Разбор слова «венесуэла»: для переноса, на слоги, по составу

Объяснение правил деление (разбивки) слова «венесуэла» на слоги для переноса.

Онлайн словарь Soosle.ru поможет: фонетический и морфологический разобрать слово «венесуэла» по составу, правильно делить на слоги по провилам русского языка, выделить части слова, поставить ударение, укажет значение, синонимы, антонимы и сочетаемость к слову «венесуэла».

Содержимое:

- 1 Слоги в слове «венесуэла» деление на слоги

- 2 Как перенести слово «венесуэла»

- 3 Синонимы слова «венесуэла»

- 4 Значение слова «венесуэла»

- 5 Как правильно пишется слово «венесуэла»

- 6 Ассоциации к слову «венесуэла»

Слоги в слове «венесуэла» деление на слоги

Количество слогов: 5

По слогам: ве-не-су-э-ла

Как перенести слово «венесуэла»

ве—несуэла

вене—суэла

венесу—эла

венесуэ—ла

Синонимы слова «венесуэла»

Значение слова «венесуэла»

1. государство на севере Южной Америки. Омывается Карибским морем и Атлантическим океаном на севере, граничит с Гайаной на востоке, Бразилией на юге и Колумбией на западе. (Викисловарь)

Как правильно пишется слово «венесуэла»

Правописание слова «венесуэла»

Орфография слова «венесуэла»

Правильно слово пишется:

Нумерация букв в слове

Номера букв в слове «венесуэла» в прямом и обратном порядке:

Ассоциации к слову «венесуэла»

-

Колумбия

-

Перу

-

Бразилия

-

Панама

-

Аргентина

-

Чили

-

Куба

-

Мексика

-

Ямайка

-

Индонезия

-

Куб

-

Хосе

-

Гвинея

-

Абхазия

-

Нефть

-

Таиланд

-

Аравия

-

Ассамблея

-

Иран

-

Пакистан

-

Люксембург

-

Родригес

-

Сборная

-

Марокко

-

Победительница

-

Америка

-

Словакия

-

Ареал

-

Индия

-

Энрике

-

Канада

-

Ирак

-

Исландия

-

Зеландия

-

Выборы

-

Бельгия

-

Тунис

-

Амазонка

-

Албания

-

Алжир

-

Нидерланды

-

Сингапур

-

Симона

-

Португалия

-

Представительница

-

Независимость

-

Флорида

-

Латвия

-

Диктатура

-

Сирия

-

Норвегия

-

Австралия

-

Испания

-

Президент

-

Ливия

-

Референдум

-

Социализм

-

Великобритания

-

Румыния

-

Вьетнам

-

Корея

-

Мальта

-

Конгресс

-

Пакт

-

Антонио

-

Экспорт

-

Конго

-

Хорватия

-

Северо-запад

-

Узбекистан

-

Свержение

-

Рафаэль

-

Республика

-

Карибский

-

Товарищеский

-

Саудовский

-

Нефтяной

-

Сборный

-

Апостольский

-

Кубинский

-

Отборочный

-

Президентский

-

Демократический

-

Латинский

-

Тропический

-

Атлантический

-

Весовой

-

Коммунистический

-

Испанский

-

Молодёжный

-

Федеративный

-

Южный

-

Полномочный

-

Северо-восточный

-

Парламентский

-

Дебютировать

-

Эмигрировать

-

Распространить

-

Обитать

-

Произрастать

«Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela» redirects here. For the period when it was known as the «Republic of Venezuela» from 1953 to 1999, see Republic of Venezuela.

Coordinates: 7°N 65°W / 7°N 65°W

|

Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela República Bolivariana de Venezuela (Spanish) |

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Motto: Dios y Federación («God and Federation») |

|

| Anthem: Gloria al Bravo Pueblo («Glory to the Brave People») |

|

Land controlled by Venezuela shown in dark green; claimed but uncontrolled land shown in light green. |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Caracas 10°30′N 66°55′W / 10.500°N 66.917°W |

| Official languages | Spanish[b] |

| Recognized regional languages |

26 languages

|

| Other spoken languages | English German Portuguese Italian Chinese Arabic |

| Ethnic groups

(2011)[1] |

|

| Religion

(2020)[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Venezuelan |

| Government | Federal presidential republic |

|

• President |

Nicolás Maduro (disputed) |

|

• Vice President |

Delcy Rodríguez |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence from Spain | |

|

• Declared |

5 July 1811 |

|

• from Gran Colombia |

13 January 1830 |

|

• Recognized |

29 March 1845 |

|

• Current constitution |

20 December 1999[3] |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

916,445 km2 (353,841 sq mi) (32nd) |

|

• Water (%) |

3.2%[d] |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate |

29,789,730[4] (50th) |

|

• Density |

33.74/km2 (87.4/sq mi) (144st) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2013) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | medium · 120th |

| Currency | Venezuelan bolívar (VED) |

| Time zone | UTC−4 (VET) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (CE) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +58 |

| ISO 3166 code | VE |

| Internet TLD | .ve |

|

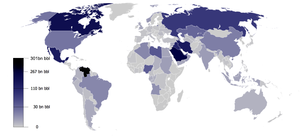

Venezuela (; American Spanish: [beneˈswela] (listen)), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (Spanish: República Bolivariana de Venezuela),[8] is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It has a territorial extension of 916,445 km2 (353,841 sq mi), and its population was estimated at 29 million in 2022.[9] The capital and largest urban agglomeration is the city of Caracas.

The continental territory is bordered on the north by the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, on the west by Colombia, Brazil on the south, Trinidad and Tobago to the north-east and on the east by Guyana. The Venezuelan government maintains a claim against Guyana to Guayana Esequiba.[10] Venezuela is a federal presidential republic consisting of 23 states, the Capital District and federal dependencies covering Venezuela’s offshore islands. Venezuela is among the most urbanized countries in Latin America;[11][12] the vast majority of Venezuelans live in the cities of the north and in the capital.

The territory of Venezuela was colonized by Spain in 1522 amid resistance from indigenous peoples. In 1811, it became one of the first Spanish-American territories to declare independence from the Spanish and to form part, as a department, of the first federal Republic of Colombia (historiographically known as Gran Colombia). It separated as a full sovereign country in 1830. During the 19th century, Venezuela suffered political turmoil and autocracy, remaining dominated by regional military dictators until the mid-20th century. Since 1958, the country has had a series of democratic governments, as an exception where most of the region was ruled by military dictatorships, and the period was characterized by economic prosperity. Economic shocks in the 1980s and 1990s led to major political crises and widespread social unrest, including the deadly Caracazo riots of 1989, two attempted coups in 1992, and the impeachment of a President for embezzlement of public funds charges in 1993. The collapse in confidence in the existing parties saw the 1998 Venezuelan presidential election, the catalyst for the Bolivarian Revolution, which began with a 1999 Constituent Assembly, where a new Constitution of Venezuela was imposed. The government’s populist social welfare policies were bolstered by soaring oil prices,[13] temporarily increasing social spending,[14] and reducing economic inequality and poverty in the early years of the regime.[15] However, poverty began to increase in the 2010s.[16] The 2013 Venezuelan presidential election was widely disputed leading to widespread protest, which triggered another nationwide crisis that continues to this day.[17] Venezuela has experienced democratic backsliding, shifting into an authoritarian state.[18] It ranks low in international measurements of freedom of the press and civil liberties and has high levels of perceived corruption.[19]

Venezuela is a developing country and ranks 113th on the Human Development Index. It has the world’s largest known oil reserves and has been one of the world’s leading exporters of oil. Previously, the country was an underdeveloped exporter of agricultural commodities such as coffee and cocoa, but oil quickly came to dominate exports and government revenues. The excesses and poor policies of the incumbent government led to the collapse of Venezuela’s entire economy.[20][21] The country struggles with record hyperinflation,[22][23] shortages of basic goods,[24] unemployment,[25] poverty,[26] disease, high child mortality, malnutrition, severe crime and corruption. These factors have precipitated the Venezuelan migrant crisis where more than three million people have fled the country.[27] By 2017, Venezuela was declared to be in default regarding debt payments by credit rating agencies.[28][29] The crisis in Venezuela has contributed to a rapidly deteriorating human rights situation, including increased abuses such as torture, arbitrary imprisonment, extrajudicial killings and attacks on human rights advocates. Venezuela is a charter member of the UN, Organization of American States (OAS), Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), ALBA, Mercosur, Latin American Integration Association (LAIA) and Organization of Ibero-American States (OEI).

