ожог солнечный

-

1

ожог

Большой русско-английский медицинский словарь > ожог

-

2

ожог

Русско-английский словарь по общей лексике > ожог

-

3

солнечный ожог

Русско-английский синонимический словарь > солнечный ожог

-

4

солнечный ожог

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > солнечный ожог

-

5

солнечный ожог коры

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > солнечный ожог коры

-

6

солнечный ожог листьев

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > солнечный ожог листьев

-

7

солнечный ожог

2) sunblister, sunburn

sunscald, sunscorch

Русско-английский биологический словарь > солнечный ожог

-

8

солнечный ожог коры

Русско-английский биологический словарь > солнечный ожог коры

-

9

солнечный ожог

Русско-английский словарь по деревообрабатывающей промышленности > солнечный ожог

-

10

солнечный ожог

Русско-английский словарь по пищевой промышленности > солнечный ожог

-

11

солнечный ожог

Русско-английский сельскохозяйственный словарь > солнечный ожог

-

12

солнечный ожог

Большой русско-английский медицинский словарь > солнечный ожог

-

13

солнечный ожог

Русско-английский словарь по общей лексике > солнечный ожог

-

14

солнечный ожог

Русско-английский экологический словарь > солнечный ожог

-

15

солнечный ожог

Русско-английский научный словарь > солнечный ожог

-

16

зимний солнечный ожог

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > зимний солнечный ожог

-

17

L55

Classification of Diseases (English-Russian) > L55

-

18

L55.0

рус Солнечный ожог первой степени

eng Sunburn of first degree

Classification of Diseases (English-Russian) > L55.0

-

19

L55.1

рус Солнечный ожог второй степени

eng Sunburn of second degree

Classification of Diseases (English-Russian) > L55.1

-

20

L55.2

рус Солнечный ожог третьей степени

eng Sunburn of third degree

Classification of Diseases (English-Russian) > L55.2

См. также в других словарях:

-

ОЖОГ СОЛНЕЧНЫЙ — мед. Солнечный ожог ожог, вызванный избыточным воздействием искусственного или солнечного ультрафиолетового излучения. Клиническая картина ожога развивается в первые 1 24 ч. Характерные признаки: от незначительного покраснения с последующим… … Справочник по болезням

-

ожог солнечный — О. кожи, вызванный воздействием солнечного излучения … Большой медицинский словарь

-

Эритема Солнечная, Ожог Солнечный (Sunburn) — поражение кожи, вызванное длительным или непривычно сильным воздействием на нее солнечных лучей. Интенсивность солнечного ожога может быть различной: от простой гиперемии кожи до появления крупных, болезненных заполненных жидкостью волдырей,… … Медицинские термины

-

ЭРИТЕМА СОЛНЕЧНАЯ, ОЖОГ СОЛНЕЧНЫЙ — (sunburn) поражение кожи, вызванное длительным или непривычно сильным воздействием на нее солнечных лучей. Интенсивность солнечного ожога может быть различной: от простой гиперемии кожи до появления крупных, болезненных заполненных жидкостью… … Толковый словарь по медицине

-

Солнечный удар — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Солнечный удар (значения). Солнечный удар, гиперинсоляция, гелиоз (heliоplegia) болезненное состояние, расстройство работы головного мозга вследствие продолжительного воздействия солнечного… … Википедия

-

Солнечный ожог — … Википедия

-

излучение Солнца — ▲ излучение ↑ Солнце солнце (# спряталось за тучи. проглянуло. выглянуло). солнечный (# лучи. # ветер). светило. пригревать. припекать. на солнце (греться #) на припеке. гелио… (гелиоустановка). инсоляция. жара. жаркий (# день). солнцепек. ↓… … Идеографический словарь русского языка

-

ПЕРЕГРЕВАНИЕ И ТЕПЛОВОЙ УДАР — мед. Перегревание (тепловой обморок, тепловая прострация, тепловой коллапс) и тепловой удар (гиперпирексия, солнечный удар, перегревание организма) патологические реакции организма на высокую температуру окружающей среды, связанные с… … Справочник по болезням

-

МКБ-10: Класс XII — … Википедия

-

МКБ-10: Код L — Служебный список статей, созданный для координации работ по развитию темы. Данное предупреждение не устанавл … Википедия

-

Вредители и болезни роз — Поражение роз болезнями и вредителями может значительно снижать их декоративность, а в отдельных случаях приводить к гибели растений[1]. Патогенная микофлора роз насчитывает около 270 видов[2]. В условиях Москвы и Московской области отмечается… … Википедия

Вспомним пресловутое правило написания «о» и «ё» после шипящих. Только здесь уже отдельный подраздел — правописание слов с корнями -жог-/-жёг-. После его объяснения станет понятнее, как правильно писать: ожог или ожёг.

В чём основная сложность? При написании слова с -жог-/-жёг- нужно вспомнить, какая это часть речи и на какой вопрос она отвечает.

Для начала уясним важное правило выбора «о/ё» в глагольных формах:

В суффиксах глаголов, причастий и всех слов, образованных от глаголов, под ударением пишется буква «ё». Печёт, бережёт, выкорчёвывать, упрощённый, лишённый, ночёвка (отглагольное существительное от «ночевать»), тушёнка (от глагола «тушить»), жжёнка (от глагола «жечь»).

Автор жжёт. Мы обязательно зажжём.

В общем, глаголы любят букву «ё» или «е» рядом с шипящими в окончаниях (жжёшь, толчёте, стрижёте, скажешь, пишешь) и совершенно не дружат с буквой «о».

Теперь о выборе между —жёг-/-жог-. Если мы имеем в виду глагол, то нужно писать именно -жёг:

Ожечь(ся) — ожёг(ся)

Обжечь(ся) — обжёг(ся)

Отжечь(ся) — отжёг(ся).

Возжечь(ся) — возжёг(ся)

Существительные будут писаться с -жог-.

Разница между «поджог», «ожог» и «поджёг», «ожёг»

Поджёг — прошедшее время глагола «поджечь». Он (что сделал?) поджёг свой системный блок.

Поджог — существительное. Совершить (что?) поджог своего системного блока из-за проигрыша в «Косынку».

Ожёг — прошедшее время глагола «ожечь»:

1. Синоним «Обжечь» в значении «Причинить ожоги или боль чем-либо горячим».

2. Вызвать ощущение жгучей боли, жжения. Ожёг руку (что сделал?).

Ожог — существительное. Получил (что?) ожог руки.

Существительные пишутся с -жог-: изжога, поджог, ожог, недожог (оно существует, представьте себе!), пережог, разжог.

Глаголы пишутся с -жёг: поджёг, ожёг, недожёг, пережёг, разжёг и т. д.

Читать ещё: Колют или колят? Правильное спряжение глагола

Подписывайтесь на мой телеграм-канал по русскому языку

Что такое солнечный ожог?

Солнечный ожог кожи — это острая воспалительная реакция тканей на чрезмерное воздействие ультрафиолетовых лучей. Повреждение может быть поверхностным или глубоким. Изменения происходят на микроскопическом уровне, то есть патологически изменяются клетки кожи⁴.

С дерматологической точки зрения такой тип воспаления относится к острым фотодерматозам. В норме кожу защищает пигмент меланин, который также придает ей цвет. Его количество определяется генетикой и наследственностью. Поэтому в одинаковых условиях одни люди загорают, другие — «обгорают».

Большое терапевтическое значение имеет своевременное оказание первой помощи при солнечном ожоге.

- Если есть возможность, быстро охладите обожженный участок и перейдите в защищенное от прямых солнечных лучей место. Подставьте обожженную зону на несколько минут под проточную воду или сделайте прохладный компресс. Таким образом вы остановите невидимое глазу разрушение внутриклеточных структур.

- Примите прохладный душ без использования грубого или сильнощелочного мыла.

- Избегайте дальнейшего воздействия ультрафиолета на кожу вплоть до полного исчезновения следов травмы.

- Больше отдыхайте.

- Ограничьте тяжелую физическую нагрузку, временно прекратите посещение спортивного зала.

- Увлажняйте кожные покровы с помощью специальных эмолентов без содержания масел и спирта, лосьонов с алоэ.

- Бережно обращайтесь с шелушащимися участками, продолжая увлажнять их до полного самостоятельного отхождения корок.

- Выраженный зуд можно уменьшить с помощью антигистаминных препаратов, которые обычно применяют при аллергии.

- Для уменьшения зуда и жжения используйте кремы с низким содержанием гидрокортизона или других глюкокортикостероидных гормонов местного действия.

- При общем недомогании примите противовоспалительное средство (ибупрофен, парацетамол, ацетилсалициловая кислота). Оно быстро снизит общую температуру тела, немного ослабит болевые ощущения.

- Пейте больше минеральной воды и других жидкостей. При любой температурной травме нарушается водно-солевой баланс в организме.

Волдыри

Если появились волдыри, наложите простую марлевую повязку, чтобы предотвратить попадание бактерий на поврежденные ткани. Обратитесь к врачу! Пузыри нельзя специально разрывать, так как это замедлит процесс заживления. Под тонкой корочкой рана заживет лучше и быстрее.

Что нельзя делать при солнечном ожоге

- Наносить на обгоревшую кожу средства с содержанием спирта или масел.

