Как правильно пишется словосочетание «сын божий»

- Как правильно пишется слово «сын»

- Как правильно пишется слово «божий»

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: приуготовить — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к слову «сын»

Ассоциации к слову «божий»

Синонимы к словосочетанию «сын божий»

Предложения со словосочетанием «сын божий»

- И могли сыны божьи гулять, каждый по своему саду, и рвать плоды любые, и торговать ими.

- Однако сейчас, на пороге третьего тысячелетия от рождения человека, названного сыном божьим, в эти истории уже мало верится.

- Но, конечно, из великой битвы ангелов победителем выходит сын божий, его противник, он и делается утешителем падших.

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словосочетанием «сын божий»

- Господи Иисусе Христе, Сыне Божий, помилуй нас!

- Но когда Вавилов рычал под окном: «Господи Исусе Христе, сыне божий, помилуй нас!» — в дремучей бороде его разверзалась темная яма, в ней грозно торчали три черных зуба и тяжко шевелился язык, толстый и круглый, как пест.

- Диавол есть только первая в зле тварь, в нем воплотилось начало, противоположное Сыну Божьему, он есть образ творения, каким оно не должно быть.

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Значение слова «сын»

-

СЫН, -а, зват. (устар.) сы́не, мн. сыновья́, —ве́й, —вья́м и (высок.) сыны́, —ов, м. 1. Лицо мужского пола по отношению к своим родителям. (Малый академический словарь, МАС)

Все значения слова СЫН

Значение слова «божий»

-

БО́ЖИЙ, —ья, —ье. Прил. к бог. Божья воля. Божий храм. (Малый академический словарь, МАС)

Все значения слова БОЖИЙ

Афоризмы русских писателей со словом «сын»

- Тебе знаком ли сын богов,

Любимец муз и вдохновенья?

Узнал ли б меж земных сынов

Ты речь его, его движенья? - Истинный человек и сын отечества есть одно и то же.

- Я — сын земли, дитя планеты малой,

Затерянной в пространстве мировом…

Я — сын земли, где дни и годы — кратки,

Где сладостна зеленая весна,

Где тягостны безумных душ загадки,

Где сны любви баюкает луна. - (все афоризмы русских писателей)

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Смотрите также

СЫН, -а, зват. (устар.) сы́не, мн. сыновья́, —ве́й, —вья́м и (высок.) сыны́, —ов, м. 1. Лицо мужского пола по отношению к своим родителям.

Все значения слова «сын»

БО́ЖИЙ, —ья, —ье. Прил. к бог. Божья воля. Божий храм.

Все значения слова «божий»

-

И могли сыны божьи гулять, каждый по своему саду, и рвать плоды любые, и торговать ими.

-

Однако сейчас, на пороге третьего тысячелетия от рождения человека, названного сыном божьим, в эти истории уже мало верится.

-

Но, конечно, из великой битвы ангелов победителем выходит сын божий, его противник, он и делается утешителем падших.

- (все предложения)

- Сын Человеческий

- божий сын

- сын бога

- искупительная жертва

- Благая Весть

- (ещё синонимы…)

- дочь

- сынок

- сынишка

- сыночек

- преемник

- (ещё ассоциации…)

- дар

- промысл

- дарить

- талант

- милость

- (ещё ассоциации…)

- старший сын

- сын бога

- отец сына

- сын умер

- смотреть на сына

- (полная таблица сочетаемости…)

- с божьей помощью

- икона божьей матери

- выйти на свет божий

- (полная таблица сочетаемости…)

- Разбор по составу слова «сын»

- Разбор по составу слова «божий»

- Как правильно пишется слово «сын»

- Как правильно пишется слово «божий»

сын Божий

- сын Божий

-

сын Б’ожий (Дан.3:25 ) — в оригинале «сын богов» (выражение, употребленное Навуходоносором-язычником для описания Ангела).

Библия. Ветхий и Новый заветы. Синоидальный перевод. Библейская энциклопедия..

.

1891.

Синонимы:

Смотреть что такое «сын Божий» в других словарях:

-

сын божий — богочеловек, иисус из назарета, галилеянин, христос, спаситель, спас, сын человеческий, иисус христос, иисус Словарь русских синонимов. сын божий сущ., кол во синонимов: 9 • богочеловек (12) • … Словарь синонимов

-

Сын Божий — Сын Б’ожий Мессия и Спаситель людей, Господь Иисус Христос (Мат.1:21 ; Лук.1:32 33,35; Иоан.1:33 34). Предыдущая статья (сын) может помочь более полно понять значение, заложенное в выражении «Сын Божий», ибо Иисус Христос есть явление… … Библия. Ветхий и Новый заветы. Синодальный перевод. Библейская энциклопедия арх. Никифора.

-

Сын Божий — Сын Б’ожий Мессия и Спаситель людей, Господь Иисус Христос (Мат.1:21 ; Лук.1:32 33,35; Иоан.1:33 34). Предыдущая статья (сын) может помочь более полно понять значение, заложенное в выражении «Сын Божий», ибо Иисус Христос есть явление… … Полный и подробный Библейский Словарь к русской канонической Библии

-

Сын Божий — см. Иисус Христос см. Имена Иисуса Христа … Библейская энциклопедия Брокгауза

-

Сын Божий — евр. Бен Элохим. Сын Божий в самом высоком значении слова Мессия (Пс. 2:7; Дан. 3: 25; Лук. 1:35; Иоан. 1:18,34), о Котором уже в Прит. 30:4 мудрец спрашивает: «Кто поставил все пределы земли? Какое имя Ему? И какое имя Сыну Его, знаешь ли?» … Словарь библейских имен

-

сын Божий — сын Б’ожий (Дан.3:25 ) в оригинале «сын богов» (выражение, употребленное Навуходоносором язычником для описания Ангела) … Полный и подробный Библейский Словарь к русской канонической Библии

-

Сын Божий — и Сын человеческий см. Христос … Энциклопедический словарь Ф.А. Брокгауза и И.А. Ефрона

-

Сын Божий — (Мат.4:3 и др.) так называется второе Лицо Святые Троицы по Своему Божеству, по Своему единству с Богом Отцом. Ты Сын Мой, говорит о Нем Псалмопевец от лица Господа, Я ныне родил Тебя (Пс.2:7 ) … Библия. Ветхий и Новый заветы. Синодальный перевод. Библейская энциклопедия арх. Никифора.

-

Сын Божий — ♦ (ENG Son of God) индивид, находящийся в особых отношениях с Богом как сын или чадо Бога (Гал. 4:6 7). В Ветхом Завете так называются народ Израиля (Исх. 4:22 23), Давид (2 Цар. 7:14) и цари (Пс. 2:7). В Новом Завете единственным Сыном… … Вестминстерский словарь теологических терминов

-

Сын Божий — … Википедия

For the second person of the Trinity, see God the Son.

Historically, many rulers have assumed titles such as the son of God, the son of a god or the son of heaven.[1]

The term «son of God» is used in the Hebrew Bible as another way to refer to humans who have a special relationship with God. In Exodus, the nation of Israel is called God’s firstborn son.[2] Solomon is also called «son of God».[3][4] Angels, just and pious men, and the kings of Israel are all called «sons of God.»[5]

In the New Testament of the Christian Bible, «Son of God» is applied to Jesus on many occasions.[5] On two occasions, Jesus is recognized as the Son of God by a voice which speaks from Heaven. Jesus explicitly and implicitly describes himself as the Son of God and he is also described as the Son of God by various individuals who appear in the New Testament.[5][6][7][8] Jesus is called the «son of God,» and followers of Jesus are called, «Christians.»[9] As applied to Jesus, the term is a reference to his role as the Messiah, or Christ, the King chosen by God.[10] (Matthew 26:63). The contexts and ways in which Jesus’ title, Son of God, means something more or something other than the title Messiah remain the subject of ongoing scholarly study and discussion.

The term «Son of God» should not be confused with the term «God the Son» (Greek: Θεός ὁ υἱός), the second Person of the Trinity in Christian theology. The doctrine of the Trinity identifies Jesus as God the Son, identical in essence but distinct in person with regard to God the Father and God the Holy Spirit (the first and third Persons of the Trinity). Nontrinitarian Christians accept the application to Jesus of the term «Son of God», which is found in the New Testament.

