This article is about the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. For the Republic of Korea, see South Korea.

Coordinates: 40°N 127°E / 40°N 127°E

|

Democratic People’s Republic of Korea 조선민주주의인민공화국 (Korean) |

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Emblem |

|

| Anthem: 애국가 Aegukka «The Patriotic Song» |

|

Territory controlled by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in dark green; territory claimed but not controlled in light green |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Pyongyang 39°2′N 125°45′E / 39.033°N 125.750°E |

| Official languages | Korean (Munhwaŏ) |

| Official script | Chosŏn’gŭl |

| Religion

(2007) |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary one-party socialist republic under a totalitarian hereditary dictatorship |

|

• General Secretary of the WPK and President of the State Affairs |

Kim Jong-un |

|

• Premier of Cabinet and Vice President of the SAC |

Kim Tok-hun |

|

• Chairman of the SPA Standing Committee and First Vice President of the SAC |

Choe Ryong-hae |

|

• Chairman of the SPA |

Pak Thae-song |

| Legislature | Supreme People’s Assembly |

| Formation | |

|

• Soviet administration |

3 October 1945 |

|

• 1st provisional govt. |

8 February 1946 |

|

• 2nd provisional govt. |

22 February 1947 |

|

• DPRK established |

9 September 1948 |

|

• Current constitution |

27 December 1972 |

|

• Admitted to the UN |

17 September 1991 |

|

• Panmunjom Declaration |

27 April 2018 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

120,540 km2 (46,540 sq mi)[1] (98th) |

|

• Water (%) |

0.11 |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate |

25,955,138[2] (55th) |

|

• Density |

212/km2 (549.1/sq mi) (45th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate |

|

• Total |

$40 billion[3] |

|

• Per capita |

$1,800[4] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

|

• Total |

$16 billion[5] |

|

• Per capita |

$640 |

| Currency | Korean People’s won (₩) (KPW) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Pyongyang Time[6]) |

| Date format |

|

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +850[7] |

| ISO 3166 code | KP |

| Internet TLD | .kp[8] |

North Korea,[b] officially the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK),[c] is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and Tumen rivers, and South Korea to the south at the Korean Demilitarized Zone. North Korea’s border with South Korea is a disputed border as both countries claim the entirety of the Korean Peninsula. The country’s western border is formed by the Yellow Sea, while its eastern border is defined by the Sea of Japan. North Korea, like its southern counterpart, claims to be the legitimate government of the entire peninsula and adjacent islands. Pyongyang is the capital and largest city.

In 1910, Korea was annexed by the Empire of Japan. In 1945, after the Japanese surrender at the end of World War II, Korea was divided into two zones along the 38th parallel, with the north occupied by the Soviet Union and the south occupied by the United States. Negotiations on reunification failed, and in 1948, separate governments were formed: the socialist and Soviet-aligned Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in the north, and the capitalist, Western-aligned Republic of Korea in the south. The Korean War began in 1950, with an invasion by North Korea, and lasted until 1953. The Korean Armistice Agreement brought about a ceasefire and established a demilitarized zone (DMZ), but no formal peace treaty has ever been signed.

Post-war North Korea benefited greatly from economic aid and expertise provided by other Eastern Bloc countries, particularly the Soviet Union and China. However, relations between North Korea and the Soviet Union soured after the ascension of Nikita Khrushchev to the Soviet premiership in 1953, as Khrushchev denounced Stalinism while Kim Il-sung, North Korea’s first leader, upheld it. Kim briefly turned to China in the late 1950s before purging both pro-Soviet and pro-Chinese elements from the ruling Workers’ Party of Korea and promoting his personal philosophy of Juche as the state ideology. From the 1970s, South Korea’s economy began to boom whilst North Korea entered a state of stagnation. Pyongyang’s international isolation sharply accelerated from the 1980s onwards as the Cold War came to an end and China opened up to the West. The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 then brought about a full-scale collapse of the North Korean economy. From 1994 to 1998, North Korea suffered a famine that resulted in the deaths of between 240,000 and 420,000 people, and the population continues to suffer from malnutrition.

According to Article 1 of the state constitution, North Korea is an «independent socialist state».[d] It holds elections, though they have been described by independent observers as sham elections, as North Korea is a totalitarian dictatorship with a comprehensive cult of personality around the Kim family. The Workers’ Party of Korea is the ruling party of North Korea and leads the Democratic Front for the Reunification of Korea, the sole legal political movement in the country. According to Article 3 of the constitution, Kimilsungism–Kimjongilism is the official ideology of North Korea. The means of production are owned by the state through state-run enterprises and collectivized farms. Most services—such as healthcare, education, housing, and food production—are subsidized or state-funded.

North Korea follows Songun, or «military first» policy, for its Korean People’s Army. It possesses nuclear weapons, and is the country with the second highest number of military and paramilitary personnel, with a total of 7.769 million active, reserve, and paramilitary personnel, or approximately 30% of its population. Its active duty army of 1.28 million soldiers is the fourth-largest in the world, consisting of 4.9% of its population. A 2014 inquiry by the United Nations into abuses of human rights in North Korea concluded that «the gravity, scale and nature of these violations reveal a state that does not have any parallel in the contemporary world,» with Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch holding similar views. The North Korean government denies these abuses. In addition to being a member of the United Nations since 1991, North Korea is also a member of the Non-Aligned Movement, G77, and the ASEAN Regional Forum.

Names

The name Korea is derived from the name Goryeo (also spelled Koryŏ). The name Goryeo itself was first used by the ancient kingdom of Goguryeo (Koguryŏ) which was one of the great powers in East Asia during its time.[10] The 10th-century kingdom of Goryeo succeeded Goguryeo,[11][12][13][14] and thus inherited its name, which was pronounced by visiting Persian merchants as «Korea».[15] The modern spelling of Korea first appeared in the late 17th century in the travel writings of the Dutch East India Company’s Hendrick Hamel.[16]

After the division of the country into North and South Korea, the two sides used different terms to refer to Korea: Chosun or Joseon (조선) in North Korea, and Hanguk (한국) in South Korea. In 1948, North Korea adopted Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (Korean: 조선민주주의인민공화국, Chosŏn Minjujuŭi Inmin Konghwaguk; listen) as its new legal name. In the wider world, because the government controls the northern part of the Korean Peninsula, it is commonly called North Korea to distinguish it from South Korea, which is officially called the Republic of Korea in English. Both governments consider themselves to be the legitimate government of the whole of Korea.[17][18] For this reason, the people do not consider themselves as ‘North Koreans’ but as Koreans in the same divided country as their compatriots in the South, and foreign visitors are discouraged from using the former term.[19]

History

Founding

After the First Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War, Korea was ruled by Japan from 1910 to 1945. Korean resistance groups known as Dongnipgun (Liberation Army) operated along the Sino-Korean border, fighting guerrilla warfare against Japanese forces. Some of them took part in allied action in China and parts of South East Asia. One of the guerrilla leaders was the communist Kim Il-sung, who later became the first leader of North Korea.

After the Japanese surrender at the end of World War II in 1945, the Korean Peninsula was divided into two zones along the 38th parallel, with the northern half of the peninsula occupied by the Soviet Union and the southern half by the United States. Negotiations on reunification failed. Soviet general Terentii Shtykov recommended the establishment of the Soviet Civil Authority in October 1945, and supported Kim Il-sung as chairman of the Provisional People’s Committee for North Korea, established in February 1946. In September 1946, South Korean citizens rose up against the Allied Military Government. In April 1948, an uprising of the Jeju islanders was violently crushed. The South declared its statehood in May 1948 and two months later the ardent anti-communist Syngman Rhee[20] became its ruler. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea was established in the North on 9 September 1948. Shtykov served as the first Soviet ambassador, while Kim Il-sung became premier.

Soviet forces withdrew from the North in 1948, and most American forces withdrew from the South in 1949. Ambassador Shtykov suspected Rhee was planning to invade the North and was sympathetic to Kim’s goal of Korean unification under socialism. The two successfully lobbied Joseph Stalin to support a quick war against the South, which culminated in the outbreak of the Korean War.[21][22][23][24]

Korean War

Territory often changed hands early in the war, until the front stabilized.

