В русском языке немало слов, вызывающих трудности при написании, и одним из них является «оттуда». Как пишется оно? Только слитно, хотя есть один вариант раздельного написания, причём больше разговорный. Например, один человек спрашивает другого: «Как мне пройти в библиотеку?» – «Вам от тудА». То есть, «от» здесь не является ни приставкой, ни предлогом, а искажённым словом «вот», с «потерянной» буквой «В». Для всех прочих случаев действует правило: местоимённое наречие «оттуда» следует писать слитно.

Слова «оттуда»пишется только слитно.

Сложности русского языка

Существуют омонимы, которые имеют в своём составе либо предлог, либо приставку. То есть, если конкретное слово «работает в паре» с предлогом, то оно пишется раздельно, если в его состав входит приставка, то слитно. Например: «от чего» и «отчего». Но как пишется слово оттуда? Только слитно, за исключением случая, когда указательная частица «вот» теряет букву «В» по воле человека, не желающего её произносить. Чтобы знать наверняка, как писать «оттуда», необходимо принять к сведению, что наречия, образованные от местоимённых слов, пишутся слитно. Что касается грамматических нюансов, то «оттудо», «аттуда», «отуда» – это всё неправильные варианты.

Слитное или раздельное написание

Иногда при письме люди так торопятся, что пишут это слово через дефис. Разумеется, этот вариант будет неверным. Но не менее часто «писатель» стоит перед дилеммой: «от туда» или «оттуда»?! Возможно, его с верного пути сбивают правила написания предлогов и приставок. В этом слове «от» является приставкой, а, как известно, приставки всегда неотделимы от корня. Местоимённое указательное наречие образовалось за счёт присоединения к наречию «туда» приставки «от».

Чтобы проверить себя и точно узнать, как пишется «от туда» или «оттуда», можно использовать одну народную хитрость. При возникновении малейших сомнений, в проблемное слово нужно вставить ещё одно. Например: «от куда туда». Понятно, что это лингвистическая единица не только смотрится нелепо, но и не звучит, а это значит, что вопроса: как пишется «оттуда» слитно или раздельно больше возникнуть не должно, поскольку вариант всего один, вне зависимости от того, в каком контексте наречие используется. Кстати, производные – «народное» «оттудова» и «неопределённое» «оттуда-то» также подразумевают слитное написание приставки «от».

Морфология

Часть речи «оттуда» – указательное местоимённое наречие, играющее в предложение определённую синтаксическую роль и всегда являющееся обстоятельством. Слово относится к разряду неизменяемых, и используется в предложении по мере надобности. Распространённый пример: «Откуда»? – «Отсюда!», «Оттуда – Туда».

Правописание этих слов надо знать:

- «Когда-нибудь»

- «Кто-нибудь»

- «Одногруппники»

В русском языке есть трудные для понимания орфографические правила. Если в них не разобраться, то многие слова будут употребляться неправильно. Не исключение и лексемы «не куда» или «некуда». Как следует писать «не» – слитно или раздельно? На какой слог падает ударение? Ответим на эти вопросы ниже.

Как правильно пишется?

В зависимости от контекста возможно использование двух представленных вариантов – «не куда» и «некуда».

Морфемный разбор слова «некуда»

Выполним полный морфемный анализ лексемы «некуда»:

некуда

- «не» – префикс;

- «куда» – корень.

Всё слово выступает основой – «некуда».

В каких случаях пишут «некуда»

«Некуда» – это отрицательное местоименное наречие, которое, согласно правилу, пишется слитно. В рассматриваемом случае «не» выступает неотъемлемой частью слова, а именно префиксом, на который падает ударение, – «не́куда».

В предложении слово играет роль предикатива и употребляется с неопределённой формой глагола движения или направления действия в значении «нет такого места, куда пойти, поехать и т.д.». Нередко сочетается со сравнительной степенью прилагательного или наречия, чтобы выразить крайний предел какого-либо свойства или качества.

Отметим, что если бы ударение падало на корень, то правильное написание выглядело бы так – «никуда́».

Примеры предложений

Посмотрим, в каких контекстах используется наречие «некуда»:

- Дальше бежать преступнику было некуда, поэтому он решил сдаться.

- Сегодня время движется медленнее некуда.

- Лариса задрала ногу выше некуда, чтобы обратить на себя внимание.

- Если подруга выгонит Таню, ей некуда будет пойти.

- Игорю некуда было сесть, кроме как за столик преподавателей.

- Приятель заверил, что нам некуда торопиться.

- Мальчик рассказал мне, что ему некуда податься.

- Отец жаловался, что в нашем городе некуда идти работать.

В каких случаях пишут «не куда»

Реже в предложениях с противопоставлением сочетание отрицательной частицы «не» и относительного наречия «куда» пишется раздельно – «не куда». Ударной оказывается конечная гласная «а».

Примеры предложений

Прочитаем контексты, в которых встречается сочетание «не куда»:

- Главное – не куда едешь, а что везёшь.

- Ольге Михайловне пришлось идти не куда хотелось, а куда её вели.

- Борис был готов двигаться куда следует, а не куда ему заблагорассудиться.

- Впрочем, сестра поняла, что важно не куда, а с кем.

Ошибочное написание слов «не куда» и «некуда»

Некорректно писать «некуда» раздельно, если это отрицательное наречие. Неправильно писать «не куда» слитно, если это сочетание отрицательной частицы «не» и наречия «куда» в предложении с противопоставлением.

Заключение

Из вышесказанного следует, что два варианта отвечают норме русского языка – «не куда» и «некуда».

Необходимо учитывать условия употребления данных единиц. Так, отрицательное наречие «некуда» с ударным префиксом всегда пишется слитно. Раздельное написание частицы «не» и наречия «куда» встречается не так часто в предложениях с противопоставлением.

Как пишется «не туда» или «ни туда» зависит от контекста, от смысла сообщения.

Местоименное наречие «туда» конкретно не обозначает место, а только указывает на него. С частицей «не» употреблю его, например, в таком высказывании:

Не туда следует положить эту вещь.

Не туда вам следует идти.

Не туда вы смотрите.

С повторяющимся союзом «ни…ни» употребляется наречие «туда» в устойчивом словосочетании, как и ряд аналогичных оборотов:

ни туда ни сюда;

ни там ни сям;

ни то ни сё;

ни то ни другое;

ни днем ни ночью.

Застряла машина в топкой грязи, и ни туда и ни сюда!

Хотя союз «ни…ни» повторяющийся, но запятая не ставится в фразеологическом обороте.

1

Как пишется не туда?

Как правильно ни туда?

Как следует писать правильно не туда или ни туда?

10 ответов:

8

0

Как пишется «не туда» или «ни туда» зависит от контекста, от смысла сообщения.

Местоименное наречие «туда» конкретно не обозначает место, а только указывает на него. С частицей «не» употреблю его, например, в таком высказывании:

Не туда следует положить эту вещь.

Не туда вам следует идти.

Не туда вы смотрите.

С повторяющимся союзом «ни…ни» употребляется наречие «туда» в устойчивом словосочетании, как и ряд аналогичных оборотов:

ни туда ни сюда;

ни там ни сям;

ни то ни сё;

ни то ни другое;

ни днем ни ночью.

Застряла машина в топкой грязи, и ни туда и ни сюда!

Хотя союз «ни…ни» повторяющийся, но запятая не ставится в фразеологическом обороте.

7

0

Данное нам сочетание в предложениях может употребляться с частицей «не» и «ни»;

Пример с частицей «не»:

- не туда мы с тобой вчера ходили;

- мы попали не туда;

Частица «ни» в предложении усиливает отрицание;

Например:

Ни туда, ни сюда;

5

0

В зависимости от контекста может стоять отрицательная частица не, а может ни.

Рассмотрим поподробнее, какие могут встречаться случаи.

Если нужно получить отрицание, то есть «н* туда в значении «не в том направлении», то пишем частицу не: не туда.

Мы свернули не туда и заблудились. Он долго шел не туда и лишь в конце дня решил свериться с картой.

Частица ни используется для усиления значения:

Повозка намертво застряла в грязи, измученные беженцы не могли сдвинуть ее ни туда, ни назад.

Как правило, ни входит в состав союза ни… ни, часто встречается во фразеологических оборотах:

Ни туда, ни сюда,

Ни так, ни сяк.

4

0

Что интересное и тот и другой вариант написания будут верными.

Тут нужно смотреть от контекста предложения и уже ориентироваться какую частицу верно написать.

Как правило частица «ни» усиливает отрицание.

Примеры предложений:

«Наша машина застряла в грязи, и ее невозможно было вытянуть ни туда, ни сюда».

«Он вышел на улицу и дальше не смог не пройти ни туда и ни сюда, везде были просто огромные лужи».

Частица «не» употребляется и пишется в речи с менее выраженным отрицанием.

Примеры предложений:

«Василий заблудился в лесу, а все потому что пошел не туда, куда нужно было свернуть».

«Алена зашла явно не туда».

2

0

Со словом «туда» можно употреблять как частицу «не», так и ее «двойника» — частицу «ни»: правильность написания и употребления буквы «е» или «и» будет определяться контекстом (содержанием) конкретного предложения. Если в предложении подразумевается простое отрицание, то пишется частица «не».

Например.

Мы долго шли, но только через три часа поняли, что идем не туда.

Я посмотрел не туда, куда указывал спутник, а чуть правее — в сторону ближайшего леса.

А вот частица «ни» используется для усиления отрицания и, соответственно, употребляется в предложениях, где есть отрицательное сказуемое.

Например.

Нам предложили ехать в город, но мы не поехали ни туда, ни к дяде на дачу.

1

0

Если отрицание встречается дважды, пишется НИ оба раза.

Примеры:

Ни туда, ни сюда.