Rulers and imperial titles[edit]

Throughout history, emperors and rulers ranging from the Western Zhou dynasty (c. 1000 BC) in China to Alexander the Great (c. 360 BC) to the Emperor of Japan (c. 600 AD) have assumed titles that reflect a filial relationship with deities.[1][11][12][13]

The title «Son of Heaven» i.e. 天子 (from 天 meaning sky/heaven/god and 子 meaning child) was first used in the Western Zhou dynasty (c. 1000 BC). It is mentioned in the Shijing book of songs, and reflected the Zhou belief that as Son of Heaven (and as its delegate) the Emperor of China was responsible for the well-being of the whole world by the Mandate of Heaven.[11][12] This title may also be translated as «son of God» given that the word Tiān in Chinese may either mean sky or god.[14] The Emperor of Japan was also called the Son of Heaven (天子 tenshi) starting in the early 7th century.[15]

Among the Eurasian nomads, there was also a widespread use of «Son of God/Son of Heaven» for instance, in the third century BC, the ruler was called Chanyü[16] and similar titles were used as late as the 13th century by Genghis Khan.[17]

Examples of kings being considered the son of god are found throughout the Ancient Near East. Egypt in particular developed a long lasting tradition. Egyptian pharaohs are known to have been referred to as the son of a particular god and their begetting in some cases is even given in sexually explicit detail. Egyptian pharaohs did not have full parity with their divine fathers but rather were subordinate.[18]: 36 Nevertheless, in the first four dynasties, the pharaoh was considered to be the embodiment of a god. Thus, Egypt was ruled by direct theocracy,[19] wherein «God himself is recognized as the head» of the state.[20] During the later Amarna Period, Akhenaten reduced the Pharaoh’s role to one of coregent, where the Pharaoh and God ruled as father and son. Akhenaten also took on the role of the priest of god, eliminating representation on his behalf by others. Later still, the closest Egypt came to the Jewish variant of theocracy was during the reign of Herihor. He took on the role of ruler not as a god but rather as a high-priest and king.[19]

According to the Bible, several kings of Damascus took the title son of Hadad. From the archaeological record a stela erected by Bar-Rakib for his father Panammuwa II contains similar language. The son of Panammuwa II a king of Sam’al referred to himself as a son of Rakib.[18]: 26–27 Rakib-El is a god who appears in Phoenician and Aramaic inscriptions.[21] Panammuwa II died unexpectedly while in Damascus.[22] However, his son the king Bar-Rakib was not a native of Damascus but rather the ruler of Sam’al it is unknown if other rules of Sam’al used similar language.

In Greek mythology, Heracles (son of Zeus) and many other figures were considered to be sons of gods through union with mortal women. From around 360 BC onwards Alexander the Great may have implied he was a demigod by using the title «Son of Ammon–Zeus».[23]

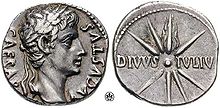

A denarius minted circa 18 BC. Obverse: CAESAR AVGVSTVS; reverse: DIVVS IVLIV(S)

In 42 BC, Julius Caesar was formally deified as «the divine Julius» (divus Iulius) after his assassination. His adopted son, Octavian (better known as Augustus, a title given to him 15 years later, in 27 BC) thus became known as divi Iuli filius (son of the divine Julius) or simply divi filius (son of the god).[24] As a daring and unprecedented move, Augustus used this title to advance his political position in the Second Triumvirate, finally overcoming all rivals for power within the Roman state.[24][25]

The word which was applied to Julius Caesar when he was deified was divus, not the distinct word deus. Thus, Augustus called himself Divi filius, not Dei filius.[26] The line between been god and god-like was at times less than clear to the population at large, and Augustus seems to have been aware of the necessity of keeping the ambiguity.[26] As a purely semantic mechanism, and to maintain ambiguity, the court of Augustus sustained the concept that any worship given to an emperor was paid to the «position of emperor» rather than the person of the emperor.[27] However, the subtle semantic distinction was lost outside Rome, where Augustus began to be worshiped as a deity.[28] The inscription DF thus came to be used for Augustus, at times unclear which meaning was intended.[26][28] The assumption of the title Divi filius by Augustus meshed with a larger campaign by him to exercise the power of his image. Official portraits of Augustus made even towards the end of his life continued to portray him as a handsome youth, implying that miraculously, he never aged. Given that few people had ever seen the emperor, these images sent a distinct message.[29]

Later, Tiberius (emperor from 14 to 37 AD) came to be accepted as the son of divus Augustus and Hadrian as the son of divus Trajan.[24] By the end of the 1st century, the emperor Domitian was being called dominus et deus (i.e. master and god).[30]

Outside the Roman Empire, the 2nd-century Kushan King Kanishka I used the title devaputra meaning «son of God».[31]

Baháʼí Faith[edit]

In the writings of the Baháʼí Faith, the term «Son of God» is applied to Jesus,[32] but does not indicate a literal physical relationship between Jesus and God,[33] but is symbolic and is used to indicate the very strong spiritual relationship between Jesus and God[32] and the source of his authority.[33] Shoghi Effendi, the head of the Baháʼí Faith in the first half of the 20th century, also noted that the term does not indicate that the station of Jesus is superior to other prophets and messengers that Baháʼís name Manifestation of God, including Buddha, Muhammad and Baha’u’llah among others.[34] Shoghi Effendi notes that, since all Manifestations of God share the same intimate relationship with God and reflect the same light, the term Sonship can in a sense be attributable to all the Manifestations.[32]

Christianity[edit]

In Christianity, the title «Son of God» refers to the status of Jesus as the divine son of God the Father.[35][36] It derives from several uses in the New Testament and early Christian theology. The term is used in all four gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, and the Pauline and Johannine literature.

Another interpretation stems from the Judaic understanding of the title, which describes all human beings as being Sons of God. In parts of the Old Testament, historical figures like Jacob and Solomon are referred to as Sons of God, referring to their descent from Adam. Biblical scholars use this title as a way of affirming Jesus’ humanity, that he is fully human as well as fully God.

Islam[edit]

In Islam, Jesus is known as Īsā ibn Maryam (Arabic: عيسى بن مريم, lit. ‘Jesus, son of Mary’), and is understood to be a prophet and messenger of God (Allah) and al-Masih, the Arabic term for Messiah (Christ), sent to guide the Children of Israel (banī isrā’īl in Arabic) with a new revelation, the al-Injīl (Arabic for «the gospel»).[37][38][39]

Islam rejects any kinship between God and any other being, including a son.[40][41] Thus, rejecting the belief that Jesus is the begotten son of God, God himself[42] or another god.[43] As in Christianity, Islam believes Jesus had no earthly father. In Islam Jesus is believed to be born due to the command of God «be».[44] God ordered[40] the angel Jibrīl (Gabriel) to «blow»[45] the soul of Jesus into Mary[46][47] and so she gave birth to Jesus.

Judaism[edit]

Although references to «sons of God», «son of God» and «son of the LORD» are occasionally found in Jewish literature, they never refer to physical descent from God.[48][49] There are two instances where Jewish kings are figuratively referred to as a god.[50]: 150 The king is likened to the supreme king God.[51] These terms are often used in the general sense in which the Jewish people were referred to as «children of the LORD your God».[48]

When it was used by the rabbis, the term referred to Israel in particular or it referred to human beings in general, it was not used as a reference to the Jewish mashiach.[48] In Judaism the term mashiach has a broader meaning and usage and can refer to a wide range of people and objects, not necessarily related to the Jewish eschaton.

Gabriel’s Revelation[edit]

Gabriel’s Revelation, also called the Vision of Gabriel[52] or the Jeselsohn Stone,[53] is a three-foot-tall (one metre) stone tablet with 87 lines of Hebrew text written in ink, containing a collection of short prophecies written in the first person and dated to the late 1st century BC.[54][55] It is a tablet described as a «Dead Sea scroll in stone».[54][56]

The text seems to talk about a messianic figure from Ephraim who broke evil before righteousness[clarification needed] by three days.[57]: 43–44 Later the text talks about a “prince of princes» a leader of Israel who was killed by the evil king and not properly buried.[57]: 44 The evil king was then miraculously defeated.[57]: 45 The text seems to refer to Jeremiah Chapter 31.[57]: 43 The choice of Ephraim as the lineage of the messianic figure described in the text seems to draw on passages in Jeremiah, Zechariah and Hosea. This leader was referred to as a son of God.[57]: 43–44, 48–49

The text seems to be based on a Jewish revolt recorded by Josephus dating from 4 BC.[57]: 45–46 Based on its dating the text seems to refer to Simon of Peraea, one of the three leaders of this revolt.[57]: 47

Dead Sea Scrolls[edit]

In some versions of Deuteronomy the Dead Sea Scrolls refer to the sons of God rather than the sons of Israel, probably in reference to angels. The Septuagint reads similarly.[50]: 147 [58]

4Q174 is a midrashic text in which God refers to the Davidic messiah as his son.[59]

4Q246 refers to a figure who will be called the son of God and son of the Most High. It is debated if this figure represents the royal messiah, a future evil gentile king or something else.[59][60]

In 11Q13 Melchizedek is referred to as god the divine judge. Melchizedek in the bible was the king of Salem. At least some in the Qumran community seemed to think that at the end of days Melchizedek would reign as their king.[61] The passage is based on Psalm 82.[62]

Pseudepigrapha[edit]

In both Joseph and Aseneth and the related text The Story of Asenath, Joseph is referred to as the son of God.[50]: 158–159 [63] In the Prayer of Joseph both Jacob and the angel are referred to as angels and the sons of God.[50]: 157

Talmud[edit]

This style of naming is also used for some rabbis in the Talmud.[50]: 158

See also[edit]

- Jesus, King of the Jews

- Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament

- Uzair

References[edit]

- ^ a b Introduction to the Science of Religion by Friedrich Muller 2004 ISBN 1-4179-7401-X page 136

- ^ (Exodus 4:22)

- ^ The Tanach — The Torah/Prophets/Writings. Stone Edition. 1996. p. 741. ISBN 0-89906-269-5.

