Как правильно пишется слово «шалтай-болтай»

шалта́й-болта́й

шалта́й-болта́й, -я (пустяки, вздор; бездельник), неизм. (попусту; без дела, занятия) и Шалта́й-Болта́й, Шалта́я-Болта́я (персонаж прибаутки и лит. персонаж)

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: гомонить — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Синонимы к слову «шалтай-болтай»

Предложения со словом «шалтай-болтай»

- Если ты будешь продолжать смотреть на всех и каждого, то никогда не будешь индивидуальностью, ты будешь просто шалтай-болтай.

- – Верно, родной, дальше шалтай-болтай за жирной бараниной и кукурузной лепёшкой будет…

- – Вы не против, если я похищу у вас эту молодую даму? – Шалтай-Болтай прервался прежде, чем успел представиться, и тонкая рука просунулась под мою.

- (все предложения)

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Смотрите также

ШАЛТА́Й-БОЛТА́Й, нескл., м. Прост. 1. Пустяки, вздор.

Все значения слова «шалтай-болтай»

-

Если ты будешь продолжать смотреть на всех и каждого, то никогда не будешь индивидуальностью, ты будешь просто шалтай-болтай.

-

– Верно, родной, дальше шалтай-болтай за жирной бараниной и кукурузной лепёшкой будет…

-

– Вы не против, если я похищу у вас эту молодую даму? – Шалтай-Болтай прервался прежде, чем успел представиться, и тонкая рука просунулась под мою.

- (все предложения)

- бездельник

- шаромыга

- зря

- зазря

- дуриком

- (ещё синонимы…)

Правильное написание:

шалта́й-болта́й, -я (пустяки, вздор; бездельник), неизм. (попусту; без дела, занятия) и Шалта́й-Болта́й, Шалта́я-Болта́я (персонаж прибаутки)

Рады помочь вам узнать, как пишется слово «шалтай-болтай».

Пишите и говорите правильно.

О словаре

Сайт создан на основе «Русского орфографического словаря», составленного Институтом русского языка имени В. В. Виноградова РАН. Объем второго издания, исправленного и дополненного, составляет около 180 тысяч слов, и существенно превосходит все предшествующие орфографические словари. Он является нормативным справочником, отражающим с возможной полнотой лексику русского языка начала 21 века и регламентирующим ее правописание.

Как написать слово «шалтай-болтай» правильно? Где поставить ударение, сколько в слове ударных и безударных гласных и согласных букв? Как проверить слово «шалтай-болтай»?

шалта́й-болта́й

Правильное написание — шалтай-болтай, , безударными гласными являются: а, о.

Выделим согласные буквы — шалтай—болтай, к согласным относятся: ш, л, т, й, б, звонкие согласные: л, й, б, глухие согласные: ш, т.

Количество букв и слогов:

- букв — 13,

- слогов — 4,

- гласных — 4,

- согласных — 8.

Формы слова: шалта́й-болта́й, -я (пустя-ки, вздор; бездельник), неизм. (попусту; без дела, занятия) и Шалта́й-Бол-та́й, Шалта́я-Болта́я (персонаж прибаутки).

Правильно слово пишется: шалта́й-болта́й

Сложное слово, состоящее из 2 частей.

- шалтай

- Ударение падает на 2-й слог с буквой а.

Всего в слове 6 букв, 2 гласных, 4 согласных, 2 слога.

Гласные: а, а;

Согласные: ш, л, т, й. - болтай

- Ударение падает на 2-й слог с буквой а.

Всего в слове 6 букв, 2 гласных, 4 согласных, 2 слога.

Гласные: о, а;

Согласные: б, л, т, й.

Номера букв в слове

Номера букв в слове «шалтай-болтай» в прямом и обратном порядке:

- 12

ш

1 - 11

а

2 - 10

л

3 - 9

т

4 - 8

а

5 - 7

й

6 -

—

- 6

б

7 - 5

о

8 - 4

л

9 - 3

т

10 - 2

а

11 - 1

й

12

Слово «шалтай-болтай» состоит из 12-ти букв и 1-го дефиса.

Разбор по составу

Разбор по составу (морфемный разбор) слова шалтай-болтай делается следующим образом:

шалтай—болтай

Морфемы слова: шалтай, болтай — корни, , — окончание, шалтай — основы.

Сложное слово, состоящее из 2 частей

шалтай

Правильное ударение в этом слове падает на 2-й слог. На букву а

болтай

Правильное ударение в этом слове падает на 2-й слог. На букву а

Посмотреть все слова на букву Ш

А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

шалта́й-болта́й, -я (пустяки, вздор; бездельник), неизм. (попусту; без дела, занятия) и Шалта́й-Болта́й, Шалта́я-Болта́я (персонаж прибаутки и лит. персонаж)

Рядом по алфавиту:

ша́левый

шале́ть , -е́ю, -е́ет

шали́ть , шалю́, шали́т

шалма́н , -а (сниж.)

шаловли́вость , -и

шаловли́вый

шало́м , неизм.

шалопа́истый

шалопа́й , -я

шалопа́йничать , -аю, -ает

шалопа́йство , -а

шалопу́т , -а (сниж.)

шалопу́тный , (сниж.)

ша́лость , -и

шало́т , -а

шалта́й-болта́й , -я (пустяки, вздор; бездельник), неизм. (попусту; без дела, занятия) и Шалта́й-Болта́й, Шалта́я-Болта́я (персонаж прибаутки и лит. персонаж)

шалу́н , -уна́

шалуни́шка , -и, р. мн. -шек, м. и ж.

шалу́нья , -и, р. мн. -ний

шалфе́й , -я

шалфе́йный

шалыга́н , -а (сниж.)

шалыга́нить , -ню, -нит (сниж.)

ша́лый

шаль , -и

шальва́ры , -а́р

ша́лька , -и, р. мн. ша́лек

шально́й

шаля́й-валя́й , неизм. (сниж.)

шаля́пинский , (от Шаля́пин)

шама́н , -а

шалтай-болтай

- шалтай-болтай

-

шалтай-болтай, нескл. и неизм.

Слитно или раздельно? Орфографический словарь-справочник. — М.: Русский язык.

.

1998.

