| Pharaoh of Egypt | |

|---|---|

The Pschent combined the Red Crown of Lower Egypt and the White Crown of Upper Egypt |

|

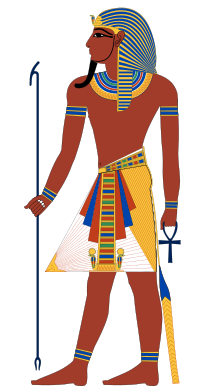

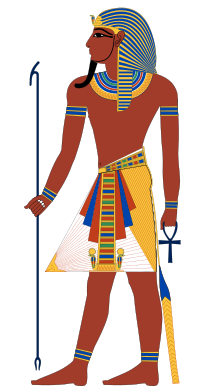

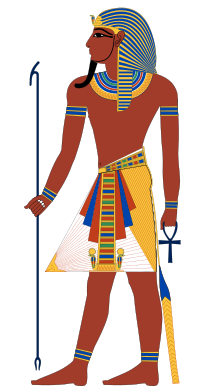

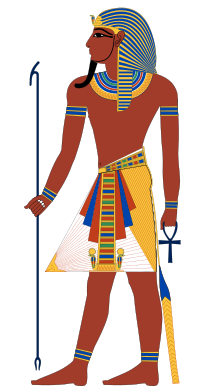

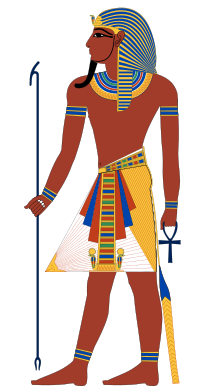

A typical depiction of a pharaoh usually depicted the king wearing the nemes headdress, a false beard, and an ornate shendyt (kilt) |

|

| Details | |

| Style | Five-name titulary |

| First monarch | King Narmer or King Menes (by tradition) (first use of the term pharaoh for a king, rather than the royal palace, was c. 1210 B.C. with Merneptah during the nineteenth dynasty) |

| Last monarch |

[2] |

| Formation | c. 3150 BC |

| Abolition |

|

| Residence | Varies by era |

| Appointer | Divine right |

| pr-ˤ3 «Great house» |

|---|

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |

|

|

||||||||

| nswt-bjt «King of Upper and Lower Egypt» |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |

Pharaoh (, ;[3] Egyptian: pr ꜥꜣ;[note 1] Coptic: ⲡⲣ̅ⲣⲟ, romanized: Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: פַּרְעֹה Parʿō)[4] is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the annexation of Egypt by the Roman Empire in 30 BC.[5] However, regardless of gender, «king» was the term used most frequently by the ancient Egyptians for their monarchs through the middle of the Eighteenth Dynasty during the New Kingdom. The term «pharaoh» was not used contemporaneously for a ruler until a possible reference to Merneptah, c. 1210 BC during the Nineteenth Dynasty, nor consistently used until the decline and instability that began with the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty.

In the early dynasties, ancient Egyptian kings had as many as three titles: the Horus, the Sedge and Bee (nswt-bjtj), and the Two Ladies or Nebty (nbtj) name.[6] The Golden Horus and the nomen and prenomen titles were added later.[7]

In Egyptian society, religion was central to everyday life. One of the roles of the king was as an intermediary between the deities and the people. The king thus was deputised for the deities in a role that was both as civil and religious administrator. The king owned all of the land in Egypt, enacted laws, collected taxes, and defended Egypt from invaders as the commander-in-chief of the army.[8] Religiously, the king officiated over religious ceremonies and chose the sites of new temples. The king was responsible for maintaining Maat (mꜣꜥt), or cosmic order, balance, and justice, and part of this included going to war when necessary to defend the country or attacking others when it was believed that this would contribute to Maat, such as to obtain resources.[9]

During the early days prior to the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, the Deshret or the «Red Crown», was a representation of the kingdom of Lower Egypt,[10] while the Hedjet, the «White Crown», was worn by the kings of the kingdom of Upper Egypt.[11] After the unification of both kingdoms into one united Egypt, the Pschent, the combination of both the red and white crowns was the official crown of kings.[12] With time new headdresses were introduced during different dynasties such as the Khat, Nemes, Atef, Hemhem crown, and Khepresh. At times, a combination of these headdresses or crowns worn together was depicted.

Etymology

The word pharaoh ultimately derives from the Egyptian compound pr ꜥꜣ, */ˌpaɾuwˈʕaʀ/ «great house», written with the two biliteral hieroglyphs pr «house» and ꜥꜣ «column», here meaning «great» or «high». It was the title of the royal palace and was used only in larger phrases such as smr pr-ꜥꜣ «Courtier of the High House», with specific reference to the buildings of the court or palace.[13] From the Twelfth Dynasty onward, the word appears in a wish formula «Great House, May it Live, Prosper, and be in Health», but again only with reference to the royal palace and not a person.

Sometime during the era of the New Kingdom, pharaoh became the form of address for a person who was king. The earliest confirmed instance where pr ꜥꜣ is used specifically to address the ruler is in a letter to the eighteenth dynasty king, Akhenaten (reigned c. 1353–1336 BC), that is addressed to «Great House, L, W, H, the Lord».[14][15] However, there is a possibility that the title pr ꜥꜣ first might have been applied personally to Thutmose III (c. 1479–1425 BC), depending on whether an inscription on the Temple of Armant may be confirmed to refer to that king.[16] During the Eighteenth dynasty (sixteenth to fourteenth centuries BC) the title pharaoh was employed as a reverential designation of the ruler. About the late Twenty-first Dynasty (tenth century BC), however, instead of being used alone and originally just for the palace, it began to be added to the other titles before the name of the king, and from the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty (eighth to seventh centuries BC, during the declining Third Intermediate Period) it was, at least in ordinary use, the only epithet prefixed to the royal appellative.[17]

From the Nineteenth dynasty onward pr-ꜥꜣ on its own, was used as regularly as ḥm, «Majesty».[18][note 2] The term, therefore, evolved from a word specifically referring to a building to a respectful designation for the ruler presiding in that building, particularly by the time of the Twenty-Second Dynasty and Twenty-third Dynasty.[citation needed]

The first dated appearance of the title «pharaoh» being attached to a ruler’s name occurs in Year 17 of Siamun (tenth century BC) on a fragment from the Karnak Priestly Annals, a religious document. Here, an induction of an individual to the Amun priesthood is dated specifically to the reign of «Pharaoh Siamun».[19] This new practice was continued under his successor, Psusennes II, and the subsequent kings of the twenty-second dynasty. For instance, the Large Dakhla stela is specifically dated to Year 5 of king «Pharaoh Shoshenq, beloved of Amun», whom all Egyptologists concur was Shoshenq I—the founder of the Twenty-second Dynasty—including Alan Gardiner in his original 1933 publication of this stela.[20] Shoshenq I was the second successor of Siamun. Meanwhile, the traditional custom of referring to the sovereign as, pr-ˤ3, continued in official Egyptian narratives.[citation needed]

The title is reconstructed to have been pronounced *[parʕoʔ] in the Late Egyptian language, from which the Greek historian Herodotus derived the name of one of the Egyptian kings, Koinē Greek: Φερων.[21] In the Hebrew Bible, the title also occurs as Hebrew: פרעה [parʕoːh];[22] from that, in the Septuagint, Koinē Greek: φαραώ, romanized: pharaō, and then in Late Latin pharaō, both -n stem nouns. The Qur’an likewise spells it Arabic: فرعون firʿawn with n (here, always referring to the one evil king in the Book of Exodus story, by contrast to the good king in surah Yusuf’s story). The Arabic combines the original ayin from Egyptian along with the -n ending from Greek.

In English, the term was at first spelled «Pharao», but the translators of the King James Bible revived «Pharaoh» with «h» from the Hebrew. Meanwhile, in Egypt, *[par-ʕoʔ] evolved into Sahidic Coptic ⲡⲣ̅ⲣⲟ pərro and then ərro by mistaking p- as the definite article «the» (from ancient Egyptian pꜣ).[23]

Other notable epithets are nswt, translated to «king»; ḥm, «Majesty»; jty for «monarch or sovereign»; nb for «lord»;[18][note 3] and ḥqꜣ for «ruler».

Regalia

Scepters and staves

Sceptres and staves were a general symbol of authority in ancient Egypt.[24] One of the earliest royal scepters was discovered in the tomb of Khasekhemwy in Abydos.[24] Kings were also known to carry a staff, and Anedjib is shown on stone vessels carrying a so-called mks-staff.[25] The scepter with the longest history seems to be the heqa-sceptre, sometimes described as the shepherd’s crook.[26] The earliest examples of this piece of regalia dates to prehistoric Egypt. A scepter was found in a tomb at Abydos that dates to Naqada III.

Another scepter associated with the king is the was-sceptre.[26] This is a long staff mounted with an animal head. The earliest known depictions of the was-scepter date to the First Dynasty. The was-scepter is shown in the hands of both kings and deities.

The flail later was closely related to the heqa-scepter (the crook and flail), but in early representations the king was also depicted solely with the flail, as shown in a late pre-dynastic knife handle that is now in the Metropolitan museum, and on the Narmer Macehead.[27]

The Uraeus

The earliest evidence known of the Uraeus—a rearing cobra—is from the reign of Den from the first dynasty. The cobra supposedly protected the king by spitting fire at its enemies.[28]

Crowns and headdresses

Narmer wearing the white crown

Narmer wearing the red crown

Deshret

The red crown of Lower Egypt, the Deshret crown, dates back to pre-dynastic times and symbolised chief ruler. A red crown has been found on a pottery shard from Naqada, and later, Narmer is shown wearing the red crown on both the Narmer Macehead and the Narmer Palette.