- ^ The Tanach — The Torah/Prophets/Writings. Stone Edition. 1996. p. 1923. ISBN 0-89906-269-5.

- ^ a b c «Catholic Encyclopedia: Son of God». Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ One teacher: Jesus’ teaching role in Matthew’s gospel by John Yueh-Han Yieh 2004 ISBN 3-11-018151-7 pages 240–241

- ^ Dwight Pentecost The words and works of Jesus Christ 2000 ISBN 0-310-30940-9 page 234

- ^ The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1988 ISBN 0-8028-3785-9 pages 571–572

- ^ «International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Sons of God (New Testament)». BibleStudyTools.com. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary (10th ed.) (2001). Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster.

- ^ a b China : a cultural and historical dictionary by Michael Dillon 1998 ISBN 0-7007-0439-6 page 293

- ^ a b East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History by Patricia Ebrey, Anne Walthall, James Palais 2008 ISBN 0-547-00534-2 page 16

- ^ A History of Japan by Hisho Saito 2010 ISBN 0-415-58538-4 page

- ^ The Problem of China by Bertrand Russell 2007 ISBN 1-60520-020-4 page 23

- ^ Boscaro, Adriana; Gatti, Franco; Raveri, Massimo, eds. (2003). Rethinking Japan: Social Sciences, Ideology and Thought. Vol. II. Japan Library Limited. p. 300. ISBN 0-904404-79-X.

- ^ Britannica, Encyclopaedia. «Xiongnu». Xiongnu (people) article. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ^ Darian Peters (July 3, 2009). «The Life and Conquests of Genghis Khan». Humanities 360. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014.

- ^ a b Adela Yarbro Collins, John Joseph Collins (2008). King and Messiah as Son of God: Divine, Human, and Angelic Messianic Figures in Biblical and Related Literature. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802807724. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ a b Jan Assmann (2003). The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs. Harvard University Press. pp. 300–301. ISBN 9780674012110. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ «Catholic Encyclopedia». Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ K. van der Toorn; Bob Becking; Pieter Willem van der Horst, eds. (1999). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible DDD. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 686. ISBN 9780802824912. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ K. Lawson Younger, Jr. «Panammuwa and Bar-Rakib: two structural analyses» (PDF). University of Sheffield. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Cartledge, Paul (2004). «Alexander the Great». History Today. 54: 1.

- ^ a b c Early Christian literature by Helen Rhee 2005 ISBN 0-415-35488-9 pages 159–161

- ^ Augustus by Pat Southern 1998 ISBN 0-415-16631-4 page 60

- ^ a b c The world that shaped the New Testament by Calvin J. Roetzel 2002 ISBN 0-664-22415-6 page 73

- ^ Experiencing Rome: culture, identity and power in the Roman Empire by Janet Huskinson 1999 ISBN 978-0-415-21284-7 page 81

- ^ a b A companion to Roman religion edited by Jörg Rüpke 2007 ISBN 1-4051-2943-3 page 80

- ^ Gardner’s art through the ages: the western perspective by Fred S. Kleiner 2008 ISBN 0-495-57355-8 page 175

- ^ The Emperor Domitian by Brian W. Jones 1992 ISBN 0-415-04229-1 page 108

- ^ Encyclopedia of ancient Asian civilizations by Charles Higham 2004 ISBN 978-0-8160-4640-9 page 352

- ^ a b c Lepard, Brian D (2008). In The Glory of the Father: The Baháʼí Faith and Christianity. Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-1-931847-34-6.

- ^ a b Taherzadeh, Adib (1977). The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, Volume 2: Adrianople 1863–68. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. p. 182. ISBN 0-85398-071-3.

- ^ Hornby, Helen, ed. (1983). Lights of Guidance: A Baháʼí Reference File. New Delhi, India: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 491. ISBN 81-85091-46-3.

- ^ J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann, Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2010, p. 634-635

- ^ Schubert M. Ogden, The Understanding of Christian Faith, Wipf and Stock Publishers, USA, 2010, p. 74

- ^ Glassé, Cyril (2001). The new encyclopedia of Islam, with introduction by Huston Smith (Édition révisée. ed.). Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. p. 239. ISBN 9780759101906.

- ^ McDowell, Jim, Josh; Walker, Jim (2002). Understanding Islam and Christianity: Beliefs That Separate Us and How to Talk About Them. Euguen, Oregon: Harvest House Publishers. p. 12. ISBN 9780736949910.

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, p.158

- ^ a b «Surah An-Nisa [4:171]». Surah An-Nisa [4:171]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ^ «Surah Al-Ma’idah [5:116]». Surah Al-Ma’idah [5:116]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ^ «Surah Al-Ma’idah [5:72]». Surah Al-Ma’idah [5:72]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ^ «Surah Al-Ma’idah [5:75]». Surah Al-Ma’idah [5:75]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ^ «Surah Ali ‘Imran [3:59]». Surah Ali ‘Imran [3:59]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ^ «Surah Al-Anbya [21:91]». Surah Al-Anbya [21:91]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ^ Jesus: A Brief History by W. Barnes Tatum 2009 ISBN 1-4051-7019-0 page 217

- ^ The new encyclopedia of Islam by Cyril Glassé, Huston Smith 2003 ISBN 0-7591-0190-6 page 86

- ^ a b c The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion by Maxine Grossman and Adele Berlin (Mar 14, 2011) ISBN 0199730040 page 698

- ^ The Jewish Annotated New Testament by Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Z. Brettler (Nov 15, 2011) ISBN 0195297709 page 544

- ^ a b c d e Riemer Roukema (2010). Jesus, Gnosis and Dogma. T&T Clark International. ISBN 9780567466426. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Jonathan Bardill (2011). Constantine, Divine Emperor of the Christian Golden Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 342. ISBN 9780521764230. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ «By Three Days, Live»: Messiahs, Resurrection, and Ascent to Heavon in Hazon Gabriel[permanent dead link], Israel Knohl, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- ^ «The First Jesus?». National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2010-08-19. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- ^ a b Yardeni, Ada (Jan–Feb 2008). «A new Dead Sea Scroll in Stone?». Biblical Archaeology Review. 34 (1).

- ^ van Biema, David; Tim McGirk (2008-07-07). «Was Jesus’ Resurrection a Sequel?». Time Magazine. Archived from the original on July 8, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ^ Ethan Bronner (2008-07-05). «Tablet ignites debate on messiah and resurrection». The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

The tablet, probably found near the Dead Sea in Jordan according to some scholars who have studied it, is a rare example of a stone with ink writings from that era — in essence, a Dead Sea Scroll on stone.

- ^ a b c d e f g Matthias Henze (2011). Hazon Gabriel. Society of Biblical Lit. ISBN 9781589835412. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ Michael S. Heiser (2001). «DEUTERONOMY 32:8 AND THE SONS OF GOD». Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ a b Markus Bockmuehl; James Carleton Paget, eds. (2007). Redemption and Resistance: The Messianic Hopes of Jews and Christians in Antiquity. A&C Black. pp. 27–28. ISBN 9780567030436. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ^ EDWARD M. COOK. «4Q246» (PDF). Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995) 43-66 [© 1995 Institute for Biblical Research]. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ^ David Flusser (2007). Judaism of the Second Temple Period: Qumran and Apocalypticism. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 249. ISBN 9780802824691. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Jerome H. Neyrey (2009). The Gospel of John in Cultural and Rhetorical Perspective. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 313–316. ISBN 9780802848666.

- ^ translated by Eugene Mason and Text from Joseph and Aseneth H. F. D. Sparks. «The Story of Asenath» and «Joseph and Aseneth». Retrieved 30 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

Bibliography[edit]

- Borgen, Peder. Early Christianity and Hellenistic Judaism. Edinburgh: T & T Clark Publishing. 1996.

- Brown, Raymond. An Introduction to the New Testament. New York: Doubleday. 1997.

- Essays in Greco-Roman and Related Talmudic Literature. ed. by Henry A. Fischel. New York: KTAV Publishing House. 1977.

- Dunn, J. D. G., Christology in the Making, London: SCM Press. 1989.

- Ferguson, Everett. Backgrounds in Early Christianity. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing. 1993.

- Greene, Colin J. D. Christology in Cultural Perspective: Marking Out the Horizons. Grand Rapids: InterVarsity Press. Eerdmans Publishing. 2003.

- Holt, Bradley P. Thirsty for God: A Brief History of Christian Spirituality. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. 2005.

- Josephus, Flavius. Complete Works. trans. and ed. by William Whiston. Grand Rapids: Kregel Publishing. 1960.

