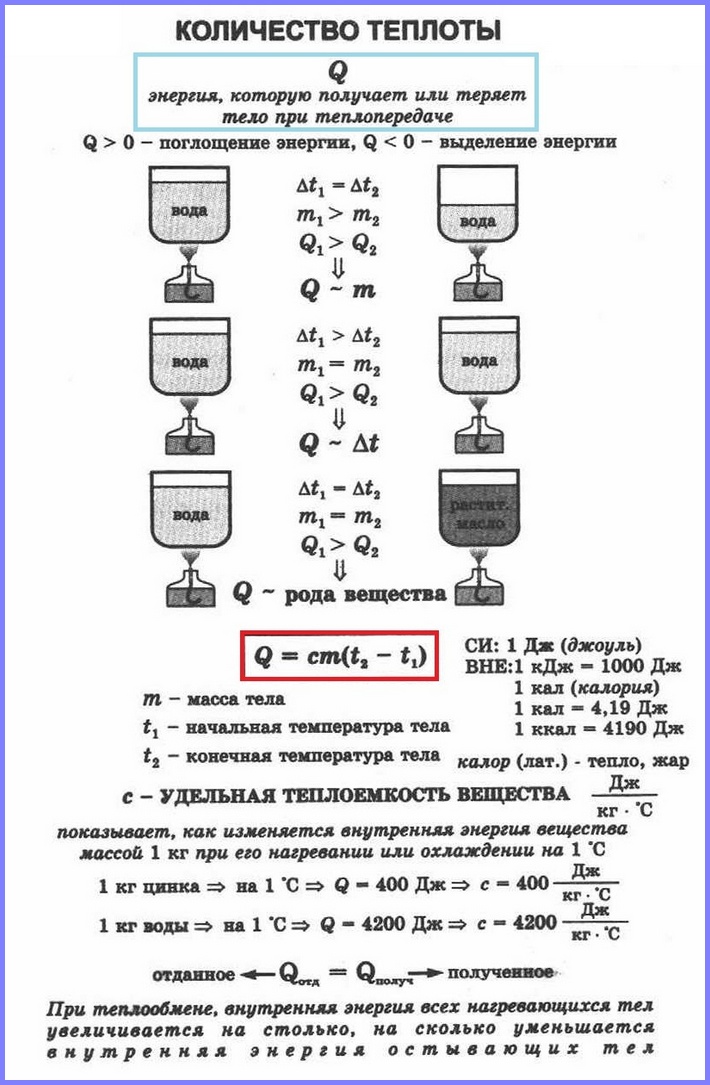

Для того чтобы нагреть на определённую величину тела, взятые при одинаковой температуре, изготовленные из различных веществ, но имеющие одинаковую массу, требуется разное количество теплоты.

Пример:

для нагревания (1) кг воды на (1°C) требуется количество теплоты, равное (4200) Дж. А если нагревать (1) кг цинка на (1°C), то потребуется всего (400) Дж.

Удельная теплоёмкость вещества — физическая величина, численно равная количеству теплоты, которое необходимо передать веществу массой (1) кг для того, чтобы его температура изменилась на (1~°C).

([c]=1frac{Дж}{кг cdot °C}).

Пример:

по таблице удельной теплоёмкости твёрдых веществ находим, что удельная теплоёмкость алюминия составляет (c(Al)=920 frac{Дж}{кг cdot °C}). Поэтому при охлаждении (1) килограмма алюминия на (1) градус Цельсия ((°C)) выделяется (920) джоулей энергии. Столько же необходимо для нагревания (1) килограмма на алюминия на (1) градус Цельсия ((°C)).

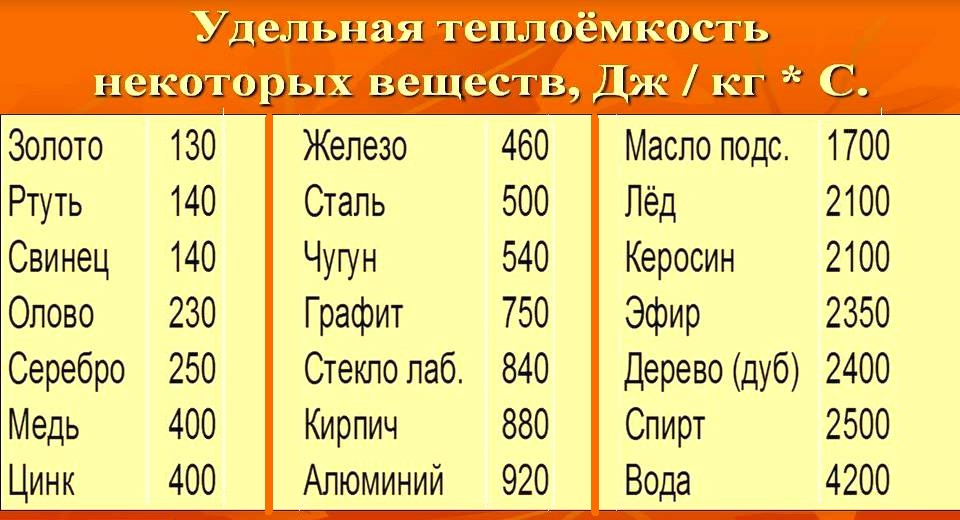

Ниже представлены значения удельной теплоёмкости для некоторых веществ.

Твёрдые вещества

|

Вещество |

(c), Дж/(кг·°C) |

| Алюминий |

(920) |

| Бетон |

(880) |

| Дерево |

(2700) |

|

Железо, сталь |

(460) |

| Золото |

(130) |

| Кирпич |

(750) |

| Латунь |

(380) |

| Лёд |

(2100) |

| Медь |

(380) |

| Нафталин |

(1300) |

| Олово |

(230) |

| Парафин |

(3200) |

| Песок |

(970) |

| Платина |

(130) |

| Свинец |

(120) |

| Серебро |

(240) |

| Стекло |

(840) |

| Цемент |

(800) |

| Цинк |

(400) |

| Чугун |

(550) |

| Сера |

(710) |

Жидкости

|

Вещество |

(c), Дж/(кг·°C) |

| Вода |

(4200) |

| Глицерин |

(2400) |

| Керосин |

(2140) |

|

Масло подсолнечное |

(1700) |

|

Масло трансформаторное |

(2000) |

| Ртуть |

(120) |

|

Спирт этиловый |

(2400) |

|

Эфир серный |

(2300) |

Газы (при постоянном давлении и температуре (20°C))

|

Вещество |

(c), Дж/(кг·°C) |

| Азот |

(1000) |

| Аммиак |

(2100) |

| Водород |

(14300) |

|

Водяной пар |

(2200) |

| Воздух |

(1000) |

| Гелий |

(5200) |

| Кислород |

(920) |

|

Углекислый газ |

(830) |

Удельная теплоёмкость реальных газов, в отличие от идеальных газов, зависит от давления и температуры. И если зависимостью удельной теплоёмкости реальных газов от давления в практических задачах можно пренебречь, то зависимость удельной теплоёмкости газов от температуры необходимо учитывать, поскольку она очень существенна.

Обрати внимание!

Удельная теплоёмкость вещества, находящегося в различных агрегатных состояниях, различна.

Пример:

вода в жидком состоянии имеет удельную теплоёмкость, равную (4200) Дж/(кг·°C), в твёрдом состоянии (лёд) — (2100) Дж/(кг·°C), в газообразном состоянии (водяной пар) — (2200) Дж/(кг·°C).

Вода — вещество особенное, обладающее самой высокой среди жидкостей удельной теплоёмкостью. Но самое интересное, что теплоёмкость воды снижается при температуре от (0°C) до (37°C) и снова растёт при дальнейшем нагревании (рис. (1)).

Рис. (1). График удельной теплоёмкости воды

В связи с этим вода в морях и океанах, нагреваясь летом, поглощает из окружающей среды огромное количество теплоты. А зимой вода остывает и отдаёт в окружающую среду большое количество теплоты. Это явление оказывает влияние на климат данного региона. Летом здесь нет изнуряющей жары, а зимой — лютых морозов.

Высокая удельная теплоёмкость воды нашла широкое применение в различных областях: от медицинских грелок до систем отопления и охлаждения.

Задумывались ли вы, почему воду используют при тушении пожаров? Из-за большой теплоёмкости. При соприкосновении с горящим предметом вода забирает у него большое количество теплоты. Оно значительно больше, чем при использовании такого же количества любой другой жидкости.

Помимо непосредственного отвода тепла, вода гасит пламя ещё и косвенным образом. Водяной пар, образующийся при контакте с огнём, окутывает горящее тело, предотвращая поступление кислорода, без которого горение невозможно.

Какой водой эффективнее тушить огонь: горячей или холодной? Горячая вода тушит огонь быстрее, чем холодная. Дело в том, что нагретая вода скорее превратится в пар, а значит, и отсечёт поступление воздуха к горящему объекту.

Источники:

Рис. 1. Автор: Epop — собственная работа. Общественное достояние, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10750129.