Hedjet

The white crown of Upper Egypt, the Hedjet, was worn in the Predynastic Period by Scorpion II, and, later, by Narmer.

Pschent

This is the combination of the Deshret and Hedjet crowns into a double crown, called the Pschent crown. It is first documented in the middle of the First Dynasty of Egypt. The earliest depiction may date to the reign of Djet, and is otherwise surely attested during the reign of Den.[29]

Khat

The khat headdress consists of a kind of «kerchief» whose end is tied similarly to a ponytail. The earliest depictions of the khat headdress comes from the reign of Den, but is not found again until the reign of Djoser.

Nemes

The Nemes headdress dates from the time of Djoser. It is the most common type of royal headgear depicted throughout Pharaonic Egypt. Any other type of crown, apart from the Khat headdress, has been commonly depicted on top of the Nemes. The statue from his Serdab in Saqqara shows the king wearing the nemes headdress.[29]

Atef

Osiris is shown to wear the Atef crown, which is an elaborate Hedjet with feathers and disks. Depictions of kings wearing the Atef crown originate from the Old Kingdom.

Hemhem

The Hemhem crown is usually depicted on top of Nemes, Pschent, or Deshret crowns. It is an ornate, triple Atef with corkscrew sheep horns and usually two uraei. The depiction of this crown begins among New Kingdom rulers during the Early Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt.

Khepresh

Also called the blue crown, the Khepresh crown has been depicted in art since the New Kingdom. It is often depicted being worn in battle, but it was also frequently worn during ceremonies. It used to be called a war crown by many, but modern historians refrain from defining it thus.

Physical evidence

Egyptologist Bob Brier has noted that despite their widespread depiction in royal portraits, no ancient Egyptian crown has ever been discovered. The tomb of Tutankhamun that was discovered largely intact, contained such royal regalia as a crook and flail, but no crown was found among his funerary equipment. Diadems have been discovered.[30] It is presumed that crowns would have been believed to have magical properties and were used in rituals. Brier’s speculation is that crowns were religious or state items, so a dead king likely could not retain a crown as a personal possession. The crowns may have been passed along to the successor, much as the crowns of modern monarchies.[31]

Titles

During the Early Dynastic Period kings had three titles. The Horus name is the oldest and dates to the late pre-dynastic period. The Nesu Bity name was added during the First Dynasty. The Nebty name (Two Ladies) was first introduced toward the end of the First Dynasty.[29] The Golden falcon (bik-nbw) name is not well understood. The prenomen and nomen were introduced later and are traditionally enclosed in a cartouche.[32] By the Middle Kingdom, the official titulary of the ruler consisted of five names; Horus, Nebty, Golden Horus, nomen, and prenomen [33] for some rulers, only one or two of them may be known.

Horus name

The Horus name was adopted by the king, when taking the throne. The name was written within a square frame representing the palace, named a serekh. The earliest known example of a serekh dates to the reign of king Ka, before the First Dynasty.[34] The Horus name of several early kings expresses a relationship with Horus. Aha refers to «Horus the fighter», Djer refers to «Horus the strong», etc. Later kings express ideals of kingship in their Horus names. Khasekhemwy refers to «Horus: the two powers are at peace», while Nebra refers to «Horus, Lord of the Sun».[29]

Nesu Bity name

The Nesu Bity name, also known as prenomen, was one of the new developments from the reign of Den. The name would follow the glyphs for the «Sedge and the Bee». The title is usually translated as king of Upper and Lower Egypt. The nsw bity name may have been the birth name of the king. It was often the name by which kings were recorded in the later annals and king lists.[29]

Nebty name

The earliest example of a Nebty (Two Ladies) name comes from the reign of king Aha from the First Dynasty. The title links the king with the goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt, Nekhbet and Wadjet.[29][32] The title is preceded by the vulture (Nekhbet) and the cobra (Wadjet) standing on a basket (the neb sign).[29]

Golden Horus

The Golden Horus or Golden Falcon name was preceded by a falcon on a gold or nbw sign. The title may have represented the divine status of the king. The Horus associated with gold may be referring to the idea that the bodies of the deities were made of gold and the pyramids and obelisks are representations of (golden) sun-rays. The gold sign may also be a reference to Nubt, the city of Set. This would suggest that the iconography represents Horus conquering Set.[29]

Nomen and prenomen

The prenomen and nomen were contained in a cartouche. The prenomen often followed the King of Upper and Lower Egypt (nsw bity) or Lord of the Two Lands (nebtawy) title. The prenomen often incorporated the name of Re. The nomen often followed the title, Son of Re (sa-ra), or the title, Lord of Appearances (neb-kha).[32]

See also

- List of pharaohs

- Roman pharaoh

- Coronation of the pharaoh

- Curse of the pharaohs

- Egyptian chronology

- Pharaohs in the Bible

Notes

- ^ Likely pronounced parūwʾar in Old Egyptian (c. 2500 BC) and Middle Egyptian (c. 1700 BC), and pərəʾaʿ or pərəʾōʿ in Late Egyptian (c. 800 BC)

- ^ The Bible refers to Egypt as the «Land of Ham».

- ^ nb.f means «his lord», the monarchs were introduced with (.f) for his, (.k) for your.[18]

References

- ^ a b Clayton 1995, p. 217. «Although paying lip-service to the old ideas and religion, in varying degrees, pharaonic Egypt had in effect died with the last native pharaoh, Nectanebo II in 343 BC»

- ^ a b von Beckerath, Jürgen (1999). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. Verlag Philipp von Zabern. pp. 266–267. ISBN 978-3422008328.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- ^ «Strong’s Hebrew Concordance — 6547. Paroh». Bible Hub.

- ^ Clayton, Peter A. Chronicle of the Pharaohs the Reign-by-reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson, 2012. Print.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (2002-09-11). Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-66420-7.

- ^ Bierbrier, Morris L. (2008-08-14). Historical Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6250-0.

- ^ «Pharaoh». AncientEgypt.co.uk. The British Museum. 1999. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Mark, Joshua (2 September 2009). «Pharaoh — World History Encyclopedia». World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Hagen, Rose-Marie; Hagen, Rainer (2007). Egypt Art. New Holland Publishers Pty, Limited. ISBN 978-3-8228-5458-7.

- ^ «The royal crowns of Egypt». Egypt Exploration Society. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ Gaskell, G. (2016-03-10). A Dictionary of the Sacred Language of All Scriptures and Myths (Routledge Revivals). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-58942-6.

- ^ A. Gardiner, Ancient Egyptian Grammar (3rd edn, 1957), 71–76.

- ^ Hieratic Papyrus from Kahun and Gurob, F. LL. Griffith, 38, 17.

- ^ Petrie, W. M. (William Matthew Flinders); Sayce, A. H. (Archibald Henry); Griffith, F. Ll (Francis Llewellyn) (1891). Illahun, Kahun and Gurob : 1889-1890. Cornell University Library. London : D. Nutt. pp. 50.

- ^ Robert Mond and O.H. Meyers. Temples of Armant, a Preliminary Survey: The Text, The Egypt Exploration Society, London, 1940, 160.

- ^ «pharaoh» in Encyclopædia Britannica. Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008.

- ^ a b c Doxey, Denise M. (1998). Egyptian Non-Royal Epithets in the Middle Kingdom: A Social and Historical Analysis. BRILL. p. 119. ISBN 90-04-11077-1.

- ^ J-M. Kruchten, Les annales des pretres de Karnak (OLA 32), 1989, pp. 474–478.

- ^ Alan Gardiner, «The Dakhleh Stela», Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 19, No. 1/2 (May, 1933) pp. 193–200.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories 2.111.1. See Anne Burton (1972). Diodorus Siculus, Book 1: A Commentary. Brill., commenting on ch. 59.1.

- ^ Elazar Ari Lipinski: «Pesach – A holiday of questions. About the Haggadah-Commentary Zevach Pesach of Rabbi Isaak Abarbanel (1437–1508). Archived 2017-03-16 at the Wayback Machine Explaining the meaning of the name Pharaoh.» Published first in German in the official quarterly of the Organization of the Jewish Communities of Bavaria: Jüdisches Leben in Bayern. Mitteilungsblatt des Landesverbandes der Israelitischen Kultusgemeinden in Bayern. Pessach-Ausgabe Nr. 109, 2009, ZDB-ID 2077457-6, S. 3–4.

- ^ Walter C. Till: «Koptische Grammatik». VEB Verlag Enzyklopädie, Leipzig, 1961. p. 62.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 158.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 159.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 160.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 161.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 162.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001 ISBN 978-0-415-26011-4

- ^ Shaw, Garry J. The Pharaoh, Life at Court and on Campaign. Thames and Hudson, 2012, pp. 21, 77.

- ^ Bob Brier, The Murder of Tutankhamen, 1998, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Dodson, Aidan and Hilton, Dyan. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2004. ISBN 0-500-05128-3

- ^ Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press 2000, p. 477

- ^ Toby A. H. Wilkinson, Early Dynastic Egypt, Routledge 1999, pp. 57f.

Bibliography

- Shaw, Garry J. The Pharaoh, Life at Court and on Campaign, Thames and Hudson, 2012.