North Korean, Chinese, and Soviet forces

South Korean, U.S., Commonwealth, and United Nations forces

The military of North Korea invaded the South on 25 June 1950, and swiftly overran most of the country. The United Nations Command (UNC) was subsequently established following the UN Security Council’s recognition of North Korean aggression against South Korea. The motion passed because the Soviet Union, a close ally of North Korea and a member of the UN Security Council, was boycotting the UN over its recognition of the Republic of China rather than the People’s Republic of China.[25] The UNC, led by the United States, intervened to defend the South, and rapidly advanced into North Korea. As they neared the border with China, Chinese forces intervened on behalf of North Korea, shifting the balance of the war again. Fighting ended on 27 July 1953, with an armistice that approximately restored the original boundaries between North and South Korea, but no peace treaty was signed.[26] Approximately 3 million people died in the Korean War, with a higher proportional civilian death toll than World War II or the Vietnam War.[27][28][29][30][31] In both per capita and absolute terms, North Korea was the country most devastated by the war, which resulted in the death of an estimated 12–15% of the North Korean population (c. 10 million), «a figure close to or surpassing the proportion of Soviet citizens killed in World War II,» according to Charles K. Armstrong.[32] As a result of the war, almost every substantial building in North Korea was destroyed.[33][34] Some have referred to the conflict as a civil war, with other factors involved.[35]

A heavily guarded demilitarized zone (DMZ) still divides the peninsula, and an anti-communist and anti-North Korea sentiment remains in South Korea. Since the war, the United States has maintained a strong military presence in the South which is depicted by the North Korean government as an imperialist occupation force.[36] It claims that the Korean War was caused by the United States and South Korea.[37]

Post-war developments

The post-war 1950s and 1960s saw an ideologicial shift in North Korea, as Kim Il-sung sought to consolidate his power. Kim Il-sung was highly critical of Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev and his de-Stalinization policies, and echoed Chinese critiques of Khrushchev as «revisionist».[38] During the 1956 August Faction Incident, Kim Il-sung successfully resisted efforts by the Soviet Union and China to depose him in favor of Soviet Koreans or the pro-Chinese Yan’an faction.[39][40] Some scholars believe that the 1956 August incident was an example of North Korea demonstrating political independence.[39][40][41] However, most scholars consider the final withdrawal of Chinese troops from North Korea in October 1958 to be the latest date when North Korea became effectively independent. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, North Korea sought to distinguish itself internationally by becoming a leader of the Non-Aligned Movement and promoting the ideology of Juche.[42] In United States policymaking, North Korea was considered among the Captive Nations.[43] Despite its efforts to break out of the Soviet and Chinese spheres of influence, North Korea remained closely aligned with both countries throughout the Cold War.[44]

Industry was the favored sector in North Korea. Industrial production returned to pre-war levels by 1957. In 1959, relations with Japan had improved somewhat, and North Korea began allowing the repatriation of Japanese citizens in the country. The same year, North Korea revalued the North Korean won, which held greater value than its South Korean counterpart. Until the 1960s, economic growth was higher than in South Korea, and North Korean GDP per capita was equal to that of its southern neighbor as late as 1976.[45] However, by the 1980s, the economy had begun to stagnate; it started its long decline in 1987 and almost completely collapsed after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, when all Soviet aid was suddenly halted.[46]

An internal CIA study acknowledged various achievements of the North Korean government post-war: compassionate care for war orphans and children in general, a radical improvement in the status of women, free housing, free healthcare, and health statistics particularly in life expectancy and infant mortality that were comparable to even the most advanced nations up until the North Korean famine.[47] Life expectancy in the North was 72 before the famine which was only marginally lower than in the South.[48] The country once boasted a comparatively developed healthcare system; pre-famine North Korea had a network of nearly 45,000 family practitioners with some 800 hospitals and 1,000 clinics.[49]

The relative peace between the North and South following the armistice was interrupted by border skirmishes, celebrity abductions, and assassination attempts. The North failed in several assassination attempts on South Korean leaders, such as in 1968, 1974, and the Rangoon bombing in 1983; tunnels were found under the DMZ and tensions flared over the axe murder incident at Panmunjom in 1976.[50] For almost two decades after the war, the two states did not seek to negotiate with one another. In 1971, secret, high-level contacts began to be conducted culminating in the 1972 July 4th North–South Joint Statement that established principles of working toward peaceful reunification. The talks ultimately failed because in 1973, South Korea declared its preference that the two Koreas should seek separate memberships in international organizations.[51]

Post Cold War

In 1992, as Kim Il-sung’s health began deteriorating, Kim Jong-il slowly began taking over various state tasks. Kim Il-sung died of a heart attack in 1994, with Kim Jong-il declaring a three-year period of national mourning before officially announcing his position as the new leader afterwards.[52]

North Korea promised to halt its development of nuclear weapons under the Agreed Framework, negotiated with U.S. president Bill Clinton and signed in 1994. Building on Nordpolitik, South Korea began to engage with the North as part of its Sunshine Policy.[53][54] Kim Jong-il instituted a policy called Songun, or «military first».[55]

Flooding in the mid-1990s exacerbated the economic crisis, severely damaging crops and infrastructure and led to widespread famine which the government proved incapable of curtailing, resulting in the deaths of between 240,000 and 420,000 people. In 1996, the government accepted UN food aid.[56]

21st century

The international environment changed once George W. Bush became U.S. President in 2001. His administration rejected South Korea’s Sunshine Policy and the Agreed Framework. Bush included North Korea in his axis of evil in his 2002 State of the Union address. The U.S. government accordingly treated North Korea as a rogue state, while North Korea redoubled its efforts to acquire nuclear weapons.[57][58][59] On 9 October 2006, North Korea announced it had conducted its first nuclear weapons test.[60][61]

U.S. President Barack Obama adopted a policy of «strategic patience», resisting making deals with North Korea.[62] Tensions with South Korea and the United States increased in 2010 with the sinking of the South Korean warship Cheonan[63] and North Korea’s shelling of Yeonpyeong Island.[64][65]

On 17 December 2011, Kim Jong-il died from a heart attack. His youngest son Kim Jong-un was announced as his successor.[66] In the face of international condemnation, North Korea continued to develop its nuclear arsenal, possibly including a hydrogen bomb and a missile capable of reaching the United States.[67]

Throughout 2017, following Donald Trump’s ascension to the US presidency, tensions between the United States and North Korea increased, and there was heightened rhetoric between the two, with Trump threatening «fire and fury» if North Korea ever attacked U.S. territory[68] amid North Korean threats to test missiles that would land near Guam.[69] The tensions substantially decreased in 2018, and a détente developed.[70] A series of summits took place between Kim Jong-un of North Korea, President Moon Jae-in of South Korea, and President Trump.[71]

On 10 January 2021, Kim Jong-un was formally elected as the General Secretary in 8th Congress of the Workers’ Party of Korea, a title previously held by Kim Jong-il.[72] On 24 March 2022, North Korea conducted a successful ICBM test launch for the first time since the 2017 crisis.[73] In September 2022, North Korea passed a law that declared itself a nuclear state.[74]

Geography

Topographic map of North Korea

North Korea occupies the northern portion of the Korean Peninsula, lying between latitudes 37° and 43°N, and longitudes 124° and 131°E. It covers an area of 120,540 square kilometers (46,541 sq mi).[1] To its west are the Yellow Sea and Korea Bay, and to its east lies Japan across the Sea of Japan.