In thermodynamics, the specific heat capacity (symbol cp) of a substance is the heat capacity of a sample of the substance divided by the mass of the sample, also sometimes referred to as massic heat capacity. Informally, it is the amount of heat that must be added to one unit of mass of the substance in order to cause an increase of one unit in temperature. The SI unit of specific heat capacity is joule per kelvin per kilogram, J⋅kg−1⋅K−1.[1] For example, the heat required to raise the temperature of 1 kg of water by 1 K is 4184 joules, so the specific heat capacity of water is 4184 J⋅kg−1⋅K−1.[2]

Specific heat capacity often varies with temperature, and is different for each state of matter. Liquid water has one of the highest specific heat capacities among common substances, about 4184 J⋅kg−1⋅K−1 at 20 °C; but that of ice, just below 0 °C, is only 2093 J⋅kg−1⋅K−1. The specific heat capacities of iron, granite, and hydrogen gas are about 449 J⋅kg−1⋅K−1, 790 J⋅kg−1⋅K−1, and 14300 J⋅kg−1⋅K−1, respectively.[3] While the substance is undergoing a phase transition, such as melting or boiling, its specific heat capacity is technically infinite, because the heat goes into changing its state rather than raising its temperature.

The specific heat capacity of a substance, especially a gas, may be significantly higher when it is allowed to expand as it is heated (specific heat capacity at constant pressure) than when it is heated in a closed vessel that prevents expansion (specific heat capacity at constant volume). These two values are usually denoted by

The term specific heat may also refer to the ratio between the specific heat capacities of a substance at a given temperature and of a reference substance at a reference temperature, such as water at 15 °C;[4] much in the fashion of specific gravity. Specific heat capacity is also related to other intensive measures of heat capacity with other denominators. If the amount of substance is measured as a number of moles, one gets the molar heat capacity instead, whose SI unit is joule per kelvin per mole, J⋅mol−1⋅K−1. If the amount is taken to be the volume of the sample (as is sometimes done in engineering), one gets the volumetric heat capacity, whose SI unit is joule per kelvin per cubic meter, J⋅m−3⋅K−1.

One of the first scientists to use the concept was Joseph Black, an 18th-century medical doctor and professor of medicine at Glasgow University. He measured the specific heat capacities of many substances, using the term capacity for heat.[5]

Definition[edit]

The specific heat capacity of a substance, usually denoted by

where

Like the heat capacity of an object, the specific heat capacity of a substance may vary, sometimes substantially, depending on the starting temperature

These parameters are usually specified when giving the specific heat capacity of a substance. For example, «Water (liquid):

However, the dependency of

Specific heat capacity is an intensive property of a substance, an intrinsic characteristic that does not depend on the size or shape of the amount in consideration. (The qualifier «specific» in front of an extensive property often indicates an intensive property derived from it.[8])

Variations[edit]

The injection of heat energy into a substance, besides raising its temperature, usually causes an increase in its volume and/or its pressure, depending on how the sample is confined. The choice made about the latter affects the measured specific heat capacity, even for the same starting pressure

- If the pressure is kept constant (for instance, at the ambient atmospheric pressure), and the sample is allowed to expand, the expansion generates work as the force from the pressure displaces the enclosure or the surrounding fluid. That work must come from the heat energy provided. The specific heat capacity thus obtained is said to be measured at constant pressure (or isobaric), and is often denoted

,

, etc.

- On the other hand, if the expansion is prevented — for example by a sufficiently rigid enclosure, or by increasing the external pressure to counteract the internal one — no work is generated, and the heat energy that would have gone into it must instead contribute to the internal energy of the sample, including raising its temperature by an extra amount. The specific heat capacity obtained this way is said to be measured at constant volume (or isochoric) and denoted

,

,

, etc.

The value of

Applicability[edit]

The specific heat capacity can be defined and measured for gases, liquids, and solids of fairly general composition and molecular structure. These include gas mixtures, solutions and alloys, or heterogenous materials such as milk, sand, granite, and concrete, if considered at a sufficiently large scale.

The specific heat capacity can be defined also for materials that change state or composition as the temperature and pressure change, as long as the changes are reversible and gradual. Thus, for example, the concepts are definable for a gas or liquid that dissociates as the temperature increases, as long as the products of the dissociation promptly and completely recombine when it drops.

The specific heat capacity is not meaningful if the substance undergoes irreversible chemical changes, or if there is a phase change, such as melting or boiling, at a sharp temperature within the range of temperatures spanned by the measurement.

Measurement[edit]

The specific heat capacity of a substance is typically determined according to the definition; namely, by measuring the heat capacity of a sample of the substance, usually with a calorimeter, and dividing by the sample’s mass . Several techniques can be applied for estimating the heat capacity of a substance as for example fast differential scanning calorimetry.[10][11]

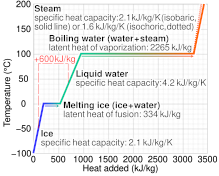

Graph of temperature of phases of water heated from −100 °C to 200 °C – the dashed line example shows that melting and heating 1 kg of ice at −50 °C to water at 40 °C needs 600 kJ

The specific heat capacities of gases can be measured at constant volume, by enclosing the sample in a rigid container. On the other hand, measuring the specific heat capacity at constant volume can be prohibitively difficult for liquids and solids, since one often would need impractical pressures in order to prevent the expansion that would be caused by even small increases in temperature. Instead, the common practice is to measure the specific heat capacity at constant pressure (allowing the material to expand or contract as it wishes), determine separately the coefficient of thermal expansion and the compressibility of the material, and compute the specific heat capacity at constant volume from these data according to the laws of thermodynamics.[citation needed]

Units[edit]

International system[edit]

The SI unit for specific heat capacity is joule per kelvin per kilogram J/kg⋅K, J⋅K−1⋅kg−1. Since an increment of temperature of one degree Celsius is the same as an increment of one kelvin, that is the same as joule per degree Celsius per kilogram: J/(kg⋅°C). Sometimes the gram is used instead of kilogram for the unit of mass: 1 J⋅g−1⋅K−1 = 0.001 J⋅kg−1⋅K−1.

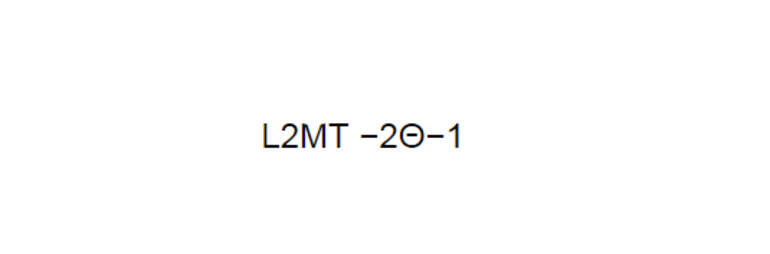

The specific heat capacity of a substance (per unit of mass) has dimension L2⋅Θ−1⋅T−2, or (L/T)2/Θ. Therefore, the SI unit J⋅kg−1⋅K−1 is equivalent to metre squared per second squared per kelvin (m2⋅K−1⋅s−2).

Imperial engineering units[edit]

Professionals in construction, civil engineering, chemical engineering, and other technical disciplines, especially in the United States, may use English Engineering units including the pound (lb = 0.45359237 kg) as the unit of mass, the degree Fahrenheit or Rankine (°R = 5/9 K, about 0.555556 K) as the unit of temperature increment, and the British thermal unit (BTU ≈ 1055.056 J),[12][13] as the unit of heat.

In those contexts, the unit of specific heat capacity is BTU/lb⋅°R, or 1 BTU/lb⋅°R = 4186.68J/kg⋅K.[14] The BTU was originally defined so that the average specific heat capacity of water would be 1 BTU/lb⋅°F.[15] Note the value’s similarity to that of the calorie — 4187 J/kg⋅°C ≈ 4184 J/kg⋅°C (~.07%) — as they are essentially measuring the same energy, using water as a basis reference, scaled to their systems’ respective lbs and °F, or kg and °C.

Calories[edit]

In chemistry, heat amounts were often measured in calories. Confusingly, two units with that name, denoted «cal» or «Cal», have been commonly used to measure amounts of heat:

- the «small calorie» (or «gram-calorie», «cal») is 4.184 J, exactly. It was originally defined so that the specific heat capacity of liquid water would be 1 cal/°C⋅g.

- The «grand calorie» (also «kilocalorie», «kilogram-calorie», or «food calorie»; «kcal» or «Cal») is 1000 small calories, that is, 4184 J, exactly. It was defined so that the specific heat capacity of water would be 1 Cal/°C⋅kg.

While these units are still used in some contexts (such as kilogram calorie in nutrition), their use is now deprecated in technical and scientific fields. When heat is measured in these units, the unit of specific heat capacity is usually

- 1 cal/°C⋅g («small calorie») = 1 Cal/°C⋅kg = 1 kcal/°C⋅kg («large calorie») = 4184 J/kg⋅°K[16] = 4.184 kJ/kg⋅°K.

Note that while cal is 1⁄1000 of a Cal or kcal, it is also per gram instead of kilogram: ergo, in either unit, the specific heat capacity of water is approximately 1.

Physical basis[edit]

The temperature of a sample of a substance reflects the average kinetic energy of its constituent particles (atoms or molecules) relative to its center of mass. However, not all energy provided to a sample of a substance will go into raising its temperature, exemplified via the equipartition theorem.

Monatomic gases[edit]

Quantum mechanics predicts that, at room temperature and ordinary pressures, an isolated atom in a gas cannot store any significant amount of energy except in the form of kinetic energy. Thus, heat capacity per mole is the same for all monatomic gases (such as the noble gases). More precisely,

Therefore, the specific heat capacity (per unit of mass, not per mole) of a monatomic gas will be inversely proportional to its (adimensional) atomic weight

For the noble gases, from helium to xenon, these computed values are

| Gas | He | Ne | Ar | Kr | Xe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

4.00 | 20.17 | 39.95 | 83.80 | 131.29 |

(J⋅K−1⋅kg−1) (J⋅K−1⋅kg−1)

|

3118 | 618.3 | 312.2 | 148.8 | 94.99 |

(J⋅K−1⋅kg−1) (J⋅K−1⋅kg−1)

|

5197 | 1031 | 520.3 | 248.0 | 158.3 |

Polyatomic gases[edit]

On the other hand, a polyatomic gas molecule (consisting of two or more atoms bound together) can store heat energy in other forms besides its kinetic energy. These forms include rotation of the molecule, and vibration of the atoms relative to its center of mass.