Синонимы:

Смотреть что такое «шалтай-болтай» в других словарях:

-

шалтай-болтай — шаляй валяй, бездельник, вздор, напрасно, дуром, дуриком Словарь русских синонимов. шалтай болтай см. напрасно Словарь синонимов русского языка. Практический справочник. М.: Русский язык. З. Е. Александрова … Словарь синонимов

-

ШАЛТАЙ-БОЛТАЙ — ШАЛТАЙ БОЛТАЙ, нескл., муж. (прост.). Вздор, пустяки. Несет шалтай болтай всякий. || Вздорный человек. Толковый словарь Ушакова. Д.Н. Ушаков. 1935 1940 … Толковый словарь Ушакова

-

ШАЛТАЙ-БОЛТАЙ — ШАЛТАЙ БОЛТАЙ, нареч. (разг. неод.). Без всякого дела, цели, занятия (о времяпрепровождении; первонач. о пустой болтовне). Целыми днями по двору слоняется шалтай болтай. Толковый словарь Ожегова. С.И. Ожегов, Н.Ю. Шведова. 1949 1992 … Толковый словарь Ожегова

-

Шалтай-Болтай — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Шалтай Болтай (значения). Шалтай Болтай Humpty Dumpty … Википедия

-

Шалтай-болтай — Прост. Пренебр. 1. Вздор, пустяки, пустая болтовня. [Даша:] Захотела ты от этих ваших модниц! У них что? Только шалтай болтай в голове (Григорович. Столичный воздух). Непреложных законов она (политика) не даёт, почти всегда врёт, но насчёт шалтай … Фразеологический словарь русского литературного языка

-

шалтай-болтай — {{шалтай болт{}а{}й}} I. неизм.; м. Разг. Пустяки, вздор. Не дело, а так шалтай болтай. II. нареч. Попусту, напрасно, без всякого дела, цели, занятия (о времяпрепровождении). Целыми днями слоняется шалтай болтай … Энциклопедический словарь

-

шалтай-болтай — 1. неизм.; м. разг. Пустяки, вздор. Не дело, а так шалтай болтай. 2. нареч. Попусту, напрасно, без всякого дела, цели, занятия (о времяпрепровождении) Целыми днями слоняется шалтай болтай … Словарь многих выражений

-

шалтай-болтай — шалта/й болта/й, нареч., разг. Целый день шалтай болтай по дому слоняется (без всякого дела) … Слитно. Раздельно. Через дефис.

-

Шалтай-Болтай (значения) — Шалтай Болтай: Шалтай Болтай персонаж английского детского стихотворения и книги Льюиса Кэрролла «Алиса в Зазеркалье» Шалтай Болтай российский фэнзин, посвящённый фантастике … Википедия

-

Шалтай-Болтай (фэнзин) — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Шалтай Болтай (значения). Шалтай Болтай Специализация: фантастика Периодичность: 4 номера в год Язык: русский Адрес редакции: Волгоград … Википедия

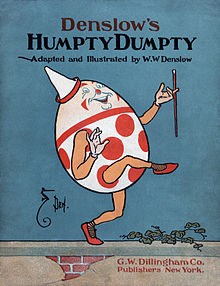

| «Humpty Dumpty» | |

|---|---|

Illustration by W. W. Denslow, 1904 |

|

| Nursery rhyme | |

| Published | 1797 |

Humpty Dumpty is a character in an English nursery rhyme, probably originally a riddle and one of the best known in the English-speaking world. He is typically portrayed as an anthropomorphic egg, though he is not explicitly described as such. The first recorded versions of the rhyme date from late eighteenth-century England and the tune from 1870 in James William Elliott’s National Nursery Rhymes and Nursery Songs.[1] Its origins are obscure, and several theories have been advanced to suggest original meanings.

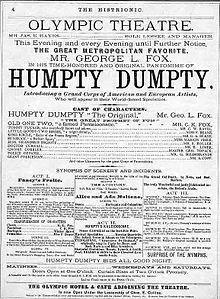

Humpty Dumpty was popularized in the United States on Broadway by actor George L. Fox in the pantomime musical Humpty Dumpty.[2] The show ran from 1868 to 1869, for a total of 483 performances, becoming the longest-running Broadway show until it was surpassed in 1881 by Hazel Kirke.[3] As a character and literary allusion, Humpty Dumpty has appeared or been referred to in many works of literature and popular culture, particularly English author Lewis Carroll’s 1871 book Through the Looking-Glass, in which he was described as an egg. The rhyme is listed in the Roud Folk Song Index as No. 13026.

Lyrics and melody[edit]

The rhyme is one of the best known in the English language. The common text from 1954 is:[4]

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men

Couldn’t put Humpty together again.

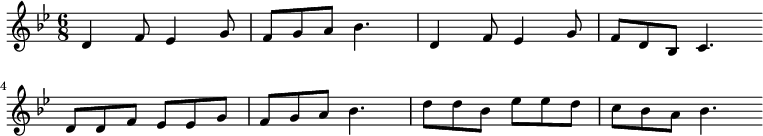

It is a single quatrain with external rhymes[5] that follow the pattern of AABB and with a trochaic metre, which is common in nursery rhymes.[6] The melody commonly associated with the rhyme was first recorded by composer and nursery rhyme collector James William Elliott in his National Nursery Rhymes and Nursery Songs (London, 1870), as outlined below:[7]

Origins[edit]

Illustration from Walter Crane’s Mother Goose’s Nursery Rhymes (1877), showing Humpty Dumpty as a boy

.

The earliest known version was published in Samuel Arnold’s Juvenile Amusements in 1797[1] with the lyrics:[4]

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

Four-score Men and Four-score more,

Could not make Humpty Dumpty where he was before.

William Carey Richards (1818–1892) quoted the poem in 1843, commenting, «when we were five years old … the following parallel lines… were propounded as a riddle … Humpty-dumpty, reader, is the Dutch or something else for an egg».[8]

A manuscript addition to a copy of Mother Goose’s Melody published in 1803 has the modern version with a different last line: «Could not set Humpty Dumpty up again».[4] It was published in 1810 in a version of Gammer Gurton’s Garland.[9] (Note: Original spelling variations left intact.)

Humpty Dumpty sate on a wall,

Humpti Dumpti had a great fall;

Threescore men and threescore more,

Cannot place Humpty dumpty as he was before.

In 1842, James Orchard Halliwell published a collected version as:[10]

Humpty Dumpty lay in a beck.

With all his sinews around his neck;

Forty Doctors and forty wrights

Couldn’t put Humpty Dumpty to rights!

The modern-day version of this nursery rhyme, as known throughout the UK since at least the mid-twentieth century, is as follows:

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall;

All the King’s horses

And all the King’s men,

Couldn’t put Humpty together again.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the 17th century, the term «humpty dumpty» referred to a drink of brandy boiled with ale.[4] The riddle probably exploited, for misdirection, the fact that «humpty dumpty» was also eighteenth-century reduplicative slang for a short and clumsy person.[11] The riddle may depend upon the assumption that a clumsy person falling off a wall might not be irreparably damaged, whereas an egg would be. The rhyme is no longer posed as a riddle, since the answer is now so well known. Similar riddles have been recorded by folklorists in other languages, such as «Boule Boule» in French, «Lille Trille» in Swedish and Norwegian, and «Runtzelken-Puntzelken» or «Humpelken-Pumpelken» in different parts of Germany—although none is as widely known as Humpty Dumpty is in English.[4][12]

Meaning[edit]

The rhyme does not explicitly state that the subject is an egg, possibly because it may have been originally posed as a riddle.[4] There are also various theories of an original «Humpty Dumpty». One, advanced by Katherine Elwes Thomas in 1930[13] and adopted by Robert Ripley,[4] posits that Humpty Dumpty is King Richard III of England, depicted as humpbacked in Tudor histories and particularly in Shakespeare’s play, and who was defeated, despite his armies, at Bosworth Field in 1485.