- Letham, Robert. The Work of Christ. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. 1993.

- Macleod, Donald. The Person of Christ. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. 1998.

- McGrath, Alister. Historical Theology: An Introduction to the History of Christian Thought. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. 1998.

- Neusner, Jacob. From Politics to Piety: The Emergence of Pharisaic Judaism. Providence, R. I.: Brown University. 1973.

- Norris, Richard A. Jr. The Christological Controversy. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. 1980.

- O’Collins, Gerald. Christology: A Biblical, Historical, and Systematic Study of Jesus. Oxford:Oxford University Press. 2009.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav. Development of Christian Doctrine: Some Historical Prolegomena. London: Yale University Press. 1969.

- _______ The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100–600). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1971.

- Schweitzer, Albert. Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of the Progress from Reimarus to Wrede. trans. by W. Montgomery. London: A & C Black. 1931.

- Tyson, John R. Invitation to Christian Spirituality: An Ecumenical Anthology. New York: Oxford University Press. 1999.

- Wilson, R. Mcl. Gnosis and the New Testament. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. 1968.

- Witherington, Ben III. The Jesus Quest: The Third Search for the Jew of Nazareth. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. 1995.

- _______ “The Gospel of John.» in The Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels. ed. by Joel Greene, Scot McKnight and I. Howard

For the second person of the Trinity, see God the Son.

Historically, many rulers have assumed titles such as the son of God, the son of a god or the son of heaven.[1]

The term «son of God» is used in the Hebrew Bible as another way to refer to humans who have a special relationship with God. In Exodus, the nation of Israel is called God’s firstborn son.[2] Solomon is also called «son of God».[3][4] Angels, just and pious men, and the kings of Israel are all called «sons of God.»[5]

In the New Testament of the Christian Bible, «Son of God» is applied to Jesus on many occasions.[5] On two occasions, Jesus is recognized as the Son of God by a voice which speaks from Heaven. Jesus explicitly and implicitly describes himself as the Son of God and he is also described as the Son of God by various individuals who appear in the New Testament.[5][6][7][8] Jesus is called the «son of God,» and followers of Jesus are called, «Christians.»[9] As applied to Jesus, the term is a reference to his role as the Messiah, or Christ, the King chosen by God.[10] (Matthew 26:63). The contexts and ways in which Jesus’ title, Son of God, means something more or something other than the title Messiah remain the subject of ongoing scholarly study and discussion.

The term «Son of God» should not be confused with the term «God the Son» (Greek: Θεός ὁ υἱός), the second Person of the Trinity in Christian theology. The doctrine of the Trinity identifies Jesus as God the Son, identical in essence but distinct in person with regard to God the Father and God the Holy Spirit (the first and third Persons of the Trinity). Nontrinitarian Christians accept the application to Jesus of the term «Son of God», which is found in the New Testament.

Rulers and imperial titles[edit]

Throughout history, emperors and rulers ranging from the Western Zhou dynasty (c. 1000 BC) in China to Alexander the Great (c. 360 BC) to the Emperor of Japan (c. 600 AD) have assumed titles that reflect a filial relationship with deities.[1][11][12][13]

The title «Son of Heaven» i.e. 天子 (from 天 meaning sky/heaven/god and 子 meaning child) was first used in the Western Zhou dynasty (c. 1000 BC). It is mentioned in the Shijing book of songs, and reflected the Zhou belief that as Son of Heaven (and as its delegate) the Emperor of China was responsible for the well-being of the whole world by the Mandate of Heaven.[11][12] This title may also be translated as «son of God» given that the word Tiān in Chinese may either mean sky or god.[14] The Emperor of Japan was also called the Son of Heaven (天子 tenshi) starting in the early 7th century.[15]

Among the Eurasian nomads, there was also a widespread use of «Son of God/Son of Heaven» for instance, in the third century BC, the ruler was called Chanyü[16] and similar titles were used as late as the 13th century by Genghis Khan.[17]

Examples of kings being considered the son of god are found throughout the Ancient Near East. Egypt in particular developed a long lasting tradition. Egyptian pharaohs are known to have been referred to as the son of a particular god and their begetting in some cases is even given in sexually explicit detail. Egyptian pharaohs did not have full parity with their divine fathers but rather were subordinate.[18]: 36 Nevertheless, in the first four dynasties, the pharaoh was considered to be the embodiment of a god. Thus, Egypt was ruled by direct theocracy,[19] wherein «God himself is recognized as the head» of the state.[20] During the later Amarna Period, Akhenaten reduced the Pharaoh’s role to one of coregent, where the Pharaoh and God ruled as father and son. Akhenaten also took on the role of the priest of god, eliminating representation on his behalf by others. Later still, the closest Egypt came to the Jewish variant of theocracy was during the reign of Herihor. He took on the role of ruler not as a god but rather as a high-priest and king.[19]

According to the Bible, several kings of Damascus took the title son of Hadad. From the archaeological record a stela erected by Bar-Rakib for his father Panammuwa II contains similar language. The son of Panammuwa II a king of Sam’al referred to himself as a son of Rakib.[18]: 26–27 Rakib-El is a god who appears in Phoenician and Aramaic inscriptions.[21] Panammuwa II died unexpectedly while in Damascus.[22] However, his son the king Bar-Rakib was not a native of Damascus but rather the ruler of Sam’al it is unknown if other rules of Sam’al used similar language.

In Greek mythology, Heracles (son of Zeus) and many other figures were considered to be sons of gods through union with mortal women. From around 360 BC onwards Alexander the Great may have implied he was a demigod by using the title «Son of Ammon–Zeus».[23]

A denarius minted circa 18 BC. Obverse: CAESAR AVGVSTVS; reverse: DIVVS IVLIV(S)

In 42 BC, Julius Caesar was formally deified as «the divine Julius» (divus Iulius) after his assassination. His adopted son, Octavian (better known as Augustus, a title given to him 15 years later, in 27 BC) thus became known as divi Iuli filius (son of the divine Julius) or simply divi filius (son of the god).[24] As a daring and unprecedented move, Augustus used this title to advance his political position in the Second Triumvirate, finally overcoming all rivals for power within the Roman state.[24][25]

The word which was applied to Julius Caesar when he was deified was divus, not the distinct word deus. Thus, Augustus called himself Divi filius, not Dei filius.[26] The line between been god and god-like was at times less than clear to the population at large, and Augustus seems to have been aware of the necessity of keeping the ambiguity.[26] As a purely semantic mechanism, and to maintain ambiguity, the court of Augustus sustained the concept that any worship given to an emperor was paid to the «position of emperor» rather than the person of the emperor.[27] However, the subtle semantic distinction was lost outside Rome, where Augustus began to be worshiped as a deity.[28] The inscription DF thus came to be used for Augustus, at times unclear which meaning was intended.[26][28] The assumption of the title Divi filius by Augustus meshed with a larger campaign by him to exercise the power of his image. Official portraits of Augustus made even towards the end of his life continued to portray him as a handsome youth, implying that miraculously, he never aged. Given that few people had ever seen the emperor, these images sent a distinct message.[29]

Later, Tiberius (emperor from 14 to 37 AD) came to be accepted as the son of divus Augustus and Hadrian as the son of divus Trajan.[24] By the end of the 1st century, the emperor Domitian was being called dominus et deus (i.e. master and god).[30]

Outside the Roman Empire, the 2nd-century Kushan King Kanishka I used the title devaputra meaning «son of God».[31]

Baháʼí Faith[edit]

In the writings of the Baháʼí Faith, the term «Son of God» is applied to Jesus,[32] but does not indicate a literal physical relationship between Jesus and God,[33] but is symbolic and is used to indicate the very strong spiritual relationship between Jesus and God[32] and the source of his authority.[33] Shoghi Effendi, the head of the Baháʼí Faith in the first half of the 20th century, also noted that the term does not indicate that the station of Jesus is superior to other prophets and messengers that Baháʼís name Manifestation of God, including Buddha, Muhammad and Baha’u’llah among others.[34] Shoghi Effendi notes that, since all Manifestations of God share the same intimate relationship with God and reflect the same light, the term Sonship can in a sense be attributable to all the Manifestations.[32]

Christianity[edit]

In Christianity, the title «Son of God» refers to the status of Jesus as the divine son of God the Father.[35][36] It derives from several uses in the New Testament and early Christian theology. The term is used in all four gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, and the Pauline and Johannine literature.

Another interpretation stems from the Judaic understanding of the title, which describes all human beings as being Sons of God. In parts of the Old Testament, historical figures like Jacob and Solomon are referred to as Sons of God, referring to their descent from Adam. Biblical scholars use this title as a way of affirming Jesus’ humanity, that he is fully human as well as fully God.

