Все категории

- Фотография и видеосъемка

- Знания

- Другое

- Гороскопы, магия, гадания

- Общество и политика

- Образование

- Путешествия и туризм

- Искусство и культура

- Города и страны

- Строительство и ремонт

- Работа и карьера

- Спорт

- Стиль и красота

- Юридическая консультация

- Компьютеры и интернет

- Товары и услуги

- Темы для взрослых

- Семья и дом

- Животные и растения

- Еда и кулинария

- Здоровье и медицина

- Авто и мото

- Бизнес и финансы

- Философия, непознанное

- Досуг и развлечения

- Знакомства, любовь, отношения

- Наука и техника

1

Большая медведица пишется с большой или маленькой буквы?

с какой буквы пишется большая медведица?

2 ответа:

3

0

Сложные астрономические названия (то есть имена собственные из двух или более слов, относящиеся к астрономии) пишутся, как правило, таким образом, чтобы все слова были с большой буквы.

Родовые слова-пояснения при этом пишут с маленькой (планета, звезда, созвездие, комета и так далее).

К числу таких составных названий относится и Большая Медведица (буквы «Б» и «М» — заглавные).

Например:

«Про созвездие Большая Медведица».

Аналогично:

- Млечный Путь.

- Волосы Вероники.

Обратите внимание, что согласование («про созвездие Большой Медведицы») было бы некорректно.

Если же мы будем говорить о самках медведя и одну из них признаем «большой медведицей», а вторую, например, «малой медведицей», то это нарицательные слова. Большие буквы отменяются.

1

0

Следует писать — Большая Медведица. Так же, как и Млечный путь, Южный Крест, Гончие Псы.

А вот слова «туманность», «созвездие», «звезда» пишутся с маленькой буквы: туманность Андромеды, созвездие Большого Пса, звезда Эрцгерцога Карла.

С маленькой буквы также пишутся и «альфа», «бета»: альфа Малой Медведицы, бета Весов.

Читайте также

«Не требуется» — это даже и не слово, а два слова. Первое — частица, а второе — глагол.

Думается, что такое предположение не было голословным, поскольку второе слово («требуется») отвечает на вопрос «что делает?» (или «что делается?», если создавать вопрос с обычной формальностью, не вдаваясь в смысл). Да и обладает другими категориальными признаками глагола.

А первое слово («не») не может быть признано приставкой, потому что если в языке есть слово «требуется», но не может быть слова «нетребуется». Это понятно из правила, обуславливающего соответствующую раздельность глаголов с «НЕ».

_

Итак, глагол «требоваться относится к совокупности тех, которые не сливаются с «НЕ». Писать «нетребуется» нельзя.

Ещё одно простейшее доказательство того — возможность принудительного разделения «НЕ» и глагола вставленным словом. Например: «не очень требуется», «не слишком требуется», «не каждый год требуется» и так далее.

Других доказательств не потребуется.

Предложение.

- «А что, разве не требуется даже подтверждения своей почты?».

«Чёрно-белый» — это сложное имя прилагательное, являющееся высокочастотным представителем так называемой колоративной лексики (выражение цвета) с возможной коннотацией «блеклый во всех отношениях» и с модальностью «отрицание цвета».

Как известно, коннотативные значения никогда не берут верх при объяснении орфографии слов, поэтому в данном случае мы должны воспринимать это прилагательное только как цветообозначение. Такие слова пишется с дефисом. К тому же части слова «чёрно-белый» совершенно семантически равноправны.

Писать «чёрно белый» (раздельно) или «чёрнобелый» (слитно) нельзя.

Например (предложения).

- «Любая чёрно-белая фотография носит в себе оттенки старины».

- «В третьем зале музея стояли чёрно-белые телевизоры».

- «Ваня Мельничаненко почему-то воспринимал мир только в чёрно-белых тонах».

1) Утверждение: Это непреступный (находящийся в рамках закона) случай простой женской хитрости.

2) Отрицание:

Случай этот — не преступный, здесь скорее нарушение общественной морали.

Случай этот отнюдь не преступный.

Планы у подростков были не преступные, а вполне безобидные.

Надо сказать, что обе формы, слитная и раздельная, используются крайне редко, в отличие от омофона «неприступный» (с большой частотностью). Особенно это касается слитного написания, когда поисковик указывает на ошибку и предлагает найти слово «неприступный».

Сочетание «со мной» (ударение на «О«, которая после «Н«) — это ни что другое, как предлог «С» с местоимением «Я«. Но мы эмпирически понимаем, что говорить «Пойдём с я» нельзя.

- «Со» — вариант «с», иногда используемый, в частности, перед [м] плюс согласная. Например: «со многими». Это из разряда «подо», «предо», «передо», «ко», «во», «надо», «обо» и так далее.

- «Мной» («мною») — это указанное выше «Я» в творительном падеже. «С кем? — со мной (со мною)». Личное местоимение.

Предлоги нельзя в таких случаях подсоединять к личным местоимениям. Подобные примеры: «с тобой (с тобою)», «с ней (с нею»)», «с ним».

Писать «сомной» нельзя. Нужен пробел.

Предложения:

- «Со мной всё в полном порядке, Трофим, а с тобой ничего не случилось ли?».

- «Будь со мной, Игнатий, не когда тебе это необходимо, а всегда».

Слово «повеселее» находится в составе систематизированного языка, в числе подобных единиц («получше», «понастойчивее», «похуже» и так далее).

Элемент «по-«, который мы при написании таких слов порой не знаем, к приставкам его отнести или к предлогам, является всё-таки приставкой.

Оттолкнёмся от имени прилагательного «весёлый» и от наречия «весело». И у первого, и у второго слов имеются формы (одинаковые!) сравнительной степени, которые образуются так:

- «Весёлый — веселее — повеселее».

- «Весело — веселее — повеселее».

К простейшей классической форме прибавляется наша приставка, преобразуя её в разговорную. Этот приём — системный. Пишется приставка слитно. Писать «по веселее» (или «по веселей») нельзя.

Например.

- «Повеселее, повеселее, Родион, не засыпай!».

Всего найдено: 14

Может ли добавление суффикса изменять род слова? Недавно довелось услышать (лепили пельмени): «Ух какое пельменище у тебя получилось!» Или правильно только «какой пельменище получился»?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Существительные, образованные с помощью суффикса -ищ(е) с увеличительным значением от слов мужского рода, относятся к мужскому роду: гвоздь — гвоздище, дождь — дождище, завод — заводище, медведь — медведище, сугроб — сугробище, холод — холодище, пельмень — пельменище.

Добрый вечер! Подскажите, пожалуйста, как правильно: …находится под созвездиями Большая и Малая Медведица, Большая и Малая Медведицы, Большой и Малой Медведицы, Большой и Малой Медведиц?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Существительное при двух определениях ставится в единственном числе, если перечисляемые разновидности предметов или явлений внутренне связаны. Поэтому предпочтительно: находится под созвездиями Большая и Малая Медведица.

Помиловать медведицу Можно так казать?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В принципе, можно, но нужно смотреть по контексту.

Определить вид придаточного предложения и составить схему. В детстве мы впервые узнавали,что мир гораздо шире комнаты с игрушками,что в синеющем за бугром лесу живут трусливые зайцы,неповоротливые медведи с хитрые лисицы.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

«Справка» не выполняет домашних заданий.

Здравствуйте! Правильно ли написаны следующие предложения?

Сотни тысяч птиц вьют гнезда среди скал, и еще больше останавливаются во время миграции.

А зимой остров навещают белые медведи в поисках своей любимой добычи: кольчатой нерпы и морского зайца.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Предложения написаны верно.

Добрый день.

Подскажите, как пишутся названия спортивных клубов, состоящие из двух слов: «Красные к(К)рылья», «Сочинские л(Л)еопарды», «Чеховские м(М)едведи»?

Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В названиях спортивных команд с большой буквы пишется первое слово и все собственные имена. Правильно: «Красные крылья», «Сочинские леопарды», «Чеховские медведи».

В учебнике по русскому языку для 6 класса есть пример: «Медведица вышла из леса с ТРОИМИ медвежатами». На мой взгляд, надо писать «С ТРЕМЯ медвежатами». Непонятно, почему числительное в школьном учебнике превратилось в собирательное. Как же правильно?

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Здесь можно использовать и собирательное, и количественное числительное, ср.: три медвежонка, трое медвежат.

К вопросу № 254849.

Хотелось бы уточнить, на каком основании Вы считаете некорректным выражение «лицо кавказской национальности». Утверждение о том, что такой национальности в природе не существует, представляется по меньшей мере странным. Ни для кого не секрет, что на Кавказе проживает множество этносов, различных по численности. При этом слово «кавказский» вполне может употребляться в значении «относящийся к Кавказу», таким образом данное выражение употребляется в обобщающем значении, употребление единственного числа (хотя национальностей на Кавказе много) также не противоречит законам русского языка (т.к. единственное число регулярно употребляется в значении множественного в том же обобщенном значении, например: «человек человеку — волк»). Думается, что с этой точки зрения выражение «лицо кавказской национальности» имеет столько же прав на существование, как и выражение «народы Севера»…

В ответе на вопрос специалисту службы скорее следовало бы уточнить, что являясь канцелярским штампом, выражение «лицо кавказской национальности» должно употребляться ограниченно (хотя немаркированного, нейтрального эквивалента у него в СРЯ нет, за исключением разве что «кавказец» (нейтральность вызывает сомнения) или описательных оборотов «выходец с Кавказа, уроженец Кавказа», причем соответствие опять-таки не вполне точное, т.к. множество представителей данных этносов родились и проживают именно в РФ, т.е. по сути и не являются выходцами с Кавказа.