Early European visitors to Korea remarked that the country resembled «a sea in a heavy gale» because of the many successive mountain ranges that crisscross the peninsula.[75] Some 80 percent of North Korea is composed of mountains and uplands, separated by deep and narrow valleys. All of the Korean Peninsula’s mountains with elevations of 2,000 meters (6,600 ft) or more are located in North Korea. The highest point in North Korea is Paektu Mountain, a volcanic mountain with an elevation of 2,744 meters (9,003 ft) above sea level.[75] Considered a sacred place by North Koreans, Mount Paektu holds significance in Korean culture and has been incorporated in the elaborate folklore and personality cult around the Kim family.[76] For example, the song, «We Will Go To Mount Paektu» sings in praise of Kim Jong-un and describes a symbolic trek to the mountain. Other prominent ranges are the Hamgyong Range in the extreme northeast and the Rangrim Mountains, which are located in the north-central part of North Korea. Mount Kumgang in the Taebaek Range, which extends into South Korea, is famous for its scenic beauty.[75]

The coastal plains are wide in the west and discontinuous in the east. A great majority of the population lives in the plains and lowlands. According to a United Nations Environmental Programme report in 2003, forest covers over 70 percent of the country, mostly on steep slopes.[77] North Korea had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.02/10, ranking it 28th globally out of 172 countries.[78] The longest river is the Amnok (Yalu) River which flows for 790 kilometers (491 mi).[79] The country contains three terrestrial ecoregions: Central Korean deciduous forests, Changbai Mountains mixed forests, and Manchurian mixed forests.[80]

Climate

North Korea map of Köppen climate classification

North Korea experiences a combination of continental climate and an oceanic climate,[77][81] but most of the country experiences a humid continental climate within the Köppen climate classification scheme. Winters bring clear weather interspersed with snow storms as a result of northern and northwestern winds that blow from Siberia.[81] Summer tends to be by far the hottest, most humid, and rainiest time of year because of the southern and southeastern monsoon winds that carry moist air from the Pacific Ocean. Approximately 60 percent of all precipitation occurs from June to September.[81] Spring and autumn are transitional seasons between summer and winter. The daily average high and low temperatures for Pyongyang are −3 and −13 °C (27 and 9 °F) in January and 29 and 20 °C (84 and 68 °F) in August.[81]

Administrative divisions

Largest cities or towns in North Korea 2008 Census |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Administrative division | Pop. | Rank | Name | Administrative division | Pop. | ||

Pyongyang  Hamhung |

1 | Pyongyang | Pyongyang Capital City | 3,255,288 | 11 | Sunchon | South Pyongan | 297,317 |  Chongjin  Nampo |

| 2 | Hamhung | South Hamgyong | 768,551 | 12 | Pyongsong | South Pyongan | 284,386 | ||

| 3 | Chongjin | North Hamgyong | 667,929 | 13 | Haeju | South Hwanghae | 273,300 | ||

| 4 | Nampo | South Pyongan Province | 366,815 | 14 | Kanggye | Chagang | 251,971 | ||

| 5 | Wonsan | Kangwon | 363,127 | 15 | Anju | South Pyongan | 240,117 | ||

| 6 | Sinuiju | North Pyongan | 359,341 | 16 | Tokchon | South Pyongan | 237,133 | ||

| 7 | Tanchon | South Hamgyong | 345,875 | 17 | Kimchaek | North Hamgyong | 207,299 | ||

| 8 | Kaechon | South Pyongan | 319,554 | 18 | Rason | Rason Special Economic Zone | 196,954 | ||

| 9 | Kaesong | North Hwanghae | 308,440 | 19 | Kusong | North Pyongan | 196,515 | ||

| 10 | Sariwon | North Hwanghae | 307,764 | 20 | Hyesan | Ryanggang | 192,680 |

Government and politics

North Korea functions as a highly centralized, one-party totalitarian dictatorship.[e] According to its 2019 constitution, it is a self-described revolutionary and socialist state «guided in its building and activities only by great Kimilsungism–Kimjongilism».[86] In addition to the constitution, North Korea is governed by the Ten Principles for the Establishment of a Monolithic Ideological System (also known as the «Ten Principles of the One-Ideology System») which establishes standards for governance and a guide for the behaviors of North Koreans.[87] The Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK), a communist party led by a member of the Kim family,[88][89] has an estimated 6.5 million members[90] and dominates every aspect of North Korean politics. It has two satellite organizations, the Korean Social Democratic Party and the Chondoist Chongu Party[91] which participate in the WPK-led Democratic Front for the Reunification of Korea of which all political officers are required to be members.[92]

Kim Jong-un of the Kim family is the current Supreme Leader or Suryeong of North Korea.[93] He heads all major governing structures: he is General Secretary of the Workers’ Party of Korea, President of the State Affairs, Chairman of the Central Military Commission of the WPK, and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces.[94][95] His grandfather Kim Il-sung, the founder and leader of North Korea until his death in 1994, is the country’s «eternal President»,[96] while his father Kim Jong-il who succeeded Kim Il-sung as the leader was announced «Eternal General Secretary» and «Eternal Chairman of the National Defence Commission» after his death in 2011.[94]

According to the Constitution of North Korea, there are officially three main branches of government. The first of these is the State Affairs Commission (SAC), which acts as «the supreme national guidance organ of state sovereignty».[97][98] Its role is to deliberate and decide the work on defense building of the State, including major policies of the State, and to carry out the directions of the president of the commission, Kim Jong-Un.

Legislative power is held by the unicameral Supreme People’s Assembly (SPA). Its 687 members are elected every five years by universal suffrage,[99] though the elections have been described by outside observers as sham elections.[100][101] Supreme People’s Assembly sessions are convened by the SPA Standing Committee, whose Chairman (Choe Ryong-hae since 2019) is the third-ranking official in North Korea.[102] Deputies formally elect the Chairman, the vice-chairmen and members of the Presidium and take part in the constitutionally appointed activities of the legislature: pass laws, establish domestic and foreign policies, appoint members of the cabinet, review and approve the state economic plan, among others.[103] The SPA itself cannot initiate any legislation independently of party or state organs. It is unknown whether it has ever criticized or amended bills placed before it, and the elections are based around a single list of WPK-approved candidates who stand without opposition.[104]

Executive power is vested in the Cabinet of North Korea, which has been headed by Premier Kim Tok-hun since 14 August 2020,[105] who’s officially the second-ranking official after Kim Jong-un.[102] The Premier represents the government and functions independently. His authority extends over two vice-premiers, 30 ministers, two cabinet commission chairmen, the cabinet chief secretary, the president of the Central Bank, the director of the Central Bureau of Statistics and the president of the Academy of Sciences. A 31st ministry, the Ministry of People’s Armed Forces, is under the jurisdiction of the State Affairs Commission.[106]

North Korea, like its southern counterpart, claims to be the legitimate government of the entire Korean Peninsula and adjacent islands.[107] Despite its official title as the «Democratic People’s Republic of Korea», some observers have described North Korea’s political system as an absolute monarchy[108][109][110] or a «hereditary dictatorship».[111] It has also been described as a Stalinist dictatorship.[112][113][114][115]

Political ideology

Further information: Juche

Kimilsungism–Kimjongilism is the official ideology of North Korea and the WPK, and is the cornerstone of party works and government operations.[86] Juche, part of the larger Kimilsungism–Kimjongilism along with Songun under Kim Jong-un,[116] is viewed by the official North Korean line as an embodiment of Kim Il-sung’s wisdom, an expression of his leadership, and an idea which provides «a complete answer to any question that arises in the struggle for national liberation».[117] Juche was pronounced in December 1955 in a speech called On Eliminating Dogmatism and Formalism and Establishing Juche in Ideological Work in order to emphasize a Korea-centered revolution.[117] Its core tenets are economic self-sufficiency, military self-reliance and an independent foreign policy. The roots of Juche were made up of a complex mixture of factors, including the cult of personality centered on Kim Il-sung, the conflict with pro-Soviet and pro-Chinese dissenters, and Korea’s centuries-long struggle for independence.[118] Juche was introduced into the constitution in 1972.[119][120]

Juche was initially promoted as a «creative application» of Marxism–Leninism, but in the mid-1970s, it was described by state propaganda as «the only scientific thought… and most effective revolutionary theoretical structure that leads to the future of communist society». Juche eventually replaced Marxism–Leninism entirely by the 1980s,[121] and in 1992 references to the latter were omitted from the constitution.[122] The 2009 constitution dropped references to communism and elevated the Songun military first policy while explicitly confirming the position of Kim Jong-il.[123] However, the constitution retains references to socialism.[124] The WPK reasserted its commitment to communism in 2021.[89] Juche‘s concepts of self-reliance have evolved with time and circumstances, but still provide the groundwork for the spartan austerity, sacrifice, and discipline demanded by the party.[125] Scholar Brian Reynolds Myers views North Korea’s actual ideology as a Korean ethnic nationalism similar to statism in Shōwa Japan and European fascism.[126][127][128]

