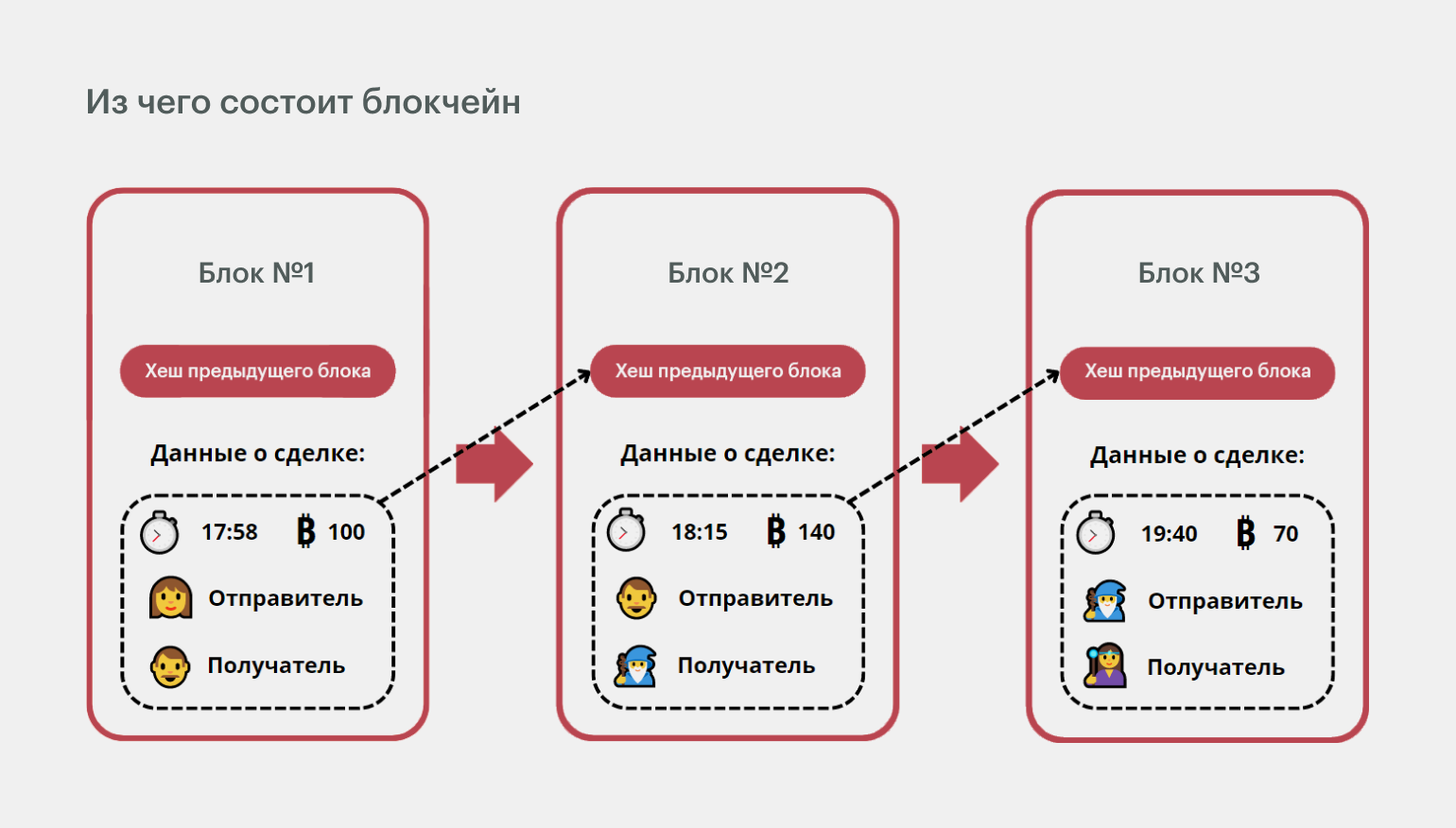

A blockchain is a type of distributed ledger technology (DLT) that consists of growing lists of records, called blocks, that are securely linked together using cryptography.[1][2][3][4] Each block contains a cryptographic hash of the previous block, a timestamp, and transaction data (generally represented as a Merkle tree, where data nodes are represented by leaves). The timestamp proves that the transaction data existed when the block was created. Since each block contains information about the previous block, they effectively form a chain (compare linked list data structure), with each additional block linking to the ones before it. Consequently, blockchain transactions are irreversible in that, once they are recorded, the data in any given block cannot be altered retroactively without altering all subsequent blocks.

Blockchains are typically managed by a peer-to-peer (P2P) computer network for use as a public distributed ledger, where nodes collectively adhere to a consensus algorithm protocol to add and validate new transaction blocks. Although blockchain records are not unalterable, since blockchain forks are possible, blockchains may be considered secure by design and exemplify a distributed computing system with high Byzantine fault tolerance.[5]

A blockchain was created by a person (or group of people) using the name (or pseudonym) Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008[6] to serve as the public distributed ledger for bitcoin cryptocurrency transactions, based on previous work by Stuart Haber, W. Scott Stornetta, and Dave Bayer.[7] The implementation of the blockchain within bitcoin made it the first digital currency to solve the double-spending problem without the need of a trusted authority or central server. The bitcoin design has inspired other applications[3][2] and blockchains that are readable by the public and are widely used by cryptocurrencies. The blockchain may be considered a type of payment rail.[8]

Private blockchains have been proposed for business use. Computerworld called the marketing of such privatized blockchains without a proper security model «snake oil»;[9] however, others have argued that permissioned blockchains, if carefully designed, may be more decentralized and therefore more secure in practice than permissionless ones.[4][10]

History

Cryptographer David Chaum first proposed a blockchain-like protocol in his 1982 dissertation «Computer Systems Established, Maintained, and Trusted by Mutually Suspicious Groups.»[11] Further work on a cryptographically secured chain of blocks was described in 1991 by Stuart Haber and W. Scott Stornetta.[4][12] They wanted to implement a system wherein document timestamps could not be tampered with. In 1992, Haber, Stornetta, and Dave Bayer incorporated Merkle trees into the design, which improved its efficiency by allowing several document certificates to be collected into one block.[4][13] Under their company Surety, their document certificate hashes have been published in The New York Times every week since 1995.[14]

The first decentralized blockchain was conceptualized by a person (or group of people) known as Satoshi Nakamoto in 2008. Nakamoto improved the design in an important way using a Hashcash-like method to timestamp blocks without requiring them to be signed by a trusted party and introducing a difficulty parameter to stabilize the rate at which blocks are added to the chain.[4] The design was implemented the following year by Nakamoto as a core component of the cryptocurrency bitcoin, where it serves as the public ledger for all transactions on the network.[3]

In August 2014, the bitcoin blockchain file size, containing records of all transactions that have occurred on the network, reached 20 GB (gigabytes).[15] In January 2015, the size had grown to almost 30 GB, and from January 2016 to January 2017, the bitcoin blockchain grew from 50 GB to 100 GB in size. The ledger size had exceeded 200 GB by early 2020.[16]

The words block and chain were used separately in Satoshi Nakamoto’s original paper, but were eventually popularized as a single word, blockchain, by 2016.[17]

According to Accenture, an application of the diffusion of innovations theory suggests that blockchains attained a 13.5% adoption rate within financial services in 2016, therefore reaching the early adopters’ phase.[18] Industry trade groups joined to create the Global Blockchain Forum in 2016, an initiative of the Chamber of Digital Commerce.

In May 2018, Gartner found that only 1% of CIOs indicated any kind of blockchain adoption within their organisations, and only 8% of CIOs were in the short-term «planning or [looking at] active experimentation with blockchain».[19] For the year 2019 Gartner reported 5% of CIOs believed blockchain technology was a ‘game-changer’ for their business.[20]

Structure and design

Blockchain formation. The main chain (black) consists of the longest series of blocks from the genesis block (green) to the current block. Orphan blocks (purple) exist outside of the main chain.

A blockchain is a decentralized, distributed, and often public, digital ledger consisting of records called blocks that are used to record transactions across many computers so that any involved block cannot be altered retroactively, without the alteration of all subsequent blocks.[3][21] This allows the participants to verify and audit transactions independently and relatively inexpensively.[22] A blockchain database is managed autonomously using a peer-to-peer network and a distributed timestamping server. They are authenticated by mass collaboration powered by collective self-interests.[23] Such a design facilitates robust workflow where participants’ uncertainty regarding data security is marginal. The use of a blockchain removes the characteristic of infinite reproducibility from a digital asset. It confirms that each unit of value was transferred only once, solving the long-standing problem of double-spending. A blockchain has been described as a value-exchange protocol.[24] A blockchain can maintain title rights because, when properly set up to detail the exchange agreement, it provides a record that compels offer and acceptance.[citation needed]

Logically, a blockchain can be seen as consisting of several layers:[25]

- infrastructure (hardware)

- networking (node discovery, information propagation[26] and verification)

- consensus (proof of work, proof of stake)

- data (blocks, transactions)

- application (smart contracts/decentralized applications, if applicable)

