Все категории

- Фотография и видеосъемка

- Знания

- Другое

- Гороскопы, магия, гадания

- Общество и политика

- Образование

- Путешествия и туризм

- Искусство и культура

- Города и страны

- Строительство и ремонт

- Работа и карьера

- Спорт

- Стиль и красота

- Юридическая консультация

- Компьютеры и интернет

- Товары и услуги

- Темы для взрослых

- Семья и дом

- Животные и растения

- Еда и кулинария

- Здоровье и медицина

- Авто и мото

- Бизнес и финансы

- Философия, непознанное

- Досуг и развлечения

- Знакомства, любовь, отношения

- Наука и техника

0

Как пишется слово гугл по-английски?

Как написать слово гугл по-английски?

Как написать слово гугл на английском?

6 ответов:

0

0

Google. Стоит зайти в интернет и практически на каждом сайте можно найти это слово. На любом языке.

0

0

Зная основы английской грамматики можно вполне себе даже угадать верное написание этого слова — google, удвоенная «о» дает звук «у», а последняя гласная не произносится, поэтому транскрипция слова получается «гугл». Это слово в современном языке употребляется довольно часто, хотя изначально это название поисковой системы и корпорации ее создавшей. Уже есть производные слова, например, глагол «гуглить» значит «искать в поисковике». Так что верный ответ — «google».

0

0

Это удивительное слово, которое нельзя перевести, но можно написать Google. Это какой-то сложный математический термин. Что-то, связанное с единицей со ста нулями.

Но, название компании получилось действительно уникальное.

0

0

Гугл является американской компанией, в нашей стране она известна по поисковику в сети интернет, название на английском выглядит следующим образом: Google. В настоящее время это второй по популярности поисковик в нашей стране.

0

0

В «гугл» по-английски пишется следующим образом-«Google«<wbr />-как мы видим прибавилось немного букв.

А всем известная фраза «окей гугл» по английски будет выглядеть следующим образом «Okey Google«;

Надеюсь вам помог мой ответ.

0

0

Из основ английского языка и его грамматики можно, даже не задаваться вопросом как пишется буква У в английской версии. Это двойная ОО и тем самым мы получаем полноценное название крупнейшей компании google.

Читайте также

нужно получить root-права и сканировать систему root-антивирусом, возможно, вредоносные программы расположились в папке /system/app. Если Вы хорошо разбираетесь в системе андроид, знакомы с системными папками, сервисами и файлами, то можете осторожно(на свой страх и риск) вручную удалить подозрительные apk файлы. Другой способ решения проблемы — перепрошивка планшета.

В Гугле очень легко переводить страницы. Есть разные способы.

Как перевести веб-страницу с иностранного языка на русский или другой язык:

- Первый способ. Мне нужно перевести страницу Villa San Carlo Borromeo Michail K. Anikushin. Ввожу адрес страницы в поле поиска Google. Чаще всего Гугл сразу предлагает автоматический перевод на основной (родной) язык, который установлен на вашем компьютере. У меня это русский, у белорусов — белорусский, у французов — французский.

Нажимаю на ссылку «перевести страницу». Открывается страница, переведенная с языка оригинала на русский язык. Наверху написано «Переводчик» и указано с какого языка на какой язык переведена страница. В данном случае страница переведена с английского на русский. Я могу выбрать другой язык, на который хочу перевести страницу. Нажимаю на указатель в поле, где указан язык перевода. Выпадает меню. Выбираем любой язык.

<hr />

- Второй способ. Копируем адрес веб-страницы и вводим его поле поиска Гугл. Тут же открываем вкладку «Ещё» и нажимаем на «переводчик». Автоматом откроется переведенная страница. А дальше можно выбирать любой язык перевода, как описано в первом способе.

<hr />

Как в Гугл-переводчике перевести веб-страницу с русского языка на иностранный:

- В случае, если нужно перевести веб-страницу с родного языка на иностранный, сначала нужно открыть Гугл-переводчик, ввести адрес страницы в поле для перевода, а потом уже выбирать язык, на который хотите перевести веб-страницу.

<hr />

- Если я захожу в поисковик Гугл другой страны, тогда русский язык становится иностранным. В этом случае нужно просто вводить адрес веб-сайта в поле поиска. Мне будет предложено перевести страницу, как в первых двух случаях. Вот что получается в результате.

<hr />

Гугл-переводчик это автомат. Недостатки автоматического перевода:

Зачастую перевод бывает некорректный.

Если веб-страница очень большая, она иногда переводится не полностью, а лишь частично. А иногда это зависит от языка оригинала.

В этих случаях нужно копировать непереведенный или некорректно переведенный текст и отдельно вставлять его в поле перевода.

Перевод фразы Select all images with rivers очень прост, для понятности можно разобрать по словам.

Select- переводится как -выбирать

all- слово переводится как — все

images- переводится как -картинки

with-переводится как -с (чем-либо или кем-либо)

rivers- переводится как-реки, множественное число из-за буквы s на конце.

В итоге получаем фразу- выберите все картинки с реками. Или можно перевести так- выберите все картинки, на которых изображены реки

Вы не пробовали самый простой вариант: просто под поисковой строкой настроить язык на русский- Google.se предлагается на: русский

или же:

Нажать на слово, указанное стрелкой (оно у вас будет на шведском языке написано).

- В открывшемся предложенном столбце действий нажать на самое верхнее (оно означает-настройки поиска).

- Далее на открывшейся странице в левой стороне будет четыре строки, вам нужно будет нажать на вторую сверху (это языки)и выбрать русский язык.

- Не забыть сохранить внизу, левое синим цветом обозначенное слово.

Пользуюсь только ГУГЛом, но он никогда меня не умаривал. Непонимаю как может умаривать то,что призвано помогать.

This article is about the company. For the search engine provided by the company, see Google Search. For other uses, see Google (disambiguation).

The Google logo used since 2015 |

|

Google’s headquarters, the Googleplex |

|

| Formerly | Google Inc. (1998–2017) |

|---|---|

| Type | Subsidiary (LLC) |

| Industry |

|

| Founded | September 4, 1998; 24 years ago[a] in Menlo Park, California, United States |

| Founders |

|

| Headquarters | 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway,

Mountain View, California , U.S. |

|

Area served |

Worldwide |

|

Key people |

Sundar Pichai (CEO) |

| Products | List of products |

|

Number of employees |

139,995 (2021) |

| Parent | Alphabet Inc. |

| Website | about.google google.com |

| Footnotes / references [5][6][7][8] |

Google LLC () is an American multinational technology company focusing on search engine technology, online advertising, cloud computing, computer software, quantum computing, e-commerce, artificial intelligence,[9] and consumer electronics. It has been referred to as «the most powerful company in the world»[10] and one of the world’s most valuable brands due to its market dominance, data collection, and technological advantages in the area of artificial intelligence.[11][12][13] Its parent company Alphabet is considered one of the Big Five American information technology companies, alongside Amazon, Apple, Meta, and Microsoft.

Google was founded on September 4, 1998, by Larry Page and Sergey Brin while they were PhD students at Stanford University in California. Together they own about 14% of its publicly listed shares and control 56% of its stockholder voting power through super-voting stock. The company went public via an initial public offering (IPO) in 2004. In 2015, Google was reorganized as a wholly owned subsidiary of Alphabet Inc. Google is Alphabet’s largest subsidiary and is a holding company for Alphabet’s Internet properties and interests. Sundar Pichai was appointed CEO of Google on October 24, 2015, replacing Larry Page, who became the CEO of Alphabet. On December 3, 2019, Pichai also became the CEO of Alphabet.[14]

The company has since rapidly grown to offer a multitude of products and services beyond Google Search, many of which hold dominant market positions. These products address a wide range of use cases, including email (Gmail), navigation (Waze & Maps), cloud computing (Cloud), web browsing (Chrome), video sharing (YouTube), productivity (Workspace), operating systems (Android), cloud storage (Drive), language translation (Translate), photo storage (Photos), video calling (Meet), smart home (Nest), smartphones (Pixel), wearable technology (Pixel Watch & Fitbit), music streaming (YouTube Music), video on demand (YouTube TV), artificial intelligence (Google Assistant), machine learning APIs (TensorFlow), AI chips (TPU), and more. Discontinued Google products include gaming (Stadia), Glass,[citation needed] Google+, Reader, Play Music, Nexus, Hangouts, and Inbox by Gmail.[15][16]

Google’s other ventures outside of Internet services and consumer electronics include quantum computing (Sycamore), self-driving cars (Waymo, formerly the Google Self-Driving Car Project), smart cities (Sidewalk Labs), and transformer models (Google Brain).[17]

Google and YouTube are the two most visited websites worldwide followed by Facebook and Twitter. Google is also the largest search engine, mapping and navigation application, email provider, office suite, video sharing platform, photo and cloud storage provider, mobile operating system, web browser, ML framework, and AI virtual assistant provider in the world as measured by market share. On the list of most valuable brands, Google is ranked second by Forbes[18] and fourth by Interbrand.[19] It has received significant criticism involving issues such as privacy concerns, tax avoidance, censorship, search neutrality, antitrust and abuse of its monopoly position.

