-западе Крымского полуострова, на побережье Чёрного моря. Незамерзающий морской торговый и рыбный порт, промышленный, научно-технический, рекреационный и культурно-исторический центр. Носит звание «Город-Герой». В Севастополе расположена главная военно-морская база Черноморского флота Российской Федерации. Город Севастополь входит в перечень исторических поселений федерального значения России и в список исторических населённых мест Украины.

Все значения слова «Севастополь»

Предложения со словом «севастополь»

-

Севастополь держался до конца июня, несмотря на все усилия захватчиков овладеть городом непрестанными штурмами.

-

Севастополь почувствовал только отголоски землетрясения, здания и сооружения практически не пострадали.

-

Севастополь отправил эскадру из шести военных кораблей приветствовать своего главного живописца.

- (все предложения)

Синонимы к слову «севастополь»

- чёрное море

- канонерская лодка

- лидер эсминцев

- госпитальное судно

- охрана водного района

- (ещё синонимы…)

Синонимы к слову «Севастополь»

- Одесса

- Новороссийск

- Киев

- Ленинград

- Смоленск

- (ещё синонимы…)

Ассоциации к слову «Севастополь»

- Ялта

- город

- море

- Крым

- Россия

- (ещё ассоциации…)

|

Sevastopol

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

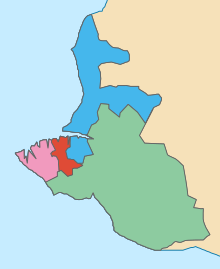

Orthographic projection of Sevastopol (in green) |

|

Map of the Crimean Peninsula with Sevastopol highlighted |

|

|

Sevastopol Location of Sevastopol within Crimea Sevastopol Location of Sevastopol within Europe Sevastopol Sevastopol (Europe) |

|

| Coordinates: 44°36′18″N 33°31′21″E / 44.605°N 33.5225°ECoordinates: 44°36′18″N 33°31′21″E / 44.605°N 33.5225°E | |

| Country | Territory of Ukraine, occupied by Russia[1] |

| Status | Independent city1 |

| Founded | 1783 (240 years ago) |

| Government

(under Russian occupation)[2] |

|

| • Body | Legislative Assembly |

| • Governor | Mikhail Razvozhayev |

| Area | |

| • City | 864 km2 (334 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 100 m (300 ft) |

| Population

(2021) |

|

| • City | 547,820 |

| • Density | 630/km2 (1,600/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 479,394 |

| Demonym(s) | Sevastopolitan, Sevastopolian |

| Time zone | UTC+03:00 |

Sevastopol ([a]), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea. Due to its strategic location and the navigability of the city’s harbours, Sevastopol has been an important port and naval base throughout its history. Since the city’s founding in 1783 it has been a major base for Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, and it was previously a closed city during the Cold War. The total administrative area is 864 square kilometres (334 sq mi) and includes a significant amount of rural land. The urban population, largely concentrated around Sevastopol Bay, is 479,394,[3] and the total population is 547,820.[4]

Sevastopol, along with the rest of Crimea, is internationally recognised as part of Ukraine, and under the Ukrainian legal framework, it is administratively one of two cities with special status (the other being Kyiv). However, it has been occupied by Russia since 27 February 2014, before Russia annexed Crimea on 18 March 2014 and gave it the status of a federal city of Russia. Both Ukraine and Russia consider the city administratively separate from the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the Republic of Crimea. The city’s population has an ethnic Russian majority and a substantial minority of Ukrainians.

Sevastopol’s unique naval and maritime features have been the basis for a robust economy. The city enjoys mild winters and moderately warm summers, characteristics that help make it a popular seaside resort and tourist destination, mainly for visitors from the former Soviet republics. The city is also an important centre for marine biology research. In particular, the military has studied and trained dolphins in the city for military use since the 1960s.[5]

Etymology

The name of Sevastopolis was originally chosen in the same etymological trend as other cities in the Crimean peninsula; it was intended to express its ancient Greek origins. It is a compound of the Greek adjective, σεβαστός (sebastós, Byzantine Greek pronunciation: [sevasˈtos]; ‘venerable’) and the noun πόλις (pólis, ‘city’). Σεβαστός is the traditional Greek equivalent (see Sebastian) of the Roman honorific Augustus, originally given to the first emperor of the Roman Empire, Augustus and later awarded as a title to his successors.

Despite its Greek origin, the name is not from Ancient Greek times. The city was probably named after Empress («Augusta») Catherine II of the Russian Empire who founded Sevastopol in 1783. She visited the city in 1787, accompanied by Joseph II, the Emperor of Austria, and other foreign dignitaries.

In the west of the city, there are well-preserved ruins of the ancient Greek port city of Chersonesos, founded in the 5th[6] century BC by settlers from Heraclea Pontica. This name means «peninsula», reflecting its immediate location. It is not related to the ancient Greek name for the Crimean Peninsula as a whole: Chersonēsos Taurikē («the Taurian Peninsula»).

The name of the city is spelled as:

- English: Sevastopol, the current prevalent spelling; the previously common spelling Sebastopol is still used by some publications, and formerly by The Economist.[7][8] The current spelling has the pronunciation ,[9][10] while the former spelling has the pronunciation .[11][12]

- Ukrainian: Севасто́поль, pronounced [sewɐˈstɔpolʲ]; Russian: Севасто́поль, pronounced [sʲɪvɐˈstopəlʲ].[13]

- Crimean Tatar: Aqyar, pronounced [aqˈjar], or Sivastopol.

History

Ancient Chersonesus

In the 6th century BC, a Greek colony was established in the area of the modern-day city. The Greek city of Chersonesus existed for almost two thousand years, first as an independent democracy and later as part of the Bosporan Kingdom. In the 13th and 14th centuries, it was sacked by the Golden Horde several times and was finally totally abandoned. The modern day city of Sevastopol has no connection to the ancient and medieval Greek city, but the ruins are a popular tourist attraction located on the outskirts of the city.

Part of the Russian Empire

«Soldier and Sailor» Memorial to Heroic Defenders of Sevastopol

Sevastopol was founded in June 1783 as a base for a naval squadron under the name Akhtiar[14] (White Cliff),[15] by Rear Admiral Thomas MacKenzie (Foma Fomich Makenzi), a native Scot in Russian service; soon after Russia annexed the Crimean Khanate. Five years earlier, Alexander Suvorov ordered that earthworks be erected along the harbour and Russian troops be placed there.

In February 1784, Catherine the Great ordered Grigory Potemkin to build a fortress there and call it Sevastopol. The realisation of the initial building plans fell to Captain Fyodor Ushakov who in 1788 was named commander of the port and of the Black Sea squadron.[16] The city was established on western shore of Southern Bay which branches away from bigger Sevastopol Bay. The ruins of the ancient Chersonesus were situated to the west. The newly built settlement became an important naval base and later a commercial seaport. In 1797, under an edict issued by Emperor Paul I, the military stronghold was again renamed Akhtiar. Finally, on 29 April (10 May), 1826, the Senate returned the city’s name to Sevastopol.[citation needed] In 1803 to 1864 along with Mykolaiv the city was part of Nikolayev–Sevastopol Military Governorate.

Crimean War

From 1853 to 1856, the Crimean peninsula’s strategic position in controlling the Black Sea caused it to be the site of the principal engagements of the Crimean War, where Russia lost to a French-led alliance.[17]

After a minor skirmish at Köstence (now Constanța), the allied commanders decided to attack Sevastopol as Russia’s main naval base in the Black Sea. After extended preparations, allied forces landed on the peninsula in September 1854 and marched to a point south of Sevastopol after winning the Battle of the Alma on 20 September. The Russians counterattacked on 25 October in what became the Battle of Balaclava and were repulsed, but the British Army’s forces were seriously depleted as a result. A second Russian counterattack, at Inkerman in November, ended in a stalemate as well. The front settled into the siege of Sevastopol, involving brutal conditions for troops on both sides.

