Объясняем.

Сборная Марокко – сенсация ЧМ-2022, первая африканская команда, которая дошла до полуфинала турнира. В футбольном устройстве страны разобрались, в причинах миграции жителей тоже, теперь обсудим название королевства.

Марокко или Морокко? Почему англичане пишут с «о», а мы – с «а»? Как так вышло? А как говорят в самой стране? А во Франции, которая повлияла на всю марокканскую культуру?

Неанглоязычные страны ориентируются на французскую форму написания – из-за колониального прошлого Марокко

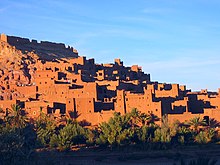

Марокко получило название от бывшей столицы – города Марракеш, который появился в XI веке. Как отмечает географ Евгений Поспелов в топонимическом словаре «Географические названия мира», старая часть Марракеша окружена крепостными стенами. Отсюда название – слово «марракуш» переводится как «укрепленный».

По словам Поспелова, сами марокканцы называют страну Эль-Мамляка-эль-Магрибия («королевство Магрибия») или Эль-Магриб-аль-Акса («дальний запад»), но для европейской части название меняется: «В Европе в конце XIX века получает распространение французская форма названия страны Maroc, используемая в различных графических вариантах: Morocco, Marok, Marokko и т.п. Исключением является Испания, где страна называется Marruecos, что ближе к названию города Марракеш».

Во французском языке Марокко записывается как Maroc, в английском – как Morocco. Большинство неанглоязычных стран ориентируются на французский вариант, потому что в XX веке Марокко находилось под протекторатом Франции, которая тогда расширяла колонии в Северной Африке. Марокко, как и Тунис, получило независимость в 1956 году, но сохранило связь с французской культурой и языком как пережитком колониальной эпохи.

У Франции с Тунисом тесные, но сложные отношения: колониальные травмы, 700 тысяч эмигрантов, 30% экспорта, освистанный гимн на матче

Русский вариант Марокко напоминает гибрид, а английское написание – смесь искажений и фонетических особенностей

Вероятно, французский вариант повлиял на запись кириллицей из-за тесных связей России и Франции. При этом русский вариант выглядит как гибрид французского и английского языков, где есть и удвоенный согласный, и «а» в первом слоге. Уроженка Касабланки и главный редактор журнала Taste of Maroc Нада Киффа рассказывала:

«Марокканцы, включая меня, обычно транслитерируют слова с учетом французской фонетической системы и учитывают, что французский – второй официальный язык Марокко после классического арабского. Однако американец может неправильно произнести французское фонетическое написание марокканского слова.

Например, «oua» или «oue» в начале французского слова – эквивалент «w» в английском языке; «ch» по-французски – то же самое, что «sh» по-английски. К этому добавляется, что некоторые арабские буквы и эквивалентные им звуки не существуют в латинском алфавите. Это приводит к разным транслитерациям одного и того же марокканского слова: «ouarda» / «warda» («роза»); «ouarka» / «warqa» («тонкое тесто»); «barkouk» / «barqoq» («чернослив»); «chiba» / «sheba» («полынь»).

«Marrakech» из французского языка становится «Marrakesh» в английском, а французский вариант «Maroc» превращается в «Morocco» на английском. Хотя по-арабски это просто аль-Магриб [это и обозначение региона в западной части Северной Африки, куда входит Марокко, и сокращенное для марокканцев название страны]. Знаю, что французский «Maroc» происходит от «Marrakech», но не могу сказать, откуда взялся «Morocco».

Возможно, расхождение связано с различиями фонетических систем и искажениями в английском языке. Из-за скопления согласных звуков в арабских словах короткие гласные могут выпадать, что усложняет восприятие иностранцами. При транслитерации «Marrakech» на другой язык в первом слоге гласный может восприниматься и записываться как «а» или как «о». При этом первый «о» в английском «Morocco» произносится коротко, поэтому неноситель языка может услышать «а».

ФИФА пишет английский вариант с «о», но на табло использует трехбуквенный код MAR. Это снова отсылки к зависимости от Франции

ФИФА присваивает каждой стране уникальный трехбуквенный код, который используется во время официальных соревнований. В обзорах матчей Марокко на ЧМ-2022 в названии роликов указан англоязычный вариант Morocco, но на табло – MAR. Это объясняется колониальной интервенцией, когда Марокко оказался под протекторатом Франции.

Большинство стран-участниц ФИФА имеют интуитивные сокращения по английским вариантам названий: Brazil – BRA, England – ENG, Germany – GER. У некоторых стран есть несовпадения между английским вариантом и кодом: Spain, но ESP (испанский вариант – España); Saudi Arabia, но KSA (полное название страны – Королевство Саудовская Аравия).

Издание Slate объясняло: «Коды чаще всего используются в международных спортивных соревнованиях и позволяют различать страны, названия которых не совпадают на разных языках. Наличие уникального кода гарантирует, что участники чемпионата мира по футболу или Олимпийских игр не столкнутся с языковыми барьерами и всегда будут иметь стандартизированный способ общения при упоминании других стран».

Кстати, а какого рода Марокко?

Род слова Марокко регулярно вызывает споры. Наименование Марокко относится к несклоняемым существительным. Правило не дает однозначной трактовки, к какому роду его относить. В книге «Русская грамматика» объясняется:

«Род несклоняемых имен собственных – географических названий и наименований периодических изданий определяется или 1) родом нарицательного слова, по отношению к которому имя собственное служит наименованием, или 2) звуковым строением самого имени собственного».

По первому пункту «Русская грамматика» дает такие примеры: «прекрасный (город) Сан-Франциско», «спокойная (река) Миссисипи», «бурная (река) По». При этом есть исключения: «В том случае, когда собственное название города или местности оканчивается на -о, -е или -и, ему может придаваться характеристика среднего рода: «это знаменитое Ровно».

В справочнике Дитмара Розенталя тоже выделяется вариант с отнесением к среднему роду: «Отступления от правила объясняются влиянием аналогии, употреблением слова в другом значении, тенденцией относить к среднему роду иноязычные несклоняемые слова на -о».

Если подстраиваться под род нарицательного понятия, то Марокко – это королевство и государство, но и страна. Но если ориентироваться на вариант «страна» и согласовать Марокко с прилагательным женского рода, то появятся непривычные сочетания «большая Марокко» или «красивая Марокко». В географических словарях Марокко первично фиксируется как королевство и государство, поэтому правильнее отталкиваться от них.

Итог: Марокко – средний род, так как существует тенденция относить иноязычные несклоняемые существительные на -о к среднему роду + ориентация на род нарицательного понятия, к которому относится имя собственное.

Йошко Гвардиол – это почти полный тезка Хосепа Гвардиолы. Откуда в Хорватии такая фамилия?

Фото: Gettyimages.ru/Alex Livesey, Stu Forster, Dean Mouhtaropoulos

For the instrument, see Maraca.

Coordinates: 32°N 6°W / 32°N 6°W

|

Kingdom of Morocco

|

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Motto: الله، الوطن، الملك (Arabic) ⴰⴽⵓⵛ, ⴰⵎⵓⵔ, ⴰⴳⵍⵍⵉⴷ (Standard Moroccan Tamazight) |

|

| Anthem: النشيد الوطني (Arabic) ⵉⵣⵍⵉ ⴰⵏⴰⵎⵓⵔ (Standard Moroccan Tamazight) «National Anthem» |

|

![Location of Morocco in northwest Africa Dark green: Undisputed territory of Morocco Lighter green: Western Sahara, a territory claimed and occupied mostly by Morocco as its Southern Provinces[note 1]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/78/Morocco_%28orthographic_projection%2C_WS_claimed%29.svg/250px-Morocco_%28orthographic_projection%2C_WS_claimed%29.svg.png)

