§ 13. Географические названия

1. Географические названия пишутся с прописной буквы: Арктика, Европа, Финляндия, Кавказ, Крым, Байкал, Урал, Волга, Киев.

С прописной буквы пишутся также неофициальные названия территорий:

1) на -ье, образованные с помощью приставок за-, по-, под-, пред-, при-: Забайкалье, Заволжье; Поволжье, Пообье; Подмосковье; Предкавказье, Предуралье; Приамурье, Приморье;

2) на -ье, образованные без приставки: Оренбуржье, Ставрополье;

3) на -щин(а): Полтавщина, Смоленщина, Черниговщина.

2. В составных географических названиях все слова, кроме служебных и слов, обозначающих родовые понятия (гора, залив, море, озеро, океан, остров, пролив, река и т. п.), пишутся с прописной буквы: Северная Америка, Новый Свет, Старый Свет, Южная Африка, Азиатский материк, Северный Ледовитый океан, Кавказское побережье, Южный полюс, тропик Рака, Красное море, остров Новая Земля, острова Королевы Шарлотты, остров Земля Принца Карла, остров Святой Елены, Зондские острова, полуостров Таймыр, мыс Доброй Надежды, мыс Капитана Джеральда, Берингов пролив, залив Святого Лаврентия, Главный Кавказский хребет, гора Магнитная, Верхние Альпы (горы), Онежское озеро, город Красная Поляна, река Нижняя Тунгуска, Москва-река, вулкан Везувий.

В составных географических названиях существительные пишутся с прописной буквы, только если они утратили свое лексическое значение и называют объект условно: Белая Церковь (город), Красная Горка (город), Чешский Лес (горный хребет), Золотой Рог (бухта), Болванскай Нос (мыс). Ср.: залив Обская губа (губа — ‘залив’), отмель Куршская банка (банка — ‘мель’).

В составное название населенного пункта могут входить самые разные существительные и прилагательные. Например:

Белая Грива

Большой Исток

Борисоглебские Слободы

Верхний Уфалей

Высокая Гора

Горные Ключи

Гусиное Озеро

Дальнее Константиново

Железная Балка

Жёлтая Река

Зелёная Роща

Золотая Гора

Зубова Поляна

Каменный Яр

Камское Устье

Камышовая Бухта

Капустин Яр

Кичменгский Городок

Княжьи Горы

Конские Раздоры

Красная Равнина

Красный Базар

Липовая Долина

Липин Бор

Лисий Нос

Лиственный Мыс

Лукашкин Яр

Малая Пурга

Малиновое Озеро

Мокрая Ольховка

Мурованные Куриловцы

Мутный Материк

Нефтяные Камни

Нижние Ворцта

Новая Дача

Песчаный Брод

Петров Вал

Светлый Яр

Свинцовый Рудник

Свободный Порт

Сенная Губа

Серебряные Пруды

Старый Ряд

Турий Рог

Чёрный Отрог и т. п.

3. Части сложного географического названия пишутся с прописной буквы и соединяются дефисом, если название образовано:

1) сочетанием двух существительных (сочетание имеет значение единого объекта): Эльзас-Лотарингия, Шлезвиг-Гольштейн (но: Чехословакия, Индокитай), мыс Сердце-Камень;

2) сочетанием существительного с прилагательным: Новгород-Северский, Переславль-Залесский, Каменец-Подольский, Каменск-Уральский, Горно-Алтайск;

3) сложным прилагательным: Западно-Сибирская низменность, Южно-Австралийская котловина, Военно-Грузинская дорога, Волго-Донской канал;

4) сочетанием иноязычных элементов: Алма-Ата, Нью-Йорк.

4. Иноязычные родовые наименования, входящие в состав географических названий, но не употребляющиеся в русском языке в качестве нарицательных существительных, пишутся с прописной буквы: Йошкар-Ола (ола — ‘город’), Рио-Колорадо (рио — ‘река’), Сьерра-Невада (сьерра — ‘горная цепь’).

Однако иноязычные родовые наименования, вошедшие в русский язык в качестве нарицательных существительных, пишутся со строчной буквы: Варангер-фиорд, Беркли-сквер, Уолл-стрит, Мичиган-авеню.

5. Артикли, предлоги и частицы, находящиеся в начале иноязычных географических названий, пишутся с прописной буквы и присоединяются дефисом: Ле-Крезо, Лос-Эрманос, острова Де-Лонга. Так же: Сан-Франциско, Санта-Крус, Сен-Готард, Сент-Этьен.

6. Служебные слова, находящиеся в середине сложных географических названий (русских и иноязычных), пишутся со строчной буквы и присоединяются двумя дефисами: Комсомольск-на-Амуре, Ростов-на-Дону, Никольское-на-Черемшане, Франкфурт-на-Майне, Рио-де-Жанейро, Пинар-дель-Рио, Сан-Жозе-дус-Кампус, Сан-Жозе-де-Риу-Прету, Сан-Бендетто-дель-Тронто, Лидо-ди-Остия, Реджо-нель-Эмилия, Шуази-ле-Руа, Орадур-сюр-Глан, Абруццо-э-Молизе, Дар-эс-Салам.

7. Названия стран света пишутся со строчной буквы: восток, запад, север, юг; вест, норд, ост. Так же: северо-запад, юго-восток; норд-ост, зюйд-ост.

Однако названия стран света, когда они входят в состав названий территорий или употребляются вместо них, пишутся с прописной буквы: Дальний Восток, Крайний Север, народы Востока (т. е. восточных стран), страны Запада, регионы Северо-Запада.

«Словосочетание». Урок в 5-м классе

Цели урока:

- дать понятие словосочетания; научить отличать словосочетание от слова;

- сформировать умение вычленять словосочетания из предложений;

- находить главное и зависимое слово;

- определять вид словосочетания (именное, глагольное);

- производить их синтаксический разбор;

- воспитание любви и уважения к родному краю.

Оборудование: портрет А.М.Пешковского, фотографии с изображением озера Байкал, отрывки из стихотворений А.С.Пушкина, С.А.Есенина.

I. Организационный момент

Здравствуйте, ребята. Я рада вас приветствовать сегодня на уроке. Посмотрите на свои парты: есть ли рабочая тетрадь, учебник, ручка, карандаш, всё ли в порядке. Очень хорошо. Садитесь.

II. Проверка усвоения изученного материала

На прошлом уроке мы с вами познакомились с такими понятиями как синтаксис и пунктуация. Сейчас я хочу проверить, как вы усвоили пройденный материал.

- Что такое синтаксис? (Синтаксис – это раздел науки о языке, в котором изучаются словосочетания и предложения, их строение.) (Добиваюсь от учащихся развернутых ответов на вопросы.)

- Что такое пунктуация? (Правила употребления знаков препинания изучает пунктуация.)

- Какие знаки препинания вы знаете?

- Кто такой Александр Матвеевич Пешковский? (А.М.Пешковский – выдающийся учёный-лингвист. Главная его книга посвящена синтаксису.)

Молодцы!

Теперь откройте тетради, запишите число, классная работа и тему урока «Словосочетание».

III. Изучение новой темы

Сегодня на уроке мы с вами подробнее познакомимся со словосочетанием. Сейчас всё ваше внимание обратите на доску.

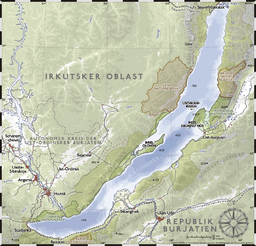

На доске развешаны фотографии с изображением озера Байкал. (Рисунок 1, Рисунок 2, Рисунок 3 , Рисунок 4, Рисунок 5, Рисунок 6.)

- Что вы видите на фотографиях? Ответы записать в столбики. (1-й столбик: озеро Байкал, берег, горы, вода, деревья.)

- Что вы можете сказать о том, какой Байкал, какая в нём вода, природа вокруг? Ответы записать на доске. (2-й столбик: бескрайнее озеро, голубая вода, прозрачная вода, высокие горы, гигантские кедры и т. д.)

- Посмотрите внимательно на слова в столбиках, где более точно, конкретно говорится об озере, воде, природе? В том, где записаны одни слова или сочетания слов? (Более точно говорится об озере, воде, горах в том столбике, где записаны сочетания слов.) Перепишите в тетрадь эти сочетания.

Такие сочетания слов называются словосочетаниями. Прочитаем все вместе: сло-во-со-че-та-ние. Молодцы!

Физкультминутка

Все встали из-за парт. Представьте, что вы красивая грациозная птица – лебедь. Спинки выпрямили, немного назад прогнулись, сладко-сладко потянулись, крыльями помахали, полетали. Разогрелись? Садитесь.

Откроем учебники и прочитаем правило на стр. 126 (о словосочетании), 128-129,130 (главное и зависимое слово в словосочетании; что не является словосочетанием; виды словосочетаний по главному слову), 132 (порядок разбора словосочетания).

- Что такое словосочетание? (Словосочетание – это сочетание слов, связанных между собой по смыслу и грамматически. Например, голубое небо, чистая вода.) По цепочке придумайте каждый по одному словосочетанию.

- Что значит: связаны грамматически? (Грамматическая связь между словами в словосочетании выражается с помощью окончания зависимого слова или окончания и предлога.)

- Из каких частей состоит словосочетание? (Словосочетание состоит из главного и зависимого слов.)

- Что не является словосочетанием? (Словосочетанием не являются: грамматическая основа предложения и однородные члены предложения.)