Sevastopol finally fell after eleven months, after the French had assaulted Fort Malakoff. Isolated and facing a bleak prospect of invasion by the West if the war continued, Russia sued for peace in March 1856. France and Britain welcomed the development, owing to the conflict’s domestic unpopularity. The Treaty of Paris, signed on 30 March 1856, ended the war and forbade Russia from basing warships in the Black Sea.[18] This hampered the Russians during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 and in the aftermath of that conflict, Russia moved to reconstitute its naval strength and fortifications in the Black Sea.[19]

World War II

During World War II, Sevastopol withstood intensive bombardment by the Germans in 1941–42, supported by their Italian and Romanian allies during the Battle of Sevastopol. German forces used railway artillery—including history’s largest-ever calibre railway artillery piece in battle, the 80-cm calibre Schwerer Gustav—and specialised mobile heavy mortars to destroy Sevastopol’s extremely heavy fortifications, such as the Maxim Gorky Fortresses. After fierce fighting, which lasted for 250 days,[20][21][22] the fortress city finally fell to Axis forces in July 1942.[23] It was intended to be renamed to «Theodorichshafen«[24] (in reference to Theodoric the Great and the fact that the Crimea had been home to Germanic Goths until the 18th or 19th century) in the event of a German victory against the Soviet Union, and like the rest of the Crimea was designated for future colonisation by the Third Reich. It was liberated by the Red Army on 9 May 1944 and was awarded the Hero City title a year later.

Part of Ukrainian SSR

During the Soviet era, Sevastopol became a so-called «closed city». This meant that any non-residents had to apply to the authorities for a temporary permit to visit the city.

On 29 October 1948, the Presidium of Supreme Council of the Russian SFSR issued an ukaz (order) which confirmed the special status of the city.[25] Soviet academic publications since 1954, including the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, indicated that Sevastopol, Crimean Oblast was part of the Ukrainian SSR.[26][15]

In 1954, under Nikita Khrushchev, both Sevastopol and the remainder of the Crimean peninsula were administratively transferred from being territories within the Russian SFSR to being territories administered by the Ukrainian SSR. Administratively, Sevastopol was a municipality excluded from the adjacent Crimean Oblast.[citation needed][further explanation needed] The territory of the municipality was 863.5 km2 and it was further subdivided into four raions (districts). Besides the City of Sevastopol proper, it also included two towns—Balaklava (having had no status until 1957), Inkerman, urban-type settlement Kacha, and 29 villages.[27]

For the 1955 Ukrainian parliamentary elections on 27 February, Sevastopol was split into two electoral districts, Stalinsky and Korabelny (initially requested three Stalinsky, Korabelny, and Nakhimovsky).[25] Eventually,[clarification needed] Sevastopol received two people’s deputies of the Ukrainian SSR elected to the Verkhovna Rada,[clarification needed] A. Korovchenko and M. Kulakov.[25][28]

In 1957, the town of Balaklava was incorporated into Sevastopol.

Part of Ukraine

The Black Sea Fleet Museum

Following Ukraine’s declaration of independence from the USSR in 1991, Sevastopol became the principal base of the Ukrainian navy. As the key naval base of the former Soviet Black Sea Fleet, it was a source of tensions for Russia–Ukraine relations until a set-term lease agreement was signed in 1997.

On 10 July 1993, the Russian parliament passed a resolution declaring Sevastopol to be «a federal Russian city».[29] At the time, many supporters of President Boris Yeltsin had ceased taking part in[clarification needed] the parliament’s work.[30] On 20 July 1993, the United Nations Security Council denounced the decision of the Russian parliament. According to Anatoliy Zlenko, it was the first time that the council had to review and qualify actions of a legislative body.[25]

On 14 April 1993, the Presidium of the Crimean Parliament called for the creation of the presidential post of the Crimean Republic.[clarification needed] A week later, the Russian deputy, Valentin Agafonov, said that Russia was ready to supervise a referendum on Crimean independence and include the republic as a separate entity in the CIS. On 28 July 1993, one of the leaders of the Russian Society of Crimea, Viktor Prusakov, said that his organisation was ready for an armed mutiny and establishment of Russian administration of Sevastopol.

In September, the commander of the joint Russian-Ukrainian Black Sea Fleet, Eduard Baltin [ru], accused Ukraine of converting some of his fleet and conducting an armed assault on his personnel and threatened to take countermeasures placing the fleet on alert. (In June 1992, the Russian president Yeltsin and the Ukrainian president Leonid Kravchuk had agreed to divide the former Soviet Black Sea Fleet between Russia and Ukraine. Eduard Baltin had been appointed commander of the Black Sea Fleet by Yeltsin and Kravchuk on 15 January 1993.)

The Moscow mayor Yuriy Luzhkov campaigned to claim[clarification needed] the city, and in December 1996, the Russian Federation Council officially endorsed the claim, threatening negotiations. Due to these revanchist claims, Ukraine proposed a «special partnership» with NATO in January 1997.[31]

In May 1997, Russia and Ukraine signed the Russian–Ukrainian Friendship Treaty, ruling out Moscow’s territorial claims to Ukraine.[32] This was followed by the Partition Treaty on the Status and Conditions of the Black Sea Fleet on 28 May 1997. A separate agreement established the terms of a long-term lease of land, facilities, and resources in Sevastopol and the Crimea by Russia.[citation needed] Russia kept its naval base, with around 15,000 troops stationed in Sevastopol.[33]

The ex-Soviet Black Sea Fleet and its facilities were divided between Russia’s Black Sea Fleet and the Ukrainian Naval Forces. The two navies co-used some of the city’s harbours and piers, while others were demilitarised or used by either[clarification needed] country. Sevastopol remained the location of the Russian Black Sea Fleet headquarters, and the Ukrainian Naval Forces Headquarters were also located in the city. A judicial row periodically continued over the naval hydrographic infrastructure both in Sevastopol and on the Crimean coast (especially lighthouses historically maintained by the Soviet and Russian Navy and also used for civil navigation support).

As in the rest of Crimea, Russian remained the predominant language of the city, although following the independence of Ukraine there were some attempts at Ukrainisation, with very little success. Russian society in general and even some outspoken government representatives never accepted the loss of Sevastopol and tended to regard it as temporarily separated from Russia.[34]

In July 2009, the chairman of the Sevastopol city council, Valeriy Saratov (Party of Regions),[35] said that Ukraine should increase the amount of compensation it is paying to the city of Sevastopol for hosting the foreign Russian Black Sea Fleet, instead of requesting such compensation from the Russian government and the Russian Ministry of Defense in particular.[36]

On 27 April 2010, Russia and Ukraine ratified the Russian Ukrainian Naval Base for Gas treaty, which extended the Russian Navy’s lease of Crimean facilities for 25 years after 2017 (through 2042) with the option to prolong the lease in five-year extensions. The ratification process in the Ukrainian parliament encountered stiff opposition and even resulted in a brawl in the parliament chamber. Eventually, the treaty was ratified by a 52% majority vote—236 of 450. The Russian Duma ratified the treaty by a 98% majority.[37]

Occupation and annexation by Russia

On 23 February 2014, a pro-Russian rally took place in Nakhimov Square declaring allegiance to Russia and protesting against the new government in Kyiv following the overthrow of the president, Viktor Yanukovych.[38] On 27 February, pro-Russian militia, including Russian troops, seized control of government buildings in Crimea, and by 28 February, controlled other strategic locations such as the military airport in Sevastopol.[39][40]

On 16 March 2014, an internationally unrecognized referendum was held in Sevastopol with official results claiming an 89.51% turnout and 95.6% of voters choosing to join Russia. Ukraine and almost all other countries of the United Nations General Assembly consider the referendum illegal and illegitimate.[41][42]

On 18 March, Russia annexed Crimea, incorporating the Republic of Crimea and federal city of Sevastopol as federal subjects of Russia.[43][44] However, the annexation remains internationally unrecognized, with most countries recognizing Sevastopol as a city with special status within Ukraine.[45] While Russia has taken defacto control of Sevastopol and Crimea, the international community considers the area part of Ukraine.[46][47][48]

Geography

Satellite image of the Sevastopol area.