History

Early years

Google began in January 1996 as a research project by Larry Page and Sergey Brin when they were both PhD students at Stanford University in California.[20][21][22] The project initially involved an unofficial «third founder», Scott Hassan, the original lead programmer who wrote much of the code for the original Google Search engine, but he left before Google was officially founded as a company;[23][24] Hassan went on to pursue a career in robotics and founded the company Willow Garage in 2006.[25][26]

While conventional search engines ranked results by counting how many times the search terms appeared on the page, they theorized about a better system that analyzed the relationships among websites.[27] They called this algorithm PageRank; it determined a website’s relevance by the number of pages, and the importance of those pages that linked back to the original site.[28][29] Page told his ideas to Hassan, who began writing the code to implement Page’s ideas.[23]

Page and Brin originally nicknamed the new search engine «BackRub», because the system checked backlinks to estimate the importance of a site.[20][30][31] Hassan as well as Alan Steremberg were cited by Page and Brin as being critical to the development of Google. Rajeev Motwani and Terry Winograd later co-authored with Page and Brin the first paper about the project, describing PageRank and the initial prototype of the Google search engine, published in 1998. Héctor García-Molina and Jeff Ullman were also cited as contributors to the project.[32] PageRank was influenced by a similar page-ranking and site-scoring algorithm earlier used for RankDex, developed by Robin Li in 1996, with Larry Page’s PageRank patent including a citation to Li’s earlier RankDex patent; Li later went on to create the Chinese search engine Baidu.[33][34]

Eventually, they changed the name to Google; the name of the search engine was a play on the word googol,[20][35][36] a very large number written 10100 (1 followed by 100 zeros), picked to signify that the search engine was intended to provide large quantities of information.[37]

Google’s original homepage had a simple design because the company founders had little experience in HTML, the markup language used for designing web pages.[38]

The domain name www.google.com was registered on September 15, 1997,[39] and the company was incorporated on September 4, 1998. It was based in the garage of Susan Wojcicki[22] in Menlo Park, California. Craig Silverstein, a fellow PhD student at Stanford, was hired as the first employee.[22][40][41]

Google was initially funded by an August 1998 investment of $100,000 from Andy Bechtolsheim,[20] co-founder of Sun Microsystems, a few weeks prior to September 7, 1998, the day Google was officially incorporated. This initial investment served as a motivation to incorporate the company to be able to use the funds.[42][43] Page and Brin initially approached David Cheriton for advice because he had a nearby office in Stanford, and they knew he had startup experience, having recently sold the company he co-founded, Granite Systems, to Cisco for $220 million. David arranged a meeting with Page and Brin and his Granite co-founder Andy Bechtolsheim. The meeting was set for 8 AM at the front porch of David’s home in Palo Alto and it had to be brief because Andy had another meeting at Cisco, where he now worked after the acquisition, at 9 AM. Andy briefly tested a demo of the website, liked what he saw, and then went back to his car to grab the check. David Cheriton later also joined in with a $250,000 investment.[44][45]

Google received money from two other angel investors in 1998: Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos, and entrepreneur Ram Shriram.[46] Page and Brin had first approached Shriram, who was a venture capitalist, for funding and counsel, and Shriram invested $250,000 in Google in February 1998. Shriram knew Bezos because Amazon had acquired Junglee, at which Shriram was the president. It was Shriram who told Bezos about Google. Bezos asked Shriram to meet Google’s founders and they met 6 months after Shriram had made his investment when Bezos and his wife were in a vacation trip to the Bay Area. Google’s initial funding round had already formally closed but Bezos’ status as CEO of Amazon was enough to persuade Page and Brin to extend the round and accept his investment.[47][48]

Between these initial investors, friends, and family Google raised around $1,000,000, which is what allowed them to open up their original shop in Menlo Park, California.[49]

After some additional, small investments through the end of 1998 to early 1999,[46] a new $25 million round of funding was announced on June 7, 1999,[50] with major investors including the venture capital firms Kleiner Perkins and Sequoia Capital.[43] Both firms were initially reticent about investing jointly in Google, as each wanted to retain a larger percentage of control over the company to themselves. Larry and Sergey however insisted in taking investments from both. Both venture companies finally agreed to investing jointly $12.5 million each due to their belief in Google’s great potential and through mediation of earlier angel investors Ron Conway and Ram Shriram who had contacts in the venture companies.[51]

Growth

In March 1999, the company moved its offices to Palo Alto, California,[52] which is home to several prominent Silicon Valley technology start-ups.[53] The next year, Google began selling advertisements associated with search keywords against Page and Brin’s initial opposition toward an advertising-funded search engine.[54][22] To maintain an uncluttered page design, advertisements were solely text-based.[55] In June 2000, it was announced that Google would become the default search engine provider for Yahoo!, one of the most popular websites at the time, replacing Inktomi.[56][57]

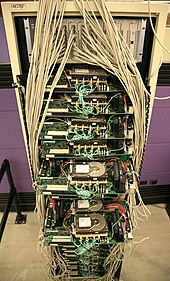

Google’s first production server[58]

In 2003, after outgrowing two other locations, the company leased an office complex from Silicon Graphics, at 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway in Mountain View, California.[59] The complex became known as the Googleplex, a play on the word googolplex, the number one followed by a googol zeroes. Three years later, Google bought the property from SGI for $319 million.[60] By that time, the name «Google» had found its way into everyday language, causing the verb «google» to be added to the Merriam-Webster Collegiate Dictionary and the Oxford English Dictionary, denoted as: «to use the Google search engine to obtain information on the Internet».[61][62] The first use of the verb on television appeared in an October 2002 episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer.[63]

Additionally, in 2001 Google’s investors felt the need to have a strong internal management, and they agreed to hire Eric Schmidt as the chairman and CEO of Google.[49] Eric was proposed by John Doerr from Kleiner Perkins. He had been trying to find a CEO that Sergey and Larry would accept for several months, but they rejected several candidates because they wanted to retain control over the company. Michael Moritz from Sequoia Capital at one point even menaced requesting Google to immediately pay back Sequoia’s $12.5m investment if they did not fulfill their promise to hire a chief executive officer, which had been made verbally during investment negotiations. Eric wasn’t initially enthusiastic about joining Google either, as the company’s full potential hadn’t yet been widely recognized at the time, and as he was occupied with his responsibilities at Novell where he was CEO. As part of him joining, Eric agreed to buy $1 million of Google preferred stocks as a way to show his commitment and to provide funds Google needed.[64]

Initial public offering

On August 19, 2004, Google became a public company via an initial public offering. At that time Larry Page, Sergey Brin, and Eric Schmidt agreed to work together at Google for 20 years, until the year 2024.[65] The company offered 19,605,052 shares at a price of $85 per share.[66][67] Shares were sold in an online auction format using a system built by Morgan Stanley and Credit Suisse, underwriters for the deal.[68][69] The sale of $1.67 billion gave Google a market capitalization of more than $23 billion.[70]