Kim family

North Korean citizens paying respect to the statues of Kim Il-sung (left) and Kim Jong-il at the Mansudae Grand Monument

Since the founding of the nation, North Korea’s supreme leadership has stayed within the Kim family, which in North Korea is referred to as the Mount Paektu Bloodline. It is a three-generation lineage descending from the country’s first leader, Kim Il-sung. Kim Il-sung developed North Korea around the Juche ideology, and stayed in power until his death.[129] Kim developed a cult of personality closely tied to the state philosophy of Juche, which was later passed on to his successors: his son Kim Jong-il in 1994 and grandson Kim Jong-un in 2011. In 2013, Clause 2 of Article 10 of the newly edited Ten Fundamental Principles of the Workers’ Party of Korea stated that the party and revolution must be carried «eternally» by the «Mount Paektu Bloodline».[130]

According to New Focus International, the cult of personality, particularly surrounding Kim Il-sung, has been crucial for legitimizing the family’s hereditary succession.[131] The control the North Korean government exercises over many aspects of the nation’s culture is used to perpetuate the cult of personality surrounding Kim Il-sung,[132] and Kim Jong-il.[133] While visiting North Korea in 1979, journalist Bradley Martin wrote that nearly all music, art, and sculpture that he observed glorified «Great Leader» Kim Il-sung, whose personality cult was then being extended to his son, «Dear Leader» Kim Jong-il.[134]

Claims that the family has been deified are contested by North Korea researcher B. R. Myers: «Divine powers have never been attributed to either of the two Kims. In fact, the propaganda apparatus in Pyongyang has generally been careful not to make claims that run directly counter to citizens’ experience or common sense.»[135] He further explains that the state propaganda painted Kim Jong-il as someone whose expertise lay in military matters and that the famine of the 1990s was partially caused by natural disasters out of Kim Jong-il’s control.[136]

The song «No Motherland Without You», sung by the North Korean army choir, was created especially for Kim Jong-il and is one of the most popular tunes in the country. Kim Il-sung is still officially revered as the nation’s «Eternal President». Several landmarks in North Korea are named for Kim Il-sung, including Kim Il-sung University, Kim Il-sung Stadium, and Kim Il-sung Square. Defectors have been quoted as saying that North Korean schools deify both father and son.[137] Kim Il-sung rejected the notion that he had created a cult around himself, and accused those who suggested this of «factionalism».[138] Following the death of Kim Il-sung, North Koreans were prostrating and weeping to a bronze statue of him in an organized event;[139] similar scenes were broadcast by state television following the death of Kim Jong-il.[140]

Critics maintain that Kim Jong-il’s personality cult was inherited from his father. Kim Jong-il was often the center of attention throughout ordinary life. His birthday is one of the most important public holidays in the country. On his 60th birthday (based on his official date of birth), mass celebrations occurred throughout the country.[141] Kim Jong-il’s personality cult, although significant, was not as extensive as his father’s. One point of view is that Kim Jong-il’s cult of personality was solely out of respect for Kim Il-sung or out of fear of punishment for failure to pay homage,[142] while North Korean government sources consider it genuine hero worship.[143]

Foreign relations

As a result of its isolation, North Korea is sometimes known as the «hermit kingdom», a term that originally referred to the isolationism in the latter part of the Joseon Dynasty.[144] Initially, North Korea had diplomatic ties only with other communist countries, and even today, most of the foreign embassies accredited to North Korea are located in Beijing rather than in Pyongyang.[145] In the 1960s and 1970s, it pursued an independent foreign policy, established relations with many developing countries, and joined the Non-Aligned Movement. In the late 1980s and the 1990s its foreign policy was thrown into turmoil with the collapse of the Soviet Bloc. Suffering an economic crisis, it closed a number of its embassies. At the same time, North Korea sought to build relations with developed free market countries.[146]

North Korea joined the United Nations in 1991 together with South Korea. North Korea is also a member of the Non-Aligned Movement, G77 and the ASEAN Regional Forum.[147] As of 2015, North Korea had diplomatic relations with 166 countries and embassies in 47 countries.[146] North Korea does not have diplomatic relations with Argentina, Botswana,[148] Estonia, France,[149] Iraq, Israel, Japan, Taiwan,[150] and the United States.[f][151][152] As of September 2017, France and Estonia are the last two European countries that do not have an official relationship with North Korea.[153] In July 2022, Ukraine severed its diplomatic relations with North Korea following North Korea’s recognition of Luhansk People’s Republic and Donetsk People’s Republic.[154]

North Korea enjoys a close relationship with China which is often called North Korea’s closest ally.[155][156] Relations were strained beginning in 2006 because of China’s concerns about North Korea’s nuclear program.[157] Relations improved after Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and Chinese President visited North Korea in April 2019.[158] North Korea continues to have strong ties with several Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia,[159] and Indonesia. Relations with Malaysia were strained in 2017 by the assassination of Kim Jong-nam.

North Korean leader Kim Jong-un meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin, 25 April 2019

North Korea was previously designated a state sponsor of terrorism by the U.S.[160] because of its alleged involvement in the 1983 Rangoon bombing and the 1987 bombing of a South Korean airliner.[161] On 11 October 2008, the United States removed North Korea from its list of states that sponsor terrorism after Pyongyang agreed to cooperate on issues related to its nuclear program.[162] North Korea was re-designated a state sponsor of terrorism by the U.S. under the Trump administration on 20 November 2017.[163] The kidnapping of at least 13 Japanese citizens by North Korean agents in the 1970s and the 1980s has had a detrimental effect on North Korea’s relationship with Japan.[164]

US President Donald Trump met with Kim in Singapore on 12 June 2018. An agreement was signed between the two countries endorsing the 2017 Panmunjom Declaration signed by North and South Korea, pledging to work towards denuclearizing the Korean Peninsula.[165] They met in Hanoi from 27 to 28 February 2019, but failed to achieve an agreement.[166] On 30 June 2019, Trump met with Kim along with Moon Jae-in at the Korean DMZ.[167]

Inter-Korean relations

The Korean Demilitarized Zone with South Korea remains the most heavily fortified border in the world.[168] Inter-Korean relations are at the core of North Korean diplomacy and have seen numerous shifts in the last few decades. North Korea’s policy is to seek reunification without what it sees as outside interference, through a federal structure retaining each side’s leadership and systems. In 1972, the two Koreas agreed in principle to achieve reunification through peaceful means and without foreign interference.[169] On 10 October 1980, then North Korean leader Kim Il-sung proposed a federation between North and South Korea named the Democratic Federal Republic of Korea in which the respective political systems would initially remain.[170] However, relations remained cool well until the early 1990s, with a brief period in the early 1980s when North Korea offered to provide flood relief to its southern neighbor.[171] Although the offer was initially welcomed, talks over how to deliver the relief goods broke down and none of the promised aid ever crossed the border.[172]

The two countries also organized a reunion of 92 separated families.[173]

South Korean aid convoy entering North Korea through the Demilitarized Zone, 1998

The Sunshine Policy instituted by South Korean president Kim Dae-jung in 1998 was a watershed in inter-Korean relations. It encouraged other countries to engage with the North, which allowed Pyongyang to normalize relations with a number of European Union states and contributed to the establishment of joint North-South economic projects. The culmination of the Sunshine Policy was the 2000 Inter-Korean summit, when Kim Dae-jung visited Kim Jong-il in Pyongyang.[174] Both North and South Korea signed the June 15th North–South Joint Declaration, in which both sides promised to seek peaceful reunification.[175] On 4 October 2007, South Korean president Roh Moo-hyun and Kim Jong-il signed an eight-point peace agreement.[176]

However, relations worsened when South Korean president Lee Myung-bak adopted a more hard-line approach and suspended aid deliveries pending the de-nuclearization of the North. In 2009, North Korea responded by ending all of its previous agreements with the South.[177] It deployed additional ballistic missiles[178] and placed its military on full combat alert after South Korea, Japan and the United States threatened to intercept a Unha-2 space launch vehicle.[179] The next few years witnessed a string of hostilities, including the alleged North Korean involvement in the sinking of South Korean warship Cheonan,[63] mutual ending of diplomatic ties,[180] a North Korean artillery attack on Yeonpyeong Island,[181] and growing international concern over North Korea’s nuclear program.[182]

In May 2017, Moon Jae-in was elected President of South Korea with a promise to return to the Sunshine Policy.[183] In February 2018, a détente developed at the Winter Olympics held in South Korea.[70] In April, South Korean President Moon Jae-in and Kim Jong-un met at the DMZ, and, in the Panmunjom Declaration, pledged to work for peace and nuclear disarmament.[184] In September, at a joint news conference in Pyongyang, Moon and Kim agreed upon turning the Korean Peninsula into a «land of peace without nuclear weapons and nuclear threats».[185]

Law enforcement and internal security

A North Korean police car in 2017; the Chosŏn’gŭl lettering on the side translates to «Traffic safety».