Islam[edit]

In Islam, Jesus is known as Īsā ibn Maryam (Arabic: عيسى بن مريم, lit. ‘Jesus, son of Mary’), and is understood to be a prophet and messenger of God (Allah) and al-Masih, the Arabic term for Messiah (Christ), sent to guide the Children of Israel (banī isrā’īl in Arabic) with a new revelation, the al-Injīl (Arabic for «the gospel»).[37][38][39]

Islam rejects any kinship between God and any other being, including a son.[40][41] Thus, rejecting the belief that Jesus is the begotten son of God, God himself[42] or another god.[43] As in Christianity, Islam believes Jesus had no earthly father. In Islam Jesus is believed to be born due to the command of God «be».[44] God ordered[40] the angel Jibrīl (Gabriel) to «blow»[45] the soul of Jesus into Mary[46][47] and so she gave birth to Jesus.

Judaism[edit]

Although references to «sons of God», «son of God» and «son of the LORD» are occasionally found in Jewish literature, they never refer to physical descent from God.[48][49] There are two instances where Jewish kings are figuratively referred to as a god.[50]: 150 The king is likened to the supreme king God.[51] These terms are often used in the general sense in which the Jewish people were referred to as «children of the LORD your God».[48]

When it was used by the rabbis, the term referred to Israel in particular or it referred to human beings in general, it was not used as a reference to the Jewish mashiach.[48] In Judaism the term mashiach has a broader meaning and usage and can refer to a wide range of people and objects, not necessarily related to the Jewish eschaton.

Gabriel’s Revelation[edit]

Gabriel’s Revelation, also called the Vision of Gabriel[52] or the Jeselsohn Stone,[53] is a three-foot-tall (one metre) stone tablet with 87 lines of Hebrew text written in ink, containing a collection of short prophecies written in the first person and dated to the late 1st century BC.[54][55] It is a tablet described as a «Dead Sea scroll in stone».[54][56]

The text seems to talk about a messianic figure from Ephraim who broke evil before righteousness[clarification needed] by three days.[57]: 43–44 Later the text talks about a “prince of princes» a leader of Israel who was killed by the evil king and not properly buried.[57]: 44 The evil king was then miraculously defeated.[57]: 45 The text seems to refer to Jeremiah Chapter 31.[57]: 43 The choice of Ephraim as the lineage of the messianic figure described in the text seems to draw on passages in Jeremiah, Zechariah and Hosea. This leader was referred to as a son of God.[57]: 43–44, 48–49

The text seems to be based on a Jewish revolt recorded by Josephus dating from 4 BC.[57]: 45–46 Based on its dating the text seems to refer to Simon of Peraea, one of the three leaders of this revolt.[57]: 47

Dead Sea Scrolls[edit]

In some versions of Deuteronomy the Dead Sea Scrolls refer to the sons of God rather than the sons of Israel, probably in reference to angels. The Septuagint reads similarly.[50]: 147 [58]

4Q174 is a midrashic text in which God refers to the Davidic messiah as his son.[59]

4Q246 refers to a figure who will be called the son of God and son of the Most High. It is debated if this figure represents the royal messiah, a future evil gentile king or something else.[59][60]

In 11Q13 Melchizedek is referred to as god the divine judge. Melchizedek in the bible was the king of Salem. At least some in the Qumran community seemed to think that at the end of days Melchizedek would reign as their king.[61] The passage is based on Psalm 82.[62]

Pseudepigrapha[edit]

In both Joseph and Aseneth and the related text The Story of Asenath, Joseph is referred to as the son of God.[50]: 158–159 [63] In the Prayer of Joseph both Jacob and the angel are referred to as angels and the sons of God.[50]: 157

Talmud[edit]

This style of naming is also used for some rabbis in the Talmud.[50]: 158

See also[edit]

- Jesus, King of the Jews

- Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament

- Uzair

References[edit]

- ^ a b Introduction to the Science of Religion by Friedrich Muller 2004 ISBN 1-4179-7401-X page 136

- ^ (Exodus 4:22)

- ^ The Tanach — The Torah/Prophets/Writings. Stone Edition. 1996. p. 741. ISBN 0-89906-269-5.

- ^ The Tanach — The Torah/Prophets/Writings. Stone Edition. 1996. p. 1923. ISBN 0-89906-269-5.

- ^ a b c «Catholic Encyclopedia: Son of God». Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ One teacher: Jesus’ teaching role in Matthew’s gospel by John Yueh-Han Yieh 2004 ISBN 3-11-018151-7 pages 240–241

- ^ Dwight Pentecost The words and works of Jesus Christ 2000 ISBN 0-310-30940-9 page 234

- ^ The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1988 ISBN 0-8028-3785-9 pages 571–572

- ^ «International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Sons of God (New Testament)». BibleStudyTools.com. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary (10th ed.) (2001). Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster.

- ^ a b China : a cultural and historical dictionary by Michael Dillon 1998 ISBN 0-7007-0439-6 page 293

- ^ a b East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History by Patricia Ebrey, Anne Walthall, James Palais 2008 ISBN 0-547-00534-2 page 16

- ^ A History of Japan by Hisho Saito 2010 ISBN 0-415-58538-4 page

- ^ The Problem of China by Bertrand Russell 2007 ISBN 1-60520-020-4 page 23

- ^ Boscaro, Adriana; Gatti, Franco; Raveri, Massimo, eds. (2003). Rethinking Japan: Social Sciences, Ideology and Thought. Vol. II. Japan Library Limited. p. 300. ISBN 0-904404-79-X.

- ^ Britannica, Encyclopaedia. «Xiongnu». Xiongnu (people) article. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ^ Darian Peters (July 3, 2009). «The Life and Conquests of Genghis Khan». Humanities 360. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014.

- ^ a b Adela Yarbro Collins, John Joseph Collins (2008). King and Messiah as Son of God: Divine, Human, and Angelic Messianic Figures in Biblical and Related Literature. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802807724. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ a b Jan Assmann (2003). The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs. Harvard University Press. pp. 300–301. ISBN 9780674012110. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ «Catholic Encyclopedia». Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ K. van der Toorn; Bob Becking; Pieter Willem van der Horst, eds. (1999). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible DDD. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 686. ISBN 9780802824912. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ K. Lawson Younger, Jr. «Panammuwa and Bar-Rakib: two structural analyses» (PDF). University of Sheffield. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Cartledge, Paul (2004). «Alexander the Great». History Today. 54: 1.

- ^ a b c Early Christian literature by Helen Rhee 2005 ISBN 0-415-35488-9 pages 159–161

- ^ Augustus by Pat Southern 1998 ISBN 0-415-16631-4 page 60

- ^ a b c The world that shaped the New Testament by Calvin J. Roetzel 2002 ISBN 0-664-22415-6 page 73

- ^ Experiencing Rome: culture, identity and power in the Roman Empire by Janet Huskinson 1999 ISBN 978-0-415-21284-7 page 81

- ^ a b A companion to Roman religion edited by Jörg Rüpke 2007 ISBN 1-4051-2943-3 page 80

- ^ Gardner’s art through the ages: the western perspective by Fred S. Kleiner 2008 ISBN 0-495-57355-8 page 175

- ^ The Emperor Domitian by Brian W. Jones 1992 ISBN 0-415-04229-1 page 108

- ^ Encyclopedia of ancient Asian civilizations by Charles Higham 2004 ISBN 978-0-8160-4640-9 page 352

- ^ a b c Lepard, Brian D (2008). In The Glory of the Father: The Baháʼí Faith and Christianity. Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-1-931847-34-6.

- ^ a b Taherzadeh, Adib (1977). The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, Volume 2: Adrianople 1863–68. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. p. 182. ISBN 0-85398-071-3.

- ^ Hornby, Helen, ed. (1983). Lights of Guidance: A Baháʼí Reference File. New Delhi, India: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 491. ISBN 81-85091-46-3.

- ^ J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann, Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2010, p. 634-635

- ^ Schubert M. Ogden, The Understanding of Christian Faith, Wipf and Stock Publishers, USA, 2010, p. 74

- ^ Glassé, Cyril (2001). The new encyclopedia of Islam, with introduction by Huston Smith (Édition révisée. ed.). Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. p. 239. ISBN 9780759101906.

- ^ McDowell, Jim, Josh; Walker, Jim (2002). Understanding Islam and Christianity: Beliefs That Separate Us and How to Talk About Them. Euguen, Oregon: Harvest House Publishers. p. 12. ISBN 9780736949910.