Location of Morocco in northwest Africa |

|

| Capital | Rabat 34°02′N 6°51′W / 34.033°N 6.850°W |

| Largest city | Casablanca 33°32′N 7°35′W / 33.533°N 7.583°W |

| Official languages |

|

| Spoken languages |

|

| Foreign languages |

|

| Ethnic groups

(2012)[5] |

|

| Religion

[2][6] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Moroccan |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary semi-constitutional monarchy[7] |

|

• King |

Mohammed VI |

|

• Prime Minister |

Aziz Akhannouch |

| Legislature | Parliament |

|

• Upper house |

House of Councillors |

|

• Lower house |

House of Representatives |

| Establishment | |

|

• Idrisid dynasty |

788 |

|

• ‘Alawi dynasty (current dynasty) |

c. 1668 |

|

• Protectorate established |

30 March 1912 |

|

• Independence |

7 April 1956 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

446,300 km2 (172,300 sq mi) or 710,850 km2 (274,460 sq mi)[a] (39th or 57th) |

|

• Water (%) |

0.056 (250 km2) |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate |

37,984,655[8] (39th) |

|

• 2014 census |

33,848,242[9] |

|

• Density |

50.0/km2 (129.5/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2015) | 40.3[11] medium |

| HDI (2021) | medium · 124th |

| Currency | Moroccan dirham (MAD) |

| Time zone | UTC+1[13] UTC+0 (during Ramadan)[14][15][16] |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +212 |

| ISO 3166 code | MA |

| Internet TLD | .ma المغرب. |

|

Website |

|

|

Morocco (),[note 3] officially the Kingdom of Morocco,[note 4] is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to the east, and the disputed territory of Western Sahara to the south. Mauritania lies to the south of Western Sahara. Morocco also claims the Spanish exclaves of Ceuta, Melilla and Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera, and several small Spanish-controlled islands off its coast.[17] It spans an area of 446,300 km2 (172,300 sq mi)[18] or 710,850 km2 (274,460 sq mi),[b] with a population of roughly 37 million. Its official and predominant religion is Islam, and the official languages are Arabic and Berber; the Moroccan dialect of Arabic and French are also widely spoken. Moroccan identity and culture is a mix of Arab, Berber, and European cultures. Its capital is Rabat, while its largest city is Casablanca.[19]

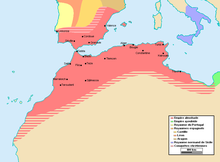

In a region inhabited since the Paleolithic Era over 300,000 years ago, the first Moroccan state was established by Idris I in 788. It was subsequently ruled by a series of independent dynasties, reaching its zenith as a regional power in the 11th and 12th centuries, under the Almoravid and Almohad dynasties, when it controlled most of the Iberian Peninsula and the Maghreb.[20] In the 15th and 16th centuries, Morocco faced external threats to its sovereignty, with Portugal seizing some territory and the Ottoman Empire encroaching from the east. The Marinid and Saadi dynasties otherwise resisted foreign domination, and Morocco was the only North African nation to escape Ottoman dominion. The ‘Alawi dynasty, which rules the country to this day, seized power in 1631, and over the next two centuries expanded diplomatic and commercial relations with the Western world. Morocco’s strategic location near the mouth of the Mediterranean drew renewed European interest; in 1912, France and Spain divided the country into respective protectorates, reserving an international zone in Tangier. Following intermittent riots and revolts against colonial rule, in 1956, Morocco regained its independence and reunified.

Since independence, Morocco has remained relatively stable. It has the fifth-largest economy in Africa and wields significant influence in both Africa and the Arab world; it is considered a middle power in global affairs and holds membership in the Arab League, the Union for the Mediterranean, and the African Union.[21] Morocco is a unitary semi-constitutional monarchy with an elected parliament. The executive branch is led by the King of Morocco and the prime minister, while legislative power is vested in the two chambers of parliament: the House of Representatives and the House of Councillors. Judicial power rests with the Constitutional Court, which may review the validity of laws, elections, and referendums.[22] The king holds vast executive and legislative powers, especially over the military, foreign policy and religious affairs; he can issue decrees called dahirs, which have the force of law, and can also dissolve the parliament after consulting the prime minister and the president of the constitutional court.

Morocco claims ownership of the non-self-governing territory of Western Sahara, which it has designated its Southern Provinces. In 1975, after Spain agreed to decolonise the territory and cede its control to Morocco and Mauritania, a guerrilla war broke out between those powers and some of the local inhabitants. In 1979, Mauritania relinquished its claim to the area, but the war continued to rage. In 1991, a ceasefire agreement was reached, but the issue of sovereignty remained unresolved. Today, Morocco occupies two-thirds of the territory, and efforts to resolve the dispute have thus far failed to break the political deadlock.

Name of Morocco

Morocco’s modern official Arabic name al-Mamlakah al-Maghribiyyah (المملكة المغربية) may best be translated as ‘The Kingdom of the Western Place’.

Historically, the territory has been part of what the Muslim geographers referred to as al-Maghrib al-Aqṣā [ar] (المغرب الأقصى, ‘the Farthest West [of the Islamic world]’ designating roughly the area from Tiaret to the Atlantic) in contrast with neighbouring regions of al-Maghrib al-Awsaṭ [ar] (المغرب الأوسط, ‘the Middle West’: Tripoli to Béjaïa) and al-Maghrib al-Adná [ar] (المغرب الأدنى, ‘the Nearest West’: Alexandria to Tripoli).[23] Morocco has also been referred to politically by a variety of terms denoting the Sharifi heritage of the Alawi dynasty, such as al-Iyālah ash-Sharīfah (الإيالة الشريفة) or al-Imbarāṭūriyyah ash-Sharīfah (الإمبراطورية الشريفة), rendered in French as l’Empire chérifien and in English as the ‘Sharifian Empire’.[24][25]

The word Morocco is derived from the name of the city of Marrakesh, which was its capital under the Almoravid dynasty and the Almohad Caliphate.[26] The origin of the name Marrakesh is disputed,[27] but it most likely comes from the Berber phrase amur n Yakuš, where amur can have the meanings «part, lot, promise, protection»[28] and Yakuš (and its variants Yuš and Akuš) means «God».[29] The expression amur n Ṛebbi where Ṛebbi is another word for God (borrowed from arabic رَبِّي (rabbī) «My Lord») means «divine protection».[30] The modern Berber name for Marrakesh is Mṛṛakc (in the Berber Latin script). In Turkish, Morocco is known as Fas, a name derived from its ancient capital of Fes. However, in other parts of the Islamic world, for example in Egyptian and Middle Eastern Arabic literature before the mid-20th century, the name commonly used to refer to Morocco was Murrakush (مراكش).[31]

That name is still used for the nation today in some languages, including Persian, Urdu, and Punjabi. The English name Morocco is an anglicisation of the Spanish name for the country, Marruecos. That Spanish name was also the basis for the old Tuscan word for the country, Morrocco, from which the modern Italian word for the country, Marocco, is derived.

History

Prehistory and antiquity

The area of present-day Morocco has been inhabited since at least Paleolithic times, beginning sometime between 190,000 and 90,000 BC.[32] A recent publication has suggested that there is evidence for even earlier human habitation of the area: Homo sapiens fossils that had been discovered in the late 2000s near the Atlantic coast in Jebel Irhoud were recently dated to roughly 315,000 years ago.[33] During the Upper Paleolithic, the Maghreb was more fertile than it is today, resembling a savanna, in contrast to its modern arid landscape.[34] Twenty-two thousand years ago, the pre-existing Aterian culture was succeeded by the Iberomaurusian culture, which shared similarities with Iberian cultures. Skeletal similarities have been suggested between the human remains found at Iberomaurusian «Mechta-Afalou» burial sites and European Cro-Magnon remains. The Iberomaurusian culture was succeeded by the Beaker culture in Morocco.

Mitochondrial DNA studies have discovered a close ancestral link between Berbers and the Saami of Scandinavia. This evidence supports the theory that some of the peoples who had been living in the Franco-Cantabrian refuge area of southwestern Europe during the late-glacial period migrated to northern Europe, contributing to its repopulation after the last ice age.[35]

In the early part of the Classical Antiquity period, Northwest Africa and Morocco were slowly drawn into the wider emerging Mediterranean world by the Phoenicians, who established trading colonies and settlements there, the most substantial of which were Chellah, Lixus, and Mogador.[36] Mogador was established as a Phoenician colony as early as the 6th century BC.[37][page needed]

Morocco later became a realm of the Northwest African civilisation of ancient Carthage, and part of the Carthaginian empire. The earliest known independent Moroccan state was the Berber kingdom of Mauretania, under King Baga.[38] This ancient kingdom (not to be confused with the modern state of Mauritania) flourished around 225 BC or earlier.

Mauretania became a client kingdom of the Roman Empire in 33 BC. Emperor Claudius annexed Mauretania directly in 44 AD, making it a Roman province ruled by an imperial governor (either a procurator Augusti, or a legatus Augusti pro praetore).

During the so-called «crisis of the 3rd century,» parts of Mauretania were reconquered by Berber tribes. As a result, by the late 3rd century, direct Roman rule had become confined to a few coastal cities, such as Septum (Ceuta) in Mauretania Tingitana and Cherchell in Mauretania Caesariensis. When, in 429 AD, the area was devastated by the Vandals, the Roman Empire lost its remaining possessions in Mauretania, and local Mauro-Roman kings assumed control of them. In the 530s, the Eastern Roman Empire, under Byzantine control, re-established direct imperial rule of Septum and Tingi, fortified Tingis and erected a church.

