Настёнка =)

Знаток

(280)

7 лет назад

Смотря что Амон («сокрытый», «потаенный»), в египетской мифологии бог солнца. Священное животное Амона — баран и гусь (оба — символы мудрости) . Бога изображали в виде человека (иногда с головой барана) , со скипетром и в короне, с двумя высокими перьями и солнечным диском. Культ Амона зародился в Фивах, а затем распространился по всему Египту. Жена Амона, богиня неба Мут, и сын, бог луны Хонсу, составляли вместе с ним фиванскую триаду. Во времена Среднего царства Амон стал именоваться Амоном-Ра, поскольку культы двух божеств соединились, приобретя государственный характер. Позднее Амон приобрел статус любимого и особо почитаемого бога фараонов, и во времена Восемнадцатой Династии фараонов был объявлен главой египетских богов. Амон-Ра даровал победы фараону и считался его отцом. Амон почитался и как мудрый, всеведущий бог, «царь всех богов», небесный заступник, защитник угнетенных («везир для бедных»). А ОМОН- отряд милиции особого назначения)))

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

Аббревиатура, неизменяемая. Используется в качестве существительного.

Произношение[править]

- МФА: [ɐˈmon]

омофоны: Амон

Семантические свойства[править]

ОМОН

Значение[править]

- сокр. от отряд милиции особого назначения ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

- сокр. от отряд мобильный особого назначения ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

- СОБР

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

|

Перевод[править]

| Список переводов | |

Анаграммы[править]

- моно, моно

Библиография[править]

- Новые слова и значения. Словарь-справочник по материалам прессы и литературы 80-х годов / Под ред. Е. А. Левашова. — СПб. : Дмитрий Буланин, 1997.

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

§ 205. Звуковые

инициальные аббревиатуры пишутся прописными буквами, напр.: ООН,

МИД, НОТ, ОМОН, ГАИ, СПИД, ГЭС, ГРЭС По традиции пишутся строчными

буквами некоторые (немногие) звуковые аббревиатуры: вуз, втуз,

дот, дзот. Отдельные звуковые аббревиатуры могут писаться и прописными,

и строчными буквами, напр.: НЭП и нэп,

ЗАГС и загс.

При склонении звуковых аббревиатур окончания пишутся только

строчными буквами (без отделения окончания от аббревиатуры дефисом или

апострофом), напр.: рабочие ЗИЛа, работать в МИДе, пьеса

поставлена МХАТом.

Суффиксальные производные от звуковых аббревиатур пишутся

только строчными буквами, напр.: ооновский, тассовский,

мидовский, антиспидовый, омоновец, гаишник.

Примечание 1. Аббревиатуры, состоящие из двух

самостоятельно употребляющихся инициальных аббревиатур, являющихся названиями

разных организаций, пишутся раздельно, напр.: ИРЯ РАН (Институт русского языка

Российской академии наук).

Примечание 2 к § 204 и 205. В отличие от

графических сокращений (см. § 209), после букв, составляющих

аббревиатуры инициального типа, точки не ставятся.

Рады помочь вам узнать, как пишется слово «ОМОН».

Пишите и говорите правильно.

О словаре

Сайт создан на основе «Русского орфографического словаря», составленного Институтом русского языка имени В. В. Виноградова РАН. Объем второго издания, исправленного и дополненного, составляет около 180 тысяч слов, и существенно превосходит все предшествующие орфографические словари. Он является нормативным справочником, отражающим с возможной полнотой лексику русского языка начала 21 века и регламентирующим ее правописание.

Амон или омон

Автор Моргунов Макс задал вопрос в разделе Лингвистика

Пишется Амон или Омон ? и получил лучший ответ

Ответ от Felix-Dias[новичек]

Омон (отряд милиций особого назначения)

Ответ от Dima Nazarbaev123[новичек]

Омон-отряд мобильный особого назначения

Ответ от Настёнка =)[новичек]

Смотря что Амон («сокрытый», «потаенный»), в египетской мифологии бог солнца. Священное животное Амона — баран и гусь (оба — символы мудрости) . Бога изображали в виде человека (иногда с головой барана) , со скипетром и в короне, с двумя высокими перьями и солнечным диском. Культ Амона зародился в Фивах, а затем распространился по всему Египту. Жена Амона, богиня неба Мут, и сын, бог луны Хонсу, составляли вместе с ним фиванскую триаду. Во времена Среднего царства Амон стал именоваться Амоном-Ра, поскольку культы двух божеств соединились, приобретя государственный характер. Позднее Амон приобрел статус любимого и особо почитаемого бога фараонов, и во времена Восемнадцатой Династии фараонов был объявлен главой египетских богов. Амон-Ра даровал победы фараону и считался его отцом. Амон почитался и как мудрый, всеведущий бог, «царь всех богов», небесный заступник, защитник угнетенных («везир для бедных»). А ОМОН- отряд милиции особого назначения)))

Ответ от Предводитель Команчей[гуру]

Смотря что ты имеешь ввиду — древнеегипетского бога (Амон) или российские силовые структуры (ОМОН).

Ответ от 1 2[гуру]

Омон

Ответ от Поднятая рука[гуру]

мамонт

Ответ от Single Tear[активный]

Омон

Ответ от Азербайджанец[эксперт]

тебе нужен бог Амон Ра? или менты ОМОН?

Ответ от ЕвГений Косперский[гуру]

Амон Ра — через А

ОМОН — подразделение полиции через О

Ответ от Гудбай, ответы…[гуру]

Амон — бог древнеегипетской мифологии, а ОМОН — врывается к вам ночью с автоматами и связывают вас наручниками)

Ответ от серега ZID[новичек]

омномном

Ответ от Александр[гуру]

Говорим — Партия, подразумеваем -Ленин… Что в вашем случае подразумевается… одному вам и известно=).

Ответ от 3 ответа[гуру]

Привет! Вот подборка тем с похожими вопросами и ответами на Ваш вопрос: Пишется Амон или Омон ?

«Amen Ra» redirects here. For the Belgian band, see Amenra.

«Amon-Ra» redirects here. For the American football player, see Amon-Ra St. Brown.

| Amun | |

|---|---|

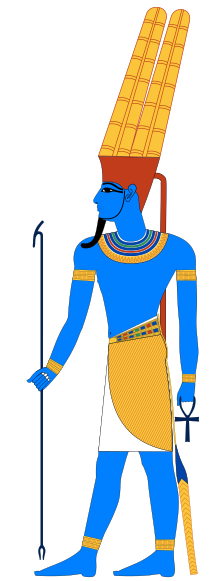

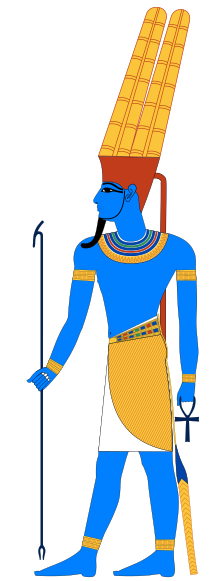

After the Amarna period, Amun was painted with blue skin, symbolizing his association with air and primeval creation. Amun was also depicted in a wide variety of other forms. |

|

| Name in hieroglyphs | |

| Major cult center | Thebes |

| Symbol | two vertical plumes, the ram-headed Sphinx (Criosphinx) |

| Consort |

|

| Offspring | Khonsu |

| Greek equivalent | Zeus |

Amun (; also Amon, Ammon, Amen; Ancient Egyptian: jmn, reconstructed as /jaˈmaːnuw/ (Old Egyptian and early Middle Egyptian) → /ʔaˈmaːnəʔ/ (later Middle Egyptian) → /ʔaˈmoːn/ (Late Egyptian), Coptic: Ⲁⲙⲟⲩⲛ, romanized: Amoun; Greek Ἄμμων Ámmōn, Ἅμμων Hámmōn; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤌𐤍,[1] romanized: ʾmn) was a major ancient Egyptian deity who appears as a member of the Hermopolitan Ogdoad. Amun was attested from the Old Kingdom together with his wife Amunet. With the 11th Dynasty (c. 21st century BC), Amun rose to the position of patron deity of Thebes by replacing Montu.[2]

After the rebellion of Thebes against the Hyksos and with the rule of Ahmose I (16th century BC), Amun acquired national importance, expressed in his fusion with the Sun god, Ra, as Amun-Ra (alternatively spelled Amon-Ra or Amun-Re).

Amun-Ra retained chief importance in the Egyptian pantheon throughout the New Kingdom (with the exception of the «Atenist heresy» under Akhenaten). Amun-Ra in this period (16th to 11th centuries BC) held the position of transcendental, self-created[3] creator deity «par excellence»; he was the champion of the poor or troubled and central to personal piety.[4] With Osiris, Amun-Ra is the most widely recorded of the Egyptian gods.[4]

As the chief deity of the Egyptian Empire, Amun-Ra also came to be worshipped outside Egypt, according to the testimony of ancient Greek historiographers in Libya and Nubia. As Zeus-Ammon, he came to be identified with Zeus in Greece.

Early history[edit]

Amun and Amaunet are mentioned in the Old Egyptian Pyramid Texts.[5]

The name Amun (written imn) meant something like «the hidden one» or «invisible».[6]

Amun rose to the position of tutelary deity of Thebes after the end of the First Intermediate Period, under the 11th Dynasty. As the patron of Thebes, his spouse was Mut. In Thebes, Amun as father, Mut as mother and the Moon god Khonsu as their son formed the divine family or the «Theban Triad».

Temple at Karnak[edit]

The history of Amun as the patron god of Thebes begins in the 20th century BC, with the construction of the Precinct of Amun-Re at Karnak under Senusret I. The city of Thebes does not appear to have been of great significance before the 11th Dynasty.