In 1785, Francis Grose’s Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue noted that a «Humpty Dumpty» was «a short clumsy [sic] person of either sex, also ale boiled with brandy»; no mention was made of the rhyme.[14]

Punch in 1842 suggested jocularly that the rhyme was a metaphor for the downfall of Cardinal Wolsey; just as Wolsey was not buried in his intended tomb, so Humpty Dumpty was not buried in his shell.[15]

Professor David Daube suggested in The Oxford Magazine of 16 February 1956 that Humpty Dumpty was a «tortoise» siege engine, an armored frame, used unsuccessfully to approach the walls of the Parliamentary-held city of Gloucester in 1643 during the Siege of Gloucester in the English Civil War. This was on the basis of a contemporary account of the attack, but without evidence that the rhyme was connected.[16] The theory was part of an anonymous series of articles on the origin of nursery rhymes and was widely acclaimed in academia,[17] but it was derided by others as «ingenuity for ingenuity’s sake» and declared to be a spoof.[18][19] The link was nevertheless popularized by a children’s opera All the King’s Men by Richard Rodney Bennett, first performed in 1969.[20][21]

From 1996, the website of the Colchester tourist board attributed the origin of the rhyme to a cannon recorded as used from the church of St Mary-at-the-Wall by the Royalist defenders in the siege of 1648.[22] In 1648, Colchester was a walled town with a castle and several churches and was protected by the city wall. The story given was that a large cannon, which the website claimed was colloquially called Humpty Dumpty, was strategically placed on the wall. A shot from a Parliamentary cannon succeeded in damaging the wall beneath Humpty Dumpty, which caused the cannon to tumble to the ground. The Royalists (or Cavaliers, «all the King’s men») attempted to raise Humpty Dumpty on to another part of the wall, but the cannon was so heavy that «All the King’s horses and all the King’s men couldn’t put Humpty together again». Author Albert Jack claimed in his 2008 book Pop Goes the Weasel: The Secret Meanings of Nursery Rhymes that there were two other verses supporting this claim.[23] Elsewhere, he claimed to have found them in an «old dusty library, [in] an even older book»,[24] but did not state what the book was or where it was found. It has been pointed out that the two additional verses are not in the style of the seventeenth century or of the existing rhyme, and that they do not fit with the earliest printed versions of the rhyme, which do not mention horses and men.[22]

In popular culture[edit]

Humpty Dumpty has become a highly popular nursery rhyme character. American actor George L. Fox (1825–77) helped to popularise the character in nineteenth-century stage productions of pantomime versions, music, and rhyme.[25] The character is also a common literary allusion, particularly to refer to a person in an insecure position, something that would be difficult to reconstruct once broken, or a short and fat person.[26]

Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass[edit]

Humpty Dumpty appears in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass (1871), a sequel to Alice in Wonderland from six years prior. Alice remarks that Humpty is «exactly like an egg,» which Humpty finds to be «very provoking» in the looking-glass world. Alice clarifies that she said he looks like an egg, not that he is one. They discuss semantics and pragmatics[27] when Humpty Dumpty says, «my name means the shape I am,» and later:[28]

«I don’t know what you mean by ‘glory,’ » Alice said.

Humpty Dumpty smiled contemptuously. «Of course you don’t—till I tell you. I meant ‘there’s a nice knock-down argument for you!'»

«But ‘glory’ doesn’t mean ‘a nice knock-down argument’,» Alice objected.

«When I use a word,» Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, «it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.»

«The question is,» said Alice, «whether you can make words mean so many different things.»

«The question is,» said Humpty Dumpty, «which is to be master—that’s all.»

Alice was too much puzzled to say anything, so after a minute Humpty Dumpty began again. «They’ve a temper, some of them—particularly verbs, they’re the proudest—adjectives you can do anything with, but not verbs—however, I can manage the whole lot! Impenetrability! That’s what I say!»

This passage was used in Britain by Lord Atkin in his dissenting judgement in the seminal case Liversidge v. Anderson (1942), where he protested about the distortion of a statute by the majority of the House of Lords.[29] It also became a popular citation in United States legal opinions, appearing in 250 judicial decisions in the Westlaw database as of 19 April 2008, including two Supreme Court cases (TVA v. Hill and Zschernig v. Miller).[30]

A. J. Larner suggested that Carroll’s Humpty Dumpty had prosopagnosia on the basis of his description of his finding faces hard to recognise:[31]

«The face is what one goes by, generally,» Alice remarked in a thoughtful tone.

«That’s just what I complain of,» said Humpty Dumpty. «Your face is the same as everybody has—the two eyes,—» (marking their places in the air with his thumb) «nose in the middle, mouth under. It’s always the same. Now if you had the two eyes on the same side of the nose, for instance—or the mouth at the top—that would be some help.»

James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake[edit]

James Joyce used the story of Humpty Dumpty as a recurring motif of the Fall of Man in the 1939 novel Finnegans Wake.[32][33] One of the most easily recognizable references is at the end of the second chapter, in the first verse of the Ballad of Persse O’Reilly:

Have you heard of one Humpty Dumpty

How he fell with a roll and a rumble

And curled up like Lord Olofa Crumple

By the butt of the Magazine Wall,

(Chorus) Of the Magazine Wall,

Hump, helmet and all?

In film, literature and music[edit]

Robert Penn Warren’s 1946 American novel All the King’s Men is the story of populist politician Willie Stark’s rise to the position of governor and eventual fall, based on the career of the infamous Louisiana Senator and Governor Huey Long. It won the 1947 Pulitzer Prize and was twice made into a film in 1949 and 2006, the former winning the Academy Award for best motion picture.[34] This was echoed in Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward’s book All the President’s Men, about the Watergate scandal, referring to the failure of the President’s staff to repair the damage once the scandal had leaked out. It was filmed as All the President’s Men in 1976, starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman.[35]

In 1983, an advert for Kinder Surprise featuring a realistic version of the Humpty Dumpty character (designed by Mike Quinn, who worked at the Jim Henson’s Creature Shop) and directed by Mike Portelly, was banned shortly after release, due to being highly unsettling. The advert aired only on ITV and its franchises.

In 2016 film of Alice Through the Looking Glass, Humpty Dumpty was voiced by Wally Wingert.

In the 2011 film Puss In Boots, Humpty Dumpty was voiced by Zach Galifianakis.[36]

In 2021, American band AJR released a song titled «Humpty Dumpty» on their album OK Orchestra. The song uses the nursery rhyme as a parallel for hiding one’s true emotions as things, typically unpleasant, happen to the singer.