On November 13, 2006, Google acquired YouTube for $1.65 billion in Google stock,[71][72][73][74] On March 11, 2008, Google acquired DoubleClick for $3.1 billion, transferring to Google valuable relationships that DoubleClick had with Web publishers and advertising agencies.[75][76]

By 2011, Google was handling approximately 3 billion searches per day. To handle this workload, Google built 11 data centers around the world with several thousand servers in each. These data centers allowed Google to handle the ever-changing workload more efficiently.[49]

In May 2011, the number of monthly unique visitors to Google surpassed one billion for the first time.[77][78]

In May 2012, Google acquired Motorola Mobility for $12.5 billion, in its largest acquisition to date.[79][80][81] This purchase was made in part to help Google gain Motorola’s considerable patent portfolio on mobile phones and wireless technologies, to help protect Google in its ongoing patent disputes with other companies,[82] mainly Apple and Microsoft,[83] and to allow it to continue to freely offer Android.[84]

2012 onward

In June 2013, Google acquired Waze, a $966 million deal.[85] While Waze would remain an independent entity, its social features, such as its crowdsourced location platform, were reportedly valuable integrations between Waze and Google Maps, Google’s own mapping service.[86]

Google announced the launch of a new company, called Calico, on September 19, 2013, to be led by Apple Inc. chairman Arthur Levinson. In the official public statement, Page explained that the «health and well-being» company would focus on «the challenge of ageing and associated diseases».[87]

Entrance of building where Google and its subsidiary Deep Mind are located at 6 Pancras Square, London

On January 26, 2014, Google announced it had agreed to acquire DeepMind Technologies, a privately held artificial intelligence company from London.[88] Technology news website Recode reported that the company was purchased for $400 million, yet the source of the information was not disclosed. A Google spokesperson declined to comment on the price.[89][90] The purchase of DeepMind aids in Google’s recent growth in the artificial intelligence and robotics community.[91]

According to Interbrand’s annual Best Global Brands report, Google has been the second most valuable brand in the world (behind Apple Inc.) in 2013,[92] 2014,[93] 2015,[94] and 2016, with a valuation of $133 billion.[95]

On August 10, 2015, Google announced plans to reorganize its various interests as a conglomerate named Alphabet Inc. Google became Alphabet’s largest subsidiary and the umbrella company for Alphabet’s Internet interests. Upon completion of the restructuring, Sundar Pichai became CEO of Google, replacing Larry Page, who became CEO of Alphabet.[96][97][98]

On August 8, 2017, Google fired employee James Damore after he distributed a memo throughout the company that argued bias and «Google’s Ideological Echo Chamber» clouded their thinking about diversity and inclusion, and that it is also biological factors, not discrimination alone, that cause the average woman to be less interested than men in technical positions.[99] Google CEO Sundar Pichai accused Damore of violating company policy by «advancing harmful gender stereotypes in our workplace», and he was fired on the same day.[100][101][102]

Between 2018 and 2019, tensions between the company’s leadership and its workers escalated as staff protested company decisions on internal sexual harassment, Dragonfly, a censored Chinese search engine, and Project Maven, a military drone artificial intelligence, which had been seen as areas of revenue growth for the company.[103][104] On October 25, 2018, The New York Times published the exposé, «How Google Protected Andy Rubin, the ‘Father of Android'». The company subsequently announced that «48 employees have been fired over the last two years» for sexual misconduct.[105] On November 1, 2018, more than 20,000 Google employees and contractors staged a global walk-out to protest the company’s handling of sexual harassment complaints.[106][107] CEO Sundar Pichai was reported to be in support of the protests.[108] Later in 2019, some workers accused the company of retaliating against internal activists.[104]

On March 19, 2019, Google announced that it would enter the video game market, launching a cloud gaming platform called Google Stadia.[109]

On June 3, 2019, the United States Department of Justice reported that it would investigate Google for antitrust violations.[110] This led to the filing of an antitrust lawsuit in October 2020, on the grounds the company had abused a monopoly position in the search and search advertising markets.[111]

In December 2019, former PayPal chief operating officer Bill Ready became Google’s new commerce chief. Ready’s role will not be directly involved with Google Pay.[112]

In April 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Google announced several cost-cutting measures. Such measures included slowing down hiring for the remainder of 2020, except for a small number of strategic areas, recalibrating the focus and pace of investments in areas like data centers and machines, and non-business essential marketing and travel.[113] Most employees were also working from home due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the success of it even led to Google announcing that they would be permanently converting some of their jobs to work from home [114]

The 2020 Google services outages disrupted Google services: one in August that affected Google Drive among others, another in November affecting YouTube, and a third in December affecting the entire suite of Google applications. All three outages were resolved within hours.[115][116][117]

In 2021, the Alphabet Workers Union was founded, composed mostly of Google employees.[118]

In January 2021, the Australian Government proposed legislation that would require Google and Facebook to pay media companies for the right to use their content. In response, Google threatened to close off access to its search engine in Australia.[119]

In March 2021, Google reportedly paid $20 million for Ubisoft ports on Google Stadia.[120] Google spent «tens of millions of dollars» on getting major publishers such as Ubisoft and Take-Two to bring some of their biggest games to Stadia.[121]

In April 2021, The Wall Street Journal reported that Google ran a years-long program called «Project Bernanke» that used data from past advertising bids to gain an advantage over competing for ad services. This was revealed in documents concerning the antitrust lawsuit filed by ten US states against Google in December.[122]

In September 2021, the Australian government announced plans to curb Google’s capability to sell targeted ads, claiming that the company has a monopoly on the market harming publishers, advertisers, and consumers.[123]

In 2022, Google began accepting requests for the removal of phone numbers, physical addresses and email addresses from its search results. It had previously accepted requests for removing confidential data only, such as Social Security numbers, bank account and credit card numbers, personal signatures, and medical records. Even with the new policy, Google may remove information from only certain but not all search queries. It would not remove content that is «broadly useful», such as news articles, or already part of the public record.[124]

In May 2022, Google announced that the company had acquired California based, MicroLED display technology development and manufacturing Start-up Raxium. Raxium is set to join Google’s Devices and Services team to aid in the development of micro-optics, monolithic integration, and system integration.[125][126]

Products and services

Search engine

Google indexes billions of web pages to allow users to search for the information they desire through the use of keywords and operators.[127] According to comScore market research from November 2009, Google Search is the dominant search engine in the United States market, with a market share of 65.6%.[128] In May 2017, Google enabled a new «Personal» tab in Google Search, letting users search for content in their Google accounts’ various services, including email messages from Gmail and photos from Google Photos.[129][130]

Google launched its Google News service in 2002, an automated service which summarizes news articles from various websites.[131] Google also hosts Google Books, a service which searches the text found in books in its database and shows limited previews or and the full book where allowed.[132]

Advertising

Google on ad-tech London, 2010

Google generates most of its revenues from advertising. This includes sales of apps, purchases made in-app, digital content products on Google and YouTube, Android and licensing and service fees, including fees received for Google Cloud offerings. Forty-six percent of this profit was from clicks (cost per clicks), amounting to US$109,652 million in 2017. This includes three principal methods, namely AdMob, AdSense (such as AdSense for Content, AdSense for Search, etc.) and DoubleClick AdExchange.[133]

In addition to its own algorithms for understanding search requests, Google uses technology its acquisition of DoubleClick, to project user interest and target advertising to the search context and the user history.[134][135]

In 2007, Google launched «AdSense for Mobile», taking advantage of the emerging mobile advertising market.[136]

Google Analytics allows website owners to track where and how people use their website, for example by examining click rates for all the links on a page.[137] Google advertisements can be placed on third-party websites in a two-part program. Google Ads allows advertisers to display their advertisements in the Google content network, through a cost-per-click scheme.[138] The sister service, Google AdSense, allows website owners to display these advertisements on their website and earn money every time ads are clicked.[139] One of the criticisms of this program is the possibility of click fraud, which occurs when a person or automated script clicks on advertisements without being interested in the product, causing the advertiser to pay money to Google unduly. Industry reports in 2006 claimed that approximately 14 to 20 percent of clicks were fraudulent or invalid.[140] Google Search Console (rebranded from Google Webmaster Tools in May 2015) allows webmasters to check the sitemap, crawl rate, and for security issues of their websites, as well as optimize their website’s visibility.