Ни кола, ни двора.

Ни тятя, ни мама.

Если отрицание встречается один раз, пишется НЕ.

Примеры:

Повернул не туда.

Не туда пошел.

1

0

Можно писать и так и эдак, то есть и с частицей «не» и с частицей «Ни».

Если отрицание надо усилить, то пишем «ни», если отрицание без усиления, то пишем «не».

То есть надо смотреть по контексту, ибо оба варианта рабочих.

0

0

И так пишется и так. Смотря в каком случае применяется фраза. «Ни туда», например, пишется в случае, когда в выражении имеется смысл «никуда» или «в никуда». Например, всем хорошо известное выражение «И ни туда, и ни сюда».

А «не туда» пишется в тех случаях, когда имеется ввиду, что направлено действие не в ту сторону. Например, «Полез не туда, куда надо», «Пошел не туда», «Не туда смотришь».

Надеюсь, что мой ответ помог Вам разобраться в вопросе.

0

0

Множественное отрицание пишется с более сильным отрицанием ни туда и ни сюда , а вот если отрицание в единственном числе — не туда то пишется всегда с более слабым отрицанием не , таким образом разделяется множественное и единственное число .

0

0

В данном случае написания частиц «не», «ни» возможно, как той, так и другой, в зависимости от текста, где она используется.

«Ни»:

На улице пробка, движение ни туда ни сюда.

(Здесь дважды применяется частица «ни» для усиления отрицания).

«Не»:

Мы не туда повернули и заблудились.

«Не» туда пошел и заблудился.

(Убрав «не» смысл потеряется).

Читайте также

Разница между этими двумя словами и написаниями в том, что:

Можно за раз увидеть сто зараз. Можно и зараз увидеть за сто раз. Но в этих предложениях мы видим не только зараз, но и следующее:

«За раз» — раздельное написание подсказывает нам о том, что сказано «за один раз». Это и имеется в виду. Вставка слова «один» является вовсе не искусственной. Она как бы дополняет сокращённое высказывание до полного.

«Зараз» — это одна из грамматических форм имени существительного «зараза»: «множество зараз», «нет этих зараз» и так далее. Пишется слитно.

_

Как известно, слово «зараза» может появиться в предложении не только в значении «инфекция», но и как ругательство («человек, который, подобно инфекции, бесполезен, докучлив и так далее»). В этом смысле множественное число («заразы») становится естественным, у него имеется родительный падеж, который мы и не должны путать с «за раз».

«Не» с прилагательными мы пишем слитно, если к слову можно подобрать синоним без частицы «не». Слово «нещедрый» можно заменить синонимом без «не» — скупой, поэтому слово «нещедрый» пишем слитно. Пример: «С его стороны — это был нещедрый подарок».

Правильно будет писаться слово «незадачливый» слитно. Во-первых,потому,что это слово без частицы «не» не употребляется.(нет в русском языке слова «задачливый»). Во-вторых, это слово можно заменить синонимом без частицы «не» — проблемный, бесталанный. Примеры: «Сегодня день выдался какой-то незадачливый».

Слово «не лежачий» будет писаться раздельно,так как заменить его синонимом с частицей «не» нельзя. Примеры: «Дедушка этот еще не лежачий, он молодец», «Под не лежачий камень вода как раз и течёт, а вот под лежачий — нет».

Прежде всего следует определить, к какой части речи относится слово конкретно.

Оно является наречием (отвечает на вопрос как? каким образом?).

В одних случаях НЕ с наречием конкретно пишется слитно, в других — раздельно.

СЛИТНО наречие конкретно пишется с НЕ, если его можно заменить синонимом без НЕ: неконкретно — абстрактно (отвлечённо, обобщённо, расплывчато, приблизительно).

Пример:

- Манера депутата неконкретно отвечать на неудобные вопросы вызвала глухое раздражение аудитории.

РАЗДЕЛЬНО наречие конкретно с частицей НЕ пишется, если в предложении имеется противопоставление с союзом «а».

Пример:

- Журналисты, бравшие интервью у артиста Логинова, с досадой признавались, что тот всегда умудрялся не конкретно, а туманно рассказать о своей личной жизни.

Однако, при наличии другого противительного союза — «но» — НЕ с наречием конкретно пишется слитно.

Пример:

- Он пописывал статейки, в которых неконкретно, но талантливо высмеивал недостатки местной власти.

(в данном случае наречия «неконкретно» и «талантливо» не противопоставляются друг другу, не являются антонимами).

При наличии слов далеко, вовсе, отнюдь НЕ с наречием конкретно пишется раздельно.

Пример:

- Он облегчённо вздохнул, поняв, что обидные слова были обращены отнюдь не конкретно к нему.

Не туда ты смотришь, поэтому и не видишь эту птичку с оранжевой грудкой.

Не туда или «нетуда»?

Оно произносится на одном дыхании, так что кажется, что это единое слово. Но все же установлю часть речи, чтобы выяснить, как оно пишется с «не».

Смотришь куда? не туда.

Слово «туда» только указывает на место, конкретно его не обозначая, при этом отвечает на обстоятельственный вопрос.

Значит, отнесу его к местоименным наречиям, как и слова «здесь», «там», «оттуда».

Местоименные наречия с частицей «не» пишутся раздельно, кроме отрицательных наречий, в составе которых не- является приставкой:

некуда, некогда, неоткуда, незачем.

Слово не туда пишется раздельно с отрицательной частицей не.

Содержание

- Пойди туда, не знаю куда, принеси то, не знаю что.

- Поди туда-не знаю куда, принеси то-не знаю что — русская народная сказка

- Поди туда-не знаю куда, принеси то-не знаю что читать

Пойди туда, не знаю куда, принеси то, не знаю что.

В некотором государстве жил-был царь. Был у него на службе стрелок по имени Андрей.

Пошел раз Андрей-стрелок на охоту. Ходил, ходил по лесу-всё без толку. Наконец приметил на дереве горлицу. Дай, думает, стрельну хоть эту. Стрельнул и ранил её.

А горлица ему и говорит: Не губи меня, Андрей-стрелок! Отнеси лучше домой-счастье великое добудешь себе.

-Удивился Андрей, всё ж послушал её.

Принёс он горлицу домой, положил на окошко, а она с окошка да оземь! Ударилась и обернулась девицей Марьей-царевной.

Сказала Марья-царевна стрелку: Сумел меня взять, умей и удержать — неспешным пирком, да за свадебку.

-Обрадовался Андрей-стрелок и, не откладывая, сыграл весёлую свадьбу.

Вот пошла молва, что у царёва стрелка жена-красавица. Захотелось самому царю на неё поглядеть. Оделся он в простое платье и поехал в слободу.

Постучался царь в стрелкову избу. Отворила ему Марья — царевна, а он одну ногу через порог занёс, другую не в силах: стоит перед ним несказанная красота!

Марья-царевна подождала-подождала, потом повернула царя за плечи и дверь закрыла. Защемила царя сердечная зазноба, захотелось ему жениться на красавице.

Воротился он во дворец, призвал к себе советника и говорит: „Надумай, как извести Андрея-стрелка. А нет, так сниму голову с плеч!»

Пошёл царский советник, нос повесил. Навстречу ему баба-яга: „Так и так, знаю я твою заботу. Но я тебя научу, как царю угодить».

И вот по навету советника зовёт царь к себе Андрея — стрелка и велит: „Поди туда-не знаю куда, принеси то-не знаю что. А нет, так сниму голову с плеч!»

Вернулся Андрей-стрелок домой невесел. Спрашивает Марья — царевна, какая у него невзгода. Он ей всё как есть рассказал.

Дождалась Марья-царевна ночи, развернула волшебную книгу, читала-читала да бросила: про царёву загадку ничего в книге не сказано.

А утром дала она Андрею клубок ниток и наказала: „Кинь его. Куда он покатится, туда и ты иди». И ещё дала вышитое полотенце, чтобы чужим не утирался.

Попрощался Андрей с Марьей-царевной, поклонился на четыре стороны и пошёл за клубком. Клубок катится, нитка от него тянется…

Только Андрей из дому, а тут царь наехал, чтобы Марью-царевну силой увезти. Но она горлицей обернулась и улетела. В сердцах спалил царь стрелкову избу.

Скоро сказка сказывается, да не скоро дело делается. Много царств и земель прошёл Андрей и вот пришёл к избушке на курьих ножках. А перед избушкой три девицы гуляют.

Приветили они Андрея-стрелка. В гости зовут, умываться подают. А как увидали у него полотенце, так и руками всплеснули: „Да ведь это наша сестрица вышивала, Марья-царевна!»

Покликали скорей матушку. Андрей-стрелок ей в ноги поклонился и обо всём рассказал, ничего не утаил. Решила старушка помочь Андрею-стрелку.

Послала она сестриц из горницы. Вынула каждая свой платочек, махнули и слетелись тут птицы небесные, сбежались звери лесные, приползли гады болотные.

Спрашивают их сестрицы, не знают ли они, как дойти туда-не знаю куда, принести то-не знаю что. — „Нет, мы про то не слыхали», — отвечают они.

Вдруг прыгает вперёд старая лягушка и говорит: „Проводила б я Андрея-стрелка туда-не знаю куда, да больно стара. Пусть уж сам донесёт меня в парном молоке до огненной реки».

Посадил лягушку в кувшин с молоком и понес её Андрей к огненной реке. А через реку эту ни зверь не перескочит, ни птица не перелетит. — „Ну, добрый молодец, теперь садись мне на спину», — говорит лягушка.

Сел Андрей, стала она тут дуться. Дулась — дулась, да как скакнёт — и перепрыгнула огненную реку.

Дальше лягушка послала Андрея по тропинке одного. Шёл он, шёл и видит: изба не изба, без окон, без крыльца — вот и пришёл он туда-не знаю куда.