Major construction work in the Precinct of Amun-Ra took place during the 18th Dynasty when Thebes became the capital of the unified ancient Egypt.

Construction of the Hypostyle Hall may have also begun during the 18th Dynasty, though most building was undertaken under Seti I and Ramesses II. Merenptah commemorated his victories over the Sea Peoples on the walls of the Cachette Court, the start of the processional route to the Luxor Temple. This Great Inscription (which has now lost about a third of its content) shows the king’s campaigns and eventual return with items of potential value and prisoners. Next to this inscription is the Victory Stela, which is largely a copy of the more famous Merneptah Stele found in the funerary complex of Merenptah on the west bank of the Nile in Thebes.[7] Merenptah’s son Seti II added two small obelisks in front of the Second Pylon, and a triple bark-shrine to the north of the processional avenue in the same area. This was constructed of sandstone, with a chapel to Amun flanked by those of Mut and Khonsu.

The last major change to the Precinct of Amun-Re’s layout was the addition of the first pylon and the massive enclosure walls that surrounded the whole Precinct, both constructed by Nectanebo I.

New Kingdom[edit]

Amon-Ra (l’esprit des quatre elements, lame du monde matérial), N372.2., Brooklyn Museum

Bas-relief depicting Amun as pharaoh

Identification with Min and Ra[edit]

Fragment of a stela showing Amun enthroned. Mut, wearing the double crown, stands behind him. Both are receiving offerings from Ramesses I, now lost. From Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

When the army of the founder of the Eighteenth Dynasty expelled the Hyksos rulers from Egypt, the victor’s city of origin, Thebes, became the most important city in Egypt, the capital of a new dynasty. The local patron deity of Thebes, Amun, therefore became nationally important. The pharaohs of that new dynasty attributed all of their successes to Amun, and they lavished much of their wealth and captured spoil on the construction of temples dedicated to Amun.[8] The victory against the «foreign rulers» achieved by pharaohs who worshipped Amun caused him to be seen as a champion of the less fortunate, upholding the rights of justice for the poor.[4] By aiding those who traveled in his name, he became the Protector of the road. Since he upheld Ma’at (truth, justice, and goodness),[4] those who prayed to Amun were required first to demonstrate that they were worthy, by confessing their sins. Votive stelae from the artisans’ village at Deir el-Medina record:

[Amun] who comes at the voice of the poor in distress, who gives breath to him who is wretched … You are Amun, the Lord of the silent, who comes at the voice of the poor; when I call to you in my distress You come and rescue me … Though the servant was disposed to do evil, the Lord is disposed to forgive. The Lord of Thebes spends not a whole day in anger; His wrath passes in a moment; none remains. His breath comes back to us in mercy … May your kꜣ be kind; may you forgive; It shall not happen again.[9]

Amun-Min as Amun-Ra ka-Mut-ef from the temple at Deir el Medina.

Ka-mut-ef, «Bull of His Mother» as a ram-headed lion in the Avenue of Sphinxes at Karnak Temple

Subsequently, when Egypt conquered Kush, they identified the chief deity of the Kushites as Amun. This Kush deity was depicted as ram-headed, more specifically a woolly ram with curved horns. Amun thus became associated with the ram arising from the aged appearance of the Kush ram deity, and depictions related to Amun sometimes had small ram’s horns, known as the Horns of Ammon. A solar deity in the form of a ram can be traced to the pre-literate Kerma culture in Nubia, contemporary to the Old Kingdom of Egypt. The later (Meroitic period) name of Nubian Amun was Amani, attested in numerous personal names such as Tanwetamani, Arkamani, and Amanitore. Since rams were considered a symbol of virility, Amun also became thought of as a fertility deity, and so started to absorb the identity of Min, becoming Amun-Min. This association with virility led to Amun-Min gaining the epithet Kamutef, meaning «Bull of his mother»,[6] in which form he was found depicted on the walls of Karnak, ithyphallic, and with a scourge, as Min was.

As the cult of Amun grew in importance, Amun became identified with the chief deity who was worshipped in other areas during that period, namely the sun god Ra. This identification led to another merger of identities, with Amun becoming Amun-Ra. In the Hymn to Amun-Ra he is described as

Lord of truth, father of the gods, maker of men, creator of all animals, Lord of things that are, creator of the staff of life.[10]

-

Amun (New Kingdom)[a]

-

Amun (Post Amarna)[a]

-

Amun-Ra

-

Amun-Min

Amarna Period[edit]

Hieroglyphs on the backpillar of Amenhotep III’s statue. There are two places where Akhenaten’s agents erased the name Amun, later restored on a deeper surface. The British Museum, London

During the latter part of the eighteenth dynasty, the pharaoh Akhenaten (also known as Amenhotep IV) advanced the worship of the Aten, a deity whose power was manifested in the sun disk, both literally and symbolically. He defaced the symbols of many of the old deities, and based his religious practices upon the deity, the Aten. He moved his capital away from Thebes, but this abrupt change was very unpopular with the priests of Amun, who now found themselves without any of their former power. The religion of Egypt was inexorably tied to the leadership of the country, the pharaoh being the leader of both. The pharaoh was the highest priest in the temple of the capital, and the next lower level of religious leaders were important advisers to the pharaoh, many being administrators of the bureaucracy that ran the country.

The introduction of Atenism under Akhenaten constructed a monolatrist worship of Aten in direct competition with that of Amun. Praises of Amun on stelae are strikingly similar in language to those later used, in particular, the Hymn to the Aten:

When thou crossest the sky, all faces behold thee, but when thou departest, thou are hidden from their faces … When thou settest in the western mountain, then they sleep in the manner of death … The fashioner of that which the soil produces, … a mother of profit to gods and men; a patient craftsman, greatly wearying himself as their maker … valiant herdsman, driving his cattle, their refuge and the making of their living … The sole Lord, who reaches the end of the lands every day, as one who sees them that tread thereon … Every land chatters at his rising every day, in order to praise him.[11]

When Akhenaten died, Akhenaten’s successor, Smenkhkare, became pharaoh and Atenism remained established during his brief 2-year reign. When Smenkhkare died, an enigmatic female pharaoh known as Neferneferuaten took the throne for a brief period but it is unclear what happened during her reign. After Neferneferuaten’s death, Akhenaten’s 9-year-old son Tutankhaten succeeded her. At the beginning of his reign, the young pharaoh reversed Atenism, re-establishing the old polytheistic religion and renaming himself Tutankhamun. His sister-wife, then named Ankhesenpaaten, followed him and was renamed Ankhesenamun. Worship of the Aten ceased for the most part and worship of Amun-Ra was restored.

During the reign of Horemheb, Akhenaten’s name was struck from Egyptian records, all of his religious and governmental changes were undone, and the capital was returned to Thebes. The return to the previous capital and its patron deity was accomplished so swiftly that it seemed this monolatrist cult and its governmental reforms had never existed.

Theology[edit]

The god of wind Amun came to be identified with the solar god Ra and the god of fertility and creation Min, so that Amun-Ra had the main characteristic of a solar god, creator god and fertility god. He also adopted the aspect of the ram from the Nubian solar god, besides numerous other titles and aspects.

As Amun-Re, he was petitioned for mercy by those who believed suffering had come about as a result of their own or others’ wrongdoing.

Amon-Re «who hears the prayer, who comes at the cry of the poor and distressed…Beware of him! Repeat him to son and daughter, to great and small; relate him to generations of generations who have not yet come into being; relate him to fishes in the deep, to birds in heaven; repeat him to him who does not know him and to him who knows him … Though it may be that the servant is normal in doing wrong, yet the Lord is normal in being merciful. The Lord of Thebes does not spend an entire day angry. As for his anger – in the completion of a moment there is no remnant … As thy Ka endures! thou wilt be merciful![12]

In the Leiden hymns, Amun, Ptah, and Re are regarded as a trinity who are distinct gods but with unity in plurality.[13] «The three gods are one yet the Egyptian elsewhere insists on the separate identity of each of the three.»[14] This unity in plurality is expressed in one text:

All gods are three: Amun, Re and Ptah, whom none equals. He who hides his name as Amun, he appears to the face as Re, his body is Ptah.[15]

Henri Frankfort suggested that Amun was originally a wind god and pointed out that the implicit connection between the winds and mysteriousness was paralleled in a passage from the Gospel of John: «The wind blows where it wishes, and you hear the sound of it, but do not know where it comes from and where it is going.»[John 3:8][16]

A Leiden hymn to Amun describes how he calms stormy seas for the troubled sailor:

The tempest moves aside for the sailor who remembers the name of Amon. The storm becomes a sweet breeze for he who invokes His name … Amon is more effective than millions for he who places Him in his heart. Thanks to Him the single man becomes stronger than a crowd.[17]

Third Intermediate Period[edit]

Theban High Priests of Amun[edit]

While not regarded as a dynasty, the High Priests of Amun at Thebes were nevertheless of such power and influence that they were effectively the rulers of Egypt from 1080 to c. 943 BC. By the time Herihor was proclaimed as the first ruling High Priest of Amun in 1080 BC—in the 19th Year of Ramesses XI—the Amun priesthood exercised an effective hold on Egypt’s economy. The Amun priests owned two-thirds of all the temple lands in Egypt and 90 percent of her ships and many other resources.[18] Consequently, the Amun priests were as powerful as the pharaoh, if not more so. One of the sons of the High Priest Pinedjem would eventually assume the throne and rule Egypt for almost half a century as pharaoh Psusennes I, while the Theban High Priest Psusennes III would take the throne as king Psusennes II—the final ruler of the 21st Dynasty.