- Назовите виды словосочетаний по главному слову. (Если в словосочетании главное слово имя существительное или прилагательное, то оно называется именным. Если главное слово – глагол, то словосочетание называется глагольным.)

IV. Тренировочные упражнения

1) Возвратимся к словосочетаниям, которые вы записали. Выделим в них главное и зависимое слово, зададим вопрос, составим схему, назовём вид.

(Даю образец разбора) В словосочетании прозрачная вода главное слово – вода, так как от него мы зададим вопрос: вода (какая?) – прозрачная. Прозрачная зависимое слово. Главное слово выражено именем существительным, поэтому вид словосочетания – именное. Зависимое слово – выражено именем прилагательным. Зависимое слово связано с главным по смыслу и с помощью окончания.

Учащиеся анализируют записанные словосочетания по образцу.

Физкультминутка

Далеко – близко. Называю сначала удаленный предмет, а через 2–3 секунды – предмет, расположенный близко. Учащиеся быстро отыскивают взглядом предметы. Для расслабления зрения упражнение проводится несколько раз.

2) Составьте словосочетания из слов, запишите и разберите их: солнечная, день; чистый, озеро; смотрит, громкий; раскинулось, широкий; приехать, озеро, вкусный, книга. (Двое учеников работают у доски.)

Из каких пар слов не удалось составить словосочетания? Почему? (Из пар слов смотрит, громкий, вкусный книга невозможно составить словосочетания, так как эти слова друг с другом не сочетаются, нет смысла.)

3) Однако, писатели и поэты, создавая свои произведения, сочетали такие слова, которые называли какие-либо явления, не существующие в действительности.

Прочитайте отрывки из стихотворений, выделите словосочетания. Подумайте о том, употребляем ли мы такие выражения в повседневной речи, какова роль этих словосочетаний в стихотворении.

Сквозь волнистые туманы

Пробирается луна,

На печальные поляны

Льет печально свет она. (А.С.Пушкин.)

На пушистых ветках

Снежною каймой

Распустились кисти

Белой бахромой. (С.А.Есенин)

Словосочетание типа «существительное + прилагательное» может употребляться как в прямом значении (сообщать не только конкретные сведения о предмете, например, лесная поляна, сломанные ветки – здесь зависимое слово прилагательное), так и в переносном (передавать чувства, отношение автора к описываемому предмету, явлению: печальные поляны, пушистые ветки, снежная кайма – здесь зависимое слово прилагательное, которое называют эпитетом). Поэты и писатели часто пользуются выразительностью переносного значения слова и создают специальные средства художественной изобразительности: метафору, олицетворение, эпитет и др. Об этом подробнее мы говорим на уроках литературы.

V. Самостоятельная работа

1) Прочитайте выразительно текст, записанный на доске, выпишите словосочетания, произведите их разбор.

Байкал – самое глубокое и многоводное озеро на Земле.

«Море» – так зовут это огромное озеро все местные жители. Оно лежит в гористых берегах.

Впадина Байкала содержит в себе самое большое на нашей планете скопление пресной воды.

VI. Итог урока

- В каком разделе науки о языке изучается словосочетание? Приведите примеры словосочетаний. (Словосочетание изучается в таком разделе науки о языке, который называется – синтаксис. Например, добрый друг, зелёный лес.)

- Что такое словосочетание?

- Из каких частей состоит словосочетание?

- Назовите вид словосочетаний по главному слову?

- Что не является словосочетанием?

Домашнее задание: выучить правило на стр. 126, 128, 129, 130; письменно упр. 391 или 392.

Литература:

1. М.М.Разумовская, С.И.Львова, В.И.Капинос и др. Русский язык. 5 класс: учебник для общеобразовательных учреждений. – М.: Дрофа, 2007.

2. М.Т.Баранов, Л.Т.Григорян, Т.А.Ладыженская и др. Русский язык. 7 класс: учебник для общеобразовательных учреждений. – М.: Просвещение, 1997.

3. А.С.Пушкин. Избранные произведения. – М.,1978.

4. С.А.Есенин. Стихотворения и поэмы. – М., 1973.

Поиск ответа

Всего найдено: 27

Как правильно писать: Я был на озере Байкал или на озере Байкал е? Заранее благодарна за ответ.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно: Я был на озере Байкал . Названия озер не склоняются в сочетании с родовым словом озеро. Исключение составляют случаи, когда топоним выражен прилагательным: на Онежском озере.

Добрый день! Вопрос о грамматике и синтаксисе. Верны ли следующие рассуждения о синтаксисе географических надписей вне предложений: 1. Если на географической карте встречается надпись «оз. Байкал «, то можно сказать, что здесь озеро — главное слово, Байкал — приложение. 2. Если в алфавитном указателе встречается надпись » Байкал , оз.», то можно сказать, что здесь озеро — обособленное приложение, стоящее после имени собственного. 3. Если название озера — прилагательное, но оно записано в виде «оз. Телецкое», то в данном контексте это прилагательное субстантивировано.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Во втором случае можно говорить об уточняющем обороте. Непонятно, какова цель этих рассуждений.

Добрый день! У меня турецкая фамилия Байкал , сын пошёл в 1 класс учитель начала склонять его фамилию. Реньше нам и мы никогда её не склоняли. Соответственно учитель высказала свое не довольство, когда попросили её не склонять. К озеру, фамилия отношения не имеет. Пишется на родном языке Baykal. Помогите пожалуйста разобраться.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Мужскую фамилию Байкал следует склонять вне зависимости от ее происхождения, однако следует также учитывать пожелания носителя фамилии.

Здравствуйте! Как правильно: в За байкал ье или на За байкал ье?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Найдите в данных предложениях ошибки, укажите тип ошибки, предложите исправленный вариант. 1)Главная сила Сибири – в ее обильной минерально-сырьевой базе. 2) Галина отдыхала очень в хорошем доме отдыха. 3) Поднявшись на гору, перед туристами открылись живописные окрестности. 4) Хозяйка сняла со стола чемодан и отодвинула его в сторону. 5) Байкал – самое наиглубочайшее озеро в мире. 6) Как они проявляют патриотизм к Родине?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Мы не выполняем домашние задания.

Здравствуйте! Как правильно написать (поселок городского типа сокращенно) — ЗА БАЙКАЛ ЬСКИЙ КРАЙ, ПГТ. ЗА БАЙКАЛ ЬСК или ЗА БАЙКАЛ ЬСКИЙ КРАЙ, пгт. ЗА БАЙКАЛ ЬСК?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В справочниках рекомендаций о написании сокращений в случае, если весь текст набран прописными буквами, нет. Возможны оба варианта – и строчными, и прописными. Обратите внимание: нормативны сокращения без точек и с тремя точками – пгт и п. г. т.

Здравствуйте!

Можно видеть, что на сайте Грамоты.ру задавалось довольно много вопросов относительно написания прописных/строчных букв в таких словосочетаниях, как Северо-Запад и северо-западный. Но прошу специалистов пояснить, если написание: «Северо-западное отделение…», «Санкт-петербургский институт…», «Нью-йоркский саммит…» и др. — являются некорректными, то ПОЧЕМУ, и какие здесь могут быть нюансы вроде официального названия организации или мероприятия либо их принадлежности к какой-то местности, и не более.

В другой формулировке: укажите, пожалуйста, на конкретное правило, согласно которому вторая часть сложного слова, пишущегося через дефис, в качестве прилагательного в составе официальных названий организаций должна начинаться с прописной буквы.

Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В названиях, начинающихся на Северо- (и Северно- ), Юго- (и Южно- ), Восточно-, Западно-, Центрально- , с прописной буквы пишутся (через дефис) оба компонента первого сложного слова, напр.: Северо- Байкал ьское нагорье, Восточно-Китайское море, Западно-Сибирская низменность, Центрально-Черноземный район, Юго-Западный административный округ. Так же пишутся в составе географических названий компоненты других пишущихся через дефис слов и их сочетаний, напр.: Индо-Гангская равнина, Волго-Донской канал, Военно-Грузинская дорога, Алма-Атинский заповедник.

В названиях учреждений, организаций, начинающихся географическими определениями с первыми компонентами Северо- (и Северно- ), Юго- (и Южно- ), Восточно-, Западно-, Центрально- , а также пишущимися через дефис прилагательными от географических названий, с прописной буквы пишутся, как и в собственно географических названиях, оба компонента первого сложного слова, напр.: Северо-Кавказская научная географическая станция, Западно-Сибирский металлургический комбинат, Санкт-Петербургский государственный университет, Орехово-Зуевский педагогический институт, Нью-Йоркский филармонический оркестр.

Прилагательные, образованные от географических названий, пишутся с прописной буквы, если они являются частью составных наименований – географических и административно-территориальных, индивидуальных имен людей, названий исторических эпох и событий, учреждений, архитектурных и др. памятников, военных округов и фронтов. В остальных случаях они пишутся со строчной буквы. Например: северокавказская природа и Северо-Кавказский регион, Северо-Кавказский военный округ.

См.: Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации. Полный академический справочник / Под ред. В. В. Лопатина. М., 2006 (и более поздние издания).

Добрый день! Как правильно: на озере Байкал или на озере Байкал е?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: на озере Байкал . Названия озер не склоняются в сочетании с родовым словом озеро. Исключение составляют случаи, когда топоним выражен прилагательным: на Онежском озере.

Добрый день, уважаемая грамота! Интересует написание некоторых географических названий.