Etymology

According to the most popular and accepted version, in 1499, an expedition led by Alonso de Ojeda visited the Venezuelan coast. The stilt houses in the area of Lake Maracaibo reminded the Italian navigator, Amerigo Vespucci, of the city of Venice, Italy, so he named the region Veneziola, or «Little Venice».[30] The Spanish version of Veneziola is Venezuela.[31]

Martín Fernández de Enciso, a member of the Vespucci and Ojeda crew, gave a different account. In his work Summa de geografía, he states that the crew found indigenous people who called themselves the Veneciuela. Thus, the name «Venezuela» may have evolved from the native word.[32]

Previously, the official name was Estado de Venezuela (1830–1856), República de Venezuela (1856–1864), Estados Unidos de Venezuela (1864–1953), and again República de Venezuela (1953–1999).

History

Pre-Columbian history

Evidence exists of human habitation in the area now known as Venezuela from about 15,000 years ago. Leaf-shaped tools from this period, together with chopping and plano-convex scraping implements, have been found exposed on the high riverine terraces of the Rio Pedregal in western Venezuela.[33] Late Pleistocene hunting artifacts, including spear tips, have been found at a similar series of sites in northwestern Venezuela known as «El Jobo»; according to radiocarbon dating, these date from 13,000 to 7,000 BC.[34]

It is not known how many people lived in Venezuela before the Spanish conquest; it has been estimated at around one million.[35] In addition to indigenous peoples known today, the population included historical groups such as the Kalina (Caribs), Auaké, Caquetio, Mariche, and Timoto–Cuicas. The Timoto–Cuica culture was the most complex society in Pre-Columbian Venezuela, with pre-planned permanent villages, surrounded by irrigated, terraced fields. They also stored water in tanks.[36] Their houses were made primarily of stone and wood with thatched roofs. They were peaceful, for the most part, and depended on growing crops. Regional crops included potatoes and ullucos.[37] They left behind works of art, particularly anthropomorphic ceramics, but no major monuments. They spun vegetable fibers to weave into textiles and mats for housing. They are credited with having invented the arepa, a staple in Venezuelan cuisine.[38]

After the conquest, the population dropped markedly, mainly through the spread of new infectious diseases from Europe.[35] Two main north–south axes of pre-Columbian population were present, who cultivated maize in the west and manioc in the east.[35] Large parts of the llanos were cultivated through a combination of slash and burn and permanent settled agriculture.[35]

Colonization

The German Welser Armada exploring Venezuela.

In 1498, during his third voyage to the Americas, Christopher Columbus sailed near the Orinoco Delta and landed in the Gulf of Paria.[39] Amazed by the great offshore current of freshwater which deflected his course eastward, Columbus expressed in a letter to Isabella and Ferdinand that he must have reached Heaven on Earth (terrestrial paradise):

Great signs are these of the Terrestrial Paradise… for I have never read or heard of such a large quantity of fresh water being inside and in such close proximity to salt water; the very mild temperateness also corroborates this; and if the water of which I speak does not proceed from Paradise then it is an even greater marvel, because I do not believe such a large and deep river has ever been known to exist in this world.[40]

Spain’s colonization of mainland Venezuela started in 1522, establishing its first permanent South American settlement in the present-day city of Cumaná.

German colonization

In the 16th century, the king of Spain granted a concession in Venezuela to the Welser family of German bankers and merchants. Klein-Venedig [41] became the most extensive initiative in the German colonization of the Americas from 1528 to 1546. The Welser family of Augsburg and Nuremberg were bankers to the Habsburgs and financiers of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, who was also King of Spain and had borrowed heavily from them to pay bribes for his Imperial election.[42]

In 1528, Charles V granted the Welsers the right to explore, rule and colonize the territory, as well as to seek the mythical golden town of El Dorado.[43][44][45] The first expedition was led by Ambrosius Ehinger, who established Maracaibo in 1529. After the deaths of first Ehinger (1533), then Nikolaus Federmann, and Georg von Speyer (1540), Philipp von Hutten persisted in exploring of the interior. In absence of von Hutten from the capital of the province, the crown of Spain claimed the right to appoint a governor. On Hutten’s return to the capital, Santa Ana de Coro, in 1546, the Spanish governor Juan de Carvajal had Hutten and Bartholomeus VI. Welser executed. Subsequently, Charles V revoked Welser’s concession. The Welsers transported German miners to the colony, in addition to 4,000 African slaves to paint sugar cane plantations. Many of the German colonists died from tropical diseases, to which they had no immunity, or through frequent wars with the indigenous inhabitants.

Late 15th century to early 17th century

Native caciques (leaders) such as Guaicaipuro (c. 1530–1568) and Tamanaco (died 1573) attempted to resist Spanish incursions, but the newcomers ultimately subdued them; Tamanaco was put to death by order of Caracas’ founder, Diego de Losada.[46]

In the 16th century, during the Spanish colonization, indigenous peoples such as many of the Mariches, themselves descendants of the Kalina, were converted to Roman Catholicism. Some of the resisting tribes or leaders are commemorated in place names, including Caracas, Chacao and Los Teques. The early colonial settlements focused on the northern coast,[35] but in the mid-18th century, the Spanish pushed farther inland along the Orinoco River. Here, the Ye’kuana (then known as the Makiritare) organized serious resistance in 1775 and 1776.[47]

Spain’s eastern Venezuelan settlements were incorporated into New Andalusia Province. Administered by the Royal Audiencia of Santo Domingo from the early 16th century, most of Venezuela became part of the Viceroyalty of New Granada in the early 18th century, and was then reorganized as an autonomous Captaincy General starting in 1777. The town of Caracas, founded in the central coastal region in 1567, was well-placed to become a key location, being near the coastal port of La Guaira whilst itself being located in a valley in a mountain range, providing defensive strength against pirates and a more fertile and healthy climate.[48]

Independence and 19th century

After a series of unsuccessful uprisings, Venezuela, under the leadership of Francisco de Miranda, a Venezuelan marshal who had fought in the American Revolution and the French Revolution, declared independence as the First Republic of Venezuela on 5 July 1811.[49] This began the Venezuelan War of Independence. A devastating earthquake that struck Caracas in 1812, together with the rebellion of the Venezuelan llaneros, helped bring down the republic.[50] Simón Bolívar, new leader of the independentist forces, launched his Admirable Campaign in 1813 from New Granada, retaking most of the territory and being proclaimed as El Libertador («The Liberator»). A second Venezuelan republic was proclaimed on 7 August 1813, but lasted only a few months before being crushed at the hands of royalist caudillo José Tomás Boves and his personal army of llaneros.[51]

The end of the French invasion of homeland Spain in 1814 allowed the preparation of a large expeditionary force to the American provinces under general Pablo Morillo, with the goal to regain the lost territory in Venezuela and New Granada. As the war reached a stalemate on 1817, Bolívar reestablished the Third Republic of Venezuela on the territory still controlled by the patriots, mainly in the Guayana and Llanos regions. This republic was short-lived as only two years later, during the Congress of Angostura of 1819, the union of Venezuela with New Granada was decreed to form the Republic of Colombia (historiographically Republic of Gran Colombia). The war continued for some years, until full victory and sovereignty was attained after Bolívar, aided by José Antonio Páez and Antonio José de Sucre, won the Battle of Carabobo on 24 June 1821.[52] On 24 July 1823, José Prudencio Padilla and Rafael Urdaneta helped seal Venezuelan independence with their victory in the Battle of Lake Maracaibo.[53] New Granada’s congress gave Bolívar control of the Granadian army; leading it, he liberated several countries and founded the Republic of Colombia (Gran Colombia).[52]

Sucre, who won many battles for Bolívar, went on to liberate Ecuador and later become the second president of Bolivia. Venezuela remained part of Gran Colombia until 1830, when a rebellion led by Páez allowed the proclamation of a newly independent Venezuela, on 22 September;[54] Páez became the first president of the new State of Venezuela.[55] Between one-quarter and one-third of Venezuela’s population was lost during these two decades of warfare (including perhaps one-half of the Venezuelans of European descent),[56] which by 1830, was estimated at 800,000.[57]

The colors of the Venezuelan flag are yellow, blue, and red: the yellow stands for land wealth, the blue for the sea that separates Venezuela from Spain, and the red for the blood shed by the heroes of independence.[58]

Slavery in Venezuela was abolished in 1854.[57] Much of Venezuela’s 19th-century history was characterized by political turmoil and dictatorial rule, including the Independence leader José Antonio Páez, who gained the presidency three times and served a total of 11 years between 1830 and 1863. This culminated in the Federal War (1859–1863), a civil war in which hundreds of thousands died in a country with a population of not much more than a million people. In the latter half of the century, Antonio Guzmán Blanco, another caudillo, served a total of 13 years between 1870 and 1887, with three other presidents interspersed.

