The Last Supper is the final meal that, in the Gospel accounts, Jesus shared with his apostles in Jerusalem before his crucifixion.[2] The Last Supper is commemorated by Christians especially on Holy Thursday.[3] The Last Supper provides the scriptural basis for the Eucharist, also known as «Holy Communion» or «The Lord’s Supper».[4]

The First Epistle to the Corinthians contains the earliest known mention of the Last Supper. The four canonical gospels state that the Last Supper took place in the week of Passover, days after Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem, and before Jesus was crucified on Good Friday.[5][6] During the meal, Jesus predicts his betrayal by one of the apostles present, and foretells that before the next morning, Peter will thrice deny knowing him.[5][6]

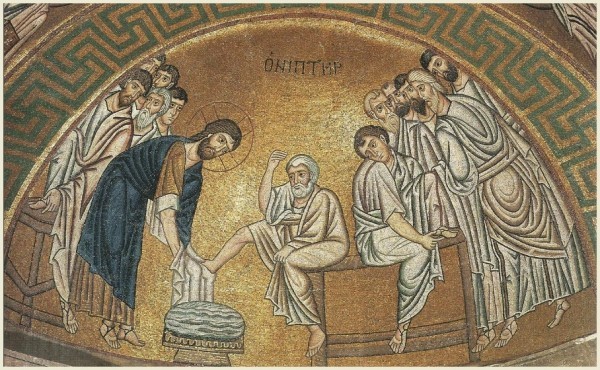

The three Synoptic Gospels and the First Epistle to the Corinthians include the account of the institution of the Eucharist in which Jesus takes bread, breaks it and gives it to those present, saying «This is my body given to you».[5][6] The Gospel of John tells of Jesus washing the feet of the apostles,[John 13:1–15] giving the new commandment «to love one another as I have loved you»,[John 13:33–35] and has a detailed farewell discourse by Jesus, calling the apostles who follow his teachings «friends and not servants», as he prepares them for his departure.[John 14–17][7][8]

Some scholars have looked to the Last Supper as the source of early Christian Eucharistic traditions.[9][10][11][12][13][14] Others see the account of the Last Supper as derived from 1st-century eucharistic practice as described by Paul in the mid-50s.[10][15][16][17]

Terminology

The term «Last Supper» does not appear in the New Testament,[18][19] but traditionally many Christians refer to such an event.[19] Many Protestants use the term «Lord’s Supper», stating that the term «last» suggests this was one of several meals and not the meal.[20][21] The term «Lord’s Supper» refers both to the biblical event and the act of «Holy Communion» and Eucharistic («thanksgiving») celebration within their liturgy. Evangelical Protestants also use the term «Lord’s Supper», but most do not use the terms «Eucharist» or the word «Holy» with the name «Communion».[22]

The Eastern Orthodox use the term «Mystical Supper» which refers both to the biblical event and the act of Eucharistic celebration within liturgy.[23] The Russian Orthodox also use the term «Secret Supper» (Church Slavonic: «Тайная вечеря», Taynaya vecherya).

Scriptural basis

The last meal that Jesus shared with his apostles is described in all four canonical Gospels (Mt. 26:17–30, Mk. 14:12–26, Lk. 22:7–39 and Jn. 13:1–17:26) as having taken place in the week of the Passover.[citation needed] This meal later became known as the Last Supper.[6] The Last Supper was likely a retelling of the events of the last meal of Jesus among the early Christian community, and became a ritual which recounted that meal.[24]

Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians,[11:23–26] which was likely written before the Gospels, includes a reference to the Last Supper but emphasizes the theological basis rather than giving a detailed description of the event or its background.[5] [6]

Background and setting

The overall narrative that is shared in all Gospel accounts that leads to the Last Supper is that after the triumphal entry into Jerusalem early in the week, and encounters with various people and the Jewish elders, Jesus and his disciples share a meal towards the end of the week. After the meal, Jesus is betrayed, arrested, tried, and then crucified.[5][6]

Key events in the meal are the preparation of the disciples for the departure of Jesus, the predictions about the impending betrayal of Jesus, and the foretelling of the upcoming denial of Jesus by Apostle Peter.[5][6]

Prediction of Judas’ betrayal

In Matthew 26:24–25, Mark 14:18–21, Luke 22:21–23 and John 13:21–30 during the meal, Jesus predicted that one of the apostles present would betray him.[25] Jesus is described as reiterating, despite each apostle’s assertion that he would not betray Jesus, that the betrayer would be one of those who were present, and saying that there would be «woe to the man who betrays the Son of man! It would be better for him if he had not been born.»[Mark 14:20–21]

In Matthew 26:23–25 and John 13:26–27, Judas is specifically identified as the traitor. In the Gospel of John, when asked about the traitor, Jesus states:

«It is the one to whom I will give this piece of bread when I have dipped it in the dish.» Then, dipping the piece of bread, he gave it to Judas, the son of Simon Iscariot. As soon as Judas took the bread, Satan entered into him.

— Evans 2003, pp. 465–477 Fahlbusch 2005, pp. 52–56

Institution of the Eucharist

The three Synoptic Gospel accounts describe the Last Supper as a Passover meal,[26][27] disagreeing with John.[27] Each gives somewhat different versions of the order of the meal. In chapter 26 of the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus prays thanks for the bread, divides it, and hands the pieces of bread to his disciples, saying «Take, eat, this is my body.» Later in the meal Jesus takes a cup of wine, offers another prayer, and gives it to those present, saying «Drink from it, all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. I tell you, I will never again drink of this fruit of the vine until that day when I drink it new with you in my Father’s kingdom.»

In chapter 22 of the Gospel of Luke, however, the wine is blessed and distributed before the bread, followed by the bread, then by a second, larger cup of wine, as well as somewhat different wordings. Additionally, according to Paul and Luke, he tells the disciples «do this in remembrance of me.» This event has been regarded by Christians of most denominations as the institution of the Eucharist. There is recorded celebration of the Eucharist by the early Christian community in Jerusalem.[7]

The institution of the Eucharist is recorded in the three Synoptic Gospels and in Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians. As noted above, Jesus’s words differ slightly in each account. In addition, Luke 22:19b–20 is a disputed text which does not appear in some of the early manuscripts of Luke. Some scholars, therefore, believe that it is an interpolation, while others have argued that it is original.[28][29]

A comparison of the accounts given in the Gospels and 1 Corinthians is shown in the table below, with text from the ASV. The disputed text from Luke 22:19b–20 is in italics.

| Mark 14:22–24 | And as they were eating, he took bread, and when he had blessed, he brake it, and gave to them, and said, Take ye: this is my body. | And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks, he gave to them: and they all drank of it. And he said unto them, ‘This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many.’ |

|---|---|---|

| Matthew 26:26–28 | And as they were eating, Jesus took bread, and blessed, and brake it; and he gave to the disciples, and said, ‘Take, eat; this is my body.’ | And he took a cup, and gave thanks, and gave to them, saying, ‘Drink ye all of it; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many unto remission of sins.’ |

| 1 Corinthians 11:23–25 | For I received of the Lord that which also I delivered unto you, that the Lord Jesus in the night in which he was betrayed took bread; and when he had given thanks, he brake it, and said, ‘This is my body, which is for you: this do in remembrance of me.’ | In like manner also the cup, after supper, saying, ‘This cup is the new covenant in my blood: this do, as often as ye drink it, in remembrance of me.’ |

| Luke 22:19–20 | And he took bread, and when he had given thanks, he brake it, and gave to them, saying, ‘This is my body which is given for you: this do in remembrance of me.’ | And the cup in like manner after supper, saying, ‘This cup is the new covenant in my blood, even that which is poured out for you.’ |

Jesus’ actions in sharing the bread and wine have been linked with Isaiah 53:12 which refers to a blood sacrifice that, as recounted in Exodus 24:8, Moses offered in order to seal a covenant with God. Some scholars interpret the description of Jesus’ action as asking his disciples to consider themselves part of a sacrifice, where Jesus is the one due to physically undergo it.[30]

Although the Gospel of John does not include a description of the bread and wine ritual during the Last Supper, most scholars agree that John 6:58–59 (the Bread of Life Discourse) has a Eucharistic nature and resonates with the «words of institution» used in the Synoptic Gospels and the Pauline writings on the Last Supper.[31]

Prediction of Peter’s denial

In Matthew 26:33–35, Mark 14:29–31, Luke 22:33–34 and John 13:36–8 Jesus predicts that Peter will deny knowledge of him, stating that Peter will disown him three times before the rooster crows the next morning. The three Synoptic Gospels mention that after the arrest of Jesus, Peter denied knowing him three times, but after the third denial, heard the rooster crow and recalled the prediction as Jesus turned to look at him. Peter then began to cry bitterly.[32][33]

Elements unique to the Gospel of John

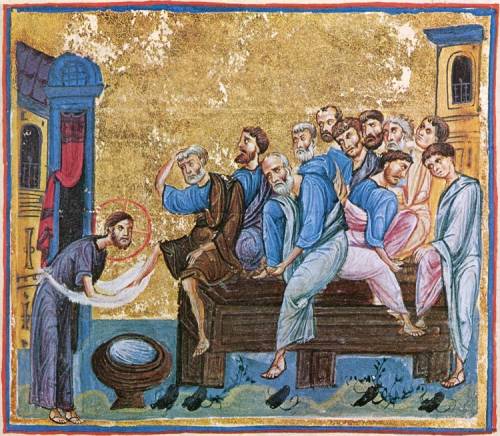

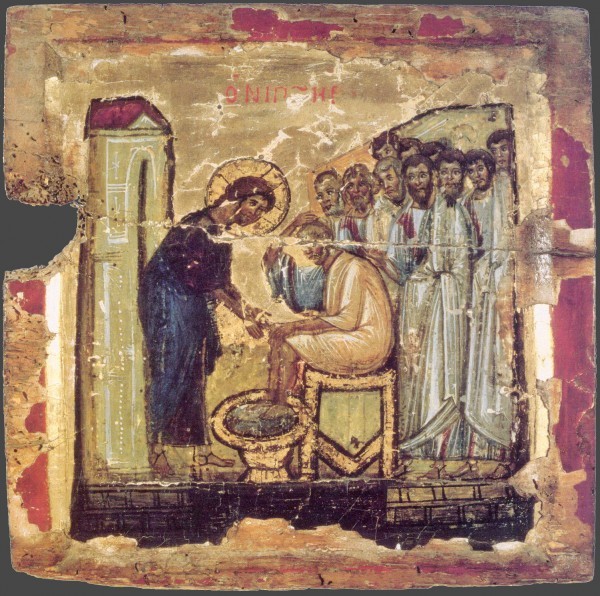

John 13 includes the account of the washing the feet of the Apostles by Jesus before the meal.[34] In this episode, Apostle Peter objects and does not want to allow Jesus to wash his feet, but Jesus answers him, «Unless I wash you, you have no part with me»,[Jn 13:8] after which Peter agrees.