- Прикладывать к пострадавшему участку кожи лед, вазелин, сметану.

- Применять народные методы — это может быть опасно! Домашние средства могут усилить степень разрушения тканей и препятствовать увлажнению кожи.

- Употреблять алкоголь — спиртное усугубляет обезвоживание.

Симптомы и признаки солнечных ожогов

Симптомы солнечного ожога могут включать:

- покраснение, местное повышение температуры в области повреждения;

- отечность, боль в месте повреждения;

- образование небольших пузырьков с прозрачным содержимым, которые могут лопаться;

- повышение общей температуры тела;

- жжение;

- головные боли;

- зуд;

- жажда;

- чувство стянутости в месте покраснения;

- тошнота;

- резкая слабость;

- покраснение, боль, жжение глаз.

В тяжелых случаях человек может получить ожоги второй степени. При этом кожа повреждается до более глубоких слоев, развивается дисбаланс солей и жидкости в организме. На фоне обширного воспаления легко может присоединиться вторичная инфекция, возможен летальный исход из-за шока или обезвоживания.

Солнечный ожог, в отличие от термического, проявляется не сразу. Первые признаки пострадавший замечает примерно через 4 часа после пребывания на солнце. Через 34-36 часов симптомы усиливаются (особенно боль), но проходят за 3-5 суток. На 4-7 день кожа нередко начинает шелушиться, отслаиваться.

Кто находится в группе дополнительного риска?

Некоторые люди от рождения более уязвимы перед солнечными лучами, чем другие. Это зависит от генетических особенностей, наследственности, сопутствующих заболеваний, а также возраста.

Проще всего обгорают люди со светлым типом кожи и голубыми глазами⁴. Ультрафиолетовое излучение также небезопасно для беременных женщин, детей, пожилых. Загара следует избегать, если у родственников или у вас был рак кожи.

Лечение солнечных ожогов

Специфическое лечение нужно пострадавшим с обширной ожоговой поверхностью. К врачу также следует немедленно обратиться при стойком повышении температуры тела, нарушении сознания, обезвоживании.

В условиях медицинского учреждения применяют такие методы лечения солнечных ожогов¹:

- обезболивание с учетом тяжести состояния — парацетамол, ибупрофен, новокаин, морфин, трамадол;

- введение успокоительных препаратов при выраженном болевом шоке — транквилизаторы, нейролептики;

- инфузионная (дезинтоксикационная) терапия — капельницы с растворами солей, кристаллоидов, коллоидов для восполнения жидкостных потерь, предупреждения шока и судорожного синдрома;

- противовоспалительное лечение, профилактика/лечение вторичных инфекций — антибиотики широкого спектра действия (по показаниям), нестероидные противовоспалительные препараты, противогрибковые средства;

- ранняя профилактика осложнений со стороны сердечно-сосудистой системы — антиагреганты (ацетилсалициловая кислота, клопидогрель), допамин, препараты для контроля артериального давления;

- предупреждение проблем с желудком на фоне массивной терапии и возможного шока — ингибиторы протонной помпы (пантопразол, омепразол);

- местное лечение — очищение ран, наложение повязок, обработка растворами антисептиков и мазями (метилурацил, салициловая мазь, хлорамфеникол);

- симптоматическая терапия — в соответствии с рекомендациями врачей-консультантов;

- глюкокортикоидные гормоны (преднизолон, дексаметазон) — строго по показаниям;

- витаминотерапия — аскорбиновая кислота, тиамин, пиридоксин, цианокобаламин;

- переливание крови или ее компонентов при необходимости;

- по показанию — хирургическое лечение (удаление отмерших частей раны, пересадка кожных лоскутов, пластические операции);

- экстренная профилактика столбняка.

Объем лечебных мероприятий зависит от площади повреждения, самочувствия и симптомов у конкретного пациента. Лекарственные средства назначают также индивидуально, с учетом переносимости и сопутствующих заболеваний.

Большинство людей вылечивается от ультрафиолетового повреждения самостоятельно, так как ожоги редко превышают 2 степень. Больных в тяжелом состоянии переводят в реанимацию, где могут подключить к аппарату искусственной вентиляции легких¹.

Сметана не поможет

Использование кисломолочных продуктов для спасения от ожогов не имеет под собой никакой лечебной основы и может навредить еще больше. Кефир, сметана, простокваша содержат большое количество бактерий, грибков, жира. Наносить их на поврежденную кожу, уязвимую для вторичных инфекций, — плохая идея.

Средства профилактики солнечных ожогов

Лучше не избавляться от полученной травмы, а предупредить ее появление. Профилактические меры нужно соблюдать не только летом в солнечную погоду, но и в пасмурные дни. В особой защите нуждаются люди с чувствительной светлой кожей.

Берегите кожу от солнца и не забывайте о способах профилактики⁴.

- Избегайте нахождения под солнцем в наиболее яркие часы — с 10:00 до 16:00. Если этого невозможно, старайтесь находиться в тени.

- Откажитесь от посещения соляриев — искусственный загар несет определенные риски для здоровья в виде онкологических заболеваний.

- На улице надевайте головные уборы с широкими полями, а также одежду, которая максимально закрывает тело. Людям, имеющим повышенную чувствительность к ультрафиолету, нужно использовать специальную солнцезащитную одежду. Из подобных тканей шьют даже купальники с длинными рукавами и высоким воротником.

- Часто и обильно пользуйтесь солнцезащитным кремом, который имеет уровень защиты SPF не менее 15-30 (зависит от фототипа). Его следует наносить даже в зимнее время. На морской курорт нужно брать водостойкие средства, обновляйте их каждые 2 часа и после купания.

- На улице носите специальные солнцезащитные очки, так как глаза не менее уязвимы перед солнечным светом.

- Избегайте загара, если недавно принимали антибиотики или мочегонные препараты.

Беременным женщинам, пожилым и детям до 3-4 лет лучше вообще не загорать. При наличии хронических, аутоиммунных и/или аллергических заболеваний нужно получить консультацию врача перед поездкой на отдых.

Фототипы кожи и SPF-защита

Уязвимость кожных покровов перед ультрафиолетовым излучением определяется их фототипом. Светлокожие люди I-III типов подвержены повышенному риску получения солнечных ожогов. Это связано с меньшим содержанием пигмента меланина, который в норме блокирует ультрафиолетовое излучение.

Зная свой фототип, можно правильно подобрать солнцезащитные средства. При выборе следует ориентироваться на показатель SPF (Sun Protection Factor). Чем выше показатель этого фактора, тем эффективнее блокировка ультрафиолетовых лучей⁶.

Предпочтение лучше отдавать качественным средствам с доказанной эффективностью и безопасностью. Состав будет отличаться для жирной, нормальной и чувствительной (склонной к аллергии) кожи. Ни один солнцезащитный крем не останавливает УФ-излучение на 100 %.

| Тип кожи | Особенности | Способность к загару | Предпочитаемый SPF для защиты |

| I (кельтский) | Бледно-беловатая кожа (часто с веснушками), голубые глаза, светлые или рыжие волосы | Вообще не загорает, а только обгорает | Лосьоны, спреи, кремы с максимальным SPF (то есть не менее 30) круглогодично. Всегда в сочетании с солнцезащитной одеждой, специальными очками |

| II (европейский светлокожий) | Голубые, зеленые, серые глаза. Волосы — от светлых до русых, каштановых оттенков. Кожа светлая | Быстро сгорает, очень плохо загорает | Регулярное применение средств с SPF 20-30, желательно с минеральным фильтром |

| III (европейский темнокожий) | Цвет глаз серый или карий. Волосы больше русые, темно-каштановые. Кожные покровы немного смуглые | Сначала возникает солнечный ожог, который потом видоизменяется в загар | Защита должна быть на уровне SPF 15-20 с соблюдением общих профилактических мероприятий. После появления загара можно перейти на средства с SPF-6 |

| IV (средиземноморский) | Глаза и волосы темных оттенков. Кожа смуглая, ближе к оливковому цвету. Встречается среди азиатов, кавказцев, индийцев | Загар ложится легко и быстро, редко появляются ожоги | Несмотря на способность к равномерному загару, кожные покровы все еще нуждаются в увлажнении и защите от фотостарения. SPF не менее 6 |

| V (средневосточный) | Разные варианты темных оттенков волос и глаз. Кожа очень смуглая | Почти никогда не сгорают. После длительного пребывания на солнце быстро появляется равномерный загар | Рекомендуется применение средств с минимальным уровнем SPF-защиты |

| VI (африканский) | Очень темные кожные покровы, глаза, волосы | Солнечные ожоги почти не характеры | Достаточно увлажняющего крема. Однако при планировании длительного пребывания под солнцем также нужны солнцезащитные средства |

Люди с темной и смуглой кожей также подвергают себя риску рака. Отсутствие ожога не означает, что кожные покровы не подвергаются воздействию ультрафиолетовых лучей. Многочасовое пребывание под открытым солнцем в знойную погоду может вызывать ожог даже у темнокожего человека.

Солнцезащитные кремы необходимы всем людям вне зависимости от фототипа и пола, просто разного уровня защиты. Мужчины, работающие под открытым небом, нередко получают обширные ожоги, которые потом инфицируются из-за несоблюдения гигиенических правил. То же самое касается детей раннего возраста и подростков, которые много времени проводят на улице.