A view of the Bay of Sevastopol.

Fiolent rocks formation on the coast of Sevastopol.

The city of Sevastopol is located at the southwestern tip of the Crimean peninsula in a headland known as Heracles peninsula on a coast of the Black Sea. The city is designated a special city-region of Ukraine which besides the city itself includes several of its outlying settlements. The city itself is concentrated mostly in the western portion of the region and around the long Bay of Sevastopol. This bay is a ria, a river canyon drowned by Holocene sea-level rise, and the outlet of Chorna River. Away in a remote location southeast of Sevastopol is located the former city of Balaklava (since 1957 incorporated within Sevastopol), the bay of which in Soviet times served as a main port for the Soviet diesel-powered submarines.

The coastline of the region is mostly rocky, in a series of smaller bays, a great number of which are located within the Bay of Sevastopol. The biggest of them are Southern Bay (within the Bay of Sevastopol), Archer Bay, a gulf complex that consists of Deergrass Bay, the Bay of Cossack, Salty Bay, and many others. There are over thirty bays in the immediate region.

Through the region flow three rivers: the Belbek, Chorna, and Kacha. All three mountain chains of Crimean mountains are represented in Sevastopol, the southern chain by the Balaklava Highlands, the inner chain by the Mekenziev Mountains, and the outer chain by the Kara-Tau Upland (Black Mountain).

Climate

Sevastopol has a semi-arid climate (Köppen: BSk), closely bordering on a humid subtropical climate. Due to the summer mean straddling 22 °C (72 °F) it is also bordering on a four-season oceanic climate, with cool winters and warm to hot summers.

The average yearly temperature is 15–16 °C (59–61 °F) during the day and around 9 °C (48 °F) at night. In the coldest months, January and February, the average temperature is 5–6 °C (41–43 °F) during the day and around 1 °C (34 °F) at night. In the warmest months, July and August, the average temperature is around 26 °C (79 °F) during the day and around 19 °C (66 °F) at night. Generally, summer/holiday season lasts 5 months, from around mid-May and into September, with the temperature often reaching 20 °C (68 °F) or more in the first half of October.

The average annual temperature of the sea is 14.2 °C (58 °F), ranging from 7 °C (45 °F) in February to 24 °C (75 °F) in August. From June to September, the average sea temperature is greater than 20 °C (68 °F). In the second half of May and the first half of October; the average sea temperature is about 17 °C (63 °F). The average rainfall is about 400 millimetres (16 in) per year. There are about 2,345 hours of sunshine duration per year.[49]

| Climate data for Sevastopol | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.9 (42.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.9 (48.0) |

13.6 (56.5) |

19.2 (66.6) |

23.5 (74.3) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.3 (79.3) |

22.4 (72.3) |

17.8 (64.0) |

12.3 (54.1) |

8.1 (46.6) |

15.9 (60.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.9 (37.2) |

2.8 (37.0) |

5.4 (41.7) |

9.8 (49.6) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.5 (67.1) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.1 (71.8) |

18.1 (64.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

8.8 (47.8) |

5.0 (41.0) |

12.1 (53.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.2 (31.6) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

2.0 (35.6) |

6.1 (43.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

17.9 (64.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

9.9 (49.8) |

5.4 (41.7) |

2.0 (35.6) |

8.5 (47.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 26 (1.0) |

25 (1.0) |

24 (0.9) |

27 (1.1) |

18 (0.7) |

26 (1.0) |

32 (1.3) |

33 (1.3) |

42 (1.7) |

32 (1.3) |

42 (1.7) |

52 (2.0) |

379 (15) |

| Average precipitation days | 6 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 31 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 72 | 75 | 145 | 202 | 267 | 316 | 356 | 326 | 254 | 177 | 98 | 64 | 2,352 |

| Source: pogodaiklimat.ru[50] |

Politics and government

Ukrainian administration

According to the Constitution of Ukraine, Sevastopol is administered as a City with special status. Executive power in Sevastopol is exercised by the Sevastopol City State Administration, led by a chairman (also known as mayor) appointed by the Ukrainian president.[51] The Sevastopol City Council is the legislature of Sevastopol.

Sevastopol is administratively divided into four districts:

- Gagarin Raion

- Lenin Raion

- Nakhimov Raion

- Balaklava Raion

Russian occupation

On 18 March 2014, Russia claimed to have annexed Crimea with Sevastopol being administered as a federal city of Russia, the others being Moscow and St. Petersburg.

- Executive

The head of the executive branch in the city is the Governor of Sevastopol. According to the city charter, amended on 29 November 2016, the governor is elected in a direct election for a term of five years and no more than two consecutive terms.[52] The current governor is Mikhail Razvozhayev.

- Legislature

During the annexation of Ukrainian Crimea by Russia, the pro-Russian City Council threw its support behind Russian citizen Alexei Chaly as a «people’s mayor» and said it would not recognise orders from Kyiv.[53][54] After Russia annexed Crimea, the Legislative Assembly of Sevastopol replaced the City Council.

- Administrative and municipal divisions

Within the Russian municipal framework, the territory of the federal city of Sevastopol is divided into nine municipal okrugs and the town of Inkerman. While individual municipal divisions are contained within the borders of the administrative districts, they are not otherwise related to the administrative districts.

Economy

|

|

This section is missing information about Sevastopol’s economic output by economic sector. Please expand the section to include this information. Further details may exist on the talk page. (March 2014) |

Apart from navy-related civil facilities, Sevastopol hosts some other notable industries. An example is Stroitel,[55] one of the leading plastic manufacturers in Russia.

Industry

- Sevastopol Aircraft Plant, SMZ Sevastopol Shipyards (main at Naval Bay) & Inkerman Shipyards, Balaklava Bay Shipyard

- Impuls 2 SMZ

- Chornomornaftogaz § Chernomorneftegaz (Chjornomor), oil/gas extraction, petrochemical, jack rigs and oil platforms, LNG and oil tankers.

- AO FNGUP Granit subsidiary of Almaz Antej, assembly, overhaul, and maintenance of SAM and radar EW complexes, ADS services.

- Sevastopol (Parus SPriborMZ, Mayak, NPO Elektron, NPP Kvant, Tavrida Elektronik, Musson, and other industrial plants)

- Sevastopol Economic Industrial Zone SevPZ (SE area)

- Persej SMZ ship repair and floating dock yard plant (South Bay, Sevastopol)

- Sevastopol ship repair and floating docks yards (various)

- Metallurgy, Chemical Plants, and other industries.

- Agriculture: rice, wheat, grapes, tea, fruits, and tobacco (lesser).

- Mining: iron, titanium, manganese, aluminum, calcite silicates, and amethyst.

- Kerch bridge, Taurida highway, Sevastopol GasTES plus solar FV plants, gas and petrol depots, and coal derivatives.

Infrastructure

There are different types of transport in Sevastopol:

- Bus – 101 lines

- Trolley bus – 14 lines

- Minibus – 52 lines

- Cutter – 6 lines

- Ferry – 1 line

- Express bus – 15 lines

- HEV train (local, suburban route) – 1 route

- Airport – 1

Sevastopol Shipyard comprises three facilities that together repair, modernise, and re-equip Russian Naval ships and submarines.[56] The Sevastopol International Airport is used as a military aerodrome at the moment and being reconstructed to be used by international airlines.

