Русский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | талму́д | талму́ды |

| Р. | талму́да | талму́дов |

| Д. | талму́ду | талму́дам |

| В. | талму́д | талму́ды |

| Тв. | талму́дом | талму́дами |

| Пр. | талму́де | талму́дах |

тал—му́д

Существительное, неодушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 1a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Корень: -талмуд- [Тихонов, 1996].

Произношение[править]

- МФА: [tɐɫˈmut]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- религ. в иудаизме — собрание толкований ветхого завета и догматических религиозно-этических и правовых положений иудаизма, сложившихся к IV веку до н. э. — V в. н. э. ◆ Древнееврейский язык, пятикнижие, талмуд и гемору он знал в совершенстве и, занимаясь обучением еврейских детей всей этой премудрости, жил не только безбедно, но даже с некоторым комфортом. П. Ф. Якубович, «В мире отверженных», Том 2 // «Русское богатство», 1898 г. [НКРЯ]

- перен., шутл. большая, громоздкая книга ◆ Стеклов, не заглядывая в толстый, потрёпанный жизнью талмуд, сказал знакомое: «Продляем на неделю галоперидол и хинидин», – и отодвинул карту на край стола. Константин Корсар, «Досье поэта-рецидивиста», 2013 г.

Синонимы[править]

- Талмуд

Антонимы[править]

- —

- —

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

|

Этимология[править]

Происходит от ивр. תַּלְמוּד «учение, учёба», далее из למד (lamád) «учиться».

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Перевод[править]

| собрание догматических религиозно-этических и правовых положений иудаизма | |

|

| толстая, громоздкая книга | |

Библиография[править]

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

This article is about the Babylonian Talmud. For the Jerusalem Talmud, see Jerusalem Talmud.

«Talmudic» redirects here. «Talmudic Aramaic» refers to the Jewish Babylonian Aramaic as found in the Talmud.

The Talmud (; Hebrew: תַּלְמוּד, romanized: Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (halakha) and Jewish theology.[1][2] Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the centerpiece of Jewish cultural life and was foundational to «all Jewish thought and aspirations», serving also as «the guide for the daily life» of Jews.[3]

The term Talmud normally refers to the collection of writings named specifically the Babylonian Talmud (Talmud Bavli), although there is also an earlier collection known as the Jerusalem Talmud (Talmud Yerushalmi).[4] It may also traditionally be called Shas (ש״ס), a Hebrew abbreviation of shisha sedarim, or the «six orders» of the Mishnah.

The Talmud has two components: the Mishnah (משנה, c. 200 CE), a written compendium of the Oral Torah; and the Gemara (גמרא, c. 500 CE), an elucidation of the Mishnah and related Tannaitic writings that often ventures onto other subjects and expounds broadly on the Hebrew Bible. The term «Talmud» may refer to either the Gemara alone, or the Mishnah and Gemara together.

The entire Talmud consists of 63 tractates, and in the standard print, called the Vilna Shas, there are 2,711 double-sided folios.[5] It is written in Mishnaic Hebrew and Jewish Babylonian Aramaic and contains the teachings and opinions of thousands of rabbis (dating from before the Common Era through to the fifth century) on a variety of subjects, including halakha, Jewish ethics, philosophy, customs, history, and folklore, and many other topics. The Talmud is the basis for all codes of Jewish law and is widely quoted in rabbinic literature.

Etymology[edit]

Talmud translates as «instruction, learning», from the Semitic root LMD, meaning «teach, study».[6]

History[edit]

Oz veHadar edition of the first page of the Babylonian Talmud, with elements numbered in a spiraling rainbowː (1) Joshua Boaz’s Mesorat haShas, (2) Joel Sirkis’s Hagahot (3) Akiva Eiger’s Gilyon haShas, (4) Completion of Rashi’s commentary from the Soncino printing, (5) Nissim ben Jacob’s commentary, (6) Hananel ben Hushiel’s commentary, (7) a survey of the verses quoted, (8) Joshua Boaz’s Ein Mishpat/Ner Mitzvah, (9) the folio and page numbers, (10) the tractate title, (11) the chapter number, (12), the chapter heading, (13), Rashi’s commentary, (14) the Tosafot, (15) the Mishnah, (16) the Gemara, (17) an editorial footnote.

An early printing of the Talmud (Ta’anit 9b); with commentary by Rashi

Originally, Jewish scholarship was oral and transferred from one generation to the next. Rabbis expounded and debated the Torah (the written Torah expressed in the Hebrew Bible) and discussed the Tanakh without the benefit of written works (other than the Biblical books themselves), though some may have made private notes (megillot setarim), for example, of court decisions. This situation changed drastically due to the Roman destruction of the Jewish commonwealth and the Second Temple in the year 70 and the consequent upheaval of Jewish social and legal norms. As the rabbis were required to face a new reality—mainly Judaism without a Temple (to serve as the center of teaching and study) and total Roman control over Judaea, without at least partial autonomy—there was a flurry of legal discourse and the old system of oral scholarship could not be maintained. It is during this period that rabbinic discourse began to be recorded in writing.[a][b]

The oldest full manuscript of the Talmud, known as the Munich Talmud (Codex Hebraicus 95), dates from 1342 and is available online.[c]

Babylonian and Jerusalem[edit]

The process of «Gemara» proceeded in what were then the two major centers of Jewish scholarship: Galilee and Babylonia. Correspondingly, two bodies of analysis developed, and two works of Talmud were created. The older compilation is called the Jerusalem Talmud or the Talmud Yerushalmi. It was compiled in the 4th century in Galilee. The Babylonian Talmud was compiled about the year 500, although it continued to be edited later. The word «Talmud», when used without qualification, usually refers to the Babylonian Talmud.

While the editors of Jerusalem Talmud and Babylonian Talmud each mention the other community, most scholars believe these documents were written independently; Louis Jacobs writes, «If the editors of either had had access to an actual text of the other, it is inconceivable that they would not have mentioned this. Here the argument from silence is very convincing.»[7]

Jerusalem Talmud[edit]

A page of a medieval Jerusalem Talmud manuscript, from the Cairo Geniza

The Jerusalem Talmud, also known as the Palestinian Talmud, or Talmuda de-Eretz Yisrael (Talmud of the Land of Israel), was one of the two compilations of Jewish religious teachings and commentary that was transmitted orally for centuries prior to its compilation by Jewish scholars in the Land of Israel.[8] It is a compilation of teachings of the schools of Tiberias, Sepphoris, and Caesarea. It is written largely in Jewish Palestinian Aramaic, a Western Aramaic language that differs from its Babylonian counterpart.[9][10]

This Talmud is a synopsis of the analysis of the Mishnah that was developed over the course of nearly 200 years by the Academies in Galilee (principally those of Tiberias and Caesarea.) Because of their location, the sages of these Academies devoted considerable attention to the analysis of the agricultural laws of the Land of Israel. Traditionally, this Talmud was thought to have been redacted in about the year 350 by Rav Muna and Rav Yossi in the Land of Israel. It is traditionally known as the Talmud Yerushalmi («Jerusalem Talmud»), but the name is a misnomer, as it was not prepared in Jerusalem. It has more accurately been called «The Talmud of the Land of Israel».[11]

The eye and the heart are two abettors to the crime.

Its final redaction probably belongs to the end of the 4th century, but the individual scholars who brought it to its present form cannot be fixed with assurance. By this time Christianity had become the state religion of the Roman Empire and Jerusalem the holy city of Christendom. In 325 Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor, said «let us then have nothing in common with the detestable Jewish crowd.»[12] This policy made a Jew an outcast and pauper. The compilers of the Jerusalem Talmud consequently lacked the time to produce a work of the quality they had intended. The text is evidently incomplete and is not easy to follow.

The apparent cessation of work on the Jerusalem Talmud in the 5th century has been associated with the decision of Theodosius II in 425 to suppress the Patriarchate and put an end to the practice of semikhah, formal scholarly ordination. Some modern scholars have questioned this connection.

Just as wisdom has made a crown for one’s head, so, too, humility has made a sole for one’s foot.

Despite its incomplete state, the Jerusalem Talmud remains an indispensable source of knowledge of the development of the Jewish Law in the Holy Land. It was also an important primary source for the study of the Babylonian Talmud by the Kairouan school of Chananel ben Chushiel and Nissim ben Jacob, with the result that opinions ultimately based on the Jerusalem Talmud found their way into both the Tosafot and the Mishneh Torah of Maimonides. Ethical maxims contained in the Jerusalem Talmud are scattered and interspersed in the legal discussions throughout the several treatises, many of which differing from those in the Babylonian Talmud.[13]

Following the formation of the modern state of Israel there is some interest in restoring Eretz Yisrael traditions. For example, rabbi David Bar-Hayim of the Makhon Shilo institute has issued a siddur reflecting Eretz Yisrael practice as found in the Jerusalem Talmud and other sources.