Кожа у детей и подростков заживает быстрее, но и защитные свойства у нее гораздо хуже. Младенцы до 6 месяцев не должны загорать под солнцем вообще. При любой погоде кожу малышей нужно защищать с помощью одежды, разрешенных косметологических средств, нахождения в тени и под навесом.

Детей 1-4 лет с уязвимыми фототипами (I-III) необходимо обучать способам защиты от солнца как можно раньше. Перед поездкой в жаркие страны дополнительно проконсультируйтесь с педиатром по поводу использования солнцезащитных кремов. Нередко на них бывает аллергия, это нужно выяснить заранее.

Солнцезащитное средства (санскрины) минимизируют способность к загару, снижают вероятность получения солнечного повреждения. Правильное использование SPF-кремов важно для долгосрочной защиты, профилактики онкологии и фотостарения. При этом нужно учитывать следующие рекомендации⁶.

- Выбирайте солнцезащитный крем или лосьон в соответствии с типом кожи и ее особенностями.

- Перед покупкой нанесите небольшое количество средства на запястье, оставив на 5-15 минут: если появилось раздражение, покраснение или зуд, следует отдать предпочтение другому производителю.

- Внимательно ознакомьтесь с описанием — крем должен защищать как от UVA-спектра, так и UVB.

- Наносите санскрин на все открытые участки тела, включая малозаметные зоны (края ушей, губы, задняя поверхность шеи, ступни).

- Используйте защитные средства не только летом, а круглый год.

- Чтобы крем правильно работал, защитные средства наносите за 20-30 минут до выхода, так как нужно время на образование пленки, блокирующей ультрафиолетовое излучение.

- Слой средства должен быть плотный, равномерный — экономия тут неуместна.

- Каждые 2 часа наносите крем заново, предварительно смыв остатки предыдущей порции.

Причины солнечных ожогов

Основная причина солнечного ожога — агрессивное воздействие ультрафиолетовых лучей. Они могут исходить от самого солнца или искусственных источников (солярии, ультрафиолетовые лампы). Кожа по-разному реагирует на лучи с разной длиной волны (единица измерения — нм). К воспалительной реакции чаще всего приводят спектры UVB и UVA⁴.

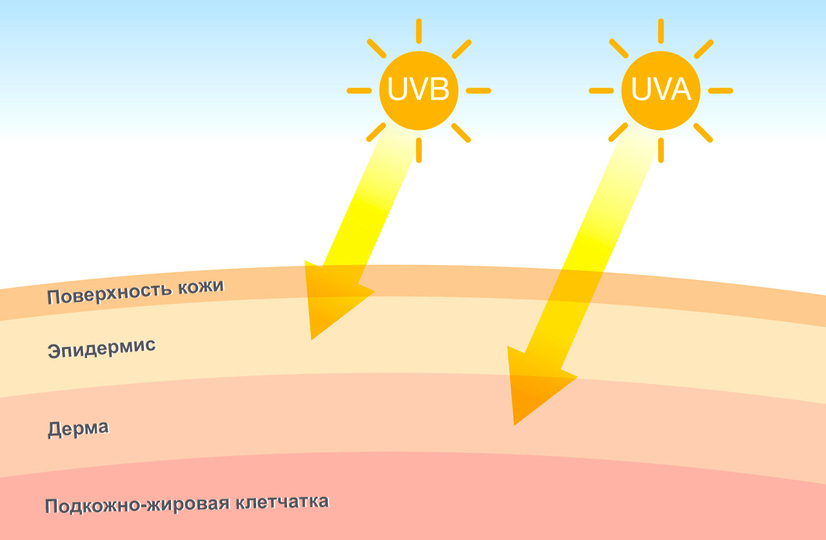

Существует 3 типа ультрафиолетового излучения, на которые покровы тела реагируют по-разному:

- UVA (320-400 нм) — проникает в глубокие слои кожи, повреждая зоны роста новых клеток. Легко достигают поверхности Земли, но слабее UVB почти в 1000 раз. Избыток UVA-воздействия вызывает дряблость, морщинистость, сухость кожи. Доказана способность UVA нарушать структуру клеток, иммунный ответ, движение крови по мелким сосудам.

- UVB (280-320 нм) — сильно повреждают преимущественно верхние слои кожи (эпидермис). До дермы попадает около 10% ультрафиолетовых лучей. Высокие дозы повреждают генетическую структуру (ДНК) клеток, что может привести к аутоиммунным реакциям или онкологическому заболеванию.

- UVC (100-280) — короткие ультрафиолетовые лучи, плохо достигающие поверхности Земли. Задерживаются в верхних слоях атмосферы. Но по силе считаются наиболее повреждающими.

UVA-излучение является основной причиной формирования повышенной чувствительности к солнечному свету. Избыток ультрафиолета принимает участие в развитии солнечной крапивницы, системной красной волчанки, фотодерматита, порфирии.

Факторы риска получения сильного ожога

Вероятность повреждения кожи повышается при наличии таких факторов риска:

- пребывание на улице с открытыми участками тела с 10:00 до 16:00;

- солнечная погода;

- близость к экватору;

- проживание на возвышенности: каждые 300 метров ультрафиолетовое излучение увеличивается на 4%;

- прием фотосенсибилизирующих препаратов, которые делают кожу более чувствительной перед действием ультрафиолетового излучения;

- нахождение в местах с истонченным озоновым слоем атмосферы;

- светлый цвет кожи;

- большое количество родинок на теле;

- светлые, рыжие волосы;

- голубые, серые глаза;

- регулярная физическая активность или работа на свежем воздухе без дополнительной защиты;

- применение лосьонов для загара;

- частое посещение соляриев;

- использование ультрафиолетовых ламп;

- избыточный вес;

- злоупотребление алкогольными напитками и психоактивными веществами;

- загар в естественных условиях — пляж, открытая местность.

Купание в обычных футболках почти не спасает от солнечного ожога. Белая хлопчатобумажная ткань пропускает около 20% УФ-излучения. Но влажная кожа обгорает быстрее, к тому же лучи дополнительно отражаются от воды.

Если не хотите получить солнечный ожог во время купания, выбирайте специальную солнцезащитную одежду с длинными рукавами и воротом. Ее ткань обрабатывают особыми химическими растворами или красителями, обеспечивающими повышенную защиту от солнца.

Чтобы обезопасить себя от агрессивного воздействия ультрафиолета, кожа начинает вырабатывать больше меланина. Дополнительное количество пигмента создает загар, который не является признаком хорошего здоровья. Более темный пигментированный слой блокирует проникновение основной массы ультрафиолетового света. Но при длительном интенсивном облучении такой защиты недостаточно — развивается ожог.

Обгореть можно и в снежных горах

Солнечный ожог можно получить в прохладные или пасмурные дни. Вода, снег, песок и другие блестящие поверхности способны отражать ультрафиолетовые лучи, которые потом попадают на поверхность тела. До 80% ультрафиолетового излучения проникает сквозь облака.

Снег, особенно в горной местности, — это основной отражатель солнечных лучей. Лыжники и сноубордисты используют специальные защитные очки с толстым стеклом именно для защиты глаз. В противном случае повышается вероятность повреждения глаз с развитием «снежной слепоты».

Опасность солнечных ожогов

Регулярное обгорание на солнце в может привести к развитию следующих осложнений в будущем⁴:

- преждевременное старение кожи (фотостарение);

- появление глубоких морщин;

- расширение подкожных мелких сосудов, которые становятся видны на щеках, носу, ушах;

- появление веснушек;

- повреждение сетчатки, роговицы, хрусталика глаза;

- обесцвечивание отдельных участков кожного покрова (солнечное лентиго);

- предраковое изменение поврежденных солнцем структур (солнечный кератоз);

- повреждение генетического материала (ДНК) клеток может вызывать рак кожи — меланому⁵.

Один сильный ультрафиолетовый ожог повышает риск онкологических заболеваний в будущем. Повторные или множественные повреждения в несколько раз повышают риск развития меланомы.

Классификация солнечных ожогов

Согласно международной классификации болезней (МКБ 10), повреждение вследствие ультрафиолетового воздействия является диагнозом. Заболевание классифицируют по глубине повреждения кожи. Различают несколько степеней солнечных ожогов¹.

I степень. Ожоговый очаг располагается в пределах верхнего слоя кожи — эпидермиса. Повреждение поверхностное с признаками воспаления, позднее наблюдается шелушение. Заживление происходит самостоятельно в течение 10 дней. В некоторых случаях после выздоровления в ранее поврежденном участке временно остается осветленное пятно (депигментация).

II степень. Ожог называют дермальным (пограничным), так как затрагиваются более глубокие слои кожи (до сосочкового слоя дермы). Выражены симптомы воспаления — покраснение, отек, боль. Нарушается циркуляция крови по мелким сосудам, отек распространяется на подкожно-жировую клетчатку. Сальные и потовые железы, а также волосяные фолликулы остаются неповрежденными. Для заживления такой травмы требуется до 18-21 дня. Могут остаться послеожоговые рубцы, осветленные участки депигментации.