Sevastopol maintains a large port facility in the Bay of Sevastopol and in smaller bays around the Heracles peninsula. The port handles traffic from passengers (local transportation and cruise), cargo, and commercial fishing. The port infrastructure is fully integrated with the city of Sevastopol and the naval bases of the Black Sea Fleet.

Panorama of the Sevastopol port entrance (left) with its monument to Russian ships which were sunk in the Crimean War to blockade the harbour (far right side).

Tourism

Due to its military history, most streets in the city are named after Russian and Soviet military heroes. There are hundreds of monuments and plaques in various parts of Sevastopol commemorating its military past.

Attractions include:

- Chersonessos National Archaeological Reserve

- MP Kroshitsky Sevastopol Art Museum

- Sevastopol Museum of Local History

- Aquarium-Museum of the Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

- Dolphinarium of Sevastopol

- Sevastopol Zoo

- The Monument to the scuttled ships on the Marine Boulevard

- The Panorama Museum (The Heroic Defence of Sevastopol during the Crimean War)

- Malakhov Kurgan (Barrow) with its White Tower

- Admirals’ Burial Vault

- The Black Sea Fleet Museum

- The Storming of Sapun-gora of 7 May 1944, the Diorama Museum (World War II)

- Naval museum complex «Balaklava», decommissioned underground submarine base, now opened to the public

- Cheremetieff brothers museum «Crimean war 1853–1856»

- Museum of the underground forces of 1942–1944

- Museum Historical Memorial Complex «35th Coastal Battery»

- The Naval Museum «Michael’s battery»

- Fraternal (Communal) War Cemetery

-

Sevastopol Artillery Bay view.

-

The seaside of Sevastopol.

-

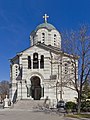

St. Vladimir’s Cathedral at ‘the city hill’.

-

Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral.

-

View of the Northern side.

-

Old city cemetery.

-

Main railway station.

-

The Panorama Museum (The Heroic Defence of Sevastopol during the Crimean War).

Demographics

|

|

This section is missing information about the different religions practised in Sevastopol; its education system (schools, colleges, and universities); and its healthcare system (clinics and hospitals). Please expand the section to include this information. Further details may exist on the talk page. (March 2014) |

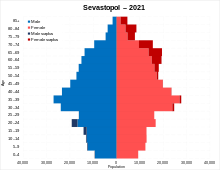

Population pyramid of Sevastopol as of the 2021 Russian Census

The population of Sevastopol is 509,992, consisting of 479,394 urban residents and 30,598 rural (January 2021), making it the most populous city of the Crimean Peninsula.[3]

The city has retained an ethnic Russian majority throughout its history.[need quotation to verify] In 1989 the proportion of Russians living in the city was 74.4%,[57] and by the time of the Ukrainian National Census, 2001, the ethnic groups of Sevastopol included Russians (71.6%), Ukrainians (22.4%), Belarusians (1.6%), Tatars (0.7%), Crimean Tatars (0.5%), Armenians (0.3%), Jews (0.3%), Moldovans (0.2%), and Azerbaijanis (0.2%).[58]

|

|

Vital statistics for 2015:

- Births: 5 471 (13.7 per 1000)

- Deaths: 6 072 (15.2 per 1000)

Life expectancy

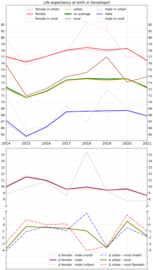

In 2015, Sevastopol had the largest decrease in life expectancy at birth among all regions of Russia.

In 2020, after beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Sevastopol became the only region of Russia where there was increase of life expectancy.

In 2021, average life expectancy at birth in Sevastopol was 72.25 years (67.87 for males and 76.43 for females).[59][60]

-

Life expectancy in Sevastopol [59][60]

-

Life expectancy with calculated differences

-

Life expectancy in Sevastopol in comparison with Crimea on average and neighboring regions of the country

-

Life expectancy in Sevastopol in comparison with Crimea on average (in detail)

Culture

|

|

This section is missing information about architecture, arts, cuisine, literature, media, and music in Sevastopol. Please expand the section to include this information. Further details may exist on the talk page. (March 2014) |

There are many historical buildings in the central and eastern parts of the city and Balaklava, some of which are architectural monuments. The Western districts have modern architecture. More recently, numerous skyscrapers have been built. Balaklava Bayfront Plaza (on hold), currently under construction, will be one of the tallest buildings in Ukraine, at 173 m (568 ft) with 43 floors.[61]

After the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea the city’s monument to Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny was removed and handed over to Kharkiv.[62]

Education

- Economics and Humanities Institute (Branch), Crimean Federal University

- Sevastopol National Technical University

- Sevastopol National University of Nuclear Energy and Industry

Notable people

- Arkady Averchenko (1881–1925) a Russian playwright and satirist.

- Oleksiy Bessarabov (born 1976) a Ukrainian journalist

- Igor Cassini (1915–2002) a Russian-American syndicated gossip columnist for the Hearst newspaper chain.

- Aleksei Chaly (born 1961) a businessman and former de facto mayor of Sevastopol.

- Alexander Galich (1918–1977) a Soviet poet, playwright, singer-songwriter and dissident.

- Gulyayev Dmitry Igorevich (born 1986), stage name Dimal, rapper, songwriter and entertainer, based in Malta.

- Lola Gjoka (1910–1985) an Albanian pianist

- Tatiana Godovalnikova (born 1962) a Russian contemporary artist.

- Rimma Kazakova (1932–2008) a Soviet/Russian poet who wrote popular songs.

- Sasha Krasny (1882– 1995), a Russian poet and songwriter.

- Aleksandr Kuznetsov (born 1992) a Ukrainian-Russian actor in Russian films and TV

- Ileana Leonidoff (1893–1968) emigrée actress in silent films; then dancer and choreographer.

- Kseniya Mishyna (born 1989) a Ukrainian film and stage actress.

- Mikhail Samoilovich Neiman (1905–1975) a Soviet physicist and academic professor.

- Aleksandr Nosatov (born 1963) an admiral in the Russian Navy.

- Ivan Papanin (1894–1986) a Soviet polar explorer, scientist and Counter Admiral

- Sergei Pinchuk (born 1971) a vice-admiral in the Russian Navy.

- Olga von Root (1902–1967), Russian noblewoman, singer, and stage actress

- Mikhail Sablin (1869–1920), an admiral in the Imperial Russian Navy

- Anton Shkaplerov (born 1972) a Russian cosmonaut with four spaceflights.

- Antonina Shuranova (1936–2003) a Russian stage, TV and film actress.

- Alexandra Voronin (1905—1993) the Russian wife of Norwegian fascist Vidkun Quisling

Sport

- Lyudmila Aksyonova (born 1947) 400 metre athlete, team bronze medallist at the 1976 Summer Olympics

- Aleksandr Fyodorov (born 1981) water polo player and team bronze medallist at the 2004 Summer Olympics.