Babylonian Talmud[edit]

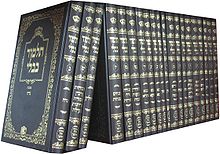

A full set of the Babylonian Talmud

The Babylonian Talmud (Talmud Bavli) consists of documents compiled over the period of late antiquity (3rd to 6th centuries).[14] During this time, the most important of the Jewish centres in Mesopotamia, a region called «Babylonia» in Jewish sources and later known as Iraq, were Nehardea, Nisibis (modern Nusaybin), Mahoza (al-Mada’in, just to the south of what is now Baghdad), Pumbedita (near present-day al Anbar Governorate), and the Sura Academy, probably located about 60 km (37 mi) south of Baghdad.[15]

The Babylonian Talmud comprises the Mishnah and the Babylonian Gemara, the latter representing the culmination of more than 300 years of analysis of the Mishnah in the Talmudic Academies in Babylonia. The foundations of this process of analysis were laid by Abba Arika (175–247), a disciple of Judah ha-Nasi. Tradition ascribes the compilation of the Babylonian Talmud in its present form to two Babylonian sages, Rav Ashi and Ravina II.[16] Rav Ashi was president of the Sura Academy from 375 to 427. The work begun by Rav Ashi was completed by Ravina, who is traditionally regarded as the final Amoraic expounder. Accordingly, traditionalists argue that Ravina’s death in 475[17] is the latest possible date for the completion of the redaction of the Talmud. However, even on the most traditional view, a few passages are regarded as the work of a group of rabbis who edited the Talmud after the end of the Amoraic period, known as the Savoraim or Rabbanan Savora’e (meaning «reasoners» or «considerers»).

Comparison of style and subject matter[edit]

There are significant differences between the two Talmud compilations. The language of the Jerusalem Talmud is a western Aramaic dialect, which differs from the form of Aramaic in the Babylonian Talmud. The Talmud Yerushalmi is often fragmentary and difficult to read, even for experienced Talmudists. The redaction of the Talmud Bavli, on the other hand, is more careful and precise. The law as laid down in the two compilations is basically similar, except in emphasis and in minor details. The Jerusalem Talmud has not received much attention from commentators, and such traditional commentaries as exist are mostly concerned with comparing its teachings to those of the Talmud Bavli.[18]

Neither the Jerusalem nor the Babylonian Talmud covers the entire Mishnah: for example, a Babylonian Gemara exists only for 37 out of the 63 tractates of the Mishnah. In particular:

- The Jerusalem Talmud covers all the tractates of Zeraim, while the Babylonian Talmud covers only tractate Berachot. The reason might be that most laws from the Order Zeraim (agricultural laws limited to the Land of Israel) had little practical relevance in Babylonia and were therefore not included.[19] The Jerusalem Talmud has a greater focus on the Land of Israel and the Torah’s agricultural laws pertaining to the land because it was written in the Land of Israel where the laws applied.

- The Jerusalem Talmud does not cover the Mishnaic order of Kodashim, which deals with sacrificial rites and laws pertaining to the Temple, while the Babylonian Talmud does cover it. It is not clear why this is, as the laws were not directly applicable in either country following the Temple’s destruction in year 70. Early Rabbinic literature indicates that there once was a Jerusalem Talmud commentary on Kodashim but it has been lost to history (though in the early Twentieth Century an infamous forgery of the lost tractates was at first widely accepted before being quickly exposed).

- In both Talmuds, only one tractate of Tohorot (ritual purity laws) is examined, that of the menstrual laws, Niddah.

The Babylonian Talmud records the opinions of the rabbis of the Ma’arava (the West, meaning Israel/Palestine) as well as of those of Babylonia, while the Jerusalem Talmud seldom cites the Babylonian rabbis. The Babylonian version also contains the opinions of more generations because of its later date of completion. For both these reasons, it is regarded as a more comprehensive[20][21] collection of the opinions available. On the other hand, because of the centuries of redaction between the composition of the Jerusalem and the Babylonian Talmud, the opinions of early amoraim might be closer to their original form in the Jerusalem Talmud.

The influence of the Babylonian Talmud has been far greater than that of the Yerushalmi. In the main, this is because the influence and prestige of the Jewish community of Israel steadily declined in contrast with the Babylonian community in the years after the redaction of the Talmud and continuing until the Gaonic era. Furthermore, the editing of the Babylonian Talmud was superior to that of the Jerusalem version, making it more accessible and readily usable.[22] According to Maimonides (whose life began almost a hundred years after the end of the Gaonic era), all Jewish communities during the Gaonic era formally accepted the Babylonian Talmud as binding upon themselves, and modern Jewish practice follows the Babylonian Talmud’s conclusions on all areas in which the two Talmuds conflict.

Structure[edit]

The structure of the Talmud follows that of the Mishnah, in which six orders (sedarim; singular: seder) of general subject matter are divided into 60 or 63 tractates (masekhtot; singular: masekhet) of more focused subject compilations, though not all tractates have Gemara. Each tractate is divided into chapters (perakim; singular: perek), 517 in total, that are both numbered according to the Hebrew alphabet and given names, usually using the first one or two words in the first mishnah. A perek may continue over several (up to tens of) pages. Each perek will contain several mishnayot.[23]

Mishnah[edit]

The Mishnah is a compilation of legal opinions and debates. Statements in the Mishnah are typically terse, recording brief opinions of the rabbis debating a subject; or recording only an unattributed ruling, apparently representing a consensus view. The rabbis recorded in the Mishnah are known as the Tannaim (literally, «repeaters,» or «teachers»). These tannaim—rabbis of the second century CE—«who produced the Mishnah and other tannaic works, must be distinguished from the rabbis of the third to fifth centuries, known as amoraim (literally, «speakers»), who produced the two Talmudim and other amoraic works».[24]

Since it sequences its laws by subject matter instead of by biblical context, the Mishnah discusses individual subjects more thoroughly than the Midrash, and it includes a much broader selection of halakhic subjects than the Midrash. The Mishnah’s topical organization thus became the framework of the Talmud as a whole. But not every tractate in the Mishnah has a corresponding Gemara. Also, the order of the tractates in the Talmud differs in some cases from that in the Mishnah.

Baraita[edit]

In addition to the Mishnah, other tannaitic teachings were current at about the same time or shortly after that. The Gemara frequently refers to these tannaitic statements in order to compare them to those contained in the Mishnah and to support or refute the propositions of the Amoraim.

The baraitot cited in the Gemara are often quotations from the Tosefta (a tannaitic compendium of halakha parallel to the Mishnah) and the Midrash halakha (specifically Mekhilta, Sifra and Sifre). Some baraitot, however, are known only through traditions cited in the Gemara, and are not part of any other collection.[25]

Gemara[edit]

In the three centuries following the redaction of the Mishnah, rabbis in Palestine and Babylonia analyzed, debated, and discussed that work. These discussions form the Gemara. The Gemara mainly focuses on elucidating and elaborating the opinions of the Tannaim. The rabbis of the Gemara are known as Amoraim (sing. Amora אמורא).[26]

Much of the Gemara consists of legal analysis. The starting point for the analysis is usually a legal statement found in a Mishnah. The statement is then analyzed and compared with other statements used in different approaches to biblical exegesis in rabbinic Judaism (or – simpler – interpretation of text in Torah study) exchanges between two (frequently anonymous and sometimes metaphorical) disputants, termed the makshan (questioner) and tartzan (answerer). Another important function of Gemara is to identify the correct biblical basis for a given law presented in the Mishnah and the logical process connecting one with the other: this activity was known as talmud long before the existence of the «Talmud» as a text.[27]

Minor tractates[edit]

In addition to the six Orders, the Talmud contains a series of short treatises of a later date, usually printed at the end of Seder Nezikin. These are not divided into Mishnah and Gemara.

Language[edit]

Within the Gemara, the quotations from the Mishnah and the Baraitas and verses of Tanakh quoted and embedded in the Gemara are in either Mishnaic or Biblical Hebrew. The rest of the Gemara, including the discussions of the Amoraim and the overall framework, is in a characteristic dialect of Jewish Babylonian Aramaic.[28] There are occasional quotations from older works in other dialects of Aramaic, such as Megillat Taanit. Overall, Hebrew constitutes somewhat less than half of the text of the Talmud.