North Korea has a civil law system based on the Prussian model and influenced by Japanese traditions and communist legal theory.[186] Judiciary procedures are handled by the Supreme Court (the highest court of appeal), provincial or special city-level courts, people’s courts, and special courts. People’s courts are at the lowest level of the system and operate in cities, counties and urban districts, while different kinds of special courts handle cases related to military, railroad, or maritime matters.[187]

Judges are theoretically elected by their respective local people’s assemblies, but in practice they are appointed by the Workers’ Party of Korea. The penal code is based on the principle of nullum crimen sine lege (no crime without a law), but remains a tool for political control despite several amendments reducing ideological influence.[187] Courts carry out legal procedures related to not only criminal and civil matters, but also political cases as well.[188] Political prisoners are sent to labor camps, while criminal offenders are incarcerated in a separate system.[189]

The Ministry of Social Security (MSS) maintains most law enforcement activities. It is one of the most powerful state institutions in North Korea and oversees the national police force, investigates criminal cases and manages non-political correctional facilities.[190] It handles other aspects of domestic security like civil registration, traffic control, fire departments and railroad security.[191] The State Security Department was separated from the MPS in 1973 to conduct domestic and foreign intelligence, counterintelligence and manage the political prison system. Political camps can be short-term reeducation zones or «kwalliso» (total control zones) for lifetime detention.[192] Camp 15 in Yodok[193] and Camp 18 in Bukchang[194] have been described in detailed testimonies.[195]

The security apparatus is extensive,[196] exerting strict control over residence, travel, employment, clothing, food and family life.[197] Security forces employ mass surveillance. It is believed they tightly monitor cellular and digital communications.[198]

Human rights

A map of political prison camps in North Korea. An estimated 40% of prisoners die of malnutrition.[199]

North Korea is widely described as having the worst human rights record in the world.[200] A 2014 UN inquiry into human rights in North Korea concluded that, «The gravity, scale and nature of these violations reveal a state that does not have any parallel in the contemporary world»,[201] with Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch holding similar views.[200][202][203] North Koreans have been referred to as «some of the world’s most brutalized people» by Human Rights Watch, because of the severe restrictions placed on their political and economic freedoms.[202][203] The North Korean population is strictly managed by the state and all aspects of daily life are subordinated to party and state planning. Employment is managed by the party on the basis of political reliability, and travel is tightly controlled by the Ministry of People’s Security.[204] North Koreans do not have a choice in the jobs they work and are not free to change jobs at will.[205]

There are severe restrictions on the freedom of association, expression and movement; arbitrary detention, torture and other ill-treatment result in death and execution.[206] Citizens in North Korea are denied freedom of movement including the right to leave the country[207] at will and its government denies access to international human rights observers.[208]

The State Security Department extrajudicially apprehends and imprisons those accused of political crimes without due process.[209] People perceived as hostile to the government, such as Christians or critics of the leadership,[210] are deported to labor camps without trial,[211] often with their whole family and mostly without any chance of being released.[212] Forced labor is part of an established system of political repression.[205]

Based on satellite images and defector testimonies, an estimated 200,000 prisoners are held in six large political prison camps,[210][213] where they are forced to work in conditions approaching slavery.[214] Supporters of the government who deviate from the government line are subject to reeducation in sections of labor camps set aside for that purpose. Those who are deemed politically rehabilitated may reassume responsible government positions on their release.[215]

North Korean defectors[216] have provided detailed testimonies on the existence of the total control zones where abuses such as torture, starvation, rape, murder, medical experimentation, forced labor, and forced abortions have been reported.[195] On the basis of these abuses, as well as persecution on political, religious, racial, and gender grounds, forcible transfer of populations, enforced disappearance of persons, and forced starvation, the United Nations Commission of Inquiry has accused North Korea of crimes against humanity.[217][218][219] The International Coalition to Stop Crimes Against Humanity in North Korea (ICNK) estimates that over 10,000 people die in North Korean prison camps every year.[220]

With 1,100,000 people in modern slavery (via forced labor), North Korea is ranked highest in the world in terms of the percentage of population in modern slavery, with 10.4 percent enslaved according to the Walk Free Foundation’s 2018 Global Slavery Index.[221][222] North Korea is the only country in the world that has not explicitly criminalized any form of modern slavery.[223] A United Nations report listed slavery among the crimes against humanity occurring in North Korea.[224]

Based on interviews with defectors, North Korean women are routinely subjected to sexual violence, unwanted sexual contact, and rape. Men in positions of power, including police, high-ranking officials, market supervisors, and guards can abuse women at will and are not prosecuted for it. It happens so often that it is accepted as a routine part of life. Women assume they can not do anything about it. The only ones with protection are those whose husbands or fathers are themselves in positions of power.[225]

The North Korean government does not fully comply with the minimum standards for the elimination of human trafficking and is not making significant efforts to do so. The most common form of trafficking involves North Korean women and girls forced into marriage or prostitution in China.[205]

The North Korean government rejects the human rights abuse claims,[226][227][228] calling them «a smear campaign» and a «human rights racket» aimed at government change.[229][230][231] In a 2014 report to the UN, North Korea dismissed accusations of atrocities as «wild rumors».[226] The official state media, KCNA, responded with an article that included homophobic insults against the author of the human rights report, Michael Kirby, calling him «a disgusting old lecher with a 40-odd-year-long career of homosexuality … This practice can never be found in the DPRK boasting of the sound mentality and good morals … In fact, it is ridiculous for such gay [sic] to sponsor dealing with others’ human rights issue.»[227][228] The government, however, admitted some human rights issues related to living conditions and stated that it is working to improve them.[231]

Military

The North Korean armed forces, or the Korean People’s Army (KPA), is estimated to comprise 1,280,000 active and 6,300,000 reserve and paramilitary troops, making it one of the largest military institutions in the world.[232] With an active duty army consisting of 4.9% of its population, the KPA is the fourth largest active military force in the world behind China, India and the United States.[233] About 20 percent of men aged 17–54 serve in the regular armed forces,[233] and approximately one in every 25 citizens is an enlisted soldier.[234][235]

The KPA is divided into five branches: Ground Force, Navy, Air Force, Special Operations Force, and Rocket Force. Command of the KPA lies in both the Central Military Commission of the Workers’ Party of Korea and the independent State Affairs Commission, which controls the Ministry of People’s Armed Forces.[236]

Of all the KPA’s branches, the Ground Force is the largest, comprising approximately one million personnel divided into 80 infantry divisions, 30 artillery brigades, 25 special warfare brigades, 20 mechanized brigades, 10 tank brigades and seven tank regiments.[237] It is equipped with 3,700 tanks, 2,100 armored personnel carriers and infantry fighting vehicles,[238] 17,900 artillery pieces, 11,000 anti-aircraft guns[239] and some 10,000 MANPADS and anti-tank guided missiles.[240] The Air Force is estimated to possess around 1,600 aircraft (with between 545 – 810 serving combat roles), while the Navy operates approximately 800 vessels, including the largest submarine fleet in the world.[232][241] The KPA’s Special Operation Force is also the world’s largest special forces unit.[241]

The Memorial of Soldiers at the Mansudae Grand Monument

North Korea is a nuclear-armed state,[234][242] though the nature and strength of its arsenal is uncertain. In January 2018, estimates of North Korea’s nuclear arsenal ranged between 15 and 60 bombs, probably including hydrogen bombs.[67] Delivery capabilities[243] are provided by the Rocket Force, which has some 1,000 ballistic missiles with a range of up to 11,900 km (7,400 mi).[244]

According to a 2004 South Korean assessment, North Korea also possesses a stockpile of chemical weapons estimated to amount to between 2,500–5,000 tons, including nerve, blister, blood, and vomiting agents, as well as the ability to cultivate and produce biological weapons including anthrax, smallpox, and cholera.[245][246] As a result of its nuclear and missile tests, North Korea has been sanctioned under United Nations Security Council resolutions 1695 of July 2006, 1718 of October 2006, 1874 of June 2009, 2087 of January 2013,[247] and 2397 in December 2017.

