Всего найдено: 7

Добрый день! Подскажите, пожалуйста, ка правильно писать не сухопутный или несухопутный? Спасибо

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Возможны оба варианта (раздельно — при подчеркивании отрицания либо при противопоставлении).

Уважаемые сотрудники Грамоты, спрашиваю уже не в первый раз — ответьте, пожалуйста! Какое управление верно при слове «главком» — родительный падеж или творительный? «Главком сухопутных войск» или «главком сухопутными войсками»?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно: главком сухопутными войсками. Подробнее см. от вопросе 252501.

Уважаемая Грамота, подскажите как правильно писать слово «вермахт», как название сухопутных сил Третьего Рейха — со строчной или с Прописной буквы. На мой взгляд это имя собственное и поэтому должно писаться с Прописной, некоторые современные авторы так и пишут, но основная масса пишет со строчной. Может это идеологическое наследие советской системы давлеет над правилами написания? Заранее спасибо

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно написание строчными буквами: вермахт, люфтваффе и т. д.

как правильно: формирование российско-северокорейской морской и сухопутной границ(ы)?

каким правилом регламентируется написание?

Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Здесь корректно: …границы.

Я знаю, что можно говорить автобус идет и автобус едет. Объясните пожалуйста почему возмжны оба варианта?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Названия средств сухопутного механического и воздушного транспорта обычно сочетаются с глаголом _идти_. Слово _мотоцикл_ сочетается с глаголом _ехать_, названия средств передвижения по воде сочетаются как с глаголом _идти_, так и с глаголом _плыть_ (см. «Справочник по правописанию и литературной правке» Д. Э. Розенталя).

У Короленко в рассказе «Ат-Даван» встречается фраза: А родитель мой, надо сказать, хотя и из ластовых был, но место имел доходное и, понятное дело, сыну тоже дал порядочного ходу. Что значит «из ластовых»?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В словаре морских терминов указано: _Существовавшие до 60-х годов ластовые экипажи имели в своем ведении мелкие портовые суда и плавучие средства (баржи, матеры, плашкоуты и т. д.), так называемые ластовые суда. В отличие от флотских экипажей, ведавших боевыми судами, служащие в Л. экипаже имели чины не морские, а сухопутные._

Следует сделать вывод, что _из ластовых_ означает, что отец героя Короленко был портовым служащим.

Здравствуйте, этот дикторский текст для фильма, предназначенный для просмотра широкой аудитории. Как стилистически правильно должен выглядеть текст, чтобы был легко воспринят слушителями?

Первые страницы летописи Федерального центра были написаны в суровые годы войны. Тогда в его опытных цехах было изготовлено более полумиллиона зарядов к реактивным снарядам М-13 и М-З1. С легендарных «Катюш» началось в нашей стране развитие ракетной техники на твердом топливе…

Более полувека предприятие разрабатывает и изготавливает

баллиститные и смесевые твердые ракетные топлива и заряды из них для всех родов войск и вооружений, ракет-носителей и космических объектов.Здесь создана непрерывная технология производства баллиститных порохов и твердых ракетных топлив, а также зарядов различных форм и габаритов с широким спектром управляемых свойств.

Разработана и внедрена безопасная промышленная технология производства смесевых твердых ракетных топлив с высоким уровнем энергомассовых характеристик и экологической частотой продуктов сгорания.Федеральный центр является автором и разработчиком технологии изготовления корпусов твердотопливных ракетных двигателей из современных композиционных материалов, в том числе сверхпрочных цельномотанных корпусов типа «кокон».

За годы работы предприятием сдано в эксплуатацию более 460 номенклатур твердотопливных зарядов различного назначения.

Так для сухопутных войск страны отработаны заряды к 59 ракетным комплексам, в том числе к активно-реактивным снарядам «Ель-2», «Буревестник-2», «Баклан», «Краснополь».

К артиллерийским установкам и комплексам «Б-4М», «Пион», «Гиацинт», «2СЗМ», «Смельчак».

К реактивным системам залпового огня «Град», «Град-1», «Ураган».

Для войск ПВО страны отработаны заряды к 10 ракетным комплексам, среди них комплексы: «С-200», «Печора», «Куб», «Шторм»,

«Волга», «Тунгуска».

Военно-морскому флоту России сданы на вооружение заряды к 35 ракетным системам.

Для военно-воздушных сил страны отработаны заряды к 30 боевым ракетам.

В ракетных комплексам тактического и стратегического назначения «Темп-С», «Ока» и «Ока-У», «Точка» и «Точка-У», «Пионер», «Тополь», также используются заряды отработанные «Салютом».Убедительным признанием его заслуг, в общем, для всех деле укреплении безопасности нашей страны, стало открытие монумента «Создателям ядерного щита России».

Федеральный центр «Салют» – один из ведущих научных центров страны по проблемам долговечности твердотопливных зарядов. По результатам проведенных здесь комплексных исследований продлены сроки эксплуатации зарядов к более чем 50 ракетным комплексам, стоящим на вооружении в России, Емени, Сирии, на Кубе, Замбии, Перу и ряде других стран.

Снятые с вооружения пороха и твердые ракетные топлива, после их утилизации эффективно используются для решения народно-хозяйственных задач, например: в качестве детонирующих зарядов сейсморазведки и для рыхления твердых горных пород, в качестве безкорпусного генератора давления в скважинах с целью изучения притока к ним нефти и газа.С помощью гранипоров – гранулированных взрывчатых веществ на основе баллиститов, ведется разработка полезных ископаемых открытым способом.

Федеральный центр является неизменным участником практически всех космических программ, осуществляемых в России. По этим программам отработаны заряды и двигатели к 24 космическим комплексам. Это система аварийного спасения космонавтов, двигатели мягкой посадки, стабилизации, увода, разделения ступеней, торможения космических объектов для комплексов «Восток», «Восход», «Луна», «Марс», «Союз-ТМ», «Протон», «Морской старт», «Циклон», «Молния» и других.

В начале 90-х годов Федеральных центр приступил к разработке технологий двойного назначения и выпуска на их основе наукоемкой гражданской продукции. Так на базе оборонных технологий были созданы уникальные источники электрической энергии – импульсные МГД-генераторы. Они предназначены для глубинного зондирования земной коры и поиска полезных ископаемых.

Разработаны специальные, аэрозольобразующие составы с ингибирующими добавками для принципиально новых средств объемного пожаротушения. Это огнетушители «Степ» и «Степ2», которые эффективно заменяют хладоновые средства борьбы с огнём.

«Степ» и «Степ2» — надежная защита от пожара электростанций, производственных и складских помещений, всех видов транспорта, объектов добычи и переработки нефти и газа и ряда других объектов.

«Степ» и «Степ2» успешно прошли испытания в России и за рубежом. Сегодня они экспортируются во многие страны мира.На основе использование твердотопливных газогенераторов и емкостей из композиционных материалов, созданы быстродействующие установки жидкостного тушения крупных пожаров. Создана опытно- промышленная установка для синтеза алмазов из специальных углеродосодержащих твердотопливных составов.

Основные области применениям таких алмазов шлифовально- полировальные пасты и алмазно-абразивные инструменты.

На базе технологии производства корпусов ракетных двигателей освоен выпуск различных емкостей: контейнеров, труб и другого химически стойкого оборудования. Разработана технология, налажен выпуск оборудования и материалов для керамической сварки, огнеупорных покрытий высокотемпературных печей.

На основе самораспространяющегося высокотемпературного синтеза, разработана технология переработки металлосодержащих отходов в стойкие неорганические пигменты различных цветов и оттенков.Сегодня Федеральный центр является одним из крупнейших в России изготовителем субстанций для производства сердечно-сосудистых препаратов.

Среди других видов гражданской продукции «Салюта», следует отметить бездымные фейерверочные составы, полимерные магниты, технику и материалы для разметки дорог, лаки и краски.

«Салют» – один из участников проекта «СТАРТ 1». Его основу составляет носитель, созданный на базе многоступенчатой твердотопливной ракеты мобильного грунтового стратегического комплекса.

«СТАРТ 1» предназначен для вывода на околоземные орбиты космических аппаратов с целью развертывания систем спутниковой связи, создании новых материалов, разведки полезных ископаемых, экологического мониторинга и других целей.

Федеральный центр «Салют» приглашает все заинтересованные организации к сотрудничеству в области разработки производства и сбыта своей продукции.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

К сожалению, мы не имеем возможности ответить на столь объёмный вопрос.

Поиск ответа

Здравствуйте, уважаемая Грамота. Есть ли примеры, когда слово “юг” пишется с прописной буквы. спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Да, например: Война Севера и Юга (в США, ист.), Вооружённые силы Юга России (белая армия).