This difference in language is due to the long time period elapsing between the two compilations. During the period of the Tannaim (rabbis cited in the Mishnah), a late form of Hebrew known as Rabbinic or Mishnaic Hebrew was still in use as a spoken vernacular among Jews in Judaea (alongside Greek and Aramaic), whereas during the period of the Amoraim (rabbis cited in the Gemara), which began around the year 200, the spoken vernacular was almost exclusively Aramaic. Hebrew continued to be used for the writing of religious texts, poetry, and so forth.[29]

Even within the Aramaic of the Gemara, different dialects or writing styles can be observed in different tractates. One dialect is common to most of the Babylonian Talmud, while a second dialect is used in Nedarim, Nazir, Temurah, Keritot, and Me’ilah; the second dialect is closer in style to the Targum.[30]

Scholarship[edit]

From the time of its completion, the Talmud became integral to Jewish scholarship. A maxim in Pirkei Avot advocates its study from the age of 15.[31] This section outlines some of the major areas of Talmudic study.

Geonim[edit]

The earliest Talmud commentaries were written by the Geonim (c. 800–1000) in Babylonia. Although some direct commentaries on particular treatises are extant, our main knowledge of the Gaonic era Talmud scholarship comes from statements embedded in Geonic responsa that shed light on Talmudic passages: these are arranged in the order of the Talmud in Levin’s Otzar ha-Geonim. Also important are practical abridgments of Jewish law such as Yehudai Gaon’s Halachot Pesukot, Achai Gaon’s Sheeltot and Simeon Kayyara’s Halachot Gedolot. After the death of Hai Gaon, however, the center of Talmud scholarship shifts to Europe and North Africa.

Halakhic and Aggadic extractions[edit]

One area of Talmudic scholarship developed out of the need to ascertain the Halakha. Early commentators such as rabbi Isaac Alfasi (North Africa, 1013–1103) attempted to extract and determine the binding legal opinions from the vast corpus of the Talmud. Alfasi’s work was highly influential, attracted several commentaries in its own right and later served as a basis for the creation of halakhic codes. Another influential medieval Halakhic work following the order of the Babylonian Talmud, and to some extent modelled on Alfasi, was «the Mordechai«, a compilation by Mordechai ben Hillel (c. 1250–1298). A third such work was that of rabbi Asher ben Yechiel (d. 1327). All these works and their commentaries are printed in the Vilna and many subsequent editions of the Talmud.

A 15th-century Spanish rabbi, Jacob ibn Habib (d. 1516), composed the Ein Yaakov. Ein Yaakov (or En Ya’aqob) extracts nearly all the Aggadic material from the Talmud. It was intended to familiarize the public with the ethical parts of the Talmud and to dispute many of the accusations surrounding its contents.

[edit]

The commentaries on the Talmud constitute only a small part of Rabbinic literature in comparison with the responsa literature and the commentaries on the codices. When the Talmud was concluded the traditional literature was still so fresh in the memory of scholars that no need existed for writing Talmudic commentaries, nor were such works undertaken in the first period of the gaonate. Paltoi ben Abaye (c. 840) was the first who in his responsum offered verbal and textual comments on the Talmud. His son, Zemah ben Paltoi paraphrased and explained the passages which he quoted; and he composed, as an aid to the study of the Talmud, a lexicon which Abraham Zacuto consulted in the fifteenth century. Saadia Gaon is said to have composed commentaries on the Talmud, aside from his Arabic commentaries on the Mishnah.[32]

There are many passages in the Talmud which are cryptic and difficult to understand. Its language contains many Greek and Persian words that became obscure over time. A major area of Talmudic scholarship developed to explain these passages and words. Some early commentators such as Rabbenu Gershom of Mainz (10th century) and Rabbenu Ḥananel (early 11th century) produced running commentaries to various tractates. These commentaries could be read with the text of the Talmud and would help explain the meaning of the text. Another important work is the Sefer ha-Mafteaḥ (Book of the Key) by Nissim Gaon, which contains a preface explaining the different forms of Talmudic argumentation and then explains abbreviated passages in the Talmud by cross-referring to parallel passages where the same thought is expressed in full. Commentaries (ḥiddushim) by Joseph ibn Migash on two tractates, Bava Batra and Shevuot, based on Ḥananel and Alfasi, also survive, as does a compilation by Zechariah Aghmati called Sefer ha-Ner.[33] Using a different style, rabbi Nathan b. Jechiel created a lexicon called the Arukh in the 11th century to help translate difficult words.

By far the best-known commentary on the Babylonian Talmud is that of Rashi (Rabbi Solomon ben Isaac, 1040–1105). The commentary is comprehensive, covering almost the entire Talmud. Written as a running commentary, it provides a full explanation of the words and explains the logical structure of each Talmudic passage. It is considered indispensable to students of the Talmud. Although Rashi drew upon all his predecessors, his originality in using the material offered by them was unparalleled. His commentaries, in turn, became the basis of the work of his pupils and successors, who composed a large number of supplementary works that were partly in emendation and partly in explanation of Rashi’s, and are known under the title «Tosafot.» («additions» or «supplements»).

The Tosafot are collected commentaries by various medieval Ashkenazic rabbis on the Talmud (known as Tosafists or Ba’alei Tosafot). One of the main goals of the Tosafot is to explain and interpret contradictory statements in the Talmud. Unlike Rashi, the Tosafot is not a running commentary, but rather comments on selected matters. Often the explanations of Tosafot differ from those of Rashi.[32]

In Yeshiva, the integration of Talmud, Rashi and Tosafot, is considered as the foundation (and prerequisite) for further analysis; this combination is sometimes referred to by the acronym «gefet» ( גפ״ת — Gemara, perush Rashi, Tosafot).

Among the founders of the Tosafist school were Rabbi Jacob ben Meir (known as Rabbeinu Tam), who was a grandson of Rashi, and, Rabbenu Tam’s nephew, rabbi Isaac ben Samuel. The Tosafot commentaries were collected in different editions in the various schools. The benchmark collection of Tosafot for Northern France was that of R. Eliezer of Touques. The standard collection for Spain was that of Rabbenu Asher («Tosefot Harosh»). The Tosafot that are printed in the standard Vilna edition of the Talmud are an edited version compiled from the various medieval collections, predominantly that of Touques.[34]

Over time, the approach of the Tosafists spread to other Jewish communities, particularly those in Spain. This led to the composition of many other commentaries in similar styles.

Among these are the commentaries of Nachmanides (Ramban), Solomon ben Adret (Rashba), Yom Tov of Seville (Ritva) and Nissim of Gerona (Ran); these are often titled “Chiddushei …” (“Novellae of …”).

A comprehensive anthology consisting of extracts from all these is the Shittah Mekubbetzet of Bezalel Ashkenazi.

Other commentaries produced in Spain and Provence were not influenced by the Tosafist style. Two of the most significant of these are the Yad Ramah by rabbi Meir Abulafia and Bet Habechirah by rabbi Menahem haMeiri, commonly referred to as «Meiri». While the Bet Habechirah is extant for all of Talmud, we only have the Yad Ramah for Tractates Sanhedrin, Baba Batra and Gittin. Like the commentaries of Ramban and the others, these are generally printed as independent works, though some Talmud editions include the Shittah Mekubbetzet in an abbreviated form.

In later centuries, focus partially shifted from direct Talmudic interpretation to the analysis of previously written Talmudic commentaries. These later commentaries are generally printed at the back of each tractate. Well known are «Maharshal» (Solomon Luria), «Maharam» (Meir Lublin) and «Maharsha» (Samuel Edels), which analyze Rashi and Tosafot together; other such commentaries include Ma’adanei Yom Tov by Yom-Tov Lipmann Heller, in turn a commentary on the Rosh (see below), and the glosses by Zvi Hirsch Chajes.

Another very useful study aid, found in almost all editions of the Talmud, consists of the marginal notes Torah Or, Ein Mishpat Ner Mitzvah and Masoret ha-Shas by the Italian rabbi Joshua Boaz, which give references respectively to the cited Biblical passages, to the relevant halachic codes (Mishneh Torah, Tur, Shulchan Aruch, and Se’mag) and to related Talmudic passages.

Most editions of the Talmud include brief marginal notes by Akiva Eger under the name Gilyon ha-Shas, and textual notes by Joel Sirkes and the Vilna Gaon (see Textual emendations below), on the page together with the text.

Commentaries discussing the Halachik-legal content include «Rosh», «Rif» and «Mordechai»; these are now standard appendices to each volume. Rambam’s Mishneh Torah is invariably studied alongside these three; although a code, and therefore not in the same order as the Talmud, the relevant location is identified via the «Ein Mishpat», as mentioned.

A recent project, Halacha Brura,[35] founded by Abraham Isaac Kook, presents the Talmud and a summary of the halachic codes side by side, so as to enable the «collation» of Talmud with resultant Halacha.

Pilpul[edit]

During the 15th and 16th centuries, a new intensive form of Talmud study arose. Complicated logical arguments were used to explain minor points of contradiction within the Talmud. The term pilpul was applied to this type of study. Usage of pilpul in this sense (that of «sharp analysis») harks back to the Talmudic era and refers to the intellectual sharpness this method demanded.