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, p.158

- ^ a b «Surah An-Nisa [4:171]». Surah An-Nisa [4:171]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ^ «Surah Al-Ma’idah [5:116]». Surah Al-Ma’idah [5:116]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ^ «Surah Al-Ma’idah [5:72]». Surah Al-Ma’idah [5:72]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ^ «Surah Al-Ma’idah [5:75]». Surah Al-Ma’idah [5:75]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ^ «Surah Ali ‘Imran [3:59]». Surah Ali ‘Imran [3:59]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ^ «Surah Al-Anbya [21:91]». Surah Al-Anbya [21:91]. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ^ Jesus: A Brief History by W. Barnes Tatum 2009 ISBN 1-4051-7019-0 page 217

- ^ The new encyclopedia of Islam by Cyril Glassé, Huston Smith 2003 ISBN 0-7591-0190-6 page 86

- ^ a b c The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion by Maxine Grossman and Adele Berlin (Mar 14, 2011) ISBN 0199730040 page 698

- ^ The Jewish Annotated New Testament by Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Z. Brettler (Nov 15, 2011) ISBN 0195297709 page 544

- ^ a b c d e Riemer Roukema (2010). Jesus, Gnosis and Dogma. T&T Clark International. ISBN 9780567466426. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Jonathan Bardill (2011). Constantine, Divine Emperor of the Christian Golden Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 342. ISBN 9780521764230. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ «By Three Days, Live»: Messiahs, Resurrection, and Ascent to Heavon in Hazon Gabriel[permanent dead link], Israel Knohl, Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- ^ «The First Jesus?». National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2010-08-19. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- ^ a b Yardeni, Ada (Jan–Feb 2008). «A new Dead Sea Scroll in Stone?». Biblical Archaeology Review. 34 (1).

- ^ van Biema, David; Tim McGirk (2008-07-07). «Was Jesus’ Resurrection a Sequel?». Time Magazine. Archived from the original on July 8, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ^ Ethan Bronner (2008-07-05). «Tablet ignites debate on messiah and resurrection». The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

The tablet, probably found near the Dead Sea in Jordan according to some scholars who have studied it, is a rare example of a stone with ink writings from that era — in essence, a Dead Sea Scroll on stone.

- ^ a b c d e f g Matthias Henze (2011). Hazon Gabriel. Society of Biblical Lit. ISBN 9781589835412. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ Michael S. Heiser (2001). «DEUTERONOMY 32:8 AND THE SONS OF GOD». Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ a b Markus Bockmuehl; James Carleton Paget, eds. (2007). Redemption and Resistance: The Messianic Hopes of Jews and Christians in Antiquity. A&C Black. pp. 27–28. ISBN 9780567030436. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ^ EDWARD M. COOK. «4Q246» (PDF). Bulletin for Biblical Research 5 (1995) 43-66 [© 1995 Institute for Biblical Research]. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- ^ David Flusser (2007). Judaism of the Second Temple Period: Qumran and Apocalypticism. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 249. ISBN 9780802824691. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Jerome H. Neyrey (2009). The Gospel of John in Cultural and Rhetorical Perspective. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 313–316. ISBN 9780802848666.

- ^ translated by Eugene Mason and Text from Joseph and Aseneth H. F. D. Sparks. «The Story of Asenath» and «Joseph and Aseneth». Retrieved 30 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

Bibliography[edit]

- Borgen, Peder. Early Christianity and Hellenistic Judaism. Edinburgh: T & T Clark Publishing. 1996.

- Brown, Raymond. An Introduction to the New Testament. New York: Doubleday. 1997.

- Essays in Greco-Roman and Related Talmudic Literature. ed. by Henry A. Fischel. New York: KTAV Publishing House. 1977.

- Dunn, J. D. G., Christology in the Making, London: SCM Press. 1989.

- Ferguson, Everett. Backgrounds in Early Christianity. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing. 1993.

- Greene, Colin J. D. Christology in Cultural Perspective: Marking Out the Horizons. Grand Rapids: InterVarsity Press. Eerdmans Publishing. 2003.

- Holt, Bradley P. Thirsty for God: A Brief History of Christian Spirituality. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. 2005.

- Josephus, Flavius. Complete Works. trans. and ed. by William Whiston. Grand Rapids: Kregel Publishing. 1960.

- Letham, Robert. The Work of Christ. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. 1993.

- Macleod, Donald. The Person of Christ. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. 1998.

- McGrath, Alister. Historical Theology: An Introduction to the History of Christian Thought. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. 1998.

- Neusner, Jacob. From Politics to Piety: The Emergence of Pharisaic Judaism. Providence, R. I.: Brown University. 1973.

- Norris, Richard A. Jr. The Christological Controversy. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. 1980.

- O’Collins, Gerald. Christology: A Biblical, Historical, and Systematic Study of Jesus. Oxford:Oxford University Press. 2009.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav. Development of Christian Doctrine: Some Historical Prolegomena. London: Yale University Press. 1969.

- _______ The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100–600). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1971.

- Schweitzer, Albert. Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of the Progress from Reimarus to Wrede. trans. by W. Montgomery. London: A & C Black. 1931.

- Tyson, John R. Invitation to Christian Spirituality: An Ecumenical Anthology. New York: Oxford University Press. 1999.

- Wilson, R. Mcl. Gnosis and the New Testament. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. 1968.

- Witherington, Ben III. The Jesus Quest: The Third Search for the Jew of Nazareth. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. 1995.

- _______ “The Gospel of John.» in The Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels. ed. by Joel Greene, Scot McKnight and I. Howard

(SON OF GOD) Термин, указывающий на Божественность Иисуса из Назарета как единственного Сына Бога. Уникальное сыновство Иисуса противоположно представлениям о сыновстве, популярным в Древнем мире. В эллинистическом мире считалось, что человек — «сын богов» во многих отношениях: в мифологическом, посредством сожительства Бога со смертной женщиной, чьи потомки обладали сверхъестественными силами; в политике, когда военачальникам и императорам воздавали почести в рамках римского имперского культа; в медицине, когда врачей называли «сыновьями Асклепия»; а иногда — когда кому-либо приписывались чудесные силы или способности и он приобретал титул или репутацию «богочеловека». Термин в Ветхом Завете. В ВЗ люди, жившие до времен Ноя (Быт 6:1-4), «ангелы» (в том числе сатана, Иов 1:6; Иов 2:1) и прочие небесные создания (Пс 28:1; Пс 81:6; Пс 88:7) назвайы «сынами Бога». Израиль как народ был избранным сыном Бога. Это корпоративное сыновство стала основанием для избавления Израиля из Египта: «Израиль есть сын Мой, первенец Мой» (Исх 4:22; Иер 31:9).

Корпоративное сыновство было контекстом, в котором рассматривалось сыновство частное, например, божественные санкции Давида как царя: «Я буду ему отцом, и он будет Мне сыном» (2Цар 7:14).

Давид был «усыновлен» согласно Божьему постановлению: «Ты Сын Мой; Я ныне родил Тебя» (Пс 2:7); эти слова были также пророчеством о сыновстве Иисуса из царского рода Давида (Мф 3:17; Мк 1:11; Лк 3:22; Деян 13:33; Евр 1:5; Евр 5:5).

В других мессианских пророчествах Мессия из рода Давида назван божественными именами «Еммануил» (Ис 7:13-14) и «Бог крепкий, Отец вечности» (Ис 9:6-7).

Эти пророчества исполнились в Иисусе (Мф 1:23; Мф 21:4-10; Мф 22:41-45).

В евангелиях. В евангелиях описываются и стороны сыновства Иисуса как Сына Божьего. Первый момент — это Его вечное личное сыновство. Личное сыновство Иисуса определено в выводе Петра: «Ты — Христос, Сын Бога Живого» (Мф 16:16), и в том, как Иисус Сам называет Себя перед судом: «Ты ли Христос, Сын Благословенного? Иисус сказал: Я…» (Мк 14:61-62).

В обоих случаях речь идет о личности или сущности, которой Он вечно обладает. Задолго до сотворения, в вечности, Отец и Сын наслаждались общением друг с другом. Мы знаем об этом, потому что так говорится в Библии — но без особых подробностей. По большей части Писание молчит о том, что происходило до существования мира. Однако есть несколько стихов, слегка приподнимающих завесу и позволяющих нам взглянуть на эти возвышенные, божественные отношения, вечно существовавшие между Отцом и Сыном. Из всех книг Библии об отношениях между Отцом и Сыном больше всего говорится в Евангелии от Иоанна. Именно из-под вдохновенного пера Иоанна вышли строки: «В начале было Слово, и Слово было у Бога, и Слово было Бог». Это довольно упрощенный перевод. На греческом языке картина выглядит более живописно: «В начале было Слово, и Слово было лицом к лицу с Богом, и Слово само было Богом». Представьте себе Слово, Божьего Сына до воплощения, лицом к лицу с Богом. Выражение «лицом к лицу» — это перевод греческого предлога pros (сокращенная форма от prosopon pros prosopon, «лицом к лицу», распространенного выражения в греческом койне).

Это выражение указывает на близкое общение. Отец и Сын наслаждались таким близким общением в вечности. Какое удовольствие они должны были получать друг от друга! Когда Сын Божий стал человеком и начал Свое служение на земле, Он упоминал об отношениях с Отцом, которыми наслаждался до сотворения мира. Иисус говорил о том, что видел и слышал, когда был с Отцом до пришествия на землю (см. Ин 3:13; Ин 8:38).

Иисус жаждал вернуться в эти славные сферы. В Своей молитве, прежде чем отправиться на крест (в Ин 17), Он просил Отца прославить Его той славой, которой Он обладал вместе с Отцом до существования мира (Ин 17:5).