In the Gospel of John, after the departure of Judas from the Last Supper, Jesus tells his remaining disciples [John 13:33] that he will be with them for only a short time, then gives them a New Commandment, stating:[35][36] «A new command I give you: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another. By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another.» in John 13:34–35. Two similar statements also appear later in John 15:12: «My command is this: Love each other as I have loved you», and John 15:17: «This is my command: Love each other.»[36]

At the Last Supper in the Gospel of John, Jesus gives an extended sermon to his disciples.[John 14–16] This discourse resembles farewell speeches called testaments, in which a father or religious leader, often on the deathbed, leaves instructions for his children or followers.[37]

This sermon is referred to as the Farewell discourse of Jesus, and has historically been considered a source of Christian doctrine, particularly on the subject of Christology. John 17:1–26 is generally known as the Farewell Prayer or the High Priestly Prayer, given that it is an intercession for the coming Church.[38] The prayer begins with Jesus’s petition for his glorification by the Father, given that completion of his work and continues to an intercession for the success of the works of his disciples and the community of his followers.[38]

Time and place

Date

Historians estimate that the date of the crucifixion fell in the range AD 30–36.[39][40][41] Isaac Newton and Colin Humphreys have ruled out the years 31, 32, 35, and 36 on astronomical grounds, leaving 7 April AD 30 and 3 April AD 33 as possible crucifixion dates.[42] Humphreys 2011, pp. 72, 189 proposes narrowing down the date of the Last Supper as having occurred in the evening of Wednesday, 1 April AD 33, by revising Annie Jaubert’s double-Passover theory.

Historically, various attempts to reconcile the three synoptic accounts with John have been made, some of which are indicated in the Last Supper by Francis Mershman in the 1912 Catholic Encyclopedia.[43] The Maundy Thursday church tradition assumes that the Last Supper was held on the evening before the crucifixion day (although, strictly speaking, in no Gospel is it unequivocally said that this meal took place on the night before Jesus died).[44]

A new approach to resolve this contrast was undertaken in the wake of the excavations at Qumran in the 1950s when Annie Jaubert argued that there were two Passover feast dates: while the official Jewish lunar calendar had Passover begin on a Friday evening in the year that Jesus died, a solar calendar was also used, for instance by the Essene community at Qumran, which always had the Passover feast begin on a Tuesday evening. According to Jaubert, Jesus would have celebrated the Passover on Tuesday, and the Jewish authorities three days later, on Friday.[citation needed]

Humphreys has disagreed with Jaubert’s proposal on the rounds that the Qumran solar Passover would always fall after the official Jewish lunar Passover. He agrees with the approach of two Passover dates, and argues that the Last Supper took place on the evening of Wednesday 1 April 33, based on his recent discovery of the Essene, Samaritan, and Zealot lunar calendar, which is based on Egyptian reckoning.[45][46]

In a review of Humphreys’ book, the Bible scholar William R Telford points out that the non-astronomical parts of his argument are based on the assumption that the chronologies described in the New Testament are historical and based on eyewitness testimony. In doing so, Telford says, Humphreys has built an argument upon unsound premises which «does violence to the nature of the biblical texts, whose mixture of fact and fiction, tradition and redaction, history and myth all make the rigid application of the scientific tool of astronomy to their putative data a misconstrued enterprise.»[47]

Location

According to later tradition, the Last Supper took place in what is today called The Room of the Last Supper on Mount Zion, just outside the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem, and is traditionally known as The Upper Room. This is based on the account in the Synoptic Gospels that states that Jesus had instructed two disciples (Luke 22:8 specifies that Jesus sent Peter and John) to go to «the city» to meet «a man carrying a jar of water», who would lead them to a house, where they would find «a large upper room furnished and ready».[Mark 14:13–15] In this upper room they «prepare the Passover».

No more specific indication of the location is given in the New Testament, and the «city» referred to may be a suburb of Jerusalem, such as Bethany, rather than Jerusalem itself.

A structure on Mount Zion in Jerusalem is currently called the Cenacle and is purported to be the location of the Last Supper. Bargil Pixner claims the original site is located beneath the current structure of the Cenacle on Mount Zion.[48]

The traditional location is in an area that, according to archaeology, had a large Essene community, a point made by scholars who suspect a link between Jesus and the group.[49]

Saint Mark’s Syrian Orthodox Church in Jerusalem is another possible site for the room in which the Last Supper was held, and contains a Christian stone inscription testifying to early reverence for that spot. Certainly the room they have is older than that of the current cenaculum (crusader – 12th century) and as the room is now underground the relative altitude is correct (the streets of 1st century Jerusalem were at least twelve feet (3.7 metres) lower than those of today, so any true building of that time would have even its upper story currently under the earth). They also have a revered Icon of the Virgin Mary, reputedly painted from life by St Luke.

Theology of the Last Supper

St. Thomas Aquinas viewed The Father, Christ, and the Holy Spirit as teachers and masters who provide lessons, at times by example. For Aquinas, the Last Supper and the Cross form the summit of the teaching that wisdom flows from intrinsic grace, rather than external power.[50] For Aquinas, at the Last Supper Christ taught by example, showing the value of humility (as reflected in John’s foot washing narrative) and self-sacrifice, rather than by exhibiting external, miraculous powers.[50][51]

Aquinas stated that based on John 15:15 (in the Farewell discourse) in which Jesus said: «No longer do I call you servants; …but I have called you friends». Those who are followers of Christ and partake in the Sacrament of the Eucharist become his friends, as those gathered at the table of the Last Supper.[50][51][52] For Aquinas, at the Last Supper Christ made the promise to be present in the Sacrament of the Eucharist, and to be with those who partake in it, as he was with his disciples at the Last Supper.[53]

John Calvin believed only in the two sacraments of Baptism and the «Lord’s Supper» (i.e., Eucharist). Thus, his analysis of the Gospel accounts of the Last Supper was an important part of his entire theology.[54][55] Calvin related the Synoptic Gospel accounts of the Last Supper with the Bread of Life Discourse in John 6:35 that states: «I am the bread of life. He who comes to me will never go hungry.»[55]

Calvin also believed that the acts of Jesus at the Last Supper should be followed as an example, stating that just as Jesus gave thanks to the Father before breaking the bread,[1 Cor. 11:24] those who go to the «Lord’s Table» to receive the sacrament of the Eucharist must give thanks for the «boundless love of God» and celebrate the sacrament with both joy and thanksgiving.[55]

Remembrances

The institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper is remembered by Roman Catholics as one of the Luminous Mysteries of the Rosary, the First Station of a so-called New Way of the Cross and by Christians as the «inauguration of the New Covenant», mentioned by the prophet Jeremiah, fulfilled at the last supper when Jesus «took bread, and after blessing it broke it and gave it to them, and said, ‘Take; this is my body.’ And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks he gave it to them, and they all drank of it. And he said to them, ‘This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many.‘«[Mk. 14:22–24] [Mt. 26:26–28][Lk. 22:19–20] Other Christian groups consider the Bread and Wine remembrance to be a change to the Passover ceremony, as Jesus Christ has become «our Passover, sacrificed for us»,[1 Cor. 5:7] and hold that partaking of the Passover Communion (or fellowship) is now the sign of the New Covenant, when properly understood by the practicing believer.

These meals evolved into more formal worship services and became codified as the Mass in the Catholic Church, and as the Divine Liturgy in the Eastern Orthodox Church; at these liturgies, Catholics and Eastern Orthodox celebrate the Sacrament of the Eucharist. The name «Eucharist» is from the Greek word εὐχαριστία (eucharistia) which means «thanksgiving».

Early Christianity observed a ritual meal known as the «agape feast»[a] These «love feasts» were apparently a full meal, with each participant bringing food, and with the meal eaten in a common room. They were held on Sundays, which became known as the Lord’s Day, to recall the resurrection, the appearance of Christ to the disciples on the road to Emmaus, the appearance to Thomas and the Pentecost which all took place on Sundays after the Passion.

Passover parallels

Since the late 20th century, with growing consciousness of the Jewish character of the early church and the improvement of Jewish-Christian relations, it became common among some lay people to associate the Last Supper with the Passover Seder.[citation needed] Some evangelical groups borrowed Seder customs, like Haggadahs, and incorporated them in new rituals meant to mimic the Last Supper;[citation needed] likewise, many secularized Jews presume that the event was a Seder. This identification is somewhat erroneous, as a Passover meal during the Second Temple Period would include the consumption of a full lamb. The earliest elements in the current Passover Seder (a fortiori the full-fledged ritual, which is first recorded in full only in the ninth century) are a rabbinic enactment instituted in remembrance of the Temple, which was still standing during the Last Supper.[56]

In Islam

The fifth chapter in the Quran, Al-Ma’ida (the table) contains a reference to a meal (Sura 5:114) with a table sent down from God to ʿĪsá (i.e., Jesus) and the apostles (Hawariyyin). However, there is nothing in Sura 5:114 to indicate that Jesus was celebrating that meal regarding his impending death, especially as the Quran states that Jesus was never crucified to begin with. Thus, although Sura 5:114 refers to «a meal», there is no indication that it is the Last Supper.[57] However, some scholars believe that Jesus’ manner of speech during which the table was sent down suggests that it was an affirmation of the apostles’ resolves and to strengthen their faiths as the impending trial was about to befall them.[58]

Historicity

According to John P. Meier and E. P. Sanders, Jesus having a final meal with his disciples is almost beyond dispute among scholars, and belongs to the framework of the narrative of Jesus’s life.[59][60] I. Howard Marshall states that any doubt about the historicity of the Last Supper should be abandoned.[11]

Some Jesus Seminar scholars consider the Last Supper to have derived not from Jesus’ last supper with the disciples but rather from the gentile tradition of memorial dinners for the dead.[61] In their view, the Last Supper is a tradition associated mainly with the gentile churches that Paul established, rather than with the earlier, Jewish congregations.[61] Such views echo that of 20th century Protestant theologian Rudolf Bultmann, who also believed the Eucharist to have originated in Gentile Christianity.[16][17]

On the other hand, an increasing number of scholars has reasserted the historicity of the institution of the Eucharist, reinterpreting it from a Jewish eschatological point of view: according to Lutheran theologian Joachim Jeremias, for example, the Last Supper should be seen as a climax of a series of Messianic meals held by Jesus in anticipation of a new Exodus.[62] Similar views are echoed in more recent works by Catholic biblical scholars such as John P. Meier and Brant Pitre, and by Anglican scholar N.T. Wright.[63][14][64]