Pilpul practitioners posited that the Talmud could contain no redundancy or contradiction whatsoever. New categories and distinctions (hillukim) were therefore created, resolving seeming contradictions within the Talmud by novel logical means.

In the Ashkenazi world the founders of pilpul are generally considered to be Jacob Pollak (1460–1541) and Shalom Shachna. This kind of study reached its height in the 16th and 17th centuries when expertise in pilpulistic analysis was considered an art form and became a goal in and of itself within the yeshivot of Poland and Lithuania. But the popular new method of Talmud study was not without critics; already in the 15th century, the ethical tract Orhot Zaddikim («Paths of the Righteous» in Hebrew) criticized pilpul for an overemphasis on intellectual acuity. Many 16th- and 17th-century rabbis were also critical of pilpul. Among them are Judah Loew ben Bezalel (the Maharal of Prague), Isaiah Horowitz, and Yair Bacharach.

By the 18th century, pilpul study waned. Other styles of learning such as that of the school of Elijah b. Solomon, the Vilna Gaon, became popular. The term «pilpul» was increasingly applied derogatorily to novellae deemed casuistic and hairsplitting. Authors referred to their own commentaries as «al derekh ha-peshat» (by the simple method)[36] to contrast them with pilpul.[37]

Sephardic approaches[edit]

Among Sephardi and Italian Jews from the 15th century on, some authorities sought to apply the methods of Aristotelian logic, as reformulated by Averroes.[38] This method was first recorded, though without explicit reference to Aristotle, by Isaac Campanton (d. Spain, 1463) in his Darkhei ha-Talmud («The Ways of the Talmud»),[39] and is also found in the works of Moses Chaim Luzzatto.[40]

According to the present-day Sephardi scholar José Faur, traditional Sephardic Talmud study could take place on any of three levels.[41]

- The most basic level consists of literary analysis of the text without the help of commentaries, designed to bring out the tzurata di-shema’ta, i.e. the logical and narrative structure of the passage.[42]

- The intermediate level, iyyun (concentration), consists of study with the help of commentaries such as Rashi and the Tosafot, similar to that practiced among the Ashkenazim.[43] Historically Sephardim studied the Tosefot ha-Rosh and the commentaries of Nahmanides in preference to the printed Tosafot.[44] A method based on the study of Tosafot, and of Ashkenazi authorities such as Maharsha (Samuel Edels) and Maharshal (Solomon Luria), was introduced in late seventeenth century Tunisia by rabbis Abraham Hakohen (d. 1715) and Tsemaḥ Tsarfati (d. 1717) and perpetuated by rabbi Isaac Lumbroso[45] and is sometimes referred to as ‘Iyyun Tunisa’i.[46]

- The highest level, halachah (Jewish law), consists of collating the opinions set out in the Talmud with those of the halachic codes such as the Mishneh Torah and the Shulchan Aruch, so as to study the Talmud as a source of law; the equivalent Ashkenazi approach is sometimes referred to as being «aliba dehilchasa».

Today most Sephardic yeshivot follow Lithuanian approaches such as the Brisker method: the traditional Sephardic methods are perpetuated informally by some individuals. ‘Iyyun Tunisa’i is taught at the Kisse Rahamim yeshivah in Bnei Brak.

Brisker method[edit]

In the late 19th century another trend in Talmud study arose. Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik (1853–1918) of Brisk (Brest-Litovsk) developed and refined this style of study. Brisker method involves a reductionistic analysis of rabbinic arguments within the Talmud or among the Rishonim, explaining the differing opinions by placing them within a categorical structure. The Brisker method is highly analytical and is often criticized as being a modern-day version of pilpul. Nevertheless, the influence of the Brisker method is great. Most modern-day Yeshivot study the Talmud using the Brisker method in some form. One feature of this method is the use of Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah as a guide to Talmudic interpretation, as distinct from its use as a source of practical halakha.

Rival methods were those of the Mir and Telz yeshivas.[47]

See Chaim Rabinowitz § Telshe and Yeshiva Ohel Torah-Baranovich § Style of learning.

Critical method[edit]

As a result of Jewish emancipation, Judaism underwent enormous upheaval and transformation during the 19th century. Modern methods of textual and historical analysis were applied to the Talmud.

Textual emendations[edit]

The text of the Talmud has been subject to some level of critical scrutiny throughout its history. Rabbinic tradition holds that the people cited in both Talmuds did not have a hand in its writings; rather, their teachings were edited into a rough form around 450 CE (Talmud Yerushalmi) and 550 CE (Talmud Bavli.) The text of the Bavli especially was not firmly fixed at that time.

Gaonic responsa literature addresses this issue. Teshuvot Geonim Kadmonim, section 78, deals with mistaken biblical readings in the Talmud. This Gaonic responsum states:

… But you must examine carefully in every case when you feel uncertainty [as to the credibility of the text] – what is its source? Whether a scribal error? Or the superficiality of a second rate student who was not well versed?….after the manner of many mistakes found among those superficial second-rate students, and certainly among those rural memorizers who were not familiar with the biblical text. And since they erred in the first place… [they compounded the error.]

— Teshuvot Geonim Kadmonim, Ed. Cassel, Berlin 1858, Photographic reprint Tel Aviv 1964, 23b.

In the early medieval era, Rashi already concluded that some statements in the extant text of the Talmud were insertions from later editors. On Shevuot 3b Rashi writes «A mistaken student wrote this in the margin of the Talmud, and copyists [subsequently] put it into the Gemara.»[d]

The emendations of Yoel Sirkis and the Vilna Gaon are included in all standard editions of the Talmud, in the form of marginal glosses entitled Hagahot ha-Bach and Hagahot ha-Gra respectively; further emendations by Solomon Luria are set out in commentary form at the back of each tractate. The Vilna Gaon’s emendations were often based on his quest for internal consistency in the text rather than on manuscript evidence;[48] nevertheless many of the Gaon’s emendations were later verified by textual critics, such as Solomon Schechter, who had Cairo Genizah texts with which to compare our standard editions.[49]

In the 19th century, Raphael Nathan Nota Rabinovicz published a multi-volume work entitled Dikdukei Soferim, showing textual variants from the Munich and other early manuscripts of the Talmud, and further variants are recorded in the Complete Israeli Talmud and Gemara Shelemah editions (see Critical editions, above).

Today many more manuscripts have become available, in particular from the Cairo Geniza. The Academy of the Hebrew Language has prepared a text on CD-ROM for lexicographical purposes, containing the text of each tractate according to the manuscript it considers most reliable,[50] and images of some of the older manuscripts may be found on the website of the National Library of Israel (formerly the Jewish National and University Library).[51] The NLI, the Lieberman Institute (associated with the Jewish Theological Seminary of America), the Institute for the Complete Israeli Talmud (part of Yad Harav Herzog) and the Friedberg Jewish Manuscript Society all maintain searchable websites on which the viewer can request variant manuscript readings of a given passage.[52]

Further variant readings can often be gleaned from citations in secondary literature such as commentaries, in particular, those of Alfasi, Rabbenu Ḥananel and Aghmati, and sometimes the later Spanish commentators such as Nachmanides and Solomon ben Adret.

Historical analysis, and higher textual criticism[edit]

Historical study of the Talmud can be used to investigate a variety of concerns. One can ask questions such as: Do a given section’s sources date from its editor’s lifetime? To what extent does a section have earlier or later sources? Are Talmudic disputes distinguishable along theological or communal lines? In what ways do different sections derive from different schools of thought within early Judaism? Can these early sources be identified, and if so, how? Investigation of questions such as these are known as higher textual criticism. (The term «criticism» is a technical term denoting academic study.)

Religious scholars still debate the precise method by which the text of the Talmuds reached their final form. Many believe that the text was continuously smoothed over by the savoraim.

In the 1870s and 1880s, rabbi Raphael Natan Nata Rabbinovitz engaged in the historical study of Talmud Bavli in his Diqduqei Soferim. Since then many Orthodox rabbis have approved of his work, including Rabbis Shlomo Kluger, Joseph Saul Nathansohn, Jacob Ettlinger, Isaac Elhanan Spektor and Shimon Sofer.

During the early 19th century, leaders of the newly evolving Reform movement, such as Abraham Geiger and Samuel Holdheim, subjected the Talmud to severe scrutiny as part of an effort to break with traditional rabbinic Judaism. They insisted that the Talmud was entirely a work of evolution and development. This view was rejected as both academically incorrect, and religiously incorrect, by those who would become known as the Orthodox movement. Some Orthodox leaders such as Moses Sofer (the Chatam Sofer) became exquisitely sensitive to any change and rejected modern critical methods of Talmud study.

