На чтение 2 мин Просмотров 36

Обновлено 21.01.2021

Название компании Xiaomi многие пользователи читают совершенно по-разному. Наиболее распространенные варианты – это Сяоми, Ксиаоми, Шаоми и даже Ксяоми и Сиоми. Какой же из этих вариантов правильный и как читать Xiaomi по-русски разберемся в нашей статье.

Во всем мире, включая Китай, название бренда на английском пишется как Xiaomi, однако в зависимости от конкретного языка и даже диалекта название в различных уголках мира произносится совершенно по-разному.

Как читать Xiaomi?

Для того чтобы ответить на данный вопрос, следует обратиться к написанию бренда иероглифами. В Китае применяется два иероглифа для обозначения компании:

- 小 – Xiǎo, читается как «сяо»;

- 米 – mǐ (ми).

Это означает, что сами китайцы слышат название как «Сяоми», а ударение приходится на последний слог. Кстати, российские лингвисты считают, что именно этот вариант считается правильным. Кстати, данные иероглифы можно перевести как «маленький рис».

Как произносится Xiaomi на английском языке?

Однако большинство пользователей по всему миру читают название популярного китайского бренда с английского языка, чем и объясняется наличие множество вариантов произношения. Так, большинство англоязычных пользователей считает, что правильный вариант – «Ксиаоми», что связано с особенностями чтения буквы «X». Аналог можно провести с название компании Xerox, которая звучит «Ксерокс».

В то же время многие англоязычные люди читают «X» как русскую «З», поэтому в США вполне можно услышать и название «Зиаоми». С точки же зрения русского языка при чтении бренда с английского Xiaomi правильно читается как «Ксиаоми».

В итоге можно сделать вывод о том, что для Xiaomi оптимальными вариантами произношения на русском языке являются два варианта – «Сяоми» с ударением на «и» и Ксиаоми, если читать название с английского языка.

|

|

Headquarters in Haidian District, Beijing |

|

|

Trade name |

Xiaomi |

|---|---|

|

Native name |

小米集团 |

|

Romanized name |

Xiǎomǐ |

| Type | Public |

|

Traded as |

|

| Industry |

|

| Founded | 6 April 2010; 12 years ago |

| Headquarters | Haidian District,

Beijing, China |

|

Area served |

Worldwide |

|

Key people |

|

| Products |

|

| Brands |

|

| Revenue | (2021)[1] |

|

Operating income |

|

|

Net income |

|

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

|

Number of employees |

33,427 (31 December 2021)[1] |

| Subsidiaries |

|

| Website | mi.com |

| Xiaomi | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Chinese | 小米 | |||||

| Literal meaning | Millet | |||||

|

A Xiaomi Exclusive Service Centre for customer support in Kuala Lumpur

Xiaomi Corporation (;[2] Chinese: 小米), commonly known as Xiaomi and registered as Xiaomi Inc., is a Chinese designer and manufacturer of consumer electronics and related software, home appliances, and household items. Behind Samsung, it is the second largest manufacturer of smartphones in the world, most of which run the MIUI operating system. The company is ranked 338th and is the youngest company on the Fortune Global 500.[3][4]

Xiaomi was founded in 2010 in Beijing by now multi-billionaire Lei Jun when he was 40 years old, along with six senior associates. Lei had founded Kingsoft as well as Joyo.com, which he sold to Amazon for $75 million in 2004. In August 2011, Xiaomi released its first smartphone and, by 2014, it had the largest market share of smartphones sold in China. Initially the company only sold its products online; however, it later opened brick and mortar stores.[5] By 2015, it was developing a wide range of consumer electronics.[6] In 2020, the company sold 146.3 million smartphones and its MIUI operating system has over 500 million monthly active users.[7] In the second quarter of 2021, Xiaomi surpassed Apple Inc. to become the second-largest seller of smartphones worldwide, with a 17% market share, according to Canalys.[8] It also is a major manufacturer of appliances including televisions, flashlights, unmanned aerial vehicles, and air purifiers using its Internet of Things and Xiaomi Smart Home product ecosystems.

Xiaomi keeps its prices close to its manufacturing costs and bill of materials costs by keeping most of its products in the market for 18 months, longer than most smartphone companies,[9][10] The company also uses inventory optimization and flash sales to keep its inventory low.[11][12]

History[edit]

2010–2013[edit]

On 6 April 2010 Xiaomi was co-founded by Lei Jun and six others:

- Lin Bin (林斌), vice president of the Google China Institute of Engineering

- Zhou Guangping (周光平), senior director of the Motorola Beijing R&D center

- Liu De (刘德), department chair of the Department of Industrial Design at the University of Science and Technology Beijing

- Li Wanqiang (黎万强), general manager of Kingsoft Dictionary

- Huang Jiangji (黄江吉), principal development manager

- Hong Feng (洪峰), senior product manager for Google China

Lei had founded Kingsoft as well as Joyo.com, which he sold to Amazon for $75 million in 2004.[13] At the time of the founding of the company, Lei was dissatisfied with the products of other mobile phone manufacturers and thought he could make a better product.

On 16 August 2010, Xiaomi launched its first Android-based firmware MIUI.[14]

In 2010, the company raised $41 million in a Series A round.[15]

In August 2011, the company launched its first phone, the Xiaomi Mi1. The device had Xiaomi’s MIUI firmware along with Android installation.[13][16]

In December 2011, the company raised $90 million in a Series B round.[15]

In June 2012, the company raised $216 million of funding in a Series C round at a $4 billion valuation. Institutional investors participating in the first round of funding included Temasek Holdings, IDG Capital, Qiming Venture Partners and Qualcomm.[13][17]

In August 2013, the company hired Hugo Barra from Google, where he served as vice president of product management for the Android platform.[18][19][20][21] He was employed as vice president of Xiaomi to expand the company outside of mainland China, making Xiaomi the first company selling smartphones to poach a senior staffer from Google’s Android team. He left the company in February 2017.[22]

In September 2013, Xiaomi announced its Xiaomi Mi3 smartphone and an Android-based 47-inch 3D-capable Smart TV assembled by Sony TV manufacturer Wistron Corporation of Taiwan.[23][24]

In October 2013, it became the fifth-most-used smartphone brand in China.[25]

In 2013, Xiaomi sold 18.7 million smartphones.[26]

2014–2017[edit]

In February 2014, Xiaomi announced its expansion outside China, with an international headquarters in Singapore.[27][28]

In April 2014, Xiaomi purchased the domain name mi.com for a record US$3.6 million, the most expensive domain name ever bought in China, replacing xiaomi.com as the company’s main domain name.[29][30]

In September 2014, Xiaomi acquired a 24.7% some part taken in Roborock.[31][32]

In December 2014, Xiaomi raised US$1.1 billion at a valuation of over US$45 billion, making it one of the most valuable private technology companies in the world. The financing round was led by Hong Kong-based technology fund All-Stars Investment Limited, a fund run by former Morgan Stanley analyst Richard Ji.[33][34][35][36][37]

In 2014, the company sold over 60 million smartphones.[38] In 2014, 94% of the company’s revenue came from mobile phone sales.[39]

In April 2015, Ratan Tata acquired a stake in Xiaomi.[40][41]

On 30 June 2015, Xiaomi announced its expansion into Brazil with the launch of locally manufactured Redmi 2; it was the first time the company assembled a smartphone outside of China.[42][43][44]

However, the company left Brazil in the second half of 2016.[45]

On 26 February 2016, Xiaomi launched the Mi5, powered by the Qualcomm Snapdragon 820 processor.[46]

On 3 March 2016, Xiaomi launched the Redmi Note 3 Pro in India, the first smartphone to powered by a Qualcomm Snapdragon 650 processor.[47]

On 10 May 2016, Xiaomi launched the Mi Max, powered by the Qualcomm Snapdragon 650/652 processor.[48]

In June 2016, the company acquired patents from Microsoft.[49]

In September 2016, Xiaomi launched sales in the European Union through a partnership with ABC Data.[50]

Also in September 2016, the Xiaomi Mi Robot vacuum was released by Roborock.[51][52]

On 26 October 2016, Xiaomi launched the Mi Mix, powered by the Qualcomm Snapdragon 821 processor.[53]

On 22 March 2017, Xiaomi announced that it planned to set up a second manufacturing unit in India in partnership with contract manufacturer Foxconn.[54][55]

On 19 April 2017, Xiaomi launched the Mi6, powered by the Qualcomm Snapdragon 835 processor.[56]

In July 2017, the company entered into a patent licensing agreement with Nokia.[57]

On 5 September 2017, Xiaomi released Xiaomi Mi A1, the first Android One smartphone under the slogan: Created by Xiaomi, Powered by Google. Xiaomi stated started working with Google for the Mi A1 Android One smartphone earlier in 2017. An alternate version of the phone was also available with MIUI, the MI 5X.[58]