- Sir Alan Gardiner Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs, Third Edition, Revised. London: Oxford University Press, 1964. Excursus A, pp. 71–76.

- Jan Assmann, «Der Mythos des Gottkönigs im Alten Ägypten», in Christine Schmitz und Anja Bettenworth (hg.), Menschen — Heros — Gott: Weltentwürfe und Lebensmodelle im Mythos der Vormoderne (Stuttgart, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2009), pp. 11–26.

External links

- Digital Egypt for Universities

Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Pharaohs.

| Pharaoh of Egypt | |

|---|---|

The Pschent combined the Red Crown of Lower Egypt and the White Crown of Upper Egypt |

|

A typical depiction of a pharaoh usually depicted the king wearing the nemes headdress, a false beard, and an ornate shendyt (kilt) |

|

| Details | |

| Style | Five-name titulary |

| First monarch | King Narmer or King Menes (by tradition) (first use of the term pharaoh for a king, rather than the royal palace, was c. 1210 B.C. with Merneptah during the nineteenth dynasty) |

| Last monarch |

[2] |

| Formation | c. 3150 BC |

| Abolition |

|

| Residence | Varies by era |

| Appointer | Divine right |

| pr-ˤ3 «Great house» |

|---|

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |

|

|

||||||||

| nswt-bjt «King of Upper and Lower Egypt» |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |

Pharaoh (, ;[3] Egyptian: pr ꜥꜣ;[note 1] Coptic: ⲡⲣ̅ⲣⲟ, romanized: Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: פַּרְעֹה Parʿō)[4] is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the annexation of Egypt by the Roman Empire in 30 BC.[5] However, regardless of gender, «king» was the term used most frequently by the ancient Egyptians for their monarchs through the middle of the Eighteenth Dynasty during the New Kingdom. The term «pharaoh» was not used contemporaneously for a ruler until a possible reference to Merneptah, c. 1210 BC during the Nineteenth Dynasty, nor consistently used until the decline and instability that began with the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty.

In the early dynasties, ancient Egyptian kings had as many as three titles: the Horus, the Sedge and Bee (nswt-bjtj), and the Two Ladies or Nebty (nbtj) name.[6] The Golden Horus and the nomen and prenomen titles were added later.[7]

In Egyptian society, religion was central to everyday life. One of the roles of the king was as an intermediary between the deities and the people. The king thus was deputised for the deities in a role that was both as civil and religious administrator. The king owned all of the land in Egypt, enacted laws, collected taxes, and defended Egypt from invaders as the commander-in-chief of the army.[8] Religiously, the king officiated over religious ceremonies and chose the sites of new temples. The king was responsible for maintaining Maat (mꜣꜥt), or cosmic order, balance, and justice, and part of this included going to war when necessary to defend the country or attacking others when it was believed that this would contribute to Maat, such as to obtain resources.[9]

During the early days prior to the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, the Deshret or the «Red Crown», was a representation of the kingdom of Lower Egypt,[10] while the Hedjet, the «White Crown», was worn by the kings of the kingdom of Upper Egypt.[11] After the unification of both kingdoms into one united Egypt, the Pschent, the combination of both the red and white crowns was the official crown of kings.[12] With time new headdresses were introduced during different dynasties such as the Khat, Nemes, Atef, Hemhem crown, and Khepresh. At times, a combination of these headdresses or crowns worn together was depicted.

Etymology

The word pharaoh ultimately derives from the Egyptian compound pr ꜥꜣ, */ˌpaɾuwˈʕaʀ/ «great house», written with the two biliteral hieroglyphs pr «house» and ꜥꜣ «column», here meaning «great» or «high». It was the title of the royal palace and was used only in larger phrases such as smr pr-ꜥꜣ «Courtier of the High House», with specific reference to the buildings of the court or palace.[13] From the Twelfth Dynasty onward, the word appears in a wish formula «Great House, May it Live, Prosper, and be in Health», but again only with reference to the royal palace and not a person.

Sometime during the era of the New Kingdom, pharaoh became the form of address for a person who was king. The earliest confirmed instance where pr ꜥꜣ is used specifically to address the ruler is in a letter to the eighteenth dynasty king, Akhenaten (reigned c. 1353–1336 BC), that is addressed to «Great House, L, W, H, the Lord».[14][15] However, there is a possibility that the title pr ꜥꜣ first might have been applied personally to Thutmose III (c. 1479–1425 BC), depending on whether an inscription on the Temple of Armant may be confirmed to refer to that king.[16] During the Eighteenth dynasty (sixteenth to fourteenth centuries BC) the title pharaoh was employed as a reverential designation of the ruler. About the late Twenty-first Dynasty (tenth century BC), however, instead of being used alone and originally just for the palace, it began to be added to the other titles before the name of the king, and from the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty (eighth to seventh centuries BC, during the declining Third Intermediate Period) it was, at least in ordinary use, the only epithet prefixed to the royal appellative.[17]

From the Nineteenth dynasty onward pr-ꜥꜣ on its own, was used as regularly as ḥm, «Majesty».[18][note 2] The term, therefore, evolved from a word specifically referring to a building to a respectful designation for the ruler presiding in that building, particularly by the time of the Twenty-Second Dynasty and Twenty-third Dynasty.[citation needed]

The first dated appearance of the title «pharaoh» being attached to a ruler’s name occurs in Year 17 of Siamun (tenth century BC) on a fragment from the Karnak Priestly Annals, a religious document. Here, an induction of an individual to the Amun priesthood is dated specifically to the reign of «Pharaoh Siamun».[19] This new practice was continued under his successor, Psusennes II, and the subsequent kings of the twenty-second dynasty. For instance, the Large Dakhla stela is specifically dated to Year 5 of king «Pharaoh Shoshenq, beloved of Amun», whom all Egyptologists concur was Shoshenq I—the founder of the Twenty-second Dynasty—including Alan Gardiner in his original 1933 publication of this stela.[20] Shoshenq I was the second successor of Siamun. Meanwhile, the traditional custom of referring to the sovereign as, pr-ˤ3, continued in official Egyptian narratives.[citation needed]

The title is reconstructed to have been pronounced *[parʕoʔ] in the Late Egyptian language, from which the Greek historian Herodotus derived the name of one of the Egyptian kings, Koinē Greek: Φερων.[21] In the Hebrew Bible, the title also occurs as Hebrew: פרעה [parʕoːh];[22] from that, in the Septuagint, Koinē Greek: φαραώ, romanized: pharaō, and then in Late Latin pharaō, both -n stem nouns. The Qur’an likewise spells it Arabic: فرعون firʿawn with n (here, always referring to the one evil king in the Book of Exodus story, by contrast to the good king in surah Yusuf’s story). The Arabic combines the original ayin from Egyptian along with the -n ending from Greek.

In English, the term was at first spelled «Pharao», but the translators of the King James Bible revived «Pharaoh» with «h» from the Hebrew. Meanwhile, in Egypt, *[par-ʕoʔ] evolved into Sahidic Coptic ⲡⲣ̅ⲣⲟ pərro and then ərro by mistaking p- as the definite article «the» (from ancient Egyptian pꜣ).[23]

Other notable epithets are nswt, translated to «king»; ḥm, «Majesty»; jty for «monarch or sovereign»; nb for «lord»;[18][note 3] and ḥqꜣ for «ruler».

Regalia

Scepters and staves

Sceptres and staves were a general symbol of authority in ancient Egypt.[24] One of the earliest royal scepters was discovered in the tomb of Khasekhemwy in Abydos.[24] Kings were also known to carry a staff, and Anedjib is shown on stone vessels carrying a so-called mks-staff.[25] The scepter with the longest history seems to be the heqa-sceptre, sometimes described as the shepherd’s crook.[26] The earliest examples of this piece of regalia dates to prehistoric Egypt. A scepter was found in a tomb at Abydos that dates to Naqada III.

Another scepter associated with the king is the was-sceptre.[26] This is a long staff mounted with an animal head. The earliest known depictions of the was-scepter date to the First Dynasty. The was-scepter is shown in the hands of both kings and deities.

The flail later was closely related to the heqa-scepter (the crook and flail), but in early representations the king was also depicted solely with the flail, as shown in a late pre-dynastic knife handle that is now in the Metropolitan museum, and on the Narmer Macehead.[27]

The Uraeus

The earliest evidence known of the Uraeus—a rearing cobra—is from the reign of Den from the first dynasty. The cobra supposedly protected the king by spitting fire at its enemies.[28]

Crowns and headdresses

Narmer wearing the white crown

Narmer wearing the red crown

Deshret

The red crown of Lower Egypt, the Deshret crown, dates back to pre-dynastic times and symbolised chief ruler. A red crown has been found on a pottery shard from Naqada, and later, Narmer is shown wearing the red crown on both the Narmer Macehead and the Narmer Palette.

Hedjet

The white crown of Upper Egypt, the Hedjet, was worn in the Predynastic Period by Scorpion II, and, later, by Narmer.

Pschent

This is the combination of the Deshret and Hedjet crowns into a double crown, called the Pschent crown. It is first documented in the middle of the First Dynasty of Egypt. The earliest depiction may date to the reign of Djet, and is otherwise surely attested during the reign of Den.[29]

Khat

The khat headdress consists of a kind of «kerchief» whose end is tied similarly to a ponytail. The earliest depictions of the khat headdress comes from the reign of Den, but is not found again until the reign of Djoser.