Уважаемая грамота! В ответе на вопрос № 287860 исправьте ошибку. Вопрос: Корректна ли пунктуация? Оперативная обстановка продолжает оставаться сложной, несмотря на то что, по данным Центра по примирению враждующих сторон, на территории Сирии с начала перемирия к режиму прекращения боевых действий присоединились вооруженные формирования. Ответ справочной службы русского языка: Пунктуация верна. ______________ Запятая ставится либо перед союзом “несмотря на то что”, либо перед “что”, но никак не две запятых сразу.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В предложении из вопроса 287860 запятой перед что нет. Запятая стоит после что, перед вводным сочетанием по данным Центра по примирению враждующих сторон.

Здравствуйте. Корректна ли пунктуация? Оперативная обстановка продолжает оставаться сложной, несмотря на то что, по данным Центра по примирению враждующих сторон, на территории Сирии с начала перемирия к режиму прекращения боевых действий присоединились вооруженные формирования.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Может ли определение одного причастного оборота быть в другом причастном обороте?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Вы имели в виду определяемое слово? Тогда может, например: Он родился в семье военных и проделал весь путь, на роду написанный людям, делающим военную карьеру [С. Татевосов. Князь тьмы в малиновом берете // «Коммерсантъ-Власть», 1999], Казаки же долго не могли отрешиться от этого жестокого приёма, отталкивавшего от нас многих, желавших перейти на нашу сторону [А. И. Деникин. Очерки русской смуты. Том IV. Вооруженные силы Юга России (1922)].

. и являемся на старт, вооруженные любым фотографирующим устройством.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Поставленная Вами запятая нужна.

Здравствуйте! Как правильно писать: Вооруженные (С,с)илы РФ? На вопросы № 262393 и № 244687 сайт отвечает по-разному.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Дело в том, что рекомендуемое лингвистическими источниками написание этого сочетания противоречит (как нередко бывает) написанию, принятому в официальной письменной речи. Орфографически верно: Вооруженные силы РФ, но в современной официальной документации принято: Вооруженные Силы РФ . Такой вариант зафиксирован, например, в «Кратком справочнике по оформлению актов Совета Федерации Федерального Собрания Российской Федерации» (этот справочник рекомендуется как нормативный источник для оформления официальной документации).

Сколько прописных букв в словах ” вооруженные силы”

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно: вооруженные силы , но Вооруженные Силы РФ .

Как правильно: Вооружённые силы или Вооружённые Силы?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Как правильно: Вооруженные силы РФ или Вооруженные Силы РФ?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Лингвистические словари фиксируют написание Вооруженные силы РФ , однако в официальных документах принято написание с прописной буквы всех слов в этом сочетании. Вариант Вооруженные Силы Российской Федерации зафиксирован, например, в «Кратком справочнике по оформлению актов Совета Федерации Федерального Собрания Российской Федерации» (этот справочник рекомендуется как нормативный источник для оформления официальной документации).

Как правильно пишется словосочетание Вооруженные силы или Вооруженные Силы?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Скажите, в каких случаях ” Вооруженные силы” пишется со строчной, а в каких с прописной? Вооруженные силы РФ и просто вооруженные силы… Хотелось бы внести ясность. Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Согласно орфографическому словарю, правильно: Вооружённые с и лы РФ. В тексте газетной статьи сочетание вооруженые силы может писаться строчными буквами.

Добрый день. Очень люблю читать ленту. Спасибо за ответы. 1) Когда, вооруженные , мы вновь подошли к окну… 2) Когда мы, вооруженные , вновь подошли к окну… Верна ли пунктуация?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Пунктуация в обоих случаях верна.

И Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации (ПРОП) 2006 г.(Под ред. В. В. Лопатина. М.: Эксмо, 2006), и новый академический «Русский орфографический словарь» (2-изд. М., 2005), и «Справочник издателя и автора» (СИА) под ред. Мильчина (М.: ОЛМА-пресс, 2003) предписывают написание с прописной буквы всех трех слов в названии ‘Содружество Независимых Государств’. В ПРОП (разд. «Орфография», § 170) это объясняется тем, что СНГ относится к «государственным объединениям». В СИА (п. 3.8.3), где понятию «государственное объединение» придается, судя по всему, иной смысл, говорится, что в названиях «групп, союзов и объединений государств» с прописной буквы пишется первое слово, а также собственные имена, однако в приведенном там списке примеров СНГ объявлено исключением: ‘Европейское экономическое сообщество… Лига арабских государств… НО: Содружество Независимых Государств’. Подобное написание развернутого названия СНГ тем более удивительно, что ПРОП-2006 (разд. «Орфография», § 170) вполне резонно рекомендуют писать с прописной буквы только первое слово в названиях высших учреждений РФ типа ‘Государственная дума, Федеральное собрание, Конституционный суд, Вооруженные силы’ — невзирая на их «торжественное» написание в Конституции РФ. («Поддерживаемая лингвистами тенденция к употреблению прописной буквы только в первом слове» таких названий констатируется и в СИА (п. 3.11.2, прим.).) Ваше мнение?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

В действительности здесь два разных вопроса. Первый – об административно-территориальных наименованиях, таких как Содружество Независимых Государств). Здесь и чиновники, и лингвисты согласны в том, что все три слова в этом наименовании нужно писать с большой буквы.

Второй вопрос – о названиях органов власти, организаций, учреждений. Лингвистические справочники предписывают ипользовать большую (прописную) букву только как первую букву в названии правительственного государственного учреждения, органа власти (и поэтому написание _Государственная дума_ логично). Но сложившаяся практика письма иная: в названиях многих государственных учреждений прописная буква встречается более чем один раз. К сожалению, привести к общему знаменателю написания названий госучреждений очень трудно, так как каких-либо закономерностей в чрезмерном употреблении прописных букв не прослеживается. Наша точка зрения: названия правительственных учреждений нужно писать так, чтобы затруднения с прописной буквой не возникали. Поэтому позиция нового справочника кажется нам обоснованной.

Добрый день. Подскажите, пожалуйста: 1)есть ли различие в написании словосочетаний типа [i]Вооружённые силы[/i] и [i]Генеральный штаб[/i] в зависимости от того, идёт речь про российские или зарубежные; 2)как вообще регулируются такие написания и какими источниками рекомендуете пользоваться, желательно – онлайновыми. Заранее спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Согласно словарю «Как правильно? С большой буквы или с маленькой?» (В. В. Лопатин, И. В. Нечаева, Л. К. Чельцова): _ Вооруженные силы РФ, Генеральный штаб, вооруженные силы_. Однако в «Кратком справочнике по оформлению актов Совета Федерации Федерального Собрания Российской Федерации» зафиксированы следующие варианты: _ Вооруженные Силы РФ, Генеральный штаб РФ_. Этот справочник рекомендуется как нормативный источник для оформления официальной документации. Как писать _ вооруженные силы_ с указанием других стран, информации в справочниках нет.

См. также ответ № 186221.

Как правильно писать ” Вооружённые Силы” или “Вооружённые силы”?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Верно: _ вооруженные силы_, но _ Вооруженные Силы РФ_.

Источник статьи: http://new.gramota.ru/spravka/buro/search-answer?s=%D0%92%D0%9E%D0%9E%D0%A0%D0%A3%D0%96%D0%95%D0%9D%D0%9D%D0%AB%D0%95

Как пишется сухопутные войска

С прописной буквы пишутся:

- Вооруженные Силы Российской Федерации

- Генеральный штаб Вооруженных Сил Российской Федерации

- Ракетные войска стратегического назначения

- Сухопутные войска

- Военно-воздушные силы

- Военно-Морской Флот

* * *

- Воздушно-десантные войска

- Железнодорожные войска Российской Федерации

- Тыл Вооруженных Сил Российской Федерации

* * *

- Главное оперативное управление Генерального штаба Вооруженных Сил Российской Федерации

- Главное командование внутренних войск Министерства внутренних дел Российской Федерации

- Главный штаб Сухопутных войск

Со строчной буквы пишутся:

- войска гражданской обороны

- внутренние войска Министерства внутренних дел Российской Федерации

- войска Федерального агентства правительственной связи и информации при Президенте Российской Федерации

- войска Пограничной службы Российской Федерации

Названия военных округов Вооруженных Сил Российской Федерации пишутся:

- Ленинградский военный округ

- Московский военный округ

- Северо-Кавказский военный округ

- Приволжский военный округ

- Уральский военный округ

- Сибирский военный округ

- Дальневосточный военный округ

Названия должностей пишутся:

- Верховный Главнокомандующий Вооруженными Силами Российской Федерации

- начальник Генерального штаба Вооруженных Сил Российской Федерации первый заместитель Министра обороны Российской Федерации

- начальник связи Вооруженных Сил Российской Федерации

- главный инспектор-координатор Главного командования внутренних войск Министерства внутренних дел Российской Федерации

- директор Федеральной службы железнодорожных войск Российской Федерации командующий Железнодорожными войсками Российской Федерации

- главнокомандующий Военно-Морским Флотом

- главнокомандующий Сухопутными войсками

- командующий Воздушно-десантными войсками

- командующий войсками Московского военного округа

- командующий Северным флотом

- командующий войсками Ленинградского военного округа

Источник статьи: http://old.nasledie.ru/vlact/5_7/5_7_1/spravochnik/article.php?art=8

Как правильно пишется словосочетание «сухопутное войско»

- Как правильно пишется слово «сухопутный»

- Как правильно пишется слово «войско»

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: поперечина — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к слову «войска»

Синонимы к словосочетанию «сухопутное войско»

Предложения со словосочетанием «сухопутное войско»

- Те и другие присягали, подобно сухопутным войскам, на верность полководцу, набиравшему их.