III степень (почти не встречается при солнечных ожогах). Сильно повреждаются все слои кожи, подкожно-жировая клетчатка, мышцы, связки, кости. Больной нуждается в срочном хирургическом лечении, так как самостоятельно такой дефект не может нормально зажить. После выздоровления практически всегда остаются рубцовые деформации, нарушается пигментация кожи.

Для постановки диагноза значение также имеет площадь полученной травмы. При небольших повреждениях пользуются «правилом ладони», площадь которой составляет примерно 1% поверхности всего тела человека. Ладонь дистанционно прикладывают к пораженному месту, чтобы примерно понять, сколько тканей пострадало от солнца¹.

Риск солнечного ожога повышается, если человек принимает фотосенсибилизирующие препараты. К ним относятся ретиноиды, зверобой, нестероидные противовоспалительные средства, некоторые мочегонные (тиазидные диуретики) и антибиотики (тетрациклины, фторхинолоны, сульфаниламиды).

Заключение

Солнечный ожог относится к доброкачественным видам острого повреждения кожи, которое обычно проходит без медицинского вмешательства. Но в редких случаях ожог бывает настолько серьезный, что больных госпитализируют в ожоговые центры для специфического лечения. Регулярное и интенсивное воздействие ультрафиолетовых лучей напрямую связано с ускоренным старением кожи, появлением морщин и пигментных пятен. Люди, не защищающие себя от повреждающего действия солнца, чаще сталкиваются с онкологией⁵. Появление солнечного ожога — не самая приятная ситуация, однако его можно предотвратить.

Источники

- Ожоги термические и химические. Ожоги солнечные. Ожоги дыхательных путей. Клинические рекомендации. Министерство здравоохранения Российской Федерации. Год утверждения: 2017.

- Вавилова А.А. Диссертация на соискание ученой степени кандидата медицинских наук. Дифференцированная терапия хроностарения и фотоповреждения кожи скинбустерами и ретиноидами. 2020.

- Болотная Л.А. Фотодерматозы // ДВКС. 2009.

- Guerra KC, Urban K, Crane JS. Sunburn. [Updated 2021 Aug 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan

- Chang YM, Barrett JH, Bishop DT, Armstrong BK, Bataille V, Bergman W, Berwick M, Bracci PM, Elwood JM, Ernstoff MS, Gallagher RP, Green AC, Gruis NA, Holly EA, Ingvar C, Kanetsky PA, Karagas MR, Lee TK, Le Marchand L, Mackie RM, Olsson H, Østerlind A, Rebbeck TR, Sasieni P, Siskind V, Swerdlow AJ, Titus-Ernstoff L, Zens MS, Newton-Bishop JA. Sun exposure and melanoma risk at different latitudes: a pooled analysis of 5700 cases and 7216 controls. Int J Epidemiol. 2009 Jun;38(3):814-30. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp166. Epub 2009 Apr 8. PMID: 19359257; PMCID: PMC2689397.

- Li H, Colantonio S, Dawson A, Lin X, Beecker J. Sunscreen Application, Safety, and Sun Protection: The Evidence. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019 Jul/Aug;23(4):357-369. doi: 10.1177/1203475419856611. Epub 2019 Jun 20. PMID: 31219707.

| Sunburn | |

|---|---|

|

|

| A sunburned neck | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| Complications | Skin cancer |

| Risk factors | Working outdoors, skin unprotected by clothes or sunscreen, skin type, age |

| Prevention | Use of sunscreen, sun protective clothing |

Sunburn is a form of radiation burn that affects living tissue, such as skin, that results from an overexposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, usually from the Sun. Common symptoms in humans and animals include: red or reddish skin that is hot to the touch or painful, general fatigue, and mild dizziness. Other symptoms include blistering, peeling skin, swelling, itching, and nausea. Excessive UV radiation is the leading cause of (primarily) non-malignant skin tumors,[1][2] and in extreme cases can be life-threatening. Sunburn is an inflammatory response in the tissue triggered by direct DNA damage by UV radiation. When the cells’ DNA is overly damaged by UV radiation, type I cell-death is triggered and the tissue is replaced.[3]

Sun protective measures including sunscreen and sun protective clothing are widely accepted to prevent sunburn and some types of skin cancer. Special populations, including children, are especially susceptible to sunburn and protective measures should be used to prevent damage.

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Typically, there is initial redness, followed by varying degrees of pain, proportional in severity to both the duration and intensity of exposure.

Other symptoms can include blistering, swelling (edema), itching (pruritus), peeling skin, rash, nausea, fever, chills, and fainting (syncope). Also, a small amount of heat is given off from the burn, caused by the concentration of blood in the healing process, giving a warm feeling to the affected area. Sunburns may be classified as superficial, or partial thickness burns. Blistering is a sign of second degree sunburn.[4]

Variations[edit]

Minor sunburns typically cause nothing more than slight redness and tenderness to the affected areas. In more serious cases, blistering can occur. Extreme sunburns can be painful to the point of debilitation and may require hospital care.

Duration[edit]

Sunburn can occur in less than 15 minutes, and in seconds when exposed to non-shielded welding arcs or other sources of intense ultraviolet light. Nevertheless, the inflicted harm is often not immediately obvious.

After the exposure, skin may turn red in as little as 30 minutes but most often takes 2 to 6 hours. Pain is usually strongest 6 to 48 hours after exposure. The burn continues to develop for 1 to 3 days, occasionally followed by peeling skin in 3 to 8 days. Some peeling and itching may continue for several weeks.

Skin cancer[edit]

Ultraviolet radiation causes sunburns and increases the risk of three types of skin cancer: melanoma, basal-cell carcinoma and squamous-cell carcinoma.[1][2][5] Of greatest concern is that the melanoma risk increases in a dose-dependent manner with the number of a person’s lifetime cumulative episodes of sunburn.[6] It has been estimated that over 1/3 of melanomas in the United States and Australia could be prevented with regular sunscreen use.[7]

Causes[edit]

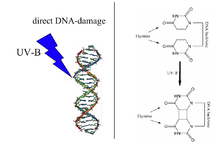

The cause of sunburn is the direct damage that a UVB photon can induce in DNA (left). One of the possible reactions from the excited state is the formation of a thymine-thymine cyclobutane dimer (right).

Sunburn is caused by UV radiation from the sun, but «sunburn» may result from artificial sources, such as tanning lamps, welding arcs, or ultraviolet germicidal irradiation. It is a reaction of the body to direct DNA damage from UVB light. This damage is mainly the formation of a thymine dimer. The damage is recognized by the body, which then triggers several defense mechanisms, including DNA repair to revert the damage, apoptosis and peeling to remove irreparably damaged skin cells, and increased melanin production to prevent future damage.

Melanin readily absorbs UV wavelength light, acting as a photoprotectant. By preventing UV photons from disrupting chemical bonds, melanin inhibits both the direct alteration of DNA and the generation of free radicals, thus indirect DNA damage. However, human melanocytes contain over 2,000 genomic sites that are highly sensitive to UV, and such sites can be up to 170-fold more sensitive to UV induction of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers than the average site[8] These sensitive sites often occur at biologically significant locations near genes.

Sunburn causes an inflammation process, including production of prostanoids and bradykinin. These chemical compounds increase sensitivity to heat by reducing the threshold of heat receptor (TRPV1) activation from 109 °F (43 °C) to 85 °F (29 °C).[9] The pain may be caused by overproduction of a protein called CXCL5, which activates nerve fibers.[10]

Skin type determines the ease of sunburn. In general, people with lighter skin tone and limited capacity to develop a tan after UV radiation exposure have a greater risk of sunburn. The Fitzpatrick’s Skin phototypes classification describes the normal variations of skin responses to UV radiation. Persons with type I skin have the greatest capacity to sunburn and type VI have the least capacity to burn. However, all skin types can develop sunburn.[11]

Fitzpatrick’s skin phototypes:

- Type 0: Albino

- Type I: Pale white skin, burns easily, does not tan

- Type II: White skin, burns easily, tans with difficulty

- Type III: White skin, may burn but tans easily

- Type IV: Light brown/olive skin, hardly burns, tans easily

- Type V: Brown skin, usually does not burn, tans easily

- Type VI: Black skin, very unlikely to burn, becomes darker with UV radiation exposure[12]

Age also affects how skin reacts to sun. Children younger than six and adults older than sixty are more sensitive to sunlight.[13]

There are certain genetic conditions, for example xeroderma pigmentosum, that increase a person’s susceptibility to sunburn and subsequent skin cancers. These conditions involve defects in DNA repair mechanisms which in turn decreases the ability to repair DNA that has been damaged by UV radiation.[14]

Medications[edit]

The risk of a sunburn can be increased by pharmaceutical products that sensitize users to UV radiation. Certain antibiotics, oral contraceptives, antidepressants, acne medications, and tranquillizers have this effect.[15]

UV intensity[edit]

The UV Index indicates the risk of getting a sunburn at a given time and location. Contributing factors include:[13]

- The time of day. In most locations, the sun’s rays are strongest between approximately 10 am and 4 pm daylight saving time.[16]

- Cloud cover. UV is partially blocked by clouds; but even on an overcast day, a significant percentage of the sun’s damaging UV radiation can pass through clouds.[17][18]

- Proximity to reflective surfaces, such as water, sand, concrete, snow, and ice. All of these reflect the sun’s rays and can cause sunburns.