Нужно также заметить, что у выражения «лицо кавказской национальности» имеется выраженная негативная коннотация, которая опять-таки вызвана не языковыми причинами, а актуальными социально-экономическими процессами на пространстве бывшего Союза ССР. Однако с учетом того, что у данного выражения существует грубо-просторечный эквивалент (приводить данную лексему здесь бессмысленно в силу ее общеизвестности), по отношению к сленговому эквиваленту данный описательный оборот является скорее эвфемизмом! Будучи же фразеологической единицей, оборот имеет полное право на идиоматичность и уникальность формы, т.е. не обязан в языке соотноситься с аналогами типа *лицо карпатской национальности. К слову сказать, для «выходцев с Украины» такого эвфемизма не существует, в силу этнической однородности населения Украины. То есть вместо соответствующего сленгового слова достаточно сказать «украинец». Фразеологизм «лицо кавказской национальности» заполняет, таким образом, лакуну в языке.

Замечу, что с точки зрения языковой типологии ситуация с этим выражением в русском языке не является уникальной. В США не принято говорить «Negro» (и т.п.), общепризнанное наименование чернокожего населения США — «Afroamerican», и говорить так — «politically correct».

Так что нет никаких оснований отрицать, что выражение «лицо кавказской национальности» — реальный языковой факт. Скорее можно утверждать, что в зависимости от условий речевого акта можно выбирать только между «очень плохим» и «слегка грубоватым» вариантами. Такова дистрибуция данного семантического поля в СРЯ, и причины этому, как говорилось выше, не языковые. Не думаю также, что по соображениям политкорректности следует «деликатно» соглашаться с противниками данного оборота в ущерб объективно существующей речевой практике. А вы попробуйте для начала убедить носителей СРЯ, что так говорить неправильно. Что вам скажут? Что люди, которые сами по-русски не всегда грамотно говорят, начинают ударяться в оголтелый пуризм. Если уж на то пошло, то слово «Russian» за границей тоже вызывает противоречивые чувства не в последнюю очередь вследствие разгульного поведения наших соотечественников, оказавшихся за рубежом, за границей и по сей день некоторые думают, что у нас в стране по улицам медведи ходят (и не обязательно на привязи с кольцом в носу).

Так что хотелось бы обратиться к противникам пресловутого выражения — не надо стремиться изменить язык, это совершенно бессмысленное занятие. язык реагирует на изменения в обществе, поэтому разумно и правильно было бы изменить стереотипы поведения представителей упомянутых национальностей в РФ. чтобы собственным примером разрушать коннотации (а вот это вполне реально).

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Спасибо за комментарий. Предлагаем Вам высказать Вашу точку зрения на нашем «Форуме».

Здравствуйте!

Мой вопрос похож на вопрос 233169.

Но я хотела бы уточнить: а какая литература является в данном случае специализированной?

Если я пишу «файлы помощи» к торговой платформе для валютных рынков, должна ли я «закавычивать» слова «медведи«, «быки», или можно писать их без кавычек и с большой буквы? Или как?

Заранее спасибо за ответ.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Слова _«быки»_ и _«медведи»_ в таком значнии следует писать в кавычках во всех текстах.

Задавала вам этот вопрос вчера, но не получила ответ. Подскажите, нужно ли закавычивать слова шорт и лонг, и писать слова медведи и быки в кавычках и с большой буквы.

Несколько сложнее выглядит схема открытия короткой позиции, или «шорта».

Трейдеры, открывающие «лонг», на бирже зовутся «Быками», а открывающие «шорт» – «Медведями».

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Эти слова в неспециализированной литературе следует писать в кавычках с маленькой буквы.

Как правильно — «в созвездии Ориона» или «в созвездии Орион», «в созвездии Большой Медведицы» или «в созвездии Большая Медведица»? (интересует общее правило, приложимое ко всем созвездиям). Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно: _в созвездии Орион, в созвездии Большая Медведица_.

Скажите, пожалуйста, каковы правила употребления сочетаний типа «в городе Москва/Москве, в созвездии Большая Медведица/Большой Медведицы»? Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

1. О городе Москве см. в http://spravka.gramota.ru/blang.html?id=167 [Письмовнике]. 2. Корректно: _в созвездии Большая Медведица_.

1. 1. В вышедшем академическом справочнике «Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации» (под ред. Лопатина) рекомендуется отделять слово «например» перед подчинительным союзом: Я это всё равно сделаю, например, когда рак на горе свистнет. Это отменяет правило, которое было у Розенталя: «если перед подчинительным союзом стоят слова «особенно, лишь, например и т. д., то они запятыми не отделяются»? 2. У Розенталя было правило, согласно которому «если после обобщающих слов стоят слова «как то, а именно, то есть, например», то перед ними ставится запятая, а после них двоеточие». В академическом справочнике приводтся только слова «как например, например, как то, а именно», а «то есть» нет. Это значит, что теперь будет правильным так: Там были многие звери, в том числе медведи, рыси, косули, обезьяны, барсуки?

2. Верна ли пунктуация? И со словами: «Я покидаю этот фарс» — под аплодисменты зала удалился. Если не верно, то скажите, пожалуйста, как верно и почему именно так.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

1. Пожалуйста, укажите, в каком параграфе нового академического справочника Вы встретили данную рекомендацию.

2. Не совсем понятна логика вопроса: Вы спрашиваете про _то есть_, а пример приводите со словами _в том числе_. Рекомендации ставить двоеточие после слов _в том числе_ нет ни у Розенталя, ни в новом справочнике. Таким образом, приведенный Вами пример написан правильно. Что касается слов _то есть_, то, действительно, в новом справочнике они не указаны при перечислении уточняющих слов (при обобщающих словах), после которых ставится двоеточие. Мы постараемся уточнить этот вопрос у авторов справочника.

3. Корректно: _И со словами «Я покидаю этот фарс» под аплодисменты зала удалился_. Если прямая речь непосредственно включается в авторское предложение в качестве его члена, то она заключается в кавычки, знаки же препинания ставятся по условиям авторского предложения.

Подскажите пожалуйста, какой корень в слове «медведица»

медвед или два мед и вед. (Также как слово ландыш)Заранее спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корни: _медвед, ландыш_.

| Constellation | |

List of stars in Ursa Major |

|

| Abbreviation | UMa |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Ursae Majoris |

| Pronunciation | , genitive |

| Symbolism | the Great Bear |

| Right ascension | 10.67h |

| Declination | +55.38° |

| Quadrant | NQ2 |

| Area | 1280 sq. deg. (3rd) |

| Main stars | 7, 20 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars |

93 |

| Stars with planets | 21 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 7 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 8 |

| Brightest star | ε UMa (Alioth) (1.76m) |

| Messier objects | 7 |

| Meteor showers | Alpha Ursae Majorids Leonids |

| Bordering constellations |

Draco Camelopardalis Lynx Leo Minor Leo Coma Berenices Canes Venatici Boötes |

| Visible at latitudes between +90° and −30°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of April. The Big Dipper or Plough |

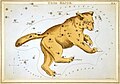

Ursa Major (; also known as the Great Bear) is a constellation in the northern sky, whose associated mythology likely dates back into prehistory. Its Latin name means «greater (or larger) bear,» referring to and contrasting it with nearby Ursa Minor, the lesser bear.[1] In antiquity, it was one of the original 48 constellations listed by Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD, drawing on earlier works by Greek, Egyptian, Babylonian, and Assyrian astronomers.[2] Today it is the third largest of the 88 modern constellations.

Ursa Major is primarily known from the asterism of its main seven stars, which has been called the «Big Dipper,» «the Wagon,» «Charles’s Wain,» or «the Plough,» among other names. In particular, the Big Dipper’s stellar configuration mimics the shape of the «Little Dipper.» Two of its stars, named Dubhe and Merak (α Ursae Majoris and β Ursae Majoris), can be used as the navigational pointer towards the place of the current northern pole star, Polaris in Ursa Minor.

Ursa Major, along with asterisms that incorporate or comprise it, is significant to numerous world cultures, often as a symbol of the north. Its depiction on the flag of Alaska is a modern example of such symbolism.

Ursa Major is visible throughout the year from most of the Northern Hemisphere, and appears circumpolar above the mid-northern latitudes. From southern temperate latitudes, the main asterism is invisible, but the southern parts of the constellation can still be viewed.

Characteristics[edit]

Ursa Major covers 1279.66 square degrees or 3.10% of the total sky, making it the third largest constellation.[3] In 1930, Eugène Delporte set its official International Astronomical Union (IAU) constellation boundaries, defining it as a 28-sided irregular polygon. In the equatorial coordinate system, the constellation stretches between the right ascension coordinates of 08h 08.3m and 14h 29.0m and the declination coordinates of +28.30° and +73.14°.[4] Ursa Major borders eight other constellations: Draco to the north and northeast, Boötes to the east, Canes Venatici to the east and southeast, Coma Berenices to the southeast, Leo and Leo Minor to the south, Lynx to the southwest and Camelopardalis to the northwest. The three-letter constellation abbreviation «UMa» was adopted by the IAU in 1922.[5]

Features[edit]

Asterisms[edit]

The constellation Ursa Major as it can be seen by the unaided eye.