Вошёл и спрятался за печью. Немного погодя застучало, загремело, и входит в избу мужичок с ноготок, борода с локоток, да как крикнет: „Эй, сват Наум, есть хочу!»

А когда он ушёл, Андрей тоже позвал: „Сват Наум, накорми меня!“ — И появились на столе кушанья разные, вина и меды. Андрей сам за стол садится и свата Наума приглашает.

Обрадовался Андрей-стрелок, что нашёл наконец то-не знаю что, и, поевши, пошли они со сватом Наумом дальше. Шли, шли, притомился Андрей — передохнуть бы! И только подумал…

…как подхватил его буйный ветер и понёс над морем. Глядь, посреди моря островок, на нём дворец с крышей золотой, вокруг сад. Посоветовал сват Наум Андрею передохнуть здесь.

Только велел он Андрею глаз с моря не сводить. Долго ли, коротко ли с западной стороны плывут к острову три корабля.

Как пристали корабли, повёл Андрей-стрелок купцов-корабельщиков во дворец. Вокруг птицы поют, по дорожкам чудные звери прыгают.

Глядят не наглядятся гости: сколько раз по этому морю плавали, а такого чуда не видывали. Говорит им Андрей, что это его слуга, сват Наум, всё сам сделал.

И попросил Андрей свата Наума накормить дорогих гостей. Откуда ни возьмись, появился накрытый стол, на нём кушанья разные, закуски да заедки, вина красные.

Купцы только ахают и предлагают Андрею меняться: им слугу, свата Наума, а ему-три диковинки.

Первая диковинка — дубинка. Только скажи: „Ну-ка, дубинка, обломай ему бока», — и дубинка сама начнёт колотить.

Вторая диковинка — топор. Повернул его обухом — тяп да ляп: топор сам корабль стяпал, с пушками да с храбрыми моряками.

Третья диковинка-дудка. Задудел-войско появилось: и конница, и пехота.

Ну и обменялись: получил Андрей-стрелок три диковинки.

Вернулись корабельщики на корабли и давай пировать: пьют, едят, знай, только на свата Наума покрикивают. Перепились допьяна и спать повалились.

А стрелок сидит один в тереме, пригорюнился: „Эх, домой бы скорей, на родную сторонушку, к молодой жене Марье-царевне».

Только подумал — подхватил его вихрь и понёс. Опустился он на родную землю, смотрит: вместо домишка его обгорелая труба торчит.

Повесил он голову ниже плеч и пошёл из города на синее море, на пустое место. Вдруг, откуда ни возьмись, прилетает сизая горлица.

Ударилась горлица о землю и обернулась Марьей-царевной. Обнялись они, поздоровались, стали друг друга расспрашивать. Рассказала Марья-царевна, как сжёг царь их дом.

Попросил тут Андрей своего верного слугу у синего моря дворец поставить. Не успели оглянуться — дворец уж готов! Зажили в нём Андрей-стрелок с Марьей-царевной без горя, без беды.

Прослышал про то царь, разгневался, а гонцы ему весть несут — мол, так и так, всё исполнил Андрей-стрелок: ходил туда-не знаю куда, добыл то-не знаю что.

Тут царь и совсем осерчал. Собрал своё войско и пошёл дворец разорять.

Увидел Андрей царское войско, схватил топор, повернул его обухом кверху — тяп-ляп: стяпал топор корабль, и другой, и третий, с пушками, с моряками. Пошли корабли дворец защищать.

Задул Андрей в дудку — помчались на царское войско и конница, и пехота, с музыкой, со знамёнами.

Разгорелся жаркий бой. Сам царь на подмогу своим войскам прискакал.

Тогда Андрей-стрелок вынул дубинку: „Ну-на, дубинка, обломай бока этому царю! «-Принялась дубинка за дело. Так разошлась, что пустился царь от неё через чисто поле, только его и видели.

Тут и сражению конец пришёл.

Обрадовался народ, повалил из города и стал просить Андрея-стрелка, чтоб отныне он правил их землёй. Андрей спорить не стал и пообещал решать все дела государства по чести и по совести.

Источник

Поди туда-не знаю куда, принеси то-не знаю что — русская народная сказка

Сказка расскажет о стрельце Андрее и его прекрасной жене Марье-царевне, чья красота не дала покоя царю и захотел он изжить Андрея со свету…

Поди туда-не знаю куда, принеси то-не знаю что читать

В некотором государстве жил-был царь, холост — не женат. Был у него на службе стрелок по имени Андрей.

Пошел раз Андрей-стрелок на охоту. Ходил, ходил целый день по лесу—не посчастливилось, не мог на дичь напасть. Время было к вечеру, идет он обратно — кручинится. Видит — сидит на дереве горлица.

«Дай, — думает, — стрельну хоть эту».

Стрельнул и ранил ее, — свалилась горлица с дерева на сырую землю. Поднял ее Андрей, хотел свернуть ей голову, положить в сумку.

А горлица говорит ему человеческим голосом:

— Не губи меня, Андрей-стрелок, не руби моей головы, возьми меня живую, принеси домой, посади на окошко. Да смотри, как найдет на меня дремота — в ту пору бей меня правой рукой наотмашь: добудешь себе великое счастье.

Удивился Андрей-стрелок: что такое? С виду совсем птица, а говорит человеческим голосом. Принес он горлицу домой, посадил на окошко, а сам стоит дожидается.

Прошло немного времени, горлица положила головку под крылышко и задремала. Андрей вспомнил, что она ему наказывала, ударил ее правой рукой наотмашь. Упала горлица наземь и обернулась девицей, Марьей-царевной, да такой прекрасной, что ни вздумать, ни взгадать, только в сказке сказать.

Говорит Марья-царевна стрелку:

— Сумел меня взять, умей и удержать — неспешным пирком да за свадебку. Буду тебе честной да веселой женой.

На том они и поладили. Женился Андрей-стрелок на Марье-царевне и живет с молодой женой — потешается. А службы не забывает: каждое утро ни свет ни заря идет в лес, настреляет дичи и несет на царскую кухню.

Пожили они так недолго, Марья-царевна говорит:

— Бедно живешь ты, Андрей!

— Да, как сама видишь.

— Добудь-ка рублей сотню, купи на эти деньги разного шелку, я все дело поправлю.

Послушался Андрей, пошел к товарищам, у кого рубль, у кого два занял, накупил разного шелку и принес жене. Марья-царевна взяла шелк и говорит:

— Ложись спать, утро вечера мудренее. Андрей лег спать, а Марья-царевна села ткать. Всю ночь ткала и выткала ковер, какого в целом свете не видывали: на нем все царство расписано, с городами и деревнями, с лесами и нивами, и птицы в небе, и звери на горах, и рыбы в морях; кругом луна и солнце ходят…

Наутро Марья-царевна отдает ковер мужу:

— Понеси на гостиный двор, продай купцам, да смотри — своей цены не запрашивай, а что дадут, то и бери.

Андрей взял ковер, повесил на руку и пошел по гостиным рядам.

Подбегает к нему один купец:

— Послушай, почтенный, сколько спрашиваешь?

— Ты торговый человек, ты и цену давай.

Вот купец думал, думал — не может оценить ковра. Подскочил другой, за ним — еще. Собралась купцов толпа великая, смотрят на ковер, дивуются, а оценить не могут.

В то время проезжал мимо рядов царский советник, и захотелось ему узнать, про что толкует купечество. Вышел из кареты, насилу пропихался через великую толпу и спрашивает:

— Здравствуйте, купцы, заморские гости! О чем речь у вас?

— Так и так, ковра оценить не можем.

Царский советник посмотрел на ковер и сам дался диву:

— Скажи, стрелок, скажи по правде истинной: откуда добыл такой славный ковер?

— Так и так, моя жена вышила.

— Сколько же тебе дать за него?

— А я и сам не знаю. Жена наказала не торговаться: сколько дадут, то и наше.

— Ну, вот тебе, стрелок, десять тысяч.

Андрей взял деньги, отдал ковер и пошел домой. А царский советник поехал к царю и показывает ему ковер.

Царь взглянул—на ковре все его царство как на ладони. Он так и ахнул:

— Ну, что хочешь, а ковра я тебе не отдам!

Вынул царь двадцать тысяч рублей и отдает советнику из рук в руки. Советник деньги взял и думает: «Ничего, я себе другой, еще лучше, закажу».

Сел опять в карету и поскакал в слободу. Разыскал избушку, где живет Андрей-стрелок, и стучится в дверь. Марья-царевна отворяет ему. Царский советник одну ногу через порог занес, а другую не переносит, замолчал и про свое дело забыл: стоит перед ним такая красавица, век бы глаз от нее не отвел, все бы смотрел да смотрел.

Марья-царевна ждала-ждала ответа да повернула царского советника за плечи и дверь закрыла. Насилу он опомнился, нехотя поплелся домой. И с той поры и ест — не наест и пьет — не запьет: все ему представляется стрелкова жена.

Заметил это царь и стал выспрашивать, что за кручина у него такая.

Советник говорит царю:

— Ах, видел я у одного стрелка жену, все о ней думаю! И ни запить это, ни заесть, никаким зельем не заворожить.

Пришла царю охота самому посмотреть стрелкову жену. Оделся он в простое платье, поехал в слободу, нашел избенку, где живет Андрей-стрелок, и стучится в дверь. Марья-царевна отворила ему. Царь одну ногу через порог занес, другую и не может, совсем онемел: стоит перед ним несказанная красота.

Марья-царевна ждала-ждала ответа, повернула царя за плечи и дверь закрыла.

Защемила царя сердечная зазноба. «Чего,—думает, — хожу холост, не женат? Вот бы жениться на этой красавице! Не стрельчихой ей быть, на роду ей написано быть царицей».