These extra degrees of freedom or «modes» contribute to the specific heat capacity of the substance. Namely, when heat energy is injected into a gas with polyatomic molecules, only part of it will go into increasing their kinetic energy, and hence the temperature; the rest will go to into those other degrees of freedom. In order to achieve the same increase in temperature, more heat energy will have to be provided to a mol of that substance than to a mol of a monatomic gas. Therefore, the specific heat capacity of a polyatomic gas depends not only on its molecular mass, but also on the number of degrees of freedom that the molecules have.[17][18][19]

Quantum mechanics further says that each rotational or vibrational mode can only take or lose energy in certain discrete amount (quanta). Depending on the temperature, the average heat energy per molecule may be too small compared to the quanta needed to activate some of those degrees of freedom. Those modes are said to be «frozen out». In that case, the specific heat capacity of the substance is going to increase with temperature, sometimes in a step-like fashion, as more modes become unfrozen and start absorbing part of the input heat energy.

For example, the molar heat capacity of nitrogen N

2 at constant volume is

2 (736 J⋅K−1⋅kg−1) is greater than that of an hypothetical monatomic gas with the same molecular mass 28 (445 J⋅K−1⋅kg−1), by a factor of 5/3.

This value for the specific heat capacity of nitrogen is practically constant from below −150 °C to about 300 °C. In that temperature range, the two additional degrees of freedom that correspond to vibrations of the atoms, stretching and compressing the bond, are still «frozen out». At about that temperature, those modes begin to «un-freeze», and as a result

Derivations of heat capacity[edit]

Relation between specific heat capacities[edit]

Starting from the fundamental thermodynamic relation one can show,

where,

A derivation is discussed in the article Relations between specific heats.

For an ideal gas, if

where

Specific heat capacity[edit]

The specific heat capacity of a material on a per mass basis is

which in the absence of phase transitions is equivalent to

where

For gases, and also for other materials under high pressures, there is need to distinguish between different boundary conditions for the processes under consideration (since values differ significantly between different conditions). Typical processes for which a heat capacity may be defined include isobaric (constant pressure,

A related parameter to

For pure homogeneous chemical compounds with established molecular or molar mass or a molar quantity is established, heat capacity as an intensive property can be expressed on a per mole basis instead of a per mass basis by the following equations analogous to the per mass equations:

where n = number of moles in the body or thermodynamic system. One may refer to such a per mole quantity as molar heat capacity to distinguish it from specific heat capacity on a per-mass basis.

Polytropic heat capacity[edit]

The polytropic heat capacity is calculated at processes if all the thermodynamic properties (pressure, volume, temperature) change

The most important polytropic processes run between the adiabatic and the isotherm functions, the polytropic index is between 1 and the adiabatic exponent (γ or κ)

Dimensionless heat capacity[edit]

The dimensionless heat capacity of a material is

where

- C is the heat capacity of a body made of the material in question (J/K)

- n is the amount of substance in the body (mol)

- R is the gas constant (J⋅K−1⋅mol−1)

- N is the number of molecules in the body. (dimensionless)

- kB is the Boltzmann constant (J⋅K−1)

Again, SI units shown for example.

Read more about the quantities of dimension one[22] at BIPM

In the Ideal gas article, dimensionless heat capacity

Heat capacity at absolute zero[edit]

From the definition of entropy

the absolute entropy can be calculated by integrating from zero kelvins temperature to the final temperature Tf

The heat capacity must be zero at zero temperature in order for the above integral not to yield an infinite absolute entropy, thus violating the third law of thermodynamics. One of the strengths of the Debye model is that (unlike the preceding Einstein model) it predicts the proper mathematical form of the approach of heat capacity toward zero, as absolute zero temperature is approached.

Solid phase[edit]

The theoretical maximum heat capacity for larger and larger multi-atomic gases at higher temperatures, also approaches the Dulong–Petit limit of 3R, so long as this is calculated per mole of atoms, not molecules. The reason is that gases with very large molecules, in theory have almost the same high-temperature heat capacity as solids, lacking only the (small) heat capacity contribution that comes from potential energy that cannot be stored between separate molecules in a gas.

The Dulong–Petit limit results from the equipartition theorem, and as such is only valid in the classical limit of a microstate continuum, which is a high temperature limit. For light and non-metallic elements, as well as most of the common molecular solids based on carbon compounds at standard ambient temperature, quantum effects may also play an important role, as they do in multi-atomic gases. These effects usually combine to give heat capacities lower than 3R per mole of atoms in the solid, although in molecular solids, heat capacities calculated per mole of molecules in molecular solids may be more than 3R. For example, the heat capacity of water ice at the melting point is about 4.6R per mole of molecules, but only 1.5R per mole of atoms. The lower than 3R number «per atom» (as is the case with diamond and beryllium) results from the “freezing out” of possible vibration modes for light atoms at suitably low temperatures, just as in many low-mass-atom gases at room temperatures. Because of high crystal binding energies, these effects are seen in solids more often than liquids: for example the heat capacity of liquid water is twice that of ice at near the same temperature, and is again close to the 3R per mole of atoms of the Dulong–Petit theoretical maximum.

For a more modern and precise analysis of the heat capacities of solids, especially at low temperatures, it is useful to use the idea of phonons. See Debye model.

Theoretical estimation[edit]

The path integral Monte Carlo method is a numerical approach for determining the values of heat capacity, based on quantum dynamical principles. However, good approximations can be made for gases in many states using simpler methods outlined below. For many solids composed of relatively heavy atoms (atomic number > iron), at non-cryogenic temperatures, the heat capacity at room temperature approaches 3R = 24.94 joules per kelvin per mole of atoms (Dulong–Petit law, R is the gas constant). Low temperature approximations for both gases and solids at temperatures less than their characteristic Einstein temperatures or Debye temperatures can be made by the methods of Einstein and Debye discussed below.

Water (liquid): CP = 4185.5 J⋅K−1⋅kg−1 (15 °C, 101.325 kPa)

Water (liquid): CVH = 74.539 J⋅K−1⋅mol−1 (25 °C)

For liquids and gases, it is important to know the pressure to which given heat capacity data refer. Most published data are given for standard pressure. However, different standard conditions for temperature and pressure have been defined by different organizations. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) changed its recommendation from one atmosphere to the round value 100 kPa (≈750.062 Torr).[notes 1]

Calculation from first principles[edit]

The path integral Monte Carlo method is a numerical approach for determining the values of heat capacity, based on quantum dynamical principles. However, good approximations can be made for gases in many states using simpler methods outlined below. For many solids composed of relatively heavy atoms (atomic number > iron), at non-cryogenic temperatures, the heat capacity at room temperature approaches 3R = 24.94 joules per kelvin per mole of atoms (Dulong–Petit law, R is the gas constant). Low temperature approximations for both gases and solids at temperatures less than their characteristic Einstein temperatures or Debye temperatures can be made by the methods of Einstein and Debye discussed below.

Relation between heat capacities[edit]

Measuring the specific heat capacity at constant volume can be prohibitively difficult for liquids and solids. That is, small temperature changes typically require large pressures to maintain a liquid or solid at constant volume, implying that the containing vessel must be nearly rigid or at least very strong (see coefficient of thermal expansion and compressibility). Instead, it is easier to measure the heat capacity at constant pressure (allowing the material to expand or contract freely) and solve for the heat capacity at constant volume using mathematical relationships derived from the basic thermodynamic laws.

The heat capacity ratio, or adiabatic index, is the ratio of the heat capacity at constant pressure to heat capacity at constant volume. It is sometimes also known as the isentropic expansion factor.

Ideal gas[edit]

[23]

For an ideal gas, evaluating the partial derivatives above according to the equation of state, where R is the gas constant, for an ideal gas

Substituting

this equation reduces simply to Mayer’s relation:

The differences in heat capacities as defined by the above Mayer relation is only exact for an ideal gas and would be different for any real gas.

Specific heat capacity[edit]

The specific heat capacity of a material on a per mass basis is

which in the absence of phase transitions is equivalent to

where

For gases, and also for other materials under high pressures, there is need to distinguish between different boundary conditions for the processes under consideration (since values differ significantly between different conditions). Typical processes for which a heat capacity may be defined include isobaric (constant pressure,

From the results of the previous section, dividing through by the mass gives the relation

A related parameter to

For pure homogeneous chemical compounds with established molecular or molar mass, or a molar quantity, heat capacity as an intensive property can be expressed on a per-mole basis instead of a per-mass basis by the following equations analogous to the per mass equations:

where n is the number of moles in the body or thermodynamic system. One may refer to such a per-mole quantity as molar heat capacity to distinguish it from specific heat capacity on a per-mass basis.

Polytropic heat capacity[edit]

The polytropic heat capacity is calculated at processes if all the thermodynamic properties (pressure, volume, temperature) change:

The most important polytropic processes run between the adiabatic and the isotherm functions, the polytropic index is between 1 and the adiabatic exponent (γ or κ).