In 2017, Xiaomi opened Mi Stores in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The EU’s first Mi Store was opened in Athens, Greece in October 2017.[59] In Q3 2017, Xiaomi overtook Samsung to become the largest smartphone brand in India. Xiaomi sold 9.2 million units during the quarter.[60] On 7 November 2017, Xiaomi commenced sales in Spain and Western Europe.[61]

2018–present[edit]

A Xiaomi Store in Loulé, Portugal

In April 2018, Xiaomi announced a smartphone gaming brand called Black Shark. It had 6GB of RAM coupled with Snapdragon 845 SoC, and was priced at $508, which was cheaper than its competitors.[62]

On 2 May 2018, Xiaomi announced the launch of Mi Music and Mi Video to offer «value-added internet services» in India.[63] On 3 May 2018, Xiaomi announced a partnership with 3 to sell smartphones in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Austria, Denmark, and Sweden[64]

In May 2018, Xiaomi began selling smart home products in the United States through Amazon.[65]

In June 2018, Xiaomi became a public company via an initial public offering on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, raising $4.72 billion.[66]

On 7 August 2018, Xiaomi announced that Holitech Technology Co. Ltd., Xiaomi’s top supplier, would invest up to $200 million over the next three years to set up a major new plant in India.[67][68]

In August 2018, the company announced POCO as a mid-range smartphone line, first launching in India.[69]

In Q4 of 2018, the Xiaomi Poco F1 became the best selling smartphone sold online in India.[70] The Pocophone was sometimes referred to as the «flagship killer» for offering high-end specifications at an affordable price.[71][72][70]

In October 2019, the company announced that it would launch more than 10 5G phones in 2020, including the Mi 10/10 Pro with 5G functionality.[73]

On 17 January 2020, Poco became a separate sub-brand of Xiaomi with entry-level and mid-range devices.[74][75]

In March 2020, Xiaomi showcased its new 40W wireless charging solution, which was able to fully charge a smartphone with a 4,000mAh battery from flat in 40 minutes.[76][77]

In October 2020, Xiaomi became the third largest smartphone maker in the world by shipment volume, shipping 46.2 million handsets in Q3 2020.[78]

On 30 March 2021, Xiaomi announced that it will invest US$10 billion in electric vehicles over the following ten years.[79] On 31 March 2021, Xiaomi announced a new logo for the company, designed by Kenya Hara.[80][81]

In July 2021, Xiaomi became the second largest smartphone maker in the world, according to Canalys.[8] It also surpassed Apple for the first time in Europe, making it the second largest in Europe according to Counterpoint.

In August 2021, the company acquired autonomous driving company Deepmotion for $77 million.[82][83]

Innovation and development[edit]

In the 2021 review of WIPO’s annual World Intellectual Property Indicators Xiaomi was ranked as 2nd in the world, with 216 designs in industrial design registrations being published under the Hague System during 2020.[84] This position is up on their previous 3rd place ranking in 2019 for 111 industrial design registrations being published.[85]

On 8 February 2022, Lei released a statement on Weibo to announce plans for Xiaomi to enter the high-end smartphone market and surpass Apple as the top seller of premium smartphones in China in three years. To achieve that goal, Xiaomi will invest US$15.7 billion in R&D over the next five years, and the company will benchmark its products and user experience against Apple’s product lines.[86] Lei described the new strategy as a «life-or-death battle for our development» in his Weibo post, after Xiaomi’s market share in China contracted over consecutive quarters, from 17% to 14% between Q2 and Q3 2021, dipping further to 13.2% as of Q4 2021.[87][88][89]

According to a recent report by Canalys, Xiaomi leads Indian smartphone sales in Q1. Xiaomi is one of the leaders of the smartphone makers in India which maintains device affordability.[90]

In 2022, Xiaomi announced and debuted the company’s humanoid robot prototype to the public, while the current state of the robot is very limited in its abilities, the announcement was made to mark the companies ambitions to integrate AI into its product designs as well as develop their humanoid robot project into the future.[91]

Partnerships[edit]

Xiaomi and Harman Kardon[edit]

In 2021, Harman Kardon has collaborated with Xiaomi for its newest smartphones, the Xiaomi Mi 11 series are the first smartphones to feature with Harman Kardon-tuned dual speaker setup.[92]

Xiaomi and Leica[edit]

In 2022, Leica Camera entered a strategic partnership with Xiaomi to jointly develop Leica cameras to be used in Xiaomi flagship Android smartphones, succeeding the partnership between Huawei and Leica. The first smartphones under this new partnership were the Xiaomi 12S Ultra and Xiaomi MIX Fold 2, launched in July and August 2022, respectively.[93]

Xiaomi Studios[edit]

In 2021, Xiaomi began collaborating with directors to create short films shot entirely using the Xiaomi Mi 11 line of phones. In 2022, they made two shorts with Jessica Henwick.[94] The first, Bus Girl won several awards[95] and was long listed for Best British Short at the 2023 BAFTA Awards.[96]

Corporate identity[edit]

Name etymology[edit]

Xiaomi (小米) is the Chinese word for «millet».[97] In 2011 its CEO Lei Jun suggested there are more meanings than just the «millet and rice».[98] He linked the «Xiao» (小) part to the Buddhist concept that «a single grain of rice of a Buddhist is as great as a mountain»,[99] suggesting that Xiaomi wants to work from the little things, instead of starting by striving for perfection,[98] while «mi» (米) is an acronym for Mobile Internet and also «mission impossible», referring to the obstacles encountered in starting the company.[98][100] He also stated that he thinks the name is cute.[98] In 2012 Lei Jun said that the name is about revolution and being able to bring innovation into a new area.[101] Xiaomi’s new «Rifle» processor[102] has given weight to several sources linking the latter meaning to the Communist Party of China’s «millet and rifle» (小米加步枪) revolutionary idiom[103][104] during the Second Sino-Japanese War.[105][106][107][108]

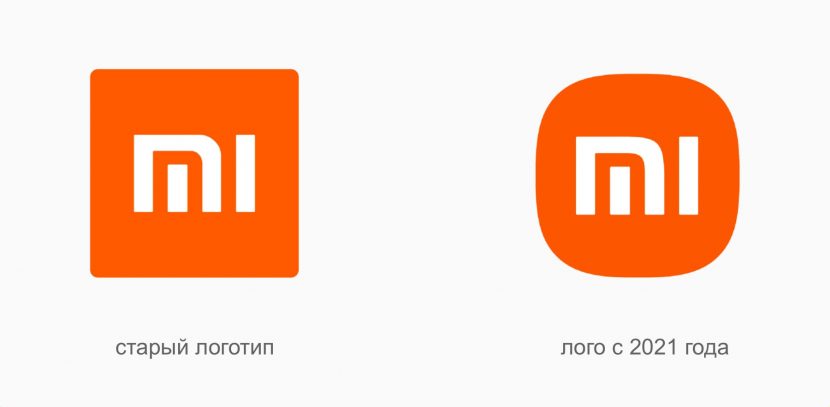

Logo and mascot[edit]

First Xiaomi logo

(2010–2021)

Current logo

(2021–present)

A Mi-Home store with the new logo

Xiaomi’s first logo consisted of a single orange square with the letters «MI» in white located in the center of the square. This logo was in use until 31 March 2021, when a new logo, designed by well-known Japanese designer Kenya Hara, replaced the old one, consisting of the same basic structure as the previous logo, but the square was replaced with a «squircle» with rounded corners instead, with the letters «MI» remaining identical to the previous logo, along with a slightly darker hue.