- При этом в 1918 г. в составе военной авиации сухопутных войск истребительная авиация занимала 40,1 %, а удельный вес разведывательной авиации уменьшился более чем в два раза.

- Это предприятие медленно умирало из-за хронического отсутствия денег, так что 1 октября 1932 года он присоединился к отделу вооружений сухопутных войск.

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словосочетанием «сухопутное войско»

- По этому плану Австрия обязывалась выставить армию в 30 0000 человек, Россия должна была выслать 115 000, а Англия, как не имеющая сухопутного войска, обязывалась выплатить полтора миллиона фунтов стерлингов и три миллиона стерлингов ежегодной субсидии.

- В этом почти соглашается сам г. Устрялов, когда возражает против Перри, сказавшего, что «Лефорт находился при Петре с 12-летнего возраста царя, беседовал с ним о странах Западной Европы, о тамошнем устройстве войск морских и сухопутных, о торговле, которую западные народы производят во всем свете посредством мореплавания и обогащаются ею».

- Светлейший князь Потемкин-Таврический, президент государственной военной коллегии, генерал-фельдмаршал, великий гетман казацких екатеринославских и черноморских войск, главнокомандующий екатеринославскою армиею, легкою конницей, регулярною и нерегулярною, флотом черноморским и другими сухопутными и морскими военными силами, сенатор екатеринославский, таврический и харьковский генерал-губерантор, ее императорского величества генерал-адъютант, действительный камергер, войск генерал-инспектор, лейб-гвардии Преображенского полка полковник, корпуса кавалергардов и полков екатеринославского кирасирского, екатеринославского гренадерского и смоленского драгунского шеф, мастерской оружейной палаты главный начальник и орденов российских: святого апостола Андрея Первозванного, святого Александра Невского, святого великомученника и победоносца Георгия и святого равноапостольного князя Владимира, больших крестов и святой Анны; иностранных: прусского — Черного Орла, датского — Слона, шведского — Серафима, польского — Белого Орла и Святого Станислава кавалер — отошел в вечность.

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Сочетаемость слова «войска»

- советские войска

русские войска

немецкие войска - войска фронта

войска противника

войска округа - часть войск

командующий войсками

управление войсками - войска отступают

войска ушли

войска бежали - собирать войска

служить в войска

командовать войсками - (полная таблица сочетаемости)

Значение словосочетания «сухопутные войска»

-

Сухопу́тные войска́ — формирование (вид вооружённых сил (ВС)) многих государств мира, наряду с военно-морским флотом (силами) и военно-воздушными силами (флотом). (Википедия)

Все значения словосочетания СУХОПУТНЫЕ ВОЙСКА

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Числа, знаки, сокращения

Века обозначаются римскими цифрами.

Предложение с цифр не начинается.

Знаки №, % от числа пробелами не отбиваются.

Наращение (буквенное падежное окончание) используется в записи порядковых числительных: ученик 11-го класса; 1-й вагон из центра; 5-й уровень сложности; занять 2-е и 3-е места; в начале 90-х годов. Наращение должно быть однобуквенным, если последней букве числительного предшествует гласный звук: 5-й (пятый, пятой), 5-я (пятая), и двухбуквенным, если последней букве числительного предшествует согласный: 5-го, 5-му.

Международный стандарт обозначения времени, принятый и в России, – через двоеточие: 18:00.

Для обозначения крупных чисел (тысяч, миллионов, миллиардов) используются сочетания цифр с сокращением тыс., млн, млрд, а не цифры с большим количеством нулей.

После сокращений млн и млрд точка не ставится, а после тыс. – ставится.

Слово «вуз» пишется строчными буквами.

В некоторых аббревиатурах используются и прописные, и строчные буквы, если в их состав входит однобуквенный союз или предлог. Напр.: КЗоТ – Кодекс законов о труде; МиГ – Микоян и Гуревич (марка самолета).

Географические названия

Вместо «Чечня» пишется «Чеченская республика».

В Конституции РФ прописан вариант «Республика Тыва».

Правильно писать Шарм-эль-Шейх.

Правильно писать сектор Газа.

Употребляется только с Украины / на Украину.

Предпочтительнее употреблять варианты «власти Эстонии», «университеты Европы» и т. п. вместо «эстонские власти», «европейские университеты».

Правильно: в г. Нижнем Новгороде, в г. Санкт-Петербурге, в городе Москве, в городе Владивостоке, в Видном, из Видного, но: в городе Видное, из города Видное; в Великих Луках, но: в городе Великие Луки.

Топонимы славянского происхождения на -ов(о), -ев(о), -ин(о), -ын(о) традиционно склоняются: в Останкине, в Переделкине, к Строгину, в Новокосине, из Люблина.

В названии типа «Москва-река» склоняются обе части: Москвы-реки, Москве-реке, Москву-реку, Москвой-рекой, о Москве-реке.

Прописные («большие») / строчные («маленькие») буквы и кавычки

Названия высших выборных учреждений зарубежных стран обычно пишутся со строчной буквы. Например: риксдаг, кнессет, конгресс США, бундесрат, сейм и т. п.

Первое слово выборных учреждений временного или единичного характера в исторической литературе пишут с прописной буквы. Напр.: Временное правительство (1917 г. в России), Генеральные штаты, Государственная дума, III Дума.

Артикли, предлоги, частицы ван, да, дас, де, дель, дер, ди, дос, дю, ла, ле, фон и т. п. в западноевропейских фамилиях и именах пишутся со строчной буквы и отдельно от других составных частей. Напр.: Людвиг ван Бетховен, Леонардо да Винчи.

Составные части арабских, тюркских и других восточных личных имен (ага, ал, аль, ар, ас, аш, бей, бен, заде, оглы, шах, эль и др.) пишутся, как правило, со строчной буквы и присоединяются к имени через дефис. Напр.: Зайн ал-Аби-дин, аль-Джахм, Харун ар-Рашид, Турсун-заде.

С прописной буквы пишутся названия стран света, когда они употребляются вместо географических названий. Напр.: народы Востока (то есть восточных стран), Дальний Восток, страны Запада, Крайний Север.

В названиях республик РФ все слова пишутся с прописной буквы. Напр.: Республика Алтай, Кабардино-Балкарская Республика, Республика Северная Осетия.

В названиях краев, областей, округов родовое или видовое понятие пишется со строчной буквы, а слова, обозначающие индивидуальное название, – с прописной. Напр.: Приморский край, Агинский Бурятский автономный округ.

В названиях групп, союзов и объединений государств политического характера с прописной буквы пишется первое слово, а также собственные имена. Напр.: Азиатско-Тихоокеанский совет, Европейское экономическое сообщество (ЕЭС), Лига арабских государств (ЛАГ).

В названиях важнейших международных организаций с прописной буквы пишутся все слова, кроме служебных. Напр.: Общество Красного Креста и Красного Полумесяца, Организация Объединенных Наций (ООН), Совет Безопасности ООН.

В названиях зарубежных информационных агентств все слова, кроме родового, пишутся с прописной буквы и название в кавычки не заключается. Напр.: агентство Франс Пресс, Ассошиэйтед Пресс.

В собственных названиях академий, научно-исследовательских учреждений, учебных заведений с прописной буквы пишется только первое слово (даже если оно является родовым названием или названием, указывающим специальность), а также собственные имена, входящие в сложное название. Напр.: Российская академия наук, Военно-воздушная академия им. Ю. А. Гагарина, Российский университет дружбы народов.

В названиях зрелищных учреждений (театры, музеи, парки, ансамбли, хоры и т. п.) с прописной буквы пишется только первое слово, а также собственные имена, входящие в название. Напр.: Государственный академический Большой театр России, Центральный академический театр Российской армии, Московская государственная консерватория им. П. И. Чайковского, Государственная оружейная палата.

В названиях фирм, акционерных обществ, заводов, фабрик и т. п. с условным наименованием в кавычках с прописной буквы пишется первое из поставленных в кавычки слов; родовое же название и название, указывающее специализацию, пишутся со строчной буквы. Напр.: кондитерская фабрика «Красный Октябрь», научно-производственная фирма «Российская нефть», акционерное общество «Аэрофлот – Российские международные авиалинии».

Сокращенные названия, составленные из частей слов, пишутся с прописной буквы, если обозначают учреждения единичные, и со строчной, если служат наименованиями родовыми. В кавычки они не заключаются. Напр.: Гознак, Внешэкономбанк, но: спецназ.