Blocks

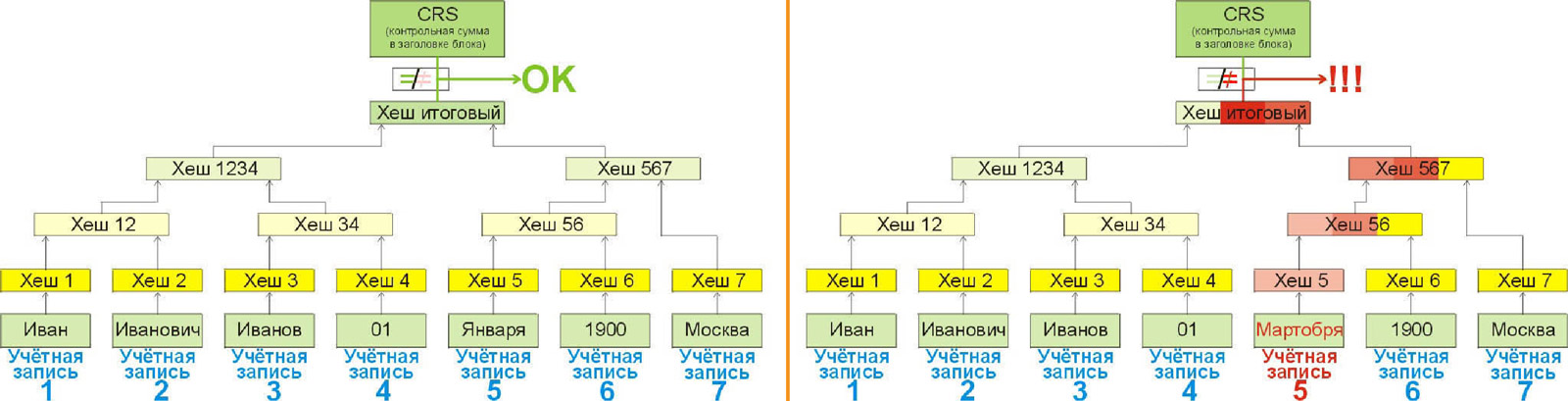

Blocks hold batches of valid transactions that are hashed and encoded into a Merkle tree.[3] Each block includes the cryptographic hash of the prior block in the blockchain, linking the two. The linked blocks form a chain.[3] This iterative process confirms the integrity of the previous block, all the way back to the initial block, which is known as the genesis block (Block 0).[27][28] To assure the integrity of a block and the data contained in it, the block is usually digitally signed.[29]

Sometimes separate blocks can be produced concurrently, creating a temporary fork. In addition to a secure hash-based history, any blockchain has a specified algorithm for scoring different versions of the history so that one with a higher score can be selected over others. Blocks not selected for inclusion in the chain are called orphan blocks.[28] Peers supporting the database have different versions of the history from time to time. They keep only the highest-scoring version of the database known to them. Whenever a peer receives a higher-scoring version (usually the old version with a single new block added) they extend or overwrite their own database and retransmit the improvement to their peers. There is never an absolute guarantee that any particular entry will remain in the best version of history forever. Blockchains are typically built to add the score of new blocks onto old blocks and are given incentives to extend with new blocks rather than overwrite old blocks. Therefore, the probability of an entry becoming superseded decreases exponentially[30] as more blocks are built on top of it, eventually becoming very low.[3][31]: ch. 08 [32] For example, bitcoin uses a proof-of-work system, where the chain with the most cumulative proof-of-work is considered the valid one by the network. There are a number of methods that can be used to demonstrate a sufficient level of computation. Within a blockchain the computation is carried out redundantly rather than in the traditional segregated and parallel manner.[33]

Block time

The block time is the average time it takes for the network to generate one extra block in the blockchain. By the time of block completion, the included data becomes verifiable. In cryptocurrency, this is practically when the transaction takes place, so a shorter block time means faster transactions. The block time for Ethereum is set to between 14 and 15 seconds, while for bitcoin it is on average 10 minutes.[34]

Hard forks

A hard fork is a change to the blockchain protocol that is not backward-compatible and requires all users to upgrade their software in order to continue participating in the network. In a hard fork, the network splits into two separate versions: one that follows the new rules and one that follows the old rules.

For example, Ethereum was hard-forked in 2016 to «make whole» the investors in The DAO, which had been hacked by exploiting a vulnerability in its code. In this case, the fork resulted in a split creating Ethereum and Ethereum Classic chains. In 2014 the Nxt community was asked to consider a hard fork that would have led to a rollback of the blockchain records to mitigate the effects of a theft of 50 million NXT from a major cryptocurrency exchange. The hard fork proposal was rejected, and some of the funds were recovered after negotiations and ransom payment. Alternatively, to prevent a permanent split, a majority of nodes using the new software may return to the old rules, as was the case of bitcoin split on 12 March 2013.[35]

A more recent hard-fork example is of Bitcoin in 2017, which resulted in a split creating Bitcoin Cash.[36] The network split was mainly due to a disagreement in how to increase the transactions per second to accommodate for demand.[37]

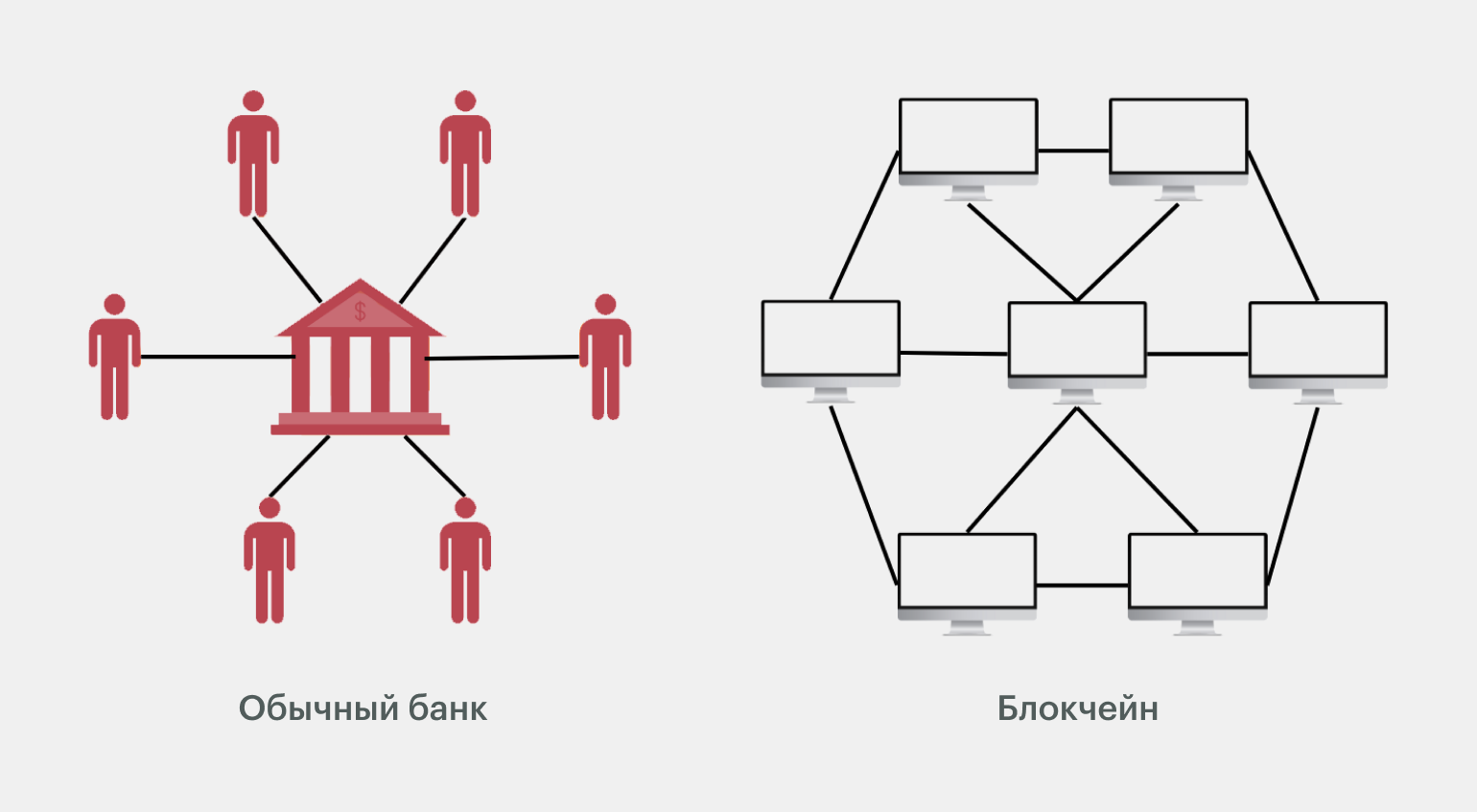

Decentralization

By storing data across its peer-to-peer network, the blockchain eliminates some risks that come with data being held centrally.[3] The decentralized blockchain may use ad hoc message passing and distributed networking.[38]

In a so-called «51% attack» a central entity gains control of more than half of a network and can then manipulate that specific blockchain record at will, allowing double-spending.[39]

Peer-to-peer blockchain networks lack centralized points of vulnerability that computer crackers can exploit; likewise, they have no central point of failure. Blockchain security methods include the use of public-key cryptography.[40]: 5 A public key (a long, random-looking string of numbers) is an address on the blockchain. Value tokens sent across the network are recorded as belonging to that address. A private key is like a password that gives its owner access to their digital assets or the means to otherwise interact with the various capabilities that blockchains now support. Data stored on the blockchain is generally considered incorruptible.[3]

Every node in a decentralized system has a copy of the blockchain. Data quality is maintained by massive database replication[41] and computational trust. No centralized «official» copy exists and no user is «trusted» more than any other.[40] Transactions are broadcast to the network using the software. Messages are delivered on a best-effort basis. Early blockchains rely on energy-intensive mining nodes to validate transactions,[28] add them to the block they are building, and then broadcast the completed block to other nodes.[31]: ch. 08 Blockchains use various time-stamping schemes, such as proof-of-work, to serialize changes.[42] Later consensus methods include proof of stake.[28] The growth of a decentralized blockchain is accompanied by the risk of centralization because the computer resources required to process larger amounts of data become more expensive.[43]

Finality

Finality is the level of confidence that the well-formed block recently appended to the blockchain will not be revoked in the future (is «finalized») and thus can be trusted. Most distributed blockchain protocols, whether proof of work or proof of stake, cannot guarantee the finality of a freshly committed block, and instead rely on «probabilistic finality»: as the block goes deeper into a blockchain, it is less likely to be altered or reverted by a newly found consensus.[44]