Dimensionless heat capacity[edit]

The dimensionless heat capacity of a material is

where

is the heat capacity of a body made of the material in question (J/K),

- n is the amount of substance in the body (mol),

- R is the gas constant (J/(K⋅mol)),

- N is the number of molecules in the body (dimensionless),

- kB is the Boltzmann constant (J/(K⋅molecule)).

In the ideal gas article, dimensionless heat capacity

More generally, the dimensionless heat capacity relates the logarithmic increase in temperature to the increase in the dimensionless entropy per particle

Alternatively, using base-2 logarithms,

Heat capacity at absolute zero[edit]

From the definition of entropy

the absolute entropy can be calculated by integrating from zero to the final temperature Tf:

Thermodynamic derivation[edit]

In theory, the specific heat capacity of a substance can also be derived from its abstract thermodynamic modeling by an equation of state and an internal energy function.

State of matter in a homogeneous sample[edit]

To apply the theory, one considers the sample of the substance (solid, liquid, or gas) for which the specific heat capacity can be defined; in particular, that it has homogeneous composition and fixed mass

The state of the material can then be specified by three parameters: its temperature

Those variables are not independent. The allowed states are defined by an equation of state relating those three variables:

For some simple materials, like an ideal gas, one can derive from basic theory the equation of state

Conservation of energy[edit]

The absolute value of this quantity is undefined, and (for the purposes of thermodynamics) the state of «zero internal energy» can be chosen arbitrarily. However, by the law of conservation of energy, any infinitesimal increase

hence

If the volume of the sample (hence the specific volume of the material) is kept constant during the injection of the heat amount

where

For the heat capacity at constant pressure, it is useful to define the specific enthalpy of the system as the sum

therefore

If the pressure is kept constant, the second term on the left-hand side is zero, and

The left-hand side is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure

Connection to equation of state[edit]

In general, the infinitesimal quantities

Here

This analysis also holds no matter how the energy increment

Relation between heat capacities[edit]

For any specific volume

and

for any values of

Then, from the fundamental thermodynamic relation it follows that

This equation can be rewritten as

where

both depending on the state

The heat capacity ratio, or adiabatic index, is the ratio

Calculation from first principles[edit]

The path integral Monte Carlo method is a numerical approach for determining the values of heat capacity, based on quantum dynamical principles. However, good approximations can be made for gases in many states using simpler methods outlined below. For many solids composed of relatively heavy atoms (atomic number > iron), at non-cryogenic temperatures, the heat capacity at room temperature approaches 3R = 24.94 joules per kelvin per mole of atoms (Dulong–Petit law, R is the gas constant). Low temperature approximations for both gases and solids at temperatures less than their characteristic Einstein temperatures or Debye temperatures can be made by the methods of Einstein and Debye discussed below. However, attention should be made for the consistency of such ab-initio considerations when used along with an equation of state for the considered material.[26]

Ideal gas[edit]

For an ideal gas, evaluating the partial derivatives above according to the equation of state, where R is the gas constant, for an ideal gas[27]

Substituting

this equation reduces simply to Mayer’s relation:

The differences in heat capacities as defined by the above Mayer relation is only exact for an ideal gas and would be different for any real gas.

See also[edit]

Physics portal

- Specific heat of melting (Enthalpy of fusion)

- Specific heat of vaporization (Enthalpy of vaporization)

- Frenkel line

- Heat capacity ratio

- Heat equation

- Heat transfer coefficient

- History of thermodynamics

- Joback method (Estimation of heat capacities)

- Latent heat

- Material properties (thermodynamics)

- Quantum statistical mechanics

- R-value (insulation)

- Specific heat of vaporization

- Specific melting heat

- Statistical mechanics

- Table of specific heat capacities

- Thermal mass

- Thermodynamic databases for pure substances

- Thermodynamic equations

- Volumetric heat capacity

Notes[edit]

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «Standard Pressure». doi:10.1351/goldbook.S05921.

References[edit]

- ^ Open University (2008). S104 Book 3 Energy and Light, p. 59. The Open University. ISBN 9781848731646.

- ^ Open University (2008). S104 Book 3 Energy and Light, p. 179. The Open University. ISBN 9781848731646.

- ^ Engineering ToolBox (2003). «Specific Heat of some common Substances».

- ^ (2001): Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed.; as quoted by Encyclopedia.com. Columbia University Press. Accessed on 2019-04-11.

- ^

Laidler, Keith, J. (1993). The World of Physical Chemistry. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-855919-4. - ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-06-04, retrieved 2021-12-16

- ^ «Water – Thermal Properties». Engineeringtoolbox.com. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, Physical Chemistry Division. «Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry» (PDF). Blackwell Sciences. p. 7.

The adjective specific before the name of an extensive quantity is often used to mean divided by mass.

- ^ Lange’s Handbook of Chemistry, 10th ed. page 1524

- ^ Quick, C. R.; Schawe, J. E. K.; Uggowitzer, P. J.; Pogatscher, S. (2019-07-01). «Measurement of specific heat capacity via fast scanning calorimetry—Accuracy and loss corrections». Thermochimica Acta. Special Issue on occasion of the 65th birthday of Christoph Schick. 677: 12–20. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2019.03.021. ISSN 0040-6031.

- ^ Pogatscher, S.; Leutenegger, D.; Schawe, J. E. K.; Uggowitzer, P. J.; Löffler, J. F. (September 2016). «Solid–solid phase transitions via melting in metals». Nature Communications. 7 (1): 11113. Bibcode:2016NatCo…711113P. doi:10.1038/ncomms11113. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4844691. PMID 27103085.

- ^

Koch, Werner (2013). VDI Steam Tables (4 ed.). Springer. p. 8. ISBN 9783642529412. Published under the auspices of the Verein Deutscher Ingenieure (VDI). - ^

Cardarelli, Francois (2012). Scientific Unit Conversion: A Practical Guide to Metrication. M.J. Shields (translation) (2 ed.). Springer. p. 19. ISBN 9781447108054. - ^ From direct values: 1BTU/lb⋅°R × 1055.06J/BTU × (1/0.45359237)lb/kg x 9/5°R/K = 4186.82J/kg⋅K

- ^ °F=°R

- ^ °C=°K

- ^ Feynman, R., The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. 1, ch. 40, pp. 7–8

- ^ Reif, F. (1965). Fundamentals of statistical and thermal physics. McGraw-Hill. pp. 253–254.

- ^ Kittel, Charles and Kroemer, Herbert (2000). Thermal physics. Freeman. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-7167-1088-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thornton, Steven T. and Rex, Andrew (1993) Modern Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Saunders College Publishing

- ^ Chase, M.W. Jr. (1998) NIST-JANAF Themochemical Tables, Fourth Edition, In Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, Monograph 9, pages 1–1951.

- ^ «About the unit one«.

- ^ Yunus A. Cengel and Michael A. Boles,Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach, 7th Edition, McGraw-Hill, 2010, ISBN 007-352932-X.

- ^ Fraundorf, P. (2003). «Heat capacity in bits». American Journal of Physics. 71 (11): 1142. arXiv:cond-mat/9711074. Bibcode:2003AmJPh..71.1142F. doi:10.1119/1.1593658. S2CID 18742525.

- ^ Feynman, Richard The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. 1, Ch. 45

- ^ S. Benjelloun, «Thermodynamic identities and thermodynamic consistency of Equation of States», Link to Archiv e-print Link to Hal e-print

- ^ Cengel, Yunus A. and Boles, Michael A. (2010) Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach, 7th Edition, McGraw-Hill ISBN 007-352932-X.

Further reading[edit]

- Emmerich Wilhelm & Trevor M. Letcher, Eds., 2010, Heat Capacities: Liquids, Solutions and Vapours, Cambridge, U.K.:Royal Society of Chemistry, ISBN 0-85404-176-1. A very recent outline of selected traditional aspects of the title subject, including a recent specialist introduction to its theory, Emmerich Wilhelm, «Heat Capacities: Introduction, Concepts, and Selected Applications» (Chapter 1, pp. 1–27), chapters on traditional and more contemporary experimental methods such as photoacoustic methods, e.g., Jan Thoen & Christ Glorieux, «Photothermal Techniques for Heat Capacities,» and chapters on newer research interests, including on the heat capacities of proteins and other polymeric systems (Chs. 16, 15), of liquid crystals (Ch. 17), etc.

External links[edit]

- (2012-05may-24) Phonon theory sheds light on liquid thermodynamics, heat capacity – Physics World The phonon theory of liquid thermodynamics | Scientific Reports

In thermodynamics, the specific heat capacity (symbol cp) of a substance is the heat capacity of a sample of the substance divided by the mass of the sample, also sometimes referred to as massic heat capacity. Informally, it is the amount of heat that must be added to one unit of mass of the substance in order to cause an increase of one unit in temperature. The SI unit of specific heat capacity is joule per kelvin per kilogram, J⋅kg−1⋅K−1.[1] For example, the heat required to raise the temperature of 1 kg of water by 1 K is 4184 joules, so the specific heat capacity of water is 4184 J⋅kg−1⋅K−1.[2]

Specific heat capacity often varies with temperature, and is different for each state of matter. Liquid water has one of the highest specific heat capacities among common substances, about 4184 J⋅kg−1⋅K−1 at 20 °C; but that of ice, just below 0 °C, is only 2093 J⋅kg−1⋅K−1. The specific heat capacities of iron, granite, and hydrogen gas are about 449 J⋅kg−1⋅K−1, 790 J⋅kg−1⋅K−1, and 14300 J⋅kg−1⋅K−1, respectively.[3] While the substance is undergoing a phase transition, such as melting or boiling, its specific heat capacity is technically infinite, because the heat goes into changing its state rather than raising its temperature.