Some rabbis advocated a view of Talmudic study that they held to be in-between the Reformers and the Orthodox; these were the adherents of positive-historical Judaism, notably Nachman Krochmal and Zecharias Frankel. They described the Oral Torah as the result of a historical and exegetical process, emerging over time, through the application of authorized exegetical techniques, and more importantly, the subjective dispositions and personalities and current historical conditions, by learned sages. This was later developed more fully in the five-volume work Dor Dor ve-Dorshav by Isaac Hirsch Weiss. (See Jay Harris Guiding the Perplexed in the Modern Age Ch. 5) Eventually, their work came to be one of the formative parts of Conservative Judaism.

Another aspect of this movement is reflected in Graetz’s History of the Jews. Graetz attempts to deduce the personality of the Pharisees based on the laws or aggadot that they cite, and show that their personalities influenced the laws they expounded.

The leader of Orthodox Jewry in Germany Samson Raphael Hirsch, while not rejecting the methods of scholarship in principle, hotly contested the findings of the Historical-Critical method. In a series of articles in his magazine Jeschurun (reprinted in Collected Writings Vol. 5) Hirsch reiterated the traditional view and pointed out what he saw as numerous errors in the works of Graetz, Frankel and Geiger.

On the other hand, many of the 19th century’s strongest critics of Reform, including strictly orthodox rabbis such as Zvi Hirsch Chajes, used this new scientific method. The Orthodox rabbinical seminary of Azriel Hildesheimer was founded on the idea of creating a «harmony between Judaism and science». Other Orthodox pioneers of scientific Talmud study were David Zvi Hoffmann and Joseph Hirsch Dünner.

The Iraqi rabbi Yaakov Chaim Sofer notes that the text of the Gemara has had changes and additions, and contains statements not of the same origin as the original. See his Yehi Yosef (Jerusalem, 1991) p. 132 «This passage does not bear the signature of the editor of the Talmud!»

Orthodox scholar Daniel Sperber writes in «Legitimacy, of Necessity, of Scientific Disciplines» that many Orthodox sources have engaged in the historical (also called «scientific») study of the Talmud. As such, the divide today between Orthodoxy and Reform is not about whether the Talmud may be subjected to historical study, but rather about the theological and halakhic implications of such study.

Contemporary scholarship[edit]

Some trends within contemporary Talmud scholarship are listed below.

- Orthodox Judaism maintains that the oral Torah was revealed, in some form, together with the written Torah. As such, some adherents, most notably Samson Raphael Hirsch and his followers, resisted any effort to apply historical methods that imputed specific motives to the authors of the Talmud. Other major figures in Orthodoxy, however, took issue with Hirsch on this matter, most prominently David Tzvi Hoffmann.[53]

- Some scholars hold that there has been extensive editorial reshaping of the stories and statements within the Talmud. Lacking outside confirming texts, they hold that we cannot confirm the origin or date of most statements and laws, and that we can say little for certain about their authorship. In this view, the questions above are impossible to answer. See, for example, the works of Louis Jacobs and Shaye J.D. Cohen.

- Some scholars hold that the Talmud has been extensively shaped by later editorial redaction, but that it contains sources we can identify and describe with some level of reliability. In this view, sources can be identified by tracing the history and analyzing the geographical regions of origin. See, for example, the works of Lee I. Levine and David Kraemer.

- Some scholars hold that many or most of the statements and events described in the Talmud usually occurred more or less as described, and that they can be used as serious sources of historical study. In this view, historians do their best to tease out later editorial additions (itself a very difficult task) and skeptically view accounts of miracles, leaving behind a reliable historical text. See, for example, the works of Saul Lieberman, David Weiss Halivni, and Avraham Goldberg.

- Modern academic study attempts to separate the different «strata» within the text, to try to interpret each level on its own, and to identify the correlations between parallel versions of the same tradition. In recent years, the works of R. David Weiss Halivni and Dr. Shamma Friedman have suggested a paradigm shift in the understanding of the Talmud (Encyclopaedia Judaica 2nd ed. entry «Talmud, Babylonian»). The traditional understanding was to view the Talmud as a unified homogeneous work. While other scholars had also treated the Talmud as a multi-layered work, Dr. Halivni’s innovation (primarily in the second volume of his Mekorot u-Mesorot) was to differentiate between the Amoraic statements, which are generally brief Halachic decisions or inquiries, and the writings of the later «Stammaitic» (or Saboraic) authors, which are characterised by a much longer analysis that often consists of lengthy dialectic discussion. The Jerusalem Talmud is very similar to the Babylonian Talmud minus Stammaitic activity (Encyclopaedia Judaica (2nd ed.), entry «Jerusalem Talmud»). Shamma Y. Friedman’s Talmud Aruch on the sixth chapter of Bava Metzia (1996) is the first example of a complete analysis of a Talmudic text using this method. S. Wald has followed with works on Pesachim ch. 3 (2000) and Shabbat ch. 7 (2006). Further commentaries in this sense are being published by Dr Friedman’s «Society for the Interpretation of the Talmud».[54]

- Some scholars are indeed using outside sources to help give historical and contextual understanding of certain areas of the Babylonian Talmud. See for example the works of the Prof Yaakov Elman[55] and of his student Dr. Shai Secunda,[56] which seek to place the Talmud in its Iranian context, for example by comparing it with contemporary Zoroastrian texts.

Translations[edit]

Talmud Bavli[edit]

There are six contemporary translations of the Talmud into English:

Steinsaltz[edit]

- The Noé Edition of the Koren Talmud Bavli, Adin Steinsaltz, Koren Publishers Jerusalem was launched in 2012. It has a new, modern English translation and the commentary of rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, and was praised for its «beautiful page» with «clean type».[57] Opened from the right cover (front for Hebrew and Aramaic books), the Steinsaltz Talmud edition has the traditional Vilna page with vowels and punctuation in the original Aramaic text. The Rashi commentary appears in Rashi script with vowels and punctuation. When opened from the left cover the edition features bilingual text with side-by-side English/Aramaic translation. The margins include color maps, illustrations and notes based on rabbi Adin Steinsaltz’s Hebrew language translation and commentary of the Talmud. Rabbi Tzvi Hersh Weinreb serves as the Editor-in-Chief. The entire set, which has vowels and punctuation (including for Rashi) is 42 volumes.

- The Talmud: The Steinsaltz Edition (Random House) contains the text with punctuation and an English translation based on Rabbi Steinsaltz’ complete Hebrew language translation of and commentary on the entire Talmud. Incomplete—22 volumes and a reference guide. There are two formats: one with the traditional Vilna page and one without. It is available in modern Hebrew (first volume published 1969), English (first volume published 1989), French, Russian and other languages.

- In February 2017, the William Davidson Talmud was released to Sefaria.[58] This translation is a version of the Steinsaltz edition which was released under creative commons license.[59]

Artscroll[edit]

- The Schottenstein Edition of the Talmud (Artscroll/Mesorah Publications), is 73 volumes,[60] both with English translation[61] and the Aramaic/Hebrew only.[62] In the translated editions, each English page faces the Aramaic/Hebrew page it translates. Each Aramaic/Hebrew page of Talmud typically requires three to six English pages of translation and notes. The Aramaic/Hebrew pages are printed in the traditional Vilna format, with a gray bar added that shows the section translated on the facing page. The facing pages provide an expanded paraphrase in English, with translation of the text shown in bold and explanations interspersed in normal type, along with extensive footnotes. Pages are numbered in the traditional way but with a superscript added, e.g. 12b4 is the fourth page translating the Vilna page 12b. Larger tractates require multiple volumes. The first volume was published in 1990, and the series was completed in 2004.

Soncino[edit]

- The Soncino Talmud (1935-1948),[63][64] Isidore Epstein, Soncino Press (26 volumes; also formerly an 18 volume edition was published). Notes on each page provide additional background material. This translation: Soncino Babylonian Talmud is published both on its own and in a parallel text edition, in which each English page faces the Aramaic/Hebrew page. It is available also on CD-ROM. Complete.

- The travel edition[65][66] opens from left for English, from right for the Gemara, which, unlike the other editions, does not use «Tzurat HaDaf;»[67] instead, each normal page of Gemara text is two pages, the top and the bottom of the standard Daf (albeit reformatted somewhat).[68]

Other English translations[edit]

- The Talmud of Babylonia. An American Translation, Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, others. Atlanta: 1984–1995: Scholars Press for Brown Judaic Studies. Complete.

- Rodkinson: Portions[69] of the Babylonian Talmud were translated by Michael L. Rodkinson (1903). It has been linked to online, for copyright reasons (initially it was the only freely available translation on the web), but this has been wholly superseded by the Soncino translation. (see below, under Full text resources).