The outline of the seven bright stars of Ursa Major form the asterism known as the «Big Dipper» in the United States and Canada, while in the United Kingdom it is called the Plough [6] or (historically) Charles’ Wain.[7] Six of the seven stars are of second magnitude or higher, and it forms one of the best-known patterns in the sky.[8][9] As many of its common names allude, its shape is said to resemble a ladle, an agricultural plough, or wagon. In the context of Ursa Major, they are commonly drawn to represent the hindquarters and tail of the Great Bear. Starting with the «ladle» portion of the dipper and extending clockwise (eastward in the sky) through the handle, these stars are the following:

- α Ursae Majoris, known by the Arabic name Dubhe («the bear»), which at a magnitude of 1.79 is the 35th-brightest star in the sky and the second-brightest of Ursa Major.

- β Ursae Majoris, called Merak («the loins of the bear»), with a magnitude of 2.37.

- γ Ursae Majoris, known as Phecda («thigh»), with a magnitude of 2.44.

- δ Ursae Majoris, or Megrez, meaning «root of the tail,» referring to its location as the intersection of the body and tail of the bear (or the ladle and handle of the dipper).

- ε Ursae Majoris, known as Alioth, a name which refers not to a bear but to a «black horse,» the name corrupted from the original and mis-assigned to the similarly named Alcor, the naked-eye binary companion of Mizar.[10] Alioth is the brightest star of Ursa Major and the 33rd-brightest in the sky, with a magnitude of 1.76. It is also the brightest of the chemically peculiar Ap stars, magnetic stars whose chemical elements are either depleted or enhanced, and appear to change as the star rotates.[10]

- ζ Ursae Majoris, Mizar, the second star in from the end of the handle of the Big Dipper, and the constellation’s fourth-brightest star. Mizar, which means «girdle,» forms a famous double star, with its optical companion Alcor (80 Ursae Majoris), the two of which were termed the «horse and rider» by the Arabs.

- η Ursae Majoris, known as Alkaid, meaning the «end of the tail». With a magnitude of 1.85, Alkaid is the third-brightest star of Ursa Major.[11][12]

Except for Dubhe and Alkaid, the stars of the Big Dipper all have proper motions heading toward a common point in Sagittarius. A few other such stars have been identified, and together they are called the Ursa Major Moving Group.

Ursa Major and Ursa Minor in relation to Polaris

The stars Merak (β Ursae Majoris) and Dubhe (α Ursae Majoris) are known as the «pointer stars» because they are helpful for finding Polaris, also known as the North Star or Pole Star. By visually tracing a line from Merak through Dubhe (1 unit) and continuing for 5 units, one’s eye will land on Polaris, accurately indicating true north.

Another asterism known as the «Three Leaps of the Gazelle»[13] is recognized in Arab culture. It is a series of three pairs of stars found along the southern border of the constellation. From southeast to southwest, the «first leap», comprising ν and ξ Ursae Majoris (Alula Borealis and Australis, respectively); the «second leap», comprising λ and μ Ursae Majoris (Tania Borealis and Australis); and the «third leap», comprising ι and κ Ursae Majoris, (Talitha Borealis and Australis respectively).

Other stars[edit]

W Ursae Majoris is the prototype of a class of contact binary variable stars, and ranges between 7.75m and 8.48m.

47 Ursae Majoris is a Sun-like star with a three-planet system.[14] 47 Ursae Majoris b, discovered in 1996, orbits every 1078 days and is 2.53 times the mass of Jupiter.[15] 47 Ursae Majoris c, discovered in 2001, orbits every 2391 days and is 0.54 times the mass of Jupiter.[16] 47 Ursae Majoris d, discovered in 2010, has an uncertain period, lying between 8907 and 19097 days; it is 1.64 times the mass of Jupiter.[17] The star is of magnitude 5.0 and is approximately 46 light-years from Earth.[14]

The star TYC 3429-697-1 (9h 40m 44s 48° 14′ 2″), located to the east of θ Ursae Majoris and to the southwest of the «Big Dipper») has been recognized as the state star of Delaware, and is informally known as the Delaware Diamond.[18]

Deep-sky objects[edit]

Several bright galaxies are found in Ursa Major, including the pair Messier 81 (one of the brightest galaxies in the sky) and Messier 82 above the bear’s head, and Pinwheel Galaxy (M101), a spiral northeast of η Ursae Majoris. The spiral galaxies Messier 108 and Messier 109 are also found in this constellation. The bright planetary nebula Owl Nebula (M97) can be found along the bottom of the bowl of the Big Dipper.

M81 is a nearly face-on spiral galaxy 11.8 million light-years from Earth. Like most spiral galaxies, it has a core made up of old stars, with arms filled with young stars and nebulae. Along with M82, it is a part of the galaxy cluster closest to the Local Group.

M82 is a nearly edgewise galaxy that is interacting gravitationally with M81. It is the brightest infrared galaxy in the sky.[19] SN 2014J, an apparent Type Ia supernova, was observed in M82 on 21 January 2014.[20]

M97, also called the Owl Nebula, is a planetary nebula 1,630 light-years from Earth; it has a magnitude of approximately 10. It was discovered in 1781 by Pierre Méchain.[21]

M101, also called the Pinwheel Galaxy, is a face-on spiral galaxy located 25 million light-years from Earth. It was discovered by Pierre Méchain in 1781. Its spiral arms have regions with extensive star formation and have strong ultraviolet emissions.[19] It has an integrated magnitude of 7.5, making it visible in both binoculars and telescopes, but not to the naked eye.[22]

NGC 2787 is a lenticular galaxy at a distance of 24 million light-years. Unlike most lenticular galaxies, NGC 2787 has a bar at its center. It also has a halo of globular clusters, indicating its age and relative stability.[19]

NGC 2950 is a lenticular galaxy located 60 million light-years from Earth.

NGC 3079 is a starburst spiral galaxy located 52 million light-years from Earth. It has a horseshoe-shaped structure at its center that indicates the presence of a supermassive black hole. The structure itself is formed by superwinds from the black hole.[19]

NGC 3310 is another starburst spiral galaxy located 50 million light-years from Earth. Its bright white color is caused by its higher than usual rate of star formation, which began 100 million years ago after a merger. Studies of this and other starburst galaxies have shown that their starburst phase can last for hundreds of millions of years, far longer than was previously assumed.[19]

NGC 4013 is an edge-on spiral galaxy located 55 million light-years from Earth. It has a prominent dust lane and has several visible star forming regions.[19]

I Zwicky 18 is a young dwarf galaxy at a distance of 45 million light-years. The youngest-known galaxy in the visible universe, I Zwicky 18 is about 4 million years old, about one-thousandth the age of the Solar System. It is filled with star forming regions which are creating many hot, young, blue stars at a very high rate.[19]

The Hubble Deep Field is located to the northeast of δ Ursae Majoris.

Meteor showers[edit]

The Kappa Ursae Majorids are a newly discovered meteor shower, peaking between November 1 and November 10.[23]

[edit]

HD 80606, a sun-like star in a binary system, orbits a common center of gravity with its partner, HD 80607; the two are separated by 1,200 AU on average. Research conducted in 2003 indicates that its sole planet, HD 80606 b is a future hot Jupiter, modeled to have evolved in a perpendicular orbit around 5 AU from its sun. The 4-Jupiter mass planet is projected to eventually move into a circular, more aligned orbit via the Kozai mechanism. However, it is currently on an incredibly eccentric orbit that ranges from approximately one astronomical unit at its apoapsis and six stellar radii at periapsis.[24]

History[edit]

Ursa Major shown on a carved stone, c.1700, Crail, Fife

Ursa Major has been reconstructed as an Indo-European constellation.[25] It was one of the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd century AD astronomer Ptolemy in his Almagest, who called it Arktos Megale.[a] It is mentioned by such poets as Homer, Spenser, Shakespeare, Tennyson and also by Federico Garcia Lorca, in «Song for the Moon».[27] Ancient Finnish poetry also refers to the constellation, and it features in the painting Starry Night Over the Rhône by Vincent van Gogh.[28][29] It may be mentioned in the biblical book of Job, dated between the 7th and 4th centuries BC, although this is often disputed.[30]

Mythology[edit]

The constellation of Ursa Major has been seen as a bear, usually female,[31] by many distinct civilizations.[32] This may stem from a common oral tradition of Cosmic Hunt myths stretching back more than 13,000 years.[33] Using statistical and phylogenetic tools, Julien d’Huy reconstructs the following Palaeolithic state of the story: «There is an animal that is a horned herbivore, especially an elk. One human pursues this ungulate. The hunt locates or get to the sky. The animal is alive when it is transformed into a constellation. It forms the Big Dipper.»[34]

Greco-Roman tradition[edit]

In Greek mythology, Zeus (the king of the gods, known as Jupiter in Roman mythology), lusts after a young woman named Callisto, a nymph of Artemis (known to the Romans as Diana). Zeus’s jealous wife Hera, (Juno to the Romans), discovers that Callisto has a son named Arcas as the result of her rape by Zeus and transforms Callisto into a bear as a punishment.[35] Callisto, while in bear form, later encounters her son Arcas. Arcas almost spears the bear, but to avert the tragedy Zeus whisks them both into the sky, Callisto as Ursa Major and Arcas as the constellation Boötes. Ovid called Ursa Major the Parrhasian Bear, since Callisto came from Parrhasia in Arcadia, where the story is set.[36]

The Greek poet Aratus called the constellation Helike, (“turning» or “twisting”), because it turns around the celestial pole. The Odyssey notes that it is the sole constellation that never sinks below the horizon and «bathes in the Ocean’s waves,» so it is used as a celestial reference point for navigation.[37] It has also been called the “Wain» or “Plaustrum”, a Latin word referring to a horse-drawn cart.[38]

Hindu tradition[edit]

In Hinduism, Ursa Major/Big dipper/ Great Bear is known as Saptarshi, each of the stars representing one of the Saptarishis or Seven Sages (Rishis) viz. Bhrigu, Atri, Angiras, Vasishtha, Pulastya, Pulaha, and Kratu. The fact that the two front stars of the constellations point to the pole star is explained as the boon given to the boy sage Dhruva by Lord Vishnu.[39]

Judeo-Christian tradition[edit]

One of the few star groups mentioned in the Bible (Job 9:9; 38:32; – Orion and the Pleiades being others), Ursa Major was also pictured as a bear by the Jewish peoples. «The Bear» was translated as «Arcturus» in the Vulgate and it persisted in the King James Version of the Bible.