Byzantine Fault Tolerance-based proof-of-stake protocols purport to provide so called «absolute finality»: a randomly chosen validator proposes a block, the rest of validators vote on it, and, if a supermajority decision approves it, the block is irreversibly committed into the blockchain.[44] A modification of this method, an «economic finality», is used in practical protocols, like the Casper protocol used in Ethereum: validators which sign two different blocks at the same position in the blockchain are subject to «slashing», where their leveraged stake is forfeited.[44]

Openness

Open blockchains are more user-friendly than some traditional ownership records, which, while open to the public, still require physical access to view. Because all early blockchains were permissionless, controversy has arisen over the blockchain definition. An issue in this ongoing debate is whether a private system with verifiers tasked and authorized (permissioned) by a central authority should be considered a blockchain.[45][46][47][48][49] Proponents of permissioned or private chains argue that the term «blockchain» may be applied to any data structure that batches data into time-stamped blocks. These blockchains serve as a distributed version of multiversion concurrency control (MVCC) in databases.[50] Just as MVCC prevents two transactions from concurrently modifying a single object in a database, blockchains prevent two transactions from spending the same single output in a blockchain.[51]: 30–31 Opponents say that permissioned systems resemble traditional corporate databases, not supporting decentralized data verification, and that such systems are not hardened against operator tampering and revision.[45][47] Nikolai Hampton of Computerworld said that «many in-house blockchain solutions will be nothing more than cumbersome databases,» and «without a clear security model, proprietary blockchains should be eyed with suspicion.»[9][52]

Permissionless (public) blockchain

An advantage to an open, permissionless, or public, blockchain network is that guarding against bad actors is not required and no access control is needed.[30] This means that applications can be added to the network without the approval or trust of others, using the blockchain as a transport layer.[30]

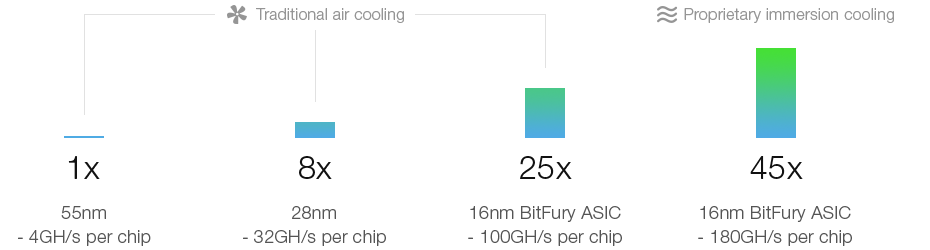

Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies currently secure their blockchain by requiring new entries to include proof of work. To prolong the blockchain, bitcoin uses Hashcash puzzles. While Hashcash was designed in 1997 by Adam Back, the original idea was first proposed by Cynthia Dwork and Moni Naor and Eli Ponyatovski in their 1992 paper «Pricing via Processing or Combatting Junk Mail».

In 2016, venture capital investment for blockchain-related projects was weakening in the USA but increasing in China.[53] Bitcoin and many other cryptocurrencies use open (public) blockchains. As of April 2018, bitcoin has the highest market capitalization.

Permissioned (private) blockchain

Permissioned blockchains use an access control layer to govern who has access to the network.[54] In contrast to public blockchain networks, validators on private blockchain networks are vetted by the network owner. They do not rely on anonymous nodes to validate transactions nor do they benefit from the network effect.[55] Permissioned blockchains can also go by the name of ‘consortium’ blockchains.[56] It has been argued that permissioned blockchains can guarantee a certain level of decentralization, if carefully designed, as opposed to permissionless blockchains, which are often centralized in practice.[10]

Disadvantages of permissioned blockchain

Nikolai Hampton pointed out in Computerworld that «There is also no need for a ’51 percent’ attack on a private blockchain, as the private blockchain (most likely) already controls 100 percent of all block creation resources. If you could attack or damage the blockchain creation tools on a private corporate server, you could effectively control 100 percent of their network and alter transactions however you wished.»[9] This has a set of particularly profound adverse implications during a financial crisis or debt crisis like the financial crisis of 2007–08, where politically powerful actors may make decisions that favor some groups at the expense of others,[57] and «the bitcoin blockchain is protected by the massive group mining effort. It’s unlikely that any private blockchain will try to protect records using gigawatts of computing power — it’s time-consuming and expensive.»[9] He also said, «Within a private blockchain there is also no ‘race’; there’s no incentive to use more power or discover blocks faster than competitors. This means that many in-house blockchain solutions will be nothing more than cumbersome databases.»[9]

Blockchain analysis

The analysis of public blockchains has become increasingly important with the popularity of bitcoin, Ethereum, litecoin and other cryptocurrencies.[58] A blockchain, if it is public, provides anyone who wants access to observe and analyse the chain data, given one has the know-how. The process of understanding and accessing the flow of crypto has been an issue for many cryptocurrencies, crypto exchanges and banks.[59][60] The reason for this is accusations of blockchain-enabled cryptocurrencies enabling illicit dark market trade of drugs, weapons, money laundering, etc.[61] A common belief has been that cryptocurrency is private and untraceable, thus leading many actors to use it for illegal purposes. This is changing and now specialised tech companies provide blockchain tracking services, making crypto exchanges, law-enforcement and banks more aware of what is happening with crypto funds and fiat-crypto exchanges. The development, some argue, has led criminals to prioritise the use of new cryptos such as Monero.[62][63][64] The question is about the public accessibility of blockchain data and the personal privacy of the very same data. It is a key debate in cryptocurrency and ultimately in the blockchain.[65]

Standardisation

In April 2016, Standards Australia submitted a proposal to the International Organization for Standardization to consider developing standards to support blockchain technology. This proposal resulted in the creation of ISO Technical Committee 307, Blockchain and Distributed Ledger Technologies.[66] The technical committee has working groups relating to blockchain terminology, reference architecture, security and privacy, identity, smart contracts, governance and interoperability for blockchain and DLT, as well as standards specific to industry sectors and generic government requirements.[67][non-primary source needed] More than 50 countries are participating in the standardization process together with external liaisons such as the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), the European Commission, the International Federation of Surveyors, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) and the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE).[67]

Many other national standards bodies and open standards bodies are also working on blockchain standards.[68] These include the National Institute of Standards and Technology[69] (NIST), the European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardization[70] (CENELEC), the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers[71] (IEEE), the Organization for the Advancement of Structured Information Standards (OASIS), and some individual participants in the Internet Engineering Task Force[72] (IETF).

Centralized blockchain

Although most of blockchain implementation are decentralized and distributed, Oracle launched a centralized blockchain table feature in Oracle 21c database. The Blockchain Table in Oracle 21c database is a centralized blockchain which provide immutable feature. Compared to decentralized blockchains, centralized blockchains normally can provide a higher throughput and lower latency of transactions than consensus-based distributed blockchains.[73][74]

Types

Currently, there are at least four types of blockchain networks — public blockchains, private blockchains, consortium blockchains and hybrid blockchains.

Public blockchains

A public blockchain has absolutely no access restrictions. Anyone with an Internet connection can send transactions to it as well as become a validator (i.e., participate in the execution of a consensus protocol).[75][self-published source?] Usually, such networks offer economic incentives for those who secure them and utilize some type of a Proof of Stake or Proof of Work algorithm.

Some of the largest, most known public blockchains are the bitcoin blockchain and the Ethereum blockchain.

Private blockchains

A private blockchain is permissioned.[54] One cannot join it unless invited by the network administrators. Participant and validator access is restricted. To distinguish between open blockchains and other peer-to-peer decentralized database applications that are not open ad-hoc compute clusters, the terminology Distributed Ledger (DLT) is normally used for private blockchains.

Hybrid blockchains

A hybrid blockchain has a combination of centralized and decentralized features.[76] The exact workings of the chain can vary based on which portions of centralization and decentralization are used.

Sidechains

A sidechain is a designation for a blockchain ledger that runs in parallel to a primary blockchain.[77][78] Entries from the primary blockchain (where said entries typically represent digital assets) can be linked to and from the sidechain; this allows the sidechain to otherwise operate independently of the primary blockchain (e.g., by using an alternate means of record keeping, alternate consensus algorithm, etc.).[79][better source needed]

Uses

Bitcoin’s transactions are recorded on a publicly viewable blockchain.

Blockchain technology can be integrated into multiple areas. The primary use of blockchains is as a distributed ledger for cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin; there were also a few other operational products that had matured from proof of concept by late 2016.[53] As of 2016, some businesses have been testing the technology and conducting low-level implementation to gauge blockchain’s effects on organizational efficiency in their back office.[80]

In 2019, it was estimated that around $2.9 billion were invested in blockchain technology, which represents an 89% increase from the year prior. Additionally, the International Data Corp has estimated that corporate investment into blockchain technology will reach $12.4 billion by 2022.[81] Furthermore, According to PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), the second-largest professional services network in the world, blockchain technology has the potential to generate an annual business value of more than $3 trillion by 2030. PwC’s estimate is further augmented by a 2018 study that they have conducted, in which PwC surveyed 600 business executives and determined that 84% have at least some exposure to utilizing blockchain technology, which indicates a significant demand and interest in blockchain technology.[82]

In 2019 the BBC World Service radio and podcast series Fifty Things That Made the Modern Economy identified blockchain as a technology that would have far-reaching consequences for economics and society. The economist and Financial Times journalist and broadcaster Tim Harford discussed why the underlying technology might have much wider applications and the challenges that needed to be overcome.[83] First broadcast 29 June 2019.

The number of blockchain wallets quadrupled to 40 million between 2016 and 2020.[84]

A paper published in 2022 discussed the potential use of blockchain technology in sustainable management[85]

Cryptocurrencies

Most cryptocurrencies use blockchain technology to record transactions. For example, the bitcoin network and Ethereum network are both based on blockchain.