Jasper Fforde’s 2005 British novel The Big Over Easy is an exercise in absurdity, in which Humpty Stuyvesant Van Dumpty III has been murdered and Detective Jack Spratt of the Nursery Crime Division is set the task of solving the mystery.

Taylor Swift references it in her song «The Archer», the fifth track on her album Lover, modifying it slightly and turning it into «all the king’s horses, all the king’s men, couldn’t put me together again».[37]

In science[edit]

Humpty Dumpty has been used to demonstrate the second law of thermodynamics. The law describes a process known as entropy, a measure of the number of specific ways in which a system may be arranged, often taken to be a measure of «disorder». The higher the entropy, the higher the disorder. After his fall and subsequent shattering, the inability to put him together again is representative of this principle, as it would be highly unlikely (though not impossible) to return him to his earlier state of lower entropy, as the entropy of an isolated system never decreases.[38][39][40]

See also[edit]

- List of nursery rhymes

References[edit]

- ^ a b Emily Upton (24 April 2013). «The Origin of Humpty Dumpty». What I Learned Today. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ Kenrick, John (2017). Musical Theatre: A History. ISBN 9781474267021. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ «Humpty Dumpty«. IBDB.com. Internet Broadway Database.

- ^ a b c d e f g Opie & Opie (1997), pp. 213–215.

- ^ J. Smith, Poetry Writing (Teacher Created Resources, 2002), ISBN 0-7439-3273-0, p. 95.

- ^ P. Hunt, ed., International Companion Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature (London: Routledge, 2004), ISBN 0-203-16812-7, p. 174.

- ^ J. J. Fuld, The Book of World-Famous Music: Classical, Popular, and Folk (Courier Dover Publications, 5th ed., 2000), ISBN 0-486-41475-2, p. 502.

- ^ Richards, William Carey (March–April 1844). «Monthly chat with readers and correspondents». The Orion. Penfield, Georgia. II (5 & 6): 371.

- ^ Joseph Ritson, Gammer Gurton’s Garland: or, the Nursery Parnassus; a Choice Collection of Pretty Songs and Verses, for the Amusement of All Little Good Children Who Can Neither Read Nor Run (London: Harding and Wright, 1810), p. 36.

- ^ J. O. Halliwell-Phillipps, The Nursery Rhymes of England (John Russell Smith, 6th ed., 1870), p. 122.

- ^ E. Partridge and P. Beale, Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (Routledge, 8th ed., 2002), ISBN 0-415-29189-5, p. 582.

- ^ Lina Eckenstein (1906). Comparative Studies in Nursery Rhymes. pp. 106–107. OL 7164972M. Retrieved 30 January 2018 – via archive.org.

- ^ E. Commins, Lessons from Mother Goose (Lack Worth, Fl: Humanics, 1988), ISBN 0-89334-110-X, p. 23.

- ^ Grose, Francis (1785). A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue. S. Hooper. pp. 90–.

- ^ «Juvenile Biography No IV: Humpty Dumpty». Punch. 3: 202. July–December 1842.

- ^ «Nursery Rhymes and History», The Oxford Magazine, vol. 74 (1956), pp. 230–232, 272–274 and 310–312; reprinted in: Calum M. Carmichael, ed., Collected Works of David Daube, vol. 4, «Ethics and Other Writings» (Berkeley, CA: Robbins Collection, 2009), ISBN 978-1-882239-15-3, pp. 365–366.

- ^ Alan Rodger. «Obituary: Professor David Daube». The Independent, 5 March 1999.

- ^ I. Opie, ‘Playground rhymes and the oral tradition’, in P. Hunt, S. G. Bannister Ray, International Companion Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature (London: Routledge, 2004), ISBN 0-203-16812-7, p. 76.

- ^ Iona and Peter Opie, ed. (1997) [1951]. The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-19-860088-6.

- ^ C. M. Carmichael (2004). Ideas and the Man: remembering David Daube. Studien zur europäischen Rechtsgeschichte. Vol. 177. Frankfurt: Vittorio Klostermann. pp. 103–104. ISBN 3-465-03363-9.

- ^ «Sir Richard Rodney Bennett: All the King’s Men». Universal Edition. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ a b «Putting the ‘dump’ in Humpty Dumpty». The BS Historian. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ^ A. Jack, Pop Goes the Weasel: The Secret Meanings of Nursery Rhymes (London: Allen Lane, 2008), ISBN 1-84614-144-3.

- ^ «The Real Story of Humpty Dumpty, by Albert Jack». Archived 27 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Penguin.com (USA). Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- ^ L. Senelick, The Age and Stage of George L. Fox 1825–1877 (University of Iowa Press, 1999), ISBN 0877456844.

- ^ E. Webber and M. Feinsilber, Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of Allusions (Merriam-Webster, 1999), ISBN 0-87779-628-9, pp. 277–8.

- ^ F. R. Palmer, Semantics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2nd edn., 1981), ISBN 0-521-28376-0, p. 8.

- ^ L. Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass (Raleigh, North Carolina: Hayes Barton Press, 1872), ISBN 1-59377-216-5, p. 72.

- ^ G. Lewis (1999). Lord Atkin. London: Butterworths. p. 138. ISBN 1-84113-057-5.

- ^ Martin H. Redish and Matthew B. Arnould, «Judicial review, constitutional interpretation: proposing a ‘Controlled Activism’ alternative», Florida Law Review, vol. 64 (6), (2012), p. 1513.

- ^ A. J. Larner (1998). «Lewis Carroll’s Humpty Dumpty: an early report of prosopagnosia?». Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 75 (7): 1063. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.027599. PMC 1739130. PMID 15201376.

- ^ J. S. Atherton, The Books at the Wake: A Study of Literary Allusions in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1959, SIU Press, 2009), ISBN 0-8093-2933-6, p. 126.

- ^ Worthington, Mabel (1957). «Nursery Rhymes in Finnegans Wake». The Journal of American Folklore. 70 (275): 37–48. doi:10.2307/536500. JSTOR 536500.

- ^ G. L. Cronin and B. Siegel, eds, Conversations With Robert Penn Warren (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2005), ISBN 1-57806-734-0, p. 84.

- ^ M. Feeney, Nixon at the Movies: a Book About Belief (Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press, 2004), ISBN 0-226-23968-3, p. 256.

- ^ Puss in Boots (2011) — IMDb, retrieved 30 November 2022

- ^ Taylor Swift – The Archer, retrieved 2 September 2022

- ^ Chang Kenneth (30 July 2002). «Humpty Dumpty Restored: When Disorder Lurches Into Order». The New York Times. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ Lee Langston. «Part III – The Second Law of Thermodynamics» (PDF). Hartford Courant. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ W.S. Franklin (March 1910). «The Second Law Of Thermodynamics: Its Basis In Intuition And Common Sense». The Popular Science Monthly: 240.