East Asian traditions[edit]

In China and Japan, the Big Dipper is called the «North Dipper» 北斗 (Chinese: běidǒu, Japanese: hokuto), and in ancient times, each one of the seven stars had a specific name, often coming themselves from ancient China:

-

- «Pivot» 樞 (C: shū J: sū) is for Dubhe (Alpha Ursae Majoris)

- «Beautiful jade» 璇 (C: xuán J: sen) is for Merak (Beta Ursae Majoris)

- «Pearl» 璣 (C: jī J: ki) is for Phecda (Gamma Ursae Majoris)

- «Balance»[40] 權 (C: quán J: ken) is for Megrez (Delta Ursae Majoris)

- «Measuring rod of jade» 玉衡 (C: yùhéng J: gyokkō) is for Alioth (Epsilon Ursae Majoris)

- «Opening of the Yang» 開陽 (C: kāiyáng J: kaiyō) is for Mizar (Zeta Ursae Majoris)

- Alkaid (Eta Ursae Majoris) has several nicknames: «Sword» 劍 (C: jiàn J: ken) (short form from «End of the sword» 劍先 (C: jiàn xiān J: ken saki)), «Flickering light» 搖光 (C: yáoguāng J: yōkō), or again «Star of military defeat» 破軍星 (C: pójūn xīng J: hagun sei), because travel in the direction of this star was regarded as bad luck for an army.[41]

In Shinto, the seven largest stars of Ursa Major belong to Ame-no-Minakanushi, the oldest and most powerful of all kami.

In South Korea, the constellation is referred to as «the seven stars of the north». In the related myth, a widow with seven sons found comfort with a widower, but to get to his house required crossing a stream. The seven sons, sympathetic to their mother, placed stepping stones in the river. Their mother, not knowing who put the stones in place, blessed them and, when they died, they became the constellation.

Native American traditions[edit]

The Iroquois interpreted Alioth, Mizar, and Alkaid as three hunters pursuing the Great Bear. According to one version of their myth, the first hunter (Alioth) is carrying a bow and arrow to strike down the bear. The second hunter (Mizar) carries a large pot – the star Alcor – on his shoulder in which to cook the bear while the third hunter (Alkaid) hauls a pile of firewood to light a fire beneath the pot.

The Lakota people call the constellation Wičhákhiyuhapi, or «Great Bear.»

The Wampanoag people (Algonquian) referred to Ursa Major as «maske,» meaning «bear» according to Thomas Morton in The New England Canaan.[42]

The Wasco-Wishram Native Americans interpreted the constellation as 5 wolves and 2 bears that were left in the sky by Coyote.[43]

Germanic traditions[edit]

To Norse pagans, the Big Dipper was known as Óðins vagn, «Woden’s wagon». Likewise Woden is poetically referred to by Kennings such as vagna verr ‘guardian of the wagon’ or vagna rúni ‘confidant of the wagon’[44]

Uralic traditions[edit]

In the Finnish language, the asterism is sometimes called by its old Finnish name, Otava. The meaning of the name has been almost forgotten in Modern Finnish; it means a salmon weir. Ancient Finns believed the bear (Ursus arctos) was lowered to earth in a golden basket off the Ursa Major, and when a bear was killed, its head was positioned on a tree to allow the bear’s spirit to return to Ursa Major.

In the Sámi languages of Northern Europe, part of the constellation (i.e. the Big Dipper minus Dubhe and Merak, is identified as the bow of the great hunter Fávdna (the star Arcturus). In the main Sámi language, North Sámi it is called Fávdnadávgi («Fávdna’s Bow») or simply dávggát («the Bow»). The constellation features prominently in the Sámi national anthem, which begins with the words Guhkkin davvin dávggaid vuolde sabmá suolggai Sámieanan, which translates to «Far to the north, under the Bow, the Land of the Sámi slowly comes into view.» The Bow is an important part of the Sámi traditional narrative about the night sky, in which various hunters try to chase down Sarva, the Great Reindeer, a large constellation that takes up almost half the sky. According to the legend, Fávdna stands ready to fire his Bow every night but hesitates because he might hit Stella Polaris, known as Boahji («the Rivet»), which would cause the sky to collapse and end the world.[45]

Southeast Asian traditions[edit]

In Burmese, Pucwan Tārā (ပုဇွန် တာရာ, pronounced «bazun taya») is the name of a constellation comprising stars from the head and forelegs of Ursa Major; pucwan (ပုဇွန်) is a general term for a crustacean, such as prawn, shrimp, crab, lobster, etc.

In Javanese, it is known as «lintang jong,» which means «the jong constellation.» Likewise, in Malay it is called «bintang jong.»[46]

Esoteric lore[edit]

In Theosophy, it is believed that the Seven Stars of the Pleiades focus the spiritual energy of the seven rays from the Galactic Logos to the Seven Stars of the Great Bear, then to Sirius, then to the Sun, then to the god of Earth (Sanat Kumara), and finally through the seven Masters of the Seven Rays to the human race.[47]

Graphic visualisation[edit]

In European star charts, the constellation was visualized with the ‘square’ of the Big Dipper forming the bear’s body and the chain of stars forming the Dipper’s «handle» as a long tail. However, bears do not have long tails, and Jewish astronomers considered Alioth, Mizar, and Alkaid instead to be three cubs following their mother, while the Native Americans saw them as three hunters.

H. A. Rey’s alternative asterism for Ursa Major can be said to give it the longer head and neck of a polar bear, as seen in this photo, from the left side.

Noted children’s book author H. A. Rey, in his 1952 book The Stars: A New Way to See Them, (ISBN 0-395-24830-2) had a different asterism in mind for Ursa Major, that instead had the «bear» image of the constellation oriented with Alkaid as the tip of the bear’s nose, and the «handle» of the Big Dipper part of the constellation forming the outline of the top of the bear’s head and neck, rearwards to the shoulder, potentially giving it the longer head and neck of a polar bear.[48]

-

Ursa Major as depicted in Urania’s Mirror, a set of constellation cards published in London c.1825.

-

Johannes Hevelius drew Ursa Major as if being viewed from outside the celestial sphere.

-

Ursa Major is also pictured as the Starry Plough, the Irish flag of Labour, adopted by James Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army in 1916, which shows the constellation on a blue background; on the state flag of Alaska; and on the House of Bernadotte’s variation of the coat of arms of Sweden. The seven stars on a red background of the flag of the Community of Madrid, Spain, may be the stars of the Plough asterism (or of Ursa Minor). The same can be said of the seven stars pictured in the bordure azure of the coat of arms of Madrid, capital of that country.

See also[edit]

- Ursa Major (Chinese astronomy)

- Ursa Minor

- Southern Cross

- Celestial cartography

- Constellation family

- Former constellations

- Lists of stars by constellation

- Constellations listed by Johannes Hevelius

- Constellations listed by Lacaille

- Constellations listed by Petrus Plancius

- Constellations listed by Ptolemy

Notes[edit]

- ^ Ptolemy named the constellation in Greek Ἄρκτος μεγάλη (Arktos Megale) or the great bear. Ursa Minor was Arktos Mikra[26]

References[edit]

- ^ «Chandra: Constellation Ursa Major». chandra.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2022-07-07.

- ^ «Constellation | COSMOS». astronomy.swin.edu.au. Retrieved 2022-07-07.

- ^ «Constellations Lacerta–Vulpecula».

- ^ «Ursa Major, Constellation Boundary». The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ «The Constellations». Archived from the original on 2013-07-08. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- ^ Reader’s Digest Association (August 2005). Planet Earth and the Universe. Reader’s Digest Association, Limited. ISBN 978-0-276-42715-2. Archived from the original on 2021-04-15. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ^ «Charles’ Wain». Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ André G. Bordeleau (22 October 2013). Flags of the Night Sky: When Astronomy Meets National Pride. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 131–. ISBN 978-1-4614-0929-8. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ James B. Kaler (28 July 2011). Stars and Their Spectra: An Introduction to the Spectral Sequence. Cambridge University Press. pp. 241–. ISBN 978-0-521-89954-3. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ a b Jim Kaler (2009-09-16). «Stars: «Alioth»«. Archived from the original on 2019-12-11. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- ^ Mark R. Chartrand (1982). Skyguide, a Field Guide for Amateur Astronomers. Golden Press. Bibcode:1982sfga.book…..C. ISBN 978-0-307-13667-1. Archived from the original on 2021-04-15. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- ^ Ridpath, at p. 136.