Иисус хотел вернуть Свое изначальное равенство Отцу — нечто, от чего Он сознательно отказался ради замысла Отца (см. Флп 2:6-7).

Когда Он молился Отцу, с Его уст сорвалась замечательная фраза: «Отче!.. Ты… возлюбил Меня прежде основания мира» (Ин 17:24).

Сын Бога, Его единственный Сын, был единственным объектом любви Отца. Вторая сторона сыновства Иисуса — это сыновство по рождению. Непосредственным духовным Отцом Иисуса был Бог. Иисус — Сын Божий, потому что Его воплощение и рождество в качестве человека было вызвано Святым Духом. В Евангелии от Матфея зачатие Иисуса происходит «от Духа Святого» (Мф 1:20).

Он будет назван Иисусом (что значит «Яхве есть спасение»), «ибо Он спасет людей Своих от грехов их» (Мф 1:21), и «Еммануилом» («с нами Бог»), потому что Он Сам — Бог во плоти (Мф 1:23).

У Луки зачатие Иисуса происходит от Святого Духа и силой Всевышнего (Лк 1:31,35), поэтому Иисус назван «Сыном Божиим» (Лк 1:35).

Если бы отцом Иисуса был человек, Иосиф, Его называли бы «Иисусом, сыном Иосифа». Учение Луки явно свидетельствует, что, так как отцом Иисуса был Божий Дух, Этого Сына Девы Марии правильно называть «Иисусом, Сыном Божиим». Третий аспект сыновства — мессианское сыновство. Иисус — Сын и представитель Отца, земная миссия Которого — учреждение Царства Божьего. При крещении Его миссия началась с признания Его Отцом: «Сей есть Сын Мой возлюбленный, в Котором Мое благоволение» (Мф 3:17; см. Пс 2:7).

Подобный глас с небес раздался и в момент преображения Иисуса (Лк 9:35).

Как Сын-Мессия Иисус в совершенстве выполнил задание искупления, порученное Ему Отцом. В посланиях Нового Завета. Павел говорит о сущностном, онтологическом сыновстве Иисуса — не как об отдельно взятом факте, но в контексте Его искупительных деяний. Как Сын Божий, Иисус обрел человеческую природу (Рим 1:3), и как Сын Божий Он воскрес и воцарился в силе (Мф 28:18; Рим 1:4; 1Кор 15:28). 0 воплощении говорится так: «Бог послал Сына Своего» (Рим 8:3; Гал 4:4) для искупления человечества, искупления, которое свершилось «смертью Сына Его» (Рим 5:10; Рим 8:29,32).

Следовательно, верующие могут иметь «общение Сына Его Иисуса Христа, Господа нашего» (1Кор 1:9), и могут жить верой в «Сына Божия» (Гал 2:20).

Первая проповедь Павла была «об Иисусе, что Он есть Сын Божий» (Деян 9:20); позже Павел объяснял это в свете Пс 2:7 (см. Деян 13:33).

В Послании к евреям Иисус — «Сын», «первенец» Бога и Его личный «наследник», творец и хранитель вселенной и «сияние славы» Бога (Евр 1:2-12; Евр 3:6; Евр 5:5).

Как Сын, Он — последний и вечный Первосвященник, Который вознесся на небеса и Чья посредническая деятельность пребудет вечно (Евр 4:14; Евр 6:6; Евр 7:3,28).

В 1Ин 4-5 вера в Иисуса как воплощенного Сына Божьего названа необходимым условием для спасения; неверие исходит от духа антихриста.

Смотрите также: Мессия; Сын Человеческий; учение Иисуса Христа; христология.

- Сын Божий по естеству и сыны Божии по благодати прот. Е. Воронцов

- Сын Божий – Спаситель мира и спасение еп. Вениамин (Милов)

- Бог – Спаситель мира протопр. Михаил Помазанский

- Сын Божий – спаситель человека свт. Филарет (Гумилевский)

- О Слове и Сыне Божием, доказательство, заимствованное из разума прп. Иоанн Дамаскин

- Почему вочеловечился Сын Божий, а не Отец и не Дух и в чем Он преуспел, вочеловечившись? прп. Иоанн Дамаскин

- Учение Апостолов о Господе нашем Иисусе Христе, Единородном Сыне Божием свщмч. Ириней Лионский

- Беседа о Единосущии Сына Божия с Богом Отцом свт. Мелетий Антиохийский

- Бытие Сына Божия свт. Григорий Нисский

- Учение Евномия о Сыне Божием и опровержение этого учения св. Григорием Нисским В.И. Несмелов

- Тест: Богочеловек Иисус Христос

- Квиз: Кто такой Иисус Христос?

Сын Бо́жий (греч. Υἱός Θεοῦ) – Логос (от греч. λόγος (логос) – слово, мысль), Бог Сын, Слово Божие, вторая Ипостась Святой Троицы.

Как и все Лица (Ипостаси) Святой Троицы, Сын Божий обладает всеми Божественными свойствами. Как и все Лица (Ипостаси) Святой Троицы, Сын Божий равночестен в Своем Божественном достоинстве Отцу и Святому Духу.

Как и все Лица (Ипостаси) Святой Троицы Сын Божий единосущен с Ними, обладает единой Божественной сущностью (природой) со Отцом и Святым Духом. Как и всем Лицам (Ипостасям) Святой Троицы Сыну Божьему воздается единое и нераздельное поклонение, то есть поклоняясь Ему, христиане поклоняются вместе с Ним Отцу и Святому Духу, имея в виду Их общее Божество, единую Божественную сущность.

От двух Других Лиц Святой Троицы Сына Божьего отличает личностное (ипостасное) свойство. Оно заключается в том, что Бог Сын рождается Богом-Отцом. Он рождается из Божественного существа (естества) Отца, а не из ничего или другим образом. Он рождается не так, чтобы от существа Отца что-либо отделилось или Отец чего-либо лишался. Рождение Сына Божия есть рождение неразлучное, Сын родился от Отца, но не отделился от Него. Рождение Сына Божия есть рождение вечное, оно никогда не начиналось и никогда не оканчивалось.

Рождение Сына Божия Отцом есть вечное и неразлучное рождение Божественного Слова Божественным Умом. «Нет и не будет слова, которое выше этого Слова. Оно не лишено Ума или Жизни, но обладает Умом и Жизнью, поскольку имеет рождающий Его Ум, существующий сущностным образом, то есть Отца, и Жизнь, то есть Святой Дух, существующую сущностным образом и сосуществующую с Ним», – говорит св. Максим Исповедник. «Свет Отца, Слово Великого Ума, превосходящее всякое слово, Высший Свет высочайшего Света, Единородный Сын, Сияющий вместе с Великим Духом, Добрый Царь, Правитель мира, Податель жизни, Создатель всего, что есть и будет. Тобою все живет», – воспевает Божественное Слово св. Григорий Богослов.

Для того, чтобы понять как Божественный Ум рождает Божественное Слово святые отцы указывали на ум и мысль (внутреннее слово) человека, являющегося Образом Божьим. «Ум наш – образ Отца; слово наше (непроизнесенное слово мы обыкновенно называем мыслью) – образ Сына; дух – образ Святого Духа, – учит святитель Игнатий Брянчанинов. – Как в Троице-Боге три Лица неслитно и нераздельно составляют одно Божественное Существо, так в троице-человеке три лица составляют одно существо, не смешиваясь между собой, не сливаясь в одно лицо, не разделяясь на три существа. Ум наш родил и не перестает рождать мысль, мысль, родившись, не перестает снова рождаться и вместе с тем перебывает рожденной, сокровенной в уме. Ум без мысли существовать не может, и мысль – без ума. Начало одного непременно есть и начало другой; существование ума есть непременно и существование мысли».

Бог Отец сотворил мир Словом Своим во Святом Духе. Он «Словом рассеял тьму, Словом произвел свет, основал землю, распределил звезды, разлил воздух, установил границы моря, протянул реки, одушевил животных, сотворил человека по Своему подобию, привел все в порядок», – говорит св. Григорий Богослов. На Предвечном Совете Святой Троицы принято решение о воплощении Слова Божьего, предначертано принятие Им человеческого естества. «И Слово стало плотию, и обитало с нами, полное благодати и истины; и мы видели славу Его, славу, как Единородного от Отца», – говорит Иоанн Богослов (Ин.1:14).

В Воплотившемся Божьем Слове – Богочеловеке Иисусе Христе, Который есть Бог и Слово Отца, по сущности обитает вся полнота Божества телесно (Кол.2:9). Приняв человеческую природу, Божественное Слово соединило тварное и Нетварное естество, открыв уверовавшему в Него человеку путь к обожению.

Уяснению смысла имени «Слово Божье» могут способствовать следующие аналогии:

- человеческий ум рождает мысль-слово и Бог-Отец рождает Бога-Слово.

- мысль отображает совершенства породившего её ума, и Бог-Слово есть Его: «образ Бога невидимого» (Кол.1:15), «сияние славы и образ ипостаси Его» (Евр.1:3).