Foundation and early Islamic era

The Muslim conquest of the Maghreb, which started in the middle of the 7th century, was achieved by the Umayyad Caliphate early into the following century. It brought both the Arabic language and Islam to the area. Although part of the larger Islamic Empire, Morocco was initially organized as a subsidiary province of Ifriqiya, with the local governors appointed by the Muslim governor in Kairouan.[39]

The indigenous Berber tribes adopted Islam, but retained their customary laws. They also paid taxes and tribute to the new Muslim administration.[40] The first independent Muslim state in the area of modern Morocco was the Kingdom of Nekor, an emirate in the Rif Mountains. It was founded by Salih I ibn Mansur in 710, as a client state to the Umayyad Caliphate. After the outbreak of the Berber Revolt in 739, the Berbers formed other independent states such as the Miknasa of Sijilmasa and the Barghawata.

al-Qarawiyyin, founded in Fes in the 9th century, was a major spiritual, literary, and intellectual center.

According to medieval legend, Idris ibn Abdallah had fled to Morocco after the Abbasids’ massacre of his tribe in Iraq. He convinced the Awraba Berber tribes to break their allegiance to the distant Abbasid caliphs in Baghdad and he founded the Idrisid dynasty in 788. The Idrisids established Fes as their capital and Morocco became a centre of Muslim learning and a major regional power. The Idrisids were ousted in 927 by the Fatimid Caliphate and their Miknasa allies. After Miknasa broke off relations with the Fatimids in 932, they were removed from power by the Maghrawa of Sijilmasa in 980.

Berber empires and dynasties

From the 11th century onwards, a series of Berber dynasties arose.[41][42][43] Under the Sanhaja Almoravid dynasty and the Masmuda Almohad dynasty,[44] Morocco dominated the Maghreb, al-Andalus in Iberia, and the western Mediterranean region. From the 13th century onwards the country saw a massive migration of the Banu Hilal Arab tribes. In the 13th and 14th centuries the Zenata Berber Marinids held power in Morocco and strove to replicate the successes of the Almohads through military campaigns in Algeria and Spain. They were followed by the Wattasids. In the 15th century, the Reconquista ended Muslim rule in Iberia and many Muslims and Jews fled to Morocco.[45]

Portuguese efforts to control the Atlantic sea trade in the 15th century did not greatly affect the interior of Morocco even though they managed to control some possessions on the Moroccan coast but not venturing further afield inland.

Early modern period

In 1549, the region fell to successive Arab dynasties claiming descent from the Islamic prophet, Muhammad: first the Sharifian Saadi dynasty who ruled from 1549 to 1659, and then the Alaouite dynasty, who remain in power since the 17th century. Morocco faced aggression from Spain in the north, and the Ottoman Empire’s allies pressing westward.

Under the Saadi dynasty, the country ended the Aviz dynasty of Portugal at the Battle of Alcácer Quibir in 1578. The reign of Ahmad al-Mansur brought new wealth and prestige to the Sultanate, and a large expedition to West Africa inflicted a crushing defeat on the Songhay Empire in 1591. However, managing the territories across the Sahara proved too difficult. After the death of al-Mansur, the country was divided among his sons.

After a period of political fragmentation and conflict during the decline of the Saadi dynasty, Morocco was finally reunited by the ‘Alawi (or Alaouite) sultan al-Rashid in the late 1660s, who took Fez in 1666 and Marrakesh in 1668.[19]: 230 [46]: 225 The ‘Alawis succeeded in stabilising their position, and while the kingdom was smaller than previous ones in the region, it remained quite wealthy. Against the opposition of local tribes Ismail Ibn Sharif (1672–1727) began to create a unified state.[47] With his Jaysh d’Ahl al-Rif (the Riffian Army) he re-occupied Tangier from the English who had abandoned it in 1684 and drove the Spanish from Larache in 1689. Portuguese abandoned Mazagão, their last territory in Morocco, in 1769. However, the Siege of Melilla against the Spanish ended in defeat in 1775.

Morocco was the first nation to recognise the fledgling United States as an independent nation in 1777.[48][49][50] In the beginning of the American Revolution, American merchant ships in the Atlantic Ocean were subject to attack by the Barbary pirates. On 20 December 1777, Morocco’s Sultan Mohammed III declared that American merchant ships would be under the protection of the sultanate and could thus enjoy safe passage. The Moroccan–American Treaty of Friendship, signed in 1786, stands as the U.S.’s oldest non-broken friendship treaty.[51][52]

French and Spanish protectorates: 1912 to 1956

As Europe industrialised, Northwest Africa was increasingly prized for its potential for colonisation. France showed a strong interest in Morocco as early as 1830, not only to protect the border of its Algerian territory, but also because of the strategic position of Morocco with coasts on the Mediterranean and the open Atlantic.[54] In 1860, a dispute over Spain’s Ceuta enclave led Spain to declare war. Victorious Spain won a further enclave and an enlarged Ceuta in the settlement. In 1884, Spain created a protectorate in the coastal areas of Morocco.

Tangier’s population in 1873 included 40,000 Muslims, 31,000 Europeans and 15,000 Jews.[55]

In 1904, France and Spain carved out zones of influence in Morocco. Recognition by the United Kingdom of France’s sphere of influence provoked a strong reaction from the German Empire; and a crisis loomed in 1905. The matter was resolved at the Algeciras Conference in 1906. The Agadir Crisis of 1911 increased tensions between European powers. The 1912 Treaty of Fez made Morocco a protectorate of France, and triggered the 1912 Fez riots.[56] Spain continued to operate its coastal protectorate. By the same treaty, Spain assumed the role of protecting power over the northern coastal and southern Saharan zones.[57]

Tens of thousands of colonists entered Morocco. Some bought up large amounts of rich agricultural land, while others organised the exploitation and modernisation of mines and harbours. Interest groups that formed among these elements continually pressured France to increase its control over Morocco – a control which was also made necessary by the continuous wars among Moroccan tribes, part of which had taken sides with the French since the beginning of the conquest. The French colonial administrator, Governor general Marshal Hubert Lyautey, sincerely admired Moroccan culture and succeeded in imposing a joint Moroccan-French administration, while creating a modern school system. Several divisions of Moroccan soldiers (Goumiers or regular troops and officers) served in the French army in both World War I and World War II, and in the Spanish Nationalist Army in the Spanish Civil War and after (Regulares).[58] The institution of slavery was abolished in 1925.[59]

Between 1921 and 1926, a Berber uprising in the Rif Mountains, led by Abd el-Krim, led to the establishment of the Republic of the Rif. The Spanish lost more than 13,000 soldiers at Annual in July–August 1921.[60] The rebellion was eventually suppressed by French and Spanish troops.

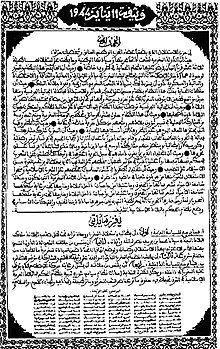

In 1943, the Istiqlal Party (Independence Party) was founded to press for independence, with discreet US support. That party subsequently provided most of the leadership for the nationalist movement.

France’s exile of Sultan Mohammed V in 1953 to Madagascar and his replacement by the unpopular Mohammed Ben Aarafa sparked active opposition to the French and Spanish protectorates. The most notable violence occurred in Oujda where Moroccans attacked French and other European residents in the streets. France allowed Mohammed V to return in 1955, and the negotiations that led to Moroccan independence began the following year.[61] In March 1956 the French protectorate was ended and Morocco regained its independence from France as the «Kingdom of Morocco». A month later Spain forsook its protectorate in Northern Morocco to the new state but kept its two coastal enclaves (Ceuta and Melilla) on the Mediterranean coast which dated from earlier conquests, but on which Morocco still claims sovereignty to this day. Sultan Mohammed became king in 1957.

Post-independence

Upon the death of Mohammed V, Hassan II became King of Morocco on 3 March 1961. Morocco held its first general elections in 1963. However, Hassan declared a state of emergency and suspended parliament in 1965. In 1971, there was a failed attempt to depose the king and establish a republic. A truth commission set up in 2005 to investigate human rights abuses during his reign confirmed nearly 10,000 cases, ranging from death in detention to forced exile. Some 592 people were recorded killed during Hassan’s rule according to the truth commission.