У вас размещено правило (http://www.gramota.ru/spravka/rules/?rub=mtz):

Буква ь не пишется: В прилагательных с суффиксом -ск-, образованных от существительных на ь, например: казанский (Казань), кемский (Кемь), сибирский (Сибирь), зверский (зверь), январский (январь).

Возник вопрос: почему ь сохраняется в словах гомельский, мариупольский, ставропольский?

У Розенталя находим более точное правило:

Если основа имени существительного оканчивается на -нь и -рь, то перед суффиксом -ск- буква ь не пишется, например: конь – конский, зверь – зверский, Рязань – рязанский, Сибирь – сибирский, Тюмень – тюменский.

(Далее и там и там даются исключения – прилагательные, образованные от названий месяцев и от некоторых иноязычных географических наименований, в частности китайских.)

Вопрос по поводу прилагательных на -льский от основ на -ль снялся сам собой, но возник еще один вопрос. Как тогда быть с прилагательными от основ на -мь? Пермь и Кемь образуют пермский и кемский. Чем это объяснить, если у Розенталя упоминаются только слова на -нь и -рь?

И последнее: от чего зависит наличие/отсутствие ь в прилагательных от слов на -л/-ль: байкал ьский от Байкал , уральский от Урал, барнаульский от Барнаул? Л всегда смягчается? И как правильно: кызылский или кызыльский?

Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Вот что написано о прилагательных с суфиксом — ск — в полном академическом справочнике «Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации» под ред. В. В. Лопатина:

«В большинстве прилагательных с суффиксом — ск — согласный л перед суффиксом мягкий, поэтому после л пишется ь , например: сельский, уральский, барнаульский. Однако в некоторых прилагательных, образованных от нерусских собственных географических названий, сохраняется твердый л , поэтому ь не пишется, например: кызылский, ямалский (наряду с вариантами кызыльский, ямальский )».

«В большинстве прилагательных с суффиксом — ск — согласные н и р перед суффиксом – твердые, поэтому ь в них не пишется: конский, казанский, тюменский, рыцарский, январский, егерский. Однако в следующих прилагательных эти согласные перед суффиксом -ск- мягкие, в них после н и р пишется ь: день-деньской, июньский, сентябрьский, октябрьский, ноябрьский, декабрьский , а также во многих прилагательных, образованных от нерусских собственных географических названий на -нь , например: тянь-шаньский, тайваньский, пномпеньский, торуньский, сычуаньский, тяньцзиньский » .

Что касается слов пермский и кемский , то мягкий знак в них не пишется по простой причине: согласный м произносится перед суффиксом — ск — твердо.

Скажите, пожалуйста, как правильнее назвать жителей г. Байкал ьска — байкал ьцы или байкал ьчане?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Словарь И. Л. Городецкой, Е. А. Левашова «Русские названия жителей» (М., 2003) – наиболее полный справочник по названиям жителей – фиксирует оба слова (т. е. оба названия правильны), но при этом предпочтение отдает варианту байкал ьцы.

Скажите, пожалуйста, что такое «карбозный перевоз»? Выражение встречается в городской летописи начала 19 века при описании наводнения.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В словаре Даля зафиксировано слово карбаз (характерное для за байкал ьских говоров), означающее «паром». Вы не уточнили, в летописи какого города встречается это выражение, но, если этот город расположен в За байкал ье, можно предположить, что имеется в виду паромная переправа.

«Вытащить из озера Байкал » или «вытащить из озера Байкал А»?

Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Здравствуйте! Что в данном случае нужно ставить » Байкал тудно описать(,)(-) Байкал надо видеть».

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Возможны варианты пунктуации: Байкал трудно описать, Байкал надо видеть. Байкал трудно описать – Байкал надо видеть. Можно и разделить предложение на два: Байкал трудно описать. Байкал надо видеть. Окончательное решение принимает автор текста.

Уважаемая Грамота,

XIV Байкал ьская Всероссийская конференция — нужно ли писать «всероссийская» с большой буквы?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Слова Международный, Всемирный, Всероссийский в названиях конференций, конгрессов, фестивалей, конкурсов и т. п. пишутся с прописной. Правда, обычно эти слова следуют сразу за порядковым номером мероприятия (если он есть), например: II Всероссийская научно-практическая конференция «Название конференции». Но и в приведенном Вами примере написание с прописной верно.

Скажите, пожалуйста, надо ли запятая между «там» и «в центре»:

Самый холодный регион России — Сибирь. Там, в центре находится озеро Байкал , недалеко от города Иркутска.

Мне не уверено, правильно ли эти предложения.

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корректно: Там, в центре, недалеко от Иркутска, находится.

Как пишется озеро Байкал правильно

Озеро Байкал – это крупнейшее в мире хранилище самой чистой питьевой воды, здесь содержится 19% от всех мировых запасов. Но это далеко не единственная ценность России и мира, делающая это озеро уникальным. В современной медицине есть такое направление как лечение сочетанием уникальных природных факторов. С этой точки зрения Байкал является центром оздоровления, равного которому на Земле нет и не будет.

Как пишется слово сочетание озеро Байкал?

- Географические названия пишутся с прописной буквы: Байкал, Крым, Волга, Днестр и другие.

- Пол-Байкала — пишется через дефис, согласно правилу правописания «пол»+ слово, Байкал начинается с согласной буквы

- Географической название как правило не склоняется, — поход на озеро Байкал

- Северный Байкал пишутся оба слова с больших букв

- По Байкалу — пишется раздельно, пример, — Предлагаем вам разнообразные круизы по Байкалу

Значения озера

Озеро имеет тектоническое происхождение, находится в трещине земной коры и за счет этого является самым глубоким озером в мире. Оно имеет форму полумесяца, что имеет важное значение в ряде религиозных культов. Возраст озера около 30 миллионов лет. Сейсмическая активность в районе озера не прекращается до настоящего времени, что говорит о том, что формирование озера продолжается.

Вода в Байкале содержит уникально мало примесей минералогического и биологического происхождения, зато содержит очень много кислорода. Она самостоятельным лечебным фактором. Еще Авиценна писал об оздоравливающем действии легкой, беспримесной воды, которая очищает организм, вымывая из него шлаки и яды. Есть мнение и о том, что вода Байкала является «истинной, первозданной» водой, возвращающей организму его настоящие силы, пока заблокированные тысячелетиями цивилизации. Интересно, что это мнение разделяют не только врачи-натуропаты, но и некоторые ученые.

Рекреация на Байкале осложнена тем, что вода в озере холодна даже в середине лета. Местные жители предпочитают купаться в небольших заливах и бухтах в районе Баргузинского залива и реки Слюдянки. Здесь находится зона отдыха «Байкальская гавань». Надо учитывать, что активная рекреация способствует загрязнению района и при выборе мест для оздоровления не только тела, но и души надо рассматривать менее оживленные места.

Кроме воды в качестве оздоравливающих факторов можно рассматривать живую природу берегов Байкала, уникальные леса с растениями-эндемиками, естественную ионизацию воздуха и существующие традиции народной медицины, а также развивающуюся практику тибетской медицины. В обоих видах традиционного лечения широко используются местные лекарственные растения.

Ионизация воздуха, происходящая за счет излучения, идущего из трещины земной коры, улучшает мозговую и сердечно-сосудистую деятельность, снижает возможность мигреней, сердцебиений, микроинсультов.

Природные факторы влияют при их активном использовании, ежедневным прогулкам не менее часа, глубокому дыханию. По лесам и предгорьям вокруг Байкала проходит «Большая байкальская тропа» — любимое место для двух-трехдневных прогулок пеших туристов. Такая прогулка позволит оздоровить организм и придать ему тонус минимум на пол-года.

Оздоровление на Байкале – процесс, требующей подготовки. Просто поездка поможет привести организм в порядок и оздоровить, но если серьезно подойти к задаче и составить себе систему, учитывающую все факторы приведения души и тела в порядок, то можно поправить здоровье на годы, если не на десятилетия.

источники:

http://new.gramota.ru/spravka/buro/search-answer?s=%D0%91%D0%B0%D0%B9%D0%BA%D0%B0%D0%BB

http://gto-normativy.ru/kak-pishetsya-ozero-bajkal-pravilno/

Озеро Байкал – это крупнейшее в мире хранилище самой чистой питьевой воды, здесь содержится 19% от всех мировых запасов. Но это далеко не единственная ценность России и мира, делающая это озеро уникальным. В современной медицине есть такое направление как лечение сочетанием уникальных природных факторов. С этой точки зрения Байкал является центром оздоровления, равного которому на Земле нет и не будет.

Как пишется слово сочетание озеро Байкал?

- Географические названия пишутся с прописной буквы: Байкал, Крым, Волга, Днестр и другие.

- Пол-Байкала — пишется через дефис, согласно правилу правописания «пол»+ слово, Байкал начинается с согласной буквы

- Географической название как правило не склоняется, — поход на озеро Байкал

- Северный Байкал пишутся оба слова с больших букв

- По Байкалу — пишется раздельно, пример, — Предлагаем вам разнообразные круизы по Байкалу

Значения озера

Озеро имеет тектоническое происхождение, находится в трещине земной коры и за счет этого является самым глубоким озером в мире. Оно имеет форму полумесяца, что имеет важное значение в ряде религиозных культов. Возраст озера около 30 миллионов лет. Сейсмическая активность в районе озера не прекращается до настоящего времени, что говорит о том, что формирование озера продолжается.