Decline[edit]

In the 10th century BC, the overwhelming dominance of Amun over all of Egypt gradually began to decline.

In Thebes, however, his worship continued unabated, especially under the Nubian Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt, as Amun was by now seen as a national god in Nubia. The Temple of Amun, Jebel Barkal, founded during the New Kingdom, came to be the center of the religious ideology of the Kingdom of Kush.

The Victory Stele of Piye at Gebel Barkal (8th century BC) now distinguishes between an «Amun of Napata» and an «Amun of Thebes».

Tantamani (died 653 BC), the last pharaoh of the Nubian dynasty, still bore a theophoric name referring to Amun in the Nubian form Amani.

Iron Age and classical antiquity[edit]

Depiction of Amun in a relief at Karnak (15th century BC)

Nubia and Sudan[edit]

In areas outside Egypt where the Egyptians had previously brought the cult of Amun his worship continued into classical antiquity. In Nubia, where his name was pronounced Amane or Amani, he remained a national deity, with his priests, at Meroe and Nobatia,[19] regulating the whole government of the country via an oracle, choosing the ruler, and directing military expeditions. According to Diodorus Siculus, these religious leaders were even able to compel kings to commit suicide, although this tradition stopped when Arkamane, in the 3rd century BC, slew them.[20]

In Sudan, excavation of an Amun temple at Dangeil began in 2000 under the directorship of Drs Salah Mohamed Ahmed and Julie R. Anderson of the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM), Sudan and the British Museum, UK, respectively. The temple was found to have been destroyed by fire and Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) and C14 dating of the charred roof beams have placed the construction of the most recent incarnation of the temple in the 1st century AD. This date is further confirmed by the associated ceramics and inscriptions. Following its destruction, the temple gradually decayed and collapsed.[21]

Siwa Oasis[edit]

In Siwa Oasis, located Western Egypt, there remained a solitary oracle of Amun near the Libyan Desert.[22] The worship of Ammon was introduced into Greece at an early period, probably through the medium of the Greek colony in Cyrene, which must have formed a connection with the great oracle of Ammon in the Oasis soon after its establishment. Iarbas, a mythological king of Libya, was also considered a son of Hammon. When Alexander the Great advanced on Egypt in later 332 BC, he was regarded as a liberator.[23] He was pronounced son of Amun at this oracle,[24] thus conquering Egypt without a fight. Henceforth, Alexander often referred to Zeus-Ammon as his true father, and after his death, currency depicted him adorned with the Horns of Ammon as a symbol of his divinity.[25]

According to the 6th century author Corippus, a Libyan people known as the Laguatan carried an effigy of their god Gurzil, whom they believed to be the son of Ammon, into battle against the Byzantine Empire in the 540s AD.[26]

Levant[edit]

Amun is likely mentioned in the Hebrew Bible as אמון מנא Amon of No in Jeremiah 46:25 (also translated the horde of No and the horde of Alexandria), and Thebes possibly is called נא אמון No-Amon in Nahum 3:8 (also translated populous Alexandria). These texts were presumably written in the 7th century BC.[27]

The Lord of hosts, the God of Israel, said: «Behold, I am bringing punishment upon Amon of Thebes, and Pharaoh and Egypt and her gods and her kings, upon Pharaoh and those who trust in him.»

Greece[edit]

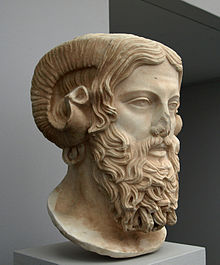

Zeus-Ammon. Roman copy of a Greek original from the late 5th century BC. The Greeks of the lower Nile Delta and Cyrenaica combined features of supreme god Zeus with features of the Egyptian god Amun-Ra.

Amun, worshipped by the Greeks as Ammon, had a temple and a statue, the gift of Pindar (d. 443 BC), at Thebes,[28] and another at Sparta, the inhabitants of which, as Pausanias says,[29] consulted the oracle of Ammon in Libya from early times more than the other Greeks. At Aphytis, Chalcidice, Amun was worshipped, from the time of Lysander (d. 395 BC), as zealously as in Ammonium. Pindar the poet honored the god with a hymn. At Megalopolis the god was represented with the head of a ram (Paus. viii.32 § 1), and the Greeks of Cyrenaica dedicated at Delphi a chariot with a statue of Ammon.

Such was its reputation among the Classical Greeks that Alexander the Great journeyed there after the battle of Issus and during his occupation of Egypt, where he was declared the metaphorical «son of Amun» by the oracle. Even during this occupation, Amun, identified by these Greeks as a form of Zeus,[30] continued to be the principal local deity of Thebes.[8]

Several words derive from Amun via the Greek form, Ammon, such as ammonia and ammonite. The Romans called the ammonium chloride they collected from deposits near the Temple of Jupiter-Amun in ancient Libya sal ammoniacus (salt of Amun) because of proximity to the nearby temple.[31] Ammonia, as well as being the chemical, is a genus name in the foraminifera. Both these foraminiferans (shelled Protozoa) and ammonites (extinct shelled cephalopods) bear spiral shells resembling a ram’s, and Ammon’s, horns. The regions of the hippocampus in the brain are called the cornu ammonis – literally «Amun’s Horns», due to the horned appearance of the dark and light bands of cellular layers.

In Paradise Lost, Milton identifies Ammon with the biblical Ham (Cham) and states that the gentiles called him the Libyan Jove.

See also[edit]

- List of solar deities

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Originally, Amun was depicted with red-brown skin during the New Kingdom, with two plumes on his head, the ankh symbol, and the was sceptre. After the Amarna period, Amun was instead painted with blue skin.

References[edit]

- ^ RÉS 367

- ^ David Warburton, Architecture, Power, and Religion: Hatshepsut, Amun and Karnak in Context, 2012, p. 211 ISBN 9783643902351

- ^ Dick, Michael Brennan (1999). Born in heaven, made on earth: the making of the cult image in the ancient Near East. Warsaw, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. p. 184. ISBN 1575060248.

- ^ a b c d Arieh Tobin, Vincent (2003). Redford, Donald B. (ed.). Oxford Guide: The Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology. Berkley Books. p. 20. ISBN 0-425-19096-X.

- ^ «Die Altaegyptischen Pyramidentexte nach den Papierabdrucken und Photographien des Berliner Museums». 1908.

- ^ a b Hart, George (2005). The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-415-36116-3.

- ^ Blyth, Elizabeth (2006). Karnak: Evolution of a Temple. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 164. ISBN 978-0415404860.

- ^ a b

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Griffith, Francis Llewellyn (1911). «Ammon». In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 860–861. This cites:

- Erman, Handbook of Egyptian Religion (London, 1907)

- Ed. Meyer, art. «Ammon» in Roscher’s Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie

- Pietschmann, arts. «Ammon», «Ammoneion» in Pauly-Wissowa, Realencyclopädie

- Works on Egyptian religion quoted (in the encyclopædia) under Egypt, section Religion

- ^ Lichtheim, Miriam (1976). Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 105–106. ISBN 0-520-03615-8.

- ^ Budge, E.A. Wallis (1914). An Introduction to Egyptian Literature (1997 ed.). Minneola, New York: Dover Publications. p. 214. ISBN 0-486-29502-8..

- ^ Wilson, John A. (1951). The Burden of Egypt (1963 ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-226-90152-7.

- ^ Wilson 1951, p. 300

- ^ Morenz, Siegried (1992). Egyptian Religion. Translated by Ann E. Keep. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 0-8014-8029-9.

- ^ Frankfort, Henri; Wilson, John A.; Jacobsen, Thorkild (1960). Before Philosophy: The Intellectual Adventure of Ancient Man. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing Company. p. 75. ISBN 978-0140201987.

- ^ Assmann, Jan (2008). Of God and Gods. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-299-22554-4.

- ^ Frankfort, Henri (1951). Before Philosophy. Penguin Books. p. 18. ASIN B0006EUMNK.

- ^ Jacq, Christian (1999). The Living Wisdom of Ancient Egypt. New York City: Simon & Schuster. p. 143. ISBN 0-671-02219-9.

- ^ Clayton, Peter A. (2006). Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. London, England: Thames & Hudson. p. 175. ISBN 978-0500286289.

- ^ Herodotus, The Histories ii.29

- ^ Griffith 1911.

- ^ Sweek, Tracey; Anderson, Julie; Tanimoto, Satoko (2012). «Architectural Conservation of an Amun Temple in Sudan». Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies. London, England: Ubiquity Press. 10 (2): 8–16. doi:10.5334/jcms.1021202.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece x.13 § 3

- ^ Ring, Trudy; Salkin, Robert M; Berney, KA; Schellinger, Paul E, eds. (1994). International dictionary of historic places. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1994–1996. pp. 49, 320. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6.

- ^ Bosworth, A. B. (1988). Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 71–74.

- ^ Dahmen, Karsten (2007). The Legend of Alexander the Great on Greek and Roman Coins. Taylor & Francis. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-415-39451-2.

- ^ Mattingly, D.J. (1983). «The Laguatan: A Libyan Tribal Confederation in the Late Roman Empire» (PDF). Libyan Studies. London, England: Society for Libyan Studies. 14: 98–99. doi:10.1017/S0263718900007810. S2CID 164294564.

- ^ «Strong’s Concordance / Gesenius’ Lexicon». Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ^ Pausanias. Description of Greece. ix.16 § 1.

- ^ Pausanias. Description of Greece. iii.18 § 2.

- ^ Jeremiah. xlvi.25.

- ^ «Eponyms». h2g2. BBC Online. 11 January 2003. Archived from the original on 2 November 2007. Retrieved 8 November 2007.