The criminal enterprise Silk Road, which operated on Tor, utilized cryptocurrency for payments, some of which the US federal government has seized through research on the blockchain and forfeiture.[86]

Governments have mixed policies on the legality of their citizens or banks owning cryptocurrencies. China implements blockchain technology in several industries including a national digital currency which launched in 2020.[87] To strengthen their respective currencies, Western governments including the European Union and the United States have initiated similar projects.[88]

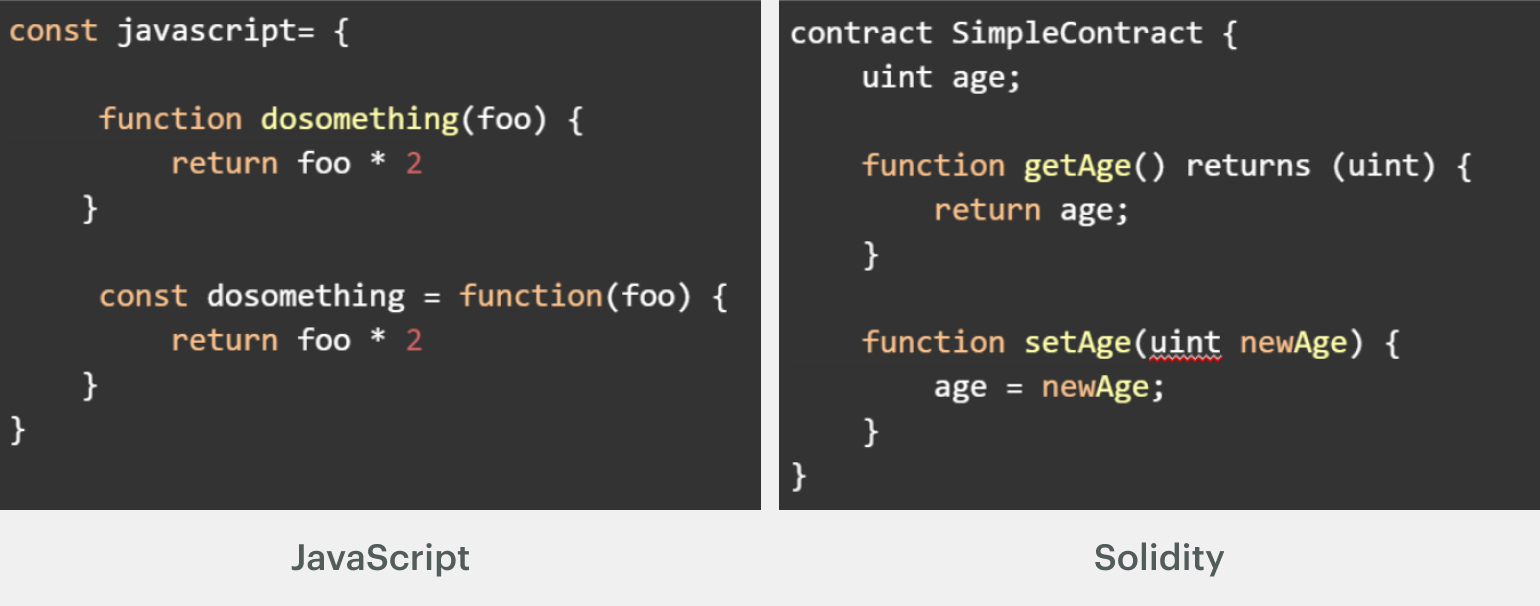

Smart contracts

Blockchain-based smart contracts are proposed contracts that can be partially or fully executed or enforced without human interaction.[89] One of the main objectives of a smart contract is automated escrow. A key feature of smart contracts is that they do not need a trusted third party (such as a trustee) to act as an intermediary between contracting entities — the blockchain network executes the contract on its own. This may reduce friction between entities when transferring value and could subsequently open the door to a higher level of transaction automation.[90] An IMF staff discussion from 2018 reported that smart contracts based on blockchain technology might reduce moral hazards and optimize the use of contracts in general. But «no viable smart contract systems have yet emerged.» Due to the lack of widespread use their legal status was unclear.[91][92]

Financial services

According to Reason, many banks have expressed interest in implementing distributed ledgers for use in banking and are cooperating with companies creating private blockchains,[93][94][95] and according to a September 2016 IBM study, this is occurring faster than expected.[96]

Banks are interested in this technology not least because it has the potential to speed up back office settlement systems.[97] Moreover, as the blockchain industry has reached early maturity institutional appreciation has grown that it is, practically speaking, the infrastructure of a whole new financial industry, with all the implications which that entails.[98]

Banks such as UBS are opening new research labs dedicated to blockchain technology in order to explore how blockchain can be used in financial services to increase efficiency and reduce costs.[99][100]

Berenberg, a German bank, believes that blockchain is an «overhyped technology» that has had a large number of «proofs of concept», but still has major challenges, and very few success stories.[101]

The blockchain has also given rise to initial coin offerings (ICOs) as well as a new category of digital asset called security token offerings (STOs), also sometimes referred to as digital security offerings (DSOs).[102] STO/DSOs may be conducted privately or on public, regulated stock exchange and are used to tokenize traditional assets such as company shares as well as more innovative ones like intellectual property, real estate,[103] art, or individual products. A number of companies are active in this space providing services for compliant tokenization, private STOs, and public STOs.

Games

Blockchain technology, such as cryptocurrencies and non-fungible tokens (NFTs), has been used in video games for monetization. Many live-service games offer in-game customization options, such as character skins or other in-game items, which the players can earn and trade with other players using in-game currency. Some games also allow for trading of virtual items using real-world currency, but this may be illegal in some countries where video games are seen as akin to gambling, and has led to gray market issues such as skin gambling, and thus publishers typically have shied away from allowing players to earn real-world funds from games.[104] Blockchain games typically allow players to trade these in-game items for cryptocurrency, which can then be exchanged for money.[105]

The first known game to use blockchain technologies was CryptoKitties, launched in November 2017, where the player would purchase NFTs with Ethereum cryptocurrency, each NFT consisting of a virtual pet that the player could breed with others to create offspring with combined traits as new NFTs.[106][105] The game made headlines in December 2017 when one virtual pet sold for more than US$100,000.[107] CryptoKitties also illustrated scalability problems for games on Ethereum when it created significant congestion on the Ethereum network in early 2018 with approximately 30% of all Ethereum transactions[clarification needed] being for the game.[108][109]

By the early 2020s, there had not been a breakout success in video games using blockchain, as these games tend to focus on using blockchain for speculation instead of more traditional forms of gameplay, which offers limited appeal to most players. Such games also represent a high risk to investors as their revenues can be difficult to predict.[105] However, limited successes of some games, such as Axie Infinity during the COVID-19 pandemic, and corporate plans towards metaverse content, refueled interest in the area of GameFi, a term describing the intersection of video games and financing typically backed by blockchain currency, in the second half of 2021.[110] Several major publishers, including Ubisoft, Electronic Arts, and Take Two Interactive, have stated that blockchain and NFT-based games are under serious consideration for their companies in the future.[111]

In October 2021, Valve Corporation banned blockchain games, including those using cryptocurrency and NFTs, from being hosted on its Steam digital storefront service, which is widely used for personal computer gaming, claiming that this was an extension of their policy banning games that offered in-game items with real-world value. Valve’s prior history with gambling, specifically skin gambling, was speculated to be a factor in the decision to ban blockchain games.[112] Journalists and players responded positively to Valve’s decision as blockchain and NFT games have a reputation for scams and fraud among most PC gamers,[104][112] Epic Games, which runs the Epic Games Store in competition to Steam, said that they would be open to accepted blockchain games, in the wake of Valve’s refusal.[113]

Supply chain

There have been several different efforts to employ blockchains in supply chain management.

- Shipping industry — Incumbent shipping companies and startups have begun to leverage blockchain technology to facilitate the emergence of a blockchain-based platform ecosystem that would create value across the global shipping supply chains.[114]

- Precious commodities mining — Blockchain technology has been used for tracking the origins of gemstones and other precious commodities. In 2016, The Wall Street Journal reported that the blockchain technology company Everledger was partnering with IBM’s blockchain-based tracking service to trace the origin of diamonds to ensure that they were ethically mined.[115] As of 2019, the Diamond Trading Company (DTC) has been involved in building a diamond trading supply chain product called Tracr.[116]

- Food supply — As of 2018, Walmart and IBM were running a trial to use a blockchain-backed system for supply chain monitoring for lettuce and spinach — all nodes of the blockchain were administered by Walmart and were located on the IBM cloud.[117]

- Fashion industry — There is an opaque relationship between brands, distributors, and customers in the fashion industry, which will prevent the sustainable and stable development of the fashion industry. Blockchain makes up for this shortcoming and makes information transparent, solving the difficulty of sustainable development of the industry.[118]

Domain names

There are several different efforts to offer domain name services via the blockchain. These domain names can be controlled by the use of a private key, which purports to allow for uncensorable websites. This would also bypass a registrar’s ability to suppress domains used for fraud, abuse, or illegal content.[119]

Namecoin is a cryptocurrency that supports the «.bit» top-level domain (TLD). Namecoin was forked from bitcoin in 2011. The .bit TLD is not sanctioned by ICANN, instead requiring an alternative DNS root.[119] As of 2015, it was used by 28 websites, out of 120,000 registered names.[120] Namecoin was dropped by OpenNIC in 2019, due to malware and potential other legal issues.[121] Other blockchain alternatives to ICANN include The Handshake Network,[120] EmerDNS, and Unstoppable Domains.[119]