Consumer services

Web-based services

Google offers Gmail for email,[141] Google Calendar for time-management and scheduling,[142] Google Maps for mapping, navigation and satellite imagery,[143] Google Drive for cloud storage of files,[144] Google Docs, Sheets and Slides for productivity,[144] Google Photos for photo storage and sharing,[145] Google Keep for note-taking,[146] Google Translate for language translation,[147] YouTube for video viewing and sharing,[148] Google My Business for managing public business information,[149] and Duo for social interaction.[150] In March 2019, Google unveiled a cloud gaming service named Stadia.[109] A job search product has also existed since before 2017,[151][152][153] Google for Jobs is an enhanced search feature that aggregates listings from job boards and career sites.[154]

Some Google services are not web-based. Google Earth, launched in 2005, allowed users to see high-definition satellite pictures from all over the world for free through a client software downloaded to their computers.[155]

Software

Google develops the Android mobile operating system,[156] as well as its smartwatch,[157] television,[158] car,[159] and Internet of things-enabled smart devices variations.[160]

It also develops the Google Chrome web browser,[161] and ChromeOS, an operating system based on Chrome.[162]

Hardware

Google Pixel smartphones on display in a store

In January 2010, Google released Nexus One, the first Android phone under its own brand.[163] It spawned a number of phones and tablets under the «Nexus» branding[164] until its eventual discontinuation in 2016, replaced by a new brand called Pixel.[165]

In 2011, the Chromebook was introduced, which runs on ChromeOS.[166]

In July 2013, Google introduced the Chromecast dongle, which allows users to stream content from their smartphones to televisions.[167][168]

In June 2014, Google announced Google Cardboard, a simple cardboard viewer that lets user place their smartphone in a special front compartment to view virtual reality (VR) media.[169]

Other hardware products include:

- Nest, a series of voice assistant smart speakers that can answer voice queries, play music, find information from apps (calendar, weather etc.), and control third-party smart home appliances (users can tell it to turn on the lights, for example). The Google Nest line includes the original Google Home[170] (later succeeded by the Nest Audio), the Google Home Mini (later succeeded by the Nest Mini, the Google Home Max, the Google Home Hub (later rebranded as the Nest Hub), and the Nest Hub Max.

- Nest Wifi (originally Google Wifi), a connected set of Wi-Fi routers to simplify and extend coverage of home Wi-Fi.[171]

Enterprise services

Google Workspace (formerly G Suite until October 2020[172]) is a monthly subscription offering for organizations and businesses to get access to a collection of Google’s services, including Gmail, Google Drive and Google Docs, Google Sheets and Google Slides, with additional administrative tools, unique domain names, and 24/7 support.[173]

On September 24, 2012,[174] Google launched Google for Entrepreneurs, a largely not-for-profit business incubator providing startups with co-working spaces known as Campuses, with assistance to startup founders that may include workshops, conferences, and mentorships.[175] Presently, there are seven Campus locations: Berlin, London, Madrid, Seoul, São Paulo, Tel Aviv, and Warsaw.

On March 15, 2016, Google announced the introduction of Google Analytics 360 Suite, «a set of integrated data and marketing analytics products, designed specifically for the needs of enterprise-class marketers» which can be integrated with BigQuery on the Google Cloud Platform. Among other things, the suite is designed to help «enterprise class marketers» «see the complete customer journey», generate «useful insights», and «deliver engaging experiences to the right people».[176] Jack Marshall of The Wall Street Journal wrote that the suite competes with existing marketing cloud offerings by companies including Adobe, Oracle, Salesforce, and IBM.[177]

Internet services

In February 2010, Google announced the Google Fiber project, with experimental plans to build an ultra-high-speed broadband network for 50,000 to 500,000 customers in one or more American cities.[178][179] Following Google’s corporate restructure to make Alphabet Inc. its parent company, Google Fiber was moved to Alphabet’s Access division.[180][181]

In April 2015, Google announced Project Fi, a mobile virtual network operator, that combines Wi-Fi and cellular networks from different telecommunication providers in an effort to enable seamless connectivity and fast Internet signal.[182][183]

Corporate affairs

Stock price performance and quarterly earnings

Google’s initial public offering (IPO) took place on August 19, 2004. At IPO, the company offered 19,605,052 shares at a price of $85 per share.[66][67] The sale of $1.67 billion gave Google a market capitalization of more than $23 billion.[70] The stock performed well after the IPO, with shares hitting $350 for the first time on October 31, 2007,[184] primarily because of strong sales and earnings in the online advertising market.[185] The surge in stock price was fueled mainly by individual investors, as opposed to large institutional investors and mutual funds.[185] GOOG shares split into GOOG class C shares and GOOGL class A shares.[186] The company is listed on the NASDAQ stock exchange under the ticker symbols GOOGL and GOOG, and on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol GGQ1. These ticker symbols now refer to Alphabet Inc., Google’s holding company, since the fourth quarter of 2015.[187]

In the third quarter of 2005, Google reported a 700% increase in profit, largely due to large companies shifting their advertising strategies from newspapers, magazines, and television to the Internet.[188][189][190]

For the 2006 fiscal year, the company reported $10.492 billion in total advertising revenues and only $112 million in licensing and other revenues.[191] In 2011, 96% of Google’s revenue was derived from its advertising programs.[192]

Google generated $50 billion in annual revenue for the first time in 2012, generating $38 billion the previous year. In January 2013, then-CEO Larry Page commented, «We ended 2012 with a strong quarter … Revenues were up 36% year-on-year, and 8% quarter-on-quarter. And we hit $50 billion in revenues for the first time last year – not a bad achievement in just a decade and a half.»[193]

Google’s consolidated revenue for the third quarter of 2013 was reported in mid-October 2013 as $14.89 billion, a 12 percent increase compared to the previous quarter.[194] Google’s Internet business was responsible for $10.8 billion of this total, with an increase in the number of users’ clicks on advertisements.[195] By January 2014, Google’s market capitalization had grown to $397 billion.[196]

Tax avoidance strategies

Google uses various tax avoidance strategies. On the list of largest technology companies by revenue, it pays the lowest taxes to the countries of origin of its revenues. Google between 2007 and 2010 saved $3.1 billion in taxes by shuttling non-U.S. profits through Ireland and the Netherlands and then to Bermuda. Such techniques lower its non-U.S. tax rate to 2.3 per cent, while normally the corporate tax rate in, for instance, the UK is 28 per cent.[197] This has reportedly sparked a French investigation into Google’s transfer pricing practices.[198]

In 2020, Google said it had overhauled its controversial global tax structure and consolidated all of its intellectual property holdings back to the US.[199]

Google Vice-president Matt Brittin testified to the Public Accounts Committee of the UK House of Commons that his UK sales team made no sales and hence owed no sales taxes to the UK.[200] In January 2016, Google reached a settlement with the UK to pay £130m in back taxes plus higher taxes in future.[201] In 2017, Google channeled $22.7 billion from the Netherlands to Bermuda to reduce its tax bill.[202]

In 2013, Google ranked 5th in lobbying spending, up from 213th in 2003. In 2012, the company ranked 2nd in campaign donations of technology and Internet sections.[203]

Corporate identity

Google’s logo from 2013 to 2015

The name «Google» originated from a misspelling of «googol»,[204][205] which refers to the number represented by a 1 followed by one-hundred zeros. Page and Brin write in their original paper on PageRank:[32] «We chose our systems name, Google, because it is a common spelling of googol, or 10100 and fits well with our goal of building very large-scale search engines.» Having found its way increasingly into everyday language, the verb «google» was added to the Merriam Webster Collegiate Dictionary and the Oxford English Dictionary in 2006, meaning «to use the Google search engine to obtain information on the Internet.»[206][207] Google’s mission statement, from the outset, was «to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful»,[208] and its unofficial slogan is «Don’t be evil».[209] In October 2015, a related motto was adopted in the Alphabet corporate code of conduct by the phrase: «Do the right thing».[210] The original motto was retained in the code of conduct of Google, now a subsidiary of Alphabet.