Artistic depictions

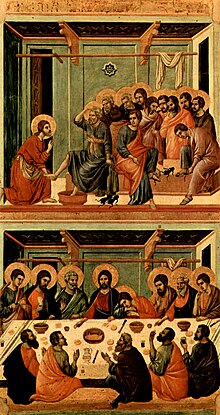

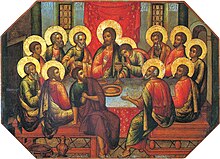

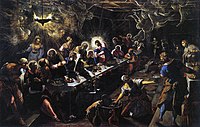

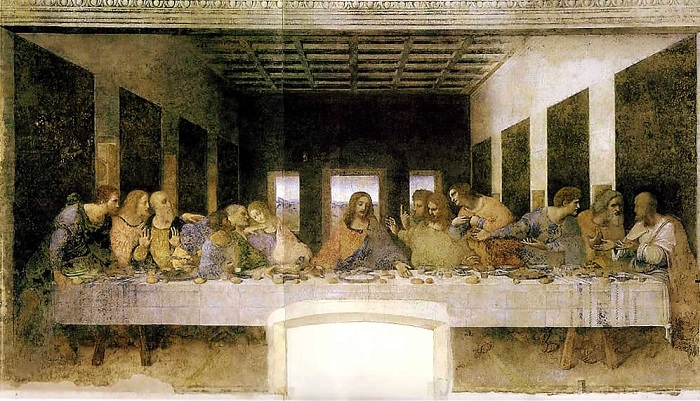

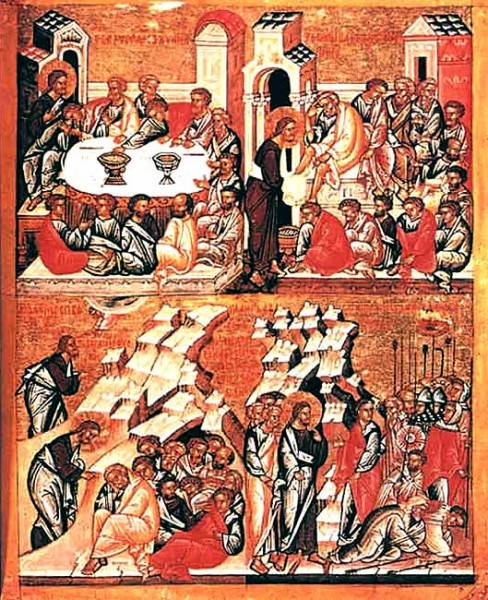

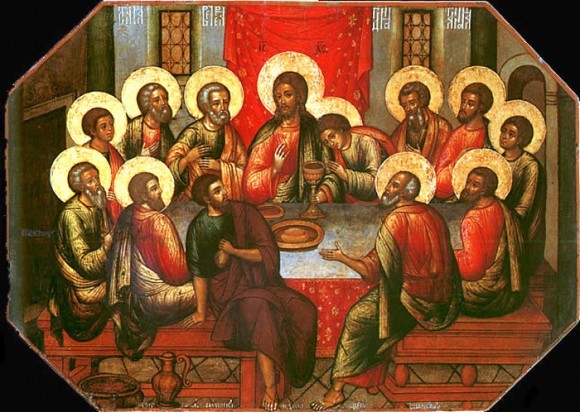

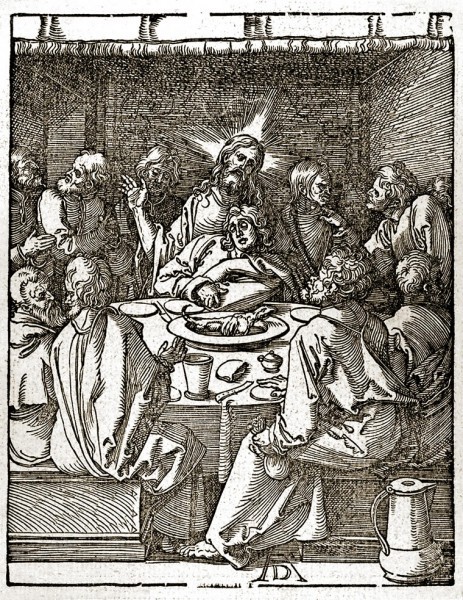

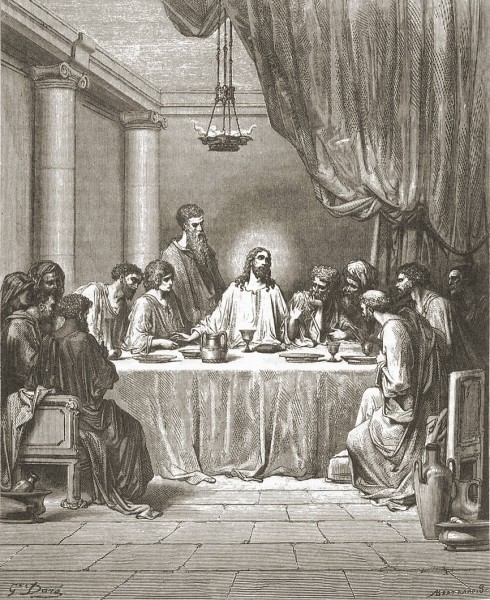

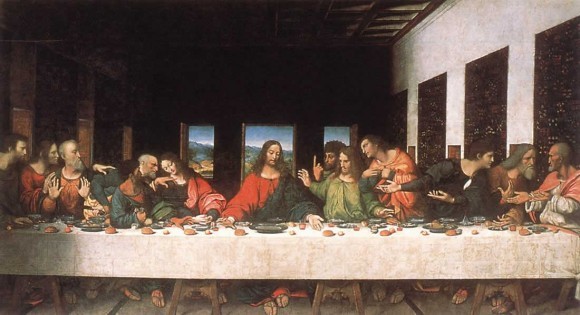

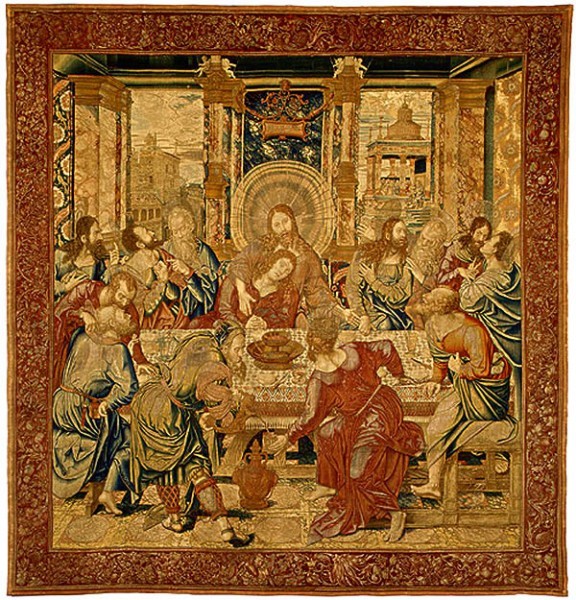

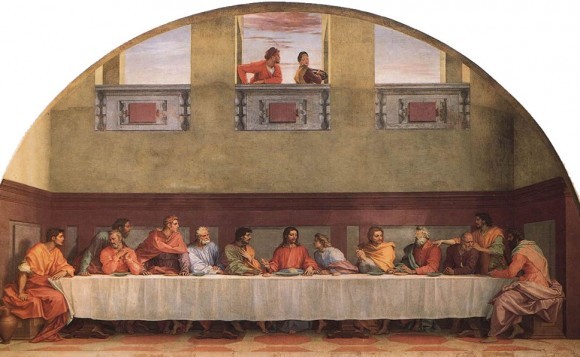

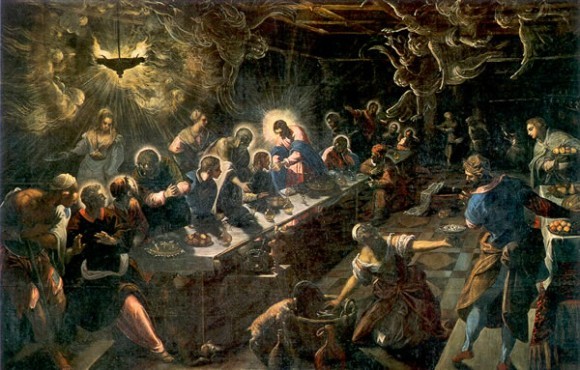

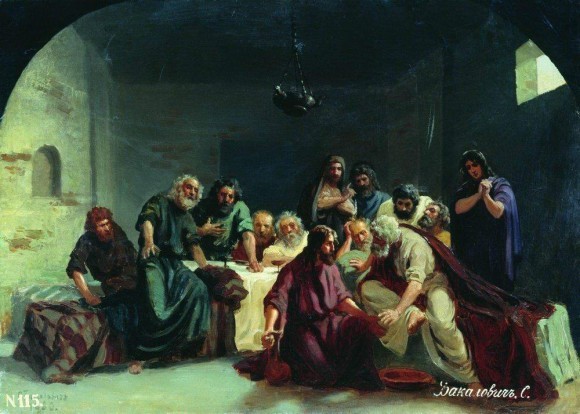

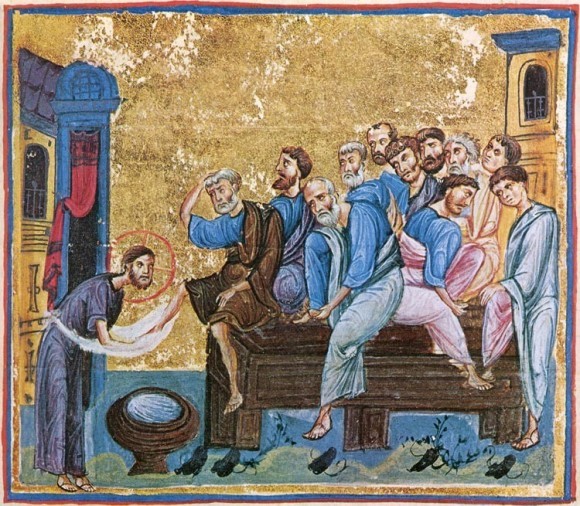

The Last Supper has been a popular subject in Christian art.[1] Such depictions date back to early Christianity and can be seen in the Catacombs of Rome. Byzantine artists frequently focused on the Apostles receiving Communion, rather than the reclining figures having a meal. By the Renaissance, the Last Supper was a favorite topic in Italian art.[65]

There are three major themes in the depictions of the Last Supper: the first is the dramatic and dynamic depiction of Jesus’s announcement of his betrayal. The second is the moment of the institution of the tradition of the Eucharist. The depictions here are generally solemn and mystical. The third major theme is the farewell of Jesus to his disciples, in which Judas Iscariot is no longer present, having left the supper. The depictions here are generally melancholy, as Jesus prepares his disciples for his departure.[1] There are also other, less frequently depicted scenes, such as the washing of the feet of the disciples.[66]