Specific TLDs include «.eth», «.luxe», and «.kred», which are associated with the Ethereum blockchain through the Ethereum Name Service (ENS). The .kred TLD also acts as an alternative to conventional cryptocurrency wallet addresses, as a convenience for transferring cryptocurrency.[122]

Other uses

Blockchain technology can be used to create a permanent, public, transparent ledger system for compiling data on sales, tracking digital use and payments to content creators, such as wireless users[123] or musicians.[124] The Gartner 2019 CIO Survey reported 2% of higher education respondents had launched blockchain projects and another 18% were planning academic projects in the next 24 months.[125] In 2017, IBM partnered with ASCAP and PRS for Music to adopt blockchain technology in music distribution.[126] Imogen Heap’s Mycelia service has also been proposed as a blockchain-based alternative «that gives artists more control over how their songs and associated data circulate among fans and other musicians.»[127][128]

New distribution methods are available for the insurance industry such as peer-to-peer insurance, parametric insurance and microinsurance following the adoption of blockchain.[129][130] The sharing economy and IoT are also set to benefit from blockchains because they involve many collaborating peers.[131] The use of blockchain in libraries is being studied with a grant from the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services.[132]

Other blockchain designs include Hyperledger, a collaborative effort from the Linux Foundation to support blockchain-based distributed ledgers, with projects under this initiative including Hyperledger Burrow (by Monax) and Hyperledger Fabric (spearheaded by IBM).[133][134][135] Another is Quorum, a permissionable private blockchain by JPMorgan Chase with private storage, used for contract applications.[136]

Oracle introduced a blockchain table feature in its Oracle 21c database.[73][74]

Blockchain is also being used in peer-to-peer energy trading.[137][138][139]

Blockchain could be used in detecting counterfeits by associating unique identifiers to products, documents and shipments, and storing records associated with transactions that cannot be forged or altered.[140][141] It is however argued that blockchain technology needs to be supplemented with technologies that provide a strong binding between physical objects and blockchain systems.[142] The EUIPO established an Anti-Counterfeiting Blockathon Forum, with the objective of «defining, piloting and implementing» an anti-counterfeiting infrastructure at the European level.[143][144] The Dutch Standardisation organisation NEN uses blockchain together with QR Codes to authenticate certificates.[145]

2022 Jan 30 Beijing and Shanghai are among the cities designated by China to trial blockchain applications.[146]

Blockchain interoperability

With the increasing number of blockchain systems appearing, even only those that support cryptocurrencies, blockchain interoperability is becoming a topic of major importance. The objective is to support transferring assets from one blockchain system to another blockchain system. Wegner[147] stated that «interoperability is the ability of two or more software components to cooperate despite differences in language, interface, and execution platform». The objective of blockchain interoperability is therefore to support such cooperation among blockchain systems, despite those kinds of differences.

There are already several blockchain interoperability solutions available.[148] They can be classified into three categories: cryptocurrency interoperability approaches, blockchain engines, and blockchain connectors.

Several individual IETF participants produced the draft of a blockchain interoperability architecture.[149]

Energy consumption concerns

Some cryptocurrencies use blockchain mining — the peer-to-peer computer computations by which transactions are validated and verified. This requires a large amount of energy. In June 2018 the Bank for International Settlements criticized the use of public proof-of-work blockchains for their high energy consumption.[150][151][152]

Early concern over the high energy consumption was a factor in later blockchains such as Cardano (2017), Solana (2020) and Polkadot (2020) adopting the less energy-intensive proof-of-stake model. Researchers have estimated that Bitcoin consumes 100,000 times as much energy as proof-of-stake networks.[153][154]

In 2021, a study by Cambridge University determined that Bitcoin (at 121 terawatt-hours per year) used more electricity than Argentina (at 121TWh) and the Netherlands (109TWh).[155] According to Digiconomist, one bitcoin transaction required 708 kilowatt-hours of electrical energy, the amount an average U.S. household consumed in 24 days.[156]

In February 2021, U.S. Treasury secretary Janet Yellen called Bitcoin «an extremely inefficient way to conduct transactions», saying «the amount of energy consumed in processing those transactions is staggering».[157] In March 2021, Bill Gates stated that «Bitcoin uses more electricity per transaction than any other method known to mankind», adding «It’s not a great climate thing.»[158]

Nicholas Weaver, of the International Computer Science Institute at the University of California, Berkeley, examined blockchain’s online security, and the energy efficiency of proof-of-work public blockchains, and in both cases found it grossly inadequate.[159][160] The 31TWh-45TWh of electricity used for bitcoin in 2018 produced 17-23 million tonnes of CO2.[161][162] By 2022, the University of Cambridge and Digiconomist estimated that the two largest proof-of-work blockchains, Bitcoin and Ethereum, together used twice as much electricity in one year as the whole of Sweden, leading to the release of up to 120 million tonnes of CO2 each year.[163]

Some cryptocurrency developers are considering moving from the proof-of-work model to the proof-of-stake model.[164]

Academic research

In October 2014, the MIT Bitcoin Club, with funding from MIT alumni, provided undergraduate students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology access to $100 of bitcoin. The adoption rates, as studied by Catalini and Tucker (2016), revealed that when people who typically adopt technologies early are given delayed access, they tend to reject the technology.[165] Many universities have founded departments focusing on crypto and blockchain, including MIT, in 2017. In the same year, Edinburgh became «one of the first big European universities to launch a blockchain course», according to the Financial Times.[166]

Adoption decision

Motivations for adopting blockchain technology (an aspect of innovation adoptation) have been investigated by researchers. For example, Janssen, et al. provided a framework for analysis,[167] and Koens & Poll pointed out that adoption could be heavily driven by non-technical factors.[168] Based on behavioral models, Li[169] has discussed the differences between adoption at the individual level and organizational levels.

Collaboration

Scholars in business and management have started studying the role of blockchains to support collaboration.[170][171] It has been argued that blockchains can foster both cooperation (i.e., prevention of opportunistic behavior) and coordination (i.e., communication and information sharing). Thanks to reliability, transparency, traceability of records, and information immutability, blockchains facilitate collaboration in a way that differs both from the traditional use of contracts and from relational norms. Contrary to contracts, blockchains do not directly rely on the legal system to enforce agreements.[172] In addition, contrary to the use of relational norms, blockchains do not require a trust or direct connections between collaborators.

Blockchain and internal audit

| External video |

|---|

The need for internal audits to provide effective oversight of organizational efficiency will require a change in the way that information is accessed in new formats.[174] Blockchain adoption requires a framework to identify the risk of exposure associated with transactions using blockchain. The Institute of Internal Auditors has identified the need for internal auditors to address this transformational technology. New methods are required to develop audit plans that identify threats and risks. The Internal Audit Foundation study, Blockchain and Internal Audit, assesses these factors.[175] The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants has outlined new roles for auditors as a result of blockchain.[176]

Journals

In September 2015, the first peer-reviewed academic journal dedicated to cryptocurrency and blockchain technology research, Ledger, was announced. The inaugural issue was published in December 2016.[177] The journal covers aspects of mathematics, computer science, engineering, law, economics and philosophy that relate to cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin.[178][179]

The journal encourages authors to digitally sign a file hash of submitted papers, which are then timestamped into the bitcoin blockchain. Authors are also asked to include a personal bitcoin address on the first page of their papers for non-repudiation purposes.[180]

See also

- Changelog – a record of all notable changes made to a project

- Checklist – an informational aid used to reduce failure

- Economics of digitization

- Privacy and blockchain

- Version control – a record of all changes (mostly of software project) in a form of a graph

References

- ^ Morris, David Z. (15 May 2016). «Leaderless, Blockchain-Based Venture Capital Fund Raises $100 Million, And Counting». Fortune. Archived from the original on 21 May 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ a b Popper, Nathan (21 May 2016). «A Venture Fund With Plenty of Virtual Capital, but No Capitalist». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i «Blockchains: The great chain of being sure about things». The Economist. 31 October 2015. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

The technology behind bitcoin lets people who do not know or trust each other build a dependable ledger. This has implications far beyond the crypto currency.

- ^ a b c d e Narayanan, Arvind; Bonneau, Joseph; Felten, Edward; Miller, Andrew; Goldfeder, Steven (2016). Bitcoin and cryptocurrency technologies: a comprehensive introduction. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-17169-2.

- ^ Iansiti, Marco; Lakhani, Karim R. (January 2017). «The Truth About Blockchain». Harvard Business Review. Harvard University. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

The technology at the heart of bitcoin and other virtual currencies, blockchain is an open, distributed ledger that can record transactions between two parties efficiently and in a verifiable and permanent way.

- ^ Satoshi Nakamoto (October 2008). «Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System» (PDF). Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ «The World’s Oldest Blockchain Has Been Hiding in the New York Times Since 1995». www.vice.com. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ «Blockchain may finally disrupt payments from Micropayments to credit cards to SWIFT». dailyfintech.com. 10 February 2018. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Hampton, Nikolai (5 September 2016). «Understanding the blockchain hype: Why much of it is nothing more than snake oil and spin». Computerworld. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ a b Bakos, Yannis; Halaburda, Hanna; Mueller-Bloch, Christoph (February 2021). «When Permissioned Blockchains Deliver More Decentralization Than Permissionless». Communications of the ACM. 64 (2): 20–22. doi:10.1145/3442371. S2CID 231704491.

- ^ Sherman, Alan T.; Javani, Farid; Zhang, Haibin; Golaszewski, Enis (January 2019). «On the Origins and Variations of Blockchain Technologies». IEEE Security Privacy. 17 (1): 72–77. arXiv:1810.06130. doi:10.1109/MSEC.2019.2893730. ISSN 1558-4046. S2CID 53114747.

- ^ Haber, Stuart; Stornetta, W. Scott (January 1991). «How to time-stamp a digital document». Journal of Cryptology. 3 (2): 99–111. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.46.8740. doi:10.1007/bf00196791. S2CID 14363020.