The original Google logo was designed by Sergey Brin.[211] Since 1998, Google has been designing special, temporary alternate logos to place on their homepage intended to celebrate holidays, events, achievements and people. The first Google Doodle was in honor of the Burning Man Festival of 1998.[212][213] The doodle was designed by Larry Page and Sergey Brin to notify users of their absence in case the servers crashed. Subsequent Google Doodles were designed by an outside contractor, until Larry and Sergey asked then-intern Dennis Hwang to design a logo for Bastille Day in 2000. From that point onward, Doodles have been organized and created by a team of employees termed «Doodlers».[214]

Google has a tradition of creating April Fools’ Day jokes. Its first on April 1, 2000, was Google MentalPlex which allegedly featured the use of mental power to search the web.[215] In 2007, Google announced a free Internet service called TiSP, or Toilet Internet Service Provider, where one obtained a connection by flushing one end of a fiber-optic cable down their toilet.[216]

Google’s services contain easter eggs, such as the Swedish Chef’s «Bork bork bork,» Pig Latin, «Hacker» or leetspeak, Elmer Fudd, Pirate, and Klingon as language selections for its search engine.[217] When searching for the word «anagram,» meaning a rearrangement of letters from one word to form other valid words, Google’s suggestion feature displays «Did you mean: nag a ram?»[218]

Workplace culture

On Fortune magazine’s list of the best companies to work for, Google ranked first in 2007, 2008 and 2012,[219][220][221] and fourth in 2009 and 2010.[222][223] Google was also nominated in 2010 to be the world’s most attractive employer to graduating students in the Universum Communications talent attraction index.[224] Google’s corporate philosophy includes principles such as «you can make money without doing evil,» «you can be serious without a suit,» and «work should be challenging and the challenge should be fun.»[225]

As of September 30, 2020, Alphabet Inc. had 132,121 employees,[226] of which more than 100,000 worked for Google.[8] Google’s 2020 diversity report states that 32 percent of its workforce are women and 68 percent are men, with the ethnicity of its workforce being predominantly white (51.7%) and Asian (41.9%).[227] Within tech roles, 23.6 percent were women; and 26.7 percent of leadership roles were held by women.[228] In addition to its 100,000+ full-time employees, Google used about 121,000 temporary workers and contractors, as of March 2019.[8]

Google’s employees are hired based on a hierarchical system. Employees are split into six hierarchies based on experience and can range «from entry-level data center workers at level one to managers and experienced engineers at level six.»[229] As a motivation technique, Google uses a policy known as Innovation Time Off, where Google engineers are encouraged to spend 20% of their work time on projects that interest them. Some of Google’s services, such as Gmail, Google News, Orkut, and AdSense originated from these independent endeavors.[230] In a talk at Stanford University, Marissa Mayer, Google’s vice-president of Search Products and User Experience until July 2012, showed that half of all new product launches in the second half of 2005 had originated from the Innovation Time Off.[231]

In 2005, articles in The New York Times[232] and other sources began suggesting that Google had lost its anti-corporate, no evil philosophy.[233][234][235] In an effort to maintain the company’s unique culture, Google designated a Chief Culture Officer whose purpose was to develop and maintain the culture and work on ways to keep true to the core values that the company was founded on.[236] Google has also faced allegations of sexism and ageism from former employees.[237][238] In 2013, a class action against several Silicon Valley companies, including Google, was filed for alleged «no cold call» agreements which restrained the recruitment of high-tech employees.[239] In a lawsuit filed January 8, 2018, multiple employees and job applicants alleged Google discriminated against a class defined by their «conservative political views[,] male gender[,] and/or […] Caucasian or Asian race».[240]

On January 25, 2020, the formation of an international workers union of Google employees, Alpha Global, was announced.[241] The coalition is made up of «13 different unions representing workers in 10 countries, including the United States, United Kingdom, and Switzerland.»[242] The group is affiliated with UNI Global Union, which represents nearly 20 million international workers from various unions and federations. The formation of the union is in response to persistent allegations of mistreatment of Google employees and a toxic workplace culture.[242][243][240] Google had previously been accused of surveilling and firing employees who were suspected of organizing a workers union.[244] In 2021 court documents revealed that between 2018 and 2020 Google ran an anti-union campaign called Project Vivian to «convince them (employees) that unions suck».[245]

Office locations

Google’s New York City office building houses its largest advertising sales team.

Google’s headquarters in Mountain View, California is referred to as «the Googleplex», a play on words on the number googolplex and the headquarters itself being a complex of buildings. Internationally, Google has over 78 offices in more than 50 countries.[246]

In 2006, Google moved into about 300,000 square feet (27,900 m2) of office space at 111 Eighth Avenue in Manhattan, New York City. The office was designed and built specially for Google, and houses its largest advertising sales team.[247] In 2010, Google bought the building housing the headquarter, in a deal that valued the property at around $1.9 billion.[248][249] In March 2018, Google’s parent company Alphabet bought the nearby Chelsea Market building for $2.4 billion. The sale is touted as one of the most expensive real estate transactions for a single building in the history of New York.[250][251][252][253] In November 2018, Google announced its plan to expand its New York City office to a capacity of 12,000 employees.[254] The same December, it was announced that a $1 billion, 1,700,000-square-foot (160,000 m2) headquarters for Google would be built in Manhattan’s Hudson Square neighborhood.[255][256] Called Google Hudson Square, the new campus is projected to more than double the number of Google employees working in New York City.[257]

By late 2006, Google established a new headquarters for its AdWords division in Ann Arbor, Michigan.[258] In November 2006, Google opened offices on Carnegie Mellon’s campus in Pittsburgh, focusing on shopping-related advertisement coding and smartphone applications and programs.[259][260] Other office locations in the U.S. include Atlanta, Georgia; Austin, Texas; Boulder, Colorado; Cambridge, Massachusetts; San Francisco, California; Seattle, Washington; Kirkland, Washington; Birmingham, Michigan; Reston, Virginia, Washington, D.C.,[261] and Madison, Wisconsin.[262]

Google’s Dublin Ireland office, headquarters of Google Ads for Europe

It also has product research and development operations in cities around the world, namely Sydney (birthplace location of Google Maps)[263] and London (part of Android development).[264] In November 2013, Google announced plans for a new London headquarter, a 1 million square foot office able to accommodate 4,500 employees. Recognized as one of the biggest ever commercial property acquisitions at the time of the deal’s announcement in January,[265] Google submitted plans for the new headquarter to the Camden Council in June 2017.[266][267] In May 2015, Google announced its intention to create its own campus in Hyderabad, India. The new campus, reported to be the company’s largest outside the United States, will accommodate 13,000 employees.[268][269]

Google’s Global Offices sum a total of 85 Locations worldwide,[270] with 32 offices in North America, 3 of them in Canada and 29 in United States Territory, California being the state with the most Google’s offices with 9 in total including the Googleplex. In the Latin America Region Google counts with 6 offices, in Europe 24 (3 of them in UK), The Asia Pacific region counts with 18 offices principally in India and China, and the Africa Middle East region counts 5 offices.