The specific heat capacity of a substance, especially a gas, may be significantly higher when it is allowed to expand as it is heated (specific heat capacity at constant pressure) than when it is heated in a closed vessel that prevents expansion (specific heat capacity at constant volume). These two values are usually denoted by

The term specific heat may also refer to the ratio between the specific heat capacities of a substance at a given temperature and of a reference substance at a reference temperature, such as water at 15 °C;[4] much in the fashion of specific gravity. Specific heat capacity is also related to other intensive measures of heat capacity with other denominators. If the amount of substance is measured as a number of moles, one gets the molar heat capacity instead, whose SI unit is joule per kelvin per mole, J⋅mol−1⋅K−1. If the amount is taken to be the volume of the sample (as is sometimes done in engineering), one gets the volumetric heat capacity, whose SI unit is joule per kelvin per cubic meter, J⋅m−3⋅K−1.

One of the first scientists to use the concept was Joseph Black, an 18th-century medical doctor and professor of medicine at Glasgow University. He measured the specific heat capacities of many substances, using the term capacity for heat.[5]

Definition[edit]

The specific heat capacity of a substance, usually denoted by

where

Like the heat capacity of an object, the specific heat capacity of a substance may vary, sometimes substantially, depending on the starting temperature

These parameters are usually specified when giving the specific heat capacity of a substance. For example, «Water (liquid):

However, the dependency of

Specific heat capacity is an intensive property of a substance, an intrinsic characteristic that does not depend on the size or shape of the amount in consideration. (The qualifier «specific» in front of an extensive property often indicates an intensive property derived from it.[8])

Variations[edit]

The injection of heat energy into a substance, besides raising its temperature, usually causes an increase in its volume and/or its pressure, depending on how the sample is confined. The choice made about the latter affects the measured specific heat capacity, even for the same starting pressure

- If the pressure is kept constant (for instance, at the ambient atmospheric pressure), and the sample is allowed to expand, the expansion generates work as the force from the pressure displaces the enclosure or the surrounding fluid. That work must come from the heat energy provided. The specific heat capacity thus obtained is said to be measured at constant pressure (or isobaric), and is often denoted

,

, etc.

- On the other hand, if the expansion is prevented — for example by a sufficiently rigid enclosure, or by increasing the external pressure to counteract the internal one — no work is generated, and the heat energy that would have gone into it must instead contribute to the internal energy of the sample, including raising its temperature by an extra amount. The specific heat capacity obtained this way is said to be measured at constant volume (or isochoric) and denoted

,

,

, etc.

The value of

Applicability[edit]

The specific heat capacity can be defined and measured for gases, liquids, and solids of fairly general composition and molecular structure. These include gas mixtures, solutions and alloys, or heterogenous materials such as milk, sand, granite, and concrete, if considered at a sufficiently large scale.

The specific heat capacity can be defined also for materials that change state or composition as the temperature and pressure change, as long as the changes are reversible and gradual. Thus, for example, the concepts are definable for a gas or liquid that dissociates as the temperature increases, as long as the products of the dissociation promptly and completely recombine when it drops.

The specific heat capacity is not meaningful if the substance undergoes irreversible chemical changes, or if there is a phase change, such as melting or boiling, at a sharp temperature within the range of temperatures spanned by the measurement.

Measurement[edit]

The specific heat capacity of a substance is typically determined according to the definition; namely, by measuring the heat capacity of a sample of the substance, usually with a calorimeter, and dividing by the sample’s mass . Several techniques can be applied for estimating the heat capacity of a substance as for example fast differential scanning calorimetry.[10][11]

Graph of temperature of phases of water heated from −100 °C to 200 °C – the dashed line example shows that melting and heating 1 kg of ice at −50 °C to water at 40 °C needs 600 kJ

The specific heat capacities of gases can be measured at constant volume, by enclosing the sample in a rigid container. On the other hand, measuring the specific heat capacity at constant volume can be prohibitively difficult for liquids and solids, since one often would need impractical pressures in order to prevent the expansion that would be caused by even small increases in temperature. Instead, the common practice is to measure the specific heat capacity at constant pressure (allowing the material to expand or contract as it wishes), determine separately the coefficient of thermal expansion and the compressibility of the material, and compute the specific heat capacity at constant volume from these data according to the laws of thermodynamics.[citation needed]

Units[edit]

International system[edit]

The SI unit for specific heat capacity is joule per kelvin per kilogram J/kg⋅K, J⋅K−1⋅kg−1. Since an increment of temperature of one degree Celsius is the same as an increment of one kelvin, that is the same as joule per degree Celsius per kilogram: J/(kg⋅°C). Sometimes the gram is used instead of kilogram for the unit of mass: 1 J⋅g−1⋅K−1 = 0.001 J⋅kg−1⋅K−1.

The specific heat capacity of a substance (per unit of mass) has dimension L2⋅Θ−1⋅T−2, or (L/T)2/Θ. Therefore, the SI unit J⋅kg−1⋅K−1 is equivalent to metre squared per second squared per kelvin (m2⋅K−1⋅s−2).

Imperial engineering units[edit]

Professionals in construction, civil engineering, chemical engineering, and other technical disciplines, especially in the United States, may use English Engineering units including the pound (lb = 0.45359237 kg) as the unit of mass, the degree Fahrenheit or Rankine (°R = 5/9 K, about 0.555556 K) as the unit of temperature increment, and the British thermal unit (BTU ≈ 1055.056 J),[12][13] as the unit of heat.

In those contexts, the unit of specific heat capacity is BTU/lb⋅°R, or 1 BTU/lb⋅°R = 4186.68J/kg⋅K.[14] The BTU was originally defined so that the average specific heat capacity of water would be 1 BTU/lb⋅°F.[15] Note the value’s similarity to that of the calorie — 4187 J/kg⋅°C ≈ 4184 J/kg⋅°C (~.07%) — as they are essentially measuring the same energy, using water as a basis reference, scaled to their systems’ respective lbs and °F, or kg and °C.

Calories[edit]

In chemistry, heat amounts were often measured in calories. Confusingly, two units with that name, denoted «cal» or «Cal», have been commonly used to measure amounts of heat:

- the «small calorie» (or «gram-calorie», «cal») is 4.184 J, exactly. It was originally defined so that the specific heat capacity of liquid water would be 1 cal/°C⋅g.

- The «grand calorie» (also «kilocalorie», «kilogram-calorie», or «food calorie»; «kcal» or «Cal») is 1000 small calories, that is, 4184 J, exactly. It was defined so that the specific heat capacity of water would be 1 Cal/°C⋅kg.

While these units are still used in some contexts (such as kilogram calorie in nutrition), their use is now deprecated in technical and scientific fields. When heat is measured in these units, the unit of specific heat capacity is usually

- 1 cal/°C⋅g («small calorie») = 1 Cal/°C⋅kg = 1 kcal/°C⋅kg («large calorie») = 4184 J/kg⋅°K[16] = 4.184 kJ/kg⋅°K.

Note that while cal is 1⁄1000 of a Cal or kcal, it is also per gram instead of kilogram: ergo, in either unit, the specific heat capacity of water is approximately 1.

Physical basis[edit]

The temperature of a sample of a substance reflects the average kinetic energy of its constituent particles (atoms or molecules) relative to its center of mass. However, not all energy provided to a sample of a substance will go into raising its temperature, exemplified via the equipartition theorem.

Monatomic gases[edit]

Quantum mechanics predicts that, at room temperature and ordinary pressures, an isolated atom in a gas cannot store any significant amount of energy except in the form of kinetic energy. Thus, heat capacity per mole is the same for all monatomic gases (such as the noble gases). More precisely,

Therefore, the specific heat capacity (per unit of mass, not per mole) of a monatomic gas will be inversely proportional to its (adimensional) atomic weight

For the noble gases, from helium to xenon, these computed values are

| Gas | He | Ne | Ar | Kr | Xe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

4.00 | 20.17 | 39.95 | 83.80 | 131.29 |

(J⋅K−1⋅kg−1) (J⋅K−1⋅kg−1)

|

3118 | 618.3 | 312.2 | 148.8 | 94.99 |

(J⋅K−1⋅kg−1) (J⋅K−1⋅kg−1)

|

5197 | 1031 | 520.3 | 248.0 | 158.3 |

Polyatomic gases[edit]

On the other hand, a polyatomic gas molecule (consisting of two or more atoms bound together) can store heat energy in other forms besides its kinetic energy. These forms include rotation of the molecule, and vibration of the atoms relative to its center of mass.

These extra degrees of freedom or «modes» contribute to the specific heat capacity of the substance. Namely, when heat energy is injected into a gas with polyatomic molecules, only part of it will go into increasing their kinetic energy, and hence the temperature; the rest will go to into those other degrees of freedom. In order to achieve the same increase in temperature, more heat energy will have to be provided to a mol of that substance than to a mol of a monatomic gas. Therefore, the specific heat capacity of a polyatomic gas depends not only on its molecular mass, but also on the number of degrees of freedom that the molecules have.[17][18][19]

Quantum mechanics further says that each rotational or vibrational mode can only take or lose energy in certain discrete amount (quanta). Depending on the temperature, the average heat energy per molecule may be too small compared to the quanta needed to activate some of those degrees of freedom. Those modes are said to be «frozen out». In that case, the specific heat capacity of the substance is going to increase with temperature, sometimes in a step-like fashion, as more modes become unfrozen and start absorbing part of the input heat energy.