Nemes

The Nemes headdress dates from the time of Djoser. It is the most common type of royal headgear depicted throughout Pharaonic Egypt. Any other type of crown, apart from the Khat headdress, has been commonly depicted on top of the Nemes. The statue from his Serdab in Saqqara shows the king wearing the nemes headdress.[29]

Atef

Osiris is shown to wear the Atef crown, which is an elaborate Hedjet with feathers and disks. Depictions of kings wearing the Atef crown originate from the Old Kingdom.

Hemhem

The Hemhem crown is usually depicted on top of Nemes, Pschent, or Deshret crowns. It is an ornate, triple Atef with corkscrew sheep horns and usually two uraei. The depiction of this crown begins among New Kingdom rulers during the Early Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt.

Khepresh

Also called the blue crown, the Khepresh crown has been depicted in art since the New Kingdom. It is often depicted being worn in battle, but it was also frequently worn during ceremonies. It used to be called a war crown by many, but modern historians refrain from defining it thus.

Physical evidence

Egyptologist Bob Brier has noted that despite their widespread depiction in royal portraits, no ancient Egyptian crown has ever been discovered. The tomb of Tutankhamun that was discovered largely intact, contained such royal regalia as a crook and flail, but no crown was found among his funerary equipment. Diadems have been discovered.[30] It is presumed that crowns would have been believed to have magical properties and were used in rituals. Brier’s speculation is that crowns were religious or state items, so a dead king likely could not retain a crown as a personal possession. The crowns may have been passed along to the successor, much as the crowns of modern monarchies.[31]

Titles

During the Early Dynastic Period kings had three titles. The Horus name is the oldest and dates to the late pre-dynastic period. The Nesu Bity name was added during the First Dynasty. The Nebty name (Two Ladies) was first introduced toward the end of the First Dynasty.[29] The Golden falcon (bik-nbw) name is not well understood. The prenomen and nomen were introduced later and are traditionally enclosed in a cartouche.[32] By the Middle Kingdom, the official titulary of the ruler consisted of five names; Horus, Nebty, Golden Horus, nomen, and prenomen [33] for some rulers, only one or two of them may be known.

Horus name

The Horus name was adopted by the king, when taking the throne. The name was written within a square frame representing the palace, named a serekh. The earliest known example of a serekh dates to the reign of king Ka, before the First Dynasty.[34] The Horus name of several early kings expresses a relationship with Horus. Aha refers to «Horus the fighter», Djer refers to «Horus the strong», etc. Later kings express ideals of kingship in their Horus names. Khasekhemwy refers to «Horus: the two powers are at peace», while Nebra refers to «Horus, Lord of the Sun».[29]

Nesu Bity name

The Nesu Bity name, also known as prenomen, was one of the new developments from the reign of Den. The name would follow the glyphs for the «Sedge and the Bee». The title is usually translated as king of Upper and Lower Egypt. The nsw bity name may have been the birth name of the king. It was often the name by which kings were recorded in the later annals and king lists.[29]

Nebty name

The earliest example of a Nebty (Two Ladies) name comes from the reign of king Aha from the First Dynasty. The title links the king with the goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt, Nekhbet and Wadjet.[29][32] The title is preceded by the vulture (Nekhbet) and the cobra (Wadjet) standing on a basket (the neb sign).[29]

Golden Horus

The Golden Horus or Golden Falcon name was preceded by a falcon on a gold or nbw sign. The title may have represented the divine status of the king. The Horus associated with gold may be referring to the idea that the bodies of the deities were made of gold and the pyramids and obelisks are representations of (golden) sun-rays. The gold sign may also be a reference to Nubt, the city of Set. This would suggest that the iconography represents Horus conquering Set.[29]

Nomen and prenomen

The prenomen and nomen were contained in a cartouche. The prenomen often followed the King of Upper and Lower Egypt (nsw bity) or Lord of the Two Lands (nebtawy) title. The prenomen often incorporated the name of Re. The nomen often followed the title, Son of Re (sa-ra), or the title, Lord of Appearances (neb-kha).[32]

See also

- List of pharaohs

- Roman pharaoh

- Coronation of the pharaoh

- Curse of the pharaohs

- Egyptian chronology

- Pharaohs in the Bible

Notes

- ^ Likely pronounced parūwʾar in Old Egyptian (c. 2500 BC) and Middle Egyptian (c. 1700 BC), and pərəʾaʿ or pərəʾōʿ in Late Egyptian (c. 800 BC)

- ^ The Bible refers to Egypt as the «Land of Ham».

- ^ nb.f means «his lord», the monarchs were introduced with (.f) for his, (.k) for your.[18]

References

- ^ a b Clayton 1995, p. 217. «Although paying lip-service to the old ideas and religion, in varying degrees, pharaonic Egypt had in effect died with the last native pharaoh, Nectanebo II in 343 BC»

- ^ a b von Beckerath, Jürgen (1999). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. Verlag Philipp von Zabern. pp. 266–267. ISBN 978-3422008328.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- ^ «Strong’s Hebrew Concordance — 6547. Paroh». Bible Hub.

- ^ Clayton, Peter A. Chronicle of the Pharaohs the Reign-by-reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson, 2012. Print.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (2002-09-11). Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-66420-7.

- ^ Bierbrier, Morris L. (2008-08-14). Historical Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6250-0.

- ^ «Pharaoh». AncientEgypt.co.uk. The British Museum. 1999. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Mark, Joshua (2 September 2009). «Pharaoh — World History Encyclopedia». World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Hagen, Rose-Marie; Hagen, Rainer (2007). Egypt Art. New Holland Publishers Pty, Limited. ISBN 978-3-8228-5458-7.

- ^ «The royal crowns of Egypt». Egypt Exploration Society. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ Gaskell, G. (2016-03-10). A Dictionary of the Sacred Language of All Scriptures and Myths (Routledge Revivals). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-58942-6.

- ^ A. Gardiner, Ancient Egyptian Grammar (3rd edn, 1957), 71–76.

- ^ Hieratic Papyrus from Kahun and Gurob, F. LL. Griffith, 38, 17.

- ^ Petrie, W. M. (William Matthew Flinders); Sayce, A. H. (Archibald Henry); Griffith, F. Ll (Francis Llewellyn) (1891). Illahun, Kahun and Gurob : 1889-1890. Cornell University Library. London : D. Nutt. pp. 50.

- ^ Robert Mond and O.H. Meyers. Temples of Armant, a Preliminary Survey: The Text, The Egypt Exploration Society, London, 1940, 160.

- ^ «pharaoh» in Encyclopædia Britannica. Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008.

- ^ a b c Doxey, Denise M. (1998). Egyptian Non-Royal Epithets in the Middle Kingdom: A Social and Historical Analysis. BRILL. p. 119. ISBN 90-04-11077-1.

- ^ J-M. Kruchten, Les annales des pretres de Karnak (OLA 32), 1989, pp. 474–478.

- ^ Alan Gardiner, «The Dakhleh Stela», Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 19, No. 1/2 (May, 1933) pp. 193–200.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories 2.111.1. See Anne Burton (1972). Diodorus Siculus, Book 1: A Commentary. Brill., commenting on ch. 59.1.

- ^ Elazar Ari Lipinski: «Pesach – A holiday of questions. About the Haggadah-Commentary Zevach Pesach of Rabbi Isaak Abarbanel (1437–1508). Archived 2017-03-16 at the Wayback Machine Explaining the meaning of the name Pharaoh.» Published first in German in the official quarterly of the Organization of the Jewish Communities of Bavaria: Jüdisches Leben in Bayern. Mitteilungsblatt des Landesverbandes der Israelitischen Kultusgemeinden in Bayern. Pessach-Ausgabe Nr. 109, 2009, ZDB-ID 2077457-6, S. 3–4.

- ^ Walter C. Till: «Koptische Grammatik». VEB Verlag Enzyklopädie, Leipzig, 1961. p. 62.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 158.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 159.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 160.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 161.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 162.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001 ISBN 978-0-415-26011-4

- ^ Shaw, Garry J. The Pharaoh, Life at Court and on Campaign. Thames and Hudson, 2012, pp. 21, 77.

- ^ Bob Brier, The Murder of Tutankhamen, 1998, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Dodson, Aidan and Hilton, Dyan. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2004. ISBN 0-500-05128-3

- ^ Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press 2000, p. 477

- ^ Toby A. H. Wilkinson, Early Dynastic Egypt, Routledge 1999, pp. 57f.

Bibliography

- Shaw, Garry J. The Pharaoh, Life at Court and on Campaign, Thames and Hudson, 2012.

- Sir Alan Gardiner Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs, Third Edition, Revised. London: Oxford University Press, 1964. Excursus A, pp. 71–76.

- Jan Assmann, «Der Mythos des Gottkönigs im Alten Ägypten», in Christine Schmitz und Anja Bettenworth (hg.), Menschen — Heros — Gott: Weltentwürfe und Lebensmodelle im Mythos der Vormoderne (Stuttgart, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2009), pp. 11–26.

External links

- Digital Egypt for Universities

Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Pharaohs.