The Spanish enclave of Ifni in the south was returned to Morocco in 1969. The Polisario movement was formed in 1973, with the aim of establishing an independent state in the Spanish Sahara. On 6 November 1975, King Hassan asked for volunteers to cross into the Spanish Sahara. Some 350,000 civilians were reported as being involved in the «Green March».[62] A month later, Spain agreed to leave the Spanish Sahara, soon to become Western Sahara, and to transfer it to joint Moroccan-Mauritanian control, despite the objections and threats of military intervention by Algeria. Moroccan forces occupied the territory.[45]

Moroccan and Algerian troops soon clashed in Western Sahara. Morocco and Mauritania divided up Western Sahara. Fighting between the Moroccan military and Polisario forces continued for many years. The prolonged war was a considerable financial drain on Morocco. In 1983, Hassan cancelled planned elections amid political unrest and economic crisis. In 1984, Morocco left the Organisation of African Unity in protest at the SADR’s admission to the body. Polisario claimed to have killed more than 5,000 Moroccan soldiers between 1982 and 1985.

Algerian authorities have estimated the number of Sahrawi refugees in Algeria to be 165,000.[63] Diplomatic relations with Algeria were restored in 1988. In 1991, a UN-monitored ceasefire began in Western Sahara, but the territory’s status remains undecided and ceasefire violations are reported. The following decade saw much wrangling over a proposed referendum on the future of the territory but the deadlock was not broken.

Political reforms in the 1990s resulted in the establishment of a bicameral legislature in 1997 and Morocco’s first opposition-led government came to power in 1998.

Protestors in Casablanca demand that authorities honor their promises of political reform.

King Hassan II died in 1999 and was succeeded by his son, Mohammed VI. He is a cautious moderniser who has introduced some economic and social liberalisation.[64]

Mohammed VI paid a controversial visit to the Western Sahara in 2002. Morocco unveiled an autonomy blueprint for Western Sahara to the United Nations in 2007. The Polisario rejected the plan and put forward its own proposal. Morocco and the Polisario Front held UN-sponsored talks in New York City but failed to come to any agreement. In 2010, security forces stormed a protest camp in the Western Sahara, triggering violent demonstrations in the regional capital El Aaiún.

In 2002, Morocco and Spain agreed to a US-brokered resolution over the disputed island of Perejil. Spanish troops had taken the normally uninhabited island after Moroccan soldiers landed on it and set up tents and a flag. There were renewed tensions in 2005, as hundreds of African migrants tried to storm the borders of the Spanish enclaves of Melilla and Ceuta. Morocco deported hundreds of the illegal migrants. In 2006, the Spanish Premier Zapatero visited Spanish enclaves. He was the first Spanish leader in 25 years to make an official visit to the territories. The following year, Spanish King Juan Carlos I visited Ceuta and Melilla, further angering Morocco which demanded control of the enclaves.

During the 2011–2012 Moroccan protests, thousands of people rallied in Rabat and other cities calling for political reform and a new constitution curbing the powers of the king. In July 2011, the King won a landslide victory in a referendum on a reformed constitution he had proposed to placate the Arab Spring protests. Despite the reforms made by Mohammed VI, demonstrators continued to call for deeper reforms. Hundreds took part in a trade union rally in Casablanca in May 2012. Participants accused the government of failing to deliver on reforms.

Geography

Toubkal, the highest peak in Northwest Africa, at 4,167 m (13,671 ft)

Morocco has a coast by the Atlantic Ocean that reaches past the Strait of Gibraltar into the Mediterranean Sea. It is bordered by Spain to the north (a water border through the Strait and land borders with three small Spanish-controlled exclaves, Ceuta, Melilla, and Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera), Algeria to the east, and Western Sahara to the south. Since Morocco controls most of Western Sahara, its de facto southern boundary is with Mauritania.

The internationally recognised borders of the country lie between latitudes 27° and 36°N, and longitudes 1° and 14°W. Adding Western Sahara, Morocco lies mostly between 21° and 36°N, and 1° and 17°W (the Ras Nouadhibou peninsula is slightly south of 21° and west of 17°).

The geography of Morocco spans from the Atlantic Ocean, to mountainous areas, to the Sahara desert. Morocco is a Northern African country, bordering the North Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, between Algeria and the annexed Western Sahara. It is one of only three nations (along with Spain and France) to have both Atlantic and Mediterranean coastlines.

A large part of Morocco is mountainous. The Atlas Mountains are located mainly in the centre and the south of the country. The Rif Mountains are located in the north of the country. Both ranges are mainly inhabited by the Berber people. At 446,550 km2 (172,414 sq mi), Morocco excluding Western Sahara is the fifty-seventh largest country in the world. Algeria borders Morocco to the east and southeast, though the border between the two countries has been closed since 1994.

Spanish territory in Northwest Africa neighbouring Morocco comprises five enclaves on the Mediterranean coast: Ceuta, Melilla, Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera, Peñón de Alhucemas, the Chafarinas islands, and the disputed islet Perejil. Off the Atlantic coast the Canary Islands belong to Spain, whereas Madeira to the north is Portuguese. To the north, Morocco is bordered by the Strait of Gibraltar, where international shipping has unimpeded transit passage between the Atlantic and Mediterranean.

The Rif mountains stretch over the region bordering the Mediterranean from the north-west to the north-east. The Atlas Mountains run down the backbone of the country,[65] from the northeast to the southwest. Most of the southeast portion of the country is in the Sahara Desert and as such is generally sparsely populated and unproductive economically. Most of the population lives to the north of these mountains, while to the south lies the Western Sahara, a former Spanish colony that was annexed by Morocco in 1975 (see Green March).[note 5] Morocco claims that the Western Sahara is part of its territory and refers to that as its Southern Provinces.

Morocco’s capital city is Rabat; its largest city is its main port, Casablanca. Other cities recording a population over 500,000 in the 2014 Moroccan census are Fes, Marrakesh, Meknes, Salé and Tangier.[66]

Morocco is represented in the ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 geographical encoding standard by the symbol MA.[67] This code was used as the basis for Morocco’s internet domain, .ma.[67]

Climate

Köppen climate types in Morocco

In terms of area, Morocco is comprised predominantly of «hot summer Mediterranean climate» (Csa) and «hot desert climate» (BWh) zones.

Central mountain ranges and the effects of the cold Canary Current, off the Atlantic coast, are significant factors in Morocco’s relatively large variety of vegetation zones, ranging from lush forests in the northern and central mountains, giving way to steppe, semi-arid and desert areas in the eastern and southern regions. The Moroccan coastal plains experience remarkably moderate temperatures even in summer. On the whole, this range of climates is similar to that of Southern California.

In the Rif, Middle and High Atlas Mountains, there exist several different types of climates: Mediterranean along the coastal lowlands, giving way to a humid temperate climate at higher elevations with sufficient moisture to allow for the growth of different species of oaks, moss carpets, junipers, and Atlantic fir which is a royal conifer tree endemic to Morocco. In the valleys, fertile soils and high precipitation allow for the growth of thick and lush forests. Cloud forests can be found in the west of the Rif Mountains and Middle Atlas Mountains. At higher elevations, the climate becomes alpine in character, and can sustain ski resorts.

Southeast of the Atlas mountains, near the Algerian borders, the climate becomes very dry, with long and hot summers. Extreme heat and low moisture levels are especially pronounced in the lowland regions east of the Atlas range due to the rain shadow effect of the mountain system. The southeasternmost portions of Morocco are very hot, and include portions of the Sahara Desert, where vast swathes of sand dunes and rocky plains are dotted with lush oases.

In contrast to the Sahara region in the south, coastal plains are fertile in the central and northern regions of the country, and comprise the backbone of the country’s agriculture, in which 95% of the population live. The direct exposure to the North Atlantic Ocean, the proximity to mainland Europe and the long stretched Rif and Atlas mountains are the factors of the rather European-like climate in the northern half of the country. That makes Morocco a country of contrasts. Forested areas cover about 12% of the country while arable land accounts for 18%. Approximately 5% of Moroccan land is irrigated for agricultural use.

In general, apart from the southeast regions (pre-Saharan and desert areas), Morocco’s climate and geography are very similar to the Iberian peninsula. Thus Morocco has the following climate zones:

- Mediterranean: Dominates the coastal Mediterranean regions of the country, along the (500 km strip), and some parts of the Atlantic coast. Summers are hot to moderately hot and dry, average highs are between 29 °C (84.2 °F) and 32 °C (89.6 °F). Winters are generally mild and wet, daily average temperatures hover around 9 °C (48.2 °F) to 11 °C (51.8 °F), and average low are around 5 °C (41.0 °F) to 8 °C (46.4 °F), typical to the coastal areas of the west Mediterranean. Annual Precipitation in this area vary from 600 to 800 mm in the west to 350–500 mm in the east. Notable cities that fall into this zone are Tangier, Tetouan, Al Hoceima, Nador and Safi.