North America

Latin America

Europe

Asia Pacific

Africa & Middle East

Infrastructure

Google data centers are located in North and South America, Asia, and Europe.[271] There is no official data on the number of servers in Google data centers; however, research and advisory firm Gartner estimated in a July 2016 report that Google at the time had 2.5 million servers.[272] Traditionally, Google relied on parallel computing on commodity hardware like mainstream x86 computers (similar to home PCs) to keep costs per query low.[273][274][275] In 2005, it started developing its own designs, which were only revealed in 2009.[275]

Google built its own private submarine communications cables; the first, named Curie, connects California with Chile and was completed on November 15, 2019.[276][277] The second fully Google-owned undersea cable, named Dunant, connects the United States with France and is planned to begin operation in 2020.[278] Google’s third subsea cable, Equiano, will connect Lisbon, Portugal with Lagos, Nigeria and Cape Town, South Africa.[279] The company’s fourth cable, named Grace Hopper, connects landing points in New York, US, Bude, UK and Bilbao, Spain, and is expected to become operational in 2022.[280]

Environment

In October 2006, the company announced plans to install thousands of solar panels to provide up to 1.6 Megawatt of electricity, enough to satisfy approximately 30% of the campus’ energy needs.[281][282] The system is the largest rooftop photovoltaic power station constructed on a U.S. corporate campus and one of the largest on any corporate site in the world.[281] Since 2007, Google has aimed for carbon neutrality in regard to its operations.[283]

Google disclosed in September 2011 that it «continuously uses enough electricity to power 200,000 homes», almost 260 million watts or about a quarter of the output of a nuclear power plant. Total carbon emissions for 2010 were just under 1.5 million metric tons, mostly due to fossil fuels that provide electricity for the data centers. Google said that 25 percent of its energy was supplied by renewable fuels in 2010. An average search uses only 0.3 watt-hours of electricity, so all global searches are only 12.5 million watts or 5% of the total electricity consumption by Google.[284]

In 2010, Google Energy made its first investment in a renewable energy project, putting $38.8 million into two wind farms in North Dakota. The company announced the two locations will generate 169.5 megawatts of power, enough to supply 55,000 homes.[285] In February 2010, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission granted Google an authorization to buy and sell energy at market rates.[286] The corporation exercised this authorization in September 2013 when it announced it would purchase all the electricity produced by the not-yet-built 240-megawatt Happy Hereford wind farm.[287]

In July 2010, Google signed an agreement with an Iowa wind farm to buy 114 megawatts of power for 20 years.[288]

In December 2016, Google announced that—starting in 2017—it would purchase enough renewable energy to match 100% of the energy usage of its data centers and offices. The commitment will make Google «the world’s largest corporate buyer of renewable power, with commitments reaching 2.6 gigawatts (2,600 megawatts) of wind and solar energy».[289][290][291]

In November 2017, Google bought 536 megawatts of wind power. The purchase made the firm reach 100% renewable energy. The wind energy comes from two power plants in South Dakota, one in Iowa and one in Oklahoma.[292] In September 2019, Google’s chief executive announced plans for a $2 billion wind and solar investment, the biggest renewable energy deal in corporate history. This will grow their green energy profile by 40%, giving them an extra 1.6 gigawatt of clean energy, the company said.[293]

In September 2020, Google announced it had retroactively offset all of its carbon emissions since the company’s foundation in 1998.[294] It also committed to operating its data centers and offices using only carbon-free energy by 2030.[295] In October 2020, the company pledged to make the packaging for its hardware products 100% plastic-free and 100% recyclable by 2025. It also said that all its final assembly manufacturing sites will achieve a UL 2799 Zero Waste to Landfill certification by 2022 by ensuring that the vast majority of waste from the manufacturing process is recycled instead of ending up in a landfill.[296]

Climate change denial and misinformation

Google donates to politicians who deny climate change, including Jim Inhofe, and sponsors climate change denial political groups including the State Policy Network and the Competitive Enterprise Institute.[297][298][299] The company also actively funds and profits from climate disinformation by monetizing ad spaces on most of the largest climate disinformation sites.[300] Google continued to monetize and profit from sites propagating climate disinformation even after the company updated their policy to prohibit placing their ads on similar sites.[301]

Philanthropy

In 2004, Google formed the not-for-profit philanthropic Google.org, with a start-up fund of $1 billion.[302] The mission of the organization is to create awareness about climate change, global public health, and global poverty. One of its first projects was to develop a viable plug-in hybrid electric vehicle that can attain 100 miles per gallon. Google hired Larry Brilliant as the program’s executive director in 2004[303] and Megan Smith has since replaced him as director.[304]

In March 2007, in partnership with the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute (MSRI), Google hosted the first Julia Robinson Mathematics Festival at its headquarters in Mountain View.[305] In 2011, Google donated 1 million euros to International Mathematical Olympiad to support the next five annual International Mathematical Olympiads (2011–2015).[306][307] In July 2012, Google launched a «Legalize Love» campaign in support of gay rights.[308]

In 2008, Google announced its «project 10100» which accepted ideas for how to help the community and then allowed Google users to vote on their favorites.[309] After two years of silence, during which many wondered what had happened to the program,[310] Google revealed the winners of the project, giving a total of ten million dollars to various ideas ranging from non-profit organizations that promote education to a website that intends to make all legal documents public and online.[311]

Responding to the humanitarian crisis after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Google announced a $15 million donation to support Ukrainian citizens.[312] The company also decided to transform its office in Warsaw into a help center for refugees.[313]

Criticism and controversies

San Francisco activists protest privately owned shuttle buses that transport workers for tech companies such as Google from their homes in San Francisco and Oakland to corporate campuses in Silicon Valley.

Google has had criticism over issues such as aggressive tax avoidance,[314] search neutrality, copyright, censorship of search results and content,[315] and privacy.[316][317]

Other criticisms are alleged misuse and manipulation of search results, its use of other people’s intellectual property, concerns that its compilation of data may violate people’s privacy, and the energy consumption of its servers, as well as concerns over traditional business issues such as monopoly, restraint of trade, anti-competitive practices, and patent infringement.

Google formerly complied with Internet censorship policies of the People’s Republic of China,[318] enforced by means of filters colloquially known as «The Great Firewall of China», but no longer does so. As a result, all Google services except for Chinese Google Maps are blocked from access within mainland China without the aid of virtual private networks, proxy servers, or other similar technologies.

2018

In July 2018, Mozilla program manager Chris Peterson accused Google of intentionally slowing down YouTube performance on Firefox.[319][320] In April 2019, former Mozilla executive Jonathan Nightingale accused Google of intentionally and systematically sabotaging the Firefox browser over the past decade in order to boost adoption of Google Chrome.[321]

In August 2018, The Intercept reported that Google is developing for the People’s Republic of China a censored version of its search engine (known as Dragonfly) «that will blacklist websites and search terms about human rights, democracy, religion, and peaceful protest».[322][323] However, the project had been withheld due to privacy concerns.[324][325]

2019

In 2019, a hub for critics of Google dedicated to abstaining from using Google products coalesced in the Reddit online community /r/degoogle.[326] The DeGoogle grassroots campaign continues to grow as privacy activists highlight information about Google products, and the associated incursion on personal privacy rights by the company.

In November 2019, the Office for Civil Rights of the United States Department of Health and Human Services began investigation into Project Nightingale, to assess whether the «mass collection of individuals’ medical records» complied with HIPAA.[327] According to The Wall Street Journal, Google secretively began the project in 2018, with St. Louis-based healthcare company Ascension.[328]

2022

In a 2022 National Labor Relations Board ruling, court documents suggested that Google sponsored a secretive project — Project Vivian to counsel its employees and to discourage them from forming unions.[329]

Racially-targeted surveillance

Google has aided controversial governments in mass surveillance projects, sharing with police and military the identities of those protesting racial injustice. In 2020, they shared with the FBI information collected from all Android users at a Black Lives Matter protest in Seattle,[330] including those who had opted out of location data collection.[331][332]

Google is also part of Project Nimbus, a $1.2 billion deal in which the technology companies Google and Amazon will provide Israel and its military with artificial intelligence, machine learning, and other cloud computing services, including building local cloud sites that will «keep information within Israel’s borders under strict security guidelines.»[333][334][335] The contract has been criticized by shareholders as well as their employees over concerns that the project will lead to further abuses of Palestinians’ human rights in the context of the ongoing illegal occupation and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[336][337] Ariel Koren, a former marketing manager for Google’s educational products and an outspoken critic of the project, wrote that Google «systematically silences Palestinian, Jewish, Arab and Muslim voices concerned about Google’s complicity in violations of Palestinian human rights—to the point of formally retaliating against workers and creating an environment of fear,» reflecting her view that the ultimatum came in retaliation for her opposition to and organization against the project.[333][338]

Anti-trust, privacy, and other litigation

The European Commission, which imposed three fines on Google in 2017, 2018, and 2019