For example, the molar heat capacity of nitrogen N

2 at constant volume is

2 (736 J⋅K−1⋅kg−1) is greater than that of an hypothetical monatomic gas with the same molecular mass 28 (445 J⋅K−1⋅kg−1), by a factor of 5/3.

This value for the specific heat capacity of nitrogen is practically constant from below −150 °C to about 300 °C. In that temperature range, the two additional degrees of freedom that correspond to vibrations of the atoms, stretching and compressing the bond, are still «frozen out». At about that temperature, those modes begin to «un-freeze», and as a result

Derivations of heat capacity[edit]

Relation between specific heat capacities[edit]

Starting from the fundamental thermodynamic relation one can show,

where,

A derivation is discussed in the article Relations between specific heats.

For an ideal gas, if

where

Specific heat capacity[edit]

The specific heat capacity of a material on a per mass basis is

which in the absence of phase transitions is equivalent to

where

For gases, and also for other materials under high pressures, there is need to distinguish between different boundary conditions for the processes under consideration (since values differ significantly between different conditions). Typical processes for which a heat capacity may be defined include isobaric (constant pressure,

A related parameter to

For pure homogeneous chemical compounds with established molecular or molar mass or a molar quantity is established, heat capacity as an intensive property can be expressed on a per mole basis instead of a per mass basis by the following equations analogous to the per mass equations:

where n = number of moles in the body or thermodynamic system. One may refer to such a per mole quantity as molar heat capacity to distinguish it from specific heat capacity on a per-mass basis.

Polytropic heat capacity[edit]

The polytropic heat capacity is calculated at processes if all the thermodynamic properties (pressure, volume, temperature) change

The most important polytropic processes run between the adiabatic and the isotherm functions, the polytropic index is between 1 and the adiabatic exponent (γ or κ)

Dimensionless heat capacity[edit]

The dimensionless heat capacity of a material is

where

- C is the heat capacity of a body made of the material in question (J/K)

- n is the amount of substance in the body (mol)

- R is the gas constant (J⋅K−1⋅mol−1)

- N is the number of molecules in the body. (dimensionless)

- kB is the Boltzmann constant (J⋅K−1)

Again, SI units shown for example.

Read more about the quantities of dimension one[22] at BIPM

In the Ideal gas article, dimensionless heat capacity

Heat capacity at absolute zero[edit]

From the definition of entropy

the absolute entropy can be calculated by integrating from zero kelvins temperature to the final temperature Tf

The heat capacity must be zero at zero temperature in order for the above integral not to yield an infinite absolute entropy, thus violating the third law of thermodynamics. One of the strengths of the Debye model is that (unlike the preceding Einstein model) it predicts the proper mathematical form of the approach of heat capacity toward zero, as absolute zero temperature is approached.

Solid phase[edit]

The theoretical maximum heat capacity for larger and larger multi-atomic gases at higher temperatures, also approaches the Dulong–Petit limit of 3R, so long as this is calculated per mole of atoms, not molecules. The reason is that gases with very large molecules, in theory have almost the same high-temperature heat capacity as solids, lacking only the (small) heat capacity contribution that comes from potential energy that cannot be stored between separate molecules in a gas.

The Dulong–Petit limit results from the equipartition theorem, and as such is only valid in the classical limit of a microstate continuum, which is a high temperature limit. For light and non-metallic elements, as well as most of the common molecular solids based on carbon compounds at standard ambient temperature, quantum effects may also play an important role, as they do in multi-atomic gases. These effects usually combine to give heat capacities lower than 3R per mole of atoms in the solid, although in molecular solids, heat capacities calculated per mole of molecules in molecular solids may be more than 3R. For example, the heat capacity of water ice at the melting point is about 4.6R per mole of molecules, but only 1.5R per mole of atoms. The lower than 3R number «per atom» (as is the case with diamond and beryllium) results from the “freezing out” of possible vibration modes for light atoms at suitably low temperatures, just as in many low-mass-atom gases at room temperatures. Because of high crystal binding energies, these effects are seen in solids more often than liquids: for example the heat capacity of liquid water is twice that of ice at near the same temperature, and is again close to the 3R per mole of atoms of the Dulong–Petit theoretical maximum.

For a more modern and precise analysis of the heat capacities of solids, especially at low temperatures, it is useful to use the idea of phonons. See Debye model.

Theoretical estimation[edit]

The path integral Monte Carlo method is a numerical approach for determining the values of heat capacity, based on quantum dynamical principles. However, good approximations can be made for gases in many states using simpler methods outlined below. For many solids composed of relatively heavy atoms (atomic number > iron), at non-cryogenic temperatures, the heat capacity at room temperature approaches 3R = 24.94 joules per kelvin per mole of atoms (Dulong–Petit law, R is the gas constant). Low temperature approximations for both gases and solids at temperatures less than their characteristic Einstein temperatures or Debye temperatures can be made by the methods of Einstein and Debye discussed below.

Water (liquid): CP = 4185.5 J⋅K−1⋅kg−1 (15 °C, 101.325 kPa)

Water (liquid): CVH = 74.539 J⋅K−1⋅mol−1 (25 °C)

For liquids and gases, it is important to know the pressure to which given heat capacity data refer. Most published data are given for standard pressure. However, different standard conditions for temperature and pressure have been defined by different organizations. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) changed its recommendation from one atmosphere to the round value 100 kPa (≈750.062 Torr).[notes 1]

Calculation from first principles[edit]

The path integral Monte Carlo method is a numerical approach for determining the values of heat capacity, based on quantum dynamical principles. However, good approximations can be made for gases in many states using simpler methods outlined below. For many solids composed of relatively heavy atoms (atomic number > iron), at non-cryogenic temperatures, the heat capacity at room temperature approaches 3R = 24.94 joules per kelvin per mole of atoms (Dulong–Petit law, R is the gas constant). Low temperature approximations for both gases and solids at temperatures less than their characteristic Einstein temperatures or Debye temperatures can be made by the methods of Einstein and Debye discussed below.

Relation between heat capacities[edit]

Measuring the specific heat capacity at constant volume can be prohibitively difficult for liquids and solids. That is, small temperature changes typically require large pressures to maintain a liquid or solid at constant volume, implying that the containing vessel must be nearly rigid or at least very strong (see coefficient of thermal expansion and compressibility). Instead, it is easier to measure the heat capacity at constant pressure (allowing the material to expand or contract freely) and solve for the heat capacity at constant volume using mathematical relationships derived from the basic thermodynamic laws.

The heat capacity ratio, or adiabatic index, is the ratio of the heat capacity at constant pressure to heat capacity at constant volume. It is sometimes also known as the isentropic expansion factor.

Ideal gas[edit]

[23]

For an ideal gas, evaluating the partial derivatives above according to the equation of state, where R is the gas constant, for an ideal gas

Substituting

this equation reduces simply to Mayer’s relation:

The differences in heat capacities as defined by the above Mayer relation is only exact for an ideal gas and would be different for any real gas.

Specific heat capacity[edit]

The specific heat capacity of a material on a per mass basis is

which in the absence of phase transitions is equivalent to

where

For gases, and also for other materials under high pressures, there is need to distinguish between different boundary conditions for the processes under consideration (since values differ significantly between different conditions). Typical processes for which a heat capacity may be defined include isobaric (constant pressure,

From the results of the previous section, dividing through by the mass gives the relation

A related parameter to

For pure homogeneous chemical compounds with established molecular or molar mass, or a molar quantity, heat capacity as an intensive property can be expressed on a per-mole basis instead of a per-mass basis by the following equations analogous to the per mass equations:

where n is the number of moles in the body or thermodynamic system. One may refer to such a per-mole quantity as molar heat capacity to distinguish it from specific heat capacity on a per-mass basis.

Polytropic heat capacity[edit]

The polytropic heat capacity is calculated at processes if all the thermodynamic properties (pressure, volume, temperature) change:

The most important polytropic processes run between the adiabatic and the isotherm functions, the polytropic index is between 1 and the adiabatic exponent (γ or κ).

Dimensionless heat capacity[edit]

The dimensionless heat capacity of a material is

where

is the heat capacity of a body made of the material in question (J/K),

- n is the amount of substance in the body (mol),

- R is the gas constant (J/(K⋅mol)),

- N is the number of molecules in the body (dimensionless),

- kB is the Boltzmann constant (J/(K⋅molecule)).

In the ideal gas article, dimensionless heat capacity

More generally, the dimensionless heat capacity relates the logarithmic increase in temperature to the increase in the dimensionless entropy per particle

Alternatively, using base-2 logarithms,

Heat capacity at absolute zero[edit]

From the definition of entropy

the absolute entropy can be calculated by integrating from zero to the final temperature Tf:

Thermodynamic derivation[edit]

In theory, the specific heat capacity of a substance can also be derived from its abstract thermodynamic modeling by an equation of state and an internal energy function.