- Sub-Mediterranean: It influences cities that show Mediterranean characteristics, but remain fairly influenced by other climates owing to their either relative elevation, or direct exposure to the North Atlantic Ocean. We thus have two main influencing climates:

-

- Oceanic: Determined by the cooler summers, where highs are around 27 °C (80.6 °F) and in terms of the Essaouira region, are almost always around 21 °C (69.8 °F). The medium daily temperatures can get as low as 19 °C (66.2 °F), while winters are chilly to mild and wet. Annual precipitation varies from 400 to 700 mm. Notable cities that fall into this zone are Rabat, Casablanca, Kénitra, Salé and Essaouira.

-

- Continental: Determined by the bigger gap between highs and lows, that results in hotter summers and colder winters, than found in typical Mediterranean zones. In summer, daily highs can get as high as 40 °C (104.0 °F) during heat waves, but usually are between 32 °C (89.6 °F) and 36 °C (96.8 °F). However, temperatures drop as the sun sets. Night temperatures usually fall below 20 °C (68.0 °F), and sometimes as low as 10 °C (50.0 °F) in mid-summer. Winters are cooler, and can get below the freezing point multiple times between December and February. Also, snow can fall occasionally. Fès for example registered −8 °C (17.6 °F) in winter 2005. Annual precipitation varies between 500 and 900 mm. Notable cities are Fès, Meknès, Chefchaouen, Beni-Mellal and Taza.

- Continental: Dominates the mountainous regions of the north and central parts of the country, where summers are hot to very hot, with highs between 32 °C (89.6 °F) and 36 °C (96.8 °F). Winters on the other hand are cold, and lows usually go beyond the freezing point. And when cold damp air comes to Morocco from the northwest, for a few days, temperatures sometimes get below −5 °C (23.0 °F). It often snows abundantly in this part of the country. Precipitation varies between 400 and 800 mm. Notable cities are Khenifra, Imilchil, Midelt and Azilal.

- Alpine: Found in some parts of the Middle Atlas Mountain range and the eastern part of the High Atlas Mountain range. Summers are very warm to moderately hot, and winters are longer, cold and snowy. Precipitation varies between 400 and 1200 mm. In summer highs barely go above 30 °C (86.0 °F), and lows are cool and average below 15 °C (59.0 °F). In winters, highs average around 8 °C (46.4 °F), and lows go well below the freezing point. In this part of country, there are many ski resorts, such as Oukaimeden and Mischliefen. Notable cities are Ifrane, Azrou and Boulmane.

- Semi-arid: This type of climate is found in the south of the country and some parts of the east of the country, where rainfall is lower and annual precipitations are between 200 and 350 mm. However, one usually finds Mediterranean characteristics in those regions, such as the precipitation pattern and thermal attributes. Notable cities are Agadir, Marrakesh and Oujda.

South of Agadir and east of Jerada near the Algerian borders, arid and desert climate starts to prevail.

Due to Morocco’s proximity to the Sahara desert and the North Sea of the Atlantic Ocean, two phenomena occur to influence the regional seasonal temperatures, either by raising temperatures by 7–8 degrees Celsius when sirocco blows from the east creating heatwaves, or by lowering temperatures by 7–8 degrees Celsius when cold damp air blows from the northwest, creating a coldwave or cold spell. However, these phenomena do not last for more than two to five days on average.

Countries or regions that share the same climatic characteristics with Morocco are Portugal, Spain and Algeria and the U.S. state of California.

Climate change is expected to significantly impact Morocco on multiple dimensions. As a coastal country with hot and arid climates, environmental impacts are likely to be wide and varied. As of the 2019 Climate Change Performance Index, Morocco was ranked second in preparedness behind Sweden.[68]

Biodiversity

An adult male Barbary macaque carrying his offspring, a behaviour rarely found in other primates.

Morocco has a wide range of biodiversity. It is part of the Mediterranean basin, an area with exceptional concentrations of endemic species undergoing rapid rates of habitat loss, and is therefore considered to be a hotspot for conservation priority.[69] Avifauna are notably variant.[70] The avifauna of Morocco includes a total of 454 species, five of which have been introduced by humans, and 156 are rarely or accidentally seen.[71]

The Barbary lion, hunted to extinction in the wild, was a subspecies native to Morocco and is a national emblem.[2] The last Barbary lion in the wild was shot in the Atlas Mountains in 1922.[72] The other two primary predators of northern Africa, the Atlas bear and Barbary leopard, are now extinct and critically endangered, respectively. Relict populations of the West African crocodile persisted in the Draa river until the 20th century.[73]

The Barbary macaque, a primate endemic to Morocco and Algeria, is also facing extinction due to offtake for trade[74] human interruption, urbanisation, wood and real estate expansion that diminish forested area – the macaque’s habitat.

Trade of animals and plants for food, pets, medicinal purposes, souvenirs and photo props is common across Morocco, despite laws making much of it illegal.[75][76] This trade is unregulated and causing unknown reductions of wild populations of native Moroccan wildlife. Because of the proximity of northern Morocco to Europe, species such as cacti, tortoises, mammal skins, and high-value birds (falcons and bustards) are harvested in various parts of the country and exported in appreciable quantities, with especially large volumes of eel harvested – 60 tons exported to the Far East in the period 2009‒2011.[77]

Morocco is home to six terrestrial ecoregions: Mediterranean conifer and mixed forests, Mediterranean High Atlas juniper steppe, Mediterranean acacia-argania dry woodlands and succulent thickets, Mediterranean dry woodlands and steppe, Mediterranean woodlands and forests, and North Saharan steppe and woodlands.[78] It had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.74/10, ranking it 66th globally out of 172 countries.[79]

Politics

Morocco was an authoritarian regime according to the Democracy Index of 2014.[80] The Freedom of the Press 2014 report gave it a rating of «Not Free».[81] This has improved since, however, and Morocco has been ranked as a «hybrid regime» by the Democracy Index since 2015;[82] while the Freedom of the Press report in 2017 continued to find that Morocco’s press continued to be «not free,» it gave «partly free» ratings for its «Net Freedom» and «Freedom in the World» more generally.[83]

Following the March 1998 elections, a coalition government headed by opposition socialist leader Abderrahmane Youssoufi and composed largely of ministers drawn from opposition parties, was formed. Prime Minister Youssoufi’s government was the first ever government drawn primarily from opposition parties, and also represents the first opportunity for a coalition of socialists, left-of-centre, and nationalist parties to be included in the government until October 2002. It was also the first time in the modern political history of the Arab world that the opposition assumed power following an election. The current government is headed by Aziz Akhannouch.

The Constitution of Morocco provides for a monarchy with a Parliament and an independent judiciary. With the 2011 constitutional reforms, the King of Morocco retains less executive powers whereas those of the prime minister have been enlarged.[84][85]

The constitution grants the king honorific powers (among other powers); he is both the secular political leader and the «Commander of the Faithful» as a direct descendant of the Prophet Mohammed. He presides over the Council of Ministers; appoints the Prime Minister from the political party that has won the most seats in the parliamentary elections, and on recommendations from the latter, appoints the members of the government.

The constitution of 1996 theoretically allowed the king to terminate the tenure of any minister, and after consultation with the heads of the higher and lower Assemblies, to dissolve the Parliament, suspend the constitution, call for new elections, or rule by decree. The only time this happened was in 1965. The King is formally the commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

Legislative branch

The legislature’s building in Rabat.

Since the constitutional reform of 1996, the bicameral legislature consists of two chambers. The Assembly of Representatives of Morocco (Majlis an-Nuwwâb/Assemblée des Répresentants) has 325 members elected for a five-year term, 295 elected in multi-seat constituencies and 30 in national lists consisting only of women. The Assembly of Councillors (Majlis al-Mustasharin) has 270 members, elected for a nine-year term, elected by local councils (162 seats), professional chambers (91 seats) and wage-earners (27 seats).

The Parliament’s powers, though still relatively limited, were expanded under the 1992 and 1996 and even further in the 2011 constitutional revisions and include budgetary matters, approving bills, questioning ministers, and establishing ad hoc commissions of inquiry to investigate the government’s actions. The lower chamber of Parliament may dissolve the government through a vote of no confidence.

The latest parliamentary elections were held on 8 September 2021. Voter turnout in these elections was estimated to be 50.35% of registered voters.

Military

US Marines and Moroccan soldiers during exercise African Lion in Tan-Tan.

Morocco’s military consists of the Royal Armed Forces—this includes the Army (the largest branch), the Navy, the Air Force, the Royal Guard, the Royal Gendarmerie and the Auxiliary Forces. Internal security is generally effective, and acts of political violence are rare (with one exception, the 2003 Casablanca bombings which killed 45 people[86]).