In 1895, a longstanding dispute with Great Britain about the territory of Guayana Esequiba, which Britain claimed as part of British Guiana and Venezuela saw as Venezuelan territory, erupted into the Venezuela Crisis of 1895. The dispute became a diplomatic crisis when Venezuela’s lobbyist, William L. Scruggs, sought to argue that British behavior over the issue violated the United States’ Monroe Doctrine of 1823, and used his influence in Washington, D.C., to pursue the matter. Then, U.S. president Grover Cleveland adopted a broad interpretation of the doctrine that did not just simply forbid new European colonies, but declared an American interest in any matter within the hemisphere.[59] Britain ultimately accepted arbitration, but in negotiations over its terms was able to persuade the U.S. on many of the details. A tribunal convened in Paris in 1898 to decide the issue and in 1899 awarded the bulk of the disputed territory to British Guiana.[60]

In 1899, Cipriano Castro, assisted by his friend Juan Vicente Gómez, seized power in Caracas, marching an army from his base in the Andean state of Táchira. Castro defaulted on Venezuela’s considerable foreign debts and declined to pay compensation to foreigners caught up in Venezuela’s civil wars. This led to the Venezuela Crisis of 1902–1903, in which Britain, Germany and Italy imposed a naval blockade of several months before international arbitration at the new Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague was agreed. In 1908, another dispute broke out with the Netherlands, which was resolved when Castro left for medical treatment in Germany and was promptly overthrown by Juan Vicente Gómez (1908–1935).

20th century

Flag of Venezuela between 1954 and 2006.

The discovery of massive oil deposits in Lake Maracaibo during World War I[61] proved to be pivotal for Venezuela and transformed the basis of its economy from a heavy dependence on agricultural exports. It prompted an economic boom that lasted into the 1980s; by 1935, Venezuela’s per capita gross domestic product was Latin America’s highest.[62] Gómez benefited handsomely from this, as corruption thrived, but at the same time, the new source of income helped him centralize the Venezuelan state and develop its authority.

He remained the most powerful man in Venezuela until his death in 1935, although at times he ceded the presidency to others. The gomecista dictatorship (1935–1945) system largely continued under Eleazar López Contreras, but from 1941, under Isaías Medina Angarita, was relaxed. Angarita granted a range of reforms, including the legalization of all political parties. After World War II, immigration from Southern Europe (mainly from Spain, Italy, Portugal, and France) and poorer Latin American countries markedly diversified Venezuelan society.[63]

Rómulo Betancourt (president 1945–1948 / 1959–1964), one of the major democracy leaders of Venezuela.

In 1945, a civilian-military coup overthrew Medina Angarita and ushered in a three-year period of democratic rule (1945–1948) under the mass membership party Democratic Action, initially under Rómulo Betancourt, until Rómulo Gallegos won the 1947 Venezuelan presidential election (generally believed to be the first free and fair elections in Venezuela).[64][65] Gallegos governed until overthrown by a military junta led by the triumvirate Luis Felipe Llovera Páez [es], Marcos Pérez Jiménez, and Gallegos’ Defense Minister, Carlos Delgado Chalbaud, in the 1948 Venezuelan coup d’état.

The most powerful man in the military junta (1948–1958) was Pérez Jiménez (though Chalbaud was its titular president) and was suspected of being behind the death in office of Chalbaud, who died in a bungled kidnapping in 1950. When the junta unexpectedly lost the election it held in 1952, it ignored the results and Pérez Jiménez was installed as president, where he remained until 1958.[citation needed]

The military dictator Pérez Jiménez was forced out on 23 January 1958.[53] In an effort to consolidate a young democracy, the three major political parties (Acción Democrática (AD), COPEI and Unión Republicana Democrática (URD), with the notable exception of the Communist Party of Venezuela), signed the Puntofijo Pact power-sharing agreement. The two first parties would dominate the political landscape for four decades.

During the presidencies of Rómulo Betancourt (1959–1964, his second term) and Raúl Leoni (1964–1969) in the 1960s, substantial guerilla movements occurred, including the Armed Forces of National Liberation and the Revolutionary Left Movement, which had split from AD in 1960. Most of these movements laid down their arms under Rafael Caldera’s first presidency (1969–1974); Caldera had won the 1968 election for COPEI, being the first time a party other than Democratic Action took the presidency through a democratic election. The new democratic order had its antagonists. Betancourt suffered an attack planned by the Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo in 1960, and the leftists excluded from the Pact initiated an armed insurgency by organizing themselves in the Armed Forces of National Liberation, sponsored by the Communist Party and Fidel Castro. In 1962 they tried to destabilize the military corps, with failed revolts in Carúpano and Puerto Cabello. At the same time, Betancourt promoted a foreign policy, the Betancourt Doctrine, in which he only recognized elected governments by popular vote.[need quotation to verify]

The election in 1973 of Carlos Andrés Pérez coincided with an oil crisis, in which Venezuela’s income exploded as oil prices soared; oil industries were nationalized in 1976. This led to massive increases in public spending, but also increases in external debts, which continued into the 1980s when the collapse of oil prices during the 1980s crippled the Venezuelan economy. As the government started to devalue the currency in February 1983 to face its financial obligations, Venezuelans’ real standards of living fell dramatically. A number of failed economic policies and increasing corruption in government led to rising poverty and crime, worsening social indicators, and increased political instability.[66]

In the 1980s, the Presidential Commission for State Reform (COPRE) emerged as a mechanism of political innovation. Venezuela was preparing for the decentralization of its political system and the diversification of its economy, reducing the large size of the State. The COPRE operated as an innovation mechanism, also by incorporating issues into the political agenda that were generally excluded from public deliberation by the main actors of the Venezuelan democratic system. The most discussed topics were incorporated into the public agenda: decentralization, political participation, municipalization, judicial order reforms and the role of the State in a new economic strategy. The social reality of the country made the changes difficult to apply.[67]

Economic crises in the 1980s and 1990s led to a political crisis. Hundreds of people were killed by Venezuelan security forces and the military in the Caracazo riots of 1989 during the presidency of Carlos Andrés Pérez (1989–1993, his second term) and after the implementation of economic austerity measures.[68] Hugo Chávez, who in 1982 had promised to depose the bipartisanship governments, used the growing anger at economic austerity measures to justify a coup d’état attempt in February 1992;[69][70] a second coup d’état attempt occurred in November.[70] President Carlos Andrés Pérez (re-elected in 1988) was impeached under embezzlement charges in 1993, leading to the interim presidency of Ramón José Velásquez (1993–1994). Coup leader Chávez was pardoned in March 1994 by president Rafael Caldera (1994–1999, his second term), with a clean slate and his political rights reinstated, allowing Chávez to win and maintain the presidency continuously from 1999 until his death in 2013. Chávez won the elections of 1998, 2000, 2006 and 2012 and the presidential referendum of 2004. The only gaps in his presidency occurred during the two-day de facto government of Pedro Carmona Estanga in 2002 and when Diosdado Cabello Rondón acted as interim president for a few hours.[citation needed]

Bolivarian government: 1999–present

The Bolivarian Revolution refers to a left-wing populism social movement and political process in Venezuela led by Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez, who founded the Fifth Republic Movement in 1997 and the United Socialist Party of Venezuela in 2007. The «Bolivarian Revolution» is named after Simón Bolívar, an early 19th-century Venezuelan and Latin American revolutionary leader, prominent in the Spanish American wars of independence in achieving the independence of most of northern South America from Spanish rule. According to Chávez and other supporters, the «Bolivarian Revolution» seeks to build a mass movement to implement Bolivarianism—popular democracy, economic independence, equitable distribution of revenues, and an end to political corruption—in Venezuela. They interpret Bolívar’s ideas from a populist perspective, using socialist rhetoric.