- The season of the year. The position of the sun in late spring and early summer can cause a more-severe sunburn.

- Altitude. At a higher altitude it is easier to become burnt, because there is less of the earth’s atmosphere to block the sunlight. UV exposure increases about 4% for every 1000 ft (305 m) gain in elevation.

- Proximity to the equator (latitude). Between the polar and tropical regions, the closer to the equator, the more direct sunlight passes through the atmosphere over the course of a year. For example, the southern United States gets fifty percent more sunlight than the northern United States.

Erythemal dose rate at three Northern latitudes. (Divide by 25 to obtain the UV Index.) Source: NOAA.

Because of variations in the intensity of UV radiation passing through the atmosphere, the risk of sunburn increases with proximity to the tropic latitudes, located between 23.5° north and south latitude. All else being equal (e.g., cloud cover, ozone layer, terrain, etc.), over the course of a full year, each location within the tropic or polar regions receives approximately the same amount of UV radiation. In the temperate zones between 23.5° and 66.5°, UV radiation varies substantially by latitude and season. The higher the latitude, the lower the intensity of the UV rays. Intensity in the northern hemisphere is greatest during the months of May, June and July—and in the southern hemisphere, November, December and January. On a minute-by-minute basis, the amount of UV radiation is dependent on the angle of the sun. This is easily determined by the height ratio of any object to the size of its shadow (if the height is measured vertical to the earth’s gravitational field, the projected shadow is ideally measured on a flat, level surface; furthermore, for objects wider than skulls or poles, the height and length are best measured relative to the same occluding edge). The greatest risk is at solar noon, when shadows are at their minimum and the sun’s radiation passes most directly through the atmosphere. Regardless of one’s latitude (assuming no other variables), equal shadow lengths mean equal amounts of UV radiation.

The skin and eyes are most sensitive to damage by UV at 265–275 nm wavelength, which is in the lower UVC band that is almost never encountered except from artificial sources like welding arcs. Most sunburn is caused by longer wavelengths, simply because those are more prevalent in sunlight at ground level.

Ozone depletion[edit]

In recent decades, the incidence and severity of sunburn have increased worldwide, partly because of chemical damage to the atmosphere’s ozone layer. Between the 1970s and the 2000s, average stratospheric ozone decreased by approximately 4%, contributing an approximate 4% increase to the average UV intensity at the earth’s surface. Ozone depletion and the seasonal «ozone hole» have led to much larger changes in some locations, especially in the southern hemisphere.[19]

Tanning[edit]

Suntans, which naturally develop in some individuals as a protective mechanism against the sun, are viewed by most in the Western world as desirable.[20] This has led to an overall increase in exposure to UV radiation from both the natural sun and tanning lamps. Suntans can provide a modest sun protection factor (SPF) of 3, meaning that tanned skin would tolerate up to three times the UV exposure as pale skin.[21]

Sunburns associated with indoor tanning can be severe.[22]

The World Health Organization, American Academy of Dermatology, and the Skin Cancer Foundation recommend avoiding artificial UV sources such as tanning beds, and do not recommend suntans as a form of sun protection.[23][24][25]

Diagnosis[edit]

A sunburned leg below the shorts line

Differential diagnosis[edit]

The differential diagnosis of sunburn includes other skin pathology induced by UV radiation including photoallergic reactions, phototoxic reactions to topical or systemic medications, and other dermatologic disorders that are aggravated by exposure to sunlight. Considerations for diagnosis include duration and intensity of UV exposure, use of topical or systemic medications, history of dermatologic disease, and nutritional status.

- Phototoxic reactions: Non-immunological response to sunlight interacting with certain drugs and chemicals in the skin which resembles an exaggerated sunburn. Common drugs that may cause a phototoxic reaction include amiodarone, dacarbazine, fluoroquinolones, 5-fluorouracil, furosemide, nalidixic acid, phenothiazines, psoralens, retinoids, sulfonamides, sulfonylureas, tetracyclines, thiazides, and vinblastine.[26]

- Photoallergic reactions: Uncommon immunological response to sunlight interacting with certain drugs and chemicals in the skin. When in excited state by UVR, these drugs and chemicals form free radicals that react to form functional antigens and induce a Type IV hypersensitivity reaction. These drugs include 6-methylcoumarin, aminobenzoic acid and esters, chlorpromazine, promethazine, diclofenac, sulfonamides, and sulfonylureas. Unlike phototoxic reactions which resemble exaggerated sunburns, photoallergic reactions can cause intense itching and can lead to thickening of the skin.[26]

- Phytophotodermatitis: UV radiation induces inflammation of the skin after contact with certain plants (including limes, celery, and meadow grass). Causes pain, redness, and blistering of the skin in the distribution of plant exposure.[11]

- Polymorphic light eruption: Recurrent abnormal reaction to UVR. It can present in various ways including pink-to-red bumps, blisters, plaques and urticaria.[11]

- Solar urticaria: UVR-induced wheals that occurs within minutes of exposure and fades within hours.[11]

- Other skin diseases exacerbated by sunlight: Several dermatologic conditions can increase in severity with exposure to UVR. These include systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), dermatomyositis, acne, atopic dermatitis, and rosacea.[11]

Additionally, since sunburn is a type of radiation burn,[27][28] it can initially hide a severe exposure to radioactivity resulting in acute radiation syndrome or other radiation-induced illnesses, especially if the exposure occurred under sunny conditions. For instance, the difference between the erythema caused by sunburn and other radiation burns is not immediately obvious. Symptoms common to heat illness and the prodromic stage of acute radiation syndrome like nausea, vomiting, fever, weakness/fatigue, dizziness or seizure[29] can add to further diagnostic confusion.

Prevention[edit]

Sunburn effect (as measured by the UV Index) is the product of the sunlight spectrum at the earth’s surface (radiation intensity) and the erythemal action spectrum (skin sensitivity). Long-wavelength UV is more prevalent, but each milliwatt at 295 nm produces almost 100 times more sunburn than at 315 nm.

Skin peeling on the upper arm as a result of sunburn – the destruction of lower layers of the epidermis causes rapid loss of the top layers

Tanning of the forearm (visible darkening of the skin) after extended sun exposure

The most effective way to prevent sunburn is to reduce the amount of UV radiation reaching the skin. The World Health Organization, American Academy of Dermatology, and Skin Cancer Foundation recommend the following measures to prevent excessive UV exposure and skin cancer:[30][31][32]

- Limiting sun exposure between the hours of 10 am and 4 pm, when UV rays are the strongest

- Seeking shade when UV rays are most intense

- Wearing sun-protective clothing including a wide brim hat, sunglasses, and tightly-woven, loose-fitting clothing

- Using sunscreen

- Avoiding tanning beds and artificial UV exposure

UV intensity[edit]

The strength of sunlight is published in many locations as a UV Index. Sunlight is generally strongest when the sun is close to the highest point in the sky. Due to time zones and daylight saving time, this is not necessarily at 12 noon, but often one to two hours later. Seeking shade including using umbrellas and canopies can reduce the amount of UV exposure, but does not block all UV rays. The WHO recommends following the shadow rule: «Watch your shadow – Short shadow, seek shade!»[30]

Grapes[edit]

A 2022 study found that eating 60 grapes a day can stop you getting sunburn. Scientists found people who ate three-quarters of a punnet every day for two weeks were better protected against damage to the skin from ultraviolet light. Polyphenols found naturally in the fruits are thought to be responsible for the resistance.[33]

Sunscreen[edit]

Commercial preparations are available that block UV light, known as sunscreens or sunblocks. They have a sun protection factor (SPF) rating, based on the sunblock’s ability to suppress sunburn: The higher the SPF rating, the lower the amount of direct DNA damage. The stated protection factors are correct only if 2 mg of sunscreen is applied per square cm of exposed skin. This translates into about 28 mL (1 oz)[failed verification] to cover the whole body of an adult male, which is much more than many people use in practice.[34] Sunscreens function as chemicals such as oxybenzone and dioxybenzone (organic sunscreens) or opaque materials such as zinc oxide or titanium oxide (inorganic sunscreens) that both mainly absorb UV radiation. Chemical and mineral sunscreens vary in the wavelengths of UV radiation blocked. Broad-spectrum sunscreens contain filters that protect against UVA radiation as well as UVB. Although UVA radiation does not primarily cause sunburn, it does contribute to skin aging and an increased risk of skin cancer.

Sunscreen is effective and thus recommended for preventing melanoma[35] and squamous cell carcinoma.[36] There is little evidence that it is effective in preventing basal cell carcinoma.[37] Typical use of sunscreen does not usually result in vitamin D deficiency, but extensive usage may.[38]

Recommendations[edit]

Research has shown that the best sunscreen protection is achieved by application 15 to 30 minutes before exposure, followed by one reapplication 15 to 30 minutes after exposure begins. Further reapplication is necessary only after activities such as swimming, sweating, and rubbing.[39] This varies based on the indications and protection shown on the label—from as little as 80 minutes in water to a few hours, depending on the product selected. The American Academy of Dermatology recommends the following criteria in selecting a sunscreen:[40]

- Broad spectrum: protects against both UVA and UVB rays

- SPF 30 or higher

- Water resistant: sunscreens are classified as water resistant based on time, either 40 minutes, 80 minutes, or not water resistant

Eyes[edit]

The eyes are also sensitive to sun exposure at about the same UV wavelengths as skin; snow blindness is essentially sunburn of the cornea. Wrap-around sunglasses or the use by spectacle-wearers of glasses that block UV light reduce the harmful radiation. UV light has been implicated in the development of age-related macular degeneration,[41] pterygium[42] and cataract.[43] Concentrated clusters of melanin, commonly known as freckles, are often found within the iris.