Fines and lawsuits

European Union

On June 27, 2017, the company received a record fine of €2.42 billion from the European Union for «promoting its own shopping comparison service at the top of search results.»[339]

On July 18, 2018,[340] the European Commission fined Google €4.34 billion for breaching EU antitrust rules. The abuse of dominant position has been referred to Google’s constraint applied to Android device manufacturers and network operators to ensure that traffic on Android devices goes to the Google search engine. On October 9, 2018, Google confirmed[341] that it had appealed the fine to the General Court of the European Union.[342]

On October 8, 2018, a class action lawsuit was filed against Google and Alphabet due to «non-public» Google+ account data being exposed as a result of a bug that allowed app developers to gain access to the private information of users. The litigation was settled in July 2020 for $7.5 million with a payout to claimants of at least $5 each, with a maximum of $12 each.[343][344][345]

On March 20, 2019, the European Commission imposed a €1.49 billion ($1.69 billion) fine on Google for preventing rivals from being able to «compete and innovate fairly» in the online advertising market. European Union competition commissioner Margrethe Vestager said Google had violated EU antitrust rules by «imposing anti-competitive contractual restrictions on third-party websites» that required them to exclude search results from Google’s rivals.[346][347]

On September 14, 2022, Google lost the appeal over €4.125bn (£3.5bn) fine, which was ruled to be paid after it was proved by the European Commission that Google forced Android phone-makers to carry Google’s search and web browser apps. Since the initial accusations, Google changed its policy.[348]

France

On January 21, 2019, French data regulator CNIL imposed a record €50 million fine on Google for breaching the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation. The judgment claimed Google had failed to sufficiently inform users of its methods for collecting data to personalize advertising. Google issued a statement saying it was «deeply committed» to transparency and was «studying the decision» before determining its response.[349]

On January 6, 2022, France’s data privacy regulatory body CNIL fined Alphabet’s Google a 150 million euros (US$169 million) for not allowing its Internet users an easy refusal of Cookies along with Facebook.[350]

United States

After U.S. Congressional hearings in July 2020,[351] and a report from the U.S. House of Representatives’ Antitrust Subcommittee released in early October[352] the United States Department of Justice filed an antitrust lawsuit against Google on October 20, 2020, asserting that it has illegally maintained its monopoly position in web search and search advertising.[353][354] The lawsuit alleged that Google engaged in anticompetitive behavior by paying Apple between $8 billion-$12 billion to be the default search engine on iPhones.[355] Later that month, both Facebook and Alphabet agreed to «cooperate and assist one another» in the face of investigation into their online advertising practices.[356][357]

Private browsing lawsuit

In early June 2020, a $5 billion class-action lawsuit was filed against Google by a group of consumers, alleging that Chrome’s Incognito browsing mode still collects their user history.[358][359] The lawsuit became known in March 2021 when a federal judge denied Google’s request to dismiss the case, ruling that they must face the group’s charges.[360][361] Reuters reported that the lawsuit alleged that Google’s CEO Sundar Pichai sought to keep the users unaware of this issue.[362]

Gender discrimination lawsuit

In 2017, three women sued Google, accusing the company of violating California’s Equal Pay Act by underpaying its female employees. The lawsuit cited the wage gap was around $17,000 and that Google locked women into lower career tracks, leading to smaller salaries and bonuses. In June 2022, Google agreed to pay an $118 million settlement to 15,550 female employees working in California since 2013. As a part of the settlement, Google also agreed to hire a third party to analyze its hiring and compensation practices.[363][364][365]

U.S. government contracts

Following media reports about PRISM, the NSA’s massive electronic surveillance program, in June 2013, several technology companies were identified as participants, including Google.[366] According to unnamed sources, Google joined the PRISM program in 2009, as YouTube in 2010.[367]

Google has worked with the United States Department of Defense on drone software through the 2017 Project Maven that could be used to improve the accuracy of drone strikes.[368] In April 2018, thousands of Google employees, including senior engineers, signed a letter urging Google CEO Sundar Pichai to end this controversial contract with the Pentagon.[369] Google ultimately decided not to renew this DoD contract, which was set to expire in 2019.[370]

See also

- Outline of Google

- History of Google

- List of Google products

- Google China

- Google logo

- Googlization

- Google.org

- Google ATAP

- List of mergers and acquisitions by Alphabet

Notes

- ^ Google was incorporated on September 4, 1998, however, since 2002, the company has celebrated its anniversaries on various days in September, most frequently on September 27.[1][2][3] The shift in dates reportedly happened to celebrate index-size milestones in tandem with the birthday.[4]

References

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Alex (September 4, 2014). «Google Used to Be the Company That Did ‘Nothing But Search’«. Time.

- ^ «When is Google’s birthday – and why are people confused?». The Telegraph. September 27, 2019. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022.

- ^ Griffin, Andrew (September 27, 2019). «Google birthday: The one big problem with the company’s celebratory doodle». The Independent.

- ^ Wray, Richard (September 5, 2008). «Happy birthday Google». The Guardian.

- ^ «Company – Google». January 16, 2015. Archived from the original on January 16, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ Claburn, Thomas (September 24, 2008). «Google Founded By Sergey Brin, Larry Page… And Hubert Chang?!?». InformationWeek. UBM plc. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- ^ «Locations— Google Jobs». Archived from the original on September 30, 2013. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- ^ a b c Wakabayashi, Daisuke (May 28, 2019). «Google’s Shadow Work Force: Temps Who Outnumber Full-Time Employees (Published 2019)». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 18, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Condon, Stephanie (May 7, 2019). «Google I/O: From ‘AI first’ to AI working for everyone». ZDNet. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Jack, Simon (November 21, 2017). «Google — powerful and responsible?». BBC News. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ McCormick, Rich (June 2, 2016). «Elon Musk: There’s only one AI company that worries me». The Verge. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Justice Department Sues Monopolist Google For Violating Antitrust Laws». www.justice.gov. October 20, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Land of the Giants: The Titans of Tech | CNN+». plus.cnn.com. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ Feiner, Lauren (December 3, 2019). «Larry Page steps down as CEO of Alphabet, Sundar Pichai to take over». CNBC. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Brady, Heather; Kirk, Chris (March 15, 2013). «The Google Graveyard». Slate. Archived from the original on March 16, 2013. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ^ Booker, Logan (March 17, 2013). «Google Graveyard Does Exist». gizmodo. Gizmodo. Archived from the original on May 18, 2018. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ^ «Inside X, Google’s top-secret moonshot factory». Wired UK. ISSN 1357-0978. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ Swant, Marty. «THE WORLD’S VALUABLE BRANDS». Forbes. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «BEST GLOBAL BRANDS». Interbrand. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d «How we started and where we are today – Google». about.google. Archived from the original on April 22, 2020. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

- ^ Brezina, Corona (2013). Sergey Brin, Larry Page, Eric Schmidt, and Google (1st ed.). New York: Rosen Publishing Group. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-4488-6911-4. LCCN 2011039480.

- ^ a b c d «Our history in depth». Google Company. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Fisher, Adam (July 10, 2018). «Brin, Page, and Mayer on the Accidental Birth of the Company that Changed Everything». Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- ^ McHugh, Josh (January 1, 2003). «Google vs. Evil». Wired. Archived from the original on June 2, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ «Willow Garage Founder Scott Hassan Aims To Build A Startup Village». IEEE Spectrum. September 5, 2014. Archived from the original on August 24, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ D’Onfro, Jillian (February 13, 2016). «How a billionaire who wrote Google’s original code created a robot revolution». Business Insider. Archived from the original on August 24, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ Page, Lawrence; Brin, Sergey; Motwani, Rajeev; Winograd, Terry (November 11, 1999). «The PageRank Citation Ranking: Bringing Order to the Web». Stanford University. Archived from the original on November 18, 2009.

- ^ «Helpful products. For everyone». Google, Inc. Archived from the original on February 10, 2010.