- Svitlana Matevusheva (born 1981) a sailor and team silver medallist at the 2004 Summer Olympics

- Alexander Onischuk (born 1975) a Ukrainian-American chess Grandmaster

- Galina Prozumenshchikova (1948–2015) a Soviet breaststroke swimmer; five Olympic medals in 1964, 1968 and 1972

Gallery

-

View of Sevastopol

-

Nakhimov Square

-

Palace of Culture

-

Lunacharsky Theater

-

Artillery Bay

-

2012 Navy Day joint celebration (Russian AF)

-

2012 Navy Day joint celebration (Ukrainian AF)

-

-

Victory Day in Sevastopol, 9 May 2014

See also

- 2121 Sevastopol – asteroid discovered in 1971 by Soviet astronomer Tamara Mikhailovna Smirnova and named after the city.[63]

- Sebastopol, Victoria

- Novorossiysk (new planned headquarters of the Black Sea Fleet)

Notes

- ^ Russian: Севасто́поль, tr. Sevastópolʹ, IPA: [sʲɪvɐˈstopəlʲ]; Ukrainian: Севасто́поль, romanized: Sevastópolʹ, IPA: [seʋɐˈstɔpolʲ] (

listen); Medieval Greek: Σεβαστούπολις, romanized: Sevastoúpolis, IPA: [sevasˈtupolis]; Crimean Tatar: Акъя́р, romanized: Aqyár, IPA: [aqˈjar]

References

- ^ This place is located on the Crimean peninsula, which is internationally recognized as part of Ukraine, but since 2014 under Russian occupation. According to the administrative-territorial division of Ukraine, there are the Ukrainian divisions (the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city with special status of Sevastopol) located on the peninsula. Russia claims these as federal subjects of the Russian Federation (the Republic of Crimea and the federal city of Sevastopol).

- ^ Zinets, Natalia (August 2022). «Russian strikes kill Ukrainian grain tycoon; drone hits Russian naval base». Reuters.

- ^ a b «Численность населения по муниципальным округам г. Севастополя на начало 2021 года» (PDF). crimea.gks.ru (in Russian). Federal State Statistic Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ «Оценка численности постоянного населения по субъектам Российской Федерации». Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ Narula, Svati Kirsten (26 March 2014). «Ukraine Was Never Crazy About Its Killer Dolphins, Anyway». The Atlantic. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ «Ancient Chersonesos» [Ancient Chersonesos]. wmf.org/. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ «Sailors still battling fire on Russian cruiser». Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ «Britannica entry for Sevastopol». Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, archived from the original on 10 October 2020, retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ «definition: meaning, pronunciation and origin of the word». Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2014. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ «definition: meaning, pronunciation and origin of the word». Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2014. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ «definition: meaning, pronunciation and origin of the word». Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2014. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ «definition: meaning, pronunciation and origin of the word». Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2014. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ «Sevastopol», The Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedia, UK: Leksika

- ^ a b Севастополь (Sevastopol) (in Russian). Moscow: Great Soviet Encyclopedia.

- ^ «Основание и развитие Севастополя (Osnovaniye i razvitiye Sevastopolya)» [Foundation and development of Sevastopol] (in Russian). Sevastopol.info. 28 May 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ «Crimean War (1853–1856)». Gale Encyclopedia of World History: War. 2. 2008. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015.

- ^ Figes 2010, p. 415.

- ^ «Czarist Navy in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877». www.globalsecurity.org.

- ^ Pitt, Barrie (1966). History of the Second World War. Vol. 5. Purnell. OCLC 1110288057.

- ^ Willmott, H. P. (2008). The Great Crusade: A New Complete History of the Second World War. Potomac Books, Inc. p. 269. ISBN 978-1-61234-387-7. OCLC 755581494.

- ^ Hall, Michael Clement (2014). The Crimea. A very short history. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-304-97576-8. OCLC 980143992.

- ^ «WW2 Aerial Reconnaissance Studies — Sevastopol, Balaclava and the Crimea 1942-1943». Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Trial of the Major War Criminals Before the International Military Tribunal, Nuremberg, 14 November 1945-1 October 1946: Proceedings. Vol. 1–42. International Military Tribunal. 1947. p. 168. ISBN 0-404-53650-6. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d «Українське життя в Севастополi Михайло ЛУКІНЮК ОБЕРЕЖНО: МІФИ! Міф про юридичну належність Севастополя Росії» [Ukrainian life in Sevastopol Mykhailo LUKINYUK CAUTION: MYTHS! The myth of the legal affiliation of Sevastopol in Russia]. ukrlife.org. Archived from the original on 8 December 2014 – via archive.org.

- ^ Great Soviet Encyclopedia 1976, Vol.23. p. 104

- ^ Kuzio, Taras (15 April 1998). Contemporary Ukraine. ISBN 0-7656-3150-4.

- ^ «Статьи / газета Флот України: ПОЧТИ 50 ЛЕТ НАЗАД. СЕВАСТОПОЛЬ В 1955 ГОДУ» (in Russian). 8 December 2014. Archived from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ Secession as an International Phenomenon: From America’s Civil War to Contemporary Separatist Movements edited by Don Harrison Doyle (page 284)

- ^ Schmemann, Serge (10 July 1993), «Russian Parliament Votes a Claim to Russian Port of Sevastopol», The New York Times

- ^ Glenn E., Curtis (1998). Russia: A Country Study. Washington DC: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. xcii. ISBN 0-8444-0866-2. OCLC 36351361.

- ^ «Review of Ukraine base lease ‘fatal,’ Russia warns». People’s Daily. Beijing, China. 28 December 2005. Archived from the original on 17 January 2006. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ Oğuz, Şafak (1 May 2017). «Russian Hybrid Warfare and Its Implications in The Black Sea». Bölgesel Araştırmalar Dergisi. 1 (1): 10. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020 – via Paperity.org.

- ^ «Лужков знайшов у серці рану і хоче почувати себе в Криму як вдома» [Luzhkov has found a wound in his heart and wants to feel at home in the Crimea]. pravda.com.ua (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 19 March 2007. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ^ «Calm sea in Sevastopol», Kyiv Post, 4 September 2009, archived from the original on 15 September 2008

- ^ «Sevastopol authorities asking to raise compensation fees for Russian Black Sea Fleet’s basing», Kyiv Post, 28 July 2009, archived from the original on 1 March 2012

- ^ «Parliamentary chaos as Ukraine ratifies fleet deal», World, UK: BBC, 27 April 2010

- ^ «Ukraine crisis fuels secession calls in pro-Russian south». The Guardian. 23 February 2014.

- ^ «Gunmen ‘seize control’ of airport in Ukraine’s Crimea region». France 24. 28 February 2014.

- ^ «Putin reveals secrets of Russia’s Crimea takeover plot». BBC News. 9 March 2015.

- ^ На сессии городского Совета утверждены результаты общекрымского референдума 16 марта 2014 года [Session of the City Council approved the results of the general referendum on March 16, 2014] (in Russian). Official site of the Sevastopol City Council. 17 March 2014. Archived from the original on 22 July 2014.

- ^ «Crimeans vote over 90 percent to quit Ukraine for Russia». Reuters. 16 March 2014.

- ^ «Putin signs laws on reunification of Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol with Russia». ITAR TASS. 21 March 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ^ Распоряжение Президента Российской Федерации от 17 March 2014 No. 63-рп ‘О подписании Договора между Российской Федерацией и Республикой Крым о принятии в Российскую Федерацию Республики Крым и образовании в составе Российской Федерации новых субъектов’. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ^ Taylor & Francis (2020). «Republic of Crimea». The Territories of the Russian Federation 2020. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-003-00706-7.

Note: The territories of the Crimean peninsula, comprising Sevastopol City and the Republic of Crimea, remained internationally recognised as constituting part of Ukraine, following their annexation by Russia in March 2014.

- ^ «Does Russia have a case?». BBC News. 5 March 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ «Russia takes defacto control of Ukraine’s Crimea region». 3 March 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ «Russia’s southern seas after Crimea». Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ «The duration of sunshine in some cities of the former USSR» (in Russian). Meteoweb. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ «Sevastopol Climate Summary». pogodaiklimat.ru. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ^ «The City State Administration». Sevastopol City State Administration. Archived from the original on 11 February 2014.

- ^ «Закон города Севастополя от 29 ноября 2016 года № 292-ЗС «О внесении изменений в Устав города Севастополя»«. sevzakon.ru.