The UN maintains a small observer force in Western Sahara, where a large number of Moroccan troops are stationed. The Sahrawi Polisario Front maintains an active militia of an estimated 5,000 fighters in Western Sahara and has engaged in intermittent warfare with Moroccan forces since the 1970s.

Foreign relations

Morocco is a member of the United Nations and belongs to the African Union (AU), Arab League, Arab Maghreb Union (UMA), Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), the Non-Aligned Movement and the Community of Sahel–Saharan States (CEN_SAD). Morocco’s relationships vary greatly between African, Arab, and Western states. Morocco has had strong ties to the West in order to gain economic and political benefits.[87] France and Spain remain the primary trade partners, as well as the primary creditors and foreign investors in Morocco. From the total foreign investments in Morocco, the European Union invests approximately 73.5%, whereas, the Arab world invests only 19.3%. Many countries from the Persian Gulf and Maghreb regions are getting more involved in large-scale development projects in Morocco.[88]

Morocco claims sovereignty over Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla.

Morocco was the only African state not to be a member of the African Union due to its unilateral withdrawal on 12 November 1984 over the admission of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic in 1982 by the African Union (then called Organisation of African Unity) as a full member without the organisation of a referendum of self-determination in the disputed territory of Western Sahara. Morocco rejoined the AU on 30 January 2017.[89][90] In August 2021, Algeria severed diplomatic relations with Morocco.[91]

A dispute with Spain in 2002 over the small island of Perejil revived the issue of the sovereignty of Melilla and Ceuta. These small enclaves on the Mediterranean coast are surrounded by Morocco and have been administered by Spain for centuries.

Morocco was given the status of major non-NATO ally by the George W. Bush administration in 2004.[92] Morocco was the first country in the world to recognise US sovereignty (in 1777).

Morocco is included in the European Union’s European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) which aims at bringing the EU and its neighbours closer.

Western Sahara status

Morocco annexed Western Sahara in 1975.

Due to the conflict over Western Sahara, the status of the Saguia el-Hamra and Río de Oro regions is disputed. The Western Sahara War saw the Polisario Front, the Sahrawi rebel national liberation movement, battling both Morocco and Mauritania between 1976 and a ceasefire in 1991 that is still in effect. A United Nations mission, MINURSO, is tasked with organizing a referendum on whether the territory should become independent or recognised as a part of Morocco.

Part of the territory, the Free Zone, is a mostly uninhabited area that the Polisario Front controls as the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic. Its administrative headquarters are located in Tindouf, Algeria. As of 2006, no UN member state had recognised Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara.[93] In 2020, the United States under the Trump administration became the first Western country to back Morocco’s contested sovereignty over the disputed Western Sahara region, on the agreement that Morocco would simultaneously normalize relations with Israel.[94]

In 2006, the government of Morocco suggested autonomous status for the region, through the Moroccan Royal Advisory Council for Saharan Affairs (CORCAS). The project was presented to the United Nations Security Council in mid-April 2007. The proposal was encouraged by Moroccan allies such as the United States, France and Spain.[95] The Security Council has called upon the parties to enter into direct and unconditional negotiations to reach a mutually accepted political solution.[96]

Administrative divisions

The administrative regions of Morocco

Morocco is officially divided into 12 regions,[97] which, in turn, are subdivided into 62 provinces and 13 prefectures.[98]

Regions

- Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima

- Oriental

- Fès-Meknès

- Rabat-Salé-Kénitra

- Béni Mellal-Khénifra

- Casablanca-Settat

- Marrakesh-Safi

- Drâa-Tafilalet

- Souss-Massa

- Guelmim-Oued Noun

- Laâyoune-Sakia El Hamra

- Dakhla-Oued Ed-Dahab

Human rights

During the early 1960s to the late 1980s, under the leadership of Hassan II, Morocco had one of the worst human rights records in both Africa and the world. Government repression of political dissent was widespread during Hassan II’s leadership, until it dropped sharply in the mid-1990s. The decades during which abuses were committed are referred to as the Years of Lead (Les Années de Plomb), and included forced disappearances, assassinations of government opponents and protesters, and secret internment camps such as Tazmamart. To examine abuses committed during the reign of King Hassan II (1961–1999), the government under King Mohammed set up an Equity and Reconciliation Commission (IER).[99][100]

According to a Human Rights Watch annual report in 2016, Moroccan authorities restricted the rights to peaceful expression, association and assembly through several laws. The authorities continue to prosecute both printed and online media which criticizes the government or the king (or the royal family).[101] There are also persistent allegations of violence against both Sahrawi pro-independence and pro-Polisario demonstrators[102] in Western Sahara; a disputed territory which is occupied by and considered by Morocco as part of its Southern Provinces. Morocco has been accused of detaining Sahrawi pro-independence activists as prisoners of conscience.[103]

Homosexual acts as well as pre-marital sex are illegal in Morocco, and can be punishable by six months to three years of imprisonment.[104][105] It is illegal to proselytise for any religion other than Islam (article 220 of the Moroccan Penal Code), and that crime is punishable by a maximum of 15 years of imprisonment.[106][107] Violence against women and sexual harassment have been criminalized. The penalty can be from one month to five years, with fines ranging from $200 to $1,000.[108]

In May 2020, hundreds of Moroccan migrant workers were stranded in Spain amid restrictions imposed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Spanish government stated that it was holding discussions with the Moroccan government about repatriating the migrant workers via a «humanitarian corridor,» and the migrants later headed home.[109]

Economy

Boulevard des FAR (Forces Armées Royales)

Morocco’s economy is considered a relatively liberal economy governed by the law of supply and demand. Since 1993, the country has followed a policy of privatisation of certain economic sectors which used to be in the hands of the government.[110] Morocco has become a major player in African economic affairs,[111] and is the fifth largest economy in Africa by GDP (PPP). Morocco was ranked as the first African country by the Economist Intelligence Unit’s quality-of-life index, ahead of South Africa.[112] However, in the years since that first-place ranking was given, Morocco has slipped into fourth place behind Egypt.

Map of Morocco’s exports as of 2017

Government reforms and steady yearly growth in the region of 4–5% from 2000 to 2007, including 4.9% year-on-year growth in 2003–2007 helped the Moroccan economy to become much more robust compared to a few years earlier. For 2012 the World Bank forecast a rate of 4% growth for Morocco and 4.2% for following year, 2013.[113]

The services sector accounts for just over half of GDP and industry, made up of mining, construction and manufacturing, is an additional quarter. The industries that recorded the highest growth are tourism, telecoms, information technology, and textile.

Tourism

Tourism is one of the most important sectors in Moroccan economy. It is well developed with a strong tourist industry focused on the country’s coast, culture, and history. Morocco attracted more than 13 million tourists in 2019. Tourism is the second largest foreign exchange earner in Morocco after the phosphate industry. The Moroccan government is heavily investing in tourism development, in 2010 the government launched its Vision 2020 which plans to make Morocco one of the top 20 tourist destinations in the world and to double the annual number of international arrivals to 20 million by 2020,[114] with the hope that tourism will then have risen to 20% of GDP.

Large government sponsored marketing campaigns to attract tourists advertised Morocco as a cheap and exotic, yet safe, place for tourists. Most of the visitors to Morocco continue to be European, with French nationals making up almost 20% of all visitors. Most Europeans visit between April and August.[115] Morocco’s relatively high number of tourists has been aided by its location—Morocco is close to Europe and attracts visitors to its beaches. Because of its proximity to Spain, tourists in southern Spain’s coastal areas take one- to three-day trips to Morocco.

Since air services between Morocco and Algeria have been established, many Algerians have gone to Morocco to shop and visit family and friends. Morocco is relatively inexpensive because of the devaluation of the dirham and the increase of hotel prices in Spain. Morocco has an excellent road and rail infrastructure that links the major cities and tourist destinations with ports and cities with international airports. Low-cost airlines offer cheap flights to the country.

View of the medina (old city) of Fes.

Tourism is increasingly focused on Morocco’s culture, such as its ancient cities. The modern tourist industry capitalises on Morocco’s ancient Berber, Roman and Islamic sites, and on its landscape and cultural history. 60% of Morocco’s tourists visit for its culture and heritage.