Вода в Байкале содержит уникально мало примесей минералогического и биологического происхождения, зато содержит очень много кислорода. Она самостоятельным лечебным фактором. Еще Авиценна писал об оздоравливающем действии легкой, беспримесной воды, которая очищает организм, вымывая из него шлаки и яды. Есть мнение и о том, что вода Байкала является «истинной, первозданной» водой, возвращающей организму его настоящие силы, пока заблокированные тысячелетиями цивилизации. Интересно, что это мнение разделяют не только врачи-натуропаты, но и некоторые ученые.

Рекреация на Байкале осложнена тем, что вода в озере холодна даже в середине лета. Местные жители предпочитают купаться в небольших заливах и бухтах в районе Баргузинского залива и реки Слюдянки. Здесь находится зона отдыха «Байкальская гавань». Надо учитывать, что активная рекреация способствует загрязнению района и при выборе мест для оздоровления не только тела, но и души надо рассматривать менее оживленные места.

Кроме воды в качестве оздоравливающих факторов можно рассматривать живую природу берегов Байкала, уникальные леса с растениями-эндемиками, естественную ионизацию воздуха и существующие традиции народной медицины, а также развивающуюся практику тибетской медицины. В обоих видах традиционного лечения широко используются местные лекарственные растения.

Ионизация воздуха, происходящая за счет излучения, идущего из трещины земной коры, улучшает мозговую и сердечно-сосудистую деятельность, снижает возможность мигреней, сердцебиений, микроинсультов.

Природные факторы влияют при их активном использовании, ежедневным прогулкам не менее часа, глубокому дыханию. По лесам и предгорьям вокруг Байкала проходит «Большая байкальская тропа» — любимое место для двух-трехдневных прогулок пеших туристов. Такая прогулка позволит оздоровить организм и придать ему тонус минимум на пол-года.

Оздоровление на Байкале – процесс, требующей подготовки. Просто поездка поможет привести организм в порядок и оздоровить, но если серьезно подойти к задаче и составить себе систему, учитывающую все факторы приведения души и тела в порядок, то можно поправить здоровье на годы, если не на десятилетия.

Всего найдено: 29

Подскажите, пожалуйста, склоняется ли первая часть в названии Петровск-Забайкальский?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В названии склоняются обе части, что отражено в «Академосе».

Здравствуйте! Скажите пожалуйста, как правильно написать «Загадка лох-несского озера»? Название озера через дефис, как и слово «Лох-Несс»? И как использовать заглавные буквы? Заранее спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Название озера — Лох-Несс. Поэтому употреблять образованное от названия прилагательное вместе со словом озеро некорректно. Это примерно то же самое, что сказать «байкальское озеро».

Как правильно писать: Я был на озере Байкал или на озере Байкале? Заранее благодарна за ответ.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно: Я был на озере Байкал. Названия озер не склоняются в сочетании с родовым словом озеро. Исключение составляют случаи, когда топоним выражен прилагательным: на Онежском озере.

Добрый день! Вопрос о грамматике и синтаксисе. Верны ли следующие рассуждения о синтаксисе географических надписей вне предложений: 1. Если на географической карте встречается надпись «оз. Байкал«, то можно сказать, что здесь озеро — главное слово, Байкал — приложение. 2. Если в алфавитном указателе встречается надпись «Байкал, оз.», то можно сказать, что здесь озеро — обособленное приложение, стоящее после имени собственного. 3. Если название озера — прилагательное, но оно записано в виде «оз. Телецкое», то в данном контексте это прилагательное субстантивировано.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Во втором случае можно говорить об уточняющем обороте. Непонятно, какова цель этих рассуждений.

Добрый день! У меня турецкая фамилия Байкал, сын пошёл в 1 класс учитель начала склонять его фамилию. Реньше нам и мы никогда её не склоняли. Соответственно учитель высказала свое не довольство, когда попросили её не склонять. К озеру, фамилия отношения не имеет. Пишется на родном языке Baykal. Помогите пожалуйста разобраться.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Мужскую фамилию Байкал следует склонять вне зависимости от ее происхождения, однако следует также учитывать пожелания носителя фамилии.

Здравствуйте! Как правильно: в Забайкалье или на Забайкалье?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно: (жить) в Забайкалье.

Найдите в данных предложениях ошибки, укажите тип ошибки, предложите исправленный вариант. 1)Главная сила Сибири – в ее обильной минерально-сырьевой базе. 2) Галина отдыхала очень в хорошем доме отдыха. 3) Поднявшись на гору, перед туристами открылись живописные окрестности. 4) Хозяйка сняла со стола чемодан и отодвинула его в сторону. 5) Байкал – самое наиглубочайшее озеро в мире. 6) Как они проявляют патриотизм к Родине?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Мы не выполняем домашние задания.

Здравствуйте! Как правильно написать (поселок городского типа сокращенно) — ЗАБАЙКАЛЬСКИЙ КРАЙ, ПГТ. ЗАБАЙКАЛЬСК или ЗАБАЙКАЛЬСКИЙ КРАЙ, пгт. ЗАБАЙКАЛЬСК?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В справочниках рекомендаций о написании сокращений в случае, если весь текст набран прописными буквами, нет. Возможны оба варианта – и строчными, и прописными. Обратите внимание: нормативны сокращения без точек и с тремя точками – пгт и п. г. т.

Здравствуйте!

Можно видеть, что на сайте Грамоты.ру задавалось довольно много вопросов относительно написания прописных/строчных букв в таких словосочетаниях, как Северо-Запад и северо-западный. Но прошу специалистов пояснить, если написание: «Северо-западное отделение…», «Санкт-петербургский институт…», «Нью-йоркский саммит…» и др. — являются некорректными, то ПОЧЕМУ, и какие здесь могут быть нюансы вроде официального названия организации или мероприятия либо их принадлежности к какой-то местности, и не более.

В другой формулировке: укажите, пожалуйста, на конкретное правило, согласно которому вторая часть сложного слова, пишущегося через дефис, в качестве прилагательного в составе официальных названий организаций должна начинаться с прописной буквы.

Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Приводим формулировки правил.

В названиях, начинающихся на Северо- (и Северно-), Юго- (и Южно-), Восточно-, Западно-, Центрально-, с прописной буквы пишутся (через дефис) оба компонента первого сложного слова, напр.: Северо-Байкальское нагорье, Восточно-Китайское море, Западно-Сибирская низменность, Центрально-Черноземный район, Юго-Западный административный округ. Так же пишутся в составе географических названий компоненты других пишущихся через дефис слов и их сочетаний, напр.: Индо-Гангская равнина, Волго-Донской канал, Военно-Грузинская дорога, Алма-Атинский заповедник.

В названиях учреждений, организаций, начинающихся географическими определениями с первыми компонентами Северо- (и Северно-), Юго- (и Южно-), Восточно-, Западно-, Центрально-, а также пишущимися через дефис прилагательными от географических названий, с прописной буквы пишутся, как и в собственно географических названиях, оба компонента первого сложного слова, напр.: Северо-Кавказская научная географическая станция, Западно-Сибирский металлургический комбинат, Санкт-Петербургский государственный университет, Орехово-Зуевский педагогический институт, Нью-Йоркский филармонический оркестр.

Прилагательные, образованные от географических названий, пишутся с прописной буквы, если они являются частью составных наименований – географических и административно-территориальных, индивидуальных имен людей, названий исторических эпох и событий, учреждений, архитектурных и др. памятников, военных округов и фронтов. В остальных случаях они пишутся со строчной буквы. Например: северокавказская природа и Северо-Кавказский регион, Северо-Кавказский военный округ.

См.: Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации. Полный академический справочник / Под ред. В. В. Лопатина. М., 2006 (и более поздние издания).

Добрый день! Как правильно: на озере Байкал или на озере Байкале?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: на озере Байкал. Названия озер не склоняются в сочетании с родовым словом озеро. Исключение составляют случаи, когда топоним выражен прилагательным: на Онежском озере.

Добрый день, уважаемая грамота! Интересует написание некоторых географических названий.

У вас размещено правило (http://www.gramota.ru/spravka/rules/?rub=mtz):

Буква ь не пишется: В прилагательных с суффиксом -ск-, образованных от существительных на ь, например: казанский (Казань), кемский (Кемь), сибирский (Сибирь), зверский (зверь), январский (январь).

Возник вопрос: почему ь сохраняется в словах гомельский, мариупольский, ставропольский?

У Розенталя находим более точное правило:

Если основа имени существительного оканчивается на -нь и -рь, то перед суффиксом -ск- буква ь не пишется, например: конь – конский, зверь – зверский, Рязань – рязанский, Сибирь – сибирский, Тюмень – тюменский.

(Далее и там и там даются исключения – прилагательные, образованные от названий месяцев и от некоторых иноязычных географических наименований, в частности китайских.)

Вопрос по поводу прилагательных на -льский от основ на -ль снялся сам собой, но возник еще один вопрос. Как тогда быть с прилагательными от основ на -мь? Пермь и Кемь образуют пермский и кемский. Чем это объяснить, если у Розенталя упоминаются только слова на -нь и -рь?

И последнее: от чего зависит наличие/отсутствие ь в прилагательных от слов на -л/-ль: байкальский от Байкал, уральский от Урал, барнаульский от Барнаул? Л всегда смягчается? И как правильно: кызылский или кызыльский?

Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Вот что написано о прилагательных с суфиксом —ск— в полном академическом справочнике «Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации» под ред. В. В. Лопатина:

«В большинстве прилагательных с суффиксом —ск— согласный л перед суффиксом мягкий, поэтому после л пишется ь, например: сельский, уральский, барнаульский. Однако в некоторых прилагательных, образованных от нерусских собственных географических названий, сохраняется твердый л, поэтому ь не пишется, например: кызылский, ямалский (наряду с вариантами кызыльский, ямальский)».

«В большинстве прилагательных с суффиксом —ск— согласные н и р перед суффиксом – твердые, поэтому ь в них не пишется: конский, казанский, тюменский, рыцарский, январский, егерский. Однако в следующих прилагательных эти согласные перед суффиксом -ск- мягкие, в них после н и р пишется ь: день-деньской, июньский, сентябрьский, октябрьский, ноябрьский, декабрьский, а также во многих прилагательных, образованных от нерусских собственных географических названий на -нь, например: тянь-шаньский, тайваньский, пномпеньский, торуньский, сычуаньский, тяньцзиньский».

Что касается слов пермский и кемский, то мягкий знак в них не пишется по простой причине: согласный м произносится перед суффиксом —ск— твердо.

Скажите, пожалуйста, как правильнее назвать жителей г. Байкальска — байкальцы или байкальчане?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Словарь И. Л. Городецкой, Е. А. Левашова «Русские названия жителей» (М., 2003) – наиболее полный справочник по названиям жителей – фиксирует оба слова (т. е. оба названия правильны), но при этом предпочтение отдает варианту байкальцы.

Скажите, пожалуйста, что такое «карбозный перевоз»? Выражение встречается в городской летописи начала 19 века при описании наводнения.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В словаре Даля зафиксировано слово карбаз (характерное для забайкальских говоров), означающее «паром». Вы не уточнили, в летописи какого города встречается это выражение, но, если этот город расположен в Забайкалье, можно предположить, что имеется в виду паромная переправа.

«Вытащить из озера Байкал» или «вытащить из озера БайкалА»?

Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корректно: из озера Байкал.

Здравствуйте! Что в данном случае нужно ставить «Байкал тудно описать(,)(-) Байкал надо видеть».

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Возможны варианты пунктуации: Байкал трудно описать, Байкал надо видеть. Байкал трудно описать – Байкал надо видеть. Можно и разделить предложение на два: Байкал трудно описать. Байкал надо видеть. Окончательное решение принимает автор текста.

| Lake Baikal | |

|---|---|

Satellite photo of Baikal, 2001 |

|

|

Lake Baikal Lake Baikal Lake Baikal |

|

|

|

| Location | Siberia, Russia |

| Coordinates | 53°30′N 108°0′E / 53.500°N 108.000°ECoordinates: 53°30′N 108°0′E / 53.500°N 108.000°E |

| Lake type | Ancient lake, Continental rift lake |

| Native name |

|

| Primary inflows | Selenga, Barguzin, Upper Angara |

| Primary outflows | Angara |

| Catchment area | 560,000 km2 (216,000 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | Mongolia and Russia |

| Max. length | 636 km (395 mi) |

| Max. width | 79 km (49 mi) |

| Surface area | 31,722 km2 (12,248 sq mi)[1] |

| Average depth | 744.4 m (2,442 ft; 407.0 fathoms)[1] |

| Max. depth | 1,642 m (5,387 ft; 898 fathoms)[1] |

| Water volume | 23,615.39 km3 (5,670 cu mi)[1] |

| Residence time | 330 years[2] |

| Shore length1 | 2,100 km (1,300 mi) |

| Surface elevation | 455.5 m (1,494 ft) |

| Frozen | January–May |

| Islands | 27 (Olkhon Island) |

| Settlements | Severobaykalsk, Slyudyanka, Baykalsk, Ust-Barguzin |

|

UNESCO World Heritage Site |

|

| Criteria | Natural: vii, viii, ix, x |

| Reference | 754 |

| Inscription | 1996 (20th Session) |

| Area | 8,800,000 ha |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. |

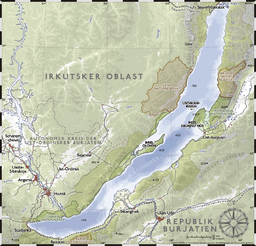

Lake Baikal (,[3] Russian: Oзеро Байкал, romanized: Ozero Baykal [ˈozʲɪrə bɐjˈkaɫ])[a] is a rift lake in Russia. It is situated in southern Siberia, between the federal subjects of Irkutsk Oblast to the northwest and the Republic of Buryatia to the southeast. With 23,615.39 km3 (5,670 cu mi) of water,[1] Lake Baikal is the world’s largest freshwater lake by volume, containing 22–23% of the world’s fresh surface water,[5][6] more than all of the North American Great Lakes combined.[7] It is also the world’s deepest lake,[8] with a maximum depth of 1,642 metres (5,387 feet; 898 fathoms),[1] and the world’s oldest lake,[9] at 25–30 million years.[10][11] At 31,722 km2 (12,248 sq mi)—slightly larger than Belgium—Lake Baikal is the world’s seventh-largest lake by surface area.[12] It is among the world’s clearest lakes.[13]

Lake Baikal is home to thousands of species of plants and animals, many of them endemic to the region. It is also home to Buryat tribes, who raise goats, camels, cattle, sheep, and horses[14] on the eastern side of the lake,[15] where the mean temperature varies from a winter minimum of −19 °C (−2 °F) to a summer maximum of 14 °C (57 °F).[16] The region to the east of Lake Baikal is referred to as Transbaikalia or as the Transbaikal,[17] and the loosely defined region around the lake itself is sometimes known as Baikalia. UNESCO declared Baikal a World Heritage Site in 1996.[18]

Geography and hydrography[edit]

The Yenisey basin, which includes Lake Baikal

Lake Baikal is in a rift valley, created by the Baikal Rift Zone, where the Earth’s crust is slowly pulling apart.[12] At 636 km (395 mi) long and 79 km (49 mi) wide, Lake Baikal has the largest surface area of any freshwater lake in Asia, at 31,722 km2 (12,248 sq mi), and is the deepest lake in the world at 1,642 metres (5,387 feet; 898 fathoms). The bottom of the lake is 1,186.5 m (3,893 ft; 648.8 fathoms) below sea level, but below this lies some 7 km (4.3 mi) of sediment, placing the rift floor some 8–11 km (5.0–6.8 mi) below the surface, the deepest continental rift on Earth.[12]

In geological terms, the rift is young and active – it widens about 2 cm (0.8 in) per year. The fault zone is also seismically active; hot springs occur in the area and notable earthquakes happen every few years. The lake is divided into three basins: North, Central, and South, with depths about 900 m (3,000 ft), 1,600 m (5,200 ft), and 1,400 m (4,600 ft), respectively. Fault-controlled accommodation zones rising to depths about 300 m (980 ft) separate the basins. The North and Central basins are separated by Academician Ridge, while the area around the Selenga Delta and the Buguldeika Saddle separates the Central and South basins. The lake drains into the Angara, a tributary of the Yenisey. Notable landforms include Cape Ryty on Baikal’s northwest coast.

Baikal’s age is estimated at 25–30 million years, making it the most ancient lake in geological history.[10][11] It is unique among large, high-latitude lakes, as its sediments have not been scoured by overriding continental ice sheets. Russian, U.S., and Japanese cooperative studies of deep-drilling core sediments in the 1990s provide a detailed record of climatic variation over the past 6.7 million years.[19][20]

Longer and deeper sediment cores are expected in the near future. Lake Baikal is the only confined freshwater lake in which direct and indirect evidence of gas hydrates exists.[21][22][23]

The lake is surrounded by mountains; the Baikal Mountains on the north shore, the Barguzin Range on the northeastern shore and the Primorsky Range stretching along the western shore. The mountains and the taiga are protected as a national park. It contains 27 islands; the largest, Olkhon, is 72 km (45 mi) long and is the third-largest lake-bound island in the world. The lake is fed by as many as 330 inflowing rivers.[24] The main ones draining directly into Baikal are the Selenga, the Barguzin, the Upper Angara, the Turka, the Sarma, and the Snezhnaya. It is drained through a single outlet, the Angara.

Regular winds exist in Baikal’s rift valley.[25] The Kultuk blows southwest and the Verkhovik blows north or northeast. In addition, transverse winds blow locally and over shorter distances. The Sarma (named after the Sarma River) blows northwest in the autumn through the Sarma valley and the strait of Olkhon Island. The Barguzin (named after the Barguzin river) blows northeast in the spring.