Титул древнеегипетских правителей

| Фараон Египта | |

|---|---|

Пшент объединил Красная Корона из Нижнего Египта и Белая Корона из Верхнего Египта Пшент объединил Красная Корона из Нижнего Египта и Белая Корона из Верхнего Египта |

|

Типичное изображение фараона обычно изображало царя в nemes головной убор, накладная борода и богато украшенный шендыт (юбка). (после Джосера Третьей династии) Типичное изображение фараона обычно изображало царя в nemes головной убор, накладная борода и богато украшенный шендыт (юбка). (после Джосера Третьей династии) |

|

| Детали | |

| Стиль | Пятиименный титуляр |

| Первый монарх | Король Нармер или Король Менес (по традиции). (первое использование термина фараон для короля, а не королевского дворца, было около 1210 г. до н.э. с Мернептахом во время девятнадцатой династии) |

| Последний монарх |

|

| Формация | c. 3150 г. до н.э. |

| Отмена |

|

| Место жительства | Зависит от эпохи |

| Назначение | Божественное право |

|

|

| пр. -ˤ3. «Великий дом». в иероглифах |

|---|

|

.. .. .. .. |

||||||||

| nswt-bjt. «Царь Верхнего. и Нижнего Египта». в иероглифах |

|---|

Фараон (, США также ; коптский : ⲡⲣ̅ⲣⲟ Pǝrro) — это общепринятое название, которое сейчас используется для монархов Древнего Египта из Первой династии (ок. 3150 г. до н.э.) до аннексии Египта Римской империей в 30 г. до н.э., хотя термин «фараон» не использовался одновременно для правителя до Мернептах, ок. 1210 г. до н. Э., Во время Девятнадцатой династии, термин «царь» был наиболее часто используемым до середины восемнадцатой династии. В ранних династиях древние египетские цари имели до трех титулов : Гор, Седж и Пчела (nswt-bjtj ) и имя Две дамы или Небти (nbtj ). Позже были добавлены Золотой Гор, а также номен и преномен.

В египетском обществе религия занимала центральное место в повседневной жизни. Одна из ролей фараона заключалась в посредничестве между божествами и людьми. Таким образом, фараон замещал божества в роли гражданского и религиозного администратора. Фараон владел всей землей в Египте, издавал законы, собирал налоги и защищал Египет от захватчиков, будучи главнокомандующим армией. С религиозной точки зрения фараон совершал религиозные обряды и выбирал места для новых храмов. Фараон отвечал за поддержание Маат (mꜣꜥt ), или космического порядка, равновесия и справедливости, и частично это включало в себя войну, когда это необходимо, чтобы защитить страну или нападение на других, когда считалось, что это будет способствовать Маат, например, для получения ресурсов.

В первые дни, предшествовавшие объединению Верхнего и Нижнего Египта, Дешрет или «Красная Корона» была символом царства Нижнего Египта, в то время как Хеджет, «Белая Корона», носили цари царства Верхнего Египта. После объединения обоих царств в единый Египет, Пшент, комбинация красной и белой короны была официальной короной королей. Со временем новые головные уборы были введены во времена различных династий, таких как Хат, Немес, Атеф, корона Хемхема и Хепреш.. Иногда изображалось, что эти головные уборы или короны носят вместе.

Содержание

- 1 Этимология

- 2 Регалии

- 2.1 Скипетры и посохи

- 2.2 Урей

- 3 Короны и головные уборы

- 3.1 Дешрет

- 3.2 Хеджет

- 3.3 Пщент

- 3,4 Кат

- 3,5 Немес

- 3,6 Атеф

- 3,7 Хемхем

- 3,8 Хепреш

- 3,9 Вещественные доказательства

- 4 Титулы

- 4,1 Имя Хоруса

- 4,2 Имя Несу Бити

- 4.3 Имя Небти

- 4.4 Golden Horus

- 4.5 Номен и преномен

- 5 См. Также

- 6 Примечания

- 7 Ссылки

- 8 Библиография

- 9 Внешние ссылки

Этимология

Слово фараон в конечном итоге происходит от египетского соединения pr ꜥꜣ, * / ˌpaɾuwˈʕaʀ / «великий дом», написанного двумя двусторонними иероглифами pr » дом »и ꜥꜣ« колонна », что здесь означает« большой »или« высокий ». Он использовался только в более крупных фразах, таких как smr пр-ꜥꜣ «Придворный Высокого Дома», со специфической ссылкой на здания двора или дворца. Начиная с Двенадцатой династии и далее, это слово появляется в формуле желания «Великий Дом, да будет он Жить, процветать и быть здоровым », но опять же только в отношении королевского дворца. а не человек.

Где-то в эпоху Нового царства, Второй промежуточный период фараон стал формой обращения для человека, который был королем. Самый ранний подтвержденный случай, когда pr ꜥꜣ используется специально для обращения к правителю, — это письмо к Эхнатону (правил ок. 1353–1336 гг. До н.э.), которое адресовано «Великому дому, L, W, H, Господь ». Однако существует вероятность того, что титул пр ꜥꜣ применялся к Тутмосу III (ок. 1479–1425 до н. Э.), В зависимости от того, можно ли подтвердить, что надпись на Храме Арманта относится к этому царю. Во время восемнадцатой династии (с шестнадцатого по четырнадцатый века до н.э.) титул фараона использовался как благоговейное обозначение правителя. О конце Двадцать первой династии (X век до н.э.), однако, вместо того, чтобы использоваться отдельно, как раньше, его начали добавлять к другим титулам перед именем правителя, а с Двадцать -Пятая династия (восьмой-седьмой века до н.э.) это был, по крайней мере, в обычном употреблении, единственный эпитет с префиксом королевского апеллятива.

Из девятнадцатой династии и далее пр-сам по себе, использовался так же регулярно, как ḥm, «Величество». Этот термин, таким образом, произошел от слова, конкретно относящегося к зданию, к уважительному обозначению правителя, председательствующего в этом здании, особенно во времена Двадцать второй династии и двадцать третьей династии.

Например, первое датированное появление титульного фараона, связанного с именем правителя, происходит в 17 году Сиамуна во фрагменте из Карнакских Жреческих летописей. Здесь посвящение человека в священство Амона датируется периодом правления фараона Сиамуна. Эта новая практика была продолжена при его преемнике Псусенне II и последующих королях двадцать второй династии. Например, стела Большая Дахла специально приурочена к 5 году правления царя «Фараона Шошенка, возлюбленного Амона », которого все египтологи соглашаются, Шошенк I — основателем Двадцать вторая династия — включая Алана Гардинера в его оригинальной публикации этой стелы в 1933 году. Шошенк I был вторым преемником Сиамуна. Между тем, старый обычай называть государя просто пр-continued3 продолжился в традиционных египетских повествованиях.

К этому времени Позднеегипетское слово реконструируется и произносится * [parʕoʔ ] откуда Геродот получил имя одного из египетских царей, Греческий Койне : Φερων. В еврейской Библии заголовок также встречается как на иврите : פרעה [parːoːh]; отсюда в Септуагинте, греческий коине : φαραώ, романизированный: pharaō, а затем в позднем латинском pharaō, оба -n корень существительных. Коран аналогичным образом произносит это арабский : فرعون firʿawn с n (здесь всегда имеется в виду один злой царь в Книге Исход истории, по в отличие от доброго царя в суре Юсуфа ). Арабский сочетает в себе исходное ayin из египетского языка с окончанием -n из греческого.

В английском языке этот термин сначала записывался как «Фараон», но переводчики Библии короля Иакова возродили «Фараон» с «h» из еврейского. Между тем, в самом Египте * [par-ʕoʔ] превратился в сахидский коптский ⲡⲣ̅ⲣⲟ pərro, а затем ərro, приняв p- за определенный артикль «the» (от древн. Египетский pꜣ ).

Другие известные эпитеты: nswt, переведенный как «король»; ḥm, «Величие»; jty для «монарх или государь»; nb для «господина» и ḥqꜣ для «правителя».

Regalia

Скипетры и посохи

Скипетр Хасехемви из бисера (Музей изящных искусств в Бостоне)

Скипетры и посохи были общим знаком власти в Древнем Египте. Один из самых ранних царских скипетров был обнаружен в гробнице Хасехемви в Абидосе. Известно также, что короли носили посох, и фараон Анеджиб изображен на каменных сосудах, несущих так называемый мкс-посох. Скипетр с самой длинной историей, кажется, является гека-скипетром, иногда описывается как пастуший посох. Самые ранние образцы этого регалий относятся к доисторическому Египту. скипетр был найден в гробнице в Абидосе, которая датируется Накадой III.

Другой скипетр, связанный с царем, — это скипетр. Это длинный посох с головой животного. Самые ранние известные изображения скипетра относятся к Первой династии. Вас-скипетр изображен в руках как королей, так и божеств.

цеп позже был тесно связан с гека-скипетром (посох и цеп ), но в ранних изображениях царь также изображался исключительно с цепом, как показано на поздней додинастической рукоятке ножа, которая сейчас находится в музее Метрополитен, и на Нармер Мэйсхед.

Урей

Самое раннее известное свидетельство Урея — вздыбившаяся кобра — происходит из периода правления Дена из первой династии. Кобра якобы защищала фараона, поливая врагов огнем.

Короны и головные уборы

Нармер Палитра

Дешрет

Красная корона Нижнего Египта, Дешрет корона, восходит к додинастическим временам и символизировала главного правителя. Красная корона была найдена на черепке керамики из Накада, а позже Нармер показан с красной короной как на Narmer Macehead, так и на Нармер Палитра.

Хеджет

Белая корона Верхнего Египта, Хеджет, носилась в додинастический период Скорпионом II, а позже и Нармер.