Воротился царь во дворец и задумал думу нехорошую — отбить жену от живого мужа. Призывает он советника и говорит:

— Надумай, как извести Андрея-стрелка. Хочу на его жене жениться. Придумаешь — награжу городами, и деревнями, и золотой казной, не придумаешь — сниму голову с плеч.

Закручинился царский советник, пошел и нос повесил. Как извести стрелка, не придумает. Да с горя и завернул в кабак винца испить.

Подбегает к нему кабацкая теребень в рваном кафтанишке:

— О чем, царский советник, пригорюнился, зачем нос повесил?

— Поди прочь, кабацкая теребень!

— А ты меня не гони, лучше стаканчик винца поднеси, я тебя на ум наведу.

Поднес ему царский советник стаканчик винца и рассказал про свое горе.

Кабацкая теребень и говорит ему:

— Извести Андрея-стрелка дело нехитрое — сам-то он прост, да жена у него больно хитра. Ну, да мы загадаем загадку такую, что ей не справиться. Воротись к царю и скажи: пускай он пошлет Андрея-стрелка на тот свет узнать, как поживает покойный царь-батюшка. Андрей уйдет и назад не вернется.

Царский советник поблагодарил кабацкую теребень — и бегом к царю:

— Так и так, можно стрелка извести. И рассказал, куда нужно его послать и зачем. Царь обрадовался, велел позвать Андрея-стрелка.

— Ну, Андрей, служил ты мне верой-правдой, сослужи еще службу: сходи на тот свет, узнай, как поживает мой батюшка. Не то мой меч—твоя голова с плеч…

Андрей воротился домой, сел на лавку и голову повесил. Марья-царевна его спрашивает:

— Чего невесел? Или невзгода какая?

Рассказал ей Андрей, какую царь задал ему службу.

— Есть о чем горевать! Это не служба, а службишка, служба будет впереди. Ложись спать, утро вечера мудренее.

Утром рано, только проснулся Андрей, Марья-царевна дает ему мешок сухарей и золотое колечко.

— Поди к царю и проси себе в товарищи царского советника, а то, скажи, тебе не поверят, что был ты на том свете. А как выйдешь с товарищем в путь-дорогу, брось перед собой колечко, оно тебя доведет.

Андрей взял мешок сухарей и колечко, попрощался с женой и пошел к царю просить себе дорожного товарища. Делать нечего, царь согласился, велел советнику идти с Андреем на тот свет.

Вот они вдвоем и вышли в путь-дорогу. Андрей бросил колечко — оно катится. Андрей идет за ним полями чистыми, мхами-болотами, реками-озерами, а за Андреем царский советник тащится.

Устанут идти, поедят сухарей — и опять в путь.

Близко ли, далеко ли, скоро ли, коротко ли, пришли они в густой, дремучий лес, спустились в глубокий овраг, и тут колечко остановилось.

Андрей и царский советник сели поесть сухарей. Глядь, мимо них на старом-престаром царе два черта дрова везут — большущий воз — и погоняют царя дубинками, один с правого бока, другой с левого.

— Смотри, никак, это наш покойный царь-батюшка?

— Твоя правда, это он самый дрова везет.

Андрей и закричал чертям:

— Эй, господа черти! Освободите мне этого покойничка хоть на малое время, мне нужно кой о чем его расспросить.

— Есть нам время дожидаться! Сами, что ли, дрова повезем?

— А возьмите у меня свежего человека на смену. Ну, черти отпрягли старого царя, на его место впрягли в воз царского советника и давай его с обеих сторон погонять дубинками, — тот гнется, а везет.

Андрей стал спрашивать старого царя про его житье-бытье.

— Ах, Андрей-стрелок, — отвечает царь, — плохое мое житье на том свете! Поклонись от меня сыну да скажи, что я накрепко заказываю людей не обижать, а то и с ним то же станется.

Только успели они поговорить, черти уж назад едут с порожней телегой. Андрей попрощался со старым царем, взял у чертей царского советника, и пошли они в обратный путь.

Приходят в свое царство, являются во дворец.

Царь увидел стрелка и в сердцах накинулся на него:

— Как ты смел назад воротиться?

— Так и так, был я на том свете у вашего покойного родителя. Живет он плохо, велел вам кланяться да накрепко наказывал людей не обижать.

— А чем докажешь, что ходил на тот свет и моего родителя видел?

— А тем я докажу, что у вашего советника на спине и теперь еще знаки видны, как его черти дубинками погоняли.

Тут царь уверился, делать нечего — отпустил Андрея домой. А сам говорит советнику.

— Вздумай, как извести стрелка, не то мой меч — твоя голова с плеч.

Пошел царский советник, еще ниже нос повесил. Заходит в кабак, сел за стол, спросил вина. Подбегает к нему кабацкая теребень:

— Что, царский советник, пригорюнился? Поднеси-ка мне стаканчик, я тебя на ум наведу.

Советник поднес ему стаканчик винца и рассказал про свое горе. Кабацкая теребень ему говорит:

— Воротись назад и скажи царю, чтобы задал он стрелку вот какую службу — ее не то что выполнить, трудно и выдумать: послал бы его за тридевять земель, в тридесятое царство добыть кота Баюна…

Царский советник побежал к царю и рассказал, какую службу задать стрелку, чтобы он назад не вернулся. Царь посылает за Андреем.

— Ну, Андрей, сослужил ты мне службу, сослужи другую: ступай в тридесятое царство и добудь мне кота Баюна. Не то мой меч — твоя голова с плеч.

Пошел Андрей домой, ниже плеч голову повесил и рассказывает жене, какую царь задал ему службу.

— Есть о чем кручиниться! — Марья-царевна говорит. — Это не служба, а службишка, служба будет впереди. Ложись спать, утро вечером мудренее.

Андрей лег спать, а Марья-царевна пошла на кузницу и велела кузнецам сковать три колпака железных, железные клещи и три прута: один железный, другой медный, третий оловянный.

Утром рано Марья-царевна разбудила Андрея:

— Вот тебе три колпака да клещи и три прута, ступай за тридевять земель, в тридесятое государство. Трех верст не дойдешь, станет одолевать тебя сильный сон — кот Баюн на тебя дремоту напустит. Ты не спи, руку за руку закидывай, ногу за ногу волочи, а где и катком катись. А если уснешь, кот Баюн убъет тебя.

И тут Марья-царевна научила его, как и что делать, и отпустила в дорогу.

Скоро сказка сказывается, не скоро дело делается — пришел Андрей-стрелок в тридесятое царство. За три версты стал его одолевать сон. надевает Андрей на голову три колпака железных, руку за руку закидывает, ногу за ногу волочит — идет, а где и катком катится.

Кое-как выдержал дремоту и очутился у высокого столба.

Кот Баюн увидел Андрея, заворчал, зауркал да со столба прыг ему на голову — один колпак разбил и другой разбил, взялся было за третий. Тут Андрей-стрелок ухватил кота клещами, сволок наземь и давай отлаживать прутьями. Наперво сек железным прутом — изломал железный, принялся угощать медным — и этот изломал и принялся бить оловянным.

Оловянный прут гнется, не ломится, вокруг хребта обвивается. Андрей бьет, а кот Баюн начал сказки рассказывать: про попов, про дьяков, про поповых дочерей. Андрей его не слушает, знай охаживает прутом.

Невмоготу стало коту — видит, что заговорить нельзя, он и взмолился:

— Покинь меня, добрый человек! Что надо, все тебе сделаю.

Андрей пошел в обратный путь и кота за собой повел. Добрался до своего царства, приходит с котом во дворец и говорит царю:

— Так и так, службу выполнил, добыл вам кота Баюна.

Царь удивился и говорит:

— А ну, кот Баюн, покажи большую страсть.

Тут кот свои когти точит, на царя их ладит, хочет у него белую грудь раздирать, из живого сердце вынимать.

— Андрей-стрелок, уйми, пожалуйста, кота Баюна!

Андрей кота унял и в клетку запер, а сам пошел домой, к Марье-царевне. Живет-поживает, тешится с молодой женой. А царя еще пуще знобит зазноба сердечная. Опять призвал он советника:

— Что хочешь придумай, изведи Андрея-стрелка, не то мой меч — твоя голова с плеч.

Царский советник идет прямо в кабак, нашел там кабацкую теребень в рваном кафтанишке и просит его выручить, на ум навести. Кабацкая теребень стаканчик вина выпил, усы вытер.

— Ступай, — говорит, — к царю и скажи: пусть пошлет Андрея-стрелка туда — не знаю куда, принести то — не знаю что. Этой задачи Андрей во веки веков не выполнит и назад не вернется.

Советник побежал к царю и все ему доложил. Царь посылает за Андреем.

— Сослужил ты мне две службы, сослужи третью: сходи туда — не знаю куда, принеси то — не знаю что. Сослужишь — награжу по-царски, а не то мой меч — твоя голова с плеч.

Пришел Андрей домой, сел на лавку и заплакал. Марья-царевна его спрашивает:

— Что, милый, невесел? Или еще невзгода какая?

— Эх, — говорит, — через твою красу все напасти несу! Велел мне царь идти туда — не знаю куда, принести то — не знаю что.

— Вот это служба так служба! Ну ничего, ложись спать, утро вечера мудренее.

Марья-царевна дождалась ночи, развернула волшебную книгу, читала, читала, бросила книгу и за голову схватилась: про цареву загадку в книге ничего не сказано. Марья-царевна вышла на крыльцо, вынула платочек и махнула. Налетели всякие птицы, набежали всякие звери.

Марья-царевна их спрашивает:

— Звери лесные, птицы поднебесные, — вы, звери, всюду рыскаете, вы, птицы, всюду летаете, — не слыхали ль, как дойти туда — не знаю куда, принести то — не знаю что?