External links[edit]

- Library of Congress’ Facsimile of the 1899 illustrated edition of Through the Looking-Glass

- The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly

| «Humpty Dumpty» | |

|---|---|

Illustration by W. W. Denslow, 1904 |

|

| Nursery rhyme | |

| Published | 1797 |

Humpty Dumpty is a character in an English nursery rhyme, probably originally a riddle and one of the best known in the English-speaking world. He is typically portrayed as an anthropomorphic egg, though he is not explicitly described as such. The first recorded versions of the rhyme date from late eighteenth-century England and the tune from 1870 in James William Elliott’s National Nursery Rhymes and Nursery Songs.[1] Its origins are obscure, and several theories have been advanced to suggest original meanings.

Humpty Dumpty was popularized in the United States on Broadway by actor George L. Fox in the pantomime musical Humpty Dumpty.[2] The show ran from 1868 to 1869, for a total of 483 performances, becoming the longest-running Broadway show until it was surpassed in 1881 by Hazel Kirke.[3] As a character and literary allusion, Humpty Dumpty has appeared or been referred to in many works of literature and popular culture, particularly English author Lewis Carroll’s 1871 book Through the Looking-Glass, in which he was described as an egg. The rhyme is listed in the Roud Folk Song Index as No. 13026.

Lyrics and melody[edit]

The rhyme is one of the best known in the English language. The common text from 1954 is:[4]

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men

Couldn’t put Humpty together again.

It is a single quatrain with external rhymes[5] that follow the pattern of AABB and with a trochaic metre, which is common in nursery rhymes.[6] The melody commonly associated with the rhyme was first recorded by composer and nursery rhyme collector James William Elliott in his National Nursery Rhymes and Nursery Songs (London, 1870), as outlined below:[7]

Origins[edit]

Illustration from Walter Crane’s Mother Goose’s Nursery Rhymes (1877), showing Humpty Dumpty as a boy

.

The earliest known version was published in Samuel Arnold’s Juvenile Amusements in 1797[1] with the lyrics:[4]

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

Four-score Men and Four-score more,

Could not make Humpty Dumpty where he was before.

William Carey Richards (1818–1892) quoted the poem in 1843, commenting, «when we were five years old … the following parallel lines… were propounded as a riddle … Humpty-dumpty, reader, is the Dutch or something else for an egg».[8]

A manuscript addition to a copy of Mother Goose’s Melody published in 1803 has the modern version with a different last line: «Could not set Humpty Dumpty up again».[4] It was published in 1810 in a version of Gammer Gurton’s Garland.[9] (Note: Original spelling variations left intact.)

Humpty Dumpty sate on a wall,

Humpti Dumpti had a great fall;

Threescore men and threescore more,

Cannot place Humpty dumpty as he was before.

In 1842, James Orchard Halliwell published a collected version as:[10]

Humpty Dumpty lay in a beck.

With all his sinews around his neck;

Forty Doctors and forty wrights

Couldn’t put Humpty Dumpty to rights!

The modern-day version of this nursery rhyme, as known throughout the UK since at least the mid-twentieth century, is as follows:

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall;

All the King’s horses

And all the King’s men,

Couldn’t put Humpty together again.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, in the 17th century, the term «humpty dumpty» referred to a drink of brandy boiled with ale.[4] The riddle probably exploited, for misdirection, the fact that «humpty dumpty» was also eighteenth-century reduplicative slang for a short and clumsy person.[11] The riddle may depend upon the assumption that a clumsy person falling off a wall might not be irreparably damaged, whereas an egg would be. The rhyme is no longer posed as a riddle, since the answer is now so well known. Similar riddles have been recorded by folklorists in other languages, such as «Boule Boule» in French, «Lille Trille» in Swedish and Norwegian, and «Runtzelken-Puntzelken» or «Humpelken-Pumpelken» in different parts of Germany—although none is as widely known as Humpty Dumpty is in English.[4][12]

Meaning[edit]

The rhyme does not explicitly state that the subject is an egg, possibly because it may have been originally posed as a riddle.[4] There are also various theories of an original «Humpty Dumpty». One, advanced by Katherine Elwes Thomas in 1930[13] and adopted by Robert Ripley,[4] posits that Humpty Dumpty is King Richard III of England, depicted as humpbacked in Tudor histories and particularly in Shakespeare’s play, and who was defeated, despite his armies, at Bosworth Field in 1485.

In 1785, Francis Grose’s Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue noted that a «Humpty Dumpty» was «a short clumsy [sic] person of either sex, also ale boiled with brandy»; no mention was made of the rhyme.[14]

Punch in 1842 suggested jocularly that the rhyme was a metaphor for the downfall of Cardinal Wolsey; just as Wolsey was not buried in his intended tomb, so Humpty Dumpty was not buried in his shell.[15]

Professor David Daube suggested in The Oxford Magazine of 16 February 1956 that Humpty Dumpty was a «tortoise» siege engine, an armored frame, used unsuccessfully to approach the walls of the Parliamentary-held city of Gloucester in 1643 during the Siege of Gloucester in the English Civil War. This was on the basis of a contemporary account of the attack, but without evidence that the rhyme was connected.[16] The theory was part of an anonymous series of articles on the origin of nursery rhymes and was widely acclaimed in academia,[17] but it was derided by others as «ingenuity for ingenuity’s sake» and declared to be a spoof.[18][19] The link was nevertheless popularized by a children’s opera All the King’s Men by Richard Rodney Bennett, first performed in 1969.[20][21]

From 1996, the website of the Colchester tourist board attributed the origin of the rhyme to a cannon recorded as used from the church of St Mary-at-the-Wall by the Royalist defenders in the siege of 1648.[22] In 1648, Colchester was a walled town with a castle and several churches and was protected by the city wall. The story given was that a large cannon, which the website claimed was colloquially called Humpty Dumpty, was strategically placed on the wall. A shot from a Parliamentary cannon succeeded in damaging the wall beneath Humpty Dumpty, which caused the cannon to tumble to the ground. The Royalists (or Cavaliers, «all the King’s men») attempted to raise Humpty Dumpty on to another part of the wall, but the cannon was so heavy that «All the King’s horses and all the King’s men couldn’t put Humpty together again». Author Albert Jack claimed in his 2008 book Pop Goes the Weasel: The Secret Meanings of Nursery Rhymes that there were two other verses supporting this claim.[23] Elsewhere, he claimed to have found them in an «old dusty library, [in] an even older book»,[24] but did not state what the book was or where it was found. It has been pointed out that the two additional verses are not in the style of the seventeenth century or of the existing rhyme, and that they do not fit with the earliest printed versions of the rhyme, which do not mention horses and men.[22]

In popular culture[edit]

Humpty Dumpty has become a highly popular nursery rhyme character. American actor George L. Fox (1825–77) helped to popularise the character in nineteenth-century stage productions of pantomime versions, music, and rhyme.[25] The character is also a common literary allusion, particularly to refer to a person in an insecure position, something that would be difficult to reconstruct once broken, or a short and fat person.[26]

Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass[edit]

Humpty Dumpty appears in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass (1871), a sequel to Alice in Wonderland from six years prior. Alice remarks that Humpty is «exactly like an egg,» which Humpty finds to be «very provoking» in the looking-glass world. Alice clarifies that she said he looks like an egg, not that he is one. They discuss semantics and pragmatics[27] when Humpty Dumpty says, «my name means the shape I am,» and later:[28]

«I don’t know what you mean by ‘glory,’ » Alice said.