Sources[edit]

- David Klotz, Adoration of the Ram: Five Hymns to Amun-Re from Hibis Temple (New Haven, 2006)

- David Warburton, Architecture, Power, and Religion: Hatshepsut, Amun and Karnak in Context, 2012, ISBN 9783643902351.

- E. A. W. Budge, Tutankhamen: Amenism, Atenism, and Egyptian Monotheism (1923).

Further reading[edit]

- Assmann, Jan (1995). Egyptian Solar Religion in the New Kingdom: Re, Amun and the Crisis of Polytheism. Kegan Paul International. ISBN 978-0710304650.

- Ayad, Mariam F. (2009). God’s Wife, God’s Servant: The God’s Wife of Amun (c. 740–525 BC). Routledge. ISBN 978-0415411707.

- Cruz-Uribe, Eugene (1994). «The Khonsu Cosmogony». Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 31: 169–189. doi:10.2307/40000676. JSTOR 40000676.

- Gabolde, Luc (2018). Karnak, Amon-Rê : La genèse d’un temple, la naissance d’un dieu (in French). Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire. ISBN 978-2-7247-0686-4.

- Guermeur, Ivan (2005). Les cultes d’Amon hors de Thèbes: Recherches de géographie religieuse (in French). Brepols. ISBN 978-90-71201-10-3.

- Klotz, David (2012). Caesar in the City of Amun: Egyptian Temple Construction and Theology in Roman Thebes. Association Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth. ISBN 978-2-503-54515-8.

- Kuhlmann, Klaus P. (1988). Das Ammoneion. Archäologie, Geschichte und Kultpraxis des Orakels von Siwa (in German). Verlag Phillip von Zabern in Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3805308199.

- Otto, Eberhard (1968). Egyptian art and the cults of Osiris and Amon. Abrams.

- Roucheleau, Caroline Michelle (2008). Amun temples in Nubia: a typological study of New Kingdom, Napatan and Meroitic temples. Archaeopress. ISBN 9781407303376.

- Thiers, Christophe, ed. (2009). Documents de théologies thébaines tardives. Université Paul-Valéry.

- Zandee, Jan (1948). De Hymnen aan Amon van papyrus Leiden I. 350 (in Dutch). E.J. Brill.

- Zandee, Jan (1992). Der Amunhymnus des Papyrus Leiden I 344, Verso (in German). Rijksmuseum van Oudheden. ISBN 978-90-71201-10-3.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amun.

- Wim van den Dungen, Leiden Hymns to Amun

- (in Spanish) Karnak 3D :: Detailed 3D-reconstruction of the Great Temple of Amun at Karnak, Marc Mateos, 2007

- Amun with features of Tutankhamun (statue, c. 1332–1292 BC, Penn Museum)

«Amen Ra» redirects here. For the Belgian band, see Amenra.

«Amon-Ra» redirects here. For the American football player, see Amon-Ra St. Brown.

| Amun | |

|---|---|

After the Amarna period, Amun was painted with blue skin, symbolizing his association with air and primeval creation. Amun was also depicted in a wide variety of other forms. |

|

| Name in hieroglyphs | |

| Major cult center | Thebes |

| Symbol | two vertical plumes, the ram-headed Sphinx (Criosphinx) |

| Consort |

|

| Offspring | Khonsu |

| Greek equivalent | Zeus |

Amun (; also Amon, Ammon, Amen; Ancient Egyptian: jmn, reconstructed as /jaˈmaːnuw/ (Old Egyptian and early Middle Egyptian) → /ʔaˈmaːnəʔ/ (later Middle Egyptian) → /ʔaˈmoːn/ (Late Egyptian), Coptic: Ⲁⲙⲟⲩⲛ, romanized: Amoun; Greek Ἄμμων Ámmōn, Ἅμμων Hámmōn; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤌𐤍,[1] romanized: ʾmn) was a major ancient Egyptian deity who appears as a member of the Hermopolitan Ogdoad. Amun was attested from the Old Kingdom together with his wife Amunet. With the 11th Dynasty (c. 21st century BC), Amun rose to the position of patron deity of Thebes by replacing Montu.[2]

After the rebellion of Thebes against the Hyksos and with the rule of Ahmose I (16th century BC), Amun acquired national importance, expressed in his fusion with the Sun god, Ra, as Amun-Ra (alternatively spelled Amon-Ra or Amun-Re).

Amun-Ra retained chief importance in the Egyptian pantheon throughout the New Kingdom (with the exception of the «Atenist heresy» under Akhenaten). Amun-Ra in this period (16th to 11th centuries BC) held the position of transcendental, self-created[3] creator deity «par excellence»; he was the champion of the poor or troubled and central to personal piety.[4] With Osiris, Amun-Ra is the most widely recorded of the Egyptian gods.[4]

As the chief deity of the Egyptian Empire, Amun-Ra also came to be worshipped outside Egypt, according to the testimony of ancient Greek historiographers in Libya and Nubia. As Zeus-Ammon, he came to be identified with Zeus in Greece.

Early history[edit]

Amun and Amaunet are mentioned in the Old Egyptian Pyramid Texts.[5]

The name Amun (written imn) meant something like «the hidden one» or «invisible».[6]

Amun rose to the position of tutelary deity of Thebes after the end of the First Intermediate Period, under the 11th Dynasty. As the patron of Thebes, his spouse was Mut. In Thebes, Amun as father, Mut as mother and the Moon god Khonsu as their son formed the divine family or the «Theban Triad».

Temple at Karnak[edit]

The history of Amun as the patron god of Thebes begins in the 20th century BC, with the construction of the Precinct of Amun-Re at Karnak under Senusret I. The city of Thebes does not appear to have been of great significance before the 11th Dynasty.

Major construction work in the Precinct of Amun-Ra took place during the 18th Dynasty when Thebes became the capital of the unified ancient Egypt.

Construction of the Hypostyle Hall may have also begun during the 18th Dynasty, though most building was undertaken under Seti I and Ramesses II. Merenptah commemorated his victories over the Sea Peoples on the walls of the Cachette Court, the start of the processional route to the Luxor Temple. This Great Inscription (which has now lost about a third of its content) shows the king’s campaigns and eventual return with items of potential value and prisoners. Next to this inscription is the Victory Stela, which is largely a copy of the more famous Merneptah Stele found in the funerary complex of Merenptah on the west bank of the Nile in Thebes.[7] Merenptah’s son Seti II added two small obelisks in front of the Second Pylon, and a triple bark-shrine to the north of the processional avenue in the same area. This was constructed of sandstone, with a chapel to Amun flanked by those of Mut and Khonsu.

The last major change to the Precinct of Amun-Re’s layout was the addition of the first pylon and the massive enclosure walls that surrounded the whole Precinct, both constructed by Nectanebo I.

New Kingdom[edit]

Amon-Ra (l’esprit des quatre elements, lame du monde matérial), N372.2., Brooklyn Museum

Bas-relief depicting Amun as pharaoh

Identification with Min and Ra[edit]

Fragment of a stela showing Amun enthroned. Mut, wearing the double crown, stands behind him. Both are receiving offerings from Ramesses I, now lost. From Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

When the army of the founder of the Eighteenth Dynasty expelled the Hyksos rulers from Egypt, the victor’s city of origin, Thebes, became the most important city in Egypt, the capital of a new dynasty. The local patron deity of Thebes, Amun, therefore became nationally important. The pharaohs of that new dynasty attributed all of their successes to Amun, and they lavished much of their wealth and captured spoil on the construction of temples dedicated to Amun.[8] The victory against the «foreign rulers» achieved by pharaohs who worshipped Amun caused him to be seen as a champion of the less fortunate, upholding the rights of justice for the poor.[4] By aiding those who traveled in his name, he became the Protector of the road. Since he upheld Ma’at (truth, justice, and goodness),[4] those who prayed to Amun were required first to demonstrate that they were worthy, by confessing their sins. Votive stelae from the artisans’ village at Deir el-Medina record:

[Amun] who comes at the voice of the poor in distress, who gives breath to him who is wretched … You are Amun, the Lord of the silent, who comes at the voice of the poor; when I call to you in my distress You come and rescue me … Though the servant was disposed to do evil, the Lord is disposed to forgive. The Lord of Thebes spends not a whole day in anger; His wrath passes in a moment; none remains. His breath comes back to us in mercy … May your kꜣ be kind; may you forgive; It shall not happen again.[9]

Amun-Min as Amun-Ra ka-Mut-ef from the temple at Deir el Medina.

Ka-mut-ef, «Bull of His Mother» as a ram-headed lion in the Avenue of Sphinxes at Karnak Temple

Subsequently, when Egypt conquered Kush, they identified the chief deity of the Kushites as Amun. This Kush deity was depicted as ram-headed, more specifically a woolly ram with curved horns. Amun thus became associated with the ram arising from the aged appearance of the Kush ram deity, and depictions related to Amun sometimes had small ram’s horns, known as the Horns of Ammon. A solar deity in the form of a ram can be traced to the pre-literate Kerma culture in Nubia, contemporary to the Old Kingdom of Egypt. The later (Meroitic period) name of Nubian Amun was Amani, attested in numerous personal names such as Tanwetamani, Arkamani, and Amanitore. Since rams were considered a symbol of virility, Amun also became thought of as a fertility deity, and so started to absorb the identity of Min, becoming Amun-Min. This association with virility led to Amun-Min gaining the epithet Kamutef, meaning «Bull of his mother»,[6] in which form he was found depicted on the walls of Karnak, ithyphallic, and with a scourge, as Min was.