The sale of weapons to North Korea by other states is prohibited by UN sanctions, and the KPA’s conventional capabilities are limited by a number of factors including obsolete equipment, insufficient fuel supplies and a shortage of digital command and control assets. To compensate for these deficiencies, the KPA has deployed a wide range of asymmetric warfare technologies including anti-personnel blinding lasers,[248] GPS jammers,[249] midget submarines and human torpedoes,[250] stealth paint,[251] and cyberwarfare units.[252] In 2015, North Korea was reported to employ 6,000 sophisticated computer security personnel in a cyberwarfare unit operating out of China.[253] KPA units were blamed for the 2014 Sony Pictures hack[253] and have allegedly attempted to jam South Korean military satellites.[254]

Much of the equipment in use by the KPA is engineered and manufactured by the domestic defense industry. Weapons are manufactured in roughly 1,800 underground defense industry plants scattered throughout the country, most of them located in Chagang Province.[255] The defense industry is capable of producing a full range of individual and crew-operated weapons, artillery, armored vehicles, tanks, missiles, helicopters, submarines, landing and infiltration craft and Yak-18 trainers, and may even have limited jet aircraft manufacturing capacity.[196] According to North Korean state media, military expenditure amounted to 15.8 percent of the state budget in 2010.[256] The U.S. State Department has estimated that North Korea’s military spending averaged 23% of its GDP from 2004 to 2014, the highest level in the world.[257] North Korea successfully tested a new type of submarine-launched ballistic missile on 19 October 2021.[258]

Society

Demographics

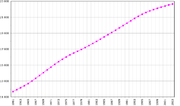

Development of life expectancy in North Korea and South Korea

With the exception of a small Chinese community and a few ethnic Japanese, North Korea’s 25,971,909[259][260] people are ethnically homogeneous.[261] Demographic experts in the 20th century estimated that the population would grow to 25.5 million by 2000 and 28 million by 2010, but this increase never occurred due to the North Korean famine.[262] It began in 1995, lasted for three years and resulted in the deaths of between 240,000 and 420,000 North Koreans.[56]

International donors led by the United States initiated shipments of food through the World Food Program in 1997 to combat the famine.[263] Despite a drastic reduction of aid under the George W. Bush administration,[264] the situation gradually improved: the number of malnourished children declined from 60% in 1998[265] to 37% in 2006[266] and 28% in 2013.[267] Domestic food production almost recovered to the recommended annual level of 5.37 million tons of cereal equivalent in 2013,[268] but the World Food Program reported a continuing lack of dietary diversity and access to fats and proteins.[269] By the mid-2010s national levels of severe wasting, an indication of famine-like conditions, were lower than in other low-income countries and about on par with developing nations in the Pacific and East Asia. Children’s health and nutrition is significantly better on a number of indicators than in many other Asian countries.[270]

The famine had a significant impact on the population growth rate, which declined to 0.9% annually in 2002.[262] It was 0.5% in 2014.[271] Late marriages after military service, limited housing space and long hours of work or political studies further exhaust the population and reduce growth.[262] The national birth rate is 14.5 births per year per 1,000 population.[272] Two-thirds of households consist of extended families mostly living in two-room units. Marriage is virtually universal and divorce is extremely rare.[273]

Health

North Korea has a life expectancy of 72.3 years in 2019, according to HDR 2020.[274] While North Korea is classified as a low-income country, the structure of North Korea’s causes of death (2013) is unlike that of other low-income countries.[275] Instead, it is closer to worldwide averages, with non-communicable diseases—such as cardiovascular disease and cancers—accounting for 84 percent of the total deaths in 2016.[276]

According to the World Bank report of 2016 (based on WHO’s estimate), only 9.5% of the total deaths recorded in North Korea are attributed to communicable diseases and maternal, prenatal and nutrition conditions, a figure which is slightly lower than that of South Korea (10.1%) and one fifth of other low-income countries (50.1%) but higher than that of high income countries (6.7%).[277] Only one out of ten leading causes of overall deaths in North Korea is attributed to communicable diseases (lower respiratory infection), a disease which is reported to have declined by six percent since 2007.[278]

In 2013, cardiovascular disease as a single disease group was reported as the largest cause of death in North Korea.[275] The three major causes of death in North Korea are stroke, COPD and Ischaemic heart disease.[278] Non-communicable diseases risk factors in North Korea include high rates of urbanization, an aging society, and high rates of smoking and alcohol consumption amongst men.[275]

Maternal mortality is lower than other low-income countries, but significantly higher than South Korea and other high income countries, at 89 per 100,000 live births.[279] In 2008 child mortality was estimated to be 45 per 1,000, which is much better than other economically comparable countries. Chad for example had a child mortality rate of 120 per 1,000, despite the fact that Chad was most likely wealthier than North Korea at the time.[48]

Healthcare Access and Quality Index, as calculated by IHME, was reported to stand at 62.3, much lower than that of South Korea.[280]

According to a 2003 report by the United States Department of State, almost 100% of the population has access to water and sanitation.[281] 80% of the population had access to improved sanitation facilities in 2015.[282]

North Korea has the highest number of doctors per capita amongst low-income countries, with 3.7 physicians per 1,000 people, a figure which is also significantly higher than that of South Korea, according to WHO’s data.[283]

Conflicting reports between Amnesty and WHO have emerged where the Amnesty report claimed that North Korea had an inadequate health care system. On the contrary, the Director of the World Health Organization claimed that North Korea’s healthcare system was considered the envy of the developing world and had «no lack of doctors and nurses».[284]

A free universal insurance system is in place.[285] Quality of medical care varies significantly by region[286] and is often low, with severe shortages of equipment, drugs and anesthetics.[287] According to WHO, expenditure on health per capita is one of the lowest in the world.[287] Preventive medicine is emphasized through physical exercise and sports, nationwide monthly checkups and routine spraying of public places against disease. Every individual has a lifetime health card which contains a full medical record.[288]

Education

The 2008 census listed the entire population as literate.[273] An 11-year free, compulsory cycle of primary and secondary education is provided in more than 27,000 nursery schools, 14,000 kindergartens, 4,800 four-year primary and 4,700 six-year secondary schools.[265] 77% of males and 79% of females aged 30–34 have finished secondary school.[273] An additional 300 universities and colleges offer higher education.[265]

Most graduates from the compulsory program do not attend university but begin their obligatory military service or proceed to work in farms or factories instead. The main deficiencies of higher education are the heavy presence of ideological subjects, which comprise 50% of courses in social studies and 20% in sciences,[289] and the imbalances in curriculum. The study of natural sciences is greatly emphasized while social sciences are neglected.[290] Heuristics is actively applied to develop the independence and creativity of students throughout the system.[291] The study of Russian and English was made compulsory in upper middle schools in 1978.[292]

Language

North Korea shares the Korean language with South Korea, although some dialectal differences exist within both Koreas.[265] North Koreans refer to their Pyongyang dialect as munhwaŏ («cultured language») as opposed to the dialects of South Korea, especially the Seoul dialect or p’yojun’ŏ («standard language»), which are viewed as decadent because of its use of loanwords from Chinese and European languages (particularly English).[293][294] Words of Chinese, Manchu or Western origin have been eliminated from munhwa along with the usage of Chinese hancha characters.[293] Written language uses only the Chosŏn’gŭl (Hangul) phonetic alphabet, developed under Sejong the Great (1418–1450).[295][296]