- ^ Bayer, Dave; Haber, Stuart; Stornetta, W. Scott (March 1992). Improving the Efficiency and Reliability of Digital Time-Stamping. Sequences. Vol. 2. pp. 329–334. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.71.4891. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-9323-8_24. ISBN 978-1-4613-9325-2.

- ^ Oberhaus, Daniel (27 August 2018). «The World’s Oldest Blockchain Has Been Hiding in the New York Times Since 1995». www.vice.com. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ Nian, Lam Pak; Chuen, David LEE Kuo (2015). «A Light Touch of Regulation for Virtual Currencies». In Chuen, David LEE Kuo (ed.). Handbook of Digital Currency: Bitcoin, Innovation, Financial Instruments, and Big Data. Academic Press. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-12-802351-8.

- ^ «Blockchain Size». Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ Johnsen, Maria (12 May 2020). Blockchain in Digital Marketing: A New Paradigm of Trust. Maria Johnsen. p. 6. ISBN 979-8-6448-7308-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «The future of blockchain in 8 charts». Raconteur. 27 June 2016. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ «Hype Killer — Only 1% of Companies Are Using Blockchain, Gartner Reports | Artificial Lawyer». Artificial Lawyer. 4 May 2018. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ Kasey Panetta. (31 October 2018). «Digital Business: CIO Agenda 2019: Exploit Transformational Technologies.» Gartner website Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Armstrong, Stephen (7 November 2016). «Move over Bitcoin, the blockchain is only just getting started». Wired. Archived from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ^ Catalini, Christian; Gans, Joshua S. (23 November 2016). «Some Simple Economics of the Blockchain» (PDF). SSRN. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2874598. hdl:1721.1/130500. S2CID 46904163. SSRN 2874598. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- ^ Tapscott, Don; Tapscott, Alex (8 May 2016). «Here’s Why Blockchains Will Change the World». Fortune. Archived from the original on 13 November 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ Bheemaiah, Kariappa (January 2015). «Block Chain 2.0: The Renaissance of Money». Wired. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ Chen, Huashan; Pendleton, Marcus; Njilla, Laurent; Xu, Shouhuai (12 June 2020). «A Survey on Ethereum Systems Security: Vulnerabilities, Attacks, and Defenses». ACM Computing Surveys. 53 (3): 3–4. arXiv:1908.04507. doi:10.1145/3391195. ISSN 0360-0300. S2CID 199551841.

- ^ Shishir, Bhatia (2 February 2006). Structured Information Flow (SIF) Framework for Automating End-to-End Information Flow for Large Organizations (Thesis). Virginia Tech.

- ^ «Genesis Block Definition». Investopedia. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d Bhaskar, Nirupama Devi; Chuen, David LEE Kuo (2015). «Bitcoin Mining Technology». Handbook of Digital Currency. pp. 45–65. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-802117-0.00003-5. ISBN 978-0-12-802117-0.

- ^ Knirsch, Unterweger & Engel 2019, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Antonopoulos, Andreas (20 February 2014). «Bitcoin security model: trust by computation». Radar. O’Reilly. Archived from the original on 31 October 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ a b Antonopoulos, Andreas M. (2014). Mastering Bitcoin. Unlocking Digital Cryptocurrencies. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media. ISBN 978-1449374037. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ^ Nakamoto, Satoshi (October 2008). «Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System» (PDF). bitcoin.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ «Permissioned Blockchains». Explainer. Monax. Archived from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ Kumar, Randhir; Tripathi, Rakesh (November 2019). «Implementation of Distributed File Storage and Access Framework using IPFS and Blockchain». 2019 Fifth International Conference on Image Information Processing (ICIIP). IEEE: 246–251. doi:10.1109/iciip47207.2019.8985677. ISBN 978-1-7281-0899-5. S2CID 211119043.

- ^ Lee, Timothy (12 March 2013). «Major glitch in Bitcoin network sparks sell-off; price temporarily falls 23%». Arstechnica. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Smith, Oli (21 January 2018). «Bitcoin price RIVAL: Cryptocurrency ‘faster than bitcoin’ will CHALLENGE market leaders». Express. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ «Bitcoin split in two, here’s what that means». CNN. 1 August 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Hughes, Laurie; Dwivedi, Yogesh K.; Misra, Santosh K.; Rana, Nripendra P.; Raghavan, Vishnupriya; Akella, Viswanadh (December 2019). «Blockchain research, practice and policy: Applications, benefits, limitations, emerging research themes and research agenda». International Journal of Information Management. 49: 114–129. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.02.005. hdl:10454/17473. S2CID 116666889.

- ^ Roberts, Jeff John (29 May 2018). «Bitcoin Spinoff Hacked in Rare ‘51% Attack’«. Fortune. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ^ a b Brito, Jerry; Castillo, Andrea (2013). Bitcoin: A Primer for Policymakers (PDF) (Report). Fairfax, VA: Mercatus Center, George Mason University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ Raval, Siraj (2016). Decentralized Applications: Harnessing Bitcoin’s Blockchain Technology. O’Reilly Media, Inc. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-1-4919-2452-5.

- ^ Kopfstein, Janus (12 December 2013). «The Mission to Decentralize the Internet». The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

The network’s ‘nodes’ — users running the bitcoin software on their computers — collectively check the integrity of other nodes to ensure that no one spends the same coins twice. All transactions are published on a shared public ledger, called the ‘block chain.’

- ^ Gervais, Arthur; Karame, Ghassan O.; Capkun, Vedran; Capkun, Srdjan. «Is Bitcoin a Decentralized Currency?». InfoQ. InfoQ & IEEE computer society. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^ a b c Deirmentzoglou, Evangelos; Papakyriakopoulos, Georgios; Patsakis, Constantinos (2019). «A Survey on Long-Range Attacks for Proof of Stake Protocols». IEEE Access. 7: 28712–28725. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2901858. eISSN 2169-3536. S2CID 84185792.

- ^ a b Voorhees, Erik (30 October 2015). «It’s All About the Blockchain». Money and State. Archived from the original on 1 November 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ Reutzel, Bailey (13 July 2015). «A Very Public Conflict Over Private Blockchains». PaymentsSource. New York, NY: SourceMedia, Inc. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ a b Casey MJ (15 April 2015). «Moneybeat/BitBeat: Blockchains Without Coins Stir Tensions in Bitcoin Community». The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ «The ‘Blockchain Technology’ Bandwagon Has A Lesson Left To Learn». dinbits.com. 3 November 2015. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ DeRose, Chris (26 June 2015). «Why the Bitcoin Blockchain Beats Out Competitors». American Banker. Archived from the original on 30 March 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Greenspan, Gideon (19 July 2015). «Ending the bitcoin vs blockchain debate». multichain.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Tapscott, Don; Tapscott, Alex (May 2016). The Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology Behind Bitcoin is Changing Money, Business, and the World. ISBN 978-0-670-06997-2.

- ^ Barry, Levine (11 June 2018). «A new report bursts the blockchain bubble». MarTech. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ a b Ovenden, James. «Blockchain Top Trends In 2017». The Innovation Enterprise. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ a b Bob Marvin (30 August 2017). «Blockchain: The Invisible Technology That’s Changing the World». PC MAG Australia. ZiffDavis, LLC. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ Prisco, Giulio. «Sandia National Laboratories Joins the War on Bitcoin Anonymity». Bitcoin Magazine: Bitcoin News, Articles, Charts, and Guides. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ «Blockchains & Distributed Ledger Technologies». BlockchainHub. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ O’Keeffe, M.; Terzi, A. (7 July 2015). «The political economy of financial crisis policy». Bruegel. Archived from the original on 19 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Dr Garrick Hileman & Michel Rauchs (2017). «GLOBAL CRYPTOCURRENCY BENCHMARKING STUDY» (PDF). Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance. University of Cambridge Judge Business School. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019 – via crowdfundinsider.

- ^ Raymaekers, Wim (March 2015). «Cryptocurrency Bitcoin: Disruption, challenges and opportunities». Journal of Payments Strategy & Systems. 9 (1): 30–46. Archived from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ «Why Crypto Companies Still Can’t Open Checking Accounts». 3 March 2019. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ Christian Brenig, Rafael Accorsi & Günter Müller (Spring 2015). «Economic Analysis of Cryptocurrency Backed Money Laundering». Association for Information Systems AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Greenberg, Andy (25 January 2017). «Monero, the Drug Dealer’s Cryptocurrency of Choice, Is on Fire». Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on 10 December 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Orcutt, Mike. «It’s getting harder to hide money in Bitcoin». MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ «Explainer: ‘Privacy coin’ Monero offers near total anonymity». Reuters. 15 May 2019. Archived from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ «An Untraceable Currency? Bitcoin Privacy Concerns — FinTech Weekly». FinTech Magazine Article. 7 April 2018. Archived from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ «Blockchain». standards.org.au. Standards Australia. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ a b «ISO/TC 307 Blockchain and distributed ledger technologies». iso.org. ISO. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ Deshmukh, Sumedha; Boulais, Océane; Koens, Tommy. «Global Standards Mapping Initiative: An overview of blockchain technical standards» (PDF). weforum.org. World Economic Forum. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ «Blockchain Overview». NIST. 25 September 2019. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ «CEN and CENELEC publish a White Paper on standards in Blockchain & Distributed Ledger Technologies». cencenelec.eu. CENELEC. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ «Standards». ieee.org. IEEE Blockchain. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ Hardjono, Thomas. «An Interoperability Architecture for Blockchain/DLT Gateways». ietf.org. IETF. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ a b «Details: Oracle Blockchain Table». Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ a b «Oracle Blockchain Table». Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ «How Companies Can Leverage Private Blockchains to Improve Efficiency and Streamline Business Processes». Perfectial.