- ^ «Ukraine: Sevastopol installs pro-Russian mayor as separatism fears grow». The Guardian. 25 February 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ «Sevastopol City Council refuses to recognize Kyiv leadership». Kyiv Post. 2 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Stroitel, Tradekey.com See https://www.tradekey.com/company/Stroitel-1284650.html

- ^ «Sevmorverf (Sevastopol Shipyard)». Federation of American Scientists. 24 August 2000. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ «Всеукраїнський перепис населення 2001 | English version | Results | General results of the census | National composition of population». 2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ «2001 Ukrainian census». Ukrcensus.gov.ua. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ a b «Демографический ежегодник России» [The Demographic Yearbook of Russia] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service of Russia (Rosstat). Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ a b «Ожидаемая продолжительность жизни при рождении» [Life expectancy at birth]. Unified Interdepartmental Information and Statistical System of Russia (in Russian). Archived from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ «Balaklava Bayfront Plaza, Sevastopol». SkyscraperPage.com. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ «В Харькове появится памятник Сагайдачному». Status Quo (in Russian).

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 172. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.

External links

- «Sevastopol» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 707.

- Official website (in Russian) (Russian administration)

- Official website at the Wayback Machine (archive index) (Ukrainian administration)

- Satellite picture by Google Maps

- The murder of the Jews of Sevastopol during World War II, at Yad Vashem website.

|

Sevastopol

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

Orthographic projection of Sevastopol (in green) |

|

Map of the Crimean Peninsula with Sevastopol highlighted |

|

|

Sevastopol Location of Sevastopol within Crimea Sevastopol Location of Sevastopol within Europe Sevastopol Sevastopol (Europe) |

|

| Coordinates: 44°36′18″N 33°31′21″E / 44.605°N 33.5225°ECoordinates: 44°36′18″N 33°31′21″E / 44.605°N 33.5225°E | |

| Country | Territory of Ukraine, occupied by Russia[1] |

| Status | Independent city1 |

| Founded | 1783 (240 years ago) |

| Government

(under Russian occupation)[2] |

|

| • Body | Legislative Assembly |

| • Governor | Mikhail Razvozhayev |

| Area | |

| • City | 864 km2 (334 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 100 m (300 ft) |

| Population

(2021) |

|

| • City | 547,820 |

| • Density | 630/km2 (1,600/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 479,394 |

| Demonym(s) | Sevastopolitan, Sevastopolian |

| Time zone | UTC+03:00 |

Sevastopol ([a]), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea. Due to its strategic location and the navigability of the city’s harbours, Sevastopol has been an important port and naval base throughout its history. Since the city’s founding in 1783 it has been a major base for Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, and it was previously a closed city during the Cold War. The total administrative area is 864 square kilometres (334 sq mi) and includes a significant amount of rural land. The urban population, largely concentrated around Sevastopol Bay, is 479,394,[3] and the total population is 547,820.[4]

Sevastopol, along with the rest of Crimea, is internationally recognised as part of Ukraine, and under the Ukrainian legal framework, it is administratively one of two cities with special status (the other being Kyiv). However, it has been occupied by Russia since 27 February 2014, before Russia annexed Crimea on 18 March 2014 and gave it the status of a federal city of Russia. Both Ukraine and Russia consider the city administratively separate from the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the Republic of Crimea. The city’s population has an ethnic Russian majority and a substantial minority of Ukrainians.

Sevastopol’s unique naval and maritime features have been the basis for a robust economy. The city enjoys mild winters and moderately warm summers, characteristics that help make it a popular seaside resort and tourist destination, mainly for visitors from the former Soviet republics. The city is also an important centre for marine biology research. In particular, the military has studied and trained dolphins in the city for military use since the 1960s.[5]

Etymology

The name of Sevastopolis was originally chosen in the same etymological trend as other cities in the Crimean peninsula; it was intended to express its ancient Greek origins. It is a compound of the Greek adjective, σεβαστός (sebastós, Byzantine Greek pronunciation: [sevasˈtos]; ‘venerable’) and the noun πόλις (pólis, ‘city’). Σεβαστός is the traditional Greek equivalent (see Sebastian) of the Roman honorific Augustus, originally given to the first emperor of the Roman Empire, Augustus and later awarded as a title to his successors.

Despite its Greek origin, the name is not from Ancient Greek times. The city was probably named after Empress («Augusta») Catherine II of the Russian Empire who founded Sevastopol in 1783. She visited the city in 1787, accompanied by Joseph II, the Emperor of Austria, and other foreign dignitaries.

In the west of the city, there are well-preserved ruins of the ancient Greek port city of Chersonesos, founded in the 5th[6] century BC by settlers from Heraclea Pontica. This name means «peninsula», reflecting its immediate location. It is not related to the ancient Greek name for the Crimean Peninsula as a whole: Chersonēsos Taurikē («the Taurian Peninsula»).

The name of the city is spelled as:

- English: Sevastopol, the current prevalent spelling; the previously common spelling Sebastopol is still used by some publications, and formerly by The Economist.[7][8] The current spelling has the pronunciation ,[9][10] while the former spelling has the pronunciation .[11][12]

- Ukrainian: Севасто́поль, pronounced [sewɐˈstɔpolʲ]; Russian: Севасто́поль, pronounced [sʲɪvɐˈstopəlʲ].[13]

- Crimean Tatar: Aqyar, pronounced [aqˈjar], or Sivastopol.

History

Ancient Chersonesus

In the 6th century BC, a Greek colony was established in the area of the modern-day city. The Greek city of Chersonesus existed for almost two thousand years, first as an independent democracy and later as part of the Bosporan Kingdom. In the 13th and 14th centuries, it was sacked by the Golden Horde several times and was finally totally abandoned. The modern day city of Sevastopol has no connection to the ancient and medieval Greek city, but the ruins are a popular tourist attraction located on the outskirts of the city.

Part of the Russian Empire

«Soldier and Sailor» Memorial to Heroic Defenders of Sevastopol

Sevastopol was founded in June 1783 as a base for a naval squadron under the name Akhtiar[14] (White Cliff),[15] by Rear Admiral Thomas MacKenzie (Foma Fomich Makenzi), a native Scot in Russian service; soon after Russia annexed the Crimean Khanate. Five years earlier, Alexander Suvorov ordered that earthworks be erected along the harbour and Russian troops be placed there.

In February 1784, Catherine the Great ordered Grigory Potemkin to build a fortress there and call it Sevastopol. The realisation of the initial building plans fell to Captain Fyodor Ushakov who in 1788 was named commander of the port and of the Black Sea squadron.[16] The city was established on western shore of Southern Bay which branches away from bigger Sevastopol Bay. The ruins of the ancient Chersonesus were situated to the west. The newly built settlement became an important naval base and later a commercial seaport. In 1797, under an edict issued by Emperor Paul I, the military stronghold was again renamed Akhtiar. Finally, on 29 April (10 May), 1826, the Senate returned the city’s name to Sevastopol.[citation needed] In 1803 to 1864 along with Mykolaiv the city was part of Nikolayev–Sevastopol Military Governorate.

Crimean War

From 1853 to 1856, the Crimean peninsula’s strategic position in controlling the Black Sea caused it to be the site of the principal engagements of the Crimean War, where Russia lost to a French-led alliance.[17]

After a minor skirmish at Köstence (now Constanța), the allied commanders decided to attack Sevastopol as Russia’s main naval base in the Black Sea. After extended preparations, allied forces landed on the peninsula in September 1854 and marched to a point south of Sevastopol after winning the Battle of the Alma on 20 September. The Russians counterattacked on 25 October in what became the Battle of Balaclava and were repulsed, but the British Army’s forces were seriously depleted as a result. A second Russian counterattack, at Inkerman in November, ended in a stalemate as well. The front settled into the siege of Sevastopol, involving brutal conditions for troops on both sides.