The best known depiction of the Last Supper is Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, which is considered the first work of High Renaissance art, due to its high level of harmony.[67]

Among other representations, Tintoretto’s depiction is unusual in that it includes secondary characters carrying or taking the dishes from the table,[68] and Salvador Dali’s depiction combines the typical Christian themes with modern approaches of Surrealism.[69]

- Depictions of Last Supper

-

-

The Last Supper (Dark side of the Eucharist), by Benjamin West, mid 18 century

-

-

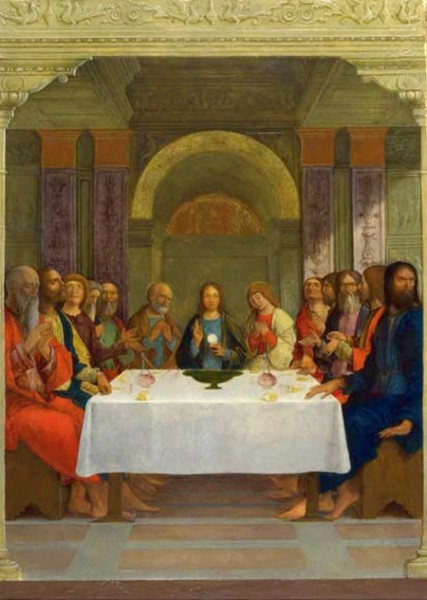

The first Eucharist, depicted by Juan de Juanes in The Last Supper, c. 1562

-

Miniature depiction from c. 1230

-

-

Last Supper, sculpture, c. 1500

-

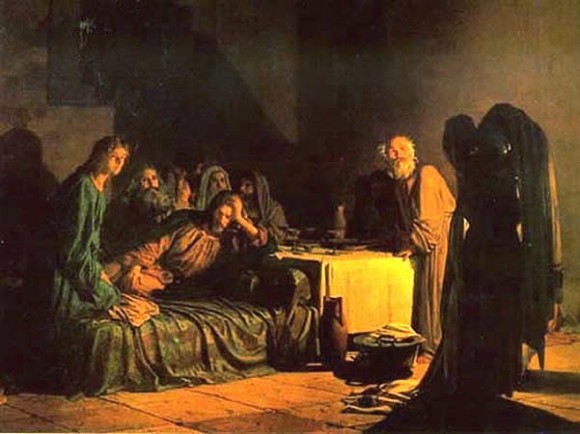

The Last Supper, by Bouveret, 19th century

-

Music

The Lutheran Passion hymn «Da der Herr Christ zu Tische saß» (When the Lord Christ sat at the table) derives from a depiction of the Last Supper.[importance of example(s)?]

See also

- Book of the Secret Supper

- Friday the 13th

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- List of dining events

References

Notes

- ^ Agape is one of the four main Greek words for love (Lewis 1960). It refers to the idealised or high-level unconditional love rather than lust, friendship, or affection (as in parental affection). Though Christians interpret Agape as meaning a divine form of love beyond human forms, in modern Greek the term is used in the sense of «I love you» (romantic love).

Citations

- ^ a b c Zuffi 2003, pp. 254–259.

- ^ Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 958, Last Supper.

- ^ Windsor & Hughes 1990, p. 64.

- ^ Hazen 2002, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d e f Evans 2003, pp. 465–477.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fahlbusch 2005, pp. 52–56.

- ^ a b Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 570, Eucharist.

- ^ Kruse 2004, p. 103.

- ^ Bromiley 1979, p. 164.

- ^ a b Wainwright & Tucker 2006.

- ^ a b Marshall 2006, p. 33.

- ^ Jeremias 1966, p. 51–62.

- ^ Meier 1991, pp. 302–309.

- ^ a b Pitre 2011.

- ^ Funk 1998, pp. 1–40, Intruduction.

- ^ a b Bultmann 1963.

- ^ a b Bultmann 1958.

- ^ Armentrout & Slocum 1999, p. 292.

- ^ a b Fitzmyer 1981, p. 1378.

- ^ Bower 2003, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Anon. 1992, p. 37.

- ^ Thompson 1996, pp. 493–494.

- ^ McGuckin 2010, pp. 293, 297.

- ^ Harrington 2001, p. 49.

- ^ Cox & Easley 2007, p. 182.

- ^ Sherman, Robert J. (2 March 2004). King, Priest, and Prophet: A Trinitarian Theology of Atonement. A&C Black. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-567-02560-9. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ a b Saulnier, Stéphane (3 May 2012). Calendrical Variations in Second Temple Judaism: New Perspectives on the ‘Date of the Last Supper’ Debate. BRILL. p. 3. ISBN 978-90-04-16963-0. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ Marshall et al. 1996, p. 697.

- ^ Blomberg 2009, p. 333.

- ^ Brown et al. 626[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Freedman 2000, p. 792.

- ^ Perkins 2000, p. 85.

- ^ Lange 1865, p. 499.

- ^ Harris 1985, pp. 302–311.

- ^ Köstenberger 2002, pp. 149–151.

- ^ a b Yarbrough 2008, p. 215.

- ^ Funk & Hoover 1993.

- ^ a b Ridderbos 1997, pp. 546–76.

- ^ Barnett 2002, pp. 19–21.

- ^ Riesner 1998, pp. 19–27.

- ^ Köstenberger, Kellum & Quarles 2009, pp. 77–79.

- ^ Humphreys 2011, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Mershman 1912.

- ^ Green 1990, p. 333.

- ^ Humphreys 2011, pp. 162, 168.

- ^ Narayana 2011.

- ^ Telford 2015, pp. 371–376.

- ^ Pixner 1990.

- ^ Kilgallen 265[incomplete short citation]

- ^ a b c Dauphinais & Levering 2005, p. xix.

- ^ a b Wawrykow 2005a, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Pope 2002, p. 22.

- ^ Wawrykow 2005b, p. 124.

- ^ Rice & Huffstutler 2001, pp. 66–68.

- ^ a b c Chen 2008, pp. 62–68.

- ^ Poupko & Sandmel 2017.

- ^ Beaumont 2005, p. 145.

- ^ Khalife 2012.

- ^ Sanders 1995, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Meier 1991, p. 398.

- ^ a b Funk 1998, pp. 51–161, Mark.

- ^ Jeremias 1966, p. 51-62.

- ^ Meier 1994, pp. 302–309.

- ^ Wright 2014.

- ^ McNamee 1998, p. 22–32.

- ^ Zuffi 2003, p. 252.

- ^ Buser 2006, pp. 382–383.

- ^ Nichols 1999, p. 234.

- ^ Stakhov & Olsen 2009, pp. 177–178.

Sources

- Anon. (1992). Liturgical Year: The Worship of God. Supplemental liturgical resource. Presbyterian Publishing Corporation. ISBN 978-0-664-25350-9.

- Armentrout, D.S.; Slocum, R.B. (1999). An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church: A User-Friendly Reference for Episcopalians. Church Publishing Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-89869-211-2.

- Barnett, Paul (2002). Jesus and the Rise of Early Christianity. A History of New Testament Times. ISBN 0830826998.

- Beaumont, Ivor Mark (2005). Christology in dialogue with Muslims. ISBN 1870345460.

- Blomberg, Craig (2009). Jesus and the Gospels. Nashville: B & H Pub. Group. ISBN 978-1-4336-6842-5. OCLC 727647948.

- Bower, Peter (2003). The companion to the Book of common worship. Louisville, Ky: Geneva Press Office of Theology and Worship, Presbyterian Church (U.S.A. ISBN 0-664-50232-6. OCLC 51059177.

- Buser, Thomas (2006). Experiencing art around us. Australia United States: Thomson Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0-534-64114-6. OCLC 58986528.

- Casey, Maurice (2010). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian’s Account of His Life and Teaching. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-567-64517-3.

- Chen, David (2008). Calvin’s passion for the church and the Holy Spirit. United States: Xulon Press. ISBN 978-1-60647-346-7. OCLC 459711693.

- Cox, Steven; Easley, Kendell H. (2007). Harmony of the Gospels. Nashville, Tenn: Holman Bible Pub. ISBN 978-0-8054-9444-0. OCLC 83596188.

- Bromiley, G. W. (1979). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837837.

- Cross, F. L.; Livingstone, E. A. (2005). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd rev. ed.). Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192802903.

- Dauphinais, Michael; Levering, Matthew, eds. (2005). Reading John with St. Thomas Aquinas. ISBN 9780813214054.

- Dix, Gregory} (1945). The Shape of the Liturgy. Dacre Press.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0060738174.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (9 July 2016). «Did Matthew Write in Hebrew? Did Jesus Institute the Lord’s Supper? Did Josephus Mention Jesus? Weekly Readers’ Mailbag July 9, 2016». The Bart Ehrman Blog. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Evans, Craig A. (2003). The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary. ISBN 0781438683.

- Fahlbusch, Erwin (2005). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Vol. 4. ISBN 978-0802824165.

- Fitzmyer, Joseph, ed. (1981). The Gospel according to Luke : introduction, translation, and notes. Vol. 28A. Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-00515-6. OCLC 6918343.

- Freedman, D. N. (2000). Eerdmans dictionary of the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. ISBN 90-5356-503-5. OCLC 782943561.

- Funk, Robert W.; Hoover, Roy W. (1993). The five gospels. Jesus Seminar. HarperSanFrancisco.

- Funk, Robert W. (1998). The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus. Jesus Seminar. HarperSanFrancisco.

- Green, William Scott (1990). Judaism and Christianity in the first century. ISBN 9780824081744.

- Harrington, Daniel (2001). The church according to the New Testament : what the wisdom and witness of early Christianity teach us today. Franklin, Wis: Sheed & Ward. ISBN 1-58051-111-2. OCLC 47869562.

- Harris, Stephen L. (1985). «John». Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield.

- Hazen, Walter (2002). Inside Christianity. Lorenz Educational Press. ISBN 978-0787705596.

- Humphreys, Colin J. (2011). The Mystery of the Last Supper. Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 978-0521732000.

- Jeremias, J. (1966). The Eucharistic Words of Jesus. New Testament library. Scribner.

- Kasser, R.; Meyer, M.; Wurst, G.; Gaudard, F. (2008). The Gospel of Judas, Second Edition. National Geographic Society. ISBN 978-1-4262-0415-9.

- Khalife, Maan (2012). «Last Supper of Jesus According to Islam».

- Köstenberger, Andreas (2002). Encountering John : the Gospel in historical, literary, and theological perspective. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic. ISBN 0-8010-2603-2. OCLC 52964348.