Не заключаются в кавычки названия фирм, компаний, банков, предприятий, представляющие собой сложносокращенные слова и аббревиатуры, если нет родового слова: ЛУКОЙЛ, Газпром, РЖД, НТВ. При наличии родового слова написанное кириллицей название заключается в кавычки: компания «ЛУКОЙЛ», ОАО «Газпром», ОАО «РЖД», телеканал «НТВ».

Первое слово и собственные имена в полных официальных названиях партий и движений пишутся с прописной буквы. Напр.: Всероссийская конфедерация труда, Союз женщин России, Демократическая партия России, Коммунистическая партия РФ.

Названия неофициального характера пишутся со строчной буквы (в том числе аналогичные названия дореволюционных партий в России). Напр.: партия консерваторов (в Великобритании и др. странах), партия меньшевиков, партия кадетов.

Названия партий, движений символического характера заключают в кавычки, первое слово пишут с прописной буквы. Напр.: партия «Народная воля», «Демократический выбор России», движение «Женщины России», исламское движение «Талибан», «Аль-Каида».

Названия движений ФАТХ и ХАМАС представляют собой аббревиатуры, поэтому пишутся они прописными буквами и в кавычки не заключаются. Эти слова склоняются!

Высшие должности РФ пишут с прописной буквы только в официальных документах (законах, указах, дипломатических документах): Президент Российской Федерации, Председатель Правительства РФ. В остальных случаях – со строчной! Напр.: На совещании присутствовали президент РФ, председатель Государственной думы, министры.

Высшие почетные звания РФ пишутся с прописной буквы: Герой Российской Федерации, а также почетные звания бывшего СССР: Герой Советского Союза, Герой Социалистического Труда.

Другие должности и звания всегда пишутся со строчной буквы: помощник Президента РФ, губернатор, мэр, маршал, генерал, лауреат Нобелевской премии.

Названия высших и других государственных должностей пишут со строчной буквы. Напр.: император Японии, королева Нидерландов, президент Французской Республики.

Названия высших должностей в крупнейших международных организациях пишутся со строчной буквы. Напр.: генеральный секретарь Лиги арабских государств, председатель Совета Безопасности ООН.

В названиях исторических эпох и периодов, революций, восстаний, конгрессов, съездов с прописной буквы пишут первое слово и собственные имена. Напр.: эпоха Возрождения, Высокое Возрождение (также: Раннее, Позднее Возрождение), Ренессанс, Средние века, Парижская коммуна; Великая Октябрьская социалистическая революция, Великая французская революция, Медный бунт; Всероссийский съезд Советов, Съезд народных депутатов РФ.

Названия исторических эпох, событий и т. п., не являющиеся собственными именами, пишутся со строчной буквы: античный мир, гражданская война (но как имя собственное: Гражданская война в России 1918–1921 гг.), феодализм.

Века, культуры, геологические периоды пишутся со строчной буквы. Напр.: бронзовый век, каменный век, ледниковый период, юрский период.

В названиях древних государств, княжеств, империй, королевств пишут с прописной буквы все слова, кроме родовых понятий «княжество», «империя», «королевство» и т. п. Напр.: Восточная Римская империя, Древний Египет, Киевская Русь, Русская земля.

В названиях знаменательных дат, революционных праздников, крупных массовых мероприятий с прописной буквы пишут первое слово и собственные имена. Напр.: Первое мая, Всемирный день авиации и космонавтики, Год ребенка (1979), День Конституции РФ, Новый год, День Победы, но: с днем рождения.

В названиях некоторых политических, культурных, спортивных и других мероприятий, имеющих общегосударственное или международное значение, с прописной буквы пишут первое слово и собственные имена. Напр.: Всемирный экономический форум, Марш мира, Всемирный фестиваль молодежи и студентов, Олимпийские игры, Кубок мира по футболу, Кубок Дэвиса.

В названиях с начальным порядковым числительным в цифровой форме с прописной буквы пишется следующее за цифрой слово: 1 Мая, 8 Марта, XI Международный конкурс имени П. И. Чайковского. Если числительное в словесной форме, то с большой буквы пишется только оно: Первое мая, Восьмое марта.

Правильно: «голубые фишки».

Правильно: круглый стол (без кавычек).

Названия, связанные с религией

С прописной буквы пишутся слово Бог (в значении единого верховного существа) и имена богов во всех религиях. Напр.: Иегова, Саваоф, Яхве, Иисус Христос, Аллах, Брахма; имена языческих богов, напр.: Перун, Зевс. Так же пишутся собственные имена основателей религий. Напр.: Будда, Мухаммед (Магомет, Магомед), Заратуштра (Заратустра); апостолов, пророков, святых, напр.: Иоанн Предтеча, Иоанн Богослов, Георгий Победоносец.

С прописной буквы пишутся все имена лиц Святой Троицы (Бог Отец, Бог Сын, Бог Дух Святой) и слово Богородица, а также все слова, употребляющиеся вместо слова Бог (напр.: Господь, Спаситель, Создатель, Всевышний, Вседержитель) и слова Богородица (напр.: Царица Небесная, Пречистая Дева, Матерь Божия), а также прилагательные, образованные от слов Бог, Господь, напр.: Господня воля, на всё воля Божия, храм Божий, Божественная Троица, Божественная литургия.

В устойчивых сочетаниях, употребляющихся в разговорной речи вне прямой связи с религией, следует писать «бог» (а также «господь») со строчной буквы. Напр.: (не) бог весть; бог (господь) его знает.

Слова, обозначающие важнейшие для православной традиции понятия, пишутся с прописной буквы. Напр.: Крест Господень, Святые Дары.

С прописной буквы пишется первое слово в названиях различных конфессий. Напр.: Русская православная церковь, Римско-католическая церковь, Армянская апостольская церковь.

В названиях религиозных праздников с прописной буквы пишут первое слово и собственные имена. Напр., в христианстве: Пасха Христова, Рождество, Вход Господень в Иерусалим, Крещение Господне; в других религиях: Курбан-Байрам, Рамадан, Ханука.

С прописной буквы пишутся первые слова в словосочетаниях, обозначающих названия постов и недель (седмиц): Великий пост, Петров пост, Светлая седмица, Страстная седмица, а также слова Масленица (Масленая неделя), Святки.

В названиях органов церковного управления с прописной буквы пишется первое слово. Напр.: Священный синод Русской православной церкви, Архиерейский собор, Московская патриархия, Центральное духовное управление мусульман России.

В названиях духовных званий и должностей, в официальных наименованиях высших религиозных должностных лиц с прописной буквы пишутся все слова, кроме служебных и местоимений. Напр.: Патриарх Московский и всея Руси, Вселенский Константинопольский Патриарх, Папа Римский, но: Во время беседы президент и патриарх… Наименования других духовных званий и должностей пишутся со строчной буквы. Напр.: митрополит Волоколамский и Юрьевский, архиепископ, кардинал, игумен, священник, дьякон.

В названиях церквей, монастырей, икон пишутся с прописной буквы все слова, кроме родовых терминов (церковь, храм, собор, лавра, монастырь, семинария, икона, образ) и служебных слов. Напр.: Казанский собор, Киево-Печерская лавра, храм Зачатия Праведной Анны, храм Христа Спасителя.

Названия культовых книг пишутся с прописной буквы. Напр.: Библия, Священное Писание, Евангелие, Ветхий Завет, Коран, Тора.

Названия церковных служб и их частей пишутся со строчной буквы. Напр.: литургия, вечерня, месса, крестный ход, всенощная.

Названия, относящиеся к военной тематике

В важнейших военных названиях РФ, видах войск с прописной буквы пишется первое слово, а также имена собственные. Напр.: Генеральный штаб Вооруженных сил РФ, Ракетные войска стратегического назначения, Сухопутные войска, Военно-воздушные силы.

В названиях управлений и подразделений Министерства обороны РФ с прописной буквы пишется первое слово, а также имена собственные. Напр.: Главное оперативное управление Генерального штаба Вооруженных сил РФ, Главный штаб Сухопутных войск.

В названии военных округов и гарнизонов первое слово пишется с прописной буквы. Напр.: Московский военный округ, Северо-Кавказский военный округ, Саратовский гарнизон.

В собственных наименованиях войн пишутся с прописной буквы первое слово и собственные имена. Напр.: Балканские войны, Отечественная война 1812 года, Первая мировая война, но: Великая Отечественная война (традиционное написание); афганская война (1979–1989 гг.).

В названиях боев, сражений, направлений с прописной буквы пишется первое слово (при дефисном написании – обе части названия). Напр.: Берлинское направление, Бородинское сражение, 1-й Украинский фронт, Юго-Западный фронт.

В названиях воинских частей, соединений с прописной буквы пишутся собственные имена. Напр.: Вятский полк, Краснознамённый Балтийский флот, Сибирское казачье войско, 1-я Конная армия.