- ^ «Ursa Major & Ursa Minor». Winter Sky Tour. Archived from the original on 2012-12-19.

- ^ a b Levy 2005, p. 67.

- ^ «Planet 47 Uma b». The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Paris Observatory. 11 July 2012. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ «Planet 47 Uma c». The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Paris Observatory. 11 July 2012. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ «Planet 47 Uma d». The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Paris Observatory. 11 July 2012. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ «Delaware Facts & Symbols – Delaware Miscellaneous Symbols». delaware.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-03-28. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wilkins, Jamie; Dunn, Robert (2006). 300 Astronomical Objects: A Visual Reference to the Universe (1st ed.). Buffalo, New York: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-175-3.

- ^ Cao, Y; Kasliwal, M. M; McKay, A; Bradley, A (2014). «Classification of Supernova in M82 as a young, reddened Type Ia Supernova». The Astronomer’s Telegram. 5786: 1. Bibcode:2014ATel.5786….1C.

- ^ Levy 2005, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Seronik, Gary (July 2012). «M101: A Bear of a Galaxy». Sky & Telescope. 124 (1): 45. Bibcode:2012S&T…124a..45S.

- ^ Jenniskens, Peter (September 2012). «Mapping Meteoroid Orbits: New Meteor Showers Discovered». Sky & Telescope: 23.

- ^ Laughlin, Greg (May 2013). «How Worlds Get Out of Whack». Sky and Telescope. 125 (5): 29. Bibcode:2013S&T…125e..26L.

- ^

Mallory, J.P.; Adams, D.Q. (August 2006). «Chapter 8.5: The Physical Landscape of the Proto-Indo-Europeans». Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford, GBR: Oxford University Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780199287918. OCLC 139999117.The most solidly ‘reconstructed’ Indo-European constellation is Ursa Major, which is designated as ‘The Bear’ (Chapter 9) in Greek and Sanskrit (Latin may be a borrowing here), although even the latter identification has been challenged.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. «Ptolemy’s Almagest: First printed edition, 1515». Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ «Canción para la luna — Federico García Lorca — Ciudad Seva». Archived from the original on 2015-05-10. Retrieved 2015-08-16.

- ^ Frog (2018-01-30). «Myth». Humanities. 7 (1): 14. doi:10.3390/h7010014. ISSN 2076-0787.

- ^ Clayson, Hollis (2002). «Exhibition Review: «Some Things Bear Fruit»? Witnessing the Bonds between Van Gogh and Gauguin». The Art Bulletin. 84 (4): 670–684. doi:10.2307/3177290. ISSN 0004-3079. JSTOR 3177290.

- ^ Botterweck, G. Johannes, ed. (1994). Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, Volume 7. Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-0-8028-2331-1. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- ^ Allen, R. H. (1963). Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning (Reprint ed.). New York, NY: Dover Publications Inc. pp. 207–208. ISBN 978-0-486-21079-7. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- ^ Gibbon, William B. (1964). «Asiatic parallels in North American star lore: Ursa Major». Journal of American Folklore. 77 (305): 236–250. doi:10.2307/537746. JSTOR 537746.

- ^ Bradley E Schaefer, The Origin of the Greek Constellations: Was the Great Bear constellation named before hunter nomads first reached the Americas more than 13,000 years ago?, Scientific American, November 2006, reviewed at The Origin of the Greek Constellations Archived 2017-04-01 at the Wayback Machine; Yuri Berezkin, The cosmic hunt: variants of a Siberian – North-American myth Archived 2015-05-04 at the Wayback Machine. Folklore, 31, 2005: 79–100.

- ^ d’Huy Julien, Un ours dans les étoiles: recherche phylogénétique sur un mythe préhistorique Archived 2021-12-20 at the Wayback Machine, Préhistoire du sud-ouest, 20 (1), 2012: 91–106; A Cosmic Hunt in the Berber sky : a phylogenetic reconstruction of Palaeolithic mythology Archived 2020-05-28 at the Wayback Machine, Les Cahiers de l’AARS, 15, 2012.

- ^ «Ursa Major, The Great Bear». Ian Ridpath’s Star Tales.

- ^ Ovid, Heroides (trans. Grant Showerman) Epistle 18

- ^ Homer, Odyssey, book 5, 273

- ^ «Apianus’s depictions of Ursa Major and Ursa Minor». Ian Ridpath’s Star Tales.

- ^ Mahadev Haribhai Desai (1973). Day-to-day with Gandhi: Secretary’s Diary. Sarva Seva Sangh Prakashan. Archived from the original on 2022-05-13. Retrieved 2021-01-06.

- ^ «English-Chinese Glossary of Chinese Star Regions, Asterisms and Star Names». Hong Kong Space Museum. Archived from the original on 17 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ The Bansenshukai, written in 1676 by the ninja master Fujibayashi Yasutake, speak several times about these stars, and show a traditional picture of the Big Dipper in his book 8, volume 17, speaking about astronomy and meteorology (from Axel Mazuer’s translation).

- ^ Thomas, Morton (13 September 1883). The new English Canaan of Thomas Morton. Published by the Prince Society. OL 7142058M.

- ^ Clark, Ella Elizabeth (1963). Indian Legends of the Pacific Northwest. University of California Press. Archived from the original on 2022-05-13. Retrieved 2019-05-01.

- ^ Cleasby, Richard; Vigfússon, Guðbrandur (1874). An Icelandic-English Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 674.

- ^ Naturfagsenteret.no: Stjernehimmelen (https://www.naturfagsenteret.no/c1515376/binfil/download2.php?tid=1509706)

- ^ Burnell, A.C. (2018). Hobson-Jobson: Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words And Phrases. Routledge. p. 472. ISBN 9781136603310.

- ^ Baker, Dr. Douglas The Seven Rays:Key to the Mysteries 1952

- ^ «Archived representation of H.A. Rey’s asterism for Ursa Major». Archived from the original on 2014-04-07.

- Bibliography

- Levy, David H. (2005). Deep Sky Objects. Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-59102-361-6.

- Thompson, Robert; Thompson, Barbara (2007). Illustrated Guide to Astronomical Wonders: From Novice to Master Observer. O’Reilly Media, Inc. ISBN 978-0-596-52685-6.

Further reading[edit]

- Ian Ridpath and Wil Tirion (2007). Stars and Planets Guide, Collins, London. ISBN 978-0-00-725120-9. Princeton University Press, Princeton. ISBN 978-0-691-13556-4.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ursa Major.

- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Ursa Major

- The clickable Ursa Major

- AAVSO: The Myths of Ursa Major

- The Origin of the Greek Constellations (paywalled)

- Star Tales – Ursa Major

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (medieval and early modern images of Ursa Major)

| Constellation | |

List of stars in Ursa Major |

|

| Abbreviation | UMa |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Ursae Majoris |

| Pronunciation | , genitive |

| Symbolism | the Great Bear |

| Right ascension | 10.67h |

| Declination | +55.38° |

| Quadrant | NQ2 |

| Area | 1280 sq. deg. (3rd) |

| Main stars | 7, 20 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars |

93 |

| Stars with planets | 21 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 7 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 8 |

| Brightest star | ε UMa (Alioth) (1.76m) |

| Messier objects | 7 |

| Meteor showers | Alpha Ursae Majorids Leonids |

| Bordering constellations |

Draco Camelopardalis Lynx Leo Minor Leo Coma Berenices Canes Venatici Boötes |

| Visible at latitudes between +90° and −30°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of April. The Big Dipper or Plough |

Ursa Major (; also known as the Great Bear) is a constellation in the northern sky, whose associated mythology likely dates back into prehistory. Its Latin name means «greater (or larger) bear,» referring to and contrasting it with nearby Ursa Minor, the lesser bear.[1] In antiquity, it was one of the original 48 constellations listed by Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD, drawing on earlier works by Greek, Egyptian, Babylonian, and Assyrian astronomers.[2] Today it is the third largest of the 88 modern constellations.

Ursa Major is primarily known from the asterism of its main seven stars, which has been called the «Big Dipper,» «the Wagon,» «Charles’s Wain,» or «the Plough,» among other names. In particular, the Big Dipper’s stellar configuration mimics the shape of the «Little Dipper.» Two of its stars, named Dubhe and Merak (α Ursae Majoris and β Ursae Majoris), can be used as the navigational pointer towards the place of the current northern pole star, Polaris in Ursa Minor.

Ursa Major, along with asterisms that incorporate or comprise it, is significant to numerous world cultures, often as a symbol of the north. Its depiction on the flag of Alaska is a modern example of such symbolism.

Ursa Major is visible throughout the year from most of the Northern Hemisphere, and appears circumpolar above the mid-northern latitudes. From southern temperate latitudes, the main asterism is invisible, but the southern parts of the constellation can still be viewed.