- человеческое слово бывает причиной начала творческих действий, и мир сотворен через Слово Отца (Ин.1:3; Евр.1:2).

- мысль, рождаясь и формируясь, обращается в уме, и Сын пребывает в Отце: «Я в Отце и Отец во Мне» (Ин.14:11).

- человеческая мысль-слово рождается умом бесстрастно (без соития, в результате которого зачинается и рождается сам человек), и Сын Божий бесстрастно рождён от Отца: «из чрева прежде денницы подобно росе рождение Твое» (Пс.109:3).

Личное свойство Бога Сына

митр. Макарий (Булгаков). Догматическое Богословие

Такие же твердые основания в св. Писании имеет учение Православной Церкви и о личном свойстве Бога Сына. Ибо Oн весьма часто называется здесь:

а) Сыном Бога Отца, например: Отец любит Сына, и вся показует ему, яже сам творит.., якоже бо Отец воскрешает мертвыя и живит, тако и Сын, ихже хощет, живит (Ин.5:20, 21; Ин.14:13, 17:1; Мф.11:27);

б) Сыном единородным: тако возлюби Бог мир, яко и Сына своего единородного дал да всяк веруяй в онь не погибнет, но имать живот вечный Ин.3:16, 18, 1:14), и притом –

в) таким, который пребывает в самом лоне Отца: Бога никтоже виде нигдеже:е единородный Сын, сый в лоне Отчи, той исповеда (Ин.1:18):

г) Сыном истинным: вемы, яко Сын Божий прииде, и дал есть нам свет и разум, да познаем Бога истинного и да будем во истиннем Сыне его Иисусе Христе (1Ин.5:20);

д) Сыном собственным: иже Сына своего не пощаде, но за нас всех предал есть его: како убо не и с ним вся нам дарствует (Рим.8:32)?

Излишне было бы доказывать, что как в этих, так и во всех других местах Писания Господь Иисус называется Сыном Божиим в подлинном смысле, а не каком-либо переносном, когда мы уже знаем, что свящ. книги приписывают Ему и Божеское естество, и Божеские свойства и единосущие со Отцем и Духом. Защищая это учение о личном свойстве Бога Сына от разных перетолкований еретиков, древние пастыри Церкви старались раскрывать следующие мысли:

«Бога не видел никто никогда; Единородный Сын, сущий в недре Отчем, Он явил». (Ин.1:18) «Так возлюбил Бог мир, что отдал Сына Своего единородного…» (Ин.3:16) В Кол.1:15 сказано, что Сын есть «образ Бога невидимого, рожденный прежде всякой твари».

Пролог Евангелия от Иоанна: «Слово было у Бога». В греческом тексте стоит «у Бога» – «pros ton Theon». В.Н. Лосский пишет: «Это выражение указывает на движение, на динамическую близость, можно было бы перевести скорее «к», чем «у». «Слово было к Богу», т. е. таким образом «прос» содержит в себе идею отношения, и это отношение между Отцом и Сыном есть предвечное рождение, так само Евангелие вводит нас в жизнь Божественных Лиц Пресвятой Троицы».

Сын рождается из существа или естества Отца, а не из ничего или каким другим образом

Сын рождается из существа или естества Отча, а не отинуды, не из ничего. Это – а) следует из самого понятия о рождении: «рождение в том и состоит, что из сущности рождающего производится рождаемое, подобное по сущности, точно так, как при творении и созидании, наоборот, творимое и созидаемое происходит отвне, а не из сущности творящего и созидающего» (Иоанн Дамаск. Точное Изложение прав. веры кн. 1, гд. 8; Athanas. de decret, Synod. Nicen. n. 6); и – б) подтверждается ясными словами Писания: из чрева прежде денницы родих тя (Пс.109:3). «Если – из чрева: то спрашивается, ужели можно верить, что Сын рожден из ничего»? (Hilar. dc Trinit. lib. VI).

«Это не значит, что Бог имеет чрево; но поелику истинные, а не ложные порождения, обыкновенно, раждаются из чрева родителей; то Бог наименовал Себя в рождении имеющим чрево, к посрамлению нечестивых, чтобы они, хотя помыслив о собственной своей природе, познали, что Сын есть истинный плод Отца, как исходящий из Его чрева».

Василий вел. прот. Евном. кн. VII.

Хотя Сын рождается из самого существа Отца, но не так, чтобы от существа Отца что либо при этом отделялось или Отец чего либо лишался

Впрочем, хотя Сын рождается из самого существа Отца, но не так, чтобы от существа Отца что-либо при этом отделялось, или чтобы и Отец чего-либо лишался, или Сын имел какой-либо недостаток: нет, – «неразделимый Бог безраздельно родил Сына», «родил Премудрость, но Сам не остался без премудрости; родил Силу, но не изнемог; родил Бога, но сам не лишился божества, и ничего не потерял, не умалился, не изменился: равно и Рожденный не имеет никакого недостатка. Совершен Родивший, совершенно Рожденное. Родивший Бог, Бог и Рожденный» (Кирилл Иерусалимский. Огласительные поучения XI, п. 18). Или, если указать на близкое подобие: Сын родился от Отца, как свет от света.

Рождение Сына Божия есть рождение вечное и, следовательно, никогда не начиналось и никогда не оканчивалось

Рождение Сына Бoжия есть рождение вечное, и следовательно, никогда не начиналось, никогда и не оканчивалось. Потому-то сам Бог Отец говорит Сыну в одном месте: прежде денницы родих тя (Пс.109:3), т. е. родил прежде всех веков, безначально, а в другом: аз днесь родих тя (Пс.2:7), т. е. родил только теперь, или рождаю вечно. Потому же и в других местах Писания употребляется безразлично – и то, что Бог изрек Слово, которое есть Сын, и то, что Бог изрекает Слово, или иначе, что Сын родился от Отца, и что Сын рождается от Отца. Впрочем, чтобы это, непостижимое для нас, вечное рождение Сына выражать ближе к нашим обыкновенным понятиям, гораздо лучше говорить, что Сын родился от Отца предвечно, нежели, – что Сын вечно рождается: ибо что рождается, то еще не родилось, а Сын рожден.

Сын родился от Отца, но не отделился от Него, т. е. родился неразлучно

Наконец, должно помнить, что Сын родился от Отца, но не отделился от Него, или что тоже, родился неразлучно. Потому и называется сущим в лоне Отчем (Ин.1:18), во Отце пребывающим (Ин.10:38). «Как огонь и происходящий от него свет, – говорит св. Иоанн Дамаскин, – существуют вместе; не прежде бывает огонь, а потом уже свет, но огонь и свет вместе, – и как свет всегда рождается от огня, и всегда в нем пребывает и отнюдь от него не отделяется: так рождается и Сын от Отца, никак не отделяясь от Него, но всегда существуя в Нем. Только свет, который рождается от огня, не отделяясь от него, и который всегда в нем пребывает, не имеет собственной самостоятельности без огня (потому что свет естественное качество огня); напротив, единородный Сын Божий, неотдельно и неразлучно от Отца рожденный и всегда в Нем пребывающий, имеет свою Ипостась, отличную от Ипостаси отчей» (Иоанн. Дамаск, кн. 1, гл. 8, стр. 20–21; снес. гл. 13, стр. 46).

Цитаты о Сыне Божием

«Кто побеждает мир, как не тот, кто верует, что Иисус есть Сын Божий?

Сей есть Иисус Христос, пришедший водою и кровию и Духом, не водою только, но водою и кровию, и Дух свидетельствует о Нем, потому что Дух есть истина.

Ибо три свидетельствуют на небе: Отец, Слово и Святый Дух; и Сии три суть едино.

И три свидетельствуют на земле: дух, вода и кровь; и сии три об одном.

Если мы принимаем свидетельство человеческое, свидетельство Божие – больше, ибо это есть свидетельство Божие, которым Бог свидетельствовал о Сыне Своем.

Верующий в Сына Божия имеет свидетельство в себе самом; не верующий Богу представляет Его лживым, потому что не верует в свидетельство, которым Бог свидетельствовал о Сыне Своем.

Свидетельство сие состоит в том, что Бог даровал нам жизнь вечную, и сия жизнь в Сыне Его. Имеющий Сына (Божия) имеет жизнь; не имеющий Сына Божия не имеет жизни.

Сие написал я вам, верующим во имя Сына Божия, дабы вы знали, что вы, веруя в Сына Божия, имеете жизнь вечную».

1Ин.5:5-13

«Спаситель наш Иисус Христос есть Сын Божий, и называется так по естеству, а не именуется только Сыном, в не собственном смысле сего слова, как мы, будучи тварию; что Он не имеет начала, но вечен; почему по самой Ипостаси Своей Он и в бесконечные веки будет царствовать с Отцем».

свт. Григорий Нисский

«Сын Божий по естеству, вочеловечившись и соделавшись родоначальником человеков, соделал их сынами Божиими по благодати».

свт. Игнатий (Брянчанинов)