State of matter in a homogeneous sample[edit]

To apply the theory, one considers the sample of the substance (solid, liquid, or gas) for which the specific heat capacity can be defined; in particular, that it has homogeneous composition and fixed mass

The state of the material can then be specified by three parameters: its temperature

Those variables are not independent. The allowed states are defined by an equation of state relating those three variables:

For some simple materials, like an ideal gas, one can derive from basic theory the equation of state

Conservation of energy[edit]

The absolute value of this quantity is undefined, and (for the purposes of thermodynamics) the state of «zero internal energy» can be chosen arbitrarily. However, by the law of conservation of energy, any infinitesimal increase

hence

If the volume of the sample (hence the specific volume of the material) is kept constant during the injection of the heat amount

where

For the heat capacity at constant pressure, it is useful to define the specific enthalpy of the system as the sum

therefore

If the pressure is kept constant, the second term on the left-hand side is zero, and

The left-hand side is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure

Connection to equation of state[edit]

In general, the infinitesimal quantities

Here

This analysis also holds no matter how the energy increment

Relation between heat capacities[edit]

For any specific volume

and

for any values of

Then, from the fundamental thermodynamic relation it follows that

This equation can be rewritten as

where

both depending on the state

The heat capacity ratio, or adiabatic index, is the ratio

Calculation from first principles[edit]

The path integral Monte Carlo method is a numerical approach for determining the values of heat capacity, based on quantum dynamical principles. However, good approximations can be made for gases in many states using simpler methods outlined below. For many solids composed of relatively heavy atoms (atomic number > iron), at non-cryogenic temperatures, the heat capacity at room temperature approaches 3R = 24.94 joules per kelvin per mole of atoms (Dulong–Petit law, R is the gas constant). Low temperature approximations for both gases and solids at temperatures less than their characteristic Einstein temperatures or Debye temperatures can be made by the methods of Einstein and Debye discussed below. However, attention should be made for the consistency of such ab-initio considerations when used along with an equation of state for the considered material.[26]

Ideal gas[edit]

For an ideal gas, evaluating the partial derivatives above according to the equation of state, where R is the gas constant, for an ideal gas[27]

Substituting

this equation reduces simply to Mayer’s relation:

The differences in heat capacities as defined by the above Mayer relation is only exact for an ideal gas and would be different for any real gas.

See also[edit]

Physics portal

- Specific heat of melting (Enthalpy of fusion)

- Specific heat of vaporization (Enthalpy of vaporization)

- Frenkel line

- Heat capacity ratio

- Heat equation

- Heat transfer coefficient

- History of thermodynamics

- Joback method (Estimation of heat capacities)

- Latent heat

- Material properties (thermodynamics)

- Quantum statistical mechanics

- R-value (insulation)

- Specific heat of vaporization

- Specific melting heat

- Statistical mechanics

- Table of specific heat capacities

- Thermal mass

- Thermodynamic databases for pure substances

- Thermodynamic equations

- Volumetric heat capacity

Notes[edit]

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the «Gold Book») (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) «Standard Pressure». doi:10.1351/goldbook.S05921.

References[edit]

- ^ Open University (2008). S104 Book 3 Energy and Light, p. 59. The Open University. ISBN 9781848731646.

- ^ Open University (2008). S104 Book 3 Energy and Light, p. 179. The Open University. ISBN 9781848731646.

- ^ Engineering ToolBox (2003). «Specific Heat of some common Substances».

- ^ (2001): Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed.; as quoted by Encyclopedia.com. Columbia University Press. Accessed on 2019-04-11.

- ^

Laidler, Keith, J. (1993). The World of Physical Chemistry. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-855919-4. - ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-06-04, retrieved 2021-12-16

- ^ «Water – Thermal Properties». Engineeringtoolbox.com. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, Physical Chemistry Division. «Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry» (PDF). Blackwell Sciences. p. 7.

The adjective specific before the name of an extensive quantity is often used to mean divided by mass.

- ^ Lange’s Handbook of Chemistry, 10th ed. page 1524

- ^ Quick, C. R.; Schawe, J. E. K.; Uggowitzer, P. J.; Pogatscher, S. (2019-07-01). «Measurement of specific heat capacity via fast scanning calorimetry—Accuracy and loss corrections». Thermochimica Acta. Special Issue on occasion of the 65th birthday of Christoph Schick. 677: 12–20. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2019.03.021. ISSN 0040-6031.

- ^ Pogatscher, S.; Leutenegger, D.; Schawe, J. E. K.; Uggowitzer, P. J.; Löffler, J. F. (September 2016). «Solid–solid phase transitions via melting in metals». Nature Communications. 7 (1): 11113. Bibcode:2016NatCo…711113P. doi:10.1038/ncomms11113. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4844691. PMID 27103085.

- ^

Koch, Werner (2013). VDI Steam Tables (4 ed.). Springer. p. 8. ISBN 9783642529412. Published under the auspices of the Verein Deutscher Ingenieure (VDI). - ^

Cardarelli, Francois (2012). Scientific Unit Conversion: A Practical Guide to Metrication. M.J. Shields (translation) (2 ed.). Springer. p. 19. ISBN 9781447108054. - ^ From direct values: 1BTU/lb⋅°R × 1055.06J/BTU × (1/0.45359237)lb/kg x 9/5°R/K = 4186.82J/kg⋅K

- ^ °F=°R

- ^ °C=°K

- ^ Feynman, R., The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. 1, ch. 40, pp. 7–8

- ^ Reif, F. (1965). Fundamentals of statistical and thermal physics. McGraw-Hill. pp. 253–254.

- ^ Kittel, Charles and Kroemer, Herbert (2000). Thermal physics. Freeman. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-7167-1088-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thornton, Steven T. and Rex, Andrew (1993) Modern Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Saunders College Publishing

- ^ Chase, M.W. Jr. (1998) NIST-JANAF Themochemical Tables, Fourth Edition, In Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, Monograph 9, pages 1–1951.

- ^ «About the unit one«.

- ^ Yunus A. Cengel and Michael A. Boles,Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach, 7th Edition, McGraw-Hill, 2010, ISBN 007-352932-X.

- ^ Fraundorf, P. (2003). «Heat capacity in bits». American Journal of Physics. 71 (11): 1142. arXiv:cond-mat/9711074. Bibcode:2003AmJPh..71.1142F. doi:10.1119/1.1593658. S2CID 18742525.

- ^ Feynman, Richard The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. 1, Ch. 45

- ^ S. Benjelloun, «Thermodynamic identities and thermodynamic consistency of Equation of States», Link to Archiv e-print Link to Hal e-print

- ^ Cengel, Yunus A. and Boles, Michael A. (2010) Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach, 7th Edition, McGraw-Hill ISBN 007-352932-X.

Further reading[edit]

- Emmerich Wilhelm & Trevor M. Letcher, Eds., 2010, Heat Capacities: Liquids, Solutions and Vapours, Cambridge, U.K.:Royal Society of Chemistry, ISBN 0-85404-176-1. A very recent outline of selected traditional aspects of the title subject, including a recent specialist introduction to its theory, Emmerich Wilhelm, «Heat Capacities: Introduction, Concepts, and Selected Applications» (Chapter 1, pp. 1–27), chapters on traditional and more contemporary experimental methods such as photoacoustic methods, e.g., Jan Thoen & Christ Glorieux, «Photothermal Techniques for Heat Capacities,» and chapters on newer research interests, including on the heat capacities of proteins and other polymeric systems (Chs. 16, 15), of liquid crystals (Ch. 17), etc.

External links[edit]

- (2012-05may-24) Phonon theory sheds light on liquid thermodynamics, heat capacity – Physics World The phonon theory of liquid thermodynamics | Scientific Reports

Уде́льная теплоёмкость — физическая величина, численно равная количеству теплоты, которое необходимо передать телу массой 1 кг для того, чтобы его температура изменилась на 1 Кельвин. Удельная теплоемкость обозначается буквой c и измеряется в Дж/кг*Кельвин.

Единицей СИ для удельной теплоёмкости является джоуль на килограмм-кельвин. Следовательно, удельную теплоёмкость можно рассматривать как теплоёмкость единицы массы вещества. На значение удельной теплоёмкости влияет температура вещества. К примеру, измерение удельной теплоёмкости воды даст разные результаты при 20 °C и 60 °C.

Формула расчёта удельной теплоёмкости:

Значения удельной теплоёмкости некоторых веществ

| Элемент | Агрегатное состояние | Удельная теплоёмкость Дж/(г·K) |

|---|---|---|

| воздух (сухой) | газ | 1,005 |

| воздух (100 % влажность) | газ | 1,0301 |

| алюминий | твёрдое тело | 0,930 |

| бериллий | твёрдое тело | 1,8245 |

| латунь | твёрдое тело | 0,377 |

| олово | твёрдое тело | 0,218 |

| медь | твёрдое тело | 0,385 |

| сталь | твёрдое тело | 0,500 |

| алмаз | твёрдое тело | 0,502 |

| этанол | жидкость | 2,460 |

| золото | твёрдое тело | 0,129 |

| графит | твёрдое тело | 0,720 |

| гелий | газ | 5,190 |

| водород | газ | 14,300 |

| железо | твёрдое тело | 0,444 |

| свинец | твёрдое тело | 0,130 |

| чугун | твёрдое тело | 0,540 |

| вольфрам | твёрдое тело | 0,134 |

| литий | твёрдое тело | 3,582 |

| ртуть | жидкость | 0,139 |

| азот | газ | 1,042 |

| Нефтяные масла (фракция нефти) зависит от углеводородных составляющих | жидкость | 1,67 — 2,01 |

| кислород | газ | 0,920 |

| кварцевое стекло | твёрдое тело | 0,703 |

| вода 373К (100 °C) | газ | 2,020 |

| сусло пивное | жидкость | 3,927 |

| вода | жидкость | 4,183 |

| лёд | твёрдое тело | 2,060 |

| Значения приведены для стандартных условий, если это не оговорено особо. |

| Вещество | Агрегатное состояние | Удельная теплоёмкость кДж*(кг−1·K−1) |

Объёмная теплоёмкость кДж*(дм³−1·K−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| асфальт | твёрдое тело | 0,92 | 1,2 |

| полнотелый кирпич | твёрдое тело | 0,84 | 1,344 |

| силикатный кирпич | твёрдое тело | 1 | 1,7 |

| бетон | твёрдое тело | 0,88 | 1,7 |

| кронглас (стекло) | твёрдое тело | 0,67 | 1,709 |

| флинт (стекло) | твёрдое тело | 0,503 | 2,1 |

| оконное стекло | твёрдое тело | 0,84 | 2,1 |

| гранит | твёрдое тело | 0,790 | 2,1 |

| гипс | твёрдое тело | 1,09 | 2,507 |

| мрамор, слюда | твёрдое тело | 0,880 | 2,4 |

| песок | твёрдое тело | 0,835 | 1,2 |

| сталь | твёрдое тело | 0,47 | 3,713 |

| почва | твёрдое тело | 0,80 | |

| древесина | твёрдое тело | 1,7 | 1 |

См. также

- Теплоёмкость

- Объёмная теплоёмкость

- Скрытая теплота

Примечания

Литература

Ссылки

|

|

|

|

В этой статье не хватает ссылок на источники информации.