Characteristics[edit]

Ursa Major covers 1279.66 square degrees or 3.10% of the total sky, making it the third largest constellation.[3] In 1930, Eugène Delporte set its official International Astronomical Union (IAU) constellation boundaries, defining it as a 28-sided irregular polygon. In the equatorial coordinate system, the constellation stretches between the right ascension coordinates of 08h 08.3m and 14h 29.0m and the declination coordinates of +28.30° and +73.14°.[4] Ursa Major borders eight other constellations: Draco to the north and northeast, Boötes to the east, Canes Venatici to the east and southeast, Coma Berenices to the southeast, Leo and Leo Minor to the south, Lynx to the southwest and Camelopardalis to the northwest. The three-letter constellation abbreviation «UMa» was adopted by the IAU in 1922.[5]

Features[edit]

Asterisms[edit]

The constellation Ursa Major as it can be seen by the unaided eye.

The outline of the seven bright stars of Ursa Major form the asterism known as the «Big Dipper» in the United States and Canada, while in the United Kingdom it is called the Plough [6] or (historically) Charles’ Wain.[7] Six of the seven stars are of second magnitude or higher, and it forms one of the best-known patterns in the sky.[8][9] As many of its common names allude, its shape is said to resemble a ladle, an agricultural plough, or wagon. In the context of Ursa Major, they are commonly drawn to represent the hindquarters and tail of the Great Bear. Starting with the «ladle» portion of the dipper and extending clockwise (eastward in the sky) through the handle, these stars are the following:

- α Ursae Majoris, known by the Arabic name Dubhe («the bear»), which at a magnitude of 1.79 is the 35th-brightest star in the sky and the second-brightest of Ursa Major.

- β Ursae Majoris, called Merak («the loins of the bear»), with a magnitude of 2.37.

- γ Ursae Majoris, known as Phecda («thigh»), with a magnitude of 2.44.

- δ Ursae Majoris, or Megrez, meaning «root of the tail,» referring to its location as the intersection of the body and tail of the bear (or the ladle and handle of the dipper).

- ε Ursae Majoris, known as Alioth, a name which refers not to a bear but to a «black horse,» the name corrupted from the original and mis-assigned to the similarly named Alcor, the naked-eye binary companion of Mizar.[10] Alioth is the brightest star of Ursa Major and the 33rd-brightest in the sky, with a magnitude of 1.76. It is also the brightest of the chemically peculiar Ap stars, magnetic stars whose chemical elements are either depleted or enhanced, and appear to change as the star rotates.[10]

- ζ Ursae Majoris, Mizar, the second star in from the end of the handle of the Big Dipper, and the constellation’s fourth-brightest star. Mizar, which means «girdle,» forms a famous double star, with its optical companion Alcor (80 Ursae Majoris), the two of which were termed the «horse and rider» by the Arabs.

- η Ursae Majoris, known as Alkaid, meaning the «end of the tail». With a magnitude of 1.85, Alkaid is the third-brightest star of Ursa Major.[11][12]

Except for Dubhe and Alkaid, the stars of the Big Dipper all have proper motions heading toward a common point in Sagittarius. A few other such stars have been identified, and together they are called the Ursa Major Moving Group.

Ursa Major and Ursa Minor in relation to Polaris

The stars Merak (β Ursae Majoris) and Dubhe (α Ursae Majoris) are known as the «pointer stars» because they are helpful for finding Polaris, also known as the North Star or Pole Star. By visually tracing a line from Merak through Dubhe (1 unit) and continuing for 5 units, one’s eye will land on Polaris, accurately indicating true north.

Another asterism known as the «Three Leaps of the Gazelle»[13] is recognized in Arab culture. It is a series of three pairs of stars found along the southern border of the constellation. From southeast to southwest, the «first leap», comprising ν and ξ Ursae Majoris (Alula Borealis and Australis, respectively); the «second leap», comprising λ and μ Ursae Majoris (Tania Borealis and Australis); and the «third leap», comprising ι and κ Ursae Majoris, (Talitha Borealis and Australis respectively).

Other stars[edit]

W Ursae Majoris is the prototype of a class of contact binary variable stars, and ranges between 7.75m and 8.48m.

47 Ursae Majoris is a Sun-like star with a three-planet system.[14] 47 Ursae Majoris b, discovered in 1996, orbits every 1078 days and is 2.53 times the mass of Jupiter.[15] 47 Ursae Majoris c, discovered in 2001, orbits every 2391 days and is 0.54 times the mass of Jupiter.[16] 47 Ursae Majoris d, discovered in 2010, has an uncertain period, lying between 8907 and 19097 days; it is 1.64 times the mass of Jupiter.[17] The star is of magnitude 5.0 and is approximately 46 light-years from Earth.[14]

The star TYC 3429-697-1 (9h 40m 44s 48° 14′ 2″), located to the east of θ Ursae Majoris and to the southwest of the «Big Dipper») has been recognized as the state star of Delaware, and is informally known as the Delaware Diamond.[18]

Deep-sky objects[edit]

Several bright galaxies are found in Ursa Major, including the pair Messier 81 (one of the brightest galaxies in the sky) and Messier 82 above the bear’s head, and Pinwheel Galaxy (M101), a spiral northeast of η Ursae Majoris. The spiral galaxies Messier 108 and Messier 109 are also found in this constellation. The bright planetary nebula Owl Nebula (M97) can be found along the bottom of the bowl of the Big Dipper.

M81 is a nearly face-on spiral galaxy 11.8 million light-years from Earth. Like most spiral galaxies, it has a core made up of old stars, with arms filled with young stars and nebulae. Along with M82, it is a part of the galaxy cluster closest to the Local Group.

M82 is a nearly edgewise galaxy that is interacting gravitationally with M81. It is the brightest infrared galaxy in the sky.[19] SN 2014J, an apparent Type Ia supernova, was observed in M82 on 21 January 2014.[20]

M97, also called the Owl Nebula, is a planetary nebula 1,630 light-years from Earth; it has a magnitude of approximately 10. It was discovered in 1781 by Pierre Méchain.[21]

M101, also called the Pinwheel Galaxy, is a face-on spiral galaxy located 25 million light-years from Earth. It was discovered by Pierre Méchain in 1781. Its spiral arms have regions with extensive star formation and have strong ultraviolet emissions.[19] It has an integrated magnitude of 7.5, making it visible in both binoculars and telescopes, but not to the naked eye.[22]

NGC 2787 is a lenticular galaxy at a distance of 24 million light-years. Unlike most lenticular galaxies, NGC 2787 has a bar at its center. It also has a halo of globular clusters, indicating its age and relative stability.[19]

NGC 2950 is a lenticular galaxy located 60 million light-years from Earth.

NGC 3079 is a starburst spiral galaxy located 52 million light-years from Earth. It has a horseshoe-shaped structure at its center that indicates the presence of a supermassive black hole. The structure itself is formed by superwinds from the black hole.[19]

NGC 3310 is another starburst spiral galaxy located 50 million light-years from Earth. Its bright white color is caused by its higher than usual rate of star formation, which began 100 million years ago after a merger. Studies of this and other starburst galaxies have shown that their starburst phase can last for hundreds of millions of years, far longer than was previously assumed.[19]

NGC 4013 is an edge-on spiral galaxy located 55 million light-years from Earth. It has a prominent dust lane and has several visible star forming regions.[19]

I Zwicky 18 is a young dwarf galaxy at a distance of 45 million light-years. The youngest-known galaxy in the visible universe, I Zwicky 18 is about 4 million years old, about one-thousandth the age of the Solar System. It is filled with star forming regions which are creating many hot, young, blue stars at a very high rate.[19]

The Hubble Deep Field is located to the northeast of δ Ursae Majoris.

Meteor showers[edit]

The Kappa Ursae Majorids are a newly discovered meteor shower, peaking between November 1 and November 10.[23]

[edit]

HD 80606, a sun-like star in a binary system, orbits a common center of gravity with its partner, HD 80607; the two are separated by 1,200 AU on average. Research conducted in 2003 indicates that its sole planet, HD 80606 b is a future hot Jupiter, modeled to have evolved in a perpendicular orbit around 5 AU from its sun. The 4-Jupiter mass planet is projected to eventually move into a circular, more aligned orbit via the Kozai mechanism. However, it is currently on an incredibly eccentric orbit that ranges from approximately one astronomical unit at its apoapsis and six stellar radii at periapsis.[24]

History[edit]

Ursa Major shown on a carved stone, c.1700, Crail, Fife

Ursa Major has been reconstructed as an Indo-European constellation.[25] It was one of the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd century AD astronomer Ptolemy in his Almagest, who called it Arktos Megale.[a] It is mentioned by such poets as Homer, Spenser, Shakespeare, Tennyson and also by Federico Garcia Lorca, in «Song for the Moon».[27] Ancient Finnish poetry also refers to the constellation, and it features in the painting Starry Night Over the Rhône by Vincent van Gogh.[28][29] It may be mentioned in the biblical book of Job, dated between the 7th and 4th centuries BC, although this is often disputed.[30]

Mythology[edit]

The constellation of Ursa Major has been seen as a bear, usually female,[31] by many distinct civilizations.[32] This may stem from a common oral tradition of Cosmic Hunt myths stretching back more than 13,000 years.[33] Using statistical and phylogenetic tools, Julien d’Huy reconstructs the following Palaeolithic state of the story: «There is an animal that is a horned herbivore, especially an elk. One human pursues this ungulate. The hunt locates or get to the sky. The animal is alive when it is transformed into a constellation. It forms the Big Dipper.»[34]