- Köstenberger, Andreas J.; Kellum, Leonard Scott; Quarles, Charles L. (2009). The cradle, the cross, and the crown : an introduction to the New Testament. Nashville, Tenn: B & H Academic. ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3. OCLC 369138111.

- Kruse, Colin G. (2004). The Gospel according to John. ISBN 0802827713.

- Lange, Johann Peter (1865). The Gospel according to Matthew. Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner.

- Lewis, C. S. (1960). The Four Loves. Geoffrey Bles. OCLC 30879763.

- Marshall, I. Howard; Millard, A. R.; Packer, J. I.; Wiseman, by Donald J. (1996). New Bible dictionary (3rd ed.). Leicester: InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-1439-8. OCLC 34943226.

- McGuckin, John (2010). The Orthodox Church : an Introduction to its History, Doctrine, and Spiritual Culture. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4443-3731-0. OCLC 811493276.

- McNamee, Maurice (1998). Vested angels : eucharistic allusions in early Netherlandish paintings. Leuven: Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-0007-3. OCLC 39715499.

- Meier, John P. (1991). A Marginal Jew: The roots of the problem and the person. Doubleday. p. 398. ISBN 978-0-385-26425-9.

- Mershman, Francis (1912). «The Last Supper» . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Narayana, Nagesh (18 April 2011). «Last Supper was on Wednesday, not Thursday, challenges Cambridge professor Colin Humphreys». International Business Times. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- Nichols, Tom (1999). Tintoretto : tradition and identity. London: Reaktion. ISBN 1-86189-120-2. OCLC 41958923.

- Perkins, Pheme (2000). Peter : apostle for the whole church. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. ISBN 0-567-08743-3. OCLC 746853124.

- Pixner, Bargil (May–June 1990). «The Church of the Apostles found on Mount Zion». Biblical Archaeology Review. 16 (3). Archived from the original on 9 March 2018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Pope, Stephen (2002). The ethics of Aquinas. Washington, D.C: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 0-87840-888-6. OCLC 47838307.

- Poupko, Yehiel; Sandmel, David (6 April 2017). «Jesus Didn’t Eat a Seder Meal». ChristianityToday.com. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- Ridderbos, Herman (1997). «The Farewell Prayer». The Gospel according to John: a theological commentary. Grand Rapids, Mich: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. ISBN 978-0-8028-0453-2. OCLC 36133366.

- Rice, Howard; Huffstutler, James C. (2001). Reformed worship. Louisville: Geneva Press. ISBN 0-664-50147-8. OCLC 45363586.

- Riesner, R. (1998). Paul’s Early Period: Chronology, Mission Strategy, Theology. Translated by D. Stott. W.B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-4166-7.

- Sanders, E. P. (1995). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin. ISBN 978-0140144994.

- Stakhov, A.P.; Olsen, S.A. (2009). The Mathematics of Harmony: From Euclid to Contemporary Mathematics and Computer Science. K & E series on knots and everything. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-277-582-5.

- Telford, William R. (2015). «Review of The Mystery of the Last Supper: Reconstructing the Final Days of Jesus». The Journal of Theological Studies. 66 (1): 371–76. doi:10.1093/jts/flv005.

- Thompson, B. (1996). Humanists and Reformers: A History of the Renaissance and Reformation. Wm B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6348-5.

- Vermes, Geza (2004). The authentic gospel of Jesus. London: Penguin.

- Wainwright, G.; Tucker, K.B.W. (2006). The Oxford History of Christian Worship. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-513886-3.

- Wawrykow, Joseph (2005a). The A-Z of Thomas Aquinas. London: SCM Press. ISBN 0-334-04012-4. OCLC 61666905.

- Wawrykow, Joseph (2005b). The Westminster handbook to Thomas Aquinas. Louisville, Ky: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22469-1. OCLC 57530148.

- Windsor, Gwyneth; Hughes, John (1990). Worship and Festivals. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0435302733.

- Yarbrough, Robert (2008). 1-3 John. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0-8010-2687-4. OCLC 225852361.

- Zuffi, Stefano (2003). Gospel figures in art. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN 978-0892367276.

External links

- «Last Supper» on Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

The Last Supper is the final meal that, in the Gospel accounts, Jesus shared with his apostles in Jerusalem before his crucifixion.[2] The Last Supper is commemorated by Christians especially on Holy Thursday.[3] The Last Supper provides the scriptural basis for the Eucharist, also known as «Holy Communion» or «The Lord’s Supper».[4]

The First Epistle to the Corinthians contains the earliest known mention of the Last Supper. The four canonical gospels state that the Last Supper took place in the week of Passover, days after Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem, and before Jesus was crucified on Good Friday.[5][6] During the meal, Jesus predicts his betrayal by one of the apostles present, and foretells that before the next morning, Peter will thrice deny knowing him.[5][6]

The three Synoptic Gospels and the First Epistle to the Corinthians include the account of the institution of the Eucharist in which Jesus takes bread, breaks it and gives it to those present, saying «This is my body given to you».[5][6] The Gospel of John tells of Jesus washing the feet of the apostles,[John 13:1–15] giving the new commandment «to love one another as I have loved you»,[John 13:33–35] and has a detailed farewell discourse by Jesus, calling the apostles who follow his teachings «friends and not servants», as he prepares them for his departure.[John 14–17][7][8]

Some scholars have looked to the Last Supper as the source of early Christian Eucharistic traditions.[9][10][11][12][13][14] Others see the account of the Last Supper as derived from 1st-century eucharistic practice as described by Paul in the mid-50s.[10][15][16][17]

Terminology

The term «Last Supper» does not appear in the New Testament,[18][19] but traditionally many Christians refer to such an event.[19] Many Protestants use the term «Lord’s Supper», stating that the term «last» suggests this was one of several meals and not the meal.[20][21] The term «Lord’s Supper» refers both to the biblical event and the act of «Holy Communion» and Eucharistic («thanksgiving») celebration within their liturgy. Evangelical Protestants also use the term «Lord’s Supper», but most do not use the terms «Eucharist» or the word «Holy» with the name «Communion».[22]

The Eastern Orthodox use the term «Mystical Supper» which refers both to the biblical event and the act of Eucharistic celebration within liturgy.[23] The Russian Orthodox also use the term «Secret Supper» (Church Slavonic: «Тайная вечеря», Taynaya vecherya).

Scriptural basis

The last meal that Jesus shared with his apostles is described in all four canonical Gospels (Mt. 26:17–30, Mk. 14:12–26, Lk. 22:7–39 and Jn. 13:1–17:26) as having taken place in the week of the Passover.[citation needed] This meal later became known as the Last Supper.[6] The Last Supper was likely a retelling of the events of the last meal of Jesus among the early Christian community, and became a ritual which recounted that meal.[24]

Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians,[11:23–26] which was likely written before the Gospels, includes a reference to the Last Supper but emphasizes the theological basis rather than giving a detailed description of the event or its background.[5] [6]

Background and setting

The overall narrative that is shared in all Gospel accounts that leads to the Last Supper is that after the triumphal entry into Jerusalem early in the week, and encounters with various people and the Jewish elders, Jesus and his disciples share a meal towards the end of the week. After the meal, Jesus is betrayed, arrested, tried, and then crucified.[5][6]

Key events in the meal are the preparation of the disciples for the departure of Jesus, the predictions about the impending betrayal of Jesus, and the foretelling of the upcoming denial of Jesus by Apostle Peter.[5][6]

Prediction of Judas’ betrayal

In Matthew 26:24–25, Mark 14:18–21, Luke 22:21–23 and John 13:21–30 during the meal, Jesus predicted that one of the apostles present would betray him.[25] Jesus is described as reiterating, despite each apostle’s assertion that he would not betray Jesus, that the betrayer would be one of those who were present, and saying that there would be «woe to the man who betrays the Son of man! It would be better for him if he had not been born.»[Mark 14:20–21]

In Matthew 26:23–25 and John 13:26–27, Judas is specifically identified as the traitor. In the Gospel of John, when asked about the traitor, Jesus states:

«It is the one to whom I will give this piece of bread when I have dipped it in the dish.» Then, dipping the piece of bread, he gave it to Judas, the son of Simon Iscariot. As soon as Judas took the bread, Satan entered into him.

— Evans 2003, pp. 465–477 Fahlbusch 2005, pp. 52–56

Institution of the Eucharist

The three Synoptic Gospel accounts describe the Last Supper as a Passover meal,[26][27] disagreeing with John.[27] Each gives somewhat different versions of the order of the meal. In chapter 26 of the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus prays thanks for the bread, divides it, and hands the pieces of bread to his disciples, saying «Take, eat, this is my body.» Later in the meal Jesus takes a cup of wine, offers another prayer, and gives it to those present, saying «Drink from it, all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. I tell you, I will never again drink of this fruit of the vine until that day when I drink it new with you in my Father’s kingdom.»

In chapter 22 of the Gospel of Luke, however, the wine is blessed and distributed before the bread, followed by the bread, then by a second, larger cup of wine, as well as somewhat different wordings. Additionally, according to Paul and Luke, he tells the disciples «do this in remembrance of me.» This event has been regarded by Christians of most denominations as the institution of the Eucharist. There is recorded celebration of the Eucharist by the early Christian community in Jerusalem.[7]

The institution of the Eucharist is recorded in the three Synoptic Gospels and in Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians. As noted above, Jesus’s words differ slightly in each account. In addition, Luke 22:19b–20 is a disputed text which does not appear in some of the early manuscripts of Luke. Some scholars, therefore, believe that it is an interpolation, while others have argued that it is original.[28][29]

A comparison of the accounts given in the Gospels and 1 Corinthians is shown in the table below, with text from the ASV. The disputed text from Luke 22:19b–20 is in italics.

| Mark 14:22–24 | And as they were eating, he took bread, and when he had blessed, he brake it, and gave to them, and said, Take ye: this is my body. | And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks, he gave to them: and they all drank of it. And he said unto them, ‘This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many.’ |

|---|---|---|

| Matthew 26:26–28 | And as they were eating, Jesus took bread, and blessed, and brake it; and he gave to the disciples, and said, ‘Take, eat; this is my body.’ | And he took a cup, and gave thanks, and gave to them, saying, ‘Drink ye all of it; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many unto remission of sins.’ |

| 1 Corinthians 11:23–25 | For I received of the Lord that which also I delivered unto you, that the Lord Jesus in the night in which he was betrayed took bread; and when he had given thanks, he brake it, and said, ‘This is my body, which is for you: this do in remembrance of me.’ | In like manner also the cup, after supper, saying, ‘This cup is the new covenant in my blood: this do, as often as ye drink it, in remembrance of me.’ |

| Luke 22:19–20 | And he took bread, and when he had given thanks, he brake it, and gave to them, saying, ‘This is my body which is given for you: this do in remembrance of me.’ | And the cup in like manner after supper, saying, ‘This cup is the new covenant in my blood, even that which is poured out for you.’ |

Jesus’ actions in sharing the bread and wine have been linked with Isaiah 53:12 which refers to a blood sacrifice that, as recounted in Exodus 24:8, Moses offered in order to seal a covenant with God. Some scholars interpret the description of Jesus’ action as asking his disciples to consider themselves part of a sacrifice, where Jesus is the one due to physically undergo it.[30]

Although the Gospel of John does not include a description of the bread and wine ritual during the Last Supper, most scholars agree that John 6:58–59 (the Bread of Life Discourse) has a Eucharistic nature and resonates with the «words of institution» used in the Synoptic Gospels and the Pauline writings on the Last Supper.[31]

Prediction of Peter’s denial

In Matthew 26:33–35, Mark 14:29–31, Luke 22:33–34 and John 13:36–8 Jesus predicts that Peter will deny knowledge of him, stating that Peter will disown him three times before the rooster crows the next morning. The three Synoptic Gospels mention that after the arrest of Jesus, Peter denied knowing him three times, but after the third denial, heard the rooster crow and recalled the prediction as Jesus turned to look at him. Peter then began to cry bitterly.[32][33]

Elements unique to the Gospel of John

John 13 includes the account of the washing the feet of the Apostles by Jesus before the meal.[34] In this episode, Apostle Peter objects and does not want to allow Jesus to wash his feet, but Jesus answers him, «Unless I wash you, you have no part with me»,[Jn 13:8] after which Peter agrees.