Pschent

Это комбинация коронок Deshret и Hedjet в двойную корону, называемую короной Pschent. Впервые это зарегистрировано в середине Первой династии Египта. Самое раннее изображение может относиться к периоду правления Джета, и в противном случае, несомненно, засвидетельствовано во время правления Дена.

Кат

кат головной убор состоит из своего рода «косынки», конец которой завязан аналогично конскому хвосту. Самые ранние изображения ката-головного убора относятся к эпохе правления Дена, но не встречаются снова до правления Джосера.

Немеса

Немеса головной убор датируется временами Джосера. Это самый распространенный тип короны, который изображался во всем Египте фараонов. Любой другой тип короны, кроме головного убора ката, обычно изображался на вершине Немеса. Статуя из его Сердаба в Саккара изображает царя в головном уборе Немеса.

Атеф

Показано, что Осирис носит корону Атеф, которая представляет собой замысловатый хеджет с перьями и дисками. Изображения фараонов в короне Атефа восходят к Древнему царству.

Hemhem

Корона Hemhem обычно изображается поверх Nemes, Pschent или Deshret короны. Это богато украшенный тройной атеф со штопорными бараньими рогами и обычно двумя уреями. Использование (изображение) этой короны начинается во времена ранней восемнадцатой династии Египта.

Хепреш

Также называемая синей короной, Хепреш корона изображалась в искусстве с тех пор. Новое царство. Его часто изображают одетым в битву, но его также часто носили во время церемоний. Многие называли его военным венцом, но современные историки воздерживаются от его определения.

Вещественные доказательства

Египтолог Боб Брайер отметил, что, несмотря на их широко распространенное изображение на королевских портретах, древняя египетская корона никогда не была обнаружена. Гробница Тутанхамона, обнаруженная в значительной степени неповрежденной, действительно содержала такие регалии, как его посох и цеп, но среди погребального инвентаря не было найдено короны. Обнаружены диадемы. Предполагается, что короны обладали магическими свойствами. Брайер предполагает, что короны были религиозными или государственными предметами, поэтому мертвый фараон, скорее всего, не мог сохранить корону в качестве личной собственности. Короны могли быть переданы преемнику.

Титулы

В раннединастический период короли имели три титула. Имя Гора является самым старым и относится к позднему додинастическому периоду. Имя Несу-Бити было добавлено во время Первой династии. Имя Небти (Две дамы) впервые было введено в конце Первой династии. Название «Золотой сокол» (bik-nbw) не совсем понятно. преномен и номен были введены позже и традиционно заключены в картуш. К Среднему царству официальный титул правителя состоял из пяти имен; Гор, Небти, Золотой Гор, номен и преномен для некоторых правителей, только один или два из них могут быть известны.

Имя Гора

Имя Гора было принято королем, когда он взошел на трон. Название было написано в квадратной рамке, изображающей дворец, и называлось серех. Самый ранний известный пример сереха относится к правлению царя Ка, до Первой династии. Имя Гор нескольких ранних королей выражает связь с Гором. Ага относится к «Хорусу-воину», Джер относится к «Гору сильному» и т. Д. Более поздние короли выражают идеалы королевской власти в своих именах Гора. Хасехемви относится к «Гор: две силы в мире», в то время как Небра относится к «Гору, Владыке Солнца».

Имя Несу Бити

Имя Несу-биты, также известное как преномен, было одним из новых достижений времен правления Дена. Название будет следовать за глифами «Осока и пчела». Титул обычно переводится как царь Верхнего и Нижнего Египта. Имя nsw bity могло быть именем при рождении короля. Это часто было именем, под которым короли записывались в более поздних анналах и списках королей.

Имя Небти

Самый ранний пример имени Небти (Две дамы ) происходит из царствования царя Ага из Первой династии. Титул связывает царя с богинями Верхнего и Нижнего Египта Нехбет и Ваджет. Титулу предшествуют стервятник (Нехбет) и кобра (Ваджет), стоящие на корзине (знак неб).

Золотой Гор

Золотой Гор или Названию Golden Falcon предшествовал сокол на золотом или золотом знаке. Возможно, титул олицетворял божественный статус короля. Гор, связанный с золотом, может иметь отношение к идее о том, что тела божеств были сделаны из золота, а пирамиды и обелиски являются изображениями (золотого) солнца -лучей. Золотой знак также может быть ссылкой на Нубт, город Сет. Это наводит на мысль, что иконография представляет Гора, завоевывающего Сет.

Номен и преномен

преномен и номен содержались в картуше. Prenomen часто следовали за титулом царя Верхнего и Нижнего Египта (nsw bity) или владыки двух земель (nebtawy). В преномене часто встречается имя Re. Имя часто следовало за титулом Сын Ре (sa-ra) или титулом Повелителя явлений (neb-kha).

См. Также

- Список фараонов

- Римский фараон

- Коронация фараона

- Проклятие фараонов

- Египетская хронология

- Фараоны в Библии

Примечания

Ссылки

Библиография

- Шоу, Гарри Дж. Фараон, Жизнь при дворе и кампании, Темза и Гудзон, 2012.

- Сэр Алан Гардинер Грамматика египетского языка : Введение в изучение иероглифов, третье издание, исправленное. Лондон: Oxford University Press, 1964. Excursus A, pp. 71–76.

- Ян Ассманн, «Der Mythos des Gottkönigs im Alten Ägypten», в Christine Schmitz und Anja Bettenworth (hg.), Menschen — Heros — Gott: Weltentwürfe und Lebensmodelle im Mythos der Vormoderne (Штутгарт, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2009), стр. 11–26.

Внешние ссылки

- Цифровой Египет для университетов

| У Wikivoyage есть путеводитель по Фараоны. |

ФАРАОН

- ФАРАОН

-

общепринятое обозначение др.-егип. царей, с XXII династии — титул царя. Термин «Ф.» происходит от др.-егип. слова «пер-о» (букв. — большой дом), переданного библейской традицией как Ф. (др.-евр. парох, греч. Parao). Первоначально термин «Ф.» обозначал «царский дворец» и лишь с XVIII династии (с эпохи Нового царства) — самого царя. До XXII династии слово «Ф.» не входило в царскую титулатуру, состоявшую из 5 «великих имен»: личного имени и 4 царских имен (к-рые давались при вступлении на престол).

Ф. носил разл. короны: белую — Верх. Египта, красную — Ниж. Египта, двойную — соединение белой и красной как символ власти над объединенным гос-вом и др. Ф. был верховным распорядителем зем., сырьевых и продовольств. ресурсов и населения Египта. Согласно др.-егип. верованиям, Ф. был сыном солнца, земным воплощением Гора и наследником Осириса. Грандиозные памятники-пирамиды и храмы увековечили имена Ф.

Лит.: Gauthier H., Le livre des rois d’Egypte, v. 1-5, (Le Cairo), 1907-17; Rosene G., De la divinité du pharaon, P., 1961.

Советская историческая энциклопедия. — М.: Советская энциклопедия .

.

1973—1982.

Синонимы:

Смотреть что такое «ФАРАОН» в других словарях:

-

Фараон — общепринятое обозначение древнеегипетских царей, с XXII династии титул царя. Термин Фараон происходит от древнеегипетского слова пер о (буквально, большой дом), переданного библейской традицией как Фараон. Первоначально термин Фараон обозначал… … Энциклопедия мифологии

-

ФАРАОН — (фр. faraon, еврейск. paroh царь). 1) Название древне египетских царей. 2) азартная игра во французские карты, названная так потому, что один из королей изображал фараона. Словарь иностранных слов, вошедших в состав русского языка. Чудинов А.Н.,… … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

-

Фараон — обозначение древнеегипетских царей, позднее титул царя. Термин фараон происходит от древнеегипетского большой дом. Первоначально обозначал царский дворец, а позднее с 16 в. до н.э. самого царя. Фараон носил различные короны: белую как царь… … Исторический словарь

-

фараон — кличка городового (Ушаков) См … Словарь синонимов

-

Фараон — (егип. пер о, большой дом ), титул егип. царя, в Библии нередко употребляется как имя собств. В этой связи возникают многочисл. затруднения при выяснении личностей, названных в Библии Ф., поскольку библ. сообщения о них бесспорно не… … Библейская энциклопедия Брокгауза

-

ФАРАОН — ФАРАОН, фараона, муж. (греч. pharao с египетского). 1. Титул древне египетских царей (ист.). 2. Кличка городового (дорев. прост. презр.). 3. только ед. Род азартной игры в карты, сходный с баккара. «Дамы играли в фараон.» Пушкин. Толковый словарь … Толковый словарь Ушакова

-

фараон — ФАРАОН, а, м. Милиционер. Ср. устар. уг. «фараон» полицейский, жандарм … Словарь русского арго

-

ФАРАОН — древнеегипетский царь. Считался сыном бога Солнца и обладал неограниченной властью … Юридический словарь

-

ФАРАОН — традиционное обозначение древнеегипетских царей, с 16 в. до н. э. титул царя. Происходит от египетского пер о ( большой дом ) в первоначальном значении царский дворец … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

ФАРАОН 1 — ФАРАОН 1, а, м. Толковый словарь Ожегова. С.И. Ожегов, Н.Ю. Шведова. 1949 1992 … Толковый словарь Ожегова