-

Cliffs on Olkhon Island

-

-

The river Turka at its mouth before joining Lake Baikal

Water characteristics[edit]

Lake Baikal’s water is especially clear

Baikal is one of the clearest lakes in the world.[13] During the winter, the water transparency in open sections can be as much as 30–40 m (100–130 ft), but during the summer it is typically 5–8 m (15–25 ft).[26] Baikal is rich in oxygen, even in deep sections,[26] which separates it from distinctly stratified bodies of water such as Lake Tanganyika and the Black Sea.[27][28]

In Lake Baikal, the water temperature varies significantly depending on location, depth, and time of the year. During the winter and spring, the surface freezes for about 4–5 months; from early January to early May–June (latest in the north), the lake surface is covered in ice.[29] On average, the ice reaches a thickness of 0.5 to 1.4 m (1.6–4.6 ft),[30] but in some places with hummocks, it can be more than 2 m (6.6 ft).[29] During this period, the temperature slowly increases with depth in the lake, being coldest near the ice-covered surface at around freezing, and reaching about 3.5–3.8 °C (38.3–38.8 °F) at a depth of 200–250 m (660–820 ft).[31] After the surface ice breaks up, the surface water is slowly warmed up by the sun, and in May–June, the upper 300 m (980 ft) or so becomes homothermic (same temperature throughout) at around 4 °C (39 °F) because of water mixing.[26][31] The sun continues to heat up the surface layer, and at the peak in August can reach up to about 16 °C (61 °F) in the main sections[31] and 20–24 °C (68–75 °F) in shallow bays in the southern half of the lake.[26][32] During this time, the pattern is inverted compared to the winter and spring, as the water temperature falls with increasing depth. As the autumn begins, the surface temperature falls again and a second homothermic period at around 4 °C (39 °F) of the upper circa 300 m (980 ft) occurs in October–November.[26][31] In the deepest parts of the lake, from about 300 m (980 ft), the temperature is stable at 3.1–3.4 °C (37.6–38.1 °F) with only minor annual variations.[31]

The average surface temperature has risen by almost 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) in the last 50 years, resulting in a shorter period where the lake is covered by ice.[11] At some locations, hydrothermal vents with water that is about 50 °C (122 °F) have been found. These are mostly in deep water but locally have also been found in relatively shallow water. They have little effect on the lake’s temperature because of its huge volume.[31]

Stormy weather on the lake is common, especially during the summer and autumn, and can result in waves as high as 4.5 m (15 ft).[26]

-

Lake Baikal as seen from the OrbView-2 satellite

-

Spring ice melt underway on Lake Baikal, on 4 May: Notice the ice-covered north, while much of the south is already ice-free.

-

Circle of thin ice, diameter of 4.4 km (2.7 mi) at the lake’s southern tip, probably caused by convection

Fauna and flora[edit]

Lake Baikal is rich in biodiversity. It hosts more than 1,000 species of plants and 2,500 species of animals based on current knowledge, but the actual figures for both groups are believed to be significantly higher.[26][33] More than 80% of the animals are endemic.[33]

Flora[edit]

The watershed of Lake Baikal has numerous floral species represented. The marsh thistle (Cirsium palustre) is found here at the eastern limit of its geographic range.[34]

Submerged macrophytic vascular plants are mostly absent, except in some shallow bays along the shores of Lake Baikal.[35] More than 85 species of submerged macrophytes have been recorded, including genera such as Ceratophyllum, Myriophyllum, Potamogeton, and Sparganium.[32] The invasive species Elodea canadensis was introduced to the lake in the 1950s.[35] Instead of vascular plants, aquatic flora is often dominated by several green algae species, notably Draparnaldioides, Tetraspora, and Ulothrix in water shallower than 20 m (65 ft); although Aegagrophila, Cladophora, and Draparnaldioides may occur deeper than 30 m (100 ft).[35] Except for Ulothrix, there are endemic Baikal species in all these green algae genera.[35] More than 400 diatom species, both benthic and planktonic, are found in the lake, and about half of these are endemic to Baikal; however, significant taxonomic uncertainties remain for this group.[35]

Fauna[edit]

Mammals[edit]

The Baikal seal or nerpa (Pusa sibirica) is endemic to Lake Baikal.[36]

A wide range of land mammals can be found in the habitats around the lake, such as the Eurasian brown bear (Ursus arctos arctos), Eurasian wolf (Canis lupus lupus), red fox (Vulpes vulpes), sable (Martes zibellina), stoat (Mustela erminea), elk (Alces alces), wapiti (Cervus canadensis), reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), Siberian roe deer (Capreolus pygargus), Siberian musk deer ((Moschus moschiferus), wild boar (Sus scrofa), red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris), Siberian chipmunk (Eutamias sibiricus), marmots (Marmota sp.), lemmings (Lemmus sp.), and mountain hare (Lepus timidus).[37] Until the Early Middle Ages, populations of the European bison (Bison bonasus) were found near the lake; this represented the easternmost range of the species.[38]

Birds[edit]

There are 236 species of birds that inhabit Lake Baikal, 29 of which are waterfowl.[39] Although named after the lake, both the Baikal teal and Baikal bush warbler are widespread in eastern Asia.[40][41]

Fish[edit]

Fewer than 65 native fish species occur in the lake basin, but more than half of these are endemic.[26][44] The families Abyssocottidae (deep-water sculpins), Comephoridae (golomyankas or Baikal oilfish), and Cottocomephoridae (Baikal sculpins) are entirely restricted to the lake basin.[26][45] All these are part of the Cottoidea and are typically less than 20 cm (8 in) long.[35] Of particular note are the two species of golomyanka (Comephorus baicalensis and C. dybowskii). These long-finned, translucent fish typically live in open water at depths of 100–500 m (330–1,640 ft), but occur both shallower and much deeper. Together with certain abyssocottid sculpins, they are the deepest living freshwater fish in the world, occurring to near the bottom of Lake Baikal.[46] The golomyankas are the primary prey of the Baikal seal and represent the largest fish biomass in the lake.[47] Beyond members of Cottoidea, there are few endemic fish species in the lake basin.[26][44]

The omul (Coregonus migratorius) is endemic to Lake Baikal, and is a source of income to locals.

The most important local species for fisheries is the omul (Coregonus migratorius), an endemic whitefish.[26] It is caught, smoked, and then sold widely in markets around the lake. Also, a second endemic whitefish inhabits the lake, C. baicalensis.[48] The Baikal black grayling (Thymallus baicalensis), Baikal white grayling (T. brevipinnis), and Baikal sturgeon (Acipenser baerii baicalensis) are other important species with commercial value. They are also endemic to the Lake Baikal basin.[42][43][49][50]

Invertebrates[edit]

The lake hosts a rich endemic fauna of invertebrates. The copepod Epischura baikalensis is endemic to Lake Baikal and the dominating zooplankton species there, making up 80 to 90% of total biomass.[51] It is estimated that the epischurans filter as much as a thousand cubic kilometers of water a year, or the lake’s entire volume every twenty-three years.[52]

Among the most diverse invertebrate groups are the amphipod and ostracod crustaceans, freshwater snails, annelid worms and turbellarian worms:

Amphipod and ostracod crustaceans[edit]

A «giant» Brachyuropus reicherti (Acanthogammaridae) amphipod caught during ice fishing in the lake. Red-orange is its natural, living coloration

More than 350 species and subspecies of amphipods are endemic to the lake.[33] They are exceptionally diverse in ecology and appearance, ranging from the pelagic Macrohectopus to the relatively large deep-water Abyssogammarus and Garjajewia, the tiny herbivorous Micruropus, and the parasitic Pachyschesis (parasitic on other amphipods).[53] The «gigantism» of some Baikal amphipods, which has been compared to that seen in Antarctic amphipods, has been linked to the high level of dissolved oxygen in the lake.[54] Among the «giants» are several species of spiny Acanthogammarus and Brachyuropus (Acanthogammaridae) found at both shallow and deep depths.[55] These conspicuous and common amphipods are essentially carnivores (will also take detritus), and can reach a body length up to 7 cm (2.8 in).[53][55]

Similar to another ancient lake, Tanganyika, Baikal is a center for ostracod diversity. About 90% of the Lake Baikal ostracods are endemic,[56] meaning that there are c. 200 endemic species.[57] This makes it the second-most diverse group of crustacean in the lake, after the amphipods.[56] The vast majority of the Baikal ostracods belong in the families Candonidae (more than 100 described species) and Cytherideidae (about 50 described species),[56][58] but genetic studies indicate that the true diversity in at least the latter family has been heavily underestimated.[59] The morphology of the Baikal ostracods is highly diverse.[56]

Snails and bivalves[edit]

As of 2006, almost 150 freshwater snails are known from Lake Baikal, including 117 endemic species from the subfamilies Baicaliinae (part of the Amnicolidae) and Benedictiinae (part of the Lithoglyphidae), and the families Planorbidae and Valvatidae.[60] All endemics have been recorded between 20 and 30 m (66 and 98 ft), but the majority mainly live at shallower depths.[60] About 30 freshwater snail species can be seen deeper than 100 m (330 ft), which represents the approximate limit of the sunlight zone, but only 10 are truly deepwater species.[60] In general, Baikal snails are thin-shelled and small. Two of the most common species are Benedictia baicalensis and Megalovalvata baicalensis.[61] Bivalve diversity is lower with more than 30 species; about half of these, all in the families Euglesidae, Pisidiidae, and Sphaeriidae, are endemic (the only other family in the lake is the Unionidae with a single nonendemic species).[61][62] The endemic bivalves are mainly found in shallows, with few species from deep water.[63]

Aquatic worms[edit]

With almost 200 described species, including more than 160 endemics, the center of diversity for aquatic freshwater oligochaetes is Lake Baikal.[64] A smaller number of other freshwater annelids is known: 30 species of leeches (Hirudinea),[65] and 4 polychaetes.[64] Several hundred species of nematodes are known from the lake, but a large percentage of these are undescribed.[64]

More than 140 endemic flatworm (Plathelminthes) species are in Lake Baikal, where they occur on a wide range of bottom types.[66] Most of the flatworms are predatory, and some are relatively brightly marked. They are often abundant in shallow waters, where they are typically less than 2 cm (1 in) long, but in deeper parts of the lake, the largest, Baikaloplana valida, can reach up to 30 cm (1 ft) when outstretched.[35][66]

Sponges[edit]