Xiaomi’s mascot, Mitu, is a white rabbit wearing an Ushanka (known locally as a «Lei Feng hat» in China) with a red star and a red scarf around its neck.[109][110] Later red star on hat was replaced by company’s logo.[111]

Reception[edit]

Imitation of Apple Inc.[edit]

Xiaomi has been accused of imitating Apple Inc.[112][113] The hunger marketing strategy of Xiaomi was described as riding on the back of the «cult of Apple».[13]

After reading a book about Steve Jobs in college, Xiaomi’s chairman and CEO, Lei Jun, carefully cultivated a Steve Jobs image, including jeans, dark shirts, and Jobs’ announcement style at Xiaomi’s earlier product announcements.[114][115][116][117] He was characterized as a «counterfeit Jobs.»[118][119]

In 2013, critics debated how much of Xiaomi’s products were innovative,[117][18][120] and how much of their innovation was just really good public relations.[120]

Others point out that while there are similarities to Apple, the ability to customize the software based upon user preferences through the use of Google’s Android operating system sets Xiaomi apart.[121] Xiaomi has also developed a much wider range of consumer products than Apple.[87]

Violation of GNU General Public License[edit]

In January 2018, Xiaomi was criticized for its non-compliance with the terms of the GNU General Public License. The Android project’s Linux kernel is licensed under the copyleft terms of the GPL, which requires Xiaomi to distribute the complete source code of the Android kernel and device trees for every Android device it distributes. By refusing to do so, or by unreasonably delaying these releases, Xiaomi is operating in violation of intellectual property law in China, as a WIPO state.[122] Prominent Android developer Francisco Franco publicly criticized Xiaomi’s behaviour after repeated delays in the release of kernel source code.[123] Xiaomi in 2013 said that it would release the kernel code.[124] The kernel source code was available on the GitHub website in 2020.[125]

Privacy concerns and data collection[edit]

As a company based in China, Xiaomi is obligated to share data with the Chinese government under the China Internet Security Law and National Intelligence Law.[126][127] There were reports that Xiaomi’s Cloud messaging service sends some private data, including call logs and contact information, to Xiaomi servers.[128][129] Xiaomi later released an MIUI update that made cloud messaging optional and that no private data was sent to Xiaomi servers if the cloud messaging service was turned off.[130]

On 23 October 2014, Xiaomi announced that it was setting up servers outside of China for international users, citing improved services and compliance to regulations in several countries.[131]

On 19 October 2014, the Indian Air Force issued a warning against Xiaomi phones, stating that they were a national threat as they sent user data to an agency of the Chinese government.[132]

In April 2019, researchers at Check Point found a security breach in Xiaomi phone apps.[133][134] The security flaw was reported to be preinstalled.[135]

On 30 April 2020, Forbes reported that Xiaomi extensively tracks use of its browsers, including private browser activity, phone metadata and device navigation, and more alarmingly, without secure encryption or anonymization, more invasively and to a greater extent than mainstream browsers. Xiaomi disputed the claims, while confirming that it did extensively collect browsing data, and saying that the data was not linked to any individuals and that users had consented to being tracked.[136] Xiaomi posted a response stating that the collection of aggregated usage statistics data is used for internal analysis, and would not link any personally identifiable information to any of this data.[137] However, after a followup by Gabriel Cirlig, the writer of the report, Xiaomi added an option to completely stop the information leak when using its browser in incognito mode.[138]

Censorship[edit]

In September 2021, amidst a political spat between China and Lithuania, the Lithuanian Ministry of National Defence urged people to dispose the Chinese-made mobile phones and avoid buying new ones,[139] after the National Cyber Security Centre of Lithuania claimed that Xiaomi devices have built-in censorship capabilities that can be turned on remotely.[140]

Xiaomi denied the accusations, saying that it «does not censor communications to or from its users», and that they would be engaging a third-party to assess the allegations. They also stated that regarding data privacy, it was compliant with two frameworks for following Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), namely its ISO/IEC 27001 Information Security Management Standards and the ISO/IEC 27701 Privacy Information Management System.[141]

Legal actions[edit]

State administration of radio, film and television issue[edit]

In November 2012, Xiaomi’s smart set-top box stopped working one week after the launch due to the company having run foul of China’s State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television.[142][143][144] The regulatory issues were overcome in January 2013.[145]

Misleading sales figures[edit]

The Taiwanese Fair Trade Commission investigated the flash sales and found that Xiaomi had sold fewer smartphones than advertised.[146] Xiaomi claimed that the number of smartphones sold was 10,000 units each for the first two flash sales, and 8,000 units for the third one. However, FTC investigated the claims and found that Xiaomi sold 9,339 devices in the first flash sale, 9,492 units in the second one, and 7,389 for the third.[147] It was found that during the first flash sale, Xiaomi had given 1,750 priority ‘F-codes’ to people who could place their orders without having to go through the flash sale, thus diminishing the stock that was publicly available. The FTC fined Xiaomi NT$600,000.[148]

Shut down of Australia store[edit]

In March 2014, Xiaomi Store Australia (an unrelated business) began selling Xiaomi mobile phones online in Australia through its website, XiaomiStore.com.au.[149] However, Xiaomi soon «requested» that the store be shut down by 25 July 2014.[149] On 7 August 2014, shortly after sales were halted, the website was taken down.[149] An industry commentator described the action by Xiaomi to get the Australian website closed down as unprecedented, saying, «I’ve never come across this [before]. It would have to be a strategic move.»[149] At the time this left only one online vendor selling Xiaomi mobile phones into Australia, namely Yatango (formerly MobiCity), which was based in Hong Kong.[149] This business closed in late 2015.[150]

Temporary ban in India due to patent infringement[edit]

On 9 December 2014, the High Court of Delhi granted an ex parte injunction that banned the import and sale of Xiaomi products in India. The injunction was issued in response to a complaint filed by Ericsson in connection with the infringement of its patent licensed under fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory licensing.[151] The injunction was applicable until 5 February 2015, the date on which the High Court was scheduled to summon both parties for a formal hearing of the case. On 16 December, the High Court granted permission to Xiaomi to sell its devices running on a Qualcomm-based processor until 8 January 2015.[152] Xiaomi then held various sales on Flipkart, including one on 30 December 2014. Its flagship Xiaomi Redmi Note 4G phone sold out in six seconds.[153] A judge extended the division bench’s interim order, allowing Xiaomi to continue the sale of Qualcomm chipset-based handsets until March 2018.[154]

U.S. sanctions due to ties with People’s Liberation Army[edit]

In January 2021, the United States government named Xiaomi as a company «owned or controlled» by the People’s Liberation Army and thereby prohibited any American company or individual from investing in it.[155] However, the investment ban was blocked by a US court ruling after Xiaomi filed a lawsuit in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, with the court expressing skepticism regarding the government’s national security concerns.[156] Xiaomi denied the allegations of military ties and stated that its products and services were of civilian and commercial use.[157] In May 2021, Xiaomi reached an agreement with the Defense Department to remove the designation of the company as military-linked.[158]

Lawsuit by KPN alleging patent infringement[edit]

On 19 January 2021, KPN, a Dutch landline and mobile telecommunications company, sued Xiaomi and others for patent infringement. KPN filed similar lawsuits against Samsung in 2014 and 2015 in a court in the US.[159]

Lawsuit by Wyze alleging invalid patent[edit]

In July 2021, Xiaomi submitted a report to Amazon alleging that Wyze Labs had infringed upon its 2019 «Autonomous Cleaning Device and Wind Path Structure of Same» robot vacuum patent. On 15 July 2021, Wyze filed a lawsuit against Xiaomi in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington, arguing that prior art exists and asking the court for a declaratory judgment that Xiaomi’s 2019 robot vacuum patent is invalid.[160]

Asset seizure in India[edit]

In April 2022, India’s Enforcement Directorate seized assets from Xiaomi as part of an investigation into violations of foreign exchange laws.[161] The asset seizure was subsequently put on hold by a court order, but later upheld.[162][163][164]

Overseas Manufacturing[edit]

Inauguration Plant in Pakistan[edit]

Xiaomi’s mobile device manufacturing plant was inaugurated on March 4 2022 to begin production in Pakistan. The plant was set up in conjunction with Select Technologies (Pvt) Limited, an Air Link fully owned subsidiary. The production plant is located in Lahore.[165]

As of July 2022, the future of the plant is uncertain due to the 2021–2022 global supply chain crisis.[166]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f «Annual Results» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ «How to say: Xiaomi». BBC News. 12 November 2018. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ^ «Xiaomi moves up on Fortune’s Global 500 list (#338)». gsmarena.com. 2 August 2021. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- ^ «Global 500: Xiaomi». Fortune. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Kan, Michael (16 May 2014). «Why Are Xiaomi Phones So Cheap?». Computerworld. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ «The China Smartphone Market Picks Up Slightly in 2014Q4, IDC Reports». IDC. 17 February 2015. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015.

- ^ Palli, Praneeth (23 November 2021). «Xiaomi UI Has Gained More Than 500M Monthly Active Users». Mashable. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ a b «Xiaomi becomes number two smartphone vendor for first time ever in Q2 2021». Canalys. 15 July 2021. Archived from the original on 3 August 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ^ «How can Xiaomi sell its phones so cheaply?». The Daily Telegraph. London. 6 June 2014. Archived from the original on 18 June 2014.

- ^ Seifert, Dan (29 August 2013). «What is Xiaomi? Here’s the Chinese company that just stole one of Android’s biggest stars». The Verge. Archived from the original on 10 July 2014.

- ^ Triggs, Rob (22 December 2014). «The Xiaomi model is taking over the world». Android Authority. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ Kan, Michael (16 May 2014). «Why are Xiaomi phones so cheap?». PC World. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d Wong, Sue-Lin (29 October 2012). «Challenging Apple by Imitation». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013.