- The Babylonian Talmud: A Translation and Commentary, edited by Jacob Neusner[70] and translated by Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, Alan Avery-Peck, B. Barry Levy, Martin S. Jaffe, and Peter Haas, Hendrickson Pub; 22-Volume Set Ed., 2011. It is a revision of «The Talmud of Babylonia: An Academic Commentary,» published by the University of South Florida Academic Commentary Series (1994–1999). Neusner gives commentary on transition in use langes from Biblical Aramaic to Biblical Hebrew. Neusner also gives references to Mishnah, Torah, and other classical works in Orthodox Judaism.

Translations into other languages[edit]

- The Extractiones de Talmud, a Latin translation of some 1,922 passages from the Talmud, was made in Paris in 1244–1245. It survives in two recensions. There is a critical edition of the sequential recension:

- Cecini, Ulisse; Cruz Palma, Óscar Luis de la, eds. (2018). Extractiones de Talmud per ordinem sequentialem. Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 291. Brepols.

- A circa 1000 CE translation of (some parts of)[71] the Talmud to Arabic is mentioned in Sefer ha-Qabbalah. This version was commissioned by the Fatimid Caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah and was carried out by Joseph ibn Abitur.[72]

- The Talmud was translated by Shimon Moyal into Arabic in 1909.[73] There is one translation of the Talmud into Arabic, published in 2012 in Jordan by the Center for Middle Eastern Studies. The translation was carried out by a group of 90 Muslim and Christian scholars.[74] The introduction was characterized by Raquel Ukeles, Curator of the Israel National Library’s Arabic collection, as «racist», but she considers the translation itself as «not bad».[75]

- In 2018 Muslim-majority Albania co-hosted an event at the United Nations with Catholic-majority Italy and Jewish-majority Israel celebrating the translation of the Talmud into Italian for the first time.[76] Albanian UN Ambassador Besiana Kadare opined: “Projects like the Babylonian Talmud Translation open a new lane in intercultural and interfaith dialogue, bringing hope and understanding among people, the right tools to counter prejudice, stereotypical thinking and discrimination. By doing so, we think that we strengthen our social traditions, peace, stability — and we also counter violent extremist tendencies.”[77]

Talmud Yerushalmi[edit]

- Talmud of the Land of Israel: A Preliminary Translation and Explanation Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, others. University of Chicago Press. This translation uses a form-analytical presentation that makes the logical units of discourse easier to identify and follow. Neusner’s mentor Saul Lieberman, then the most prominent Talmudic scholar alive, read one volume shortly before his death and wrote a review, published posthumously, in which he describes dozens of major translation errors in the first chapter of that volume alone, also demonstrating that Neusner had not, as claimed, made use of manuscript evidence; he was «stunned by Neusner’s ignorance of rabbinic Hebrew, of Aramaic grammar, and above all the subject matter with which he deals» and concluded that «the right place for [Neusner’s translation] is the wastebasket».[78] This review was devastating for Neusner’s career.[79] At a meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature a few months later, during a plenary session designed to honor Neusner for his achievements, Morton Smith (also Neusner’s mentor) took to the lectern and announced that «I now find it my duty to warn» that the translation «cannot be safely used, and had better not be used at all». He also called Neusner’s translation «a serious misfortune for Jewish studies». After delivering this speech, Smith marched up and down the aisles of the ballroom with printouts of Lieberman’s review, handing one to every attendee.[80][81]

- Schottenstein Edition of the Yerushalmi Talmud Mesorah/Artscroll. This translation is the counterpart to Mesorah/Artscroll’s Schottenstein Edition of the Talmud (i.e. Babylonian Talmud).

- The Jerusalem Talmud, Edition, Translation and Commentary, ed. Guggenheimer, Heinrich W., Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin, Germany

- German Edition, Übersetzung des Talmud Yerushalmi, published by Martin Hengel, Peter Schäfer, Hans-Jürgen Becker, Frowald Gil Hüttenmeister, Mohr&Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany

- Modern Elucidated Talmud Yerushalmi, ed. Joshua Buch. Uses the Leiden manuscript as its based text corrected according to manuscripts and Geniza Fragments. Draws upon Traditional and Modern Scholarship[82]

Index[edit]

«A widely accepted and accessible index»[83] was the goal driving several such projects.:

- Michlul haMa’amarim, a three-volume index of the Bavli and Yerushalmi, containing more than 100,000 entries. Published by Mossad Harav Kook in 1960.[84]

- Soncino: covers the entire Talmud Bavli;[85][86] released 1952; 749 pages

- HaMafteach («the key»): released by Feldheim Publishers 2011, has over 30,000 entries.[83]

- Search-engines: Bar Ilan University’s Responsa Project CD/search-engine.[83]

Printing[edit]

Bomberg Talmud 1523[edit]

The first complete edition of the Babylonian Talmud was printed in Venice by Daniel Bomberg 1520–23[88][89][90][91] with the support of Pope Leo X.[92][93][94][95] In addition to the Mishnah and Gemara, Bomberg’s edition contained the commentaries of Rashi and Tosafot. Almost all printings since Bomberg have followed the same pagination. Bomberg’s edition was considered relatively free of censorship.[96]

Froben Talmud 1578[edit]

Ambrosius Frobenius collaborated with the scholar Israel Ben Daniel Sifroni from Italy. His most extensive work was a Talmud edition published, with great difficulty, in 1578–81.[97]

Benveniste Talmud 1645[edit]

Following Ambrosius Frobenius’s publication of most of the Talmud in installments in Basel, Immanuel Benveniste published the whole Talmud in installments in Amsterdam 1644–1648,[98] Although according to Raphael Rabbinovicz the Benveniste Talmud may have been based on the Lublin Talmud and included many of the censors’ errors.[99] «It is noteworthy due to the inclusion of Avodah Zarah, omitted due to Church censorship from several previous editions, and when printed, often lacking a title page.[100]

Slavita Talmud 1795 and Vilna Talmud 1835[edit]

The edition of the Talmud published by the Szapira brothers in Slavita[101] was published in 1817,[102] and it is particularly prized by many rebbes of Hasidic Judaism. In 1835, after a religious community copyright[103][104] was nearly over,[105] and following an acrimonious dispute with the Szapira family, a new edition of the Talmud was printed by Menachem Romm of Vilna.

Known as the Vilna Edition Shas, this edition (and later ones printed by his widow and sons, the Romm publishing house) has been used in the production of more recent editions of Talmud Bavli.

A page number in the Vilna Talmud refers to a double-sided page, known as a daf, or folio in English; each daf has two amudim labeled א and ב, sides A and B (recto and verso). The convention of referencing by daf is relatively recent and dates from the early Talmud printings of the 17th century, though the actual pagination goes back to the Bomberg edition. Earlier rabbinic literature generally refers to the tractate or chapters within a tractate (e.g. Berachot Chapter 1, ברכות פרק א׳). It sometimes also refers to the specific Mishnah in that chapter, where «Mishnah» is replaced with «Halakha», here meaning route, to «direct» the reader to the entry in the Gemara corresponding to that Mishna (e.g. Berachot Chapter 1 Halakha 1, ברכות פרק א׳ הלכה א׳, would refer to the first Mishnah of the first chapter in Tractate Berachot, and its corresponding entry in the Gemara). However, this form is nowadays more commonly (though not exclusively) used when referring to the Jerusalem Talmud. Nowadays, reference is usually made in format [Tractate daf a/b] (e.g. Berachot 23b, ברכות כג ב׳). Increasingly, the symbols «.» and «:» are used to indicate Recto and Verso, respectively (thus, e.g. Berachot 23:, :ברכות כג). These references always refer to the pagination of the Vilna Talmud.

Critical editions[edit]

The text of the Vilna editions is considered by scholars not to be uniformly reliable, and there have been a number of attempts to collate textual variants.

- In the late 19th century, Nathan Rabinowitz published a series of volumes called Dikduke Soferim showing textual variants from early manuscripts and printings.

- In 1960, work started on a new edition under the name of Gemara Shelemah (complete Gemara) under the editorship of Menachem Mendel Kasher: only the volume on the first part of tractate Pesachim appeared before the project was interrupted by his death. This edition contained a comprehensive set of textual variants and a few selected commentaries.