As the cult of Amun grew in importance, Amun became identified with the chief deity who was worshipped in other areas during that period, namely the sun god Ra. This identification led to another merger of identities, with Amun becoming Amun-Ra. In the Hymn to Amun-Ra he is described as

Lord of truth, father of the gods, maker of men, creator of all animals, Lord of things that are, creator of the staff of life.[10]

-

Amun (New Kingdom)[a]

-

Amun (Post Amarna)[a]

-

Amun-Ra

-

Amun-Min

Amarna Period[edit]

Hieroglyphs on the backpillar of Amenhotep III’s statue. There are two places where Akhenaten’s agents erased the name Amun, later restored on a deeper surface. The British Museum, London

During the latter part of the eighteenth dynasty, the pharaoh Akhenaten (also known as Amenhotep IV) advanced the worship of the Aten, a deity whose power was manifested in the sun disk, both literally and symbolically. He defaced the symbols of many of the old deities, and based his religious practices upon the deity, the Aten. He moved his capital away from Thebes, but this abrupt change was very unpopular with the priests of Amun, who now found themselves without any of their former power. The religion of Egypt was inexorably tied to the leadership of the country, the pharaoh being the leader of both. The pharaoh was the highest priest in the temple of the capital, and the next lower level of religious leaders were important advisers to the pharaoh, many being administrators of the bureaucracy that ran the country.

The introduction of Atenism under Akhenaten constructed a monolatrist worship of Aten in direct competition with that of Amun. Praises of Amun on stelae are strikingly similar in language to those later used, in particular, the Hymn to the Aten:

When thou crossest the sky, all faces behold thee, but when thou departest, thou are hidden from their faces … When thou settest in the western mountain, then they sleep in the manner of death … The fashioner of that which the soil produces, … a mother of profit to gods and men; a patient craftsman, greatly wearying himself as their maker … valiant herdsman, driving his cattle, their refuge and the making of their living … The sole Lord, who reaches the end of the lands every day, as one who sees them that tread thereon … Every land chatters at his rising every day, in order to praise him.[11]

When Akhenaten died, Akhenaten’s successor, Smenkhkare, became pharaoh and Atenism remained established during his brief 2-year reign. When Smenkhkare died, an enigmatic female pharaoh known as Neferneferuaten took the throne for a brief period but it is unclear what happened during her reign. After Neferneferuaten’s death, Akhenaten’s 9-year-old son Tutankhaten succeeded her. At the beginning of his reign, the young pharaoh reversed Atenism, re-establishing the old polytheistic religion and renaming himself Tutankhamun. His sister-wife, then named Ankhesenpaaten, followed him and was renamed Ankhesenamun. Worship of the Aten ceased for the most part and worship of Amun-Ra was restored.

During the reign of Horemheb, Akhenaten’s name was struck from Egyptian records, all of his religious and governmental changes were undone, and the capital was returned to Thebes. The return to the previous capital and its patron deity was accomplished so swiftly that it seemed this monolatrist cult and its governmental reforms had never existed.

Theology[edit]

The god of wind Amun came to be identified with the solar god Ra and the god of fertility and creation Min, so that Amun-Ra had the main characteristic of a solar god, creator god and fertility god. He also adopted the aspect of the ram from the Nubian solar god, besides numerous other titles and aspects.

As Amun-Re, he was petitioned for mercy by those who believed suffering had come about as a result of their own or others’ wrongdoing.

Amon-Re «who hears the prayer, who comes at the cry of the poor and distressed…Beware of him! Repeat him to son and daughter, to great and small; relate him to generations of generations who have not yet come into being; relate him to fishes in the deep, to birds in heaven; repeat him to him who does not know him and to him who knows him … Though it may be that the servant is normal in doing wrong, yet the Lord is normal in being merciful. The Lord of Thebes does not spend an entire day angry. As for his anger – in the completion of a moment there is no remnant … As thy Ka endures! thou wilt be merciful![12]

In the Leiden hymns, Amun, Ptah, and Re are regarded as a trinity who are distinct gods but with unity in plurality.[13] «The three gods are one yet the Egyptian elsewhere insists on the separate identity of each of the three.»[14] This unity in plurality is expressed in one text:

All gods are three: Amun, Re and Ptah, whom none equals. He who hides his name as Amun, he appears to the face as Re, his body is Ptah.[15]

Henri Frankfort suggested that Amun was originally a wind god and pointed out that the implicit connection between the winds and mysteriousness was paralleled in a passage from the Gospel of John: «The wind blows where it wishes, and you hear the sound of it, but do not know where it comes from and where it is going.»[John 3:8][16]

A Leiden hymn to Amun describes how he calms stormy seas for the troubled sailor:

The tempest moves aside for the sailor who remembers the name of Amon. The storm becomes a sweet breeze for he who invokes His name … Amon is more effective than millions for he who places Him in his heart. Thanks to Him the single man becomes stronger than a crowd.[17]

Third Intermediate Period[edit]

Theban High Priests of Amun[edit]

While not regarded as a dynasty, the High Priests of Amun at Thebes were nevertheless of such power and influence that they were effectively the rulers of Egypt from 1080 to c. 943 BC. By the time Herihor was proclaimed as the first ruling High Priest of Amun in 1080 BC—in the 19th Year of Ramesses XI—the Amun priesthood exercised an effective hold on Egypt’s economy. The Amun priests owned two-thirds of all the temple lands in Egypt and 90 percent of her ships and many other resources.[18] Consequently, the Amun priests were as powerful as the pharaoh, if not more so. One of the sons of the High Priest Pinedjem would eventually assume the throne and rule Egypt for almost half a century as pharaoh Psusennes I, while the Theban High Priest Psusennes III would take the throne as king Psusennes II—the final ruler of the 21st Dynasty.

Decline[edit]

In the 10th century BC, the overwhelming dominance of Amun over all of Egypt gradually began to decline.

In Thebes, however, his worship continued unabated, especially under the Nubian Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt, as Amun was by now seen as a national god in Nubia. The Temple of Amun, Jebel Barkal, founded during the New Kingdom, came to be the center of the religious ideology of the Kingdom of Kush.

The Victory Stele of Piye at Gebel Barkal (8th century BC) now distinguishes between an «Amun of Napata» and an «Amun of Thebes».

Tantamani (died 653 BC), the last pharaoh of the Nubian dynasty, still bore a theophoric name referring to Amun in the Nubian form Amani.

Iron Age and classical antiquity[edit]

Depiction of Amun in a relief at Karnak (15th century BC)

Nubia and Sudan[edit]

In areas outside Egypt where the Egyptians had previously brought the cult of Amun his worship continued into classical antiquity. In Nubia, where his name was pronounced Amane or Amani, he remained a national deity, with his priests, at Meroe and Nobatia,[19] regulating the whole government of the country via an oracle, choosing the ruler, and directing military expeditions. According to Diodorus Siculus, these religious leaders were even able to compel kings to commit suicide, although this tradition stopped when Arkamane, in the 3rd century BC, slew them.[20]

In Sudan, excavation of an Amun temple at Dangeil began in 2000 under the directorship of Drs Salah Mohamed Ahmed and Julie R. Anderson of the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (NCAM), Sudan and the British Museum, UK, respectively. The temple was found to have been destroyed by fire and Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) and C14 dating of the charred roof beams have placed the construction of the most recent incarnation of the temple in the 1st century AD. This date is further confirmed by the associated ceramics and inscriptions. Following its destruction, the temple gradually decayed and collapsed.[21]

Siwa Oasis[edit]

In Siwa Oasis, located Western Egypt, there remained a solitary oracle of Amun near the Libyan Desert.[22] The worship of Ammon was introduced into Greece at an early period, probably through the medium of the Greek colony in Cyrene, which must have formed a connection with the great oracle of Ammon in the Oasis soon after its establishment. Iarbas, a mythological king of Libya, was also considered a son of Hammon. When Alexander the Great advanced on Egypt in later 332 BC, he was regarded as a liberator.[23] He was pronounced son of Amun at this oracle,[24] thus conquering Egypt without a fight. Henceforth, Alexander often referred to Zeus-Ammon as his true father, and after his death, currency depicted him adorned with the Horns of Ammon as a symbol of his divinity.[25]

According to the 6th century author Corippus, a Libyan people known as the Laguatan carried an effigy of their god Gurzil, whom they believed to be the son of Ammon, into battle against the Byzantine Empire in the 540s AD.[26]

Levant[edit]

Amun is likely mentioned in the Hebrew Bible as אמון מנא Amon of No in Jeremiah 46:25 (also translated the horde of No and the horde of Alexandria), and Thebes possibly is called נא אמון No-Amon in Nahum 3:8 (also translated populous Alexandria). These texts were presumably written in the 7th century BC.[27]

The Lord of hosts, the God of Israel, said: «Behold, I am bringing punishment upon Amon of Thebes, and Pharaoh and Egypt and her gods and her kings, upon Pharaoh and those who trust in him.»

Greece[edit]

Zeus-Ammon. Roman copy of a Greek original from the late 5th century BC. The Greeks of the lower Nile Delta and Cyrenaica combined features of supreme god Zeus with features of the Egyptian god Amun-Ra.

Amun, worshipped by the Greeks as Ammon, had a temple and a statue, the gift of Pindar (d. 443 BC), at Thebes,[28] and another at Sparta, the inhabitants of which, as Pausanias says,[29] consulted the oracle of Ammon in Libya from early times more than the other Greeks. At Aphytis, Chalcidice, Amun was worshipped, from the time of Lysander (d. 395 BC), as zealously as in Ammonium. Pindar the poet honored the god with a hymn. At Megalopolis the god was represented with the head of a ram (Paus. viii.32 § 1), and the Greeks of Cyrenaica dedicated at Delphi a chariot with a statue of Ammon.