- ^ @Xiaomi (11 August 2020). «On August 16, 2010, the first version of MIUI was officially launched. MIUI first caught some real attention on XDA, the US-based developers’ forum» (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b Russell, Jon (26 June 2012). «Chinese smartphone maker Xiaomi confirms new $216 million round of funding». TheNextWeb. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ «Xiaomi Phone with MIUI OS: a $310 Android with 1.5GHz dual-core SoC and other surprises». Engadget. 16 August 2011. Archived from the original on 23 September 2011.

- ^ «Xiaomi the money! Who is this mobile company that’s poaching Tech’s top shelf talent?». PC World. 29 August 2013. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

- ^ a b Lee, Dave (29 August 2013). «Google executive Hugo Barra poached by China’s Xiaomi». BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ «What Ex-Google Exec Hugo Barra Can Do for China’s Xiaomi». Bloomberg BusinessWeek. 29 August 2013. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013.

- ^ Montlake, Simon (14 August 2013). «China’s Xiaomi Hires Ex-Google VP To Run Overseas Business». Forbes. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013.

- ^ Kevin Parrish (29 August 2013). «Google Executive Departs During ‘Love Quadrangle’ Rumors». Tomshardware.com. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ «Hugo Barra is leaving his position as head of international at Xiaomi after 3.5 years». TechCrunch. 22 January 2017. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017.

- ^ Lawler, Richard (5 September 2013). «Xiaomi unveils new Android-powered 5-inch MI3, 47-inch smart TV in China». Engadget. Archived from the original on 7 September 2013.

- ^ «Chinese Tech Sensation Xiaomi Launches An Android-Based 47-inch 3D-Capable Smart TV». CEOWORLD Magazine. 5 September 2013. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ «Xiaomi outperforms HTC to become fifth most used smartphone brand in China, says TrendForce». DigiTimes. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013.

- ^ Millward, Steven (2 July 2014). «Xiaomi sells 26.1 million smartphones in first half of 2014, still on target for 60 million this year». Tech in Asia. Archived from the original on 7 September 2014.

- ^ Liu, Catherine (13 February 2014). «Xiaomi Sets Singapore Launch Date As It Prepares For Global Expansion». TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ «Xiaomi to Set Up International Headquarters in Singapore». Hardwarezone. 19 February 2014. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014.

- ^ Low, Aloysius (24 April 2014). «Xiaomi spends $3.6 million on new two-letter domain». CNET. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ «XiaoMi Purchased Mi.com Domain For A Record $3.6 Million, New URL For Global Users». Archived from the original on 12 August 2014.

- ^ Liao, Rita (3 September 2020). «Xiaomi backs Dyson’s Chinese challenger Dreame in $15 million round». TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ «Xiaomi-backed Roborock gets listed; raises $641 million». Gizmo China. 24 February 2020. Archived from the original on 9 May 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ «Team Profile – All-Stars Investment Limited». All-Stars Investment Limited. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014.

- ^ Smith, Dave (20 December 2014). «The ‘Apple Of China’ Raises Over $1 Billion, Valuation Skyrockets To More Than $45 Billion». Business Insider. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014.

- ^ «Xiaomi CEO Tries to Follow in Steve Jobs’ Footsteps». Caixin. 6 July 2018. Archived from the original on 7 August 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ MacMillan, Douglas; Carew, Rick (29 December 2014). «Xiaomi raises another $1.1 billion to become most-valuable tech start-up». MarketWatch. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ^ Osawa, Juro (20 December 2014). «China’s Xiaomi Raises Over $1 Billion in Investment Round». The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014.

- ^ Russell, Jon (3 January 2015). «Xiaomi Confirms It Sold 61M Phones In 2014, Has Plans To Expand To More Countries». TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 31 October 2017.

- ^ Bershidsky, Leonid (6 November 2014). «Xiaomi’s Killer App? Its Business Model». Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015.

- ^ «Ratan Tata acquires stake in Chinese handset maker Xiaomi». Business Today. 27 April 2015. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015.

- ^ «Ratan Tata acquires stake in Xiaomi». Express Computer. Press Trust of India. 28 April 2015. Archived from the original on 16 May 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ Russell, Jon (30 June 2015). «Xiaomi Expands Its Empire To Brazil, Will Sell First Smartphone There July 7». TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015.

- ^ Shu, Catherine (28 August 2013). «Xiaomi, What Americans Need To Know». TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 30 August 2013.

- ^ Chao, Loretta (1 July 2015). «Xiaomi Launches Its First Smartphone Outside Asia». The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 6 February 2017.

- ^ Veloso, Thássius (19 January 2017). «Xiaomi abandona lojas virtuais e some da internet brasileira». TechTudo (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 22 January 2017.

- ^ Kelion, Leo (26 February 2016). «MWC 2016: Xiaomi unveils ceramic-backed Mi5 smartphone». BBC News. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ «Xiaomi Redmi Note 3 India Launch Set for March 3». NDTV. 10 March 2016. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Olson, Parmy (10 May 2016). «Xiaomi Launches Its Biggest Phone, The 6.4-Inch Mi Max». Forbes. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Ribeiro, John (1 June 2016). «Xiaomi acquires patents from Microsoft ahead of US entry plans». Computerworld. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ «Chinese device giant Xiaomi makes European channel debut with ABC Data». www.channelnomics.eu. Archived from the original on 11 January 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ «Roborock vs. Xiaomi Are Not The Same Robots». 22 April 2020. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ «Xiaomi Mi Robot Features and Specs». 2020. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ «Xiaomi Mi Mix launched in China: Specifications, price of the edgeless phone». The Indian Express. 26 October 2016. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ «XIAOMI PARTNERS WITH FOXCONN TO OPEN SECOND MANUFACTURING UNIT IN ANDHRA PRADESH». Firstpost. 20 March 2017. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Compare: «Xiaomi to open second manufacturing facility in India». EIU Digital Solutions. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

Xiaomi Inc plans to set up a second manufacturing unit in India to cater to a growing demand for smartphones in the Asian country, according to media reports on March 22nd, citing a company announcement.

- ^ Kharpal, Arjun (19 April 2017). «Xiaomi’s latest $362 flagship phone has the same chip as Samsung’s Galaxy S8 and no headphone jack». CNBC. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ «Nokia and Xiaomi ink patent and equipment deal». TechCrunch. 5 July 2017. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Byford, Sam (5 September 2017). «Xiaomi’s Mi A1 is a flagship Android One phone for India». The Verge. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ «Xiaomi in Europa? – Xiaomi Store eröffnet in Athen». Techniktest-Online (in German). 8 October 2017. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ «Xiaomi joins Samsung to become India’s top smartphone company on back of Redmi Note 4». India Today. 14 November 2017. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018.

- ^ Savov, Vlad (7 November 2017). «Xiaomi expands into western Europe with flagship Mi Mix 2 at the vanguard». The Verge. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017.

- ^ «XIAOMI ANNOUNCES BLACK SHARK GAMING SMARTPHONE WITH SNAPDRAGON 845, 6 GB RAM AT CNY 2,999». Firstpost. 14 April 2018. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Tan, Jason (3 May 2018). «Xiaomi Rolls Out Music, Video Apps in India». Caixin. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ Deahl, Dani (3 May 2018). «Xiaomi’s availability is expanding in Europe». The Verge. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Russell, Jon (10 May 2018). «Xiaomi is bringing its smart home devices to the US — but still no phones yet». TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Lau, Fiona; Zhu, Julie (29 June 2018). «China’s Xiaomi raises $4.72 billion after pricing HK IPO at bottom of range: sources». Reuters. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ «Smartphone Upstart Xiaomi Brings Partner to India to Curry Local Favor». Caixin. 7 August 2018. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ «Xiaomi brings smartphone component manufacturing to India with Holitech Technology». blog.mi.com. 7 August 2018. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Chakraborty, Sumit (28 August 2018). «Xiaomi Poco F1 With Snapdragon 845 Launched, Price Starts at Rs. 20,999». NDTV. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ a b Valiyathara, Anvinraj (29 March 2019). «Xiaomi Poco F1 surpasses OnePlus 6 to become no. 1 smartphone in online sales in India». Gizmochina. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ^ Subramaniam, Vaidyanathan. «Killing the flagship killer — Xiaomi’s new Poco F1 is just too enticing to ignore». Notebookcheck. Archived from the original on 2 December 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ «Xiaomi sells 700,000 Pocophone F1 units in 3 months». GSMArena.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ^ «China’s Xiaomi says plans to launch more than 10 5G phones next year». Reuters. 20 October 2019. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ^ Singh, Jagmeet (25 November 2020). «Poco Is Becoming an Independent Brand Globally, After Being Part of Xiaomi for Over 2 Years». NDTV. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ «Xiaomi India spins-off POCO into an independent brand». xda-developers. 17 January 2020. Archived from the original on 17 January 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ «Xiaomi’s new wireless charging tech can fully charge a phone in 40 minutes». Android Central. 2 March 2020. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ «Xiaomi demoes 40W wireless fast charger». GSMArena.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ «China’s Xiaomi surpasses Apple as world’s No. 3 smartphone maker». Nikkei Asia. 30 October 2020. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ «Xiaomi Enters Electric Vehicles Space, Pledges $10 Billion Investment». NDTV. Reuters. 30 March 2021. Archived from the original on 6 April 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ Zhou, Viola (31 March 2021). «Xiaomi Spent 3 Years To Create a New Logo That Looks Just Like the Old One». Vice. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Ali, Darab (31 March 2021). «Believe It Or Not, Xiaomi Has a New Logo and It Has Been Under Development Since 2017!». News18. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Schroeder, Stan (26 August 2021). «Xiaomi acquires autonomous driving company Deepmotion for $77 million». Mashable. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ «Xiaomi will reportedly acquire autonomous driving startup Deepmotion for $77.4 mn». Business Insider. 27 August 2021. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ «World Intellectual Property Indicators 2021» (PDF). WIPO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ World Intellectual Property Organization (2020). World Intellectual Property Indicators 2020. www.wipo.int. World IP Indicators (WIPI). World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). doi:10.34667/tind.42184. ISBN 9789280532012. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ 军, 雷 (8 February 2022). «微博国际版». Weibo. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ a b «Xiaomi is transforming into a high-end smartphone brand to compete with Apple». KrASIA. 9 February 2022. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ «China Smartphone Market Share: By Quarter». Counterpoint Research. 30 November 2021. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ «China’s Smartphone Market Grew 1.1% in 2021 Despite Soft Demand and Supply Chain Disruptions, IDC Reports». IDC. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ «Canalys: Xiaomi leads Indian smartphone sales in Q1, Realme gained the most». GSMArena.com. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ «Chinese tech company reveals robot weeks before Tesla». cnn.com. 16 August 2022.