- Some thirteen volumes have been published by the Institute for the Complete Israeli Talmud (a division of Yad Harav Herzog), on lines similar to Rabinowitz, containing the text and a comprehensive set of textual variants (from manuscripts, early prints and citations in secondary literature) but no commentaries.[106]

There have been critical editions of particular tractates (e.g. Henry Malter’s edition of Ta’anit), but there is no modern critical edition of the whole Talmud. Modern editions such as those of the Oz ve-Hadar Institute correct misprints and restore passages that in earlier editions were modified or excised by censorship but do not attempt a comprehensive account of textual variants. One edition, by rabbi Yosef Amar,[107] represents the Yemenite tradition, and takes the form of a photostatic reproduction of a Vilna-based print to which Yemenite vocalization and textual variants have been added by hand, together with printed introductory material. Collations of the Yemenite manuscripts of some tractates have been published by Columbia University.[108]

Editions for a wider audience[edit]

A number of editions have been aimed at bringing the Talmud to a wider audience. Aside from the Steinsaltz and Artscroll/Schottenstein sets there are:

- The Metivta edition, published by the Oz ve-Hadar Institute. This contains the full text in the same format as the Vilna-based editions,[109] with a full explanation in modern Hebrew on facing pages as well as an improved version of the traditional commentaries.[110]

- A previous project of the same kind, called Talmud El Am, «Talmud to the people», was published in Israel in the 1960s–80s. It contains Hebrew text, English translation and commentary by Arnost Zvi Ehrman, with short ‘realia’, marginal notes, often illustrated, written by experts in the field for the whole of Tractate Berakhot, 2 chapters of Bava Mezia and the halachic section of Qiddushin, chapter 1.

- Tuvia’s Gemara Menukad:[109] includes vowels and punctuation (Nekudot), including for Rashi and Tosafot.[109] It also includes «all the abbreviations of that amud on the side of each page.»[111]

Incomplete sets from prior centuries[edit]

- Amsterdam (1714, Proops Talmud and Marches/de Palasios Talmud): Two sets were begun in Amsterdam in 1714, a year in which «acrimonious disputes between publishers within and between cities» regarding reprint rights also began. The latter ran 1714–1717. Neither set was completed, although a third set was printed 1752–1765.[103]

Other notable editions[edit]

Lazarus Goldschmidt published an edition from the «uncensored text» of the Babylonian Talmud with a German translation in 9 volumes (commenced Leipzig, 1897–1909, edition completed, following emigration to England in 1933, by 1936).[112]

Twelve volumes of the Babylonian Talmud were published by Mir Yeshiva refugees during the years 1942 thru 1946 while they were in Shanghai.[113] The major tractates, one per volume, were: «Shabbat, Eruvin, Pesachim, Gittin, Kiddushin, Nazir, Sotah, Bava Kama, Sanhedrin, Makot, Shevuot, Avodah Zara»[114] (with some volumes having, in addition, «Minor Tractates»).[115]

A Survivors’ Talmud was published, encouraged by President Truman’s «responsibility toward these victims of persecution» statement. The U.S. Army (despite «the acute shortage of paper in Germany») agreed to print «fifty copies of the Talmud, packaged into 16-volume sets» during 1947–1950.[116] The plan was extended: 3,000 copies, in 19-volume sets.

Role in Judaism[edit]

The Talmud represents the written record of an oral tradition. It provides an understanding of how laws are derived, and it became the basis for many rabbinic legal codes and customs, most importantly for the Mishneh Torah and for the Shulchan Aruch. Orthodox and, to a lesser extent, Conservative Judaism accept the Talmud as authoritative, while Samaritan, Karaite, Reconstructionist, and Reform Judaism do not.

Sadducees[edit]

The Jewish sect of the Sadducees (Hebrew: צְדוּקִים) flourished during the Second Temple period.[117] Principal distinctions between them and the Pharisees (later known as Rabbinic Judaism) involved their rejection of an Oral Torah and their denying a resurrection after death.

Karaism[edit]

Another movement that rejected the Oral Torah as authoritative was Karaism, which arose within two centuries after the completion of the Talmud. Karaism developed as a reaction against the Talmudic Judaism of Babylonia. The central concept of Karaism is the rejection of the Oral Torah, as embodied in the Talmud, in favor of a strict adherence only to the Written Torah. This opposes the fundamental Rabbinic concept that the Oral Torah was given to Moses on Mount Sinai together with the Written Torah. Some later Karaites took a more moderate stance, allowing that some element of tradition (called sevel ha-yerushah, the burden of inheritance) is admissible in interpreting the Torah and that some authentic traditions are contained in the Mishnah and the Talmud, though these can never supersede the plain meaning of the Written Torah.

Reform Judaism[edit]

The rise of Reform Judaism during the 19th century saw more questioning of the authority of the Talmud. Reform Jews saw the Talmud as a product of late antiquity, having relevance merely as a historical document. For example, the «Declaration of Principles» issued by the Association of Friends of Reform Frankfurt in August 1843 states among other things that:

The collection of controversies, dissertations, and prescriptions commonly designated by the name Talmud possesses for us no authority, from either the dogmatic or the practical standpoint.

Some took a critical-historical view of the written Torah as well, while others appeared to adopt a neo-Karaite «back to the Bible» approach, though often with greater emphasis on the prophetic than on the legal books.

Humanistic Judaism[edit]

Within Humanistic Judaism, Talmud is studied as a historical text, in order to discover how it can demonstrate practical relevance to living today.[118]

Present day[edit]

Orthodox Judaism continues to stress the importance of Talmud study as a central component of Yeshiva curriculum, in particular for those training to become rabbis. This is so even though Halakha is generally studied from the medieval and early modern codes and not directly from the Talmud. Talmudic study amongst the laity is widespread in Orthodox Judaism, with daily or weekly Talmud study particularly common in Haredi Judaism and with Talmud study a central part of the curriculum in Orthodox Yeshivas and day schools. The regular study of Talmud among laymen has been popularized by the Daf Yomi, a daily course of Talmud study initiated by rabbi Meir Shapiro in 1923; its 13th cycle of study began in August 2012 and ended with the 13th Siyum HaShas on January 1, 2020. The Rohr Jewish Learning Institute has popularized the «MyShiur – Explorations in Talmud» to show how the Talmud is relevant to a wide range of people.[119]

Conservative Judaism similarly emphasizes the study of Talmud within its religious and rabbinic education. Generally, however, Conservative Jews study the Talmud as a historical source-text for Halakha. The Conservative approach to legal decision-making emphasizes placing classic texts and prior decisions in a historical and cultural context and examining the historical development of Halakha. This approach has resulted in greater practical flexibility than that of the Orthodox. Talmud study forms part of the curriculum of Conservative parochial education at many Conservative day-schools, and an increase in Conservative day-school enrollments has resulted in an increase in Talmud study as part of Conservative Jewish education among a minority of Conservative Jews. See also: The Conservative Jewish view of the Halakha.

Reform Judaism does not emphasize the study of Talmud to the same degree in their Hebrew schools, but they do teach it in their rabbinical seminaries; the world view of liberal Judaism rejects the idea of binding Jewish law and uses the Talmud as a source of inspiration and moral instruction. Ownership and reading of the Talmud is not widespread among Reform and Reconstructionist Jews, who usually place more emphasis on the study of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh.

In visual arts[edit]

In Carl Schleicher’s paintings[edit]

Rabbis and Talmudists studying and debating Talmud abound in the art of Austrian painter Carl Schleicher (1825–1903); active in Vienna, especially c. 1859–1871.

-

Jewish Scene I

-

Jewish Scene II

-

A Controversy Whatsoever on Talmud[120]

-

At the Rabbi’s

Jewish art and photography[edit]

-

Jews studying Talmud, París, c. 1880–1905

-

Samuel Hirszenberg, Talmudic School, c. 1895–1908

-

Maurycy Trębacz, The Dispute, c. 1920–1940

-

Solomon’s Haggadoth, bronze relief from the Knesset Menorah, Jerusalem, by Benno Elkan, 1956

-

Hilel’s Teachings, bronze relief from the Knesset Menorah

-

Jewish Mysticism: Jochanan ben Sakkai, bronze relief from the Knesset Menorah

-

Yemenite Jews studying Torah in Sana’a

Other contexts[edit]

The study of Talmud is not restricted to those of the Jewish religion and has attracted interest in other cultures. Christian scholars have long expressed an interest in the study of Talmud, which has helped illuminate their own scriptures. Talmud contains biblical exegesis and commentary on Tanakh that will often clarify elliptical and esoteric passages. The Talmud contains possible references to Jesus and his disciples, while the Christian canon makes mention of Talmudic figures and contains teachings that can be paralleled within the Talmud and Midrash. The Talmud provides cultural and historical context to the Gospel and the writings of the Apostles.[121]

South Koreans reportedly hope to emulate Jews’ high academic standards by studying Jewish literature. Almost every household has a translated copy of a book they call «Talmud», which parents read to their children, and the book is part of the primary-school curriculum.[122][123] The «Talmud» in this case is usually one of several possible volumes, the earliest translated into Korean from the Japanese. The original Japanese books were created through the collaboration of Japanese writer Hideaki Kase and Marvin Tokayer, an Orthodox American rabbi serving in Japan in the 1960s and 70s. The first collaborative book was 5,000 Years of Jewish Wisdom: Secrets of the Talmud Scriptures, created over a three-day period in 1968 and published in 1971. The book contains actual stories from the Talmud, proverbs, ethics, Jewish legal material, biographies of Talmudic rabbis, and personal stories about Tokayer and his family. Tokayer and Kase published a number of other books on Jewish themes together in Japanese.[124]