- ^ Page, Larry (August 18, 1997). «PageRank: Bringing Order to the Web». Stanford Digital Library Project. Archived from the original on May 6, 2002. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- ^ Battelle, John (August 2005). «The Birth of Google». Wired. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ «Backrub search engine at Stanford University». Archived from the original on December 24, 1996. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- ^ a b Brin, Sergey; Page, Lawrence (1998). «The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual Web search engine» (PDF). Computer Networks and ISDN Systems. 30 (1–7): 107–117. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.115.5930. doi:10.1016/S0169-7552(98)00110-X. ISSN 0169-7552. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- ^ ««About: RankDex»«. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2010., RankDex

- ^ «Method for node ranking in a linked database». Google Patents. Archived from the original on October 15, 2015. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ Koller, David (January 2004). «Origin of the name «Google»«. Stanford University. Archived from the original on June 27, 2012.

- ^ Hanley, Rachael (February 12, 2003). «From Googol to Google». The Stanford Daily. Stanford University. Archived from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ «Google! Beta website». Google, Inc. Archived from the original on February 21, 1999. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ Williamson, Alan (January 12, 2005). «An evening with Google’s Marissa Mayer». Alan Williamson. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved July 5, 2010.

- ^ «Google.com WHOIS, DNS, & Domain Info – DomainTools». WHOIS. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016.

- ^ «Craig Silverstein’s website». Stanford University. Archived from the original on October 2, 1999. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ Kopytoff, Verne (September 7, 2008). «Craig Silverstein grew a decade with Google». San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications, Inc. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012.

- ^ Long, Tony (September 7, 2007). «Sept. 7, 1998: If the Check Says ‘Google Inc.,’ We’re ‘Google Inc.’«. Wired.

- ^ a b Kopytoff, Verne (April 29, 2004). «For early Googlers, key word is $». San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 19, 2009.

- ^ Jolis, Jacob (April 16, 2010). «Frugal after Google». The Stanford Daily. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- ^ «The Invention And History Of Google | Silicon Valley: The Untold Story». YouTube. Discovery UK. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- ^ a b Auletta, Ken (2010). Googled: The End of the World as We Know it (Reprint ed.). New York, N.Y.: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-311804-6. OCLC 515456623.

On September 7, 1998, the day Google officially incorporated, he [Shriram] wrote out a check for just over $250,000, one of four of this size the founders received.

- ^ Canales, Katie. «The unlikely way Jeff Bezos became one of the first investors in Google, which probably made him a billionaire outside of Amazon». Business Insider. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- ^ Bhagat, Rasheeda (January 12, 2012). «The sherpa who funded Google’s ascent». The Hindu Business Line.

- ^ a b c Hosch, William L.; Hall, Mark. «Google Inc». Britannica. Britannica. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved March 17, 2019.

- ^ «Google Receives $25 Million in Equity Funding» (Press release). Palo Alto, Calif. June 7, 1999. Archived from the original on February 12, 2001. Retrieved February 16, 2009.

- ^ Vise, David; Malseed, Mark (2005). «Chapter 5. Divide and Conquer». The Google Story.

- ^ Weinberger, Matt (October 12, 2015). «Google’s cofounders are stepping down from their company. Here are 43 photos showing Google’s rise from a Stanford dorm room to global internet superpower». Business Insider. Axel Springer SE. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017.

- ^ «A building blessed with tech success». CNET. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on May 23, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ^ Stross, Randall (September 2008). «Introduction». Planet Google: One Company’s Audacious Plan to Organize Everything We Know. New York: Free Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-1-4165-4691-7. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- ^ «Google Launches Self-Service Advertising Program». News from Google. October 23, 2000. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ^ Naughton, John (July 2, 2000). «Why’s Yahoo gone to Google? Search me». The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 31, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2019 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ «Yahoo! Selects Google as its Default Search Engine Provider – News announcements – News from Google – Google». googlepress.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on January 31, 2019. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ Google Server Assembly. Computer History Museum. 1999. Archived from the original on July 22, 2010. Retrieved July 4, 2010.

- ^ Olsen, Stephanie (July 11, 2003). «Google’s movin’ on up». CNET. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2010.

- ^ «Google to buy headquarters building from Silicon Graphics». American City Business Journals. June 16, 2006. Archived from the original on April 18, 2010.

- ^ Krantz, Michael (October 25, 2006). «Do You «Google»?». Google, Inc. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ Bylund, Anders (July 5, 2006). «To Google or Not to Google». msnbc.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2006. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ Meyer, Robinson (June 27, 2014). «The First Use of ‘to Google’ on Television? Buffy the Vampire Slayer». The Atlantic. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ Vise, David; Malseed, Mark (2005). «Chapter 9. Hiring a Pilot». The Google Story.

- ^ Lashinsky, Adam (January 29, 2008). «Google wins again». Fortune. Time Warner. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ a b «GOOG Stock». Business Insider.

- ^ a b «2004 Annual Report» (PDF). Google, Inc. Mountain View, California. 2004. p. 29. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ La Monica, Paul R. (April 30, 2004). «Google sets $2.7 billion IPO». CNN Money. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ Kawamoto, Dawn (April 29, 2004). «Want In on Google’s IPO?». ZDNet. Archived from the original on December 28, 2011. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ a b Webb, Cynthia L. (August 19, 2004). «Google’s IPO: Grate Expectations». The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on November 12, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ Arrington, Michael (October 9, 2006). «Google Has Acquired YouTube». TechCrunch. AOL. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ^ Sorkin, Andrew Ross; Peters, Jeremy W. (October 9, 2006). «Google to Acquire YouTube for $1.65 Billion». The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 9, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ^ Arrington, Michael (November 13, 2006). «Google Closes YouTube Acquisition». TechCrunch. AOL. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ^ Auchard, Eric (November 14, 2006). «Google closes YouTube deal». Reuters. Thomson Reuters. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ^ Lawsky, David (March 11, 2008). «Google closes DoubleClick merger after EU approval». Reuters.

- ^ Story, Louise; Helft, Miguel (April 14, 2007). «Google Buys DoubleClick for $3.1 Billion». The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- ^ Worstall, Tim (June 22, 2011). «Google Hits One Billion Visitors in Only One Month». Forbes.

- ^ Efrati, Amir (June 21, 2011). «Google Notches One Billion Unique Visitors Per Month». The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ «Google Completes Takeover of Motorola Mobility». IndustryWeek. Agence France-Presse. May 22, 2012.

- ^ Tsukayama, Hayley (August 15, 2011). «Google agrees to acquire Motorola Mobility». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012.

- ^ «Google to Acquire Motorola Mobility — Google Investor Relations». Google. Archived from the original on August 17, 2011. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- ^ Page, Larry (August 15, 2011). «Official Google Blog: Supercharging Android: Google to Acquire Motorola Mobility». Official Google Blog. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012.

- ^ Hughes, Neil (August 15, 2011). «Google CEO: ‘Anticompetitive’ Apple, Microsoft forced Motorola deal». AppleInsider. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011.

- ^ Cheng, Roger (August 15, 2011). «Google to buy Motorola Mobility for $12.5B». CNet News. Archived from the original on October 6, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ Kerr, Dara (July 25, 2013). «Google reveals it spent $966 million in Waze acquisition». CNET. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ Lunden, Ingrid (June 11, 2013). «Google Bought Waze For $1.1B, Giving A Social Data Boost To Its Mapping Business». TechCrunch. AOL. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ Wakefield, Jane (September 19, 2013). «Google spin-off Calico to search for answers to ageing». BBC News. Archived from the original on September 19, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- ^ Chowdhry, Amit (January 27, 2014). «Google To Acquire Artificial Intelligence Company DeepMind». Forbes. Archived from the original on January 29, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Helgren, Chris (January 27, 2014). «Google to buy artificial intelligence company DeepMind». Reuters. Archived from the original on January 27, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Ribeiro, Jon (January 27, 2014). «Google buys artificial intelligence company DeepMind». PC World. Archived from the original on January 30, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Opam, Kwame (January 26, 2014). «Google buying AI startup DeepMind for a reported $400 million». The Verge. Vox Media. Archived from the original on July 8, 2017. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- ^ «Rankings – 2013 – Best Global Brands – Interbrand». Interbrand. Archived from the original on October 22, 2016. Retrieved October 23, 2016.