- ^ «Xiaomi Mi 11 is a breakthrough in terms of audio capabilities. Sound by Harman / Kardon».

- ^ «Mi Global Home». Mi Global Home. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ https://www.wired.com/story/phone-cameras-in-film/

- ^ https://www.imdb.com/title/tt15301300/awards/?ref_=tt_awd

- ^ https://www.bafta.org/film/longlists-2023-ee-BAFTA-film-awards

- ^ Wong, Sue-Lin (29 October 2012). «Challenging Apple by Imitation». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d «雷军诠释小米名称寓意:要做移动互联网公司». Tencent Technology (in Chinese). 14 July 2011. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- ^ «Five amazing facts you didn’t know about Xiaomi». The Indian Express. 6 August 2021. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Millward, Steven (15 July 2011). «Xiaomi Phone Specs Leak – Dual-Core Android Coming This Year». Tech in Asia. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013.

- ^ Lee, Melanie (27 February 2012). «Interview: China’s Xiaomi hopes for revolution in». Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 June 2021. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ «Xiaomi to introduce ‘Rifle’ mobile application processor in May». Phone Arena. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016.

- ^ Xiaoye You (29 January 2010). Writing in the Devil’s Tongue: A History of English Composition in China. SIU Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-8093-8691-8. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

millet plus rifles

- ^ Cheng, James Chester (1980). Documents of Dissent: Chinese Political Thought Since Mao. Hoover Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-8179-7303-2. Archived from the original on 9 May 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Griffith, Erin (29 June 2013). «Why the ‘Steve Jobs of China’ is crucial to the country’s innovative future (Book excerpt)». PandoDaily. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013.

- ^ Kelleher, Kevin (14 October 2013). «China’s Xiaomi Poses Threat to Smartphone Giants Apple and Samsung». Time. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013.

- ^ Fan, Jiayang (6 September 2013). «Xiaomi and Hugo Barra: A Homegrown Apple in China?». The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ «UPDATE 1-China’s Xiaomi to get $4 bln valuation after funding-source». Chicago Tribune. Reuters. 5 June 2012. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013.

- ^ Ong, Josh (19 August 2012). «The Loyalty of Xiaomi Fans Rivals Apple ‘Fanboys’, Google ‘Fandroids’«. TNW. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013.

- ^ «China Un-Bans Facebook, Twitter in Shanghai | Tech Blog». TechNewsWorld. 24 September 2013. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ «Xiaomi Mi Fans Festival 2020 Starts Today! Here Are The Crazy Price on Xiaomi Gadgets». Gearbest. Retrieved 21 June 2022.

- ^ Amadeo, Ron (24 August 2014). «Xiaomi Mi4 review: China’s iPhone killer is unoriginal but amazing». Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015.

- ^ «Xiaomi’s Mi Pad Is Almost a Spitting Image of the iPad». Mashable. 14 May 2014. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014.

- ^ Atithya Amaresh (5 June 2013). «Meet The ‘Steve Jobs’ Of China». Efytimes.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ^ Vanessa Tan (21 September 2011). «Xiaomi Phones Face Serious Quality Questions». Tech in Asia. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ «In China an Empire Built by Aping Apple». The New York Times. 5 June 2013. Archived from the original on 6 February 2017.

- ^ a b Kovach, Steve (22 August 2013). «Xiaomi (Or ‘The Apple Of China’) Is The Most Important Tech Company You’ve Never Heard Of». Business Insider. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013.

- ^ Fan, Jiayang (6 September 2013). «Xiaomi and Hugo Barra: A Homegrown Apple in China?». The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013.

- ^ Estes, Adam Clark (5 June 2013). «What Apple Should Steal from China’s Steve Jobs». Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 8 June 2013.

- ^ a b Kan, Michael (23 August 2013). Can China’s Xiaomi make it globally?. PC World. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013.

- ^ Custer, C. (10 June 2013). «The New York Times Gets Xiaomi Way, Way Wrong». Tech in Asia. Archived from the original on 5 September 2013.

- ^ Amadeo, Ron (17 January 2018). «Hackers can’t dig into latest Xiaomi phone due to GPL violations». Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Dominik Bosnjak (18 January 2018). «Xiaomi Violating GPL 2.0 License With Mi A1 Kernel Sources». Android Headlines. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ «Exclusive: Xiaomi device kernel will be open sourced!». MIUI Android. 17 September 2013. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017.

- ^ «MiCode/Xiaomi Mobile Phone Kernel Open Source». GitHub. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ^ Cimpanu, Catalin (9 February 2019). «China’s cybersecurity law update lets state agencies ‘pen-test’ local companies». ZDNet. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Mohan, Geeta (27 July 2020). «How China’s Intelligence Law of 2017 authorises global tech giants for espionage». India Today. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Borak, Masha (1 May 2020). «Xiaomi phones send search and browsing data to China, researcher says». South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Mihalcik, Carrie; Hautala, Laura (1 May 2020). «Xiaomi, accused of tracking ‘private’ phone use, defends data practices». CNET. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ «LIVE post: Evidence and statement in response to media coverage on our privacy policy». Blog. Xiaomi. 2 May 2021. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ Tung, Liam (23 October 2014). «Xiaomi moving international user data and cloud services out of Beijing». ZDNet. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014.

- ^ Sagar, Pradip (19 October 2014). «Chinese Smartphones a Security Threat, says IAF». The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014.

- ^ «Vulnerability in Xiaomi Pre-Installed Security App». Check Point. 4 April 2019. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ Solomon, Shoshanna (4 April 2019). «Check Point researchers find security breach in Xiaomi phone app». The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ Ng, Alfred (4 April 2019). «Xiaomi phones came with security flaw preinstalled». CNET. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- ^ Brewster, Thomas (30 April 2020). «Exclusive: Warning Over Chinese Mobile Giant Xiaomi Recording Millions Of People’s ‘Private’ Web And Phone Use». Forbes. Archived from the original on 19 February 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ «Live Post: Evidence and Statement in Response to Media Coverage on Our Privacy Policy». 2 May 2020. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ «Change This Browser Setting to Stop Xiaomi from Spying On Your Incognito Activities». The Hacker News. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ «Lithuania urges people to throw away Chinese phones». BBC. 22 September 2021. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ «Xiaomi Denies Censorship Accusations from Lithuania – September 24, 2021». Daily News Brief. 24 September 2021. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ Horwitz, Josh (27 September 2021). «China’s Xiaomi hires expert over Lithuania censorship claim». Reuters. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Bischoff, Paul (26 November 2012). «How and Why Xiaomi Ran Afoul of China’s Media Regulator». Tech in Asia. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013.

- ^ Bischoff, Paul (23 November 2012). «Xiaomi TV Set-Top Box Service Suspended, Regulatory Kerfuffle Perhaps to Blame». Tech in Asia. Archived from the original on 20 September 2013.