Agadir is a major coastal resort and has a third[citation needed] of all Moroccan bed nights. It is a base for tours to the Atlas Mountains. Other resorts in north Morocco are also very popular.[116][117]

Casablanca is the major cruise port in Morocco, and has the best developed market for tourists in Morocco, Marrakech in central Morocco is a popular tourist destination, but is more popular among tourists for one- and two-day excursions that provide a taste of Morocco’s history and culture. The Majorelle botanical garden in Marrakech is a popular tourist attraction. It was bought by the fashion designer Yves Saint-Laurent and Pierre Bergé in 1980. Their presence in the city helped to boost the city’s profile as a tourist destination.[118]

As of 2006, activity and adventure tourism in the Atlas and Rif Mountains are the fastest growth area in Moroccan tourism. These locations have excellent walking and trekking opportunities from late March to mid-November. The government is investing in trekking circuits. They are also developing desert tourism in competition with Tunisia.[119]

Agriculture

Agriculture in Morocco employs about 40% of the nation’s workforce. Thus, it is the largest employer in the country. In the rainy sections of the northwest, barley, wheat, and other cereals can be raised without irrigation. On the Atlantic coast, where there are extensive plains, olives, citrus fruits, and wine grapes are grown, largely with water supplied by artesian wells. Livestock are raised and forests yield cork, cabinet wood, and building materials. Part of the maritime population fishes for its livelihood. Agadir, Essaouira, El Jadida, and Larache are among the important fishing harbors.[120] Both the agriculture and fishing industries are expected to be severely impacted by climate change.[121]

Moroccan agricultural production also consists of orange, tomatoes, potatoes, olives, and olive oil. High quality agricultural products are usually exported to Europe. Morocco produces enough food for domestic consumption except for grains, sugar, coffee and tea. More than 40% of Morocco’s consumption of grains and flour is imported from the United States and France.

Agriculture industry in Morocco enjoyed a complete tax exemption until 2013. Many Moroccan critics said that rich farmers and large agricultural companies were taking too much benefit of not paying the taxes and that poor farmers were struggling with high costs and are getting very poor support from the state. In 2014, as part of the Finance Law, it was decided that agricultural companies with a turnover of greater than MAD 5 million would pay progressive corporate income taxes.[122]

Infrastructure

Al Boraq RGV2N2 high-speed trainset at Tanger Ville railway station in November 2018

According to the Global Competitiveness Report of 2019, Morocco Ranked 32nd in the world in terms of Roads, 16th in Sea, 45th in Air and 64th in Railways. This gives Morocco the best infrastructure rankings in the African continent.[123]

Modern infrastructure development, such as ports, airports, and rail links, is a top government priority. To meet the growing domestic demand, the Moroccan government invested more than $15 billion from 2010 to 2015 in upgrading its basic infrastructure.[124]

Morocco has one of the best road systems on the continent. Over the past 20 years, the government has built approximately 1770 kilometers of modern roads, connecting most major cities via toll expressways. The Moroccan Ministry of Equipment, Transport, Logistics, and Water aims to build an additional 3380 kilometers of expressway and 2100 kilometers of highway by 2030, at an expected cost of $9.6 billion. It focuses on linking the southern provinces, notably the cities of Laayoune and Dakhla to the rest of Morocco.

In 2014, Morocco began the construction of the first high-speed railway system in Africa linking the cities of Tangiers and Casablanca. It was inaugurated in 2018 by the King following over a decade of planning and construction by Moroccan national railway company ONCF. It is the first phase of what is planned to eventually be a 1,500 kilometeres (930 mi) high-speed rail network in Morocco. An extension of the line to Marrakesh is already being planned.

Morocco also has the largest port in Africa and the Mediterranean called Tanger-Med, which is ranked the 18th in the world with a handling capacity of over 9 million containers. It is situated in the Tangiers free economic zone and serves as a logistics hub for Africa and the world.[125]

Energy

In 2008, about 56% of Morocco’s electricity supply was provided by coal.[126] However, as forecasts indicate that energy requirements in Morocco will rise 6% per year between 2012 and 2050,[127] a new law passed encouraging Moroccans to look for ways to diversify the energy supply, including more renewable resources. The Moroccan government has launched a project to build a solar thermal energy power plant[128] and is also looking into the use of natural gas as a potential source of revenue for Morocco’s government.[127]

Morocco has embarked upon the construction of large solar energy farms to lessen dependence on fossil fuels, and to eventually export electricity to Europe.[129]

On 17 April 2022, Rabat- Moroccan agency for solar energy (Masen) and the ministry of energy transition and sustainable development announced the launch of phase one of the mega project Nor II solar energy plant which is a multi-site solar energy project with a total capacity set at 400 megawatts (MN).

Narcotics

Cannabis field at Ketama Tidighine mountain, Morocco

Since the 7th century, cannabis has been cultivated in the Rif region.[130] In 2004, according to the UN World Drugs Report, cultivation and transformation of cannabis represents 0.57% of the national GDP of Morocco in 2002.[131] According to a French Ministry of the Interior 2006 report, 80% of the cannabis resin (hashish) consumed in Europe comes from the Rif region in Morocco, which is mostly mountainous terrain in the north of Morocco, also hosting plains that are very fertile and expanding from Melwiyya River and Ras Kebdana in the East to Tangier and Cape Spartel in the West. Also, the region extends from the Mediterranean in the south, home of the Wergha River, to the north.[132] In addition to that, Morocco is a transit point for cocaine from South America destined for Western Europe.[133]

Water supply and sanitation

Water supply and sanitation in Morocco is provided by a wide array of utilities. They range from private companies in the largest city, Casablanca, the capital, Rabat,

and two other cities,[clarification needed] to public municipal utilities in 13 other cities, as well as a national electricity and water company (ONEE). The latter is in charge of bulk water supply to the aforementioned utilities, water distribution in about 500 small towns, as well as sewerage and wastewater treatment in 60 of these towns.

There have been substantial improvements in access to water supply, and to a lesser extent to sanitation, over the past fifteen years. Remaining challenges include a low level of wastewater treatment (only 13% of collected wastewater is being treated), lack of house connections in the poorest urban neighbourhoods, and limited sustainability of rural systems (20 percent of rural systems are estimated not to function). In 2005 a National Sanitation Program was approved that aims at treating 60% of collected wastewater and connecting 80% of urban households to sewers by 2020. The issue of lack of water connections for some of the urban poor is being addressed as part of the National Human Development Initiative, under which residents of informal settlements have received land titles and have fees waived that are normally paid to utilities in order to connect to the water and sewer network.

Science and technology

The Moroccan government has been implementing reforms to improve the quality of education and make research more responsive to socio-economic needs. In May 2009, Morocco’s prime minister, Abbas El Fassi, announced greater support for science during a meeting at the National Centre for Scientific and Technical Research. The aim was to give universities greater financial autonomy from the government to make them more responsive to research needs and better able to forge links with the private sector, in the hope that this would nurture a culture of entrepreneurship in academia. He announced that investment in science and technology would rise from US$620,000 in 2008 to US$8.5 million (69 million Moroccan dirhams) in 2009, in order to finance the refurbishment and construction of laboratories, training courses for researchers in financial management, a scholarship programme for postgraduate research and incentive measures for companies prepared to finance research, such as giving them access to scientific results that they could then use to develop new products.[134] Morocco was ranked 77th in the Global Innovation Index in 2021, down from 74th in 2019.[135][136][137][138]

The Moroccan Innovation Strategy was launched at the country’s first National Innovation Summit in June 2009 by the Ministry of Industry, Commerce, Investment and the Digital Economy. The Moroccan Innovation Strategy fixed the target of producing 1,000 Moroccan patents and creating 200 innovative start-ups by 2014. In 2012, Moroccan inventors applied for 197 patents, up from 152 two years earlier. In 2011, the Ministry of Industry, Commerce and New Technologies created a Moroccan Club of Innovation, in partnership with the Moroccan Office of Industrial and Commercial Property. The idea is to create a network of players in innovation, including researchers, entrepreneurs, students and academics, to help them develop innovative projects.[139]

The Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research is supporting research in advanced technologies and the development of innovative cities in Fez, Rabat and Marrakesh. The government is encouraging public institutions to engage with citizens in innovation. One example is the Moroccan Phosphate Office (Office chérifien des phosphates), which has invested in a project to develop a smart city, King Mohammed VI Green City, around Mohammed VI University located between Casablanca and Marrakesh, at a cost of DH 4.7 billion (circa US$479 million).[139][140]

As of 2015, Morocco had three technoparks. Since the first technopark was established in Rabat in 2005, a second has been set up in Casablanca, followed, in 2015, by a third in Tangers. The technoparks host start-ups and small and medium-sized enterprises specializing in information and communication technologies (ICTs), ‘green’ technologies (namely, environmentally friendly technologies) and cultural industries.[139]