Звери и птицы ответили:

— Нет, Марья-царевна, мы про то не слыхивали. Марья-царевна махнула платочком — звери и птицы пропали, как не бывали. Махнула в другой раз — появились перед ней два великана:

— Что угодно? Что надобно?

— Слуги мои верные, отнесите меня на середину Океан-моря.

Подхватили великаны Марью-царевну, отнесли на Океан-море и стали на середине, на самой пучине — сами стоят, как столбы, а ее на руках держат. Марья-царевна махнула платочком, и приплыли к ней все гады и рыбы морские.

— Вы, гады и рыбы морские, вы везде плаваете, на всех островах бываете, не слыхали ль, как дойти туда — не знаю куда, принести то — не знаю что?

— Нет, Марья-царевна, мы про то не слыхали.

Закручинилась Марья-царевна и велела отнести себя домой. Великаны подхватили ее, принесли на Андреев двор, поставили у крыльца.

Утром рано Марья-царевна собрала Андрея в дорогу и дала ему клубок ниток и вышитую ширинку.

— Брось клубок перед собой, — куда он покатится, туда и ты иди. Да смотри, куда бы ни пришел, будешь умываться, чужой ширинкой не утирайся, а утирайся моей.

Андрей попрощался с Марьей-царевной, поклонился на четыре стороны и пошел за заставу. Бросил клубок перед собой, клубок покатился — катится да катится. Андрей идет за ним следом.

Скоро сказка сказывается, не скоро дело делается. Много царств и земель прошел Андрей. Клубок катится, нитка от него тянется; стал клубок маленький, с куриную головочку; вот уж до чего стал маленький, не видно и на дороге… Дошел Андрей до леса, видит: стоит избушка на курьих ножках.

— Избушка, избушка, повернись ко мне передом, к лесу задом!

Избушка повернулась, Андрей вошел и видит: на лавке сидит седая старуха, прядет кудель.

— Фу, фу, русского духу слыхом не слыхано, видом не видано, а нынче русский дух сам пришел. Вот изжарю тебя в печи да и съем и на косточках покатаюсь.

Андрей отвечает старухе:

— Что ты, старая баба-яга, станешь есть дорожного человека! Дорожный человек костоват и черен, ты наперед баньку истопи, меня вымой, выпари, тогда и ешь.

Баба-яга истопила баньку. Андрей выпарился, вымылся, достал женину ширинку и стал ею утираться.

— Откуда у тебя ширинка? Ее моя дочь вышивала.

— Твоя дочь мне жена, мне и ширинку дала.

— Ах, зять возлюбленный, чем же мне тебя потчевать?

Тут баба-яга собрала ужин, наставила всяких кушаньев, вин и медов. Андрей не чванится—сел за стол, давай уплетать. Баба-яга села рядом—он ест, она выспрашивает, как он на Марье-царевне женился да живут ли они хорошо? Андрей все рассказал: как женился и как царь послал его туда — не знаю куда, добыть то — не знаю что.

— Вот бы ты помогла мне, бабушка!

— Ах, зятюшка, ведь про это диво дивное даже я не слыхивала. Знает про это одна старая лягушка, живет она в болоте триста лет… Ну ничего, ложись спать, утро вечера мудренее.

Андрей лег спать, а баба-яга взяла два голика, полетела на болото и стала звать:

— Бабушка, лягушка-скакушка, жива ли?

— Выдь ко мне из болота.

Старая лягушка вышла из болота, баба-яга ее спрашивает:

— Знаешь ли, где то — не знаю что?

— Укажи, сделай милость. Зятю моему дана служба: пойти туда—не знаю куда, взять то—не знаю что.

— Я б его проводила, да больно стара, мне туда не допрыгать. Донесет твой зять меня в парном молоке до огненной реки, тогда скажу.

Баба-яга взяла лягушку-скакушку, полетела домой, надоила молока в горшок, посадила туда лягушку и утром рано разбудила Андрея:

— Ну, зять дорогой, одевайся, возьми горшок с парным молоком, в молоке—лягушка, да садись на моего коня, он тебя довезет до огненной реки. Там коня брось и вынимай из горшка лягушку, она тебе скажет.

Андрей оделся, взял горшок, сел на коня бабы-яги. Долго ли, коротко ли, конь домчал его до огненной реки. Через нее ни зверь не перескочит, ни птица не перелетит.

Андрей слез с коня, лягушка ему говорит:

— Вынь меня, добрый молодец, из горшка, надо нам через реку переправиться.

Андрей вынул лягушку из горшка и пустил наземь.

— Ну, добрый молодец, теперь садись мне на спину.

— Что ты, бабушка, эка маленькая, чай, я тебя задавлю.

— Не бойся, не задавишь. Садись да держись крепче.

Андрей сел на лягушку-скакушку. Начала она дуться. Дулась, дулась — сделалась словно копна сена.

— Крепко ли держишься?

Опять лягушка дулась, дулась—сделалась еще больше, словно стог сена.

— Крепко ли держишься?

Опять она дулась, дулась — стала выше темного леса, да как скакнет — и перепрыгнула через огненную реку, перенесла Андрея на тот берег и сделалась опять маленькой.

— Иди, добрый молодец, по этой тропинке, увидишь терем—не терем, избу—не избу, сарай—не сарай, заходи туда и становись за печью. Там найдешь то — не знаю что.

Андрей пошел по тропинке, видит: старая изба — не изба, тыном обнесена, без окон, без крыльца. Он туда вошел и спрятался за печью.

Вот немного погодя застучало, загремело по лесу, и входит в избу мужичок с ноготок, борода с локоток, да как крикнет:

— Эй, сват Наум, есть хочу!

Обработал быка до последней косточки, выпил целый бочонок пива.

— Эй, сват Наум, убери объедки!

И вдруг стол пропал, как и не бывало, — ни костей, ни бочонка… Андрей дождался, когда уйдет мужичок с ноготок, вышел из-за печки, набрался смелости и позвал:

— Сват Наум, покорми меня… Только позвал, откуда ни возьмись, появился стол, на нем разные кушанья, закуски и заедки, вина и меды. Андрей сел за стол и говорит:

— Сват Наум, садись, брат, со мной, станем есть-пить вместе.

Отвечает ему невидимый голос:

— Спасибо тебе, добрый человек! Столько лет я здесь служу, горелой корки не видывал, а ты меня за стол посадил.

Смотрит Андрей и удивляется: никого не видно, а кушанья со стола словно кто метелкой сметает, вина и меды сами в рюмку наливаются — рюмка скок, скок да скок.

— Сват Наум, покажись мне!

— Нет, меня никто не может видеть, я то — не знаю что.

— Сват Наум, хочешь у меня служить?

— Отчего не хотеть? Ты, я вижу, человек добрый!

Вот они поели. Андрей и говорит:

— Ну, прибирай все да пойдем со мной.

Пошел Андрей из избенки, оглянулся:

— Сват Наум, ты здесь?

— Здесь, не бойся, я от тебя не отстану.

Дошел Андрей до огненной реки, там его дожидается лягушка:

— Добрый молодец, нашел то — не знаю что?

Андрей опять сел на нее, лягушка начала раздуваться, раздулась, скакнула и перенесла его через огненную реку.

Тут он лягушку-скакушку поблагодарил и пошел путем-дорогой в свое царство. Идет, идет, обернется:

— Сват Наум, ты здесь?

— Здесь. Не бойся, я от тебя не отстану.

Шел, шел Андрей, дорога далеко — прибились его резвые ноги, опустились его белые руки.

— Эх, — говорит, — до чего же я уморился!

— Что же ты мне давно не сказал? Я бы тебя живо на место доставил.

Подхватил Андрея буйный вихрь и понес — горы и леса, города и деревни так внизу и мелькают. Летит Андрей над глубоким морем, и стало ему страшно.

— Сват Наум, передохнуть бы!

Сразу ветер ослаб, и Андрей стал спускаться на море. Глядит—где шумели одни синие волны, появился островок, на островке стоит дворец с золотой крышей, кругом сад прекрасный…

Сват Наум говорит Андрею:

— Отдыхай, ешь, пей да на море поглядывай. Будут плыть мимо три купеческих корабля. Ты купцов зазови да угости, употчевай хорошенько — у них есть три диковинки. Ты меня променяй на эти диковинки — не бойся, я к тебе назад вернусь.

Долго ли, коротко ли, с западной стороны плывут три корабля. Корабельщики увидали остров, на нем дворец с золотой крышей и кругом сад прекрасный.

— Что за чудо? — говорят. — Сколько раз мы тут плавали, ничего, кроме синего моря, не видели. Давай пристанем!

Три корабля бросили якоря, три купца-корабельщика сели на легкую лодочку, поплыли к острову. А уж Андрей-стрелок их встречает.

— Пожалуйте, дорогие гости.

Купцы-корабельщики идут дивуются: на тереме крыша как жар горит, на деревах птицы поют, по дорожкам чудные звери прыгают.

— Скажи, добрый человек, кто здесь выстроил это чудо чудное?

— Мой слуга, сват Наум, в одну ночь построил.

Андрей повел гостей в терем:

— Эй, сват Наум, собери-ка нам попить, поесть!

Откуда ни возьмись, явился накрытый стол, на нем — вина и кушанья, чего душа захочет. Купцы-корабельщики только ахают.

— Давай, — говорят, — добрый человек, меняться: уступи нам своего слугу, свата Наума, возьми у нас за него любую диковинку.

— Отчего ж не поменяться? А каковы будут ваши диковинки?

Один купец вынимает из-за пазухи дубинку. Ей только скажи: «Ну-ка, дубинка, обломай бока этому человеку!» — дубинка сама начнет колотить, какому хочешь силачу обломает бока.