Sevastopol finally fell after eleven months, after the French had assaulted Fort Malakoff. Isolated and facing a bleak prospect of invasion by the West if the war continued, Russia sued for peace in March 1856. France and Britain welcomed the development, owing to the conflict’s domestic unpopularity. The Treaty of Paris, signed on 30 March 1856, ended the war and forbade Russia from basing warships in the Black Sea.[18] This hampered the Russians during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 and in the aftermath of that conflict, Russia moved to reconstitute its naval strength and fortifications in the Black Sea.[19]

World War II

During World War II, Sevastopol withstood intensive bombardment by the Germans in 1941–42, supported by their Italian and Romanian allies during the Battle of Sevastopol. German forces used railway artillery—including history’s largest-ever calibre railway artillery piece in battle, the 80-cm calibre Schwerer Gustav—and specialised mobile heavy mortars to destroy Sevastopol’s extremely heavy fortifications, such as the Maxim Gorky Fortresses. After fierce fighting, which lasted for 250 days,[20][21][22] the fortress city finally fell to Axis forces in July 1942.[23] It was intended to be renamed to «Theodorichshafen«[24] (in reference to Theodoric the Great and the fact that the Crimea had been home to Germanic Goths until the 18th or 19th century) in the event of a German victory against the Soviet Union, and like the rest of the Crimea was designated for future colonisation by the Third Reich. It was liberated by the Red Army on 9 May 1944 and was awarded the Hero City title a year later.

Part of Ukrainian SSR

During the Soviet era, Sevastopol became a so-called «closed city». This meant that any non-residents had to apply to the authorities for a temporary permit to visit the city.

On 29 October 1948, the Presidium of Supreme Council of the Russian SFSR issued an ukaz (order) which confirmed the special status of the city.[25] Soviet academic publications since 1954, including the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, indicated that Sevastopol, Crimean Oblast was part of the Ukrainian SSR.[26][15]

In 1954, under Nikita Khrushchev, both Sevastopol and the remainder of the Crimean peninsula were administratively transferred from being territories within the Russian SFSR to being territories administered by the Ukrainian SSR. Administratively, Sevastopol was a municipality excluded from the adjacent Crimean Oblast.[citation needed][further explanation needed] The territory of the municipality was 863.5 km2 and it was further subdivided into four raions (districts). Besides the City of Sevastopol proper, it also included two towns—Balaklava (having had no status until 1957), Inkerman, urban-type settlement Kacha, and 29 villages.[27]

For the 1955 Ukrainian parliamentary elections on 27 February, Sevastopol was split into two electoral districts, Stalinsky and Korabelny (initially requested three Stalinsky, Korabelny, and Nakhimovsky).[25] Eventually,[clarification needed] Sevastopol received two people’s deputies of the Ukrainian SSR elected to the Verkhovna Rada,[clarification needed] A. Korovchenko and M. Kulakov.[25][28]

In 1957, the town of Balaklava was incorporated into Sevastopol.

Part of Ukraine

The Black Sea Fleet Museum

Following Ukraine’s declaration of independence from the USSR in 1991, Sevastopol became the principal base of the Ukrainian navy. As the key naval base of the former Soviet Black Sea Fleet, it was a source of tensions for Russia–Ukraine relations until a set-term lease agreement was signed in 1997.

On 10 July 1993, the Russian parliament passed a resolution declaring Sevastopol to be «a federal Russian city».[29] At the time, many supporters of President Boris Yeltsin had ceased taking part in[clarification needed] the parliament’s work.[30] On 20 July 1993, the United Nations Security Council denounced the decision of the Russian parliament. According to Anatoliy Zlenko, it was the first time that the council had to review and qualify actions of a legislative body.[25]

On 14 April 1993, the Presidium of the Crimean Parliament called for the creation of the presidential post of the Crimean Republic.[clarification needed] A week later, the Russian deputy, Valentin Agafonov, said that Russia was ready to supervise a referendum on Crimean independence and include the republic as a separate entity in the CIS. On 28 July 1993, one of the leaders of the Russian Society of Crimea, Viktor Prusakov, said that his organisation was ready for an armed mutiny and establishment of Russian administration of Sevastopol.

In September, the commander of the joint Russian-Ukrainian Black Sea Fleet, Eduard Baltin [ru], accused Ukraine of converting some of his fleet and conducting an armed assault on his personnel and threatened to take countermeasures placing the fleet on alert. (In June 1992, the Russian president Yeltsin and the Ukrainian president Leonid Kravchuk had agreed to divide the former Soviet Black Sea Fleet between Russia and Ukraine. Eduard Baltin had been appointed commander of the Black Sea Fleet by Yeltsin and Kravchuk on 15 January 1993.)

The Moscow mayor Yuriy Luzhkov campaigned to claim[clarification needed] the city, and in December 1996, the Russian Federation Council officially endorsed the claim, threatening negotiations. Due to these revanchist claims, Ukraine proposed a «special partnership» with NATO in January 1997.[31]

In May 1997, Russia and Ukraine signed the Russian–Ukrainian Friendship Treaty, ruling out Moscow’s territorial claims to Ukraine.[32] This was followed by the Partition Treaty on the Status and Conditions of the Black Sea Fleet on 28 May 1997. A separate agreement established the terms of a long-term lease of land, facilities, and resources in Sevastopol and the Crimea by Russia.[citation needed] Russia kept its naval base, with around 15,000 troops stationed in Sevastopol.[33]

The ex-Soviet Black Sea Fleet and its facilities were divided between Russia’s Black Sea Fleet and the Ukrainian Naval Forces. The two navies co-used some of the city’s harbours and piers, while others were demilitarised or used by either[clarification needed] country. Sevastopol remained the location of the Russian Black Sea Fleet headquarters, and the Ukrainian Naval Forces Headquarters were also located in the city. A judicial row periodically continued over the naval hydrographic infrastructure both in Sevastopol and on the Crimean coast (especially lighthouses historically maintained by the Soviet and Russian Navy and also used for civil navigation support).

As in the rest of Crimea, Russian remained the predominant language of the city, although following the independence of Ukraine there were some attempts at Ukrainisation, with very little success. Russian society in general and even some outspoken government representatives never accepted the loss of Sevastopol and tended to regard it as temporarily separated from Russia.[34]

In July 2009, the chairman of the Sevastopol city council, Valeriy Saratov (Party of Regions),[35] said that Ukraine should increase the amount of compensation it is paying to the city of Sevastopol for hosting the foreign Russian Black Sea Fleet, instead of requesting such compensation from the Russian government and the Russian Ministry of Defense in particular.[36]

On 27 April 2010, Russia and Ukraine ratified the Russian Ukrainian Naval Base for Gas treaty, which extended the Russian Navy’s lease of Crimean facilities for 25 years after 2017 (through 2042) with the option to prolong the lease in five-year extensions. The ratification process in the Ukrainian parliament encountered stiff opposition and even resulted in a brawl in the parliament chamber. Eventually, the treaty was ratified by a 52% majority vote—236 of 450. The Russian Duma ratified the treaty by a 98% majority.[37]

Occupation and annexation by Russia

On 23 February 2014, a pro-Russian rally took place in Nakhimov Square declaring allegiance to Russia and protesting against the new government in Kyiv following the overthrow of the president, Viktor Yanukovych.[38] On 27 February, pro-Russian militia, including Russian troops, seized control of government buildings in Crimea, and by 28 February, controlled other strategic locations such as the military airport in Sevastopol.[39][40]

On 16 March 2014, an internationally unrecognized referendum was held in Sevastopol with official results claiming an 89.51% turnout and 95.6% of voters choosing to join Russia. Ukraine and almost all other countries of the United Nations General Assembly consider the referendum illegal and illegitimate.[41][42]

On 18 March, Russia annexed Crimea, incorporating the Republic of Crimea and federal city of Sevastopol as federal subjects of Russia.[43][44] However, the annexation remains internationally unrecognized, with most countries recognizing Sevastopol as a city with special status within Ukraine.[45] While Russia has taken defacto control of Sevastopol and Crimea, the international community considers the area part of Ukraine.[46][47][48]

Geography

Satellite image of the Sevastopol area.