Such was its reputation among the Classical Greeks that Alexander the Great journeyed there after the battle of Issus and during his occupation of Egypt, where he was declared the metaphorical «son of Amun» by the oracle. Even during this occupation, Amun, identified by these Greeks as a form of Zeus,[30] continued to be the principal local deity of Thebes.[8]

Several words derive from Amun via the Greek form, Ammon, such as ammonia and ammonite. The Romans called the ammonium chloride they collected from deposits near the Temple of Jupiter-Amun in ancient Libya sal ammoniacus (salt of Amun) because of proximity to the nearby temple.[31] Ammonia, as well as being the chemical, is a genus name in the foraminifera. Both these foraminiferans (shelled Protozoa) and ammonites (extinct shelled cephalopods) bear spiral shells resembling a ram’s, and Ammon’s, horns. The regions of the hippocampus in the brain are called the cornu ammonis – literally «Amun’s Horns», due to the horned appearance of the dark and light bands of cellular layers.

In Paradise Lost, Milton identifies Ammon with the biblical Ham (Cham) and states that the gentiles called him the Libyan Jove.

See also[edit]

- List of solar deities

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Originally, Amun was depicted with red-brown skin during the New Kingdom, with two plumes on his head, the ankh symbol, and the was sceptre. After the Amarna period, Amun was instead painted with blue skin.

References[edit]

- ^ RÉS 367

- ^ David Warburton, Architecture, Power, and Religion: Hatshepsut, Amun and Karnak in Context, 2012, p. 211 ISBN 9783643902351

- ^ Dick, Michael Brennan (1999). Born in heaven, made on earth: the making of the cult image in the ancient Near East. Warsaw, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. p. 184. ISBN 1575060248.

- ^ a b c d Arieh Tobin, Vincent (2003). Redford, Donald B. (ed.). Oxford Guide: The Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology. Berkley Books. p. 20. ISBN 0-425-19096-X.

- ^ «Die Altaegyptischen Pyramidentexte nach den Papierabdrucken und Photographien des Berliner Museums». 1908.

- ^ a b Hart, George (2005). The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-415-36116-3.

- ^ Blyth, Elizabeth (2006). Karnak: Evolution of a Temple. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 164. ISBN 978-0415404860.

- ^ a b

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Griffith, Francis Llewellyn (1911). «Ammon». In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 860–861. This cites:

- Erman, Handbook of Egyptian Religion (London, 1907)

- Ed. Meyer, art. «Ammon» in Roscher’s Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie

- Pietschmann, arts. «Ammon», «Ammoneion» in Pauly-Wissowa, Realencyclopädie

- Works on Egyptian religion quoted (in the encyclopædia) under Egypt, section Religion

- ^ Lichtheim, Miriam (1976). Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 105–106. ISBN 0-520-03615-8.

- ^ Budge, E.A. Wallis (1914). An Introduction to Egyptian Literature (1997 ed.). Minneola, New York: Dover Publications. p. 214. ISBN 0-486-29502-8..

- ^ Wilson, John A. (1951). The Burden of Egypt (1963 ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-226-90152-7.

- ^ Wilson 1951, p. 300

- ^ Morenz, Siegried (1992). Egyptian Religion. Translated by Ann E. Keep. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 0-8014-8029-9.

- ^ Frankfort, Henri; Wilson, John A.; Jacobsen, Thorkild (1960). Before Philosophy: The Intellectual Adventure of Ancient Man. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing Company. p. 75. ISBN 978-0140201987.

- ^ Assmann, Jan (2008). Of God and Gods. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-299-22554-4.

- ^ Frankfort, Henri (1951). Before Philosophy. Penguin Books. p. 18. ASIN B0006EUMNK.

- ^ Jacq, Christian (1999). The Living Wisdom of Ancient Egypt. New York City: Simon & Schuster. p. 143. ISBN 0-671-02219-9.

- ^ Clayton, Peter A. (2006). Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. London, England: Thames & Hudson. p. 175. ISBN 978-0500286289.

- ^ Herodotus, The Histories ii.29

- ^ Griffith 1911.

- ^ Sweek, Tracey; Anderson, Julie; Tanimoto, Satoko (2012). «Architectural Conservation of an Amun Temple in Sudan». Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies. London, England: Ubiquity Press. 10 (2): 8–16. doi:10.5334/jcms.1021202.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece x.13 § 3

- ^ Ring, Trudy; Salkin, Robert M; Berney, KA; Schellinger, Paul E, eds. (1994). International dictionary of historic places. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1994–1996. pp. 49, 320. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6.

- ^ Bosworth, A. B. (1988). Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 71–74.

- ^ Dahmen, Karsten (2007). The Legend of Alexander the Great on Greek and Roman Coins. Taylor & Francis. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-415-39451-2.

- ^ Mattingly, D.J. (1983). «The Laguatan: A Libyan Tribal Confederation in the Late Roman Empire» (PDF). Libyan Studies. London, England: Society for Libyan Studies. 14: 98–99. doi:10.1017/S0263718900007810. S2CID 164294564.

- ^ «Strong’s Concordance / Gesenius’ Lexicon». Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ^ Pausanias. Description of Greece. ix.16 § 1.

- ^ Pausanias. Description of Greece. iii.18 § 2.

- ^ Jeremiah. xlvi.25.

- ^ «Eponyms». h2g2. BBC Online. 11 January 2003. Archived from the original on 2 November 2007. Retrieved 8 November 2007.

Sources[edit]

- David Klotz, Adoration of the Ram: Five Hymns to Amun-Re from Hibis Temple (New Haven, 2006)

- David Warburton, Architecture, Power, and Religion: Hatshepsut, Amun and Karnak in Context, 2012, ISBN 9783643902351.

- E. A. W. Budge, Tutankhamen: Amenism, Atenism, and Egyptian Monotheism (1923).

Further reading[edit]

- Assmann, Jan (1995). Egyptian Solar Religion in the New Kingdom: Re, Amun and the Crisis of Polytheism. Kegan Paul International. ISBN 978-0710304650.

- Ayad, Mariam F. (2009). God’s Wife, God’s Servant: The God’s Wife of Amun (c. 740–525 BC). Routledge. ISBN 978-0415411707.

- Cruz-Uribe, Eugene (1994). «The Khonsu Cosmogony». Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 31: 169–189. doi:10.2307/40000676. JSTOR 40000676.

- Gabolde, Luc (2018). Karnak, Amon-Rê : La genèse d’un temple, la naissance d’un dieu (in French). Institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire. ISBN 978-2-7247-0686-4.

- Guermeur, Ivan (2005). Les cultes d’Amon hors de Thèbes: Recherches de géographie religieuse (in French). Brepols. ISBN 978-90-71201-10-3.

- Klotz, David (2012). Caesar in the City of Amun: Egyptian Temple Construction and Theology in Roman Thebes. Association Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth. ISBN 978-2-503-54515-8.

- Kuhlmann, Klaus P. (1988). Das Ammoneion. Archäologie, Geschichte und Kultpraxis des Orakels von Siwa (in German). Verlag Phillip von Zabern in Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3805308199.

- Otto, Eberhard (1968). Egyptian art and the cults of Osiris and Amon. Abrams.

- Roucheleau, Caroline Michelle (2008). Amun temples in Nubia: a typological study of New Kingdom, Napatan and Meroitic temples. Archaeopress. ISBN 9781407303376.

- Thiers, Christophe, ed. (2009). Documents de théologies thébaines tardives. Université Paul-Valéry.

- Zandee, Jan (1948). De Hymnen aan Amon van papyrus Leiden I. 350 (in Dutch). E.J. Brill.

- Zandee, Jan (1992). Der Amunhymnus des Papyrus Leiden I 344, Verso (in German). Rijksmuseum van Oudheden. ISBN 978-90-71201-10-3.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amun.

- Wim van den Dungen, Leiden Hymns to Amun

- (in Spanish) Karnak 3D :: Detailed 3D-reconstruction of the Great Temple of Amun at Karnak, Marc Mateos, 2007

- Amun with features of Tutankhamun (statue, c. 1332–1292 BC, Penn Museum)

Амон

- Амон

-

Ам’он, -а (мифол.)

Русский орфографический словарь. / Российская академия наук. Ин-т рус. яз. им. В. В. Виноградова. — М.: «Азбуковник».

.

1999.

Синонимы:

Смотреть что такое «Амон» в других словарях:

-

АМОН — (ìmn, букв. «сокрытый», «потаённый»), в египетской мифологии бог солнца. Центр культа А. Фивы, покровителем которых он считался. Священное животное А. баран. Обычно А. изображали в виде человека (иногда с головой барана) в короне с двумя высокими … Энциклопедия мифологии

-

Амон — (Аммон) ( надежный , верный (см. Аминь)): 1) градоначальник Самарии во времена Ахава (3Цар 22:26; 2Пар 18:25); 2) сын и наследник иуд. царя Манассии (641 640 гг. до Р.Х.). Он вступил на престол 22 летним и царствовал всего 2 года, продолжая… … Библейская энциклопедия Брокгауза

-

АМОН — в древнеегипетской мифологии бог покровитель г. Фивы, постепенно стал отождествляться с верховным богом Ра (Амон Ра) … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

Амон — древнеегипетский бог плодородия, первоначально местный (в Фивах); позже бог света, уподобившийся богу солнца Ре (или Ра) и одинаково почитавшийся. Отсюда А. = Ре. С течением времени А. стал главным богом Египта. Культ А. «царя богов» процветал в… … Литературная энциклопедия

-

амон — Ра Словарь русских синонимов. амон сущ., кол во синонимов: 2 • бог (375) • ра (4) … Словарь синонимов

-

амоніт — 1 іменник чоловічого роду викопний молюск амоніт 2 іменник чоловічого роду вибухова речовина … Орфографічний словник української мови

-

АМОН — АМОН, в египетской мифологии бог солнца, покровитель города Фивы. Почитался в облике барана … Современная энциклопедия

-

Амон — (м) скрытый Египетские имена. Словарь значений … Словарь личных имен

-

Амон — библейское название египетского главного божества Озириса ипосвященного его культу города Фивы (Ифp. XLVI, 25; Авак. III, 8).Филологи стараются найти корень этого имени в египетском языке и виероглифах и приискивают ему различные значения, но… … Энциклопедия Брокгауза и Ефрона

-

амоніяк — амоніак (безбарвний газ із різким запахом), сморідець, аміа[я]к … Словник синонімів української мови

-

амоніак — іменник чоловічого роду … Орфографічний словник української мови

Как правильно пишется слово «Амон»

Амо́н

Амо́н, -а (мифол.)