Другой купец вынимает из-под полы топор, повернул его обухом кверху—топор сам начал тяпать: тяп да ляп—вышел корабль. С парусами, с пушками, с храбрыми моряками. Корабли плывут, пушки палят, храбры моряки приказа спрашивают.

Повернул топор обухом вниз—сразу корабли пропали, словно их и не было.

Третий купец вынул из кармана дудку, загудел — войско появилось: и конница, и пехота, с ружьями, с пушками. Войска идут, музыка гремит, знамена развеваются, всадники скачут, приказа спрашивают.

Купец задудел с другого конца в дудку — и нет ничero, все пропало.

— Хороши ваши диковинки, да моя стоит дороже. Хотите меняться—отдавайте мне за моего слугу, свата Наума, все три диковинки.

— Как знаете, иначе меняться не стану.

Купцы думали, думали: «На что нам дубинка, топор да дудка? Лучше поменяться, со сватом Наумом будем безо всякой заботы день и ночь и сыты и пьяны».

Отдали купцы-корабельщики Андрею дубинку, топор и дудку и кричат:

— Эй, сват Наум, мы тебя берем с собой! Будешь нам служить верой и правдой?

Отвечает им невидимый голос:

— Отчего не служить? Мне все равно, у кого ни жить.

Купцы-корабельщики вернулись на свои корабли и давай пировать — пьют, едят, знай покрикивают:

— Сват Наум, поворачивайся, давай того, давай того!

Перепились все допьяна, где сидели, там и спать свалились.

А стрелок сидит один в тереме, пригорюнился.

«Эх, — думает, — где-то теперь мой верный слуга, сват Наум?»

— Я здесь. Чего надобно?

— Сват Наум, не пора ли нам на родную сторонушку, к молодой жене? Отнеси меня домой.

Опять подхватил Андрея вихрь и понес в его царство, на родную сторону.

А купцы проснулись, и захотелось им опохмелиться:

— Эй, сват Наум, собери-ка нам попить-поесть, живо поворачивайся!

Сколько ни звали, ни кричали, все нет толку. Глядят, и острова нет: на месте его шумят одни синие волны.

Погоревали купцы-корабельщики: «Эх, надул нас недобрый человек!»—да делать нечего, подняли паруса и поплыли, куда им было надобно.

А Андрей-стрелок прилетел на родимую сторону, опустился возле своего домишки, смотрит: вместо домишки обгорелая труба торчит.

Повесил он голову ниже плеч и пошел из города на синее море, на пустое место. Сел и сидит. Вдруг, откуда ни возьмись, прилетает сизая горлица, ударилась об землю и оборотилась его молодой женой, Марьей-царевной.

Обнялись они, поздоровались, стали друг друга спрашивать, друг другу рассказывать.

— С той поры как ты из дому ушел, я сизой горлицей летаю по лесам да по рощам. Царь три раза за мной посылал, да меня не нашли и домишко сожгли.

— Сват Наум, нельзя ли нам на пустом месте у синего моря дворец поставить?

— Отчего нельзя? Сейчас будет исполнено.

Не успели оглянуться—и дворец поспел, да такой славный, лучше царского, кругом — зеленый сад, на деревьях птицы поют, по дорожкам чудные звери скачут.

Взошли Андрей-стрелок с Марьей-царевной во дворец, сели у окошка и разговаривают, друг на друга любуются. Живут, горя не знают, и день, и другой, и третий.

А царь в то время поехал на охоту, на синее море, и видит: на том месте, где ничего не было, стоит дворец.

— Какой это невежа без спроса вздумал на моей земле строиться?

Побежали гонцы, все разведали и докладывают царю, что тот дворец поставлен Андреем-стрелком и живет он в нем с молодой женой, Марьей-царевной.

Еще пуще разгневался царь, посылает узнать, ходил ли Андрей туда — не знаю куда, принес ли то — не знаю что.

Побежали гонцы, разведали и докладывают:

— Андрей-стрелок ходил туда—не знаю куда и добыл то — не знаю что.

Тут царь и совсем осерчал, приказал собрать войско, идти на взморье, тот дворец разорить дотла, а самого Андрея-стрелка и Марью-царевну предать лютой смерти.

Увидал Андрей, что идет на него сильное войско, скорее схватил топор, повернул его обухом кверху. Топор тяп да ляп — стоит на море корабль, опять тяп да ляп — стоит другой корабль. Сто раз тяпнул — сто кораблей поплыло по синему морю.

Андрей вынул дудку, задудел — появилось войско: и конница, и пехота, с пушками, со знаменами. Начальники скачут, приказа ждут. Андрей приказал начать сражение. Музыка заиграла, барабаны ударили, полки двинулись. Пехота ломит царских солдат, конница скачет, в плен забирает. А со ста кораблей пушки так и бьют по столичному городу.

Царь видит: войско его бежит, кинулся сам к войску — останавливать. Тут Андрей вынул дубинку:

— Ну-ка, дубинка, обломай бока этому царю!

Тут и сражению конец пришел. Повалил из города народ и стал просить Андрея-стрелка, чтобы взял он в свои руки все государство.

Андрей спорить не стал. Устроил пир на весь мир и вместе с Марьей-царевной правил он этим государством до глубокой старости.

Источник

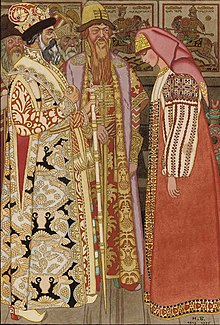

| Go I Know Not Whither and Fetch I Know Not What | |

|---|---|

Illustration by Ivan Bilibin. |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Go I Know Not Whither and Fetch I Know Not What |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 465, «The Man persecuted because of his beautiful wife» |

| Mythology | Slavic |

| Country | Russia |

| Region | Russia, Eurasia |

| Published in | Narodnye russkie skazki |

| Related |

|

Go I Know Not Whither and Fetch I Know Not What (Russian: Пойди туда, не знаю куда, принеси то, не знаю что, translit. Poydi tuda, ne znau kuda, prinesi to, ne znau chto) is a Russian fairy tale collected by Alexander Afanasyev in Narodnye russkie skazki.

Synopsis[edit]

A royal hunter shoots a bird; wounded, it begs him not to kill it but to take it home, and when it goes to sleep, strike its head. He does so, and the bird becomes a beautiful woman. She proposes that they marry, and they do. After the marriage, she sees how hard he has to hunt and tells him to borrow one or two hundred rubles. He does so, and then buys silks with them. She conjures two spirits and sets them to make a marvelous carpet. Then she gives the carpet to her husband and tells him to accept whatever price he is given. The merchants do not know how much to pay for it, and finally, the king’s steward buys it for ten thousand rubles. The king sees it and gives the steward twenty-five thousand for it.

The steward goes to the hunter’s house to get another and sees his wife. He falls madly in love with her, and the king sees it. The steward tells him why, and the king goes himself and sees the hunter’s wife. He decides that he should marry her instead and demands the steward devise a way to be rid of the husband. The steward, with a stranger’s advice, has him sent to the land of the dead to ask of the former King’s behavior, in the hope that he never returns. The hunter being told of this tells his wife. She gives him a magic ring and says that he must take the king’s steward with him as a witness, to prove that he really has visited the Underworld. He does. After their return and seeing how the King’s father was punished by the devils for his sins, the hunter thinks he fulfilled his duty, but the King becomes angry and just sends him back home. But who really gets the anger of the monarch, is the steward, who is ordered again to find another way to let the hunter disappear, or else the steward will be executed. The man asks again for advice from the stranger and he/she tells him to catch a large man-eating magical cat called Bajun who lives on an iron column in the thrice tenth kingdom. But against all their evil plans, the hunter catches the beast, with the help of his wife.

The king is enraged with the steward, who again goes to the same stranger. This time, the steward tells the king to send the hunter to «go I know not whither and bring back I know not what.» The wife conjures spirits and all the beasts and birds to see if they know how to «go I know not whither and bring back I know not what.» Then she goes out to sea and summons all the fish. But none of them can help her, so she gives him a ball, which if rolled before him would lead him where he needs to go, and a handkerchief, with directions to wipe his face with it whenever he washes. He leaves. The king sends a carriage for his «wife». She turns back into a bird and leaves.

Her husband finally comes to the old witch Baba Yaga. She gives him food and lets him rest; then she brings him water to wash. He wipes his face not with their towel but his handkerchief. She recognizes it as their sister’s. She questions him, and he tells his story. The witch, who had never heard of something like that, knows an old frog who she thinks may know something.

Baba Yaga gives him a jug to carry the frog, which can’t walk fast enough. He does so, and the frog directs him to a river, where it tells him to get on the frog, and it swells large enough to carry him across. There, it directs him to listen to the old men who will arrive soon. He does and hears them summon «Shmat Razum» to serve them. Then the old men leave, and he hears Shmat Razum lament how they treated him. The men ask Shmat Razum to serve the hunter instead, and Shmat Razum agrees.

Shmat Razum carries him back. The hunter stops at a golden arbor, where he meets three merchants. With Shmat Razum’s directions, he exchanges his servant for three marvels, which could summon up a garden, a fleet of ships, and an army. But after a day, Shmat Razum returns to the hunter.

In his own country, the hunter has Shmat Razum build a castle. His wife returns to him there. The former king of the country sees the castle and marches against the hunter. The new king, with the help of his wife, summons the fleet and the army. They defeat the other king and the hunter is chosen as the king in his place.