Hugo Chávez: 1999–2013

A collapse in confidence in the existing parties led to Chávez being elected president in 1998 and the subsequent launch of a «Bolivarian Revolution», beginning with a 1999 constituent assembly to write a new Constitution of Venezuela. Chávez also initiated Bolivarian missions, programs aimed at helping the poor.[71]

In April 2002, Chávez was briefly ousted from power in the 2002 Venezuelan coup d’état attempt following popular demonstrations by his opponents,[72] but Chavez returned to power after two days as a result of demonstrations by poor Chávez supporters in Caracas and actions by the military.[73][74]

Chávez also remained in power after an all-out national strike that lasted from December 2002 to February 2003, including a strike/lockout in the state oil company PDVSA.[75] Capital flight before and during the strike led to the reimposition of currency controls (which had been abolished in 1989), managed by the CADIVI agency. In the subsequent decade, the government was forced into several currency devaluations.[76][77][78][79][80] These devaluations have done little to improve the situation of the Venezuelan people who rely on imported products or locally produced products that depend on imported inputs while dollar-denominated oil sales account for the vast majority of Venezuela’s exports.[81] According to Sebastian Boyd writing at Bloomberg News, the profits of the oil industry have been lost to «social engineering» and corruption, instead of investments needed to maintain oil production.[82]

Chávez survived several further political tests, including an August 2004 recall referendum. He was elected for another term in December 2006 and re-elected for a third term in October 2012. However, he was never sworn in for his third period, due to medical complications. Chávez died on 5 March 2013 after a nearly two-year fight with cancer.[83] The presidential election that took place on Sunday, 14 April 2013, was the first since Chávez took office in 1999 in which his name did not appear on the ballot.[84][self-published source?]

Nicolás Maduro

2013–2018

Poverty and inflation began to increase into the 2010s.[16] Nicolás Maduro was elected in 2013 after the death of Chavez. Chavez picked Maduro as his successor and appointed him vice president in 2013. Maduro was elected president in a shortened[clarification needed] election in 2013 following Chavez’s death.[79][85][86]

Nicolás Maduro has been the president of Venezuela since 14 April 2013, when he won the second presidential election after Chávez’s death, with 50.61% of the votes against the opposition’s candidate Henrique Capriles Radonski, who had 49.12% of the votes. The Democratic Unity Roundtable contested his election as fraud and as a violation of the constitution. An audit of 56% of the vote showed no discrepancies,[87] and the Supreme Court of Venezuela ruled that under Venezuela’s Constitution, Nicolás Maduro was the legitimate president and was invested as such by the Venezuelan National Assembly (Asamblea Nacional).[88] Opposition leaders and some international media consider the government of Maduro to be a dictatorship.[89][90][91][92] Since February 2014, hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans have protested over high levels of criminal violence, corruption, hyperinflation, and chronic scarcity of basic goods due to policies of the federal government.[93][94][95][96][97] Demonstrations and riots have resulted in over 40 fatalities in the unrest between Chavistas and opposition protesters[98] and opposition leaders, including Leopoldo López and Antonio Ledezma were arrested.[98][99][100][101][102][103] Human rights groups condemned the arrest of Leopoldo López.[104] In the 2015 Venezuelan parliamentary election, the opposition gained a majority.[105]

Venezuela devalued its currency in February 2013 due to rising shortages in the country,[80][106] which included those of milk, flour, and other necessities. This led to an increase in malnutrition, especially among children.[107][108] Venezuela’s economy had become strongly dependent on the exportation of oil, with crude accounting for 86% of exports,[109] and a high price per barrel to support social programs. Beginning in 2014 the price of oil plummeted from over $100/bbl to $40/bbl a year and a half later. This placed pressure on the Venezuelan economy, which was no longer able to afford vast social programs. To counter the decrease in oil prices, the Venezuelan Government began taking more money from PDVSA, the state oil company, to meet budgets, resulting in a lack of reinvestment in fields and employees. Venezuela’s oil production decreased from its height of nearly 3 to 1 million barrels (480 to 160 thousand cubic metres) per day.[110][111][112][113] In 2014, Venezuela entered an economic recession.[114] In 2015, Venezuela had the world’s highest inflation rate with the rate surpassing 100%, which was the highest in the country’s history.[115] In 2017, Donald Trump’s administration imposed more economic sanctions against Venezuela’s state-owned oil company PDVSA and Venezuelan officials.[116][117][118] Economic problems, as well as crime and corruption, were some of the main causes of the 2014–present Venezuelan protests.[119][120] Since 2014, roughly 5.6 million people have fled Venezuela.[121]

In January 2016, President Maduro decreed an «economic emergency», revealing the extent of the crisis and expanding his powers.[122] In July 2016, Colombian border crossings were temporarily opened to allow Venezuelans to purchase food and basic household and health items in Colombia.[123] In September 2016, a study published in the Spanish-language Diario Las Américas[124] indicated that 15% of Venezuelans are eating «food waste discarded by commercial establishments».

Close to 200 riots had occurred in Venezuelan prisons by October 2016, according to Una Ventana a la Libertad, an advocacy group for better prison conditions. The father of an inmate at Táchira Detention Center in Caracas alleged that his son was cannibalized by other inmates during a month-long riot, a claim corroborated by an anonymous police source but denied by the Minister of Correctional Affairs.[125]

In 2017, Venezuela experienced a constitutional crisis in the country. In March 2017, opposition leaders branded President Maduro a dictator after the Maduro-aligned Supreme Tribunal, which had been overturning most National Assembly decisions since the opposition took control of the body, took over the functions of the assembly, pushing a lengthy political standoff to new heights.[89] The Supreme Court backed down and reversed its decision on 1 April 2017.[citation needed] A month later, President Maduro announced the 2017 Venezuelan Constituent Assembly election and on 30 August 2017, the 2017 Constituent National Assembly was elected into office and quickly stripped the National Assembly of its powers.[citation needed]

In December 2017, President Maduro declared that leading opposition parties would be barred from taking part in the following year’s presidential vote after they boycotted mayoral polls.[126]

Since 2018

Maduro won the 2018 election with 67.8% of the vote. The result was challenged by countries including Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Brazil, Canada, Germany, France and the United States who deemed it fraudulent and moved to recognize Juan Guaidó as president.[127][128][129][130] Other countries including Cuba, China, Russia, Turkey, and Iran continued to recognize Maduro as president,[131][132] although China, facing financial pressure over its position, reportedly began hedging its position by decreasing loans given, cancelling joint ventures, and signaling willingness to work with all parties.[133] A Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokeswoman denied the reports, describing them as «false information».[134]

In January 2019 the Permanent Council of the Organization of American States (OAS) approved a resolution «to not recognize the legitimacy of Nicolas Maduro’s new term as of the 10th of January of 2019».[135]

In August 2019, United States President Donald Trump signed an executive order to impose a total economic embargo against Venezuela.[136] In March 2020, the Trump administration indicted Maduro and several Venezuelan officials, including the Chief Justice of the Supreme Tribunal, on charges of drug trafficking, narcoterrorism, and corruption.[137][non-primary source needed]

In June 2020, a report by the US organisation Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights documented enforced disappearances in Venezuela that occurred in the years 2018 and 2019. During the period, 724 enforced disappearances of political detainees were reported. The report stated that Venezuelan security forces subjected victims, who had been disappeared, to illegal interrogation processes accompanied by torture and cruel or inhuman treatment. The report stated that the Venezuelan government strategically used enforced disappearances to silence political opponents and other critical voices it deemed a threat.[138][139]

Geography

Topographic map of Venezuela

Venezuela is located in the north of South America; geologically, its mainland rests on the South American Plate. It has a total area of 916,445 km2 (353,841 sq mi) and a land area of 882,050 km2 (340,560 sq mi), making Venezuela the 33rd largest country in the world. The territory it controls lies between latitudes 0° and 16°N and longitudes 59° and 74°W.

Shaped roughly like a triangle, the country has a 2,800 km (1,700 mi) coastline in the north, which includes numerous islands in the Caribbean and the northeast borders the northern Atlantic Ocean. Most observers describe Venezuela in terms of four fairly well defined topographical regions: the Maracaibo lowlands in the northwest, the northern mountains extending in a broad east–west arc from the Colombian border along the northern Caribbean coast, the wide plains in central Venezuela, and the Guiana Highlands in the southeast.