В названиях орденов, не выделяемых кавычками, с прописной буквы пишется первое слово, кроме слова «орден». Напр.: орден Мужества, орден Дружбы, орден Отечественной войны I степени, орден Святого Георгия. В названиях орденов и знаков отличия бывшего СССР с прописной буквы по традиции пишутся все слова, кроме слова «орден», напр.: орден Трудового Красного Знамени, орден Октябрьской Революции.

В названиях орденов, медалей и знаков отличия, выделяемых кавычками, с прописной буквы пишут первое слово названия в кавычках и имена собственные. Напр.: орден «За заслуги перед Отечеством», медаль «В память 850-летия Москвы».

В названиях премий с прописной буквы пишется первое слово, кроме слова «премия». Напр.: Нобелевская премия, Международная премия Мира, Гран-при, но: премия «Золотая маска» (при названии в кавычках).

Документы, произведения печати, музыкальные произведения, памятники искусства

В названиях документов с предшествующим родовым словом, не включенным в название, родовое слово пишется со строчной буквы, а само название заключают в кавычки и пишут с прописной. Напр.: указ Президента РФ «О мерах по оздоровлению государственных финансов», закон «О свободе совести и религиозных объединениях», программа «Партнерство ради мира».

Названия документов без предшествующего стоящего вне названия родового слова (устав, инструкция и т. п.) принято не заключать в кавычки и начинать с прописной буквы. Напр.: Версальский договор, Декларация ООН, Конституция РФ, Договор об общественном согласии, Гражданский кодекс РФ, Декларация прав и свобод человека и гражданина. Если приводится неполное или неточное название документа, то используется написание со строчной буквы, напр.: На очередном заседании закон о пенсиях не был утвержден.

В выделяемых кавычками названиях книг, газет, журналов и т. п. первое слово и собственные имена пишут с прописной буквы. Напр.: комедия «Горе от ума», роман «Война и мир», «Новый мир». Это же правило относится к зарубежным книгам, газетам и журналам. Напр.: «Аль-Ахрам», «Нью-Йорк таймс».

Названия телеканалов, не являющиеся аббревиатурами, заключаются в кавычки: «Россия», «Домашний».

Иноязычные названия организаций, учреждений, представляемые аббревиатурами, в кавычки не заключаются: Би-би-си, Си-эн-эн.

Названия организаций, учреждений, написанные латиницей, в кавычки не заключаются: Russia Today.

Условные названия товаров и сортов растений

Условные названия продуктовых, парфюмерных и т. д. товаров заключают в кавычки и пишут с прописной буквы. Напр.: сыр «Российский», конфеты «Красная Шапочка», шоколад «Вдохновение».

Условные названия видов и сортов растений, овощей и т. п. выделяются кавычками и пишутся со строчной буквы. Напр.: клубника «виктория», яблоки «пепин литовский», огурцы «золотой петушок».

Общепринятые названия растений пишутся со строчной буквы без кавычек. Напр.: алоэ, антоновка, белый налив.

Корабли, поезда, самолеты, машины

Условные индивидуальные названия заключаются в кавычки и пишутся с прописной буквы. Напр.: крейсер «Аврора», самолет «Максим Горький», шхуна «Бегущая по волнам».

Названия производственных марок технических изделий (в том числе машин) заключаются в кавычки и пишутся с прописной буквы: автомобили «Москвич-412», «Волга», «Вольво», самолеты «Боинг-707», «Руслан». Однако названия самих этих изделий (кроме названий, совпадающих с собственными именами – личными и географическими) пишутся в кавычках со строчной буквы, напр.: «кадиллак», «москвич», «тойота», но: «Волга», «Ока» (совпадают с именами собственными, поэтому пишутся с прописной буквы). Исключения: «жигули», «мерседес» (совпадают с именами собственными, но пишутся со строчной).

Серийные обозначения машин в виде инициальных аббревиатур, сочетающихся с номерами или без номеров, пишутся без кавычек. Напр.: Ан-22, БелАЗ, ЗИЛ, ГАЗ-51, Ил-18, КамАЗ, Ту-104, Як-9, Су-30.

Условные названия средств покорения космоса заключают в кавычки и пишут с прописной буквы. Напр.: искусственный спутник Земли «Космос-1443», космические корабли «Восток-2», шаттл «Индевор», орбитальная станция «Мир».

Знаки препинания

В начале предложения однако запятой не выделяется.

Тире ставится перед это, это есть, это значит, вот, если с помощью этих слов сказуемое присоединяется к подлежащему.

В названиях трасс типа Симферополь – Ялта требуется тире с пробелами, кавычки не нужны. В кавычки заключаются условные названия автотрасс: автотрасса «Дон».

В сложных союзах запятая ставится один раз – или перед всем союзом, или в середине: для того чтобы, тем более что. В начале предложения сложные союзы обычно не расчленяются: Для того чтобы получить саженцы, нужно заполнить купон и отправить его по адресу.

Если союз как имеет значение «в качестве», то перед как запятая не ставится. Напр.: Я говорю как литератор (в качестве литератора).

Придаточное предложение без главного не употребляется, поэтому нельзя разбивать сложноподчиненное предложение точкой. Напр., неправильно: Пожар не смогли потушить. Потому что не было вертолета.

Двоеточие ставится в сложном предложении, если на месте двоеточия можно вставить слова что; а именно; потому что; увидел/услышал/почувствовал, что. Об одном прошу вас (а именно): стреляйте скорее. Помню также (что): она любила хорошо одеваться.

Тире в сложном предложении ставится, если между частями можно вставить союз и, но или а, поэтому, словно, это. Также тире ставится, если перед первой частью можно вставить когда, если. Напр.: Игнат спустил курок – (и) ружье дало осечку. Я умираю – (поэтому) мне ни к чему лгать. (Когда) Ехал сюда – рожь начинала желтеть. (Если) Будет дождик – будут и грибки.

Разное

Местоимения Вы и Ваш пишутся с прописной буквы как форма вежливого обращения к одному лицу. Напр.: Прошу Вас…, Сообщаем Вам… При обращении к нескольким лицам эти местоимения пишутся с маленькой буквы. Напр.: уважаемые коллеги, ваше письмо…

«… на сумму 50 рублей». Предлог в не нужен!

Правильно: линии электропередачи.

Союзы также и тоже пишутся слитно, если их можно заменить друг другом. Если же такая замена невозможна, то это не союзы, а сочетания указательного местоимения то или так с частицей же, которые пишутся отдельно. Частицу же в таком случае часто можно просто опустить.

Предлог несмотря на пишется слитно: Мы отправились в путь, несмотря на дождь.

Нежелательно употреблять собирательные числительные двое, трое и др. со словами, обозначающими род деятельности, должность или звание. То есть лучше писать два президента, три академика (а не двое президентов, трое академиков).

Правильно: включить в повестку дня, но стоять на повестке дня.

Использованы материалы книги «Писать легко: как сочинять тексты, не дожидаясь вдохновения». Автор — Ольга Соломатина. Купить книгу в «ЛитРес»

НАЗВАНИЯ, ОТНОСЯЩИЕСЯ К ВОЕННОЙ ТЕМАТИКЕ

• С прописной буквы пишутся:

Вооруженные Силы Российской Федерации

Генеральный штаб Вооруженных Сил Российской Федерации

виды Вооруженных Сил Российской Федерации:

Сухопутные войска

Военно-воздушные силы

Военно-Морской Флот

рода войск Вооруженных Сил Российской Федерации:

Ракетные войска стратегического назначения

Воздушно-десантные войска

Космические войска

Железнодорожные войска Российской Федерации

• Со строчной буквы пишутся:

войска гражданской обороны

внутренние войска Министерства внутренних дел Российской Федерации

•Названия военных округов Вооруженных Сил Российской Федерации пишутся следующим образом:

Ленинградский военный округ и под.

• Названия должностей пишутся в соответствии со следующими моделями :

Верховный Главнокомандующий Вооруженными Силами Российской Федерации

главнокомандующий Военно-Морским Флотом и под.

командующий Воздушно-десантными войсками и под.

командующий войсками Ленинградского военного округа

государственный оборонный заказ на 2004 год

ОБЩЕСТВЕННЫЕ ОБЪЕДИНЕНИЯ

• В названиях общественных движений, политических партий, профсоюзов, фондов, творческих союзов и других общественных объединений с прописной буквы пишутся первое слово и имена собственные:

Всероссийская конфедерация труда

Агропромышленный союз России

Олимпийский комитет России

Союз женщин России

Фонд защиты гласности Российской Федерации

Российский детский фонд

Российское общество Красного Креста

Ассоциация коренных малочисленных народов Севера и Дальнего Востока

Российский союз промышленников и предпринимателей (работодателей)

Аграрная партия России

Союз театральных деятелей Российской Федерации и под.

• Первое слово названия общественного объединения при наличии условного наименования, заключенного в кавычки, а также название его центрального органа, если эти названия не начинаются словом Всероссийский, пишутся со строчной буквы:

общество «Мемориал»

правление Союза художников России

совет Конфедерации журналистских союзов

Всероссийский союз «Обновление»

• Названия должностей руководителей общественных объединений пишутся со строчной буквы:

председатель Федерации независимых профсоюзов России

президент Российского союза промышленников и предпринимателей (работодателей)

ПРЕДПРИЯТИЯ, УЧРЕЖДЕНИЯ, ОРГАНИЗАЦИИ.