- ^ Sun, Celine (24 November 2012). «Xiaomi suspends set-top box amid illegal content talk». South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013.

- ^ Bischoff, Paul (25 January 2013). «Xiaomi Box Finally Gets Regulatory Approval, Can Soon Go on Sale». Tech in Asia. Archived from the original on 18 September 2013.

- ^ «Xiaomi Fined For Misleading Their Consumers, Selling Less Units Than Advertised». Yahoo! News. 5 August 2014. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014.

- ^ «公平交易委員會新聞資料» [Fair Trade Commission Press Kit] (in Chinese). Taiwanese Fair Trade Commission. 31 July 2014. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014.

- ^ «Xiaomi gets slapped with a $20,000 fine for misleading consumers in Taiwan». The Next Web. 31 July 2014. Archived from the original on 4 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Ibrahim, Tony (15 August 2014). «Xiaomi Global shuts down Australian online stores». PC World. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Dudley-Nicholson, Jennifer (29 November 2015). «Yatango Shopping online website goes white leaving customers thousands of dollars out of pocket». News.com.au. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ «Xiaomi banned in India following Delhi High Court injunction». the techportal.in. 10 December 2014. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ «Xiaomi India ban partially lifted by Delhi HC». The Times of India. 16 December 2014. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015.

- ^ «Xiaomi Redmi Note 4G sold out on Flipkart in 6 seconds». India Today. 30 December 2014. Archived from the original on 14 April 2015.

- ^ «Xiaomi Violating Delhi High Court’s Interim Order, Says Ericsson». NDTV. 5 February 2015. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015.

- ^ Stone, Mike (14 January 2021). «Trump administration adds China’s Comac, Xiaomi to Chinese military blacklist». Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ Yaffe-Bellany, David (23 March 2021). «Xiaomi Wins Court Ruling Blocking U.S. Restrictions on It». Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ @Xiaomi (15 January 2021). «Clarification Announcement» (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ «U.S. Agrees to Remove Xiaomi From Blacklist After Lawsuit». Bloomberg News. 12 May 2021. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ «Koninklijke KPN N.V. v. Xiaomi Corporation et al». Justia. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Bishop, Todd (20 July 2021). «Wyze sues Xiaomi and Roborock to invalidate robotic vacuum patent and save its Amazon listing». GeekWire. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ «India seizes $725 million China’s Xiaomi over remittances». Associated Press. 30 April 2022. Archived from the original on 3 May 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ Kalra, Aditya (6 May 2022). «Indian court lifts block on $725 million of Xiaomi’s assets in royalty case». Reuters. Archived from the original on 6 May 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ «India enforcement body says $682 mln block on Xiaomi’s bank assets upheld». Reuters. 30 September 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ Dixit, Nimitt; Arora, Namrata (6 October 2022). «India court declines relief to Xiaomi over $676 mln asset freeze». Reuters. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ «Xiaomi to start manufacturing mobile devices in Pakistan from March 04». March 2022.

- ^ «Smartphone assembly units may shut down in Pakistan». June 2022.

External links[edit]

Coordinates: 40°02′45″N 116°18′41″E / 40.0457°N 116.3115°E

На чтение 6 мин Просмотров 1.5к. Опубликовано 13.12.2020

Обновлено 13.12.2020

Несмотря на тенденции всеобщей глобализации и проникновения иностранных слов во все языки, полиглотов по-прежнему немного. С появлением в продаже смартфонов Xiaomi, как произносится название этого бренда, стало предметом жарких споров. И неудивительно: если даже с английскими транскрипциями нередко возникают проблемы, что уж говорить о правильном прочтении китайских логотипов.

Содержание

- Что вообще значит Xiaomi

- Звучание согласно системе пиньин

- Вице-президент о произношении слова

- Правила произношения, написания и чтения

- На русском языке

- На английском языке

- Как правильно произносятся названия смартфонов Xiaomi

Что вообще значит Xiaomi

Несмотря на то что фирма появилась на рынке более 10 лет назад, пользователи до сих пор используют множество вариантов — можно услышать и «ксяоми», и «сяоми», и «сяаоми», и «шаоми» или «ксиаоми». Чтобы ответить на вопрос, какой из них является верным, придется углубиться в тонкости языка Поднебесной и выяснить значение термина.

Понятнее станет, если обратиться к переводу. Наименование компании Xiaomi переводится как «маленький рис» или «рисовое зерно». Оно обозначатся на письме двумя иероглифами:

- 小, получивший на латинице аналог Xiao, читается как [сяо];

- 米 — для англоязычных стран Mi, читается как [ми].

Учитывая, как фраза переводится с китайского, вариант «сяоми» можно считать наиболее точным. При этом ударение ставится на последний слог. Казалось бы, можно считать спор решенным. Однако и этот ответ не является однозначным.

Интересно!

Изначально предполагалось, что фирма будет называться Red Star, но название оказалось уже зарегистрированным. И вместо красной звезды символом было выбрано рисовое зернышко, как олицетворение скромности и трудолюбия, и залог изобилия.

Звучание согласно системе пиньин

Китайский язык — один из сложнейших для обучения. Иностранцу трудно справиться с произношением, ведь значение слова может измениться в зависимости от интонации, с которой оно было произнесено. Имеется 4 основных тона, и один нулевой. Для того, чтобы адаптировать особенности речи для европейцев, была специально придумана система пиньин. С ее помощью легче будет понять, как правильно произносить Xiaomi.

Правильное интонирование дает услышать протяжный первый слог [сяо] (или даже [сяяо]) и второй [мии] — оба они относятся к третьему, длинному тону. Таким образом, большинство лингвистов сошлись на том, что верной будет считаться траскрипция Xiaomi как [сяоми].

Вице-президент о произношении слова

Но европейские специалисты — это одно. Интересно, как называют бренд на родине, в КНР. В интервью на эту тему для индийского телевидения свое мнение озвучил один из членов правления компании, ее вице-президент Хьюго Барр. Он сказал, что «сяоми» правильно говорить как «шао-ми», проведя аналогию с фразой «show me the money» (в сленговом варианте означает «деньги на бочку»). Так что для Поднебесной название бренда звучит как шаоми. Хотя, возможно, со стороны господина Барра это было шуткой, или он, будучи бразильцем, затрудняется произнести смягченный звук «с».

В общем, правильным произношением Xiaomi можно считать или «сяоми», или «шаоми». Отдать предпочтение можно любому, учитывая в применении транскрипции особенности интонирования, принятого в Китае, и как переводится «сяоми» с китайского языка.

Интересно!

Если обратиться к буддийским легендам, то в одной из них встречается рассказ о «xiao» — зернышке риса, которое выросло размером с гору. Такое толкование наполняет название особым смыслом.

Правила произношения, написания и чтения

Разночтения в наименовании фирмы и ее продукции часто зависят от региона, в котором ведутся продажи. Продавцы, а следом за ними и покупатели часто не знали, как правильно сказать — ксиаоми или сяоми. Пользователи коверкали язык, употребляя ошибочные конструкции. Порой в интернет-магазинах можно было вообще встретить написание ксиоми, совсем уже не имеющее отношения к торговой марке.

Чтобы избежать путаницы и не гадать, какое же устройство требуется покупателю, пришлось обратиться к лингвистам. Наиболее актуальной стала официальная русифицированная транскрипция, употребляющаяся в России и странах СНГ, и англоязычная версия для Азии и Европы. Характерно, что по-русски и по-английски Xiaomi правильно произносится по-разному.

На русском языке

Поскольку компания выпускает огромное количество моделей, ориентированных на потребителей среднего и нижнего ценового сегмента, она быстро завоевала популярность на российском рынке. Несмотря на это, далеко не все поклонники бренда даже спустя десятилетие после появления смартфонов на рынке знают, как читается Xiaomi по-русски.

Если руководствоваться системой пиньин, при произношении слоги надо растягивать, так что слово будет звучать как сяяо-мии, а ударение делается на вторую часть. Однако такое произношение довольно сложное, так что в разговорном варианте длительность гласных сократилась, а ударение переместилось с конца в середину, на букву «о». Так что теперь на русском языке Xiaomi произносится как «сяóми».

На английском языке

В англоговорящих странах свои особенности произношения. Например, в США принято читать первую букву «X» как «Z». Так что там можно услышать даже такой вариант, как «зиаоми». Однако большинство считают правильной транскрипцией для «х» — [кс]. Так что, учитывая, как слово пишется на английском, появился вариант ксяоми, ксиоми или ксиаоми.

Принимая во внимание эти нюансы, можно сказать, что наиболее верным будет учитывать транскрипционное прочтение с китайского или использовать англоязычное название. Тогда правильным будет говорить сяоми или ксяоми. Прочие же формы будут ошибочными.