The tender skin of the eyelids can also become sunburned, and can be especially irritating.

Lips[edit]

The lips can become chapped (cheilitis) by sun exposure. Sunscreen on the lips does not have a pleasant taste and might be removed by saliva. Some lip balms (ChapSticks) have SPF ratings and contain sunscreens.

Feet[edit]

The skin of the feet is often tender and protected, so sudden prolonged exposure to UV radiation can be particularly painful and damaging to the top of the foot. Protective measures include sunscreen, socks, and swimwear or swimgear that covers the foot.

Diet[edit]

Dietary factors influence susceptibility to sunburn, recovery from sunburn, and risk of secondary complications from sunburn. Several dietary antioxidants, including essential vitamins, have been shown to have some effectiveness for protecting against sunburn and skin damage associated with ultraviolet radiation, in both human and animal studies. Supplementation with Vitamin C and Vitamin E was shown in one study to reduce the amount of sunburn after a controlled amount of UV exposure.[44]

A review of scientific literature through 2007 found that beta carotene (Vitamin A) supplementation had a protective effect against sunburn, but that the effects were only evident in the long-term, with studies of supplementation for periods less than 10 weeks in duration failing to show any effects.[45] There is also evidence that common foods may have some protective ability against sunburn if taken for a period before the exposure.[46][47]

Protecting children[edit]

Babies and children are particularly susceptible to UV damage which increases their risk of both melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers later in life. Children should not sunburn at any age and protective measures can ensure their future risk of skin cancer is reduced.[48]

- Infants 0–6 months: Children under 6mo generally have skin too sensitive for sunscreen and protective measures should focus on avoiding excessive UV exposure by using window mesh covers, wide brim hats, loose clothing that covers skin, and reducing UV exposure between the hours of 10am and 4pm.

- Infants 6–12 months: Sunscreen can safely be used on infants this age. It is recommended to apply a broad-spectrum, water-resistant SPF 30+ sunscreen to exposed areas as well as avoid excessive UV exposure by using wide-brim hats and protective clothing.

- Toddlers and Preschool-aged children: Apply a broad-spectrum, water-resistant SPF 30+ sunscreen to exposed areas, use wide-brim hats and sunglasses, avoid peak UV intensity hours of 10am-4pm and seek shade. Sun protective clothing with a SPF rating can also provide additional protection.

Artificial UV exposure[edit]

The WHO recommends that artificial UV exposure including tanning beds should be avoided as no safe dose has been established.[49] When one is exposed to any artificial source of occupational UV, special protective clothing (for example, welding helmets/shields) should be worn. Such sources can produce UVC, an extremely carcinogenic wavelength of UV which ordinarily is not present in normal sunlight, having been filtered out by the atmosphere.

Treatment[edit]

The primary measure of treatment is avoiding further exposure to the sun. The best treatment for most sunburns is time; most sunburns heal completely within a few weeks.

The American Academy of Dermatology recommends the following for the treatment of sunburn:[50]

- For pain relief, take cool baths or showers frequently.

- Use soothing moisturizers that contain aloe vera or soy.

- Anti-inflammatory medications such as ibuprofen or aspirin can help with pain.

- Keep hydrated and drink extra water.

- Do not pop blisters on a sunburn; let them heal on their own instead.

- Protect sunburned skin (see: Sun protective clothing and Sunscreen) with loose clothing when going outside to prevent further damage while not irritating the sunburn.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; such as ibuprofen or naproxen), and aspirin may decrease redness and pain.[51][52] Local anesthetics such as benzocaine, however, are contraindicated.[53] Schwellnus et al. state that topical steroids (such as hydrocortisone cream) do not help with sunburns,[52] although the American Academy of Dermatology says they can be used on especially sore areas.[53] While lidocaine cream (a local anesthetic) is often used as a sunburn treatment, there is little evidence for the effectiveness of such use.[54]

A home treatment that may help the discomfort is using cool and wet cloths on the sunburned areas.[52] Applying soothing lotions that contain aloe vera to the sunburn areas was supported by multiple studies,[55][56] though others have found aloe vera to have no effect.[52] Note that aloe vera has no ability to protect people from new or further sunburn.[57] Another home treatment is using a moisturizer that contains soy.[53]

A sunburn draws fluid to the skin’s surface and away from the rest of the body. Drinking extra water is recommended to help prevent dehydration.[53]

See also[edit]

- Sun tanning

- Freckles

- Skin cancer

- Snow blindness

- Chapped lips

References[edit]

- ^ a b World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer «Do sunscreens prevent skin cancer» Archived 26 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine Press release No. 132, 5 June 2000

- ^ a b World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer «Solar and ultraviolet radiation» IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Volume 55, November 1997

- ^ Sunburn at eMedicine

- ^ «How to treat sunburn | American Academy of Dermatology». www.aad.org. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ «Facts About Sunburn and Skin Cancer», Skin Cancer Foundation

- ^ Dennis LK, Vanbeek MJ, Beane Freeman LE, Smith BJ, Dawson DV, Coughlin JA (August 2008). «Sunburns and risk of cutaneous melanoma: does age matter? A comprehensive meta-analysis». Annals of Epidemiology. 18 (8): 614–27. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.04.006. PMC 2873840. PMID 18652979.

- ^ Olsen CM, Wilson LF, Green AC, Biswas N, Loyalka J, Whiteman DC (January 2018). «How many melanomas might be prevented if more people applied sunscreen regularly?». The British Journal of Dermatology. 178 (1): 140–147. doi:10.1111/bjd.16079. PMID 29239489. S2CID 10914195.

- ^ Premi S, Han L, Mehta S, Knight J, Zhao D, Palmatier MA, Kornacker K, Brash DE. Genomic sites hypersensitive to ultraviolet radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Nov 26;116(48):24196-24205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1907860116. Epub 2019 Nov 13. PMID 31723047

- ^ Linden DJ (2015). Touch: The Science of Hand, Heart and Mind. Viking. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ Dawes JM, Calvo M, Perkins JR, Paterson KJ, Kiesewetter H, Hobbs C, Kaan TK, Orengo C, Bennett DL, McMahon SB (July 2011). «CXCL5 mediates UVB irradiation-induced pain». Science Translational Medicine. 3 (90): 90ra60. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3002193. PMC 3232447. PMID 21734176.

- ^ a b c d e Wolff K, Johnson R, Saavedra A (2013). Fitzpatrick’s color atlas and synopsis of clinical dermatology (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-179302-5. OCLC 813301093.

- ^ Wolff, K, ed. (2017). «PHOTOSENSITIVITY, PHOTO-INDUCED DISORDERS, AND DISORDERS BY IONIZING RADIATION». Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology (8th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ a b «Sunburn – Topic Overview». Healthwise. 15 November 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ Kraemer KH, DiGiovanna JJ (1993). «Xeroderma Pigmentosum». In Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJ, Stephens K, Amemiya A (eds.). GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301571.

- ^ «Avoiding Sun-Related Skin Damage». Fact-Sheets.com. 2004. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ «Tanning – Ultraviolet (UV) Radiation». Health Center for Devices and Radiological. United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ «Global Solar UV Index: A Practical Guide» (PDF). World Health Organization. 2002. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

Up to 80% of solar UV radiation can penetrate light cloud cover.

- ^ «How UV Index Is Calculated». EPA. 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

Clear skies allow virtually 100% of UV to pass through, scattered clouds transmit 89%, broken clouds transmit 73%, and overcast skies transmit 31%.

- ^ «Twenty Questions and Answers About the Ozone Layer» (PDF). Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2010. World Meteorological Organization. 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ^ «Suntan». Healthwise. 27 March 2005. Retrieved 26 August 2006.

- ^ «The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer» (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2014. p. 20.

A UVB-induced tan provides minimal sun protection, equivalent to an SPF of about 3.

- ^ Guy GP, Watson M, Haileyesus T, Annest JL (February 2015). «Indoor tanning-related injuries treated in a national sample of US hospital emergency departments». JAMA Internal Medicine. 175 (2): 309–11. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6697. PMC 4593495. PMID 25506731.

- ^ «Prevention — SkinCancer.org». skincancer.org. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ^ «Dangers of indoor tanning | American Academy of Dermatology». www.aad.org. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ^ «WHO | Artificial tanning devices: public health interventions to manage sunbeds». WHO. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ^ a b Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J (8 April 2015). Harrison’s principles of internal medicine (19th ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-07-180215-4. OCLC 893557976.

- ^ «What Are the Types and Degrees of Burns?».

- ^ «Sunburn – Health Encyclopedia – University of Rochester Medical Center».