СРЕДСТВА МАССОВОЙ ИНФОРМАЦИИ

ПРЕДПРИЯТИЯ, ОБЪЕДИНЕНИЯ, АКЦИОНЕРНЫЕ ОБЩЕСТВА

• С прописной буквы пишется первое слово в названиях предприятий, объединений, акционерных обществ:

Новокузнецкий алюминиевый завод

Благовещенская хлопкопрядильная фабрика

Челябинский металлургический комбинат

Государственная инвестиционная корпорация

• В названиях предприятий, объединений, акционерных обществ, финансово-промышленных групп, выделяемых кавычками, первое слово и имена собственные пишутся с прописной буквы:

производственное объединение «Якутуголь»

федеральное государственное унитарное предприятие «Рособоронэкспорт»

закрытое акционерное общество «Петербургский тракторный завод»

открытое акционерное общество «Газпром»

общество с ограниченной ответственностью «ЛУКОЙЛ — Западная Сибирь»

В названиях предприятий, объединений, акционерных обществ слово Российский всегда пишется с прописной буквы, тогда как слово государственный может писаться как с прописной, так и строчной буквы:

Российская корпорация «Алмаззолото»

Государственная авиационная корпорация «Туполев», но:

государственная транспортная компания «Россия»

• В названиях, в состав которых входит слово имени или с номером родовое название и название, указывающее на профиль предприятия, пишутся со строчной буквы:

металлургический завод имени А.И. Серова

фабрика детской книги №1

колхоз имени Ю.А. Гагарина

• Если названия со словом имени начинаются с географического определения, то первое слово пишется с прописной буквы:

Орловский машиностроительный завод имени Медведева

| Ground Forces of the Russian Federation | |

|---|---|

| Сухопутные войска Российской Федерации | |

Emblem of the Russian Ground Forces |

|

| Founded | 1550[1] 1992 (current form) |

| Country | |

| Type | Army |

| Size | 360,000 active duty[2] |

| Part of | |

| Headquarters | Frunzenskaya Embankment 20-22, Moscow |

| Patron | Saint Alexander Nevsky[3] |

| Colors | Red Black Grey Green |

| March | Forward, infantry! Вперёд, пехота! |

| Anniversaries | 1 October |

| Engagements |

|

| Website | structure.mil.ru/structure/forces/ground.htm |

| Commanders | |

| Commander-in-Chief | |

| First Deputy Commander-in-Chief | |

| Deputy Commander-in-Chief | |

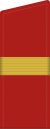

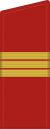

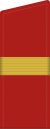

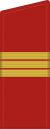

| Insignia | |

| Flag |  |

| Patch |  |

| Middle emblem |  |

| Insignia |  |

The Russian Ground Forces (Russian: Сухопутные войска [СВ], romanized: Sukhoputnyye voyska [SV]), also known as the Russian Army (Russian: Армия России, romanized: Armiya Rossii, lit. ‘Army of Russia’), are the land forces of the Russian Armed Forces.

The primary responsibilities of the Russian Ground Forces are the protection of the state borders, combat on land, and the defeat of enemy troops.

The President of Russia is the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation. The Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Ground Forces is the chief commanding authority of the Russian Ground Forces. He is appointed by the President of Russia. The Main Command of the Ground Forces is based in Moscow.

Mission[edit]

The primary responsibilities of the Russian Ground Forces are the protection of the state borders, combat on land, the security of occupied territories, and the defeat of enemy troops. The Ground Forces must be able to achieve these goals both in nuclear war and non-nuclear war, especially without the use of weapons of mass destruction. Furthermore, they must be capable of protecting the national interests of Russia within the framework of its international obligations.

The Main Command of the Ground Forces is officially tasked with the following objectives:[6]

- the training of troops for combat, on the basis of tasks determined by the Armed Forces’ General Staff

- the improvement of troops’ structure and composition, and the optimization of their numbers, including for special troops

- the development of military theory and practice

- the development and introduction of training field manuals, tactics, and methodology

- the improvement of operational and combat training of the Ground Forces

History[edit]

As the Soviet Union dissolved, efforts were made to keep the Soviet Armed Forces as a single military structure for the new Commonwealth of Independent States. The last Minister of Defence of the Soviet Union, Marshal Yevgeny Shaposhnikov, was appointed supreme commander of the CIS Armed Forces in December 1991.[7] Among the numerous treaties signed by the former republics, in order to direct the transition period, was a temporary agreement on general purpose forces, signed in Minsk on 14 February 1992. However, once it became clear that Ukraine (and potentially the other republics) was determined to undermine the concept of joint general purpose forces and form their own armed forces, the new Russian government moved to form its own armed forces.[7]

Russian President Boris Yeltsin signed a decree forming the Russian Ministry of Defence on 7 May 1992, establishing the Russian Ground Forces along with the other branches of the military. At the same time, the General Staff was in the process of withdrawing tens of thousands of personnel from the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany, the Northern Group of Forces in Poland, the Central Group of Forces in Czechoslovakia, the Southern Group of Forces in Hungary, and from Mongolia.

Thirty-seven Soviet Ground Forces divisions had to be withdrawn from the four groups of forces and the Baltic States, and four military districts—totalling 57 divisions—were handed over to Belarus and Ukraine.[8] Some idea of the scale of the withdrawal can be gained from the division list. For the dissolving Soviet Ground Forces, the withdrawal from the former Warsaw Pact states and the Baltic states was an extremely demanding, expensive, and debilitating process.[9]

As the military districts that remained in Russia after the collapse of the Union consisted mostly of the mobile cadre formations, the Ground Forces were, to a large extent, created by relocating the formerly full-strength formations from Eastern Europe to under-resourced districts. However, the facilities in those districts were inadequate to house the flood of personnel and equipment returning from abroad, and many units «were unloaded from the rail wagons into empty fields.»[10]

The need for destruction and transfer of large amounts of weaponry under the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe also necessitated great adjustments.

Post-Soviet reform plans[edit]

The Ministry of Defence newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda published a reform plan on 21 July 1992. Later one commentator said it was «hastily» put together by the General Staff «to satisfy the public demand for radical changes.»[11] The General Staff, from that point, became a bastion of conservatism, causing a build-up of troubles that later became critical. The reform plan advocated a change from an Army-Division-Regiment structure to a Corps-Brigade arrangement. The new structures were to be more capable in a situation with no front line, and more capable of independent action at all levels.[12]

Cutting out a level of command, omitting two out of three higher echelons between the theatre headquarters and the fighting battalions, would produce economies, increase flexibility, and simplify command-and-control arrangements.[12] The expected changeover to the new structure proved to be rare, irregular, and sometimes reversed. The new brigades that appeared were mostly divisions that had broken down until they happened to be at the proposed brigade strengths. New divisions—such as the new 3rd Motor Rifle Division in the Moscow Military District, formed on the basis of disbanding tank formations—were formed, rather than new brigades.

Few of the reforms planned in the early 1990s eventuated, for three reasons: Firstly, there was an absence of firm civilian political guidance, with President Yeltsin primarily interested in ensuring that the Armed Forces were controllable and loyal, rather than reformed.[11][13] Secondly, declining funding worsened the progress. Finally, there was no firm consensus within the military about what reforms should be implemented. General Pavel Grachev, the first Russian Minister of Defence (1992–96), broadly advertised reforms, yet wished to preserve the old Soviet-style Army, with large numbers of low-strength formations and continued mass conscription. The General Staff and the armed services tried to preserve Soviet-era doctrines, deployments, weapons, and missions in the absence of solid new guidance.[14]

British military expert, Michael Orr, claims that the hierarchy had great difficulty in fully understanding the changed situation, due to their education. As graduates of Soviet military academies, they received great operational and staff training, but in political terms they had learned an ideology, rather than a wide understanding of international affairs. Thus, the generals—focused on NATO expansion in Eastern Europe—could not adapt themselves and the Armed Forces to the new opportunities and challenges they faced.[15]

Crime and corruption in the ground forces[edit]

The new Russian Ground Forces inherited an increasing crime problem from their Soviet predecessors. As draft resistance grew in the last years of the Soviet Union, the authorities tried to compensate by enlisting men with criminal records and who spoke little or no Russian. Crime rates soared, with the military procurator in Moscow in September 1990 reporting a 40-percent increase in crime over the previous six months, including a 41-percent rise in serious bodily injuries.[16] Disappearances of weapons rose to rampant levels, especially in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus.[16]

Generals directing the withdrawals from Eastern Europe diverted arms, equipment, and foreign monies intended to build housing in Russia for the withdrawn troops. Several years later, the former commander in Germany, General Matvei Burlakov, and the Defence Minister, Pavel Grachev, had their involvement exposed. They were also accused of ordering the murder of reporter Dmitry Kholodov, who had been investigating the scandals.[16] In December 1996, Defence Minister Igor Rodionov ordered the dismissal of the Commander of the Ground Forces, General Vladimir Semyonov, for activities incompatible with his position — reportedly his wife’s business activities.[17]

A 1995 study by the U.S. Foreign Military Studies Office[18] went as far as to say that the Armed Forces were «an institution increasingly defined by the high levels of military criminality and corruption embedded within it at every level.» The FMSO noted that crime levels had always grown with social turbulence, such as the trauma Russia was passing through. The author identified four major types among the raft of criminality prevalent within the forces—weapons trafficking and the arms trade; business and commercial ventures; military crime beyond Russia’s borders; and contract murder. Weapons disappearances began during the dissolution of the Union and has continued. Within units «rations are sold while soldiers grow hungry … [while] fuel, spare parts, and equipment can be bought.»[19] Meanwhile, voyemkomats take bribes to arrange avoidance of service, or a more comfortable posting.