The northern mountains are the extreme northeastern extensions of South America’s Andes mountain range. Pico Bolívar, the nation’s highest point at 4,979 m (16,335 ft), lies in this region. To the south, the dissected Guiana Highlands contain the northern fringes of the Amazon Basin and Angel Falls, the world’s highest waterfall, as well as tepuis, large table-like mountains. The country’s center is characterized by the llanos, which are extensive plains that stretch from the Colombian border in the far west to the Orinoco River delta in the east. The Orinoco, with its rich alluvial soils, binds the largest and most important river system of the country; it originates in one of the largest watersheds in Latin America. The Caroní and the Apure are other major rivers.

Venezuela borders Colombia to the west, Guyana to the east, and Brazil to the south. Caribbean islands such as Trinidad and Tobago, Grenada, Curaçao, Aruba, and the Leeward Antilles lie near the Venezuelan coast. Venezuela has territorial disputes with Guyana, formerly United Kingdom, largely concerning the Essequibo area and with Colombia concerning the Gulf of Venezuela. In 1895, after years of diplomatic attempts to solve the border dispute, the dispute over the Essequibo River border flared up. It was submitted to a «neutral» commission (composed of British, American, and Russian representatives and without a direct Venezuelan representative), which in 1899 decided mostly against Venezuela’s claim.[citation needed]

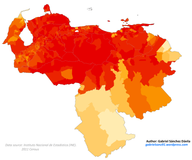

Climate

Venezuela map of Köppen climate classification

Venezuela is entirely located in the tropics over the Equator to around 12° N. Its climate varies from humid low-elevation plains, where average annual temperatures range as high as 35 °C (95.0 °F), to glaciers and highlands (the páramos) with an average yearly temperature of 8 °C (46.4 °F). Annual rainfall varies from 430 mm (16.9 in) in the semiarid portions of the northwest to over 1,000 mm (39.4 in) in the Orinoco Delta of the far east and the Amazonian Jungle in the south. The precipitation level is lower in the period from August through April. These periods are referred to as hot-humid and cold-dry seasons. Another characteristic of the climate is this variation throughout the country by the existence of a mountain range called «Cordillera de la Costa» which crosses the country from east to west. The majority of the population lives in these mountains.[140]

The country falls into four horizontal temperature zones based primarily on elevation, having tropical, dry, temperate with dry winters, and polar (alpine tundra) climates, amongst others.[141][142][143] In the tropical zone—below 800 m (2,625 ft)—temperatures are hot, with yearly averages ranging between 26 and 28 °C (78.8 and 82.4 °F). The temperate zone ranges between 800 and 2,000 m (2,625 and 6,562 ft) with averages from 12 to 25 °C (53.6 to 77.0 °F); many of Venezuela’s cities, including the capital, lie in this region. Colder conditions with temperatures from 9 to 11 °C (48.2 to 51.8 °F) are found in the cool zone between 2,000 and 3,000 m (6,562 and 9,843 ft), especially in the Venezuelan Andes, where pastureland and permanent snowfield with yearly averages below 8 °C (46 °F) cover land above 3,000 meters (9,843 ft) in the páramos.

The highest temperature recorded was 42 °C (108 °F) in Machiques,[144] and the lowest temperature recorded was −11 °C (12 °F), it has been reported from an uninhabited high altitude at Páramo de Piedras Blancas (Mérida state),[145] even though no official reports exist, lower temperatures in the mountains of the Sierra Nevada de Mérida are known.

Biodiversity and conservation

Venezuela lies within the Neotropical realm; large portions of the country were originally covered by moist broadleaf forests. One of 17 megadiverse countries,[146] Venezuela’s habitats range from the Andes Mountains in the west to the Amazon Basin rainforest in the south, via extensive llanos plains and Caribbean coast in the center and the Orinoco River Delta in the east. They include xeric scrublands in the extreme northwest and coastal mangrove forests in the northeast.[140] Its cloud forests and lowland rainforests are particularly rich.[147]

Animals of Venezuela are diverse and include manatees, three-toed sloth, two-toed sloth, Amazon river dolphins, and Orinoco Crocodiles, which have been reported to reach up to 6.6 m (22 ft) in length. Venezuela hosts a total of 1,417 bird species, 48 of which are endemic.[148] Important birds include ibises, ospreys, kingfishers,[147] and the yellow-orange Venezuelan troupial, the national bird. Notable mammals include the giant anteater, jaguar, and the capybara, the world’s largest rodent. More than half of Venezuelan avian and mammalian species are found in the Amazonian forests south of the Orinoco.[149]

For the fungi, an account was provided by R.W.G. Dennis[150] which has been digitized and the records made available on-line as part of the Cybertruffle Robigalia database.[151] That database includes nearly 3,900 species of fungi recorded from Venezuela, but is far from complete, and the true total number of fungal species already known from Venezuela is likely higher, given the generally accepted estimate that only about 7% of all fungi worldwide have so far been discovered.[152]

Among plants of Venezuela, over 25,000 species of orchids are found in the country’s cloud forest and lowland rainforest ecosystems.[147] These include the flor de mayo orchid (Cattleya mossiae), the national flower. Venezuela’s national tree is the araguaney, whose characteristic lushness after the rainy season led novelist Rómulo Gallegos to name it «[l]a primavera de oro de los araguaneyes» (the golden spring of the araguaneyes). The tops of the tepuis are also home to several carnivorous plants including the marsh pitcher plant, Heliamphora, and the insectivorous bromeliad, Brocchinia reducta.

Venezuela is among the top 20 countries in terms of endemism.[153] Among its animals, 23% of reptilian and 50% of amphibian species, including the Trinidad poison frog, are endemic.[153][154] Although the available information is still very small, a first effort has been made to estimate the number of fungal species endemic to Venezuela: 1334 species of fungi have been tentatively identified as possible endemics of the country.[155] Some 38% of the over 21,000 plant species known from Venezuela are unique to the country.[153]

Venezuela is one of the 10 most biodiverse countries on the planet, yet it is one of the leaders of deforestation due to economic and political factors. Each year, roughly 287,600 hectares of forest are permanently destroyed and other areas are degraded by mining, oil extraction, and logging. Between 1990 and 2005, Venezuela officially lost 8.3% of its forest cover, which is about 4.3 million ha. In response, federal protections for critical habitat were implemented; for example, 20% to 33% of forested land is protected.[149] Venezuela had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.78/10, ranking it 19th globally out of 172 countries.[157] The country’s biosphere reserve is part of the World Network of Biosphere Reserves; five wetlands are registered under the Ramsar Convention.[158] In 2003, 70% of the nation’s land was under conservation management in over 200 protected areas, including 43 national parks.[159] Venezuela’s 43 national parks include Canaima National Park, Morrocoy National Park, and Mochima National Park. In the far south is a reserve for the country’s Yanomami tribes. Covering 32,000 square miles (82,880 square kilometres), the area is off-limits to farmers, miners, and all non-Yanomami settlers.

Venezuela was one of the few countries that did not enter an INDC at COP21.[160][161] Many terrestrial ecosystems are considered endangered, specially the dry forest in the northern regions of the country and the coral reefs in the Caribbean coast.[162][163][164]

There are some 105 protected areas in Venezuela, which cover around 26% of the country’s continental, marine and insular surface.[citation needed]

Hydrography

The country is made up of three river basins: the Caribbean Sea, the Atlantic Ocean and Lake Valencia, which forms an endorheic basin.[165]

On the Atlantic side it drains most of Venezuela’s river waters. The largest basin in this area is the extensive Orinoco basin[166] whose surface area, close to one million km2, is greater than that of the whole of Venezuela, although it has a presence of 65% in the country. The size of this basin — similar to that of the Danube — makes it the third largest in South America, and it gives rise to a flow of some 33,000 m³/s, making the Orinoco the third largest in the world, and also one of the most valuable from the point of view of renewable natural resources. The Rio or Brazo Casiquiare is unique in the world, as it is a natural derivation of the Orinoco that, after some 500 km in length, connects it to the Negro River, which in turn is a tributary of the Amazon. The Orinoco receives directly or indirectly rivers such as the Ventuari, the Caura, the Caroní, the Meta, the Arauca, the Apure and many others. Other Venezuelan rivers that empty into the Atlantic are the waters of the San Juan and Cuyuní basins. Finally, there is the Amazon River, which receives the Guainía, the Negro and others. Other basins are the Gulf of Paria and the Esequibo River.

The second most important watershed is the Caribbean Sea. The rivers of this region are usually short and of scarce and irregular flow, with some exceptions such as the Catatumbo, which originates in Colombia and drains into the Maracaibo Lake basin. Among the rivers that reach the Maracaibo lake basin are the Chama, the Escalante, the Catatumbo, and the contributions of the smaller basins of the Tocuyo, Yaracuy, Neverí and Manzanares rivers.

A minimum drains to the Lake Valencia basin.[167] Of the total extension of the rivers, a total of 5400 km are navigable. Other rivers worth mentioning are the Apure, Arauca, Caura, Meta, Barima, Portuguesa, Ventuari and Zulia, among others.

The country’s main lakes are Lake Maracaibo[168] -the largest in South America- open to the sea through the natural channel, but with fresh water, and Lake Valencia with its endorheic system. Other noteworthy bodies of water are the Guri reservoir, the Altagracia lagoon, the Camatagua reservoir and the Mucubají lagoon in the Andes. Navigation in Lake Maracaibo through the natural channel is useful for the mobilization of oil resources.

Relief

The Venezuelan natural landscape[169] is the product of the interaction of tectonic plates[169] that since the Paleozoic have contributed to its current appearance. On the formed structures, seven physical-natural units have been modeled, differentiated in their relief and in their natural resources.

The relief of Venezuela has the following characteristics: coastline with several peninsulas[170] and islands, adenas of the Andes mountain range (north and northwest), Lake Maracaibo (between the chains, on the coast);[171] Orinoco river delta,[172] region of peneplains and plateaus (tepui, east of the Orinoco) that together form the Guyanas massif (plateaus, southeast of the country).

The oldest rock formations in South America are found in the complex basement of the Guyanas highlands[173] and in the crystalline line of the Maritime and Cordillera massifs in Venezuela. The Venezuelan part of the Guyanas Altiplano consists of a large granite block of gneiss and other crystalline Archean rocks, with underlying layers of sandstone and shale clay.[174]

The core of granite and cordillera is, to a large extent, flanked by sedimentary layers from the Cretaceous,[175] folded in an anticline structure. Between these orographic systems there are plains covered with tertiary and quaternary layers of gravel, sands and clayey marls. The depression contains lagoons and lakes, among which is that of Maracaibo, and presents, on the surface, alluvial deposits from the Quaternary,[176] on layers of the Cretaceous and Tertiary particularly important; because of them oil infiltrations emerge.

- The coasts

They present a landscape with intermountain depressions (separated by mountains), mountainous areas, a massif and an island group.

- Lara-Falcón-Yaracuy System

The reliefs of mountain ranges contrast with those of the peninsula, coastal plains and intermountain depressions.

- Lake Maracaibo Basin

The basin of the lake and the plains of the Gulf of Venezuela make up two plains: the northern one, drier, and the southern one, humid and with swamps.[171]

- The Andes

The corpulent volumes of mountain ranges and mountain ranges predominate, as well as intramontane valleys (located within the mountains).

- The plains

They form extensive sedimentary basins, with a predominantly flat relief,[177] except the eastern Llanos, which show plateaus, and the Unare depression, formed by the erosion of the mesa.

- Guiana Shield

It exhibits a varied relief, shaped by different rocks, orogenic events and erosion over millions of years. That is why here there are peneplains, mountain ranges, foothills and the characteristic tepuis.[173]

- Orinoco Delta

With few contrasts, it builds a complex system of lands and waters, with varied sedimentary contributions and innumerable channels and islands.[172]

Valleys

The valleys are undoubtedly the most important type of landscape in the Venezuelan territory,[178] not because of their spatial extension, but because they are the environment where most of the country’s population and economic activities are concentrated. On the other hand, there are valleys throughout almost all the national space, except in the great sedimentary basins of the Llanos and the depression of the Maracaibo Lake, except also in the Amazonian peneplains.[179]

By their modeling, the valleys of the Venezuelan territory belong mainly to two types: valleys of fluvial type and valleys of glacial type.[180] Much more frequent, the former largely dominate the latter, which are restricted to the highest parts of the Andes. Moreover, most glacial valleys are relics of a past geologic epoch, which culminated some 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. They are frequently retouched today by fluvial events. Consequently, any attempt to categorize the Venezuelan valleys, based exclusively on the characteristics of their modeling, would be quite elementary.

The deep and narrow Andean valleys are very different from the wide depressions of Aragua and Carabobo, in the Cordillera de la Costa, or from the valleys nestled in the Mesas de Monagas. These examples indicate that the configuration of the local relief is decisive in identifying regional types of valleys. Likewise, due to their warm climate, the Guayana valleys are distinguished from the temperate or cold Andean valleys by their humid environment. Both are, in turn, different from the semi-arid depressions of the states of Lara and Falcón.

The Andean valleys, essentially agricultural, precociously populated but nowadays in loss of speed, do not confront the same problems of space occupation as the strongly urbanized and industrialized valleys of the central section of the Cordillera de la Costa. On the other hand, the unpopulated and practically untouched Guiana valleys are another category this area is called the Lost World (Mundo Perdido).[179]

The Andean valleys are undoubtedly the most impressive of the Venezuelan territory because of the energy of the encasing reliefs, whose summits often dominate the valley bottoms by 3,000 to 3,500 meters of relative altitude. They are also the most picturesque in terms of their style of habitat, forms of land use, handicraft production and all the traditions linked to these activities. these activities[179]

Deserts

Venezuela has a great diversity of landscapes and climates,[181] including arid and dry areas. The main desert in the country is in the state of Falcon near the city of Coro. It is now a protected park, the Médanos de Coro National Park.[182] The park is the largest of its kind in Venezuela, covering 91 square kilometres. The landscape is dotted with cacti and other xerophytic plants that can survive in humidity-free conditions near the desert.

Desert wildlife includes mostly lizards, iguanas and other reptiles. Although less frequent, the desert is home to some foxes, giant anteaters and rabbits. There are also some native bird populations, such as the sparrowhawk, tropical mockingbird, scaly dove and crested quail.

Other desert areas in the country include part of the Guajira Desert in the Guajira Municipality in the north of Zulia State[183] and facing the Gulf of Venezuela, the Médanos de Capanaparo[184] in the Santos Luzardo National Park in Apure State, the Medanos de la Isla de Zapara[185] in Zulia State, the so-called Hundición de Yay[186] in the Andrés Eloy Blanco Municipality of Lara State, and the Urumaco Formation also in Falcón State.

Government and politics

Following the fall of Marcos Pérez Jiménez in 1958, Venezuelan politics were dominated by the Third Way Christian democratic COPEI and the center-left social democratic Democratic Action (AD) parties; this two-party system was formalized by the puntofijismo arrangement. Economic crises in the 1980s and 1990s led to a political crisis which resulted in hundreds dead in the Caracazo riots of 1989, two attempted coups in 1992, and impeachment of President Carlos Andrés Pérez for corruption in 1993. A collapse in confidence in the existing parties saw the 1998 election of Hugo Chávez, who had led the first of the 1992 coup attempts, and the launch of a «Bolivarian Revolution», beginning with a 1999 Constituent Assembly to write a new Constitution of Venezuela.

The opposition’s attempts to unseat Chávez included the 2002 Venezuelan coup d’état attempt, the Venezuelan general strike of 2002–2003, and the Venezuelan recall referendum, 2004, all of which failed. Chávez was re-elected in December 2006 but suffered a significant defeat in 2007 with the narrow rejection of the 2007 Venezuelan constitutional referendum, which had offered two packages of constitutional reforms aimed at deepening the Bolivarian Revolution.

Two major blocs of political parties are in Venezuela: the incumbent leftist bloc United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), its major allies Fatherland for All (PPT) and the Communist Party of Venezuela (PCV), and the opposition bloc grouped into the electoral coalition Mesa de la Unidad Democrática. This includes A New Era (UNT) together with allied parties Project Venezuela, Justice First, Movement for Socialism (MAS) and others. Hugo Chávez, the central figure of the Venezuelan political landscape since his election to the presidency in 1998 as a political outsider, died in office in early 2013, and was succeeded by Nicolás Maduro (initially as interim president, before narrowly winning the 2013 Venezuelan presidential election).

The Venezuelan president is elected by a vote, with direct and universal suffrage, and is both head of state and head of government. The term of office is six years, and (as of 15 February 2009) a president may be re-elected an unlimited number of times. The president appoints the vice president and decides the size and composition of the cabinet and makes appointments to it with the involvement of the legislature. The president can ask the legislature to reconsider portions of laws he finds objectionable, but a simple parliamentary majority can override these objections.