Как правильно произносятся названия смартфонов Xiaomi

Разобравшись с наименованием бренда, его звучанием и переводом, проще ориентироваться в маркировке модельных линеек. И в первую очередь интересно совпадение логотипа с названием флагмана, телефона, который также называется Mi. В английском написании он имеет двойственное толкование. С одной стороны аббревиатура расшифровывается как сокращение от «Mobile Internet», а с другой — от «Mission Impossible» (миссия невыполнима). Так создатели хотели подчеркнуть, что компания способна справиться с любыми трудностями.

Приставка «red» в популярной серии Redmi переводится как «умный, хитрый, приспособленный», сразу намекая на то, что модели этой линейки более продвинутые по сравнению с остальными. А префикс «note» ведет происхождение от сокращенного notepad или notebook — блокнот, что указывает на увеличенный размер экрана.

Говоря о продукции компании, нельзя оставить в стороне и прошивку MIUI — ведь именно с разработки оригинальной оболочки началась ее деятельность. Название системы состоит из двух аббревиатур: фирменного MI, о значении которого писалось выше, и UI — от User Interface. В английской транскрипции MIUI читается как «Me You I» (можно приблизительно перевести «от меня к тебе»).

Для помощи пользователям в преодолении языкового барьера в 2018 году Xiaomi выпустили компактный транслейтор. Устройство получило название Mijia AI и способность в режиме реального времени осуществлять перевод между 14 языками. История возникновения названия, его значение и звучание на китайском поможет решить вопрос, как правильно произнести Xiaomi, — оно произносится по-русски как «сяоми» с ударением на второй слог.

Сегодня поговорим о том, как произносится «Xiaomi», что означает перевод названия китайской компании на русский язык и куда ставится ударение в слове.

Содержание

- Как читается Xiaomi

- Как переводится Xiaomi на русский язык

- Перевод Redmi на русский

- ТОП-20 употреблений слова Xiaomi

Как читается Xiaomi

На китайском языке слово Xiaomi пишется двумя иероглифами 小米. Что касается транскрипции, то эти иероглифы читаются как 小 – Xiǎo [сяо] и 米 – mǐ [ми]. В итоге получается слово Сяоми с ударением на последний слог.

Русскоговорящим людям произносить слово с ударением на последнюю гласную «И» достаточно непривычно, поэтому ударение как-то само переместилось на вторую гласную «О», что вполне допускается, хотя и не совсем корректно.

Правильно произносить именно Сяоми или Ксяоми тоже допустимо? В китайском языке буква X читается не как «икс» или «экс». Поэтому называть компанию «Ксиаоми» некорректно.

Как переводится Xiaomi на русский язык

С переводом Xiaomi на русский язык тоже не всё просто. Согласно официальным словарям китайского языка, слово переводится как «маленькая рисинка» и пишется при помощи двух иероглифов 小米, которые латинским алфавитом можно прописать, как xiao и mi. В некоторых вариациях перевод можно трактовать как «рисовое зёрнышко».

Хотя причём здесь рис не совсем понятно, ведь речь идёт о технологическом гиганте Поднебесной, а не о заливных полях Маньчжурии. Возможно, так компания хотела увеличить свою значимость, ведь рис для китайцев как хлеб насущный.

Однако вероятна и такая трактовка, согласно которой нужно много трудиться для того, чтобы получить желаемое. Это и символизирует метафизическое рисовое зёрнышко. Учитывая какое гигантское количество смартфонов (каталог) компания выпускает на рынок, трудятся они в соответствии с названием.

Президент Xiaomi Лэй Цзюнь высказался по поводу перевода недвусмысленно. Он заявил, что в основе названия компании лежит буддистская концепция, согласно которой Xiao – это огромное зерно риса, размером с Фудзияму или даже Джомолунгму. Глава Xiaomi конкретно дал понять, что считает свою компанию великой.

В пределах Китая оно так и есть, однако до показателей мировых гигантов индустрии ей пока ещё далеко. Но если «огромное рисовое зёрнышко размером с гору» будет продолжать в том же духе, то скоро станет главным производителем смартфонов в мире.

Перевод Redmi на русский

С названием суббренда Redmi тоже весьма интересная ситуация, ведь под этим лейблом выпускают доступные телефоны с неплохими характеристиками.

Согласно правилам китайского языка, название состоит из двух частей — red и mi. Причём Red взято с английского, что означает «красный», а mi – это всё тот же рис. Получается «красный рис», что достаточно необычно, хоть и непонятно, что именно сподвигло китайцев на создание такого бренда.

Вероятно, здесь есть какая-то отсылка к коммунистическому строю, который сейчас используется в Китае и к всесильной Компартии. Не зря ведь маскот Xiaomi и Redmi – заяц в ушанке с красной звездой (его можно увидеть, включив на телефоне режим Fastboot).

Маскот Xiaomi.

ТОП-20 употреблений слова Xiaomi

Многие люди не знают, как правильно произносится Xiaomi на русском языке. Они пишут и переводят его так, что господина Лэй Цзюнь удар бы хватил, узнай он об этом.

Мы не поленились, собрали все возможные произношения бренда Сяоми, которые люди вводили в поиске Яндекса за последний месяц на момент публикации этой статьи. На базе этих данных составили ТОП произношений названия компании Поднебесной.

ТОП-20 произношения слова Xiaomi на русском языке:

| № | Фраза | Запросов в месяц |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | сяоми | 1172382 |

| 2 | ксиаоми | 696970 |

| 3 | ксиоми | 623263 |

| 4 | ксяоми | 156976 |

| 5 | хиаоми | 76718 |

| 6 | хаоми | 48222 |

| 7 | хиоми | 44110 |

| 8 | хайоми | 21287 |

| 9 | сиоми | 17305 |

| 10 | хаеми | 4222 |

| 11 | саоми | 3041 |

| 12 | ксаеми | 1461 |

| 13 | сиами | 1372 |

| 14 | саеми | 714 |

| 15 | ксайоми | 598 |

| 16 | сайоми | 470 |

| 17 | хеоми | 424 |

| 18 | шаоми | 421 |

| 19 | хауми | 330 |

| 20 | сиеми | 297 |

Есть ещё «Хайеми», «Хуоми» и другие не очень популярные произношения. А правильно только СяомИ.

8 мая 2020просмотров: 2285

Название всемирно известного бренда Xiaomi вызывает у русскоязычных пользователей два закономерных вопроса — как правильно произносить это сочетание букв, и что оно означает. Люди в разных странах мира говорят «Шаоми», «Ксяоми», «Ксиоми» — в общем — в двух десятках вариаций, большинство из которых являются неправильными. А как же будет правильно? Попробуем расставить точки над «i» и объяснить, как произносится на русском Xiaomi.

Как произносится Xiaomi?

Чтобы передать китайские иероглифы буквами латинского алфавита, используют систему письма «Пиньинь». На сегодняшний день эта система является официальным международным инструментом транскрипции иероглифов. И все люди, желающие изучить сложный китайский язык, обязательно осваивают Пиньинь.

Для тех, кто владеет английским, самым логичным вариантом произношения будет «Ксяоми». Логичным, но ошибочным. Зная основы Пиньинь, можно без труда понять, как правильно произносить Xiaomi. Латинская буква «X» в этой системе читается как звук «С», поэтому название бренда следует произносить «Сяоми». Именно такое название бренда является общепринятым на международном уровне. Причем ударение падает не на второй слог [о], а на последний [ми].

Что означает Xiaomi?

Как читается Xiaomi — мы разобрались. Но теперь вам наверняка хотелось бы узнать, что означает это слово. Как перевести Xiaomi на русский язык? В переводе с китайского языка название популярного бренда означает «Маленькая рисинка» или «Рисовое зернышко», а в некоторых толкованиях — «Просо».

В жизни китайцев рис имеет чрезвычайно важное значение. Как для русского человека хлеб является основой рациона, так и жители Поднебесной считают рис «всему головой» и чрезвычайно уважают эту полезную злаковую культуру. Выращивание риса — это кропотливая работа, отнимающая массу времени и сил. Но именно такой подход стал фундаментом благополучия китайского народа.

Китайцы 21-го столетия не только не утратили уважение к рису, но и отдали ему должное в мире современных технологий. Как ни один житель Поднебесной не обходится в повседневной жизни без риса, так не может он обойтись без полезных гаджетов — смартфонов, компьютеров и другой техники. Бренд Xiaomi органично объединил эти две ценности в своем названии и широкой линейке продукции.

А глава компании Лэй Цзюнь так прямо и сказал, что

… слог Xiao в названии бренда означает зерно риса размером с гору, что перекликается с концепцией буддизма.

Что касается слога Mi, в нем тоже можно найти скрытый смысл — если отойти от системы Пиньинь и китайского языка. Логотип Mi, известный всему миру, можно толковать как Mobile Internet (мобильный интернет).