At least 18 species of sponges occur in the lake,[67] including about 15 species from the endemic family Lubomirskiidae (the remaining are from the nonendemic family Spongillidae).[68][69] In the nearshore regions of Baikal, the largest benthic biomass is sponges.[67] Lubomirskia baicalensis, Baikalospongia bacillifera, and B. intermedia are unusually large for freshwater sponges and can reach 1 m (3.3 ft) or more.[67][70] These three are also the most common sponges in the lake.[67] While the Baikalospongia species typically have encrusting or carpet-like structures, L. baikalensis often has branching structures and in areas where common may form underwater «forests».[71] Most sponges in the lake are typically green when alive because of symbiotic chlorophytes (zoochlorella), but can also be brownish or yellowish.[72]

History[edit]

The Baikal area, sometimes known as Baikalia, has a long history of human habitation. Near the village of Mal’ta, some 160 km northwest of the lake, remains of a young human male known as MA-1 or «Mal’ta Boy» are indications of local habitation by the Mal’ta–Buret’ culture ca. 24,000 BP. An early known tribe in the area was the Kurykans.[73]

Located in the former northern territory of the Xiongnu confederation, Lake Baikal is one site of the Han–Xiongnu War, where the armies of the Han dynasty pursued and defeated the Xiongnu forces from the second century BC to the first century AD. They recorded that the lake was a «huge sea» (hanhai) and designated it the North Sea (Běihǎi) of the semimythical Four Seas.[74] The Kurykans, a Siberian tribe who inhabited the area in the sixth century, gave it a name that translates to «much water». Later on, it was called «natural lake» (Baygal nuur) by the Buryats and «rich lake» (Bay göl) by the Yakuts.[75] Little was known to Europeans about the lake until Russia expanded into the area in the 17th century. The first Russian explorer to reach Lake Baikal was Kurbat Ivanov in 1643.[76]

Russian expansion into the Buryat area around Lake Baikal[77] in 1628–58 was part of the Russian conquest of Siberia. It was done first by following the Angara River upstream from Yeniseysk (founded 1619) and later by moving south from the Lena River. Russians first heard of the Buryats in 1609 at Tomsk. According to folktales related a century after the fact, in 1623, Demid Pyanda, who may have been the first Russian to reach the Lena, crossed from the upper Lena to the Angara and arrived at Yeniseysk.[78]

Vikhor Savin (1624) and Maksim Perfilyev (1626 and 1627–28) explored Tungus country on the lower Angara. To the west, Krasnoyarsk on the upper Yenisei was founded in 1627. A number of ill-documented expeditions explored eastward from Krasnoyarsk. In 1628, Pyotr Beketov first encountered a group of Buryats and collected yasak (tribute) from them at the future site of Bratsk. In 1629, Yakov Khripunov set off from Tomsk to find a rumored silver mine. His men soon began plundering both Russians and natives. They were joined by another band of rioters from Krasnoyarsk, but left the Buryat country when they ran short of food. This made it difficult for other Russians to enter the area. In 1631, Maksim Perfilyev built an ostrog at Bratsk. The pacification was moderately successful, but in 1634, Bratsk was destroyed and its garrison killed. In 1635, Bratsk was restored by a punitive expedition under Radukovskii. In 1638, it was besieged unsuccessfully.[citation needed]

In 1638, Perfilyev crossed from the Angara over the Ilim portage to the Lena River and went downstream as far as Olyokminsk. Returning, he sailed up the Vitim River into the area east of Lake Baikal (1640) where he heard reports of the Amur country. In 1641, Verkholensk was founded on the upper Lena. In 1643, Kurbat Ivanov went further up the Lena and became the first Russian to see Lake Baikal and Olkhon Island. Half his party under Skorokhodov remained on the lake, reached the Upper Angara at its northern tip, and wintered on the Barguzin River on the northeast side.[citation needed]

In 1644, Ivan Pokhabov went up the Angara to Baikal, becoming perhaps the first Russian to use this route, which is difficult because of the rapids. He crossed the lake and explored the lower Selenge River. About 1647, he repeated the trip, obtained guides, and visited a ‘Tsetsen Khan’ near Ulan Bator. In 1648, Ivan Galkin built an ostrog on the Barguzin River which became a center for eastward expansion. In 1652, Vasily Kolesnikov reported from Barguzin that one could reach the Amur country by following the Selenga, Uda, and Khilok Rivers to the future sites of Chita and Nerchinsk. In 1653, Pyotr Beketov took Kolesnikov’s route to Lake Irgen west of Chita, and that winter his man Urasov founded Nerchinsk. Next spring, he tried to occupy Nerchensk, but was forced by his men to join Stephanov on the Amur. Nerchinsk was destroyed by the local Tungus, but restored in 1658.[citation needed]

The Trans-Siberian Railway was built between 1896 and 1902. Construction of the scenic railway around the southwestern end of Lake Baikal required 200 bridges and 33 tunnels. Until its completion, a train ferry transported railcars across the lake from Port Baikal to Mysovaya for a number of years. The lake became the site of the minor engagement between the Czechoslovak legion and the Red Army in 1918. At times during winter freezes, the lake could be crossed on foot, though at risk of frostbite and deadly hypothermia from the cold wind moving unobstructed across flat expanses of ice. In the winter of 1920, the Great Siberian Ice March occurred, when the retreating White Russian Army crossed frozen Lake Baikal. The wind on the exposed lake was so cold, many people died, freezing in place until spring thaw. Beginning in 1956, the impounding of the Irkutsk Dam on the Angara River raised the level of the lake by 1.4 m (4.6 ft).[79]

As the railway was built, a large hydrogeographical expedition headed by F.K. Drizhenko produced the first detailed contour map of the lake bed.[9]

-

-

Russian map circa 1700, Baikal (not to scale) is at top

Research[edit]

Ice cover survey on the lake

Several organizations are carrying out natural research projects on Lake Baikal. Most of them are governmental or associated with governmental organizations. The Baikalian Research Centre is an independent research organization carrying out environmental, educational and research projects at Lake Baikal.[80]

In July 2008, Russia sent two small submersibles, Mir-1 and Mir-2, to descend 1,592 m (5,223 ft) to the bottom of Lake Baikal to conduct geological and biological tests on its unique ecosystem. Although originally reported as being successful, they did not set a world record for the deepest freshwater dive, reaching a depth of only 1,580 m (5,180 ft).[81] That record is currently held by Anatoly Sagalevich, at 1,637 m (5,371 ft) (also in Lake Baikal aboard a Pisces submersible in 1990).[81][82] Russian scientist and federal politician Artur Chilingarov, the leader of the mission, took part in the Mir dives[83] as did Russian president Vladimir Putin.[84]

Since 1993, neutrino research has been conducted at the Baikal Deep Underwater Neutrino Telescope (BDUNT). The Baikal Neutrino Telescope NT-200 is being deployed in Lake Baikal, 3.6 km (2.2 mi) from shore at a depth of 1.1 km (0.68 mi). It consists of 192 optical modules.[85]

Economy[edit]

Baikal fishermen fish for 15 commercially used species. The omul, found only in Baikal, accounts for most of the catch.[86]

The lake, nicknamed «the Pearl of Siberia», drew investors from the tourist industry as energy revenues sparked an economic boom.[87] Viktor Grigorov’s Grand Baikal in Irkutsk is one of the investors, who planned to build three hotels, creating 570 jobs. In 2007, the Russian government declared the Baikal region a special economic zone. A popular resort in Listvyanka is home to the seven-story Hotel Mayak. At the northern part of the lake, Baikalplan (a German NGO) built together with Russians in 2009 the Frolikha Adventure Coastline Track, a 100 km (62 mi)-long long-distance trail as an example for sustainable development of the region. Baikal was also declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1996. Rosatom plans to build a laboratory near Baikal, in conjunction with an international uranium plant and to invest $2.5 billion in the region and create 2,000 jobs in the city of Angarsk.[87]

Lake Baikal is a popular destination among tourists from all over the world. According to the Russian Federal State Statistics Service, in 2013, 79,179 foreign tourists visited Irkutsk and Lake Baikal; in 2014, 146,937 visitors. The most popular places to stay by the lake are Listvyanka village, Olkhon Island, Kotelnikovsky cape, Baykalskiy Priboi, resort Khakusy and Turka village. The popularity of Lake Baikal is growing from year to year, but there is no developed infrastructure in the area. For the quality of service and comfort from the visitor’s point of view, Lake Baikal still has a long way to go.

The ice road to Olkhon Island is the only legal ice road on Lake Baikal. The route is prepared by specialists every year and it opens when the ice conditions allow it. In 2015, the ice road to Olkhon was open from 17 February to 23 March. The thickness of the ice on the road is about 60 cm (24 in), maximum capacity allowed – 10 t (9.8 long tons; 11 short tons); it is open to the public from 9 am to 6 pm. The road through the lake is 12 km (7.5 mi) long and it goes from the village Kurkut on the mainland, to Irkutskaya Guba on Olkhon Island.[88]

Ecotourism[edit]

Baikal has a number of different tourist activities, depending on the season. Generally, Baikal has two top tourist seasons. The first season is ice season, which starts usually in mid-January and lasts till mid-April.[89] During this season ice depth increases up to 140 centimeters, that allows safe vehicle driving on the ice cover (except heavy vehicles, such as tourist buses, that do not take this risk). This allows access to the figures of ice that are formed at rocky banks of Olkhon Island, including Cape Hoboy, the Three Brothers rock, and caves to the North of Khuzhir. It also provides access to small islands like Ogoy Island and Zamogoy.