The president may ask the National Assembly to pass an enabling act granting the ability to rule by decree in specified policy areas; this requires a two-thirds majority in the Assembly. Since 1959, six Venezuelan presidents have been granted such powers.

The unicameral Venezuelan parliament is the Asamblea Nacional («National Assembly»). The number of members is variable – each state and the Capital district elect three representatives plus the result of dividing the state population by 1.1% of the total population of the country.[187] Three seats are reserved for representatives of Venezuela’s indigenous peoples. For the 2011–2016 period the number of seats is 165.[188] All deputies serve five-year terms.

The voting age in Venezuela is 18 and older. Voting is not compulsory.[189]

The legal system of Venezuela belongs to the Continental Law tradition. The highest judicial body is the Supreme Tribunal of Justice or Tribunal Supremo de Justicia, whose magistrates are elected by parliament for a single two-year term. The National Electoral Council (Consejo Nacional Electoral, or CNE) is in charge of electoral processes; it is formed by five main directors elected by the National Assembly. Supreme Court president Luisa Estela Morales said in December 2009 that Venezuela had moved away from «a rigid division of powers» toward a system characterized by «intense coordination» between the branches of government. Morales clarified that each power must be independent adding that «one thing is separation of powers and another one is division».[190]

Suspension of constitutional rights

The 2015 parliamentary elections were held on 6 December 2015 to elect the 164 deputies and three indigenous representatives of the National Assembly. In 2014, a series of protest and demonstrations began in Venezuela, attributed[by whom?] to inflation, violence and shortages in Venezuela. The government has accused the protest of being motivated by fascists, opposition leaders, capitalism and foreign influence,[191] despite being largely peaceful.[192]

President Maduro acknowledged PSUV defeat, but attributed the opposition’s victory to an intensification of an economic war. Despite this, Maduro said «I will stop by hook or by crook the opposition coming to power, whatever the costs, in any way».[193] In the following months, Maduro fulfilled his promise of preventing the democratically and constitutionally elected National Assembly from legislating. The first steps taken by PSUV and government were the substitution of the entire Supreme court a day after the Parliamentary Elections[194] contrary to the Constitution of Venezuela, acclaimed as a fraud by the majority of the Venezuelan and international press.[195][196][197][198] The Financial Times described the function of the Supreme Court in Venezuela as «rubber stamping executive whims and vetoing legislation».[199] The PSUV government used this violation to suspend several elected opponents,[200] ignoring again the Constitution of Venezuela. Maduro said that «the Amnesty law (approved by the Parliament) will not be executed» and asked the Supreme Court to declare it unconstitutional before the law was known.[201]

On 16 January 2016, Maduro approved an unconstitutional economic emergency decree,[202] relegating to his own figure the legislative and executive powers, while also holding judiciary power through the fraudulent designation of judges the day after the election on 6 December 2015.[194][195][196][197][198] From these events, Maduro effectively controls all three branches of government. On 14 May 2016, constitutional guarantees were in fact suspended when Maduro decreed the extension of the economic emergency decree for another 60 days and declared a State of Emergency,[203] which is a clear violation of the Constitution of Venezuela[204] in the Article 338th: «The approval of the extension of States of emergency corresponds to the National Assembly.» Thus, constitutional rights in Venezuela are considered suspended in fact by many publications[205][206][207] and public figures.[208][209][210]

On 14 May 2016, the Organization of American States was considering the application of the Inter-American Democratic Charter[211] sanctions for non-compliance to its own constitution.

In March 2017, the Venezuelan Supreme Court took over law making powers from the National Assembly[212] but reversed its decision the following day.[213]

Foreign relations

Throughout most of the 20th century, Venezuela maintained friendly relations with most Latin American and Western nations. Relations between Venezuela and the United States government worsened in 2002, after the 2002 Venezuelan coup d’état attempt during which the U.S. government recognized the short-lived interim presidency of Pedro Carmona. In 2015, Venezuela was declared a national security threat by U.S. president Barack Obama.[214][215][216] Correspondingly, ties to various Latin American and Middle Eastern countries not allied to the U.S. have strengthened. For example, Palestinian foreign minister Riyad al-Maliki declared in 2015 that Venezuela was his country’s «most important ally».[217]

Venezuela seeks alternative hemispheric integration via such proposals as the Bolivarian Alternative for the Americas trade proposal and the newly launched Latin American television network teleSUR. Venezuela is one of five nations in the world—along with Russia, Nicaragua, Nauru, and Syria—to have recognized the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Venezuela was a proponent of OAS’s decision to adopt its Anti-Corruption Convention[218] and is actively working in the Mercosur trade bloc to push increased trade and energy integration. Globally, it seeks a «multi-polar» world based on strengthened ties among undeveloped countries.

President Maduro among other Latin American leaders participating in a 2017 ALBA gathering

On 26 April 2017, Venezuela announced its intention to withdraw from the OAS.[219] Venezuelan Foreign Minister Delcy Rodríguez said that President Nicolás Maduro plans to publicly renounce Venezuela’s membership on 27 April 2017. It will take two years for the country to formally leave. During this period, the country does not plan on participating in the OAS.[220]

Venezuela is involved in a long-standing disagreement about the control of the Guayana Esequiba area.

Venezuela may suffer a deterioration of its power in international affairs if the global transition to renewable energy is completed. It is ranked 151 out of 156 countries in the index of Geopolitical Gains and Losses after energy transition (GeGaLo).[221]

Military

The Bolivarian National Armed Forces of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (Fuerza Armada Nacional Bolivariana, FANB) are the overall unified military forces of Venezuela. It includes over 320,150 men and women, under Article 328 of the Constitution, in 5 components of Ground, Sea and Air. The components of the Bolivarian National Armed Forces are: the Venezuelan Army, the Venezuelan Navy, the Venezuelan Air Force, the Venezuelan National Guard, and the Venezuelan National Militia.

As of 2008, a further 600,000 soldiers were incorporated into a new branch, known as the Armed Reserve. The president of Venezuela is the commander-in-chief of the national armed forces. The main roles of the armed forces are to defend the sovereign national territory of Venezuela, airspace, and islands, fight against drug trafficking, to search and rescue and, in the case of a natural disaster, civil protection. All male citizens of Venezuela have a constitutional duty to register for the military service at the age of 18, which is the age of majority in Venezuela.

Law and crime

Murder rate (murder per 100,000 citizens) from 1998 to 2018.

Sources: OVV,[222][223] PROVEA,[224][225] UN[224][225][226]

* UN line between 2007 and 2012 is simulated missing data.

In Venezuela, a person is murdered every 21 minutes.[230] Violent crimes have been so prevalent in Venezuela that the government no longer produces the crime data.[231] In 2013, the homicide rate was approximately 79 per 100,000, one of the world’s highest, having quadrupled in the past 15 years with over 200,000 people murdered.[232] By 2015, it had risen to 90 per 100,000.[233] The country’s body count of the previous decade mimics that of the Iraq War and in some instances had more civilian deaths even though the country is at peacetime.[234] The capital Caracas has one of the greatest homicide rates of any large city in the world, with 122 homicides per 100,000 residents.[235] In 2008, polls indicated that crime was the number one concern of voters.[236] Attempts at fighting crime such as Operation Liberation of the People were implemented to crack down on gang-controlled areas[237] but, of reported criminal acts, less than 2% are prosecuted.[238] In 2017, the Financial Times noted that some of the arms procured by the government over the previous two decades had been diverted to paramilitary civilian groups and criminal syndicates.[199]

Venezuela is especially dangerous for foreign travelers and investors who are visiting. The United States Department of State and the Government of Canada have warned foreign visitors that they may be subjected to robbery, kidnapping for a ransom or sale to terrorist organizations[239] and murder, and that their own diplomatic travelers are required to travel in armored vehicles.[240][241] The United Kingdom’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office has advised against all travel to Venezuela.[242] Visitors have been murdered during robberies and criminals do not discriminate among their victims. Former Miss Venezuela 2004 winner Mónica Spear and her ex-husband were murdered and their 5-year-old daughter was shot while vacationing in Venezuela, and an elderly German tourist was murdered only a few weeks later.[243][244]