Humpty Dumpty smiled contemptuously. «Of course you don’t—till I tell you. I meant ‘there’s a nice knock-down argument for you!'»

«But ‘glory’ doesn’t mean ‘a nice knock-down argument’,» Alice objected.

«When I use a word,» Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, «it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.»

«The question is,» said Alice, «whether you can make words mean so many different things.»

«The question is,» said Humpty Dumpty, «which is to be master—that’s all.»

Alice was too much puzzled to say anything, so after a minute Humpty Dumpty began again. «They’ve a temper, some of them—particularly verbs, they’re the proudest—adjectives you can do anything with, but not verbs—however, I can manage the whole lot! Impenetrability! That’s what I say!»

This passage was used in Britain by Lord Atkin in his dissenting judgement in the seminal case Liversidge v. Anderson (1942), where he protested about the distortion of a statute by the majority of the House of Lords.[29] It also became a popular citation in United States legal opinions, appearing in 250 judicial decisions in the Westlaw database as of 19 April 2008, including two Supreme Court cases (TVA v. Hill and Zschernig v. Miller).[30]

A. J. Larner suggested that Carroll’s Humpty Dumpty had prosopagnosia on the basis of his description of his finding faces hard to recognise:[31]

«The face is what one goes by, generally,» Alice remarked in a thoughtful tone.

«That’s just what I complain of,» said Humpty Dumpty. «Your face is the same as everybody has—the two eyes,—» (marking their places in the air with his thumb) «nose in the middle, mouth under. It’s always the same. Now if you had the two eyes on the same side of the nose, for instance—or the mouth at the top—that would be some help.»

James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake[edit]

James Joyce used the story of Humpty Dumpty as a recurring motif of the Fall of Man in the 1939 novel Finnegans Wake.[32][33] One of the most easily recognizable references is at the end of the second chapter, in the first verse of the Ballad of Persse O’Reilly:

Have you heard of one Humpty Dumpty

How he fell with a roll and a rumble

And curled up like Lord Olofa Crumple

By the butt of the Magazine Wall,

(Chorus) Of the Magazine Wall,

Hump, helmet and all?

In film, literature and music[edit]

Robert Penn Warren’s 1946 American novel All the King’s Men is the story of populist politician Willie Stark’s rise to the position of governor and eventual fall, based on the career of the infamous Louisiana Senator and Governor Huey Long. It won the 1947 Pulitzer Prize and was twice made into a film in 1949 and 2006, the former winning the Academy Award for best motion picture.[34] This was echoed in Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward’s book All the President’s Men, about the Watergate scandal, referring to the failure of the President’s staff to repair the damage once the scandal had leaked out. It was filmed as All the President’s Men in 1976, starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman.[35]

In 1983, an advert for Kinder Surprise featuring a realistic version of the Humpty Dumpty character (designed by Mike Quinn, who worked at the Jim Henson’s Creature Shop) and directed by Mike Portelly, was banned shortly after release, due to being highly unsettling. The advert aired only on ITV and its franchises.

In 2016 film of Alice Through the Looking Glass, Humpty Dumpty was voiced by Wally Wingert.

In the 2011 film Puss In Boots, Humpty Dumpty was voiced by Zach Galifianakis.[36]

In 2021, American band AJR released a song titled «Humpty Dumpty» on their album OK Orchestra. The song uses the nursery rhyme as a parallel for hiding one’s true emotions as things, typically unpleasant, happen to the singer.

Jasper Fforde’s 2005 British novel The Big Over Easy is an exercise in absurdity, in which Humpty Stuyvesant Van Dumpty III has been murdered and Detective Jack Spratt of the Nursery Crime Division is set the task of solving the mystery.

Taylor Swift references it in her song «The Archer», the fifth track on her album Lover, modifying it slightly and turning it into «all the king’s horses, all the king’s men, couldn’t put me together again».[37]

In science[edit]

Humpty Dumpty has been used to demonstrate the second law of thermodynamics. The law describes a process known as entropy, a measure of the number of specific ways in which a system may be arranged, often taken to be a measure of «disorder». The higher the entropy, the higher the disorder. After his fall and subsequent shattering, the inability to put him together again is representative of this principle, as it would be highly unlikely (though not impossible) to return him to his earlier state of lower entropy, as the entropy of an isolated system never decreases.[38][39][40]

See also[edit]

- List of nursery rhymes

References[edit]

- ^ a b Emily Upton (24 April 2013). «The Origin of Humpty Dumpty». What I Learned Today. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ Kenrick, John (2017). Musical Theatre: A History. ISBN 9781474267021. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ «Humpty Dumpty«. IBDB.com. Internet Broadway Database.

- ^ a b c d e f g Opie & Opie (1997), pp. 213–215.

- ^ J. Smith, Poetry Writing (Teacher Created Resources, 2002), ISBN 0-7439-3273-0, p. 95.

- ^ P. Hunt, ed., International Companion Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature (London: Routledge, 2004), ISBN 0-203-16812-7, p. 174.

- ^ J. J. Fuld, The Book of World-Famous Music: Classical, Popular, and Folk (Courier Dover Publications, 5th ed., 2000), ISBN 0-486-41475-2, p. 502.

- ^ Richards, William Carey (March–April 1844). «Monthly chat with readers and correspondents». The Orion. Penfield, Georgia. II (5 & 6): 371.

- ^ Joseph Ritson, Gammer Gurton’s Garland: or, the Nursery Parnassus; a Choice Collection of Pretty Songs and Verses, for the Amusement of All Little Good Children Who Can Neither Read Nor Run (London: Harding and Wright, 1810), p. 36.

- ^ J. O. Halliwell-Phillipps, The Nursery Rhymes of England (John Russell Smith, 6th ed., 1870), p. 122.

- ^ E. Partridge and P. Beale, Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (Routledge, 8th ed., 2002), ISBN 0-415-29189-5, p. 582.

- ^ Lina Eckenstein (1906). Comparative Studies in Nursery Rhymes. pp. 106–107. OL 7164972M. Retrieved 30 January 2018 – via archive.org.

- ^ E. Commins, Lessons from Mother Goose (Lack Worth, Fl: Humanics, 1988), ISBN 0-89334-110-X, p. 23.

- ^ Grose, Francis (1785). A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue. S. Hooper. pp. 90–.

- ^ «Juvenile Biography No IV: Humpty Dumpty». Punch. 3: 202. July–December 1842.