- ^ «Acute Radiation Syndrome | CDC». 23 October 2020.

- ^ a b «Sun protection». World Health Organization. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ «Prevention Guidelines — SkinCancer.org». skincancer.org. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ «Prevent skin cancer | American Academy of Dermatology». www.aad.org. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2022/12/04/eating-grapes-can-help-protect-skin-against-sunburn-scientists/was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Faurschou A, Wulf HC (April 2007). «The relation between sun protection factor and amount of suncreen applied in vivo». The British Journal of Dermatology. 156 (4): 716–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07684.x. PMID 17493070. S2CID 22599824.

- ^ Kanavy HE, Gerstenblith MR (December 2011). «Ultraviolet radiation and melanoma». Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 30 (4): 222–8. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2011.08.003. PMID 22123420.

- ^ Burnett ME, Wang SQ (April 2011). «Current sunscreen controversies: a critical review». Photodermatology, Photoimmunology & Photomedicine. 27 (2): 58–67. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2011.00557.x. PMID 21392107.

- ^ Kütting B, Drexler H (December 2010). «UV-induced skin cancer at workplace and evidence-based prevention». International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 83 (8): 843–54. doi:10.1007/s00420-010-0532-4. PMID 20414668. S2CID 40870536.

- ^ Norval M, Wulf HC (October 2009). «Does chronic sunscreen use reduce vitamin D production to insufficient levels?». The British Journal of Dermatology. 161 (4): 732–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09332.x. PMID 19663879. S2CID 12276606.

- ^ Diffey BL (December 2001). «When should sunscreen be reapplied?». Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 45 (6): 882–5. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.117385. PMID 11712033.

- ^ «How to select a sunscreen | American Academy of Dermatology». www.aad.org. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Glazer-Hockstein C, Dunaief JL (January 2006). «Could blue light-blocking lenses decrease the risk of age-related macular degeneration?». Retina. 26 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1097/00006982-200601000-00001. PMID 16395131.

- ^ Solomon AS (June 2006). «Pterygium». The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 90 (6): 665–6. doi:10.1136/bjo.2006.091413. PMC 1860212. PMID 16714259.

- ^ Neale RE, Purdie JL, Hirst LW, Green AC (November 2003). «Sun exposure as a risk factor for nuclear cataract». Epidemiology. 14 (6): 707–12. doi:10.1097/01.ede.0000086881.84657.98. PMID 14569187. S2CID 40041207.

- ^ Eberlein-König B, Placzek M, Przybilla B (January 1998). «Protective effect against sunburn of combined systemic ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and d-alpha-tocopherol (vitamin E)». Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 38 (1): 45–8. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70537-7. PMID 9448204.

- ^ Köpcke W, Krutmann J (2008). «Protection from sunburn with beta-Carotene—a meta-analysis». Photochemistry and Photobiology. 84 (2): 284–8. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00253.x. PMID 18086246. S2CID 86776862.

- ^ Stahl W, Sies H (September 2007). «Carotenoids and flavonoids contribute to nutritional protection against skin damage from sunlight». Molecular Biotechnology. 37 (1): 26–30. doi:10.1007/s12033-007-0051-z. PMID 17914160. S2CID 22417600.

- ^ Schagen, S. K.; Zampeli, V. A.; Makrantonaki, E.; Zouboulis, C. C. (2012). «Discovering the link between nutrition and skin aging». Dermato-Endocrinology. 4 (3): 298–307. doi:10.4161/derm.22876. PMC 3583891. PMID 23467449.

- ^ «Children — SkinCancer.org». skincancer.org. 13 September 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ «WHO | Artificial tanning devices: public health interventions to manage sunbeds». WHO. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ «How to treat sunburn | American Academy of Dermatology». www.aad.org. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ «Sunburn – Home Treatment». Healthwise. 15 November 2013. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d Schwellnus MP (2008). The Olympic textbook of medicine in sport. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 337. ISBN 978-1-4443-0064-2.

- ^ a b c d «How to treat sunburn». American Academy of Dermatology. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ Arndt KA, Hsu JT (2007). Manual of Dermatologic Therapeutics. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-7817-6058-4.

- ^ Maenthaisong R, Chaiyakunapruk N, Niruntraporn S, Kongkaew C (September 2007). «The efficacy of aloe vera used for burn wound healing: a systematic review». Burns. 33 (6): 713–8. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2006.10.384. PMID 17499928.

- ^ Luo, X.; Zhang, H.; Wei, X.; Shi, M.; Fan, P.; Xie, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, N. (2018). «Aloin Suppresses Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammatory Response and Apoptosis by Inhibiting the Activation of NF-κB». Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 23 (3): 517. doi:10.3390/molecules23030517. PMC 6017010. PMID 29495390.

- ^ Feily A, Namazi MR (February 2009). «Aloe vera in dermatology: a brief review». Giornale Italiano di Dermatologia e Venereologia. 144 (1): 85–91. PMID 19218914.

External links[edit]

- Sunburn at Curlie

| Sunburn | |

|---|---|

|

|

| A sunburned neck | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| Complications | Skin cancer |

| Risk factors | Working outdoors, skin unprotected by clothes or sunscreen, skin type, age |

| Prevention | Use of sunscreen, sun protective clothing |

Sunburn is a form of radiation burn that affects living tissue, such as skin, that results from an overexposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, usually from the Sun. Common symptoms in humans and animals include: red or reddish skin that is hot to the touch or painful, general fatigue, and mild dizziness. Other symptoms include blistering, peeling skin, swelling, itching, and nausea. Excessive UV radiation is the leading cause of (primarily) non-malignant skin tumors,[1][2] and in extreme cases can be life-threatening. Sunburn is an inflammatory response in the tissue triggered by direct DNA damage by UV radiation. When the cells’ DNA is overly damaged by UV radiation, type I cell-death is triggered and the tissue is replaced.[3]

Sun protective measures including sunscreen and sun protective clothing are widely accepted to prevent sunburn and some types of skin cancer. Special populations, including children, are especially susceptible to sunburn and protective measures should be used to prevent damage.

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Typically, there is initial redness, followed by varying degrees of pain, proportional in severity to both the duration and intensity of exposure.

Other symptoms can include blistering, swelling (edema), itching (pruritus), peeling skin, rash, nausea, fever, chills, and fainting (syncope). Also, a small amount of heat is given off from the burn, caused by the concentration of blood in the healing process, giving a warm feeling to the affected area. Sunburns may be classified as superficial, or partial thickness burns. Blistering is a sign of second degree sunburn.[4]

Variations[edit]

Minor sunburns typically cause nothing more than slight redness and tenderness to the affected areas. In more serious cases, blistering can occur. Extreme sunburns can be painful to the point of debilitation and may require hospital care.

Duration[edit]

Sunburn can occur in less than 15 minutes, and in seconds when exposed to non-shielded welding arcs or other sources of intense ultraviolet light. Nevertheless, the inflicted harm is often not immediately obvious.

After the exposure, skin may turn red in as little as 30 minutes but most often takes 2 to 6 hours. Pain is usually strongest 6 to 48 hours after exposure. The burn continues to develop for 1 to 3 days, occasionally followed by peeling skin in 3 to 8 days. Some peeling and itching may continue for several weeks.

Skin cancer[edit]

Ultraviolet radiation causes sunburns and increases the risk of three types of skin cancer: melanoma, basal-cell carcinoma and squamous-cell carcinoma.[1][2][5] Of greatest concern is that the melanoma risk increases in a dose-dependent manner with the number of a person’s lifetime cumulative episodes of sunburn.[6] It has been estimated that over 1/3 of melanomas in the United States and Australia could be prevented with regular sunscreen use.[7]

Causes[edit]

The cause of sunburn is the direct damage that a UVB photon can induce in DNA (left). One of the possible reactions from the excited state is the formation of a thymine-thymine cyclobutane dimer (right).

Sunburn is caused by UV radiation from the sun, but «sunburn» may result from artificial sources, such as tanning lamps, welding arcs, or ultraviolet germicidal irradiation. It is a reaction of the body to direct DNA damage from UVB light. This damage is mainly the formation of a thymine dimer. The damage is recognized by the body, which then triggers several defense mechanisms, including DNA repair to revert the damage, apoptosis and peeling to remove irreparably damaged skin cells, and increased melanin production to prevent future damage.

Melanin readily absorbs UV wavelength light, acting as a photoprotectant. By preventing UV photons from disrupting chemical bonds, melanin inhibits both the direct alteration of DNA and the generation of free radicals, thus indirect DNA damage. However, human melanocytes contain over 2,000 genomic sites that are highly sensitive to UV, and such sites can be up to 170-fold more sensitive to UV induction of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers than the average site[8] These sensitive sites often occur at biologically significant locations near genes.