Информация должна быть проверяема, иначе она может быть поставлена под сомнение и удалена. |

«Количество теплоты. Удельная теплоёмкость»

Количество теплоты

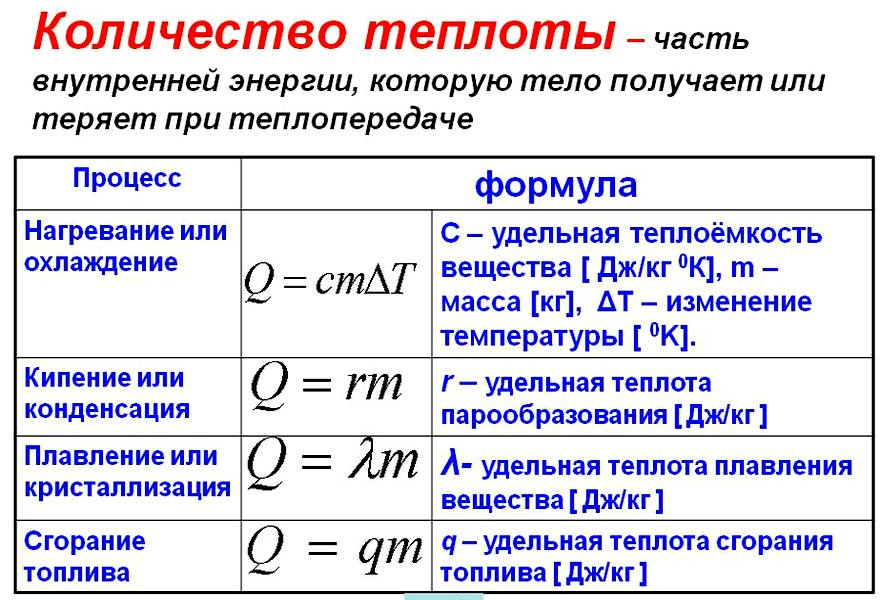

Изменение внутренней энергии путём совершения работы характеризуется величиной работы, т.е. работа является мерой изменения внутренней энергии в данном процессе. Изменение внутренней энергии тела при теплопередаче характеризуется величиной, называемой количествоv теплоты.

Количество теплоты – это изменение внутренней энергии тела в процессе теплопередачи без совершения работы. Количество теплоты обозначают буквой Q.

Работа, внутренняя энергия и количество теплоты измеряются в одних и тех же единицах — джоулях (Дж), как и всякий вид энергии.

В тепловых измерениях в качестве единицы количества теплоты раньше использовалась особая единица энергии — калория (кал), равная количеству теплоты, необходимому для нагревания 1 грамма воды на 1 градус Цельсия (точнее, от 19,5 до 20,5 °С). Данную единицу, в частности, используют в настоящее время при расчетах потребления тепла (тепловой энергии) в многоквартирных домах. Опытным путем установлен механический эквивалент теплоты — соотношение между калорией и джоулем: 1 кал = 4,2 Дж.

При передаче телу некоторого количества теплоты без совершения работы его внутренняя энергия увеличивается, если тело отдаёт какое-то количество теплоты, то его внутренняя энергия уменьшается.

Если в два одинаковых сосуда налить в один 100 г воды, а в другой 400 г при одной и той же температуре и поставить их на одинаковые горелки, то раньше закипит вода в первом сосуде. Таким образом, чем больше масса тела, тем большее количество тепла требуется ему для нагревания. То же самое и с охлаждением.

Количество теплоты, необходимое для нагревания тела зависит еще и от рода вещества, из которого это тело сделано. Эта зависимость количества теплоты, необходимого для нагревания тела, от рода вещества характеризуется физической величиной, называемой удельной теплоёмкостью вещества.

Удельная теплоёмкость

Удельная теплоёмкость – это физическая величина, равная количеству теплоты, которое необходимо сообщить 1 кг вещества для нагревания его на 1 °С (или на 1 К). Такое же количество теплоты 1 кг вещества отдаёт при охлаждении на 1 °С.

Удельная теплоёмкость обозначается буквой с. Единицей удельной теплоёмкости является 1 Дж/кг °С или 1 Дж/кг °К.

Значения удельной теплоёмкости веществ определяют экспериментально. Жидкости имеют большую удельную теплоёмкость, чем металлы; самую большую удельную теплоёмкость имеет вода, очень маленькую удельную теплоёмкость имеет золото.

Поскольку кол-во теплоты равно изменению внутренней энергии тела, то можно сказать, что удельная теплоёмкость показывает, на сколько изменяется внутренняя энергия 1 кг вещества при изменении его температуры на 1 °С. В частности, внутренняя энергия 1 кг свинца при его нагревании на 1 °С увеличивается на 140 Дж, а при охлаждении уменьшается на 140 Дж.

Количество теплоты Q, необходимое для нагревания тела массой m от температуры t1°С до температуры t2°С, равно произведению удельной теплоёмкости вещества, массы тела и разности конечной и начальной температур, т.е.

Q = c ∙ m (t2 — t1)

По этой же формуле вычисляется и количество теплоты, которое тело отдаёт при охлаждении. Только в этом случае от начальной температуры следует отнять конечную, т.е. от большего значения температуры отнять меньшее.

Это конспект по теме «Количество теплоты. Удельная теплоёмкость». Выберите дальнейшие действия:

- Перейти к следующему конспекту: «Уравнение теплового баланса»

- Вернуться к списку конспектов по Физике

- Посмотреть решение типовых задач на количество теплоты

Определение термина

Физическая величина, характеризующая, сколько тепловой энергии требуется на единицу вещества, и есть удельная теплоемкость, или энтальпия. Также она позволяет определить, сколько тепла необходимо отвести от единицы того или иного соединения, чтобы изменить на 1 градус его температуру. Неважно, по какой системе измеряется этот параметр:

- Кельвина;

- Цельсия;

- Фаренгейта.

Единицей измерения удельной теплоемкости является джоуль, поделенный на килограмм и градус Кельвина. Есть и особая, внесистемная единица, представляющая собой показатель калорий, который имеет вид произведения килограммов и градусов Цельсия. Обозначается теплоемкость удельного типа посредством специальных индексов. Допустим, в ситуации, когда наблюдаются постоянные отметки давления, используется индекс p. Когда постоянство сохраняет объем, его место занимает буква v. Единица, в которой измеряется удельная теплоёмкость — килоджоуль.

Молярная теплоёмкость – отдельный показатель. Это количество тепловой энергии, которое показывает требующееся для нагрева 1 моль вещества на каждый градус. Во время плавления выделяется также определенный объем тепловой энергии. Теплопроводность — разновидность теплопередачи, когда энергия перемещается от нагретой области вещества к более холодной, посредством передвижения частиц. На уроках физики проводится объяснение физического смысла теплоёмкости. Ее размерность обозначена так:

Физическая величина может быть охарактеризована различными способами. В частности, допускается формулировка, согласно которой ее можно представить в виде комбинации теплоемкости вещества к его массе.

Теплоемкость, в свою очередь, это физическая величина. Она отображает объем тепла, который надо подвести либо отвести от вещества для изменения показателя его температуры. Если это объект, масса которого превышает 1 кг, определять этот показатель надо, как для единичного значения.

Примеры для тех или иных веществ

Путем экспериментов удалось выяснить, что показатель является различным для тех или иных веществ. Например, в отношении воды имеется показатель 4,187 кДж. Наибольшим он является у водорода. Для него установлено нормальное значение 14,300 кДж. Наименьшее оно у золота — 0,129 кДж.

Благодаря современным достижениям науки можно увеличить скорость обнаружения интересующих значений и свойств. Если раньше приходилось искать по справочнику соответствующую таблицу, то теперь на любом телефоне появилась опция для поиска через интернет. Наиболее примечательные вещества, теплоёмкость которых представляет интерес чаще всего это:

- воздушные массы (идеальные и реальные газы) — 1,005 кДж;

- металл алюминий — 0,930 кДж;

- медь — 0,385 кДж.

Лабораторная работа

На школьных уроках определяется теплоемкость в отношении твердых веществ. Ее удаётся подсчитать при сравнении с тем показателем, который уже известен. Таблица удельной теплоемкости создана специально для удобства подсчетов.

Берут воду и твердый объект в нагретом состоянии, после чего производят замер температуры обоих. Отпускают твердое тело в жидкость и дожидаются момента теплового равновесия. Чтобы организовать такой эксперимент, необходим колориметр. Соответственно, имея такой прибор, можно пренебрегать небольшими потерями энергии.