In 2012, the Hassan II Academy of Science and Technology identified a number of sectors where Morocco has a comparative advantage and skilled human capital, including mining, fisheries, food chemistry and new technologies. It also identified a number of strategic sectors, such as energy, with an emphasis on renewable energies such as photovoltaic, thermal solar energy, wind and biomass; as well as the water, nutrition and health sectors, the environment and geosciences.[139][141]

On 20 May 2015, less than a year after its inception, the Higher Council for Education, Training and Scientific Research presented a report to the king offering a Vision for Education in Morocco 2015–2030. The report advocated making education egalitarian and, thus, accessible to the greatest number. Since improving the quality of education goes hand in hand with promoting research and development, the report also recommended developing an integrated national innovation system which would be financed by gradually increasing the share of GDP devoted to research and development (R&D) from 0.73% of GDP in 2010 ‘to 1% in the short term, 1.5% by 2025 and 2% by 2030’.[139]

Demographics

Morocco has a population of around 37,076,584 inhabitants (2021 est.).[142][143] It is estimated that between 44%[144] to 67%[145] of residents have Arab ancestral origins and between 31%[145] to 41%[146] have Berber ancestral origins. A sizeable portion of the population is identified as Haratin and Gnawa (or Gnaoua), West African or mixed race descendants of slaves, and Moriscos, European Muslims expelled from Spain and Portugal in the 17th century.[147]

According to the 2014 Morocco population census, there were around 84,000 immigrants in the country. Of these foreign-born residents, most were of French origin, followed by individuals mainly from various nations in West Africa and Algeria.[148] There are also a number of foreign residents of Spanish origin. Some of them are descendants of colonial settlers, who primarily work for European multinational companies, while others are married to Moroccans or are retirees. Prior to independence, Morocco was home to half a million Europeans; who were mostly Christians.[149] Also, prior to independence, Morocco was home to 250,000 Spaniards.[150] Morocco’s once prominent Jewish minority has decreased significantly since its peak of 265,000 in 1948, declining to around 2,500 today.[151]

Morocco has a large diaspora, most of which is located in France, which has reportedly over one million Moroccans of up to the third generation. There are also large Moroccan communities in Spain (about 700,000 Moroccans),[152] the Netherlands (360,000), and Belgium (300,000).[153] Other large communities can be found in Italy, Canada, the United States, and Israel, where Moroccan Jews are thought to constitute the second biggest Jewish ethnic subgroup.[154]

Religion

The religious affiliation in the country was estimated by the Pew Forum in 2010 as 99% Muslim, with all remaining groups accounting for less than 1% of the population.[155] Of those affiliated with Islam, virtually all are Sunni Muslims, with Shia Muslims accounting for less than 0.1%.[156] Despite most Moroccans being affiliated with Islam (~100% according to the Arab Barometer in 2018),[157] almost 15% nonetheless describe themselves as non-religious according to a 2018 survey conducted for the BBC by the research network Arab Barometer.[158] Another 2021 Arab Barometer survey found that 67.8% of Moroccans identified as religious, 29.1% as somewhat religious, and 3.1% as not religious.[157] The 2015 Gallup International poll reported that 93% of Moroccans considered themselves to be religious.[159]

The interior of a mosque in Fes

Prior to independence, Morocco was home to more than 500,000 Christians (mostly of Spanish and French ancestry). Many Christian settlers left to Spain or France after the independence in 1956.[160] The predominantly Catholic and Protestant foreign-resident Christian community consists of approximately 40,000 practising members. Most foreign resident Christians reside in the Casablanca, Tangier, and Rabat urban areas. Various local Christian leaders estimate that between 2005 and 2010 there are 5,000 citizen converted Christians (mostly ethnically Berber) who regularly attend «house» churches and live predominantly in the south.[161] Some local Christian leaders estimate that there may be as many as 8,000 Christian citizens throughout the country, but many reportedly do not meet regularly due to fear of government surveillance and social persecution.[162] The number of the Moroccans who converted to Christianity (most of them secret worshippers) are estimated between 8,000 and 50,000.[163][164][165][166][167][168]

The most recent estimates put the size of the Casablanca Jewish community at about 2,500,[169][170] and the Rabat and Marrakesh Jewish communities at about 100 members each. The remainder of the Jewish population is dispersed throughout the country. This population is mostly elderly, with a decreasing number of young people.[162]

The Baháʼí Faith community, located in urban areas, numbers 350 to 400 persons.[162]

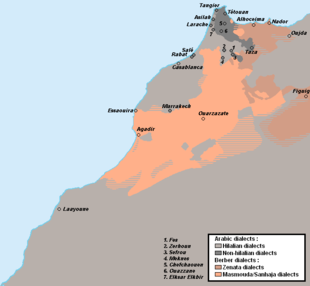

Languages

Linguistic map of Morocco

Morocco’s official languages are Arabic and Berber.[7][171] The country’s distinctive group of Moroccan Arabic dialects is referred to as Darija. Approximately 89.8% of the whole population can communicate to some degree in Moroccan Arabic.[172] The Berber language is spoken in three dialects (Tarifit, Tashelhit and Central Atlas Tamazight).[173] In 2008, Frédéric Deroche estimated that there were 12 million Berber speakers, making up about 40% of the population.[174] The 2004 population census reported that 28.1% of the population spoke Berber.[172]

French is widely used in governmental institutions, media, mid-size and large companies, international commerce with French-speaking countries, and often in international diplomacy. French is taught as an obligatory language in all schools. In 2010, there were 10,366,000 French-speakers in Morocco, or about 32% of the population.[175][3]

According to the 2004 census, 2.19 million Moroccans spoke a foreign language other than French.[172] English, while far behind French in terms of number of speakers, is the first foreign language of choice, since French is obligatory, among educated youth and professionals.

According to Ethnologue, as of 2016, there are 1,536,590 individuals (or approximately 4.5% of the population) in Morocco who speak Spanish.[176] Spanish is mostly spoken in northern Morocco and the former Spanish Sahara because Spain had previously occupied those areas.[177] Meanwhile, a 2018 study by the Instituto Cervantes found 1.7 million Moroccans who were at least proficient in Spanish, placing Morocco as the country with the most Spanish speakers outside the Hispanophone world (unless the United States is also excluded from Spanish-speaking countries).[178] A significant portion of northern Morocco receives Spanish media, television signal and radio airwaves, which reportedly facilitate competence in the language in the region.[179]

After Morocco declared independence in 1956, French and Arabic became the main languages of administration and education, causing the role of Spanish to decline.[179]

Although seldom spoken in Morocco proper, the vast diaspora of Moroccans in the Netherlands or in the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium who are often dual citizens, tend to speak the Dutch language either as joint mother tongue or second language.

Education

Education in Morocco is free and compulsory through primary school. The estimated literacy rate for the country in 2012 was 72%.[180] In September 2006, UNESCO awarded Morocco amongst other countries such as Cuba, Pakistan, India and Turkey the «UNESCO 2006 Literacy Prize».[181]

Morocco has more than four dozen universities, institutes of higher learning, and polytechnics dispersed at urban centres throughout the country. Its leading institutions include Mohammed V University in Rabat, the country’s largest university, with branches in Casablanca and Fès; the Hassan II Agriculture and Veterinary Institute in Rabat, which conducts leading social science research in addition to its agricultural specialties; and Al-Akhawayn University in Ifrane, the first English-language university in Northwest Africa,[182] inaugurated in 1995 with contributions from Saudi Arabia and the United States.

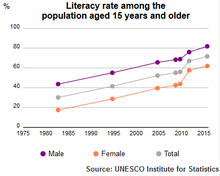

UIS Literacy Rate Morocco population above 15 years of age 1980–2015

The al-Qarawiyin University, founded by Fatima al-Fihri in the city of Fez in 859 as a madrasa,[183] is considered by some sources, including UNESCO, to be the «oldest university of the world».[184] Morocco has also some of prestigious postgraduate schools, including: Mohammed VI Polytechnic University, l’Institut National des Postes et Télécommunication (INPT), École Nationale Supérieure d’Électricité et de Mecanique (ENSEM), EMI, ISCAE, INSEA, National School of Mineral Industry, École Hassania des Travaux Publics, Les Écoles nationales de commerce et de gestion, École supérieure de technologie de Casablanca.[185]

Health

Many efforts are made by countries around the world to address health issues and eradicate disease, Morocco included. Child health, maternal health, and diseases are all components of health and well-being. Morocco is a developing country that has made many strides to improve these categories. However, Morocco still has many health issues to improve on. According to research published, in 2005 only 16% of citizens in Morocco had health insurance or coverage.[186] In data from the World Bank, Morocco experiences high infant mortality rates at 20 deaths per 1,000 births (2017)[187] and high maternal mortality rates at 121 deaths per 100,000 births (2015).[188]