Religion

Officially, North Korea is an atheist state.[297][298] Although its constitution guarantees freedom of religion in Article 68, the principle is limited by the requirement that religion may not be used as a pretext to harm the state, introduce foreign forces, or harm the existing social order.[86][299] Despite this constitutional guarantee of freedom of religion and the right to religious ceremonies,[300] according to Human Rights Watch, religious practice is restricted.[301][302] Although proselytizing is prohibited due to concerns about foreign influence, the number of Christian churchgoers nonetheless more than doubled between the 1980s and the early 2000s due to the recruitment of Christians who previously worshipped privately or in small house churches.[303] The Open Doors mission, a Protestant group based in the United States and founded during the Cold War era, claims the most severe persecution of Christians in the world occurs in North Korea.[304]

There are no known official statistics of religions in North Korea. According to Religious Intelligence in 2007, 64% of the population are irreligious, 16% practice Korean shamanism, 14% practice Chondoism, 4% are Buddhist, and 2% are Christian.[305] Amnesty International has expressed concerns about religious persecution in North Korea.[207] Pro-North groups such as the Paektu Solidarity Alliance deny these claims, saying that multiple religious facilities exist across the nation.[306] Some religious places of worship are located in foreign embassies in the capital city of Pyongyang.[307] Five Christian churches built with state funds stand in Pyongyang: three Protestant, one Roman Catholic, and one Russian orthodox.[303] Critics claim these are showcases for foreigners.[308][309]

Buddhism and Confucianism still influence spirituality.[310] Chondoism («Heavenly Way») is an indigenous syncretic belief combining elements of Korean shamanism, Buddhism, Taoism and Catholicism that is officially represented by the WPK-controlled Chondoist Chongu Party.[311] Chondoism is recognized and favored by the government, being seen as an indigenous form of «revolutionary religion».[299]

Formal ranking of citizens’ loyalty

According to North Korean documents and refugee testimonies,[312] all North Koreans are sorted into groups according to their Songbun, an ascribed status system based on a citizen’s assessed loyalty to the government. Based on their own behavior and the political, social, and economic background of their family for three generations as well as behavior by relatives within that range, Songbun is allegedly used to determine whether an individual is trusted with responsibility, given opportunities,[313] or even receives adequate food.[312][314]

Songbun allegedly affects access to educational and employment opportunities and particularly whether a person is eligible to join North Korea’s ruling party.[313] There are 3 main classifications and about 50 sub-classifications. According to Kim Il-sung, speaking in 1958, the loyal «core class» constituted 25% of the North Korean population, the «wavering class» 55%, and the «hostile class» 20%.[312] The highest status is accorded to individuals descended from those who participated with Kim Il-sung in the resistance against Japanese occupation before and during World War II and to those who were factory workers, laborers, or peasants in 1950.[315]

While some analysts believe private commerce recently changed the Songbun system to some extent,[316] most North Korean refugees say it remains a commanding presence in everyday life.[312] The North Korean government claims all citizens are equal and denies any discrimination on the basis of family background.[317]

Economy

Historical GDP per capita estimates of North Korea, 1820–2018

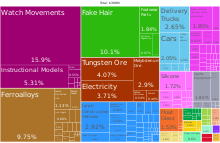

A proportional representation of North Korea exports, 2019

North Korea has maintained one of the most closed and centralized economies in the world since the 1940s.[318] For several decades, it followed the Soviet pattern of five-year plans with the ultimate goal of achieving self-sufficiency. Extensive Soviet and Chinese support allowed North Korea to rapidly recover from the Korean War and register very high growth rates. Systematic inefficiency began to arise around 1960, when the economy shifted from the extensive to the intensive development stage. The shortage of skilled labor, energy, arable land and transportation significantly impeded long-term growth and resulted in consistent failure to meet planning objectives.[319] The major slowdown of the economy contrasted with South Korea, which surpassed the North in terms of absolute GDP and per capita income by the 1980s.[320] North Korea declared the last seven-year plan unsuccessful in December 1993 and thereafter stopped announcing plans.[321]

The loss of Eastern Bloc trading partners and a series of natural disasters throughout the 1990s caused severe hardships, including widespread famine. By 2000, the situation improved owing to a massive international food assistance effort, but the economy continues to suffer from food shortages, dilapidated infrastructure and a critically low energy supply.[322] In an attempt to recover from the collapse, the government began structural reforms in 1998 that formally legalized private ownership of assets and decentralized control over production.[323] A second round of reforms in 2002 led to an expansion of market activities, partial monetization, flexible prices and salaries, and the introduction of incentives and accountability techniques.[324] Despite these changes, North Korea remains a command economy where the state owns almost all means of production and development priorities are defined by the government.[322]

North Korea has the structural profile of a relatively industrialized country[325] where nearly half of the Gross Domestic Product is generated by industry[326] and human development is at medium levels.[327] Purchasing power parity (PPP) GDP is estimated at $40 billion,[3] with a very low per capita value of $1,800.[4] In 2012, Gross national income per capita was $1,523, compared to $28,430 in South Korea.[328] The North Korean won is the national currency, issued by the Central Bank of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.[329] The economy has been developing dramatically in recent years despite sanctions. According to the Sejong Institute these changes have been «astonishing».[330]

The economy is heavily nationalized.[331] Food and housing are extensively subsidized by the state; education and healthcare are free;[285] and the payment of taxes was officially abolished in 1974.[332] A variety of goods are available in department stores and supermarkets in Pyongyang,[333] though most of the population relies on small-scale jangmadang markets.[334][335] In 2009, the government attempted to stem the expanding free market by banning jangmadang and the use of foreign currency,[322] heavily devaluing the won and restricting the convertibility of savings in the old currency,[287] but the resulting inflation spike and rare public protests caused a reversal of these policies.[336] Private trade is dominated by women because most men are required to be present at their workplace, even though many state-owned enterprises are non-operational.[337]

Industry and services employ 65%[338] of North Korea’s 12.6 million labor force.[339] Major industries include machine building, military equipment, chemicals, mining, metallurgy, textiles, food processing and tourism.[340] Iron ore and coal production are among the few sectors where North Korea performs significantly better than its southern neighbor—it produces about 10 times more of each resource.[341] Using ex-Romanian drilling rigs, several oil exploration companies have confirmed significant oil reserves in the North Korean shelf of the Sea of Japan, and in areas south of Pyongyang.[342] The agricultural sector was shattered by the natural disasters of the 1990s.[343] Its 3,500 cooperatives and state farms[344] were moderately successful until the mid-1990s[345] but now experience chronic fertilizer and equipment shortages. Rice, corn, soybeans and potatoes are some of the primary crops.[322] A significant contribution to the food supply comes from commercial fishing and aquaculture.[322] Smaller specialized farms, managed by the state, also produce high-value crops, including ginseng, honey, matsutake and herbs for traditional Korean and Chinese medicine.[346] Tourism has been a growing sector for the past decade.[347] North Korea has been aiming to increase the number of foreign visitors through projects like the Masikryong Ski Resort.[348]

Foreign trade surpassed pre-crisis levels in 2005 and continues to expand.[349][350] North Korea has a number of special economic zones (SEZs) and Special Administrative Regions where foreign companies can operate with tax and tariff incentives while North Korean establishments gain access to improved technology.[351] Initially four such zones existed, but they yielded little overall success.[352] The SEZ system was overhauled in 2013 when 14 new zones were opened and the Rason Special Economic Zone was reformed as a joint Chinese-North Korean project.[353] The Kaesong Industrial Region is a special economic zone where more than 100 South Korean companies employ some 52,000 North Korean workers.[354] As of August 2017, China is the biggest trading partner of North Korea outside inter-Korean trade, accounting for more than 84% of the total external trade ($5.3 billion) followed by India at 3.3% share ($205 million).[355] In 2014, Russia wrote off 90% of North Korea’s debt and the two countries agreed to conduct all transactions in rubles.[356] Overall, external trade in 2013 reached a total of $7.3 billion (the highest amount since 1990[357]), while inter-Korean trade dropped to an eight-year low of $1.1 billion.[358]

Infrastructure and transport

Satellite image of the Korean Peninsula at night, contrasting use of night-time lighting in North and South Korea.[359]