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: третированный — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к слову «Амон»

Синонимы к слову «амон»

Предложения со словом «амон»

- АМОН, имя обозначает «сокрытый», «потаённый», бог солнца.

- Мамона – по этимологии «ма’амон» – переводится как «ценности, взятые в залог», иными словами, это религия кредита.

- – Бране крис амон айон, – вероятно, подвела итог собеседница, а может и приговор огласила.

- (все предложения)

Значение слова «Амон»

-

Амо́н — древнеегипетский бог чёрного небесного пространства, воздуха. Позже, при Новом царстве — бог солнца (Амон-Ра). Считался покровителем Фив. (Википедия)

Все значения слова АМОН

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Смотрите также

Амо́н — древнеегипетский бог чёрного небесного пространства, воздуха. Позже, при Новом царстве — бог солнца (Амон-Ра). Считался покровителем Фив.

Все значения слова «Амон»

-

АМОН, имя обозначает «сокрытый», «потаённый», бог солнца.

-

Мамона – по этимологии «ма’амон» – переводится как «ценности, взятые в залог», иными словами, это религия кредита.

-

– Бране крис амон айон, – вероятно, подвела итог собеседница, а может и приговор огласила.

- (все предложения)

- священный бык

- двойная корона

- повергаться ниц

- крылатый диск

- жреческое сословие

- (ещё синонимы…)

- подмога

- Египет

- (ещё ассоциации…)

Смотреть что такое АМОН в других словарях:

АМОН

бог в древнеегипетской религии. В основе древнейшего образа А. лежало почитание воздушной стихии. А. считался богом-покровителем г. Фив (См. Фи… смотреть

АМОН

Амон

Ра

Словарь русских синонимов.

амон

сущ., кол-во синонимов: 2

• бог (375)

• ра (4)

Словарь синонимов ASIS.В.Н. Тришин.2013.

.

Синонимы:

бог, ра… смотреть

АМОН

АМОН(ìmn, букв. «сокрытый», «потаённый»), в египетской мифологии бог солнца. Центр культа А. — Фивы, покровителем которых он считался. Священное животн… смотреть

АМОН

Один из важнейших богов египетского пантеона, имя которого переводится как «скрытый», «сокровенный». Изображался в облике мужчины с кожей голубого или золотого цвета, увенчанного шути — ступообразной короной, украшенной двумя страусиными перьями. Иногда Амон также предстает в облике своих священных животных — овна и гуся. «Скрытый от глаз богов так, что сутью своей неведом; тот, что выше небес, дальше мира загробного, истинным обликом богам неведомый» величайший, чтобы быть познанным, могущественнейший, чтобы быть узнанным» (из Лейденского гимна богу), Амон — изначально бог неба и грозы, позже — «великая сокровенная душа, что над всеми богами», предвечный и непознаваемый владыка вселенной, который, согласно некоторым текстам, произнесший в момент творения изначальное слово, поднявшись в облике птицы над водами хаоса.

— В Фивах Амон почитался как супруг богини Мут и отец Хонсу; величественный храм бога в Карнаке и поныне потрясает воображение своей грандиозностью и является самым значительным египетским храмом эпохи Нового царства (1550 — 1078 гг. до н. э.). Амон в одной из своих ипостасей (Амон Камутеф) также почитался в итифаллической форме, часто отождествляясь с богом плодородия Мином. В Карнаке Амон считался владыкой местной Эннеады, Ипетсут песеджет, в которую, помимо богов Эннеады Гелиополя, входили Хор, Хатхор и некоторые божества Арманта.

— Имя Амона впервые упоминается в «Текстах пирамид»; как Амон Кематеф, вместе со своим женским дополнением Амаунет, бог почитался в числе восьми предвечных хтонических божеств Огдоады Гермополя и изображался в виде лягушки или змея, в знак возрождения скидывающего свою кожу. Древнейшие храмы Амона были воздвигнуты в Фивах, где он почитался как локальное божество с конца правления VI династии (2347 — 2216 гг. до н. э.). Рост значимости культа бога был связан с воцарением фараона XI династии Ментухотепа II (2046 — 1995 г. до н. э.), фиванца по происхождению, выдвинувшего бога-покровителя своего города в число величайших божеств древнего мира. Уже в «белом святилище» Сенусерта I (1956 — 1911 гг. до н. э.) в Карнаке Амон величается титулом «царь богов». Средним царством датируются древнейшие сохранившиеся до нашего времени постройки в центральном святилище бога — Карнакском храме.

— В эпоху Нового царства Амон был отождествлен с богом солнца Ра; Амон-Ра, фиванская ипостась солнечного божества, стала «государственным» богом, покровительствовавшим завоевательным походам фараонов XVIII-XX династий, владыкой великого египетского царства, простиравшегося от берегов Евфрата на севере до четвертого порога Нила на юге. В конце правления XX династии фиванское жречество Амона использовало популярность культа бога для утверждения независимого теократического государства бога Амона со столицей в Карнаке. Кроме того, новая теологическая доктрина, созданная фиванским жречеством, утверждала, что именно Амон в облике великого змея Кематефа создал все остальные города и их локальных богов, упокоившись после этого в Фивах, под священным холмом Джеме на территории храма в Мединет Абу.

— Возвышение фараонов-нубийцев XXV династии привело к возрождению государственного характера культа Амона; второе великое святилище бога, находившееся у священной горы Гебель Баркал на севере Судана, было объявлено «южным Карнаком», столицей нового государства кушитских фараонов. Также в Нубии, в Вади эс-Себуа почиталась особая ипостась бога — Амон Путей, покровительствовавшая путешественникам и странникам; также считалось, что магическая сила великого имени Амона защищала находящегося на воде.

— Согласно текстам крипт птолемеевского храма богини Опет в Карнаке, Амон — великая божественная сила, одухотворяющая всю вселенную, ба Бога предвечного. Рельефы северной крипты храма изображают десять бау солнечного Амона-Ра. Каждая из этих душ персонифицирует одну из божественных энергий бога, одухотворяющих мир: солнце (правый глаз), луну (левый глаз), воздушное пространство (Шу), воды предвечные (Нун), огонь (Тефнут), человечество (жизненная сила ка царя), все земные четвероногие существа, все крылатые существа, все твари подводные (бог-крокодил из Шедет), силы подземные (бог-змей Нехебкау). Могущество души бога наполняло своей животворящей силой его тело; это совершенно очевидно, если учитывать расположенное на стене этой же крипты изображение итифаллической птицы с головой Амона, которая парит над пробуждающимся в окружении Исиды и Нефтиды Осирисом. Надпись рядом гласит: «Амон, почитаемая ба Осириса».

— Согласно изображениям, высеченным на стенах храма Хатшепсут (1479 — 1458 гг. до н. э.) в Дейр эль-Бахри, храма в Луксоре и Рамессеума, именно Амон приходился божественным отцом каждого фараона, зачиная его с царицей-матерью во время теогамии — божественного брака, заключаемого на небесах по воле бога. Раз в год, во время великого общегосударственного праздника Опет, Амон Карнакский, посещая на своей священной ладье Усерхетамон, увенчанной эгидами с головами овнов, храм в Луксоре, символически вновь рождал своего сына — божественного царя. В этих важнейших ритуалах участвовали фараон, его супруга, другие члены царской семьи, исполнявшие второстепенные роли. Cоюз царственной пары становился, таким образом, подобием божественного брака, во время которого царь не только уподоблялся Амону, зачинающего своего сына, но и сливался с образом бога, «обновляя» тем самым свои потенциалы и вновь доказывая свое неизменное право на божественное творение, правление, поддержание Маат. Сам Амон в момент теогамии также изменял свою сущность: из вселенского владыки, повелителя Карнака, он на короткое время проявлялся как «Амон-Ра, Владыка своего Гарема», т. е. Амон Луксорский, отец царя. Как только царь получает возрождение, или «повторение рождений» в мир, Амон вновь становится предвечным божеством, «Владыкой Небес, Царем Богов». В основе двух ипостасей Амона — «Карнакского» и «Луксорского» лежит единый образ божества; их основное различие состояло в том, что в отличие от «вселенского властителя» в Карнаке, Южный Амон, прежде всего, выполняет функции божественного предка царя, поминальный культ которого поддерживается его земным наследником.

— В основе египетского понимания мироздания лежала взаимосвязь божественной и царской власти: Амон обеспечивал существование царя, его «возлюбленный сын» поддерживал цикличность бессмертного бытия бога. Божественное присутствие чувствуется в каждом действии фараонов как внутри страны, так и во внешнеполитических перипетиях: Амон стоит за спиной Рамсеса II (1279 — 1212 гг. до н. э.) во время Кадешской битвы, Амон дарует победы Тутмосу III (1479 — 1425 гг. до н. э.) в обмен на воздвигнутые царем храмы, Амон повергает к стопам Аменхотепа III (1388 — 1351 гг. до н. э.) все стороны света, который в милости своей одаривает их «дыханием жизни».