Analysis[edit]

Tale type[edit]

The tale is classified in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index as ATU 465, «The Man persecuted because of his beautiful wife». This tale type involves a unmarried man capturing an animal and bringing it home. When the man is not at home, the animal takes off its animal skin and becomes a beautiful maiden. The hunter returns, burns the skin and marries the maiden. Some time later, an emperor, lord or nobleman of superior rank lusts after the wife of supernatural origin and sends the mortal husband on impossible quests.[1]

In the third revision of the international index, German folklorist Hans-Jörg Uther subsumed subtypes AaTh 465A, AaTh 465B, AaTh 465C and AaTh 465D under a single tale type, ATU 465.[2]

Role of the animal bride[edit]

Professor Susan Hoogasian-Villa mentioned variants where the hero (a prince or a hunter) marries a maiden that becomes an aquatic animal (mostly fish, but sometimes a frog or a tortoise) or a kind of bird.[3] Graham Anderson also noted that the supernatural wife in this tale type appears to show «amphibious connections», since she wears the disguise of a water animal (fish, turtle, frog).[4]

Scholars Ibrahim Muhawi and Sharif Kanaana, in the Arab and Palestinian parallels they gathered, noted that the human husband is a fisherman «in most other [tales]».[5] Likewise, Greek researcher Marilena Papachristophorou described that, in Greek variants, the animal bride comes in the shape of a turtle and the human husband is «usually a fisherman».[6] Folklorist Lev Barag [ru] noted the resemblance between a Belarusian variant and tales from Asian peoples wherein a poor and destitute youth marries the daughter of a god.[7]

Scholar Joanna Hubbs interpreted the tale under a mythological lens, and stated that the female characters of the story are representations of a powerful female divinity. Thus, in the tale, the male hunter achieves the happy ending due to the actions of his wife and her magical family.[8] Likewise, scholars Ibrahim Muhawi and Sharif Kanaana stated that «in each case [of every tale]», the male protagonist is helped by his wife and her relatives (mother and/or sisters).[9]

Role of the hero’s rival[edit]

Some scholars point out the hero’s main rival may be his own father.[10][11] The paternal antagonist also occurs in Greek variants, according to scholars Anna Angelopoulou and Aigle Broskou.[12]

Armenian scholarship suggests that tale type ATU 465 underlies a theme of incest, reminiscent of the Greek myth of Oedipus. For instance, Tamar Hayrapetyan argues that an «archaic» version may preserve the hero’s father lusting after his own daughter-in-law, while later tradition excises the incest theme altogether and replaces the father for a stranger.[13]

Variants[edit]

Professor Stith Thompson argued that the tale is «essentially East European», «at home in Russia», but could also be found in the Near East, in Baltic[14][15] and Scandinavian countries.[16] According to Japanese scholar Seki Keigo, the tale type is «common in eastern Europe, India, and China».[17]

Literary predecessors[edit]

The oldest attestation of the tale type is found in ancient East Asian literature of the 7th century, namely Chinese and Japanese.[18] Seki Keigo pinned down its appearance in some literary collections of his country, such as in Nihongi, the Ryoi-ki and the Sangoku Denki [ja].[19]

Scholar David Blamires argues for the existence of the tale type in the medieval work Gesta Romanorum. In the tale, an emperor is desirous to possess not the knight’s wife, but the knight’s lands, and orders him to bring a black horse, a black falcon, a black dog and a black horn. The knight’s wife guides her husband through the impossible quest.[20]

Europe[edit]

Professor Jack V. Haney stated that subtypes 465A and 465C appear as the «typical combination» in East Slavic, Baltic and Turkic,[21] but type 465C only appears in Northeastern Europe and in Turkic traditions.[22]

In a «Cossack» (Ukrainian) tale, The Story of Ivan and the Daughter of the Sun, the peasant Ivan obtains a wife in the form of a dove maiden whose robe he stole when she was bathing. Some time later, a nobleman lusts after Ivan’s dove maiden wife and plans to get rid of the peasant.[23]

In an Armenian variant, The Maiden of the Sea (La fille de la mer), a poor widow, on her deathbed, instructs her only son to throw a loaf of bread into the sea, just as she did in life. One day, the youth arrives home and sees the place all clean and tidy. Suspecting something is amiss, the boy stays in waiting and sees a fish coming out of the sea and taking their fishskin off, revealing itself to be a beautiful maiden. The youth seizes her and she screams for help, to which a voice claims from the sea that the human is its son-in-law. The fish maiden and the youth marry and, one day, the Prince, passing by their cottage, sights the maiden and becomes enamored with her. He then orders her husband to meet his outlandish demands.[24][25]

Baltic variants of the tale type (formerly AaTh 465A), like Žaibas ir Perkūnas tabokinėje, attest the presence of Baltic thunder god Perkūnas.[26]

In one Estonian variant, the human husband acquires a maiden from above as his wife, and in another the mother-in-law is the ruler of the Sun.[27]

Russia[edit]

In a tale by Bernard Isaacs, Go I Know Not Where, Fetch I Know Not What, the hunter shoots a turtledove, which transforms into a maiden called Tsarevna Marya. When the hunter goes on the quest for the «something» the Tsar wants, he meets Baba Yaga, who the narrative describes as the mother of his wife.[28]

In a tale translated by Jeremiah Curtin, Go to the Verge of Destruction and Bring Back Shmat-Razum, one of the king’s sharpshooters, named Fedot, spares a blue dove and she becomes a «soul-maiden», a lovely tsar’s daughter. When her husband is tasked with bringing back «Shmat-Razum», he meets three princesses and their aged mother — her wife’s family.[29] The tale was also translated by Nisbet Bain with the title Go I Know Not Whither—Fetch I Know Not What.[30]

In a tale published by journalist Post Wheeler, Schmat-Razum, the bowman Taraban, while on a hunt, sees seven white ducks with silver wings beneath a tree. When they alight near the «sea-ocean», the seven birds take off their silver wings and become maidens. Taraban hides the silver wings of one of them. The other six white ducks depart, but one stays behind. The maiden asks the stranger to give her wings back and, if they are a youth, she will marry him. They marry, but Taraban shows up at court to explain to the Tzar he married without his permission. Taraban presents his wife to the Tzar and his court, and they decide to send the bowman to look for «Schmat-Razum», to try to get rid of him.[31]

In a tale translated by Charles Downing as I know-not-what of I-know-not-where, the archer is called Petrushka. While on a hunt, he finds an injured dove and brings it home. The dove becomes a human girl named Masha, the Dove Maiden. After a while the emperor becomes enamored with Masha, and sends her husband on an errand to find «I-Know-Not-What» in a place called «I-Know-Not-Where». The archer completes the task with the help of Baba Yaga and a magical frog named Babushka-Lyagushka-Skakushka («Grandmother Hopping Frog»).[32][33]

In a tale collected in the White Sea region from Russian storyteller Matvei M. Korguev [ru] with the title «Ондрей-стрелец» («Ondrey, the Archer»), Ondrey is a member of the royal archers, and one day decides to go alone on a hunt. He shoots a female falcon (Russian: соколица, «sokolitsa») with an arrow and goes to kill it, but the falcon, with human voice, pleads for its life and asks to be taken to his home. He does and the falcon becomes a human maiden. They live as man and wife for some time. Months into their domestic arrangement, the falcon maiden wants to help her human husband improve is material wealth, so she weaves for him a carpet, and tells him to sell by the nighest price. The prince’s servant buys it a hangs on a castle wall. The prince admires the handwork and asks about its origins. The servant says Ondrey’s wife did it. They go to Ondrey’s hut and his wife opens the door. They admire her great beauty, and, after returning to the palace, plot to kill Ondrey and take the maiden. Thus, the prince, advised by a witch, sends Ondrey on dangerous errands: first, to get a golden sheep’s head from Buyan; then a golden pig hair; lastly, to go «don’t know where», fetch «don’t know what». The falcon maiden, named Elena the Beautiful, summons magical help to produce the golden sheep’s head and the pig hair. As for the «don’t know whay», Elena gives her husband a yarn he must roll out and follow the thread where it ends. With tears in his eyes, he says goodbye to his wife and follows the ball of yarn. It stops at a castle, where his wife’s family lives. With the help of his mother-in-law, a wise sorceress, he locates the «don’t know what»: a spirit named Svat Naum.[34]

Kalmyk people[edit]

According to Baira Goryaeva, expert on Kalmyk folklore, tale type 465A, in the Kalmyk tale corpus, shows that the hero (of humble origins) marries a daughter of Khurmusta-Tengri, a celestial deity.[35]

In a Kalmyk tale, Tsarkin Khan and the Archer, an Archer steals the robe of a «golden-crowned» swan maiden when she was in human form and marries her. Later, the titular Tsarkin Khan wants to marry the Archer’s swan maiden wife and plans to get rid of him by setting dangerous tasks.[36]

Gagauz people[edit]

In a tale from the Gagauz people, Concerning the Sun, collected by Moshkov and translated by Charles Fillingham Coxwell [de], a tsar orders his three sons to shoot three arrows to decide their fates. The elders’ arrows land near human maidens; the youngest’s falls nears a tortoise. The tsar’s son takes the tortoise home and goes hunting. When he returns at night, he sees the place clean and tidy and a meal prepared for him. He discovers that the tortoise changes into a beautiful human maiden and gets rid of her shell. Some time later, his father, the tsar, sees his daughter-in-law and decides to have her for himself. So he goes to his son and tasks him with getting his dead mother (the tsar’s dead wife)’s ring, by going into the other world. The magical wife, now human, instructs her human husband to go to the sea and shout into a hole, her mother will appear and give him the keys to the earth. The tsar’s son obeys his wife and uses the keys on the locks of the earth; the enters the earth and begins a journey. Every stop he is asked by a person about a problem, and the tsar’s son promises to bring the questions to God (tale type ATU 461, «Three Hairs from the Devil’s Beard»). He reaches a shining castle, and meets the mother of the Sun, who tells him that the Sun has his mother’s ring.[37] Coxwell compared the initial episode to the Russian tale Frog Princess and German (Grimm) tale The Three Feathers.[38]