-

ФАРАОН 2 — ФАРАОН 2, а, м. Род азартной карточной игры. Толковый словарь Ожегова. С.И. Ожегов, Н.Ю. Шведова. 1949 1992 … Толковый словарь Ожегова

| Pharaoh of Egypt | |

|---|---|

The Pschent combined the Red Crown of Lower Egypt and the White Crown of Upper Egypt |

|

A typical depiction of a pharaoh usually depicted the king wearing the nemes headdress, a false beard, and an ornate shendyt (kilt) |

|

| Details | |

| Style | Five-name titulary |

| First monarch | King Narmer or King Menes (by tradition) (first use of the term pharaoh for a king, rather than the royal palace, was c. 1210 B.C. with Merneptah during the nineteenth dynasty) |

| Last monarch |

[2] |

| Formation | c. 3150 BC |

| Abolition |

|

| Residence | Varies by era |

| Appointer | Divine right |

| pr-ˤ3 «Great house» |

|---|

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |

|

|

||||||||

| nswt-bjt «King of Upper and Lower Egypt» |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |

Pharaoh (, ;[3] Egyptian: pr ꜥꜣ;[note 1] Coptic: ⲡⲣ̅ⲣⲟ, romanized: Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: פַּרְעֹה Parʿō)[4] is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the annexation of Egypt by the Roman Empire in 30 BC.[5] However, regardless of gender, «king» was the term used most frequently by the ancient Egyptians for their monarchs through the middle of the Eighteenth Dynasty during the New Kingdom. The term «pharaoh» was not used contemporaneously for a ruler until a possible reference to Merneptah, c. 1210 BC during the Nineteenth Dynasty, nor consistently used until the decline and instability that began with the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty.

In the early dynasties, ancient Egyptian kings had as many as three titles: the Horus, the Sedge and Bee (nswt-bjtj), and the Two Ladies or Nebty (nbtj) name.[6] The Golden Horus and the nomen and prenomen titles were added later.[7]

In Egyptian society, religion was central to everyday life. One of the roles of the king was as an intermediary between the deities and the people. The king thus was deputised for the deities in a role that was both as civil and religious administrator. The king owned all of the land in Egypt, enacted laws, collected taxes, and defended Egypt from invaders as the commander-in-chief of the army.[8] Religiously, the king officiated over religious ceremonies and chose the sites of new temples. The king was responsible for maintaining Maat (mꜣꜥt), or cosmic order, balance, and justice, and part of this included going to war when necessary to defend the country or attacking others when it was believed that this would contribute to Maat, such as to obtain resources.[9]

During the early days prior to the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, the Deshret or the «Red Crown», was a representation of the kingdom of Lower Egypt,[10] while the Hedjet, the «White Crown», was worn by the kings of the kingdom of Upper Egypt.[11] After the unification of both kingdoms into one united Egypt, the Pschent, the combination of both the red and white crowns was the official crown of kings.[12] With time new headdresses were introduced during different dynasties such as the Khat, Nemes, Atef, Hemhem crown, and Khepresh. At times, a combination of these headdresses or crowns worn together was depicted.

Etymology

The word pharaoh ultimately derives from the Egyptian compound pr ꜥꜣ, */ˌpaɾuwˈʕaʀ/ «great house», written with the two biliteral hieroglyphs pr «house» and ꜥꜣ «column», here meaning «great» or «high». It was the title of the royal palace and was used only in larger phrases such as smr pr-ꜥꜣ «Courtier of the High House», with specific reference to the buildings of the court or palace.[13] From the Twelfth Dynasty onward, the word appears in a wish formula «Great House, May it Live, Prosper, and be in Health», but again only with reference to the royal palace and not a person.

Sometime during the era of the New Kingdom, pharaoh became the form of address for a person who was king. The earliest confirmed instance where pr ꜥꜣ is used specifically to address the ruler is in a letter to the eighteenth dynasty king, Akhenaten (reigned c. 1353–1336 BC), that is addressed to «Great House, L, W, H, the Lord».[14][15] However, there is a possibility that the title pr ꜥꜣ first might have been applied personally to Thutmose III (c. 1479–1425 BC), depending on whether an inscription on the Temple of Armant may be confirmed to refer to that king.[16] During the Eighteenth dynasty (sixteenth to fourteenth centuries BC) the title pharaoh was employed as a reverential designation of the ruler. About the late Twenty-first Dynasty (tenth century BC), however, instead of being used alone and originally just for the palace, it began to be added to the other titles before the name of the king, and from the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty (eighth to seventh centuries BC, during the declining Third Intermediate Period) it was, at least in ordinary use, the only epithet prefixed to the royal appellative.[17]

From the Nineteenth dynasty onward pr-ꜥꜣ on its own, was used as regularly as ḥm, «Majesty».[18][note 2] The term, therefore, evolved from a word specifically referring to a building to a respectful designation for the ruler presiding in that building, particularly by the time of the Twenty-Second Dynasty and Twenty-third Dynasty.[citation needed]

The first dated appearance of the title «pharaoh» being attached to a ruler’s name occurs in Year 17 of Siamun (tenth century BC) on a fragment from the Karnak Priestly Annals, a religious document. Here, an induction of an individual to the Amun priesthood is dated specifically to the reign of «Pharaoh Siamun».[19] This new practice was continued under his successor, Psusennes II, and the subsequent kings of the twenty-second dynasty. For instance, the Large Dakhla stela is specifically dated to Year 5 of king «Pharaoh Shoshenq, beloved of Amun», whom all Egyptologists concur was Shoshenq I—the founder of the Twenty-second Dynasty—including Alan Gardiner in his original 1933 publication of this stela.[20] Shoshenq I was the second successor of Siamun. Meanwhile, the traditional custom of referring to the sovereign as, pr-ˤ3, continued in official Egyptian narratives.[citation needed]

The title is reconstructed to have been pronounced *[parʕoʔ] in the Late Egyptian language, from which the Greek historian Herodotus derived the name of one of the Egyptian kings, Koinē Greek: Φερων.[21] In the Hebrew Bible, the title also occurs as Hebrew: פרעה [parʕoːh];[22] from that, in the Septuagint, Koinē Greek: φαραώ, romanized: pharaō, and then in Late Latin pharaō, both -n stem nouns. The Qur’an likewise spells it Arabic: فرعون firʿawn with n (here, always referring to the one evil king in the Book of Exodus story, by contrast to the good king in surah Yusuf’s story). The Arabic combines the original ayin from Egyptian along with the -n ending from Greek.

In English, the term was at first spelled «Pharao», but the translators of the King James Bible revived «Pharaoh» with «h» from the Hebrew. Meanwhile, in Egypt, *[par-ʕoʔ] evolved into Sahidic Coptic ⲡⲣ̅ⲣⲟ pərro and then ərro by mistaking p- as the definite article «the» (from ancient Egyptian pꜣ).[23]

Other notable epithets are nswt, translated to «king»; ḥm, «Majesty»; jty for «monarch or sovereign»; nb for «lord»;[18][note 3] and ḥqꜣ for «ruler».

Regalia

Scepters and staves

Sceptres and staves were a general symbol of authority in ancient Egypt.[24] One of the earliest royal scepters was discovered in the tomb of Khasekhemwy in Abydos.[24] Kings were also known to carry a staff, and Anedjib is shown on stone vessels carrying a so-called mks-staff.[25] The scepter with the longest history seems to be the heqa-sceptre, sometimes described as the shepherd’s crook.[26] The earliest examples of this piece of regalia dates to prehistoric Egypt. A scepter was found in a tomb at Abydos that dates to Naqada III.

Another scepter associated with the king is the was-sceptre.[26] This is a long staff mounted with an animal head. The earliest known depictions of the was-scepter date to the First Dynasty. The was-scepter is shown in the hands of both kings and deities.

The flail later was closely related to the heqa-scepter (the crook and flail), but in early representations the king was also depicted solely with the flail, as shown in a late pre-dynastic knife handle that is now in the Metropolitan museum, and on the Narmer Macehead.[27]

The Uraeus

The earliest evidence known of the Uraeus—a rearing cobra—is from the reign of Den from the first dynasty. The cobra supposedly protected the king by spitting fire at its enemies.[28]

Crowns and headdresses

Narmer wearing the white crown

Narmer wearing the red crown

Deshret

The red crown of Lower Egypt, the Deshret crown, dates back to pre-dynastic times and symbolised chief ruler. A red crown has been found on a pottery shard from Naqada, and later, Narmer is shown wearing the red crown on both the Narmer Macehead and the Narmer Palette.

Hedjet

The white crown of Upper Egypt, the Hedjet, was worn in the Predynastic Period by Scorpion II, and, later, by Narmer.

Pschent

This is the combination of the Deshret and Hedjet crowns into a double crown, called the Pschent crown. It is first documented in the middle of the First Dynasty of Egypt. The earliest depiction may date to the reign of Djet, and is otherwise surely attested during the reign of Den.[29]

Khat

The khat headdress consists of a kind of «kerchief» whose end is tied similarly to a ponytail. The earliest depictions of the khat headdress comes from the reign of Den, but is not found again until the reign of Djoser.

Nemes

The Nemes headdress dates from the time of Djoser. It is the most common type of royal headgear depicted throughout Pharaonic Egypt. Any other type of crown, apart from the Khat headdress, has been commonly depicted on top of the Nemes. The statue from his Serdab in Saqqara shows the king wearing the nemes headdress.[29]

Atef

Osiris is shown to wear the Atef crown, which is an elaborate Hedjet with feathers and disks. Depictions of kings wearing the Atef crown originate from the Old Kingdom.