- ^ «Nursery Rhymes and History», The Oxford Magazine, vol. 74 (1956), pp. 230–232, 272–274 and 310–312; reprinted in: Calum M. Carmichael, ed., Collected Works of David Daube, vol. 4, «Ethics and Other Writings» (Berkeley, CA: Robbins Collection, 2009), ISBN 978-1-882239-15-3, pp. 365–366.

- ^ Alan Rodger. «Obituary: Professor David Daube». The Independent, 5 March 1999.

- ^ I. Opie, ‘Playground rhymes and the oral tradition’, in P. Hunt, S. G. Bannister Ray, International Companion Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature (London: Routledge, 2004), ISBN 0-203-16812-7, p. 76.

- ^ Iona and Peter Opie, ed. (1997) [1951]. The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-19-860088-6.

- ^ C. M. Carmichael (2004). Ideas and the Man: remembering David Daube. Studien zur europäischen Rechtsgeschichte. Vol. 177. Frankfurt: Vittorio Klostermann. pp. 103–104. ISBN 3-465-03363-9.

- ^ «Sir Richard Rodney Bennett: All the King’s Men». Universal Edition. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ a b «Putting the ‘dump’ in Humpty Dumpty». The BS Historian. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- ^ A. Jack, Pop Goes the Weasel: The Secret Meanings of Nursery Rhymes (London: Allen Lane, 2008), ISBN 1-84614-144-3.

- ^ «The Real Story of Humpty Dumpty, by Albert Jack». Archived 27 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Penguin.com (USA). Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- ^ L. Senelick, The Age and Stage of George L. Fox 1825–1877 (University of Iowa Press, 1999), ISBN 0877456844.

- ^ E. Webber and M. Feinsilber, Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of Allusions (Merriam-Webster, 1999), ISBN 0-87779-628-9, pp. 277–8.

- ^ F. R. Palmer, Semantics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2nd edn., 1981), ISBN 0-521-28376-0, p. 8.

- ^ L. Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass (Raleigh, North Carolina: Hayes Barton Press, 1872), ISBN 1-59377-216-5, p. 72.

- ^ G. Lewis (1999). Lord Atkin. London: Butterworths. p. 138. ISBN 1-84113-057-5.

- ^ Martin H. Redish and Matthew B. Arnould, «Judicial review, constitutional interpretation: proposing a ‘Controlled Activism’ alternative», Florida Law Review, vol. 64 (6), (2012), p. 1513.

- ^ A. J. Larner (1998). «Lewis Carroll’s Humpty Dumpty: an early report of prosopagnosia?». Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 75 (7): 1063. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.027599. PMC 1739130. PMID 15201376.

- ^ J. S. Atherton, The Books at the Wake: A Study of Literary Allusions in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1959, SIU Press, 2009), ISBN 0-8093-2933-6, p. 126.

- ^ Worthington, Mabel (1957). «Nursery Rhymes in Finnegans Wake». The Journal of American Folklore. 70 (275): 37–48. doi:10.2307/536500. JSTOR 536500.

- ^ G. L. Cronin and B. Siegel, eds, Conversations With Robert Penn Warren (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2005), ISBN 1-57806-734-0, p. 84.

- ^ M. Feeney, Nixon at the Movies: a Book About Belief (Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press, 2004), ISBN 0-226-23968-3, p. 256.

- ^ Puss in Boots (2011) — IMDb, retrieved 30 November 2022

- ^ Taylor Swift – The Archer, retrieved 2 September 2022

- ^ Chang Kenneth (30 July 2002). «Humpty Dumpty Restored: When Disorder Lurches Into Order». The New York Times. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ Lee Langston. «Part III – The Second Law of Thermodynamics» (PDF). Hartford Courant. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ W.S. Franklin (March 1910). «The Second Law Of Thermodynamics: Its Basis In Intuition And Common Sense». The Popular Science Monthly: 240.

External links[edit]

- Library of Congress’ Facsimile of the 1899 illustrated edition of Through the Looking-Glass

- The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly

1.

… поражают своей неожиданностью. Например, когда Шалтай-Болтай говорит Алисе, что та должна думать обо всем, Алиса резонно … бы думать обо всем, — возражает Шалтай-Болтай. — Я сказал лишь, что ты должна думать. — А разве имеет … проблема из философии морали, — отвечает Шалтай-Болтай, — но она завела бы нас слишком далеко. Проблема действительно интересная …

Смаллиан Рэймонд. Алиса в стране смекалки

2.

… 5. Алиса идет на d6 (Шалтай-Болтай) 6. Алиса идет на d7 (лес) 7. Белый Конь берет … Болванс Чик, Маргаритка ЧЕРНЫЕ Фигуры: Шалтай-Болтай, Плотник, Морж, Черная Королева, Черный Король, Ворон, Черный Рыцарь, Лев … водой, а в шестой расположился Шалтай-Болтай… Но ты молчишь? — Разве… я должна… что-то сказать? — запинаясь …

Кэрролл Льюис. Алиса в зазеркалье

3.

… имя. Именно к дереву обращается Шалтай-болтай, не глядя на Алису. Вызубренное наизусть объявляет битвы. Всюду ушибы … Когда я беру слово,- говорит Шалтай-Болтай, — оно означает то, что я хочу, не больше и не … разделяющееся на прошлое и будущее. Шалтай-Болтай категорично различал два 45 ЛОГИКА СМЫСЛА типа слов: «Некоторые слова …

Делез Жиль. Логика смысла

4.

… шествие немногословный крепыш по кличке Шалтай-Болтай передал шедшему впереди него Косте свою сумку и, перед тем … старлей Толик по кличке Молоток, Шалтай-Болтай с фигурой, как у несгораемого шкафа, весь какой-то разболтанный … работе. …Шопеном, как выяснилось, увлекался Шалтай-Болтай. Узнав об этом, Глеб твердо решил, что вся физиономистика — суть …

Воронин Андрей. Слепой 1-18

5.

… cracks in the egg’. ‘Exactly’. — Шалтай-Болтай — это чистейшее воплощение человеческого состояния. Слушайте внимательно, сэр. Что есть … Парадокс, разве нет? Ибо как Шалтай-Болтай может быть жив, если он еще не родился ? Л в … Когда я употребляю слово, — сказал Шалтай-Болтай довольно презрительно, — оно означает только то, что мне от него …

Обломов Сергей. Медный кувшин старика Хоттабыча

6.

… Из муки Испекли нам Пирожки! «ШАЛТАЙ-БОЛТАЙ» Шалтай-Болтай Сидел на стене. Шалтай-Болтай Свалился во сне. Вся королевская конница, Вся королевская рать Не … может Шалтая, Не может Болтая, Шалтая-Болтая, Болтал-Шалтая, Шалтая-Болтая собрать! «ШКОЛЬНИК» Школьник, школьник, Что так рано Ты спешишь Сегодня … Печатается по сб. «Сказки», 1966. Шалтай-Болтай. — Впервые в книге «Дом, который построил Джек», 1923. По поводу …

Маршак С.Я.. Произведения для детей

7.

… вкладывая эти объяснения в уста Шалтая-Болтая) все неологизмы первой (и последней) строфы баллады «Джаббервокки». «Brillig» (в … сварнело», «варкалось», «розгрень», «сверкалось»), говорит Шалтай-Болтай, означает четыре часа пополудни, когда начинаютварить обед. «Stithy» означает «lithe … РАН ИНИОН. — М., 1995,}. Сам Шалтай-Болтай «упакован» в седьмой из этих pacкатов:»Bothallchoratorschmnmmaromidgansmnuminarumdrmnstrumina_h_ u_m_p …

Галинская И.Л.. Льюис Кэролл и загадки его текстов

8.

… Белой Королевы Алиса перенеслась к Шалтай-Болтаю. — Возможно, это Лога своей толщиной напомнил мне о нем. Книжная … и не меньше, — презрительно произнес Шалтай-Болтай. — Вопрос в том, подчинится ли оно вам, — сказала Алиса. — Вопрос … из нас здесь хозяин, — сказал Шалтай-Болтай. Потом реальная Алиса (впрочем, намного ли она реальнее той, другой …

Фармер Филипп. Мир реки 1-3

9.

… образом не встретила преграды и … * * * ШАЛТАЙ-БОЛТАЙ сидел на стене . ШАЛТАЙ-БОЛТАЙ свалился во сне . И вся королевская конница, и вся королевская … может ШАЛТАЯ, Не может БОЛТАЯ, ШАЛТАЯ-БОЛТАЯ, БОЛТАЯ-ШАЛТАЯ, ШАЛТАЯ-БОЛТАЯ собрать ! ** Герман отчаянно замотал головой, тщетно пытаясь понять смысл этого … тут ему на ум пришло : » Шалтай-Болтай сидел на стене, Шалтай- Болтай свалился во сне … !» Где же раньше он мог слышать эти …

Мистер Алекс. Транссферы

10.

… странная для умирающего, преследует меня. Шалтай-Болтай сидел на стене. Это, кажется, была мысль Джеффа Коуди? О … помню… помню… …смерть в одиночестве… ШАЛТАЙ-БОЛТАЙ * * * «И сказал Господь Ною: грядет конец рода человеческого, ибо переполнилась … и сидел на ней, как Шалтай-Болтай — и каким-то образом в какой-то момент взросления и …

Каттнер Генри. Рассказы

Если вы нашли ошибку, пожалуйста, выделите фрагмент текста и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

Толковый словарь русского языка. Поиск по слову, типу, синониму, антониму и описанию. Словарь ударений.

Найдено определений: 15

шалтай-болтай

ТОЛКОВЫЙ СЛОВАРЬ

м. разг.

Персонаж прибаутки.

ТОЛКОВЫЙ СЛОВАРЬ УШАКОВА

ШАЛТА́Й-БОЛТАЙ, нескл., муж. (прост.). Вздор, пустяки. Несет шалтай-болтай всякий.

|| Вздорный человек.

ТОЛКОВЫЙ СЛОВАРЬ ОЖЕГОВА

ШАЛТА́Й-БОЛТА́Й, нареч. (разг. неод.). Без всякого дела, цели, занятия (о времяпрепровождении; первонач. о пустой болтовне). Целыми днями по двору слоняется шалтай-болтай.

ЭНЦИКЛОПЕДИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

{{шалта́й-болт{}а{}й}}

I. неизм.; м. Разг. Пустяки, вздор. Не дело, а так шалтай-болтай.

II. нареч. Попусту, напрасно, без всякого дела, цели, занятия (о времяпрепровождении). Целыми днями слоняется шалтай-болтай.

АКАДЕМИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

нескл., м. прост.

1. Пустяки, вздор.

[Даша:] Захотела ты от этих ваших модниц! У них что? Только шалтай-болтай в голове. Григорович, Столичный воздух.

2. в знач. нареч.

Попусту, напрасно.

— Чем так шалтай-болтай ходить и с голоду околевать, давно бы на хутора пошел. Чехов, Нахлебники.

ФРАЗЕОЛОГИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

Прост. Пренебр.

1. Вздор, пустяки, пустая болтовня.

[Даша:] Захотела ты от этих ваших модниц! У них что? Только шалтай-болтай в голове (Григорович. Столичный воздух).

Непреложных законов она (политика) не даёт, почти всегда врёт, но насчёт шалтай-болтай и изощрения ума — она неисчерпаема и материала даёт много (Чехов. Письмо А. С. Суворину, 4 янв. 1889).

2. Без дела, попусту (проводить время).

— Чем так шалтай-болтай ходить и с голоду околевать, давно бы на хутора пошёл (Чехов. Нахлебники).

СЛИТНО. РАЗДЕЛЬНО. ЧЕРЕЗ ДЕФИС

шалта/й-болта/й, нареч., разг.

Целый день шалтай-болтай по дому слоняется (без всякого дела).

ОРФОГРАФИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

шалта́й-болта́й, -я (пустя-ки, вздор; бездельник), неизм. (попусту; без дела, занятия) и Шалта́й-Бол-та́й, Шалта́я-Болта́я (персонаж прибаутки)

ФОРМЫ СЛОВ

1. шалта́й-болта́й, шалта́й-болта́и, шалта́й-болта́я, шалта́й-болта́ев, шалта́й-болта́ю, шалта́й-болта́ям, шалта́й-болта́й, шалта́й-болта́и, шалта́й-болта́ем, шалта́й-болта́ями, шалта́й-болта́е, шалта́й-болта́ях

2. шалта́й-болта́й, шалта́й-болта́и, шалта́й-болта́я, шалта́й-болта́ев, шалта́й-болта́ю, шалта́й-болта́ям, шалта́й-болта́я, шалта́й-болта́ев, шалта́й-болта́ем, шалта́й-болта́ями, шалта́й-болта́е, шалта́й-болта́ях

СИНОНИМЫ

сущ., кол-во синонимов: 8

шаляй-валяй, бездельник, вздор, напрасно, дуром, дуриком

МОРФЕМНО-ОРФОГРАФИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

шалта́й/-болта́й/ и шалта́й/-болта́й, неизм. и нескл., м.

ГРАММАТИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

Шалта́й-Болта́й мо, 6а + 6а

ЭТИМОЛОГИЧЕСКИЙ СЛОВАРЬ

шалта́й-болта́й

«пустая болтовня, чушь», оренб., сиб. (Даль), шалта́ть, шалтыха́ть «болтать, лепетать (о детях)», псковск., тверск. (Даль). Возм., рифмованное образование, в основе которого лежит болта́ть. Иначе, как арготическое образование с приставкой ша- из сокращенного болта́ть, объясняет это слово Фасмер (WuS 3, 201).

ПОЛЕЗНЫЕ СЕРВИСЫ