There are approximately 33 prisons holding about 50,000 inmates.[245] They include; El Rodeo outside of Caracas, Yare Prison in the northern state of Miranda, and several others. Venezuela’s prison system is heavily overcrowded; its facilities have capacity for only 14,000 prisoners.[246]

Human rights

Human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have increasingly criticized Venezuela’s human rights record, with the former organization noting in 2017 that the Chavez and subsequently the Maduro government have increasingly concentrated power in the executive branch, eroded constitutional human rights protections and allowed the government to persecute and repress its critics and opposition.[247] Other persistent concerns as noted by the report included poor prison conditions, the continuous harassment of independent media and human rights defenders by the government. In 2006, the Economist Intelligence Unit rated Venezuela a «hybrid regime» and the third least democratic regime in Latin America on the Democracy Index.[248] The Democracy index downgraded Venezuela to an authoritarian regime in 2017, citing continued increasingly dictatorial behaviors by the Maduro government.[249]

Corruption

Corruption in Venezuela is high by world standards and was so for much of the 20th century. The discovery of oil worsened political corruption,[250] and by the late 1970s, Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonso’s description of oil as «the Devil’s excrement» had become a common expression in Venezuela.[251] Venezuela has been ranked one of the most corrupt countries on the Corruption Perceptions Index since the survey started in 1995. The 2010 ranking placed Venezuela at number 164, out of 178 ranked countries in government transparency.[252] By 2016, the rank had increased to 166 out of 178.[253] Similarly, the World Justice Project ranked Venezuela 99th out of 99 countries surveyed in its 2014 Rule of Law Index.[254]

This corruption is shown with Venezuela’s significant involvement in drug trafficking, with Colombian cocaine and other drugs transiting Venezuela towards the United States and Europe. In the period 2003 — 2008 Venezuelan authorities seized the fifth-largest total quantity of cocaine in the world, behind Colombia, the United States, Spain and Panama.[255] In 2006, the government’s agency for combating illegal drug trade in Venezuela, ONA, was incorporated into the office of the vice-president of the country. However, many major government and military officials have been known for their involvement with drug trafficking; especially with the October 2013 incident of men from the Venezuelan National Guard placing 1.3 tons of cocaine on a Paris flight knowing they would not face charges.[256]

Administrative divisions

Map of the Venezuelan federation

Venezuela is divided into 23 states (estados), a capital district (distrito capital) corresponding to the city of Caracas, and the Federal Dependencies (Dependencias Federales, a special territory). Venezuela is further subdivided into 335 municipalities (municipios); these are subdivided into over one thousand parishes (parroquias). The states are grouped into nine administrative regions (regiones administrativas), which were established in 1969 by presidential decree.[citation needed]

The country can be further divided into ten geographical areas, some corresponding to climatic and biogeographical regions. In the north are the Venezuelan Andes and the Coro region, a mountainous tract in the northwest, holds several sierras and valleys. East of it are lowlands abutting Lake Maracaibo and the Gulf of Venezuela.[citation needed]

The Central Range runs parallel to the coast and includes the hills surrounding Caracas; the Eastern Range, separated from the Central Range by the Gulf of Cariaco, covers all of Sucre and northern Monagas. The Insular Region includes all of Venezuela’s island possessions: Nueva Esparta and the various Federal Dependencies. The Orinoco Delta, which forms a triangle covering Delta Amacuro, projects northeast into the Atlantic Ocean.[citation needed]

Additionally, the country maintains a historical claim on the territory it calls Guyana Esequiba, which is equivalent to about 160,000 square kilometers and corresponds to all the territory administered by Guyana west of the Esequibo River.

In 1966 the British and Venezuelan governments signed the Geneva Agreement to resolve the conflict peacefully. In addition to this agreement, the Port of Spain Protocol of 1970 set a deadline to try to resolve the issue, without success to date.[citation needed]

|

Bolívar Amazonas Apure Zulia Táchira Barinas Mérida Trujillo Lara Portuguesa Guárico Cojedes Yaracuy Falcón Carabobo Aragua Miranda D. C. Vargas Anzoátegui Sucre Nueva Esparta Monagas Delta Amacuro Federal Dependencies Trinidad and Tobago Guyana Colombia Brazil Caribbean Sea Atlantic Ocean |

|||

| State | Capital | State | Capital |

|---|---|---|---|

| Puerto Ayacucho | Mérida | ||

| Barcelona | Los Teques | ||

| San Fernando de Apure | Maturín | ||

| Maracay | La Asunción | ||

| Barinas | Guanare | ||

| Ciudad Bolívar | Cumaná | ||

| Valencia | San Cristóbal | ||

| San Carlos | Trujillo | ||

| Tucupita | San Felipe | ||

| Caracas | Maracaibo | ||

| Coro | La Guaira | ||

| San Juan de los Morros | El Gran Roque | ||

| Barquisimeto | |||

| 1 The Federal Dependencies are not states. They are just special divisions of the territory. |

Largest cities

|

Largest cities or towns in Venezuela [257] |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | State | Pop. | Rank | Name | State | Pop. | ||

Caracas Maracaibo |

1 | Caracas | Capital District | 2,904,376 | 11 | Ciudad Bolívar | Bolívar | 342,280 |  Valencia  Barquisimeto |

| 2 | Maracaibo | Zulia | 1,906,205 | 12 | San Cristóbal | Táchira | 263,765 | ||

| 3 | Valencia | Carabobo | 1,396,322 | 13 | Cabimas | Zulia | 263,056 | ||

| 4 | Barquisimeto | Lara | 996,230 | 14 | Los Teques | Miranda | 252,242 | ||

| 5 | Ciudad Guayana | Bolívar | 706,736 | 15 | Puerto la Cruz | Anzoátegui | 244,728 | ||

| 6 | Maturín | Monagas | 542,259 | 16 | Punto Fijo | Falcón | 239,444 | ||

| 7 | Barcelona | Anzoátegui | 421,424 | 17 | Mérida | Mérida | 217,547 | ||

| 8 | Maracay | Aragua | 407,109 | 18 | Guarenas | Miranda | 209,987 | ||

| 9 | Cumaná | Sucre | 358,919 | 19 | Ciudad Ojeda | Zulia | 203,435 | ||

| 10 | Barinas | Barinas | 353.851 | 20 | Guanare | Portuguesa | 192,644 |

Economy

A proportional representation of Venezuela exports, 2019

Venezuela has a market-based mixed economy dominated by the petroleum sector,[258][259] which accounts for roughly a third of GDP, around 80% of exports, and more than half of government revenues. Per capita GDP for 2016 was estimated to be US$15,100, ranking 109th in the world.[53] Venezuela has the least expensive petrol in the world because the consumer price of petrol is heavily subsidized. The private sector controls two-thirds of Venezuela’s economy.[260]

A part of the Venezuelan economy depends on remittances.

The Central Bank of Venezuela is responsible for developing monetary policy for the Venezuelan bolívar which is used as currency. The president of the Central Bank of Venezuela serves as the country’s representative in the International Monetary Fund. The U.S.-based conservative think tank The Heritage Foundation, cited in The Wall Street Journal, claims Venezuela has the weakest property rights in the world, scoring only 5.0 on a scale of 100; expropriation without compensation is not uncommon.

As of 2011, more than 60% of Venezuela’s international reserves was in gold, eight times more than the average for the region. Most of Venezuela’s gold held abroad was located in London. On 25 November 2011, the first of US$11 billion of repatriated gold bullion arrived in Caracas; Chávez called the repatriation of gold a «sovereign» step that will help protect the country’s foreign reserves from the turmoil in the U.S. and Europe.[261] However government policies quickly spent down this returned gold and in 2013 the government was forced to add the dollar reserves of state owned companies to those of the national bank to reassure the international bond market.[262]

Annual variation of real GDP according to the Central Bank of Venezuela (2016 preliminary)[263][264]

Manufacturing contributed 17% of GDP in 2006. Venezuela manufactures and exports heavy industry products such as steel, aluminium and cement, with production concentrated around Ciudad Guayana, near the Guri Dam, one of the largest in the world and the provider of about three-quarters of Venezuela’s electricity. Other notable manufacturing includes electronics and automobiles, as well as beverages, and foodstuffs. Agriculture in Venezuela accounts for approximately 3% of GDP, 10% of the labor force, and at least a quarter of Venezuela’s land area. The country is not self-sufficient in most areas of agriculture. In 2012, total food consumption was over 26 million metric tonnes, a 94.8% increase from 2003.[citation needed]