North Korea’s energy infrastructure is obsolete and in disrepair. Power shortages are chronic and would not be alleviated even by electricity imports because the poorly maintained grid causes significant losses during transmission.[360][361] Coal accounts for 70% of primary energy production, followed by hydroelectric power with 17%.[362] The government under Kim Jong-un has increased emphasis on renewable energy projects like wind farms, solar parks, solar heating and biomass.[363] A set of legal regulations adopted in 2014 stressed the development of geothermal, wind and solar energy along with recycling and environmental conservation.[363][364] North Korea’s long-term objective is to curb fossil fuel usage and reach an output of 5 million kilowatts from renewable sources by 2044, up from its current total of 430,000 kilowatts from all sources. Wind power is projected to satisfy 15% of the country’s total energy demand under this strategy.[365]

North Korea also strives to develop its own civilian nuclear program. These efforts are under much international dispute due to their military applications and concerns about safety.[366]

Transport infrastructure includes railways, highways, water and air routes, but rail transport is by far the most widespread. North Korea has some 5,200 kilometers (3,200 mi) of railways mostly in standard gauge which carry 80% of annual passenger traffic and 86% of freight, but electricity shortages undermine their efficiency.[362] Construction of a high-speed railway connecting Kaesong, Pyongyang and Sinuiju with speeds exceeding 200 kilometers per hour (120 mph) was approved in 2013.[367][needs update] North Korea connects with the Trans-Siberian Railway through Rajin.

Road transport is very limited—only 724 kilometers (450 mi) of the 25,554 kilometers (15,879 mi) road network are paved,[368] and maintenance on most roads is poor.[369] Only 2% of the freight capacity is supported by river and sea transport, and air traffic is negligible.[362] All port facilities are ice-free and host a merchant fleet of 158 vessels.[370] Eighty-two airports[371] and 23 helipads[372] are operational and the largest serve the state-run airline, Air Koryo.[362] Cars are relatively rare,[373] but bicycles are common.[374][375] There is only one international airport—Pyongyang International Airport—serviced by Russia and China (see List of public airports in North Korea)

Science and technology

R&D efforts are concentrated at the State Academy of Sciences, which runs 40 research institutes, 200 smaller research centers, a scientific equipment factory and six publishing houses.[376] The government considers science and technology to be directly linked to economic development.[377][378] A five-year scientific plan emphasizing IT, biotechnology, nanotechnology, marine technology, and laser and plasma research was carried out in the early 2000s.[377] A 2010 report by the South Korean Science and Technology Policy Institute identified polymer chemistry, single carbon materials, nanoscience, mathematics, software, nuclear technology and rocketry as potential areas of inter-Korean scientific cooperation. North Korean institutes are strong in these fields of research, although their engineers require additional training, and laboratories need equipment upgrades.[379]

Unha-3 space launch vehicle at Sohae Satellite Launching Station

Under its «constructing a powerful knowledge economy» slogan, the state has launched a project to concentrate education, scientific research and production into a number of «high-tech development zones». International sanctions remain a significant obstacle to their development.[380] The Miraewon network of electronic libraries was established in 2014 under similar slogans.[381]

Significant resources have been allocated to the national space program, which is managed by the National Aerospace Development Administration (formerly managed by the Korean Committee of Space Technology until April 2013)[382][383] Domestically produced launch vehicles and the Kwangmyŏngsŏng satellite class are launched from two spaceports, the Tonghae Satellite Launching Ground and the Sohae Satellite Launching Station. After four failed attempts, North Korea became the tenth spacefaring nation with the launch of Kwangmyŏngsŏng-3 Unit 2 in December 2012, which successfully reached orbit but was believed to be crippled and non-operational.[384][385] It joined the Outer Space Treaty in 2009[386] and has stated its intentions to undertake crewed and Moon missions.[383] The government insisted the space program is for peaceful purposes, but the United States, Japan, South Korea and other countries maintained that it serves to advance North Korea’s ballistic missile program.[387] On 7 February 2016, a statement broadcast on Korean Central Television said that a new Earth observation satellite, Kwangmyongsong-4, had successfully been put into orbit.[388]

Usage of communication technology is controlled by the Ministry of Post and Telecommunications. An adequate nationwide fiber-optic telephone system with 1.18 million fixed lines[389] and expanding mobile coverage is in place.[7] Most phones are installed for senior government officials and installation requires written explanation why the user needs a telephone and how it will be paid for.[390] Cellular coverage is available with a 3G network operated by Koryolink, a joint venture with Orascom Telecom Holding.[391] The number of subscribers has increased from 3,000 in 2002[392] to almost two million in 2013.[391] International calls through either fixed or cellular service are restricted, and mobile Internet is not available.[391]

Internet access itself is limited to a handful of elite users and scientists. Instead, North Korea has a walled garden intranet system called Kwangmyong,[393] which is maintained and monitored by the Korea Computer Center.[394] Its content is limited to state media, chat services, message boards,[393] an e-mail service and an estimated 1,000–5,500 websites.[395] Computers employ the Red Star OS, an operating system derived from Linux, with a user shell visually similar to that of OS X.[395] On 19 September 2016, a TLDR project noticed the North Korean Internet DNS data and top-level domain was left open which allowed global DNS zone transfers. A dump of the data discovered was shared on GitHub.[8][396]

Culture

Despite a historically strong Chinese influence, Korean culture has shaped its own unique identity.[397] It came under attack during the Japanese rule from 1910 to 1945, when Japan enforced a cultural assimilation policy. Koreans were forced to learn and speak Japanese, adopt the Japanese family name system and Shinto religion, and were forbidden to write or speak the Korean language in schools, businesses, or public places.[398]

After the peninsula was divided in 1945, two distinct cultures formed out of the common Korean heritage. North Koreans have little exposure to foreign influence.[399] The revolutionary struggle and the brilliance of the leadership are some of the main themes in art. «Reactionary» elements from traditional culture have been discarded and cultural forms with a «folk» spirit have been reintroduced.[399]

Korean heritage is protected and maintained by the state.[400] Over 190 historical sites and objects of national significance are cataloged as National Treasures of North Korea, while some 1,800 less valuable artifacts are included in a list of Cultural Assets. The Historic Monuments and Sites in Kaesong and the Complex of Koguryo Tombs are UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[401]

Art

Visual arts are generally produced in the esthetic of Socialist realism. North Korean painting combines the influence of Soviet and Japanese visual expression to instill a sentimental loyalty to the system.[403] All artists in North Korea are required to join the Artists’ Union, and the best among them can receive an official license to portray the leaders. Portraits and sculptures depicting Kim Il-sung, Kim Jong-il and Kim Jong-un are classed as «Number One works».

Most aspects of art have been dominated by Mansudae Art Studio since its establishment in 1959. It employs around 1,000 artists in what is likely the biggest art factory in the world where paintings, murals, posters and monuments are designed and produced.[404] The studio has commercialized its activity and sells its works to collectors in a variety of countries including China, where it is in high demand.[403] Mansudae Overseas Projects is a subdivision of Mansudae Art Studio that carries out construction of large-scale monuments for international customers.[404] Some of the projects include the African Renaissance Monument in Senegal,[405] and the Heroes’ Acre in Namibia.[406]

World Heritage

In the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, the Goguryeo tumulus is registered on the World Heritage list of UNESCO. These remains were registered as the first World Heritage property of North Korea in the UNESCO World Heritage Committee (WHC) in July 2004. There are 63 burial mounds in the tomb group, with clear murals preserved. The burial customs of the Goguryeo culture have influenced Asian civilizations beyond Korea, including Japan.[407]

Music

The government emphasized optimistic folk-based tunes and revolutionary music throughout most of the 20th century.[399] Ideological messages are conveyed through massive orchestral pieces like the «Five Great Revolutionary Operas» based on traditional Korean ch’angguk.[408] Revolutionary operas differ from their Western counterparts by adding traditional instruments to the orchestra and avoiding recitative segments.[409] Sea of Blood is the most widely performed of the Five Great Operas: since its premiere in 1971, it has been played over 1,500 times,[410] and its 2010 tour in China was a major success.[409] Western classical music by Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Stravinsky and other composers is performed both by the State Symphony Orchestra and student orchestras.[411]