Georgia[edit]

According to Georgian scholarship, tale type ATU 402, «The Frog as Bride», is «contaminated» with (former) tale type AaTh 465C, «Beautiful Wife (The Journey to the Other World)»: the task the hero’s rival sets him is to visit Hell (Other World) in search of something (a soul of a deceased person, an object).[39]

In a Georgian tale, The Frog’s Skin, three brothers try their luck in finding a bride by shooting three arrows at random locations. The third brother’s arrow falls near a lake; a frong jumps out of it and he takes it home. His elder brothers find human girls as brides, whereas he has to remain with a frog, but such is his fate. One day, after he returns from work, he sees that the house has been swept and cleaned up. He decides to discover who is this mysterious housekeeper: he hides one day and sees that the frog casts off its amphibian skin to become a human maiden. The man takes skin to burn it. Despite his frog-wife’s protests, he does it anyway. Some time later, news reach the ears of the lord of the country of the man’s beautiful wife. Hellbent on earning her as his wife, the lord threatens the man with nearly impossible tasks or death. His wife reminds him of her warning, but gives him the means to save himself: he should go to the edge of the lake where he found her and summon for Mother and Father. The last task is to go to the Other World in search of the lord’s mother and get from her a ring.[40]

In a Georgian tale translated by Caucasologist Heinz Fähnrich [de] with the title Die Tochter der Sonne («The Daughter of the Sun»), three friends work together in the fields. One of them loses his harvest and leaves to look for work elsewhere. He works for a rich man and promises to collect all the hay in one day. He almost fulfills his promise, until he sees the Sun and begs it not to st until he has finished the last one. The sun sets and night comes; the man loses his work and goes to another employer, where he works as a shepherd. A wolf comes and takes a sheep to the woods. The man follows the wolf and rests a bit near a river. He then sees three Sun maidens descending from the sky to bathe in a lake. The man takes one of the Sun maidens to his poor hut and marries her. The Sun maiden gives him a magical ring. Some time later, the poor man wants to invite the monarch to see his humble house, but his wife warns against it. He invites the king, who sends his nazirs and viziers in his stead. The nazirs and viziers go the man’s hut and see the Sun maiden. They report back to the king that a beautiful maiden is married to a poor man, when she is fit to be a king’s wife. The king then sends the poor man to get the golden ram of the Sun. The man goes to his father-in-law and gets the ram. Next, the king orders the man to go to the Afterlife to retrieve the king’s mother’s ring. His wife gives him an apple and tells him to follow it wherever it rolls. The man follows the apple and finds a deer with giant antlers, an emaciated bull and a priest carrying a church on his back who ask him the answers for their problems. He also meets a strange couple, a woman building a tower with eggs, a baker who burns bread in an oven, and they explain they are being punished for misdeeds in their lives.[41]

Greece[edit]

According to Marilena Papachristophorou, Greek scholar Georgios A. Megas [el] supposed that the Greek oikotype (the animal wife as a turtle and the human husband as a fisherman) originated from an Oriental source.[42]

Author Barbara Ker Wilson translated a Greek tale with the title The Tortoise-Wife. In this tale, a poor fisherman named Elias catches a sea tortoise and brings it home. When he is away, the sea tortoise becomes a human maiden, does the chores and prepares the food, then goes back to being a tortoise again. One day, Elias discovers the tortoise maiden and wants to make her his wife. She consents to their marriage, but behs him not to burn the tortoise shell, lest future trouble befalls them. Despite her warnings, Elias burns the tortoise shell, so the maiden remains human at all times. Some time later, the king discovers the fisherman’s beautiful wife and summons him to his court. Elias is given difficult tasks by the king, which he accomplishes with the help of his wife’s sea tortoise mother.[43]

Armenia[edit]

In a 1991 article, researcher Suzanna A. Gullakian [hy] noted a similar combination between tale types 402, «The Frog Bride», and 465, «The Man persecuted because of his Beautiful Wife», in Armenia. She also argued that this combination was «stable» and «part of the Armenian tale corpus», with at least 8 variants recorded.[44]

Asia[edit]

Turkey[edit]

Variants of the tale type in Turkey attest, for example, the coming of the fairy maiden (a peri) out of a piece of wood the male character (named Mehmet Efendi) took home.[45]

In a Turkish tale published by Ignác Kúnos with the title The Fish-Peri, a young, poor fisherman catches a fish so beautiful it saddens him to sell it or cook it, so he decides to keep it in a well. The next day, after he returns from his fishing trip at night, he sees the place neat and tidy, and wonders who could have done it. He spies on the person responsible for it, and sees that the fish has become a beautiful maiden. The youth takes the fish skin and throws it in the fire. The fish maiden consents to become his wife. However, news of her beauty reach the ears of the Padishah, who begins to lust after the maiden, and sets the fisherman on three difficult quests: to build a palace of gold and diamond in the middle of the sea in 40 days; to prepare a feast so grand everyone would eat and there would still be much food left; to have a mule hatch out of an egg, and to find a year-old infant who could talk and walk.[46]

Middle East[edit]

In the Arabian Nights collection, the tale of Prince Ahmad and the Fairy Peri Banu is also classified as belonging to the tale type. Preceded by tale type ATU 653A, «The Rarest Thing in the World», the story continues as Prince Ahmad marries the Peri Banou, the daughter of the king of the jinni. The prince, after a while, visits his father, who becomes enamoured by his daughter-in-law.[47]

Central Asia[edit]

In a Tuvan tale, Ösküs-ool and the Daughter of Kurbustu-Khan, poor orphan boy Ösküs-ool seeks employment with powerful khans. He is tasked with harvesting their fields before the sun sets, of before the moon sets. Nearly finishing both chores, the boy pleads to the moon and the sun to not set for a little longer, but time passes. The respective khans think they never finished the job, berate and whip him. Some time later, while living on his own, the daughter of Khurbustu-khan comes from the upper world in the form of a swan. The boy hides her clothing and she marries him, now that she is stranded on Earth. Some time later, an evil Karaty-khan demands that the youth produces a palace of glass and an invincible army of iron men for him — feats that he accomplishes thanks to his wife’s advice and with help from his wife’s relatives.[48]

Korea[edit]

In a Korean tale, The Snail Woman, a poor farmer laments his solitude, but a woman’s voice asks him to live with him. The youth sees no one but a tiny snail that he brings home. During the day, he toils in the rice fields, while the snail becomes a woman, does the chores and returns to the shell. The youth returns at night and amazes at the cleanliness of the place. He decides to discover who is responsible. On the third day, he sees that the snail becomes a human woman. He stops her before she returns to the shell. The snail woman reveals she is the daughter of the Dragon King, enchanted to be a mollusk. The enchantment is over and they live as husband and wife. A wealthy magistrate sees the woman and becomes enamoured. He decides to force the farmer to difficult tasks. The Dragon King’s daughter says her father will help him.[49][a]

Japan[edit]

The tale type 465 is also registered in Japan, with the name Tono no Nandai. Scholar Hiroko Ikeda reported 28 variants.[51] Seki Keigo reported 39 variants, and noted its popularity in Japanese oral tradition.[52]

In his system of Japanese folktales, Seki Keigo indexed a second type related to the story, which he titled The Flute-player Bridegroom. In this cycle, a woman from the world above descends to earth and marries a human flute player, because she enjoys his flute playing. A local feudal lord imposes three tasks on the flute-player, otherwise he must surrender his wife to the feudal lord. After they deal with the lord’s advances, the tale segues into the human’s visit to his wife’s home.[53]

Khmu people[edit]

Another variant, titled The Orphan and the Sky Maidens, was collected from the Kammu people of Southeast Asia.[54]

Buryat people[edit]

In a Buryat tale, «Молодец и его жена-лебедь» (Mongolian: «Сагаан шубуугаар haмга хэhэн хубуун»; English: Molodets and his Swan-Wife), a down-on-his-luck boy tries to get a job herding horses in the steppes, lumbering for an old man and even planting crops, but no such luck. He decides to earn his living by fishing in a lake. And thus he spends his days. One day, he sees seven white birds coming down to the lake shore and decides to follow them. He sees they transforming into seven maidens. He hides and fetches the clothing of one of them, who gets left behind and the other depart. The bird-girl calls for the stranger: if a young man, she’ll be his wife; if an old man, she’ll be his daughter. The youth reveals himself, returns the birdskin and they marry. One day, the bird maiden draws her portrait on a piece of paper that the wind blows away for seven days and seven nights, until the portrait lands on the lap of Abahai-khan, who falls madly in love with the maiden depicted and goes on a frantic search for her. He and his ministers discover she is the wife of the poor youth who lives near the lake. The Khan tries to send the poor youth on perilous quests to get rid of him, but, with his wife’s help, he prevails and becomes the next khan.[55]

Africa[edit]

Egypt[edit]

Scholar Hasan El-Shamy cited that the tale Histoire du pêcheur et de son fils («The Story of the Fisherman and his Son»),[56] collected by Guillaume Spitta-Bey in late-19th century, showed «the undisputable typological character» of type 465. In this tale, the king falls in love with the wife of a fisherman and conspires with his vizier to send him on dangerous quests.[57][58]

Sudan[edit]

In a Sudanese tale, The fisherman and the prince, a humble fisherman catches a fish, brings to his hut and goes to the market. When he returns, he sees a great palace and a beautiful maiden, who reveals she was the fish, enchanted into that form. They marry. One day, the maiden bathes in the river and draws the attention of a local prince. The prince tries to create impossible riddles for the fisherman, but he answers it with his wife’s help.[59] This tale was also classified by scholar Hasan El-Shamy under type 465.[60]