Greco-Roman tradition[edit]

In Greek mythology, Zeus (the king of the gods, known as Jupiter in Roman mythology), lusts after a young woman named Callisto, a nymph of Artemis (known to the Romans as Diana). Zeus’s jealous wife Hera, (Juno to the Romans), discovers that Callisto has a son named Arcas as the result of her rape by Zeus and transforms Callisto into a bear as a punishment.[35] Callisto, while in bear form, later encounters her son Arcas. Arcas almost spears the bear, but to avert the tragedy Zeus whisks them both into the sky, Callisto as Ursa Major and Arcas as the constellation Boötes. Ovid called Ursa Major the Parrhasian Bear, since Callisto came from Parrhasia in Arcadia, where the story is set.[36]

The Greek poet Aratus called the constellation Helike, (“turning» or “twisting”), because it turns around the celestial pole. The Odyssey notes that it is the sole constellation that never sinks below the horizon and «bathes in the Ocean’s waves,» so it is used as a celestial reference point for navigation.[37] It has also been called the “Wain» or “Plaustrum”, a Latin word referring to a horse-drawn cart.[38]

Hindu tradition[edit]

In Hinduism, Ursa Major/Big dipper/ Great Bear is known as Saptarshi, each of the stars representing one of the Saptarishis or Seven Sages (Rishis) viz. Bhrigu, Atri, Angiras, Vasishtha, Pulastya, Pulaha, and Kratu. The fact that the two front stars of the constellations point to the pole star is explained as the boon given to the boy sage Dhruva by Lord Vishnu.[39]

Judeo-Christian tradition[edit]

One of the few star groups mentioned in the Bible (Job 9:9; 38:32; – Orion and the Pleiades being others), Ursa Major was also pictured as a bear by the Jewish peoples. «The Bear» was translated as «Arcturus» in the Vulgate and it persisted in the King James Version of the Bible.

East Asian traditions[edit]

In China and Japan, the Big Dipper is called the «North Dipper» 北斗 (Chinese: běidǒu, Japanese: hokuto), and in ancient times, each one of the seven stars had a specific name, often coming themselves from ancient China:

-

- «Pivot» 樞 (C: shū J: sū) is for Dubhe (Alpha Ursae Majoris)

- «Beautiful jade» 璇 (C: xuán J: sen) is for Merak (Beta Ursae Majoris)

- «Pearl» 璣 (C: jī J: ki) is for Phecda (Gamma Ursae Majoris)

- «Balance»[40] 權 (C: quán J: ken) is for Megrez (Delta Ursae Majoris)

- «Measuring rod of jade» 玉衡 (C: yùhéng J: gyokkō) is for Alioth (Epsilon Ursae Majoris)

- «Opening of the Yang» 開陽 (C: kāiyáng J: kaiyō) is for Mizar (Zeta Ursae Majoris)

- Alkaid (Eta Ursae Majoris) has several nicknames: «Sword» 劍 (C: jiàn J: ken) (short form from «End of the sword» 劍先 (C: jiàn xiān J: ken saki)), «Flickering light» 搖光 (C: yáoguāng J: yōkō), or again «Star of military defeat» 破軍星 (C: pójūn xīng J: hagun sei), because travel in the direction of this star was regarded as bad luck for an army.[41]

In Shinto, the seven largest stars of Ursa Major belong to Ame-no-Minakanushi, the oldest and most powerful of all kami.

In South Korea, the constellation is referred to as «the seven stars of the north». In the related myth, a widow with seven sons found comfort with a widower, but to get to his house required crossing a stream. The seven sons, sympathetic to their mother, placed stepping stones in the river. Their mother, not knowing who put the stones in place, blessed them and, when they died, they became the constellation.

Native American traditions[edit]

The Iroquois interpreted Alioth, Mizar, and Alkaid as three hunters pursuing the Great Bear. According to one version of their myth, the first hunter (Alioth) is carrying a bow and arrow to strike down the bear. The second hunter (Mizar) carries a large pot – the star Alcor – on his shoulder in which to cook the bear while the third hunter (Alkaid) hauls a pile of firewood to light a fire beneath the pot.

The Lakota people call the constellation Wičhákhiyuhapi, or «Great Bear.»

The Wampanoag people (Algonquian) referred to Ursa Major as «maske,» meaning «bear» according to Thomas Morton in The New England Canaan.[42]

The Wasco-Wishram Native Americans interpreted the constellation as 5 wolves and 2 bears that were left in the sky by Coyote.[43]

Germanic traditions[edit]

To Norse pagans, the Big Dipper was known as Óðins vagn, «Woden’s wagon». Likewise Woden is poetically referred to by Kennings such as vagna verr ‘guardian of the wagon’ or vagna rúni ‘confidant of the wagon’[44]

Uralic traditions[edit]

In the Finnish language, the asterism is sometimes called by its old Finnish name, Otava. The meaning of the name has been almost forgotten in Modern Finnish; it means a salmon weir. Ancient Finns believed the bear (Ursus arctos) was lowered to earth in a golden basket off the Ursa Major, and when a bear was killed, its head was positioned on a tree to allow the bear’s spirit to return to Ursa Major.

In the Sámi languages of Northern Europe, part of the constellation (i.e. the Big Dipper minus Dubhe and Merak, is identified as the bow of the great hunter Fávdna (the star Arcturus). In the main Sámi language, North Sámi it is called Fávdnadávgi («Fávdna’s Bow») or simply dávggát («the Bow»). The constellation features prominently in the Sámi national anthem, which begins with the words Guhkkin davvin dávggaid vuolde sabmá suolggai Sámieanan, which translates to «Far to the north, under the Bow, the Land of the Sámi slowly comes into view.» The Bow is an important part of the Sámi traditional narrative about the night sky, in which various hunters try to chase down Sarva, the Great Reindeer, a large constellation that takes up almost half the sky. According to the legend, Fávdna stands ready to fire his Bow every night but hesitates because he might hit Stella Polaris, known as Boahji («the Rivet»), which would cause the sky to collapse and end the world.[45]

Southeast Asian traditions[edit]

In Burmese, Pucwan Tārā (ပုဇွန် တာရာ, pronounced «bazun taya») is the name of a constellation comprising stars from the head and forelegs of Ursa Major; pucwan (ပုဇွန်) is a general term for a crustacean, such as prawn, shrimp, crab, lobster, etc.

In Javanese, it is known as «lintang jong,» which means «the jong constellation.» Likewise, in Malay it is called «bintang jong.»[46]

Esoteric lore[edit]

In Theosophy, it is believed that the Seven Stars of the Pleiades focus the spiritual energy of the seven rays from the Galactic Logos to the Seven Stars of the Great Bear, then to Sirius, then to the Sun, then to the god of Earth (Sanat Kumara), and finally through the seven Masters of the Seven Rays to the human race.[47]

Graphic visualisation[edit]

In European star charts, the constellation was visualized with the ‘square’ of the Big Dipper forming the bear’s body and the chain of stars forming the Dipper’s «handle» as a long tail. However, bears do not have long tails, and Jewish astronomers considered Alioth, Mizar, and Alkaid instead to be three cubs following their mother, while the Native Americans saw them as three hunters.

H. A. Rey’s alternative asterism for Ursa Major can be said to give it the longer head and neck of a polar bear, as seen in this photo, from the left side.

Noted children’s book author H. A. Rey, in his 1952 book The Stars: A New Way to See Them, (ISBN 0-395-24830-2) had a different asterism in mind for Ursa Major, that instead had the «bear» image of the constellation oriented with Alkaid as the tip of the bear’s nose, and the «handle» of the Big Dipper part of the constellation forming the outline of the top of the bear’s head and neck, rearwards to the shoulder, potentially giving it the longer head and neck of a polar bear.[48]

-

Ursa Major as depicted in Urania’s Mirror, a set of constellation cards published in London c.1825.

-

Johannes Hevelius drew Ursa Major as if being viewed from outside the celestial sphere.

-

Ursa Major is also pictured as the Starry Plough, the Irish flag of Labour, adopted by James Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army in 1916, which shows the constellation on a blue background; on the state flag of Alaska; and on the House of Bernadotte’s variation of the coat of arms of Sweden. The seven stars on a red background of the flag of the Community of Madrid, Spain, may be the stars of the Plough asterism (or of Ursa Minor). The same can be said of the seven stars pictured in the bordure azure of the coat of arms of Madrid, capital of that country.

See also[edit]

- Ursa Major (Chinese astronomy)

- Ursa Minor

- Southern Cross

- Celestial cartography

- Constellation family

- Former constellations

- Lists of stars by constellation

- Constellations listed by Johannes Hevelius

- Constellations listed by Lacaille

- Constellations listed by Petrus Plancius

- Constellations listed by Ptolemy

Notes[edit]

- ^ Ptolemy named the constellation in Greek Ἄρκτος μεγάλη (Arktos Megale) or the great bear. Ursa Minor was Arktos Mikra[26]

References[edit]

- ^ «Chandra: Constellation Ursa Major». chandra.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2022-07-07.

- ^ «Constellation | COSMOS». astronomy.swin.edu.au. Retrieved 2022-07-07.

- ^ «Constellations Lacerta–Vulpecula».