Это в полной мере соответствует концепции бренда. Продукция Xiaomi способна удовлетворить запросы любого современного человека, живущего в мире продвинутых цифровых технологий.

|

|

Headquarters in Haidian District, Beijing |

|

|

Trade name |

Xiaomi |

|---|---|

|

Native name |

小米集团 |

|

Romanized name |

Xiǎomǐ |

| Type | Public |

|

Traded as |

|

| Industry |

|

| Founded | 6 April 2010; 12 years ago |

| Headquarters | Haidian District,

Beijing, China |

|

Area served |

Worldwide |

|

Key people |

|

| Products |

|

| Brands |

|

| Revenue | (2021)[1] |

|

Operating income |

|

|

Net income |

|

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

|

Number of employees |

33,427 (31 December 2021)[1] |

| Subsidiaries |

|

| Website | mi.com |

| Xiaomi | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Chinese | 小米 | |||||

| Literal meaning | Millet | |||||

|

A Xiaomi Exclusive Service Centre for customer support in Kuala Lumpur

Xiaomi Corporation (;[2] Chinese: 小米), commonly known as Xiaomi and registered as Xiaomi Inc., is a Chinese designer and manufacturer of consumer electronics and related software, home appliances, and household items. Behind Samsung, it is the second largest manufacturer of smartphones in the world, most of which run the MIUI operating system. The company is ranked 338th and is the youngest company on the Fortune Global 500.[3][4]

Xiaomi was founded in 2010 in Beijing by now multi-billionaire Lei Jun when he was 40 years old, along with six senior associates. Lei had founded Kingsoft as well as Joyo.com, which he sold to Amazon for $75 million in 2004. In August 2011, Xiaomi released its first smartphone and, by 2014, it had the largest market share of smartphones sold in China. Initially the company only sold its products online; however, it later opened brick and mortar stores.[5] By 2015, it was developing a wide range of consumer electronics.[6] In 2020, the company sold 146.3 million smartphones and its MIUI operating system has over 500 million monthly active users.[7] In the second quarter of 2021, Xiaomi surpassed Apple Inc. to become the second-largest seller of smartphones worldwide, with a 17% market share, according to Canalys.[8] It also is a major manufacturer of appliances including televisions, flashlights, unmanned aerial vehicles, and air purifiers using its Internet of Things and Xiaomi Smart Home product ecosystems.

Xiaomi keeps its prices close to its manufacturing costs and bill of materials costs by keeping most of its products in the market for 18 months, longer than most smartphone companies,[9][10] The company also uses inventory optimization and flash sales to keep its inventory low.[11][12]

History[edit]

2010–2013[edit]

On 6 April 2010 Xiaomi was co-founded by Lei Jun and six others:

- Lin Bin (林斌), vice president of the Google China Institute of Engineering

- Zhou Guangping (周光平), senior director of the Motorola Beijing R&D center

- Liu De (刘德), department chair of the Department of Industrial Design at the University of Science and Technology Beijing

- Li Wanqiang (黎万强), general manager of Kingsoft Dictionary

- Huang Jiangji (黄江吉), principal development manager

- Hong Feng (洪峰), senior product manager for Google China

Lei had founded Kingsoft as well as Joyo.com, which he sold to Amazon for $75 million in 2004.[13] At the time of the founding of the company, Lei was dissatisfied with the products of other mobile phone manufacturers and thought he could make a better product.

On 16 August 2010, Xiaomi launched its first Android-based firmware MIUI.[14]

In 2010, the company raised $41 million in a Series A round.[15]

In August 2011, the company launched its first phone, the Xiaomi Mi1. The device had Xiaomi’s MIUI firmware along with Android installation.[13][16]

In December 2011, the company raised $90 million in a Series B round.[15]

In June 2012, the company raised $216 million of funding in a Series C round at a $4 billion valuation. Institutional investors participating in the first round of funding included Temasek Holdings, IDG Capital, Qiming Venture Partners and Qualcomm.[13][17]

In August 2013, the company hired Hugo Barra from Google, where he served as vice president of product management for the Android platform.[18][19][20][21] He was employed as vice president of Xiaomi to expand the company outside of mainland China, making Xiaomi the first company selling smartphones to poach a senior staffer from Google’s Android team. He left the company in February 2017.[22]

In September 2013, Xiaomi announced its Xiaomi Mi3 smartphone and an Android-based 47-inch 3D-capable Smart TV assembled by Sony TV manufacturer Wistron Corporation of Taiwan.[23][24]

In October 2013, it became the fifth-most-used smartphone brand in China.[25]

In 2013, Xiaomi sold 18.7 million smartphones.[26]

2014–2017[edit]

In February 2014, Xiaomi announced its expansion outside China, with an international headquarters in Singapore.[27][28]

In April 2014, Xiaomi purchased the domain name mi.com for a record US$3.6 million, the most expensive domain name ever bought in China, replacing xiaomi.com as the company’s main domain name.[29][30]

In September 2014, Xiaomi acquired a 24.7% some part taken in Roborock.[31][32]

In December 2014, Xiaomi raised US$1.1 billion at a valuation of over US$45 billion, making it one of the most valuable private technology companies in the world. The financing round was led by Hong Kong-based technology fund All-Stars Investment Limited, a fund run by former Morgan Stanley analyst Richard Ji.[33][34][35][36][37]

In 2014, the company sold over 60 million smartphones.[38] In 2014, 94% of the company’s revenue came from mobile phone sales.[39]

In April 2015, Ratan Tata acquired a stake in Xiaomi.[40][41]

On 30 June 2015, Xiaomi announced its expansion into Brazil with the launch of locally manufactured Redmi 2; it was the first time the company assembled a smartphone outside of China.[42][43][44]

However, the company left Brazil in the second half of 2016.[45]

On 26 February 2016, Xiaomi launched the Mi5, powered by the Qualcomm Snapdragon 820 processor.[46]

On 3 March 2016, Xiaomi launched the Redmi Note 3 Pro in India, the first smartphone to powered by a Qualcomm Snapdragon 650 processor.[47]

On 10 May 2016, Xiaomi launched the Mi Max, powered by the Qualcomm Snapdragon 650/652 processor.[48]

In June 2016, the company acquired patents from Microsoft.[49]

In September 2016, Xiaomi launched sales in the European Union through a partnership with ABC Data.[50]

Also in September 2016, the Xiaomi Mi Robot vacuum was released by Roborock.[51][52]

On 26 October 2016, Xiaomi launched the Mi Mix, powered by the Qualcomm Snapdragon 821 processor.[53]

On 22 March 2017, Xiaomi announced that it planned to set up a second manufacturing unit in India in partnership with contract manufacturer Foxconn.[54][55]

On 19 April 2017, Xiaomi launched the Mi6, powered by the Qualcomm Snapdragon 835 processor.[56]

In July 2017, the company entered into a patent licensing agreement with Nokia.[57]

On 5 September 2017, Xiaomi released Xiaomi Mi A1, the first Android One smartphone under the slogan: Created by Xiaomi, Powered by Google. Xiaomi stated started working with Google for the Mi A1 Android One smartphone earlier in 2017. An alternate version of the phone was also available with MIUI, the MI 5X.[58]

In 2017, Xiaomi opened Mi Stores in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The EU’s first Mi Store was opened in Athens, Greece in October 2017.[59] In Q3 2017, Xiaomi overtook Samsung to become the largest smartphone brand in India. Xiaomi sold 9.2 million units during the quarter.[60] On 7 November 2017, Xiaomi commenced sales in Spain and Western Europe.[61]

2018–present[edit]

A Xiaomi Store in Loulé, Portugal

In April 2018, Xiaomi announced a smartphone gaming brand called Black Shark. It had 6GB of RAM coupled with Snapdragon 845 SoC, and was priced at $508, which was cheaper than its competitors.[62]

On 2 May 2018, Xiaomi announced the launch of Mi Music and Mi Video to offer «value-added internet services» in India.[63] On 3 May 2018, Xiaomi announced a partnership with 3 to sell smartphones in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Austria, Denmark, and Sweden[64]

In May 2018, Xiaomi began selling smart home products in the United States through Amazon.[65]

In June 2018, Xiaomi became a public company via an initial public offering on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, raising $4.72 billion.[66]

On 7 August 2018, Xiaomi announced that Holitech Technology Co. Ltd., Xiaomi’s top supplier, would invest up to $200 million over the next three years to set up a major new plant in India.[67][68]

In August 2018, the company announced POCO as a mid-range smartphone line, first launching in India.[69]

In Q4 of 2018, the Xiaomi Poco F1 became the best selling smartphone sold online in India.[70] The Pocophone was sometimes referred to as the «flagship killer» for offering high-end specifications at an affordable price.[71][72][70]