Beyond the Russian frontier, drugs were smuggled across the Tajik border—supposedly being patrolled by Russian guards—by military aircraft, and a Russian senior officer, General Major Alexander Perelyakin, had been dismissed from his post with the United Nations peacekeeping force in Bosnia-Hercegovina (UNPROFOR), following continued complaints of smuggling, profiteering, and corruption. In terms of contract killings, beyond the Kholodov case, there have been widespread rumours that GRU Spetsnaz personnel have been moonlighting as mafiya hitmen.[20]

Reports such as these continued. Some of the more egregious examples have included a constant-readiness motor rifle regiment’s tanks running out of fuel on the firing ranges, due to the diversion of their fuel supplies to local businesses.[19] Visiting the 20th Army in April 2002, Sergey Ivanov said the volume of theft was «simply impermissible».[19]

Some degree of change is under way.[21]

Abuse of personnel, sending soldiers to work outside units—a long-standing tradition which could see conscripts doing things ranging from being large scale manpower supply for commercial businesses to being officers’ families’ servants—is now banned by Sergei Ivanov’s Order 428 of October 2005. What is more, the order is being enforced, with several prosecutions recorded.[21] President Putin also demanded a halt to dishonest use of military property in November 2005: «We must completely eliminate the use of the Armed Forces’ material base for any commercial objectives.»

The spectrum of dishonest activity has included, in the past, exporting aircraft as scrap metal; but the point at which officers are prosecuted has shifted, and investigations over trading in travel warrants and junior officers’ routine thieving of soldiers’ meals are beginning to be reported.[21] However, British military analysts comment that «there should be little doubt that the overall impact of theft and fraud is much greater than that which is actually detected».[21] Chief Military Prosecutor Sergey Fridinskiy said in March 2007 that there was «no systematic work in the Armed Forces to prevent embezzlement».[21]

In March 2011, Military Prosecutor General Sergei Fridinsky reported that crimes had been increasing steadily in the Russian ground forces for the past 18 months, with 500 crimes reported in the period of January to March 2011 alone. Twenty servicemen were crippled and two killed in the same period as a result. Crime in the ground forces was up 16% in 2010 as compared to 2009, with crimes against other servicemen constituting one in every four cases reported.[22]

Compounding this problem was also a rise in «extremist» crimes in the ground forces, with «servicemen from different ethnic groups or regions trying to enforce their own rules and order in their units«, according to the Prosecutor General. Fridinsky also lambasted the military investigations department for their alleged lack of efficiency in investigative matters, with only one in six criminal cases being revealed. Military commanders were also accused of concealing crimes committed against servicemen from military officials.[23]

A major corruption scandal also occurred at the elite Lipetsk pilot training center, where the deputy commander, the chief of staff and other officers allegedly extorted 3 million roubles of premium pay from other officers since the beginning of 2010. The Tambov military garrison prosecutor confirmed that charges have been lodged against those involved. The affair came to light after a junior officer wrote about the extortion in his personal blog. Sergey Fridinskiy, the Main Military Prosecutor acknowledged that extortion in the distribution of supplementary pay in army units is common, and that «criminal cases on the facts of extortion are being investigated in practically every district and fleet.”[24]

In August 2012, Prosecutor General Fridinsky again reported a rise in crime, with murders rising more than half, bribery cases doubling, and drug trafficking rising by 25% in the first six months of 2012 as compared to the same period in the previous year. Following the release of these statistics, the Union of the Committees of Soldiers’ Mothers of Russia denounced the conditions in the Russian army as a «crime against humanity».[25]

In July 2013, the Prosecutor General’s office revealed that corruption in the same year soared 450% as compared to the previous year, costing the Russian government 4.4 billion rubles (US$130 million), with one in three corruption-related crimes committed by civil servants or civilian personnel in the military forces. It was also revealed that total number of registered crimes in the Russian armed forces had declined in the same period, although one in five crimes registered were corruption-related.[26]

Internal crisis of 1993[edit]

The Russian Ground Forces reluctantly became involved in the Russian constitutional crisis of 1993 after President Yeltsin issued an unconstitutional decree dissolving the Russian Parliament, following its resistance to Yeltsin’s consolidation of power and his neo-liberal reforms. A group of deputies, including Vice President Alexander Rutskoi, barricaded themselves inside the parliament building. While giving public support to the President, the Armed Forces, led by General Grachev, tried to remain neutral, following the wishes of the officer corps.[27] The military leadership were unsure of both the rightness of Yeltsin’s cause and the reliability of their forces, and had to be convinced at length by Yeltsin to attack the parliament.

When the attack was finally mounted, forces from five different divisions around Moscow were used, and the personnel involved were mostly officers and senior non-commissioned officers.[9] There were also indications that some formations deployed into Moscow only under protest.[27] However, once the parliament building had been stormed, the parliamentary leaders arrested, and temporary censorship imposed, Yeltsin succeeded in retaining power.

Chechen Wars[edit]

First Chechen War[edit]

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Chechens declared independence in November 1991, under the leadership of a former Air Forces officer, General Dzhokar Dudayev.[28] The continuation of Chechen independence was seen as reducing Moscow’s authority; Chechnya became perceived as a haven for criminals, and a hard-line group within the Kremlin began advocating war. A Security Council meeting was held 29 November 1994, where Yeltsin ordered the Chechens to disarm, or else Moscow would restore order. Defense Minister Pavel Grachev assured Yeltsin that he would «take Grozny with one airborne assault regiment in two hours.»[29]

The operation began on 11 December 1994 and, by 31 December, Russian forces were entering Grozny, the Chechen capital. The 131st Motor Rifle Brigade was ordered to make a swift push for the centre of the city, but was then virtually destroyed in Chechen ambushes. After finally seizing Grozny amid fierce resistance, Russian troops moved on to other Chechen strongholds. When Chechen militants took hostages in the Budyonnovsk hospital hostage crisis in Stavropol Kray in June 1995, peace looked possible for a time, but the fighting continued. Following this incident, the separatists were referred to as insurgents or terrorists within Russia.

Dzhokar Dudayev was assassinated in a Russian airstrike on 21 April 1996, and that summer, a Chechen attack retook Grozny. Alexander Lebed, then Secretary of the Security Council, began talks with the Chechen rebel leader Aslan Maskhadov in August 1996 and signed an agreement on 22/23 August; by the end of that month, the fighting ended.[30]

The formal ceasefire was signed in the Dagestani town of Khasavyurt on 31 August 1996, stipulating that a formal agreement on relations between the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria and the Russian federal government need not be signed until late 2001.

Writing some years later, Dmitri Trenin and Aleksei Malashenko described the Russian military’s performance in Chechniya as «grossly deficient at all levels, from commander-in-chief to the drafted private.»[31] The Ground Forces’ performance in the First Chechen War has been assessed by a British academic as «appallingly bad».[32]

Writing six years later, Michael Orr said «one of the root causes of the Russian failure in 1994–96 was their inability to raise and deploy a properly trained military force.»[33]

Second Chechen War[edit]

The Second Chechen War began in August 1999 after Chechen militias invaded neighboring Dagestan, followed quickly in early September by a series of four terrorist bombings across Russia. This prompted Russian military action against the alleged Chechen culprits.

In the first Chechen war, the Russians primarily laid waste to an area with artillery and airstrikes before advancing the land forces. Improvements were made in the Ground Forces between 1996 and 1999; when the Second Chechen War started, instead of hastily assembled «composite regiments» dispatched with little or no training, whose members had never seen service together, formations were brought up to strength with replacements, put through preparatory training, and then dispatched. Combat performance improved accordingly,[34] and large-scale opposition was crippled.