In the Gospel of John, after the departure of Judas from the Last Supper, Jesus tells his remaining disciples [John 13:33] that he will be with them for only a short time, then gives them a New Commandment, stating:[35][36] «A new command I give you: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another. By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another.» in John 13:34–35. Two similar statements also appear later in John 15:12: «My command is this: Love each other as I have loved you», and John 15:17: «This is my command: Love each other.»[36]

At the Last Supper in the Gospel of John, Jesus gives an extended sermon to his disciples.[John 14–16] This discourse resembles farewell speeches called testaments, in which a father or religious leader, often on the deathbed, leaves instructions for his children or followers.[37]

This sermon is referred to as the Farewell discourse of Jesus, and has historically been considered a source of Christian doctrine, particularly on the subject of Christology. John 17:1–26 is generally known as the Farewell Prayer or the High Priestly Prayer, given that it is an intercession for the coming Church.[38] The prayer begins with Jesus’s petition for his glorification by the Father, given that completion of his work and continues to an intercession for the success of the works of his disciples and the community of his followers.[38]

Time and place

Date

Historians estimate that the date of the crucifixion fell in the range AD 30–36.[39][40][41] Isaac Newton and Colin Humphreys have ruled out the years 31, 32, 35, and 36 on astronomical grounds, leaving 7 April AD 30 and 3 April AD 33 as possible crucifixion dates.[42] Humphreys 2011, pp. 72, 189 proposes narrowing down the date of the Last Supper as having occurred in the evening of Wednesday, 1 April AD 33, by revising Annie Jaubert’s double-Passover theory.

Historically, various attempts to reconcile the three synoptic accounts with John have been made, some of which are indicated in the Last Supper by Francis Mershman in the 1912 Catholic Encyclopedia.[43] The Maundy Thursday church tradition assumes that the Last Supper was held on the evening before the crucifixion day (although, strictly speaking, in no Gospel is it unequivocally said that this meal took place on the night before Jesus died).[44]

A new approach to resolve this contrast was undertaken in the wake of the excavations at Qumran in the 1950s when Annie Jaubert argued that there were two Passover feast dates: while the official Jewish lunar calendar had Passover begin on a Friday evening in the year that Jesus died, a solar calendar was also used, for instance by the Essene community at Qumran, which always had the Passover feast begin on a Tuesday evening. According to Jaubert, Jesus would have celebrated the Passover on Tuesday, and the Jewish authorities three days later, on Friday.[citation needed]

Humphreys has disagreed with Jaubert’s proposal on the rounds that the Qumran solar Passover would always fall after the official Jewish lunar Passover. He agrees with the approach of two Passover dates, and argues that the Last Supper took place on the evening of Wednesday 1 April 33, based on his recent discovery of the Essene, Samaritan, and Zealot lunar calendar, which is based on Egyptian reckoning.[45][46]

In a review of Humphreys’ book, the Bible scholar William R Telford points out that the non-astronomical parts of his argument are based on the assumption that the chronologies described in the New Testament are historical and based on eyewitness testimony. In doing so, Telford says, Humphreys has built an argument upon unsound premises which «does violence to the nature of the biblical texts, whose mixture of fact and fiction, tradition and redaction, history and myth all make the rigid application of the scientific tool of astronomy to their putative data a misconstrued enterprise.»[47]

Location

According to later tradition, the Last Supper took place in what is today called The Room of the Last Supper on Mount Zion, just outside the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem, and is traditionally known as The Upper Room. This is based on the account in the Synoptic Gospels that states that Jesus had instructed two disciples (Luke 22:8 specifies that Jesus sent Peter and John) to go to «the city» to meet «a man carrying a jar of water», who would lead them to a house, where they would find «a large upper room furnished and ready».[Mark 14:13–15] In this upper room they «prepare the Passover».

No more specific indication of the location is given in the New Testament, and the «city» referred to may be a suburb of Jerusalem, such as Bethany, rather than Jerusalem itself.

A structure on Mount Zion in Jerusalem is currently called the Cenacle and is purported to be the location of the Last Supper. Bargil Pixner claims the original site is located beneath the current structure of the Cenacle on Mount Zion.[48]

The traditional location is in an area that, according to archaeology, had a large Essene community, a point made by scholars who suspect a link between Jesus and the group.[49]

Saint Mark’s Syrian Orthodox Church in Jerusalem is another possible site for the room in which the Last Supper was held, and contains a Christian stone inscription testifying to early reverence for that spot. Certainly the room they have is older than that of the current cenaculum (crusader – 12th century) and as the room is now underground the relative altitude is correct (the streets of 1st century Jerusalem were at least twelve feet (3.7 metres) lower than those of today, so any true building of that time would have even its upper story currently under the earth). They also have a revered Icon of the Virgin Mary, reputedly painted from life by St Luke.

Theology of the Last Supper

St. Thomas Aquinas viewed The Father, Christ, and the Holy Spirit as teachers and masters who provide lessons, at times by example. For Aquinas, the Last Supper and the Cross form the summit of the teaching that wisdom flows from intrinsic grace, rather than external power.[50] For Aquinas, at the Last Supper Christ taught by example, showing the value of humility (as reflected in John’s foot washing narrative) and self-sacrifice, rather than by exhibiting external, miraculous powers.[50][51]

Aquinas stated that based on John 15:15 (in the Farewell discourse) in which Jesus said: «No longer do I call you servants; …but I have called you friends». Those who are followers of Christ and partake in the Sacrament of the Eucharist become his friends, as those gathered at the table of the Last Supper.[50][51][52] For Aquinas, at the Last Supper Christ made the promise to be present in the Sacrament of the Eucharist, and to be with those who partake in it, as he was with his disciples at the Last Supper.[53]

John Calvin believed only in the two sacraments of Baptism and the «Lord’s Supper» (i.e., Eucharist). Thus, his analysis of the Gospel accounts of the Last Supper was an important part of his entire theology.[54][55] Calvin related the Synoptic Gospel accounts of the Last Supper with the Bread of Life Discourse in John 6:35 that states: «I am the bread of life. He who comes to me will never go hungry.»[55]

Calvin also believed that the acts of Jesus at the Last Supper should be followed as an example, stating that just as Jesus gave thanks to the Father before breaking the bread,[1 Cor. 11:24] those who go to the «Lord’s Table» to receive the sacrament of the Eucharist must give thanks for the «boundless love of God» and celebrate the sacrament with both joy and thanksgiving.[55]

Remembrances

The institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper is remembered by Roman Catholics as one of the Luminous Mysteries of the Rosary, the First Station of a so-called New Way of the Cross and by Christians as the «inauguration of the New Covenant», mentioned by the prophet Jeremiah, fulfilled at the last supper when Jesus «took bread, and after blessing it broke it and gave it to them, and said, ‘Take; this is my body.’ And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks he gave it to them, and they all drank of it. And he said to them, ‘This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many.‘«[Mk. 14:22–24] [Mt. 26:26–28][Lk. 22:19–20] Other Christian groups consider the Bread and Wine remembrance to be a change to the Passover ceremony, as Jesus Christ has become «our Passover, sacrificed for us»,[1 Cor. 5:7] and hold that partaking of the Passover Communion (or fellowship) is now the sign of the New Covenant, when properly understood by the practicing believer.

These meals evolved into more formal worship services and became codified as the Mass in the Catholic Church, and as the Divine Liturgy in the Eastern Orthodox Church; at these liturgies, Catholics and Eastern Orthodox celebrate the Sacrament of the Eucharist. The name «Eucharist» is from the Greek word εὐχαριστία (eucharistia) which means «thanksgiving».

Early Christianity observed a ritual meal known as the «agape feast»[a] These «love feasts» were apparently a full meal, with each participant bringing food, and with the meal eaten in a common room. They were held on Sundays, which became known as the Lord’s Day, to recall the resurrection, the appearance of Christ to the disciples on the road to Emmaus, the appearance to Thomas and the Pentecost which all took place on Sundays after the Passion.