The ice itself has a transparency of one meter depth, having different patterns of crevasses, bubbles, and sounds.[citation needed] That is why this season is popular for hiking, ice-walking, ice-skating, and bicycle-riding.[90] An ice route around Olkhon is around 200 km. Some tourists may spot a Baikal seal along the route. Local entrepreneurs offer overnight in Yurt on ice. Also this season attracts fans of ice fishing. This activity is most popular on Buryatia side of Baikal (Ust-Barguzin). Non-fishermen may try fresh Baikal fish in local village markets. (Listvyanka, Ust-Barguzin).

The ice season ends in mid-April. Owing to increasing temperatures ice starts to melt and becomes shallow and fragile, especially in places with strong under-ice flows. A range of factors contribute to an increased risk of falling through the ice towards the end of the season, resulting in multiple deaths in Russia each year, although exact data for Baikal are unknown.[91] Viktor Viktorovych Yanukovych, son of former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, reportedly died after his car fell through the ice while driving on Baikal in 2015.[92][93]

The second tourist season is summer, which lets tourists dive deeper into virgin Baikal nature. Hiking trails become open,[94] many of them cross two mountain ranges: Baikal Range on the western side and Barguzin Range on the eastern side of Baikal. The most popular trail starts in Listvyanka and goes along the Baikal coast to Bolshoye Goloustnoye. The total length of the route is 55 km, but the most part of tourists usually take only a part of it – a section of 25 km to Bolshie Koty. It has a lower difficulty level and could be passed by people without special skills and gear.

Small tourist vessels operate in the area, availing bird-watching, animal watching (especially Baikal seal), and fishing. Water in the lake stays extremely cold in most places (does not exceed 10 C most of the year), but in few gulfs like Chivirkuy it can be comfortable for swimming.[95]

Olkhon’s most-populated village Khuzhir is an ecotourist destination.[96] Baikal has always been popular in Russia and CIS-countries, but for the last few years[when?] Baikal has seen an influx of visitors from China and Europe.[97]

Environmental concerns[edit]

Environmentalists have previously acknowledged pollution at Lake Baikal.[98][99][100] It faces a series of detrimental phenomena including the disappearance of the omul fish, the rapid growth of putrid algae and the death of endemic species of sponges across its area.[100] Environmental advocacy for the lake began in the late 1950s.[101] Since 2010, more than 15,000 metric tons of toxic waste have flowed into the lake.

Baykalsk Pulp and Paper Mill[edit]

Baykalsk Pulp and Paper Mill in 2008, 5 years before its closure

The Baykalsk Pulp and Paper Mill was constructed in 1966, directly on the shoreline of Lake Baikal. The plant bleached paper using chlorine and discharged waste directly into Lake Baikal. The decision to construct the plant on the Lake Baikal resulted in strong protests from Soviet scientists; according to them, the ultra-pure water of the lake was a significant resource and should have been used for innovative chemical production (for instance, the production of high-quality viscose for the aeronautics and space industries). The Soviet scientists felt that it was irrational to change Lake Baikal’s water quality by beginning paper production on the shore. It was their position that it was also necessary to preserve endemic species of local biota, and to maintain the area around Lake Baikal as a recreation zone.[102] However, the objections of the Soviet scientists faced opposition from the industrial lobby and only after decades of protest, the plant was closed in November 2008 due to unprofitability.[103][104]

On 4 January 2010, production was resumed. On 13 January 2010, Russian President Vladimir Putin introduced changes in legislation legalising the operation of the plant; this action brought about a wave of protests from ecologists and local residents.[105] These changes were based on the determination President Putin made through a visual verification of Lake Baikal’s condition from a miniature submarine, where he said: «I could see with my own eyes – and scientists can confirm – Baikal is in good condition and there is practically no pollution».[106] Despite this, in September 2013, the mill underwent a final bankruptcy, with the last 800 workers slated to lose their jobs by 28 December 2013.[107] The mill has since shut down, though its reservoirs of lignin sludge remain an environmental hazard.[108][109]

Cancelled East Siberia–Pacific Ocean oil pipeline[edit]

The lake in the winter. The ice is thick enough to support pedestrians and snowmobiles.

Russian oil pipelines state company Transneft[110] was planning to build a trunk pipeline that would have come within 800 m (2,600 ft) of the lake shore in a zone of substantial seismic activity. Environmental activists in Russia,[111] Greenpeace, Baikal pipeline opposition[112] and local citizens[113] were strongly opposed to these plans, due to the possibility of an accidental oil spill that might cause significant damage to the environment. According to the Transneft’s president, numerous meetings with citizens near the lake were held in towns along the route, especially in Irkutsk.[114] Transneft agreed to alter its plans when Russian president Vladimir Putin ordered the company to consider an alternative route 40 kilometers (25 mi) to the north to avoid such ecological risks.[115] Transneft has since decided to move the pipeline away from Lake Baikal, so that it will not pass through any federal or republic natural reserves.[116][117] Work began on the pipeline two days after President Putin agreed to changing the route away from Lake Baikal.[118]

Proposed uranium enrichment center[edit]

In 2006, the Russian government announced plans to build the world’s first international uranium enrichment center at an existing nuclear facility in Angarsk, a city on the river Angara some 95 km (59 mi) downstream from the lake’s shores. Critics and environmentalists argued it would be a disaster for the region and are urging the government to reconsider.[119]

After enrichment, only 10% of the uranium-derived radioactive material would be exported to international customers,[119] leaving 90% near the Lake Baikal region for storage. Uranium tailings contain radioactive and toxic materials, which if improperly stored, are potentially dangerous to humans and can contaminate rivers and lakes.[119]

An enrichment center was constructed in the 2010s.[120]

Chinese-owned bottled water plant[edit]

Chinese-owned AquaSib had been purchasing land alongside the lake and in 2019 started building a bottling plant and pipeline in the town of Kultuk. The goal was to export 190 million liters of water to China even though the lake had been experiencing historically low water levels. This spurred protests by the local population that the lake would be drained of its water, at which point the local government halted the plans pending analysis.[121]

Other pollution sources[edit]

According to The Moscow Times and Vice, an increasing number of an invasive species of algae thrives in the lake from hundreds of tons of liquid waste, including fuel and excrement, regularly disposed into the lake by tourist sites, and up to 25,000 tons of liquid waste are disposed of every year by local ships.[122][123]

Historical traditions[edit]

An 1883 British map using the More Baikal (Baikal Sea) designation, rather than the conventional Ozero Baikal (Lake Baikal)

The first European to reach the lake is said to have been Kurbat Ivanov in 1643.[124]

In the past, the Baikal was referred to by many Russians as the «Baikal Sea» (море Байкал, More Baikal), rather than merely «Lake Baikal» (озеро Байкал, Ozero Baikal).[125]

This usage is attested already in the Life of Protopope Avvakum (1621–1682),[126] and on the late-17th-century maps by Semyon Remezov.[127] It is also attested in the famous song, now passed into the tradition, that opens with the words Славное море, священный Байкал (Glorious sea, [the] sacred Bajkal).

To this day, the strait between the western shore of the Lake and the Olkhon Island is called Maloye More (Малое море), i.e. «the Little Sea».

Lake Baikal is nicknamed «Older sister of Sister Lakes (Lake Khövsgöl and Lake Baikal)».[128]

According to 19th-century traveler T. W. Atkinson, locals in the Lake Baikal Region had the tradition that Christ visited the area:

The people have a tradition in connection with this region which they implicitly believe. They say «that Christ visited this part of Asia and ascended this summit, whence he looked down on all the region around. After blessing the country to the northward, he turned towards the south, and looking across the Baikal, he waved his hand, exclaiming ‘Beyond this there is nothing.‘» Thus they account for the sterility of Daouria, where it is said «no corn will grow.»[129]

Lake Baikal has been celebrated in several Russian folk songs. Two of these songs are well known in Russia and its neighboring countries, such as Japan.

- «Glorious Sea, Sacred Baikal» (Славное мope, священный Байкал) is about a katorga fugitive. The lyrics as documented and edited in the 19th century by Dmitriy P. Davydov (1811–1888).[130] See «Barguzin River» for sample lyrics.

- «The Wanderer» (Бродяга) is about a convict who had escaped from jail and was attempting to return home from Transbaikal.[131] The lyrics were collected and edited in the 20th century by Ivan Kondratyev.

The latter song was a secondary theme song for the Soviet Union’s second color film, Ballad of Siberia (1947; Сказание о земле Сибирской).

See also[edit]

- Russian Far East

- Seven Wonders of Russia

Notes[edit]

- ^ (Buryat: Байгал далай, romanized: Baigal dalai;[4] Mongolian: Байгал нуур, romanized: Baigal nuur)

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f «A new bathymetric map of Lake Baikal. Morphometric Data. INTAS Project 99-1669. Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium; Consolidated Research Group on Marine Geosciences (CRG-MG), University of Barcelona, Spain; Limnological Institute of the Siberian Division of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Irkutsk, Russian Federation; State Science Research Navigation-Hydrographic Institute of the Ministry of Defense, St. Petersburg, Russian Federation». Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ M.A. Grachev. «On the present state of the ecological system of lake Baikal». Limnological Institute, Siberian Division of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ «Baikal». Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ Dervla Murphy (2007) Silverland: A Winter Journey Beyond the Urals, London, John Murray, p. 173