Most of the prominent past Chechen separatist leaders had died or been killed, including former President Aslan Maskhadov and leading warlord and terrorist attack mastermind Shamil Basayev. However, small-scale conflict continued to drag on; as of November 2007, it had spread across other parts of the Russian Caucasus.[35] It was a divisive struggle, with at least one senior military officer dismissed for being unresponsive to government commands: General Colonel Gennady Troshev was dismissed in 2002 for refusing to move from command of the North Caucasus Military District to command of the less important Siberian Military District.[36]

The Second Chechen War was officially declared ended on 16 April 2009.[37]

Reforms under Sergeyev[edit]

When Igor Sergeyev arrived as Minister of Defence in 1997, he initiated what were seen as real reforms under very difficult conditions.[38]

The number of military educational establishments, virtually unchanged since 1991, was reduced, and the amalgamation of the Siberian and Trans-Baikal Military Districts was ordered. A larger number of army divisions were given «constant readiness» status, which was supposed to bring them up to 80 percent manning and 100 percent equipment holdings. Sergeyev announced in August 1998 that there would be six divisions and four brigades on 24-hour alert by the end of that year. Three levels of forces were announced; constant readiness, low-level, and strategic reserves.[39]

However, personnel quality—even in these favored units—continued to be a problem. Lack of fuel for training and a shortage of well-trained junior officers hampered combat effectiveness.[40] However, concentrating on the interests of his old service, the Strategic Rocket Forces, Sergeyev directed the disbanding of the Ground Forces headquarters itself in December 1997.[41] The disbandment was a «military nonsense», in Orr’s words, «justifiable only in terms of internal politics within the Ministry of Defence».[42] The Ground Forces’ prestige declined as a result, as the headquarters disbandment implied—at least in theory—that the Ground Forces no longer ranked equally with the Air Force and Navy.[42]

Reforms under Putin[edit]

A Russian airborne exercise in 2017

Under President Vladimir Putin, more funds were committed, the Ground Forces Headquarters was reestablished, and some progress on professionalisation occurred. Plans called for reducing mandatory service to 18 months in 2007, and to one year by 2008, but a mixed Ground Force, of both contract soldiers and conscripts, would remain. (As of 2009, the length of conscript service was 12 months.)[43]

Funding increases began in 1999; after some recovery in the Russian economy and the associated rise in income, especially from oil, «Russia’s officially reported defence spending [rose] in nominal terms at least, for the first time since the formation of the Russian Federation».[44] The budget rose from 141 billion rubles in 2000 to 219 billion rubles in 2001.[45] Much of this funding has been spent on personnel—there have been several pay rises, starting with a 20-percent rise authorised in 2001. The current professionalisation programme, including 26,000 extra sergeants, was expected to cost at least 31 billion roubles ($1.1 billion USD).[46] Increased funding has been spread across the whole budget, with personnel spending being matched by greater procurement and research and development funding.

However, in 2004, Alexander Goltz said that, given the insistence of the hierarchy on trying to force contract soldiers into the old conscript pattern, there is little hope of a fundamental strengthening of the Ground Forces. He further elaborated that they are expected to remain, to some extent, a military liability and «Russia’s most urgent social problem» for some time to come.[47] Goltz summed up by saying: «All of this means that the Russian armed forces are not ready to defend the country and that, at the same time, they are also dangerous for Russia. Top military personnel demonstrate neither the will nor the ability to effect fundamental changes.»[47]

More money is arriving both for personnel and equipment; Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin stated in June 2008 that monetary allowances for servicemen in permanent-readiness units will be raised significantly.[48] In May 2007, it was announced that enlisted pay would rise to 65,000 roubles (US$2,750) per month, and the pay of officers on combat duty in rapid response units would rise to 100,000–150,000 roubles (US$4,230–$6,355) per month. However, while the move to one year conscript service would disrupt dedovshchina, it is unlikely that bullying will disappear altogether without significant societal change.[21] Other assessments from the same source point out that the Russian Armed Forces faced major disruption in 2008, as demographic change hindered plans to reduce the term of conscription from two years to one.[49][50]

Serdyukov reforms[edit]

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (July 2021) |

A major reorganisation of the force began in 2007 by the Minister for Defence Anatoliy Serdyukov, with the aim of converting all divisions into brigades, and cutting surplus officers and establishments.[51][52] However, this affected units of continuous readiness (Russian: ЧПГ – части постоянной готовности) only. It was intended to create 39 to 40 such brigades by 1 January 2016, including 39 all-arms brigades, 21 artillery and MRL brigades, seven brigades of army air defence forces, 12 communication brigades, and two electronic warfare brigades. In addition, the 18th Machine Gun Artillery Division stationed in the Far East remained, and there will be an additional 17 separate regiments.[citation needed] The changes were unprecedented in their scale.

In the course of the reorganization, the 4-chain command structure (military district – field army – division – regiment) that was used until then was replaced with a 3-chain structure: strategic command – operational command – brigade. Brigades are supposed to be used as mobile permanent-readiness units capable of fighting independently with the support of highly mobile task forces or together with other brigades under joint command.[53]

In a statement on 4 September 2009, RGF Commander-in-Chief Vladimir Boldyrev said that half of the Russian land forces were reformed by 1 June and that 85 brigades of constant combat preparedness had already been created. Among them are the combined-arms brigade, missile brigades, assault brigades and electronic warfare brigades.[54]

During General Mark Hertling’s term as Commander, United States Army Europe in 2011-2012, he visited Russia at the invitation of the Commander of the Ground Forces, «Colonel-General (corresponding to an American lieutenant general) Aleksandr Streitsov ..at preliminary meetings» with the Embassy of the United States, Moscow, the U.S. Defence Attache told Hertling that the Ground Forces «while still substantive in quantity, continued to decline in capability and quality. My subsequent visits to the schools and units [Colonel General] Streitsov chose reinforced these conclusions. The classroom discussions were sophomoric, and the units in training were going through the motions of their scripts with no true training value or combined arms interaction—infantry, armor, artillery, air, and resupply all trained separately.»[55]

Reforms under Sergey Shoygu[edit]

|

|

This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (July 2021) |

Sergey Shoygu meeting with Indian officials in 2018

After Sergey Shoygu took over the role of minister of defense, the reforms Serdyukov had implemented were reversed. He also aimed to restore trust with senior officers as well as the defense ministry in the wake of the intense resentment Serduykov’s reforms had generated. He did this a number of ways but one of the ways was integrating himself by wearing a military uniform.[56]

Shoygu ordered 750 military exercises, such as Vostok 2018. The exercises also seemed to have helped validate the general direction of reform. The effect of this readiness was seen during Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014. Since Anatoliy Serdyukov had already completed the unpopular reforms (military downsizing and reorganization), it was relatively easy for Shoygu to be conciliatory with the officer corps and Ministry of Defense.[57]

Rearmament has been an important goal of reform. With the goal of 70% modernization by 2020. This was one of the main goals of these reforms. From 1998 to 2001, the Russian Army received almost no new equipment. Sergey Shoygu took a less confrontational approach with the defense industry. By showing better flexibility on terms and pricing, the awarding of new contracts for the upcoming period was much better. Shoygu promised that future contracts would be awarded primarily to domestic firms. While easing tensions, these concessions also weakened incentives for companies to improve performance.[58]

Shoygu also focused on forming battalion tactical groups (BTGs) as the permanent readiness component of the Russian army, rather than brigade-sized formations. According to sources quoted by the Russian Interfax agency, this was due to a lack of the manpower needed for permanent-readiness brigades. BTGs made up the preponderance of units deployed by Russia in the Donbass war. By August 2021 Shoygu claimed that the Russian army had around 170 BTGs.[59][60][61]

Russo-Ukrainian War[edit]

Russia conducted a military buildup on the Ukrainian border starting in late 2021. By mid February 2022, elements of the 29th, 35th and 36th Combined Arms Armies (CAAs) were deployed to Belarus,[62] supported by additional S-400 systems, a squadron of Su-25 and a squadron of Su-35; additional S-400 systems and four Su-30 fighters were deployed to the country for joint use with Belarus. Russia also had the 20th and 8th CAAs and the 22nd AC regularly deployed near the Ukrainian border, while elements of 41st CAA were deployed to Yelnya, elements of 1st TA and 6th CAA were deployed to Voronezh[63] and elements of the 49th[64] and the 58th CAA were deployed to Crimea. The 1st and 2nd AC were rumoured to be operating in the Donbass region during this time.[65] In all, Russia deployed some 150,000 soldiers around Ukraine during this time, in preparation for the eventual Russian invasion.

On 11 February, the US and western nations communicated that Putin had decided to invade Ukraine, and on 12 February, the US and Russian embassies in Kiev started to evacuate personnel.[66] On February 24, Russian troops began invading Ukraine.[67]

During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian tank losses were reported by the use of Ukrainian sophisticated anti-tank weapons and a lack of air support the Russian army has been described by Phillips O’Brien, a professor of strategic studies at St Andrews University as “a boxer who has a great right hook and a glass jaw.”[68] Quoting Napoleon “In war, moral power is to physical as three parts out of four.” Retired US four-star general Curtis Scaparrotti has blamed confusion and poor morale amongst Russian soldiers over their mission as to their poor performance.[69]