Passover parallels

Since the late 20th century, with growing consciousness of the Jewish character of the early church and the improvement of Jewish-Christian relations, it became common among some lay people to associate the Last Supper with the Passover Seder.[citation needed] Some evangelical groups borrowed Seder customs, like Haggadahs, and incorporated them in new rituals meant to mimic the Last Supper;[citation needed] likewise, many secularized Jews presume that the event was a Seder. This identification is somewhat erroneous, as a Passover meal during the Second Temple Period would include the consumption of a full lamb. The earliest elements in the current Passover Seder (a fortiori the full-fledged ritual, which is first recorded in full only in the ninth century) are a rabbinic enactment instituted in remembrance of the Temple, which was still standing during the Last Supper.[56]

In Islam

The fifth chapter in the Quran, Al-Ma’ida (the table) contains a reference to a meal (Sura 5:114) with a table sent down from God to ʿĪsá (i.e., Jesus) and the apostles (Hawariyyin). However, there is nothing in Sura 5:114 to indicate that Jesus was celebrating that meal regarding his impending death, especially as the Quran states that Jesus was never crucified to begin with. Thus, although Sura 5:114 refers to «a meal», there is no indication that it is the Last Supper.[57] However, some scholars believe that Jesus’ manner of speech during which the table was sent down suggests that it was an affirmation of the apostles’ resolves and to strengthen their faiths as the impending trial was about to befall them.[58]

Historicity

According to John P. Meier and E. P. Sanders, Jesus having a final meal with his disciples is almost beyond dispute among scholars, and belongs to the framework of the narrative of Jesus’s life.[59][60] I. Howard Marshall states that any doubt about the historicity of the Last Supper should be abandoned.[11]

Some Jesus Seminar scholars consider the Last Supper to have derived not from Jesus’ last supper with the disciples but rather from the gentile tradition of memorial dinners for the dead.[61] In their view, the Last Supper is a tradition associated mainly with the gentile churches that Paul established, rather than with the earlier, Jewish congregations.[61] Such views echo that of 20th century Protestant theologian Rudolf Bultmann, who also believed the Eucharist to have originated in Gentile Christianity.[16][17]

On the other hand, an increasing number of scholars has reasserted the historicity of the institution of the Eucharist, reinterpreting it from a Jewish eschatological point of view: according to Lutheran theologian Joachim Jeremias, for example, the Last Supper should be seen as a climax of a series of Messianic meals held by Jesus in anticipation of a new Exodus.[62] Similar views are echoed in more recent works by Catholic biblical scholars such as John P. Meier and Brant Pitre, and by Anglican scholar N.T. Wright.[63][14][64]

Artistic depictions

The Last Supper has been a popular subject in Christian art.[1] Such depictions date back to early Christianity and can be seen in the Catacombs of Rome. Byzantine artists frequently focused on the Apostles receiving Communion, rather than the reclining figures having a meal. By the Renaissance, the Last Supper was a favorite topic in Italian art.[65]

There are three major themes in the depictions of the Last Supper: the first is the dramatic and dynamic depiction of Jesus’s announcement of his betrayal. The second is the moment of the institution of the tradition of the Eucharist. The depictions here are generally solemn and mystical. The third major theme is the farewell of Jesus to his disciples, in which Judas Iscariot is no longer present, having left the supper. The depictions here are generally melancholy, as Jesus prepares his disciples for his departure.[1] There are also other, less frequently depicted scenes, such as the washing of the feet of the disciples.[66]

The best known depiction of the Last Supper is Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, which is considered the first work of High Renaissance art, due to its high level of harmony.[67]

Among other representations, Tintoretto’s depiction is unusual in that it includes secondary characters carrying or taking the dishes from the table,[68] and Salvador Dali’s depiction combines the typical Christian themes with modern approaches of Surrealism.[69]

- Depictions of Last Supper

-

-

The Last Supper (Dark side of the Eucharist), by Benjamin West, mid 18 century

-

-

The first Eucharist, depicted by Juan de Juanes in The Last Supper, c. 1562

-

Miniature depiction from c. 1230

-

-

Last Supper, sculpture, c. 1500

-

The Last Supper, by Bouveret, 19th century

-

Music

The Lutheran Passion hymn «Da der Herr Christ zu Tische saß» (When the Lord Christ sat at the table) derives from a depiction of the Last Supper.[importance of example(s)?]

See also

- Book of the Secret Supper

- Friday the 13th

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- List of dining events

References

Notes

- ^ Agape is one of the four main Greek words for love (Lewis 1960). It refers to the idealised or high-level unconditional love rather than lust, friendship, or affection (as in parental affection). Though Christians interpret Agape as meaning a divine form of love beyond human forms, in modern Greek the term is used in the sense of «I love you» (romantic love).

Citations

- ^ a b c Zuffi 2003, pp. 254–259.

- ^ Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 958, Last Supper.

- ^ Windsor & Hughes 1990, p. 64.

- ^ Hazen 2002, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d e f Evans 2003, pp. 465–477.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fahlbusch 2005, pp. 52–56.

- ^ a b Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 570, Eucharist.

- ^ Kruse 2004, p. 103.

- ^ Bromiley 1979, p. 164.

- ^ a b Wainwright & Tucker 2006.

- ^ a b Marshall 2006, p. 33.

- ^ Jeremias 1966, p. 51–62.

- ^ Meier 1991, pp. 302–309.

- ^ a b Pitre 2011.

- ^ Funk 1998, pp. 1–40, Intruduction.

- ^ a b Bultmann 1963.

- ^ a b Bultmann 1958.

- ^ Armentrout & Slocum 1999, p. 292.

- ^ a b Fitzmyer 1981, p. 1378.

- ^ Bower 2003, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Anon. 1992, p. 37.

- ^ Thompson 1996, pp. 493–494.

- ^ McGuckin 2010, pp. 293, 297.

- ^ Harrington 2001, p. 49.

- ^ Cox & Easley 2007, p. 182.

- ^ Sherman, Robert J. (2 March 2004). King, Priest, and Prophet: A Trinitarian Theology of Atonement. A&C Black. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-567-02560-9. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ a b Saulnier, Stéphane (3 May 2012). Calendrical Variations in Second Temple Judaism: New Perspectives on the ‘Date of the Last Supper’ Debate. BRILL. p. 3. ISBN 978-90-04-16963-0. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ Marshall et al. 1996, p. 697.

- ^ Blomberg 2009, p. 333.

- ^ Brown et al. 626[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Freedman 2000, p. 792.

- ^ Perkins 2000, p. 85.

- ^ Lange 1865, p. 499.

- ^ Harris 1985, pp. 302–311.

- ^ Köstenberger 2002, pp. 149–151.

- ^ a b Yarbrough 2008, p. 215.

- ^ Funk & Hoover 1993.

- ^ a b Ridderbos 1997, pp. 546–76.

- ^ Barnett 2002, pp. 19–21.

- ^ Riesner 1998, pp. 19–27.

- ^ Köstenberger, Kellum & Quarles 2009, pp. 77–79.

- ^ Humphreys 2011, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Mershman 1912.

- ^ Green 1990, p. 333.

- ^ Humphreys 2011, pp. 162, 168.

- ^ Narayana 2011.

- ^ Telford 2015, pp. 371–376.

- ^ Pixner 1990.

- ^ Kilgallen 265[incomplete short citation]

- ^ a b c Dauphinais & Levering 2005, p. xix.

- ^ a b Wawrykow 2005a, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Pope 2002, p. 22.

- ^ Wawrykow 2005b, p. 124.

- ^ Rice & Huffstutler 2001, pp. 66–68.

- ^ a b c Chen 2008, pp. 62–68.

- ^ Poupko & Sandmel 2017.

- ^ Beaumont 2005, p. 145.

- ^ Khalife 2012.

- ^ Sanders 1995, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Meier 1991, p. 398.

- ^ a b Funk 1998, pp. 51–161, Mark.

- ^ Jeremias 1966, p. 51-62.

- ^ Meier 1994, pp. 302–309.

- ^ Wright 2014.

- ^ McNamee 1998, p. 22–32.

- ^ Zuffi 2003, p. 252.

- ^ Buser 2006, pp. 382–383.

- ^ Nichols 1999, p. 234.

- ^ Stakhov & Olsen 2009, pp. 177–178.

Sources

- Anon. (1992). Liturgical Year: The Worship of God. Supplemental liturgical resource. Presbyterian Publishing Corporation. ISBN 978-0-664-25350-9.

- Armentrout, D.S.; Slocum, R.B. (1999). An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church: A User-Friendly Reference for Episcopalians. Church Publishing Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-89869-211-2.

- Barnett, Paul (2002). Jesus and the Rise of Early Christianity. A History of New Testament Times. ISBN 0830826998.

- Beaumont, Ivor Mark (2005). Christology in dialogue with Muslims. ISBN 1870345460.

- Blomberg, Craig (2009). Jesus and the Gospels. Nashville: B & H Pub. Group. ISBN 978-1-4336-6842-5. OCLC 727647948.

- Bower, Peter (2003). The companion to the Book of common worship. Louisville, Ky: Geneva Press Office of Theology and Worship, Presbyterian Church (U.S.A. ISBN 0-664-50232-6. OCLC 51059177.

- Buser, Thomas (2006). Experiencing art around us. Australia United States: Thomson Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0-534-64114-6. OCLC 58986528.

- Casey, Maurice (2010). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian’s Account of His Life and Teaching. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-567-64517-3.

- Chen, David (2008). Calvin’s passion for the church and the Holy Spirit. United States: Xulon Press. ISBN 978-1-60647-346-7. OCLC 459711693.

- Cox, Steven; Easley, Kendell H. (2007). Harmony of the Gospels. Nashville, Tenn: Holman Bible Pub. ISBN 978-0-8054-9444-0. OCLC 83596188.

- Bromiley, G. W. (1979). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837837.

- Cross, F. L.; Livingstone, E. A. (2005). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd rev. ed.). Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192802903.

- Dauphinais, Michael; Levering, Matthew, eds. (2005). Reading John with St. Thomas Aquinas. ISBN 9780813214054.

- Dix, Gregory} (1945). The Shape of the Liturgy. Dacre Press.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0060738174.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (9 July 2016). «Did Matthew Write in Hebrew? Did Jesus Institute the Lord’s Supper? Did Josephus Mention Jesus? Weekly Readers’ Mailbag July 9, 2016». The Bart Ehrman Blog. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Evans, Craig A. (2003). The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary. ISBN 0781438683.

- Fahlbusch, Erwin (2005). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Vol. 4. ISBN 978-0802824165.

- Fitzmyer, Joseph, ed. (1981). The Gospel according to Luke : introduction, translation, and notes. Vol. 28A. Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-00515-6. OCLC 6918343.

- Freedman, D. N. (2000). Eerdmans dictionary of the Bible. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. ISBN 90-5356-503-5. OCLC 782943561.

- Funk, Robert W.; Hoover, Roy W. (1993). The five gospels. Jesus Seminar. HarperSanFrancisco.

- Funk, Robert W. (1998). The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus. Jesus Seminar. HarperSanFrancisco.

- Green, William Scott (1990). Judaism and Christianity in the first century. ISBN 9780824081744.

- Harrington, Daniel (2001). The church according to the New Testament : what the wisdom and witness of early Christianity teach us today. Franklin, Wis: Sheed & Ward. ISBN 1-58051-111-2. OCLC 47869562.

- Harris, Stephen L. (1985). «John». Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield.

- Hazen, Walter (2002). Inside Christianity. Lorenz Educational Press. ISBN 978-0787705596.

- Humphreys, Colin J. (2011). The Mystery of the Last Supper. Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 978-0521732000.

- Jeremias, J. (1966). The Eucharistic Words of Jesus. New Testament library. Scribner.

- Kasser, R.; Meyer, M.; Wurst, G.; Gaudard, F. (2008). The Gospel of Judas, Second Edition. National Geographic Society. ISBN 978-1-4262-0415-9.