The first South Korean publication of 5,000 Years of Jewish Wisdom was in 1974, by Tae Zang publishing house. Many different editions followed in both Korea and China, often by black-market publishers. Between 2007 and 2009, Reverend Yong-soo Hyun of the Shema Yisrael Educational Institute published a 6-volume edition of the Korean Talmud, bringing together material from a variety of Tokayer’s earlier books. He worked with Tokayer to correct errors and Tokayer is listed as the author. Tutoring centers based on this and other works called «Talmud» for both adults and children are popular in Korea and «Talmud» books (all based on Tokayer’s works and not the original Talmud) are widely read and known.[124]

Criticism[edit]

Historian Michael Levi Rodkinson, in his book The History of the Talmud, wrote that detractors of the Talmud, both during and subsequent to its formation, «have varied in their character, objects and actions» and the book documents a number of critics and persecutors, including Nicholas Donin, Johannes Pfefferkorn, Johann Andreas Eisenmenger, the Frankists, and August Rohling.[125] Many attacks come from antisemitic sources such as Justinas Pranaitis, Elizabeth Dilling, or David Duke. Criticisms also arise from Christian, Muslim,[126][127][128] and Jewish sources,[129] as well as from atheists and skeptics.[130] Accusations against the Talmud include alleged:[125][131][132][133][134][135][136]

- Anti-Christian or anti-Gentile content[137][138][139][140]

- Absurd or sexually immoral content[141]

- Falsification of scripture[142][143][144]

Defenders of the Talmud point out that many of these criticisms, particularly those in antisemitic sources, are based on quotations that are taken out of context, and thus misrepresent the meaning of the Talmud’s text and its basic character as a detailed record of discussions that preserved statements by a variety of sages, and from which statements and opinions that were rejected were never edited out.

Sometimes the misrepresentation is deliberate, and other times simply due to an inability to grasp the subtle and sometimes confusing and multi-faceted narratives in the Talmud. Some quotations provided by critics deliberately omit passages in order to generate quotes that appear to be offensive or insulting.[145][146]

Middle Ages[edit]

At the very time that the Babylonian savoraim put the finishing touches to the redaction of the Talmud, the emperor Justinian issued his edict against deuterosis (doubling, repetition) of the Hebrew Bible.[147] It is disputed whether, in this context, deuterosis means «Mishnah» or «Targum»: in patristic literature, the word is used in both senses.

Full-scale attacks on the Talmud took place in the 13th century in France, where Talmudic study was then flourishing. In the 1230s Nicholas Donin, a Jewish convert to Christianity, pressed 35 charges against the Talmud to Pope Gregory IX by translating a series of blasphemous passages about Jesus, Mary or Christianity. There is a quoted Talmudic passage, for example, where Jesus of Nazareth is sent to Hell to be boiled in excrement for eternity. Donin also selected an injunction of the Talmud that permits Jews to kill non-Jews. This led to the Disputation of Paris, which took place in 1240 at the court of Louis IX of France, where four rabbis, including Yechiel of Paris and Moses ben Jacob of Coucy, defended the Talmud against the accusations of Nicholas Donin. The translation of the Talmud from Aramaic to non-Jewish languages stripped Jewish discourse from its covering, something that was resented by Jews as a profound violation.[148] The Disputation of Paris led to the condemnation and the first burning of copies of the Talmud in Paris in 1242.[149][150][e] The burning of copies of the Talmud continued.[151]

The Talmud was likewise the subject of the Disputation of Barcelona in 1263 between Nahmanides (Rabbi Moses ben Nahman) and Christian convert, Pablo Christiani. This same Pablo Christiani made an attack on the Talmud that resulted in a papal bull against the Talmud and in the first censorship, which was undertaken at Barcelona by a commission of Dominicans, who ordered the cancellation of passages deemed objectionable from a Christian perspective (1264).[152][153]

At the Disputation of Tortosa in 1413, Geronimo de Santa Fé brought forward a number of accusations, including the fateful assertion that the condemnations of «pagans», «heathens», and «apostates» found in the Talmud were, in reality, veiled references to Christians. These assertions were denied by the Jewish community and its scholars, who contended that Judaic thought made a sharp distinction between those classified as heathen or pagan, being polytheistic, and those who acknowledge one true God (such as the Christians) even while worshipping the true monotheistic God incorrectly. Thus, Jews viewed Christians as misguided and in error, but not among the «heathens» or «pagans» discussed in the Talmud.[153]

Both Pablo Christiani and Geronimo de Santa Fé, in addition to criticizing the Talmud, also regarded it as a source of authentic traditions, some of which could be used as arguments in favor of Christianity. Examples of such traditions were statements that the Messiah was born around the time of the destruction of the Temple and that the Messiah sat at the right hand of God.[154]

In 1415, Antipope Benedict XIII, who had convened the Tortosa disputation, issued a papal bull (which was destined, however, to remain inoperative) forbidding the Jews to read the Talmud, and ordering the destruction of all copies of it. Far more important were the charges made in the early part of the 16th century by the convert Johannes Pfefferkorn, the agent of the Dominicans. The result of these accusations was a struggle in which the emperor and the pope acted as judges, the advocate of the Jews being Johann Reuchlin, who was opposed by the obscurantists; and this controversy, which was carried on for the most part by means of pamphlets, became in the eyes of some a precursor of the Reformation.[153][155]

An unexpected result of this affair was the complete printed edition of the Babylonian Talmud issued in 1520 by Daniel Bomberg at Venice, under the protection of a papal privilege.[156] Three years later, in 1523, Bomberg published the first edition of the Jerusalem Talmud. After thirty years the Vatican, which had first permitted the Talmud to appear in print, undertook a campaign of destruction against it. On the New Year, Rosh Hashanah (September 9, 1553) the copies of the Talmud confiscated in compliance with a decree of the Inquisition were burned at Rome, in Campo dei Fiori (auto de fé). Other burnings took place in other Italian cities, such as the one instigated by Joshua dei Cantori at Cremona in 1559. Censorship of the Talmud and other Hebrew works was introduced by a papal bull issued in 1554; five years later the Talmud was included in the first Index Expurgatorius; and Pope Pius IV commanded, in 1565, that the Talmud be deprived of its very name. The convention of referring to the work as «Shas» (shishah sidre Mishnah) instead of «Talmud» dates from this time.[157]

The first edition of the expurgated Talmud, on which most subsequent editions were based, appeared at Basel (1578–1581) with the omission of the entire treatise of ‘Abodah Zarah and of passages considered inimical to Christianity, together with modifications of certain phrases. A fresh attack on the Talmud was decreed by Pope Gregory XIII (1575–85), and in 1593 Clement VIII renewed the old interdiction against reading or owning it.[citation needed] The increasing study of the Talmud in Poland led to the issue of a complete edition (Kraków, 1602–05), with a restoration of the original text; an edition containing, so far as known, only two treatises had previously been published at Lublin (1559–76). After an attack on the Talmud took place in Poland (in what is now Ukrainian territory) in 1757, when Bishop Dembowski, at the instigation of the Frankists, convened a public disputation at Kamieniec Podolski, and ordered all copies of the work found in his bishopric to be confiscated and burned.[158] A «1735 edition of Moed Katan, printed in Frankfurt am Oder» is among those that survived from that era.[113] «Situated on the Oder River, Three separate editions of the Talmud were printed there between 1697 and 1739.»

The external history of the Talmud includes also the literary attacks made upon it by some Christian theologians after the Reformation since these onslaughts on Judaism were directed primarily against that work, the leading example being Eisenmenger’s Entdecktes Judenthum (Judaism Unmasked) (1700).[159][160][161] In contrast, the Talmud was a subject of rather more sympathetic study by many Christian theologians, jurists and Orientalists from the Renaissance on, including Johann Reuchlin, John Selden, Petrus Cunaeus, John Lightfoot and Johannes Buxtorf father and son.[162]

19th century and after[edit]

The Vilna edition of the Talmud was subject to Russian government censorship, or self-censorship to meet government expectations, though this was less severe than some previous attempts: the title «Talmud» was retained and the tractate Avodah Zarah was included. Most modern editions are either copies of or closely based on the Vilna edition, and therefore still omit most of the disputed passages. Although they were not available for many generations, the removed sections of the Talmud, Rashi, Tosafot and Maharsha were preserved through rare printings of lists of errata, known as Chesronos Hashas («Omissions of the Talmud»).[163] Many of these censored portions were recovered from uncensored manuscripts in the Vatican Library. Some modern editions of the Talmud contain some or all of this material, either at the back of the book, in the margin, or in its original location in the text.[164]