- ^ [Distributed Ledger Technology: Hybrid Approach, Front-to-Back Designing and Changing Trade Processing Infrastructure, By Martin Walker, First published:, 24 OCT 2018 ISBN 978-1-78272-389-9]

- ^ Siraj Raval (18 July 2016). Decentralized Applications: Harnessing Bitcoin’s Blockchain Technology. «O’Reilly Media, Inc.». pp. 22–. ISBN 978-1-4919-2452-5.

- ^ Niaz Chowdhury (16 August 2019). Inside Blockchain, Bitcoin, and Cryptocurrencies. CRC Press. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-1-00-050770-6.

- ^ U.S. Patent 10,438,290

- ^ Katie Martin (27 September 2016). «CLS dips into blockchain to net new currencies». Financial Times. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Castillo, Michael (16 April 2019). «blockchain 50: Billion Dollar Babies». Financial Website. SourceMedia. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ Davies, Steve (2018). «PwC’s Global Blockchain Survey». Financial Website. SourceMedia. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ «BBC Radio 4 — Things That Made the Modern Economy, Series 2, Blockchain». BBC. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ Liu, Shanhong (13 March 2020). «Blockchain — Statistics & Facts». Statistics Website. SourceMedia. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ Du, Wenbo; Ma, Xiaozhi; Yuan, Hongping; Zhu, Yue (1 August 2022). «Blockchain technology-based sustainable management research: the status quo and a general framework for future application». Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 29 (39): 58648–58663. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-21761-2. ISSN 1614-7499. PMC 9261142. PMID 35794327.

- ^ KPIX-TV. (5 November 2020). «Silk Road: Feds Seize $1 Billion In Bitcoins Linked To Infamous Silk Road Dark Web Case; ‘Where Did The Money Go'». KPIX website[permanent dead link] Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Aditi Kumar and Eric Rosenbach. (20 May 2020). «Could China’s Digital Currency Unseat the Dollar?: American Economic and Geopolitical Power Is at Stake». Foreign Affairs website Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Staff. (16 February 2021). «The Economist Explains: What is the fuss over central-bank digital currencies?» The Economist website Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Franco, Pedro (2014). Understanding Bitcoin: Cryptography, Engineering and Economics. John Wiley & Sons. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-119-01916-9. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Casey M (16 July 2018). The impact of blockchain technology on finance : a catalyst for change. London, UK. ISBN 978-1-912179-15-2. OCLC 1059331326.

- ^ Governatori, Guido; Idelberger, Florian; Milosevic, Zoran; Riveret, Regis; Sartor, Giovanni; Xu, Xiwei (2018). «On legal contracts, imperative and declarative smart contracts, and blockchain systems». Artificial Intelligence and Law. 26 (4): 33. doi:10.1007/s10506-018-9223-3. S2CID 3663005.

- ^ Virtual Currencies and Beyond: Initial Considerations (PDF). IMF Discussion Note. International Monetary Fund. 2016. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-5135-5297-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ Epstein, Jim (6 May 2016). «Is Blockchain Technology a Trojan Horse Behind Wall Street’s Walled Garden?». Reason. Archived from the original on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

mainstream misgivings about working with a system that’s open for anyone to use. Many banks are partnering with companies building so-called private blockchains that mimic some aspects of Bitcoin’s architecture except they’re designed to be closed off and accessible only to chosen parties. … [but some believe] that open and permission-less blockchains will ultimately prevail even in the banking sector simply because they’re more efficient.

- ^ Redrup, Yolanda (29 June 2016). «ANZ backs private blockchain, but won’t go public». Australia Financial Review. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

Blockchain networks can be either public or private. Public blockchains have many users and there are no controls over who can read, upload or delete the data and there are an unknown number of pseudonymous participants. In comparison, private blockchains also have multiple data sets, but there are controls in place over who can edit data and there are a known number of participants.

- ^ Shah, Rakesh (1 March 2018). «How Can The Banking Sector Leverage Blockchain Technology?». PostBox Communications. PostBox Communications Blog. Archived from the original on 17 March 2018.

Banks preferably have a notable interest in utilizing Blockchain Technology because it is a great source to avoid fraudulent transactions. Blockchain is considered hassle free, because of the extra level of security it offers.

- ^ Kelly, Jemima (28 September 2016). «Banks adopting blockchain ‘dramatically faster’ than expected: IBM». Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 September 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ Arnold, Martin (23 September 2013). «IBM in blockchain project with China UnionPay». Financial Times. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Ravichandran, Arvind; Fargo, Christopher; Kappos, David; Portilla, David; Buretta, John; Ngo, Minh Van; Rosenthal-Larrea, Sasha (28 January 2022). «Blockchain in the Banking Sector: A Review of the Landscape and Opportunities».

- ^ «UBS leads team of banks working on blockchain settlement system». Reuters. 24 August 2016. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ «Cryptocurrency Blockchain». capgemini.com. Archived from the original on 5 December 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ Kelly, Jemima (31 October 2017). «Top banks and R3 build blockchain-based payments system». Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ «Are Token Assests the Securities of Tomorrow?» (PDF). Deloitte. February 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- ^ Hammerberg, Jeff (7 November 2021). «Potential impact of blockchain on real estate». Washington Blade.

- ^ a b Clark, Mitchell (15 October 2021). «Valve bans blockchain games and NFTs on Steam, Epic will try to make it work». The Verge. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Mozuch, Mo (29 April 2021). «Blockchain Games Twist The Fundamentals Of Online Gaming». Inverse. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ «Internet firms try their luck at blockchain games». Asia Times. 22 February 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Evelyn Cheng (6 December 2017). «Meet CryptoKitties, the $100,000 digital beanie babies epitomizing the cryptocurrency mania». CNBC. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Laignee Barron (13 February 2018). «CryptoKitties is Going Mobile. Can Ethereum Handle the Traffic?». Fortune. Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ «CryptoKitties craze slows down transactions on Ethereum». 12 May 2017. Archived from the original on 12 January 2018.

- ^ Wells, Charlie; Egkolfopoulou, Misrylena (30 October 2021). «Into the Metaverse: Where Crypto, Gaming and Capitalism Collide». Bloomberg News. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Orland, Kyle (4 November 2021). «Big-name publishers see NFTs as a big part of gaming’s future». Ars Technica. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ a b Knoop, Joseph (15 October 2021). «Steam bans all games with NFTs or cryptocurrency». PC Gamer. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ Clark, Mitchell (15 October 2021). «Epic says it’s ‘open’ to blockchain games after Steam bans them». The Verge. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Jovanovic, Marin; Kostić, Nikola; Sebastian, Ina; Sedej, Tomaz (2022). «Managing a blockchain-based platform ecosystem for industry-wide adoption: The case of TradeLens». Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 184: 121981. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121981. ISSN 0040-1625. S2CID 252185296.

- ^ Nash, Kim S. (14 July 2016). «IBM Pushes Blockchain into the Supply Chain». The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 18 July 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ^ Gstettner, Stefan (30 July 2019). «How Blockchain Will Redefine Supply Chain Management». Knowledge@Wharton. The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ^ Corkery, Michael; Popper, Nathaniel (24 September 2018). «From Farm to Blockchain: Walmart Tracks Its Lettuce». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ «Blockchain basics: Utilizing blockchain to improve sustainable supply chains in fashion». Strategic Direction. 37 (5): 25–27. 8 June 2021. doi:10.1108/SD-03-2021-0028. ISSN 0258-0543. S2CID 241322151.

- ^ a b c Sanders, James; August 28 (28 August 2019). «Blockchain-based Unstoppable Domains is a rehash of a failed idea». TechRepublic. Archived from the original on 19 November 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ a b Orcutt, Mike (4 June 2019). «The ambitious plan to reinvent how websites get their names». MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Cimpanu, Catalin (17 July 2019). «OpenNIC drops support for .bit domain names after rampant malware abuse». ZDNet. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ «.Kred launches as dual DNS and ENS domain». Domain Name Wire | Domain Name News. 6 March 2020. Archived from the original on 8 March 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ K. Kotobi, and S. G. Bilen, «Secure Blockchains for Dynamic Spectrum Access : A Decentralized Database in Moving Cognitive Radio Networks Enhances Security and User Access», IEEE Vehicular Technology Magazine, 2018.

- ^ «Blockchain Could Be Music’s Next Disruptor». 22 September 2016. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016.

- ^ Susan Moore. (16 October 2019). «Digital Business: 4 Ways Blockchain Will Transform Higher Education». Gartner website Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ «ASCAP, PRS and SACEM Join Forces for Blockchain Copyright System». Music Business Worldwide. 9 April 2017. Archived from the original on 10 April 2017.

- ^ Burchardi, K.; Harle, N. (20 January 2018). «The blockchain will disrupt the music business and beyond». Wired UK. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Bartlett, Jamie (6 September 2015). «Imogen Heap: saviour of the music industry?». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Wang, Kevin; Safavi, Ali (29 October 2016). «Blockchain is empowering the future of insurance». Tech Crunch. AOL Inc. Archived from the original on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Gatteschi, Valentina; Lamberti, Fabrizio; Demartini, Claudio; Pranteda, Chiara; Santamaría, Víctor (20 February 2018). «Blockchain and Smart Contracts for Insurance: Is the Technology Mature Enough?». Future Internet. 10 (2): 20. doi:10.3390/fi10020020.

- ^ «Blockchain reaction: Tech companies plan for critical mass» (PDF). Ernst & Young. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ^ Carrie Smith. Blockchain Reaction: How library professionals are approaching blockchain technology and its potential impact. Archived 12 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine American Libraries March 2019.