A view of the Bay of Sevastopol.

Fiolent rocks formation on the coast of Sevastopol.

The city of Sevastopol is located at the southwestern tip of the Crimean peninsula in a headland known as Heracles peninsula on a coast of the Black Sea. The city is designated a special city-region of Ukraine which besides the city itself includes several of its outlying settlements. The city itself is concentrated mostly in the western portion of the region and around the long Bay of Sevastopol. This bay is a ria, a river canyon drowned by Holocene sea-level rise, and the outlet of Chorna River. Away in a remote location southeast of Sevastopol is located the former city of Balaklava (since 1957 incorporated within Sevastopol), the bay of which in Soviet times served as a main port for the Soviet diesel-powered submarines.

The coastline of the region is mostly rocky, in a series of smaller bays, a great number of which are located within the Bay of Sevastopol. The biggest of them are Southern Bay (within the Bay of Sevastopol), Archer Bay, a gulf complex that consists of Deergrass Bay, the Bay of Cossack, Salty Bay, and many others. There are over thirty bays in the immediate region.

Through the region flow three rivers: the Belbek, Chorna, and Kacha. All three mountain chains of Crimean mountains are represented in Sevastopol, the southern chain by the Balaklava Highlands, the inner chain by the Mekenziev Mountains, and the outer chain by the Kara-Tau Upland (Black Mountain).

Climate

Sevastopol has a semi-arid climate (Köppen: BSk), closely bordering on a humid subtropical climate. Due to the summer mean straddling 22 °C (72 °F) it is also bordering on a four-season oceanic climate, with cool winters and warm to hot summers.

The average yearly temperature is 15–16 °C (59–61 °F) during the day and around 9 °C (48 °F) at night. In the coldest months, January and February, the average temperature is 5–6 °C (41–43 °F) during the day and around 1 °C (34 °F) at night. In the warmest months, July and August, the average temperature is around 26 °C (79 °F) during the day and around 19 °C (66 °F) at night. Generally, summer/holiday season lasts 5 months, from around mid-May and into September, with the temperature often reaching 20 °C (68 °F) or more in the first half of October.

The average annual temperature of the sea is 14.2 °C (58 °F), ranging from 7 °C (45 °F) in February to 24 °C (75 °F) in August. From June to September, the average sea temperature is greater than 20 °C (68 °F). In the second half of May and the first half of October; the average sea temperature is about 17 °C (63 °F). The average rainfall is about 400 millimetres (16 in) per year. There are about 2,345 hours of sunshine duration per year.[49]

| Climate data for Sevastopol | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.9 (42.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.9 (48.0) |

13.6 (56.5) |

19.2 (66.6) |

23.5 (74.3) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.3 (79.3) |

22.4 (72.3) |

17.8 (64.0) |

12.3 (54.1) |

8.1 (46.6) |

15.9 (60.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.9 (37.2) |

2.8 (37.0) |

5.4 (41.7) |

9.8 (49.6) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.5 (67.1) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.1 (71.8) |

18.1 (64.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

8.8 (47.8) |

5.0 (41.0) |

12.1 (53.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.2 (31.6) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

2.0 (35.6) |

6.1 (43.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

17.9 (64.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

9.9 (49.8) |

5.4 (41.7) |

2.0 (35.6) |

8.5 (47.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 26 (1.0) |

25 (1.0) |

24 (0.9) |

27 (1.1) |

18 (0.7) |

26 (1.0) |

32 (1.3) |

33 (1.3) |

42 (1.7) |

32 (1.3) |

42 (1.7) |

52 (2.0) |

379 (15) |

| Average precipitation days | 6 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 31 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 72 | 75 | 145 | 202 | 267 | 316 | 356 | 326 | 254 | 177 | 98 | 64 | 2,352 |

| Source: pogodaiklimat.ru[50] |

Politics and government

Ukrainian administration

According to the Constitution of Ukraine, Sevastopol is administered as a City with special status. Executive power in Sevastopol is exercised by the Sevastopol City State Administration, led by a chairman (also known as mayor) appointed by the Ukrainian president.[51] The Sevastopol City Council is the legislature of Sevastopol.

Sevastopol is administratively divided into four districts:

- Gagarin Raion

- Lenin Raion

- Nakhimov Raion

- Balaklava Raion

Russian occupation

On 18 March 2014, Russia claimed to have annexed Crimea with Sevastopol being administered as a federal city of Russia, the others being Moscow and St. Petersburg.

- Executive

The head of the executive branch in the city is the Governor of Sevastopol. According to the city charter, amended on 29 November 2016, the governor is elected in a direct election for a term of five years and no more than two consecutive terms.[52] The current governor is Mikhail Razvozhayev.

- Legislature

During the annexation of Ukrainian Crimea by Russia, the pro-Russian City Council threw its support behind Russian citizen Alexei Chaly as a «people’s mayor» and said it would not recognise orders from Kyiv.[53][54] After Russia annexed Crimea, the Legislative Assembly of Sevastopol replaced the City Council.

- Administrative and municipal divisions

Within the Russian municipal framework, the territory of the federal city of Sevastopol is divided into nine municipal okrugs and the town of Inkerman. While individual municipal divisions are contained within the borders of the administrative districts, they are not otherwise related to the administrative districts.

Economy

|

|

This section is missing information about Sevastopol’s economic output by economic sector. Please expand the section to include this information. Further details may exist on the talk page. (March 2014) |

Apart from navy-related civil facilities, Sevastopol hosts some other notable industries. An example is Stroitel,[55] one of the leading plastic manufacturers in Russia.

Industry

- Sevastopol Aircraft Plant, SMZ Sevastopol Shipyards (main at Naval Bay) & Inkerman Shipyards, Balaklava Bay Shipyard

- Impuls 2 SMZ

- Chornomornaftogaz § Chernomorneftegaz (Chjornomor), oil/gas extraction, petrochemical, jack rigs and oil platforms, LNG and oil tankers.

- AO FNGUP Granit subsidiary of Almaz Antej, assembly, overhaul, and maintenance of SAM and radar EW complexes, ADS services.

- Sevastopol (Parus SPriborMZ, Mayak, NPO Elektron, NPP Kvant, Tavrida Elektronik, Musson, and other industrial plants)

- Sevastopol Economic Industrial Zone SevPZ (SE area)

- Persej SMZ ship repair and floating dock yard plant (South Bay, Sevastopol)

- Sevastopol ship repair and floating docks yards (various)

- Metallurgy, Chemical Plants, and other industries.

- Agriculture: rice, wheat, grapes, tea, fruits, and tobacco (lesser).

- Mining: iron, titanium, manganese, aluminum, calcite silicates, and amethyst.

- Kerch bridge, Taurida highway, Sevastopol GasTES plus solar FV plants, gas and petrol depots, and coal derivatives.

Infrastructure

There are different types of transport in Sevastopol:

- Bus – 101 lines

- Trolley bus – 14 lines

- Minibus – 52 lines

- Cutter – 6 lines

- Ferry – 1 line

- Express bus – 15 lines

- HEV train (local, suburban route) – 1 route

- Airport – 1

Sevastopol Shipyard comprises three facilities that together repair, modernise, and re-equip Russian Naval ships and submarines.[56] The Sevastopol International Airport is used as a military aerodrome at the moment and being reconstructed to be used by international airlines.