— С эпохи Нового царства особое значение придавалась оракулу Амона Карнакского, посредством которого решались важнейшие государственные дела, а также утверждались претенденты на пост верховного жреца бога. В оазисе Сива находился другой, не менее знаменитый оракул Амона, признавший сыном бога Александра Македонского. Храмы и святилища Амона также находились в Солебе, Герф Хуссейне, Абу-Симбеле, Дерре, Каве, Пнубсе, Саи, Гемпаатоне, Напате и многих других городах и селениях Нубии; в Вади Мийа (Восточная пустыня), Пер-Рамсесе, и, наконец, в Танисе; здесь в ограде храма бога в 1938 году экспедицией П. Монтэ были обнаружены гробницы царей XXI династии, сокровища которых могут быть сравнимы только с содержимым гробницы Тутанхамона.

— На протяжении многих веков особой популярностью в Фивах пользовалась особенно милостивая ипостась бога — «Амон, слушающий просящего». Этому божеству были воздвигнуты бесчисленные стелы, многие из которых украшены изображениями ушей бога, «внимающего молитвам, отзывающегося на призыв несчастного, дающего дыхание жизни несчастному».

— Верховный жрец храма Амона в Карнаке носил титул хем нечер тепи эн Амон, или «первый раб бога Амона», ему подчинялись бесчисленные слуги и огромное хозяйство владыки Фив. Во время III Переходного периода (1078 — 525 гг. до н. э.) управление храмом перешло в руки верховной жрицы, «супруги бога», которая давала обет безбрачия и выбирала свою преемницу из числа дочерей правящего фараона. Последняя известная «супруга бога», Анхнеснеферибра II, возглавляла жречество Амона вплоть до завоевания Египта персами в 525 г. до н. э.

Библиография

Я. Ассман «Египет. Теология и благочестие ранней цивилизации». — М., 1999.

Э. Е. Кормышева «Религия Куша».— М., 1984.

М. А. Коростовцев «Религия древнего Египта». — М., 1976.

К. Михаловский «Карнак». — Варшава, 1970.

О. И. Павлова «Амон Фиванский. Ранняя история культа». — М., 1984.

В. В. Солкин «Египет. Вселенная фараонов». — М., 2001.

«Жилище бога в Нубийской пустыне». // Вокруг света, 10 (1991). С. 28-33.

J. Assmann «Egyptian solar religion in the New Kingdom: Ra, Amun and the crisis of polytheism». — London, 1995.

P. Barguet «Le temple d’Amon-Re a Karnak: essai d’exegese». — Le Caire, 1962.

S. -A Naguib. «Le Clerge Feminin d’Amon Thebain a la 21e Dynastie». — Leuven, 1990.

E. Otto «Osiris und Amun, Kult und Heilige Statten». — Munich, 1966.

K. Sethe «Amun und die acht Urgotter». — Leipzig, 1929.

G. A. Wainright «The Relationship of Amun to Zeus and his Connection with Meteorites. // JEA 16 (1930), pp. 35-39.

G. A. Wainright «The Origin of Amun». // JEA 49 (1963), pp. 21-24.

J. Zandee «De Hymnen aan Amon von Papyrus Leiden 1350». — Leiden, 1948.

ВНИМАНИЕ: Эта статья не может быть использована без ссылки на автора, так как составляет часть готовящейся к изданию работы «Древний Египет. Энциклопедия».

© В. В. Солкин… смотреть

АМОН

в егип. миф. бог солнца. Центр культа А. — Фивы, покровит. к-рых он считался. Свящ. животное А. — баран. Обычно А. изображ. в виде человека (и… смотреть

АМОН

в егип. миф. бог солнца. Центр культа А. — Фивы, покровит. к-рых он считался. Свящ. животное А. — баран. Обычно А. изображ. в виде человека (иногда с головой барана) в короне с двумя высок. перья-ми и солнеч. диском. Почит. А. зарод. в Верх. Египте, в частности в Фивах, а затем распростр. на С. и по всему Египту. Жена А. — богиня неба Мут, сын — бог луны Хонсу, составл. вместе с ним т.н. фиванск. триаду. Иногда его женой назыв. богиню Амаунет. Первонач. А. был близок фиванск. богу войны Монту, считавш. при фараонах ХI династии Сред. царства (21 в. до н.э.) одним из гл. божеств пантеона. С возвыш. ХII династии (20 — 18 вв. до н.э.) А. отожд. с ним (Амон-Ра-Монту) и вскоре вытесн. его культ. В период Сред. царства с А. отожд. также бог плодородия Мин. В эпоху ХVIII (Фиван-ской) династии Нового царства (16 — 14 вв. до н.э.) А. станов. всеегип. богом, его культ приобр. гос. хар-р. А. отожд. с богом солнца Ра (Амон-Ра, впервые это имя встреч. в «Текс-тах пирамид»), он почит. как «царь всех богов» (греч. — Амон-Ра-Со-тер, егип. — Амон-Ра-несут-нечер), счит. богом-творцом, создав. все сущее и в частн., его ставят во главе гелиопольской эннеады и гермопольской огдоады богов). Крупнейший и наиболее древ. храм А. — Карнакский (в Фивах), во время праздника А. («прекрас. праздника долины») из него при огром. стечении народа вынос. на барке статую А. Воплощ. в ней божество изрек. в этот день свою волю, вещало оракулы, решало спорные дела. Культ А. получил распростр. в Куше (Др. Нубии), где также принял гос. хар-р. Среди многочисл. местных ипостасей А. гл. роль принадл. А. храма Напаты. Оракулы этого храма избирали царя, к-рый после коронации, соверш. в храме, посещал святилища А. в Гемпатоне и Пнубсе, где подтвержд. его избрание…. смотреть

АМОН

Амон (Аммон) («надежный», «верный» (см. Аминь)): 1) градоначальник Самарии во времена Ахава (3Цар 22:26; 2Пар 18:25); 2) сын и наследник иуд. царя Ман… смотреть

АМОН

амо́н

в древнеегипетской мифологии — бог Солнца, то же, что ра.

Новый словарь иностранных слов.- by EdwART, ,2009.

амон

в древнеегипетской мифологии … смотреть

АМОН

(греч., егип. спрятанный), высшее егип. божество; А. изображался человеком с двумя перьями на голове или с бараньей или гусиной головой. Свящ. … смотреть

АМОН

АМОН — древнеегипетский бог плодородия, первоначально — местный (в Фивах); позже — бог света, уподобившийся богу солнца Ре (или Ра) и одинаково… смотреть

АМОН

бог в др.-егип. религии. В основе древнейшего образа А. лежало почитание воздушной стихии. Главное значение А. приобрел как бог-покровитель г. Фив, ста… смотреть

АМОН

(«сокрытый», «потаенный») Высшее египетское божество, отождествляемое с Зевсом. Жрецы признали Александра Македонского сыном Зевса-Амона, т. е. фарао… смотреть

АМОН

1) В древнеегипетской мифологии бог-покровитель города Фивы, постепенно стал отождествляться с верховным богом Ра (Амон-Ра).

2) Малая планета номер 3554, Атон. Среднее расстояние до Солнца 0,97 а. е. (145,6 млн. км), эксцентриситет орбиты 0,281, наклон к плоскости эклиптики 23,4 градусов. Период обращения вокруг Солнца 350,64 суток. Имеет неправильную форму, максимальный поперечник 2,5 км, масса 1,60*10^13 кг. Была открыта Каролиной и Евгением Шумейкерами 4 марта 1986 и получила условное обозначение 1986 EB. Название было утверждено Международным Астрономическим Союзом в честь Амона.

Астрономический словарь.EdwART.2010.

Синонимы:

бог, ра… смотреть

АМОН

(Амун), первый фиванский бог, который стал почитаться во всем Древнем Египте. Когда правители Фив основали XVIII династию, изгнавшую из Египта завоеват… смотреть

АМОН

АМОН(Амун), первый фиванский бог, который стал почитаться во всем Древнем Египте. Когда правители Фив основали XVIII династию, изгнавшую из Египта завоевателей-гиксосов и захватившую сирийские территории (в северном направлении — до Евфрата), Амон превратился в главное божество всего Древнего Востока. Его называли Амоном-Ра и изображали в облике человека, голову которого венчает солнечный диск, обрамленный двумя страусовыми перьями. Эхнатон (правил ок. 1379 — 1362 до н.э.) запретил почитание Амона, заменив его культом солнечного бога Атона. После смерти Эхнатона Амон был восстановлен в своих правах верховного бога…. смотреть

АМОН

АМОН — древнеегипетский бог плодородия, первоначально — местный (в Фивах); позже — бог света, уподобившийся богу солнца Ре (или Ра) и одинаково почита… смотреть

АМОН

древнеегипетский бог плодородия, первоначально — местный (в Фивах); позже — бог света, уподобившийся богу солнца Ре (или Ра) и одинаково почитавшийся. Отсюда А. = Ре. С течением времени А. стал главным богом Египта. Культ А. — «царя богов» — процветал в эпоху 18–20 династий. В этот период возникла обширная богословская лит-ра и религиозная поэзия (гимны), посвященная А. Культ А. проник в Грецию и Рим, где А. отождествлялся с Зевсом и Юпитером. А. изображался в виде человека с бараньей головой, но чаще — восседающим на троне со скипетром в одной руке и крестом в другой…. смотреть

АМОН

1) Орфографическая запись слова: амон2) Ударение в слове: Ам`он3) Деление слова на слоги (перенос слова): амон4) Фонетическая транскрипция слова амон :… смотреть

АМОН

Амон

(м) — скрытый