- ^ «IBM Blockchain based on Hyperledger Fabric from the Linux Foundation». IBM.com. 9 January 2018. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ^ Hyperledger (22 January 2019). «Announcing Hyperledger Grid, a new project to help build and deliver supply chain solutions!». Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Mearian, Lucas (23 January 2019). «Grid, a new project from the Linux Foundation, will offer developers tools to create supply chain-specific applications running atop distributed ledger technology». Computerworld. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ «Why J.P. Morgan Chase Is Building a Blockchain on Ethereum». Fortune. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ Andoni, Merlinda; Robu, Valentin; Flynn, David; Abram, Simone; Geach, Dale; Jenkins, David; McCallum, Peter; Peacock, Andrew (2019). «Blockchain technology in the energy sector: A systematic review of challenges and opportunities». Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 100: 143–174. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2018.10.014. S2CID 116422191. Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ «This Blockchain-Based Energy Platform Is Building A Peer-To-Peer Grid». 16 October 2017. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ «Blockchain-based microgrid gives power to consumers in New York». Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Ma, Jinhua; Lin, Shih-Ya; Chen, Xin; Sun, Hung-Min; Chen, Yeh-Cheng; Wang, Huaxiong (2020). «A Blockchain-Based Application System for Product Anti-Counterfeiting». IEEE Access. 8: 77642–77652. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2972026. ISSN 2169-3536. S2CID 214205788.

- ^ Alzahrani, Naif; Bulusu, Nirupama (15 June 2018). «Block-Supply Chain: A New Anti-Counterfeiting Supply Chain Using NFC and Blockchain». Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Cryptocurrencies and Blockchains for Distributed Systems. CryBlock’18. Munich, Germany: Association for Computing Machinery: 30–35. doi:10.1145/3211933.3211939. ISBN 978-1-4503-5838-5. S2CID 169188795.

- ^ Balagurusamy, V. S. K.; Cabral, C.; Coomaraswamy, S.; Delamarche, E.; Dillenberger, D. N.; Dittmann, G.; Friedman, D.; Gökçe, O.; Hinds, N.; Jelitto, J.; Kind, A. (1 March 2019). «Crypto anchors». IBM Journal of Research and Development. 63 (2/3): 4:1–4:12. doi:10.1147/JRD.2019.2900651. ISSN 0018-8646. S2CID 201109790.

- ^ Brett, Charles (18 April 2018). «EUIPO Blockathon Challenge 2018 -«. Enterprise Times. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ «EUIPO Anti-Counterfeiting Blockathon Forum».

- ^ «PT Industrieel Management». PT Industrieel Management. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ «China selects pilot zones, application areas for blockchain project». Reuters. 31 January 2022.

- ^ Wegner, Peter (March 1996). «Interoperability». ACM Computing Surveys. 28: 285–287. doi:10.1145/234313.234424. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ Belchior, Rafael; Vasconcelos, André; Guerreiro, Sérgio; Correia, Miguel (May 2020). «A Survey on Blockchain Interoperability: Past, Present, and Future Trends». arXiv:2005.14282 [cs.DC].

- ^ Hardjono, T.; Hargreaves, M.; Smith, N. (2 October 2020). An Interoperability Architecture for Blockchain Gateways (Technical report). IETF. draft-hardjono-blockchain-interop-arch-00.

- ^ Hyun Song Shin (June 2018). «Chapter V. Cryptocurrencies: looking beyond the hype» (PDF). BIS 2018 Annual Economic Report. Bank for International Settlements. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

Put in the simplest terms, the quest for decentralised trust has quickly become an environmental disaster.

- ^ Janda, Michael (18 June 2018). «Cryptocurrencies like bitcoin cannot replace money, says Bank for International Settlements». ABC (Australia). Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- ^ Hiltzik, Michael (18 June 2018). «Is this scathing report the death knell for bitcoin?». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ Ossinger, Joanna (2 February 2022). «Polkadot Has Least Carbon Footprint, Crypto Researcher Says». Bloomberg. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan Spencer (13 September 2021). «Blockchain proof-of-stake – not all are equal». www.smart-energy.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Criddle, Christina (February 20, 2021) «Bitcoin consumes ‘more electricity than Argentina’.» BBC News. (Retrieved April 26, 2021.)

- ^ Ponciano, Jonathan (March 9, 2021) «Bill Gates Sounds Alarm On Bitcoin’s Energy Consumption–Here’s Why Crypto Is Bad For Climate Change.» Forbes.com. (Retrieved April 26, 2021.)

- ^ Rowlatt, Justin (February 27, 2021) «How Bitcoin’s vast energy use could burst its bubble.» BBC News. (Retrieved April 26, 2021.)

- ^ Sorkin, Andrew et al. (March 9, 2021) «Why Bill Gates Is Worried About Bitcoin.» New York Times. (Retrieved April 25, 2021.)

- ^ Illing, Sean (11 April 2018). «Why Bitcoin is bullshit, explained by an expert». Vox. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ Weaver, Nicholas. «Blockchains and Cryptocurrencies: Burn It With Fire». YouTube video. Berkeley School of Information. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ Köhler, Susanne; Pizzol, Massimo (20 November 2019). «Life Cycle Assessment of Bitcoin Mining». Environmental Science & Technology. 53 (23): 13598–13606. Bibcode:2019EnST…5313598K. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b05687. PMID 31746188.

- ^ Stoll, Christian; Klaaßen, Lena; Gallersdörfer, Ulrich (2019). «The Carbon Footprint of Bitcoin». Joule. 3 (7): 1647–1661. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2019.05.012.

- ^ «US lawmakers begin probe into Bitcoin miners’ high energy use». Business Standard India. 29 January 2022 – via Business Standard.

- ^ Cuen, Leigh (March 21, 2021) «The debate about cryptocurrency and data consumption.» TechCrunch. (Retrieved April 26, 2021.)

- ^ Catalini, Christian; Tucker, Catherine E. (11 August 2016). «Seeding the S-Curve? The Role of Early Adopters in Diffusion» (PDF). SSRN. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2822729. S2CID 157317501. SSRN 2822729.

- ^ Arnold, M. (2017) «Universities add blockchain to course list», Financial Times: Masters in Finance, Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ Janssen, Marijn; Weerakkody, Vishanth; Ismagilova, Elvira; Sivarajah, Uthayasankar; Irani, Zahir (2020). «A framework for analysing blockchain technology adoption: Integrating institutional, market and technical factors». International Journal of Information Management. Elsevier. 50: 302–309. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.08.012.

- ^ Koens, Tommy; Poll, Erik (2019), «The Drivers Behind Blockchain Adoption: The Rationality of Irrational Choices», Euro-Par 2018: Parallel Processing Workshops, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 11339, pp. 535–546, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-10549-5_42, hdl:2066/200787, ISBN 978-3-030-10548-8, S2CID 57662305

- ^ Li, Jerry (7 April 2020). «Blockchain Technology Adoption: Examining the Fundamental Drivers». Proceedings of the 2020 2nd International Conference on Management Science and Industrial Engineering. Association for Computing Machinery: 253–260. doi:10.1145/3396743.3396750. S2CID 218982506. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020 – via ACM Digital Library.

- ^ Hsieh, Ying-Ying; Vergne, Jean-Philippe; Anderson, Philip; Lakhani, Karim; Reitzig, Markus (12 February 2019). «Correction to: Bitcoin and the rise of decentralized autonomous organizations». Journal of Organization Design. 8 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/s41469-019-0041-1. ISSN 2245-408X.

- ^ Felin, Teppo; Lakhani, Karim (2018). «What Problems Will You Solve With Blockchain?». MIT Sloan Management Review.

- ^ Beck, Roman; Mueller-Bloch, Christoph; King, John Leslie (2018). «Governance in the Blockchain Economy: A Framework and Research Agenda». Journal of the Association for Information Systems: 1020–1034. doi:10.17705/1jais.00518. S2CID 69365923.

- ^ Popper, Nathaniel (27 June 2018). «What is the Blockchain? Explaining the Tech Behind Cryptocurrencies (Published 2018)». The New York Times.

- ^ Hugh Rooney, Brian Aiken, & Megan Rooney. (2017). Q&A. Is Internal Audit Ready for Blockchain? Technology Innovation Management Review, (10), 41.

- ^ Richard C. Kloch, Jr Simon J. Little, Blockchain and Internal Audit Internal Audit Foundation, 2019 ISBN 978-1-63454-065-0

- ^ Alexander, A. (2019). The audit, transformed: New advancements in technology are reshaping this core service. Accounting Today, 33(1)

- ^ Extance, Andy (30 September 2015). «The future of cryptocurrencies: Bitcoin and beyond». Nature. 526 (7571): 21–23. Bibcode:2015Natur.526…21E. doi:10.1038/526021a. ISSN 0028-0836. OCLC 421716612. PMID 26432223.

- ^ Ledger (eJournal / eMagazine, 2015). OCLC. OCLC 910895894.

- ^ Hertig, Alyssa (15 September 2015). «Introducing Ledger, the First Bitcoin-Only Academic Journal». Motherboard. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Rizun, Peter R.; Wilmer, Christopher E.; Burley, Richard Ford; Miller, Andrew (2015). «How to Write and Format an Article for Ledger» (PDF). Ledger. 1 (1): 1–12. doi:10.5195/LEDGER.2015.1 (inactive 31 December 2022). ISSN 2379-5980. OCLC 910895894. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2022 (link)

Further reading

- Crosby, Michael; Nachiappan; Pattanayak, Pradhan; Verma, Sanjeev; Kalyanaraman, Vignesh (16 October 2015). BlockChain Technology: Beyond Bitcoin (PDF) (Report). Sutardja Center for Entrepreneurship & Technology Technical Report. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- Jaikaran, Chris (28 February 2018). Blockchain: Background and Policy Issues. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Archived from the original on 2 December 2018. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- Kakavand, Hossein; De Sevres, Nicolette Kost; Chilton, Bart (12 October 2016). The Blockchain Revolution: An Analysis of Regulation and Technology Related to Distributed Ledger Technologies (Report). Luther Systems & DLA Piper. SSRN 2849251.