- ^ «Ursa Major, Constellation Boundary». The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ «The Constellations». Archived from the original on 2013-07-08. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- ^ Reader’s Digest Association (August 2005). Planet Earth and the Universe. Reader’s Digest Association, Limited. ISBN 978-0-276-42715-2. Archived from the original on 2021-04-15. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ^ «Charles’ Wain». Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ André G. Bordeleau (22 October 2013). Flags of the Night Sky: When Astronomy Meets National Pride. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 131–. ISBN 978-1-4614-0929-8. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ James B. Kaler (28 July 2011). Stars and Their Spectra: An Introduction to the Spectral Sequence. Cambridge University Press. pp. 241–. ISBN 978-0-521-89954-3. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ a b Jim Kaler (2009-09-16). «Stars: «Alioth»«. Archived from the original on 2019-12-11. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- ^ Mark R. Chartrand (1982). Skyguide, a Field Guide for Amateur Astronomers. Golden Press. Bibcode:1982sfga.book…..C. ISBN 978-0-307-13667-1. Archived from the original on 2021-04-15. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- ^ Ridpath, at p. 136.

- ^ «Ursa Major & Ursa Minor». Winter Sky Tour. Archived from the original on 2012-12-19.

- ^ a b Levy 2005, p. 67.

- ^ «Planet 47 Uma b». The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Paris Observatory. 11 July 2012. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ «Planet 47 Uma c». The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Paris Observatory. 11 July 2012. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ «Planet 47 Uma d». The Extrasolar Planet Encyclopaedia. Paris Observatory. 11 July 2012. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ «Delaware Facts & Symbols – Delaware Miscellaneous Symbols». delaware.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-03-28. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wilkins, Jamie; Dunn, Robert (2006). 300 Astronomical Objects: A Visual Reference to the Universe (1st ed.). Buffalo, New York: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-175-3.

- ^ Cao, Y; Kasliwal, M. M; McKay, A; Bradley, A (2014). «Classification of Supernova in M82 as a young, reddened Type Ia Supernova». The Astronomer’s Telegram. 5786: 1. Bibcode:2014ATel.5786….1C.

- ^ Levy 2005, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Seronik, Gary (July 2012). «M101: A Bear of a Galaxy». Sky & Telescope. 124 (1): 45. Bibcode:2012S&T…124a..45S.

- ^ Jenniskens, Peter (September 2012). «Mapping Meteoroid Orbits: New Meteor Showers Discovered». Sky & Telescope: 23.

- ^ Laughlin, Greg (May 2013). «How Worlds Get Out of Whack». Sky and Telescope. 125 (5): 29. Bibcode:2013S&T…125e..26L.

- ^

Mallory, J.P.; Adams, D.Q. (August 2006). «Chapter 8.5: The Physical Landscape of the Proto-Indo-Europeans». Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford, GBR: Oxford University Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780199287918. OCLC 139999117.The most solidly ‘reconstructed’ Indo-European constellation is Ursa Major, which is designated as ‘The Bear’ (Chapter 9) in Greek and Sanskrit (Latin may be a borrowing here), although even the latter identification has been challenged.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. «Ptolemy’s Almagest: First printed edition, 1515». Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ «Canción para la luna — Federico García Lorca — Ciudad Seva». Archived from the original on 2015-05-10. Retrieved 2015-08-16.

- ^ Frog (2018-01-30). «Myth». Humanities. 7 (1): 14. doi:10.3390/h7010014. ISSN 2076-0787.

- ^ Clayson, Hollis (2002). «Exhibition Review: «Some Things Bear Fruit»? Witnessing the Bonds between Van Gogh and Gauguin». The Art Bulletin. 84 (4): 670–684. doi:10.2307/3177290. ISSN 0004-3079. JSTOR 3177290.

- ^ Botterweck, G. Johannes, ed. (1994). Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, Volume 7. Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-0-8028-2331-1. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- ^ Allen, R. H. (1963). Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning (Reprint ed.). New York, NY: Dover Publications Inc. pp. 207–208. ISBN 978-0-486-21079-7. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- ^ Gibbon, William B. (1964). «Asiatic parallels in North American star lore: Ursa Major». Journal of American Folklore. 77 (305): 236–250. doi:10.2307/537746. JSTOR 537746.

- ^ Bradley E Schaefer, The Origin of the Greek Constellations: Was the Great Bear constellation named before hunter nomads first reached the Americas more than 13,000 years ago?, Scientific American, November 2006, reviewed at The Origin of the Greek Constellations Archived 2017-04-01 at the Wayback Machine; Yuri Berezkin, The cosmic hunt: variants of a Siberian – North-American myth Archived 2015-05-04 at the Wayback Machine. Folklore, 31, 2005: 79–100.

- ^ d’Huy Julien, Un ours dans les étoiles: recherche phylogénétique sur un mythe préhistorique Archived 2021-12-20 at the Wayback Machine, Préhistoire du sud-ouest, 20 (1), 2012: 91–106; A Cosmic Hunt in the Berber sky : a phylogenetic reconstruction of Palaeolithic mythology Archived 2020-05-28 at the Wayback Machine, Les Cahiers de l’AARS, 15, 2012.

- ^ «Ursa Major, The Great Bear». Ian Ridpath’s Star Tales.

- ^ Ovid, Heroides (trans. Grant Showerman) Epistle 18

- ^ Homer, Odyssey, book 5, 273

- ^ «Apianus’s depictions of Ursa Major and Ursa Minor». Ian Ridpath’s Star Tales.

- ^ Mahadev Haribhai Desai (1973). Day-to-day with Gandhi: Secretary’s Diary. Sarva Seva Sangh Prakashan. Archived from the original on 2022-05-13. Retrieved 2021-01-06.

- ^ «English-Chinese Glossary of Chinese Star Regions, Asterisms and Star Names». Hong Kong Space Museum. Archived from the original on 17 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ The Bansenshukai, written in 1676 by the ninja master Fujibayashi Yasutake, speak several times about these stars, and show a traditional picture of the Big Dipper in his book 8, volume 17, speaking about astronomy and meteorology (from Axel Mazuer’s translation).

- ^ Thomas, Morton (13 September 1883). The new English Canaan of Thomas Morton. Published by the Prince Society. OL 7142058M.

- ^ Clark, Ella Elizabeth (1963). Indian Legends of the Pacific Northwest. University of California Press. Archived from the original on 2022-05-13. Retrieved 2019-05-01.

- ^ Cleasby, Richard; Vigfússon, Guðbrandur (1874). An Icelandic-English Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 674.

- ^ Naturfagsenteret.no: Stjernehimmelen (https://www.naturfagsenteret.no/c1515376/binfil/download2.php?tid=1509706)

- ^ Burnell, A.C. (2018). Hobson-Jobson: Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words And Phrases. Routledge. p. 472. ISBN 9781136603310.

- ^ Baker, Dr. Douglas The Seven Rays:Key to the Mysteries 1952

- ^ «Archived representation of H.A. Rey’s asterism for Ursa Major». Archived from the original on 2014-04-07.

- Bibliography

- Levy, David H. (2005). Deep Sky Objects. Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-59102-361-6.

- Thompson, Robert; Thompson, Barbara (2007). Illustrated Guide to Astronomical Wonders: From Novice to Master Observer. O’Reilly Media, Inc. ISBN 978-0-596-52685-6.

Further reading[edit]

- Ian Ridpath and Wil Tirion (2007). Stars and Planets Guide, Collins, London. ISBN 978-0-00-725120-9. Princeton University Press, Princeton. ISBN 978-0-691-13556-4.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ursa Major.

- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Ursa Major

- The clickable Ursa Major

- AAVSO: The Myths of Ursa Major

- The Origin of the Greek Constellations (paywalled)

- Star Tales – Ursa Major

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (medieval and early modern images of Ursa Major)

Содержание

- Большая медведица пишется с большой или маленькой буквы?

- Поиск ответа

- Большая медведица с большой или маленькой буквы как пишется

- Правописание географических наименований

Большая медведица пишется с большой или маленькой буквы?

с какой буквы пишется большая медведица?

Сложные астрономические названия (то есть имена собственные из двух или более слов, относящиеся к астрономии) пишутся, как правило, таким образом, чтобы все слова были с большой буквы.

Родовые слова-пояснения при этом пишут с маленькой (планета, звезда, созвездие, комета и так далее).

«Про созвездие Большая Медведица».

Аналогично:

Обратите внимание, что согласование («про созвездие Большой Медведицы») было бы некорректно.

Если же мы будем говорить о самках медведя и одну из них признаем «большой медведицей», а вторую, например, «малой медведицей», то это нарицательные слова. Большие буквы отменяются.

А вот слова «туманность», «созвездие», «звезда» пишутся с маленькой буквы: туманность Андромеды, созвездие Большого Пса, звезда Эрцгерцога Карла.

С маленькой буквы также пишутся и «альфа», «бета»: альфа Малой Медведицы, бета Весов.

Думается, что такое предположение не было голословным, поскольку второе слово («требуется») отвечает на вопрос «что делает?» (или «что делается?», если создавать вопрос с обычной формальностью, не вдаваясь в смысл). Да и обладает другими категориальными признаками глагола.

А первое слово («не») не может быть признано приставкой, потому что если в языке есть слово «требуется», но не может быть слова «нетребуется». Это понятно из правила, обуславливающего соответствующую раздельность глаголов с «НЕ».

Итак, глагол «требоваться относится к совокупности тех, которые не сливаются с «НЕ». Писать «нетребуется» нельзя.

Других доказательств не потребуется.

Предложение.