Sunburn causes an inflammation process, including production of prostanoids and bradykinin. These chemical compounds increase sensitivity to heat by reducing the threshold of heat receptor (TRPV1) activation from 109 °F (43 °C) to 85 °F (29 °C).[9] The pain may be caused by overproduction of a protein called CXCL5, which activates nerve fibers.[10]

Skin type determines the ease of sunburn. In general, people with lighter skin tone and limited capacity to develop a tan after UV radiation exposure have a greater risk of sunburn. The Fitzpatrick’s Skin phototypes classification describes the normal variations of skin responses to UV radiation. Persons with type I skin have the greatest capacity to sunburn and type VI have the least capacity to burn. However, all skin types can develop sunburn.[11]

Fitzpatrick’s skin phototypes:

- Type 0: Albino

- Type I: Pale white skin, burns easily, does not tan

- Type II: White skin, burns easily, tans with difficulty

- Type III: White skin, may burn but tans easily

- Type IV: Light brown/olive skin, hardly burns, tans easily

- Type V: Brown skin, usually does not burn, tans easily

- Type VI: Black skin, very unlikely to burn, becomes darker with UV radiation exposure[12]

Age also affects how skin reacts to sun. Children younger than six and adults older than sixty are more sensitive to sunlight.[13]

There are certain genetic conditions, for example xeroderma pigmentosum, that increase a person’s susceptibility to sunburn and subsequent skin cancers. These conditions involve defects in DNA repair mechanisms which in turn decreases the ability to repair DNA that has been damaged by UV radiation.[14]

Medications[edit]

The risk of a sunburn can be increased by pharmaceutical products that sensitize users to UV radiation. Certain antibiotics, oral contraceptives, antidepressants, acne medications, and tranquillizers have this effect.[15]

UV intensity[edit]

The UV Index indicates the risk of getting a sunburn at a given time and location. Contributing factors include:[13]

- The time of day. In most locations, the sun’s rays are strongest between approximately 10 am and 4 pm daylight saving time.[16]

- Cloud cover. UV is partially blocked by clouds; but even on an overcast day, a significant percentage of the sun’s damaging UV radiation can pass through clouds.[17][18]

- Proximity to reflective surfaces, such as water, sand, concrete, snow, and ice. All of these reflect the sun’s rays and can cause sunburns.

- The season of the year. The position of the sun in late spring and early summer can cause a more-severe sunburn.

- Altitude. At a higher altitude it is easier to become burnt, because there is less of the earth’s atmosphere to block the sunlight. UV exposure increases about 4% for every 1000 ft (305 m) gain in elevation.

- Proximity to the equator (latitude). Between the polar and tropical regions, the closer to the equator, the more direct sunlight passes through the atmosphere over the course of a year. For example, the southern United States gets fifty percent more sunlight than the northern United States.

Erythemal dose rate at three Northern latitudes. (Divide by 25 to obtain the UV Index.) Source: NOAA.

Because of variations in the intensity of UV radiation passing through the atmosphere, the risk of sunburn increases with proximity to the tropic latitudes, located between 23.5° north and south latitude. All else being equal (e.g., cloud cover, ozone layer, terrain, etc.), over the course of a full year, each location within the tropic or polar regions receives approximately the same amount of UV radiation. In the temperate zones between 23.5° and 66.5°, UV radiation varies substantially by latitude and season. The higher the latitude, the lower the intensity of the UV rays. Intensity in the northern hemisphere is greatest during the months of May, June and July—and in the southern hemisphere, November, December and January. On a minute-by-minute basis, the amount of UV radiation is dependent on the angle of the sun. This is easily determined by the height ratio of any object to the size of its shadow (if the height is measured vertical to the earth’s gravitational field, the projected shadow is ideally measured on a flat, level surface; furthermore, for objects wider than skulls or poles, the height and length are best measured relative to the same occluding edge). The greatest risk is at solar noon, when shadows are at their minimum and the sun’s radiation passes most directly through the atmosphere. Regardless of one’s latitude (assuming no other variables), equal shadow lengths mean equal amounts of UV radiation.

The skin and eyes are most sensitive to damage by UV at 265–275 nm wavelength, which is in the lower UVC band that is almost never encountered except from artificial sources like welding arcs. Most sunburn is caused by longer wavelengths, simply because those are more prevalent in sunlight at ground level.

Ozone depletion[edit]

In recent decades, the incidence and severity of sunburn have increased worldwide, partly because of chemical damage to the atmosphere’s ozone layer. Between the 1970s and the 2000s, average stratospheric ozone decreased by approximately 4%, contributing an approximate 4% increase to the average UV intensity at the earth’s surface. Ozone depletion and the seasonal «ozone hole» have led to much larger changes in some locations, especially in the southern hemisphere.[19]

Tanning[edit]

Suntans, which naturally develop in some individuals as a protective mechanism against the sun, are viewed by most in the Western world as desirable.[20] This has led to an overall increase in exposure to UV radiation from both the natural sun and tanning lamps. Suntans can provide a modest sun protection factor (SPF) of 3, meaning that tanned skin would tolerate up to three times the UV exposure as pale skin.[21]

Sunburns associated with indoor tanning can be severe.[22]

The World Health Organization, American Academy of Dermatology, and the Skin Cancer Foundation recommend avoiding artificial UV sources such as tanning beds, and do not recommend suntans as a form of sun protection.[23][24][25]

Diagnosis[edit]

A sunburned leg below the shorts line

Differential diagnosis[edit]

The differential diagnosis of sunburn includes other skin pathology induced by UV radiation including photoallergic reactions, phototoxic reactions to topical or systemic medications, and other dermatologic disorders that are aggravated by exposure to sunlight. Considerations for diagnosis include duration and intensity of UV exposure, use of topical or systemic medications, history of dermatologic disease, and nutritional status.

- Phototoxic reactions: Non-immunological response to sunlight interacting with certain drugs and chemicals in the skin which resembles an exaggerated sunburn. Common drugs that may cause a phototoxic reaction include amiodarone, dacarbazine, fluoroquinolones, 5-fluorouracil, furosemide, nalidixic acid, phenothiazines, psoralens, retinoids, sulfonamides, sulfonylureas, tetracyclines, thiazides, and vinblastine.[26]

- Photoallergic reactions: Uncommon immunological response to sunlight interacting with certain drugs and chemicals in the skin. When in excited state by UVR, these drugs and chemicals form free radicals that react to form functional antigens and induce a Type IV hypersensitivity reaction. These drugs include 6-methylcoumarin, aminobenzoic acid and esters, chlorpromazine, promethazine, diclofenac, sulfonamides, and sulfonylureas. Unlike phototoxic reactions which resemble exaggerated sunburns, photoallergic reactions can cause intense itching and can lead to thickening of the skin.[26]

- Phytophotodermatitis: UV radiation induces inflammation of the skin after contact with certain plants (including limes, celery, and meadow grass). Causes pain, redness, and blistering of the skin in the distribution of plant exposure.[11]

- Polymorphic light eruption: Recurrent abnormal reaction to UVR. It can present in various ways including pink-to-red bumps, blisters, plaques and urticaria.[11]

- Solar urticaria: UVR-induced wheals that occurs within minutes of exposure and fades within hours.[11]

- Other skin diseases exacerbated by sunlight: Several dermatologic conditions can increase in severity with exposure to UVR. These include systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), dermatomyositis, acne, atopic dermatitis, and rosacea.[11]

Additionally, since sunburn is a type of radiation burn,[27][28] it can initially hide a severe exposure to radioactivity resulting in acute radiation syndrome or other radiation-induced illnesses, especially if the exposure occurred under sunny conditions. For instance, the difference between the erythema caused by sunburn and other radiation burns is not immediately obvious. Symptoms common to heat illness and the prodromic stage of acute radiation syndrome like nausea, vomiting, fever, weakness/fatigue, dizziness or seizure[29] can add to further diagnostic confusion.

Prevention[edit]

Sunburn effect (as measured by the UV Index) is the product of the sunlight spectrum at the earth’s surface (radiation intensity) and the erythemal action spectrum (skin sensitivity). Long-wavelength UV is more prevalent, but each milliwatt at 295 nm produces almost 100 times more sunburn than at 315 nm.

Skin peeling on the upper arm as a result of sunburn – the destruction of lower layers of the epidermis causes rapid loss of the top layers

Tanning of the forearm (visible darkening of the skin) after extended sun exposure

The most effective way to prevent sunburn is to reduce the amount of UV radiation reaching the skin. The World Health Organization, American Academy of Dermatology, and Skin Cancer Foundation recommend the following measures to prevent excessive UV exposure and skin cancer:[30][31][32]

- Limiting sun exposure between the hours of 10 am and 4 pm, when UV rays are the strongest

- Seeking shade when UV rays are most intense

- Wearing sun-protective clothing including a wide brim hat, sunglasses, and tightly-woven, loose-fitting clothing

- Using sunscreen

- Avoiding tanning beds and artificial UV exposure

UV intensity[edit]

The strength of sunlight is published in many locations as a UV Index. Sunlight is generally strongest when the sun is close to the highest point in the sky. Due to time zones and daylight saving time, this is not necessarily at 12 noon, but often one to two hours later. Seeking shade including using umbrellas and canopies can reduce the amount of UV exposure, but does not block all UV rays. The WHO recommends following the shadow rule: «Watch your shadow – Short shadow, seek shade!»[30]

Grapes[edit]

A 2022 study found that eating 60 grapes a day can stop you getting sunburn. Scientists found people who ate three-quarters of a punnet every day for two weeks were better protected against damage to the skin from ultraviolet light. Polyphenols found naturally in the fruits are thought to be responsible for the resistance.[33]

Sunscreen[edit]