- Khalife, Maan (2012). «Last Supper of Jesus According to Islam».

- Köstenberger, Andreas (2002). Encountering John : the Gospel in historical, literary, and theological perspective. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic. ISBN 0-8010-2603-2. OCLC 52964348.

- Köstenberger, Andreas J.; Kellum, Leonard Scott; Quarles, Charles L. (2009). The cradle, the cross, and the crown : an introduction to the New Testament. Nashville, Tenn: B & H Academic. ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3. OCLC 369138111.

- Kruse, Colin G. (2004). The Gospel according to John. ISBN 0802827713.

- Lange, Johann Peter (1865). The Gospel according to Matthew. Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner.

- Lewis, C. S. (1960). The Four Loves. Geoffrey Bles. OCLC 30879763.

- Marshall, I. Howard; Millard, A. R.; Packer, J. I.; Wiseman, by Donald J. (1996). New Bible dictionary (3rd ed.). Leicester: InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-1439-8. OCLC 34943226.

- McGuckin, John (2010). The Orthodox Church : an Introduction to its History, Doctrine, and Spiritual Culture. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4443-3731-0. OCLC 811493276.

- McNamee, Maurice (1998). Vested angels : eucharistic allusions in early Netherlandish paintings. Leuven: Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-0007-3. OCLC 39715499.

- Meier, John P. (1991). A Marginal Jew: The roots of the problem and the person. Doubleday. p. 398. ISBN 978-0-385-26425-9.

- Mershman, Francis (1912). «The Last Supper» . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Narayana, Nagesh (18 April 2011). «Last Supper was on Wednesday, not Thursday, challenges Cambridge professor Colin Humphreys». International Business Times. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- Nichols, Tom (1999). Tintoretto : tradition and identity. London: Reaktion. ISBN 1-86189-120-2. OCLC 41958923.

- Perkins, Pheme (2000). Peter : apostle for the whole church. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. ISBN 0-567-08743-3. OCLC 746853124.

- Pixner, Bargil (May–June 1990). «The Church of the Apostles found on Mount Zion». Biblical Archaeology Review. 16 (3). Archived from the original on 9 March 2018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Pope, Stephen (2002). The ethics of Aquinas. Washington, D.C: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 0-87840-888-6. OCLC 47838307.

- Poupko, Yehiel; Sandmel, David (6 April 2017). «Jesus Didn’t Eat a Seder Meal». ChristianityToday.com. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- Ridderbos, Herman (1997). «The Farewell Prayer». The Gospel according to John: a theological commentary. Grand Rapids, Mich: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. ISBN 978-0-8028-0453-2. OCLC 36133366.

- Rice, Howard; Huffstutler, James C. (2001). Reformed worship. Louisville: Geneva Press. ISBN 0-664-50147-8. OCLC 45363586.

- Riesner, R. (1998). Paul’s Early Period: Chronology, Mission Strategy, Theology. Translated by D. Stott. W.B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-4166-7.

- Sanders, E. P. (1995). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin. ISBN 978-0140144994.

- Stakhov, A.P.; Olsen, S.A. (2009). The Mathematics of Harmony: From Euclid to Contemporary Mathematics and Computer Science. K & E series on knots and everything. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-277-582-5.

- Telford, William R. (2015). «Review of The Mystery of the Last Supper: Reconstructing the Final Days of Jesus». The Journal of Theological Studies. 66 (1): 371–76. doi:10.1093/jts/flv005.

- Thompson, B. (1996). Humanists and Reformers: A History of the Renaissance and Reformation. Wm B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6348-5.

- Vermes, Geza (2004). The authentic gospel of Jesus. London: Penguin.

- Wainwright, G.; Tucker, K.B.W. (2006). The Oxford History of Christian Worship. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-513886-3.

- Wawrykow, Joseph (2005a). The A-Z of Thomas Aquinas. London: SCM Press. ISBN 0-334-04012-4. OCLC 61666905.

- Wawrykow, Joseph (2005b). The Westminster handbook to Thomas Aquinas. Louisville, Ky: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22469-1. OCLC 57530148.

- Windsor, Gwyneth; Hughes, John (1990). Worship and Festivals. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0435302733.

- Yarbrough, Robert (2008). 1-3 John. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0-8010-2687-4. OCLC 225852361.

- Zuffi, Stefano (2003). Gospel figures in art. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN 978-0892367276.

External links

- «Last Supper» on Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

Тайная вечеря.

Леонардо да Винчи – самая загадочная и неизученная личность прошлых лет. Кто-то приписывает ему божий дар и причисляет к лику святых, кто-то, напротив, считает его безбожником, продавшим душу дьяволу. Но гений великого итальянца неоспорим, поскольку все, к чему когда-либо прикасалась рука великого живописца и инженера, моментально наполнялось скрытым смыслом. Сегодня мы поговорим о знаменитом произведении «Тайная вечеря» и множествах секретов, которое оно скрывает.

Месторасположение и история создания:

Церковь Санта-Мария-делле-Грацие.

Знаменитая фреска находится в церкви Санта-Мария-делле-Грацие, расположенной на одноименной площади Милана. А точнее – на одной из стен трапезной. Как утверждают историки, художник специально изобразил на картине точно такие же стол и посуду, какие были на тот момент в церкви. Этим он пытался показать, что Иисус и Иуда (добро и зло) гораздо ближе к людям, чем кажется.

Заказ на написание произведения живописец получил от своего патрона — миланского герцога Людовико Сфорца в 1495 году. Правитель славился распутной жизнью и с юных лет был окружен юными вакханками. Ситуацию нисколько не меняло наличие у герцога прекрасной и скромной жены Беатриче д’Эсте, которая искренне любила супруга и в силу своего кроткого нрава не могла перечить его образу жизни. Надо признать, что Людовико Сфорца искренне почитал свою жену и был по-своему к ней привязан. Но истинную силу любви распутный герцог ощутил только в момент скоропостижной кончины своей супруги. Скорбь мужчины была столь велика, что он на 15 дней не покидал своей комнаты. А когда вышел, то первым делом заказал Леонардо да Винчи фреску, о которой некогда просила его покойная супруга, и навсегда прекратил все развлечения при дворе.

Тайная вечеря в трапезной.

Произведение было выполнено в 1498 году. Его размеры составили 880 на 460 см. Многие ценители творчества художника сошлись во мнении, что лучше всего «Тайную вечерю» можно рассмотреть, если отойти на 9 метров в сторону и приподняться 3,5 метров вверх. Тем более что посмотреть есть на что. Уже при жизни автора фреска считалась его лучшим произведением. Хотя, назвать картину фреской было бы неправильным. Дело в том, что Леонардо да Винчи писал произведение не на мокрой штукатурке, а на сухой, чтобы иметь возможность редактировать ее несколько раз. Для этого художник нанес на стену толстый слой яичной темпры, которая впоследствии сослужила дурную службу, начав разрушаться всего через 20 лет после написания картины. Но об этом чуть позже.

Идея произведения:

Эскиз Тайной вечери.

«Тайная вечеря» изображает последний пасхальный ужин Иисуса Христа с учениками-апостолами, состоявшийся в Иерусалиме накануне его ареста римлянами. Согласно писанию, Иисус сказал во время трапезы, что один из апостолов предаст его. Леонардо да Винчи постарался изобразить реакцию каждого из учеников на пророческую фразу Учителя. Для этого он ходил по городу, говорил с простыми людьми, смешил их, расстраивал, обнадеживал. А сам при этом наблюдал за эмоциями на лицах. Целью автора было отображение знаменитого ужина с чисто человеческой точки зрения. Именно поэтому он изобразил всех присутствующих в ряд и никому не пририсовал нимба над головой (как это любили делать другие художники).

Интересные факты:

Вот мы и дошли до самой интересной части статьи: секретов и особенностей, скрытых в произведении великого автора.

Иисус на фреске Тайная вечеря.

1. Как утверждают историки, сложнее всего Леонардо да Винчи далось написание двух персонажей: Иисуса и Иуды. Художник старался сделать их воплощением добра и зла, поэтому долго не мог найти подходящих моделей. Однажды итальянец увидел в церковном хоре юного певчего – настолько одухотворенного и чистого, что сомнений не осталось: вот он – прототип Иисуса для его «Тайной вечери». Но, несмотря на то, что образ Учителя был написан, Леонардо да Винчи еще долго корректировал его, считая недостаточно совершенным.

Последним ненаписанным персонажем на картине оставался Иуда. Художник часами бродил по самым злачным местам, выискивая среди опустившихся людей модель для написания. И вот почти через 3 года ему повезло. В канаве валялся абсолютно опустившийся тип в состоянии сильного алкогольного опьянения. Художник приказал привести его в мастерскую. Мужчина почти не держался на ногах и не соображал, куда он попал. Однако, уже после того, как образ Иуды был написан, пьяница подошел к картине и признался, что уже видел ее раньше. На недоумение автора человек ответил, что три года назад он был совсем другим, вел правильный образ жизни и пел в церковном хоре. Именно тогда к нему подошел какой-то художник с предложением написать с него Христа. Так, согласно мнению историков, Иисус и Иуда были списаны с одного и того же человека в разные периоды его жизни. Это еще раз подчеркивает тот факт, что добро и зло идут так близко, что иногда грань между ними неощутима.

Кстати, во время работы Леонардо да Винчи отвлекал настоятель монастыря, который постоянно торопил художника и утверждал, что тот должен сутками писать картину, а не стоять перед ней в раздумьях. Однажды живописец не выдержал и пообещал настоятелю списать с него Иуду, если тот не перестанет вмешиваться в творческий процесс.

Иисус и Мария Магдалина.

2. Самым обсуждаемым секретом фрески является фигура ученика, расположившегося по правую руку от Христа. Считается, что это не кто иной, как Мария Магдалина и ее месторасположение указывает на тот факт, что она была не любовницей Иисуса, как это принято считать, а его законной женой. Этот факт подтверждает буква «М», которую образуют контуры тел пары. Якобы она означает слово «Matrimonio», которое в переводе означает «брак». Некоторые историки спорят с этим утверждением и настаивают, что на картине проглядывается подпись Леонардо да Винчи — буква «V». В пользу первого утверждения выступает упоминание о том, что Мария Магдалина омывала ноги Христу и вытирала их своими волосами. Согласно традициям, сделать это могла только законная жена. Более того, считается, что женщина на момент казни мужа была беременной и родила впоследствии дочь Сару, которая положила начало династии Меровингов.

3. Некоторые ученые утверждают, что необычное расположение учеников на картине не случайно. Дескать, Леонардо да Винчи разместил людей по… знакам зодиака. Согласно этой легенде, Иисус был козерогом, а его возлюбленная Мария Магдалина – девой.

Мария Магдалина.