Hemhem

The Hemhem crown is usually depicted on top of Nemes, Pschent, or Deshret crowns. It is an ornate, triple Atef with corkscrew sheep horns and usually two uraei. The depiction of this crown begins among New Kingdom rulers during the Early Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt.

Khepresh

Also called the blue crown, the Khepresh crown has been depicted in art since the New Kingdom. It is often depicted being worn in battle, but it was also frequently worn during ceremonies. It used to be called a war crown by many, but modern historians refrain from defining it thus.

Physical evidence

Egyptologist Bob Brier has noted that despite their widespread depiction in royal portraits, no ancient Egyptian crown has ever been discovered. The tomb of Tutankhamun that was discovered largely intact, contained such royal regalia as a crook and flail, but no crown was found among his funerary equipment. Diadems have been discovered.[30] It is presumed that crowns would have been believed to have magical properties and were used in rituals. Brier’s speculation is that crowns were religious or state items, so a dead king likely could not retain a crown as a personal possession. The crowns may have been passed along to the successor, much as the crowns of modern monarchies.[31]

Titles

During the Early Dynastic Period kings had three titles. The Horus name is the oldest and dates to the late pre-dynastic period. The Nesu Bity name was added during the First Dynasty. The Nebty name (Two Ladies) was first introduced toward the end of the First Dynasty.[29] The Golden falcon (bik-nbw) name is not well understood. The prenomen and nomen were introduced later and are traditionally enclosed in a cartouche.[32] By the Middle Kingdom, the official titulary of the ruler consisted of five names; Horus, Nebty, Golden Horus, nomen, and prenomen [33] for some rulers, only one or two of them may be known.

Horus name

The Horus name was adopted by the king, when taking the throne. The name was written within a square frame representing the palace, named a serekh. The earliest known example of a serekh dates to the reign of king Ka, before the First Dynasty.[34] The Horus name of several early kings expresses a relationship with Horus. Aha refers to «Horus the fighter», Djer refers to «Horus the strong», etc. Later kings express ideals of kingship in their Horus names. Khasekhemwy refers to «Horus: the two powers are at peace», while Nebra refers to «Horus, Lord of the Sun».[29]

Nesu Bity name

The Nesu Bity name, also known as prenomen, was one of the new developments from the reign of Den. The name would follow the glyphs for the «Sedge and the Bee». The title is usually translated as king of Upper and Lower Egypt. The nsw bity name may have been the birth name of the king. It was often the name by which kings were recorded in the later annals and king lists.[29]

Nebty name

The earliest example of a Nebty (Two Ladies) name comes from the reign of king Aha from the First Dynasty. The title links the king with the goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt, Nekhbet and Wadjet.[29][32] The title is preceded by the vulture (Nekhbet) and the cobra (Wadjet) standing on a basket (the neb sign).[29]

Golden Horus

The Golden Horus or Golden Falcon name was preceded by a falcon on a gold or nbw sign. The title may have represented the divine status of the king. The Horus associated with gold may be referring to the idea that the bodies of the deities were made of gold and the pyramids and obelisks are representations of (golden) sun-rays. The gold sign may also be a reference to Nubt, the city of Set. This would suggest that the iconography represents Horus conquering Set.[29]

Nomen and prenomen

The prenomen and nomen were contained in a cartouche. The prenomen often followed the King of Upper and Lower Egypt (nsw bity) or Lord of the Two Lands (nebtawy) title. The prenomen often incorporated the name of Re. The nomen often followed the title, Son of Re (sa-ra), or the title, Lord of Appearances (neb-kha).[32]

See also

- List of pharaohs

- Roman pharaoh

- Coronation of the pharaoh

- Curse of the pharaohs

- Egyptian chronology

- Pharaohs in the Bible

Notes

- ^ Likely pronounced parūwʾar in Old Egyptian (c. 2500 BC) and Middle Egyptian (c. 1700 BC), and pərəʾaʿ or pərəʾōʿ in Late Egyptian (c. 800 BC)

- ^ The Bible refers to Egypt as the «Land of Ham».

- ^ nb.f means «his lord», the monarchs were introduced with (.f) for his, (.k) for your.[18]

References

- ^ a b Clayton 1995, p. 217. «Although paying lip-service to the old ideas and religion, in varying degrees, pharaonic Egypt had in effect died with the last native pharaoh, Nectanebo II in 343 BC»

- ^ a b von Beckerath, Jürgen (1999). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. Verlag Philipp von Zabern. pp. 266–267. ISBN 978-3422008328.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

- ^ «Strong’s Hebrew Concordance — 6547. Paroh». Bible Hub.

- ^ Clayton, Peter A. Chronicle of the Pharaohs the Reign-by-reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson, 2012. Print.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (2002-09-11). Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-66420-7.

- ^ Bierbrier, Morris L. (2008-08-14). Historical Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6250-0.

- ^ «Pharaoh». AncientEgypt.co.uk. The British Museum. 1999. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Mark, Joshua (2 September 2009). «Pharaoh — World History Encyclopedia». World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Hagen, Rose-Marie; Hagen, Rainer (2007). Egypt Art. New Holland Publishers Pty, Limited. ISBN 978-3-8228-5458-7.

- ^ «The royal crowns of Egypt». Egypt Exploration Society. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ Gaskell, G. (2016-03-10). A Dictionary of the Sacred Language of All Scriptures and Myths (Routledge Revivals). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-58942-6.

- ^ A. Gardiner, Ancient Egyptian Grammar (3rd edn, 1957), 71–76.

- ^ Hieratic Papyrus from Kahun and Gurob, F. LL. Griffith, 38, 17.

- ^ Petrie, W. M. (William Matthew Flinders); Sayce, A. H. (Archibald Henry); Griffith, F. Ll (Francis Llewellyn) (1891). Illahun, Kahun and Gurob : 1889-1890. Cornell University Library. London : D. Nutt. pp. 50.

- ^ Robert Mond and O.H. Meyers. Temples of Armant, a Preliminary Survey: The Text, The Egypt Exploration Society, London, 1940, 160.

- ^ «pharaoh» in Encyclopædia Britannica. Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008.

- ^ a b c Doxey, Denise M. (1998). Egyptian Non-Royal Epithets in the Middle Kingdom: A Social and Historical Analysis. BRILL. p. 119. ISBN 90-04-11077-1.

- ^ J-M. Kruchten, Les annales des pretres de Karnak (OLA 32), 1989, pp. 474–478.

- ^ Alan Gardiner, «The Dakhleh Stela», Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 19, No. 1/2 (May, 1933) pp. 193–200.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories 2.111.1. See Anne Burton (1972). Diodorus Siculus, Book 1: A Commentary. Brill., commenting on ch. 59.1.

- ^ Elazar Ari Lipinski: «Pesach – A holiday of questions. About the Haggadah-Commentary Zevach Pesach of Rabbi Isaak Abarbanel (1437–1508). Archived 2017-03-16 at the Wayback Machine Explaining the meaning of the name Pharaoh.» Published first in German in the official quarterly of the Organization of the Jewish Communities of Bavaria: Jüdisches Leben in Bayern. Mitteilungsblatt des Landesverbandes der Israelitischen Kultusgemeinden in Bayern. Pessach-Ausgabe Nr. 109, 2009, ZDB-ID 2077457-6, S. 3–4.

- ^ Walter C. Till: «Koptische Grammatik». VEB Verlag Enzyklopädie, Leipzig, 1961. p. 62.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 158.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 159.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 160.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 161.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 162.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wilkinson, Toby A. H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001 ISBN 978-0-415-26011-4

- ^ Shaw, Garry J. The Pharaoh, Life at Court and on Campaign. Thames and Hudson, 2012, pp. 21, 77.

- ^ Bob Brier, The Murder of Tutankhamen, 1998, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Dodson, Aidan and Hilton, Dyan. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2004. ISBN 0-500-05128-3

- ^ Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press 2000, p. 477

- ^ Toby A. H. Wilkinson, Early Dynastic Egypt, Routledge 1999, pp. 57f.

Bibliography

- Shaw, Garry J. The Pharaoh, Life at Court and on Campaign, Thames and Hudson, 2012.

- Sir Alan Gardiner Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs, Third Edition, Revised. London: Oxford University Press, 1964. Excursus A, pp. 71–76.

- Jan Assmann, «Der Mythos des Gottkönigs im Alten Ägypten», in Christine Schmitz und Anja Bettenworth (hg.), Menschen — Heros — Gott: Weltentwürfe und Lebensmodelle im Mythos der Vormoderne (Stuttgart, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2009), pp. 11–26.

External links

- Digital Egypt for Universities

Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Pharaohs.

| Pharaoh of Egypt | |

|---|---|

The Pschent combined the Red Crown of Lower Egypt and the White Crown of Upper Egypt |

|

A typical depiction of a pharaoh usually depicted the king wearing the nemes headdress, a false beard, and an ornate shendyt (kilt) |

|

| Details | |

| Style | Five-name titulary |

| First monarch | King Narmer or King Menes (by tradition) (first use of the term pharaoh for a king, rather than the royal palace, was c. 1210 B.C. with Merneptah during the nineteenth dynasty) |

| Last monarch |

[2] |

| Formation | c. 3150 BC |

| Abolition |

|

| Residence | Varies by era |

| Appointer | Divine right |

| pr-ˤ3 «Great house» |

|---|

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |

|

|

||||||||

| nswt-bjt «King of Upper and Lower Egypt» |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |